THE GROVE (SOUTH FRONT).

Some minor punctuation and spelling errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and punctuation has been retained.

WILD NATURE WON BY KINDNESS. Illustrated. School Edition, limp cloth, 1s. 6d. Presentation Edition, imitation leather, in box, 5s.

“A charming collection.... Will be found a pleasant companion to young people in their holiday haunts.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

MORE ABOUT WILD NATURE. Illustrated. Paper, 1s.; cloth, 2s.

“No better book can be given to juvenile naturalists.”—Graphic.

THE GROVE (SOUTH FRONT).

Dear Miss Ormerod,—

For thirty years you have been a pioneer in the fields of agricultural zoology and chemistry, and it may most truly be said that no woman has ever done so much as you have to protect agriculture against its natural enemies. In the special departments to which you have devoted your life, it is universally admitted that you are without a rival.

My little volumes do not compete with work so serious as yours, yet you have gratified me with your commendation of their truthfulness, and you have permitted me the pleasure of dedicating to you this one, in some chapters of which I deal with the classes which are most familiar to yourself.

ENCOURAGED by the extremely kind reception which has been awarded to my previous books, and by the assurances, which have reached me from the most unexpected sources, that they have been found pleasant and profitable, I am venturing to offer to the same indulgent public a third collection of personal studies of natural history.

I recognise clearly that my little volumes have been received with so much favour, because, in spite of their simplicity and their lack of scientific importance, they are, so far as they go, original. That is to say, I have not much to give, but what I have is of my own gathering. I have not borrowed from other and cleverer writers, but have set down as plainly as I could what I have myself observed and experienced.

It is my privilege to be unusually well placed for the minute study of living creatures, and in that study I find a pleasure so intense that I long to attract others to the same well-spring of pleasure. Unpretending as are the chronicles of the inmates of my house and garden, they are scrupulously true, and every fact that a veracious observer records is a contribution, however small, to our general sum of knowledge.

It only remains to say that a few of these chapters have appeared in Nature Notes and in The Girl’s Own Paper. The rest are now printed for the first time.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| LEMURS | 15 |

| TOMMY AND PEARLIE | 27 |

| MUNGO | 39 |

| SQUIRRELS | 51 |

| FAIRY | 57 |

| ASNAPPER | 73 |

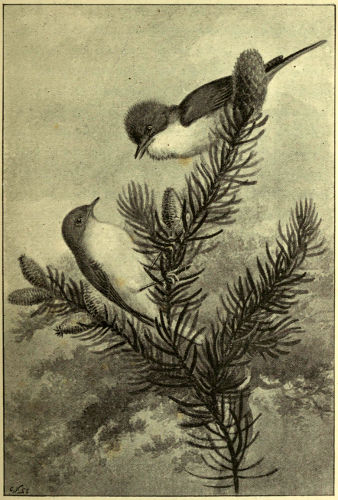

| WILLOW-WRENS | 83 |

| TAME DOVES | 91 |

| FEEDING BIRDS | 103 |

| STARVING TORTOISES | 115 |

| TEACHING CHILDREN | 127 |

| STUDYING NATURE | 139 |

| INSECT OBSERVATION | 153 |

| SOLITARY BEES AND WASPS | 165 |

| DRONE FLIES | 191 |

| THE PRAYING MANTIS | 201 |

| THE CORK MOTH | 211 |

| THE CLOTHES MOTH | 219 |

| THE DEATH-WATCH | 231 |

| CHEESE-MITES AND FLIES | 237 |

| LEPISMÆ | 245 |

| POT-POURRI | 255 |

| A WATER BOUQUET | 265 |

| ARTISTIC PITHWORK | 271 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| THE GROVE (SOUTH FRONT) | Frontispiece |

| TOMMY | 31 |

| PEARLIE BASKING BEFORE THE FIRE | 35 |

| FAIRY SINGING | 65 |

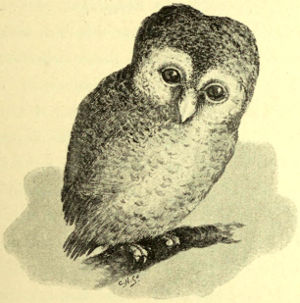

| YOUNG BROWN OWL (ASNAPPER) | 79 |

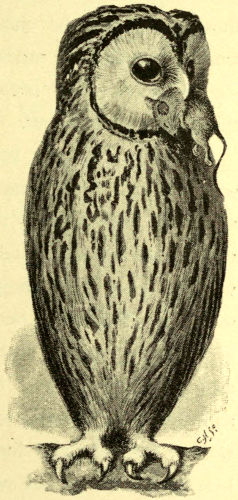

| ASNAPPER | 81 |

| MY WINDOW VISITORS | 106 |

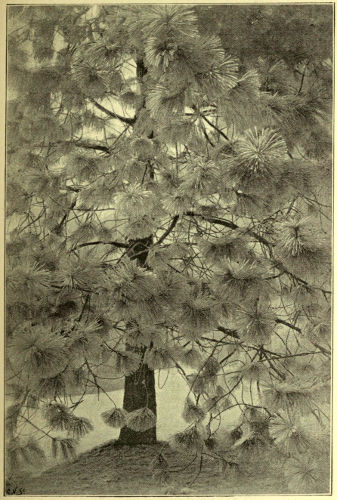

| FIR-TREE IN WINTER | 109 |

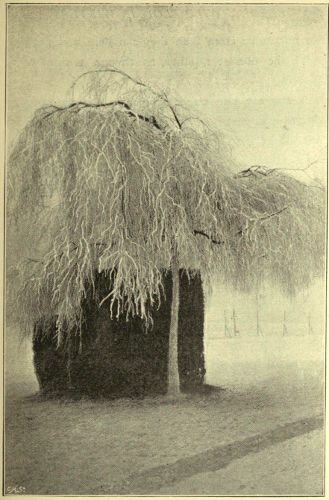

| YEW-TREE SEAT AND WEEPING BIRCH | 111 |

| VARIEGATED DEODAR | 177 |

AMONGST the many curious animals I had kept and studied, there had never, so far, been a specimen of the monkey tribe. I had always feared that I could not meet their requirements in the way of food and temperature, and that a proper place for such creatures did not exist at the Grove.

However, the offer of a pair of lemurs tempted me into many consultations and much searching amongst the books in the library, in order to find out all that could be learned about the nature of these animals, until I found myself speculating as to whether it would not, after all, be possible to make them happy.

Lemurs are inhabitants of the island of Madagascar, where they live in the woods, feeding on fruits. All accounts agree in describing them as quiet, gentle creatures, very agile in their movements and nocturnal in their habits.

The word lemur was employed by the ancients to describe the unbodied spirits of men, whether beneficent or malignant; the festivals called lemuria were appointed for the appeasing and “laying” of ghosts. The animals received their name from their almost noiseless movements; they must, I suppose, look very ghastly and uncanny as they flit about on the tree-branches at night.

The more I read about them the more it appeared to me that I must not lightly pass by such an opportunity of obtaining rare subjects for naturalistic study. So the lemurs were accepted, and I sent a man to the other side of London to bring them, cage and all, with great care to their new home.

Until I knew their size and something about their requirements I could not very well prepare a place for them, and I reckoned on their living in the cage that they came in for a few days at least after their arrival. What, then, was my dismay when the lemurs arrived to find that they were packed in a small hamper, and that no cage had come with them, as it had been found too large to be conveyed by any cab or other sort of carriage.

Plainly the poor animals could not stay in the hamper, and I had nothing large enough to hold them. They were so timid that I was afraid to let them loose in the conservatory; they might have sprung up to the roof and remained there, where it would be cold, and as I had been very specially warned to guard them against draughts, I was puzzled indeed to know what to do with them. At last a large circular linen-basket was found, which made a temporary home until we could think of some better place in which to keep them.

When the hamper was opened the poor frightened creatures were seen, locked in each other’s arms, gazing at us with round glassy eyes. It was some days before we could really see what beautiful animals they were, since their timidity was so great that, though they would eat bananas out of my hand gently enough, nothing would induce them to come out of their hiding-place and be friendly.

As soon as possible, a bay at one end of the conservatory was wired in, some tree-branches were fixed for the lemurs to climb upon, and a large plant-case, with glass sides and top, and soft hay within, made a cosy retreat when they wished for complete retirement.

