“Follow the colors of the Nineteenth.”—General Webb.

REMINISCENCES

OF THE

NINETEENTH

MASSACHUSETTS

REGIMENT

By Capt. JOHN G. B. ADAMS.

BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER

PRINTING COMPANY, 18 POST

OFFICE SQUARE, 1899....

Copyright, 1899,

By John G. B. Adams.

PREFACE.

——————

For thirty-four years I have waited patiently for some one to write a history of the 19th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, but fearing that it may never be accomplished, I have concluded to send out this story. I do not dignify it by calling it a history. It is simply a soldier’s story, told by one of the “boys.” Most of it is written from memory. The account of prison life is taken from an imperfect diary, kept by the writer while a prisoner of war.

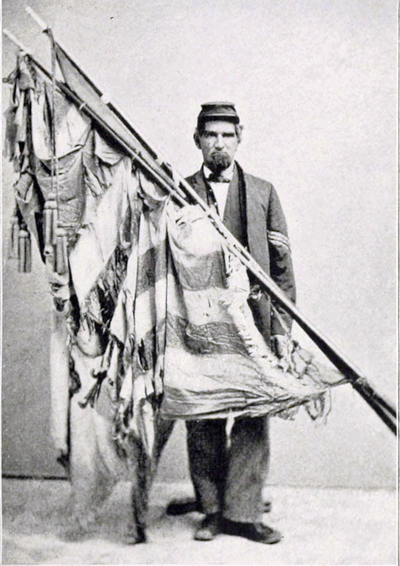

I sincerely hope the publication of this volume will inspire other comrades, and that from the memories thus evoked some one may gather further material whereby the deeds of the men who so bravely followed the flags of the State and Nation for four long, weary years may be preserved.

JOHN G. B. ADAMS.

CONTENTS.

——————

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Call to Arms, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Our Journey South, | 7 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Battles of Ball’s Bluff and Edward’s Ferry.—Experiences at Darnestown and Rockville, | 12 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Our First Campaign.—Battle of Fair Oaks, | 23 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Battles at Peach Orchard, Glendale and Malvern Hill, | 32 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Battles of Fairfax Court House, Flint Hill and Antietam, | 41 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Battles of Fredericksburg and Marye’s Heights, | 49 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Battles of Chancellorsville, Thoroughfare Gap and Gettysburg.—Wounded at Gettysburg and ordered Home, | 63 |

| CHAPTER IX.[viii] | |

| Regiment ordered Home.—Receptions.—My First Call upon Governor Andrew.—Return to the Front, | 78 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Battles of the Wilderness, Todd’s Tavern and Laurel Hill.—Engagement at the Bloody Angle, | 87 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Battles at Totopotomoy Creek and Cold Harbor, | 95 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Experiences in Rebel Prisons.—Libby, Macon, | 104 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Macon (continued), Charleston.—Under Fire of Our Batteries on Morris Island, | 116 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Columbia.—Presidential Election, | 132 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Escape, | 138 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Capture and Return to Columbia, | 161 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Exchange and Return North, | 174 |

Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment.

CHAPTER I.

THE CALL TO ARMS.

At the breaking out of the war I was a resident of the quiet but patriotic town of Groveland. Sumter had been fired upon and all was excitement. I could not work, and on the 18th of April, 1861, walked to Haverhill with my elder brother and Mark Kimball. We went to the armory of the Hale Guards, who were making active preparations to march, and I returned home that night resolved to go with them if possible. The next day we walked to Haverhill again, and I at once interviewed Captain Messer, but was informed that the company was more than full, so I could not go with it.

I had said nothing to my brother or Mark of my intention, but as we were walking home I found that we all had the same desire,—to enlist at once. We talked the matter over and concluded that as Company A of the 1st Battalion of Rifles, an old militia company located in West Newbury, and then under arms, would soon be ordered away, we would join it. That night we walked to West Newbury (five miles), found the company at the armory in the town hall and enrolled our names. Company A was one of three that composed the 1st Battalion of Rifles, commanded by Maj. Ben. Perley Poore. They had been organized several[2] years and were known as “Poore’s Savages.” They were armed with Winsor rifles and sabre bayonets, the rifle and bayonet weighing about fifteen pounds. The uniform was dark green, trimmed with light green, and as I donned it for the first time it was hard to tell which was the greener, the soldier or the uniform. We had a peculiar drill. Most of it, as I can remember, consisted of running around the town hall in single file, giving an Indian war-whoop and firing into the corner of the hall as we ran.

I was a soldier now. I did not walk the streets as I had done, but marched, always turning “a square corner.” People grasped me by the hand and congratulated me on my courage. (I did not see where the courage came in.) The Sons of Temperance, of which my brother Isaac and myself were members, presented us at a public meeting with two suits of underclothes and havelocks, housewives, testaments, etc., so that before we received our army outfit we had enough to load a mule.

We waited for orders to march, but none came, and from being heroes we began to be looked upon with disgust, and we were the most disgusted of all. As we would meet friends on the street they would say, “Is it not about time to have another public meeting to bid you fellows good-by?” or, “You will want some more shirts before you leave.” So mortified did we become that, instead of marching down through the village to drill, we sneaked away through a back street.

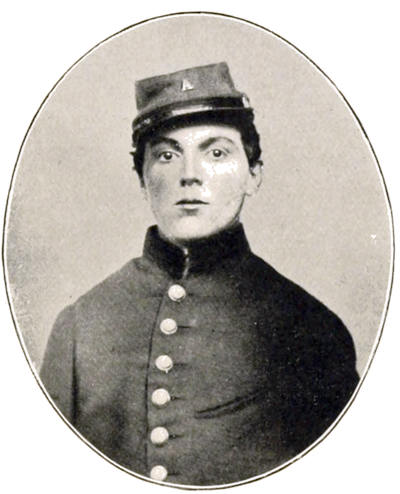

PRIVATE “JOHNNIE” ADAMS.

April, 1861.

The company began to get demoralized. Men were leaving every day, going to other States or to regiments that had been ordered to the front. At last we rebelled, and sent our officers to the Governor with a vote passed by the company, that unless we were ordered into camp at once we would disband. After a few days we were furnished with a large tent for the men, a wall tent for the officers and a supply of rations. Our camp was located on the land of one of our members, Private Sylvester, and was named “Camp Sylvester.” We were without arms except three guns for guard duty, as our old Winsors had been turned in. Company A was officered as follows: Captain, Moses P. Stanwood; First Lieutenant, J. Warren Brown; Second Lieutenant, Benjamin Wilson; Third Lieutenant, Isaac H. Boyd; Fourth Lieutenant, Jones Frankle. The third and fourth lieutenants were soon discharged, as army regulations only provided for two. Lieutenant Boyd went into the ranks, Lieutenant Frankle was made major of the 17th Massachusetts.

Our discipline in Camp Sylvester was not as strict as it was later in the war. We mounted one guard. After we had been once around we concluded that the lieutenants ought to stand their share, so we put them on. One night we caught a calf and after the officers were asleep we turned him into their tent. We did many things that later would have sent us to the guard-house.

About the second week in July we were ordered to Lynnfield to join the 19th regiment. We were the second company in camp, Company C of Rowley arriving about two hours before us. Our tents were a peculiar pattern, neither wall nor A, but between the two, having accommodations for ten men, and each tent had three windows or ventilators. For a time we were under the command of Col. Lyman Dyke, who also commanded the 17th regiment, located near us.

At Lynnfield I was promoted to sixth corporal, and my troubles began. I was one day detailed for guard, the 17th[4] and 19th regiments doing guard duty together. When I posted my relief I had one more man than posts, so I made a new post. The officer of the day asked me what I did with the supernumerary. I said that I put him on in rear of the ice-house. He desired to know who gave me authority to create new posts, and I replied that I supposed I was to use up my men. As soon as the guards were posted they began to call “Corporal of the Guard.” When I went to them they wanted a drink of water. I asked the officer of the day if it was my duty to carry water to them. He said it was. So I toted the water pail the two hours my relief was on. At night the men went to their quarters. I found where they slept, and made arrangements to call them. I would put my head into a tent and call, “Third relief!” and instead of the men coming out, a boot with an oath came at me. As I could not get enough for a relief I turned out the drummer and had him beat the long roll. This brought out the officer of the day but very few of the men, as they did not know what it meant any more than I did. Collecting what I could we started to relieve the guard, but I soon found that I had more than men enough, as at nearly every post we found the musket stuck into the ground and the man missing. When relieved in the morning I was disgusted with being an officer, and longed for the freedom of a private.

