Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 10, 1895. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 841. | two dollars a year. |

The tide ran so swiftly that at first it appeared to George that he did not gain an inch on the drifting boat, and the short choppy waves dashing against his face almost drove his breath away at times. The day when his brother William had saved him from drowning at Stanham Mills came back to him.

But surely he was drawing nearer! he could see the hull much more distinctly, and could hear the loose oars rolling across the thwarts.

Desperately he forged along; he was calling on his nerves, his vital force, for a last effort. In a moment more he reached the stern, and, placing his knee on the rudder, fell inside the boat.

To save himself he could not lift a finger now; he lay there perfectly conscious, sprawled in the stern sheets, his chest heaving, his head thrown back—played out in every muscle. It was fully half an hour before he moved, and when he did so the sense of his position came fully upon him.

All about reached the opaque white wall, and although a short time before it had been so warm, George now felt chilled—his teeth were rattling. This reminded him of the coats, and the letter in Carter's pocket that had nearly cost his life.

Getting on his knees he perceived to his astonishment that the boat was half filled with water, and that the coats were floating in it at his feet.

At once he set to work, and there being nothing else to use he took his hat and Carter's and baled with both hands.

This exercise warmed him, and started his blood and pulse going once again.

When the water had been put over the side, George wrung out the coats and drew the sail about his shoulders. But first he found the letter that had caused all the trouble. It was addressed, "To the Convention at White Plains," and in the corner was inscribed, "A plan to destroy the British fleet by means of floating barrels of gunpowder, suggested by Mason Hewes, Colonel III. N. J., Reg't of Foot."

"One of the Colonel's schemes," said George to himself. But this did not seem so important as a memorandum in Carter's hand, made on a slip of paper, and showing the disposition of the American forces on Long Island.

He tore up the latter, but Colonel Hewes's address to the convention he attached to a bit of iron that he found, ready at a moment's notice to drop it overboard.

"I haven't the least idea where I am," he remarked, "so I had best be content with being alive. Oh, if this abominable fog would only clear away!"

It had been quite late in the afternoon when the boys had left the little cove at the foot of Brooklyn Heights, and now the light that filtered through the mist was growing dimmer. The ebb was still on, for the boat was drifting slowly. Another half-hour passed.

"What is that?" exclaimed George, suddenly, for a lapping sound came to his ears; it was the noise of the little tide waves against the prow of a vessel at anchor—he had heard it often along the wharves. As he peered out with his face over the side he heard loud and distinct, almost above him, the rattle and click of a block and tackle.

"'Vast 'eeaving there," called out a voice, so close that George started. "Belay, you lubbers," called the voice again.

A strange odor filled the air, a smell compounded of so many things that it cannot be described. George knew it to be that of a crowded ship—the smell of a man-of-war.

"I must be right among them," he murmured.

All at once, so close to him that he could almost reach it with an oar, loomed a great black shape, and over his head extended the muzzles of a line of guns, and above them another, and still above, a third.

"A seventy-four!" said George, crouching down in the bottom of the boat beneath the sail.

Slowly he drifted past; he could see the white streaks on her sides, and hear snatches of songs and the hum of voices. At last he was directly beneath the bulging quarter galleries, and a voice called out,

"What's that below?"

"A boat, sir, adrift," some one answered, in gruff sailor tones.

"Any one in her, Quartermaster?" inquired the first again.

"Can't see, sir," was the reply.

"Tumble into the cutter, then, and take after her," came the order.

The shrilling of a boatswain's pipe followed, and the hoarse bawl, "All first cutters away," started George to action.

"Now for another swim," he said, as he passed the battle-ship's mighty stern. "The shore of Staten Island must be off there to the left."

He hove both coats into the water, and, taking Mr. Hewes's epistle in his teeth, lowered himself after them. He hated to sacrifice the spy-glass, but overboard it went with the rest.

He had taken but a few dozen strokes when the thrumming of oars sounded plainly, and he rolled over on his back to listen—the oars stopped.

"Cutter there!" came from the deck of the seventy-four. "Have you found that boat?"

"Ay, ay, sir," the cutter hailed in return. "There's nothing in it but a hat."

George smiled and struck out again. "That shore's a long ways off," he thought, after he had swum for some time steadily, and as he made this remark to himself his knee struck something hard; he dropped his feet to sound, and found that the water scarcely reached his waist.

Tired and faint, he waded up to a shelving beach and fell forward in the sand. But he could not stay there long, for he knew that Staten Island was overrun with English soldiers. He must find some place to hide.

The fog had lessened, but it was growing dark. A ship's bell struck the hour, and the sound was taken up by a hundred others in a chorus of clanging and ding-donging out in the mist.

George walked up the beach. The water's edge was littered with débris from the fleet—baskets and empty boxes, crates, and drift-wood of all sorts. Something caught his eye, and he stooped and picked up a stout-handled boat-hook.

"Some poor fellow got the rope's end for losing this," he said. "It may come in handy for me." He shouldered it and walked quickly away. A few rods further on he came across a narrow pier or causeway that ran from the bank above the beach to a boat-landing some distance out.

There was just room for a man to crawl underneath. George stooped on his hands and knees and worked his way in as far as he could with comfort. Then he half buried himself in the dry sand. Tired with his two long swims and with the excitement of the last few hours, he went to sleep. But it was not for long. Suddenly he awoke—a great fear was on him. Why had he not thought of it before? Had Carter reached the shore? George had heard no sound from him after he had turned to speak of leaving the paper in the boat.

The reason that Carter did not hail, as tacitly agreed upon, is simply told. He could not have raised his voice if the fate of the country depended on his doing it, for he never remembered reaching land at all.

When George had left him, Carter had kept straight ahead, but made the great mistake of trying to fight against the swiftly running tide.

It buffeted him hither and thither, until he became utterly exhausted, and could just keep himself afloat and no more by weakly treading water. The direction of the shore he lost completely for some minutes, when all at once he heard the rippling sound again. Desperately he struck out, and then, oh joy! he heard the sound of voices.

Carter tried to shout, but a sturdy wave catching him fair in the face muffled the cry and almost foundered him. He remembered taking two or three strokes after that; then all went black.

"I'm certain I heard a cry out here," said a voice in the fog. High-pitched and distinct, the tones were very different from those that answered.

"You have ears like a rabbit's, then," growled a deep bass. "For I heard nothing. Come, as I was saying—"

"Pardon me. Just hearken for a minute. It may sound again," interrupted the first speaker.

Two figures leaned out over the Battery wall.

The owner of the deep voice was a large man who sloped off in all directions. A huge scratch-wig was pulled over his forehead. The other would have attracted attention anywhere. Above a tightly buttoned snuff-colored coat appeared a thin pinched face, whose little eyes looked out above prominent cheek bones, and whose chin was thrust forward from a voluminous neckcloth. His movements were quick and active as a weasel's. As he peered through the mist he pointed with his finger as if he were following something of whose constantly changing position he were not exactly sure.

"Yes; there it is," he said at last. "Gadzooks, it's a man's body! Here goes for it."

The little man vaulted to the top of the wall, and made a beautiful clean-cut dive out into the water. The counter-current set up by the ebb tide swirled softly against the sea-wall. It was easier swimming than a few rods further out.

"Hulloa!" called a voice at last.