It was very enjoyable to let the new pets into their pleasant home. They instantly and fully approved of it, climbing at once to the highest branch, and gazing down at us with a far happier expression in their great eyes than they had hitherto shown. And now for the first time we could appreciate the beauty of their silky-white fur and wonderful tails.

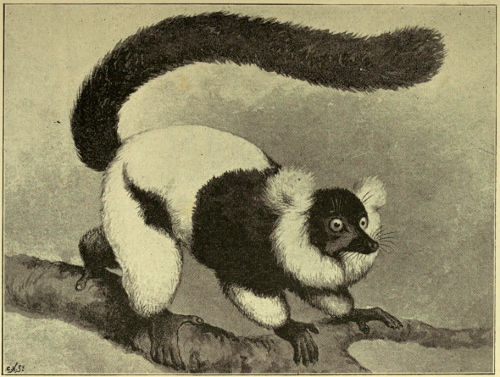

I found out that these were specimens of the Ruffed Lemur, the most beautiful of the ten species found in Madagascar. I will try and describe them, though it will not be easy to give a very clear idea of creatures which vary so much in aspect according to the position they adopt.

Sitting on the top of their glass house, side by side, with their long furry tails coiled around them, they looked like two huge Persian cats, but standing or climbing they showed themselves to be true monkeys, although far exceeding the ordinary monkey in gracefulness.

Round the head was a full ruff of long white hairs, setting off the gentle, fox-like face, which was mostly black, as were the small, well-shaped hands and feet. Lemurs have four fingers and a thumb on the hands, and the great toe and four smaller ones, as well as the fingers, have perfect nails, which makes the creatures look very human.

The thick woolly fur was white, with large patches of black, and the tail, three-quarters of a yard in length, was precisely like a lady’s black fur boa, and was used much in the same way, either laid gracefully across the back or over the feet, or wherever else warmth might be required.

When I offered food to these lemurs they had a curious way of obtaining it when not quite within their reach. The little black hand was stretched out and took a firm but very gentle grasp of my fingers, drawing them nearer until the coveted fruit could be reached, and even if the banana could have been taken direct they preferred to hold my hand, and did it so prettily that I was tempted always to make them reach out for it.

Considering the ghost-like character associated with these animals, we thought that “Spectre” and “Phantom” would be appropriate names; they do not, however, respond to any endearing epithets, and only manifest emotion when a banana is offered for their acceptance.

I fancy they are somewhat unintelligent; they differ greatly from the ordinary type of monkey, in that they sit still by the hour together, and have no idea of mischief or of helping themselves in any way; for instance, a monkey, if feeling cold, will accept a shawl and wrap it round him, finding the comfort of it; but these creatures would sit and shiver and die of cold before the idea of covering themselves would enter their dull brains.

They are masters of the art of expressing surprise and contempt. If something is offered to them that they do not like, they bridle up and turn away their heads as much as to say, “Dear me, no! nothing earthly would induce me to touch a thing like that; remove it at once!”

My greatest surprise in connection with the lemurs took place about two months after their arrival. I had carried Mungo[1] to see them, and carefully holding him by his string, I allowed him to stand and gaze up at them through the wires.

He had often done this before, and beyond a few angry snorts and their usual grunting sounds they had taken no notice, but on this occasion they both at the same moment set up the most terrific roar that I ever heard. I do not exaggerate when I declare that it really seemed as loud as the roar of a lion at the Zoo. I was close to them, and it was so utterly unexpected I don’t think I was ever quite so astonished in all my life. The sound was truly awful, and it lasted for half a minute or more, till I felt completely stunned, and was glad enough to retreat to a quiet room where my nerves could recover from the shock.

I think the Madagascar woods where these animals dwell must be most gruesome places at night, with these black and white creatures flitting about in the branches, abruptly uttering their terrific roars at intervals.

A family quarrel among lemurs must be a thing to remember. Besides this, they also give a loud groan now and then, which irresistibly reminds one of Punch’s “moaning gipsy in the back garden.” Such a groan must sound additionally weird at night in the dark woods.

When I gave my friends an account of the scare I had had, one of them returned with me to the conservatory to be favoured with a special performance of “Ghosts.” Mungo was brought in once more, and up rose the awful sound, with such effect that my friend turned and fled, even though she had been forewarned. Fear is quite irresistibly awakened by the strange quality of the sound given forth by these animals. Having very slight means of defending themselves, I imagine this roaring power has been bestowed upon them to enable them to scare their foes, and drive away through fear such enemies as their soft hands could never overcome in fair fight.

After keeping these lemurs about a year, I found that by no amount of kindness or coaxing could I get them to be really friendly, and I feared they were not over-happy without companions of their own kind. They were doubtless caught too old to be tamed. It was therefore deemed best to present them to the Zoo, where, under the kind and skilful treatment they receive, they are, I believe, in splendid health and spirits.

Visitors to the monkey-house can identify them from the description I have here given, and cannot fail to admire the agile movements and furry beauty of my quondam pets.

“So abundant, indeed, are lemurs in Madagascar, that, according to M. Grandidier, who has done so much to increase our knowledge of this group, at least one individual is almost sure to be found in every little copse throughout the island.”

ALTHOUGH I was unsuccessful in taming my handsome ruffed lemurs, Spectre and Phantom, I felt that lemurs were delightful animals to keep as pets, and I resolved that if an opportunity offered for obtaining other and more tameable specimens of the same kind I would certainly try again, and with my past experience I hoped to attain good results.

One day I heard that a young specimen of a Ruffed Lemur had been seen in a cage at the top of a cart full of birds and curious animals, a sort of small travelling menagerie which was stopping for a few days at a town five miles off. A mounted messenger was sent off at once with a basket, and full directions about the purchase of the little lemur, and, to my great delight, when the man returned with it, it proved to be all I could desire, quite young and healthy and very tame.

It must have been a pleasant change from the cold, draughty cage it had been used to, to the large wired-in recess in my conservatory, which was always kept at a genial temperature, and where, leaping from branch to branch, the agile little creature could play its graceful frolics from morning till night, hanging head downwards, swinging on a trapeze like a born acrobat, and evidently enjoying its life as much as if it had been in its native woods. The showman had always called the lemur Tommy, so we supposed that was an indication of its sex, and retained the name to which it had been accustomed.

TOMMY.

One day in summer I had one of my large parties of poor people in the garden, and Tommy was led about with a long string, greatly to the delight of my visitors. The lemur was in no way frightened by the crowd; he made friends with everybody, and hopped about from one group to another quite at his ease. After a time a harp and violin began to sound, and then Tommy’s love of music became apparent, for he seated himself close to the players, and there he remained quite riveted by the unusual sounds, gazing intently at the harpist as if spellbound.

They were but village musicians, and I was not a little surprised when, on my remarking how music was appreciated by the lemur, one of the men remarked, “It keeps reminding me of King Robert of Sicily and his 'solemn ape.’” One hardly expected such a knowledge of Longfellow’s poetry in a country rustic!

It is not the first time I have been scared by the display of unlooked-for intelligence, as the following anecdote will show.

Many years ago I was talking to my cook on culinary matters in the dining-room, when she suddenly looked up at a majolica plate over the doorway, and said, “That’s a mythological subject isn’t it, ma’am?” I replied that it was. She then said, “Is that Pan in the foreground?” I said, “No, but it is a Satyr.” “Well,” replied Cookie, “I was saying the other day to the butler, if there were creatures of that sort to be seen nowadays it would go far to prove the Darwinian theory—wouldn’t it, ma’am?” History does not record my reply! I gazed at the creature depicted on the plate, half man and half animal, and felt there was much acumen in my learned servant’s remark, but, the question of that day’s dinner being once settled, I thought it best to leave the Darwinian theory alone, lest I might not prove equal to the occasion.

