| Vol. II.—No. 104. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, October 25, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

All the boys cried, "Shame!"

Tom Reid, who was scarcely regarded as a boy now, so nearly grown was he, went up to Hen Little, and catching him by the shoulder and shaking him, said:

"It seems to me you pick out your boy to bully. You ought to be ashamed of yourself, to hit a fellow under your size and not half your strength, and I've a notion to thrash you for it myself."

Nobody heard what Hen Little replied, because all the boys were talking at once now; but somehow, when Vic Whitney rose from the ground, his clothes torn, his nose bleeding, and his books muddy, everybody saw that he was going to say something, and everybody listened. What he said was this:

"Hen Little, I've borne with you for two years; I've taken all your meannesses as mere teasing, and I've thought you only a little rough; but now I tell you you're a coward and a bully, and I give you warning that I'll whip you for this day's work, if it's ten years hence."

"Boys," said Tom Reid, "I move that, as students of this High School, we hereby exclude Hen Little from all our games and sports, and regard him as an outside barbarian, until he makes a proper apology to Vic Whitney for what he has done."

"Second the motion!" cried a dozen voices, while all the girls clapped their hands.

"Wait a minute, please," called Vic; "don't put that motion, Tom. Let me say a word. I thank you all for your sympathy, but I beg you not to do what you're doing. I've made this matter a quarrel now, and it's my quarrel, not yours. I've told Hen Little that I shall whip him for this, and I shall do it, you may depend. But that ought to settle it, so far as you are concerned. Hen is bigger than I am, and much stronger; but I shall thrash him in due time, and it ain't fair to punish him twice for one offense. If you punish him, I can't, without doing an injustice, and I don't want to do that. Please withdraw your motion, Tom."

"But this sort of thing is a disgrace to the school," said Tom.

"Very well; but I am going to punish it myself," replied Vic, "and that will clear the school. I've a right to be the one to do it."

"But you can't thrash Hen Little," cried half a dozen boys in a breath.

"No, not now. But I shall be able to do it after a while. Trust me, and do me the favor I have asked. Withdraw your motion, and treat Hen as if nothing had happened, and I'll take care of the rest."

There was something in Vic's manner which awed the boys into respectful obedience. They were outraged with Hen Little, and would have enjoyed "making the school too hot for him," but they obeyed Vic Whitney. When Vic had secured their promise to this effect, he gathered up his books and walked away toward his home.

Little had teased him mercilessly during the whole of the two years since they both entered the High School, but Vic had borne it all as mere teasing, not to be resented. At the end of the last term, however, Vic had successfully offered himself for examination with the class in advance of his own, having worked of nights to get ahead, and in this way he had distanced his own class, and made himself a sort of hero in the school. At the same examination Hen Little had failed to pass with the class, and his mortification took the form of hatred of his former classmate, who had succeeded in making two steps forward while he failed to make one. His teasing became positive persecution, but Vic continued to endure it with a smiling face.

One day, however, just after school, as Vic was starting toward home, with his books under his arm, he accidentally passed too near a gymnasium rope on which Hen Little was swinging. A slight collision was the result, and Hen lost his hold on the rope, with no more serious consequence than a fall to his knees. Springing up, he rushed at Vic, and without a word of warning, dealt him a severe blow on the nose, knocking him down into a little puddle. It was a particularly brutal and wanton attack, and so, as I began by saying, all the boys cried, "Shame!" and the scene already described ensued.

Vic Whitney seemed calm enough when he begged the boys to refrain from their proposed measure of vengeance, but as he walked away homeward he was in reality very much disturbed. His sense of justice was outraged beyond endurance, and his feeling was that he would wrong himself if he failed to administer the punishment he had promised Hen Little.

If Vic could have concealed the affair from his mother by saying nothing about it, he would have done so; but that was impossible. The torn clothing and the swollen nose required an explanation. When he had told the story, and declared his purpose, his mother sought gently to calm his spirit; but finding that impossible in his present mood, she quietly dropped the matter, hoping at some later time to dissuade Vic from his intention.

After supper Vic went out without saying where he was going. He walked up the street, and entered the office of Dr. McCutcheon, his father's life-long friend.

"Well, my boy," said the doctor, "what's the matter? Have you been hurt?"

"No; it's nothing," said Vic; "and I didn't come for sticking-plasters or poultices. I want your advice."

"You shall have it. What is the trouble?"

"I want you to tell me just how I should live, while developing my muscles, in order that I may gain strength and activity as rapidly as possible."

"What! going to make a prize-fighter of yourself? I thought you cared more for triumphs won with your head."

"No, I'm not going to be a prize-fighter," replied Vic; "but I am going to get up all the muscle there is in me, and I want to know about diet, etc."

"Well," said the doctor, "perhaps you are a trifle flabby for want of exercise, and I'm not sure that you can do better than train a little. As to diet, quit coffee and tea, eat plenty of roast beef and other wholesome plain food, let pastry alone, and don't study just before or just after a hearty meal; get ten hours' sleep in every twenty-four, if you can; and it won't take much training to make you robust."

Clearly the doctor had no thought that Vic intended anything more than to make himself robust and healthy; but Vic had secured the information he wanted.

The next day he fitted up a number of gymnastic appliances in the cow barn. He fastened ring ropes to the beams, and constructed some parallel bars; he swung a ladder horizontally, and hung a bag of sand on a level with his breast. Then his training began. When he got out of bed in the morning he took a cold bath, and rubbed himself well with a coarse towel. Then slipping on some light clothing, he went out and ran around two or three blocks at a good round pace. On his return, after taking breath, he swung by his hands on his ring ropes, drawing himself up first with both hands, and then, after a week's practice, with one hand at a time. The horizontal bars and the ladder came next, each furnishing a variety of exercises for different muscles. Finally, Vic would stand in front of his sand bag and strike it with his fists a great many times.

At first these muscular exercises made him stiff and sore, but this effect soon passed away, and day by day he increased the amount of exercise taken. His muscles grew in size and hardened. Feats that had been impossible to him at first, became easy, and the exercise which at first seemed to exhaust him became positively delightful. Devising new exercises and new apparatus every week, he presently found that he was acquiring something besides strength—he was growing expert in all manner of agile feats. He practiced trapeze performances, and rapidly acquired an accuracy of eye, a steadiness of nerves,[Pg 819] which made easy and safe many cat-like feats, in which, if he had attempted them a few weeks before, he must certainly have broken his neck.

His mother had anxiously watched his conduct; and one evening she seized upon a favorable moment for remonstrance, seeking to dissuade him from his purpose of vengeance. He heard her silently, and when she had done, he replied, very calmly, but very resolutely:

"Mother, what you say is all true and right in principle. It is wrong to cherish anger and to seek vengeance, but that isn't my case. I don't hate Hen Little: I pity his meanness and his cowardice. I am not seeking vengeance, but justice, and I have a right to that. If I were to give up thrashing him, I should look at myself with contempt. I shall punish him, not because I hate him—for I don't—but because I must assert my own manhood."

The widow was perplexed by this view of the case. She could not quite believe it was right, and yet she could not conscientiously say it was wrong.

"Well, my son," she replied, "I fear you are wrong; but you may be right. At any rate, I can not take the responsibility of urging you to submit to anything that you feel to be a degradation. Feeling as you do, you must decide the matter for yourself."

"I have decided it," said Vic; "and the decision is that I must thrash Hen Little."

Vic and his mother were sitting in the doorway during this conversation. Vic had finished his lessons, and the hour was late, but the night was so pleasant that the pair sat there chatting long after their usual bed-time. Just as Vic ended the discussion with the remark quoted above, the fire-bells rang out with that eager, noisy, frightened clangor which fire-bells have only in small cities where a fire calls the whole population forth. Vic seized his hat and ran, guided by the glare which already appeared at the opposite end of the town.

The burning house was one of the largest in the little city, a building three stories in height; and before the excited volunteer fire companies could get a stream of water running, the fire was evidently beyond their control. It had broken out in the lower story, near the stairway; and finding that efforts to stay its course were idle, the firemen and spectators did little more than place ladders at a second-story window for the escape of the family, who had been sleeping. When all were out, there was nothing to do but to stand and watch the bonfire, as no other house was near enough to be in danger.

Presently a head appeared at one of the windows of the third story, and a cry for help was heard. A shudder ran through the crowd, for there was no help to be given. The fire had burned both the stairways, and there was no ladder long enough to reach beyond the second story. Some of the spectators stood stupefied; others ran about aimlessly, trying to do something, but having no idea what.

