| CHAPTER | |

| I. | H.M.S. "POMPEY" |

| II. | THE RESULT OF THE LEADING STOKER'S CURIOSITY |

| III. | GREENWOOD SENIOR'S DISCOVERY |

| IV. | THE SECRET PETROL-DEPÔT |

| V. | EXPLANATIONS |

| VI. | AN EXCELLENT NIGHT'S WORK |

| VII. | THE DAY FOLLOWING |

| VIII. | SPY AND SUPER-SPY |

| IX. | AN ADVENTURE ON THE HILLS |

| X. | THE FOILED RAID |

| XI. | ONE ZEPPELIN THE LESS |

| XII. | AN OCEAN DUEL |

| XIII. | ADRIFT |

| XIV. | A BREACH OF NEUTRALITY |

| XV. | A PRISONER OF WAR |

| XVI. | THE FIRST DAY OF CAPTIVITY |

| XVII. | A DASH FOR LIBERTY |

| XVIII. | THE DERELICT OBSERVATION BALLOON |

| XIX. | THE DESERTED HOUSE |

| XX. | TRESSIDAR SOLVES A MYSTERY |

| XXI. | CHECKMATE |

| XXII. | THE SHELL-BATTERED HOSPITAL |

| XXIII. | AT AULDHAIG ONCE MORE |

| XXIV. | A FIGHT TO A FINISH |

| XXV. | IN THE MOMENT OF TRIUMPH |

| XXVI. | THE HOME-COMING OF THE S.S. "MEROPE" |

| XXVII. | A DAY ON DARTMOOR |

| XXVIII. | —AND A NIGHT |

| XXIX. | WHEN THE TRAWLERS SHOWED FIGHT |

| XXX. | A NOVEL DUCK HUNT |

| XXXI. | MONITORS IN ACTION |

| XXXII. | THE "ANZAC'S" DAY |

| XXXIII. | A SPLINTER OF SHELL |

| XXXIV. | EXIT OBERFURST |

| XXXV. | TRESSIDAR'S REWARD |

A bugle-call rang out shrill and clear in the wintry air.

"Thank goodness—at last," murmured Eric Greenwood. "That's an end to 'Action Stations' for the time being. Let me see. Tomorrow coal ship, next day make up the money. Payment on Friday, and ten to one there'll be half a gale of wind—and paper money is a strafed nuisance."

Thus musing, Assistant Paymaster Greenwood, R.N.R., completed his preparations for vacating the fore-top of H.M.S. "Pompey," where he had been acting as assistant to the lieutenant in charge of the fire-control arrangements.

The fore-top, a caged-in structure measuring roughly eight feet by eight, was situated ninety feet above the upper deck. In long-range actions it took the place of the conning-tower as "the brains of the ship," for in that limited aerial perch seven officers and men, all working with a common set purpose, were able to direct salvoes of death-dealing missiles with uncanny accuracy to a target invisible to the guns' crews at their stations behind six inches of Krupp steel.

"Carry on, old man," said Vickers, the lieutenant, indicating a small trap-hatch in the floor of the top. "Be careful; there's ice about."

Greenwood had already made up his mind to be careful. A man who, up to within fifteen months ago, had led an eminently sedate existence as a bank clerk does not take to work aloft with the same agility and confidence inspired by years of training at Osborne and Dartmouth.

At the outbreak of war Eric Greenwood was a ledger clerk at a bank in a quiet Devonshire country town. The notion of serving under the White Ensign had never occurred to him, even in his wildest dreams, until the Admiralty called for additional accountant officers for the Royal Naval Reserve. Eric promptly sent in his application. It was curtly acknowledged; and then followed weeks of tedious, sickening suspense, until, when hope seemed dead, the bank clerk received an envelope marked "O.H.M.S.," the contents of which transformed him into an acting assistant paymaster, R.N.R.

After a short term at the Naval Barracks at Devonport, Greenwood was sent to a small base on the east coast of Scotland. It seemed as if he were fated to remain ashore until the termination of the war, when, to his unbounded satisfaction, he was appointed to H.M.S. "Pompey."

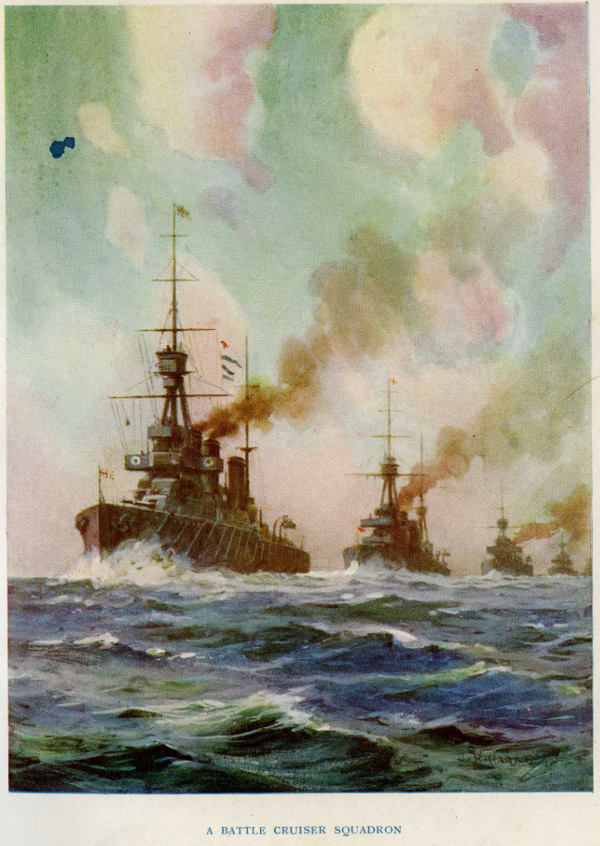

The "Pompey" was an armoured cruiser of 14,000 tons, armed with two 9.2-in. and fourteen 6-in. guns, in addition to several weapons of lighter calibre. Although by no means a modern vessel, she was generally considered to be a "tough nut" and able to give a good account of herself on The Day—that long-expected and long-deferred event—when the Germans finally made up their minds to decide by ordeal of battle whether they could attempt to wrench the trident of sea-power from Britannia's grasp.

Lieutenant Vickers's caution was necessary, for as the A.P. lowered himself through the narrow opening, his feet came in contact with the ratlines of the wire-shrouds. They were slippery with ice, for it had been drizzling, as it almost always did in the North Sea when it was not blowing a gale, and the moisture settling on the rigging had frozen hard.

The ship was rolling considerably. At one moment the starboard shrouds were almost perpendicular, at another they inclined at such an angle that Greenwood was almost lying on his face at full length upon a gigantic wire net. Clouds of eddying, pungent smoke enveloped him, for the vessel had a following wind. The keen blast seemed to cut him like a knife in spite of his bulky, additional clothing.

The young officer descended rapidly. He was anxious to gain the deck for two reasons. He wanted to warm himself by the wardroom fire; he was also aware that a destroyer had a few hours previously sent on board a batch of mails—the first for nearly a fortnight. After thirteen days of patrol work without being in touch with land, the prospect of receiving letters from home was one that outweighed all others, unless, perhaps—harrowing thought!—the mail-bag was a blank so far as Eric was concerned.

"Hello, old bird! A trifle nippy up in your little perch!" exclaimed a voice as Greenwood stepped over the threshold of the wardroom door.

The speaker was a tall, broad-shouldered sub-lieutenant, Ronald Tressidar by name. Between these two there existed a friendship that was almost of lifelong duration, for their respective homes were in the same Devonshire town. Of recent years they had seen little of each other. Their careers were set upon totally different lines till by a pure coincidence they found themselves appointed to H.M.S. "Pompey."

"Beastly cold," agreed Greenwood as he made his way to the letter-rack. Thanks be! There was a goodly sheaf of envelopes bearing his name. Eagerly the A.P. possessed himself of his correspondence and sought a chair in the sadly depleted wardroom, for upon the outbreak of hostilities the cosy atmosphere of the place had given way to a state of almost Spartan simplicity.

Silence reigned. The rest of the officers off duty were literally devouring their greetings from home or else were burying their heads between the pages of newspapers that were at least three days old.

In the warm glow, with his mind fully occupied with thoughts of home and distant friends, Greenwood forgot completely the rigorous period of "Action Stations" in the fore-top. But all things come to an end. Reluctantly the A.P. folded his letters and placed them in his pocket. As he did so he caught Tressidar's eye.

"Anything startling?" asked the sub., taking a vacant place on the lounge within a couple of feet of Greenwood's chair.

"Heaps," replied the A.P. "For one thing, an aeroplane came down on the pater's greenhouse. No one hurt. I can imagine the governor cutting up rough about it. He never could see the humorous side of anything. The mater is still knitting for the troops. I pity the poor fellows who get hold of any of the gear she turns out. Once upon a time in the dire days of my youth she knitted me a pair of socks. I didn't forget to chip her about them, too."

"She makes awfully decent cakes," remarked Tressidar reminiscently.

"She does," agreed the A.P. "And I remember the time when we brought a hammer and a cold chisel to the tea-table and pretended to split the almond paste asunder."

