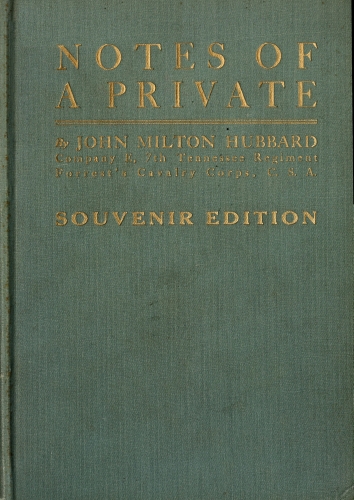

By

JOHN MILTON HUBBARD

Company E, 7th Tennessee Regiment

Forrest’s Cavalry Corps, C. S. A.

ST. LOUIS, MO.:

NIXON-JONES PRINTING CO.

1911

Copyright 1909,

By J. M. Hubbard.

To those Southern soldiers who, regardless of their sentiments as to the abstract right of secession, whether sleeping in known or unknown graves, hobbling through life on crutches, or trying to meet the demands of the best citizenship, went into the Confederate Army, at the behest of an overwhelming majority of the Southern people, and who remained in the field to the bitter end, this little book is most respectfully inscribed by

THE AUTHOR.

Gainesville, Ala., May 11, 1865.

Private J. M. Hubbard of Company E, Seventh Regiment, Tennessee Cavalry, C. S. A., residing in Hardeman County, Tennessee, having been, with the approval of the proper authorities, paroled, is permitted to return to his home, not to be disturbed by the United States authorities, so long as he observes his parole and the laws in force where he may reside.

By order

E. R. S. CANBY,

Major-General, U. S. A.

E. S. DENNIS,

Brig.-Gen. Commanding for U. S.

I certify on honor that the within-named soldier is the rightful owner of one horse.

HARDY HARRIS,

Lieutenant Commanding Co. E,

7th Tenn. Cavalry, C. S. A.

| PAGE | ||

| Dedication | 3 | |

| Parole | 4 | |

| Preface—First Edition | 7 | |

| Preface—Souvenir Edition | 8 | |

| Chapter I | —Mustering in—“Good-Bye Sweethearts” | 9 |

| Chapter II | —Service in Five States—The Armstrong Raid | 21 |

| Chapter III | —Davis’ Bridge and Corinth | 36 |

| Chapter IV | —Van Dorn at Holly Springs | 46 |

| Chapter V | —Some Personals and Portraitures | 63 |

| Chapter VI | —Organization of “Forrest’s Cavalry Corps”—The Sooy Smith Raid—Fort Pillow | 86 |

| Chapter VII | —Brices’ Cross Roads | 103 |

| Chapter VIII | —Harrisburg | 122 |

| Chapter IX | —The Memphis Raid | 135 |

| Chapter X | —Incidents of the Middle Tennessee Raid | 150 |

| Chapter XI | —Hood’s Expedition—The Wilson Raid to Selma | 178 |

| Chapter XII | —Conclusion | 194 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| Forrest’s Farewell Address | 201 | |

| The Forrest Equestrian Statue | 200 | |

| A Kindly Remembrance | 206 | |

In writing this book the author has relied almost entirely on his own memory for such reminiscences, sketches and portraitures of character as are printed on its pages. He served the entire period of the Civil War in Company E, Seventh Tennessee Cavalry, which regiment was commanded successively by Colonels W. H. Jackson, J. G. Stocks and W. L. Duckworth, assisted by Lieutenant-Colonel W. F. Taylor and Major C. C. Clay. Few private soldiers saw more of the war, or had better opportunities for observation. His company served in parts of five States, and traveled thousands of miles under the orders of many different generals. He believes that a careful perusal of these pages will afford entertainment to people who admire Southern valor, and amusement and instruction to girls and boys who will, perhaps, be stimulated thereby to read more pretentious books concerning the greatest war of modern times. This belief and a keen desire to preserve in permanent form some sort of memento for his own and the descendants of the members of the old company have chiefly prompted him in undertaking a task which, while a work of love, has required much labor to accomplish. He trusts that in the form and style of the book and in the manner of presentation of the varied list of subjects, even the partiality of friends will find little to excuse.

378 South Lauderdale Street,

June 1, 1909. Memphis, Tenn.

On the first day of June, 1909, the first copies of this book were placed upon the market, and within the first thirty days my personal sales paid the entire cost of the edition, which was exhausted within a few months. Its success may be said to have been immediate, and for this I am greatly indebted to those who bought the book, read it, and gave me personally many a kindly expression of the pleasure they had derived from its perusal. Many of the expressions came from capable men and women, here and elsewhere, whose favorable opinion of a literary production I would always be willing to take as a flattering compliment to an author. In truth, the assurances that I have contributed to the pleasure of so many good people have been far more gratifying to me than the ready sales of the book.

The comments of scholarly friends, too partial perhaps, which I cover with the words that the book is as meritorious as a literary performance as it is interesting as an authentic history will abide with me.

But why call this a “Souvenir Edition”? Candidly, a mere conceit, an ephemeral fancy, or the want of a better name. And yet, I shall continue to hope that all my readers, when looking upon these pages, will have at least one happy remembrance of him who has here attempted to instruct and please them.

J. M. H.,

May 30th, 1911. Memphis, Tenn.

I am to write here of men with whom I was associated in a great war, and of things in which I was a participant. To do even and exact justice shall be my aim, and there shall be no motive other than to give truthful accounts of men and events as they came under my personal observation.

When we mounted our horses at the Bills Corner, in Bolivar, Tennessee, and started for the war, there were one hundred and one of us. This company was composed largely of a jolly, rollicking set of young men from the farms of Hardeman County, who knew little of restraint and less of discipline. Like any other hundred and one men, promiscuously enlisted, some of these in time became fine soldiers, others fairly so, while still others dropped out of the ranks and abandoned the cause. One hundred and eighty-nine names were finally carried on the rolls, but from these a large company could have been taken which added nothing to the renown acquired by our regiment before the close of the war. Considering the fierce political contest through which the country had just passed and the thorough discussion of the questions at issue, the rapid enlistment of volunteers was surprising. It was evident that the election of a President by a party entirely sectional, and the open threats of a radical press in regard to slavery, had aroused an exuberance of Southern sentiment which the conservative element could not withstand. There was a strong feeling for preserving the Union in our community, but on that bright morning in May, 1861, the sentiment for war seemed to be in the ascendant. There were the usual extravagant talk and nonsense, but all were patriotic and meant well. I was of the conservatives who had voted steadily against secession and was prepared to maintain my mental equilibrium in almost any kind of political revulsion. Some of the more enthusiastic women threatened to put petticoats on the young fellows who did not enter the ranks promptly. These same women worked till their fingers were sore in getting the soldiers ready for service. We knew nothing about war and had a problem in deciding just what to carry along. No page in the old school histories had told us how little a soldier must get along on, and there was no experienced campaigner present to tell us. Some of us thought that a white shirt or two would be essential. Razors, combs, brushes and hand glasses were in our outfits. It bothered us to reduce these things to a small package that we could handle easily. We had many details to settle. Saddle-bags? They had all been appropriated by the “early birds”—the fellows who were afraid the war would be over before they could get to it. We resorted to the use of the old-fashioned wallet, an article fashioned after the similitude of a pillow-slip, closed at both ends and with a slit in the middle. Made of stout osnaburgs, it proved to be a sufficient receptacle. But the “wallet” was not tidy enough for the “trim soldier,” and in case of rain the contents were drenched. All this was remedied afterward by experience in packing, necessity for economy, and by spoils captured on the field. We, too, got to using McClellan saddles with large pockets, rubber cloths and regulation blankets. Indeed, later on, if Grant had met one of us, he would have pronounced us “correct” from halter to spur, if only he could have been blinded to the suit of gray or butternut. There came a time when we had new Yankee guns and were constantly on the lookout for cartridges of the right caliber. You see, we “paid some attention to details,” if we did sometimes leave in a hurry.

