Which begins in a Manner not at all wonderful.

HALLOO Boys, halloo Boys, Huzza! Huzza! Huzza!

Come, Tom, make haste, the Fair is begun. Here is Jack Pudding, with the gridiron on his back, and all the boys hallooing.

Make haste, make haste, but don’t get into the crowd: for little boys are often trod upon, and even crushed to death by mixing with the mob. If you would be safe, by all means avoid a crowd. Look yonder, Dick Wilson there has done the very thing I cautioned you against. He has got into the middle of that great mob. A silly chit; that boy is always thrusting his nose into difficulties: surely there never was such an impertinent little monkey. How shall we get him out? See how the rogue scuffles and roars. He deserves all the squeezing he has got, because he will never take advice; and yet I am sorry for him. Who tapped me on the shoulder? O Sam, what are you come puffing and blowing! Why you look as busy as a fool in the fair. Well, what news do you bring from the region of nonsense? I have not seen it, and should be glad to know what is done, without the trouble of attending.

Sam Gooseberry’s Account of the wonderful Things of the Fair.

WHY there is such a mobbing at the other side of the fair, says Sam, as you never saw in your life, and one fat fellow has got among them that has made me laugh immoderately—Stand further, good folks, says he, what a mob is here! Who raked all this filthy crowd together? Honest friend, take away your elbow. What a beastly crew am I got among! What a smell! Oh, and such squeezing. Why, you overgrown sloven, says a footman, that stood by, who makes half so much noise and crowding as you? reduce your own fat paunch to a reasonable compass, sirrah, and there will be room enough for us all. Upon this, the whole company set up a shout, and crowding around my friend Tunbelly, so left an opening, through which I made my escape, and have brought off Dick Wilson with me, who, by being heartily squeezed, and having twelve of his ten toes trod off, is now cured of his impertinent curiosity. But you desire an account of the fair, and I mean to gratify you. The first thing I saw which gave me pleasure, was old Gaffer Gingerbread’s stall.—See him, see

The man of the world for gingerbread. What do you buy, what do you buy? says the old gentleman; please to buy a gingerbread wife, sir; here’s a very delicate one. Indeed there is too much gold on the nose; but that is no objection to those who drive Smithfield bargains, and marry their wives by weight. Will you please to have a gingerbread husband, madam; I assure you, you may have a worse; or a watch, madam; here are watches for belles, beaux, bucks, and blockheads. But here comes Master Punch. See, there he is, with his hunch at his back. The crowd that came with him obliged us to leave the place: but just as we were going, Giles called out, Gentlemen, buy a house before you go. ’Tis better to buy than to build. You have heard of the Cock that crowed in the morn, that waked the Priest all shaven and shorn, that married the Man all tattered and torn, that kissed the Maiden all forlorn, that milked the Cow with the crumpled horn, that tossed the Dog, that worried the Cat, that killed the Rat, that ate the Malt, that lay in the House that Jack built. If there is any part you do not like, you may eat it; buy, gentlemen, buy, and don’t build. Many of my friends have ruined themselves by building. The insufferable folly of building a fine house, has obliged many a man to lie in the street. Observe what the poet says on the subject:

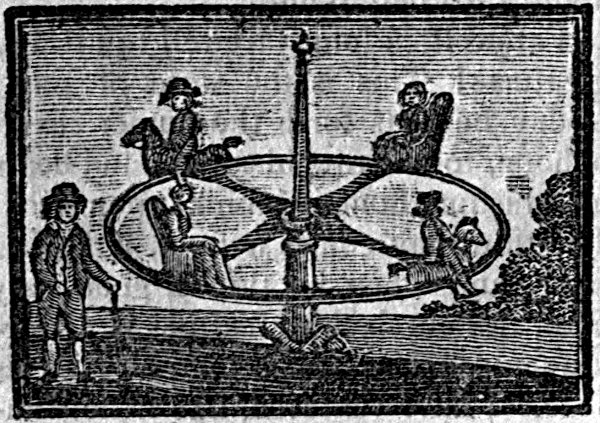

A little further we saw one with the Wheel of Fortune before him, playing with children for oranges. What do you say? Twenty may play as well as one. Ay, and all may lose I suppose. Go away, sirrah, what, do you teach, children to game!—Gaming is a scandalous practice. The gamester, the liar, the thief, and the pickpocket, are first cousins, and ought all to be turned out of company.

