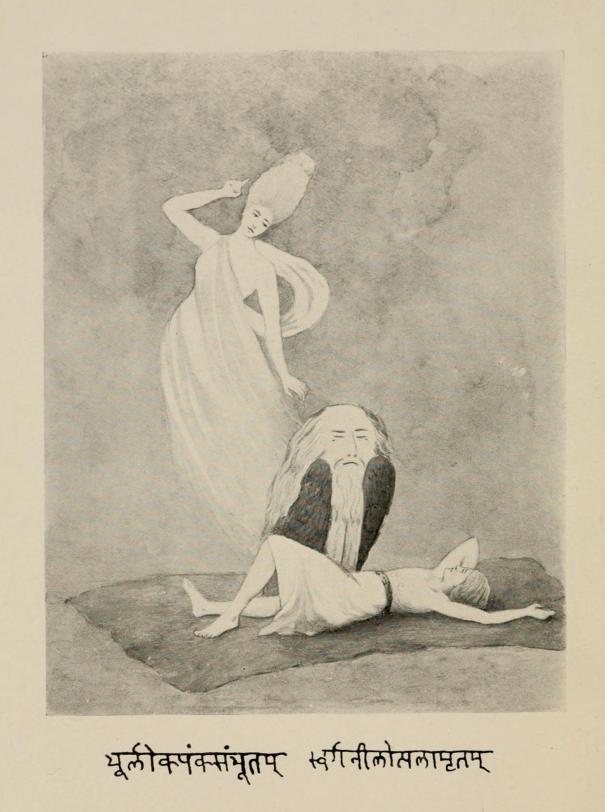

Frontispiece

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Draught of the Blue -- An Essence of the Dusk, by F. W. Bain This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: A Draught of the Blue -- An Essence of the Dusk Author: F. W. Bain Release Date: May 23, 2015 [EBook #49033] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A DRAUGHT OF THE BLUE *** Produced by Al Haines

Together with

An Essence of the Dusk

Translated from the Original Manuscripts

By

F. W. Bain

G. P. Putnam's Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

COPYRIGHT, 1906

BY

F. W. BAIN

(For "An Essence of the Dusk")

Published, January, 1907

Reprinted, March, 1907; September, 1908

July, 1910; September, 1911

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

Contents

Translated from the Original Manuscript

Ah! lotus infinite! ah! wild sweet Blue!

Sense, in thy azure ocean dipped, must die.

Introduction

The sun goes down, for those alone, who stand on a revolving sphere: and so, in Nature's universal life, Death is but a dissolving view, a word without a meaning: real only to the accidental unit, to whose local and momentary combination it sets a term. Death is a thing of nought, phenomenal, kaleidoscopic: a juggle of the Mother of Illusion, Prakriti or Máyá, whose magic scene not only never dies, but like her own wild animals, sleeps even with an open eye. You never catch her napping. And often, when you think that you have done it, she winks at you, just as it were to show you your mistake. As sometimes, on a hot midsummer day, when the delicate blue smoke from cottage chimneys rises straight into the air, and Nature holds her breath: you think, she is asleep: and all at once, there comes a little whisper, and a ripple passes over all the golden ears of corn, and in another moment, all is still. Or on a cliff that overhangs a glassy sea, you lie and dream, and think, the very water sleeps: and then, a sudden change of colour flushes the ocean opal for only a single instant, and is gone. Or in a wood at noon, you listen to the silence, and a rustle suddenly quivers in the trees, and dies away. Murmurs and echoes: moments and emotions of the pulses of the world: hints and indications, still, small voices more significant than storms, of the never-sleeping thrill and throb of universal action.

"Every tremor gravitation excites in any planet is immediately transmitted to the farthest limits of the system, in oscillations corresponding in their periods with the causes that produce them, like sympathetic notes in music, or vibrations from the deep tones of an organ.... The human frame may be regarded as an elastic system, the different parts of which are capable of receiving the tremors of elastic media, and of vibrating in unison with their innumerable undulations."

So far sober modern science, never dreaming that it is exactly reproducing (translate the thing only from physics into ethics) the old Hindoo idea, that moral conservation of energy, whose fundamental axiom it is, that no ACTION, good or bad, however small, is or ever can be lost, but like a stone thrown into the water, generates innumerable consequences, running in all directions to infinity, producing permanent impressions and effects, that follow and fatally determine, eternal and indelible, the fortunes of their DOER, through the series of interminable births and deaths: births that are no beginning, and deaths that are not an end. Thus do we go on making for ourselves our weal or woe: and as we go, the hounds of deeds long buried in oblivion are on our track.

Doubtless a little story might have a more delicious name than the one before us: but doubtless it never had. We may understand it either of a young woman or the moon: and in either case, it means more things than one. I. The new moon, seen for a single instant, in the sky, or on the lotus, or on the forehead of Maheshwara. II. A beauty with eyes like a great blue lotus, or the colour of heaven. For all these things have a quality in common, the mystic blue.

Strange, how deep an impression the colour blue seems to have made upon the Indian mind. Gods and peacocks, creepers and lotuses, clouds and pools and skies and seas, elephants and maidens' glances are all mixed up together in their language by their "participation" in this "Platonic idea," this transcendental blue. Something of this, indeed, is readily intelligible in every land: but in India, it is more so. The blue is bluer, there. Wouldst the poet understand, Travel in the poet's land. I will not say, with Goethe, Kenst thou that land: but simply tell the reader something that I saw at Mahabaleshwar in 1903.

The month of May, and with it, the hot weather, was drawing to a close. The woods were green, but very, very dry, and all their ferny fringes by the red road-sides were parched and powdered thick with ruddy dust. Each morning, when I stood in my verandah, looking down the valley, I could see a floor of cloud, now rolled out like a table-cloth, now tossing like a troubled sea, now floating, wreath on wreath, like a ballet dancer's gauzy flounces, half opaque and half transparent, over the distant Konkan, three thousand feet and more below, waiting for the rising sun to touch it with a rosy blush and kiss it, into invisibility. And every evening, just as he went away, the hot haze hanging like a filmy veil about the hills thickened back into solidity, and beautiful cold mists, reborn, rolled swiftly up the valley, blotting out the picture, and hiding all with their ghostly shifting curtain. And so, from morn to night, and night to morning, it went on, till lines of bullock carts began to gather and wander down the hill, and people were preparing to pack and flit and vanish: for the monsoon was approaching, when no one not a native of those parts can remain upon the hill, unless he wishes to go mad.

And then it began to rain. Suddenly, like the Day of Judgment, there fell from the sky in a solid lump rain, like no rain that I had ever seen before, with the roar of an avalanche and the thunder of Indra and lightning that hissed like a serpent, crashing and smashing down on the roof as if it would break it in. It was dark at midday, and deadly cold, for there went up a mist from the earth, to meet the flood from heaven, making as it were a solid wall through which it was impossible to see a yard. There was nothing to be done but to sit and wait. So for five nights and days that angry rain raged and hammered upon the earth, and tore her with savage fury, growing fiercer as it went on[1]: till all at once, just as though the gates above had been suddenly shut, it stopped, as abruptly as it had begun, about five in the afternoon.

I went out, and wandered slowly up the hill. The air was soft, and quite warm, and heavy with the smell of smells, the fragrance of fresh earth. Here and there, the paths were gone, washed clean away, looking like red skeletons of their former selves, with rock for bones, all their earthy covering gone. And here and there, a little off the road, a pale orchid sheltered beneath a bough, or a dainty cobra-lily, nestling snug under an overhanging trunk, peeped with incomparable shy reserve through some dark vista in the trees. A mongoose ran across the road, stopped, just half-way, to stare for an instant at me with its startled weasel eye, and leaped into cover on the opposite side.[2] In a few minutes I gained a point of view, and turned to look,—over a sea of green, and what a green!

