TRAVELS

IN

BRAZIL.

BY

HENRY KOSTER.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, AND BROWN,

PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1816.

Printed by A. Strahan,

New-Street-Square, London.

TO

ROBERT SOUTHEY, ESQ.

POET LAUREATE,

MEMBER OF THE ROYAL SPANISH ACADEMY, AND OF THE ROYAL SPANISH

ACADEMY OF HISTORY,

THESE TRAVELS

ARE INSCRIBED

By HENRY KOSTER,

IN

MEMORIAL

OF

AFFECTIONATE RESPECT AND GRATITUDE.

PREFACE.

-

DURING my residence in Brazil, I had no intention of publishing any account of what I had seen and heard in that country. Some time after my return to England, I was encouraged to put together the information which I might be able to impart. The reader will be more disposed to excuse what defects he may find, when he is informed that I went out young, that I did not gather any knowledge of the country in a systematic manner with the idea of giving it to the public, and that the idiom of a foreign language is perhaps more familiar to me than that of my own. But among judicious readers the style of works of this description will be regarded as of little importance. I have had the advantage of Mr Southey’s advice and extensive library. I have to thank Dr. Traill for his aid in preparing the Appendix; though as he did not see the whole of it, if there are any errors they must be attributed to me, not to him. The drawings for the plates were executed by a near relative, from very rough sketches of my own, assisted[vi] by description. The outline of the map is taken from Mr. Arrowsmith’s large map of South America; and the names and situations of some places are corrected, and others are inserted from my own knowledge. The plan of the harbour of Pernambuco was furnished to me by an English gentleman resident at Recife, who is indefatigable in the search of whatever may contribute to the increase of knowledge.

CONTENTS.

| CHAP. I. | |

| DEPARTURE from Liverpool.—Arrival at Pernambuco.—The Town and Harbour of Recife.—The Governor.—The Trade | Page 1 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Visit to the Governor.—The Climate.—First Ride into the Country.—Residence at a Village in the neighbourhood of Recife.—Olinda.—Holy Thursday.—Good Friday.—Easter Sunday.—Profession of a Friar.—St. Peter’s Day.—Visit to a Brazilian Family.—A Dance.—Another Visit to Olinda | 12 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| The Government.—The Taxes.—The Public Institutions.—Criminals.—Prisons.—Military Establishments.—The Island of Fernando de Noronha | 30 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

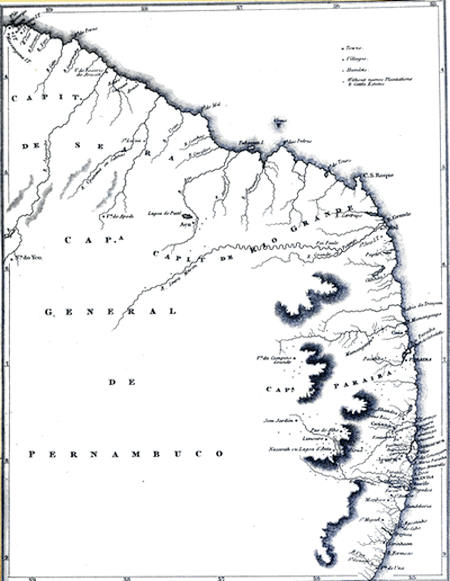

| Journey to Goiana.—Journey from Goiana to Paraiba, and back to Goiana | 42 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Journey from Goiana to Rio Grande.—The City of Natal.—The Governor | 56 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Continuation of the Journey.—From Natal to Açu | 73 |

| CHAP. VII. | |

| Continuation of the Journey.—From Açu to Aracati.—From Aracati to Searà.—Indians.—The late Governor.—The Family of the Feitozas | 97 |

| [viii]CHAP. VIII. | |

| Return.—From Searà to Natal.—Sertanejos.—Cattle.—Vegetable Wax.—From Natal to Recife | 129 |

| CHAP. IX. | |

| Voyage from Pernambuco to Maranham.—St. Luiz.—Trade.—Wild Indians.—The Governor.—Alcantara.—The Author sails from St. Luiz, and arrives in England | 164 |

| CHAP. X. | |

| The Author sets sail from Gravesend, and arrives at Pernambuco.—State of Recife.—Journey to Bom Jardim with a Capitam-mor, and return to Recife | 186 |

| CHAP. XI. | |

| Residence at Jaguaribe.—Journey to Goiana.—Illness.—Return to Jaguaribe | 211 |

| CHAP. XII. | |

| Journey to Uninha.—Continuation of my Residence at Jaguaribe.—Negro Brotherhood of Olinda.—Blessing the Sugar Works.—Mandingueiras and Valentoens | 235 |

| CHAP. XIII. | |

| Removal of the Author to Itamaraca.—The Island.—Conception and Pillar.—The Festival of Our Lady of the Rosary.—Journey to Goiana.—The Toque.—The Cowpox | 258 |

| CHAP. XIV. | |

| Ants, Snakes, and other Reptiles.—River of Iguaraçu.—Building a House.—Several Species of Timber Trees.—The Pinham, Mutamba, and Gameleira Trees.—The Whale | 285 |

| CHAP. XV. | |

| Recruiting.—Images.—Animals.—Maracàs.—Apollinario, Mandinga, and Poultry.—Hieroglyphics.—Festival of Our Lady of Conception.—Fandangos.—The Fort.—A Christening.—The Intrudo.—The Author leaves Brazil | 305 |

| CHAP. XVI. | |

| Agriculture.—Sugar Plantations | 336 |

| CHAP. XVII. | |

| Agriculture.—Cotton | 365 |

| [ix]CHAP. XVIII. | |

| The Free Population | 384 |

| CHAP. XIX. | |

| Slavery | 402 |

| CHAP. XX. | |

| Impolicy of the Slave Trade | 445 |

| CHAP. XXI. | |

| The Treaties of Friendship and Alliance, and of Commerce and Navigation between the Crowns of Great Britain and Portugal, signed at Rio de Janeiro on the 19th February 1810 | 457 |

| Appendix | 475 |

DIRECTIONS FOR PLACING THE PLATES.

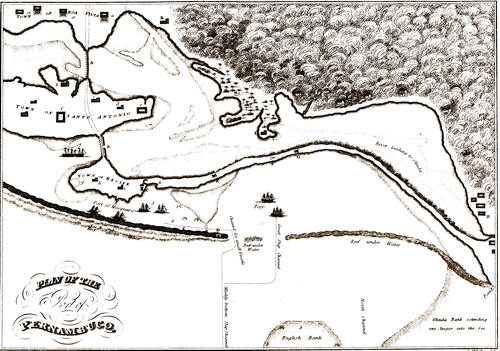

| Plan of the Port of Pernambuco | to face the References. |

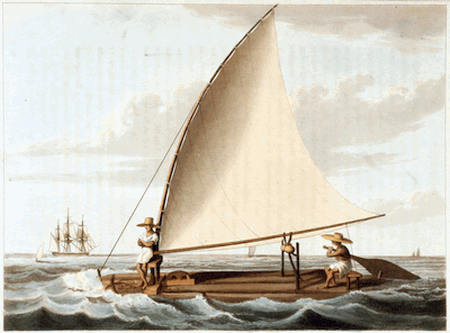

| A Jangada | page 3 |

| Map of the Route | 42 |

| Crossing a River | 53 |

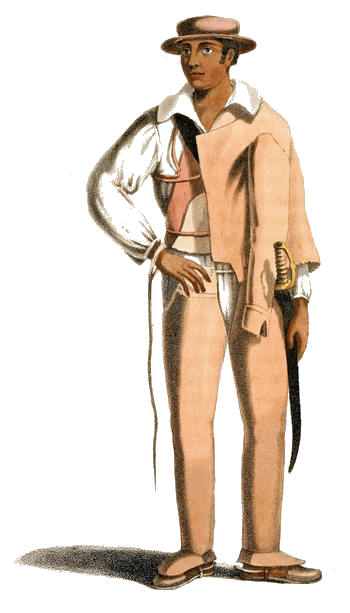

| A Sertanejo | 87 |

| Fishing Canoe | 175 |

| A Lady going to visit | 188 |

| A Cotton-carrier | 194 |

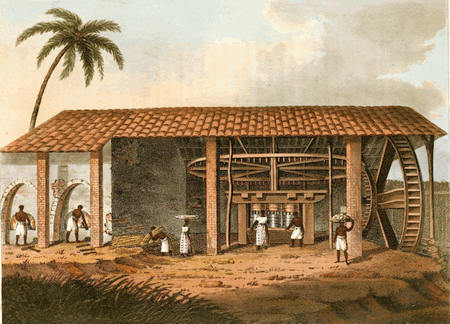

| A Sugar-Mill | 336 |

| A Planter and his Wife on a Journey | 384 |

REFERENCES

TO THE

PLAN OF THE PORT OF PERNAMBUCO.

