‘Adonijah no longer saw in the person of Lucia Claudia

the beautiful and beloved object of his secret affections,

but an idolatrous heathen priestess.’

ADONIJAH,

A TALE OF THE JEWISH DISPERSION.

BY

MISS JANE MARGARET STRICKLAND.

“Oh weep for those who wept by Babel’s stream,

Whose shrines are desolate—whose land a dream

Weep for the harp of Judah’s broken shell,

Mourn where their God hath dwelt—the godless dwell.”

Byron.

“Hebrew, come forth! dread not the light of day,

Dread not the insulter’s cry.

The arch that rose o’er thy captivity,

No more shall turn thee from thy destined way.”

Sotheby.

LONDON:

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, AND CO.

IPSWICH: J. M. BURTON AND CO.

PREFACE.

The period included in the reigns of Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian, was remarkable for two memorable events in the annals of ecclesiastical history; the first persecution of the Christian Church by the sixth Roman sovereign, and the dissolution of the Jewish polity by Titus.

The destruction of Jerusalem was stupendous, not only as an act of divine wrath, but as being the proximate cause of the dispersion of a whole nation, upon which a long series of sorrow, spoliation, and oppression lighted, in consequence of the curse the Jews had invoked, when in reply to the remonstrances of Pilate they had cried out, “His blood be upon us and our children.” The church below, represented in Scripture as a type of the heavenly Jerusalem above, and having its seat then in the doomed city, was not to continue there, lest the native Jews composing it should gather round them a people of their own nation, in a place destined to remain desolate till the time when the dispersed of Israel should be converted, and rebuild their city and temple. The city bearing the ancient name of Jerusalem does not indeed occupy the same site, being built round the sacred spot where the garden once stood, in which a mortal sepulchre received the lifeless form of the Saviour of the world.

But happier times seem dawning on the dispersed of Judea. Our own days have seen the foundations of a Jewish Christian church laid in Jerusalem; our Queen Victoria and the King of Prussia united to commence a work of love, thereby fulfilling in part the promise made to the Jews of old, “And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and queens thy nursing mothers.” To those readers who feel interested in the dispersed of Israel and Judea, these pages may afford, perhaps, information on an important subject as well as amusement.

Reydon Hall,

March, 1856.

ADONIJAH.

“But woe to hill, and woe to vale,

Against them shall go forth a wail!

And woe to bridegroom, and to bride,

For death shall on the whirlwind ride!

And woe to thee, resplendent shrine,

The sword is out for thee and thine!”

Croly.

The splendid regnal talents undoubtedly possessed by the Emperor Nero, and the great architectural genius he displayed in rebuilding his capital, had not atoned in the eyes of the Romans for the flagitiousness of his character.

His public munificence to the people, whom a mighty conflagration had rendered homeless, met with no gratitude, because he was believed to be the author of the calamity which had levelled the ancient city with the dust. This sweeping charge has no real historical foundation; and perhaps if the Emperor had not profited by the general misfortune, such a wild conjecture would never have been recorded nor believed.

His appropriation of a large part of the ground-plot, whereon to found his Golden House and its stately parks and gardens, gave to the vague report colour and stability; therefore Nero, finding no assertion of his could disprove the imputation, resolved to fix it upon a class little known and less regarded—a people composed of all ranks and nations, yet united by a peculiar faith in one brotherhood of love. Nero was no stranger to the vital doctrines of Christianity; he had heard St. Paul, when the mighty Apostle of the Gentiles had stood before his tribunal,—to which circumstance allusion has been made by himself in the Second Epistle to Timothy, “And I was delivered out of the lion’s mouth.”[1] Since that momentous period the heart of Nero had become hard and inaccessible to mercy; for the conversion of his favourite mistress and his cup-bearer by St. Paul had awakened his undying hatred against the Christian religion and its teachers.[2]

His terrible persecution had shocked a people accustomed to spectacles of horror. “Humanity relented”, remarks Tacitus, “in favour of the Christians,”—an expression which does not, however, imply that Christianity was tolerated, but that its professors were no longer sought for to load the cross or feed the flames.

The Church at this period, thinned in Rome by the martyrdoms of the fearful Saturnalia the Emperor had kept in his imperial gardens some years before, was scattered abroad or hidden in the Arenaria, its existence being only known by isolated cases brought before the tribunals of Helius and his infamous colleague Tigellinus for judgment.

Its influence, however apparently limited, was not unfelt; for in the midst of the blindness of Atheism and idolatry the light shone out, though surrounded by darkness—darkness that might be felt. The prophecies were fast accomplishing which the Divine Head of the Church had spoken respecting the Jews; for the inexpiable war had begun, and the sword of the Gentile was mowing down the thousands of Israel.

During his progress through Greece, the sight of the Isthmus of Corinth inspired Nero with the gigantic idea of cutting a barrier through, which occasioned an impediment to commerce, and rendered the navigation difficult and dangerous to the mariner.[3] This undertaking has been left incomplete—a vast work to be effected perhaps in modern times, in which science has achieved wonders never before accomplished by mere human labour.

The prejudices the Romans cherished against the man who had degraded the sovereign by singing on the stage, made a project so grand and useful appear a mad and ridiculous design. Nero, bending all his natural energy to this object, either did not care for, or remained ignorant of, the opinion of his subjects. He despatched letters to the prefect of Rome for labourers to be supplied from the public prisons, and Corbulo and Vespasian, his lieutenants in Armenia and Judea, received his imperial orders for the instant transmission to Corinth of the captives they had taken in the Parthian and Jewish wars.

The plan of cutting through the Isthmus was not, however, popular with the people it was intended to benefit; for the Corinthians ventured to remind the Emperor that Demetrius Poliorcetes, Julius Cæsar, and Caligula had in succession made the attempt, but had fallen by the sword soon after the work had commenced.

To a man of genius, ambitious of distinction, and possessed of the resources of a vast empire, these objections appeared of little moment, and Nero deemed his star too fortunate to set, like that of those princes, untimely in blood. He was not only animated by the hope of bequeathing a vast work of great public utility to posterity, but revelled in the pleasurable idea of gratifying his vanity by exhibiting himself before a vast concourse in the amiable light of a benefactor to Greece, Asia, and indeed to the whole world.

It was seldom Nero appeared in the appropriate costume of a Roman Emperor, the use of the imperial mantle of Tyrian purple and golden laurel being strictly confined by him to state occasions. A loose robe, dishevelled ringlets, and bare feet suited his notions of comfort, and ordinarily composed his attire; but the occasion seemed to demand more attention to outward appearance than he generally thought proper to bestow. He resumed, with the imperial costume, an elegance natural to him, and would have successfully represented the majesty of the greatest throne of the universe, if he had not resolved to display the sweetness of his voice to the vast multitude during the imposing ceremonial of opening the trench intended to divide the Isthmus. Arrayed in purple, the golden laurel-wreath of the Cæsars encircling his unwarlike brow, he advanced towards the shore, singing a hymn in praise of the marine deities, holding in his hand the gold pickaxe with which he designed to break the virgin ground. Amidst the lengthened plaudits of a vast multitude, Nero struck the first stroke into the earth, and raising a basket of sand upon his imperial shoulder looked proudly round him as if to claim a second burst of applause from flattering Greeks and degenerate Romans.

The clapping of hands and loud acclamations his admonitory glance demanded rent the air, and were echoed back from the surrounding mountains, to hail the exertions of the master of the world. Even the unhappy workmen, instructed by their taskmasters, swelled with their voices and fingers the flattering plaudit. One voice alone was mute; for Adonijah, a captive Hebrew, was new to slavery and despised the effeminate tyrant whom the chances of war had made the arbiter of his destiny. The ears of Nero, ringing with the adulatory huzza, perceived not the omission, but his quick restless eye caught for an instant among the crowd of workmen the scornful smile that curled the proud lip of the Jew; then lost his features in the dense mass of labourers surrounding him, whose hands were intended to complete what his imperial ones had begun. Yet, though swallowed up in those living waves, the form, the noble outline, of Adonijah dwelt in the memory of Nero; for never had he beheld hatred, scorn, and despair united with such manly and heroic beauty.

Who was this unknown slave who disdained the Emperor of Rome? Nero frowned as he internally asked the question; the self-abhorrent feeling that often made him a burden to himself was stealing over him, even in the face of this triumphant day, when the well-timed flattery of Julius Claudius, a young patrician who stood high in his favour, dispelled the gathering cloud on the imperial brow, and restored Nero to himself. The example of Julius was followed by the court; and the sovereign, forgetting the cause of his disquiet, left Adonijah to breathe a foreign air and to mingle the bitter bread of captivity with weeping.