For every leaf on every tree was washed and wet, and glistened as if coated with fresh paint. The rich glow of a yellow evening sun deepened and intensified the wonderful red colour of patches of naked rock, raw scars laid bare by little slips of land on places on the hill. Cascades of water shot spouting and splashing into the valleys from innumerable scarps and shelves along the heights; and as I listened, I could hear the streams, hidden in the dense foliage, rushing and gurgling down the steep slopes, carrying with them as they went all the loose soil and pebbles they could find. And all along the ridges of the hills, to right and left, on Elphinstone and Lodwick points, hung brooding enormous masses of white cloud, the purest, the strangest, the most indescribably magnificent and beautiful clouds that I ever saw, whiter than snow, brighter than polished silver, save only where their lower edges were charged with heavy rain, fleeces of colossal milk-white rams, dipped by the master painter, Deity, in giant vats of purple ink. Down and away below them the staircase of the Ghauts, long lines of broken hill, were stepping away into the plain, with every distant detail sharp and clear, cut as it were in copper, till all merged in the far horizon, on which a blink of burnished gold flashed back from the unseen sea, lying right in the eye of the setting sun. I listened, and in the silence, broken only by the ruckle of the rushing water, somewhere away upon the hill, I heard a cock crow. And at that moment, right above me, I looked and saw: a mass of shining cloud swung slowly open, and through the gap, in the deep abyss of heaven, appeared a spot, a panel, a little lozenge, of blue: pure, unsullied, silent, elemental, Indian blue.

There, there, was the unearthly colour, the colour of the mystic lotus, and the long-eyed languishing Indian Gods. I knew in that instant what Kalidas meant, when he compared the virtue of the just to a patch of heaven fallen down to earth, the blue celestial leaven in this world of frenzied storm and weeping rain. There was the azure paradox, the blue that is all but black, dark, transparent, clear as crystal, shut out from eyes that live in plains by earth's encircling fog. But over every mountain is peace, and the kosmic blue.

MAHABALESHWAR,

April, 1905.

[1] In but a part of the last night, there fell eight inches and a half of rain! Time for time, Mahabaleshwar can probably laugh at Cherrapunji. The valleys are scooped out as if with a trowel.

[2] This mongoose was, no doubt, wondering "what the devil I did there": for during the rains he and his fellows have the hillsides entirely to themselves.

Contents

I. Sky-Crystal

II. Sprung from the Mud

III. Purusha and Prakriti

IV. Bubbles

V. A Painted Lady

VI. Shadows

VII. Twilight

VIII. Quintessence

IX. Echoes and Regrets

Note.—The words below the Vignette may be thus translated:

Earth, the Root, and Heaven, the Hue;

Marsh of Mire, and Flower of Blue;

A Dead Lotus

I

To the pitchy dark of that awful wood,[1] where plunging Ganges lost her way through a night of a thousand years: when the lonely Moon turned ashy pale, mocked by a million moons that danced in the hollows of the rushing waves: we bow.

On the edge of the great southern forest, there lived, a thousand years ago, an aged King and Queen, who counted all the world as grass, for want of a son and heir. And finding all other methods fruitless, in the end they gave themselves wholly up to meditating, night and day, on the sole of the Great God's foot: until at last Maheshwara felt pity for that childless couple, and revealed himself to them both at once, in a double dream. So when he asked them what they wanted, the King asked simply for a son. But the Queen, being smitten with deep devotion at the sight of the Great God's moonlit hair, exclaimed: O Boon Giver, let my son resemble thee, were it only in a single fraction of an atom of his being. Touch me now with the very end of one of thy tangled locks of hair, and so shall I become instinct with a tiny portion of thy divinity. Then said Shiwa to himself: Even a single jot of me will be much too powerful for the rest of this human being's substance, and disturb the balance of the whole. But be it as this mother wills. For she has made her choice, and I granted the boon beforehand.[2] And I can see that he has to dree the weird[3] of his former births.

Then he took from his head a single hair, and broke it off, and placed it in her hand. And then he disappeared, and that royal pair awoke, and eagerly compared their dreams, which corresponded in every particular. And when they looked, lo! shut fast in the hand of the Queen was a single hair, that glowed like a wire of flame.[4]

Then full of joy, they worshipped the God: and they placed that hair in a golden shrine, and built around it a temple. And when in course of time the Queen gave birth to a son, they called him by a suitable name, Rudrálaka.[5] And as the baby became a child, he did not belie his name. For his thick dark hair was shot with a tinge of gleaming red, and in the sun it shone like fire, and it resembled the mane of a horse. And as the boy became a man, his strength became prodigious; and his passions were wild and furious and proportioned to his strength. And he was as unruly and unmanageable as a young colt of high spirit, and so full of wayward obstinacy and headstrong self-will, that his father said in private to his mother: Now, but that the hair in thy hand was red, this son of thine would seem to take after, not the Great God himself, but his bull.[6]

And when his manhood was complete, like a river in flood in the rainy season, it overflowed all common bounds. And he ran wild among men and women, overcoming all the men in every feat of strength and agility, and like a great black bee in a flower garden, rifling all the women of their honey and their hearts and their good behaviour, and playing havoc among them, till the mischief created by his own red hair began, as it were, to turn that of his father and mother white. Then they said: Come, we will marry him, and then no doubt he will settle down and become clear, like strong wine after fermentation, and turn into a pillar of his family and the state. But as soon as they proposed it, Rudrálaka laughed in their faces. And he exclaimed: Who carries a flower, when it is faded, and what are women but flowers, fit only to be gathered, in the moment of their bloom, and worn for an hour and thrown away? And he is wise, who knows how to get from the bee its honey, and yet elude its sting. Now a maiden is all honey, but a wife is a buzzing sting. Moreover, women are like mountains, and like snakes, and fire, and the mirage, beautiful in the distance, and the further off, the better: and like them, rugged, and biting, and burning, and luring to destruction all who come too near. But of all things this is worst, that every woman wishes, like a king, to reign alone, and is utterly unable to endure the very name of rival, even in her dreams: so that every husband has in his wife, either a despotic tyrant, or an exasperated foe, whom nothing can appease or soothe but absolute submission. And thus his life is sapped and sucked and drawn into the being of his wife, till it wholly disappears, like that of a noble tree, embraced and treacherously kissed into a premature decay by a beautiful and clinging creeper. And no matter how glorious the flower, I will not be the tree: nor would I buy a wife, were she ten thousand times more beautiful than Rádhá, by the slavery even of a single day. And what is the need to pay so dear for things that are always ready to give themselves away for nothing, and would rather give themselves away than be bought at any price? For women are always longing to give themselves away, and care only for men that they do not know: being forgetful of all kindness, and unbound by obligation, and seeing in their husband nothing but his faults; while every passing stranger has their heart, as soon as he appears, just as long as he is strange. For Love is himself a stranger, and cannot become familiar without ceasing to be Love: and women live for Love alone, being, like flowers, nothing but his instruments: and he is like the amber, and they are like the grass.

So when they found that, in spite of all that they could say, he would not be persuaded, but that the more they tried, the harder grew his obstinacy, his parents gave it up. And soon afterwards, their hearts broke with grief, and they died, leaving him unmarried, and fearing for him, and the kingdom, and their ancestors, and themselves, lest all should go to ruin by reason of the incorrigible perversity of this cutter of their race's stalk.[7]

And then, just as though he had only waited for their death, no sooner had his two parents gone away on the great road, than this marriage-hating son of theirs went hunting in the forest. And he rode a horse of spirit like his own, which after a while broke from control and fled at full speed, carrying him in an instant out of sight of all his attendants. And it brought him, deep in the heart of the wood, to his destiny, in the form of a woman, the daughter of an old ascetic, whose beauty, like a deadly snake, bit and slew, in a single moment, his antipathy to the state of marriage, by the poison of its childlike charm. And utterly beside himself, he wooed her then and there, and brought her home on his own horse, and made her his wife and Queen. And she changed him so completely, that he to whom a wife was slavery, became a woman's willing slave: so much so, that he could not bear to let her out of his sight even for a single instant. And he became, like an image of Arddhanári,[8] inseparable from his wife, holding her in his arms night and day, and chafing, like a wild animal kept without food in a cage, if she left him only to drink water. And the God of the flowery bow laughed, to see his infatuation; and he said softly to himself: A converted scoffer is, after all, the best adorer: for even a very clever swan would fail to separate this milk-and-water.[9] But the King's subjects were overjoyed; and they said: Now, then, his parents will be happy. And if his passion is so violent, that at present he utterly neglects his kingly duties, no matter. For when it has become cool, he will be the very crest-jewel of his race.

