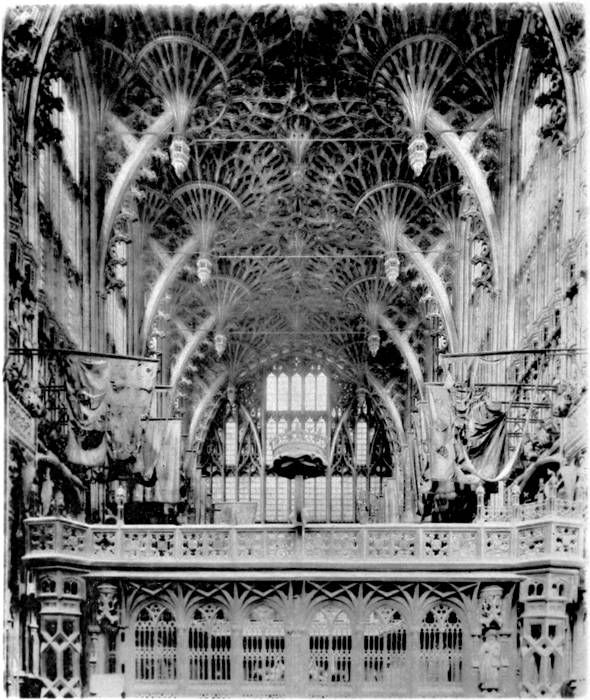

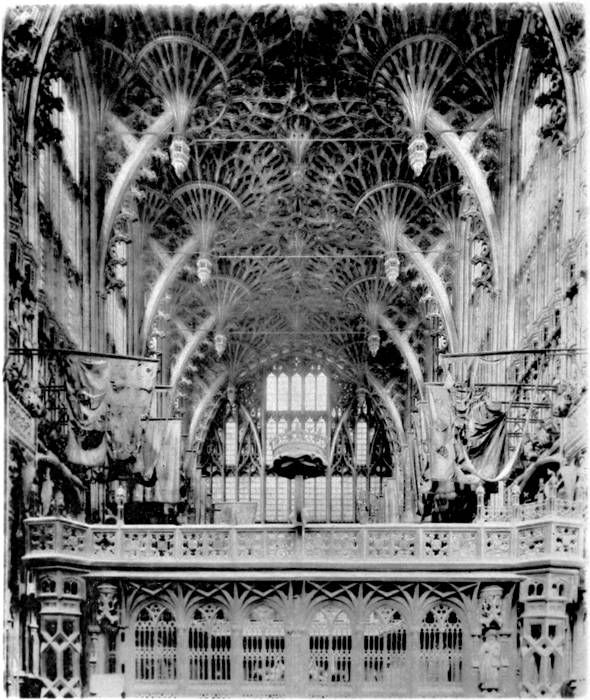

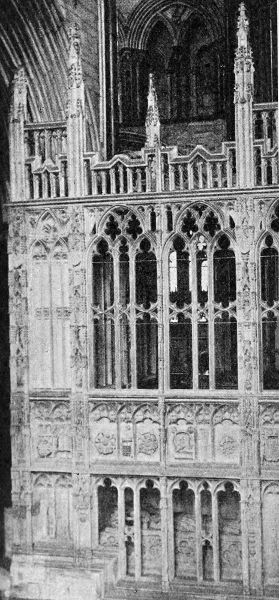

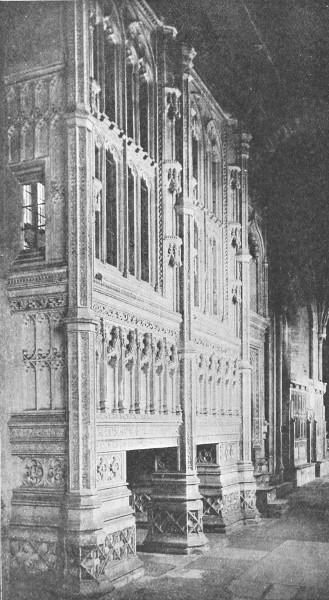

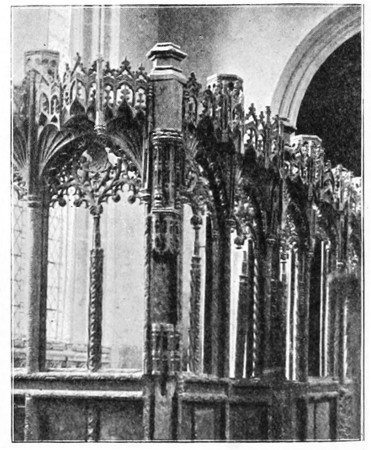

Plate I.

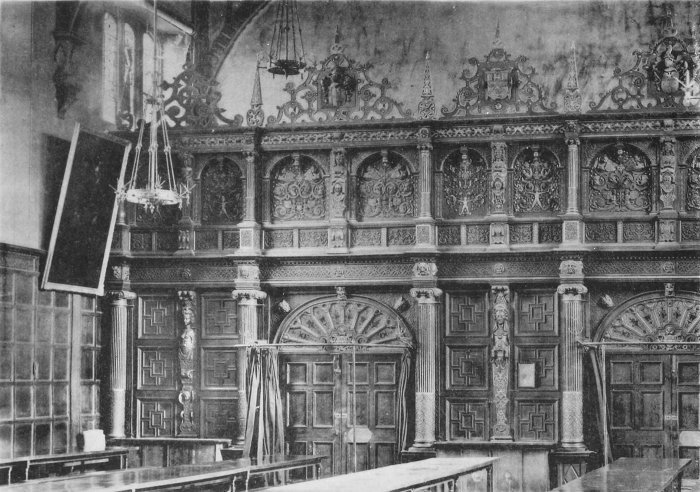

HENRY VII.'S CHAPEL, WESTMINSTER ABBEY.

INTERIOR VIEW, SHOWING VAULTING AND SCREEN.

EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE

IN ENGLAND.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

Architecture of the

Renaissance in England.

ILLUSTRATED BY A SERIES OF VIEWS

AND DETAILS FROM BUILDINGS ERECTED

BETWEEN THE YEARS 1560 and 1635, WITH

HISTORICAL AND CRITICAL TEXT....

The Illustrations comprise 145 Folio Plates, 118 being reproduced

from Photographs taken expressly for the work, and

180 Blocks in the Text.

2 vols., large folio, in cloth portfolios £7 7s. Net.

or half morocco, gilt £8 8s. Net.

Plate I.

HENRY VII.'S CHAPEL, WESTMINSTER ABBEY.

INTERIOR VIEW, SHOWING VAULTING AND SCREEN.

A HISTORICAL & DESCRIPTIVE ACCOUNT OF THE

TUDOR, ELIZABETHAN, & JACOBEAN PERIODS,

1500-1625

FOR THE USE OF STUDENTS AND OTHERS

BY

J. ALFRED GOTCH, F.S.A.

AUTHOR OF "ARCHITECTURE OF THE

RENAISSANCE IN ENGLAND," ETC.

WITH EIGHTY-SEVEN COLLOTYPE AND OTHER PLATES AND

TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

LONDON

B. T. BATSFORD, 94 HIGH HOLBORN

MDCCCCI

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS,

LONDON AND TONBRIDGE.

[v]

It should, perhaps, be observed that although this book is entitled Early Renaissance Architecture in England, it deals with much the same period as that covered by my former work The Architecture of the Renaissance in England, but with the addition of the first half of the sixteenth century. The two books, however, have nothing in common beyond the fact that they both illustrate the work of a particular period. The former book exhibits a series of examples, to a large scale, of Elizabethan and Jacobean buildings, with a brief account of each: whereas this one takes the form of a handbook in which the endeavour is made to trace in a systematic manner the development of style from the close of the Gothic period down to the advent of Inigo Jones.

It is not the inclusion of the first half of the sixteenth century which alone has led to the adoption of the title Early Renaissance: the limitation of period which these words indicate appeared particularly necessary in consequence of the recent publication of two other books, one being the important work of Mr. Belcher and Mr. Macartney, illustrating buildings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, under the title of Later Renaissance Architecture in England; and the other being Mr. Reginald Blomfield's scholarly book, A History of Renaissance Architecture in England, which, although it starts with the beginning of the sixteenth century, does not dwell at any length upon the earlier work, but is chiefly devoted to an exhaustive survey of that of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The value of a work on Architecture is greatly enhanced by[vi] illustrations, and I am much indebted to the numerous gentlemen who, with great courtesy, have placed the fruits of their pencil, brush, or camera at my disposal: their names are given in the Lists of Plates and Illustrations. More particularly I desire to acknowledge the kindness of the Committee of that very useful publication The Architectural Association Sketch Book, in giving permission for some of their plates to be reproduced; and among other contributors I have especially to thank Colonel Gale, Mr. W. Haywood, and Mr. Harold Brakspear; while to Mr. Ryland Adkins I am indebted for several valuable suggestions in connection with the text of the Introductory chapter. Mr. Bradley Batsford has rendered ungrudging assistance at every stage of the undertaking, which has particularly benefited from his broad and liberal views in regard to the illustrations. My thanks are also due to those ladies and gentlemen who allowed me to examine, and sometimes to measure and photograph their houses; and I am indebted to Mr. Chart, the Clerk of Works at Hampton Court Palace, for much useful information imparted during my investigations there.

Each illustration is utilized to explain some point in the text, but in many cases the reference is purposely made short, the illustration being left to tell its own story.

J. ALFRED GOTCH.

West Hill, Kettering.

August, 1901.

[vii]

| CHAP. | PAGE | ||

| I.— | INTRODUCTORY | 1 | |

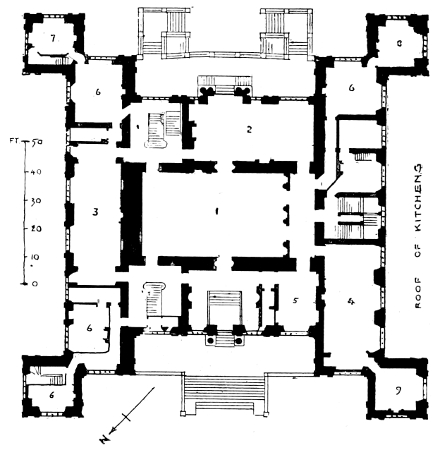

| II.— | THE INVASION OF THE FOREIGN STYLE | 10 | |

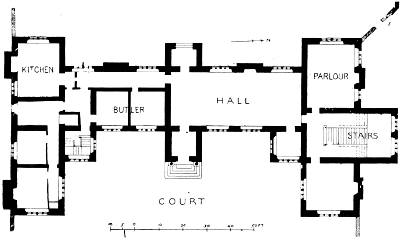

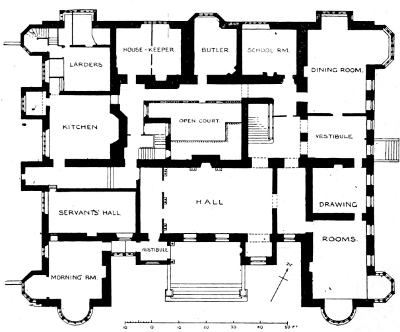

| III.— | THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HOUSE PLAN from about 1450 to 1635 | 41 | |

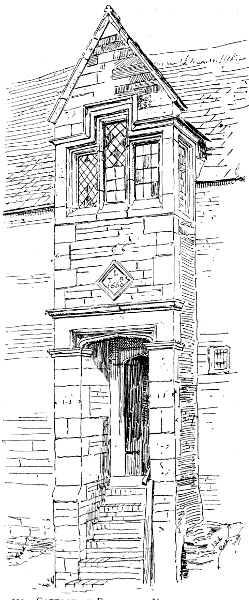

| IV.— | EXTERIOR FEATURES—The Lay-out of Houses, Lodges and Gateways, Doorways and Porches | 73 | |

| V.— | EXTERIOR FEATURES—General Aspect, External Appearance, Windows of various kinds | 94 | |

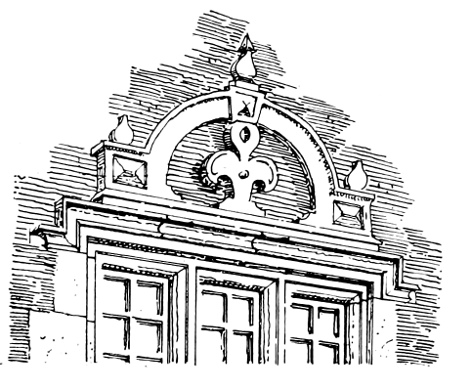

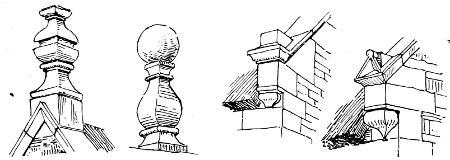

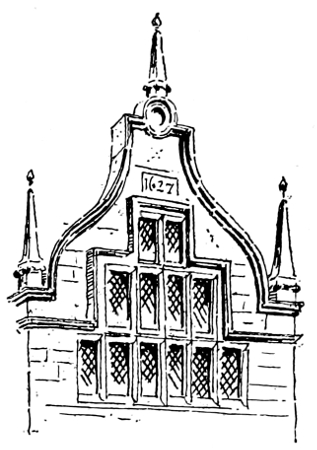

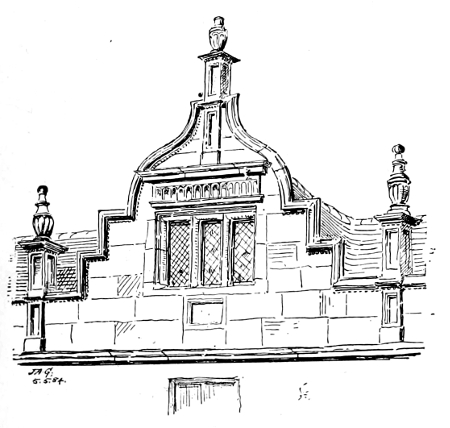

| VI.— | EXTERIOR FEATURES—Gables, Finials, Parapets, Chimneys, Rain-water Heads, Gardens | 116 | |

| VII.— | INTERIOR FEATURES—Royal Progresses, The Manner of Decorating Rooms, Wood-Panelling | 138 | |

| VIII.— | INTERIOR FEATURES—Treatment of the Hall, Open Roofs, The Smaller Rooms, Doors and Door Furniture, Chimney-pieces, Ceilings, Pendants, Friezes | 159 | |

| IX.— | INTERIOR FEATURES—Staircases, The Great Chamber, The Long Gallery, Glazing, &c. | 184 | |

| X.— | MISCELLANEOUS WORK—Street Houses, Market Houses, Almshouses, Town Halls, Village Crosses, Schools, Churches and their Fittings, &c. | 200 | |

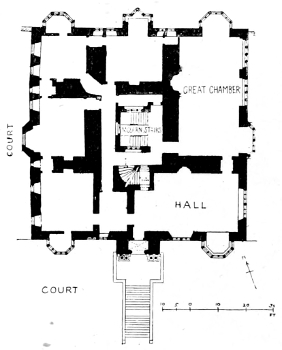

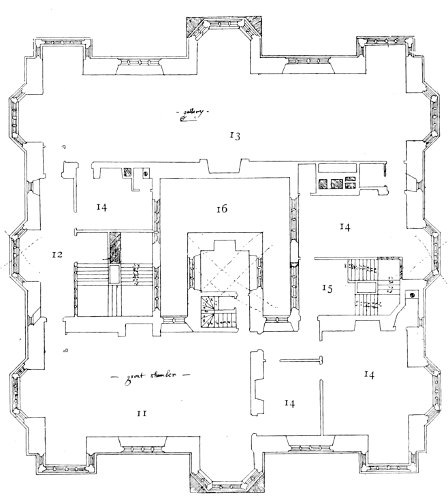

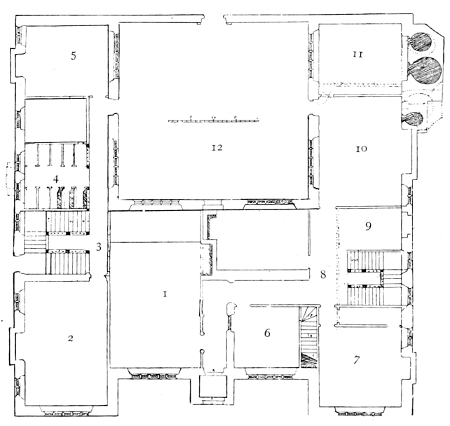

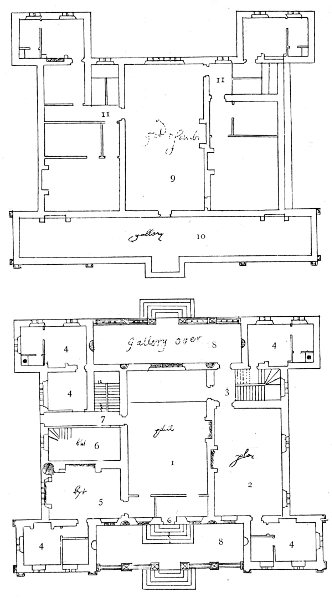

| XI.— | SIXTEENTH CENTURY HOUSE-PLANNING—Illustrated from the Collection of John Thorpe's Drawings | 226 | |

| XII.— | ARCHITECTURAL DESIGNERS OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY | 253 | |

| List of Works on Early Renaissance Architecture | 267 | ||

| Index | 271 | ||

[viii]

[ix]

Note.—The letters "A.A.S.B." denote that the subject is reproduced from The Architectural Association Sketch Book, with authority of the Draughtsman and by permission of the Committee.

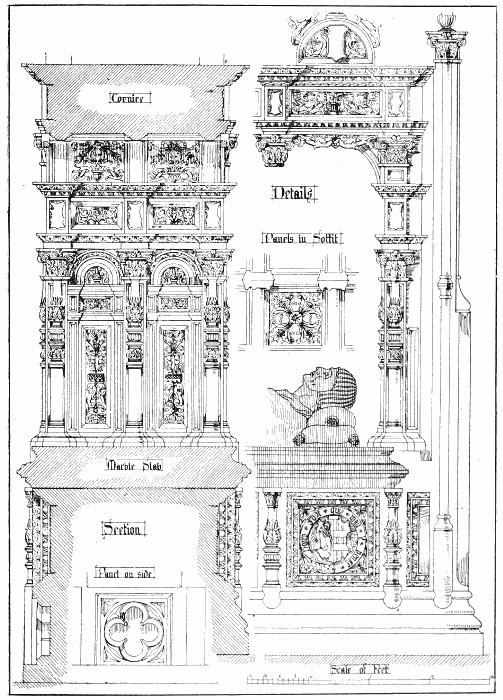

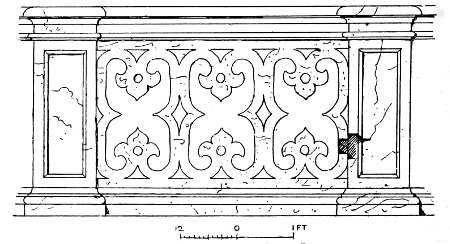

| PLATE | ||||

| I. | — |

Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster Abbey, Interior View S. B. Bolas, London, photo. |

Frontis– piece. |

|

| FACING PAGE |

||||

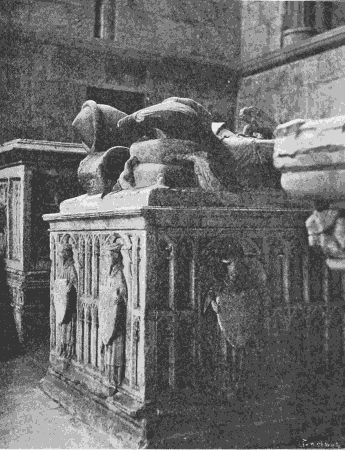

| II. | — |

Henry VII.'s Tomb in Westminster Abbey H. O. Cresswell, del. |

14 | |

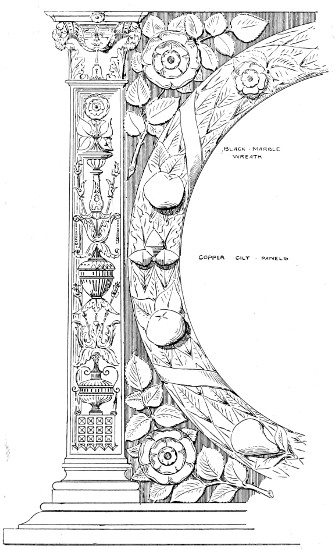

| III. | — |

Details from the Tomb of Henry, Lord Marney, Layer Marney Church Fred Chancellor, del. |

18 | |

| IV. |

|

Fan Vaulting, Chapel of the Redmount, King's Lynn W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. Vaulting of Porch, Cowdray House, Sussex J. A. G., photo. |

|

18 |

| V. | — |

The Countess of Salisbury's Chantry, Christchurch; View from Choir |

20 | |

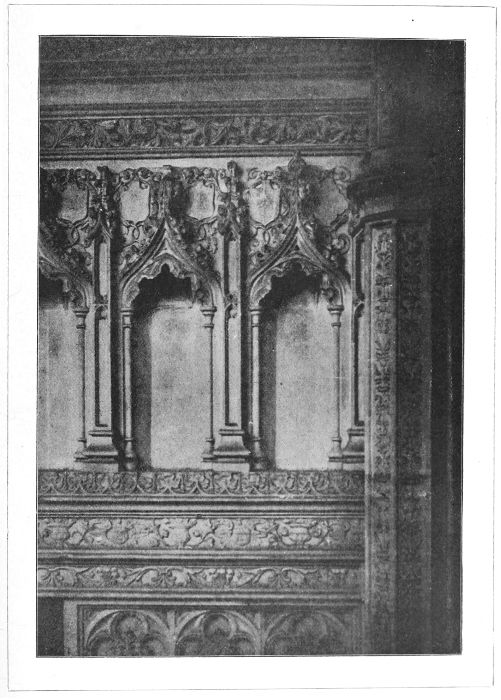

| VI. | — |

The Countess of Salisbury's Chantry, Christchurch; Detail of Niches on North Side |

22 | |

| VII. |

|

Part of Screen, St. Cross, Winchester W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. Paulet Tomb, Basing Church J. A. G., photo. |

|

26 |

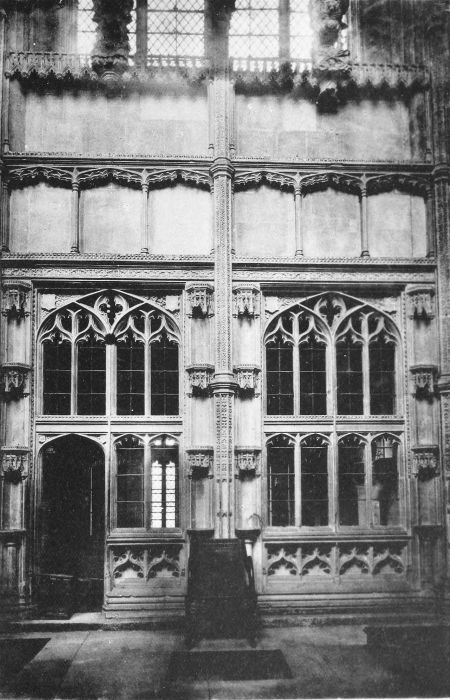

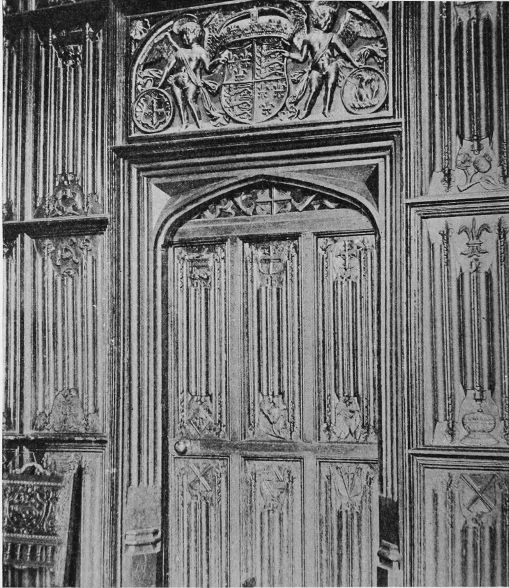

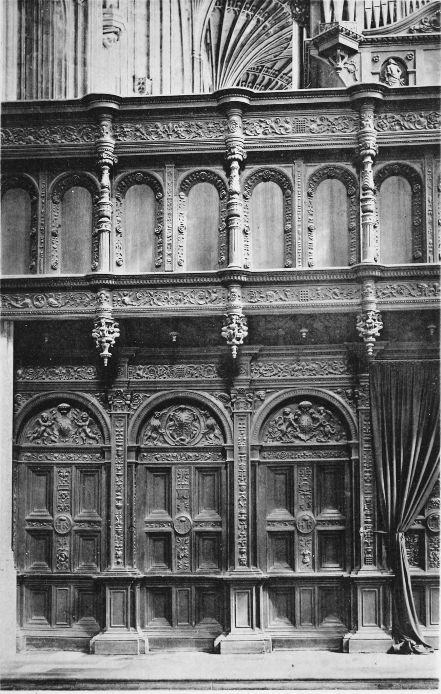

| VIII. | — |

Screen in the Chapel, King's College, Cambridge |

28 | |

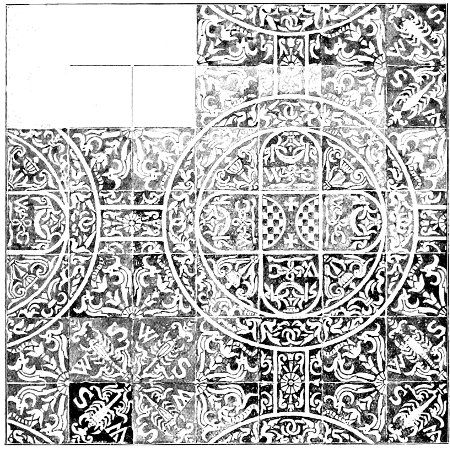

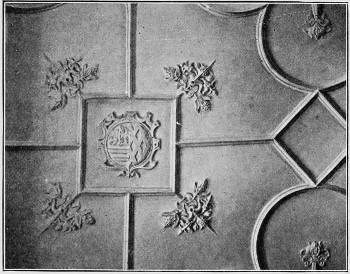

| IX. |

|

Title Paving from Lacock Abbey Harold Brakspear, del. Single Tiles from the same Pavement W. Haywood, del. |

|

38 |

| X. | — |

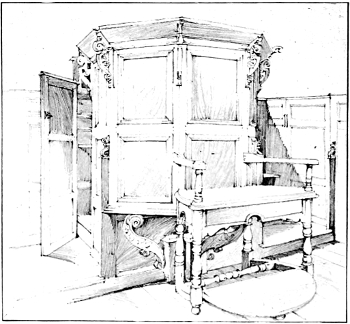

Chest From St. Mary Overie, Southwark Victor T. Jones, del. [A.A.S.B.] |

40 | |

| XI. | — |

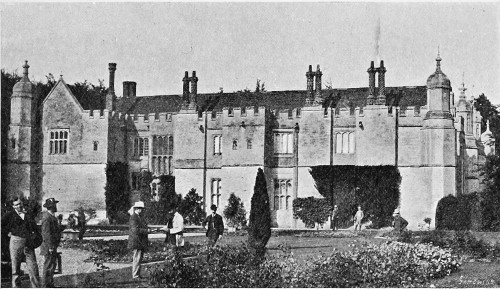

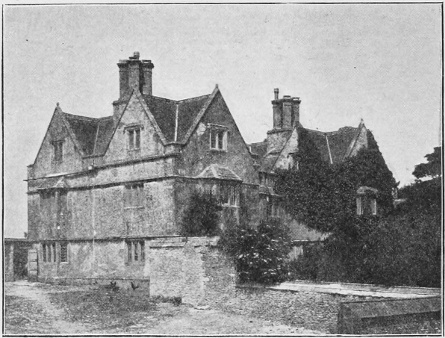

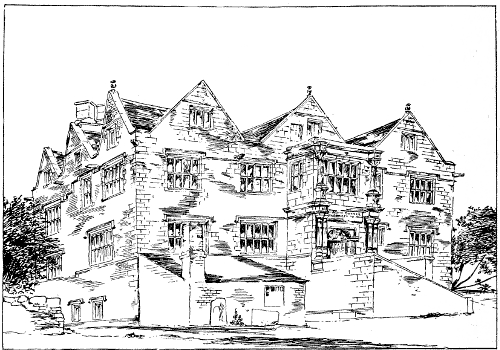

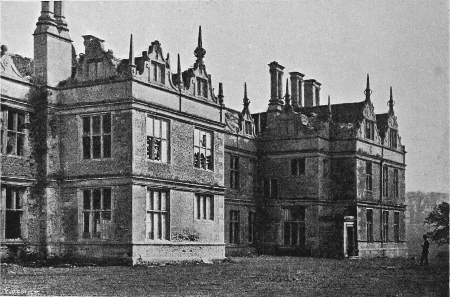

Compton Winyates; General View |

47 | |

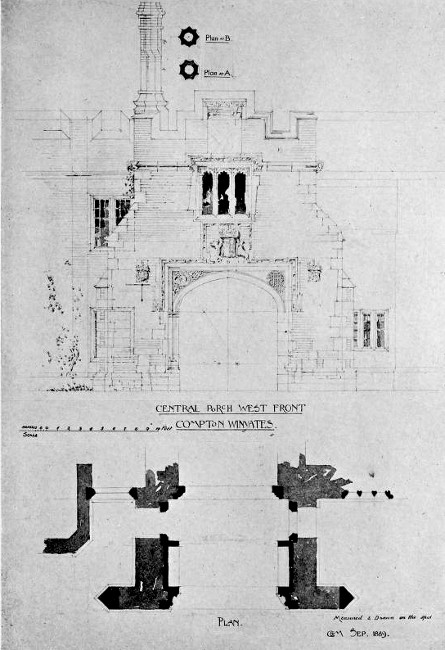

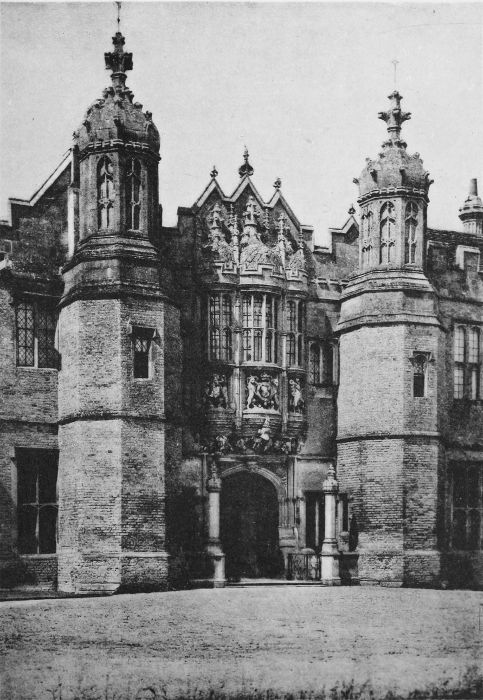

| XII. | — |

Compton Winyates; The Entrance Porch C. E. Mallows, del. |

48 | |

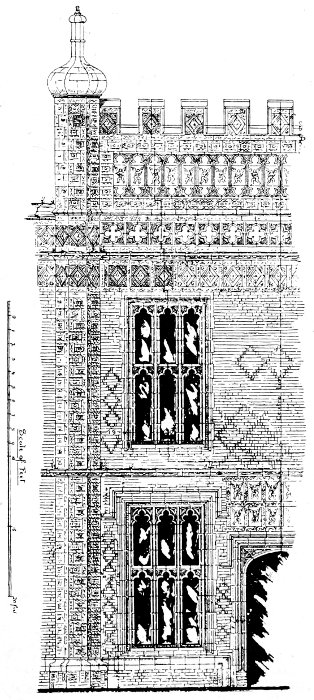

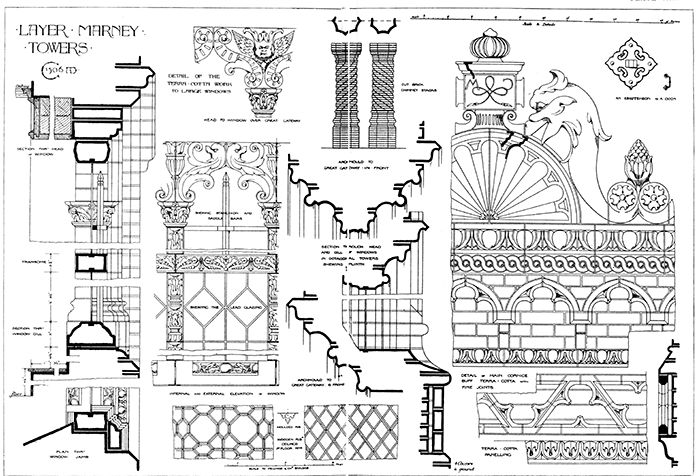

| XIII. | — |

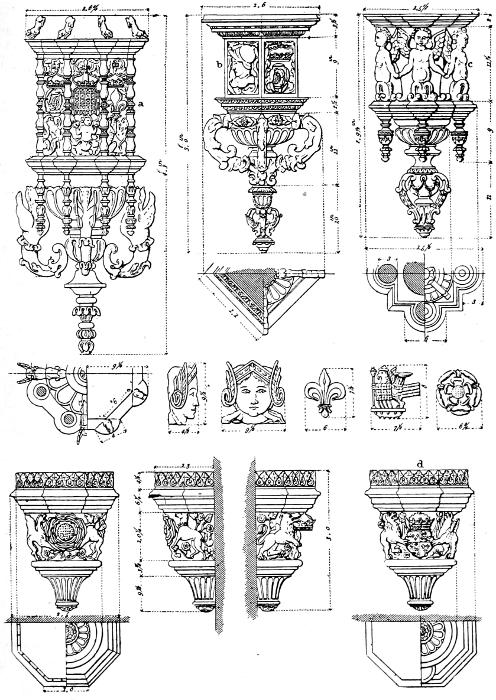

(DOUBLE)—Details from Layer Marney Tower Arnold B. Mitchell, del. |

52-3 [x] | |

| XIV. | — |

The Entrance Gateway, Hengrave Hall J. Palmer Clarke, Bury St. Edmund's, photo. |

