| Vol. XX.—No. 981.] | OCTOBER 15, 1898. | [Price One Penny. |

[Transcriber's Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

OLD ENGLISH COTTAGE HOMES.

HOUSEHOLD HINTS.

"OUR HERO."

LESSONS FROM NATURE.

ABOUT PEGGY SAVILLE.

HAWKWEED.

IN THE TWILIGHT SIDE BY SIDE.

QUEENS AS NEEDLEWOMEN.

WHERE SWALLOWS BUILD.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

THE GIRL'S OWN QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS COMPETITION.

ENTHUSIASM: AN ADDRESS TO SCHOOL-GIRLS.

All rights reserved.]

As our papers upon "The Characteristic Church Towers of English Counties" appear to have interested our readers, it is possible they may be willing to peruse these remarks upon the old dwellings, and some other objects which surround country churches.

We fear there can be no doubt that our village architecture has deteriorated, and that the cottage of to-day is scarcely, if ever, as beautiful as that of former times.

Nor is this our only cause for regret, for, unfortunately, our beautiful old village architecture is disappearing so rapidly, that it is to be feared there will be nothing left to convey to the minds of those who come after us any idea of its charm.

When one speaks of "English villages," it is advisable to point out that those small country towns which are erected after the same manner and method are included; that is to say, those which are contained in one single parish, and which possess houses of small scale with rustic adjuncts, gardens, orchards, farm-buildings, etc. There is architecturally no difference between a village and a town of this description. It makes no difference whether the houses are built in rows or are detached. The beautiful village of Ayot St. Lawrence, in Hertfordshire, has houses arranged in rows, and so had Eaton, in Norfolk, before its rebuilding some years back. The notion that country houses should always be detached, or semi-detached, has led to much injudicious arrangement in suburban building estates. If there is land to spare, isolate your houses, but if not, no good end is answered by detaching them so as to leave wretched narrow passages between them, which are always damp, gloomy, and too frequently become{34} receptacles for disused and broken articles, which would be far better put on the fire or given to the dustman. If houses are detached, or semi-detached, there should always be a space twelve or fifteen feet between them (unless, of course, the houses are very low), otherwise the rooms bordering upon the opening are damp and cold.

English country towns differ completely from continental ones chiefly for this reason. On the Continent, towns were nearly always fortified and surrounded by walls, though often their population was that of a mere village. These little fortified places are in Germany called "dwarf cities," to distinguish them from the "dorf," or "village." In England, however, small towns were rarely fortified or walled, except when they were situated upon the sea-coast, where they had to be ready to resist the landing of some foreign enemy. Lyme-Regis, Dorsetshire, is an example of a small English fortified town, and it is quite strange how much the place (of course we refer to the old portions of it) impresses one with its continental aspect, because directly a town is "circumvallated," every building within it has to be erected upon a contracted space, and the houses are consequently developed in height, so that they in no way differ from those of a city; in fact, the small town might, architecturally, be a piece of some large city.

Such English towns as Amersham, Lavenham, Clare, Wheathamstead, etc., are, architecturally, large villages, and probably originated in the same manner—i.e., they were dependencies upon some lordship or monastery.

The English word "village" is derived from the Roman word "villa." The villa was the castle or manorial house of the proprietor of the land surrounded by a series of humble structures inhabited by his labourers and "serfs." This was the "village" or dependency of the villa, and hence its inhabitants were called "villains" (villani). Now we are aware that some modern writers attempt to derive these words from the German "wealh" (a welchman), yet the old and usually received idea seems so obvious that we accept it.

How the meaning of the words "villa" and "villain" have been changed, and yet how singularly the old word "village" has retained its meaning!

The modern stucco, semi-detached "desirable residence," with its four or six rooms, with its "rustic porch" and gritty front garden, is a strange parody upon the stately villa of old, and the good, honest villager is neither a "villain" nor "a Welshman." He may sometimes be the latter, and justly proud of his origin, but, in any case, he is very unlike our conception of a villain. If recent newspaper reports can be trusted, that character is rather personified by the London "loafer" and his most modern representative "the Hooligan."

When the villages increased in size and became important, usually in the 13th century, many of them claimed municipal privileges, were called towns, and erected "town halls," which are often highly-picturesque structures. That at Ledbury, Herefordshire, is an interesting example which probably dates from the 16th century. They are generally supported upon pillars so as to leave the ground-floor an open, covered space which served as a market.

Very charming are these villages and small country towns with their quaint old cottages and picturesque little houses bordering the wide street. Great elms shade the foot-path, and sweet gardens are at the side or back of each dwelling. Perhaps a clear river winds its way amidst the ruddy buildings, its banks converted into diminutive kitchen-gardens, and crossed here and there by bridges. The long low building of a water-mill seems to block the way altogether, but in reality it simply utilises the water to turn its wheels, and we shall find the river on the opposite side with its waters banked up some six or eight feet higher, changed in character, looking more still and deep, reflecting the surrounding objects in a still, silent pool, shaded by lofty trees, its banks clothed with deep grass plantains, huge docks and marsh mallows, a spot where, on a sunny day, an irresistible inclination seizes one to lie down on the cool earth. The clinging foliage seems to second the invitation, and one throws oneself down upon this sweet verdant couch to "dream with one's eyes open," for who could close them in such an enchanting spot? But somehow or other, whether it is the "whirr" of the water-wheel, the fragrant scents of the plants we are crushing, or the peace surrounding one, time seems to glide away, and, upon consulting our watch, we discover the mysterious fact that the day has become two hours shorter! Of course we have not been to sleep!

Such village scenes and sensations are to be witnessed at Amersham, Cringleford, and many other spots in England which have still retained their old village surroundings.

(To be continued.)

A good black straw hat and bonnet, changed at the seasons with suitable blossoms, is the most economical and ladylike fashion, but the artificial flowers should be very good of their kind—those with silk or velvet petals look the best and most natural, and can be used a second season if carefully brushed and put away.

Those who have to wear spectacles and eyeglasses should be very careful that the centre of the glass is exactly opposite the centre of the eye. If not, they should be altered to make them so.

If hair is washed with soap it is apt to make it brittle, so it should be afterwards rinsed with a little borax in water.

A little ammonia in the water in which china is washed makes it glossier and nicer in appearance.

A dress well made and of good material outlives several that are not, and gives more satisfaction to the wearer, but it should be carefully chosen as to colour, and not be too aggressive in pattern or tint.

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "The Girl at the Dower House," etc.

IN THE YEAR 1803.

"A letter from Paris! Grandmamma, a letter from Paris!" cried Molly, as she rushed into the dining-room of Mrs. Fairbank's Bath house, situated not far from the renowned Pump-room. "Look! And it will be about Roy! And it is in my papa's handwriting."

Polly followed close in rear of the eager child, hardly less eager herself. She might at least hope for a message from Denham, perhaps to say that a letter was coming.

Mrs. Fairbank, a comely elderly lady—in these days, with the same weight of years, she would be no more than cheerfully middle-aged—adjusted her horn spectacles, laid the letter on her knee, tied her loosened cap-strings, and scrutinised Molly's excited face.

"You make too much of things, child," she remarked. "Whatever may befall, it is never worth while to discompose yourself."

Then she lifted the letter, examined it, weighed it in either hand, laid it down anew, and resumed her knitting. Molly's agony of suspense and Polly's wistful eyes alike failed to touch her. Young folks, if well brought up, were expected to submit without question to the will of their elders, and Mrs. Fairbank had always been an excellent disciplinarian. This was, in her eyes, much too good an opportunity for a lesson in self-control to be neglected.

Molly stood, squeezing her hands together, wondering if the slow moments would ever pass. Mrs. Fairbank serenely knitted, stopped to count, and knitted again.

"I met Mrs. Peirce and Will in Milsom Street after breakfast," she observed. "Mrs. Peirce informed me that the Admiral had a letter yestere'en from his nephew, Mr. Albert Peirce."

