A Tale of the Tyrol.

BY

The Author of "Mary Powell."

Pro libertate victi, pro fama victores.

LONDON:

Printed for Arthur Hall, Virtue, & Co.

25, Paternoster Row.

1858.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Thunder Storm | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Inn Kitchen | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Shooting Match | 25 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Wolfsthrun | 40 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| "'Tis Time!" | 47 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The First Success | 63 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Innsbruck | 78 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Still Successful | 92 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Home | 103 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Guerilla Warfare | 118 |

| CHAPTER XI.[iv] | |

| Tyrolese Courtship | 130 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Berg Isel | 145 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The latter end of a Fray, and the beginning of a Feast | 159 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Troubled Waters | 171 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Gorge of the Eisach | 182 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Third Victory of Berg Isel | 195 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Reverses | 210 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Danger | 224 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Winter on the Mountains | 239 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Châlet | 253 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Tyranny rampant, Grace triumphant | 266 |

THE YEAR NINE.

IT was dusk; and the mountains were reverberating with loud thunder-claps, while the rain helped to swell a turbid river that swept through the valley, and past the door of a small wirth-haus or inn, known less by its sign of "The Crown," than as "am Sand," by reason of the strip of sand on which it was built.

A cheerful looking, comely woman, clad in a superabundance of woollen petticoats, was busy at the stove, cooking the supper of a foot-traveller who read a crumpled newspaper at the window; while surrounding the kitchen-table, three or four peasants, who had been driven in by the rain, were hungrily[2] supping milk-porridge from a large bowl common to them all. A pretty girl of sixteen, after adding to their meal a basket of coarse rye-cakes, spread a small table for the stranger, who, as soon as his supper was served, fell upon it with avidity. His hostess, meanwhile, retired to the end of the kitchen, where there was a great meal-bin, and began to set the bread for the morrow's baking, closely watched, all the time, by two little girls with long braids of hair hanging down their backs.

"The thunder still rumbles," said a man who was quietly smoking near the stove. He was about forty years of age; his person was strong and manly, with slightly rounded shoulders; his full, dark eyes beamed with gentleness; his clustering, deep brown hair fell low on his broad forehead, and continued round his face in a beard that became coal-black towards the chin. He looked kind and enduring rather than impetuous, and not unaptly represented the image of strength in repose.

He wore a close-fitting grass-green coat over a scarlet waistcoat, on which hung a rosary and crucifix between his green, embroidered braces; black knee-breeches, scarlet stockings, and laced half-boots. The quiet self-possession of his manner bespoke him the wirth, or master of the inn.

"The thunder still rumbles," said he.

"Aye aye, Sandwirth," answered one of the[3] peasants, grinning; "better to be under cover than half-way between this and St. Martin's."

"Father," said a lad, running into the house, "two men are coming hither. And I think," added he eagerly, under his breath, "the tallest of them is Joseph Speckbacher."

"Hist!" said his father, laying aside his pipe, while he glanced furtively at the stranger.

At the same time, the rustics, having finished their supper, departed, without caring for the skirt of the storm, which they pronounced clearing off, though large drops continued to fall heavily.

"Those labourers seem content with homely fare," said the traveller, pushing aside his plate.

"They don't taste meat once a fortnight," said the Sandwirth, "and yet you see what strong, active fellows they are. Shall you take a bed here, sir, to-night?"

"No, I would sooner go on, if it were not for the storm."

"It will soon blow over," said the Wirth.

"Perhaps you have a book to lend me, meanwhile?"

"Oh, yes," said the girl Theresa, bringing him one with alacrity.

"This? Hum! the 'South German Plutarch,'" muttered the traveller—"I doubt if I shall not drop asleep over it."

And, laying his legs up on a wooden stool, he began to turn over the leaves.

Two men here came in, panting and laughing. "What a storm!" cried one, laying his conical hat with its drenched feather on the table. "How are you, Anderl?" extending his brown muscular hand to him.

"Well; praised be Jesus Christ!" said the Sandwirth, reverently; to which the two others replied with seriousness—

"For ever and ever, Amen!"

It is the usual Tyrolese ejaculation, when a new comer enters the house. There is something simple and solemn in it, when spoken reverently, which it always is.

"How is your good Maria?" said the Sandwirth's wife, coming forward. "And your little boy, Anderl's namesake?"

"Well, both of them, thanks to God; though Maria has now three youngsters on her hands. But, Sandwirth, have you heard the news? The Archduke—"

"Hist!" again said the Sandwirth softly, laying his hand on the other's breast; and indicating by a wary glance of his eye, the presence of the stranger. The other replied by a look. His companion, a younger man, gave a gesture of impatience, and whispered, "Is he going to stay?"

"All in good time," said the Sandwirth cheerily. "We are just going to sup, and you will join us. One thing at a time will last the longer."

"Aye, Anderl, that is always your word," said his wife, good-humouredly, as she placed about four pounds of boiled bacon on the table. "You never could bear to season eating with business."

"Have you a good horse to sell, just now, Sandwirth?" said the younger and shorter of the newly arrived, by way of general conversation.

"How should I have a horse to sell?" returned the Wirth, dragging a heavy wooden bench towards the table. "I know no more of selling horses, Franz, than you do of selling brandy."

At which they all laughed, as a capital joke. The family and their two friends then sat down to their homely meal.

"So you are going to give us a shooting-match on Sunday," said the young man whom the Wirth had called Franz.

"Ye—s," said the Sandwirth reluctantly; "but I don't altogether like it."

"You don't? And why not, Sandwirth?"

"I doubt it's being quite right."

"Why, it brings you plenty of custom!"

"Aye, Franz; and, in your eyes, that settles the question; but I doubt if it be a good way of spending the Sabbath. If I were a maker of laws, which[6] I'm never likely to be, I'd put down Sabbath-breaking."

"But, Sandwirth," said the taller man, in a peculiarly full, rich, earnest voice, "the Sandwirths, your ancestors, used to give Sabbath shooting-matches on this very spot. Look at the glorious old targets hanging like trophies on your wall. I remember, the first time I ever came in sight of this house was on a Sunday afternoon, and the sharp, quick, rattling reports of the rifles echoed among the hills. You yourself stood umpire among a knot of young fellows in green jackets and red sashes; and your grey-headed father sat at a long table covered with hammers, screw-drivers, powder-flasks, ramrods, and everything that could be wanted."

"He did so, Speckbacher. You bring the scene before me." And the Wirth's deep-set, large dark eyes seemed dwelling on some far-off picture.

"You yourself hit the bull's eye twice, Anderl!"

"I did so, Joseph. 'Twas the day that I told old Gasper, who called me a beardless boy, that if he lived long enough, he should see my beard reach my girdle; and he laughed and said, when that day came, he would give me two oxen."

"So that's the reason you wear a beard!" cried Franz. "But, Sandwirth, surely such a match as that we have been speaking of, was fine sport! I[7] call it play, not work; and therefore no breaking of the Sabbath."

The Sandwirth, however, would not retract.

"Play like that," said he, thoughtfully and impressively, as though he weighed every word before he spoke it, "is often as fatiguing as work; and it sometimes leads to quarrels, and to taking God's holy name in vain. Anyhow, it is not rest; and God bade us rest, mind you, on the Sabbath-day."

"Pleasure is rest," said Franz.

"No, pleasure is often the hardest of work," said the Sandwirth.

"That's true, too," said Speckbacher, as if a sudden light streamed in upon him.

"Well, I know, to lie on my back with nothing to do but twiddle my thumbs, would to me be the hardest work of all," said Franz.

"I wonder," said Speckbacher, after a short pause, "if such are your views, that you mean to have a Sunday shooting-match at all."

"I've a purpose," said the Wirth in a low voice; and then, in a louder key, as he rose and went towards the door, "I am going forth to look at the weather, sir," said he. "The storm has, I think, overblown; but if not, and you like to pass the night here, my wife shall prepare you a bed."

"By no means; if the weather is really clearing[8] up," said the traveller, "I shall yet push on; for it is not late."

"The clouds have rolled off, and the valley is sparkling in the last sun-gleam," said the Wirth.

"Very well. How much to pay?"

"Fifty kreutzers," said the hostess.

"Can you change me this zwanziger?"

While the good woman was mustering change, the traveller rested his chin on his knuckles, and attentively surveyed Speckbacher.