"Hulloa! This way," answered the large man, who was deftly casting loose a stout rope made fast to a ring-bolt in one of the stone posts. "Here. This way."

"I have him," said the one in the water, panting slightly. "But whether alive or dead I know not. It's the body of a lad," he added, as he caught the rope the big man hurled to him.

Quickly he tied the end under Carter's armpits, and finding room for his fingers and toes in clefts in the masonry, he climbed unassisted to the Battery wall.

Together both men pulled the apparently drowned boy to the top.

"Jabez, you are one of the greatest I know of," said the big man, as he helped to carry the senseless figure to a grass-plot.

"Tush!" was the answer. "I'm a good swimmer, mayhap, for my light weight and growing years, that's all." Indeed, this had been proved, for the small one had not even paused to remove his coat. "The lad's alive," he went on, speaking with his ear pressed close to Carter's chest. "Bear a hand quickly, we must get him in-doors."

"Ay, but where?" rejoined the larger.

"To our friend the widow's. 'Tis but a step."

Again they picked up their burden and disappeared in the mist.

When Carter Hewes came to his senses he found himself in a little room that was nearly filled by the big four-poster bed in which he lay. His head throbbed, and he felt faint and weary. But the feeling of being safe and warm was so comforting that he did not at once worry as to his whereabouts.

Some persons were talking close to him; he could hear the words they said, but at first he could not raise himself. At last he got up, however, on his elbow. The voices came from behind the closed door at the head of his bed.

"I am sick of hiding here like a fat badger in a strange hole that, by-the-way, is much too small for comfort," grumbled a deep voice.

"Take heart. It's for a righteous cause," answered a high-pitched one.

"Why not declare ourselves, and have it done with?" returned the first.

"The time's not ripe. We will be able to accomplish much more—and to play the rôle will require no dissembling."

"That's well enough, but I'm tired of it all," came the grumble. "Suppose the British do not take the city."

"Tush! New York cannot be held. Remember that we—" The reply stopped, for a woman's voice broke in.

"How's the young gentleman?" inquired a loud feminine whisper with an unmistakable brogue.

"I'm just going in to see how fares it with him," was the response.

Carter dropped back on the pillow, and half closed his eyelids. There was a small mirror at the foot of the bed, and in the reflection he saw the door open and a face peep in. He caught a glimpse of a pair of keen eyes, a large nose, and a strong determined jaw. Immediately the door closed.

"He's asleep," was whispered out in the hall. "'Tis the best thing; when he wakens you can ask him questions. But not a word as to who fetched him here."

"No, sur, not a word," the woman replied.

Whether it was the suggestion contained in the warning or not that worked the charm, it is hard to tell. The fact was, however, that in a moment Carter began to snore. It was dusk when he awakened the second time. He felt much stronger, and a flood of recollections that had not bothered him before came over him.

"Where was George? I hope and trust he's safe; God grant so," he said out loud. Then he weakly stepped out on the floor, and made his way to the window. "Hullo!" he said; "I know where I am, thank goodness." He had looked out on the Battery green. "Now to find out to whom I am indebted," he added, walking to the door. "Ahem," he said, loudly, to attract attention. Then, "I beg pardon. Is there any one in?"

No answer, although Carter thought he heard a movement up stairs. Again he called, then he whistled.

"They must be all out—or dead!" he ejaculated. "What am I to do for clothes?"

As he turned back into the room he saw a much-worn coat hanging over a chair, a pair of shoes with brass buckles, and some thick yarn stockings. He tried them on; the coat was a trifle tight, so were the shoes, but he squeezed into them, and went down the stairway. No one was there.

"Well, I can't wait to thank my unknown friends to-day," he said; "I'll call again." He slowly walked out of the doorway, looking over his shoulder every step or so.

It had grown very dark in the last few minutes, so dark that a number of people had lit candles in their houses. Carter noticed that they shone with a peculiar greenish light; some shutters were closed noisily. When he reached the green he paused. Many a thunder-storm had he seen gathering before, but never a sight like that. To the south-west rose a sheer wall of blue-black cloud, and overhead were circling and twisting huge billows, like the smoke of burning tar; a few big drops spattered out of the sky. But there was dead silence—not a sound of thunder or a quiver of light.

"Looks like rain," said a facetious burgher, who stood with gaping mouth and face upturned.

Carter did not answer, but hurried on; somehow he felt that he was dreaming. He had half expected to see the British fleet anchored off the Battery. There was not a sail in sight, so he made straight for the headquarters of George's regiment, praying that there they would have news of him.

"No one's heard of Sergeant Frothingham since yester-morning," replied a number of George's squad. "He got leave for a day and hain't come back," the man added, grinning.

This was the first intimation Carter had that he had been unconscious twenty-four hours. He felt sick at heart. His regiment was over on Long Island, his father was there also, and he knew few people in the town. George's commander was his own cousin, however, and getting the direction of Captain Clarkson's house, he started out. It was dark as a mine shaft in the street—hardly light enough to see the walk ahead.

The young soldier plunged through the door of a public-house only a few steps further on. It had commenced to blow, and the wind roared furiously in the swaying elms outside. Occasionally the lightning made it bright as day. Carter sank into a big oak chair.

"Ah, Lieutenant Hewes! Not over on the island?" said some one, clapping his hand on the lad's shoulder. "Where have you been?"

"I do not know exactly," murmured Carter, faintly, looking up at the handsome face of Lieutenant Alexander Hamilton, whom he had met often on the drill-grounds.

"That means there's a story to be told," went on the other. "Come, join me in my dining. Don't let the elements interfere with our natural appetites."

Carter did not know that part of his faintness came from lack of food. But when a big bit of tender mutton was placed before him, he ate with every mouthful putting life into him.

As he was about to begin to tell the tale of adventure of the previous day he felt something hard in the lining of the borrowed coat, and inserting his fingers, he drew forth a small note-book; he uttered an exclamation of surprise.

"George Frothingham—his book, 1774," he read, and sat there too astonished to speak. "That was the year he left school—to go to Mr. Wyeth's," said Carter out loud. Again the anguish and fear shook him, for it recalled the last time he had seen George's face, and this book in the pocket of a strange coat. What meant it?

Lieutenant Hamilton looked as if he feared that his friend's senses had left him suddenly.

"Let us have the story, Comrade Hewes," he said.

But it was never to be told. An interruption occurred just then that changed the current of every thought, and stirred the room to a pitch of action.

The door was burst open, and a man dripping with rain came in; he carried a lantern, whose light had been extinguished.

"Oh! but it's a frightful night for a body to be out,"[Pg 128] he said. "Three persons were killed by the thunder-bolts on Broadway. But have ye heard the cannon firing?"

"You're crazy," said some one. "Cannon on such a night as this! But, hearkee!"

Three distinct reports sounded in quick succession.

"That's no thunder," said the landlord.

"The signal guns!" exclaimed Lieutenant Hamilton.

Again the door was forced open, and, accompanied by a blast of wind and rain, a soldier plunged into the room. His hat was gone, and his loose hair was plastered down his face.

"A spy has arrived through the storm from Staten Island!" he shouted. "The British are landing in force at Gravesend. Officers are ordered to their commands at once."

Ten days after the lawn party Aunt Patty and Cynthia were alone once more in the old farm-house, for Ida had departed to Rocky Beach to spend the month of August with Angela Leverton.

