The Project Gutenberg EBook of Aesop's Fables, by J. H. Stickney

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Aesop's Fables

A Version for Young Readers

Author: J. H. Stickney

Illustrator: Charles Livingston Bull

Release Date: May 21, 2015 [EBook #49010]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AESOP'S FABLES ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Emmy and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A Version for

Young Readers

By

Illustrated by

Charles Livingston Bull

Ginn and Company

Boston—New York—Chicago—London

Atlanta—Dallas—Columbus—San Francisco

COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY GINN AND COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

321.11

THE Athenæum Press

GINN AND COMPANY·PROPRIETORS·BOSTON·U.S.A.

THE good fortune which has attended the earlier edition of this book is a proof that there is less occasion now than formerly to plead the cause of fables for use in elementary schools. And yet their value is still too little recognized. The homely wisdom, which the fables represent so aptly, was a more common possession of intelligent people of a generation or two ago than it is at the present time. It had then a better chance of being passed on by natural tradition than is now the case among the less homogeneous parentage of our school children. And there has never been a greater need than now for the kind of seed-sowing for character that is afforded by this means. As in the troubled times in Greece in Æsop’s day, twenty-five centuries ago, moral teaching to be salutary must be largely shorn of didactic implications and veiled with wit and satire. This insures its most vital working wherever its teaching is pertinent. To be[iv] whipped, warned, shamed, or encouraged, and so corrected, over the heads of animals as they are represented in the expression of their native traits, is the least offensive way that can fall to a person’s lot. Among several hundred episodes, knowledge of which is acquired in childhood as a part of an educational routine, most conservative estimates would allow for large, substantial results in practical wit and wisdom, to be reaped as later life calls for them.

It is well recognized by scholars, and should be taught to children, that not all the fables attributed to Æsop are of so early a date. Imitations of his genius all along the centuries have masqueraded under his name. Facts about him appear in the Introduction.

No occasion has been found to change in this edition the style of presentation so highly approved in the original one; but, as a considerable number of the stories, especially in the earlier pages of the book, are amplified somewhat in language form to accommodate them to the needs of children unfamiliar with the animals portrayed, it has been thought wise to present these in the briefer form in which they are generally known to adult readers. These[v] are to be found in an Appendix to the present volume. The ingenious teacher will find numerous ways in which this duplication of stories may be turned to account. Comparison of the two forms will suggest many exercises to be performed by the pupils themselves, in which the longer forms of the fables may be built up from the shorter forms, and vice versa. The teacher who is interested in dramatic work will find also that many of the fables will make excellent material for dramatic presentation in the classroom.

THE EDITOR

|

APPENDIX

|

MODERN versions of Æsop go back no further than 480 A.D. In their earliest use they are related to the folklore current among all primitive peoples. This folklore had risen in Greece to the rank of literary form a thousand years before the above-mentioned revival in Germany, France, and England. As the creation of Æsop it was the answer to a need for trenchant, but veiled, characterization of men and measures in the dangerous times of the Tyrants. In mirth-provoking utterances, quite apart from personal criticism, things could be intimated with all the force of specific judgments, yet in such veiled form that to resent them was tacit confession that they applied. Later on, when free speech became safer, the grammarians and rhetoricians raised these clever, pithy stories to the literary form they have since maintained.

There is for Æsop’s Fables no authorized original version. Always, it appears, they were subject to interpolations and special versions. They took on metrical forms in Latin, and in later times in French. It is the particular distinction of a real fable that it bears this amplification, yet can at any time and from any true version shake off the accessories of particular phrasing and in its bare facts meet all the requirements of a literary and artistic whole. It is this static character which has made the fable of such value to language students. Even little children, comparing different versions, learn to distinguish the raw material of a real story from its varying renderings. Subjoined is an account of Æsop, called the Inventor and Father of Fable in its present form.

The life of Æsop, like that of Homer, the most famous of Greek poets, is involved in much obscurity. Sardis, the capital of Lydia; Samos, a Greek island; Mesembria, an ancient colony in Thrace; and Cotiæum, the[xv] chief city of a province of Phrygia, contend for the distinction of being his birthplace. Although the honor thus claimed cannot be definitely assigned to any one of these places, yet there are a few incidents now generally accepted by scholars as established facts relating to the birth, life, and death of Æsop. He is, by an almost universal consent, allowed to have been born about the year 620 B.C. and to have been by birth a slave. He was owned by two masters in succession, Xanthus and Jadmon, both inhabitants of Samos, the latter of whom gave him his liberty as a reward for his learning and wit. One of the privileges of a freedman in the ancient republics of Greece was the permission to take an active interest in public affairs; and Æsop, like the philosophers Phædo, Menippus, and Epictetus in later times, raised himself from the indignity of a servile condition to a position of high renown. In his desire alike to instruct and to be instructed, he traveled through many countries, and among others came to Sardis, the capital of the famous king of Lydia, the great patron, in that day, of learning and of learned men. At the court of Crœsus he met with[xvi] Solon, Thales, and other sages, and is related so to have pleased his royal master by the part he took in the conversations held with these philosophers that Crœsus applied to him an expression which has since passed into a proverb—μαλλον ὁ Φρὑξ, “The Phrygian has spoken better than all.”

On the invitation of Crœsus he fixed his residence at Sardis, and was employed by that monarch in various difficult and delicate affairs of state. In his discharge of these commissions he visited the different petty republics of Greece. At one time he is found in Corinth, and at another in Athens, endeavoring, by the narration of some of his wise fables, to reconcile the inhabitants of those cities to the administration of their rulers. One of these missions, undertaken at the command of Crœsus, was the occasion of his death. Having been sent to Delphi with a large sum of gold for distribution among the citizens, he was so indignant at their covetousness that he refused to divide the money and sent it back to his master. The Delphians, enraged at this treatment, accused him of impiety and, in spite of his sacred character as ambassador, executed[xvii] him as a public criminal. But the great fabulist did not lack posthumous honors, for a statue was erected to his memory at Athens, the work of Lysippus, one of the most famous of Greek sculptors. These few facts are all that can be relied on with any degree of certainty in reference to the birth, life, and death of Æsop.

The fable on pages 197-200 is a translation of La Fontaine’s metrical version of one of the most popular of the Æsop Fables. La Fontaine, who died at Paris in 1695, was a popular writer of drama and the most noted of the French fabulists. Following this, on pages 201-214, are fables from the Russian of Kriloff, a writer who for nearly twenty years was one of the librarians at the Imperial Public Library at St. Petersburg, in which city he died in 1844.

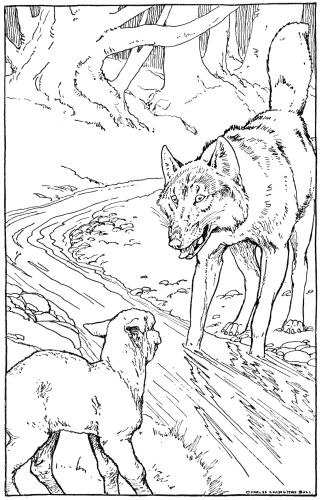

ONE day a Wolf and a Lamb happened to come at the same time to drink from a brook that ran down the side of the mountain.

The Wolf wished very much to eat the Lamb, but meeting her as he did, face to face, he thought he must find some excuse for doing so.

So he began by trying to pick a quarrel, and said angrily: “How dare you come to my brook and muddy the water so that I cannot drink it? What do you mean?”

The Lamb, very much alarmed, said gently: “I do not see how it can be that[4] I have spoiled the water. You stand higher up the stream, and the water runs from you to me, not from me to you.”

“Be that as it may,” said the Wolf, with a snarl, “you are a rascal all the same, for I have heard that last year you said bad things of me behind my back.”

“Dear Mr. Wolf,” cried the poor Lamb, “that could not be, for a year ago I was not born; I am only six months old.”

Finding it of no use to argue any more, the Wolf began to snarl and show his teeth. Coming closer to the Lamb, he said, “You little wretch, if it was not you it was your father, so it’s all the same”; and he pounced upon the poor Lamb and ate her up.

A LITTLE fox was out playing one day, when a Lion came roaring along. “Dear me,” said the Fox, as he hid behind a tree, “I never saw a Lion before. What a terrible creature! His voice makes me tremble.”

The next time the Fox met the Lion he was not so much afraid, but he kept a safe distance and said to himself, “I wish he would not make such a noise!”

The third time they met, the Fox was not frightened at all. He ran up to the Lion, and said, “What are you roaring about?”

And the Lion was so taken by surprise that, without saying a word, he let the Fox walk away.

It would not be safe for little foxes always to follow the example of this one; but it is often true that what our fear makes seem a lion in the way has no danger in it if we meet it bravely.

A DOG once had a nice piece of meat for his dinner. Some say that it was stolen, but others, that it had been given him by a butcher, which we hope was the case.

Dogs like best to eat at home, and he went trotting along with the meat in his mouth, as happy as a king.

On the dog’s way there was a stream with a plank across it. As the water was still and clear, he stopped[7] to take a look at it. What should he see, as he gazed into its bright depths, but a dog as big as himself, looking up at him, and lo! the dog had meat in his mouth.

