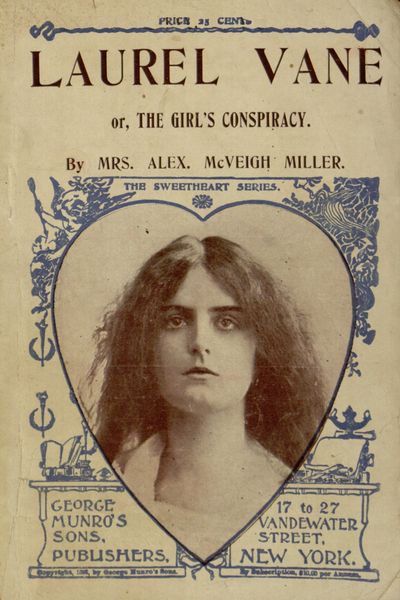

PRICE 25 CENTS

or, THE GIRL'S CONSPIRACY.

By MRS. ALEX. McVEIGH MILLER.

THE SWEETHEART SERIES.

|

GEORGE MUNRO'S SONS, PUBLISHERS, Copyright 1896, by George Munro's Sons. |

17 to 27 VANDEWATER STREET, NEW YORK. By Subscription, $10.00 per Annum. |

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHAPTER XXX.

CHAPTER XXXI.

CHAPTER XXXII.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

CHAPTER XXXV.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

CHAPTER XL.

CHAPTER XLI.

CHAPTER XLII.

CHAPTER XLIII.

CHAPTER XLIV.

CHAPTER XLV.

CHAPTER XLVI.

CHAPTER XLVII.

CHAPTER XLVIII.

CHAPTER XLIX.

CHAPTER L.

CHAPTER LI.

CHAPTER LII.

CHAPTER LIII.

CHAPTER LIV.

CHAPTER LV.

CHAPTER LVI.

CHAPTER LVII.

CHAPTER LVIII.

CHAPTER LIX.

CHAPTER LX.

CHAPTER LXI.

CHAPTER LXII.

CHAPTER LXIII.

CHAPTER LXIV.

CHAPTER LXV.

CHAPTER LXVI.

CHAPTER LXVII.

CHAPTER LXVIII.

CHAPTER LXIX.

Model Letter-Writer and Lovers' Oracle.

WITH HANDSOME LITHOGRAPHED COVER.

PRICE 10 CENTS.

This book is a complete guide for both ladies and gentlemen in elegant and fashionable letter-writing: containing perfect examples of every form of correspondence, business letters, love letters, letters to relatives and friends, wedding and reception cards, invitations to entertainments, letters accepting and declining invitations, letters of introduction and recommendation, letters of condolence and duty, widows' and widowers' letters, love letters for all occasions, proposals of marriage, letters between betrothed lovers, letters of a young girl to her sweetheart, correspondence relating to household management, letters accompanying gifts, etc. Every form of letter used in affairs of the heart will be found in this little book. It contains simple and full directions for writing a good letter on all occasions. The latest forms used in the best society have been carefully followed. It is an excellent manual of reference for all forms of engraved cards and invitations.

The New York Fashion Bazar Book of the Toilet.

WITH HANDSOME LITHOGRAPHED COVER.

PRICE 10 CENTS.

This is a little book which we can recommend to every lady for the Preservation and Increase of Health and Beauty. It contains full directions for all the arts and mysteries of personal decoration, and for increasing the natural graces of form and expression. All the little affections of the skin, hair, eyes, and body, that detract from appearance and happiness, are made the subjects of precise and excellent recipes. Ladies are instructed in how to reduce their weight without injury to health and without producing pallor and weakness. Nothing necessary to a complete toilet book of recipes and valuable information has been overlooked in the compilation of this volume.

The New York Fashion Bazar Book of Etiquette.

WITH HANDSOME LITHOGRAPHED COVER.

PRICE 10 CENTS.

This book is a guide to good manners and the ways of fashionable society, a complete hand-book of behavior, containing all the polite observances of modern life; the etiquette of engagements and marriages; the manners and training of children; the arts of conversation and polite letter-writing; invitations to dinners, evening parties and entertainments of all descriptions; table manners; etiquette of visits and public places; how to serve breakfasts, luncheons, dinners and teas; how to dress, travel, shop, and behave at hotels and watering-places. This book contains all that a lady or gentleman requires for correct behavior on all social occasions.

The foregoing works are for sale by all newsdealers, or will be sent to any address, postage free, on receipt of price, by the publishers.

Address GEORGE MUNRO'S SONS,

Munro's Publishing House,

17 to 27 Vandewater Street, New York.

DR. T. FELIX GOURAUD'S

Oriental Cream

OR MAGICAL BEAUTIFIER

For the Skin and Complexion

The only toilet preparation in America that has stood the actual test of public approval for over half a century.

It will purify and beautify the skin and remove Pimples, Blackheads, Moth Patches, Rash, Freckles and Vulgar Redness, Yellow and Muddy Skin, giving a delicately clear and refined complexion. It is highly recommended by leading society and professional ladies, and cannot be surpassed when preparing for evening attire.

Price $1.50 per bottle.

For sale at druggists' and fancy goods dealers', or will be sent direct on receipt of price.

The most satisfactory article for applying Gouraud's Oriental Cream. 50 cents each, by mail on receipt of price.

An ideal antiseptic toilet powder for infants and adults. Exquisitely perfumed. 25 cents a box by mail.

FERD. T. HOPKINS, Proprietor, 37 Great Jones Street, New York

or,

THE GIRLS' CONSPIRACY.

By MRS. ALEX McVEIGH MILLER.

Copyright 1883, by George Munro.

(SWEETHEART)

NEW YORK:

GEORGE MUNRO'S SONS, PUBLISHERS,

17 to 27 Vandewater Street.

for the Woman of Fashion

à la Spirite

C/B Corsets

Straight Front Models

A great Emperor once asked one of his noble subjects what would secure his country the first place among the nations of the earth. The nobleman's grand reply was "Good mothers." Now, what constitutes a good mother? The answer is conclusive. She who, regarding the future welfare of her child, seeks every available means that may offer to promote a sound physical development, to the end that her offspring may not be deficient in any single faculty with which nature has endowed it. In infancy there is no period which is more likely to affect the future disposition of the child than that of teething, producing as it does fretfulness, moroseness of mind, etc., which if not checked will manifest itself in after days.

Guaranteed under the Food and Drugs Act, June 30th, 1906. Serial Number 1098.

An Old and Well-Tried Remedy

MRS. WINSLOW'S SOOTHING SYRUP has been used for over SIXTY YEARS by MILLIONS of MOTHERS for their CHILDREN WHILE TEETHING, WITH PERFECT SUCCESS. IT SOOTHES the CHILD, SOFTENS the GUMS, ALLAYS all PAIN; CURES WIND COLIC, and is the best remedy for DIARRHŒA. Sold by Druggists in every part of the world. Be sure and ask for MRS. WINSLOW'S SOOTHING SYRUP, and take no other kind.

All the clocks of the great, thronged city clanged out the hour of midnight from their hoarse, brazen throats simultaneously, and as the last tremulous echo died away on the air, a human soul that had wasted its glorious talents, and squandered its heritage of genius in a reckless, dissipated life, was launched out on the great, shoreless tide of eternity.

And in the same moment of time a young, fair, innocent girl, the dead man's only child, was cast adrift, friendless and forlorn, upon the mercies of the cold, hard world.

She fell, like one dead, by the bedside, and the wealth of her burnished golden hair fell like a pitying veil over the slender form that had bent like a flower before the relentless blast of fate.

The coarse, but not unkindly, lodging house people bore her into her own little room, and left her there alone to recover, while they prepared the dead man for burial to-morrow.

It was but a little while that this blessed unconsciousness lasted, when Laurel Vane struggled up to her feet to push back with little, trembling hands the cloud of golden hair from her white brow, and stare with great, frightened, somber eyes out into the strange, unknown future.

What terrible temptation, what love and sorrow and bitter despair that future held in its keeping for her was yet mercifully hidden from her sight by the thick curtain of mystery that ever hides To-morrow from our curious eyes.

The daughter of a genius, who had beclouded his gifted brain with the fumes of strong drink, and who had only written his brilliant articles under the stress of compulsion, and to keep the wolf from the door, the girl realized that she was left alone and penniless, with not a friend to pity or protect her. It came over her suddenly, and with a great thrill of horror, that her father's last article—finished only yesterday, before that sudden illness laid its chilly, fatal hand upon him—must be carried to the publishing house and the money received therefor before she could bury her dead!

