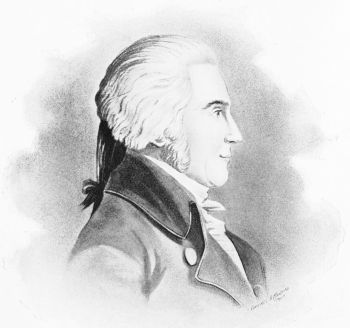

WILLIAM R. DAVIE.

COLLECTED AND COMPILED BY

W. J. PEELE,

A MEMBER OF THE RALEIGH BAR

DAVIE, MACON, MURPHY, GASTON, BADGER, SWAIN, RUFFIN,

BRAGG, GRAHAM, MOORE, PETTIGREW, PENDER,

RAMSEUR, GRIMES, HILL

Let us pass not through the earth so fair,

Leaving no witness the truth to bear

That we've lived and loved and labored here.

RALEIGH

1898

Copyrighted 1897

BY

W. J. PEELE

PUBLISHED BY

THE NORTH CAROLINA PUBLISHING SOCIETY

THE LORD BALTIMORE PRESS

THE FRIEDENWALD COMPANY

BALTIMORE, MD.

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

TO

THOSE WHO HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO MAKE IT,

TO THE

DESCENDANTS OF THOSE WHO ARE ITS SUBJECTS,

AND TO

ALL NORTH CAROLINIANS WHO SEEK TO EMULATE

THE VIRTUES IT

RECORDS.

| PREFACE. | |

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| WILLIAM R. DAVIE. | By Walter Clark. |

| NATHANIEL MACON. | By { Thomas Benton. |

| { Weldon N. Edwards. | |

| Speech on the Missouri Compromise. | |

| ARCHIBALD D. MURPHY. | By William A. Graham. |

| Historical Address at the University. | |

| WILLIAM GASTON. | By W. H. Battle. |

| Address at the University. | |

| GEORGE E. BADGER. | By William A. Graham. |

| Speech on Slavery and the Union. | |

| DAVID L. SWAIN. | By Z. B. Vance. |

| Address: "Early Times in Raleigh." | |

| THOMAS RUFFIN. | By William A. Graham. |

| Opinion in "Ex parte Bradley." | |

| THOMAS BRAGG. | By Pulaski Cowper. |

| Account of a Political Discussion. | |

| WILLIAM A. GRAHAM. | By Montford McGehee. |

| BARTHOLOMEW F. MOORE | By Ed. Graham Haywood. |

| Argument in State vs. Will. | |

| J. JOHNSTON PETTIGREW | By Mrs. C. P. Spencer. |

| The Character of the British; | |

| An Evening at Seville. | |

| WILLIAM D. PENDER. | By W. A. Montgomery. |

| STEPHEN D. RAMSEUR. | By W. R. Cox. |

| BRYAN GRIMES. | By H. A. London. |

| Surrender at Appomattox. | |

| DANIEL H. HILL | By A. C. Avery. |

| Address: "The Old South." |

| DAVIE | Frontispiece |

| MACON | facing p. 81 |

| MURPHY | facing p. 111 |

| GASTON | facing p. 150 |

| BADGER | facing p. 181 |

| SWAIN | facing p. 229 |

| RUFFIN | facing p. 284 |

| BRAGG | facing p. 306 |

| GRAHAM | facing p. 333 |

| MOORE | facing p. 378 |

| PETTIGREW | facing p. 413 |

| PENDER | facing p. 436 |

| RAMSEUR | facing p. 456 |

| GRIMES | facing p. 495 |

| HILL | facing p. 524 |

The publication, in a permanent form, of the most valuable sketches and speeches which have been produced in our State will aid materially in laying the foundation for a distinctive literature. In the beginning, character only is essential; art is a development, and will assume its comely form in due season if it springs from virtue. The undeserving are the fearful and the unbelieving, and these are they who are morbidly anxious to graft borrowed ideals of literary culture upon the native stock.

The people are entitled to the sources of history (the knowledge of which, in this State, is confined to a very few), because from among the people must always arise the man who breaks the monopoly which sequesters the facts of public interest for private interpretation.

Failure in some writers to give the sources of information and of ideas, and to give credit or quote where these are already well expressed, has caused much confusion in the historical data of this State. This practice is fatal to any considerable literary reputation and an unwitting confession of incapacity.

The educational value of these sketches and speeches, and of such as may be published at a later period, is probably what will chiefly recommend this undertaking to the consideration of the public. A good course of home reading about worthy men close enough to the reader to stimulate his interest can hardly be overvalued, and it is the best substitute for the training of the schools as well as a powerful assistant in such training.

It will be remarked that some of the best sketches of our distinguished dead have been written to be spoken; but they are none the less effectual among North Carolinians, who have generally been hearers rather than readers: those, therefore, who have desired their attention have cultivated oratory. The style of the effective writer, however, is more condensed than that of the orator—freer from passion and local prejudice and fitter to paint for posterity pictures of the past.

To the ladies of the memorial associations of North Carolina, and to those who have generously responded to the honor of their calls, our people are indebted for the collection, in the form of addresses, and the consequent preservation of some valuable historical matter. This is especially true of the Ladies' Memorial Association of Raleigh, as the sketches of Grimes, Ramseur, Pender, and Hill, here published, will attest.

No less deserving are those who of their own accord, or at the request of others, have prepared sketches of such as have done deeds worthy of remembrance. Born of some patriotic North Carolina woman, a man will arise who will use the stubborn facts so preserved to bruise the serpent-head of false history.

It will not be understood, of course, that an attempt is made in this volume to publish the lives of all distinguished North Carolinians—there are others, perhaps, as worthy as any which here appear; and should this book be approved and sufficiently sustained by reading people, another volume may be added at some future time.

My main object will be attained if interest in those who have done something worthy of remembrance is stimulated.

Much of what is called biography and history is a tiresome chronicle of the successive advancement in office of some who have advanced little in better things. Service, not[11] office, is the inspired test of greatness. He who would be greatest among you must be the servant of all.

In this materialistic age it is nothing strange that some North Carolina writers have praised such as have done well mainly for themselves; and while I do not remember that, in the collection here published, place and station are set forth as an end rather than a means to good, yet here, as elsewhere and everywhere, the thoughtful reader will be on his guard against any squint in favor of false ideals.

As Jannes and Jambres withstood Moses by the art of counterfeiting the symbols of Heaven's appointment, a devilish power, so this age suffers much from spurious greatness, persistently advertised, as bearing the image and superscription of virtue.

Human limitation is such that a character is sometimes worthy of study which only effectually illustrates one great virtue growing among defects; and human nature, unless morbid, instead of being contaminated, will be encouraged that weakness can deserve fame. The defects which criticism may discover in any character here portrayed may be used, under intelligent guidance, to gain the sympathy of the young rather than mar their ideals—which must be composite pictures of the virtues of many, or else imaged on the soul by contemplation of the life and work of One who was the Servant of all.

W. J. P.

This book is written of North Carolinians by North Carolinians. Many of the writers are no less distinguished than their subjects, and these together give it local color, distinctiveness, and personality which ought to make it interesting to ourselves and valuable to those who seek to know us through intrinsic evidence.

Wherever practicable the subjects are allowed also to speak for themselves. "Biography is the only true history," says Carlyle. The history of North Carolina has not yet been written, and never will be, until each pioneer investigator confines himself to a short period—say a decade. Then, eventually, perhaps, some genius for generalization and condensation will arise and in a single life-time combine the whole into one work. Meanwhile this generation may bind up and preserve the material.