He was undeniably one of Nature's chieftains. His height was uncommon, and his lofty carriage of the neck and head, when excited, worthy of one of the old Greeks. But often that gallant head drooped, and a look of deep depression shaded his countenance. There was something intrepid in his mien; he was one from whom you would never expect to hear a lie, or a sentiment that was base. His language was homely, but energetic; his features were good, his hair and eyes coal-black. His age might be thirty-five.

Franz was full ten years younger, and had tolerable features, but a kind of rakish, good-for-nothing air that was rather repelling.

"Why won't you have anything to say to me?" he was asking Theresa. "You seem to be knitting all your wits into that blue worsted stocking. If Rudolf, now, were here, you'd brighten up directly."

"But as he isn't, there's no occasion for it," said Theresa, carelessly, and continuing to knit with all her might.

"What a pleasant voice you have, Theresa! I wish you would sing us a song."

"That's likely, isn't it?" said the girl.

"Come now, do."

"Thank you, I am going to take my little sisters to bed." And she moved away from him. He looked after her with a mixture of admiration and pique.

Just as the traveller, after some inquiries about the roads, was about to depart, two more men hastily entered. The first was a Capuchin friar, of stalwart make, with the hood of his brown woollen gown pulled so forward that nothing could readily be made out of him but a thick, flowing beard of the hue that partial mothers are apt to call auburn, though others often pronounce it red.

"The peace of God rest on this house, through Jesus Christ our Lord!" said he.

"For ever and ever!" meekly responded the rest.

The Capuchin's companion was a light, active young mountaineer of three-and-twenty, brown as a nut, and well becoming the picturesque national costume. As soon as Theresa, who was just leaving the kitchen, saw him, she reddened very much, and hastily withdrew.

"How the Passeyr is swollen already!" said the Capuchin.

"Is the water out?" cried the traveller, suddenly. "Then I don't know that I've any mind to go on."

"Pooh, pooh!" said the Sandwirth, rather impatiently, "the river cannot have overflowed its banks. You see it has not hindered these foot-travellers. However, sir," changing his tone to one more conciliatory, "if you will oblige us with your company, you shall have as good and clean a bed as any in the Tyrol, though I cannot promise you a flounced pillow and satin damask coverlet, such as you might get at Botzen."

"No, no, I'll take my chance," said the man of indecision. "Is there any one here that will see me through the valley?"

"You cannot well miss your road, sir; but my boy Johann shall start you on it, if you will."

"Thank you; I will give him a few kreutzers."

"No need, sir, thank you."

And the Sandwirth saw him out, and gave him some encouragement about the weather, and watched him off; and then returned laughing. The others laughed too.

"Gone at last!" exclaimed Franz. "I thought he never would make up his mind."

"Now for business," said Speckbacher, looking eager.

"I have hardly spoken to Father Joachim yet," said the Sandwirth, approaching the Capuchin, and kneeling. "Your blessing, father!"

The Capuchin, before blessing him, threw back his hood, thereby revealing a frank, determined, intelligent countenance. He was by no means an old man; probably a few years younger, even, than Speckbacher, and apparently his equal in strength.

"Anna, is there still any supper left?" said the Sandwirth, rather apprehensively.

"Certainly," replied his wife; "I hope Father Joachim will never find our larder quite empty. Johann caught a trout weighing three pounds, this morning."

"Draw in, Rudolf," said the Sandwirth cheerfully to the young mountaineer; "and don't sit at that awful distance, my lad, as if you were not one of us."

Rudolf bashfully obeyed. At the same time, Theresa, who had tucked up her little sisters with considerable expedition, re-entered, and began sedulously to assist her mother in preparing Father Joachim's supper. She had not been absent many minutes, yet had contrived to slip on clean white full sleeves under her trim violet velvet bodice—a circumstance which did not escape the vigilant eye of Franz.

"WHO was that stranger, Anderl?" said Father Joachim.

"A flat-faced Bavarian, I think, father," said the Sandwirth: "cunning as a fox! He took note of every word we said."

"You said nothing incautious, then, I hope?"

"Nothing whatever, father; we talked of shooting-matches and Sabbath-breaking."

"Good. Now then—here is a bag of money."

"For what, father?"

"For laying in stores of various sorts; which you, as an innkeeper, may do without suspicion. You may, perhaps, even contrive to conceal some ammunition."

"Doubtless, father; though this is not a particularly good hiding-place."

"You will be at some expense too about your shooting-matches."

"You think them quite justifiable, father?"

"Quite, my son. I think, in this instance, the[13] end will justify the means. This will be a holy war; and the meetings, ostensibly for sport, will cover our arrangements. None among us are traitors, but some may be indiscreet, and these must not be trusted, but quietly sent away to the mountain châlets. This will be mortifying, but they will still be of service, for some must keep our flocks and herds, or how can the others be spared to fight? There must be one common purpose among us, without heart-burnings or jealousies."

"There must. There shall."

"It is easy to say there must,—there shall,—but are you yourself, Hofer, willing to co-operate with Martin Teimer, or perhaps even occasionally to be subordinate to him? There has been some coldness, I think, between you?"

"On my side, none," said the Sandwirth, after a little hesitation; "I bear him no ill will, nor do I know why he should bear any to me. The man's an able man; more so than I; and has already been raised from a private to a major in the militia, though, just now, he only keeps a tobacco-shop, which is no better, I take it, than keeping a wirth-haus. That's neither here nor there. I'll co-operate with him, or serve under him, whenever it needs."

"This is the spirit that must reign among us all," said Father Joachim. "We must exemplify the[14] Scripture rule, 'Let each esteem other better than himself.' 'Him that is greatest among you, let him be your servant;' if by being so, he can be of the most good. Do you go with me, my children? Can you submit to this? Will you be content?"

"We will!" was simultaneously responded. The two young men spoke lowest: Rudolf, from the modesty natural to him; Franz, because he thought the requirement rather hard.

"Then listen to me. Prepare for action. In a few days we shall rise."

"Hurrah! hurrah!"

And short, loud, abrupt shouts burst from the men's lips. The next instant, their glowing eyes were fixed on the Capuchin in profound silence.

"Yes, my children,—here is the proclamation," continued Father Joachim, drawing a paper from his bosom; "hear it—

"'To arms, Tyroleans! To arms! The hour of deliverance is at hand. Your beloved emperor, Francis, calls on you to arm in a most holy cause, which, after a long and treacherous peace, stands forth like a rock in the deluge, the last remaining defence of the liberties of Europe!

"'You must now either rise while Napoleon is busy in another part of Europe, attempting to load the Spaniards with a foreign yoke, or wait till he has accomplished that project, and returns to crush[15] Austria, the only remaining obstacle to his aim at universal power.

"'Your choice is made! Then look up to us! Everything is already in motion. You will again see at your head your beloved Archduke John, to whom every inch of the Tyrol is known and endeared, and whose greatest pain is ever to be separated from you.

"'It is impossible that a separation between Austria and Tyrol, like that of 1805, can again take place—a separation so bitterly felt! Bavaria declared that the Tyrolese should not only retain their ancient rights and freedom, but that their welfare should be promoted in every possible manner, and "that no iota of their constitution should be changed."

"'How your honest hearts rejoiced at this royal promise! But how has it been kept? You have seen your abbeys and monasteries destroyed, your church property confiscated, your churches profaned, your bishops and priests banished. Your knights and nobles have been stripped of their old, hereditary honours; your cities and courts of justice, your industrious citizens and tradespeople, have alike had their interests sacrificed; heavy taxes have been imposed, and no mercy has been shown towards those who could not pay them.

"'Tyroleans! when you recollect all this,—when[16] you consider the treacherous conduct of the Bavarians, and remember that you have never taken the oath of allegiance to them,—you will have but one thought, one purpose; and your lips will alone utter the word Deliverance!'"

"God save the emperor!" ejaculated the Sandwirth.

"And bless our cause!" added Speckbacher, deeply moved.

"It will be comparatively easy," said Father Joachim, "for Bavaria to penetrate our country as far as Innsbruck; but, from that point, our enemies will find themselves in a complete network of defiles, ravines, gorges, and valleys—"

"From which, if we let them escape, we shall be fools!" cried Speckbacher.

"They are many, and we are few, my son."

"They fight for kreutzers, and we for freedom, father."

"True; and therefore I believe we shall win the day, but it will be a hard-fought one. From Carinthia the foe will approach us through the valley of the Drave; from Italy through the valley of the Adige. We must hem them in, and cut them off, before they effect a junction. No time must be lost in fortifying the mountain passes. On the 9th of April, a division of Austrian troops will advance—"

"God be thanked! Under the Archduke John?"

