TUSCAN FOLK-LORE

AND

SKETCHES

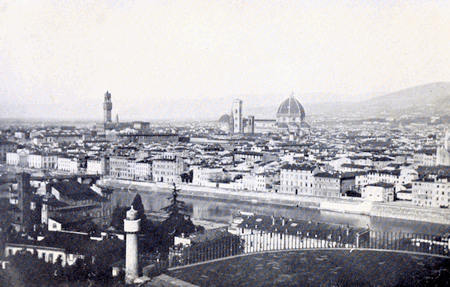

See p. 172

FLORENCE FROM THE PIAZZALE MICHEL ANGELO

“A Land of Cypresses and Olives”

TUSCAN FOLK-LORE

AND SKETCHES

TOGETHER WITH SOME

OTHER PAPERS

BY

ISABELLA M. ANDERTON

Edited, with a BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE, by her brothers

H. Orsmond Anderton and Basil Anderton

London

ARNOLD FAIRBAIRNS

20 Cheapside, E.C.

1905

THE CAMPFIELD PRESS

ST. ALBANS

CONTENTS

| PAGE |

TUSCAN FOLK-LORE—

| INTRODUCTION | 9 |

| A TUSCAN SNOW-WHITE AND THE DWARFS | 11 |

| MONTE ROCHETTINO | 17 |

| TERESINA, LUISA, AND THE BEAR | 25 |

| A TUSCAN BLUEBEARD | 30 |

| TASSA | 37 |

| PADRE ULIVO | 46 |

| THE SOUND AND SONG OF THE LOVELY SIBYL | 55 |

| THE SNAKE’S BOUDOIR | 65 |

| POMO AND THE GOBLIN HORSE | 67 |

TUSCAN SKETCHES—

| A TUSCAN COUNTRYSIDE AND THE FESTA AT IL MELO | 73 |

| A WEDDING IN THE PISTOIESE | 87 |

| OLIVE-OIL MAKING NEAR FLORENCE | 98 |

| A TUSCAN FARMHOUSE | 106 |

| THE FLORENTINE CALCIO: GAME OF KICK | 117 |

ELBA—

| A MONTH IN ELBA— | I. | 127 |

| ”——”——”——” | II. | 137 |

| THE FIRST STEP OF A MIGHTY FALL | 149 | |

FUGITIVE PIECES—

| A TALE FROM THE BORDERLAND | 167 |

| THE PHANTOM BRIDE | 172 |

| CYPRESSES AND OLIVES | 180 |

| LOVELORNNESS (AFTER THE MANNER OF THE EDDA) | 184 |

| KOIT AND ÄMARIK (AN ESTHONIAN FOLK-TALE) | 186 |

TWO TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ITALIAN OF ADA NEGRI—

| THE GREAT | 191 |

| THE WORKMAN | 193 |

THREE LITERARY STUDIES—

| GIOSUÉ CARDUCCI | 199 |

| GIOVANNI PASCOLI | 230 |

| LANG’S “MAKING OF RELIGION”—(ITALIAN) | 257 |

APPENDIX—

| BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE | 267 |

TUSCAN FOLK-LORE

THE following stories were told to me by various peasants during a summer stay amid the Tuscan Apennines above Pistoia. I had gone there with a companion in search of quiet for the summer holidays. But I fell ill, and, there being no nurses and no doctors, was tended by an old peasant woman, who, living alone (for her sons had married and left her), was only too glad to spend the warmth of her heart in “keeping me company” and tending me to the best of her ability. Long were the hours which she spent by my bedside, or by my hammock in the woods, knitting and telling me stories. She would take no payment for her time, for was she not born a twin-sister? and everyone knows that a twin-sister, left alone, must needs attach herself to someone else in the emptiness of her heart. So old Clementina attached herself to me as long as I stopped in that village; and when I left it she would write me, by means of the scrivano, long[10] letters full of village news, and expressions of affection in the sweet poetical Tuscan tongue.

Indelibly is the remembrance of the kind hospitality of those peasants impressed on my mind. For Clementina, although my dearest, was by no means my only friend. I had to leave her as soon as I could be moved, for a village which boasted at any rate a chemist’s and a butcher’s; and there, in the two months of my stay, wandering about among the little farms, either alone, or in the company of a woman whose husband had sent her back for the summer to her native place, I had continual opportunities of chatting with the people and enjoying their disinterested hospitality. Such records as I have preserved I give to the public, thinking that others, too, might like to penetrate into that quiet country world, see the workings of the peasant mind in one or two of their stories, and note the curiously altered versions of childhood acquaintances or of old legends which have found their way into those remote regions: note, too, the lack of imagination, and the shrewdness visible in the tales which are indigenous. As regards style, I have endeavoured to preserve as closely as possible the old woman’s diction.

A TUSCAN SNOW-WHITE AND THE DWARFS

IT was old Clementina—a white-haired, delicate-featured peasant woman, with a brightly-coloured handkerchief tied cornerwise on her head, a big ball of coarse white wool stuck on a little stick in the right-hand side of the band of her big apron, and the sock she was knitting carried in the other hand. My companion had gone down to Pistoia to do some shopping: I was alone in our rooms in the straggling primitive little village that clings to the hill among the chestnut woods above. Clementina thought I must be very lonely; besides, she was anxious to know what sort of things these extraordinary “forestieri”—foreigners—did all by themselves. They wrote, she believed—well, but how did they look when they were writing, and what sort of tools did they use? So she suddenly appeared in the doorway with a bright smile, and:—“Buon giorno a Lei.” It was just lunch time, so I pushed aside my work, glad enough, as it happened, to see her; begged her to sit down and[12] tell me while I ate, one of those nice stories which she, as great-grandmother, must know so well.

My lunch was the “necci” of the country people—a cake of sweet chestnut-flour cooked in leaves of the same tree and eaten with cheese—mountain strawberries, brown bread and country wine. Through the open window of the whitewashed room came the noises of the village street, the fresh mountain breeze and the bright sunlight which lighted up the old woman’s well-cut features and kindling brown eyes, as, seating herself with the grace of any lady, she leaned forward and began:—

Once upon a time there lived a king who had one little girl called Elisa. She was a dear little girl, and her father and mother loved her very much. But presently her mother died, and the step-mother got quite angry with jealousy of the poor little thing. She thought and she thought what she could do to her, and at last she called a witch and said:—

“Get rid of Elisa for me.”

The witch spirited her away into some meadows a long, long way off, in quite another country, and left her there all alone; so that poor little Elisa was very frightened. Presently there came by three fairies who loved her because she was so pretty, and asked her who she was. She said she was a king’s daughter, but she did not know where her home was or[13] how she had come to be where she was now, and that she was very unhappy.

“Come with us,” said the fairies, “and we will take care of you.”

So they led her into another field where was a big hole. They took her down into the hole, and there was the most beautiful palace that Elisa had ever seen in her life.

“This palace is yours,” said the fairies, “live here, and do just as you like.”

Well, time went by and Elisa forgot her home, and was very happy, when one night her step-mother had a dream. She dreamt that Elisa was not dead, but alive and happy. She called the witch again, and said:—

“Elisa is not dead, she is alive and well. Take some schiacciata (a kind of cake), put poison in it, and take it to her. She is very fond of schiacciata, and will be sure to eat it.”

So the witch went to the hole and called “Elisa.”

“What do you want?” said Elisa.

“Here’s some schiacciata for you.”

“I don’t want schiacciata,” said Elisa; “I have plenty.”

“Well, I’ll put it here, and you can take it if you like”: so she put it down and went away.

Presently there came by a dog, who ate the schiacciata and immediately fell down dead. In the evening the fairies came home, took up the dog and showed him to Elisa.

“See you never take anything that anyone brings you,” said they, “or this will happen to you, too.”

Then they put the dog into their garden.

After a time the queen dreamt again that Elisa was alive and happy, so she called the witch and said:—

“Elisa is very fond of flowers; pick a bunch and cast a spell upon them, so that whoever smells them shall be bewitched.”

The witch did as she was told, and took the flowers to the hole.

“Elisa,” she called down.

“What is it?” said Elisa.

“Here are some flowers for you.”

“Well, you can put them down and go away. I don’t want them.”

