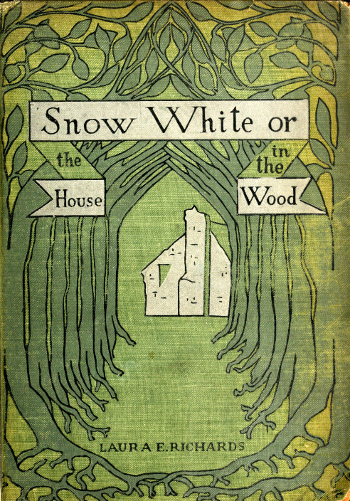

OR, THE HOUSE IN THE WOOD

BY LAURA E. RICHARDS

AUTHOR OF "CAPTAIN JANUARY," "MELODY," "THREE MARGARETS," "QUEEN HILDEGARDE," ETC.

BOSTON

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1900

By Dana Estes & Company

Colonial Press:

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, Mass., U.S.A.

TO

E. A. R.

WITH AFFECTIONATE GREETING

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | The House | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | The Child | 7 |

| CHAPTER III. | The Man | 17 |

| CHAPTER IV. | Asking Questions | 26 |

| CHAPTER V. | Phillips; and a Story | 38 |

| CHAPTER VI. | Milking the Cow | 50 |

| CHAPTER VII. | The Story | 60 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | The Key of the Fields | 72 |

| CHAPTER IX. | Restored to Life | 83 |

| CHAPTER X. | Good-bye | 90 |

The house was so well hidden, one might almost stumble against it before one became aware of it. All round the woods stood tall and dense, old woods of pine and hemlock, with here and there great smooth, squat beeches, and ragged, glistening yellow birches. For the most part they jostled one another so close that one almost fancied they must be uncomfortable; but in one spot they fell away from a steep, rocky bank or ledge, drawing back and standing in a circle at some little distance, leaving an open space of sunny green, at the foot of the rock. It was on this open space that the house looked; and as the house was built of stone, and leaned up against the ledge behind it, one could hardly tell where man's hand had begun, or where left off. The stones might almost have been flung together by a boy at play; yet, rough as they were, they fitted close, and kept the weather out. The roof was of bark; the whole thing was half-covered with creepers that made their way down in a leisurely fashion from the ledge above, not too inquisitive, but still liking to know what was going on. To this end they looked in at the windows, which stood open all summer long, and saw many things which must have surprised them. The squirrels went in boldly, several times a day; so did the birds, the braver of them; and all came out looking pleased with themselves and with things in general. So there was necessarily something or somebody pleasant inside the house.

I said that the trees stood well back from the house in the wood. I ought to have excepted three, a stately pine, and two glorious yellow birches, which stood close to it, as close as might be. In fact, part of the hut seemed to be built round the bole of the pine, which disappeared for several feet, as if the stones had clasped it in a rough embrace, and refused to let go their hold. The birches were a few feet from the door, but near enough for one to lean out of window and pull off the satin fringes. Their roots swelled out above the ground, and twisted themselves into curves that might make a delightful seat, under the green bending canopy, through whose waving folds the trunk glistened like a giant prince of rags and tatters. In the centre of the tiny glade stood a buttonwood-tree, whose vast girth seemed curiously out of proportion to its surroundings. The pine and the birches were noble trees; all the forest round was full of towering stems and knotted, powerful branches; but beside the great buttonwood, they seemed like sturdy dwarfs. If there had been any one to measure the trunk, he would have found a girth of twenty-five feet or more, near the base; while above the surrounding forest, it towered a hundred feet and more in air. At a height of twelve or fifteen feet appeared an opening, two or three feet in diameter. A hollow? surely! not so large as that in the Lycian plane-tree, where Licinius Mucianus dined with nineteen companions,—yes, and slept too, and enjoyed himself immensely,—but large enough to hold two or three persons with all comfort, if not convenience. As for the number of squirrels it might hold, that was past counting; they were running in and out all day long, and made such a noise that they disturbed the woodpeckers, and made them irritable on a hot day.

There never was such a wood for birds! Partly from its great age, partly from favourable accidents of soil and aspect, it had accumulated an unusual variety of trees; and any bird, looking about for a good building site, was sure of finding just the particular tree he liked best, with building materials, food, and every other requisite to heart's desire. So the trees rustled and quivered with wings, and rang with song, all day long, except in the hot sleepy noons, when most respectable birds keep within nests, and only the woodthrush from time to time sends out his few perfect notes, to show that all times are alike to the true singer. Not content with the forest itself, some families—I think they were ruby-crowned wrens and bluebirds—had made their nests in the creepers that matted the roof of the hut with green; and the great buttonwood was a positive metropolis, densely populated with titmice, warblers, and flycatchers of every description. If anybody lived in the stone hut, he would not want for company, what with the birds and the squirrels, and the woodchucks that came and went across the little green as unconcernedly as if it were their own front dooryard. Decidedly, the inhabitant, if there were one, must be of kin to the wildwood creatures, for his dwelling and its surroundings evidently belonged as much to the forest people as to him.

On the day when my story begins, the house in the wood was the only lifeless thing, or so it seemed, in the whole joyous little scene. It was a day in early May, and the world was so delighted with itself that it laughed and twinkled all over. The trees were hardly yet in full leaf, but had the gray-green misty look of spring, that makes one see Erl-König's daughters shimmering in every willow, and rustling out of sight behind the white birch-trunks. The great buttonwood had put out its leaves, covered with thick white down; the air was full of sweet smells, for it had rained in the night, and wet leaves, pine needles, new ferns, and a hundred other lovely awakening things, made the air a life-giving ether. The little green was starred with anemones and eyebrights; under the cool of the trees one might see other things glimmering, exquisite shadowy forms,—hepaticas, were they, or fairies in purple and gray fur? One felt the presence of mayflowers, though one could not see them unless one went close and pulled away the brown dry leaves; then the lovely rosy creatures would peep out and laugh, as only mayflowers can when they play at hide and seek. There seemed to be a robin party going on under the buttonwood-tree. A dozen of them or more were running and hopping and strutting about, with their breasts well forward, doing amazing things in the matter of worms. Yes, it must surely have rained in the night, or there could not have been such a worm-harvest. There seemed almost to be enough for the robins, and any one who knows robins is aware that this is an extravagant statement. The titmice had apparently not been invited; they sat in the branches and looked on, or hopped and ran about their green leafy city. There was no need for them to travel all that distance to the ground; besides, they considered worms vulgar and coarse food. A self-respecting titmouse, who provides over two hundred grubs a day for himself and his family, may well be content to live in his own city, the murmuring, rustling place where grubs lie close on the bough and under the bark, and where flies are ready for the bill; he has no need to pierce the friendly earth, and drag up her unsightly creeping things, to swallow piecemeal. A titmouse has his opinion of robins, though he is on intimate terms with most birds in the forest.

Now and then some sudden wave of instinct or purpose would run through all the great army of birds,—those in the buttonwood city, the robins struggling on the green, and far in the dim forest depths thrush and song-sparrow and warbler. First a stray note here and there, setting the pitch, it might be; then, fuller and fuller, a chorus, rising high and higher, fluting, trilling, whistling, singing away like mad, every little ruffled throat of them all. Praise, was it, or profession of belief, or simply of joy of being alive and able to sing under green leaves and summer sun?

But even these outbursts of rapture did not rouse the house in the wood. It lay there in the morning glory, gray, silent, senseless, crouched against the wall of rock behind it.

The child had grown tired of the road. At first it had been delightful to patter along in the soft white dust, leaving the print of her feet so clear behind her. She might be a hundred little girls, she thought, instead of one. The prints reached away back, as far as she could see, hundreds and hundreds of little trotty feet, each with its toes marked as plain as if you drew them with a pencil. And the dust felt soft and smooth, and when you put your foot down it went up puff in the air, and made little clouds; only when it got in your throat it made you cough and sneeze, and it was gritty in your eyes, too. By and by, as I said, she grew tired of this, and it was a new joy to see the little river that came running along just then.