She went away in gay good humor, eager—as are all young people—for a change. But she was very affectionate when she parted with her aunt and sister.

"I do wish you were going also, Cynthia," she said.

Cynthia's plain, sweet face lighted up with pleasure.

"Do you, really?" she asked.

"Yes, I do, really," answered Ida. "I would be willing to stay at home myself if you could go in my stead, Cynthia."

She gave a pleasant greeting to old Jake Storm when the stage stopped for her; and as it bore her away she waved her handkerchief from a window until the old farm-house and the two watchers at the gate were no longer to be seen. How little she dreamed what was to happen to her before she saw Brookville again!

"How we miss Ida!" said Aunt Patty or Cynthia half a dozen times a day during the next week, and with what pleasure they read her frequent letters! Their tone was entirely different from that of those she had written during her stay at Aunt Stina's.

"She actually inquires about Moses," laughed Cynthia one day, as she laid down a letter just received from Ida.

As Moses was only a lame white turkey, this interest on Ida's part seemed surprising when contrasted with the utter indifference she had shown to everything about the farm on her arrival in June.

Ida herself was surprised at the amount of thought she gave to those she had left behind. More than once she astonished Angela by remarking that she "wondered what Aunt Patty and Cynthia were doing now," and often, when wandering along the beach, she wished Cynthia could see the waves breaking against the rocks, and hear the lap of the surf.

One day—a day fraught with much importance as it turned out—Angela and Ida drove to the little town of Edgerton to attend to some shopping for Mrs. Leverton, who was an invalid—or fancied herself one.

It was late in the afternoon when they started homeward, and they were bowling along at a good round rate on the hard road, when suddenly Ida laid a hand on the reins.

"Stop a moment, Angela," she said. "Look at that poor woman sitting under that old tree. She must be ill."

"It is more likely that she is intoxicated," answered Angela.

The woman was young, but her appearance was singularly forlorn, for she was ragged, barefoot, and wore a man's straw hat on her dishevelled black hair. She sat with her back against the tree, her chin sunk on her breast, and her eyes closed. In her arms was a baby wrapped in a faded red shawl, and near by was a cart, in which was heaped a miscellaneous collection of household goods. She did not look up as the phaeton stopped, nor appear to hear the voices of the girls.

"I think we ought to find out what is the matter with her," said Ida.

"Oh, it isn't necessary; she is only a common tramp," rejoined Angela.

"She looks as if she were in some sort of a stupor," said Ida.

"Then we had better drive on; she may have some dreadful disease. Ida, surely you are not going to get out. How foolish!"

"Well, it may be foolish; but I cannot drive on without finding out first what is the matter with the poor thing," said Ida, as she stepped out of the phaeton.

Strangely enough, the thought of Aunt Patty had come into her mind. Would Aunt Patty have driven by without making an effort to help? Of course not.

The woman raised her head as Ida drew near, and her heavy eyes opened slowly. She stared dully at Ida without speaking.

"ARE YOU ILL?" ASKED IDA.

"ARE YOU ILL?" ASKED IDA.

"Are you ill?" asked Ida.

"I'm dyin', I guess," answered the poor creature in a thick voice. "I don't know what's the matter of me. I ache all over, 'n' my head's 'most burstin' open."

"Oh, Ida, do—do come away," cried Angela from the phaeton.

But Ida paid no attention to her. She bent over the woman, and, drawing off her gloves, put her soft cool hand on the flushed forehead.

"You have a high fever," she said, "and you ought not to stay here; it will soon be dark. Have you no home nor friends?"

"I'm tryin' to get to my sister in Edgerton," was the reply. "I've walked all the way from Stormville, a-draggin' that cart 'n' a-carryin' of my baby. I can't go no further. I'm clear worn out."

Ida went out into the road again. "Angela! we can't go off and leave this poor woman here to die," she said.

"I don't see what we can possibly do for her," rejoined Angela.

"We might put her in the phaeton and drive her to Edgerton."

"Put her into my nice phaeton! That horrid, dirty woman!" Angela stared at her friend in astonishment at such an extraordinary proposition. "Indeed, she shall not come anywhere near me! I am sure she has some dreadful contagious disease."

"Angela, we can't go off and leave her here. It would be utterly heartless."

Angela set her mouth stubbornly. "Other people will probably come along and do something for her," she said. "There may be a dozen wagons along here before night."

"We can't be sure that even one will pass; this road is not much travelled," said Ida.

"She must take her chances, then." Angela's tone was cool. "Come, do get in, and let us drive on, Ida. We have wasted too much time already."

Ida hesitated. Her gaze wandered from Angela to the sick woman, whose head had fallen forward again. Then her face brightened suddenly. "The cart!" she said. "Why did I not think of it before? I can get her into that cart; it will be quite large enough if I take out all those things."

"But what good will that do?" asked Angela. "How will she be any better off in the cart?"

"I can pull it, and take her to Edgerton in that way."

"Ida!" Angela almost shrieked.

"Yes, I can, and I will, unless," and she smiled winningly, "you will allow me to put the cart behind the phaeton? Then Prince can pull us all."

"Well, I suppose I can do that much," said Angela, reluctantly; "but how will we look!"

"We needn't care for that. People who want to laugh can do so."

"And are you going to handle all those horrid cooking utensils in that cart? And that soiled pillow and blanket? Oh, Ida, I wouldn't touch them for anything you could offer."

Ida laughed. "It's in a good cause," she said, cheerfully.

A few minutes later the sick woman and her child were in the cart, and the little cavalcade set out for Edgerton. As the cart was old and rickety they feared it would fall to pieces under any strain, so Prince was made to walk.

As they reached the outskirts of Edgerton they saw Dr. Stone of that place coming jogging toward them in his low buggy, driving his big gray horse. He pulled up as he met the girls, and listened with interest to the account Ida gave of their charge.

"I fear you have done an imprudent thing for yourselves," he said, "but of course it was only natural and right that you should want to help the poor creature. She must go to the hospital ward of the county poor-house. That's the only place for her. I will drive there at once and order a man to be sent for her." He sprang out of his buggy and drew the cart to one side of the road. "She is asleep, and will not miss you," he said, "and as you have a long drive before you, I advise you to start at once."

The girls were only too thankful to be relieved of their troublesome charge.

"But I venture to say that we have already caught the fever from her," said Angela, as she once more turned Prince's head toward home, "and if I fall ill I will never forgive you, Ida."

"If either of us is to suffer it will be I," said Ida.

"Well, that would be only fair; for you know I didn't want you to go near her, and you would do it. You even handled those soiled things in that miserable cart."

"I know my Aunt Patty would have blamed me had I followed your advice," said Ida.

"Well, you need not have cared for that. What if she did?" replied Angela.

"It would have mattered a great deal," answered Ida, in a low voice. "I don't believe my Aunt Patty ever did an unkind or a cowardly thing in her life."

Four days later Ida was lying one morning on a wicker-work lounge on the front porch of Mr. Leverton's cottage, when the man employed to take care of the horses returned from a trip to the post-office, and handed her a letter.

ARRIVAL OF AUNT STINA'S LETTER.

ARRIVAL OF AUNT STINA'S LETTER.

Ida took it listlessly. She had not felt well since the night before; her head had ached; she had pains in her limbs, and felt dull and sleepy.

