The Project Gutenberg EBook of What Do You Read?, by Boyd Ellanby This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: What Do You Read? Author: Boyd Ellanby Release Date: August 21, 2015 [EBook #49754] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT DO YOU READ? *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By Boyd Ellanby

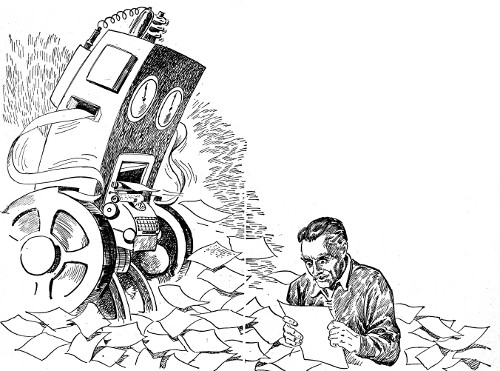

Illustrated by Malcolm Smith

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Other Worlds March

1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Writers have long dreamed of a plot machine, but the machines in Script-Lab did much more than plot the story—they wrote it. Why bother with human writers when the machines did the job so much faster and better?

Herbert would have preferred the seclusion of a coptor-taxi, but he knew he could not afford it. The Bureau paid its writers adequately, but not enough to make them comfortable in taxis. In front of his apartment house, he took the escalator to the Airway. It must have been pleasant, he thought as he stepped onto the moving sidewalk, to be a writer in the days when they were permitted to receive royalties and, presumably, to afford taxi fare.

On the rare occasions when he was forced to travel in the city, he usually tried to insulate himself from the Airway crowds by trying to construct new plots for his fiction. In his younger days, of course, he had occupied the time in reading the classics, but lately, so great was the confusion of the city, he preferred to close his eyes, and try to devise a reverse twist for one of his old stories.

Today, he found it harder than usual to concentrate. The Airway was crowded, and he had never heard the people so noisy. Up ahead half a block, there was a sharp scream. Herbert opened his eyes and peered ahead to see what had happened. Someone had been pushed through the railing of the Airway, and as his section rolled on and passed, he could see lying on the pavement below the body of a young cripple, his hands still holding a broken crutch.

Herbert shuddered. He felt sick, and closed his eyes again.

"Wonder how that happened?" said the man in front of him.

"He probably got in the way," said a girl, callously.

The man ahead made no comment, and Herbert dismissed his own puzzlement. Could he make a plot out of this incident of the crippled boy? he wondered.

He shifted to the slower track, descended the escalator, and stepped onto the street across from the Bureau of Public Entertainment. He had to wait a moment, for an ambulance was clanging down the street; then he crossed to the stone-faced building.

As he rode up the elevator, he wondered again why John had ordered him to come to lunch. He realized that he was no longer a young man, but he certainly did not feel ready to be pensioned. And in the last year he had actually written more fiction than in any other year of his life. Very little of it had been used, for some reason, but story for story he thought it matched any of his previous output.

Ludwig received him with little ceremony. "Sit down, Herbert. It was good of you to come. Miss Dodson," he called through the intercom, "this is strictly off the air. Nothing is to be recorded. Is that clear?"

"Well, John," said Carre. "You're looking harassed, if I may say so. Are they working you too hard? Or are you just faced with the unpleasant job of firing an old friend? I realize, of course, that AFE aren't using much of my stuff just now."

Ludwig smiled unhappily and shook his head. "I'm not planning to fire you, Herbert. But you know, of course, that you're in the same boat with the other Writers, and that boat is in choppy waters. Frankly, I'm not very happy about the situation. The five-year experimental period is coming to an end. This Bureau has the job of providing entertainment, and that includes, among many other categories, literature. Books, articles, and stories. And I'm faced with a difficult decision: shall we employ Writers, or use Script-Lab? You are only one of the many people we support, of course, and both you and Script-Lab furnish material to Adult Fiction, Earth, who distribute it as they see fit."

Herbert Carre nibbled at his graying moustache. "I know. And for the last year, for some reason, AFE has not seen fit to use much of my stuff. And yet it's no different. I write just the same sort of thing I always did."

"Tastes change, Herbert. Script-Lab reports that the public seem to prefer the machine-made stories. I have a week to make a definite decision, and I'm particularly anxious to finish the job because I've been asked to transfer, at the earliest possible moment, to the Bureau of Public Safety. The Committee are inclined, on the whole, to favor the enlarging of Script-Lab, and transferring all the Writers to some other department."

"Great Gamma! You mean all literature will be machine-made from now on?"