Her dead! She could scarcely realize that her fond, though erring father, the profound scholar, the erratic genius who had loved his little girl even while he had unpardonably neglected her, was gone from her for evermore. With trembling footsteps she glided to the room where the people, having robed him for the grave, had left him alone in the solemn majesty of death.

A terrible shudder shook her frame as she beheld that sheeted[Pg 4] something lying in stiff, rigid outline upon the narrow bed. Half frightened, she drew back the snowy linen and gazed upon the handsome, marble-white features, to whose pallid grace death had added a solemn dignity all its own.

Great bursting sobs of regret and sorrow shook the daughter's frame as she gazed on that loved face, where in life the stamp of genius had been marred by the traces of dissipation and vulgar pleasures. Laurel was little more than a child, yet she knew that her father had recklessly wasted his God-given talents and sated his soul on the dry husks of life. Yet in all her sorrow and pity, in all her fear of the untried future, no thought of anger or blame came to her as she kept her sorrowful vigil by his side. There were others who blamed him that he had left this tender flower, his "Laurel blossom," as he poetically called her, alone and penniless in the hard, cold world. But she, his daughter, had nothing but tears and love for him now when he lay before her dead.

In a few hours they would carry him away, her beloved, forever out of her sight, but even those last few hours she could not have to spend with him. She was too forlorn and poor to give herself these last moments with him. She must carry his last manuscript to the office and receive the money before she could pay for his coffin and hearse. And already the lodging-house keepers were adjuring her to hasten in burying him. It was so gloomy having a corpse in the house, they said, unfeelingly.

So, at the earliest office hours, Laurel presented herself at the editor's desk with the small roll of manuscript clasped tightly in her little black gloved hand.

The clerk stared almost rudely at the young face from which she put aside the shielding veil with one timid hand.

"A little beauty, if only she weren't so pale and tear-stained," was his mental comment.

"I have brought Mr. Vane's article for the magazine. Can I have the money for it now?" she asked, falteringly.

"Very sorry, but the editor isn't in. You may leave the paper, and Mr. Vane can call for his money later in the day," replied the clerk, devouring her sweet face with his bold, admiring eyes.

The red mouth trembled, the wide, somber dark eyes brimmed over with quick tears.

"He—he cannot come—he is dead!" she answered in uneven tones, "and," flushing crimson in a sensitive shame at her own poverty, "I must have the money to bury him!"

"Ah, dead? Very sorry, I'm sure," said the clerk, a little startled out of his coolness; "and you are his daughter?"

"Yes, I am Laurel Vane."

"The editor doesn't come down to his office till noon. He always examines articles and pays for them himself. Very sorry your father is dead—a fine writer when he chose to take up the pen. Can I do anything else for you, Miss Vane?" went on the bold-eyed young man, rather pitying her sorrow and timidity, inasmuch as she was fair to look upon.

"If you will give me the address I will go to Mr. Gordon's private residence. I must have the money without delay," she answered, faintly.

He scribbled the address on a card for her, and after bowing her out in his most killing air, he went back to tell the printers that "old Vane had drunk himself to death at last, and left a devilish pretty little daughter without a penny."

"With a name as pretty as her face—Laurel Vane!" he added.

"He might have had a prouder laurel for his brow than a penniless daughter if he had not been so fond of his glass," said the printers, grimly.

And this was Louis Vane's epitaph.

While Laurel directed her faltering steps to the editor's up-town residence, all unconscious that the finger of Fate was pointing the way.

Mr. Gordon was one of the most successful editors and publishers of the day, and his brown-stone house on one of the fashionable avenues of the great city looked like a palace to Laurel's unaccustomed eyes. She went slowly up the broad steps and rang the bell a little nervously, feeling her courage desert her at thought of the interview with the stern editor. No thought came to her that her first meeting with that august personage would be in a darker, more fateful hour than this.

The smart serving-man who opened the door stared at our simply clad heroine a little superciliously. He could not recognize a lady apart from a fine dress.

"I wish to see Mr. Gordon, please," Laurel said, with quiet dignity.

"Mr. Gordon is out, mem," was the disappointing reply.

"Where is he gone? When will he come back?" exclaimed Laurel, in piteous disappointment.

"He's gone into the country, and he won't be back until to-night," was the concise reply.

The day was warm, but the girl shivered as if the ground had been swept from beneath her feet by the icy blast of winter. An unconscious cry broke from her quivering lips, and she clasped her little hands tightly together.

"Oh, what shall I do now?" she moaned, despairingly.

"I'm sure I don't know, mem," said the man impudently, and making an impatient move to shut the door in her face.

He might have done so with impunity, for Laurel, gazing before her with dazed, despairing gaze, was for the moment incapable of speech or action, but at that moment a door opened sharply on the side of the hall, a swish of silk sounded softly, and a clear, sweet voice inquired:

"Who is that asking for papa, Charles?"

Charles opened the door and fell back obsequiously. A lovely blue-eyed girl, richly dressed, came toward Laurel.

"I am Mr. Gordon's daughter. Is your business important?" she inquired with girlish curiosity.

She thought she had never seen anything so sweet and sad as the dark, wistful eyes Laurel flashed upward to meet her gaze.

"Oh, yes, yes, it is very important," she faltered, incoherently. "Perhaps you could—that is, if you would—"

Miss Gordon smiled a little at the tripping speech, but not unkindly.

"Come in. I will do what I can," she said, and led Laurel past the discomfited Charles into a lovely little anteroom, with flowers and books and pictures, that made it a little feminine paradise.

She pushed a little cushioned blue-satin chair toward Laurel.

"Sit down and tell me what you want of papa," she said, gently; and Laurel's impulsive heart went out in a great flood of gratitude to this beautiful stranger who looked and spoke so sweetly.

She grasped the back of the chair tightly with both hands, and turned her dark, beseeching eyes on Miss Gordon's face.

"I have brought Mr. Vane's manuscript for the magazine," she added. "He—my papa—is dead," she added, with a rush of bitter tears, "and we are so poor I must have the money to pay for his funeral."

Instantly Beatrix Gordon drew out her dainty pearl port-monnaie. "You poor child!" she said, compassionately. "What is the price of the article?"

Laurel named it, and Miss Gordon counted the money out into the little trembling hand, and received the manuscript.

"I am very sorry Mr. Vane is dead," she said. "He was a very gifted writer. Has he left you all alone, my poor girl?" with gentle compassion.

"All alone," Laurel echoed, drearily.

Then suddenly she caught Miss Gordon's hand, and covered it with tears and kisses.

"You have been so kind and so noble to me, that I will do anything on earth for you, Miss Gordon," she sobbed out, gratefully.

Then she hurried away to bury her dead, little thinking in what way Beatrix Gordon would claim her promise.

"Come in," said Laurel, faintly, in answer to the sharp rap at the door.

The cheap, plain funeral was over, and the orphan sat alone in the deepening twilight in the shabby little room, now invested with a somber dignity all its own since the presence of death had so lately been there.

Laurel's head was bowed upon her hands, and tears coursed slowly, each one a scalding drop of woe, down her white cheeks.

The door opened, and the woman from whom Mr. Vane had rented the two shabby little rooms entered abruptly. She was a coarse, hard-featured creature, devoid of sympathy or sensibility. She looked coldly at the weeping girl.

"The rent's due to-day, Miss Vane," she said, roughly. "Have you got the money to pay it?"

Laurel silently counted over the contents of her slim purse.

"Here is the money, Mrs. Groves, and it is the last cent I have on earth," she said, drearily, as she placed the silver in the woman's greedy outstretched hand.

"Is that so? Then of course you'll not be wanting the rooms any longer. I will trouble you to move out early in the morning, so's I may rent them to somebody else," exclaimed Mrs. Groves.

Laurel sprung to her feet in dismay, a terrified look on her fair young face.

"Oh, madam, I have nowhere to go—so soon!" she cried out pleadingly. "Perhaps you will let me keep the one little room until I can find work. I will be sure to pay you!"

"I can't depend on no such uncertain prospects," declared Mrs. Groves, unfeelingly. "I've got to be pretty certain where my money's coming from before I rent my rooms. So out you go in the morning, and if you don't leave quietly I'll have your trunk hoisted out on the sidewalk in a jiffy, so there!"

With this emphatic threat the rude landlady banged herself out of the room, and Laurel sunk down with a low moan of terror upon the floor.