Recruits were fast arriving. Company A went into camp with about sixty men, and every day some new man was voted in, as we had not given up the old militia method of electing our members. Skeleton companies were arriving, consisting of an officer and a few men, who were given a letter and assigned a place in line. Among the first to arrive was Captain Mahoney. His company was given the[5] letter E. Captain Mahoney was an energetic officer and anxious to drill his men. Long before daybreak, with his first sergeant, McNamara, he would turn out the recruits, and as we lay in our tents we could hear him calling, “Left! Left! McNamara, tread on that man’s heels!”

It was not very long before we had the required number of companies, the last to arrive being the Boston Tiger Fire Zouaves, and my story from this point will include the regiment as well as Company A.

One day in August we saw a military man looking over the camp. We soon learned that it was Colonel Hincks, who had just returned from three months’ service with the 8th Massachusetts. In a few days he was assigned to the command of the 19th and from that moment what had been a uniformed mob became a regiment of soldiers. With him came Lieutenant-Colonel Devereaux, who had been captain of the Salem Zouaves, and soon after Maj. Henry J. How. One of the Salem Zouaves was assigned to each company as a drill-master, and we soon saw that our three months’ drilling had been worse than useless, as we had to begin over again, and it “was hard to teach old dogs new tricks;” but the Zouaves won our respect and every man was anxious to do his best. Very soon a change took place in the line officers,—a Zouave was commissioned in nearly every company. Company A retained Captain Stanwood, but lost both lieutenants, C. M. Merritt, who had been an officer in the 8th, being made first lieutenant, and Isaac H. Boyd, who had enlisted as a private, second lieutenant.

On August 27 we were ordered to strike tents and prepare to march. That night, for the first time, we slept on the ground, with only the blue sky for shelter. The next day[6] we took cars for Boston. Our knapsacks were slung for the first time and loaded with everything that it was possible to stow away.

Being anxious that my “best girl” should see me in the full garb of a warrior, I arrayed myself in heavy marching order and went to an ambrotype saloon to have my picture taken. I have seen that picture since the war. In an ambrotype everything is reversed, so my musket is at my left shoulder, haversack and canteen on the wrong side,—in fact, I was wrong end to in every respect.

Our wagon train was larger than that of an army corps in active service. Each company had a four-horse wagon, headquarters two, quartermaster four; I think there were twenty besides the ambulances. We arrived in Boston in the afternoon. It was the second time I had been in the city, and as we halted on the Common, and no friend came to bid me good-by, the first feeling of homesickness came over me, and I began to realize that at last we were real soldiers and that the enjoyments of camp life at home were fast falling to the rear. We went to New York by the Fall River line. I had never been on a steamboat before and was very sick. Landing in New York, we marched up Broadway. My knapsack weighed a ton and I was so sick that I could not hold up my head, yet dared not fall out for fear I should get lost. We were marched to a barrack and given some thin soup and a testament. I had already two testaments in my knapsack, but I took this, although I wished they had put a little more money in the soup and passed the testament. I do not remember what route we took from New York, but we went part of the way by boat and arrived in Philadelphia the next morning.

CHAPTER II.

OUR JOURNEY SOUTH.

Upon our arrival in Philadelphia we heard a signal gun and learned that it was to inform the people connected with the cooper’s shop that we were coming. We marched to that place and found a nice breakfast served by the first ladies of the city. This was the only home-like meal we had received since leaving Massachusetts, and our hearts went out to the loyal people, and our thanks were expressed in three rousing cheers for them. But we hastened on, and soon took the cars for Washington. At Baltimore we left the cars and marched across the city. We passed through Pitt Street, where the sixth Massachusetts, a few months before, had marked the route with their blood. Every throat was opened as we sang “John Brown,” but our knees were a little weak, for we expected a stone would strike us at any moment. We found the roof of the depot on the Washington side of the city filled with bullet holes, the result of the riot of April 19.

From Baltimore to Washington we passed soldiers doing guard duty on the railroad, and for the first time saw men being punished at the guard-house. We saw one man with his head through a barrel, another carrying a heavy log of wood. At night we arrived in Washington and were landed at the Soldiers’ Rest. A Pennsylvania regiment was ahead of us, so we were obliged to wait until they had been to supper.[8] We marched into the barracks before the tables were reset. The waiters removed the tin dishes, then jumped on to the tables and with dirty brooms began to sweep as they walked along. This was too much for Massachusetts. On the tables not cleared were remnants of the meal left by the Pennsylvanians. Soon the air was filled with bread, pork and tin dippers. The waiters were unable to stand the attack and retreated in good order. After quiet was restored our men cleared the tables and the rations were brought in, consisting of mouldy soft bread, boiled salt pork and very poor coffee. Colonel Hincks being informed of our treatment found the officer in charge and gave him religious instructions. We received nothing better that night, but the next morning when the 19th marched in to breakfast our colonel’s “draft had been honored” and we had a square meal.

The Pennsylvania regiment occupying the barracks, we had to sleep on the ground. The night was warm, and being very tired we were soon fast asleep. About four o’clock we were awakened by something grunting around us, and found that we were in the midst of a drove of hogs. We had never seen hogs running at large at home, and believing some one’s swine had escaped from the pen, we concluded to do a neighborly act and catch them. The race began, but with poor success for us, as they could run a mile in 2.40 or less.

After our sport we found an old pump, where we made our morning toilet. We boys did not mind this new mode of living much; we sang, said “it was all in the three years,” and was nothing after you got used to it. Not so with the older men. I remember one instance: returning from the pump I saw one of the men leaning against the[9] barracks, the tears streaming down his cheeks. I said, “What is the matter, Peter?” He replied, “I didn’t think I was coming out here to be rooted over by d—d hogs.” “Oh,” I said, “if we get nothing worse than this I won’t complain.” “Well,” said he, “if we do I won’t stay.” He was discharged soon after.

After breakfast we slung knapsacks and marched down Pennsylvania Avenue to our camp ground on Meridian Hill. We had brought our tents from Massachusetts and all our camp equipage, including bed sacks, but we could find nothing to fill them with, so we spread them on the ground empty. The ground was filled with gravel stones and was not as “soft as downy pillows are,” but so hard that I believe the imprints of those stones are on me yet. At Meridian Hill we began active drilling. The duties of the field officers were divided, Colonel Hincks taking charge of the battalion drills, Lieutenant-Colonel Devereaux the manual, while Major How had the instruction of the guard. We were encamped on the side of the hill, and marching in battalion drill was very hard, yet “from early morn till dewy eve” we were executing company or battalion movements.

Since our arrival in Washington all had a fear of being poisoned; we hesitated to buy camp pies of any but old negro aunties, and a guard was constantly posted with loaded musket over the spring which supplied us with water. One night a nervous comrade was on duty, and thinking that, in the darkness, he saw some one approaching to poison the spring, discharged his piece. Immediately the camp was alarmed. Without waiting to fall in line the cry went up “Row! Row!” and without muskets all rushed for the[10] spring. The officers cried “Halt! Halt! Fall in!” but you might as well have undertaken to stop a Dakota blizzard, and not till the men had been to the spring and investigated was order restored. The next day a square was formed and a short but impressive address was delivered by Colonel Hincks which had the desired effect.

On Sundays at this camp we were marched out by companies, seated in the shade and the Articles of War were read to us by our officers. As I remember them whatever you did you were to be shot, “or such other punishment as may be inflicted by courts-martial.”