"From Aunt Stina," she said to Angela, who sat near her, reading. "She writes from Paris," she added, as she tore the letter open.

"Read me anything very interesting," said Angela. "I hope she tells about the Paris fashions."

But Ida read down to the bottom of the first page without communicating a word of its contents. Then suddenly she gave a sigh that was almost a sob, and covered her face with her hands.

"Why, Ida! what is the matter?" Angela threw down her book and flew to the side of the lounge.

"I can't tell you—don't ask me," said Ida, in a smothered voice.

"Is your Aunt Stina ill?"

"Oh, no; it isn't that. It is only— Oh, Angela, I have been so ungrateful, so unkind; I—" she broke off, sobbing, the letter crushed in her hand.

"In what way have you been ungrateful and unkind? I don't understand you at all. In fact, Ida, you're not at all like you were last spring. I have been noticing it ever since you came here to visit us. I don't know how to describe it; but you're altogether changed!"

Ida sobbed on. It was that first page of her Aunt Stina's letter which had affected her so powerfully. It ran as follows:

"I must decline to accept your thanks for the box you received early in July. I do not deserve any credit whatever. Your sister wrote me that you needed the dress, and enclosed thirty dollars from your Aunt Patty, which I was directed to spend for you as I saw fit. Cynthia requested me not to write you that they had arranged the surprise for you. I suppose they did not wish you to be burdened with a debt of gratitude. But after this length of time it can do no harm for you to learn that your Aunt Patty and not I bore the expense of your outfit for Mrs. Lennox's lawn party."

So that was how Aunt Patty had spent the money she had received for the yellow heifer. What wonder that Ida, remembering what she had said about her aunt's shabby clothes, should be overwhelmed with contrition now?

"Ida," said Angela, after regarding her friend in silence a few moments, "I do believe you caught the fever from[Pg 130] that woman tramp you insisted on taking into Edgerton."

"I deserve to be punished in some way," said Ida. "Not for my interest in that poor sick woman," she added, as Angela stared at her with an expression of surprise, "but for various offences. I have been selfish, inconsiderate, deceitful, and unkind."

"Ida, you are certainly going to be ill," said Angela. "I never heard you talk that way before."

Angela's supposition proved correct. By night Ida had a high fever, and the pains in her limbs had grown very much worse.

Doctor Stone was sent for, and pronounced her sickening with scarletina.

Soon after he had made his visit Ida fell asleep, and dozed at intervals all night. At about eight o'clock she woke from a longer nap than usual. The sun was shining in between the slats of the closed blinds, but the house seemed strangely still. She listened intently, but could hear no one stirring, no sound of voices; only the sullen roar of the mighty ocean.

Her throat was parched; her blood seemed to course through her veins like liquid fire.

"Oh, if I only had a drink of water; how good it would feel," she said aloud.

As she spoke, a portly figure rose slowly from a seat by one of the windows. It was Old Dinah, the black cook Mrs. Leverton employed every summer.

"Dinah'll get yo' the water, honey," she said.

"Dinah!" exclaimed Ida. "Why, what are you doing up here?"

"I's nursin' yo', honey, de bes' I knows how. De doctor, he done tole me de directions."

"But where are Angela and Mrs. Leverton, and why is the house so still?"

"Dey's all gone, my lamb. Dey cl'ared outer heah early dis mawnin'. Miss Angela, she didn't give her mammy no res' after she done knowed yo' had de fever. Dey lef' me ter take keer ob yo' till yo' aunt git heah. Dey done sent er telegraph fo' her las' ebenin'."

Ida's first feeling at finding herself thus deserted was one of poignant humiliation and pain, but like balm to her wounded spirit came the thought that Aunt Patty would soon be with her—the dear Aunt Patty whom she had never known how to value until lately. Oh, how she longed to see that kind face, to feel those strong, tender arms about her; to bear the gentle loving voice which she had never heard utter one unkind or impatient word to any one!

"I will tell her how sorry I am that I ever hurt and grieved her," thought Ida. "I will never again be too proud and stubborn to confess my faults, and ask pardon of those that love me."

But when Aunt Patty arrived at Rocky Beach—having travelled as fast as steam and stage could bring her—Ida was delirious, and did not recognize her.

The tears coursed down the old woman's cheeks as she stood beside the bed, watching the restless movements of the pretty young head, shorn of all its golden locks; listening to the whispering voice as it babbled incoherently of Cynthia, the farm, Mrs. Lennox, Angela, and a hundred other persons and things.

"She will require the most careful and assiduous nursing," said the doctor. "Only that can pull her safely through."

"She shall have it," answered Aunt Patty. "I'll take her back as well as ever to the old farm six weeks from now, please God."

The crisis of the fever came on the ninth day. Dr. Stone came early, and staid until midnight. Then he left Ida sleeping quietly, the flush gone from her thin cheeks, her breath coming regularly.

"She will live," he said, as he parted with Aunt Patty outside, under the quiet stars. "All danger is over now, I believe."

It was several days, however, before Ida knew who it was who bent over her so lovingly, who soothed and tended her with all a mother's care, whose kindly hands bathed her fevered face, whose feet were ever ready to move at the least need.

A week later, however, Ida was able to sit up, and the healthy color was stealing into her pale cheeks. She enjoyed sitting by the open window, where she could watch the restless ocean. Mrs. Leverton had written that they must stay in the cottage until Ida was entirely well. Old Dinah kept house for them, and had become devoted to Aunt Patty.

"Yo' aunt ain't nuffin' on fash'nable style," she confided to Ida, "but she's a bawn lady, sho's de worl'. She doan nebbah hector nobody."

"I think you'll be able to travel by Saturday, Ida," Aunt Patty said one day. "Doctor Stone thinks there wouldn't be any risk now in your undertaking the journey."

"And, oh, how glad I will be to get home again," said Ida.

"Does it really seem like home, dear?"

"Yes, Aunt Patty. A better home than I deserve, and I can't share it again with you and Cynthia until I have told you something."

Aunt Patty drew near the chair in which Ida sat, and, standing at the back of it, put both arms around her. She could feel that Ida trembled a little.

"Of course you'll forgive me," went on Ida, "for you are so good, you could never feel harshly toward any one, however great the provocation. I did many unkind and even cruel things when I was at the farm this summer, Aunt Patty. When I think of them I don't understand how I could have acted so. I know it would be impossible for me to do such things now."

"You have had a change of heart, Ida."

"Oh, Aunt Patty, I hope so. There was need of a change. I can look back and see it now, though I used to think myself almost perfection."

"And now?"

"I see all my faults," said Ida, "and I realize how patient, generous, and forgiving you and Cynthia were all those unhappy weeks. Aunt Patty, one of the things I must tell you is that I deceived Cynthia about that lawn party. Mrs. Lennox did invite her."

"She knew that, dear."

"Knew that she was invited? Oh, Aunt Patty!"

"Yes; you see, I felt sure Mrs. Lennox must have intended to invite you both, and as Cynthia was so terribly hurt and disappointed, what did I do but go straight to Mrs. Lennox and ask her about it. She said of course Cynthy was to come, and she would depend on seein' her; that she was so sorry her invitation had not been understood."

"And you told Cynthia?"

"Yes; but not meaning any harm to you, Ida. I never thought but what you had made a mistake, and as you seemed a little unhappy ever since Mrs. Lennox had called. I made sure you were grievin' because Cynthy wasn't to go with you."

