Book cover

Book cover

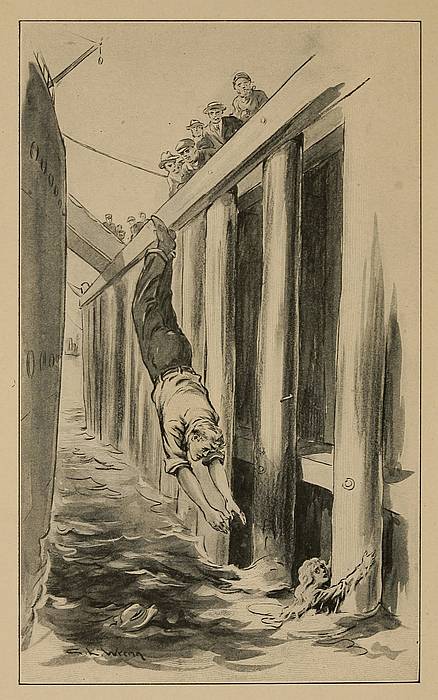

Then, shoving the men aside, he dived from the edge of the dock.—Page 8.

Jack Ready was making his way home. He was a tall, well-set-up lad of sixteen, and when in a good mood was a wholesome, cheerful-looking youngster.

But now, as he trudged along the rough, deeply rutted road that skirted the crowded wharves and slips of the Erie Basin, his attitude toward life was anything but amiable.

“It just seems as if I get turned down everywhere,” he muttered to himself as he turned aside to avoid a big automobile truck that was rumbling away from a squat, ugly-looking tank steamer lying at a dock not far off. “Too young, they all say. If only I could get a chance at a wireless key, I’d show them, but—Oh! what’s the use! It’s me for a shore berth till I’m old enough to try again, I guess. Hullo, what’s the matter over there?”

His attention had been caught by a sudden stir on the dock alongside the home-looking “tank.” She was a type of oil carrier familiar to the boy, as many vessels of a similar sort docked in the Erie Basin, New York’s biggest laying-up place for freight ships. This particular craft was black and powerful looking, with two pole masts bristling with derricks, and a tall funnel right astern painted black, with a red top.

But it was not the appearance of the steamer that interested the boy. It was a sudden rush and stir on the wharf alongside that had arrested his steps.

He could see the men, who had been engaged in various tasks about the vessel, running about and shouting and pointing down at the water between the ship’s side and the pier.

Evidently something very out of the ordinary was occurring. Glad of any opportunity to divert his thoughts from his fruitless search for employment as a wireless operator, Jack ran toward the scene of the excitement.

As he came closer he could distinguish some of the shouts.

“Throw her a rope, somebody!”

“She’s still down there!”

“No, she isn’t!”

These and a dozen other agitated cries and contradictions were flying about from mouth to mouth, and on the faces of the speakers there were looks of the greatest agitation.

“What is it? What’s the matter?” demanded Jack, running to the edge of the dock where the crowd of ’longshoremen and deck hands and sailors were clustered.

“It’s Mrs. Jukes’ little girl. She—she’s fallen overboard!” cried a man.

“She’s down there in the water,” explained another one. “She was clinging to a pile a minute ago. We’re trying to get a rope to her.”

“What! There’s a child down there and nobody’s gone after her?” cried Jack indignantly.

As he spoke he stripped off his coat and removed his boots almost with one operation. Then, shoving the men aside, he dived from the edge of the dock into the strip of dark, dirty water that lay between the ship and the wharf.

Clinging frantically to one of the piles supporting the dock was a little girl with a wealth of fair hair and a pretty, flower-like face. Too terrified even to scream, she was holding to the rough woodwork with all her little strength, but the expression of her face showed plainly that the struggle could not last much longer. In fact, as Jack, with a few strong, swift strokes, reached her side her grip relaxed altogether, and she slipped back into the oil-streaked water just in time for his strong arms to seize and hold her.

It was all over so quickly that hardly a moment seemed to have elapsed from the instant that the lad sprang from the stringpiece of the dock to the time when the cheering crowd above beheld him clinging to the rough surface of the pile with one hand, while with the other he supported the child, who had fainted and lay white-faced and weak in his grasp.

“Throw me a rope, some of you,” cried the boy, and in a jiffy a stout rope, with a loop in it, came shaking down to him.

He gently placed the loop under the child’s arm-pits, and when this was done, and it was not accomplished without difficulty, he signaled to the onlookers above to hoist up the unconscious little form. They hauled with a will, and in almost as brief a time as it takes to tell it Marjorie Jukes, daughter of the owner of the Titan Line of tank steamers, was on the dock once more with a doctor, hastily summoned from another vessel, attending to her.

Jack’s turn at the rope came then, and by dint of scrambling on his part and stout pulling from a dozen brawny arms above he, too, was presently once more in safety. Just as he reached the dock, dripping wet from his immersion, he heard the doctor asking how the child had come to go overboard.

“Her dad, he’s Jacob Jukes, the big ship-owner, was ashore there in the warehouses with the captain, fixing up an invoice,” Jack heard one of the sailors explaining. “Little Miss here was playing on the dock, waiting till her dad came back.

“All at once, afore any of us knowed a thing, there she was overboard. We all lost our heads, I guess. Anyhow, if it hadn’t been for a lad that suddenly bobbed up from no place in particular she might have drown-ded.”

“Here’s her dad coming now!” cried another.

Someone had found the ship-owner, and, hatless and white-faced, he was racing down to the dock from the gloomy red brick pile of warehouses ashore.

“She’s all right, sir!” shouted one of the sailors. “See, she’s openin’ her eyes, sir!”

“Thank God!” breathed her father reverently. “I should never have left her. Get my automobile, somebody. I must rush her home at once.”

In a few minutes a big limousine came purring down the dock from the rear yard of the storehouses. In the meantime Mr. Jukes, a handsome, florid-faced man of about fifty years of age, with a somewhat overbearing manner, as perhaps became his importance and wealth, had been informed of Jack’s brave rescue while he stood with his little daughter bundled up tenderly in his arms, the water from her wet clothing streaming, unregarded by him, down his broadcloth coat.

“Where is he? Where is that boy?” he demanded. “I want to see him. I must reward him handsomely.”

But Jack had vanished.

“He must be found. Does nobody know his name?” asked Mr. Jukes as if he were issuing an order. “I want to see him at once. Who is he? Does he live hereabouts?”

But nobody appeared to know. As for Jack, being satisfied that the child was out of all danger, and having no desire to pose as a hero, he had slipped off home at the earliest opportunity, shivering slightly in his wet clothing, for it was late fall and a chilly wind swept about the crowded docks and ship-filled slips.

It was an odd home for which Jack was bound. Tucked away in a quiet corner of the bustling Basin was a sort of ocean graveyard. Here old ships that had outlived their usefulness lay in peace until they were sold to be broken up or to be converted into barges or to meet some such end. Tall-sparred clippers that had once proudly swept the seven seas, rusty old tramp steamers, looking like the wrecks of marine hoboes that they were, and venerable ferryboats, all rubbed sides in this salt water cemetery.

In the farthest part of this quiet corner of the Basin lay a derelict two-masted schooner of an entirely different type from the other craft. To begin with, she was much smaller, and then again, instead of displaying rusty iron sides, or gaping, bleached wooden ones, she was gayly painted, with red and green hull and bulwarks. Her deck-house astern was a veritable marine garden, and bright-colored blossoms of all kinds, even though the season was late, bloomed from numerous boxes placed on the roof and about the taffrail.

A plank connected this queer-looking craft with the shore, and a column of smoke ascending from a pipe stuck through the cabin roof, as well as the curtained windows and general look of neatness, showed that someone made a home on this retired wanderer of the seas. It bore the name “Venus” on either side of a dilapidated figurehead, doubtless intended to represent the goddess of love. The effigy’s one remaining eye sadly surveyed the deep-sea vagabonds about her.

If the above evidences that the old schooner was used as a habitation had been lacking, there still would have remained proof that Captain Toby Ready made his home there, for, nailed to one side of the flowering cabin-house, was a large sign. On it in sprawling characters of white on a black background was the following inscription:

Here it was that Jack had made his home since the death of his father, Captain Amos Ready, at sea some years before. His Uncle Toby was thus left his sole surviving relative, for his mother had died soon after Jack’s birth. So Jack had lived with his eccentric relative on the old schooner, bought by Captain Toby many years before as a Snug Harbor.