So the witch put them down and went home. Soon some sheep and a shepherd came by; the sheep saw the flowers, smelt them and became spell-bound; the shepherd went to drive off the sheep, and became spell-bound too. When the fairies came home that night, they found the sheep and the shepherd, showed them to Elisa as a warning, and put them too into their garden.

But the queen dreamt a third time, and a third time she called the witch, saying:—

“Elisa is well and happy. Take a pair of golden slippers this time, pianelle (slippers with a covering for the toe only), bewitch them, and[15] take them to Elisa: those she will certainly put on.”

And the queen was right. When the witch had gone away from the hole Elisa came up to look at the pretty golden pianelle. First she took them in her hands, and then she put one on, and afterwards the other. As soon as she had done it she was quite spell-bound, and could not move. When the fairies came home they were very sad. They took her up and put her into the garden, with the dog, the sheep, and the shepherd, because they did not know what else to do with her.

There she stayed a long time, till one day the king’s son rode by as he went out hunting. He looked through the garden gate, and saw Elisa.

“Oh, look,” said he to the hunters, “look at that lovely girl who does not move; I never saw anyone so beautiful. I must have her.”

So he went into the garden, took Elisa, carried her home, and put her into a glass case in his room. Now he spent all the time in his room; he would never come out, and would not even let the servants in to make his bed, for he loved Elisa more and more every day, and could not bear to leave her, or to let anyone else see her.

“What can be in there?” said the servants; “we can’t keep his room clean if we’re not allowed to go into it.”

So they watched their opportunity, and one[16] day when the prince had gone to take the holy water, they made their way in to dust.

“Oh! oh!” said they, “the prince was quite wise to keep his room shut up. What a beautiful woman, and what lovely slippers!”

With that one went up, and said, “This slipper’s a little dusty; I’ll dust it.”

While he was doing so, it moved; so he pushed it a little more, and it came off altogether. Then he took off the other too, and immediately Elisa came back to life. When the prince came home he wanted to marry her at once; but his father said:—

“How do you know who she is? She may be a beggar’s daughter.”

“Oh, no,” said Elisa, “I’m a princess,” and she told them her father’s name.

Then a grand wedding feast was prepared, to which her father and step-mother were invited; and they came, not knowing who the bride was to be. When they saw Elisa, the father was very glad, but the step-mother was so angry that she went and hanged herself. Nevertheless the marriage feast went off merrily. Elisa and the prince were very happy, and presently united the two kingdoms under their single rule. If they’re not alive now, they must be dead; and if they’re not dead, they must still be alive.

MONTE ROCHETTINO

We were in the chestnut woods; I swinging lazily in my hammock, Clementina with her knitting, sitting on the grass beside me, a pretty clear pool reflecting the trees at our feet.

“Do you know the story of Monte Rochettino?” asked Clementina, taking a piece of dry bread to keep her mouth moist.

“No,” said I.

So she settled herself comfortably and began the following curious tale, in which ever and anon one seems to recognise a likeness to the old Greek legend of Cupid and Psyche; but a likeness all distorted in transmission through ignorant, unimaginative minds:—

Once upon a time there was a widow with three daughters. (“Women always have three daughters in fairy tales,” she added, by way of parenthesis.) This widow was very poor, so that when a famine came over the country she and her children were almost dying with hunger, and had to go out into the fields and get grass to eat. Once as they were looking[18] for food they found a beautiful golden cabbage. The eldest girl took a zappa (a sort of pickaxe with only one arm to it) and tried to root up the cabbage. This she could not succeed in doing, but she broke off a leaf which she took to the market, and sold for a hundred gold scudi.

The next day the second daughter went, worked all day at the cabbage, and broke off two leaves. Away she went with them to the market, and got two hundred gold scudi.

The third morning the youngest daughter took the zappa, and went into the field. At the very first stroke the whole cabbage came up, and a little man jumped out of the earth; a very tiny little man he was, but beautifully dressed. He took the maiden by the hand, and led her down a flight of stairs underground. There she found herself in a beautiful palace, such as she had never dreamt of, all golden and shining. The little man gave her a bunch of keys, and said:—

“This palace is yours, you may do what you like, and go where you like in it. You are the mistress of it. The master of it, your husband, you will not see, he will only come to you at night. Be happy, and make no effort to look at him, or you will lose everything. If you want anything in the daytime call Monte Rochettino.”

With that the little man vanished. The maiden wandered all over the new dwelling, and[19] when it was dark she laid herself down and waited for her husband, the master of the palace. So time went on. She loved her husband, although she had never seen him, and felt that she would be very happy if only she could know something about her mother and sisters.

At last she could bear the suspense no longer, and one morning she called “Monte Rochettino!”

In an instant the little man stood before her.

“Oh, Monte Rochettino,” said she, “let me go home and see my mother and sisters. Poor things, they must be so sad at losing me; they’ll think I am dead.”

“You’ll betray me,” said Monte Rochettino.

“No, no, I won’t: I promise you: only let me just go and see them.”

“Well, go, but be sure you don’t betray me, and be back in three days.”

So the girl went home, and her mother and sisters did all they could to prove their joy at seeing her, poor things. Then they asked her where she lived, and she told them she lived with her husband in a beautiful palace underground; but that her husband came to her at night, and she had never seen him. Then her mother said to her:—

“I will give you these matches and this candle. When he is asleep, light the candle, and see what he has round his neck.”

So the girl took the matches and the candle and went back to the palace.

“Well, have you betrayed me?” said Monte Rochettino.

“No,” said she.

“The better for you,” answered the little man.

That night while her husband was asleep, the girl got up softly, lighted the candle, and saw a box round her husband’s neck. The key was in the lock, she turned it, and went in.[1] She found herself in a room where was a woman weaving.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I am weaving swaddling clothes for the king’s son, who is about to be born.”

Then she went into another room and found a woman sewing.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I am making robes for the king’s son, who is about to be born.”

In the next room she found a shoemaker.

“What are you doing?” she asked again.

“Making shoes for the king’s son, who is about to be born.”

Then she went back, locked the box again, and held the candle low down to look at her husband. As she did so a drop of wax fell on his neck, and he woke.

“You have betrayed me,” said he, “and must lose me.”

In an instant she found herself standing above-ground, her zappa over her shoulder, and clad only in her nightdress, poor thing. She went a little way, and found the king’s washerwomen at work. They gave her some clothes and said:—

“You see that hill yonder? Walk all day till you come to it, and there you will find a shepherd, who will take you in for to-night.” (But really, they had been sent by her husband, and so had the shepherd.)

The poor girl walked all day, and in the evening came to the shepherd. He received her kindly, gave her supper and a bed, and in the morning made her some coffee and gave her breakfast. Then he said:—

“You see that other hill, over there? Walk all day till you come to it, there you will find my brother” (but really it was himself) “who will be kind to you. And now take this chestnut, but be sure you don’t open it unless you are in great need.”

So the poor thing walked all day until she reached the second hill and found the second shepherd. He gave her supper, a bed, and coffee in the morning, and then said:—

“Go on to the next hill, where you will find a third shepherd, my brother; ask him to take you in. Now take this nut, but be sure[22] you don’t crack it unless you are in great need.”

That evening she reached the third shepherd, who treated her as the others had done. In the morning he said to her:—

“You must pass this first hill, and then you will find another; go up that, and you will come to a palace. In the palace lives a queen, who lost her little son, and who now receives poor women, and has them taken care of for forty days; she will be kind to you.” Then he gave her a walnut, saying:—“Mind you don’t crack it, unless you are in great need.”

So the poor creature walked and walked and walked, and in the evening reached the palace.

The queen received her kindly, and had her taken care of for forty days. Then she sent a servant, who said:—

“The queen says you must be off, she can’t keep you any longer.”

“Oh dear, oh dear,” said the poor woman, “whatever shall I do? I have nowhere to go. I’ll crack the chestnut.”

She did so, and out jumped a lovely little golden dog, which capered about and caressed her and fawned on her. She sent it as a present to the queen, who said:—

“Why, this woman is richer than I am; let her stay forty days more.”

So the poor thing remained forty days[23] longer, and then the servant came again to send her away. This time she cracked the nut, and out came two beautiful golden capons. These, too, she sent to the queen, who said:—

“This is certainly a wonderful woman, let her stay another forty days.”