56 | |

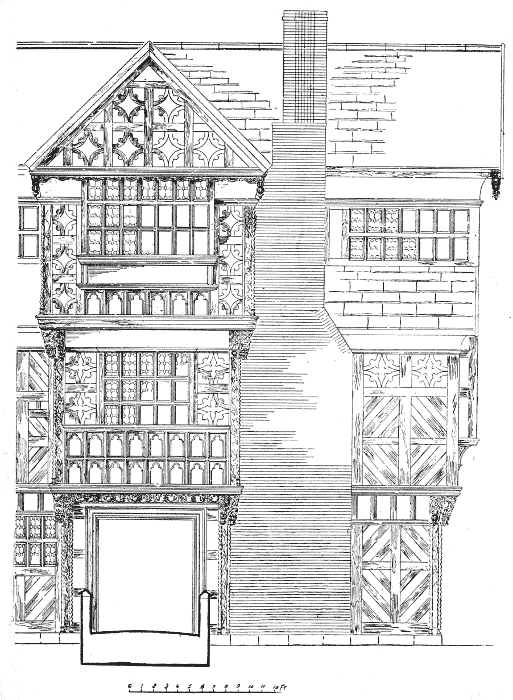

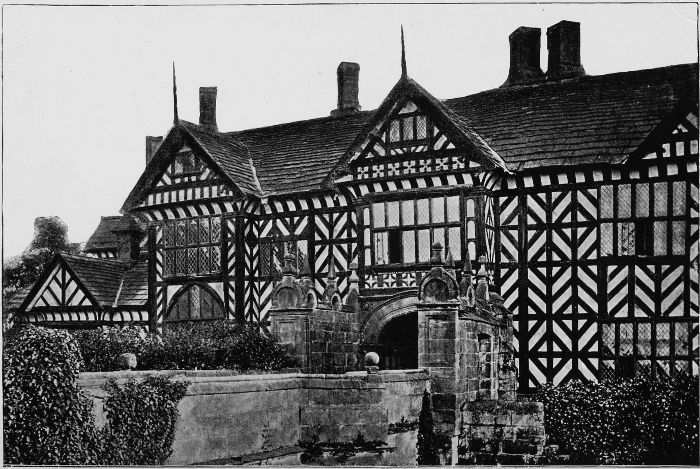

| XV. | — |

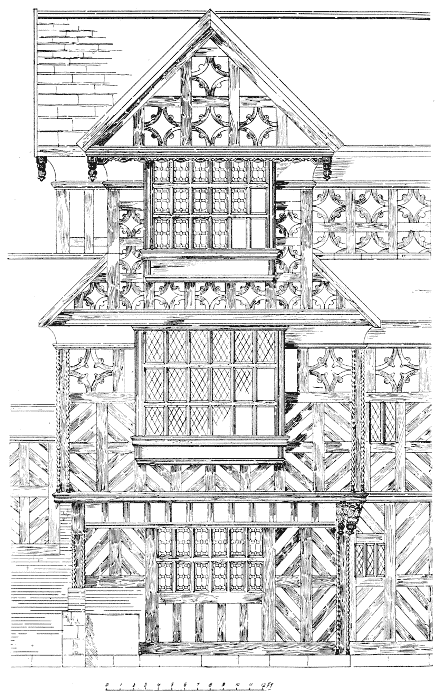

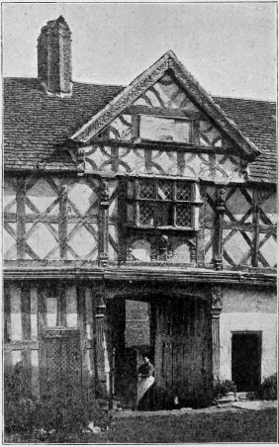

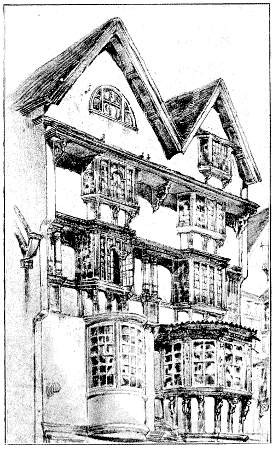

The Entrance Porch, Moreton Old Hall Maxwell Ayrton, del. |

58 | |

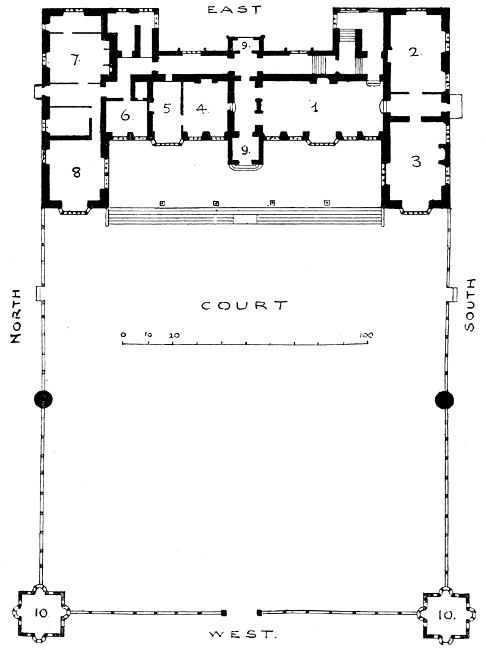

| XVI. | — |

A Gable from the Front, Moreton Old Hall Maxwell Ayrton, del. |

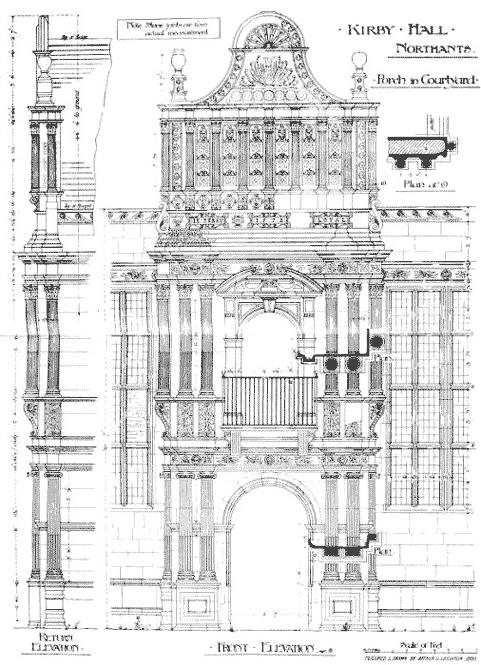

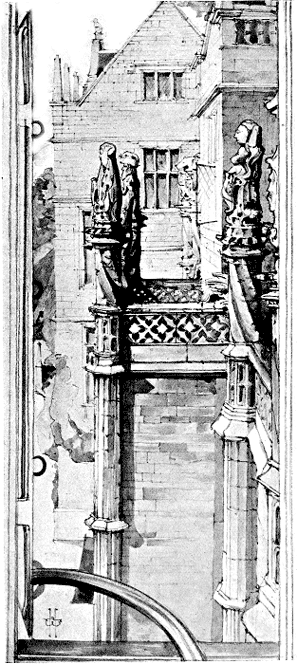

58 | |

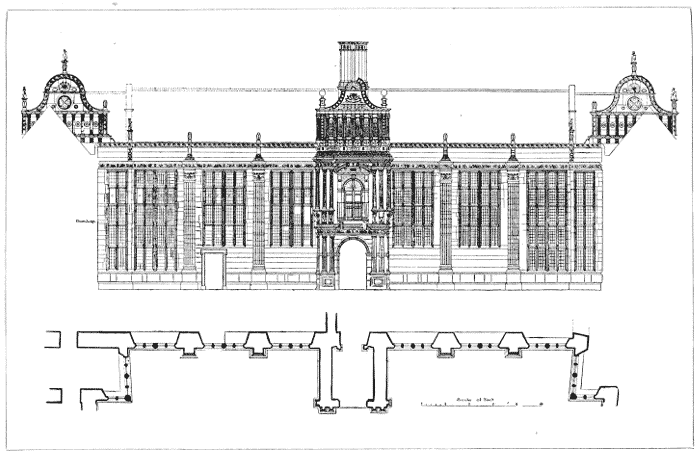

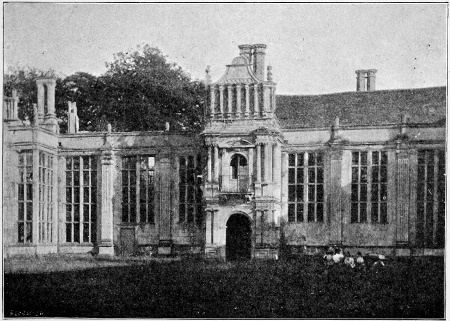

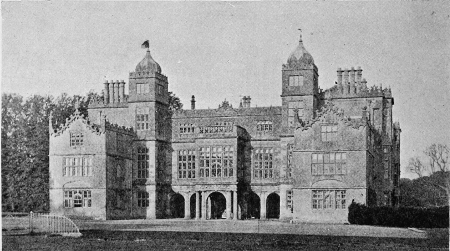

| XVII. | — |

South Side of Courtyard, Kirby Hall M. Starmer Hack, del. |

60 | |

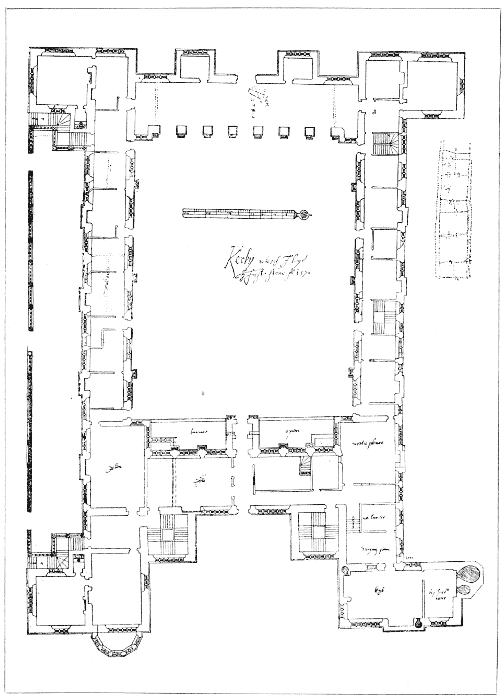

| XVIII. | — |

John Thorpe's Ground Plan for Kirby Hall From the Soane Museum Collection. |

62 | |

| XIX. | — |

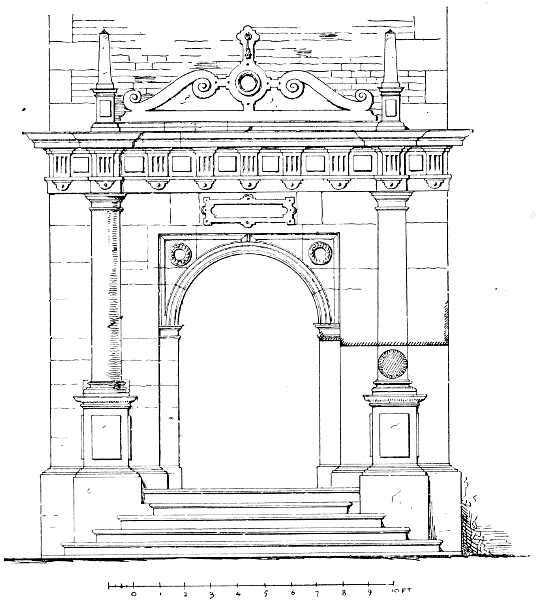

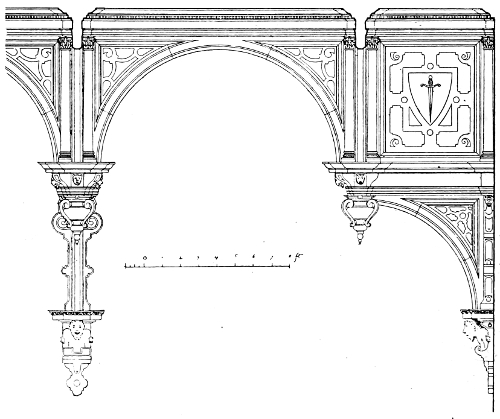

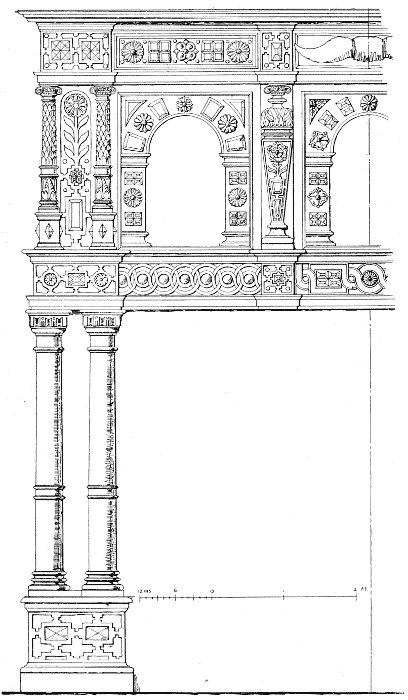

(DOUBLE)—Details of Porch in Court, Kirby Hall Arthur G. Leighton, del. |

64-5 | |

| XX. | — |

The Entrance Porch, Montacute House From a water-colour by W. Haywood. |

66 | |

| XXI. | — |

The Entrance Front and Gatehouse, Doddington Hall. By permission from Rev. R. E. G. Cole's History of Doddington |

69 | |

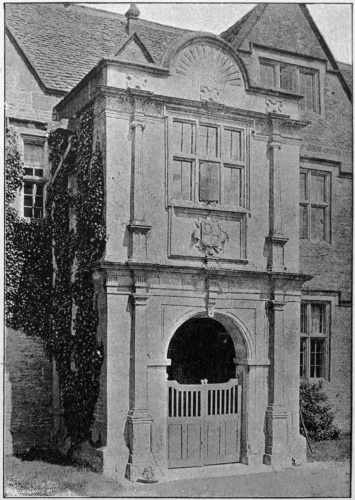

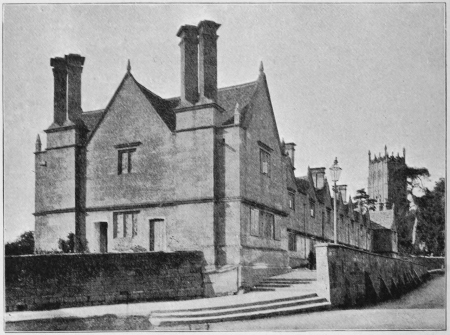

| XXII. | — |

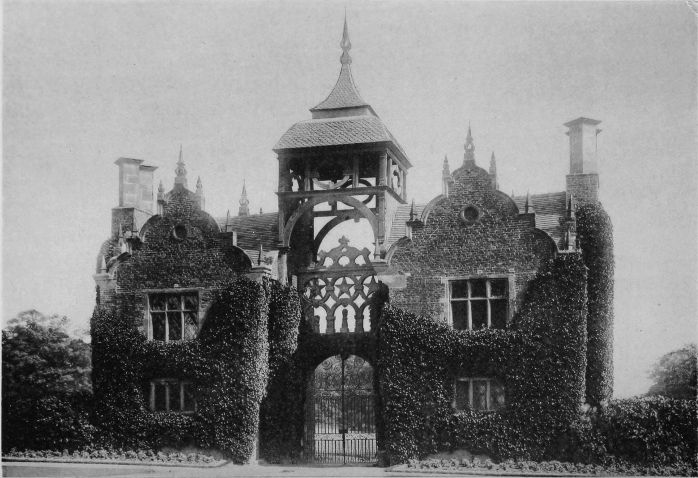

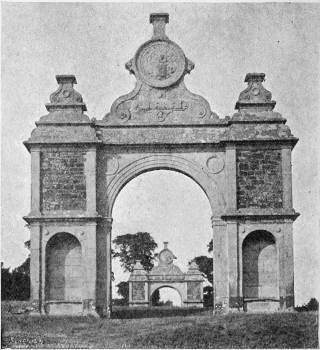

The Gatehouse at Stanway |

78 | |

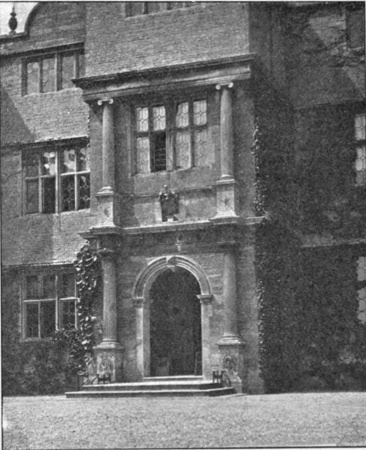

| XXIII. | — |

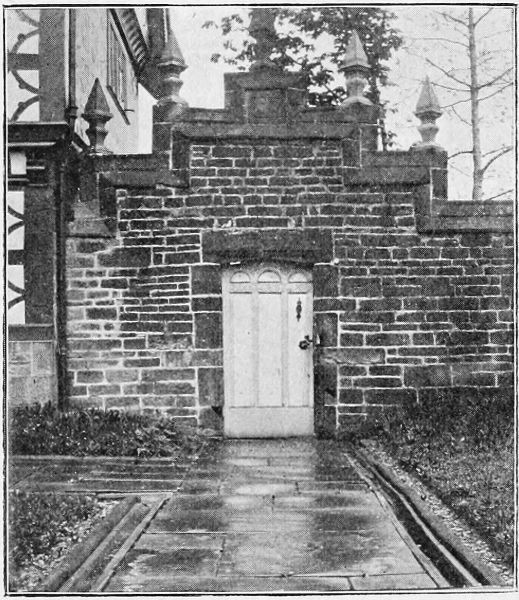

The Gatehouse at Westwood |

79 | |

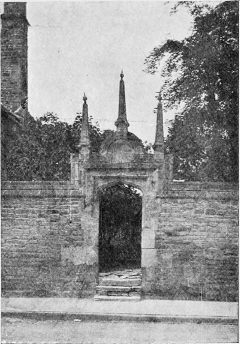

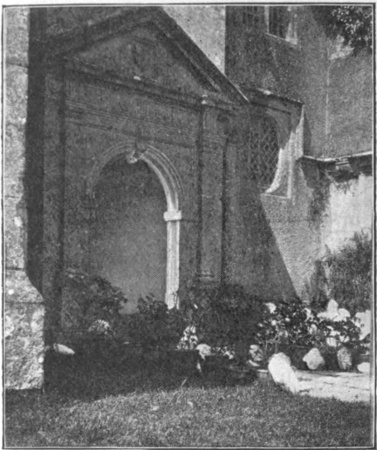

| XXIV. |

|

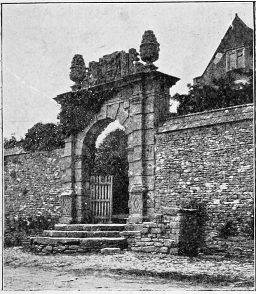

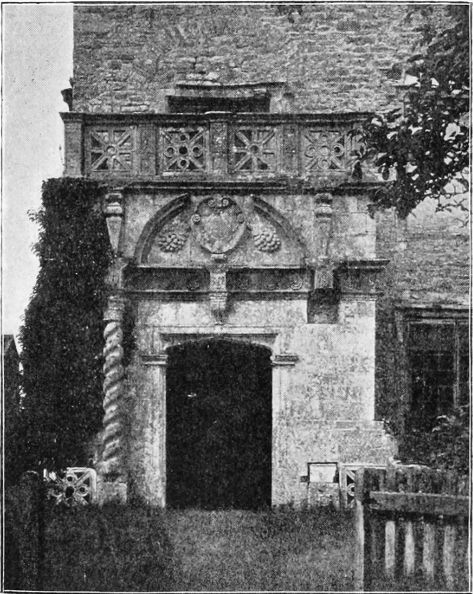

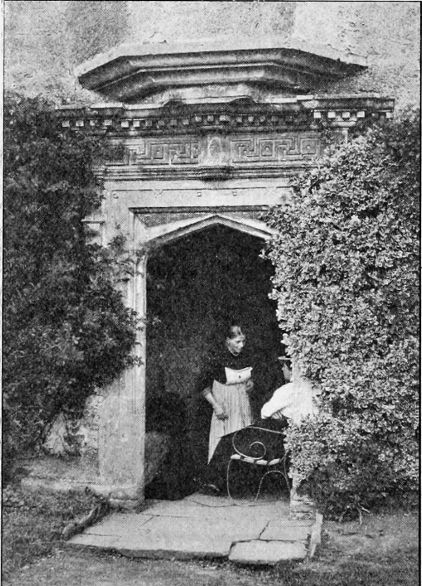

Doorway at Chipchase Castle J. P. Gibson, Hexham, photo. Porch of the Manor House, Upper Slaughter W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

|

85 |

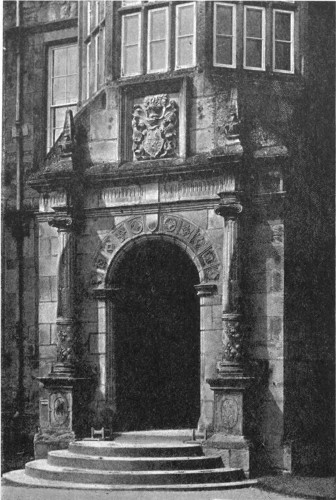

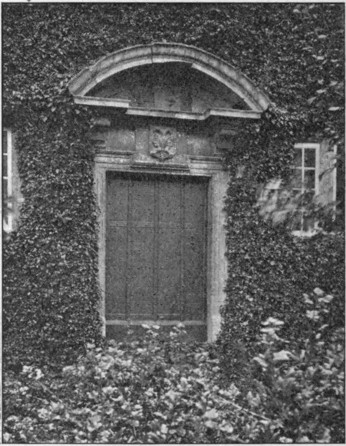

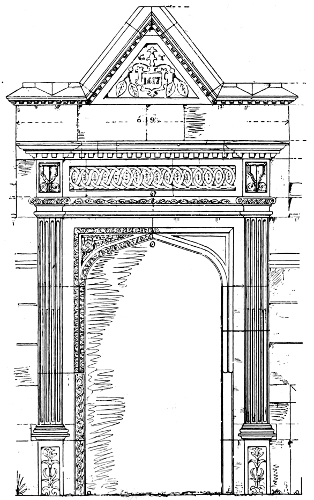

| XXV. |

|

The Grand Staircase, Wardour Castle G. W. Wilson, Aberdeen, photo. Doorway in Court, Hatfield House Col. Gale, photo. |

|

86 |

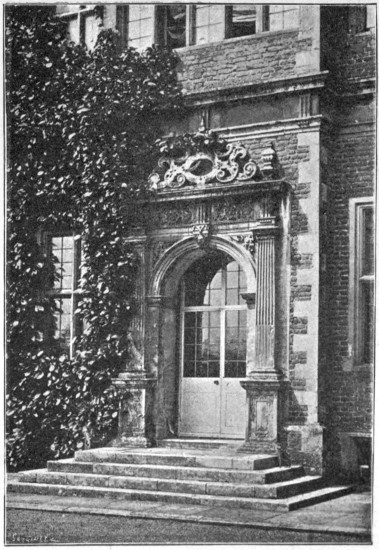

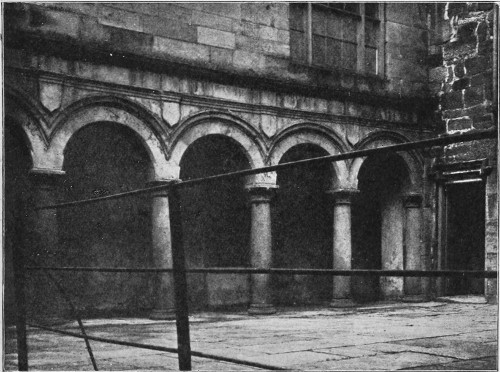

| XXVI. | — |

Arcaded Porch at Cranborne Manor House |

91 | |

| XXVII. | — |

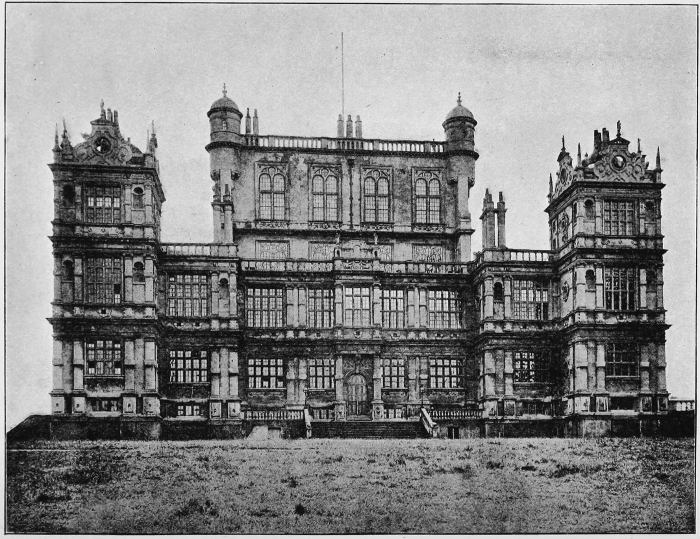

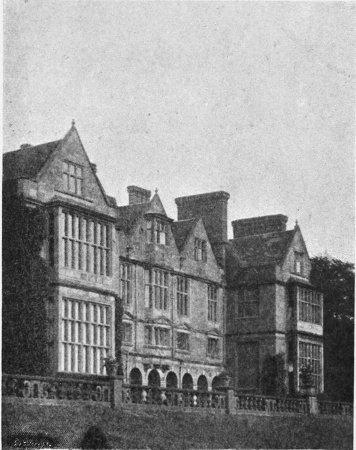

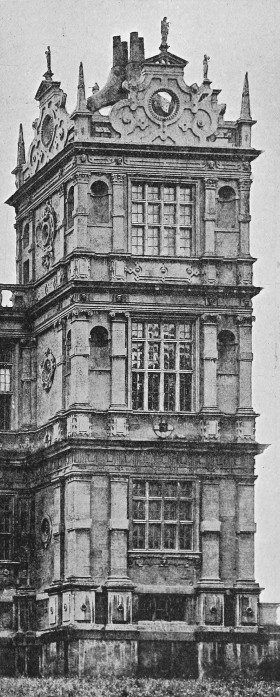

Wollaton Hall; General View |

97 | |

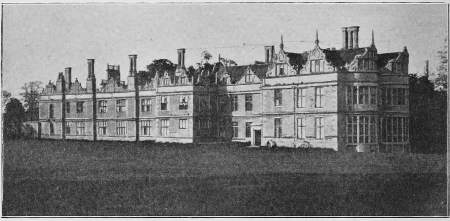

| XXVIII. | — |

Burghley House; General View G. W. Wilson, Aberdeen, photo. |

98 | |

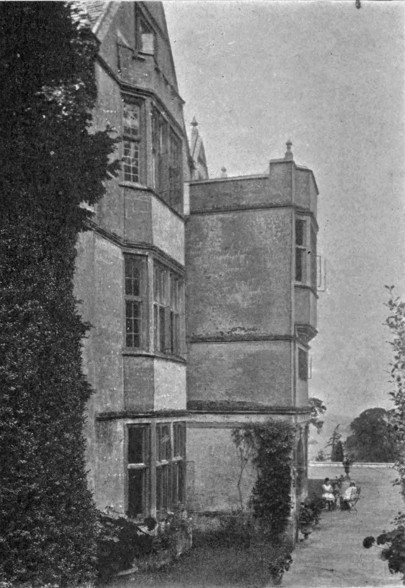

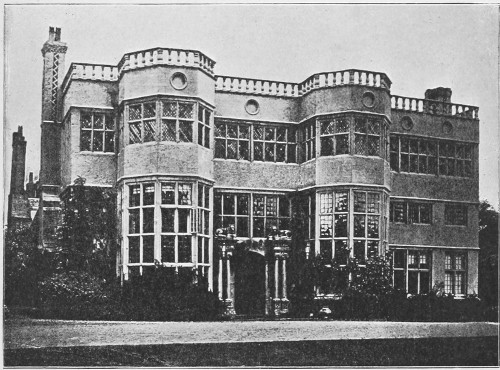

| XXIX. |

|

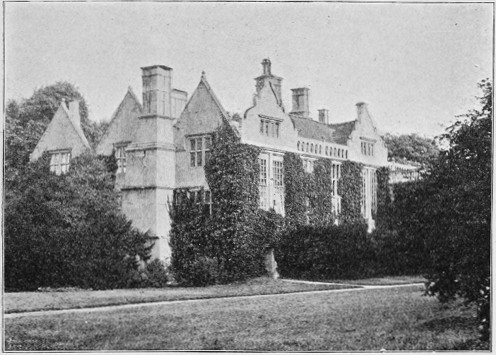

Exton Old Hall, Rutland J. A. G., photo. The Manor House, Glinton J. A. G., photo. |