Meantime the boy at the window cried aloud and piteously for help. His father and mother were not less frantic than he. They had believed that all the family were safely out, supposing that Hen—for it was Hen Little—had passed down one flight from his third-story bedroom, and had escaped with the rest. Seeing him now at the window, they lost their wits, and cried to him to leap out, without thinking that to do so would be instant death to him. Yet there was apparently nothing to be done, and the situation was appalling. The crowd shuddered to think that the boy, whom they all knew, must be burned to death there in their sight.

Presently a cry arose at the rear of the crowd, and Vic Whitney came running with all his might, shouting:

"Don't jump, Hen! Stay where you are! Don't jump out!"

Vic had run to a neighboring house, and brought away a clothes-line.

"Has anybody a string?" he shouted—"a kite cord—anything—quick!"

A boy handed him a kite cord, and Vic quickly tied one end of it around his own body. Then turning to Tom Reid, he said:

"Unwind fifty feet or so, break it off, and tie the end to this rope, so that I can pull the rope up. Be quick."

Leaving Tom to execute this direction, Vic ran forward, stepped upon the railing of the front steps, and grasping a window-shutter which luckily was open, and therefore not in the blaze that licked its tongue out of the window, he drew himself lightly up to its top, crying out as he did so, "Play a stream of water on me."

The fireman obeyed, and none too soon, for all the clothing on Vic's right side was scorching. From the top of this shutter Vic reached the window-sill above, and disappeared in a dense cloud of black smoke. It was for only a moment, however. Having his wits about him, he held his breath to avoid suffocation, and quickly climbed to the top of the window, and into the air again. Another moment, and he had grasped the sill of the third-story window. A gust of wind blew a flame from below right upon him. He felt his arms blister and his head swim. One second more, and he must loosen his hold, and fall. The crowd below uttered a moan of horror. The wind shifted instantly, however, and in spite of the agony he suffered from the burns, Vic made a last effort, and drew himself up to the window where Hen had stood. Hen was no longer there, and the room was too full of smoke for Vic to see into it. He knew what had happened. Hen had become unconscious from suffocation, and had fallen on the floor by the window. Hastily drawing up the kite cord, to which Tom Reid had fastened the end of the clothes-line, Vic soon had the rope in his hand. Reaching down from the window-sill, he fastened the line around Hen's body, and swung him out, the crowd below yelling itself hoarse as he lowered away. A few seconds sufficed to let Hen down to the ground, where the doctors took charge of him.

Meantime Vic had to think of saving himself. He fastened the rope at the window, and was on the point of slipping down it, when a fierce flame burst from the window immediately beneath, burning the rope off like a thread, and cutting off all chance of escape in that direction.

Vic saw his extreme danger, but as he afterward said, his mind seemed to be unnaturally calm and alert. There was fire below him, through which it was impossible to pass, and the roof was in a blaze. But he remembered that the lightning-rod of this house, instead of passing straight to the earth, was carried down along the roof to the corner nearest him, and thence down the corner to the ground. Seizing this slender chance of life, he climbed to the top of the window, and grasped the stout gutter pipe that ran along the eaves.

Swinging from this by his hands, he worked his way slowly and painfully toward the corner, while the people below actually held their breath. Whether the gutter would hold the boy's weight or not was terribly uncertain, and the people stood on tiptoe, as if they could thereby lessen the weight, and increase his small chance for life. Slowly he worked along toward the corner, and at last his hand grasped the friendly lightning-rod. A few seconds later he was safely on the ground, but so badly burned that it was necessary to carry him home on a shutter.

A week later, when Dr. McCutcheon pronounced Vic out of danger, a company of his school-mates came to see him. They filed into his room, and took their places in a sort of line. Then Hen Little entered, and walking up to the bedside, he said:

"I've had my thrashing, Vic, and I've brought all the[Pg 820] boys that were present on that other day to hear me say so. I want to ask your pardon for all I've done to you. I deserved punishment; now I've got it; and if it ain't enough, you may thrash me with your fists as soon as you get well, and I won't raise a finger." Then, turning to the boys, he said: "Vic called me a coward that day when I abused him, and he was right. I acted cowardly, and I want to say so to all of you. I'm thoroughly ashamed of myself."

Vic held out his hand, which was bandaged almost to the finger-tips, and said: "Hen, I take it all back. There isn't a cowardly bone in the body of a boy who can apologize in that way for a fault. Let's be friends hereafter."

AUTHOR OF "TOBY TYLER," ETC.

Every one knew that Tip's life depended on their getting home quickly, and all the strength they could command was expended on the oars to such purpose that in a trifle more than two hours the boat was moored alongside Dunham's wharf again.

TIP AND THE DOCTOR.

TIP AND THE DOCTOR.

Without stopping for anything, the entire party followed Tim and Bill to Dr. Abbott's office, and there they could hardly prevent themselves from cheering when the doctor told them that Tip's injuries were by no means serious, and that he would soon be well, although it was possible that he might always be lame in one hind-leg.

The shot were soon extracted, and Tip taken to the most comfortable spot in Mr. Tucker's barn, where it is safe to say he did not suffer from want of attention.

That night, after Bobby and Tim had told the story of their camping out, Mr. Tucker thoroughly frightened them by saying that on the next day he was going to take Tim back to Selman to see Captain Babbige.

Tim's face grew very pale, and it was plain to be seen that he was in the greatest terror, while Bobby was thrown into a perfect fever of excitement.

"I am not going to leave you there, Tim, if I can help it, for I intend to do by you as I would some one should do by my Bobby if I had been called to meet the Great Father. As matters now stand, you have no right to be here, nor I to keep you; for Captain Babbige is your lawful guardian, whom I hope you did not leave without sufficient cause. To-morrow night we will start for Selman, and there the law shall decide whether you may not be permitted to choose another guardian."

Bobby caught eagerly at the idea that Tim would soon return, with a perfect right to stay on Minchin's Island, but the homeless boy took a more gloomy view of the case. He felt certain that Captain Babbige would force him to remain with him, and the future now looked as dark as a day or two before it had looked bright.

So positive did he feel that he should not be allowed to return, that, if Tip's wound had been any less severe he would have taken him with him; but as it was, he made Bobby promise faithfully to send him as soon as he should be able to travel.

The next day, when the boy population of Minchin's Island learned that Tim was to be taken back to the man who had abused him so cruelly, they held a sort of indignation meeting back of Mr. Tucker's barn, where the matter was discussed.

Some of the more excitable among them proposed that, since the steamer on which Tim was to leave would not touch at the island until nearly six o'clock, there was plenty of time for him to run away again, making it impossible for Mr. Tucker to carry him back. They argued that he could build himself a hut in the woods, where, protected by Tip, he could live the jolliest kind of a life, and they all could come to see him as summer boarders.

But Tim rejected all such counsel, giving good reason for doing so.

"Mr. Tucker says I ought not have run away in the first place, an' I s'pose he knows, though it does seem hard to have to stay where folks are so awful ugly to you. Now he says I must go back, an' I wouldn't be any kind of a feller if I run away from him after he's been so good to me. I'd like to go out in the woods to live if it wouldn't rain any, and I'd do anything rather than go back to Selman; but Mr. Tucker says I ought to go, an' I'm goin', whatever Captain Babbige does to me."

Every boy present knew that Tim was right, and those who had first advised him felt ashamed of having done so, while all united in cheering him for his resolution, until Tip, awakened by the noise, barked loudly, which, to Tim's mind at least, was proof that he approved of his master's decision.

That night Tim was escorted to the steamer by a large number of boys, and while he was on the wharf he felt reasonably brave, even though he was obliged to pass directly in front of Captain Pratt. But when the steamer left the dock, and the cheers of the boys died away in the distance, he fully expected to be summoned to the wheel-house. But Captain Pratt paid no attention to him, and on the following day Selman was reached without any incident worthy of mention.

There Tim was never exactly certain how the matter was arranged. He knew that he was taken into court almost as if he had been a criminal, that many questions were asked him by the Judge, and that a number of gentlemen[Pg 821] whom he knew told of the ill-treatment he had received from Captain Babbige.

Then it seemed as if Mr. Tucker had been accused of something, for he told about his business and himself, and showed a great number of letters from people on Minchin's Island, all speaking of him as a kind and good man.