"Wasn't that the cake your sister Doris made?"

"Might have been, now you mention it," said Greenwood. "Talking of Doris, she's now a probationer in the Reserve Nursing Service, and she's appointed to Auldhaig."

"Is that so?" asked Tressidar with ill-feigned disinterestedness. Nevertheless a deep flush overspread his tanned and weather-beaten features. The sub. had always been extremely partial to the girl, but Doris had been in the habit of keeping him severely in his place. That was long before the war.

"Strange that she should be sent to our base," continued Eric. "We may see something of her this Christmas, for I heard the fleet paymaster say that we are likely to remain in harbour until early in the New Year. He had the tip from the engineer-commander, who submitted a list of defects as long as your arm."

As a matter of fact Ronald Tressidar knew more about Doris Greenwood's plans than did her brother, for a letter from the girl was reposing in his pocket. Generally outspoken and communicative in most matters, Tressidar maintained a studious reticence in his chum's presence whenever the subject of Greenwood's nineteen-year-old sister was discussed.

"There's 'Action Stations' again!" exclaimed a lieutenant-commander as a bugle blared on deck.

Instantly there was a rush on the part of the occupants of the wardroom, to the accompaniment of the sharp cracks of the quick-firers.

But before Tressidar gained the deck the danger—at least for the time being—was over. The "Pompey" had ported helm, while at less than twenty yards on the port beam the surface of the water was marked by a pair of diverging lines that indicated the track of a torpedo. By a smart display of helmsmanship the cruiser had escaped destruction.

Already the skipper, who after an arduous night had turned in, was on the bridge, with his feet in carpet slippers and the legs of his pyjama suit showing below the bottom of his great-coat.

"See any signs of a periscope, Mr. Flanders?" he inquired of the officer of the watch.

"No, sir," was the reply. "We opened fire at what turns out to be a floating spar. The torpedo came from broad on our port beam before I ordered the helm to be put hard over."

"Good!" exclaimed Captain Raxworthy. "We'll see if we can't nab her."

In ordinary circumstances a battleship or cruiser that has the good luck to be missed by a hostile torpedo steams off at full speed from the dangerous locality. Should destroyers or patrol boats be in the vicinity, they are brought up at full speed to attempt to intercept the submarine. But on this occasion the "Pompey" was alone in this remote portion of the North Sea.

Contrary to precedent, Captain Raxworthy gave orders for the cruiser to slow down and come to a standstill. At the same time volumes of steam were allowed to hiss through the steam-pipes. All the six-inch and light quick-firers were manned, ready at the first glimpse of the hostile periscope to let fly such a weight of metal that the still submerged hull of the submarine would stand no chance of resisting the powerful shells.

The skipper of the "Pompey" was correct in his surmise. By slowing down and letting off steam the cruiser behaved in much the same way as if she had been actually torpedoed. The crew of the submarine heard the sounds that apparently betokened the cruiser in her death-agonies, and they could not resist the temptation to approach the surface and survey their work through the periscope.

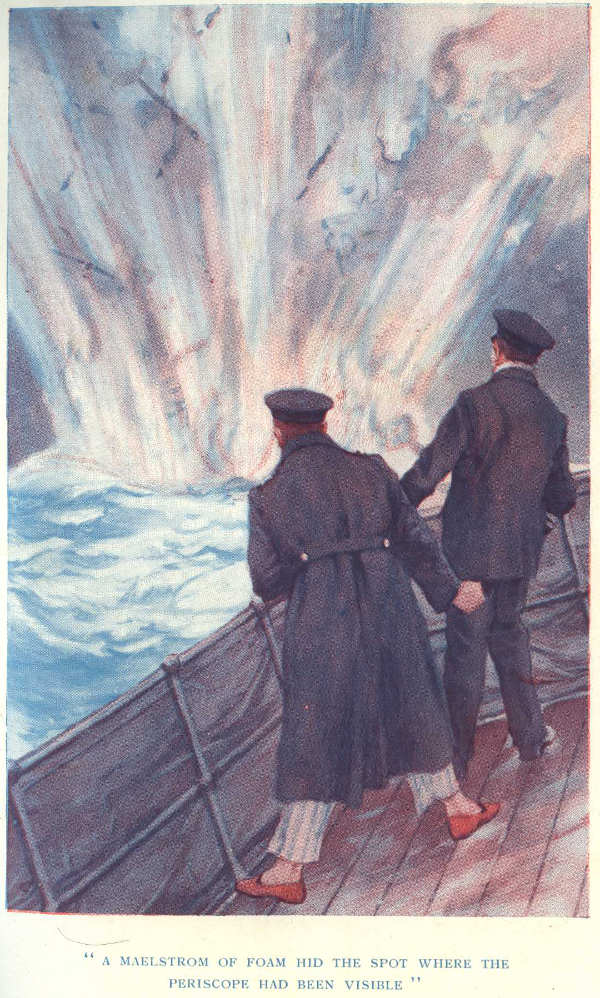

Four hundred yards away on the "Pompey's" starboard quarter a pole-like object shot stealthily above the surface. It wanted the trained eyes of a seaman to discern the ripple of foam that denoted the position. Half a dozen or more of the "Pompey's" crew spotted the expected target.

The next instant twenty shells were shrieking through the air on their way towards the doomed submarine. A perfect maelstrom of foam, mingled with smoke and fragments of metal hid the spot where the periscope had been visible.

The columns of foam subsided; the smoke drifted rapidly away in the strong breeze; but ominous air-bubbles and an ever-increasing oily patch that had the effect of quieting the crested waves denoted the undisputed fact that yet another unterseeboot had shot her last bolt. Eight hours later H.M.S. "Pompey" entered Auldhaig Firth.

"Clear lower deck. Hands fall in to coal ship."

The hoarse orders following the shrill trills of the bos'n's mates' pipes rang from end to end of H.M.S. "Pompey". In the stokers' messes men arrayed in motley garbs, for the most part consisting of old canvas suits and coloured handkerchiefs tied tightly over their foreheads, cleared out at the double to fall in on the quarter-deck.

Stoker James Jorkler, otherwise known as Rhino Jorkler, heard the order not without emotion. He was a tall, sparely-built man of about twenty-four years of age. At first sight he lacked physique, until one noticed the ripple of supple muscles on his partly-bared arms. His face was long and pointed, his eyes blue and deeply set underneath a pair of thick and overhanging brows. His hair closely cropped, tended to exaggerate the elongation of his head. His features betrayed neither signs of good humour nor bad temper, but rather an intelligence bordering upon cunning.

Three months previously the Royal Navy in a somewhat excusable haste had accepted the services of James Jorkler. In war time, with a heavy drain upon personnel the authorities had to be a trifle less particular as to whom they enlisted for temporary service, and amongst a batch of stoker recruits was Jorkler.

His answers upon enlistment evidently satisfied the petty officer responsible for obtaining the necessary particulars. He was a Canadian, he declared, born at Woodstock, New Brunswick. Former occupation? Trimmer on board a White Star liner. His discharge papers confirmed that statement. Next of kin? James Jorkler rubbed his chin thoughtfully. He was on the point of replying that he did not possess such a luxury, but upon consideration he gave the name of Jonas Brocklebunk, his half-brother, of Leith.

Promptly the newly entered stoker was fired off to the R.N. Barracks at Portsmouth. His cap-ribbon, like those of the rest of the men borne on the books of that establishment, was embellished with the words "H.M.S. Victory," although his acquaintance with the time-honoured three-decker was limited to a distant glimpse of the ship as she swung to her moorings in Portsmouth Harbour.

The rest of the stokers' mess could not come to a unanimous decision concerning the tall recruit. His reserve puzzled them. Although he made no attempt to "choke off" any questions, he kept much to himself. He had no bosom pal. He showed no inclination to "split brass rags" with any of his messmates, who, for some unexplained reason, nicknamed him "Rhino."

When in due time he emerged from his course of preliminary training and was drafted to H.M.S. "Pompey," the name stuck. He showed neither appreciation nor resentment at it; it would have been useless to have done either. So he accepted the sobriquet without any outward and visible sign of interest in his messmates' solicitude for his need of a nickname.

The mess-deck was all but cleared. Jorkler, usually amongst the first to respond to orders, lingered until he was almost the last. Then, kneeling over his ditty-box, he unlocked and threw back the lid, delving amongst his belongings until he found what he required. "Wot the 'Ades 'ave you got there, mate?" broke in a deep voice.

Jorkler turned with a start to find that a leading stoker was standing behind him.

"Kind of souvenir," he replied weakly. "I guess is isn't of any interest to you."

"Thought as it might be a plug o' 'bacca," continued the man. "Fact is, I believes it is. 'Ow about it?"

"Reckon you're wrong," snapped Jorkler with returning confidence as he slammed and locked the box.

"Too jolly fishy to my liking," rejoined the petty officer bluntly. "You just wait till we've done coaling and I'll see for myself wot your little game is. Strikes me it ain't all jonnick."

