The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

1

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

This project is best displayed in html or ebook readers due to the spacing issues in tables caused by unicode characters.

W J McGee apparently preferrred his initials without periods. The initials W J are retained as scanned.

The letter "q" does not have a superscript character in unicode. Superscripts with a "q" are formatted with a caret and any additional superscript characters in braces in the text version.

Pages 129-end are asterisked in the original text because they overlap the pagination of the following article.

Seventeenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1895-96, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1898, pages 1—344*

2

3

| Page | ||

| Plate I. | Seriland | 9 |

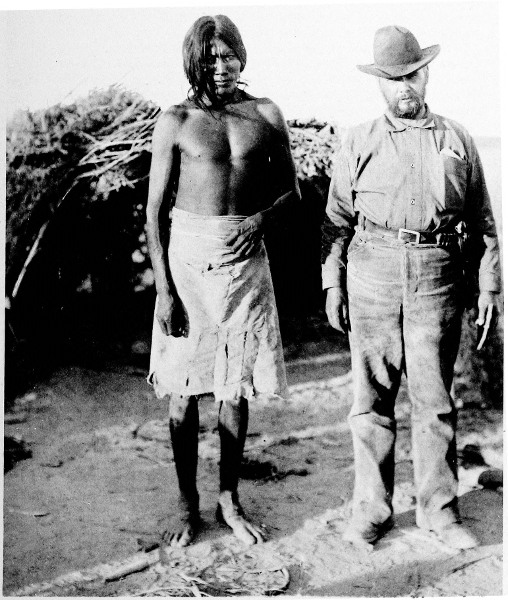

| II. | Pascual Encinas, conqueror of the Seri | 13 |

| IIIa. | Seri frontier | 40 |

| IIIb. | Sierra Seri, from Encinas desert | 40 |

| IVa. | Sierra Seri, from Tiburon island | 42 |

| IVb. | Punta Ygnacio, Tiburon bay | 42 |

| Va. | Western shore of Tiburon bay | 44 |

| Vb. | Eastern shore of Tiburon bay | 44 |

| VIa. | Recently occupied rancheria, Tiburon island | 80 |

| VIb. | Typical house interior, Tiburon island | 80 |

| VIIa. | House framework, Tiburon island | 110 |

| VIIb. | House covering, Tiburon island | 110 |

| VIII. | Sponge used for house covering, Tiburon island | 112 |

| IXa. | House skeleton, Tiburon island | 114 |

| IXb. | Interior house structure, Tiburon island | 114 |

| X. | Typical Seri house on the frontier | 117 |

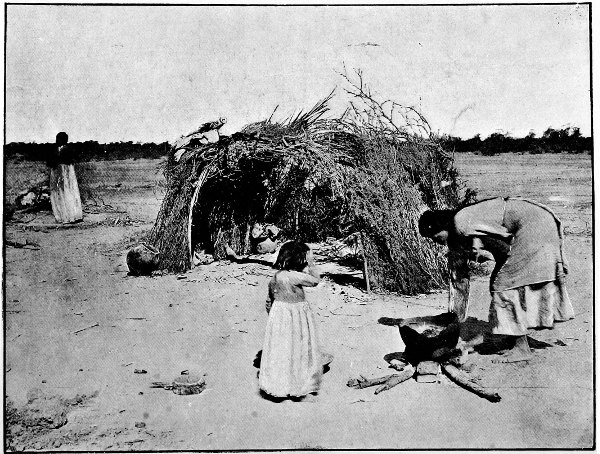

| XI. | Occupied rancheria on the frontier | 119 |

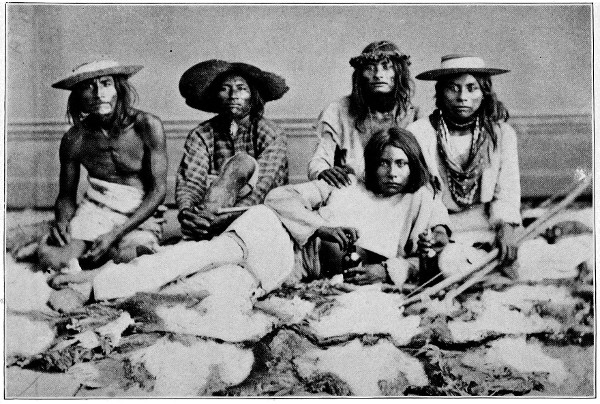

| XII. | Group of Seri Indians on trading excursion | 121 |

| XIII. | Group of Seri Indians on the frontier | 137* |

| XIV. | Seri family group | 139* |

| XV. | Seri mother and child | 142* |

| XVI. | Group of Seri boys | 144* |

| XVII. | Mashém, Seri interpreter | 146* |

| XVIII. | “Juana Maria”, Seri elderwoman | 150* |

| XIX. | Typical Seri warrior | 154* |

| XX. | Typical Seri matron | 156* |

| XXI. | Seri runner | 158* |

| XXII. | Seri matron | 160* |

| XXIII. | Youthful Seri warrior | 162* |

| XXIV. | Seri belle | 164* |

| XXV. | seri maiden | 166* |

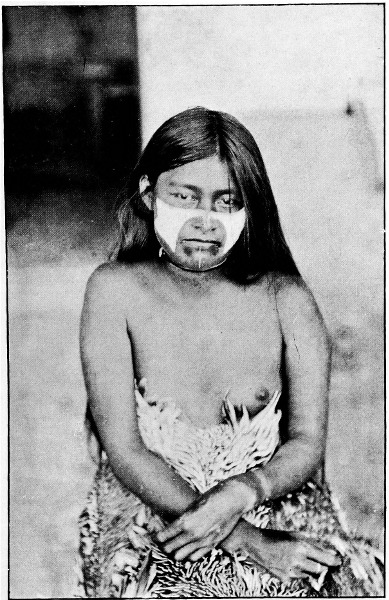

| XVI. | Characteristic face-painting | 168* |

| XXVII. | Face-painting paraphernalia | 170* |

| XXVIII. | seri Archer at Rest | 200* |

| XXIX. | Seri archer at attention | 202* |

| XXX. | Seri bow, arrow, and quiver | 204* |

| XXXI. | Seri balsa in the national museum | 217* |

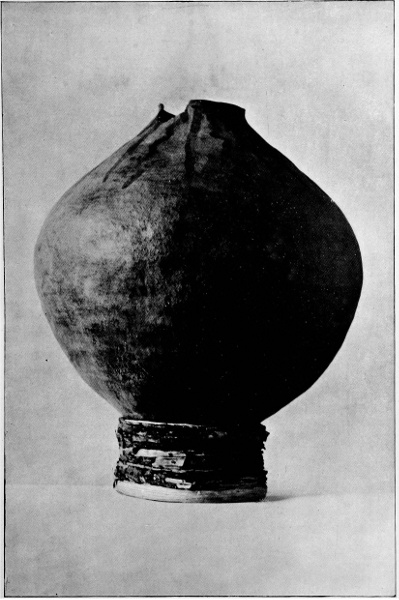

| XXXII. | painted Olla, With Olla Ring (Museum Number 155373) | 222* |

| XXXIII. | Plain olla (Museum number 155373) | 226* |

| XXXIV. | Domestic anvil, side (Museum number 178858) | 234* |

| XXXV. | domestic Anvil, Top (Museum Number 178858) | 234* |

| XXXVI. | Domestic anvil, bottom (Museum number 178858) | 234* |

| XXXVII. | domestic Anvil (Reduced), Top and Side (Museum Number 178838) | 237* |

| XXXVIII. | Metate (reduced), top and edge (Museum number 178839) | 237* |

| XXXIX. | Long-used metate (reduced), top (Museum number 178840) | 238*6 |

| XL. | long-used Metate (Reduced), Bottom (Museum Number 178840) | 238* |

| XLI. | Natural pebble bearing slight marks of use (Museum number 178841) | 240* |

| XLII. | Natural pebble used as bone-crusher (Museum number 178842) | 240* |

| XLIII. | Little-worn pebble used for all domestic purposes (Museum number 174570) | 243* |

| XLIV. | Natural pebble used as crusher and grinder (Museum number 178843) | 243* |

| XLV. | Natural pebble slightly used as hammer and anvil (Museum number 178844) | 244* |

| XLVI. | Natural pebble slightly used as grinder (Museum number 178845) | 247* |

| XLVII. | Natural pebble slightly used as domestic implement (Museum number 178846) | 247* |

| XLVIII. | Natural pebble slightly worn by use (Museum number 178847) | 249* |

| XLIX. | natural Pebble Considerably Worn in Use As Grinder (Museum Number 178848) | 249* |

| L. | Natural pebble considerably worn as cutter and grinder (Museum number 178849) | 251* |

| LI. | Natural pebble considerably used as hammer, grinder, and anvil (top and edge) (Museum number 178850) | 253* |

| LII. | Natural pebble considerably used as hammer, grinder, and anvil (bottom and edge) (Museum number 178850) | 253* |