Mrs. Fairbank's eyes wandered round the room in quest of something else to remark upon.

"My dear Polly, you must surely have forgot! That piece of knitting which was to have been done to-day——"

"I'll set to work upon it, ma'am. It won't take me but a very short time. O Jack!"—and a note of relief could be heard.

"Jack!" gasped Molly, under her breath.

"My dear Jack!" and Mrs. Fairbank suspended her knitting to glance up in pleased surprise.

The young man who walked in—he was hardly more than a boy in years—bore small resemblance to Polly, though he was her brother. He was of squarer build, slightly under medium height, and muscular in make; his features were irregular, and the eyes were light blue instead of brown. Beyond those good-humoured blue eyes and a fresh complexion, Jack Keene had no pretensions to good looks; but many people, beside his grandmother, counted him a very pleasant young fellow. Mrs. Fairbank, after the manner of old ladies, simply doted on her grandson. In her view he could almost do no wrong.

"Jack, Jack, there's a letter," whispered Molly, clutching at him. "And, oh! she won't open it. She won't tell us how they are!"

"All right," murmured Jack. He understood Molly's whisper and the look in Polly's face; and as he kissed his grandmother he took up the letter which reposed upon her knee. No human being except Jack might have ventured on such a liberty, but he was a privileged being. "Ah, from France!" quoth Jack, with composure. "Will you allow me to open it, ma'am? You are busy, and news of any sort or kind from France in these days is to be welcomed."

Mrs. Fairbank took the letter from him with as near an approach to displeasure in her manner as she ever showed towards Jack.

"You are pleased to be impatient," she remarked, with a sound of reproof.

"Exceedingly, ma'am." Jack was always extra polite when bent upon his own way.

Mrs. Fairbank examined the foreign missive afresh, studied the stamp, and at length broke the seal, taking out a tiny enclosure, which was addressed to Molly.

"From Roy," she said. "I think"—and there was a dubious pause—"I think I may permit you to read this to yourself, child. Doubtless your mamma has already seen it."

Molly fled to the window-seat, curled herself up there, and plunged into the delights of Roy's epistle, seeing and hearing nothing else. Mrs. Fairbank's face of growing concern failed to reach her perceptions, and a murmured consultation which took place might have gone on in China for all the impression that it made upon Molly. Roy's prim round handwriting spoke to her as follows:—

"My dear Molly,—We got here yesterday all right, and it pours with rain to-day, so I am going to write to you. It is great fun being abroad, and all the children jabber away in French lingo, and don't know one word of English. I tried to speak to one man in French, but he didn't know what I meant any better than when I talked English, so I think they must be rather stupid, don't you?

"We had such a voyage. It took ten whole hours getting from Dover to Calais, and I was dreadfully ill, and I haven't got right yet. My back aches like anything, but I don't mean to make a fuss, because that wouldn't be like a soldier.

"We had to stop a night in Calais; they do fidget so about papers and things, there was no getting on sooner. And then we had a chaise de poste, with three horses side by side, and the horses were harnessed with ropes, not like our English harness. The ropes broke twice, and the postillions jumped off, just like monkeys, to put things right. They didn't seem to mind the ropes breaking one bit, and Den says he supposes they are used to it. But we hadn't got used to it.

"We slept one night at Montreuil, and another at Amiens, and then we got to Chantilly. And the roads were most horribly bad, and so they are here in Paris, and when it rains hard, like to-day, the streets are flooded, and it smells so, and nobody can walk along without wading, at least in some parts.

"We saw such a lot of ruined houses on our way to Paris, called chateaux. They used to be so pretty, Den says, and people lived in them, ladies and gentlemen, just as they do in country houses in England. And then they had their heads cut off in the Revolution, and the chateaux were left to go to wrack and ruin. I heard a lady say so yesterday. She is English, and she said it was very horrid, such a lot of people being killed, only just because they belonged to the nobility. Some of the chateaux that we saw had only poor people in them, and the windows were broken and the roofs were gone from the summer-houses, and the gardens were all wild and untidy. It is thirteen or fourteen years since the Revolution began, and when I get home I mean to read about it all with you.

"I do wish you were here too, for there are heaps of things that I want to tell you. Everything is so different from England. It is nice to see, but I don't want to live in France. I like old England much much the best.

"I have not been out to-day yet. Mamma thinks I have caught a bad cold. I wish people didn't take colds; they are such stupid silly things. Perhaps I shall be all right to-morrow, and then Den will take me all about everywhere. O dear me, I don't think I can write any more; I feel so sea-sick and funny. And Papa says——"

There was no ending to the letter, and Molly read it through a second time. Then she hugged and kissed it tenderly, and at length carried it across to the others.

"Roy has forgot to sign his name," she said. "I suppose he went out to see the sights, and did not remember. My mamma thinks he has caught a cold."

"Roy is far from well, my dear," Mrs. Fairbank observed solemnly. "He was taken ill with a most unexpected disorder while writing to you, and could not conclude. It is truly unfortunate."

"Roy—ill!"

"'Tis not good manners to repeat other people's words, Molly. Yes; Roy has the small-pox. Doubtless he took it into his constitution before ever he left England. He must have caught the infection from one of his school-fellows."

Polly wound her kind arms round the image of childish woe.

"But numbers and numbers of people have the small-pox, Molly," she said. "'Tis truly but a few who altogether escape, you know. And many get over the complaint. Doubtless Roy will soon be well again—in a few weeks." This was lame comfort, but what better could Polly say, in those days of the awful unchecked scourge.

"Will his face be all marked?" sadly asked Molly, thinking of the innumerable seamed and disfigured faces which she knew. "Will he become like to Mr. Bryce?"

"Oh, I hope not, indeed. All who have it are not scarred. Captain Ivor is not, yet he has had it." Polly's lips trembled, and she set them firmly. "Think, Molly, is not Captain Ivor a dear brave man? He has taken Roy into another house, and he will not let your father or mother go near to Roy, or anyone that has not had the disorder. They never have, as you know. And they were never inoculated, so they might catch it. And he is nursing Roy himself. The people in the hotel would not keep Roy, so soon as they knew that he had the small-pox, but a room has been found, and Captain Ivor is there with him. And they hope it will not be a severe attack. So in a little while I do think we shall hear that he is better."

Molly was hard to comfort, and what wonder? Polly would have liked to keep the ill news from her for some days, till perhaps better accounts should arrive, but Mrs. Fairbank viewed the matter differently. "Worse news might come, instead of better," she said.

No doubt that was true. Still, Molly might have been spared many weary days of suspense. All her spirit went out of her, and she seemed to care for nothing, except clinging to Polly and being told over and over again that Roy would probably soon be well. Letters then were not, as now, an everyday affair. Posts were slow and uncertain, and postage was expensive, and people thought twice before putting pen to paper. Roy's father promised to write again speedily, yet he waited till there should be something definite to tell.

So day passed after day, and no further tidings arrived. The suspense was almost as hard for Polly as for Molly; harder, perhaps, in some respects, only as Ivor had had the disease, and had nursed a friend through it two years earlier without being affected, he might be counted personally safe. Nursing in those days was not a science; trained nurses were unknown; and Roy could hardly have been in better hands than those of the young Grenadier officer. But Polly knew that his stay in Paris was likely to be much lengthened. Weeks might pass before Roy would be well enough to travel, and before it would be safe for either of them to go freely among other people. Ideas as to the nature and extent of infection were vague, but small-pox was the terror of everybody, and while there was little system in avoidance of the danger, there was any amount of scare.

In all probability Denham would spend the whole of his leave in attendance upon the boy, and when he returned he would have no time to spare for Bath. Polly would have no chance of showing off her tall Grenadier among friends and acquaintances. At present her fears extended no further.