And then, while he was entirely bewitched and enthralled by his passion for his new young moon of a bride, some neighbouring kings, his hereditary enemies, hearing of his condition, and seizing their opportunity, combined together, and attacked him. And after a while, his subjects on the frontier, being ruined, paid no taxes. So driven by necessity, he said to his wife, with a sigh: There is no help for it, and now I must absolutely leave thee for a little while, to pull these thorns up by the roots: for if not, the kingdom will be destroyed. Yet only for a very little while: for I will return almost before I have started. And collecting his army, he put himself at its head, and threw himself upon those kings, and scattered them like leaves in a storm of wind, and reduced them to beg for mercy: for he was beside himself with rage, seeing in them not so much enemies of his kingdom as causes of his unwilling separation from his wife. And having speedily gained his object, he sent relays of horses, and posted them at intervals all the way from his camp to his capital. And then at last, one morning, he mounted a horse, and started with but one attendant, and a heart on fire, to return to his wife.

So they rode, all day long, at full speed: stopping only as long as was necessary to let them leap from one horse to another, as if wishing to rival the sun in his course; till that unhappy companion of the King was almost dead from fatigue, for he was not supported like his master by the burning desire to arrive. But the King rode on as it were in a dream, seeing nothing before him but the edge of the far horizon, and the image of his wife beyond. And so the day went by, and as the sun was going down, they drew near to the capital, and saw its walls before them, away on the distant plain. And the King uttered a shout, and he drove his spurs deep into the flanks of his flying horse, and left his follower far behind. And he rode into the city like a whirlwind, and dashed through its streets, scattering the people, and spurning them as it were from his horse's hoofs. And he reached his palace, and rode through the gates into the court, and threw himself to the ground. And he stood on the palace steps, and called aloud with a joyous voice: Ho! go quickly, and tell the Queen that the King has come, and waits only for her permission, to kneel at her lotus-feet.

Then the guards, who stood around, gazed at the King and at each other, in silence and dismay. And as they waited, there came to the King an old chamberlain, who stood before him with joined hands, and stooping; and his face was grey with fear. And he said, with a shaking voice: Let the King show mercy. Has he not met the couriers? The Queen died of a burning fever, only three days ago.

And the King fell to the earth, as though one had struck him on the head with an iron club.

[1] The hair of Shiwa, who caught the Ganges as it fell from heaven upon his head. It took the river a thousand years to find its way out.

[2] [Greek: Theus anaitíos, aitía d' heloménou.]

[3] I must ask the reader to excuse me for using a Scottish expression, for there is no English equivalent. It means to work out the fate that is laid upon him by what has been done in a previous existence.

[4] The English reader should know, not only that the Great God's hair is red or tawny, but that he has in his nature a strain of wildness, something on the border-land of insanity.

[5] The hair, or the abode, of Shiwa.

[6] Nandi, whose hair is white.

[7] Because, as Lucian said, without an heir to perform the due ceremonies, the unfortunate shades would have to go hungry and thirsty.

[8] Shiwa and Párwatí combined.

[9] Kshira nira, milk-and-water, is a technical term in Hindoo erotics for a very close embrace. The swan is credited by Hindoo poets with the power of separating the two: a curious idea, of which it is not easy to see the origin.

II

And they took him up, and carried him in, and laid him on a bed. And there he remained, like a dead man, and for so long, that they begun to doubt whether he were not dead indeed. But at last, the physicians by their remedies brought him back to the body. But his reason had fled. For he raved and fought, struggling with the strength of a giant, and biting like a wild beast, tearing his own hair, and shouting for his wife. And he threw himself upon his attendants, and handled them so that they feared for their lives: and he ran through the palace hunting for his wife, and calling her by name. And when he could not find her, he fell on all whom he met, and beat them, and came so near to killing many, that at last his ministers took counsel, and caused him to be bound. So after raging for many days, taking neither food nor drink, he fell into a burning fever, as if he wished to follow his wife by the very road she went herself; and he lay for many weeks on the very threshold of the door of death. But his strength was such that he could not die. And so, after a long while, he came back, very slowly, and as it were against his will, to life and to himself: and little by little recovered health, and took once more to his kingly duties, and the bearing of the burden of the state. But it was, as if his better part had died, refusing to be parted from his wife, in the other world, and leaving behind in this only so much of his soul as was necessary to enable him to live at all. For he never moved from his palace, roaming about its rooms, always silent, and always alone, with his head sunk down upon his breast, and his sad eyes fixed upon the ground: and over his dark face there never passed the whiteness of a smile: for his dead wife's shadow lay across it, and her figure moved before him night and day; and her sweetness, not to be forgotten, and never to return, rankled in his heart like a thorn, and goaded it, and gnawed it, and festered in his soul: and sleep forsook his eyes, which were wild, and haggard, and such that all who saw them feared him, and were wary in his presence: for every now and then he broke out into paroxysms of grief mixed with laughter, during which he seemed, as it were, not to know what he was doing, and was as dangerous to approach as a wild mother elephant robbed by hunters of her calf. And so he lived, and months went by, and the grey hairs came before their time and settled in his head, and sowed as it were its fire with the ashes of grey grief: and age saw her opportunity, and began unheeded and unhindered to furrow wrinkles in his brow, and dig deep corners at the ends of his stern shut lips.

III

Now it happened, on a day, when the Great God was roaming through the sky with Umá in his arms, that they passed close by the moon. And suddenly, they heard in the stillness a mournful voice, like the note of a chakrawákí bewailing her lost mate, exclaiming at intervals: Alas! alas! So they stopped and alighted on the surface of the cold-rayed orb, and wandered about in his camphored air, guided by the sound, till they came all at once upon a Siddhá.[1] And she was sitting under a sandal tree, leaning her head against the trunk, with large tears in her great blue eyes, and a cloud of dark dishevelled hair floating about her bare white bosom, whose two colossal pearls rose and fell, heaving and fretting as if regretting their absent ocean home. Then filled with compassion and curiosity, Umá exclaimed: What can be the meaning of this sighing Siddhá? And Maheshwara divined the truth. But he said: Ask her. Thereupon Párwatí said: O thou lotus lady, what is thy trouble? And the Siddhá said: O Daughter of the Mountain, I have attained, by superfluity of merit, to this position of a Siddhá, which notwithstanding is only a grief and no pleasure to me. For I remember my former birth, and I can see my husband, sorrowing for my absence away below. And now I would give all that remains of my unexhausted stock of accumulated merit for a single moment of the time that is past, did it last no longer than the twinkling of an eye. For what is the use of my Siddháhood, or anything else, without my lord? Or why am I cursed with reminiscence, and not rather rewarded with oblivion? For memory binds my soul, and links it like a red hot chain to the burning fire of a dead delight.

Then Párwatí said in private to the God: Canst thou not do something for this lovely Siddhá? And Maheshwara replied: This is the nature of women, that for the sake of their single lover, they would annihilate the three worlds. But what has pity to do with the constitution of the universe? Or how can time return again, and all be thrown into confusion, simply to allow two foolish lovers to meet once more? So there is nothing whatever to be done. But Párwatí coaxed him and cajoled him, knowing the power of her two white arms, until at last he said: Since I can refuse thee nothing, and thou art absolutely set upon it, I will, to please thee, cause these two unhappy persons to re-enact their little drama, and taste again the nectar of that love which they so much regret: but only in a dream. For dreams were established by the Creator for this very reason, that a remedy might be found for the irrevocable nature of reality. For that must be as it has been, and cannot be recalled or changed: but anything may happen in a dream. And yet, this pair of lovers would be wiser, were they content to let alone, and leave things as they are. For they will but make their misery more, by the very means they wish to take to lessen and remove it. But be that as it may.

And then, he cast upon the Siddhá a kindly glance. And he said: Silly child, that wouldst be wiser than those who framed the three great worlds, be now consoled. Thou shalt, at least, have thy way, for a little while, and meet the lord of thy heart again, halfway between heaven and earth.

And hearing this, the Siddhá fell before him, and took his foot, and kissed it, and placed it in her bosom. And she said: O saviour of the shipwrecked that are sinking in the waves of time, O send me thy succour soon, for I am like one dying of thirst in the desert for the blue water of my husband's arms.

[1] The moon, according to some philosophers, is the home of those pure spirits, who have purged themselves in former births sufficiently to deserve a certain grade of beatitude or bliss.