|

100 |

| XXX. | — |

Mount Grace Priory, Yorkshire |

106 | |

| XXXI. | — |

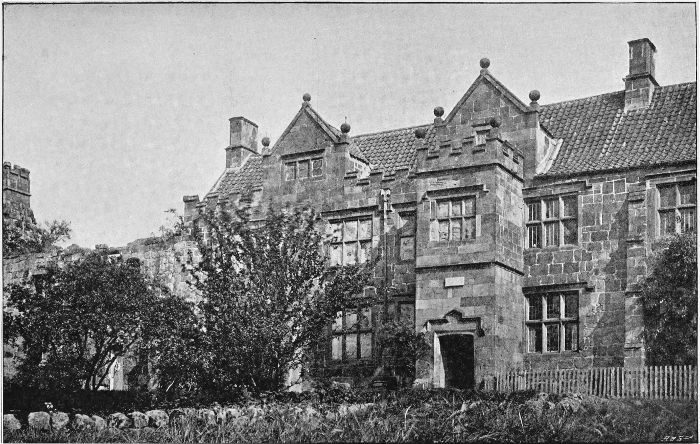

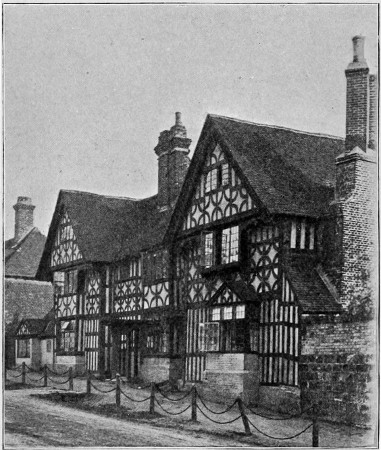

View of Front, Speke Hall |

107 | |

| XXXII. | — |

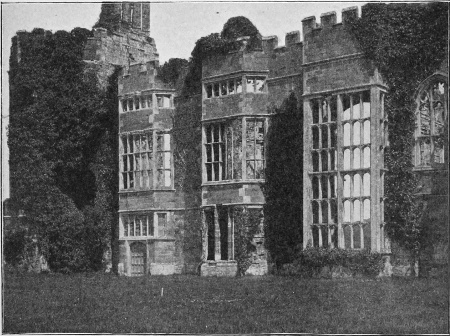

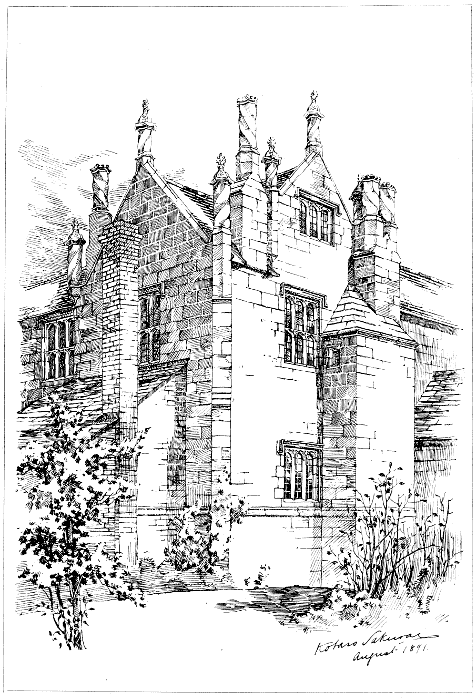

Part of the Front, Barrington Court Kotaro Sakurai, del. [A.A.S.B.] |

110 | |

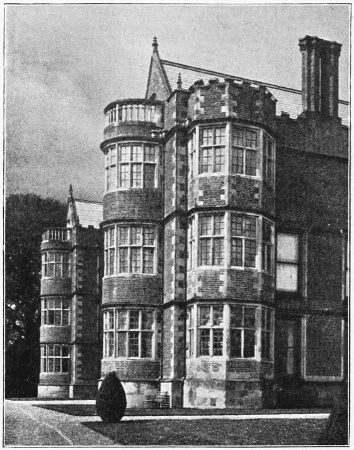

| XXXIII. |

|

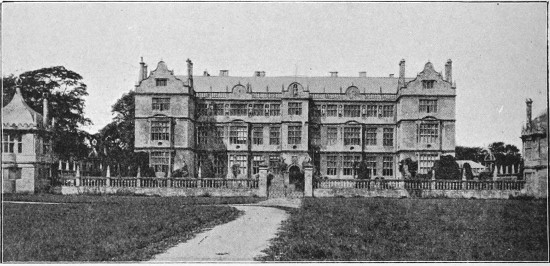

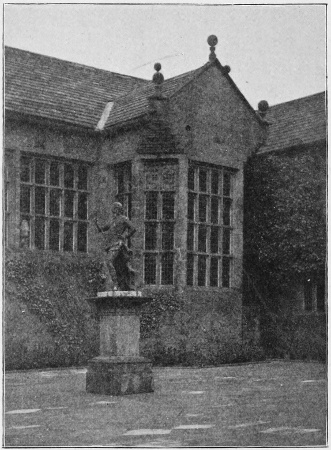

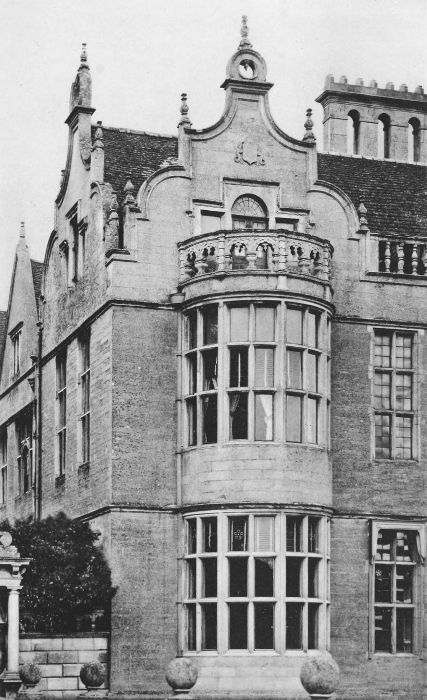

Astley Hall Bedford Lemere, London, photo. Kirby Hall; The Bay Windows Col. Gale, photo. |

|

112 [xi] |

| XXXIV. | — |

Gables at Lilford Hall |

112 | |

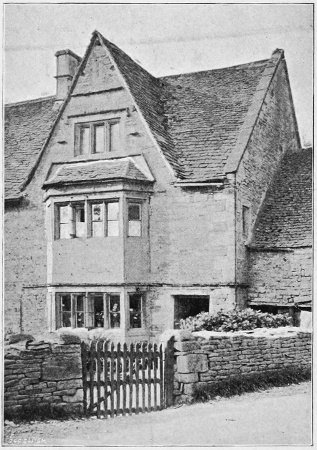

| XXXV. |

|

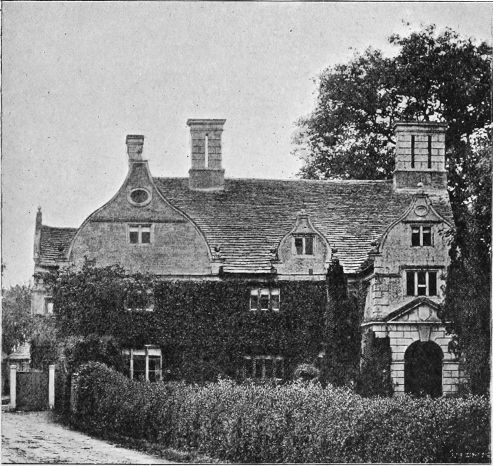

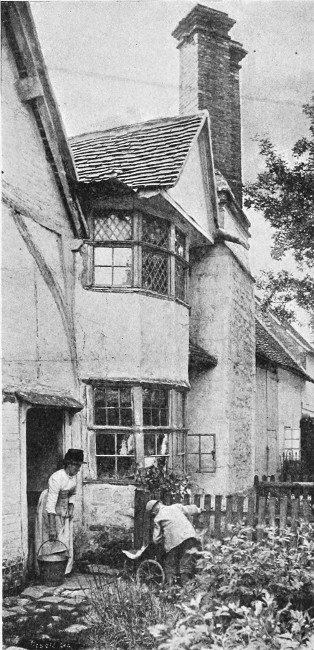

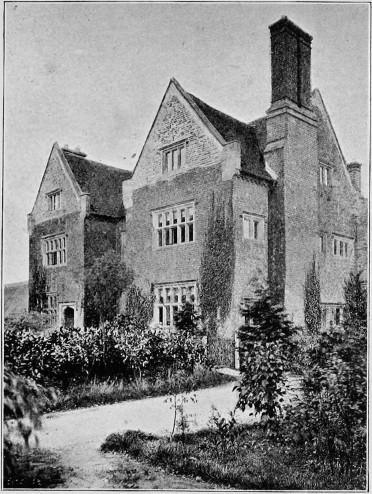

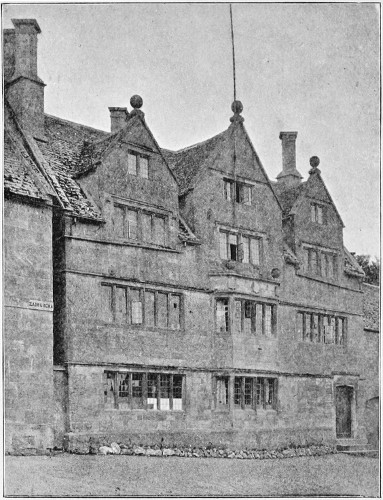

Holmshurst, Burwash W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. Tudor House, Broadway W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

|

118 |

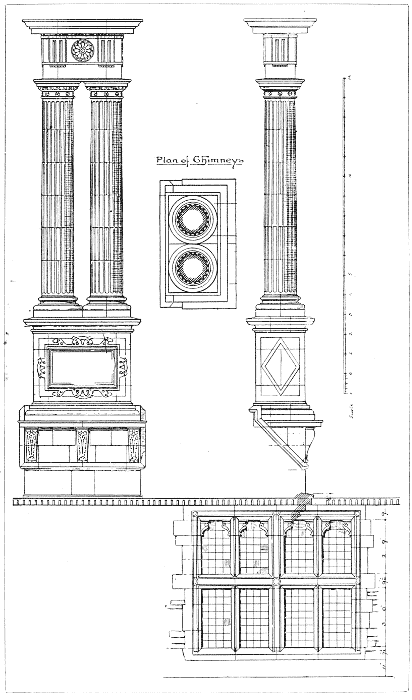

| XXXVI. | — |

Chimney-stack and Window from Lacock Abbey Harold Brakspear, del. |

128 | |

| XXXVII. | — |

Blickling Hall; Part of Entrance Front |

130 | |

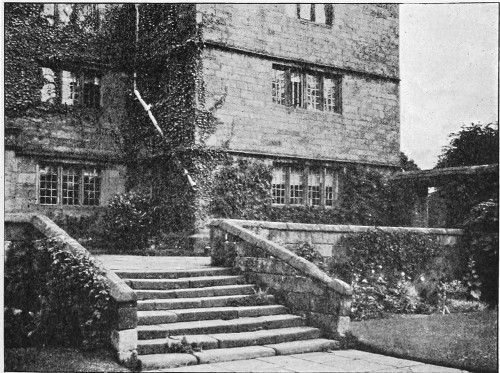

| XXXVIII. |

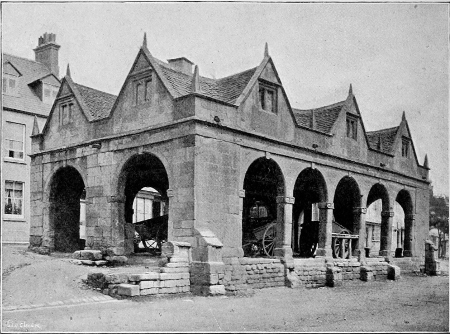

|

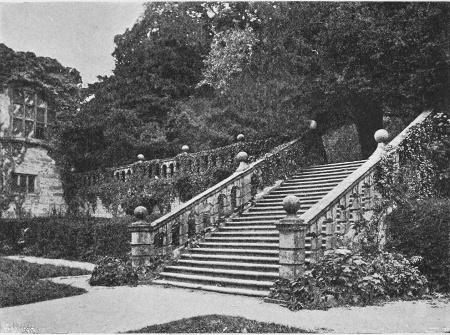

Steps to Terrace, Haddon Hall Terrace Wall, Claverton House J. L. Robinson, photo. |

|

133 |

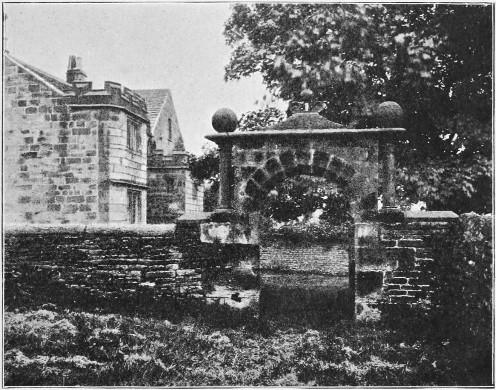

| XXXIX. |

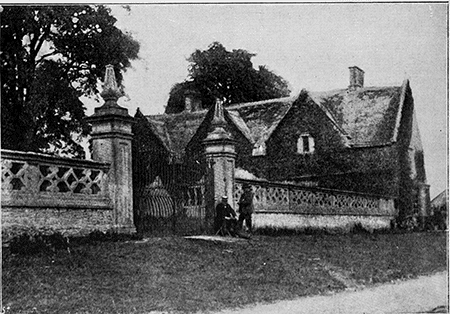

|

Gateway, Highlow Hall, near Hathersage J. A. G., photo. Terrace Steps, Eyam Hall J. A. G., photo. |

|

136 |

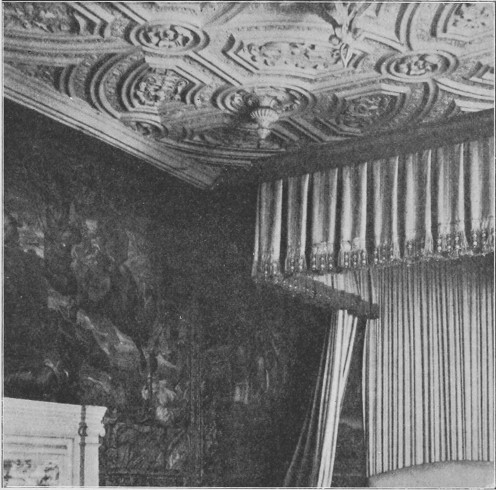

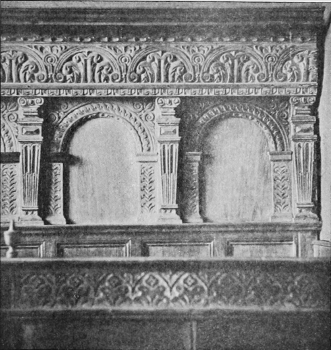

| XL. |

|

Side of Bay in the Dining Room, Haddon Hall J. A. G., photo. Panelling in the Dining Room, Haddon Hall J. A. G., photo. |

|

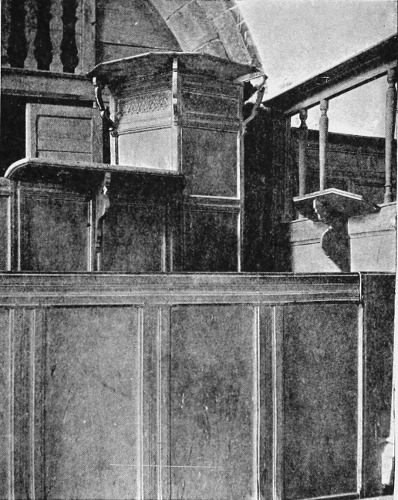

153 |

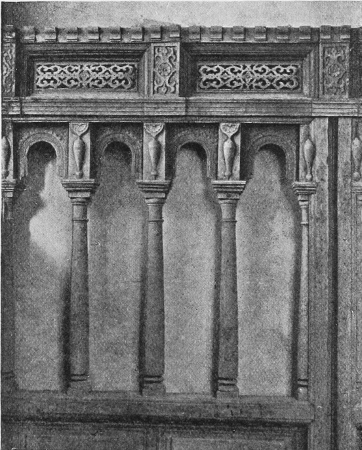

| XLI. |

|

Woodwork in Chapel, Haddon Hall

Bay Window in the Drawing Room, Haddon Hall J. A. G., photo. |

|

154 |

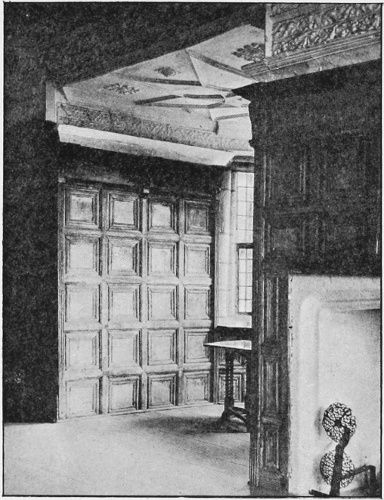

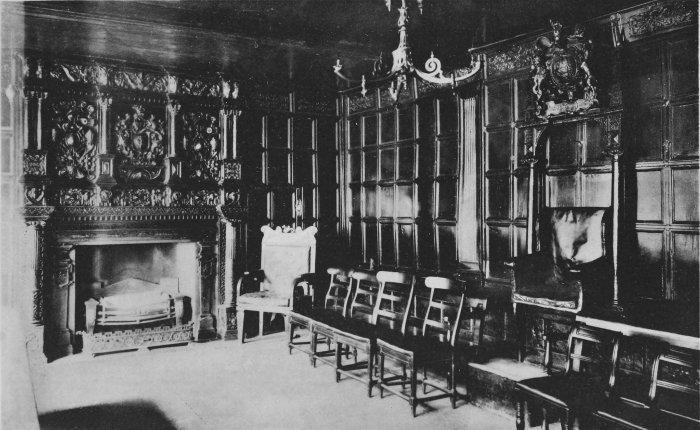

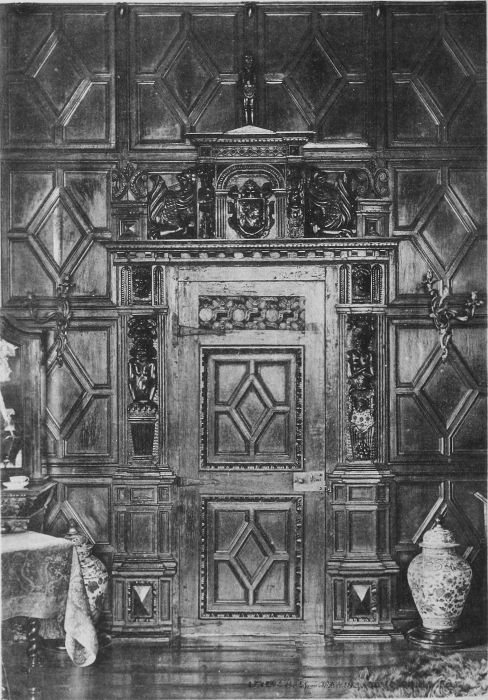

| XLII. | — |

An Interior from Carbrook Hall, near Sheffield |

157 | |

| XLIII. | — |

Side of Room at Benthall Hall B. J. Fletcher, del. |

156 | |

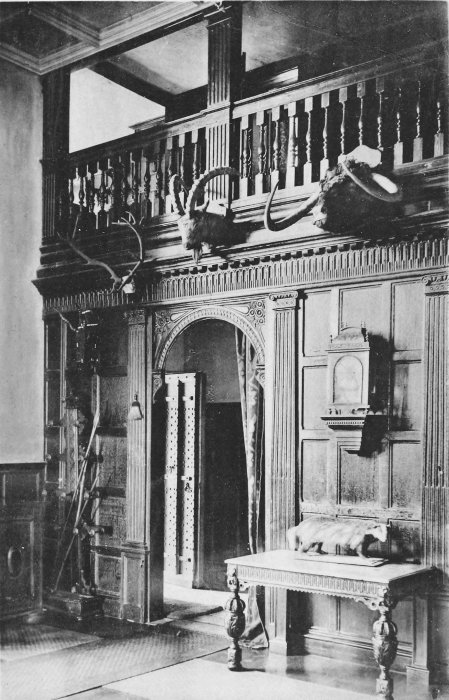

| XLIV. | — |

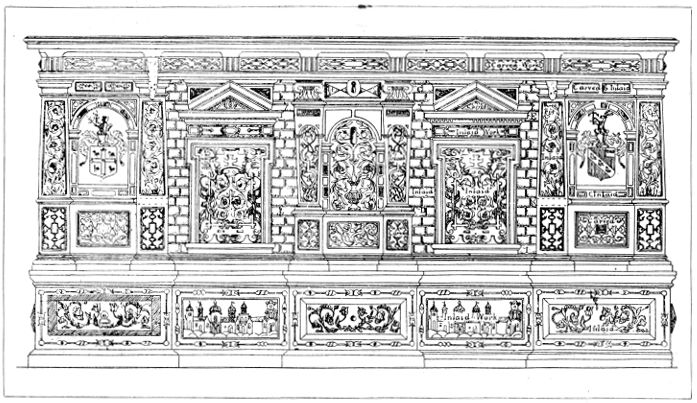

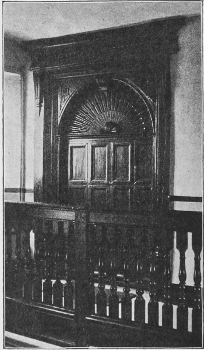

Screen in the Hall, Wadham College, Oxford |

159 | |

| XLV. | — |

Screen in the Hall, Trinity College, Cambridge |

160 | |

| XLVI. | — |

Screen in the Hall, Woollas Hall Harold Baker, Birmingham, photo. |

160 | |

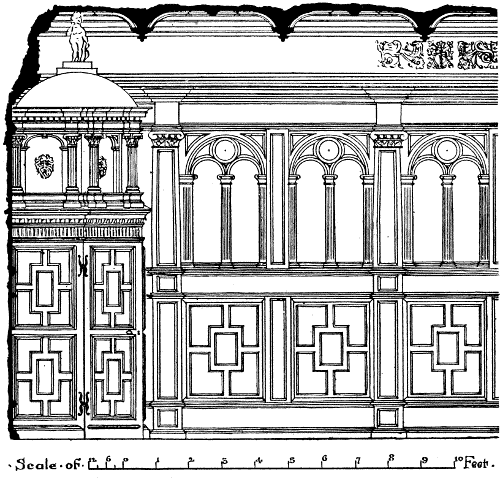

| XLVII. | — |

The Great Chamber, South Wraxall Manor House Ernest W. Gimson, del. |

162 | |

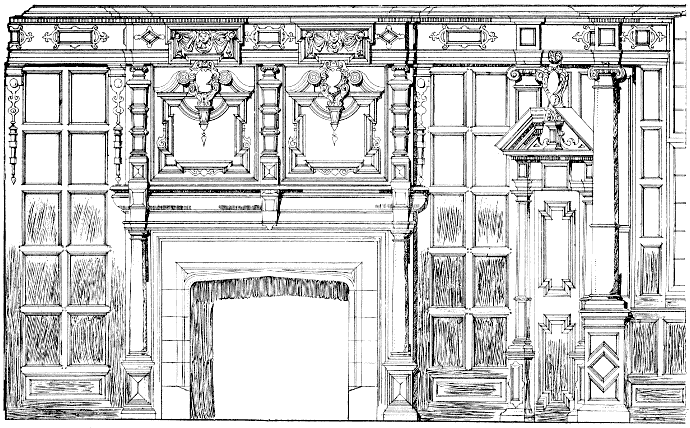

| XLVIII. | — |

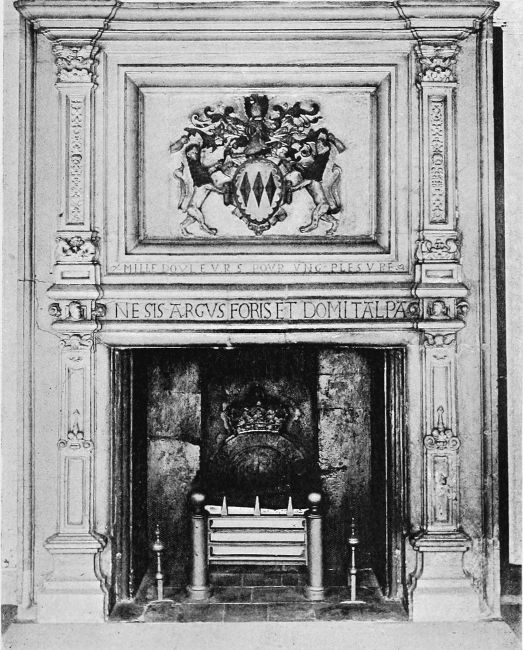

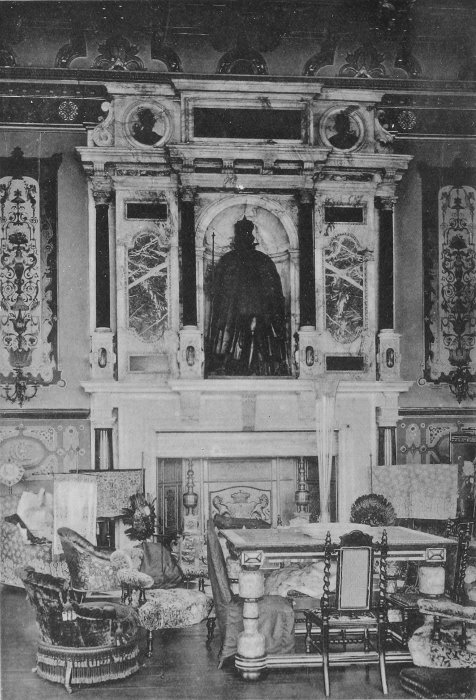

Fireplace and Panelling in the Mayor's Room, Old Town Hall, Leicester |

162 | |

| XLIX. | — |

Side of a Room, the "Reindeer" Inn, Banbury John Stewart, del. |

162 | |

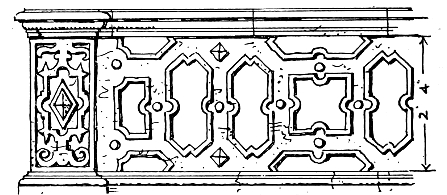

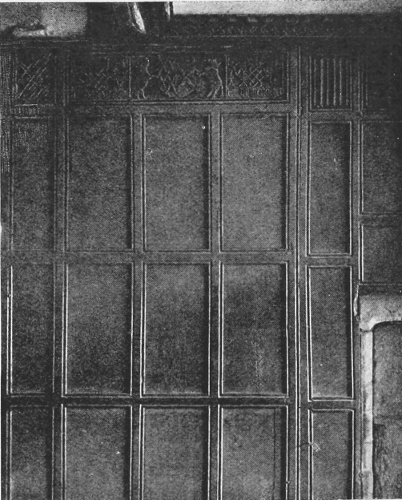

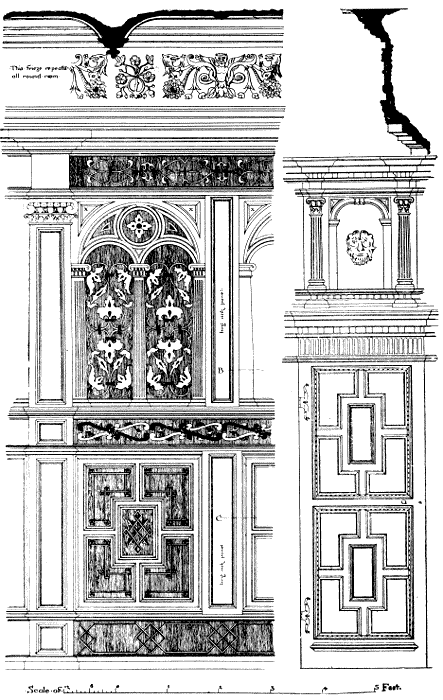

| L. | — |

Details of Panelling from Sizergh Hall F. Dare Clapham, del. |

163 | |

| LI. | — |

Interior Porch, Broughton Castle |

163 | |

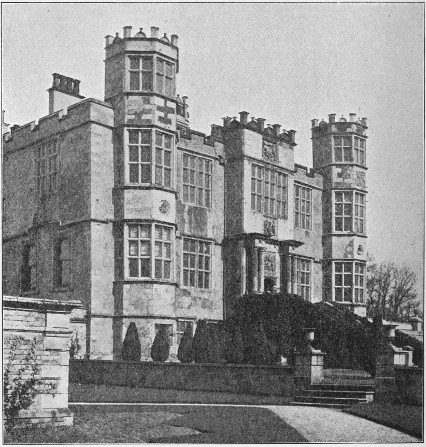

| LII. | — |

The Presence Chamber at Hardwick Hall A. Seaman, Chesterfield, photo. |

164 | |

| LIII. | — |

Doorway in a House at Bristol |

164 | |

| LIV. | — |

A Doorway from Levens Hall F. B. Turner, Flamborough, photo. |

165 | |

| LV.[xii] |

|

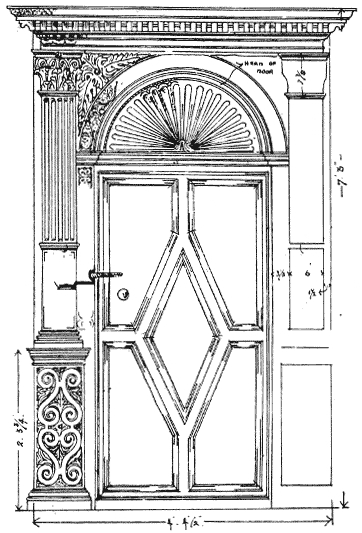

Doorway, Gayton Manor House J. A. G., del. Doorway, St. Peter's Hospital, Bristol T. Locke Worthington, del. [A.A.S.B.] |

|

166 |

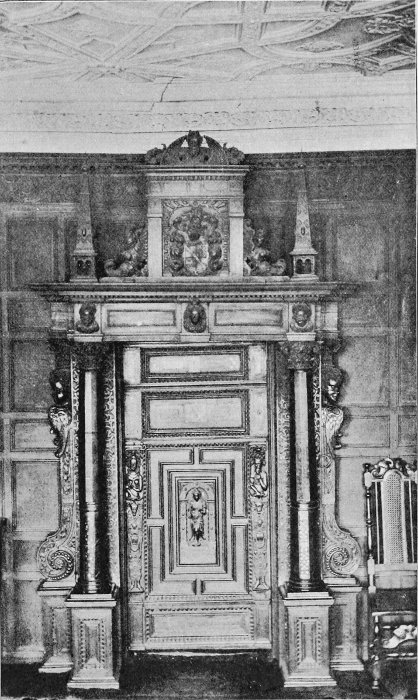

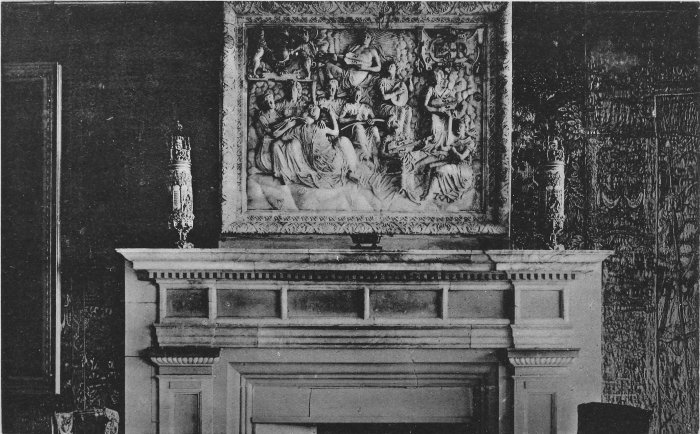

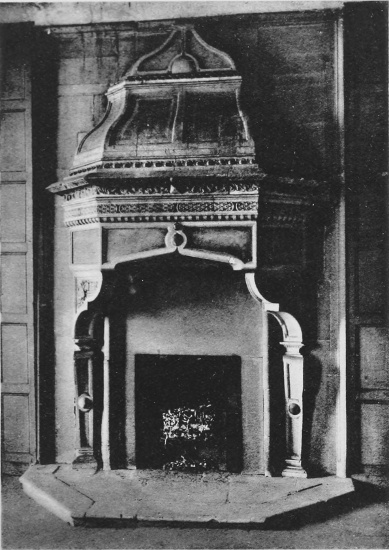

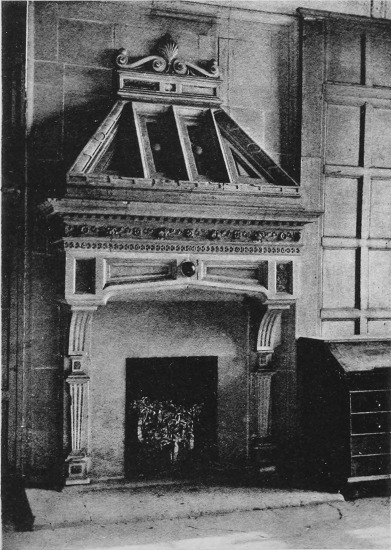

| LVI. | — |

Chimney-piece from Boughton House |

168 | |

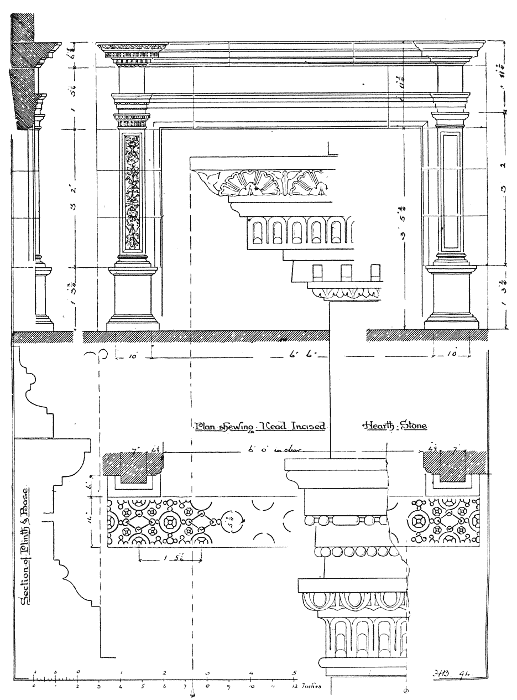

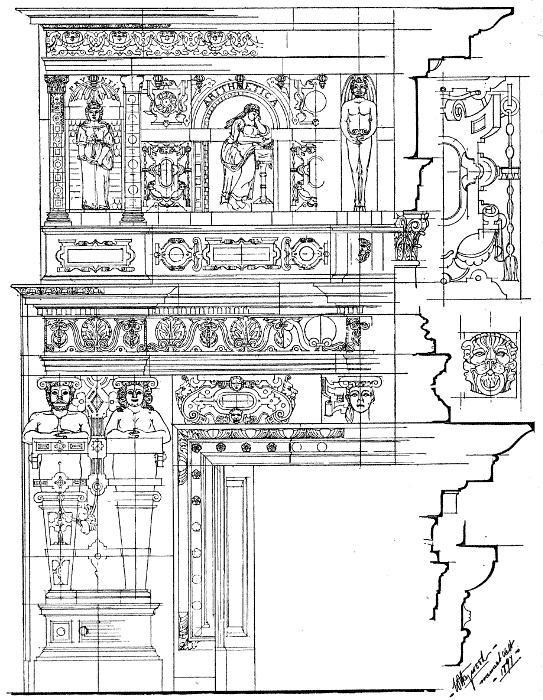

| LVII. | — |

Chimney-piece from Lacock Abbey Harold Brakspear, del. |

168 | |

| LVIII. | — |

A Chimney-piece from Barlborough Hall Col. Gale, photo. |

168 | |

| LIX. | — |

Chimney-piece in King James's Room, Hatfield House Col. Gale, photo. |

169 | |

| LX. | — |

Chimney-piece in the Great Chamber, South Wraxall Manor House W. Haywood, del. |

169 | |

| LXI. | — |

Chimney-piece from Hardwick Hall J. L. Robinson, photo. |

169 | |

| LXII. | — |

Chimney-piece from Ford House, Newton Abbot J. A. G., del. |

170 | |

| LXIII. | — |

Chimney-piece at Whiston, Sussex Col. Gale, photo. |

171 | |

| LXIV. | — |

Two Chimney-pieces From Bolsover Castle Col. Gale, photo. |

171 | |

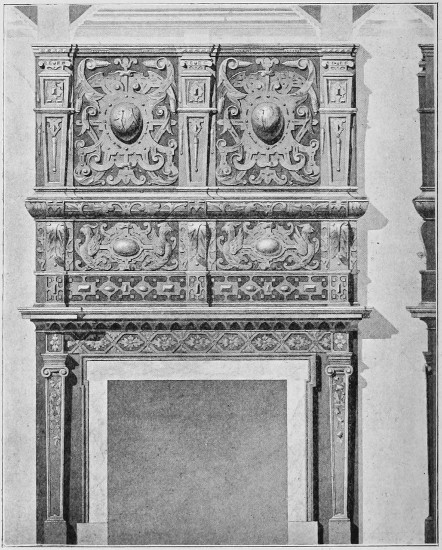

| LXV. | — |

Chimney-piece at Bromley-by-Bow Palace |

172 | |

| LXVI. | — |

Chimney-piece from Castle Ashby Bedford Lemere, London, photo. |

172 | |

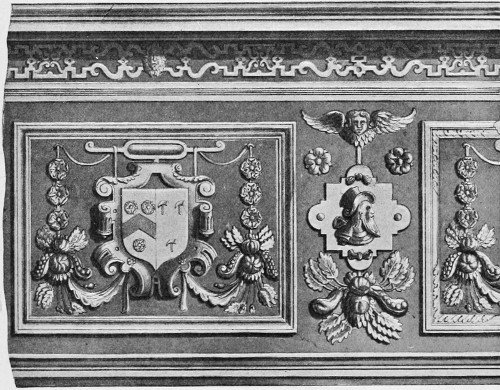

| LXVII. | — |

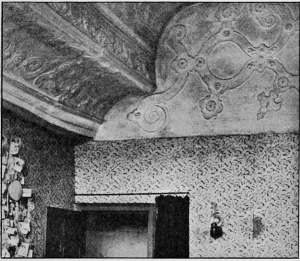

Ceiling and Frieze from Cardinal Wolsey's Closet, Hampton Court Palace J. A. G., photo. |

