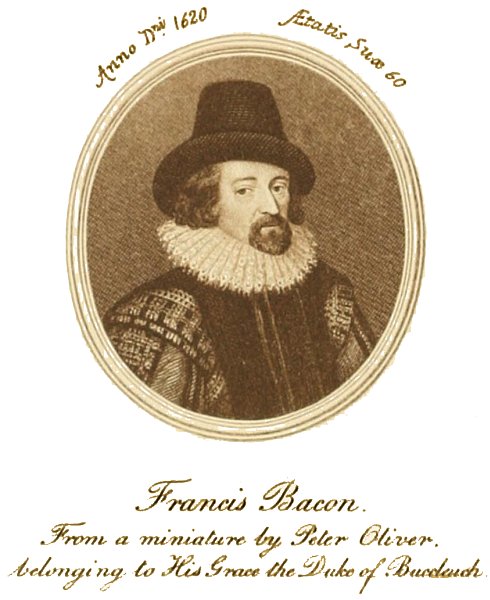

Francis Bacon.

From a miniature by Peter Oliver.

belonging to His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch.

Francis Bacon.

From a miniature by Peter Oliver.

belonging to His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch.

BY

ALBERT F. CALVERT.

London:

DEAN & SON, LIMITED,

160A, Fleet Street.

1902.

Taunton:

E. GOODMAN AND SON, PHŒNIX PRINTING WORKS.

To anticipate for this little book that it may prove the means of convincing a single Baconian of the error of his ways, would be to express a hope that has only the faintest chance of realisation. Baconianism is so wilful and so obstinate that it is not amenable to any treatment that has yet been invented. It has its root in an entire misconception of the character and temperament of the man Bacon; it is nourished on the grossest misrepresentation of the man Shakespeare that the memory of an author has ever been subjected to. So long as the fallacy, backed up by specious argument, was confined to the consideration of the mighty few, it was scarcely necessary to enter into the lists with the Baconian champions, but the new and energetic move which is now being made to cast down Shakespeare from the “topmost pinnacle in the temple of fame,” and to set up the figure of Bacon in his stead, has had the result of bringing the subject once more into public view. In the circumstances, the publication of the following summary of the evidence may be found not inopportune. It may not effectvi a cure in the case of confirmed Baconians, but I have a modest hope that it will enable the unprejudiced inquirer to be on his guard against the hallucination. The Baconians have woven a cunning mesh of fact and fable to entangle the mind of the unwary; the task I have set myself is to review the premises, test the arguments, and combat the conclusions upon which Bacon’s pretensions to the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is alleged to rest, and to explain the reasons that we hold for ascribing the authorship of the Plays to Shakespeare.

While the majority of Shakespearean students are impatient of discussion, the disciples of the Baconian theory are prompt and eager and voluminous in the propagation of their arguments. Indeed, they have, all along, had the lion’s share in the controversy, and by their much speaking, have stormed the ears of that section of the public which neither thinks for itself, nor will be at the trouble to verify what it is told. Bacon has been born again in the biographies of his devotees, and Shakespeare, by the same agency, has been edited out of recognition. Bacon’s brilliant intellectual qualities have been taken as the basis of all argument, the human and temperamental side of his character has been boldly made amenable to the exigencies of argument, and his many glaringly reprehensible actions have been carefully ignored. I have endeavoured, in the ensuing pages, not so much to give a picture of the complete man, as to show what he was capable of in the way of selfishness, trickery and subterfuge. He was capable of the basest ingratitude andvii meanness, of the employment of barbarity when it suited his purpose, of unctuous servility and boundless egoism. He had neither the temperament nor the poetical ability nor the time to write the Plays; had he the meanness of spirit to claim them as his own? We shall see!

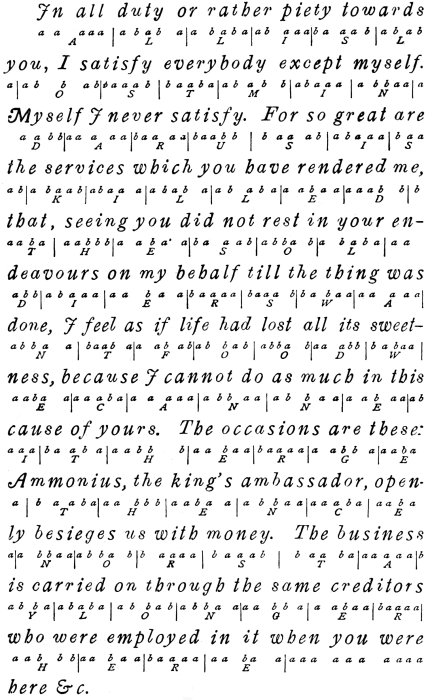

The conclusions I have formed with respect to the two cipher revelations which are now agitating the minds of both Shakespeareans and Baconians are derived partly from my estimate of the character of Bacon, partly from the apparent sincerity of Mrs. Gallup, and partly again from what I know of other and entirely independent decipherations of further Bacon messages, which are now being actively made in this country. Of Mrs. Gallup I only know that which her book and her publishers reveal. Of Dr. Orville W. Owen, the discoverer of the word-cipher I learn, from an American source, quoted by way of a testimonial in one of the doctor’s books, that he is “a man who has reached middle age,” and who has “never shown the slightest sign of possessing unusual or extraordinary literary skill, or genius.” In other words, his sponsors assure us that he is incapable of writing those portions of Shakespeare which form so great a part of his decipherations, or even the connecting passages which appear to have been contributed by Bacon. We must accept this opinion as a tribute of personal character.

