Transcriber’s note: Table of Contents added by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

Marines in

World War II

Commemorative Series

By Major Charles D. Melson

U.S. Marine Corps (Ret)

by Major Charles D. Melson, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret)

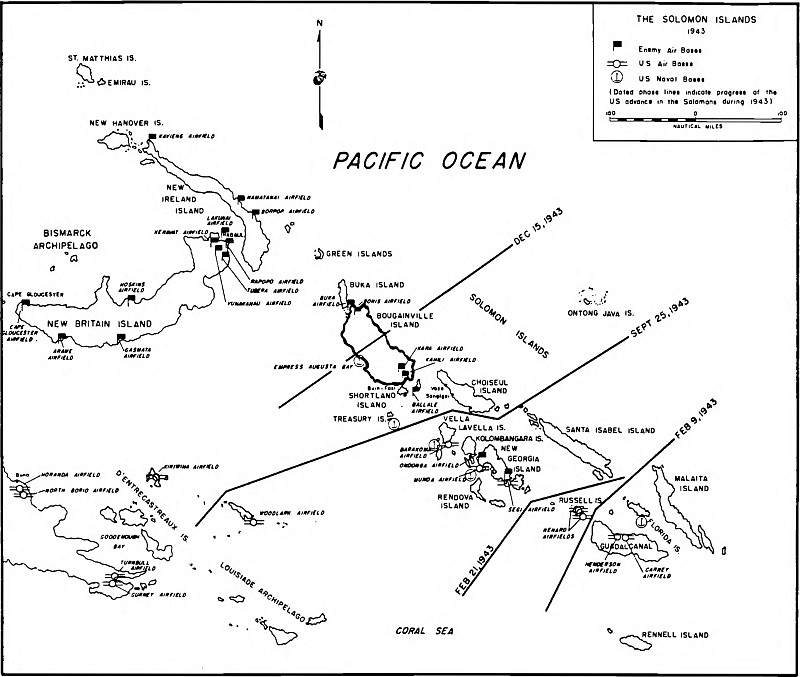

Operation Watchtower was the codename assigned by the Joint Chiefs of Staff for the reduction of the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul, on the easternmost tip of New Britain Island in the Bismarck Archipelago. The plan called for the South Pacific Area forces of Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley (relieved in November 1942 by Vice Admiral William F. Halsey) to move up the chain of the Solomon Islands toward Rabaul, beginning with the Guadalcanal landings on 7 August 1942. In December that year, patrol flights taking off from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal and from the decks of U.S. fleet carriers in the waters around the Solomon Islands discovered the Japanese hard at work on a well-camouflaged airfield at Munda on the northern end of New Georgia. This new field posed a definite threat to the Allies still fighting to wrest Guadalcanal from the enemy. It had to be taken, or at the very least, neutralized. U.S. pilots also reported another field being completed on Kolombangara across the Kula Gulf from New Georgia.

In response to these potential threats, Operation Toenails, landings in the New Georgia Islands in the Central Solomons with the capture of Munda as the primary objective, were planned, scheduled, and mounted. The first step leading to the invasion of New Georgia was the occupation of the Russell Islands, 65 miles northwest of Guadalcanal, which would serve as a forward base on which airfields would be constructed. Operation Cleanslate on 21 February 1943 saw the Marine 3d Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Harry B. Liversedge) land on Pavuvu, and the 43d Infantry Division (less a regimental combat team) invade Banika. Both landings were unopposed. The 11th Defense Battalion landed on Banika the same day and had its guns in place by noon. By 15 April, Allied aircraft began operating from the first of two new airstrips the Seabees constructed on Banika.

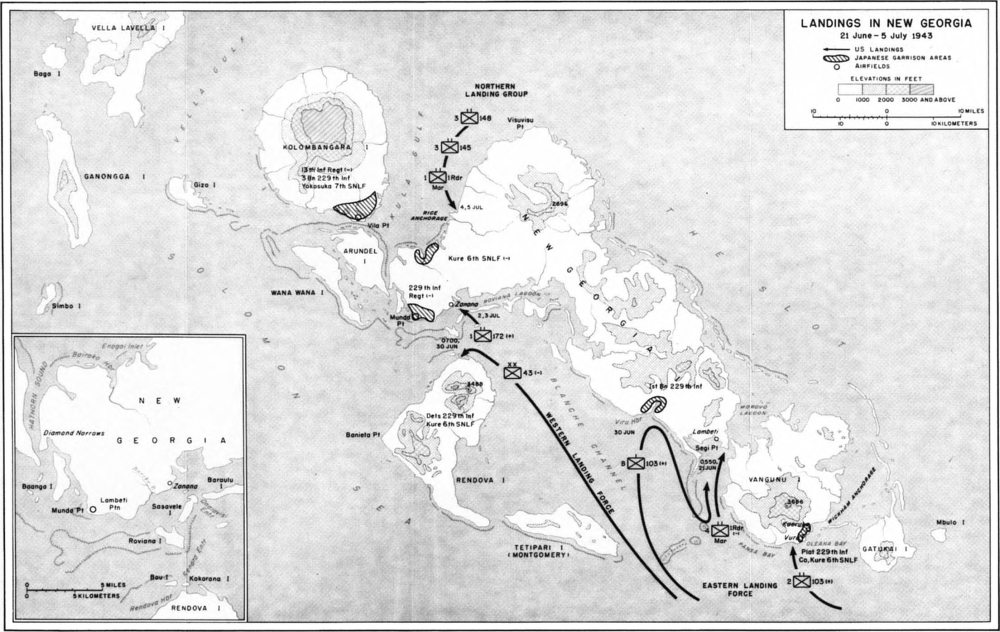

The primary objective of Operation Toenails was the capture of the airfield on Munda in the New Georgia group. Preliminary landings to support the main effort were to be made at Wickham Anchorage on Vangunu Island, Viru Harbor, and the Bairoko Harbor areas of New Georgia. Rendova Island and smaller islands nearby, across Blanche Channel to the south of New Georgia, were to be occupied next and used as supply bases and also as artillery positions for delivering supporting fire for the main attack on Munda. The plan called for ground forces then to drive the Japanese into the Munda Point area and once they were there, Allied air, artillery, and tanks could support the main landing. The enemy “would be annihilated or forced into a costly withdrawal,” according to the Allied concept of the operation.

For Toenails, Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, Amphibious Force Commander, divided his assigned forces into two task groups: Western Force, which he would personally command, was to seize Rendova, Munda, and Bairoko. The Eastern Force, under Rear Admiral George H. Fort, also an experienced amphibious force commander, was directed to capture Wickham Anchorage, Segi Point, and Viru Harbor. Turner’s ground commander was Army Major General John H. Hester, who headed the New Georgia Occupation Force (43d Infantry Division; Marine 9th Defense Battalion; the 136th Field Artillery Battalion from the 37th Infantry Division; the 24th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees); Company O of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion; the 1st Commando, Fiji Guerrillas; and assigned service troops). Fort’s Eastern Force included Army Colonel Daniel H. Hundley’s Army 103d Regimental Combat Team (RCT), less a battalion with Hester; Companies N, P, and Q of the 4th Raider Battalion; elements of the 70th Coast Artillery (Antiaircraft) Battalion; parts of the 20th Seabees;2 and service units. Colonel Harry B. Liversedge’s 1st Marine Raider Regiment (less the 2d, 3d, and 4th Battalions) was designated ready reserve for the operation, while the Army’s 37th Infantry Division (less the 129th RCT and most of the 148th RCT) was held in general reserve on Guadalcanal ready to move on five days’ notice.

THE SOLOMON ISLANDS

1943

Hester’s corps headquarters was formed by taking half of the 43d Division staff, the rest remaining with the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Leonard F. Wing, USA. Over 30,000 men were in the units assigned to the New Georgia Occupation Force, the majority of which were Army troops, Marine and Seabee units, patrol-torpedo (PT) boat squadrons, and naval base personnel. Marines from the 10th and 11th Defense battalions were in reserve as reinforcements.

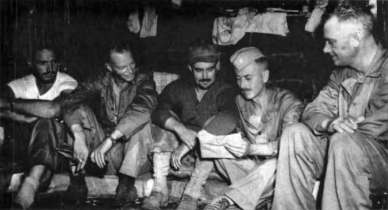

Col Harry B. Liversedge commanded the 1st Marine Raider Regiment and the XIV Corps Northern Landing Group. His mixed Army and Marine command was used as infantry rather than in the special operations role for which the raiders had been trained and equipped. Isolated from the main attack on Munda, he had to commit his forces to supporting operations.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

Defending the New Georgia Island Group were the Southeast Detachment of Major General Noboru Sasaki and the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force under Rear Admiral Minoru Ota (later to die as commander of Japanese naval forces at Okinawa); subordinate units included the 13th Infantry Regiment, 229th Infantry Regiment, Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force, and the Yokosuka 7th Special Naval Landing Force. New Georgia and Kolombangara, and enemy outposts on Rendova, Santa Isabel, Choiseul, and Vella Lavella, were strongly defended. The number of Japanese occupying the outlying islands was3 comparatively small. The forces on Kolombangara were “estimated” at 10,000 troops while those on New Georgia were figured to be between 4,000 and 5,000.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

LtCol William J. Scheyer, third from the left, was the 9th Defense Battalion commander. He is shown at his New Georgia command post with Col John W. Thomason, Jr., second from the left, from Admiral Nimitz’ CinCPac headquarters at Pearl Harbor, and Maj Zedford W. Burriss of the 10th Defense Battalion on the left.