| LIII. | Hammer and grinder (Museum number 178851) | 255* |

| LIV. | implement Shaped by Use (Museum Number 178853) | 255* |

| LV. | Implement perfected by use (Museum number 178853) | 257* |

| LVI. | Perfected implement found in use (Museum number 178854) | 259* |

| Figure 1. | Nomenclatural map of Seriland | 16 |

| 2. | Gateway to Seriland—gorge of Rio Bacuache | 27 |

| 3. | Tinaja Anita | 29 |

| 4. | Beyond Encinas desert—the saguesa | 33 |

| 5. | Embarking on Bahia Kunkaak in la lancha Anita | 48 |

| 6. | Anterior and left lateral aspect of Seri cranium | 142* |

| 7. | Snake-skin belt | 170* |

| 8. | Dried flower necklace | 171* |

| 9. | Seed necklace | 172* |

| 10. | Nut pendants | 172* |

| 11. | Shell beads | 172* |

| 12. | Wooden beads | 172* |

| 13. | Necklace of wooden beads | 173* |

| 14. | Rattlesnake necklace | 174* |

| 15. | Seri olla ring | 184* |

| 16. | Water-bearer’s yoke | 184* |

| 17. | Symbolic mortuary olla | 185* |

| 18. | Symbolic mortuary dish | 185* |

| 19. | Shell-cup | 186* |

| 20. | Turtle-harpoon | 187* |

| 21. | fish-spearhead | 193* |

| 22. | African archery posture | 202* |

| 23. | Desiccated pork | 205* |

| 24. | Seri basket | 208* |

| 25. | Scatophagic supplies | 213* |

| 26. | Seri marlinspikes | 217* |

| 27. | The balsa afloat | 218* |

| 28. | Seri balsa as seen by Narragansett party | 219*7 |

| 29. | Seri hairbrush | 226* |

| 30. | Seri cradle | 226* |

| 31. | Hair spindle | 227* |

| 32. | Human-hair cord | 228* |

| 33. | Horsehair cord | 228* |

| 34. | Mesquite-fiber rope | 229* |

| 35. | Bone awl | 230* |

| 36. | Wooden awls | 230* |

| 37. | Seri arrowheads | 246* |

| 38. | Diagrammatic outline of industrial development | 253* |

| 39. | Mortuary olla | 289* |

| 40. | Woman’s fetishes | 290* |

| 41. | Food for the long journey | 291* |

| 42. | Mortuary cup | 291* |

8

BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT PL. I

SERILAND

9THE SERI INDIANS

By W J McGEE

Something has been known of the Seri Indians (Seris, Ceris, Ceres, Heris, Tiburones) since the time of Coronado, yet they remain one of the least-studied tribes of North America. The first systematic investigation of the tribe was made in the course of expeditions by the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1894 and 1895; it was far from complete.

The Seri Indians are a distinctive tribe in habits, customs, and language, inhabiting Tiburon island in Gulf of California and a limited adjacent area on the mainland of Sonora (Mexico). They call themselves Kun-kaak or Kmike: their common appellation is from the Opata, and may be translated “spry”. Their habitat is arid and rugged, consisting chiefly of desert sands and naked mountain rocks, with permanent fresh water in only two or three places; it is barred from settled Sonora by a nearly impassable desert. Two centuries ago the population of the tribe was estimated at several thousands, but it has been gradually reduced by almost constant warfare to barely three hundred and fifty, of whom not more than seventy-five are adult males, or warriors.

The Seri men and women are of splendid physique; they have fine chests, with slender but sinewy limbs, though the hands and especially the feet are large; their heads, while small in relation to stature, approach the average in size; the hair is luxuriant and coarse, ranging from typical black to tawny in color, and is worn long. They are notably vigorous in movement, erect in carriage, and remarkable for fleetness and endurance.

The Seri subsist chiefly on turtles, fish, mollusks, water-fowl, and other food of the sea; they also take land game, and consume cactus fruits, mesquite beans, and a few other vegetal products of their sterile domain. Most of their food is eaten raw. They neither plant nor cultivate, and are without domestic animals, save dogs which are largely of coyote blood.

The habitations of the Seri are flimsy bowers of cactus and shrubbery, sometimes shingled rudely with turtle-shells and sponges; in some 10 cases these are in clusters pertaining to matronymic family groups; in other cases they are isolated, and are then often abandoned and reoccupied repeatedly, and are apparently common property of the tribe. The habitations afford some protection from sun and wind, but not from cold and wet, which are hardly known in winterless and nearly rainless Seriland.

The Seri clothing consists essentially of a kilt or skirt extending from waist to knees; sometimes a pelican-skin robe is worn as a blanket or mantle, and used also as bedding; the head and feet, as well as the bust and arms, are habitually bare, though a loose-sleeved wammus reaching not quite to the waist is sometimes worn. These garments were formerly woven of coarse threads or cords made from native vegetal fibers; the belt is generally of twisted human hair, of horse hair, of dressed deerskin, or of snake skin; the robe consists of four, six, or eight pelican skins sewed together with sinew. The pelican-skin robes are still used, though the aboriginal fabric is commonly replaced by cotton stuffs obtained through barter or plunder. Cords of human hair and skins of serpents are used for necklaces.

The sports and games of the Seri Indians include racing and dancing, and there are ceremonial dances at the girls’ puberty feasts, accompanying the rude music of improvised drums. Decoration is ordinarily limited to symbolic face-painting, which is seen especially among the females, and to crude ornamentation of the scanty apparel. A peculiar pottery is manufactured, and the pieces are sometimes decorated with simple designs in plain colors.

The bow and arrow are habitually used, especially in warfare, and turtles and fish are taken by means of harpoons, shafted with cane and usually tipped with bone, charred wood, or flotsam metal. The arrows are sometimes provided with chipped stone points, though the art of chipping seems to be accultural and shamanistic. The ordinary stone implements are used for crushing bone and severing sinew or flesh, and also for mulling seeds and other food substances; they are mere cobbles, selected for fitness, and retained only if their fitness is increased by the wear of use, after the manner of protolithic culture. Graceful balsas are made from canes, bound together with mesquite-fiber cords; and on these the people freely navigate the narrow but stormy strait separating Tiburon and the neighboring islets from the mainland. They make a distinctive pottery, which is remarkably light and fragile. Its chief use is carrying water to habitations (always located miles from the spring or tinaja) or on desultory wanderings. Shells are used for cups, and to some extent for implements. They have a few baskets, which are not greatly different from those made by neighboring tribes.

The modern Seri are loosely organized in a number of maternal groups or clans, which are notable for the prominence given to mother-right in marriage and for some other customs; and there are indications that the clan organization was more definite before the tribe was so 11 greatly reduced. The leading clans are those of the Pelican, the chief tribal tutelary, and the Turtle, a minor tutelary. At present polygyny prevails, professedly and evidently because of the preponderance of females due to the decimation of warriors in battle; but both custom and tradition tell of former monogamy, with a suggestion of polyandry. The primary marriage is negotiated between the mothers of the would-be groom and the prospective bride; if the mother and daughter in the latter family look with favor on the proposal, the candidate is subjected to rigorous tests of material and moral character; and if these are successfully passed the marriage is considered complete, and the husband becomes a privileged and permanent guest in the wife’s household. Family feeling, especially maternal affection, is strong; but petty dissensions are common save when internal peace is constrained by external strife. The strongest tribal characteristic is implacable animosity toward aliens, whether Indian or Caucasian; certainly for three and a half centuries, and probably for many more, the Seri have been almost constantly on the warpath against one alien group or another, and have successfully stayed Spanish, Mexican, and American invasion. In their estimation the brightest virtue is the shedding of alien blood, while the blackest crime in their calendar is alien conjugal union.

The Seri vocabulary is meager and essentially local; the kinship terms are strikingly scanty, and there are fairly full designations for food materials and other local things, while abstract terms are few. Two or three recorded vocables seem to resemble those of the Yuman languages, while the numerals and all other known terms are distinct. The grammatic construction of Seri speech appears not to differ greatly from that of other tongues of Sonora and Arizona; it is highly complex and associative. The speech is fairly euphonious, much more so than that of the neighboring Papago and Yaqui Indians.

The Seri Indians appear to recognize a wide variety of mystical potencies and a number of zoic deities, all of rather limited powers. The Pelican, Turtle, Moon, and Sun seem to lead their thearchy. Creation is ascribed to the Ancient of Pelicans—a mythical bird of marvelous wisdom and melodious song—who first raised Isla Tassne, and afterward Tiburon and the rest of the world, above the primeval waters. Individual fetishes are used, and there is some annual ceremony at the time of ripening of cactus fruits, and certain observances at the time of the new moon. The most conspicuous ceremony is the girls’ puberty feast. The dead are clothed in their finest raiment, folded and fastened in small compass like Peruvian mummies, placed in shallow graves, and covered with turtle-shells, when the graves are filled with earth and heaped with stones or thorny brambles for protection against beasts of prey. Fetishes, weapons, and other personal belongings are buried with the body, as well as a dish of food and an olla of water, and there are curious customs connected with the place of 12 sepulture. There is a weird, formal mourning for dead matrons, and suggestions of fear of or veneration for the manes.

