"AT LAST!"

(Reproduced by special permission of the Proprietors of Punch.)

Punch, January 23, 1918.]

[Frontispiece.

"When there is a fervent aspiration after better things, springing from a strong feeling of human brotherhood and a firm belief in the goodness and righteousness of God, such aspiration carries with it an invincible confidence that somehow, somewhere, somewhen, it must receive its complete fulfilment; for it is prompted by the Spirit which fills and orders the Universe throughout its whole development."

J. B. Mayor: Virgil's Messianic

Eclogue.

"AT LAST!"

(Reproduced by special permission of the Proprietors of Punch.)

Punch, January 23, 1918.]

[Frontispiece.

The Women's Victory—and

After:

Personal

Reminiscences, 1911-1918

By Millicent Garrett Fawcett,

LL.D., once President, N.U.W.S.S.

London: Sidgwick & Jackson, Ltd.

First published in 1920

I wish to dedicate this little book to the thousands of faithful friends and gallant comrades whose brave unwearied work, steadfastly maintained through many years, made Women's Suffrage in Great Britain no longer a dream but a reality. Many of them have passed away, but their work, its results, and our gratitude remain. Whether in the flesh or out of the flesh, I have been accustomed to think of them as the Goodly Fellowship of the Prophets; for they foresaw what was coming, proclaimed it, and devoted themselves in making it come in the right way. All my gratitude goes out to them, especially to—

E.G.A. : C.C.O. : E.F.R. : I.O.F. :

A.G. : R.G. : E.P. : E.A. :

R.S. : E.G. : H.A. :

S.G. : I.H.W. :

E.I.

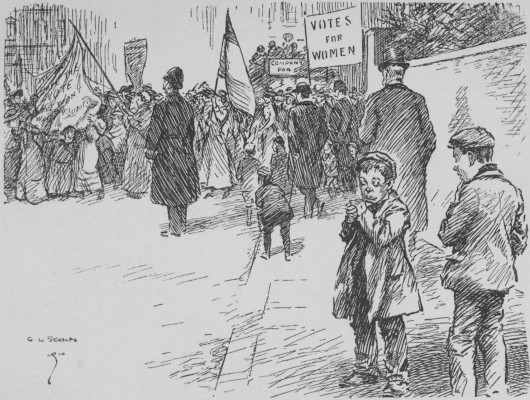

Through the kindness of the Proprietors of Punch, I am allowed to use as illustrations some of their excellent pictures demonstrating the growth of the suffrage movement. For this permission, and also for their valued support and sympathy, continued over many years, my heartfelt thanks are hereby tendered.

MILLICENT GARRETT FAWCETT.

London,

January, 1920.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE TWO DEPUTATIONS | 1 |

| II. | THE DEFEAT OF THE CONCILIATION BILL | 20 |

| III. | THE ELECTION FIGHTING FUND | 30 |

| IV. | THE FIASCO OF THE GOVERNMENT REFORM BILL | 39 |

| V. | THE PILGRIMAGE AND THE DERBY DAY, 1913 | 54 |

| VI. | THE TURN OF THE TIDE | 68 |

| VII. | THE WORLD WAR AND WOMEN'S WAR WORK | 86 |

| VIII. | WOMEN'S WAR WORK AS IT AFFECTED PUBLIC OPINION | 106 |

| IX. | THE LAST PHASE | 121 |

| X. | THE DIFFERENCE THE VOTE HAS MADE | 156 |

| APPENDIX | 169 | |

| INDEX | 173 | |

(Reproduced by special permission of the Proprietors of "Punch.")

| TO FACE PAGE | |

| "AT LAST" | frontispiece |

| THE CATCH OF THE SEASON | 16 |

| A PLEASURE DEFERRED | 52 |

| PRO PATRIA | 113 |

| THE MAN OF THE WORLD | 117 |

THE WOMEN'S VICTORY—AND AFTER

"I have a passionate love for common justice and common sense."—Sydney Smith.

In 1911 I wrote a little book called "Women's Suffrage: a Short History of a Great Movement." My intention in the following pages is to bring my story up to February 6th, 1918, when the Royal Assent was given to the Representation of the People Act, which for the first time placed women on the register of parliamentary voters.

In 1911 I ended my book on a note of confidence. I felt quite sure that we were going to win soon, but I did not the least foresee the wonderful series of events which actually led to so complete and great a victory.

Not that all the signs were favourable in 1911—very far from it. There were many ominous clouds on the horizon, and one of the chief of them was the known hostility of Mr. Asquith, then Prime Minister, and at the zenith of his power. His acuteness [2]and dexterity in offence and defence were unrivalled, and most suffragists believed that he intended to wreck our cause on the rocks of Adult Suffrage, for which there had been no demand in the country.

In 1908, almost immediately after he became Prime Minister, Mr. Asquith had announced his intention before the expiration of that Parliament to bring in an Electoral Reform Bill; this Bill, he had declared, would not include women; but he pledged his Government not officially to oppose a woman suffrage amendment "if drafted on democratic lines." The Parliament elected in 1906 with an overwhelming Liberal majority was dissolved in 1909 without the fulfilment of this intention. There were two General Elections in 1910 without the introduction of a Reform Bill. But the suffrage societies continued without intermission to keep up a tremendously active agitation for the enfranchisement of women. The various methods employed have been sufficiently described in my earlier book. It is enough here to state that a large majority of Members of the House of Commons, belonging to all parties, were pledged to support women's suffrage; that various private Members' Bills for extending the franchise to women had passed their second reading in the Commons every year since Mr. Asquith became Prime Minister; that the strength of our support in the rank and [3]file of the Liberal—and also in the Conservative—Party was constantly growing, and that the Labour Party had definitely placed the enfranchisement of women upon its official programme. In January, 1913, immediately after what will be hereafter described as the Franchise Bill fiasco of Mr. Asquith's Government, the Labour Party, at its annual conference, passed by an enormous majority a resolution reaffirming its support of women's suffrage, and calling "upon the party in Parliament to oppose any Franchise Bill in which women are not included." This was the most signal service to our cause which had then been rendered by any political party.

It was followed at the next meeting of the Trades Union Congress by the adoption of the following resolution:

"That this meeting expresses its deep dissatisfaction with the Government's treatment of the franchise question ... and protests against the Prime Minister's failure to redeem his repeated pledges to women, and calls upon the Parliamentary Committee to press for the immediate enactment of a Government Reform Bill, which must include the enfranchisement of women."

Over forty trade unions, including the most important, such as the N.U.R. and the A.S.E., adopted resolutions supporting the enfranchisement of women.

The formation of the Conciliation Committee in the House of Commons in 1910 has been sufficiently described in my earlier book (p. 73). Its object was to unite all suffragists in the House, and secure their support for a suffrage Bill which was believed to represent their greatest common measure. They decided that this would be found in a Bill to enfranchise women householders—those women, in fact, who had for about forty years been admitted to the local franchises. The Bill was called the Conciliation Bill because it had reconciled differences existing between various types of suffragists inside the House of Commons.

In July, 1910, two days of the Government's time had been given for a full-dress debate upon the Conciliation Bill. Hostile speeches from Mr. Asquith and Mr. Austen Chamberlain, on the ground of their complete opposition to all kinds of women's suffrage, were followed by equally vehement and hostile speeches from Mr. Lloyd George and Mr. Winston Churchill, on the ground that this particular Bill did not go far enough, and was so drafted as not to admit of amendment. In anticipation of, and during, the Parliamentary debate, The Times came out with a hostile article every day for nearly a fortnight, and its columns contained numerous letters prophesying all kinds of horrors and disasters which were to be expected if women were allowed to vote; many were of the type satirized in "Rejected [5]Addresses," "What fills the Butchers' Shops with Large Blue Flies?" Notwithstanding all this, the division on the Second Reading resulted in a majority of 110 for the Bill, a far larger figure than the Government had been able to command for any of its party measures.

