Transcriber’s Notes

Punctuation has been standardized.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and have been accumulated in a table following the index.

Transcriber Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes are not identified in the text, but have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book.

Note to Kindle users: the .mobi format does not translate a large table in chapter 15 properly. The left side may be cut off on some devices. My apologies.

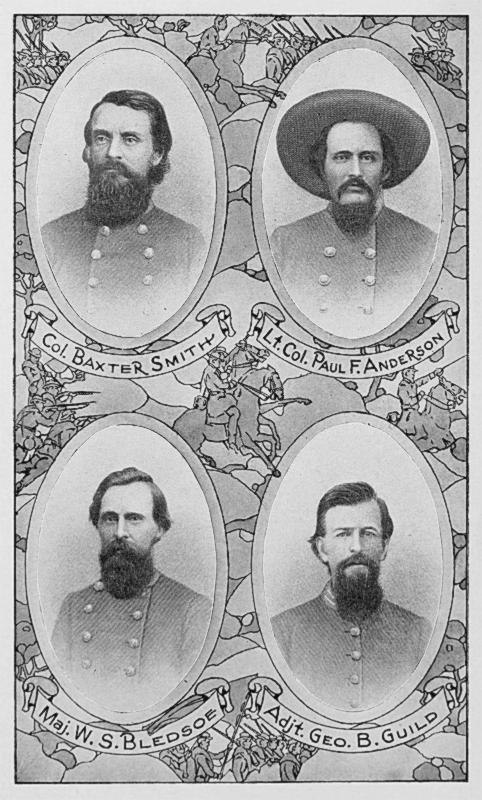

| Col.Baxter Smith | Lt. Col. Paul F. Anderson |

| Maj. W. S. Bledsoe | Adjt. Geo. B. Guild |

WHEELER’S CORPS, ARMY

OF TENNESSEE

By GEORGE B. GUILD

NASHVILLE, TENN.

1913

Dedication

To those comrades “who went with us but came not back again,” many of whom are sleeping in their blankets in unknown graves on the battlefields where they fell

The rough board that perhaps a comrade placed at the head to direct the footsteps of inquiring friends has long since rotted down; and the little mound they spread above their soldier breast has been leveled by the plowshare or the long years that have passed since then. But there the wild flower sheds its sweetest perfume to the morning air, and the song bird warbles its lay to the setting sun, and at night the stars of heaven, as they climb the Milky Way, look down and grow brighter as they pass.

| Introductory | |

| I. |

Organization and Early Movements Outpost Duty at Franklin, Tenn.—Battle of Murfreesboro—Retreat to Shelbyville. |

| II. |

From Fort Donelson to Chickamauga Fort Donelson—Woodbury, Tenn.—Trousdale’s Ferry on Caney Fork River—Resisting Rosecrans’s Advance on Shelbyville and Tullahoma—Bragg’s Retreat to Chattanooga—Wheeler’s Cavalry at Rome, Ga.—Battle of Chickamauga. |

| III. | Wheeler’s Raid into Middle Tennessee in 1863 |

| IV. |

In East Tennessee Return to the Army of Tennessee at Missionary Ridge—Report of Lieutenant Colonel Anderson on the Battle of Chickamauga—Battles of Lookout Mountain and Orchard Knob—Missionary Ridge and Ringgold, Ga. |

| V. |

Campaigning in Georgia Gen. Joseph E. Johnston Succeeds General Bragg as Commander in Chief—Remarks about General Bragg—General Sherman Advances on Dalton, Ga.—March to Atlanta, Ga.—Battles of Resaca and Kingston—New Hope Church—Kennesaw Mountain—Marietta and Atlanta—General Johnston Superseded by General Hood. |

| VI. |

General Wheeler’s Capture of the Commands of Generals McCook and Stoneman Raid of General Wheeler into Tennessee in 1864—Behind the Lines. |

| VII. |

In Tennessee, Virginia, and Harassing Sherman March through East Tennessee—Battle of Saltville, Va.—Return to Atlanta, Ga.—Sherman’s March to the Sea. |

| VIII. |

The South Carolina Campaign Remarks about General Hood—Battle of Aiken, S. C.—Battle of Fayetteville, N. C. |

| IX. |

In North Carolina Change in Brigade Officers—Gen. Joseph E. Johnston Succeeds General Hood and Assumes Command in North Carolina—Battle of Averyboro, N. C.—Bentonville, N. C. |

| X. |

Further Movements in North Carolina, and the Beginning of the End Reorganization of the Army at Smithfield, N. C.—General Johnston Ordered to Greensboro, N. C.—Meets Confederate States Officials—General Johnston Confers with General Sherman, and an Agreement Made to End the War. |

| XI. |

The End of the Struggle Surprise of the Army at Information of Surrender—Sherman-Johnston Capitulation Rejected at Washington—Another Agreement Looking to a Surrender on Terms Given General Lee at Appomattox—General Johnston’s Farewell Address to the Army—General Wheeler’s Address to the Cavalry. |

| XII. | Casualty Lists |

| XIII. | Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and Other Officers |

| XIV. | An Address and a Speech |

| XV. | A Few Facts from History |

| XVI. | After the War |

| XVII. |

General Bragg’s Kentucky Campaign in 1862 (By Baxter Smith) |

| XVIII. | Members of the Regiment Now Living |

| Appendix | |

| Index |

Since the surrender of the Confederate army, in the spring of 1865, I have been frequently asked by members of the Regiment to write its history. I have always promised, but have failed to comply till now I find myself attempting it forty-seven years afterwards. Many of those who survived the surrender have died. Some have removed to parts unknown, and a very few remain from whom I can obtain necessary information. So I am forced to write mostly from a personal recollection, without memorandum or note. This I regret; for it forces me to speak of some, while I have forgotten others equally as worthy of mention. I offer this as my apology for an imperfect record.

It has been my effort to write a narrative of my own Regiment. Necessarily it can be of but little interest to the public, although it embraces a cursory history of the Army of Tennessee, of which it was a part. I see that some repetition appears in its pages, growing out of a predisposition to emphasize some facts, which I ask you to excuse.

The Fourth Tennessee Cavalry did not assume regimental form until General Bragg had returned from his Kentucky campaign, in the fall of 1862. It was made up of detachments that had served under different commanders since the beginning of the war. At its organization Baxter Smith was made Colonel; Paul F. Anderson, Lieutenant Colonel; W. Scott Bledsoe, Major; J. A. Minnis, Adjutant; W. A. Rushing, Sergeant Major; Marcellus Grissim, Quartermaster, with R. O. McLean, Bob Corder, and John Price his assistants; Captain Bone, Commissary, with Lieut. J. A. Arnold and Captain McLean his assistants; Dr. W. T. Delaney, Surgeon, with Dr. Tom Allen his assistant; Rev. W. W. Hendrix, Chaplain; Sergeant Finney, Ordnance Officer; J. A. Stewart and James B. Nance, Regimental Buglers; Bob Gann and Bennett Chapman, Wagon Masters.

The commissioned officers of the companies were:

Company A.—Captain, D. W. Alexander; First Lieutenant, Rice McLean; Second Lieutenant, J. N. Orr; Third Lieutenant, Charles Beard. Recruited in Marshall County, Tenn.

Company B.—Captain, C. H. Ingles; First Lieutenant, Joe Massengale; Second Lieutenant, Joe Massengale; Third Lieutenant, G. W. Carmack. Recruited in Sullivan County, Tenn.

Company C.—Captains, Frank Cunningham1 and George C. Moore; First Lieutenant, James Hogan; Second Lieutenant, R. S. Scruggs; Third Lieutenant, Samuel Scoggins. Recruited in Smith County, Tenn.

Company D.—Captain, J. M. Phillips; First Lieutenant, Bob Bone; Second Lieutenant, J. T. Barbee; Third Lieutenant, J. A. Arnold. Recruited in DeKalb and Wilson Counties, Tenn.

Company E.—Captain, H. A. Wyly; First Lieutenant, H. L. Preston; Second Lieutenant, W. S. Sullivan; Third Lieutenant, John Fathera. Recruited in Cannon County, Tenn.