175 | |

| LXVIII. | — |

Ceiling at Deene Hall J. A. G., photo. |

177 | |

| LXIX. | — |

Ceiling from the "Reindeer" Inn, Banbury J. A. G., photo. |

178 | |

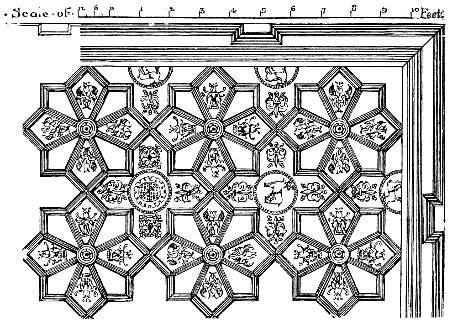

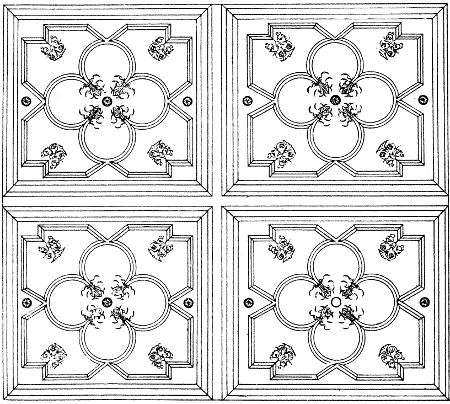

| LXX. | — |

Ceiling of the Great Chamber, Aston Hall From W. Niven's Account of Aston Hall. |

180 | |

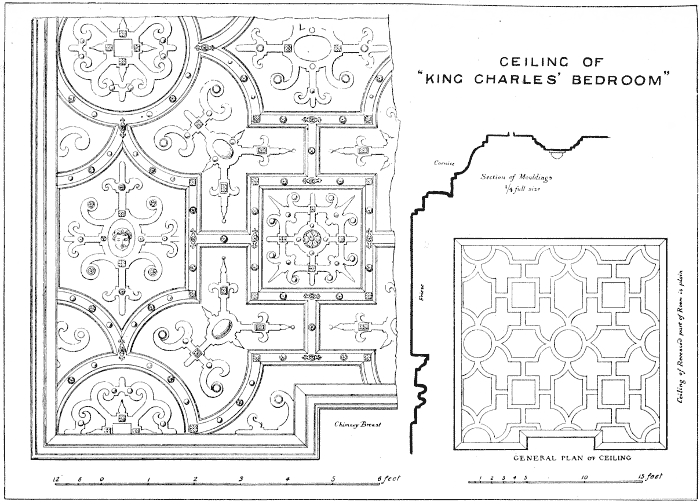

| LXXI. | — |

Ceiling of King Charles' Bedroom, Aston Hall From W. Niven's Account of Aston Hall. |

180 | |

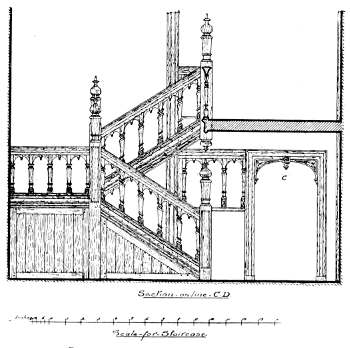

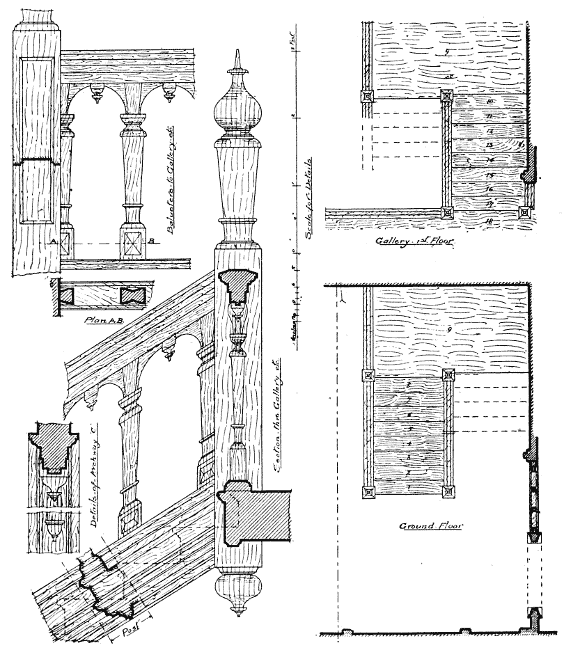

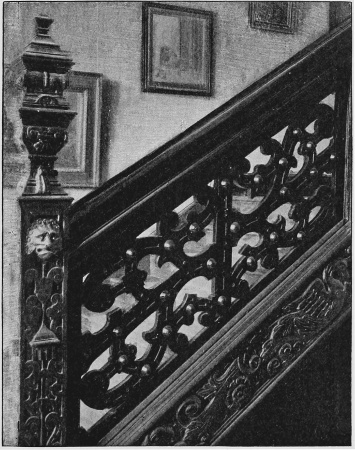

| LXXII. | — |

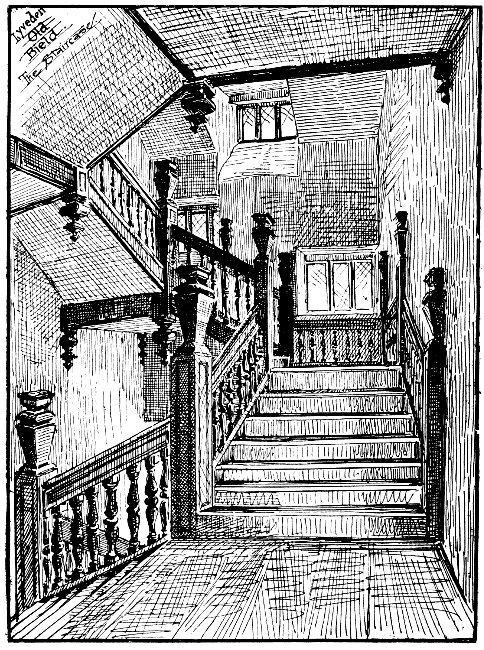

Staircase from Burghley House, Stamford After Richardson. |

187 | |

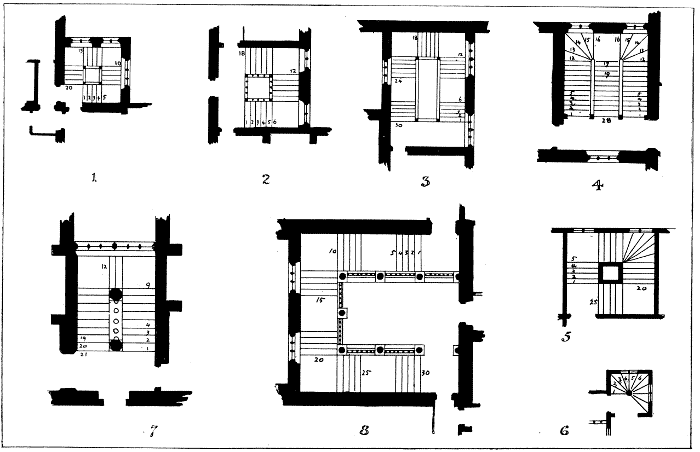

| LXXIII. | — |

Plans of Staircases from John Thorpe's Drawings In the Soane Museum Collection. |

189 | |

| LXXIV. | — |

Staircase, Audley End C. J. Richardson, del. |

194 | |

| LXXV. | — |

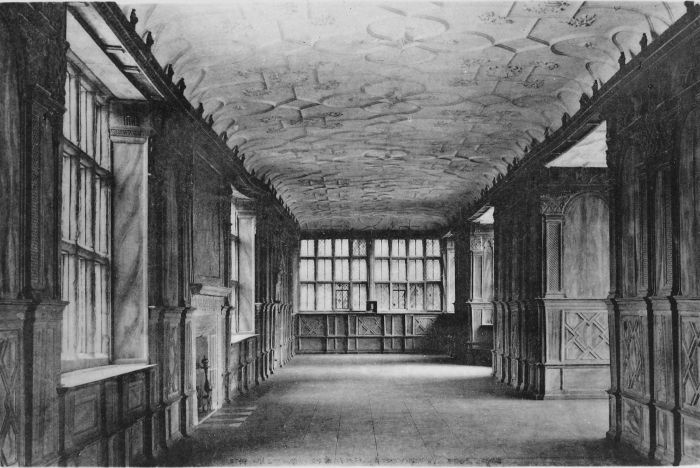

The Long Gallery, Haddon Hall G. W. Wilson, Aberdeen, photo. |

196 | |

| LXXVI. | — |

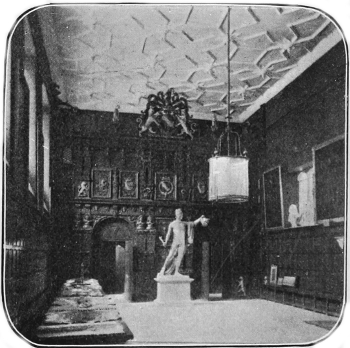

The Long Gallery, Aston Hall[xiii] |

196 | |

| LXXVII. | — |

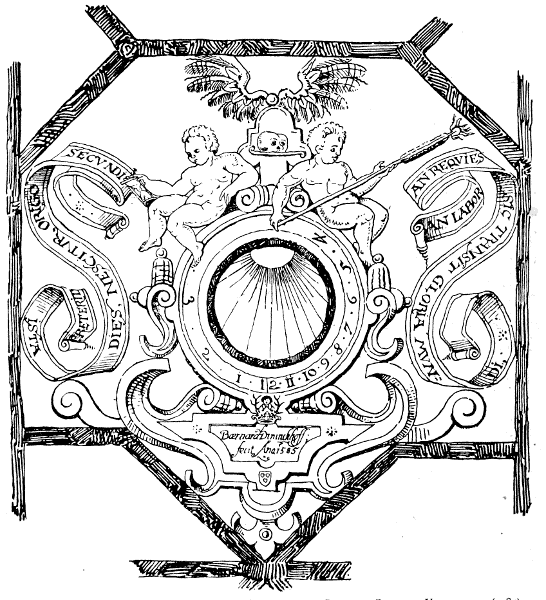

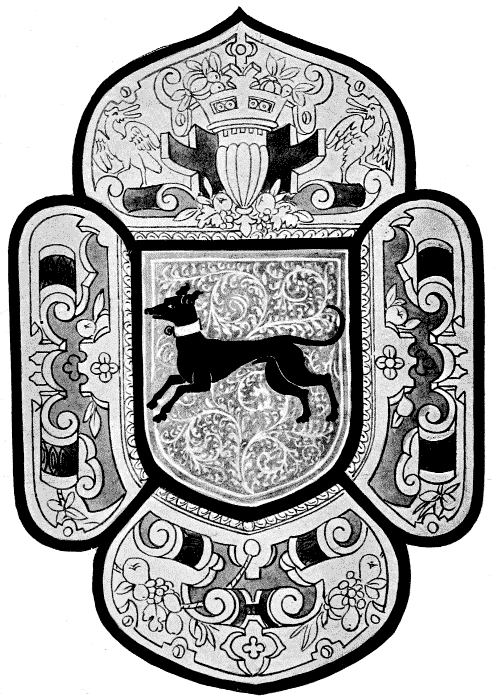

Glass Panel from Moreton Old Hall John West, del. |

198 | |

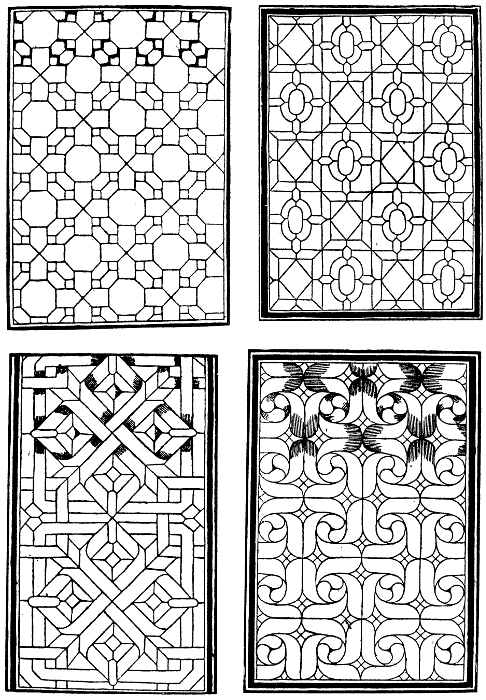

| LXXVIII. | — |

Four Examples of Lead Glazing from W. Gedde's "Booke of Sundry Draughtes," 1611 |

199 | |

| LXXIX. | — |

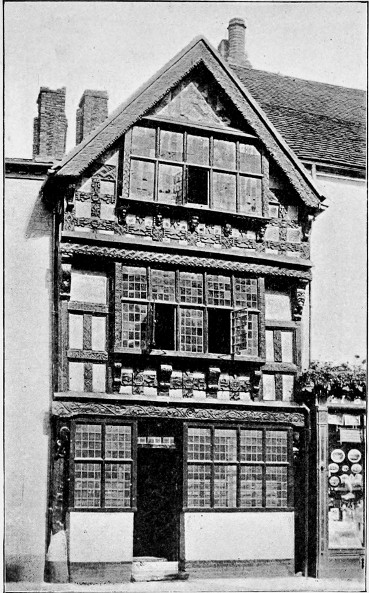

Two Street Houses from Oxford and Stratford-on-Avon |

202 | |

| LXXX. | — |

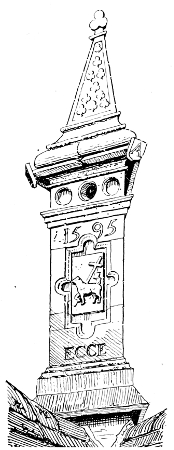

The Village Cross, Brigstock Miss Dryden, photo. |

211 | |

| LXXXI. | — |

Details of the Chichester Tomb, Pilton Church |

218 | |

| LXXXII. | — |

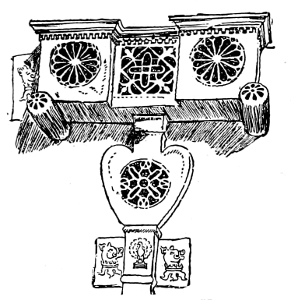

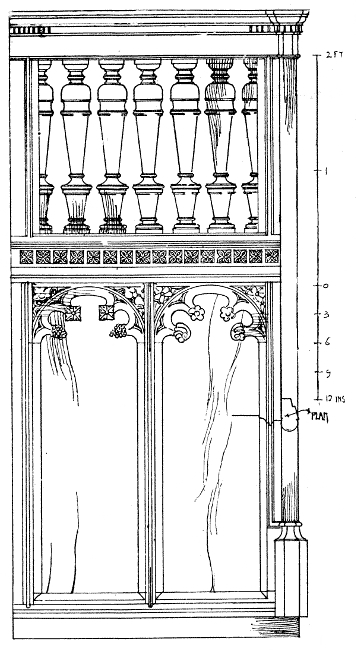

Choir Screen from All Saints' Church, Tilney C. A. Nicholson, del. |

219 | |

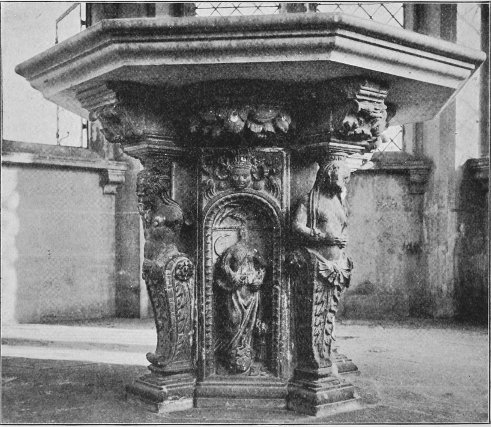

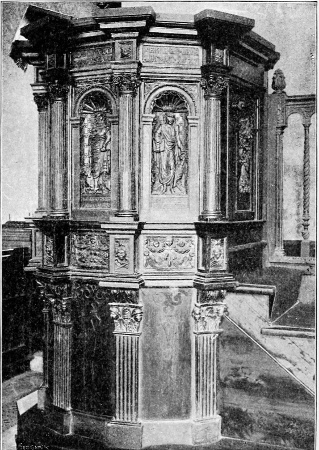

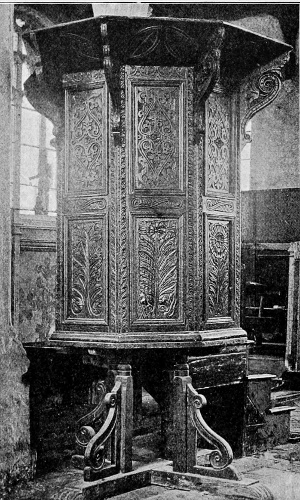

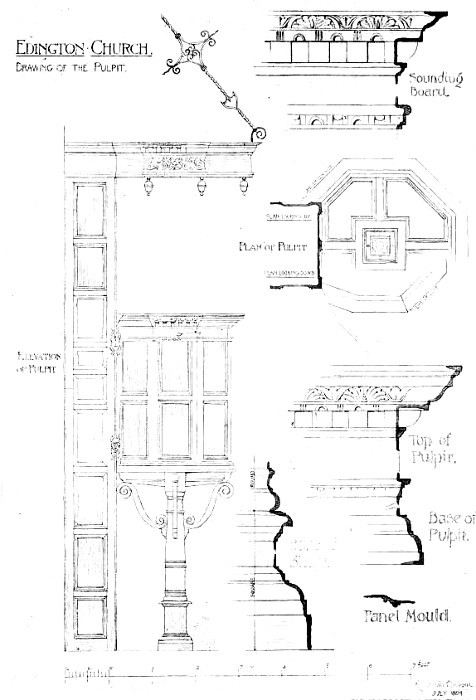

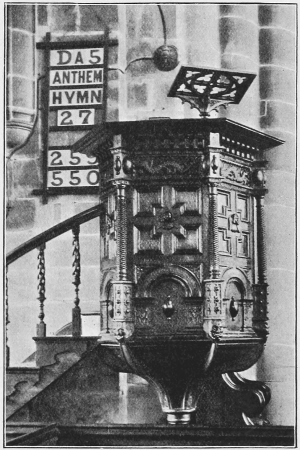

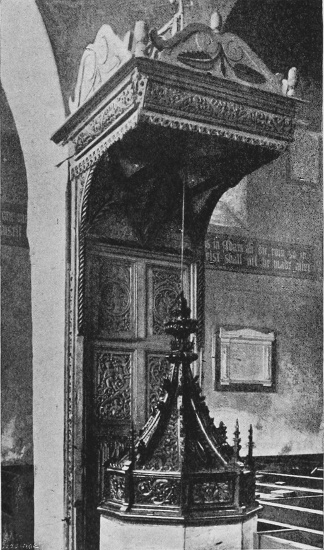

| LXXXIII. | — |

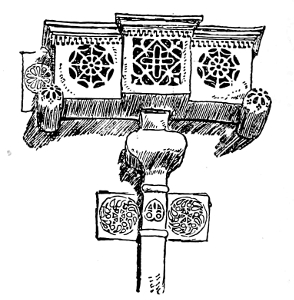

Pulpit in Edington Church R. Shekleton Balfour, del. |

221 | |

| LXXXIV. | — |

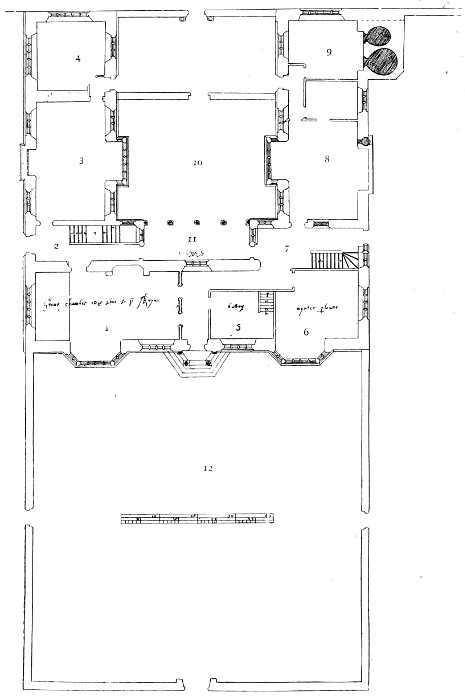

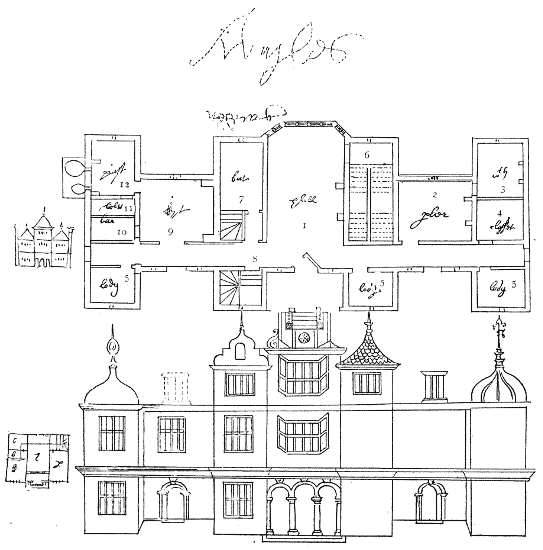

John Thorpe's Drawing for Sir Jarvis Clifton's House From the Soane Museum Collection. |

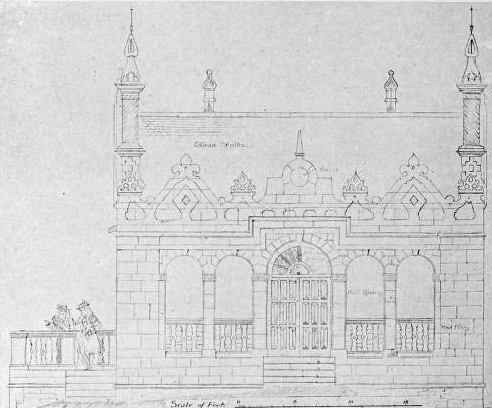

231 | |

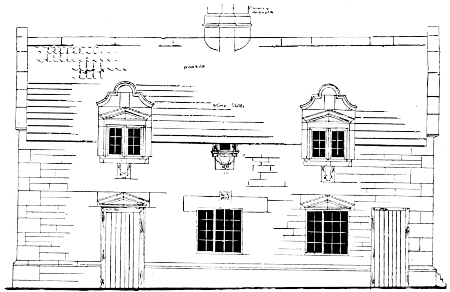

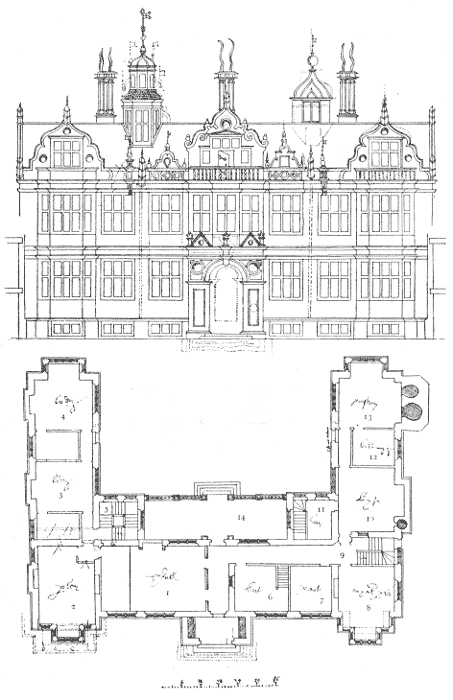

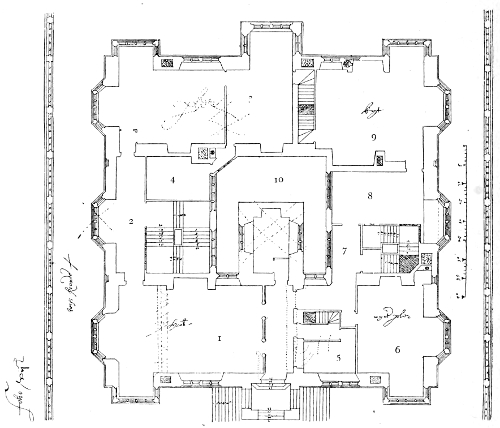

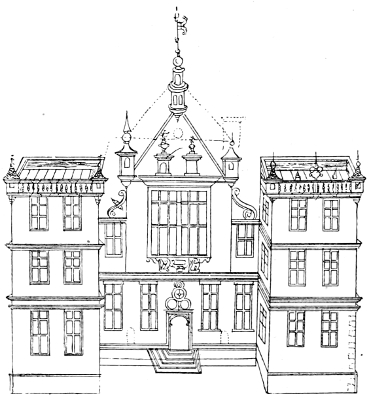

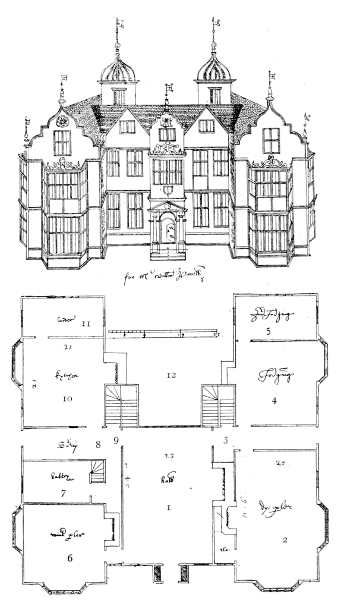

| LXXXV. | — |

Unnamed Plan and Elevation John Thorpe. |

234 | |

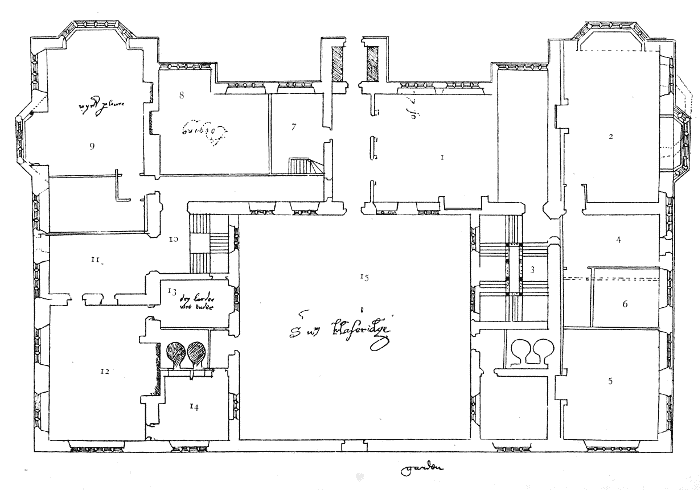

| LXXXVI. | — |

Plan "for Sir Wm.} Haseridge" John Thorpe. |

235 | |

| LXXXVII. | — |

Elevation of Plan Entitled "for Sir Wm.} Haseridge" John Thorpe. |

235 | |

[xiv]

[xv]

Note.—The letters "A.A.S.B." denote that the subject is reproduced from The Architectural Association Sketch Book, with authority of the Draughtsman and by permission of the Committee.

| ILLUSTRATION | PAGE | ||

| 1. |

Tomb of Prince Arthur in Worcester Cathedral J. L. Robinson, photo. |

10 | |

| 2. |

Tomb of one of the Cokayne Family, Ashbourne Church. J. A. G., photo. |

11 | |

| 3. |

Henry VII.'s Tomb; Detail of Ornament H. O. Cresswell, del. |

12 | |

| 4. |

Tomb of John Harrington, Exton Church J. A. G., photo. |

13 | |

| 5. |

Tomb of Thomas Cave, Stanford Church J. A. G., photo. |

13 | |

| 6. |

" " " End Panel J. A. G., photo. |

14 | |

| 7. |

Tomb of Sir George Vernon, Bakewell Church J. A. G., photo. |

14 | |

| 8. |

Tomb of Sir Thomas Andrew, Charwelton Church Miss Dryden, photo. |

15 | |

| 9. |

Tomb of —— Bradbourne, Ashbourne Church J. A. G., photo. |

16 | |

| 10. |

Panel from the Tomb of Elizabeth Drury, Hawstead Church. J. A. G., del. |

17 | |

| 11. |

Tomb of Henry, Lord Marney, Layer Marney Church Fred Chancellor, del. |

18 | |

| 12. |

Carving from the Sedilia, Wymondham Church. J. A. G., del. |

19 | |

| 13. |

Cowdray House, Sussex; Vaulting Rib of Porch. J. A. G., del. |

19 | |

| 14. |

Chantry of the Countess of Salisbury, Christchurch, from the North Aisle |

20 | |

| 15. |

The Salisbury Chantry, Christchurch; Detail of Carving. J. A. G., photo. |

21 | |

| 16. |

Prior Draper's Chantry, Christchurch; Head of Doorway. |

21 | |

| 17. |

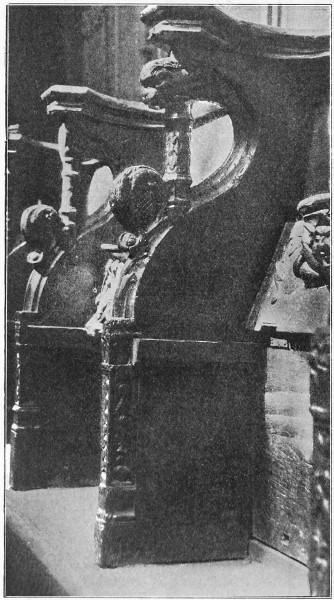

Christchurch; Divisions between Miserere Seats J. A. G., photo.[xvi] |

22 | |

| 18. |

" Bench-end in Choir J. A. G., photo. |

23 | |

| 19. |

Doorway and Panelling in the Gallery at the Vyne, near Basingstoke J. A. G., photo. |