But we are off for Jackson to be mustered in. At Medon the good people who had that day given a farewell dinner to their home company had a bountiful spread for us. As Company E of the Seventh Cavalry we advanced in line of battle over this very spot at the old brick church on the “Armstrong raid,” and here we had the first real taste of heavy firing. Our gallant young Captain Tate here used his favorite word, “Steady,” which we had heard so often on drill, and reproached us for trying to dodge the balls.

Our mustering officer was A. W. Campbell, who rose to the rank of Brigadier-General, and it was another coincidence that Company E was in his brigade at the surrender. Like Chalmers, he carried his good breeding into camp, and even in the woods there was an air of refinement in all his ways. We had six weeks of hot weather and strenuous drill on the Jackson Fair Grounds. Plentiful rations and boxes from home, but in these fifty years I haven’t forgotten the Jackson flies. I remember that a Bolivar girl said they were “the laziest flies she had ever seen.” This depended upon the point of view. They came on with a rush, but were a little slow in getting out of the way.

Orders came to march to Randolph by way of Bolivar. We were all happy in the prospect of spending a few days at home. We were now soldiers sure enough—in the estimation of our friends. Hadn’t we been in camp six long, hot weeks? Pleasures incident to such occasions are sufficiently sweet to last a long time. Alas! they never do.

“Boots and saddles” for Randolph. At the “old factory” on Clear Creek the people of the Whiteville country prepared a dinner for us that was simply above criticism, except to say that it was perfect in every particular. We had our first bivouac at Stanton. Moving under a July sun and along miles and miles of dusty road, we reached the vicinity of Randolph tired and hungry. We reverted to the “flesh pots” and dreamed of Medon and Whiteville, and other good things that we had seen. The hills and valleys were covered with the tents of the Provisional Army of Tennessee, under General John L. T. Sneed. We certainly got the impression here that the war was a fixed fact. Preparations went forward day and night. It was time for serious reflection. Some of us, though young men, had been thinking over the grave questions for some time, particularly during the exciting political canvass of the previous year. Many who admitted the abstract right of secession but had voted against it as wrong under the circumstances, if not impracticable, were yet hoping that a wicked war would somehow be averted. All the elements of opposition to the Republicans had a popular majority in the election of 1860 of over one million votes, and a majority of eight in the Senate and twenty-one in the House. They could have contested Republican measures or even blocked legislation for two more years. Lincoln had always protested against the policy of interfering with slavery in the States. Was there not here food for reflection on the part of the thoughtful soldier, who was about to stake everything, even life itself, upon the result of a war in which he knew the chances of success were against him? He could reason that wise and patriotic statesmanship could change the whole policy of government in less than two years.

But here comes the battle of Bull Run, in which the Federal Army was scattered to the four winds. Oh, yes, we just knew now that we could whip three or four to one! How easy it was to conclude that the very best thing to do was to present a united front and, if not our independence, we could at least get liberal concessions in regard to slavery in the territories. But this is merely a reminiscence, and I am not an Herodotus.

We called the place, assigned us near Randolph, Camp Yellow Jacket. There was good reason for this, for thousands of yellow jackets were in the ground on which we proposed to make our beds and stake our horses. In a day or two we cleared the camp of these pests so that it was habitable. Two cavalry companies from Memphis were in camp near us—Logwood’s and White’s. In riding near these one day I met a soldier speeding a magnificent black horse along a country road as if for exercise, and the pleasure of being astride of so fine an animal. On closer inspection I saw it was Bedford Forrest, only a private like myself, whom I had known ten years before down in Mississippi. I had occasion afterward to see a good deal of him.

We were to be a part of Pillow’s Army of Occupation, and to that end, we went aboard the steamer Ohio with orders to debark at New Madrid, Mo. Soon there came a great victory to McCulloch and Price at Oak Hill, and some folks said that we would march straight to St. Louis. We reported to General M. Jeff Thompson of the Missouri State troops, forty miles in the interior. Though Missouri was a Southern State, we soon began to feel that we were bordering on the enemy’s country. We had hurriedly gone forward without our wagon train and were somewhat dependent upon the Missourians for rations. When our Captain spoke to the General in regard to our needs, he blurted out these words: “By God, Captain Neely, my men can soon furnish your men with as much beef as they want and a pile of bread as high as a tree.” We got the rations. Thompson’s men were armed mostly with shotguns and old-fashioned squirrel rifles. Trained to the use of firearms and largely destitute of fear, they were dangerous antagonists. The General, as I remember him, was a wiry little fellow, active as the traditional cat and a fine horseman. He was mounted on a milk-white stallion with black spots. He dashed around among his men like a boy on his first pony, and was invariably followed by his big Indian orderly, dressed largely in the garb of his tribe. These men told us much about their little combats with the “home guards,” and made us feel that we were getting still nearer to real war. False alarms were frequent and afforded us plenty of material to excite our risibles when the imaginary danger had passed. Still further out we encamped on the farm of General Watkins, who was a half brother of Henry Clay. Rations were not at hand in abundance for a day or two, but the owner of the farm donated to us a twenty-acre field in the roasting ear. Some of the boys said that Alf. Coleman ate thirty ears a day while it lasted—the same he took out for his horse. Green corn, roasted in the shuck, or baked before a hot fire, is very palatable. I had learned this “down on the old plantation” in the Pee Dee country. We really enjoyed camp life here, as it was not so full of dull routine. A lively little scout or an amusing picket incident made our daily duties a little more spicy than usual, while scarcely a man escaped being the butt of a ridiculous joke or a little “white lie.” A funny little story got into camp which concerned a young man of the company, who had been enjoying a short furlough at home. The ladies there, ever mindful of the welfare of the soldiers, had made up a lot of small red flannel aprons, which were said to be good for warding off disease, if worn next to the person. The young fellow had been presented with one and instructed as to its benefit, but not as to the manner of wearing it. He wore it on the outside and strutted about the town to the great amusement of many good people.

It was on this expedition that the now famous story was started on R. U. Brown. It was told by the reserve picket that Private Brown, while on post at midnight in the great swamp near Sikeston, called Nigger Head, imagined that a big old owl in the distance was saying “Who, who, who are you?” Taking it for a human voice, Brown tremblingly replied “R. U. Brown, sir, a friend of yours.” Dick never heard the last of this story while the war lasted, and at the Reunion in Memphis many a one of the “old boys” greeted him with the same old words that rang in his ears just forty years before. He and Coleman, afterwards sutler of the regiment, I am happy to know, are still alive in Texas. Like others, who sickened and died or met death on the firing line, they were gloriously good fellows to have in camp.

It was during our stay in Missouri that we made an expedition to Charleston, situated in that vast flat prairie just west of the mouth of the Ohio, which we always reverted to with the keenest pleasure. The Federal Cavalry from Bird’s Point had been making almost daily visits to the town, which was strongly Southern in sentiment. This was thought to be a fine opportunity to show them “a taste of our quality,” or perhaps to capture the visiting detachment. But all was quiet in the village, as the enemy had made their visit and departed. Night was at hand and we were dirty, tired and hungry. It seemed to me that the whole population went to cooking for and feeding the soldiers. This was another one of those “big eating times” that we never did forget. When we were ready to depart, even the pretty maidens would say to us, “Which will you have in your canteen, whisky, water or milk?” It was thought best not to take any risk as to snake bites in the great swamp, which we had to recross, and I think the command took whisky to a man. The inhabitants must have enjoyed a freedom from intoxicants for a season, for their town “had gone dry” by an immense majority. We learned afterwards that there was a “whisky famine.” We never saw Charleston again, as we very soon received orders to advance into Kentucky and take post at Columbus. We were among the first troops to reach that point. The Kentuckians seemed to be pleased with our coming and recruiting went forward encouragingly. We pitched our tents out on the Clinton road and near the camp of the Haywood Rangers, commanded by Captain Haywood of Brownsville. This company, whose members seemed to have been reared in the saddle, had been with us from the beginning of our service, and, I may say here, that it stood by us till the end. The history of Company E is largely the history of Company D. The men of the two companies were brothers-in-arms, who could confidently rely upon the valor of each other, and those now living are loving friends to this day. Through the long hard winter, or till the evacuation of Columbus, the two companies guarded the Clinton and Milburn roads. For a while we reported directly to Albert Sydney Johnston. His noble personality and soldierly bearing were impressive and stamped him as a man born to command.