"Don't get excited, Herb! That's what I've got to decide. But if they can really write it just as well, why not? You remember Hartridge, don't you? Class behind me at college, majored in electronics? He's in charge of the machine experiment and he's about convinced us that his machines can turn out manuscripts at lower cost, more rapidly and of better quality than you Writers can. And he says the public like his product better. Have you seen any of it?"

"No," said Carre, "I don't know that I have. You know I never read anything but the classics, for pleasure; nothing later than Thackeray, or, at the latest, James Joyce. What principle do they work on?"

"I'm not an electronics man. Hartridge tells me they are specially sensitive blocks of tubes, and that memory, including all the basic plots of fiction, and all the basic varieties of dialog have been built into them."

Carre shuddered. "I will never believe, in the face of any evidence, that machines can take the place of human writers. What machine could have written 'Alice'?"

"Calm down, Herbert. I want your help. I haven't followed developments since the days of the early electronic computers, and I haven't time for studying them now. And, unfortunately, I never read modern fiction any more—no time for anything but official reports. Now I've always respected your judgment. I want your opinion of the adequacy of the material put out by Script-Lab."

"Have you forgotten," said Carre, "that I am a Writer? Aren't you afraid of a biased report?"

"Not from you. I need a competent judge. And if you are forced to bring in a favorable report, you know I'd find you a place in some other field. I might even get you a pension."

"I hope not. Not yet."

"Go over and see Hartridge, look over his machines, and bring me a critical estimate of the quality of their work—not just literary quality, of course; we're interested also in entertainment value. Don't be prejudiced. I imagine you'd be the last to deny that writing can be damned hard work."

"You're right," said Carre. "I would be the last person to deny it. Somehow, I've always liked the work, but if the machines can really take our place, I will try to bow out gracefully."

Once again Carre took the escalator to the Airway and moved across the city. He tried to think of fiction plots, but he could not control his mind. He was worried. The people standing near him were quarreling, their shrill voices hurt his ears, and the crowd was so dense that he could not move away.

Age, he feared, was making him irritable. As he approached his station, he pushed towards the escalator. He brushed against a woman who was reading a plastibacked book. She looked up, frowned, and then stamped viciously on his extended foot. Half-stunned with pain and amazement, Herbert managed to get to the escalator, went down, and limped slowly through the doorway of Computer House. What had possessed the woman? he wondered. He'd barely brushed her sleeve, in passing.

He stood before the door labelled "Manuscript Laboratory: Dr. Philip Hartridge," and pushed the button. The door opened, but two husky guards with pistols in hand blocked his entrance.

"Your name, please, and your business?"

Herbert fought a tendency to stammer. His foot still hurt him, he had developed a headache, and he felt bewildered.

"I just want—My name is Herbert Carre and I want to see Dr. Hartridge. Why, we've known each other for years!"

"Identification, please?"

They examined his identity card and his Bureau papers, and nodded. Then one returned his pistol to its holster and approached him.

"Just as a formality, if you please. Dr. Hartridge apologizes for this." He ran his hands over Herbert's shabby blouse and trousers, then stepped back.

"That's all, Mr. Carre," he said. "You can go in." They preceded him into the reception room, advanced to the rear wall and pushed a series of buttons in a complex pattern. A double door, made of metal instead of the innocent oak it had seemed to be, slowly swung open.

Philip Hartridge rose from his desk and extended his hand.

"Awfully good to see you, Carre," he said. "It must have been nearly ten years. Sorry you've never come over to see us sooner. We're very proud of Script-Lab. How are things?"

"Not bad," said Herbert. "I'm still feeling overwhelmed by the elaborate protective system you have here. What explains the body-guards? I didn't suppose this laboratory was classified."

Hartridge leaned back in his chair. "It's not classified. Those men are here to protect me from possible violence."

"Violence? Great Gamma, do you mean personal threats?"

"Yes. Only last week, my 'coptor exploded a few minutes after I started the motor. By a lucky chance, I had gone back to the house to get my brief-case. But someone had certainly tried to kill me."

"Why on earth, Hartridge, should some one—"

"It might be one of several people," he said. "But I think it's my brother Ben. He would, of course, like to have my share of the money our father left us. But I'll take care he doesn't get it." He grinned, and patted his hip. "It's rather more likely to be the other way around. But we won't waste time in trivialities, Carre. Ludwig called me. I know you want to see our set-up here. Come in and see the machines."

They walked through another set of double doors and into the Laboratory.

The noise was deafening. Twenty enormous machines sat in the room. Each was contained in a dull plastic case, and the control panels were a maze of dials, buttons, and red and green indicator lights. An electric typewriter was connected to and operated by each machine, and through each typewriter ran an endless roll of paper, which emerged to be cut off into eleven-inch lengths by automatic knives.