IV

And at that very moment, the King her husband on the earth was sitting in his palace hall, musing on her memory, and dreaming of the past, and listening to the musicians, playing before him as he sat. So as they played, as luck would have it, they fell upon an air, which ran into his heart, and pierced it like a poisoned needle: for it was the favourite air of his vanished Queen. And as he listened, the tears came rushing into his eyes, blinding them with love-longing and the blackness of despair. And he started up, and called aloud, in a voice of thunder: Away! begone! Wretches, have ye conspired together to break my heart in two? And instantly, those unlucky players stopped affrighted, and fled before his wrath like hares. And as all shrank before him, the domestic chaplain came forward, and said politely: O King, without are waiting certain merchants, jewellers, who have come here by appointment, to lay their jewels at thy feet.

Then the King said, with a sigh: What are all their gems to me? And yet, no matter: let them all come in.

So in came all the merchants, and showed the King each what he had. And the King went up and down, saying sadly to himself: Now every pleasure is a pain, and every joy, a grief. For what are jewels to me, now that she is no more, on whom I would have hung them till she sank beneath their weight? And then, as if in irony, he took the jewels and began to put them on himself. And taking from the merchants all they had, he hung himself all over, loading himself with gorgeous gems, with emeralds and rubies, and pearls and amethysts and diamonds, and sapphires, and every other stone, till he flashed as it were with a thousand hues, and resembled an incarnation of the spoiling of the sea.

So as he went from one merchant to another, adding to his store, he came suddenly on an old merchant, who stood a little apart from the rest, with nothing visible to sell. And his head was of enormous size, and bare,[1] and bald on the top, and from its sides long thick white hair ran down over his shoulders, and mingled with his beard. And his face was wrinkled all over, like the skin of a withered fruit. And the King stopped and considered him, amazed at the extraordinary size of his head, which resembled a monstrous gourd. And then he said: Ha! merchant: thou art idle. Where are thy valuables, and what is thy commodity? Doubtless that must be a treasure, which thou keepest wrapped away so carefully from common eyes. But come, produce it: that I may add it to all these. Then said the merchant: All these are well enough: and yet, the thing that I have brought the King is more than all together, and yet again, less than the least. Then the King said: Of what, then, art thou a seller? And the merchant said: O King, I am a seller of dreams.

And the King looked at him awhile, and was seized with sudden laughter. And he exclaimed: What is this, and who ever heard of a seller of dreams? Art thou mad, or art thou only an old buffoon? Then that old merchant fixed his eyes upon the King. And he said:

O King, who can tell, whether he is mad or not? But as for me, know, that mine are no common dreams, but they are such as many would give all they had, and more than all they had, to dream. For I can make the past present, and I can find that which is lost, and join together whom time has parted, and turn regret to laughing joy: and I can mend the broken-hearted, and bring love's fierce emotion back, and into faded flowers of passion I can breathe again their old sweet bloom, and make to echo in living ears the music of lips that have long been dead.

And as he spoke, the King stood, and his heart rose up into his mouth. For the words of the old merchant played on it, as if it were a lute, and tugged at it like a cord; and the memory of his wife surged suddenly in his soul, and swept it like a wind. And all at once, he seized that old man by the throat, with hands that trembled with the ecstasy of rage, and shook him like a leaf. And his voice faltered with passion, as he said: Old fool, dost thou mock me? Dost thou promise, without performing? Beware! for thou art playing with a fire that will shrivel thee like a blade of grass.

Then said the old merchant, with laughter in his wrinkled eyes: O King, thou art a child, not recognising thy physician, and seeking a quarrel with the only one who can give thee a medicine suited to thy case. For I am a physician, not of the body, but of the soul. So now, tell me: wilt thou buy from me a dream, or not? And the King looked at him for a moment; and he drew a long breath, and the tears stood in his eyes. And he said: Sell me indeed a dream, such as I wish, and thou hast described, and I tell thee this, that I will not haggle with thee over the price. Then the old man laughed softly, and he said: Maháráj, who ever speaks of the price, before he has seen and tried the goods? First, thou shalt have thy dream; and as to the price, we will leave it: and thou thyself shalt name it, at the end. For maybe, didst thou know the price, thou wouldst hesitate to buy at all.

Then he put his hand into his breast, and drew out a little flask. And he held that little crystal flask up in the air, looking for a ray of light. And when he could not find one, that old man muttered under his breath: Sun, sun, send me a ray. And at that very moment, there shot into the room a ray of light, right on the little flask. And then that old man said: O King, see! this is a little of the very essence of the nectar of the cold-rayed moon, where I have been this morning, to fetch it from that lord of herbs. And the King looked, and lo! there danced in that little flask a liquor that laughed and bubbled, and its deep blue was exactly the same as the colour of his dead wife's eyes. And like them, it smiled at him, changing from hue to hue, till it seemed to him that those very eyes were looking straight into his own, out of the little flask. And quickly he put out his hand, and snatched it, and took the stopper from its mouth. And there came from it a perfume that carried to his nostrils the scent of his dead wife's hair. And his brain reeled, and he put it hastily to his lips, to drink. And as he did so, suddenly there came into his head a thought. And he paused in the very act, looking at that old merchant, out of the corner of his eye. And he said to himself: Ha! What if this old seeming merchant were an emissary of those foes of mine, whom I defeated, to give me a deadly draught? Or even so, what matter? Let me drink quickly, the more poisonous, the better. For life without her will not be worse, even when turned to death.

And then, at a single gulp, he drank the contents of the flask. And instantly, he sank back, and lay on the cushions on which he fell, buried in a magic sleep.

But as soon as he saw that the King slept, that old merchant stooped down, and squatted quickly on the floor, with his two hands grounded between his feet, and his knees reaching to his ears. And there he remained, with closed eyes, couched in the pitcher posture like a lonely, water-watching crane, and still, as if he had been painted on the wall.

[1] I.e. he had no turban on. In the East, on entering a house the head remains covered; it is the shoes which are removed.

Love's Looking-Glass

I

SKY-CRYSTAL

But the King's soul rose out of his body, like a snake escaping from its slough. And he hovered for only a single instant, over that empty shell of him, lying, loaded with priceless gems, on the floor below, and then shot up into the blue sky, like a flame parted from its wick. And as he flew like a thought through space, going like the wind he knew not where, the King said to himself: Ha! so then, I was not deceived. Certainly, that old impostor was not a merchant, but a secret agent of my foes, and now I am dead, beyond a doubt. And that delicious poison was as speedy as it was beautiful and sweet. And now I can say farewell to life without regret. And yet I should like to know, where in the world I can be going.

So as he floated in the air, bathed in unutterable peace, there came over his mounting soul a feeling of supreme disdain and loathing for his body that was lying down below. And he said to himself, as he closed his eyes: Ah! joy, for I have left behind that wretched sheath, with all its poor surroundings and its miserable mundane ties. I have emerged, as it were, from a charnel ground, and surely that divine liquor was, as that old vendor said, a very potent essence of nectar and celestial wine, mixed of the icy camphor and the oozy juices of the moon.[1] For I feel like one intoxicated, and I swim, as it were, in perfume, whose pungent and excessive sweetness almost robs me of my giddied sense; and I lie on the azure ether as if on a silken couch, poised as it were between earth and heaven, and yet I seem to soar like some earth-despising spirit-roamer in the sky.

Then after a while, he opened his eyes, and looked round, and saw himself alone in the vault of space, surrounded by the stars. And he was rushing like a comet[2] through the mansions of the moon, and he saw Chitrá, and Swáti, and Rohini and the Hunter,[3] and the rest, and far in the north, the polar star. And he looked down on the Seven Rishis,[4] and saw, far below him, the icy summits of the Snowy Mountain, with the yellow digit of the moon clinging to the peak of Kailas, like the earth of old on the horn of the holy Boar.[5]

And then suddenly, memory pierced him like a needle. And he cried out: Alas! I am still alone, and in this respect, even death has brought no change. And what then is the use of death, if it does not restore me to my wife? And what is the use of this rushing speed? For I am hurrying, against my will, into the very zenith of infinite space.