She was no coward, reader, this forlorn little heroine of ours, but she knew scarcely more of the wide world outside her cheap lodging-house than a baby. She had lived in one poor place or another with her erratic father all her life, keeping their poor little rooms with untaught skill, meagerly supported by his neglected talent, and with not an idea of how to earn her own living. Mr. Vane had educated her after his own desultory fashion, but not in a practical way that she could utilize now in her need. She wondered with a shudder of dread what she should do, and where she should go to-morrow when she was turned out into the streets, of which she felt horribly afraid, and which her father had seldom permitted her to traverse alone.

She pushed open the casement and looked out. Night had fallen, and under the glare of the gaslight Laurel saw wicked men and ribald women tramping the streets. To-morrow night she would be out on the horrible pavements among them, with nowhere to go, and not a friend in all the wide, wicked city. Perhaps they would murder her, these wolves of the street, when she was cast out like a helpless white lamb astray from the fold.

Shivering, she recalled some verses she had somewhere read. They seemed to fit her own forlorn strait.

"Oh, what shall I do?" she moaned, tremblingly. "It were a thousand times better, papa, if I had died with you."

The room door opened suddenly and without warning, and Mrs. Groves reappeared.

"Here's a young man asking for you, Miss Vane. P'r'aps he'll tell you how to make a honest living now your pa's dead," she said, with a coarse, significant chuckle.

She hustled the visitor across the threshold, and, closing the door, stumped loudly down the passage, but returned in a moment on tip-toe, to play the eavesdropper.

The room was all in darkness save for the gaslight that streamed[Pg 8] through the open window. Laurel turned quickly to light her little lamp, wondering who her visitor might be.

To her amazement she saw the rather good-looking and bold-eyed clerk she had met at the publishing-house that morning.

"Good evening, Miss Vane," he said, insinuatingly. "I ventured to call, thinking that you might need a friend."

The quick instinct of purity took alarm in Laurel's breast. She drew back coldly as he offered her his smooth, white hand.

"I needed a friend this morning, but you did not seem to remember it then," she said, scathingly.

"I—ah—oh, I was taken by surprise, then. I had not my wits about me," he stammered, disconcerted. "Pray pardon my forgetfulness. I have been thinking about you all day, and wishing I could help you. Here is my card. Pray command my services."

Laurel took the bit of gilt-edged pasteboard, and read the name written on it in smooth copper-plate. It was

"Ross Powell."

The young man had seated himself, meanwhile, with the coolest self-possession. Laurel looked at him with her great, wistful, dark eyes.

"Do you really mean what you say?" she inquired, a faint ring of hope in her dejected voice.

"Yes. I infer that your father has left you without means of support, and I wish to offer you a good situation," Mr. Powell replied, suavely, with a sparkle in his bold gray eyes.

The girl clasped her little hands impulsively together. Hope and fear struggled together on her fair young face.

"But I don't know how to do anything," she cried, ingenuously. "I have never been to school like other girls. I've always kept papa's rooms and mended his clothes, and made my own dresses, but I couldn't do anything like that well enough for any one else."

Ross Powell's gray eyes sparkled wickedly. He kept the lids drooped over them, that Laurel might not see their evil gleam.

"Oh, yes, you could!" he exclaimed. "I know some one who wants a little housekeeper just like you, to keep two beautiful rooms in order as you did for your father. Will you come, Laurel?"

"Who is the person?" she inquired, flushing sensitively at his familiar utterance of her name.

Ross Powell moved his chair to Laurel's side, and gazed deep into her beautiful, wondering dark eyes.

"The person is myself," he replied, in low, lover-like tones. "I have fallen in love with you, my beautiful little Laurel, and I want you to come and be my little fairy housekeeper. I will love and cherish you as the darling of my heart."

Laurel regarded him a moment in blank silence. There was a look of genuine perplexity on her innocent face.

She spoke at length in a low, doubtful tone.

"Are you asking me to be your wife, sir?" was her naïve question.

He flushed and looked rather abashed at the innocent question.

"Why, no, my dear, not exactly," he answered, regaining his self-possession in a moment. "I don't wish to saddle myself with[Pg 9] a wife yet; but it would be about the same thing. I would worship you, my beautiful Laurel, and you should have fine dresses and jewels, visit the theaters and operas, live in beautiful rooms; while I, your adoring slave—"

"Stop, Ross Powell!"

She had stood like one turned to stone, gazing and listening for a moment; but now her young voice rang like a clarion through the room: "Stop, Ross Powell!"

He sprung from his seat, and moving to her side attempted to take her hand. She tore it from him and struck him an ignominious slap in the face with that small white member. Her eyes blazed, her cheeks burned.

She crossed to the door, and threw it open so suddenly that Mrs. Groves was disclosed in the act of listening, but Laurel paid no heed to her as she shuffled away, crestfallen, and for once ashamed of herself.

The flashing eyes of the girl seemed to wither the villain where he stood gazing sullenly upon her, with the red mark of that frantic blow upon his face.

"Go, Ross Powell," she said, pointing a disdainful finger at him. "Go, and may the good God in heaven punish you doubly and trebly for this dastardly outrage on an unprotected girl!"

He slunk across the threshold like the base, evil-hearted coward that he was, but out in the narrow passage he turned and looked back at her with a malevolent glare on his crimson-marked face.

"You have made an enemy, Laurel Vane," he hissed. "I would have given you love and protection, but you have chosen my hatred instead. I shall not forget you. I shall always remember that blow in my face, and I shall have my revenge for it. Look well to your future, my beautiful fury!"

Laurel slammed and locked the door in the face of the angry wretch, and fell upon the floor again, giving vent to her outraged feelings in a storm of passionate tears.

But it seemed as though she were not destined to have any peace or quiet that evening. Again a rap sounded on the door.

She brushed away her falling tears and opened it in fear and trembling.

A smart, pretty girl was her visitor this time.

"I am Miss Gordon's maid," said the newcomer, and she slipped a perfumed little envelope into Laurel's hand.

Laurel opened it and read, with bewildered eyes:

"My dear little Laurel,—I wish to see you very much, but there are reasons why I cannot come to you, so I have sent my maid, Clarice, to bring you to me. I have been thinking of you all day, and of your sweet promise to do anything on earth for me. I believe that we can mutually help each other. Come quickly, dear. Have no fear but that Clarice will guide you safely to me.

"Your friend,

"Beatrix Gordon."

"Will you come, Miss Vane?" asked the pretty maid intelligently.

"Yes," Laurel answered, hopefully, and so went forth to her future.

One of the most magnificent of the many palace homes that adorn the glorious Hudson River belonged to St. Leon Le Roy.

It was a beautiful, picturesque structure with graceful towers, projecting oriel windows, charming balconies, and marble steps that led down into spacious grounds so beautifully laid out that one never wearied of the miniature lakes, the sparkling fountains, the splendid shrubbery, the rare flowers, and the costly statuary that dotted the velvety green lawns that sloped down to the water's edge. It was a miniature paradise without, and the interior of the dwelling was no less beautiful and tasteful. Cultured taste and rare refinement had united with great wealth to make it a complete and perfect ideal of a home. Perhaps the first St. Leon Le Roy, when he had built this beautiful home and carried his blooming bride there, had not been far wrong when he called it "Eden."

Whether he had found it a veritable Eden mattered little to him now. He had passed to his rest in "the land that is fairer than day," and his son reigned in his stead, a king by right of his imperious will, and worshiped blindly by the queen-dowager his mother.

He was tall, dark, and stately, with an almost godlike beauty marred somewhat by an expression of cynicism, coldness, and pride, all curiously blended together. He was past the prime of youth, being about five-and-thirty, and his varied experience of men and things had left cold, distrustful lines about his firm, mustached lips, and a mocking light in his proud dark eyes.