"How do you stand the noise?" asked Carre. "Why don't you use Silent Typers?"

"Oh, the machines don't mind the noise. Silent Typers would be an unnecessary expense, and as a matter of fact, I've come to like the sound. It's soothing, after a time."

Carre strolled slowly, rather mournfully, from one monster to another, glancing at the emerging manuscripts.

"The rate of output," said Hartridge, "is not less than a hundred words a minute, and they never have to stop to look up their facts, or to struggle with a balky plot. Can you do as well?"

"I wish I could," said Carre. "I know so little about electronics. Do the machines use much current?"

"No, that's another of their virtues, they're very economical. The tubes are so efficient that all twenty machines are run from this one source, right here—Don't touch it! It's not ordinary house current, you know. We start with eight thousand volts,—it saves on metal and transformers."

Herbert found it hard to think against the clatter of the typewriters. "I'm ashamed to admit," he said, "that I feel a kind of envy, they seem to compose with such ease."

Hartridge laughed. "No trouble at all! I tell you, my pretty typewriters are going to put you out of business. You can see for yourself, Carre, that there's no need for you human writers. We are doing a perfect job here, and we could supply all the material—novels, stories, fact articles, biographies—that the country could read. AFE has been using more and more of our scripts, as you probably know."

"I know."

"I can't say exactly why it is, but we do seem to be able to hit the public taste better than you Writers." He reached over and patted one of the plastic cases, as though it had been an affectionate dog.

"Do your machines do nothing but write new material?" asked Carre, as he strolled on.

"That depends on the demand. Sometimes we have a call for some out-of-print item, or some work which is so hard to get hold of that we simply have the machines re-do it. After Number Twelve, here, produced the entire English translation of 'War and Peace' without a single semantic error, we were not afraid to trust them with anything. As a matter of fact, we've got Number Eight re-writing some nineteenth-century items that have not been available for years—things that were destroyed or banned during the Atomic Wars, but which the present government finds acceptable. Would you like to see?"

Carre stood in front of Number Eight in fascination as the metal arms hammered out the words and lines. After a moment, he frowned. "I seem to remember this! I must have read it in my early boyhood. It seems so long ago. Joan of Arc! But I don't remember its happening just this way."

"Just goes to show you can't trust your memory, Carre. You know the machines are perfectly logical, and they can't make a mistake."

"No, of course not. Odd, though." He brushed his hand over a forehead grown wet.

The knife flashed down, cut the paper, and the page fell into its basket. Hartridge picked it up.

"Would you like this sheet, as a memento? Number Eight can easily re-do it."

"Thank you."

"And is there anything else I can show you? I don't mind admitting I'm very proud of my machines."

"Well," said Carre, "perhaps you might let me have some of your current manuscripts, just for tonight? I can make a comparative study, for Ludwig, and return them sometime tomorrow."

"Nothing easier." He assembled a bundle of stapled sheets and put them in a box, and then rang for the guards, to show him out.

"Take care of yourself, Carre. See you tomorrow."

Herbert sat, that evening, in his book-lined room, reading manuscripts. He looked more and more puzzled, and ill at ease. He got up, after a time, to pace the room, and on a sudden impulse he left the apartment and hurried up the street.

It had grown dark outside, and he hurried. He could not stand the thought of the Airway, so he walked. He had covered nearly half a mile when, at the corner ahead, two Street-taxis approached each other at right angles. The drivers glared at each other. Neither slowed to let the other pass; they crashed, and began to burn. Carre hurried on, trying not to hear the screams of the people or the siren of the approaching ambulance. No wonder, he thought, that they need Ludwig in the Bureau of Public Safety; people were behaving so irrationally!

He climbed the steps of the City Library, and advanced to the desk.

"I should like to see files of the magazines published by Adult Fiction, Earth, if you please."

"But which magazine, sir? They publish hundreds."

"Well, as a start, let me see those which publish light fiction."

For two hours he sat in the Scholar's Room, skimming the pages of the magazines—Sagebrush Westerns, Romance and Marriage, Pinkerton's Own, Harper's, and a dozen others. He read with concentration, and made few notes. On his way home he stopped at a news-machine and selected an armful of the current issues to take home with him. He read in his room until nearly dawn, and when he did lie down he could not sleep, or rest.

"I don't believe it," he whispered to himself. "It can't be true." And, half an hour later, "How did it happen?"

