Captn. JONATHAN CARVER.

From the Original Picture in the possession of J.C. Lettsom M.D.

Published as the Act directs, by R. Stewart, No. 287, near Gt. Turnstile, Holborn Novr. 16, 1780.

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Captn. JONATHAN CARVER.

From the Original Picture in the possession of J.C. Lettsom M.D.

Published as the Act directs, by R. Stewart, No. 287, near Gt. Turnstile, Holborn Novr. 16, 1780.

Printed for C. Dilly, in the Poultry; H. Payne, in Pall-mall; and J. Phillips, in George-Yard, Lombard-Street.

FEW works have had a more rapid sale than the following; two large editions having been disposed of in two years. This induced the proprietors to print a third: but, as soon as this impression was finished, I purchased both the printed copies and the copy-right.

I have since added to the work, some Account of the Author’s life, and an Index to the Travels, which are published separately, for the convenience of the purchasers of the first and second editions; on whom, I was unwilling to raise an extraordinary tax for the third edition.

London, March 30, 1781.

SIR,

WHEN the Public are informed that I have long had the Honour of your Acquaintance——that my Design in publishing the following Work has received your Sanction——that the Composition of it has stood the Test of your Judgment——and that it is by your Permission a Name so deservedly eminent in the Literary World is prefixed to it, I need not be apprehensive of its Success; as your Patronage will unquestionably give them Assurance of its Merit.

For this public Testimony of your Favour, in which I pride myself, accept, Sir, my most grateful Acknowledgments; and believe me to be, with great Respect,

The favourable reception this Work has met with, claims the Author’s most grateful acknowledgments. A large edition having run off in a few months, and the sale appearing to be still unabated, a new impression is become necessary. On this occasion was he to conceal his feelings, and pass over, in silence, a distinction so beneficial and flattering, he would justly incur the imputation of ingratitude. That he might not do this, he takes the opportunity, which now presents itself, of conveying to the Public (though in terms inadequate to the warm emotions of his heart) the sense he entertains of their favour; and thus transmits to them his thanks.

In this new edition, care has been taken to rectify those errors which have unavoidably proceeded from the hurry of the press, and likewise any incorrectness in the language that has found its way into it.

The credibility of some of the incidents related in the following pages, and some of the stories introduced therein, having been questioned, particularly the prognostication of the Indian priest on the banks of Lake Superior, and the story of the Indian and his rattle snake, the author thinks it necessary to avail himself of the same opportunity, to endeavour to eradicate any impressions that might have been made on the minds of his readers, by the apparent improbability of these relations.

As to the former, he has related it just as it happened. Being an eye-witness to the whole transaction (and, he flatters himself, at the time, free from every trace of sceptical obstinacy or enthusiastic credulity) he was consequently able to describe every circumstance minutely and impartially. This he has done; but without endeavouring to account for the means by which it was accomplished. Whether the prediction was the result of prior observations, from which certain consequences were expected to follow by the sagacious priest, and the completion of it merely accidental; or whether he was really endowed with supernatural powers, the narrator left to the judgment of his readers; whose conclusions, he supposes, varied according as the mental faculties of each were disposed to admit or reject facts that cannot be accounted for by natural causes.

The story of the rattle snake was related to him by a French gentleman of undoubted veracity; and were the readers of this work as thoroughly acquainted with the sagacity and instinctive proceedings of that animal, as he is, they would be as well assured of the truth of it. It is well known, that those snakes which have survived through the summer the accidents reptiles are liable to, periodically retire to the woods, at the approach of winter; where each (as curious observers have remarked) takes possession of the cavity it had occupied the preceding year. As soon as the season is propitious, enlivened by the invigorating rays of the sun, they leave these retreats, and make their way to the same spot, though ever so distant, on which they before had found subsistence, and the means of propagating their species. Does it then require any extraordinary exertions of the mind to believe, that one of these regular creatures, after having been kindly treated by its master, should return to the box, in which it had usually been supplied with food, and had met with a comfortable abode, and that nearly about the time the Indian, from former experiments, was able to guess at? It certainly does not; nor will the liberal and ingenuous doubt the truth of a story so well authenticated, because the circumstances appear extraordinary in a country where the subject of it is scarcely known.

These explanations the author hopes will suffice to convince his readers, that he has not, as travellers are sometimes supposed to do, amused them with improbable tales, or wished to acquire importance by making his adventures savour of the marvellous.

THERE is a disposition peculiar to every mind, that early predominates, and continues its influence through every period of life. Many circumstances may, indeed, obscure or divert its progress; but on all interesting occasions this constitutional bias will recur, and exhibit the natural character and genius of the individual.

Jonathan Carver, the author of the following work, was grandson of William Joseph Carver, of Wigan, in Lancashire, who was a captain in the army under king William, and served in Ireland with such distinguished reputation, that that prince was pleased to reward him with the government of Connecticut in New-England, which appears to have been the first appointment to that station by the crown.

Our author was born, anno 1732, at Stillwater, in the province of Connecticut, since rendered famous by the surrender of the army under General Burgoyne; his father, who resided at this place, and acted as a justice of the peace, died, when he was only fifteen years of age. He had received the rudiments of as liberal an education as could be procured in that neighbourhood, and, being designed for the practice of medicine, he was soon after his father’s death placed with a gentleman of that profession in Elizabeth Town, in the same province. A profession that requires not only a close and regular attention, but likewise a steady perseverance, was not suited to that spirit of bold enterprize and adventure, which seemed to be the ruling passion of our author, who, at the age of eighteen, purchased an ensigncy in the Connecticut regiment, in which, as I have been informed, he acquired so much reputation, as to obtain the command of a company. Of this event, however, I have not found the least mention among his papers, nor, indeed, of any other important circumstance of his life till the year 1757, when he was in the army under General Webb, and fortunately escaped the dreadful massacre at Fort William Henry, where nearly 1500 brave troops were destroyed in cold blood by the Indians in the French army of General Montcalm.

In the ensuing year, 1758, a battalion of light infantry, commanded by Colonel Oliver Partridge, was raised in the province of Massachusets Bay, by order of Governor Pownall, for the purpose of invading Canada, in which our author served as second lieutenant of Captain Hawks’s company; and in 1760 he was advanced to be captain of a company in Colonel Whetcomb’s regiment of foot, during the administration of Governor Hutchinson. In Governor Barnard’s time, in 1762, Captain Carver commanded a company of foot in Colonel Saltonstall’s regiment.

I have not been able to collect any anecdotes of our author, during his military services; but from the written recommendations in my hands, of persons high in office, under whom he acted, he appears to have acquitted himself with great reputation, and much to the satisfaction of his superior officers. These recommendations are not confined to military conduct merely; they uniformly introduce him as a person of piety, and of a good moral character. Throughout the narrative of his travels, indeed, an animated regard to the duties of religion is evidently prevalent, which must procure a credibility to the facts he mentions, that might otherwise be suspended. If authors, who have visited countries unknown to their contemporaries, had always been actuated by a sacred regard to truth and moral rectitude, history in general would have been developed with just and convincing relations, and not left involved in doubt and obscurity.

This firm integrity and undaunted courage appeared evident upon every interesting occasion: they were, indeed, essentially requisite to conduct him through the most dangerous enterprizes with a perseverance that is more generally the offspring of true fortitude, than of daring boldness or impetuosity of imagination.

With so many favourable requisites for success and advancement, descended from parents respectable for their military and civil dignity, as well as for their fortune; endued with courage, sagacity, and a spirit of enterprize, rarely united in one individual, it might be an object of enquiry, why Captain Carver, whose conduct was so excellent, in a moral as well as in a military view, should never have been promoted above the command of a company.

It is a truth confirmed by history, that true fortitude is the genuine offspring of an humble mind. Whatever we acquire by industry and labour, we are apt highly to estimate; it is a kind of new creation of our own; and a persuasion of this, inspires ambition, and even a forward ardour for distinction; and what a partial imagination magnifies to ourselves, we naturally magnify to others, and gradually acquire a consequence, and reap rewards adequate, if not superior, to desert: but the naturally brave is naturally modest; what is innate, does not present itself to the imagination as its own; it neither begets vanity, nor excites ambition; and thus great endowments, which might have been cherished, and turned to the most important advantages, are frequently neglected, and lost to society. Whatever natural or acquired excellencies were possessed by Captain Carver, not only seemed unnoticed by himself, but were accompanied by a diffidence, which in some instances was extraordinary indeed; and the reader must be convinced of this, when he is informed, that Captain Carver died, through want, with three commissions in his pocket.