At Meridian Hill we had our first Sunday morning inspection; the order was for all men to be in line. This included cooks, teamsters, clerks and all other detailed men. To the regular members of the company it was a grand sight to see these extra duty men in line. Fowler, the wagoner, had not seen his musket since it was given him at Lynnfield and knew nothing of the manual, neither did Uncle Burrill, who was regimental mail carrier. Lieutenant-Colonel Devereaux came down the line and the men threw up their guns for inspection. Fowler had watched the men on his right, and when his turn came threw his gun up in fair shape. The colonel took it, looked at the musket, then at Fowler. “What do you mean by bringing such a musket for inspection?” “It ought to be all right,” said Fowler, “it is bran new and I have never used it since it was given to me.” With a reprimand the colonel, passing on, soon came to Uncle Burrill, who was not quite as sharp as Fowler, and had not watched the men on his right. When the colonel stood before him uncle remained quiet and modestly blushed. The colonel surveyed him from head to foot. “Why don’t[11] you bring up your musket?” Uncle took it in his right hand and pushed it towards him. “Don’t you know any better than that?” asked the lieutenant-colonel. “No,” said Uncle B.; “I wish that I hadn’t come out here, I was sure that I should get into trouble if I did.” With a smile the lieutenant-colonel passed on, and after that, extra duty men were excused from Sunday morning inspections.

CHAPTER III.

BATTLES OF BALL’S BLUFF AND EDWARD’S FERRY.—EXPERIENCES AT DARNESTOWN AND ROCKVILLE.

In a few weeks we broke camp and took up our line of march to the front. Our destination was the Potomac, near Poolsville. It was our first march and to us “tender feets” a hard one. The older men of the company laughed at us boys, said we would never be able to march that distance, but before night we left those who had laughed by the roadside. (I think our experience, that the boys fresh from school or from indoor life were able to endure more than men of mature years, was general.) Just before we arrived at Rockville, Md., we received ten rounds of ball cartridges and the command was given, “Load at will! Load!” I shall never forget the sensation I experienced as my ramrod forced home the first ball. We were told that at Rockville a strong secession sentiment existed, and I expected to kill a rebel or be a dead Yankee before night. We marched through the town and found it as quiet as a New England village. The second night of our march we arrived at Poolsville. Here we met the 15th Massachusetts, and Company A of the 19th was entertained by Company A of the 15th. Next morning we marched to Camp Benton, which was to be our home for several months.

We were brigaded with the 20th Massachusetts, 7th Michigan, 42d New York (Tammany regiment), Captain[13] Saunders’s company of sharpshooters and Captain Vaughn’s Rhode Island battery. Our brigade was commanded by Gen. F. W. Lander; the headquarters of the division were at Poolsville, called “corps of observation,” commanded by Gen. Chas. P. Stone. At Camp Benton the discipline was brought to the regular army standard; drills were almost constant; each afternoon we were drilled in battalion movements, in heavy marching order, and in every possible way fitted for active service. Dress coats with brass shoulder scales and leather neck stocks were issued, and when not in line or on guard our spare moments were spent in cleaning brasses. If any men ever earned thirteen dollars a month we did. Besides the camp guard we mounted what was called grand guard, consisting of a detail from each regiment in the brigade posted on the outskirts of the camp, the tour of duty being twenty-four hours. Often the long roll would beat after we had retired for the night; we would turn out and double quick to Edward’s Ferry, march up the tow path of the canal, lay on our arms the rest of the night, and the next morning march back to camp. At first we expected the rebels were crossing the river, but as we saw no movement in that direction we looked upon these excursions as a part of the drill, the days not being long enough to give us the desired instructions. The enlisted men were not the only ones who had to work, as the line officers came in for their share. Well do I remember day after day marching to execute the movement “To the rear by the right flank pass the defile.” At last Colonel Hincks became discouraged, and throwing down his sword said, “Let every officer go to his tent, take his tactics and study them, and to-morrow if any one fails to understand this movement there will be a[14] vacancy in this regiment.” We came out next day and in fair shape executed the movement.

Many incidents occurred at Camp Benton that are pleasant to recall. We were in a country where there were many slaves, all anxious to serve our officers, and nearly every day some citizen would come into camp hunting for his runaway negro. One day a man came to the colonel and was sure one of his negroes was in our camp. Colonel Hincks sent for Sergeant McGinnis of Company K and ordered him to assist in the search. By the look the colonel gave McGinnis it was understood that the slave was not to be found. McGinnis went into the woods with the man. As soon as they were out of sight he halted and cut a switch. “Look here!” said McGinnis, “do you suppose we left Massachusetts and came out here to hunt negroes?” and to add force to his argument he touched the old fellow up with the switch. The man was indignant and said he would report McGinnis to the colonel. “Go ahead and I will go with you.” Both went to the colonel, and the citizen told his story with tears in his eyes. Colonel Hincks turned to McGinnis and said, “Sergeant McGinnis, is this true?” “Colonel, do you think I would be seen doing such a thing?” was the reply. “No,” said the colonel; “Sergeant McGinnis is a man of truth and I must take his word. You have deceived me, sir; leave this camp and never enter it again.” The man, fearing McGinnis might get another chance at him, left as quickly as possible.

Here is another instance of the ready wit of a soldier. We had in Company A an Irishman, who was one day detailed for headquarters guard. The night was dark and rainy and the morning found Mike, pacing his beat in front[15] of the colonel’s tent, wet to his skin. Colonel Hincks came out and Mike said, “Colonel, will you allow me to speak a word with you?” “What is it?” said the colonel. “Well, colonel, I wish you believed as you did before the war. Then you believed in putting none but Americans on guard and here I am, an Irishman, wet to the skin, having been on guard all night.” The colonel laughed and retired. (Colonel Hincks had edited a Know-Nothing paper whose motto was, “Put none but Americans on guard.”)

Early in October we were ordered to the river and picketed it from Edward’s Ferry to a point above Harrison’s Island. By visits of general and field officers we could see that a movement against the enemy was intended. On the 20th, ten of the best shots of the regiment were selected for some important service. With our officers they crossed to Harrison’s Island to reconnoitre. Early the next morning the regiments began to arrive. Two small scows were brought to a point opposite the island and Company A was detailed to ferry the troops across. At first we pushed the boats over with long poles, but the current being very strong they drifted down the river and it was hard to land. After one or two trips a rope was obtained from a passing canal boat and stretched across the river, making transportation much easier.

In a short time we heard musketry on the other side and knew that the battle had begun. The 19th regiment was the last to cross. As we landed on the island the sound of the minie balls greeted us for the first time. We met four men bearing a stretcher, on which was the lifeless form of Colonel Baker of the 1st California. He was the first man we had seen killed in battle. We were marched across the[16] island, meeting wounded and half-naked men who swam the river. On arriving at the other side we found there was work for us to do. The only transportation from the island to the Virginia shore was one scow. By this a load could be sent over, then marched up a steep bank called Ball’s Bluff. The rebels, being strongly intrenched at the top, could kill or capture our men before another load could land. At last a retreat was ordered as our men were stampeded. They rushed down the hill and into the boat. The little craft being overloaded was soon swamped, men were swimming the river to escape, and many a poor fellow, not able to swim, went down before our eyes; others were shot by the rebels when almost within our lines. At night those not required at the landing were deployed to the right and left. A drenching rain set in and without overcoats or blankets we remained shivering until morning. Lieutenant Dodge and twelve men, under a flag of truce, were sent over to bury the dead. Alex. Short was the volunteer from Company A, and he received injuries from which he never fully recovered. While the flag of truce was out a rebel horseman was seen pursuing a Union soldier who was running to the river. A man in Company H on the island fired and the horseman fell. Immediately the rebels closed in on the burial party and held them as prisoners. It required all the energy and courage that Colonel Hincks possessed to have them released. The next day we picketed the island, cared for the men we had rescued, and on the morning of the 23d recrossed to the Maryland side, wet, cold and disheartened. A few shots from our batteries told that Ball’s Bluff battle was over.

For the number of men engaged this was the most disastrous battle of the war. No man in his right mind would have[17] sent out such an expedition. There was no way to retreat and no chance to send reinforcements, except a scow load at a time. The movement was condemned by every one. It was said that General Stone was a traitor, that signal lights would be placed at a house on the Virginia side and that he would go down to the river and meet men from the rebel army. The truth we never knew, but General Stone was relieved, and it was late in the war before he was given another command.