On November 12th, in anticipation of the second General Election in 1910, Mr. Asquith gave a pledge in the House of Commons that his Government would, if still in power, give facilities in the next Parliament for "proceeding effectively" with a Bill to enfranchise women if so framed as to permit of free amendment. The second General Election of 1910 took place immediately after this, in December, and again resulted in a majority for Mr. Asquith and the Liberal Party.

On the reassembling of the new House the Conciliation Bill Committee was reformed, Lord Lytton and Mr. Brailsford again acting respectively as chairman and hon. secretary. The Bill was redrafted on the same lines as regards its provisions, but in a form which admitted of free amendment. Our friends were lucky in the ballot, and the debate and division taking place on May 5th, 1911, it was found that the majority of 110 in 1910 had grown to a majority of 167 in 1911—only 88 Members voting against it.

Militantism, or, as it would now be called, "direct action," had been suspended from the beginning [6]of 1911 in view of Mr. Asquith's promise to grant time for "proceeding effectively" with all the stages of a Suffrage Bill during that Session. It should be noted that these two suffrage victories in the House of Commons in July, 1910, and May, 1911, had taken place, in each case, when Members were fresh from contact with their constituencies after the General Elections of January and December, 1910. The contrary was often most ignorantly, if not maliciously, asserted by antisuffragists. After the big majority for the Conciliation Bill in May, 1911, Mr. Lloyd George promised that in the next Session a week of Government time should be given for the Second Reading and further stages of the Bill, assuming, of course, its having received a Second Reading. Sir Edward Grey further explained the value of this offer, and said (June 1st, 1911) that a definite opportunity had been promised to the House of Commons, and that it was important that people should understand that it was a "real opportunity," and "not a bogus offer." In a letter to Lord Lytton, dated June 15th, Mr. Asquith endorsed what Sir Edward Grey (now Viscount Grey of Fallodon) had said; and writing again on August 23rd, he made it clear that his promise applied to the Conciliation Bill, and not to any other women's suffrage measure. Therefore it was not astonishing that suffragists of all shades of opinion had high hopes of a real victory in the Session of 1912.

Then came, quite suddenly, a characteristic blow from Mr. Asquith. On November 7th, 1911, in answer to a deputation of the People's Suffrage Federation, introduced by Mr. Arthur Henderson, M.P., Mr. Asquith stated that he intended to introduce an Electoral Reform Bill during the coming Session of 1912. This Bill was to be on very wide lines; all existing franchises were to be swept away, plural voting abolished, and the period of residence materially reduced. The vote in this Bill was, Mr. Asquith said, to be based on male citizenship. His exact words were: "We believe a man's right to vote depends on his being a citizen, and primâ facie a man who is a citizen of full age and competent understanding ought to be entitled to a vote." When pressed by Mr. Henderson to say what he intended to do about women, he dismissed the inquiry with the curt remark that his opinions on the subject were well known, and had suffered no modification or change during the last few years.

The announcement made a tremendous stir, and not in suffrage circles only. The women's point of view was strongly urged in many quarters, and to an unprecedented extent by a large proportion of the general Press throughout the country.

Our own paper, The Common Cause, pointed out the bad statesmanship which acknowledged "the intolerable slur of disfranchisement" where men [8]were concerned, and professed a desire to extend the franchise to all citizens of full age and competent understanding, and yet did nothing to remove this intolerable slur from the women of the country, and thus by implication accepted the theory that women should be held in the bondage of perpetual nonage, and could never be rightly described as of competent understanding.

If this attitude on Mr. Asquith's part was intended to provoke a renewed outburst of militantism, it certainly had the desired effect. Even the mildest and most pacific of suffragists felt that she had received from the Prime Minister a personal insult. One of them, by no means identified up to that time with militant tactics, wrote to the Press that Mr. Asquith's words "had filled her with an impulse of blind rage." Those who represented the constitutional suffrage movement constantly felt themselves in face of a double danger—the discredit to their movement of the window smashing and other unjustifiable methods of violence, and the continued and often very subtle opposition of the head of the party most identified with the advocacy of parliamentary reform.

The joint deputation of all the suffrage societies to Mr. Asquith on November 18th, 1911, has been sufficiently described in what I call my first volume. I may, however, here be allowed to repeat that, on behalf of the National Union of [9]Women's Suffrage Societies, four categorical questions were then put to Mr. Asquith:

1. Was it the intention of the Government that the Reform Bill should be passed through all its stages in the Session of 1912?

2. Will the Bill be drafted in such a manner as to admit of amendments introducing women on other terms than men?

3. Will the Government undertake not to oppose such amendments?

4. Will the Government regard any amendment enfranchising women which is carried in the House of Commons as an integral part of the Bill, to be defended by the Government in all its later stages?

To each of these questions Mr. Asquith gave the answer, absolutely unqualified and unconditioned, "Certainly."

His whole attitude and manner were far more conciliatory than they had ever been before, and, whether designedly or not, certainly had the effect of strengthening our hopes of a speedy victory. Referring to his own position, he said: "It is perfectly consistent with the self-respect and the best traditions of our public life that in relation to a question which divides parties, not only the head of the Government, but the Government itself, should say that if the House of Commons on its responsibility is prepared to transform or extend a measure which we are agreed in thinking necessary—a [10]measure for the franchise as regards men—and to confer the franchise on women, we shall not only acquiesce in that proposal, but we shall treat it as the considered judgment of Parliament, and shall make ourselves responsible for carrying it out."

What a contrast these suave words presented to Mr. Asquith's method of receiving earlier suffrage deputations only those who had taken part in both could fully appreciate.

Mr. Lloyd George was present, and was pressed by the deputation to speak. He did so very briefly, and said: "I shall take the first opportunity of setting forth my views in reference to this matter.... The only thing I would say now is this, and I say it after twenty-one years' experience of Parliament: Do not commit yourselves too readily to the statement that this is a trick upon women's suffrage. If you find next year as a result of this 'trick' that several millions of women have been added in a Bill to the franchise, that this Bill has been sent to the House of Lords by the Government, and that the Government stand by that Bill, whatever the Lords do,[1] then those who have committed themselves to that ill-conditioned suggestion will look very foolish."

That closed the deputation; but Mr. Lloyd George sent the following message to the National Union [11]almost immediately afterwards: "The Prime Minister's pronouncement as to the attitude to be adopted by the Government towards the question seems to me to make the carrying of a women's suffrage amendment on broad democratic lines to next year's Franchise Bill a certainty. I am willing to do all in my power to help those who are labouring to reach a successful issue in the coming Session. Next year provides the supreme opportunity, and nothing but unwise handling of that chance can compass failure."

No doubt Mr. Lloyd George's reference to the risk of unwise handling was directed to the suffragists themselves. But it was soon to be proved that "unwise handling" was quite as likely to proceed from the head of the Government. Mr. Asquith had received the suffragists on November 18th. Twenty-six days after this, on December 14th, he received an antisuffrage deputation. It was introduced by Lord Curzon, and among those who spoke were Mrs. Humphry Ward, Miss Violet Markham, and Sir C. Henry. Mr. MacCallum Scott, Member for Bridgeton, Glasgow, was also present. In the course of his reply, Mr. Asquith made it quite clear that his sympathies were entirely with the deputation; and he encouraged them to put more vigour into their methods of opposing the extension of the franchise to women, advising them "to take off their coats," or whatever was "the equivalent [12]raiment to which he should allude when addressing ladies."

He also chaffed them genially about the Referendum, a subject on which the deputation had not been able to agree among themselves. All this was quite good sword-play, and no reasonable suffragists could fairly object to it. But there was one passage in his reply to which they did most vehemently object, as they felt that it went far to render perfectly worthless the reassuring words he had addressed to themselves about three weeks earlier. The words to which we objected were these: "As an individual I am in entire agreement with you that the grant of the parliamentary suffrage to women in this country would be a political mistake of a very disastrous kind." How could a Prime Minister reconcile it with his responsibility to his country to acquiesce in and help to carry through all its stages in both Houses of Parliament a constitutional change which he himself believed to be "a political mistake of a very disastrous kind"?