1st and 2d Marine Aircraft Wing squadrons based in the Russells and Guadalcanal under the control of Brigadier General Francis P. Mulcahy’s 2d Marine Aircraft Wing forward echelon staff would provide air support for the operation. The staging areas for the attack on New Georgia were Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands, where the Marine 4th Base Depot, commanded by Colonel George F. Stockes, established a supply dump for XIV Corps.

In mid-Spring 1943, reconnaissance parties from the units slated to take part in the New Georgia campaign began patrolling in the areas designated for landings. Solomon Islanders acted as guides and scouts led by British resident administrators and Australian navy intelligence personnel, who, as Coastwatchers, hid in the hills in the enemy rear areas. From here they radioed information about Japanese troop, air, and naval sightings and movements to Allied listening stations. With the exception of two or three members from each patrol party who remained behind to arrange for guides and to give homing signals to Allied vessels on their approach, all patrols returned to their parent units by 25 June 1943. For these individuals, the campaign was already underway.

The Central Solomons campaign was launched by the raiders at Viru Harbor before the landings at Rendova and the Dragons Peninsula. A burial detail renders honors to those Marines who were killed in action. The Marines here are clothed in both the familiar sage-green herringbone twill and camouflage utility uniforms which were worn during the campaign by the raiders. The firing squad is armed with Garand M-1 rifles.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 57581

The Solomon Islands were some of the least known and underdeveloped areas in the world. John4 Miller, Jr., himself a former Marine, veteran of Guadalcanal, and after the war an Army historian, considered it “one of the worst possible places” to fight a war. All the islands had much in common, he went on, and “much that is common is unpleasant.” The islands were mountainous, jungle covered, pest-ridden, and possessed a hot-wet tropical climate. There were no roads, major ports, or developed facilities. New Georgia was all of this, and more.

Allied landings were met by ground and air defense, as seen in this photograph taken from the USS Algorab (AKA 8) on D-Day, 30 June 1943. Japanese were bombing Rendova Harbor in the background while the transport group moves to sea under “Condition Red.” During this raid the flagship USS McCawley (AP 10) was hit, but Allied air cover kept most of the enemy aircraft away.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The New Georgia campaign began for the 1st Marine Raider Regiment when Admiral Turner received a request for support and/or rescue from the resident coastwatcher at Segi Point, Donald G. Kennedy. The Japanese were moving into his base area where the Allies planned to build an auxiliary fighter strip. Responding to the request for help, Turner loaded Lieutenant Colonel Michael S. Currin’s 4th Raider Battalion on high speed destroyer transports (APDs) and sent it north to Segi Point. Captain Malcolm N. McCarthy met the raiders in a dugout canoe to guide the ships in. McCarthy felt certain that Company P’s commander, Captain Anthony Walker, would have5 his men’s weapons at the ready, and “I kept hollering, ‘Hold Your Fire!’”

LANDINGS IN NEW GEORGIA

21 June–5 July 1943

Currin went ashore with part of his headquarters and Companies O and P, followed by Army and Navy forces to begin the airstrip. After linking up with Kennedy, Currin turned his attention to his initial goal, the seizure of the protected anchorage at Viru Harbor. He had to accomplish this prior to the arrival of the invasion force on 30 June, and on the night of 27 June, he and his Marines set out by rubber boats across the mouths of the Akuru and Choi rivers for Viru.

After an eight-mile paddle, the raiders arrived at Regi Village early on 28 June. Led by native guides, Currin began the approach march to Viru Harbor. Fighting a stubborn combination of terrain, weather, and Japanese patrols, the raiders were short of their objective on 30 June. Meanwhile, the landing force arrived on schedule and stood off the beach after taking fire from Japanese coastal defense guns.

The approach to Rendova Harbor as seen from the deck of an LSD carrying Marines ashore. It sails through the narrow Renard Entrance with Rendova Peak in the background and the Lever Brothers’ landing at the right just around the bend.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The raiders launched their attack at 0900, 1 July, to seize Tetemara and Tombe Villages. Captain Walker attacked Tombe with part of his company, while the remainder attacked Tetemara with First Lieutenant Raymond L. Luckel’s Company O. After six hours of fighting and a Japanese counterattack, the objectives were captured. Sergeant Anthony P. Coulis’ Company P machine gun squad finished mopping up and searched for food and6 water. The 4th Raider Battalion lost 13 killed and 15 wounded in this action. The Japanese defenders withdrew, with an estimated 61 dead and 100 wounded. Currin turned the beachhead over to the Army occupation force and was taken back on board ship and returned to Guadalcanal. The remainder of the 4th Battalion headquarters and two companies, led by battalion executive officer Major James Clark, carried out separate tasks in accordance with plans to secure Wickham Anchorage at Vangunu Island to protect lines of communication from the Russells and Guadalcanal for the New Georgia operation. On 30 June, Captain Earle O. Snell, Jr.’s Company N and Captain William L. Flake’s Company Q supported an Army landing force by going ashore at Oloana Bay, where it joined a scouting party and Coastwatchers already there. Raider Irvin L. Cross later wrote that he and the other raiders disembarked from his assault transport “in Higgins Boats during a typhoon. In the dark it was impossible to see the landing craft from the deck.” Despite a confused landing in poor conditions, by afternoon the Marines and units of the Army 2d Battalion, 103d Infantry reached the Kaeruka River and attacked the Japanese located there. This position was taken and then defended. A member of Company Q, John McCormick, recalled that the attack “was not very productive,” but that a battle went on all day with the Japanese, who had gotten “quickly organized” and fought back with their machine guns and mortars. On 2 July, the Japanese tried to land three barges with supplies, but were met on the beach and shot up. The raiders lost 14 killed and 26 wounded securing Vangunu. The next raider deployment was like those at Viru and Vangunu, a supporting exercise to back the main XIV Corps effort to take Munda Point. Soon after the Rendova landings, Colonel Liversedge’s mission was changed from being the landing force reserve to being an assault force designated the Northern Landing Group directed to attack Japanese positions on New Georgia’s northwest coast at the Dragon’s Peninsula.

Three of the 1st Raider Regiment’s four battalions had been sent elsewhere. Liversedge’s landing group consisted of the Marine raider regimental headquarters, the 1st Raider Battalion; the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry; and the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry. Because the operating area was too far from the main landing force for support, fire support and supply came from the sea and air. Communications were dependent upon radio until a land-line linkup could be made with the rest of the occupation force to the south.

Liversedge was assigned several tasks. First he was to land and move against the Japanese forces at Enogai Inlet and Bairoko Harbor. Then he was to block the so-called Bairoko Trail and disrupt Japanese troop and supply movements between7 Bairoko Harbor and Munda. The enemy, weather, and terrain together conspired against this venture from the beginning and the raiders found themselves in a protracted frontline fight rather than a swift strike in the Japanese rear. One of Liversedge’s battalion commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith II, observed on embarking at Guadalcanal that although they shot off no fireworks on Independence Day, “we consoled ourselves with the knowledge that there would be plenty of those later.”

Department of Defense Photo (USA) 111SC324513

Soldiers and Marines consolidate their positions and construct barbed wire obstacles on the Dragons Peninsula after the attack on Bairoko. Their apparent condition, mixture of clothing, and the ever-present jungle provide eloquent testimony to the physical demands of the campaign.

On 5 July, the Northern Landing Group landed at Rice Anchorage east of Enogai and Bairoko. A narrow beach, difficult landing conditions, and concerns for an enemy naval attack caused the destroyer-transport force to depart, taking the raiders’ long-range radio with it. The landing from eight APDs and destroyers (DDs) was unopposed and met only by porters and scouts (Corry’s Boys) under Australian Flight Officer John A. Corrigan. Griffith described them as small men, “but their brown bodies were wiry and their arm, leg and back muscles were powerful. They wore gaudy cheap cotton lap-lap, or lavalavas.” These 150 New Georgians were the Northern Landing Group’s supply transport in a region without roads.