24 | |

| 20. |

Screen on the North Side of Choir, Winchester Cathedral (with Mortuary Chest) |

25 | |

| 21. |

Canopy of Stalls, Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster A. W. Pugin, del. |

26 | |

| 22. |

Detail from Stalls, Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster G. G. Woodward, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

27 | |

| 23. |

The Spring Pew, Lavenham Church J. L. Robinson, photo. |

27 | |

| 24. |

Detail from the Spring Pew, Lavenham Church C. R. Pink, del. |

28 | |

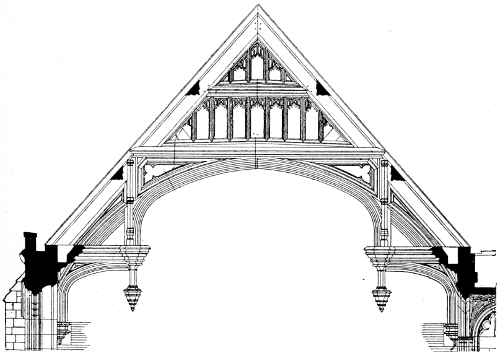

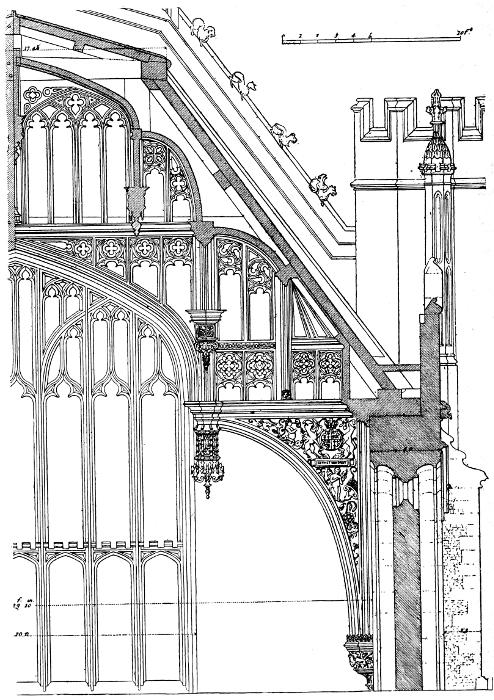

| 25. |

Roof of the Hall, Eltham Palace E. and S. H. Barnsley, del. |

29 | |

| 26. |

Roof of the Great Hall, Hampton Court Palace A. W. Pugin, del. |

30 | |

| 27. |

Details from the Roof of the Great Hall, Hampton Court. A. W. Pugin, del. |

31 | |

| 28. |

Hampton Court; Head of Door to Great Hall. J. A. G., photo. |

32 | |

| 29. |

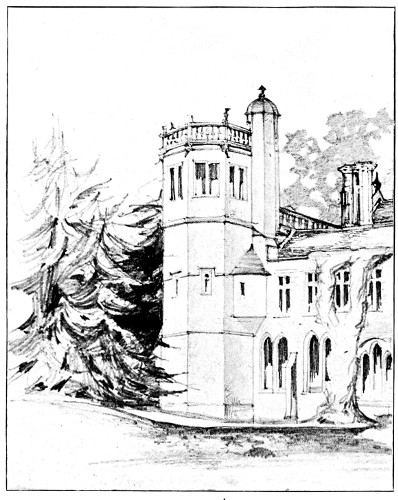

Lacock Abbey; Tower at South-east Corner W. Haywood, del. |

36 | |

| 30. |

" " Stone Table in Tower Sidney Brakspear, photo. |

37 | |

| 31. |

" " Stone Table in Tower Sidney Brakspear, photo. |

38 | |

| 32. |

" " The Stables W. Haywood, del. |

39 | |

| 32A. |

Panel from the Sedilia, Wymondham Church J. A. G., del. |

40 | |

| 33. |

Great Chalfield House; Plan After T. L. Walker. |

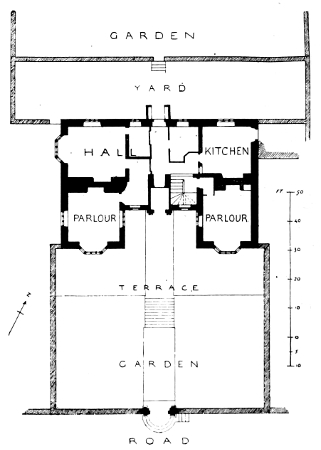

43 | |

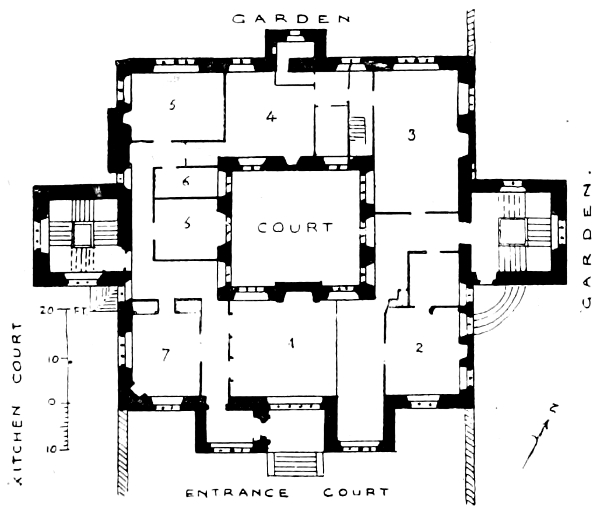

| 34. |

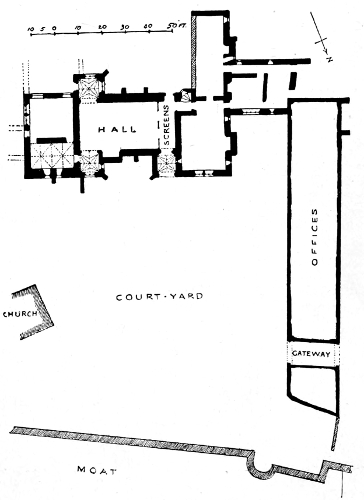

Oxburgh Hall; Ground Plan After J. Britton. |

44 | |

| 35. |

" " Entrance Tower J. L. Robinson, photo. |

45 | |

| 36. |

East Barsham House; Ground Plan After A. W. Pugin. |

46 | |

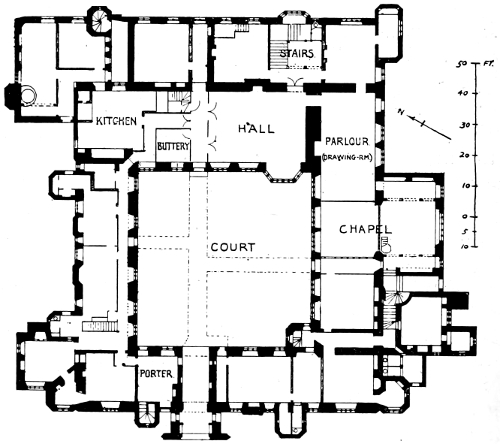

| 37. |

Compton Winyates; Ground Plan After Heber Rimmer. |

48 | |

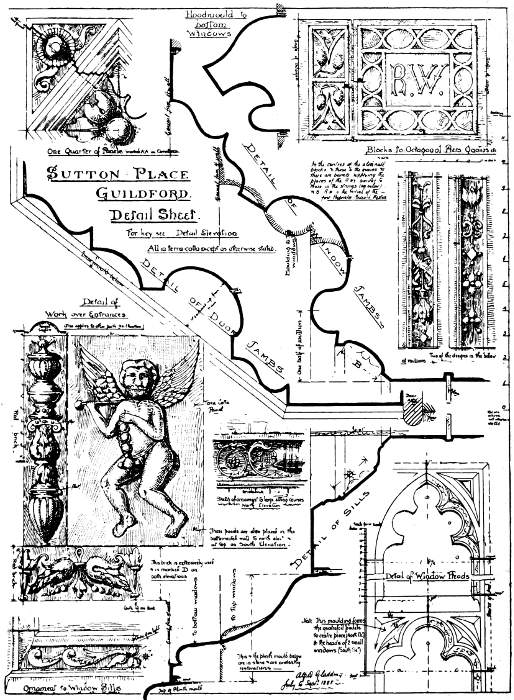

| 38. |

Sutton Place, near Guildford; Ground Plan S. Forster Hayward, del. |

49 | |

| 39. |

" " Details A. C. Gladding, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

50 | |

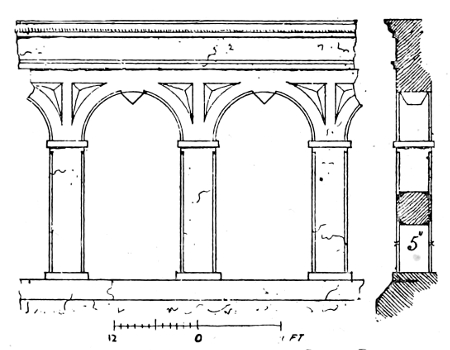

| 40. |

" " Part Elevation of Courtyard A. C. Gladding, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

51 | |

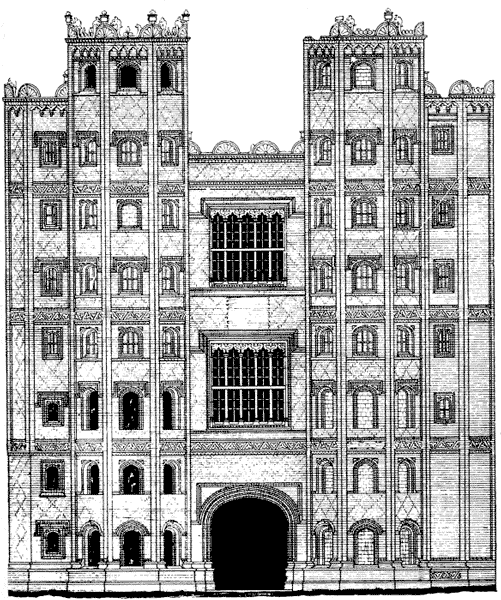

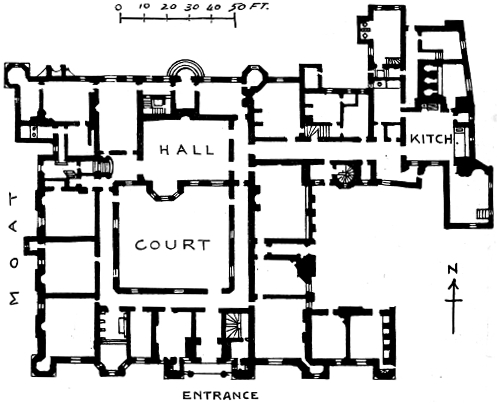

| 41. |

Layer Marney Tower; Entrance Tower Arnold B. Mitchell, del |

53 | |

| 42. |

Hengrave Hall; Ground Plan After J. Britton. |

54 | |

| 43. |

" " West Front J. L. Robinson, photo. |

55 | |

| 44. |

" " Corbelling of Bay Window over Entrance Archway J. A. G., del. [xvii] |

56 | |

| 45. |

Moreton Old Hall; Ground Plan After J. Strong. |

57 | |

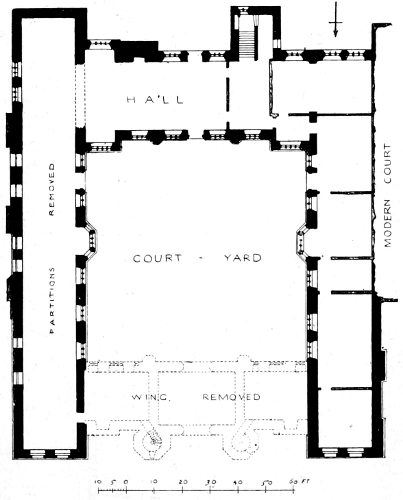

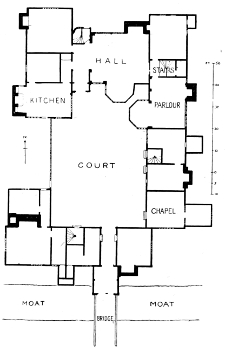

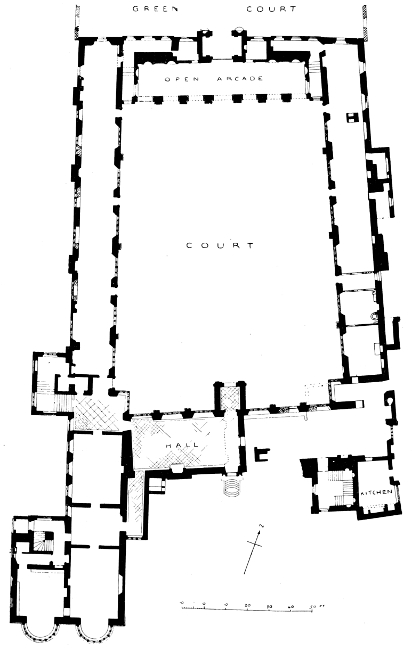

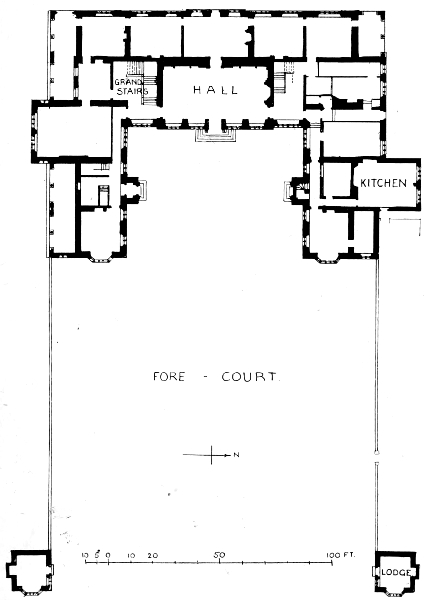

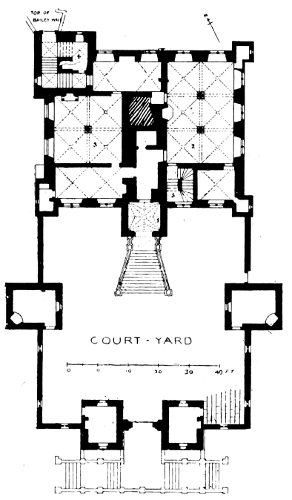

| 46. |

Kirby Hall; Ground Plan A. G. Leighton, del. |

61 | |

| 47. |

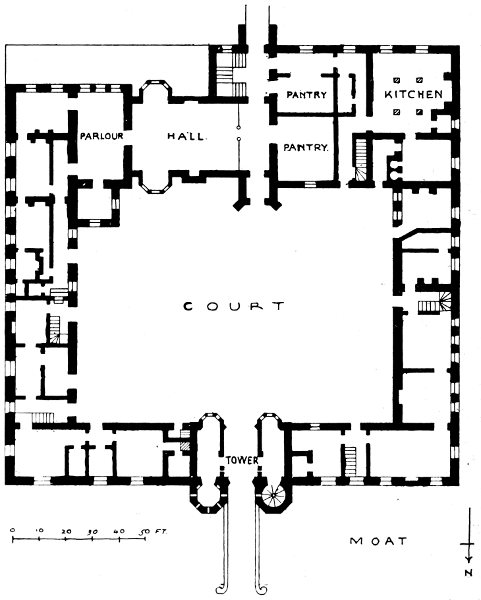

Montacute House; Ground Plan After J. N. Johnston. |

65 | |

| 48. |

" " West Front, with Court and Garden-houses J. L. Robinson, photo. |

66 | |

| 49. |

Barlborough Hall; Plan of Principal Floor J. A. G., del. |

67 | |

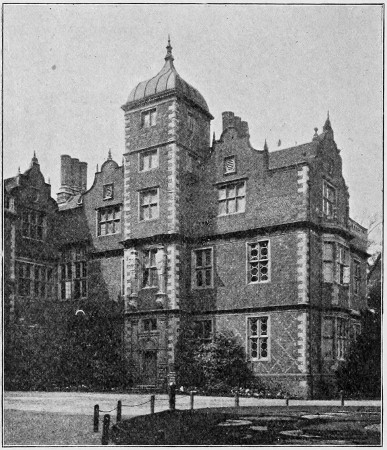

| 50. |

" " Entrance Front Col. Gale, photo. |

68 | |

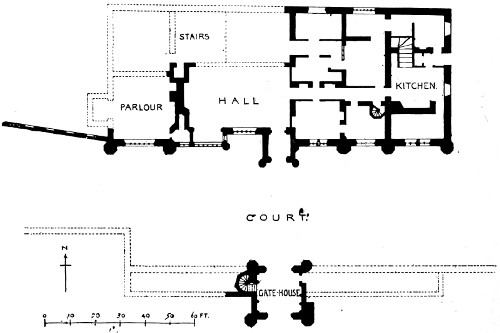

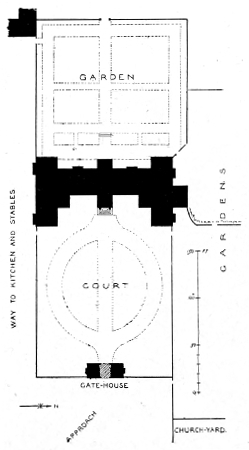

| 51. |

Doddington Hall; Ground Plan J. A. G., del. |

69 | |

| 52. |

Burton Agnes Hall; Ground Plan J. A. G., del. |

70 | |

| 53. |

Aston Hall, near Birmingham; Ground Plan After W. Niven. |

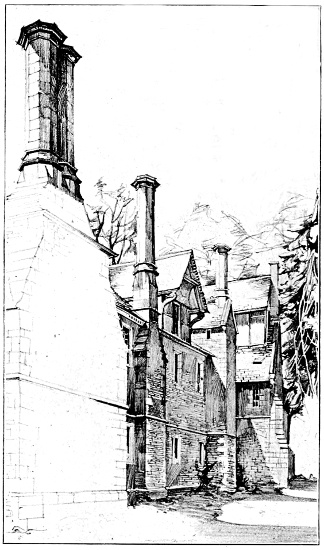

71 | |

| 54. |

" " " North Wing Harold Baker, photo. |

72 | |

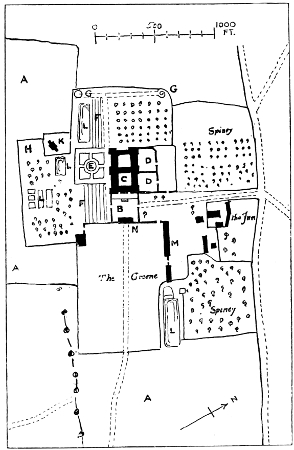

| 55. |

Holdenby House; Plan of Lay-out From an old Survey. |

75 | |

| 56. |

Doddington Hall; Block Plan J. A. G., del. |

77 | |

| 57. |

Stokesay Castle; The Gatehouse Col. Gale, photo. |

78 | |

| 58. |

Cold Ashton Manor House; Entrance Gateway J. A. G., photo. |

79 | |

| 59. |

Winwick; Gateway to Manor House J. A. G., photo. |

79 | |

| 60. |

Gateway to Almshouses, Oundle J. A. G., photo. |

80 | |

| 61. |

Holdenby House; Gateways to Base-court Miss Dryden, photo. |

80 | |

| 62. |

Kenyon Peel Hall; Gateway at Side of Court J. A. G., photo. |

81 | |

| 63. |

Doddington Hall; Entrance Doorway J. A. G., del. |

82 | |

| 64. |

Porch at Chelvey Court, Somerset J. A. G., photo. |

83 | |

| 65. |

Doorway at Nailsea Court, Somerset J. A. G., photo. |

84 | |

| 66. |

Doorway at Gayhurst Manor House J. A. G., photo. |

85 | |

| 67. |

Doorway at Cold Ashton Manor House J. A. G., photo. |

86 | |

| 68. |

Doorway at Cheney Court J. A. G., photo. |

86 | |

| 69. |

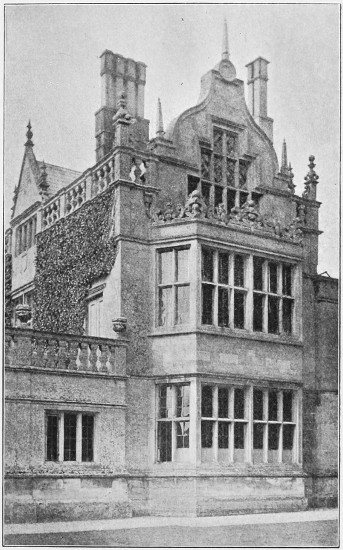

Woollas Hall; Part of Entrance Front Harold Baker, photo. |

87 | |

| 70. |

Porch at Gorhambury, near St. Albans (photo) |

88 | |

| 71 |

Hambleton Old Hall (photo) |

89 | |

| 72. |

Chastleton House; Ground Plan After J. A. Cossins. |

90 | |

| 73. |

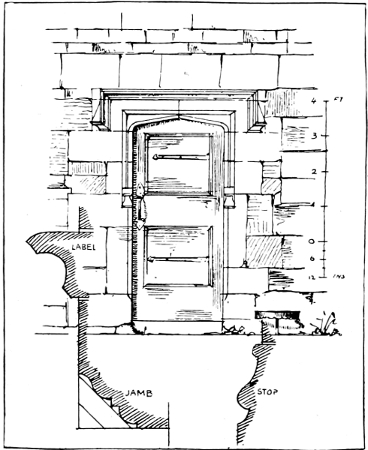

Doorway at Lyddington John Bilson, del. |

91 | |

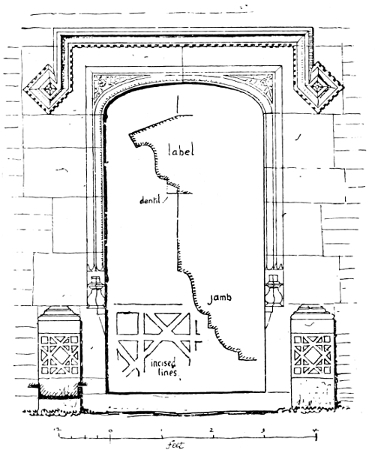

| 74. |

Doorway at Broadway J. A. G., del. |

92 | |

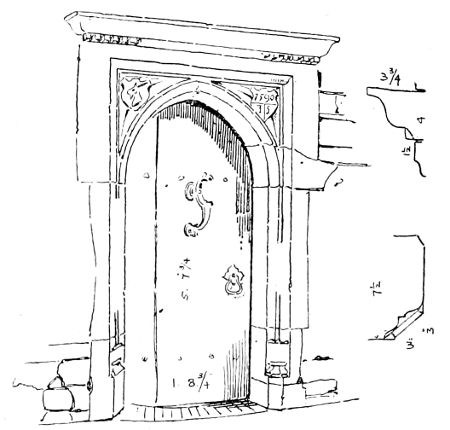

| 75. |

Doorway at Aylesford Hall W. Talbot Brown, del. |

93 | |

| 76. |

Kirby Hall; South Side of Court F. W. Bull, photo. |

95 | |

| 77. |

" " West Front J. A. G., photo. |

96 | |

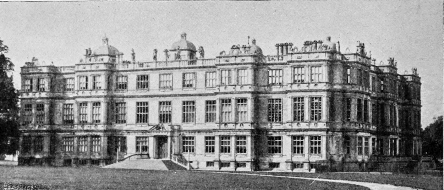

| 78. |

Longleat House, Wiltshire (photo) |

96 | |

| 79. |

Wollaton Hall; Plan of Principal Floor After P. K. Allen. |

97 | |

| 80. |

Charlton House, Wiltshire (photo) |

98 | |

| 81. |

Aston Hall; The South Front Harold Baker, photo. |

99 | |

| 82. |

Corsham Court, Wiltshire J. L. Robinson, photo. [xviii] |

100 | |

| 83. |

Kentwell Hall J. L. Robinson, photo. |

100 | |

| 84. |

Cheney Court J. A. G., photo. |

101 | |

| 85. |

The Manor House, Cold Ashton J. A. G., photo. |

102 | |

| 86. |

" " " " Ground Plan J. A. G., del. |

102 | |

| 87. |

Bolsover Castle J. A. G., photo. |

103 | |

| 88. |

" " Ground Plan J. A. G., del |

104 | |

| 89. |

Condover Hall; The Garden Front J. L. Robinson, photo. |

105 | |

| 90. |

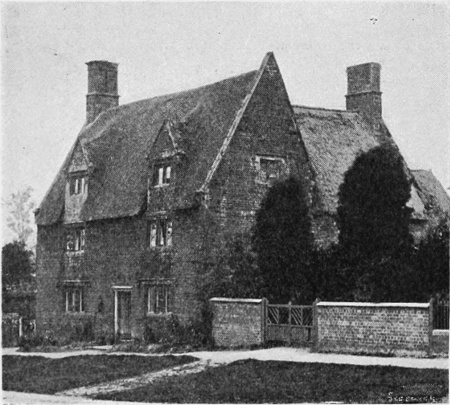

Clegg Hall, near Rochdale W. Riley, del. |

106 | |

| 91. |

Courtyard, Ingelby Manor (photo) |

107 | |

| 92. |

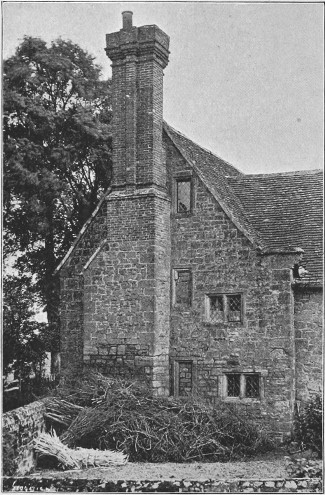

House at Mayfield W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

108 | |

| 93. |

Cowdray House; Part of Court J. A. G., photo. |

109 | |

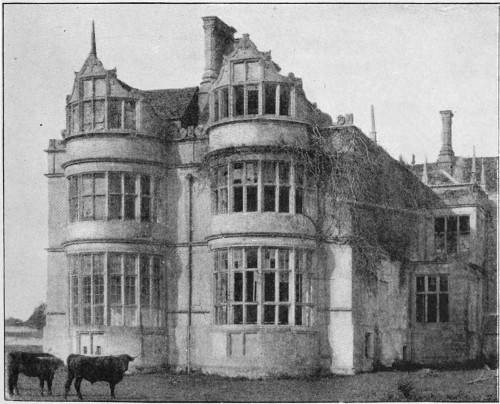

| 94. |

Hoghton Tower; Bay of Hall J. A. G., photo. |

110 | |

| 95. |

Burton Agnes Hall; Bay Windows Frith, Reigate, photo. |

111 | |

| 96. |

House at Bourton-on-the-Water W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

112 | |

| 97. |

Cottage at Steventon Col. Gale, photo. |

113 | |

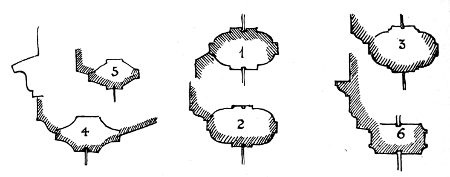

| 98. |

Sections of Various Window Jambs and Mullions J. A. G., del. |

114 | |

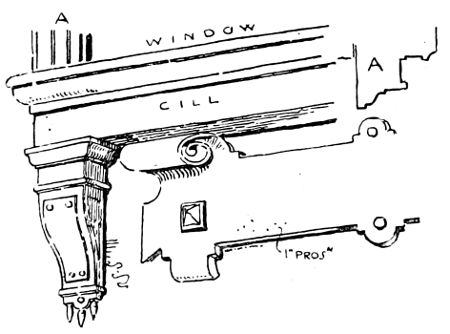

| 99. |

Window Sill at Wollaton Hall W. Talbot Brown, del. |

114 | |

| 99A. |

Head of Window from Hatfield House J. A. G., del. |

115 | |

| 100. |

A Northamptonshire Cottage Miss Dryden, photo. |

116 | |

| 101. |

Stone Finials and Kneelers J. A. G., del. |

117 | |

| 102. |

The Manor House, Finstock W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

117 | |

| 103. |

Cottage at Rothwell J. A. G., del. |

118 | |

| 104. |

Cottage at Treeton, near Sheffield C. Hadfield, del. |

119 | |

| 105. |

Cottage at Steventon Col. Gale, photo. |

120 | |

| 106. |

Wollaton Hall; One of Corner Towers (photo) |

121 | |

| 107. |

Kirby Hall; Part of West Front Col. Gale, photo. |

122 | |

| 108. |

Gable in the Court, Rushton Hall J. A. G., del. |

123 | |

| 109. |

Gable in the Court, Apethorpe Hall J. A. G., del. |

123 | |

| 110. |

Exton Old Hall; Stone Parapet J. A. G., del. |

124 | |

| 111. |

Bramshill House; Stone Parapet After H. Shaw. |

124 | |

| 112. |

Audley End; Stone Parapet After C. J. Richardson. |

124 | |

| 113. |

Rushton Hall; Gable on East Front Col. Gale, photo. |

125 | |

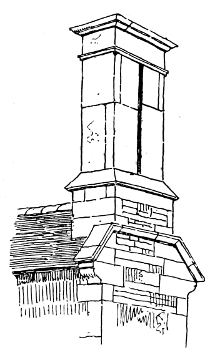

| 114. |

Chimney at Droitwich W. Habershon, del. |

126 | |

| 115. |

Brick Chimney from Huddington Court House J. A. G., del. |

127 | |

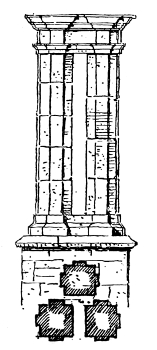

| 116. |

Brick Chimney from Bardwell Manor House J. A. G., del. |

127 | |

| 117. |

Chimney at Toller Fratrum J. A. G., del. |

127 | |

| 118. |

Chimney at Kirby Hall J. A. G., del. |

127 | |

| 119. |

Typical Chimney in the Midlands J. A. G., del. |

129 | |

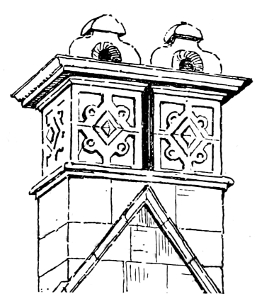

| 120. |

Chimney at Chipping Campden J. A. G., del. |

129 | |

| 121. |

Chimney at Drayton House J. A. G., del. |

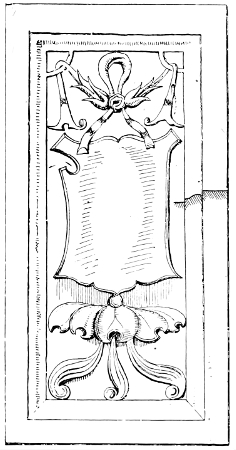

129 | |

| 122. |

Chimney at Triangular Lodge, Rushton J. A. G., del. |

129 | |

| 123. |

Bean Lodge, near Petworth W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. [xix] |

130 | |

| 124. |

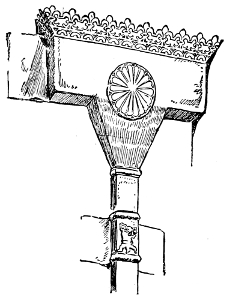

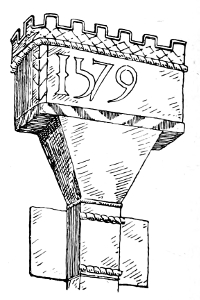

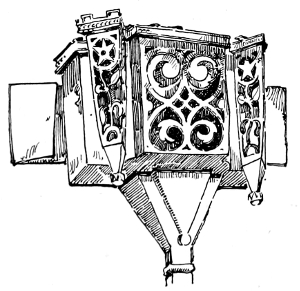

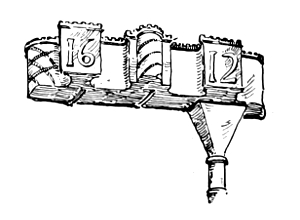

Lead Rain-water Head from Haddon Hall From Mr. W. R. Lethaby's Leadwork, by permission of Macmillan Co. |

131 | |

| 125. |

Lead Rain-water Head from Haddon Hall From Mr. W. R. Lethaby's Leadwork, by permission of Macmillan Co. |

131 | |

| 126. |

Lead Rain-water Head from Haddon Hall From Mr. W. R. Lethaby's Leadwork, by permission of Macmillan Co. |