-

A. The bridge of Boa Vista.

B. The bridge of Recife.

C. Fort Bom Jezus.

D. Fort Picam.

E. Fort Brum.

F. Cross of Patram.

G. Fort Buraco.

H. The village of Arrombados.

I. The church of St. Amaro.

K. Jerusalem.

a. Houses and gardens.

b. The Carmelite convent.

c. The Church of Sacramento (parish).

d. The Franciscan convent.

e. The Treasury.

f. The Palace.

g. The cotton wharf (commonly called Forte do Mato).

h. The Madre de Deos convent.

i. The church of Corpo Santo (parish).

k. The Intendencia da Marinha (dock yard) and King’s wharf.

To enter the port, coming in from sea, keep Fort Picam and Fort Brum in one, until you have the point of Olinda bearing N., then steer due N., until the cross of Patram is in one with the coco-nut trees on St. Amaro, then steer directly for the same cross of Patram, until you open the inner part of the reef above water, with Fort Picam to the southward, where you may come to anchor, or stand on to the southward into the harbour of Mosqueiro.

To enter the channel for smaller vessels coming from sea, keep the same mark, Fort Picam and Fort Brum in one, until you are within a quarter of a mile of Fort Picam, then bring the two southern watch towers on Fort Brum in one, you clearing the northern extremity of the reef above water, and hauling short round the same, keep the reef close aboard until you are in the harbour of Mosqueiro.

TRAVELS IN BRAZIL.

-

CHAPTER I.

DEPARTURE FROM LIVERPOOL.—ARRIVAL AT PERNAMBUCO.—THE TOWN AND HARBOUR OF RECIFE.—THE GOVERNOR.—THE TRADE.

IF my health had not required a change of climate, I should not perhaps so soon have accomplished the wish I had often expressed of leaving England for a short time. An immediate removal was judged expedient; and as the ports of Spain and Portugal were either closed to British subjects, or at least not in a state to be visited by an invalid, I determined upon Brazil; to which my friends agreed.—I fixed upon Pernambuco, because a gentleman, who had for many years been acquainted with my family, was about to embark for that place, and from the favourable reports of the people and climate which I had received from several persons. On the 2d November 1809, I set sail from Liverpool in the ship Lucy.

We had a very prosperous passage of thirty-five days, without any occurrence worthy of particular notice.

I was agreeably awakened very early on the morning of the 7th December, with the news that we were in sight of land, and likely to get into harbour this day. We soon discovered two vessels, with all sail set, making for us; these proved to be two English merchant-ships, bound likewise to Pernambuco; they had never before been at this port, and therefore wished to receive some information respecting it; they judged that, from the manner in[2] which our vessel made for the land, her commander must be acquainted with it, which was the case, this being the second voyage of the Lucy to Pernambuco.

The land is low, and consequently not to be seen at any considerable distance; but as we approached it, we distinguished the hill upon which stands the city of Olinda, a little to the northward; and some leagues to the southward, the Cape of St. Agostinho; a nearer view discovered to us the town of St. Antonio do Recife, almost a-head with the shipping in front of it; the dreary land between it and Olinda, which is one league distant, and coco[1] groves northward, as far as the eye can reach; southward of the town are also seen great numbers of coco trees, woods, and scattered cottages. The situation of Olinda is the highest in the neighbourhood; and though not very high, is still not despicable. Its appearance from the sea is most delightful; its white-washed churches and convents upon the tops and sides of the hill; its gardens and trees, interspersed amongst the houses, afford a promise of great extent, and hold out expectations of great beauty. The sands, which extend one league to the southward of it, are relieved by two fortresses erected upon them, and by the ships in the lower harbour. Then follows the town of Recife, with the appearance of being built in the water, so low is the sand-bank upon which it has been raised; the shipping immediately in front partly conceal it; and the bold reef of rocks on the outside of these, with the surf dashing violently against and over it, give to them the appearance of being ashore; and as no outlet is seen, they seem to be hemmed in. The small tower or fort at the northern end of the reef, however, soon claims attention, and points out the entrance. We approached the land rather to the southward of the town, and coasted, under very easy sail, at a short distance from the reef, waiting for a pilot. It was not yet noon, the sea was smooth, the sun was bright, and every thing looked pleasant. The buildings are all white-washed; the sun shone upon them, and gave to them a glittering silvery appearance.

A Jangada.

Nothing this day created so much astonishment on board our ship, amongst those who had not been before upon this coast, as the Jangadas, sailing about in all directions. These are simply rafts of six logs, of a peculiar species of light timber, lashed or pinned together; a large latine sail; a paddle used as a rudder; a sliding keel let down between the two centre logs; a seat for the steersman, and a long forked pole, upon which is hung the vessel containing water, the provisions, &c. These rude floats have a most singular appearance at sea, no hull being apparent even when near them. They are usually managed by two men, and go closer to the wind than any description of vessel.

A large row-boat at last made its appearance, doubling the end of the reef near the small fort, which was declared to be that which brings off the pilots. The patram-mor, harbour-master, in his naval uniform, likewise came on board. A large launch followed the pilot, manned chiefly by negroes, almost naked; the colour of these men; the state in which they were; their noise and bustle, when certainly there was no occasion for it, and their awkwardness, were to me all new. This very first communication with the shore gave me an idea, for the moment, that the manners of the country at which I had arrived, were still more strange than they actually proved to be. These visitors were followed by others of a very different description; two boats came alongside, manned by Englishmen, and conveying several English gentlemen. The former belonged to British ships loading in the harbour, and the latter were young men who had come out to Pernambuco to settle as merchants.

The pilot placed himself near to the ship’s windlass; a Portugueze sailor was sent to take the helm, but still the vociferation was extreme; the man seemed to think that, by speaking very loud, he would make the English seamen understand his language; and what with his bawling to them and to his own people, and their noise, the[4] confusion was excessive; however, we doubled the fort in safety, and came to anchor in the upper harbour. The reef is very perpendicular near to the bar; and to one unacquainted with the port, there is every appearance of the vessel being about to drive upon it. I then accompanied my fellow-passenger; we left the ship and proceeded to the shore. Here was a new scene indeed. We had taken the letter-bag with us; the crowd of well-dressed persons upon the quay was great; they saw the bag, and soon their anxiety for news overcame their politeness; the letters were asked for, and at last we gave them up, and they were scrambled for, each man seeking his own. We had landed at the custom-house wharf upon a busy day, and the negroes too were all clamour and bustle. Their hideous noise when carrying any load, bawling out some ditty of their own language, or some distich of vulgar Portugueze rhyme; the numerous questions asked by many persons who met us, and the very circumstance of seeing a population consisting chiefly of individuals of a dark colour, added to the sound of a new language, with which, although I was acquainted, still I had not since very early youth been in a country where it was generally spoken; all combined to perplex and to confuse. I was led along by those who were accustomed to these scenes, and we proceeded to the house of one of the first merchants in the place. We were ushered up one pair of stairs into a room in which were several piles of piece-goods, a table covered with papers, and several chairs. There were four or five persons in the room besides the owner of the house. I delivered my letter of introduction to him, and was treated with the greatest civility. Our next visit was to a colonel, who is also a merchant, from whom I met with the same behaviour.

As there are no inns or furnished lodgings at Recife, or at[2]Olinda, an acquaintance of my fellow-passenger obtained some temporary rooms for us, and supplied us with what we wanted. We are therefore at last quietly settled in our new habitation, if I may be allowed to call it quiet, whilst some twenty black women are under the windows[5] bawling out, in almost all tones and keys of which the human voice is capable,—oranges, bananas, sweetmeats, and other commodities, for sale.