"Under General Chastelar and Baron Hormayr. You look disappointed, Hofer; but they are good men and true.—Directly they begin to march, the Tyrol must rise. You must ring your alarm-bells and kindle your beacons; send messages to every dwelling within reach, and billets inscribed ''Tis time' to those afar off. Saw-dust scattered on the rivers will be a signal to the men lower down the valleys that you are in arms. The foe will probably endeavour to reach the Brenner by way of Brixen—"

"He must be intercepted!"

"Undoubtedly. Who will lead the men of the Passeyrthal over the Jauffen? Andreas Hofer, will you?"

A deep red flush rose to the Sandwirth's temples. He rose; and, in a low, firm voice, replied—

"I will."

"Let us make some memoranda, then, of men and places—"

Some humble writing implements were placed on the table; and Hofer, after trying the point of a stumpy pen on his thumb, offered it, with a crumpled piece of paper, to Father Joachim, who, however, produced his own pocket-book, while the Sandwirth and Speckbacher reckoned up to him the number of men they thought they might muster. Rudolf presently went round to Theresa, and whispered, "Can[18] you give me some bits of wood? I might be cutting some billets and inscribing them."

She mutely nodded, went out, and returned with her apron full. He took out his clasp-knife and quietly set to work; and Franz, after a lazy fashion, helped him.

"Five thousand strong," at length said the Capuchin.

"There or thereabouts," said Hofer. "Speckbacher must count up the men about Halle."

His little boy here stole up to him.

"So, Johann," said his father, in a lowered voice, while Speckbacher reckoned up the men of Halle, "you set the stranger on his way. Did he say anything to you?"

"Only asked a heap of questions about the shooting match, father."

"Humph! Nothing else?"

"Only about Speckbacher—"

"What of me?" hastily said Speckbacher, overhearing him.

"Only who you were. I said you took wood to the salt-works."

"Humph! Was that all?"

"He asked me about Franz."

"What did you tell him?" said Franz.

"Oh, nothing—I only said you sold horses; and sometimes brandy."

"You might have let that alone, youngster," muttered Franz, looking a little annoyed; while the others laughed.

"What said you of me, my little man?" inquired Father Joachim, without pausing from his writing.

"What could I say, father, but that you were Father Joachim, of the Capuchin convent at Brixen, and that we all loved your reverence dearly?" said Johann.

"You told him my name, then," muttered Father Joachim.

"Did you say anything of Rudolf, Johann?" said Theresa softly, with a little pull at her brother's hair.

"I said he was a goodish sort of a fellow," said Johann doggedly; "and that I believed he came here to look after you."

"I'll pay you for it!" whispered she indignantly; and giving him a little push, she hastily went out; Rudolf furtively looking after her.

"My little lad," said the Capuchin gently, "you must learn more discretion, or you will be a child all your life. Well, Hofer, I think these will be enough?"

"Enough and to spare," said the Sandwirth; "with God's blessing."

"Children, let us ask it."

Every knee was bent in prayer, while Father[20] Joachim fervently invoked the aid of the God of battles. This concluded the conference. Solemnized, and with burning hearts, they retired to rest; while the Bavarian traveller carried the very little he knew to the best market for it.

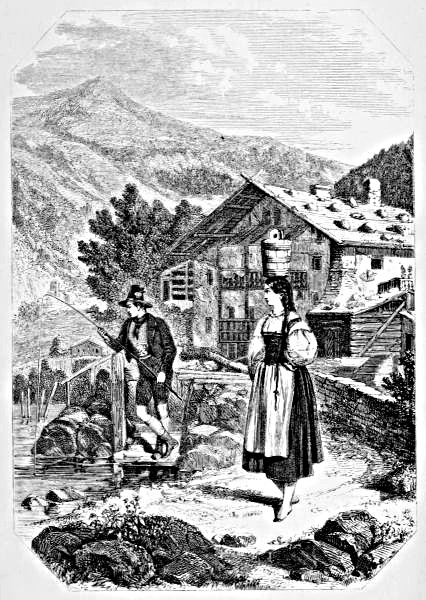

A lovely April morning succeeded this eventful night. Scarcely had the sun begun to gild the mountain-tops, when Theresa stood beside the river with her milk-pail on her head, inquiring of Rudolf, who was fishing in the shade, how many trout he had caught for Father Joachim's breakfast.

Carrying a pail or pitcher on the head gives the neck an erect, noble carriage—reining it up, as it were: and Theresa, in her short, scanty grass-green petticoat, and black bodice laced with scarlet, might have stood for the Princess Nausicaa, as her laughing black eyes looked down on the young fisherman from beneath their long lashes.

"There's a wary fellow under that yellow stone," answered Rudolf; "I caught a gleam, just now, of his bright back-fin."

"I don't believe you did—I dare say it was only the water that sparkled. I would undertake to milk all the cows in the Passeyrthal, before you caught fish enough for dinner."

"Try me," said he, leaning back on his elbow to look up full at her. "Though I have but a four-acre farm, it's in full cultivation, quite productive[21] enough for you and me, with a good wooden cottage on it, too. I'll catch you a fish for dinner every day."

"What nonsense, Rudolf, you do talk!"

"No nonsense at all. I'm quite in earnest; but you do love to cut up a poor fellow."

"No, I don't," said Theresa, looking down, though she could not bend her head. "Shall you come to the shooting-match on Sunday?"

"To be sure I shall. The match will be only a feint."

"Do you like the prospect of war?"

"Certainly—Don't you?"

"If my father does not get hurt, nor—nor one or two friends—"

"Martin Teimer, I suppose."

"What care I for Martin Teimer?"

"Franz Raffel, then!"

"Rudolf, how can you be so stupid?"

"Speckbacher—"

"Certainly, for one. We all love dear Speckbacher."

"Theresa! What wild tales they tell of him! They say that, being early left his own master, it soon ceased to be sufficient excitement to him to follow the roe or wage war with the lammergeyer from morning to-night, in the most savage, inaccessible places, so that he at length left his home altogether, and joined a set of lawless companions who dwelt[22] among the caverns; supporting himself with his rifle when it was successful, but at other times joining predatory parties into the Bavarian dominions."

"Something I have heard of this," said Theresa, in a low voice; "but Maria Schmeider reclaimed him—"

"No, he was checked by the sudden and terrible end of one of his companions—"

"At any rate, he has been one of the best of husbands, and most honest of men, ever since he married; and their little cottage at Rinn is the scene of perfect happiness—"

"There is a touch of romance in him, still, however. Franz told me just now, as we returned from mass, that on their road yesterday, through thunder and lightning, Speckbacher gave him such wonderful descriptions of the salt caverns near Halle, that it seemed like a fairy tale."

"Very likely," said Theresa. "I have heard him speak of them to my father, and say how he should delight to take him through them. My father liked the idea, but I confess it would make me shudder. All sunlight is excluded; you begin by plunging down three hundred steps that seem as though conducting you to the very centre of the earth; the red light of your torch falls on murky subterranean lakes, beneath towering walls of sparkling salt. How horrible, should one fall into one of those lakes![23] Speckbacher says there are no fewer than forty-eight caverns, and that some of the galleries connecting them are three leagues in length. He called it a capital place for hide and seek."

"Aye, or for storing brandy, as that scamp Franz said," muttered Rudolf.

"Much obliged," said Franz, sauntering up. "Hope I'm no interruption."

"None at all," said Rudolf, watching his trout.

"Listeners never hear good of themselves," said Theresa tartly.

"I didn't know you were talking secrets, or I wouldn't have intruded," said Franz, throwing himself on the grass. "So I'm a scamp, am I?"

"Well, I'm sorry I used the word, and that's truth," said the good-natured Rudolf.

"I suppose you think it, though," said Franz, jerking a stone into the river.

"Oh, don't trouble the water!" cried Theresa, hastily. "How can you be such a spoil-sport?"

"Spoil-sport, am I?" said Franz doggedly. "Well, perhaps I am. Now I know my titles and designations. Franz Scamp Spoil-sport."

"Better take care not to deserve them, then," said Theresa pettishly. "If you stay out here much longer, we shall breakfast without you."

And pitching her voice, which was both sweet and clear, rather high, she went towards the house,[24] singing one of the popular national airs in praise of liberty.