At the end of the forty days the queen sent the servant again, saying:—

“You’ll eat up all my kingdom. Be off with you.”

Then the woman cracked the walnut, and found a beautiful golden wool-winder, which she sent to the queen.

“I never had such things,” said the queen, “this woman is richer than I am. Let her stop as long as she likes.”

Then the poor woman was glad indeed, and stayed there quietly until she gave birth to a little daughter. The servant took the baby into the kitchen to put on the swaddling-bands; while she was doing so a beautiful white dove alighted on the window-sill, and said:—

“If the cocks no longer sang,

If the bells no longer rang,

If you knew this, oh mother mine,

Lovely you’d be, oh daughter mine.”

Then the servant went to the queen and told her what had happened.

“To-morrow I’ll come myself,” said she, “and see the dove, and hear what it says.”

As soon as she had heard it, she had all the[24] cocks in the town killed, and all the bells tied up: and the next morning she carried the babe into the kitchen herself. No sooner had she sat down than the dove alighted on her shoulder. She unswaddled the baby, and the little thing stretched out its tiny arms in joy at feeling itself free. As it did so, it touched the dove, who was instantly changed into a handsome young man. The queen knew him for her son, the poor woman for her husband, and there was great feasting and joy in all the palace. If they’re not alive, they must be dead: if they’re not dead, they’re still living.

TERESINA, LUISA, AND THE BEAR

Clementina had been doing her shopping in the village and now the two children and I were walking home with her. It was near the time of sunset, and the Apennines, blue-purple as the sun gradually dropped behind them, unrolled themselves before us, chain behind chain, as we advanced along the road with the valley on the left and the chestnut-covered hill on the right.

“A story, nonna mia,” begged I, and “A story,” echoed the children: “tell us the story about Teresina.” So Clementina began:—

Once there was a woman who had two daughters: at least, one was a daughter, and the other a step-daughter. Now the daughter, named Luisa, was ugly and wicked: but the step-daughter, Teresina, was so good and beautiful that everybody loved her. This made Luisa very jealous, and she began to think what she might do to get rid of Teresina. One evening she said to her mother:—

“Mother, send Teresina into the woodhouse[26] to-night, so that the bear may come and eat her while she’s alone in the forest.”

So the mother gave Teresina a piece of dry bread and said to her:—

“Take your distaff and go and spin wool in the woodhouse to-night.”

“Very well,” said Teresina, and went out into the forest; and the dog and the cat went with her.

When she got into the woodhouse she shut the door, pulled out her piece of bread, and began to eat her supper.

“Miaou, miaou,” said pussy, and patted her arm.

“Ah, poor little pussy, are you hungry too? Here’s a piece of bread for you.”

“Bow-wow,” said the dog, and put his front paws on her knee.

“Yes, little one, here’s a piece for you too, you must be hungry, I’m sure.”

When she had finished her bread she began to spin, but she had not been at work long when she heard a knock at the door.

“Who’s there?”

“The bear,” was the answer.

“Oh dear, what shall I do?” said Teresina.

“Tell him you’ll let him in when he brings you a dress like the sun,” said the dog.

So Teresina did as she was advised; and the bear went in a very short time to Paris, and came back with a dress as beautiful as the sun.

“Tell him he must bring one like the moon,” said the cat.

The bear brought that too.

“Now ask for one like the sky with the stars in it,” said the dog: and the bear soon came back with that as well.

“What shall I do now?” asked Teresina.

“You must ask for a nice silk handkerchief for your head.”

So the bear brought the most beautiful that ever was seen.

“What can I say next?” said Teresina, “I shall have to let him in.”

“No, no, ask for a fan.”

The bear brought a fan such as Teresina had never imagined.

“One thing more,” said the dog; “ask for a chest of linen.”

Again Teresina followed the animal’s advice, and almost immediately the bear appeared at the door with the chest of linen. But just as he arrived the sun rose, and he was obliged to go away. Then Teresina put the chest on her head, took up her dresses, her handkerchief and her fan, and went away home with the cat and the dog.

When she appeared among the trees before the house, Luisa was first of all very much disappointed, for she thought that the bear had certainly eaten her sister; but when Teresina showed all her beautiful things, then Luisa fairly cried with spite.

“Give them to me, Teresina,” she said; “you must and shall give them to me!”

“No, no,” said Teresina, “they’re mine and I shall keep them.”

“Then, mother,” exclaimed Luisa, “let me go to the woodhouse to-night. I will go to the woodhouse to-night and see the bear. I will, I will!”

So the mother gave her a nice slice of polenta with plenty of cheese, and in the evening Luisa went off, followed by the cat and dog.

“Miaou, miaou,” said the cat, when Luisa began to eat.

“Bow-wow,” said the dog.

“Get away, ugly beasts,” said Luisa, and kicked at them with her heavy nailed boots. Then came a knock at the door.

“What shall I do?” asked Luisa.

“Open,” said the cat and the dog, “it’s the bear with the dresses.”

So Luisa opened the door, and the bear came and ate her all up.

But Teresina put on her beautiful dresses when she went out walking: and one day the king’s son saw her, and loved her because she looked so good and beautiful. So Teresina married the prince, and afterwards became queen of the land.

“Are there any bears about the mountains now, nonna?” I asked, when the story was finished.

“No, there are none now. I saw one once, though. A man was leading it about with a chain.”

“I saw one once, too,” said little Elisa. “It was at a fair at that village over there,” pointing to a cluster of houses on the hillside.

“And what was it like?” I asked.

“It was covered with hair, had two legs, the head of a horse and the feet of a Christian.”

And the child really believed she was describing what she had seen.

A TUSCAN BLUEBEARD

Soon after this we reached Clementina’s house. The old woman gave the beef-steak and the medicine to her neighbour (whose husband, just returned from Maremma, was down with fever), took up a large wicker-covered flask, and called us to go with her to the “fonte fresca” to get water. So we moved off through the chestnut woods, and soon found the spring, half-hidden by the ferns and long grass. It fully deserved its name and reputation; the water was so cold and sparkling as to be almost exhilarating, and I felt a sudden new sympathy with the feeling which prompted the Greeks to such efforts to obtain the water of well-known springs.

When we had emerged from the wood on our way back, Clementina put down her flask and seated herself on a bank with her back to the sunset. We threw ourselves on the grass at her feet, and the old woman, beginning again, told us the following version of our old friend Bluebeard:—

Once upon a time there was a woman who[31] had three daughters. One day a sexton knocked at her door and said:—

“Good wife, give me a piece of bread.”

The woman said to the eldest daughter:—

“Take the poor man a piece of bread: he looks very wretched.”

But when the girl got outside the door with the bread, the sexton said:—

“It’s you I want,” and he caught her up and carried her away.

After a while they reached a field where there was a hole in the ground. In the hole the girl saw steps, and when they got to the bottom of these, she found herself in the most beautiful palace she had ever seen.

“Now,” said the man, “this palace shall belong to you. I shall be away all day, but shall come back every evening; so you need not be lonely. While I am away you may amuse yourself as you like. Here are the keys; you can explore the whole palace except the room which this key opens; there you are never to go.”

“Very well,” said the girl, “I won’t.”

“Take this ring,” continued the man, putting one on her finger. “So long as the gold remains bright, I shall know you have been obedient. When it is cloudy, I shall know you have opened the door.”

For some days the girl was quite happy exploring the wonders of this underground palace; but little by little she began to want[32] to see what was in the room which was forbidden her; and at last the desire to open that door quite overcame her dread of punishment. She put in the key, turned it, pushed open the door, and went in.

She found herself in a marble courtyard opening on to a beautiful garden. In the middle of the courtyard was a pond, in which was swimming a lovely gold-red fish.

“Oh, I must catch you,” said the girl, and plunged her hand into the water. But the fish bit her so sharply that she withdrew her hand immediately, and then she saw that the ring was covered with blood. She rubbed and rubbed, but the blood would not come off; the ring was stained and cloudy, and sadly she went out, locking the door behind her.

When the man came home that night he found her sad and dejected.

“Ah,” said he, “you have disobeyed me. Let me see the ring.”

She tried to hide her hand, but it was no good. He looked at the ring, and then cut off her head, and put head and body against one of the columns in the marble courtyard.