“I’ll try to get that,” said he; “then with both mine and his what a feast I shall have!” As quick as thought he snapped at the meat, but in doing so he had to open his mouth, and his own piece fell to the bottom of the stream.

Then he saw that the other dog had lost his piece, too. He went sadly home. In trying to grasp a shadow he lost his substance.

“MY child,” said a Crab to her son, “why do you walk so awkwardly? If you wish to make a good appearance, you should go straight forward, and not to one side as you do so constantly.”

“I do wish to make a good appearance, mamma,” said the young Crab; “and if you will show me how, I will try to walk straight forward.”

“Why, this is the way, of course,” said the mother, as she started off to the right. “No, this is the way,” said she, as she made another attempt, to the left.

The little Crab smiled. “When you learn to do it yourself, you can teach me,” he said, and went back to his play.

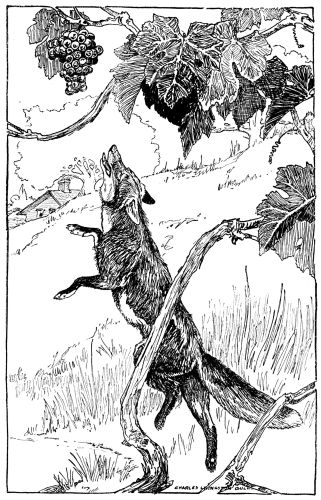

IT WAS a sultry day, and a Fox was almost famishing with hunger and thirst. He was just saying to himself that anything would be acceptable to him, when, looking up, he spied some great clusters of ripe, black grapes hanging from a trellised vine.

“What luck!” he said; “if only they weren’t quite so high, I should be sure of a fine feast. I wonder if I can get them. I can think of nothing that would so refresh me.”

Jumping into the air is not the easiest thing in the world for a Fox to do; but he gave a great spring and nearly reached the lowest clusters.

“I’ll do better next time,” he said.

He tried again and again, but did[10]

[11]

not succeed so well as at first. Finding

that he was losing his strength

and that he had little chance of getting

the grapes, he walked slowly off,

grumbling as he did so: “The grapes

are sour, and not at all fit for my

eating. I’ll leave them to the greedy

birds. They eat anything.”

ONE day a Wolf, who was eating his dinner much too fast, swallowed a bone, which stuck in his throat and pained him very much. He tried to get it out, but could not.

Just then he saw a Crane passing by. “Dear friend,” said he to the Crane, “there is a bone sticking in my throat. You have a good long[12] neck; can’t you reach down and pull it out? I will pay you well for it.”

“I’ll try,” said the Crane. Then he put his head into the Wolf’s mouth, between his sharp teeth, and reaching down, pulled out the bone.

“There!” said the Wolf, “I am glad it is out; I must be more careful another time.”

“I will go now, if you will pay me,” said the Crane.

“Pay you, indeed!” cried the Wolf. “Be thankful that I did not bite your head off when it was in my mouth. You ought to be content with that.”

Gentle, kindly folk sometimes have to learn that kindness must be mixed with caution.

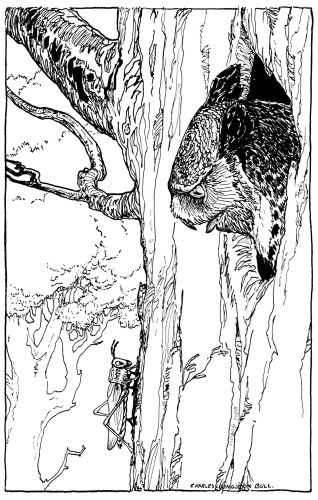

THE Ants and the Grasshoppers lived together in the great field. The Ants were busy all the time gathering a store of grain to lay by for winter use. They gave themselves so little pleasure that their merry neighbors, the Grasshoppers, began at last to take scarcely any notice of them.

When the frost came, it put an end to the work of the Ants and the chirping and merrymaking of the Grasshoppers. But one fine winter’s day, when the Ants were employed in spreading their grain in the sun to dry, a Grasshopper, who was nearly perishing with hunger, chanced to pass by.

“Good day to you, kind neighbor,”[14] said she; “will you not lend me a little food? I will certainly pay you before this time next year.”

“How does it happen that you have no food of your own?” asked an old Ant. “There was an abundance in the field where we lived side by side all summer, and your people seemed to be active enough. What were you doing, pray?”

“Oh,” said the Grasshopper, forgetting his hunger, “I sang all the day long, and all the night, too.”

“Well, then,” interrupted the Ant, “I must not deprive my own family for you. If Grasshoppers find it so gay to sing away the summer, they must starve in winter,” and she went on with her work, all the while singing the old song, “We ants never borrow; we ants never lend.”

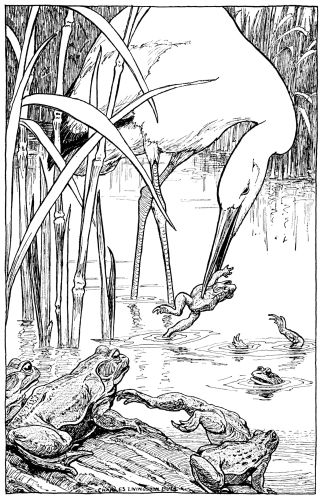

THERE were once some Frogs who lived together in perfect security in a beautiful lake. They were a large company, and were very comfortable, but they came to think that they might be still happier if they had a King to rule over them.

So they sent to Jupiter, their god, to ask him to give them a King.

Jupiter laughed at their folly, for he knew that they were better off as they were; but he said to them, “Well, here is a King for you,” and into the water he threw a big Log.

It fell with such a splash that the Frogs were terrified and hid themselves in the deep mud under the water.

By and by, one braver than the rest peeped out to look at the King, and saw the Log, as it lay quietly on the top of the water. Soon, one after another they all came out of their hiding places and ventured to look at their great King.

As the Log did not move, they swam round it, keeping a safe distance away, and at last one by one hopped upon it.

“This is not a King,” said a wise old Frog; “it is nothing but a stupid Log. If we had a King, Jupiter would pay more attention to us.”

Again they sent to Jupiter, and begged him to give them a King who could rule over them.

Jupiter did not like to be disturbed

again by the silly Frogs, and this

time he sent them a Stork, saying,[17]

[18]

“You will have some one to rule

over you now.”

As they saw the Stork solemnly walking down to the lake, they were delighted.

“Ah!” they said, “see how grand he looks! How he strides along! How he throws back his head! This is a King indeed. He shall rule over us,” and they went joyfully to meet him.

As their new King came nearer, he paused, stretched out his long neck, picked up the head Frog, and swallowed him at one mouthful. And then the next—and the next!

“What is this?” cried the Frogs, and they began to draw back in terror.

But the Stork with his long legs easily followed them to the water, and kept on eating them as fast as he could.

“Oh! if we had only been—” said the oldest Frog. He was going to add “content,” but was eaten up before he could finish the sentence.

The remaining Frogs cried to Jupiter to help them, but he would not listen. And the Stork-King ate them for breakfast, dinner, and supper, every day, till in a short time there was not a Frog left in the lake. Poor, foolish Frogs, not to have known when they were well off.

A DONKEY once put on a Lion’s skin which some hunters had spread out to dry. It did not fit the Donkey very well, but he found that in it he could frighten all the timid, foolish little animals, so he amused himself by chasing them about.

By and by he met a Fox, and tried to frighten him by roaring.

“My dear Donkey,” said the wise Fox, “you are braying, and not roaring. I might, perhaps, have been frightened by your looks, if you had not tried to roar; but I know your voice too well to mistake you for a Lion.”

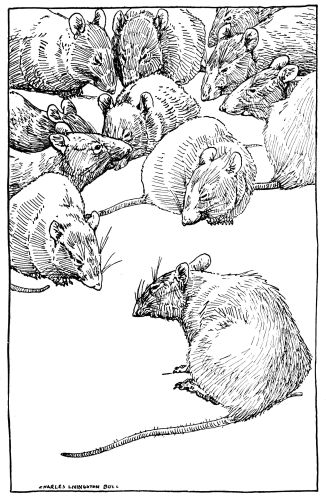

SOME little Mice, who lived in the walls of a house, met together one night, to talk of the wicked Cat and to consider what could be done to get rid of her. The head Mice were Brown-back, Gray-ear, and White-whisker.

“There is no comfort in the house,” said Brown-back. “If I but step[21] into the pantry to pick up a few crumbs, down comes the Cat, and I have hardly time to run to my nest again.”

“What can we do?” asked Gray-ear. “Shall we all run at her at once and bite her, and frighten her away?”

“No,” said White-whisker; “she is so bold we could not frighten her. I have thought of something better than that. Let us hang a bell round her neck. Then, if she moves, the bell will ring, and we shall hear it, and have time to run away.”

“O yes! yes!” cried all the Mice. “That is a capital idea. We will bell the Cat! Hurrah! hurrah! No more fear of the Cat!” and they danced in glee.

When their glee had subsided a little, Brown-back asked, “But who will hang the bell round her neck?”

No one answered. “Will you?” he asked of White-whisker.

“I don’t think I can,” replied White-whisker; “I am lame, you know. It needs some one who can move quickly.”

“Will you, Gray-ear?” said Brown-back.

