WALKS

NEAR EDINBURGH.

BY

MARGARET WARRENDER

With Illustrations by the Author

"Haud fast by the past"

EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS

1890

(All Rights Reserved.)

MORRISON AND GIBB, PRINTERS, EDINBURGH.

TO MY GRAND-AUNT

LADY JOHN SCOTT

FROM WHOM MANY OF THESE STORIES ARE DERIVED

THIS BOOK

IS GRATEFULLY AND AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED.

[Pg 6]

| PAGE | |

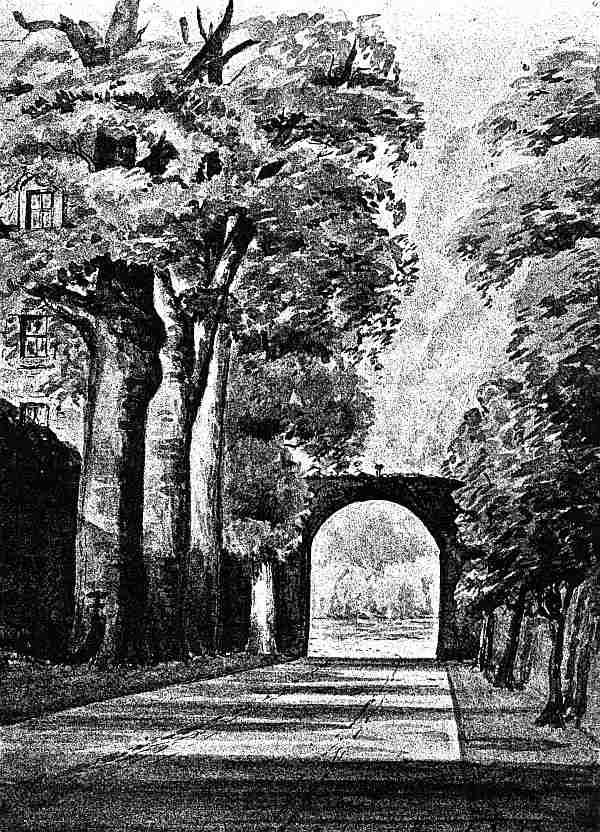

| ARCHWAY AT BRUNTISFIELD, | Frontispiece |

| BRUNTISFIELD HOUSE, | 12 |

| BATTLE-STONE AT COMISTON, | 26 |

| CRAIGLOCKHART TOWER, | 32 |

| LIBERTON TOWER, | 51 |

| THE INCH, | 71 |

| DOORWAY AT PEFFER MILL, | 78 |

| CRAIGMILLAR CASTLE, | 81 |

| DUDDINGSTON LOCH, | 99 |

| LOCHEND, | 123 |

| TOMB IN CORSTORPHINE CHURCH, | 130 |

| THE CAT-STANE, | 136 |

| SAUGHTON BRIDGE, | 142 |

| CAROLINE PARK, | 149 |

| GATEWAY AT CAROLINE PARK, | 153 |

| CARVED STONE AT LAURISTON CASTLE, | 156[Pg 7] |

| PAGE | |

| WALK I. | |

| Bruntisfield—St. Margaret's Convent—Canaan Lane—Hermitage of Braid—Morton Hall—Dreghorn—Colinton—Craiglockhart—Craighouse— Merchiston Castle—The Wryteshouses, | 9-42 |

WALK II. |

|

| St. Roque—The Grange—Blackford—Liberton—St. Catherine's Well—Gilmerton—The Burnt Grange—The Drum—Moredun—The Inch, | 43-73 |

WALK III. |

|

| Cameron Toll—Prestonfield—Peffer Mill—Craigmillar— Edmonstone—Niddrie—Duddingston—St. Leonards, | 75-107 |

WALK IV. |

|

| St. Margaret's Well—St. Anthony's Chapel—Muschat's Cairn—Jock's Lodge—Portobello—Restalrig, | 109-125 [Pg 8] |

WALK V. |

|

| Corstorphine—The Cat-Stane—Gogar—Hatton— Saughton Hall—Dalry, | 127-144 |

WALK VI. |

|

| Warriston—Caroline Park—Muirhouse—Lauriston Castle—Cramond—Braehead—Cammo—Barnton— Craigcrook—Ravelston, | 145-167 |

Index, |

169-181 |

WALKS NEAR EDINBURGH.

Bruntisfield—St. Margaret's Convent—Canaan Lane— Hermitage of Braid—Morton Hall—Dreghorn—Colinton— Craiglockhart—Craighouse—Merchiston Castle—The Wryteshouses.

At the outset of these walks, I must pause and explain to my imaginary companions where we are going, and what we are going to see. Let them not raise their hopes too high! I am taking them neither to the dark and mysterious wynds of the Old Town, nor to the beautiful and distant glen of the Esk, nor farther afield, to Linlithgow's "lonely bower." My sphere is a humbler one. The Old Town of Edinburgh has been so much and so ably written upon, that it can only be from idleness that any one is ignorant of its history. Roslin, Hawthornden, Dalkeith, Linlithgow, have each their separate guide-books, with every detail most fully given. But extending round Edinburgh, at a distance of from three to five miles, are a number of curious old places, and remains of antiquity, of which the traditions [Pg 10] are gradually dying away. The great extension of the town of late years has swept away the memory of some; others, from having changed owners at short intervals, have lost the recollections of their former days; others, again, can only have their history unravelled by a diligent search through scarce, and sometimes voluminous works.

To collect some of these stories and out-of-the-way facts together has been my object; and if those who have neither time nor money for more distant expeditions will accompany me on an afternoon ramble, I think they will find much to interest them. I have avoided statistics of any kind,—they are the dry bones of description, and can easily be looked up if they are wanted,—and I have limited myself to the desultory information, which would naturally be poured forth in the course of a walk. The first one begins very much within the suburbs, but, as one writes most readily of what one knows best, I begin with my own home.

Bruntisfield is the last of the old houses in the immediate vicinity of Edinburgh which is still inhabited by its owners. Merchiston Castle and the Grange are let; the Wryteshouse has long disappeared; but Bruntisfield, in spite of recent additions and alterations, still preserves much of the character of the semi-fortified mansion, with protecting outworks, which centuries ago frowned over the Boroughmuir. Its antiquity is even more apparent inside than outside, from the thickness of the walls, the diversities of the levels, and the steep little turret stairs. [Pg 11]

The earliest owners of Bruntisfield appear to have been the Lauders of Haltoun (or Hatton, as it is called now). In 1452 we find James II. granting a charter to his consort, Queen Marie, "for the very sincere affection which he bears towards her," of the lands of Haltoun, the Plat, Weschal, Nortoun, Broumysfelde (Bruntisfield), the North Row of Rathow, and the rents of Gogar, belonging to the king by the forfeiture of the late "William de Laudre of Haltoun." The Lauders seem to have been shortly after restored, for in 1490 King James IV. granted a charter to "Sir Alexander Lawdre of Haltoun of the lands of Broumsfield." The same Sir Alexander, seven years later (1497), assigned "Brounisfeld, with its mansion-house, garden and herbarium (or park), to his son Alexander Lawder," who in James IV.'s confirmation of the charter (1506) is quaintly styled "the king's familiar," and who held these lands of his father by the yearly payment of a red rose. Bruntisfield appears to have been considered a suitable appanage for the heir-apparent of Haltoun, for in August 1586 we find James VI. confirming a charter of Sir William Lauder granting these lands to his eldest son Alexander.

Soon after this (in 1603) Bruntisfield passed away from the Lauders, being sold by Alexander Lauder to John Fairlie, probably a cadet of the family of Braid.[1] He apparently altered and added to the house, as it would seem from the [Pg 12] date 1605, which with the initials I. F.—E. W., is over some of the windows. The original house was of much older date, as we have evidence that a mansion-house stood here in 1457.

In 1695 William Fairlie sold Bruntisfield to George Warrender, afterwards Lord Provost of Edinburgh, and created a baronet in 1715. His family was of French extraction,—his ancestor, a De Warende, having come from Picardy in the train of Mary of Guise. By degrees he acquired other lands lying contiguous to Bruntisfield, by purchase from Rigg of Riggsland, Biggar of Whitehouse, and Dick of Grange; and these form the property of Bruntisfield as it now stands.