Seriland is surrounded with prehistoric works, telling of a numerous population who successfully controlled the scant waters for irrigation, built villages and temples and fortresses, cultivated crops, kept domestic animals, and manufactured superior fictile and textile wares; but (save possibly in one spot) these records of aboriginal culture cease at the borders of Seriland. In their stead a few slightly worn pebbles and bits of pottery are found here and there, deeply embedded in the soil and weathered as by the suns of ages. There are also a few cairns of cobbles marking the burial places, and at least one cobble mound of striking dimensions but of unknown meaning; and there are a few shell-mounds, one so broad and high as to form a cape in the slowly transgressing shoreline (Punta Antigualla), and in which the protolithic implements and other relics are alike from the house-dotted surface to the tide level, 90 feet below.

The absence of relics of a superior culture, and the presence of Seri relics throughout deposits of high antiquity, suggest that the tribe is indigenous to Seriland; and this indication harmonizes with the peculiar isolation of the territory, the lowly culture and warlike habits of the people, the essentially distinct language, the singular marriage custom, and the local character of the beast-gods. And all these features combine to mark the Seri as children of the soil, or autochthones.

Present knowledge of Seriland and its inhabitants is based primarily on the work of two expeditions by the Bureau of American Ethnology, conducted in 1894 and 1895, respectively; and, secondarily, on researches into the cartography and literature (descriptive, historical, and scientific) of the region. Both of the expeditions were projected largely for the purpose of making collections among little-known native tribes in the interests of the National Museum, and the general ethnologic inquiries were ancillary to this purpose.

The 1894 expedition was directed chiefly toward work among the Papago Indians in the vaguely defined territory known as Papagueria, lying south of Gila river and west of the Sierra Madre in southwestern Arizona and western Sonora (Mexico). Outfitting at Tucson early in October, the party moved southward, visiting the known Papago rancherias and seeking others, and thus defining the eastern limits of the Papago country. On the approach to the southern limits of the tribal range toward Rio Sonora, the evil repute of the Seri Indians sounded larger and larger, suggesting the desirability of scientific study of the tribe; and it was decided to attempt investigation. Accordingly the party was reorganized at Hermosillo, and, with the sanction of the Secretary of State and Acting Governor, Señor Don Ramón Corral, proceeded to Rancho San Francisco de Costa Rica, 13 where a temporary Seri rancheria was found occupied by about sixty of the tribe, including subchief Mashém, who speaks Spanish. In this part of the work the expedition was accompanied by Señor Pascual Encinas, the owner of the rancho visited, and doubtless the best informed white man concerning the habits, customs, personnel, and habitat of the tribe. About a week was spent in intercourse with the occupants of the rancheria, when the studies were brought to an end through the illness of Señor Encinas, and the consequent necessity for return to Hermosillo. The expedition then proceeded northwestward and northward along a route so laid as to define the western limits of Papagueria proper, and reached Tucson near the end of the year. In addition to the leader, the party comprised Mr William Dinwiddie, photographer; José Lewis, Papago interpreter, and E. P. Cunningham, teamster. The outfit was furnished chiefly by Mr J. M. Berger, of San Xavier (near Tucson). On the visit to the Seri frontier the party was accompanied by Señor Encinas, Don Arturo Alvemar-Leon (who acted as Spanish interpreter), and two or three attachés of Molino del Encinas.1

BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT PL. II

PASCUAL ENCINAS, CONQUEROR OF THE SERI

The second expedition was directed primarily toward investigation of the Seri, and only incidentally to continuation of the researches among the Papago. Outfitting at Tucson in October (again with the aid of Mr Berger), the expedition proceeded southward by a route different from those previously traversed, and carried forward a plane-table route survey covering a considerable zone from the international boundary at Sasabe to Rio Sonora. Descending the previously unmapped course of Rio Bacuache, the expedition reached the Rancho de San Francisco de Costa Rica on December 1, 1895, and, although conditions were found unfavorable in that the Seri were on the warpath, immediately prepared for the extension of the work into Seriland.

A preliminary trip was made into the mainland portion of the Seri habitat, terminating at the crest of Johnson peak, the highest point in Sierra Seri. The triangulation and topographic surveys were carried over the territory traversed, and several points were fixed on Isla Tiburon; but the natives, agitated by a skirmish with vaqueros on the frontier a day or two earlier, had withdrawn to remoter parts of the territory, and were not encountered. The party returned to Costa Rica, a rude boat was completed, transported across the desert via Pozo Escalante to Embarcadero Andrade, and launched in Bahia Kunkaak. The surveys were extended to the southern portion of Sierra Seri and Isla Tassne, and, after various difficulties and delays due to dearth of fresh water, to gales, and to other causes, the party (enlarged for the purpose) finally landed on Tiburon. Many Seri rancherias were found on 14 both sides of Bahia Kunkaak and El Infiernillo. Some of these had been occupied almost to the hour of the visit, but the occupants had taken flight, leaving most of their unattached possessions behind, and were not seen, though it was evident that, like wary birds and game animals, they kept the invaders in sight from points of vantage and hidden lairs. The eastern scarps and foot-slopes of Sierra Kunkaak were traversed extensively and repeatedly; its crest was crossed by Mr Johnson with a small party at a point west of Punta Narragansett, and the triangulation and topographic sketching were connected with the work on the mainland and carried over practically the entire surface of the island, being tied to the work of the Hydrographic Office about the coasts. Then, despairing of finding the wary natives, and having exhausted food supplies, the party returned to the mainland and thence to Costa Rica, arriving in the evening of December 31.

The original party comprised, in addition to the leader, Mr Willard D. Johnson, topographer; Mr J. W. Mitchell, photographer; Hugh Morris, Papago interpreter, and José Contrares, teamster. The party engaged in the expedition to Sierra Seri comprised the leader, Messrs Johnson and Mitchell, Mr L. K. Thompson of Hermosillo, Don Andrés Noriega of Costa Rica, José Contrares, and two Papago Indian guards, Miguel and Anton, of Costa Rica. The Tiburon party was made up of the leader, Messrs Johnson and Mitchell, S. C. Millard of Los Angeles, and Señores Andrés Noriega and Ygnacio Lozania, together with Ruperto Alvarez, a Yaqui Indian guard, and Miguel, Anton, Mariana, Anton Ortiz, and Anton Castillo, Papago guards; while Hugh Norris and José Contrares, with half a dozen Papago guards and other attachés of the rancho at Costa Rica, maintained an intermittent supply station at Embarcadero Andrade. Señor Encinas cooperated in the work of the expedition, part of the time at Costa Rica and part at Molino del Encinas, his principal hacienda in the outskirts of Hermosillo; while Mr Thompson and Dr W. J. Lyons aided in the work, the former at both Hermosillo and Costa Rica and the latter at Hermosillo.

The return trip from Costa Rica lay via Hermosillo, and permitted the extension of the plane-table surveys to this longitude. While at the city advantage was taken of the opportunity to obtain linguistic and other data from “El General” Kolusio, a full-blood Seri retained at the capital by the State for occasional duty as a Seri interpreter, who was obligingly assigned to the service of the party by Señor Don Ramón Corral, then governor of Sonora. At Hermosillo the leader of the expedition left the main party, which then proceeded northwestward and northward along the route followed by the 1894 expedition on the return journey, the party comprising Mr Johnson, in charge, with Messrs Mitchell and Millard, Hugh Norris, and José Contrares; and the plane-table surveys were continued and combined with the route surveys made on the outward journey. 15

The principal ethnologic results of both expeditions relating to the Seri Indians are incorporated in the following pages; the data concerning the Papago are reserved for further study. The topographic surveys of the 1895 expedition covered a zone averaging 50 miles in width, extending from the international boundary to somewhat beyond Rio Sonora. Mr Johnson, by whom these surveys were executed, was on furlough from the United States Geological Survey, and his resumption of survey work prevented the construction of finished maps, except that of Seriland (plate I), which forms but a small fraction of the area surveyed. The results of the remaining, and by far the greater, part of the topographic surveys are withheld pending completion of the inquiries concerning the Papago Indians.

The geographic nomenclature found requisite in the field and in writing is partly new and partly restored, yet conforms with general and local custom so far as practicable; and nearly all of the new names have been applied in commemoration of explorers or pioneers. Most of the names pertaining to Seriland proper are incorporated in the map forming plate I; the others (including a few minor corrections) appear in the outline map forming figure 1, prepared after the larger sheet was printed.2

The following list of place-names is designed primarily to give the meaning and raison d’être of the nomenclature; with a single exception,3 the names are Hispanized or Mexicanized in accordance with local usage.

*Seriland: Extra-vernacular name of tribe, with English locative.

Mar de Cortés (Sea of Cortés=Gulf of California): Customary Sonoran designation, applied by Ulloa (1539) in honor of Hernando Cortés, first discoverer of the gulf.