The year after his commission under Colonel Saltonstall was signed, the peace of Versailles took place, namely, anno 1763, when our author, having discharged his military obligations to his country, retired from the army. But his natural turn for enterprize, and the pursuit of novelty, did not suffer him to enjoy a life of useless ease; he began to consider, to use his own sentiments (having rendered his country some services during the war) how he might continue still serviceable, and contribute, as much as lay in his power, to make that vast acquisition of territory, gained by Great Britain in North America, advantageous to it; and here he commences his own biographer, continuing his relation in the following history of his travels, till his visit to England in the year 1769.

Though I have not been able to procure many additional anecdotes of this ingenious traveller, yet a respect to his memory, and a sense of his services to the nation at large, excited a desire to bring together a few outlines of his character, and probably at some future period, when the present unhappy contest between this kingdom and the American colonies shall have subsided, particulars of more importance than I have been able to meet with, may be procured from that part of the world, which he has taken so much useful labour to describe.

This barrenness of materials is, however, in some degree compensated by the important relations he has communicated in the succeeding pages, which not only regard himself, but likewise a part of the great American continent, hitherto almost unknown to the inhabitants of Europe, and even to those of the cultivated parts of the same continent.

In his descriptions of these vast regions, he seems to have embraced every opportunity of pointing out the advantages which might be derived in a commercial view, from a just knowledge of them, and of the policy of the various tribes who possess them. In his picturesque view of the scenery round Lake Pepin, his imagination, animated as it was by the magnitude, the novelty, and grandeur of the objects, is not so far transported, as to interrupt the most scrupulous attention to the situation, as improveable for commercial and national advantages.

In the midst of a new and rich creation, he suggested the probability of rendering this lake, and its variegated environs, the center of immense traffick, with a people whose names and tribes were scarcely known to the commercial parts of either side of the British empire, but whose dispositions and pursuits seemed calculated to promote and secure this interesting and national benefit.

The lake, which is about twenty miles in length, and six in breadth, and through which the Mississippi directs its course, is about two thousand miles from the entrance into the gulf of Mexico, and as many westerly from Quebec, Boston, and New-York; it is situated between 42 and 43 degrees of north latitude. The plains in its vicinity are extensive, and fit for immediate cultivation: elk, deer, and other quadrupeds, including the beaver, otter, mink, martin, sable, musk-rat, and the largest buffaloes in America, are the inhabitants of this region, whilst various species of wild fowl frequent the lake, whose waters are stored with fish in great abundance; vegetation is luxuriant in the meadows, where the maple is indigenous, of whose sap the Indians make great quantities of sugar, capable of fermentation, and of producing spirit; the grapes hang in such clusters, that almost any quantity of brandy might, under a like process, be distilled from them; rice, a grain adapted to many useful purposes of life, is also very plentiful.

The number of hunting Indians, who frequent Lake Pepin, is not less than 2000, each of whom brings about one hundred pounds weight of beaver to barter, which, at the lowest price, in the London market, is five shillings a pound; hence a trade at this place will command annually 200000 crowns worth of furs, besides skins. But there is reason to conclude, that when a general mart is established here, furnished with a sufficient assortment of goods, and a supply of liquors, that there would be a more general resort of traders.

The French, indeed, supported a trade at this lake, before the English had made a conquest of the country; but they never attempted the lucrative branch of distilling spirituous liquors upon the spot, though they have been conveyed hither two thousand miles of difficult carriage, and produced considerable profit.

It may be doubted in a moral, if not in a political view, whether such a traffic of rendering the means of inebriation more easily attainable, should meet with the encouragement of the legislature. Captain Carver, however, computed that 2000 gallons of brandy could be made on the spot, as cheap as in the West-Indies; and that by avoiding the expence of 3000 miles carriage also, the traders would make a saving of 2000 per cent. besides duties and various contingencies: and as, by a moderate computation, every gallon of spirits will produce there what will amount to ten pounds in the London market, it must eventually prove a most lucrative branch of trade, if pursued with proper caution and policy.

The great plenty of the edible necessaries of life, will afford a cheap, easy, and salutary supply; and the goodness of the soil, with very little labour, will render provisions still more easily attainable, and altogether form a place of traffic hitherto unequalled.

From Captain Carver’s long residence in the neighbourhood of Lake Pepin, among the Naudowissie and Chipéway Indians, he acquired a knowledge of their languages, and an intimacy with many of their chiefs, which, with his spirited and judicious conduct in acting as a mediator between these two nations, conciliated their attachment and friendship; and as an acknowledgment of their grateful sense of his happy interference, the Naudowissies gave him a formal grant of a tract of land, lying on the north side of Lake Pepin. The original, duly subscribed by two chiefs, is in my possession; and as an Indian deed of conveyance may prove a curiosity to many readers, I shall here insert a copy of it.

“To Jonathan Carver, a chief under the most mighty and potent George the Third, King of the English and other nations, the fame of whose courageous warriors have reached our ears, and has been more fully told us by our good brother Jonathan aforesaid, whom we rejoice to see come among us, and bring us good news from his country. We, chiefs of the Naudowissies, who have hereto set our seals, do by these presents for ourselves and heirs for ever, in return for the many presents, and other good services done by the said Jonathan to ourselves and allies, give, grant, and convey to him the said Jonathan, and to his heirs and assigns for ever, the whole of a certain tract or territory of land, bounded as follows: (viz.) from the fall of St. Anthony, running on the east banks of the Mississippi, nearly south-east, as far as the south end of Lake Pepin, where the Chipéway river joins the Mississippi, and from thence eastward five days travel, accounting twenty English miles per day, and from thence north six days travel, at twenty English miles per day, and from thence again to the fall of St. Anthony, on a direct straight line. We do for ourselves, heirs, and assigns, for ever, give unto the said Jonathan, his heirs and assigns, for ever, all the said lands, with all the trees, rocks, and rivers therein, reserving for ourselves and heirs the sole liberty of hunting and fishing on land not planted or improved by the said Jonathan, his heirs and assigns, to which we have affixed our respective seals, at the great cave, May the first, one thousand seven hundred and sixty-seven.”

Hawnopawjatin his mark (top)

Otohtongoomlisheaw his mark (bottom)

Soon after the above period, our author concluded to return to Boston, where he arrived in 1768, having been absent two years and five months, during which time he had travelled about seven thousand miles. After digesting his journal and charts, he sailed for England, and arrived there in the year 1769. The reasons which induced him to undertake this voyage, are amply related by himself in his travels (page 177.) to which I refer.

Few objects have excited a more general enquiry than the discovery of a north-west passage, in order to open a communication with the great pacific ocean and the East Indies, by a shorter navigation than by doubling those immense promontories, the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn. Every allurement of gain, and national emolument, has been proposed to encourage the attempt, but, hitherto, every attempt hath been fruitless, though the most experienced seamen have engaged in the undertaking. Our traveller suggested an attempt by land, across the north west parts of North America, and actually drew a chart of his proposed route for effecting his project, which, however visionary it may now be deemed, affords at least a proof of the enterprizing spirit of Captain Carver, and which he would, probably, have attempted, had any encouragement been afforded him: (introd. pag. 6. and append. pag. 539, et seq.)

When he visited England, he appeared with the most favourable credentials of his character in every respect: many of these are now in my possession; but that which seemed to promise the most beneficial advantages, was conferred upon him by General Gage, and, in consequence of a petition presented to the king, and referred to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, our traveller had formed the fond hope of seeing his labours so far rewarded, as to be reimbursed those sums he had expended in the service of government, agreeable to the relation conveyed in the introduction to his travels.

In a large, free, and widely extended government, where every motion depends upon a variety of springs, the lesser and subordinate movements must be acted upon by the greater, and consequently the more inferior operations of state will be so distant, as not to be perceived in the grand machine: whether Captain Carver’s disappointments resulted from these principles, or that government did not estimate his services in equal proportion to his own idea of them, is not so easily ascertained, as that he thought himself not only neglected, but treated with injustice.

The condition of a suppliant is what his mind must have submitted to with reluctance. Men of superior endowments are liable to be jealous of the least inattention, which they are apt to consider as an insult on their distress. A feeling mind, like his, conscious of its dignity and superior merit, might not be able to stoop to that importunity and adulation, which are sometimes requisite to insure the smiles and favours of those in power; otherwise it might naturally be suggested, that his extensive acquaintance with America, and with the customs and languages of the Indians, in the interior parts of that vast continent, then the theatre of an unnatural and bloody contest, would have pointed him out as a most useful instrument in the hands of government.