There is not sufficient political homogeneity among North Carolinians at this time to enable us to endorse with unanimity the true theory of our history for the past seventy years—especially in our relation to the General Government.

This generation, too, is inundated with cheap and often insidiously false sectional literature from the North.

Such literature is gradually glozing over and reconciling our people to the sinister changes which are being subtly wrought in American institutions.

The innovators can now persuade the misinformed and careless that just criticism of themselves and their cupidity, and just defense of the principles and motives which actuated[14] us in the late war between the States, is rank treason against the United States Government.

To publish what our sages and warriors have taught and fought for rises, therefore, to the dignity of a duty, as tending to correct erroneous impressions common among us and still more common among others, and as giving a particular account rendered by many witnesses, of men and times to be remembered by posterity, rightly or wrongly, forever.

This introduction is intended to present also a bird's-eye view of the field in which were cast the lives and labors of the subjects of this book. Incidentally, too, I indicate a theory of Southern history which, if not obvious enough upon its bare statement, or from the facts here briefly set forth, will one day be demonstrated to the satisfaction of the seeker after truth. It involves an analysis of the character, influence, and interests of the North acting on the South.

The inoculation of New England semi-foreign views of the Federal Constitution (for half New England is foreign born) goes on apace. With conceit, born of provincialism, these people have magnified their Mayflower scrap of local history into national importance; they have dinned it with such Codrus-like persistency into our ears that the average North Carolinian knows their story better than he does that of the settlement of Roanoke Island. We read their books, papers, and periodicals, though many reflect upon us, and nearly all are unfair to us; but they do not read ours. It would be a surprise to the publishers if one hundred copies of this book should be sold north of Mason and Dixon's line—a line which still exists against our literature, our ideas, and our construction of fundamental law. Most probably not one of their monthlies would publish what I am now writing.

The most un-American section of the Union is New England. Bounded on the west and north by British Canada and on the east by the Atlantic ocean (which may be said now to[15] belong also to Great Britain), it is the hotbed of British ideas of government and society; and, in the event of a third war with the "mother country" (as it still affectionately terms the nation whose government has always been the enemy of our liberty, growth, and progress) it may be a hotbed for a hundred times more traitors than it had in the War of 1812. Like our great cities, this section is a danger-spot in the Union.

Many of its political and social leaders vie with those of New York in rushing over to England and Germany to get the foreign construction of our Federal Constitution, and foreign consent to proposed financial legislation by Congress, and foreign sanction of the orders, social preferences and privileges, and marriages of our "corner"-made aristocracy.

These leaders, too, are less and less the owners of the wealth they handle, and are becoming more and more the mere agents of English capitalists and the dupes and tools of foreign marriage-brokers. About three thousand million dollars of British capital is said to be invested in a section of the Union. This copartnership of foreign and domestic wealth gives to Great Britain a voice in our government—a representation in Congress from whole groups of States. How many Northeastern Senators and Representatives have differed in late years from British views of what our financial policy should be? Foreign and domestic monopolists and bondholders have the same interests, the same social sympathies and affinities, a common cause, the same victims and enemies, the same want of confidence in popular government; therefore, what doth hinder them from forming a treasonable alliance, offensive and defensive, against the people? They have already formed it: the money-kings in all nations, in control of all kings and governments, have an understanding with one another, and, by concentration, they can easily crush any movement, for amelioration, among the people of any one nation at a time.[16] There is a brotherhood, too, of incorporated rate, fare, and tax collectors as well as of bondholders. United they stand.

The Hamiltonian theory of government has been in adoption, and the Hamiltonian school of politicians has been in control of the Union for nearly forty years, and they may now be judged by their fruits: they have given us a more corruptly administered government than that our fathers rebelled against in 1775; and they are fulfilling with startling fidelity and rapidity all the prophecies which Henry, Jefferson, Macon, and Randolph made about them.

It is a knowledge of these things which has organized a great rebellion in the United States, especially among those who live outside the great cities and homes of monopoly—a rebellion which has begun to control political parties, and which, in the last general election, mustered nearly six and a half million voters—voters who were hurled, for once, against the great international brotherhood of plunderers by legislation. Some, however, who were in it are not of it; these, when they comprehend it, will become offended and walk no more with it. A new declaration of independence is being formulated to voice its spirit, and it awaits its Jefferson, if, indeed, as some believe, he has not already come in the person of Bryan, a Western man descended from Southern ancestors, and seeming to have at heart the interests of all sections.

It is a significant fact, in this connection, that from two-thirds to three-fourths of the foreign voters in the Union marched under the allied leadership of foreign and domestic monopoly and ill-gotten wealth. Two-thirds, at least, of the native-born white voters were in this great rebellion, and the life and soul of it. The negro voted almost solidly with the foreigners and with his new masters, for he will have masters of some kind yet for many years. I note the status and attitude of the negro seriously (and let him that readeth understand),[17] for if this ever-deepening conflict comes to bullets, those who now tell the old Federal soldier to vote as he shot, will tell the negro to shoot as he voted; and he will so shoot. The negro vote, under the easy control of a sectional faction of political manipulators, is as dangerous a menace to our institutions as our foreign population indoctrinated with European medievalism—kingcraft and priestcraft.

Much, if not most, of our foreign immigration now comes from cities, and pours itself into the already corrupted life of our own great cities. ("Syrian Orontes pours its filth into The Tiber."—Juv.) It does not buy land, it sells votes; it specifically performs the political contracts of its priests; it buys and sells political jobs; it officers ward politics. It is one of the arms—and the negro is the other—by which greed and monopoly, the twin devils which dance attendance upon national decline, are consolidating our government.

No great city has ever been fit for self-government and civil liberty. From Babylon to Nineveh, from Nineveh to Carthage, from Carthage to Rome, from Rome to Venice, and from Venice to New York and Chicago (neither of which can elect an honest board of aldermen), it is the same old story of avarice which finally overreaches itself. This is the sin which, when finished, brings forth the death of nations.

In vain did Virgil and Horace sing their deathless melodies of country homes to a people whose blood was already poisoned with the lust for gain and fevered with the excitement of artificial life.

The South, the rural South, in spite of many shortcomings, is the great conservator of our institutions. It is the distinctively American section of the Union, jealous of all foreign domination or interference, and stands firm in the patriot's faith that we as a nation can work out our own salvation without the aid of European capital or distinctively European ideas of finance, government or society.

Though contaminated by modern machine politics, and much hampered by the race question, the South still clings to local self-government and to the dignity of Statehood as the only sure foundation for civil liberty and perpetual Union. Long taxed unfairly, by the subtle operation of the Federal tariff and internal revenue and currency laws, out of money which has long enriched another section, in the shape of pensions, internal improvements, and "protection to home industries," the South is still the section most loyal to constitutional government, having infinitely more genuine affection for it than the pension-pampered patriotism of such as make merchandise out of "saving the Union."

These considerations are sufficient to inspire in us an effort to write our own histories, expound to our children the principles of fundamental law, and teach them the safeguards of our institutions. The collection and arrangement of the following sketches, with a few crude suggestions of my own, is what I have contributed towards this end.

Except in so far as "history is philosophy teaching by examples," I take little pleasure in it, and should be at no pains to preserve or popularize it. But seeing, as I think I see, the drift and tendencies of these times, and believing that a correct and widespread understanding of the lessons of recent events is the first postulate in determining the remedy for existing and prospective evils, I take an abiding interest in every earnest endeavor to marshal the facts and discover the theories which will explain them—for facts without theories are dead. The field of investigation is white unto harvest, but the laborers for love are few—the hirelings are many.