The boy had helped his uncle compound his liniments and medicines, which had a ready sale among the old-time ship captains. They had more faith in Uncle Toby’s remedies than in a whole shipload of doctors. Captain Toby had, in his day, commanded fast clippers and other sailing vessels. On long voyages he had amused himself by studying pharmacy till he believed himself the equal of the entire college of surgeons. At any rate, if his medicines did no good, at least they never did any harm, and Jack was kept busy delivering orders for Captain Toby’s compounds to various vessels.

With such a line of sea-going ancestry, it was natural that the boy should have a hankering for the sea. But, together with his love of a seafaring life, Jack had developed another passion, and this was for wireless telegraphy.

Slung between the two bare masts of the old schooner was the antennæ of a wireless apparatus, and down below, in his own sanctum in the schooner’s cabin, Jack had a set of instruments. It was a crude enough station, which is hardly to be wondered at, considering that the boy had constructed most of the apparatus himself.

But Jack had a natural leaning for this sort of work, and his home-made station gave satisfactory results, although he could not catch messages for more than fifty miles or so. This, however, had not prevented him from becoming an adept at the key, and his one great ambition was to get a berth on one of the liners as a wireless operator.

So far, however, he had met with nothing but rebuffs. Wireless men appeared to be as common as blackberries.

“Come back when you’re older. We can’t use kids,” the head of a big wireless concern had told him. And that was the substance of most of the replies to his applications for a job at the work he loved.

That day he had tramped on foot to Manhattan and made his weary round once more, with the same result. Footsore and thoroughly discouraged, he had trudged back over Brooklyn Bridge and across town to the region of the Basin, where the air bristled with masts and derricks, and queer, foreign, spicy smells issued from the doors of warehouses. He walked, for the excellent reason that he was young and strong, and every nickel saved meant a better chance to improve the equipment of his station on the old Venus.

He cheered up a bit as he came in sight of his floating home. He had grown to like his odd way of life, and he had a sincere affection for his eccentric old uncle. Determined not to let the old man see his disappointment, he struck up “Nancy Lee,” whistling it bravely as he crossed the rickety gangplank, walked over the scrupulously scrubbed deck and dived down the companionway into one of the strangest homes that any boy in all New York ever inhabited.

As Jack entered the cabin he was greeted by a succession of shrill shrieks and whoops.

“Ahoy, my hearty! Never say die! Don’t give up the ship! Kra-a-a-a!”

“That is good advice, Methusaleh,” laughed the boy, addressing himself to a disreputable-looking parrot that stood balancing itself on a perch in a cage that hung in one corner of this queer abode.

The ports which the cabin had originally boasted had been enlarged and formed into windows, through which the light streamed cheerfully. Red cotton curtains hung at these casements and gave a dash of color to the dark wooden walls of the place. In the center was a swinging table and some rickety chairs; at one end was a sea-stove, a relic of the schooner’s sea-going days, and at the opposite end of the cabin, at the stern portion of it, was a bulkhead and a door.

From beyond this door came the clinking of glasses and the sound of pounding. It was Captain Toby hard at work in his sanctum compounding his medicines. Jack turned into another door alongside the stove, on the other side of which there was a similar portal.

These doors led into the cabins respectively of Jack and his uncle. Jack’s cabin was a neat little combination workshop and sleeping place.

On a shelf opposite his bunk was his wireless set, with the wires leading down to it from the aerials above. Another shelf held his stock of books, mostly of a scientific character, dealing with his favorite pursuit. The rest of the space in the not very large cabin was occupied by a work bench, cluttered with tools and stray bits of apparatus.

Jack had no wish to worry his uncle with an account of the happenings of the afternoon, so, before seeking him, he slipped out of his wet clothes and donned the overalls in which he usually worked. There was another reason for this, too, for the suit in which he had dived to the rescue of little Marjorie Jukes was the only one he boasted.

Having hung up his garments carefully, so that they would dry as free from wrinkles as possible, Jack left the cabin and made for his uncle’s sanctum in the stern.

“Well, Jack, my hearty, what luck?” inquired the old man as the boy entered.

Jack shook his head.

“The same old story, Uncle Toby. What are you busy at?”

“An order for the ‘Golden Embrocation and Universal Remedy for Man and Beast’ for Cap’n Styles of the Sea Witch,” rejoined his uncle in his deep voice, hoarse from many years of shouting orders above gales and storms. “If you really want to go to sea, Jack, I’ll get you a berth with Cap’n Styles. The Sea Witch is a fine old Yankee ship; not one of your smoke-eating tea-kettles.”

“But she has no wireless?” questioned Jack, gazing about him at the compartment, which was stocked with the tools of the captain’s trade: herbs in bundles, bottles, pestles and mortars and so forth. A strong aromatic odor filled the air, and the captain hummed cheerily as he poured a yellow, evil-smelling liquid from a big retort into half a dozen bottles, destined to cure the ills of Captain Styles.

“Wireless! Of course not, my hearty. What does a fine sailing ship want with a wireless? Take my word for it, Jack, wireless is only a newfangled idee, and it won’t last. Give a sailor sea-room and a good ship and all that fol-de-rol is only in his way.”

“And yet I saw the news of another rescue at sea by means of the wireless when I was looking at a newspaper bulletin-board to-day,” rejoined the lad. “The crew of a burning tramp steamer was rescued by a liner that had been summoned to their aid by the apparatus. If it hadn’t been for wireless, that ship might have burned up with all hands, and no one ever have known her fate.”

His uncle grunted in the manner of one unconvinced.

“Well, I ain’t saying that wireless mayn’t be all right for one of them floating wash-boilers, but for Yankee sailors, good rigging and canvas and a stout, sweet hull is good enough to go to sea with.”

As he went on with his work, he began rumbling in a gruff, throaty bass:

“That’s the music, Jack,” said he. “I wish you’d go inter sails instead of steam, and follow the examples of your dad and your uncle, yes, and of your granddaddy, Noah Ready, afore ’em.”

Jack made no rejoinder, but set about straightening up the litter in the place. The contention between them was an old one, and always ended in the same way. His uncle knew many seafaring men of the old school who would gladly have given Jack a berth on their craft. But they were all in command of “wind-jammers,” and the boy’s heart was set on the wireless room of a liner, or at any rate a job on some wireless-equipped vessel.

Meantime the captain went on compounding and mixing and pouring, rumbling away at his old sea songs. He was an odd-looking character, as odd in his way as his chosen place of residence.

Years of service on the salt-water had tanned his wrinkled skin almost to a mahogany color. Under his chin was a fringe of white whiskers, and his round head—covered with a bristly white thatch—was set low between a pair of gigantic shoulders. He was dressed in a fantastic miscellany of water-side slops which flapped where they should have been tight, and wrinkled where they should have been loose. Add to this an expression of whimsical kindness, a wooden leg and a wide, rough scar,—the memento of a battle with savages in the South Seas,—and you have a portrait of Captain Toby Ready.

Presently the captain drew out a huge silver watch.

“Two bells. Time to stand by for supper, lad,” he said. “That stuff’ll have to go to Cap’n Styles to-morrow. There’s plenty of time; he don’t sail for goin’ on a week yet. Slip your cable, like a good lad, and set a course for the bakery. We’re short of bread.”

“And I’m short of the money to get it,” said Jack.

The captain thrust a hairy paw into his pocket and drew out an immense purse. He extracted a coin from it and handed it to the boy.

“An’ how much, lad, is a penny saved?” he inquired, peering at Jack from under his bushy white brows.

“A penny earned,” laughed Jack.

“Co’-rect,” chuckled the captain, grinning at Jack’s quick reply to the almost invariable formula, “an’ if Captain Toby Ready had thought o’ that when he was young, he wouldn’t be here on the craft Wenus making medicines fer sea-cap’ns with a tummy ache.

“I’ve got an apple pie in the oven, Jack,” said he, as the boy left the “drug-store,” as he and his uncle called it, “so cut along and hurry back.”

“Aye, aye, sir!” cried the boy, bounding up the cabin stairs with alacrity.

Apple pies were not common on board the Venus, nor was Jack too old to appreciate his uncle’s announcement.

When Jack returned, he was surprised to hear voices in the cabin. His uncle had a habit of talking to himself, but there was another voice mingling with the old sailor’s deep, rumbling tones.

Wondering greatly who the visitor could be, for somehow the voice sounded different from the bellowings of the old sea cronies who visited the Venus either on business or socially, Jack descended the cabin stairs.

The swinging lamp was lighted and shone down on his uncle and another man, seated on opposite sides of the table.

“By the great main boom, the lad never told me a word of it!” his uncle was saying. “Dived overboard an’ saved your little gal, eh? Well, sir, Jack’s a chip of the old block!”