An impatient discontent rested on his handsome features as he sat in a beautiful morning-room with his mother the second day after the beginning of this story. The handsome, richly dressed old lady was reading aloud from a letter that had just been received with the morning's mail:

"My dear Mrs. Le Roy,—I am in a dilemma, and I turn to you, my old friend, although I have not seen you in many years, believing that you will aid and abet me in my innocent scheme. My daughter, Beatrix, has formed a foolish engagement with a young man of small income and no prospects. She is both beautiful and accomplished, and as the sole heiress of her father's wealth I cannot endure to see her become the prey of a designing fortune-hunter. My plan is to separate them by sending Beatrix away from the city and getting rid of her lover by some clever scheme before she returns. If possible, Mr. Gordon will have him sent to Europe (I would like to send the wretch to Kamtchatka if I could!) on some lucrative mission. Both our hearts are deeply set on this plan. Indeed, delicate invalid as I am, my nerves are so unstrung by this affair, that I feel I shall perish unless I can rescue my child from this undesirable entanglement. And now, dear Mrs. Le Roy, for your share in our little scheme. I know that during the absence of your son in Europe, you are leading a quiet, retired life, at your beautiful home on the Hudson. I wish to have Beatrix visit you[Pg 11] for a few months, while we get her obnoxious lover out of the way for good. So sure am I of your consent, that I have pretended to Beatrix that you have already invited her, and on the day after to-morrow I shall send her down to Eden in care of her maid. I would accompany her myself, only that I am a confirmed invalid. My dear friend, you must take the best care of my treasure. See that she sends no letters to any one but her father or me. Allow no stranger to visit her. I depend hopefully on your co-operation in this matter, for my daughter is a fitting mate for the best, and I will not sacrifice her to a poor man. You will pardon my prolix letter, for the sake of a mother's anxiety.

"Yours,

"Isabel Gordon."

She closed the letter and looked up at St. Leon, who stood in the embrasure of a lace-draped window gazing carelessly out at the beautiful grounds. A mocking sneer curled his thin lips as he returned to her.

"A scheming woman of the world," he said, sententiously. "I hope you will not lend yourself to her iniquitous plan."

Mrs. Le Roy glanced at her letter again.

"You see she really gives me no chance for refusing, simply taking my consent for granted," she said, dubiously.

"No matter. Write her that you cannot receive Miss Beatrix. Tell her I came home yesterday, and that I am an ogre who would frighten her beauty away. What! is all the peace of my home-coming to be marred by the coming of a romantic love-sick girl?" he exclaimed.

"I will write her not to come, then, St. Leon—but, heavens, look at the date of this letter! It has miscarried! She should be here to-day!" exclaimed the lady nervously.

"Telegraph her, then—anything—only keep the girl away!" exclaimed Le Roy, testily.

"I will do so immediately, St. Leon," exclaimed his mother, all in a flutter that was quite unusual to her high-bred dignity.

But "fate is above us all!" At this moment a trained obsequious servant opened the door, and announced respectfully:

"Miss Gordon."

The agitated lady and her haughty, handsome son both looked at the door with an irrepressible start.

A sixteen year old girl was wavering on the threshold, staring into the elegant room and at the cold, curious faces of the mother and son with parted lips, and large, somber, frightened dark eyes. Over the simple, short traveling dress, of plain, dark-gray material, her rich, burnished golden hair flowed in billows of brightness beneath the wide brim of her simple hat. A neat pretty maid hovered in the background, looking far more cool and self-possessed than her lovely young mistress.

St. Leon Le Roy's quick eyes caught and held for a moment the gaze of those startled ones. He saw a pale, pure face, exquisitely[Pg 12] molded, with perfect features, save, as he said to himself, her nose was a trifle too short, and her lips too full. But then the defect of her nose lent character to her face, and the pouting lips showed tenderness. "A baby face," he said to himself, disdainfully, noting the quiver of the lips, that trembled like a child's about to cry.

The girl's dark eyes turned quickly from that haughty, handsome face as if in fear, and sought comfort in the woman's, but it was cold and haughty too. There was no welcome on it save what cold, conventional courtesy required. She advanced and gave the newcomer the tips of her fingers and the side of her cheek to kiss.

"Welcome to Eden, Miss Gordon," she said, chillingly, and then she led her up to her son. "Allow me to present my son, St. Leon. He only returned from Europe yesterday," she added.

They bowed to each other with chill courtesy, these two, and that was all. He was too annoyed at her coming to be ordinarily civil, and she was too frightened at her grave, stern-looking host to put out her little mite of a hand to him.

"You have quite surprised me, Beatrix—I suppose I must call you Beatrix," said Mrs. Le Roy, trying to infuse some warmth into her frigid manner. "You see, your mamma's letter miscarried, and I have but just received it, so you must excuse my not sending the carriage to meet you."

"Certainly," Beatrix murmured, coloring warmly for a moment, and veiling her splendid eyes beneath their long fringed lashes, while a sigh of relief escaped her lips as her hostess continued:

"I dare say you would like to be shown your room now, that you may remove the dust of travel. It is very unpleasant, taking a journey this warm weather."

Beatrix agreed with her, and when she had herself conducted her and the maid Clarice to a lovely suite of rooms, all silver and azure, Mrs. Le Roy returned to her son.

He still stood in the embrasure of the window, pulling his dark mustache rather sulkily with his slender brown fingers.

"Was there ever such a contretemps!" she exclaimed, going up to him. "What shall we do, St. Leon?"

"Nothing," he answered, rather shortly.

"Nothing?" she echoed, helplessly, yet with an accent of relief in her voice.

"Why, what is there to do?" he inquired, impatiently. "She is here, whether we want her or not. We are not barbarians; we cannot send our guest away. Besides, I have changed my mind; Mrs. Gordon was right."

"Right!" she echoed, gazing up into his face inquiringly.

"My lady-mamma, has our guest quite upset your equanimity?" he inquired, smiling down at her perturbed face. "You echo my words with parrot-like pertinacity!"

"If I am disturbed, St. Leon, it is on your account," she replied, with dignity. "I could endure the girl's visit very well myself."

"So can I, I think," he returned, musingly. "She is not at all what my fancy painted her—a self-possessed fashionable beauty, who would rather compel me to dance attendance upon her. I could see that the little thing was rather afraid of me; I dare say she will keep out of my way."

"I have no doubt of it. She was positively shy and awkward. Not at all like her mother, whom I remember as a brilliant belle who held her own with queenly dignity," said Mrs. Le Roy. "I cannot blame Isabel for her caution; Beatrix looks too young to have a lover."

"'She's o'er young to marry yet,' certainly," assented her son. "We will keep the ewe-lamb safe, mamma, and woe be to the wolf that comes prowling around the precious fold."

He spoke so dryly that she could not tell whether he was in jest or earnest, and his expression was just as inscrutable as his tone. While she was puzzling over both, Beatrix returned.

Her plain gray traveling-dress had been exchanged for a pretty, soft, white robe with delicate laces about it, and she carried a wide sun hat in her small, dimpled hands.

The big dark eyes did not look quite so frightened now. They looked yearningly out at the beautiful grounds.

"May I go out there?" she asked. "I have never seen such a beautiful spot in my life before!"

St. Leon looked at the girl as she made her timid request. Her eyes drooped from his quickly, and the frightened look came into them again.

He was unaccountably vexed, although a moment before he had been pleased, because she was afraid of him.

"Why should the little goose fear me? I am not an ogre," he said to himself, shortly, turning back to the window, while Mrs. Le Roy answered politely:

"Certainly, child, and I will go with you to show you the way."

They went out together, and St. Leon watched them from the window, appearing and disappearing among the winding walks, the girl's white figure bending here and there among the gay parterres of flowers, the morning sunshine lighting her waving tresses into splendor. Mrs. Le Roy had given her carte blanche as to the flowers, and she was eagerly filling her hands with the scented beauties.

After a little, he remembered that his mother was growing old, and that she must be weary of keeping pace with those light, quick footsteps. He hesitated, and then went out to them.

"Chère maman, you must be tired," he said. "Sit down here on this garden-seat and rest, and I will take your place with Miss Gordon."

Beatrix turned with quick compunction.

"Are you tired?" she said, looking at Mrs. Le Roy with the long, curling lashes lifted from her expressive eyes. "I am so sorry. I forgot that it isn't new to you as it is to me. Shall we go in?"

"By no means," answered the lady. "I will sit here and rest, and St. Leon shall be your escort."

She flashed him a little glance, quickly withdrawn.

"Perhaps you wouldn't like," she said.

He laughed, and walked on by her side by way of answer, thinking[Pg 14] to himself that she was rather prettier than he had thought at first. The wide sun-hat was tilted carelessly back from the fair low brow with its childish fringe of sunny locks, and the dark eyes with their long curling lashes looked darker still by contrast. A soft color had come into her face, and shy smiles of pleasure hovered around her lips. She looked like a child, with the front of her white overskirt held up in her hands and filled with flowers.

"Do you like flowers?" he asked her.

"I love them," she answered, with a distinct emphasis on the words. "I love them, and I never saw so many and such lovely flowers as you have here."