At nine next morning he was sitting in the reception room of the Bureau of Public Entertainment, with brief-case on his knees, waiting for Ludwig. It was nearly noon before Ludwig himself arrived, and summoned his visitor.

He sat at his desk, his white hair rumpled, and nervously fingered his watch chain as Carre took the chair opposite.

"Sorry to keep you waiting, Herbert. The Commissioners over in Safety have a bad situation to handle, and I've been trying to advise them. I'll be glad when this writing business is straightened out, and I can give full attention to Safety. What did you think of Script-Lab?"

"Well, it's very efficient."

"I knew that," said Ludwig. "Machines are built to be efficient. But what do you think of their output? How does it compare with the work of the Writers?"

Carre cleared his throat. "John, don't you read the magazines any more?"

"No. No time. Do you?"

"I haven't, until yesterday. I read them, all night. I hardly know how to express myself. John, something is wrong with the machines."

"Nonsense! There can't be anything wrong with them. They're fed the plots, fed the variations, and then with perfect logic they create their stories. You're not an electronics expert, you know."

Carre stared at the floor. Ludwig sighed.

"I'm sorry, Herbert. I'm just too tired to be decently courteous. But what I wanted from you, after all, was a literary evaluation and not a scientific one."

"I express myself so badly. There's something wrong, something I can't exactly define, with what they write."

Ludwig looked exasperated. "But what, man? Be concrete."

"I'll try. Here's a short story that was made yesterday. Glance over it, please, and tell me how it strikes you."

Ludwig read through the manuscript with his accustomed rapidity. "I don't see anything particularly wrong about it," he said. "Murder mysteries have never been to my taste, and I don't know that I exactly approve of the hero's killing his benefactress with an undetectable poison, and then inheriting her fortune and marrying her niece. Undetectable poisons are all nonsense, anyway."

"The story doesn't seem to you—unhealthy?"

"I don't know what you're getting at! It's on the grim side, I suppose, but isn't most modern fiction a little grim? How about your own stuff?"

"I think there's a difference. I know I've written a few mysteries, and even some tragic stories, but I don't believe I've ever written anything exactly like this. And this is typical. They're doing reprints, too, of books that were destroyed or lost during the Atomic Wars. Do you remember Joan of Arc? Mark Twain's version? Here is a page from Script-Lab's manuscript."

Ludwig took the sheet and read aloud: "By-and-by a frantic man in priest's garb came wailing and lamenting and tore through the crowd and the barrier of soldiers and flung himself on his knees by Joan's cart and put up his hands in supplication, crying out—

'"O, forgive, forgive!"

'It was Loyseleur!

'And Joan's heart knew nothing of forgiveness, nothing of compassion, nothing of pity for all that suffer and have been offensive—'"

Ludwig looked up with a frown. "That's odd. It's been so long since I saw that book—I was only a boy—but that isn't just the way I remember it."

"That's what Script-Lab is writing."

"But the machines, don't—"

"I know. They don't make mistakes."

The buzz of the visi-sonor interrupted them, and the Commissioner of Public Safety spoke from the screen.

"For heaven's sake, Ludwig, shelve the book-business and get over here. We've had a rash of robberies with violence, a dozen bad street accidents, and two suspicious deaths of diabetics in coma. We need help."

Ludwig was already reaching for his brief case. "Right away," he said, and flicked the switch.

"John!" Carre begged, "This book matter is serious. You can't just drop it! Come with me to Hartridge's lab and see for yourself!"

"I can't. No time. You heard the Commissioner."

"Tomorrow morning?"

"Can't make it. Have to go to a funeral. A niece of mine who died suddenly of cancer. Poor girl. We thought she was doing so well, too, with the hormone injections. Not that her husband will break his heart, from what I know of the scoundrel."

Carre followed him towards the door. "Then make it tomorrow afternoon! It's vital!"

Ludwig pulled out his watch, and thought for a second. "All right. Meet you there tomorrow at three." The door slammed behind him.

They followed the guards through the chrome steel doors into the room with the machines. All twenty typewriters were hammering out their hundred words a minute.

"It is an honor to have a visit from you, Commissioner Ludwig," said Hartridge. "We're very proud of Script-Lab. You'll agree, I know, that the experiment has been eminently successful. Tough on you, of course, Carre. But you Writers can always land on your feet."

"The decision has not yet been made," said Ludwig. "Now to business." He pulled a chair up to the desk, opened his brief case, and took out some papers.

"Before I examine the machines, I'd like to check with you the facts and figures that Carre has compiled for me. In 1971, the first year of the experiment, only ten per cent of Script-Lab's output of stories, books, and articles was accepted by Adult Fiction, Earth. Right?"