At this threat Jorkler started to his feet Fortunately for the leading stoker there were others still in the mess, otherwise——

Jorkler set his jaw tightly and followed his inquisitor on deck. At the first opportunity he would nip below and throw the object of discussion overboard rather than let the leading stoker see it.

It was still night, with a cold, drizzling rain. Overhead arc-lamps threw a pale gleam upon the serried lines of men—seamen, stokers, and marines—on the quarter-deck. Everything liable to be affected by coal-dust had been covered up. The huge 9.2-in. guns were swathed in sacking; canvas covers encased the closed hatchways; whips for hoisting inboard the sacks of coal, trollies for bearing them to the nearest shoots, and a medley of other gear were in readiness, while steam was already raised to operate the winches.

Skilfully a large "haulabout"—a hulk converted into a floating coal-depôt—was manoeuvred alongside to starboard. To port a couple of deeply laden lighters had already been made fast.

"Commence—carry on!" shouted the commander from the after-bridge.

Instantly it seemed as if pandemonium had broken loose. With a rush the men set to work, for, if possible, H.M.S. "Pompey" was to break her own record.

Winches clattered. Jets of steam drifted across the slippery deck. Men shouted, knocked one another and each other, and worked till, in spite of the chilliness of the morning, their faces, quickly blacked with coal-dust, ran with perspiration.

Most of the junior officers joined in the actual labour. They found that even handling sacks of coal was preferable to standing by and shivering in the damp air. Clad in garments that outvied the bizarre rig of the hands, sub-lieutenants and midshipmen were soon toiling like Trojans.

With an almost reckless disregard for life and limb, sacks in batches of half a dozen at the time were hoisted from the coaling craft and dumped with a dull crash upon the cruiser's deck. Woe-betide the luckless wight who failed to heed the warning cry of "Stand by, there!" Like a pack of wolves the energetic men threw themselves upon the bags and dragged them to the shoots, until the ship vibrated with the clatter of coal descending to the bunkers.

At eight bells the word was passed to "Stand easy." A hasty breakfast, consisting largely of coal-dust washed down with ship's cocoa, was served out. The mess-decks were seething with human beings resembling imps and satyrs in their grimy garbs and blackened faces.

Reluctantly Stoker Jorkler came to the conclusion that this was no time to go to his ditty-box. Up to the present no opportunity had occurred.

Again the ship's company resumed their labours. It was now daybreak. The rain still fell, unheeded by the enthusiastic toilers. The only people who minded the horrible climatic conditions were the band, who, to keep up the spirits of the coaling party, were discussing lively airs in which rag-time predominated.

Suddenly an engine-room artificer working the main derrick hoist gave vent to an oath. "Here, one of you; bear a hand," he claimed. "I've nipped my fingers."

Without a word Stoker Jorkler relieved the luckless man at the steam winch. The E.R.A., with two fingers crushed to a pulp, hurried away to the sick-bay; while Jorkler, whose knowledge of machinery and of winches in particular was far from perfect, remained in control of the hoisting gear. He, of the whole of the ship's company, didn't exactly see why he should break his back over sacks of coal when he could take on the comparatively light job of running the steam hoist.

"Avast heaving there on the main derrick!" shouted Sub-lieutenant Tressidar, whose quick eye had noticed that something had gone wrong aloft.

Jorkler obeyed promptly, shutting off steam and applying the band-brake. A hundred pairs of eyes followed the direction of the sub's outstretched hand. The wire hawser had "jumped" the sheave at the end of the derrick that, projecting at an angle of forty-five degrees, terminated fifty feet or more above the deck of the lighter.

"Up aloft, one of you," continued Tressidar, addressing the men whose operations had perforce to be suspended.

But before the order could be carried out a man working in the lighter gripped the wire rope, shouting for the winch to be put in motion.

Dangling at the end of the rope as he rose swiftly into the air was a burly figure rigged out in grimy canvas. With his teeth gleaming in contrast to his black face and with a dash of colour imparted by the scarlet handkerchief bound round his head, the volunteer for the dangerous service cut a picturesque figure.

Stoker Jorkler gave an involuntary start. He recognised the man as Leading Stoker Smith, the petty officer whose insistence had given him such a bad turn. For a few seconds he thought—and thought hard.

The winch was still in motion. Higher and higher rose the petty officer until his head was almost level with the huge metal block at the end of the derrick.

Sub-lieutenant Tressidar raised his hand as a signal for the winch to be stopped. Jorkler, his eyes fixed upon the man who had aroused his enmity, made no effort to obey.

Leading Stoker Smith realised his peril. The wire rope which he was grasping was being drawn completely through the sheave. He changed his grip from the rope to the metal block, but the latter afforded no adequate hold.

"Stop winding, you blithering idiot!" roared the commander, who from the after-bridge was a witness of all that occurred.

Still Jorkler, ostentatiously fumbling with the mechanism, allowed the winch to revolve. The end of the rope, including the eye-splice, pulled through the sheave and fell with a thud upon the deck, the men scattering right and left to avoid it in its descent.

In the midst of his peril Smith espied a short length of rope bent to the end of the derrick. Again he shifted his hold, and, grasping the rope's-end, strove to fling his legs athwart the steeply sloping spar.

As he did so the rope parted like pack-thread. Groans escaped the on-lookers as the doomed man, with arms and legs outstretched, hurtled through the air. To the spectators he seemed to fall slowly, but with a sickening crash his back came into contact with a beam in the hold of the lighter.

A dozen of his shipmates rushed to his assistance, but the man was beyond mortal aid.

"What the deuce have you been up to?" inquired the engineer-lieutenant of the man at the winch.

"Sorry, sir," replied Jorkler with well-feigned grief. "The engine got out of gear. Is he dead, sir?"

"As if he could be anything else!" retorted the irate officer. "Stand aside, you blithering idiot! There'll be something for you to answer." Five minutes later the interrupted work was resumed. The lifeless victim had been removed; only sheer hard work could dispel the gloom that had fallen on the ship's company.

Beneath the mask of regret Jorkler was smiling to himself; from which it was evident that the mysterious "thing" that had excited his victim's curiosity was something of great importance, since Jorkler put its value above that of the life of a shipmate.

He was a firm believer in the adage, "Dead men tell no tales."

On the following day the county coroner and twelve good men and true assembled, as the law directs, to inquire into the manner of Leading Stoker Smith's death.

Although not knowing the difference between a derrick and a hand spike, a whip or a tackle, they listened with an air of profound wisdom to the engineer-lieutenant's technical explanations. They heard Stoker Jorkler's account, although most of his sentences were Dutch to the Highlanders who formed the jury. They accepted the commander's statement that everything had been done to safeguard the interests of the crew, and, satisfied, returned a verdict of Accidental Death.

Leading Stoker Smith received the only salute to which a lower deck man is entitled—three volleys over his grave; and the "thing" still remained locked away in Rhino Jorkler's ditty-box.

Early on the following afternoon a train in connection with the night express for King's Cross arrived at Auldhaig station from Edinburgh.

Amongst the passengers were Mr. Theodore Greenwood and his daughter Doris. The former's object in making the long and tedious journey from Devonshire to the bleak north-east coast of Scotland was twofold. He wanted to hand his daughter over safely to the Naval Hospital—and this in spite of the nineteen-year-old young lady's assurances that she was quite capable of travelling alone. He also thought that there might be a possibility of seeing Eric, since he knew that the "Pompey's" base was at Auldhaig. Notwithstanding the fact that the Assistant Paymaster R.N.R. had studiously adhered to the regulations and had made no mention of where the ship was or what she was doing, that information had been forthcoming.

Nor was Mr. Greenwood alone in the possession of the supposed secret, for already several of the officers' wives and families had braved the rigours of the wintry climate and had taken either furnished houses or apartments in the town, which since the war had developed out of all knowledge.

Having duly rid himself of his responsibility of handing Doris over to the Head Nursing Sister, Mr. Greenwood set out on his quest for H.M.S. "Pompey." Being naturally of a somewhat nervous disposition, he hesitated to ask if the cruiser were in harbour, reflecting that such a question might lead to his arrest as a spy. In his imagination he fancied that everyone he met eyed him with suspicion.

At length he arrived at the shore of an arm of the intricate harbour. Lying at moorings in the channel were half a dozen destroyers, but there were no signs of any vessel approaching the armoured cruiser in tonnage.

For some moments he stopped to read a notice-board on which was set forth a list of things that the inhabitants of Auldhaig must or must not do, the document being signed by the senior naval officer of the port.

"There's nothing like taking every possible precaution," murmured Mr. Greenwood approvingly. "One cannot be too particular in wartime."

Just then an old fisherman sauntered by. To him the stranger addressed himself, inquiring if he knew whether the "Pompey" was in harbour.

The old Scot shook his head.

"I dinna ken what you say, mon," he said.

Mr. Greenwood repeated his question.

"Oh—ay. Weel, tak yon path——"

He gave his questioner lengthy and bewildering directions which not only left the Devon man completely tied up in knots, but with also a reply to a misunderstood question, for the old man had come to the conclusion that Mr. Greenwood was asking the way to Ponhaugh, a small fishing-village about four miles from Auldhaig by the cliff-path.