Meanwhile public events marched on with strides, and that month of May, 1803, was astir with events. The maintenance of peace between England and France became daily more and more precarious. The feverish ambition of Napoleon could know no rest, so long as he was fearlessly confronted by a single nation in Europe.

One chief bone of contention was Malta. Napoleon had set his heart upon getting Malta for himself, and England was equally bent on keeping him out of Malta. By the treaty of the preceding year, England had undertaken to evacuate the island, and to restore it to the knights of St. John. But the withdrawal of English troops had been of necessity delayed, until some means could be devised to save it from the grip of Buonaparte; and the First Consul, by deliberately breaking some of his own undertakings in the treaty, set England free as to her undertakings also. Therefore Malta still remained in the hands of England, as did Egypt and the Cape of Good Hope, each a source of jealous longing on the part of the First Consul.

This state of tension steadily increased, until the breaking out of war became merely a question of days. Large numbers of English had seized the rare opportunity of a year free from fighting to travel in France; and at this time there were something like eight or ten thousand English, mainly of the upper classes, in that country.

It was unknown to them that, pending negotiations, the First Consul caused careful returns to be sent to himself of the names and addresses of all English people then within French borders. This bears a suspicious look, when read in the light of his after act, and possibly he already had in his mind the step which was soon to scandalise all Christendom. The French papers heartily assured English travellers of their absolute safety, even supposing that war should break out, and doubtless the editors of those papers meant what they said. Few men, if any, French or English, could have foreseen what was coming.

A homeward stampede took place, and the thousands were, by some accounts, rapidly reduced to hundreds. A good many lingered, however, not all detained, as were the Barons, by illness. War-clouds might threaten, but that private travellers should be affected by a declaration of war was a thing unheard of.

In May, suddenly at the last, though the step had been expected, the English Ambassador was recalled from Paris, and immediately the French Ambassador was recalled from London. Meanwhile, as a second step, the English Government, issuing letters of marque, seized a number of French vessels, which happened then to be lying in English ports. This, it was said, actually took place before the Declaration of War could reach Paris. If so, even though the deed was within English rights, being sanctioned by previous centuries of custom, one must regret its extreme haste. But no excuse can be found for Napoleon's illegal and cruel act of reprisal, which indeed appeared to have been planned beforehand.

Like a thundercrash came the order, before the close of May, arresting all peaceable English travellers or residents in France, and rendering them "Prisoners of War," or "Détenus," to be confined in France during the pleasure of the First Consul.

Here is the shortened form of that direful order, as it was printed in English newspapers, spreading dismay through hundreds of English homes, and awakening a burst of anger against the man who had dealt the blow.

"The Government of the Republic, having heard read by the Minister of Marines and Colonies a despatch from the Marine Prefect at Brest, dated this day, announcing that two English frigates had taken two French merchant vessels in the Bay of Audierne, without any previous declaration of war, and in manifest violation of the laws of nations;

"First: It is prescribed to all commanders of squadrons or naval divisions of the Republic, captains of its ships and other vessels of war, to chase those of the King of England, as well as those vessels belonging to his subjects, and to attack, capture, and conduct them into the ports of the Republic;

"Secondly: Commissions will be delivered in course to those French privateers for which they are demanded;

"Thirdly: All the English, from the age of eighteen to sixty, or holding any commission from His Britannic Majesty, who are at present in France, shall immediately be constituted Prisoners of War, to answer for those citizens of the Republic who may have been arrested and made prisoners by the vessels or subjects of His Britannic Majesty, previous to any declaration of war.

"The First Consul,

"(Signed) Buonaparte."

(To be continued.)

By JEAN A. OWEN, Author of "Forest, Field and Fell," etc.

INTRODUCTORY.

Christ, the divine teacher, has taught us to go to nature for moral and spiritual lessons. "Consider the lilies of the field," He says to those who are anxious about, and careworn with the things of this life: and that old triangle of a problem with its hard points: "What shall we eat? what shall we drink? and wherewithal shall we be clothed?" does press heavily on many even of those who read our Girl's Own Paper. The fall of the sparrow, too, He tells us, is noted by His Father and ours. He bids those who are neglectful of the talents given to them, learn a lesson of the barren fig-tree. Again the rapid and marvellous development of the mustard-tree, in the mouth of the great teacher, becomes an image of the faith that He bids us have. And even when speaking of the yearning love He had for souls, He did not disdain to use the simile: "As a hen gathereth her young." And so, if the eyes are quick to note all that surrounds us, all the wonderful life, "the infinitely small" as well as "the infinitely great," and the heart makes room for love, it will be possible to learn, from the first year of our lives, until the day of our death here, lessons from nature which no man or woman has ever yet exhausted, nor ever will.

One of my earliest memories is of an old-world garden where our mother, who was an ardent lover of the beautiful, would direct the attention of my sisters and myself to the pencilling on the petal of this and that flower. God's finger painted the velvety face of the pansy, she told us. And how often I pondered over this expression and wondered if that finger did its work in the garden when we were asleep.

Our dear mother gave us a love for nature which has been our resource and consolation in many a sorrow, and which has filled the void of what would otherwise have been weary, monotonous hours.

Ruskin said, "Despise the earth or slander it, fix your eyes on its gloom and forget its loveliness, and we do not thank you for your languid or despairing perception of brightness in Heaven. But rise up actively on the earth, learn what there is in it, and when, after that, you say 'Heaven is bright,' it will be a precious truth." Lord Bacon spoke fitly of the "respondences of nature," and he with many other great minds has dwelt on the marvellous analogies of nature. These analogies are indeed evidences of the unity of creation. And there are prefigurations which we may note in the animal kingdom, in the various habits of the creatures, their works, economies and instincts. Human art is prefigured in the work of the bee, the wasp, and the beaver. Democritus averred that men learned weaving from spiders and architecture from birds. Virgil said that the bees had in them a portion of the divine mind.

The Psalmist likened a good man to a tree planted by a river; Wordsworth writes constantly in a strain which bears witness to his belief that between man and the flowers of the field there is the closest affinity; in quaint George Herbert's poems we note also the same teaching. Look them up, if you do not remember them, especially that dear one called "The Flower."

How many great men have been influenced in their careers, careers which have been great factors in the world's growth, by the sight of what to many an unobservant or unthinking mind would seem too insignificant an object for notice.

There was the great traveller and explorer, Mungo Park, who was employed by the so-called African association to explore the interior regions of Africa. Once, weary, disappointed, and baffled, he was on the point of giving way to despair, when he suddenly came on a little plant the sight of which, and the thoughts which its beauty suggested, revived his courage and probably saved his life.

Most of you will remember also that beautiful story of Picciola, the prison flower, the seed of which had fallen on the paved yard of a prison where a noble Italian was confined. When he was in the lowest state of despondency, and in danger perhaps of madness, the tiny plant awakened interest, and daily delighted the poor prisoner as its beauties unfolded, opening a little world of interest to the starved heart and mind. When at last he was set at liberty he caused his wall-flower to be transplanted and placed it in a border, in a place of honour in his castle grounds. It had been made the instrument of his salvation.

Some persons talk of things being insignificant or too small to notice. Perhaps it will surprise some of our readers to hear that a common house-fly is said to occupy the middle place in creation as regards the size of known creatures. Most people can see big things, but the gift of seeing tiny objects belongs rather to the few, and yet it may be cultivated, and great enjoyment may be found in observing things which seem to common minds to be unworthy of note—the simple, homely, and smaller life that surrounds us. Mr. Leo Grindon, a great student of life and a noted botanist, says very truly—

"To learn how to see and delight in little things, as well as in large, is, in fact, to make no slight progress both in true intelligence and in aptitude for genuine pleasure. Many laugh at the idea of being pleased with little things, which, they say, 'please little minds.' They should remember that the great mass of the population of our planet consists of the merest pigmies, diminutive birds and fishes, tiny insects, animalcules, only visible through a microscope, so that to turn away from little things is to be indifferent to almost everything the world contains. Besides, with Uranus eighty times greater than the whole earth, Neptune a hundred and fifty times greater, Saturn more than seven hundred times, and Jupiter more than fourteen hundred, it is rather inconsistent to talk about littleness in the objects of a world itself (comparatively) so puny."