The reader will remember that in closing the previous chapter I stated that Company E had been ordered to leave Missouri and take post at Columbus, Kentucky. The company was not then designated by letter, as it belonged to no regiment, but was known as the Hardeman Avengers. In company with our sturdy friends, the Haywood Rangers, afterwards Company D of the Seventh Tennessee Cavalry, we reached Columbus the first day of September, 1861, being about the first troops to occupy an advanced post among a people, who were then making a rather unsuccessful effort to play the role of neutrals. We were now in a “hog and hominy” country, and the soldiering was of the holiday kind. We made long marches through the Purchase and saw many evidences of Southern sympathy. Indeed, the whole population seemed to be friendly to us, as even those with Northern sympathies prudently kept quiet. Then, as now, I accorded people the right to think as they pleased, and to act upon their convictions. Throughout the contest, I zealously held to the principle that we should not make war upon old men, women and children. In the light of this principle, I was able to enjoy to the fullest extent a ridiculous attempt at concealment of real sentiment. For instance, somewhere in the Mayfield country, the column was one day passing a farm house upon the veranda of which was sitting a corpulent old gentleman, whose adipose matter hung sufficiently low to largely cover his femurs, as he sat with his pedal extremities slightly elevated on the rude baluster. While he wildly gesticulated he lustily shouted, “Hurrah for Jeff Davis and the Southern Confederacy!” At another part of the house a little girl was making strenuous efforts to haul down the stars and stripes, which doubtless was emblematic of the real sentiments of the household. The old fellow “got the horse laugh.” In our peregrinations through the several counties of the Purchase it seemed to me that we were riding much to little purpose, as the Federals ventured little beyond their lines at Paducah. I learned afterward that these exercises made us take on the ways of a soldier, and taught us valuable lessons in the bivouac. These stood us in good stead when, afterwards, we were forced to use to the best advantage very scanty resources.

In this month of September, 1861, it was learned that a force of Federals had occupied an advanced camp on Mayfield creek near Blandville. The five companies of Tennessee Cavalry having been organized into what was, for some months, known as Logwood’s Battalion, were ordered to attack this force. Here we were to hear bullets whistle for the first time. The command seemed to be eager to enjoy the sensation of battle. As a private, I was supposed to be in profound ignorance of the “plan of campaign,” but I could see enough to know that the maneuvering was for the purpose of surrounding the camp and forcing a surrender. Our company was drawn up in the woods within gunshot of the enemy, but we had no clear view of their actions. There was random firing on both sides, but there was no fixed purpose to press the fighting. Green as we were, we would have gone into that camp, had we been so ordered. There were men in that line, who afterwards, as officers and privates, became famous fighters and, in many cases, went to death on the firing line. Almost any one of Forrest’s real veterans would, at a later day, have considered it a light undertaking, with the backing of five hundred such men, to have “gobbled up the whole thing”—perhaps without the firing of a gun. And yet nobody seemed to be blamed for the failure of this expedition, for we were all ignorant of real war. We had had another lesson in that which would eventually make us veterans. We had heard the buzz of bullets.

The engagement turned out to be a trifling affair, though there was some excitement in the ranks, especially about the time Mike McGrath of the Haywood Rangers had his horse shot under him and had to leave the scene mounted behind another soldier. It was not so funny then, but the little things done in the excitement gave occasion for joking when we got back to our quarters. There was a well known citizen who seemed to be acting as our guide. They called him Captain Blake. Sixteen years after that, while making an extensive trip in Texas for a well known newspaper, I found this Captain Blake holding a prominent office in the town of Granbury. Our short experience as soldiers together was then a pleasant reminiscence, but he, too, had become a veteran by coming south with the Kentucky troops and never returning to his home till after the surrender.

About this time we received into the company four Kentuckians, three of whom cut some figure as private soldiers and helped to make Company E noted for its steadiness in battle and promptness to act in emergencies. These were John Duncan, Cad Linthicum, Ranse Billington and an old fellow whom we all knew as “Old Fulton.” The first three were typical young men of the Purchase, reared in the hills bordering the Ohio river bottoms. They were true sportsmen in all that the term implies, but were never so busy in a game of poker, or so much interested in discussing the good points of “Forrest’s sorrel” or of “Treadwell’s gray” that they could not, on a moment’s notice, have mounted their own good steeds and been off at a rattling pace to an important picket post, or upon an adventurous scout. The sandy hair, the clear blue eye, the firm set jaw of Duncan—the rollicking manner, the girl-like cheeks, the merry shout in battle of Linthicum—the even temper, the great good humor, even when facing peril, of Billington, and the fine horsemanship of each made them men of mark among their comrades, while their apparent lack of fear and love of adventure won the absolute confidence of their superiors. Linthicum was wounded at Collierville, Tenn., in October, 1863, about the time that the Thirteenth Regulars with General Sherman and staff were hastily abandoning their train from Memphis to take refuge within the Federal works. Duncan was shot through both arms in the fight at Prairie Mound, Miss., where Jeffrey Forrest was killed. A few months before the surrender, these three men were transferred to Henderson’s Scouts, in which they found service exactly suited to their inclination. Happily, they lived to return to their beloved Kentucky, where, as good citizens, they spent many years in peaceful pursuits. They have passed to the great beyond.

Well, as to “Old Fulton.” I should say he had been reared in an atmosphere of gall, wormwood and vinegar. With a desperate temper and no sweetness of soul, upon the slightest provocation he would fly into a towering rage. If asked as to his age, a tart reply, interlarded with oaths, was the result. His stringy hair and long flowing beard were evidences of age. His cadaverous appearance, high cheek bones, piercing gray eyes, alert head set in a long skinny frame, and his fiery passions would have presented an interesting study to the excursionist into the fields of anthropology. This old Kentuckian had joined the Tennesseeans for the purpose, as he said, of soon killing a few Yankees. He never gratified his supreme desire, for within a few months, having, perhaps, tired of camp life, he got his discharge and set his face towards Kentucky. After his departure, we could revert with amusement to “Old Fulton’s” effort to start a camp fire at Island No. 10, with wet wood. When the smoke had blinded the old man, and his patience and wind were exhausted, he leaped upon the pile of fagots and, uttering violent oaths, kicked them in every direction. This exhibition of temper was rather amusing.