Franz followed the songstress into the house; and Rudolf, who, having exchanged his worm for a smaller one, (for trout loathe large baits,) was just going to try his luck again when little Johann, running up to him, and looking on for a minute with very round eyes, exclaimed—

"Why, you mustn't do that!—Why, that's father's pet trout, that feeds out of his hand and weighs fifteen pounds! Why, that trout has lived under that stone twenty-eight years! Father'll be finely angry with you, I can tell you, if you think of eating that trout! Why, he'd as soon eat me!"

SUNDAY afternoon presented a busy scene at the wirth-haus. Groups of gaily-dressed peasants were standing about, many talking fast and eagerly, others quietly, and a little apart. Here stood a woman in an extinguisher-shaped black worsted cap, with her massive arms akimbo, talking to another apparently strong enough to build a house, who wore a globular cap of fur; while, between them, stood a third in a grass-green gown, very short-waisted, and with three rows of red binding round the skirt, her head covered by a gaudy handkerchief, tied under the chin. They looked worthy compatriots of the women of the Vorarlberg, who, during the Thirty Years' War, drove a Swedish division out of the Lechthal, and killed them to a man. There was more of the lioness that might be roused to defend her cubs, in them, however, than of the poissarde; they had hard hands, strong arms, kind hearts, and firm wills.

The young girls, who were mostly sunburnt, and pleasant-looking rather than pretty, had bestowed[26] considerable attention on their hair, which was braided in long shining tails, tied with gay ribands, and surmounted in some cases by jaunty little straw hats, rather bigger than daisies, and wreathed with primroses, blue hyacinths, and anemones. Among the young men and lads, red sashes, green jackets, and blue stockings were rife; each had his tall, conical hat with gold cord and tassels, flower, or feather; his rifle, plated buckles, and flower in his button-hole. They did not seem to have much to say to the young girls, for flirtation is very little countenanced in the Tyrol.

The target was set up at a distance of two hundred and fifty paces. There were the benches, the beer-tables, and the long board on tressels, covered with balls, powder-flasks, and everything likely to be wanted for the sport. The rifles that were to do such goodly service were heavy and clumsy, with triggers so delicate as almost to be set off by a gust of wind. Theresa actively assisted her mother in waiting on the company. Johann sidled up to little Anderl Speckbacher and got him off to a bank, where they could watch the shooting, their arms round each other's necks. The two little girls held their mother's apron as long as they could, and finally found themselves some juvenile companions.

Franz was very smart; but, somehow, his clothes always looked as if they had been made for some[27]body else; and were worn with a slouching air, as if he felt too fine for his company. On the other hand, Rudolf's glossy suit of green velveteen fitted without a crease, and he did not seem to think either of himself or his dress, but to have alert, disengaged attention for whatever was going on.

Talking to Hofer and Speckbacher was a man of thirty, with piercing blue eyes, a bold but not prepossessing countenance, indicative of great sharpness, and stooping a little, neither like a mountaineer nor a soldier, though he had been a militia captain and major. This was Martin Teimer, who had come from Clagenfurt to talk over the rising with his compatriots. He had been appointed by General Chastelar, chief of the peasants of the Upper Innthal, and seemed rather inclined, his two companions thought, to plume himself on it. These three men had an eye to everything that was going on around them; and now and then separated and mingled among the groups, speaking to men here and there, till, in time, they had had a short private colloquy with every man on the ground; returning to each other from time to time, and comparing notes.

Meanwhile, the rifles were in full action: now circle one, now circle two was hit, now the bull's eye; and even without looking round, it was easy to tell by the cheerful, the triumphant, or the moderated[28] acclamations, what had been the rifleman's success.

Speckbacher, returning from one of these progresses, observed to Hofer, "I don't much like that youth, Franz Raffel; he is shallow, vain-glorious, and given to talk. He would be better among the châlets."

"Thither he shall go, if we can get him," said Hofer; "but he is somewhat slippery to get hold of; half his time, he is skulking about, smuggling brandy across the frontier; and as we want a good store of it just now, I at present make him useful."

"Rudolf is worth a score of him," said Speckbacher; "and I think your pretty Theresa thinks so too. I would not discourage that youngster, Anderl, even if Martin Teimer were to come forward—"

"Of a surety, no," said Hofer, quietly. "The lad is a good lad. We shall see what stuff he is made of this summer; and, if he quits himself well, he shall have Theresa at the end of it. You and I were little more than two-and-twenty when we took our brides to church; and Theresa is already nearly as old as her mother was. But we have other matters in hand just now. I see one or two together whom I want to speak to, only Franz is within earshot of them. Do you draw him off."

Speckbacher immediately went up to him, and asked whether he could let him have some brandy;[29] and Hofer joined a couple of elderly men, who were just sitting down side by side on a bench under a tree.

"There hasn't been such a match as this a good while," one was saying; "but, dear me, what matches we used to have when I was a lad! I'm not more than fifteen or twenty years older than that marksman who is taking aim now, but I don't believe he'll hit the white. Crack! Well, they're making a piece of work about it—I suppose he's hit the bull's eye."

"Here comes one that can do more than that," said the other. "Anderl! you have not shot, to-day."

"Boys' play," said Hofer with indifference.

"But you could show them what a man can do."

"Brag, neighbours? No good of brag. Besides, these lads shoot well, many of them. There was some good shooting before you came."

"People always say that of everything," said the other. "I've no spirit for these things now."

"Ah, things will befall shortly, that will put you in spirits."

"What mean you, Sandwirth? Is anything going to happen?"

Hofer nodded.

The two men put their heads close to his, and looked eager.

"We shall rise, soon."

"Rise? What, the Tyrol?"

Another nod.

"Under whom?"

"Nobody in particular. All of us under God."

They lifted up their hands and eyes.

"But is it certain? How do you know?"

"Of some one that knows. Quite certain."

"Himmel!—Did you get us together to-day to tell us this?"

"Yes."

"'Tis time!" cried one of the men in an impassioned under-tone. "Why should we be turned over from one master to another like a flock of sheep? How did the King of Bavaria guarantee our ancient rights and usages? With a piece of sheepskin. None of his promises have been kept: our representative States have been suppressed, our public funds seized, our Church property confiscated; and, as though this were not enough, taxes have been imposed upon us. The Emperor is afraid of France; but are we?"

"Not one of us, as we shall presently show them," said Hofer. "Buonaparte is already in the field against our Emperor, but we shall be quickly down upon him. Communications have been opened with the Archduke John, who is immediately[31] going to effect a powerful diversion. Troops are about to march to our assistance."

"Why, neighbour, if you were to speak this out, every Tyrolese would rise directly!"

"True; but the moment, though close at hand, is not quite come. In a day or two, perhaps, you will receive a little billet inscribed ''Tis time'—the whole country will be up directly!"

"Come, I'll try my hand at the rifle this moment!" cried the old man, throwing aside his stick, and hastening towards the crowd. He was known and respected—they made way for him.

"Old Spickbart is going to try a shot!" cried Franz to Rudolf—"What sport! I'll bet you a quart of brandy he don't hit the target at all!"

The good man's hand shook so that his ball only hit the outer circle.

"I'll try again," said he.

"Yes, do," said the Sandwirth kindly; and looking round him as he spoke. There was not a smile, except on the face of Franz.

"You and I used often to shoot together," said Hofer. "Now then. Don't be in a hurry."

This time Spickbart hit the bull's eye. He was much applauded, and looked greatly elated.

"Ah, I thought I could!" said he, wagging his head. "The fault was only in my hand; not in my eye.—Now, you, Hofer."

"No, no," said Hofer.

"Oh yes, Sandwirth! Please, Sandwirth!" cried many voices.

"You silly boys," said he, looking about for his own rifle; "what do you want me to play with you for?"

A feather from some hat lay at his feet. He picked it up and gave it to Rudolf.

"There, go and hold it up fifty paces beyond the target."

"Rather you than me," said Franz with a shrug, as Rudolf walked off.

"I'm not a bit afraid," said Rudolf.

He had no need to be. Crack went the rifle; puff went the feather. There it lay, in two little fragments; Rudolf's finger and thumb unhurt.

"Well—that was the coolest thing!" ejaculated Franz, as the hills rang with acclamations.

"Yes, he's cool enough, that lad; without any brag," said Hofer, quietly putting down his piece.

"Franz was not thinking of him," said Speckbacher, grasping his friend's hand.

"I was," said Hofer softly. "I've tested the boy."

Speckbacher gave him a quick look.

"He stood fire well."