Undeterred by the situation, Liversedge moved out on jungle trails in pouring rain to his first objectives, leaving two Army companies to secure the rear. In Griffith’s words, they “alternately stumbled up one side of a hill and slipped and slid down the other.” The 1st Raider Battalion pushed on to reach the Giza Giza River by the night of 5 July with the larger and heavier Army battalions following. Here Liversedge split his force. The 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry was sent south to block the Bairoko Trail and the remaining units went north towards the Japanese on the Dragons Peninsula. On the night of 6 July, the naval Battle of Kula Gulf erupted with the resultant loss of the cruiser USS Helena (CL 50). This isolated the Northern Landing Group from even naval support. The villages of Maranusa I and Triri were occupied and patrols were soon in contact with the enemy, members of the 6th Special Naval Landing Force, so-called Japanese “marines.”

On 9 July, the Enogai defenses were reached and, after an air strike, Liversedge launched an immediate attack with Lieutenant Colonel Griffith’s 1st Raider Battalion. Captain Thomas A. Mullahey’s Company A was on the left, Captain John P. Salmon’s Company C in the center, Captain Edwin B. Wheeler’s Company B on the right, with Company D under Captain Clay A. Boyd in reserve. Employing machine guns and grenades, the battalion advanced toward the Japanese position until halted at nightfall. The Japanese were well dug-in and well armed with machine guns and mortars, but their heavy-caliber coast defense artillery could only be used seaward. Supported by 60mm mortars, the raiders resumed the attack the morning of 10 July, and took Enogai Village. Richard C. Ackerman, a Marine with Company C, remembered “we soon came to a lagoon which stopped our forward motion. Our right flank, though, did overrun the enemy’s warehouse and food storage area.” The Japanese lost 300 men at a cost of 47 Marines killed, another 74 wounded, and 4 men missing. The battalion had fought for 30 hours without rations or water resupply. Army troops carried up water and K-rations and candy bars received in an air drop. The elimination of the Japanese coast defense artillery at Enogai allowed American destroyers and torpedo boats to operate unhampered in the Kula Gulf, where they disrupted Japanese barge traffic.

Under Japanese air attacks, the 1st Marine Raider Regiment consolidated its gains and blocking positions, while Colonel Liversedge studied the Bairoko Harbor defenses. Communications, resupply, and fire support were problem areas. The Japanese improved their own dispositions and continued to bring in troops and supplies from Kolombangara by sea and then moved them overland to Munda Point. The main Japanese line was on a ridge in front of the Americans. The enemy fighting positions were log and coral bunkers that made excellent use of terrain and interlocking8 machine-gun fire supported by heavy mortars. On the night of 12–13 July, the Navy intercepted a Japanese troop landing at Kolombangara. Four days later, on 17 July, Liversedge pulled the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry back to Triri Village for closer mutual support, while other Army companies continued to hold the Rice Anchorage area and communications routes.

Reinforced on 18 July by the 4th Raider Battalion, Liversedge planned to attack Bairoko on 20 July 1943. The attack was launched on schedule despite the failure of a requested airstrike to arrive. Liversedge sent in Griffith’s battalion, followed by Currin’s battalion, to find an undefended flank or a breakthrough point. Griffith committed Wheeler’s Company B and Company C under First Lieutenant Frank A. Kemp. His other companies had been used to bring these two up to strength. Currin’s battalion fielded four companies, but was some 200 men understrength. Companies B and C soon stalled on the Japanese defenses. Captain Walker took Company P forward for support, while Snell’s Company N tried to find an open flank along the shoreline to the north. One of Snell’s men, Frank Korowitz, remembered feeling that he wanted to get up and run when Japanese attacked by surprise at close range, but “I also felt that I would rather be killed than have anyone know I was scared.” Liversedge fed in his remaining units to cover the gaps that developed between the two battalions and no longer had a reserve. Walker recalled, “without some kind of fire support (naval gunfire or air) these raiders could not penetrate the fortified enemy line.” McCormick, with Company Q, wrote that the Japanese had plenty of time to prepare and had “machine gun pits in the natural shelter provided by the roots of banyan trees and cut fire lanes through the underbrush.” The combination of machine guns, mortars, and snipers guaranteed “almost instant death” to any Marine caught in these fields of fire.

At 1445, a Japanese mortar barrage was followed with a counterattack in the 1st Battalion area. After this, another assault attempted by the Marines of Company Q lead by Captain Lincoln N. Holdzkom bogged down within sight of Bairoko Harbor. By now there was a loss of almost 250 Marines, a 30 percent casualty rate. The 1st Marine Raider Regiment had 46 killed and another 200 or so wounded, and about half the wounded were litter cases. Liversedge made no further headway and withdrew that night to Enogai. It required another 150 men to move the casualties back and all units were in defensive positions by 1400, 21 July.

By then, the effects of the fighting and living conditions had taken a toll in sickness and exhaustion of the Northern Landing Group. Liversedge was ordered to hold what he had with available forces. Resupply and casualty evacuation were by air and there was no further reinforcement, except a 50-man detachment under Captain Joseph W. Mehring, Jr., of the 11th Defense Battalion that provided needed 40mm and .50-caliber antiaircraft guns at Rice Anchorage.

1st Raider Regiment casualties from the attack on Bairoko had to be treated in place or evacuated by aircraft. Some 200 casualties were carried from the field, then taken by rubber boat to Consolidated PBY Catalinas. After this picture was taken a Japanese air attack disrupted this effort and damaged one aircraft.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 152113

Bairoko Harbor was attacked by destroyers and torpedo boats, and bombed by B-17 Flying Fortresses. On 2 August, XIV Corps informed Liversedge that Munda Point was reached and his force should cut off retreating Japanese near Zieta. On 9 August, the Northern Landing Group linked up with elements of the 25th Infantry Division advancing from Munda Point and assumed control of the 1st Marine Raider Regiment. Scattered fighting continued around Bairoko until 24 August when it was occupied by the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry. The Japanese defenders, the Special Naval Landing Force men, had pulled out by sea. Occupying Corrigan’s “Christian Rest and Recreation” camp of thatched lean-to’s, the Marines totaled their casualties for this effort; regimental headquarters had 1 killed and 8 wounded, 1st Raider Battalion lost 74 killed and 139 wounded, 4th Raider Battalion had 54 dead and 168 wounded; and all suffered from the unhealthy conditions 9of the area. By 31 August 1943, the 1st Marine Raider Regiment was back on Guadalcanal for reorganization scheduled in September, officially noting the presence of “bunks, movies, beer, chow.”

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60483

The dead had to wait until the wounded were taken care of and the battlefield was secured to be buried. In some cases it was not until after the Japanese had withdrawn or been solidly beaten before burial details could recover the dead Marines.

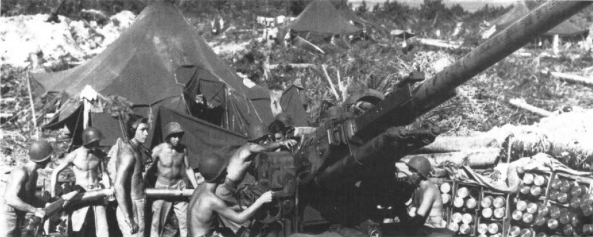

Elements of four Marine defense battalions played an important part in the Central Solomons campaign. Attached to the XIV Corps to support of the attack on Munda Point was the 9th Defense Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William J. Scheyer. The battalion was organized with an artillery group (Batteries A and B), a heavy antiaircraft group (Batteries C through F), a light antiaircraft group (Batteries G through I), and a headquarters and service battery. The 9th Defense Battalion’s participation in the Guadalcanal campaign from December 1942 had provided it needed experience, as the island was typical of conditions to be found in the Central Solomons. Some Marines from the light antiaircraft group were withdrawn from gun crews to train with the battalion’s tank platoon for tank-infantry operations. The greatest challenge in preparing for the campaign was Lieutenant Colonel Archie E. O’Neil’s conversion of his seacoast artillery into a field artillery unit, at the same time absorbing 145 new men into the group. This was accomplished in 22 days, a feat that Admiral Halsey complimented.

This picture gives a clear view of the beach congestion that plagued the landing of the artillery group with its 155mm guns. At right is a .50-caliber antiaircraft gun of the Special Weapons Group.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

One of the major equipment changes for the campaign was the acquisition of 155mm guns as replacements for the older M1918 French Grande Puissance Filloux (GPF) guns. The battalion exchanged 90mm guns with the Army 70th Coast Artillery Battalion, giving the antiaircraft group new guns. High-speed and standard dual-mounts10 for 20mm guns were also obtained. These were adapted by the 9th from 37mm gun mounts, giving the light antiaircraft group greatly increased mobility by replacing the stationary naval single-mounts. The 9th Defense Battalion obtained additional .30-caliber heavy, water-cooled machine guns, and trained the battalion band to employ them with Headquarters and Service Battery. The battalion acquired three Landing Vehicle Tracked Alligator amphibious tractors for the operation, and then was augmented by a whole amphibious tractor platoon of nine vehicles from the 3d Marine Division.

Marine Corps Historical Collection.

The antiaircraft group of the 9th Defense Battalion moves ashore at Rendova. Here a TD9 tractor pulls a 90mm gun from an LST. The TD9 tractor would soon prove too light to move through the muddy terrain beyond the beach.