About the first of October, 1861, Haywood’s and Neely’s companies were ordered to Camp Beauregard in Graves county to picket and scout for Bowen’s brigade. This was a charming place for holiday soldiering, situated near the village of Feliciana. As the cavalry was encamped outside the infantry lines and there was little fear of attack, the discipline was sufficiently lax to permit us to draw upon the surrounding country for luxuries. These consisted of such things as old hams, chickens and “peach and honey.” The boys did not neglect their opportunities. But life at Camp Beauregard was soon to be a thing of the past. The Federals were known to be making a move from Cairo. We reached Columbus just in time to witness the battle of Belmont across the river. This was the 7th day of November. Grant’s army was driven back to their transports. Here we saw Federal prisoners for the first time, and as many of them were wounded, we seemed to be a little nearer real war. Going into winter quarters we entered upon the monotonous duty of picketing the Milburn road. Dreary nights and weary days. Dull camp routine and nothing to excite interest. But there was to be a change. The news that Fort Donelson had fallen came in the last days of February. The excitement meant that we were leaving Kentucky. With our friends, the Rangers, we were ordered to Island No. 10. Here our hardships increased, as we were poorly supplied with tents and cold rains were falling. The gunboats were replying to our heavy guns, but to little purpose, as the range was poor. They would send an occasional shot clear into the timber, and there was no telling when one might land right in our camp. Our nervousness on this account soon wore off, as we were exposed thus for seventeen days. In the meantime, the river rapidly rose and there was a rushing current through Reelfoot Lake in our rear. This put us on an island. I know that our captain wished to be ordered to the main land. The order came, but there was great fear that it would be countermanded, as Mackall was just superseding McCown, who had given the order. There was hot haste to get beyond the reach of orders. After floundering around for a day in trying to reach a steamer, which it was said would be available in the back water, we concluded that our only resource was to reach a dry spot on the lake shore and collect a few old flatboats and to reach the east side. In making our way to the lake we found much of the back water up to the saddle skirts. We readily secured one old rickety boat, which would carry five men with their horses and accoutrements. As the lake here was five miles wide, and the water still rising, our crossing would surely be slow and perilous. At this juncture, Tom Joyner, George Bradford and I rode five miles along shore, secured a boat, and having led our horses aboard, pulled for the camp. Everything went well with the ten men and ten horses till we were “half seas over.” Then an adverse wind struck our boat, while the other boat, already much in advance seemed to glide over the water. It was exasperating, but we “hove to” by the side of a friendly raft of logs and awaited more propitious breezes or a lucky calm. We were fortunate in reaching land before nightfall and in getting a good supper at a farm house. But next morning the boats must be carried over that stretch of water in order to rescue our fellow soldiers from an impending peril. When we reached the camp only a detail had been left there to inform us that the rest of the command had gone aboard of a steamer in the back water, which was on its way to Randolph. One time happy they! Thrice and four times happy we! We had escaped the perils of the deep waters and the terrors of a Northern prison. Some of us had had a twenty-mile ride on Reelfoot, but strenuous effort had been rewarded.

We had a long ride to Bolivar, and reached home just in time to hear the guns at Shiloh. Four companies of infantry, one of artillery and one of cavalry, recruited in Hardeman county, were in that battle. Harrowing rumors of our losses came thick and fast, and little else was discussed. The death of Johnston and the retreat of the army seemed to us like a crushing defeat. Stragglers and wounded men from the army began to pass through the country and spread the news of the disaster. Then came the news that Island No. 10 had surrendered. It was a time for solemn thought—for quiet deliberation. The holding of the great river became now a doubtful proposition. This involved the abandonment of West Tennessee. A few of our men even now went to their homes to stay. The faithful set about reorganizing the company, which was to await orders. We were really making a fresh start for the war under discouraging circumstances. Our sacred honor and plighted faith to our state were involved. It was no time for faint hearts. Death before dishonor seemed to be the prevailing sentiment and when we got on the move, the old time spirit returned.

We had now seen scarcely a year of service, but had traversed parts of three states and crossed and recrossed the Mississippi river. At Trenton, we were to take our place as Company E in what was for many months known as the First Tennessee Cavalry under Colonel W. H. Jackson. In numbering by seniority, we took the seventh place, though some of the companies composing the regiment were among the first to volunteer. There was the usual jealousy on the part of some because an outsider had been placed over us as Colonel, but Jackson was a trained soldier, and constantly grew in favor with officers and men. If Jackson did not apparently have the dash of some other officers, his impression on soldiers was of solidity, good sense and firmness. Judging from incidents of the service, he must have had the implicit confidence of Van Dorn and Forrest. More could not be said of any soldier.

But we must give up Tennessee—a sad thought. After a clash with some Federal Cavalry at Lockridge’s Mill, in Weakley county in which there was more of stampede than of fighting on their part, we retired toward the state line. We moved out leisurely, as no force was crowding us. We heard the noise of battle at Memphis on the 6th of June, 1862, and camped that night at Germantown. We soon heard of the defeat of the Confederate fleet in front of the city and of the Federal occupation. Next day found us in camp on Coldwater river, a few miles from Holly Springs. Then began a series of marches and countermarches in North Mississippi and trips to the borders of Tennessee. In one of these, a detachment of our command came near capturing General Grant at the house of Josiah Deloach. This gave rise to the story, after the war, that for his timely warning on the occasion Grant made Deloach postmaster of Memphis.

If I were to attempt to record more than a tithe of the events incident to our service in Mississippi during our first summer there, or do more than to touch the high places, as I skim along, these reminiscences would be too tedious for perusal.

William J. Tate, who had been elected lieutenant at the late regimental reorganization, was now promoted to the captaincy of Company E. Suffice it to say here that he had no superior as an officer in the regiment, and I shall have something more to say of him, when I come to speak of his death.

But the Armstrong raid. This was an expedition into West Tennessee under the command of General Frank Armstrong. Advancing by way of Grand Junction, we encountered a Federal force near Middleburg the 29th of August. There was some fighting between the Second Missouri Cavalry under Colonel McCulloch and the Second Illinois under Colonel Hogg, who was killed. In a combat at close quarters between McCulloch and Hogg, the latter was killed by Tom Turner, a young Missourian, to save the life of McCulloch. Captain Champion of the Second Missouri was killed here. As his body was borne from the field by two of his troopers, I saw, for the first time, a dead Confederate, who had been slain in battle. As the purpose of the raid seemed to be the cutting off of the army at Bolivar by tearing up the railroad, which led to its base of supplies, we crossed Hatchie river and struck the railroad at Medon. The Federal garrison here was small, but without artillery we found it impossible to dislodge them, so well were they protected in and about the depot with cotton bales and other material. Nothing was accomplished by the attack and several Confederates were either killed or wounded. It did so happen that Company E, in the charge on foot at the old brick church, passed over the same ground where it had been so royally entertained by the people of that vicinity the day it was mustered into service. Here Captain Bassett of Company C, Memphis, and Major Duckworth, afterwards Colonel of the regiment, were severely wounded, Bassett being permanently disabled. The command drew off to the east and went into camp at the Casey Savage farm. The Federals having received re-enforcements presented a bold front next morning when we passed to the west of the railroad. Here was a fine chance for a fight of which we did not avail ourselves, though the enemy were in an open field. With our force, we could have driven them to shelter or effected their capture. This was the first day of September, 1862, and we were to fight the battle of Briton’s Lane that day. We were to encounter a force, consisting of two infantry regiments, a section of artillery and a small detachment of cavalry. Our army could have enveloped them, and should have done so. The regiments were fought in detail, some of them scarcely getting into the engagement at all. The Seventh Tennessee was ordered to charge on foot through a corn field, from which the fodder had been stripped, against a heavy line of infantry lying behind a stout worm fence and in the woods. A galling fire was poured into Company E, but some of its men reached the fence. Dr. Joe Allen of Whiteville mounted the fence and fell dead on the enemy’s side of it. John Bradford of Toone, and Willie Wendel, a school boy of Bolivar, were killed near the fence. D. E. Durrett of Bolivar received a wound which put him on crutches to the day of his death, which occurred a few years ago, and Tom Joyner and John Fortune were severely wounded. How so many men got out of that field alive is one of those unaccountable things that sometimes occur in war. The whole command was discouraged by the operations of this raid, and thought that, if we had gained anything at all, we had paid dearly for it. The weather was hot and dry. When we returned to Mississippi the men were thoroughly dispirited and their horses in bad condition. True soldiers quickly recover from a disaster, when well treated in camp, and even horses seem to follow the example of the men. How sweet was the rest just then! But this respite was not for long. Even then Van Dorn and Price were arranging the details to attack Rosecrans at Corinth.