"Yes, and expects no notice taken of it. Did it never occur to you that William Tell's little son was as brave as William Tell?"

"Never till this minute! Do you hear that, Anderl?"

Speckbacher's little son pressed his hand, and then stroked it, looking up in his father's face.

"I should not have minded having the apple set on my head for you to shoot at, father."

"Would not you, my little boy?" And Speckbacher's brown hand fondly stroked the boy's brown curls.

The sun was now nearly set. Hofer, as the best shot, was carried round the ground, with flags, songs, and garlands; and another target added as a trophy to those on his already honoured walls. He and Speckbacher had pretty well ascertained whom they could depend on; a few more earnest words spoken, and they were all on their way to their homes.

Hofer re-entered the house, with his hand on Rudolf's shoulder.

"Here's a young fellow, now," said he cheerfully to his wife, "who had faith that I would not blow his right hand to pieces, and disable him for life, just out of brag."

"Of course you would not, Sandwirth," said Rudolf. "What good would it have done you?"

"Ah, my boy, I might have attempted something I could not achieve!"

"You? No! you'll never do that."

"Well, I hope not. How well everything has[34] gone off to-day! I am so glad Spickbart hit the bull's eye."

"I am so glad you hit the feather," said his wife.

"Oh, there was nothing in that. Poor Spickbart is getting in years, and a little shaky; but there's a man's true spirit in him yet."

"What a bustle and noise there has been; I'm glad it's over."

"So am I, Anna. But it has been a very important meeting."

"A few of the girls wanted to get up a dance; but I knew that would never do."

"You were quite right. Let us dance when the day is won, not before."

"Art weary, man?"

"A little, dear. Open a fresh bottle of beer."

She did, and sat down close opposite to him, looking at him affectionately with her large brown eyes.

Rudolf and Theresa were talking in low, lover-like tones, at the door, under covert of the balustraded gallery. The young ones were at play.

Franz presently lounged in.

"I'm going now, Sandwirth," said he, approaching Hofer, whose hand was locked in his wife's. "Any commands?"

"Only about the brandy."

"Oh, yes, we talked that over before. You shall have it."

"What impression has this day made on you, Franz?"

"Well—it's been very hot, for the time of year."

"I was not thinking of the weather. Have you had a pleasant afternoon's sport?"

"Well, no—there was too much business mixed up with it. Sport is one thing, and business another. Besides, I only hit the bull's eye twice, and Rudolf hit it five times; whereas, the last time, you know—"

"Yes, I remember."

"So that, altogether, you see—No, it was a poor match, I call it. Sport's sport, and business is business; isn't it, Sandwirth?"

"I can't gainsay that. Well, Franz, I'm afraid you don't look forward with much pleasure to a busy campaign this summer."

"I hope to do my duty as well as other people," said Franz, looking down. "What must be done, must. Of course, we shall none of us like it."

"Do you call that speaking like a bold, hearty young man? Why, you ought to rouse up at the sound of the war trump!"

"Oh, yes, of course; so I do."—yawning.

"Thou'rt sleepy, lad," said Anna, rather contemptuously.

"No, I'm quite awake," said Franz.

"Now," said the Sandwirth, "there will be plenty of different kinds of work to do this summer; so[36] that all people's tastes may be suited. There will be plenty of fighting; those who are active and stirring, and fond of their country, will like that. There will be plenty of message-carrying from one post to another; this will be attended with occasional risk, and will require much activity and dexterity, and will be equally honourable and useful with the other. There will be plenty of hard labour, felling trees, rolling stones, making barricades, carrying ammunition up precipitous heights; this will be as useful as the others: plenty of night-watching; this will be fatiguing rather than dangerous, and as useful as the others. Then, while so many are away from their herds and their flocks, some will be absolutely needed to look after the stock; and these will be as useful as the others. Which of all these various posts will best suit your fancy?"

"Well, that requires consideration," said Franz, pulling a wooden stool to the table, and sitting down opposite to Hofer. "Let me see. First, there's fighting. You know, Sandwirth, that I've dealt so long in foreign brandy, that I know a little what danger is—"

"Of course; and therefore—"

"And therefore, if I don't choose fighting, people can't say I'm afraid. Can they, now?"

"Whether they can or no, is little to the purpose."

"Just so. Well, then; as to the message-carrying; that, as you say, is useful, but dangerous; to which I may add vexatious."

"I don't know why it need be."

"Don't you? Why, I look upon it as one of the most plaguy, uninteresting, abasing employments a fellow can undertake; and without getting any credit by it."

"Let it pass, then. There are plenty whom it will suit very well."

"Oh yes! Well, then, let me see. What comes next? Oh, manual labour. Felling trees, and so forth. Do you know, Sandwirth, my mother asked me, last Christmas, to chop up a billet of wood for the fire, and I hit myself such a blow on the left hand with the axe,—here, just at the fleshy part of the thumb,—that I carry the mark of it, as you may see, to this day. And my mother said it might have brought on lock-jaw!"

"Did she, though?"

"Death in three days," said Franz solemnly. "These handicraft jobs, you see, require practice. They amount almost to trades. Now, a trade requires an apprenticeship; and I've never had one to a woodcutter: so that, altogether, I might do myself more hurt than anybody else."

"Many people do."

"That's considered then. Well, what comes[38] next? Night-watching. Oh, yes, I would not at all mind taking my turn at that, though I'm a dreadful one for falling asleep."

"A sleepy sentinel would not be of much use."

"No; only everybody must sleep sometimes; and they that work hardest sleep soundest."

"Just so."

"As for carrying provisions up the hills, little chaps like your Johann are equal to that, I think."

"I should hope so."

"—Which they are not with regard to looking after stock. That's a man's business. As you said, it's just as useful and honourable as the others—"

"I said useful, though not honourable,—"

"No, you didn't say it, you know—I knew what you meant. And it isn't every one that understands stock, or would be for taking the trouble of it."

"No, indeed! You're quite right there."

"So that, as I do understand it, and don't mind the trouble of it,—why, to oblige you, I'll undertake it."

"Thank you heartily, Franz! You will indeed oblige me very much!"

"Come, that's cordial!" said Franz, as Hofer held out his hand to him. "I'm quite glad I've decided as I have."

"So am I. I hoped you would get round to it, but did not know how to propose it."

"Oh, I'll do it; and do it well. Bless you! you mightn't have had a head of cattle left!"

"And then where should we be?"

"There's no knowing," said Franz, with a sapient shake of the head. "Well, good night."

The voices at the door had been perfectly silent during this dialogue; and Hofer had once or twice heard a stifled laugh.

Franz, however, pre-occupied, and quite self-satisfied with what he considered a masterly piece of tactics, walked off.

"What a deal of trouble that young fellow has saved me, to be sure!" muttered Hofer. Then, raising his voice, "Now, then, dear children, come in and sing the vesper hymn."

PERCHED on a certain height not far from Sterzing, stands a certain old castle, one of the many that crest the Tyrolese mountains, and which, on investigation, too often disappoint the traveller by proving either desolate ruins, or garrisoned to overflowing by Austrian soldiers. But the castle in question was both habitable and inhabited; a good and even luxurious breakfast was spread in the lofty hall, which combined the adjuncts of modern civilization with the romantic architecture of feudal times; and a fine-looking military man, perhaps turned fifty, sat reading despatches, while his daughter, a young lady of eighteen, poured out coffee for him and a young cavalry officer, who was already attacking the potted game.

"This seems an admirable proclamation of the Archduke's," said the Baron, at length throwing aside his papers and beginning his breakfast. "You will soon have plenty to do, Gerhardi."

"I hope we may," said Colonel Gerhardi. "Our[41] just and numerous complaints will lie before the tribunal of the world. The Archduke calls it a holy war, and so do I. So great a power as Napoleon Buonaparte's cannot be opposed alone, and therefore all the nations ought to make common cause against him."

"Ought and will are two things," said Baron Sternach drily. "I should embark in this war with much more readiness than I do, if I saw our way safely and victoriously out of it; but if, after a fruitless though brilliant struggle, we are reduced to make inglorious conditions of peace, it would have been better to leave the matter alone."

"Ah, papa, don't throw cold water on us!" cried Hildegarde. "Why should not we be the liberators of Europe? As soon as the rising once takes place, I know you will take part in it as warmly as any."

"Certainly; for the danger of the brave is always less than that of the coward; even if duty and discipline have no influence. My only fear is lest we rush hastily into an unconsidered struggle with a foe whose power, hitherto, nothing has been able to withstand."