Jerusalem, that holy city, over whose coming miseries the Lord of life had wept, was now “encompassed round with” the “armies” of the Gentile. The time of her desolation was at hand, and “the cup of the Lord’s fury” like a torrent was overflowing the land. The very heavens showed fearful signs of her approaching doom, for nightly a blazing star, resembling a sword, hung over the devoted city, while the cry of “Woe, woe to the inhabitants of Jerusalem!” rang through every street. Yet her fanatic tribes still confidently expected the coming of the Messiah, still obstinately contested every foot of their beloved land.

Never had Rome, since she first flew her conquering eagles, encountered a foe so fiercely determined to be free. Bent upon exterminating the Roman name, the Jew, whenever he gained a transitory advantage, left no foe to breathe. From the hour in which he conquered Cestius Gallus and his legions he never sheathed the sword, but obstinately maintained the contest till the prophecies were fulfilled, and “Zion became a heap of desolation.”

The time of the dispersion of the tribes of Israel was then about to be accomplished; and the recent victories of Vespasian had given the first fruits of the glory and beauty of the Holy Land into the enemy’s hand. Among these Adonijah was numbered, for he had been taken in arms at Jotapata;[4] but, unlike its obsequious governor Josephus, disdained to receive favour or pay servile homage to the conquering Roman general.

He had, during the siege, more than once scornfully rejected the overtures of Vespasian, who vainly tried to seduce him from his duty. Nay, more, when an apostate Jew without the walls, once numbered among his chosen friends, dared, at the bidding of the victor, to tamper with his honour, a javelin, flung with so true an aim that it reached the traitor’s heart and pinned him to the ground, was the only answer the bold young leader deigned to give to the infamous suggestion.

Something like enthusiasm warmed the cold bosom of Vespasian when informed of the tragical fate of his messenger, and a desire to converse with the heroic stripling whose fidelity was so incorruptible made him command his soldiers, when about to storm the city, to take him alive—a solitary exception of mercy to the general order of the day.

Adonijah, throughout the carnage of that dreadful assault, vainly sought the sole reward that Jewish valour might then claim—a warrior’s grave. His parents, his kindred, his faithful friends, all perished with Jotapata, while he was delivered alive and unwounded into Vespasian’s hands. Bold, haughty, zealous of the law—a Pharisee in sect, and despising all other nations—to be taken captive by the Gentile conqueror was bitterer than death to Adonijah, who, like Job, “cursed his day” and fiercely resented his preservation.

Vespasian, who hoped to make his captive a means to gain over his countrymen, commanded Josephus, the late governor of the conquered city, to visit and induce him by his eloquence and learning to favour his views.

Adonijah received his old commander with lively affection and devoted respect. All that man could do had been done by Josephus, and his young partisan shed tears while he pressed him to his bosom; but when his revered chief spake of submission to the Roman yoke, and hinted things still less consistent with the duty of a patriot, he turned away with indignation, sorrow, and contempt, nor would he again listen to the man who had ceased to love his country.

Then Vespasian himself, accompanied by his son Titus, condescended to visit his captive, but he too found him alike insensible to threats or promises. He charged his prisoner with ingratitude.

“Ingratitude!” scornfully reiterated the Hebrew. “You have left nothing breathing to claim near kindred with Adonijah. The last sound that smote mine ear as your people were leading me away a fettered captive, was the cry of my virgin sister. A Roman ruffian’s hand was twisted in her consecrated locks, his sword was glittering over her devoted head; I heard her cry, but could not save her from his fury. O Tamar! O my sister! Would to God I had died for thee, my sister! Such are the deeds, vindictive Roman, for which thou claimest my gratitude: but know, I hate existence, and loathe thee for prolonging mine.”

Incensed by the boldness of this language, Vespasian included his intractable prisoner in the number of those captives[5] required by Nero to carry into effect his projected scheme of cutting through the Isthmus of Corinth.

Bitterer than death, bitterer even than slavery, were the feelings that wrung the bosom of the exile as he turned a last look upon the land of his nativity. All he loved had perished there by the sword, yet he did not, he could not regret them, while he felt the chains of the Gentile around his impatient limbs. They were free—they would rise again and inherit the paradise of the faithful—while he must wither in slavery. No soft emotion for any fair virgin of his people shared the indignant feelings of his heart at this moment, though patriotism claimed not all his burning regret; for ungratified revenge, that ought at least to have had a Roman for its object, occasioned a part of his present grief.

Born of the house and lineage of David, Adonijah gloried in his proud descent, “though the sceptre had departed from Judah,” and the base Idumean line reigned on the throne of her ancient kings. Ithamar, a young leader in the Jewish war, boasting the same advantages, rivalled him in arms, and from a rival became his enemy. Both were obstinately bent on delivering their country from a foreign yoke, and for that end would have shed their blood drop by drop—would have done anything but give up their animosity.

It is difficult to define from what cause this unnatural hatred and rivalry sprang up. Perhaps it derived its source from religious differences, Adonijah being a strict Pharisee, Ithamar a Sadducee, and both were bigoted to the peculiar doctrines of their several sects. Their individual hatred, however, bore a more decided character than that they cherished against Rome. Those who are acquainted with the dreadful records of the last days of Jerusalem will not be surprised at the ill-feeling here described as existing between Adonijah and Ithamar.

The moral justice of the Pharisee of that day was comprised in the well-known maxim, “Thou shalt love thy friend, and hate thine enemy;” an axiom adopted by the rival Sadducee in the same spirit, and acted upon with equal fidelity. A perfect unanimity in this one respect existing between the disciples of these differing sects.

The idea that Ithamar would rejoice in his degradation was like fire to the proud heart of Adonijah, who shook his chained hands in impotent despair as the mortifying thought intruded upon him. Must he then die unrevenged, and be led into captivity, while Ithamar enjoyed freedom? He wrapped his face in his mantle, and sank into a state of sullen gloom, whose darkness no beam of hope could penetrate. Yet, in the true spirit of the Pharisee, even while longing to gratify revenge—the worst passion that can defile the human heart—he considered himself a perfect follower of the holy law of God.

|

Hegesippus, the earliest ecclesiastical historian,—quoted by Eusebius,—establishes the fact that an interval of years elapsed between the first and second appearance of St. Paul before the imperial tribunal. |

|

The reader will find this curious fact in the works of Clemens Alexandrinus and Chrysostom. It is quoted also by Doddridge. |

“Night is the time for care;

Brooding on hours misspent,

To see the spectre of despair

Come to our lonely tent,

Like Brutus, midst his slumbering host,

Startled by Cæsar’s stalwart ghost.”

J. Montgomery.

The Emperor of Rome was intensely jealous of the fame of the great Roman to whom he had given an immense share of power, little indeed inferior to that formerly granted by the senate to Pompey the Great. He did not distrust the commander of whose probity he had received so many proofs; but the splendid career of Domitius Corbulo excited odious comparisons between the sovereign and his lieutenant. His dislike was well known to his confidants, and by them was communicated to Arrius Varus, a brave but unprincipled young man, who, thinking it afforded him an opportunity of pushing his own fortunes at Corbulo’s expense, secretly accused his commander of treason, in a letter addressed to the emperor himself.

Nero did not believe the accusation, and he was undecided respecting the use to which he should put it; for he required the services of his lieutenant in the East, and had not quite made up his mind to kill the man whom Tiridates had styled “a most valuable slave.” He resolved to be guided by circumstances, and contented himself with writing to Domitius Corbulo a pressing invitation to visit his court at Corinth.[6] With the profound dissimulation in which Nero was an adept, he informed him of the accusation made by Varus, assuring him at the same time that he did not believe in its truth. The apparent frankness and generosity of his sovereign made the impression he had intended on the honourable mind of his general, who came to Corinth without the slightest suspicion of any sinister design entertained by Nero. He was accompanied by a few friends alone, and without a guard. Among those individuals who were honoured by his confidence was a military tribune or colonel, named Lucius Claudius, whose distant relationship to the emperor gave him some importance in the eyes of the Roman people; a cadet of a house associated by its greatness or guilt with every page of the republican and imperial history,—which had given to Rome more consuls, dictators, and censors than any other line,—which boasted Appius Cæcus, and Nero, the conqueror of Asdrubal,—and of which also had sprung Appius Claudius the decemvir, Clodius the demagogue, Tiberius the emperor, Drusus and Germanicus, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. Lucius Claudius had apparently entered life under peculiarly fortunate circumstances; though the military tribune did not resemble in character his ambitious ancestral race. The men we have just cited of the proud Claudian line were before their times, while he was behind those in which he lived. His noble temper, frank, generous, fearless, and true, had been formed by his revered commander, by whom Lucius had been trained to arms; his life had been passed in the camp, far from the corruption of Nero’s court and capital. His father was no more, his brother Julius, one of Nero’s dissipated companions, was with the emperor at Corinth, and his sister Lucia Claudia was the youngest of the vestal priestesses, but he had not seen her since the hour in which she was dedicated to Vesta.