On 27 June 1943, the battalion consisted of a total of 1,459 officers and men, reinforced with additional personnel from the 3d Marine Division and I Marine Amphibious Corps. Most of these Marines had been on Guadalcanal for seven months. At one time or another, 40 percent of them had malaria and the debilitating effects of the tropics had been felt by the entire unit. But the 9th was a well-trained, experienced unit, outfitted with the best equipment then available to Marine defense battalions. In the words of Lieutenant Colonel Scheyer, “the prospect of closing with the enemy was all that was needed to supply morale.”

The first Japanese aircraft shot down from the beach was credited to this gun crew on its first day ashore. From the left are 1stLt William A. Buckingham, PFC Francis W. O’Brien, Cpl Paul V. Duhamel, and PFC Nemo Hancock, Jr., of the 9th Defense Battalion.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 56812

On 29 June, the 9th Defense Battalion was attached to XIV Corps for the duration of the New Georgia operation. The battalion was given the mission assisting in the capture, occupation, and defense of Rendova Island, by landing on the beaches south of Renard Channel entrance. Here it was to move immediately into position to provide antiaircraft defense. A third mission was to fire 155mm guns on the enemy installations, bivouac areas, and the airfield at Munda. As a fourth task, the tank platoon would support the attack on Munda Airfield. Fifth, the battalion would be prepared to repel attack by hostile surface vessels. When the Japanese forces on New Georgia Island were overrun, the battalion would then move as a whole or in part to Munda to defend the field when Allied air units moved in and began operating. All these assigned tasks reflected the battalion’s varied capabilities.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

A 40mm gun and crew look skyward for Japanese aircraft as the XIV Corps landing continues. Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs) are run up on the beach in the background, as working parties unload them by hand.

Lieutenant Colonel Scheyer said on leaving Guadalcanal that the Japanese “have a mistaken notion that they must die for their Emperor and our job is to help them do that just as fast as we possibly can.” At 1600 on 29 June, the 9th’s first echelon, 28 officers and 641 enlisted Marines, combat loaded on board the USS Libra (AK-53) and USS Algorab (AK-25), the vessels assigned to transport the battalion, and sailed from Guadalcanal. At Munda, a Japanese defender observed that a “blue signal flare from Rendova Point went up. I saw four enemy warships ... this morning, rain clouds hovered over us. At Rendova, four cruisers, three destroyers, eight transports and countless numbers of boats appeared.”

At 0635 the morning of 30 June, the first units of the XIV Corps’ assault wave began landing on Kokorana Island and East Beach of Rendova. They were met by Coastwatcher Flight Lieutenant D. C. Horton and guides from the amphibious reconnaissance patrols.

Both on Kokorana and on Rendova, lead elements of the 9th found themselves landing ahead of the assault forces, meeting only light resistance. The battalion band soon took out an enemy machine gun position. Major Robert C. Hiatt’s reconnaissance party from the artillery group killed another enemy soldier, who was said to have been stripped of souvenirs before hitting the ground. The defenders withdrew inland to harass the Americans from the hills and swamps.

Throughout the day, enemy air attacks were turned back by friendly fighters. Allied fighters over the area on 30 June reportedly destroyed over 100 enemy aircraft. One attack by Japanese float planes got through to strike at the naval task force and damaged Admiral Turner’s flagship, USS McCawley (AP 10), so heavily that it had to be sunk that night by a PT boat. At 1600, a lone Mitsubishi A6M Zeke fighter strafed the beach without causing any damage and was driven off by defense battalion machine gun fire, without causing damage. Both the Algorab and Libra were unloaded with the assistance of the 24th Naval Construction Battalion. The 24th, and other Seabee units, supported the 9th in unloading cargo and moving equipment and contributed materially to the general success of the battalion on those first days and the battalion was “in their debt.” On the first day of landing, Battery E of the Antiaircraft Group set up on Kokorana and was prepared to fire by 1645; all Special Weapons Group light antiaircraft guns landed and were emplaced along the coast to protect the XIV Corps’ beachhead; sites were located for the 155mm and the remaining 90mm batteries. Battery demolition crews ventured near and into enemy territory to blast out fields of fire for the gun positions.

Weather and terrain made unloading and emplacement extremely difficult for XIV Corps, the 43d Infantry Division, and the 9th Defense Battalion. Torrential rains began on 30 June and continued almost without cessation, rendering what passed for roads impassable and causing great congestion on the beaches as men and supplies came ashore. Areas believed suitable for occupation proved to be swampy. Steel matting and corduroy roads constructed with coconut logs were utilized, but even these were ineffective. Tanks, guns,12 and vehicles of all types mired down in the incredible mud and only the sturdiest tractors or manpower extricated them. The congestion of supplies on the beachhead rendered them and the troops moving themselves and the supplies inland vulnerable to enemy air attack.

In many cases, 9th Defense Battalion equipment had to be dismantled and carried to assigned areas. The 9th’s motor transport section performed as best it could with the resources available and until the majority of its vehicles burned out from the strain of operating in the Rendova muck. Their task was made easier by the amphibious tractors, which were the only sure means of transportation and these had troubles of their own as they threw off their tracks on uneven terrain. “Frances,” “Tootsie,” and “Gladys” were three amphibious tractors in the beach area manned by nine 3d Division Marines who operated continuously keeping supplies moving from position to position. All tractors were damaged eventually in the Japanese air attacks that followed.

The 9th Defense Battalion’s second echelon arrived on LSTs (Landing Ships Tank) 395 and 354 and disembarked at Rendova on 1 July as Allied fighter cover continued to turn back enemy air attacks. Joseph J. Pratl with Battery A, which came in on LST 354, wrote the ship was “big and slow moving, loaded with ammunition of every description.... Unloading was done quickly, 155mm guns13 and their tractors soon made mud and made a slime which made walking around difficult to say the least.” By the end of the day, Captain Henry H. Reichner’s Battery A was in firing position. A third battalion echelon arrived in LSTs 342 and 398 and disembarked on 2 July. That morning Captain Walter C. Well’s Battery B was emplaced and Battery A commenced shelling enemy positions in the Munda area. On 3 July, both batteries of “Long Toms” fired for effect on the Munda airfield and enemy artillery positions on Baanga Island. At Munda; a defender wrote, “They must be firing like the dickens. Sometimes they all come at once. I don’t exactly appreciate this shelling.”

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60590

Supplies are landed by XIV Corps for ComAir New Georgia. The terrain behind the beach did not allow for rapid movement and for the dispersal of supplies which soon piled up at an unmanageable rate and became extremely vulnerable to Japanese attack.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

Sailors and soldiers make a corduroy road from coconut logs across an exceptionally muddy spot.

A 155mm Long Tom is dragged through the mud of Rendova en route to a new position from which it could punish Japanese positions and at the same time defend against Japanese counterattacks.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The combat experience of the 9th paid dividends, especially during the first week ashore. The Marines knew how to dig in for air attacks and this saved lives. At 1335, 2 July, 18 Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers and Zeke fighter escorts entered the area from the southwest and pattern-bombed the beachhead, causing considerable damage and many casualties. Zero fighters flew over the beach area at tree-top level, strafing and bombing the beach and landing craft. Gasoline storage tanks14 and an explosives dump were hit and several fires were started in the area. Battery A’s Pratl recounted, “we saw the bombers, we assumed them to be American B-25s. We hit foxholes and the earth shook like a rubber band as three bombs fell” near his battery.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60656

Capt Henry H. Reichner’s Battery A loads its Long Toms on an LCT to move to Piru Plantation from Tambusolo Island. These moves were staggered to provide continuous artillery support during this phase and were carried out with speed and efficiency.

On board a beached landing ship, tank, Francis E. Chadwick, of Battery B, was hauling ammunition for a Navy 40mm antiaircraft gun when the “LST was showered in water. You could feel the heat from the bombs. The noise was deafening.” Army and Navy units suffered the most from lack of preparation and the area around the landing beach became known as “Suicide Point.”

The Japanese struck back hard at the New Georgia invasion force with bombers and fighters. Allied combat air patrols shot down many of the enemy, but some got through to damage Marine positions on Rendova. This area became known as “Suicide Point” after fuel and explosives dumps were hit during the 2 July 1943 raid.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

Four 9th Defense Battalion men were killed, one was missing, and 22 were wounded as a result of the raid. Damage to the battalion included two 155mm guns hit, two 40mm guns hit, three amphibious tractors hit, one TD18 tractor demolished, and an unknown amount of supplies and personal gear destroyed. One bomb landed between15 the trail legs of one 155mm gun in Battery A, but failed to detonate. This put the gun out of action until the bomb was excavated, pulled clear, and detonated. That day, the battalion bomb disposal teams successfully removed or destroyed a total of 9 bombs and 65 unexploded projectiles of 105mm or larger (Over 9,000 pieces of smaller enemy or damaged friendly ordnance were recovered by the end of the campaign by these teams). Some light antiaircraft guns fired at the raiding planes, but downed none. The damage caused by this attack was due in part to the lack of working surveillance radar, and friendly fighter cover had been withdrawn because of weather. The battalion’s SCR270 and 516 radars had not yet been installed and the E Battery SCR268 radar had been fueled with diesel from a drum marked “gasoline,” putting it out of action at the time of the attack.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60624

Behind a revetment of sandbags and coconut logs, this 9th Defense Battalion crew manning a 90mm antiaircraft gun keeps vigilant watch against Japanese air attacks on positions at the beach at Rendova.