“Excuse me,” answered Gray-ear; “I have not been well since that time when I was almost caught in the trap.”

“Who will bell the Cat, then?” said Brown-back. “If it is to be done, some one must do it.”

Not a sound was heard, and one by one the little Mice stole away to their holes, no better off than they were before.

When there is trouble there is need of some one to act, as well as some one to advise.

A KID coming home alone one night met a big Wolf. “Oh, oh, I know you will kill me,” said the little Kid; “but please play me a tune, so that I may have one more dance before I die; I am so fond of dancing.”

“Very well,” said the Wolf, “I will try, for I should like to see you dance before I eat you.”

Then the Wolf took up the shepherd’s pipe that was lying near, and began to play. But while he was playing, and the Kid was dancing a jig, the Dogs heard the sound, and came running up.

“It is my own fault,” said the Wolf, as the Dogs caught him. “My business is to kill Kids and eat them, and[24] not to play for them to dance. Why did I try to be a Piper, when I am really only a Butcher?”

“You didn’t play very well, either,” said the Kid.

A NIGHTINGALE sitting on the top of an oak, singing her evening song, was spied by a hungry Hawk, who swooped down and seized her. The frightened Nightingale prayed the Hawk to let her go.

“If you are hungry,” said she, “why not catch some large bird? I am not big enough for even a luncheon.”

“Do you happen to see many large birds flying about?” said the Hawk.[25] “You are the only bird I have seen to-day, and I should be foolish indeed to let you go for the sake of larger birds that are not in sight. A morsel is better than nothing.”

A THIRSTY Crow once spied a pitcher, and flew to it to see if by chance there was any water in it.

When she looked in, she saw that there was water, but that it was so far from the top that she could not reach it, though she stretched her neck as far as she could.

She stopped, and thought to herself, “How shall I get that water? I am perishing with thirst, and there must be some way for me to get[26] some of it.” Some pebbles were lying on the ground; and, picking them up in her beak, she dropped them one by one into the pitcher.

They sank to the bottom; and at last the water was pushed up by them to the top, so that the Crow could easily drink it.

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” said the Crow.

AN Ant, walking by the river one day, said to himself, “How nice and cool this water looks! I must drink some of it.” But as he began to drink, his foot slipped, and he fell in.

“Oh, somebody please help me, or I shall drown!” cried he.

A Dove, sitting in a tree that overhung the river, heard him, and threw him a leaf. “Climb up on that leaf,” said she, “and you will float ashore.”

The Ant climbed up onto the leaf, which the wind blew to the shore, and he stepped upon dry land again.

“Good-by, kind Dove,” said he, as he ran home. “You have saved my life, and I wish I could do something for you.”

“Good-by,” said the Dove; “be careful not to fall in again.”

A few days after this, when the Dove was busy building her nest, the Ant saw a man just raising his gun to shoot her.

He ran quickly, and bit the man’s leg so hard that he cried “Oh! oh!” and dropped his gun.

This startled the Dove, and she[28] flew away. The man picked up his gun, and walked on.

When he was gone, the Dove came back to her nest.

“Thank you, my little friend,” she said. “You have saved my life.”

And the little Ant was overjoyed to think he had been able to do for the Dove what the Dove had so lately done for him.

AN Ox, drinking at a pool, chanced to set his foot on a young Frog, and crushed him to death.

His brothers and sisters, who were playing near, ran at once to tell their mother what had happened. “Oh, Mother,” they cried, “a very huge[29] beast, with four great feet, came to the pool, and crushed our brother to death in an instant, with his hard, cloven heel.”

The old Frog was very vain. She was rather large, as Frogs go, and gave herself airs on account of it. “Was the cruel beast so very large?” she said. “How big?”

“Oh!” said the young Frogs. “It was a terrible monster!”

“Was it as big as this?” she said, blowing and puffing herself out.

“Oh, much bigger,” replied the young Frogs.

“As big as this, then?” she added, puffing and blowing with all her might.

“A great deal bigger,” they answered.

“Well, was it so big?”

“Oh, Mother!” cried the Frogs; “pray do not try to be so big. If[30] you were to puff till you burst, you could not make yourself half so big as the creature we tell you of.”

But the silly old Frog would not give up. She tried again to puff herself out, saying, “As big as”—and she did indeed burst.

It is useless to attempt what is impossible.

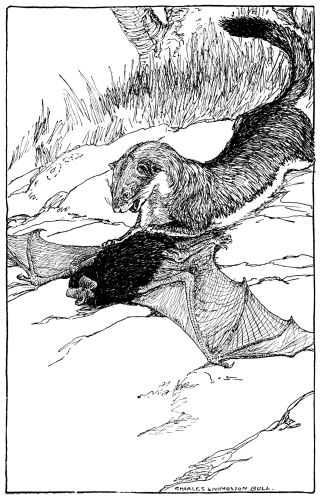

A BAT, trying to fly one day, fell to the ground, and a Weasel caught him. The Bat begged the Weasel not to kill him.

“There is nothing I hate like a bird,” said the Weasel; “I always kill them.”

“But I am not a bird,” said the

Bat, as he folded his wings close to[31]

[32]

his sides; “birds don’t come tumbling

down as I did; and besides,

don’t you see my little smooth head,

and my ears?”

“Yes, yes,” said the Weasel, “I did not notice them at first. I see, you are a mouse”; so he let the Bat go.

Some time after, the Bat took another flight, and again fell to the ground. Another Weasel came out of his hole and caught him.

“Pray don’t kill me,” said the Bat.

“Certainly I shall,” said the Weasel; “I kill mice wherever I find them.”

“But stop a moment,” said the Bat, spreading his wings; “I am not a mouse. Don’t you see my great wings? A mouse can’t fly, can it?”

“I beg your pardon,” said the Weasel; “I did not know that you were a bird; I thought you were a[33] mouse. I see I was mistaken.” Then he let him go.

So the cunning Bat escaped a second time, but it is not often safe to use such arguments.

A FOX once happened to fall into a deep well. He tried in every way to get out, but at last began to think that it was impossible, and that he must die there, a prisoner. While he was thinking how sad that would be, a thirsty Goat came and looked down into the well, wishing that he could get some water. He soon saw the Fox.

“Halloo,” said the Goat, “what are you doing down there? Is the water good?”

“The best I ever tasted,” answered the Fox. “It is cool, and clear, and delicious. Come down and try it yourself.”

“I will,” said the Goat, “for I am nearly dead with thirst.”

So he jumped down, and drank as much water as he wanted.

“Oh, how refreshing!” cried he.

“Yes,” said the Fox; “and now, if you have finished drinking, let me ask how you expect to get out of this well again.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” replied the Goat. “How do you expect to get out?”

“That is what I have been wondering about for the last hour,” said the Fox, “and have just now thought of a good plan. If you will put your forefeet high up on the wall, I will[35] climb up your back, and so get out, and then, of course, I can help you out.”

“Very well,” said the Goat, who was a simple creature, “that is a good plan. How I wish I had your brains!” He put his forefeet on the wall, and the Fox easily climbed out and started to go on his way.

“Wait a moment,” called the Goat; “you forgot to help me out.”

“You foolish fellow!” said the Fox, with a mocking laugh; “you ought to have thought how you would get out, before you jumped down. I fell in, but you went down of your own accord. Look before you leap next time,” and off he ran.

A WOMAN had a Hen that laid an egg every day. The eggs were large, and sold for a good price. The Woman often thought, as she took them to market: “How glad they all are to get my eggs! I could sell as many more just as easily.”

It began to look a small thing to her to get but a single egg each day. “If I were to give a double allowance of barley, the Hen might be made to lay two eggs a day instead of one,” she said.

So she doubled the food, and the Hen grew very fat and sleek; but she stopped laying eggs.

A SLEEPY Dog went to the barn, and jumped into a manger full of hay, curling himself up there for an afternoon nap.

When he had been sleeping comfortably for some time, the Oxen came in for their supper.

The Dog awoke in a great rage at being disturbed, and began to growl and bark at them. He would not let them get at the hay.

“Stop a moment,” said one of the Oxen. “Do you want to eat this hay?”

“No,” said the Dog; “I shouldn’t think of such a thing.”

“Very well, then,” said the Ox, “we do want to eat it, for we are hungry and tired.”

“Oh, go away,” growled the Dog, “and let me sleep.”

“What an ugly, snappish fellow!” said the Ox. “He will neither eat the hay himself nor let us eat it!”

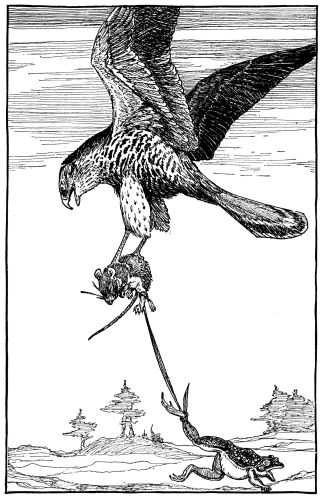

A MOUSE, who had always lived on the land, and a Frog, who passed most of his time in the water, became friends.

The Mouse showed the Frog his nest and everything he could think of that was pleasant to see; and the Frog invited the Mouse to go home with him and see all the beautiful things that are under the water.