Lucius came to Corinth, like his commander, without distrust or apprehension, for Nero was beloved in the provinces; his guilt, his licentiousness, were little known on the distant Roman frontier; and when Corbulo requested an audience of his sovereign, he had employed the interval in seeking for his brother. Upon learning that Julius Claudius was in the theatre, witnessing the imperial performance, he had retired to take the repose his weary frame required.

Nero, when he received intelligence of his lieutenant’s arrival, was dressed for the stage, in the habit proper to the comic part he was about to perform. The unsuitableness of his garb to that of a Roman emperor, about to give audience to the greatest commander of the time, and the impossibility of denying himself to a man like Domitius Corbulo, decided the fate of his general. Nero took the easiest way of settling a difficult point of etiquette, by sending a centurion with the imperial mandate, commanding his officer to end his days.

Corbulo without a guard or means of defence, received the ungrateful message with the stoical fortitude of an ancient Roman. “I have deserved this,” was his brief remark to his friends as he fell upon his sword. Nero went on the stage to play his part out, and in its comic excitement forgot the tragedy of which he had made his brave lieutenant the hero. The plaudits of his audience were at length over, and Nero, withdrawing to his dormitory, gave the watchword, and received the report from the centurion on duty of Corbulo’s death. The last speech of his lieutenant awakened a throng of conflicting passions in his bosom; he called for wine and drank deeply to drown remorse, but instead of the oblivion he sought, he became franticly delirious and rushed forth into the midnight air, none of his attendants daring to detain or follow their miserable prince, who, passing through the streets with mad precipitation, never halted till he found himself near the scene of his labours, the Isthmian trench. The beauty of the moonlight, the deep stillness of the night, undisturbed even by a wandering breeze, allayed the fever in the emperor’s throbbing veins. Thousands were sleeping around him, sleeping in their chains. He contemplated the toil-worn wretches with feelings of envy. He gazed intently upon them as they lay fettered in pairs upon the earth, and as his mind became more calm he examined their features with curiosity and interest. In sleep the mask, habitual cunning or reserve wears by day, is thrown off, and the true character may be distinctly traced. On the brows of the Roman criminals their crimes were legibly written. Pride, sensuality, rapacity, cunning, and cruelty, marked them as the outcasts of the corrupt and wicked city, the spiritual Babylon. The Jewish captives, who were all young and chosen men, bore the expression of sullen gloom, unsatisfied revenge, defiance, indignation, and despair; and even in slumber murmured, complained, or acted again the strife they had maintained so vainly against the Roman arms. One alone of all these thousands smiled, and he was the noblest and fairest of them all. From his parted lips a holy strain of melody broke forth, then died away in imperfect murmurs; but the listening tyrant recognised in the sleeper the slave whose scornful look had awakened his angry passions on the day when he opened the trench. Adonijah’s dreams are of his own land. He is going up to Jerusalem, to keep the feast of the Passover. His slaughtered brethren are with him, and Tamar, that fair and virgin sister, that Nazarite dedicated from childhood to the Lord, is dancing before them with the timbrel in her hand, singing, “I was glad when they said unto me, Let us go into the house of the Lord.” Suddenly, with the capriciousness of fancy, the scene changes. Again he hears the war-cry of his own people, again hangs upon the flying legions of Cestius Gailus, captures the idol standard, and calls upon the name of the Messiah, the promised deliverer of Israel. He comes, the mighty, the long-expected. The Romans are driven forth from the sacred soil, the valley of Hamoth Gog is full of slaughter, and Adonijah hails the king of Judah, the anointed one of the Lord, with holy joy. But swifter than lightning vanishes the glorious vision from his sight, he awakes, and finds himself a slave in a foreign land.

He looked around him doubtfully. The land before him is like the garden of Eden, and the breezes that fan his glowing cheek are fresh and balmy as those that wander over his beloved Judea. The mountains, whose summits are gilded in the radiant moonlight, remind him of those that encompass the holy city. His perception is still visionary and indistinct, the blue waves on either side the Isthmus, the scene of his labours, his raven locks wet with the dews of night, appeal to his scattered senses. The chains upon his free-born limbs sullenly clank as he rises from the earth, memory resumes her powers, he remembers that he is a slave.

Despair seizes upon his heart, his thoughts revert to his beloved sister. He no longer sees her bounding along the rocky heights in all the beauty of holiness and youthful enthusiasm, her form graceful as the palm-tree, from which she derives her name, but mentally views her sinking beneath the cruel sword of the Gentile. Her cry is in his ears, and again he utters the bitter cry, “O Tamar! O my sister! would to God that I had died with thee, my sister! Why was I not buried beneath the ruins of Jotapata? Why am I cast forth like an abominable branch to wither in this strange land?”

The wretched Hebrew sank upon the ground, wrapped his face in his garment, and sobbed aloud in the bitterness of his heart.

Though the emperor was ignorant of the language in which these words were spoken, he knew they were the accents of despair. A few minutes since he believed himself to be the most wretched man in his wide dominions, but this slave appeared as miserable, was he as guilty? as himself; for Nero, burdened with his crimes, felt that utter misery can only dwell with sin.

He addressed the slave in the Greek language, and bade him declare the cause of his passionate complaints.

Surprised, and not immediately recognising the emperor, who was still attired as a comedian, Adonijah unveiled his convulsed features and replied in the same tongue, one which was familiar to him.

“Why troublest thou me with questions? I was free—I am a slave. I had kindred ties—I am alone among the thousands of Israel. I had a God, and he has forsaken me. Whose sorrow can be compared to my sorrow? who among the children of men can be compared in misery to me?”

A wild scornful laugh broke upon the ear of Adonijah, who started upon his feet and gazed upon the figure, doubtful whether the being before him was of earthly mould or one of those evil spirits who were believed to haunt unfrequented places. In breaking the ground groans were said to have been heard, and blood had been seen to issue as from fresh wounds, and apparitions had warned the workmen to forbear. Superstitious feelings crept over the bold spirit of Adonijah; he pronounced the name of God and looked once more upon the countenance of the emperor. The wild expression of derision was gone, despair alone pervaded it. The features, the brow, were beautiful, but it was beauty stained with sin; the lineaments were youthful, though marked with an age of crime; the sneer on the lip bespoke scorn of himself and all mankind, but the eye was cruel, and expressed lawless power rather than princely majesty; although, degraded as he was, there was still an air that showed he had been accustomed to command. In this second glance Adonijah recognised the master of the Roman world.

“Is this all thy sum of care, and darest thou claim from Nero the supremacy of sorrow?” continued the prince. “Slave, thou art happier in thy chains than Cæsar on his throne! Dost thou see the dagger of the assassin lurking under the garments of every person who approaches thee? Art thou loathed by those who flatter thee, and secretly cursed by those who bend the knee before thee? Hast thou plunged in all riot, known all vice, revelled in all luxury, and only found satiety and loathing? Hast thou found pleasure weariness, happiness a chimera, and virtue an empty name? Speak, audacious slave.”

“Not so, Cæsar, for all the commandments of my God I have kept unbroken from my youth,” returned the self-righteous Hebrew. “Happiness dwells not with excess, for as Solomon saith, ‘Better is the wise poor man than the son of a king that doeth evil.’ Thou art wretched because thou art guilty.”

“Once, once I was innocent,” groaned the emperor; “years of sin have not effaced the recollection of that blessed time. No indignant phantom then banished slumber from my pillow, for I was guiltless in those happy hours. Then came ambition, and I grasped the imperial sceptre, and stained my hands with blood, innocent blood. My mother, my wife, my kindred, all perished. Rome was laid in ashes, but not by me; but the Christians died to remove from me the imputation of that crime. Hark! hear you not those cries? See you not a ghostly train approaching?” The eyes of the horror-stricken emperor fearfully expanded, he grasped the arm of the slave, muttering, “ ’Tis Agrippina, ’tis my mother; the scorpion-whip is in her hand, she comes, she comes to torture me. Octavia, gentle Octavia, stay her relentless hand. Mother, spare your wretched son. I did not bid them slay thee; it was the men you gave me for my guides that urged me to that crime.” Cold drops stood on the brow of the emperor, the muscles of his throat worked frightfully, and while he leaned against the person of Adonijah for support, the Hebrew felt the agonized and audible pulsation of his heart thrill through his own nerves. From this momentary trance of horror the terrors of conscience again awakened Nero. “Thou, too,” shrieked he—“thou, too, Corbulo—dost thou pursue me?” Then, with a cry of horror that dispelled slumber from every weary eye, he fled in frantic haste from the new phantom his delirious horror had created.