Company F.—Captain, J. R. Lester; First Lieutenant, C. S. Burgess; Second Lieutenant, W. H. Phillips; Third Lieutenant, James Williamson. Recruited in Wilson County, Tenn.

Company G.—Captain, J. W. Nichol; First Lieutenant, Dave Youree; Second Lieutenant,—McKnight; Third Lieutenant, J. A. Sagely. Recruited in Cannon and Rutherford Counties, Tenn.

Company H.—Captain, Sam Glover; Lieutenants, Green, Light, William Gaut, and William Fields. Recruited in Hamilton County and Bridgeport, Ala.

Company I.—Captain, Bob Bledsoe; Lieutenants, William Hildreth, J. W. Storey, Foster Bowman, and Elliott. Recruited in Fentress County, Tenn.

Company K.—Captain, Jim Britton; Lieutenants, W. Corbett and Dewitt Anderson. Recruited in Wilson, Sumner, and Davidson Counties, Tenn.

Company L.2—Captain, J. J. Parton; Lieutenants, Henry, Russell, and Tillery. Recruited in Knox County, Tenn.

The Regiment was assigned to a brigade composed of the Eighth Texas, Eleventh Texas, First Kentucky, and Fourth Tennessee Regiments and Malone’s Alabama Battalion, Col. Tom Harrison as Senior Colonel commanding the brigade, Maj. Gen. John A. Wharton commanding the division (Gen. Joe Wheeler’s Corps, Army of Tennessee), and sent to Franklin, Tenn., on outpost duty. General Bragg, with the infantry force, was at Murfreesboro, confronting General Rosecrans’s Federal army at Nashville.

It is well enough to state here that there were two Fourth Tennessee Cavalry Regiments in the army—Colonel Stearns’s Fourth Tennessee and Colonel Smith’s Fourth Tennessee. They had been serving in different departments of the army, one under General Forrest and the other under General Wheeler, most of the time, and we did not know the fact until late in the war. Both had made character under that name, and each tacitly agreed to remain as they had been known, which they did. At the date of the organization of the Fourth Tennessee Cavalry Regiment it numbered one thousand men, rank and file, made up principally of stout, healthy, and vigorous young men. As stated, our first service as a regiment was at Franklin, on General Bragg’s front and left flank, some twenty miles from Murfreesboro and eighteen miles from Nashville, where we were kept busy for some two months or more in picketing, scouting on all the roads leading toward Murfreesboro from Nashville, occasionally having some hot contests with the enemy, killing, wounding, and capturing some, and losing some ourselves. At one time we scouted toward Nashville in the night, and remained all day in the vicinity, expecting the enemy to come out, as was their custom, on foraging expeditions, which they failed to do. But before leaving we concluded to give them a closer dare. In the evening we came up the Charlotte Pike as far as what is now West Nashville, and, going up Richland Creek, we came in contact with a force of the enemy at Bosley Springs, and, charging them, drove them back to the Harding Pike, capturing some and pursuing the others to where the old penitentiary wall stood, on Church Street. We remained in line a short distance down the road till near sundown; but no enemy appearing, we repaired to our station at Franklin.

The enemy made frequent scouts in the neighborhood of Franklin, sometimes resulting in quite a battle. I remember that in one of these Captain McMillin, a brother of Ex-Governor McMillin, was killed. He was on a visit to some acquaintances in the Regiment, and went out with the Regiment to meet one of these scouts of the enemy.

In the latter part of December, 1862, Rosecrans marched on Murfreesboro. The Regiment skirmished with his advance till he reached the place. Capt. J. R. Lester, of Company F, was desperately wounded in one of these skirmishes. We thought at the time that his wound was mortal, but he returned to his company in a few weeks, and served with them till the surrender at Greensboro, N. C. When Colonel Smith as Senior Colonel assumed the command of the brigade, Capt. J. R. Lester was made his Inspector General, and surrendered as such.

On reaching Murfreesboro we were placed on the right of our line on the Lebanon Pike, where General Bragg supposed the enemy would first attack; but changing his plans during the night, he attacked with his left flank about daylight. A terrific battle ensued here. It seems the enemy at the time was moving to attack Bragg from that flank, and the two armies unexpectedly met in deadly conflict. The battle raged in all its fury for hours. Charge after charge and countercharge was made time and again, with heavy losses on both sides. The Confederates, steadily advancing, gradually forced the enemy back, capturing many pieces of artillery and small arms, with many prisoners. Among the captured was General Willich and his German Brigade. Gen. Jim Rains, of the Confederate army, and General Sill, of the Federal army, were killed in one of these assaults. Before night the Federal army was forced back to the Nashville Pike, at right angles to the position they held when first attacked. The Confederates had gained a great victory. The loss of each was about equal—say, ten thousand. Six thousand Federal prisoners were captured, and several batteries of artillery, besides thousands of muskets and ammunition. The next morning every one expected the battle to be renewed, and were much disappointed that General Bragg did not follow up his advantage, instead of which he remained inactive for several days. In the meantime he ordered General Wheeler, with his cavalry corps, to the rear of General Rosecrans, toward Nashville. All along the way to La Vergne we were picking up prisoners, and everything indicated a defeat and rout of the enemy. At the latter place we came up with a long train of wagons moving toward Nashville with an escort of several thousand cavalry. We engaged them, and, after a considerable battle, they retreated. We captured and destroyed some two hundred wagons, some prisoners were taken, and a good many men on both sides were killed and wounded. Many of Rosecrans’s men had reached Nashville, reporting that his army had been badly beaten. Still no movement had been made by General Bragg at Murfreesboro. The enemy had taken advantage of this inactivity by collecting together their broken columns and taking position on high ground on the banks of Stones River, and crowned it with a number of batteries—fifty-seven pieces—well protected, awaiting the movement of General Bragg. On the first day of January he attacked this well-fortified place of the enemy with the single division of General Breckenridge. After a most gallant assault by Breckenridge, he was repulsed with heavy loss. That night the cavalry of Wheeler occupied the works of the infantry when they withdrew toward Shelbyville. General Bragg, it seems, had sent off during this lull in movements all of his wounded and the prisoners he had taken. At daylight on the 2d of January, 1863, Wheeler’s cavalry also withdrew, following the infantry toward Shelbyville. No pursuit was made. The Federals were as much surprised as the Confederates at the result, and it was sometime during the day before they could realize the fact of the withdrawal of Bragg’s troops. Much adverse criticism was made of General Bragg’s failure to take advantage of the victory he had obtained in the first days of the battle, and especially of the assault he made against the well-prepared works of the enemy, when it should have been with his entire army instead of a single division. Such was the opinion of the humblest soldier in his army.

General Bragg upon reaching Shelbyville went regularly into camp, and remained there some three or four months drilling, recruiting, and strengthening his army. General Wheeler, with his corps, was on the front watching the movement of the Federal army at Murfreesboro, scouting all the approaches, with an occasional scrap with the enemy, sometimes approaching the dignity of a battle.

In January, 1863, Wheeler’s Corps was ordered to Fort Donelson with a view of capturing the garrison stationed there. General Forrest was ordered up from West Tennessee to coöperate with Wheeler. On reaching the place, Wheeler made his arrangements to attack, and did attack the fortifications; but General Forrest refusing to coöperate, he was repulsed and the expedition was a failure. Wheeler lost quite a number of men. Col. Frank McNairy, a well-known citizen of Nashville, was killed in leading a charge. The weather was extremely cold. The streams were full of ice and the dirt roads were frozen hard, making it a matter of difficulty to pass over. Men and horses suffered greatly, as much as at any time during the war. On going back to Shelbyville, the Fourth Tennessee was detached and sent by General Bragg to Woodbury to relieve a portion of General Morgan’s command under Captain Hutchison, who was killed in an engagement with the enemy the day before we reached there. He was a fine soldier, and his death was much regretted. His home was at Springfield, Tenn., where he is affectionately remembered. The Regiment was at Woodbury some weeks, during which time we had frequent battles with the enemy coming up from Murfreesboro, where the Federal army was still stationed. We lost quite a number of men, killed and wounded. In one of these engagements Colonel Smith received a saber cut, and would probably have been killed had not the bugler of the Regiment, J. A. Stewart, relieved the situation by a well-directed shot from his pistol. From Woodbury we were ordered over to Trousdale’s Ferry, on the Caney Fork River. We went from there on a scout toward Nashville, and, turning off the Lebanon Pike, went to a point on the Cumberland River a mile above Edgefield Junction, where we waited, in ambush, for a train on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad to come in sight. We had a piece of artillery with us, commanded by Lieutenant White; and when a long train made its appearance, he opened on it, and about the first shot went into the steam chest of the engine, bringing the train to a stop in full view of our position. The train was loaded with horses; and after demolishing it and everything in sight, we retired.