After that he went back to the girl’s home, and again asked for bread.

“Go,” said the mother to the second daughter, “carry the poor man something to eat.”

But when the second daughter came to him he treated her as he had done the first. He[33] carried her off to the underground palace, gave her the keys, and a ring, and told her, too, that she might do anything she liked, except open that door.

It happened to the second as it had done to the first. She got tired of wandering about the palace with nothing to do, opened the door, and went into the marble courtyard. She, too, tried to catch the fish; she, too, was bitten; her ring became cloudy, and she was beheaded and put beside her sister.

Then the man returned, and carried away the youngest girl. Now the youngest is always cleverer than her elder sisters; and so it happened in this case. After she had spent some time in the palace, she, too, determined to open the forbidden door. So she took off her ring, put it in her work-basket, and went in. She tried to catch the fish, as her sisters had done, and then began to wander about. She soon saw her sisters’ heads and bodies, and that made her sad. When it was near evening she left the courtyard, put on her ring, and went to meet her husband as brightly and cheerfully as ever.

“Ah,” said the man, “I can see that you have not disobeyed me. You’re a dear, good little wife.”

Every day, as soon as her husband was gone, the girl took her work into the garden and sat there, knitting or playing with the fish, but she was unhappy because of her sisters.

One morning as she was at work she saw[34] a little lizard without a tail; the tail was lying on the ground beside it. She watched the creature and saw it bite a leaf off a certain plant, turn its head over its back, and touch its body and its tail with the leaf. Instantly tail and body grew together, and the lizard ran off quite merrily.

“Aha,” thought the girl, “now I know what to do!” So she picked the plant, went into the courtyard, put her sisters’ heads on to their respective bodies, touched the necks with the plants, and there were her sisters quite well again. Then she took them upstairs and hid them.

That evening she said to her husband, “I am afraid my mother must be very unhappy. She is old and poor, and now there is no one to work for her or take care of her. Let me go and see her.”

“No,” said the man; “I can’t spare you.”

“Well, then, let me fill a chest with clothes and money, and you shall carry it to her.”

“Very well,” said the man; “have it ready by to-morrow morning.”

So the girl put linen and gold into a chest. Then she made her eldest sister get in, and shut down the lid.

“Now,” she said to her husband, “you must not set down the chest at all: remember, I can see you all the way. Go straight there and back again, for I want you at home.”

The man put the chest on his head and set[35] off. After a time he began to want to put down his burden for a little, and said to himself:—

“My wife can’t possibly see me; there’s this hill between me and her”: and he began to set down the chest.

“Do you think I can’t see you?” a voice said. “Silly man, I can see you everywhere.”

“Oh dear, oh dear,” said the man to himself, “what a clever wife mine is! She can see me even through a hill. And how fond of me she is! She knows what I am doing wherever I am.” So he staggered on to his mother-in-law’s, threw down the box, and went home again.

A little while after the second sister was sent home in the same way, and now the girl began to think how she could get away herself. One evening she said to her husband:—

“I want you to take some more things to my mother. I shall get everything ready to-night. Don’t wake me in the morning before you go, as I shall come to bed very late. I have to make the bread.”

The man went off to bed, and the girl set to work. She made a great doll of dough and put it in her bed; then she put clothes and money into the chest, crept in herself, and pulled down the lid.

The next morning the man got up early. “Wife, wife,” he shouted, “good-bye!”

No answer. “Ah, I forgot, she was up[36] late making bread. She’s a dear little wife, and works very hard.”

So he crept on tiptoe to her bedside, saw the figure under the clothes, and went out as quietly as he had gone in.

Then he took the chest and started. Again he wanted to set down his burden, again the warning voice stopped him, and at last he flung down the box at his mother-in-law’s door, declaring that this was the last he would bring her.

When he got home he called, “Wife! wife!”

Still no answer. “What, is she still asleep? She must be tired”; and he went to shake her. Then he found that there was no wife there, but only a figure of dough, and that he was alone once more in his underground palace.

TASSA

Clementina had enticed me to her cottage with the promise of country beans cooked in country fashion, to be followed by a story under the chestnut woods. So at about four in the afternoon, when the heat of the day was over in the breezy mountain village, I sauntered through the street, past the swarming black-eyed children, and the cheerful, smiling washerwomen busy at the tank under the pump, out on the white road beyond; and, gazing now at the landscape on the left, now at the ever-varying forms of the Apennines before me—

“Ever some new head or breast of them,

Thrusts into view,”

says Browning—now climbing the bank on the right for flowers or mountain-strawberries, I arrived, after half an hour’s stroll, at the little hamlet of Ciecafumo.

There stood the cluster of smoke-blackened cottages, with the large patch of rye, beans, etc. (apparently common property), before them, against a background of magnificent[38] chestnut trees. Passing under a picturesque archway, and crossing a cobbled space which did duty as a street, I pushed open the wooden door of Clementina’s house. Before me was a flight of stairs which might have been washed towards the end of the last century: on the right the kitchen; and, dim in the blue, arching wood-smoke, Clementina, with eyes as bright as ever under her kerchief; and sprightly little Nella, barefooted, and, still more extraordinary, bareheaded.

It was a large, low room, with stone walls and a gaping plank ceiling, which formed also the floor of the room above, all encrusted with the black lichen-like deposit, harder than the stone itself, produced by the smoke of wood-fires. In one corner was a tiny window, and on the same side with it the hearth, with a wooden roof over it in lieu of chimney. The wood-fire, the cat, the red pipkin with the old woman bending over it, formed a pretty interior against the dark shadows of the great stack of brushwood which, with a flight of very rickety stairs, occupied the further end of the room.

“Where do the stairs lead, Nonna?” I asked.

“Oh, those lead into the cat’s rooms. You can go up if you like, but I advise you not to. It’s years since I have been there, and I expect they’re rather dirty.”

It need hardly be said that I did not go up.[39] The beans being now ready, a space was cleared on one of the two tables, which, loaded with most heterogeneous material, were propped up against the wall opposite the fire. Above the tables was the one patch of colour on the black walls—a coloured print or so of saints, a couple of rosaries, and a tiny hanging tin lamp. The old woman spread a coarse, newly-washed table-napkin on the space she had cleared, and placed on it a hunch of bread (brought that morning from the village), one glass, a little bottle of oil, and some salt in a piece of paper. The wicker-covered water-flask was put on the ground beside us; three chairs were produced, and three soup-plates, with brass spoons. Then the beans were divided and dressed with oil and salt, the bread was carved into three parts with a great clasp-knife from the old woman’s pocket, and we made a very excellent and nourishing meal. The one glass did duty for all three of us, being rinsed out with a peculiar jerk on to the stone floor after each had drunk.

“Now the story, Nonna,” said I.

So Clementina took up her knitting, and, locking the door behind us, we went out into the fresh, sweet evening air. We sat down under a huge chestnut tree. A number of little girls came clustering around us, busily engaged in making chestnut-leaf pockets for their wild strawberries and whortle-berries, and the old woman began:—

Once upon a time there was a poor woman who had one daughter. One day, as this daughter was out in the forest getting firewood she struck her axe into a hollow tree. As soon as she had done so, a beautiful lady appeared and said to her:—

“Will you come with me, little girl? I will take care of you, and give you everything you want.”

So the little girl said yes, she would go, and the lady, who was really a fairy, took her to a beautiful palace.

“Now,” said this fairy, “when you’re alone, and want me, you must call me Tassa, but when anyone else is with you, you must call me Aunt. You won’t always see me, but as soon as you call me I shall come to you. You may do what you like and go where you like in this palace.”

So the girl lived for some time in the palace in the forest, and grew more and more beautiful every day. At last it happened that the king’s son, out hunting in that forest, came to the palace and saw the girl at the window. He rode round trying to find a door, but there was none.

“Let me come in and talk to you,” he said to the girl. So she went into the next room, and called out “Tassa.”

“What do you want, pretty maiden?”

“The king’s son asks to come and talk to me.”

“Let him come.”

And immediately the prince saw a door and went in. After a little while he said:—

“I should like to marry you; you are the most beautiful woman I have seen.”

So the girl went into the next room and called “Tassa.”

“What is it, pretty maiden?”