One member of the antisuffrage deputation, Mr. MacCallum Scott, M.P., interpreted this expression of his political chief as an S.O.S. call to his party, and in a letter addressed to the Standard early in the following Session he called upon his brother Liberal M.P.'s, whether they were pledged to suffrage or not, to rally to the support of the Prime Minister and to deliver him from "the humiliation" of having to [13]fulfil the promises he had made to the suffragists recounted in the earlier pages of this chapter.

From this time every possible intrigue and trick and misrepresentation were resorted to in order to defeat the suffragists when they next submitted their question to the vote of the House of Commons. Nevertheless, our strongest friends inside the Government continued to be very confident. In December, Sir Edward Grey, Mr. Asquith's Foreign Secretary, and a very leading member of the Government, and Mr. Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, addressed a large meeting of the Women's Liberal Federation in the Horticultural Hall, Westminster. Sir Edward Grey spoke strongly and very reassuringly about the practical certainty of the addition of women's suffrage to the coming Government Reform Bill, and Mr. Lloyd George made an eloquent speech in the same sense. The event proved them to have been entirely mistaken, not through our blundering, but in consequence of serious mistakes made by the Government itself.

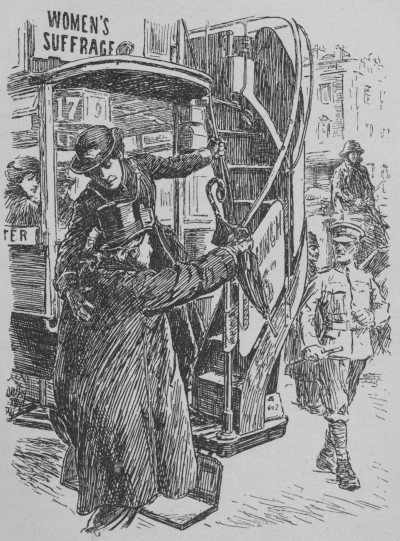

Looking back over the last years of our struggle, we could not but see that our chief antagonist was Mr. Asquith. Opposition from a Liberal, with all the Liberal traditions of devotion to the principles of representative government and a wide suffrage, was far more damaging to our cause than opposition from Conservatives. It was Mr. Asquith, more [14]than any other one person, who prevented the Liberal Party becoming a Reform Party, and including women in their general scheme of enfranchisement. In 1906, very shortly after the unprecedented Liberal triumph of that year, the Liberals returned were by an immense majority supporters of the enfranchisement of women. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the Prime Minister, was one of these, and received a large representative suffrage deputation in May of that year. He told them that they had made out a "conclusive and irrefutable case," but promised them no practical action whatever from the Government of which he was the head; the only advice which he gave the deputation was that they should go on "pestering." He evidently thought that the best course for suffragists to pursue was to make themselves as great a nuisance as possible until their claim was granted. There must have been obstacles in his own Government which prevented his giving us any more favourable answer, and there can be little doubt that these obstacles were not so much to be found among the Harcourts and the Hobhouses, but in the more formidable personality of his Home Secretary, Mr. Asquith, who was destined, as events proved, within less than two years to be his successor as Prime Minister. Mr. Asquith had no grasp whatever of the significance of our movement. When what was called "militancy" came upon the [15]scene, very much encouraged, of course, by Sir H. Campbell-Bannerman's speech, he did not attribute it, as he should have done, to the consequences of justice long delayed; he saw nothing in it but a means of defeating the whole movement, opportunities for covering its supporters with ridicule and himself with additional prestige. Thus he would in a public speech compare himself with Orpheus, and the whole suffrage party—for he then made no distinction between militants and non-militants—with the wild women of Thrace. We were "the rout that made the hideous war," and he, with mock humility, our victim. He never really understood the social and educational changes in the position of women which had been going on for the last two generations, and made a corresponding change in their political status an urgent necessity. One of his chief weapons against us was this assumed inability to distinguish between the militants and non-militants, and this was quite as much marked in the early stages of the militant movement, when nothing more tragic had been done than asking inconvenient questions at meetings, waving flags, and making speeches in the lobby of the House, and so forth, as it was later, when the militant movement became month by month increasingly aggressive and dangerous. A statesman, whether in England, India, Ireland, or Egypt, face to face with grave and persistent disorder, while [16]taking immediate steps to restore order, does not content himself with the mere employment of physical force; he enquires into the moral causes of the disorder, and seeks by wise legislation to remove them. This Mr. Asquith never did in regard to women; for his eleventh hour conversion to women's suffrage, although welcome, was more then for his own good than ours. Punch's picture of the "Conductorette" helping Mr. Asquith into the suffrage bus, with the exclamation, "Come along, sir; better late than never," exactly described his position in 1917.

THE CATCH OF THE SEASON.

Conductorette (to Mr. Asquith): "Come along, sir; better late than never."

(Reproduced by special permission of the Proprietors of Punch.)

Punch, April 4, 1917.]

[Facing page 16.

I well remember the long series of suffrage deputations which it fell to my lot to introduce to Mr. Asquith, and his gradual change of manner in receiving us. Some of the incidents of these interviews were extremely amusing, and we laughed over them as soon as we were by ourselves. The first was when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer in Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman's Government. We had with us Miss Emily Davies, the founder of Girton College; Lady Strachey, wife of the well-known Indian administrator; Miss Frances Sterling; Miss I. O. Ford; and other well-known suffrage leaders from our various societies. While we were still in the waiting-room, I was sent for by myself for a preliminary interview with Mr. Asquith's private secretary. I found him a rather agitated-looking young man, who said: "I want you, Mrs. Fawcett, [17]to give me your personal word of honour that no member of your deputation will employ physical violence." "Indeed," I replied, "you astonish me. I had no idea you were so frightened." He instantly repudiated being frightened, and I rejoined: "Someone must be frightened, or such a request would never have been made of me; but as it is made, without hesitation I give you my most solemn word of honour that no member of my deputation will either employ or threaten violence." The idea of it, considering who they were, entertained me, and I took no pains to conceal my amusement. I rejoined my deputation, and almost instantly the gentleman I had just left reappeared to conduct us to the reception room, I walking first, side by side with the secretary. As we entered the room, where Mr. Asquith was sitting with his back to the light on our right, I observed in the opposite corner on our extreme left a lady I did not know. So I said to the secretary in a clear voice, "I give no guarantee for that lady; I do not know her." "Oh, that," he rejoined, and again showed some agitation—"that lady is Miss Asquith." Members of the deputation told me afterwards that they had also seen Mrs. Asquith sitting behind her husband's chair, but I did not see her myself.[2] I remember [18]the extremely forbidding expression of Mr. Asquith's face, and how, after a little, when I was speaking to him, I ceased to look at him on this account, and looked at the space just above his head. Of course he gave us no encouragement. One of his expressions was that he "had yet to learn that there was any widely spread desire among women themselves for their enfranchisement." A member of the deputation, Miss I. O. Ford, of Leeds, who all her life had been very much in sympathy and in constant communication with industrial women in the North of England, replied to this, that if Mr. Asquith would come with her to meetings of working-women in Yorkshire, she could show him that there were thousands of women who keenly desired the vote. He replied, in his most forbidding air: "The prospect does not greatly attract me."

This interview was a specimen of Mr. Asquith in his most hostile mood. It was our lot to taste the insolence of office and the proud man's contumely. It was part of our job. We rather resented being made a show of for the benefit of his family; but this, after all, was a small matter. His manner, possibly [19]adopted to impress his wife and daughter, was indicative of his deeply seated opposition to our aims, and it was extremely interesting to watch how, by slow degrees, it was modified until it became, even while he was still in opposition to us, cordial and pleasant. Once, I remember, I could not resist saying to him that I had never seen a man so much improved. But this was very near the time when our victory was a certainty.

Suffragists had entered upon the Session of 1912 with two strings to their bow. The first was a definite promise from the Prime Minister of a week, or more if necessary, of parliamentary time for the Second Reading and all the necessary subsequent stages of the Conciliation Bill.