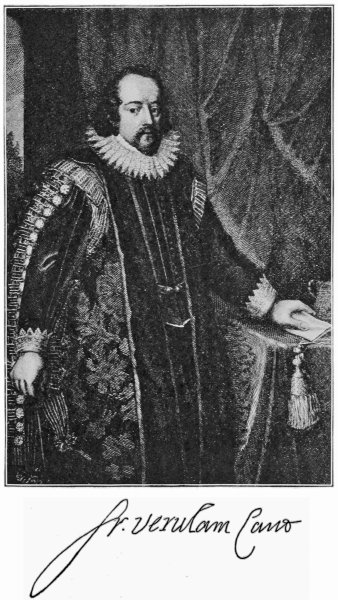

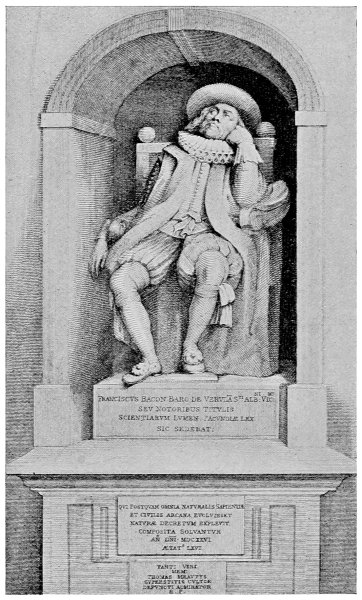

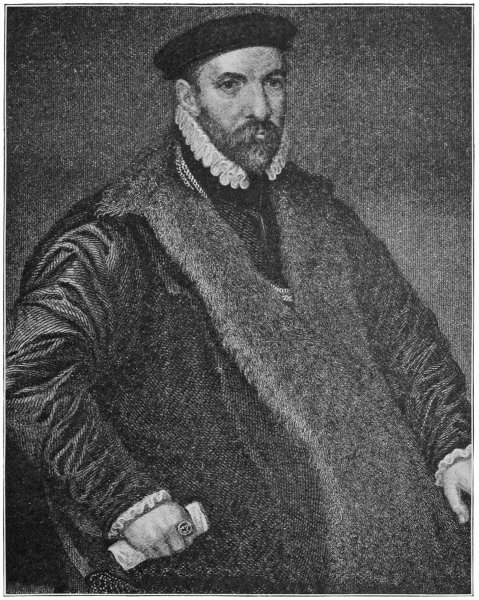

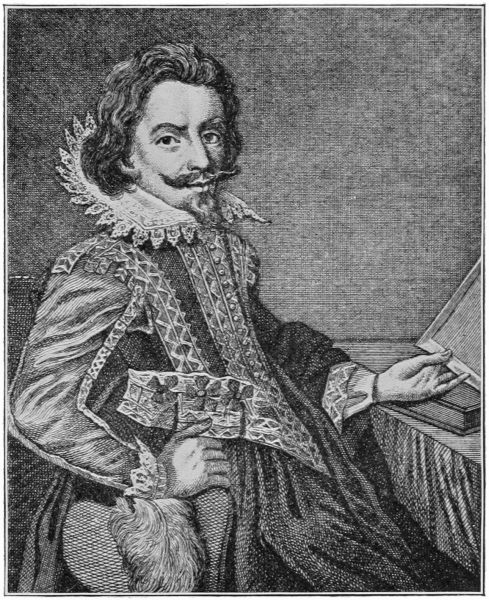

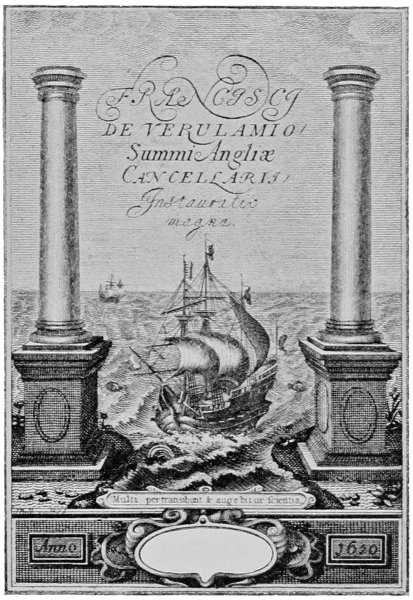

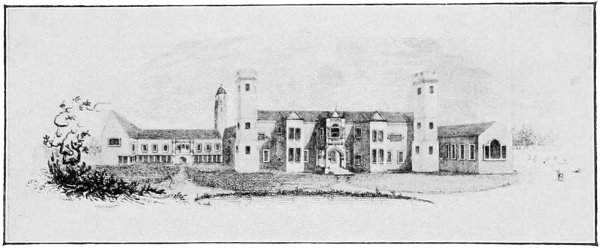

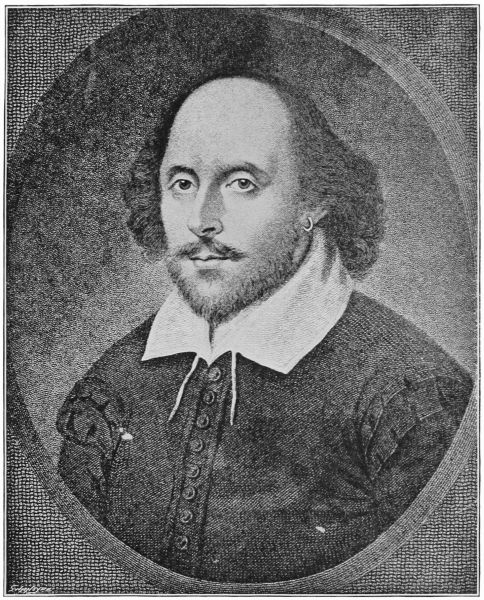

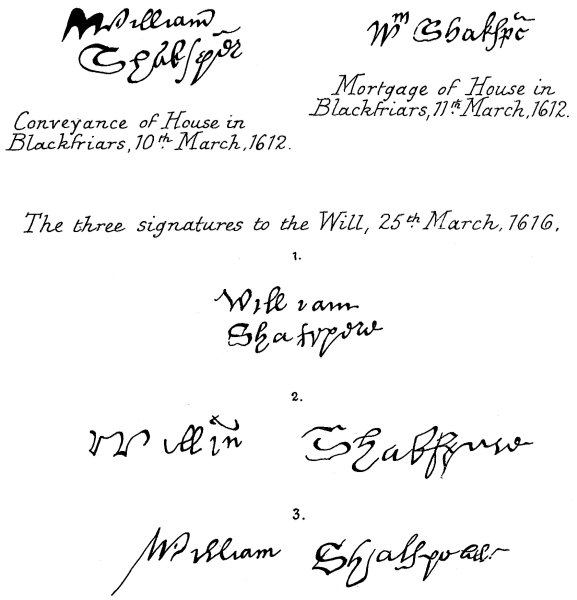

Concerning the illustrations, I may be allowed to say a few explanatory words. The two photogravure reproductions are taken respectively from a miniature by Peterviii Oliver, belonging to the Duke of Buccleuch, and from a very rare print of Bacon. The print from Vansomer’s painting, the picture of Bacon’s monument, and the portraits of Sir Nicholas Bacon, Sir Nathaniel Bacon, the Earl of Essex and Queen Elizabeth, and the views of Stratford-on-Avon and Gorhambury will, I trust, be found of general interest. The facsimile pages from “Sylva Sylvarum” and the “Novum Organum,” with their allegorical devises and fine workmanship, illustrate the contrast between the manner in which the works of Bacon and those of Shakespeare were given to the world. The portraits of Shakespeare contained here are well known to students. The reproduction of the bust will be familiar to all visitors to Stratford, the “Droeshout” Engraving is the picture which forms the frontispiece to the First Folio, and the original of the Chandos portrait is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Albert F. Calvert.

“Royston,” Eton Avenue,

London, N.W.

| Page. | |

| Francis Bacon, from a Miniature by Oliver | Frontispiece. |

| Francis Bacon (aged 18), from a Miniature by Hilliard | 4 |

| Francis Bacon as Lord Chancellor (Vansomer) | 12 |

| Francis Bacon as Lord Chancellor | 16 |

| Francis Bacon’s Monument in St. Michael’s Church | 20 |

| Sir Nicholas Bacon, Portrait and Autographs | 24 |

| Anna Lady Bacon, Mother of Francis Bacon | 32 |

| Sir Nathaniel Bacon | 36 |

| St. Michael’s Church | 44 |

| Queen Elizabeth | 48 |

| Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex | 52 |

| Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester | 56 |

| Frontispiece to Sylva Sylvarum | 60 |

| Frontispiece to Novum Organum | 68 |

| Gorhambury, Three Views, 1568, 1795, 1821 | 72 |

| William Shakespeare, The Droeshout Etching | 80 |

| William Shakespeare, The Chandos Portrait | 84 |

| William Shakespeare, The Bust at Stratford-on-Avon | 96 |

| Shakespeare’s House | 108 |

| Chancel of Trinity Church (Stratford-on-Avon) | 112 |

| Shakespeare Autographs | 116 |

| Ann Hathaway’s Cottage at Shottery | 120 |

| Dr. Owen’s Wheel for Deciphering | 128 |

| Page. | |

| Bacon, the Product of His Age | 1 |

| Bacon, the Friend of Essex and Cecil | 9 |

| Bacon, as the Creature of Buckingham | 18 |

| Bacon and Shakespeare Contrasted | 25 |

| Baconian Fallacies Respecting Shakespeare | 29 |

| Mr. Theobald, a Baconian by Intuition | 35 |

| Was Shakespeare the “Upstart Crow?” | 40 |

| Wm. Shakespeare, Money Lender and Poet | 46 |

| The “True Shakespeare” | 50 |

| Mr. Theobald’s Parallels and Mr. Bayley’s Conclusions | 55 |

| The Bi-Literal Cipher | 62 |

| Bacon’s “Sterne and Tragicle History” | 71 |

| Bacon, the Author of all Elizabethan-Jacobean Literature | 78 |

| Bacon and “Divine Aide” | 88 |

| Shakespeare and Bacon in Collaboration | 92 |

| The Tragical Historie of our Late Brother Robert, Earl of Essex | 99 |

| Bacon, the Poet | 107 |

| “Did Shakespeare Write Bacon?” | 111 |

| The Case for Shakespeare | 115 |

| Were Shakespeare and Bacon Acquainted? | 124 |

| In Conclusion | 129 |

It is impossible to sympathise with, or even to regard seriously, the spirit in which a small, but growing section of the reading public of America, and of this country, has plunged into the controversy respecting the authorship of the so-called Shakespeare plays. The fantastic doubt which compelled individual scholars to investigate a theory of their own inventing, to lay, so to speak, the ghost they had themselves raised, has inspired distrust in the minds that had no beliefs, and generated scepticism in those where no faith was. The search for the truth has degenerated into a wild-goose chase; the seekers after some new thing have made the quest their own; ignorance has plagiarised from prejudice; the “grand old Bacon-Shakespeare controversy,” as Whistler said of Art, is upon the town—“to be chucked under the chin by the passing gallant—to be enticed within the gates of the householder—to be coaxed into company as a proof of culture and refinement.” The difficulties that such a2 controversy present to the tea-table oracles are both numerous, and exceeding obstinate. The people who read Shakespeare form a pitiably insignificant proportion of the community, but they are multitudinous compared with those who have the remotest acquaintance with the works of Francis Bacon. Bacon is known to some as Elizabeth’s little Lord Keeper, to others his name recalls the fact that he was James the First’s Lord Chancellor, but outside his Essays, and, perhaps, The New Atlantis, his great philosophical dissertations, the pride and treasure which he so carefully preserved in Latin, lest they should be lost in the decay of modern languages, are a sealed book to all, except a few odd scholars at the Universities. Bacon is an extinct volcano. The fact is not creditable to the culture of the age, but it is incontrovertible.

It has, on this account, been found necessary for Baconians to describe to their readers what manner of man this was whom they would perch on Shakespeare’s pedestal, and they have accomplished their task in the manner best calculated to lend plausibility to their theories. Moreover, they have displayed a subtle appreciation of the magnitude of their undertaking. The Shakespeare plays, in common with all great works, reflect in some degree the personality of their creator. The Baconian students cannot deny that there are many characteristics in their candidate which only the most devout can reconcile with the spirit of the plays. It, therefore, became further necessary to ring the changes on their candidate; to employ the arguments of induction and deduction as best suited the exigencies of the task. In creating the idol of Bacon, much had to be read into the subject, and it would seem that the simplest method by which they could advance the claims of Bacon was by discrediting the claims of Shakespeare. In estimating the character of Viscount St. Alban, we have3 the solid foundation of fact for our guidance; the personal details of Shakespeare’s career may be written upon a page of note paper. The original Baconians seized upon these few details to distort them to their own ends, and their followers have done their best to perpetuate the outrage.