“This is the hand of God,” said Adonijah, turning his eyes on the awakened thousands, amongst whom he might have vainly sought for guilt or woe like Nero’s. Even his own misery was nothing in comparison to the terrors that haunted the bosom of the master of the world.

The murmured inquiry that passed along that chained host was like the sound of many waters, but died away instantly into such stillness that the murmur of the waves might be distinctly heard on either shore. The strangely mingled multitude, composed of every creed and nation, looked anxiously around, then pointing to the earth, from whose inmost cavities they superstitiously imagined these shrieks had issued, sank down upon her bosom to sleep and dream of home. Adonijah alone knew the cries came from the tortured spirit of the mighty potentate who ruled the kingdoms of the world, and he remained awake. He had lost his partner in misfortune by death, and no unhappy countryman shared his chain—a circumstance that left him more liberty than those whose deep slumbers he vainly envied.

“The Jews, like their bigoted sires of yore,

By gazing on the clouds, their God adore:

Our Roman customs they contemn and jeer,

But learn and keep their country rites with fear.

That worship only they in reverence have,

Which in dark volumes their great Moses gave.

So they are taught, and do it to obey

Their fathers, who observe the Sabbath-day.”

Juvenal.

The morrow was the Sabbath of the Lord. Unused to labour, the toil-worn Hebrew slaves hailed its approach with joy. Even a Roman enemy had respected the sacred day of rest, but the bosom of Nero was a stranger to the generous feelings of Titus. The boon the prisoners confidently expected he would concede to them was peremptorily refused, and the work was commanded to be carried on as on other days. The Hebrews looked upon each other in silence, and with dejected countenances took up their tools, groaning within themselves, yet preparing to obey the mandate of the emperor. Adonijah contemplated these preparations with a glance, in which pity, indignation, surprise, and contempt were strangely blended. The burning blush of shame overspread his fine countenance as he cried, “Will ye indeed sin against the Lord, my brethren, and disobey his commandment at the bidding of a heathen master?”

Some of the captives sighed and pointed to their chains; others boldly averred “that it was useless to serve a God who had utterly forsaken them;” the timid reminded Adonijah that resistance would be vain, that they must obey Cæsar or perish miserably.

“Better is it for ye to die, O house of Israel, than to suffer such bitter bondage. Death is to be chosen rather than sacrilege. The Lord of Hosts perchance hath only hidden his face from us for a little while, and may yet turn our captivity as the rivers in the south. We are too many to be given up to the sword; the tyrant cannot spare our labours from his vain attempt.” The ardent youth paused and looked around him upon his countrymen, hoping to excite a kindred feeling among the children of his people.

Sighs and groans alone met his ear, like the last wail of crushed and broken hearts—hearts that felt their degradation, but that could not yet resolve to die.

“Hearken to me, my countrymen,” continued the speaker; “this Nero, whom ye fear more than Jehovah, hath nearly filled up the measure of his crimes. I saw him last night, when the terror of the Lord was upon him, driven forth to wander like the impious king of Babylon in madness and misery, and will ye obey such a one rather than God?”

The sullen Jews gave him no reply, but silently resumed their detested tasks.

Burning tears of indignation filled the eyes of the devoted and enthusiastic Adonijah. He threw himself upon the earth, exclaiming as he did so, “Here will I hallow the Sabbath of the Lord, even in the midst of this idolatrous land will I glorify His name.”

“What are you about to do, rash man?” said a military tribune, approaching Adonijah, and accosting him through the medium of the Greek tongue.

“To die,” replied the Hebrew, undauntedly regarding the interrogator.

“For what?” remarked Lucius Claudius sarcastically, “for a mere superstitious observance that doubtless took its rise from an indolent love of ease.”

“No, Roman, no,” returned the captive, “our Sabbath was hallowed and ordained by God Himself when He rested from all His works upon the seventh day, and pronounced them good. The first Sabbath was celebrated by the holy angels, for it is written, ‘The morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy.’ ”

Lucius Claudius put back with his hand the lictors who approached to seize Adonijah, and then drawing nearer to the Hebrew, said in a low voice, “I have heard strange things respecting the worship ye pay some unknown god in the temple at Jerusalem. ’Tis said that Antiochus Epiphanes found there the image of a vile animal in the secret place ye call the Holy of Holies.”

“Roman, ’tis false,” replied the slave. “We worship the great First Cause, the Source of light and life—the creative and preserving Power who formed the universe and all that is therein, and continually sustaineth by His good providence the things that He hath made, and we worship Him under no similitude, for nothing is worthy in heaven above, nor earth beneath, to typify His glorious majesty.”

The tribune listened to this description of the only true God with the ear of a man who hears surprising truths for the first time in his life, which he neither rejects altogether, nor receives. Like Felix, he contented himself with saying, “I will hear thee again on this matter;” adding, “Take the counsel of a Roman who wishes you well, resume your labours, which it shall be the care of Lucius Claudius to lighten, and look for better times.” Thus saying, he placed the tools that lay near Adonijah in that daring Hebrew’s hand, with the air of a man more accustomed to command than persuade.

Adonijah put them back with a gesture indicative of horror. “No, generous Roman, I cannot break a Commandment which has been hallowed by me from my youth; I have fought for my faith and my country, I will die as I have lived, true to the God of my forefathers.”

“You have been a warrior, and death appears less dreadful to a soul like yours than slavery; but look around you, Hebrew, for it is no soldier’s death that is preparing for you; to a lofty mind the shame of the scourge and the cross is bitterer even than the torturing pangs they inflict.”

The lofty glow of enthusiasm faded from the flushed cheek of Adonijah, and the spirit that could have endured the sharpest pangs unmoved, shrank in horror from the idea of disgrace; but this weakness was momentary, the next instant he raised his majestic head and said, “Be it so, be mine that doom of shame, for even that will I endure for the honour of my God.”

A tear glistened in the manly eye of Lucius Claudius, but he was evidently ashamed of the unwonted guest, for he hastily dashed away the intruding witness of his sympathy. “Why were you not a Roman, noble youth?” cried he; then after a pause, he added, “If I can procure your freedom, will you cease to be an enemy to Rome.”

“Not while your idol ensigns pollute the hills of Judea can I cease to be a foe to Rome. Released from slavery, I should again wage war with your people, and fight or die in defence of the land that gave me birth.”

“Then you would disdain to serve me, though the bonds of friendship should soften those of slavery. Tell me why a haughty warrior could submit to chains at all? I had thrown myself upon my sword; but perhaps life then had charms.”

“Suicide is held in abomination by us Jews,” replied Adonijah, “for we know the spirit shall survive the grave; to be united again to the body at the resurrection, when every man shall be judged according to his works. The Gentiles, plunged in dark idolatry, are ignorant of this great truth, and therefore, shrinking from the trials of adversity, to avoid the lesser evil rush upon the greater. Life for me has no charms, though I endure its burden. Seest thou yonder tree, over which the storm hath lately passed? In its days of strength and beauty it was a fitting emblem of Adonijah, so now in its ruin you may behold a lively image of his desolation. Like him it still exists, though like him it will never renew its branches, or fulfil the glorious promise of its youth. Yet, generous Roman, I should not refuse to serve him who would save me from a shameful and accursed death.”

The reverence and self-devotion of Adonijah for the Supreme Being was perfectly unintelligible to the tribune, whose mind, although it had shaken off the superstitious idolatry of his ancestors, was deeply infected with the atheistical philosophy of the times. Matter was the only divinity the young soldier acknowledged; for Lucius Claudius believed either “that there were no gods, or gods that cared not for mankind.” The existence of the soul after death, and a future state of reward and punishment, had never been entertained by him for a moment. The heathen mythology indeed darkly inculcated these two great points of faith, but Lucius Claudius derided the heathen deities whose attributes rather gave him the idea of bad men exercising ill-gotten power than those which his reason ascribed to divinity. Murder, rapine, lust, and cruelty, that in life deserved, in his opinion, the scourge and cross, had been deified by flattering men after death. Yet, though refusing to pay any worship to the host of idols Rome with blind stupidity had gathered from all the countries she had conquered, Lucius Claudius had dedicated his fair young sister to the service of Vesta before his departure for the Parthian war, either from the idea prevalent among free-thinking men, even in our day, that women ought to be religious, or that he thought to secure Lucia Claudia from those snares which a corrupt city like Rome offered to her youth and beauty. Julius Claudius, the younger brother of the tribune, was esteemed too careless and dissolute a character to be intrusted with the guardianship of a lady of whose family every daughter had been chaste.