*Pasaje Ulloa (Ulloa passage): Generic Spanish; specific applied in honor of Captain Francisco de Ulloa, first navigator of the passage and the upper gulf, 1539.

*Estrecho Alarcon (Alarcon strait): Named in honor of Hernando de Alarcon, second navigator of the gulf; 1540.

El Infiernillo (The Little Hell): Local designation, retained by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N. (miswritten “Estrecho Infiernillo” on larger map).

† Boca Infierno (Mouth of Hell): A colloquial local designation (miswritten “Puerto Infierno” on larger map).

*Bahia Kunkaak (Kunkaak bay): Generic Spanish; specific the vernacular name of the Seri tribe (miswritten “Tiburon bay” on plates IV and V). 16

Fig. 1—Nomenclatural map of Seriland.

17

Bahia Kino (Kino bay): Long-standing name given in honor of Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino, an early Jesuit missionary (the “Bahia San Juan Bautista” of various early maps); adopted in Anglicized form by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

†Bahia Tepopa (Tepopa bay): Specific a corruption of Tepoka, the extra-vernacular name of a local tribe related to the Seri; applied in 1746 by Padre Consag, and used by most navigators and cartographers of later dates, though it does not appear on the charts of the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Bahia Agua Dulce (Freshwater bay): Named by Lieutenant R. W. H. Hardy, R. N., 1826; name retained (in Anglicized form) by Hydrographic Office, U. S. N. (The name is misplaced on Hardy’s map, but the bay is correctly located in his text, p. 293.)

†Bahia Bruja (Witch bay): Named (in honor of his vessel) by its discoverer, Lieutenant Hardy, 1826.

*Bahia Espence (Spence bay): Named in honor of Pilot Tomás Espence (Thomas Spence), second circumnavigator of the island, who landed in the bay in 1844.

†Estero Cochla (Cockle inlet): Named by Lieutenant Hardy, 1826.

*Bajios de Ugarte (Ugarte shoals): Named in honor of Padre Juan de Ugarte, first visitor to the shoals and circumnavigator of Tiburon, 1721.

*Rada Ballena (Whale roadstead): Named from the stranding of a whale about 1887, an incident of much note among the Seri.

*Anclaje Dewey (Dewey anchorage): Named in honor of its discoverer, Commander (now Admiral) George Dewey, in charge of the surveys by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N., 1873.

Laguna la Cruz (Lagoon of the Cross): Name adopted (Anglicized) by Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.; the “Laguna de los Cercaditos” (Lagoon of the Little Banks) of Colonel Francisco Andrade, 1844.

Isla Tiburon (Shark island): Name of long standing; used alternatively with “Isla San Agustin” since the seventeenth century, both names being apparently applied to Isla Tassne by several writers, and also to Isla Angel de la Guarda (the second largest island in the gulf) by Kino and others, while the present Tiburon was regarded as a peninsula.

Isla San Esteban (Saint Stephen island): Name of long standing; in consistent use since early in the seventeenth century.

*Isla Tassne (Pelican island): Name recast by the use of the Seri specific in lieu of the Spanish (Alcatráz), which is too hackneyed for distinctive use.

Isla Turner (Turner island): Name used (and probably applied in honor of Rear-Admiral Thomas Turner, U. S. N.) by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Isla Patos (Duck island—i. e., Island of Ducks): Name of long standing; adopted by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Roca Foca (Seal rock): Name used (and probably applied) by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Peña Blanca (White crag): Name used (and probably applied) by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Punta Tepopa (Tepopa point): Named (probably corruptly) from a local tribe related to the Seri; used by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Punta Sargent (Sargent point): Name applied by Lieutenant Hardy in 1826 to what is now known as Punta Tepopa; adopted for the minor point by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

*Punta Perla (Pearl point): Name applied in commemoration of the traditional pearl fisheries of the vicinity.

*Punta Arena (Sand point): A descriptive designation.

*Punta Tortuga (Turtle point): Name applied in recognition of the extensive turtle fisheries of the Seri in the vicinity. 18

*Punta Tormenta (Hurricane point): Name applied in recognition of the nearly continuous gales and tide-rips by which navigation is rendered hazardous, and by which the long sand-spit has been built.

Punta Miguel (Miguel point): Recast from “San Miguel point”, partly through association with the name of a Papago guard accompanying the expedition of 1895; in the old form the name is of long standing, was probably applied by Escalante in 1700, and was adopted by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N., 1873.

*Punta Granita (Granite point): A descriptive designation.

*Punta Blanca (White point): A descriptive designation.

*Punta Narragansett (Narragansett point): Specific (of Algonquian Indian derivation) applied in commemoration of the vessel employed in the surveys by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N., in 1873, the point being that at which the commander of the Narragansett located the principal Seri rancheria of that time and made observations on the tribe.

*Punta Ygnacio (Ygnacio point): Specific applied in honor of Don Ygnacio Lozania, a trusted aid in the 1895 expedition, who had visited this point in connection with the Andrade expedition of 1844; described as “Dark bluff” on charts of the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

*Punta Antigualla (Antiquity point—i. e., Point of Antiquities): Name applied in recognition of a great shell-mound which has retarded the transgression of the sea and produced the point.

Punta Kino (Kino point): Name of long standing; specific in honor of the early missionary; used by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

*Punta Mashém (Mashém point): Specific in honor of the Seri chief Mashém (sometimes called Francisco Estorga or Juan Estorga), who speaks Spanish and acted as Seri-Spanish interpreter in 1894.

Punta Monumenta (Monument point): Named by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Punta Colorada (Red point): Recast from the “Red Bluff point” of the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

Punta Willard (Willard point): Origin of name unknown; used by the Hydrographic Office, U. S. N.

*Embarcadero Andrade (Andrade landing): Named in memory of the embarcation for Tiburon of Colonel Francisco Andrade, 1844.

*Campo Navidad (Christmas camp): Named in memory of a camp occupied December 24-26 by the expedition of 1895.

*Sierra Seri (Seri range): Generic Spanish, specific the extra-vernacular tribe name.

*Sierra Kunkaak (Kunkaak range): Specific the vernacular tribe name.

*Sierra Menor (Minor range): A descriptive designation.

*Cerros Anacoretos (Anchorite hills): A designation suggested to Topographer Johnson by the solitary series of spurs rising singly or in scattered groups from the sheetflood-carved desert plain.

*Johnson Peak: Name applied in commemoration of the first and only ascent of the peak, and of its occupation as a survey station, December 7 and 8, 1895, by Willard D. Johnson, accompanied by John Walter Mitchell and Miguel (Papago Indian).

*Desierto Encinas (Encinas desert): Generic Spanish, specific in honor of the intrepid settler on the outskirts of the desert, Señor Pascual Encinas.

*Playa Noriega (Noriega playa): Generic Spanish, specific in honor of Don Andrés Noriega, kinsman of Señora Anita Encinas, a resident on the outskirts of the desert, and the leading Mexican aid in the expedition of 1895.

*Arenales de Gil (Gil sandbanks): Generic Spanish, specific in honor of Fray Juan Crisóstomo Gil de Bernabe, sole missionary to Seriland, massacred at this point in 1773.

*Rio Sonora (Sonora river): Generic Spanish, specific a long standing and originally colloquial corruption of Señora, a designation said to have been applied 19 by Spanish pioneers to a hospitable native chieftainess; afterwards apparently fixed through the name of an early mining camp and garrison and perhaps by similarity to a local aboriginal (Opata) term connoting maize, i. e., sonot.

Rio Bacuache (Bacuache river): Name of long standing; specific doubtless from the Opata term bacot, “snake”, with a locative termination, i. e., “Snake place”.

†Arroyo Carrizal (Reedy arroyo): Generic and specific Spanish; colloquial designation used by the Seri chief Mashém in describing the island; a traditional name of long standing.

†Arroyo Agua Dulce (Freshwater arroyo): A traditional name like the former, also used by Mashém.

*Arroyo Millard (Millard arroyo): Named in memory of S. C. Millard, aid and interpreter in the expedition of 1895 (died 1897).

*Arroyo Mariana (Mariana arroyo): Named in honor of Mariana (Papago Indian), a guard accompanying the 1895 expedition, who had once approached this arroyo on a hunting expedition.

*Arroyo Mitchell (Mitchell arroyo): Named in honor of John Walter Mitchell, photographer of the 1895 expedition.

†Pozo Escalante (Escalante well): Generic Spanish, specific in honor of Sergeant Juan Bautista de Escalante, the first Caucasian to cross El Infiernillo (in 1700), who is reputed to have dug the shallow well still existing; the name has been retained ever since alternatively with “Agua Amarilla” (Yellow water); doubtless the “Carrizal” of certain early maps; the site of the only mission ever established in Seriland, and of the massacre of Fray Crisóstomo Gil in 1773.

*Pozo Hardy (Hardy well): Named in honor of Lieutenant R. W. H. Hardy, R. N., second known Caucasian visitor to the spot, 1826.