“Can you swim?” asked the Frog.

“Not much,” said the Mouse.

“No matter,” said the Frog; “I will tie your foot to my foot with a piece of this strong grass, and then I can pull you along nicely.” The Frog laughed as he said this. He thought it would be good fun for him, but he well knew that the Mouse would not enjoy it.

When the Frog had tied the Mouse’s foot to his own, they started together across the meadow. They soon came to the edge of the water, and the Frog jumped in, pulling the Mouse in with him.

“Oh, how cool and nice the water is, after the dry, hot land!” said the Frog, as he swam gayly about. But the poor Mouse was frightened.

“Please let me go,” said he, “or I shall die.”

“Oh, never mind,” said the unkind[41] Frog; “you will get used to the water. I just love it.”

But soon the poor Mouse was drowned, and floated up to the top of the water, while the Frog frisked about down below.

Just then a Hawk saw the Mouse, and pounced upon it.

As he flew away with it the Frog was dragged out of the water, too, for he was still tied to the Mouse.

“Stop, stop!” cried the Frog. “Let me go. It is the Mouse you want.”

“Come along,” said the Hawk; “I want you both. I will eat you first, for I like Frog meat even better than I do Mouse.”

In a few moments the Hawk had made a good supper, and there was nothing left of either the false Frog or the foolish Mouse.

A MAN who had a fine flock of Sheep put them all into a field, and hired a Boy to take care of them, while he worked near by with his Men.

The Sheep went nibbling the grass all day, up and down the hills and along the brook; and all that the Boy had to do was to look out for the Wolf, and see that he did not come prowling into the field.

After a while the Boy began to wish that something would happen, it was so tiresome staying there all alone, with no one to speak to and nothing to do. He wished he could be with the Men in the next field, or that they could come and stay with[43] him. All at once he thought to himself, “I will make them think the Wolf has come. That will be great fun.”

So he called out as loudly as he could, “Help! help! The Wolf!” and all the Men came running up.

When they found it was only a joke, they laughed, and went back to their work.

On the next day the Boy tried the same trick again. As before, the Men dropped their mattocks and spades, for fear there might be danger, and ran to the help of the Boy. He only laughed at them for their pains, and this time they did not relish the joke. Still the Boy did not give it up. Again he shouted “Wolf! Wolf!” till the Men took no notice of him when he called them, no matter how loudly or how long he shouted.

After a while, the Wolf did get into the field. Then in real terror the Boy called and called: “Pray do come and help me. The Wolf is killing the sheep. The Wolf! the Wolf!” But no one gave heed to his cries. Finding only a terrified coward in care of the flock, the Wolf left few of them uninjured.

ALL day long a Fisherman had been toiling and had caught nothing.

“I will make one more effort,” thought he, “and then I must go home.”

He threw in his line, and soon drew up a very small perch.

The little Fish was terribly frightened when he found himself out of[45] water, and with a sharp hook sticking in his mouth; and he said to the Fisherman:

“O sir, take pity upon me, and throw me into the water again! See what a little thing I am. I should not make one mouthful for you now; but if you leave me in the water, I shall grow large and stout, and then I shall be worth catching. You can make a dinner of me then, or sell me for a good price.”

“Ah!” said the Fisherman, “it is true you are small, but I have you safely now. If I should throw you back, I might never catch you again. You are better than nothing. I will keep you”; and he put the little Fish into his basket, and took him home with him.

A CROW stole a piece of cheese one day, and flew with it up into a tree, so as to eat it at her leisure.

As she sat there, holding it in her beak, a Fox chanced to pass by, and looking up saw her. “How good that cheese smells!” thought he; “I’ll have it, sure as I’m a Fox.”

Coming close to the tree, he said, “My dear Madam, what a beautiful creature you are! I was not aware till this moment what rare beauty your family possesses. What eyes! What glossy feathers! What grace of form! Is your voice as charming to hear, as your person is to look upon? If it is, you well deserve to be called the Queen of Birds. Will[47] you not do me the favor to sing to me?”

Now it is well known that the Caw! Caw! of the Crow family is not musical. She ought to have been on her guard, but so delighted was she with the flattery of the Fox that she forgot to be wary. She opened her mouth to show the Fox the sweetness of her voice, when—down fell the bit of cheese, which was exactly what was expected.

The Fox ate it at one mouthful, then stopped to say, “Thank you, madam. I am quite satisfied. Your voice is well enough, I have no doubt. What a pity it is you are so sadly wanting in wit!”

The Crow learned that we do well to be on our guard when people flatter us.

A FOWLER caught a Partridge, and was just going to kill it.

“Wait a moment,” said the Partridge; “don’t kill me.”

“Why not?” said the Fowler.

“Because I like to live,” said the Partridge; “and, besides, if you let me go, I will bring some of my friends and neighbors here, and you can catch them, and that will be better than only one poor bird.”

“You are willing, then, that your friends and neighbors should die, to save your own life?” said the Fowler. “Wicked Partridge! you have lived long enough.” And he killed it.

A PIGEON who was very thirsty saw a goblet of water painted on a signboard.

Without stopping to see what it was, she flew to it with a loud whir, and dashing against the signboard, jarred herself terribly. Having broken her wings, she fell to the ground, and was caught by a man, who said, “Your zeal should never outrun your caution.”

A GREAT city was once besieged, and all its inhabitants were gathered together to consider by what means it might be protected from the enemy.

A Bricklayer earnestly recommended bricks as the best materials for successful defense.

A Carpenter with equal energy proposed timber as a preferable means of defense.

Hearing which, a Currier stood up and said, “Sirs, I differ with you wholly. There is no material for resistance equal to a covering of hides, and nothing in the present case so good as leather.”

Every man for his own trade.

IN A FOREST, deep, shady, and still, there once lived a company of Hares.

Whenever a leaf fell rustling to the ground, or a squirrel, jumping in the[51] branches, broke a twig, the Hares started and trembled, they were so timid.

One day there came a great wind, rushing through the tops of the trees with a roaring noise, and waving the branches back and forth.

It frightened the Hares so much that they all started together, running as fast as they could to get out of the forest, which had been their home.

“What a sad state is ours,” they said, “never to eat in comfort, to sleep always in fear, to be startled by a shadow, and fly with beating heart at the rustling of the leaves. Better death, by far. Let us drown ourselves in yonder lake.”

But when they came to the lake, it happened that there were scores[52] of frogs sporting on the banks; who, when they heard the sound of footsteps, jumped into the water.

The timid Hares were startled by the splash; but, as they saw the frogs dive to the bottom of the lake, a wise old Hare said, “Stop a moment! let us consider. Here are creatures that are more timid than we—they are afraid even of us. See, they are drowning themselves for fear of us! It may not be so bad with us as we thought. Perhaps we have been foolish, as foolish as the frogs, who are alarmed when there is no danger. Let us make the best of our lot, and try to be brave in it.” So back they went again to the forest.

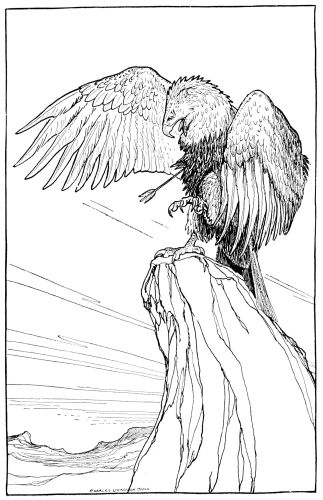

A MOST rapacious Eagle had his eyrie on a lofty rock. Sitting there, he could watch the movements of the animals he wished to make his prey, and, waiting his opportunity, seize them and bear them away.

The poor creatures had no protection from such a foe. But an archer saw him one day watching, from his place of concealment, the movements of an unsuspicious hare; and, taking aim, he wounded him mortally.

The Eagle gave one look at the Arrow that had entered his heart, and saw that its feathers had been furnished by himself, when descending to secure prey.

“Ah!” said the Eagle, “it is indeed a double grief that I should perish by an Arrow feathered from my own wing.”

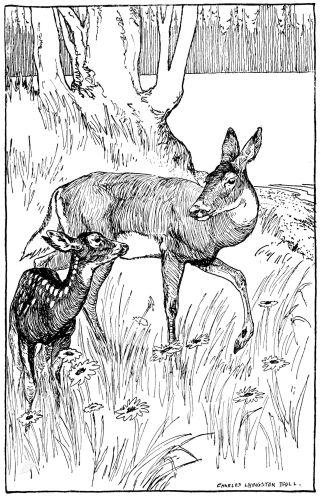

ONE day a mother Eagle came flying out of her nest to look for food for her babies. She circled round and round, far up in the air, looking down upon the earth with her keen eyes.

By and by she saw a little baby Fox, whose mother had left it alone while, like the Eagle, she went for food.

Down came the bird, whir went her wings, and away she soared again, with the little Fox clutched fast in her claws.

The poor mother Fox just at that moment came running home to her child, and saw it being carried away.

“O Eagle!” she cried, “leave me my one little baby. Remember your own children, and how you would feel if one of them should be taken away. Oh, bring back my poor cub!”

But the cruel Eagle, thinking that the Fox could never reach her, in her nest high in the pine tree, flew away with the little Fox, and left the poor mother to cry.