131 | |

| 127. |

Pipe Head from Sherborne Henry Shaw, del. |

131 | |

| 128. |

Lead Pipe Head from Knole House W. Talbot Brown, del. |

132 | |

| 129. |

Lead Pipe Head from Bramshill House W. Talbot Brown, del. |

132 | |

| 130. |

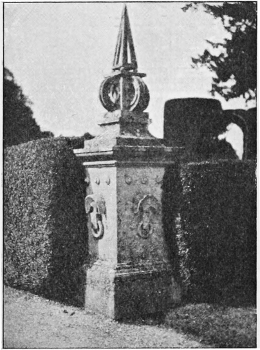

Gayhurst; Stone Pillar in Garden J. A. G., photo. |

133 | |

| 131. |

Gateway in a House at Lindfield Arthur Ardron, del. |

134 | |

| 132 |

Chipping Campden; The Garden-house Percy D. Smith, del. |

136 | |

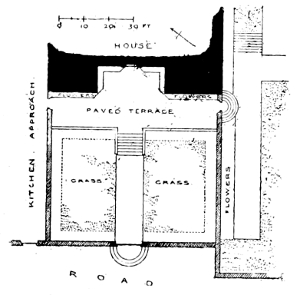

| 133. |

Eyam Hall; Plan of Lay-out J. A. G., del. |

137 | |

| 134. |

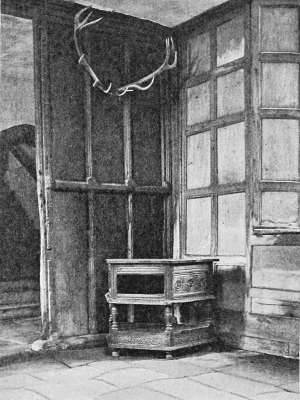

Bedroom in Deene Hall; Plaster Ceiling; Tapestry on Walls. J. A. G., photo. |

147 | |

| 135. |

Haddon Hall; A Corner of the Great Hall J. A. G., photo. |

149 | |

| 136. |

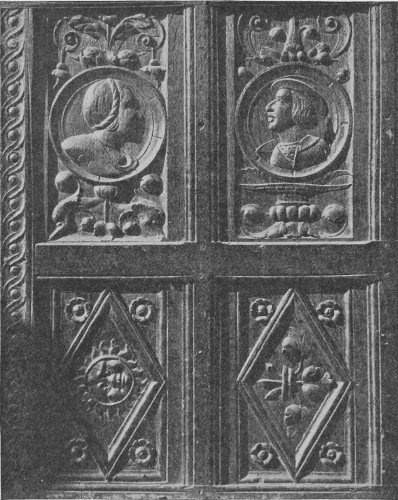

Panelling of the Time of Henry VIII. J. A. G., photo. |

150 | |

| 137. |

Example of Linen Panelling, Stanford Church J. A. G., photo. |

151 | |

| 138. |

A Panel of the Time of Henry VIII. J. A. G., photo. |

152 | |

| 139. |

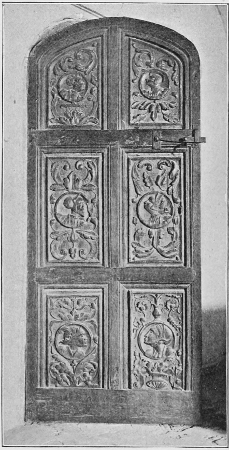

Door at Castle Rising W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

153 | |

| 140. |

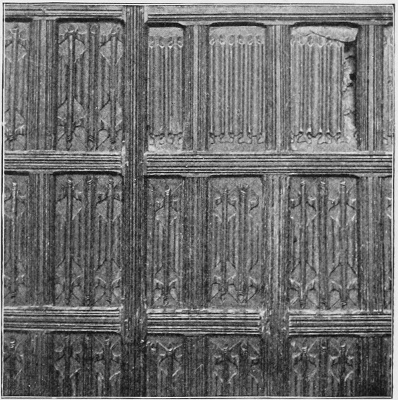

Panelling of Door at Beckington Abbey J. A. G., photo. |

154 | |

| 141. |

Door at Nailsea Court J. A. G., photo. |

155 | |

| 142. |

Part of Reredos (removed) at Stowe-Nine-Churches J. A. G., photo. |

156 | |

| 143. |

Part of the Court Pew, Chelvey Church J. A. G., photo. |

157 | |

| 144. |

Part of Screen (removed), Stowe-Nine-Churches J. A. G., photo. |

158 | |

| 145. |

The Hall, Knole House (photo) |

159 | |

| 146. |

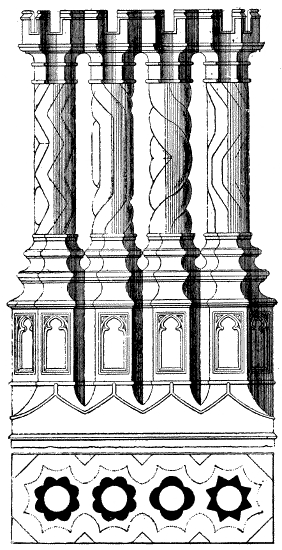

Wollaton Hall; The Roof of the Great Hall Percy K. Allen, del. |

160 | |

| 147. |

Roof of Great Hall, Kirby George P. Bankart, photo. |

161 | |

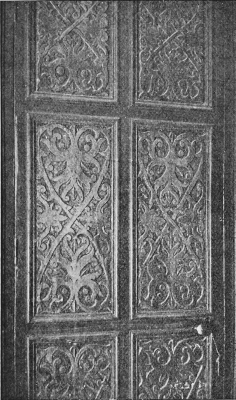

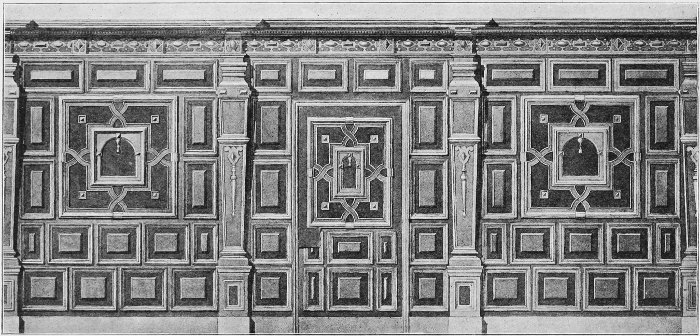

| 148. |

Panelling from Sizergh Hall (now in South Kensington Museum) F. Dare Clapham, del. |

163 | |

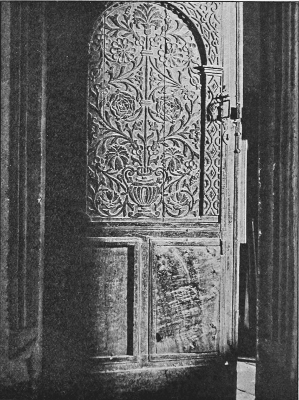

| 149. |

Doorway, Abbott's Hospital, Guildford J. A. G., photo. |

164 | |

| 150. |

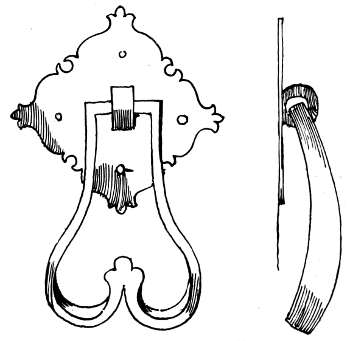

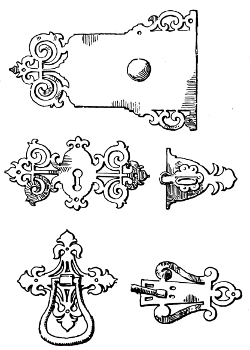

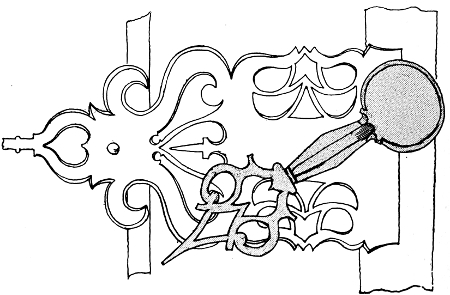

Latch from Abbott's Hospital, Guildford E. A. Rickards, del. [A.A.S.B.]. [xx] |

165 | |

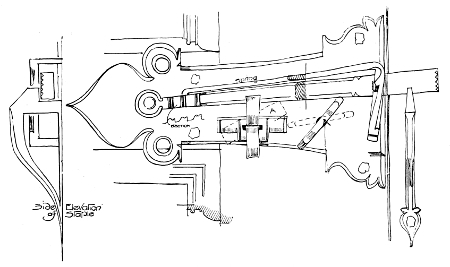

| 151. |

Latch from Haddon Hall R. S. Dods, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

165 | |

| 152. |

Lock-plates, Latches, &c. After C. J. Richardson. |

166 | |

| 153. |

Casement Fastener from Haddon Hall R. S. Dods, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

166 | |

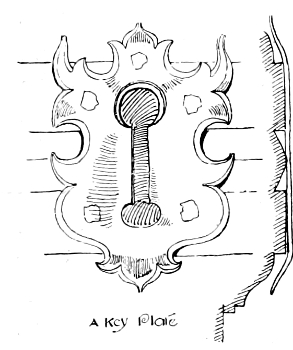

| 154. |

Key-plate from Abbott's Hospital, Guildford E. A. Rickards, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

167 | |

| 155. |

A Knocker After C. J. Richardson. |

167 | |

| 156. |

Wood Chimney-piece, Benthall Hall B. J. Fletcher, del. |

170 | |

| 157. |

Stone Chimney-piece, Bolsover Castle. J. L. Robinson, photo. |

171 | |

| 158. |

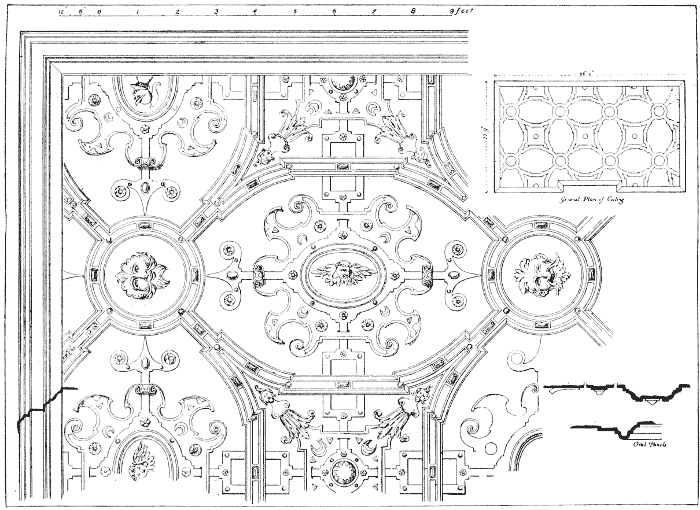

Ceiling of the Presence Chamber, Hampton Court. After Nash. |

173 | |

| 159. |

Bosses from Ceilings at Hampton Court J. A. G., photo. |

174 | |

| 160. |

Patera to a Ceiling at Hampton Court J. A. G., del. |

175 | |

| 161. |

Part of the Ceiling in the Long Gallery, Haddon Hall. J. A. G., photo. |

176 | |

| 162. |

Part of a Coved Ceiling at Beckington Abbey J. A. G., photo. |

177 | |

| 163. |

Coved Ceiling, Beckington Abbey J. A. G., photo. |

177 | |

| 164. |

Part of a Ceiling from Sizergh Hall (now in South Kensington Museum) F. Dare Clapham, del. |

178 | |

| 165. |

Ceiling from Benthall Hall B. J. Fletcher, del. |

179 | |

| 166. |

Ceiling in Gatehouse, Haddon Hall R. S. Dods, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

180 | |

| 167. |

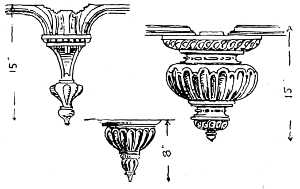

Pendants of Plaster Ceilings After C. J. Richardson. |

181 | |

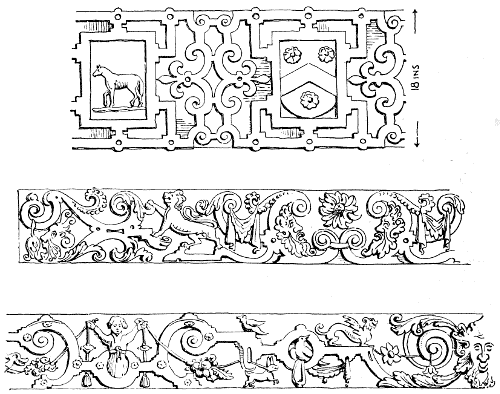

| 168. |

Examples of Plaster Friezes from Montacute, Audley End, and Charlton House After C. J. Richardson. |

182 | |

| 169. |

Plaster Frieze from Montacute House C.J. Richardson, del. |

183 | |

| 170. |

Part of Plaster Frieze, Carbrook Hall W. Talbot Brown, del. |

184 | |

| 171. |

Ceiling of a Triangular Bay Window at Little Charlton House After C. J. Richardson. |

184 | |

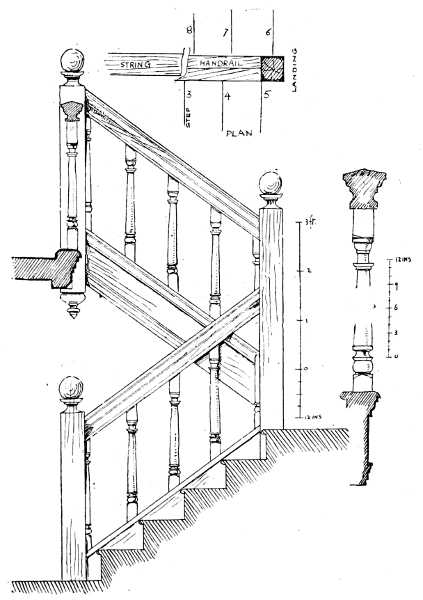

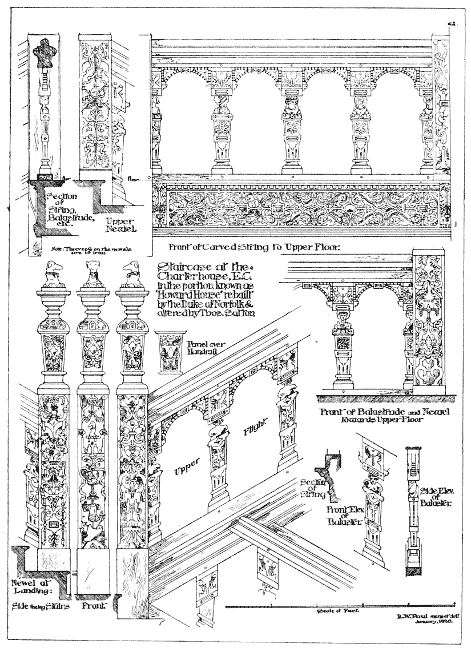

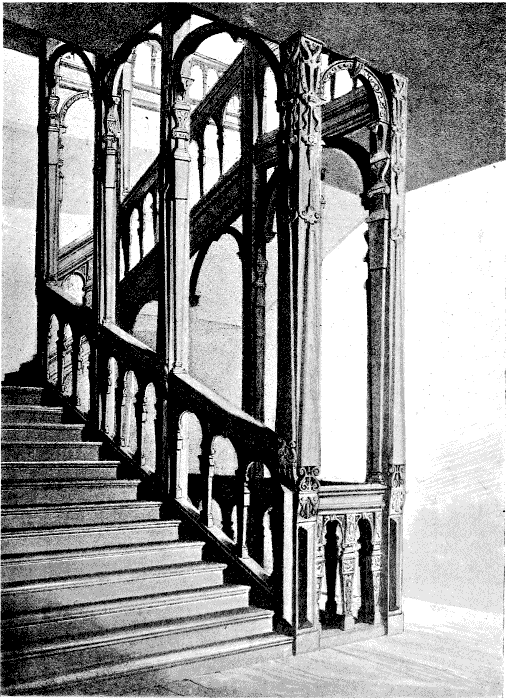

| 172. |

Staircase at Lyveden Old Building J. A. G., del. |

186 | |

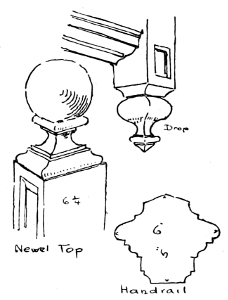

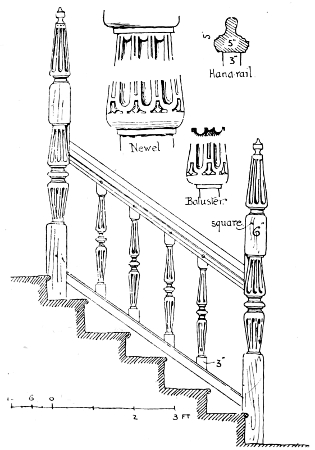

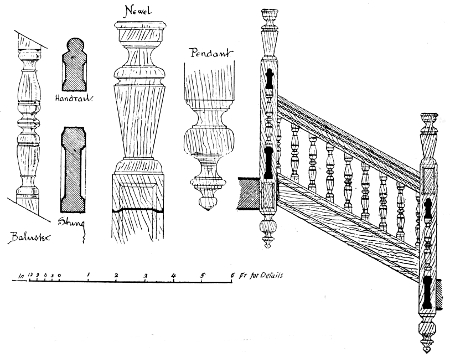

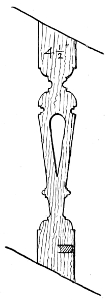

| 173. |

Details of Staircase, Hambleton Old Hall W. Talbot Brown, del. |

187 | |

| 174. |

Staircase from East Quantockshead J. A. G., del. |

187 | |

| 175. |

Details of Staircase, Lyveden Old Building J. A. G., del. |

188 | |

| 176. |

Pierced Baluster J. A. G., del. |

189 | |

| 177. |

Staircase at Ockwells Manor House H. C. Pullin, del. |

189 | |

| 178. |

" " " " Plans and Details H. C. Pullin, del. |

190 | |

| 179. |

Staircase at Benthall Hall, Shropshire J. L. Robinson, photo. |

191 | |

| 180. |

Staircase at a House at Warwick J. A. G., del. [xxi] |

192 | |

| 181. |

Staircase at the Charterhouse Roland W. Paul, del. |

193 | |

| 182. |

Portion of Glazing from Ightham Church J. A. G., del. |

197 | |

| 183. |

Glass Panel from one of the Windows at Gilling Castle. J. A. G., del. |

198 | |

| 184. |

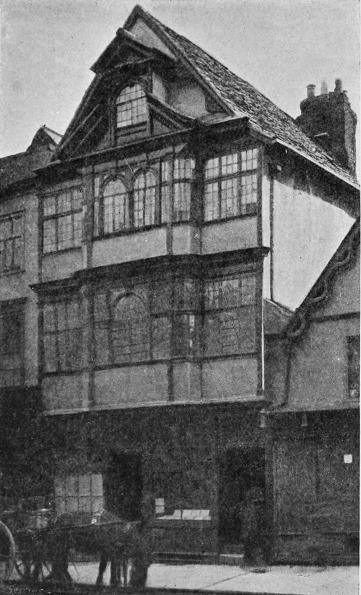

House formerly in North Street, Exeter W. R. Lethaby, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

200 | |

| 185. |

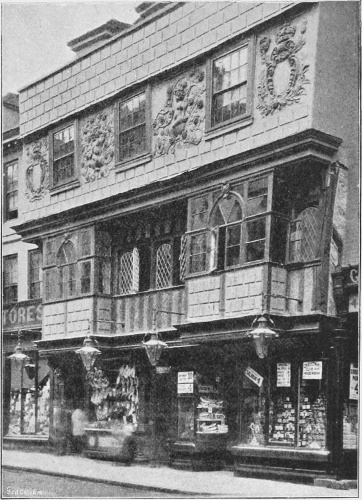

House in the High Street, Canterbury W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

201 | |

| 186. |

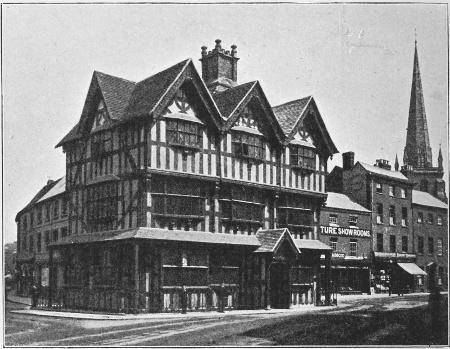

Old House, High Town, Hereford. Valentine, Dundee, photo. |

202 | |

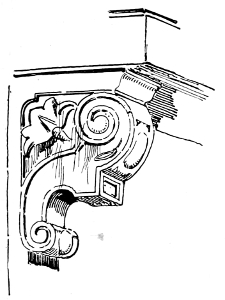

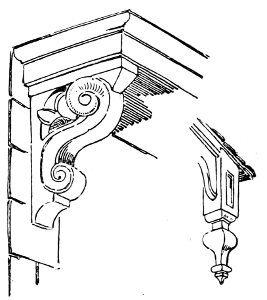

| 187. |

Corbels, "King's Arms," Sandwich W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

204 | |

| 188. |

Corbel at Canterbury W. Talbot Brown, del. |

205 | |

| 189. |

Corbel at Canterbury W. Talbot Brown, del. |

205 | |

| 190. |

Corbel at Orton Waterville W. Talbot Brown, del. |

205 | |

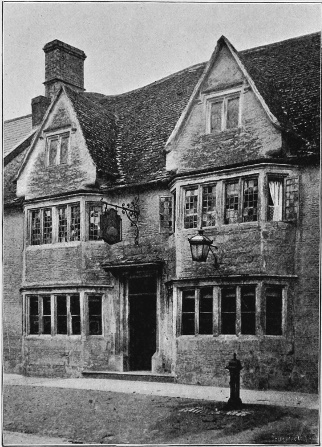

| 191. |

The "Swan" Inn, Lechlade W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

206 | |

| 192. |

Desk in Almshouses, Corsham W. Haywood, del. |

207 | |

| 193. |

Almshouses, Chipping Campden. W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

208 | |

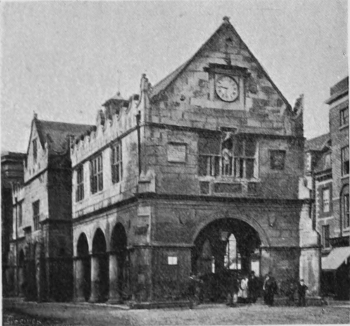

| 194. |

Market House, Shrewsbury (photo) |

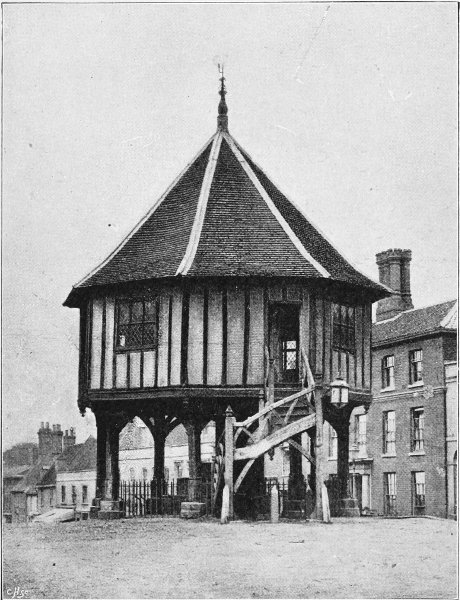

208 | |

| 195. |

Market House, Wymondham (photo) |

209 | |

| 196. |

Market House, Chipping Campden W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

210 | |

| 197. |

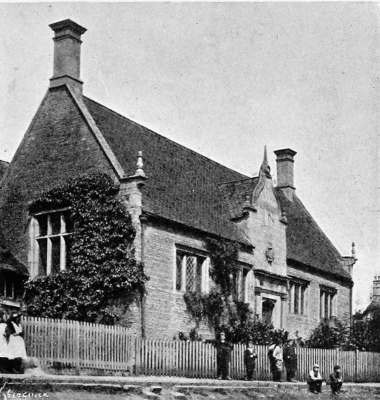

School at Burton Latimer Miss Dryden, photo. |

211 | |

| 198. |

Mill at Bourne Pond, Colchester Col. Gale, photo. |

212 | |

| 199. |

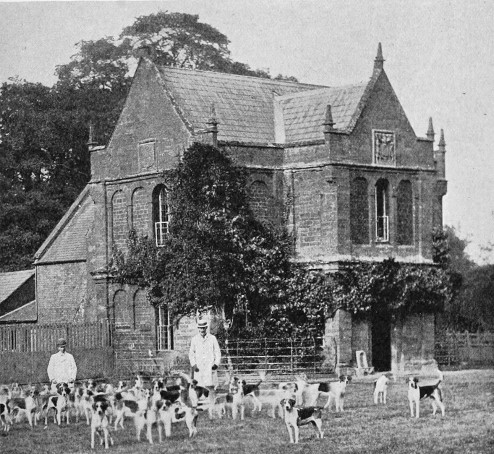

Hawking-tower, Althorp Park (photo) |

213 | |

| 200. |

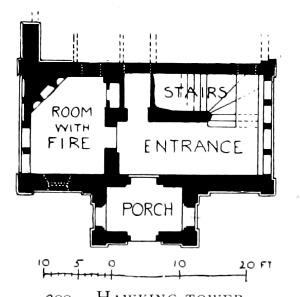

Plan of Hawking-tower, Althorp Park J. A. G., del. |

213 | |

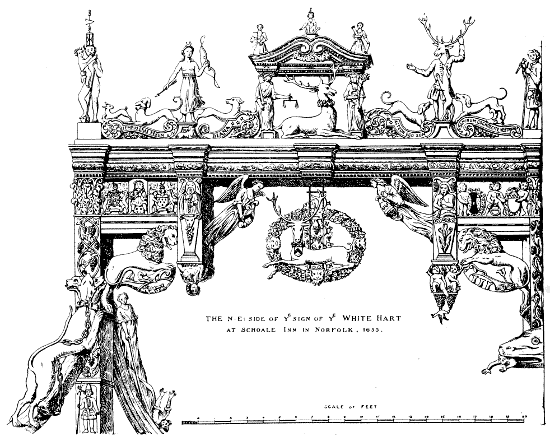

| 201. |

The Sign of the "White Hart" Inn, formerly at Scole E. A. Heffer, del. |

214 | |

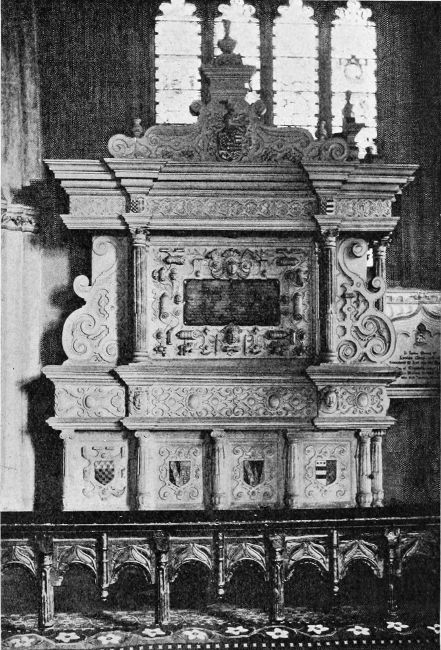

| 202. |

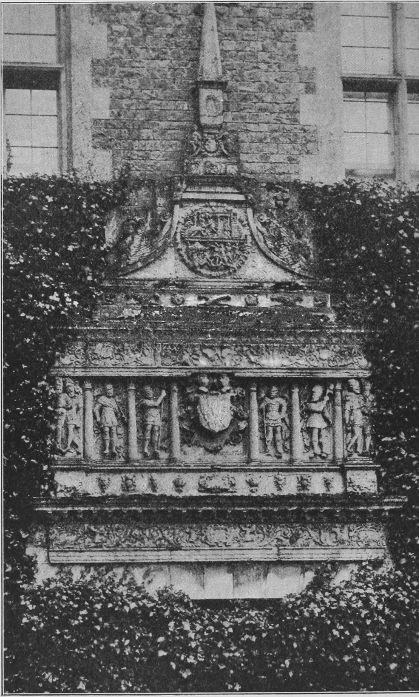

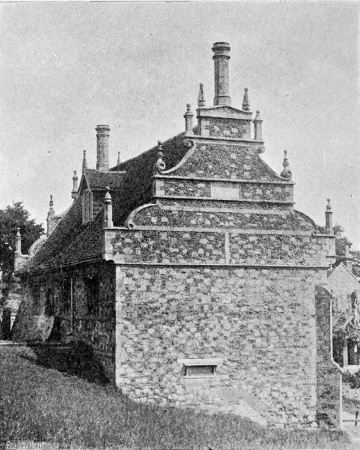

The Chichester Tomb, Pilton Church Vickery Brothers, Barnstaple, photo. |

215 | |

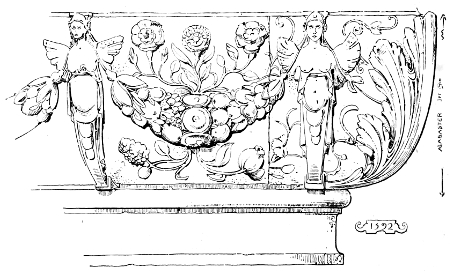

| 203. |

Alabaster Frieze from one of the Foljambe Tombs, Chesterfield Church W. Talbot Brown, del. |

216 | |

| 204. |

Tomb of G. Reed, Bredon Church Harold Baker, photo. |

217 | |

| 205. |

Tomb of Sir Wm. Spencer, Yarnton Church Harold Baker, photo. |

218 | |

| 206. |

The Pulpit, Worth Church W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

219 | |

| 207. |

The Pulpit, Blythborough Church W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

220 | |

| 208. |

The Pulpit, Chesterfield Church J. A. G., photo. |

221 | |

| 209. |

Font Cover and Canopy, Pilton Church W. Galsworthy Davie, photo. |

222 | |

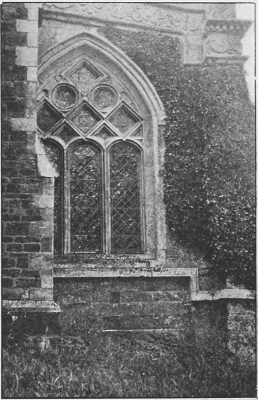

| 210. |

Window of North Aisle, Kelmarsh Church J. A. G., photo. |

223 | |

| 211. |

Keystones from Compton Winyates Church W. Talbot Brown, del. [xxii] |

223 | |

| 212. |

Door in the Screen of the Chapel, Peterhouse College, Cambridge R. S. Dods, del. [A.A.S.B.]. |

224 | |

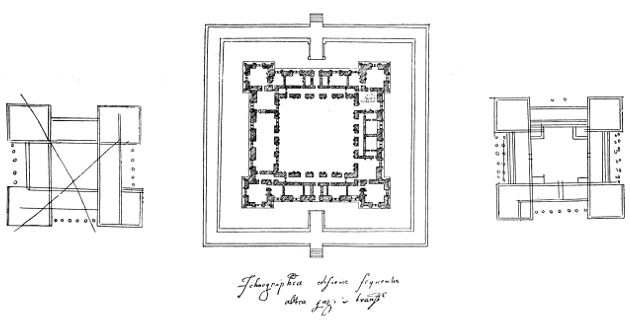

| 213. |

Plan of the Château of Anssi-le-Franc copied from Du Cerceau John Thorpe. |

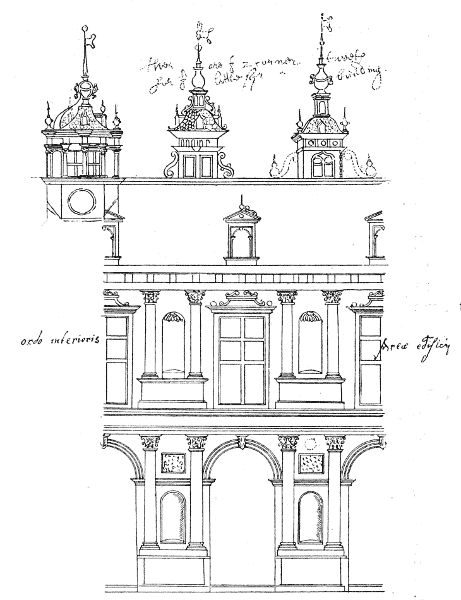

227 | |

| 214. |

Part Elevation of the Château of Anssi-le-Franc, with three Turrets added John Thorpe. |