When we had somewhat recovered from the fatigue and demoralization incident to the Armstrong raid, four companies of the Seventh Tennessee and four of the First Mississippi were ordered to march under Lieutenant Colonel F. A. Montgomery of the latter regiment in the direction of Hernando, Miss. Colonel Grierson with his Sixth Illinois Cavalry was making a scout from Memphis, and the eight companies were to watch his movements. I remember we passed down through Byhalia and Cockrum and across Coldwater river on the road towards Hernando. Then turning north and marching leisurely along we recrossed the Coldwater at Holloway’s bridge, quite a rude affair, about ten miles southwest of Byhalia. The men seemed to think that we were only making one of our usual marches for practice. But when we had reached the foothills on the east side, there was a commotion in the ranks and we were ordered to countermarch, while the word passed down the line that Grierson was in our rear. He had crossed the bridge and was following us. In a few minutes the whole command was in the greatest excitement. As soon as the immediate presence of the enemy was discovered, a company of the Seventh Regiment was thrown front into line, but, unfortunately, very near the enemy, who had advanced on foot and were well concealed in the heavy timber. There was brisk firing from the Federal line, which portended certain death to the men and horses of our front company. There was a bolt to the rear, and what is known to the participants as the Coldwater stampede was on. Nothing could surpass it in excitement. The other companies had been drawn up by company front with Company E next in position to the one so near the enemy. When the latter had reached our front, it had acquired about sufficient momentum to dash through on their excited horses, which seemed to have gotten beyond the control of their riders. The Federals saw their opportunity and promptly advanced, delivering a galling fire as they did so. The demoralization was imparted from man to man and the scare from horse to horse till it became a rout. Some of the men of Company E spoke encouraging words to one another, when they saw what was coming, and denounced the retreat as cowardly. In some, this was no doubt a manifestation of inborn bravery, in others, of self-esteem or personal pride. From whatever motive, it was a creditable act, for it was one of those occasions when a man can take his own measure to see whether or not he is a brave soldier, or is prompted by other impulses. But however much inclined some were to stand firm, it was only a moment before all were borne to the rear. Concert of action was impossible, and those who at first resolved to resist, were very soon getting away with those who seemed to be making the best time. The command did not exactly take to the woods, but there was no delay in crossing a stout fence which put us into a corn field where the fall crop of crabgrass seemed to be the rankest I had ever seen. We happened to be going in the direction of the rows or we would have played havoc with the crop. As it was, we trampled great paths through the crabgrass and spoiled a fine lot of hay. Everybody seemed willing to halt when we got on the other side and had an open field between us and the enemy. The command was reorganized with dispatch, after which there were various expressions as to the cause of the disaster. Smarting with shame and mortification, a great majority of the detachment would then and there have put up the fight of their lives, had they been coolly led into action. Clearly, we had been outgeneraled by one of the most alert of Federal officers, the first on his side to gain a reputation as a bold raider.

How vividly I recall my own feelings and those expressed by others, when we retired from the scene of the affair just related! Everybody had some incident of the disaster to relate, and the usual funny things were said about how the boys got over that first fence and through that cornfield, though it did look like smiling at a funeral.

When the excitement was at its height and Grierson’s men were yelling like demons turned loose, Sherrill Tisdale’s horse was running madly to the rear with his rider trying to keep himself in the saddle by holding desperately to the mane. Tisdale fell to the ground and was captured, but his fine young horse, afterward ridden by the late Emmett Hughes, escaped and would have carried his owner to safety.

John Allen, a brother of Dr. Joe Allen, killed only a few days before at Briton’s Lane, was shot through the foot before our line was broken. He was riding a splendid mule which carried him out of danger by leaping two big logs, lying one upon the other. Joe and John Allen with their brother Thompson, who served in another regiment, were, like their father, Long John Allen, of Whiteville, noted for their sprightly intellectuality, physical and moral courage and height. John used to turn his six feet four inches to an amusing account when he encountered a citizen with whom he wished to swap horses. Putting his hand to his right ear he would ask his new acquaintance to talk very loud, intimating that he was very deaf. “Old Innocent,” usually a man of short stature as compared with John’s, who had, on the quiet, plenty of confidence in his own ability as a judge of horseflesh, would tiptoe to John and raise his voice to a high key. John, like a born actor, would turn his right eye down on his unsuspecting subject while he winked with his left to his audience. John Allen’s penchant for horse trading caused him sometimes to be mounted on a mule.

Company E now knew that there was work to be done in the immediate future. The Federals had garrisoned many places on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, and were making incursions into Mississippi. Steps were taken to unite the armies of Price and Van Dorn for the purpose of making an attack on Corinth where General Rosecrans was posted. As preliminary to this attack, Colonel W. H. Jackson was ordered to take his own and the First Mississippi Cavalry under Pinson and make a reconnoisance in the direction of Corinth. At Davis’ bridge on Big Hatchie river Jackson somewhat unexpectedly came upon Ingersoll’s Eleventh Illinois Cavalry and some regulars just going into camp. The vidette, who had just taken post, was taken in and the rest was easy. Pinson in front charged across the bridge and into the camp of the enemy, who were largely engaged in gathering corn from a field to the right of the road, while the Seventh Tennessee brought up the rear and waked the echoes with the rebel yell. The firing was promiscuous, but there were few casualties. Pinson was the only Confederate wounded. He manifested the spirit and courage of the hero, as we bore him to the Davis residence on a cot secured for the purpose. He had very good reason to think that the ball had penetrated the intestines, but he, nevertheless, spoke cheerfully to anxious enquirers as “boys,” and said that it was only “a small matter” and that he “was all right.” Happily he was.

The spoils were great, considering the few minutes the battle lasted, consisting of one hundred and eighty fine Illinois horses with their accoutrements and arms. We captured only fifty or sixty prisoners, as it was just at nightfall, and most of the enemy took refuge in the timber. I always thought that those fine horses and accoutrements should have been distributed among the boys where most needed and their inferior articles taken up. This might have been done under a board of survey in such a way as not only to increase the efficiency of the command, but also to stimulate it for future enterprises. But we didn’t get a halter. All went to supply the demands of other commands. There was one particularly fine horse in the captured lot which had been thoroughly trained and was evidently something of a pet, as we say, of his former owner. Jim Weatherly of Somerville, was not long in discovering his fine points and “smart tricks,” and soon had him “going his way.” The beautiful brown with two white feet had to be turned in, and Weatherly was disconsolate. Thereafter, when any legitimate capture fell in the way of the boys, mum was the word. It was now September, 1862, and Price and Van Dorn were ready to move on Corinth. This movement was made from Ripley, Miss., in two divisions commanded by Price and Lovell, with Van Dorn as chief. The army was well equipped, well fed and in fine spirits. It had not rained for many weeks, and the dusty roads and scarcity of water made the marches, which were necessary to effect the concentration of the two armies, severe ones for all branches of the service. But the prospect of making a successful assault on the works at Corinth and capturing Rosecrans and his army buoyed up the spirits of the soldiers. Ten miles out on the Chiwalla hills the cavalry encountered a small Federal force which was easily swept back. Company A of the Seventh Tennessee, was active in this affair as Jackson’s escort and lost the first man killed on the expedition. I was with a detachment of Company E that had been ordered forward and deployed as skirmishers. I came upon the corpse of the soldier, which had, for the moment, been left where he had fallen. It was the body of John Young of Memphis. This was the first day of October, 1862. The next day was spent in getting the proper dispositions made for the assault. On the 3rd, the earth seemed to tremble with the thunder of artillery and the roar of small arms. It was a struggle to the death in which both sides lost heavily. The position had been rendered strong by heavy earthworks and much of the front had been covered by fallen timber, which made the approach to the main works difficult. All that day it went well with the Confederates, though the killed and wounded were numerous. As the cavalry took no part in the main battle, we could see pretty well what was going on in the rear. There it was a bloody spectacle as the killed and wounded were borne back for treatment and burial. That was the first time for me to see our poor fellows wrapped in their blankets and buried in shallow trenches. The horror of it! Even on the morning of the fourth, those of us in the rear thought that all was well in front, for we had heard that Price, who was fighting on the north of the railroad, had gone over the heavy works and into the town. And so he had, but the brave men under Lovell on the right under the terrible fire of the Federals had failed to make a successful assault. Suddenly there was a calm, which we could not understand. But it soon flashed upon us that we were beaten, and our army was in full retreat. During the previous night McPherson’s division from Jackson had re-enforced Rosecrans and was ready to press the retreating Confederates. Hurlburt’s division, too, was marching from Bolivar to intercept the retreating column. There was now likely to be some lively work for the cavalry. When we reached Davis’ bridge, the scene of the affair heretofore related, Hurlburt was there to dispute our passage. With McPherson in our rear we were apparently “in a box.” Shrewd generalship on the part of the Federals would have captured our whole army. Van Dorn boldly attacked Hurlburt at the bridge, while his trains were ordered to take the only road of escape—that up Hatchie river. The cavalry preceded the trains, and, crossing the river, attacked Hurlburt in his rear. For several hours there were two Federal and two Confederate forces engaged and one of each fronting two ways. Van Dorn drew off at the proper time and followed his trains. The Federals were not disposed to follow, as good generalship would have dictated, for our troops, worn out and hungry, could have made but a feeble resistance. The streams had no water in them and our soldiers drank the wells dry. When a beef was killed the hungry men were cutting the flesh from the carcass before the hide was off. In the midst of this distress, I had my only sight of Sterling Price. He was riding at the head of a small escort and apparently in deepest thought. He had left many of the brave men whom he loved dead on the field of Corinth. He was the idol of his men, a great Missourian and a good man. But the result at Corinth had made him sad. The disaster brought other troubles in its train.