*Aguaje Anton (Anton water, or water-hole): Generic a common Mexican term; specific applied in memory of Anton (Papago Indian), a guard and visitor to the spot in the expedition of 1895.

*Aguaje Parilla (Parilla water): A traditional water (not found by the expedition of 1895) named in memory of Colonel Diego Ortiz Parilla, the vaunted destroyer of the Seri in 1749, whose imposing expedition may have reached this point.

*Barranca Salina (Saline gorge): Generic colloquial Mexican, specific denoting the character of the practically permanent water; the designation applied by Mexican vaqueros and Papago hunters, who occasionally visit the locality.

*Tinaja Anita (Anita basin): Generic a useful Mexican term for a water-pocket, or rock basin containing water supplied by storms or seepage; specific a tribute to Anita Newcomb McGee, M. D., Actg. Asst. Surg. U. S. A.; perhaps the “Aguaje de Andrade” of 1844.

*Tinaja Trinchera (Entrenched basin): Specific a common Mexican term for the ancient entrenchments found on many mountains of Papagueria; applied in recognition of a few low, loose-laid stone walls about the tinaja, the only structures of the kind known in Seriland.

Rancho San Francisco de Costa Rica: Name applied by the founder, Señor Pascual Encinas, about 1850.

Rancho Santa Ana: Name applied by the founder, Señor Encinas, about 1870.

Rancho Libertad: Name applied by the founder, Señor Encinas, about 1875.

The fairly full geographic nomenclature of Seriland merely expresses the necessity for place-names, felt in some measure by all intelligent beings, and realized especially by explorers and describers of the region. Excepting the ranchos and perhaps Pozo Escalante, they denote natural features only, and, with the same exceptions, the features are seen but rarely or from great distances by enlightened men. Despite 20 the wealth of place-names and the strongly accentuated configuration which the nomenclature expresses, Seriland is one of the most hopeless deserts of the American hemisphere.

Since most of the field work of the two expeditions lay in the neighboring Republic of Mexico, it became necessary to ask official sanction for the operations from the Mexican government; and it is a pleasure to say that every possible privilege and courtesy were extended by both federal and state officials. Especial acknowledgments are due to the Mexican minister (and afterward ambassador) to the United States, his Excellency Don Mateo Romero (now deceased); to the Ministro de Fomento of the Mexican Republic, Excelencia Don Fernando Leal; and to the governor of the State of Sonora, Señor Don Ramón Corral. Equal acknowledgments are due to various United States officials, notably Honorable W. Woodville Rockhill, First Assistant Secretary of State when the expeditions were planned; and it is a pleasure to advert to the active interest taken in both expeditions by Honorable S. P. Langley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and to the careful attention given the 1894 expedition by the late Dr G. Brown Goode, Assistant Secretary of the Institution.

Mr Willard D. Johnson did invaluable service in connection with the second expedition, particularly in the execution of surveys and the construction of maps in inimitable style. Mr William Dinwiddie is to be credited with the excellent photographs made during the 1894 expedition, with the representation of the devices used in Seri face-painting, and with various other aids to the investigation; while Mr J. W. Mitchell is to be credited with the photographs made on Isla Tiburon, and with other contributions to the success of the 1895 expedition. Acknowledgments are due also to all of the participants in both expeditions, whose names appear in other paragraphs. Their contributions were not primarily intellectual, yet were of a kind and amount to be forever remembered among men who have worked and hungered and thirsted and stood guard together. The deepest debt connected with the field work is to the now venerable but ever vigorous pioneer, Señor Pascual Encinas; and no small part of this debt goes over to his estimable spouse, Señora Anita Encinas, who twice traversed the long road from Hermosillo to Costa Rica in the interest of the 1895 expedition.

The scientific results of the researches have been enriched by invaluable contributions from Director Powell’s store of ethnologic knowledge, and by suggestions from Messrs Frank Hamilton Cushing, F. W. Hodge, James Mooney, and other collaborators in the Bureau of American Ethnology. The qualities of the colored illustrations are due largely to the artistic skill of Mr Wells M. Sawyer, by whom they were designed, and of Mr DeLancey Gill, by whom the proofs were revised. The Spanish translations are due chiefly to Colonel F. F. 21 Hilder, ethnologic translator of the Bureau, partly to Mr Emanuele Fronani; though neither can be charged with errors of interpretation or of Englishing, both finally shaped by the author. The somatic determinations and discussions were by Dr Ales Hrdlička, of New York; the tests for arrow poison were made by Dr S. Weir Mitchell, of Philadelphia; while the philologic comparisons were made almost wholly (with notable thoroughness and perspicacity, and in such wise as to illustrate the wealth and utility of the linguistic collections of the Bureau) by Mr J. N. B. Hewitt. Finally, it has become due, probably for the first time in the nearly four centuries of their history, to make public acknowledgment of services by Seri Indians, viz., subchief Mashém, the real sponsor for the Bureau vocabulary and many other data, and “El General” Kolusio, the outlaw interpreter of Hermosillo and contributor to certain historical identifications. 22

Seriland, the home from time immemorial of the Seri Indians, lies in northwestern Mexico, forming a part of the State of Sonora. It comprises Tiburon island, the largest and most elevated insular body in Gulf of California, together with a few islets and an adjacent tract of mainland; the center of the district being marked approximately by the intersection of the parallel of 29° with the meridian of 112°. The territory is divided by the narrow but turbulent strait, El Infiernillo. It is bounded on the west and south by the waters of the gulf with its eastward extensions to Kino bay, on the east by a nearly impassable desert, and on the north by a waterless stretch of sandy plains and rugged sierras 50 to 100 miles in extent.

Tiburon island is about 30 miles in length from north to south and 12 to 20 miles in width; its area, with that of the adjacent islets, is barely 500 square miles. The mainland tract held by the Seri is without definite boundary; measured to the middle of the limiting desert on the east and halfway across the waterless zone on the north, its area may be put at 1,500 square miles. To this land area of 2,000 square miles may be added the water area of the strait, with its northern and southern embouchures, and the coastwise waters habitually navigated by the Seri balsas as far as Kino bay, making half as much more of water area. Such is the district which the Seri claim and seek to control, and have practically protected against invasion for nearly four centuries of history and for uncounted generations of prehistory.

Seriland forms part of a great natural province lying west of the Sierra Madre of western Mexico and south of an indefinite boundary about the latitude of Gila river, which may be designated the Sonoran province; it differs from Powell’s province of the Basin ranges in that it opens toward the sea, and also in other respects; and it is allied in many of its characteristics to the arid piedmont zone lying west of the Andes in South America.

In general configuration the province may be likened to a great roof-slope stretching southwestward from a comb in the Sierra Madre to a broad eaves-trough forming Gulf of California, the slope rising steeper toward the crest and lying flatter toward the coast; but the expanse is warped by minor swells, guttered by waterways, and dormered by outlying 23 ranges and buttes. The most conspicuous inequality of the slope (partly because of its coincidence with tide-level) is offered by the rugged ranges of Seriland. These may be considered four in number, all approximately parallel with each other and with the coast; the first is a series of eroded remnants (Cerros Anacoretos) from 600 to 1,200 feet in height; the second is the exceedingly rugged Sierra Seri, culminating in Johnson peak 5,000 feet above tide; the third is Sierra Kunkaak, attaining about 4,000 feet in its highest point; the fourth is Sierra Menor, some 2,000 feet high, with the northern extremity sliced off obliquely by marine erosion. The principal arm of Desierto Encinas lies between the first two ranges, El Infiernillo separates the second and third, while a subdesert valley divides the third from the fourth. The valleys correspond more closely than the ranges; if the land level were 100 feet higher the strait and its terminal bays would become an arid valley like the others, while if the sea-level were 500 feet higher the four ranges would become separate islands similar to Angel de la Guarda and others in the gulf.