That was what the child sang, for she had a way of singing when she was alone. Without hesitating, she plumped into the river, and the water was cool and delicious to her hot little toes. She walked along, holding her petticoats high, though there was no need of that, as they were short enough before; splashing just enough to make silver sparkles at every step. The river did not seem to grow deeper; it was just precisely made to wade in, the child thought. For some way the banks were fringed with meadow-rue, and she had to stop every little while to admire the fluffy white blossoms, and the slender, graceful stems. Then came alders, stubby and thick, with last year's berries still clinging here and there to the black twigs. Then, somehow, all at once there began to be trees along by the river side. The child had been so absorbed in making sparkles and shouting at them, she had forgotten the banks for awhile; now, when she looked up, there was no more meadow-rue. Trees came crowding down to the water's edge; trees were all about her, ranks upon ranks of them; wherever she looked, she saw only green rustling tents and waving curtains.

"I am in a woods!" said the child. She laughed aloud at the idea, and looked round again, full of joy and wonder. It was pretty enough, surely. The woods were not so thick but that sunbeams could find their way down through the branches, dappling the green gloom with fairy gold. Here and there the gold lay on the river, too, and that was a wonderful thing, handfuls of gold and diamonds flung down from the sky, shimmering and sparkling on a crystal floor; but in other places the water slept still and black in the shadow, only broken where a stone humped itself out, shining and mossy, with the silver breaking over it and running down with cheerful babblings into the soft blackness below.

By and by there was a stone so big that its top stood out dry and brown above the water. It was a flat top, and the child sat down on it, and gathered her petticoats about her, and let her feet rest in the cool flowing. That was a great pleasure, to be really part of the brook, or of the rock. She laughed aloud, suddenly, and kicked a little; till the bright drops flew over her head; then she began to sing and talk, both together.

"Well, and if Miss Tyler won't be surprised! she will say 'Oh, dear me! where is that child?' and then she will look everywhere, and everywhere, and everywhere, and I won't be nowhere!" She broke out into a funny little bubbling laugh, and the brook laughed in almost exactly the same way, so that the child nodded at it, and kicked up the sparkles again, to show her appreciation.

"And then they will send out all over the village, and everybody will say, 'Oh, yes, we seed that child. We seed her going into the store, and we seed her going into the house, and we seed her running about all over the place.' Yes! but, nobody seed me run, and nobody seed me go, and nobody don't know nothing, and nothing don't nobody know!" and she bubbled again. This time a green frog came up out of the water and looked at her, and said "Croak," in an inquisitive tone.

"Why did I?" said the child, looking at him sidewise. "Well, if I tell, won't you tell anybody, never no more? honest Injun? Well, then, I won't tell you! I don't tell things to frogs!" She splashed a great splash, and the frog departed in anger.

"Huh!" said the child. "He was noffin but an old frog. He wasn't a fairy; though there was the Frog Prince, you know." She frowned thoughtfully, but soon shook her head. "No, that wasn't him, I'm sure it wasn't. He'd have had gold spots on his green, and this frog hadn't a single one, he hadn't. He wasn't a prince; I'd know a frog that was a prince, minute I seed him, I 'spect. And he'd say:

"'King's daughter youngest, open the door!'

"And then I would, and he would come in, and—and—I'd put him in Miss Tyler's plate, and wouldn't she yellup and jump? and Mamma—"

Here the child suddenly looked grave. "Mamma!" she repeated, "Mamma. Well, she went away and left me first, and that was how it was. When you leave this kinds of child alone, it runs away, that's what it does; and Miss Tylers isn't any kind of persons to leave this kinds of child wiz, anyhow, and so I told them at first.

"That's a long one. When I come to some fairies I'll make more. When I am big, I'll talk that way all the time, wiz poetry in it."

She was silent for a few minutes, watching the bubbles that came sailing down the stream. Most of the way they were clear like glass, with a little rim of foam where they joined on, she thought; but when they came to a certain place, where a shaft of yellow light came down and made sparkles on the water, every bubble turned rainbow colour, most beautiful. Only, some of them would go the wrong way, over into the shadow.

"Hi!" she shouted to them. "Come over here and be rainbows! you are a stupid, you are! If I was a bubble, I would know enough to come to the right place, and be a rainbow, yes, I would. I'll kick you, old bubble, if you go there!" Stretching out her foot, she stretched it a little too far, and sat down in the stream with a souse. She scrambled out hastily, but this time on the bank. She had had enough of the brook, and was red with anger. "You needn't have your old stones so slippery!" she said. "I needn't have sat on your old stone, anyhow, but I thought it might be pleased. And my feet was cold, and I won't stay there any more, not a single minute, so you can make all the noise you want to, and noffin but frogs will stay in you, and not prince frogs One Bit, only just common ones, so now!"

She shook her head at the brook, and turned away. Then she turned back again, and her baby forehead clouded.

"See here!" said the child. "I 'spect I'm lost."

There seemed no doubt about that. There was no sign of a path anywhere. The still trees came crowding down to the water's edge, sometimes leaning far over, so that their drooping branches met across the still pools. On every side were green arcades, long reaches of shimmering leaves, cool deeps of fern; nothing else. The child had never known fear, and it did not come to her now. She reflected for a moment; then her brow cleared. "I must find a House in the Wood!" she announced to the brook. She spoke with decision, and cheerfulness reigned in her mind. Of course there was a house somewhere; there always was, in every wood. Sometimes two children lived in it, and the brother was a white fawn all day, and turned into a boy at night; that would be fun! and sometimes it was an old woman—oh, dear, yes, but sometimes that old woman was a witch, and put you in a chicken-coop, and ate you up when you were fat. Yes; but you would know that house, because it was all made of candy and pancakes and things, and you could just run round behind it, and pull off some pancakes from the shed, p'r'aps, and then run away as fast as ever you could, and old womans couldn't run half so fast as children, and so! But the best house, on the whole, would be the Dwarf House. Yes, that was the one to look for. The house where seven dwarfs lived, and they had the table all ready set when you came, and you took a little out of one bowl, and a little out of another cup; and then they came in and found you asleep, and said, "Who is this sweet maiden?" and then you stayed and cooked for them, just like Snow-white, and—and—it was just lovely!

"Well, I wish it would be pretty soon!" said the child. "I'm pretty hungry, I 'spect p'raps."

She was a brave child; she was hungry, and her legs and feet ached; but she pushed on cheerfully, sometimes talking and singing, sometimes silent, making her way through the tangle of ferns and hanging branches; following the brook, because there was a little boy in the newspaper that her papa read, and he got lost, and just he followed the brook, and it brought him right along to where there were people, and he had blackberries all the way. She looked for blackberries, but they are hard to find in early May, except in the Fairy Books. There, as the child knew very well, you had only to go to the right place and take a broom and brush away the snow, and there you found strawberries, the finest that ever were seen, to take home to your sick sister. It was true that you had to be very good and polite to the proper old woman, or else you would never find the strawberries; but the child would be polite, she truly would. She would sweep the old woman's house, and give her half her own bread—only she had no bread! Here a great pang of emptiness smote the child; she felt that there was a sob about somewhere, waiting to get into her throat. It should not come in; she shook her head, and pressed on. It was all right; God was close by, anyhow, and he had to take care of children, because he said he would. So it was all right, only—

Suddenly the child stopped; for it was all right. She had found the House in the Wood.

Standing breast-high in ferns, she looked away from the brook; and there was a break in the trees, and beyond the break a space of sunny green, with a huge tree in the middle; and on the farther side the house itself. Gray and silent; leaning against a great rock-face behind it; the door shut, but the windows standing wide open; the roof all green and blossoming, like a queer little garden place,—there it was, exactly the way it was in the Fairy Books. The child saw at once that there was no danger of cannibal old women here. This house was not made of pancakes, and the windows were not barley sugar at all, but plain glass. No, this was the house of the Seven Dwarfs; and she was really in a fairy story, and she was going to have the best time she had ever had in her life.

The child stood quiet for a few minutes, looking in pure delight. Perhaps one of the dwarfs would come out. She thought she might feel a little shy if one were to come out just this very minute. Then she remembered that they must all be out at work in the forest, for they always were, and they did not come back till night.

"Well, I can't wait!" she said, decidedly. "First place, Snow-white didn't, not a minute she didn't wait. And besides, I'm too hungry, and I s'pose everything is ready and waiting inside, and so I'll go."

She advanced boldly across the green, but paused again at the door. No sound came from the house. The creepers waved on the roof, the birds made an amazed and amazing chatter in the great buttonwood-tree; but that was all. The child pushed the door, the latch yielded, and the door swung slowly open. Two steps, and she stood inside.