With the advantages, however, of an intimate knowledge of Indian affairs, he united a determined loyalty to the king, and a fixed attachment to his American countrymen; and thus the principle of acting agreeably to the feelings of conscience, would equally operate upon him respecting the contending parties. He had repeatedly risked his life in the service of his prince, against whose government he was equally averse from drawing his sword, as against his transatlantic brethren: he might not, therefore, be deemed an important acquisition to the ruling powers here, and the prayer of his petition was scarcely heard in the clamours of popular commotion.

Persons of ingenuity, however oppressed by their own sufferings, in a busy commercial country, may strike out some means of subsistence; but, in a domestic state, where many depend upon the industry of an individual, the difficulty of procuring support is not only rendered more affecting to the feeling mind, but likewise greatly augmented. Captain Carver, after having exhausted his fortune, had now a family to support, without knowing how to turn his abilities to any means of succouring them. Distress of mind begets debility of body, which is still aggravated by penury, and a want of the common necessaries of life. His constitution, naturally firm, gradually grew weaker and weaker; but his regard to his family animated his spirit to exertions beyond the strength of his body, which enabled him to preserve existence through the winter of 1779, by acting as a clerk in a lottery-office; but the vital powers, succoured as they were by this casual support, diminished by certain, though imperceptible, degrees, till at length a putrid fever supervening a long continued dysentery brought on by want, put an end to the life of a man, who, after rendering, at the expence of fortune and health, and the risk of life, many important services to his country, perished through want in the first city of the world.

In size, Captain Carver was rather above the middle stature, and of a firm muscular texture; his features expressed a firmness of mind and boldness of resolution; and he retained a florid complexion to his latest moments.

In conversation he was social and affable, where he was familiar; but his extreme diffidence and modesty kept him in general reserved in company. In his familiar epistles, he commanded an easy and agreeable manner of writing; and some pieces of his poetry, which have been communicated to me, afford proofs of his lively imagination and of the harmony of his versification.

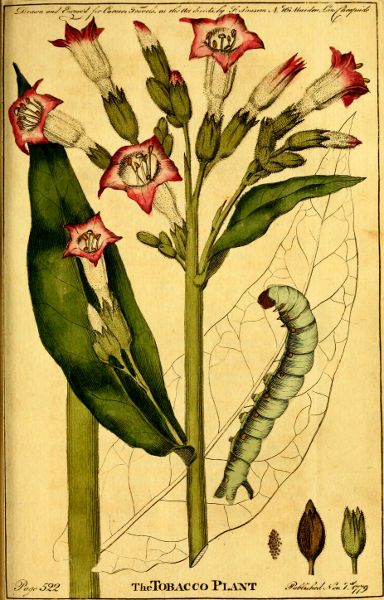

His only authentic publications I have seen are the present work, and a Treatise on the Culture of the Tobacco Plant, anno 1779. The former will speak for itself: the opinion of the public has, indeed, been fully testified by the rapid sale of two large editions of this work in the space of the last two years.

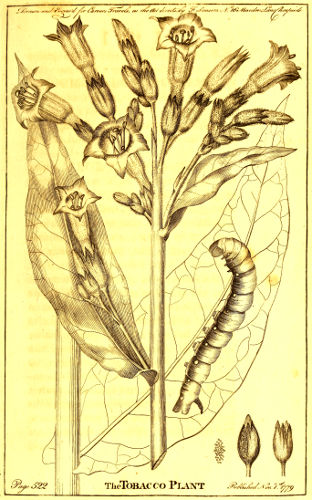

The Treatise on Tobacco is a small octavo of fifty-four pages, containing two engravings of the plant, and an account of its cultivation on the American continent. As this vegetable constitutes one of the most considerable branches of commerce betwixt the old and new hemispheres of the world, and thrives luxuriously in Europe as well as in America, it is now pretty generally known: from the elegance of the plant and beauty of its flowers, it is cultivated in gardens for ornament; in which character it will appear from a view of the annexed engraving of it.

It was first sent into Spain, in 1560: from Tabaco, a province of Yucatan, by Hermandez de Toledo, and from the place of its growth it received the name which it still bears.

Drawn and Engrav’d for Carver’s Travels, as the act directs by F. Sanson N. 16 Maiden Lane Cheapside

The Tobacco Plant

Published Novr. 1st. 1779

It was called, by the French, Nicotiana, after John Nicot, who went soon after it was discovered, as ambassador to that court, from Francis the Second of Portugal, and carried some of it with him.

Before the present contest between Great-Britain and the Colonies, about 96,000 hogsheads were annually imported from Maryland and Virginia, which, with the duties on the home consumption, and the returns on foreign export, produced an immense revenue to this country.

The general uses of Tobacco are well known; besides which, it is found nearly equal to the best oak-bark for tanning leather, especially with thinner sorts of hides; and would probably be used for this purpose, were it as cheap as the bark of the oak.

Few subjects have been more copiously treated on than Tobacco: Monardes, Stephanus, Everhartus, Thorius, Neander, Pauli, have each wrote upon it largely. Neander published a volume on this subject, entitled, Tobacologia, and ornamented it with plates, to exhibit its cultivation and manner of preparation; and, lately, Captain Carver published the above-mentioned Treatise on the Culture of this Plant, with a view to instruct landholders in the method of cultivating it with profit, and to this pamphlet I shall refer the reader for further particulars.

Our author died on the 31st of January 1780, at the age of forty-eight years, and lies interred in Holywell-Mount burying-ground.

| INTRODUCTION, | i |

| The Author sets out from Boston on his Travels, | 17 |

| Description of Fort Michillimackinac, | 18 |

| Description of Fort Le Bay, | 21 |

| Description of the Green Bay, | 26 |

| Description of Lake Michigan, | 28 |

| Arrives at the Town of the Winnebagoes, | 32 |

| Excursion of the Winnebagoes towards the Spanish Settlements, | 35 |

| Description of the Winnebago Lake, | 37 |

| Instance of Resolution of an Indian Woman, | 40 |

| Description of the Fox River, | 41 |

| Remarkable Story of a Rattle Snake, | 43 |

| The great Town of the Saukies, | 46 |

| Upper Town of the Ottagaumies, | 48 |

| Description of the Ouisconsin River, | ib. |

| Lower Town of the Ottagaumies, or La Prairie Le Chien, | 50 |

| An Attack by some Indian Plunderers, | 51 |

| Description of the Mississippi from the Mouth of the Ouisconsin to Lake Pepin, | 54 |

| Description of Lake Pepin, | 55 |

| Remarkable Ruins of an ancient Fortification, | 57 |

| The River Bands of the Naudowessie Indians, | 59 |

| Adventure with a Party of these, and some of the Chipéways, | 60 |

| Description of a remarkable Cave, | 63 |

| Uncommon Behaviour of the Prince of the Winnebagoes at the Falls of St. Anthony, | 66 |

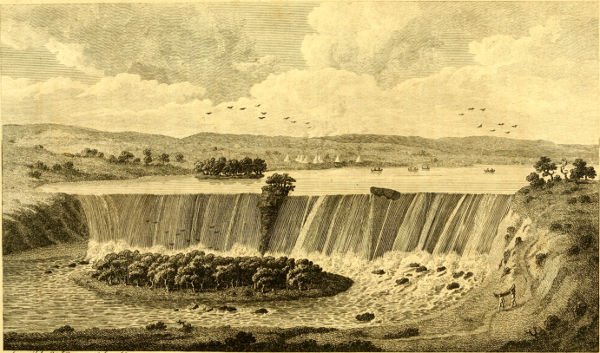

| Description of the Falls, | 69 |

| Extent of the Author’s Travels, | 71 |

| Description of the River St. Pierre, | 74 |

| Sources of the Four great Rivers of North America, | 76 |

| Reflections on their Affinity, | 77 |

| The Naudowessies of the Plains, with whom the Author wintered in the Year 1766, | 80 |

| The Author returns to the Mouth of the River St. Pierre, | 84 |

| Account of a violent Thunder-storm, | 85 |

| Speech made by the Author in a Council held by the Naudowessies at the great Cave, | 86 |