At this instant up came Dick Sadbury, crying. And what do you think he cries for? Why he has been at the gaming table, or in other words at the Wheel of Fortune, and lost all the money that was given him by his father and mother, and the fairings that he received from Mr. Long, Mr. Williams, and Mrs. Goodenough. At first he won an orange, put it into his pocket, and was pleased; and then he won a knife, whipt it up, and was happy; after this he won many other things, till at last Fortune turned against him, as at one time or other she always does against those that come to her wheel and seek her favours, and he was choused out of all his money, and brought nothing away but a half-penny jew’s-harp. Why do you bellow so, you monkey? Go away, and learn more sense for the future.

Never game, or if you do, never play for money. Avoid a gamester as you would a mad dog, or as a wolf that comes to devour you.

Hey day! who comes here? O, this is the Mountebank.

But hear him! hear his speech, and observe the Merry Andrew.

Gentlemen and Ladies, I am the doctor of all doctors, the great doctor of doctors, who can doctor you all. I ease your pains gratis, cure you for nothing, and sell you my packets that you may never be sick again. (Enter Andrew blowing on a scrubbing-broom.) Sirrah, where have you been this morning?

Andrew. Been, sir! why I have been on my travels, sir, with my knife, sir; I have travelled round this great apple. Besides this, I have travelled through the fair, sir, and bought all these gingerbread books at a man’s stall, who sells learning by weight and measure, arithmetic by the gross, geometry by the square, and physic and philosophy by the pound. So I bought the philosophy: and left the physic for you, master.

Doctor. Why, sirrah, do you never take physic?

Andrew. Yes, master, sometimes.

Doctor. What sort do you take?

Andrew. Any sort, no matter what; ’tis all one to me.

Doctor. And how do you take it?

Andrew. Why I take it—I take it—and put it upon a shelf: and if I don’t get well, I take it down again, and work it off with good strong ale. But you shall hear me read in my golden books, master.

Doctor. Sirrah, you blockhead. I’ll break your head.

Andrew. What, for reading my book, sir?

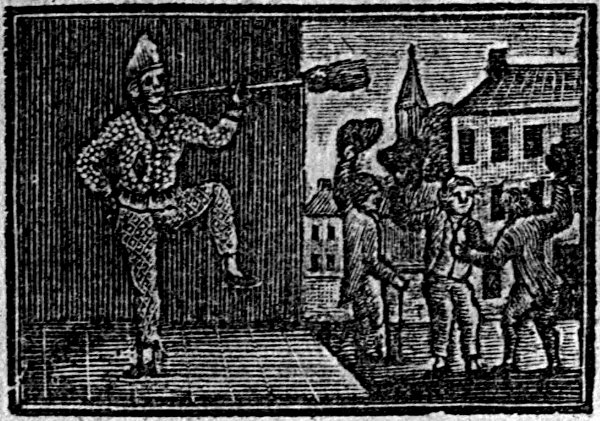

Doctor. No; for your impudence, puppy. But come, good people, throw up your handkerchiefs, you lose time by attending to that blundering booby; and by and by you’ll be in a hurry, and we shall not be able to serve you. Consider, gentlemen and ladies, in one of these packets is deposited a curious gold ring, which the purchaser, whoever he may happen to be, will have for a shilling, together with all the packet of medicines; and every other adventurer will have a packet for one shilling, which he may sell for ten times that sum.

Andrew. Master, master, I’ll tell you how to get this ring, and a great deal of money into the bargain.

Doctor. How, sirrah?

Andrew. Why, buy up all of them yourself, and you will be sure of the ring, and have the packets to sell for ten shillings a-piece.

Doctor. That’s true; but you are covetous, sirrah: you are covetous, and want to get money.

Andrew. And, master, I believe you don’t want to get physic.

Doctor. Yes I do.

Andrew. Then ’tis to get rid of it. But,

Huzza, halloo boys, halloo boys, halloo.

Sam Sensible’s Account of what he had seen in the Fair; particularly a Description of the Up-and-down, and other Things.

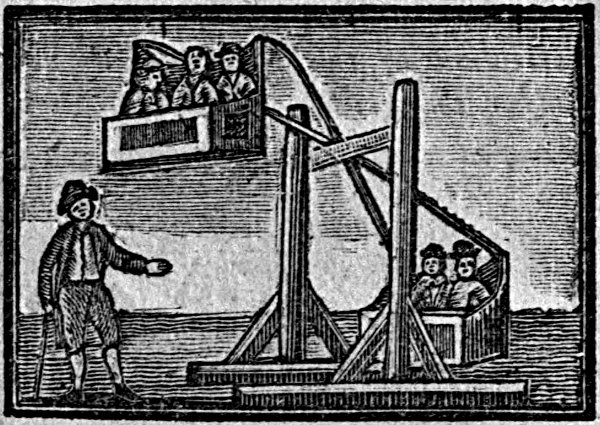

IT is strange! but some children will never take advice, and always are running into dangers and difficulties. That silly chit, Wat Wilful, has been riding upon the Up-and-down, and is fallen off, and almost killed. You know what I mean by the Up-and-down? It is a horse in a box, a horse that flies in the air, like that which the ancient poets rode on.