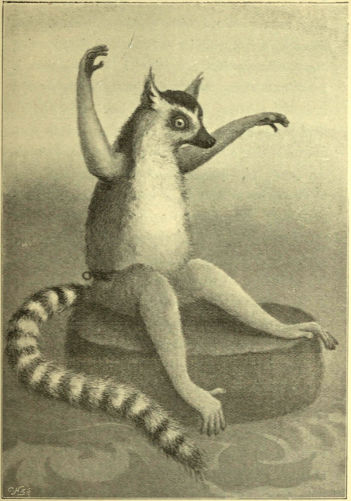

This, however, is a digression. I have now to record the advent of Tommy’s companion, Pearlie. It seemed well that the lemur should have a playmate, and I often endeavoured to provide one, but was unsuccessful, until one day, on visiting the Bedford Conservatories in Covent Garden, I saw some pretty grey creature curled up in a cage, and on inquiry I found that it was a specimen of another species, the Ring-Tailed Lemur, quite young and very tame. It was just what I wanted, so the little animal was carefully packed in a hamper, and I brought it home with me.

I feared to place this little lemur at once with Tommy, lest they might not agree, so, for the night, the new pet was placed in a large basket, and covered with a railway rug. Next morning it was discovered on the top of the highest picture frame, having forced its way out of the basket. A banana soon tempted it to come down, and in the most friendly manner it sat upon my shoulder and seemed delighted to be caressed and played with. Before long, when the two lemurs had become accustomed to each other, they were allowed to meet, and quickly became the greatest friends, playing together for hours and affording us constant amusement in watching their graceful gambols.

PEARLIE BASKING BEFORE THE FIRE.

These lemurs are always giving me surprises. I was quite unprepared for the remarkable power the ring-tailed lemur possesses of running swiftly up the flat surface of a door, but this Pearlie did with the greatest ease, and then sat calmly looking down at me from the top as if enjoying my amazement. I was led to examine his paws, and found they were provided with elastic pads somewhat like a fly’s foot with its suckers, and then reading about this particular species I learned that it inhabits a rocky tableland without trees, so that it is not arboreal in its habits, but is formed with leather-like palms to its hands to enable it to keep a firm footing on wet and slippery rocks, where it is not possible for human beings, although barefooted, to follow it. When he is brought into a sitting-room it is very needful to have a leading-string attached to Pearlie’s waistband, else he darts away and is at the top of a picture frame out of reach in a moment. His agility is only second to that of the Gibbon—the wonderful spider-like monkey one may sometimes see at the Zoological Gardens performing marvels of agility in swinging, by means of his attenuated arms and legs.

During the summer months my lemurs much enjoy being in the open air, and on fine days they are tethered on the lawn, where they amuse my visitors with their graceful frolics. The entire absence of odour, their cleanly habits, and their delicate tastes as to diet render these animals especially desirable as pets; they enjoy fruit of all kinds—lettuces, clover-blossoms, and rose-petals, while dates, raisins, and bread and milk supply solid items of food. Thus fed and warmly housed these creatures can be kept in splendid health with very little trouble.

Pearlie was so named from his fur being of a soft pearl-grey colour, the long tail being banded with alternate rings of black and white. His face and chest are also curiously marked in black and white, the eyes bright orange, and the general expression is as gentle as that of a little cat.

We found out in the course of time that Tommy was of the gentler sex! Her name must therefore be considered the diminutive for Thomasina—at least I see no other way out of the difficulty, as a new name would not be responded to or understood.

Pearlie’s portrait requires a word of explanation. His great delight in cold weather is to be allowed to sit on a hassock before the drawing-room fire and bask in its warmth. The instant he is seated before the cheerful blaze, up go his little arms in a worshipping attitude like a veritable Parsee. Thus he will remain for hours content and happy as long as I am in the room, but if left alone he makes a pitiful cry and starts off in search of some of his friends, as though life were not endurable without human companionship. I think this is always the case where animals are treated with uniform kindness; they must be able to trust those who feed and care for them, and when that perfect trust is established they yield a love that is often quite touching in its intensity. These two lemurs are very different in character. Tommy is absolutely selfish and strongly self-willed, timid and cautious. Pearlie shines by contrast, and is ready to give up, gentle, affectionate, and confiding. It is true they are of different species, and that may in a measure account for the differing characters they exhibit, but seeing they were both obtained when quite young, and treated alike with unvarying kindness, one would have thought that original tendencies would have become more thoroughly effaced. Allowing for Tommy’s moral failings, one must own that he and Pearlie are delightful specimens of the monkey tribe. They keep their lovely fur spotlessly clean, are quite inodorous, always ready to be caressed, and add greatly to the interest of my conservatory by their lively movements and graceful antics.

MUNGO, the Ichneumon, whose early life was chronicled in “More about Wild Nature,” has now been a household pet for nearly four years, and must be nearly six years old.

I do not know how long these animals generally live, but as yet Mungo shows no signs of age or infirmity. He is as full of fun and as inquisitive as ever, but not so bent upon mischief as in his youthful days. He now has the range of house and garden, and goes wherever he likes without even a collar to remind him of captivity.

The chief trouble is in connection with my visitors—those at least who have a strong objection to “wild animals about the house”; nothing, however, can possibly be less “wild” than Mungo, for he is just like a tame cat. He does not dream of biting or scratching, and is never so happy as when curled up in the lap of some indulgent friend; yet, as he unfortunately looks like a ferret, many people find it very hard to believe that he can be perfectly harmless.

Mungo delights to spend his mornings basking in the sun on the window-sill of my bedroom, where he is sufficiently elevated to watch all that goes on in the garden. He is scarcely ever asleep; as Mr. Rudyard Kipling says so truly, in the delightful account he gives of an Indian Mongoose in the Jungle Book, “He is eaten up from nose to tail with curiosity,” and whilst seeming to slumber, the active little cinnamon-coloured nose is ever on the work sniffing out the varied movements of the household.

As summer comes on we naturally let the fire die out; and Mungo strongly disapproves of this custom, for he dearly loves to bask on a little wool mat before a hot fire. Now, however, he adopts another plan—when he finds the fire is out he quietly climbs over the wire-guard, goes under the grate and there lies down amongst the warm ashes. He has even done this whilst there remained some fire in the grate, and I much fear he may make an auto-da-fe of himself some day by setting his long hair alight, which would be a terrible fate indeed for our cherished pet.

Mungo’s love of warmth leads to another undesirable habit. He will steal into the bedrooms and hide himself under the duvets, and—low be it spoken!—he has been found cosily rolled up in a nightdress!

It may naturally be asked, “Why is he not kept in a suitable wired-in place where he can do no harm?” Simply because he makes himself perfectly miserable in confinement; he tears at the wirework till his paws are bleeding, and foams at the mouth with misery and rage. No one could keep an amiable little animal in such purgatory; it would be kinder to end its life at once, and such a fate cannot even be thought of.

Mungo is a diplomatist! Liberty he has schemed to obtain, and after years of astute planning, and almost reasoning, he has reached his end, and we must acknowledge ourselves beaten, for to all intents and purposes he is now master of the situation and may do pretty much what he pleases.

There is, however, still a crumpled roseleaf in his lot; the softest bed and the sunniest nook to bask in will not satisfy Mungo without human society, and as we cannot give up all other occupations in order to sit with him, he is often to be seen wandering about like an unquiet spirit until he finds some friendly lap where he can curl himself up and enjoy all those conditions of warmth, ease, and society which form his idea of perfect bliss.

I am sure Mungo is a staunch Conservative as to his political views! He hates changes of any kind, since they interfere with his personal comfort and methodical habits. He likes to have a morning sleep in a sunny spot, and then his profound interest in a certain rhododendron bed, where rabbit-holes and mole-tracks are to be found, leads him to steal across the lawn and disappear amongst the bushes. I rather fancy he has grand times there, for if I attempt to coax him to come with me, his pert little nose will appear amidst the leaves, and with a frisk and a leap of absolute disobedience and fun he will return to his playground and remain there till it pleases him to come indoors again. His next desire is to enjoy a quiet afternoon under a warm duvet, and as he behaves with absolute propriety and only covets warmth and quietness, I am indulgent enough to allow him the luxury of being in my room until evening, when he is fed, wrapped up in a wool mat and a piece of baize and placed safely in his cage for the night.

Although Mungo would often absent himself for hours at a time, we were so sure to see him trotting quietly home when his frolics were ended, that somehow the possibility of an accident happening to him never crossed our minds. When, however, one day he did not return by evening, and night came on and no one had seen or heard anything of my pet, I felt certain he had met with some sad fate—most probably had been caught in a snare or trap set by the poachers on the common. Next day, gardeners and farm-men were sent out in all directions to look for him. The search went on for many hours, and at last I heard the welcome cry, “Mungo is found!” Poor little fellow! but how my heart ached to see him in torturing pain with a wild, scared look in his eyes. He had, as we suspected, strayed across the boundary on to the common, and there he had been caught in a spring-trap, which had completely crushed one of his fore-paws.