But the mother Fox did not stop to cry long. She ran to a fire that was burning in the field, caught up a blazing stick of wood, and ran with it in her mouth to the pine tree where the Eagle had her nest.

The Eagle saw her coming, and knew that the Fox would soon have[57] the tree on fire, and that all her young ones would be burned. So, to save her own brood, she begged the Fox to stop, and brought her back her little one, safe and sound.

A DRUM once boasted to a Vase of Sweet Herbs in this way: “Listen to me! My voice is loud and can be heard far off. I stir the hearts of men so that when they hear my bold roaring they march out bravely to battle.”

The Vase spoke no words, but gave out a fine, sweet perfume, which filled the air and seemed to say: “I cannot speak, and it is not well to be proud, but I am full of good things that[58] are hidden within me, and that gladly come forth to give cheer and comfort. People are drawn to me in their need, and they remember me afterward with gratitude. But you have nothing in you but noise, and you must be struck to make you give that out. I would not boast so much if I were you.”

ONCE there were two Frogs who were dear friends.

One lived in a deep pond in the woods, where the trees hung over the water, and where no one came to disturb him.

The other lived in a small pool. This was not a good place for a Frog, or any one else, to live in, for the country road passed through the[59] pool, and all the horses and wagons had to go that way, so that it was not quiet like the pond, and the horses made the water muddy and foul.

One day the Frog from the pond said to the other, “Do come and live with me; I have plenty of food and water, and nothing to disturb me; and it is so pleasant in my pond. Now here there is very little food, and not much water, and the road passes through your pool, so that you must always be afraid of passers-by.”

“Thank you,” said the other Frog; “you are very kind, but I am quite content here. There is water enough; those who pass never trouble me; and as to food, I had a good dinner day before yesterday. I am used to[60] this place, you know, and do not like change. But come and see me as often as you can.”

The next time the Frog from the pond came to visit his friend, he could not find him.

“Too late!” sang a Bird, who lived in a tree that overhung the pool.

“What do you mean?” said the Frog.

“Dead and gone!” said the Bird. “Run over by a wagon and killed, two days ago, and a big Hawk came and carried him off.”

“Alas! if he had only taken my advice, he might have been well and happy now,” said the Frog, as he turned sadly towards home; “but he would have his way, and I have lost my friend.”

IT ONCE happened that a hungry Lion woke to find a Mouse just under his paw. He caught the tiny creature, and was about to make a mouthful of him, when the little fellow looked up, and began to beg for his life.

In most piteous tones the Mouse said: “Do not eat me. I meant no harm coming so near you. If you would only spare my life now, O Lion, I would be sure to repay you!”

The Lion laughed scornfully at this, but it amused him so much that he lifted his paw and let his brave little prisoner go free.

It befell the great Lion, not long afterward, to be in as evil a case as[62] had been the helpless Mouse. And it came about that his life was to be saved by the keeping of the promise he had ridiculed.

He was caught by some hunters, who bound him with a strong rope, while they went away to find means for killing him.

Hearing his loud groans, the Mouse came promptly to his rescue, and gnawed the great rope till the royal captive could set himself free.

“You laughed,” the little Mouse said, “at the idea of my being able to be of service to you. You little thought I should repay you. But you see it has come to pass that you are as grateful to me as I was once to you. The weak have their place in the world as truly as the strong.”

A YOUNG Mouse, that had not seen much of the world, came home one day and said: “O mother! I have had such a fright! I saw a great creature strutting about on two legs. I wonder what it was! On his head was a red cap. His eyes were fierce and stared at me, and he had a sharp mouth.

“All at once he stretched his long neck, and opened his mouth so wide, and roared so loud, that I thought he was going to eat me up, and I ran home as fast as I could. I was sorry that I met him, for I had just seen a lovely animal, greater even than he, and would have made friends[64] with her. She had soft fur like ours, only it was gray and white. Her eyes were mild and sleepy, and she looked at me very gently and waved her long tail from side to side. I thought she wished to speak to me, and I would have gone near her, but that dreadful thing began to roar, and I ran away.”

“My dear child,” said the mother, “you did well to run away. The fierce thing you speak of would have done you no harm. It was a harmless Cock. But that soft, pretty thing was the Cat, and she would have eaten you up in a minute, for she is the worst enemy you have in the whole world. Appearances are not always to be trusted.”

ONCE upon a time a man came to a forest to ask the Trees if they would give him some wood to make a handle for his Ax.

The Trees thought this was very little to ask of them, and they gave him a good piece of hard wood. But as soon as the man had fitted the handle to his Ax, he went to work to chop down all the best Trees in the forest.

As they fell groaning and crashing to the ground, they said mournfully one to another, “Our kindness was misplaced. We suffer for our own foolishness.”

A JACKDAW sat chattering upon the back of a Sheep.

“Peace, I pray you, noisy bird,” said the Sheep. “You are wearing my life out If I were a dog, you would not think of serving me so.”

“That is true,” replied the Jackdaw; “you are right. I never meddle with the surly and revengeful; but I love to plague gentle, helpless creatures like you, that can not do me any harm in return.”

“I wonder if all cowards are not like the Jackdaw,” mused the Sheep, as it went on contentedly browsing on the hillside.

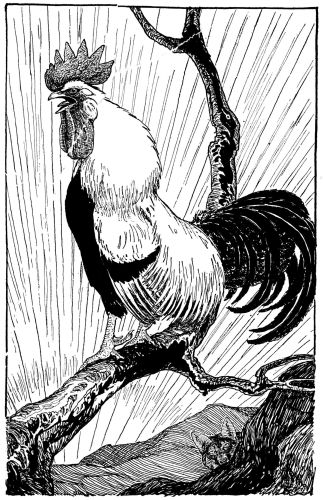

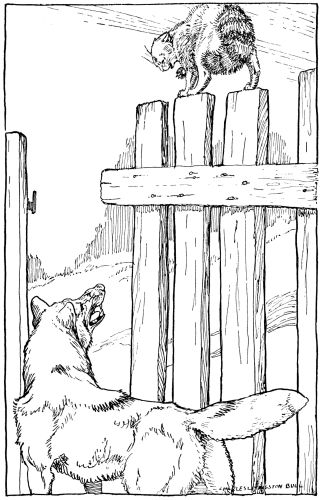

A HUNGRY Cat, who had tried in vain to find a Mouse for her supper, at last caught a young Cock.

“You are a noisy creature,” she said to him, “and have lived long enough. You disturb every one in the house by your loud crowing in the morning.”

“You are mistaken,” answered the Cock; “I disturb no one. I crow to wake the family. They would not know when to get up but for me.”

“Never mind,” said the Cat; “don’t trouble yourself to make excuses; I have had no breakfast and no dinner; I shall eat you for my supper.”

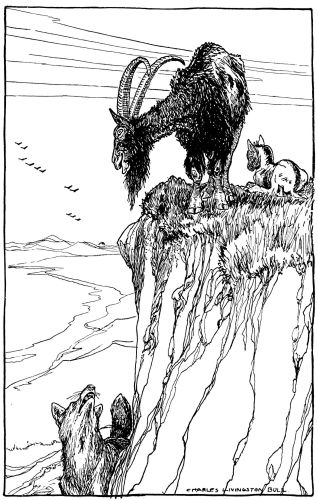

A WOLF saw a Goat feeding at the top of a steep precipice, where he could not reach her.

“My dear friend,” said the Wolf, “be careful! I am afraid you will fall and break your neck. Do come down to the meadow, where the grass is fresh and green.”

“Are you very hungry?” said the Goat. “And is it your dinner time? And would you like to eat me? I think I will not go down to the meadow to-day, thank you.”

And she capered contentedly about on the edge of the rock, as safe from falling as she was from the greedy Wolf with his false care for her.

A HEN who had no nest of her own found some eggs, and, in the kindness of her heart, thought she would take care of them, and keep them warm.

But they were the eggs of a viper; and by and by the little snakes began to come out of the shell.

A Swallow, who was passing, stopped to look at them.

“What a foolish creature you were, to hatch those eggs!” said the Swallow. “Don’t you know that as soon as the little snakes grow big enough, they will bite some one—probably you first of all?”

“Then,” said the Hen, as she stood on one leg and looked at the ugly little snakes, first with one eye and[71] then with the other, “you think I have done more harm than good?”

“I certainly do,” said the Swallow, as she flew away. “Good judgment is better than thoughtless kindness.”

ONE very stormy day a Poor Man came to a rich man’s house to beg.

“Away with you!” said the servants; “do not come here troubling us.”

Then said the Man, “Only let me come in and dry my clothes at your fire.” This, the servants thought, would not cost them anything; so they let him come in.

The Poor Man then asked the cook to let him have a pan, so that he could make some stone broth.

“Stone broth!” said the cook. “I should like to see how you can make broth out of a stone”; so she gave him a pan. The Man filled it with water from the pump, and then put into it a stone from the road. “But you must have some salt,” said the cook.

“Do you think so?” courteously replied the stranger. She gave him the salt, and before long she added some peas, some mint, and thyme. At last she brought him all the scraps of meat she could find, so that the Poor Man’s broth made him a good dinner.