The Lauders of Haltoun became extinct in the 17th century, and their representation devolved on the Maitland family by the marriage of Elizabeth Lauder, the heiress of Haltoun, with Charles, fourth Earl of Lauderdale. That descent we have inherited through my father's mother, Lady Julian Maitland; so that, after a lapse of nearly three hundred years, the descendants of the original possessors inhabit the old house again. [Pg 13]

After the purchase of Bruntisfield by George Warrender, it remained for nearly a hundred years in possession of the younger branch of the family, which came to an end in 1820 by the death of Hugh Warrender, an old bachelor, who was Crown Agent for Scotland.[2] [Pg 14] He was succeeded by his cousin, my grand-uncle, the Right Hon. Sir George Warrender, M.P., who on taking possession discovered the existence of a secret room. The house was then thickly covered with ivy. Lee, the Royal Academician, and an architect that Sir George had brought down from London with him, were the first to suspect its existence, from finding more windows outside than they could account for. The old woman who had charge of the house denied for a long time any knowledge of such a room; but, frightened by Sir George's threats, she at length showed them the narrow entrance, that was concealed behind a piece of tapestry. This was torn down, and the door forced open, and a room was found, just as it had been left by some former occupant,—the ashes still in the grate. Whether, as one story said, it had been used as a hiding-place in troubled times,—or whether, according to another legend, it had been the room of a [Pg 15] dearly loved child of the house, after whose death it had been hurriedly shut up, never to be entered again by the broken-hearted parents,—there are now no means of knowing; but the blood-stains on the floor point to some darker tragedy, and a tradition still lingers that, not long after the discovery of the room, a skeleton was found buried below the windows. It is still known as the Ghost-room, though nothing has been seen, at any rate for many years.

The newly-built houses which now closely surround Bruntisfield have swept away two curious landmarks of the past. One was the mound of earth on which James IV. stood to review his army, preparatory to the expedition which ended so disastrously at Flodden.[3] The other was a flat, moss-grown stone which lay in the park, almost hidden by the grass and daisies growing round it. On it was carved a skull, surmounted by a winged hour-glass and a mutilated scroll; and below it a shield bearing a saltier, and the initials M. I. R. and the date 1645. "The M.," says Wilson in his Reminiscences of Old Edinburgh, "surmounted the shield, indicative of the standing of the deceased as a Master of Arts, and so telling of a scholar and a gentleman, who slept there apart from his kin, a victim to that last and most fatal visitation of the plague." When that part of the park was built over, [Pg 16] the stone was carefully removed from its ancient site, and placed in safety against a wall in the garden of Bruntisfield, where, though much obliterated by weather, its carvings can still be traced.

Once outside the gate of Bruntisfield, we find ourselves on the Links, but there is little of their former country wildness left about them now. Houses hem them closely in on every side. The straight paths, formal rows of young trees, and stiff plots of shrubbery, give them the look of a suburban common. The occasional golf-player, a rare sight now, seems like a ghost of the past still lingering in his old haunts. Let us call back the past as it was two hundred and fifty years ago, and what a different scene is here! Before us lies an open, undulating muirland, covered with whin and broom, and in the more sheltered hollows grow thickets of thorn and natural oak. This is the great Boroughmuir, which stretches far away to the hills of Braid, and in more remote times formed part of the ancient forest of Drumselch. A long winding loch lies between us and the town, in the low ground which future generations were to call the Meadows. Its placid waters and reed-fringed shores are the haunts of innumerable wild-fowl. The moor is bare and desolate, but here and there rises a stern, grey tower, half fortress, half dwelling-house, with a few humble cottages clustering round it for protection and defence. Such is the Wryteshouse, the ancient home of the Napiers, its walls enriched with quaint carvings and inscriptions, which [Pg 17] crowns the gently rising ground at the south-west corner of the loch. The evening breeze no longer brings us the sweet sound of St. Catherine's vesper bell, for long before the day whose story is unrolled before us the tide of the Reformation had swept wildly through the land; but the shattered walls still remain to bear witness to the piety of an elder generation. St. Roque's Chapel is in ruins, but the victims of the plague still find a last resting-place near the shrine of their patron saint.

Such, then, was the Boroughmuir two hundred and fifty years ago, the great gathering ground on which so many troops had assembled before marching against the Southron, and on which so many skirmishes had taken place in the civil wars that rent the country in Queen Mary's time; but it requires an effort of the imagination to realize it all now!

The house opposite Bruntisfield was formerly the residence of Dr. Gillis, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Edinburgh, whose remains rest in the vaults of St. Margaret's Convent, a few yards farther south, on the opposite side of the road. The late Mr. Hope Scott and his first wife (Sir Walter Scott's grand-daughter) are buried there also. This was the first religious house built in Scotland since the Reformation. It was founded in 1835, and belongs to the Ursuline order. Though much of the building is new, part remains of the old mansion of Whitehouse, where Principal Robertson lived while writing his history of Charles V. Before that even it had been the scene of [Pg 18] literary work, for John Home is said to have written part of the tragedy of "Douglas" at Whitehouse.[4] Two other convents existed on the Boroughmuir before the Reformation. They are now so completely swept away, that the only memory left of them is a much-corrupted form of their names. The Pleasance and the Sciennes, standing not very far from each other, at the south-eastern end of the Meadows, mark the spot where once stood the convents of St. Mary of Placentia and St. Catherine of Sienna. The latter belonged to the Dominican order. It was founded in the 15th century by Marjory, second wife of William, third Earl of Orkney and first Earl of Caithness, but most of the building was erected some years later at the expense of Lady Janet Hepburn, eldest daughter of Patrick, first Earl of Bothwell, and widow of George, fourth Lord Seton, who fell at Flodden. She survived her husband forty-five years, and spent the greater part of that time (after her son came of age) at the convent of St. Catherine. The papal bull by which the foundation was confirmed is dated 1517. In 1547 the convent was dispersed. Up to within the last few years, a small portion of the original building still survived.[5]

[Pg 19] Proceeding to the bottom of the Whitehouse Loan, we now turn to the right, and then again sharp to the left, and find ourselves in Canaan Lane; a name which recalls the Covenanting times, when the Old Testament was the source of most names of either places or persons. This is a very biblical neighbourhood. Canaan Lodge, Mount Hebron, Eden Bank, the Land of Goshen, are among the names which surround us. The only one of these houses to which any interest is attached is Canaan Lodge, where once lived Dr. Gregory, whose name is widely known in every nursery. To complete the biblical illusion, the little stream—now pent between walls, and hardly more than a ditch—which takes its rise in Craiglockhart Hill and flows eastwards, is the Jordan Burn. On the other side lies Egypt, not many years ago a quiet country farm, now built over.

On leaving Canaan Lane, we again turn to the left, and soon find ourselves crossing the Suburban Railway. Two roads offer themselves, both leading southwards, and uniting about a mile and a quarter farther on. The eastmost of the two, though the oldest and steepest, is the most picturesque, so we will follow it.

After crossing the brow of the hill, a shady glen opens to our left, with a carriage drive leading into it, along the banks of the little stream. This is the Hermitage of Braid, a curious old place, and, till you explore its deep and narrow valley, it is impossible to realize its extreme seclusion. The banks are so steep, and descend so abruptly, that the beeches and sycamores, which appear like scrubby [Pg 20] bushes from the neighbouring fields, are in reality forest trees rising from the sides of the burn. So closely are their branching tops entwined, that few rays of sunlight can straggle down to the dim green twilight beneath. The house is small and square, with pepper-box turrets at the four corners, and was built about the year 1780. The first owners of Braid of whom we hear, were the Fairlies.[6] During the Reformation, the Laird of Braid was one of the earliest who received its doctrines, and was a personal friend and zealous defender of John Knox. In the 17th century Braid belonged to the Dicks of Craighouse. From them it passed to the Browns of Gorgie, and finally, at the end of the last century, it was bought, together with the neighbouring property of Craighouse, by Charles Gordon of Cluny. He married Miss Trotter of Morton Hall, and was the father of Colonel John Gordon, and of three daughters,—Jacky, [Pg 21] afterwards Lady Stair,—Charlotte, Lady Johnstone of Westerhall,—and Mary, who died unmarried. The two elder were very beautiful and very wild. There are innumerable references to Miss Jacky in contemporary letters and memoirs. The adventures of her stormy youth scandalized even the free-spoken and easy-going people of her time, and will hardly bear repetition now. She eventually married John, seventh Earl of Stair, in 1804, but the marriage was an unhappy one, and Lord Stair made use of a notorious Colonel Dalzell to rid himself of his wife. The plot succeeded, and they were divorced; but when she discovered the shameful artifice that had been practised, the horror of it sent an already excitable mind off its balance, and for years Lady Stair was kept under restraint at her brother's house of the Hermitage. The tradition still lingers, that at nightfall passers-by along this lonely road were often startled by her screams. She recovered her senses some years before her death, and passed the remainder of her life in Edinburgh, an altered woman in every respect, and died there in 1847, and is buried on the north side of St. Cuthbert's Churchyard.