Gaining the outskirts of the town, Mr. Greenwood commenced the long climb to the edge of the rugged granite cliffs. From the moment he struck the open country he did not see another person of whom he might make further inquiries, but with complete reliance upon the old fisherman's directions he walked briskly along the narrow, winding path.

This he followed for nearly two miles without finding any signs of his quest. Instead, he made the disconcerting discovery that the track split into two parts, one branch trending inland, the other descending steeply to the beach.

Mr. Greenwood took the latter route. Upon gaining the shore he found that the track ended at the firm sands that fronted the base of the rugged and indented line of cliffs.

Undaunted, he proceeded, expecting as he rounded each projection to find the non-existent harbour in which he supposed H.M.S. "Pompey" to be lying; but headland after headland was passed without any satisfactory result.

Presently he arrived at a little bay. The distance between the two enclosing promontories was less than a hundred yards apart. The shore was of sand, but, unlike the rest of the beach, was interrupted by a series of low ledges of rock. Between the water's edge and the base of the cliffs the distance averaged twenty yards, although the waves were almost washing the wall of granite at either end of the bay.

Suddenly Mr. Greenwood caught sight of a cylindrical object lying on the shore. It was a little larger than a football and glistened in the dull light. At every undulation it was flung upon the sand, whence it receded in the undertow until thrown back by the succeeding wave. Attached to it was a short length of frayed rope.

"That must be a mine," decided the alarmed man. "The authorities must be informed."

Although half inclined to retrace his steps, he walked cautiously past it, keeping as close to the cliffs as possible, until he gained the furthermost headland. Here, to his dismay, he found the distant aspect was a misleading one, for his progress was barred by a deep gulley through which the tide was surging right up to the wall of granite.

"I hope the tide is going down," thought Mr. Greenwood.

To satisfy his curiosity on that point he wasted ten precious minutes, only to be ocularly assured that the tide was on the flood, and that there was no possible chance of going further.

Again he passed the cylindrical object. By this time it was within a few feet of one of the ledges of rock.

"When the waves throw it against those rocks it will explode," commented Mr. Greenwood. "How dangerous! Thank goodness I have yet time to put a safe distance between me and that infernal machine."

Thirty seconds later he "brought up all standing." Where a short time previously had been an expanse of hard sand, the waves were lapping against the cliff. His retreat was cut off.

Even then, at the expense of wet feet, he might have negotiated the passage, since the water was only about a foot or eighteen inches in depth; but Mr. Greenwood hesitated and, figuratively, was lost.

Step by step he retreated before the rapidly rising tide, each step taking him nearer again to the object of his apprehension. A belt of seaweed rising six or seven feet from the sand marked the limit of mean high tides on the face of the cliffs. It was evident that nowhere within the arms of the bay was safety to be found except by scaling the frowning precipice.

Discarding his umbrella—he wedged it tightly into a crevice in the granite in the hope that he might be able to retrieve his trusty friend—Mr. Greenwood sought for a suitable spot at which to commence his hazardous feat. At the same time he kept an anxious watch upon the derelict mine, which, having escaped being cast upon the ledge, was now being carried close to the main wall of rock.

In his heated imagination he fancied himself fifty or a hundred feet up the cliff with the powerful explosive going off and hurling him to a terrible death upon the rocks beneath. He shouted, but only the echoes of his own voice mocked his appeal for aid. In vain he looked seaward, where the mists of evening were already creeping over the wild North Sea. Not a sail was visible.

Mr. Greenwood was one of those men who, by disposition timid and unassuming, possessed a great reserve of courage and determination when called upon to extricate themselves from a tight corner. And, having found himself in a tight corner, he acted accordingly.

After a brief search he discovered a rift in the cliff, which at this point was not so sheer as it appeared at first sight. In any case the footholds obtainable extended sufficiently high to enable him to climb above high-water mark. Here he could wait until the tide fell and take his chance with the mine.

The first six feet gave him great trouble, for the weed and kelp afforded little foothold, but beyond this height he was able to maintain a steady progress. Up and up he climbed, not daring to look down, although the attraction of that deadly cylinder was almost irresistible. He wanted to watch its progress towards the base of the solid rock.

At length, fifty feet above the sea, he gained a fairly broad ledge, the presence of which was invisible from the beach. Nor could it be seen from the top of the cliffs, for higher up they projected well beyond the ledge, the face being so smooth that further climbing was a matter of sheer impossibility.

"At any rate, I am safe for the time being," soliloquised Mr. Greenwood. "That is something to be thankful for, although I would infinitely prefer the comfort of a bed to the prospect of spending a winter's night less than halfway up a wall of rock. And even if that mine explodes I think this ledge will provide sufficient protection to minimise the force of the detonation."

Cautiously extending himself, he peered over the edge. In the fast-gathering gloom he could just discern the mine as it rolled to and fro on the shelving sand. The waves had almost borne it to the base of the rocks.

A new danger now confronted the stranded man. Perilous as the climb had been, the descent was doubly dangerous. When the time came, he could no more essay the feat of regaining the beach than he could hope to clamber up the remaining two hundred feet of beetling cliff. Unless aid were forthcoming, he was in danger of perishing of cold and hunger.

Mr. Greenwood's next step was to prepare for his approaching vigil while there was yet light enough for him to see. The ledge was almost twelve feet in length and five in its widest part, gradually diminishing to nothing at either end. One portion was covered by a withered bush, a circumstance that aroused the investigator's curiosity, since it seemed remarkable that vegetation could grow on the face of a granite cliff.

"Thank goodness I have pipe, matches, and tobacco," he thought philosophically. Now that the immediate danger was past, he determined to make the best of things.

He again directed his attention upon the bush. To use it as a seat would be preferable to sitting on the hard, cold rock.

As he sat the bush gave way. In vain he clutched wildly for support. Toppling backwards, he disappeared into what appeared to be the solid rock.

For some moments he lay helpless, too dazed to realise what had occurred. He was almost in darkness. A peculiar pungent smell assailed his nostrils. Could it be possible that he owed his present predicament to the explosion of the derelict mine?

After a while Mr. Greenwood raised himself. Grimly he reflected that his visit to Auldhaig had not been uneventful. Adventures were crowding upon each other's heels. His zest for excitement was increasing.

The bush had broken his fall. He found himself on a flat floor of what appeared to be a cavern. Where the foliage had been, appeared an irregular opening through which the dim twilight filtered without sufficient intensity to reveal his surroundings.

"One thing, I've a roof over my head," he soliloquised. "Now I am getting on. But I really cannot understand this peculiar odour. It reminds me very forcibly of a garage. Yes, petrol fumes. To be on the safe side I don't think I'll smoke just at present. In fact, I think it would be well to investigate."

Cautiously and on all-fours Mr. Greenwood commenced his tour of discovery, crawling lest there should be a hole in the floor.

Soon his head came in contact with a metallic object. It was a filled petrol tin, one of dozens, possibly hundreds, stacked in orderly manner against one wall of the cave.

"Now, that's strange," murmured Mr. Greenwood "It is pretty certain that that lot would not have been brought into this place from the cliff, so there must be an outlet besides the hole through which I tumbled. Why should a place like this be chosen to store petrol? And why was the hole so carefully hidden with a dead bush? It looks jolly fishy. Of course I've heard plenty of talk of German secret petrol-bases in Great Britain, but I never believed the tales. By smoke! I fancy I've stumbled upon one now. The first question is, how am I to find a way out without being seen?"

Resuming his cautious crawl, Mr. Greenwood penetrated into the recesses of the cave, keeping within touch of the rows of petrol-cans on his right. Contrary to his expectations, the floor was smooth, though tending to rise in the direction in which he was proceeding.

At about twenty yards from the hole through which he had tumbled, he remembered that he had left his tracks uncovered. No need to creep on all-fours now, for he had the irregular patch of light to guide him. Grasping the displaced bush, he replaced it in the opening, and chuckling to himself he again resumed his tour of exploration.

His spirits were rising rapidly. The love of adventure, that had lain dormant for years, was reasserting itself. Also he began to realise that he had now a chance of doing something definite for his country—a chance that hitherto had been denied him on account of his age.

He had quite forgotten the derelict mine. The fears that he had entertained on that score had been completely dispelled by the thought that he had lighted upon a discovery of real national importance—the existence of a secret base for hostile submarines.

For quite a hundred yards he groped his way. The darkness was so intense that it appeared to have weight—to press upon his eyes. The tunnel, too, had contracted, for by extending both his arms he could touch the enclosing walls. Once or twice he stood erect to relieve the aching muscles of his back. He could then just touch the roof, which, although of solid rock, was bone-dry.

Suddenly his forehead came in contact with a hard object. It was the bottommost step of a stout ladder. The steps extended from side to side, for the tunnel was still contracting. Further progress, except by the ladder, was impossible, since the wall of rock terminated a short distance beyond the base of the steps.

Mr. Greenwood examined his surroundings with great exactitude before attempting the ascent. Everything had to be performed by the sense of touch. The steps were of far greater thickness than the usual type of ladder, and were more apart. Apparently they had been constructed to bear very heavy weights, each one being strengthened by means of a circular iron bar on the underside.