Some of the men asked to be permitted to go over and get some of the horses; but Colonel Smith would not allow it, as he had another trip in contemplation, to wit: to go over to the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. Near Smyrna we captured a long train of cars full of officers and soldiers without firing a gun. The men were allowed to help themselves bountifully to the rich booty; and being paroled, the prisoners were permitted to pursue their journey toward Nashville on foot. From there we returned to our post at Trousdale’s Ferry. In a short while thereafter Colonel Smith and Adjutant Minnis were captured by the enemy under the following circumstances: They had been across the river inspecting the picket posts on that side, and on their return to camp after dark they were captured by a scout of the enemy which had been piloted around the pickets by a Union man of that vicinity. As soon as it was ascertained, a squad from the picket post pursued them to the vicinity of Carthage, about seven miles. They came in view of the scouts with the prisoners, whom they managed to keep so exposed that the Confederates were afraid to fire at them for fear of killing Colonel Smith and Minnis. The writer was appointed to fill the place of Adjutant Minnis, and served in this capacity till the battle of Fayetteville, N. C., in February, 1865, when he was appointed Adjutant General of the brigade, and served and surrendered as such at Greensboro, N. C., April 26, 1865. We remained some days longer on the Caney Fork, till General Rosecrans commenced his movement against General Bragg, when we were ordered to Shelbyville. We reached there in time to resist the advance of the enemy, having some well-contested battles with them, in which a good many of our men were killed and wounded, and inflicting a like loss on the enemy. Here the greater part of Colonel Malone’s Battalion, of Alabama, was captured, and we saw no more of them during the war.

When Rosecrans began his movement on Shelbyville with a heavy column, he sent a like column down the Chattanooga Railway toward Tullahoma. In order to meet this movement, General Bragg fell back to Tullahoma, where the two columns of the enemy were expected to concentrate.

The Army of Tennessee remained at Tullahoma some three or four weeks, during which time they were kept busy drilling, collecting supplies, recruiting, etc. The conscript law of the Confederate government was in full force, and Bragg received from this source quite an accession to his army. Some of these made as good soldiers as we had, but as a general thing they were a very uncertain quantity and would not do to depend on. In a short time General Rosecrans’s army appeared before Tullahoma. It had been largely recruited and numbered double the strength of the Army of Tennessee. In one of the cavalry battles around Tullahoma that great soldier, Gen. James Starnes, had been killed. His death created quite a gloom, and, had he lived, he would certainly have won higher rank. Judge McLemore, of Franklin, succeeded to his command.

General Bragg began his retrograde movement toward Chattanooga in June (I think), very wisely concluding to draw the Federals farther from his base before risking another general engagement. General Wheeler covered his rear, which the enemy’s cavalry assailed very vigorously, using their batteries freely. This continued until we passed over Cumberland Mountain, both armies losing quite a number in killed and wounded, some prisoners being taken. After passing the mountain a lull in the operations of both armies ensued. The Confederate infantry had passed on to Chattanooga. Wheeler’s cavalry, reaching the Tennessee River, passed over the bridge at Bridgeport on the plank flooring that had been laid upon the girders. After reaching Shellmound, on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, General Wheeler was ordered to go to Rome, Ga., with a view to recuperating his much-jaded cavalry horses. Here we remained for two months or more and had the only real rest that we got during our service in the army. Rome was then a pleasant little city of about five thousand inhabitants, surrounded by a rich and fertile country. Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps numbered about five thousand, rank and file. The quartermasters of the respective regiments would buy a field of corn, move to it, and remain until it was exhausted, and then move on to another purchase. The horses would be fed on the corn, stalks and all, using a plentiful supply of salt, besides grazing them on grass for an hour or two each day. It was wonderful how they improved, and by the time we left there they looked as if they had been prepared for a State Fair.

The soldiers, too, were supplied with an abundance of substantial and wholesome rations. The strictest discipline prevailed. Drills were the order of the day, with both officers and privates, at least two hours each morning and evening. Prayer meetings and services by the respective chaplains were held regularly, were well attended, and many conversions took place. Drs. Bunting and Hendricks, our brigade and regimental chaplains, were kept busy and active in their duties, and we know that many lasting and substantial conversions were made through their efforts. We also had an election for Tennessee State officers while there. The Tennessee troops voted for Judge Robert L. Caruthers for Governor and for their respective Congressmen in their districts. The State Department was at Chattanooga at that time, and we suppose that the returns of the election were made to them. We have never seen any published returns of the election, but suppose it held. We suppose it was the only election ever held that had no graft or liquor dispensed as an inducement—truly a prohibition affair.

By the time we were ordered to move, Wheeler’s Corps was in splendid condition, both men and horses. Rumors were pending of a great battle, and all were anxious to be off to the war again. Early in September, 1863, we were ordered to the front. At La Fayette, Ga., we met a portion of General Bragg’s infantry. He had remained quietly at Chattanooga until the enemy made their appearance in front of the city, when he retreated south; and, marching back to La Fayette, he surprised the enemy, when General Rosecrans hastened to get his scattered army together to give battle. General Thomas, with his large corps, had crossed the Tennessee River at Bridgeport, marching across Sand Mountain toward Rome, Ga., and was separated some distance from General Rosecrans. Our brigade was sent back to Tryon Factory with the infantry brigade of General Helm to meet a Federal command, which we did. After some sharp fighting they retreated with a view of joining the main column of Rosecrans. We continued on their trail, after several hard contests with them, notably at Bluebird Gap and other places, till General Thomas had taken position in McElmore’s Cove, when General Bragg made his dispositions to capture them. General Hindman’s Division was ordered to a gap in the mountain to prevent Thomas’s escape; but for some reason he did not reach it in time to prevent it, and Thomas hurried to join with General Rosecrans. This failure on the part of General Hindman to get to the designated point in time is said to have brought about an inquiry of court-martial. It was evident that but for this failure we would have captured General Thomas’s splendid corps. General Wheeler continued his skirmishing with the right wing of General Rosecrans’s army till we reached the field of Chickamauga on the evening of the 19th of December.

We relieved General Breckenridge’s Division at Glass Mill, on the Chickamauga, where they had had a considerable battle with the enemy under General Negley. Other parts of General Bragg’s line on his right had been hotly engaged during the day and late in the evening by the combined attack of Generals Cleburne and Cheatham. Some success had been obtained by them.

I here insert a paper prepared by me after a visit to the battle field of Chickamauga more than twenty years afterwards, and which I was invited to read before Donelson Bivouac and an assemblage of the Daughters of the Confederacy in their hall at Gallatin:

The battle of Chickamauga was fought on Saturday and Sunday, September 19 and 20, 1863, the farthest extremity of the field being about thirteen miles southwest of Chattanooga, extending up to about seven miles of that city, which is about the dividing line between the States of Georgia and Tennessee. General Rosecrans was in command of the Federal forces, and General Bragg was in command of the Confederates.

We are standing to-day on the exact spot in the old field near Glass Mill where we dismounted to fight, and from which we advanced to take part in that bloody and hard-fought battle between American soldiers. We feel that we are standing upon consecrated ground, baptized as it has been by the best and purest blood that ever pulsated in human veins. It was here, amid the smoke of battle, that the forms of personal friends and comrades faded from our sight and we beheld them no more. As we gaze up into the blue skies that panoply these mountains and valleys, we seem to feel that their spirits hover around here yet, and that we can again commune with them. As imagination paints, we feel that same inspiring emotion which nothing on earth can excite save the busy preparation for battle. As we listen to its roar—the boom of cannon, the crash of musketry, the shouts of advancing columns—we experience the light, airy feeling, twitching of the nerves, and restless expectation that an impending conflict alone can produce, and feel that we breathe an atmosphere high above this earth.