Even the very bravest child may be excused for feeling a little strange in such a house as this. She felt her heart beating in her ears, and her throat was dry; but as she looked about her, everything was so perfectly right that her sense of fitness asserted itself once more, and she was content and glad. The room in which she stood was not large, except for dwarfs; for them it would be a great hall. It was floored and walled with clean, shining wood, and there were two doors, one at either end. There was an open fire-place, in which two black iron dogs with curly tails held up some logs of wood that were smouldering and purring in a comfortable way, as if they had been lighted more for pleasure than for warmth. Near the fire stood an easy-chair, and another chair was drawn up by a table that stood in the window. It was on seeing this table that the child began to fear all was not quite right. It was a neat little table, just about high enough for dwarfs, if they were not very short dwarfs; it was laid with a snowy cloth, as they always are; but—where were the seven places? there was only one at this table. There was a plate, a knife and fork, a cup and saucer, a little loaf of bread and a little pat of butter, a pitcher of milk, and a comb of golden honey. What did this mean?

"Well, I can't help it," said the child, suddenly. "If they is gone away all but one of them, I can't help it; they shouldn't play that way, and I'm hungry. Just I'll take a little bit, as Snow-white did. Just that's what I'll do!"

She seated herself at the table, and poured some milk into the cup. Oh, how good it was! She broke off a bit of bread, and nibbled it; her spirits rose, and she began to feel again that she was having the most splendid time that ever was. She broke out into her song—

Then she stopped, for the door of the further room opened quietly, and the dwarf came in.

The child's song broke off in a little scream, for things are sometimes startling even when you have been expecting them; but the scream bubbled into a laugh. "Ah! I—I mean I'm laughing because you look so funny. I took some bread and milk because I was hungry." She stopped abruptly, feeling that sob somewhere about her again. The dwarf advanced toward her, and she held on to the back of the chair; but he held out his hand and smiled.

"How do you do?" he said. "I am very glad to see you; pray sit down again and finish your supper."

"It's your supper," said the child, who was honest. "I didn't mean to steal it; I don't know p'r'aps there isn't enough for both of us." She had a way of leaving out words in her sentences that sometimes confused people, but the dwarf seemed to understand.

"There's plenty for both!" he said. "Come! I'll sit down here, and you shall give me some milk. I am hungry, too. Have some honey!" He nodded at her, and smiled again; he had the most delightful smile the child had ever seen. Somebody once said you could warm yourself at it as at a fire. The child took a piece of bread, and looked at him over it as she nibbled. He was not a tiny dwarf, not one of the kind that get into flowers, and fight with grass-blades, and that sort of thing. No, indeed! he was just a little man; why, he was taller than she was, though not so very much taller. He had brown hair and a soft brown beard; his eyes were brown, too, and full of light. All brown and gray, for his dress was gray and soft, "kind of humplety velvet," the child said to herself, though it was really only corduroy. He seemed all of a piece with the house, and the gray rock behind it. Now he looked at her, and smiled again.

"You look as if you were wondering something very much," he said. "Have some more milk! What are you wondering?"

"Partly I was wondering where the rest of you was!" said the child.

"The rest of me?" said the man. "There isn't any more of me. This is all there is. Don't you think it's enough?" He smiled still, but this time it was only his mouth, and his eyes looked dark, as if something hurt him.

"I mean the others," the child explained. "The rest of the seven. I guess it's six, p'r'aps. There was seven of 'em where Snow-white came to, you know."

"Seven what?" asked the man.

"Dwarfs!" said the child.

"Oh!" said the man.

He was silent for a moment, as if he were thinking; then he laughed, and the child laughed, too. "Isn't it funny?" she said. "What are you laughing at?"

"Yes, it is funny!" said the man. "Why, you are just like Snow-white, aren't you? but there aren't any more dwarfs. I'm the only one there is here."

The child thought that was a pity. "You could have much more fun if there were seven of you," she said. "Why don't you get some more?" Then suddenly recollecting herself, she added, hastily, "I never did cook, but I can stir porridge, and dust I can, too, and I 'spect I could make your bed, 'cause it wouldn't be so big, you see. I tried to make beds, but I get all mixed up in the sheets, and the blankets are horrid, and I never know which is the wrong side of the spread. So you see!"

"I see!" said the man.

"But I 'spect I could make yours, don't you? Should you mind if once I didn't get the spread right, you know?"

"Not a bit. Besides, I don't like spreads. We'll throw it away."

"Oh, let's!" said the child. "Hurrah! Do you say hurrah?"

"Hurrah!" said the man. "Do you mind if I smoke a pipe?"

No, the child did not mind at all. So he brought a most beautiful pipe, and filled and lighted it; then he sat down, and looked at the child thoughtfully.

"I suppose you ought to tell me where you came from," he said. "It isn't half so much fun, but I suppose they will be missing you at home, don't you? Your mamma—"

The child hastened to explain. Her mamma was away, had gone quite away with her papa, and left her, the child, alone with Miss Tyler and the nurse. Now Miss Tyler was no kinds of a person to leave a child wiz; she poked and she fussed, and she said it was shocking whenever you did anything, but just anything at all except sit still and learn hymns. "I hate hymns!" said the child.

"So do I!" said the man, fervently. "It's a pity about Miss Tyler. Where is it you came from, Snow-white?"

"Oh! it's somewhere else; a long way off. I can't go back there. Dwarfs never send people back there; they let them stay and do the work. And I'm almost as big as you are!" the child ended, with a little quaver.

"So you are," said the man. "Now we'll wash the dishes, and forget all about it for to-night, anyhow."

It was glorious fun washing the dishes, such pretty dishes, blue and white, with houses and birds on them. They went into the kitchen through one of the doors, and there all the things were bright and shining, as if they were made of silver. The child asked the dwarf if they were really silver, but he said oh, dear, no, only Britannia. That sounded like nonsense, because the child knew that Britannia ruled the waves, her papa sang a song about it; but she thought perhaps dwarfs didn't understand about that, so she said nothing. The dwarf brought a little cricket, and she stood on that and wiped the dishes while he washed them; and he said he never liked washing them so much before, and she said she never liked wiping them so much. Everything was as handy as possible. The dish-pan was as bright as the rest of the things, and there were plenty of clean towels, and when you shook the soap-shaker about, it made the most charming bubbles in the clean hot water.

"Do you ever make bubbles in your pipe?" said the child.

"Not in this one," said the dwarf. "I used to have a pipe for them; perhaps I can find one for you by and by."

"I made bubbles in the river," she announced, polishing a glass vigorously. "There was a stone, and I sat on it, and bubbles I made wiz kicks, you know, in the water; and songs I made, too, and the river went bubble, too, all the time. There was a frog, too, and he came and said things to me, but I kicked at him. He wasn't the Frog Prince, 'cause he had no gold spots on him. Do you know the Frog Prince? Does he live here in this river? Do you have gold balls when you play ball?"

"I'll get one," said the dwarf, recklessly. "It's no fun playing ball alone, but now we'll have one, I shouldn't wonder. How far did you come along the river, Snow-white?"

"Miles!" said Snow-white.

"And didn't you have shoes and stockings when you started?"

Yes, the child had had shoes and stockings, but she took them off to see her toes make dust-toes in the dust. Did ever the dwarf do that? It was fun! She left them away back there, miles away, before she came to the river and the woods. And her hat—

She laughed suddenly. "Did ever you put flowers in your hat and send it sailing for a boat?"

"Is that what you did, Snow-white?"

"Yes! and it was fun. It went bob, bob, right along wiz the water and bubbles; and then it tipped against a stone, and then it went round the corner, and—and that's all I know," she ended, suddenly.

"You are sleepy, Snow-white," said the dwarf. "See! the dishes are all done; now we will put them away in the cupboard, and then we will see about putting you away to bed."

The child objected that it was still daylight; she tried to look wide awake, and succeeded for a few minutes, while they were putting away the dishes in the most charming little hanging cupboard with glass doors; but after that her head grew heavy, and her eyelids, as she expressed it, kept flopping into her eyes.

"Where am I going to sleep?" she asked. "There ought to be little white beds, you know, and one would be too big, and the next would be too small, and—no, that's the Three Bears, isn't it? I don't see any beds at all in this place." She began to rub her eyes, and it was clear that there must be no further delay.

"Come in here," said the man. "Here is your bed, all ready for you."