The man who sat opposite the captain was a portly gentleman with a bald brow, gold-rimmed glasses and close-cropped gray mustache. He spoke with curt, sharp emphasis, as if his minutes were dollars.

“Lucky that a watchman saw and recognized the boy as he sneaked away,” this individual replied. “If it had not been for that, I might never have found him. But I must see him. Where is he?”

“Here he is, sir, to answer for himself,” said the captain, as he heard Jack’s step on the stair.

As the boy entered the cabin the ship-owner jumped to his feet. He crossed the place with a quick, rapid stride and grasped Jack’s free hand.

“I’m proud to shake hands with a youngster like you,” he said in his swift, incisive way, “yes, sir, proud. If it had not been for you, my daughter might have drowned with those dolts all standing round doing nothing. Jove——”

He mopped his forehead in an agitated way at the very thought of what might have happened.

“That’s all right, sir,” said Jack, “I’m glad I was there when I happened to be. When I knew the little girl was all right, I came away.”

The boy had recognized the shipping magnate from pictures of him that he had seen in the papers. Had he not come around another way from the bakery, he would have been prepared for this august visitor by the sight of his limousine, lying at the head of the dock.

“’Sarn it all, why didn’t you spin me the yarn?” sputtered the captain in an aggrieved tone.

“Oh! there really wasn’t much to tell,” said Jack. “The little girl was clinging to a pile and I went down and got her up. That’s all there was to it. If I hadn’t done it, somebody else would.”

“That is just the point,” roared Mr. Jukes, “somebody else wouldn’t.”

He drew out a check-book and signed his name to a check. He shoved this across the table to Jack, who was standing by his uncle.

“Fill that in for any amount you like, lad,” he said in his dictatorial way. “Make it a good, round sum. Jacob Jukes’ account can stand it.”

Jack colored and hesitated.

“Well, what’s the matter, boy?” sputtered the ship-owner, noting the boy’s hesitation. “That check won’t bite you. I know a whole lot of lads who’d have grabbed at it before it was out of my hand.”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” rejoined Jack, “you’re very generous and—and all that. Maybe you’ll think me ungrateful, but I can’t take that check.”

“Wha—what! Can’t take my check! What’s the matter with the boy?”

“Hev you slipped the cable of your senses, Jack?” hoarsely exclaimed his uncle, in what was meant to be a whisper.

“I don’t want money for just doing a little thing like that,” said the boy stubbornly.

“You don’t mean it. Come, take that check at once. Don’t be a fool!” urged Mr. Jukes with a very red face. “Why can’t you do as I tell you!”

The magnate’s tone was almost angry. He was not used to having his commands disobeyed, and he was commanding Jack to take the check. But the boy resolutely shook his head.

“Why, confound it all, I can’t understand it. Make him take the check at once, captain.”

“Don’t see how I can, if he’s so sot and stubborn about it,” rejoined the captain. Then, turning to Jack, he made another appeal. “Why won’t you take it, Jack?” he growled. “Shiver my timbers, what ails you?”

“Nothing; but I can’t accept money from Mr. Jukes or anybody else, for doing what I did,” said the boy quietly.

Mr. Jukes, with a crimson face, gave up the battle. He reached across the table, took the check and slowly tore it into fragments.

“It is the first time in my experience that I ever encountered such a singular lad as this. Hang me if I don’t think there’s a screw loose somewhere. But after what you did for me this afternoon, never hesitate to call on me if you need anything at any time. Here’s my card.”

He rose, and with a comical mixture of astonishment and indignation on his face, regarded Jack somewhat as he might have looked at some strange freak in nature.

“Thank you, sir,” said the boy, taking the bit of pasteboard, “I didn’t mean to offend you; but—but, well, I couldn’t take that check, that’s all.”

“Well, well, we’ll say no more about it,” said the great man testily. “But remember, I’ll always stand your friend if I can.”

He started to leave the cabin, when he suddenly brought up “all standing,” as the captain would have said, with a sharp exclamation of pain.

“What is it, sir?” demanded that veteran with some concern. “Your figurehead looks like you had some sort of a pain.”

“It is nothing. Just a sharp twinge of my old trouble, rheumatism,” explained the great man. “The damp air of the Basin may have brought it on.”

“Anchor right where you are!” exclaimed the captain, and before Mr. Jukes could say another word, he had darted into the “drug-store” and was back with a bottle full of a villainous-looking black liquid.

“My rheumatiz’ and gout remedy,” he explained.

“Yes, but I am under medical treatment. I——”

“Keel-haul all your doctors. Throw their medicine overboard,” burst out the captain. “Try a few applications of Cap’n Ready’s Rheumatiz and Gout Specific. Cap’n Joe Trotter of the Flying Scud cured himself with two bottles. Take it! Try it! Rub it in twice a day, night and morning, and in a week you’ll be as spry as a boy, as taut and sound as a cable.”

“Well, well, I’ll try it,” said the magnate good-naturedly in reply to Captain Toby’s outburst of eloquence; “how much is it?”

“One dollar, guaranteed to work if used as directed, or your money back,” rattled on the captain, pocketing a bill which Mr. Jukes peeled off a roll that made Captain Toby open his eyes.

And so, burdened with a bottle of the “Rheumatiz and Gout Specific,” and with the memory of the first person he had ever met who was not willing to accept his bounty, the shipping magnate stepped ashore from the Venus.

“He’ll be dancing a hornpipe in a week,” prophesied Captain Toby; “the Specific has never failed.”

But if he could have seen Mr. Jukes carefully drop the bottle overboard as soon as he reached the shore end of the dock, his opinion of him would have fallen considerably. As it was, the old seaman was loud in his praise.

“Think of him, the skipper of a big corporation and all that, wisiting us on the Wenus!” he exclaimed. “Why, Jack, that’ll be something to tell about. The great Mr. Jukes! Maybe this’ll all lead to something! If the Specific works like it did on Cap’n Joe Trotter, he may make me his physician in ordinary.”

“Let’s hope it won’t work the same way on him that it did on Captain Zeb Holliday,” said Jack with a smile.

“Huh! That deck-swabbing lubber!” cried the captain, with intense scorn. “He drank it instead of rubbing it in, although the directions was wrote on the bottle plain as print. But, Jack, lad, why didn’t you take that check? Consarn it all——”

“It’s no good talking about it, uncle,” said the boy, cutting him short; “I couldn’t take it; that’s all there is to that.”

“Confound you for a young jackass! Douse my topsails, but I’m proud of you, lad!” roared the captain, bringing down a mighty hand on Jack’s shoulders. “And now let’s pipe all hands to supper.”

Two days later, Jack happened to pass the dock where the Titan liner lay. She was taking aboard her cargo from a pipe-line—crude, black oil destined for Antwerp. Because of the adventure in which he had participated alongside her, Jack felt an interest in the ugly, powerful tanker. As he was looking at her, he noticed some men busy at the tops of her squat steel masts.

All at once they began to haul something aloft. What it was, Jack recognized the next moment. It was the antennæ of a wireless plant. They were installing a station on the ship, which bore the name “Ajax” on her round, whaleback stern.

Jack’s heart gave a sudden leap. A great idea had come to him. Mr. Jukes owned the Titan Line. The ship-owner had said to him only two nights before: “Remember, I’ll always stand your friend if I can. Never hesitate to call on me if you need anything at any time.”

And right then Jack needed something mighty badly. He needed the job of wireless operator on board the Ajax.

The power of eight thousand horses was driving the big tanker Ajax through the Lower Bay, out past Sandy Hook, and on to the North Atlantic.

As the big black steel craft felt the lift and heave of the ocean swells, she wallowed clumsily and threw the spray high above her blunt bow. Very different looked this “workman” of the seas from the spick and span liner they passed, just after they had dropped the pilot.

Grim, business-like, and built for “the job,” the Ajax looked like a square-jawed bulldog beside the yacht-like grayhound of the ocean, whose whistled salute she returned with a toot of her own siren.

Like all craft of her type, the Ajax had hardly any freeboard. In the bow was a tall superstructure where the crew and the minor officers lived. Here, too, was the wheel-house and the navigating bridge. In the extreme stern was another superstructure, square in shape, whereas the bow-house was like a big cylinder pierced with port-holes.

From the stern upper-works projected the big black funnel with the red top, distinctive of the Titan liners, and in this stern structure, too, dwelt the captain, the superior officers and the first and second engineers.

From the stern superstructure and the chart-house to the crew’s quarters in the bow, there stretched a narrow bridge running the entire length of the craft. This was to enable the crews of the great floating tank to move about on her, for on board a tank steamship there are no decks when there is any kind of a sea running. The steel plates that form the top of the tank are submerged, and nothing of the hull is visible but the two towering structures at the bow and stern, the bridge connecting them, and the funnel and masts.