The morale of the army was not good, the citizens were discouraged and many a soldier gave up the fight and went to his home within the Federal lines. We retired to the vicinity of Holly Springs.

After the battle of Corinth the Confederate army under Van Dorn was entirely on the defensive. Grant and Sherman advanced from Memphis into Mississippi with the evident purpose of taking Vicksburg in the rear. The cavalry had frequent skirmishes with the Federal advance and no little excitement. There was an encounter with Sherman’s troops near Old Lamar in Marshall County, Miss. In relating this incident, I feel the need of a faculty that would enable me to tell three or four things at the same time and make my readers have a clear conception of a number of particulars which run through the mind so rapidly that it is difficult to arrange them in a well connected narrative. As in a dream, we travel over a vast extent of country and talk with many people in the short space of a few seconds, so when armed forces unexpectedly clash, we can see very many things at the same moment, but can speak of only one incident at a time. In the last days of a very dry October the Seventh Tennessee Cavalry was marching by fours in a dusty lane with ditches intervening between the road and the fences. The enemy must have seen that a fine opportunity was at hand, and advanced rapidly on our flank. The clouds of dust so obscured the vision that it was impossible to see just where the enemy were. Having the advantage of an open field they made good use of it. The Confederates were compelled to fall back or be enveloped. The command to right about by fours was given. This order threw about one-half the regiment into a position fronting the other half, which had, in the confusion, never heard it. The red dirt rose in clouds as those who were trying to get to the rear struggled to pass by those who had not heard the command. Horses and riders went into the ditches in a confused mass.

The time for obeying orders had passed. Amid the shouts of the enemy’s flanking lines, the neighing of horses and the curses of desperate men, there seemed to be one thought uppermost, and that was to get out of this trouble alive, if possible. No doubt there were instances of individual bravery and unselfish acts of gallantry, quite common occurrences in the Seventh Regiment, but nobody had anything of this incident to relate on that score around future campfires. Many had thrilling stories of how they escaped. Captain W. J. Tate of Company E, and Captain C. C. Clay went into the ditch together. Tate lost his saddle, but got hold of Clay’s, which he placed on his own horse, mounted and rode out of danger. Captain Clay with many others was captured. This all happened in much less time than it takes to tell it, but it was a remarkable stampede, the second and last the regiment ever was in. The fighting was so constant from that time till Christmas, 1862, that the men learned to stand firm on the firing line and to fall back in good order.

It were a long story to tell of the sullen retreat of the army even now not fully recovered from the effects of the disastrous Corinth campaign. Mansfield Lovell’s division and Price’s Trans-Mississippi veterans, however, were always ready for a fight. The cold, rainy days of winter were upon us, and nothing seemed quite so sure as a great battle on the line of the Tallahatchie. That line was abandoned and the enemy made a fierce attack on our rear guard of cavalry at Oxford. We were expected to hold them in check till our trains were safe beyond the Yokona. It was one of those times in which the woods were alive with bluecoats. But I shall intermit this narrative here and insert a sketch, which is entirely apropos, though printed some time ago. It follows:

Editor Commercial Appeal:

Whenever I hear the patriotic spirit of the Southern women alluded to, I somehow revert to an incident that came under my observation on the 2nd day of December, 1862, at Oxford, Miss. Price and Van Dorn had been forced to abandon the line of the Tallahatchie and were falling back to the line of the Yalobusha. Our cavalry was making a stubborn resistance against overwhelming forces of the Federals in order to hold them in check long enough to allow our trains to get beyond immediate danger. A cold rain was falling and there seemed to be no bottom to the roads. The citizens were panic-stricken and the army was in no good spirits. It had not entirely recovered from the disastrous repulse at Corinth, and the terrible weather added to the distress. “Blue ruin” seemed to stare us in the face. Colonel Wheeler of the First Tennessee Cavalry was temporarily in command of W. H. Jackson’s brigade, which was trying to hold the Abbeville road. There was no picket in our front and there was a call for somebody to reconnoiter. There was no positive order from the Colonel commanding, but as he rode along the front of our company he said: “Some of you men with carbines go out there and see where they are.” It was one of those times when it was nobody’s business in particular, but everybody’s in general. Just then I asked Sam Clinton, who recently died at Bolivar, if he would go with me. We rode forward, followed by four other men of other companies. I remember that Sam and I realized the danger and would have preferred to be somewhere else. We stirred up a hornet’s nest, for very soon there was one report, and a singing minie passed over our heads. Instantly, a heavy skirmish line of Kansas Jayhawkers, who knew how to shoot, rose up in the bushes on each side of the road. We replied in kind, but retreated at a rapid pace. Only one of the six was struck, Private Wilson of Company B, of Covington, who had his thigh bone fractured and became a permanent cripple. The retreat even was so hot that I hastily concluded to quit the road and try the timber. In forcing my horse, “Old Snip,” up an embankment the wet and thawing earth gave way, and Snip and I fell in such a position, with my left foot under him, that it was difficult to rise. I had to think fast. I spurred the poor beast with my right foot to force him to an effort to rise so that I could recover my left. The next thing was to recover my navy six and saddle bags, containing my scant “wardrobe” which had become detached and fallen in the mud. Replacing my pistol in the holster, throwing my saddle bags on my shoulder and holding on to my carbine, I turned my attention to Snip, who had by a supreme effort recovered his feet and was ready for any emergency. Following my lead, he mounted the embankment and we had the protection of the timber. Just then the gallant Joe Wicks of Memphis, the adjutant of our regiment, came with orders for the squad to fall back. We had already taken orders from the Jayhawkers. But poor Joe Wicks, we never saw him more. Dashing into the thicket, he said he had other orders to deliver. In a few minutes his riderless horse came dashing back to the command. He never delivered his orders, but was buried by the good people of Oxford.

But I started out to say something about the Confederate women. If I have any excuse for this preliminary, it is, that my readers may have a faint appreciation of the troubles that come to a poor private of a retreating army in midwinter. As for the Confederate women, it is always in order, even in the middle of an effective paragraph, to say your best about them, but, if I had some happy trick of phrase or knack of language, which I just now heartily desire, I would write in the language of loftiest eulogy in their praise. However, let us think that there never were any others just like them.

