That was a Capital Stroke, Dave

BY

ROY J. SNELL

Eight Full Page Illustrations

By

GLEN SHEFFER

THE GOLDSMITH PUBLISHING CO.

CHICAGO NEW YORK

Copyright 1941, by

M. A. Donohue & Company

Printed in the United States of America

It was one of those rare autumn days in England. The sky was blue as blue. The trees cast dark shadows across the hillside. The sheep wandered contentedly along the slope. To Cherry Ramsey, for one full moment it seemed that nothing could possibly be wrong with the world.

Then with a sudden light spring she shot from her sunny corner to scan the sky and to exclaim softly to the collie at her feet:

“Flash old boy, it’s an airplane. Perhaps it’s a bomb-bomber.” That last word always choked her. How she hated those Nazi marauders! No, all was not right with the world! Perhaps it never would be again for a long, long time!

“But Flash old boy,” there was hot fire in her voice, “we must all do our best and trust God. That’s what mother always says, and she’s nearly always right.”

Flash, the splendid golden collie, stood up, appeared to listen, then whined as if he had truly understood. And who will say he did not?

For one more full moment the scene remained just as it had been. In the foreground were low hills and sheep feeding. Beyond that lay a level field where two grown youths in their late teens bent over their task of harvesting Brussels sprouts. Beyond all this were trees and barns—a farm home,—Cherry’s own home.

As she stood there, lips parted, ears straining in their attempt to build up a mental picture of the rapidly approaching airplane, she saw the two boys straighten up, then gaze skyward.

“Ah! They hear it!” she whispered. Then she tried with a sudden flash of the imagination to picture the thoughts running through the minds at that moment of those strangely different boys. The plane proved to be a German bomber.

Then suddenly her heart stood still. The plane had come zooming out from behind the nearby hills, and in a flash she had caught sight of the hated cross on the right of the plane, the swastika on its tail.

At that same instant the taller of the two boys turned to his companion to say:

“I suppose that’s what you call a bomber?” His was the sharp, brisk accent of a Midwest American.

“Not precisely that,” was the slow drawling reply of his typically English companion. “It’s a Messerschmitt 110, I’d say. They do use them for daylight bombing. But that plane is really a fighter. The best the Jerries have. If our boys go after one of them when it flies over to do a little bombing, it lays eggs and puts off at a fearful rate, or turns in for a scrap.

“And I say!” his voice rose, “There’ll be a scrap! There’s a Spitfire after her. Good old Spitfire! Go after ’em, old boy! Here we are, with a ringside seat!” He dropped back to take his place on a bag of Brussels sprouts. The tall, dark, curly-haired American youth stood where he was, watching the two planes. His eyes were wide with excitement and wonder. This was but his third day in England. Until this moment he had seen nothing of the war. Even now, with the peace of open country all about him, it did not seem possible that those two silver ships up there in the sky would really fight an air duel, that men might come hurtling down from out the sky to a terrible crushing death.

An exclamation from his companion brought him back to reality.

“Oh! I say!” came in sharp, rising tones. “There’s another of our fighters! Now there’ll surely be a scrap! That Messerschmitt can’t escape both of them! That,” he said with a sudden intake of breath, “is one of your American fighters. It’s called a Tomahawk.”

“Are they good?” Dave asked, his eyes still on the sky.

“Good!” Brand exploded, “Of course they’re good! Air cooled engine. Do 350 per hour. And can they climb! Practically straight up! It’s going to be grand!” he exclaimed, his eyes glued upon the spot where the three planes were circling. “They’ll do that old Messerschmitt in before you can say Jack Robinson.”

“They should. Two to one,” Dave Barnes, the other boy spoke slowly, no sarcasm in his voice, only cool appraisal. He was an American. This was not his war. For him this was but a ringside seat to something rather big.

The lips of the English boy, Brandon Ramsey, drew into a tense white line. This was his war. Perhaps he knew the men in those one-seated fighters. He could not be sure of that, but there was an airbase for fighters not three miles from his home. He knew nearly all the fliers. As for the enemy plane, why was it here? To drop bombs on defenseless villagers, or to spy out targets for some other plane that carried tons of explosives. Who could say?

“Two to one.” His was not a happy laugh. “There are three men in that Messerschmitt. They’re in an armored cabin. Our boys are right out there in the open.” There was a touch of anger in his voice.

“I—I’m sorry,” Dave murmured, brushing a hand before his eyes. “I’ve been in England for so short a time. Guess I don’t see things your way just yet.”

“That’s all right,” was the prompt and generous response. Brand gave Dave’s knee a slap. “You’ll pick it up fast. That is,” he added, “if that Messerschmitt isn’t still carrying its bombs and if he doesn’t land one of them right on us.”

“Why would he do that?” The American boy’s eyes opened wide.

“Lighten his load. Besides, a bullet might strike a bomb. Then whew! He’d fly into a thousand pieces. He—”

The English boy stopped suddenly, for at that instant there came a sput—sput—sput from the sky.

“They’re at it!” Dave’s voice was low and tense.

The burst of fire which was short and sharp had come from the Spitfire.

“Short, broadside,” Brand explained. “You can’t do much with a broadside. Other plane’s going too fast. They’re out of range, just like that. They—

“Look!” he exclaimed in a voice tense with emotion. “The Tomahawk is going after that plane from behind! He—

“Nope.” He let loose a low hiss of disgust.

“He’s gone into a power dive.”

It was true. All the planes had been high, perhaps up 15,000 feet. Now the Messerschmitt slipped into a dive that took it half the distance to earth. The American boy was ready to dodge and run for it when just as suddenly as it had gone into the dive the Nazi plane came out of it to level off just above the farm home.

“Look!” Brand gripped his companion’s arm hard. “He’s dropped a bomb!”

Terror stricken, fascinated, white-hot with anger, the English boy watched a silver spot against the dark blue sky go down—down—down.

And on the hillside, far above her home, tall, slender, beautiful twenty-year old Cherry Ramsey, with the color gone from her cheeks, also watched the terrifying missile speed from the sky.

“Where will it strike?” Her alert mind registered the question her lips did not speak, while her eyes took in the house, the barn, the out-buildings, the orchard—every spot dear to her childhood.

And then the silence of the countryside was torn by a sudden burst of sound that made the very hills tremble.

For one full moment while the trio on the hillside kept their places, breathless, expectant, a cloud of dust and smoke obscured the view.

During this moment Cherry became conscious of the dog that lay whining at her feet. Bending low, she patted his sleek head. “Yes, I know it’s terrible,” she soothed. “You don’t like it. We don’t either. But we all must endure it for England’s sake.”

As if he understood, the dog nestled silently at her feet.

The smoke cleared. The girl sighed with relief. The bomb had fallen in the orchard. A single apple tree, one of the early pippins, had been uprooted. A slight loss. The tree was quite old.

And then with a shock it came to her that everything—the house, the barn, the dovecotes,—all about the place was old, old and very dear.

Then again her lips parted in sudden fright, for a second silver spot, larger than the first, had appeared against the sky. Watching its swift descent, she grabbed at her painfully beating heart. At first it seemed that it must fall upon the house. “Alice is there,” her reeling brain registered the thought. Then came a sense of relief. The house would be spared. Then it was to be the barn where two fine colts were housed that would receive the full force of the blow.

“No,” she sighed. “Farther up the hill.”

The bomb fell not ten feet from a small square building. Like a tree, uprooted by the blast, this tiny house leapt high in air, then collapsing, crashed to earth. At the same instant dust and smoke concealed all.

As if struck a blow from behind, the girl leapt forward, stood there tense, motionless for a period of seconds, then disregarding the loyal collie whining at her heels, went dashing down the hill.

The apparently insignificant building had once been a smoke-house. Perhaps that had been fifty years before. When Cherry was a child it had been converted into a playhouse. There, hours on end, she and her sister Alice had played with their dolls and at keeping house. They, to be sure had abandoned both dolls and playhouse long ago. But from time to time other children had come to live on the Ramsey Farm. Both playhouse and dolls had been theirs. At this moment two cute children, Tillie and Peggy, from the London slums, were staying at the Ramsey Farm. This old smoke-house was their favorite haunt. As Cherry sped down the hill allowing herself not one glance at the brightening sky, she dared not ask the question that haunted her terror-stricken mind. “Oh, God!” she whispered, “It can’t be true!”

From the spot where Dave and Brand stood the ancient playhouse could not be seen. That tragedy might have befallen some member of their household they did not so much as dream. Enough that by some miracle the house and barns had been spared and that the hated enemy plane, having delivered its load, was now speeding away.

But not so fast. The speedy British Spitfire had made a broad circle and was prepared to meet the enemy head on.

As Brand Ramsey stood stiffly at attention, watching every move of those fighting planes, his fingers clenched and unclenched nervously. Not so his American companion. Standing at ease, smiling a little, his lips parted, he might have been at a tennis match.

How often, during his early days on an American farm this boy, Dave Barnes, had watched a fight between two catbirds and a hawk. How insignificant the catbirds had appeared, how terrifying, with curved beak and needle-like claws, the hawk. And yet how often, quite disheartened, the gray intruder had soared away. In the fight being fought above them now he saw the battle of catbirds and hawk. Which would win? His sympathies had ever been with the catbirds. It was so now. And yet he whispered to himself, “It’s not my war.”