But for all her homely outlines the Ajax was a workman-like craft and fast for her build. In favorable weather she could make twelve knots and better, and her skipper, Captain Braceworth, and his crew were proud of the ship.

On the day of which we are speaking, however, there was one member of the ship’s company to whom the big tanker was as fine a craft as sailed the Seven Seas. This was a young lad dressed in a neat uniform of blue serge, who sat in a small, steel-walled cabin in the after superstructure. The lad was Jack Ready, sailing his first trip as an ocean wireless boy. As he listened to and caught signals out of the maze of messages with which the air was filled, his cheeks glowed and his eyes shone. He had attained the first step of his ambition. Some day, perhaps, he would be an operator on such a fine craft as the liner they had just passed and with which he had exchanged wireless greetings.

Jack had secured the berth of wireless man on the Ajax with even less difficulty than he had thought he would encounter. Mr. Jukes, although a busy, brusque man, was really glad to be able to do something for the lad who had done so much for him, and as soon as Jack had proved his ability to handle a key he got the job.

It had come about so quickly, that as he sat there before the newly installed instruments,—it will be recalled that the Ajax was making her first trip as a wireless ship,—the boy had to kick himself slyly under the operating table to make sure he was awake!

“I’m the luckiest boy in the world,” said the young operator to himself, as gazing from the open door of the cabin, he watched the coast slip by and the rollers begin to take on the true Atlantic swell.

His reverie was interrupted by the entrance of Mr. Harvey, the first officer.

“Message from the captain to the owners,” he said briefly; “hustle it along.”

It was only a routine message, but Jack thrilled to the finger tips as he sent out the call for the station at Sea Gate, from whence the message would be transmitted to New York. It was the first bit of regular business he had handled in his chosen calling.

The air appeared to be filled with a perfect storm of messages coming and going. Newspapers were sending despatches of world-wide importance. Ships were reporting. Here and there an amateur,—Jack was out of this class now, and held them in proper contempt,—was “butting in” with some inquiry or message. And friends and relatives of persons outward or homeward bound across the ocean track added their burden to the mighty symphony of “wireless” that filled the ether.

But at last Jack raised the Sea Gate station, and in a second his first message from shipboard was crackling and spitting from the aerial. He sent crisply, and in a business-like way. The operator at Sea Gate could hardly have guessed that the message was coming from a lad who had but that day taken his place at an ocean wireless station.

When this message had been sent, Jack sat in for an answer. Before long, out of the maze of other calls, he picked his summons and crackled out his reply, adding O.K. G.—“Go ahead.” When he had finished taking the message, merely a formal acknowledgment of the captain’s farewell despatch, Jack grounded his instruments and went forward with the reply in search of the skipper.

He found the Ajax wallowing through a somewhat heavy sea. Looking down from the narrow bridge, he could see the decks with their covered winches, steam-pipes and man-holes only at times through a smother of green water and white foam that swept over them.

Jack clawed his way forward and found the captain with his first officer on the bridge. The wheel was in the hands of a rugged, grizzled quartermaster, who stood like a figure of stone, his eyes glued to the swinging compass card. Occasionally, however, he gave an almost imperceptible move to the spokes of the brass-inlaid wheel he grasped, and a mighty rumbling of machinery followed. For the Ajax, like practically every vessel of to-day, steered by steam-power, and a twist of the wrist was sufficient to move the mighty rudder that was distant almost a tenth of a mile from the wheel-house.

But the boy did not give much observation to all this. He was intent on his duty. Touching his cap, he held out the neatly written message,—of which he had kept a carbon copy on his file.

“Despatch, sir!” he said respectfully.

The captain took the message and read it, and then eyed the boy attentively.

Captain Braceworth was a big figure of a man, bronzed, bearded and Viking-like. He was also known as a strict disciplinarian. Jack had not spoken to him till that moment. He decided that he liked the skipper’s looks, in spite of an air of cold authority that dwelt in his steady eyes.

“So you’re our wireless man, eh?” asked the skipper.

“Yes, sir. Mr. Jukes——”

“Humph! I know all about that. I understand this is your first voyage. Well, you have lots to learn. Do your duty and you’ll have no trouble with me. If not, you will find it very uncomfortable.”

He turned away and began talking to his first officer. Jack made his way back to his cabin with mingled feelings. The captain had spoken to him sharply, almost gruffly. He began to revise his opinion of the man.

“He is a martinet and no mistake,” thought the boy; “a bully too, I’ll bet. But pshaw, Jack Ready, what’s the use of kicking? You’ve got what you wanted; now go through with it. After all, if I do my duty, he can’t hurt me.”

But as he took his seat at his instruments again, Jack, somehow, didn’t feel quite so chipper as he had half an hour before. In his own estimation he had rated himself pretty highly as the wireless man of the Ajax.

“But I reckon I don’t count much more than one of the crew,” he muttered to himself as the memory of the captain’s brusque, authoritative manner rankled in his mind.

Having sent his “T.R.”—as the first message from an outward bound ship is, for some mysterious reason known,—Jack occupied himself by occasionally chatting with some other operator and exchanging positions.

As the Ajax forged on, the boy began feeling ahead with his key for the wireless stations at Sagaponack or Siasconset. Messages to and from Nantucket he had already caught, and had sent in a report of the Ajax and her position.

Supper time came and Jack ate his meal in company with the second and third engineers. The captain and the other officers were far too important to sit down with a wireless man on his first voyage. The second engineer was a lively youth with a crop of hair as red as the open door of one of his own furnaces. His junior was not more than two years older than Jack, a stalwart lad, with a bright, intelligent face, named Billy Raynor.

Young Raynor and Jack struck up quite a friendship at supper, and after the red-headed second, whose name was Bicket, had left the table, they fell to discussing the ship and its officers.

“I happened to be on the bridge,—message from the chief,—this afternoon when you were talking to the old man,” said Raynor. “From the look on your face, I fancy you thought him a bit overbearing.”

Jack flushed. He did not know that he had let his mortification be visible.

“Well, I had expected rather a different reception, I must say; but I’m not such a baby as to kick about anything like that, or even a good deal worse.”

“That’s the way to talk,” approved Raynor. “The old man’s bark is worse than his bite, although I don’t come much in contact with him. Mr. Herrick, the chief, is my boss.”

He rose to go below to his duties.

“Some time when I’m off watch, I’d like to come up to your coop and have a chat with you about wireless,” he said.

“I wish you would,” said Jack, heartily glad to find,—for he was beginning to feel lonely,—that there was at least one congenial soul on the big steel monster, of which he formed a part of the crew.

Jack’s day ended at eight o’clock, but before his time to go off duty, there came a peremptory message from the captain. The weather had been steadily growing worse, the sea was mounting and the wind increasing. Jack was to stay at his post and try to catch messages from vessels farther out at sea, concerning conditions on the course.

As the night wore on, the gale increased in violence. The tanker wallowed through giant seas, the spray sweeping over even the elevated bridge linking her bow and stern. Her hull, with its cargo of oil and coal and the mighty boilers and engines that drove her forward, was as submerged as a submarine.

The young wireless operator sat vigilantly at his key. The night was a bad one for wireless communication, although a storm does not, of necessity, interfere with the “waves.”

At last, about ten o’clock, he succeeded in obtaining communication with the Kaiser, one of the big German liners, some one thousand miles to the eastward.

Back and forth through the storm the two operators talked. The Kaiser’s man reported heavy weather, rain-squalls and big seas.

“But it is not bothering us,” he added; “we’re hitting up an eighteen knot clip.”

“Can’t say the same here,” flashed back Jack; “we have been slowed down for an hour or more. This is a bad storm, all right.”

“You must be a ‘greeny’; this is nothing,” came back the answer from the Kaiser man.

“It is my first voyage as a wireless man,” crackled out Jack’s key.

“Bully for you! You send like a veteran,” came back the rejoinder; and then, before Jack could send his appreciation of the compliment, something happened to the communication and the conversation was cut off.

When he opened the door to go forward with his message for the skipper, the puff of wind that met the boy almost threw him from his feet. But he braced himself against the screaming gale and worked his way along the bridge. He wished he had put on oil-skins before he started, for the spray was breaking in cataracts over the narrow bridge along which he had to claw his way like a cat.

“Well, whatever else a ‘Tanker’ may be, she is surely not a dry ship in a gale of wind,” muttered the boy to himself, as he reached the end of his journey.