In the scope of this volume it is not possible, nor is it necessary, to attempt an intimate analysis of the characters of Bacon and Shakespeare, but a resumé of the leading incidents in their lives, a brief review for the purpose of making a comparison of their respective temperaments, will not be out of place. In the following pages my endeavour has been to arrange, as systematically as possible, the reasons for my belief—for these I invite a courteous hearing; as for the conclusions I have formed, I am content to abide by them.

My last desire in dealing with the career of Lord Bacon has been to find reasons for supposing him to be the author of Shakespeare’s plays. That endeavour has been made by his many champions with more sanguinity than I could display, and I have carefully weighed every argument and fact advanced in his favour. I have read, and re-read, and argued against myself, the claims which have been put forward with so much earnestness and evident conviction. But against these I have had to set the bald facts that make the claim untenable. The biographers of Bacon have been burdened with the ungrateful necessity of finding excuses, and of making endless apologies for their hero. Bacon’s greatest editor, the scholar who devoted some 30 years to the work—who brought more knowledge, and disclosed more analytical acumen and skilled judgment in his task than any editor ever brought to bear upon the life and works of a single author—has stated his reasons for his disbelief in the Baconian theory. When it is remembered that Spedding’s knowledge of Shakespeare4 was “extensive and profound, and his laborious and subtle criticism derived additional value from his love of the stage,” his decision on the subject must be accepted, if not as incontrovertible, at least, as the most damaging blow to the Baconian theory we shall ever get.

A well-known writer, in declaring that a man’s morality has nothing to do with his prose, perpetrated an aphorism which Baconians have adduced to reconcile the psychological differences which we find between Bacon, the man, and Bacon, the author of the plays traditionally attributed to Shakespeare. The least erudite student of Shakespeare has felt the magic of the dramatist’s boundless sympathy, his glowing imagination, his gentleness, truth and simplicity. His mind, as Hazlitt recognised, contained within itself the germs of all faculty and feeling, and Mr. Sidney Lee, in his general estimate of Shakespeare’s genius, has written, “In knowledge of human nature, in wealth of humour, in depth of passion, in fertility of fancy, and in soundness of judgment, he has not a rival.” Henry Chettle refers to “his uprightness of dealing which argues his honesty,” the author of The Return from Parnassus apostrophised him as “sweet Master Shakespeare,” and Ben Jonson, his friend and fellow labourer, wrote of him, “I loved the man, and do honour his memory, on this side idolatry as much as any. He was indeed honest, and of an open and free nature.”

FRANCIS BACON.

AGED 18.

1578.

From a Miniature by Hilliard.

An author’s morality, or rather his lack of it, may not detract from the grace and clarity of his style, but it must inevitably leave its mark in his matter. There is poetry that reveals only the brilliance of the writer’s brain—if such can be termed poetry; there is prose which lays bare the writer’s heart. In Shakespeare we have verse which evidences the possession of both the mental and the temperamental qualities in the highest perfection. There is5 Shakespeare the genius, the artist, the creator, the master manipulator of theatrical machinery. There is Shakespeare the man—the citizen of whom Jonson wrote in terms of the warmest affection. In what degree do we find these qualities which are inseparably associated with Shakespeare in the character of Francis Bacon?

For every act of Bacon’s life we are met with apologies, explanations, and extravagant defences. Lord Macaulay’s bitter and brilliant analysis of the Lord Chancellor (a retaliatory treatise prompted by the ingenuity and perversions of his enamoured champions), has been robbed of its sting by the less brilliant, but more knowledgable and judicious Spedding, who in his Evenings with a Reviewer, clearly and dispassionately reduces Macaulay’s estimate to its correct biographical and critical level. But there are acts in the life of Bacon that, shorn of all the swaddling clothes of specious explanation, reveal the man in a light which, in spite of valiant speculation and portentous argument, in spite even of Bacon’s sworn word, render his claims to the mantle of Shakespeare an absurdity—and an impertinence.

Francis Bacon, the youngest son of Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, by his second wife (Ann, daughter of Sir Anthony Coke), was born on 22nd January, 1561. He was the product of the age in which he lived. A politician by heredity, a student by nature, a courtier and place-seeker by force of circumstances, he fulfilled his inevitable destiny. In a court in which the politics were based on the teachings of Machiavelli, in which intrigue was a sport and a fine art, where flattery and lying were necessities, and personal advancement the one incentive to every act, Bacon intrigued, supplicated, flattered, cringed, and lied himself into prominence. Nor must the future Lord Chancellor be judged too harshly on6 that account. He was only gambling with the current coin of his environment. By nature, he was averse to Jesuitry, but he was forced by circumstances and his ambitions to employ it. “What the art of oratory was in democratic Athens,” Dr. Edwin A. Abbott writes, “that the art of lying and flattery was for a courtier in the latter part of the Elizabethan monarchy.” In this atmosphere of falseness and deception Bacon, with good credentials, a fine intellect, little money, many influential acquaintances, but few true friends, had to battle for his own fortunes. It is evident that he early recognised the exigencies of the warfare. He absorbed and assimilated the poison of his surroundings; he was both malleable and inventive. His frame of mind is best illustrated by two of his maxims. Truth, he declares is noble, and falsehood is base; yet “mixture of falsehood is like alloy in the coin of gold and silver, which may make the metal work the better.” Again, “The best composition and temperament is to have openness in fame and opinion, secrecy in habit, dissimulation in seasonable use, and a power to feign if there be no remedy.”

In the Elizabethan Court, the man who desired preferment had to plead for it. At the age of 16, Francis Bacon, after leaving Cambridge, had been admitted as “an ancient” of Gray’s Inn, and in the following year was sent to Paris in the suite of Sir Amias Paulet, the English Ambassador. Two years later, on the death of his father, he returned to England, to find himself destitute of the patrimony he had expected to inherit, and forced to select the alternative of immediate work or the accumulation of debts. In this emergency he applied to his uncle, Lord Burghley, for advancement, and attempted to win the favour of the Queen by addressing to her a treatise entitled, Advice to Queen Elizabeth. This letter is remarkable for its lofty tone, its statesmanship, and7 boldness, but it is marred by the appendix, in which the author states that he is bold to entertain his opinions, “till I think that you think otherwise.” This fatal pliancy, this note of excessive obsequiousness, lasted him through life.

The want of success, which attended his first efforts to gain official recognition, caused Bacon to decide, once and for all, upon his choice of a career. His path lay either in the way of politics, which meant preferment, power, and wealth; or science, philosophy, and the development of the arts and inventions that tend to civilise the life of man. No work seemed to him so meritorious as the latter, and for this he considered himself best adapted. “Whereas, I believe myself born for the service of mankind,” he declared, in 1603, in the preface to The Interpretation of Nature; and in a letter to Lord Treasurer Burghley, “I have taken all knowledge to be my province.” Again, “I found in my own nature a special adaptation for the contemplation of truth.... Imposture in every shape I utterly detested.” But, as he proceeds to explain, “my birth, my rearing, and education,” pointed not towards philosophy, but towards “politics;” love of truth and detestation of imposture was in his heart, but “the power to feign if there be no remedy” was there engraved also; the practical value of the “mixture of falsehood” was in his blood. And the want of money influenced him in forming his decision. In 1621, when his public career came to its disgraceful close, he declared that his greatest sin had been his desertion of philosophy and his having allowed himself to be diverted into politics. “Besides my innumerable sins,” he cries out in his confession to the “Searcher of Souls,” “I confess before Thee that I am debtor to Thee for the gracious talent of Thy gifts and graces, which I have neither put into a8 napkin, nor put it as I ought to exchangers, where it might have made most profit; but misspent it in things for which I was least fit, so that I may truly say, my soul has been a stranger in the course of my pilgrimage.” At the beginning of his history, Bacon pleads his birth, his rearing and education as excuses for his choice of a career, and at its close, in De Augmentis, he throws the blame on “destiny” for carrying him into a political vortex. Dr. Abbott sums up his life-story in a phrase—multum incola; with it his public career began and ended.

Having failed to secure the goodwill of Burghley, Bacon addressed himself to the Earl of Essex, and when, in 1593, Francis came under the Queen’s displeasure, Essex pleaded for his re-instatement in the Royal favour. Bacon himself practised every abasement, and, ever failing, debased himself to what he himself described as an exquisite disgrace. From this time until the day when there were “none so poor to do him reverence,” the Earl of Essex was Bacon’s warm friend, patron, and benefactor. He tided him over his monetary difficulties, made him his counsellor, and among other gifts presented him with a piece of land worth between £7,000 and £8,000. Bacon repaid his friendship with advice, which, it may be presumed, was well meant. But Bacon, the alleged author of the plays which portray an unrivalled knowledge of human nature, betrayed a singular and unaccountable lack of intuition into character. His counsel was, in a large measure, sound and sagacious, but it was utterly spoiled by the trickiness which breathes through every precept. If Bacon had possessed the knowledge of men that we find in Shakespeare, he would have known that his maxims were peculiarly unfit for Essex, who was the last10 man in the world to carry into effect such a scheme of systematic dissimulation. Dr. Abbott considers that few things did the Earl more harm than that the friend in whom he placed most trust gave him advice that was rather cunning than wise. Indeed, Essex was following the counsel of Bacon when he offered himself, in 1599, for the command in Ireland. From this command he returned to England a disgraced man, and his downfall culminated in his death two years later. And in the hour of his humiliation and dire need, when the Royal disfavour kept all his friends from him, Bacon’s elder brother, Sir Anthony Bacon, and the author of the Sidney papers regarded Bacon as one of the active enemies of his former patron.