His war or no, he followed every move of those birdlike things that whirling, zooming, dipping, soaring, appeared at any moment ready to crash head on and burst into flames.

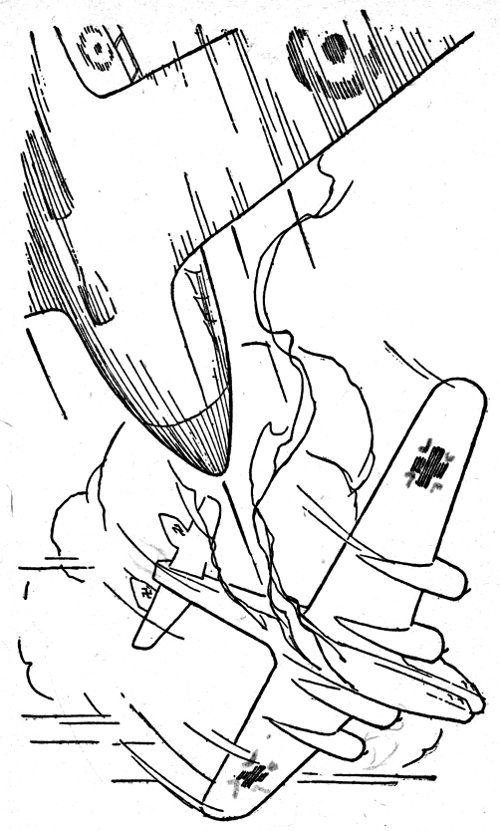

Now the Spitfire was beneath the enemy, coming up. Now! Oh! Now! The boy drew a deep breath. Now the Spitfire was on the Messerschmitt’s tail. “Now!” he breathed.

Once more a sharp exclamation escaped his lips, for banking sharply, the enemy slid out of the trap. At that instant, with tail to the enemy, the Tomahawk was doing a broad circle to re-enter the scrap.

“Oh! Oh! Watch out!” Brand, the English boy shouted, as if he could call a warning to the pilot in the American plane. The Messerschmitt had turned the tables and was at the Tomahawk’s back. Brand wanted to stop his ears from the rat—tat—tat that he knew must come. Instead, he stood there mute, staring with all his might.

And then it came, a ripping, tearing burst of sound, as if the very sky was being torn to shreds.

“He—he got him!” Brand’s lips went white as the Tomahawk, after banking so sharply it seemed to stand on its right wing, went into a spin.

Only then did the American boy realize to the full that this was a battle, not a show affair that these were men and planes, not birds, and that the brave fellow in that spinning airplane was apparently about to be beaten to a pulp on the cruel earth of the hillside. Instinctively he closed his eyes and began to count,—“One—two—three.” Thirty seconds, he thought, then all will be over.

He had counted only to fifteen when a sharp cry—“Hooray!” sent his eyes wide open again.

“He—he came out of it!” Brand exulted with a wild wave of his arms.

It was true. The apparently doomed pilot had somehow pulled his plane out of that fateful spin. What was more, he was not leaving the field. Instead, he was once again climbing rapidly.

“Look!” Brand exclaimed. “That Messerschmitt has had enough! She’s climbing! She’s afraid of that Tomahawk. Thinks she can outclimb him. The Tomahawk’s motor is not so good at dizzy heights. But, boy! How they can climb! Half a mile a minute!”

They were climbing now, all three planes. The enemy plane had the lead by many hundreds of feet. First after her came the Spitfire. Then the Tomahawk.

It was an all but perpendicular race, a glorious thing to see. Slowly, surely, the game little Spitfire, seeming only a nighthawk at that distance, closed in upon the enemy. Behind her, closing in faster, faster, ever faster, was the Tomahawk.

“See! What did I tell you!” Brand’s voice rose with enthusiasm. “That Tomahawk is a climber! You Americans should be proud of that ship!”

“I suppose we are.” Dave scarcely heard. A born mathematician, he was trying by some occult system to determine the outcome of this strange race.

“In twenty seconds,” he pulled out a thin gold watch, “the Tomahawk will pass the Spitfire. Forty seconds more and—well—you’ll see.” His lips trembled as his words trailed off.

Hardly had he finished speaking when the small planes were abreast. Brand even imagined he saw the Tomahawk’s pilot wave to the other as he passed.

Forty tense seconds and then there came a ripping of the sky, longer, more terrifying than any they had yet heard. Half below, and half on the Messerschmitt’s tail, the Tomahawk was finding sweet revenge.

“That’s enough. No ship can take that and keep on flying!” the English boy breathed. At the same instant the attacking Tomahawk slipped away in a graceful spiral glide.

“What a ship!” the American boy breathed. “It can take it, and dish it out!”

The Messerschmitt had had more than enough. Black bits of wreckage began dropping from the mortally wounded plane. Among these were three larger spots, darker than the rest. Presently above these three white mushrooms blossomed against the sky. “Parachutes!” Brand exclaimed. “They’re coming down! Land somewhere up the slope. Come on! We’ve got to get them!”

Gone from Dave’s mind was the thought that this was not his war, as he sped after his companion. Two facts were registered on his mind as he raced ahead—a one-legged man using a crutch had stopped his plow-team in the field and was racing toward the slope—a large collie dog was scooting across a low meadow. The dog appeared intent upon joining the one-legged man.

In the meantime, quite ignoring the battle in the sky, two streaks of red and gold—Cherry the girl, and Flash the dog—had gone racing down the slope. In her golden sweater and red plaid skirt the girl seemed little more than a sprite. The collie might well have been her golden shadow. That she was quite a real person she herself knew full well. Her painfully beating heart told her that.

Even as she raced on, her eyes were searching the ruins that had once been the playhouse of her childhood. They were looking for some trace of red or blue calico,—shocking proof that her fears had been well founded and that two small girls had been in the playhouse at the time the bomb fell.

It was only after she had reached the top of the stile leading from the field to the house that she caught a loud: “Yoo-hoo! Yoo-hoo, Cherry!”

One look, and she crumpled down on the stile steps to burst into a flood of tears, tears of pure joy.

All gay in red and blue calico Tillie and Peggy stood in the farmhouse doorway. A moment more and they had left the house to come racing toward Cherry.

In the meantime the fighting planes had gone beyond the hill, quite out of her sight. Soon she was hugging two tumble-haired young sprites to her bosom, and exclaiming: “Tillie! Peggy! You are safe! I was, Oh! So afraid!”

“But the playhouse is all blowed up.” Tillie dabbed at her eyes.

“Yes!” exclaimed Peggy, dancing a jig. “But were we bombed! And was it exciting! Just like fireworks! Only bigger! Much louder! There was smoke, and then Oops! Up went everything!”

In vast astonishment Cherry stared at this small bit of humanity from the slums of London. Her eyes were on the child for a full minute. Then, mustering up her courage she managed a low chuckle. Then, springing to her feet, she cried: “Come on! Let’s go see! We’ll make it a race!” And so the four of them, three girls and a dog, went racing away.

When at last they stood by the ruins of what had once been a grand playhouse, almost a living thing to her, Cherry was ready to weep.

How very much that playhouse had meant to her! It was only an abandoned smoke-house, with the pleasant odor of burning wood and smoking meat still clinging to it, but she had made of it a sort of second home. What grand times she and Alice had known there! And of late, how Tillie and Peggy had gloried in it! They had called it “Home of our Dolls.”

“The dolls!” Cherry exclaimed as she recalled it all. “Where are they?”

As if in answer to her appeal, the dog, Flash, went racing about to return almost at once with the remains of a doll held lightly between his teeth.

“Oh! Poor Wilhelmina!” Peggy cried. “She has lost her head!”

“Yes,” said a sober voice behind her. “And if those terrible Nazis had succeeded as they hoped to, in dropping a bomb on our house you and I would have been minus our heads too.” It was a tall, strongly built girl in her late teens who spoke. She wore a blue calico apron. Her hands were white with flour.

“Alice!” Cherry demanded, as a look of terror came into her eyes. “Do you really think they meant to bomb the house?”

“Of course they did!”

“Why? What have we done?”

“They did it because we belong to England. They hate all of England. They will destroy every bit of England if they can!” The girl’s voice rose. “But they can’t! They shall not. There will always be an England!”

At that moment the plain, strongly built girl with flour on her hands appeared transformed. No Joan of Arc could have looked stronger, more daring, than she.

Cherry looked at the headless doll and was silent.

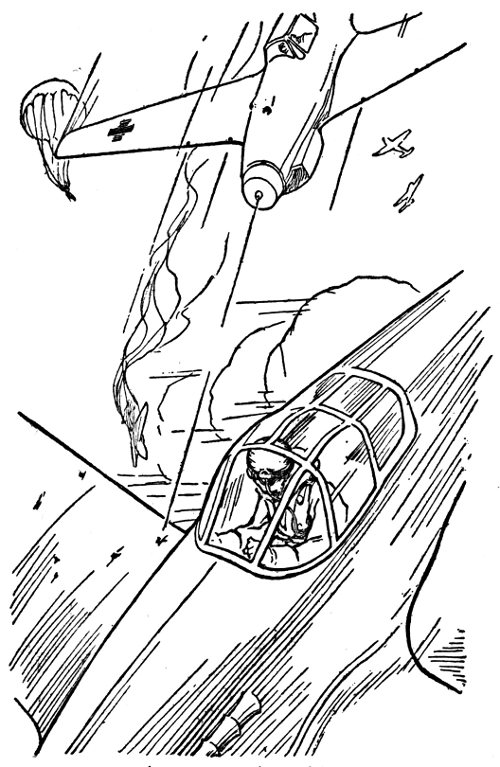

In the meantime, racing breathlessly, the two boys watched the drifting of the white enemy parachutes across the sky. It had seemed at first that they would land not so far from the spot where they had stood. But a brisk wind carried them farther and farther away.