"The tables will turn on him, some day, sir, you'll see," said Colonel Gerhardi.

"I hope I may see it. All we have to do, just now, is to obey our superior in command; and he[42] gives the word to advance. Did you ever chance to see Hofer?"

"Yes, Baron; I have seen him twice. He was one of the peasant deputies to the States once, I think? A plain, homely, honest-hearted fellow, seemingly. We didn't think much of him."

"Not as much, perhaps, as he deserved. I saw him in the year 1805, when he was chosen from his native valley as deputy to the Archduke John; which showed that the Tyrolese already looked upon him with considerable confidence, though he could not have been much turned of thirty. And he was summoned again by the Archduke, you know, to Vienna, this January, which shows that he saw some ground of reliance in him."

"As a matter-of-fact witness, I should suppose, Baron. He would tell the Archduke exactly what was the state of popular feeling, and how many fighting men could be depended on, without the least hesitation or exaggeration. I conclude him to be a man of strict truth; who would neither speak disparagingly of a rival, nor praise him insincerely to curry favour. This struck me with regard to what he said of Martin Teimer. Hormayr put it to him closely: was Teimer a reliable man, or was he not? Hofer spoke very briefly of him; he would not dispraise him, even by an inuendo: neither would he say more in his praise than he felt. Baron[43] Hormayr noticed this to us afterwards, as if Hofer were jealous of him; but I did not think him so. I thought he spoke the simple truth."

"And few there be that speak it," said the Baron. "Well, we shall soon see what is in them both. Hormayr is a sensible, gentlemanlike man, and good officer."

"A little wanting in ardour, don't you think, Baron?"

"Pooh, pooh, you young fellows have too much. You think to carry things by a coup-de-main."

"That's what Buonaparte did, sir, many times in Italy. We were continually too slow for him."

"Well, well, we shall not be, now. We begin to-morrow; and that is near enough at hand even for you, I should think."

"You are not afraid of leaving my cousin here, Baron?"

"Why should I be? Women and children will be respected. I mean her and her aunt to be very useful to us; for I expect that this empty old castle will be filled with wounded men, and Hildegarde must tend them like the heroines of old song."

"Ah, that I gladly will," cried Hildegarde. "As soon as you and Adolph ride off, I shall summon the servants, tell them what is to be expected, and superintend their immediate preparations for the reception of the sick."

"The strong-rooms and dungeons must be looked to also," said the Baron; "for we may expect many prisoners."

"Ah, papa! don't put any of them down into those dark holes full of newts and toads, only fit for the barbarous times!"

"Certainly not; but we must provide for their security, nevertheless, or they may seize the castle and put you into one of the dark holes, instead."

"Ugh!—I am sure I should not live through the night! My hair would turn quite white. Why, Adolph, you have no idea what terrible stories are told of those dungeons—"

"Old wives' tales—"

"True tales. Bones have been found. Human hair sticking to the wall. Stains of blood!—"

"Well, well, we are not going to repeat those things. You may pet your prisoners as much as you like, so long as you do not let them run away, nor run away with them."

"With one of them, papa, I suppose you meant to say. Well, I accept your carte-blanche; but you must leave me the cellar-key."

"To treat the captive knight like the fair, Saracen?"

"Sick men require wine, papa. And I must have beef and mutton, and bread and beer, in unlimited quantities, for those who are well."

"Nay, Hildegarde, as my fortune is not unlimited, I see it will be to my interest to effect a very speedy exchange of prisoners—if the enemy have the good luck to make any. But here are we reckoning on the captured and wounded before the battle is fought!"

And, hastily despatching his breakfast, the Baron collected his papers together, and went away to give various orders.

"I hope the campaign will be a short and a brilliant one," said Hildegarde anxiously. "I shall so long for papa to return."

"My mother will soon join you," said Adolph. "But if you are in the least fear—"

"Oh no! All my fears are for him; I have none for myself. There is nothing I shall more gladly do than help to nurse the poor men who have been wounded in fighting for our liberties. Terrible gashes and amputations, indeed, I do not feel quite equal to. If we could get a medical man to remain in the castle,—"

"Why should not you? Some of the Capuchins are very clever. Father Joachim Haspinger has been an army chaplain, and is preparing for service again. He is as good, I am told, at setting a limb as at breaking a head. His reputation and influence among the peasantry are immense. What a pleasant day that was, Hildegarde, when we visited the Capuchin convent at Brixen!"

"Yes; and, do you know, we had another very pleasant excursion in the Passeyrthal after you had rejoined your regiment. A storm came on, and we took refuge in Hofer's Inn, am Sand. We did not see him; but his wife and pretty daughter were very attentive to us.—Ah! the horses are coming round," said Hildegarde, interrupting herself; and her eyes filled with tears as her father returned to take leave of her; but she brushed them away, and kissed him with a smile. She accompanied them to the gate.

DING-DONG, ding-dong! Clang!—go the little and great church bells. Bang! go the cannon; crack, crack! the rifles. The Tyrol is up!

The night of the eighth of April was dark and gloomy. General Chastelar and Baron Hormayr passed it in riding through the Austrian troops to give the necessary orders for the intended movement, and to see that everything was in a state of preparation. The stillness which reigned around was only broken by the measured tramp of many feet, the hollow rattle of artillery, the lumbering of ammunition-wagons, and now and then a clear-toned voice issuing a brief order.

Hofer and Martin Teimer, during this wakeful night, were busy in the Sandwirth's kitchen, drawing up a general order to this effect:—

"On the 11th of April General Chastelar will arrive at Innsbruck, and General Hiler at Brixen.

"The Archduke John directs the men of Pusterthal to occupy the pass of Mulbach, and the[48] Rittnern that of the Kuntersweg, that we may be possessed of the strongest position before the Bavarians are alarmed, and attempt to fly from Brixen to Botzen.

"Kolbe, by order of the Archduke, is to command at Kuntersweg, take charge of prisoners, and protect the persons and papers of those Bavarian officers who have been distinguished for their inveteracy against the Austrian government and the Tyrol from all injury and ill-treatment; but on no pretence to allow them to proceed from Ritten to Botzen. At Kaltern Joseph Morandel is chosen commander by the Archduke, and has received orders what to do. Count Arzt commands at Nonsburg, and Baron Hormayr is Commissary-General.

"Given at Sand, in Passeyr, on the 9th of April, 1809.

"Martin Teimer,

"Andrew Hofer, Publican."

While it was yet dark, Teimer was hastening over the mountains to Oberinthal, to join the Austrians; and Hofer to the muster-ground of the men of Passeyr, appointed on the shooting-match day. With dawning light, the eagerly-watching peasants, lower down the rivers, saw sawdust floating on the surface of the Passeyr and the Inn, and understood[49] the signal; while, among the hills and mountains, billets, inscribed "'Tis time!" flew from hand to hand, from house to house, like the fiery cross: and men hastily caught up their rifles, buckled on their shot-belts, and poured forth.

At three o'clock in the morning the Austrian advanced guard was in motion. Chastelar and Hormayr harangued their troops, inciting them to ardour; and before the march had lasted a couple of hours, the thunder of distant guns and the tumultuous din of alarm-bells resounded through the valleys. Innumerable fires were discovered on the heights; and as Chastelar's division advanced up the Drauthal, thousands of men, women, and children came forth to meet it, waving green boughs, and pressing forwards to kiss the hands and even the feet of their deliverers. The force consisted, in all, of sixteen battalions of foot, and three squadrons of horse.

Meanwhile, Hofer, at the head of five thousand strong, was crossing the Jauffen, to intercept the enemy between Brixen and the Brenner.

On reaching the muster-ground, a succession of short, abrupt, hearty cheers had greeted him. He said little more than "Are we all ready, brothers? Then no time is to be lost;" but his look was as gay as a bridegroom's, and they started forth like guests hurrying to a wedding.

Passing the little village of St. Leonard, they struck up to the old Castle of Jauffen; and then began to climb a steep and stony path resembling the dry bed of a torrent, being strewn with boulders; shaded here and there with walnuts and budding elders. Presently the path ran along a precipitous slope, high above the valley, and occasionally crossing chasms on most insecure-looking bridges of poles, carelessly laid across, that required Tyrolean nerves to tread in confidence. These men thought nothing whatever about it, unless the idea occurred how easily they could pull the loose poles after them if the enemy were behind.