"Our spring is in our lightsome girlish days."

Spring is the season of growth. Let us try to promote a healthy mental growth by studying together in the wonderful book of nature and appropriating some of those helpful lessons which she has to teach us.

The wise man, in the Book of Proverbs, speaks of the ant as one of "four things which are little upon the earth," and yet are "exceeding wise." He says that the ants are "a people not strong, yet they prepare their meat in the summer." That is, when all in nature is at its richest, when food abounds, they use forethought and gather in enough to sustain themselves before the winter draws near, and the usual food supplies have failed.

The Book of Job, that Eastern drama which is so wonderful in its lessons suited to human experiences in all time, is marvellously comprehensive in its illustrations drawn from the natural world. We are taken there into the regions of ice and snow, and again we pass through the rich verdure of the tropics. We try to sound the frozen deeps, and anon survey the hot desert plains; we wander where the lion seeks his prey, and through dense forests where behemoth, or the elephant, feeds. The coral and the pearls are there, so are the gold ore, the iron, and the brass. The Author shows us the ostrich "that scorneth the horse and its rider, the hawk that stretched her wings towards the south like our peregrine, the wander falke"—the eagle that makes her nest on high yet "is with the slain on the earth beneath." And this great observer says, "Ask now the beasts and they shall teach thee, and the fowls and they shall tell thee, or speak to the earth and it shall teach thee, and the fishes of the sea shall declare unto thee."

The lessons to be learned from the ant are, of course, diligence and a careful or prudent forethought for the future. Solomon says that the ant "has no guide, overseer, or ruler," yet she provides, having gathered in during the summer and the harvest time. How many of us there are who seem to need tutors and governors to urge us on through the duties of life, not only in childhood, but far on into man and womanhood. Compulsory pressure from without alone rouses some of us to action. Man thinks himself the lord of creation, and is yet far outdone by a weak insect, not only in energy and persistent work, but often positively in intelligence.

Perhaps you have, many of you, read of the so-called warrior ants, the Termites bellicosi of the more tropical regions. They do not belong to the same order of insects as our own ants, and we are happily not subjected to the havoc which their building and devouring works. Two species of termites have, however, got established in France, notably in Rochefort, La Rochelle, and Aix, and there they have undermined and utterly ruined a number of houses. In one town they gnawed away the supports of a dining-room before their ravages were detected, and the floor gave way during a party, the host and his guests suddenly falling through together.

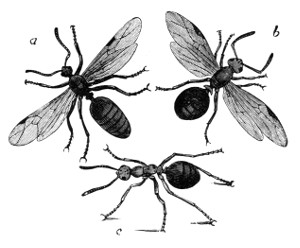

Artillery charged with grapeshot has been employed to destroy great fortresses that these ants have made in a tropical country. In South Africa the termites work enormous havoc. They live in a social republic of their own. Some of them, the males, have wings; the workmen, the soldiers, and the queens however have none. The workmen construct their buildings, the soldiers defend the colony and keep order, and the females, or queens, are worshipped by all the others. These become in point of fact mere egg-laying machines, which have at last to remain tied to one spot.

Twenty feet high their nesting-homes often are, and pyramidal in shape. Wild cattle can climb upon them with impunity without crushing them, the walls are so solid. A dozen men can find shelter in some of their chambers, and native hunters do often lie in wait inside them when out after wild animals. They construct galleries also which are as wide as the bore of a large cannon, and which run three and four feet underground. The nests are said to be five hundred times as high as the ant's body, and it has been estimated that if we built our houses as high, proportionately, they would be four or five times as high as the pyramids of Egypt, on which we look with such wonder and awe.

In speaking of the havoc some ants make, let us also remember some good service rendered. In the West Indies there is a red cockroach which is four times as large as the English one. It smells horridly, and scents everything that it touches, is far more destructive than the ant, and quite omnivorous. Now, although one cockroach in bulk outweighs two hundred ants, the latter little creatures kill and devour innumerable cockroaches. Whenever an ant comes upon a cockroach that is at rest, eating, or in its hole, suddenly myriads appear, swarm round it, as if by magic, surround it completely, and then, with one consent, rush all over it, and as it is dragged away, you see only a mass of ants moving along. All the time they carry they are busily devouring it, until only its shell is left.

We read also that in forests in Switzerland and Sweden the ants form lofty hillocks which serve as a compass to travellers who have lost their way by night or in a fog. The nests being always made from east to west, their peak is at the east end, which is steep, the ridge sloping, however, gently down to the nest. So the wanderer can tell from these ant-hills in which direction he ought to go.

Tamerlane, the great Tartar prince, learned a helpful lesson from an ant once, when he had taken refuge from the pursuing enemy in a ruined building. Having to stay there for hours, at the end of his resources, ready to give way to despair, his attention was attracted by an ant which was carrying something larger than itself up a high wall. Noticing that it often let its burden drop, he began to count the number of times that it began the ascent again, and he found that sixty-nine times it failed, its burden falling to the ground. The seventieth time was a success. "This sight," he said, "gave me courage at the moment, and I have never forgotten the lesson it taught me."

Our own ants afford a marvellous study for those who can and will give a little time to—as Solomon says—the considering of their ways. Ants are said to stand higher than any other insects in intelligence—so-called instinct. And insects in general have more of this faculty developed in them than have any other creatures. They are watchful, unwearying nurses; they take the eggs out on fine warm days so as to warm and strengthen the coming ants, and they will wait, to be cut in bits, rather than forsake their charge. When the eggs are hatched, the nurses clean and brush their young, and even shampoo the thin skin which cover their limbs, so that they can go free. Each grown ant knows its own business and can, when necessary, fight its own battles, and yet there is always a community; they have all things in common and work for the general good. They are enduring, persevering, faithful in friendships, and most industrious. One writer has said, in describing an ant-hill, that whilst there was a twittering of birds, and a buzz and hum of insect life around, the ants were all silent, only "the sort of low hiss which arose from the collected workers, resembled the noise of a London street more than any form of speech."

Their power of self-sacrifice is a marvellous fact. A man once saw a line of ants, on travel, trying to pass a little rapid stream. They hooked themselves on to each other so as to form a chain which was carried in a slanting direction by the current to the opposite shore. Many of this chain were drowned, dropping off in the forming process; those in front were often baffled and overwhelmed in the rushing current. At last the bridge was completed and the main body of the army of ants marched across the stream in safety upon the massed bodies of their self-sacrificing companions.

Milton has written of "the parsimonious emmet, provident of the future...." "In small room, large heart enclosed." A writer has stated that a son of Mr. Darwin dissected the head and brain of an ant, which latter the great scientist declared to be "one of the most marvellous atoms of matter in the world," more marvellous even than the brain of man. Speaking of the brain of ants, Sir John Lubbock says, "The head bears the principal organs of sense, and contains the brain, as the anterior portion of the nervous system may fairly be called."

Forethought is at the root of all thrift, and thrift underlies all civilisation as well as personal well-being. We seem at times, some of us, rather to despise a saving disposition, as if this necessarily implied meanness in its subject. Yet the greatest benefactors of our race have been nearly all great savers at some period of their lives. And there is little true generosity in the soul of the woman who spends all she gets, even if her means go largely to others, if, through failing to lay by something for a rainy day, during the winter of life she is thrown on the charity of her fellows for her support. As someone says, nothing should be left at loose ends. It is only the few who become rich through large undertakings, the majority of mankind prosper by means of carefulness and the practice of the details of thrift. "Thrift is the best means of thriving."