The second string was embodied in the series of promises given by Mr. Asquith to the suffrage deputation described in the last chapter. These promises we had been assured by Mr. Lloyd George were of the very utmost value; to cast doubt upon them was "an imputation of deep dishonour" which he vehemently repudiated. Sir Edward Grey shared Mr. Lloyd George's opinion, and assured us that we now had "a real opportunity" of victory.

Our first struggle was over the Second Reading [21]of the Conciliation Bill, and it was not long before we discovered that the dice were being loaded against us. We had, however, in our favour the big majorities for the Bill in 1910 and 1911, the promises and past support of M.P.'s of all the parties, numbering more than half the House of Commons. This position seemed too strong to be abandoned, and we therefore encouraged our friends in the House to ballot for a day for the Second Reading. The 28th of March was secured. The text and title of the Bill were exactly the same as had been read a second time the previous year by a majority of 167.

As the day for the Second Reading approached we became aware that all kinds of new influences hostile to us were in operation. These were for the most part in the nature of Lobby gossip, and, not being publicly made, could not be publicly refuted. One, however, had been made public—viz., Mr. MacCallum Scott's appeal to Liberals, published in the Standard, as mentioned in the last chapter, not to allow their leader, Mr. Asquith, to be subjected to "the humiliation" of having to fulfil the promises he had given to suffragists in the previous November. This method of detaching Liberal M.P.'s from the support of the Bill was very freely used. It was said that if this Bill were carried it would break up the Ministry, and in particular it was widely [22]rumoured that the Prime Minister and other antisuffrage members of the Government would resign. These rumours were never contradicted. Mr. Lloyd George's name was also freely used in this connection. Had he not openly expressed his dislike of the Bill? He had spoken against it in 1910; and in his speech at Bath in November, 1911, he had boasted that it had been "torpedoed" by the promise of a wider measure. The Irish Nationalists were peculiarly susceptible to the line of argument that the success of women's suffrage would mean the break up of the Government. The Home Rule Bill had been passed in all its stages twice by the House of Commons in two successive Sessions, but it required, under the Parliament Act, to be passed three times in three successive Sessions before it could be placed on the Statute Book, notwithstanding its rejection by the House of Lords. The continued violence of the militants—smashing windows, slashing the canvas of valuable pictures, burning the contents of letter-boxes, letting off explosives in empty churches, etc.—caused intense irritation and resentment among the general public, and afforded an excuse to those M.P.'s who had promised their support to our movement to break their word. On March 28th thirteen members of the Labour Party were absent in their constituencies in consequence of the labour unrest connected with the coal strike. The result of this combination of unfavourable conditions resulted in the defeat of the Bill [23]by a majority of 14. Our Labour supporters could have saved the Bill had they been present in their full strength. It was a heavy disappointment, and the utmost was of course made of it by the antisuffragists, including, first and foremost, Mr. Asquith.

Analyzing the causes of our defeat, we found that, whereas in 1911 thirty-one followers of Mr. John Redmond had supported the Bill, including Mr. William Redmond, Professor Kettle, Mr. Stephen Gwynn, and other men in a leading position in their party, in 1912 not a single one voted for it. The only Irish Nationalists who continued their support to the Bill were three O'Brienites, Mr. William O'Brien himself, Mr. Timothy Healy, and Mr. Gilhooley. Twenty-two Liberals, twelve Nationalists, and eight Conservatives, who had hitherto supported the Bill, now voted against it. A far larger number withdrew their support, but did not give a hostile vote.

What perturbed us more than anything else was the knowledge that the same underhand and unscrupulous methods which had been used to defeat the Conciliation Bill would also in all probability be used to defeat the women's suffrage amendments to the Government Reform Bill. We appealed, quite unsuccessfully, to our leading friends in the Government to check these hostile influences.

One outstanding instance of the methods employed [24]against us must here be described. Some years before, Dr. Louisa Martindale, a lady of the highest character and professional standing, belonging to a family universally respected in their place of residence in the South of England, had written a book called "Beneath the Surface." It was, in a far briefer form, on the lines of Mr. A. Flexner's well-known book on the History of Prostitution in Europe. It was in part historical and in part a warning to men and women of the physical risks connected with promiscuous sexual intercourse, and its dangers to the race as well as to the individual. The literature department of the N.U.W.S.S. stocked this volume, and placed its title in the list of books and pamphlets they were prepared to supply. Then suddenly there appeared in the list of questions to be addressed by M.P.'s to members of the Government one by the Marquis of Tullibardine (now the Duke of Atholl), to ask the Home Secretary if he intended to prosecute the N.U.W.S.S. for circulating an "obscene book," meaning the one by Dr. Martindale. The Home Secretary, Mr. R. McKenna, could give no positive answer; he must take time to make enquiries; the question must be repeated. A few days later it was repeated; again the Home Secretary delayed his reply; he found it necessary to consult the Law Officers. The Under Secretary for the Home Department answered these questions more than once, but at last owned [25]that the Law Officers advised that a prosecution would not be successful. As no one in his senses could possibly think that this little book was obscene, it would have been simpler to reply that the prosecution would be unsuccessful on this account; but this straightforward course was avoided. It became evident to us that the object of the whole business was to bring up the question in the House of Commons as often as possible with a view of prejudicing the public against the suffrage and the suffragists, and to produce the impression that we were people who delighted in the circulation of vile literature. This went on for about a fortnight, when I happened to have the opportunity of a conversation, on an entirely different subject, with a highly placed officer of the Government, a member of the House of Lords. While I was talking to him on the subject on which I had come to see him, it occurred to me to speak to him also about the little plot to discredit the suffrage movement in which the Home Secretary was playing the leading rôle. "Is it with your knowledge and consent, Lord ——," I asked, "that your colleague, Mr. McKenna, is keeping before the public as long as he possibly can the interesting fact that he is unable to make up his mind whether or not to prosecute me and the N.U.W.S.S., of which I am President, for circulating obscene literature? Three questions have already been asked on this subject in the House of Commons [26]within the last eleven days, and it is impossible to say how many more times the point will be discussed in the House and reported in every paper in Great Britain."[3] I also told him something of Dr. Louisa Martindale, her high character and first-rate professional position, and also (rather maliciously on my part) that her family were very active and highly esteemed Liberals in Sussex, and that gratuitous insults to them would be keenly resented, and might possibly even have a political reaction. He appeared startled, and, as far as I could gather, had had no previous knowledge of what had been going on. He said very little, and promised me nothing. But from that date the attack upon Dr. Martindale, her book, and the N.U.W.S.S., entirely ceased. The incident did not increase our esteem for the antisuffrage party in the House of Commons. A few months later I had proof, if proof were needed, that the Government did not seriously believe me to be a person capable of circulating obscene literature, for I was invited by the Government to become a member of the Royal Commission on Venereal Disease, a position which could certainly not have been offered if the Government had shared Mr. McKenna's doubts [27]as to my character. I was not able to accept the invitation because my suffrage work entirely absorbed me, and I saw no prospect of its claims becoming less urgent in the near future.

The Session of 1912 dragged its interminable length along. It lasted for thirteen months, from January, 1912, to January, 1913, both inclusive. The Government were slow in producing their Reform Bill. In May, however, it was brought forward, and it did not come up for Second Reading until July 12th, 1912. In the Second Reading debate Mr. Asquith, Prime Minister and Leader of the House, expressed himself as follows:

"This Bill does not propose to confer the franchise on women; whatever extensions of the franchise it makes are to male persons only. Speaking for myself, I cannot help remembering that the House at an earlier stage of the Session rejected with, I think, sufficient emphasis the proposal to confer the franchise on women; and, so far as I am concerned, I dismiss at this moment as altogether improbable the hypothesis that the House of Commons is likely to stultify itself by reversing in the same Session the considered judgment at which it has arrived."