Rosecrans in advancing from Chattanooga had marched by his right flank toward the Alabama line. He had supposed that General Bragg was retreating; and when Bragg marched back, taking position at La Fayette, Ga., he seemingly became alarmed and, with a view of getting together his scattered columns, marched back toward Chattanooga along the line of Missionary Ridge, covered by the mountainous country and the Chickamauga River south of his line of march. About ten days before the battle Wharton’s Division of cavalry, to which he belonged, was ordered up from Rome, Ga., where we had been since our retreat from Middle Tennessee. This inactivity had become tiresome, and the order to move was received with delight. The air was pregnant with rumors. A great battle was said to be imminent. The men moved with alacrity and determination, for they felt that the opportunity was at hand when they could regain lost territory and drive the enemy beyond their homes. Some scouting and skirmishing took place before the general engagement. We remember that at Tryon Factory, Bluebird Gap, McLemore’s Cove, and other places we had hard fighting, driving in their right flank. General Forrest with his cavalry had opened the fight at Reed’s Bridge, on the Chickamauga, on Friday, the 18th. On Saturday, the 19th, most of the Confederate army had passed to the north side of the river and confronted the enemy, whose right wing rested at Lee & Gordon’s mill and extended in a northern direction, covering the roads leading from La Fayette to Chattanooga. Fighting took place during the day, and late in the evening, by a united charge by Cleburne’s and Cheatham’s Divisions, they drove the enemy and gained some advantage, but with considerable loss. General Longstreet arrived late that evening, and a portion of his corps came upon the field that night—to wit, McLaws’s and Hood’s small divisions, numbering not exceeding eight thousand muskets. This was the only portion of his corps that participated in the next day’s battle. On consultation that night at Bragg’s headquarters, the Confederate army was divided into two wings, General Polk to command the right and General Longstreet the left. The order was for Polk to commence the fight on the morrow at daylight, when it was to be taken up successively along the line to the left. For some cause the attack did not commence until late in the day, which circumstance did and has since caused serious comment regarding the result. We thought then and see now that if the Confederates had had two more hours of daylight General Thomas would have shared the fate of McCook and Crittenden, commanding the other two corps of the enemy, and would have been completely shattered and broken to pieces. This failure of the brave old Bishop to come to time was afterwards the subject of court-martial investigation, though no one ever doubted his courage or loyalty to the cause for which he afterwards gave his life; yet history will hold him responsible for the great mistake, whether caused by subordinates or not. It was midday, we suppose, when General Wharton’s Division was dismounted in the old field upon the bank of the Chickamauga at Glass’s Mill. They formed the left of Bragg’s line of battle, with Hood’s Division on our right at Lee & Gordon’s mill. We judged from the firing that the line of battle was some five miles in length, and that the battle was raging with desperate fury at this time.

It was Sunday—a calm, clear September day in the mountains of Georgia, amid scenery that Switzerland could not excel in romantic grandeur. The rich green foliage of the mountains served as a background, and from its sides and gorges arose in dense volumes the sulphurous smoke of battle. The fiery wave of battle boiled and surged in its maddening fury during the evening and until nightfall. Commencing on the right, the deafening thunder would roll along the line toward the left, when it would be taken up and swept back to where it started. The sound indicated with accuracy the result in different parts of the field; for as a column would advance to the charge you would first hear the rapid and quick discharge of the batteries, indicating that their position was threatened, then would come a crash of musketry as if every tree in the forest had fallen, and high above all this the shouts of the Confederates. For a moment a deathlike silence would ensue just there, unmistakably evidencing the fact that the battery had been taken or driven from the field. This would hardly die away at a given point before it would be repeated successively along the line and echoed back again, swelling at times to such a mighty chorus manufactured from the thunders of war that it seemed that both heaven and earth would be torn asunder. Truly

“Such a din was there,

As if men fought on earth below

And fiends in upper air.”

We feel our inability to give more than a faint conception of the grandeur of the scene that met the eyes and fell upon the ears of those who participated in the battle of Chickamauga. They can never cease to remember it. The roar of the four hundred cannon from Round Top and Cemetery Hill, at Gettysburg, which preceded Pickett’s charge, has never been equaled, though the casualties resulting from this grand artillery duel were comparatively few; while at Chickamauga all day long on Sunday there was a series of infantry charges upon batteries in chosen position, in which whole companies and regiments were swept away like the morning mist before the rays of the sun.

While sitting upon our horses listening to all this, we noticed a courier gallop up to General Wharton and deliver a message. We were ordered to dismount, as heretofore stated, and advance toward a battery that was shelling us from an eminence across the Chickamauga and about one-half mile distant. The order to advance was received with lusty cheers, for the men were chafing to go forward. The brigade was composed of the Eighth and Eleventh Texas, the First Kentucky, and the Fourth Tennessee Regiments. Col. Thomas Harrison, of the Eighth Texas, commanded the brigade as senior officer, and Lieut. Col. Paul Anderson was in command of the Fourth Tennessee, which was on the right of the brigade. We moved in column down the road leading to the river and, fording the stream near the mill, formed a line of battle in regular infantry style in the edge of low, level beech woods, and, placing our skirmishers a short distance in front, advanced through the woods. The enemy knew that we were coming and kept up an incessant shelling of the woods, some of our men being injured by limbs of trees torn off by the cannon balls. We had advanced but a short distance when the skirmishers became hotly engaged, which was the signal for a rapid advance, and we swept through the woods, driving the enemy before us. They rallied at a fence at the edge of the woodland, delivered an effective volley, and fell back across a little field to a new line behind a fence and on the edge of another woodland along an eminence where their artillery was planted. As our line emerged from the wood into the open space this battery, shotted with grape, and the line behind the fence, armed with seven-shooting Spencer rifles, opened on us, and a perfect hailstorm of deadly missiles filled the air. Being commanded to lie down, we did so for a few moments, and then arose and charged across the field. Just here we sustained our heaviest loss, and in a few moments the Fourth Tennessee had forty men shot down as we arose from the ground. As we rushed across the field the line sustaining the battery broke; and as they ran off many were killed and wounded, two or three hundred of them surrendering in a body. We were struck here with the gallantry of a Federal officer. He was on horseback and with drawn saber was attempting to hold his men to their position. He was killed, and his body fell into our hands. Papers upon his person indicated that he was colonel of the First Ohio Regiment. We went half a mile farther until we drove them beyond Crawfish Springs, the field hospital of the Federal army. This explained, what we could not understand at the time, why we were making a fight so far from the line of our infantry. The Federals had been driven from the line of the Chickamauga, and, this being the only water accessible to them, they had made Crawfish Springs their field hospital. We have learned since that we were fighting the division of Gen. George Crook. Both sides lost quite a number in killed and wounded. Where a stand had been made they were thick upon the ground. The line of attack for a mile was well defined; but, really, though we gained the fight and drove them from the field, our loss in killed and wounded was as great as theirs. The immense crowd of men, tents, vehicles, etc., at Crawfish Springs caused us to believe at first that we had captured the whole Federal army. Dead men in rail pens for protection and wounded men in large circus tents were scattered about over acres of ground, with the accustomed retinue of hospital assistants and not a few shirkers from the fight. This spring is one of the largest and purest of clear water I have ever seen. Its volume is large enough to supply a great city, and the stream that flows from it is that of a small river. After detailing a guard to hold the captives, the remainder of the command were marched back to their horses. The road was full of our ambulances, litters, etc., bearing off the dead and wounded. Here was presented that other phase of grim-visaged war, sickening to look upon: friends and comrades dead and dying who a few hours before were full of life and soldierly enthusiasm; men with their pale, ashy countenances turned toward the sky. Such scenes dissipate the excitement that the advance creates. A friend who was mortally wounded recognized me as we passed. As he evidently wished to say something to me, I stopped and took his cold, icy hand. Fixing his glassy eyes upon me, he said in a faltering voice: “Let my people at home know that I died like a true soldier.” He died that night; and his body rests somewhere upon the field his valor helped to win, though his name will never appear in the “count of the battle.” His was the fate of thousands of gallant spirits whose memory lives in the hearts of a small circle of acquaintances, but whose heroism has made their commanders great in song and story.