Bacon’s biographers have strained every effort in explaining and excusing his action in the ensuing trials. Not only have they failed to exculpate him, but themselves must realise the futility of their most ingenious endeavours to clear his character of this foul blot. Abbott, his impartial biographer, says: “We may acquit him of everything but a cold-blooded indifference to his friend’s interest and a supreme desire to pose (even at a friend’s cost) as a loyal and much-persecuted servant of the Queen.” But, truly, the most that can be said in extenuation of his behaviour, is little indeed, when the friend is a man to whom he had written, “I do think myself more beholding to you than to any man.”

What, however, are the facts? When the first proceedings were taken against Essex in the Star Chamber, Bacon absented himself from the Court, his excuse to the Queen being, he said, “Some indisposition of body.” His actual letter to Elizabeth explains that his absence was compelled by threats of violence on the part of the Earl’s followers, whom he openly charges with a purpose to take11 the Queen’s life. “My life has been threatened, and my name libelled. But these are the practices of those ... that would put out all your Majesty’s lights, and fall on reckoning how many years you have reigned.” Abbott considers that we need not accuse Bacon of deliberately intending by these words to poison the Queen’s mind against his former friend, while Professor Gardiner adduces this imputation as a proof that Bacon was liable to “occasional ill-temper.” Contemporary judgment did not so interpret the wording of the excuse. The treacherous nature of the insinuation provoked a feeling of amazement and anger. That his brother Anthony believed Bacon to be capable of so great vileness is evident, and even Lord Cecil, the Earl’s greatest enemy, wrote to Francis begging him to be, as he himself was, “merely passive, and not active,” in insuring the fallen Favourite’s utter ruin.

In the face of these warnings and remonstrances, Bacon wrote to the Queen expressing his desire to serve her in the second stage of the proceedings against Essex. He asked that an important rôle might be assigned to him, but although he was only entrusted with a subsidiary part, he performed his task so adroitly as to earn the deep resentment of the friends of Essex. Within a fortnight of the Earl’s liberation Bacon again offered his services to Essex, who accepted them!

What followed? Bacon devised a plan to secure the Earl’s re-instatement in the Royal favour. The artifice employed was to bring before the notice of Elizabeth, a correspondence—ostensibly between Essex and his brother Anthony—exhibiting the loyalty and love of the former for the Queen. The letters were composed by Bacon, and while they are interesting as specimens of the author’s literary power, and are illustrative of his “chameleonlike instinct of adapting his style to his atmosphere,” they12 were calculated, by the interpolation of artful passages, to advance the interests of Bacon, rather than those of Essex, with the Queen. It is significant also that the demeanour which Bacon in these letters caused the Earl to assume, he used against him when Essex was subsequently arraigned for treason. Unless we are prepared to accept the statements of Bacon in this connection, it is impossible to view his participation in this second trial without a feeling of the deepest abhorrence. Bacon had no right to be in Court at all. As one of the “learned counsel,” his presence was not required, but in the capacity of “friend of the accused,” his evidence could not fail to be greatly damaging to the Earl’s case. He proffered his evidence, not only with readiness, but with a ferocious efficacy. We have no evidence beyond Bacon’s own word—the word of a man who was striving to put the best complexion on a foul act of treachery—that he deprecated the task. “Skilfully confusing together” the original proposal, and the abortive execution of Essex’s outbreak, he insisted that the rising, which in truth was a sudden after-thought, was the result of three months’ deliberation, and he concentrated all his efforts on proving that Essex was “not only a traitor, but a hypocritical traitor.” No other piece of evidence adduced at the trial had greater weight in procuring the verdict against the Earl. Bacon subsequently pleaded in extenuation of his behaviour that he was acting under pressure from the Crown, but we have the knowledge that on the first occasion he had offered his services, and we can only conclude that at the price of sacrificing the friend who had loaded him with kindnesses, he had determined to make this trial a stepping-stone to Royal favour. To serve this end, friendship, honour, obligation were brushed aside; for, as Bacon has said in one of his essays, the man who wishes to succeed “must know all the13 conditions of the serpent.” The price Bacon received for the blood of Essex was £1,200, or £6,000 in our currency. “The Queen,” he wrote to a friendly creditor, “hath done somewhat for me, though not in the perfection I hoped.” Bacon had, it is fair to infer from this remark, betrayed his friend; had, in fact, delivered him to the headsman for the hope of pecuniary reward.

Fr. verulam Cano

In what degree Bacon was responsible for the drawing up of a Declaration of the Treasons of Essex, which Lord Clarendon described as a “pestilent libel,” is impossible to decide. He tells us that his task was little more than that of an amanuensis to the Council and the Queen, but this excuse fails him in the case of his Apology, put forth as a vindication of the author in the estimation of the nobles, from the charge of having been false to the Earl of Essex. The paper is admittedly full of inaccuracies, conveying to us the picture, “not of his actual conduct, but of what he felt his conduct ought to have been.” Dr. Abbott dismisses this literary and historical effort as interesting only as a “psychological history of the manifold and labyrinthine self-deception to which great men have been subjected.”

On the accession of James I., Bacon again threw himself into the political arena, determined to neglect no chance of ingratiating himself with the new Sovereign. He poured forth letters to any and everybody who had the power to forward his cause. He dwelt in these epistles upon the services of his brother Anthony, who had carried on secret and intimate negotiations with Scotland. Sir Thomas Challoner, the confirmed friend of Essex, received a letter from him; he appealed to the Earl of Northumberland; and became the “humble and much devoted” servant of Lord Southampton, on the eve of that nobleman’s release from the Tower (where Bacon had helped to14 place him as an accomplice of Essex). To each he turned with the same request that they would bury the axe, and “further his Majesty’s good conceit and inclination towards me.”

At this time, Bacon, desperately apprehensive of rebuff, was anxious to conciliate all parties, and to secure friends at Court. He was willing, nay, eager, to be Greek, Roman, or Hebrew, in order to attain his object—even he would avow a gift of poesy to make his calling and election sure. Writing to Sir John Davies, the poet, Bacon, the politician and philosopher, who did not publish two lines of rhyme until twenty-one years later, desired him to “be good to concealed poets.” Reading this statement in connection with the other epistles he indicted at the same crisis, we realise how little dependence can be placed upon the implied confession that he had written anonymous poetry. His letters to Southampton, to Michael Hickes (Cecil’s confidential man), to David Foules and Sir Thomas Challoner, and to the King himself, all betray the same feverish desire to be all things to all men. He assured Hickes that Lord Cecil is “the person in the State” whom he “loves most,” and at the same moment he placed his whole services at the disposal of Cecil’s rival, the Earl of Northumberland! When the star of Northumberland began to pale, Bacon importuned Cecil to procure him a knighthood to gratify the ambition of an “Alderman’s daughter, a handsome maiden,” whom he had found “to my liking.” But for a while Bacon found the struggle for recognition unavailing. The King found him an acquired taste—or rather a taste that his Majesty had yet to acquire—and after grovelling to all and sundry, he desisted at the moment from the attempt to gain the King’s grace, “because he had completely failed, and for no other reason.”

15 But although Bacon went into retirement, he divided his leisure between his literary labours and his quest for political advancement. In all his political pamphlets, his one ambition was to divine and reflect the Royal views. In 1590 he had nothing but condemnation for the Nonconformist party; in 1604 he had strenuously pleaded the cause of Nonconformity; in 1616 he as strenuously opposed the slightest concession being made to the Nonconformers. In 1604 he was returned to Parliament; three years later, his zeal in anticipating the King’s wishes, and supporting his proposals, was rewarded by his appointment to the Solicitor-Generalship. In the following year he was made clerk of the Star Chamber, and immediately set himself to secure the displacement of Hobart, the Attorney-General.

Bacon’s conduct towards the Earl of Essex has already been considered. Had this been the only instance of the kind in his career, his apologists would have achieved something more than public opinion can grant them in their endeavours to explain it away. But his behaviour towards Cecil is another lurid illustration of his duplicity and ingratitude. During the last fourteen years of his life Cecil had been the friend and patron of Bacon, whose letters to him are couched in almost passionate terms of loyalty and “entire devotion.” In one epistle he declares himself “empty of matter,” but “out of the fulness of my love,” he writes to express “my continual and incessant love for you, thirsting for your return.” Cecil was his refuge and deliverer in 1598, and again in 1603, when he was arrested for debt, and Bacon was not empty of reason when he asserted in another letter, “I write to myself in regard to my love to you, you being as near to me in heart’s blood as in blood of descent.” In 1611, a short while before Cecil’s death, he wrote this last profession of his affection:—

16 “I do protest before God, without compliment, that if I knew in what course of life to do you best service, I would take it, and make my thoughts, which now fly to many pieces, be reduced to that centre.”

In May of 1612 Cecil died. Within a week Bacon had proffered his services to the King in the place of his cousin, of whom he wrote:—

“He (Cecil) was a fit man to keep things from growing worse, but no very fit man to reduce things to be much better; for he loved to keep the eyes of all Israel a little too much upon himself.”