But now as to the particular incident. Oxford was a town of tearful women and weeping maids. This added to our overflowing cup. On the verandah of a cottage, somewhere just south of the courthouse, was standing one of the maidens, who did not seem to be weeping, for her spirit had risen to the occasion. With dark blue eyes and flowing hair, she was animation incarnate. She was most forcibly expressing her opinion about our giving over the town to the merciless Yankees. Her short skirts and youthful appearance, somewhat mollified her impeachment, for, if we had taken her opinion as solid truth, and had seen ourselves as she, for the moment, saw us, we should have been convinced that we were the most cowardly aggregation of “skedaddling” cavalry in the Confederacy. In just twenty days, we had ample revenge and surcease from humiliation at Holly Springs, where the Federal loss of army stores, right in the rear of Grant’s army, went into the millions, and was the greatest loss of supplies that occurred on a single occasion during the war. Historians have not even done this affair under Van Dorn the scantiest justice.

But who was our little maiden, she of the patriotic impulses? Everybody wanted to know, for we hoped to have her think better of us. Cad Linthicum, our little Kentuckian, who somehow had a penchant for knowing all the girls in divers places, said it was Taylor Cook. And so it was Taylor Cook. Then “Taylor Cook” went down the line. She had become famous in a twinkling. The Seventh Tennessee Cavalry would have willingly adopted her as “The Daughter of the Regiment,” if she could have appreciated the honor. She was worthy to become the wife of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s only son. And she did. When I pause at her grave in beautiful Elmwood, I think of that sad day at Oxford.

J. M. HUBBARD.

Erstwhile of Company E,

Seventh Tenn. Cavalry.

On the 3rd day of December, 1862, the Seventh Regiment had placed the Yokona between itself and the enemy. We destroyed the bridges in order to hold them in check. Here we committed about our first depredation on a citizen. We burnt his fence rails. Remember it was cold and wet and we had no axes. The boys spoke of it as an outrage (sic), but felt good as they dried themselves around the burning rails. We consoled ourselves with the reflection that, if the owner were as patriotic as he should have been, he never would utter a word of complaint. Many a time, when the temperature was low, we had occasion to revert with pleasure to the generous fires near Springdale, an old antebellum stagestand.

“Boots and saddles,” for the Federal cavalry had already gotten between the Seventh Regiment and Water Valley. There was but one thing to do. Put on a bold front and run over them or through them. This was so quickly done by our advance that the rear never came in sight of the enemy. The road was now clear and we continued to move south. The next day, just north of Coffeeville, we assisted in forming an ambuscade to entrap the Federal cavalry. This was attended with sufficient success to enable our whole army to take post at Grenada.

We were getting well along into the second year of the war, and our prospects were getting worse on the “Memphis lines.” North Mississippi was in the hands of the Federals, and nothing seemed more probable or possible than that we should be driven further toward the Gulf. Van Dorn had had rather poor success as the commander of an army or the projector of a campaign, but the Confederate authorities knew he was a born cavalryman. He appeared to be the very man to lead a bold movement to the rear of Grant’s army on the Tallahatchie. A corps composed entirely of cavalry was organized to take the road with Holly Springs as an objective point. This place had been abundantly supplied with everything needed by an army of twenty thousand men, encamped south of it, and was garrisoned by about three thousand of all arms. Most of the storehouses around the public square were full of provisions, clothing and medical stores. A large livery stable had been converted into an immense arsenal for the storage of arms and ammunition. There was a long string of cars on the tracks, sufficient, perhaps, to make three good trains, which it was said were loaded with supplies for the army. The sutlers and the small dealers who follow an army, were fully supplied, as if they expected to make a permanent stay in the Sunny South. The cotton speculators were in force, and had hundreds of bales in storage. Van Dorn did not expect to transport any part of these vast supplies south. His purpose was to surprise the garrison at daylight, parole the prisoners and destroy the stores. So after making a march of one day and two nights, much of which was at a trot, and during which we had, after starting from Grenada, swept around by way of Benela, Houston, Pontotoc and New Albany, about 100 miles, we surprised and captured the Federal outpost and entered the town at a gallop. On that clear, frosty morning of December 20th, 1862, the Seventh Regiment was marching in the rear of a column so long and moving so rapidly that we made the last mile or two at about full speed. When we did reach the town, our horses were hot and smoking and men greatly excited. Colonel Murphy, the Federal commander of the post, had already been surprised in his bed and the Confederates were on every corner. Men, women and children were sounding praises to the Confederates. We could hardly realize that we were in possession of the largest booty secured by any army, so far, in the war. Everybody wanted to carry away something, but it was hard to make a selection. Here were great inducements to plunder and such a condition of demoralization existed as might cause the officers to lose control of their men. Whisky, brandy and wines of the best quality and in unbroken packages were among the spoils of war, and everybody so disposed could help himself. And pretty much everybody was disposed. A. S. Coleman, he of the Missouri roasting ear story and sutler of the regiment, had left his wagon at Grenada and had donned his fighting clothes for the raid. He acted as a sort of free lance, who had the assurance to assume special privileges. He visited some of the richest depots early and selected such articles as he knew would please the boys. He soon hove in sight of Company E with a string of hats as long as a plough line wound about him and his horse. What looked like the effigy of a man, clothed in blue trousers of large dimensions and cut in twain at the waist and footless, sat bolt upright on the pommel of Coleman’s saddle. When the contents of the effigy were displayed, we found we had more good liquor than we had room for. All were in fine trim now to attack the commissary stores. As in the case of the fine liquors, the boys did materially reduce the visible supply of good things. People of all classes, without regard even to previous condition of servitude, were told to walk up and help themselves. Children reveled in the pleasures of the occasion, and grown people declared that it was the grandest day the town had ever seen. The work of destruction began in the afternoon. The arsenal was destroyed, all cars with their contents and houses used for the storage of cotton were burned. Town and country were enveloped in smoke and the report of explosives was heard when we were many miles from the scene of destruction. Van Dorn had so completely reaped the fruits of victory that his praise was on every tongue. The men rode out of Holly Springs at nightfall in high glee and perfectly willing to incur other dangers further north. The loss to the Federals has been estimated as high as $3,000,000.

I have been at some pains to find out about how many men Van Dorn had at Holly Springs, but the affair has been so lightly regarded by writers and the records are so lacking in specific statements, that I am only able to state that I had the impression at the time his force numbered about four thousand men. He had no artillery. A statement here as to strength is immaterial in this case, as one thousand men, or maybe less, could have accomplished all that was done. For the Federals, it was a complete surprise and a humiliating disaster. The Confederates could hardly realize that they had participated in one of the most brilliant military exploits of the war. They had lost one man killed, John Graves, of Company A. When our column was on the road next morning, after a brief rest, it looked very like a Federal column, as thousands of new blue overcoats had been captured and were utilized on this clear frosty morning. Van Dorn reached Davis’ Mills, now Michigan City, early in the morning of the 21st of December. This place is about twenty miles north of Holly Springs and on Wolf River. The Federal force here was small, but well protected by a fort, rifle pits and a barricaded millhouse. The Confederates, on foot, assailed the position furiously as if they expected to take it by assault. The fire from the little garrison was so galling from across the river, quite an insignificant stream at that point, that they sheltered themselves for a time behind an earthen mill dam constructed along the bank. Here we had a slight loss in killed and wounded. The retreat to our horses was perilous and the enemy made the most of it. While lying in the ditch beside the milldam, a hat elevated above our protection was apt to receive two or three bullet holes. Lieutenant Statler of Company E had a Holly Springs hat ruined by a minie ball passing through the band and on through his hair. Poor fellow, when I found his dead body, the day after the battle of Harrisburg, July 14th, 1864, I noticed that the ball that killed him had passed through his hat band.