While we were engaged at the bluff Company K crossed at Edward’s Ferry with General Lander. They had a sharp skirmish with the rebels and our brave brigade commander received the wound which resulted in his death soon after. We returned to our old camp and were soon busy getting ready for winter.

About this time we were called upon to bear our first loss, not by death but by the resignation of Captain Stanwood. Lieutenant Merritt was promoted to the vacant position, Second Lieutenant Boyd to first lieutenant and Quartermaster Sergeant O. F. Briggs to second lieutenant.

We were about to undergo our first winter in camp and had not learned to stockade our tents; we pinned them close to the ground, dug a flue for a fireplace, building a chimney outside topped with a barrel, and had plenty of smoke but little fire. Neither had we yet learned the art of sleeping in tents; we would put on all our clothes, including overcoats, bring the capes up over our heads, lie down and shiver. Experience soon taught as that to undress and throw our clothing over us was much the better way.

On Thanksgiving the officers of the regiment gave a ball; men were detailed to build a ball-room, and quite a nice[18] building was the result of their labors. Ladies came from Washington and Baltimore and a good time was enjoyed. We enlisted men looked on from a distance and thought of the pleasures we had surrendered for a chance to serve our country.

After getting snugly fixed for winter an order came to move, and soon we were on the march for Muddy Branch, to take the place of General Banks’s division, which had been ordered to Harper’s Ferry. Here the regiment was assigned various duties. A part of Company A was sent to Rockville. First Sergeant Cook, myself as corporal, and ten men were ordered to Darnestown. Our quarters at Darnestown were in an old barn on the main street, and at Rockville in buildings on the fair ground. Our duty at Darnestown was to prevent men coming to town from camp and to allow none to pass towards Washington, below the rank of a brigadier-general, without proper papers. We had three posts, each at a store. The citizens of the town were in sympathy with the South, but as we behaved like gentlemen they were very kind, often sending us biscuits for breakfast and at Christmas furnishing a liberal supply of egg-nog. We were welcomed at any house, and often when off duty spent a pleasant hour by their firesides. Soon after we began duty Sergeant Cook received a furlough of thirty days and I was commander-in-chief of the Darnestown army.

I had no trouble with the enlisted men, but the officers “kicked” when I asked them to show their leave of absence. My duty was to inspect the coach when it arrived on its way to Washington, and if any officer or soldier was on board to ask him to show his pass. I will relate one[19] instance. I opened the coach door one morning and said, “I will see your leave of absence, if you please,” to an officer who wore the strap of a major. He growled out, “Call your officer; I don’t show my leave of absence to any enlisted man.” I replied, “I am the only officer here; I have my orders in writing from headquarters and know my duty.” He put his head out of the coach window and said, “Driver, go on.” I called to the sentry on duty, “If that driver starts, shoot him off the box.” The driver did not start, and after swearing awhile the major gave in, but declared he would report me,—and he did. In a few days Major How rode up. I turned out the guard, and after presenting arms stood at attention. “Corporal, dismiss your guard, I want to see you a moment.” Taking me one side he said, “You have been reported to the headquarters of the regiment.” I explained the case to him. He patted me on the shoulder and said, “Corporal, you are right; you are in command of this post, and if the Apostle Paul undertakes to go through this town, unless he wears the uniform of a brigadier-general, don’t you let him go without showing his pass, and if he refuses bring him to camp.” No corporal in the Union army felt better than I did that day, and I was glad that the major had reported me.

In February we were relieved by another detail from the regiment and ordered to Rockville. The night before we left, Mrs. Hayes, of one of the first families of the town, gave us an oyster supper, and her daughter, who was a pleasant young lady but a red-hot “reb,” presented me with a rebel flag. Thirty-eight years have passed since those days, but I shall never forget the kindness of those Darnestown people, and trust that to-day they are prosperous and happy.

After a time we reported to the company at Rockville and found the three field officers examining the non-commissioned officers. Although we had been acting as “non-coms” since we left Massachusetts, none had received warrants from the colonel. First Sergeant Cook and I joined the procession. I was never more frightened in my life, as I had never spoken to the colonel or lieutenant-colonel, and the examination was unexpected. The marks were from one to five. In a few days, at dress parade, Captain Merritt read the list. He called First Sergeant Adams. I thought he meant my brother Isaac, who had been examined as a sergeant, and I was pleased with his good fortune, when the captain called “First Sergeant J. G. B. Adams,” and explained to the company that I had passed the best examination and was promoted to that position. I did not want the place. First Sergeant Cook was a good man and was my friend. I went to the captain, told him I would prefer to be second sergeant and let First Sergeant Cook remain. This arrangement was made and I was happy.

Our duty at Rockville was very light. The boys had made the acquaintance of many agreeable people there; I was introduced, and the time passed pleasantly.

The colored people were holding revival meetings. As we had never witnessed anything of the kind before we all attended, without regard to religious convictions. The singing was of that wild, melodious nature that only colored people can render. The clapping of hands and stamping of feet, all in time, cause a thrill of excitement to run through the coldest veins. With the colored people the effect is such that they are lost to all else but the emotions of the hour. When striving with the spirit it is a strife in reality.[21] One night they held a meeting of unusual interest, and Company A was represented by a large delegation. Among the number was Uncle Ben Falls. Ben had joined the company just before we left Lynnfield. He had been a sailor and his kind heart and ready wit made him a favorite with all. That night Ben was deeply interested. He joined in the hymn, and although his voice might not accord with the rest there was no doubt but what he sang with the same spirit. Soon the excitement reached its height; sobs and groans were heard in all parts of the room, shouts of “Glory!” went up from every heart. The spirit took possession of a girl named Malinda, who was owned at the hotel where our officers boarded, and was acquainted with our boys. She shrieked and groaned and in her striving fell to the floor. The people shouted, “Hold Malinda! Oh, Lord, hold Malinda! The spirit has got Malinda! Oh, Lord, hold her!” but none went near her. This was too much for Ben. He rushed to the front, sat on her and held her down. This brought Malinda and the rest to their senses and the meeting soon closed.

We enjoyed the pleasures of Rockville but a short time after our detail joined the company, as we were ordered back to camp. A new company, recruited in Salem and commanded by Capt. Chas. U. Devereaux, a brother of our lieutenant-colonel, had joined the regiment. They were given the letter H and nicknamed the “Lapstone Light Infantry,” old Company H being disbanded and the men transferred to other companies.

March 1, by order of Colonel Hincks, I assumed the duties of first sergeant, and of all the trying positions I have ever filled this was the most so. If any one thinks that the life[22] of an orderly sergeant in active service is an amiable one let him try it. When the men are not growling about you the captain is growling at you, and you are constantly between two fires. About one-third of the men in Company A had been members of the “Old Battalion,” and the town meeting tactics that prevailed in the militia had not quite died out. I was a recruit, and my promotion was not hailed with joy by the old men. It was said by them that they were detailed for guard rainy days, and that in other ways I favored the new men. They drew up a petition asking for a change, and some twenty men signed it and, through a committee, presented it to Captain Merritt. “What is this?” said the captain. “A petition for a change in first sergeant,” was the reply. “Petition! This is mutiny. Go to your quarters, and if I hear more of this I will have every man court-marshalled and sent to ‘Dry Tortugus!’” That settled the youngsters, and I was ever after obeyed and respected.

CHAPTER IV.

OUR FIRST CAMPAIGN.—BATTLE OF FAIR OAKS.

About the middle of March we broke camp and took up our line of march for our first campaign. We bade good-by to our tents, which had sheltered us since we left Massachusetts, and sent them to Washington with our extra personal baggage, where I expect they are to-day, as we never received them again. We marched to the river, then up the tow-path of the canal to Harper’s Ferry, forded the Potomac at Point of Rocks, and for the first time our feet pressed the sacred soil of Virginia. We saw here the devastations of war,—the ruins of the old arsenal that had been burned by the rebels, the dilapidated and vacant houses,—but most interesting to us was the old engine-house, where John Brown made his gallant fight. This we found filled with rebel prisoners. “Truly,” we said, “his soul is marching on.” As soon as arms were stacked we rushed to the arsenal ruins for relics. I found an old gun-lock and several other parts of muskets. These I packed in my knapsack,—and the next day threw them away. With other regiments we marched up the valley to join Banks’s division, and bivouacked at Charlestown in the field where John Brown was hanged.