Let us end this little study by reminding ourselves of that thoughtful dictum of Ruskin's, "Economy, whether public or private, means the wise management of labour ... first applying your labour rationally; secondly, preserving its produce carefully; lastly, distributing its produce seasonably."

(To be continued.)

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of "A Girl in Springtime," "Sisters Three," etc.

The school-room was a long, bare apartment running along one side of the house, and boasting three tall windows, through which the sun poured in on a shabby carpet and ink-stained tables. Everything looked well worn and, to a certain extent, dilapidated, yet there was an air of cheerful comfort about the whole which is not often found in rooms of the kind. Mrs. Asplin revelled in beautiful colours, and would tolerate no drab and saffron papers in her house; so the walls were covered with a rich soft blue; the cushions on the wicker chairs rang the changes from rose to yellow. A brilliant Japanese screen stood in one corner, and a wire stand before the open grate held a number of flowering plants. A young fellow of seventeen or eighteen was seated at one end of the table employed in arranging a selection of foreign stamps. This was Maxwell, the Vicar's eldest surviving son, who was to go up to Oxford at the beginning of the year, and was at present reading under his father's supervision. His sister Mellicent, was perched on the table itself, watching his movements, and vouchsafing scraps of advice. Her suggestions were received with sniffs of scornful superiority, but Mellicent prattled on unperturbed, being a plump, placid person, with flaxen hair, blue eyes, and somewhat obtuse sensibilities. The elder girl was sitting reading by the window, leaning her head on her hand, and showing a long, thin face, comically like her father's, with the same deep, straight lines running down her cheeks. She was neither so pretty nor so even-tempered as her sister, but she had twice the character, and was a young person who made her individuality felt in the house, while Maxwell was the beauty of the family, with his mother's crisp, dark locks, grey eyes, and rich brunette colouring.

These three young people were the Vicar's only surviving children, but there were two more occupants of the room, the two lads who were being coached to enter the University at the same time as his own son. Number one was a fair, dandified-looking youth, who sat astride a cane deck chair, with his trousers hitched up so as to display long, narrow feet, shod in scarlet silk socks and patent leather slippers. He had fair hair, curling over his forehead; large, bold, blue eyes, an aquiline nose, and an air of being very well satisfied with the world in general and himself in{39} particular. This was Oswald Elliston, the son of a country squire, who had heard of the successes of Mr. Asplin's pupils, and was storing up disappointment for himself in expecting similar exploits from his own handsome, but by no means over-brilliant son. The second pupil had a small microscope in his hand, and was pouring over a collection of "specimens," with his shoulders hitched up to his ears, in a position the reverse of elegant. Every now and then he would bend his head to write down a few notes on the paper beside him, showing a square-chinned face, with heavy eyebrows and strong, roughly-marked features. His clothes were well-worn, his cuffs invisible, and his hair ruffled into wild confusion by the unconscious rubbings of his hands, and this was the Honourable Robert Darcy, third son of Lord Darcy, a member of the Cabinet, and a politician of world-wide fame.

The servants at the vicarage were fond of remarking, apropos of the Honourable Robert, that he "didn't look it," which remark would have been a subject of sincere gratification to the lad himself had it been overheard, for there was no surer way of annoying him than by referring to his position, or giving him the prefix to which he was entitled.

The young folks looked up inquiringly as Mr. and Mrs. Asplin entered the room, for the hour after tea was set apart for recreation, and the elders were usually only too glad to remain in their own quiet little sanctum. Oswald, the gallant, sprang to his feet and brought forward a chair for Mrs. Asplin, but she waved him aside, and broke impetuously into words.

"Children! we have news for you. You are going to have a new companion. Father has had a letter this afternoon about another pupil——"

Mellicent yawned, and Esther looked calmly uninterested, but the three lads were full of interest. Their faces turned towards the Vicar with expressions of eager curiosity.

"A new fellow! This term! From what school, sir?"

"A ladies' boarding-school at Brighton!" Mrs. Asplin spoke rapidly, so as to be beforehand with her husband, and her eyes danced with mischievous enjoyment as she saw the dismay depicted on the three watching faces. A ladies' school! Maxwell, Oswald, and Robert had a vision of a pampered pet in curls, and round jacket, and their backs stiffened in horrified indignation at the idea that grown men of seventeen and eighteen should be expected to associate with a "kid" from a ladies' school!

The Vicar could not restrain a smile, but he hastened to correct the mistake. "It's not a 'fellow' at all, this time. It's a girl! We have had a letter from Arthur Saville's mother asking us to look after her daughter while she is in India. She will come to us very soon and stay, I suppose, for three or four years, sharing your lessons, my dears, and studying with you——"

"A girl! Good gracious! Where will she sleep?" cried Mellicent, with characteristic, matter-of-fact curiosity, while Esther chimed in with further eager inquiries.

"What is her name? How old is she? What is she like? When will she come? Why is she leaving school?"

"Not very happy. Peggy. In the little box room over the study. About fifteen, I believe. Haven't the least idea. In a few weeks from now," said Mrs. Asplin, answering all the questions at once in her impulsive fashion, while she walked round the table, stroked Maxwell's dark curls, bent an interested glance at Robert's collection, and laid a hand on Esther's back to straighten bowed shoulders. "She is Arthur's sister, so she is sure to be nice, and both her parents will be in India, so you must all be kind to the poor little soul, and give her a hearty welcome."

Silence! Nobody had a word to say in response to this remark, but the eyes of the young people met furtively across the table, and Mr. Asplin felt that they were only waiting until their seniors should withdraw, before bursting into eager conversation.

"Better leave them to have it out by themselves," he whispered significantly to his wife, then added aloud, "Well, we won't interrupt you any longer. Don't turn the play-hour into work, Rob! You will study all the better for a little relaxation. You have proved the truth of that axiom, Oswald—eh?" and he went laughing out of the room, while Oswald held the door open for his wife, smiling assent in his lazy fashion.

"Another girl!" he exclaimed, as he reseated himself on his chair, and looked with satisfaction at his well-shod feet. "This is an unexpected blow! A sister of the redoubtable Saville! From all I have heard of him I should imagine a female edition would be rather a terror in a quiet household. I never saw Saville; what sort of a fellow was he to look at, don't you know?"

Millicent reflected.

"He had a nose," she said solemnly. Then, as the others burst into hilarious laughter, "Oh, it's no use shrieking at me; I mean what I say," she insisted. "A big nose—like Wellington's. When people are very clever they always have big noses. I imagine Peggy small, with a little, thin face, because she was born in India, and lived there until she was six years old, and a great big nose in the middle."

"Sounds appetising," said Maxwell shortly. "I don't! I imagine Peggy like her mother, with blue eyes and brown hair. Mrs. Saville is awfully pretty. I have seen her often, and if her daughter is like her——"

"I don't care in the least how she looks," said Esther, severely. "It's her character that matters. Indian children are generally spoiled, and if she has been to a boarding-school she may give herself airs. Then we shall quarrel. I am not going to be patronised by a girl of fourteen. I expect she will be Mellicent's friend, not mine."

"I wonder what sums she is in," said Mellicent, dreamily. "Rob! what do you think about it? Are you glad or sorry? You haven't said anything yet."

Robert raised his eyes from his microscope, and looked her up and down very much as a big Newfoundland dog looks at the terrier which disturbs its slumber.

"It's nothing to me," he said loftily. "She may come if she likes." Then, with sudden recollection, "Does she learn the violin? Because we have one girl in this house who is learning the violin, and life won't be worth living if there is a second."

He tucked his big note-book under his chin as he spoke, and began sawing across it with a pencil, wagging his head and rolling his eyes in imitation of Mellicent's own manner of practising, and producing at the same time such long-drawn, cat-like wails from between his closed lips as made the listeners shriek with laughter. Mellicent, however, felt bound to expostulate.