Captain Babbige was there, apparently in a very uncomfortable frame of mind, and he spoke to Tim in the kindest manner possible, asking him if he hadn't always treated him as a son.

Tim was not sure how fathers did treat sons, except in one or two cases; but he told the Captain of what he had said about wanting him to die, and then coaxed the Judge—oh, so hard!—to let him go back with Mr. Tucker.

Then some other people had a good deal to say, the Judge talked some more, and after they were all through, Mr. Tucker told Tim it had been decided he could go back to Minchin's Island.

Tim's delight was so great that it seemed impossible for him to keep his feet on the ground. And when he was back at the island again, in the midst of the crowd of boys who had come to welcome him for the second time, his joy found vent in words.

And when Tim got into Mr. Tucker's house, where Bobby cheered until he was hoarse, and Mrs. Tucker kissed him again and again, he found it impossible even to speak, because of a great lump in his throat, which was not caused by sorrow; but he said over and over to himself that no one should regret in the man what they had done for the homeless orphan boy.

We all know, in a general way, that nothing grows unless it is alive, and yet who ever thinks of bread dough as having life in it? There never was a garden bed so full of living plants as is the loaf when it is moulded into shape, and ready to be put into the oven. If you have never watched the mixing of bread, I would advise you to go and look at it the first chance you have, for it is a very curious and entertaining bit of gardening. The cook first prepares her seed, which is the yeast. There are several ways of planting yeast, as there are of planting other seed. You may either soak it to make the seed sprout quickly, or you may start the little plants in a hot-bed, or, again, you may buy your young seedlings, and transplant them into your own garden plot. Just so you may get your yeast seed ready to plant. The yeast cake may be only melted in warm water, or it may be set to start in a cup of water and flour by the warm kitchen fire, or you may buy the yeast already grown at the baker's.

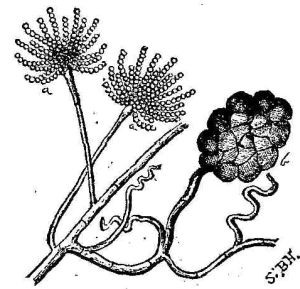

Fig. 1—Toad-stools.

Fig. 1—Toad-stools.

When the seed or seedlings are ready, the garden plot is prepared. The cook heaps up in her bread bowl quarts of snowy flour. Into this heap, after making a hole, she pours her prepared yeast. Working the bread is only another name for the careful scattering of the seed through all the dough, that it may spring up and grow, and fill the whole mass with the tiny plants.

The yeast plant is not a common kind of plant, but belongs to the same class as mushrooms and toad-stools, and the fuzzy, cottony growth that we call mould. There are two kinds of plants that we may find almost anywhere in the fields and woods, and even in the city yards—the fungi and the green plants. The yeast plant is one of the fungi. These are very different in most respects from the green plants: they can live and grow and thrive in darkness; they do not have either leaves or flowers, and they usually spring up and die very quickly. The greatest real difference between the two kinds is, however, that the fungi live on food that has been alive before—on plants, or animals, or decaying matter, while the green plants live on what they get out of the earth and the air and the water.

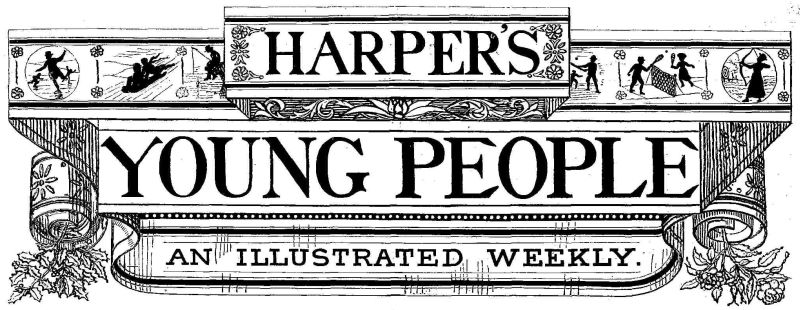

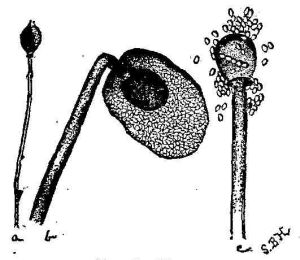

Fig. 2.—Yeast Plant.

Fig. 2.—Yeast Plant.The simplest of all the fungi is the yeast plant. It begins its life as a tiny egg-shaped bag, or sac (Fig. 2 a). This cell, as it is called, is filled with a very curious jelly, perhaps the most wonderful thing in all the world. It is found in everything that lives and grows. By its help the little yeast plant can take the flour and water, and can change it so that while the paste is used up and disappears, the cells grow larger, and sprout out buds. You have particles of this jelly, or protoplasm, lining your mouth and stomach, and the food you eat is changed into flesh and blood and bones by this wonder-working magician. In the figures, the grainy substance is the protoplasm.

This jelly all seems to be pretty much alike, but there is some marvellous difference somewhere—a difference that science has never reached. The yeast cell takes in certain food, and grows, but it never makes anything but other or larger yeast cells. The food you eat and digest makes just you; more of you, perhaps, but still you, yourself, and nobody else.

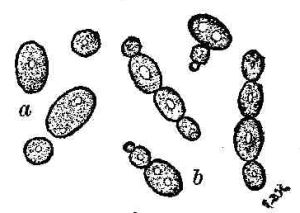

Fig. 3.—Mould.

Fig. 3.—Mould.

Like all living things, the tiny yeast cell must eat and breathe, or it will die. It feeds, not by opening its mouth and taking in its food, but by lying bathed in it, and soaking it up through its skin. When the cook dissolves her yeast cake, and puts it into the spongy dough, she is putting the little plant into its food bath. The cells which have been so long in prison, shut up in the darkness and cold of the dried yeast, begin to look alive, and stretch themselves, and enjoy their liberty. They take kindly to their food right away, and begin helping themselves to what they find about them. They do not merely soak up the flour[Pg 822] and water in which they are plunged, but they manage to extract from the compound just what they need.

The cells must not only feed in order to live, but they must breathe, they must somehow get oxygen, which is the gas that our breathing takes out of the air. And this they extract, as a miner does gold, by separating it from its ore. There is a certain amount of sugar in wheat, which gives to good bread and to cracked wheat their delicate sweetness of flavor. Sugar is made up of a number of different substances, which the yeast cell has the power of separating. It takes the oxygen for its own use, and leaves behind the other things that make up the sugar.

Feeding and breathing in this way, by taking what it needs from the flour, the cell grows. When it has reached its mature size, it rests quietly for a while as if it were gathering strength for the effort, and then it sends out a little bud, which grows like the parent cell, until another bud and another grow from it. When the plant is grown, it is very unlike our notion of a plant; it is really nothing more than a little chain of sacs growing end to end. As soon as the little plant has exhausted all the sugar and food substance of the flour, it stops growing, the cells separate, and remain quite still.

There is just one time in the growth of the plant when the dough is right for baking. Before it has grown enough, the bubbles through the dough are too few or too small. These bubbles are the carbonic acid gas left behind when the oxygen has been taken out of the sugar, and there must be plenty of them to make the bread light. If the bread is left too long to rise, the cells get more than their share of the wheat sugar, and the bread is sour. Just at the right stage, which every good bread-maker can tell by experience, a thorough baking will destroy the alcohol, and the bread will be both sweet and light.

When the yeast plant is sowed on the top of the flour and water, instead of being buried in it, all this is very different. The plant takes its food from the paste, but it does not need the sugar, so it lets that alone. It can get its oxygen in a much simpler way, right from the air, as we do, and does not need to go through the labor of smelting it out of the sugar. The raising of our bread by yeast is entirely due to the efforts of the tiny cells to get a breath of air when we have smothered them up in the dough.

Fig. 4.—Mould.

Fig. 4.—Mould.There are other plants besides the yeast plant that act in the same way. Have you never heard your mother say, when she opened a jar of preserves, "These are all right, I know, for they are covered with mould"? Mould is a good deal like yeast in some things; if the germ cell, or spore, falls upon the top of the sweetmeats, it can get plenty of oxygen from the air, and so lets the sugar alone. But if it is nearly drowned in the syrup, it will get its oxygen somehow, and so the sugar has to be sacrificed, and the preserves are left to spoil. What else could you expect of such little mischief-makers if you shut them up with the sweetmeats?