Earning special credit during this period were the battalion’s attached Navy corpsmen and doctors, who performed their work in the midst of enemy raids and under the most trying conditions. Besides caring for the 9th’s casualties at the battalion aid station set up on the exposed East Beach of Rendova, battalion surgeon Lieutenant Commander Miles C. Krepelas treated many Navy wounded, and Army troops returning from New Georgia who could not locate their own medical detachments.

Casualties were treated at the 9th Defense Battalion and 43d Infantry Division medical clearing stations. More than 200 Americans were killed or injured during the 2 July raid.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 56829

Battalion S-4 Major Albert F. Lucas was faced with the extremely difficult task of supplying the widely dispersed elements of the16 battalion. Captain Lynn D. Ervin, Battery G commander, remembered that after he landed, working parties from headquarters brought around water and rations to the dispersed firing batteries until they had established their own field kitchens. The preparation and delivery of food required a major effort throughout the campaign because the battalion elements were widely spread out in the target area and the battalion had to feed all other units which did not have their own messing facilities. Hot meals were provided once a day and the artillery group’s pastry cook raised morale by providing doughnuts and other baked goods during some of the more difficult periods.

At this same time, XIV Corps began its Munda drive by moving from Rendova to New Georgia, supported by the Army 136th Field Artillery Battalion and the 9th Defense Battalion. Zanana Beach had been selected for the 43d Infantry Division’s landing. The division order stated that the 43d, less the 103d Regimental Combat Team, would “land on New Georgia Island, capture or destroy all enemy encountered, and secure the Munda Airfield.” On 3 July, the 172d Infantry moved by landing craft to New Georgia, followed the next day by the 169th Infantry. The Munda drive had begun.

The 9th’s communications and radar personnel carried on vital installation work and respliced telephone lines as soon as they were damaged in the air raids. The air control and reporting system of the defense battalion and Commander Aircraft New Georgia was installed on 4 July when Condition Red was sounded again. At 1430, the Japanese attempted a repetition of the 2 July raid as 16 Betty bombers and their fighter escort broke through17 the Allied combat air patrol overhead and penetrated the area on the same course followed before. Zeke fighters roared in at tree-top level strafing defenses. As the enemy planes came in, several light antiaircraft guns opened fire and a few seconds later Captain Tracy’s E Battery on Kokorana Island began firing. Tracy recalled “bursts were right on target, requiring no correction ... the flight entered a large cloud. Pieces of planes were noted falling out of the cloud.” This fire caught the enemy by surprise and of the 16 bombers only four got their bombs away. Battery E had expended 88 rounds of ammunition and a world’s record was established. Twelve bombers and a fighter were destroyed by the 9th’s fire, the bombers and the Zeke chalked up to Battery E and Special Weapons Group respectively. That day cheers were heard all over Rendova “like a Babe Ruth homer in Yankee Stadium.” Credit was given the operators of the range section, though Frank LaMountain said if he had not kept the generator going this would not have been the case. The battalion had one officer killed and three enlisted Marines wounded; a heavy machine gun and the remote control system of one 40mm gun were destroyed.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60616

While Marine antiaircraft artillery dealt with air raids, 155mm Long Toms were fired at targets some eight miles or more away round-the-clock, in all weather, taking a toll of the defenders.

On 5 July, a detachment of 52 men with four 40mm guns and four .50-caliber machine guns under the command of First Lieutenant John R. Wismer moved to Zanana Beach on New Georgia to provide antiaircraft and beach defense protection for the 43d Infantry Division which had landed in that area.

A fire direction center processed target information from observation posts and air spotters, which group commander LtCol Archie E. O’Neil and executive officer Maj Robert C. Hiatt translated into firing data on Rendova.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60596

Major naval surface actions occurred on 12 July as the U.S. Navy intercepted Japanese destroyers and cruisers attempting to resupply forces on Vila and Munda. The ships’ gunfire, sounding like massive thunder and looking like a lightning storm, permitting little sound sleep, was observed from18 Rendova. The next day, a 90mm battery, three searchlights, and a light antiaircraft detachment arrived from the 11th Defense Battalion. The 90mm battery was staged on Kokorana until the 9th Defense Battalion displaced to New Georgia, then it went into firing positions. Light antiaircraft guns were positioned on both Kokorana and Rendova. Marines from the 11th Defense Battalion assisted the 9th in manning the radars and the 11th’s sound locator supported Battery E.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The Northern Landing Group, built around the 1st Marine Raider Regiment, landed at Rice Anchorage on 5 July and proceeded cross-country to take Enogai on Dragons Peninsula. The Marine third from the left hefts a Boys rifle used by the raiders as an antitank weapon.

Camouflaged Japanese 140mm naval guns with their ammunition intact were found and put out of action at Enogai by the raiders’ landward attack.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 127G59009A

At 0800, 13 July, U.S. Army infantry units landed at Laiana Beach, about 2½ miles east of Munda airfield, and continued the drive towards Munda Point. A detachment of 22 men with one 40mm gun, one twin 20mm gun, and two .50-caliber machine guns from the 9th Defense Battalion under First Lieutenant Colin J. Reeves, went to Laiana20 Beach on New Georgia to defend the landing site.

APPROACH TO BAIROKO

5–20 JULY 1943

Marine Corps Historical Collection

With Wismer’s detachment were Cpl Maier J. Rothschild, at left, and Pvt John Wantuck, at right. Both earned the Navy Cross during the fighting at Zanana in defense of the beachhead. Wantuck died there.

Captain Robert W. Blake’s platoon of light tanks now played an important part in the assault and capture of Munda Airfield. The airfield was defended by various aviation personnel, antiaircraft units, and the 229th Infantry Regiment. During the next five days, 9th Defense Battalion tanks spearheaded the advance, knocking out enemy log bunkers, pillboxes, and other strong points. On a number of occasions during the assault on the enemy’s final defense positions north of Ilanana, the tank platoon operated in the densely wooded and irregular terrain, under conditions believed highly unsuitable for tank employment. For the first time, the Japanese attacked the tanks with magnetic mines and Molotov cocktails, bottles of gasoline with lit wicks. On the morning of 15 July, the tanks broke through the enemy’s strong positions after Army infantry had repeatedly been thrown back. The XIV Corps attack on Munda was stalled by both the dogged resistance of the defenders and the rugged terrain.

The “Murderers Row” of 155mm guns continued shelling the Munda Airfield, Baanga Island, and other outlying islands throughout this phase. The primary targets were antiaircraft and field artillery positions, and ammunition dumps. Directed by both ground and air observers, this firing proved very effective. “The artillery shelling’s accuracy has become a real thing. We can never tell when we are to die,” wrote a Munda defender. On 15 July, landing craft carried Battery A to Tambusolo Island where it was assigned the mission of covering the western approach to Blanche Channel with 155s against the incursion of still dangerous Japanese ships. On the night of 17 July at Zanana, 9th Defense Battalion Marines were involved in some memorable fighting. A few days earlier, Lieutenant Wismer led a patrol which killed four members of an enemy patrol and captured a fifth, from whom they learned that a Japanese force of 150 men was in the vicinity. A rear command post of the 43d Infantry Division with approximately 125 troops, nearly all specialists commanded by a legal officer, was in the beachhead area. The Marines under Wismer21 deployed for ground defense and Private John Wantuck and Corporal Maier J. Rothschild manned two salvaged Army .30-caliber light machine guns covering trails leading to the perimeter of the Zanana area. Colonel Satoshi Tomonari’s 13th Infantry Regiment attacked with several groups during the night, forcing Lieutenant Wismer’s defenders back to their gun pits, while Wantuck and Rothschild remained forward of the lines engaging the Japanese with machine-gun fire on each assault. The Marines were attacked by a regiment that had “the determination of a suicide squad and under the command of the Regimental Commander they are determined to fight to the last man.”

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60625

Other defense battalion Marines skillfully employed their 90mm gun batteries and their radar-operated fire control systems to keep enemy aircraft high and away from their ground targets. Gun positions were built above the water table as seen here.