| Adventure with a Party of Indians near Lake Pepin, | 95 |

| Description of the Country adjacent to the River St. Pierre, | 100 |

| Account of different Clays found near the Marble River, | 101 |

| Description of the Chipéway River, | 102 |

| Extraordinary Effects of a Hurricane, | 103 |

| The Author arrives at the Grand Portage on the North-west Borders of Lake Superior, | 107 |

| Account of the Lakes lying farther to the North-west: Lake Bourbon, Lake Winnepeek, Lake Du Bois, Lake La Pluye, Red Lake, &c. | ib. |

| Account of a Nation of Indians supposed to have been tributary to the Mexican Kings, | 118 |

| Account of the shining Mountains, | 121 |

| A singular Prediction of the Chief Priest of the Killistinoes verified, | 123 |

| Description of Lake Superior, | 132 |

| Story of the two Chipéways landing on the Island of Mauropas, | 135 |

| Account of great Quantities of Copper Ore, | 139 |

| Description of the Falls of St. Marie, | 142 |

| Account of Lake Huron, | 144 |

| Account of Saganaum and Thunder Bays, | 145 |

| Extraordinary Phænomenon in the Straights of Michillimackinac, | 146 |

| Description of Lake St. Claire, | 150 |

| Description of the River, Town, and Fort of Detroit, | 153 |

| Remarkable Rain at Detroit, | 153 |

| Attack of Fort Detroit by Pontiac, | 154 |

| Description of Lake Erie, | 166 |

| Description of the River and Falls of Niagara, | 169 |

| Description of Lake Ontario, | 170 |

| Description of the Oniada Lake, Lake Champlain, and Lake George, | 172 |

| Account of a Tract of Land granted to Sir Ferdinando Gorges, and Captain John Mason, | 173 |

| The Author’s Motives for undertaking his Travels, | 177 |

| CHAP. I. | |

| The Origin of the Indians, | 181 |

| Sentiments of various Writers on this Point, | 182 |

| Sentiments of Monsieur Charlevoix, | 192 |

| Sentiments of James Adair, Esq; | 202 |

| Sentiments of the Author of this Work, | 208 |

| Corroboration of the latter by Doctor Robertson | 216 |

| CHAP. II. | |

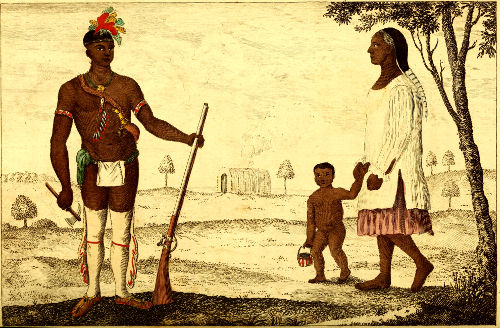

| Of the Persons, Dress, &c. of the Indians, | 219 |

| An Account of those who have written on this Subject, | 220 |

| Description of the Persons of the Indians, | 223 |

| Description of their Dress, | 225 |

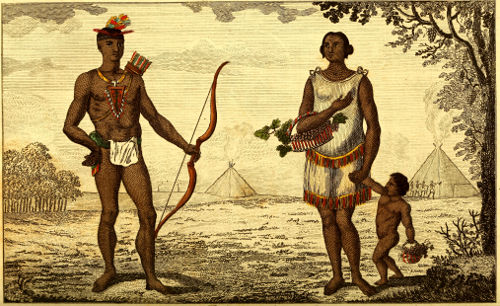

| Description of the Dress of the Ottagaumies, with a Plate, | 229 |

| Description of the Dress of the Naudowessies, with Ditto, | 230 |

| The Manner in which they build their Tents and Huts, | 231 |

| Their domestic Utensils, | 233 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Of the Manners, Qualifications, &c. of the Indians, | 235 |

| Peculiar Customs of the Women, | 236 |

| The circumspect and stoical Disposition of the Men, | 237 |

| Their amazing Sagacity, | 241 |

| Remarkable Story of one of the Naudowessie Women, | 245 |

| The Liberality of the Indians, and their Opinion respecting Money, | 247 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| Their Method of reckoning Time, &c. | 250 |

| The Names by which they distinguish the Months, | 251 |

| Their Idea of the Use of Figures, | 253 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Of their Government, &c. | 255 |

| Their Division into Tribes, | ib. |

| The Chiefs of their Bands, | 257 |

| The Members that compose their Councils, | 259 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Of their Feasts, | 262 |

| Their usual Food, | 263 |

| Their Manner of dressing and eating their Victuals, | 264 |

| CHAP. VII. | |

| Of their Dances, | 266 |

| The Manner in which they dance, | 267 |

| The Pipe or Calumate Dance, | 268 |

| The War Dance, | 269 |

| The Pawwaw Dance, | 270 |

| An uncommon Admission into a Society, among the Naudowessies, | 272 |

| The Dance of the Indians on the Banks of the Mississippi, referred to in the Journal, | 279 |

| The Dance of the Sacrifice, | 282 |

| CHAP. VIII. | |

| Of their Hunting, | 283 |

| Their Preparation before they set out, | 285 |

| Their Manner of hunting the Bear, | 286 |

| Their Manner of hunting the Buffalo, Deer, &c. | 287 |

| Their Manner of hunting the Beaver, | 289 |

| CHAP. IX. | |

| Of their Manner of making War, &c. | 293 |

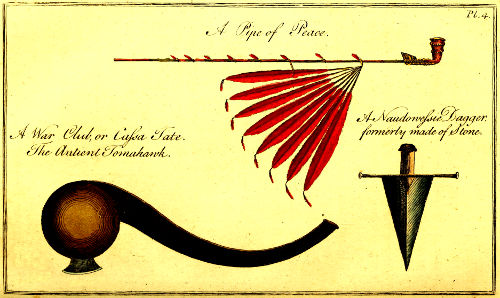

| The Indian Weapons, with a Plate, | 296 |

| Their Motives of making War, | 297 |

| Preparations before they take the Field, | 301 |

| The Manner in which they solicit other Nations to become their Auxiliaries, | 305 |

| Their Manner of declaring War, | 307 |

| Their Method of engaging their Enemies, | 310 |

| An Instance of the Efficacy of it in the Defeat of General Braddock, | 311 |

| A Detail of the Massacre at Fort William-Henry in the Year 1757, | 313 |

| Acuteness and Alacrity of the Indians in pursuing their Enemies, | 327 |

| Their Manner of Scalping, | 328 |

| The Manner in which they retreat and carry off their Prisoners, | 330 |

| A remarkable Instance of Heroism in a Female Prisoner, | 332 |

| Treatment of their Prisoners, | 335 |

| The Origin of their selling Slaves, | 346 |

| CHAP. X. | |

| Of their Manner of making Peace, &c. | 351 |

| Account of an Engagement between the Iroquois and the Ottagaumies and Saukies, | 352 |

| Manner in which they conduct a Treaty of Peace, | 358 |

| Description of the Pipe of Peace, | 359 |

| Description of the Belts of Wampum, | 362 |

| CHAP. XI. | |

| Of their Games, | 363 |

| The Game of the Ball, | 364 |

| The Game of the Bowl or Platter, | 365 |

| CHAP. XII. | |

| Of their Marriage Ceremonies, | 367 |

| The Manner in which the Tribes near Canada celebrate their Marriages, | 369 |

| The Form of Marriage among the Naudowessies, | 373 |

| Their Manner of carrying on an Intrigue, | 375 |

| Of the Indian Names, | 378 |

| CHAP. XIII. | |

| Of their Religion, | 380 |

| Their Ideas of a Supreme Being, | 381 |

| Their Ideas of a future State, | 383 |

| Of their Priests, | 384 |

| The Sentiments of Others on the religious Principles of the Indians opposed, | 386 |

| CHAP. XIV. | |

| Of their Diseases, &c. | 389 |

| The Complaints to which they are chiefly subject, | ib. |

| The Manner in which they construct their Sweating Stoves, | 390 |

| The Methods in which they treat their Diseases, | 391 |

| An extraordinary Instance of the Judgment of an Indian Woman in a desperate Case, | 395 |