That is to say, the rejection of the Conciliation Bill by a majority of 14 in the previous March was to be taken as "the considered judgment of the House of Commons," whereas its passage in May, 1911, by a majority of 167 counted for nothing at all. What the passage just quoted did stand for was the continued and bitter hostility of the Prime Minister [28]to women's suffrage in any form, and as a renewal of his S.O.S. call to his followers to come to his deliverance. The fortunes of all the little politicians "in the make" are absolutely in the hands of the Prime Minister—more so at that moment than perhaps at any other period of our history. To please the Prime Minister and serve his purposes indicated the road which led to success and preferment, and he made it absolutely plain what was the best possible way to please him in this matter of women's enfranchisement.

This was truly a time when we had "to go on dancing when the fiddle stopped," and we did not decline the task. We held two immense meetings in the Albert Hall, the combined collections at which totalled nearly £13,000, and also organized an even more than usually vigorous campaign throughout the country in support of the inclusion of women in the Government Reform Bill; there were twenty-one by-elections during the year, in all of which the N.U.W.S.S. took an active part, making suffrage a very live issue in the country, and we also lost no opportunity of raising the question in the House on other Bills which came before it.

But the change from a majority of 167 in 1911 to a minority of 14 in 1912 gave a fatal shock to what had hitherto been our election policy—namely, the support at all contested elections of the candidate [29](irrespective of party) whom we deemed from his answers to our questions, his personal record, and other indications, to be "the best friend of women's suffrage." When the Conciliation Bill was defeated in March, 1912, 42 of these "best friends" had voted against the Bill, and 91 had abstained from supporting it. To lean on such "friends" as these was to lean on a broken reed. We did not abandon the essential principle of our election policy, but we gave a new and improved interpretation of the meaning to be attributed to the words "best friend"; and as a result of a special council held for the purpose in May, 1912, it was decided that a friend of suffrage who had the support of his party upon our question was a better friend than one who belonged to a party which was either hostile or neutral. The immense powers of party in our politics made it practically certain that this was the only safe line to take. There were, it is true, a handful of men, in both the Liberal and Conservative ranks, who had shown themselves such strong and convinced suffragists as to be capable of disregarding the party whip when it was used against us. These we defined as "tried friends"—tried not only on the platform, but in the fiery ordeal of the House of Commons, and these we excepted from the new definition we had agreed to make of the words "the best friend of women's suffrage."

"My centre is giving way, my right wing is falling back. The situation is excellent. I am attacking."—Marshal Foch to G.H.Q.

The change of policy indicated at the end of the last chapter was adopted after full deliberation and discussion at a council meeting at which our 411 societies were represented, and at which, as was to be expected, there was an important minority who objected to it. For at this council we resolved on a change of rules. The general objects of the N.U.W.S.S. in by-elections were defined as follows:

1. To shorten the term of office of the Cabinet as at present constituted, especially by opposing antisuffrage Ministers.

2. To strengthen any party in the House of Commons which adopts women's suffrage as part of its official programme.

At by-elections we decided that the N.U. should support those candidates whose return would best promote the foregoing objects, provided that:

(a) No Government candidate should be supported.

[31](b) No candidate shall be supported who does not answer all the National Union questions in the affirmative.

Another clause provided for the exemption of "tried friends" from these regulations. It would, of course, have been an absurdity for suffragists to oppose such men as the late Mr. Walter McLaren or Lord Robert Cecil, who had shown through the stress and strain of many years of parliamentary life that they were prepared to act independently of party in cases where electoral justice to women was involved.

But our change of policy was in effect a declaration of war against the official Liberal Party and of support of the Labour Party, which was the only party which had made women's suffrage part of its programme.

This not unnaturally laid us open to the charge of having abandoned our non-party attitude; but I thought at the time, and I think still, that it was the only possible attitude for a truly non-party association such as ours to adopt. We were making no break with our non-party professions so long as we were prepared to give our whole-hearted support to any party which made the enfranchisement of women part of its programme. We found analogies in the attitude of other non-party organizations, and also in what was happening in the suffrage work in Sweden. In our own country we were [32]so far fortunate that none of the political parties had officially identified itself with opposition to suffrage. Men of unrivalled distinction in the Conservative Party for many years past had supported women's suffrage; the names of Lord Beaconsfield, Lord Salisbury (the great Prime Minister), Mr. Arthur Balfour, Lord John Manners, Lord Robert Cecil, need only be mentioned to show that it was an absolute impossibility for the Conservative Party, as a party, to oppose women's suffrage. The same could be said for the Liberals, past and present: The Hon. Charles Villiers, Mr. J. S. Mill, Sir H. Campbell-Bannerman, Sir Edward Grey, Mr. Lloyd George, Mr. Acland, and Sir John Simon, held the antisuffragists in their own party in check; moreover, the rank and file of Liberals were largely in our favour, and all the Liberal catchwords could be cited ad nauseam in our support. There could therefore be absolutely no question of opposition to women's franchise becoming an item in the Liberal programme.

In Sweden, however, the Conservative Party had definitely identified itself with antisuffragism; and the Swedish Suffrage Society, non-party like our own, had been obliged by force of circumstances to put itself into opposition to the party in their own country which definitely opposed the one object for which their society existed.

We no doubt occupied an analogous position [33]with regard to our own political situation; but we had a very important advantage in the existence of one party, the Labour Party, which had officially accepted women's suffrage, and had shown the sincerity of its support by being willing to record its votes in the House in favour of a limited form of enfranchisement for women, although its own inclinations, and probably also its party interests, were in favour of a much more extended measure. The Swedish suffragists opposed the one party which had made hostility to their enfranchisement part of its programme; the N.U.W.S.S. supported the one party which had taken the opposite course by definitely adopting women's suffrage as part of its programme. I maintain that by so doing neither the Swedish nor the British suffrage societies forfeited their claim to describe themselves as "non-party." We welcomed members of all parties into our ranks, and were prepared to give impartial support to any party which made our object its own.

It is interesting now to look back at the N.U.W.S.S. report in the year 1912, and to see the care with which we defined our position. No Government candidate was to be supported, because the Government, under Mr. Asquith, had shown the most determined opposition to our enfranchisement. When a Conservative candidate was supported, it was because we deemed this the best way of securing [34]the defeat of a Government candidate; when the Labour candidate was supported, it was made clear that this was done because the Labour Party was the only party which had made women's suffrage part of its programme, and had, moreover, rendered us the signal service of calling upon its parliamentary representatives to oppose any Franchise Bill which did not include women.

A society which disregarded such signal services as these could only be described as abandoning its non-party attitude and identifying itself with opposition to those who had shown themselves the strongest supporters of our movement.

It was not enough for us to put on record our intention of doing our best to strengthen the position of the Labour Party at by-elections; we also made plans to help Labour members to defend their seats at the time of a general election. A special committee was formed to organize the support of Labour candidates, and to raise a sum of money for this purpose. It was thus that the Election Fighting Fund was inaugurated in May, 1912. Two thousand pounds was at once subscribed in the room, before any special appeal had been made; and during the short time between the starting of the fund and the outbreak of the European War it was sufficiently replenished by constant gifts from our own members to enable us to keep up the work with vigour and efficiency. The fund [35]had not been a month in existence before it was used in support of the Labour candidate at the Holmfirth by-election; and there were shortly afterwards three other by-elections—at Hanley, Crewe, and Midlothian—at which the Election Fighting Fund and its band of organizers and speakers were used in support of Labour candidates. We were authoritatively assured that the Liberals knew that they would have held the seats at Crewe and Midlothian had the attitude of their party been satisfactory on women's suffrage. In 1913 the E.F.F. work was put into operation at Houghton-le-Spring, Keighley, and Lanark; and in 1914 in North-West Durham, Leith Burghs, and North-East Derbyshire. There were therefore ten elections in all during the almost exactly two years in which the E.F.F. policy was vigorously worked by the N.U.W.S.S., and during which six seats, counting for twelve votes in a division, were transferred from the Liberal to the Conservative side of the House. We were very well satisfied by these results, although of course disappointed that no Labour candidate had won a seat: in every case, however, the number of votes recorded for Labour had greatly increased. We had a splendid band of first-class speakers and organizers to work in each constituency; and at each successive election the whole place rang with women's suffrage and our meetings were crowded and enthusiastic—very often [36]much more crowded and enthusiastic than those of the candidates. In the first election the Liberal against whom we had worked got in, but his majority was reduced to less than half what it had been at the last contest. The next election was less satisfactory; but at the third, a seat formerly held by a Liberal by a majority of 1,704 was gained by a Conservative supporter of suffrage, and it was generally acknowledged in the district that the vigorous help of the N.U.W.S.S. was the deciding factor in defeating the Liberal candidate. The Labour candidate polled nearly double the number of votes which his party had secured at the last three-cornered contest, and consequently was the means of securing the defeat of the Government candidate. Our success at Crewe was followed by a still more notable victory in Midlothian, the famous seat won by Mr. Gladstone in 1879, and from that date looked upon as an impregnable stronghold of Liberalism. In September, 1912, the former Liberal majority of 3,157 was converted into a Conservative majority of 32, the Labour candidate, who stood for the first time, polling 2,413 votes.