The following morning, Wantuck was found dead from gunshot and sword wounds. Rothschild was wounded in a hand-to-hand encounter with an enemy officer, whom he killed. Wantuck and Rothschild killed 18, wounded 12 to 15 others, and put a 90mm mortar crew out of action. The senior Army officer present, Major Charles C. Cox, credited these two Marines and timely artillery fire with saving the division rear and beachhead area. Rothschild and Wantuck each received a Navy Cross for their action. In all, Wismer’s detachment had repulsed four different columns, killing 18, wounding others, and capturing a prisoner. Over 100 Japanese bodies were found later on the field by Army units.

Pharmacist’s Mate First Class Francis G. Peters was with the Zanana detachment. While with the unit, he performed as a one-man clearing station for evacuating the wounded, mainly Army personnel, who were taken from the beach by boat. He remembered the attack of 17 July because the Japanese “penetrated as close as 25 yards and I could see them shooting at our men on the AA guns.” After the attack, his work really began, tending to the wounded, including a couple of Japanese soldiers.

While the fighting for New Georgia was ongoing, there were several changes in the command structure of the campaign. Major General Oscar W. Griswold relieved General Hester as commander of XIV Corps, and Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson relieved Admiral Turner as commander of Task Force 31. The buildup of forces on New Georgia continued with the arrival of elements of Major General J. Lawton Collins’ 25th Infantry Division on 21 July and the arrival the next day of the remainder of the 37th Infantry Division. What one division failed to accomplish would now be attempted by two, the 43d and the 37th.

To keep the pressure on Munda and to prevent Japanese reinforcement from Bairoko, plans were made for the Northern Landing Group to attack on 20 July 1943. The commanders involved review the plan: left to right, Maj Charles L. Banks, LtCol Samuel B. Griffith II, LtCol Michael S. Currin, LtCol George G. Freer, and LtCol Delbert E. Shultz, the last two both U.S. Army.

U.S. Army Marine Corps Historical Collection

After their initial daytime air losses, the Japanese relied on air attacks at night with only infrequent daylight bombings. One was mounted against the Rendova area on 20 July by 6 planes, one on 1 August by another 6 planes, and22 another on 7 August by a formation of 15 aircraft. Nightly harassing raids were made over the area by different planes and pilots all dubbed “Washing Machine Charlie.” Several larger flights were turned back by 90mm fire. Marines of Battery F, the searchlight battery, remained at their posts despite Japanese strafing, and radar men at their exposed, above ground posts remained at their stations throughout the raids, also. At dawn, after one all-night raid, a Battery C Marine was at the fuze pot stark naked, “he hadn’t had time to dress.” A total of 26 enemy planes were downed by battalion antiaircraft fire over Rendova.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The 9th Defense Battalion’s 90mm Group had four gun batteries, each with its own range-finder, computer, and radar. This weapons system continued in use through the war and into the 1950s. Note the “kill” flags stencilled on the barrel.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The 9th Defense Battalion’s tank platoon lead by Capt Robert W. Blake supported the infantry attack. This vehicle is shown knocked out on top of a position at the Laiana water point. The Japanese bunker is all but indistinguishable from the debris that covered it.

A tank crewman examines the damage to his vehicle which put it out of commission. The Japanese employed a mix of antitank weapons and individual close-in tactics to counter the light tanks. Because of the loss of 9th Battalion tanks in the drive on Munda, tanks of the 10th and 11th Defense Battalions’ armored platoons were fed in as replacements.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

On 26 July 1943, the 9th’s tanks, reinforced by six others from the 10th Defense Battalion, led the assault on enemy positions near Lambetti Plantation. Tank operations were conducted over difficult terrain consisting of steep slopes, heavy underbrush, and closely spaced trees. The Japanese were in a strongly fortified defensive position, which consisted of a number of heavy bunkers and pillboxes in a clearing. In this action, which lasted approximately five hours, one of the tanks was disabled by a magnetic mine, and two men were killed and four wounded. A second assault on23 this position on 28 July by a battalion of infantry and four Marine tanks, was successful. Approximately 40 heavily fortified bunkers and pillboxes were destroyed and a large number of Japanese killed or wounded by tank fire.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60096

Another defense battalion detachment went to Laiana, where this emplaced 40mm gun of 1stLt Colin J. Reeves’ battery merges with the dense jungle growth backdrop.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 57564

The high ground at Munda airfield fell on 5 August 1943. This picture is taken at the site of the former mission on Kokengolo Hill looking towards Biblio Hill to the north.

On 1 August, a Japanese air raid hit the torpedo boat mooring basin at Rendova. Nearby on Tombusolo was Edwin Jakubowski with 9th Defense Battalion Special Weapons, firing at the attacking aircraft. “A PT Boat was strafed and blew up next to my little island. Plywood flying all over me and one of its torpedoes went by,” he recalled. Captain Theron A. Smith, commanding Battery F, had just inspected his Number 3 Searchlight Section when the attack occurred and later wrote “some Sunday, alerts and [Condition] Reds all last night and most of the day. Attacked by two dive bombers and Zeros (estimated 50) about 1600. Two PTs destroyed, another sunk and beyond salvage.” In a footnote to the campaign, Lieutenant (jg) John F. Kennedy’s PT 109 was rammed and sunk early the next morning while operating from the Rendova base.

Wreckage and debris were soon pushed aside in the rapid progress to open the field for American use. The captured airfield included aircraft, in this case a Zero fighter in a coconut and coral enclosure, that could not take off after the American landing.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

Field artillery firing missions against the New Georgia area continued to be conducted by Battery B until 3 August. The tank platoon of the 10th Defense Battalion, reinforced by five tanks from the 11th Defense Battalion and the surviving tank of the 9th Defense Battalion, led the assault on Kokengolo and Biblio Hills on 4 and 5 August. After two days of heavy fighting, they routed the defending forces. The Marine tanks then cleared the way to the principal objective of the entire New Georgia campaign, the Munda airfield, which was captured and occupied by XIV Corps Army troops on 5 August 1943. Regiments of the 25th Infantry Division pursued the Japanese as they24 withdrew north from Munda Point. On the night of 6 August a naval battle was fought in Vella Gulf, where Japanese destroyers and barges bringing in supplies and reinforcements were turned back.

DRIVE TOWARDS MUNDA POINT

2–14 July 1943

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60460

The engineering effort pushed forward and built upon the Japanese construction that remained. The work was completed within 10 days after the airfield was captured.

The battle for Munda airfield over, the Zanana Beach and Laiana Beach detachments moved on 6 August to participate in the Munda defenses. The detachments destroyed 12 enemy planes while at these locations. A day later, the 9th Defense Battalion began moving to the Munda area. The moves were so organized that there was no more than a quarter of the battalion’s weapons out of action at any one time. The battalion was transported largely by various types of landing craft, which made the displacement a slow, laborious process. Captain Well’s Battery B of the 155mm Group moved to Kindu Point on New Georgia on 8 August and was assigned the mission with its large guns of guarding the western approaches to Blanche Channel. On landing, Battery B and an Army antitank platoon cleared the area of remaining Japanese stragglers.

At Munda Airfield, immediately after the area was cleared of Japanese, construction units moved in to repair and enlarge the “emergency” field built by the enemy. By the evening of 13 August, this work had progressed sufficiently to permit four Army Curtiss P-40 Warhawks to make an unscheduled landing and to “christen” the field with a brief fly-over. This was soon followed by the arrival of Marine air units, including VMF-123 and -124. Other Marine squadrons soon arrived, including the VMF-214 “Black Sheep” of Major Gregory Boyington, who became a grudging admirer of the 9th’s antiaircraft marksmanship and a source of entertainment with his radio transmissions while flying over Munda.

Seabees clear a Japanese tunnel at the base of Kokengolo Hill for use in the face of the still present Japanese menace. This threat made the discomfort of the cave, filled with refuse and corpses, seem a small price to pay for the security of overhead cover from artillery and air attack.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

Instead of attacking the main Japanese force on Kolombangara at25 Vila, the American force isolated the enemy by landings on nearby Vella Lavella on 15 August. Admiral Halsey did not want another slugging match like Munda. A landing force was built around the uncommitted Army 35th Regimental Combat Team, commanded by the 25th Infantry Division’s assistant commander, Brigadier General Robert B. McLure, and supported by the Marine 4th Defense Battalion. The Japanese resisted in the air and sea, but enemy ground forces were too busy withdrawing to put up a determined resistance. The 4th Defense Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Harold S. Fassett, defended the beachhead against 121 attacks and downed 42 Japanese planes. The Allied occupation of these positions and pressure from Arundel and New Georgia put Vila on Kolombangara in a precarious position. In many ways, this was a prelude to the Marine Bougainville campaign as it brought I Marine Amphibious Corps and new units not involved in the fighting into the New Georgia area. American fighter cover came from the Munda and Segi Airfields.