| CHAP. XV. | |

| The Manner in which they treat their Dead, | 398 |

| A Specimen of their Funeral Harangues, | 399 |

| Their Method of burying the Dead, | 401 |

| A singular Instance of parental Affection in a Naudowessie Woman, | 403 |

| CHAP. XVI. | |

| A concise Character of the Indians, | 408 |

| Their personal and mental Qualifications, | 409 |

| Their public Character as Members of a Community, | 411 |

| CHAP. XVII. | |

| Of their Language, Hieroglyphicks, &c. | 414 |

| Of the Chipéway Tongue, | 416 |

| Descriptive Specimen of their Hieroglyphicks, | 417 |

| Vocabulary of the Chipéway Language, | 420 |

| Vocabulary of the Naudowessie Language, | 433 |

| CHAP. XVIII. | |

| Of the Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Reptiles, and Insects, which are found in the Interior Parts of North America, | 441 |

| BEASTS. | |

| The Tyger. The Bear, | 442 |

| The Wolf. The Fox, | 444 |

| Dogs. The Cat of the Mountain. The Buffalo, | 445 |

| The Deer, | 446 |

| The Elk, | 447 |

| The Moose, | 448 |

| The Carrabou, | 449 |

| The Carcajou. The Skunk, | 450 |

| The Porcupine, | 453 |

| The Woodchuck. The Racoon, | 454 |

| The Martin. The Musquash, | 455 |

| Squirrels, | 456 |

| The Beaver, | 457 |

| The Otter, | 464 |

| The Mink, | 465 |

| BIRDS. | |

| The Eagle. The Night Hawk, | 466 |

| The Fish Hawk, | 467 |

| The Whipperwill, | 468 |

| The Owl. The Crane. Ducks, | 469 |

| The Teal. The Loon, | 470 |

| The Partridge. The Woodpecker. The Wood Pigeon, | 471 |

| The Blue Jay. The Wakon Bird, | 472 |

| The Blackbird, | 473 |

| The Redbird, | 474 |

| The Whetsaw. The King Bird. The Humming Bird, | 475 |

| FISHES. | |

| The Sturgeon, | 477 |

| The Cat Fish. The Carp. The Chub, | 478 |

| SERPENTS. | |

| The Rattle Snake, | 479 |

| The Long Black Snake, | 485 |

| The Striped or Garter Snake. The Water Snake. The Hissing Snake. The Green Snake. The Thorn-tail Snake, | 486 |

| The Speckled Snake. The Ring Snake. The Two-headed Snake, | 487 |

| The Tortoise or Land Turtle, | 488 |

| LIZARDS. | |

| The Swift Lizard. The Slow Lizard. The Tree Toad, | 488, 489 |

| INSECTS. | |

| The Silk Worm, | 490 |

| The Tobacco Worm. The Bee. The Lightning Bug or Fire Fly, | 491 |

| The Water Bug. The Horned Bug. The Locust, | 493 |

| CHAP. XIX. | |

| Of the Trees, Shrubs, Roots, Herbs, Flowers, | 494 |

| TREES. | |

| The Oak, | 495 |

| The Pine Tree. The Maple, | 496 |

| The Ash, | 497 |

| The Hemlock Tree, | 498 |

| The Bass or White Wood. The Wickopick or Suckwick. The Button Wood, | 499 |

| NUT TREES. | |

| The Butter or Oil Nut, | 500 |

| The Beech Nut. The Pecan Nut, | 501 |

| The Hickory, | 502 |

| FRUIT TREES. | |

| The Vine. The Mulberry Tree. The Crab Apple Tree. The Plum Tree, | 503 |

| The Cherry Tree, | 504 |

| The Sweet Gum Tree, | 505 |

| SHRUBS. | |

| The Willow. Shin Wood, | 506 |

| The Sassafras. The Prickly Ash, | 507 |

| The Moose Wood. The Spoon Wood. The Elder, | 508 |

| The Shrub Oak. The Witch Hazle, | 509 |

| The Myrtle Wax Tree. Winter Green, | 510 |

| The Fever Bush. The Cranberry Bush, | 511 |

| The Choak Berry, | 512 |

| ROOTS and PLANTS. | |

| Spikenard. Sarsaparilla, | 513 |

| Ginsang. Gold Thread, | 514 |

| Solomon’s Seal. Devil’s Bit, | 515 |

| Blood Root, | 516 |

| HERBS. | |

| Sanicle. Rattle Snake Plantain, | 517 |

| Poor Robin’s Plantain. Toad Plantain. Rock Liverwort. Gargit or Skoke. | 518 |

| Skunk Cabbage or Poke, | 519 |

| Wake Robin. Wild Indico. Cat Mint, | 520 |

| FLOWERS, | 521 |

| FARINACEOUS and LEGUMINOUS ROOTS, &c. | |

| Maize or Indian Corn, | 522 |

| Wild Rice, | 523 |

| Beans. The Squash, | 526 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| The Probability of the interior Parts of North America becoming Commercial Colonies, | 527 |

| The Means by which this might be effected, | 529 |

| Tracts of Land pointed out, on which Colonies may be established with the greatest Advantage, | 531 |

| Dissertation on the Discovery of a North-west Passage, | 539 |

| The most certain Way of attaining it, | 540 |

| Plan proposed by Richard Whitworth, Esq. for making an Attempt from a Quarter hitherto unexplored, | 441 |

| The Reason of its being postponed, | 543 |

NO sooner was the late War with France concluded, and Peace established by the Treaty of Versailles in the Year 1763, than I began to consider (having rendered my country some services during the war) how I might continue still serviceable, and contribute, as much as lay in my power, to make that vast acquisition of territory, gained by Great Britain, in North America advantageous to it. It appeared to me indispensably needful, that Government should be acquainted in the first place with the true state of the dominions they were now become possessed of. To this purpose, I determined, as the next proof of my zeal, to explore the most unknown parts of them, and to spare no trouble or expence in acquiring a knowledge that promised to be so useful to my countrymen. I knew that many obstructions would arise to my scheme from the want of good Maps and Charts; for the French, whilst they retained their power in North America, had taken every artful method to keep all other nations, particularly the English, in ignorance of the concerns of the interior parts of it: and to accomplish this design with the greater certainty, they had published inaccurate maps and false accounts; calling the different nations of the Indians by nicknames they had given them, and not by those really appertaining to them. Whether the intention of the French in doing this, was to prevent these nations from being discovered and traded with, or to conceal their discourse, when they talked to each other of the Indian concerns, in their presence, I will not determine; but whatsoever was the cause from which it arose, it tended to mislead.

As a proof that the English had been greatly deceived by these accounts, and that their knowledge relative to Canada had usually been very confined, before the conquest of Crown-Point in 1759, it had been esteemed an impregnable fortress: but no sooner was it taken, than we were convinced that it had acquired its greatest security from false reports, given out by its possessors, and might have been battered down with a few four pounders. Even its situation, which was represented to be so very advantageous, was found to owe its advantages to the same source. It cannot be denied but that some maps of these countries have been published by the French with an appearance of accuracy; but these are of so small a size and drawn on so minute a scale, that they are nearly inexplicable. The sources of the Mississippi, I can assert from my own experience, are greatly misplaced; for when I had explored them, and compared their situation with the French Charts, I found them very erroneously represented, and am satisfied that these were only copied from the rude sketches of the Indians.

Even so lately as their evacuation of Canada they continued their schemes to deceive; leaving no traces by which any knowledge might accrue to their conquerors: for though they were well acquainted with all the Lakes, particularly with Lake Superior, having constantly a vessel of considerable burthen thereon, yet their plans of them are very incorrect. I discovered many errors in the descriptions given therein of its Islands and Bays, during a progress of eleven hundred miles that I coasted it in canoes. They likewise, on giving up the possession of them, took care to leave the places they had occupied in the same uncultivated state they had found them; at the same time destroying all their naval force. I observed myself part of the hulk of a very large vessel, burnt to the water’s edge, just at the opening from the Straits of St. Marie’s into the Lake.

These difficulties, however, were not sufficient to deter me from the undertaking, and I made preparations for setting out. What I chiefly had in view, after gaining a knowledge of the Manners, Customs, Languages, Soil, and natural Productions of the different nations that inhabit the back of the Mississippi, was to ascertain the Breadth of that vast continent, which extends from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, in its broadest part between 43 and 46 Degrees Northern Latitude. Had I been able to accomplish this, I intended to have proposed to Government to establish a Post in some of those parts about the Straits of Annian, which having been first discovered by Sir Francis Drake, of course belong to the English. This I am convinced would greatly facilitate the discovery of a North-west Passage, or a communication between Hudson’s Bay and the Pacific Ocean. An event so desirable, and which has been so often sought for, but without success. Besides this important end, a settlement on that extremity of America would answer many good purposes, and repay every expence the establishment of it might occasion. For it would not only disclose new sources of trade, and promote many useful discoveries, but would open a passage for conveying intelligence to China, and the English settlements in the East Indies, with greater expedition than a tedious voyage by the Cape of Good Hope, or the Straits of Magellan will allow of.