And even as he spoke, he stopped, and hung in the air like a fleck of cloud. And strange! as if the very thought had produced her, suddenly he found his wife in his arms. And as her own arms glided around his neck, and her bosom beat against his own, his hair stood on end with amazement and delight. And he heard the beating of his own heart, throbbing like thunder through the realms of space. And just as he was going to speak, she stopped his mouth by kissing him with soft lips opening into a smile, and eyes that reflected the colour of the sky. And she said: Quick, let us lose no time. Then he said: Ah! couldst thou die, leaving me without thee in that hell below? Then she said again: How can mortals disobey, when destiny decrees? It was from necessity that I left thee, and not from choice. But let us quickly make the most of a little time, granted only by the favour of the God who has the moon in his hair, and destined to end and disappear almost as soon as it has begun. Dost thou remember how we met, and saw each other first of all, away in the wood below? Come back now once more with me, and let us live and love again, and taste the nectar of repetition, before we part to meet no more.

And instantly the King lost his senses, and lay in a dream within a dream. And as they floated in each other's arms, between the heaven and the earth, the past rose up out of the dark, before him, spread like a picture before his eyes and breathed like a tale into his ear.

[1] Three things are essentially associated in Sanskrit poetry with the moon—icy cold, camphor, and the medicinal virtue of drugs.

[2] Falling meteors, says the Brihat Sanhita, are the fruits of virtue enjoyed in heaven dropping in visible form.

[3] Orion.

[4] The Great Bear.

[5] Wishnu, who in his third incarnation became a boar to support the earth: jaya jagadisha hare!

II

SPRUNG FROM THE MUD

And once again, he rode through the forest at headlong speed, and the trees flew by him like frightened shadows, while his horse ran on, and carried him swiftly whither it would, into the forest depths. And then at last, it stopped short, on the very edge of a great river, close to an aged banyan tree, whose hanging roots dropped from the branches to the ground, and with their network almost hid a little ruined shrine, whose roof their pillars pierced and split, and whose steps ran down into the stream beneath their sacred shade, where the quiet water was littered thick with lotus flowers and floating withered leaves. And there he fell from his horse's back and threw himself upon the ground: and he and his horse together slaked their intolerable thirst, with neither eyes nor ears for aught, till they had drunk their fill. And then, with a wisp of leaves and grass, he began to wipe the foam and sweat from the quivering limbs of that noble horse, dearer to him, till that very moment, than anything else on earth.

So as he stood, wholly intent on his horse and his work, he heard behind him a little rustle, and a low cry. And he looked round. And in that instant, like a flash of lightning, he utterly forgot his horse, and himself, and everything else in the three worlds.

For there, standing a little way off, under that old root-dropping fig, was one who resembled the guardian spirit of that virgin forest's enchanted beauty, caught in the very act of changing into a feminine form, and leaving him in doubt as he gazed, whether she was a woman or a tree, or a being mixed of both. For the coarse red bark that clothed her left bare her arms and feet, which were shaped like those of Hari's darling,[1] and it cased and swathed her soft round limbs, allowing them to escape, like the calyx of a new young flower, or a rough hard husk on the very point of bursting open, by reason of the ripeness of the tempting fruit of womanhood, hardly to be held within. And a spray of blue convolvulus[2] hung twining all about her, trailing like a creeper from her hair, which was twisted up into a great dark knot on the very top of her pretty head, and hung there like a purple bank of thunder-cloud, out of whose shadow her great blue eyes looked round as the moon with wonder at the thing they saw before them. And her chin was very pointed, shaped like a pippal leaf, and over it the mind-born god had set the seal of his bow in her face, black in the twin-arch of her brow, and red in her juicy bimbá lips. And astonishment flushed her cheeks, like fruits, with a spot of damask blush, like bloom. And a single lotus, red as blood, nestled in the little hollow dip between the mounds of her rising breasts, upland hills where the robber Love lay lurking, to spoil the traveller of his heart. And the sweeping curve of her heavy hips stole the eyes of the King away from her slender clasp-inviting waist, till it came to an end in the nook of her inward-bending knee. And her left hand rested gently on a pillar of the tree, while her right was stretched before her, bending back, palm upwards, with all its fingers spread, till the tip of its forefinger just touched her lower lip. And Love fished for the King's soul with her lovely wrist and arm, and took it in their net. And she was standing bolt upright, poised like a flower on her left foot's toes, with her right foot just behind it, exactly like a graceful fawn suddenly frozen into stone when running at its utmost speed by the sight of danger in its path. For she stood absolutely still, save that the lotus on her breast was lifted quickly up and down by the flutter of the maiden-wave on which it swam.

So they two stood, still as death, each thunderstruck by the other's vision, like a panther and its prey.[3] And then at last, after a time that seemed to each in spite of its length but a single instant, for each was lost in the other, standing on the threshold of Love's dream-bower where years are moments and time lies dead, she spoke, and broke the spell. And she said, softly: It is a man. Surely, thou art a man? And the King said, with a smile: O maid, what else? Then she said again: And thy companion, what is he? And the King said: He is a horse. Then she clapped her hands together, and exclaimed, as she held them joined: Ah! stand still a little longer, and let me watch both him and thee. For I have never seen before, either a horse or a man. So he stood still as she desired; and as she watched him, he watched her. And her blue eyes rested on him, and entered into his soul, and shook it so, that he began to tremble all over with the horror of extreme delight. And he said to himself: I too, I too, see a woman, for the very first time in all my life; which, till this very moment, has been wasted and empty and worthless, and contemptible and without a point. Ha! I am like a dark black night, that has suddenly been flooded with the rapture of a golden sun. O hail! O bright great God, in the form of that blue-eyed beautiful thing before me, that fills me with astonishment and laughter and supreme delight. And presently he said: O thou with the blue flowers in thy hair and the blue wonder in thy enormous eyes, that resemble those of a child, how can it be that in a world so full of them, thou shouldst never yet have set those eyes on either a man or a horse?

Then she started as if from a dream. And she came up close to him, and raised her hand, as though she would touch his arm: and barely touched it, with a touch like that of a leaf, which struck the King like a heavy blow. And she said, looking up at him, doubtfully: But O thou great, beautiful, deep-voiced man, how should I see either? For out of this wood I never was, and into it nothing ever comes, and in it are only its own trees, with the flowers, and the river, and the forest beasts, and my father and myself. Then the King said: Thy father? And is not he a man? And she said: Nay, if thou art, he is not. For he is old, very old, and smaller even than myself, and his hair and beard are thin and white, and his arms and legs are rough as bark, and dry and thin as sticks. And he sits always stiff and silent, plunged in meditation, resembling the stump of an ancient tree: and it is the same as if he were not alive.[4] And if thou wilt, I will show him to thee, a little way within the wood: and yet, it were better not, for it would but distract his meditation. But thou art tall and straight and strong, and glorious, and young like me: and yet far bigger than myself! for see! how even on tiptoe I reach hardly to thy shoulder. And thy hair is like the lion's mane, and thou art like him to look at, and wonderful in every way, and such as I could never have believed. For often I have thought of men, and wondered what they could be like, but never dreamed of one like thee. Look only at my hand, and thine, or at my arm, or foot, and thine, and see how small and weak[5] a thing I am, compared with thee!

And the King looked at her, as she spoke; and when she ended, he began to laugh for very joy. And he said: O beautiful little blue-eyed creature, thou dost not know thy own strength, nor where it lies, but how as to thy mother? Hadst thou, indeed, a mother, or didst thou not rather grow, like a flower, out of some forest tree? Then she said: Nay, I had a mother: but alas! long ago she went away, before I can remember. For she was a heavenly Apsaras, whom Indra sent down here below, to tempt my father in this wood, and turn him from his penance.[6] And she came and stayed with him awhile, and afterwards she went away, flying up to heaven, and leaving me behind her with my father in the wood. And the King said: I do not blame thy father: what wonder, indeed, if she overcame his resolution, did she resemble her future daughter, even a very little? And thy words require no other witness to their truth, except thyself. For beyond a doubt thou art the very daughter of an Apsaras. Then she said: And hast thou ever seen an Apsaras? And the King laughed, and he said: Nay, not until this moment. But come now, let me only tether my horse to yonder tree, and then, if thou wilt, we will sit and talk together. And I will be thy playfellow, and will tell thee things that thou dost not know, and thou shall tell me of nothing but thyself.