I have had a desire to visit these scenes ever since the war closed. Soldiers are rushed upon battle fields and rushed away, leaving a desire to visit them again. It was just twenty-four years ago and the same hour of the day when I last saw this field where Harrison’s Brigade made their fight, yet many things are true to the impressions left; and what a rush of buried memories are resurrected! The old mill where we crossed the Chickamauga looks the same. The woodman’s ax has leveled the dense beech grove on the north side through which we moved to the attack. A few scattering trees are still standing to indicate the character of timber that once stood upon the ground. Now it is an inclosed field, upon which is growing in rich luxuriance “the tall yellow corn.” I tried to follow the line of our advance, and suppose I did so from the fact that, the timber being cleared away, the high ground upon which the enemy’s battery was located is plainly to be seen. I fancied that I found the little hillock on the far edge of the woodland where we were ordered to lie down while the enemy’s shot sprinkled us with gravel. I cut a cornstalk from the spot where so many of our men were shot down, and have it yet as a memento. The low log house on Snodgrass Hill is still standing, and looks as it did then. It was here that we captured so many cannons. This point in the field is upon its southern extremity, situated between the road leading from La Fayette and the one leading from Crawfish Springs to Chattanooga. Just here the hardest fighting occurred. The field is still an immense rugged and woody forest, and no particular marks can be seen except now and then the tall stump of a tree. All through the woods for miles the bodies of the trees have been chopped by curio hunters. In a dense jungle at the foot of Snodgrass Hill I noticed a number of graves. The letters on the rotted boards indicated that they were Alabamians. The Dyer, Vittitoe, Glenn, and Ross houses have been preserved, and look as they did then. But after traveling over the field for hours, I might say with truth that there is nothing here to tell the stranger of the spot where one of the bloodiest battles in the world’s history was fought. Hundreds of brave men of both armies were buried here in their blankets, and hardly a sign seems to mark their resting place. But the name and fame of Chickamauga will live in history as long as Lookout lifts its rocky ribs to the skies or the river of death winds its way to the sea. As I stood there musing I could not but ask myself the questions: Where are the men who were actors in this bloody drama a quarter of a century ago? Where is the spirit that pervaded this immense host and drove them to deeds of blood and slaughter? The glory, pomp, and circumstance of war have departed, and to such as survived that field and the long years that have passed since then it seems as a shadowy dream, without the semblance of reality.

But to resume: On Sunday night we slept upon the field near General Longstreet’s headquarters, at the foot of Snodgrass Hill. At an early hour the Fourth Tennessee was ordered to report to him for orders. We then anticipated a renewal of the battle. He sent us forward toward Chattanooga to report the whereabouts of the enemy. I remember that we passed a little white house near the Chattanooga Road. As we approached it, I noticed a hog running through the woods with a soldier’s amputated leg in its mouth. This was one of our field hospitals, the window of which was some three or four feet from the ground. The surgeons within as they amputated a limb would throw it out of the window. The pile outside was so high that they would have to brush away the topmost limbs. Just beyond here was an elevated plateau where a hard struggle had taken place. As many as six batteries of the enemy had been broken to pieces. Horses were piled thick one upon the other, mangled and torn in every conceivable shape. Behind these batteries was a long line of Federals who had been killed where they lay. The fence had caught fire, and many of the bodies were burned into a dark crisp. Every tree and bush was marked by balls, and in some places large trees were torn to pieces. To see it, you would conclude that a small bird could not have survived the storm of bullets that swept like a cyclone through the forest.

I have seen paintings depicting the horrors of the battle field which I supposed were overdrawn; but this idea was dispelled at Chickamauga, and I appreciate now the fact that the imagination cannot always do it justice. All through the woods were telegraph wires thrown over the top of the bushes, connecting every part of the Federal line. These were incased in something resembling a cotton rope. Our men utilized them for bridle reins. Everywhere we found abandoned property and gathered up many prisoners—indicating not only a defeat, but a rout of the enemy. We sent back couriers all day long with this information, but no pursuit was made. We went forward on Missionary Ridge as far as Rossville and in sight of Chattanooga, where great consternation existed among the enemy. We were informed that some of them were escaping to the north side of the Tennessee River. On Tuesday, the 22d, with the remainder of General Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps, we came through McFarland’s Gap and skirmished with the enemy close up to the corporate limits of Chattanooga. We captured their signal flag on the point of Lookout. Its operator worked his machine until hands were laid upon him. We skirmished all day, losing some men in killed and wounded. In the evening we were withdrawn, and here ended the battle of Chickamauga.

The humblest soldier believes we could easily have captured the Federal army on Monday, the 21st of September. The superior valor of the Confederate soldier was again published to the world, but the full measure which soldierly courage had won at fearful cost was permitted to slip away. I fully concur in the comment made by a gallant Federal officer, in speaking of Chickamauga the other day, that “it was the bravest standing-up fight of the Civil War.” It has never been depicted as have been the battle fields of Virginia; but no field save Gettysburg, where the forces engaged were larger, can show such a list of killed and wounded as lay upon that field on Sunday night after the battle. The best-authenticated reports from both sides place the killed and wounded alone at 34,000. General Bragg had about 55,000 men, and General Rosecrans had about 65,000 or 70,000. The great battle of Waterloo did not reach this per centum by one-half. The Confederates captured 8,000 or 10,000 (not including their wounded), 51 pieces of artillery, 15,000 stands of arms, a large amount of ordinance stores and camp equipage. The enemy were driven from every portion of the field, leaving it in possession of the Confederates. It was fought on ground of their own choosing. In some parts they had erected breastwork protection that had to be assailed by Confederates, frequently in exposed fields; but they were driven from every inch of the field, leaving their killed and wounded in our possession. The Confederate loss in killed and wounded amounted to 17,300, and the Federal loss in killed and wounded 16,800—this for the reason that the Confederates, being the attacking party, were, of course, the more exposed.

Northern writers and speakers sometimes claim that the Confederate army was numerically larger at Chickamauga than the Federal army. I suppose this arises from the fact that they think General Longstreet was there with his entire corps of more than 20,000, when, in fact, but two reduced divisions of his corps were there to take part in the battle—namely, Hood’s and McLaws’s Divisions—and they participated only in the last day’s battle. These two divisions did not exceed 8,000. Bragg retreated to Chattanooga from Middle Tennessee a few months before with about 35,000, and the only accessions he had to his army were Quarles’s Brigade, from Mobile, numbering 3,000, Hood’s and McLaws’s Divisions, and a few loose detachments he had collected up from his department. His entire force could not have numbered more than 55,000.

These writers grow very eloquent over Missionary Ridge and draw gorgeous pictures of the “battle above the clouds.” The two fields are contiguous, and the battles were fought within a few weeks of each other. They do not admit of a comparison. I would not rob the Federal soldier of a single laurel, but what are the facts? After the battle of Chickamauga, Longstreet had left, taking with him General Bushrod Johnson’s Division of the Army of Tennessee, and other troops had returned to their stations; and General Bragg was holding Missionary Ridge with a force not exceeding 25,000 men, who were clamoring for a change of commanders. What could they now promise themselves with a smaller army against a heavily reënforced enemy? All of the renowned Federal leaders were at Missionary Ridge—Grant, Sherman, Hooker, Sheridan, and others—with an army of over 100,000. With such numerical strength and the prestige of such commanders it was possible, as it proved, to break through our thin line at a given point and, taking it in reverse, to drive the Confederates from their position. But here was committed a graver error than Bragg had made at Chickamauga, for the Confederate army should have been captured. Instead of a vigorous onset and pursuit, but a feeble one was made, and that was arrested by a single division under Pat Cleburne at Ringgold Gap, a few miles below there.

Chickamauga and Gettysburg were the two great battles of the war, the one in the Middle West and the other in the East. They were the pivotal fields upon which the cause of the South turned. Two more hours of daylight at Chickamauga on Sunday, and an assault by General Lee at Gettysburg with his entire army, would have brought about a different result. On these two occasions the Confederate had reached the zenith of his strength and enthusiasm. After this he was too intelligent not to know that he was wasting his weakening strength beating against a mighty stone which gathered force as it moved. He fought bravely and with some degree of success until the last, but with the desperation of a forlorn hope.