Lucius bribed the lictors to delay the execution of the refractory slave till he had spoken to the emperor, and departed to consult with his brother respecting the means to be taken with Nero, to avert the doom of a person whose constancy he deemed worthy even of the ancient Roman name.

“But thou, with spirit frail and light,

Wilt shine awhile and pass away,

As glowworms sparkle through the night,

But dare not stand the test of day.”

Byron.

The magnificent apartment into which the manly step of Lucius Claudius intruded was darkened with painted blinds, and yet further veiled from the beams of day by curtains of rose-coloured cloth. The furniture glittered with gold and gems, and the delicious odours of the costly bath preparing for the voluptuous Julius in the adjoining bathing-room filled the gorgeous dormitory. The sleeper was lying on a couch under a gilt canopy, wrapt in such deep repose that even the bold approach of his brother did not disturb his rest. It might be that the foot of the indignant Roman fell on a carpet of unrivalled brilliancy and softness, or that the last night’s banquet had been prolonged to an unusual hour. With an air of contempt Lucius Claudius motioned to the attendants to depart, and hastily flinging back the curtains, threw open the lattice, and suffered the morning sun and breeze to play over the beautiful but effeminate features of the slumbering Roman. For a moment the rough soldier gazed upon his brother with an expression of scorn, which quickly yielded to tenderness as the remembrance of their boyish days came across his mind. How dear had that brother once been to him, before the corruption of Nero’s court had blasted all the fair promise of his virtuous youth! and even now, degenerate as he was become, Lucius felt that he still loved him. So holy and unalterable are kindred ties and early associations to a virtuous mind.

While indulging these feelings of returning affection, Lucius suddenly remembered the occasion that brought him hither, and flinging his warlike hand upon the chords of a lute that lay near him, with some force he cried, “Wake, Sybarite, thy brother calls thee.”

The broken chords jarred dissonantly on the musical ears of the sleeper, who awoke with a peevish exclamation of displeasure on his lips, and unclosing his languid eye, looked upon the fine though sun-burnt features of his brother. “Lucius in Corinth!” cried he, “or doth sleep deceive my senses?”

“Nay; can this be Julius? Now, by Jupiter, I should believe it was my fair sister Lucia, but that the lovely maid hath offered, doubtless, her spotless vows at Vesta’s shrine some hours ago,” rejoined Lucius with a scornful smile.

“Wouldst thou have found me at the plough, good brother, like Cincinnatus? But wherefore art thou here?—old Roman, Nero loves not men of thy metal.”

“I landed with Corbulo from Parthia, at Cenchrea, yesterday,” replied Lucius somewhat drily.

“Ha! Corbulo in Corinth! sure his better genius might have warned him back.” Julius lowered his voice so that his brother did not catch the ominous conclusion of the sentence, and then resuming his ironical tone, he continued his raillery, “Corbulo still rises with the sun, as thou dost, old Roman. His master and mine have long forsworn such antiquated customs. We revel all the night, and then, fatigued with pleasure, slumber half the day. In Nero’s court thou must forget the rustic manners thou hast learned in war.”

“Never will I forego the honest plainness that becomes the Roman. Valiant Corbulo, still be my model; for in thee Rome yet may boast a citizen valiant as Scipio, frugal and wise as Cato.”

“Beware of praising Corbulo; that name is out of date at court,” returned Julius significantly.

“It should not seem so, for even Nero acknowledges the worth and valour of his brave lieutenant. ’Tis at Cæsar’s own request he comes to Corinth to receive the thanks and praises of his degenerate master. Perhaps his great example may recall Nero’s soul to virtue. But, Julius, while dwelling on the shining qualities of my valiant leader, I forget mine errand, which was to crave of Nero a Hebrew slave, condemned to labour on the Isthmian trench. This is his Sabbath, it should seem, which rather than profane, he braves the horrors of the cross and scourge. Despite his superstitious scruple, I like his spirit, and wish to place him near my person. I would crave the boon myself of Cæsar, only that the suns of the East have darkened my face, and that my long sojourn in camps hath lent a roughness to my mode of speech that might perchance ruin the cause I pleaded. Give me some counsel, Julius; thou art used to courts, and—to thy shame I speak it—art one of Nero’s friends.”

“First, then, my soldier brother, let me tell thee that a bath of asses’ milk frequently used, will soon remove the sun-specks from thy face; singing to the lyre will dulcify thy voice; and but once repeat the imperial numbers in Nero Cæsar’s ears and thy cause is won, and I may wish thee joy of an obedient servant, who will say, ‘I cannot do thy bidding; it is my Sabbath, and I must keep it holy.’ Practise what I tell thee, and the slave is thine.”

“These arts are not for me,” replied Lucius, laughing. “Go ask the boon for me, and for once I will overlook your courtier habits.”

“Well, I will do your bidding with the emperor; but be warned, Lucius, and depart from Corinth by evening-tide or earlier. Even Rome is hardly safe; your villa at Tusculum is better suited to your rustic plainness. Such men as you are dangerous, and Nero might forget his friendship for me, and only recollect that we are brothers. Go, hasten to the trench; I soon will bring thee favourable tidings.”

“A mighty spirit is eclipsed—a power

Hath passed from day to darkness.”

Byron.

The horrors of conscience so lately endured by Nero were still visible on his ghastly brow, and his gloomy eye glared ferociously upon Julius Claudius as he entered his presence. The artful courtier’s countenance, however, betrayed no alarm, and he commenced singing some verses of Nero’s composition in a voice of exquisite sweetness. The imperial frown vanished, the stern features relaxed into smiles, and when Julius Claudius besought his pardon for joining such lofty strains to notes so feeble, the illustrious bard caught up the words, which he sang in a voice destitute alike of strength or sweetness. Julius affected unbounded rapture, and Cæsar forgot his nocturnal agony in delighted vanity. The artful flatterer had but to name the favour his brother had requested, and it was instantly granted.

As soon as he had obtained the order for the transfer of Adonijah’s person, he hastened to the Isthmian trench, where he had appointed to meet his brother.

Well pleased at the success of Julius, the tribune commanded the fetters to be stricken off the limbs of the captive, who, before he made the slightest acknowledgment to his benefactor, kneeled down, and in an audible voice returned thanks to that Almighty Being whose instrument only he considered Lucius Claudius to be.

“Truly thou art likely to possess the most grateful of all servants,” remarked Julius, “and the most courteous too withal. He would make, in truth, a noble gladiator; for I never saw a form more perfect, or features more symmetrical: but for a household slave the fellow is useless. You had best send him to the circus.”

“Thy jests are bitter,” returned his brother, “but I forgive thee since the slave is mine.”

“Set sail for Rome to-night, and I am paid for all my pains,” replied Julius, with an expression of peculiar meaning on his face, as he bade Lucius Claudius farewell.

Near the gate of the city Lucius Claudius met Sabinus, the freedman of Corbulo, with consternation and grief painted on every feature. The tribune uttered the name of his revered commander. He remembered his brother’s hints, and feared that Nero’s jealousy might be awakened by the great leader’s glory. Sabinus briefly told the tragic fate of a hero worthy of a happier destiny and better times.

For a moment Lucius Claudius stood transfixed with horror, and then drawing his sword, was rushing forward with the evident intention of seeking out the emperor and revenging his friend, when Sabinus, guessing his design, caught him by the arm, and drawing him aside, represented to him the madness as well as uselessness of such an attempt. Apparently his reasons were too solid to be resisted; for, motioning Adonijah to follow him to his lodging, he entered the city with an air of forced calmness that formed a strange contrast to his late paroxysm of resentment.

Sabinus employed himself in making preparations for the funeral rites of his friend and patron, while Lucius Claudius, with Roman fortitude, forbade his countenance to wear the guise of grief; but, following his effeminate brother’s advice, engaged a passage in a merchant-ship for himself and his followers to Italy.

The shades of evening had long descended on the wooded heights of Mount Cithæron, whose rugged brow cast a deep lengthened shadow on the plain. The moon-beams slept upon the deep blue waves that washed the Isthmus, while the stately city, with its Acropolis rising like a majestic crown above it, looked, as it shone in the lunar ray, like an enchanted place called up by magic from the deep rather than the abode of man. The vivid flame that suddenly shot up along the shore, casting the figures moving solemnly around it in deep shadow, might have suggested the idea of magic rites. But the forms that paced about that blazing pile were engaged in no unholy practices. Theirs was the hallowed office of rendering the last honours to the remains of Corbulo, previously to their quitting these fatal shores.