On the bridge, weather-cloths were up, and the second officer was crouched at the starboard end of the narrow, swaying pathway. But pretty soon Jack made out the captain’s stalwart figure. The skipper elected to read the message in the chart-house. He made no comment, but informed Jack that in an hour’s time he might turn in.

Nothing more of importance came that night, and at the hour the captain had named, the young wireless boy, thoroughly tired after his first day at the key of an ocean wireless, sought his bunk. This was in the same room as the apparatus, and as he undressed, Jack figured on installing, at the first opportunity, a bell connecting with the apparatus by means of which he might be summoned from sleep if a message came during the night. He had made several experiments along these lines at his station on the old Venus, which now seemed so far away, and had met with fair success. He believed that with the improved conditions he was dealing with on the Ajax, he could make such a device practicable.

When he went on deck at daylight, he found that the storm, far from abating, had increased in violence. The speed of the Ajax had been cut down till she could not have been making more than eight knots against the teeth of the wind.

The white-crested combers towered like mountains all about her. Nothing of the hull but the superstructures were visible, and the latter looked as if they had gone adrift,—with no hull under them,—in a smother of spume and green water. It was almost startling to look down from the rail outside his cabin and see nothing but water all about, as if the superstructure had been an island.

He went back to his instruments and picked up a few messages concerning the weather. Two were from liners, and one from a small cargo steamer. All reported heavy weather with mountainous seas.

“Not much news in that,” thought the boy, as he filed the messages and prepared to go forward with his copies.

As he opened the cabin door, the man at the wheel must have let the ship fall off her course. A mighty wave came rushing up astern and broke in a torrent of green water over the gallery on which Jack stood. He was picked up like a straw and thrown against a stanchion, with all the breath knocked out of him.

Here he clung, bruised and strangling, till the wave passed.

“Seems to me that the life of an ocean wireless man is a good bit more strenuous than I thought,” muttered the boy, picking himself up and discovering that he must make fresh copies of the messages he had been taking forward.

An old German bos’un came by as Jack was picking himself up.

“Hullo! Almost man overboard,—vat?” he chuckled. “Don’d go overboard in dis vedder, Mister Vireless, aber vee nefer see you no more.”

“Did you ever see a storm as bad as this?” sputtered the dripping Jack.

“Dis not amount to much,” was the reply. “Vait till you cross in midt-vinter, den you see storms vos is storms.”

He hurried off on his work, while Jack, having recopied his messages, started forward again. This time he met with no mishaps.

On the reeling bridge he found Captain Braceworth. The captain was clinging to the railing, a shining, uncouth figure in dripping oil-skins. The clamor of wind and sea made speech almost impossible, but Jack touched the captain on the elbow to attract his attention.

In spite of his feeling, almost of aversion to the grim, strict captain, Jack felt a sensation of admiration for this stalwart, silent figure, guiding his wallowing ship through the storm as calmly as if he had been seated at a dinner table. One thing was certain, Captain Braceworth was no fair-weather sailor. Martinet though he might be, he was a man to meet a crisis calmly and with cool determination.

The captain took the messages silently and once more retired to the wheel-house to scan them. At the other end of the bridge the chief officer stood, an equally silent figure, looking out over the tempest-torn ocean. The captain was soon back on the bridge. He went over to the chief officer and Jack could see the two talking, or rather shouting.

He stood waiting respectfully for orders, crouching in the lee of the weather-cloth for protection against the screaming gale.

As soon as he saw that the captain had finished his conference with the officer, Jack came from the shelter and clawed his way to the skipper’s side.

Captain Braceworth placed his hands funnel-wise to his mouth and shouted into Jack’s ear:

“Try to get Cape Race or Siasconset, and tell the office in New York that we are in a bad gale and running under reduced speed. From the look of the glass it may last two days and delay our arrival at Antwerp.”

Jack saluted and was off like a flash, while the captain resumed his silent scrutiny of the racing billows. Five minutes later, the young wireless boy sat at his post, sending his message through the shouting, howling turmoil of wind and wave.

Experienced as he was at the key, it was, nevertheless, a novel sensation to be sitting, snug and warm in his cabin, flashing into storm-racked space, the calls for Siasconset or “the Cape.” Occasionally he groped with his key for another vessel, through which his message to the New York office might be “relayed.”

He knew that some of the big liners had a more powerful apparatus than he possessed, and if he did not succeed in raising a shore station, his message could be transmitted to one of the steamers and thence to the land.

The spark whined and crackled and flashed for fifteen minutes or more before there came, pattering on his ears through the “watch-case” receivers, a welcome reply.

It was from Cape Race. Jack delivered his message and had a short conversation with the operator. He had hardly finished, before, into his wireless sphere, other voices came calling through the storm. Back and forth through the witches’ dance of the winds, the questions, answers and bits of stray chat and deep sea gossip came flitting and crackling.

But Jack had scant time to listen to the voice-filled air. He soon shut off his key and prepared to go forward again, with the news that the message had been sent. In less than an hour some official at the office of the line in New York would be reading it, seated at his desk, while miles out on the Atlantic the ship that had sent it was tossing in the grip of the storm.

Jack thought of these things as he buttoned himself into his oil-skins, secured the flaps of his sou’wester under his chin and once more fought his way forward along that dancing, swaying bridge, below which the water swirled and swayed like myriads of storm-racked rapids.

The captain, grim as ever, was still on the bridge, but now Jack saw that both he and the officer who shared his vigil were eying the seas through the glasses. They appeared to be scanning the tumbling ranges of water-mountains in search of some object. What, Jack did not know. But their attention appeared to be fully engrossed as they handed the glasses from one to another, holding on to the rail with their free hands to keep their balance.

Presently the chief officer shook his head and shrugged his shoulders as if he had negatived some proposition of the captain’s.

The latter replaced the glasses in their box by the engine room telegraph, and Jack, deeming this a favorable opportunity, came forward with his report.

He had almost to scream it into the captain’s ear. But the great man heard and nodded gravely. Then he turned away and drew out the glasses once more and went back to scanning the heaving seas.

Jack, from the shelter of the wheel-house, within which an imperturbable quartermaster gripped the spokes of the wheel, followed the direction of the skipper’s gaze.

All at once, as the Ajax rose on the summit of a huge comber, he made out something that made his heart give a big jump.

It was a black patch that suddenly projected itself into view for an instant, and then rushed from sight as if it would never come up again.

The captain wheeled suddenly. His eyes focused on Jack.

“Operator!”

“Aye, aye, sir!”

“Have you had any calls from a ship in distress?”

“No, sir. I should have reported any message to you at once.”

“Of course. I’m not used to this wireless business, although it seems to be useful.”

“There—there’s a ship in distress yonder, sir?” Jack ventured to ask.

“Yes, they’re badly off.”

The captain tugged at his brown beard which glistened with spray.

“Call the third officer. He is in his cabin.”

Jack hastened aft and soon returned with Mr. Brown, the third officer of the Ajax, an alert, active little man. Jack ventured to linger on the bridge while they talked. His heart was filled with pity for whoever might be on board the storm-tossed derelict. He wanted to know what the captain proposed to do.

Fragments of speech were blown to the young operator’s ears as the three officers talked.

“Hopeless—Boat wouldn’t live a minute in this sea—she’ll go before eight bells—Yes, bound for Davy Jones’ locker, poor devils.”

Jack’s pulses beat fast as he heard. Could it be that the Ajax was to make no effort to rescue the crew of the wreck? His heart throbbed as if it would choke him. He felt suddenly angry, furiously angry with the three men on the bridge, who stood so calmly talking over the situation while, less than a mile away, there was a wrecked ship wallowing in the mighty seas without a chance for her life.

Had he dared, he would have stepped forward and volunteered to form part of a boat’s crew, no matter what the risk. His father’s seafaring blood ran in his veins, and he could recall hearing both Captain Amos Ready and his Uncle Toby recounting to each other, over their pipes, tales of sea-rescues.

“Uncle Toby is right,” thought the boy, with a white-hot flush of indignation; “seamanship is dead nowadays. The men who go to sea in these steel tanks are without hearts.”

They rose on the top of another mountainous wave and Jack had his first good view of the forlorn wreck. She was evidently a sailing vessel, although of what rig could not be made out, for her masts were gone. A more hopeless, melancholy sight than this storm-riven, sea-racked derelict could not be imagined. Her bowsprit still remained, and as she rose upward on a wave with the star pointed to the scurrying gray clouds, Jack’s excited fancy saw in it a mute appeal for aid.

And still the three officers stood talking, as the Ajax ploughed on. No attempt had been made to veer from her course.