The next morning Company A was ordered back to Harper’s Ferry for provost duty. The rest of the regiment[24] marched on, but in a few days returned and took position on Bolivar Heights, occupying deserted houses. Captain Merritt was appointed provost marshal at the ferry and everything was soon in military order, the company quartered in houses, the officers boarding in the town. One day Captain Merritt, with a detail from the company, made a seizure of several barrels of whiskey and a keg of gin, which were taken to a vacant store and a guard placed over them. Somehow the keg of gin disappeared; where it had gone no one knew. The next day was our last in town, having been ordered to join the regiment quite early in the morning. I noticed some of the men were very happy, but as we had been called by the other companies “Merritt’s Sabbath school children,” I thought it possible they were rehearsing for a Sabbath school concert. The increase of the spiritual manifestations told me that the cause of the inspiration must be the gin, and that it was not far away. After searching awhile I found the missing keg in the cellar. Unlike many of the men, it was nearly empty. In the midst of the seance Captain Merritt arrived. He came to order me to have the company in line ready to move at once. When he saw the condition of some of the men I guess he thought we had better move in ambulances. As we were going the rounds of the rooms we met Ben Falls, perfectly sober, having just been relieved from guard. Captain Merritt (referring to the condition of the company) said, “Ben, I am astonished.” “Well,” said Ben, “it is not my fault; I have been on guard, but I will get just as full as the rest as soon as I find the stuff.” When the time came to march all were in fair condition, and before we reached Bolivar Heights, as good as ever. As it was the first offence the men were let[25] off with a lecture from the captain, and as the opportunity was never again presented, the offence was not repeated.

With Captain Devereaux, who joined us at Muddy Branch, came more recruits, and the regiment was now full, Company A having had for a few days one hundred and two enlisted men, several of the old men were discharged, bringing us down to the required number. A fine band was attached to the regiment, and having become very well drilled in the manual, our dress parades were almost perfect, and were witnessed by nearly all the soldiers and citizens in the town.

March 24 we received marching orders. Crossing the river we took cars at Point of Rocks for Washington, where we arrived the next day. We remained in Washington two days, then marched to the navy yard and took the old transport “North America” for Fortress Monroe.

In no place is the life of a soldier so hard as on a transport. Crowded between decks like cattle, unable to cook or even make coffee, they must subsist on what rations are issued and drink the water from the casks. The crews are always liberally supplied with miserable whiskey, which they sell at a high price to those who will buy, and a few men are always found in every regiment who will get drunk if they have a chance. On shore the guard-house can be resorted to, but on board ship there is no relief from this unbearable nuisance. I do not want it understood that drunkenness was general in the army, for many men went through the war without touching liquor, and in my four years’ experience I never saw an officer or enlisted man intoxicated when going into battle. I believe that what was true during the war has been true since, and that in no[26] organization—not temperance—can be found so many total abstainers to the number of men as can be found in the ranks of the Grand Army of the Republic.

Our trip down the Potomac was pleasant, but soon after leaving the river a sudden storm struck us; our old craft leaked badly and we feared we should be swamped. The captain dared not continue, and put back to Point Lookout. Here we found a deserted hotel and several cottages. We did not stop to register, but took possession of the rooms and passed a comfortable night. Next morning we re-embarked, and reached Fortress Monroe during the night. The following day we landed and marched to Hampton, where we found the Army of the Potomac awaiting the arrival of our division. We encamped here about two weeks, quartered in Sibley tents. We were not required to drill often, and the time was pleasantly passed in visiting the several Massachusetts regiments in the army.

Early in April the grand Army of the Potomac moved towards Yorktown. It was a grand army, every regiment having its full quota. The experience of the previous months had made them reliable as soldiers. Incompetent officers and disabled men had been discharged, and those now on duty were filled with patriotic enthusiasm. They only desired a chance to fight, clear up the war and go home. Every man had confidence in General McClellan, and almost believed that he was sent by the Lord to lead us to victory. Whenever he appeared every head was uncovered and every voice raised in loud hurrahs.

We marched two days and encamped about two miles from the enemy’s works before Yorktown. We pitched our shelter tents for the first time, and began army life in[27] earnest. Our rations were served to us uncooked, and company cooks ordered to the ranks. A company cook is a peculiar being; he generally knows less about cooking than any man in the company. Not being able to learn the drill, and too dirty to appear on inspection, he is sent to the cook house to get him out of the ranks. We were not sorry when the cook house was abolished.

The first day after our arrival the 19th and 20th Massachusetts regiments, under command of General Dana, were ordered to reconnoitre the enemy’s works. We discovered a fortification near Winn’s Mill, and the 19th was ordered to march through a piece of woods, then along the front, and discern its extent. We did this under a sharp fire of musketry. It was not our intention to attack, but as Company E, commanded by the brave but impulsive Captain Mahoney, was fired upon, he ordered the men to charge the works, and would have done so had not Colonel Hincks recalled him. Like a true Irishman that he was, he did not propose to be fired upon and not fight. The regiment behaved splendidly under fire; when the musketry was the hottest the clear voice of Colonel Hincks was heard. “Change front, forward on first company!” was the order, and it was executed as correctly as on drill. We lost the first man killed in this skirmish. Andrew Fountain of Company D, Captain Wass, and several of Company K were wounded.

We went into camp and began to erect fortifications; for nearly a month we were engaged in that work, besides building corduroy roads and doing picket duty. While on picket Wm. Morgan was badly wounded by a piece of shell. He was the first man wounded in Company A.

Our camp was located in a swamp; the rain was almost constant, and the ground like a sponge. Sickness prevailed to an alarming extent; it was not an uncommon thing to march half of the company to sick call, but not all who went were sick. Active service had tired some who, when we were in camp in Maryland, were anxious to fight, and were constantly grumbling because we were not ordered in. Picket duty under fire had given these few the “shell fever.” Loss of voice was the trouble with many, caused by severe colds. One day I marched my squad of invalids to the hospital tent; with them was one of the loudest talking men in the company, but that morning he could only whisper. After the doctor had examined them all he gave me the list of excused, and my voiceless comrade was not down. “Hasn’t he excused me?” said B. “No,” was my reply, in a voice that could be heard a quarter of a mile. “D—n him, I am the sickest man in the company,” was his indignant answer; but he went on duty just the same, and never again answered sick call until wounded. Such cases were the exception, however, and every day the number grew less, as our men were ordered back to general hospital.

The works we were erecting were of the strongest kind, as it was intended to besiege Yorktown, and the heaviest guns were mounted for that purpose. Sunday morning, May 4, found the regiment on picket duty. It had been a lively night, as the shelling had been constant. Lieutenant Hume, in charge of an outpost, believed that the rebels had left the works in his front; sending his opinion back to the commanding officer, he started to cross the field. No gun was fired and he continued on. The regiment was then ordered forward double quick, as others had seen Lieutenant[29] Hume and were anxious to be first in the works, but the 19th could run either to the front or rear and our flags were the first to float from the fortifications. We found the portholes filled with Quaker guns (logs of wood). Men of straw were stationed as gunners. Every indication of a hasty retreat was shown, as in the camps in the rear of the works we found fires and breakfast smoking hot, which we eagerly disposed of. We also found letters ready for mailing, which went by northern mail instead of southern, as we sent them home.

We marched back to our old camp, packed up, and Monday morning, in a drenching rain, marched from Winn’s Mill to Yorktown. We were on the road all night and only made three miles. The mud was knee deep; we could not go out of line as the ground was full of torpedoes, yet, in all our misery, Company A started one of our old camp songs, which was taken up by other companies in the regiment, then by other regiments in the brigade, and soon the entire army was singing. This continued nearly all night. The next day we took steamers, and at night arrived at West Point. We remained on board until morning, then landed, and finding our forces engaged we were ordered to support Captain Porter, 1st Massachusetts battery. At West Point we saw a feature that we never saw before, or at any other time during the war. It was a human telegraph. A line of men was deployed some twenty feet apart, and extended from the line of battle to headquarters. The men at the front would start the message, and it would be repeated by each turning the head to the rear as he spoke. One message I remember,—“Send a man to take Daniel Webster’s place.” We supposed Daniel had been shot, but[30] if a man was wanted to fill the place of our lamented Daniel Webster, we did not think Company A could spare the man. After a sharp fight the rebels fell back and we began the march up the peninsula. The condition of the roads was such that we halted more than we marched, but at last we reached the banks of the Chickahominy River, and were ordered on picket between Bottom and Grape Vine bridges.