To another, he wrote that Cecil “had a good method, if his means had been upright,” and again to the King, on the same subject:—

“To have your wants, and necessities in particular, as it were hanged up in two tablets before the eyes of your Lords and Commons, to be talked of for four months together; to stir a number of projects and then blast them, and leave your Majesty nothing but the scandal of them; to pretend even carriage between your Majesty’s rights and the ease of the people, and to satisfy neither—these courses, and others the like, I hope, are gone with the deviser of them.”

Less than a year before, Bacon had protested before God, “without compliment,” his desire to serve Cecil, and now he protests to God in this letter to the King, that when he noted “your zeal to deliver the Majesty of God from the vain and indign comprehension of heresy and degenerate philosophy ... perculsit ilico animum that God would shortly set upon you some visible favour; and let me not live if I thought not of the taking away of that man”—the man as “near to me in heart’s blood as in the blood of descent.”

The King, who had grown weary of Cecil, may have17 accepted his death as a visible favour of God, but the favour did not evidently embrace the substitution of Bacon in his cousin’s stead. His application for the vacant post of Lord Treasurer was passed over by the King, but Bacon became Attorney-General in the following year.

Let us regard another trait in the character of this many-sided statesman. To relieve the King’s pressing necessities it was proposed that voluntary contributions should be made by the well-affected. The contributions, commonly known as Benevolences, were rarely voluntary; the “moral pressure” that was employed in their collection made them in reality extortions, and, as such, they were the cause of national dissatisfaction. During the search of the house of a clergyman named Peacham, consequent on some ecclesiastical charge, a sermon was found predicting an uprising of the people against this oppressive tax, and foretelling that the King might die like Ananias or Nabal. The sermon had neither been issued nor uttered, but the unfortunate rector, a very old man, was indicted for conspiracy and, in contravention of the law, put to the torture. Peacham had not been convicted of treason, though Bacon “hopes that the end will be good;” or, in other words, that he will be able to wring from the condemned man a confession to make good the charge.

The wretched old clergyman, after being examined in Bacon’s presence, “before torture, in torture, between torture, and after torture,” could not be made to convict19 himself, and Bacon’s comment to the King is that the man’s “raging devil seemeth to be turned into a dumb devil.” It will be noted that this infamous act of illegality and Bacon’s commentary are the deed and words of the man who is supposed by some to have declared,

We have seen Bacon as the ingrate, and Bacon as the brute; let us observe him “the meanest of mankind,” as Pope described him—who, as Abbott admits, although he refuses Pope’s description, “on sufficient occasion could creep like a very serpent.” The sufficient occasion was the sudden advance into fame of George Villiers, afterwards Duke of Buckingham. The disgrace and imprisonment of Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, whose conviction Bacon laboured so strenuously to accomplish, doubtless inspired the Attorney-General with the hope of becoming the chief adviser of the Sovereign. Great must have been his mortification when he discovered the impregnability of Villiers in the favour of the King. But although cast down, Bacon was not abashed. He had, on a previous occasion of disappointment, declared that “service must creep where it cannot go” (i.e., walk upright), and he at once determined to creep into the King’s confidence through the medium of the rising Favourite. Instantly, Bacon was on his knees to the new star. “I am yours,” he wrote, with more servile want of restraint than he had disclosed in his letters to Essex or Cecil, “surer to you than to my own life.” In speech and behaviour he lived up to his protest. He beslavered Villiers with flattery to his face, and he20 carolled his praises to those whom he felt assured would repeat his words to the spoiled Favourite. His reward was not long in the coming. In 1617 he was made Lord Keeper. He took his seat in Chancery with the most extravagant pomp, his retinue exceeding all his predecessors, says a correspondent of Carleton, “in the bravery and multitude of his servants.” The following day he wrote of the ceremony to Villiers, “There was much ado, and a great deal of the world. But this matter of pomp, which is heaven to some men, is hell to me, or purgatory at least.” This expression, if not an affectation entirely, is, at least, strangely inconsistent with the account of the vulgar pomp and display of a Feast of the Family, which is described by Bacon with so much detail in The New Atlantis.

In this year Bacon dared to interpose, for a fitful instant, between Villiers and his desires; the next moment he is reduced to a state of pathetic contrition. But the evanescent display of a spirit of independence nearly cost the Lord Keeper his position at Court. For purely personal reasons Bacon regarded, with aversion, the projected marriage between Sir John Villiers, a brother of Buckingham, and the daughter of his old rival and enemy, Sir Edward Coke. In a letter to the Earl of Buckingham he so far forgot himself and his repeated promises to hold himself as a mere instrument in the hands of the King, as to protest against the proposed marriage. Realising immediately the folly of this want of tact, he wrote to the King, and to Buckingham, justifying, or rather excusing his temerity. The King replied with a sharp rebuke, the Favourite in a short, angry note. Further letters elicited additional curt corrections from the angered Monarch, and from Buckingham. Bacon then, for the first time, realised the enormity of his presumption. His position was in danger. Excuse and justification21 were unavailing to conciliate his angry masters; absolute submission was the only way out of his predicament. Bacon submitted; he even offered to put his submission into writing to the Favourite. Buckingham, in a pencilled note, couched in tones in which arrogance is mixed with acrimonious reflection on “his confused and childish” presumption, notified his forgiveness. In reply, Bacon protested his gratitude to “my ever best Lord, now better than yourself,” and concluded, “it is the line of my life, and not the lines of my letter, that must express my thankfulness; wherein, if I fail, then God fail me, and make me as miserable, as I think myself at this time happy, by this reviver through his Majesty’s clemency and your incomparable love and favour.”

His submission nullified his early resolve not to tolerate any attempts to interfere with the course of law, and delivered him bodily into the hands of Buckingham. The Favourite took the Lord Keeper at his word, and although he put his loyalty to constant and severe tests, by making frequent application to him in favour of chancery suitors, Bacon never again forgot that “the lines of his life” must progress in undeviating conformity with the Favourite’s will. It is not profitable here to attempt to determine whether or not he gave verdicts against his own judgment, but we have the letters to show that he listened, replied, and complied with Buckingham’s requests, and in 1618 he was made Lord Chancellor, doubtless by the influence, and on the advice, of the Favourite.

During the period of Bacon’s temporary disgrace, “when the King and Buckingham had set their faces against him, and all the courtiers were yelping at his heels,” the only friend who remained staunch and constant to him was Sir Henry Yelverton, the Attorney-General. Yelverton, whose admiration for, and loyalty towards the22 Lord Chancellor were unswerving, would truckle neither to the Favourite nor to the King; although the former had assured him that those who opposed him “should discern what favour he had by the power he would use.” Within a year of Bacon’s restoration to favour Yelverton came into collision with Buckingham, and the Attorney’s accidental misconstruction of the King’s verbal instructions, served as an excuse for an information to be laid against him in the Star Chamber. We have seen how Bacon could repay friendship with ingratitude, and kindness with baseness in the case of Essex and of Cecil, but, in the instance of Yelverton, even his admirers are forced to admit that his behaviour was “peculiarly cold-blooded and ungrateful.” But the “lines of his life” had made him the serf of the Favourite, and “whatever other resolutions Bacon may have broken, none can accuse him of breaking this.” When the case came on, and when “the bill was opened by the King’s Sergeant briefly, with tears in his eyes, and Mr. Attorney, standing at the Bar, amid the ordinary Counsellors, with dejected looks, weeping tears, and a brief, eloquent, and humble oration, made a submission, acknowledging his error, but denying the corruption”—the Lord Chancellor did his utmost to resist the merciful proposal of the majority to submit the Attorney’s submission to the King. The King declined to interfere, and the termination of the case was announced to Buckingham by Bacon, in the following self-satisfied and congratulatory note:—“Yesterday we made an end of Sir Henry Yelverton’s causes. I have almost killed myself with sitting almost eight hours. But I was resolved to sit it through.” He then gives the terms of the sentence, and adds: “How I stirred the Court I leave it to others to speak; but things passed to his Majesty’s great honour.” In other words, a blunt, straightforward,23 and honourable man, who had refused to purchase his office by bribes, or by flattery, had been condemned, on a charge of corruption (of which his judges knew him to be guiltless), to a fine of £4,000 and imprisonment during the King’s pleasure, for the offence of refusing to cringe to Buckingham. These were the things that, in Bacon’s judgment, “passed to his Majesty’s great honour.”

In 1618 Bacon became Baron Verulam of Verulam; three years later he was created Viscount St. Alban, “with all the ceremonies of robes and coronet.” But his disgrace and discomfiture were soon to come. “In a few weeks,” writes Lord Macaulay, “was signally brought to the test the value of those objects for which Bacon had sullied his integrity, had resigned his independence, had violated the most sacred obligations of friendship and gratitude, had flattered the worthless, had persecuted the innocent, had tampered with judges, had tortured prisoners, had plundered suitors, had wasted on paltry intrigue all the powers of the most exquisitely constructed intellect that has ever been bestowed on any of the children of men.” On March the 14th, 1621, Bacon was charged by a disappointed suitor with taking money for the dispatch of his suit. On April the 30th, in the House of Lords, was read “the confession and humble submission of me, the Lord Chancellor.” On May the 3rd, the Lords came to a general conclusion that “the Lord Chancellor is guilty of the matters wherewith he is charged,” and it was resolved that he should be fined £40,000, imprisoned in the Tower during the King’s pleasure, declared incapable of any office, place, or employment in the State or Commonwealth, and that he should never sit in Parliament, nor come within the verge of the Court. Five years later, on April the 9th, 1626, he died at Highgate of a chill and sudden sickness, contracted24 by exposure when stuffing a fowl with snow to test the effect of snow in preserving flesh from putrefaction. He wrote, on his death bed, to Lord Arundel, to whose house he had been carried: “As for the experiment it succeeded exceeding well.”