“They’re going to leave her without trying to help her,” choked Jack, clenching his hands. “Oh! the cowards! the cowards!”

The boy made an impulsive step forward. In his excitement he was reckless of what he did. But, luckily, he came to his senses in time. Checking himself, he gloweringly watched the captain step to the wheel-house. As he did so, the commanding officer beckoned to Jack.

“I suppose he’s going to haul me over the coals for standing about here,” muttered the boy to himself; and then, impulsively, “but I don’t care. I’ll tell him what I think of him if he does!”

With defiance in his heart, Jack, nevertheless, hastened forward to obey Captain Braceworth’s motioned order.

Within the wheel-house the hub-bub of the storm was shut out. It was possible to speak without shouting. The captain’s face bore a puzzled frown as if he were thinking over some difficult problem. As Jack entered the wheel-house, he swung round on the boy:

“Oh, Ready! Stand by there a moment. I may have an order to give you.”

He stepped over to the speaking tube and hailed the engine-room.

“He’s going to give some order about saving that ship,” said the boy to himself.

But no. Captain Braceworth’s orders appeared to have nothing to do with any such plan. Jack felt his indignation surging up again as the commander, in a steady, measured voice, gave a lot of orders which, so far as Jack could hear, had to deal with pipes, pumps and something about the cargo. At all events, the boy caught the word “oil.”

“Well, if that isn’t the limit for hard-heartedness!” thought the lad to himself as he heard the calm, even tones. “What have a lot of monkey-wrench sailors like those fellows in the engineers’ department to do with saving lives, I’d like to know! If this was my dad’s ship, I’ll bet that he’d have a boat on the way to that wreck now.”

He gazed out of a port-hole. The wreck was still visible as the Ajax rode the high seas. From one of the stumps of the broken masts fluttered some sort of a signal. Jack fancied it might be the ensign reversed, a universal sign of distress on the high seas. But what ensign it was, he could not, of course, make out.

It seemed to him, too, that he could distinguish some figures on the decks, but of this he could not be certain.

“They may all be dead while this cowardly skipper is chatting with the engine-room,” he thought angrily.

“Ready!”

“Yes, sir.” It was with difficulty that Jack spoke even respectfully. He felt desperate, disgusted with all on board the “tanker.”

“I want you to stand by your wireless. Try to pick up some other steamer. Tell them there is a ship in distress out there. Wait a minute,—here’s the latitude and longitude. Send that, if you chance to pick anybody up.”

“Yes, sir.”

Fairly bursting with anger, Jack hurried off. He did not dare to let the captain see his face. He was naturally a frank, honest youth and his emotions showed plainly on his countenance when his feelings were strong.

So, after all, this miserable skipper was going to run off and desert that poor battered wreck! He was going to leave the work for somebody else, for some other ship, for some captain braver than himself to undertake.

As he was entering his wireless room, he encountered Raynor.

“What’s up? You look as black as a thunderstorm,” said the young engineer.

“No wonder,” burst out Jack, his indignation overflowing; “we’re deserting a wreck off yonder. The old man’s lost his nerve, that’s what. I’d volunteer in a moment. He ought to have launched a boat an hour ago.”

“Hold on, hold on,” said Raynor, laying a hand on the excited lad’s shoulder; “we couldn’t do anything in this sea, anyhow. The old man’s all right.—Ah! Look! What did I tell you!”

From the signal halliards above the bridge deck, a signal had just been broken out. The bits of bunting flared out brightly against the leaden sky.

“We will stand by you,” was the message young Raynor, who knew something of the International Code, spelled out.

“Good for him!” cried Jack, surprised into what was almost a cheer. “But,” he added grudgingly, “he took long enough about it.”

“Suppose you go ahead and attend to your end of the job and let the skipper manage his,” rejoined Raynor, in a quiet voice; and Jack, with a very red pair of ears, set himself down to the key.

The young third engineer was off watch, so he took a seat on the edge of Jack’s bunk and watched the lad manipulating the key with deft, certain fingers.

Crack-ger-ack-ack-ack! Crack-ger-ack-ack-ack! whined the spark as the boy alternately depressed and released the sending key. Then he switched over to “listen in.”

But no answering sounds beat against his ears. The signal had, apparently, fallen still-born on the wings of the storm. This went on for some fifteen minutes and then Jack gave up for a time.

“Nothing in our field or else my waves are too weak,” he explained to young Raynor, who listened with interest.

“I don’t understand what your wireless gibberish means,” he laughed, “but if you’ll teach me, I’ll learn some day.”

“Sure you will,” said Jack cheerfully; “it’s as easy as rolling off a log.”

“Yes, when you know how,” rejoined Raynor.

They sat silently for a time, while Jack again tried to raise some other ship, but without success.

“Looks as if the ocean must be empty just about here,” he commented.

“Would you be bound to get in touch with another ship if there was one within range of your instrument?” asked young Raynor presently.

“Not necessarily. There might be a dozen things that would interfere.”

“The storm, for instance?”

“Not that cause any more than another. There’s a lot that is mysterious about the wireless waves. Even to-day, nobody knows all about them. Sometimes, for no apparent cause, they will work better than at other times.”

“On a fine day I suppose they work best.”

Jack shook his head.

“On the contrary, at night and on foggy days, the Hertzian waves are sometimes most powerful. All things being equal, though, they work better over the sea than the land.”

“What is the longest distance a message has ever been sent by wireless?” was young Raynor’s next question.

“The last one I heard of was seven thousand miles. At that distance a ship off the coast of Brazil heard a call from Caltano, Italy. Think of that! That message had traveled across Italy, over the Mediterranean, slap across the northwestern part of Africa, and then went whanging across the Atlantic to a spot south of the Equator!”

“Going some,” was young Raynor’s comment.

“But that isn’t the most wonderful part of it. If that message went seven thousand miles in one direction, it must have gone an equal distance in an opposite one. That would make it encircle almost half the world.”

“Curves and all?” asked Raynor.

“Curves and all,” smiled Jack.

“And how fast does this stuff—the electric waves, I mean—travel?” asked the young engineer.

“Well,” said Jack, “it is estimated that a message from this side of the Atlantic would reach the Irish coast in about one-nineteenth of a second.”

“Oh, get out! I’m not going to swallow that.”

“It is true, just the same,” said Jack. “I know it is hard to believe; lots of things about wireless are.”

“Well, I mean to learn all about it I can.”

“You’ll find it well worth your while.”

“I believe that it is the most fascinating thing I’ve ever tackled.”

“In the meantime, I wish I could raise a ship,” grumbled Jack, again sending out his call.

“If we were sinking or in urgent difficulties right now, would you stick on the job till we raised some rescue ship?”

“I hope so. I’d try to,” said Jack modestly. “The history of wireless shows that every operator who has been called upon to face the music has done so without a whimper.”

While he worked at the key and the spark sent out its crepitant bark, young Raynor peered out at the tumbling sea through the port of the wireless cabin.

“Hullo!” he exclaimed presently, “we’re swinging round.”

“I can feel it,” said Jack, as the Ajax, instead of breasting the seas, began to roll about in the trough of them.

The heavy steel hull rolled until it seemed that the funnel and the masts must be torn out by the roots. Both boys hung on for dear life. After a while the motion became easier.

“Good thing I’m not inclined to be sea-sick,” said Jack, “or this would finish me.”

He gave up his key for a while and groped his way to Raynor’s side. The Ajax was creeping along and was now not more than half a mile from the wreck. But the meaning of her maneuvers was not very apparent. Jack could not understand what Captain Braceworth meant to do. Even the inexperienced eye of the young operator told him that it would be suicide to launch a boat in those mountainous seas.

The two boys opened the door and went to the rail. The Ajax had beaten her way up to windward of the doomed wreck. Suddenly Jack gave a shout.

“Hurray! Bully for Captain Braceworth! I see his plan now!”

At intervals along the bridge we have mentioned as running between bow and stern superstructures, were tall standpipes connected with pumps in the engine-room. These were used in discharging the cargo at Antwerp.

The valves of these pipes had been opened while the boys were in the wireless room, and now, as the pumps were started, jets of thick, dark-colored oil spouted from them.

As the oil spread on the sea, the wind drove it down in a great band of filmy smoothness toward the tossing wreck. As the oil spread, the big combers ceased to break dangerously, and a shimmering, smooth skin of oil spread over them till they merely rolled beneath it.

It was like magic to see the way in which the oil calmed the troubled sea.

“Well, I’ve heard my father tell of skinning a sea with oil-bags,” said Jack, “but I never expected to see it done.”

“You’ll see stranger things than that if you stay long enough in this business,” said Raynor sententiously.