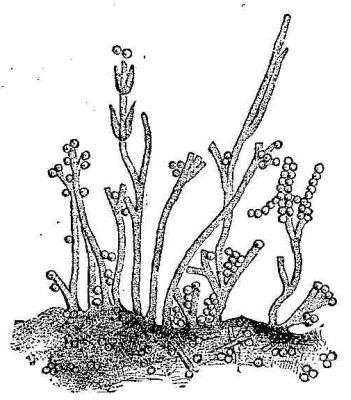

The yeast plant is so very, very small that you can not see it except with a very fine magnifying glass. But there are other plants like it which are large enough to be seen with a small and not a costly microscope.[2] These are what we call moulds. If you want to study moulds, nothing is easier than to prepare them. Mix a spoonful of flour with cold water, and spread the paste over the bottom of a plate or saucer. In a few days it will be covered all over. If you put it in a damp and dark place, the mould will sprout sooner. You might put away a piece of bread at the same time, and you will find it covered with a growth too.

Take a bit of this paste on the blade of a knife, and examine it carefully. You will see among the cottony fibres a number of little upright stems with black or white or yellow heads, which give the mould a speckled look. Under the microscope you see a perfect jungle of growth—a tangle of threads, which look like spun glass, running here and there and everywhere. From these, which are the roots of the mould, the stems spring up, bearing, instead of leaves or flowers, tiny glistening toad-stools that look as if they were made out of a pearl; or sometimes the heads are like strings of little pearls (Fig. 3), or at others they are rosettes of such strings (Fig. 4 a). The black and sage green colors come later, and are the fruit or seed-bearing portion of the plant (Fig. 4 b).

Fig. 5.—Mould.

Fig. 5.—Mould.On my saucer of paste I found in one place a plantation of delicate yellow fungi. The stems came up thick, with the little round fruit at the end of each, looking as if the whole thing was carved out of amber. In another place, over the yawning caverns made by the cracks in the paste, there were delicate forms like grasses in seed, all looking like spun glass. The largest kind of common mould, which you may see in Fig. 5, is not so beautiful as these I have just described, but it shows very well the way the fungi grow, and form their seed, and then sow themselves. This plant is easily seen without any microscope, but looked at through the little Excelsior glass, you see a great deal more. The stalks look as they do in Fig. 5 a. If you are so fortunate as to have a large microscope, and watch them from day to day, you will see them look as they do in Fig. 5 b, and finally, when the outer skin breaks, like c, in the same illustration.

A single spoonful of flour will give you this wonderful garden, with its crop of yeast plant, if you sow the seed, or, if you trust to luck, its harvest of chance-sown mould. The air is full of these spores of the mould plants, and wherever they find a place they will take possession of it, and grow up without planting or cultivating, as weeds do. You can be certain of your yeast crop, because you have sowed it; but you must take your chances with the mould. You are almost sure, however, to find in any saucer of paste the different kinds described and pictured in Figs. 3, 4, and 5.

It is worth while sometimes to get away from the every-day world, and learn the wonders that are to be found in the fairy ring to which the microscope admits us.

Mr D——, one of our neighbors, was going after his cows one night, and had a singular bit of experience. He kept the cattle near a meadow, and in going for them had to pass through a clump of bushes where raspberries and blackberries were abundant. The path was very narrow, and in some places so much overgrown by the bushes that a person might be very near an object and[Pg 823] not see it. Suddenly a large bear rose up before him, and sat on his haunches not three feet away. Mr. D—— was a tall and very powerful man, and not easily frightened, but he didn't like such familiarity as that. There was no time to retreat, and he had no weapon with which to defend himself, but he clinched his huge fist, and struck the bear a terrific blow between the eyes. Bruin was not prepared for this, and as he sat up so straight, and could not brace himself quick enough, the blow knocked him clean over upon his back in the bushes. He roared, and scrambled to his feet, and ran off as fast as his legs could carry him, much more disturbed by the event than Mr. D—— was.

A year or two after this, my father and I were out gathering raspberries one afternoon in August. We were in a field close by a wood, where several acres were covered with the bushes, and as it was newly cleared land, they grew very tall. Indeed, a person might be picking berries ten feet distant from you, and, if he kept quiet, you would not know it.

After a while we climbed upon the trunk of a fallen tree, for the sake of reaching some high bushes that were bending under the weight of luscious fruit, when we saw a bear, not more than ten feet distant, helping himself to the same berries. At first he did not see us, and we watched him for a little as he ate the fruit. It was surprising how skillfully he would take a bush in his paws and hold it down while he ate off the berries, and then let it go and catch another.

But we wanted those raspberries, and father shouted and swung his pail around his head, thinking to drive the bear away. But the beast did not propose to be disturbed in that way, and seemed to think he had as much right there as we. He simply let go the bushes, and looked at us.

Father grew impatient with swinging the pail of berries around his own head, and threw it with all his might at the head of the bear. It was well aimed, for it struck him squarely in the face. It scattered the berries all over him, and the tin pail fell rattling among the bushes and stones. I never saw such a picture of astonishment as that bear presented. For a brief instant he seemed paralyzed, and then, dropping on four feet, he ran away screaming like a child who has been frightened by a turkey-gobbler. Father's berries were spilled, but he could do nothing else for some minutes but laugh at the way that poor bear ran and screamed.

We hear stories about bears attacking people without provocation, but I believe most of them are purely imaginary or greatly exaggerated. I have hunted the black bear in the New England States, and in the British Provinces; I have threaded the forests on foot, and scoured the plains on horseback, but I never yet saw a black bear that would attack a man, unless it were a dam whose cubs were meddled with, or a bear that had been wounded and driven into a corner. Under such circumstances any animal will fight in self-defense. The chief difficulty with black bears is, not that they will hurt you, but that you can not get near enough to hurt them.

A bright little sunbeam sped earthward one day

From his father's great bosom of light;

For he heard from his beautiful home in the sky

A poor little violet mournfully sigh,

"The earth is so cold, and the winds are so high,

I am sure I shall perish ere night."

But the words barely passed from her trembling lips

When a life-giving kiss on her fell;

And the dear little sunbeam both arms round her threw,

And said, "Tremble not, I shall tarry with you,"

And he kissed back her life, till the tenderest blue

Proclaimed her the queen of the dell.

What the game of base-ball is to this country—yes, and a great deal more—cricket is to England. It is the national game, the most favored among a people who are devoted to all kinds of out-door games and sports.

Why, then, it may be asked, is it not more generally played in this country?

The answer that has been given to several similar questions may, perhaps, be given to this. We have too many railroads to build and too many rivers to bridge to devote two whole days to a single game of cricket.

Ay, my masters, build your railroads from ocean to ocean and from the great lakes to the Gulf, bridge your mighty cañons and your roaring torrents, but remember that the brain that works out the problems of the engineer and the surveyor will work the smoother and last the longer if it be greased occasionally with an excellent oil compounded of rest and recreation.

It is very possible that most of our readers have never even seen a game of cricket, especially if they live far from large cities. To the Philadelphia boy cricket is as familiar as is base-ball to most boys. If asked to name the "three Graces," he might answer, as pat as you please, "E. M., W. G., and G. F.," giving the initials of the three famous brothers Grace, whose names are familiar wherever cricket is played. But as this paper is not for boys of any one place, but for boys all over the country—nay, for boys wherever found—we will describe the game, and try to show in what lies its great favor among those who know it.

Cricket is properly played by eleven persons on each side, though where so many persons can not be brought together, a less number can play. One side bats, and the other side bowls and fields. Two batsmen go to the wickets, one at each end; and the first bowler delivers a ball to the batsman opposite to him, while the fielders take their positions at a greater or less distance from the wicket.

"Oh, well hit! well hit!"

Yes, well hit, indeed. The batsman has driven the ball right over the bowler's head, and has already crossed between the wickets twice, scoring two "runs." Yes, and he and his partner are trying another one. Good! three runs off the first ball.

But another batsman is to receive the ball this time. It is the one who was at the wicket whence the last ball was bowled. As they have made three runs, the man who hit the last ball is at the other end now.

Ah, that was a good ball, and well he played it. There was no driving that ball to "long on" or "long off" for three. It was well pitched up, and had a spin on it that made it shoot along the ground instead of rising; and so the batsman played back, and just got his bat down in time to stop it, for it was bound for his middle stump. He is a cautious player, the man at this end, and the bowling is straight and well pitched.