"I'm half inclined to use a match," thought Mr. Greenwood. "It's risky, with all those petrol fumes about, but—— No, I won't; I'll make the best of it."

Slowly he ascended. It reminded him of an infant attempting to climb a staircase for the first time. The steps, in spite of their solidity, creaked under his weight. The sounds, intensified by the enclosed surroundings, added to the uncanniness of the mysterious cave.

At the eighth step he found a trap-door above his head. It was what he expected; but the question arose, what was on the other side? He had no desire to blunder into the presence of half a dozen desperadoes, who would doubtless have no scruples in knocking him over the head and toppling his corpse down the cliff.

Even as he was considering the best thing to be done, he heard footsteps overhead and a deep voice exclaiming, "Now, then, Max; let's get on with the business. It's quite time we showed the signal. Hand me yon crowbar and bear a hand to lift this trap. It's heavy."

"No, I don't want to meet Max & Co.—at least, not just yet," soliloquised Mr. Greenwood as he hurriedly and silently descended to the floor of the tunnel. His first thought was to retrace his steps, scramble through the opening and lie at full length upon the outside ledge, until he realised that the mysterious frequenters of the cave would still be between him and freedom.

Then he remembered that there was a space between the foot of the ladder and the end of the tunnel. It was not at all likely that this would be examined.

With an agility that he did not think himself capable of, Mr. Greenwood crawled between two of the steps and crouched in his place of concealment.

Barely had he done so when the trap-door was raised. A flood of light streamed from above, although, fortunately, the flight of steps threw a strong shadow upon the recumbent form of Mr. Greenwood.

"You vos leave open der door?" inquired a guttural voice.

"Yes, Max," was the reply. "It's main heavy, and there's no call to exert ourselves to bustin'-point. No one'll come here after dark."

The speaker descended, holding an electric torch in his hand. He was a short, thick-set fellow, dressed in soiled velveteens. He looked a typical gamekeeper.

The person addressed as Max followed. He was a tall, fair-haired, broad-shouldered man of about thirty years of age. He wore a long overcoat and muffler, a hard felt hat, grey trousers and brown boots, the latter being almost hidden under a thick deposit of mud.

"I've got a rope further along," continued the short man. "When they answer our signals and send a boat, I'll lower you down. Only don't forget it's cash on the nail."

"Vot vos dat?" asked Max.

"The fifty pounds agreed upon. We'll signal at intervals, but don't be too jolly cocksure. They can't always be to time. If they show up afore four in the mornin', count yourself lucky."

The men, still talking, moved down the tunnel, until a bend, that Mr. Greenwood had passed without being aware of it, screened the light from the place where he lay concealed.

"Now or never," he thought.

Extricating himself from his cramped position, he scaled the ladder. Then, with his head almost level with the trap-door, he waited until his eyes grew accustomed to the blaze of light.

The opening was placed in the floor of a room—the kitchen of a small cottage, apparently. The two windows were heavily curtained. The door was secured, in addition to the massive lock, by a stout oaken beam resting in iron staples at either end. The furniture was scanty, consisting of a deal table, on which lay the remains of a meal and a large oil-lamp; three rush-bottomed chairs; a dresser, and a well-worn horse-hair couch. On one of the beams overhead were slung a couple of double-barrelled sporting guns. Opposite the door was another opening to a second room.

Mr. Greenwood's first impulse upon emerging from the tunnel was to slam the heavy trap-door and pile the furniture on top of it. But, he reflected, the men had a means of escape by the rope of which the short man had spoken. Moreover, they would raise the alarm and prevent the approach of the expected boat, which, more than likely, would put off from a German submarine.

No, he must make his escape without arousing suspicion. It would be an easy matter to unbar the door, but since he could not replace the cross-bar after he was outside, such a step would be unwise.

Throwing back the curtain he tried one of the windows. It was a latticed casement. With a little agility he could squeeze through, replace the curtain and trust to luck that the unsecured window might escape detection.

Two minutes later he was breathing the open air—a free man.

He looked about him. The night air blew cold. He had no idea of the direction of Auldhaig. For the time being his quest for the cruiser was out of the question.

Far away and at a considerably lower level two rows of lamps glimmered through the darkness. They were the anchor lights of the decoy boats of the fleet lying in Auldhaig Harbour. The town and the actual ships were shrouded in darkness, but every night numbers of small boats, each showing a white light, were moored at some distance from the fleet. At one time they might be placed half a dozen cables' lengths to the north'ard of the anchorage, at another a similar distance to the eastward, the idea being to mislead any Zeppelin that might attempt to drop bombs upon the harbour and shipping.

Setting his face towards the friendly lights, Mr. Greenwood began the descent of the rough hillside. Before he had gone a quarter of a mile the irresistible yearning for a pipe assailed him. Turning his back to the wind, he struck a match, and was soon puffing contentedly at his gratifying briar.

Suddenly half a dozen dark forms pounced upon him. Before he could utter a sound he was seized by a pair of muscular hands, and a hoarse voice exclaimed:

"Now, then, wot's your little game? Flashing lights at this time o' night, eh?"

Mr. Greenwood did not immediately reply. His dignity as a respectable British citizen had been outraged. He drew himself up with as much hauteur as the circumstances would permit.

"Allow me to inform you," he said stiffly, "that I will not be spoken to in this dictatorial manner."

"All right, old sport, don't bust yourself," rejoined his questioner. "Now, what are you doing here this time o' night? Wanderin' along the cliffs at ten o'clock wants a little explanation."

"As a matter of fact I was looking for H.M.S. 'Pompey,'" began Mr. Greenwood.

A roar of laughter greeted this announcement.

"D'ye expect to find her on top of a cliff?" asked the man when the merriment had subsided. "Look here, this is a serious matter. We're the Coast Patrol. We saw a light about a quarter of an hour ago and another just now."

"When I lit my pipe," added Mr. Greenwood, who, still ruffled by his reception, had decided not to impart the secret to the uncouth crowd that had waylaid him; "and what I said about the 'Pompey' is absolutely correct. I was directed along the cliffs, missed my way, and got cut off by the tide. My object was to visit my son, who is an officer on board the cruiser in question. If you have any reason to doubt my statement, inquiries on board will remove all suspicion."

"You came up over the cliffs, sir?" asked the man respectfully, for Mr. Greenwood's declaration that he was the father of a naval officer could not lightly be ignored.

"I did," replied Mr. Greenwood with studied pride. He did not think it necessary to explain how.

"Well, you're a game 'un, pardon my saying so. P'raps, sir, you won't mind if we sees you back to the town. Dooty is dooty, an' we must satisfy ourselves that you are what you says you are. Got any friends at Auldhaig?"

Mr Greenwood was adverse to causing his daughter anxiety at that time of night. At the hotel he was known only as a stranger putting up for a few days.

"I'm afraid I haven't," he replied. "But, if it is not too late, I suppose you could accompany me on board the cruiser?"

The men conferred amongst themselves; then the spokesman again addressed the object of his suspicion.

"All right, sir; that'll be the best way, I'm thinking. Best foot forward, sir. We may just catch the six-bell boat from the staith."

The speaker and another member of the patrol fell in on either side of their suspect, while the rest of the party disappeared in the opposite direction.

"We are members of the National Guard," explained the senior of the two men. "'Tain't exactly a soft job, but it's something. Not often do we come across strangers on the cliffs after dark. When we do, we generally run 'em in. My word, I'd like to know how you got up here from the beach, sir!"

Mr. Greenwood declined the bait. He was well satisfied with the way events were shaping themselves. In spite of his misadventures and the lateness of the hour, he stood a fair chance of seeing his son that night.

Half an hour's steady tramp brought him and his escort to the staith or quay. Answering the challenge of the armed seaman on sentry, the patrol men ascertained that the "Pompey's" boat had not yet put off to bring back a party of officers who had been ashore on leave.

Presently several great-coated forms appeared through the darkness. Amongst them was the commander.

"Beg pardon, sir," said the sentry. "Three civilians require passage to the 'Pompey.'"

"Eh, what?" queried the commander. "At this time of night? What for? Who are they?"

Mr. Greenwood seized the opportunity by explaining to the naval officer that he had urgent reasons for seeing his son—Assistant Paymaster Eric Greenwood, R.N.R.

"Personal reasons?" asked the commander. "I am afraid you will have to defer your visit till the morning. Sorry; but personal considerations have to stand aside in wartime. And who might your companions be?"

"My—er—my goalers, I suppose I must term them," explained Mr. Greenwood. "I am, I believe, under arrest. In addition to personal reasons I have a matter of national importance which I wish to bring to the notice of the authorities. Since I know only two people connected with the service, both of whom are officers on the 'Pompey,' I thought—— But I'd rather explain to you alone."

The commander hesitated. He was a genial man, ready to do anyone a good turn. If, however, he took the responsibility of introducing a civilian on board on the strength of what might prove to be a cock-and-bull story, he might be rapped over the knuckles by the Admiralty—and, he reflected, being rapped over the knuckles by My Lords generally resulted in the sting remaining for many a long day.