In order to illustrate the necessity of our reading and writing our own histories, I will undertake to show the main cause of the war between the States, indicating as I go along some of the errors called history, which are circulated and taught to the prejudice of the South.

Northern historians make the negro and the interest of their people in his welfare the underlying cause of the agitation which resulted in the war between the States. Some of them would have us believe that the Federal soldiers, a generation ago, fired with the love of liberty and humanity, came South on a great missionary tour to strike the fetters from the limbs of four million slaves. About fifty per cent. of these missionaries were foreigners, or foreign born, having but crude ideas of the nature of our government; many thousands of them could not even speak our language; some were Hessians, imported from foreign tyrannies expressly for the purpose of war. Many tens of thousands came for money, and hundreds of thousands were compelled to come by law. Not ten per cent. came to free the negro. Those acquainted with the esteem in which he is held at the North have never been deceived by this missionary theory of his emancipation. Listen to the words of De Tocqueville, written about 1835. This Frenchman certainly cannot be accused of having been biased against the Northern States. He says: "Whosoever has inhabited the United States must have perceived, that in those parts of the Union in which the negroes are no longer slaves, they have in nowise drawn nearer to the whites. On the contrary, the prejudice of the race appears to be stronger in the States which have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists; and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those States where servitude has never been known. * * * *

"The electoral franchise has been conferred upon the negroes in almost all the States in which slavery has been abolished; but, if they come forward to vote, their lives are in danger. If oppressed, they may bring an action at law, but they will find none but whites amongst their judges; and, although they may legally serve as jurors, prejudice repulses them from that office. The same schools do not receive the child of the black and of the European. In the theatres gold[20] cannot procure a seat for the servile race beside their former masters; in the hospitals they lie apart; and, although they are allowed to invoke the same Divinity as the whites, it must be at a different altar and in their own churches, with their own clergy. The gates of Heaven are not closed against these unhappy beings; but their inferiority is continued to the very confines of the other world; when the negro is defunct his bones are cast aside, and the distinction of condition prevails even in the equality of death. The negro is free, but he can share neither the rights, nor the pleasures, nor the labor, nor the afflictions, nor the tomb of him whose equal he has been declared to be; and he cannot meet him upon fair terms in life or in death."—Democracy in America, page 339.

The negro's freedom was accidental and merely incidental to the main purpose of the war. When the alternative was secession or war, the sentiment of the most rabid abolitionists was voiced by Horace Greeley, who was willing that the "erring sisters depart in peace." Many abolitionists were sincere, though fanatical, and they had too often invoked the doctrine of secession, for the North, to consistently object when the South invoked it. Abraham Lincoln (a shrewd, practical Western countryman, put into his high office to hold the agricultural West against the agricultural South) put the war exclusively upon the ground of saving the Union. He would save the Union, he said, whether it enslaved the negro or freed him. In his inaugural address, March, 1861, he said: "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so." Eight days before, Sumner, the abolition leader, had said in Congress: "I take this occasion to declare most explicitly that I do not think Congress has any right to interfere with slavery in a State." Neither Lincoln nor Sumner, if they are to be credited with any sincerity, had[21] stumbled upon the policy of freeing the negro; and, if they had, it would have been very impolitic to have then disclosed it, for all the border States would then have joined the South.

The negro was freed as a means to an end. The emancipation proclamation was a "war measure," and, as such, a master-stroke, for it took two hundred and fifty thousand laborers out of the South and put muskets into the hands of nearly two hundred thousand colored troops. This was the difference between success and failure, and was the turning point in the war, as was admitted by Lincoln in his message to Congress, in which he said: * * * * "and for a long time it had been hoped that the rebellion could be suppressed without resorting to it [the policy of emancipation] as a military measure." The negro incidentally caused the defeat of the South; and he was also incidentally a cause of the war, but not the causing cause—that lies deeper, and must be rightly understood at the peril of the nation.

The war was about taxation—the usual cause of revolution. A century ago it was taxation without representation; a generation ago it was unequal, discriminating, sectional, and class taxation. Out of this still grows the political strife whose quadrennial flood rises higher and higher at each election: income taxes successfully resisted by the rich; rate, fare, and tariff taxes unsuccessfully resisted by the poor—these are the fruitful causes of war—fought with ballots first, and finally, if no remedy can be found, with bullets.

The truth must be told even if it diminishes the glory of those who "saved the Union"—and made money by it. The blood of the last generation was not shed in vain, if we, with the advantages we enjoy, learn and teach the lessons which all posterity will demand of us—both for the sake of those who perished and of those who may perish if we suffer them to believe a lie. Forewarned is forearmed.

Under our Federal revenue laws, those who have produced[22] the export crops (in quantities sufficient to invite the exploits of political manufacturing and trade combinations) have long paid far more than their share of the expenses of government. They were not allowed to buy in the open market, where they sold their crops, but in the restricted "home market," at prices not fixed by open competition. But the said combinations bought these crops in a free market and sold their own products in a protected market. So they got more benefit than the government: first, in being relieved from Federal taxes, which the producers of the export crops paid; second, in incidental, then in avowed, protection; third, in the system of internal improvements which they were obliged to invent to dispose of the surplus revenues raised as an incident to giving them "protection"; and these "improvements" usually improved one section and impoverished the other.

So, early in the game, we find one class, the political combinations of manufacturers, growing rich, and another class, the ill-combined agriculturalists, growing correspondingly poor. Prior to 1860, even more than now, relatively, cotton was the great export crop of America, and was also the principal money crop of a section; so the tax suffered on account of it was sectional. Being also manufactured in a section, the benefits enjoyed on account of it were sectional. So we have the sections, as well as the classes, antagonistic, and made so by the operation of a Federal revenue law—one section growing richer and the other growing correspondingly poorer in the sight of all men.

Political parties aligned according to "geographical discriminations" (against which Washington warned but did not provide), arose and cursed each other, from 1816—the date of the first distinctively protective tariff (which, as increased in 1828 and 1830, provoked South Carolina's first acts of secession)—to 1861, the date of the Morrill tariff, with sixty per cent. protection in it, which, passed March 2d, and flaunted[23] in the face of the seven already seceded States, rendered reconciliation impossible. The Confederate Constitution declaring in its very first article against even incidental protection, conveyed no hint to the wilfully blind revenue-hunters that the most oppressed of the agricultural States had formed their combination to resist the plunder of Federal tariff, as well as other sectional aggressions.

Lincoln's policy of reenforcing Federal forts in the South (the immediate cause of the war) was bottomed on a purpose to collect this odious tax (the tariff of 1861), a policy which Alexander H. Stephens says was not determined upon until the "seven war Governors" (from the seven most protected States) offered to furnish the troops requisite to subdue the States then seceded. The border States had decided for the Union before Lincoln's acts of aggression; and he, therefore, though erroneously, supposed that they all would either aid him or remain neutral until he could "strengthen the Government" by the conquest of the cotton States.

By means of the tariff the cotton crop had been made the scapegoat upon which, in relief of wealth and monopoly, was piled the huge iniquity of Federal taxes; but more than that, and worse than that, the tariff was the engine by which the political combination of spinners and shippers forced down the price of that crop.

As far back as 1791, Hamilton and those in charge of the revenue department of the General Government (a certain school of politicians has always had a Judas-like fondness for carrying the bag), finding the express powers under the Constitution too weak for the purposes of exploit, began to lay the foundation for a new government by implied powers under court construction; by means of which they and "their successors in office" have slowly but steadily amended the Constitution, consolidated our Federation, and undermined the rights of the States. While they were experimenting to discover[24] which States it was most advantageous to form into a copartnership with the General Government, they invented an unequal and discriminating tax on carriages, which fell heaviest on New Jersey, where they were principally manufactured. Seeing the burden of half a dozen States fall on one, North Carolina and some others denounced it as infamous and unconstitutional.