After five balls, a man who has been standing by the bowler with his coat on, and seeming to take no interest in the game, turns his back on the bowler and batsman, and strolls off as if tired of looking on. Then the fielders seem to be playing at "pussy wants a corner," for they walk about and change places, and then another man begins to bowl from the other wicket.

The fact is, you did not hear the man with his coat on call, "Over!" Well, he did so. Not that the game is over, or the innings, or anything else. They are simply going to bowl from the other end, and so all the fielders have to change their positions so as to occupy the same position with regard to the batsman. The man with the coat on is one of the umpires (there is one at each wicket), and it is part of his business to count the balls bowled. When one man has bowled four or five balls, as the case[Pg 824] may be, another man bowls the same number from the other wicket.

"Well bowled! oh, good ball!"

The meaning of these cries arising from the spectators is that the new bowler has sent the middle stump of one of the batsmen flying, and our friend retires to the tent, where he is greeted with some little applause by his comrade. And so one man out of the eleven is "out."

The next man walks up and takes his place, and the game goes on. He is a careful player, this new man, but he is a hard hitter also. See how he swung his bat round to his left side, and sent that last ball to "leg" for four runs. Now he has the ball again, and for "over" after "over" he and his partner give the fielders plenty to do. Look at the board on which the score is displayed. It marks sixty runs, and only one man out. This is getting serious. The Captain of the fielders calls one of his men up to him, and says a few words. Some new tactics are to be tried.

The next "over" reveals what they are. The batsmen have become used to the bowling, and so, like a wise man, the Captain puts on a fresh bowler.

The new man's balls seem easy enough. See, there one goes for three or four runs at least. But wait a little. This underhand bowling is tempting, but it is also dangerous. A beautiful easy ball comes which the batsman steps to meet, and drives high over the heads of the near fielders, but away off there in the distance a man is posted to look after just such balls as this. He sees it coming, keeps his eye on it, runs backward a few paces, and it is in his hand before it touches the ground. And so the second man is caught out.

By the time the third man is out, the score has reached a hundred, but after that the wickets fall more quickly. The bowling is changed as often as it is found that the batsmen can master it, and the fielders are on the alert.

There is but one more wicket to fall, and the score bids fair to reach two hundred. One hundred would have seemed a good score, had they not already nearly doubled that number, and now they are straining every nerve to gain the wished-for two hundred.

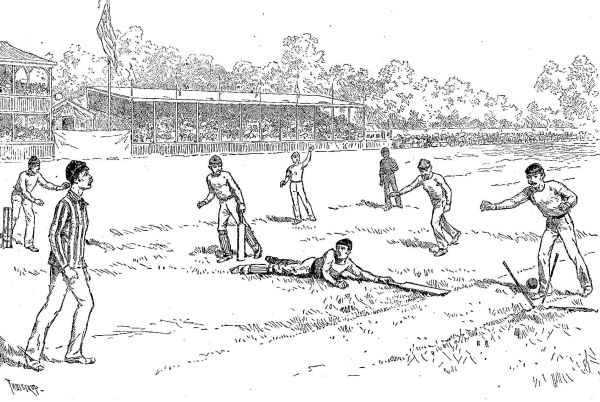

A GAME OF CRICKET—"RUN OUT."

A GAME OF CRICKET—"RUN OUT."

They are stealing runs now; that is, they are running where there is great risk of the ball being thrown up to the wicket before they can reach it; and if the ball strikes the wicket before the batsman reaches it, he is "run out." Stealing runs is a risky game, and— Yes; well, there is a proof of it. Yonder long-legged fellow has slipped and fallen, and though he stretches out his bat as far as possible, he can not reach his "ground"; he is "run out," and the innings is over for one hundred and ninety-nine runs.

The fielders retire to the shade of the tent, and two of them soon come forth to take their places with the bat, while the remainder enjoy their well-earned rest. Those who have had their innings take up their positions in the field, and the first innings of the other side begins.

Then the excitement is renewed. Shouts of applause or encouragement greet every good or unlucky deed of the players, and as the innings draws to a close, the interest increases. It takes two innings on each side to decide the match, and a game is never lost until it is won. Of course in cricket there is good luck and bad, but in this game, as in all others where skill plays the principal part, luck counts for but little in the long-run. The best players nearly always win.

Cricket may be played six months in the year, and those who play it think six months none too much. It is a social game also, and a good club can always arrange matches with neighboring clubs, and so friendly is the feeling among players that a visiting eleven nearly always declare, when they go home after a match, that they were never better treated in their lives. In the skill required, the variety of excitement, and the friendly feeling that it promotes, lie the claims of cricket to the favor it enjoys.

This poor little lamb has lost its mother, and it looks cold and famished. It is well that it has found friends who will take good care of it, for without food and shelter it would soon perish. When it has drunk the warm milk which Guy's mamma is coaxing it to take, she will make a little bed for it of some nice soft hay or wool, cover it up, and leave it in a snug, quiet place to take a nap.

Sheep and lambs love mountain and hill countries, and their pastures are almost always on breezy uplands. The first sheep ever brought to this continent were sent to Virginia from England in 1609. How bewildered and unhappy the poor things must have felt on the long voyage, with the great waves thumping against the vessel, and the wind whistling through the sails! They must have been very glad indeed when at last they touched land.

There is one English poet whose verses about lambs ought to be learned by all children. We mean Wordsworth. You remember that in a recent number of Young People we had a poem of his which was beautifully illustrated. One of his poems is called "The Pet Lamb," and it is about a little orphan lamb just like this one, which is cared for by a child named Barbara. The lamb is bleating, and straining at its cord, and she says to it:

"'Rest, little young one, rest; thou hast forgot the day

When my father found thee first in places far away.

Many flocks were on the hills, but thou wert owned by none,

And thy mother from thy side for evermore was gone.

"'Thy limbs will shortly be twice as stout as they are now;

Then I'll yoke thee to my cart, like a pony in the plough;

My playmate thou shalt be, and when the wind is cold

Our hearth shall be thy bed, our house shall be thy fold.'"

There is another poem by Wordsworth called "The Last of the Flock," which is quite different from this. It is the story of a poor peasant on the hills who had a flock of sheep which he dearly loved. He could not bear to kill or to sell them. A time of great distress came, and there was a scarcity of food. He went to the parish authorities, and asked for relief for his family. This they denied, saying to him: "You are not a poor man. You have sheep and lambs. Dispose of them." So one by one he sold them, and it almost broke his heart to do it, and at last he had only one lamb left. He loved his children, and did not wish them to suffer, but to part with his cherished flock was like giving his blood up drop by drop, and finally, as he walked on the highway, taking the last lamb to the market, the tears ran down his face. He said,

"'And of my fifty, yesterday

I had but only one,

And here it lies upon my arm,

Alas! and I have none.

To-day I fetched it from the rock;

It is the last of all my flock.'"

Most sensible people will think that the man ought to have been glad that he possessed sheep, which he could exchange for bread for his boys and girls; but here and there among the children there will be some who can understand his feeling. You would not like to part for money with a dog, a cat, or a bird which you had taken care of, even if you wanted money very much, and to the peasant the sheep and lambs had become almost as dear as his children. When he sold one, he felt almost as if he had been selling a child. As all shepherds do, he knew each sheep from every other, and their faces did not look alike, as the faces in a flock do to us, but each had an expression of its own—what we call individuality.

When the lamb in the picture shall have grown too large to take his food out of a bottle, he will crop the sweet fresh grass, and frisk about merrily, especially if his mistress now and then tempts him with a taste of salt in her hand. He will be very gentle, though full of play, and he and his baby master will have fine times together. It is rather sad to think that as time passes he will be less fond of gambolling, and will become a stupid, grazing, dreaming old sheep, not nearly so interesting as now when he is a little shivering orphan lamb.

mountain range is not at all like a garden fence. You do not just climb up one side of it, and drop down into another garden beyond. The one which arose before the Lipans that day, and through which the Apaches before them had driven their long lines of ponies, loaded with buffalo meat and all the baggage of an Indian hunting camp, was really a wide strip of very rough country, full of mountains, and rising to a high ridge in the centre. The Lipans were not very well acquainted with it, except by what they had heard from others, and there had been some murmuring among them at first when their leader announced his intention of following his war-path to the other side of such a barrier as that.