"Why not make your report to the flag captain?" suggested the commander suavely. "His shore office is open day and night, and that would save you a tedious boat journey on a cold night like this."

Mr. Greenwood could be very obstinate when occasion arose. Having gone thus far, he was determined to see the business through in the manner he had intended.

"No, sir," he replied. "I do not want to run about after flag captains at this hour of the night. If you cannot see your way clear to accede to my request, the important matter of which I hinted must wait. The responsibility which is no light one—will be transferred to other shoulders."

It was the turn of the commander to be taken aback. He was not used to be talked to like this by civilians. He tried to fix the middle-aged gentleman with his best quarter-deck glare, but the darkness foiled him. Had he been able to see the dishevelled individual in the light he would doubtless have come to the conclusion that he was being tackled by a person with an unhinged mind.

"Very well—carry on," he exclaimed. "Here's the boat. Coxswain! assist this gentleman into the stern-sheets."

"And us, sir?" began the National Guard, but the naval officer "choked him off."

"No, no," he interrupted hurriedly. "I'll be responsible for your—er—prisoner."

Guided by the coxswain, Mr. Greenwood stepped off the quay into the stern-sheets of the picquet-boat. In fifteen seconds he found himself sandwiched between two young officers, while another half a dozen completely crowded out the strictly limited space.

The coxswain sounded a bell in the engine-room. The engines were reversed and the long, lean boat backed from the quay. Then, at full speed ahead, she glided rapidly, without lights, through the pitch dark waters of Auldhaig Harbour.

"Pass the word for Mr. Greenwood," ordered the commander as Greenwood, Senior, found himself on the quarter-deck.

The voyage, short as it had been, was a revelation to him. It showed him how the navy men handle their boats on a winter's night, without a light to guide them, and unable themselves to show the orthodox red, white, and green steaming lights. He was in momentary dread of finding himself in the water owing to the picquet-boat either colliding with something or else being cut in twain by another marine race-horse. He marvelled at the sangfroid of his uniformed companions, who chatted and cut jokes with each other with the utmost unconcern. The hoarse challenge "Boat Ahoy!" from the sentry on the "Pompey's" fore-bridge and the seemingly inconsequent "Aye, aye" of the picquet-boat's coxswain gave him an insight into the ceaseless vigilance of Britain's first line of defence.

Almost in a whirl he found himself ascending the accommodation-ladder and gaining the spacious quarter-deck.

"Eric, my boy!" exclaimed Mr. Greenwood delightedly, as his son, arrayed in unfamiliar garb, ascended the companion.

"By Jove! pater, what on earth brings you here?" inquired the A.P., astonished at the identity of his visitor. Then he paused, having become aware of the presence of the commander, who stood like a guardian angel behind the benighted visitor.

"Your father has told me that he wishes to communicate a matter of urgent importance, Mr. Greenwood," said the commander. "I think it would be well if you saw him in your cabin. If, in your opinion, the business is urgent, you will please report to me."

He moved away to consult with the officer of the watch before going below. Father and son stood irresolute; Mr. Greenwood hardly knowing how to begin, while Eric was beginning to wonder how and by what possible means could his parent possess a certain knowledge that would require to be reported to the commander.

Down the ladder and the half-deck Mr. Greenwood followed his son. Here an alert sentry drew himself up as the young officer passed. Then the stolidity of his face gave place to an amused expression as he noticed the dishevelled appearance of the A.P.'s companion.

"This way," continued Eric. "My cabin's under repairs. Haven't got it quite ship-shape after that little affair off the Belgian coast. I'll take you into Tressidar's cabin. Of course you know he's shipmates with me?"

He knocked at the metal door. Receiving an invitation to enter, he opened the door and drew aside a curtain. The cabin was small and brilliantly lighted. Over the closed scuttle a curtain had been drawn to make doubly sure that no stray rays were visible from without.

Seated in an arm-chair drawn close to a very small and compact stove was Sub-lieutenant Ronald Tressidar.

"I say, old man——" began Eric; then, noticing the look of astonishment in the sub.'s eyes, he broke off and followed the direction of Tressidar's gaze. For the first time he became aware of his usually precise parent's appearance.

Mr. Greenwood wore his coat buttoned tightly round his throat. The coat was literally caked with mud and dust and in addition was rent across the right shoulder. His face was as dirty as the proverbial tinker's; on his left cheek was a line of dried blood, the result of an unheeded scratch received in his tumble in company with the dead bush. His hair, generally sleek and well brushed, was tousled and matted with wisps of grass.

"Pater!" exclaimed Eric in utter amazement.

"It's all right, my boy," declared Mr. Greenwood reassuringly. "I've had the night of my life—absolutely. No, don't go, Tressidar. Listen to what I've discovered."

"Have a stiff glass of grog, sir?" asked the sub., after Mr. Greenwood had washed his face and hands and had smoothed his ruffled hair.

"Thanks, I could do with one," replied Greenwood, Senior. "In fact, I was on the point of asking for a whisky, only I thought from your look of astonishment that you imagined I had already had one too many. No, thank Heaven, I've got off lightly, but I've left my best umbrella on the beach."

"Fire away, pater," said Eric. "We are all attention."

Mr. Greenwood "fired away." Uninterrupted he pursued his narrative until he came to the discovery of the supposed derelict mine.

"It wasn't glass by any chance?" asked Tressidar.

"Glass?" repeated Mr. Greenwood. "Well, now I come to think of it, perhaps it did resemble glass. But why do you ask?"

"Because, judging by your description of its size and buoyancy, I am inclined to think that your mine was one of the glass buoys we use for marking the position of our submarine obstructions. After on-shore gales the coastguards find hundreds of them."

The narrator mopped his forehead. A wave of horrible uncertainty swept over him. Perhaps, then, the second episode of his nocturnal. adventures would have similar harmless interpretation?

"Carry on, pater," said Eric encouragingly.

"By Jove, sir!" exclaimed Tressidar, when Mr. Greenwood arrived at his discovery of the petrol-depôt. "Cut it short, if you don't mind. Let's have the salient facts. Every minute is of extreme importance."

Five minutes later the sub. was reporting the matter to the commander, who, in turn, communicated the discovery to the captain.

In ordinary circumstances the captain of the cruiser ought to have submitted a written report to the senior naval officer at Auldhaig, but red tape had long since gone by the board so far as naval matters were concerned. Other Government departments were still tied hand and foot with fathoms of red tape. Well it was that at the Admiralty the Gordian knot had been severed on that memorable 4th of August, 1914.

In a very short space of time the skipper's plans were formed. A landing-party, under the orders of Sub-lieutenant Tressidar, was to proceed at once to the solitary cottage. Since Mr. Greenwood was very hazy as to its locality, the assistance of the National Guard forming the coast-patrol was to be requisitioned.

Two pulling-boats, in charge of the first lieutenant, were to proceed to the bay where the entrance to the cave was situated. Mr. Greenwood's description of the spot was sufficiently accurate for the place to be identified. Examination of the chart showed that for miles northward from the entrance to Auldhaig Firth there was only water deep enough for a submarine to approach within easy distance of the shore at this particular indentation, which bore the name of Sallach Dhu Bay.

Eric Greenwood asked and obtained permission to accompany the landing-party. He felt that as his father had been the means of locating the petrol-store, his son had a kind of interest in the proceedings.

Mr. Greenwood, who was now feeling the reaction of his unwonted exertions, asked to be put ashore. He was content to have a good night's rest at the hotel and learn developments in the morning.

"Bless my soul, Eric!" he exclaimed as his son, with a conspicuous revolver-holster strapped to his great-coat, appeared in the doorway of his cabin. "What are you doing with that weapon? I thought assistant paymasters were non-combatants?"

Eric grinned. He did not think fit to enlighten his parent on the matter. Mentally he recalled a certain forenoon off Ostend. For three hours he was on duty in the fore-top, with hostile shells flying thick and fast. One, he vividly remembered, hurtled a few feet from the mast, cutting away the shrouds on the starboard side, but fortunately without exploding. He and his comrades in that lofty perch had missed annihilation by almost a miracle.

"Get so much work in the ship's office that I'm glad of a breather," he remarked. "Oh, by the way, we're having a sort of informal reception on board to-morrow afternoon. Several of the officers' wives and families are turning up. You might bring Doris, and then you can sample naval hospitality in wartime. The boat will be at the staith at six bells—that's three o'clock."

"Come on, old man," called out Tressidar. "The boat's alongside. Are you ready, Mr. Greenwood?"

The cutter, in which about twenty armed seamen were already seated, had dropped back from the boom to the accommodation-ladder. Tressidar, the A.P. and a midshipman were Mr. Greenwood's companions in the stern-sheets.

At the landing-place Mr. Greenwood waited as the men silently "fell in," while a seaman hurried off to enlist the services of the National Guard to guide them to the scene of operations.

In a very short time the two coast-patrol men arrived. Briefly the situation was explained to them. Tressidar gave the order, and the landing-party moved forward and were soon lost in the darkness.