"It's not the tune at all," she said loudly. "Not like any of my pieces; and if I do roll my eyes, I don't tumble up my hair and pull faces at the ceiling, as some people do, and I know who they are, but I am too polite to say so. I hope Peggy will be my friend, because then there will be two of us, and you won't dare to tease me any more. When Arthur was here, a boy pulled my hair, and he carried him upstairs and held his head underneath the shower-bath."

"I'll pull it again, and see if Peggy will do the same," said Rob pleasantly; and poor Mellicent stared from one smiling face to another, conscious that she was being laughed at, but unable to see the point of the joke.

"When Peggy comes," she said, in an injured tone, "I hope she will be sympathetic. I'm the youngest, and I think you ought all to do what I want, instead of which you make fun, and laugh among yourselves, and send me all the messages. For instance, when Max wanted his stamps brought down——"

Maxwell passed his big hand over her hair and face, and reversing the direction, rubbed up the point of the little snub nose.

"Never mind, chubby, your day is over! We will make Peggy the message-boy now. Peggy will be a nice, meek little girl, who will like to run messages for her betters. She shall be my fag, and attend to me. I'll give her my stamps to sort."

"I rather thought of having her for fag myself; we can't admit a girl to our study unless she makes herself useful," said Oswald languidly; whereupon Rob banged the note-book on the table with clanging decision.

"Peggy belongs to me," he announced firmly. "It's no use you two fellows quarrelling. That matter is settled once for all. Peggy will be my fag; I've barleyed her for myself, and you have nothing to say in the matter."

But Esther tossed her head with an air of superior wisdom.

"Wait till she comes," she said sagely. "If Peggy is anything like her brother, you may spare yourself the trouble of planning as to what she must or must not do. It is waste of time. Peggy will be mistress over us all."

(To be continued.)

By LIZZIE DEAS.

Third Series.

By RUTH LAMB.

THE PRECIOUSNESS OF TIME.

"So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom" (Psalm xc. 12).

Once more you, my dear girl friends, and I meet to hold pleasant converse with each other.

I feel that something specially pleasant would be missing from my own life were our twilight talks to cease. It is with a sense alike of happiness and thankfulness that I look forward to your companionship for yet another year. God grant that, as in the past, so in the future, we may be very helpful to each other in crossing the rough places that have to be encountered on the path of life.

I feel that a song of thanksgiving should go up from us all for mercies already bestowed, and an earnest united prayer to God for an ever-increasing blessing upon our meetings.

One thought must come to us all this evening. Two years have passed since we first came together, hence we feel that so much of our lives has gone, and we have two years less in which to work for God.

It will be good for each of us to ask ourselves, "What have I done for Him during the time? What progress have I made in my spiritual life? Have I grown, as Jesus grew, 'in favour with God and man' during these years?"

Conscience will answer and can tell only the truth.

Such communings with your own hearts are, however, for the quiet of your own chamber, when you have shut out the world and are alone with God. Still, it may be well for us all to have a talk about the preciousness of some things of which we are too apt to take little account.

I wonder if you and I are in the habit of frittering away two invaluable gifts for which we have to give a strict account to our Father in heaven. These are, time and opportunity.

I think I hear you ask, "What do you mean by frittering? The dictionary tells us that 'to fritter' is to diminish or pare off."

I acknowledge that here we do not get quite the full meaning of the word "fritter" as we often use it in conversation. We rather understand by it the diminution of something by almost imperceptible degrees, of which no notice need be taken, because they are so small, and through the waste of which little loss is sustained by ourselves or others.

There are things in this world which are of small value in certain places, because they are so abundant; yet, in another neighbourhood, their scarcity makes them of vital importance. For instance, if we have unfailing springs of pure water to draw upon, and all our neighbours are equally well supplied, what matters it if the pail overflows, or the tap is left running? But in another place where water is scarce, the waste of it would be sinful and cruel, especially if we were well supplied and our neighbours compelled to economise every drop.

The child on the sea-shore flings the sand{42} about with reckless hands, gathers shells and leaves them behind, or throws pebbles into the water, caring nothing what becomes of them.

There is no need for care in such cases. The sea gathers the shells and pebbles and flings them back in orderly ridges on the shore. The embankments, laboriously raised by many small hands, and the trenches dug around them, are quickly equalised again. The mighty ocean sweeps all before it. Wave follows wave, and the grains of sand are hurried onward. Castles are levelled, trenches filled, and the retreating waters leave the beach smooth again and ready for the morrow's toilers.

The last murmur of the waters seems to say, "You can fritter away nothing over which we flow. We gather your scattered fragments together, and not one grain is finally lost."

You and I, dear girl companions, have certain great trusts committed to us, which are neither visible nor tangible. We hold them in common with our neighbours, though they are not given to all in the same proportion. They are made up of littles, and yet, if we fritter them away, they are gone past recovery. We can no more regain the smallest portion than we can bring back the rain-drops which have fallen into the stream and are helping to hurry it seaward, or collect the grains of dust which the wind has whirled across the plain.

Time is one of these all-important trusts. Perhaps I should say the most important, for time and our natural life virtually mean the same thing. Do they not begin and end together, so far as we are concerned? Our first breath ushers us into the realm of time, and with our last we close our eyes on it for ever.

Does it not seem strange that any human being can be found who is careless about or forgetful of the preciousness of time? People hesitate to part with a penny unless they can be sure of receiving something of equal value in exchange. Yet the same persons think nothing of frittering away, without return, that which the wealth of the whole world cannot buy back for them.

It seems natural for the very young to think lightly of the flight of time. The world—in other words, time and life—is all before them. A day flies so quickly; an hour is a mere nothing. As to the minutes and moments! What are they more than the drops that make up the ocean, or the grains of sand that form its boundary wall? Who can exhaust these?

Time, to the child, is an inexhaustible ocean into which he cannot dip too freely. What if the tide recedes? It is sure to flow again, and is, indeed, ever flowing.

You and I have surely learned lessons as to the value of time to which the child would not care to listen even. Let us think together of the value of moments. They follow each other, and are swallowed in the ocean of eternity, but there is no reflux. Not one comes a second time. If an hour has been frittered away and we can show nothing for it, all that remains for us is to make the best possible use of its successors.

Very lately I heard a great preacher say, "We should be misers in the use of time and opportunity." Do we not value too highly what we call the riches of this world? We are sparing of our gold, or our silver—even of our pence—and yet we do not pause to take account of what is beyond all price.

Have you ever thought, dear girls, that you are threefold debtors as regards the use you make of this great trust, time? We are all debtors, in the first place, to God, and must account for the use or abuse of time to the great Giver of it. We are told to "redeem the time because the days are evil."

I have in my mind the words of an old writer and profound student of the Bible who says about the text I have just quoted, "Buying up those moments which others seem to throw away; steadily improving every present moment." "Time is that on which eternity depends. In time you are to get a preparation for the kingdom of God." "Perhaps the apostle means in general, embrace every opportunity to glorify God, benefit your own souls, and do good to men."

These words carry out the idea I have suggested as to our threefold debt in relation to the use of our time. We should be misers of it, that we may the more fully carry out our divine Master's will, follow His example, obey His commandment to love our neighbour as ourselves, and, in so doing, promote our own eternal welfare.

You and I can understand the need for us to echo the prayer of the Psalmist, "So teach us to number our days that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom."

How much teaching we need! What heedless and forgetful scholars we are! How constantly we need to be reminded of the value of that which we treat so lightly, waste so often, and lose with so little regret!

All other losses cause us trouble and generally sorrow. If the child, in hurrying to spend a halfpenny, loses its one precious coin, there is eager searching with the help of companions. Joy follows its recovery, or bitter tears are shed if it is not found.