After a few more such experiments, in which it was learned effectually that the purely agricultural States could not be seduced into taking advantage of their sisters, the manipulators of the Treasury induced the General Government to coquet with the States which were more or less under the control of the political combinations of merchants, manufacturers, bankers, and speculators; and with more success.

A copartnership was perfected between the General Government and the protected States by the tariff of 1816; and the mutual considerations passed were first named "incidental benefit" for one party to the contract and "liberal construction" of implied powers for the other. Angry protests and sectional incriminations and recriminations followed, and awakened Jefferson, like "an alarm-bell at night," out of the sleep of old age. The "peculiar institution" of one section gave the other a terrible advantage, which it was quick to see and to seize; and it was used remorselessly. Greed, suddenly joining philanthropy, religion, and fanaticism, organized and led a crusade against African slavery. The agitation about the negro, as a counter-irritant to distract attention from the injustice of Federal revenue laws, was more than a success: for the shallow politicians of both sections forgot the real issue; but the beneficiaries never lost sight of it. I will use a homely illustration: A and B are doing business on opposite sides of a street; B begins to undersell A; A becomes angry, but cannot afford to tell his customers the cause; he hears that B once cheated a negro out of a mule; he makes[25] that charge; they fight; the court record of the trial shows that the fight was about the negro and the mule; but there is not a business man on the street who does not know that the record speaks a lie.

The first speech in this book opens with old Nat. Macon lecturing (in 1820) a Representative from Pennsylvania, the most protected State, for expressing a desire to see the Union dissolved rather than that slavery should be extended beyond the Mississippi.

Slavery, itself, while for several generations usually beneficial to the negro, was, doubtless, in many respects injurious to his masters. It made us provincial, of necessity, sensitive and intolerant of criticism, easily susceptible of misrepresentation, and cut us off from the sympathy of some who else had been our friends. It cramped thought, invention, progress, poetry, and literature. It enabled monopoly to divide and conquer the tillers of the soil. It tended to create caste and it degraded manual labor—as necessary as death after sin and decreed in the same Divine judgment. Skilled manual labor gutted the Confederacy by driving war-ships up its rivers: and the felt want of it, in late years, has established a great industrial institution at our State capital, the mother of many others, and destined to revolutionize education among us.

"Protection" and discrimination in the operation of the Federal revenue laws, though still potent for evil, will probably never again be the principal, causing cause of another revolution unto blood; because from three to ten per cent. of our Southern population will henceforward be directly benefited by such laws, and their interests will soften the sectional aspect of the tax. But the unequal and sectional operation of the currency laws, alienating the West as well as the South; the heaping up of nearly all the wealth of the country into one section, and most of it in a few great cities of that section;[26] the plunder of agriculture by legislation and by the unchecked conspiracy of capital; the monopoly of the carrying trade by the wealth of the cities; the growing distrust between the urban and rural populations; the sullen and fickle temper of our foreign elements—the nucleus, perhaps, of a future Prætorian Guard; the mutterings against the now "vested right" of protected labor to be fed or assisted by the government—and capital hides behind such labor; machine politics and party spirit; the prostitution of the electoral system by the national nominating mob system, which treats sovereign States as the provinces of a party; the fine Italian hand of a certain religio-political corporation in getting offices and holding the balance of power between the factions contending for public plunder; the growing intimacy of sectional wealth with foreign governments and aristocracies—these are the dangers which together threaten a perpetual Union of the States and the liberties of the people.

Before 1860, Macaulay prophesied that our government would go to pieces over a presidential election. In the face of these dangers, it is well for us to consider and carefully teach our children the causes which have worked our injury in the past, in order that we and they may be the better able to recognize and grapple them when they reappear, under changed names or in the shape of new laws.

But a tariff tax as a causing cause of the late war shall not rest upon the foregoing testimony alone. "Let the South go," exclaimed Abraham Lincoln, in 1861, "where then shall we get our revenues?" This man was noted for hitting the bull's-eye, and Divine Inspiration had forestalled him with the prophecy that the love of revenue was the root of all evil.

Thomas H. Benton is a witness who will be heard. In a speech in the Senate, in 1828, he shows how the tariff (which, except for about twelve years, had been mainly levied for revenue) had plundered the South. He said: "I feel for the[27] sad changes which have taken place in the South during the last fifty years. Before the Revolution it was the seat of wealth as well as hospitality. Money, and all it commanded, abounded there. But how is it now? All this is reversed. Wealth has fled from the South, and settled in the regions north of the Potomac; and this in the face of the fact that the South, in four staples alone, has exported produce since the Revolution to the value of eight hundred millions of dollars; and the North has exported comparatively nothing. Such an export would indicate unparalleled wealth, but what is the fact? In the place of wealth a universal pressure for money is felt—not enough for current expenses—the price of property all down—the country drooping and languishing—towns and cities decaying—and the frugal habits of the people pushed to the verge of universal self-denial for the preservation of their family estates. Such a result is a strange and wonderful phenomenon. It calls upon statesmen to inquire into the cause.

"Under Federal legislation the exports of the South have been the basis of the Federal revenue. * * * * Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia may be said to defray three-fourths of the annual expense of supporting the Federal Government; and of this great sum, annually furnished by them, nothing, or next to nothing, is returned to them in the shape of government expenditure. That expenditure flows in an opposite direction—it flows northwardly, in one uniform, uninterrupted, and perennial stream. This is the reason why wealth disappears from the South and rises up in the North. Federal legislation does all this. It does it by the simple process of eternally taking from the South and returning nothing to it. If it returned to the South the whole or even a good part of what it exacted the four States south of the Potomac might stand the action of the system, but the South must be exhausted of its money and its property by a course[28] of legislation which is forever taking away and never returning anything. Every new tariff increases the force of this action. No tariff has ever yet included Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia, except to increase the burdens imposed by them."—Benton's Thirty Years View, Vol. I, p. 98, quoted by Raphael Semmes in his Memoirs of Service Afloat.

In 1860 we find the South still furnished many millions more than two-thirds of the export crops, besides fifty millions to the North. In Colonial and Revolutionary times the South was the richest section, and so acknowledged to be in the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

No wonder that the South always insisted that the Federation was a limited partnership; and no wonder that her rapacious partners insisted on a government of unlimited powers, when they employed such powers for unequal taxation, sectional expenditures, and unlimited "protection." Those who have clamored most persistently for a "strong government" have never scrupled to sap its strength for purposes of private emolument. Those who have panted most for a consolidated republic have now fully disclosed their purpose of sequestering its assets. They have not consolidated the patriotism of the republic, but they have drawn a line of division from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes—a division of interests, division of sentiment, division of population, division of history, and a division of churches. Who can measure the hypocrisy of those writers and politicians who teach the people that the way to make the government strong is to give to one section "implied powers" to plunder the other? Having gotten their wealth by the craft of booming nationalism and centralization, they now perceive that in order to keep it they must hold themselves ready to "hedge" with the doctrine of States' rights and reserved powers. So, while college professors are confusing the mind of youth about "the[29] two opposing theories of government," the facts of opposing interests are jarring the foundations of society and wrenching the fetters which bind the States in a "more perfect Union."