“It’s going to be a race,” Brand panted, “but we’ve just got to make it. They may—may be spies. They—they must not escape!”

After climbing the sloping pasture they came to a place of scattered shrubs and trees. At last the parachute nearest them vanished behind a broad beech-tree.

“Come on!” Dave spurted ahead. “It’s now or never!”

At last, bursting out from behind a clump of trees they came upon a silken bag lying on the ground. At the same time a dark shadow vanished into a clump of low shrubs. Without a word the boys separated, one going right, the other left. The clump was small. One or the other would come upon the man. And then—

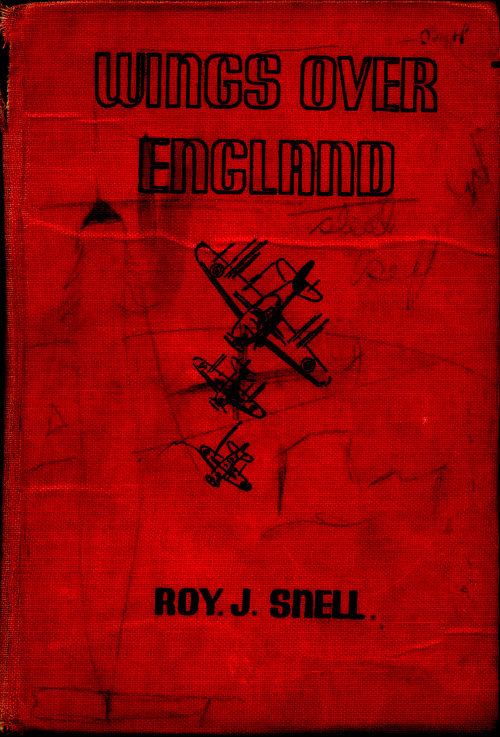

It was Brand’s luck to meet the man face to face. He was young,—not more than two years Brand’s senior. There was a savage, haunted look on his face.

“All right!” he growled, showing his teeth like an angry dog, “You asked for it. You get it!” All this in guttural English. An automatic gleamed in his hand. The English boy did not move.

The automatic rose, jerkily but steadily. Now it was aimed at the boy’s feet,—now at his thigh—his belt—and now—

At that instant something with the force of an avalanche struck the Nazi flier across the knees. As he went crashing to earth the automatic exploded harmlessly, then fell into the tall grass. Ten seconds later both Brand and Dave were holding the man down, as Brand panted:

“Tha—that was a capital stroke, Dave! I sup—suppose you’d call that a tackle!”

“Right,” Dave agreed. “It’s really quite old stuff. They do it in the movies. I guess you’d call it a part of our American way of living.” He laughed softly.

Brand went over the Nazi flier for weapons. Finding none, he searched in the grass, found the automatic, then turning about, said:

“You may get up.”

The reply was an ugly snarl. But the man, who wore a pilot’s insignia, stood up.

“Mind leading the way?” Brand said to Dave.

“Certainly not.” Turning his back on the prisoner Dave started toward the farmhouse.

“All right, you. March!” Brand snapped. The prisoner followed Dave.

With Brand bringing up the rear, they had not gone a dozen paces when from somewhere, not far distant, there came a most astounding roar.

Starting in sudden shock, Brand all but dropped his weapon.

“Wha—what’s that?” Dave’s voice trembled as he came to a dead stop.

“That’s old Jock! Something terrible is happening. Here!” Brand thrust the automatic into Dave’s hand. “You know how to use it. Press the handle, that’s all. March him down into the pasture. Don’t hesitate to shoot. This is war—our war!” He was gone. As he dashed through the brush, Brand felt his blood fairly boiling in his veins. “If anything serious has happened to good old Jock,” he thought savagely, “if one of those devils harms the old man I’ll tear him to pieces with my bare hands!”

Since no further sound reached him, guided only by that one agonizing roar, he made his way as best he could along the slope. Then breaking through a cluster of young beech-trees, he stopped short to stare. The little tableau before him seemed unreal. It might have been taken from some picture.

A young man dressed in civilian clothes, minus a coat, lay flat upon the ground. His eyes gleaming, white teeth showing in a snarl, a golden collie lay with his fore-paws on the prostrate man’s chest. Over them, leaning on his crutch, towered a great gray-haired one-legged Scot. He was saying: “Keep ’im Flash! Don’t ye let ’im stir an inch!”

At the same moment, from the pasture below came the confused murmur of many voices. This was followed by a shout: “Come on, men. They’re ’iding up ’ere somewheres!”

While the sound of voices from below grew louder, Jock said in a steady voice:

“He was changin’ to civies.”

“His uniform must be hidden somewhere close,” suggested Dave.

“Aye. That it must,” Jock agreed.

Brand was not long in locating the uniform half hidden by dead leaves. In a pocket he found an automatic.

“It’s good he didn’t have that in his hand,” said the sturdy Scot, “else I shouldn’t ha’e been here. I caught him doin’ the lightnin’ change act.

“Plannin’ to do the spy act, eh?” He spoke to the man on the ground. The answer was a surly curse.

“All right.” Brand spoke quietly to the dog. “Let him up.”

Flash looked at Jock, read an answer in his eyes, then left his post.

“Get up.” There was a sound like clinking steel in the English lad’s voice.

“He knocked me over,” Jock explained quietly. “That was easy enough, an’ me with but one leg. Then he went on to finish me off. He’s got astonishin’ strong hands, that lad has. He’s all for shakin’ a man. If it hadn’t been fer good auld Flash now—”

“He would have killed you.” Chilled hate was in Brand’s voice.

All of a sudden hands parted the branches of a small oak and there stood the brawny blacksmith from Warmington, the village below Ramsey Farm. He carried an antique fowling-piece.

“So you got one of ’em? That’s grand, me boys!” he approved. “Where now would you say the others be?”

By that time a dozen members of the Home Guard had gathered in.

“My friend from America, David Barnes, has one of them just up here a little way,” Brand replied.

“I’ll say you’ve done a fine job of it,” the blacksmith approved.

“And now then.” He turned to the prisoner. “What may your name be?” He drew pencil and notebook from his pocket.

For a moment the Nazi stood sullenly silent.

“Come now,” the blacksmith insisted. “It’s part of the regulations.”

“Hans Schlitz,” came in a low, defiant voice.

“Hans Schlitz!” The words sprang unbidden from Brand’s voice. “That’s the name of the prisoner who worked on our farm during the World War!”

“I’m his son,” the prisoner snarled. “I’ve paid you a visit to square accounts. I’m sorry we missed.”

“So you meant to bomb our house!” Brand stared almost in unbelief.

“Why not? Your father treated my father, a prisoner of war, like a dog.”

“That,” said the gray-haired blacksmith, “is not the truth. I mind it well. He was housed and fed as one of the family. He worked no harder than the men of the household. He—”

“That’s a lie!” the prisoner snarled. A crimson flush o’erspread the giant blacksmith’s face. He took a step forward. Then he muttered low—“No. It won’t do. Not at all it won’t do. Not to be brawlin’ with a swine like him.”

He stood there for a moment, head bowed as if in prayer. Then his head lifted as he said:

“Here you, Bill and Hugh, take this fellow to the guard house.

“The rest of you,” he waved an arm, “spread out an’ search for the one that’s still free. There was three of them, you all mind countin’.”

There was a murmur of assent. Then they were away. “Come on,” Brand said to Dave after the first man they had captured had been turned over to the blacksmith and a companion. “All this leaves me a bit groggy. Think of their deliberately planning to blow our house off the map!”

“Terrible!” Dave agreed.

“And my father did treat that prisoner well,” Brand said. “I remember his telling of it many times. We saw where their plane cracked up.” Brand’s voice rose. “Finding that plane is important. That third fellow may have been there and finished wrecking it. If not, we’ll be the first to look it over.”

The discovering of the wreck was no great task. The plane had cut a path through a cluster of young trees. In doing this it had stripped off its wings, but its cabin, motor, and instrument board had been left in fair condition.

“The R. A. F. will want to look at this,” Brand said. “They’ll want to know if the Huns have discovered any new tricks,—a bomb sight, or something like that.”

He tried the cabin door. It stuck. Seizing a bar from the smashed landing gear he pried the door open. As he did so something fell at his feet. It was a long, flat pigskin billfold.

Throwing back the flap, he pulled out a handful of papers. The first of these appeared to be some sort of flying orders. He could not read the German print, but the names, written in by hand, were plain enough.

“Fritz Steinbeck,” the boy read aloud. “That may be the dark-haired fellow we caught first.”

“What are the other names?” Dave asked.

“Hans Schlitz, and Nicholas Schlitz. Sayee—” Brand stared. “They may be brothers.”

“And they are!” he exclaimed in a low, tense whisper ten seconds later. “Look! Here’s their picture together.” He held up a thin card.

“Look almost like twins,” Dave suggested.