“The prince wants to marry me.”

“Let him come in a week with all his court and fetch you.”

Then the prince went away, and the fairy gave the girl a box, saying:—

“If you want to remain beautiful, take this box with you; and don’t forget to say good-bye to me before you go.”

At the end of the week the prince came with a great train of carriages and courtiers to fetch his bride, and the girl was so dazzled by the splendour, and excited at the thought of marrying the prince, that she forgot to say good-bye to the fairy, and forgot her box till she was in the carriage. Then she suddenly remembered it, jumped out, and ran upstairs to the cupboard where she had put it. Now this was a cupboard in the wall, and the door pushed up as a shutter might do. The girl raised the door and put her head in to look for the box, when bang! down came the shutter on her neck.

“Tassa, Tassa,” she shouted.

“What do you want, ugly wench?”

“I forgot to say good-bye to you. And oh, please let me out.”

Then the cupboard door was raised, and the girl went downstairs. But when she appeared everyone began to laugh, for she had a sheep’s head!

The prince made her get into the carriage, and then pulled down all the blinds, so that no one might see his ugly bride; and when he got home he had her put into the sheep stable.

Now there were three beautiful women at the king’s palace who all wanted to marry the prince, and the prince did not know which to choose. So he brought some wool and said:—

“The one who spins this best shall be my wife”; and he gave some wool to the girl with the sheep’s head as well.

The three women set to work immediately and span and span with all their might; but the poor girl in the stable threw hers into the gutter and sat down to cry, while the others came and mocked her. At last it was the eve of the day on which they were to go before the prince, and the girl sobbed and sobbed, and began to call out “Tassa, Tassa!”

“What do you want, ugly wench?”

“I’ve thrown my wool away, and I don’t know what to do.”

“Take this filbert, and when you come before the prince crack it. But you don’t deserve to be helped.”

The next day the whole court was assembled and the three women gave their skeins of wool, and then the prince turned to the girl and said:—

“What have you done?”

“Baa, baa,” said she, and cracked the filbert. There was a skein of the finest wool that could be imagined, and all said that the sheep had done best.

Then the prince gave each one a puppy, and said:—

“The one whose puppy grows into the most beautiful dog shall be my bride.”

So the three women took their puppies, and brushed them and combed them and washed them and fed them, till they were so fat they could hardly move; but the poor girl let hers run away.

The women came and mocked her as before, but all she could say was “Baa, baa!”

Again it was the eve of the day when they were to appear before the prince, and again the girl sat sobbing in her stable and calling “Tassa, Tassa!”

“What do you want, ugly wench?”

“My dog has run away, and to-morrow we go before the king.”

“Take this walnut, and crack it as you did the filbert. But you don’t deserve to be helped.”

The next day the whole court was assembled again. The three women presented their dogs,[44] which waddled about and behaved very dirtily and badly.

“And what have you done?” said the prince to the girl.

“Baa, baa,” said she, and cracked the walnut. Out jumped the most lovely tiny dog, with a golden collar and golden tinkling bells; he fawned upon the king and the prince, and quite won their hearts by his pretty manners.

“One more trial,” said the prince. “All appear before me again in a week’s time, and I will marry the most beautiful.”

All that week the three women washed themselves, and scented themselves, and rubbed themselves till they rubbed the skin off, and pomaded their hair till it shone like a looking-glass; but the girl sat among the sheep and wept.

On the last day of the week the women began to put on their fine dresses and ornaments; and the unhappy girl sobbed more bitterly than ever, and called out, “Tassa, Tassa!”

“What do you want, pretty maiden?”

“To-morrow we go before the prince. What shall I do?”

“Go with the others: and if he marries you don’t forget to say good-bye to me.”

The next morning the three women with their grand dresses, and their pomade, and their scent, strutted boldly in before the court and the prince.

“Go to the stable and bring the fourth,”[45] commanded the prince: and one of the courtiers went down.

Soon the door opened and the room was filled with a blaze of light, as the beautiful maiden, sheep no longer, entered and knelt humbly before the king.

“That is my bride,” said the prince, as he raised her and kissed her: “You others may go.”

So a grand wedding-feast was prepared, and this time the girl did not forget to say good-bye to the fairy who had been so kind to her.

PADRE ULIVO

“Strange, lingering echoes of the old demon-worship might perhaps be even now caught by the diligent listener among the grey-haired peasantry,” says George Eliot, speaking of the Midland Counties of England. Stranger yet, perhaps, is the survival of the old pagan spirit, the haunting echo of old pagan legend, which any visitor to the hills of Tuscany may verify. Let him join the peasants as they meet now in one house, now in another, to spend the long winter evenings round the fire; or let him stroll, in the early autumn, into some low, dark kitchen where neighbours sit among piles of chestnut twigs, busily stripping off the leaves and making them into bundles for winter use in the baking of chestnut cakes (necci). There, among stornelli and rispetti, he may well chance upon some such shrewd, quaint tale as the following:—

Once upon a time there was a man called Padre Ulivo. He was always cheerful, always singing, and very fond of good company. He had a barrel of wine in the cellar, and every[47] evening his friends used to come and see him, sit round the fire, eat, drink, sing, and lead a merry life. But at last the barrel was empty, and all his provisions run out, so that he had nothing more to offer to those who came, and all his pleasant evenings were at an end. Now everyone avoided him, and his cottage grew dull and lonely. One night he had just enough flour left for one small cake.

“Well,” said he, “I’ll make a little schiacciata this evening, bake it in the ashes, and to-morrow I must take what God sends.”

So he made the schiacciata, ate half of it, and got into bed. He had not been there long before he heard a knock at the door.

“Who’s there?” he called out.

“Padre Ulivo,” said a voice from outside, “we want to come in and warm ourselves at your fire; open the door to us.”

So Padre Ulivo jumped out of bed, opened the door, and there were twelve men outside.

“Wait a minute while I put on my trousers,” said he, for he was in his shirt.

“Now, Padre Ulivo,” said one of the men, “we want something to eat.”

“Something to eat! How can I give you that when I have nothing in the house! I made a little schiacciata of my last flour this evening. Look, here’s the bit I’ve not eaten.”

“No, no; you must give us something to eat—we’re hungry.”

“But, indeed, I don’t do it to deceive you. I have nothing; absolutely nothing.”

“Go and look again in the cupboard.”

“But what’s the good? It’s empty. Do you believe that I want to deceive you?”

“Go and look, at all events.”

So Padre Ulivo opened the cupboard, and found it quite full of meat and bread, and everything nice. Quite full! and of such good things as he had never hoped to have.

“Oh!” said he, “don’t think I was deceiving you; there really was nothing there last time I went to it.”

So he laid the table and they began to eat.

“But we want wine,” said the man; “go to the cellar and get some.”

“I have none,” said Padre Ulivo; “I used up all mine some time ago.”

“Go and see.”

“But it’s no good; my barrel is quite empty. Indeed it is not because I am greedy. I have none left.”

“Go and see. We’ll come too.”

So they all went down to the cellar.

“You see,” said Padre Ulivo, tapping the barrel. “Listen how hollow it sounds!”

“Draw out the spigot.”

He did so, and immediately there spurted out such a stream of wine as knocked him right against the opposite wall.

“Oh, oh!” said he. “I swear it was empty last time I came here.”

Then he filled a big jug, and they all went upstairs and made a good supper.

“Now we want to sleep here,” said the men.

“But I have only one bed,” answered Padre Ulivo; “and there are thirteen of us! I know what I’ll do, though; I’ll put the mattress on the floor, and we must manage the best way we can.”

So he put the mattress on the floor, spread sheets on it, and they slept comfortably, some on the mattress and some on the bed.

The next morning the men went away, and Padre Ulivo accompanied them for some little distance on their journey, walking behind with one who was especially friendly.

“The one in front,” said this man, “the most important of us all, is Dominiddio[2] himself. Go and ask him a favour.”

So Padre Ulivo ran on, and threw himself on his knees in the road.

“What do you want?” said Dominiddio. “I will grant you whatever you ask for.”

“I want that anyone who sits down on my chair may be unable to rise without my permission.”

“Be it so.”

And Padre Ulivo returned to his companion.

“Have you asked a favour?”

“Yes, and it’s granted.”

“What did you ask?”