He led her through the other door, and there was a tiny bedroom, all shining and clean, like the other rooms. The bed stood in one corner, white and smooth, with a plumpy pillow that seemed to be waiting for the child. She sighed, a long sigh of contented weariness, and put up her arms in a fashion which the man seemed to understand. He sat down in a low chair and took her in his arms, where she nestled like a sleepy kitten. He rocked her gently, patting her in an absent fashion; but presently she raised her eyes with an indignant gleam. "You aren't singing anything!" she said. "Sing!"

"Hush!" said the man. "How can I sing unless you are quiet?"

He hummed under his breath, as if trying to recall something; then he laughed, in a helpless sort of way, and said to the door, "Look at this, will you?" but there was really nothing to look at; and after awhile he began to sing, in a soft, crooning voice, about birds, and flowers, and children, all going to sleep: such a drowsy song, the words seemed to nod along the music till they nodded themselves sound asleep.

When he finished, the child seemed to be asleep too; but she roused herself once more. She sat up on his knee and rubbed her eyes.

"Does dwarfs know about prayers?" she said, drowsily. "Do you know about them?"

The man's eyes looked dark again. "Not much," he said; "but I know enough to hear yours, Snow-white. Will you say it on my knee here?"

But the child slipped down to the floor, and dropped her head on his knee in a business-like way.

"I don't say the rest, 'cause I don't like it. And God bless papa and mamma, and make me a goo'—l'—girl—amen. And God bless this dwarf," she added. "That's all." Then she lifted her head, and looked at the dwarf; and something in her look, flushed as she was with sleep, the light in her eyes half veiled, made the man start and flinch, and turn very pale.

"No!" he said, putting out his hands as if to push the child away. "No; leave me alone!"

The child opened her eyes a little wider, and looked at him. "What is the matter of you, dwarf?" she said. "I wasn't touching you. Are you cross?"

"No," said the man; and he smiled again. "Snow-white, if I don't put you to bed, you'll be going to sleep on my best floor, and I can't have that."

He laid her in the little bed, and tucked the bed-clothes round her smoothly; she was asleep almost before her head touched the pillow. The man stood looking at her a long time. Presently he took up one of her curls and examined it, holding it up to the fading light. It was a pretty curl, fine and soft, and of a peculiar shade of reddish brown. He went to a box and took out a folded paper. Unfolding this, took out another curl of hair, and laid it beside the child's; they might have grown on the same head.

"Though I take the wings of the morning—" said the man. Then he laid the curl back in the box, and went out and shut the door softly behind him.

"How many birds have you got, dwarf?" asked the child.

They were sitting at breakfast the next morning. To look at the child, no one would have thought she had ever been sleepy in her life; she was twinkling all over with eagerness and curiosity.

"How many?" repeated the man, absently. He hardly seemed to hear what the child said; he looked searchingly at her, and seemed to be trying to make out something that was puzzling him.

"Yes, how many?" repeated the child, with some asperity. "Seems to me you are rather stupid this morning, dwarf; but perhaps you are like bats, and sleep in the daytime. Are you like bats? Are dwarfs like bats? Can you hang up by your heels in trees? Have you got claws on them?"

Her eyes dilated with awful joy; but the man shook his head and laughed. "No, no, Snow-white. I wasn't sleepy at all; I was only thinking."

"Did you sleep last night?" asked the child, slightly disappointed. "I was in your bed, so you couldn't sleep. If you did sleep, where did you? Please give me some more bread. I don't see where you get bread; and I don't see where you slept; and you didn't tell me how many birds you had. I shall be angry pretty soon, I don't wonder."

"Snow-white," said the dwarf, "if you talk so fast, your tongue will be worn out before you are seventy."

"What is seventy?" said the child. "I hate it, anyway, and I won't be it."

"Hurrah!" said the man, "I hate it, too, and I won't be it, either. But as to the birds; how many should you think there were? Have you seen any of them?"

"I've seen lots and lots!" said the child, "and I've heard all the rest. When I woke up, they were singing and singing, as if they were seeing who could most. One of them came in the window, and he sat on my toe, and he was yellow. Then I said, 'Boo!' and then he flew away just as hard as he could fly. Do you have that bird?"

"Yes," said the man. "That is my Cousin Goldfinch. I'm sorry you frightened him away, Snow-white. If you had kept quiet, he would have sung you a pretty song. He isn't used to having people say 'Boo!' to him. He comes in every morning to see me, and sing me his best song."

"Are they all your birds?" queried the child. "Aren't you ever going to tell me how many you have? I don't think you are very polite. Miss Tyler says it's horrid rude not to answer questions."

"Miss Tyler is not here!" said the man, gravely. "I thought you said we were not to talk about her."

"So I did!" cried the child. "I say hurrah she isn't here, dwarf. Do you say it, too?"

"Hurrah!" said the man, fervently. "Now come, Snow-white, and I'll show you how many birds I have."

"Before we wash the dishes? Isn't that horrid?"

"No, not at all horrid. Wait, and you'll see."

The man crumbled a piece of bread in his hand, and went out on the green before the house, bidding the child stay where she was and watch from the window. Watching, the child saw him scatter the crumbs on the shining sward, and heard him cry in a curious kind of soft whistle:

"Coo! coo! coo!"

Immediately there was a great rustling all about; in the living green of the roof, in the yellow birches, but most of all in the vast depths of the buttonwood tree. In another moment the birds appeared, clouds and clouds of them, flying so close that their wings brushed each other; circling round and round the man, as he stood motionless under the great tree; then settling softly down, on his head, on his shoulders, on his outstretched arms, on the ground at his feet. He broke another piece from the loaf, and crumbled it, scattering the crumbs lavishly. The little creatures took their morning feast eagerly, gratefully; they threw back their tiny heads and chirped their thanks; they hopped and ran and fluttered about the sunny green space, till the whole seemed alive with swift, happy motion. Standing still among them, the man talked to them gently, and they seemed to understand. Now and then he took one in his hand and caressed it, with fingers as light as their own fluffy wings; and when he did that, the bird would throw back its head and sing; and the others would chime in, till the whole place rang with the music of them. It was a very wonderful thing, if any one had been there who understood about wonderful things; but to the child it seemed wholly natural, being like many other matters in the Fairy Books; only she wished she could do it, too, and determined she would, as soon as she learned a little more about the ways of dwarfs.

By and by, when he had fed and caressed and talked to them, the man raised his arm; and the gray fluttering cloud rose in the air with merry cries, and vanished in the leafy gloom. The child was at the door in a moment. "How do you do that?" she asked, eagerly. "Who telled you that? Why can't I do it, too? What is their names of all those birds? Why don't you answer things when I say them at you?"

"Snow-white," said the man, "I haven't yet answered the questions you asked me last night, and I haven't even begun on this morning's batch."

"But you will answer them all?" cried the child.

"Yes, I will answer them all, if you give me time."

"'Cause I have to know, you know!" said the child, with a sigh of relief.

"Yes, you have to know. But first I must ask you some questions, Snow-white. Come and sit down here on the roots of the birch; see, it makes an arm-chair just big enough for you."

The child came slowly, and seated herself as she was bid. But, though the seat was easy as a cradle, her brow was clouded.

"I don't like to answer things," she announced. "Only I like to ask them."

"But we must play fair," said the man. "It wouldn't be fair for you to have all the fun."

"No more it would. Well, I'll answer a fewly, dwarf; not many I won't, 'cause when you're little you don't have to know things first; only you have to find out about them."

"Snow-white, why did you run away from home?"

"Last night I told you that, dwarf. I made a song, too. I'll sing it for you."

She sat up, folded her hands, shut her eyes tight, and sang at the top of her voice:

"Do you like that song?" she said, opening her eyes wide at the man.

Yes, the man liked it very much, but she was not answering his question.

"I sang it that way because that way Miss Tyler sings. She shuts her eyes and opens her mouth, and screeches horrid; but I don't screech, I truly sing. Don't I truly sing? Don't you think I was a bird if you didn't see me? don't you, dwarf?"

The dwarf said he was not going to answer any more questions. The child fidgetted on her seat, sighed, said he was stupid, and finally resigned herself.

"I told you that last night!" she said again. "My mamma went to New York, and my papa, too. They leaved me alone after I told them not to. And I told them; I said if they did, then I would; and they would, and so I did. And so you see!"

She looked up suddenly at the man, and once more he winced and drew in his breath.