The town of St. Antonio do Recife, commonly called Pernambuco, though the latter is properly the name of the captaincy, consists of three compartments, connected by two bridges. A narrow, long neck of sand stretches from the foot of the hill, upon which Olinda is situated to the southward. The southern extremity of this bank expands and forms the site of that part of the town particularly called Recife, as being immediately within the reef. There is another sand-bank also of considerable extent, upon which has been built the second division, called St. Antonio, connected with that already mentioned by means of a bridge. Yet a third division of the town remains to be mentioned, called Boa Vista, which stands upon the main land to the southward of the other two, and is joined to them also by a bridge. The recife, or reef of rocks already spoken of, runs in front of these sand-banks, and receives upon it the principal force of the sea, which, at the flow of the tide, rolls over it, but is much checked by it, and strikes the quays and buildings of the town with diminished strength. The greatest part of the extent of sand between Olinda and the town which remains uncovered, is open to the sea, and the surf there is very violent. Buildings have only been raised within the protection of the reef. The tide enters between the bridges, and encircles the middle compartment. On the land side there is a considerable expanse of water, having much the appearance of a lake, which becomes narrower towards Olinda, and reaches to the very streets of that place, thus facilitating the communication between the two towns. The view from the houses that look on to these waters is very extensive and very beautiful; their opposite banks are covered with trees and white-washed cottages, varied by small open spaces and lofty coco trees.

The first division of the town is composed of brick houses of three, four, and even five stories in height; most of the streets are narrow, and some of the older houses in the minor streets are of only one[6] story in height, and many of them consist only of the ground-floor. The streets of this part, with the exception of one, are paved. In the Square are the custom-house, in one corner, a long, low, and shabby building; the sugar-inspection, which bears the appearance of a dwelling-house; a large church, not finished; a coffee-house, in which the merchants assemble to transact their commercial affairs; and dwelling-houses. There are two churches in use, one of which is built over the stone arch-way leading from the town to Olinda, at which a lieutenant’s guard is stationed. The other church belongs to the priests of the Congregaçam da Madre de Deos. Near to the gate-way above-mentioned is a small fort, close to the water-side, which commands it. To the northward is the residence of the Port-Admiral, with the government timber-yards attached to it: these are small, and the work going on in them is very trifling. The cotton-market, warehouses, and presses, are also in this part of the town.[3]

The bridge which leads to St. Antonio has an arch-way at either end, with a small chapel built upon each; and at the northern arch is stationed a serjeant’s guard of six or eight men. The bridge is formed in part of stone arches, and in part of wood: it is quite flat, and lined with small shops, which render it so narrow that two carriages cannot pass each other upon it.

St. Antonio, or the middle town, is composed chiefly of large houses and broad streets; and if these buildings had about them any beauty, there would exist here a certain degree of grandeur: but they are too lofty for their breadth, and the ground-floors are appropriated to shops, warehouses, stables, and other purposes of a like nature. The shops are without windows, and the only light they have is admitted from the door. There exists as yet very little distinction of trades; thus all descriptions of manufactured goods are sold by the same person. Some of the minor streets consist of low[7] and shabby houses. Here are the Governor’s palace, which was in other times the Jesuits’ convent; the treasury; the town-hall and prison; the barracks, which are very bad; the Franciscan, Carmelite, and Penha convents, and several churches, the interiors of which are very handsomely ornamented, but very little plan has been preserved in the architecture of the buildings themselves. It comprises several squares, and has, to a certain degree, a gay and lively appearance. This is the principal division of the town.

The bridge which connects St. Antonio with Boa Vista is constructed entirely of wood, and has upon it no shops, but is likewise narrow. The principal street of Boa Vista, which was formerly a piece of ground overflowed at high water, is broad and handsome: the rest of this third division consists chiefly of small houses, and as there is plenty of room here, it extends to some distance in a straggling manner. Neither the streets of this part of the town nor of St. Antonio are paved. A long embankment has likewise been made, which connects the sand-bank and town of St. Antonio with the main land at Affogados[4], to the south and west of Boa Vista. The river Capibaribe, so famous in Pernambucan history, discharges its waters into the channel between St. Antonio and Boa Vista, after having run for some distance in a course nearly east and west.

Some few of the windows of the houses are glazed, and have iron balconies: but the major part are without glass, and of these the balconies are enclosed by lattice-work; and no females are to be seen, excepting the negro slaves, which gives a very sombre look to the streets. The Portugueze[5], the Brazilian, and even the Mulatto women, in the middle ranks of life, do not move out of doors in the day-time; they hear mass at the churches before day-light-, and do not again stir out, excepting in sedan chairs, or in the evening on[8] foot, when occasionally a whole family will sally forth to take a walk.

The upper harbour of Recife, called the Mosqueiro, as has been already said, is formed by the reef of rocks which runs parallel with the town at a very small distance. The lower harbour, for vessels of 400 tons and upwards, called the Poço, is very dangerous, as it is open to the sea, and the beach opposite to it is very steep. The large Brazil ships, belonging to merchants of the place, lie here for months at a time, moored with four cables, two a-head and two a-stern. If precautions are not taken very speedily, the entrance to the harbour of Mosqueiro will be choaked up, owing to a breach in the reef, immediately within the small fort, which is called Picam. The port has two entrances, one of which is deeper than the other. The tide does not rise more than five and a half feet. The principal defence of the town consists in the forts Do Buraco[6] and Do Brum, both of which are built of stone, and are situated upon the sands opposite to the two entrances. Likewise there is the small fort of Bom Jezus, near to the arch-way and church of the same name; and upon the south-east point of the sand-bank of St. Antonio stands the large stone fort of Cinco Pontas, so called from its pentagonal form. They are said to be all out of order. From what I have stated, it will be seen that the ground upon which the town has been built is most peculiarly circumstanced, and that the manner in which the harbour is formed is equally rare.

The town is principally supplied with water, which is brought in canoes, either from Olinda, or from the river Capibaribe, above the influence of the tide; it comes in bulk, and although the greater part of the vessels are decked, still it is usually filthy, as too much care is not taken in their cleanliness. The wells that are sunk in the sand upon which the town stands only afford brackish water.

The three compartments of the town, together, contain about[9] 25,000 inhabitants, or more, and it is increasing rapidly; new houses are building wherever space can be found. The population consists of white persons, of mulatto and black free people, and of slaves also of several shades.

The reef of rocks, of which I have before spoken, continues along the whole coast between Pernambuco and Maranham, and in some parts it runs at a very short distance from the shore; and in this case is usually high, remaining uncovered at low water, as at Recife; but in other places it recedes from the land, and is then generally concealed. It has numberless breaks in it, through which the communication with the sea is laid open.

Recife is a thriving place, increasing daily in opulence and importance. The prosperity which it enjoys may be in some measure attributed to the character of its Governor and Captain-General, Caetano Pinto de Miranda Montenegro, who has ruled the province for the last ten years with systematic steadiness and uniform prudence. He has made no unnecessary innovations, but he has allowed useful improvements to be introduced. He has not, with hurried enthusiastic zeal, which often defeats its end, pushed forwards any novelty that struck him at the moment, but he has given his consent and countenance to any proposal backed by respectable persons. He has not interfered and intermeddled with those concerns in which governments have no business, but he has supported them when they have been once established. I here speak of commercial regulations and minor improvements in the chief town, and in the smaller settlements of the country. He is affable, and hears the complaint of a peasant or a rich merchant with the same patience; he is just, seldom exercising the power which he possesses of punishing without appeal to the civil magistrate; and when he does enforce it, the crime must be very glaring indeed. He acts upon a system, and from principle; and if it is the fate of Brazil to be in the hands of a despotic government, happy, compared to its present state, would it in general be, if all its rulers resembled him. I love[10] the place at which I so long resided, and I hope most sincerely that he may not be removed, but that he may continue to dispense to that extensive region, the blessings of a mild, forbearing administration.