"Then you ought to enjoy your visit to Eden," he said, pleased at her pleasure in his home, and little thinking how she would enjoy that visit—how all the joy and sorrow of her life would date from these summer hours.

"Yes, I should enjoy it—I know that—only—only—" she said, and paused in confusion.

"Only what? Tell me," said St. Leon Le Roy, thinking suddenly of the lover from whom the girl had been torn by her scheming parents.

"She is thinking of that fortune hunter—that wretched entanglement," he said to himself, wondering what her next words would be.

"Only," she went on with childish frankness, and giving him one of her swift, dark glances, quickly withdrawn, "I am afraid you are—are angry that I have come here!"

Oh, wondrous perceptions of innocence! He flushed a little under his handsome brown skin, and pulled nervously at his silky mustache.

"Why should you think so?" he queried.

"I don't know. I—I seemed to feel it in the air," she said, vaguely, and in a little troubled tone. "You are vexed about it—aren't you?" and she turned on him fully for the first time the full gaze of those large wondrous black eyes, before whose searching gaze even the most accomplished Ananias might have hesitated to answer falsely.

"I should be discourteous if I answered in the affirmative," he said.

"You needn't mind that—not the least bit in the world," she said, eagerly. "You see, I didn't know when I came that you were here. I thought there was only an old lady—your mamma. If you don't want me here, I must go back to—— I can go away," she said, growing strangely pale as the words left her lips.

"Perhaps you would have been better pleased if I had not been here," he said, curiously, as they walked on down a wide, graveled path, leading to the river.

"Perhaps so—I don't like men very much," she answered, with innocent frankness.

"Ridiculous affectation, when she is dead in love with a fortune-hunting scoundrel!" thought he, gnawing his mustache vexedly.

Somehow since Beatrix Gordon had come to Eden he chose to take the most contemptible view of her lover.

"Perhaps you would like me to go away?" he said, with fine sarcasm.

They had come to the pretty rustic fence that bordered the lawn. Below it was the public road, beyond this the wide, beautiful river, with the white sails coming and going on its glassy breast. Beatrix sunk down on a convenient seat with a crimson, dismayed face. Some of the flowers fell from her overskirt in the surprise with which she regarded him.

"Oh, what have I said? I didn't mean that—never!" she cried, as he stooped to restore her treasures. "I wouldn't have you go away from your beautiful home for me, Mr. Le Roy."

"Very well, I will stay. I dare say Eden is wide enough for us to keep out of each other's way," he answered, as he sat down by her side.

"Yes, surely," she cried; "and if—if you will only tell me how, I won't bother you—I won't come in your way at all."

"Very well," grimly. "We will both stay at Eden and compromise that way. We will try not to intrude upon each other. My favorite haunt is the library. If you will keep out of there, you may have the right of way in the rest of the house without materially disturbing me."

Palpable dismay lowered over the lifted face that looked so lovely in the golden sunlight.

"The library? And the books are all there—aren't they?" she asked, with a note of keen yearning in her voice.

"Yes; do you like books?" he asked, curiously.

"I love them," she answered, discarding the word "like" as she had done about the flowers. There was no half way strain in her nature. Fervent, ardent, impetuous, the word was too cold for her.

Those things that pleased her she loved.

"Then, perhaps I will lend you some books sometimes, if you will only keep out of my sanctum," he said, coolly. "Do you promise?"

"Yes, I promise," she replied, with a gentle, smothered sigh.

Then suddenly she lifted her eyes and asked him the last question he would have expected to hear from a girl nurtured in the lap of wealth and luxury.

"Mr. Le Roy, if you were a girl like I am—and if you hadn't any parents, nor home, nor friends—nor any money—nor any practical education—what would you do to earn an honest living?"

There was a palpable anxiety in voice and face. She had grown very pale, her dark eyes were distinctly wistful.

"She is thinking of that obnoxious lover. She would even dare poverty for his sake," he said to himself in displeasure.

Aloud he answered carelessly:

"It is hard to say what I should do in such a case, Miss Gordon. I believe I should throw myself into that beautiful river yonder and so end all."

In the dark after-days he remembered those words.

Beatrix Gordon looked at the beautiful river with wide, dark eyes. The summer sunshine gilded the blue waves, the white sails dotted its wide expanse like fairy shallops gliding to and fro. It was grand and dazzlingly beautiful, but the young girl shivered as she thought of the dark depths below. She turned from it to look gravely into St. Leon Le Roy's handsome face with its cold, cynical eyes.

"You would throw yourself into the river and so end all," she repeated. "Oh, Mr. Le Roy, is it so hard for a poor girl to live that suicide is the least choice of evils?"

Her little hands clasped each other tightly over the mass of glowing flowers in her lap, and her red lips trembled with earnestness. He looked at her in something like wonder.

"I do not see why Mr. Gordon's daughter should trouble herself over such a question," he said. "But since you ask me I must answer yes. The world is full of pitfalls for the young and beautiful girl who has her own living to gain. Were I in the situation you describe, I believe I should speedily end the struggle with fate by a leap into the river."

These hastily spoken words, too, he was fated to recall in an hour of which he dreamed not now.

Beatrix did not answer him. She sat very still, looking before her with a strange, far-away expression on her face. A long, deep, unconscious sigh quivered over her lips.

"You are troubled over what I said—why?" he asked, curiously.

And the girl answered, with a shiver:

"I am afraid of life."

St. Leon began to feel vaguely interested in this girl whose coming he had dreaded so much. She was not like other young ladies he had known—not what he had expected the rich Mr. Gordon's daughter to be. There was a spice of originality about her. Why should she, the petted child of wealth and luxury, think about these things of which she had talked? Was it because her lover was poor?

He did not like to think of that lover from whom her parents wished to separate her. She was a child, he said to himself—too young to burn her heart in the flame of love.

"I do not see why you should fear life. It is likely to prove very fair and bright to you, if you do your duty—if you implicitly obey the wishes of your parents," he said, watching her keenly.

The lovely face flushed crimson, but she made him no answer. She played with her flowers nervously. She was afraid of St. Leon Le Roy's keen, merciless eyes.

"You do not wish me to lecture you upon your duty?" he said, after waiting in vain for her to reply.

"No, I do not think I do," she replied, frankly.

"Then I beg your pardon. Indeed, I am not worthy of lecturing any one upon that cold, hard word, duty," he said to himself rather[Pg 17] than her. "I have not been a very dutiful son myself," a shadow crossing his dark features.

Beatrix again had no answer ready.

She went on quietly grouping her flowers into a large bunch. He watched the white hands with a lazy, æsthetic pleasure in their beauty as they gleamed among the crimson flowers of which she had gathered a larger quantity than of any other color.

He began to talk to her of the city where she lived, of the places she had visited, of people whom he supposed the Gordons would know. He was amazed at her ignorance on subjects where he would have supposed her to be at home.

"I have been to very few places, and I know very few people," she said, blushing. "I—I haven't been introduced into society yet. I am too young."

"Then where did she pick up that lover?" he asked himself. "She must have become infatuated with her dancing-master or her music-master."

But that evening when Mrs. Le Roy opened the piano and asked her to play, Beatrix begged to be excused. Being pressed, she declared that she had never learned the piano, she did not care for music—at least not very much.

No one expressed the surprise they felt. St. Leon played an aria for his mother, then they closed the piano.

"So it was not her music-master who won her heart. The circle narrows down to the professor of the terpsichorean art," he said to himself.

"My dear, I have been watching you closely," said Mrs. Le Roy, suddenly. "You do not at all resemble your mother. She had blue eyes, yours are black. Her features were quite different from yours. I have seen your father, but I forget how he looked. I suppose you are like him."

"Yes, I am like my father," Beatrix answered, but her face crimsoned, and she looked as if she were about to burst into tears. She commanded herself with an effort, and a little later, declaring that her head ached, she begged to be excused, and left the room.

"Poor girl! she is very unhappy!" said Mrs. Le Roy. "Isabel Gordon was very careless to let that child have a lover! She has no business out of the school-room."

Beatrix went swiftly to the pretty dressing-room, where the maid was, busy sewing on a dinner-dress of pink nuns' veiling for her beautiful young mistress. She sunk down upon a chair and looked at Clarice with somber, miserable eyes.

"Oh, Clarice, I shall have to give it all up," she panted. "They suspect me—I am quite sure they do!"

Clarice looked frightened and disturbed, and even reproachful.

"Oh, Miss Gordon, don't say that," she exclaimed. "After all the drilling you've had, a clever, pretty girl like you ought to be able to act your part. But it's just as I told you to-day. You're too timid and nervous."