The lost purse, or the jewel that has escaped from its setting, is neither forgotten nor deemed of slight consequence. It is sought, advertised for, and, if finally lost, is remembered with regret; the more so if it has been the gift of a friend.

The merchant will risk large sums in the hope of doubling them. If unsuccessful, he can hardly forgive himself for having thrown away that which he had. Losses of these kinds are thought of again and again in after days, and the face clouds over at the memory of them.

How few amongst those who have recklessly wasted moments, hours, and days, pause to take themselves to task, mourn over an irretrievable loss, and resolve, by God's help, to redeem the time that is left. As regards the season for making the new beginning, there is only one word to express the right one: now. Not a week hence. Not to-morrow. Not even an hour after the resolution has been come to; for time is flying always, and its redemption must begin with the moment which has revealed to us its infinite value. Henceforth we must be "misers in the use of time."

Time is often unwittingly wasted by thrifty people for want of due thought and calculation. How well I remember, in the earlier days of railway travelling, what anxiety to be in time for a train was evinced by old-fashioned people!

I used to stay in a country house which was several miles from a station, and my kindly host was so fearful of my missing the train, that he used to insist on my starting early enough to spend nearly an hour in waiting for it.

It was very difficult to turn that waiting time to any useful account, especially in the dim light of a wintry morning, for I had to catch the first train. I smile as I picture the little bare waiting-room and the scarcely-lighted fire, by which I sat and shivered and tried to cherish bright thoughts amidst dull surroundings.

Those who value their own time lightly are seldom scrupulous about wasting that of their neighbour. Have we not all been lectured, again and again, on the sin of unpunctuality?

I think I hear you ask whether unpunctuality deserves to be ranked as a sin? Let us consider the question, then decide for yourselves.

Neither you nor I would like to steal our neighbour's purse, or even help ourselves to a solitary sixpence. But if, by our neglect, carelessness or wilful selfishness, we rob him of that on which his income depends, are we not equally guilty, though the law cannot reach us for this offence? Time is money to the toiler in every branch of work, whether mental or physical, and we have no right to waste our neighbour's capital which money cannot restore to him.

So many people, old as well as young, seem unable to understand what punctuality means. Those who allow their own time to slip away unheeded, cannot see that it matters whether they are a few minutes too soon or too late for an appointment. If by some chance—a rare one—they are too soon, they plume themselves on this, and are perhaps inclined to be indignant if they are kept waiting and their time is wasted.

Dear girls, do think of this! If you make an appointment try and keep it to the minute. Be neither before nor after the time fixed, but by your punctuality redeem your own time and avoid the sin of wasting what is not your own.

Indolence is a terrible and stealthy thief that ought to be battled against, with a prayerful sense of our own weakness to resist its encroachments. Indolent people are like unpunctual ones—very prone to steal the time which their neighbour values and turns to good account.

How many busy men and women have had to work when they ought to have been resting after a finished task, because an idler has interrupted it by dropping in at the office or the home during working hours? The one object of such visitors is to while away the time which hangs heavily on their useless hands, regardless of consequences to those on whom they intrude, or too selfish to care, so long as their own end is served.

Unfortunately the sufferers have not always a remedy. Circumstances may render it unwise to complain, or politeness restrains them from doing so, even when they are inwardly chafing under the infliction. They do not like to deny themselves to these thieves of time, for whom perhaps they feel a very real affection; or it may be they cannot afford to risk giving offence on account of their relative positions. Hence they suffer in silence.

There are hard-working girls as well as older folk who suffer in like manner, through other girls who place no value on their own time and have no qualms of conscience about wasting that of their neighbours.

Take the lesson to heart, dear ones. Ask that you may realise the full value of your own time, and abstain from robbing another of what she esteems a precious trust from God.

There are unsuspected ways of wasting time which those who "use it as misers" are apt to overlook. The more eager the worker, the more interested she is in her occupation, the more likely she is to be guilty of this kind of waste in these high-pressure days.

I have no doubt there are many of these too-hard workers amongst you, my dear girl friends, who grudge the time spent in rest, who hurry over your meals, who regard innocent recreation as almost sinful, because it interrupts your labours and defers the completion of some task you have set yourselves.

Believe me, time is never more truly wasted than it is by those who work too long, without pausing to refresh the weary mind and body. Time is saved if, when nature cries aloud for rest, we put aside the work we love and do absolutely nothing until we can return to it with a sense of fitness and freshness.

"Do nothing!" you exclaim. "Why, that would be the hardest task of all. We may compel our hands to be idle or our tired limbs to rest, but thought will still be busy. The mind cannot be coerced."

Perhaps not in a sense, but if we wish it, we can turn our thoughts into a restful channel. What can be more restful and delightful than to sit with closed eyes and folded hands whilst we think over God's gracious dealings with us and make a mental catalogue of a single day's blessings? What can so renew our strength to work, as a little season spent in thanking God for the power to labour? What will be more helpful to us than a quiet time with Him whilst the world, its cares and its business are shut out, and we, alone with our Father, ask for wisdom to use without abusing our time and all the powers He has entrusted to us?

Cultivate the habit of leaving off work when nature craves for rest, and you will find it, both for soul and body, by fixing your minds on God.

You need not utter either prayer or thanksgiving, but your thoughts may overflow with both, and He who can read them will accept your heartfelt thanks and answer your unuttered prayers by giving you a sweet sense of peace and renewed power to work for Him.

Oh, it is lovely just to get away from the world and its bustle and toil for a little while and spend it in thinking of the goodness and love of God in Christ Jesus! Our work may well wait in the meantime.

I was with some dear friends who were sight-seeing in town, and who, accustomed to the quiet of a country place, were almost bewildered with the din of the great city. We were near St. Paul's, and how glad we all were to enter the great church and to rest there in a quiet corner, unconscious of all the noise and traffic which still went on around it.

My friends' stay in town was to be a short one, and they were all eager to see as many of its sights as possible. Did they grudge the little time spent in peaceful communion with God, or deem it wasted when there was so much to attract them in the great city? Ah, no!

Often afterwards, when other incidents had faded from their memories, they spoke of its sweet restfulness, and thanked God for the open door of that grand cathedral, which offered to weary wayfarers a chance of refreshment for soul and body.

Dear ones, learn a lesson from this little incident. Do not deem the time lost which is taken from the work you love for the rest you need. You will redeem it in the best way if you turn your thoughts from earth to heaven, from the world around you to its great Creator.

Unfortunately those who under-value time are more numerous than those who realise its preciousness. We often hear the expression, "I am only giving my time." As though money and goods were of infinitely greater worth. It is when health fails and life is drawing near its close that the preciousness of every moment is understood. I beg of you to remember now, that the right use of your time is your evidence to those around you of your union with Christ.

Let us finish our talk this evening by repeating two or three reasons why we should be misers in the use of time. Time and life mean the same thing to us all. Time is a debt we owe to God. All our work must be done in time. Eternity depends on the use we make of time. Time comes only once, and the present is all we can call ours.

Let us ask God to impress these great truths on our minds and to give us the will and the power to use time well.

(To be continued.)

John Taylor.

Needlework has been a favourite method of employing time, both in courts and cottages, from very early days; and one is not surprised at this, seeing that it is not only necessary for the comfort of daily life, but a very attractive occupation, one capable of great variety and of being practised without fatigue.

The history of needlework was almost unknown until Miss Lambert and the Countess of Wilton devoted their time and talents to the collection and classification of facts concerning it.

The first piece of needlework we know of is that of our first parents in the Garden of Eden, who, with a thorn, probably, for a needle, "sewed fig-leaves together to make themselves aprons."[1]

Milton refers to it thus:—

From all records of early ages we learn that the women used first a thorn and then a fish-bone sharpened at one end as a needle, to sew the skins of animals or other material together. Most of our queens have recognised the advantages of being good needlewomen, and several have left behind them beautiful specimens of work, so that we have an almost unbroken record of their achievements with the needle.