Of late years the Hermitage has been usually let, and at present is the residence of Mr. Skelton, to whom we owe so many valuable historical works.

On the opposite side of the road is the pond belonging to the Morton Hall Curling Club. A few hundred yards farther up the hill, and passing on our left the road which leads to Liberton, we reach the [Pg 22] highest point, where the road is cut through the solid rock which forms the westmost spur of the Braid Hills. From here, on a bright spring day, when the distance is cleared by a north-west wind, the view is most beautiful. Edinburgh and the sea lie at our feet; and beyond, the eye travels westward, from the fertile shores of Fife, to where the Ochils rise behind the wooded crest of Corstorphine, and then melt away into the far-off Perthshire hills, that stand above Loch Katrine, and guard the entrance to the Highlands. Far in the west a distant blue peak fading into the sky is Ben Lomond; and, on a very clear day, we may just see the shadow of the Cobbler behind it. Nearer to us is the rocky outline of the Dalmahoy hills, and between us and them stretches a fair expanse of woodland and pasture, which gradually sweeps up to where the Pentlands shut out the view to the south-west.

Just before reaching the lodge of Morton Hall, we pass the Buckstone on our left,—a large rocky fragment, on which the proprietor of the barony of Penicuik,

is bound by his tenure to sit and wind three blasts of a horn when the king shall come to hunt on the Boroughmuir. Hence the crest of the Clerks of Penicuik—a demi-forester proper, winding a horn, with the motto, "Free for a blast." [Pg 23]

Morton Hall stands to our left, with its winding drives, its woods and sheltered gardens, lying open to every gleam of the sun, and protected from the cold north winds by the high ground of the park behind. In the reign of James III. it belonged to the St. Clairs of Roslin. It became the property of the Trotters, an ancient Berwickshire family, about 1641, and now belongs to Colonel Trotter of the Grenadier Guards. John Trotter, the second in possession of Morton Hall, was a great loyalist, and was fined £500 in 1645 by Parliament, for assisting Montrose. The house, which was built towards the end of the 17th century, is a comfortable square stone building, and has in it some very fine tapestry representing the story of Perseus and Andromeda. At different places in the park occur those curious whinstone monoliths, of which a line once extended across the country, from the Pentlands to the Esk. On the south side of the Braid Hills, within the park, is a small natural sheet of water, which lies in a hollow that was called of old Elve's or Elf Kirk, denoting a place where the fairies assembled. A little distance below this, nearer Morton Hall (says the Rev. Mr. Whyte in his account of Liberton Parish), is a piece of ground called Kilmorton. The name tells us that here stood a Cella, or religious house; but no tradition survives concerning it, nor are any remains of it to be seen.

Returning to the high road, on the opposite side stands Comiston, a small place which derives its name from the Camus stone, once the [Pg 24] marchstone of its eastern boundary. This was a huge monolith which stood on the brow of the hill at Fairmilehead, and which, within the memory of the last generation, was barbarously broken up to make road-metal. Like other Camus or Cambus stones (from the celtic Cam, crooked) in different parts of the country, it had probably been set up as a landmark, or as a memorial of some contract between great chiefs.[8]

At Fairmilehead, where formerly stood a toll, four roads meet. The one to the left leads past Morton House, and along the sunny park-wall of Morton Hall, to the Burdiehouse road. Part of Morton House is very old. Like Morton Hall, the property belonged in James III.'s time to Sir Oliver Sinclair of Roslin. His successors possessed both places for many years. From them Morton House passed to the Riggs, cadets of the family of Rigg of Carberry. It now belongs to Colonel Trotter, but it is generally let, and it was here that Dr. Hill Burton, the historian, died in 1881.

Our way lies to the right, and yet, the road stretching straight in front of us,—how sorely does it tempt the wanderer on! Past Hillend, where the three ways part, and along the upper road under the shoulder of Cairketton,—and so on to where the shadows play beneath the high beech avenues of Woodhouselee,—till he turns at last to reach the wooded opening of Glencorse, and sees before him that wild, lonely loch, beneath whose silvery waters lies the ruined chapel of [Pg 25] St. Catherine of the Hopes. Let him wander up the solitary haunts of Logan Water, till the path ends, the last tree is left behind, and he finds himself in an amphitheatre of hills. They stand around him in silent majesty, while the lengthening shadows creep up their steep, grassy sides. The sky is blue and cloudless overhead,—the whispering wind is all but hushed in this sheltered spot,—not a sound is heard but the far-off bleat of a sheep, or the crow of a grouse on the moors beyond,—and then, in the solemn peacefulness of this place, let him realize if he can that a city, with its turmoil, its din, and its busy crowd, lies little more than an hour's ride from him!

But to-day we must not stray so far; and, before leaving Fairmilehead, let us turn for a moment to the recollections of a prehistoric age, of which the land on which we stand is full. It is certain that this was the site of a Roman town (the name Morton meaning "the great city," from Mhor, the Celtic "great"), to which a road led from Teviotdale, and proceeded to Cramond, an important Roman station on the Forth. To preserve the memory of the ancient Roman road, the present one was formed on its line for nearly a mile, by direction of Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, one of the most learned antiquarians of his day. Tradition says a great battle took place here between the Romans and the Picts. The Roman army was encamped on the Gallachlaw (the wooded rising ground to the east), and traces of their entrenchments can still be seen along the west approach to Morton Hall. The Pictish king was killed, and buried beneath a huge [Pg 26] tumulus, now, alas! destroyed, but in which remains of men and weapons were found.

and now all that remains to tell the tale of how this ancient people fought and struggled, is the massive, unhewn Battle-stone, lichen-covered and weather-stained, which stands a silent witness to the past. Behind it still rise the mighty hills, whose name of Pentland recalls the Pechts or Picts, who so long ago sought refuge in their fastnesses from the foreign invader.

[Pg 27] The Battle-stone, Kelstane or Caiystone, as it is variously called, stands on the right of the road, about a hundred yards west of Fairmilehead. It is a monolith of red sandstone, standing seven feet high, and reaching nearly as far below the ground. Near its base are still distinctly visible the mark of seven cup excavations, of the usual form, arranged in a row like those of the cromlech at Bonnington.

Passing the steep narrow lane to the left, which leads to Swanston,—a hill farm of Colonel Trotter's on the slope of Cairketton,—whose low, thatched, white cottages make a charming study for the artist, we reach the picturesque tiled roofs of the Hunter's Tryst. This was long ago a comfortable little ale-house. Persons still alive remember when it was kept by two respectable old women, who cooked a capital dinner. In former days it was the custom for citizens of Edinburgh to shut up their places of business early on Saturdays, and go out into the country to dine about four or five o'clock at one of these little inns. The Hunter's Tryst was a favourite resort. The Six-Feet Club used to meet here from time to time. It was an athletic society, to which Sir Walter Scott and the Ettrick Shepherd belonged.[10] We now pass the entrance-gate of Dreghorn, and, turning to the left, [Pg 28] skirt the park. This is a pretty place standing at the foot of the Howden Glen, and with the Redford Burn running through it. Though the house is modern in appearance, part of it was begun in the 17th century by Sir William Murray, Master of the Works to Charles II. He married the daughter of Sir James Foulis of Colinton, to whose family most of the surrounding land then belonged. Since then Dreghorn has passed through many hands, and now belongs to Mr. Macfie. In 1720, when the property of Mr. George Home of Kelloe, a young man came as tutor to the family, whose name—David Malloch or Mallet,—would mean as little to us now as it did to those who only saw in him the struggling pedagogue, had it not been for the one ballad, which, written as he wandered up the banks of the Redford Burn, has from that day been enshrined in every collection of ballad literature:— [Pg 29]

So run the first two verses of "William and Margaret." The opening lines were put into Mallet's head by the fragment of an old ballad spoken by "Merrythought" in Fletcher's play of "The Knight of the Burning Pestle;" but the poem itself commemorates an unhappy affair much talked of at the time.

The inscription on a tablet in honour of General Gordon, which we see as we pass the keeper's house, was put up by Mr. Macfie. He also raised the slender monument, supported by four clustered columns, a few yards farther on. It bears an inscription on one side in memory of the Covenanters (who, in 1666, were encamped here previous to the battle of Rullion Green), and on the other side some lines which refer to the ancient Roman camp which stood close by. The road now makes a steep descent, and crosses the burn by a picturesque, ivy-hung bridge, which, with the castellated gate-house beside it, and the wooded banks overhanging the stream, form a charming picture. Though so near the hills, this is a most sheltered spot, and the first snowdrops and the earliest green buds on the hawthorn may generally be found here.