"Because I am conscious of my guilt," answered the girl, sadly. "I should not be timid and nervous in my own proper character, Clarice. But you know 'conscience makes cowards of us all.' Besides, I am ignorant on many subjects which Beatrix Gordon ought to know well. The people and places they ask me about I know nothing of, and they look surprised. To-day Mrs. Le Roy asked me to play on the piano. When I said I did not know how, I wish you could have seen their faces!"

"That was rather bad. The most of young ladies know how to play on the piano," said Clarice. "But anyhow they couldn't make out a case against you for that. You might have said that you didn't care for music."

"So I did, but the lie almost blistered my lips," said the girl, "for I love music dearly, and when Mr. Le Roy played a beautiful aria I was afraid he would see my delight on my face."

"You must be careful over that. Stick to your text," warned the maid. "If you make them think you don't like music they will not think it strange you cannot play. Was there anything else unpleasant?"

"Yes; Mrs. Le Roy told me I did not at all resemble my mother. Oh, I was so frightened when she began. My heart sprung to my lips!"

"What did you say?" asked Clarice, attentively.

"I told them I resembled my father—that was true at least," answered Beatrix, sighing.

"Well, the game is not lost yet," said Clarice. "Courage, Miss Gordon—hold your own bravely as you can. Remember all that is lost if you fail."

"I try to remember it," sighed the girl. "If it were not for her, Clarice, I should break down, I know I should. It is terrible to be living a lie. Oh, Clarice, do you think she is very happy now?"

"Happy as a queen," said Clarice, enthusiastically: "and she was so good and sweet she deserved it. Oh, you mustn't regret that you made a little sacrifice for her! And is it a sacrifice, after all? Look at this grand, beautiful home, all this luxury around you. Where would you be if my mistress hadn't sent you here?"

Where, indeed? The false Beatrix Gordon shivered as if with ague, her face blanched to a pallid hue. She thought of the homeless outcasts in the horrible streets, of the dark, flowing river, of St. Leon Le Roy's careless words to her that day: "I would throw myself into the river, and so end all!"

"I should not do that unless I were driven to desperation," said the girl to herself with unconscious bravery.

She looked through the window out upon the beautiful grounds.

"It is a lovely home," she said. "I could be very happy here if I had no shadow on my heart. But I cannot forget my sin. I remember always some lines that I have read:

"I would not call it a sin if I were you," said Clarice. "That is too harsh a name. My mistress did not call it so. She said it was only a justifiable counter plot, only a harmless, girl's conspiracy."

"She ought to know best. She is older and wiser than I am," said the girl, with a gleam of hope on her face.

Clarice was very clever for a girl in her situation. As she worked away steadily on the pink dress, she artfully followed up the impression her last words had made:

"For my part I think it is the best joke I ever heard of. I do not pity the Gordons one bit. They deserve to be fooled!" she said. "There was no fault in Miss Gordon's lover, only he was not as rich as she was."

"Poverty is almost a crime in the eyes of the rich—is it not?" asked her mistress thoughtfully.

"Yes," Clarice answered, almost tartly, and she began to hum under her breath:

Her young mistress remained gazing thoughtfully from the window, the sad expression of her face hidden by the falling waves of her golden hair. Deep, heavy sighs breathed at intervals over her lips.

Several days passed quietly without anything occurring to frighten our masquerading heroine again. The Le Roys gave no sign of their surprise at anything that occurred. They had, in fact, concluded that a great deal of her oddness and originality arose from the fact of the lover in the case. When she looked sad, as she often did, they concluded she was thinking of him. When St. Leon actually came upon her weeping silently one day he thought it was on account of the separation from our hero.

It vexed him. He did not go away and leave her alone, as his mother would have done. He said to her, sarcastically:

"Are you crying for your mamma, little girl?"

Beatrix flashed him a swift, angry look through her tears, and answered:

"No!"

"At least she has the grace to be honest," he said to himself.

Some curiosity came over him regarding the man who had won the heart of this girl. He would have liked to know his name, and what he looked like, and if he was worthy of the prize he had won.

"Confide in me, Miss Gordon," he said, obeying an impulse he could not himself understand. "Tell me what your trouble is. Perhaps I can help you."

Beatrix shuddered in horror. Ah, if he knew, how little he would be inclined to help her. Rather he would spurn her from the proud gates of Eden.

"You are very kind," she faltered. "I thank you, but it is nothing."

He looked at her a little scornfully.

"I have heard that women cry for nothing," he said. "I suppose it must be true, as I now hear it confirmed by one of the sex."

She seldom saw him except at meals, and a little while in the drawing-room of an evening. The most of his time was spent in the library or out riding and walking. But one day he came to her abruptly.

"I am going up to New York for a few days," he said. "I hope you will make use of my library while I am out of the way."

"Thank you," she said, radiantly.

"If I should see your parents," he continued, "shall I give them any message for you?"

She started, and the crimson rose she was holding fell from her hands. He wondered why she grew so deadly pale, and trembled so. The sudden radiance of a moment ago had all gone from her face.

"Give them my love," she said in a husky voice, "and tell them—tell them that I am greatly enjoying my visit to Eden."

St. Leon came home one afternoon and made his way straight to the library. The thickly carpeted floor gave back no echo to his footfalls, and he stood on the threshold of the room several minutes gazing in at the open door unobserved by the single occupant of the apartment.

As he had shrewdly suspected, his mother's guest had availed herself to the full of his permission to use the library in his absence.

Quite oblivious of his near presence now, Beatrix was curled up in his great easy-chair in a cozy, kittenish attitude, her warm flushed cheek buried in the hollow of one small hand, her dark eyes bent in rapt interest on an open book in her lap. A ray of sunshine stealing through the lace curtains at the window penciled golden bars on her white dress and bright hair, making her look like a picture to whose beauty St. Leon's cultured eyes were by no means oblivious. He hesitated to startle her from her pretty negligent attitude, but as he gazed his mesmeric eyes irresistibly attracted hers. She glanced up and met his dark, burning eyes fixed with a strange inscrutable expression upon her own.

Instantly Beatrix sprung up, the book falling to the floor, a little cry of surprise on her lips, her face paling, a look of inexplicable terror in her dark eyes.

"Am I an ogre that you do me the honor to be frightened at me, Miss Gordon?" he inquired, advancing into the room, a tone of displeasure in his deep, musical voice.

"I—I was not frightened—only startled, sir," said Beatrix, faintly, as she stooped to recover her book.

She laid it upon the table and was about to leave the room when he stopped her with a slight wave of his gloved hand.

"Resume your seat, Miss Gordon. I shall not believe you are not frightened if you run away like this," he said.

She sat down with a gasp and waited. She had been full of vague fears and suspicions regarding his visit to New York. She waited with a beating heart and a pale face for his next words. He would say, with that fine scorn his mobile face was so capable of expressing:

"You are found out in your miserable conspiracy, Laurel Vane. You have come here pretending to be Mr. Gordon's daughter while you covered her elopement with her lover. The true Beatrix Gordon[Pg 21] is far away, married to the man she has chosen, in defiance of her parents and friends. Punishment cannot reach her, but you, Laurel Vane, will have to suffer for the outrage you have helped to perpetrate on the Gordons and on us."

While she waited with a sick horror to hear him utter those words, she wondered vaguely what they would do to her for her share in Beatrix Gordon's conspiracy. Could they cast her into prison? She had seen the outside of a penitentiary once. How grim and dark and forbidding it looked with its iron doors and grated windows? Would they shut her up in all her youth and beauty in such a horrible place as that, and for how long? She shuddered as she thought that it might be for life. She had no idea, in her youth and innocence, how far and how long the powerful arm of the law could reach.

But the dreadful words for which she waited while a hand of ice seemed to grip her throat, remained unspoken.

Mr. Le Roy seated himself leisurely and drew off his dark kid gloves. Then he took up the volume she had been reading, and glanced at the title.

"I hope you have enjoyed your monopoly of my library," he said.

"Yes," she answered, faintly.

"And you are sorry I have returned to oust you from its enjoyments—aren't you?" he asked, studying her young face keenly.

"I should be very rude to say so," she answered, gaining courage as the dreadful charge for which she waited was delayed.

"As to that you cannot be ruder than I was in desiring you to stay out of this room while I was at home," he replied, with an air of insincerity. "Will you pardon my selfishness, Miss Gordon, and permit me to remove the embargo?"