In political consequence, with reference to the Portuguese government, Pernambuco holds the third[7] rank amongst the provinces of Brazil; but in a commercial point of view, with reference to Great Britain, I know not whether it should not be named first.[8] Its chief exports are cotton and sugar; the former mostly comes to England, and may be accounted at 80,000 or 90,000 bags annually, averaging 160 pounds weight each bag. The latter is chiefly shipped to Lisbon. Hides, cocoa-nuts, ipecacuanha, and a few other drugs, are also occasionally sent from thence, but are exported in trifling quantities. These articles are exchanged for manufactured goods, earthenware, porter, and other articles of necessity among civilized people, and also of luxury to no very great amount. Two or three ships sail annually for Goa in the East Indies; and the trade to the coast of Africa for slaves is considerable. Several vessels from the United States arrive at Recife annually, bringing flour, of which great quantities are now consumed; furniture for dwelling-houses, and other kinds of lumber, and carrying away sugar, molasses, and rum. During the late war between the United States and England, which interrupted this trade, Recife was at first somewhat distressed for wheat-flour, but a supply arrived from Rio Grande do Sul, the most southern province of the kingdom of Brazil.[9] The[11] quality is good[10], and I rather think that some coasting-vessels will continue to supply the market with this article, notwithstanding the renewed communication with North America.

CHAPTER II.

VISIT TO THE GOVERNOR.—THE CLIMATE.—FIRST RIDE INTO THE COUNTRY.—RESIDENCE AT A VILLAGE IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF RECIFE.—OLINDA.—HOLY THURSDAY.—GOOD FRIDAY.—EASTER SUNDAY.—PROFESSION OF A FRIAR.—ST. PETER’S DAY.—VISIT TO A BRASILIAN FAMILY.—A DANCE.—ANOTHER VISIT TO OLINDA.

THE numerous arrangements necessary on our arrival, prevented our making immediately the customary visit to the governor; but on the following morning we proceeded to the palace, situated in a small square, with the guard-house on one side, at which is stationed a captain’s guard. We were ushered up stairs, remained some time in an anti-chamber with several cadets, and were then desired to enter; we passed the secretary’s room, and were shown into a very spacious apartment, in which the governor waited to receive us. He is a large handsome man, with quite the manners of a gentleman; we all sat down, and he asked several questions respecting affairs in Europe; I had some English newspapers, which I left with him, and in about half an hour we retired.

The first few days after my arrival were spent in delivering my letters of introduction. I soon became acquainted with all the English merchants, who live in a very respectable style, and have done much good in establishing some customs which the Portugueze have had the sense to follow, preserving at the same time those of their own, which are fitted to the country and the climate.

As this was the summer season, great numbers of the inhabitants were out of town; they remove to small cottages at Olinda, and upon[13] the banks of the rivers, to enjoy a purer air, and the amusement and comfort of bathing, during the months most subject to hot, parching weather. The heat is, however, seldom very oppressive; the sea-breeze, during the whole year, commences about nine o’clock in the morning, and continues until midnight. When exposed to it, even standing in the sun, the heat is so much alleviated by its influence, as to make the person so situated forget, for a moment, that in the shade he would be cooler. At the time this subsides the land-breeze rises, and continues until early in the morning, and the half hour in the forenoon which occasionally passes between the one and the other, is the most unpleasant period of the day. In the rainy season, just before the commencement of a heavy shower, the clouds are very dark, dense, and low; the breeze is suspended for a short time; there is then a sort of expectant stillness, and the weather is very sultry.

One afternoon I rode out with several young men to a village in the neighbourhood, for the purpose of delivering a letter to one of the rich merchants. We passed through Boa Vista, and proceeded along a narrow sandy road, formed by frequent passing and repassing; and along the sides of this are many of the summer residences of the wealthy inhabitants of the town, which are small, neat, white-washed cottages of one floor, with gardens in front and at the sides, planted with orange, lemon, pomegranate, and many other kinds of fruit-trees; some few are inclosed partly by low walls, but for the most part they are protected by fences of timber. About half way we came out upon the banks of the Capibaribe; the view is exceedingly pretty; houses, trees, and gardens on each side: the river bends just above, and appears lost among the trees; the canoes going gently down with the tide, or more laboriously forcing their way up against it, formed altogether a delightful prospect. The river is here rather narrower than the Thames at Richmond. Along the sides of the road, at this spot, are several black women selling oranges, other kinds of fruits and cakes, and canoe-men with their long poles, unable to delay, bargaining with them for some of their commodities. This was the first time I had left the town, and I was truly pleased with these[14] first looks of the country of which I had become an inhabitant. We again left the river, continuing along the road, still bordered by cottages of a better or worse appearance, until we reached a small village; through this we passed, and soon afterwards arrived at the end of our ride. The situation is very picturesque, upon the northern bank of the Capibaribe, and at the foot of a steep hill clothed with wood. On our arrival at the house, we entered immediately from the road into a hall with a brick floor, of which the doors and windows are very large, so as to leave the front very nearly open. We were received by the lady of the house, and her husband soon appeared; they were exceedingly civil, and ordered sweetmeats to be brought out.

Our English flat saddles created as much surprise to the people of Pernambuco, as those of the Portugueze appeared strange to us. They are high before and behind, which obliges the rider to sit very upright, and the fashion is to be as stiff as possible, and to hold quite perpendicularly a switch of most enormous length. The horses are taught a delightful amble, upon which some of them can be made to proceed with great speed.

The river Capibaribe is navigable during the whole year as far as Apepucos, half a league beyond Monteiro, the village at which my new acquaintance was now residing. It overflows its banks in the rainy season, oftentimes with great rapidity. As the lands through which it runs in this part of the country are very low, the floods are somewhat dreaded, as they occasionally extend far and wide. The straw hovels upon its banks are often carried away, and the whole neighbourhood is laid under water: canoes have been known to ply between this village and those of Poço da Panella and Caza Forte.

A Portugueze friend, with whom I had been acquainted in England, having taken a house at the former of the two last-mentioned places, I agreed to share the expence of it with him, and we immediately removed to it, to pass the summer months. The village was quite full; not a hut remained untenanted; and, as occurs in England at watering-places, families, whose dwellings in town were spacious and handsome[15] regardless of inconvenience, came to reside here during the summer in very small cottages. The Poço da Panella contains a chapel, built by subscription, a row of houses running parallel with the river, several washerwomen’s huts in front of them, and other dwellings scattered about in all directions. Here the ceremonious manners of the town are thrown aside, and exchanged for an equal degree of freedom. Our mornings were filled up, either in riding to the Recife or to some other part of the country, or in conversation at the houses of any of the families with whom we were acquainted; and the afternoons and evenings with music, dancing, playing at forfeits, or in dining with some of the English merchants, a few of whom had also removed to this place and its neighbourhood. At many of the Portugueze houses I found the card-tables occupied at nine o’clock in the morning; when one person rose another took his place; and thus they were scarcely deserted, except during the heat of the day, when each man either returned to his own home to dine, or, as is much less frequent, was requested to remain and partake with the family.

On the last day of this year I was invited to visit Olinda, that I might witness the festival of Our Lady of the Mountain. The city is, as I have already observed, situated upon a hill, very steep in front of the sea, and declining gradually on the land side. Its first appearance, on arriving upon the coast, is so beautiful, that the disappointment experienced on entering it is great; but still Olinda has many beauties, and the view from it is magnificent. The streets are paved, but are much out of repair; many of the houses are small, low, and neglected, and the gardens very little cultivated; indeed the place has been deserted for the Recife. However, one of the regiments of the line is stationed here[11]; it is the residence of the bishop, and the site of the ecclesiastical court, the seminary, which is a public college of education, and some convents and fine churches; therefore, it is by no means desolate, though its general aspect bespeaks tranquillity, regularity,[16] and a degree of neglect. The view to the southward takes in a lake of about three miles in length, of which the surface is covered with weeds and grass, and the opposite banks lined with thick woods and some cottages; the Recife and the bay behind it, formed by the entrance of the tide, extending to Olinda, but concealed in places by low and thick mangroves are also to be seen. Olinda covers much ground, but contains only about 4000 inhabitants. At this time the whole city presented a scene of bustle and amusement. The church, particularly decorated on this occasion, stands upon the highest point; the assemblage of persons was great; the church was lighted up, and a few individuals of both sexes were kneeling promiscuously in the body of it, but the service was over.