Robert Toombs said, in a speech before the Georgia Legislature, in November, 1860: "The instant the Government was organized, at the very first Congress, the Northern States evinced a general desire and purpose to use it for their own benefit, and to pervert its powers for sectional advantage, and they have steadily pursued that policy to this day. They demanded a monopoly of the business of ship-building, and got a prohibition against the sale of foreign ships to citizens of the United States, which exists to this day. They demanded a monopoly of the coasting trade, in order to get higher freights than they could get in open competition with the carriers of the world. Congress gave it to them, and they yet hold this monopoly. * * * These same shipping interests, with cormorant rapacity, have steadily burrowed their way through your legislative halls, until they have saddled the agricultural classes with a large portion of the legitimate expenses of their own business. We pay a million dollars per annum for the lights which guide them in and out of your ports. We have built, and keep up, at the cost of at least another million a year, hospitals for their sick and disabled seamen, when they wear them out and cast them ashore. We pay half a million to support and bring home those they cast away in foreign lands. They demand, and have received, millions of the public money to increase the safety of harbors and lessen the danger of navigating our rivers; all of which expenses legitimately fall upon their business, and should come out of their own pockets, instead of a common treasury.

"Even the fishermen of Massachusetts and New England demand and receive from the public treasury about half a[30] million dollars per annum as a pure bounty in their business of catching codfish. The North, at the very first Congress, demanded and received bounties, under the name of protection, for every trade, craft and calling which its people pursue, and there is not an artisan in brass, or iron, or wood, or weaver or spinner in wool or cotton, or calico-maker, or iron-master, or a coal-owner, in all the Northern or Middle States, who has not received what he calls the protection of his government on his industry to the extent of from fifteen to two hundred per cent. from the year 1791 to this day. They will not strike a blow or stretch a muscle without bounties from the government. No wonder they cry aloud for the glorious Union. They have the same reason for praising it that the craftsmen of Ephesus had for shouting 'Great is Diana of the Ephesians!' By it they get their wealth, by it they levy tribute on honest labor."

The future historian will devote a long chapter to show how the slavery agitation "ebbed and flowed with the sinking and the swelling" in the voices of protest from the much-plundered South; voices which were keyed to the pitch of secession and revolution against the tariff of 1828, and which again, in 1861, shouted in warlike defiance until they were hushed in blood. That chapter will point also in shame to the dark record which shows that on March 2, 1861, after seven States had seceded and their Representatives in Congress had withdrawn, and while four other States were preparing to secede if found necessary, greed thrust its "lewd snout" into the purity of that chastening hour when many thousand patriots still prayed that the awful catastrophe might be averted, and got by force a tariff with sixty per cent. protection in it! Hear the effect of that measure from the lips of a North Carolinian, General Clingman, who was lingering in the Senate in the hope of reconciliation: "But, Mr. President, there is another difficulty in the way, and we might as well talk of[31] this frankly. I know it is present to the minds of Senators on the other side, and they must see the difficulty. The honorable Senator from Rhode Island (Mr. Simmons) particularly, who engineered the tariff bill through, of course sees the difficulty. * * * The revenues under that tariff bill cannot be collected anywhere, I think, if the declarations which gentlemen make are to be acted out. If they are to hold that all the Confederate States are in the Union, and that you are to have no custom-houses, on the line between them and the other States, what will be the result? Goods will come into New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, and other places; they will come in paying a low tariff, and merchants from Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, and Ohio, if they choose to go down there and buy goods, will take them home and pay no duties. No man from the Northwest will go to New York and pay a duty of fifty per cent. on goods that he can get at a fifteen or twenty per cent. duty at New Orleans. That will be the course of trade, of course. Senators must see that you cannot have two tariffs, one high and one low, in operation in the country at once, with any effect produced by the high tariff. If you go to a man and say: 'You may pay me a high price or a low price for an article,' you will never get the high price. When, therefore, you attempt to carry out the new tariff, which contains rates, I think, of fifty per cent., and some of one hundred per cent., and some even above one hundred per cent., you cannot collect those rates at Boston and New York and Philadelphia, while the men who want to consume the goods can get them by paying a duty of one-third as much. That is impossible. I presume the Senator from Rhode Island, and those who acted with him, did not intend the tariff, which has lately passed, to be a mere farce, a mere thing on paper, not to be acted out. Of course they mean to get duties under it some way or other. If you do not mean to have your line of custom-houses along the border of the[32] Confederate States you must expect to stop importations there."—Speeches and Writings of T. L. Clingman, pp. 61, 62: extract from speech delivered in United States Senate, March 19, 1861.

Yes, and it was the armed attempt to "stop importations there" that brought on the war!

Why it was that the bombardment, on April 12, 1861, of a Federal fort about to be reenforced "fired the Northern heart" more than the bombardment, on January 9, 1861, of a Federal war-ship attempting to carry reinforcements to that fort, the Northern historians, like the Pharisees, "cannot tell." And they never tell that between the two bombardments sectional monopoly had brooded, and on March 2d hatched a cockatrice egg of sectional advantage; that its beneficiaries had had opportunity to touch noses with the "seven war Governors" and that the inspiration of such a touch accounts for the zeal with which they urged the President to war, when twenty-one States were trying to effect peace; that between the 15th and the 28th of March these Governors had a secret conference with the President in Washington, in which they pledged their States to support him in "collecting the revenues of the Government"; and that, thus assured, he had, to the astonishment of the South and most of his own constituents, suddenly sent the invading expedition to reenforce Fort Sumter! Did this same influence persuade Lincoln to refuse to allow the Supreme Court or even Congress to pass upon the much-mooted constitutional question of the right to secede? Of course it was familiar learning to him that all the States, especially the Northeastern, had from time to time asserted, acted on, or acquiesced in this right. Did the tariff Governors induce this man, reputed to be tender-hearted, to decide, on his own responsibility, a question of law which forced the issue of blood at a cost of a million lives, and a sinister change in the character and conduct of our government?[33] Did they seduce him into fitting out an armament to collect the revenues at Charleston, and, at the same time, leave open for construction and equivocation his doubtful and inconsistent expressions about enforcing the Federal laws and Supreme Court decisions giving protection to Southern property in slaves? Why was it that, in this awful crisis, he refused to call Congress together until he had precipitated war by his invasion and his call for volunteers, unless it was because his extra-constitutional advisers feared to trust a body which passed a conciliatory resolution even after battles had been fought and blood had been shed? Why was it that by the very terms of his war proclamation he put off the assembling of Congress for two months and nineteen days after he had declared war, unless it was because he was willing to forestall its action, and preferred to rely on the conspiring war Governors and their protected constituents to sustain him, rather than on his constitutional advisers and the Representatives of the people? Monopoly could not then trust the Supreme Court, for the Dred Scott decision showed that it might again adhere to the original view of the Constitution; and its best members were zealous to effect compromise and peace. That Lincoln and his Cabinet were against the policy of coercion, until somebody influenced them, has been confessed by at least one of its members.

A valuable side-light on the mainsprings of Lincoln's policy is furnished by Dr. R. L. Dabney. He says that while Virginia, through her convention, sitting in April, 1861, was making a last effort to save the Union, Seward sent a confidential messenger, Allen B. McGruder, to Richmond, to urge that a representative be sent to Washington in all haste. McGruder stated that he was authorized by Seward to say that Fort Sumter would be evacuated on Friday of the ensuing week and that the Pawnee would sail on the following Monday for Charleston to effect the evacuation. Colonel Baldwin, an[34] original Union man, was fixed upon as the best representative of the peace sentiment. "He and McGruder," continues Dabney, "set out on the night following and arrived in Washington early the next morning. Immediately after breakfast they drove to Mr. Seward's, when the latter took charge of Mr. Baldwin, and the two went directly to the White House, where they arrived about nine o'clock. They found Mr. Lincoln engaged, but, upon Mr. Seward's whispering in his ear, he excused himself and conducted Mr. Seward and Colonel Baldwin into a sleeping apartment and locked the door.