Padre Ulivo told him.

“Oh, you stupid man! But go and ask another favour quickly. And mind it’s something great, and something really for yourself. Remember you are speaking to Dominiddio.”

Padre Ulivo ran on again and knelt down.

“What do you want this time? You shall have it.”

“Let anyone who gets up into my fig-tree be unable to come down without my permission.”

“Very well; it shall be so.”

And Padre Ulivo came back leaping for joy.

“Well, and what did you ask for?”

Padre Ulivo told him.

“Oh, you fool! Go again, you will get one more favour; but mind you ask for something really good for yourself.”

He wanted him to ask to go to Paradise.

“Again!” said Dominiddio, when he saw Padre Ulivo in the dust before him. “Well, this is the last time. What do you want?”

“Let me always win at cards, no matter whom I may be playing with.”

“Be it so. And now no more.”

Padre Ulivo came back to his companion singing for joy.

“What have you asked for this time? Something really great?”

“Oh, yes,” said Padre Ulivo, and told him.

“Well, you’ve lost your chance now. Good-bye.”

With that he left him and Padre Ulivo went home.

Now his jolly times began again. His barrel of wine never ran dry, and his cupboard never grew empty. Everybody came to see him. They ate, drank, and led a merry life.

✴✴✴✴✴

But Padre Ulivo grew old; and one day Death came to him.

“Oh, how do you do?” said Padre Ulivo. “You want me, do you? Well, I was just beginning to fear you had forgotten me, and to wonder where you could be. Sit down and take a rest, and then I’ll come with you.”

So Death sat down on the chair in the chimney-corner, while Padre Ulivo piled on wood and made a splendid blaze.

“Now we must go,” said Death, when he was warm. “Oh, oh! what’s this?” For when he tried to get up the chair stuck to him and he could not move. “Oh, oh!” And he pulled at the chair that seemed glued firmly to him. “Padre Ulivo, let me go! I have to go for the carpenter’s daughter before sundown. Oh, oh! I can’t get up. You’ve bewitched me.”

“Promise not to come back for a hundred years, and you shall go free.”

“A hundred! A hundred and one, if you like! Only take the spell off.”

So Padre Ulivo gave him permission to rise, and Death went away.

✴✴✴✴✴

Things went on as usual for the hundred years, with feasting and merry-making. But at last, as Padre Ulivo was among his friends, Death appeared again.

“Yes, yes, I’m ready. But let us have a feast of figs first. See what splendid fruit there! I and my friends had as much as we wanted yesterday, it’s your turn to-day. Go up and help yourself; I am too old to climb.”

So Death went up the tree and picked and ate to his heart’s content.

“Now we must go,” said he. “Hullo! I can’t get down. Oh, Padre Ulivo, you’ve bewitched me again!” And he stretched out now an arm, now a leg, and twisted and turned; but it was all of no good, and the others stood below laughing at him.

“Oh, Padre Ulivo! I’ll leave you another hundred years, if you’ll only let me get down.”

“Very well; then you may come.”

So Death climbed down and went away.

✴✴✴✴✴

When the hundred years were passed, he came and stood outside the cottage.

“Padre Ulivo, Padre Ulivo, come out! I[53] shan’t come near your house this time. I don’t want to be tricked again.”

“Oh, no, I’m coming. Wait till I get my jacket.”

So he put on his coat and went with Death.

On the way they met the Devil.

“Ah, good morning, Padre Ulivo” (one can see they knew each other very well), “so you’re coming my way, are you?”

“To be sure I am. But let’s have a game at cards first.”

“By all means! What shall we play for?”

“For souls. A soul for every game.”

“Good! I’m not afraid. Nobody ever beat the Devil yet at cards.”

So they began, and Padre Ulivo won game after game.

The Devil got very angry and spit flames of fire from sheer rage, as he saw the crowd of souls collecting round Padre Ulivo.

“This will never do,” he said at last. “I shall have no fire left to warm myself at if I go on losing my fuel at this rate. Padre Ulivo, take your souls and be off. I have had enough of you.”

They left the Devil boiling over with fury, and went and knocked at the gate of Heaven.

“Who’s there?”

“Padre Ulivo.”

“I’ll go and ask if you may come in.” Then, after a little time: “Dominiddio says[54] you may come in, if you’re alone; but you must not bring anyone else.”

“Go and tell Dominiddio that when he came to me I let him in with all his friends. He ought to do the same by me.”

The porter took the message, and then came and opened the gates.

“Dominiddio says you may all come in together.”

So they threw themselves down in the armchairs of Paradise, and enjoyed themselves for ever.

Surely a tale of this kind is an eloquent commentary on the mind of the people who have preserved it. The shrewd cunning, the frank materialism, the lavish generosity, so long as there is anything to be generous with (“since it’s there,” they will say as they offer or use the last of their store), are all strongly marked features among these peasants.

At the same time, the story itself suggests a curious feeling that we have to do with Jupiter and Mercury transformed in the crucible of Christian history and Catholic dogma. The transformation is an instructive one in many ways, and it would be interesting to know whether it has taken place in any other country besides Italy.

THE SOUND AND SONG OF THE LOVELY SIBYL

It was old ’Drea I was talking to, this time. Andrea was my peasant friend’s father, a small, infirm-looking man, about eighty years of age, of great shrewdness and penetration. We were sitting in the little kitchen garden beside the bean-vines, and as we chatted his eye roamed continually over the valley and the hills beyond, with the expression of one accustomed to render an account to himself of all he saw. He told me of his life as foreman to the great landowner of that part of the country; of his journeyings from one outlying farm to another, to collect the half of the farm-produce which is the due of the owner of the soil; of his experiences as head forester down in Maremma; of the power of the priests in his young days, the days of the Archduke Peter Leopold. “Why in those days,” said he, “two lines from the parish priest would send a man to the galleys for eight years without trial. There were Giovanni and Sandro, lived opposite the post office, in that house with a[56] railing—you know it?—well, they’re old men now; but they have each served their eight years as convicts, nobody ever knew why.”

At last he asked me if I should like a story. ’Drea was a well-known story-teller and improviser, so I said nothing would please me better, and he began[3]:—

Once upon a time there was a knight who had three beautiful daughters. Now this knight determined to go to the Holy Land to fight for the tomb of our Lord, but he did not know what to do with his three daughters. At length a friend said:—“Build a tower for them,” and the idea was such a good one that he adopted it. He had a tall tower built, with three bedrooms and a sitting-room at the top of it; he locked the door at the foot and provided his daughters with a basket and a long rope with which to draw up their food. Then he gave each girl a diamond ring, and said:—

“So long as you are good, the diamonds will be bright and victorious, but if you do wrong I shall find them dull on my return.”

So he went away to fight the Saracens.

A little while after he had gone, the eldest daughter going to draw up the basket one morning, saw a poor man down below shivering with cold.

“Oh, sisters,” she said, “look at that poor man: shall we draw him up and feed him and warm him?”

“Do as you like,” said they; “we won’t be answerable for the results.”

So the girl bade the man get into the basket, drew him up, made a blazing fire, warmed him thoroughly, and gave him some dinner.

“Now you must go,” she said after a time, “you are warm, you have been fed, you have rested; what more do you want?”

“I must have supper with you.” To that the girl agreed, and then again told him to go away.

“I must sleep with you to-night,” said he.

Well, the girl did not know what to do, so she submitted.

The next morning after breakfast, the second daughter said to the man:—

“Now be off, we’ve had enough of you.”

“No, I am going to stay to dinner”: and after dinner it was:—“No, I am going to stay to supper,” and after supper the same thing as before.

The next day it was the third sister’s turn. Now the younger sisters are always more cunning than the elder ones, and this was no exception to the rule.

As before, the man stopped to breakfast, dinner and supper; but after supper the girl went to her room, saying to him:—“Wait till I call you.”

Now the tower had been built in a hurry and the floors were of plank only, not of brick or stone. Of this the maiden took advantage. She raised three or four planks just inside the door and then called:—“My light’s out, come and light it.”

The man ran to do so, but fell down the hole to the bottom of the tower; and as it was a high one he was killed by the fall.

The next morning the three sisters looked at their rings, but only that of the youngest was bright, the others were dull and clouded.

“What shall we do?” said the girls.