We cannot conclude without saying a word to the ladies who have honored this occasion with their presence. In fact, any meeting of Confederate soldiers would be incomplete without your presence. I would not be extravagant in what I say; but in truth the Southern woman has been the truest, the best, and the most devoted friend the Confederate soldier ever had. During the war she was his ministering angel in the camp, on the march, and in the hospital. She has been the light and sunshine of the desolated home that the war left him. Her sweet words of cheer have smoothed the rugged pathway of life and have guided his footsteps toward prosperity again. Her devotion has never flagged nor faltered for a moment; and to-day she is at work aiding and assisting the old, disabled, and indigent soldier, making happy his declining years. How can we forget you? We should be untrue to every principle of gratitude to do so. Before I die I want to see some lasting testimonial given expressive of our appreciation. Were I permitted to name it, it would be a shaft of the purest marble, the tall summit of which would touch the skies, and I would plant it upon the highest point of old Lookout, in full view of Chickamauga’s ensanguined field, where so many of the sons of Tennessee gave their lives for what is just and right.

In the latter part of September, 1863, just after the battle of Chickamauga, by order of General Bragg, General Wheeler was sent into Middle Tennessee with his cavalry corps. The Army of Tennessee was occupying the field they had so gallantly won at Chickamauga. He moved up the Cleveland Road to Red Clay, and forded the Tennessee River at or near Cottonport, some thirty miles above Chattanooga. The object of the raid was to cut off all supplies from the North for Rosecrans’s army, then at Chattanooga. The Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad from Bridgeport to Chattanooga was then in possession of the Confederates. The opposite bank of the Tennessee was closely picketed by the enemy, and the command was to keep as still as possible so as not to draw their attention until we had crossed. We reached the ford after a night’s ride, and rested there till daylight. I can never forget the beauty and picturesqueness of the scene that was presented that moonlight night, when four or five thousand cavalry forded the beautiful Tennessee. It happened that the Fourth Tennessee Regiment was in front; and, headed by a single guide, we descended the banks and dropped into the river, and then the line swung down the stream across the silvery surface of the broad waters, like the windings of a huge dark serpent. When we reached the opposite shore, I looked back upon the scene presented. This, with the reflection that we had turned our faces homeward again after our glorious victory, was soul-inspiring indeed. Nearly half a century has elapsed, but its recollection is as vivid in my memory as it was then. No creation of art could have been more imposing. There is too much stern reality in a soldier’s life for such to claim his attention, but this scene has left an impression that I can never forget.

As we reached the opposite shore the gray dawn of a bright September morning was breaking upon us. About one-half of the regiment was dismounted and silently moved up the bank. But a few moments had elapsed before the bang of a solitary gun was heard, and in another second bang! bang! bang! went the guns, and then a perfect fusillade. All were now wide awake, and the stillness of the scene was suddenly transformed into busy preparation for a fight. Another regiment was hurried forward, and thundered down the road leading from the river in the direction of the firing. A few more shots were heard, and all was still again. A large picket of mounted men had been driven off with the loss of several men and some prisoners. The remainder of the command moved out from the river as they came over, and in due time all were safely over. The trail of the ford was a devious one and very deep in places. One would reasonably suppose that many mishaps would have occurred, but nothing of a serious character happened.

The command then moved toward Middle Tennessee across the mountains into the Sequatchie Valley, where we went into camp for the night at the crossroads. Nothing of note occurred during the day. About daylight the following morning we were aroused by an order to saddle up and mount our horses, as the bugle sounded “boots and saddles.” In a few moments more we were moving down the valley at a rapid rate, not knowing at the time what was up. How vividly these stirring scenes flit across my memory! And how many incidents of dash and spirit do they bring to mind of the early morning “racket, when from out the empty saddlebows bravely they fell!” A few miles away we commenced overhauling Federal wagons, partially plundered; then the cry of a wagon train was raised. As the pace quickened, these captures thickened along the way; and after going ten or twelve miles down the valley to the vicinity of Jasper, there opened the richest scene that the eye of a cavalryman can behold. Along the side of the mountain hundreds of large Federal wagons were standing, with their big white covers on them, like so many African elephants, solemn in their stately grandeur. They had been rushed up there by the teamsters and abandoned. This was too rich a bonanza to be left without an escort; and in a few moments the rifles sounded from the mountain sides, indicating that we would have to do some fighting for such booty. Men were dismounted in haste and hurried to the right and left. A vigorous fire was kept up for a while, when the enemy, seeing that they were greatly outnumbered, surrendered after some casualties on both sides. The escort numbered 1,200, with many drivers of the wagons. Some of them had escaped by cutting loose the mules and mounting them. We knew that there was a large infantry force not many miles away, and we set to work destroying everything at once. Orders were given that no plunder was to be carried off. This, however, was but partially enforced. The wagons were loaded with all manner of clothing and rations for the army of General Rosecrans. Among the wagons were a number belonging to sutlers, with rich stores of all kinds. The result of the capture was seven hundred and fifty wagons, twenty-six hundred fat mules, and twelve hundred prisoners. The wagons, or the most of them, were loaded with rations for the army. The enemy were afraid to risk railroad transportation, and were endeavoring to provision their army at Chattanooga by means of wagons from McMinnville. It had rained the night before and left the roads so slippery that the wagons could not go over the steep mountain pass. Such of the mules as we could not take off were destroyed. The wagons and the greater part of their contents were destroyed on the spot, the débris covering acres of ground. I was particularly struck with the fine harness that had been stripped from the mules, as it lay chin-deep over ten acres of ground. Such a calamity as this would have been most seriously felt by us, and would have retarded movements for months; but with “Uncle Sam,” with all the world at his back, it made no perceptible difference. If it created a ripple of discomfort anywhere, we never had the satisfaction of knowing it.

From here we moved on toward McMinnville, traveling all night long with the prisoners, mules, and a few of the wagons. General Dibrell had been sent forward from the crossroads where we camped to take McMinnville. We reached there the next morning. Dibrell had captured the garrison of four hundred, with stores that had been shipped there by rail to be transported by wagon train to Chattanooga. It was said that there was a full suit of clothing for every soldier in Rosecrans’s army, besides an immense amount of rations. During the night we overtook the guard in charge of the prisoners on foot. As we passed them I noticed a boy among them who could not have been over ten or twelve years of age, dressed in full Federal uniform. I asked him what he was doing there, and he answered that he was a soldier and a marker for a Michigan regiment. I took him up behind me and carried him the remainder of the night, leaving him with the guard in charge of other prisoners captured at McMinnville. We now had about sixteen hundred prisoners on our hands, and the most perilous part of our raid was still before us. So it was concluded that we would parole them. Marching them out a few miles from McMinnville, we ordered them to hold up their right hands, swearing not to take up arms again until they were legally exchanged, and then started them toward the Kentucky line. How many of them observed their parole, we will never know; but it seemed to us then and afterwards that for every one we killed or captured half a dozen would rise up in their places. When we lost a man, he was “dead for certain,” and, worse still, none was to be had to stand in his place. In fact, it was this that forced us to quit fighting after four years, during which time we had the satisfaction of knowing that we were giving them about all they could stand up to, and this after calling to their aid the negroes and an immense foreign importation.

From McMinnville General Wheeler moved toward Murfreesboro. The column was a very long and cumbersome one with the mules and wagons we were attempting to take with us. We must have been close on the rear of the column, for by the time we reached Woodbury (one-half of the distance) we were in a gallop; and when we reached Murfreesboro we were at running speed. We found the command in line of battle close up to the town, forming a semicircle covering the roads leading to the south. We took position in line, and remained there probably half the day, expecting every moment to be ordered to charge the town. All at once we moved in column down the Shelbyville Pike. The object was then comprehended to be a feint to cover the passing of the led stock and wagons. During the halt here miles of railroad track was destroyed. Christiana is a station on the Chattanooga Railroad where a ludicrous little episode transpired en passant. The pike was about half a mile from the station, but in sight. A body of bluecoats were seen about the station, and a small troop was sent over to take them in. After approaching the place, something like a cannon was observed upon an eminence back of the station, with the gunners standing about it ready to fire. The information was sent back to the pike, and one of Lieutenant White’s guns was brought down. About the time it was placed in position to rake the station half a dozen white handkerchiefs were flaunted in the air. We went over to receive the surrender, and the would-be artillery was found to be an ordinary stovepipe set on a couple of wagon wheels. There was a set of about one hundred jolly, well-fed fellows, belonging to an Indiana regiment. They were well fixed up and were equipped with every paraphernalia for camp life—in fact, they had more plunder about them than a brigade of our army. Of this, what was not appropriated was destroyed, with apologies, however, to our newly made friends, whom we paroled and started back toward Murfreesboro. Many detours of this kind were made from the main column during the raid, and hundreds of prisoners were taken and much property was destroyed.