How far the advantages arising from such an enterprize may extend can only be ascertained by the favourable concurrence of future events. But that the completion of the scheme, I have had the honour of first planning and attempting, will some time or other be effected, I make no doubt. From the unhappy divisions that at present subsist between Great Britain and America, it will probably be some years before the attempt is repeated; but whenever it is, and the execution of it carried on with propriety, those who are so fortunate as to succeed, will reap, exclusive of the national advantages that must ensue, Emoluments beyond their most sanguine expectations. And whilst their spirits are elated by their success, perhaps they may bestow some commendations and blessings on the person that first pointed out to them the way. These, though but a shadowy recompence for all my toil, I shall receive with pleasure.

To what power or authority this new world will become dependent, after it has arisen from its present uncultivated state, time alone can discover. But as the seat of Empire from time immemorial has been gradually progressive towards the West, there is no doubt but that at some future period, mighty kingdoms will emerge from these wildernesses, and stately palaces and solemn temples, with gilded spires reaching the skies, supplant the Indian huts, whose only decorations are the barbarous trophies of their vanquished enemies.

As some of the preceding passages have already informed the Reader that the plan I had laid down for penetrating to the Pacific Ocean, proved abortive, it is necessary to add, that this proceeded not from its impracticability (for the farther I went the more convinced I was that it could certainly be accomplished) but from unforeseen disappointments. However, I proceeded so far, that I was able to make such discoveries as will be useful in any future attempt, and prove a good foundation for some more fortunate Successor to build upon. These I shall now lay before the Public in the following pages; and am satisfied that the greatest part of them have never been published by any person that has hitherto treated of the interior Nations of the Indians; particularly, the account I give of the Naudowessies, and the situation of the Heads of the four great rivers that take their rise within a few leagues of each other, nearly about the center of this great continent; viz. The River Bourbon, which empties itself into Hudson’s Bay; the Waters of Saint Lawrence; the Mississippi, and the River Oregon, or the River of the West, that falls into the Pacific Ocean at the Straits of Annian.

The impediments that occasioned my returning, before I had accomplished my purposes, were these. On my arrival at Michillimackinac, the remotest English post, in September 1766, I applied to Mr. Rogers, who was then governor of it, to furnish me with a proper assortment of goods, as presents for the Indians who inhabit the track I intended to pursue. He did this only in part; but promised to supply me with such as were necessary, when I reached the Falls of Saint Anthony. I afterwards learned that the governor fulfilled his promise in ordering the goods to be delivered to me; but those to whose care he intrusted them, instead of conforming to his orders, disposed of them elsewhere.

Disappointed in my expectations from this quarter, I thought it necessary to return to La Prairié Le Chien; for it was impossible to proceed any farther without presents to ensure me a favorable reception. This I did in the beginning of the year 1767, and finding my progress to the Westward thus retarded, I determined to direct my course Northward. I took this step with a view of finding a communication from the Heads of the Mississippi into Lake Superior, in order to meet, at the grand Portage on the North-west side of that lake, the traders that usually come, about this season, from Michillimackinac. Of these I intended to purchase goods, and then to pursue my journey from that quarter by way of the lakes de Pluye, Dubois, and Ounipique to the Heads of the river of the West, which, as I have said before, falls into the Straits of Annian, the termination of my intended progress.

I accomplished the former part of my design, and reached Lake Superior in proper time; but unluckily the traders I met there acquainted me, that they had no goods to spare; those they had with them being barely sufficient to answer their own demands in these remote parts. Thus disappointed a second time, I found myself obliged to return to the place from whence I began my expedition, which I did after continuing some months on the North and East borders of Lake Superior, and exploring the Bays and Rivers that empty themselves into this large body of water.

As it may be expected that I should lay before the Public the reasons that these discoveries, of so much importance to every one who has any connections with America, have not been imparted to them before, notwithstanding they were made upwards of ten years ago, I will give them to the world in a plain and candid manner, and without mingling with them any complaints on account of the ill treatment I have received.

On my arrival in England, I presented a petition to his Majesty in council, praying for a reimbursement of those sums I had expended in the service of government. This was referred to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations. Their Lordships from the tenor of it thought the intelligence I could give of so much importance to the nation that they ordered me to appear before the Board. This message I obeyed, and underwent a long examination; much I believe to the satisfaction of every Lord present. When it was finished, I requested to know what I should do with my papers; without hesitation the first Lord replied, That I might publish them whenever I pleased. In consequence of this permission, I disposed of them to a bookseller: but when they were nearly ready for the press, an order was issued from the council board, requiring me to deliver, without delay, into the Plantation Office, all my Charts and Journals, with every paper relative to the discoveries I had made. In order to obey this command, I was obliged to re-purchase them from the bookseller, at a very great expence, and deliver them up. This fresh disbursement I endeavoured to get annexed to the account I had already delivered in; but the request was denied me, notwithstanding I had only acted, in the disposal of my papers, conformably to the permission I had received from the Board of Trade. This loss, which amounted to a very considerable sum, I was obliged to bear, and to rest satisfied with an indemnification for my other expences.

Thus situated, my only expectations are from the favour of a generous Public; to whom I shall now communicate my Plans, Journals, and Observations, of which I luckily kept copies, when I delivered the originals into the Plantation Office. And this I do the more readily, as I hear they are mislaid; and there is no probability of their ever being published. To those who are interested in the concerns of the interior parts of North America, from the contiguity of their possessions, or commercial engagements, they will be extremely useful, and fully repay the sum at which they are purchased. To those, who, from a laudable curiosity, wish to be acquainted with the manners and customs of every inhabitant of this globe, the accounts here given of the various nations that inhabit so vast a track of it, a country hitherto almost unexplored, will furnish an ample fund of amusement and gratify their most curious expectations. And I flatter myself they will be as favourably received by the Public, as descriptions of islands, which afford no other entertainment than what arises from their novelty; and discoveries, that seem to promise very few advantages to this country, though acquired at an immense expence.

To make the following Work as comprehensible and entertaining as possible, I shall first give my Readers an account of the route I pursued over this immense continent (through which they will be able to attend me by referring to the plan prefixed) and as I pass on, describe the number of Inhabitants, the situation of the Rivers and Lakes, and the productions of the country. Having done this, I shall treat, in distinct Chapters, of the Manners, Customs, and Languages of the Indians, and to complete the whole, add a Vocabulary of the Words mostly in use among them.

And here it is necessary to bespeak the candour of the learned part of my Readers in the perusal of it, as it is the production of a person unused, from opposite avocations, to literary pursuits. He therefore begs they would not examine it with too critical an eye; especially when he assures them that his attention has been more employed on giving a just description of a country that promises, in some future period, to be an inexhaustible source of riches to that people who shall be so fortunate as to possess it, than on the style or composition; and more careful to render his language intelligible and explicit, than smooth and florid.

IN June 1766, I set out from Boston, and proceeded by way of Albany and Niagara, to Michillimackinac; a Fort situated between the Lakes Huron and Michigan, and distant from Boston 1300 miles. This being the uttermost of our factories towards the north-west, I considered it as the most convenient place from whence I could begin my intended progress, and enter at once into the Regions I designed to explore.

Referring my Readers to the publications already extant for an Account of those Parts of North America, that, from lying adjacent to the Back-Settlements, have been frequently described, I shall confine myself to a Description of the more interior parts of it, which having been but seldom visited, are consequently but little known. In doing this, I shall in no instance exceed the bounds of truth, or have recourse to those useless and extravagant exaggerations too often made use of by travellers, to excite the curiosity of the public, or to increase their own importance. Nor shall I insert any observations, but such as I have made myself, or, from the credibility of those by whom they were related, am enabled to vouch for their authenticity.

Michillimackinac, from whence I began my travels, is a Fort composed of a strong stockade, and is usually defended by a garrison of one hundred men. It contains about thirty houses, one of which belongs to the governor, and another to the commissary. Several traders also dwell within its fortifications, who find it a convenient situation to traffic with the neighbouring nations. Michillimackinac, in the language of the Chipéway Indians, signifies a Tortoise; and the place is supposed to receive its name from an Island, lying about six or seven miles to the north-east, within light of the Fort, which has the appearance of that animal.