“Nope,” Brand concluded after a second look. “The one we caught is the older of the two. I only hope,” his brow wrinkled, “that they get this fellow Nicholas. If they don’t—well—” he heaved a deep sigh. “His name may be Nicholas, but for us, if he harbors a grudge, as his brother surely does, he may prove to be Old Nick, the devil himself.” He did his best to suppress a shudder. “I’ll put this in my pocket.” He stowed the billfold away. “Turn it in at the airport tomorrow. Mother will be down tonight. I want to talk the affair over with her.

“Hey, you!” he called a moment later as a boy who could scarcely have been past sixteen put in an appearance. “You’ve got a gun.”

“That I have,” the boy grinned.

“Want a job?”

“That I do. I’m tired of tramping.”

“Right. You just keep an eye on this wreck until someone from the R. A. F. comes along.”

“A Royal Air Force man.” The boy grinned again. “I’ll sure enough be glad to meet one.”

“You’ll get a chance, all right,” Brand promised. “They won’t miss this.”

To Dave he said: “Come on. We’ll go down now.”

They made their way through the shadows cast by young trees in silence. Arrived at the upper side of the broad meadow overlooking the homestead and the village beyond, as if struck by the beauty of the view, they paused to stand there motionless.

How different were their thoughts at that moment!

The American boy was thinking: “How strangely beautiful it all is, as if it had been arranged with great care so that a famous artist might paint it.”

It was just that—the farmhouse built of native stone, centuries old, stood in the midst of orchards and gardens all green and gold with the colors of autumn. Brightest speck of all was Cherry sitting on the gray rocks.

“How like a sprite she is,” Dave was thinking. “And how like an angel she can sing!”

Beyond the farmstead was a broad, green pasture dotted with black and white cattle. To the right of this its walls shattered but still upright, a great, gray Norman castle cast a long, dark shadow.

“It’s like the shadow of war on a weary world,” the boy thought.

As his gaze turned to the left his face brightened. “The village,” he whispered. Never before, he thought, had there been such a village. With its winding street following the whimsical meandering of a narrow stream, with its houses set irregularly along hillsides that sloped away on either side, with gardens running back to the edge of a great grove of beech, oak and yew trees, it all seemed part of a picture-book dream.

“And yet,” he thought, “the people in that village are quite human. They are kind, simple and good. The baker, the blacksmith, the cobbler, and all the rest,—how really wonderful they are! And so kind to a stranger! And yet,”—He was thinking what it might be like tomorrow, or the day after—if the war lasted. And it would last!

As for Brand, he was thinking quite simply and steadfastly, “That’s my home down there. It’s always been my home—has been the home of my people for generations. And yet, if the purpose of one man, or perhaps two, had been carried out on this perfect autumn day, it would have been no home—only a pile of rocks. And beneath that pile would have been the crushed forms of three persons I love.”

“This,” he said aloud, “is war. Come on.” His voice was hoarse. “Let’s get on down.”

The house in which the Ramseys lived was large. Its kitchen was immense—large as the entire first floor of a modern American home. Its fireplace took a five-foot log at its back. Walled round with two-foot thick stone, with flagstone floor and massive beamed ceiling, this room seemed the inside of a fort. And that, in days long gone bye, it might very well have been, for a moat—in these days dry and grown up to shrubs—ran round the house.

It was in this great room, when the day’s work was done and night had shut out both the beauty and the horror of the day, that the family gathered about the cheery fire.

Over the massive glowing logs a teakettle sang. By the hearth lay Flash, the golden collie. Back of him, on a rug, the two young girls played at jacks. Dave, who sat nearest to them, noted with approval that their hair was now neatly combed, their dresses clean, their faces shining—“That’s the part Alice plays,” he thought with approval.

As his eyes swept the circle, Alice knitting, Cherry smiling over a book, Jock and Brand talking about cattle that had strayed, he thought: “This is indeed a happy home.”

At that moment there came the sound of a motor, followed by a loud honk. At once Cherry, with cheeks aglow, was at the door.

She ushered in a young man of medium height, with smooth dark hair and smiling black eyes.

“Good evening, everybody,” he exclaimed. “Thought I’d just drop by to see how you liked the bombing. Stirred you up a bit. I’ll bet on that. I—” He paused as his eyes fell on Dave. Dave was new to him. So too were the small girls who stared up at him.

“Lord Applegate,” Cherry began, “I want you—”

“Forget about the Lord part,” the young man laughed. “I’m not yet a lord. If ever I receive the title it will never fit. Call me Harmon, as you’ve always done, or Lieutenant Applegate of the R. A. F.”

“That,” Brand exclaimed, “is an honor indeed. I only wish—” He did not finish but stared enviously at the Lieutenant’s uniform. “I’d be content if I were only a private,” he whispered under his breath.

“Well, anyway,” Cherry laughingly began all over, “I want you to meet David Barnes. He’s from America. His uncle is a war reporter who knew father in the World War. And so—”

“So he’s paying you a visit. That’s fine.” The young lord who wasn’t yet a lord but was a Lieutenant in the Royal Air Force shook hands with Dave, then accepted a place beside him.

“Where did you get the children, Cherry?” Applegate asked, looking down at the pair who had resumed their game.

“Oh, they are Alice’s,” Cherry laughed.

“Nice work, Alice,” the Young Lord said. “It must have been a very long time since I was here.”

“It has been,” Alice agreed. “Quite too long. But these children,—they are refugees from London. Bombed out, you know.

“You should have seen them when they came!” she added in a low voice, with a grimace. “Their mothers came with them. But they couldn’t stand the eternal silence of this place.”

“So they left you the children?” said Applegate. “Good old Alice!”

“Oh, they’re really a joy!” The girl’s face lighted.

“But Harm!” Her face sobered. “That plane dropped a bomb on the old playhouse. Blew it to bits. You know, you used to come and play with us sometimes long ago—with dolls and things,” she added teasingly.

“With dolls! Good heavens!” he exclaimed.

“And today the dolls had their heads blown off,” Cherry added. “Just think! It might have been our heads that were blown off!”

“Yes,” the young man’s face sobered, “it might have been. That was a real scrap. Didn’t come out so badly on the whole. Did they catch the men who bailed out?”

“Two of them.” Brand’s brow wrinkled. “The Home Guard tells me the other got away.”

“Oh, they’ll catch him,” Applegate prophesied cheerfully.

“I’m not so sure about that.” Brand did not smile. “They did find his parachute and his uniform half hidden under leaves.”

“Oh! Fixing to turn into a spy!” Applegate’s face sobered.

“Alice,” the younger of the two children called. “What is a spy?”

“A spy,” said Cherry, “steals secrets.”

“And blows up castles and bridges. A terrible man!” said Alice. “I know all about it. I’ll tell you a story about a spy when it’s time for bed.”

“Ooo.” Peggy gave a delectable shiver. “After that we won’t dare go to sleep!”

“The most astonishing thing,”—Brand leaned forward in his chair—“is that one of the men we captured today is the son of the prisoner who worked on this farm more than twenty years ago.”

“What?” Applegate exclaimed. “It can’t be possible!”

“How do you expect us to believe that?” Cherry demanded with a wave of the hand.

“I’ll leave it to Dave and Jock,” Brand defended.

“That’s right,” Jock agreed. Dave nodded his head.

“See?” Brand’s voice was low. “What’s more, I’m almost sure the fellow who eluded us is his brother. If you don’t believe that, look at this picture.” He passed the paper and the photo around.

“Hans Schlitz,” Applegate said, musingly, “That’s the name, right enough. I’ve often heard my mother speak of him. Gloomy, brooding sort of fellow, he was. Probably went back to Europe after the war to tell his sons vile tales of the way he was treated. Poisoned their minds with hate.”

“Oh—ah!” Cherry shuddered. “Gives me the creeps to think of that son of his prowling about here at night.”

“Oh come!” Applegate sprang up. “It’s not as bad as all that. Come on, Cherry.” He put out his hands. “How about a song. I’ll do the honors at the old grand. Happy days.”

“I’d love it!” said Cherry, allowing herself to be led away to the corner where a huge grand piano loomed out of the shadows.

Taking up a candle, Alice carried it to that corner, set it on the piano, then tiptoed back.

With this pale light playing across their interesting mobile faces the young Lord and Cherry took their places.

The moments that followed will linger long in David’s memory. Never before had he seen or heard anything like it. The pale light playing on two bright happy faces, eager for all life, and most of all the perfect blending of mellow tones from the ancient piano with the fresh, free joy of Cherry’s voice. Ah! That was something indeed! More than once, without knowing it, he whispered:

“Oh Cherry! I didn’t know you could sing like that!”

From moment to moment the mood of the music changed. Now the girl’s slender form was swaying to “It’s a Lovely Day Tomorrow,” the next she was bringing back for good old Jock’s sake a song loved by all those of twenty years before:

“There’s a long, long trail awinding

Into the land of my dreams,

Where the nightingale is singing

And the white moon beams.”

And then, springing to a place on the long piano bench she cried: “Now! Let’s all sing, Roll out the barrel.”

Long before this songfest was over Dave found himself bursting with a wonderful plan. No, it was not his war. But he could do his bit, couldn’t he? And he would.

When quite out of breath after her last rollicking song Cherry was led to her place by the fire, she exclaimed:

“Oh! It’s wonderful just to live!”

“Yes,” the Young Lord agreed. “It is grand. And yet, perhaps tomorrow we die.