CAPTURE OF MUNDA POINT

22 July–4 August 1943

The first fighter plane to land on Munda was a VMF-215 Corsair flown by Maj Robert G. Owens, Jr., on 14 August 1943. Flight operations began immediately to cover the Vella Lavella landings.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60270

By 15 August, the 9th Defense Battalion was set up and emplaced in new dispersed positions. Three days later, another major naval surface action occurred off Vella Lavella as the U.S. Navy combatants intercepted destroyers and barges attempting to evacuate Japanese troops. From 16 through 19 August, Japanese artillery on Baanga Island shelled Munda Airfield and Kindu Point causing several casualties and some minor damage. Friendly aircraft and artillery operated against these elusive cannon and finally silenced them. The battalion suffered no casualties from this shelling, though one gun crew’s tent was demolished by a direct hit and there were several hits on other positions. The 9th’s antiaircraft guns were now fully placed to protect the airfield.26 Enemy air attacks on the Munda area, carried out at night or in the early morning, continued throughout the rest of the month. Captain Ervin’s three Battery G 40mm positions seaward of the airfield were straddled by a string of Japanese bombs that managed to just miss everyone.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The Munda drive moved into a final phase with attacks on 4 and 5 August 1943, again using Marine tanks in the lead. Tank commander Capt Robert W. Blake examines some of the improvised antitank weapons faced by his unit—a Molotov cocktail and a magnetic mine.

The landing and occupation of Arundel Island, on 27 August, further tightened the noose around Kolombangara. Army troops were supported by Captain Blake and tanks from the 9th, 10th, and 11th Defense Battalions. Major General Collins, commanding the 25th Infantry Division carrying out this assignment, commended the Marines “for the whole-hearted cooperation and assistance rendered this division” during the operations against the Japanese in the Arundel Island campaign. They performed all assigned tasks “in a splendid manner in support of the 27th Infantry, in its action....”

THE CLEAN-UP

5–27 August 1943

Captain Reichner’s Battery A moved to Piru Plantation on 29 August and two days later began shelling the Vila area of Kolombangara. The move was made by landing craft and foot. Recalled Captain27 William T. Box, with the artillery group’s advance party, “we hiked up from Munda using a native guide. I remember we hiked through jungle most of the way. I remember I was scared. I remember I was glad to see that open area with the supply parachutes” left by the Army. Soon afterwards, Battery B moved to Piru and on 2 September participated in the shelling of Vila. A Japanese defender there with the 8th Combined Special Naval Landing Force wrote in his diary, with “the situation as it is, one just can’t help but distrust the operational plans of the Imperial Headquarters.”

Marine Corps Historical Collection

Close-in air defense around the airfield was accomplished by regrouping defense battalion assets from Rendova, Laiana, and Zanana. This “Twin-Twenty” is at Munda, and is on one of several types of mobile mounts at New Georgia.

Other Japanese defenses included this 25mm automatic dual-purpose twin-barrelled gun in position on the airfield approaches. These proved to be deadly against both American air and ground forces.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 69975

The artillery group used the services of spotter aircraft, but because of enemy gunfire, switched from the light observation planes to Grumman TBFs because their armor plating gave the pilots greater protection. First Lieutenant Donald V. Sandager and Sergeant Herschel J. Cooper flew these missions over Kolombangara. “We both volunteered to a request from Major Hiatt. When we reported to Munda Airfield we had no parachutes and were told each flier had to have his own,” recalled Sandager. “The pilots were inexperienced and flew up from Guadalcanal each morning and we had to direct them to find the battery and Kolombangara. Radio communication with the battery was bad.” Admiral Halsey noted the artillery group and Lieutenant Colonel O’Neil’s ability to “utilize air spotting and the accuracy of their fire which stood out above other more experienced groups.”

Dead at his post, this Japanese soldier lies by a smashed 37mm antitank gun near the airfield. As the tanks broke through, the infantry followed and the fighting continued until the positions were overrun or buried in the rubble.

Marine Corps Historical Collection

The peak of enemy air activity over Munda Airfield occurred the night of 14–15 September when enemy planes kept gun crews at battle stations all night. The 90mm group expended 3,378 rounds, downing one plane and causing most of the enemy planes to jettison their bombs over the jungle or the sea. At Vila, a Japanese commander reported, “it had become very difficult to fire the antiaircraft guns as the enemy places their artillery upon our position immediately after we commence firing upon the aircraft.” At Piru, Japanese counterbattery fire hit the artillery group throughout September and the first two days of October. A number of the enemy artillery projectiles failed to detonate and there were no casualties from the shelling.

On 15 September, General Sasaki was ordered to evacuate his remaining 12,400 men from Kolombangara. The next month on 3 October, while flying his assigned air spotter missions, Lieutenant Sandager reported Vila evacuated; the Japanese had pulled out. Lieutenant Colonel Scheyer was pleased to state that for the “first time in this war the enemy had been driven from his base by28 bombing and artillery fire.” He concluded that at Kiska it was bombing and ship’s gunfire, at Kolombangara it was naval gunfire, bombing, and artillery fire that turned the tide. The final action of the campaign was a sea battle on 6–7 October when U.S. Navy destroyers intercepted Japanese evacuation ships during the Battle of Vella Lavella.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 58411

This 1 August 1943 bombing attack struck Marine positions on Rendova, only wounding one Marine, but destroying a height finder with flying coral.

The Japanese air effort slackened considerably in October, and came to an abrupt halt in November 1943. While at Munda Airfield, the 9th Defense Battalion accounted for eight more enemy planes. Numerous alerts, conditions red, and general quarters stand-tos that began an hour before dawn and an hour after sunset, had occurred daily for all gun crews. In early November, Battery A moved to Nusalavata Island and Battery B to Roviana Island where the 155mm guns covered Munda Bar and the eastern approach to Blanche Channel respectively. Lieutenant Colonel Scheyer remained in command of the 9th until 3 November, when he was assigned to I Marine Amphibious Corps and the command was turned over to Lieutenant Colonel Archie E. O’Neil.

On 22 November, the 9th Defense Battalion was attached to VI Corps Island Command for occupation duties. On 31 December, the battalion, with the exception of one radar crew and two searchlight sections, was relieved of the Munda Airfield defenses by the Army 77th AAA Group. The 9th Defense Battalion spent several weeks in camp in the Munda area waiting for transportation. These weeks were not idle as central camps for the several groups had to be set up and improved. Training schedules, begun in the later stages of the campaign, were carried out. Transport ships were available for the trip to the Russell Islands beginning on 13 January 1944 and continued until the entire battalion move was completed on 25 February.

29 The fighting by the 9th Defense Battalion contributed considerably to the victory of the land forces on New Georgia, and demonstrated the value of advance base defense. The 9th was in action against Japanese aircraft on 59 different days, for a total of 159 fire missions and 249 alerts, with 46 enemy planes downed. Not counted in these statistics were aircraft damaged or diverted from their intended targets and forced to undertake less accurate nighttime bombing missions. The fire of 155mm guns destroyed a number of enemy artillery positions and troops on Munda, Baanga, and Kolombangara. Numerous pillboxes and machine gun positions were destroyed and enemy troops killed by the tank platoon on New Georgia Island. Although the firing batteries and tanks were the most active elements of the battalion, other components of the battalion were deeply involved in the fighting also. The battalion also destroyed a machine gun position and killed three Japanese on Rendova and killed another 22 enemy and captured two prisoners at Zanana.

Battalion losses throughout the campaign were remarkably few: 13 dead, 1 missing, over 50 wounded in action, and other non-battle casualties. Malaria caused a number of the Marines to be evacuated. General Griswold summarized the battalion’s performance by concluding that every “officer and man of the organization has reason to feel proud of its accomplishment.” The I Marine Amphibious Corps commander, Lieutenant General Alexander A. Vandegrift, said “how proud I am to belong to the same outfit as they do.”

The first Marines to fight at New Georgia were the aircrews who were sent to blunt Japanese efforts to establish an airfield at Munda Point in December 1942. Thus began a routine air and sea pounding of the Munda Airfield until ground forces could capture it for Allied use.

For Marine flyers, these missions evoked “a parade of impressions—long over-water flights; jungle hills slipping by below; the sight of the target—airfield, ship, or town, sometimes all three; the attack and the violent defense; and then the seemingly longer, weary return....” The role of land-based aviation in the Central Solomons Campaign was critical, because the Japanese air effort had to be neutralized before Allied air and ground forces could climb up the Solomons ladder towards Rabaul. Unless the Allies could capture suitable airfields closer to the Japanese base areas at Rabaul and Bougainville, the air war would be limited in range and effect. The Guadalcanal airfields were 650 miles from Rabaul, Munda Point was a somewhat-closer 440 miles. For Marines aviators, Munda was a rung on the ladder that ended at Rabaul.