To our right, close to the burn, lies Redford House; and those colossal stone carvings which adorn the stable-wall were once part of the pediment of the old Infirmary in Edinburgh, and were removed here [Pg 30] by Mr. Macfie when that was pulled down. A few yards farther on, as we reach Colinton, the road branches to the right and left. That to the left leads, by many winding turns, to Bonally and the wild hill-country beyond. Originally a farmhouse, the late Lord Cockburn transformed Bonally in 1845 into its present form, and laid out the charming garden with its quaint laurel hedges and smooth-shaven lawns sloping down to the burn. Passing through the little wood behind it, we can reach a track which leads over the shoulder of the hill into Glencorse, close to the remains of a Roman camp; and which, though rather boggy in wet weather, is quite rideable, and from which the views are lovely beyond words.

The other houses about Colinton are hardly more than villas, standing in their own grounds, and with no particular interest attached to them, so we will return to where we branched off, and take the road to the right which passes the gate of Colinton House. This was originally known as Hales (from the Celtic Hales, a mound or hillock).[11] Ethelred, the son of Malcolm Canmore, granted it to the monks of Dunfermline, but it seems to have been an uncertain possession, as later it was taken away, and given to the canons of Holyrood, and transferred from them in 1445 to the canons of St. Anthony at Leith. After the Reformation, it was bought by James Foulis, the Clerk-Register, a man of very ancient family—his ancestor [Pg 31] having come from France in the reign of Malcolm Canmore. The old manor-house, of which the ruins still remain in the park, was the home of the Foulis; but there is no authority for the supernatural interest with which Mrs. Oliphant has chosen to invest it in her story of The Open Door. The present house was built by Sir William Forbes of Pitsligo, who bought Colinton in 1800 from Sir James Foulis. After his death, it passed into the hands of the Speaker Abercromby, first Viscount Dunfermline, to whose grand-daughter, the Hon. Mrs. Trotter, it now belongs. The high, steep bank overhanging the Water of Leith, with the little village nestling at its foot, is very picturesque; but the pride of the place lies in its magnificent cedars, and the tall old holly hedges in the garden.

Leaving Colinton behind us on the left, we proceed along the shady, beech-bordered road that leads to Craiglockhart, and soon pass the Hydropathic Establishment. To the north, sloping down to the Water of Leith, is a very old place—Redhall. Edward I. of England is said to have been here in 1298. It belonged to the ancient family of Otterburn of Redhall, which became extinct in the 17th century. The heiress, Anne Otterburn, married Sir James Hamilton (of the Priestfield family), and it was he who defended Redhall against Cromwell in 1650. The castle was besieged by ten companies of the Coldstream Guards (then known as General Monk's Regiment), which [Pg 32] eventually carried it by storm. The only vestiges left of the old castle are the red stones of which it was built (which have been largely used in the modern walls of the park), and a large memorial stone bearing the arms of the Otterburn family, very finely sculptured.[12] The place now belongs to Mr. David Chalmers.

We now see the two hills of Craiglockhart on our right. The name is probably derived from Craig-lochard (the high craig by the loch), an appropriate enough name in the old days, when its rocky sides were reflected in the great Loch of Corstorphine, which then extended to its foot. The steep face of the eastern hill is thickly wooded and ivy-grown, and traces may still be seen of the winding paths and [Pg 33] shady bowers which made it once a beautiful pleasure-ground. These were laid out about the beginning of the century by a Dr. Munro,[13] but neglect and forgetfulness has turned them to a wilderness.

No traditions remain to tell when or by whom the old tower was built, of which we can still see the ruins nestling in the shelter of the red-roofed farm buildings. The history of much of this neighbourhood seems lost in the mists of forgetfulness. Half a mile farther on, where the Union Canal comes close to the road on the left, we look across it and see a solitary gate-pillar standing in a field. This, and a curious old pillar sundial on the opposite side of the road, are all that remain of the ancient mansion of Meggetland, which, in the early part of the 18th century, belonged to a family named Sievewright; but of what it was like, what was its history, and why it was destroyed, there is no trace or record.

We are fast returning to our original starting-point; but, before making our way back by Merchiston Castle, let us turn aside for one moment at Myreside, and, taking the road to the right, in a few [Pg 34] minutes we reach the old mansion of Craighouse. This curious old place stands on the eastern slope of Craiglockhart Hill, and is approached by a venerable lime avenue. An air of mysterious antiquity hangs over the house, which, with its massive walls, and small, many-paned windows,[14] looks as if it had been the scene of more than one romantic tale. Could its walls speak, we might know the truth of that weird story (which so often has made me shudder as I gazed at them) of the unhappy Lady of Craighouse, who, overcome with grief and misery at the loss of an adored husband, shut herself up here, and spent the remainder of her life in a room all hung with black, into which the light of heaven was never permitted to enter! The lapse of years has dimmed all recollection of her name and previous history; and equally unknown is the mysterious S. C. P., whose initials, with the date 1565, are carved on the lintel of the entrance door. There is one story said to be connected with Craighouse, which I have heard all my life, and have read in collections of Scottish traditional tales, which I should have liked to relate here,—that of the deadly quarrel between Moubray of Barnbougle and the sons of the murdered Bruntfield of Craighouse,—but on attempting to verify it from ancient histories and MSS. in the Advocates' Library, I found, to my [Pg 35] disappointment, that it was a romance resting on the slenderest foundations, and in no way connected with Craighouse.

During the reign of James VI., this place belonged to a younger branch of the Kincaids of that ilk in Stirlingshire. John Kincaid, the laird's eldest son, got into great trouble in 1600, by forcibly carrying off a young and beautiful widow, named Isabel Hutcheon, who was living at the time in the house of a peaceful citizen, by the water of Leith. John Kincaid, helped by an armed party of friends and relations, took her to Craighouse, but, fortunately for her, the king happened at that very time to be riding across the neighbouring fields. Hearing her screams, he sent Lord Mar and Sir John Ramsay to see what was happening. They threatened to set Craighouse on fire, unless Mistress Hutcheon was at once released, which was done. Kincaid was tried for this outrage, and fined 2,500 marks, payable to the Treasurer. He was also ordered to deliver up his brown horse to the king.[15] Soon after this, Craighouse passed into the possession of a historically well-known man, Sir William Dick of Braid, Knight, who in his own person experienced greater alterations of fortune than usually befall one single individual. Lord Provost of Edinburgh in the time of Charles I., and so wealthy, that the value of his money and landed estates has been computed at no less than £226,000 sterling, which is nearly equal to two millions of money at the [Pg 36] present time,—he yet died in the debtors' prison. During the civil war he was alternately plucked by either party, who took from him, by forced loans, not less than £180,000 in hard cash. Going to London with his family, in hopes of recovering this money from Parliament, he was arrested for some small debts incurred there; and the remainder of his property being locked up in lands and bonds, and not readily to be got at, he was thrown into prison, where he died December 19, 1655,—a strange and sad end for one who, not long before, had been the richest commoner in the kingdom. Craighouse and Braid, with other of his possessions, were swallowed up by the mortgages upon them. Craighouse has passed through many hands since, and eventually, like the Hermitage, was bought by the Gordons of Cluny.

Returning to Myreside, we continue our walk due east, along a road bordered by villas, till we find ourselves passing on the left the narrow postern door, guarded by the lions couchant that surmount the pillars on either side. Behind it stands Merchiston. This very ancient castle, built no one knows when or by whom, has for centuries belonged to the illustrious family of Napier, they having acquired it in 1438. Their most famous son, John Napier, the inventor of logarithms, was born here in 1550. His father, Sir Alexander, who was only sixteen years old at the time of his birth, was later Master of the Mint to James VI. His mother was Janet, only daughter of Sir [Pg 37] Francis Bothwell, and sister to Adam, Bishop of Orkney. John Napier pursued his studies and researches at Merchiston. He was supposed by the vulgar to be deeply versed in magic, and to possess a familiar spirit in the shape of a jet-black cock. The story goes that once, when some petty thefts had been committed in the castle, of which one of the servants was suspected, Napier brought them all up the winding stair into a darkened room, where the cock was placed. He commanded them to stroke its back, declaring it would crow at the touch of the guilty person. During the whole ceremony the cock remained silent, but afterwards the hand of the culprit was found to be free from the soot with which the bird's feathers had been liberally sprinkled.