228 | |

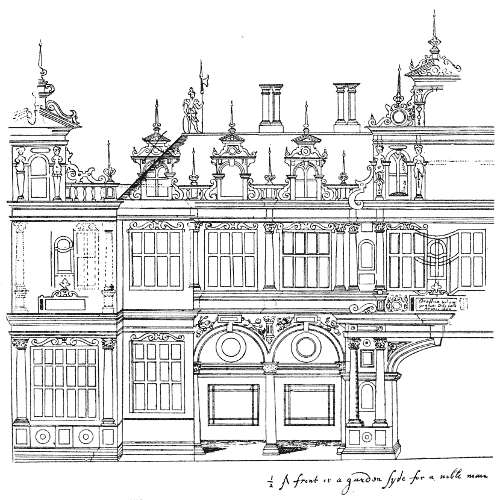

| 215. |

Elevation copied from De Vries John Thorpe. |

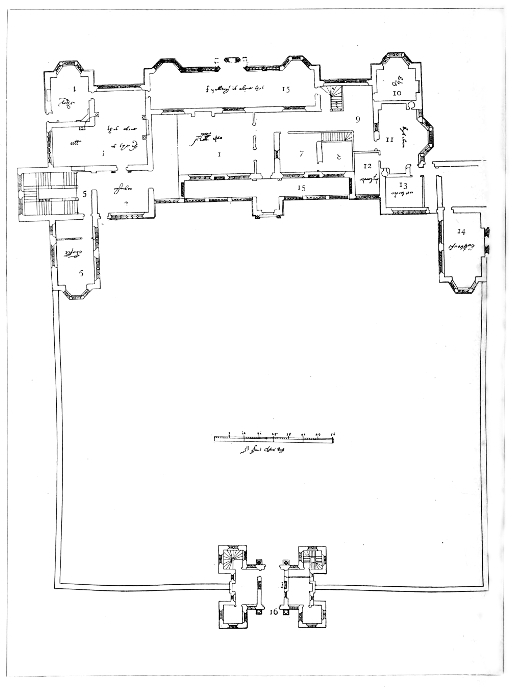

229 | |

| 216. |

An Unnamed Plan John Thorpe. |

232 | |

| 217. |

An Unnamed Ground Plan John Thorpe. |

236 | |

| 218. |

Upper Plan of Fig. 217 John Thorpe. |

237 | |

| 219. |

John Thorpe. |

238 | |

| 220. |

An Unnamed Plan John Thorpe. |

239 | |

| 221. |

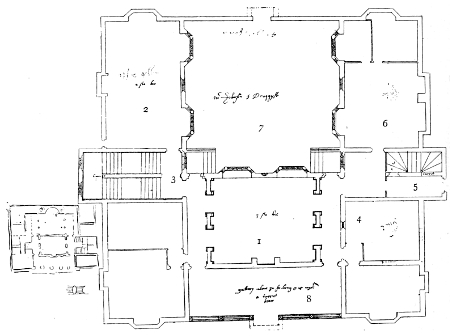

Ground and Upper Plans, Unnamed John Thorpe. |

240 | |

| 222. |

Elevations of Plans in Fig. 221 John Thorpe. |

241 | |

| 223. |

Unnamed Plan and Elevation John Thorpe. |

242 | |

| 224. |

Plan and Elevation of House for Mr. WM.} Powell John Thorpe. |

243 | |

| 225. |

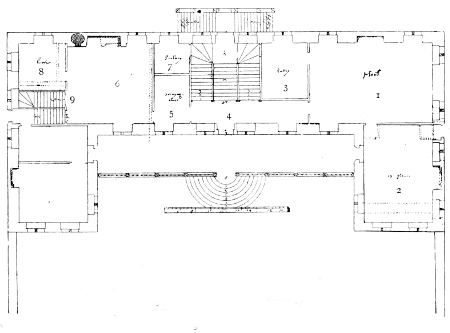

Plan of House for Mr. Johnson ye Druggist John Thorpe. |

244 | |

| 226. |

An Unnamed Plan John Thorpe. |

245 | |

| 227. |

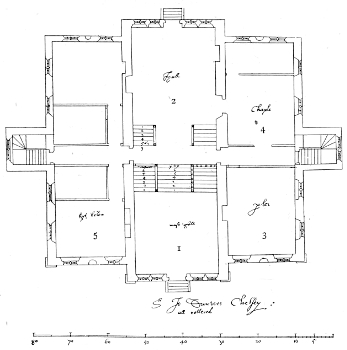

Ground Plan of House for Sir Jo. Danvers, Chelsey John Thorpe. |

246 | |

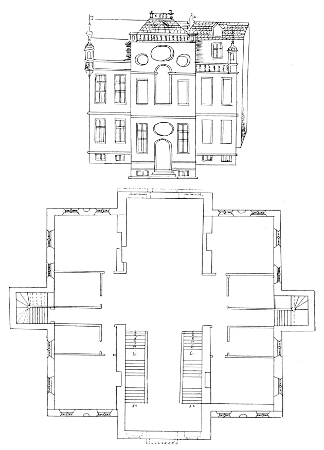

| 228. |

Upper Plan and Elevation for Sir Jo. Danvers, Chelsey John Thorpe. |

247 | |

| 229. |

An Unnamed Elevation John Thorpe. |

248 | |

| 230. |

" " John Thorpe. |

249 | |

| 231. |

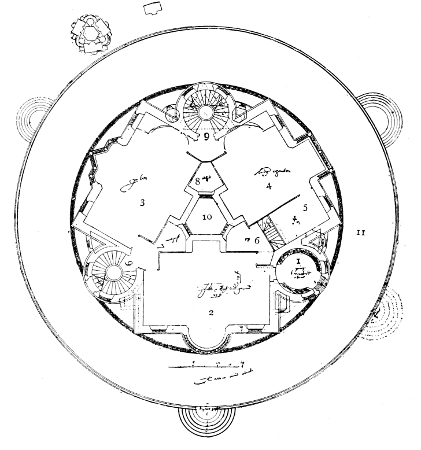

" Plan (Circular) John Thorpe. |

250 | |

[1]

EARLY RENAISSANCE

ARCHITECTURE

IN ENGLAND

INTRODUCTORY.

The progress of style in the mediæval architecture of England was regular and continuous: so much so, that any one thoroughly acquainted with its various phases can tell the date of a building within some ten years by merely examining the mouldings which embellish it. These successive phases, moreover, merge into one another so gradually, that although it has been possible to divide them into four great periods—called Norman, Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular—yet the transition from one to the other is unbroken, and the whole course of development can be traced as regularly as the change from the simplicity of the trunk of a tree to the multiplicity of its leaves. For about four centuries (A.D. 1100-1500) this growth continued, English architecture finding within itself the power of progression. But about the beginning of the sixteenth century it began to feel the influence of an outside power—that of Italy—which acted upon it with increasing force until, after two centuries, its native characteristics had nearly disappeared, and Italian buildings were copied in England almost line for line.

The object of the following pages is to display the effect of this foreign influence upon our native architecture up to the point when it became predominant, and stamped our buildings with a character more Classic than Gothic. But it will be[2] desirable first of all to glance shortly at the causes which led to Italy having this extraordinary influence, and at the general effect which that influence produced upon England.

England, in common with the rest of North-western Europe, was the home of Gothic architecture, instinct with the mystery and romantic spirit of the Middle Ages. Italy was the home of Classic architecture, which it had cherished since the great days of Rome. The Gothic manner was never thoroughly acquired in Italy, even in those parts which lay nearest to France and Germany, although it affected their buildings to a certain extent. The best examples of Italian Gothic hold a low rank in comparison with the masterpieces of the northern style. Classic forms were those in which the Italian designer naturally expressed himself, and it was these which he employed when that great revival of the Arts which took place in the fifteenth century, set him building. The earlier Renaissance in letters "the spring before the spring," of which the great figures are Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, heralded a great awakening of architectural energy, and Italian architects, in solving their new problems, mingled the results of a deep study of ancient examples with much of mediæval spirit and tendency. They set themselves resolutely to revive the architecture which had been one of the glories of ancient Rome; but they could not, even had they wished it, free themselves from the spirit of their own age, and the result was the development of a kind of architecture which used old forms in new ways, and which has gained the distinguishing title of the Renaissance style.

But the awakening in architecture was only one manifestation of the spirit which was abroad: in painting, sculpture, and all the applied arts, as well as in literature, the same vivifying tendency was at work. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, an event which flooded Western Europe with Greek scholars and Greek literature, a tremendous impulse was given to the new aspirations. A new world of history and poetry had been discovered, just as, forty years afterwards, a new world of fact and reality was discovered by Columbus and Cabot. The two events combined to excite men's imagination to an extraordinary degree, and their stimulating effect was visible in all branches of mental activity. There was a marvellous mingling of the old and the new. In the past there was an inexhaustible well of knowledge and suggestion; in the present a boundless[3] opening for enterprise and fresh experiences. Just at this juncture the invention of printing was being perfected, and it came at the precise time to help the dissemination of the new ideas. The result was that great movement of the human mind known as the Renaissance, which in the space of a century altered the life of Western Europe. In politics it shattered the international fabric of the Middle Ages; in religion it brought about the momentous change which we call the Reformation; in art it wedded faultless execution with an extraordinary fecundity of design. There followed an age richer, perhaps, than any other in original genius and fertility of mental products. Italy was at the centre of this upheaval. To her were attracted students from all parts of Europe, not excepting England. She herself was teeming with men of talent in all branches of learning and the arts. It was inevitable that she should part with some of her superfluous energy to the surrounding lands, touched as they were, though less intensely, with the new spirit. So general was the enthusiasm that her neighbours were only too glad to welcome whatever Italy could send, even if not of her very best. The new movement eventually reached the distant shores of England, but as the stream flowed across Europe it became tinged with the peculiarities of the various lands over which it passed, and each country can show its own version of the Italian Renaissance in architecture as well as in other matters. Spain has one version, France another, Germany another, and England yet another; and there is this peculiarity about the English version—that it is coloured by the two channels through which it came, France and the Netherlands.

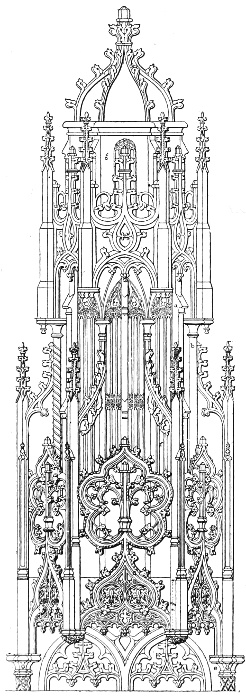

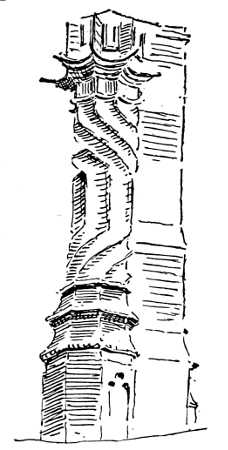

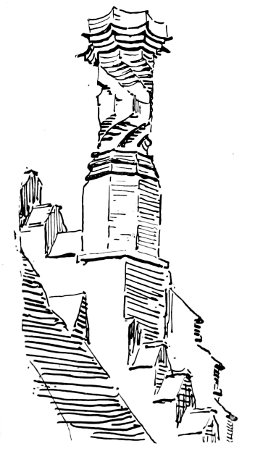

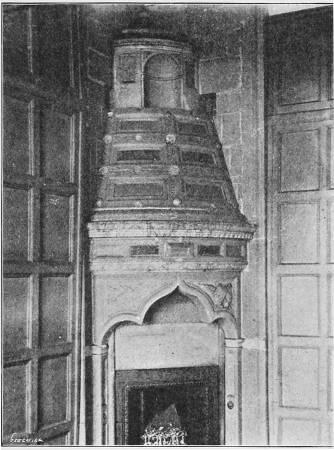

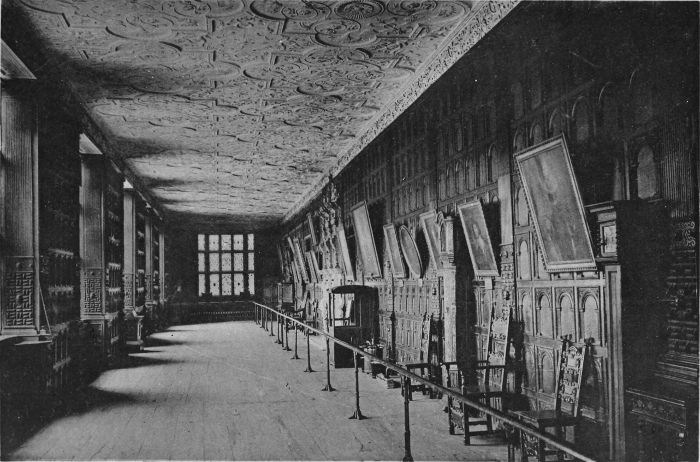

The whole circumstances of the time being conducive to the spread of Italian ideas and forms (which are only the embodiment of ideas), how did they affect English architecture? They found in England a style long established, and still endowed with considerable vigour. At no period of its history had this style been so peculiarly English in its more elaborate efforts, the special development known as fan-vaulting, for instance—of which the finest examples are to be seen in the chapel at King's College, Cambridge, and Henry VII.'s chapel at Westminster (see Plate I.)—being found only in this country.

The Gothic style of England and the Classic style of Italy[4] had next to nothing in common. Their modes of expression were essentially different. The former was elastic, informal, readily adapted to different needs. Like Cleopatra, it was of infinite variety; its component parts were small and manifold, its tendency was towards well-marked vertical lines. Its outward appearance expressed its inward arrangement: a window more or less, a buttress here, a chimney there—so long as they were wanted—offered no difficulty to the designer. Classic architecture, on the other hand, was formal and restricted by considerations of symmetry; its component parts were simple and less mobile than those of Gothic; its tendency was towards strong horizontal lines. The Gothic string-course, for instance, could jump up and down to adapt itself to a door or window; it broke round projecting piers or buttresses without hesitation. But the classic cornice continued in the same straight line, neither rising nor falling, and only breaking forward round a pier or column after due deliberation. Its projection was far greater than that of any similar feature in Gothic work: it was consequently much less ductile. Compared to Gothic detail, Classic was unwieldy, even that more pliant version of it which had recently been evolved in Italy. The ornament, however, with which the Italian designers so freely adorned their architectural work, unlike that of the ancients, was generally small in scale and elastic in character. Here, therefore, was a feature common to both styles, and we shall find that it is in the ornament of buildings that the change first took place. It will be seen that the progress of the new style was very gradual: it showed itself first in small objects, such as tombs and chantries, and in the unimportant detail of larger buildings; then it affected the more significant detail; and ultimately, after many years, it controlled the organic conception and expression: but this final development did not take place till after the close of the period which we are to consider. That which we are to watch is the struggle of the old and the new: the encounter of the new spirit steeped in classical learning, with the old Gothic traditions and methods.

The great monuments of English Gothic architecture are to be found in ecclesiastical buildings; those of the succeeding phase are domestic in character. The change of thought in religious matters, which was proceeding all through the sixteenth century, was not favourable to church building, and[5] after the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. no more churches were built. But the new nobility, rich with the spoils of the dissolved houses and the traffic of the Indies, had acquired a taste for grandeur and dignity in outward life that required great mansions for its display. It is therefore primarily in the Elizabethan mansion that we must watch the contest between the old style and the new—a contest rendered more piquant by the fact that the new style had no experience of this particular kind of building in the land of its origin. The English house had developed on lines widely different from the Italian; it had to meet other wants, it had to contend with a different climate, it was subject to other traditions. The new style when it came, had to harmonize these strange traditions as well as its own, derived from a far distant past, with the original and fertile spirit of the age. The result is one of abiding interest. Almost any of the great houses built in the reign of Elizabeth will show to the casual spectator examples of crudity in detail and imperfect classical proportion, mingled with reminiscences of Gothic notions; but a deeper scrutiny will disclose the fact that in spite of these shortcomings there is a national individuality and sense of genius in the handling of materials sufficient to raise the result to the dignity of a distinct style. Just as the "Faërie Queen" shows a jumble of heathen gods and cardinal virtues, Christian knights and Pagan nymphs, and yet withal is a consummate work of art, so the buildings of the period—

in spite of their inconsistencies, have a fertility of fancy, a wealth of ornament, and a simplicity of treatment which raise them to a similar high plane. And just as the literature of the period, as it became more in accordance with rule, lost half its originality and more than half its fascination, so Renaissance Architecture, as it passed from the Elizabethan to the Jacobean, and so to the succeeding phases, became more homogeneous, more scholarly, more true to its classical origin, and yet withal lost vitality in the process. The full meaning of that great century which stretched from the divorce of Henry VIII. to the accession of Charles I. cannot be grasped unless it is always borne in mind that not only was[6] a new style supplanting an old one, but that it was doing so at a time when the originality and richness of men's minds were at their height.

But while in England the new style was winning its way, in Italy it was passing the zenith of its vigour. The continued study of ancient monuments enabled architects to reduce the old methods of design to a system which could be acquired with ease, and architectural design became less a matter of invention than a capacity for adapting new buildings to old rules. In course of time the same state of things established itself in England. The invention of printing brought to the eye of English craftsmen not only plans and pictures of buildings recently erected in foreign lands, but also the rules which celebrated Italian architects had laid down for the proportion of buildings generally—rules founded partly on the study of ancient fabrics and partly on the august authority of Vitruvius. The application of these rules to circumstances and needs which had never been contemplated by their authors was the problem which English designers set themselves to solve. During the earlier years of their attempt they were almost baffled. Then came Inigo Jones and Sir Christopher Wren, and by their commanding genius they made the rules bend to their will; but in the eighteenth century the rules triumphed completely, and, as already said, Italian buildings were copied in England almost line for line. It is the work of the men who were baffled that we are now to examine: work which, judged from the standpoint of their better tutored successors, may almost be regarded as a failure, but work which exhibits a vitality, a fancy, and a sense of romance for which we look in vain in the more correct architecture of the eighteenth century.

It is not surprising that England, in common with the rest of Europe, should have felt the influence of Italy. It is, perhaps, rather a matter for wonder that she should not have felt it earlier; that the architectural Renaissance should have continued for more than a century, and have reached its prime in Italy before it landed on our shores and began to touch the more susceptible places of our English stonework. But Brunelleschi, who crowned the cathedral of Florence with its dome, and reared the Pitti Palace, had been dead seventy years; the delicate sculpture on the façade of the Certosa of[7] Pavia was five-and-twenty years old; and Venice was busy lining her canals with palaces, when Torrigiano brought the first Italian forms to England and applied them to the tomb of Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey.

But the way had been paved beforehand. For some fifty years it had been the custom of English scholars to repair to Italy to learn the humanities. They returned home familiar, if not in love, with Italian ideas and methods of expression, and if they themselves did nothing outwardly to hasten the impending change, it was their poverty and not their will which consented to inaction. Fine building requires money, and accordingly it is in the work of monarchs, noblemen, and great dignitaries of the Church that we find the first evidences of the Italian invasion. Henry VIII. was the outward and visible, although unconscious, agent who guided the new movement to our shores. His great Cardinal, Wolsey, was not less active in building, but Henry was the royal patron, vying with other monarchs in obtaining the services of distinguished artists to adorn his surroundings. Now most of the distinguished artists at that time were foreigners, hailing chiefly from Italy. There were plenty of excellent English workmen it is true, but it was the fashion to employ Italians. Henry's rival, Francis I. of France, had secured the services of several such men; why not he? So his efforts were frequent, although they met with comparatively small success. Italians were loth to leave their own sunny surroundings, where all men were in sympathy with them and their ways, for the chilly fogs and the barbarous manners of those "beasts of English," as Cellini called them. A few men complied with his requests; of these, Torrigiano was the most celebrated. To him Henry entrusted the making of his father's tomb, discarding the design approved by the dead monarch, and taking the work out of the English hands already engaged upon it. None of the other Italians whose names have been preserved have left any great or permanent mark in the country to which they came unwillingly, and which they left gladly. The other great foreign figure which stands out among those of minor importance is that of a German, Holbein. But though Holbein did much work in England in different branches of art, he left no school, nor can the influence of his manner be traced far, if at all, beyond his death. Names of Italians appear occasionally as being employed[8] by the King, and among them John of Padua occurs most frequently; but no one knows who he was, nor what work he left behind him. His name has often been attached to different buildings, and he has been confused with John Thorpe, but no evidence has yet been adduced actually connecting him with work that still survives. One of the curious and provoking facts about the early years of the Renaissance manner in England is the way in which Italian names elude pursuit. Work which looks as though it must have been done by a foreigner has no name that can be attached to it. Other work, which is almost as foreign in appearance, is found on investigation to be that of an Englishman.

Henry's rivalry with Francis I., his friendship and his feuds with that monarch, seem to have had some effect on architectural ornament, for much that was executed during Henry's lifetime has a French flavour about it. It is curious, indeed, to observe how little hold actual Italian detail obtained upon the fancy of English workmen. It was not direct from Italy that they would take it. The Italians were not liked by the English people at large; protests were raised by the more thoughtful against the Italianizing of our young nobles. The popular conception of the subtle Italian was embodied by Shakespeare in Iachimo and the more infernal Iago. What Italian detail we find in Henry VIII.'s time is chiefly superficial ornament, and even that is by no means of universal application. It is to be found up and down the country in considerable quantity, but side by side with work which is still thoroughly Gothic in character. Islip, the Abbot of Westminster, who laid the foundation stone of Henry VII.'s chapel, and who saw the erection of that monarch's tomb—the great central feature for which the chapel was built—was not sufficiently enamoured of the new ornament to cause his own tomb to be of the same character. On the contrary, the screen which encloses his chapel is free from any touch of actual Renaissance detail, although erected some fifteen years after Henry VII.'s tomb.

It was through Dutch and German channels that the Italian manner came to stay. This was the result partly of ties of race and religion, partly of commercial intercourse, and partly of the general imitation of Dutch methods which prevailed in England during the latter half of the sixteenth century. In[9] commercial and political as well as naval and military matters this imitation is well known to students of that period. The character of Renaissance work in England during Henry VIII.'s time inclined to Italian and the French version of Italian. After his death it inclined towards the Dutch version. In both cases it was strongly infused with English feeling; but there is this difference, that whereas the earlier phase ended abruptly, no merging of it into the latter being traceable, the second phase can be followed step by step into the pronounced Italian of Inigo Jones's mature manner. We can see how some features were dropped and others acquired, until, by the double process of shedding and assimilation, the style of Burghley House glides imperceptibly into that of the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall.

[10]

THE INVASION OF THE FOREIGN STYLE.

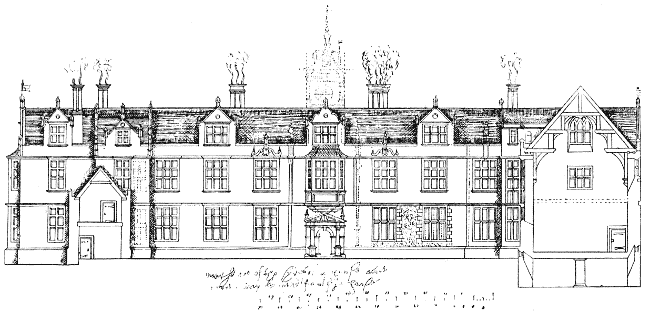

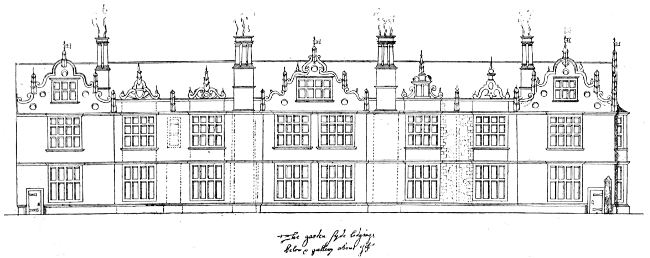

In order properly to understand the position of the Elizabethan mansion in the story of architectural development, it is necessary to examine the work which intervenes between it and the last of the Gothic period.

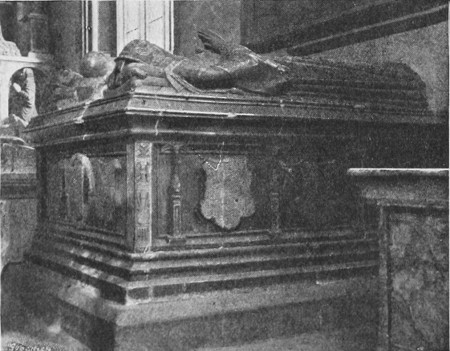

1.— Tomb of Prince Arthur (d. 1502) in Worcester Cathedral.

The first work with Renaissance detail that was done in England was the tomb of King Henry VII.—the actual altar-tomb, not the metal screen enclosing it. There is no foreign influence to be detected either in the screen or in the wonderful fan-tracery vault that spreads itself above (Plate I). These are essentially English productions, and yet there are certain parts of them which would lend themselves readily to the new-fashioned detail which was about to invade our shores; parts which in subsequent buildings were actually affected by it. But so far, that is up to the year 1509, when the king died, the chapel being still unfinished, there is no Renaissance detail. Nor is there any in the[11] fine chantry in Worcester Cathedral, wherein King Henry's eldest son, Prince Arthur, who died in 1502, lies buried (Fig. 1). The utmost that can be said is that here, as in the chapel at Westminster, the Gothic work is preparing to succumb to the new influence. It has been suggested that the king's own tomb was erected subsequently to that of his mother, the Countess of Richmond, who also lies in the Abbey. But the question is one of little importance; no long period can separate the two, and the important point is that the actual invasion of the foreign style is a well-marked event, the circumstances attending it are on record, its results still survive in an excellent state of preservation.

2.— Tomb of one of the Cokayne Family, Ashbourne Church, Derbyshire. Fifteenth Century.

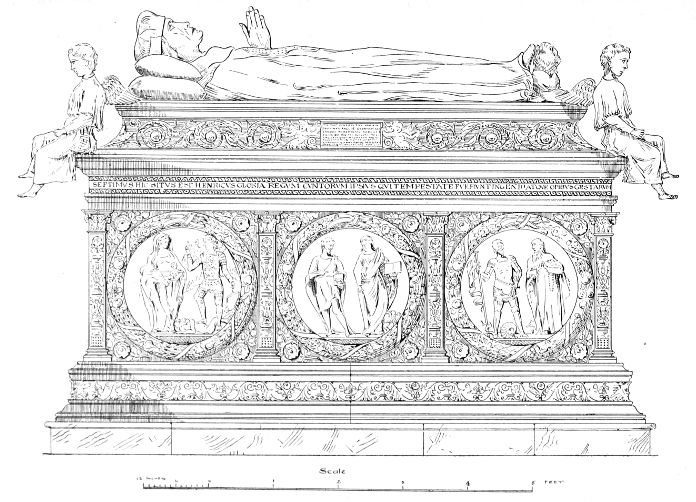

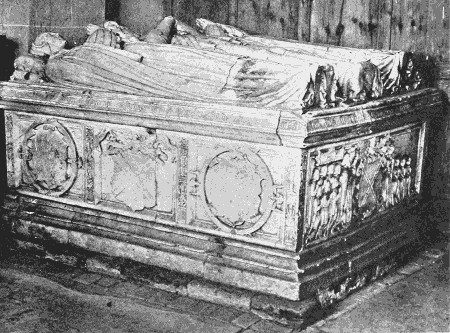

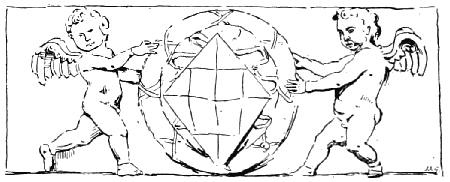

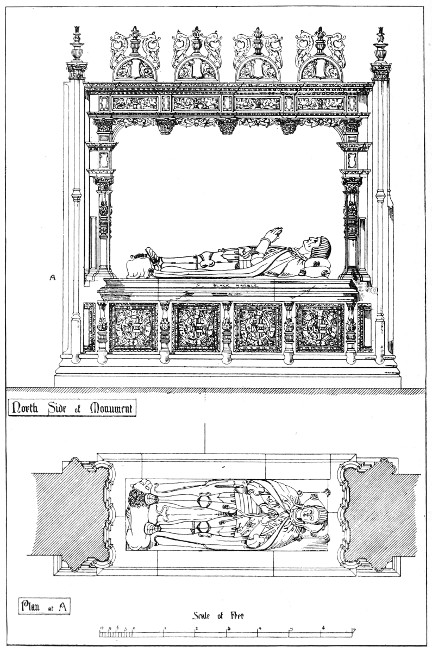

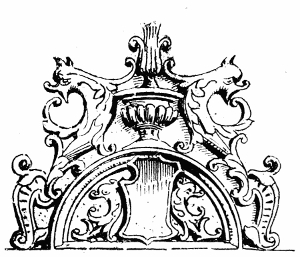

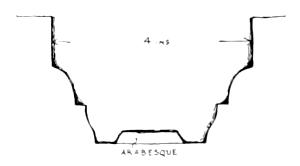

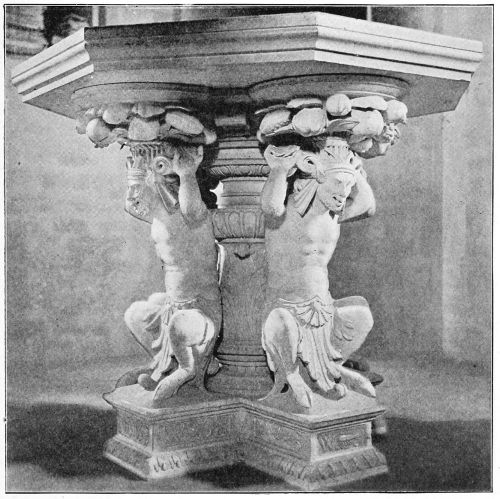

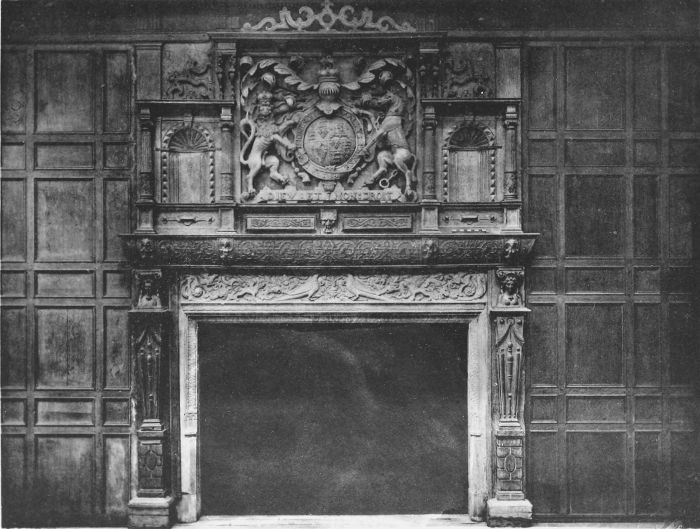

Henry VII. says in his will, dated 31st March, 1509, that he had arranged for his tomb to be made in a certain manner,[1] and from other sources we gather that the men who were to do the work were certain English craftsmen, of whom Lawrence Imber, carver; Drawswerd, sheriff of York; Humphrey Walker, founder; Nicholas Ewen, coppersmith; Robert Virtue, Robert Jenins, and John Lebons, master masons, were the chief. The last name is the only one with a foreign appearance, but it is a curious and rather significant fact that the design had been[12] made by one "Master Pageny," as he was called by his English acquaintances, but whom his own countrymen called Paganino. No other work of Master Pageny's is known in England, but it seems tolerably clear that he is the same Paganino who designed the tomb of the French King Charles VIII. at St. Denis, and that Henry's tomb was to have been like it.[2] The project, however, fell through in consequence of the death of the king, and the passing of the control of affairs into the hands of his son, Henry VIII. The new monarch discarded the old design entirely, and entrusted the work to Pietro Torrigiano, or Peter Torrisany, as he became on English lips. Torrigiano's design departed widely from English traditions. The leading idea of recumbent figures upon an altar-tomb was retained—this idea indeed held the field for another three-quarters of a century—but the old practice of adorning the sides of the tomb with cusped panels, or figures of saints in niches, or angels holding shields[13] of arms (Fig. 2), was abandoned; and instead of the restrained architectural treatment of the English tradition, where the figures were solitary, and every fold of drapery harmonised with the main architectural members, Torrigiano gave us the free treatment of the Italian sculptors. The general arrangement of the panels is simple enough (Plate II.). There are three circular wreaths on each of the longer sides of the tomb, divided by Italian pilasters adorned with arabesques, into which the rose and portcullis of the Tudors are introduced. A rose also fills each of the four spandrils formed by the circular wreaths. These wreaths were new to English eyes; so, too, was the treatment of the spandrils, where the flower is simply applied to the triangular space, instead of appearing to be a growth on the structure itself in the old Gothic way (Fig. 3). The panels themselves contain figures in action, figures which have cast away conventional attitudes and stiffness of attire, and[14] comport themselves in the most natural way imaginable. Henry's patron saints are there to the number of ten, but instead of standing in niches, statuesque and motionless, they are grouped in pairs, every pair seeming interested in a common subject, instead of each individual being rapt in solitary contemplation. As there are six panels, the ten patron saints are supplemented by two other figures—the Virgin with the Child, and St. Christopher. Another novelty appears in the shape of the four cherubs poised at each corner of the tomb; they have no niches or other architectural background; they are detached pieces of sculpture, self-reliant; their purpose, which they no longer fulfil, was to hold banners, but these have long disappeared.