"After the usual formalities, Colonel Baldwin presented his credentials. After Lincoln had read the credentials, Colonel Baldwin proceeded to state to him what was the opinion of the great body of Virginians, both in the convention and out of it. This opinion was as follows, to wit: 'That although opposed to a Presidential election upon a sectional free-soil platform, which they deplored as most dangerous and unwise, Virginia did not approve of making that, evil as it was, a casus belli, or a ground for disrupting the Union. That much as Virginia disapproved of it, if Mr. Lincoln would only adhere faithfully to the Constitution and the laws, she would support him just as faithfully as though he was the man of her choice, and would wield her whole moral force to keep the border States in the Union, and to bring back the seven seceded States; but that, while much difference of opinion existed on the question whether the right of secession was a constitutional one, all Virginians were unanimous in believing that no right existed in the Federal Government to coerce a state by force of arms.' To this Mr. Lincoln replied: 'You are too late, sir; too late!' Colonel Baldwin understood this as a clear intimation that the policy of coercion had just been determined upon, and, as he discovered, "within four days." Impressed with the deep solemnity of the occasion,[35] Colonel Baldwin made a final appeal, asking, among other things, that all questions at issue should be left for adjudication by the constitutional tribunals. Lincoln asked a few questions, the last of which was, "What will become of my tariff?" He put this question with such force of emphasis as clearly indicated that this consideration should decide the whole matter.

The peace ambassadors sent to Washington by the Virginia convention immediately upon Baldwin's return found the same difficulty. "They saw Mr. Lincoln. The tariff was still the burden of his complaint. They left the next day; and the same train which carried them to Virginia carried Lincoln's proclamation also for the seventy-five thousand troops." See North Carolina in the War Between the States, by Sloan, pp. 27, 28, 29, 30, quoting R. L. Dabney, in the Southern Historical Papers.

There was a subtle influence at Washington strong enough to veer Lincoln round from Seward, whose constituents dreaded war, to Thad. Stevens, who represented in Congress the Pennsylvania iron interest, and, in his character and person, the worst element of the worst politics that America ever saw.

Lincoln had no warrant in the Constitution for calling out the militia against the seceded States. "The Congress shall have power to declare war" (Article I, section 8, clause 11); and "The Congress shall have power to raise and support armies" (Article I, section 8, clause 12); and if, in violation of standard definition and contrary to the fact, it be said that what he inaugurated was not war, but was only an armed effort to put down insurrection, the Constitution, Article I, section 8, clause 15, replies: "The Congress shall have power to provide for the calling out of the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions." So the only warrant the President had was an old act of Congress,[36] passed February 28, 1795, shortly after the Whiskey Insurrection. This act provided: "That whenever the laws of the United States shall be opposed in any State by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings or the power vested in the marshals by this act, it shall be lawful for the President of the United States to call forth the militia of such State or of any other State or States, as may be necessary to suppress such combinations and cause the laws to be duly executed." No pretense of authority was given when a State or a combination of States opposed the United States. His construction forestalled Congress and robbed it of its exclusive right and power to "declare war," and made him the sole arbiter to dictate the nation's weal or woe.

As a matter of fact, this law, thus misconstrued, was obsolete, and so marked in the reprint of the United States Statutes at Large, in 1845, authorized by Congress. Lincoln, then, "by and with the advice and consent" of interested persons, utterly ignoring the two coordinate branches of government, unearthed for the purpose of inaugurating a most frightful war an old statute, unused from the time of its passage, and standing on the authoritative Revised Statutes marked "obsolete" for sixteen years—so received by the lawyers, and unchallenged by Congress or any member thereof.

It is no wonder that Congress, when it did assemble, in July, 1861, and found war a fact accomplished and armies already threatening Washington, should have made haste to validate the President's high-handed measures and strengthen his precarious position by an act of which section three is as follows: "That all the acts, proclamations, and orders, of the President of the United States, after the 4th of March, 1861, respecting the army and navy of the United States, and the calling out, or relating to the militia or volunteers from the States, are hereby approved and in all respects legalized[37] and made valid to the same intent and with the same effect as if they had been issued and done under previous express authority and direction of the Congress of the United States." The marginal note of the printed laws points this act specially to the proclamation of April 15, 1861, calling out the militia.

In suppressing the Whiskey Insurrection Washington acted under the "previous express authority of Congress," then lately given, "cautiously in his delicate duty," while Hamilton "was pressing for the collection of the revenue," says history. The act under which the militia was then called out, passed in 1792, required a Federal judge to certify the fact of the insurrection, and Washington took care to arm himself with the certificate of a Supreme Court Justice. The act under which Lincoln proceeded, an epitome of the former, shows on its face that it was also, when in force, in aid exclusively of court proceedings, and operative only when a Federal judge should call upon the President to assist the United States Marshals, who were purely court officers. Any other construction gives the President "the power to suppress insurrections," and the "power to declare war"; and, when war is declared the Constitution places him in command of the army and militia: so nothing would be left for Congress but to vote supplies and validate his acts, as it did Lincoln's usurpations!

Though the militia had often been needed, and sometimes called out for troubles, domestic and foreign, no President of the United States, until Lincoln, had ever issued such a call unless expressly authorized by Congress, in special acts of limited duration, which have usually specified the number of troops wanted and the term of service required. It is no wonder then that an act, treated as a dead letter since the suppression of the Whiskey Insurrection, should have been marked "obsolete" by the government publisher, with the sanction of Congress.

Unless Madison's refusal to recommend a policy of coercion against the New England States, successfully resisting the drafts for the defense of the nation in the War of 1812, be regarded as a precedent, Lincoln had but one, directly in point, and that was furnished by President Jackson in the case of South Carolina's nullification of Federal law in 1832. Jackson's zeal for the Union could not be doubted; and, in spite of his military training and arbitrary temper, he found a remedy which saved the Union without bloodshed.

On December 10, 1832, after South Carolina had nullified the tariff act, proceeded to provide a separate government, notified the President, and begun to arm and organize its militia for defense, Jackson issued a proclamation in which he besought, and threatened, and promised. Failing by such means to induce the tariff-plundered planters of the plucky little State to recede from their position, on the assembling of Congress he recommended the removal of the cause of the trouble, expressing his belief that such action would shortly put an end to resistance. Nullification still continuing, Jackson (a month later) wrote his famous message, in which he called attention to the magnitude of the opposition, and recommended to Congress to provide by law: "That in case of an attempt otherwise [than by process from the ordinary judicial tribunals of the United States] to take property [from the custody of the law] by a force too great to be overcome by the officers of the customs, it should be lawful to protect the possessions of the officers by the employment of the land and naval forces and militia under provisions similar to those authorized by the eleventh section of the Act of January 9, 1809." After recommending the revival of other expired acts to facilitate and protect the collection of the revenues and execution of Federal law, he said further: "Provisions less than these—consisting, as they do, for the most part, rather of a revival of the policy of former acts called for by the [then][39] existing emergency, than of the introduction of any unusual or rigorous enactments—would not cause the laws of the Union to be properly respected or enforced. It is believed that these would prove adequate unless the military forces of the State of South Carolina, authorized by the late act of the Legislature, should be actually embodied and called out in aid of their proceedings, and of the provisions of the ordinance generally. Even in that case, however, it is believed that no more will be necessary than a few modifications of its terms to adapt the Act of 1795 to the present emergency, as by that act the provisions of the Act of 1792 were accommodated to the crisis then existing; and, by conferring authority upon the President, to give it operation during the session of Congress, and without the ceremony of a proclamation, whenever it shall be officially made known to him by the authority of any State, or by the courts of the United States, that, within the limits of such State, the laws of the United States will be openly opposed and their execution obstructed by the actual employment of military force, or by any unlawful means, whatever, too great to be otherwise overcome."