The last village on their ascent was Walten. Up to this point they had chatted and occasionally sung a verse or two of some patriotic song; but now they must husband their breath; there would not be another rood of level ground. Now pastures, now fir-woods, here and there a lonely cottage, but still ascending. They get beyond the straggling pines, to bare, thin turf, with the rock frequently forcing itself through it. Here and there are cool, bubbling springs, at which many slake their thirst.

Poles, to guide the winter traveller, are next reached; then, a tall cross, in passing which each man reverently crosses himself. And now they are on the topmost ridge.

They look around from their seven thousand feet[51] elevation with a feeling of satisfaction. This is not the Jauffen, but above it; the amphitheatre of rocky peaks around and below them, and the wild glaciers of the Oetzthal and Stubagerthal, are familiar to them all; yet not so much so as to have lost their power of impressing the imagination. They stand a few minutes, silent and serious, in the felt presence of the God who made the mountains. The Tyrolese are deeply religious: the scenes around them continually bring them into communion with the God of nature; and the perils by which they are environed, as constantly remind them of their dependence on the God of redemption.

Onward again they go, down to a turfy little level where Hofer bids them halt. It is now nearly noon; each man has brought a rye-cake or two; they make their frugal meal, and drink water from the spring. Hofer has a bottle of beer, which he shares as far as it will go.

After this temperate repast, the five thousand resume their march. Among the firs once more; then another rude cross; then a little oratory in the rock, with a carved and painted representation of the Saviour on the crucifix in a railed recess, with seats and kneeling benches in front. Still downwards leads their path, towards Sterzinger Moss, between banks covered with wild strawberry blossoms.

Hereabouts they fell in with several peasants from the neighbourhood of Mauls and Mittelwald, who seemed in great excitement. Hofer immediately stepped on to meet them. "What is going forward, brothers?" cried he.

"Much," replied one of them eagerly. "A French column has taken possession of the bridge of Laditch, and the Bavarians have seized the bridge of St. Lorenzen. Both are being furiously contested for, and it would be well if we could get up with them in time to be of assistance to our men at either place; but here is another detachment of Bavarians close upon us."

"Never mind; we'll beat them first, and help the others afterwards."

"Are you Hofer's men?"

"Yes; that is, I am Hofer. We are all brethren. Where are the Bavarians?"

"In the Valley of the Eisach. They are this side Sterzing already."

"All the better! Never fear!"

"Fear! Certainly not—even our women and girls are not afraid. See, they are driving our hay-wagons, and singing and shouting as they come. We could not wait for them, but they will soon be up with us; and the wagons will afford us excellent cover, with the advantage of height, for firing on the enemy; besides being moveable barricades."

"Capital! He was a clever fellow who thought of it."

"A woman thought of it—my daughter Margaret!"

"Excellent!—Well, we have no time to lose."

"No, we shall see them directly. They are under Colonel Dittfurt, who wants to join General Kinkel."

"He shall not, if we can help it.—Brothers! there is little to say. These two forces must be prevented from meeting. One of them is close upon us. Prepare for immediate action."

"They're coming!" screamed a woman, standing up on the top of a wagon, piled high with hay; and her little boy immediately hitting the horses nearest him with a stick, they pulled forward with a jerk which overset the woman on the hay, and made some hundreds of men laugh. It has a curious effect when a multitude of voices utter a "He-he-he!"

Hofer saw at once where to dispose the wagons in the defile; not an unnecessary direction was given, for he was ever a man of few words; often a look, a gesture sufficed; and the Tyrolese obeyed him as the Roman legion obeyed Cæsar in Britain—"at a word, and at the moment."

Soon, those who were in the rear heard the crack of rifles in front. It would seem as though the[54] Bavarians were taken by surprise; for at first they fell back, returning only a few scattered shot; but presently they recovered themselves and began a continuous fire of musketry. As the defile, however, would only permit a small body of them to enter it, their superiority of numbers was of no advantage to them in a coup-de-main, and only availed in filling up the ranks of those who were constantly shot down. Four-fifths of their bullets were wasted on rocks, trees, and brushwood; while their ambuscaded foes, entrenched behind trusses of hay, tree-stumps, and heaps of stones, securely picked them off and hardly threw away a shot.

Margaret, quick-witted lass, danced and capered at the top of her father's wagon, crying and almost screaming, "Never mind the Bavarian smoke-pellets!"

Towards evening, a strong detachment of French afforded a diversion in favour of the Bavarians, and assailed the Tyrolese from the other end of the defile by an incessant fire, for some time without effect. At length, overpowered by numbers, they were beginning to give way, when at this critical moment Colonel Gerhardi, the "Adolph" who had breakfasted at Wolfsthrun, appeared on the heights with between two and three hundred light horse, and immediately charged the enemy, shouting loudly. In a few minutes the firing of the French[55] and Bavarians ceased; the Tyrolese uttered exclamations of joy and thankfulness, some fell on their knees to bless Heaven, while others cheered on their allies.

The Bavarians retreated towards Sterzing, with considerable loss of killed, wounded, and prisoners; while the French division fled in the opposite direction. Hofer and his men spent the night on the heights; and with dawning day were again attacked by the Bavarians, who rallied on Sterzinger Moss; but the Tyrolese sharpshooters, sheltered by the rocks, made dreadful havoc amongst them, and the artillerymen were several times shot away from their guns.

At length, the Tyrolese made a desperate charge, armed with spears, pitchforks, scythes, axes, and any implements they could muster; while others on the verge of the heights, hurled down masses of rock on their opponents. After some hours, the Bavarians gave way; and having lost several of their best officers and above two hundred and forty men killed and wounded, threw down their arms and surrendered.

The old castle of Wolfsthrun had been prepared, as well as circumstances permitted, for the reception of wounded men and prisoners, by Hildegarde Von Sternach; and she was not a little glad that Adolph's mother had already joined her, when a messenger[56] from him informed her that five hundred and eighty prisoners were being brought up to the castle.

Hofer and his companions, like hungry men as they were, were meantime devouring their remnant of rye-cakes with abundance of Spartan sauce, and slaking their thirst at the springs. At this moment, Rudolf came panting up to Hofer, whom he had found with no small difficulty.

"Sandwirth!" exclaimed he, "what a night you must have had! So have we, but we kept possession of the bridges; and General Chastelar opportunely came up to us just as the French received reinforcements from Mantua. You bade me let you know how things were going, or I would not have left, for the men of Innthal were about to attack them in front, while the men of Whippthal fell on them from the rear."

Another Tyrolese here came up, and said, "I've been looking out along the Sterzing road, Sandwirth, and met a man who told me that a strong force of Bavarians is trying to reach Innsbruck, under General Wrede; but the peasants swarm the rocks and impede their march, having broken the bridges, and blocked up the roads with felled trees. I am sorry to add, that the Bavarians, being much exasperated, are committing every sort of excess."

"No doubt of their being exasperated, brother," said Hofer. "May be, we should feel so in their[57] place; but since we see how ugly it is in them, do not let us, who have not the same excuse, be tempted to the smallest pillage, cruelty, or violence; otherwise God will cease to bless us."

How fared it, meanwhile, with Speckbacher? He was sharpening a coulter outside the stable of his little cottage at Rinn, which stands amidst a clump of larch and beech-trees; when Maria his wife smilingly came up to him to show him that his youngest infant had just cut its first tooth, and to ask him if it did not remind him of a pearl upon a rose-leaf. Just then, his rustic servant Zoppel put a little slip of wood into his hand, bearing the inscription roughly endorsed, "'Tis time!"

Down went the coulter; he kissed wife and infant, and hurried into the house, followed, wherever he went, by his little son Anderl, who wistfully eyed him as he took up his rifle.

The last word having been spoken cheerily, Speckbacher sped on his way, watched only for a minute by Maria, who felt a tear glistening in her eye and did not wish him to see it. So she re-entered the house.

Meanwhile, the little boy ran after him.

"Father! let me go too!"

"You? you little rogue! No, no, not this time. You must stay at home and take care of your mother."

"But she doesn't want taking care of, father!—Besides, there's Zoppel.—Do let me go!"

"When you are a bigger boy, you shall, I promise you."

"Perhaps there will be no fighting then."

"All the better."

"Please let me go, father!"

"What good could a little chap like you do?"

"Take care of you, father!"

"Ha, ha! Capital! I hope to take care of myself, dear boy."

"But, father, you want me to be brave, like you, when I come to be a man. How can I be, unless I look on, and see what brave men do?"