“You see,” said the Man, “that if you only try long enough, and are cheerful, making the best of what you have, you may at last get what you want.”

A MULE, hearing some Grasshoppers chirping, was much pleased with the sound, and wished that he could make such sweet music.

“What sort of food do you eat,” said he to the Grasshoppers, “that your voices are so charming?”

The Grasshoppers replied, “We live upon dew.”

The Mule then decided that he too would live upon dew. And in a short time he died of hunger, just from trying to do what he saw others doing, without first learning their reason for it.

A GNAT, who had flown about until he was tired, sat down to rest on the horn of a Bull.

After sitting there a long time, he thought he would go home. So he made a loud buzzing noise and said to the Bull, “Would you like to have me stay longer, or shall I go now?”

“Just as you please,” said the Bull. “I did not know when you came, and I am sure I shall not miss you when you go away.”

“What an amount of self-importance for such a tiny creature,” thought the sleepy Bull.

A HUNGRY Fox surprised a Crab, who had left the sea and was lying upon the beach.

“What good luck, to find a breakfast so easily,” said the Fox, as he pounced upon him.

“Well,” said the Crab, when he found that he was to be eaten, “this comes of going where I have no business; I should have stayed in the water, where I belonged.”

A DONKEY was one day walking through a pond, with a load of wood on his back, when his foot slipped and he fell.

“Help, help!” cried the poor Donkey,[76] as he struggled and kicked in the water. But his load was so heavy that he could not rise, and he groaned aloud.

The Frogs heard his groans but showed no pity. “What a foolish fellow,” said they, “to make such a fuss about a little fall into the water. What would you say if you had to live here always, as we do?”

A WOLF, prowling about to find something for supper, heard a Child crying in a house. Listening, he heard the Nurse say, “Stop crying this minute, or I will throw you out of doors to the Wolf.”

The Wolf sat down near the door, thinking within himself, “I shall soon have a good supper.”

The Baby cried and cried, till at last it went to sleep; and then the Wolf heard the Nurse say: “There, that’s a good Baby. If the naughty old Wolf comes for my darling, we’ll beat him, so we will.”

The Wolf trotted sadly home. On his way he met the Fox.

“What makes you look so sour and so forlorn, my friend?” said the Fox.

“Don’t speak to me!” growled the Wolf. “I have lost my supper just because I believed what a Nurse said to a Baby.”

A CAT, hearing that some Birds who lived in a martin box near by were ill, put on his spectacles and his overcoat, and made himself look as much as possible like[78] a doctor, and went and knocked at their door.

“I hear that you are all sick,” said he, “and have come to call on you. Let me in, and I will give you some medicine and cure you.”

“No, thank you,” said the Birds, who saw his whiskers and knew he was their enemy the Cat; “we are well enough—much better than if we should open our door and let you in.”

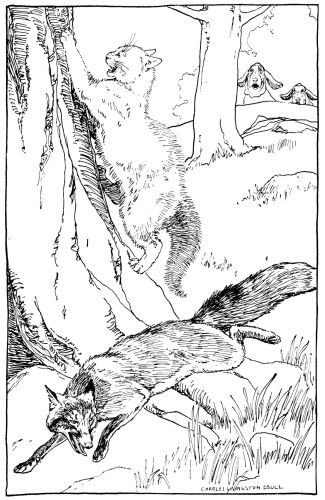

A FOX went prowling about a farmyard, not seeing a trap which the farmer had hidden there to catch him. Snap! went the trap, and the Fox found himself held fast by a strong cord. He howled[79] horribly and was almost beside himself with rage.

A Cock, hearing the noise, flew to the top of the fence. Looking over, he saw the Fox and was terribly frightened—not daring to go near him, even when he found that his old enemy could not move. But he could not refrain from giving an exulting crow.

The Fox, looking up, said: “Dear Mr. Cock, you see how unlucky I have been, and all because I came here to inquire after your health. Do please help me to break this string, or at least do not let any one know that I am caught until I have time to gnaw it with my teeth.”

The Cock said nothing, but went as fast as he could and told his master all about it. So the crafty Fox was served as the Cock thought he deserved to be.

A CAVALRY officer took the greatest of pains with his charger. As long as the war lasted, the Horse was looked upon as a companion and fellow helper. He was carefully groomed every day, and fed with hay and oats.

But when the war was over, the allowance of grain and hay ceased, and the Horse was fed with chaff and whatever he might find by the wayside. He was made a drudge too, and was often forced to carry loads much too heavy for his strength.

When, in course of time, war was again proclaimed, the soldier brought his military trappings and put them on his charger; and, after having arrayed his own person with his heavy[81] coat of mail, he mounted to ride to battle.

But the Horse, no longer equal to the burden, fell down straightway under the weight.

“You must go to the war on foot,” he said to his master, “for you have transformed me from a horse into an ass.”

He who slights his friends when he does not need their best offices must not expect them to serve him when he needs them again.

THE Fox and the Stork were on what seemed to be friendly terms. The Fox invited the Stork to a dinner for which nothing was provided but a soup, which was served on a wide, shallow dish.

The Fox presided at the feast with great dignity, and, as if to set his friend an example, proceeded to lap the soup. This he could do with the greatest ease; but the Stork, who could only dip the tip of his bill in the dish and get the tempting odor, fared badly. He praised the dinner, but soon took leave, saying to his friend that he should do himself the honor to return the compliment.

This he did in a few days, but ordered that nothing be brought to the table but some minced meat in a glass jar, the neck of which was so narrow and deep that, though he himself could eat very well, the Fox could not reach it, and so could only lick the brim for the bits that clung to it.

Reynard could not conceal his vexation, but was obliged to own that he had been rightly used.

They who practice cunning must expect to suffer by it, and he laughs best who laughs last.

A DOG and a Cock, who were neighbors, once made a little journey together.

When night came on, the Cock flew up into the branches of a tree to sleep; and the Dog found a hollow in the trunk, into which he could creep and lie down. They slept well, and as soon as the morning dawned, the Cock, as usual, began to crow.

A Fox, hearing the sound and thinking he was sure of a good breakfast, came and stood under the branches. “Good morning,” said he to the Cock.

“How glad I am to make the acquaintance of the owner of such a voice! Will you not come down here where we can chat a little?”

“Thank you, I cannot just yet,” replied the Cock; “but if you would like to come up here, go around the tree trunk, and wake my servant. He will open the door and let you in.”

The Fox did as he was requested; but as he approached the tree, the Dog sprang upon him, and tore him to pieces.

“Two can play at the same game,” said the Cock, as he looked down upon the scene.

A FLY alighted one night upon a pot of honey, and finding it very much to his taste, began to eat it along the edges.

Little by little, however, he had soon crept away from the edge and into the jar, until at last he found himself stuck fast. His legs and wings had become so smeared with the honey that he could not use them.

Just then a Moth flew by, and seeing him struggling there, said: “Oh, you foolish Fly! Were you so greedy as to be caught like that? Your appetite was too much for you.”

The poor Fly had nothing to say in reply. What the Moth said was true. But by and by, when evening came, he saw the Moth flying round a lighted[87] candle in the giddiest way, and each time a little closer to the flame, until at last he flew straight into it and was burned.

“What!” said the Fly, “are you foolish, too? You found fault with me for being too fond of honey; yet all your wisdom did not keep you from playing with fire.” It is sometimes easier to see the foolishness of others than to detect our own.

A LITTLE Boy once went in bathing where the water was too deep for him. When he found himself sinking, he cried out to a Man who was passing by, to come and help him.

“Can’t you swim?” asked the Man.

“No,” replied the Boy, “I don’t know how.”

“How foolish you were, then,” said the Man, “to go into deep water! Didn’t you know better?”

“Oh, good sir, please help me now, or I shall drown!” cried the Boy. “You can scold me when I am safe on shore again.”

A HARE one day made himself merry over the slow pace of the Tortoise, vainly boasting of his own great speed in running.

The Tortoise took the laughing and boasting in good part. “Let us try a race,” she said; “I will run with you five miles for five dollars, and the Fox out yonder shall be the judge.”

The Hare agreed, a course was arranged, and away they started together. True to his boasting the Hare was out of sight in a moment.

The Tortoise never for a moment stopped, but jogged along with a slow, steady pace, straight to the end of the course. Full of sport, the Hare first outran the Tortoise, then fell behind. Having come midway to the goal, he began to nibble at the young herbage, and to amuse himself in many ways. After a while, the day being warm, he lay down for a nap, saying: “She is behind me now. If she should go by, I can easily enough catch up.”

When the Hare awoke, the Tortoise was not in sight; and running as fast as he could, he found her comfortably dozing at their goal.

Those who are very quick are apt to be too sure. Slow and steady often wins the race.

AS AN Arab sat in his tent one cold night, he saw the curtain gently lifted, and the face of his Camel looking in.

“What is it?” he asked kindly.

“It is cold, master,” said the Camel; “suffer me, I pray thee, to hold my head within the tent.”

“By all means,” replied the hospitable Arab; and the Camel stood with his head inside the tent.

“Might I also warm my neck a little?” he entreated after a moment.

The Arab readily consented, and the Camel’s neck was thrust within the tent.