Then she said joyfully: Ah! tie him, and come quickly. And the King stood looking at her for a moment, and then he said: Sweet Blue-eyes, and art thou not afraid of me? And she looked at him enquiringly, with no shadow of suspicion, and said: Of what should I be afraid? For art thou not a man, and which of the Creator's creatures injures its own kind? And the King gazed into her soul, through the window of her clear and smiling eyes, and again he laughed aloud for sheer delight. And he said to himself: Ha! exquisite is her intoxicating simplicity, in that she does not know, that man alone is the exception to her rule. And then he said: Sweet forest flower, what if I were tempted to pluck thee, and carry thee away with me on my horse? And yet, fear nothing: for thou art very right, and I am, of all the Creator's creatures, the one who would be most loth to do thee harm. And men were made strong by the Creator for this very reason, to guard such wonderful weak things as thee. And he said to himself: Now, let my followers only not find me till the evening, and by the favour of the Deity, I will win the trust of this bewitching maiden, and get her to come away with me. Or if not, I will stay in the wood with her for ever, becoming for her sake like one of these forest trees, rooted to the spot.

And then he took his horse, and tied him to the tree. And then they went together and sat down upon the moss-grown steps that ran down into the river: he on one, and she on another, just below.

[1] The Hindoo Aphrodite.

[2] The Kámalátá is commonly described as red: this was perhaps some kind of Ipomæa, allied to the great white moon-flower of Ceylon.

[3] An "old shikarri" told me, that he saw on one occasion a panther stalking a goat. As soon as they saw each other, they both stood stock-still, so long, that at last the goat concluded his panther was a mere illusion, and recommenced his dinner, browsing with unruffled mind. He would have paid dear for his simplicity, had not his crafty stalker been this time stalked himself.

[4] These ancient forest hermits, who lived alone in jungle, doing penance and eating nothing, are one of the conventions of Hindoo fairy stories. Such a one, like the mediæval saint, a bundle of bones whose breath corrupts the world before his death, generally has a daughter, to whose rare beauty he forms the contrast: that sharp, fierce contrast, which is the essence of the East, like life and death.

[5] Abalá, "weak," "without strength," is a common Sanskrit word for a woman, Vas infirmius.

[6] Indra is represented as jealous of all ascetics, lest they should reach his total of a century of sacrifices (Shatahratu). But his battle with Raghu on this head ended in a compromise (vide Raghuwanshä, canto iii.).

III

PURUSHA AND PRAKRITI

And then, for a little while, he sat in silence, looking now at the river, and now at her. But she gazed at him with great eyes that never left him for a moment, and saw nothing but himself. And suddenly he said to her: Blue-eyes, Blue-eyes, how long is it, since I met thee in the wood? Then she said: It is but a single moment. Then he said: Thou art utterly mistaken: it is more than many thousand years. And as she looked at him in wonder, he exclaimed: Ha! there it is again, and O how beautiful thou art! O thine eyes are full of wonder and my soul is full of joy. Dear child, see, yonder is the river, flowing as it has been flowing ever since it first began; and here am I, to thee the first and only man, for thou hast never seen another, and there art thou, for me the only woman, and her very type and soul. And like the ancient Soul of Man,[1] I have been wandering about, forlorn and wretched and lonely in the dark without thee, and now at last I have found in thee my Prakriti, since thou art the very spirit of the beauty of this wood, incarnate in a woman's lovely form. And as I look at thee, laughter seems to fill my soul, for joy that I have found thee, and I feel as if, like thee, I had suddenly become a child, whereas before I was a man. And all this has come about in the moment since we met, a moment which is like a door, opening on one life, and closing on another, and it resembles the beginning and the end.

Then she said: I do not understand thee: yet speak on, without stopping: for I could look at thee and listen to thy voice, for ever. And the King said: Blue-eyes, if thou dost not understand, no matter: and possibly I am speaking at random words without a meaning, for thy great eyes deprive me of my reason, and I know not very well what I say. But now it is thy turn. And tell me, what dost thou do with thyself alone in this empty wood? Hast thou companions other than myself? Then she said: I have for companions the deer of the forest, and the parrots that live in this great tree, and the peacock that thou seest yonder on the temple wall, and the crows that come to eat the daily offering, and the flowers which I water and wear woven in my hair. And I have many things to do. For sometimes I ramble in the wood, and hunt for flowers, and watch the monkeys and the squirrels that play in the trees: and when I am tired, I sit still, playing with my hair, and rolling and unrolling it, for it is longer than I am myself and a trouble and a hindrance to me, till I knot it up thus out of the way on the top of my head, like my father's.[2] And sometimes I go and see my father, but I am afraid of him, for though his body is there, his soul is almost always absent from the body. And sometimes I sit by the river, when the wind is still, and watch in its mirror the clouds that float in the blue sky far below, like the swans upon its wave. And the river itself is a friend to me, for every day I bathe in it, and I often sit and wonder whence it comes and where it goes, and look to see what it carries down: and in the rainy season it changes, and grows red and angry, and murmurs and chafes, and swells till it reaches to the very foot of the tree. And sometimes when the moon is full, I hide in the hollow trees at night;, and peep out at the elephants as they wander down to drink. And the King said: But do the other animals not molest thee? Then she said: Nay, for they dare not: for they all know my father well, who understands their language, and has warned them. And they fear him, lest he should curse them if they harmed me, and keep them from ever rising up into humanity, being prisoned for ever by the power of his curse in the dungeon of their creeping[3] bodies. And the King said, with emphasis: Aye! they who should injure thee would indeed deserve to be immured for all eternity in the lowest of all living forms. And I thank thy excellent old father for preserving thee under the shadow of his awful curse. And yet, for all this, surely thy life was lonely? Didst thou never long for a companion of thine own kind, such a playfellow, for instance, as myself?

Then she said: Though I knew it not before, yet now that thou art come, I see that I was lonely. For often I used to watch myself reflected in the water, and talk to my image, and wish that it could answer me. And sometimes in the moonlight I would play with my shadow, and wish, oh! so much, that it could come to life. And often I used to long, not knowing what I wanted; but now I am very sure that it was thou. And when I look at thee, and hear thy voice, I cannot understand how I could have lived without thee. For thou art like another self, made visible in a human form: and yet thou art other, and more than that first self, which is I.

And the King gazed at her, with fire in his veins. And he said to himself: She is innocence itself, in a virgin form of matchless and incomparable beauty, and speaks without understanding the meaning of her own words. For love lies hiding, lurking in her soul, and yet she does not know it. And yet, though she does not, I know well, and only too well, now, what it is to be in love: for she burns my heart like a flame, all the more, that she is utterly unconscious of the power of her own beauty. And then he said: Blue-eyes, canst thou tell me this? Say, wouldst thou rather that I were in very truth the double of thyself, like thy image in the water, a woman, and not a man? And she answered, without hesitation: Nay, it is better as it is. And the King trembled with joy. And he said: Yet why? Then she pondered for a while, and then she said: I cannot tell. And yet I feel, that I would rather have thee different from myself than the same; and yet I know not why. But what does it matter, why? since it is better as it is. And the King said with emotion: Sweet, thou art right. Aye! it is far better, and it does not matter why.

And as he spoke, there came a murmur, and a rushing sound in the air. And he looked up in terror, and listened, and exclaimed: Ah! what is that? Then she said: It is nothing but the sighing of the wind in the hollows of the young bamboos.

[1] Purusha and Prakriti answer, in a sense, to our Adam and Eve: as the Germans would say, the Ur-mensch and Ur-weib of the world.

[2] Ascetics wear their hair twisted in a knot, in imitation of the prince of them all, Maheshwara.

[3] When Ovid contrasted the os sublime of man with that of the animals, he gave expression to the idea that underlies the curious Sanskrit term for the brute-creation, the horizontal-goers (tiryag-játi).