SIR NICHOLAS BACON.

From the original of Zucchero, in the collection of His Grace the Duke of Bedford.

The argument of the Baconians—the term is uniformly employed here to mean the supporters of the Baconian theory of the authorship of Shakespeare—is based on the honest belief that the varied qualifications necessary for the production of the Plays were possessed by only one man of the period in which they were written. And having resolutely determined that the man could be no other than Francis Bacon, they set themselves to work with the same resoluteness, to bend, twist, and contort all facts and evidence to suit their theory. It is clearly impossible to credit any of Shakespeare’s contemporary dramatists with the authorship, because their acknowledged work is so immeasurably inferior to his, that any such suggestion must appear ridiculous. It is safe to assume that no writer who had produced poems or plays inferior to those of Shakespeare could be attributed with the authorship of these plays—Shakespeare can only be compared with himself. And the only author who cannot be compared, in this way, to his instant discomfiture, is Bacon, whose published work is, in form and style and essence utterly dissimilar from that of Shakespeare. If a brilliant intellect, wide knowledge, and classical26 attainments were the only requisite qualifications for the production of the greatest poetry of the world, then Bacon’s claim would stand on a sure foundation. He was intimately acquainted, no man better, with the philosophy of the law; he was an eminent classical scholar, a writer of beautiful English, compact in expression, and rich in fancy. He had an extensive acquaintance with literature and history, he was a brilliant orator; but unto all these great gifts was not added the gentle nature, the broad sympathy and knowledge of humanity, the wealth of humour, the depth of passion, the creative power of poetry, which is so strikingly manifested in the plays of William Shakespeare.

Our knowledge of the gentleness of Shakespeare’s nature, his uprightness, his honesty, his modesty, is disclosed in his poems, and corroborated by the evidence of his contemporaries. His poetry breathes the gentleness and the lovable nature with which his personal friends credited him. What is there in any analysis of Bacon, beyond his marvellous mental attainments, which single him out as the probable, even possible, creator of King Lear, Brutus, Juliet, Rosalind, and Shylock? Coldness of heart, and meanness of spirit, are faults of temperament which cannot, by the greatest stretch of imagination be associated with the author of Lear’s desolating pathos and Arthur’s deeply pathetic appeal to Hubert. The points in Bacon’s career, which have been dealt with in the foregoing pages, were selected of malice prepense; not to detract from the greatness of the Lord Chancellor, as a literary genius and philosopher, but as demonstrating the impossibility of associating such a nature with the authorship of the poetry attributed to him. By his deeds we know him to have been a man whose nature was largely made up of ingratitude, untruth, flattery, meanness, cruelty, and servility. His treatment of Essex, of Cecil,27 and of Yelverton, can only be stigmatised as “peculiarly cold-blooded and ungrateful;” his persecution of Peacham convicts him of cruelty, bordering on savageness; his meanness is illustrated by the selfish unreasonableness displayed by his attitude towards Trott, his long-suffering creditor. His servile submission to Buckingham has scarcely a parallel in English history.

Deep as was his mind, and profound his knowledge, Bacon possessed no high standard of virtue or morality; he had no intuitive knowledge of mankind, and even as regards his dealings with the people amongst whom his life was passed, he evidenced a singular defectiveness as a reader of character. The sweeping generalities of his observations would be a poor stock-in-trade for a writer of melodrama. In his books he exhibits the cunning, the casuistry and unscrupulousness of an Elizabethan politician and time server. His advice and his opinions betray a mean view of life and its obligations. He had no sense of duty towards his fellow men where duty clashed with his personal interests. His methods are instinct with craft, artifice, and finesse—his advice to Essex, and to the King, was, for this very reason, misleading and abortive. It is incontrovertible that Bacon’s writings and Shakespeare’s plays are crammed with all kinds of erudition, and Coleridge has claimed for the latter that they form “an inexhaustible mine of virgin wealth.” But not a single argument can be advanced to show that Shakespeare could not easily have acquired such erudition and scholarship as the writing of the plays entailed, while we have all the books of Bacon to prove that the poetic genius, the colossal personality, the deep, intense appreciation of nature, and the unrivalled knowledge of man, which are the sovereign mark of the Plays, were not possessed by Bacon.

In editing the existing biographies of Lord Bacon to28 bolster up their theory, the Baconians have only conformed to the laws of absolute necessity. The cold, unvarnished facts that have been set forth in the foregoing pages are so contrary to the popular impression of what constitutes a “concealed poet,” that a more than ordinary amount of colorisation was required to make them acceptable in the author of The Tempest. But although there is reasonable excuse, and even some justification for this rose-colorisation process as applied to Bacon—for great men have almost invariably been given, by their biographers, the greatest benefit that be derived from all doubts—the champions of Bacon have far exceeded their prerogative in their attempts to defame and belittle Shakespeare. So much incorrect deduction, so much groundless suspicion, and so much palpable inaccuracy have been put forward by the Baconians, that it is imperative the few known facts in the poet’s life should be clearly stated. The following sketch is frankly intended, not so much to support the claim of Shakespeare as the author of the Plays, as to refute the many misconceptions and untruths by which his enemies have endeavoured to traduce him.

It is only necessary to read the facts concerning Shakespeare’s ancestry and parentage to dissipate some of the absurd suggestions as to the obscurity and illiteracy of the family. The poet came of good yeoman stock, and his forebears to the fourth and fifth generation were fairly substantial landowners. John Shakespeare, his father, was at one period of his life a prosperous trader in Stratford-on-Avon. He played a prominent part in municipal affairs, and became successively Town Councillor, Alderman, one of the chamberlains of the borough, and auditor of the municipal accounts. The assertion that he could not write is a distinct perversion of fact, as “there is evidence in the Stratford archives that he could write with facility.”

On the subject of the education of William Shakespeare it is inevitable that there should be conflicting opinions. Those who would deck out the memory of Bacon with the literary robe, “the garment which,” according to Mr. R. M. Theobald, is “too big and costly” for the “small and insignificant personality” of Shakespeare, will not concede that he was better educated than his father, who—the error does not lose for want of repetition—“signed30 his name by a mark.” Supporters of the traditional theory, however, reply, “we do not require evidence to show that he was an educated man—we have his works, and the evidence of Ben Jonson, John Heming, and Henry Condell to prove it.” Mr. Theobald argues that because there is no positive proof that he had any school education, it is logical to conclude that he had none. Mr. A. P. Sinnett, with the same reckless disregard for facts, says, “We know that he (William Shakespeare) was the son of a tradesman at Stratford, who could not read or write.” And in another place, “there is no rag of evidence that he (William Shakespeare) ever went to school.” Mr. W. H. Mallock describes him, still without “a rag of evidence” to support his assertion, as “a notoriously ill-educated actor, who seems to have found some difficulty in signing his own name.” All evidence we have to guide us on this point of Shakespeare’s schooling is that he was entitled to free tuition at the Grammar School at Stratford, which was re-constituted on a mediæval foundation by Edward VI. As the son of a prominent and prosperous townsman, he would, for a moral certainty, have been sent by his father to school (Mr. Sidney Lee favours the probability that he entered the school in 1571), where he would receive the ordinary instruction of the time in the Latin language and literature. The fact that the French passages in Henry V. are grammatically correct, but are not idiomatic, makes it certain that they were written by a school-taught linguist, and not by a man like Bacon, who, from his lengthy residence on the Continent, must have been a master of colloquial, idiomatic French. Ben Jonson, in his profound, and somewhat self-conscious command of classical knowledge, spoke slightingly of Shakespeare’s “small Latin and less Greek,” which is all that his plays would lead us to credit him with. His liberal use of31 translations, and his indebtedness to North’s translations of Plutarch’s Lives, also substantiates this theory.

We cannot regard, as a great scholar, an author who “gives Bohemia a coast line, makes Cleopatra play billiards, mixes his Latin, and mulls his Greek.” Mr. Reginald Haines, who has made a study of Shakespeare for the express purpose of testing his classical attainments, denies emphatically that he shows any acquaintance with Greek at all. His conclusions are worthy of consideration: “Of course there are common allusions to Greek history and mythology such as every poet would have at command, but no reference at first hand to any Greek writer.... As far as I know there are but four real Greek words to be found in Shakespeare’s works—threne, cacodemon, practic, and theoric. It is impossible to suppose that Bacon could have veiled his classical knowledge so successfully in so extensive a field for its display, or that he could, for instance, have perpetrated such a travesty of Homer as appears in Troilus and Cressida. With Latin, the case is somewhat different. Shakespeare certainly knew a little grammar-school Latin. He was familiar with Ovid, and even quotes him in the original; and he certainly knew Virgil, and Seneca, Cæsar, and something of Terence and Horace, and, as I myself believe, of Juvenal. But he very rarely quotes Latin, unless it be a proverb or some stock quotation from Mantuanus or a tag from a Latin grammar. When he uses conversational Latin, as in Love’s Labour’s Lost, the idiom is shaky. The quotations from Horace, &c., in Titus Andronicus are certainly not by Shakespeare. Nor are the Latinisms like “palliament” in that play. Still he has a very large vocabulary of Latin words such as renege, to gust (taste), and we may fairly say that Shakespeare knew Latin as well as many sixth form boys, but not as a scholar.” Two32 years ago a writer in the Quarterly Review, who had gone through all the alleged examples of erudition and evidences of wide and accurate classical scholarship in the Shakespearean plays, showed them to be entirely imaginary.