It is unnecessary to go in detail through the rest of the elections in which the N.U. in 1913, and up to June, 1914, worked the E.F.F. policy for all they were worth; the specimens of which I have given details are indicative of the remainder. When [37]we were originally discussing our change of election policy, Mr. H. N. Brailsford, who had warmly pressed it upon us, said to us, "The moment that you are able by your election work to transfer seats from one side of the House of Commons to the other, the Whips and the wire-pullers will begin to treat you with respect"; and we certainly found that this was the case. In every election in which the E.F.F. committee took part, women's suffrage was the main topic of the contest, and in every case, although we did not succeed in winning the seats for Labour candidates, the value of our work in their behalf was most warmly recognized. We never in any case subsidized the Labour candidates. Their independence was jealously preserved by their own party, and correspondingly respected by us; any attempt to infringe it would have been deeply resented. Our work in the constituency was strictly our own; we held meetings, organized processions and other demonstrations, and paid our own way with the funds our own members had subscribed for the purpose. We had nothing to conceal, nor had the Labour men for whom we worked.

The N.U.W.S.S. had always interpreted "non-party" to mean that the N.U. included members of all parties within its ranks. We therefore naturally chose as our speakers and organizers to carry out our E.F.F. work from among those of [38]our members whose personal sympathies were with the Labour Party.

The whole movement had been a source of strength to our Union, and we were looking forward to further developments when all schemes for this object were cut short by the outbreak of war on August 4th, 1914. A special meeting of the E.F.F. committee was held immediately, and decided at once that during the war the Election Fighting Fund should be used to employ the E.F.F. staff for the time being on relief work only. This will be further described in a future chapter, which will deal with the general activities of the N.U.W.S.S. during the war.

"If we can't win as fast as we could wish, we know that in the long run our opponents cannot win at all."—John Bright.

We were at this time receiving a great deal of good advice from suffrage members of the Cabinet. One of them, who ought to have known better, advised us to rouse public opinion in our support. "Why," he said, "do you not hold a few meetings, and get good speakers, like Miss Royden, to address them?" We replied that we had held 4,000 public meetings in the last four months, filling the largest halls again and again, and that Miss Royden, never very robust, had nearly killed herself by fulfilling the constant demands that were made upon her for speeches at our innumerable demonstrations. She had spoken 267 times in the last twelve months. We reminded him that there had been no agitation at all by men for a wider franchise for themselves; there had been a persistent and strenuous demand by women for their own enfranchisement; and the only official reply of the Government was to promise [40]a Bill for more suffrage to men, and no suffrage at all for women. All this was, of course, so much more grist to the mill at which we had to grind out perpetual speeches. This, as we did not fail to point out, illustrated the value of a vote: voters could get what they wanted without even asking for it; whereas the voteless had to devote years and generations, and to spend thousands of pounds, in order to voice persistent demands on the part of women for representation, demands which were as persistently and determinedly passed by unnoticed, and we were asked why we did not hold a few meetings! The House of Commons seems scarcely capable of giving intelligent attention to any subject unless it is forced to undertake the excruciating pain of thought by the demands made by voters in the constituencies. The most remarkable social revolution had been taking place for the last fifty years in the educational and professional and industrial status of women; all we asked was that a corresponding change should be made in their political status; but up to the present the only reply we could get from the Government had been rightly described by one of its members as "shuffling and delay."

At this time we derived a sort of sorry consolation by the articles which appeared in the Press on the expiration of the twenty years during which the development of motor travelling in this country [41]had been held back by ignorant legislation. The public were reminded that the first Act passed by Parliament in regard to automobile traffic enjoined that motors must not exceed the pace of four miles an hour, and must be preceded by a man on foot waving a red flag! The moral for us was that if our legislators could so little read the signs of the times in regard to a comparatively simple matter like the development of motor transport, it was not astonishing that they were at least as incapable of reading the signs of the times in regard to a great human movement which was gradually, in almost every part of the world, raising the position of women from absolute subjection to free citizenship. Our spirits were raised, too, by the fact that, though we were not winning in our own Parliament, we were winning in other Parliaments and everywhere else. A Czech woman had been returned to the Diet in Bohemia; and three new States were won for suffrage in the U.S.A. Barriers in other directions were everywhere breaking down. The very same papers which reported Mr. Asquith's reception of the antisuffrage deputation in December, 1911, when he confessed his unaltered and unalterable opposition to women's suffrage, also contained the announcement of the election of the first woman to the fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons. The more intelligent of the antisuffragists, such as Mrs. Humphry Ward, were constantly proclaiming [42]their sympathy with every step in the development of women's freedom which had already been won, such as their share in, and responsibility for, local government. In her society she was at the labouring oar, and must have been conscious that no popular movement could exist whose programme offered nothing but negatives. She felt the need of a positive programme, and even announced her intention of using the machinery of the Society for Opposing the Extension of the Parliamentary Suffrage to Women for promoting their activity in Local Government and the election of women to Local Government bodies. But she was sharply pulled up for this by Lord Curzon, who said at a meeting of the society, as reported in the Antisuffrage Review: "The funds we collect are given primarily, and I think exclusively, for resistance to the parliamentary vote for women. It is for that purpose, and that purpose alone, that our organization exists.... I hope you will be quite clear about that." Of course Mrs. Humphry Ward had to give way. Had she not just said at this same meeting "how necessary was the maintenance of the male hand upon the helm of English Government"? But the male hand of the politician is capable of adaptability to changed circumstances. Lord Curzon, twenty years earlier, had succeeded in reversing the decision of the Royal Geographical Society to elect women as Fellows—an innovation [43]which he then considered "most injurious to men and disastrous to women." Further experience must have convinced him that this injury to men and disaster to women would be a source of strength to the society; for when he found himself in the position of President of the R.G.S., and responsible with others for the increased cost of far larger and more commodious premises, he himself promoted and, I believe, proposed the election of women to the society. Council's opinion was taken, and was to the effect that "on the true construction of the charter and by-laws women were admissible." The noble President therefore had the solace of finding that the law was on his side when he said, "Ay."

The difference between Mrs. Humphry Ward and her chief in 1912 may have been the prototype of the greater difference which divided them in 1918. But at the earlier date it was Mrs. Ward who wished to go forward, and Lord Curzon who resolutely refused to follow; in 1918 the rôles were reversed. It was Lord Curzon who bowed to the inevitable and Mrs. Ward who vehemently protested that the "male hand" had betrayed her.[4]

We now resume the thread of our story in 1912 after the defeat of the Conciliation Bill by 14 votes on March 28th. One of its results was the change in the election policy of the N.U.W.S.S. described [44]in the last chapter. Outside of this, our work was concentrated on securing all possible support for the women's suffrage amendments to the Government Franchise Bill. One important advantage was gained when Mr. Redmond gave a definite promise that his party would be left free to vote on women's suffrage according to their personal convictions. The Irish Nationalists, who had in a body deserted the Conciliation Bill, had been very severely criticized for this by their own supporters, both in this country and in Ireland.