I had only a few minutes in which to decide whether the poor little animal must be put out of his misery at once or if there might be hope, by skilful amputation, of ultimate recovery. I am sure that all lovers of animals will understand the keen distress I felt at having to make such a decision, but something must be done, and as I found I could not give the death warrant, Mungo was taken to the veterinary doctor, with injunctions to spare no pains in trying to save the patient all needless suffering. Two surgeons attended to the case, and whilst under chloroform the little animal was relieved of the injured paw, and must have been remarkably well treated, for I was soon informed that Mungo was doing well and would take some “bird” for his dinner! In about a fortnight he was brought home and looked very pitiful, limping about on three legs. It was long before I could become accustomed to see him thus, but so well did the wound heal that now the limp can hardly be observed, and the little creature is as merry as ever, scampering about and playing with his own tail as lively as any kitten.

It has been an interest to me to make a study of the character of my mongoose, for a wild creature rendered perfectly tame by unvarying kind treatment gives one an excellent opportunity of observing the real nature of the animal.

I fear I must own that Mungo is absolutely selfish, his one idea is to enjoy perfect liberty and have his own way in everything. After four years’ petting he knows me well as his friend and purveyor, but he has not an atom of affection; he has, apparently, no mode of manifesting regard, the expression of his face never alters, he does not try to lick my hand or make any greeting sound. He likes to jump into my lap simply because it is a comfortable place, and, as he is very timid at any unwonted noise, he will run to me for protection, but I am afraid he views me as a means of attaining physical comfort, food, and warmth, and nothing more!

All this does not prevent my liking the curious little animal, but one cannot but be struck by the immense difference between its nature and that of the faithful dog, whose devotion to his master will lead him to refuse his food, to take long, toilsome journeys, to wait patiently for weary hours in cold wind and biting frost when bidden to guard his owner’s flock, aye, and even to yield up his life, if necessary, to do his master service.

All this shows, what I have often remarked before, that, to those who are observant of the fact, there is as much difference between the characters of various animals, and even between those of individuals of the same species, as may be found in human beings.

Possibly Mungo may be a selfish specimen of his race, and there may exist brilliant exceptions abounding in affection and other noble qualities. I can only describe him as he is, and, judging by his small cranium and its peculiarly flattened formation, I should imagine he is formed to be, not a pattern of all the virtues, but a creature of one idea, and that—snake-killing! To be proficient in that art all the characteristics I have noted in this animal are specially needed, such as lynx-like watchfulness, undaunted courage in fight, persistent curiosity and determination to care for himself under all circumstances.

We must therefore wink at his failure in moral goodness, and admire the way in which he carries out the purpose for which he was made. He worthily adorns his own special niche in Creation.

ABOUT ten years ago we began taming the wild squirrels which exist in great numbers in the woods around this house. We put Barcelona nuts in a small basket outside the dining-room window, and every day a handful thrown on the ground served to attract the notice of the little animals. In a very short time the squirrels ventured to approach, timidly at first, picking up their favourite food; they would scratch up the nuts and rush away to some quiet spot out of sight.

Generations of the graceful little rodents have been trained to come nearer and nearer to the window, until they are now so delightfully tame that I feel induced to suggest to others the means of enjoying the pleasure we find in watching our daily visitors from the woods.

My first act before breakfast is to place a handful of nuts on a small table which stands in the room close to a bay window. Hardly have I done so when in come the squirrels, sliding up to the window and leaping on to the table to enjoy the nuts. They will take nuts gently from our hands, and sitting up in the graceful position a squirrel adopts when quite at ease—its tail curved over its back, and its tiny paws holding the nut—they crack them and fling away the shells in careless fashion. A scrimmage sometimes takes place when several come in together; one bolder spirit will chase another round the room until both spring out at the window and dart across the lawn. At length the nuts on the table being eaten or carried away, the squirrels, well knowing where the supply is kept, descend to the floor and hop leisurely to a cupboard, where on the first shelf is a box full of Barcelonas. The little animals spring on to the shelf and help themselves. This they are allowed to do for a little while, as we like to watch their proceedings; but I make a protest presently, and close the cupboard door when I find my entire stock of nuts being transferred to the garden and planted all over the lawn, for the squirrels bury nuts for future use, although I am very doubtful whether they do really dig them up again.

On cold mornings when the windows cannot be opened, it is touching to see the little furry heads peep through the pane, waiting patiently for their daily meal. This they eventually share with several very tame nuthatches; these birds seeming very glad of nuts as well as fat during the winter months.

The only drawback to having wild squirrels tamed is the distraction they cause when a class of village children is being taught in the dining-room! Sydney Smith says: “A sparrow fluttering about the church is an antagonist which the most profound theologian in Europe is wholly unable to overcome,” and certainly the apparition of a bright-eyed squirrel popping up at each window in succession is enough to drive a teacher to despair. Nothing less than an abundant shower of nuts will bribe the little intruders to keep quiet for a time.

I have given these simple details because I think that possibly many of my readers may like to encourage those charming little animals when they learn how easily, by a little patient kindness, they may be attracted from the woods to become household pets of their own free will, which is, to my mind, so much more enjoyable than keeping captive animals or birds. It should, perhaps, be added that great quietness and calm are needed while the first advances are being made, and that a loud voice or a quick gesture will undo a week’s work in taming.

I AM often envied as the possessor of one of the most charming bird-pets it is possible to imagine.

“Fairy” is a tiny whitethroat, a sleek, delicate, grey-coloured bird with a white breast, lovely in form, swift in flight, and of most engaging disposition.

I met with it in this wise. A plaintive little cheeping sound attracted my attention one morning at breakfast-time, and looking outside the window, I saw a tiny, half-fledged bird sitting on the ground, looking pitifully up at me; it pleaded its hungry condition with open beak, and seemed to have no fear at my approach. Of course such a poor little motherless waif must be cared for, so I brought it in, and it received very readily the provender I offered it.

I never saw such a tiny, quaint-looking piece of bird-life. Its little throat-feathers were beginning to show on either side like a small white cravat; it had about half an inch of tail, and minute quills all over its body gave token of coming feathers. The delightful thing about it was its exceeding tameness; it would sit on my finger and gaze at me with a contemplative expression; no noise frightened it; it was quite content with life in a basket, or on the table, and therefore it became my constant companion, and has grown to be very dear to me and to a wide circle of friends.

Fairy’s advent was in July, and for the first month the early morning feeding was no small care; but love makes all things easy, and at last my small charge could feed itself, and had learnt the use of its wings.

Daily baths were taken in my soap-dish, which was amply large enough at first, but now Fairy is promoted to the sponge basin, in which she flutters to her heart’s content and dries herself afterwards by swift flights about the room. The bath over, the next thing is to search for flies on the window-panes or on the floor; these are snapped up as great dainties, and in this way Fairy greatly promoted my comfort all through the heat of August and September, 1893, by keeping my room free of winged insects.

I have only to take Fairy on my finger and direct her attention to a fly on the ceiling, when off she darts, like a hawk after its quarry, and the fly disappears like magic.

I was once much amused to watch her day after day eyeing a large spider in the corner of the room. She evidently considered very deeply whether she could tackle it; it was large and she was small, and for three days she hesitated; but at last her courage was equal to the enterprise, and the spider was seized, minced up, and eaten. My tiny pet lives on grapes, lettuce, flies, meal-worms, and, as great indulgences, cream and sugar; a tin of special bird-food supplies other items of diet. Fairy is in and out of her cage all day, and but for fear of accidents she might have the range of the house, so confident am I that she would not wish to stray from her happy home. Still, she loves an expedition, and once, having flown after me into the hall, I did not see her again for an hour or more; a hunt was needful, and after searching every room she was at last discovered cheerfully investigating the boxes in a lumber-room at the very top of the house.

I never knew such a clever, fearless little bird. She will put her small body into every corner in search of information; she visits all my friends in turn as they sit at luncheon, pulls their hair, sits on their fingers, tugs their dresses, and is, of course, universally beloved.