“Come!” He took Brand by the shoulder. “Let’s go out and see the holes those bombs dug for you. I’ve got to report to my C. O. about them.” And so the two of them disappeared into the night.

“Come Peggy. Come Tillie,” Alice called. “Time for a goodnight story. And then to bed.”

“Will you really tell us a spy story?” Peggy begged.

“Perhaps.”

“A real, true spy story!” Tillie was fairly dancing.

“Yes, I guess so.”

At that Alice, the two children, and Flash, the dog, marched into the small dining room to close the door behind them.

“It was the Young Lord who piloted that Tomahawk plane this afternoon,” Jock said in a hoarse whisper. “I have it on good authority, the very best.”

“And he said never a word about it!” Dave marvelled.

“He’s like that.” Cherry’s lips went white. “He never tells of such things. But just think! He nearly crashed!”

“So near I closed my eyes,” Dave replied admiringly. “Young Lord,” he thought. “Not a bad name for a chap like that!”

When Jock had gone stomping out to follow the Young Lord on his tour of inspection, Dave found himself alone with Cherry.

“Listen, Cherry.” He was more excited than the girl had ever known him to be. “I’ve got a grand idea!”

“That’s what England needs right now,” the girl laughed nervously. “Just think what happened today, and is likely to happen more and more.”

“That’s just it!” Dave leaned forward eagerly. “In all of England there are thousands of anxious people, millions, really, who need a touch of youthful cheer. And you can give it to them!”

“I?” The girl caught her breath. “How?”

“By singing for them as you sang for us tonight—singing over the radio.”

“Oh—o!” Cherry drew in a long breath. “I hadn’t thought of doing that. You—you see, I’m only a local song bird in a little country village. Easter at the church, you know, Christmas carols, parties, and all that. But the radio! I—I—just—”

“Don’t say you couldn’t,” Dave pleaded. “Please say you’ll try. We must each do our bit.” He had forgotten for the moment that this was not his war.

“Yes, I know,” Cherry breathed. “There’s mother, you know. She was a World War nurse. Now she’s directing an entire ward. Alice has her refugee children. And I—I just sit in the sun and tend the sheep.”

“Yes. And you might be the most talked-of girl in England!” Dave was bursting with his new idea. “Just go up to London with me tomorrow. My uncle has a trans-Atlantic news broadcast. He’ll arrange it all. Wi—will you go?”

“Sure! Shake on it.” The girl put out a slim hand.

“It’s just as I thought,” declared the Little Lord, as the men came stomping back into the room a moment later. “Those bombs were rather small. A Messerschmitt can’t carry a heavy load. But they can keep all of England on edge with their nuisance flight.”

“Cheerio!” Cherry sprang to her feet. “At least one Messerschmitt has ceased to be a nuisance, and that, I’m told, is because a certain Young Lord learned how to fly long ago.”

“All part of a day’s work,” the Young Lord grinned. “I’d like just such a scrap every morning before breakfast.”

At that the cook brought in cakes and steaming coffee and they all took seats by the great broad three-inch thick table that had served the Ramsey family for more than a hundred years.

In the meantime Alice was telling her young refugees the promised spy story.

“Once,” she began, “in that other terrible war, the one in which my father and your grandfather fought, there were two spies named Louise and Charlotte.”

“Oh!” Tillie exclaimed with a sudden start. “Are there really lady spies?”

“To be sure,” was the quiet reply.

“Goody!” Tillie clapped her hands. “I’m going to be a lady spy!”

“Yes sir!” Peggy broke in with her high, piping voice. “We’ll both be spies. You be Louise, and I’ll be Charlotte!”

“Wait and see!” the story teller warned. “Let me tell you the story. Then you may not want to be a spy at all!”

“Oh, yes we will!” Tillie insisted. “Aunt Alice (they called her aunt) do we have a spy right here on our farm?” The child’s voice was low, mysterious.

“Hush!” Alice warned. “Don’t dare to breathe a word about that.”

“Tillie!” The younger child’s voice rose sharply, “Let her tell the story!”

And so, while the children lay back among the cushions, Alice told the story of Louise and Charlotte.

“They had lived in France.” Her voice was low and mellow. “Then had come the terrible German soldiers. Louise fled before them. Charlotte hid in a cellar.

“Louise was very bright. She had been a teacher. She could speak French, German and Belgian.

“A great soldier asked her to be a spy. This frightened her nearly out of her wits. But she said ‘all right. I will do it.’

“One dark night a great giant of a man named Alphonse, who had been a smuggler and was a friend of her country, took her hand and said: ‘We will go.’”

“Wh—where did they go?” Tillie was growing excited.

“They went to the border.” Alice smiled. “At the border there was a very high barbed wire fence. You couldn’t go over it. If you tried to go under it you might touch an electric wire that would sound an alarm. Then you would be shot. If you tripped on something it might set off a mine, and you’d be blown to bits.”

“And wa—was—” Tillie got no further. Her sister’s fingers were on her lips.

“We do have a spy”

“Alphonse knew all about these things,” Alice went on. “He made a hole under the fence. The earth was very loose. He had gone under before. They got across safely. Then they were in the land where German soldiers were. And, just when they were breathing easy, a blinding white light swept along the barbed wire fence. It was searching for them.”

“And—did—”

“Alphonse and Louise dropped flat and lay there hiding their faces in the damp earth. The sweeping searchlight came and went, came and went, then came to go away for good.”

“Oh—oo!” Peggy breathed. “They didn’t get them.”

Just then Tillie sat straight up. “Aunt Alice!” she cried. “We do have a spy on our farm. I saw his face at the window. I really did, just now.” At that same instant the dog Flash growled softly.

Visibly shaken, Alice managed to regain her poise. “Shish!” was all she said. Then she went on with her story.

“When this loyal French girl reached her home where German soldiers now were living, she began making lace and selling it from town to town. What was more important, she was finding friends to help her work as a spy. One was a scientist who could do strange things with chemicals, magnifying glasses, cameras and printing presses. Another was a map maker who in shorthand could write three thousand words with invisible ink on a piece of transparent paper so small Louise could paste it to a spectacle lens and carry it across the line that way.”

“What for?” Tillie breathed.

“So none of the German spies could read it,” Alice explained.

“You see,” she went on, “things were happening over there that great French and English officers needed to know. And Louise could tell them. Once there was a terrible battle. Thousands of Germans were wounded. How many? Louise must find out.

“There was a house close to the railroad track where all the cars filled with wounded soldiers were passing. Someone hid in the dark room. Every time a car passed, she’d tap on the floor, tap, tap, tap. In the next room, seeming to study her lessons, was a school girl.”

“Just like you and me!” Tillie squeezed Peggy’s arm.

“This school girl was making marks on paper,” Alice went on. “Four marks, then one across, four more and one across.”

“Keeping track of the taps. I could do that.” Tillie was growing excited again.

“When all the trains had passed,” Alice whispered, “Louise counted up all the marks. Then she multiplied that by the number of wounded men in each car, and so she knew how many thousands had been badly wounded. But how was she to get that number across the line?”

“Paste it on her spectacle,” suggested Tillie.

“Not this time, she didn’t,” Alice smiled. “She wrote it on a paper and hid it. You’d never guess where.”

“In her shoe—in her glove—in her hair,” Tillie exploded.

“Nope. None of these.” Alice shook her head. “Let me tell you all about it, then you may guess.”

“Al—all right.” Tillie drew a long breath as she settled back.

“You see,” said Alice, “Louise was going down a dark road in the night. In one hand she carried her bag of laces, in the other a lantern. It was a tin lantern. The tin was all full of holes. Inside a candle flickered. It didn’t give much light, just enough. Suddenly a gruff voice commanded:

“‘Halt!’

“Louise was taken to a rough cabin where a short broad German spy woman lived. Everyone called her Le Grenouille, the frog. Louise and Charlotte feared and hated her.

“‘Take off your clothes’, that’s what the Frog said to Louise.

“Before obeying, Louise carefully blew out the candle in her lantern, then set it in the corner.

“All her clothes were taken off. Everything was searched,—dress, stockings, shoes,—everything. Nothing was found.

“‘All right. You may dress and be gone,’ said the Frog.

“When Louise had dressed she went on her way. That night our High Commander way across the line in France knew how many Germans had been wounded in that battle.”

“Louise, the spy, had told him,” Peggy whispered.

“She showed them the paper on which the number had been written,” said Alice. “Where do you think it was hidden?”

“In her basket!” Tillie cried.

“No.”

“In her hair,” Tillie guessed again.

“I know!” Peggy jumped up and down. “In her candle!”

“Good! That’s right! How did you guess?” Alice’s face shone.

“She—” Peggy did not finish. At that instant old Flash leapt from his corner, dashed up to the window which was above his head, and barked angrily.

At the same instant Tillie cried: “We do have a spy on our farm! I saw his face in the window! Saw him plain as day!”

They all rushed to the kitchen where the others were talking. A few excited words and the boys, with Flash at their heels, were out searching in the night.

But for one thing they might have succeeded in making a capture. The moment they stepped outside, the sky was lit by a sudden flash. Then came the roar of an explosion.

“They’re at it again,” Young Lord murmured.

“Here Flash!” Brand called. “Go find him!” But Flash only whined at his feet. The roar of that distant explosion had paralyzed him. And so, in the end they returned empty handed.