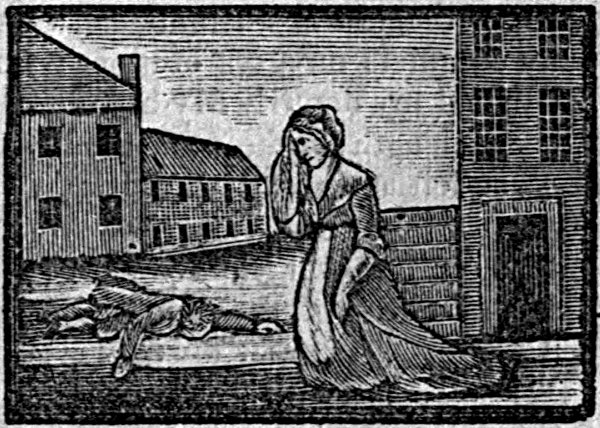

And here is poor Wat, and his mother lamenting over him.

If he had taken her advice, all had been well; for as he was going to mount, Wat, says she, don’t be so ambitious. Ambitious people generally tumble; and when once down, it is not easy to get up again. Remember what your poor father used to read about Cardinal Wolsey.

Farewell, a long farewell to all my greatness! This is the state of man: to-day he puts forth the tender leaves of hope, to-morrow blossoms, and bears his blushing honours thick upon him: The third day comes a frost, a killing frost, and when he thinks, good easy man, full surely his greatness is a ripening, nips his root, and then he falls as I do. I have ventured, like little wanton boys that swim on bladders, these many summers on a sea of glory; but far beyond my depth! My high-blown pride at length broke under me, and now has left me weary, and old with service, to the mercy of a rude stream that must for ever hide me. Vain pomp and glory of the world, I hate ye, I feel my heart new opened.

But Wilful would, and so down he tumbled, and lies there a warning to the obstinate and ambitious. Had he taken his mother’s advice, and rode upon the Roundabout, as Dick Stamp and Will Somer did, he might have whipped and spurred for an hour without doing any mischief, or receiving any hurt. But he was a proud and obstinate silly boy.

Now, my young friends, though you have had a treatise on many pleasing and important subjects, yet there is one remains, and that one should not be forgot. Therefore I shall introduce a descant on Time; and this I hope will meet with your approbation; for the sole intent of this little book is to furnish you with such lessons as may improve your understanding, and ripen your judgment.

You have just been informed by the poet, that Time is a wonder-worker, and truly it may well be called so. It is an awful revolutionist, for it brings strange things to pass, and occasions innumerable vicissitudes in the world. Though it is continually moving on, yet its advancements are so slow and progressive, that we frequently disregard its course. But, that time is uncertain, and Death may cut you off, even in your youth. Therefore improve the present hour, for you know not what the next day may bring forth. Slow as it seems to be, it steals upon us, and gently leads us from childhood to old age. When we arrive at our three-score years, then we begin to think that time runs on apace, and wish we had employed the fleeting hours to more advantage. Here, my young friends, is the fatal error which thousands experience to their cost; for they pursue their foolish vanities, and never consider that time is given us for the express purpose of preparing for eternity. Let me admonish you to think better, and always bear this truth in your minds.

It is impossible to enumerate all the advantages which are derived from education, or learning. It qualifies us for every station, and never fails to prove an invaluable ornament to its possessor. But the Dunce appears in a very different light; for he is the scoff of society, and must of necessity drudge through a life of ignorance and slavery.

It is of little consequence what your calling is, provided you fulfil your station with honesty and integrity, for that is the true source of contentment: and if you are satisfied with that state in which God hath placed you, not even kings can desire, or be possessed of more, perhaps not so much; because the higher the station, the greater the cares.

It would be thought a hard government that should tax its people one-tenth part of their time to be employed in its service; but idleness taxes many of us much more, if we reckon all that is spent in absolute sloth, or in doing of nothing, with that which is spent in idle employments or amusements, that amount to nothing. Sloth, by bringing on diseases, absolutely shortens life. “Sloth, like rust, consumes faster than labour wears, while the used key is always bright.”