The Ajax slowly cruised around the floundering wreck under reduced speed, with oil spouting constantly from the standpipes. At last all about the hulk there was spread a sort of magic circle of smooth, oily water.

Jack looked on in an agony of impatience.

“Surely he’ll send a boat now,” he said to Raynor.

But the young engineer shook his head.

“Braceworth isn’t a skipper who holds with doing things in a hurry,” he said; “wait a while.”

“Surely it is smooth enough to launch a boat now,” pursued Jack.

“If the skipper thought so, he’d do it,” rejoined Raynor.

The call to dinner came without Jack having secured communication with any other ship. He could only account for this by the supposition that the atmospheric conditions were bad. The wireless was evidently suffering from an attack of “atmospherics,” as the professional operators call it.

Before going down to his meal, Jack went forward to report to the captain. He found the burly commander with a sandwich in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other. He was having a snack on the bridge in the shelter of the weather-cloth.

Jack, despite himself, felt a quick flash of admiration for a man who could face such discomforts so dauntlessly for the sake of his duty.

The boy would have liked to ask some questions, but he did not have the courage. So he stood in silence while the skipper pondered a full minute.

“Don’t bother about it any more,” he said at length. “I think we will be able to do without help.”

Jack could contain himself no longer.

“Oh, sir, do you think we’ll be able to get those poor fellows off?”

The captain looked at him sharply.

“I don’t know anything about it,” he said. “Don’t pester me with foolish questions. It is eight bells. Be off to your dinner.”

Jack, abashed, red-faced and angry at what he felt was an undeserved snub, obeyed. At dinner he told Raynor all about it.

“Well, if you had been on the bridge all night, maybe you would feel none too amiable, either,” said his companion.

“On the bridge all night!” exclaimed Jack, who had no idea that while he was snug in his bunk the captain had been facing the storm.

“Of course. Captain Braceworth never leaves the bridge in bad weather, even if this is only a freighter and not a dandy passenger boat with pretty ladies and big swells on board,” retorted Raynor.

“I—I didn’t know that,” said Jack, rather shamefacedly. “If I had, I wouldn’t have spoken as I did.”

“I know that, youngster,” said Raynor. “And now let’s hurry through grub and get up on deck again and see what’s doing. I’ve a notion we’ll see something interesting before very long.”

When the lads returned on deck, they found that the Ajax had made another complete circle of the wreck, this time covering the first film of oil with a thicker one. They were much closer to the wreck now. Jack could count two figures in the bow and three astern.

But even as they looked, both boys gave a cry of horror. A huge wave had swept clear over the floundering hulk, and when it vanished one of the men in the stern had vanished, too.

“Oh! That’s terrible!” exclaimed Jack. “Why don’t we launch a boat?”

“No use sacrificing more lives,” said Raynor, with forced calmness, although he was white about the lips. “Braceworth knows what he’s doing, I reckon.”

“Yes, but to watch those poor fellows—it’s—it’s awful!”

Jack put his hands over his eyes to shut out, for an instant, the frantically waving arms of the men on the wreck. They were making desperate appeals. Plainly they could not understand why the liner kept circling them.

“Brace up, youngster,” said Raynor kindly. “I guess the skipper feels as bad about it as you do, but he won’t act till he can do so safely.”

The afternoon began to close in. The stormy twilight deepened into dusk and found the nerve-wracking waiting still going on. On the great gray seas the black steamer, with a wind-blown plume of smoke pouring from her salt-encrusted funnel, still solemnly circled the foundering hulk, while the storm clouds raced past overheard.

But the wind had dropped slightly and the coat of oil that now covered the waves prevented their breaking. The Ajax, already crawling up on the weather side of the wreck, appeared to reduce speed.

“There’s going to be something doing now,” prophesied Raynor.

On the bridge the captain had summoned Mr. Brown, the third officer.

“Brown,” he said, “I’m going to make a try to get those fellows off. That craft won’t last till daylight and we could never tackle the job in the dark.”

“Just what I think, sir,” rejoined the third mate.

“Very well; take one of the stern boats. Be very careful. If you hit the side, she’ll smash like an egg-shell and we could never pick you up in this. I’ll come in as close as I dare, to give you the lee water. Now be off with you and—good-luck.”

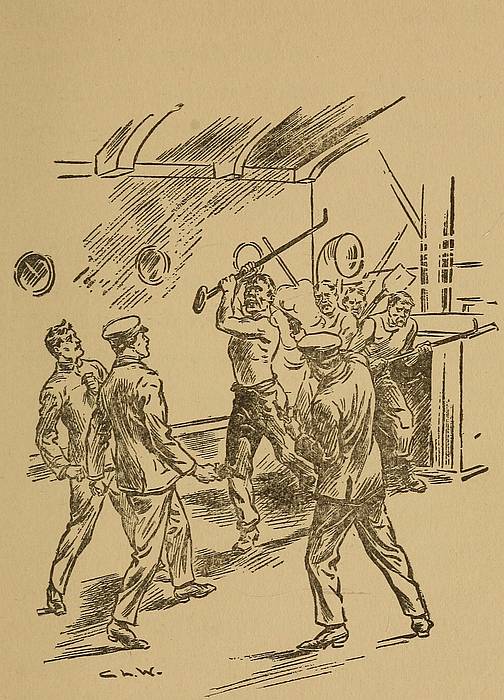

Mr. Brown hurried aft. He collected his boat crew as he went. The boat he selected was the one hung on patent davits above the wireless room. Young Raynor had been summoned to the engine-room and Jack stood there alone watching the preparations. The blood of his seafaring ancestors stirred in his veins. Mustering his courage he stepped forward.

“Mr. Brown, can I go, sir? I can row. Let me go, won’t you?”

The mate, angry at being disturbed, spun on his heel and glowered at the young wireless boy.

“What do you know about a boat?” he demanded. “You’re only a sea-going telegraph operator——”

At that instant the doughty little mate’s eye fell on a hulking big seaman who was hanging back. Plainly enough the man was afraid. He was muttering to himself as if he did not like the prospect of breasting those giant seas in the small boat.

The man was a Norwegian seaman, and Mr. Brown, who was an American, made a quick, angry spring for him as if to grip him bodily and compel him to go. Then he suddenly recollected Jack.

“Well, lad, since that hulking coward is afraid, I’ll give you a chance. Get in and look slippy. We’ve no time to lose.”

Jack shoved the big sailor aside while the fellow scowled and swore.

“Get forward, you!” roared little Mr. Brown. “I’ll attend to you when we get back. Now, youngster.”

But Jack was already in the boat. There was a shouted order and the falls began to creak in the quadrant davits. For an instant they hung between wind and water. Mr. Brown watched with the eye of a cat the proper moment to let go.

Suddenly the Ajax gave a roll far out to leeward. The boat dropped like a stone. The patent tackle set her free.

“Give way, men!” shouted the officer; and in the nick of time to avoid being shattered against the steel side of the tank by a big sea, the boat put forth on its errand of mercy.

Had the seas been breaking, the boat could not have lived a minute. The moment that she struck the water would have been her last.

But, thanks to Captain Braceworth’s up-to-date seamanship, the oil-skimmed swells, although high, were smooth, without dangerous spray and breakers.

The five seamen and the young wireless man who had volunteered at the last instant, tugged frantically at the big sweeps. Jack had been guilty of no exaggeration when he had said he could row. It had been his favorite amusement about the bay, and he was as strong as a young colt, anyhow.

In the stern at the steering oar stood Mr. Brown. His eyes were riveted on the wreck ahead.

As a monstrous green swell rushed under the boat he gave a shout:

“Lay into it, bullies! Pull for the girls, boys! That’s the stuff! Break your backs! All together now! We’ll pay Paddy Doyle for his boots!”

Mr. Brown, in his youth, had been before the mast on a whaler, and in moments of excitement he went back to the language of whalemen when out in the boats.

“H-e-a-v-e a-l-l!” he bellowed, with a strength of lung that appeared wonderful in such a diminutive man.

As the tanker’s boat was pulled by its stalwarts across the heaving seas, the men at the oars, by turning their heads, could see in what desperate straits were the handful of survivors.

“There’s a woman on board!” yelled Mr. Brown suddenly. “Pull for all you’re worth, my lads! It’s a little girl, by the Polar Star!”

As if this information had given them new strength, the men gave way with renewed energy. Jack, by twisting his head, could see, as the boat topped a wave, the sight that had excited Mr. Brown. Astern, lashed to the stump of the mizzen-mast, was the figure of a tall, spare, gray-haired man. His arms were clasped tightly around a young girl, whose hair was whipped out wildly by the wind.