In 1582, before he was nineteen years of age, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, and three years afterwards he left Stratford for London. It was during this period, says Mr. Theobald, that “the true Shakespeare was studying diligently, and filling his mind with those vast stores of learning—classic, historic, legal, scientific—which bare such splendid fruit in his after life.” As Mr. Theobald’s contention is that Bacon was the “true Shakespeare,” let us consider for a moment how young Francis was employing his abilities at this particular time. In 1579 he returned to England after a two years’ residence in France. He had revealed an early disposition to extend his studies beyond the ordinary limits of literature, and to read the smallest print of the book of nature. He was already importuning his uncle, Lord Burghley, for some advancement which might enable him to dispense with the monotonous routine of legal studies. Failing in this endeavour, he was admitted as a barrister of Gray’s Inn, was elected to Parliament for Melcombe Regis, composed his first philosophical work, which he named “with great confidence, and a magnificent title,” The Greatest Birth of Time, and another treatise entitled, Advice to Queen Elizabeth. In the case of the poet we have no record; in that of the future Lord Chancellor we get the key of the nature which rendered the man as “incapable of writing Hamlet as of making this planet.”

ANNA LADY BACON, MOTHER OF FRANCIS BACON.

(From an original picture in the collection of Lord Verulam at Gorhambury).

William Beeston, a 17th century actor, has left it on record that, after leaving Stratford, Shakespeare was for a time a country schoolmaster. In 1586 he arrived in London. His only friend in the Metropolis was Richard33 Field, a fellow townsman, whom he sought out, and with whom, as publisher, he was shortly to be associated. It is uncertain when Shakespeare joined the Lord Chamberlain’s company of actors, but documentary evidence proves that he was a member of it in 1594, and that in 1603, after the accession of James I., when they were called the King’s Players, he was one of its leaders. This company included among its chief members Shakespeare’s life-long friends, Richard Burbage, John Heming, Henry Condell, and Augustine Phillips, and it was under their auspices that his plays first saw the light.

Before they opened at the Rose on the Bankside, Southwark, in 1592, the Lord Chamberlain’s company had played at The Theatre in Shoreditch, and in 1599 they opened at the Globe, which was afterwards the only theatre with which Shakespeare was professionally associated. In this year he acquired an important share in the profits of the company, and his name appears first on the list of those who took part in the original performance of Ben Jonson’s Every Man in His Humour. Mr. Theobald states that Shakespeare had become a fairly prosperous theatre manager in 1592, but as he did not secure his interest in the business until seven years later, what probably is meant is that Shakespeare was combining the duties of stage manager, acting manager, and treasurer of the theatre. It would appear that, recognising the fact that the period in Shakespeare’s life between 1588 and 1592 is a blank “which no research can fill up,” Mr. Theobald considers that he is justified in making good the deficiency out of his own inner consciousness.

As occasion will require that Mr. Theobald’s contribution to the controversy shall presently be dealt with, it may not be out of place here to explain the object, so far as it is intelligible, of his Shakespeare Studies in Baconian34 Light (Sampson Low, 1901). It would have been a fair thing to assume that the design of the author of this volume of over 500 pages, was to prove the Baconian authorship of Shakespeare, but as Mr. Theobald has since written to the Press to protest against this interpretation of his motives, we must take his words as he gives his parallels “for what they are worth.” In the opening lines of his preface, Mr. Theobald declares that while the greatest name in the world’s literature is Shakespeare, there is in the world’s literature no greater name than Bacon. Really, it would seem that if his object is not to prove that the two names stand for one and the same individual, this statement is sheer nonsense. Before the end of the preface is reached, he frankly avows his belief that “when the time comes for a general recognition of Bacon as the true Shakespeare, the poetry will still be called “Shakespeare,” and that no one will find anything compromising in such language, any more than we do when we refer to George Eliot or George Sand, meaning Miss Evans or Madame Dudevant.” But if Mr. Theobald was as versed in his study of the subject as Mrs. Gallup, Dr. Owen, Mr. A. P. Sinnett, or even Bacon himself, he would know that when this general recognition comes to pass the author of the Plays will not be called Shakespeare, or Bacon, but Francis “Tidder, or Tudor”—otherwise Francis I. of England—provided, of course, that the bi-literallists can substantiate their cipher. But as Mr. Theobald does not design to prove the Baconian theory, he does not, of course, require the evidence of the great Chancellor, or he may, as a disparager of cipher speculations, accept such evidence “for what it is worth.”

Mr. Theobald’s “preliminaries” are chiefly remarkable for three diverse reasons. We learn therefrom that he is a Baconian by intuition—“the persuasion took hold of his mind” as soon as Holme’s Authorship of Shakespeare was placed in his hand—that he does not admit the existence of genius, and that he is intolerant of “clamours and asperities, denunciations and vituperations,” and the personal abuse employed by anti-Baconians, whom he alludes to as Hooligans, and compares with geese. So long as he keeps to the trodden path of Baconian argument, he is only about as perverse and incorrect as the rest of—to use his own expression as applied to Shakespearean students—“the clan.” But he becomes amusing when he ventures to present new arguments in support of Bacon’s claim, variously abusive in his references to Shakespeare, and desperately dogmatic in his pronouncement of the faith that is in him.

“Among the many shallow objections brought against the Baconian theory,” writes Mr. Theobald in his chapter on Bacon’s literary output, “one is founded on the assumption that Bacon was a voluminous writer, and that if we add to his avowed literary productions, the Shakespearean36 dramas, he is loaded with such a stupendous literary progeny as no author could possibly generate. Moreover, he was so busy in state business as a lawyer, judge, counsellor, member of Parliament, confidential adviser to the King, and the responsible rulers in State and Church, that he had very little spare time for authorship.”

SIR NATHANIEL BACON.

From the original, in the collection of The Right Honble the Earl of Verulam.

In order to demonstrate that this shallow objection, as Mr. Theobald calls it, is a well-founded and irrefutable statement of fact, we have only to refer to Lord Bacon’s life and to his letters. From 1579, when he returned from France, until the end of his life he was distracted between politics and science; he put forward as his reason for seeking office that he might thereby be able to help on his philosophic projects which with him were paramount, and the poignant regret of his last years was that he had allowed himself to be diverted from philosophy into politics. He found “no work so meritorious,” so serviceable to mankind, “as the discovery and development of the arts and inventions that tend to civilise the life of men.” In his letter to Lord Burghley in 1592, he expressed the hope that in the service of the State he could “bring in industrious observations, grounded conclusions, and profitable inventions and discoveries—the best state of that province”—the province embracing all nature which he had made his own. But office was denied him, and he returned to “business” and to his constant bewailings of the fact that he had no time for literature. In 1607 he settled the plan of the Instauratio Magna; which had been foreshadowed in his Advancement of Learning, published two years previously. In 1609 he wrote to Toby Mathew, “My Instauratio sleeps not,” and again, in the same year, “My great work goeth forward; and after my manner I alter ever when I add; so that nothing is finished till all is finished.” From 1609 to 1620 Bacon37 spent such leisure as he could snatch from his other work in revising the Novum Organum (the second part of his Magna Instauratio), of which his chaplain, Rawley, says that he had seen “at least twelve copies revised year by year, one after another, and amended in the frame thereof.” In 1620, when the Novum Organum was published, the author sent it into the world uncompleted, because he had begun to number his days, and “would have it saved.” This was the book he alluded to as “my great work”—the work of his life, and he issued it as a fragment because he had not been able to find time to finish it. The belief that he had “very little spare time for authorship” is no shallow objection brought against the Baconian theory—it is an irrefutable fact, proved not only out of the mouth, but in the life, of Lord Bacon.

In spite, however, of all positive evidence to the contrary, Mr. Theobald proceeds to bolster up his contention that Bacon had time, and to spare, for literary pursuits, by the following most amazing piece of logic. He contends, in the first place, that “an estimate of the entire literary output of Bacon, as a scientific and philosophical writer, proves the amount to be really somewhat small.” He takes the fourteen volumes of Spedding’s Life and Works, subtracts the prefaces, notes, editorial comments, and the biographical narrative, puts aside as of “no literary significance whatever,” all business letters, speeches, State papers, etc., and thus reduces the total amount of literature to Bacon’s credit in the seven volumes devoted to the Life to some 375 pages. “If we calculate the whole amount contained in the fourteen volumes, we shall find it may be reckoned at about six such volumes, each containing 520 pages. On this method of calculation and selection, all that Mr. Theobald can find, “for his whole life, amounts to about 70 pages per annum,38 less than six pages a month.” Turning from Bacon to Shakespeare, Mr. Theobald finds that here again is a man whose literary output has been greatly exaggerated, for “if the Shakespeare poetry was the only work of William Shakespeare, certainly he was not a voluminous writer. Thirty-one years may be taken as a moderate estimate of the duration of his literary life, i.e., from 1585 till his death in 1616. And the result is 37 plays and the minor poems—not two plays for each year.” Mr. Theobald, it will be seen, possesses the same weakness for statistics that Mr. Dick evinced for King Charles’ head; he drops in his little estimate in season and out of season, and his appraisements are as manifold as they are fallacious. The period of Shakespeare’s dramatic output was confined to twenty years, from 1591 to 1611—if he had continued writing plays till his death in 1616, Bacon’s alleged playwriting would not have ceased with such significant suddenness in 1611. But what conclusion does Mr. Theobald arrive at as the result of his estimates? No less than this, that if the whole of Shakespeare, and the whole of Bacon’s acknowledged works belong to the same author, “the writer was not a voluminous author—not by any means so voluminous as Miss Braddon or Sir Walter Scott.” That Mr. Theobald should not hesitate to class Miss Braddon’s novels with the plays of Shakespeare, which belong to the supreme rank of literature, or even with Bacon’s “royal mastery of language never surpassed, never perhaps equalled,” is the most astounding link in this astounding chain of so-called evidence. But Mr. Theobald advances it with the utmost confidence. “Therefore,” he sums up, “let this objection stand aside; it vanishes into invisibility as soon as it is accurately tested”—i.e., weighed up, like groceries, by the pound.