Long, long did those faithful friends and followers gaze upon the features of the illustrious dead, before the hand of Lucius Claudius fired the pile. With wonder Adonijah contemplated the lofty lineaments and singularly grand figure of the murdered Roman of whose fame and virtue he had heard so much; for Domitius Corbulo soared in stature as much beyond all other Romans of his day, as he exceeded them in glory.

The manly eyes of Lucius Claudius overflowed with tears, but tears soon dried up by the hope of vengeance. Each of that mourning group, dipping their hands in the streaming blood of Corbulo, swore to revenge his death on Nero, or perish in the attempt. The pile was fired; and Lucius Claudius and Sabinus watched the dissolution of the form they loved, gathered up the ashes in an urn, and, deeply sorrowing, bore them on board the vessel hired to convey them to Italy.

Adonijah beheld the classic shores of Greece receding from his sight with the indifference of one to whom all countries could only offer variety in bondage. The apathy of slavery began to steal over him; and it was not till the emotions of the long-absent Romans grew apparent as they approached the coast of Italy, that the remembrance that he was an exile from his own country returned in all its bitterness to his soul.

With feelings of rapture, of patriotism, that even prevailed over their sorrow, the Romans stretched out their arms towards their fatherland,—tears filled their eyes as each imaged to himself the dear unforgotten ties of home. “Italy, dear Italy! once more I look upon thy sacred soil,” cried Lucius Claudius. “Soon, soon shall I behold the seven-hilled city; shall see thee, dear vestal maid, sweet Lucia, sister of my heart. Sabinus, you have been at Rome since she attained to womanhood, for she was but a child when she took her virgin vows upon her. Tell me, how looked the maiden when you last beheld her?”

“Like a pure and spotless lily among the gaudier flowers of Rome,” replied Sabinus. “Her vigils have somewhat stolen the rose of childhood from her polished cheek, but lovelier looks, methinks, that holy paleness than the brightest hues of health and gladness. The vestal priestess in her sacerdotal robes eclipses the proud dames of Rome in beauty as in virtue.”

“She, she, Sabinus, and the mighty recollections of this fallen land, are all that make life bearable to me.” The tender feelings of his heart filled the tribune’s eyes; he turned to Adonijah, of whose observation he felt jealous, and said, as if in extenuation of his emotion, “Thou hast a country—perhaps a sister too.”

“I had, but she has fallen a victim to the slaughtering sword of the Gentile,” replied the Hebrew, “and gone down to the grave in the virgin beauty and glory of her youth. Yet art thou happier, Tamar, than thy miserable brother; for thy ashes are mingled with the sacred soil of thy country, whilst I am cast out to wither like an abominable branch in a strange and idolatrous land.” Then, relapsing into his own language, Adonijah poured forth a strain of wailing lamentation, with the spontaneous eloquence natural to the Eastern nations, unrestrained by the presence of Lucius Claudius and his followers.

The tribune respected his grief, nor did he intrude upon it by again addressing him; and the silence remained unbroken till the master of the vessel landed them at Baiæ, from whence they proceeded to Rome.

Vol. “Do you know this lady?”

Cor. “The noble sister of Poplicola,

The moon of Rome: chaste as the icicle

That’s curdled by the frost from purest snow,

And hangs on Dian’s temple: dear Valeria!”

The ancient city of Romulus had risen from her ashes like the fabled phœnix, with renewed youth and beauty. So greatly was her appearance altered, that Lucius Claudius knew not where to seek his ancestral home, as, regardless of the directions of his attendants and the proffered guidance of Sabinus, he wandered on bewildered and amazed amongst sumptuous edifices and streets of palaces. All indeed seemed new to his eyes and heart. It was no longer the city founded by the Latian twin, and rebuilt by Camillus, that he beheld, but the palace of Nero Cæsar, the master of the world. She looked indeed more like the metropolis of a mighty empire, though her real greatness had vanished with her ancient simplicity and virtue. Even in the midst of her grandeur and magnificence she was tottering to her fall, for her deep corruptions were gradually unbarring her gates to the Goths of future ages. All that was beautiful or venerable in her customs was gone “as a tale that is told,” and the martial form of the military tribune, the worthy representative of her illustrious sons, seemed as out of keeping with the pomp that surrounded him on every side, as the appearance would have been of one of his own warlike ancestors. The dominion of Rome indeed was departing, for a highway for the promulgation of the gospel had been opened by her armies to all lands—for which end alone she had been given rule over the nations of the earth. Neither the heathen nor the Hebrew perceived this. To Lucius Claudius the name of Rome was synonymous of victory and power; to him she was sempiternal and invincible, while to Adonijah she appeared only a magnificent prison, within whose walls he was destined to waste away his life, the living grave indeed of hope. Still, the curiosity inherent in human nature made him suddenly ask the meaning of a sad procession they encountered near the Forum.

Sabinus replied, “Some Roman citizen is led to execution, attended by the lictors with their fasces. See, the axe before him denotes that it is no slave about to suffer, but a person entitled to the privileges of the free. A Christian, I should think, by his dress and bearing. If I mistake not, Nymphidius and Tigellinus, the præfects of the prætorian camp, are present, both low-born upstarts and favourites of Nero; the first, the son of Nymphidia by Caius Cæsar,[7] as he would have it thought, and many think his person bears a strong resemblance to that frantic emperor: in cruelty he certainly can claim a kindred disposition. The victim is unknown to me, but his venerable face expresses goodness, now become a crime in Rome.”

While Sabinus was yet speaking, a magnificent chariot approached, drawn by four white horses, containing a young female attired in white robes bordered with purple. She wore on her head a species of cap decorated with ribbons, but her brow was bound with a fillet, and the beauty of her complexion, which was very fair, accorded well with her snowy drapery and modest dignity of mien. A lictor preceded the chariot, which was followed by a number of female attendants, likewise dressed in white.

The sudden halt of the vehicle gave Adonijah time to observe the vestal virgin and her suite more closely, but he noticed that every one but him stepped respectfully back to permit the cortege to pass unimpeded.[8]

The vestal and her train appeared by no means inclined to avail themselves of the passage thus opened for them by the reverential crowd; on the contrary, her attendant lictor seemed bent upon contesting some matter with those who were bearing the condemned Christian to death.

“By Jupiter, the deliverer!” cried Lucius in an animated tone: “the vestal virgin hath claimed her privilege in favour of the Christian. See, the lictors prepare to unbind him at her bidding.”

“The prætorian præfects deny her claim,” replied Sabinus, “and motion to the lictors to advance—who hesitate, yet lower their laureled fasces reverentially before the sacred maid. Hark! she speaks.”

The import of the vestal’s words might rather be guessed from her manner than understood by the ear, but it was evident that those to whom she made her claim were determined to disallow it.

“Forward, Sabinus! forward, friends and clients! forward, Roman citizens! let us defend the privileges of the vestal order.” Thus saying, Lucius Claudius endeavoured to pierce through the crowd that now closely environed the chariot, yet could not at once accomplish his intention, though he was near enough to hear the conference between the contending parties.

“No; let her ply the distaff, watch the sacred fire, be borne in triumph through the streets, enjoy the homage with which old superstitious times and customs have invested her; but let her not presume to interfere with Cæsar’s ministers in matters that concern the state,” cried Tigellinus, addressing the listening crowd.

“Roman citizens,” said the vestal, turning to the people, “I claim of you the privileges granted by holy Numa to our order. The laws of Rome grant to us the power of saving any criminal we may chance to meet upon his way to execution.” She blushed deeply as she made her dignified appeal, and her voice though sweet was tremulous.

“My sister’s voice and person, if my ears and heart tell truly,” remarked Lucius Claudius in an under tone to the freedman.

“It is indeed the Lady Lucia, the pride of Roman ladies, the glory of the vestals,” returned Sabinus.

“We will protect thy privileges, Lucia Claudia,” cried a thousand voices, which the deep tones of the delighted brother united with his followers to join.

“I swear,” continued Tigellinus, “that the meeting was premeditated. She knew Helius occupied the tribunal, and came to snatch the atheist from justice.”

“I call upon the name of Vesta to attest my truth,” replied the vestal in a firmer tone than that in which she recently made her claim; “I plead the law of Numa.”

“I abrogate it thus in Cæsar’s name,” cried Tigellinus, snatching an axe from the hand of a lictor, and upraising it to slay the Christian.