During the Indian war that followed soon after the Conquest of Canada in the year 1763, and which was carried on by an army of confederate nations composed of the Hurons, Miamies, Chipéways, Ottowaws, Pontowattimies, Mississauges, and some other tribes, under the direction of Pontiac, a celebrated Indian warrior, who had always been in the French interest, it was taken by surprize in the following manner: The Indians having settled their plan, drew near the Fort, and began a game at Ball, a pastime much used among them, and not unlike tennis. In the height of their game, at which some of the English officers, not suspecting any deceit, stood looking on, they struck the ball, as if by accident, over the stockade; this they repeated two or three times, to make the deception more complete; till at length, having by this means lulled every suspicion of the centry at the south gate, a party rushed by him; and the rest soon following, they took possession of the Fort, without meeting with any opposition. Having accomplished their design, the Indians had the humanity to spare the lives of the greatest part of the garrison and traders, but they made them all prisoners, and carried them off. However some time after they took them to Montreal, where they were redeemed at a good price. The Fort also was given up again to the English at the peace made with Pontiac by the commander of Detroit the year following.

Having here made the necessary dispositions for pursuing my travels, and obtained a credit from Mr. Rogers, the governor, on some English and Canadian traders who were going to trade on the Mississippi, and received also from him a promise of a fresh supply of goods when I reached the Falls of Saint Anthony, I left the Fort on the 3d of September, in company with these traders. It was agreed, that they should furnish me with such goods as I might want, for presents to the Indian chiefs, during my continuance with them, agreeable to the governor’s order. But when I arrived at the extent of their route, I was to find other guides, and to depend on the goods the governor had promised to supply me with.

We accordingly set out together, and on the 18th arrived at Fort La Bay. This Fort is situated on the southern extremity of a Bay in Lake Michigan, termed by the French the Bay of Puants; but which, since the English have gained possession of all the settlements on this part of the Continent, is called by them the Green Bay. The reason of its being thus denominated, is from its appearance; for on leaving Michillimackinac in the spring season, though the trees there have not even put forth their buds, yet you find the country around La Bay, notwithstanding the passage has not exceeded fourteen days, covered with the finest verdure, and vegetation as forward as it could be were it summer.

This Fort, also, is only surrounded by a stockade, and being much decayed is scarcely defensible against small arms. It was built by the French for the protection of their trade, some time before they were forced to relinquish it; and when Canada and its dependencies were surrendered to the English, it was immediately garrisoned with an officer and thirty men. These were made prisoners by the Menomonies soon after the surprise of Michillimackinac, and the Fort has neither been garrisoned or kept in repair since.

The Bay is about ninety miles long, but differs much in its breadth; being in some places only fifteen miles, in others from twenty to thirty. It lies nearly from north-east to south-west. At the entrance of it from the Lake are a string of islands, extending from north to south, called the Grand Traverse. These are about thirty miles in length, and serve to facilitate the passage of canoes, as they shelter them from the winds, which sometimes come with violence across the Lake. On the side that lies to the south-east is the nearest and best navigation.

The islands of the Grand Traverse are mostly small and rocky. Many of the rocks are of an amazing size, and appear as if they had been fashioned by the hands of artists. On the largest and best of these islands stands a town of the Ottowaws, at which I found one of the most considerable chiefs of that nation, who received me with every honour he could possibly show to a stranger. But what appeared extremely singular to me at the time, and must do so to every person unacquainted with the customs of the Indians, was the reception I met with on landing. As our canoes approached the shore, and had reached within about threescore rods of it, the Indians began a feu-de-joy; in which they fired their pieces loaded with balls; but at the same time they took care to discharge them in such a manner, as to fly a few yards above our heads: during this they ran from one tree or stump to another, shouting and behaving as if they were in the heat of battle. At first I was greatly surprised, and was on the point of ordering my attendants to return their fire, concluding that their intentions were hostile; but being undeceived by some of the traders, who informed me that this was their usual method of receiving the chiefs of other nations, I considered it in its true light, and was pleased with the respect thus paid me.

I remained here one night. Among the presents I made the chiefs, were some spirituous liquors; with which they made themselves merry, and all joined in a dance, that lasted the greatest part of the night. In the morning when I departed, the chief attended me to the shore, and, as soon as I had embarked, offered up, in an audible voice, and with great solemnity, a fervent prayer in my behalf. He prayed “that the Great Spirit would favour me with a prosperous voyage; that he would give me an unclouded sky, and smooth waters, by day, and that I might lie down, by night, on a beaver blanket, enjoying uninterrupted sleep, and pleasant dreams; and also that I might find continual protection under the great pipe of peace.” In this manner he continued his petitions till I could no longer hear them.

I must here observe, that notwithstanding the inhabitants of Europe are apt to entertain horrid ideas of the ferocity of these savages, as they are termed, I received from every tribe of them in the interior parts, the most hospitable and courteous treatment; and am convinced, that till they are contaminated by the example and spirituous liquors of their more refined neighbours, they retain this friendly and inoffensive conduct towards strangers. Their inveteracy and cruelty to their enemies I acknowledge to be a great abatement of the favourable opinion I would wish to entertain of them; but this failing is hereditary, and having received the sanction of immemorial custom, has taken too deep root in their minds to be ever extirpated.

Among this people I eat of a very uncommon kind of bread. The Indians, in general, use but little of this nutritious food: whilst their corn is in the milk, as they term it, that is, just before it begins to ripen, they slice off the kernels from the cob to which they grow, and knead them into a paste. This they are enabled to do without the addition of any liquid, by the milk that flows from them; and when it is effected, they parcel it out into cakes, and inclosing them in leaves of the basswood tree, place them in hot embers, where they are soon baked. And better flavoured bread I never eat in any country.

This place is only a small village containing about twenty-five houses and sixty or seventy warriors. I found nothing there worthy of further remark.

The land on the south-east side of the Green Bay is but very indifferent, being overspread with a heavy growth of hemlock, pine, spruce and fir trees. The communication between Lake Michigan and the Green Bay has been reported by some to be impracticable for the passage of any vessels larger than canoes or boats, on account of the shoals that lie between the islands in the Grand Traverse; but on sounding it I found sufficient depth for a vessel of sixty tons, and the breadth proportionable.

The land adjoining to the bottom of this Bay is very fertile, the country in general level, and the perspective view of it pleasing and extensive.

A few families live in the Fort, which lies on the west-side of the Fox River, and opposite to it, on the east side of its entrance, are some French settlers who cultivate the land, and appear to live very comfortably.

The Green Bay or Bay of Puants is one of those places to which the French, as I have mentioned in the Introduction, have given nicknames. It is termed by the inhabitants of its coasts, the Menomonie Bay; but why the French have denominated it the Puant or Stinking Bay I know not. The reason they themselves give for it is, that it was not with a view to mislead strangers, but that by adopting this method they could converse with each other, concerning the Indians, in their presence, without being understood by them. For it was remarked by the persons who first traded among them, that when they were speaking to each other about them, and mentioned their proper name, they instantly grew suspicious, and concluded that their visiters were either speaking ill of them, or plotting their destruction. To remedy this they gave them some other name. The only bad consequence arising from the practice then introduced is, that English and French geographers, in their plans of the interior parts of America, give different names to the same people, and thereby perplex those who have occasion to refer to them.

Lake Michigan, of which the Green Bay is a part, is divided on the north-east from Lake Huron by the Straits of Michillimackinac; and is situated between forty-two and forty-six degrees of latitude, and between eighty-four and eighty-seven degrees of west longitude. Its greatest length is two hundred and eighty miles, its breadth about forty, and its circumference nearly six hundred. There is a remarkable string of small islands beginning over against Atkin’s Farm, and running about thirty miles south-west into the Lake. These are called the Beaver Islands. Their situation is very pleasant, but the soil is bare. However they afford a beautiful prospect.

On the north-west parts of this Lake the waters branch out into two bays. That which lies towards the north is the Bay of Noquets, and the other the Green Bay just described.

The waters of this as well as the other great Lakes are clear and wholesome, and of sufficient depth for the navigation of large ships. Half the space of the country that lies to the east, and extends to Lake Huron, belongs to the Ottowaw Indians. The line that divides their territories from the Chipéways, runs nearly north and south, and reaches almost from the southern extremity of this Lake, across the high lands, to Michillimackinac, through the center of which it passes. So that when these two tribes happen to meet at the factory, they each encamp on their own dominions, at a few yards distance from the stockade.