Near by, another form was lashed to the wheel, while forward were two figures, apparently those of sailors. They also were tied, in this case to the windlass. This fact alone betrayed the desperate conditions through which the unfortunate craft had fought her way.

“She’s a down-easter, from Nova Scotia or Maine. Lumber, I guess,” opined Mr. Brown. “Good thing for them they had a lumber cargo, or she’d have been keeping company with Davy Jones by this time. Give way, men!”

But all Mr. Brown’s urgings to “hit it up” were unneeded. The crew of the boat were all Americans, and anyone who knows the merchant navy of to-day, knows that it is by a rare chance that such a thing happens. American ships are largely manned by foreigners; but aboard the Ajax,—Captain Braceworth was particular in this respect,—the majority of the crew were American. Consequently, they needed no driving to do their duty when lives were at stake.

Jack, tugging at his oar, felt the strength of ten men. His whole being thrilled to the glory of the adventure. This was real seaman’s work. This was no job for a monkey-wrench sailor, but a man’s task, requiring strength, grit and nerve.

But as they drew alongside the wreck, it was apparent that any attempt to get close enough to take off the crew must infallibly end in disaster.

Mr. Brown turned to his crew.

“Men, which of you can swim? I’m like a lame duck in the water or I’d do it myself.” (And nobody doubted that he would.) “We’ve got to get a line to that craft.”

Jack’s face flushed with excitement. He would prove worthy of his line of sea-going forbears.

“I can swim like a fish, sir! Let me try it!”

At the same time that he spoke, four other voices expressed their willingness to try. Mr. Brown looked at Jack.

“This is no job for a wireless kid to tackle,” he said grimly. “Dobson, you spoke next. I’ll send you. Get ready and make fast a line around your waist.”

But Dobson was already knotting a line about his middle. He stripped to his underwear, and, while Jack looked on with bitter disappointment in his face, the man tossed one end of the line to Mr. Brown and then, without a word, plunged overboard.

Jack watched him with a thrill of admiration, as with strong, confident strokes he cleft the sea. Then he looked in another direction. Off to the leeward was the Ajax, tossing on the seas for an instant and then vanishing till only the tops of her masts and a smudge of smoke were visible.

It was growing dusk. A wan, gray light filled the air. The next time the steamer rose on a swell, Jack saw that at her mast-head the riding lights had been switched on. They glowed like jewels in the monotonous sea-scape of lead and dull green.

Dobson reached the wreck. With clever generalship he had waited for a big sea, and then, as it rose high, he had ridden on it straight for the vessel. When the sea swept by, they saw him clinging to the main chains and after an instant begin clambering on board with the line trailing from his waist.

Those in the boat broke into a wild cheer. Jack’s voice rang out above the rest.

“There’s a real seaman,” he thought; “one of the kind my father and Uncle Toby were.”

As the hoarse shouts of the men in the boat rang over the waters, they saw the form of Dobson creeping aft along the wreckage. They watched through the thickening light as the shadowy figure toiled along. He gained the side of the old man and the little girl.

Taking the line from his waist, he made it fast to the latter’s body.

“Give way, men,” ordered Mr. Brown, and the boat was warily maneuvered under the stern of the wreck. It was dangerous, risky work, but while the small craft tossed almost under the derelict’s counter, the forms of the old man and the child were lowered into her. Although both were badly exhausted, there were stimulants in the boat, and Mr. Brown pronounced both to be safe and sound and not in any danger.

But the seaman who had made the rescues was, himself, in no condition after his long, hard swim to do any more. When the girl and the old man were safe in the boat, he, too, made a wild leap and boarded it. Immediately it was sheered off.

Jack’s heart gave a wild leap. There were still two men in the bow. What about them?

There was a second line in the boat and the young wireless man had already made it fast around his middle.

“It’s my turn now, Mr. Brown,” he urged. “Let me go now, won’t you, and get those two poor fellows in the bow?”

“Shut your mouth and sit still,” came hotly from Mr. Brown; and then a sudden exclamation, “Great guns! He’s as brave a young idiot as I ever saw!”

For Jack had taken the law into his own hands, leaped overboard into the boiling sea and was now swimming with bold, confident strokes toward the dim outlines of the derelict’s bow.

Jack leaped overboard into the boiling sea.—Page 94

Outlined dimly in the distant gloom was the hulk of the steamer. Her whistle was shrieking hoarsely, now sounding, as the mate guessed, a recall to the rescue boat before darkness closed in.

Jack was a strong, able swimmer, but never had he received such a breath-taking buffeting as fell to his lot in that wild commotion of waters. But with grim determination he fought his way to the ship’s side. Those in the boat saw him gain a foothold on the anchor chains and scramble upward; but they could not guess what a supreme effort of nerve and muscle those last few moments cost him.

As he gained the deck he was compelled, perforce, to cast himself gasping on his face, and so he lay for a space. Then, from the gloom, came a feeble call for help. It nerved him with fresh vim. Among the tangled wreckage he scrambled till he reached the place where the two men were lashed to the bitts.

Thanks to the oil-spread waters, the seas were no longer breaking over the wreck, but the two men who had lashed themselves there to avoid being swept over the side, were too feeble to sever their ties. Jack cut them loose and signaled to the boat. It was brought as close alongside as Mr. Brown dared, and one after the other the two seamen were hauled on board. Last of all came Jack. He secured the rope to his waist as it came snaking toward him from the boat like a lasso, and then jumped outward. As he sprang, he felt the hulk drop from under his feet in a wild yaw.

At the same instant the boy felt himself being drawn under water as if in the grasp of a giant hand that he was powerless to resist. Then his senses left him in a rocketing blaze of light and a roar like that of a hundred water-falls.

When he came to, he was lying on the bottom boards of the boat. From a bottle some stimulant was being administered to him. He sat up and stared about him wildly for a moment, and then saw that they were almost alongside the heaving hull of the tanker.

But of the wreck there was no sign.

“Went to Davy Jones like a plummet,” said Mr. Brown cheerfully, “and almost took you along with her, my lad. We had a fine job hauling you aboard, I can tell you.”

Now came the dangerous task of hauling up the boat of rescuers and survivors. But it was accomplished at last by dint of cool-headed work and seamanship. The two sailors were sent forward to get dry clothing and hot coffee, while the elderly man, who was Captain Ralph Dennis of the wrecked vessel, and his daughter Helen, were cared for in the officers’ quarters aft.

Feeling rather shaky and dripping like a water-rat, Jack hastened to make a change of clothing. By the time this was accomplished, the Ajax was once more on her course. Hardly had he drawn on dry socks before the old bos’n was at the door.

“The skipper wants to see you forward. I rather suspect there’s a storm brewing for you, younker,” was his greeting.

“I’ll be there right away,” said Jack, and having pulled on his boots, he hastened forward. As he went, his heart beat a little faster than usual. What fault had he committed now, he wondered. Jack was a modest youth, but he had suspected praise rather than censure for the part he had taken in the rescue.

The skipper was in the chart-house giving a few directions before he turned in, after an almost continuous twenty-four hours of duty.

He greeted Jack with a frown.

“Ready, who gave you orders to go away in that boat?” he demanded sternly.

“No one, sir, but I thought——”

“You had no business to think. This is not a man-of-war or a passenger boat, but if everyone on board did as they thought best, where would discipline be?”

Jack stood dumbly miserable. He had performed what he thought a meritorious act and this was his reward!

“I did the best I could to help when one of the men hung back, sir,” he said.

The captain’s face softened a bit, but his voice was still stern as he said:

“Mr. Brown was in charge of the boat. He should not have let you go. I blame him more than you. But remember another time that you must do nothing without orders so long as you sail under me. That is all,—and Ready.”

“Sir?”

“I understand you conducted yourself according to the best traditions of American seamanship. I was glad to hear that. Now get along with you and try to relay a message to our owners, telling them of the rescue. If there is another vessel within our range, inform me, as I wish to transfer the shipwrecked men if possible. The craft was bound from Portland, Maine, to the West Indies with lumber, and there is no sense in taking the rescued company all the way across the Atlantic.”

Jack saluted and hastened off on his task. He felt considerably lighter of heart when he left the chart-room than when he had entered it. There had been a gleam of real human sympathy in the captain’s eye. That man of iron actually had a heart after all, and Jack had read, under his gruff manner, a kindly interest in his welfare and esteem for his act in saving the two seamen.

“I’m glad I did disobey orders, anyway,” he said to himself; “if it did nothing else, it has shown the skipper to me in another light than that of a cruel task-master and slave-driver.”