Lucius Claudius sprang forward to defend his sister’s privilege, but before he gained the spot, the colleague of Tigellinus had caught his arm and preventing his design, bowed low before the vestal whose beauty had subdued his wish to slay, saying, “Forbear, Tigellinus, to infringe the privileges of the vestal order. Respect the goddess Vesta herself, in the person of the noblest and fairest of Roman ladies.” Then fixing his bold eyes admiringly upon Lucia Claudia, he continued: “The man who can resist charms like thine were worse even than the churlish Greek who wounded Venus in his ireful mood. See, the sword of justice is edgeless before the pleading voice of beauty.” He motioned to the lictors to unbind the Christian, still gazing ardently upon the fair countenance of Lucia Claudia.

From the licentious stare and free speech of Nymphidius the vestal virgin shrank abashed. Her modest eyes sank beneath those the præfect boldly turned upon her lovely face. She looked no longer like the high-minded heroine who daringly opposed bad men in power to plead her rights of mercy, but like a timid maid whom compassion had led to overcome the weakness and fearfulness of her sex, but who now blushed at the effect of her own temerity, ashamed of the triumph her virtue and charms had won. This beautiful shame, this touching timidity, the expression of wounded modesty in her bashful eyes, excited a new feeling in the bosom of the Hebrew slave, who no longer regarded the sister of Lucius as a heathen priestess, but as a woman the loveliest and purest of her sex.

Linus, the rescued Christian, turning to his preserver, thanked and blessed her; but with an air of offended dignity the vestal turned away. “Go,” she said, “amend thy creed and live.”

“So near the gate of heaven—and yet so distant!” rejoined the Christian. “Farewell, Lucia Claudia, and peace be with thee: we shall meet again.”

Linus, the second bishop of Rome, though rescued from martyrdom by Lucia Claudia, was still, he saw, an object of scornful pity in her eyes who had prolonged his life for other labours, and perhaps other trials, by her instrumentality. He thanked God who had inclined an idolatrous priestess of Vesta to assert her privilege in his favour. Some words of saving truth he would have addressed to his benefactress, but that he saw this was no time or place to preach the gospel. She looked too obdurately upon the man she had lately preserved, to listen to the wonders of redeeming love. Gratitude, however, that very essence of true Christianity, forbade Linus to forget he owed his life to her. From that day he never ceased to pray that the bright effulgence of Divine light might dispel the darkness that overshadowed the soul of the young Lucia Claudia.

She, indeed, turned coldly away from him. This was not unnatural in the heathen priestess, but it pained the Christian who withdrew to the asylum the labyrinth of the Arenaria afforded, resolving to use every effort to convert the young vestal to the pure faith of Christ.

Lucius Claudius, full of fraternal pride, gazed fondly and admiringly upon his lovely sister. His eyes betrayed indeed more emotion than he cared the crowd should witness, yet he could not delay making himself known to her.

“Noble Roman maid, thou shouldst be my own beloved Lucia. The blue eyes, the fair complexion of the Claudian line, should denote my sister,” cried he, endeavouring to force a passage to the chariot.

The vestal looked upon him intently, but her memory retained no trace of her elder brother’s person.

“ ’Tis Lucius Claudius, ’tis thy brother, returned from Parthia, to behold in thee, dear maid, all that fraternal love could hope to see,” said Lucius, advancing to greet his sister.

Lucia again raised her eyes to his face, but with a look of glad surprise, as with speechless rapture she motioned to him to ascend the chariot, and then, throwing herself upon his neck, wept with all the fond familiarity of long-remembered affection. She conducted her brother to his home in a sort of triumph, where she took leave of him, and returned to Mount Palatine where she dwelt.

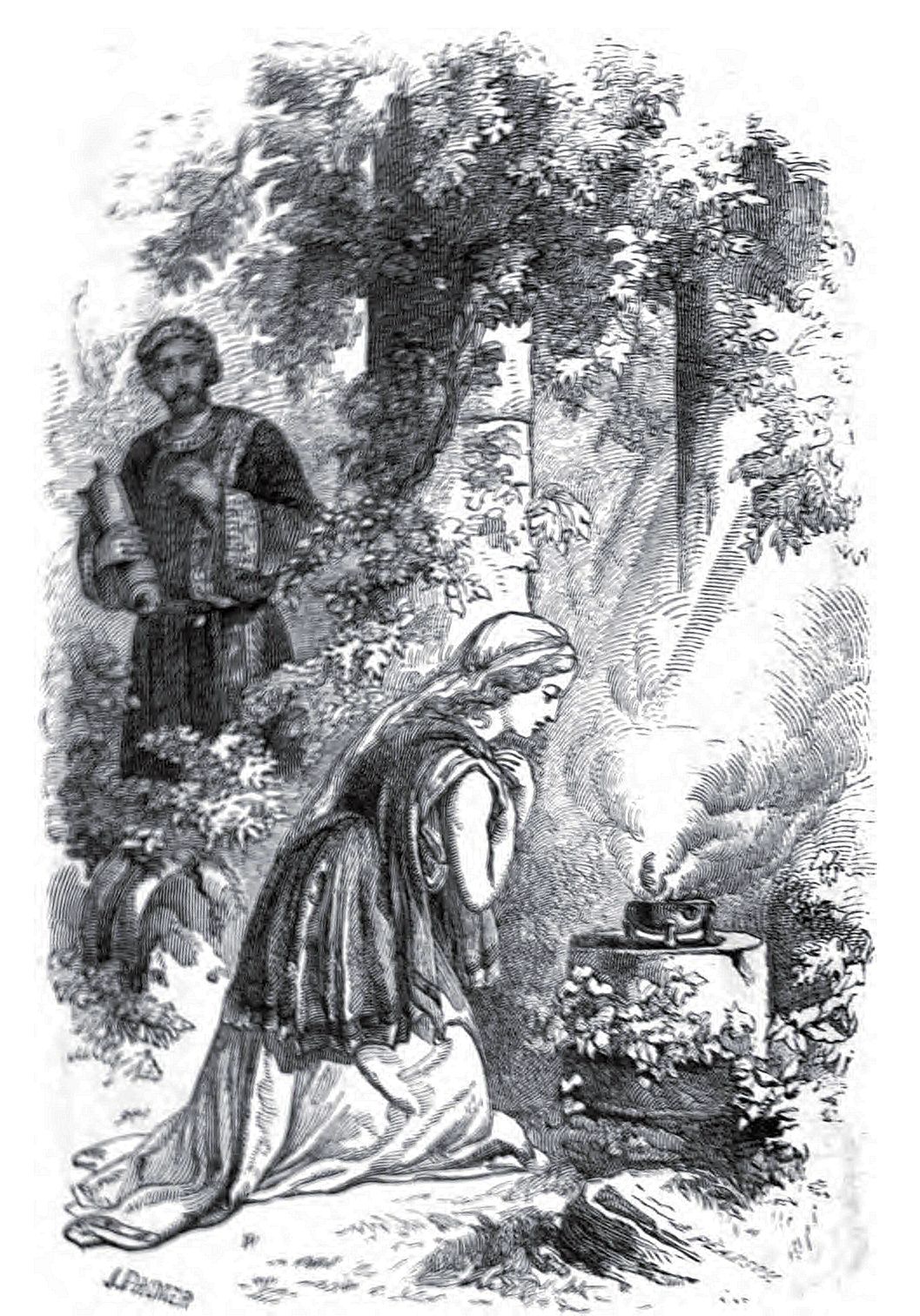

Adonijah could not efface from his mind the image of the vestal virgin; could it be that he, the strictest of the strict Pharisees, should behold with interest and tenderness this idolatrous priestess who had looked upon the stately maids of Judah with coldness. If this were love, he knew it to be forbidden by the law, and therefore sinful as it was hopeless. He tried to exclude from his mental vision the form of Lucia Claudia, but in vain; and when he slept, he slept to dream of her sweet image.

Nor was it only in the breast of the Hebrew slave that the beauty and virtue of Lucia Claudia had kindled an unextinguishable flame. Nymphidius, that bold bad man, was no less captivated with her charms and spirit. He determined to win her for his bride, in defiance alike of the sanctity of her profession or her patrician birth. To a mind so lawless what was custom? to one so aspiring what was the nobility of the beloved object but an additional motive for the alliance? His grasping hand, already struggling for the imperial sceptre of the Cæsars, would not hesitate to tear from its seclusion “this white and virgin rose,” whose purity had inspired that passion in his bosom the corrupt and dissipated ladies of the court had failed to kindle. Bad as he was, he felt the power, the majesty of virtue, and did homage to it in the person of the priestess of Vesta, and even the empire of the world without her to share its honours appeared too poor to satisfy the wild ambition of the reputed son of Caligula.

|

Caligula. |

“No gods, or gods that care not for mankind.”