“I’ll tell you,” said the youngest; “we’ll sit all in a row, and pass my ring from one to another so cleverly that nobody shall notice.”

Presently their father came back. They did as their sister advised, and he was quite satisfied. Then they all went home to live in their old house and had a merry time of it.

One day, as the eldest was looking out of the window she saw the king’s baker.

“Ah, what a handsome man,” said she. “If he were to marry me I would make, in one day, enough bread to last the court for a year.”

These words were repeated to the baker; he married her and she managed to keep her promise.

A little while afterwards the second daughter was looking out of window when she spied the king’s pastry-cook.

“How I should like to marry that fine-looking[59] man,” said she. “I would make enough cakes in a day to last a year.”

As before, the words were repeated; the girl had her wish, and managed to keep her promise.

But the third daughter saw the king’s son, and said, “If the king’s son were to marry me I would bring him three children, two boys and a girl, each with the red cross of a knight on his chest.”

This saying was repeated to the prince who married the girl and almost immediately afterwards became king. But he had not been king long before a terrible war broke out, and he had to leave his bride and go far away to fight. He put her under the charge of his mother, with strict injunctions that he should receive information as to whether his wife had kept her promise or not. Now the queen-mother was a wicked woman, who hated her daughter-in-law because she was not a princess by birth, but only the daughter of a poor knight; and the two elder sisters also hated the queen, being jealous of her, because they had to bow before her and do her homage. So these three women consulted together, and sent for a wicked witch to help them injure the poor queen. The queen had three children as she had promised, two boys and a girl, each with the red cross of a knight on his chest; but as soon as they were born, the witch let three black puppies run about the room, and took away the children[60] and put them on the river-bank in the forest hard by. Then she sent word to the king:—

“Your wife has brought you three black dogs.”

“Let her and them be well taken care of,” wrote he. But the witch and the queen-mother changed the letter into:—

“Let her be walled in at the foot of the stairs, and let everyone who goes by spit on her”; and this was done. Now we will go back to the children.

In the forest there lived a hermit; he heard small voices crying, went and looked, and found the little ones. He took them to his hut, and tended them, and they grew up like flowers, fine and strong, with the red cross always in front.

After a time the king returned from the wars; and, when he reached his palace, saw his wife at the foot of the stairs and heard all that had been done to her. At first he was angry, but they persuaded him that it was all as it should be, and he left his queen there, thin and ill. Still he was very unhappy, and to console himself he went out hunting. In the forest there lived a fairy, a friend of the hermit’s. She it was who had led the hermit to the children, and now she guided the king to the hermit’s hut. There were the children, beautiful as flowers, each with the red cross.

“That reminds me of what my wife once[61] said,” said he. “All come and have dinner with me to-morrow.”

With that he went home and told what had happened. So the queen-mother called the witch, and said:—

“What shall we do? We shall be found out.”

“No, no,” said the witch; “you leave all to me; it will be all right.”

Meanwhile the hermit had gone to ask advice from the fairy.

“You must all go,” said she. “When you come to the palace you will see a beautiful pale woman walled in at the foot of the stairs, and you will be told to spit on her; but you must refuse to do it. That is the children’s mother.”

The three children and the hermit went to the palace.

“Spit on that woman,” commanded the guard.

“No,” said they all; “such a thing would be very improper.”

“Then you can’t go in,” said the soldier. And so loud a dispute arose that the king came himself; and when he heard what was the matter, he brought them in gladly, and made them sit down at table. Then the witch who was there told a wicked lie.

“These children,” said she, “have said that they can bring the Sound and Song of the Lovely Sibyl.” But they had not promised anything of the kind.

“Very well,” said the king, “let them come back with it here.”

So the hermit and the children went away, and the eldest boy set out.

“If I am not back in seven days,” said he, “you may know that something has happened to me.”

He rode on till he came to a hermit with a white beard sitting by the roadside.

“Where are you going?” asked this hermit.

“Well-bred people don’t put questions of that sort,” answered the prince and passed on.

After the seven days were gone the second brother determined to try his luck, as the first had not yet returned. He, too, met the hermit, received the same question, gave the same answer, and rode away.

Now another seven days had elapsed, and the sister resolved to set out; but first she asked the advice of the fairy.

“After some time you will find a white-bearded hermit,” said the fairy; “don’t answer him as your brothers have done: tell him where you are going, and he will help you.”

So when she reached the old man she told him about the quest on which her brothers and herself had set out.

“Just look among my hair,” said the hermit, “and comb it. Will you?” And when she had done so he gave her a small rod and a couple of cakes, saying:—

“Ride on till you come to a palace with two[63] lions in front of it. Throw the cakes to the lions and strike the door with the rod; it will open and in the hall you will see a beautiful girl. She will tell you what you want to know.”

So the maiden thanked the hermit and rode off. When she reached the palace she followed the hermit’s directions and found the girl.

“Take this rod,” said she, “and go into yonder garden. There you will find a bird which will come fluttering round your head and shoulders. Don’t attempt to catch it, however, till it reaches your lap; then put both hands over it quickly, hold it tightly, and it will tell you how to free your brothers. That bird is the Sound and Song of the Lovely Sibyl.”

The maiden went into the garden and sure enough the bird came fluttering round her as though asking to be caught. But she did not attempt to touch it till it had settled in her lap; then she held it fast with both hands, and the bird said:—

“All these statues you see round you were once men. Those two there are your brothers. Go and touch them with the rod you hold in your hand.”

The maiden did as she was bid; her brothers returned to life and they all went away together, carrying the bird with them. When they reached home the fairy said:—

“To-morrow you must go to court. Put the bird in a box and carry it with you; and when[64] the king asks for it, put it on the table, that it may declare the wickedness of the dowager-queen, and the innocence of your mother.”

So the next day the three went to the palace and were invited to dine with the king. There were the queen-mother and the witch also present.

“Ah,” said the latter sneeringly, “you’ve kept your promise finely, haven’t you?”

“Certainly we have,” they answered.

“Why,” said the king, “where is the bird?”

They opened the box, and the Sound and Song of the Lovely Sibyl flew on to the table and told the whole black tale of deceit.

Then the queen-mother was burnt in the great public square, and the witch in a smaller square; but the children’s mother was crowned queen again amid the shouts of the people, and her husband and her children loved her dearly.

“So,” concluded old ’Drea, “innocence triumphs over vice.”

THE SNAKE’S BOUDOIR

This story was told me by a woman who lives here in Genoa during the winter, but goes up into the mountains for the summer. She says she is quite sure it is true: “ma poi non lo so.” I wish I could tell it as well as she did:—

Not far from the villa where she goes in the summer, a stream makes a pool where the women go to do their washing. The pool is surrounded by stones and rocks, and once when the women were washing they noticed a very large snake (biscia) gliding among the rocks. They watched him and saw that at a certain place he stopped, put something down behind a stone, and went away. The women went to look, and found his poison like two little horns. In the evening he came back, went to the place where he had hidden his fangs, found them, and fixed them in position again. This happened several days in succession, until one of the women suggested that they should steal the poison-fangs, and see what happened. So the next day they took them into the house with them, and stood at the window to watch the[66] biscia. When he came back and could not find his poison fangs, he gave every sign of the utmost surprise; he looked again and again behind the stone where he had left them, as though to say:—“This was certainly the place!” He examined all the stones round the pool, and at last, hissing with rage, began to dash his head against the stones. And the women were watching him all the time from the window. After a while he was so overcome with despair that he gave his head an extra hard knock and split open his skull so that he died.

POMO AND THE GOBLIN HORSE

This that I am going to tell you now, the old woman went on, happened when my great grandfather was a little boy. My grandfather used to tell it to my father before he left his native place to marry my mother; for my mother had no brothers, so my father came to live in her country. When my great grandfather was quite young, all the children used to be called in from the streets at sundown, lest they should be frightened by the black horse and his rider who for some time tormented that part of the country. This is the story of the ghost:—

There was in that village a man named Pomo, who was so lazy that he did not like to work; so he said:—

“I’ll go for a doctor.”

So he went into other districts where no one knew him, and said that he could heal people. But instead he only made them die all the more; and at last he died too. One evening soon after his death, his relations were sitting quietly in their house when they heard a great noise, and looking out, saw all the air full of[68] crows. This went on for several evenings; the house was surrounded by these birds, which flew hither and thither cawing loudly, and then vanished.