This is the season of cheerfulness and gaiety, and we were likewise to have our festival at the Poço da Panella. These festivals are always preceded by nine evenings of hymn-singing, and music, in honour of the Virgin, or the saint whose day is to be thus celebrated. On this occasion the performance for the novena, or nine evenings, consisted of a piano-forte played by a lady, the wife of a merchant, and a guitar, and some wind-instruments, played by several young men of respectability. The vocal music was also executed by the same persons, assisted by some female mulatto slaves belonging to the lady. I was somewhat surprised to hear the airs of country-dances and marches occasionally introduced. However, on the day of the festival, the performers were professional men, and in the evening fireworks were displayed. Every house in the village was crowded this day with people from all parts. My friend and I had several persons to dinner, but before we had half finished, some of their friends appeared, and without ceremony came in and helped themselves; soon all idea of regularity vanished, and things were scrambled for. In a short time both of us left our own house, and tried to gain admittance to some other, but all were in the same confusion. We were invited to a dance in the evening, at which the Governor was present; and although he is himself desirous of making every person feel at ease, still such is the dreadful idea of rank, for I know not[17] what else to call it, in this country, that the behaviour of every one was constrained, and the conversation carried on almost in a whisper.

I lost no Festivals, and amongst others, went to that of St. Amaro, the healer of wounds, at whose chapel are sold bits of ribbon, as charms, which many individuals of the lower orders of people tie round their naked ancles or their wrists, and preserve until they wear out, and drop off.

About the commencement of Lent, the villages in the neighbourhood are almost entirely deserted by the white people, who return to town to see the processions customary at this season in Catholic countries. The rains also usually begin about the end of March. I did not leave the Poço de Panella until the very last, but in the end found the place dull, and followed the rest.

On Holy Thursday, accompanied by two of my countrymen, I sallied forth at three o’clock, to see the churches, which are, on this occasion, lighted up, and highly ornamented. The whole town was in motion; the females, too, both high and low, were this afternoon parading the streets on foot, contrary to their usual custom; many of them were dressed in silks of different colours, and covered with gold chains and other trinkets, a general muster being made of all the finery that could be collected. The blaze in some of the churches, from great numbers of wax tapers, was prodigious; the object apparently aimed at was the production of the greatest quantity of light, as in some instances mirrors were fixed behind the tapers. The middle of the body of these churches is completely open; there are no pews, no distinction of places; the principal chapel is invariably at the opposite end from the chief entrance, recedes from the church, and is narrower; this part is appropriated to the officiating priests, and is railed in from the body of the church. The females, as they enter, whether white or of colour, place themselves as near to the rails as they can, squatting down upon the floor of the large open space in the centre. The men stand along either side of the body of the church, a narrow slip being in most instances railed off lengthways; or they remain near to the[18] entrance, behind the women; but every female, of whatever rank or colour, is first accommodated.

On the following day, Good Friday, the decorations of the churches, the dress of the women, and even the manner of both sexes was changed; all was dismal. In the morning I went with the same gentlemen to the church of the Sacramento, to witness a representation of our Saviour’s descent from the Cross. We entered the church by a side door; it was much crowded, and the difficulty of getting in was considerable. An enormous curtain hung from the ceiling, excluding from the sight the whole of the principal chapel. An Italian Missionary Friar of the Penha convent, with a long beard, and dressed in a thick dark brown cloth habit, was in the pulpit, and about to commence an extempore sermon. After an exordium of some length, adapted to the day, he cried out “Behold him;” the curtain immediately dropped, and discovered an enormous Cross, with a full-sized wooden image of our Saviour, exceedingly well carved and painted, and around it a number of angels represented by several young persons, all finely decked out, and each bearing a large pair of out-stretched wings, made of gauze; a man, dressed in a bob wig, and a pea green robe, as St. John, and a female kneeling at the foot of the Cross, as the Magdalen; whose character, as I was informed, seemingly that nothing might be wanting, was not the most pure. The friar continued, with much vehemence, and much action, his narrative of the crucifixion, and after some minutes, again cried out “Behold, they take him down;” when four men, habited in imitation of Roman soldiers, stepped forwards. The countenances of these persons were in part concealed by black crape. Two of them ascended ladders placed on each side against the Cross, and one took down the board, bearing the letters I.N.R.I. Then was removed the crown of thorns, and a white cloth was put over, and pressed down upon the head; which was soon taken off, and shown to the people, stained with the circular mark of the crown in blood: this done, the nails which transfix the hands, were by degrees knocked out, and this produced a violent beating of breasts among[19] the female part of the congregation. A long white linen bandage was next passed under each arm-pit of the image; the nail which secured the feet was removed; the figure was let down very gently, and was carefully wrapped up in a white sheet. All this was done by word of command from the preacher. The sermon was then quickly brought to a conclusion, and we left the church. I was quite amazed; I had heard that something of this kind was to be done, but I had no idea of the extent to which the representation would be carried.

On Saturday morning we were saluted with the bellowing of cattle, the grunting of pigs, and the cries of the negro slaves with baskets of fowls of several kinds for sale; these were to be devoured after the ensuing midnight, and many families, weary of their long abstinence, impatiently awaited the striking of the clocks, as a signal for the commencement of hostile operations, without mercy or scruple, upon turkies, pigs, &c. and all the rest of the miserable tribes which have been laid down as the lawful victims of our carnivorous nature.

On Easter Sunday I was invited by a physician to dine with him, and to attend the christening of one of his grandchildren. At dinner the party was small; the dishes, were served up two at a time to the number of ten or twelve, of all of which I was obliged to taste. From the table we adjourned to the church about four o’clock, where several persons, likewise invited, waited for us; the ceremony was performed by a friar, and each guest held a wax taper, forming a semicircle towards the altar; from hence we returned to the old gentleman’s house to supper. I met here, among others belonging to the same convent, the friar who preached the crucifixion sermon. The members of this convent are all Italians and Missionaries, but as no reinforcement has for a length of time come out from Europe, very few now remain. A long table was laid out, loaded with victuals. Several ladies were present, notwithstanding which enormous quantities of wine were drank, until the whole company began to be riotous, but still the ladies did not move. At last no order was left among them, bottles and glasses were overturned and broken in the[20] vehement wishes expressed for the prosperity of the whole family of our host, both old and young; when in the midst of this, I escaped about nine o’clock, accompanied by a Franciscan friar. We had a journey in contemplation for the next day, and thought it high time to get away. Parties of this kind are not frequent, and in a general way these people live in a very quiet manner. The old Doctor is a native of Lisbon, and a great friend to Englishmen; he was young at the time of the great earthquake, and says he shall never forget that he was in part cloathed from the necessaries sent out by the British government for the assistance of the Portugueze after that dreadful calamity.

On the following afternoon, the friar, myself, and a servant, proceeded to Iguaraçu, a small town distant from Recife seven leagues, for the purpose of witnessing the entrance of a novice into the Order of St. Francis. We arrived about nine o’clock at night at the gates of the convent; the friar rang the bell three times, as the signal of the arrival of one of the Order; a lay brother came, and asked who it was that demanded admittance; he was answered, that it was brother Joseph from the convent of Recife accompanied by a friend; the porter shut the gates again, but soon returned, saying that the Guardian, the name given to the principal of a Franciscan convent, allowed us to enter. We were conducted up a flight of steps into a long corridore, at the end of which sat the Guardian, to whom we were introduced; he directed us to the brother who had the management of the accommodations for visitors; this man placed us under the especial care of Frei Luiz, who took us to his cell. Supper was served up, upon which the Guardian came in, helped us once round to wine and made many apologies for the badness of his cook, and also excuses for the want of ingredients at this distance from Recife. The convents of St. Francis are all built exactly upon the same plan; in the form of a quadrangle, one side of which is appropriated to the church, and the remaining three to cells and to other purposes; the former are above, and to be entered from a gallery,[21] which runs round the whole building. The beds with which the friars supplied us were hard, but very acceptable after our ride.