[1]Britton's Architectural Antiquities, Vol. II.

[2]Archæological Journal, 1894, "On the work of Florentine Sculptors in England," by Alfred Higgins, F.S.A.

3.— Henry VII.'s Tomb. Detail.

4.— Tomb of John Harrington (d. 1524), Exton Church, Rutland.

5.— Tomb of Thomas Cave (d. 1558), Stanford Church, Northamptonshire.

6.— Tomb of Thomas Cave (d. 1558). End Panel.

7.— Tomb of Sir George Vernon (d. 1567), Bakewell Church, Derbyshire.

The change of idea is complete, but it is a change that never took hold of English craftsmen. They adopted the circular wreaths and the arabesqued pilasters, and so far as those features are [15]concerned we see in this tomb the prototype of many that followed after. But the figures in action do not appear again. English tradition was too strong for the Italian influence to overcome it, and the principal way in which it was affected was that the panels became frequently divided by pilasters instead of by moulded members; and that the angels, which had hitherto been solitary and devout, took on the attitude of heraldic supporters, and assumed a more mundane appearance, or endeavoured to imitate the amorini of Italian craftsmen—an effort for which they were, as a rule, too elderly.

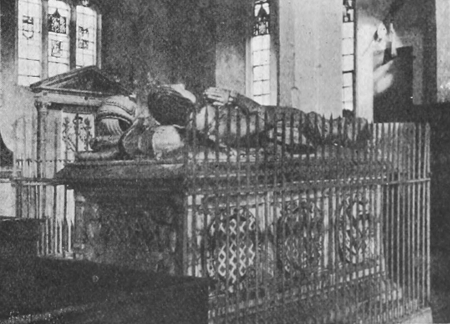

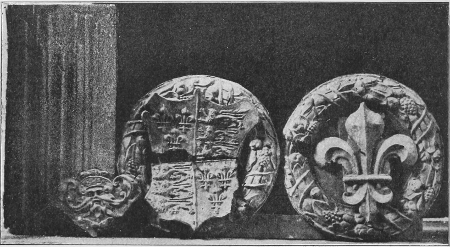

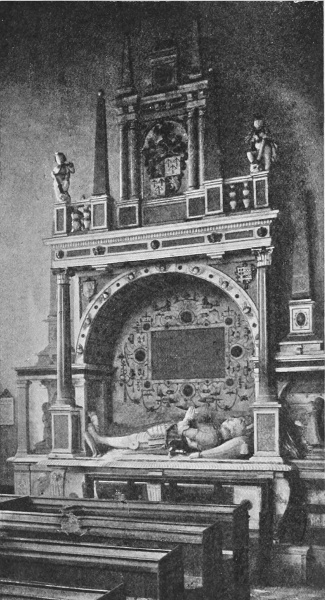

Plate II.

HENRY VII.'S TOMB IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY. SOUTH SIDE (1516).

8.—Tomb of Sir Thomas Andrew (d. 1563), Charwelton Church, Northamptonshire.

The dividing pilasters were sometimes nothing more than spiral columns, and such a column is occasionally the only sign of the new feeling. In the tomb of John Harrington, who died in 1524 (Fig. 4), a spiral column at the angles and a certain stiffness in the cusped panels indicate the impending change. This change is still more marked in the Cave tomb (Fig. 5) at Stanford Church, where (in 1558) the sides have three circular panels containing, however, shields of arms, not figures, and the upper end exhibits the family shield supported by two angels. On the other hand,[16] the opposite end (Fig. 6) shows the family of the deceased gentleman in a number of figures treated with a stiffness of pose and a conventionality of attire that still belong to the ancient style. There is a very similar tomb at Charwelton to Sir Thomas Andrew, who died in 1563 (Fig. 8). In the tomb of Sir George Vernon (Fig. 7), who died in 1567, the angle pilasters, with their vases and portcullises in low relief, recall those on Henry VII.'s tomb. The middle shield on the end is surrounded by a circular wreath, while the shape of the shield and the strange form of the dividing pilasters show a still further departure from the old detail. In the Bradbourne tomb of 1581 (Fig. 9) panels have disappeared altogether, and the sides of the tomb are occupied by figures of the children, who hold in a stiff and tiring manner, shields setting forth their marriages. There is a rather curious survival in the tomb of Elizabeth Drury at Hawstead Church, in Suffolk, where, as late as 1610, a shield of arms is supported by two amorini (Fig. 10). All these examples, selected from the tombs to be found in village churches, and covering a period of three-quarters of a century, tend to show that the Italianizing of the English workman, in this branch of art at any rate, was as incomplete as it was slow. The craftsman was, however, aware that a new influence was at work, and he was prepared to[17] succumb to it where circumstances were favourable. In certain districts circumstances were favourable, and accordingly in parts of the eastern and southern counties, notably at Layer Marney, in Essex, there are tombs in which the detail is more decidedly wrought after Italian models (Fig. 11 and Plate III.), although even here the difference is so great that any of them would look strangely out of place if transported to a church in Italy.

9.—Tomb of — Bradbourne (d. 1581), Ashbourne Church, Derbyshire.

10.—From the Tomb of Elizabeth Drury (d. 1610), Hawstead Church, Suffolk.

The eastern and southern counties appear to have been specially affected by the new movement, for we find considerable traces of it scattered over wide areas, and affecting not only small objects like tombs, but permanent structures. We shall presently see it at Layer Marney Tower, and among other places at East Barsham and Great Snoring in Suffolk; while in Wymondham Church, in Norfolk, the sedilia is made of what appear to be fragments of a tomb much resembling those at Layer Marney in character (Fig. 12). In the southern counties, Sutton Place, near Guildford, abounds in Anglo-Italian detail; some of the woodwork at the Vyne, in Hampshire, is also affected by it. There is some very interesting work of the same nature at the Chapel of the Holy Ghost, at Basingstoke; while at Christchurch, in the same county, the chantry of the Countess of Salisbury is strongly touched with the Italian influence, and at St. Cross, near Winchester, are the very beautiful fragments of a Renaissance screen (Plate VII.). Winchester itself has some good work in the choir of the Cathedral; and still further west, at Bingham Melcombe, in Dorset, there is a charming gable of mixed English and Italian detail. At Lacock Abbey, in Wiltshire, there is a considerable amount of Renaissance work, wrought when the abbey buildings were converted into a dwelling-house soon after the dissolution of the monasteries.

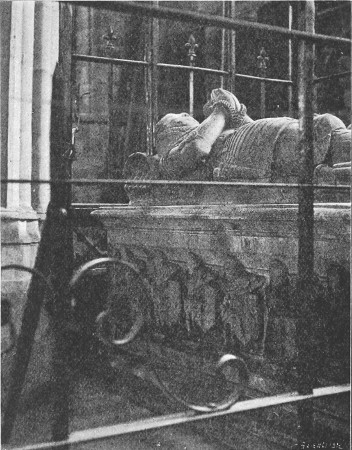

11.—Tomb of Henry, Lord Marney (d. 1523), Layer Marney Church, Essex.

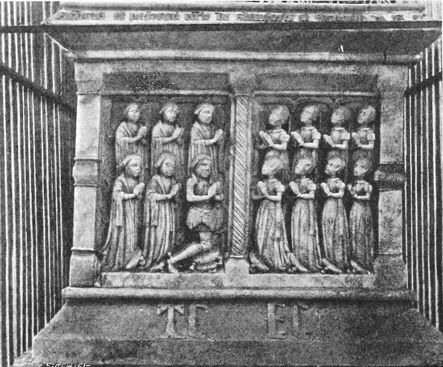

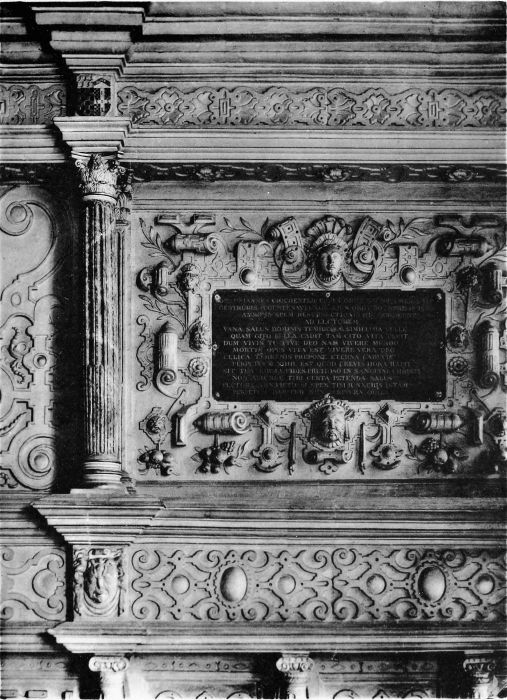

Plate III.

DETAILS FROM THE TOMB OF HENRY, LORD MARNEY.

Some of this work is in stone and some in wood, but some of it is in terra-cotta, and it would be an interesting task to[18] ascertain why this pronounced detail should have been largely confined to these particular districts. The stone and woodwork might have been carved by itinerant Italians wandering some distance from their ports of debarkation; but the terra- [19]cotta must have been cast, and need not have been cast close to where it was fixed, but abroad, and thence conveyed to almost any part of the country. Nevertheless, none of the work entirely loses its English character, whether it was done abroad or not. Some of it must certainly have been wrought by Italians, but about much of it the general impression produced is that it was done by Englishmen with Italian proclivities, rather than by Italians under English orders.

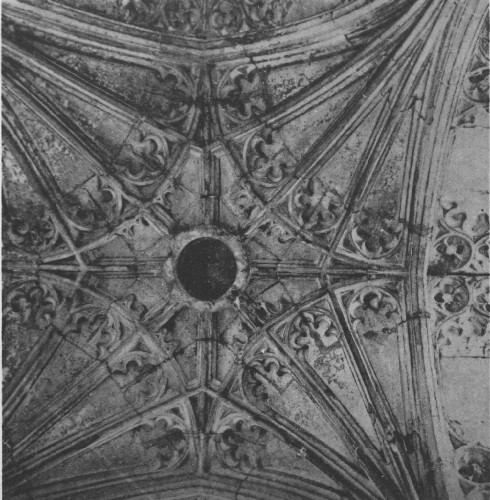

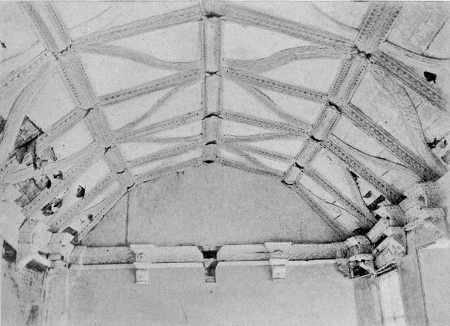

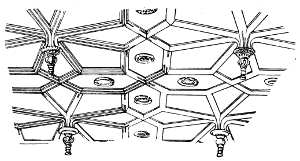

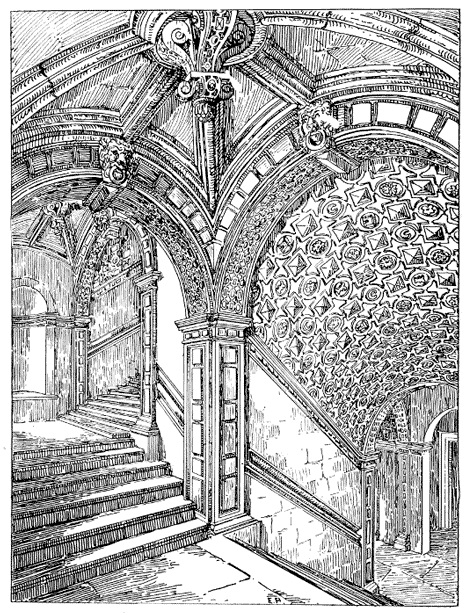

Plate IVa.

CHAPEL OF THE RED MOUNT, KING'S LYNN.

FAN-VAULTING.

Plate IVb.

COWDRAY HOUSE, SUSSEX.

FAN-VAULTING OF PORCH.

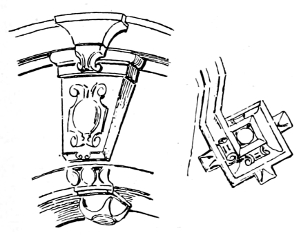

12.—From the Sedilia, Wymondham Church, Norfolk.

13.—Cowdray House, Sussex. Vaulting Rib To Porch (cir. 1540).

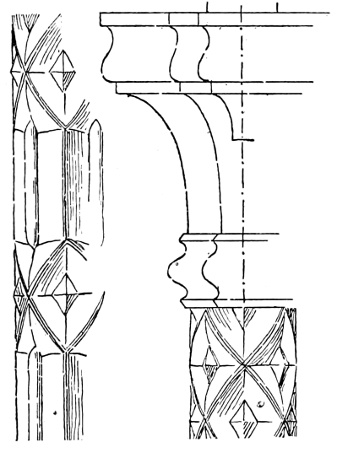

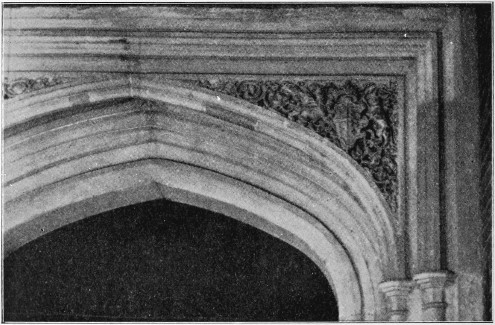

Nor was the foreign detail on the stone simply added to the English work after the native craftsmen had finished. It was not that the Englishman completed his work and then invited the Italian to come and do the carving after his own manner, but the two influences are curiously mixed. Take the fan-vaulting of the porch at Cowdray (Plate IV.), for instance. In general appearance it is of the same family as other fan-vaulting, of which the roof of the Chapel of the Red Mount at King's Lynn may be taken as a specimen. But, as might be expected, it is in the susceptible parts of the stonework that the foreign influence first shows itself,—not in the construction, but in the ornament. The spandrils at Cowdray are filled with carving; some of it is foliage, treated in the Late Gothic manner, but in one appears the head of a winged cherub, clearly not of English but Italian descent. The main ribs of the vaulting, too, have an Italian arabesque worked on them, and the point to be observed here is that the section[20] of the rib is not of the usual type, but is expressly designed to receive the arabesque (Fig. 13).

14.—Chantry of the Countess of Salisbury, Christchurch, Hampshire, from the North Aisle (cir. 1529).

Plate V.

THE SALISBURY CHANTRY, CHRISTCHURCH.

VIEW FROM THE CHOIR.

15.—The Salisbury Chantry, Christchurch. Detail of Carving.

[21]

16.—Prior Draper's Chantry, Christchurch. Head of Doorway (1529).

17.—Christchurch, Hampshire. Miserere Seats.

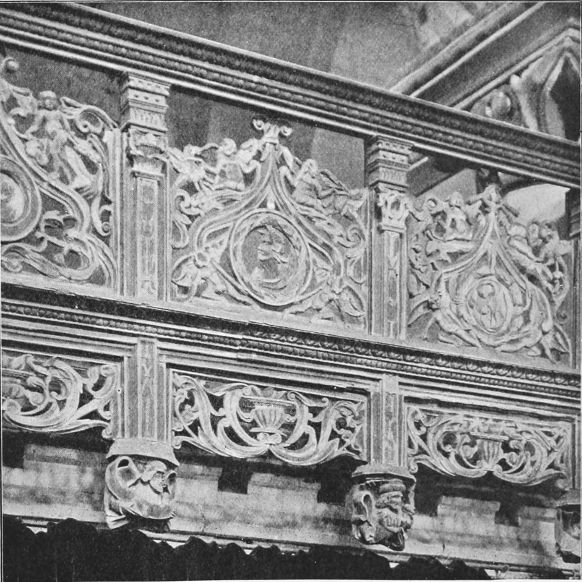

In the Countess of Salisbury's chantry at Christchurch it is much easier to imagine the Italian carver following the English mason, and adding his ornament to the other's work, for nearly all of it lies in sunk panels, the highest parts of the carving being on the same face as the surrounding margin: that is to say, the Italian found plain surfaces between the moulded members left for him to carve, and one set of these plain surfaces, on the side next to the choir, he did not carve—they still remain bare. Take away the ornament, and the chantry in general design and treatment is Late English-Gothic (Fig. 14), such as no Italian would have produced, if we except the topmost stage on the choir side, where there are two domed pinnacles of rather clumsy and unintelligible design (Plate V.). One of these has a curious feature—the somewhat [22]vulgar product of the later Italian carvers—namely, the lower drapery and the feet of a figure ascending into clouds, all executed in complete relief. On the north side, next to the aisle, are some shields in the spandrils between the niches (Plate VI.), carved in the Italian spirit, and these can hardly have been added afterwards, but must have been an integral part of the design. The arabesques on the vertical shafts and in the horizontal bands might very well have been carved by a man put on for that purpose only (Fig. 15). Altogether, it is difficult to adjust with any accuracy the claims of the English and Italian workmen; it would almost seem as though they worked together, or at any rate with a cordial understanding between them. The same may be said of the screen to Prior Draper's chantry (dated 1529) in the same church. The general design is Gothic, and while the arabesque enrichments may have been added afterwards, and the spandrils of the flat-pointed door, the same can hardly be said of the corbels to the niches over it (Fig. 16). The cresting along the top of this screen exactly resembles that over the screens at the sides of [23]the choir at Winchester Cathedral, except that the latter has not a battlemented finish (Fig. 20).

Plate VI.

THE SALISBURY CHANTRY, CHRISTCHURCH.

DETAIL OF NICHES ON NORTH SIDE.

Although it is not difficult to imagine an Italian carving this stonework at Christchurch, it is not quite so easy to attribute the interesting choir-stalls to him or a compatriot, for the Gothic feeling is too pronounced, and the angel and cherubs are not lissom and graceful enough to have descended from an Italian sky.

The divisions between the miserere seats (Fig. 17) are thoroughly Gothic in general treatment and in their mouldings, but in the carving the Italian hand shows itself, although subdued to the Gothic surroundings in which it worked. Some of the desk ends are traceried and cusped, and some have vases and foliage after the Italian manner. But here again the two putti which turn their backs in so unceremonious a way (Fig. 18) can hardly be the work of Italian chisels.

18.—Christchurch, Hampshire. Bench-end in Choir.

It is equally difficult to assign the beautiful panelling in the long gallery at the Vyne to a foreigner (Fig. 19); there is so much English feeling about it. The work conveys the impression that the carver was more at home with his linen panels than with the Italian flourishes with which he supplemented them; but the single panel over the door is evidently the work of a hand thoroughly familiar with the Italian method. We see the same mixed character wherever we look; we can point to no work—not even Henry VII.'s[24] tomb—and say, "This is wholly Italian." There is always a strong English feeling, and sometimes it is only a touch here and there which shows the foreign influence.

19.—Doorway and Panelling in the Gallery at the Vyne, Hampshire (before 1530).

20.—Screen on North Side of Choir, Winchester Cathedral (with Mortuary Chest), 1525.

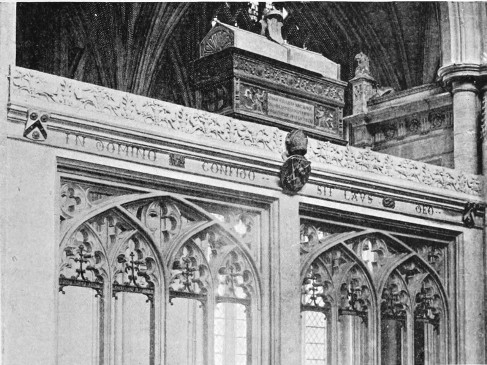

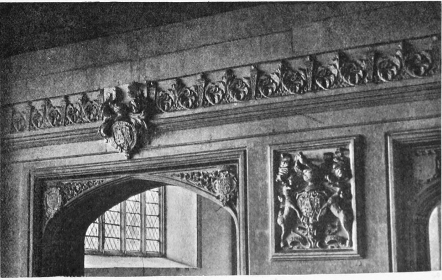

The same remark applies to the stone screens at the sides of the choir at Winchester (Fig. 20). They are Gothic in general treatment, but a little Italian carving is introduced in the cresting along the top. They were the work of Bishop Fox in 1525, who evidently had a hankering after the foreign ornament in his life, although his own chantry, in which he lies buried, is free from it; for in the neighbouring church at St. Cross are the fragments of some very beautiful screens containing charming[25] Italian work (Plate VII.). The history of these fragments is not known, but from the occurrence in them of the pelican, which was Bishop Fox's badge, they seem to be due to him, and they may possibly have come from the cathedral itself. They do not belong to their present situation, and one of the main posts is worked with a return at a very obtuse angle, indicating some such polygonal disposition as the east end of the cathedral has. On the top of the choir-screens in the cathedral are placed six oak chests, called mortuary chests, procured by Fox, in which are deposited the bones of various benefactors. They are of Italian workmanship (except two which replaced the old ones in the seventeenth century), and are suggestive as being one of the sources of inspiration to native carvers. One of them is shown in Fig. 20, and just behind it can be seen the cornice of the chantry of Bishop Gardiner, who died in 1555. The portion visible is of well-developed classic character, and indicates how the use of the foreign forms had progressed during the thirty years that had elapsed since Fox's time. Even here, however, the pinnacle at the corner—the head of a heraldic animal on a[26] pedestal—shows how the designer was unwilling or unable to shake off all the trammels of his native style.

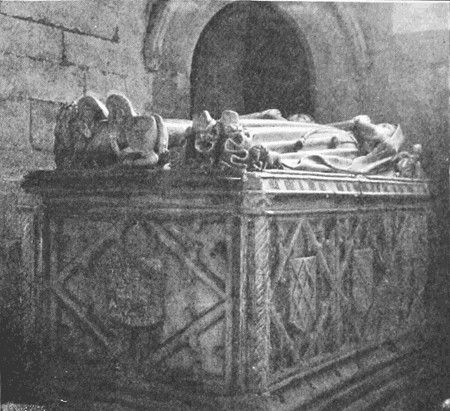

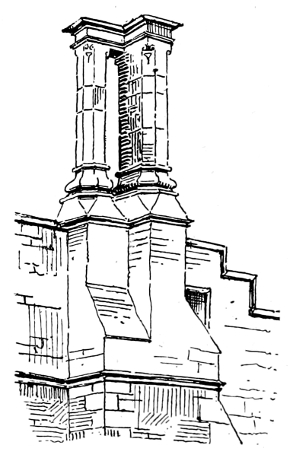

21.—Canopy of Stalls, Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster.

At Basing Church, in Hampshire, there is yet another example of the same limited use of Italian detail in the Paulet tombs, which are constructed in the thickness of the side-walls of the chancel (Plate VII.). The arches over the tombs and the doorway in the wall are all flat-pointed, and the spandrils are filled with Renaissance carving, which, in the case of the large arches, surrounds the arms of the founder. Except for these touches, and for the cresting along the top, which recalls that at Winchester, the detail is all Gothic. The large panel in the wall over the doorway seems to be of later date.

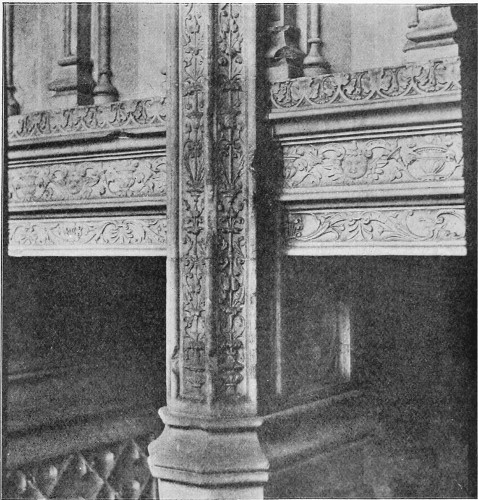

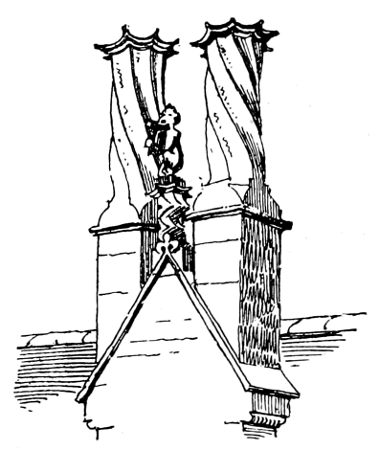

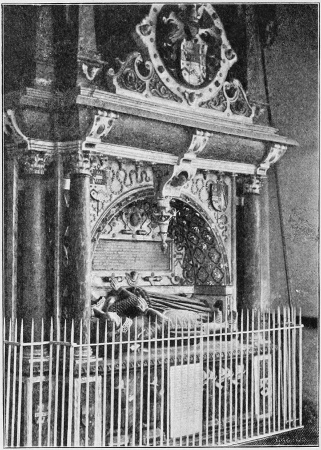

Plate VIIa.

PART OF SCREEN, ST. CROSS, WINCHESTER

(PROBABLY DUE TO BISHOP FOX, WHO DIED 1528.)

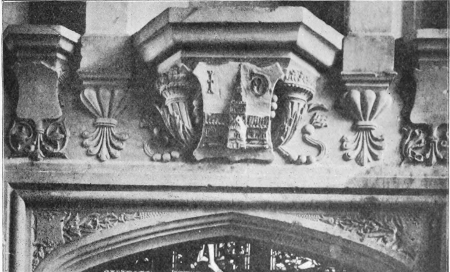

Plate VIIb.

PAULET TOMB, BASING CHURCH, HAMPSHIRE.

Another interesting piece of work of this period is found in the stalls of Henry VII.'s chapel at Westminster. The canopies (Fig. 21) are quite Gothic in character, but of a rather florid description, and although there is no actual Renaissance detail, there [27]is a tendency towards it. The caps of the pilasters are also Late Gothic, while the columns are of that honeycomb pattern which is a sign of change towards the new fashion (Fig. 22). There is woodwork of a somewhat similar character at Winchester in Langton's chapel, and in Prior Silkstede's pulpit (1520). The Spring pew in Lavenham Church, Suffolk, is another instance of the late treatment of woodwork. There are niches, canopies, fan-vaulting, and cusped tracery (Fig. 23), but a closer inspection shows that the tracery has completely departed from the simple lines of Gothic work, and has assumed fantastic forms combined of twisted strands and foliage (Fig. 24), while the columns are honeycombed or twisted into spirals.

22.—Detail from Stalls, Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster.

23.—The Spring Pew, Lavenham Church, Suffolk.

These examples all tend to show that the old traditions died hard. The new ideas were cautiously accepted, and were utilised to help the existing methods rather than to supplant them. Hitherto it has been fittings, or chantries, or tombs which have furnished examples—comparatively small and isolated pieces of work which naturally lent themselves to experiments. But we find the same general treatment in larger and more important efforts; the native tradition still holds the field, but traces of the new manner are to be found[28] in the spandril of an archway, the termination of a label, or the pendants of a roof. Compare the roof of the hall at Eltham Palace (Fig. 25) with that of the great hall at Hampton Court (1534-35). The roof at Eltham is still Gothic, without a touch of the Renaissance; the roof at Hampton Court is also still Gothic in conception and construction, but in the most susceptible parts—the pendants, the spandrils, and the corbels—the new influence makes itself felt (Fig. 26). These pendants are quite in the new style, and yet were carved by an Englishman, named Richard Rydge, of London.[3] The spandrils likewise are filled with Renaissance ornaments carved by Michael Joyner, among which the King's Arms and the "King's beasts" appear, treated in the manner customary in Late Gothic work; the Tudor badges are also carved on the pendants and corbels, amid the cherubs and balusters and foliage which go to compose the Italian ornament (Fig. 27).

[3]History of Hampton Court Palace, by Ernest Law, Vol. I.

24.—Detail from the Spring Pew, Lavenham Church, Suffolk.

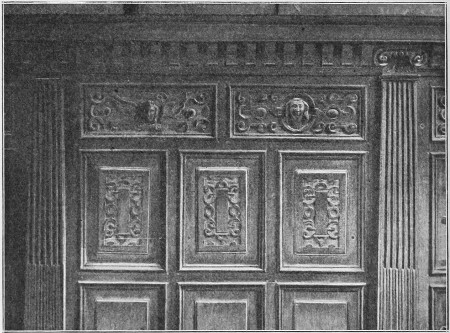

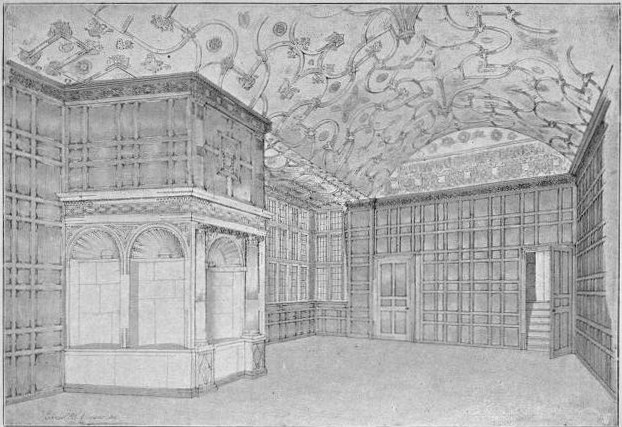

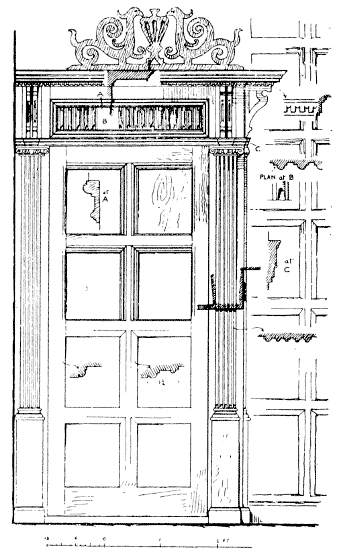

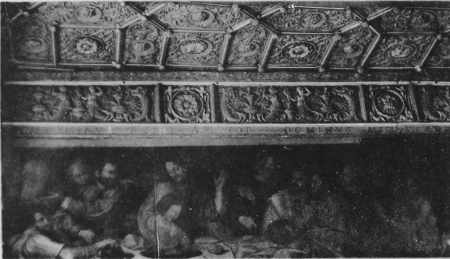

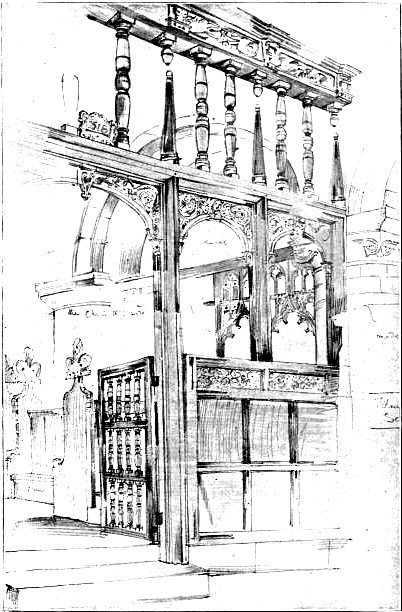

Plate VIII.

KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE.

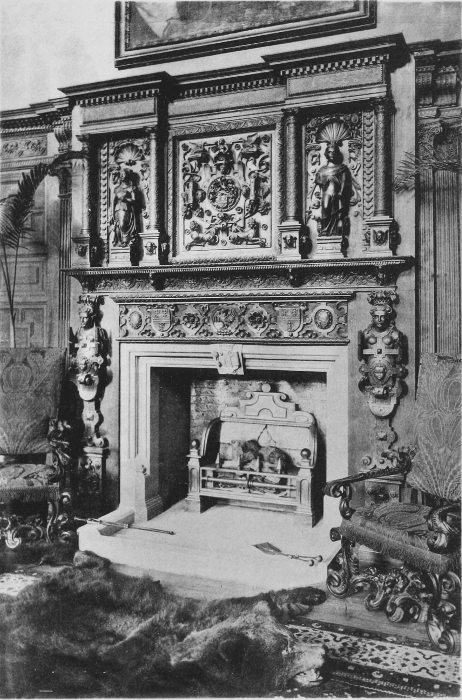

SCREEN IN THE CHAPEL (1532-6).