The Sonoran province is notably warm and dry. The vapor-laden air-currents from the Pacific drift across it and are first warmed by conduction and radiation from the sun-scorched land, to be chilled again as they roll up the steeper roof-slope to the crest; and the precipitation flows part way down the slopes, both eastward and westward from the Sierra Madre—literally the Mother (of waters) range. A climatal characteristic of the province is two relatively humid seasons, coinciding with the two principal inflections of the annual temperature-curve, i. e., in January-February and July-August, respectively. In the absence of meteorologic records the temperature and precipitation maybe inferred from the observations at Yuma and Tucson,5 which are among the warmest and driest stations in America, or indeed in the world; though it is probable that such points as Caborca, Bacuachito, and Hermosillo are decidedly warmer and perhaps slightly moister than Yuma. The ordinary midday summer temperature at these points may be estimated at about 110° in the shade (frequently rising 5° or 10° higher, but dropping 20° to 50° in case of cloudiness); the night temperature at the same season is usually 50° to 75°, though during two-thirds of the year it is liable to fall to or below the freezing point. The sun temperature is high in comparison with that measured in the shade, the exposed thermometer frequently rising to 150° or 160°, according to its construction, while black-finished metal becomes too hot to be handled, and dark sand and rocks literally scorch unprotected feet. The leading characteristic of the temperature is the wide diurnal range and the relatively narrow annual range; another characteristic is the uniformity, or periodic steadiness, of the maxima, coupled with variability and nonperiodicity of the minima. 24

The precipitation on the Sonoran province is chiefly in the form of rain; in the winter humid season snow falls frequently on the Sierra Madre and rarely on the outlying ranges; in both humid seasons (and in humid spots at all seasons) dew forms in greater or less abundance. Fog frequently gathers along the coast, especially during the winter and in the midsummer wet season, and sometimes drifts inland for miles. The mean annual precipitation may be estimated at 20 or 25 inches toward the crest and half as much toward the base of the high sierra; thence it diminishes coastward, probably to less than 2 inches; the mean for the extensive plains forming the greater part of the province may be estimated at 3 or 4 inches. The greater part of the precipitation is in 25 local storms, frequently accompanied by thunder-gusts or sudden tempests, though cold drizzles sometimes occur, especially at the height of the winter humid season. Except where the local configuration is such as to affect the atmospheric movements, the distribution of precipitation is erratic, in both time and space; some spots may receive half a dozen rains within a year, while other spots may remain rainless for several years; and the wet spot of one series of years may be the dry spot of the next.

The climatal features of Seriland are somewhat affected by the pronounced topographic features of the district. Snow sometimes falls on Sierra Seri, and probably on Sierra Kunkaak; gales gather about the rugged ranges at all seasons, and sometimes produce precipitation out of season; the extreme heat of midday and midsummer is tempered by the proximity of the tide-swept gulf; and since most of the local derangements tend to augment precipitation and reduce temperature, it would seem safe to estimate the mean annual rainfall of the tract at 4 or 5 inches, and the mean temperature at about 70°, with a mean annual range of some 30° and an extreme diurnal range of fully 80°.

The configuration and climate combine to give distinctive character to the hydrography of the Sonoran province. The melting snows and more abundant rains of the high sierras form innumerable streams flowing down the steeper slopes toward the piedmont plains, or soak into the pervious rocks to reappear as springs at lower levels; sometimes the streams unite to form considerable rivers, flowing scores of miles beyond the mountain confines; but eventually all the running waters are absorbed by the dry sands of the plains or evaporated into the drier air; and from the mouth of the Colorado to that of the Taqui, 500 miles away, no fresh water ever flows into the sea. During the winter wet season, and to a less extent during that of summer, the mountain waterways are occupied by rushing torrents, rivaling great rivers in volume, and these floods flow far over the plains; but during the normal droughts the torrents shrink to streamlets purling among the rocks, or give place to blistering sand-wastes furlongs or even miles in width and dozens of miles in length, while beyond stretch low, radially scored alluvial fans, built by the great freshets of millenniums. Only a trifling part of the rainfall of the plains ever gathers in the waterways heading in the mountains, and only another small part gathers in local channels; the lighter rains from higher clouds are so far evaporated in the lower strata of the air as to reach the earth in feeble sprinkles or not at all; the product of moderate showers is absorbed directly by earth and air; while the water of heavy rains accumulates in mud-burdened sheets, spreading far over the plains, flowing sluggishly down the slopes, yet suffering absorption by earth and air too rapidly to permit concentration in channels. These moving mud-blankets of the plains, or sheetfloods,6 are often supplemented by 26 the discharge from the waterways of adjacent sierras and buttes; they are commonly miles and frequently dozens or scores of miles in width, and the linear flow may range from a fraction of a mile to scores of miles according to the heaviness of the rainfall and the consequent dilution of the mud. Such sheetfloods, especially those produced by considerable rains, are characteristic agents of erosion throughout most of the province; their tendency is to aggrade depressions and corrade laterally, and thus to produce smooth plains of gentle slope interrupted only by exceptionally precipitous and rugged mountain remnants. A part of the sheetflood water joins the stronger mountain-born streams, particularly toward the end of the great storm whereby earth and air are saturated; another part forms ground-water, which slowly finds its way down the slopes toward the principal valleys, perhaps to reappear as springs or to supply wells. These with certain other conditions determine the water-supply available for habitation throughout Seriland and adjacent Papagueria.

Another condition of prime importance arises in a secular tilting of the entire province southwestward. This tilting is connected with the upthrust of the Sierra Madre and the uplifting of the plateau country and the southern Rocky mountain region north of the international boundary. Its rate is measured by the erosion of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado and other gorges; and its dates, in terms of the geologic time-scale, run at least from the middle Tertiary to the present, or throughout the Neocene and Pleistocene. Throughout this vast period the effect of the tilting in the Sonoran province has been to invigorate streams flowing southward, and to paralyze streams flowing toward the northerly and easterly compass-points; accordingly the streams flowing toward the gulf have eroded their channels effectively during the ages, and have frequently retrogressed entirely through outlying ranges; so that throughout the province the divides seldom correspond with the sierra crests.

A typical stream of the province is Rio Bacuache, one of the two practicable overland ways into Seriland (albeit never surveyed until traversed by the 1895 expedition). Viewed in its simple geographic aspect, this stream may be said to originate in a broad valley parallel with the gulf and the high sierra, 200 miles northeast of Kino bay; its half-dozen tributary arroyos (sun-baked sand-washes during three hundred and sixty days and mud-torrents during five days of the average year) gather in the sheetflood plain and unite at Pozo Noriega, where the ground-water gives permanent supply to a well; then the channel cleaves a rocky sierra 3,000 feet high in a narrow gorge, and within this canyon the ground-water gathered in the valley above seeps to the surface of the sand-wash and flows in a practically permanent streamlet throughout the 4 or 5 miles forming the width of the sierra; then the liquid sinks, and 25 miles of blistering sand-wash (interrupted by a single lateral spring) stretch across the next valley 27 to Pueblo Tiejo, where another sierra is cleft by the channel, and where the water again exudes and flows through a sand-lined rock-bed (figure 2). In the local terminology this portion alone is Rio Bacuache, the upper stretches of the waterway bearing different names; it supplies the settlement and fields of Bacuachito, flowing above the sands 5 to 15 miles, according to season; then it returns to the sand-wash habit for 50 miles, throughout much of which distance wells may find supply at increasing depths; finally it passes into the delta phase, and enters northeastern Seriland in a zone marked by exceptionally vigorous mesquite forests. Normally the 200 miles of stream way is actual stream only in two stretches of say 5 miles each, some 25 miles apart, and the farther of these stops midway between the head of the channel and the open sea toward which it trends and slopes; but during and after great storms it is transformed into a river approaching the Ohio or the Rhine in volume, flowing tumultuously for 150 miles, and finally sinking in the sands of Desierto Encinas, 30 to 50 miles from the coast. Viewed with respect to genesis, Rio Bacuache has responded to the stimulus of the southwestern tilting, and has retrogressed up the slope through two sierras, besides minor ranges and 100 miles of sheetflood-carved plains; while the debris thus gathered has filled the original gorge to a depth of hundreds of feet, and has overflowed the adjacent sheetflood-flattened expanses to form the great alluvial fan of eastern Seriland. The genetic conditions explain the distribution 28 of the water: the product of the semiannual storms suffices to form a meager supply of ground water, which is diffused in the sands and softer rocks of the plains, and concentrated in the narrow channels carved through the dense granites of the sierras; and enough of the flow passes the barriers to supply deep wells in the terminal fan, as at the frontier ranchos Libertad (abandoned) and Santa Ana, just as the subterranean seepage from the Sonora more richly supplies the deep well at San Francisco de Costa Rica. In these lower reaches the mineral salts, normally present in minute quantities, are concentrated so that the water from these wells is slightly saline, while deeper in the desert the scanty water is quite salt.

Fig. 2—Gateway to Seriland—gorge of Rio Bacuache.

In Seriland proper the distribution of potable water is conditioned by the meager precipitation, the local configuration (shaped largely by sheetflood erosion), and the disturbance of equilibrium of the scanty ground-water due to the tilting of the province. The most abundant permanent supply of fresh water is that of Arroyo Carrizal, which is fed by drainage and seepage from the broad and lofty mass of pervious rocks forming the southern part of Sierra Kunkaak, the abundant supply being due to the fact that the eastern tributaries are energetically retrogressing into the mass in deep gorges which effectually tap the water stored during the semiannual storms. The arroyo and valley of Agua Dulce are less favorably conditioned by reason of a trend against the tilting of the province and by reason of the narrower and lower mass of tributary rock in the northern part of the range, and the flow is impermanent, as indicated by the absence of canes and other stream plants; yet four explorers (Ugarte, 1721; Hardy, 1826; Espence, 1844; Dewey, 1875) reported fresh water, apparently in a shallow well tapping the underflow, at the embouchure of the arroyo. On the eastern slope of Sierra Kunkaak there are several arroyos which carry water for weeks or even months after the winter rains, and sometimes after those of summer; but the only permanent water—Tinaja Anita—is at the base of a stupendous cliff of exceptionally pervious and easily eroded rocks, so deeply cut that ground-water is effectually tapped, while an adjacent chasm—Arroyo Millard—is so situated that the cliff-faced spur of the sierra above the tinaja absorbs an exceptional proportion of the surface flowage from the main crest. The tinaja (figure 3) is permanent, as indicated by a canebrake some 20 by 50 feet in extent, and by a native fig and a few other trees—though the dry-season water-supply ranges from mere moisture of the rocks to a few gallons caught in rock basins within the first 50 yards of the head of the arroyo. No other permanent supplies of fresh water are known on the island, though there are a few rather persistent tinajas along the western base of Sierra Menor above Willard point.