He stood, moving his head from side to side uneasily, and presently said: “It is awkward standing thus. It would take but little more room if I were to place my forelegs inside the tent.”

“You may place your forelegs within the tent,” said the Arab. And now he had to move a little to make room, for the tent was small.

The Camel spoke again: “I keep the tent open by standing thus, and make it cold for us both. May I not stand wholly within?”

“Yes,” said the Arab, whose compassion included his beast as well as himself; “come in wholly if you wish.” But now the tent proved to be too small to hold both.

“I think, after all,” said the Camel, as he crowded himself in, “that there[92] will not be room here for us both. You are the smaller; it will be best for you to stand outside. There will be room then for me.” So he pushed a little, and the Arab with all haste went outside the tent.

A FOX was once caught in a trap by his tail. He succeeded in getting away, but was forced to leave his “brush” behind. He soon realized that his life would be a burden, from the shame and ridicule to which his tailless condition would expose him.

“I must not own that it is a misfortune not to have a bushy tail,” he said to himself.

So he set about to induce all the other Foxes to part with theirs. At the next assembly he boldly made a speech, in which he set forth the advantages of his present state.

“The tail,” he said, “is no real part of our persons, and besides being very ugly to see, it exposes us to danger from the dogs. I have never moved about with such ease as since I gave up my own.”

When he had ended his speech, a sly old Fox arose, and giving his own brush a graceful wave, said, with the kind of sneer which all Foxes know so well how to give, that if he had lost by accident his own tail, he should, without doubt, agree with his friend; but that, as the brush was a fox’s chief ornament and distinction, until such a mishap should occur as had befallen[94] his friend, he should retain his own and should advise the others to do the same. And the vote to retain the tails was given by a wave of the brush. Yet many fashions have been set by Foxes who have met with some such accident.

SOME Boys, playing near a pond, saw a number of Frogs sporting in the water.

“Let us see if we can hit them; it is great fun to make them dive,” said one; and they all began to pelt them with stones.

At last, after several Frogs had been hit, one of them put his head up out of the water, and said: “Pray stop, Boys. Throwing stones at us may be[95] great sport for you, but it is death to us. We have done you no harm, and alas! you have already killed or wounded three of our family.”

A WISE Swallow, seeing a man sow seed in a field, went behind him and picked up one of the seeds to see what it was.

She found that it was flax. “When this flax has grown,” she said to herself, “the man will make it into linen thread and use it to make nets for catching us Birds.”

So she went to all the Birds and told them what she had discovered, begging them to come and help her eat up the flaxseed before it should[96] sprout. “This field,” she said, “is as much ours as it is his. And while one of us can do but little, all working together can quickly remove our danger.”

But the Birds would not listen to her. Not one of them could she persuade to help her pick up the seeds which the farmer had sown.

By and by the flax sprang up, and the Swallow tried again to persuade the Birds to pull the young flax before it grew large. But they all made fun of her caution and let the flax keep growing.

When she saw how heedless all the Birds were, the Swallow would have nothing more to do with them, but left the woods where they lived and came among men, building her nests in barns and along the eaves of houses.

ONE wintry day a Farmer found a Snake lying on the frozen ground, quite stiff and nearly dead with cold.

In a fit of compassion the Farmer brought him carefully to his house, and laid him near the fire. But as soon as the Snake began to feel the pleasant warmth, he raised his head and tried to bite his kind friend.

“Oh!” said the Farmer, “is that the way you repay me for my trouble? You are a venomous creature, I am sure, and the sooner you die the better.” And he killed him with one blow of his stick.

A RAVEN saw a snowy Swan floating on the lake.

“No wonder the Swan is so white,” thought the Raven, as he looked at his own black feathers. “I dare say I should be, if I were all the time washing myself. I believe I’ll try it.”

Then he left his home, where he always found plenty to eat, and came and lived by the lake. He washed himself from morning till night, but he grew no whiter; and, as he found nothing to eat, he came near dying for want of food.

THERE was once a big battle between the Birds and the Beasts. Hesitating as to which to join, the Bat kept away from the contest and looked on till he thought the Beasts would win the day.

Then he went among them. When they saw him, they said, “But you are a Bird.”

“No, indeed,” said the Bat. “Look at my body covered with hair and at my mouth with its sharp teeth.”

After a while, as the fight went on, the Birds began to have the best of it, and then away flew the Bat to their side. “What Beast comes here?” said the Birds.

“I am not a Beast,” said the Bat;[100] “I am a Bird. Look at my wings. This is my battle as truly as it is yours.”

But the Birds would have nothing to do with him. And to this day the Bat seems ashamed to show himself in the daytime but hides in lonely places, away from all other creatures, and only flits about noiselessly in the dark, when both Birds and Beasts are asleep.

A MAN and his Son were once driving their Donkey along a country road, to sell him at the fair. They soon passed some girls, who were drawing water at a well.

“Look,” said one of the girls; “see those silly people trudging along in[101] the dust, while their Donkey walks at his ease.”

The Man heard what they said, and put his boy on the Donkey’s back. They had not gone far before they came to some old men.

“See here, now,” said one of them to the others, “this shows that what I said is true. Nowadays the young take no care of the old. See this boy riding while his poor old father has to walk by his side.”

Hearing this, the Man told his Son to get down, and he mounted the Donkey himself. In a little while they met three women with children in their arms.

“For shame!” said the women. “How can you let that poor boy walk when he looks so tired, and you ride like a king?”

The Man then took the boy up behind him on the saddle, and they rode on to the town. Just before they got there, some young men stopped them and said:

“Is that Donkey yours?”

“Yes,” said the Man.

“One would not think so,” said they, “by the way you load him. You look more fit to carry him than he to carry you.”

So the Man and the boy got off, tied the Donkey’s legs with a rope, fastened him to a pole, and, each taking one end of the pole, carried him along, while every one they met laughed outright.

By and by they came to a bridge. Then the Donkey began to kick, and breaking the rope, fell into the water and was drowned.

The old Man and his Son made their way home as best they could, thinking to themselves, “When we try to please everybody, we please nobody.”

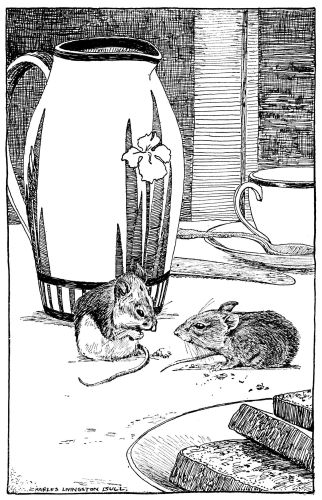

A MOUSE from the city went on a visit to a friend in the country.

The Country Mouse, with many apologies, brought out the best that he had and waited on his guest.

There was plenty of oatmeal and peas, a nice scrap of bacon, and even a paring of cheese for dessert. While the guest was dining, the Country Mouse, out of politeness, would eat none of these dainties, for fear there should not be enough for both, but[104] nibbled a piece of straw to keep his guest company.

When the dinner was over, the City Mouse said: “Old friend, I thank you for your courtesy, but I must have a plain talk with you. I do not see how you can bear to live so poor a life in this little hole. Why not come with me to the city, where you will have all sorts of good things to eat and a gay time? You are wasting your life. When you have once seen the city you will never be willing to return to this quiet place.”

After being urged a long time, the

Country Mouse at last agreed to go to

the city that very night. So they

started off together, and about midnight

came to the great house where the City

Mouse lived. In the dining room was

spread a rich feast; and the City Mouse,[105]

[106]

with many airs and graces, ran about

the table, and, picking out the nicest

bits, waited upon his country friend,

who, amazed at the good things, ate

to his heart’s content.

All at once the doors of the dining room were flung open, and in came a crowd of people, followed by a big dog, who barked loudly and ran about the room.

The Mice rushed for the hole, to escape, and the little field Mouse almost died of fright. As soon as he was able to speak, he said:

“Well! if this is city life, I have seen enough of it. Stay in this fine place if you like. I shall be only too glad to get home to my quiet, safer, country house and my plain oatmeal and peas.”

“COME, my dears,” said a Cock to his hens one morning; “I am hungry, and so are you. Let us go out. I will scratch up some nice worms and beetles for our breakfast.”

The hens stood waiting while he scratched.

But the first thing that he found was neither a beetle nor a worm but a precious stone. It may have been a ruby or an emerald.

“Dear me!” said the Cock; “what is this? a Jewel! How glad anybody else might be to have found such a prize; but I have no need of it. I would rather have a few kernels of good corn than all the Jewels in the world.”

“And so would we,” said the hens. “Nothing can do us good if it is not a thing that we ourselves want.”

ONCE there was a beautiful Hound. He had long, silky ears and a smooth, bright skin; and he was not only beautiful but strong and swift, and a faithful servant. Whenever his master went hunting, the Hound went with him and chased the deer. After many years the Hound grew old and feeble, but still he followed his master, with the other dogs.

One day a stag had been chased till it was almost tired out, and the old Hound came up with it and seized it; but his teeth were old and broken and[109] could not hold fast, so that the stag gave a sudden bound and got away. Just then the master rode up, and seeing what had happened, was very angry. He took his whip to strike his faithful old Hound.