The country adjacent either to the east or west side of this lake is composed but of an indifferent soil, except where small brooks or rivers empty themselves into it; on the banks of these it is extremely fertile. Near the borders of the Lake grow a great number of sand cherries, which are not less remarkable for their manner of growth, than for their exquisite flavour. They grow upon a small shrub not more than four feet high, the boughs of which are so loaded that they lie in clusters on the sand. As they grow only on the sand, the warmth of which probably contributes to bring them to such perfection, they are called by the French, cherries de sable, or sand cherries. The size of them does not exceed that of a small musket ball, but they are reckoned superior to any other sort for the purpose of steeping in spirits. There also grow around the Lake gooseberries, black currants, and an abundance of juniper, bearing great quantities of berries of the finest sort.

Sumack likewise grows here in great plenty; the leaf of which, gathered at Michaelmas when it turns red, is much esteemed by the natives. They mix about an equal quantity of it with their tobacco, which causes it to smoke pleasantly. Near this Lake, and indeed about all the great lakes, is found a kind of willow, termed by the French, bois rouge, in English red wood. Its bark, when only of one year’s growth, is of a fine scarlet colour, and appears very beautiful; but as it grows older, it changes into a mixture of grey and red. The stalks of this shrub grow many of them together, and rise to the height of six or eight feet, the largest not exceeding an inch diameter. The bark being scraped from the sticks, and dried and powdered, is also mixed by the Indians with their tobacco, and is held by them in the highest estimation for their winter smoaking. A weed that grows near the great lakes, in rocky places, they use in the summer season. It is called by the Indians, Segockimac, and creeps like a vine on the ground, sometimes extending to eight or ten feet, and bearing a leaf about the size of a silver penny, nearly round; it is of the substance and colour of the laurel, and is, like the tree it resembles, an evergreen. These leaves, dried and powdered, they likewise mix with their tobacco; and, as said before, smoak it only during the summer. By these three succedaneums the pipes of the Indians are well supplied through every season of the year; and as they are great smoakers, they are very careful in properly gathering and preparing them.

On the 20th of September I left the Green Bay, and proceeded up Fox River, still in company with the traders and some Indians. On the 25th I arrived at the great town of the Winnebagoes, situated on a small island just as you enter the east end of Lake Winnebago. Here the queen who presided over this tribe instead of a Sachem, received me with great civility, and entertained me in a very distinguished manner, during the four days I continued with her.

The day after my arrival I held a council with the chiefs, of whom I asked permission to pass through their country, in my way to more remote nations on business of importance. This was readily granted me, the request being esteemed by them as a great compliment paid to their tribe. The Queen sat in the council, but only asked a few questions, or gave some trifling directions in matters relative to the state; for women are never allowed to sit in their councils, except they happen to be invested with the supreme authority, and then it is not customary for them to make any formal speeches as the chiefs do. She was a very ancient woman, small in stature, and not much distinguished by her dress from several young women that attended her. These her attendants seemed greatly pleased whenever I showed any tokens of respect to their queen, particularly when I saluted her, which I frequently did to acquire her favour. On these occasions the good old lady endeavoured to assume a juvenile gaiety, and by her smiles showed she was equally pleased with the attention I paid her.

The time I tarried here, I employed in making the best observations possible on the country, and in collecting the most certain intelligence I could of the origin, language, and customs of this people. From these enquiries I have reason to conclude, that the Winnebagoes originally resided in some of the provinces belonging to New Mexico; and being driven from their native country, either by intestine divisions, or by the extension of the Spanish conquests, they took refuge in these more northern parts about a century ago.

My reasons for adopting this supposition, are, first from their unalienable attachment to the Naudowessie Indians (who, they say, gave them the earliest succour during their emigration) notwithstanding their present residence is more than six hundred miles distant from that people.

Secondly, that their dialect totally differs from every other Indian nation yet discovered; it being a very uncouth guttural jargon, which none of their neighbours will attempt to learn. They converse with other nations in the Chipéway tongue, which is the prevailing language throughout all the tribes, from the Mohawks of Canada to those who inhabit the borders of the Mississippi, and from the Hurons and Illinois to such as dwell near Hudson’s Bay.

Thirdly, from their inveterate hatred to the Spaniards. Some of them informed me that they had made many excursions to the south-west, which took up several moons. An elderly chief more particularly acquainted me, that about forty-six winters ago, he marched, at the head of fifty warriors, towards the south-west, for three moons. That during this expedition, whilst they were crossing a plain, they discovered a body of men on horseback, who belonged to the Black People; for so they call the Spaniards. As soon as they perceived them, they proceeded with caution, and concealed themselves till night came on; when they drew so near as to be able to discern the number and situation of their enemies. Finding they were not able to cope with so great a superiority by day-light, they waited till they had retired to rest; when they rushed upon them, and, after having killed the greatest part of the men, took eighty horses loaded with what they termed white stone. This I suppose to have been silver, as he told me the horses were shod with it, and that their bridles were ornamented with the same. When they had satiated their revenge, they carried off their spoil, and being got so far as to be out of the reach of the Spaniards that had escaped their fury, they left the useless and ponderous burthen, with which the horses were loaded, in the woods, and mounting themselves, in this manner returned to their friends. The party they had thus defeated, I conclude to be the caravan that annually conveys to Mexico, the silver which the Spaniards find in great quantities on the mountains lying near the heads of the Coloredo River: and the plains where the attack was made, probably, some they were obliged to pass over in their way to the heads of the River St. Fee, or Rio del Nord, which falls into the Gulph of Mexico to the west of the Mississippi.

The Winnebagoes can raise about two hundred warriors. Their town contains about fifty houses, which are strongly built with palisades, and the island on which it is situated nearly fifty acres. It lies thirty-five miles, reckoning according to the course of the river, from the Green Bay.

The River, for about four or five miles from the Bay, has a gentle current; after that space, till you arrive at the Winnebago Lake, it is full of rocks and very rapid. At many places we were obliged to land our canoes, and carry them a considerable way. Its breadth, in general, from the Green Bay to the Winnebago Lake, is between seventy and a hundred yards: the land on its borders very good, and thinly wooded with hickery, oak, and hazel.

The Winnebago Lake is about fifteen miles long from east to west, and six miles wide. At its south-east corner, a river falls into it that takes its rise near some of the northern branches of the Illinois River. This I called the Crocodile River, in consequence of a story that prevails among the Indians, of their having destroyed, in some part of it, an animal, which from their description must be a crocodile or an alligator.

The land adjacent to the Lake is very fertile, abounding with grapes, plums, and other fruits, which grow spontaneously. The Winnebagoes raise on it a great quantity of Indian corn, beans, pumpkins, squash, and water melons, with some tobacco. The Lake itself abounds with fish, and in the fall of the year, with geese, ducks, and teal. The latter, which resort to it in great numbers, are remarkably good and extremely fat, and are much better flavoured than those that are found near the sea, as they acquire their excessive fatness by feeding on the wild rice, which grow so plentifully in these parts.

Having made some acceptable presents to the good old queen, and received her blessing, I left the town of the Winnebagoes on the 29th of September, and about twelve miles from it arrived at the place where the Fox River enters the Lake on the north side of it. We proceeded up this river, and on the 7th of October reached the great Carrying Place, which divides it from the Ouisconsin.

The Fox River, from the Green Bay to the Carrying Place, is about one hundred and eighty miles. From the Winnebago Lake to the Carrying Place the current is gentle, and the depth of it considerable; notwithstanding which, in some places it is with difficulty that canoes can pass, through the obstructions they meet with from the rice stalks, which are very large and thick, and grow here in great abundance. The country around it is very fertile and proper in the highest degree for cultivation, excepting in some places near the River, where it is rather too low. It is in no part very woody, and yet can supply sufficient to answer the demands of any number of inhabitants. This river is the greatest resort for wild fowl of every kind that I met with in the whole course of my travels; frequently the sun would be obscured by them for some minutes together.

About forty miles up this river, from the great town of the Winnebagoes, stands a smaller town belonging to that nation.

Deer and bears are very numerous in these parts, and a great many beavers and other furs are taken on the streams that empty themselves into this river.

The River I am treating of, is remarkable for having been, about eighty years ago, the residence of the united bands of the Ottigaumies and the Saukies, whom the French had nicknamed, according to their wonted custom, Des Sacs and Des Reynards, the Sacks and the Foxes, of whom the following anecdote was related to me by an Indian.