“Aunt Alice,” Peggy whispered as she was being tucked in bed, “will you tell us more about those lady spies?”

“Sometime perhaps,” was the quiet reply.

After they returned from the futile search the three of them, Dave, Brand and the Young Lord stood for a time beside the car. They had talked for a moment. Then Brand walked away to the barn for one more look about before he retired for the night. It had been a strange, exciting and momentous day. Nothing quite like it had ever happened at Ramsey Farm before. He felt restless and ill at ease.

After he had gone the Young Lord asked Dave a strange question:

“What are you doing in England?”

“Why—I—nothing really,” Dave hesitated. “You see my uncle is in the news service here. He was coming over in the Clipper. He invited me to come along. So here I am. Perhaps it wasn’t quite as simple as all that, but he fixed it up.”

“I see,” the Young Lord murmured.

Did he? Dave doubted that. He made a second start. “You see I’ve had two years in college. Didn’t like it any too well, the class-room part. Oh, math was well enough. In fact I really liked it. But the rest,” he heaved a sigh. “Well, I majored mostly in football, basketball, tennis and golf. So—oo,”

“So they didn’t care much whether you stayed on?”

“I suppose not. Anyway, all the colleges in America have been crammed with fellows who haven’t anything else to do but go to college now,—”

“All that will change fast,” said the Young Lord. “The way things are going over there now those boys are going to have things to do. Ever do any flying?” he asked abruptly.

“Yes—a little—quite a bit in fact. Uncle was a flyer in the World War. Not an ace exactly, but he got to like flying. He’s always had a flying crate or two about, and naturally I had to have a turn at them.”

The Young Lord guessed, and quite shrewdly too, that Dave was being too modest about his flying.

“I’m trying out a new plane tomorrow,” he said slowly. “It’s a two-seater. Want to go up? Just a little sky patrol. Nothing’s likely to happen.”

Dave seemed to see that Tomahawk of the afternoon plunging downward apparently headed for destruction. He wanted to say “no”. For some reason his tongue wouldn’t form the word. So he said:

“Yes. Sure. I’d like to.”

“Righto.” The Young Lord reached for the door of his big old English car. “I’ll be after you in this bus at 10:00 A. M.”

His motor roared. He was away.

“Now why did I say that?” Dave asked himself aloud.

“Say what?” He started. Brand was at his side.

“I promised to go up with Applegate tomorrow.”

“Sayee! That’s corking! Just what I’d like to do! In fact,” Brand’s tone was sober, “I want to join up. Since this afternoon I want to more than ever. Mother objects. Says I’m needed to manage the farm. Says the army needs our butter and fat cattle. This farm! Of course, we love it. All of us do. But when all of England is threatened—when the others are doing their bit—to be tied to the sail! God!” Brand stamped his foot.

“It’s all the way you think, I guess.” Dave laughed lightly. “Well, I’ll be up having a look at your native land from the clouds in the morning. So, goodnight.” Half an hour later, in his bed beneath the rafters of that ancient house, Dave was asking himself: “Why did I come to England?”

The answer seemed simple enough. This war was too big to miss—that is—miss seeing. But why had he persuaded Cherry to go with him to London where bombs were falling? Why had he promised to go up with the Young Lord in the morning? He did not know the answers. All he knew was that he felt like a fly caught in a web. The web did not have a very strong hold on him yet. He could break away if he wished. But did he wish? Not knowing the answer, he fell asleep.

In another corner of that broad upstairs, her door leading into the children’s room ajar, Alice was hearing a shrill childish voice cry:

“You’re a spy, a little lady spy. I’m a frog, a great big black frog. I’m going to swallow you—swallow you right down. Here I come!”

This was followed by a low, half-suppressed exclamation, a giggle, then a loud “Shish.” After that all was silent.

Alice was nearly asleep when suddenly from far overhead there came the roar of powerful motors. London was in for one more beating. Would those terrible bombings never end?

It was with a strange thrill tickling his spine that Dave climbed into the rear of the lord’s two-seater plane the next day. This, he knew, was a fighting plane, his very first. This plane carried a sting in its nose, eight guns capable of firing nearly ten thousand shots per minute.

“Of course,” he thought, “this is broad daylight. Not much chance of picking up an enemy. And yet, there’s yesterday.”

After fastening his safety belt with great care, he waited for the takeoff. It came with a roar. They were in the air. Some ship!

He studied it with great care. It had a dual control. If something happened, just happened to go wrong with the Young Lord, he could bring the ship to earth. He might, in a pinch, do a great deal more. The firing of those guns seemed simple. He had had a great deal more flying experience than he was willing to admit,—at least 200 hours.

Seeming to read his thoughts, Applegate gave a slight squeeze at his firing button. In no uncertain tones the guns spoke. Dave was thrilled to his fingertips.

He began studying the electric switches, the emergency boost, the petrol switch, the air-speed indicator, the directional gyro, the climb indicator, and all the other instruments. A born mechanic, he could study these out one by one, eliminate the ones least needed, then picture himself guiding the ship.

Watching a mirror, studying his face, Applegate nodded in approval to the sky. As they climbed to 10,000 feet Dave saw London in the distance. Smoke hung over it. There had been a bombing, fires started. Homes of simple, honest, hard-working people who had not asked for this war had been destroyed. He hated all that.

White clouds, like distant snowbanks, were drifting through the blue as blue sky.

“Take her for a minute, will you?” The Young Lord spoke in a matter-of-fact voice.

Dave’s hands trembled as he gripped the controls. He kept the ship going on an even keel while his companion, after unstrapping heavy binoculars, studied the sky.

Suddenly Applegate threw out a hand. Swinging it to the right, he directed Dave into a fluffy white cloud.

“That’s it,” he approved. “Now just lurk around in here for a bit.”

With a tickling sensation at the back of his neck Dave “loitered round”. At the same time he was asking himself, “Why did I let myself in for this?”

Twice they came out of the cloud, but on the wrong side. At last, after one more wave of the lord’s hand, Dave headed straight out, on the side from which they had entered.

He caught his breath sharply as, on breaking out into blue sky, he sighted an airplane beneath and beyond them. He trembled as he saw the hated swastika on its tail.

“Will there be a scrap?” he asked himself. Strangely enough he felt quite cool about it. The Young Lord took the controls. The motors roared. This gave Dave time to study land and sky. As near as he could tell the other plane which was slowly circling, was just about over Ramsey Farm. “That’s why Applegate is putting on such speed,” he thought.

Just then, like a squirrel darting for shelter, the enemy plane leapt upward and into a cloud.

“You better!” Applegate growled, at the disappearing enemy.

Only when they were near the cloud did he slacken his speed. Then, like a dog waiting for a squirrel, he loitered about in the sky.

“If the enemy really wished to get away,” Dave thought, “every advantage is with him.” A whole string of clouds was drifting in from the distant sea. Was he glad or sorry? At that moment he could not have told.

After a time, like a dog watching clumps of bushes where a rabbit is hiding, the Young Lord began skirting that long procession of clouds.

They had followed almost to landsend and the shore when suddenly the Young Lord pointed to a black speck against the distant sky. Dave heaved a sigh of relief. Turning about, they headed for the airdrome.

“He was bashful, that Hun,” Applegate laughed into his mouthpiece. “Perhaps he came over to find his pals who paid us a visit yesterday. Sorry to disappoint him. Even the wreck has been carted away.”

“One of his friends is still at large,” Dave suggested. “Might have set up a signal. Black cross cut from the sod would do the trick.”

“That’s right,” Applegate agreed. “Anyway,” he laughed as they began circling for a landing, “we’re back just in time for lunch. It’s cold beef and plum pudding. You’ll stay, I hope.”

“Oh! Sure!” Dave agreed.

His visit to the flying corps’ mess was one not soon to be forgotten. He had read magazine stories of these fighters. Loud, boisterous, wild and a bit coarse, that was how they had been pictured. To his surprise he found them a simple, kindly lot, with manners that would have put many a college group to shame.

“You’ve really got to be up to things to be a-flying in this squadron,” the Young Lord explained. “And in any other, for that matter. Drinking, loud laughs, roughness—well, it doesn’t seem to go with life-and-death flying, that’s all.

“You have to be a man,” he added after a pause. “And a man’s nearly always a gentleman as well.”

When late that afternoon Dave walked with Cherry to the village to catch the bus to London, he carried a parcel under his arm. “My hiking boots,” he explained. “These hard roads have worn the soles thin.”

“Oh! I’m glad,” Cherry exclaimed. “You are going to like Uncle John. He’s our shoemaker. We call him that though I’m sure he’s really uncle to no one. He’s very old and still does all his work the hard way, by hand. Wonderful work it is, too.”

Dave did like Uncle John. Seated there at his bench, a leather apron on his lap and nails between his teeth, he seemed to have just moved out of a very old story book.

“Do you still make shoes as well as repair them?” Dave asked.

“Oh, yes, now and then.” The old man’s smile was good to see. “I’ve made all the Young Lord’s shoes since he was a baby.

“But then,” he sighed, “times have changed. You can’t get the leather any more. It used to be that I could make a pair of shoes and guarantee them for five years. Those times are gone.

“But perhaps it is best that it should be so,” he added cheerfully. “Nowdays people like change. If you only pay one pound for a pair of shoes, you can afford more than one pair.” Taking a tack from his mouth, he drove it home, then another.