Napier was also believed to possess the power of discovering hidden treasure. Among the Merchiston papers still exists a curious contract, dated July 1594, between him and Robert Logan of Restalrig, which sets forth: "Forasmuch as there were old reports and appearances that a sum of money was hid within Logan's house of Fast Castle, John Napier should do his utmost diligence to work and seek out the same." For his reward he was to have a third of the discovered treasure. "This singular contract," says Wilson, "acquires a peculiar interest when we remember the reported discovery of hidden treasure, with which the preliminary steps of the Gowrie conspiracy were effected;" Logan of Restalrig being deeply implicated in that plot, though nothing of his share in it was known at the time. [Pg 38]

The true fruit of Napier's years of toil and study appeared in 1614, when he produced his book of logarithms, which he dedicated to Prince Charles (afterwards Charles I.), and which rapidly made his name famous over Europe. He died at Merchiston in 1617, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Archibald. This was the first Lord Napier. He married Montrose's sister, and for some years he acted as tutor to his illustrious brother-in-law, who was left fatherless very young. It was his son, the second Lord Napier, who was Montrose's faithful companion and friend. He married Lady Elizabeth Erskine, and when he passed into the exile from which he never returned, she remained for some time at his castle of Merchiston, and was here when Montrose was executed. From here she sent the faithful servant, who at the dead of night stole to the unhallowed spot on the Boroughmuir where the mutilated trunk of the dead hero had been hastily buried. He carefully and reverently extracted the heart; and, wrapping it in the piece of fine linen, which to this day is treasured in the Napier charter-chest, he brought it to his mistress, who had it skilfully embalmed. It was then enclosed in a steel box made of the blade of Montrose's sword, and preserved as a precious relic. Montrose had always felt a deep affection for his nephew and his wife, and had promised at his death to leave his heart to Lady Napier, and so the pledge was redeemed. The adventures through which the heart passed afterwards, and the marvellous manner in which it was more than [Pg 39] once lost and recovered, would fill volumes. A most interesting account is given of it in the appendix to Napier's Life of Montrose. Thirlestane on the Ettrick, which came later by marriage into the family, is now the home of the Napiers, and Merchiston has been for many years let as a school. An old pear-tree in front is still pointed out as having been planted by Queen Mary; and a quaint little panelled closet is called her bedroom.

A few yards farther brings us to the main road, which runs by the west side of Bruntisfield Links, and out by Morningside. A curious relic is preserved on the crest of the hill to the south, between the turnings to Church Hill and to Newbattle Terrace. This is the block of red sandstone in which the flagstaff of the royal standard was planted, when King James IV. mustered his army on the Boroughmuir in 1513.

It is now called the Bore-stone, or Hare-stane, and is preserved from injury by being securely fastened on the top of the wall, while its history is inscribed on a bronze tablet beneath. [Pg 40]

After this brief divergence, we turn to the left, and find ourselves in a few minutes back on Bruntisfield Links, where our pilgrimage to-day began. Before ending this chapter, it might be worth while to give the true ghost-story of the Wryteshouses, as so many different versions have been told of it.

Towards the middle of the last century, the Wryteshouses was rented for a year by General Robertson of Lawers, while his own house in Perthshire was undergoing some alterations. He had at the time a black servant, who was given a room near his master's. The first morning, the man came scared and trembling to General Robertson, and said he could not stay another night in the house, for that, after he had fallen asleep, he had been roused by a noise, and saw a headless lady, with a child in her arms, walking up and down the room. General Robertson treated the story with ridicule, and the man was persuaded to sleep in the same room the following night. Next morning he again came, entreating to be allowed to go away altogether, rather than to suffer such terrors. The General would not listen to him, and would neither let him go away, nor even change his room. The man got thinner and more miserable-looking every day, and was quite out of health when, by the end of the year, they returned to Lawers.

Many years passed. General Robertson died, and was succeeded by his niece, Mrs. Williamson (whose husband, Lord Balgray, was a Lord of Session). She was one day visited at Lawers by a friend, to whose [Pg 41] family the Wryteshouses belonged. This lady asked her if, during the twelvemonth they had spent there, any of the family had heard or seen anything extraordinary. Mrs. Williamson, in answer, told her the story of the black servant. The lady was much interested, and asked whether he was still alive, and if it would be possible to hear him tell the story himself. Mrs. Williamson replied, that was quite easy, as, though now an old man, he was living close by, in a cottage that had been given him. She sent for him, and he repeated his story, and said the year he had spent at the Wryteshouses had been one of terror and misery, as, to the very last night of his stay, the lady had walked backwards and forwards in his room, with the child in her arms. Mrs. Williamson's visitor made him describe exactly the room he had inhabited, and then told him that, in making some alterations in that very room, they had lately discovered a large closet, which they had broken open. Inside they found a box containing the skeletons of a woman and a little child. The box was too short, so the woman's head had been cut off, and placed beside her. In the same closet was also found a chest full of MS. papers. One of these papers appeared to be a sort of confession, written by an ancestor of the family; who said that his elder brother (the owner of the property) had been ordered abroad to the wars, leaving his wife and child to the care and guardianship of the younger brother. He never returned, and the writer owned to having murdered both mother and child, setting about [Pg 42] a report that they had died, and by these means possessed himself of the inheritance.[17]

The Wryteshouses,—Wrychtishousis,—or Wrightshouses, as it is variously spelt, was pulled down in 1800 to make room for Gillespie's Hospital, a very ugly edifice built in accordance with the will of James Gillespie, who had amassed a large fortune as a tobacconist. The ancient family of Napier of the Wryteshouses has long been extinct. They were in no way related to the Napiers of Merchiston, but probably were a branch of Kilmahew, whose estates lay in the Lennox. The arms of the two families indicate this connection, both having a bend azure; on which Kilmahew bore three crescents, and Wryteshouses a crescent between two mullets. The Napiers of Merchiston bear arms quite distinct from either, a saltier engrailed, cantonned with four roses.[18]

St. Roque—The Grange—Blackford—Liberton—St. Catherine's Well—Gilmerton—The Burnt Grange—The Drum—Moredun—The Inch.

We begin to-day's walk at the bottom of the Whitehouse Loan, turning to the left into the ancient thoroughfare which led of old from the Linton Road to St. Giles's Grange, and is still called the Grange Loan. A villa bearing the name of St. Roque, which we pass on the right, recalls memories of the chapel which once stood here.[19] It was of great antiquity, and it is uncertain when exactly, or by whom, it was founded, but from early days it was a dependency of St. Cuthbert's. Being dedicated to the saint whose help was implored for protection from the plague, a cemetery gradually grew round it, where those who died of that dreadful malady were buried. In 1532 we find [Pg 44] that the Provost and bailies, "moved by devotion for the honour of God, and his Blessed Mother Virgin Marie, and the holy confessor Sanct Rok," granted four acres of land in the Boroughmuir to Sir John Young, the then chaplain, so that he and his successors might offer prayers for the souls of those who lay buried round, and that they might also keep the walls and windows in repair.[20] After the Reformation the performance of divine service was left off, and the building, with the land attached to it, granted to private persons; but for some time longer people continued to be buried there. The fanaticism of the time spared the chapel, and, though gradually mouldering to decay, its ruins remained safe and unharmed till the beginning of this century, when they were swept away by the vandalism of a retired tradesman, who thought they encumbered the grounds of his villa!

Before turning down Blackford Avenue, which opens to our right, a hundred yards farther on, let us glance for a moment at that curious old house, the Grange,—or, as its title more correctly stands, St. Giles's Grange. This was once the farm belonging to the cathedral [Pg 45] church of St. Giles, in the pre-Reformation days, when each church and abbey had broad lands attached to it. In the 17th century the Grange was among the large possessions of Sir William Dick; and in the wreck of his fortunes, it was preserved to his third son William by the liberality and wealth of the latter's wife, Janet M'Math. She had inherited great riches from her own family, of whom she was the last survivor, as well as from her first husband, Thomas Bannatyne. Much of this money she devoted to the needs of her second husband's family, even paying the bill of poor Sir William's funeral expenses. Her descendant, Sir Thomas Dick Lauder (who also represents a younger branch of Lauder of the Bass), is the present possessor of the Grange.

When Prince Charles held his court at Holyrood, he visited the Grange, and presented the family with the thistle from his bonnet, which is still preserved by them with great care. Robertson, the historian, spent the last years of his life here, where he died in 1793. Parts of the house are very old, but it has been a good deal added to, at different times. It is said to be haunted by a ghost in the form of a miser, who rolls a sack of gold coins about the older parts of the building. The tradition is, that if any of the family were to see him, they would become possessed of the treasure.