At Shelbyville we expected to make a fight, as it was reported that a considerable force of the enemy was there and were prepared for us. On approaching the place the next morning, we found they had evacuated the town. Before leaving they had torn down the courthouse on the Square, and with the débris blocked all the streets leading to it. Had they held their ground, certainly some blood would have been spilled before taking the place. We found a great many shops, sutler’s stores, etc., in the town, well supplied with goods of every description. These were owned by the Northern camp followers, who failed to get sufficient warning for their removal. Such plunder was considered as legitimate for capture as a United States mule or wagon, and to many it was much more acceptable. No Southern sympathizer would be granted this privilege. Commanding officers would attempt to restrain in a degree, but efforts were generally futile; and the result was that, after a raiding party had left a place, not much was left to commence business on again. Both armies pleaded alike to this charge. I noticed soldiers moving out of town with their horses heavily laden with some articles that you would imagine were the last things they would have need of. A couple of ladies had come to town that morning to make some purchases. When they saw what had happened, they waved their handkerchiefs and cheered lustily for Jeff Davis. The soldiers gathered around them, filled their buggy full of goods, and then escorted them out of the town.

From here the command moved out near the Lewisburg and Nashville Pike and went into camp. I think we remained there as long as two days. It is said that General Wheeler’s object was to await the return of scouting parties. We had created such a stir among the enemy that they took the time to set on our trail all the forces that were available. It seemed that it should have been the policy of the commanding general to have hastened our escape at this time, as the men, I am sorry to say, were so full of plunder that fighting had gone out of their minds, and they were anxious to get to a safe place where they could make an inventory of their property. However, we moved out one morning toward Lewisburg. The Fourth Tennessee and the First Kentucky Regiments were the rear guard. The first intimation that we had of the presence of the enemy was when cannon balls came crashing through the timber and we could hear the firing of our men and the enemy out on the pike, half a mile off. We sent Captain Wyly, of the Fourth Tennessee, down in that direction. He returned in a few moments, reporting that the enemy were between us and the remainder of the command. Lieut. Col. Paul Anderson and Colonel Chenyworth, of the First Kentucky, held a hasty consultation, when it was concluded that we would cut our way through. When this was announced, it was amusing to see the men falling out of their new Yankee uniforms and donning the faded gray again. It was more amusing still, as I think of it, when the gallant Colonel Chenyworth waved his sword over his head and took his position in front of his regiment, crying out in a loud voice, “Follow me, my brave Kentuckians!” as we moved down a blind pathway overhung with bushes. The two regiments had hardly gotten straightened out when bang! bang! went the enemy’s guns, seemingly only a few paces distant in the dense growth. The order was given, “Right into line;” and we moved through the woods one hundred yards or more, when we could see to our left a narrow lane leading out to the pike, and could see our men engaged fighting the enemy. Then the order was given, “Left into column,” as we made for the lane. Fortunately, this lane was old and well-worn, and the roadway dipped considerably. By drooping on their horses’ necks, this, with the fence, afforded protection to the men from the firing of the enemy, about a hundred yards across a little field. The two regiments went through with but few casualties, and joined with the remainder of the command in the fight. When I meet an old comrade who was present, he always asks: “Did you ever see as much kindling wood flying in the air as at that time?” Here opened up what is well remembered as the battle of Farmington. I wish I were prepared with the data to give a correct account of this fight, but I am unable from memory to give more than the results. I think both sides lost about equally in killed and wounded—say, about two hundred each. We fought for two hours, when General Wheeler learned that a large column of the enemy both in our rear and on the right flank was moving to surround us. The Confederates quietly and without pursuit moved off down the pike toward Lewisburg. The enemy afterwards picked up and made prisoners about one hundred of our men who had not joined the column when the fight took place. Among the number of Confederates captured at the battle of Farmington was the present well-known and efficient Secretary of the State Pension Board, Capt. John P. Hickman. He and his squad had been on detail duty, and were endeavoring to get to their company when captured. He was probably the youngest man in his company. He was confined in Rock Island Prison, and was not released until some weeks after the surrender of the armies. General Wharton, Colonel Cook, Major Christian, Captain Jarmin, and Capt. Polk Blackburn were among the wounded. Blackburn was very seriously wounded, and was thereby rendered incapable of further service during the war. He is now living at Lynnville, Giles County. Tenn., as one of the best-known and most worthy citizens of the county. He has represented that county several times in the State Legislature. The enemy ought to have destroyed us at Farmington. The Confederates were flushed with booty, and the Federals were smarting under their heavy losses in men and material.

We camped at Cornersville that night, along the road. It was quite cold, and the men had to burn (what the owner doubtless thought afterwards) a considerable amount of rails. The next day we passed through Pulaski. Here the Fourth Tennessee was detailed to hold till sundown the bridge that spans Richland Creek. The remainder of the command passed on toward the ford at Bainbridge, on the Tennessee River. We sat upon our horses that evening and watched for hours long lines of Federals as they came over the hills into the town, and expected every moment for them to open upon us. We were commanded to hold the bridge at all hazards—in fact, to be sacrificed, if need be, for the good of the cause. All of which would have read very heroically to the boys of the fourth reader of the next generation, but it was void of sentiment to us as we watched with supreme satisfaction the god of day sink behind the western horizon. Never had we seen so lovely a sunset. We ventured five minutes longer at the post, and then followed the command. We traveled all night and overtook the rear guard a few miles from the river the next morning. It consisted of about two hundred and fifty men, a remnant of Gen. John Morgan’s command after his capture in Indiana. They were in command of that gallant soldier Capt. J. D. Kirkpatrick, whom we knew well; and to many of the men we expressed our fear of their capture, as we knew that the enemy had been convinced of our intention and were now pressing us vigorously with a heavy force. We passed on to the river, which we forded without interruption, near Bainbridge, Ala. Our conjectures about Captain Kirkpatrick proved too true, for we learned afterwards from those who escaped that the enemy rushed upon them from every point of the compass, frenzied that we should escape so successfully. About one-half of the men were killed or wounded and captured, not, however, without having inflicted severe loss upon their assailants.

Thus ended Wheeler’s celebrated raid in 1863, commencing at the crossing of the Tennessee River at Cottonport, above Chattanooga, and ending with the crossing of the Tennessee River at Bainbridge, Ala.—about four weeks’ time in passing from crossing to crossing. The result was as follows: We killed, wounded, and captured of the enemy three thousand men; burned and brought out one thousand wagons; captured thirty-five hundred mules and horses, half of which I suppose we had to abandon in the fight at Farmington. I cannot estimate the loss of the enemy in stores of clothing, provisions, arms and ammunition, the destruction of miles of railroad tracks, bridges, engines, etc., but it was immense. Our own loss in men, from all causes, was eleven hundred, which loss was replaced to a great extent by new recruits and absentees we brought out with us.

We remained a short time in the vicinity of Bainbridge, Ala., getting horses shod, etc. Many soldiers who had been cut off while in Tennessee crossed the river at different points and rejoined their command. In rejoining the Army of Tennessee we again passed through the field of the battle of Chickamauga. Though it had been six weeks since we had seen it, much of the ravages of the battle were still to be seen. I regret to say that many of the bodies of the Federal soldiers were lying where they fell, but such is the state of war. Missionary Ridge extended from Rossville Gap to a point above Chattanooga where the Chickamauga River empties into the Tennessee River, and about four miles from the city. General Bragg was occupying its top, a distance of four or five miles in length, with his thin line of about twenty-five thousand muskets. From its summit the immense army of General Grant could be seen in the vicinity of Chattanooga. It was naturally a very strong position, and no army near the number of the Confederates could have driven them from it.