Saturday, May 31, the battle of Fair Oaks began. We were not relieved from picket until Sunday morning, when we were ordered to the front; here we were marched from right to left and left to right, constantly under fire but not really engaged. We were at times passing over portions of the field that had been held by the rebels, and the ground was strewn with the dead and wounded. When the battle ended we were ordered on picket, where we remained ten days, having a brush with the rebel pickets every day. We were then given a few days’ rest and ordered to the front, where we threw up a line of works and remained there while the army held the advance position.

On the 25th of June General Hooker asked for one regiment from Sumner’s corps to assist in the attack on the rebel lines in our front. The 19th was selected. We advanced in front of our intrenchments and were soon hotly engaged. Led on by our gallant colonel, we soon had the rebels in full retreat, and had the army advanced at that time I am confident we could have marched into Richmond in five hours, as we were only a few miles from the city. Just as we were ready to make the final charge an aid came to Colonel Hincks and said, “You are ordered to fall back.” “What for?” said the colonel. “Don’t you see we have got them on the run?” But the order was peremptory and[31] back we went. Our loss was very heavy for the short time engaged. Lieutenant Warner of Company H and several men were killed; Lieut. J. H. Rice, Sergt. Samuel H. Smith, William R. Meldon, Benjamin Jellison and others, in all about sixty, badly wounded.

While we had been under fire nearly all the time since arriving at Yorktown, this was the first square fight in which we had been engaged. We had no chance for the use of tactics as the woods were thick and we could see little of the enemy; but the officers and men behaved splendidly, and our only regret was to lose so many and accomplish nothing, an experience that the Army of the Potomac often had in the battles that followed.

CHAPTER V.

BATTLES AT PEACH ORCHARD, GLENDALE AND MALVERN HILL.

Company A had in its ranks men of every trade and profession, not excepting the clergy. Our minister might have been a good soldier in the army of the Lord, but was not a success in the Army of the Potomac. At the first fire he scattered and could not be rallied. I said to him, “You have been telling the boys to get ready to die, but you are not in good marching order for the other shore yourself.” “That is not it,” replied Levi; “I should not have enlisted; it always made me nervous to hear a gun fired and I don’t believe I can get used to it.” As will be shown later he never did.

Returning to our works we were ordered to throw up traverses between companies. At night cheering began on our right. An aid rode down the line and gave orders to Colonel Hincks to have the regiment cheer. “What for?” said the colonel. “I do not know,” was the reply; “it is orders from General McClellan to General Dana.” “Give my compliments to General Dana and say that we did our cheering in front of the line yesterday.” Soon we were ordered to pack up and leave everything not absolutely necessary to carry. We were ordered into line and remained under arms all night. The next morning we found the[33] retreat had begun, and, before we had recovered from our surprise, were ordered in to support Tompkins’s Rhode Island battery, and the enemy was soon upon us.

At the headquarters of the commissary department all was confusion. A pile of hard-tack as large as Faneuil Hall was set on fire. Heads of commissary whiskey barrels were knocked in and the whiskey ran in streams. This was also set on fire and men were burned as they tried to drink it. Blankets, clothing, stores of all kinds were destroyed, and one would think as an army we were going out of business, but such was not the case, as we had enough on our hands to last us the next seven days.

We made a stand at Peach Orchard and found that our corps was to cover the retreat of the army. We were slowly driven back to Savage Station, where a battery went into position and we lay in the rear as its support. One who has never supported a battery can form no idea of this duty, which is to lie just as snug to the ground as you can and take those shells coming from the enemy that the battery does not want. Our position at Savage was a dangerous one. Shells were constantly bursting in our ranks and our battery was being severely tested. It did not seem that our lines could be held much longer, yet we knew that our wagon train was crossing the bridge and we must stand our ground until they were safely over. We heard a cheer, and looking to the left saw Meagher’s Irish brigade moving forward on the run. The entire corps, forgetful of danger, sprang to their feet and cheered them wildly. On they went; grape and cannister ploughed through their ranks, but they closed up the gaps and moved on up to the mouth of the rebel batteries, whose guns were captured, and the[34] firing that had been so disastrous ceased. The Irish brigade held the line until night, when our army was withdrawn.

It was the hottest day of the year. As we changed front many fell from sunstroke. Captain Wass was so badly affected that he lost his reason and never fully recovered. Lieutenant Hume was left by the roadside and was soon captured by the enemy. At night we were stationed at the bridge until the last regiment was over, when we crossed and destroyed the bridge.

After we had rested a few hours we were ordered back, and sunrise found us engaged with the enemy. In the afternoon the terrible battle of Glendale was fought. This was June 30. About two o’clock p.m. we were ordered to charge the enemy, who were in a belt of woods. To do this we must charge over an open field. Faces turned pale as we looked over the ground. We grasped our muskets firmer and waited for the order. We had kept our knapsacks until this time,—they had become priceless treasures, filled as they were with little articles for our comfort made by loving hands, and with letters from dear ones at home,—but we threw them into a pile, and the voice of Colonel Hincks was heard: “Forward, double-quick,” and we moved across the field and entered the woods. Here we met a line clothed in Union blue, and thinking it was the 7th Michigan, of our brigade,—a regiment loved by every officer and man of the 19th,—we reserved our fire, and cried, “Don’t fire, boys, we are the 19th Massachusetts.” A galling fire in our faces drove us back, but we promptly moved forward again, still thinking it was the 7th Michigan and that they would see their mistake. Again we were repulsed, and believing we were mistaken, and that the line[35] was composed of rebels in our uniforms, we charged with a will. As they rose to receive us we saw that this time we were not mistaken, as they were rebels clothed in part in our uniforms. We had a hand-to-hand fight for a few moments, when we discovered that we were being flanked and withdrew to the edge of the woods.

Under a terrible fire we changed front. Our brave Major How fell, never to rise again; Colonel Hincks was supposed to be mortally wounded and was carried from the field; Lieut. David Lee was killed, and the ground was strewn with our dead and wounded comrades. For a moment the regiment was in confusion, but Captain Weymouth, assisted by Sergeant-Major Newcomb and others, rallied the men on the colors and the line was at once reformed and our position held. Capt. Edmund Rice was in command of the regiment. He was noted for his coolness and bravery, and the men had confidence in him. As I looked down the line of Company A many places were vacant. Ed. Hale, Volney P. Chase, Charles Boynton and several others were killed, while the list of wounded could not be ascertained at that time. Company A had lost men by death, but this was the first time any of our number had been killed in action.

Charles Boynton was one of my townsmen. He was an eccentric man and had troubled Captain Merritt by his peculiar ideas of drill, but he was as brave and patriotic a man as ever shouldered a musket. He had no patience with the slow movements of the army, and I have often heard him say that he wanted to fight every day and close up the job. When advancing in line he would constantly rush ahead of the company, his only desire being to get a shot at the rebels. I do not think it would be showing disrespect[36] to his memory should I relate one or two of the little dialogues between Captain Merritt and Boynton. Our regiment had a peculiar drill in the manual. It was formulated by Colonel Devereaux, and is nearly what is used by the army to-day. After loading we stood with our little finger on the head of the rammer until the order was given to shoulder arms. One day on drill Captain Merritt looked down the line and saw Boynton with his hand by his side. “Put your little finger on the head of the rammer, Boynton,” sang out Captain Merritt. “I won’t do it,” replied Boynton. “Won’t do it! Why not?” “Because it is all nonsense; my gun is loaded, and do you suppose I would stand up in battle like a darned fool with my little finger on the head of my rammer? No, sir, I propose to drill just as I intend to fight.”