I was curious to note whether Fairy would grow restless when the migrating season began, but her abnormal life indoors has so altered her natural instincts that she makes herself quite happy throughout the autumn, and we are truly glad that we are not called to bid adieu to such a lovable companion.

Very naturally some readers may ask, “How can they obtain a tame, happy little pet bird such as my whitethroat now is?” I can only reply, such a thing is not to be bought (or very rarely) for any amount of money, but can be attained by any one who will bring up a young fledgling from its earliest youth, with never-failing love and gentleness. There is no secret about it; it is not a gift bestowed on some and withheld from others, as many seem to suppose, judging from the number of times I have been told, “Oh, you have the gift of taming creatures.” I always disclaim the assertion and tell the simple truth, that just as you seek to win the heart of a child by invariable and patient kindness, so these innocent dumb brethren of ours yield us their devoted love if they meet with similar treatment at our hands.

We must not begin the task of bringing up a young bird without counting the cost beforehand. It means rising every morning between four and five, and having little sleep afterwards, for we must imitate the self-denying industry of the mother-bird in providing food for her young ones. If we look out over the dewy lawns at daybreak in spring and summer, we shall see thrushes, blackbirds, robins, and many other birds all actively engaged in searching for worms and insects to supply the needs of their respective families. All through the day we must think of the tender creature we have undertaken to rear, giving it every half-hour as much food as it desires, and keeping it warmly covered from cold and draughts, lest its limbs should be attacked by cramp.

This ailment seems incurable, and is the cruel fate of most fledglings that are brought away from their parents, because people forget that the warmth of the mother-bird is essential to the life of the callow brood, and I, for one, never promote the rearing of young wild birds unless, as in the case of a motherless waif like my Fairy, we try to save a little innocent life by doing what we can to imitate its natural bringing up. Absolute tameness can only be attained by unvarying gentle treatment. Never has Fairy heard a harsh word, or, as far as I know, has she had a fright of any kind.

FAIRY SINGING.

A single grip of Mungo’s cruel little jaws would end her life in a moment, but Fairy does not know it, and she sings on fearlessly as he passes her cage. I believe she would act as a certain much-petted little dog used to do when his mistress pretended to scold him severely; he would look about eagerly to see where the wicked animal addressed could be that he might fly at him. I tried to speak seriously to my small bird one day when she was particularly in my way, but she only gave me several hard pecks, and to my great amusement fought me with her tiny claws much as a gamecock would use his spurs. Fairy has the curious habit, which I have noticed in many small birds, of turning rapid somersaults by way of exercise, springing from a perch on one side of the cage up to the roof, turning over and coming down on her feet like a born acrobat.

It is curious to be able to see human passions manifested in such a tiny creature as my whitethroat, and it can rarely be seen, because it is very seldom that a bird is so absolutely tame as to feel free to show itself as it is in reality—fear being the dominant feeling in most captive birds—and that leads to the incessant fluttering and effort to escape, which hinders character from being shown.

When Fairy is out of her cage, if I open a drawer she is certain to show curiosity, and flies into it, hops about in her perky way, pecking at one thing and another to find out what each is, her beak being equivalent to a hand, and the only instrument with which she can do anything. I put some delicacy on my finger, and then she comes, and by her actions and low chirping she shows pleasure.

Before long, her sweet warbling song expresses contentment, her little sky is serene and clear, all her wants are provided for, she has no cares for the morrow, and her happy little nature comes out in cheery songs.

She picks a scarlet flower petal, and I am not sure but it may be poisonous and bad for her, so, like a careful mother, I take it out of her beak. Then comes unmistakable anger; she scolds and pecks at my fingers, and wilfully tries to get the flower petal back again.

All this is wonderfully human, and all to be found in a creature not two inches in length! If Fairy could be seen minus her feathers she would be about the size of a walnut! I do think in all respects a bird is one of the principal marvels of creation, most lovely and lovable. See the little creature taking a bath, reducing itself to a disreputable tuft of draggled feathers for the sake of cleanliness, and then fluttering and shaking itself dry again, and by means of its wonderful beak pluming its feathers into order, applying oil to them from its little gland just above the tail, and after infinite pains ending by looking soft and sleek as a piece of satin.

Instinct teaches it to do all this which we could no more imitate than we could fly. Then how touching is the motherhood of a bird. Many a human mother is put to shame by the example of a little feathered thing which has only instinct to guide her in preparing her soft, warm nursery, to which love ties her closely for two or three weeks. Bright days come and go, but she denies herself all the pleasures she sees other birds enjoying, and barely takes time to get her needful food, that she may keep warm those two little snowy eggs which are all the world to her even now, and when young creatures begin to stir beneath her faithful breast then she exchanges the quiescent life for one of incessant toil that her callow brood may not call to her in vain for the insect diet which she has to provide.

By the time the young ones can feed themselves the parents are quite thin and worn with their incessant toil, and yet in favourable seasons some kinds of birds rear a second or even a third family before the summer is over.

Although the Whitethroat is plentiful in the southern counties, I do not find that people, as a rule, are at all familiar with its appearance, and I imagine this arises from the shy habits of the bird. It flits nimbly out of sight when alarmed, and being of an inconspicuous grey colour, it requires a keen eye to distinguish it when hopping noiselessly about in weedy hedgerows, where it is so often found that it has obtained the provincial name of Nettle Creeper.

With reference to the migration of the Whitethroat, I learn from one of Canon Tristram’s delightful books on birds, that Algeria is its winter retreat. He says:—

“Each portion of the Sahara—the rocky ridges, the sand drifts, the plains—has its peculiar ornithological characteristics. But by far the most interesting localities are, as might have been anticipated, the dayats and the oases. Here are the winter quarters of many of our familiar summer visitants. The chiff-chaff, willow-wren, and whitethroat hop on every twig in the gardens shadowed by the never-failing palm; the swallow and the window martin thread the lanes and sport over the mouths of the wells in pursuit of the swarming mosquitoes.”

When spring returns, these smaller birds are led by instinct to re-cross the Mediterranean and seek their European haunts where the temperature has again become sufficiently mild to enable them to find insect food and rear their families of nestlings.

The sharp clicking note, like two stones jarred together, which this bird makes when excited, we constantly hear in our furze-bushes and hedges, proving that the whitethroat exists in some numbers in Middlesex; and now that my “Fairy” has begun to sing, I find it is a strain with which I am quite familiar. My curiosity had often been excited by hearing low, soft warbles from unseen singers on the common or in the woods; I vainly tried to see what bird it could be, but it always seemed to remain out of sight. My small pet has solved the mystery by performing for my private benefit the sweet music of her wild brethren out of doors.

I am constantly reminded of the lines in Coleridge’s “Ancient Mariner”:—

As I sit at my writing, the delicate soft warbling goes on hour after hour, and is a source of real pleasure to me, so manifestly is it the outcome of a perfectly happy little spirit telling out its inward joy in its own sweet fashion.

Captivity has no terrors for Fairy; she loves her cage, and will hardly leave it except when she occasionally takes a swift flight to and fro, and then alights on my notepaper to give a peck at my pen. She delights in sitting on the fender, fluffing up her feathers to revel in the warmth, which, in winter, is her substitute for sunshine, and before long she returns to her own little home, where she may be seen gracefully sipping the sweet juice of a grape before recommencing her song.

I often wonder how long this, my latest pet, may be spared to me! A bird’s life is such a tender thing—a moment’s carelessness may rob one of a cherished pet, and the greatest care will not always guard such a tiny swift-flying bird from injury.

May the sorrowful day be far distant that shall see me bereft of my little ray of home sunshine, my Fairy Whitethroat!

WHILST enjoying the fresh beauty of my garden in the month of May, with its wealth of flowers and rich variety of leafage, my eyes happened to light upon a greyish tuft of feathers in a rhododendron bush. Curiosity led me to examine this tuft more closely, when, to my surprise, I found it was a young brown owl—alive, but in a very exhausted condition. It appeared to be only a few weeks old, fully feathered, but unable to feed itself; I suppose it had fallen out of the nest and was dying for lack of food. I need hardly say I carried it indoors, and did my best to feed and restore the poor orphan, and right well did he second my efforts. A juicy uncooked mutton chop was cut up and mixed with feathers, and with resounding snaps of his great beak the morsels were received and swallowed. A second chop was disposed of before my friend seemed satisfied, and with such a mighty appetite I felt there would be no difficulty in rearing this vigorous infant. Next morning I found two sparrows and a mouse had been obtained. These soon disappeared, and had to be supplemented by a piece of raw meat. And if this is the daily diet of a very young owl, we may form some idea of the way in which full-grown birds must reduce the hordes of mice and rats which would otherwise overrun the country.