Till within the last few years, the most picturesque cottages imaginable stood close to the gate of the Grange. Their whitewashed walls, overhung with masses of ivy,—their thatched roofs and [Pg 46] irregular gables,—their curious outside stairs, and the air of antiquity that overshadowed them, made them dear to every artist's soul; and no scene in the vicinity of Edinburgh was more often drawn or painted. Now, alas! the mania for so-called improvement, which is the curse of the present day, has swept them away; and the Grange, like any other villa, is enclosed by a prim stone wall, ending in the most modern of lodges.

A little farther along the loaning is the Penny Well, which was restored a few years ago; but as yet I have not succeeded in discovering anything of its history or traditions. Somewhere near here there formerly existed a holy well, to which the nuns of the convent of St. Catherine of Sienna used to resort; but I do not know if it can be identified with the Penny Well. The Lovers' Loan runs along the western boundary of the garden of the Grange, in a northerly direction, till it almost reaches the Meadows. Not so many years ago it was a shady, secluded walk,—now it is only a path between high walls; and though some of the hawthorn bushes at the northern end still survive, they have been clipped and cut in, till they have lost all remembrance of their old luxuriance. It is probable that this is the remains of one of the old paths that intersected the Boroughmuir, to which we occasionally find reference in old charters.

A little west of the Grange, Blackford Avenue branches off to the south. Till the making of the Suburban Railway gave a great impetus of progress to this part of Edinburgh, it was a quiet country road, [Pg 47] shaded with trees on either side, and leading to the gateway of Blackford House. The charming description that Sir Thomas Dick Lauder gives of this place in his Scottish Rivers describes so exactly what it was early this century, and what it remained up to within a few years ago, that I cannot refrain from quoting it.

"The house was old, and not very large, and in no very remarkable style of architecture; but what there was of it—and there were a good many small rooms in it—might be said to be very rambling. There was something so venerable in the very air of its front, that no one could lift its brass knocker without a certain feeling of respectful awe. It was covered with the richest jessamines and roses, and the gravel circle before the door was always kept in a state of the most exact tidiness. On the south side of the premises there was a high and steep bank of shaven turf, with a pretty little parterre flower-garden between its base and the house, and a broad terrace walk at top, that stretched along under some noble trees, close to the boundary of the place in that direction. The fruit and vegetable garden, which had some variegated hollies of goodly size in it, occupied the gently sloping ground at some little distance in front of the house, and beyond this there was, and we think we may say is, a fine open grove of old and well-grown trees.... There we find, seated in her arm-chair, but springing from it in a moment to meet us half-way across the room, an old lady of a handsome, dignified countenance, lighted up with clear, black, benevolent [Pg 48] eyes, and of a tall and commanding figure, though modified by a very slight bend.... Those who did not know her so well as we did, might have supposed her to have been but a little above seventy years of age only, from the freshness and vigour she displayed; we, who were aware that in her younger days she had flirted with our father, knew that she had seen ninety years. But oh, how green and vigorous her old age was, both in body and mind! and how fresh and warm were all her affections!... How interesting were the old stories that she told! how easily were they narrated in the purest Scottish vernacular, and how perfectly did she bring back and vivify people, of whom we had heard much, but whom we had not lived early enough to know personally!"

The old friend whom Sir Thomas describes so touchingly was Miss Menie Trotter, one of the last of the race of old Scotch ladies, so clever, so original, almost to eccentricity, so idiomatic and plain-spoken in their expressions, and yet such perfect gentlewomen. She was the sister of the laird of Morton Hall, and, though but slenderly endowed, her liberality and charitableness to her poorer neighbours was unbounded.[21] All her life she was a very active woman. Every morning she bathed in the Jordan, which then ran pure and sparkling [Pg 49] through her garden, and afterwards she walked all over Blackford Hill before breakfast. Ten miles at a stretch was nothing to her within a few years of her death, which happened when she was above ninety.

The railway has shorn the old place of many of its attractions; and the road now runs past it, and gradually mounts up to the red sandstone gateway which leads to Blackford Hill. The hill, which formerly belonged to Morton Hall, was bought by the town of Edinburgh in 1884, to form a great public park, chiefly by the exertions of Sir George Harrison, the then Lord Provost. Though no longer a lonely and sequestered spot, the wind blows as freshly over the hill, the view is as beautiful, and the whins and thorn trees grow as freely as when Sir Walter wrote his never-to-be-forgotten lines, which rise unbidden to the traveller's thoughts, as he slowly and wearily climbs to the highest rocky point—

Leaving the hill behind us to the west, we pass through the farm of West Liberton Mains, and, after turning to the right, soon emerge on the old coach road which led from Edinburgh to Peebles and Biggar, and all the wide stretch of country between them.

Liberton crowns the hill in front of us, and when we see its modern-looking church, and the trim villas that surround it, it is difficult to realize what an old place it is. The name is supposed to be a corruption of leper-tun, as of old a hospital for lepers existed here, every vestige of which has disappeared. The earliest mention of this place occurs in charters of David I. between 1124 and 1153, some of which were witnessed by Macbeth, Baron of Liberton. It was he who granted titles and lands to the chapel, which was then subordinate to the church of St. Cuthbert. By a later charter of King David's (1143-47), Liberton was granted to the canons of Holyrood, who retained it till the Reformation. There were three subordinate chapels,—St. Margaret's, near the Balm Well of St. Catherine; the Blessed Virgin's Chapel at [Pg 51] Niddrie; and the little hunting-chapel built by James V. at the Bridgend near The Inch. Since the 16th century the barony of Upper Liberton has belonged to the Littles, and it is now in possession of their direct descendant and representative, Mr. Gordon Gilmour of Craigmillar. The old house of Liberton stands to the west of the village. An avenue of lime trees leads down to it, on one side of which stands the dovecot, in old days the distinctive privilege of the lord of the barony. Additions to the house, early in this century, have spoiled it externally, but inside it is very curious. The walls are of immense thickness, the windows are small and numerous, and over them, as well as over most of the doors and fireplaces, there are massive arches of red sandstone. The hole is still visible in the wall of the turret staircase, which, commanding the outer door, enabled the inhabitants to fire unseen on their assailants. Over one of the windows is the date 1695, but the house [Pg 52] is far older, and is known to have been in possession of the Littles in 1570. The tower, hard by, though ruined and deserted, still lifts its head proudly over the humble sheds and farm-buildings at its side, and "far o'er the Forth, looks to the north," across the deep and lonely valley in front of it, as it did in the old days, when it was the terror of the surrounding country.

In a hedge near the cross road, which leads back from Liberton House to the village, grows the wormwood (Artemisia vulgaris), with its deeply-cut, silver-lined leaves, and curious, aromatic smell. It is the only place in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh where I have noticed it growing. When we reach the main road again, we turn to the right, and, passing the large reservoir that the Edinburgh Water Company have lately built, we soon reach the east lodge of Morton Hall. On the opposite side of the road is a small place, St. Catherine's, in the garden of which still stands the famous Balm Well, to which in former days so many pilgrimages were made. The water of the spring is covered with a film of petroleum; and however frequently the film is removed, it always returns. In old days the well was much resorted to for the curing of cutaneous distempers. It owes its origin to the following miracle. St. Catherine had a commission from St. Margaret, the queen of Malcolm Canmore, to bring her some holy oil from Mount Sinai. At this very place she happened by accident to lose a few drops, and on her earnest supplication the well appeared. [Pg 53]

When James VI. was in Scotland in 1617, he went to visit it, and ordered that it should be fenced in with stones from bottom to top, and that a door and staircase should be made for it, so that it might be more easy of access. The royal commands being immediately obeyed, the well was greatly adorned, and remained so till 1650, when Cromwell's soldiers almost totally destroyed it. It was repaired again after the Restoration. St. Catherine was buried in a chapel adjoining the well, which was pulled down in the last century. It was observed that the man who pulled it down never prospered again. There are still remains of the old stonework to be seen; and now, as then, a black, oily substance floats on the top of the water, but the well is only visited in these days as a curiosity, and not with the trusting faith that its miracle-working powers excited of old.