Mr. Theobald is scarcely complimentary to Shakespeare’s39 champions in this controversy, but his language is positively libellous when he refers to Shakespeare himself. His personality is “small and insignificant;”—he is a “shrunken, sordid soul, fattening on beer, and coin, and finding sweetness and content in the stercorarium of his Stratford homestead”—a “feeble, and funny, and most ridiculous mouse.” Mr. Theobald almost argues himself not a Baconian by his assertion that “no Baconian, so far as I know, seeks to help his cause by personal abuse, or intolerant and wrathful speech.”

All that we can allege with any certainty about Shakespeare, between 1586 and 1602, is that he must have obtained employment at one or other of the only two theatres existing in London at that time (The Theatre, and The Curtain)—perhaps, as Malone has recorded, in the capacity of call-boy—that he became an actor, was employed in polishing up the stock-plays presented by the Company, and that Love’s Labour’s Lost was produced in the Spring of 1591. Assuming that Shakespeare was the author of this play—assuming, that is to say, that Ben Jonson, John Heming, and Henry Condell were neither arrant fools, nor wilful perjurers—it is evident that the “insignificant,” “shrunken, sordid soul,” “this ridiculous mouse” had education, application, a natural taste for the stage; and what is more—and more than Mr. Theobald can comprehend—he had genius. Mr. Theobald does not arrive at any such conclusion. Apart altogether from Mrs. Gallup’s cipher revelations, he is convinced by another “flash of intuition” that Ben Jonson was a fellow conspirator with Bacon in the ridiculous plot of foisting Bacon’s plays upon the world as the work of Shakespeare, and that Heming and Condell were but the tools of the disgraced Lord Chancellor.

41 But if Shakespeare was not advancing towards prosperity by the feasible methods I have conjectured, how can Mr. Theobald account for his ultimately emerging from the “depths of poverty” into a position of comparative affluence? The explanation is simplicity itself: “If a needy, and probably deserving vagabond” (page 11).—Why deserving? He was a “shrunken, sordid soul” on page 7!—“dives into the abyss of London life, lies perdu for a few years, and then emerges as a tolerably wealthy theatrical manager; you know that he must have gained some mastery of theatrical business.” So far the inference is legitimate and convincing; but how? Must he not have disclosed exceptional ability as an actor or playwright, or—? listen to Mr. Theobald!—“he must have made himself a useful man in the green room, a skilful organiser of players and stage effects—he must have found out how to govern a troop of actors, reconciling their rival egotisms, and utilising their special gifts; how to cater for a capricious public, and provide attractive entertainments. Anyhow, he would have little time for other pursuits—if a student at all, his studies would be very practical relating to matters of present or passing interest. During this dark period he has been carving his own fortune, filling his pockets, not his mind; working for the present, not for the future. But it was exactly then that the plays began to appear.”

Mr. Theobald’s argument can only be described as a reckless, illogical, and absurd distortion of possibilities, and it is the more inconsequential since it proceeds to defeat its primary object. In the first place it is supremely ridiculous to assume that the paltry services of Shakespeare in the green room and the carpenter’s shop, secured for him his pecuniary interest in the Globe Theatre, or the respect and friendship of the leading dramatists of his day, or even the enmity of jealous rivals in the craft. Yet42 Mr. Theobald attempts to substantiate his conclusions by distorting the obvious meaning of Robt. Greene’s reference to Shakespeare in A Groat’s Worth of Wit. Greene was not an actor, but a dramatist; he was a man of dissolute habits, a poet of rare charm, but a playwright of only moderate ability and repute. He was a gentleman by birth, and a scholar by training. He had the lowest opinion of actors—he envied them their success, and despised their avocation. In The Return from Parnassus he betrays his prejudice in the following lines, which are put into the mouth of a poor and envious student:—

To the jaundiced mind of Robert Greene, the accumulation of means by an actor was a crime in itself, but that a mere mummer should dare to compete with the scholar and the poet in the composition of plays—more, that he should write plays that exceeded in popularity those of the superior person, the student—was a personal affront. On his death-bed, in 1592, Greene found an outlet for his resentment in writing an ill-natured farewell to life, in which he girded bitterly at the new dramatist, whose early plays had already brought him into public notice. He warns his three brother playwrights—Marlowe, Nash, and Peele—against the “upstart crow, the only Shake-scene in the country” who “supposes he is as well able to bumbast out a blanke verse as the best of you.” How it is possible to interpret these words to mean that the “upstart crow” was not an author, “but only an actor who pretended to be an author also,” the oldest inhabitant of Colney Hatch and Mr.43 Theobald must decide between them. These anything but “cryptic” words, as Mr. Theobald describes them, can have but one interpretation, and that is the one their author intended. They do not imply that Shakespeare, the “upstart crow,” is not the author of the plays imputed to him, but that he considers his plays as good as those of the older dramatists. His profession of authorship is not questioned, but the quality of his work is savagely challenged. Any other construction put upon the passage is sheer nonsense. Mr. Theobald appeals to the “most gentle and gentlemanly critics” to be patient and tolerant with the Baconians—“men as sound in judgment and as well equipped in learning as yourselves”—but it is high time that this kind of wilful misrepresentation and perversion of common sense should be condemned in plain language. If Greene had believed that Shakespeare was wearing feathers that did not rightfully belong to him, if he were pretending to be what he really was not; if, in Mr. Theobald’s confident explanation, he had no right to profess himself an author at all, we may be quite certain that Greene would have said so outright—he would not have adopted a “cryptic” style, and left it for Mr. Theobald to decipher his meaning.

Mr. Theobald’s alternative theory that the word “Shake-scene” does not refer to Shakespeare at all, is even more preposterous. “In 1592 ‘Shakespeare’ did not exist at all, and only two or three of the plays which subsequently appeared under this name could have been written.” But those two or three plays included, as far as we can tell, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Two Gentlemen of Verona, and The Comedy of Errors—plays of sufficient promise to secure any author recognition as a poet and dramatist. If Mr. Theobald entertains any serious doubts as to the identification of Shakespeare in the “Shake-scene” of44 Greene, he may be advised to read the apology for this attack which Henry Chettle, the publisher, prefixed to a tract of Greene’s in the same year. “I am as sorry,” Chettle wrote, “as if the originall fault had been my fault, because myselfe have seene his (i.e., Shakespeare’s) demeanour no lesse civill than he (is) exelent in the qualitie he professes, besides divers of worship have reported his uprightness of dealing, which argues his honesty and his facetious grace in writing that aprooves his art.”

St. MICHAEL’S CHURCH.

Extract from the Will of Lord Bacon.

“For my burial I desire it may be in St. Michael’s Church, near St. Albans; there was my Mother buried, and it is the only Christian Church within the walls of Old Verulam.

“For my name and memory I leave it to men’s charitable speeches, and to foreign nations, and the next ages.”

This apology put forth by Henry Chettle is an invaluable attestation to the character and literary standing of Shakespeare—“his uprightness in dealing” is a matter of public report, and “his facetious grace in writing” is frankly acknowledged. At a period when professional rivalries ran strong, and no man’s reputation was above attack, a publisher and fellow author is seen regarding Shakespeare not only as a man to whom an apology was due, but to whom it appeared expedient to make one. In treating of the personal history of Shakespeare, it must be borne in mind that although the duly-attested facts regarding him are regrettably few, the poet was widely known to the leading literary and theatrical men of his day. Ben Jonson, his brother actor and dramatist, and Michael Drayton were his intimate friends. Condell and Heming remained in close relationship with Shakespeare until his death, and Richard Burbage was his partner in the business of the Globe Theatre. In Pericles and Timon, Shakespeare worked in collaboration with George Wilkins, a dramatic writer of some repute, and William Rowley, a professional reviser of plays. There were besides, the members of the Globe Company, men who lived their lives beside him, rehearsed under him, learned from him, interpreted him. Yet none of these45 men appear to have entertained the slightest doubt upon the genuineness of his claims to authorship, while every contemporaneous reference to him is couched in terms of affection and admiration. The only possible explanation of this remarkable fact is that Shakespeare and Bacon were one and the same person—a theory that the most hardened Baconian has not yet thought it advisable to advance.