The women's suffrage amendments to be moved to the Government Bill were four in number. The first stood in the name of the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey. It was to delete the word "male" from the first clause. It will be remembered that Mr. Asquith, in the previous July, had said in reference to the Bill, "Whatever extensions of the franchise it makes are to male persons only," and the Bill, therefore, had been drafted in this sense. The deletion of the word "male" from the first clause would not in itself have enfranchised a single woman, but, if accepted by the House, it would have rendered the inclusion of women by amendment a possibility. Three amendments to include women were therefore drafted, representing three degrees of comparison, corresponding, roughly, to the degrees of enthusiasm of different sections of the House for the free citizenship of women.

The first amendment represented the views of the Labour Party, and also corresponded with the aims of practically every suffrage society: it demanded the vote for women on the same terms as men. Under the new franchises contemplated in the Bill this would have enfranchised about ten and a half millions of women. We had little hope that this amendment would be carried, as our belief was that Parliament would not consent to the creation of an electorate in which women decidedly outnumbered men. Mr. Arthur Henderson, Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party, undertook to move this amendment. He was a very stanch friend of our movement, and could be relied on to support the other amendments if his own were lost.

The second amendment was to create what was virtually household suffrage for women, and proposed to give the franchise to all women over twenty-five years of age who were householders or wives of householders. It was believed that this amendment would enfranchise about six and a half millions of women. It was to be moved by Mr. (now Sir) W. H. Dickinson, also a very stalwart friend, whose tenacity had been tested on many occasions.

The third amendment, to be moved by the Hon. Alfred Lyttelton if the first and second were lost, was on the lines of the Conciliation Bill, and would have enfranchised women householders only, of [46]whom it was known there were about one and a half millions in England and Wales. Committees on party lines were organized in the House of Commons in support of these amendments, Mr. Henderson, Mr. Stephen Walsh, and Mr. Snowden, being especially active on behalf of the Labour Party; Mr. Acland, Sir Alfred Mond, the Hon. H. D. McLaren, and Mr. Dickinson, on behalf of the Liberals; Lord Robert Cecil, Mr. Goulding, Lord Wolmer, and Sir W. Bull, on behalf of the Conservatives. Members of the Government could not join these committees; but some, such as Sir John Simon, gave very valuable help and advice. The great point to aim at was to maintain the unity of the suffragists in all the parties, and thus to secure a united vote in support of any suffrage amendment which recommended itself to the House as a whole. We therefore endeavoured to obtain promises, in the event of one amendment being defeated, that those Members who had preferred it should transfer their support to the next. The Labour Party, inside and outside the House, was particularly firm and outspoken in support of this policy. "We intend to stand by the women through thick and thin," said one of their leaders. "I will fight for them, amendment by amendment, with all the strength that is in me." The annual congress of the Labour Party backed us up by the resolution recorded on p. 3. The Trade Union [47]Congress also adopted a very strong suffrage resolution.

But we soon found the parliamentary air thick with the intrigue and gossip which had succeeded in defeating the Conciliation Bill. Rumours and threats of resignation if any form of women's suffrage were carried were rife. One "Right Honourable gentleman" would take an Irish Nationalist on one side and remark casually that it was lamentable to think, after the long struggle for Home Rule, that it would be destroyed after all by the break up of the Government over women's suffrage. Sir Edward Grey, intending to counteract these rumours, rather intensified them by writing to a suffrage meeting in Glasgow in December indicating that resignation was a game which two could play at, and if antisuffrage Ministers resigned as a result of the success of one or other of the suffrage amendments, then non-success must equally be followed by the resignation of Ministers like himself pledged to its support.

It has already been noted that the Session of 1912 had begun in January; the Second Reading of the Government Reform Bill had been taken in July; on the reassembling of Parliament for the autumn Session October and November went by with no signs of any further progress with the Bill. It was the constant subject of conversation and discussion in the Lobbies, in the Press, and in general society, and many public meetings were held, but no parliamentary [48]progress was made; and when this state of things continued over the Christmas recess, and the lengthy Session of 1912 was prolonged into 1913, the more experienced of suffragists were asking each other how it could be a physical possibility to pass a controversial measure like a Reform Bill through all its stages in both Houses of Parliament at the tail end of a Session which had already lasted nearly thirteen months.

An influential meeting in support of the more democratic of the suffrage amendments to the Reform Bill had been held in the Opera House in Kingsway on December 4th. Important speeches were made by Mr. F. D. Acland, Sir John Simon, leading Liberal women, and others; but the difficulties and confusion inside the House caused by the Prime Minister's statement in the Second Reading debate, that he "could not suppose that the House would so far stultify itself as to reverse the considered judgment it had already arrived at," continued to darken the outlook, particularly by encouraging the rumours of the resignation of antisuffrage Ministers and the consequent break up of the Administration. It is to be noted that no official contradiction was given to these very prevalent rumours of resignation until the day before the House expected to go into Committee on the Bill, January 22nd, 1913. But the coup de grâce for the Reform Bill and those who were responsible for it came [49]from an altogether unexpected quarter. Three days, January 24th, 27th, and 28th, had been allotted to the women's suffrage amendments under a special "guillotine" time-table. This stage, however, was never reached, for on January 23rd Mr. Bonar Law asked the Speaker to give a ruling on the point whether the Government's own amendments to the Bill, regarding the occupation franchise for men, would not so far alter the Bill from that which had received a Second Reading in July as to necessitate its withdrawal and reintroduction in an altered form. The implied argument was, "the Bill which the House read a second time in July is not the same Bill which it is now asked to consider in committee." The Speaker replied that though he could not at that stage give a definite ruling, it was, in point of fact, his opinion that the Bill was not the Bill to which the House had assented in July, and he added that there were "other amendments regarding female suffrage which, of course, would make a huge difference in the Bill if they were inserted." The blow to the whole Bill thus foreshadowed fell like a thunder-bolt on the House, and on no portion of it more severely than on the Government, especially on the Prime Minister. Ever since May, 1908, when first Mr. Asquith had become Prime Minister, he had given various forecasts and promises about this Bill, and especially on his attitude and that of his Government to women [50]suffrage amendments. Now all these promises and forecasts were proved to be absolutely worthless, mere scraps of paper; and this owing to the conduct of the Bill by the Government itself. Whether the Speaker's ruling, which was given definitely a day or two later, was based on the incorrect naming of the Bill,[5] or on the fact that in the Second Reading debate Mr. Asquith had told the House definitely, "This Bill does not propose to confer the suffrage on women, and whatever extensions of the franchise it makes are to male persons only," was never, according to my knowledge, made public. What everybody knew was that the Government had blundered badly, that its chief had given promises which by his own action he was powerless to fulfil, and that the proposed Reform Bill promised by him in 1908, 1910, and 1911 was a complete fiasco. The new situation proved to every suffragist that our measure could never be carried through all its parliamentary stages unless it was brought forward by a united Cabinet as a Government measure. The day for such success as could be attained by a private Member's Bill was long passed.