"What's the matter?" asked the child, with quick sympathy. "Have you got a pain? is it here? is it in your front? often I have them in my front. You take a tablet, and then you curl up wiz the hot-water bottle, and perhaps it goes away pretty soon. Green apples makes it!" she nodded wisely. "Dwarfs didn't ought to eat them, any more than children. Where is the tree?"

The man did not answer this time. He seemed to be trying to pull up a weight that lay on him, or in him and sat moodily looking on the ground. At last—

"What is your mother's name?" he said; and then one saw that he had got the weight up.

"Evelyn!" said the child.

"Yes, of course!" said the man.

"What makes you say that?" asked the child. "Did ever you see her?"

"Did ever you see a toad with three tails?" said the man.

"Aren't you funny? say, is all dwarfs funny? aren't there really any more of you? didn't there ever was? where did the rest of them go? why do you stay in this place alone? I want to know all those things." She settled herself comfortably, and looked at the man confidently. But he seemed still to be labouring with something.

"Would your mother—would she be very unhappy, if she should come home and find you gone, Snow-white?"

The child opened her eyes at him.

"Oh, I s'pose she'd go crazy distracted; but she isn't coming home, not a long time isn't she coming home; that's why I comed away, and I runned away, and I said—what makes you look like that, dwarf?"

"I suppose I ought to send you home, Snow-white. I suppose you ought to go this very day, don't you?"

He stopped abruptly, for the signs were ominous; the child's lower lip was going up in the middle and coming down at the corners; her eyes were growing wider and wider, rounder and rounder; now they began to glitter.

"Don't cry!" said the man, hastily. "Don't cry, Snow-white. The other Snow-white never cried, you know."

The child sniffed tearfully. "The other Snow-white never was treated so!" she said. "Never those dwarfs tried to send her away, never. She cooked their dinner, and she swept, and they liked her, and they never said noffin, and—I haven't any hanky!" she concluded suddenly, after a vain search in her pink calico pocket.

The man handed her a great square of white cobweb linen, and she dried her eyes. "Never I heard of dwarfs sending children away!" she said, in conclusion. "I don't believe p'r'aps you aren't the right kind. Is you got any name? Not ever dwarfs has names."

"I'm afraid I have a kind of name!" the man admitted. "But it isn't much of one. You might call me Mark, though, if you like."

"That isn't no name at all. It's just you do it wiz a pencil. Aren't you funny? Truly is it your name? What made you have such a name?"

But the man declared he had lost his way in the questions. "I haven't begun on this morning's yet," he protested, "and now you are asking me to-morrow's, Snow-white. But we must do the dishes now, and then I'll show you where I slept last night. You asked me that the very first thing this morning, and you have not been still long enough yet for me to tell you."

That would be great! the child thought. On the whole, she thought perhaps he was the right kind of dwarf, after all. Why did he have a hump on his back, though? not in the Snow-white picture they did. Wasn't it funny, when she stood on the cricket she was just as tall as he? Wasn't that nice? wasn't he glad he wasn't any taller? didn't he think he was made that way just for little girls? did ever he see any little girls before? did he think she looked like Snow-white? why didn't he talk when she spoke to him?

It was a merry time, the dish-washing. The man had put away whatever it was that kept his eyes dark, and was smiling again, and chatting cheerfully. It appeared that he was an extraordinary person, after all, and quite like the books. He lived here all alone. Yes, always alone. No; he never had wanted any one else till now, but then he didn't know there were any Snow-whites; that made a great difference, you see.

Did—she broke off to laugh—did he like Snow-whites, honest and true, black and blue? Did he think she was beautiful, more beautiful than wicked stepmothers if she had one, only she hadn't, only mamma was awfully beautiful; did he know that? how did he know that? did ever he see mamma? what made him look so queer in his eyes? did he get soap in them? poor dwarf! well, why weren't there any more dwarfs, anyhow? why didn't he get six more when he comed here the first time?

It appeared that he did not want any more. It appeared that when he came away he never wished to see anybody again as long as he lived.

The child thought this so funny that she bubbled quite over, and dropped the cup she was wiping back into the hot water.

Why didn't he want to see people? had they been horrid to him?

Yes, they had been very horrid. He came away into the woods to stay till he was tired, and then he was going farther away. Where? oh, he did not know; to wherever he belonged; he was not sure where it was, but he knew the way to get there. No, not by the brook, that was too slow, he knew a quick way. Show it to her? well, no, he thought not. How long had he been here? oh, a good while. At first, after they had been horrid to him—no, he could not stop to tell her now; sometime, perhaps, when they had nothing else to do; at first he had gone across the sea, oh, a long way across; yes, he would tell her all about that by and by. Then, when he came back—

"Why do you keep stopping like that?" asked the child. "Do you forget what you was going to say? often I do! You said when you came back; did you go and tell them they was mean old things to be horrid to you, and never you wouldn't play wiz them no more?"

"No," said the man, slowly. "No, Snow-white, I didn't do that; it wouldn't have done any good, you see. I came here instead."

"Didn't you tell them at all that they was mean?"

"No; where was the use?"

"Don't they know you are here, dwarf?"

"No."

The child grew red in the face. "Well, I think you was dreadfully silly!" she said. "I would told 'em all about it, and stamped my foot at 'em, so! and—"

But the stamp was too much for the composure of the cricket, which turned over at this point, bringing the child down suddenly, with her chin against the hot dish-pan. This was a grievous matter, and consolation was the only possible thing to be thought of. The man took her in his arms, and carried her out-of-doors; she was sobbing a little, but the sobs died away as he stood with her under the great buttonwood, and bade her look up into the rustling dome.

"You asked where I slept last night, Snow-white," he said. "I slept up there, in my tree-room. Look! a good way up, just above that great branch, do you see a hole? Well, in there is a hollow, big enough to sit in or lie down and sleep in. I often go up there and sit with the brother birds; and last night I slept there, and very well I slept, too."

"Did you"—the child hesitated between a sob and a chuckle—"did you have any bed?"

"The finest bed in the world, moss and dry leaves. Would you like to come up and see, Snow-white? I think I can manage to get you up."

"Oh, what a nice dwarf you are!" cried the child, slipping down from his arms and dancing around him. "Aren't you glad I came? I'm glad you were here. How I shall get up? Stand on your hump? isn't it nice you have a hump, dwarf? was it made for little girls to stand up on? did you have them make it? did you think about little girls when you had it made? do you like to have it for me to stand on? can I jump up and down on it?"

Standing on the hump, which certainly made an excellent thing to stand on, she could grasp the lowest branch of the tree. Could she put her arms round that and hang for just a moment? Yes, she could, and did; and in an instant the active dwarf was beside her, and had her up on the branch beside him. From there it was easy to ascend, branch by branch, till they reached the black hole. The child caught her breath a moment as the man swung her in; then her laughter broke and bubbled up so loud and clear that the birds rose in a cloud from the murmuring depths of the tree, and then sank down again with chirp and twitter and gurgle of welcome, as if recognising one of their own kind.

"Well, Mr. Ellery, here I am!"

The dwarf had come down from the tree, leaving the child asleep in the tree-hollow, with Cousin Goldfinch to keep watch over her; now he was sitting in the root-seat of the yellow birch, looking up at a man who stood before him.

"Yes," said the dwarf; "here you are. Anything new? It isn't a month since you came."

The man said it was more than a month. "I've brought the papers," he said. "There are deeds to sign, and a lot of things to look over. Hadn't we better come into the house, sir?"

"Presently!" said the dwarf, looking up at the tree. He was not absolutely sure that the child was sound asleep, and if she waked suddenly she might be frightened to find herself alone.

"You are not looking well, Phillips!" he remarked, easily.

"I'm not well, Mr. Ellery," said the man, with some heat. "I'm worn out, sir, with all this business. How you can persist in such foolishness passes my comprehension. Here are leases running out, petitions coming in, bills and letters and—the office looks like the dead letter office," he broke out, "and the clerks are over their heads in work, and I am almost broke down, as I tell you, and you are—"

"By the way!" said the dwarf, settling himself comfortably, "where am I, Phillips?"

"In Thibet!" replied the other, sulkily. "Hunting the wild ass."