"Right," said Hartridge. "But that was our worst year. Since then—"

Ludwig held up his hand. "In the second year, you supplied thirty-five per cent of the needs of AFE. Check?"

"Check."

"In the two years following you supplied seventy-five per cent, and in 1976, this year you are supplying about ninety per cent of all published matter, with the Writers supplying only ten per cent. Correct?"

"Correct. A wonderful record, Commissioner."

Ludwig turned to another sheet of data. "As I understand it, you feed into the machine's memories, basic plots, factual data, conversational variants, and they do the rest?"

"That's right. We give them the material, and they create with perfect rationality. I myself read nearly everything they make, and even I am amazed at their craftsmanship. And they are so efficient, and write so swiftly!"

"Speed is no doubt a desirable feature," said Ludwig.

"But not the only one!" said Carre.

Hartridge smiled. "Professional jealously is warping your judgment, old man. It may be hard to take, but you Writers have nothing to give the world, anymore, that machines can't."

Ludwig turned his back and surveyed the room. "I would like to see, now, some of your productions."

Hartridge beamed. "As a matter of fact, I have something that ought to interest you, particularly. Just follow me, gentlemen. Here, by the way, is our power source. Note how simple and efficient the circuit design is. Ah, here we are. Knowing that you were making us a visit today, I gave to Number Seven, here, the necessary data for creating your own monologue on 'Our Duties to the Aged.' That was your doctoral thesis, I believe?"

"But that's out of print! I haven't seen a copy myself in years!"

"To Script-Lab, that is unimportant. Feed it the data, the basic premises, and it will do the rest. Would you like to see?"

The three men crowded around Number Seven, and watched the emergence of paper from the typewriter as the keys tapped the words into lines, and the carriage shifted. Ludwig, at first, showed only the pleasure which any writer feels on re-reading a good piece of work. Gradually, his face changed. He looked puzzled, uncertain, and then his skin reddened with anger.

"He looked puzzled, uncertain, and then his skin reddened with anger."

The automatic knife chopped down and severed the completed page. Ludwig scooped it up from the basket and read the page a second time. He raised his eyes to meet the tense gaze of Carre.

"Is this what you were trying to tell me, Herbert?"

"That sort of thing. Yes."

"Is something wrong, Commissioner?" said Hartridge. "I thought you'd be pleased."

"Pleased? But this is something I never wrote!"

"But you must have written it," said Hartridge. "Or are you just trying to sabotage my project with a deliberate misstatement?"

"Read it!" said Ludwig. "Read that paragraph out loud."

"'Our duties to the aged,'" read Hartridge, "'are closely bound to our duties to ourselves. When the old become infirm, they should be quietly helped out of a contented existence. After all, the only measure of the value of aged men and women should be their present usefulness to society.'

He looked up from the page. "I don't see why you're so unwilling to admit your authorship, Commissioner. There's nothing wrong with this."

"Only," Ludwig said softly, "I didn't write it. What the monologue actually said was something like this: 'Our duties to the aged are closely bound to our duties to ourselves. When the old become infirm, they should be quietly helped to a contented existence. After all, the only measure of the value of aged men and women should be their past usefulness to our society.'

"You've made your point, Carre," he went on. "If this sort of perverted advice has been fed to our people the last few years, it's no wonder we're having a wave of crimes. Be selfish! It pays. An eye for an eye! Poison the old man! Nobody will ever know and you'll get his money!"

Hartridge was still studying the typescript, and he spoke with defiance. "Number Seven's excerpt from your monologue seems perfectly sensible to me," he said. "For some reason of your own you must be lying about it. Why, the version you say you remember is utterly illogical!"

"Of course it's illogical!" said Carre. "Don't you see—"

"Of course it's illogical!" shouted Ludwig. "It was illogical for Joan to forgive her tormentor. It's illogical to take care of invalids. It's illogical to forget an injury. But it's human! How on earth is society to exist if it feels only the rational emotions? You, yourself, Hartridge, have been corrupted by reading the work of Script-Lab, and you no longer have any sense of human charity. These monsters have been undermining our whole life, because the only motivation they were provided was the most dangerous and ugly thing possible in the world of human beings—pure logic!"

As he shouted, he fumbled at his watch, unhooked the long gold chain, and with a sudden lunge, flung it across the bus bars which supplied the current to the machines.

There was a blinding flash, a hiss, and the eternal clacking of the typewriters was replaced by silence.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of What Do You Read?, by Boyd Ellanby

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT DO YOU READ? ***

***** This file should be named 49754-h.htm or 49754-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/9/7/5/49754/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.