Speckbacher felt his throat swell. He turned about, took the boy in his arms, lifted him up from the ground, and kissed him several times.

"There," said he. "Go home now, like a good boy. Another time."

There was a tear on the little boy's cheek as he stood watching the retreating figure—a tear that had not fallen from his own eyes. He brushed it off—looked at it—and then trotted away into the brushwood; from whence, as he kept running along, he could get glimpses of his father, himself unseen. Once he saw Speckbacher pause and look back; perhaps to see if his little boy had obeyed him and gone home. After that, he never looked back[59] again; he pressed forward to the things that were before him.

The young boy still went on; his short, quick steps keeping pretty well up with his father's strides. Children that walk much with their parents generally step out well. Now and then he had to force his way among the bushes, or go a little way round; for which he made up afterwards by running. He had no settled purpose, except just to keep his father a little longer in sight.

At length he grew tired and thought he must give up. Just then a man joined Speckbacher and stopped him to speak to him, pointing towards Halle. Anderl sat down and had a long rest. When Speckbacher went on again, the little boy felt refreshed, and was able to follow him with ease. Presently some men came running down the hills by various paths, and joined Speckbacher. They all walked on very fast. Afterwards they reached a vast body of men, who shouted when they saw Speckbacher till the hills rang again. When he came up to them they had a long parley, frequently pointing towards Volders and Halle; and they finished by all walking off together in that direction, with Speckbacher at their head.

The little boy now thought he could not turn back; it was too exciting to be resisted; and, as he had now had a second good rest, he trotted on[60] again, keeping up with them as a little dog does with a spirited horse.

By and by the men halted. They sat down on the grass near a spring, and pulled out some rye-cakes and began to eat. This was their supper. The sun was going down, and they did not want to fall on the Bavarians, in Volders, till dark. Anderl did not know this. He was surprised, and a little afraid, to find himself alone, so far from home, when night was drawing on; but he never thought of leaving his father. To look on and see some thousand men eating while he was fasting, was rather tantalizing; however, he did so very patiently; and when, after a long rest, they renewed their march, he saw one, who had been talking in preference to eating, leave a rye-cake behind him. As soon as they were sufficiently in advance, Anderl ran down and seized the cake, pursuing his way while he ate it.

The men were now getting among the trees, overhanging a road, and moving stealthily so as not to be easily seen. Anderl was startled by a church-clock striking quite near him; and could imperfectly make out white buildings here and there, a river, and a bridge. Presently a discharge of fire-arms was heard in advance. Some horsemen dashed along the road, and were shot down. Others dashed after them, and shared the same fate. Others[61] again and again filled up the road, maintaining a fire that would have been destructive had it not, as little Anderl observed, been expended on bushes and trees. Presently a bullet nearly hit him; only, as it did not, he picked it up and put it in his pocket. At last he had collected quite a little heap, regardless of the shot that whistled round him.

By and by he observed that his father, towards whom he had crept with the instinct of affection, ceased firing, though the enemy was not yet silenced. What could be the reason? It struck him that he must have expended all his bullets; which, indeed, was the case. So he ran up to him with his handkerchief, which was now quite full of them, and plucked him by the sleeve, saying, "Father, here are some more to go on with."

It would have been worth a world to you to see Speckbacher's start!

"You here?" said he, in amaze.

"Yes, father; I could not bear to lose sight of you, so I kept running on till the firing began; and then, when I saw how the Bavarians wasted their bullets, I picked up as many as I could. If you'll use these, father, I'll soon bring you some more."

Speckbacher could not speak. He caught him to his heart, gave him a hug, held him there a moment, and then set him down.

"Off with you into cover, you young rogue," said he; "never mind any more bullets."

And, handing a few of them to a comrade who stood close by, he said, with a choke in his voice, "These will hit the mark, surely, considering how they have been brought!"

That night Speckbacher and his companions drove the Bavarians out of Volders. At daybreak they were at the gates of Halle.

THE warm spring sun is shining on a valley watered by more than one winding river, and with green pastures dotted with cows and sheep peacefully feeding. It is closed in by hills green to their summits, with only a few patches of snow in their hollows. Behind these soar craggy and fearful rocks, above which wheel one or two vultures, and high overhead the kingly eagle; who perhaps discerns some human quarry in the depths below. Dead bodies must certainly be lying here and there in the gorges; for now and then carrion crows, sated with their impure repast, rise slowly on their flapping wings, and fly heavily away.

In the sunniest and prettiest part of the valley is a little village of some dozen whitewashed huts, that look clean and comfortable at a distance. The village is surely deserted! not a creature seems in it except an old purblind woman, sitting outside her door on a stone; and she is straining her cracked voice in vain efforts to make herself heard.

"Hannes!—Lenora!—Franz!" cries she, quite in a rage: and then pausing, as if spent,—"Why doesn't somebody answer? They've all gone away and left me, I do believe! Here's a condition to be in! Suppose now my clothes had caught fire, or the French were to come, or a wolf, or an evil spirit—precious help I should have! This is the way we old folks are treated, as soon as ever we can't slave for other people any longer. Hallo! some of you! Am I to split my throat? You'll come home and find me dead some of these days. Dear me! they won't mind; it's no use spending my breath. The village is asleep or dead, I think; I can hear a crow caw a mile off!"

When the peevish old woman became quite quiet, she heard a footstep slowly approaching her; and presently a man lounged up to her.

"Why, Franz, that must be you!" cried she; "I know your step, you always drag your feet along the ground so."

"So would anybody's feet," said Franz, "if they were as tired as I am."

"Why, what has tired you?—lying under a hedge, watching the cows."

"Don't you go to believe, mother, I've been wasting my time like that. The cows are competent to take care of themselves."

"What have you been doing, then?"

"What have I been doing? Why, now, there's a question! Why, the world's turned upside down, I think; and you sit here, blinking in the sun, and know nothing about it."

"How am I to know anything if you all run away and leave me? What's happened?"

"What's happened! Why, Speckbacher has taken Halle!"

"No!—"

"—Has, though—That's one thing. When you've given over disbelieving that, I'll tell you something else."

"Well, say thy say, tiresome boy."

"Hofer's in Innsbruck!"

"The Sandwirth? What, prisoner?"

"Prisoner! No, mother, quite the other way. We've turned out the Bavarians!"

"What, out of Innsbruck?"

"Aye, out of Innsbruck. Twenty thousand of us got together on the heights about the city—"

"Thou must needs have a finger in the pie, I warrant thee!—"

"Well, I thought, as there were so many of us, I might as well see what turned up. Well, first we cut off all their retreats, by girdling them in all round, blocking up the roads, and breaking down the bridges. Then, we opened a brisk fire on the Bavarians who were posted on the upper bridge of the Inn, and drove them from their guns."

"What then?"

"Then we rushed on, waving our hats, and shouting, 'Long live the Emperor!' striking down some of the enemy with the butt-ends of muskets, throwing others over the bridge into the water, and following the rest into the city like a swarm of bees. We soon made them feel we could sting, too. You never heard such a cracking of rifles in your life. Five thousand shooting-matches at once?—Pshaw, nothing to come near it. Then such a smoke! Then such a noise! Every one for himself and all the world else—hallooing, shouting, capering, as if they had no end to their strength, and sounding the pig-call in derision."

"I'll warrant them!"

"General Kinkel and his men were garrisoning the town; but what could they do, you know, mother? They knew the ways of the city, however—the streets, passages, gates, and so forth—better than we, so they were soon inside the houses, peppering down upon the Tyrolese from the windows. Well, now you'd surely think, that as we had the advantage of them in the open ground, the Bavarians would now have the advantage of us from the houses. Not so, mother. How it was, I know not, but they could not keep their own: our sharpshooters picked off every man-jack that showed but the tip of his nose at the windows; so at length they threw down their arms—"

"They did?"

"And cried for mercy!—Didn't we make an uproar then! However, there was still a good bit of fighting; here and there were strong posts they wouldn't give up, and stout hearts that wouldn't give in. At the barracks, I believe every man was shot down. At last, they—the Tyrolese, I should say—got to the house of the Bavarian Commander-in-Chief—Kinkel, that is,—and were calling to him to surrender, when up comes Colonel Dittfurt—"

"Who's he?"

"Oh, mother, you ought to know by this time. He it was, you know, that was the principal cause of the Tyrol being separated from Austria, and that lately said, 'With two regiments of cavalry added to his infantry, he would cut every one of us ragamuffins down.'"

"Ah, no good ever comes of brag."