"Oh, how I wish it had been a mistake," said Ida; "but it was deliberate deceit. I knew Cynthia had no gown fit for such an occasion, and I thought I might be mortified before Angela Leverton."

"Cynthy saw just how it was," said Aunt Patty. "She met me at the gate, and when I told her what Mrs. Lennox had said, she knew that it wasn't a mistake at all."

"She was very forgiving." Ida sighed heavily. "I felt conscience-stricken when I saw that she was so bitterly disappointed. And then think of how much you have to forgive me. Do you remember that day I was in the carriage with Angela, and you were coming from the village with that big box in your arms? Oh, Aunt Patty! to think I was so mean as to pretend I didn't know you! It makes me wretched now just to think of it."

"There, there!" said Aunt Patty, who could not restrain her own tears. "It doesn't matter now, dearie. We will forget all about it."

A few days later Ida was once more back at the old farm; and how different now did everything look to her.[Pg 131] The days of grumbling and complaint were past forever. She was no longer annoyed by her old aunt's unwitting offences against etiquette; and she found a new and strange pleasure in simple things which she had once regarded with indifference or aversion. She fed the fowls, learned to harness the old horse, and insisted on helping with the work of the dairy. And how proud she was of her first pat of delicious butter!

"It really seems a pity to eat it," she said, as she exhibited it in triumph to Aunt Patty.

One day she took the horse and light wagon and drove to Bell's Falls. She said she had some shopping to do there, and several errands to which she must attend.

"One of them is a commission from Doctor Stone," she said, trying not to smile, but failing signally.

Lately she had received several letters from the old doctor, but she never read them to her aunt and sister.

"Some day you may read them," she said to Aunt Patty, "but not now. Doctor Stone and I have a secret which you and Cynthia are not to know just yet."

"It seems to make you very happy, whatever it is," said Cynthia.

"Well, I am more anxious than happy just now," returned Ida. "But I can't explain why."

About a week after her trip to Bell's Falls, Ida entered the farm-house kitchen late one afternoon with two letters in her hand. Her face was glowing from her brisk walk to and from the village post-office, and her bright eyes were dancing in anticipation of some rare enjoyment.

"One of those letters for me?" asked Cynthia, who was busy at a table making rolls for supper.

"No; both for me," answered her sister, "and great news in both. One is from Aunt Stina, who says she will be home by the 1st of November, and wants me to be ready to live with her again."

"Oh, Ida!"

It was a simultaneous exclamation from Aunt Patty and Cynthia. They both looked blank, and Cynthia dropped her rolling-pin and sat down in the nearest chair, as if she felt suddenly weak.

Ida laughed. She looked wonderfully radiant and happy. "Calm yourselves," she said. "I have other plans in my head. Listen to this." She tossed Aunt Stina's letter into the wood-box back of the stove, and opened the other—a business document—which announced that Miss Ida Worley had been appointed a teacher in the grammar school at Bell's Falls at a salary of seven hundred and fifty dollars per annum, her duties to begin the following Monday. "And as Bell's Falls is only fifteen miles off, I can come home every Friday night," said Ida.

"How'd you ever get the place?" asked Cynthia, when she and Aunt Patty had exhausted their vocabulary of exclamations of delight and astonishment.

"Through Doctor Stone's influence. He knows all three of the trustees. Dear old man! He was so ready to help me!"

"Aunt Stina will be dreadfully disappointed that she isn't to have you again, Ida."

"Perhaps so, just at first. But she will hire a companion—some one who will suit her much better than I. She won't approve of my teaching, and will wonder that I prefer it to a life of idleness in her house. But I am longing to feel that I am of some use in the world—not a drone in the hive."

"You dear child!" said Aunt Patty. "Your kind and unselfish act in helping that poor fever-stricken woman has brought a great reward. Had you passed her by you would never have known Doctor Stone, and wouldn't now have a chance to show what a busy bee you can become."

"My first month's salary shall be spent in fitting out my dear Aunt Patty with everything she needs in the way of comfortable dress," said Ida, with her arms around her aunt's waist, "and the month after that every cent shall go to Cynthia. Oh, I can hardly wait to begin! How thankful I am that I came here last June. It was the beginning of a new life. And to think how I mourned and made myself utterly miserable because I couldn't go abroad with Aunt Stina!"

Cynthia's plain little face fairly beamed with joy. "And now Aunt Stina is never to have you again," she said.

"Never again! I belong now to you and Aunt Patty."

I had run away to sea, and was serving as cabin-boy on the Flying Scud. But by the time we got to Cienfuegos, Cuba, I had suffered so much from ill-treatment, that I resolved to desert before the ship sailed. I had an afternoon ashore, and while amusing myself with the sights I went into a restaurant for dinner.

At a table opposite mine was a fine-looking sailorly man, dressed in a white duck suit and a broad-brimmed Panama hat. While he sipped his coffee, and lazily smoked his long, black Cuban cigar, he appeared to take considerable notice of me. When I was ready to depart he called me to him, and asked the name of the ship I belonged to, the treatment and wages I received, and so on. He seemed so friendly and interested that I made free to tell him of my troubles, and stated that I longed for the termination of the voyage. At this he said:

"It seems, my boy, that Providence has sent me to deliver you. I am Captain of a fine ship, and am in need of a cabin-boy on account of mine having met with an accident that will keep him on shore for some time. What do you say to shipping with me? I will promise you good treatment and much better wages than the Flying Scud pays you."

Here was a golden avenue of escape for me. I was young and trustful, and Captain Ward of the Dragon—for such he told me were the names of himself and vessel—seemed so sympathetic and kindly that I gladly signified my willingness to desert to him.

"Very well," he answered, seemingly well pleased; "I am going on board now, for we are to sail immediately, and you can come right along with me."

As we made our way to the landing-stage through the fast growing darkness, Captain Ward kept up an easy, friendly flow of talk, and by the time that we were seated in the handsome long boat belonging to the Dragon I had, in the impulsiveness of youth, become strongly attached to him. When we reached the latter vessel it was too dark to observe anything more about her than the fact that she was fore-and-aft rigged, with a long yard on her foremast for bending a big square sail to when running before the wind, and had a broad, clean sweep of deck, with high bulwarks, through whose port-holes several cannon looked out. The Captain was received at the gangway by his chief mate, to whom I was pointed out with the half-laughing remark, "this is our new cabin-boy, who had the good taste to prefer the Dragon to the big ship over yonder." I went below with him, and he pointed out a tidy little state-room, which he told me I was to occupy, and said that whatever clothes I might need would be supplied to me out of the stock kept in the slop-chest. Immediately after this Captain Ward went on deck, and we lifted the anchor and put to sea.

Well, to make a shorter story of it, I will explain right here that I soon learned I had shipped on board of the most notorious slaver in the trade, and that she was commanded by a man who was acknowledged to have no rival in the way of daring and success. I heard some time later that he had been a buccaneer in the Gulf of Mexico before going into the slave trade, and that the Dragon had once flown from her masthead the fearful black flag. All this may have been, and probably was true; but this I claim freely, that during the month that I served on board I received the kindest treatment from him. It fretted me, however, to think of serving on such a vessel, and I determined to leave as soon as we returned to Cuba. But I was not to wait even that length of time, as you will soon learn.