Pursuant to these recommendations, Congress passed, March 2, 1833, the "force bill," or "bloody bill," as it was called; and the section which made it infamous in the unprotected States was as follows: "Sec. 5. And be it further enacted, that whenever the President of the United States shall be officially informed by the authorities of any State, or by a judge of any Circuit or District Court of the United States in the State, that within the limits of such State any law or laws of the United States, or the execution thereof, or of any process from the courts of the United States is obstructed by the employment of military force, or by any other unlawful means too great to be overcome by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings or by the power vested in the marshals by existing laws, it shall be lawful for him, the[40] President of the United States, forthwith to issue his proclamation declaring such fact or information, and requiring all such military or other force forthwith to disperse; and if, at any time after issuing such proclamation, any such opposition or obstruction shall be made in the manner or by the means aforesaid, the President shall be and hereby is authorized promptly to employ such means to suppress the same, and to cause said laws or process to be duly executed, as are authorized and provided in the cases therein mentioned by the Act of the 28th of February, 1795, entitled: 'An act to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, repel invasions, and repeal the act now in force for that purpose'; and also, by the Act of the 3d of March, 1807, entitled: 'An act authorizing the employment of the land and naval forces of the United States in cases of insurrection.'" Section 1 of the force bill authorized the President to call out the army, navy, and militia to aid in collecting the customs—a power which the Act of 1795 could not be construed to give. It was also provided in the act that the operation of said sections 5 and 1 should "continue until the next session of Congress, and no longer." Thus careful was Congress to limit the duration of the great powers delegated to the President, as it had usually done in other instances in which it had authorized the employment of military force. The Act of March 3, 1807, referred to in the force bill, simply gave the President authority to use the land and naval forces of the United States to assist in the execution of the laws whenever it should be lawful for him to call out the militia for the same purpose. The Act of 1795, referred to by Jackson, which he did not pretend he had a right to use against the nullifiers of the tariff act, unless it should be revived by Congress, and which he proposed should be revived, modified, and adapted to meet the emergency confronting[41] him, in the same way Congress had formerly adapted and modified the Act of 1792 by the Act of 1795, to meet the emergency of the latter year, was the very act Lincoln used to cover his assumption of power to make war on the South without the authority of Congress! He had this precedent before him, in which the warrior Jackson, swift in defense of the nation's honor against her foreign foes, was slow to dye his hands in his brothers' blood. He had before him the act in which Congress had revived the provisions of the Act of 1795, and expressly limited the duration of that revival to the time intervening before its next session; and he was lawyer enough to know, though not learned in his profession, that the substantial reenactment and enlargement of the old act, and its repeal, or limitation to a definite period, was, after the expiration of that period, a practical repeal of both—especially when it may be seen that the one was to take the place the other took in its day. See Tynen vs. The United States, 11 Wallace U. S. Reports, page 88; Pana vs. Bowles, 107 U. S. Reports, page 529, and cases cited therein; Norris vs. Crocker, 13 Howard, page 429.

Jackson, in spite of his camp association and military methods, was the embodiment of caution and conservatism, when compared to Lincoln and his "kitchen cabinet" of revenue-hunting Governors, who were as swift to declare war against their own people, under a forced construction of an old, unused, obsolete, special act, as those who now speculate in their names and fame are eager to seek treaties of partnership with our hereditary foreign foe.

They shall never, unchallenged, teach our children that Abraham Lincoln's usurpations were lawful, justified by necessity, or commended by God; lest "necessity, the plea of tyrants," or "divine right," the plea of kings and priests, or "implied powers," the plea of those who are powerful only to oppress the people and to collect and spend their revenues,[42] should constitute the excuse for destroying the remaining safeguards of our liberties.

Those accustomed to analyze motive and conduct will note with attention that the Act of August 6, 1861, intended to legalize the call for troops, was passed after the "force bill" had been reenacted and amplified by the Acts of July 13, 29, and 31, 1861—after the President had been expressly authorized by these acts and another to accept the service of volunteers and to use the army, navy, and militia to make war upon States and combinations of States, as well as upon the inhabitants of districts therein—after Congress had in these acts twice gone out of its way to refer to the old Act of 1795 as still in force, and once expressly treated it as giving the authority, which had been assumed, to begin the war; and the legalizing act itself was covered under a caption which was calculated to excite as little attention as possible. The caption reads: "An act to increase the pay of privates in the regular army and in the volunteers, and for other purposes."

The Act of 1795, when in force, gave the President no authority to determine when a state of insurrection existed, even in a Federal district; Congress proved that it realized this defect of power by hastening (July 13 and 29, 1861) to supply it to Lincoln—in respect to States as well as districts—a double confession of the weakness of his position.

The Act of 1795 afforded no assistance to collect customs, for the Whiskey Insurrectionists, against whom it was passed, resisted only the internal revenue taxes; Congress practically acknowledged this limitation, by Act of July 13, 1861, expressly and separately authorizing the President to use the army, navy, and militia to "collect the customs" of the United States.

"Even our enemies themselves being judges," there were doubts everywhere, and these doubts were everywhere resolved in favor of absolute authority and against the received construction of law and the Constitution.

An executive who usurps powers ought to be placed on a moral plane as much lower than that of a treasurer who embezzles public funds as the love of liberty in the minds of the virtuous is higher than the love of money.

Those who would derive Lincoln's assumed power to declare war from the clause of the Constitution which requires that the "President shall see that the laws are faithfully executed" betray the flimsy foundation upon which they would erect the throne of an autocrat. The faithful execution of the laws is to be secured in a lawful manner, under such powers as the Constitution gives or Congress may lawfully give to the President. If he is the sole judge of the extent of the powers conferred and the appropriateness of the means of execution, he does not need any other clause to make him the field-overseer of both the other departments of government; and this the Supreme Court has decided he is not. Tyndall vs. The United States, 12 Peters, p. 524. Lincoln did not rely upon this clause, but upon the Act of 1795, the language of which he quoted in his call for the militia of the States; and Congress, by the fifth section of the Act of July 13, 1861, showed very plainly that it recognized that he had professed to act under the Statute of 1795.

The frightful experiences of the civil war and the serpent-brood of evils which have since followed in its trail are plenary proof that the fathers were wise in not lodging the war power in the hands of any one man.

A summary of Lincoln's conduct, while there was yet peace in the land, brings out in startling relief the facts: that he dared at the behest of pampered privilege greedy for revenue, and partisan rancor thirsting for blood, without precedent, or the support of either of the other branches of the government, to place his own private interpretation upon a statute, in effect repealed, and thereby to make war on six millions of his fellow-citizens, whom he refused a right of opinion sustained[44] by abundant authority and precedent and by some of his own acts and utterances. The idol of the "higher law" fanatics, the chief of whom he placed in his cabinet—nominated on a platform which denounced the Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott case as "a dangerous political heresy, revolutionary in its tendency and subversive of the peace and harmony of the country"—elected by States, many of which defied Federal authority attempting to execute the fugitive slave law, and none of which supported such authority, except New Jersey and California—and having never publicly or privately condemned the nullification of their constitutional obligations (Article IV, section 2, clause 3) by the States of Vermont, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Michigan, Maine, Wisconsin, Kansas, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—he still proclaimed that his only motive in taking up the sword was to assert the paramount authority of Federal law!