The ceremony to be performed on the ensuing morning collected great numbers of persons from all quarters, as it is now very rare. Formerly, of every family at least one member was a friar, but now this is not the custom; children are brought up to trade, to the army, to any thing rather than to a monastic life, which is fast losing its reputation. None of the convents are full, and some of them are nearly without inhabitants.[12]

Early in the morning the church was lighted up, and about ten o’clock the family of the person about to take the vows arrived to occupy the seats prepared for them. Mass was then said, and a sermon preached; about eleven o’clock the novice, a young man of sixteen years of age, entered the principal chapel by a side door, walking between two brothers, with a large cross in his hands, and dressed in a long dark blue robe: there was then much chanting, after which he knelt down opposite to the Guardian, received the usual admonitions, was asked several questions relating to his belief in the doctrines of the church, and then made the separate vows, of defending his religion, of celibacy, and others of minor importance. The Guardian then dressed him in the habit of the Order, made of very thick, rough, dark brown cloth, which before lay stretched upon the ground in front of the altar, covered with flowers; this being done, the young man embraced all the brothers present, took leave of his relations, and left the church. Many of the friars were laughing during the ceremony, and were particularly amused at the Guardian accidentally saying, “Brother, don’t be ashamed[13];” owing to the young man being[22] much abashed. A visitor who stood near to me in the gallery, from which there are windows into the church, said, in a low voice to be heard only by those immediately around him; “See your chief himself thus advises him to put shame aside, which unfortunately you are all too much inclined to do;” at this the friars who were within hearing all laughed. Great part of the community and many other persons dined with the father of the young friar, and I among the rest; there was much eating, much drinking, and much confusion. In the evening fireworks were displayed, which ended by a transparency, representing a novice receiving the benediction of his Guardian.

It was determined that we should return to Recife this night, and that the journey was to be commenced as soon as the moon rose. The party consisted of five friars, several laymen besides myself all on horseback; some palanquins with ladies, and a number of negroes to carry them. We sallied forth about midnight; the moon was bright, and the sky quite clear. The scene was very strange; the road made in places abrupt turns, so as to give to those who were rather in advance, on looking back, a view of the whole procession, at times appearing and at times concealed among the trees; of this the friars formed an extraordinary part, in their robes tucked up round the waist, and tied with the long yellow cord of flagellation, and with their enormous white hats. At Olinda several persons remained, and the rest arrived at Recife about seven o’clock in the morning.

On the 10th of May I had a sudden attack of fever, which was accompanied with delirium; however, with the assistance of a medical man, the disorder subsided in the course of forty-eight hours, but it left me in a very weak state, from which I was some time in recovering. These fevers are well known in the country, but are not common, and in general are preceded for some days by ague. I can only account for this attack, from having suffered the window of my room, which had a western aspect, to remain open during the night, and the land breeze which rises about twelve o’clock is not accounted wholesome. A young Englishman insisted upon my removal to his house, that I might not remain in the hands of servants;[23] he brought a palanquin for this purpose, and made me get into it. With him I remained until my health was completely re-established, and was treated by him with that sort of kindness which can only be expected from a very near relation.

I dined with a friend on St. Peter’s day, the 29th June, and in the evening I proposed walking to the church, dedicated to this saint. As usual, the blaze of light was great, the congregation numerous, and the whole affair very brilliant. After the service, we recognised a party of ladies with whom we were acquainted, and one of them requested us to look for a young priest, her son; on making enquiries, we were desired to walk up stairs into a large room over the vestry, in which were several priests, and a table covered with refreshments of many descriptions. The young man came to us, and was soon followed by others, who invited us to stay and partake, but we declined and went down to the party we had joined; some of the priests accompanied us, and persuaded the ladies to ascend, and have a share of the good things; we were also requested to return, which we did. There were great quantities of fruit, cakes, sweetmeats, and wine. We met with the most marked attention from these ministers of the Roman Catholic religion; greater politeness could not have been shown to any person; even many with whom we had not been acquainted before, offered us wine, and requested to be introduced to us. I mention the conduct of these men more particularly, as I think it showed a great degree of liberality, and a wish to conciliate, and more especially as there were likewise several laymen present of their own nation[14]. About ten o’clock we left the church, and taking one family of our party home, remained with them until a very late hour.

We were invited to pass the following Sunday with this family, which consisted of the father and mother, and a son and daughter;[24] they were all Brazilians, and though the young lady had never been from Pernambuco, her manners were easy; and her conversation lively and entertaining. Her complexion was not darker than that of the Portugueze in general, her eyes and hair black, and her features on the whole good; her figure small, but well shaped. Though I have seen others handsomer, still this lady may be accounted a very fair sample of the white Brazilian females; but it is among the women of colour that the finest persons are to be found,—more life and spirit, more activity of mind and body; they are better fitted to the climate, and the mixed race seems to be its proper inhabitant. Their features too are often good, and even the colour, which in European climates is disagreeable, appears to appertain to that in which it more naturally exists; but this bar to European ideas of beauty set aside, finer specimens of the human form cannot be found than among the mulatto females whom I have seen.

We went to them to breakfast, which was of coffee and cakes. Backgammon and cards were then introduced until dinner time, at two o’clock. This consisted of great numbers of dishes, placed upon the table without any arrangement, and brought in without any regard to the regularity of courses. We were, as may be supposed, rather surprised at being complimented with pieces of meat from the plates of various persons at the table. I have often met with this custom, particularly amongst families in the interior, and this I now speak of had only resided in Recife a short time; but many of the people of the town have other ideas on these matters. Two or three knives only were placed upon the table, which obliged each person to cut all the meat upon his own plate into small pieces, and pass the knife to his next neighbour. There was, however, a plentiful supply of silver forks, and abundance of plates. Garlic formed one ingredient in almost every dish, and we had a great deal of wine during the dinner. The moment we finished, every one rose from the table, and removed into another apartment. At eight o’clock a large party assembled to tea, and we did not take our departure until a very late hour. On our arrival at home, my friend[25] and I sat together to consider of the transactions of this day, which we had thus passed entirely with a Brazilian family, and both agreed that we had been much amused, and that we had really felt much gratification, save the business at the dining table. The conversation was trifling, but entertaining; there was much wit and sport. The ladies of the house, joined by several others in the evening, talked a great deal, and would allow of no subject into which they could not enter.

It will be observed from what I have described, and from what I still have to mention, that no rule can be laid down for the society of the place in question; families of equal rank, and of equal wealth and importance, are often of manners totally different. The fact is, that society is undergoing a rapid change; not that the people imitate European customs, though these have some effect, but as there is more wealth, more luxuries are required; as there is more education, higher and more polished amusements are sought for; as the mind becomes more enlarged, from intercourse with other nations, and from reading, many customs are seen in a different light; so that, the same persons insensibly change, and in a few years ridicule and are disgusted with many of those very habits which, if they reflect for a moment, they will recollect were practised but a short time before by themselves.

On St. Anne’s day, the 29th July, two young Englishmen and myself proceeded by invitation to the house of one of the first personages of Pernambuco; a man in place, and a planter, possessing three sugar works in different parts of the country. About ten o’clock in the morning, we embarked in a canoe, and were poled and paddled across the bay, on the land side of the town. On our arrival upon the opposite shore, the tide was out, and the mud deep; in fear and trembling for our silks, two of us clang to the backs of the canoe-men, who with some difficulty put us down safe on dry land; but the third, who was heavier, for some minutes debated whether to return home was not the better plan, however, he took courage, and was, likewise, safely conducted through this region of[26] of peril. We then walked up to the house, which covers much ground, and of which the apartments are spacious, and all upon the first floor. The garden was laid out by this gentleman’s father, in the old style of straight walks, and trees cut into shapes. A large party was already assembling, as this was the anniversary of the birth-day of our hostess; but the females were all ushered into one room, and the men into another; cards and backgammon, as usual, were the amusements, but there was little of ease and freedom of conversation. At dinner, the ladies all arranged themselves on one side, and the men opposite to them; there were victuals of many kinds in great profusion, and much wine was drank. Some of the gentlemen who were intimately acquainted with the family, did not sit down at table, but assisted in attending upon the ladies. After dinner, the whole party adjourned into a large hall, and country dancing being proposed and agreed to, fiddlers were introduced, and a little after seven o’clock, about twenty couples commenced, and continued this amusement until past two o’clock. Here was the ceremony of the last century in the morning, and in the evening the cheerfulness of an English party of the present day. I never partook of one more pleasant; the conversation, at times renewed, was always genteel, but unceremonious, and I met with several well-educated persons, whose acquaintance I enjoyed during the remainder of my stay at this place.