IV

BUBBLES

And the King sighed also, with relief: for he feared that his followers had found him in the wood. And then he said: Blue-eyes, hast thou a name? Then she said: I have only the name which was my mother's. And the King said: What was that? Then she said: Long ago, when my father first saw my mother in the wood, she was standing by a bush, which had just burst into blossom all over, as if by the touch of her foot.[1] And the bees were humming and bustling eagerly all about it and her, as if they wished to kiss her, and my father saw it, and he called her by a name of his own, that has come by inheritance also to me. For my father has never called me anything else. And the King said: And what then was the name? And she said: Alichumbitá.[2] And the King clapped his hands, and exclaimed: Certainly, thy father is admirable, and thy name appropriate. And sure I am, that there must be more than the name of relationship between that happy bush and thee. And I am tempted to believe that thy story of an Apsaras was false, and that thou hadst for a mother no other than the very indwelling spirit of that sweetly-scented, bee-haunted bush. Then she said: Nay, my mother was an Apsaras. And the King exclaimed: How shall I believe thee? For already I am beginning to doubt whether thou ever hadst either mother or father, and wert not rather directly compounded by the Deity himself in the form of a bee, going from flower to flower, and culling thy composition out of every flower's fragrant essence and every blossom's painted bloom. And she said laughing: And what then was thy composition? And the King looked at her joyously, and said: The Deity was thy creator, and thou art mine. For I never lived until this moment, and this is all thy doing. Thou hast found me like an empty shell, and filled me with colour and emotion and the salt of beauty and the sound of laughter and the tossing to and fro of the waves of pleasure and delight. Now put me to thy ear, and I shall echo like the sea. Then she said: Once more, I do not understand. And the King said: O ocean, no matter. But thy shell must murmur, being full of thee, whether it will or no. And yet, this at least now thou dost surely understand, that I was right, and that ages have elapsed, since we met each other a little while ago in the wood. For I have utterly forgotten every fragment of my life that went before, and as I said, I have begun to live, only since I saw thy face. And thou hast discovered that thy life in the wood was very lonely till I came. And it is as though we had both been sleeping, and had just waked up. And now we are playfellows, and I will be King, and thou shall be Queen. Or hast thou never heard of kings and queens? Then she said: Nay, I have heard. For formerly, before my father became so utterly devoted to asceticism, he used to tell me stories. And in almost every story, there was a king and queen. Then the King said: And if then I were king, wouldst thou come away with me and be my queen? And she laughed, and said: But what sort of queen should I be, that know nothing of the duties and behaviour of a queen?

Then he said: Sweet little Queen, although thou dost not know it, thy qualifications for the post of queen are such that they could not be surpassed. And the duties are easy to be learned, and the pleasures more than thou couldst dream. Only come with me, and I will show thee what they are. Or if thou wilt, I will draw thee a picture in the air, and hold it up before thee, to show thee as in a mirror thy life as a queen, and give thee a foretaste of its nectar. Hast thou never watched the bubbles on the surface of the stream? Dost thou not know how every bubble is like a little heaven, and glows for a moment with every colour of the sky, and bursts: but the sky remains? So is it with my picture. For like a bubble, it will burst as soon as painted, being only words: but the heaven which it shows thee in its mirror shall be thine, as long as life endures.

Then she said: Draw, then, thy picture, and let me see thy heaven. And she settled herself to listen, leaning her cheek upon her hand, and looking at the King so sagely that he shook with agitation, so intense was his desire to take her in his arms. And he exclaimed: Blue eyes, come and be my Queen, and I will put thee in a palace, and build it for thee seven stories high, of ebony and sandalwood, and of silver and of gold. O come and be my Queen, and thou shalt walk on pavements more worthy of thy little feet than this rough ground, on marble of many colours, and on floors of precious stones. Only be my Queen, and I will strip thee of thy bark, and wrap thee in silky webs and tissues coloured like the rainbow, till like the moon behind a filmy cloud, thy symmetry shall borrow beauty from tell-tale veils of gossamer and envelopes of woven gauze. Ah! come with me and be my little Queen, and I will load thy neck and arms with jewels, and thou shall play with heaps of pearl, and coral, and all the riches of the sea. Aye, shouldst thou prick thy finger, I will mend it with a ruby, and shouldst thou drop a tear, I will redeem it with a diamond, and try in vain to match, with turquoise or lapis-lazuli or opal, the colour of thine eyes. Ah! come, and slaves shall serve my dainty Queen with food on golden plates, and snow cold drinks in crystal cups, and when thou wilt, pour music in thy little ear. And elephants shall carry thee about, or thou shall ride on horses, or float on silent pools starred like the sky with a multitude of lotuses, or lie on couches softer than a flower, fanned in the heat of noon with scented leaves, or listening at midnight to the moonstones, oozing as they swing in the window's trellised frames. Ah! Blue-eyes, come and be my Queen, for I cannot do without thee, and all that I have said is nothing, for it is only the casket for thy soul. For I will be there, and serve thee all day long upon my knees. Ah! I will take thy soul, and steep it in elixir, and drown it in the perfume and the fragrance of stories and of dreams, and dye it with the colour strained from the subtle essences of far-off lakes of passion and emotion, lying in the distant land beyond the blue horizon where the earth and heaven meet. Aye! I would turn the three worlds upside down, only to be near thee, and watch the shadow of the pleasures I would find there reflected in thine eyes, O thou naïvest and most exquisite of queens.

And she watched him as he spoke, and when he stopped, she continued to look at him in silence. And then to his amazement, she dropped her eyes, and the colour rose a very little in her cheek, that was overshadowed by her long soft lashes, and she said: Nay, thou art only laughing at me, knowing my inexperience. And as thou saidst, thy words are only bubbles, beautiful, and bursting as they jostle one another, and delusive. Nor is this the kind of queen that I would be. And the King said, with curiosity: And what then, O maiden difficult to please, is thy conception of a queen? And she waited for a moment, and she said, keeping her eyes fixed upon the ground: Once my father told me of a queen very different from thine. And I cannot tell thee the story as he told it, for I am not a pundit, as is he. But he told me of a king, who was set upon by enemies and driven from his throne. And when all the world abandoned him, a single friend remained to him, and that one was his queen: who followed him in exile, and lived with him in poverty, and wandered through the world behind him like his shadow, enjoying never one of the pleasures thou hast mentioned, but sharing all his evil fortune, a pleasure infinitely greater than them all. And when he died, she would not stay behind him, but followed him through the fire, into the other world.

[1] There is a beautiful Indian idea, that the foot of a pretty woman will cause a particular tree (I cannot recollect which) to break into blossom.

[2] "Kissed by the bees." (Note, that the third syllable rhymes, not with crumb, but with room, pronounced rather short.)

V

A PAINTED LADY

And the King listened with amazement, and when she ended, he looked at her with eyes that glistened, and a heart that swelled towards her as she sat with downcast eyes, as if ashamed of her words, before him on the ground. And he struck his hands together, and exclaimed to himself: Ha! very wonderful is the way of the Creator, who teaches all his creatures the law of their behaviour, without the means of any master. For this mud-born[1] pure white lotus of a maiden has understood without assistance and as it were by native instinct, the whole duty of a faithful wife, even before she has so much as seen a man. And then he said: Sweet little ascetic, apt pupil of a wise old father, whom thou dost resemble not only in thy hair, thou hast administered reproof to me, deservedly. And whereas I thought, in my folly, to instruct thee, it was I that received a lesson, in this matter of the way of queens. And now I see, that I spoke more truly than I knew, when I said that thou wert admirably fitted to be a queen. Now, therefore, thou art my guru, and I am thy disciple, and thou shalt teach me all that I do not know. Begin then, my pretty little guru: give me lessons, for I need them. And she laughed, and blushed, and said: Again thou art laughing at me: for how could a simple forest maiden teach anything to one, who like thyself, had lived in cities, and mixed with other men and women? And the King said quickly: Ah! dear Blue-eyes, just for that very reason is it that thou hast already taught me many things that I never knew before. For they who live in cities have their souls tainted as it were and poisoned by bad associations, whereas thine is as pure as the flowers in thy hair. And therefore, as thou hast taught me about queens, teach me also about kings. What should he be like, whom thou wouldst be willing to follow through the world?

And she looked at him for a moment, and then she dropped her eyes, and turned away her head, and was silent. And as he watched her, the King saw the colour rising on her neck, till it reached the roots of her dark hair, like the flush of eve climbing the snowy summit of Himalaya, when day is dead. And he said to himself in ecstasy: Ha! so this pure digit of the ice-cold moon, even in the solitary darkness of the night, before the dawn of love, has dreamed of a sun which she has never seen. And O that I could dare to think myself the sunny lover corresponding to her dream, destined to touch her soul, as my question did her body, into red! But let me beware, lest I scare my timid fawn by a too abrupt approach. And then he said: Dear little blue-eyed Queen, forgive me, if I roused thy maiden shame by a rash and ill-mannered curiosity. It is enough for me to know, that the king of thy pure fancy must be worthy of his queen: and as much above all other men, as thou art different and above all other women.