Several days later, in a river on the African coast, we loaded the Dragon with four hundred poor wretches, who had been captured to serve as slaves to the civilized Christian[Pg 132] white men across the wide Atlantic. Our lading had been much hurried, owing to a report that the American man-of-war Dale had been seen cruising off the mouth of the river the day before we arrived. Her cutters had a habit very distasteful to the slave-traders of pulling up the river at unexpected times in search of contraband cargoes. The penalty that the officers and crews of slave-ships were obliged to pay in the way of death or lengthy imprisonment, and the confiscation of their vessel and effects, often drove the slavers to open warfare with the naval forces when in tight corners. If they were captured, after warlike resistance or with slaves on board, they were considered as pirates, and suffered accordingly.

The slaves had been fed and chained securely between decks, and everything made ready for slipping out to sea by sunset, as the lookout reported the coast clear; but Captain Ward waited until the off-shore wind began to blow, about eight o'clock, before getting up his anchor. At that time, under the jib and mainsail, the Dragon commenced to work slowly down the river, the negro pilot standing on the forecastle and conning the vessel through the channel. We had almost reached the mouth of the stream. I heard the Captain say to his mate that by daylight the land would be leagues astern, and all danger from station cruisers would be at an end.

Just as we approached the last turn, where the river narrowed to about one hundred feet, the Dragon stopped suddenly, brought up against a stout hawser stretched from tree to tree on either bank, then swung around until she lay directly across the stream, and at the same instant two boats dashed alongside filled with naval sailors, who were prepared to sweep down all resistance with their cutlasses, drove the crew into the forecastle, and secured the door. I had been standing on the quarter-deck when the schooner was captured, and as the men-of-war's men forced the Captain and mate below the former picked me up in passing and carried me into the cabin with him. No sooner had we entered this than the companion-way slide was pulled over and we were prisoners, while overhead sounded the tramp of many feet as the sails were lowered and the vessel brought to an anchor.

"Quick, open one of the stern-ports!" said the Captain to the mate; then he ran into his room, from which he reappeared almost immediately and thrust a sheet of paper into my hand, exclaiming, "Show this to the naval officer when he comes below."

In another instant he and the mate had pulled off their shoes and clothes and slipped noiselessly into the dark flowing river through the open port. I entered the master's berth, in which a candle-lamp was burning, and looked at the paper that the Captain had given me. It read:

"My cabin-boy was innocent of the character of the Dragon when he signed articles.

"Roland Ward, Master."

Slaver, pirate, or any other hard name you may call him, there was something noble in the man who could think of others at such a time, and sacrifice even a few precious, fleeting moments to insure the safety of a poor little cabin-boy.

A few minutes later a naval officer, followed by several blue-jackets well armed, descended the companion-way and asked for the Captain. In order to gain time for the two men, whom I knew to be at that instant swimming for their lives, I handed him the note. He glanced over it, thrust it in his pocket, and exclaimed:

"This will keep for the present. Where is the Captain?"

I answered that he was not in the cabin.

"WHERE IS THE CAPTAIN?" HE REPEATED, IMPATIENTLY.

"WHERE IS THE CAPTAIN?" HE REPEATED, IMPATIENTLY.

"Where is the Captain?" he repeated, impatiently.

I knew that the swimmers must have reached shore, and were safe from pursuit in the darkness of the night, so I pointed to the open port. The officer stamped his foot in rage, to think that he should have been outwitted so cleverly, and ran up to the deck, where I heard him shouting to burn a blue light, and for some of his men to tumble into the boats and pull about in search of the escaping slavers.

The seamen had their trouble for nothing, as the Captain and mate succeeded in making their way back into the country, where they remained in hiding until they found an opportunity of getting back to Cuba.

During the next day the Dale made her appearance, and received the transfer of the prisoners. Although I was sent with them, the Captain's note was accepted as proof of my innocence, and I was restored to liberty and made a messenger-boy on board the man-of-war, in which capacity I served until the Dale was relieved by the sloop-of-war Vincennes, and returned to the United States a few months later.

The lieutenant who had been left in ambush and who had captured the slaver was placed on board of her in command, and she was afterwards employed successfully as a decoy for bringing a number of other slave-ships within the clutches of Uncle Sam's officers.

My advent in the village was all that I could have wished for. The local paper published my picture in man-of-war uniform, together with a history of my voyage; and I was heroized by the girls, and looked upon with sufficient admiration and burning jealousy on the part of my former school-fellows to make even my cup of satisfaction and happiness full to the brim.

The newsman at Piccadilly and St. James's Street had his bill of news wares pasted on the pavement. Even he who ran by means of a swift hansom-cab might read the huge black letters. There was but one article on the bill. Black type, three inches long, shouted:

As Fabian Wendell, London correspondent of the New York Intelligence, and his friend Carter, just from New York, were whirled out of St. James's Street into Piccadilly, Wendell's eye caught the announcement. He lifted the trap in the top of the cab and told cabby to pull into the pavement and hail the newsman.

"ALL THE PAPERS," SAID WENDELL.

"ALL THE PAPERS," SAID WENDELL.

"All the papers," said Wendell, and straightway had the afternoon rainbow—the pink Star, the yellow Globe, the white Pall Mall, the pale gray Standard, and the green Westminster.

"What is the matter?" asked Carter.

"Great news," replied Wendell, opening the Pall Mall, and pointing to a "scare head" half a column long. Under the head-lines was this short despatch:

Tripoli, June 23d.—H.M.S. Camperdown rammed H.M.S. Victoria yesterday five miles out at sea. The Victoria sank at once. Rear-Admiral Tryon, most of his officers, and over three hundred men were lost.

"The Mediterranean fleet," went on Wendell, talking to arrange his thoughts rather than to inform his friend, "has been cruising in the Levant. Victoria was the biggest and most formidable battle-ship in the world. Camperdown is almost as big. Tripoli is on the north coast of Africa—"

"No," interrupted Carter, who was looking at the Standard. "This paper says it is Tripoli, on the coast of Asia Minor."

"That's bad—small place—poor telegraph," Wendell was muttering, his forehead wrinkled so that it suggested sixty rather than twenty-three. Up went the trap in the top of the cab. "Drive to the Eastern Telegraph Company, Old Broad Street. And you get an extra fare if you do it quickly."

"What are you going to do there?" Carter inquired, as the cab began a mad dash down St. James's Street on its way to the City and Old Broad Street.

"Why, a very simple thing. I'm going to try to get a full account of this disaster, and print it in New York before an account is printed in England. Tripoli is miles away from nowhere at all. These English papers are very slow. I propose to show them what American enterprise is."

"But they are sure to be first with such a story as this, about their own navy. You have no correspondent there."

"Neither have they. I have a scheme, and the beauty of it is that even if these English fellows think of it they will dismiss it without a trial as too absurd."

"Then you admit there is practically no chance?"

"Chance? I don't admit that there is such a thing as chance. I know that it is my duty to do something. This is the only thing I can think of. The others will be hopeless and will do nothing."

At the Eastern Telegraph Building Wendell stopped in the office on the first floor long enough to write this despatch:

To the telegraph agent, Tripoli, Syria.—The New York Intelligence will pay the telegraph tolls and £200 ($1000) for two thousand words full describing the Victoria disaster. Send at once to Wendell, London.