The air war for the Central Solomons was a series of sorties—fighter sweeps and bombing runs. For aviation units, the operating area was divided into the combat area, the forward area, and the rear area. These zones shifted as the campaigns moved north towards the Rabaul area. While the 1st and 2d Marine Aircraft Wings were present in the Southern Pacific, Marines flew under a joint air command, Commander Aircraft Solomons (ComAirSols). Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s ComAirSols was comprised of three subordinate segments: Bomber, Fighter, and Strike Commands. Strike Command was led by Colonel Christian F. Schilt, who had been awarded a Medal of Honor for heroism in Nicaragua in 1928, and Fighter Command was under Colonel Edward L. Pugh; both veteran Marine aviators in a structure where experience, “not rank, seniority, or service,”30 was paramount. The Marine squadrons flew Grumman F4F Wildcats, Grumman F6F Hellcats, and Chance-Vought F4U Corsairs in Fighter Command; and Grumman or General Motors TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers in Strike Command. Also operating in the theater was Marine Aircraft Group 25, the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command (SCAT), which flew unarmed transport planes, Douglas R4D Skytrains, bringing in supplies and replacements and evacuating wounded without fighter escorts such as the bombing missions had. Some 40 other squadrons were in rearward bases, making a total of 669 aircraft available for the Central Solomons campaign. They were opposed in the air by the Japanese Eleventh Air Fleet and Japanese Army air units defending New Guinea.

The Corsair, known as the “Whistling Death” to the Japanese and the “Bent Wing Widow Maker” to the Marines, was delivered in March 1943 in time to have eight Marine squadrons available for the New Georgia campaign. The Corsair, along with the new F6F Hellcat fighter, dominated the air-to-air battle to sweep the skies of the Japanese. This superiority was enhanced by Army Air Corps aircraft, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, for example. Once introduced, each new aircraft version could do a little more than the basic models; it could fly higher, fly longer, and carry more armament than its predecessor. Advances in radio detection and ranging (radar) and communications continued as31 well to ensure the control systems kept pace with the aircraft.

One Marine with Fighter Command, Major John P. Condon, recalled that ComAirSols routinely struck the airfields of southern Bougainville “with escorted bombers, night attacks by Navy and Marine Corps TBFs, and some mining at night of the harbors.” He went on to observe that the shorter-range SBDs were “invariably escorted in their routine reduction efforts against the fields in New Georgia.” Routine did not mean safe, as the Japanese just as routinely made their fighter presence known. Naval officer and novelist James A. Michener heard a pilot observe that he was “damned glad to be the guy that draws the milk runs.” But, “if you get bumped off on one of them, why you’re just as dead as if you were over Tokyo in a kite.”

One incident occurred that symbolized the joint nature of the air effort, the destruction of the aircraft transporting Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who had planned the attack on Pearl Harbor. Allied intelligence agencies learned that the admiral and his staff would fly to Kahili on 18 April 1943. Admiral Mitscher ordered Fighter Command to intercept Yamamoto’s aircraft. Planning for this mission fell to the Fighter Command’s deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Luther S. Moore, who scheduled Army long-range P-38 Lightnings fitted with Navy navigational equipment for the task. The flight plan was prepared by the command operations officer, Major Condon. Yamamoto’s plane was intercepted and shot down, ending the life of one of Japan’s major combat leaders.

At the end of April 1943, the Japanese Eleventh Air Fleet launched a series of determined, but unsuccessful, attacks to disrupt the Allied buildup on Guadalcanal and in the Russell Islands. These continued through the month, and on 16 June, ComAirSols planes intercepted and virtually destroyed 100 Japanese aircraft before they reached their target, the New Georgia invasion fleet. By the end of the month, the Allied forces were landing on New Georgia and the Japanese lost the battle to disrupt the offensive. The Japanese responded with repeated raids against shipping and landing areas, but the balance of air power was decidedly with Commander Aircraft Solomons. A Marine airman wrote that the Japanese were creating an ever-growing number of Marine, Army, and Navy fighter aces in the process.

The first Marines to fight in the Central Solomons campaign were the airmen based on Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands. They flew the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bombers that struck at Munda and elsewhere on New Georgia prior to the landings. In 1943, the planes were painted, from top to bottom, sea blue, intermediate blue, and semi-gloss sea blue, with insignia white undersurface.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 81420

By June, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 21 was pounding away at Munda, but not without losses. Flying from Guadalcanal and Russell Islands, ComAirSols fighter and strike aircraft covered the Toenails landings and subsequent operations ashore. From 30 June 1943 through July, there were only two days that did not have “Condition Red” and32 dogfights with Japanese aircraft over the objective area by Allied combat air patrols. At the same time, Japanese naval forces were located and attacked, thus forcing the Japanese to move at night by circuitous routes with landing barges alone. Bomber and Strike Command aircraft ranged as far north as Ballale, Buin, Kahili, and the Shortlands in concert with Fifth Air Force strikes at the same locations.

Despite this pressure, the Japanese continued to attack Allied forces from the air. ComAirSols planes were not able to operate effectively at night within range of Allied antiaircraft artillery that could not tell friendly from enemy aircraft. Another obstacle to total Allied success was the dense jungle-covered terrain that hindered identification targets and accurate assessment of the results of air strikes.

For efficient air control for the New Georgia operation, Admiral Mitscher set up a new command, Commander Aircraft New Georgia (ComAir New Georgia), as part of the landing force and under Marine Brigadier General Francis P. Mulcahy, who commanded the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing. ComAir New Georgia had no aircraft of his own, but controlled everything in the air above or launched from a New Georgia airfield. Mulcahy and his staff ensured command, control, and coordination of direct support air for the New Georgia Occupation Force after it had landed.

ComAir New Georgia established its command on Rendova after the assault waves landed on D-Day, 30 June 1943. From Rendova, he began to integrate the air defense and support system to provide XIV Corps with direct air support. On 11 July, Commander Aircraft Segi under Lieutenant Colonel Perry O. Parmelee was established under Mulcahy’s direct command. The ground forces were ashore on New Georgia and pushed ahead at Zanana and Laiana and were poised at the edge of Munda Airfield at the end of July. Mulcahy provided air support to the infantry advance at Munda Point and against other Japanese-held areas on New Georgia. By the end of the campaign, Mulcahy had ordered over 1,800 preplanned sorties mainly flown by SBDs and TBFs against targets at Viru, Wickham, Munda, Enogai, and Bairoko.

The Vought F4U Corsair, such as these on the Russell Islands, provided much of the air support in the New Georgia campaign. Here they taxi out from revetments onto the air strip to meet Japanese planes coming down The Slot from Bougainville and Rabaul.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 61335B

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 59989

BGen Francis P. Mulcahy, Commander Air Solomons, at right, at his headquarters at Munda. On the left is Army Air Force Col Fiske Marshall and 1stLt Dorothy Shikoski, an Army nurse who flew with Marine transport squadrons during medical evacuations.

In addition, there were some 44 close air support strikes using ad hoc forward air control and tactical air control parties from Mulcahy’s command. This was a significant step in the evolution of the air control system that eventually formed the air-ground team for the Marines. Close air support missions were planned in detail the day prior to execution. The requested missions went to Mulcahy and, if he approved, they then were forwarded to Guadalcanal, the Russells, or Segi Point for scheduling. The next day these aircraft reported to a rendezvous point and contacted an air support party on the ground which used radio, lights, smoke, or air panels to direct the strike. General Mulcahy commented that the use of aircraft close to the frontlines “proved to be impractical” with accuracy.

The R4D Skytrains of MAG-25 delivered 100,000 pounds of food, water, ammunition, and medicine that was the Northern Landing Group’s only source of supply at times. This support prompted one Marine raider to ask that the air drop containers be combat, or spread, loaded as on one occasion they recovered 19 of a 20-container load drop and “only later discovered the missing drop contained medicinal brandy.” Air drops of supplies went to the other ground forces as well, throughout a campaign fought in difficult, trackless, terrain.

On 25 July, a massive strike consisting of 66 B-17 and B-24 bombers in concert with naval gunfire ships struck at Lambetti Plantation, followed by an 84-plane strike on antiaircraft artillery positions at Biblio Hill. This was coordinated with the final drive to take the campaign’s main objective, Munda airstrip. The Japanese continued to delay the 43d Infantry Division and another strike followed on 1 August by a 36-plane attack of SBDs and TBFs, protected by some 30 fighters.

After the capture of Munda Point, General Mulcahy moved his command from Rendova to Munda airfield to set up strike and fighter control at Kokengolo Hill. In a Japanese-built tunnel that Navy Seabees had cleared of debris and dead, Mulcahy was able to conduct round-the-clock operations. The first fighters assigned to Munda landed at 1500 on 14 August. While safe, the Seabee-cleared shelter34 was also hot and smelled of its former dead occupants. On 15 August, Mulcahy sent VMF-123 and -124 fighters from Munda and Segi fields to cover the Vella Lavella landings, during which they claimed 26 Japanese aircraft downed. On this day, VMF-124’s First Lieutenant Kenneth A. Walsh began a streak that would eventually earn him the Medal of Honor for shooting down 21 Japanese aircraft. After accounting for three aircraft over Vella Lavella, he brought his Corsair back to Munda Field with 20mm holes in the wings, several hydraulic lines cut, a holed vertical stabilizer, and a flat tire.