At last one evening there were no crows, but they suddenly heard a great clattering of hoofs in the street. They went to the window and looked out and saw a terrible black horse with a man riding on him. The horse came to the doorsteps, put his nose down to the ground, and stood there some time, while the man looked imploringly at the terrified people, but did not speak.

The next evening the horse came again. This time he stood on the threshold, with his nose against the door, but the man did not speak. In the morning the people went to tell the parroco and beg him to save them from the devil, for they were sure the black horse could be no other. The parroco lived some way off, but he said:—

“If the horse comes to-night, call me at once, and I will see if I can help you.”

That night as soon as the hoofs were heard someone ran off to the parroco, and the rest huddled into the kitchen so that they might not see the dreadful sight.

But the horse came upstairs, and stood there close by the fire with his nose on the ground and the man hid his face on the horse.

As soon as they heard him coming up the people were so frightened that they jumped[69] out of window, all but one very old woman who feared the fall more than the horse.

Just then the priest came and asked the man, in the name of God, what he wanted. The man answered:—

“I want mass said for me, that I may have rest in the lowest part of hell.”

“Well,” said the priest, “I will say it to-morrow.”

“You must say it at midnight, with your back to the altar,” answered the man, “and if you make a single mistake you will have to go to hell along with me.”

“I’ll do it for you,” said the priest, for he was a brave man; and with that the horse and man went away. But when they got among the chestnut trees there was a great noise, and flames of fire; and so the horse and rider vanished. Well, the next day the parroco tried to get someone to serve the mass, but he had great difficulty, as everyone was afraid of making a mistake and getting carried off to hell; but at last he persuaded a priest to help him, and towards midnight the two went to the church. The horse and rider stood in the entrance of the west door, and the two priests read mass, with their backs to the altar. They got through without mistake and the devil and the condemned soul disappeared and were never seen again; but the priest who had served the mass was taken up stiff and dumb with terror, and it was many weeks before he[70] could speak again. The parroco was less affected; but there was a strange glitter in his eyes for some days; and it was long before he could trust himself to talk of that night.

These stories of demon-steeds are not uncommon in the South. A notable one is that of the terrible “Belludo” of The Alhambra, which Washington Irving uses with such grim effect in his book on the old Moorish pile.

TUSCAN SKETCHES

A TUSCAN COUNTRYSIDE AND THE FESTA AT IL MELO

I had left Clementina and the little ones behind me, and had moved further up among the Apennines to a village which, perched on a low hill, overlooks the river and the winding valley. The summits of the mountains all around rise bare and scarped from dark pine and ash woods, while their bases are clothed with chestnuts. Many a long line of soldiers have the villagers seen marching up the valley on the other side of the river which flows at their feet: for the pass is an important one, being the high road from Tuscany into the Modenese. Napoleon III. and Victor Emmanuel rode through it side by side, and old men still relate how the village turned out to salute Emperor and King as they went by. The great Napoleon lives too, in the recollection of the country people, for he drew many soldiers from all the districts round for his “Summer Excursion to Moscow.” One cannot vouch, however, for the historical exactitude of some of the stories concerning him. One old woman,[74] for instance, whose husband had saved himself on the ill-fated expedition by cutting open a horse and getting inside it, firmly believed that le petit Caporal had perished miserably at Moscow, pickled in a barrel of salt!

Nor are more ancient historical associations wanting. At a very little distance lies the village of Gavinana where the lion-hearted Francesco Ferruccio, trying to burst through the mountains from Pisa to the relief of Florence, was betrayed in 1530 to the Prince of Orange. Captured in the battle which ensued, and carried, covered with wounds which must have been fatal, into the market-place before the Imperialist leader, he was there stabbed to death in cold blood, and expired with the exclamation:—“It is a noble thing to kill a dead man!”

In still more ancient times Catiline passed up the valley when trying to force the Apennines; and the public square bears the name of Piazza Catilina in honour of the monster whom Sallust took so much pains to delineate.

Legends of classical Italian literature, too, still linger here. An inn in the village is called the “Cappel d’Orlando”—(Orlando’s Hat)—after Ariosto’s famous hero; and a conical-shaped hill on the other side of the valley bears the same name. I asked one of my peasant acquaintances why it was so called, and who Orlando was. The answer was amusing as showing the country conception of[75] the temper and achievements of a knight-errant:—

“Orlando,” said the woman, “was a warrior, who rode about looking for someone to fight with. When he came to the top of that hill, he reined in his horse so violently to avoid falling over the precipice that the animal’s hoof sank deep into the rock, and the print can still be seen. He took a tremendous leap from the top of the hill down into the village below, but he left his hat behind him. It was afterwards found, and the place was then called Cappel d’Orlando.”

Another informant evidently attributed to Orlando the time-annihilating hat for which Carlyle sighs so vainly; for she added to the original story a rider, saying that Orlando, after his marvellous leap, went to Gavinana and was killed fighting against Ferruccio.

Remembrances of an older classical literature than Ariosto abound also. The Muses, Helicon, Troy, are common words among these peasants, whether in speech or in song.

As is mostly the case in Tuscany, the country people are devout; that is to say, they go to mass on Sundays, firmly believe in miracles, and miracle-working images, and are fond of walking in procession. The church of Cutigliano, the village in which I was staying, rejoices in the possession of the entire skeletons of two saints, and of two valuable palladiums—a Madonna which preserves the place from[76] epidemics, and a crucifix which regulates the supply of rain.

On the Feast of the Madonnina, the first of the palladiums is carried in state through the village, the peasants flocking in from all the hamlets near to join in the procession and chant their Ave Marias. The figure is of wood, highly painted, dressed in light blue robes, ornamented with tinsel, and with rings and rosaries on the outstretched hands.

“Did you see my nosegay right in front?” said my landlady that evening. “It was the best there. I love that Madonnina; she saved us from the cholera and from diphtheria. They came right to the foot of the hill, but did not touch us.”

“And it was the Madonnina that saved you?” I asked.

“Of course. We took her in procession through the village, and where she passed there was no illness. It’s like the uncovering of the crucifix.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Oh, don’t you know? There’s a crucifix in the church; and when it rains and rains, and the chestnuts are spoiling, we uncover it, and then the rain stops at once.”

“Why does it stop when you uncover the crucifix?” I rejoined.

“Oh, Gesú likes it to be uncovered.”

“Then why don’t you keep it always uncovered?”

“Well, it’s not the uncovering, but the candles and prayers and incense that Gesú likes.”

“Then Gesú must be vain,” remarked the woman’s husband, who is something of a heretic, “and the Church says that vanity is a sin.”

Each village in the valley has its own special saint, whose feast is the great event of the year, and is observed with more honour than any other festival. Brass bands are borrowed from other villages which are fortunate (or unfortunate) enough to possess them, and the peasants flock in new dresses and bright kerchiefs to walk in procession, pray to the saint, eat, drink, and dance. These feasts are sometimes the occasion of amusing outcrops of the old pagan spirit. Last year, for example, there was a quarrel between the inhabitants of this village, and those of another, further down the valley. When Saint Celestina’s day came round, therefore, our people determined to spite their enemies, who honoured Saint Celestina as their special protector. Brass bands were borrowed, fireworks bought, a huge balloon manufactured, a ball arranged for the evening; no pains were spared, in fact, to render the feast so attractive that even the protection of the saint herself could not draw visitors to fill the purses of her legitimate worshippers.

“But what must the saint have thought of[78] all that?” I said, as my informant was gloating over the clever revenge.

“The saint? Oh, she must have been delighted; she had such special honour that year.”

Who can say that paganism is dead in this 19th century? Images, too, and small cushion-like hearts blessed by the priest on that special day, are supposed to be of peculiar efficacy against evil. Without the latter, the so-called benediction, no mother will dress her child.

I once asked how the young women were chosen who carry the banner of the Madonna in the procession.

“Oh, they’re chosen by lot,” was the answer.

“Then it’s no particular honour, no reward for specially good character,” I remarked.

“But of course it is. God makes the lot fall on the one whom He specially wishes; it’s the greatest honour a girl can have.”