Then he went up stairs, straight to the general manager. That important person read the despatch with increasing derision, which he did not take the trouble to conceal.

"The rate from Tripoli to London is a shilling a word," he said. "Two thousand words will cost you a hundred pounds, five hundred dollars. The operator or agent at Tripoli is an ignorant Turk, who, without doubt, knows not a word of English. Tripoli is on the Turkish government lines, and we cannot send the money to him to pay for the despatch. He never heard of the New York Intelligence. You practically ask him to spend a hundred pounds with no prospect of ever seeing it again."

"Very true," said Wendell, and he took the despatch and added to it. "Will start money as soon as despatch is received." Then he gave it back to the manager, saying: "No harm to try. If I fail, I shall be out only the eleven dollars this telegram will cost me. If I win—"

He laughed, and the manager relented. "I'll mark it so that it shall be rushed through, and I'll add my own guarantee," he said, with abrupt courtesy. "As soon as an answer comes, if an answer does come, I'll see that you get it."

Wendell thanked him, and went away with Carter. He spent the rest of the day getting and sending all he could find bearing in any way upon the disaster. All England was waiting for the fuller news. The Admiralty and the Foreign Office were besieged by crowds of those who had relatives or friends in the fleet. But no further news came. The Saturday morning papers had nothing but rumors. Even the long reach of the Times could not get at that obscure Syrian village.

Wendell watched impatiently for the early editions of the Saturday afternoon papers. There was still no story. The whole civilized world was waiting. Carter was despondent over the failure of Wendell's scheme, and Wendell had almost ceased to hope. The Sunday morning papers had nothing. Sunday afternoon came a telegram in an Eastern Telegraph envelope. Wendell's hands trembled as he read:

Tripoli, Syria.—Send soon as can raise money. Old subscriber Intelligence.

Harris.

Wendell laughed hysterically as he gave it to Carter, who was really faint with excitement. "The manager said they don't know the Intelligence in Syria," he laughed, as Carter was reading and rereading. "I wonder what he will think of that?" And he hurried away a cheering telegram to the unknown Harris, who was helping him to beat the world on the news story.

"If Monday morning's papers pass it," he went on, "we're safe. But that's a slim chance."

He waited up until six o'clock Monday morning to see. The only further news was a partial list of the saved, and a formal announcement from the Commander of Camperdown that the disaster had happened. To Wendell this fortune seemed incredible.

Two thousand miles away, Harris, a medical missionary at Tripoli, was in a more agitated state than was Wendell. He was the only English-speaking person in that squalid little Asiatic port. He came from Kentucky, and got his news of America through the weekly edition of the Intelligence, for which he was a subscriber. The day after Wendell sent his despatch he was passing the telegraph office. Abdallah Gazi, the Turkish operator, called him in, and asked him to translate it. As Harris read it, he saw the whole situation.

Abdallah had been the despair of the survivors of the disaster. As he hated the English, he had pretended to be more stupid than he really was. Harris was fired with ambition to help the paper he took, published by his countrymen, in his native land. But to get together the five hundred dollars necessary was no easy thing in that miserably poor village. He gave no heed to the furious Syrian sun; he toiled and wrestled with friends and acquaintances. By Monday afternoon he had the money, and began dictating two thousand English words, letter by letter, to the operator, who spoke only Arabic. It was a long and dreary task, and not until midnight was it done.

The first sheet of the great special, telling the pitiful story of Tryon's mistake, and its horrible result, was in Wendell's hands at five o'clock that Monday afternoon. Thanks to the difference of time, the last sheet reached him at ten o'clock, two hours earlier than the time at which Harris sent it. Wendell had the wires to New York open, and had warned the Intelligence of what was coming. As New York is five hours earlier than London, the editor of the Intelligence was reading the great beat on all the newspapers in the world at half past six o'clock. At seven an extra afternoon edition of the Evening Intelligence was on the streets of New York.

Next morning Wendell slept late. When his man awakened him, he was straightway at the bundle of morning papers. Every great London daily had its first story of the Victoria disaster, in large type, with huge head-lines. The eager British people had the news at last. But the date line of the story was not Tripoli. Every despatch began: "New York, June 26th.—The Intelligence has the following special from Tripoli."

"I wish I had been in the editorial rooms of the great London Times when that special from New York came," said Fabian Wendell.

The last little leaf has fluttered down,

The trees are standing all bare and brown;

But the winter long, if you could see,

There are wee little elves in each brown tree

Spinning the dress, so green and fair,

That will one day wave in the soft spring air.

Good-by, little leaf; you did your best;

So curl away, it is time to rest.

M. E. S.

(In Two Papers.)

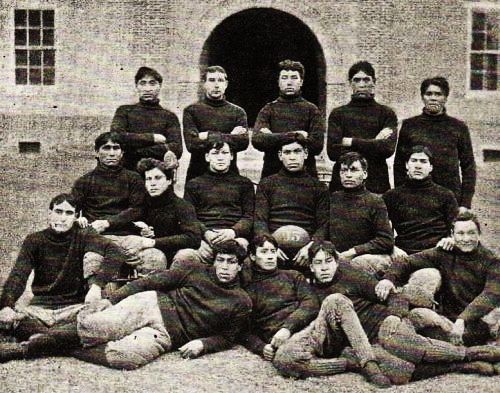

Our boys are familiar with the United States flag, with its historic stars and stripes, as it floats over public buildings and is carried in street parades. How many know it is used for a sign or a sign-board? Passing through any one of our large cities, we often see the flag drooping from a protruding staff over a common office doorway. Considering what it means, we go up to the door, and see on one side a flaming poster printed in colors, surmounted by a picture of many soldiers standing well grouped, in their bright attractive uniforms. On reading we find this to be an advertisement or an invitation on the part of the United States government to all able-bodied men so desiring to join the ranks of the army as private soldiers. It states that the man so volunteering to serve his government in this capacity will be well clothed, fed, and, besides, receive $13 per month in cash, less certain small sums retained from time to time by the government to be surrendered to the soldier upon his discharge from service. He must agree to serve faithfully, take an oath of fidelity to the United States, and to obey all superior officers for a period of three years. It was formerly five years. While reading the poster we have noticed, either leaning in the doorway or pacing up and down with erect carriage, in a neat tight-fitting blue uniform, a man who, upon being accosted, replies that he is a private, or, if we noticed a V-shaped braid upon his arm, a sergeant, belonging to some regiment of the army stationed at a distance. He is here to get men to enlist, and go back with him to his regiment and become soldiers. He enlarges upon the pleasures of the service—if cavalry, the riding, the scouting, the excitements of chasing Indians; if infantry, the enjoyments of camp life, the practice marches, the Indian campaigns, where deeds of gallantry and brave acts will be rewarded by medals and certificates of honor; if artillery, the use[Pg 135] of heavy ordnance in defending our sea-coasts, with their pleasant stations.