His speech had settled it all, however, and his warriors were ready to go with him, no matter where he should lead them. Anything rather than go back empty-handed to be laughed at.

The moment luncheon was over every man was on horseback. It was absolutely necessary to find grass before night, if their horses were to be good for anything the next day.

They knew that the particular band of Apaches they were pursuing must be two or three days' march ahead of them, but they also knew that every mountain range has its deep green valleys, and that the trail left by their enemies would surely lead through the best of these.

Up, up, up, through rugged ravines and gorges for nearly an hour, and then down again almost as far, and then, sooner than they had expected, they came upon the very thing they were looking for. It was not so large or so beautiful a valley as the one in which Many Bears and his men were encamped miles and miles beyond. It did not widen like that at its lower end into a broad and undulating plain, with a river and a forest far away, but there was plenty of grass in it for tired and hungry horses, and To-la-go-to-de at once decided that there they should halt for the night.

It was little beyond the middle of the afternoon, and a war party of Lipans has neither tents to pitch nor much baggage to care for. Little time was lost in "going into camp," and even before that was done every fifth brave was ordered out to look for game. Not only would fresh meat be better than dry if they could get any, but it would save their somewhat slender stock of provisions for another day.

"Steve! Steve Harrison!"

"What is it, Murray?"

"I've spoken to old Two Knives. You and I are to hunt."

"Hurrah for that! Which way are you going?"

"Most of the others seem to be setting out southerly. I guess they're right, so far as game is concerned. You and I'll try that gap to the northwest. There's no telling where it may lead to."

The gap he pointed at was a sombre-looking chasm, the mouth of which opened into the little valley where they were, at a distance of about half a mile.

Nobody could tell, indeed, where it might lead to, nor could any one have guessed, until he was actually in it, what a very remarkable gap it was.

The two white hunters had chosen to go on foot, and not one of their Lipan friends had accompanied them. If they were men to be "watched" at any other time, even the sharp eyes of Indian suspicion saw no need for it among the desolate solitudes of those "sierras."

They did not hear To-la-go-to-de say to some of the red hunters: "No Tongue great hunter. Bring in more antelope than anybody else. Yellow Head good too. You beat them? Ugh!"

They would try beyond a doubt, but more than one Lipan shook his head. The reputation of Murray as a slayer of game was too high to be questioned, and he had taught Steve Harrison like a father.

"Murray," said Steve, "do you mean that such a gap as that offers me a chance?"

"To get away?"

"Yes; that's what I'm thinking of."

"Can't say about that, my boy. Probably not. I don't believe it comes out on the western slope of the mountains."

"What do you want to try it for, then?"

"I don't exactly know. Game, perhaps. Then I want to teach you something more about mountains, and finding your way among them. More than that, I don't want to go the same way as any of the rest."

"I like that, anyhow. Seems as if I had ever so many questions to ask that I never felt like asking before."

"I never cared to answer any, Steve, when you did ask 'em—not so long as you and I were to be together. Now you're going away from me pretty soon, I don't mind telling some things."

"Going away? Do you mean to say you won't go too? Shall you stay and be a Lipan?"

"You'll go alone, Steve, when you go. That's all."

"Why won't you go with me?"

"That's one of the questions I don't mean to answer. You've told me all about your family and people. I'll know where to look for you, if I ever come out into the settlements."

"I wish you'd come. You're a white man. You're not a Mexican either. You're American."

"No, I'm not."

"Not an American?"

"No, Steve; I'm an Englishman. I never told you that before. One reason I don't want to go back is the very thing that sent me down into Mexico to settle years and years ago."

"I didn't ask about that."

"No good if you did."

"But you've been a sort of father to me ever since you bought me from the Lipans, after they cleaned out my uncle's hunting party, and I can't bear the thought of leaving you here."

If it had not been for his war-paint, and its contrast with his Saxon hair and eyes, Steve would have been a handsome, pleasant-looking boy, tall and strong for his years, but still a good deal of a boy, and his voice was now trembling in a very un-Indian sort of way. No true Lipan would have dreamed of betraying any emotion at parting from even so good a friend as Murray.

"Yes," said the latter, dryly, "they cleaned out the hunting party. Your uncle and his men must have run pretty well, for not one of them lost his scalp, or drew a bead on a Lipan. That's one reason they didn't knock you on the head. They came home laughing, and sold you to me for six ponies and a pipe."

"I never blamed my uncle. I've always wondered, though, what sort of a story he told my father and mother."

"Guess he doesn't amount to a great deal."

"He's rich enough, and he's fond of hunting, but there isn't a great deal of fight in him. He wouldn't make a good Lipan."

The circumstances of Steve's capture were evidently not very creditable to some of those who were concerned in it, and Murray's tone in speaking of the "uncle" who had brought him out into the Texas plains to lose him so easily was bitterly contemptuous.

At that moment they were entering the mouth of the gap, and Murray suddenly dropped all other subjects to exclaim,

"We've struck it, Steve."

"Struck what?"

"A regular cañon. See, the walls are almost perpendicular, and the bottom comes down from ledge to ledge like a flight of stairs."

Steve had been among mountains before, but he had never seen anything precisely like that.

In some places the vast chasm before him was hardly more than a hundred feet wide, while its walls of gray granite and glittering white quartz rock arose in varying heights of from three hundred to five hundred feet.

"Come on, Steve."

"You won't find any game in here. A rabbit couldn't get enough to live on among such rocks as these."

"Come right along. I want to get a look at the ledges up there. There's no telling what we may stumble upon."

Steve's young eyes were fully occupied, as they pushed forward, with the strange beauty and grandeur of the scenery above, beyond, and behind him. The air was clear and almost cool, and there was plenty of light in the shadiest nooks of the chasm.

"What torrents of water must pour down through here at some seasons of the year," he was saying to himself, when his companion suddenly stopped with a sharp,

"Hist! Look there!" and raised his rifle.

Steve looked. Away up on the edge of the beetling white crag at their right the first "game" they had seen that day was calmly gazing down upon them.

A "big-horn antelope" has the best nerves in the world, and it is nothing to him how high may be the precipice on the edge of which he is standing. His head never gets dizzy, and his feet never slip, for he was made to live in that kind of country, and feels entirely at home in spots where no other living thing cares to follow him.

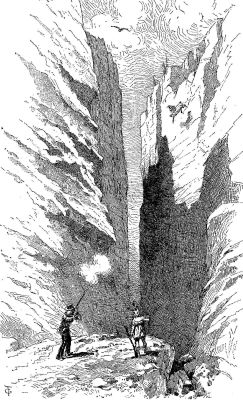

IN THE CAÑON.

IN THE CAÑON.

That was a splendid specimen of what the first settlers called the "Rocky Mountain sheep." His strong, wide, curling horns were of the largest size, and gave him an expression of dignity and wisdom as he peered down upon the hunters who had intruded upon his solitudes. He would have shown more wisdom by not looking at all, for in a moment more the sharp crack of Murray's rifle awoke the echoes of the cañon, and then with a great bound the big-horn came tumbling down among the rocks almost at Steve Harrison's feet.

"He's a little battered by his fall," said Murray, "that's a fact; but he'll be just as good eating. Let's hoist him on that bowlder and go ahead."

"He's as much as we'd like to carry in."

"That's so; but we may bag something more, and then[Pg 828] we could bring a pony up almost as far as this. I don't mean to do any too much carrying."

His broad, muscular frame looked as if it had been built expressly for that purpose, and he could have picked up at least one big-horn with perfect ease; but he had been among the Indians a good while, and they never lift a pound more than they are compelled to.

"Give me the next shot, Murray."

"I will, if it's all right. But you must use your own eyes. It won't do to throw away any chances."

The game was quickly lifted to the bowlder pointed out by Murray, and he and Steve pressed on up the great beautiful gateway deeper and deeper into the secrets of the mountain range.

Every such range has its secrets, and one by one they are found out from time to time; but there seemed to be little use in the discovery of any just then and there. It was a very useless sort of secret. What was it?

Well, it was one that had been kept by that deep chasm for nobody could guess how many thousands of years, until Steve Harrison stumbled a little as he climbed one of the broken "stairs" of quartz, and came down upon his hands and knees.

Before him the cañon widened into a sort of table-land, with crags and peaks around it, and Murray saw trees here and there, and a good many other things, but Steve exclaimed,

"Murray! Murray! Gold!"

"What! A vein?"