On the mainland tract there is a cliff-bound basin, much like that of Tinaja Anita, at the head of Arroyo Mitchell and base of Johnson peak, christened Tinaja Trinchera; but the range is narrow and the rocks 29 granitic, and hence the supply is not quite permanent.7 A practically permanent supply of water is found in one or more pools or barrancas at the head of Playa Noriega in Desierto Encinas. The liquid lies in pools gouged by freshets in the bottoms of arroyos coming in from the northward, just where the flow is checked by the spread of the waters over the always saline playa; and, since they are modified by each freshet, they are sometimes deep, sometimes shallow, sometimes entirely sand-filled. When the barrancas are clogged, or when their contents are evaporated, coyotes, deer, horses, and vaqueros obtain water by excavating a few feet in the sand lining the larger arroyos. Commonly the barranca water is too saline for Caucasian palates save in dire extremity, but the salinity diminishes as the arroyos are ascended. An apparently permanent supply of saline and nitrous water is found in a 10-foot well, known as Pozo Escalante, or Agua Amarilla (yellow water), near the southern extremity of Desierto Encinas, reputed to have been excavated by Juan Bautista de Escalante in 1700, and still remaining open; its location is such that it catches the subterranean seepage from both Bacuache and Sonora rivers. The water is potable but not palatable. Among the vaqueros of San Francisco de Costa Rica there is a vague and ancient tradition of a carrizal-marked tinaja or arroyo (Aguaje Parilla) at the eastern base of the southern portion of Sierra Seri; and both vaqueros and Indians 30 refer to one or more saline barrancas about the western base of the same semirange, probably in Arroyo Mariana.

Fig. 3—Tinaja Anita.

In brief, Arroyo Carrizal, Tinaja Anita, and Pozo Escalante are the only permanent waters, and Pozo Hardy, Barranca Salina, and Tinaja Trinchera the only subpermanent waters actually known to Caucasians in all Seriland, though it seems probable that permanent water may exist at Aguaje Parilla and in Arroyo Mariana, and impermanent supplies near Bahia Espence. There may be one or two additional places of practically permanent water in smaller quantity, and a few other places in which saline water might be found either at the surface or by slight excavation, and which may be approximately located by inspection of the map under guidance of the principles set forth in the preceding paragraphs; but this would seem to be the limit of trustworthy water supply. During the humid seasons the waters are naturally multiplied, yet it is improbable that any of the arroyos except Carrizal and Agua Dulce and a few minor gulches along the more precipitous shores shed water into the gulf save at times of extraordinary local flood.8

The geologic structure of the Sonoran province is complex and not well understood. So far as the meager observations indicate, the basal rocks are granites, frequently massive and sometimes schistose, sometimes intersected by veins of quartz, etc. The granitic mass is upthrust to form the nuclei of Sierra Madre and other considerable ranges; it also approaches the surface over large areas of plains. Resting unconformably on the granites lie heavy deposits of shales and limestones, commonly more or less metamorphosed; these rocks outcrop on the slopes of most of the main ranges and form the entire visible mass of some of the lower sierras and buttes, while they, too, sometimes approach the surface of the sheetflood-carved plain. The rocks, both calcareous and argillaceous, combine the characters of the vast Mesozoic limestone deposits of eastern Mexico and the immense shale accumulations of corresponding age in California, and hence probably represent the later half of the Mesozoic. This is the only sedimentary series recognized in the province. Both the granites and the sedimentary beds are occasionally overlain by volcanic deposits, chiefly in the form of much-eroded lava-sheets and associated tuff-beds, which sometimes form considerable ranges and buttes (notably Sierra Kunkaak, of Isla Tiburon); these remnantal volcanic deposits are probably late Mesozoic or early Tertiary. Newer volcanics occur locally, forming mesas, as about Agua Nueva (40 miles northwest of Hermosillo), or even coulees apparently filling barrancas of modern aspect, as in the vicinity of Bacuachito,9 or rising into cinder cones surrounded by 31 ejectamenta, as at Pico Pinacate, in northwestern Sonora. The various rocks are usually bare or meagerly mantled with talus in the mountains; over the greater part of the plains they are commonly veneered with sheetflood deposits, ranging from a few inches to a few yards in thickness; while the central portions of the larger valleys are lined with alluvial accumulations reaching many hundreds of feet in thickness.

The clearly interpretable geologic history began with extensive degradation and eventual baseleveling of a granitic terrane in Paleozoic or early Mesozoic time; then followed the deposition of the shales and associated limestones during the later Mesozoic; next came elevation, accompanied or followed by corrugation, chiefly in folds parallel with the present coast, whereby the granite-based sierras were produced, and accompanied also by the earlier vulcanism to which the volcanic sierras owe their existence. A vast period of degradation ensued, during which the land stood so high as to induce greater precipitation than that of today and to permit the streams to carve channels far below the present level of tide, and during which the present general configuration was developed; then came the southwestward tilting and consequent climatal desiccation, the filling of the deeper valleys, the inauguration of sheetflood erosion, some local vulcanism, and the progressive shifting of the divides.

The geologic structure affects the hydrography, especially that factor determined by subterranean circulation, or ground-water; for the superficial sheetflood and alluvial deposits are highly pervious and many of the volcanics hardly less so, while the shales and limestones are but slightly pervious and the granites nearly impervious. The geologic structure also determines the character of the soil with exceptional directness, since the dryness of the air and the dearth of vegetation reduce rock decay to a negligible quantity. The characteristically precipitous sierras and cerros are of naked ledges, save where locally mantled with a mechanical débris of the same rocks (much finer than the frost product of colder and humider regions); the soil of the normal plains is but the little-oxidized upper surface of sheetflood deposits made up of the mechanical debris of local rocks and varying in coarseness with the slope; while the soil of the valleys is detrital sand and silt, derived from tributary slopes, passing into adobe where conditions are fit, and essentially mechanical in texture and structure save where cemented by ground-water solutions at the lower levels.

The flora of the Sonoran province affords a striking example of the adjustment of vegetal life to an unfavorable environment. The prevailing vegetation is perennial, of slow growth and of stunted aspect; and it is not distributed uniformly but arranged in separate tufts or clusters, gathering into a nearly continuous mantle in wetter spots, though commonly dotting the plains sparsely, to completely disappear 32 in the driest areas. Nearly all of the plants have roots of exceptional length, and are protected from evaporation by a glazed epidermis and from animal enemies by thorns or by offensive odors and flavors; while most of the trees and shrubs are practically leafless except during the humid seasons. Grasses are not characteristic, and there is no sward, even in oases; but certain grasses grow in the shadow of the arborescent tufts and in the fields of the farmer ants, or spring up in scattered blades over the moister portions of the surface. The arborescent vegetation represents two characteristic types, viz., (1) trees and shrubs allied to those of humid lands, but modified to fit arid conditions; and (2) distinctive forms, evidently born of desert conditions and not adapted to a humid habitat, this type comprising the cacti and related forms, as well as forms apparently intermediate between the cacti and normal arborescent type. The various plants of the district, including those of the distinctive types, are communal or commensal, both among themselves and with animals, to a remarkable degree; for their common strife against the hard physical environment has forced them into cooperation for mutual support. The tufts or clusters in which the vegetation is arranged express the solidarity of life in the province; commonly each cluster is a vital colony, made up of plants of various genera and orders, and forming a home for animal life also of different genera and orders; and, although measurably inimical, these various organisms are so far interdependent that none could survive without the cooperation of the others.10

In Seriland proper, as in other parts of the Sonoran province, a prevailing tree is the mesquite (Prosopis juliflora); on the alluvial fan of Rio Sonora it grows in remarkable luxuriance, forming (with a few other trees) a practically continuous forest 20 to 40 feet in height, the gnarled trunks sometimes reaching a diameter of 2 or 3 feet; over the Rio Bacuache fan and much of the remaining plain surface it forms the dominant tree in the scattered vital colonies; and here and there it pushes well into the canyon gorges. The roots of the mesquite are of great length, and are said to penetrate to water-bearing strata at depths of 50 to 75 feet; its fruit consists of small hard beans embedded in slender woody pods. Associated with the mesquite in most stations are the still more scraggy and thorny cat-claw (Acacia greggii) and ironwood (Olneya tesota), both also yielding woody beans in limited quantity. Similarly associated, especially in the drier tracts, and characteristically abundant over the plains portions of Isla Tiburon, are the paloverdes (Parkinsonia torreyana, etc.), forming scraggy, wide-branching, greenbark trees 5 to 15 feet high, and commonly 3 to 10 inches in diameter of trunk. Over the mountain sides, especially of Sierra Seri and Sierra Kunkaak, grow sparsely the only straight-trunk trees of the region, rooted in the rocks to the average number of a few score to the square 33 mile; this is the palo blanco (Acacia willardiana). Associated with it along rocky barrancas of permanent water supply is a fig tree (Ficus palmeri), which has a habit of springing from the walls and crests of cliffs, and sending white-bark roots down the cliff-faces to the water 50 or 100 feet below, and which yields a small, insipid, and woody fruit. Interspersed among the larger trees, and spreading over the intervening spaces, particularly in the drier and more saline spots, grow a number of thorny shrubs, much alike in external appearance and habit, though representing half a dozen distinct genera (Cassia, Microrhamnus, Celtis, Krameria, Acacia, Randia, Stegnospherma, Frankenia, etc.), while considerable tracts are sparsely occupied by straggling tufts of the Sonoran greasewood, or creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), whose minute but bright green leafage relieves that prevailing gray of the landscape in which the lighter greens of the paloverde and cactus stems are lost.