“Hold! hold! O dear Master,” said he, “do not strike me. I meant to do well. It is not my fault that I am old. Remember what I have been, if you do not like me as I am now.”

JUPITER having determined, it is said, to appoint a sovereign over the birds, proclamation was made that on a certain day the candidates should present themselves before him, and he would choose the most beautiful to be king.

The Jackdaw, knowing his own ugliness, yet wishing to rule over the birds, searched through woods and fields for feathers which had fallen from the wings of his companions, and stuck them all over his body.

When the appointed day arrived, and the birds had assembled, the Jackdaw made his appearance in his many-feathered finery, and Jupiter proposed to make him king.

Upon seeing this, the other birds were indignant, and each plucking from the Jackdaw his own kind of feathers, they left the proposed king a plain Jackdaw with no claim to superior beauty.

THERE was once a man who had a Donkey and a little pet Dog. The Donkey worked all day in the fields and slept in the barn at night.

But the Lap Dog frisked about and played, jumping in his master’s lap whenever he pleased, feeding from his hand, and sleeping by his bed at night.

The Donkey grumbled a great deal at this. “How hard I work!” said he, “and I never get any pay but blows and hard words. Why should I not be petted like that wretched little Dog? It may be partly my own fault. Perhaps if I played with my master as he does, I too might be treated like him.”

So the Donkey pushed his way into the house, and jumped up on his [112]master’s knee, putting his forefeet on his shoulders and giving a loud bray.

The master, almost deafened by the noise and in danger from the great clumsy creature, called out, “Help! help!” and the servants, running in, drove the Donkey out of doors with sticks and stones.

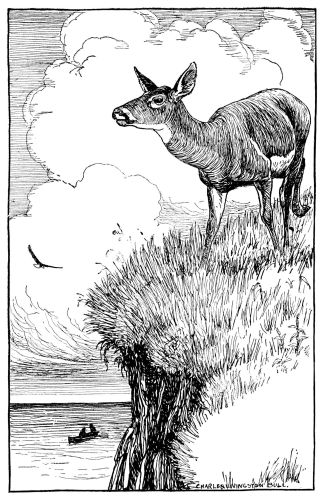

A DOE, blind in one eye, used to graze as near as she could to the edge of a cliff, so that she might keep her blind eye to the water, while with the other she kept watch against the approach of hunters or hounds on the shore.

Some boatmen sailing by saw her

standing thus on the edge of a cliff,

and finding that she did not perceive[113]

[114]

their approach, they came very close,

and taking aim, shot her.

Finding herself wounded, she said, “O unhappy creature that I am, to take such care as I did against the dangers of the land, and then, after all, to find this seashore, to which I had come for safety, so much more perilous!”

WHEN man first beheld the Camel, he was so awed by his vast size that he fled away from him in terror.

But after a time, perceiving the meekness and gentleness of the animal’s temper, he summoned courage to approach him. The Camel so readily obeyed the commands that were given him, and seemed so wanting in spirit,[115] that at last the man put a bridle in his mouth and set a child to guide him.

Since then Camels are valued for the service they render.

A WOLF met a Dog, and seeing that he looked fat and sleek, said to him, “How does it happen, my friend, that you are so plump, while I, although I run after game day and night, am half starved?”

“Why,” said the Dog, “I do not have to run after my food. I only guard the house at night, and all the family pet me and feed me with scraps from their own plates. Come and live with me, and you shall be as well off as I am.”

“That I should like,” said the Wolf. “I will at least go with you and try the life.”

As they trotted along the road together, the Wolf saw a mark on the Dog’s neck, and asked him what it was.

“Oh, that is nothing,” said the Dog; “only a little mark made by the fretting of my chain.”

“Do you wear a chain?” asked the Wolf; “and do you mean to say that you are tied up?”

“Why, yes,” said the Dog; “they tie me in the daytime, but at night I can go where I please. It is a bit annoying at first, but one soon gets used to it.”

“Good-by,” said the Wolf; “that is enough for me. Though I may not be fat, I will at least be free.”

ON THE bank of a river grew a tall Oak Tree. It stood with its roots firm in the ground, and its head high in the air, and said to itself: “How strong I am! Nothing shall make me bow. I look down upon all the other trees.”

But one day there was a storm. The terrible unseen wind came and struck the proud Oak. Crash! went the trunk, down came all the beautiful branches, and the Tree fell into the river. As the water carried it away, it passed a Reed that grew on the bank. The little Reed stood up tall and slender, and looked at the poor broken Tree.

“O Reed,” said the Tree, “how did it happen that you were not broken[118] down and spoiled when the wind came? You are so little and weak, and I was so strong and proud.”

“Ah, poor Tree!” said the Reed, “that is just the reason that the wind did not hurt me. I bent low until it had gone by, but you stood stiff and tried to stop it on its way. No one can stop the wind. It must go where it is sent, but it will not hurt those who are not proud and stubborn.”

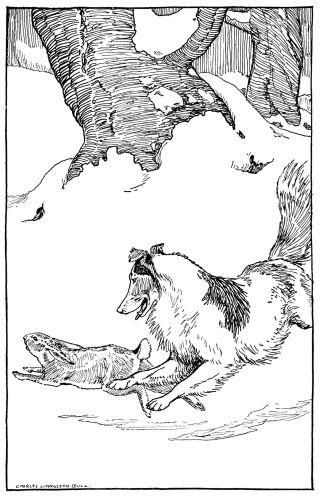

A DOG once gave chase to a Hare. Having not long since made a good meal, the Dog was not hungry, and so was not in haste to end the sport by killing the Hare.

At times he would snap at his prey,

and at times play with him and lick[119]

[120]

him with his tongue, till at last the

bewildered Hare cried:

“Pray tell me, are you an enemy or a friend? If a friend, why do you bite me so? and if an enemy, why do you caress me?”

No one can trust a person who is neither the one thing nor the other.

THE Pigeons, terrified by the frequent appearance of a Kite, asked the Hawk to help them.

“You are the only bird of our acquaintance,” they said, “that can protect us from our enemy. If you will take care of us, we shall feel safe.”

The Hawk at once consented, and took up his abode in the dovecote. But when the Pigeons had let him[121] come in, they found that he slew more of them in a single day than the Kite could possibly pounce upon in a whole year.

The oldest, wisest pigeon among them said: “When we are in trouble, we must not forget that there are other dangers than the ones we are suffering from. There is a proverb among men that tells them to avoid a remedy that is worse than the disease.”

A WAR Horse, ready for battle, with his splendid saddle and jingling bridle, came galloping swiftly along the highroad, his hoofs sounding like thunder on the hard ground.

A poor old Mule, with a heavy load[122] on his back, was going slowly down the same road.

“Out of my way,” said the War Horse, “or I will trample you in the dust!”

The poor Mule made room for him as fast as he could, and the Horse went proudly on his way.

Not long after this the Horse was shot in the eye; and, as he was no longer fit for the army, his fine saddle and bridle were taken off, and he was sold to a farmer, who made him drag heavy loads.

Since he had not been trained to the work, it came hard to him, and he complained bitterly.

The Mule, meeting him soon after, knew him and called out: “Aha! is it you? I thought pride would have a fall some day.”

THE North Wind and the Sun once fell into a dispute as to which was the stronger of the two. They related their most famous exploits, and each ended as he began, by thinking he had the greater power.

Just then a traveler came in sight, and they agreed to test the matter by trying to see which of them could soonest make the traveler remove his cloak.

The boastful North Wind was the first to try, the Sun meanwhile watching behind a gray cloud. He blew a furious blast and nearly tore the cloak from its fastenings; but the Man only held his cloak more closely, and old Boreas spent his strength in vain.

Mortified by his failure to do so simple a thing, the Wind withdrew at[124] last in despair. “I don’t believe you can do it, either,” he said.

Then out came the kindly Sun in all his splendor, dispelling the clouds that had gathered and sending his warmest rays down upon the traveler’s head.

The Man looked up gratefully, but, growing faint with sudden heat, he quickly flung aside his cloak, and hastened for comfort to the nearest shade.

Persuasion is often better than force.

TWO men were traveling together, when a Bear suddenly crossed their path.

One of the men climbed quickly into a tree, and tried to conceal himself in its branches.

Seeing that he must be attacked, the other one fell flat upon the ground; and when the Bear came up, felt him with his snout, and smelt him all over, the man held his breath, feigning death.

The Bear soon left him, for it is said a Bear will not touch a dead body.

When the Bear had gone, the man in the tree came down to join his companion, and, as a pleasant joke, inquired, “What was it that the Bear whispered in your ear when he bent over you for so long?”

His friend replied very gravely: “He gave me this bit of advice, ‘Never travel with a friend who deserts you at the approach of danger.’”

TWO Goats started at the same moment, from opposite ends, to cross a rude bridge that was only wide enough for one to cross at a time.

Meeting at the middle of the bridge, neither would yield to the other. They locked horns and fought for the right of way, until both fell into the torrent below and were drowned.

A BULL was once striving with all his might to squeeze himself through a narrow passage which led to his stall.

“I will go through,” said a young Calf, “and show you the way. I have done it many a time.”

“Save yourself the trouble,” said the Bull; “I knew the way before you were born.”