Another day the order was, “Right shoulder, shift arms.” The proper way was to make three motions, but Boynton did it in one. “Make three motions, Boynton,” said Captain Merritt. “Didn’t I get my gun on my shoulder as quick as any man in the company?” was the reply. Captain Merritt was discouraged and ordered me to punish Boynton, but I explained his peculiarities, and assured the captain that he would earn his thirteen dollars a month when fighting began. He let the matter drop. Had the Union army been composed entirely of men like Charles Boynton the war would have ended long before it did.

We held our position until midnight. It was the saddest night I ever spent. The dead and wounded of both armies lay between the lines. The wounded were constantly calling on their comrades for water, and we could hear calls for Mississippi, Georgia and Virginia, mingled with those for[37] Michigan, New York and Massachusetts. Brave men from our regiment crawled over the field, giving water to friend and foe alike. About midnight the order was whispered down the line to move. I had been from right to left of the company keeping the men awake, as we expected the order. As still as possible we crawled over the field. We had gone but a short distance when, looking back, I saw one member of the company had not started. Thinking he had fallen asleep I returned, and shaking him said, “Come, come!” As I drew close to him my eyes rested on the face of Jonathan Hudson, cold in death. He had been killed in the early evening as we lay in line and his death was not known to his comrades near him. It was the saddest sensation I ever experienced. When we arrived at the road we found many of our wounded. Colonel Hincks was on a stretcher, and as the ambulances were full he was carried a long distance before one could be found. Captain Devereaux was also badly wounded and had to be carried. We started with the body of Major How in a blanket as we had no stretchers, but being so very heavy we were forced to leave him.

Without any regimental formation we began our weary march to Malvern Hill, where we arrived at daylight, were at once ordered to support a battery, and witnessed one of the most terrible artillery battles of the war. In the afternoon our brigade was ordered to the woods and held the right of the army. The next morning, in a drenching rain, we started for Harrison’s Landing. We marched in three lines, but it was not an army, it was a mob. Artillery was stuck in the mud, wagons were abandoned and burned by the roadside. The only thought of every one was to get to Harrison’s Landing as soon as possible. Some did not stop[38] at the landing but took boats for Washington. Among these was our minister, Levi. He had managed to keep out of every battle, and now deserted, joining the advance guard in Canada.

Harrison’s Landing when dry was a sandy plain; when we arrived it was a sea of mud. Without shelter, overcoats or blankets we dropped in the mud, and being so exhausted, having been without sleep, except the little naps caught in line of battle, for seven days, we soon forgot our misery. It was two days before we could reorganize our companies. Men were coming in who we expected were killed or captured, but July 4 upon calling the roll, we found that more than half of the men who had left Massachusetts with us less than a year before had either been killed in battle, died of disease or were sick or wounded in general hospital. The death-rate at Harrison’s Landing was fearful. Men who had stood the retreat now broke down and soon died. Every hour in the day we could hear the dead march, as comrade after comrade was laid at rest. The subject for discussion around the camp-fire was the disaster to the Union army. Newspapers called it “an important change of base.” We knew that some one had been outgeneralled, and although the men had confidence in General McClellan, we believed that while we had been digging and dying before Yorktown we should have been advancing and fighting.

Looking at the campaign in the most charitable light possible, the fact remained that on April 4 the finest army ever mustered began the advance on Richmond; that we had been within five miles of that city, and that July 4 found the army on the banks of the James River, with less than half of the number it had three months before. We were not[39] disheartened. Many had expected that 1862 would see the end of the war, but it now looked as though those who were spared would see the end of their three years’ enlistment. The losses in officers had been such that many promotions were made. Four enlisted men were promoted second lieutenants, and I was one of the number. I was assigned to Company I, Capt. J. F. Plympton. By a misunderstanding between Colonel Hincks and Lieutenant-Colonel Devereaux, First Sergeant Driver and myself did not receive our commissions until August, although we continued as acting second lieutenants, the two commissioned by recommendation of Colonel Hincks not being assigned to duty.

It was impossible to obtain officers’ uniforms, so I bought a pair of brass shoulder-straps, sewed them on my well-worn blouse, borrowed a sword of Lieutenant Mumford and went on duty, as verdant an officer as could be found in the army of the Potomac.

About the middle of August I was ordered to report to First Lieut. John P. Reynolds for special duty. We were to take charge of the guard of the division wagon train that was ordered to Fortress Monroe. Our duty was an important one. We knew we were liable to attack at any time by guerillas, and constant vigilance was required. We often met small parties of mounted citizens who rode past our train. We believed they were “taking us in,” but we had not arrived at the time when men were arrested on suspicion, so we let them pass but kept our train well covered. We arrived at Fortress Monroe in due time, turned over the train and reported to the regiment at Newport News, they having marched a few day after we were ordered away.

While our duty as the advance guard had been arduous, we had not suffered as much as those who marched with the regiment. They had marched rapidly over dusty roads, under a broiling sun, and many had been sunstruck. Among the number was Capt. William A. Hill. He was not able to speak above a whisper for several days, and his condition was serious; but his courage was good and he remained on duty with the regiment. The men having rested a day, and being now veteran soldiers, had forgotten their hardships, and when we arrived were nearly all in the James River hunting for oysters.

On August 24, the brigade embarked on the steamship “Atlantic” for Washington, arriving at Alexandria the 28th,—just one year from the day we left Massachusetts.

CHAPTER VI.

BATTLES OF FAIRFAX COURT HOUSE, FLINT HILL AND ANTIETAM.

My position had changed during the past year from corporal in Company A to second lieutenant in Company I, and it took me some time to get accustomed to the new office. Up to the time I left Company A no man had been punished; but the morning that I reported for duty in Company I Captain Plympton had one man on a barrel and another on knapsack drill, and I thought I had made a mistake in not taking sparring lessons before being promoted.

I found the men of Company I as good-hearted a lot as there was in the regiment, only a little wild. The leader of the company was a young boy; he was about seventeen years old, and a private soldier, yet he was the one who settled all disputes. He was well informed in regard to the movements of the army, and had ideas respecting future campaigns that he was ready to discuss with officers or men. Soon after I joined the company he called on me and made a little speech of welcome, saying that the boys were glad I had been assigned to the company, and assured me they would make it pleasant for me. Such a reception was very gratifying. I was but twenty years of age and doubted my ability to control these men, but I commanded the company for nearly two years, and punished but one man during the[42] time. That boy has since become known and honored by every comrade in Massachusetts. The friendship formed that day for George H. Patch continued until his death, and the memory of that light-hearted, true soldier will be precious to me while life shall last.

Leaving the transports at Alexandria, we first marched to Chain Bridge, then to Tenallytown, Md. No one seemed to know where they wanted us. We went into camp and waited for orders, which, when received, were to march at once for Centreville, to reinforce General Pope. At daybreak, August 30, we crossed the bridge at Georgetown, and reached Fairfax Court House the next morning, having marched sixty-three miles in sixty-four successive hours. It was the hardest march we had made,—twenty-four hours of the time it rained in torrents. The shoes of the men were in bad condition; many marched bare-footed, and it was impossible for them to keep in the ranks. We did not have a hundred men in the ranks when we reached the line of battle.

At Fairfax Court House we found everything in confusion. Pope’s army had been defeated at the second Bull Run and were in full retreat. Without time to make coffee we were ordered in, and deployed as skirmishers to the right of the town, as it was expected the rebel cavalry would attack the flank. We remained in this position until the army had passed, when, with the 1st Minnesota, we were selected to cover the retreat. The rebel cavalry came down on us, and we had some sharp fighting as we fell back. At Flint Hill we made a stand. Night had come on and we did not care to be bothered with the rebels any longer. The 1st Minnesota formed a V with two sections of Tompkins’s[43] Rhode Island battery at this point, the 19th supporting the battery. On came the rebels, right into the trap we had set. The Minnesota boys opened fire, followed by the battery. The 19th charged with a yell; the rout was complete, as all not killed or wounded turned and fled. We had no time to follow them, as we were quite a distance from the main army. When we rejoined the column our two regiments were mistaken for the enemy, and fired upon by our own ranks. Assistant-Surgeon Hill was killed, Captain Russell disabled by his horse being shot, and several men wounded.