"I fell right down upon it. Just look there."

Murray looked, half carelessly at first, like a man who had before that day discovered plenty of such things; but then he sprang forward.

"We're in the gold country," he said. "It's all gold-bearing quartz hereaway. Steve! Steve! I declare I never saw such a vein as that. The metal stands out in nuggets."

So it did. A strip of rock nearly five feet wide was dotted and spangled with bits of dull yellow. It seemed to run right across the cañon at the edge of that level, and disappear in the solid cliffs on either side.

"Oh, what a vein!"

"It's really gold, then?"

"Gold? Of course it is. But it isn't of any use."

"Why not?"

"Who could mine for it away down here in the Apache country? How could they get machinery down here? Why, a regiment of soldiers couldn't keep off the redskins, and every pound of gold would cost two pounds before you could get it to a mint."

For all that, Murray gazed and gazed at the glittering rock, with its scattered jewels of yellow, and a strange light began to glow in his sunken eyes.

"No, Steve, I'm too old for it now. Gold's nothing to me any more. But that ledge is yours now you've found it. Some day you may come back for it."

"I will if I live, Murray."

"Well, if you ever do, I'll tell you one thing more."

"What's that?"

"Dig and wash in the sand and gravel of that cañon below for all the loose gold that's been washed down there from this ledge since the world was made. There must be bushels of it."

After that trouble with Aunt Eliza—the time she staid up on the roof and was rained on—I had no misfortunes for nearly a week. Aunt Eliza went home as soon as she was well dried, and father said that he was glad she was gone, for she talked so much all the time that he couldn't hear himself think, though I don't believe he ever did hear himself think. I tried it once. I sat down where it was real still, and thought just as regular and steady as I could; but I couldn't hear the least sound. I suppose our brains are so well oiled that they don't creak at all when we use them. However, Mr. Travers told me of a boy he knew when he was a boy. His name was Ananias G. Smith, and he would run[Pg 829] round all day without any hat on, and his hair cut very short, and the sun kept beating on his head all day, and gradually his brains dried so that whenever he tried to think, they would rattle and creak like a wheelbarrow wheel when it hasn't any grease on it. Of course his parents felt dreadfully, for he couldn't go to school without disturbing everybody as soon as he began to think about his lessons, and he couldn't stay home and think without keeping the baby awake.

As I was saying, there was pretty nearly a whole week that I kept out of trouble; but it didn't last. Boys are born to fly upward like the sparks that trouble, and yesterday I was "up to mischief again," as Sue said, though I never had the least idea of doing any mischief. How should an innocent boy, who might easily have been an orphan had things happened in that way, know all about cooking and chemistry and such, I should like to know.

It was really Sue's fault. Nothing would do but she must give a party, and of course she must have ice-cream. Now the ice-cream that our cake-shop man makes isn't good enough for her, so she got father to buy an ice-cream freezer, and said she would make the ice-cream herself. I was to help her, and she sent me to the store to order some salt. I asked her what she wanted of salt, and she said that you couldn't freeze ice-cream without plenty of salt, and that it was almost as necessary as ice.

I went to the store and ordered the salt, and then had a game or two of ball with the boys, and didn't get home till late in the afternoon. There was Sue freezing the ice-cream, and suffering dreadfully, so she said. She had to go and dress right away, and told me to keep turning the ice-cream freezer, till it froze and don't run off and leave me to do everything again you good-for-nothing boy I wonder how you can do it.

I turned that freezer for ever so long, but nothing would freeze; so I made up my mind that it wanted more salt. I didn't want to disturb anybody, so I quietly went into the kitchen and got the salt-cellar, and emptied it into the ice-cream. It began to freeze right away; but I tasted it, and it was awfully salt, so I got the jug of golden syrup and poured about a pint into the ice-cream, and when it was done it was a beautiful straw-color.

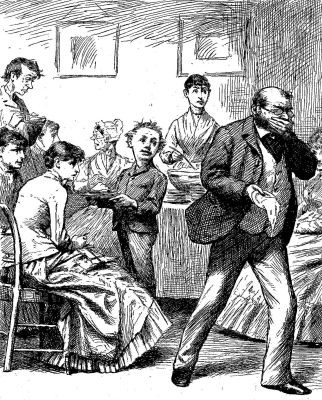

SUE'S ICE-CREAM PARTY—Drawn by A. B. Frost.

SUE'S ICE-CREAM PARTY—Drawn by A. B. Frost.

But there was an awful scene when the party tried to eat that ice-cream. Sue handed it round, and said to everybody, "This is my ice-cream, and you must be sure to like it." The first one she gave it to was Dr. Porter. He is dreadfully fond of ice-cream, and he smiled such a big smile, and said he was sure it was delightful, and took a whole spoonful. Then he jumped up as if something had bit him, and went out of the door in two jumps, and we didn't see him again. Then three more men tasted their ice-cream, and jumped up, and ran after the doctor, and two girls said, "Oh my!" and held their handkerchiefs over their faces, and turned just as pale. And then everybody else put their ice-cream down on the table, and said thank you they guessed they wouldn't take any. The party was regularly spoiled, and when I tasted the ice-cream I didn't wonder. It was worse than the best kind of strong medicine.

Sue was in a dreadful state of mind, and when the party had gone home—all but one man, who lay under the apple-tree all night and groaned like he was dying, only we thought it was cats—she made me tell her all about the salt and the golden syrup. She wouldn't believe that I had tried to do my best, and didn't mean any harm. Father took her part, and said I ought to eat some of the ice-cream, since I made it; but I said I'd rather go up stairs with him. So I went.

Some of these days people will begin to understand that they are just wasting and throwing away a boy who always tries to do his best, and perhaps they'll be sorry when it is too late.

At the end of its second volume, Harper's Young People counts its little friends in every quarter of the globe. The promises made by its conductors a year ago have been amply fulfilled. The paper has grown steadily better, fuller, brighter, and stronger, and its weekly arrival is hailed by thousands of children and youth with eager delight.

Our Post-office Box numbers among its contributors correspondents from all parts of the United States and Canada, and from Europe, Asia, Australia, and the islands of the Pacific. Wherever there is an English-speaking community or colony, there our paper finds a welcome, and from thence come evidences of interest in Our Post-office Box. The pictures of child-life drawn by little fingers are very refreshing to older eyes. We see that there is a great deal of youthful happiness in the world, as the children write freely about their studies, their pets, and their pastimes. We aim to make the Post-office Box educational, and stimulating to intelligent inquiry, and we try to answer questions, impart useful information, and enter into the children's plans for improvement and recreation. We shall hereafter give enlarged space to the letters, and in the new column C. Y. P. R. U. the Postmistress will endeavor to be in entire sympathy with the older as well as the younger readers of Young People. She intends in this department to include extracts from favorite authors, and stories from English classics, told briefly, from time to time, in her own way. Not only the little folks, but the older sisters and brothers, will have their cozy niche, whenever they wish it, in this informal column.

The exchange department will be conducted, as heretofore, as fairly, attentively, and promptly as possible. Its primary object is to afford young people an opportunity to exchange instructive and interesting articles with each other. It ought to be an adjunct to their studying of geography, history, and natural science. We request that exchangers will write their names and addresses as plainly as they can in every case, that they will always correspond with each other by postal cards before sending their valuable stamps or other treasures, and that in writing to us they will condense their offers and consult brevity, so that we may be able to print a great many of their letters in each issue.

We intend to make the puzzle department more attractive than ever.

Now, little readers and larger ones, since you write to us so warmly in our praise, since you enjoy the stories, the sketches, the poems, and the whole weekly feast the beautiful paper brings to you, will you not recommend it to others? Tell all your friends how much pleasure and benefit you derive from it, and see whether you can not increase its circulation. The more subscribers Young People shall have, the better will the publishers be able to make it, and the more tempting will be the attractions it will offer through autumn days, winter evenings, spring sunshine, and summer leisure, for busy young people, all the year round.

Norwich, Connecticut.

My cousin made me a Christmas present of this paper, and I like it very much. I think "The Cruise of the 'Ghost'" and "Paul Grayson" are very nice stories, and I wish Jimmy Brown would write another story soon. Mr. Otis's stories are very nice. I have a cunning little ram that plays with me, and I have named him "Frisky." My sister has a little turtle or terrapin which is only a little larger than a fifty-cent piece. A friend of mine has a large goat named Billy, and a little sulky in which he rides around. Will you tell me if scrap-books are acceptable for Young People's Cot in St. Mary's Hospital, New York?