The rains this season had been very slight, and scarcely ever prevented our rides into the country in the neighbourhood, to the distance of six or eight miles; but we never reached beyond the summer dwellings of the inhabitants of Recife. The villages are at this time very dull, having people of colour and negroes as residents almost exclusively. However, as I was fond of the country, I was tempted by the fineness of the weather, to remove entirely to a small cottage in the vicinity, where my time passed away pleasantly, though quietly, and in a manner very barren of events. There stands a hamlet not far distant from my new residence, called Caza Forte, formerly the site of a sugar plantation, which[27] has been suffered to decay, and now the chapel alone remains to point out the exact position. The dwelling-house of these works is said to have been defended by the Dutch against the Portugueze, who set fire to it, for the purpose of obliging their enemies to surrender. A large open piece of ground is pointed out as having been the situation upon which these transactions took place. It is distant from Recife about five miles, and the river Capibaribe runs about three quarters of a mile beyond it. I met with few of the peasants who had any knowledge of the Pernambucan war against the Dutch, but I heard this spot more frequently spoken of than any other[15]. Perhaps if I had had more communication with the southern districts of Pernambuco, I should have discovered that the war was more vividly remembered there.

I had an offer of introduction to another Brazilian family, which I readily accepted, and on the 7th August, I was summoned by my friend to accompany him to Olinda. He had been invited, and liberty had been given to take a friend. We went in a canoe, and were completely wet through on the way; but we walked about the streets of Olinda until we were again dry. The family consisted of an old lady, her two daughters, and a son, who is a priest, and one of the professors or masters of the seminary. Several persons of the same class were present, of easy and gentlemanlike manners; some of them proposed dancing, and although they did not join in the amusement, still they were highly pleased to see others entertained in this manner. Our music was a piano forte, played by one of the professors, who good-humouredly continued until the dancers themselves begged him to desist. About midnight, we left these pleasant people, and returned to the beach; the tide was out, and the canoe upon dry land; we therefore determined to walk; the sand was very heavy, the distance three miles, and after our evening’s[28] amusement, this was hard work. I did not attempt this night to go beyond Recife to my cottage, but accepted of a mattress at my friend’s residence.

Three or four families are in the practice of having weekly evening card parties, as was usual in Lisbon. I attended these occasionally, but in them there was no peculiarity of customs.

The foregoing pages will, I think, suffice to point out the kind of society to be met with in Pernambuco, but this must be sought for, as the families in which it is to be found, are not numerous. Of these, very few are in trade; they are either Portugueze families, of which the chief is in office, or Brazilian planters who are wealthy, and prefer residing in Recife or Olinda; or, as is frequently the case, a son or brother belonging to the secular priesthood, has imbibed more liberal notions, and has acquired a zest for rational society. As may naturally be supposed, the females of a family are always glad to be of more importance, to be treated with respect, to see, and to be seen. The merchants, generally speaking, for there do exist some exceptions, live very much alone; they have been originally from Portugal, have made fortunes in trade, and have married in the country; but most of them still continue to live as if they were not yet sufficiently wealthy, or at least cannot persuade themselves to alter their close and retired manner of living, and, excepting in the summer months, when sitting upon the steps of their country residencies, their families are not to be seen.

The gentleman, chiefly by whose kindness I had been introduced and enabled to partake of the pleasantest society of Pernambuco, was among the first British subjects, who availed themselves of the free communication between England and Brazil, and he even already observed a considerable change of manners in the higher class of people. The decrease in the price of all articles of dress; the facility of obtaining at a low rate, earthenware, cutlery, and table linen; in fact, the very spur given to the mind by this appearance of a new people among them; the hope of a better state of things, that their country was about to become of more importance; renewed[29] in many persons, ideas which had long lain dormant; made them wish to show, that they had money to expend, and that they knew how it should be expended.[16]

It was the custom in Pernambuco, to uncover when passing a sentinel, or on meeting a guard of soldiers marching through the streets. Soon after the opening of the port to British shipping, three English gentlemen accidentally met a corporal’s guard of four or five men, and as they passed each other, one of the latter took off the hat of one of the former, accompanying the action by an opprobrious expression; the Englishmen resented the insult, attacked and absolutely routed the guard. This dreadful mark of submission to military power was universally refused by every British subject, and has been very much discontinued even by the Portugueze. Another annoyance to these visitors was the usual respect paid to the Sacrament, carried with much pomp and ceremony to persons dangerously ill. It was expected, that every one by whom it chanced to pass, should kneel, and continue in that posture until it was out of sight; here Englishmen, in some degree, conformed in proper deference to the religion of the country, but the necessity of this also is wearing off.[17]

CHAPTER III.

THE GOVERNMENT.—THE TAXES.—THE PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS.—CRIMINALS.—PRISONS.—MILITARY ESTABLISHMENTS.—THE ISLAND OF FERNANDO DE NORONHA.

THE captaincies-general, or provinces of the first rank, in Brazil, of which Pernambuco is one, are governed by captains-general or governors, who are appointed for three years. At the end of this period the same person is continued or not, at the option of the supreme government. They are, in fact, absolute in power, but before the person who has been nominated to one of these places can exercise any of its functions, he is under the necessity of presenting his credentials to the Senado da Camara, the chamber or municipality of the principal town. This is formed of persons of respectability in the place. The governor has the supreme and sole command of the military force. The civil and criminal causes are discussed before and determined by the Ouvidor and Juiz de Fora, the two chief judicial officers, whose duties are somewhat similar, but the former is the superior in rank. They are appointed for three years, and the term may be renewed[18]. It is in these departments of the government[31] that the opportunities of amassing large fortunes are most numerous; and certain it is that some individuals take advantage of them in a manner which renders justice but a name. The governor can determine in a criminal cause without appeal, but, if he pleases, he refers it to the competent judge. The Procurador da Coroa, attorney-general, is an officer of considerable weight. The Intendente da Marinha, port admiral, is likewise consulted on matters of first importance; as are also the Escrivam da Fazenda Real, chief of the treasury, and the Juiz da Alfandega, comptroller of the customs. These seven officers form the Junta, or council, which occasionally meets to arrange and decide upon the affairs of the captaincy to which they belong.

The ecclesiastical government is scarcely connected with that above mentioned, and is administered by a bishop and a dean and chapter, with his vicar-general, &c. The governor cannot even appoint a chaplain to the island of Fernando de Noronha, one of the dependencies of Pernambuco, but acquaints the bishop that a priest is wanted, who then nominates one for the place.

The number of civil and military officers is enormous; inspectors innumerable—colonels without end, devoid of any objects to inspect—without any regiments to command; judges to manage each trifling department, of which the duties might all be done by two or three persons; thus salaries are augmented; the people are oppressed, but the state is not benefited.

Taxes are laid where they fall heavy upon the lower classes, and none are levied where they could well be borne. A tenth is raised in kind upon cattle, poultry, and agriculture, and even upon salt; this in former times appertained, as in other christian countries, to the clergy[19]. All the taxes are farmed to the highest bidders, and[32] this among the rest. They are parcelled out in extensive districts, and are contracted for at a reasonable rate, but the contractors again dispose of their shares in small portions; these are again retailed to other persons, and as a profit is obtained by each transfer the people must be oppressed, that these men may satisfy those above them and enrich themselves. The system is in itself bad, but is rendered still heavier by this division of the spoil. The tenth of cattle, as I have already said, is levied in kind upon the estates in the interior of the country, and, besides this, a duty of 320 reis per arroba of 32 lbs. is paid upon the meat at the shambles, which amounts to about twenty-five per cent. Fish pays the tenth, and afterwards a fifteenth. Every transfer of immoveable property is subject to a duty of ten per cent. and moveables to five per cent. Besides these, there are many other taxes of minor importance. Rum, both for exportation and home consumption, pays a duty of 80 reis per canada[20], which is sometimes a fourth of its value, but may be reckoned as from fifteen to twenty per cent. Cotton pays the tenth, and is again taxed at the moment of exportation 600 reis per arroba of 32 lbs. or about 1¼d. per lb. Nothing can be more injudicious, than this double duty upon the chief article of exportation from that country to Europe. The duties at the custom-house are fifteen per cent. upon imports, of which the valuation is left in some measure to the merchant to whom the property belongs. Here, I think, ten per cent. more might be raised without being felt. A tax is paid at Pernambuco for lighting the streets of the Rio de Janeiro, whilst those of Recife remain in total darkness.