“He lives in two small rooms behind the shop,” Cherry said when they were outside. “His little wife was just like him, always cheerful and kind. She died three years ago.

“Nearly all the people in the village are like that,” she added as they walked on. “The butcher has his stall in front of his home. The baker’s shop is in his basement. So is the grocer’s. Everyone works. All are kindly. They never have much, but they make it do—and are happy.”

Dave was to recall this picture with a sudden pull at his heartstrings in the days that were to come.

The bus came lurching in. They climbed aboard and were away for London.

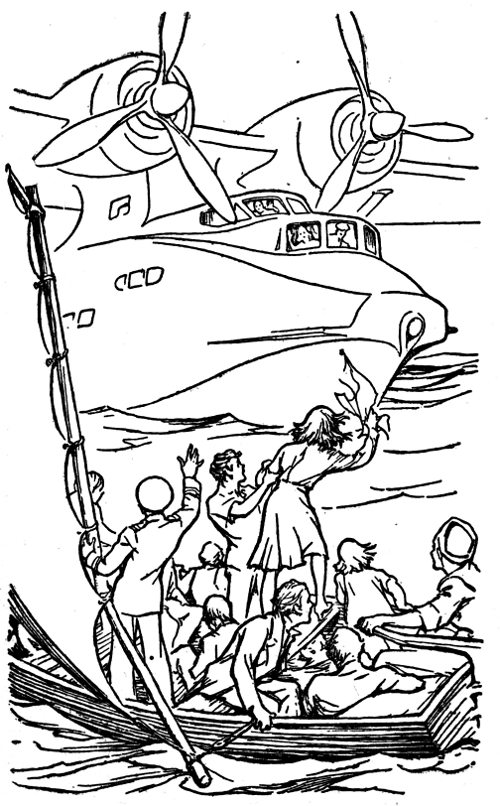

Arrived in London they hurried up to the radio studio for Cherry’s audition. Singing in a bare studio with a strange accompanist, the girl was far from doing her best. For all that the director gave her a small spot on the “People’s Choice” program at 9:00 P. M.

Once more on the street where shadows had grown long and dark, and people by hundreds were hastening home before the air raid siren sounded, Cherry gripped Dave’s arm as she said in a tragic whisper: “David, I never can stick it out. It will only be a dismal failure.”

“Nonsense!” Dave laughed. “It’s only stage-fright. Come on. My uncle took me to a rare little basement eating place once. They serve good old American coffee and waffles with maple syrup. That will put you on your toes.”

In the quiet of the sub-cellar, they drank great quantities of coffee and ate their waffles joyously.

“I—I guess I’ll make it now,” Cherry murmured. Once more they were on the deserted streets.

Then, as if to crush her high hopes, all hell let loose. The roar of powerful motors, the scream of sirens, the boom and bang of anti-aircraft guns filled all the night with terror.

“I can’t let you in ’ere now,” said a burly guard at the entrance to the broadcasting station. “It is quite impossible. You shouldn’t be ’ere at all.”

“But this lady is to sing over the radio at nine!” Dave protested.

“Can’t be ’elped.” The guard was firm. “Orders is orders. No ladies hallowed in the station during an alarm. If you’d ask me sir, I’d hadvise a subway station at once, sir. Yonder’s one not ’alf a block haway.”

The words were scarcely out of his mouth when there came a low, whining sound, followed by a flash that lit all the sky. Then came a roar fit to burst their eardrums, and a tremendous push that tossed them to the pavement five yards away.

Without a word Dave scrambled to his feet, picked the slight girl up in his arms, dashed half a block, and was down two flights of stairs to the subway station before he fully realized what he was doing.

Seated on the hard floor of the station, with thousands of people all about them, for a full moment they were completely silent. Then Dave began to laugh. Cherry joined in, and the spell was broken.

The laugh over, they looked about them. The whole long platform was filled with people. Young and old, rich and poor, salesgirls in thin, shabby coats, gray-haired ladies in mink and ermine, they all were there. And all, it seemed, were bent on making the best of an unpleasant situation. Bye and bye they would do their best to snatch a little sleep, for tomorrow would be another day.

“Look at them.” There was a catch in Dave’s throat. “They seem almost happy.”

“Yes.” Cherry’s chin went up. “They’re not going to let Hitler get them down. He wouldn’t be pleased if he could see them now!”

In a bright corner four old men were playing cards. In the shadows a shopgirl was whispering to her young man. Sitting on their bedrolls, two sedate matrons were knitting. Children were everywhere, and all of them whooping it up in hilarious fun.

“Excuse me,” said a smiling young lady. “Aren’t you Cherry Ramsey?”

“Why—why yes, I am.” Cherry looked into a pair of eager blue eyes.

“I knew it!” the young lady exclaimed. “I heard you sing at Lady Applegate’s home once. It was truly quite wonderful. Now—” she hesitated, “well, you see, I’m just helping out down here, sort of social service work, don’t you know. And I thought you might not mind, well, you know,”—she hesitated—“well, perhaps you wouldn’t mind singing a song or two for these people. They’d think it quite the berries if you would.”

“Well, that—” Cherry laughed, “that’s what I came to town for, to sing on the radio. But the guard wouldn’t let us go up to the station.”

“I shouldn’t wonder,” Miss Meeks, the social worker murmured. “Listen!” There came a deep, low rumble like the roll of distant thunder. “You can’t help loving these people, don’t you know.” Her tired face brightened as she spread out her arms. “Not one of them knows whether his home will be standing in the morning. But you see how they are.”

“Yes—yes I see.” Cherry swallowed hard.

“The radio,” Miss Meeks murmured. “Now I shouldn’t wonder. Will you sing for them, Miss Ramsey?”

Cherry nodded.

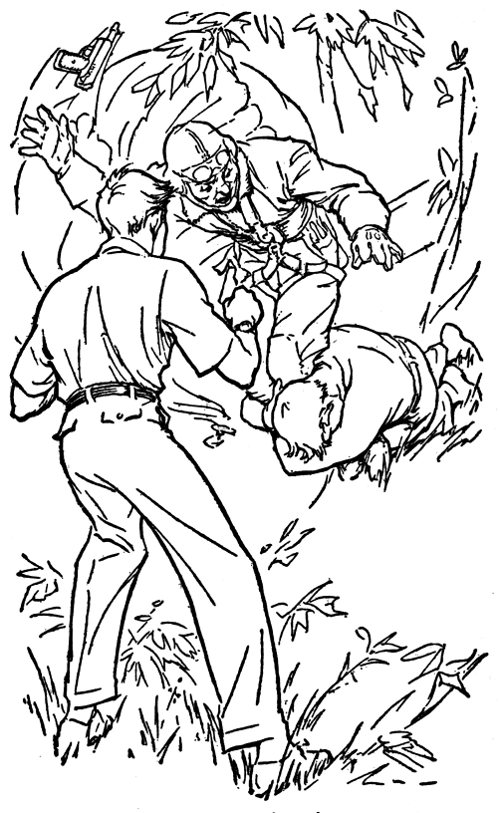

From somewhere a small piano was made to appear. A little Irish girl with a tumbled mass of red hair took her place before it. A small platform—a heavy packing box—was placed beside the piano.

After shedding her heavy coat, Cherry stood before her strange audience. All lovely in gold and blue, she caught their eyes at once. Leaning over, she whispered to the girl at the piano, giving her the name of her first song. The social worker clapped her hands for silence. Deep, appreciative silence followed.

“Miss Ramsey, a friend of Lady Applegate, from Dorset way, will sing to us,” Miss Meeks announced. “Let’s give her a hand.” The applause was tumultuous.

Somehow, a light, not too strong, was made to play on the slender girl as she sang.

“In the gloaming, Oh my darling,

When the lights are dim and low.”

She sang the song through to the end. The applause that followed drowned out the sound of exploding bombs.

“More! More!” came from every corner.

The social worker slid a microphone before the singer. Bending over, a smile on her lips, Cherry once more whispered a title. Then, lifting her voice high, she cried: “Roll out the Barrel! Everybody sing! Let’s make it ring!”

Everybody did sing,—more people than Cherry will ever know, for through the microphone that had been placed before her, Cherry was at last singing on the radio. From end to end of England the song boomed on: “Roll out the Barrel.”

Every platform in the subway had its radio. Station by station they joined in until the whole tube, miles on end, echoed with the song.

“Roll out the barrel! We’ll have a barrel of fun

Roll out the barrel! We’ll put the blues on the run.”

It seemed to Dave as he listened after that song was over, that even the Führer must have heard the applause that followed, heard and shuddered.

Dropping into a mellow mood for the oldsters who recalled that other terrible war, Cherry sang:

“There’s a long, long trail a-winding

Into the land of my dreams,

Where the nightingale is singing

And the white moon beams.”

Then, scarcely pausing for breath, leaning far forward, a bewitching smile on her face, she sang: “No! No! No! Papasista.”

When the roar of applause had died away, Dave heard a gray-haired lady in a Persian lamb coat say:

“Such a vulgar song!”

“Quite,” agreed her mink-coated friend. “Vulgar and wonderful. I quite love this war. It has given me one more chance for a fling at life.”

“All out for England!” Cherry called into the megaphone. “Everybody sing, ‘We’ll roll the old chariot along’.”

They sang. They roared. They sang.

“If Hitler’s in the way, we’ll roll it over him.

If Tubby’s in the way, we’ll roll it over him.