The next day we again crossed the Potomac to Maryland soil. The prospects were not pleasant to contemplate. We had done little but march in retreat the past six months. A line officer has little chance to see what is going on outside his regiment, and his opinion is of little importance, but I believed then, and time has only strengthened my belief, that the leading officers of the Army of the Potomac were perfectly willing General Pope should be whipped. He had taken command of the Army of Virginia with a swell order: “Headquarters in the saddle, spades to the rear, muskets to the front,” and they were glad to see the conceit taken out of him. There is a great deal of human nature shown in the world,—even in army commanders.

We now took up our line of march through Maryland. We were not the only ones who had crossed the Potomac, as the rebels had already crossed and were marching north, and we must head them off if possible. It began to look as though they would capture Washington before we captured Richmond. We marched through Rockville, where we had spent our winters so pleasantly, and met many old acquaintances,[44] but missed several of our gentlemen friends who, we learned, had joined the rebel army.

Some of the ladies, who loved the stars and bars, joked us on our “On to Richmond” movement, and were confident the war would soon end with the south victorious. The events of the past few months had been such that we had slight ground for an argument; but we assured them we were satisfied, and all we wanted was to get General Lee on this side of the river. Our march through Maryland was delightful; the farther we got into the interior the more loyal the people became, and our welcome was cordial.

We arrived at South Mountain while the battle was being fought, but took no part in it. The 16th of September we reached Antietam, and formed in line of battle. On the morning of the 17th, with our brigade in the centre, we advanced in three lines of battle, over walls and fences, through fields, under a terrible fire of artillery. The regiment was growing nervous but did not break. Colonel Hincks halted us, put us through the manual of arms, ending with parade rest. Having become steady, we moved forward to a strip of woods, and came upon the enemy strongly posted. Grape and canister, shot and shell, volleys of musketry greeted us,—and our men fell as grain before the scythe.

One-half of our officers and men were either killed or wounded. Colonel Hincks was the first to fall, again terribly wounded. Capt. George W. Batchelder was killed, and the command of the regiment and companies changed fast, as one after another officer went down. At the time we were so hotly engaged in the front we began to receive a fire from our left and rear, and discovered that we were[45] being flanked, and must change front to rear. This was done by the 19th Massachusetts and 1st Minnesota. We were now under command of Colonel Devereaux, and were ordered to take a position near a stone wall. We fired as we fell back, holding the enemy until we had reformed our lines, when we again went in and continued fighting until dark, when we were ordered to support a battery. We then had time to count the cost of the battle. Colonel Hincks was reported dying, and we mourned the loss of our brave leader. Captain Batchelder was dead. He had been my tent-mate since I had been an officer, and had rendered me valuable assistance. Every one loved him; he was an ideal volunteer soldier. Having graduated at Harvard, he entered the army as an enlisted man in the Salem Zouaves at the first call for men, and had worked hard to bring the regiment to the state of efficiency which it had reached.

I had not seen my brother since we had advanced in line. He was left general guide of the regiment, and his place was on the left. As soon as we halted I went to the company, but he was not there. The following day I searched the hospitals, but could not find him, and on the morning of the 19th, the rebels having left our front, I went where their lines had been and found him, with Jacob Hazen of Company C and George Carleton of Company B, near an old haystack. He had been shot in the right side of the neck, the ball passing out of the left shoulder; it had cut the spinal nerve, and he could not move hand or foot. I saw at once that he could not live and had him placed in an ambulance and carried to our field hospital. It was the saddest duty of my life. We had left home together, and had often talked of a happy reunion around the old fireside[46] when the war should end. Now I must write to my old mother that one of the three who had bade her good-by in ’61 would never return.

This was war, terrible war! As I was kneeling by his side, hearing his last words, a woman’s voice said, “Is he your brother?” I explained to her the fact that I was in command of my company and could not stay with him, but could not bear to have him die alone. With tears streaming down her motherly face she promised me she would not leave him, but would see him buried and would send me word where he was laid,—which promise she faithfully kept. The name of this good woman was Mrs. Mary Lee of Philadelphia, Pa. She had a son in Baxter’s Fire Zouaves, who was with her that day. Several years ago, when Post 2, G. A. R., of Philadelphia, was in Boston, I saw that one of the old battle-flags was the Fire Zouaves, and was carried by Sergeant Lee. He proved to be the son I had met that sad day at Antietam; a few months later I visited his mother in Philadelphia, who was working just the same for the soldiers as she had done during the war.

While my brother lay wounded on the field inside the rebel lines an officer of the 8th South Carolina came along, and seeing 19 on his cap asked to what regiment he belonged. Being informed that it was the 19th Massachusetts, he said he had a brother in that regiment named Daniel W. Spofford. My brother told him that his brother was wounded in the battle, and might be on the field. He searched for him but did not find him, as he was able to go to the rear before we changed front. Returning, he had my brother carried to the haystack where I found him, and rendered all the assistance possible. The name of the South Carolina[47] officer was Phineas Spofford. Both brothers survived the war. The Union soldier resides in Georgetown, Mass., the rebel in South Carolina, but he often visits his native State.

I also missed my boy Patch. He was last seen helping a sergeant from the field. He turned up in Libby Prison a few days later. My old company had met with other losses than death. Four men had deserted on the eve of battle. They had taken the canteens of the company to go in search of water. No doubt they are searching yet, as they did not return. Two were non-commissioned officers, and all were intelligent men.

The regiment was now commanded by Capt. H. G. O. Weymouth. Again we crossed the Potomac, and went to camp on Boliver Heights, near Harper’s Ferry. We did not lose the battle of Antietam because we held the ground, but made the mistake of remaining inactive while the rebels withdrew to the other side of the river, so we gained nothing.

Soon after the battle we received a large number of recruits,—the best class of men that had joined the regiment. Many of them had waited, hoping that the war would be over, and their services would not be required, but seeing the disasters that had come to the army, resolved to come and help us. Several of them were discharged as commissioned officers, and all rendered very valuable service.

We remained at Harper’s Ferry until October 30, when we received marching orders, and the army marched up Loudon valley. The night were cold, and we suffered severely. While in bivouac near Paris or New Baltimore[48] two feet of snow fell, covering us as we slept. Orders against foraging were very strict. We were not allowed to take hay from the stacks for bedding, or in any way molest private property. The idea of General McClellan seemed to be to carry on the war without hurting any one’s feelings, but once in a while we broke over. One night Corporal Phelan and Jack Robinson discovered hens at a neighboring farm-house, and finding the house not guarded took their muskets and went on duty. The people were much pleased to be so well protected. While Phelan entertained the family Jack went on duty outside to protect the hens. Soon a squawking was heard, and Corporal Phelan grasped his musket and rushed to reinforce Jack. They secured three good hens, and forgot to go back to the house, but reported to camp. When they arrived I discovered that they had plunder, and called them before me. With downcast eyes they told the story of their shame and begged for mercy. As an officer I must do my duty, and they must be punished. I ordered them to cook one of the three hens and deliver it to me. With sad hearts they obeyed the order.

CHAPTER VII.

BATTLE OF FREDERICKSBURG AND MARYE’S HEIGHTS.

We continued the march through the valley to Warrenton, where General McClellan was relieved of the command of the army and General Burnside succeeded him. Nearly all the men were sad at the loss of McClellan. He was our first love, and the men were loyal and devoted to him. I did not share in this sorrow. My faith had become shaken when we retreated from before Richmond, and when he allowed Lee’s army to get away from Antietam I was disgusted, and glad to see a change. Sad as the army felt at the loss of McClellan, they were loyal to the cause for which they had enlisted, and followed their new commander as faithfully as they had the old.

We arrived at Falmouth about the middle of November, and went into camp two miles from the town; here we spent our second Thanksgiving. No dance for the officers this year. We had a dinner of hard tack and salt pork, and should have passed a miserable day had not the commissary arrived with a supply of “Poland water,” and the officers were given a canteen each. The men had the pleasure of hearing our sweet voices in songs of praise from the “home of the fallen,” as our tent was called.