And then, with her eyes still fixed upon the ground, she began to draw upon the step with her foot. And she said softly: And in what do I differ from all other women? And the King said: Blue-eyes, ask me rather in what respect thou art the same. For thy points of difference are so many, that it would take long to tell them all. But notwithstanding, if thou wilt, I will try, and paint thy portrait for thee in contrast to the others, and hold thy image up before thee, reflected on the mirror of my soul. And she said: Try: for I desire to learn how I differ from the others. Then he said: Look, then, at me, that I may see thee before I begin. And she raised her eyes, and looked straight at him, blushing a very little, and then smiled, and looked down, and waited as he spoke.

Then the King said: Blue-eyes, every woman is a woman, and so art thou: and this is what thou hast, in common with all others of thy sex. And yet, in every special property of woman thou hast something of thine own, which marks thee like a seal, and stamps thee as a thing distinct and peculiar, and other than them all. For others have blue eyes, but thine are bluer, and other lips are red, but thine are redder, and other brows are black, but thine is blacker, and other smiles are white, but thine, O thine is like a snowflake or the petal of a new young lotus bud. Dark, dark is hair, but thine is like the midnight, and many feet are small, but not as thine are. And O thy arms are softer and more rounded, and thy waist is more enticing, and the two proud swelling sister milky foes upon thy breast, more erect and more provoking: and yet thy step is lighter and thy walk is more bewitching and thy voice's murmur sweeter and thy laughter more delicious and thy soul fresher and more frank and thy heart it may be harder than that of any woman that I have ever seen. Moreover, all others of thy sex are tame, and thou art wild. Then she said: What is the distinction, for I do not understand? And the King said: Sweet, I cannot tell thee: and yet it is a difference far greater than all the others put together. For all things that are tame are, as it were, an incarnation and embodiment of the littleness of men: but all things that are wild, as thou art, are, as it were, a portion of the Deity. For thy behaviour differs from that of other women, as does a wild vine gadding at its will from the trained flowers in a king's garden, and thy great blue eyes are utterly without hypocrisy, and resemble those of a falcon or a child. And thou thyself art like the young beautiful heifer of a wild white bull. And I know not how to tell thee what I mean, when I say that thou art wild: and yet it is just this very quality in thee which drives me to distraction. But see, now, the evening as it falls, and the water of the great river flowing with its surface unruffled by any breath of wind: see, how the cranes here and there upon the brink are mirrored in its water, and yonder pair of swans are, as it were, echoed by another pair that swim below them upside down; and the peacock on the temple wall glitters in the last rays of the sun with emerald and blue and gold: now thou seemest, as it were, a part of it all, and as it were the soul of all this body, and like a jewel in its proper setting, and at one with all the creatures of the wood. And I begin to fear, lest thou shouldst suddenly plunge into the water, and disappear, leaving me alone.

And as he spoke, there came again a murmur and a rustle in the air. And he listened and exclaimed with anxiety: Ha! what is that? Then she said: It is only the beating of the wings of the waterfowl returning to their roost for the night.

[1] This single word, a common name in Sanskrit for the lotus, possesses an incomparable, moral and æsthetic, mingled beauty, which can only be poorly rendered in English by five words instead of one. Mud-born is the word: but the meaning it covers is the pure white lotus that springs out of the thick black mire: just as the brightest rainbow is seen against the darkest cloud.

VI

SHADOWS

And the King drew a deep breath, like a man saved from a great danger. And she saw it, and said to him: Thou art afraid. Of what art thou afraid? And the King said: Ah! dear Blue-eyes, I am indeed afraid, but of this alone, lest something should occur to cut short our conversation. And shall I not be afraid of death? For as my life began with the commencement of our converse, so its end will be my death. And like a miser, the very treasure that I worship fills me with despair, because the fear of losing it mixes with the joy of its possession, and I start at every noise. And as I said before, more than anything I fear lest thou shouldst suddenly escape into the water. And I am sorely tempted to take hold of thee, and tie thee like my horse to the tree, to prevent thee from escaping.

Then she laughed and exclaimed: There is no need: for I have no desire to escape from thee. And how could I plunge into the water, unless I were a fish? Then he said: Dear, did thy father never tell thee of the nymphs that have their homes beneath the water? Or hast thou forgotten what he said? Or is it as I said, that thou thyself art one of them, seeking to deceive me? And she said: But what should lead thee to believe it? And he said: Every reason. For they are all marvellously beautiful, as thou art, and like thee, they suddenly appear, seated by pools and streams, and lure unhappy travellers like me to ruin and destruction. Then she said: And by what means do they destroy them? And the King said: Blue-eyes, by showing themselves for but an instant, and then disappearing, never to return, carrying away with them the hearts of their miserable victims, and leaving them instead inconsolable regret, and lovelorn longing for the beauty whose momentary vision robbed them of their soul. Therefore beware! and let me warn thee, that once having shown thyself, thou art absolutely bound to remain with me for ever: otherwise I shall be utterly undone. For if not, thou wert very wrong ever to have shown thyself at all, and deservest to be punished as a deceiver and a Thag.

Then she laughed, with laughter that was music to the King's ear. And she said, softly: But this is very hard: for how can those poor water-women help it, and is it any fault of theirs if they happen to be seen by those who happen to pass by and are not blind? Nor was it my fault, if I was seen by thee: rather was it thine, for coming into my wood upon thy horse. Then the King said: Blue-eyes, I blame thee not at all, always provided that thou dost not jump into the water, or leave me in any other way. And she said: But is it not rather I that have to be afraid, lest thou shouldst leave me? Is it my sex only that deceives, and are there no water-men, as well as water-women? And the King said eagerly: Ah! dear Blue-eyes, and would it be a grief to thee, if I should go away? And she waited a little while, before she replied. And then she said, looking at him with playful eyes: Didst thou not say thyself that this world was full of men? And if, then, one has come into the wood to-day, another may to-morrow. And the King started, and he looked at her with rapture. And he said to himself: Ha! she is provoking me, and ah! she is delicious. Surely the very elements must have in them the nature of a woman, since even in this empty wood, this intoxicating maiden has somehow or other managed to acquire the coquetry of her sex: most of all charming there, where it was least to be expected. And then he said aloud: Dear little daughter of an Apsaras, let thine other man beware, whoever he may be: for I will set guards about the wood, like a ring, to put to death whoever they may find.

Then she looked at him a little while, and she said: See, I have told thee all I have to tell, but thou hast told me absolutely nothing. Art thou then a king, to speak of placing guards about the wood? And the King said to himself: Ha! she is clever, and has caught me in a trap. And yet I will not tell her who I am, for if she knew, she might be dazzled by my kingdom, and fall in love with that, rather than with me. And he said: Surely, as we agreed in the beginning, if thou art a queen, I must be a king. And I will not allow any other man to tamper with my queen. And I am of good caste, and a Rajpoot, and not ashamed of my family. But what if I were in very truth a king, and banished: wouldst thou follow me through the world, as thou saidst? And she laughed and said: Nay, but I am not yet thy queen, and to follow thee is not my duty, but that of thy Queen or Queens. And the King looked at her narrowly, and said to himself: Is she speaking at random, or can it be that she is curious, or jealous, and anxious to discover whether she has a rival? And he said: Blue-eyes, King or not, this is certain, that I neither have nor will have any queen or queens whatever but thyself. Nor have I ever seen any woman in the world, till I came into this wood, that I would wish to make my wife. And therefore tell me, for as yet thou hast not answered: if I were a king indeed, wouldst thou come away and be my Queen?

And she said: I am of good family, and not independent[1]; and it is not for myself, but for my father to dispose of me. And then, the very instant she had spoken, she uttered a sharp cry, and started to her feet, and stood. And the King leaped up in terror, exclaiming: Alas, what is the matter? For he thought she had been bitten by a snake. But he looked and saw nothing. And he drew near her, and saw that she was deadly pale, and drooping like a flower left without water in the heat of noon. And he said again, with anxiety: Alichumbitá: what is it? But she never answered, but stood silent, gazing at the river, as though he were not there.