If Il Duce’s in the way, we’ll roll it over him.

If the devil’s in the way, we’ll roll it over him.

We’ll roll the old chariot along

And we won’t tag on behind.”

In the hush that followed, Cherry announced in a low, husky voice: “God save the King.”

There followed a shuffling of feet. Every man, woman and child was on his feet. Even the enemy planes above seemed to hush as the glorious National Anthem rolled over England from Dover to Newcastle.

There were tears in the social service worker’s eyes as she took Cherry’s hand. “You’ll come again, won’t you?” she said in a low voice full of meaning. “Often and often.”

“Everybody Sing”

“If—if you need me,” was the quiet reply.

“And you said you couldn’t do it!” Dave laughed happily as he guided her up the stairs and back to their sub-basement for one more cup of good American coffee.

That night members of that motley subway throng shared their beds with their new-found friends. Dave found a place with a young disabled veteran of the battle of Flanders. They slept on a thin pad and were covered by blankets none too thick. The subway was cold and drafty. For two hours Dave lay there thinking. Those were long, long thoughts. Back to the pictured walls of his mind came the peaceful pastures of Ramsey Farm, the racing planes overhead, the falling bombs, and the drifting parachutes. He rode once more with young Lord Applegate in that two-seater. His blood raced again as they played hide-and-seek with an enemy plane in the clouds. Again he heard the thundering crash of a bomb that had exploded, not, he supposed, more than two blocks from where he and Cherry had stood. What if it had been only one block, or no block at all? He tried to think this last question through, and could not quite make it. Nor could he answer to his complete satisfaction, his second and third questions,—why had he come to England? And why did he not go home? There would be a plane for Lisbon the day after tomorrow. Would he take it? He doubted it. And yet it seemed to him a voice whispered, “It is to this or no other. Think it over.” He did not think. Instead, he fell asleep.

Cherry had been given a welcome by a bright young lady who sold shoes in a great store. This young lady was wondering whether a bomb had scattered her shoes over a city block, and her job with them. In the midst of her chatter Cherry fell sound asleep.

Before they could leave the subway next morning two people were after them.

The manager of the radio station, who the night before had given Cherry such a lukewarm reception, came bustling down the stairs. She, he said, had been “Splendid! Splendid! Quite remarkable indeed! How the people had taken to her! There had been wires, phone calls,—everything. Would she come back at nine that night and sing at the studio? She should have a competent accompanist and every courtesy. Would she come?”

“No.” Cherry favored him with her brightest smile. “I won’t sing in your studio. I can’t sing in a stuffy little box with no one about except a man in a glass case who waves his arms, pretends to cut his own throat with his fingers, points to the tip of his nose, and goes through all manner of other contortions just to tell me what to do.”

All this left the man staring at her, speechless.

“But if,”—Cherry burst into a merry laugh—“if you’ll let me sing on my box with my glorious red-headed Irish girl to tickle the ivories, I’ll come back, not tonight, but very soon, and often.”

“Oh! My dear child!” the manager exploded. “You are generosity itself. But the subway is cold and drafty.”

“No place,” said Cherry, and she did not smile, “can be cold where so many warm hearts are beating as one.”

The man stared at her in speechless silence for a moment. Then he murmured, “May God forgive me if this child is not a genius.”

But here was her mother. She too had heard the broadcast and thought it marvelous. This was her day off. Her small car was just around the corner. She would take them back to Ramsey Farm in time for scrambled eggs, coffee and scones. And she did.

Mrs. Ramsey, David realized at once, was a strong, efficient person, with a will of her own. She directed the affairs of her household as the O. C. directs his squadron. Breakfast over, she called in the entire group to discuss farm affairs. She commended Jock for his fine job of plowing, and the boys for their work in the turnips and Brussels sprout patches.

“England is going to need food,” she declared. “We must all do our best. The nights are growing cold. We may get a freeze at any time, so—oo—”

“So it’s the potatoes next.” Brand gave vent to a good-natured groan. He hated picking up potatoes. Stooping over made his back ache. But theirs was a fine crop, and it must be gathered in.

Jock got out the potato plow. Soon they were all hard at work. David joined in. So too did Alice. Even the “enfants terrible”, Tillie and Peggy, helped a little. They were, however, at their best throwing clods, so in the end they were banished.

The place where the potatoes were stored held for Dave a real fascination.

“We call it the Hideout,” Alice explained, dropping down on a sack of potatoes for a short rest. “It’s as old as the hills. Did you note the moss on the roof?”

“Six inches thick,” Dave agreed. “And look at the walls! Solid masonry!”

“We believe it goes back to Feudal days.” Alice’s eyes took in the one large room, its broad stone fireplace, two narrow windows, and massive beams. “In those days it was a real hideout, I shouldn’t wonder,” she murmured.

“And might be again,” Dave suggested.

“Yes, if the Huns really come,” she agreed. “But they’ll never get this far—England will beat them back even if they swarm in on the shore like the waves of the sea.”

All that day Cherry sat curled up in a great chair before the fire in the farmhouse kitchen. She sometimes slept, sometimes thought soberly, and sometimes dreamed. To this her wise mother offered no objections. Cherry, she realized for the first time, had a great gift. She might, it seemed, be of extraordinary service to all England. She could bring them the spirit of youth, buoy them up, give them courage for the great ordeal that lay ahead.

The potatoes were stored in a narrow, dark underground tunnel that one entered through a door at the back of the Hideout.

“A grand air raid shelter,” suggested Dave.

“Hope we never need it,” Alice replied soberly, “but you never can tell.” Her brow wrinkled. She was thinking of the hole in the ground where an ancient playhouse had once stood. “How about a tramp to the village?” she suggested.

“O. K. by me,” said Dave. “I’ll see if my boots are finished.”

The boots were not finished. But then, boots at the cobbler’s never are—at least, not the first time you call.

“You’ll have to pardon the delay,” the old man apologized. “So many boys from the airdrome have brought in their boots.

“But things will go faster now.” His face brightened. “You see I have a helper.”

For the first time Dave noticed a short, sturdy young man sitting in the corner. He was sewing on a sole and never once looked up.

Dave thought with a start, “He has a vaguely familiar look. But I’ve never seen him before, that’s certain.”

“He does very fine work.” The old man rubbed his hands together. “Very fine indeed.”

Appearing a little disturbed by Dave’s lingering look at the stranger, old John followed him out of the shop to close the door behind him. “He’s quite proper,” he said, jerking a thumb backward toward the shop. “He looks like a German, but he’s a refugee, a Hollander. You understand?”

“Yes,—I”

“His papers are in perfect order. I saw to that you may well believe.” The old man laughed a trifle uncertainly. “Our local magistrate looked over those papers for me,” he went on. “We can’t take chances. But this, you see, is a rare opportunity. I’ve never made any real money, not in all my long life. And now, with all these fliers coming in—”

“Gives you a break,” said Dave. “I wish you lots of luck.” As it turned out, the old man was to need it,—lots and lots of luck.

When the cobbler opened the door to retrace his steps, Flash, the collie, who had come up as a sort of vanguard to Alice, put his nose in at the cobbler’s door, gave a long sniff, then uttered a low growl.

“Well now, I wonder what he means by that?” Dave thought as he hurried away to join Alice.

That night, after the others had retired, Mrs. Ramsey, Dave and Brand sat for a long time silently watching the fading glow of the wood fire.

“Mother,” Brand said suddenly, “I’d like to join the Royal Air Force.”

“Oh! No!” The mother’s words came short and quick. “You are needed here. Besides, there’s little enough for our aviators to do now. After the beating up we gave them, the Jerries, as you call them, are only coming over at night. You can’t find them at night. That’s work for the anti-aircraft batteries.”

“I’m not so sure of that,” Brand murmured beneath his breath. “But mother,” his voice rose, “the Huns may come over, a million of them, by air and sea, perhaps tomorrow. We must be prepared!”

“And we must be fed,” his mother replied quietly. “Perhaps later—” She did not finish. She knew a great deal about war, did the brave-hearted English mother.

“Wars,” said David, speaking before he thought, “are wrong. There should be no wars.”

Instantly the woman’s slow, steady gaze was upon him. “She’s angry with me,” he thought. His lips were parted for the words, “I’m sorry.”

But she spoke first. “You are exactly right, David. Wars are terrible. I should know. Wars have cost me those I loved far more than life. Now another war may cost me my son, and perhaps my daughters.

“Some of us,” she went on, “did what we could to prevent this war. We failed. Why? Perhaps none of us will ever know for sure.

“However,” her voice was steady and sure, “we have a war. We have no choice but to fight it. We must fight or be enslaved. Our enemy has left no room for doubt there. England has always been free.”

After that for some time, save for the slow, steady tick—tock—tick—tock of the dependable old English clock in the corner, there was silence in the great room.

Later, as they stood outside beneath the stars, Brand told Dave that for more than a year the Young Lord had been training him, teaching him how to become a fighter. “And he’s a real fighter himself, you may be sure of that.” His voice was low and strong. “He’s no braggart like some of those flying Huns. He has a real record all the same. He flew in France during the Blitzkrieg. Sometimes it was ten Messerschmitts to his one Hurricane. He got two of them. That was just one time. There were many others. You just wait!” His voice rose sharply. “I’ll be right up there beside him in a Tomahawk one of these days!”

Would he? Dave wondered.