After the affair at Davis’ Mill we retired to the neighborhood of the Lane Farm, and rested for part of the night. Our horses had a bountiful feed and a short rest. What must be done must be done quickly. So we struck the usual trot. My little blooded stallion seemed to know just what was wanted. He would lie down like a tired dog when the column made a short halt, but was all life and animation when it was moving. Across Wolf river at Moscow in the early morning, we took the road to Somerville. It was said that we would repeat the Holly Springs business at Bolivar. The men of Company E knew every road and by-path leading to the town. Our hopes were high. We were willing to head a surprise party, or lead an assault. We should be fighting in the presence of our own people—the home folks. But we passed on to Danceyville, and that did not look like going to Bolivar. A short halt and a countermarch, and we were surely on the road to Bolivar.

We had traveled over much of Fayette and Hardeman counties, but bivouacked on Clear Creek on the night of December 23rd. We had been bountifully fed right here when on our way to Randolph the year before and had slept on this ground part of a night on the Armstrong raid. When I think of this place I think of chicken pie. The rank and file were confident that we would go into Bolivar, only a few miles distant, the next morning, and have a jolly Christmas right at home. That was not to be. Our scouts and spies reported that the Federals in great force were strongly fortified and were ready for us. They had evidently heard from Holly Springs. Van Dorn drew off to Middleburg, seven miles southwest of Bolivar where a small garrison was protected by a brick storehouse with a hall above, through the walls of which they had made many portholes. Here we needed some kind of artillery. The Federals stood bravely to their guns and refused to comply with our demand to surrender. It was a detachment of the Twelfth Michigan infantry, which the community thought to be about as devilish a lot as ever came south.

At Middleburg I saw the prettiest line of battle in action that I saw in the whole war. It was Ross’ Texas brigade advancing on foot with a firing line of skirmishers several rods in advance. As we stood to the rear in reserve, I could but take pride in this fine body of Texans, as Sul Ross, afterward governor of Texas, was my schoolmate. He was a noble young fellow at college, a gallant Indian fighter before the war, a successful general in the Confederate army, an incorruptible statesman after the war and, finally, the most popular man in Texas. I was glad to call him friend. I have passed Middleburg many times since then, but always think of Ross’ line of battle. “After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well.”

Van Dorn retired, without molestation from the Federals, while Grant hastened to break camp on the Tallahatchie and to fall back to Memphis. The object of the expedition had been pretty fully accomplished.

When Van Dorn reached Ripley on his way south, Dr. Bob Mayes and I concluded that we would take a short respite from camp life and make an expedition of our own into Alabama. While maturing our plans we fully realized that we had to take the chances of being reported absent without leave. We reasoned that it was mid-winter and that neither army would make an offensive move for some time. Then everybody was in good humor because of our late success, and besides we knew that we were not serving under martinets in the persons of our high officers—a rather common conclusion in those days. So at the first favorable opportunity we two moved by the left flank and took the road to Guntown. This was the same road along which Sturgis advanced and retreated when Brice’s Cross Roads became a famous place. We passed the cross roads and the now noted Dr. Agnew and Brice residences around which the battle was to be fought. We could not tell when we might come into contact with a Federal scouting party from Corinth or a squad of bushwhackers. In such an emergency, we were not to show our weakness to the enemy, but were to bluff them, if we could, and take to the woods in good order. We had seven shots apiece and plenty of ammunition. We questioned citizens in regard to the roads and the prospects of trouble. When we struck the wild country east of the Tombigbee, we were always on the alert and were cautious how we let any man approach us. The further we went the wilder the country appeared. Rough, rocky roads wound along the streams and down through the valleys, which lay between the lofty hills. Excellent places to be shot at.

Out through the village of Allsboro, we took the road to the old town of Frankfort with lighter hearts. We spoke gratefully of the kindness of the citizens along our route, who had treated us so hospitably, and concluded that we were never in as much danger as we had thought we were. We had not seen an armed man on the trip. At Tuscumbia, Mayes took the road to Courtland, I the one to Florence. I found the bridge over the Tennessee had been destroyed, and was compelled to take the risk of crossing on a rather dilapidated oar boat. But I felt at home on the dear old soil. Little Ernest, my first born, was soon to be in my arms and loving hands, including the old servants, were to leave nothing undone to make me feel happy. I was to stand again by the grave of a bride-mother, the beloved of all Florence, and too those of her father and two brothers over which the fresh earth still lay. My tired horse is really climbing the old hill; I see the old Dr. Todd place up to my left, the antiquated buildings of older Florence, the pillared seat of justice, built in the long ago. Why, I am right up in town. I turn into Military street. The old home is in sight. My heart! My heart! Bright eyes! Bright eyes! The loved ones with the baby.

But I look around and find the place greatly changed. I see more women than men. Two colleges closed and little or no business doing in the stores. No courts in session. Many residences closed. Small groups of anxious men stand on the corners, for Bragg is fighting at Murfreesboro and many of the Florence soldiers are there. Just such meager reports were coming in as would create the greatest suspense. The town had been in the hands of the Federals much of the time since the battle of Shiloh, and had been greatly harassed by raiders. Clothing and provisions, even the necessities of life, were hard to get. So the people talked mostly of the distress and gloom brought on by the war. Men and women, heretofore prosperous and happy, were bowed down with grief and, in many cases, in dire want. These good people were subject to insult and liable to lose the last crust at the hands of a rude soldiery. In fact, they did undergo, before the war was over, sufferings more intense and cruelties more severe. The state of affairs described bore hard upon all, but especially so upon the conservative element made up largely of old gentlemen, patriotic and true, who believed that a peaceable settlement could have been effected and war avoided. I was in sympathy, from the first, with that element in politics, who, while opposed to secession, yet when war was flagrant, gave up everything and, in many cases, took up arms in behalf of the South. I mention as typical of this class William B. Wood, Henry C. Jones and R. M. Patton.

Governor Patton, a gentleman of the old school, served his state well, and had two sons killed in battle. Judge Billy Wood was Colonel of the Sixteenth Alabama Infantry. I saw Stratton Jones, son of Judge Jones, dead on the field at Pulaski. As typical of those who thought differently on public questions, I mention the names of Richard W. Walker, Edward A. O’Neal and William H. Price, true as steel and patriots all. Walker was a famous lawyer and I heard it said then that he had much to do with the formation of the Confederate Constitution. O’Neal commanded a regiment in Lee’s army and after the war was governor. Major Price was killed in the same charge at Perryville in which his friend, Major Frank Gailor, the father of Bishop Gailor, fell. I record these things in a reminiscent mood, it is true, but they serve to illustrate what had taken place all over the South and, moreover, how people of radically diverse opinions on paramount questions can stand shoulder to shoulder when they come into the presence of a common danger. When the majority of the Southern people had spoken, Florence became a unit on the subject of resistance to Federal aggression. About all of her eligible men had gone into the army, and at the time of which I write she was mourning the death of many of her bravest and best. Lee had retired from Maryland and news came that Bragg was falling back, showing that Antietam and Murfreesboro were, at most, drawn battles. Coupled with Bragg’s retreat from Kentucky after the battle of Perryville they certainly emphasized the success of the Federals in preventing a Confederate invasion of the North. “Hope springs eternal in the human breast,” and there were some cheerful faces in Florence. Among these was that of Colonel Tol Chisholm, the provost marshal, who generously furnished me with a pass that was supposed to be good from Florence to Grenada. I thought at the time that this was a wide territory for the authority of a petty provost to cover, but it was good at nearby points, and might be available, or at least better than nothing, further down the country. So having secured a splendid new mount, I turned my face toward Mississippi. There could be no concert of action between my fellow soldier, Dr. Mayes, and myself as communication was poor between Florence and Courtland. We were compelled to act independently. So, armed with Tol Chisholm’s pass against the Confederates and a good carbine and a navy six against any hostile attack that might beset me on my way, I drew rein in three or four days at Cotton Gin on the Tombigbee. I could now move at my leisure and as my good steed stepped over the muddy roads as if he scorned them, I arrived all right in Grenada.