"And a fine sport!" said the dwarf, musingly. "That shows invention, Phillips. That really shows ingenuity, do you know? You grumble, my good fellow, but you don't seem to realise what this is doing for you. You have lived forty odd years without imagination; now you are developing one; against your will, it is true, but the effect is no less admirable. I admire you, Phillips; I do indeed."

He smiled up at the man, who regarded him gloomily, yet with a look of affection.

"I wish you would give it up," he said, simply. "I wish to goodness you would give it up, Mr. Ellery, and come home. A man like you living this life—the life of an animal, sir—it's monstrous. Think of your interests, think of your estate, of all the people who looked to you; of—"

"By the way," said the dwarf again, "have you paid those legacies?"

"I know nothing about any legacies," replied the man, peevishly. "I'll have nothing to do with any such talk as that. When I see you dead and in your coffin, Mark Ellery, it'll be time enough to talk about legacies."

"I don't like coffins!" murmured the dwarf, looking up at the black hole in the great buttonwood tree. "I never intend—go on, Phillips. You paid the money, did you say?"

"Yes, sir, I did; but I did not tell the old ladies you were dead, because you were not, and I am not engaged to tell lies of that description. Professional fiction I must use, since you drive me to it; but lie to those old women I could not and did not!"

"No," said the dwarf, soothingly, "surely not; I could not expect that, Phillips. And you told them that I was—"

"In Thibet," said the man. "Hunting the wild ass. I told you that before."

"Precisely," said the dwarf. "Don't limit yourself too strictly, Phillips. You might vary the place a little oftener than you do, and find it more amusing. It would have impressed the old ladies more, for instance, if you had said that I was in Mashonaland, converting the wild ass—I mean the black man. The old ladies are well, I trust?"

"Pretty feeble, Mr. Ellery. They cried a good deal, and said you were the best and—"

"Et cetera!" said the dwarf. "Suppose we skip that part, Phillips. A—before I forget it, I want you to get me some things in town. Let me see,"—he considered, and began to check off items on his fingers. "A doll, the handsomest doll that can be found, with a trunk full of clothes, or you might say two trunks, Phillips. And—some picture-books, please, and a go-cart—no, I can make that myself. Well, then, a toy dinner-set. You might get it in silver, if you find one; and some bonbons, a lot of bonbons, say ten pounds or so. And—get me a couple of new rugs, thick, soft ones, the best you can find; and—oh! cushions; get a dozen or so cushions, satin and velvet; down pillows, you understand. What's the matter?"

The man whom he called Phillips was looking at him in a kind of terror that sent the dwarf into a sudden fit of laughter. He gave way to it for a few minutes, then restrained himself, and wiped his eyes with a fine handkerchief, like the one he had given the child. "Phillips, you certainly have the gift of amusing," he murmured. "I am not mad, my dear man; never was saner in my life, I assure you. Observe my eye; feel my pulse; do. You see I am calm, if only you wouldn't make me laugh too much. Far calmer than you are, Phillips. Now we'll come in and go over the papers. First, though,"—he glanced up at the tree again, and seemed to listen, but all was silent, save for the piping and trilling that was seldom still,—"first, is there any news? I don't mean politics. I won't hear a word of politics, you know. I mean—any—any news among—people I used to know?"

The man brightened visibly; then seemed to search his mind. "Mr. Tenby is dead, sir; left half a million. You can have that place now for a song, if you want to invest. Old Mrs. Vivian had a stroke the other day, and isn't expected to live. She'll be worth—"

The dwarf made a movement of impatience. "Old people!" he said. "Why shouldn't they die? Who cares whether they die or live, except themselves and their heirs? Are there no—young people—left in the place?"

Phillips pondered. "No one that you'd be interested in, sir," he said. "There's been a great to-do about a lost child, yesterday. Mr. Valentine's little girl ran away from home, and can't be found. Wild little thing, they say; given her governess no end of trouble. Parents away from home. They're afraid the child has been kidnapped, but I think it's likely she'll turn up; she has run away before, they say. Pretty little girl, six years old; image of her mother. Mother was a Miss—"

Here he stopped, for the dwarf turned upon him in a kind of fury and bade him be still. "What do I care about people's children?" he said. "You are an idle chatterer. Come and let me see this business, whatever it is. Curse the whole of it, deed and house, land and letter! Come on, I tell you, and when you have done, begone, and leave me in peace!"

When the child woke, she was at first too much surprised to speak. She had forgotten things, for she had been sleeping hard, as children do in their noonday naps; and she would naturally have opened her eyes upon a pink nursery with gold trimmings. Instead, here she was in—what kind of place? Around her, on all sides save one, were brown walls; walls that felt soft and crumbly, and smelt queer; yet it was a pleasant queerness. On the one side where they were not, she looked out into a green sky; or perhaps—no, it wasn't a sky, it was woods, very thick woods, and there was no ground at all. She was lying on something soft, and partly it rustled, and partly it felt like thick cold velvet. Now some of the rustling came alive, and two or three birds hopped down from somewhere and sat on her foot and sang. At that the child laughed aloud, instead of screaming, as she had just been beginning to think she might; and then in a moment there was the dwarf, looking in at the green entrance, smiling and nodding at her.

"Oh, you dear dwarf!" said the child. "I am glad to see you. I forgotted where I was in this funny place. Isn't it a funny place, dwarf? how did you get here? what made you know about it? why don't you always live here all the time? what's that that's bright up there?"

Indeed, the hollow in the tree made a good-sized room enough, if a person were not too big. The walls were pleasant to sight, touch, and smell; their colours ran from deepest black-brown up to an orange so rich and warm that it glowed like coals. When you touched the surface, it crumbled a little, soft and sympathetic, as if it came away to please you. The cushion of moss was thicker than any mattress ever made by man; altogether, a delightful place—always supposing one to be the right size. Now the dwarf and the child were exactly the right size, and there seemed no reason why they should not live here all their lives. This was evident to the child.

In one place, a natural shelf ran part way round the tree-wall; and on this shelf lay something that glittered. "What is that that's bright?" the child repeated. "Give it to me, please, dwarf!"

She stretched out her hand with an imperious gesture. The man took the object down, but did not give it to her. "This," he said "is a key, Snow-white."

"Huh!" said the child. "It looks like a pistol. What for a key is it to? where did you get it? is there doors like Bluebeard? why don't you tell me, dwarf?"

"Yes, it does look like a pistol," the man assented, weighing the object in his hand. "But it is a key, Snow-white, to—oh! all kinds of places. I don't know about the Bluebeard chamber; you see, I haven't used it yet. But it is the key of the fields, you understand."

He was speaking slowly, and for the time seemed to forget the child, and to be speaking to himself. "Freedom and forgetfulness; the sting left behind, instead of carried about with one, world without end. The weary at rest—at rest!"

"No wives?" asked the child. The man looked at her with startled eyes. "Wives?" he repeated.

"Dead ones," said the child. "Hanging up by their hairs, you know, dwarf, just heads of 'em, all the rest gone dead. Isn't that awful? Would you go in just the same? I would!"

"No, no wives!" said the dwarf; and he laughed, not his pleasant laugh, but one that sounded more like a bark, the child told him. "No wives!" he repeated; "my own or other people's, Snow-white. What should I have to do with wives, dead or alive?"

The child considered him attentively. "I don't suppose you could get one, anyhow, do you?" she said. "Always, you know, the dwarfs try to get the princesses, but never they do. You never was yellow, was you?" she asked, with a sudden note of apprehension in her voice.

"No, Snow-white, never yellow; only green."

The child bubbled over. "Was you truly green?" she cried. "Isn't that funny, dwarf? and then you turned brown, didn't you? you don't suppose I'll turn brown, do you? because I ain't green, am I? but I was just thinking, suppose you should be the Yellow Dwarf, wouldn't it be awful?"

"Probably it would. He was a pretty bad sort of fellow, was he, Snow-white? I—it's a good while since I heard anything about him, you see."

"Oh, he was just puffickly frightful! He—Do you want me to tell you the story, dwarf?"

Yes, the dwarf wanted that very much indeed.

"Well, then, if I tell you that, you must tell me one about some dwarfs what you knew. I suppose you knew lots and lots of them, didn't you? Was they different colours? was they blue and green and red? what made you turn brown when you was green? well!