Now, although the expences of the provincial governments are great, and absorb a very considerable proportion of the receipts, owing to the number of officers employed in every department, still the salaries of each are, in most instances, much too small to afford a comfortable subsistence; consequently peculation, bribery, and other crimes of the same description are to be looked for, and they become so frequent as to escape all punishment or even notice; though there are some men whose character is without reproach. The governor of Pernambuco receives a salary of 4,000,000 reis, or about 1000l. per annum. Can this be supposed to be sufficient for a man in his responsible situation, even in a country in which articles of food are cheap? His honour, however, is unimpeached; not one instance did I ever hear mentioned of improper conduct in him; but the temptation and the opportunities of amassing money are very great, and few are the persons who can resist them.

The only manufactory in Recife of any importance is that of gold and silver trinkets of every description, and of gold lace, but the quantities made of either are only sufficient for the demand of the place. The women employ themselves very generally in making thread lace and in embroidery, but the manufacture of these articles is not sufficiently extensive to allow of exportation.[21]

The public institutions are not many, but, of those that exist, some are excellent. The seminary at Olinda for the education of young persons is well conducted, and many of its professors are persons of knowledge and of liberality. It is intended principally to prepare the students for the church as secular priests, and therefore all of them wear a black gown and a cap of a peculiar form, but it is not necessary that they should ultimately take orders. Free schools are also established in most of the small towns in the country, in some of[34] which the Latin language is taught, but the major part are adapted only to give instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Neither in these nor in the seminary is any expence incurred by the pupils. The Lazarus Hospital is neglected, but patients are admitted; the other establishments for the sick are very miserable. Strange it is, that fine churches should be built, whilst many individuals are suffered to perish from the want of a suitable building under which to shelter them. But the best institution of which Pernambuco has to boast, in common with the mother country, is the Roda dos Engeitados. Infants of doubtful birth are received, taken care of, reared, and provided for. Every person knows what the wheel of a convent is,—a cylindrical box open on one side, which is fixed in the wall and turns upon a pivot; near to this is placed a bell, to be rung when any thing is put into the box, that the inhabitants of the convent may know when it should be turned. One of these wheels stands ready night and day to receive the child—the bell is rung and the box turns. Thus the lives of many are saved—thus numbers are spared from shame. Never let it be imagined that births of a secret nature will be more frequent, from the consideration that this institution exists, but it removes all motives for unnatural conduct in a mother, and it may sometimes produce reform of future conduct, by the facility afforded of concealing what has already passed.

The friars are not numerous, though they are far too much so. These useless beings[22] amount to about one hundred and fifty in number at Olinda, Recife, Iguaraçu, and Paraiba[23]. But there are[35] no nuns in the province, though of the establishments called Recolhimentos or Retreats, three exist. These are directed by elderly females, who have not taken any vows, and who educate young persons of their own sex, and receive individuals whose conduct has been incorrect, but whose characters are not notorious, and who are placed here by their relations to prevent further shame. The number of churches, chapels, and niches in the streets for saints, is quite preposterous; to these are attached a multitude of religious lay brotherhoods, of which the members are merchants, and other persons in trade, and even some are composed of mulatto and black free people. Some of these continually beg for a supply of wax, and other articles to be consumed in honour of their patron. Almost every day in the year, passengers are importuned in the streets, and the inhabitants in their houses, by some of these people, and among others, by the lazy Franciscan friars. A Portugueze gentleman refused to give money for any of these purposes, but after each application, threw into a bag, placed apart for the purpose, a 5 reis coin, the smallest in use, and in value the third part of a penny. At the end of a twelvemonth, he counted his 5 reis pieces, and found that they amounted to 30,000 reis, about 8l. 6s. He then applied to the vicar of his parish, requesting him to name some distressed person to whom he should give the money.

The Holy Office or Inquisition has never had an establishment in Brazil, but several priests resided in Pernambuco, employed as its[36] familiars, and sometimes persons judged amenable to this most horrid tribunal, have been sent under confinement to Lisbon. However, the ninth article of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, between the crowns of England and Portugal, signed at the Rio de Janeiro in 1810, has completely determined, that the power of the Inquisition shall not be recognised in Brazil. It will appear surprising to English persons, that in a place so large as Recife, there should be no printing press or bookseller. At the convent of the Madre de Deos, are sold almanacks, prints and histories of the Virgin and saints, and other productions of the same description, but of very limited size, printed at Lisbon. The post-office is conducted in a very irregular manner. The letters from England are usually delivered at the house of the merchant to whom the ship which conveyed them is consigned, or at the office of the British consul. There is no established means of forwarding letters to any part of the interior of the country, nor along the coast, so that the post-office merely receives the letter bags which are brought by the small vessels that trade with other ports along this coast, and sends the bags from Pernambuco by the same conveyances, and as there is not any regular delivery of letters, each person must inquire for his own at the office. When the commerce of Brazil was trifling, compared to its present state, a post-office managed in this manner was sufficient, but in consequence of the increased activity of the trade along the coast, and with Europe, some attention ought to be given to the subject, to facilitate communication. There is a theatre at Recife, in which are performed Portugueze farces, but the establishment is most wretchedly conducted.

The Botanic Garden at Olinda is one of those institutions which have arisen from the removal of the Court to South America; it is intended as a nursery for exotic plants, from whence they are to be distributed to those persons who are willing and capable of rearing them. Thus the bread fruit tree has been introduced, the black pepper plant, the large Otaheitan cane, and several others. I much fear, however, that the zeal shown at the commencement has somewhat[37] cooled. A botanist has been appointed with an adequate salary. He is a Frenchman, who had resided at Cayenne, and with this choice many persons were much dissatisfied, as it was thought, and with good reason, that a Portugueze subject might have been found, quite capable of taking the management of the garden.

The sight, of all others, the most offensive to an Englishman, is that of the criminals, who perform the menial offices of the palace, the barracks, the prisons, and other public buildings. They are chained in couples, and each couple is followed by a soldier, armed with a bayonet. They are allowed to stop at the shops, to obtain any trifle which they may wish to purchase, and it is disgusting to see with what unconcern the fellows bear this most disgraceful situation, laughing and talking as they go along to each other, to their acquaintance whom they may chance to meet, and to the soldier who follows them as a guard[24]. The prisons are in a very bad state, little attention being paid to the situation of their inhabitants. Executions are rare at Pernambuco; the more usual punishment inflicted, even for crimes of the first magnitude, is transportation to the coast of Africa. White persons must be removed[38] for trial to Bahia, for crimes of which the punishment is death. Even to pass sentence of death upon a man of colour, or a negro, several judicial officers must be present. There does not exist here a regular police; when an arrest is to be effected in Recife or its neighbourhood, two officers of justice are accompanied by soldiers, from one or other of the regiments of the line, for this purpose. A ronda or patrol, consisting of soldiers, parades the streets during the night, at stated periods, but it is not of much service to the town. Recife and its vicinity were formerly in a very tranquil state, owing to the exertions of one individual; he was a sergeant in the regiment of Recife, a courageous man, whose activity of mind and body had had no field upon which to act, until he was employed in the arduous task of apprehending criminals, and at last he received special orders from the governor for patroling the streets of Recife, Olinda, and the villages around them; he and his followers were much dreaded, but at his death no one stepped into his place.[25]

The military establishment is much neglected. The regular troops consist of two regiments of infantry, which ought to form together a body of 2,500 men, but they seldom collect more effective than 600; so that sufficient numbers can scarcely he mustered to do the duty of the town of Recife, of Olinda, and the forts. Their pay is less than 2¾d. per day, and a portion of the flour of the mandioc weekly, and their clothing is afforded to them very irregularly. From their miserable pay, rather more than one farthing per day is held back for a religious purpose. Recruits are made of some of the worst individuals in the province; this mode of recruiting, and their most wretched pay, account completely for the depreciated[39] character of the soldiers of the line[26]. They are formed chiefly of Brazilians, and people of colour. Besides these regiments, the militia of the town sometimes do duty without pay, and these make but a sorry shew. The militia regiments, commanded by mulatto and black officers, and formed entirely of men of these casts, are very superior in appearance; but these I shall have again an opportunity of mentioning.