Claudian.

“There surely is some guiding Power

That rightly suffers wrong,

Gives vice to bloom its little hour,

But virtue late and long.”

Camoens.

Adonijah, through the courteous kindness of his preserver, viewed the sumptuous buildings and edifices of Rome. There was much in the survey to delight and interest a stranger,—one, too, who was familiar with the historic records of this celebrated city. Nothing, however, surprised the Hebrew, who was born under the light of revelation, so much as the number and variety of the idols of Rome. He justly considered this apostasy from that natural religion which is written in the heart of every man, as the fruitful source of all the corruption and infamy into which the inhabitants of the metropolis of the world were sunk. To be vile was, in reality, to claim an affinity in nature to the very gods the people worshipped, who appeared to him to be demons or bad men, deified by fools and knaves, though some attempt had been made to improve the morals, and inspire the soul with virtue; for the Romans had raised altars to Concord, Justice, Fortitude, and Filial Piety.

In the writings of the philosophers of the period Adonijah vainly sought for any allusion to the patriarchal religion which had existed before the giving of the Law to his own people, and which must once have subsisted among the Gentile nations. They appeared to have discovered a First Cause, to whom they paid neither reverence nor worship. His own religion he found regarded with contempt, its rites derided, and adherence to its customs styled “a sullen hatred of all mankind;” the bringing forth of his people from the land of Egypt, disguised and vilified by the most absurd fables, by men who possessed great wisdom in treating all other matters, though in this respect they were indeed fools. To believe in the existence of a God, and yet to assert that He cares nothing for the creatures He has made, is to liken him to a cruel father who abandons a child in infancy, leaving him to find his way in the wilderness of that world through which he is destined to pass, without a precept and without a guide. “No gods, or gods that care not for mankind,” was the real creed of many at that period, who, according to the words of St. Paul, “professing themselves to be wise, became fools.”

A synagogue beyond the Tiber afforded Adonijah the privilege of worshipping after the manner of his fathers. The seven-branched candlestick used by the Jewish congregation has been discovered in modern times on the spot where once it stood. Adonijah, who had learned to hate the Christians before he came to Rome, found his detestation strengthened by his fellow-worshippers. The persecution in the twelfth year of Nero had banished the converts to the new faith to the dark recesses of the Arenaria, so that though the sect was known to exist in Rome it was maintained in the greatest privacy.

As many Roman proselytes had been made in Judea, before the commencement of the war, to the Jewish religion, Adonijah did not despair of making a convert of his patron, for whom he had conceived a great affection. Still, in defiance of his own zeal for religion, and the deep interest he took in the deadly struggle in which his country was then engaged, he could not forbear watching for the chariot of the vestal Lucia, or lingering round the temple of Vesta to catch a glimpse of her figure. As no image was worshipped in that fane, he hoped that, if he could win the brother from his unsettled notions, the sister, who appeared to worship an abstract idea, might be gained over to the true faith. Thus religion, wherever it exists in a revealed form, is a benevolent principle, leading its votaries to diffuse its blessings as widely as possible, but still selecting the dear ties of friendship and kindred as its first objects.

Although secretly planning the destruction of Nero and the freedom of his country, Lucius Claudius took much pleasure in the society of Adonijah. Frank and open in his temper, he boldly avowed his contempt for his country’s gods; and, though he by no means seemed inclined to treat the God of Adonijah with more veneration when speaking of Him, he felt curious respecting a religion whose followers were distinguished from all people on the face of the earth, by the peculiarity of their laws and worship. Leaning upon the arm of Adonijah as they walked together in the delightful gardens of his villa at Tivoli, he suddenly asked the Hebrew “what evidence he could bring of the actual existence of the God he worshipped.”

Adonijah naturally quoted those sacred books which contain the earliest revelations of God to man.

The heathen soldier did not appear to think the evidence he deduced conclusive, for he demanded a proof that should be at once apparent to his outward senses and convincing to his understanding.

“Such a demonstration I am prepared to give,” replied the Jew. “ ‘Behold, the heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament showeth His handy work. Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night showeth knowledge: there is no speech nor language where their voice is not heard.’ It is the hand of Omnipotence that hath placed these lights in the firmament, and by them still claims the worship due to the Creator from man.”

Lucius looked up at the glorious starry dome of heaven, and then down on the enthusiastic countenance of the slave, and smiled sceptically. “Chance or accident has placed these lights on high, Adonijah, which you superstitiously ascribe to the hand of an unknown God. This world and all things it contains, whether animate or inanimate, owes its existence to a fortuitous union of atoms, mysteriously attracted towards each other by some incomprehensible influence.”

“What gave rise to the atoms of which thou sayest all things were compounded, before they arranged themselves into form or being?” demanded the slave. “Even your belief in matter admits, of necessity, a First Cause, which you miscall Fate, Chance, Accident, but that the Hebrews acknowledge as the creative power of God. All that we see was the work of that Almighty Being whom we Hebrews adore under the name of Jehovah; worshipping Him by faith, not profaning His glory with likening Him to anything in heaven or earth, but serving Him according to the revelation He has made of Himself from the beginning of time; believing that the same Wisdom that called all things into being supports and governs them, and will continue to do so for ever.”

“I am ready to allow that you have reason on your side with respect to the existence of a First Cause, which many of the philosophers of Greece, with Seneca in our own day, have acknowledged; but then if He really cares for the creatures He has made, why is a Nero suffered to prosper while the virtuous and good are slain or sent into exile? What, then, is the use of worshipping a Being who cares nothing for the creatures He has made?”

Adonijah started back at the boldness of this speech, with gestures indicative of horror. “Lucius Claudius,” replied he, “in this world we often see the good suffer and the bad prosper, but be assured that God will punish the wicked and recompense the just at that day of final account, when the dead shall be raised, and the Judge, seated in the valley of Jehoshaphat, shall call every man to an account for his works done in the flesh.”

“The dead raised!” exclaimed the Roman; “you speak enigmas, fables. What Power, Adonijah, can unite the body and soul together again, and form man anew from his ashes?”

“The Power that first united them, ‘who formed man originally from the dust of the ground, breathing into him the breath of life, till man became a living soul.’ Thinkest thou, Lucius, that the spirit of the murdered Corbulo perished with his body? or, imbibing the cold, joyless notions of the Greek mythology, dost thou imagine it wandering round its ashes, seeking in vain its ancient prison? No, Roman, no; it hath gone to its ‘appointed place, again to be united to the flesh, and to plead against the murderer at the judgment-seat of God.’ Such is the doctrine of the Pharisees respecting the resurrection, though even among the Jews an impious sect hath arisen, holding notions as foolish as the ignorant Gentiles themselves. The sacred Scriptures can fully inform you respecting the laws and worship of the true God, and these oracles are in the hands of the Jews, and our Scribes can fully make them known to you.”

The belief in the immortality of the soul never appears more reasonable than when we lament the death of a friend. Though new to Lucius Claudius, it now appeared strange even to himself that he had never considered its possibility before. The existence of a Supreme Being, and his superintending Providence and future judgment, made a deep impression upon his mind, although these impressions did not quite amount to absolute conviction. He expressed willingness to become acquainted with what he called the Jewish records, and Adonijah indulged the hope that this upright Roman would eventually become a proselyte of justice and a believer in the one true God.

He obtained from the rulers of the synagogue the rolls containing the sacred oracles, and commenced reading and explaining them to his patron. The beauty, the sublimity of the inspired truths thus made known to the Gentile dispelled the darkness of ignorance from his mind. The great, the vital doctrine of a Messiah, presented to his view as a point of faith by the slave so strangely become his teacher, bore little resemblance to the “Man of sorrows,” whose atonement for sin was pointed out in the 53rd chapter of Isaiah, and whom the Jewish nation had obstinately rejected. They interpreted His kingdom as a temporal kingdom, and, catching at the idea so prevalent at that time that the ruler of the world was to arise out of Judea, expected their Messiah presently to appear among his people, to deliver them from the Roman yoke. Of the real end of the Messiah’s coming, “to put away sin,” Adonijah was as ignorant as his Gentile convert, who would thankfully have embraced the sublime doctrine the Pharisee rejected, if it had been made known to him.

“Whom in the sacred porch

Ezekiel saw, when by the vision led

His eye surveyed the dark idolatries

Of alienated Judah.”

Milton.