His political campaign of 1864 was fought upon a platform which pledged its supporters to "bring to punishment due their crimes the rebels and traitors arrayed against the Government"; and be it remembered by all posterity that at the end of that campaign, almost at the close of a successful war, and in spite of military interference at the polls, one million eight hundred and eight thousand seven hundred and twenty-five citizens of his own section voted to condemn him, and endorsed a platform which declared that "under pretense of a military necessity for a war power higher than the Constitution, the Constitution itself has been disregarded in every part" by him, and that "justice, humanity, liberty, and the public welfare demand that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of all the States; * * * that peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal Union of all the States," * * * that the aim of their party was "to preserve the Federal Union and the rights of all the States unimpaired," and that they considered[45] "the administrative usurpations of extraordinary and dangerous powers not granted by the Constitution * * * as calculated to prevent a restoration of the Union; that the shameful disregard of the administration of its duty to our fellow-citizens, * * * prisoners of war, deserves the severest reprobation."

As at the beginning, so at the end of the war, a vast majority of our nation was opposed to Lincoln's policy of coercion and blood; for his total vote, with the army and navy to back him, was only about four hundred thousand in excess of McClellan's, and this would have been far more than offset by the Southern vote.

The immediate cause of Lincoln's death was a sentence in his speech of April 11, 1865: "If universal amnesty is granted to the insurgents I cannot see how I can avoid exacting, in return, universal suffrage, or, at least, suffrage on a basis of intelligence and military service." "That means nigger citizenship," said his slayer to a witness. "Now, by God, I'll put him through!"—Life of Lincoln, by Herndon and Weik, Vol. III, p. 579.

It was a singular decree of Providence that, according to his own forebodings, Lincoln should have perished by the hand of violence, and that too on the fatal 15th of April, the anniversary of his proclamation for the seventy-five thousand volunteers to begin the dance of death. "He that killeth with the sword must be killed with the sword."

Let us be as thankful as we can that we are still one nation, that African slavery has ceased, and that the safeguards of liberty may be still sufficient if we are vigilant, unselfish, and brave.

The world has long respected the courage of the South; when the whole truth shall be well told it will equally respect her cause. One obvious effect of the civil war, clearly foreseen and foretold by Southern statesmen, was to Europeanize[46] American institutions. This was a fearful price to pay even for keeping the sections under one government.

Let us hope that the present war with Spain may destroy the stock-in-trade of the speculator in past patriotism.

An unoccupied field of investigation for a future historian is the part which Great Britain played in dissension, disunion, and war between the States, the sections, and the political parties. Her purpose has been accomplished. She has annihilated our foreign ocean-carrying trade—once threatening her own supremacy—and has thereby made us a third-rate naval power, for seamen, rather than ships, make a navy.

"Will your people divide?" General Clingman was frequently asked while in England in 1860. Never once was he asked if slavery would be abolished. The form of the question, in a land where abolition took its rise, struck him forcibly. Hear its explanation: "In this connection I remember a statement made to me by the late American Minister at Paris, Mr. Mason. He spoke of having had a conversation with one whose name I do not feel at liberty to mention, but whose influence on the opinion of continental Europe is considerable, who declared to him that if the Union of our States continued at no distant day we should control the world; and, therefore, as an European, he felt it to be his duty to press anti-slavery views as the only chance to divide us. I have many reasons to know that the monarchies of Europe, threatened with downfall from revolutionary movements, seek, through such channels as they control, to make similar impressions."—Speeches and Writings of T. L. Clingman, pp. 482, 483: extract from speech in United States Senate, delivered January 16, 1860.

To prove that democracy is a failure is among the chief aims of European monarchs.

Lloyd Garrison seems to have been a sincere fanatic, but all[47] the better may have served British policy. Listen to a group of facts about him, appearing at random in a friendly encyclopedia: "In 1833" [the year the stars fell] "he visited Great Britain, and on his return organized 'The American Anti-slavery Society.' He visited England again in 1846, 1848, and 1867, in which last year he was publicly breakfasted in St. James' Hall."

An extract from the London Telegraph of 1856 contains food for thought: "The aggressive spirit of the people of the United States requires an humbling, and it is for us to perform the task. England's mission is to complete the great work commenced by her in 1834, when she liberated her slaves. There are now over three million human beings in cruel bondage in the United States. If, therefore, the United States Government deny, and is resolved to question the right of Great Britain to her Central American possessions, we, the people of the British empire, are resolved to strike off the shackles from the feet of her three million slaves."

The London News, also of about the same time, encouraging its people against the possibility of rupture between England and this country, said: "However strong is the unprincipled appeal at present made to the anti-British feeling of the Northern States, that feeling is counterbalanced by another which has grown up within the last quarter of a century. The abolitionists would be with us to a man. The best of them are so now."

In 1798 the federalistic school of tax-gatherers, under the guidance of their founders, Rufus King and Hamilton, once actually lifted their eyes from the plunder of their own countrymen long enough to adopt an aggressive foreign policy, but it was a conspiracy with England, called the "Mirandy Plot," by which they sought to despoil our late allies in our war for independence, the French people, of their territory beyond the Mississippi, the honest and honorable purchase of[48] which by Jefferson, a few years later, this school denounced as unconstitutional and void.

Better than any American statesman, General Clingman seems to have understood the motives and interests of Great Britain in fomenting the slavery agitation and the estrangement of the sections. Hear him, in his address to the people of the Eighth Congressional District of North Carolina, March 16, 1856: "The United States is the great republic of the earth, and the example of our free institutions was shaking the foundations of the monarchical and aristocratic governments of Europe. This was especially the case as respects the political system of Great Britain, owing to our common language, literature, and extended commercial intercourse. The aristocracy there hold the mass of the people in subjection, and under a condition so oppressive that large numbers of white men of their own race are liable to perish miserably by famine in years of scarcity. A knowledge of the successful working of our institutions was increasing the discontent of the common people, and, fearing the loss of its sway, the aristocracy, which controls the entire power of the government, began a crusade for the abolition of slavery in the United States. They expected, in the first place, by affected sympathy for the negroes here, to divert the minds of the people at home, to some extent, from the consideration of their own sufferings, and to create the impression that other laborers were much worse off than their own. And should they succeed in breaking up our system they would exultingly point to it as an evidence against the durability of free institutions.

"With a view, therefore, to effect these objects, more than twenty years ago the British press, and book-makers generally were stimulated to embark in a systematic war against negro slavery in the United States. Abolition lecturers were sent over and money furnished to establish papers and circulate[49] pamphlets to inflame the minds of the citizens of the Northern States.

"Looking far ahead, they sought to incorporate their doctrines into the school-books and publications best calculated to influence the minds of the young and ignorant. Their views were most readily received in Massachusetts, where British influence has, for the last half century, been greatest. From this State these doctrines were gradually diffused to a great extent throughout the North."

At the time that the British politicians were taking so much interest in the slavery question of America, and deprecating with many crocodile tears our treatment of the negroes they had sold us, the Edinburgh Review of January, 1856, charges the British Government with collecting rents and taxes from its subjects in India by means of the thumb-screw and other tortures as devilish as ingenuity could devise. See Speeches and Writings of T. L. Clingman.