Fig. 4—Beyond Encinas desert—the saguesa.

Intermingling with the woody trees and shrubs in most stations, and replacing them in some, are the conspicuous and characteristic cacti in a score of forms. East of Desierto Encinas, and sometimes west of it, these are dominated by the saguaro (Cereus giganteus), though throughout most of Seriland the related saguesa (Cereus pringleii?) prevails. The saguaro is a fluted and thorn-decked column, 1 foot to 3 feet in diameter and 10 to 60 feet in height, sometimes branching into a candelabrum, while the still more monstrous saguesa (figure 4) usually consists of from three to ten such columns springing from a 34 single root; both are masses of watery pulp, revived and renewed during each humid season, and both flower in a crown of fragrant and brilliant blossoms at or near the top of column or branch, and fruit in fig-like tunas (or prickly pears) during late summer or early autumn. Ordinarily the saguesa, like the saguaro, is sparsely distributed; but there is an immense tract between Desierto Encinas and the eastern base of Sierra Seri in which it forms a literal forest, the giant trunks close-set as those of trees in normal woodlands. Hardly less imposing than the giant cactus is the wide-branching species known as pitahaya (Cereus thurburi?), in which the trunks may be ten to fifty in number, each 4 to 8 inches in diameter and 5 to 40 feet in height; and equally conspicuous, especially in eastern Seriland, is the cina (Cereus schotti), which is of corresponding size, and differs chiefly in the simpler fluting of the thorn-protected columns. Both the pitahaya and the cina flower and fruit like the saguaro, the tunas yielded by the former being especially esteemed by Mexicans as well as Indians. Another important cactus is the visnaga (Echinocactus wislizeni lecontei), which rises in a single trunk much like the saguaro, save that it is commonly but 3 to 6 feet in height and is protected by a more effective armature of straight and curved thorns; it yields a pleasantly acid, pulpy fruit, which may be extracted from its thorny setting with some difficulty; but its chief value lies in the purity and potability of the water with which the pulpy trunk is stored. The visnaga is widely distributed throughout the Sonoran province and beyond, and extends into eastern Seriland; it is rare west of Desierto Encinas and is practically absent from Isla Tiburon, where it may easily have been exterminated by the improvident Seri during the centuries of their occupancy. Most abundant of all the cacti, and less conspicuous only by reason of comparatively small size, is the cholla (an arborescent Opuntia); on many of the sheetflood-carved plains it forms extensive thickets 5 to 8 feet high, the main trunks being 2 to 6 inches in diameter, while dozens or hundreds of gaunt and thorn-covered branches extend 3 to 8 feet in all directions; and it occurs here and there throughout the district from the depths of the valleys and the coast well up to the rocky slope of the sierras. It yields quantities of fruit, somewhat like tunas, but more woody and insipid; this fruit is seldom if ever used for human food, but is freely consumed by herbivores. Much less abundant than the cholla is the nopal, or prickly pear; and there are various other opuntias, often too slender to stand alone and intertwined with stiffer shrubs which lend them support, and many of these yield small berry-like tunas. Another characteristic cactus, widespread as the cholla and abundant in nearly all parts of Seriland save on the rocky slopes, is the okatilla (Fouquiera splendens). It consists of half a dozen to a score of slender, woody, and thorn-set branches radiating from a common root, usually at angles of 30° to 45° from the vertical, and ordinarily reaching heights of 10 to 20 feet. 35

The pulp masses of the larger cacti, especially the saguaro, saguesa, pitahaya, and cina, are supported by woody skeletons in the form of vertical ribs coincident with the external flutings; within a few years after the death and decay of these desert monsters the skeletons weather out, and the vertical ribs form light and strong and approximately straight bars or shafts, valuable for many industrial purposes; while the slender arms of okatilla are equally valuable, in the fresh condition after removal of the spiny armament, and in the weathered state without special preparation.

On many of the higher plain-slopes, especially in eastern Seriland, there are pulpy stemmed shrubs and bushes, sometimes reaching the dignity of trees, which present the normal aspect of exogenous perennials during life, but which are so spongy throughout as to shrink into shreds of bark-like debris shortly after death. These are the torotes of the Sonoran province—common torote (Jatropha cardiophylla), torote amarillo (Jatropha spathulata), torote blanco (Bursera microphylla), torote prieto (Bursera laxiflora), torotito (Jatropha canescens?), etc. These plants grow in the scattered and scraggy tufts characteristic of arid districts (a typical torote tuft appears in left foreground of figure 4); they are protected from evaporation by the usual glazed epidermis, and maintained by the water absorbed during the humid seasons; but they are thornless and are protected from animal enemies by pungent odors, and at least in some cases by toxic juices. Like various plants of the province they are measurably communal—indeed, the torotito appears to be dependent on union with an insect for reproduction, like certain yuccas, and like the cina and (in some degree at least) the saguaro and other cacti.

Along the lower reaches of Rio Bacuache, and in some of the deeper gorges of Sierra Seri and Sierra Kunkaak, grow a few veritable trees of moderately straight trunk and grain and solid wood, such as the guaiacan (Guaiacum coulteri) and sanjuanito (Jacquinia pungens); both of these fruit, the former in a wahoo-like berry of medicinal properties, and the latter in a nut, edible when not quite ripe and forming a favorite rattle-bead when dry. On the flanks of such gorges the slender-branched baraprieta (Cæsalpinia gracilis) grows up in the shelter of more vigorous shrubs, its branches yielding basketry material, while its fruit is a woody bean much like that of the cat-claw. In like stations there are occasional clumps of yerba mala or yerba de flecha (Sebastiana bilocularis), an exceptionally leafy bush growing in straight stems suitable for arrowshafts, and alleged to be poisonous from root to leaf—with inherent probability, since the plant is without the thorny armature normal to the desert. Along the sand-washes, especially about their lower extremities wet only in floods, springs a subannual plant (Hymenoclea monogyra) which shrinks to stunted tussocks after a year or more of drought, but flourishes in close-set fens after floods; though of acrid flavor and sage-like odor, it is eaten by herbivores in 36 time of need, and it yields abundant seeds, consumed by birds, small animals, and men. About all of the permanent waters not invaded by white men and the white man’s stock there are brakes of cane or carrizal (Phragmites communis?); the jointed stems are half an inch to an inch in thickness and 8 to 25 feet in height; the seeds are edible, while the stems form the material for balsas and afford shafts for arrows, harpoons, fire-sticks, etc., and the silica-coated joints may be used for incising tough tissues.

The coasts of Seriland, both insular and mainland, are skirted by zones of exceptionally luxuriant shrubbery, maintained chiefly by fog moisture. Along the mountainous parts of the coast the zone is narrow and indefinite, but on the plains portions it extends inland for several miles with gradually fading characters; this is especially true in the southern portion of Desierto Encinas, where the fog effects may be observed in the vegetation 12 or 15 miles from the coast. Most of the fog fed species are identical with those of the interior, though the shrubs are more luxuriant and are otherwise distinctive in habit. On the Tiburon side of gale-swept El Infiernillo, and to some extent along other parts of the coast, some of these shrubs (notably Maytenus phyllanthroides) grow in dense hedge-like or mat-like masses, often yards in extent and permanently modeled by the wind in graceful dune-like shapes. Somewhat farther inland the flatter coastwise zones of Tiburon are rather thickly studded with shrubby clumps from 6 inches to 2 feet high, made up of Frankenia palmeri with half a dozen minor communals; while still farther inland follows the prevailing Sonoran flora of mesquite, scrubby paloverde, and chaparral (Celtis pallida), etc., only a little more luxuriant than the normal.

Throughout Seriland proper, and especially in the interior valleys of Tiburon, grasses are more prevalent than in other portions of the Sonoran province, their abundance doubtless being due to the rarity of graminivorous animals during recent centuries.