The inducements to royal ladies to become proficient in the art of needlework have been many and varied; for example, some have been influenced by the desire to set a good example to their subjects; others in order to lighten the weariness of solitary hours; others that they might record the deeds of valour and daring performed by their husbands; some because they were thrown on their own resources through lack of outdoor amusements and the absence of good roads; others for real love of it; while other few practised it from pious motives that they might contribute to the beauty of churches. Indeed, church, court, camp and state have all more or less influenced royal ladies to become good needlewomen.

Nothing creates a stronger bond of union between classes than like tastes and occupations, and it holds good specially between sovereigns and peoples. To know that probably the Queen and princesses of the royal house are occupied in the same way as the poorest cottager, either in sewing a seam, making a dress, trimming a bonnet, or embroidering a tray-cloth, creates a kindly feeling between one and the other, and bridges over the distance between them.

I remember when our Princess of Wales came over to dwell among us, it was stated that she begged to retrim the Queen's bonnets and make them pretty and fashionable, as she had always trimmed her own and her mother's. When some of the London poor heard it they were delighted, and said, "Bless her now; do you really think a laidy sich as her would a' done it?"

Nothing that has been told of Princess Henry of Battenberg has brought her so near to the hearts of the poor as the piece of news that "when she is in sorrow or perplexity she is greatly soothed by sitting down and sewing a long seam." It is something they can understand and appreciate, for it is most likely the very thing they themselves would do in like circumstances.

It has been of no slight benefit to us women and girls that our queens and princesses should have been good needlewomen, for we are, to a great extent, influenced by the daily life of those in high places; indeed, the influence of queens upon their women subjects has always been noticeable; their personal and private character, their passions and prejudices, are always more or less reflected in the women of the kingdom.

Proficiency in the art of needlework is by no means confined to the great ladies of our nation, for we hear that the princesses in the Court of Charlemagne were splendid needlewomen, and the work of Bertha, wife of Rudolph the Second of Burgundy, has a world-wide fame. She is represented on seals and monuments of her time as sitting on the throne spinning, and even when out riding continuing her work. In the old town of Payerne Canton de Freiburg, a residence of the kings of Burgundy, her bones, together with those of her husband and son, Conrad, were discovered in 1817 below the tower of the old church which she herself had built, and they were buried in the parish church, where the Queen's saddle is shown with a hole for her distaff. To this day the expression is used, as a regretful allusion to the good old times, "ce n'est pas le temps où Berthe filait."

Gisela, also, the wife of St. Stephen, king of Hungary, was a splendid needlewoman, and organised embroidery work-rooms near her palace.

The mother of Charles the Bold and Adelaide the Consort of Hugh Capet were also celebrated needlewomen.

Even nations far removed from civilisation have not been ignorant of needlework, as the discovery of gold needles, etc., in the Scandinavian tumuli testify.

To come back to our own country, the palm is certainly accorded to the Anglo-Saxon ladies for excellence in this womanly accomplishment. We have proof that those of rank and royal blood were skilled not only in the use of the needle for necessary purposes but also in elegant and intricate embroidery.

The fleece which was brought home by the Anglo-Saxon men in summer was spun into clothing by the female part of each family during the winter.

Alfred the Great in his will calls the women-part of his family the spindle side, and it was understood by our forefathers that no young woman was fit to be a wife till she had spun for herself a set of body, table and bed linen; this is why the maiden was called a spinner or spinster, and the married woman a wife or one who has been a spinner (from Anglo-Saxon wif, the verb being wyfan or wifan, to weave). Perhaps you have noticed that the armorial bearings of women are not painted on a shield like those of men but on a spindle called a lozenge. The spindle half is a Saxon term for the female line, while the spear half is the male side.

Among the Anglo-Saxon ladies Adelfleda and her three sisters, daughters of Edward the Elder, stand out as famous for their skill in all kinds of needlework, and are known in history as cunning workers.

William of Malmesbury says, "their father caused them in childhood to give their whole attention to letters and afterwards employed them in the labour of the distaff[2] and the needle."

The same authority says that Edgitha or Editha, the Queen of Edward the Confessor, was "perfect mistress of her needle," while the Saxon historian, Ingulphus, a scholar at Westminster Monastery, near to Edgitha's palace, relates of her that "she was skilful in{44} the works of the needle, and that with her own hands she embroidered the garments of her royal husband."

As a proof of the high value set on good needlework the Anglo-Saxon Gudric gave Alcina a piece of land on condition that she instructed his daughters in embroidery and needlework.

It was the custom in feudal times for high families to send their daughters to the castles of their lords there to be taught spinning, weaving and needlework under the eye of the lady chatelaine.

It was also a practice for great ladies and their attendants to pass their mornings at needlework, singing and relating stories meanwhile.

It seems that William the Conqueror on his first appearance in public after the Battle of Hastings wore a richly worked cloak of Anglo-Saxon embroidery. It may have been this fact which roused his wife Matilda to produce a piece of work which was to live for long ages as a specimen of her industry and skill with the needle. She was a jealous woman and might not have been pleased at other hands than her own working her husband's apparel. It is difficult to understand the working of a woman's mind.

There is no doubt that the work she left behind, and which is still preserved in the Cathedral of Bayeux, is perfectly marvellous, or as Dibdin says "it is an exceedingly curious document."

It is a piece of canvas or coarse linen cloth two hundred and twenty-seven feet long and twenty inches wide; on it she has wrought with woollen thread of eight different colours a picture of her husband's exploits, from Harold's first landing in Normandy to his fall at Hastings.

It is a most important record of the history of the period, because the events, costumes, and warlike instruments are faithfully portrayed.

The canvas contains many hundreds of men, horses, trees, houses, castles, ships and churches, with names and descriptions over them to make the story clear; strangely enough there are only three women in the whole picture. Taken as a whole it affords a curious insight into the manners and customs of the Norman Period.

The figures and designs for tapestry work were always prepared by some skilful artist who traced them out in the colours that were to be used by the worker either in wool or silk.

Matilda seems to have employed the dwarf artist Turold to prepare her work and illuminate the canvas: he was a dependent of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. The parts intended to represent flesh in the picture are left untouched by the needle.

It is supposed that not only was Matilda assisted in her great work by the ladies of her court but by some of the beautiful workers among the Anglo-Saxon ladies. She was a woman who would not study the feelings of those around her, nor would she consider their sorrow in having by their needle to perpetuate their sufferings and defeat.

The work which is now in Bayeux is coiled round a machine like that which lets down buckets into a well, and a woman is appointed to unroll it for visitors and explain it.

A full-sized coloured photograph of it may be seen in the South Kensington Museum, and the Society of Antiquaries have engraved the whole of the Bayeux tapestry and have coloured it like the original.

We are told in the life of St. Dunstan that he was originally in an obscure station of life, and crept into notice by means of his taste and skill in delineating sacerdotal vestments and tapestry work for great ladies. He must have had a great love of such work as well as genius, for even when he came to high estate he did not disdain making sketches for queens to work from.

We now pass on to Adelicia of Louvaine, the queen of Henry I., who was distinguished for her great beauty and talents, but especially for her proficiency in feminine accomplishments.

A standard which she embroidered in silk and gold for her father when he was engaged in recovering his patrimony was celebrated throughout Europe for the exquisite taste and skill displayed in its design and execution. For centuries it was carried in procession on Rogation days through the streets of the city of Liège, for it had been captured by the bishop of that town in 1129.

(To be continued.)

By SARAH DOUDNEY.

"It is my last day in London," said Alice Harper to herself.

The "last day" was a Sunday at the end of July, and Alice's box was packed, and ready for travelling. She had attended service that morning in a beautiful church, where she had often gained strength and comfort in her weariness; and the music was still echoing in her ears when she turned into Bruton Street. Wherever she went, she knew that she should hear that music still.