For some moments Mr. Greenwood stood still, hardly able to convince himself that he was not dreaming. Then he broke into a run in the direction of the armed men. Guided by the thud of their footfalls, he overtook them before they were clear of the market-place.

"I say, Eric," he exclaimed breathlessly. "If you've a chance there's my best umbrella on the beach. Don't forget it, if you can help it, there's a good lad."

And having eased his mind on that point, he wended his way to the Bantyre Hotel.

"There's the cottage, sir," whispered one of the guides, pointing to a dark object silhouetted against the starlit sky.

The sub. halted his party and called them to attention. Six of them with the A.P., were to accompany him to the house; the others, under the command of the midshipman, were to form a cordon round the building and also to establish communication with the boats when the crucial time arrived.

Stealthily Tressidar approached the window through which Mr. Greenwood had effected his escape. The casement was ajar. He opened it and drew the curtain aside the fraction of an inch. The room, still lighted, was deserted. Signing to his men to remain, he stole quietly through the window and approached the trap-door leading to the tunnel. He could detect the fumes of petrol. With the burning lamp the cottage was in momentary peril of being blown up by the ignition of the air and volatile spirit with which it was so highly charged. Either the occupier was a madman or a fool, he argued.

Unbarring and unlocking the door, Tressidar brought his men into the room. Extinguishing the lamp, he switched on his electric torch and led the way down the ladder to the tunnel.

Contrary to his expectations, the descent was effected without any of the seamen stumbling, dropping their rifles, or making a noise that would betray their presence. In silence the men awaited their officer's next order, which was given by signs.

Tressidar weighed the matter over in his mind. To act quickly it was necessary to have light, since the darkness gave the miscreants an undoubted advantage. To attempt to stalk them in the pitch-black darkness would be running a risk of premature discovery. As far as he knew, there was about eighty yards of tunnel, including a fairly sharp bend between him and the seaward end of the cave.

Still keeping the torch switched on, Tressidar advanced swiftly and silently down the tunnel. He found not one but two turns in the passage. Upon rounding the second, the rays of his torch fell upon the two men of whom he was in search.

They were both lying across the sill of the natural opening communicating with the outside ledge. Both had night-glasses glued to their eyes, and so intent were they in keeping the expanse of dark water under observation that they failed to notice the illumination that flooded the cave.

There was no peremptory order of "Hands up!" No dramatic covering with revolvers. The British seamen simply grasped the recumbent men and dragged them back to the floor of the cave almost before they had time to utter a sound.

"Take that fellow back to the cottage," ordered the sub., indicating the man who had been addressed as Max. "Search him, question him, then report to me."

The German was hurried off. He offered no resistance.

Tressidar waited until unmistakable sounds told him that Max and his captors were ascending the ladder, then he turned to the second prisoner.

"You are expecting to communicate with a German submarine?" he began.

"No, sir, no," expostulated the man, his face contorted with fear. "I'll explain everything. I'll make a clean breast of it. That man"—and he pointed with his thumb along the tunnel—"is an escaped prisoner. He is a German officer. Some of my pals put him on to me, and, like a fool, I said I would hide him until a fishing-boat could take him across to Holland."

"You're a British subject," declared the sub. contemptuously.

"I am, sir. Never got into trouble before this. I've been led into it, sir, honest, I have."

"Honest you haven't," corrected Tressidar sternly. "Now, listen, you know the penalty—death.

"What, for harbouring a German prisoner, sir?" asked the man.

"No—for supplying hostile vessels with petrol. You have hundreds of gallons stored here, and I'll swear you cannot satisfactorily account for that quantity. Moreover, you were heard to say that a submarine was expected about three or four in the morning. Now, look here, what are the prearranged signals?"

"Curse you!—find out," muttered the man surlily.

"I mean to," rejoined the sub. suavely. "Let me put the facts before you. You're caught red-handed. There are no extenuating circumstances. You are deliberately betraying your country for the sake of a few hundred pounds, I suppose. If you give us all the assistance that lies in your power, that fact will be taken into consideration at your trial. I'll vouch for that. Now, I'll give you five minutes to think things over."

Leaving the prisoner in charge of a couple of seamen, the sub. approached the seaward entrance. Drawing his binoculars from their case, he focussed them on the water of the bay. The tide was now on the first of the ebb, with perhaps six feet of water close to the base of the cliffs.

By the aid of the powerful night-glasses he could just discern the grey forms of the "Pompey's" two boats. The first lieutenant had lost no time in proceeding to the spot, for his preparations were already complete, and the boats were even now withdrawing to a discreet distance to await developments.

With a grunt of satisfaction Tressidar replaced his binoculars and again confronted his prisoner.

"Time's up!" he exclaimed laconically.

"I'll tell you everything——" began the man.

"And mind you speak the truth," warned the sub. "Now, fire away."

"A submarine is expected," declared the prisoner. "At what hour I cannot say—it might be any hour between now and daybreak. She won't show any lights. She'll anchor in Half Way Deep and send a boat ashore. The men will imitate the curlew call three times, and I was to reply with a cry like the hoot of an owl. Then I had to lower petrol-cans as fast as I could."

"And your companion?" inquired Tressidar. "Who is he?"

"As I said before, sir, a German officer who broke out of one of the prison camps."

"His name?"

"I don't know, sir, except that it's Max."

The prisoner, who gave his name as Thomas Telder and was a gamekeeper in the employ of a large landowner in the vicinity, was removed under escort to the cottage, while the midshipman, having questioned the German, appeared to report to his superior officer.

"The fellow's a pretty cool customer," declared the midshipman. "Now that the game's up he doesn't appear to mind in the least. He says his name's Max Falkenheim, and that he's an unter-leutnant of the cruiser 'Mainz.' He was one of those fellows who were reported to have escaped from Donington Hall by digging a tunnel."

"Jolly rummy that he should fetch up here," commented the sub. "He's a long way out of his reckoning."

"Unless the east coast of England is too closely guarded," added the midshipman. "However, the fact remains that he was within an ace of getting clear. He swears he knows nothing about the unterseeboot, but that he had agreed with that skunk to put him on board a lugger."

"H'm; well, that's good enough for us. See anything, Parsons?" added Tressidar, addressing one of the seamen who had been told to keep a sharp look-out.

"No, sir; fancied I did, but it was a wash-out."

"Any of you men know how to hoot like an owl?" asked the sub.

"Yes, sir; I do," replied a tall able seaman, who in his youth had been a farm hand in the North Riding of Yorkshire.

"Very good; stand by, and when Parsons reports the submarine's signal—three cries of the curlew—do you hoot: once only, remember. The rest of you stand easy. I say, Greenwood, you might rummage up aloft and see if there's anything of an incriminating nature in the cottage. Make sure that all the blinds are drawn. I'll give you the word as soon as the strafed U-boat is sighted, if you don't finish before."

As a matter of fact the A.P. carried out his orders long before the submarine revealed her presence. It was within an hour and twenty minutes of sunrise—the tide being well on the flood—that the long-expected cry was faintly borne to the alert ears of the watchers.

Promptly the able seaman replied, and barely had the weird echoes died away when the sub. heard the muffled sound of oars being boated and the crunch of heavy boots on the dry kelp.

"Right you vos," exclaimed a guttural voice. "Lower der cans as fast as you vos like."

In reply Sub-lieutenant Tressidar whipped out his revolver and fired three shots in quick succession into the darkness. Then, with nerves a-tingle, he waited.

It will now be necessary to follow the movements of the two pulling-boats under the orders of the first lieutenant. On putting off from the cruiser, the boats made for the harbour's mouth. Outside the sea was fairly smooth, with a long, oily swell, for during the night the wind had backed to north-west and blew diagonally off shore.

Owing to the proximity of several dangerous ledges that extended seven or eight cables' length seaward the boats had to make a long detour before they arrived at Sallach Dhu Bay.

"We can't be so very far off now," remarked the first lieutenant to the midshipman in his boat. "It's that confoundedly black that goodness only knows where we are."

"Allowing for the tide, sir, I should think we're almost over Half Way Deep. Shall I have the lead heaved, sir?"

A cast gave the depth at two fathoms—certainly not enough to float a submarine, still less to enable her to submerge. The leadsman could feel the sinker trailing over the rocky bottom, as the boat drifted with the tidal current.

Again and again the lead-line gave approximately the same soundings. The first lieutenant began to have doubts as to whether he had already overshot the looked-for spot.

Suddenly the water increased in depth to fourteen and a half fathoms. That, allowing for the state of the tide, was the depth shown in the chart for Half Way Deep—a bottle-shaped depression extending well into the otherwise shallow waters of Sallach Dhu Bay.

The kedge was let go and, riding head to tide, the boat brought up, to enable the first lieutenant to confer with the officer in the second boat.

Carefully screening the light with a piece of painted canvas, the "No. 1" consulted the boat-compass.

"North one hundred and ten east, is your course," he announced to the officer in charge of his consort. "That'll be taking into consideration the cross set of the tide. I'll pay you out a hundred and twenty fathoms of grass warp, then you'll steer due north. When you've let go all the charge, make for the shore. We'll be on the look-out for you. Suppose you've tested circuits?"