Whenever we passed the owl’s cage he gave a resounding snap with his beak, not viciously but as a friendly recognition, and somehow this habit suggested the name of the Assyrian king, the “noble Asnapper,” and this, familiarly contracted to “Snap” for every-day use, became the recognised title of our new pet.

Asnapper lived quietly enough during the day in a large cage well covered from the light, but towards evening, when he had enjoyed his second repast of raw meat, he began to wake up and long for exercise. He was allowed his liberty in the house, and made full use of this privilege by going about from room to room, either running along the floor like a grey rabbit, or taking short flights with his noiseless wings. He would gravely pursue his way up the stairs a step at a time, and seemed to enjoy watching cattle in the fields whilst sitting motionless on a window-sill.

Until the bird could feed himself it would have been no kindness to let him go out of doors and starve, so I resolved to make the creature’s life as happy as possible, whilst I had thus a good opportunity of learning the habits of an interesting species of bird. I could not help being somewhat afraid of his formidable curved beak, which looked as if it could inflict a severe wound, but I soon learned how gently Asnapper could use it; he would play with my fingers and hold them with such care that we had merry games of play at evening recreation time, when he looked to be let out of his cage and go where he pleased for an hour or two.

If allowed to be in the drawing-room the sociable bird made himself quite one of the party. Perched on the back of a chair, he would watch all that went on with a grave air of consideration, or else he would amuse himself by chasing a ball, or cotton reel, upon the floor, as if trying to make believe it was a mouse. I could not have thought there was so much latent fun in a solemn-looking owl, but then we are never out at night perched up in the tree-branches to see what goes on there amongst young owlets, so this afforded us a rather unusual glimpse into the habits and manners of the bird of wisdom in his merry days of youth.

This species, called the brown or tawny owl (Syrnium stridula), is found in most of the counties of England; it is rare in Scotland, and has not, I believe, been met with in Ireland. It generally retires to thick woods during the day, coming out at night to feed upon rabbits, moles, rats, mice, frogs, and insects.

YOUNG BROWN OWL (ASNAPPER).

When Asnapper had more food than he could consume at one meal he would hide the rest, taking pains to secrete his choice morsels in some dark corner where he thought we could not see them. His soft blue eyes used to look very roguish as he peered round to see if we were watching him; those eyes, by the way, changed to a rich dark brown as he grew older, and would be, I fancy quite black when full grown.

I have several times observed a brown owl flying quite late in the evening closely pursued by enraged blackbirds screaming their loudest notes of anger and fear, and I gather from this that the owl is apt to prey upon small birds and possibly robs their nests of eggs or young fledglings.

Several writers assert that this bird also feeds on fish, being able to catch those swimming near the surface. There can be no doubt of the extreme value of owls in reducing the number of rats and mice, and it is to be hoped that landowners, in their own interest, if for no better motive, will take pains to instruct their gamekeepers to protect such useful allies to the farmer and gardener. I met with an amusing instance of the value of the owl as a mouser when staying at a farmhouse in Surrey. The farmer’s daughter told me her brother had just discovered “a 'howl’s’ nest in the pigeon coo,” and going up a ladder to examine it more closely had found two eggs in the nest, and ranged around it were fourteen dead mice! If that was the result of one evening’s foraging, we need no other proof that owls are worthy of encouragement and protection.

This anecdote relates to a barn owl, which may well be called the “farmer’s friend,” for it delights to roost in barns and outbuildings, where it can find plenty of mice, its favourite food, and on that account it should meet with a kind welcome instead of being trapped and shot and hung up to decorate the end of some outhouse, where I often grieve to see it, in company with the equally useful little kestrel and other hawks.

ASNAPPER.

The brown owl has very different tastes as to its home, preferring a hollow tree in some secluded wood far away from human dwellings, although, from Mr. Waterton’s experience, it will sometimes fly into houses in the dusk of evening. He says: “This pretty aërial wanderer of the night often comes into my room, and after flitting to and fro on wing so soft and silent that he is scarcely heard, he takes his departure from the same window at which he entered.” Mr. Waterton suggests that these birds may be encouraged to settle in our woods; if holes are made in pollard-trees that are slightly decayed, the brown owls will readily adopt them as nesting-places.

I have not as yet heard Asnapper make any sound except the characteristic snap of his beak, and a low whining cry of eager pleasure at sight of his accustomed food. We are very familiar with the loud, melancholy hoot of his kith and kin which we frequently hear at intervals during the night in the gardens and woods around the house, and Asnapper will join in the chorus, for, as soon as he can feed himself, we shall bid him an affectionate farewell, and have the pleasure of seeing him spread his broad wings and sail away to his native woods.

ONE afternoon towards the end of May I was strolling along a garden walk which skirts the open common, when I overheard some boys saying, “Here’s the nest, she can’t fly,” &c., and fearing some cruelty was going on, I quickly went out to the lads and asked what they were doing. They pointed to a tiny willow-wren sitting on the ground unable to move because her wings were glued together with birdlime. It was the work of some bird-catcher; he had placed the sticky birdlime on bracken stems around the poor bird’s nest, which was in a tuft of grass and heather, and as she alighted with food for her young ones she was caught and held fast. It was a piteous sight! The five hungry little nestlings were cheeping for food, the bright eyes of the mother-bird looked up at me as if appealing for help. The boys were as grieved as I was; but what were we to do? I could not let the poor victims die of starvation, so I resolved to take the willow-wren and her family home and see if I could feed the little ones and release the glued wings so as to give the mother-bird power to fly once more. With great pains I did succeed so far that the bird could plume her feathers, and, after a few days, she could again use her wings. I fed the young birds, and in this duty the tender little mother aided me, and would even take food from my hand and put it into the gaping beaks that were always ready for small morsels of raw meat or meal-worms, on which diet the young wrens grew and flourished, until I was able one fine day to release the mother and children and rejoice in the thought that their innocent lives had been saved from a cruel death.

I can but hope that no reader of this book would ever dream of catching our songsters with birdlime, but there is a form of cruelty of which thousands of ladies are guilty, and against which I, for one, shall never cease to protest until the hateful fashion has entirely ceased. How often I wish I could lead those of my own sex to think of the terrible suffering they are causing to millions of birds as sweet and innocent as my little willow-wren. Can any one conceive my having had her killed and stuffed, and then placed as a trimming on my bonnet! The thought of the willow-wren’s mother-love ought to make such an idea abhorrent to any gentle-minded woman. But cannot my sisters be brought to reflect that every wing and bird’s body they wear on their headgear means the cruel death of a creature of both use and beauty that was enjoying its innocent life, and doing us only good by carrying out its appointed duties in God’s creation? I cannot express the pain it gives me to see aigrettes, wings, and whole birds still so lavishly used in trimming hats and bonnets. Loving birds as I do, I cannot help pleading for them from time to time, in the hope that public opinion may have some influence, and ladies may learn at last to be ashamed to be seen decked with an ornament which proclaims them both thoughtless and unfeeling.

The willow-wren, one of the most useful of our insect-eating birds, abounds in my old garden, and keeps the rose-trees free from aphides and other pests. It chooses very unsafe places for its nest, the smallest tuft of grass being deemed a sufficient shelter. One such nest, I remember, was located two years ago close to the field road where my hay carts were continually passing. The brave little mother seemed to have no fear, but as a heedless footstep might unwittingly have destroyed the nest, some branches were placed round the spot for her protection, and I hope she succeeded in rearing her family.

It is a charming sight to see a party of willow-wrens methodically clearing the insects from a rose-tree. Like a band of tiny acrobats they flit about sideways, upside down, in and out, until every twig has been examined and all the prey secured, then, with happy chirpings, away they flit to the next tree to resume their useful operations.

The sweet, warbling song of this migrant seems a truly summer sound, for the bird seldom arrives until the middle of April, and leaves us again about the end of September; its note therefore suggests sunshine and flowers and the hum of insect-life.