She could scarcely believe her ears. His tone was distinctly kind. Had he, then, found out nothing? Was her secret safe yet a little longer?

Seeing that she hesitated, and did not speak, he continued:

"I give you carte blanche as to the use of this room whether I am absent or present. Will you come here whenever you choose, to read, or write, or study? You will not disturb me, neither shall I disturb you."

"Thank you," she murmured, not yet daring to look at him.

"You thank me, but you do not say you will come," he said. "Will you please to look at me a moment, Miss Gordon? I like to be looked at when I am talking."

With an effort she lifted her long fringed lashes, and forced herself to meet his proud, glittering dark eyes.

"I am a spoiled child. I like to be humored," he said, with a smile that lighted his face into a subtle sweetness that first showed her how dangerously fascinating the master of Eden could be when he willed. "I want you to tell me, Miss Gordon, that you forgive my selfishness the other day, and that you will come to this room as freely as to any other room in the house. You will promise me, will you not? No one ever refuses me anything!"

"There is nothing to forgive—you had a right"—she said, incoherently. "If there was—and mind, I do not admit there was—I forgive you freely."

"Thank you. And you will come?"

"Sometimes—perhaps," she stammered.

He pulled at his dark mustache impatiently.

"I must have a more definite promise than that," he said. "I am used to having my way about everything."

Though the words were arrogant, the tone was kind. He was thoroughly in earnest. She hesitated. She did not want to be drawn into such a promise, standing too much in awe of the stately master of Eden.

"You will not promise," he said, piqued. "Very well. But you are the first woman who ever refused a request of St. Leon Le Roy's. Your forgiveness was only half hearted."

He was more vexed than she knew. His wonderful condescension had not borne the fruit he expected. He leaned back in his chair with his elbow on the table, and pulled at his dark mustache with his shapely fingers, the costly diamond on his hand flashing luridly.

"What a stubborn little mite it is to refuse to humor me," he thought to himself in displeasure.

While the small object of his displeasure watched the door with longing eyes, yearning to escape from the oppressive dignity of his presence, she felt herself growing crimson under his cold, proud gaze.

"You have not asked me yet if I saw your parents," he said, after some minutes of that oppressive silence.

"It is coming now," thought the small culprit in despair, and she felt guiltily that the color was all fading out of her cheeks under those watchful eyes. She could only stammer, faintly, "Did you?"

To her infinite joy and relief, he answered in the negative.

"No, I did not see them. I called twice, but at both times they were out—once driving in the park, and again attending a reception."

"You do not look sorry, Miss Gordon, although it was purely out of courtesy to you that I went there."

"Indeed, I am very sorry," she murmured, but she could not make her face look so.

His words were so great a relief to her that she could not look disappointed. He did not tell her how disappointed he was. He would not have owned to himself that he had hoped to hear something about that lover from whom they had separated her. He would even have liked to have seen him. It was a new thing for the blasé, world-weary St. Leon Le Roy to feel curious over anything; but he had a great deal of curiosity over the man whom Beatrix Gordon loved.

"I should like to know if he is worthy of her," was his excuse to his own heart.

But he had not seen the Gordons, and he had found out nothing about their daughter's lover.

"If he is good and true and noble I should like to help the child to happiness," he said to himself. "If he is an ignoble fortune-hunter, as they say, I should most decidedly try to forward the Gordons' plot."

And it was rather curious that in his own mind he had quite decided that the unknown young man was a villain of the deepest dye.[Pg 23] He pitied Beatrix for having fallen in love with a scamp who was only after her money. But as the days went by a change came over Beatrix that puzzled him.

Some of her shyness, her timidity, her sadness wore off. A look of contentment dawned on the fair face and in the dark eyes. Her cheeks gained color and roundness. She even laughed sometimes, a mellow laugh that was so sweet and glad it thrilled one's heart to hear it. Mrs. Le Roy was puzzled.

"She is certainly not pining for her lover," she said to her son. "At first she was so strange and sad I thought she was breaking her heart over him. But she is so young it is likely that change of scene has driven him completely out of her mind. The Gordons did well to send her here."

The day came when she changed her mind on that latter point.

In her heart Mrs. Le Roy had a secret fancy that the charms of her son had quite blotted out the image of Beatrix's absent lover from her young heart. Not that St. Leon or Beatrix gave her any reason to think so, but the wish was father to the thought. She would have been delighted if these two had fallen in love with each other, for the greatest desire of her heart was to see St. Leon married.

In the private parlor of a neat hotel in a city not very far from New York, the true Beatrix Gordon was sitting one lovely morning awaiting the coming of her husband.

Although Beatrix had deceived and deserted her parents, and foisted an impostor on the aristocratic Le Roys, she looked positively and undeniably happy this bright summer morning. Her lovely blonde face, with its crown of soft golden hair, glowed with love and happiness, and her beauty was enhanced by her becoming morning-dress of soft pale blue with delicate trimmings of rich cream tinted lace.

The door opened suddenly, and Cyril Wentworth, her handsome young husband, entered with a letter in his hand. He kissed his fair young bride, and held the delicate envelope tantalizingly out of reach.

"At last!" cried young Mrs. Wentworth eagerly, and she sprung upon a chair and gayly possessed herself of her letter. "It is from my sweet little Laurel."

She tore it open and ran her eyes quickly over the contents, while her husband watched her expressive face with deep anxiety.

She finished at last, and turned her fond, smiling blue eyes upon Cyril's questioning face.

"All goes well," she said. "They have not discovered my charming little plot yet. Papa and mamma have written, and they are both as well as usual. Clarice answered their letters, and imitated my hand and style so well that they were completely imposed upon."

"Clarice must be a clever maid," said Cyril.

"She is," said Beatrix. "Her education is far above that of her class generally. She was very valuable to me. I hated to part with[Pg 24] her, but I was obliged to send her to Eden to keep up appearances, answer mamma's letters, and keep Laurel Vane up to her part."

"And when is this farce to end?" asked Cyril.

"Oh, not for several months yet, if I can help it," answered the pretty bride, looking frightened at the very idea.

"But why keep it up so long? I cannot understand your reluctance to have your parents learn the truth, love. They cannot forbid the bans now, for we are united as fast as Church and State can bind us," said Cyril Wentworth, who had an honest, open nature; and now that he had won his bonny bride, longed to have the whole world hear what a prize he had won.

"I have a secret reason, Cyril, darling," said the fair bride, twining her arms about his neck, and looking up in his face with sweet, shining eyes. "If Laurel plays her part well and I can keep our marriage a secret a few months, some great good fortune will come to us, Cyril. If not—if it is all found out sooner—why, then," with a little contented sigh, "I shall still have you, my dear. Fate cannot take you from me!"

"I am dying of curiosity, darling," laughed Cyril Wentworth.

"No matter. You shall not hear one word till the time is up," answered Beatrix, gayly. "I forbid you to even think of the matter again, sir!"

"Your wishes are my law," answered the lover-husband, in a tone as gay as hers.

"There is one thing that troubles me," she said, presently, running her eyes again over the letter which she still held open in her hand. "Laurel writes me that Mrs. Le Roy's son has returned from his European tour, and is at Eden."

"Why should that trouble you, dearest?" he inquired, tenderly.

"Do you not see that the chances of discovery are doubled, Cyril? Mrs. Le Roy seldom leaves home, and would be far more likely to be imposed upon by our little conspiracy than would her keen-witted son. Laurel writes me that he is keen, critical, brusque. She is afraid of him."

"I have a fancy about this Mr. Le Roy," said Cyril, lightly. "He will fall in love with the pretty little impostor and marry her."

Beatrix looked grave and troubled at this novel suggestion.

"Oh, that would never do," she cried. "My little Laurel is as beautiful as a dream, but she is not a fitting mate for St. Leon Le Roy. He is wealthy and aristocratic, and, I have heard, as proud as Lucifer. And she—a drunken journalist's daughter! No, no, that would never do, Cyril. She would not dare! I am not afraid of such a thing. She shall come and live with me and be like my own sister when her stay at Eden is over, and we shall find her a husband more suitable to her than St. Leon Le Roy!"

Two months had passed, and Laurel Vane still remained at Eden, in her character of Mr. Gordon's daughter. The clever conspiracy had not been discovered yet.