"Once they was a queen, and she had twenty children, and they was all dead except the Princess All-fair, and she wouldn't marry any of the kings what wanted to marry her, and so her mother went to ask the Desert Fairy what she should do wiz her. So she took a cake for the lions, and it was made of millet and sugar-candy and crocodiles' eggs, but she went to sleep and lost it. Did ever you eat a cake like that? should you think it would be nasty? I should! Well, and so there was the Yellow Dwarf sitting in the tree—why, just the way you are, dwarf. We might play I was the queen, and you was the Yellow Dwarf. Let's play it."

"But I don't want to be a horrid one," the man objected, "and I want to hear the story, besides."

"Oh, well, so I will. Well, he said he would save her from the lion, if she would let him marry the Princess, and she didn't want to one bit, but she said she supposed she'd have to, so he saved her, and she found herself right back there in the palace. Well, and so then she was very unhappy all the time, and the Princess didn't know what upon earth was the matter wiz her, so she thought she would go and ask the Desert Fairy. So she went just the same way what her mother went, but she ate so many oranges off the tree that she lost her cake, too. That was greedy, don't you think so?"

"Very greedy! she was old enough to know better."

"Why, yes! why, I'm only six, and I don't eat so many as all that, only till I feel queer in front, and then I always stop. Do always you stop when you feel queer in front? Well! so then the Yellow Dwarf comed along, and he said her mother said she had to marry him, anyway. And the Princess said, 'How! my mother promised me to you in marriage! you, such a fright as you!'

"And he was puffickly horrid. He said, 'Well, if you don't, the lions will get you, and eat you up every scrap, and I sha'n't care a bit.' Wasn't he mean? So she said she s'posed she'd have to; and right off then she went to sleep, and there she was in her own bed, and all trimmed up wiz ribbons, and on her finger was a ring, and it was just one red hair, and she couldn't get it off. Wasn't that puffickly awful, dwarf?"

"It chills my marrow, Snow-white. Go on!"

"What is your marrow? what does it look like? why do you have it, if it gets cold so easy as that? I wouldn't! Well! So at last the Princess said she guessed she would marry the King of the Golden Mines, 'cause he was puffickly beautiful, and most prob'ly the old dwarf wouldn't dare to say a word when he found how beautiful he was, and strong and big and rich and everything."

"No!" said the dwarf, bitterly. "The poor dwarf would have no chance, certainly, against that kind of king. He might as well have given up in the beginning."

"But, Mark, this dwarf wasn't poor, or anything else but just as horrid as he could be. Why, when the Princess and the King was going to be married, all in gold and silver, wiz roses and candy and everything lovely, they saw a box coming along, and an old woman was on it and she said she was the Desert Fairy, and the Yellow Dwarf was her friend, and they shouldn't get married. So they said they didn't care, they would—oh, and she said if they did she would burn her crutch; and they said they didn't care one bit if she did. They were just as brave! And the King of the Golden Mines told her get out, or he would kill her; and then the top of the box comed off, and there was the Yellow Dwarf, and he was riding on a cat,—did ever you ride on a cat, Mark?"

"No, never."

"Well, he was; and he said the Princess promised to marry him, and the King said he didn't care, she shouldn't do noffing of the kind. So they had a fight, and while they were fighting that horrid old Fairy hit the Princess, and then the Yellow Dwarf took her up on the cat, and flewed away wiz her. That's all about the first part. Don't you think it's time for luncheon?"

"Oh, but you are never going to stop there, Snow-white! I want to know what became of them. Even if the dwarf did carry off the Princess, and even if she had promised to marry him,—for she did promise, you say,—still, of course he did not get her. Dwarfs have no rights that anybody is bound to respect, have they, Snow-white?"

"Well, I don't like the last part, because it doesn't end right. The Desert Fairy falled in love wiz the King, and she hoped he would marry her, but he said no indeed, he wouldn't have her in the same place wiz him at all; so he wouldn't stay in the house, but he went out to walk by the wall that was made of emeralds, and a mermaid came up and said she was sorry, and if he hit everything wiz this sword it would kill them, but he must never let go of it. So he thanked her very much, and he went along, and he killed lots of things, spinxes and nymps and things, and at last he came to the Princess, but then he was so glad to see her that he let go of the sword just a minute, and what do you think that horrid dwarf did? Why, he comed right along and took it, and said he shouldn't have it back unless he would give up the Princess. 'No,' said the King, 'I scorn thy favour on such terms.' And then that mean old thing stabbed him to the heart, and so he was dead; and the Princess said, 'You puffickly hideous old horrid thing, I won't marry you, anyway!' and then she fell down and perspired wizout a sigh. And that's all. And the mermaid turned them into palm-trees, because that was all she knew how to do, don't you know? and that's all. Aren't you going to get me something to eat? can't we have it up here in this place? aren't you glad I'm here to keep you company and tell you stories? don't you say hurrah for us, dwarf? I do; hurrah!"

"What let's do now?" said the child.

They had had dinner; a most exciting dinner, all coming out of tin boxes and delightful china pots. It was almost as good as Little Two-Eyes' feasts in "Little Kid Milk, Table Appear," as the child preferred to call the story. The child shut her eyes and said what she wanted, and when she opened them, there it mostly was, standing on the table before her. At least, that was the way it happened when she said chicken, and jam, and Albert biscuits; but when she said sponge cake, there was none, and the dwarf was mortified, and said he would tell the people they ought to be ashamed of themselves.

"Where all do you get them?" asked the child. "Do you stamp your foot on the floor, and say, 'JAM!' like that, hard, just as loud as you can? do you? does it come up pop through holes? will you do it now, this minute?"

No, the dwarf could not do it now, he had not the right kind of shoes on. Besides, there were other reasons.

"Well, then, what let's do?" asked the child again.

"Let us go and milk the cow," said the dwarf.

Oh, that was exciting! Was it a truly cow? did it turn into things all day, and be a cow at night, or the other way? what did it turn into? Sometimes they were fawns and sometimes they were ducks, and sometimes—what would he like to be if he didn't have to be a dwarf? could he be things if he wanted to? was he only just playing dwarf, and by and by he would turn into a Beautiful Prince all gold and silver, wiz diamond clothes and a palace all made of candy? would he?

"And then you could marry me, you know!" said the child. "I shall be grown up by that time—"

"Yes, I think you will!" said the dwarf.

"And we will be married, and I will wear a dress like the sun, and we will go in a gold coach, wiz six black horses—or do you say white, Mark?"

"I say white."

"So do I say! and fezzers on their heads; and—and—so—well, anyhow, you will show me all your treasures, you know, dwarf. You haven't showed me any yet, not any at all. Where are they?"

"I haven't but one," said the dwarf. "And that I stole."

"Really stole it? but stealing is wicked, don't you know that? can dwarfs do it? Mans can't, unless they are bad. Are dwarfs like mans at all much, Mark?"

"Not much, Snow-white. But, after all, I did not steal my treasure, I only found it."

The child was greatly relieved. That made it all right, she assured him. Always everybody could keep the things they found, though of course the wicked fairies and dragons tried to get the treasure away. She cited many cases from the Fairy Books, and the dwarf said he felt a great deal better.

"Tell me all about it," she urged. "Tell me that story what you said you knew. You haven't told me any story at all yet, Mark!"

She looked at him with marked disapproval. "It isn't the way they do!" she explained. "Why, when the Bear came to Snow-white and Rosy Red's house, he told them stories all the time till he turned into a prince."

"Yes, but I am not a bear," said the dwarf, "and I am not going to turn into a prince, you see. However, I will tell you a story, Snow-white, I truly will; only, you see, that poor cow has to be milked."

"All I forgot her!" cried the child. "Now we will hurry, Mark, and run. We will run all the way. You can't run much faster than me, 'cause your legs is short, too. Are you glad? I am! 'Most I wish I was a dwarf, to stay little like you."

"Come!" said the man. His voice sounded rough and harsh; but when the child looked up, startled, he took her in his arms, and kissed her very tenderly, and set her on his back. He would be her horse now, he said, and give her a good ride. And wasn't the hump comfortable to sit on? now she must hold on tight, and he would trot.

He trotted gently through the green wood, and the child shouted with joy, and jumped up and down on the hump. It was a round, smooth hump, and made a good seat.