A very considerable number of the general public were under the impression that we had been "had"; and there were many among suffragists who thought that a deliberate fraud or trick had been practised [51]upon us. I never shared this view. The blow was much more a blow to the Government than to the suffrage movement. It did not harm our movement in public opinion. On the contrary, public opinion was with us; the prestige and authority of the Government were lowered; and they did nothing to retrieve their position so far as we were concerned. If the Prime Minister had sent for the representatives of the suffrage societies, the Women's Liberal Federation, and other bodies standing for suffrage which had formed the deputation in November, 1911, and had said, "I have given you promises which it is unfortunately out of my power to fulfil; will you suggest any course which would be a reasonable substitute in fulfilment of my pledges?" he would have put the onus of the acceptance or rejection of such an offer upon us; but he did nothing of the sort. We asked him to receive us, but he refused to meet us or to hold any communication with us on the subject. His position, therefore, was that his promises remained unredeemed, and he made no effort to redeem them. It is true that he offered parliamentary time for the discussion of a Second Reading of a private Member's Bill. But it needed not to be a Daniel or a Solomon to see that a private Member's Bill, of which seven had passed Second Reading in the last four years, and four of them in 1908, 1909, 1910, and 1911, was no substitute for a place in a Government Bill, which, if adopted by the House, would be regarded by the Government [52]as an integral part of the measure, and defended in all its stages in both Houses of Parliament. We were furiously indignant. If a man who had owed £1,000 suddenly became bankrupt, and declined any meeting with his creditors, but offered them 1,000 gilded cardboard discs, he could not expect this conduct to assuage their indignation or soften their anger against him, for he would first have robbed them and then treated them as if they were children. One of the papers which usually supported the Government put the case thus: "If A and B arrange a deal, and A is unavoidably prevented from delivering the goods for which B bargained, it is not open to A to offer a different class of goods till he has had B's consent to the substitution." We remembered how, when the militant suffragists had said that Mr. Asquith's promises were worthless, Mr. Lloyd George had indignantly and forcibly retaliated that such a doubt was "an imputation of deep dishonour" which he absolutely repudiated. We took pleasure in recalling Dr. Johnson's description of the Duke of Devonshire of his time, and contrasting it with Mr. Asquith, to the latter's disadvantage. "If," said the Doctor of the third Duke, "he had promised you an acorn and none had grown in his woods that year, he would not have contented himself with that excuse; he would have sent to Denmark for it. So unconditional was he in keeping his word, so high his point of honour." If that was the sort of man the [53]Duke of Devonshire was, it was the sort of man Mr. Asquith was not. The N.U.W.S.S. decided at its council meeting in February, 1913, to take no part in supporting by work in the constituencies or inside the House this private Member's Bill. Our reasons were that we were now convinced that nothing but a Government Bill, backed by a united Cabinet, would be of any practical service to our cause. Of course the N.U.W.S.S. could never, under any circumstances, oppose any Bill which enfranchised any women, few or many; but we took no part whatever in its support. It came on for Second Reading in May, 1913, and met with the defeat to which from the beginning it had been foredoomed.

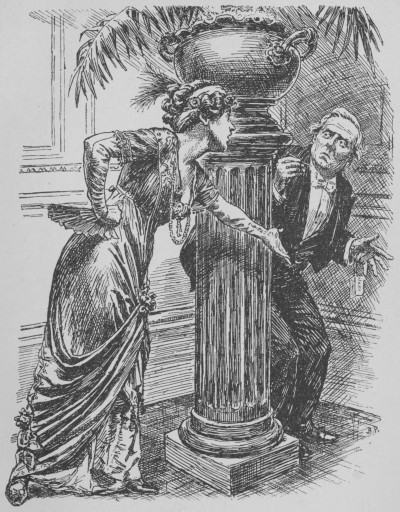

A PLEASURE DEFERRED.

Suffragist: "You've cut my dance!"

Mr. Asquith: "Yes, I know. The fact is the M.C. objected to the pattern of my waistcoat, and I had to go home and change it. But I'll tell you what! Let me put you down for an extra at our private subscription dance next season!"

(Reproduced by special permission of the Proprietors of Punch.)

Punch, February 5, 1913.]

[Facing page 52.

The last four years had witnessed the steady advance of the suffrage cause. It was now in the forefront of practical politics, and was a question which had led to more than one serious Cabinet crisis, and was capable of making or unmaking Governments. We held steadfastly to our resolution to work for nothing in Parliament but a Government measure backed by a united Cabinet. Our chief practical consideration was how to do this on constitutional lines and by non-party means. Our friend and colleague, Mrs. Harley, suggested what we afterwards called "The Pilgrimage," and her idea was taken up and carried out with enthusiasm by the whole National Union. An account of the Pilgrimage will form the subject of the next chapter.

"Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof."—Lev. xxv. 10.

The Pilgrimage was a piece of work which could only have been undertaken successfully by a powerful organization, and such the N.U.W.S.S. certainly was. We had divided the whole area of Great Britain into nineteen federations; in each federation there was a working committee meeting regularly, whose aim was to form a non-militant, non-party women's suffrage society in every parliamentary borough in its area. Each federation and each society aimed at being self-supporting; but the large sums, amounting to many thousands of pounds, collected at our big Albert Hall demonstrations in London enabled the executive committee of the whole N.U.W.S.S. to make grants for special work to specified societies or federations. Our organization was thoroughly democratic, the executive committee and all the officers being subject to election at our annual council meetings, where each society could claim representation in proportion [55]to its numbers. No new departure in policy could be undertaken without the authority of the council. In 1913 we had over 400 societies, and they were constantly increasing; in 1914, just before the war, there were over 600. We calculated that, adding together the central funds, the Election Fighting Fund, and the funds raised and expended by our societies locally, the National Union at this time was using over £45,000 a year for the furtherance of the enfranchisement of women.

We were giving full time employment to scores of organizers, mostly highly intelligent young women of University education, who not only did admirable propaganda work throughout the country, but kept headquarters informed of all important local developments and incidents bearing on our movement.

The Pilgrimage was a march of bands of our societies, all non-militant suffragists, from every part of Great Britain, converging on London, and so arranged as to reach their goal on the same day. Eight routes were selected: the great North Road, the Fen Country, the East Coast, Watling Street, the West Country Road, the Portsmouth Road, the Brighton Road, and the Kentish Pilgrims' Way. In each case the Pilgrimage procession started at the point most distant from London, carrying banners, and accompanied, where possible, by music. The pilgrims were prepared to stop and [56]hold meetings, distribute literature, and collect funds in towns and villages en route. As they proceeded their numbers rolled up; friends lent motor-cars for conveying luggage, and the most wonderfully generous hospitality was extended to them all along the route, especially in the towns where we had powerful societies. This we might have been said to expect; but what surprised us was the extraordinarily warm welcome we received from the villages we passed through. Once their inhabitants understood that we were non-militant, and had no desire to injure anybody or anything, they gave us the most cordial reception; indeed, we were often stopped as we were passing through villages which we had deemed hardly large enough for a meeting with the remonstrance, "You are surely never going to pass us by without saying a word!"

The meetings in the towns were not so uniformly friendly. Hooligans sometimes declined to believe that we were non-militant, and demonstrated their enthusiasm for law and order by throwing dead rats, potatoes, rotten eggs, and other garbage, at our speakers. No real harm was done to any of us, but occasionally the services of the police were needed to protect our speakers. This, however, was exceptional, and had reactions in our favour. For instance, one lady, well on her way towards old age, who had started on our Pilgrimage at Land's End, originally [57]intended to break off her march at Plymouth, but, being roughly treated by a band of disorderly youths at Camborne, resolved that she would accompany the pilgrims all the way to London, which she did. The start was made in each case from the points most distant from London on June 18th, and the Pilgrimage in all its eight branches arrived in London on July 25th, the final demonstration being held in Hyde Park on July 26th. Here there were nineteen platforms, representing the nineteen federations of the N.U.W.S.S. There was a huge and an entirely sympathetic crowd in the Park. When a bugle sounding from the central platform announced the putting of the resolution, there was hardly a hand held up against it.

On the next day—Sunday, July 27th—many hundreds of the pilgrims, wearing their badges and colours, assembled in Trafalgar Square and walked in procession, but without banners, to St. Paul's to attend the afternoon service. A large number of seats had been courteously reserved for them under the dome, and a sermon appropriate to the occasion was preached by Canon Simpson. We thought it just like our good luck that the first Psalm for the evening service on the twenty-seventh day of the month was the absolutely appropriate one: "When the Lord turned again the captivity of Sion, then were we like unto them that dream.... They that sow in tears shall reap in joy. He that goeth [58]on his way weeping, and bearing forth good seed, shall doubtless come again with joy, and bring his sheaves with him." A deep sense of peace and of absolute confidence in our ultimate triumph came upon us. We were as certain of it as if it had already been in our grasp.