Indeed there seemed less chance of this catastrophe than at first. Laurel, with ready adaptability, was beginning to fit herself into her[Pg 25] place. Under Clarice's constant tuitions and admonitions, her shyness and timidity had been somewhat overcome, and a pretty, graceful ease had replaced it. Her beauty had expanded and increased like a flower in the sunshine. As the first restraint of her manner wore off, she developed a rare grace and winning sweetness that, added to her native originality, made her very charming. Mrs. Le Roy, in her stately, quiet way, had grown fond of her guest.

"Although there could not be a greater contrast imagined than exists between Beatrix and her mother, I am inclined to give the palm to the former," she confided to St. Leon. "I was fond of Mrs. Gordon when she was a girl. She was a fair, sweet young girl, but she lacked the charms that distinguish Beatrix. The girl makes me think of some beautiful, timid, wild bird."

"At first you thought her awkward and uncultivated," said St. Leon, carelessly.

"It was mere shyness that has worn off long ago," answered Mrs. Le Roy. "She puzzles me still, but she no longer appears awkward and uncultured. Still I admit that her education has been an unconventional one. She knows little that a girl in her position might be expected to know. On the contrary, she has some attainments not to be looked for. She knows German and Latin and some French, but she has no accomplishments, and she cannot play the piano. She says her father educated her. I take it he is a peculiar person."

"Rather, I should say," St. Leon assents, with his slightly bored air.

"Anyhow, I believe she is perfectly cured of her fancy for that—that person. I have never heard his name yet—have you, St. Leon?"

"Yes; it is Cyril Wentworth."

"A good name. Is it possible that Beatrix told you?" exclaims his mother.

"No; I heard it once, by the merest accident, on one of my trips to New York," St. Leon answers, with bland indifference.

"And—a—ah!—what kind of a man is he, St. Leon? As black as he was painted?"

"By no means—they say even the devil is not that, you know," with a short, dry laugh. "I have even seen the fellow. He is comparatively poor—I should say that that is the worst there is to him."

"Handsome?"

"As Apollo—and better still—young," he answers, with a short, dry laugh that has a ring of bitterness in it.

The mother's heart, quick in instinct, catches the subtle intonation of almost envy in that one concluding word.

She lays her white hand on his shoulder and looks up into the handsome, proud, world-weary face with its cold, curled lips—not pityingly—St. Leon has never borne pity in his life—but with fondest love and admiration.

"As young as you, St. Leon?" she asks, speciously solving his unacknowledged wound.

"Why, mother, how you talk!" he says, not unkindly. "Why, I am old. Thirty five my last birthday, and the crow's-feet, and gray hairs not so far away!"

"Do you care, my son?" she asks him, a little wistfully.

"Care—why should I?" he asks, frowning. "And yet I have no mind to contradict the poet, who says:

His glance wanders from the window out into the beautiful grounds, where Laurel Vane is wandering, bright-eyed, bright-haired, lovely, in the golden springtime of youth.

"After all, there is nothing on earth so beautiful as youth," he says, aloud, his dark eyes following the flutter of that white robe among the trees.

She looks furtively past him and sees Laurel, too, the sunlight shining on the fair young face, her white apron-overskirt heaped high with flowers after her usual fashion, the refrain of a song on her lips that floats back to them in snatches. It is Mrs. Browning's—"The Lady's Yes."

Mrs. Le Roy laid her delicate hand, all glittering with jewels, on the shoulder of her idolized son.

"St. Leon, you talk of growing old," she said. "My son, does not the flight of time remind you that you are neglecting a duty you owe to yourself?"

He turned to look curiously into her face, and the white figure out among the trees wandered further away, seeking new delights, like the bright-winged butterflies, among the flowers. The echo of her song died in the distance.

"Duty, mother," he said, carelessly. "I did not know that the vocabulary of my life contained that hard word. I thought all I had to do was to 'eat, drink, and'"—sarcastically—"'be merry.'"

"St. Leon, you are but feigning ignorance of my meaning," she said, wistfully. "You understand me."

"Upon my honor, no," he said. "Explain yourself."

"You should marry."

A dark-red flush crept under his olive skin. His slender, straight black brows met in a frown over the proud dark eyes.

"I thought we had dropped that subject ages ago," he said, frigidly.

"Forgive me," pleadingly. "I cannot help but revive it again. St. Leon, when you quoted that epicurean motto, 'eat, drink, and be merry,' you forgot that latter clause, 'for to-morrow we die.'"

He shrugged his broad shoulders impatiently.

"Well?" he said.

"'For to-morrow we die,'" she repeated. "And oh, St. Leon, there is no heir to Eden!"

"Quelle importe?" lifting his dark brows with a slight gesture of indifference.

"Oh, my son, do not treat it with indifference," she cried. "You are the last Le Roy of your race. The fine old name will die with you, the wealth of the Le Roys will pass to strangers, unless you marry and leave an heir. I am proud. I cannot bear to have it thus. Oh, St. Leon, choose yourself a wife and me a daughter from among the fair dames of your own land."

Her handsome, haughty old face was transformed with emotion, her dark eyes dim with tears. He turned from the sight of it and looked from the window again, but the slim white figure no longer gleamed among the green trees and the bright parterres of flowers. It had strayed out of sight.

"Where shall I find you a daughter worthy of your love, my lady mother?" he said, lightly, yet with some intangible emotion beneath his tone.

She hesitated, and her glance, too, wandered from the window and came back disappointed.

"St. Leon, what do you think of Beatrix Gordon?" she asked, wistfully.

The dark eyes flashed.

"For shame, mother! Would I steal another man's betrothed?" he said.

Meanwhile, Laurel Vane had strayed carelessly on to the gates of Eden, the light song still lingering on her lips, the light of the day reflected in her eyes and on her face. She was learning to be happy, this beautiful girl over whose unconscious head hung the shadow of long years of sorrow.

She leaned her arm on the rustic gate and looked wonderingly, as she often did, across the dusty carriage-road at the beautiful river.

"Should I ever be coward enough to throw myself into its dark depths, and 'so end all'?" she asked herself, with sudden gravity.

A sudden step, the dark figure of a man looming before her, made her lift her wide, dark eyes. A cry of mingled horror, loathing, and fear burst from her lips.

"Ross Powell!"

If Laurel Vane was thunderstruck at the unexpected sight of the villain who had so deeply insulted her helpless innocence in New[Pg 28] York, Ross Powell on the other hand was delighted. His bold eyes gleamed with evil joy, his thin lips curled in a mocking smile.

"Miss Vane," he exclaimed, "is it possible that I find you again after all my fruitless search? But I might have known that such an angel would fly to Eden!"

Horror unutterable had seized upon Laurel. The song had died on her lips, the color fled from her face, she stared at her foe with parted lips, from which the breath came in palpitating gasps, while her wide, terrified eyes had the anguished look of some hunted creature.

He had come to betray her, she said to herself. All was ended now. He had found her out. He would tell the Le Roys who she was, and how she had deceived them. She could fancy Mrs. Le Roy's scathing words of condemnation. She could imagine the lightning scorn in St. Leon's proud, cold eyes.

Stifling the moan upon her lips, she cried out in passionate despair:

"Ross Powell, what has brought you here?"

"I might ask you the same question," he returned, coolly. "It certainly never entered my mind that I should find the daughter of Louis Vane a visitor at Eden."

He had spoken unwarily. His words let in a sudden light upon her mind.

He had not traced her here then. Whatever had brought him to Eden it had been some other cause than the denunciation of Beatrix Gordon's plot.

Her heart leaped with hope, then sunk heavily again. He was here, and he would find her out. She could trust to his hate and his desire for vengeance for that.

Obeying a sudden, desperate impulse, she pushed open the gate and stepped out into the road.

"You are right," she said, bitterly. "Do you think that the proud, rich Le Roys would have Laurel Vane for their guest? My errand at Eden is done, Mr. Powell. Let me pass, if you please."

He stood before her, dumbfounded at her coolness, glancing from her pale, agitated face to the flowers she carried in her apron with ostentatious care.

"Your errand," he stammered. "The flowers?"

"Yes," she answered, calmly. "I must take them home. Will you please to stand out of the way, Mr. Powell?"

"One moment," he said, still hindering her way. "Where is your home? Where can I find you?"

Her eyes flashed scornfully upon him.

"What can it matter to you?" she said. "Do you think I would receive you in my home? You, the cowardly insulter of helpless girlhood? Never! I hate you as I hate the slimy, crawling serpent! You have nothing to do with me. Out of my way!"

He caught her fiercely by the arm and hissed:

"I shall find you out! Be sure of that, my incarnation of indignant virtue! And when I do, Laurel Vane, you shall find that the serpent you hate can sting!"