"You bet," replied the other with a grin. "Between us there won't be a fish left alive in Half Way Deep, or a strafed U-boat either, I hope."

The second boat pushed off, her coxswain steering by means of a luminous compass. As soon as the strain of the connecting line grew taut, her kedge was dropped. Then both boats, approximately two hundred yards apart, allowing for the sag of the grass-rope under the influence of the tide, rowed on parallel courses, paying out lengths of sinister-looking objects that resembled strings of exaggerated sausages. This they continued to do until Half Way Deep was mined by a double chain of explosives.

The first lieutenant's boat was the first to reach the shore. Cautiously the crew scrambled out and drew her clear of the water, a petty officer handing the battery and firing-key ashore as carefully as if it were made of priceless metal.

Five minutes later the second boat loomed through the darkness.

"All correct, sir," reported her officer. "Suppose this is the bay? Wish to goodness I could smoke."

"And so do all of us, old boy," replied No. 1. "But curb your desires: you'll see plenty of smoke presently."

Huddled together under the lee side of the boats the two crews spent a tedious time, while their officers, treading softly, walked up and down the sands.

At intervals they exchanged curt sentences in whispers; otherwise the strictest silence was maintained. As the night wore on, the first lieutenant consulted the luminous dial of his watch with increasing frequency, until he began to wonder if the A.P.'s parent had been dreaming or was the victim of hallucinations. But throughout his monotonous patrol No. 1 took good care to keep within twenty yards of the firing-battery.

Presently he stopped dead and listened intently. Yes, he could just detect the faint sounds of muffled oars. The noise came from a spot considerably nearer than he anticipated: much too close to the drawn-up boats. What if the new-comers spotted the grey shapes as they lay on the sand?

The seamen heard the sounds, too, for several of them knelt up and peered over the gunwales. There was a concerted movement of the now alert men. The tedious vigil in the bitterly cold night was forgotten.

Then through the darkness came the curlew cry of the submarine's men, followed by the distant hoot of the British seaman who had been deputed to assume the rôle of an owl. What these meant the first lieutenant knew not. His pre-arranged signal had not yet been received. Bang! bang!! bang!!!

Fifty feet in the air the blackness was pierced by three vivid flashes, to the accompaniment of the sharp cracks of cordite-charged cartridges.

"Now!" shouted the first lieutenant.

The men in charge of the firing-batteries depressed the keys that completed the circuit.

Instantly the waters of Half Way Deep were lashed into two parallel columns of foam as a double chain of cascades leapt a hundred feet or so in the air. Then a terrific crash, mingled with the roar of the falling water and the thud of fragments of flying metal coming in contact with the granite cliff.

In the village of Auldhaig the concussion was severely felt. Window-panes were shivered; solidly built houses literally rocked. People, aroused from sleep, dashed blindly for the streets or to their cellars, fully convinced that the Zeppelins had arrived. Only one individual slept through it all; Mr. Greenwood, dreaming of petrol-cans, floating mines, and his lost umbrella, and buried under the bed-clothes, knew nothing of the concussion until next morning, Barely had the echoes died away ere the first lieutenant and his party were doubling along the beach towards the place where the unterseeboot's dinghy had landed.

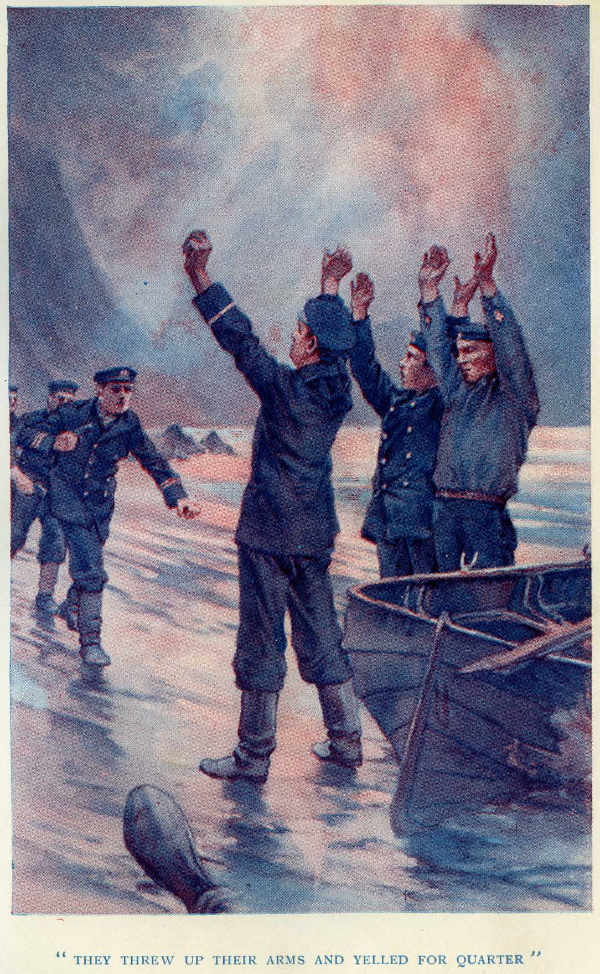

The canvas boat, with a long rent in her bilge, had been carried far up the shore by the rush of water following the tremendous upheaval. Her crew, consisting of a petty officer and two men, were too dazed to offer resistance, for upon the approach of the bluejackets they threw up their arms and yelled dismally for quarter. Almost at their feet was a large fragment of metal—one of the propeller blades of the shattered submarine.

"Are you all O.K., Mr. Tressidar?" sang out the first lieutenant.

"All correct, sir," replied Ronald. "We've nabbed the pair of them."

"Very good," rejoined No. 1. "Leave four men to guard the cottage and return to the ship. By the bye, have you a cigarette to spare? I left my case on board."

It did not occur to the speaker how he was to receive a cigarette from the sub., who was fifty feet above him, until he became aware of a dark object descending the cliffs by means of a rope.

Eric Greenwood, with a double purpose, had ordered two of the men to lower him to the beach.

"Here's my case, No. 1," he announced, as he fumbled under his pile of clothing. "Matches? You have? Would you mind giving me a passage back in the boat? I have a little commission to undertake."

Receiving permission, the A.P. made his way along the beach, the first lieutenant watching him curiously, for dawn was now breaking. Presently Eric returned with his parent's umbrella.

An hour later both boats ran alongside the "Pompey." Tressidar had already returned and had lost no time in making his report and retiring to his cabin to make up for arrears of sleep.

In spite of the early hour Captain Raxworthy was on desk, and as the first lieutenant came over the side he was waiting to congratulate him.

"An excellent night's work, Mr. Garboard!" he exclaimed delightedly—"a most excellent night's work!"

"Say, Snatcher, you're warned for D.B. party, ain't you?" inquired Stoker Jorkler. "D'ye mind if we change about?"

Stoker Flanaghan, commonly known as Snatcher, paused in the act of conveying a knifeblade well laden with peas to his capacious mouth. Such a request—for a man to voluntarily offer to undertake the disagreeable duty of cleaning and painting double bottoms—figuratively "took the wind out of his sails."

"Wot for?" he asked guardedly. "Wot's the bloomin' move?"

"Only there's leave for the starboard watch, and I'm some keen to nip ashore," replied Jorkler. "And you can have my tot of rum for a week if you do."

"Wants considerin', Rhino, old man," declared Snatcher. "Wot price the lootenant of the watch an' the jaunty?"

"They won't twig," said Jorkler. "I guess the bloke don't know the names of half the men in his watch-bill, and the master-at-arms won't care a brass farthing whether it's Snatcher Flanaghan or Rhino Jorkler who goes out of the ship so long as he comes back without being three sheets in the wind. And trust me for that, Snatcher. You've never seen me fresh?"

"True, that I ain't," replied the man reflectively, "or you wouldn't be so keen on chuckin' away your tot o' rum. Orl right, mate."

"Thanks," said Jorkler briefly, and without further delay he hurried off to change into his canvas suit for double bottom work.

Before he left the mess he had transferred a certain object from his ditty-box to his spacious jumper. Then, satisfying himself that there was no suspicious bulge to excite the curiosity of the officer of divisions, he fell in with the rest of the party.

Ten minutes later Stoker Jorkler, armed with a tin of red lead, a brush, some cotton waste, and a lighted candle, was surveying the oval-shaped aperture leading to a confined space between the outer and inner plating of the ship's hull. With him were a dozen others, similarly equipped, under the orders of a leading stoker.

It was not a pleasant occupation that Rhino had taken upon himself. In each of the cellular subdivisions of the hull a man had to crawl in as best he might, having first ascertained by means of the lighted candle that the air was sufficiently pure. Unless the candle burnt clearly, the place was dangerous to life. Stringent regulations were laid down to prevent accidents, fresh air being pumped into the double bottoms, while men were always on the watch to see that the workers were unaffected by the poisonous gases from the red lead.

"Right as ninepence," declared the leading stoker, referring to the light that gleamed in the space to which Jorkler had been detailed. "In you get, mate, and look slippy."