IT is always interesting to note how gentle kindness shown towards our pet animals and birds will bring out various traits of character in them. Curious differences will be observed even between specimens which are of the same age and family and have been treated exactly alike from their earliest years. A pet creature can only show its true nature when it is brought up so kindly as to be without fear. Alas, how seldom this is the case!

Almost all captive song-birds I have seen, excepting canaries, are sure to flutter more or less when any one approaches their cage, and this instinctive effort to escape shows timidity and unhappiness. I confess I could never find any pleasure in keeping a tiny captive which I knew was breaking its little heart in fruitless longings for fresh air and liberty.

To show what thoughtful kindness will do in creating happy confidence, I should like to relate the history of my tame doves, Peace and Patience.

These birds used to belong to a poor woman in our village; her only means of housing them was in a wooden box with a wire front. It was a wonder that they continued to live in such discomfort; yet, without a bath, a nest-box, or anything to make their lives pleasant or healthy, they showed the grace of patient endurance by living on with merely their bare allowance of food and water.

However, they were redeemed at last from their hard bondage, placed in a large wicker cage with plenty of suitable provender, enabled to sun themselves in a pleasant verandah, and to take a bath in pure water whenever they felt inclined. Their plumage soon began to improve, and became as smooth and soft as grey satin. After a time they were let out to fly about in the dining-room, and the male bird, Peace, might often be seen sitting on the marble clock, gazing at himself in the looking-glass over the mantelpiece. I suppose he admired his own reflection, for he would go again and again to bow and curtsey and coo most lovingly to the bird he saw in the glass, and never seemed to find out it was all the while himself.

In spite of this foppishness he was a most devoted mate, paying all kinds of tender attentions to his gentle little wife, following her about and often feeding her with any special dainty he might come across.

Under these new and happy circumstances Peace and Patience began to think of rearing a family, and we found them searching everywhere for materials wherewith to build their nest. Not finding much that was suitable in my sitting-rooms, they went to the flower-vases and began pulling out the orchids and maiden-hair fern to line their nest.

It looked very pretty to see the little grey bird flying across the room with a great pink flower in her beak; but we thought a more suitable substance might be offered to them, and very gladly they welcomed some little twigs and dried grass, with which, after much cooing and confabulation, they constructed the family home. In a day or two a pair of snow-white eggs appeared, and then for a fortnight the little hen-bird sat patiently brooding over them, scarcely leaving them long enough to take her necessary food.

In due time we found two little doves were hatched. Small, pink, feeble-looking creatures they were; it seemed quite wonderful to think that they could ever grow up to be like their parents.

Patience was so tame that she would let me peep under her soft feathers to see how the tiny birds were progressing, and even if I took one of her children away to show to my friends she was in no way perturbed.

It is a great surprise to see doves feeding their young ones. They take the tender little beak within their own and then pass the soft food, with which nature provides them at that time, from their own crop into the beak of the fledglings. The young birds seemed to have excellent appetites and grew rapidly, developing tiny quill-feathers all over their bodies, and in a few weeks they were clothed with soft grey plumage, so that we could hardly tell parents from children.

I have often heard doves spoken of as being less intelligent than other birds. On the contrary, my birds seem to think and almost to reason, as I believe my readers will agree when I tell them some of the clever things they have done.

One day when I was sitting in a room some distance from the verandah where the doves were, Peace found me out and came tapping with his bill against the window. I am always accustomed to attend at once to any such appeal from a bird or animal, since I generally find it to mean that they urgently require something.

In this case, as the evening was chilly, I let the three doves into their cage and brought it indoors; but I soon found all was not right, for the male bird was greatly excited, apparently longing to get out again, so I opened the cage door and the window of the room, and away he flew. Presently I heard Peace cooing loudly, and, following the sound I found him under the verandah with the young dove that was missing; he was evidently trying to show me his truant child, and as soon as I took them both up and carried them to the cage, Peace was quite happy and content.

When the weather became warm and sunny the little pair decided that their next nest should be built in some clematis growing up the pillars of the verandah. It was a charming spot to select, for the little mother-bird had flickering sunbeams shining upon her whilst she sat, and leaves to shelter her from the heat.

Now again a domestic difficulty arose and Peace came to tell me about it. What was he to do for building materials? I provided small flexible birch twigs, and was amused to find that when I offered one, the little builder took it gladly, and, flying off to the nest, presented it to his wife and she wove it into the family dwelling.

Later on in the day it seemed to me that the comfort of the home would be improved by some softer material than interlacing twigs, so I added a carpet of fine soft shavings; these also were quite approved, and after a time the nest was considered perfect. I felt inclined to call it our nest, as I provided the materials and was allowed to help in the building.

Two snowy eggs soon appeared, and then the parents took it by turns to sit upon the nest for about four hours at a time. This should teach us a beautiful lesson of unselfishness, for it must seem a little hard to have to sit still hour after hour and see another bird able to fly about enjoying the air and sunshine. I think my dove was well named Patience, but doubtless the strong feeling of mother-love made it easy, and the affectionate little father-bird seemed always ready to take his turn in the domestic duties.

The first heavy shower after the nest was built made me rather anxious for the comfort of the sitting bird; she would soon have been soaked with rain, so I racked my wits to devise a shelter. With some contrivance I managed to fix a slanting roof of stiff cardboard so as to keep off rain and scorching sunshine. By talking quietly to my pet she seemed quite to understand that she was not to be alarmed, and sat calmly on her nest whilst I fixed her shelter.

The bird that is off duty is fond of coming to visit me in the house. I am quite accustomed to see a dove sitting amongst my working materials; I have even found an egg lying on my writing-table as a modest gift and token of affection from my gentle Patience.

Peace looks very pretty when he perches on a white marble bust in the drawing-room. He dearly likes investigating anything fresh, and I once found him in the museum busily pulling an old nest to pieces, because it contained some materials he thought would be desirable for his own home.

I learn many lessons from my little doves. I see how affection begets confidence. These little creatures trust me perfectly, and that gives me true pleasure, and makes them very dear to me. I think it is thus our Heavenly Father would have us show our love to Him. He says, “I love them that love Me,” and the text goes on to say, “and those that seek Me early shall find Me.”

Then let all the dear young people who read about my doves try to learn, from their history, how they can please God by showing their love and trust in Him, by going to Him continually with all their difficulties, not doubting that He will hear, and abundantly answer their prayers.

ANY winter’s day a charming sight may be witnessed outside the long French window of my drawing-room, but this is especially the case in frosty weather, when the frozen-out birds come in flocks to partake of my bounty. Virtue is its own reward in this instance, for I derive untold pleasure from the lively scene which greets my eyes when I sit down each morning to carry on the dual occupation of writing letters and watching the birds.

This winter (February, 1895) is one of exceptional severity. More than a month of intense frost will have killed thousands of birds, especially of the insect-eating species. Tits have even attacked the woody galls upon the oak-trees, and extracted the grubs from them, thus doing the forest-trees good service.

MY WINDOW VISITORS.

It is curious how plainly individual character comes out in hungry birds. Nine robins are now, whilst I write, carrying on a guerilla warfare, pecking and flying at one another like little furies, as indeed they are. Much as I love robins, I must own they have villainous tempers, and will treat their own kith and kin with persistent cruelty.

Now a dozen or more fussy starlings have arrived for their breakfast, and eagerly pick up the coarse oatmeal, which seems to suit the requirements of most birds when they cannot get their own special diet. I like to listen to the busy chatter the starlings keep up all the time they are eating; it is varied by little tiffs, which constantly arise, when two birds spring into the air, peck at each other furiously for a moment, and then, the insult being avenged, drop down and resume their breakfast until there comes a scare about something, when away they all rush. Starlings are good emblems of perpetual motion—cheerful, busy creatures, they never seem to have a minute to spare, and make so much ado about both work and play that they are amongst the most amusing of the visitants to my window. Blackbirds, on the contrary, are sedately stolid, and usually keep in one position until their hunger is appeased, or, if compelled to fly off in the middle of their repast, they have the forethought to carry away a lump of bread or fat, which they can enjoy in private.