When we reach the blacksmith's shop at the corner, our way turns to the left, and we leave the road we have hitherto followed, to pursue its course to the shale-works and coal-pits of Straiton and Loanhead. The thick white smoke drifting along the rising ground to the south of us comes from the limekilns of Burdiehouse, which are surrounded by a labyrinth of caves, out of which the limestone has been quarried. Fossils of curious plants and fishes are found there in great quantities. It is said that the name Burdiehouse is a corruption of "Bordeaux," and that the place was so called by some of Queen Mary's French attendants who settled there. [Pg 54]

Taking the next turn to the right, we cross the small burn, and climb the steep hill to Gilmerton, passing the old Place or Manor House, which stands within gates at the west end of the village. This was the dower house of the ladies of Newbyth. Mrs. Baird, the mother of the famous general, Sir David Baird, of Mrs. Wauchope of Niddrie, and of Lady Haddo, lived here at the end of the last century. Some cottages a little farther on bear the pretty and romantic name of Laverock Hall. In former days the inhabitants of Gilmerton had a bad reputation as a lawless and turbulent set. Cut-throat Lane, the name of the road where we again turn to the left, just before reaching the railway arch, is suggestive of days when highway robberies were more common than now. Before the Glencorse railway was made, this was a desolate, lonely spot, and the rough, overgrown hedges on either side might easily have concealed a dangerous ambush.

When we reach the end of Cut-throat Lane, before turning northwards, on the way back to Edinburgh, let us pause for a moment; for down in the hollow to the south is a cottage which deserves more than a passing mention. Five centuries have elapsed since the terrible tragedy took place which turned the name of Gilmerton Grange to Burndale, or the Burnt Grange; and, whether we read the story in the quaint, unadorned language of The Memorie of the Somervilles, or with the charm of Sir Walter's verse[23] thrown round it, it alike fills the mind with horror. The tale may be briefly told as follows:— [Pg 55]

In the reign of David II., the lands of Gilmerton in Midlothian, and of Edmonstone in Clydesdale, belonged to Sir John Herring or Heron, a brave and gallant knight who had fought side by side with Sir Alexander Ramsay of Dalhousie against the English. Sir John had two daughters, Margaret and Giles; the elder of whom he intended to marry to his brother's son, Patrick, and to make them heirs to the greater part of his estate. His intentions were frustrated in a most unhappy manner. Margaret was very beautiful, and of a melancholy and devout disposition. She observed strictly all the rites and ceremonies of the Church, and for that purpose was in the habit of frequenting the Abbey of Newbattle, about three miles off. There she made the acquaintance of a young Cistercian monk, who, under a specious pretext of holiness, insinuated himself into her confidence, and then took advantage of the ascendancy he gained over her, to ensnare and betray her. Fearing that this intrigue should be detected, he arranged to meet her at the little farm called the Grange, a short distance from Gilmerton, on the road leading to Newbattle. The surrounding country was then thickly wooded, and he thought they would be more secure from observation there than at her father's house, or at the Abbey. The mistress of the Grange, a young and dissolute widow, was the more willing to lend herself to this plan, as she was also carrying on an intrigue with another monk of [Pg 56] Newbattle. In spite of the secrecy with which these meetings were conducted, suspicions arose from the undue familiarity subsisting between a lady of rank, and one so beneath her in condition, and of such doubtful character, as the mistress of the Grange, and rumours came to Sir John's ears. Being a man of violent and irritable temper, he threatened his daughter with nothing less than death, should she ever resort to the Grange again. She promised compliance with his wishes; but that very night she stole out in the darkness to meet the monk once more, and to warn him of her father's suspicions. Sir John missed her, and, discovering that her chamber was empty, proceeded to the Grange, accompanied by two servants. Finding the doors shut, and no answer made to his demands, in a fit of rage, he took a torch from his servant's hand and set fire to the thatch. A high wind was blowing, the flames rapidly spread, and in a short time the building, with every one in it, was burned to the ground. Eight or nine persons perished, including Margaret Herring and the two monks.

For this cruel act, which was aggravated into sacrilege by the fact of two of the victims being Churchmen, Sir John had to fly from the country, while his estate was forfeited to the king. His near neighbour and friend, Sir Walter Somerville of Carnwarth, undertook to intercede for his pardon. He represented to the Abbot of Newbattle how scandalous the lives of the two monks had been, even before their acquaintance with that unhappy lady, and how their villainies had [Pg 57] thrown the greatest reproach on the order to which they belonged. Finally, he prevailed upon the Abbot and the fraternity to listen to an accommodation, provided he could move the Bishop of St. Andrews to procure the absolution of the Church.

In the meantime, Sir John, with his remaining daughter, Giles, a beautiful girl of eighteen, came secretly and dwelt at Sir Walter's castle of Cowthally. Sir Walter, who was a widower at the time, fell in love with Giles, and made a bargain with her father, that, if he procured his pardon from the king, he should marry her, and that half the lands of Gilmerton should be settled on him and his wife, and the heirs of the marriage, or any other marriage, past or to come, irredeemably for ever. The matter was arranged at last by Somerville's exertions in the following manner:—

"That Sir John should make over for him and his the merk land of the Grange, where the murder was committed, to, and in favour of the Abbey of Newbattle, claiming no right therein, neither in property, superiority, nor vassalage in all time coming; and, further, that the said Sir John should, bareheaded and bare-legged, in sackcloth, crave absolution at the Bishop and Abbot's hands, and stand in the same manner at the principal door of St. Catherine's Chapel every Sabbath and holy day for one year, and paying forty pennies at every time to the poor of the parish, and one hundred merks Scots to the [Pg 58] monks of Newbattle to pray for the souls of those that died through his transgression." These conditions were accepted and performed by Sir John, whereupon he had his pardon from the king, was restored to his estate, and had absolution from the Church.

These events happened in 1375, and it was owing to them that the house of Somerville first acquired lands in Midlothian. For years afterwards Cowthally in Lanarkshire remained their principal residence; and it was not till 1584 that Hugh, the eighth Lord Somerville, began the house of the Drum[24] (the gate of which we pass on the right on our way northwards to Gilmerton), from the design of John Milne, the king's master-mason. It was finished the following year; but the pleasure of Lord Somerville in his new home was sadly marred by the melancholy event which took place there four years later, on a hot July morning in 1589, and which is related as follows in The Memorie of the Somervilles:—

"The Lord Somerville having come from Cowthally early in the morning, in regard the weather was hot, he had ridden hard to be at the Drum by ten o'clock, which having done, he laid him down to rest." The servant, with his two sons, William Master of Somerville, and John his brother, went with the horses to ane shot of land, called the [Pg 59] Pretty Shot, directly opposite the front of the house, where there was some meadow grass for grazing the horses, and willows to shadow themselves from the heat. They had not long continued in this place, when the Master of Somerville, after some little rest, awaking from his sleep, and finding his pistols that lay hard by him, wet with dew, he began to rub and dry them, when unhappily one of them went off the ratch (lock), being lying on his knee and the muzzle turned sideways. The ball struck his brother John directly in the head, and killed him outright, so that his sorrowful brother never had one word from him, albeit he begged it with many tears. A lamentable case, and much to be pitied. Two brave young gentlemen so nearly related, and dearly loving one another; who, besides their being brethren by birth, were entirely so in affection, communicating all their affairs [Pg 60] and designs to one another, wherein they were never known to differ in the least.[25] ...

"The father, hearing the shot, leapt from his bed (being then in the chamber of dais), to the south light, and, seeing his son and servants all in a cluster, cried aloud to know the matter; but, [Pg 61] receiving no answer, he suspected some mischief, and thereupon flew hastily down the stair, and went directly to the place where they were, which the gentlemen observing, they advised the Master to take him to a horse, until his father's passion and fury should be over; which, at length, upon their earnest entreaty he did, taking his direct way to Smeaton, where his lady-mother then lived, by Smeaton Ford. The father being come upon the place, first hears the lamentation of the servants, and then sees the sad spectacle of his son, all bloody and breathless, with his head laid upon a cloak, whereon he falls himself and cries aloud, 'My son, my son, dead or alive? dead or alive?' embracing him all the time, which he continued for some space, and thereby giving time for his eldest son to escape. At length, finding no motion in his dear son, all in a fury he arises and cries aloud, 'Where is that murderer? Who has done the deed?' Staring wildly about, and missing the Master, he cries out 'Oh heavens, and is it he? Must I be bereft of two sons in one day? Yes, it must be so; and he shall have no other judge or executioner but myself and these hands.' And with that immediately mounts his horse, commanding two of his servants to attend him, making protestation in the meantime that they should both go to the grave together. But God [Pg 62] was more merciful, for by this time the Master was past Smeaton Ford, and before his father came that length, he was at Fallside House, out of all danger....