John P. H.

We think the ladies who take care of the little sick children in St. Mary's Hospital can find use for pretty scrap-books.

Nashville, Tennessee.

Papa brings Harper's Young People home to me every Friday evening. I have now one hundred and one numbers. I think the old cat watching the mice play base-ball is very funny, but the water-melon turning out to be a little black baby is just as funny. I like Young People very much. Papa says I look just like the stuck-up boy in No. 76; but mamma says I am like the little boy talking to the old candy woman in No. 76. When I come to think about it, I think I am apt to be around where the old candy women are, and maybe this is why papa calls me stuck up.

My head is red, just like mamma's. I have three little sisters, named Bessie, May, and Louise, and they all have red heads too. We used to have a pair of little sorrel ponies just the color of our heads, and papa called all of us—mamma, ponies, and children—his sorrel-tops; and sometimes, when we went out driving, papa wanted to borrow a little black-haired girl from some of the neighbors, to relieve the monotony. (This is what he called it.)

If ever I come to New York, the first thing I want to do is to call and see the editor of Young People and the ladies and gentlemen who help him get up so many nice, funny things.

Goodloe L.

Kokomo, Indiana.

Our school commenced two weeks ago Monday, and I was so glad! I just love to study, and especially to have good lessons. My sister and I went to a museum several weeks ago, and among the many curious things we saw was Queen Anne's cat. It was indigo-color, with brown spots on it, and looked as if it would like to tear you to pieces; and there was also the earless white cat, which had a tuft of hair in place of ears. It did not look very savage. There was the mermaid, which had the body of a fish, and something which resembled the head of a monkey. I had many beautiful flowers this summer. I tried to raise some cotton, but did not succeed very well. It did not ripen at all. I picked off the oldest ball there was on the bush, and it was as green as grass. I would like to exchange flower seeds for Florida beans or sea-beans, also for foreign stamps, or sea-moss, or seeds for seeds, or will exchange postmarks for flower seeds.

Mollie, P. O. Box 575, Kokomo, Ind.

Groesbeck, Ohio.

I thought I would write to you to tell you about the funeral procession for President Garfield at Cincinnati. The banners were very pretty. The men on horses, and the little boys who were dressed in red pants and white waists, also looked very pretty. It was very sad to see the houses draped with black. All the business houses were closed, and the city was more quiet than if it had been Sunday. I hope President Arthur will be as good a President as Mr. Garfield was. I have not seen much about Mr. Garfield in Our Post-office Box. I go to school right across the road from my home. I think my letter is long enough.

Hazie P.

You were interested in the article in No. 102 on the boyhood of President Garfield, were you not? If more of our children had written about him, we would have had more letters to print; but we think everybody's heart was almost too full to write during the weary weeks before his death.

Flemingsburg, Kentucky.

As I have been taking your paper for a long time and have never written you a letter, I thought I would. I go to a military school, and attend drill every evening. Across from our school are several Indian mounds, and the boys opened one of them lately, and found several Indian arrows and other implements of war. I am sixteen years old, and a printer. Kindest regards for Harper's Young People, and hoping it may prosper, I remain,

C. C.

St. Lucie, Florida.

Some time ago one of your correspondents wrote a very interesting letter in answer to your inquiry about Florida sea-beans.

I send you some specimens gathered on the Atlantic beach, not very far from where the ill-fated steamer City of Vera Cruz went down last August. But these do not grow on trees; they are the product of a vine, something like that of the common horse-bean. There are vines from this variety now growing on Indian River, though they are not indigenous. I have heard they grow in abundance on the Spanish main.

Mr. Bennett, of Syracuse, New York, presented me with some implements and a work on taxidermy, and I have learned to skin birds. Are ivory-billed woodpeckers numerous in the North?

I value my paper, and I know Mr. James Otis must Be a good man by what he writes.

Johnnie C. J.

You and the others who followed the fortunes of the little runaway with so much interest will be pleased to hear that Mr. James Otis has gone to Florida in a little steam-yacht named Toby Tyler after his hero. Doubtless some account of his trip will be published in Young People.

Many thanks for the sea-beans.

The ivory-billed woodpecker is chiefly an inhabitant of the extreme Southern States, and especially those which border on the Gulf of Mexico. Very few are ever found north of Virginia. It is not a migratory bird, but is a resident where it is found. Mr. Audubon did meet one or two of the species so far north as Maryland, but they seemed away from home. West of the Lower Mississippi, it is found in all the dense forests, but the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi are its favorite resorts. It bores a hole in the trunk of a live tree, early in the spring, for its nest, always at a great height from the ground. The male and female birds relieve each other in this work. The eggs are four or five in number, pure white, equally thick at both ends, and as large as pullets' eggs. The food of this woodpecker consists of beetles, larvæ, and large grubs, and it has a great fondness for wild grapes and ripe persimmons.

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

I have taken Young People since the first number, and now I have a favor to ask. Will you not please give us a story on natural history? We have had some splendid stories; but I like "The Cruise of the 'Ghost'" the best of all, though "Tim and Tip" is very good.

I have a splendid large dog. He is an Irish setter, and his name is Spray. I wish some of the little writers to Young People could see him when I come down stairs in the morning. He is so pleased he growls as if he were trying to talk. He puts his head on one side, and looks so funny and wise. We have a very nice museum here, with a great many interesting things to be seen.

Frank A.

We expect to publish a number of articles on different branches of natural history during the year, and though they may not be precisely stories, they will be equally as entertaining.

I am thirteen years old, and have two little nephews, one ten days old, and the other two years. I have been spending the summer in the southern part of Michigan, and had a splendid time. We got up a fairy play to play warm moonlight nights. I was Thumbergia, Queen of the Elves, and we called ourselves moonlight fairies. It was great fun. I used to sit up in a tree, and read Jimmy Brown's stories. I wish he would write some more. I think he is splendid, and wish I knew him. I am very fond of little boys from four to five years old. I had four little four-year-olds this summer who liked to race so much that every morning I would have them stand in a line, and when I would count three they would all start, and run as fast as their little legs would carry them. One of them would talk all the time, and another was very slow, but all were very cunning. They are the only pets I have.

Thumbergia.

South Cortland, New York.

I am a little girl five years old. My father is Postmaster, and he has taken Harper's Weekly twenty-four years, and Young People ever since its publication. The pictures have always pleased us.

My grandma is writing this for me, as I have to print my letters, and as she is seventy-eight, you will please excuse mistakes.

Little Spry, our dog, is a great favorite of mine. My uncle went to Europe, and left him in my care. I have a great many chickens, and two cats. Papa has five horses, and my sister can ride upon them when she is home from school; I dare not. We have a variety of fruit, which is so nice. Cortland Valley is beautiful, and I am glad it is my home. The grand old maple-trees surround our house.

Now please print my letter, so that I can hear it read when the paper comes next time, and I will play on the piano for joy.

Louise R.

Jersey City, New Jersey.

I was eleven years old the 6th of last month (September, 1881). Papa got the first volume of Young People bound for my birthday present. I would not exchange it for any book I ever saw. I like all the stories. I think if Jimmy Brown would spend more time in writing to the Post-office Box, his father would not have to call him up stairs so often, and I wish he would take my advice and try it. I am glad Tim and Tip have got away from that brute, Captain Pratt. Papa thinks the boys will lose their dinner if they don't get something better than a rope to hang their kettle on. When Tip kills a bear, I hope they will send it to Harper's Young People, so you can put a picture of it in the paper. I did not mean to write so long a letter.

Lillie C. S.

Tremont, New York.

We have some very large ducks—they are as large as some geese—and we have a pair of young turkeys. I have some carrier-pigeons. I like the story of "Tim and Tip." I had two kittens, and they followed us to church one night, and afterward we heard that some boys set a dog on them, hurting one so badly that it died. Was it not a shame? When the boys found out to whom the kittens belonged, they were very sorry, and brought the other one home.

Mr. Editor, if you ever come up this way, I would like you to call in and see my pigeons. I wish all the boys and girls everywhere could take Young People.

Eddie I. L.

We would be glad to see those pigeons, and we appreciate your kind invitation. But it is not often we can venture very far away from our corner here, where the mails bring us so many letters from young people. Have you ever sent your birds with messages tied around their necks, and have they brought the answers safely back?

London, Kentucky.