The Fourth Tennessee was ordered from here to Trenton, Ga., for the purpose of picketing the gaps in Lookout Mountain, notably at Johnson’s Crook and other places some twenty miles from Chattanooga and on the extreme left. I suppose they were sent out there from the fact that a good many members of Company H lived at Bridgeport, Ala., and were familiar with the country and railroad track from there to Chattanooga. These same men had been detailed by order of General Bragg, and had given him important information preceding the battle of Chickamauga. They had been highly complimented by General Bragg on their scouts and the information they had given him. On reaching Trenton, Lieut. Col. Paul F. Anderson availed himself of the first opportunity he had had of making his report to brigade headquarters of the action the regiment had taken in the battle of Chickamauga. The same appears in the war records published by the United States government after the war. When Richmond fell the Federals captured many of the records of the Confederate government that were on file at the Capitol. We have copied it verbatim:

Headquarters Fourth Tennessee Cavalry Regiment,

In Field, Trenton, Ga., October 30, 1863.

Capt. W. B. Sayers, Adjutant General Harrison’s Brigade, Wharton’s Division, Wheeler’s Corps.

Sir: The report of the action taken by this regiment in the battle of Chickamauga has been delayed by reason of the fact that immediately after the battle we were ordered to Middle Tennessee with the balance of Wheeler’s Corps and did not return from that most eventful raid until a few days ago. On or about the 10th of September, 1863, we received while at Rome, Ga., marching orders from the commanding general, and reported to him near La Fayette, Ga., where our infantry were being mobilized. A corps of the enemy had crossed the Tennessee River at Bridgeport, Ala., and, crossing Sand Mountain, marched toward Rome. We were sent to the front, and were engaged in daily skirmishing till the battle occurred. On the 15th of September, in conjunction with Gen. Ben Harden Helm’s brigade of infantry, at Tryon Factory, on the Rome Road, we had quite a brush with the enemy, driving them off; also at Catlett’s Gap, Bluebird Gap, McLemore’s Cove, and other places, driving them toward Chattanooga to the right wing of Rosecrans’s army. On Saturday evening, September 19, Wharton’s division of cavalry relieved Gen. John C. Breckenridge’s infantry division at Glass’s Mill, on the south bank of the Chickamauga River. He had had a heavy fight there that evening with General Negley’s Federal division, and still farther to the right there had been heavy fighting. We remained in this position during the night, ascertaining that about the time Breckenridge was moved to the right Negley’s infantry had moved to the Federal left, Gen. George Crook’s cavalry taking Negley’s position at Glass’s Mill. At an early hour on Sunday morning, September 20, the skirmishers from both armies faced each other along the banks of the Chickamauga. About eleven o’clock the enemy planted a battery upon an eminence half a mile distant and commenced vigorously to shell us. At this time the battle to our right was raging with desperate fury along the whole line, and seemed to be a succession of infantry charges upon batteries in chosen position. You would first hear the rapid discharges of the guns, indicating that their position was threatened. Then would come the crash of musketry, as if every tree in the forest had fallen, and, high above all this, the shouts of the Confederates. We could tell unmistakably that we were driving them. It was twelve o’clock in the day, we suppose, when General Wharton ordered the brigade to dismount and take the battery that was shelling us from across the Chickamauga. The brigade consisted of the Eighth and Eleventh Texas, the First Kentucky, and the Fourth Tennessee, Col. Thomas Harrison commanding. The Eighth Texas remained mounted, while the other regiments counted off (No. 4 being directed to hold the horses) and formed line in infantry style. We forded the river at the mill, formed line in the edge of a low beech wood, placed our skirmishers in front, and advanced through the woods. The enemy knew we were coming, and kept shelling the woods. Some of our men were injured by the limbs of trees torn off by cannon balls. We had advanced but a short distance before the skirmishers became hotly engaged, which was the signal for a rapid advance, and we swept through the woods, driving the enemy before us. They rallied at a fence at the outer edge of the woods. After delivering an effective volley at us, they fell back rapidly across a small field to the position of their battery on the hill. As we emerged from the woods, this battery, shotted with grape and the support armed with seven-shooting Spencer rifles, opened upon us. We were commanded to lie down, which we did for a moment, then arose and charged across the field. The battery limbered up and disappeared. We killed many of the enemy as they ran off. About two hundred surrendered in a body. We pursued for some distance till we came in sight of Crawfish Springs, and were the first to reach that place, where we captured an immense host. Besides their killed and wounded, the enemy lost a large number of wagons, hospital attendants, and many shirkers from the fight. When we first came in sight, we supposed that the whole army had surrendered to us, so large was the crowd that met our sight. Our loss was considerable. The line of attack for a mile or more was well defined with the killed and wounded, and where a stand was made they lay thick upon the ground. This was our first experience with the seven-shooting Spencer rifle. We armed two of our companies from the captures. We do not think the enemy’s loss in killed or wounded exceeded our own. However, we captured several hundred prisoners on the field. Among the killed was Capt. J. J. Partin, of Company L. Lieutenants Barbee, Corbett, Preston, Scruggs, and McLean were among the wounded. The regiment’s loss in killed and wounded was forty-five, the details of which from the company officers accompanies this report.

After the capture of Crawfish Springs, we left a guard there. Being ordered to our horses, we mounted and moved rapidly to Lee and Gordon’s Mill, where we crossed the bridge and, charging down the road, captured a long line of prisoners, wagons, ambulances, etc. We bivouacked upon the field of battle Sunday night, and at an early hour on Monday morning the regiment was ordered to report to General Longstreet, which we did. He ordered us forward toward Chattanooga, and all day long we were sending him couriers, telling him that the enemy had retreated into Chattanooga, leaving behind every evidence of a complete rout and defeat. We secured many prisoners and much abandoned property. On Tuesday, September 22, with the balance of Wheeler’s cavalry, we skirmished with the enemy up to the line of the corporate limits of Chattanooga. We captured the signal flag of the enemy on the point of Lookout Mountain. The officer worked his machine until hands were laid upon him. This ended the battle of Chickamauga, and we left the field on Wednesday, the 23d, with the balance of Wheeler’s cavalry on the raid into Middle Tennessee.

Permit me to say that I never found my regiment in better fighting trim. From the highest ranking officer to the humblest private they seemed to vie with each other in the performance of a soldier’s duty. Where all demeaned themselves with such soldierly fidelity it would be invidious to make individual mention, but I must be permitted to mention the following: Surgeon W. T. Delaney, who was often in the thickest of the battle caring for the dead and wounded, and his assistant, Dr. T. A. Allen. Captain Grissim, Quartermaster, and Capt. R. O. McLean, Commissary, both rendered efficient service upon the field and in attending to the wants of the men. I would like to mention acts of individual courage of men and officers, but time forbids. A grateful country will remember them and embalm their names as heroes worthy of honor and distinction.

I am respectfully,

Paul F. Anderson,

Lieutenant Colonel Commanding Fourth Tennessee Cavalry.

George B. Guild,

Adjutant.

The Regiment remained in the vicinity of Trenton, and were not ordered back to the main army till after the battles of Lookout Mountain, Orchard Knob, and Missionary Ridge had been fought, including the battle of Ringgold, which occurred successively from the 23d to the 27th of November, 1863.

Gen. Joe Hooker’s Corps bravely led the assault up Lookout Mountain. They were gallantly resisted by General Walthall’s brave little brigade of less than one thousand Confederates. General Hooker’s men reached the Cravens house, which stands there still, and is, I suppose, three-fourths of the distance from the base and one-half the altitude of the mountain. Some distance from there the palisades of solid rock rise to the summit of the mountain, a distance of several hundred feet, very precipitately. The enemy halted at the Cravens house for the night. The next morning, everything appearing to be so quiet, a call was made for volunteers to go up and view the situation. A captain and twelve men from a Kentucky regiment went up and reported the fact that a citizen had informed them that “they had left the night before.” This ended the “Battle above the Clouds.” Lookout Mountain and Orchard Knob were both outposts of the army on Missionary Ridge, with small commands at each.