"Coming now a little to himself, he (Lord Somerville) began much to condemn this unwarrantable attempt of his upon second thoughts. Before he came back, the sad object of his sorrow was removed to the place of Drum, and the corpse decently handled by the ladies of Edmonston, Woolmet, and Sheriffhall, near neighbours, for in less than one hour the report went over all the country. Yea, before the king rose from dinner, he had notice of it, being then in Holyrood house, with the circumstance of the father's following the other son with intention to kill him; for which the king within three days thereafter (the Lord Somerville coming to wait upon his majesty), reproved him by saying, 'he was a madman, that having lost one son by so sudden an accident, should needs wilfully destroy another himself, in whom, as he was certainly informed, there was neither malice nor design, but a great misfortune, occasioned by unwary handling of the pistol, which should have rather been a matter of regret and sorrow to him, that the like had happened in his family, than that he should have sought after revenge. Therefore he commanded him to send for his eldest son, and be reconciled to him, for he knew he was a sober youth, and the very thought of his misfortune would afflict him enough, albeit he were not discountenanced by him.'"[26]

[Pg 63] The Master never held up his head again, "and now, as formerly, by his affable and obliging carriage, he had procured the epithet of the Good Master of Somerville, so from henceforth he might have been called the Sad and Sorrowful Brother; for it was observed from the very moment of that unhappy accident, until his death, which fell out about three years thereafter, he never enjoyed a comfortable hour, but was still sad and melancholy."

In January 1592, the Master died from the effects of a fever, acting on a low and broken spirit; and with him perished all the hope and expectation of the house of Cowthally. Well might their ancient retainer, as the corpse passed the outer gate, smite on his breast and cry aloud, "This day the head is clean taken off the house of Cowthally, as you would strike off the head of a sybba!"[27]

The extravagance of Gilbert, the succeeding Lord Somerville, dissipated all the family property in Lanarkshire; and the lands of Gilmerton and the Drum remained the sole possession of a family which was now so poor that the head of it dropped his ancient title and held it in abeyance.

The house of the Drum, which had been burnt soon after its completion, then rebuilt in greater splendour, and again burnt in 1629, was left in a ruinous state till 1730-40, when James, the thirteenth Lord Somerville, pulled it down, and built an entirely new [Pg 64] house, from Adam's designs. This Lord Somerville revived the title and restored the fortunes of the family. He was assisted in this by his own wise and prudent conduct, and by the advantages he gained from two rich marriages. He was an ardent Hanoverian; therefore, when in 1745 Prince Charles was holding his court at Holyrood, with a strong army in possession of the capital, Lord Somerville felt his position at the Drum, only four miles from Edinburgh, was an unpleasant one.

One night, when the family were at supper, word was brought in that the Highlanders were seen advancing up the avenue. All were in consternation. The plate was instantly thrown out of the window into the grass, which luckily was high; and Lady Somerville entrusted a casket of diamonds to her step-daughter, Anne (afterwards Mrs. Burges), with directions to conceal them. Miss Somerville ran out of the house into the deer-park, and, making a hole at the root of a tree, buried the diamonds, and crept back to the house unperceived. In the meantime, Lord and Lady Somerville had locked themselves into a closet in one of the garrets, and effectually concealed themselves. The Highlanders, about forty in number, broke into the house, and, not finding Lord Somerville, contented themselves with feasting on whatever they could get in the kitchen and cellars, and then carried off everything movable of any value. By this time a servant had escaped to the village of Gilmerton, and roused the inhabitants, who sallied forth to Lord Somerville's rescue. Half-way between the [Pg 65] village and the house they met the Highlanders. A bloody conflict ensued, in which three of the former and five of the latter were killed. It ended in the Highlanders relinquishing their booty and beating a retreat. Next day the Prince, with his usual generosity, and out of respect for Lord Somerville's high character, sent an officer's guard to protect him.

Eight months later, when the royal cause was defeated and lost, Lady Somerville bethought herself of her diamonds. Her step-daughter readily undertook to restore them, but when she went into the park, she found it by no means so easy a task as she expected. There were hundreds of trees growing there, and in the hurry and agitation of the moment, she had not observed exactly beneath which she had hidden them. She was afraid to confide her difficulties to her father, and did not think it advisable to trust in any of the servants. Finally she told her brother, and night after night the two went into the wood and hunted for the lost diamonds. At last, after much anxiety, they came upon them lying safely in the earth, the casket having completely mouldered away.[28]

In the year 1800, John, fifteenth Lord Somerville, sold the Drum to Mr. More Nisbett, to whose family it now belongs. The house was originally intended by Adams to have another wing; but the death of James, Lord Somerville, putting an end to the works, the eastern wing was never built.

We now leave the Drum on our right and proceed northwards on the main road leading from Newbattle to Edinburgh. After passing through the village of Gilmerton, we descend a long hill, and, looking over the wall to our left, perceive the venerable sycamores and chestnuts, and the high holly hedges, which hide the house of Moredun.

This place, which is of great antiquity, was originally known as Goodtrees,—corrupted by the vulgar to Gutters,—and formed part of the great Somerville property. During the minority of John, fifth Lord Somerville, these lands were alienated by his uncle and guardian, Sir John of Quathquan, who contrived to get a fresh grant from James IV., and had them settled on himself and his heirs, the Cambusnethan branch of the family. The story of how they were recovered is a curious instance of how frequently designing persons outwit themselves.

John, the third Laird of Cambusnethan, married, as his second wife, Katherine Murray,[29] a beautiful and very ambitious woman, who had been the latest of James V.'s many favourites. After his death, she lived at Crichton [Pg 67] Castle with her uncle, the Earl of Bothwell, till her marriage in 1552. Her husband settled the lands of Goodtrees and the rest of his property in Midlothian on her as a jointure, and on her eldest son after her. Not content with this ample provision, she coveted the lands of Cambusnethan also, though they were the rightful inheritance of her step-son, James, the Laird with the Velvet Eye (so called because, having lost an eye by a musket-shot, he ever after wore a patch of black velvet). Determined to lose no chance of ousting her step-son, she thought to secure the support of the head of the family by proposing an alliance between Lord Somerville's second daughter and her own son John. She accordingly went to Cowthally, and unfolded her plans to Lord Somerville, showing him the charters relating to the lands in Midlothian, which proved that her son was at any rate heir to a very considerable property. Lord Somerville asked for two days to consider the matter, and consulted his cousin, John Maitland, the future Chancellor, who was then living at Cowthally in a sort of honourable captivity. The latter told him that the lady's proposal, as far as Cambusnethan was concerned, was a very dishonourable one, and could bring no blessing with it, but that it might be worth while to see the papers, as the Lothian lands alone would be sufficient to make John Somerville a suitable son-in-law. He offered to look the papers carefully over, which, having done, he returned them to the Lady of Cambusnethan, who departed rejoicing, and thinking that she [Pg 68] had enlisted Lord Somerville on her side. He and John Maitland escorted her four miles on her way, and then went hunting.

During the sport Maitland asked his cousin, as if in joke, whether the lands of Gilmerton, Goodtrees, and the Drum had not once belonged to the elder branch of the family, and what he would bestow on the person who would show him the way to recover them. To this Lord Somerville said, smiling, "Cousin, the bargain should soon be made, if once I saw the man that made the offer." Whereupon Maitland informed him that, on going over the papers, he had found informalities in the deed of gift, which made the whole transaction void, and he showed Lord Somerville a copy he had made of the paper. He craved as his reward the white horse Lord Somerville was riding. This the latter gladly gave him, together with a silk and silver purse full of gold pieces. The purse was a much-treasured relic, having been made by Lord Somerville's mother, Janet Maitland.

Lord Somerville and Maitland at once proceeded to Edinburgh, where the former commenced a plea to recover the lands; but it was not till eight years later (in 1578), that it was finally decided in favour of Hugh, the succeeding Lord Somerville. It would not have been settled then, had not Lord Somerville, aware of Morton's avaricious nature, gone himself to the Regent to crave that his plea might be heard in the Inner House, to which opposition had hitherto been made by Cambusnethan and his party. On leaving the room, Lord Somerville drew [Pg 69] out his purse, as if to take a piece of money for the door-keeper, and left it lying negligently on the table. He went quickly down-stairs, and took no notice of the Regent's crying, "My lord, you have forgotten your purse!" By the time he came to the outer porch, one of Morton's attendants overtook him, saying the Regent desired he would return and breakfast with him. Lord Somerville knew his cause was as good as won, and so it proved; for, having been called and debated on, judgment was given in his favour on the 11th May 1578, and the lands in Midlothian returned to the head of the family, after having been for fourscore years in possession of the younger branch.