They did not get on very fast, in spite of the trotting, there was so much to see by the way. Little paths wound here and there through the forest, as if some one walked in it a great deal. The trees in this part were mostly pine and hemlock, and the ground was covered with a thick carpet of brown needles. The hermit thrush called them from deeper depths of woodland; close by, squirrels frisked and chattered among the branches, and dropped bits of pine-cone on the child's head. Were they tame? she asked; the dwarf said she should judge for herself. They sat down, and he bade her keep still, and then gave a queer whistle. Presently a squirrel came, then another, and another, till there were half a dozen of them, gray and red, with one little striped beauty. They sat up on the brown needles, and looked at the dwarf with bright, asking eyes. He took some nuts from his pocket, and then there was a scramble for his knee and his shoulder, and he fed them, talking to them the while, they whisking their tails and cocking their heads, and taking the nuts in their paws as politely as possible. One big gray fellow made a little bow, and that was charming to see.

"Good boy!" said the dwarf. "Good old Simeon! I taught him to do that, Snow-white. You need not be afraid, Sim. This is only Snow-white. She has come to do my cooking and all my work, and she will not touch you. His name is Simeon Stylites, and he lives on a pillar—I mean a dead tree, with all the branches gone. Simeon, if you are greedy, you'll get no more. Consider the example you have to set!"

"Why is he named that?" asked the child.

"Because when he sits up straight on top of his tree, and folds his paws, he looks like an old gentleman of that name, who used to live on top of a pillar, a long time ago."

"Why did he? but why couldn't he get down? but how did he get up? what did he have to eat? why don't you tell me?"

"I never thought much about his getting up," said the dwarf. "I suppose he must have shinned, don't you? and as for getting down, he just didn't. He stayed there. He used to let down a basket every day, or whenever he was hungry, and people put food in it, and then he pulled it up. What did they put? Oh, figs, I suppose, and black bread, and honey. Rather fun, don't you think, to see what would come up?"

The child sprang up and clapped her hands. "Mark," she cried, "I will be him!"

"On a pillar?" said the dwarf. "See, you have frightened Simeon away, and he hadn't had half enough; and you couldn't possibly climb his tree, Snow-white."

"In your tree! in the hole! it will be just as good as Little Kid Milk. Not in any of the stories a little girl did that; all mineself I will do it. I love you, Mark!"

She flung her arms around his neck and hugged him till he choked. When the soft arms loosened their hold, his eyes were dark.

"You love me because I have a tree?" he said, "and because you like the things in the china pots?"

"Yes!" said the child, "and because you are a dwarf, and because you are nice. Most because you are nice, Mark, when those other dwarfs is yellow and horrid and all kinds of things."

"All right!" said the dwarf. "I love you, too. Now soon we are coming to the cow. We must hurry, Snow-white."

But it was not easy to hurry. He had to look and see how the ferns were unrolling, and to say what they looked like. The child thought they were like the little brown cakes, only green, what you bought them at the cake-shop. Didn't he know the cake-shop? but could he buy things? did they let dwarfs buy things just as if they were mans? could he have money, or did he have to dig up pearls and diamonds and rubies, out of the ground? was there a place here where he dug them up? when would he show it to her?

Then there were the anemones just out; and at sight of them the child jumped up and down, and had to be told what they were. The name was very funny, she thought.

"I can make a song wiz that!" she said, and then she sang:

"It hasn't any money, this frower hasn't. All it's white, just like milk. Do you like money, Mark?"

"No, I hate it!"

"Me, too!" cried the child, bubbling into a laugh. "In my bank, I had lots and lots of money; and the man with the black shirt said about the poor children, and so I took it out and gave it to him, and then they said I couldn't have it back!"

"Who said so?" asked the dwarf.

"Miss Tyler! Well, but so I said I would, and so she punished me, and so I beat her, and she said to stay in my room, and I runned away. Are you glad I runned away, Mark?"

"Very glad, to-day, Snow-white; I don't know how it will be to-morrow. But tell me what you wanted to do with your money!"

It appeared that the child wanted to buy candy, and a pony, and a watch, and a doll with wink-eyes and hair down to her feet, and a real stove, and a popgun, and—what was this place?

The wood broke open suddenly, and there was a bit of pasture-land, with rocks scattered about, and a little round blue pond, and by the pond a brown cow grazing. At the sound of voices the cow raised her head, and seeing the dwarf, lowed gently and began to move leisurely toward him.

The child clapped her hands and danced. "Is she saying 'hurrah'?" she cried. "Does she love you? do you love her? is she"—her voice dropped suddenly—"is she real, Mark?"

"Real, Snow-white? Why, see her walk! Did you think I wound her up? She's too big; and besides, I haven't been near her."

The child brushed these remarks aside with a wave. "Does she stay all the time a cow?" she whispered, putting her mouth close to the dwarf's ear. "Or does she turn at night into a princess?" She drew back and pointed a stern finger at him. "Tell me the troof, Mark!"

The dwarf was very humble. So far as he knew, he said, she was a real cow. She mooed like one, and she acted like one; moreover, he had bought her for one. "But you see," he added, "I don't stay here at night, so how can I tell?"

They both looked at the cow, who returned the stare with unaffected interest, but with no appearance of any hidden meaning in her calm brown gaze.

"I think," said the child, after a long, searching inspection, "I think—she's—only just a cow!"

"I think so, too," said the dwarf, in a tone of relief. "I'm glad, aren't you, Snow-white? I think it would be awkward to have a princess. Now I'll milk her, and you can frisk about and pick flowers."

The child frisked merrily for a time. She found a place where there were some brownish common-looking leaves; and stepping on them just to hear them crackle, there was a pink flush along the ground, and lo! a wonder of mayflowers. They lay with their rosy cheeks close against the moss, and seemed to laugh out at the child; and she laughed, too, and danced for joy, and put some of them in her hair. Then she picked more, and made a posy, and ran to stick it in the dwarf's coat. He looked lovely, she told him, with the pink flowers in his gray coat; she said she didn't care much if he never turned into anything; he was nice enough the way he was; and the dwarf said it was just as well, and he was glad to hear it.

"And you look so nice when you smile in your eyes like that, Mark! I think I'll kiss you now."

"I never kiss ladies when I am milking," said the dwarf. And then the child said he was a horrid old thing, and she wouldn't now, anyhow, and perhaps she wouldn't at all ever in her life, and anyhow not till she went to bed.

By and by she found a place where the ground was wet, near the edge of the pond, and she could go pat, pat with her feet, and make smooth, deep prints. This grew more and more pleasant the farther she went, till presently the water came lapping cool and clear over her feet. Yes, but just then a butterfly came, a bright yellow one, and she tried to catch it, and in trying tripped and fell her length in the pond. That was sad, indeed; and it was fortunate the milking was ended just at that time, for at first she meant to cry hard, and the only thing that stopped her was riding home on the dwarf's hump, dripping water all over his gray velvet clothes. He didn't care, he said, so long as she did not drip into the milk.

"I aspect, Mark," said the child,—"do you like better I call you Mark all the time than dwarf? then I will. I do really aspect you'll have to get me a clean dress to put on."

She held up her frock, and the dwarf looked at it anxiously. It was certainly very dirty. The front was entirely covered with mud, and matters had not been improved by her scrubbing it with leaves that she pulled off the trees as they came along.

"Dear me, Snow-white!" said the dwarf. "That is pretty bad, isn't it?"

"Yes," said the child; "it is too bad! You'll have to get me another. What kind will you get?"

"Well," said the dwarf, slowly; "you see—I hardly—wait a minute, Snow-white."

He went into the house, and the child waited cheerfully, sitting in the root-seat. Of course he would find a dress; he had all the other things, and most prob'ly likely there was a box that had dresses and things in it. She hoped it would be blue, because she was tired of this pink one. There might be a hat, too; when you had that kind of box, it was just as easy to have everything as only something; a pink velvet hat with white feathers, like the lady in the circus. The child sighed comfortably, and folded her hands, and watched the robins pulling up worms on the green.

But the dwarf went into the bedroom, and began pulling out drawers and opening chests with a perplexed air. Piles of handkerchiefs, socks, underwear, all of the finest and best; gray suits like the one he had on—but never a sign of a blue dress. He took down a dressing-gown from a peg, and looked it over anxiously; it was of brown velvet, soft and comfortable-looking, but it had evidently been lived in a good deal, and it smelt of smoke; no, that would never do. He hung it up again, and looked about him helplessly.

Suddenly his brow cleared, and his eyes darkened. He laughed; not his usual melodious chuckle, but the short harsh note that the child compared to a bark.

"Why not?" he said. "It's all in the family!"