As a rule the thrushes stay away from my food supplies until they have exhausted other stores, but when they do join the throng of pensioners and accept outdoor relief, it is with a calm, fearless air, as if they had a full right to the choicest morsels. When all the rest take flight at some sudden noise, the thrushes generally remain and go on feeding with quiet dignity, as if quite above the silly frights of the vulgar herd. The busy scene would lose much of its interest without the calm effrontery of the blue tits. They perch upon the lumps of fat, assuming every possible attitude of graceful agility, and those who trench upon their domain have occasion to learn that their absurd little beaks can be exerted with considerable force and effect. The snowy lawn which forms the background to my bird-picture is a real “study in black and white.” About fifty rooks are either feeding under the tulip-tree or walking about on the frozen surface of the snow. Hardly any bird shows the inner working of its mind so clearly as the rook. One may learn from its actions the dawning of an idea and the subsequent working out of the same.

FIR-TREE IN WINTER.

One of these birds is at this moment weighing pros and cons as to whether it would be safe to join the party at the window. Whilst all are feeding quietly it decides to come, and marches slowly on; then, when the starlings take one of their sudden flights, the rook stops, looks this way and that, and feels doubtful. However, a second rook joins the waverer, and the two take courage and advance together. One of them stands on a lump of suet and breaks off pieces with its huge beak—the rook sharing with other birds the universal love of fat—the lump becomes smaller and smaller, and at last the great beak grips it firmly and away flies the rook, closely pursued by a crew of sable comrades, who are all eager to share in the spoil which they were not brave enough to secure for themselves.

YEW-TREE SEAT AND WEEPING BIRCH.

I have not spoken of the sparrows; their name is legion. And how they do eat! No other bird clears away the food so quickly. The sparrows do not move more than they can help, and peck with the utmost rapidity, as though absolutely starving.

I suppose one ought to pity a “frozen out” sparrow as much as any other bird, but I could wish there were fewer of them at these times when one wishes to befriend the rarer kinds of the birds, and, if it were possible, reserve the food mainly for them instead of the plebeian sparrows.

The kind of provision I find best and most suitable for all tastes is coarsely ground oatmeal, Indian corn, hemp-seed, sultana raisins, chopped-up fat of any kind, and boiled liver cut up finely.

The raisins attract the wild pheasants, and it is a truly beautiful sight to watch these birds feeding quietly near the window, with the morning sun glancing upon their lovely sleek plumage until they look as if made of bronze and gold. During the autumn I have sacks of acorns and beech-mast collected and laid by until the birds are distressed for food, and then a large basketful is scattered daily beneath the tulip-tree upon the lawn, to the great delight of rooks, jackdaws, pheasants, and wood-pigeons. Even two moorhens from my lake have come up through the fields and remained for the last two months, not only feeding with other birds on the lawn, but visiting the poultry yard, picking up grain with the fowls, and several times they have also roosted in the henhouse. The lovely grey and orange nuthatches haunt the dining-room windows, where they share the nuts which are daily bestowed upon the squirrels.

This place, with its surrounding woods and gardens, where all birds have been protected and encouraged for the last twenty years, naturally abounds with feathered fowl of many kinds, but in most gardens, even somewhat near a town or city, birds may be coaxed to come by constantly placing attractive food where they can pick it up without danger from cats. This is best arranged either in a basket hung at a window or in a box fastened to a high pole. Any one may find pleasure in watching the various kinds of birds flying to and fro, and, for an invalid, it would be adding a charm to daily life, besides doing a kindness to a useful tribe of creatures which are too often persecuted rather than jealously protected, as they ought to be, in return for the valuable services they render to the gardener and agriculturist.

I CANNOT refrain from drawing attention to the cruelty with which these inoffensive creatures are often treated with regard to their food. One constantly hears the remark, “We had a tortoise for a few months, but it died.” Either from carelessness or ignorance the poor tortoise is hardly ever properly fed, and, though it can endure privation for a longer time than most creatures, yet unless food is supplied it must die miserably of starvation at last. The ordinary land-tortoise feeds on cabbage, sow-thistle, lettuce-leaves, and dandelion flowers, while some specimens will enjoy bread and milk as well. I have been carefully watching a tame one in my conservatory, and find that, day after day, he eats a lettuce nearly half his own size. If, then, he requires so much food to keep him in health and vigour, how pitiable must be the condition of those kept without food, or those that are perhaps offered a dandelion flower once a week!

The water-tortoises are equally ill-used, for often from lack of knowledge they are constantly offered vegetable diet which they cannot eat, their proper food being the live creatures they find in the water they exist in. They are best fed in captivity by supplying them with little portions of raw meat, or remains of boiled cod or turbot. They are easily distinguished from the land-tortoises by their livelier movements, and by their being able to swim in water. Still even they do not care to be always afloat, so there should be a piece of cork or some small island upon which they can rest when they are tired of swimming.

One day I saw on a shelf in a village shop a handsomely marked tortoise-shell, which I rather desired to purchase for my museum. Upon inquiry I found it had been bought for a few shillings from a man who was going through the village with a truck-load of these poor creatures for sale. The shopkeeper knew nothing about the requirements of his new acquisition, and thought it would be quite happy in the water-butt, where he placed it for the night. It being a land-tortoise, it was of course found dead in the morning—one of the many victims of well intentioned ignorance. Those who sell tortoises in the streets know nothing about their habits, they only want to get rid of their stock as quickly as possible. The purchasers may never even have seen a tortoise before, and have not, as a rule, the vaguest idea of how it should be treated, so that the unfortunate creatures are almost sure sooner or later to perish miserably of mismanagement and starvation.

They are entirely vegetable feeders, so that the idea that a tortoise will clear the kitchen of black-beetles is an absurd fiction, though it is, I believe, urged by street sellers of tortoises as an inducement for the householder to purchase his stock.

One day a tortoise was brought to me by a man who said he had picked it up in one of my fields. I felt sure it must have strayed from its rightful owner, and we therefore made every inquiry amongst our neighbours round about in order to discover, if possible, its previous home. As no one would own the tortoise, we placed it in the conservatory that we might be able to observe its ways and habits, as it happened to be the first specimen of the kind that had been enrolled amongst my pets. When placed on the lawn for exercise the creature would greedily snap off every hawkweed flower he came to, and as these abounded in the turf he had happy times feasting on flowers and basking in the sun.

After keeping the tortoise about a year, it happened that a policeman living in a neighbouring village called here to see a friend of his, and this comrade (one of my gardeners) took him to see the flowers in the conservatory. After a few minutes the policeman exclaimed, “Why, there’s our Jack!” An explanation ensued, and it turned out that the tortoise had really belonged to him, as he proved by showing a little hole he had bored through the shell in order to tether Master Jack and prevent his straying away. The tortoise had been the gift of a dear friend, and the loss of this pet had been quite a sorrow in the family. “My missus will cry for joy at seeing Jack again,” said the man; and very glad was I to restore the truant to his rightful owner, whose pet he had been for four years.

Although somewhat slow and inert, a tortoise is quite worth keeping, and when well cared for, properly fed, and taken notice of, it has a good deal of a quaint sort of intelligence. The one I now possess will feed from my hand, gives an angry hiss when offended, will put on double quick speed, when the door is opened, in order to elope into the garden, and what mind he has is greatly exercised about the lemurs. I judge this because I so often find him gazing at them through the wirework, his shell tilted at an angle as if he would fain climb up to satisfy his curiosity.

To the poor people who often visit my place in summer, many of whom have never seen such a creature before, the tortoise is an object of surprise, not unmixed with fear, for one woman asked if he would “fly at her,” and others seem to suppose him a creature of ferocious tendencies, judging by the way they keep at a distance and eye him askance.

I happened to be at the Zoological Gardens one autumn day when some of the large Galapagos tortoises were fairly active, and was fortunate enough to see one digging a hole in a rather hard gravel path. The excavation was carried on entirely by the hind legs; first one and then the other went down and grasped a few stones with the claws on the foot; these stones were dropped on the surface of the ground, and down went the other leg, and slowly it brought up a little soil, and this process went steadily on for ten minutes or more, and the hole became about eight or nine inches deep. The sturdy tail of the tortoise is used as a sort of boring instrument in first beginning the hole, and when deep enough the tortoise cautiously deposits her eggs at the bottom of the cavity, and when all are laid the hole is filled up with earth, well pressed down, and the mother leaves her precious deposits to be hatched by the heat of the sun.