In glowing terms he thus pictures to a young man the life of a soldier, such as we are familiar with in history. But to have him know more fully he invites him to go into a room within, called a Recruiting Office. On coming in, his soldier friend touches his cap to a gentleman sitting at a desk writing. He reports that his companion is desirous of entering the army. This gentleman then, in a brisk businesslike way, which proves him to be an officer accustomed to command, draws from the young man an account of his past life, finds out his habits, his age, and then determines from his answers whether or not he would make a good soldier. He also shows him that soldiering is not all play, pomp, and ceremony, but work like that in any other profession, that implicit obedience is necessary, and willingness to do well the work in hand. Only in such a way could he expect to rise in the estimation of his superiors in rank and obtain promotion and reward. The officer satisfies himself that his candidate is a good one, filling the requirements of law as to a good moral character, able to read and write, and within the ages of sixteen and thirty-five; or, if under twenty-one, that he has his parents' or guardians' consent; then he will administer to him the oath of allegiance to the United States. Now, after signing a contract to serve the United States government as a soldier for the required period, our young civilian has become a recruit. Before, however, he is finally admitted, he must undergo a careful physical examination, made by a surgeon. The accepted recruit has his choice of entering the artillery, the cavalry, or the infantry.

The foregoing is all the preparation needed, but if our recruit is anxious to advance beyond the position of a private soldier, and to fill places of responsibility, it is needless to say he must prepare himself.

His first duty is to learn thoroughly his work as a private. Having done that well, he is without doubt prepared to teach others the same work. The officers are always watching for bright and intelligent men, and so will recommend for the next grade, and his captain will secure for him the appointment as corporal. Many men have not had the advantages of others before they enter the ranks, and for them to have the same chances of promotion post-schools are provided, each with a competent instructor, and under the charge of a commissioned officer.

On becoming a corporal some increase of responsibility is given our young soldier. He must wear as an indication of his rank two V-shaped stripes upon his arms and a narrow one down each trousers leg, of the color of the service insignia—red for artillery, yellow for cavalry, white for infantry. Instead of being conducted about in ranks, he now stands in line at the right end of his squad of eight men; when his squad is separate he is in command. He no longer walks post as sentry, but has charge of a relief, i. e., one of the divisions of a guard. The men of a relief all walk post at the same time. He must put his men on their posts as sentries, and stay awake and answer their calls so long as they are there. Many other duties, clerical, police, and provost, are given corporals, according to their ability.

Vacancies constantly occur in the higher positions, and the custom is to fill them from the next lower rank. If our corporal has shown his ability to command firmly but in a manner pleasant to his associates while in his present grade, his chances are the best to be recommended for an appointment as a sergeant by the captain of his company. The corporal receives $15 and a sergeant $18 per month in the artillery, cavalry, and infantry.

A sergeant's command is double that of a corporal, and on guard he divides his time in charge of the guard-house with another sergeant while overseeing the corporals and their reliefs. On drill he is over a section of two squads; in barracks he has charge of one sleeping-room; must keep order and enforce discipline. Thus still more ability to command other men must be shown. Corporals and sergeants are called "non-commissioned officers," because they receive a warrant from their colonel countersigned by the adjutant as authority of rank, in place of a commission from the President of the United States.

The labors of soldiers, privates, corporals, or sergeants are not usually arduous, except in case of war or other like emergency. Their daily routine is no more monotonous than men's ordinary pursuits in civil life, with the one exception that they are always under the command of others; but this need not trouble them; for good soldiers there is responsibility enough, according to the position they hold. Their time is pretty well occupied; for there are generally two drills a day; care of their room and equipments; in the cavalry, grooming their horses twice a day; also guard duty for a night and day at least once a week. In the artillery there is now the study of the mechanism of modern heavy guns—their loading; their firing by mechanical means and by electricity. If we think of the emergency calls upon the soldier—for example, during riots, insurrections, and such like—we find the service of enough variety and interest for the average man. Besides the positions of corporal and sergeant which I have mentioned, many other places of higher pay are open to the soldier, such as trumpeter at $14 per month; wagoner, artificer, blacksmith, and farrier or saddler, at $15.

The Engineer and Ordnance Corps also offer higher pay, because of the knowledge required to build forts, bridges, and make ammunition and prepare projectiles. Privates of engineers receive $17; corporals, $20; sergeants, $34 per month. The Signal Corps sergeants have, besides their duties as experts in signalling, to be telegraph operators; they receive $45. To each company there is a first sergeant, who is the highest non-commissioned officer. He has direct charge of the men, and keeps all company records. He receives $25 per month. All pay in the army is increased from the third year of enlistment; i. e., the longer a man shall be a soldier, the more pay he will have a year.

In the regiment there are chief trumpeters, musicians, and saddlers, rated at $22 per month; chief musicians at $60—these are band-leaders. The sergeant-major, who has charge of regimental papers, quartermaster-sergeant, who has the care of all government property in the regiment, at $23; the sergeant-major and quartermaster-sergeant of engineers at $36.

Each post has an ordnance sergeant, commissary sergeant, and quartermaster sergeant at $34. Then in the Hospital Corps the stewards rate at $45. The hospital steward is really an apothecary. Acting hospital stewards are at $25, and attendants at $18.

These positions, except the musicians, are all filled from the ranks, according to fitness and ability. The highest goal to be reached by a soldier is a commission from the President as a second lieutenant in the army.

To obtain such a commission one must first become a corporal or sergeant, and have served three years. Then he has to prove himself a gentleman and good soldier to the satisfaction of his captain, whereupon by a mark on the sleeve he will be known as a candidate for a commission. He will have time allowed him to study, and he must prepare himself thoroughly in all common-school branches, including history, especially that of our own country. The first step is to receive the recommendation of his captain; next that of his colonel; and then of his department commander, when the commanding general at Washington will order him before a preliminary board of officers to convene near his station. This board will examine him more especially as to his knowledge of the duties of a soldier and officer. If he shall pass that satisfactorily he will be sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for final examination—a more thorough one in all branches, and before a board of four officers, two of whom must be surgeons. If successful in that and in a physical examination by the surgeons, his name will be sent to Washington with recommendation by the Examining Board that he be appointed a second lieutenant of artillery, cavalry, or infantry, according to the decision of the board, recommending him for that branch of the service for which he is best fitted. All appointees of late have gone either into the cavalry or infantry.

There is nothing much more entertaining than getting up tableaux, the fun compensating for all the work and study.

In the November number of Harper's Young People, in the year 1894, there is an article explaining the stage in the parlor, with all the paraphernalia of curtain, foot-lights, and scenery. Therefore the present article will omit mechanical directions; excepting to state that for those who will not undertake tableaux on such an elaborate scale, very desirable effect may be produced by using a drapery of dark green, red, or brown canton flannel, or shawls concealing the back and sides of the room. And a curtain may be made to draw in front by suspending it over a wire or stout cord, provided the cord or wire is fastened taut and strong. A small curtain of the same color should be hung to conceal the lights, and also the persons who draw the stage curtain.

The lights should be put at the left, and they should be arranged to bring out the desired detail. Therefore the placing of them will have to be tried beforehand. Put some on the floor and others on the top of a table, and others still higher. A row of wax candles would be better foot-lights than none at all. Only be careful of draught, and keep from catching on fire by stretching a stout wire across the stage, two feet back of the candles, and from this fasten a wire netting directly over the candles, so as to completely cover the blaze from possible contact with the curtain, or other inflammable stuff. Put mirrors behind all of the stage lamps, and also behind the candles; the mirrors act as reflectors, and heighten the effect. If you cannot provide mirrors, use tin reflectors.

Before arranging tableaux vivants, ask some older person than yourselves to take charge. By so doing you will overcome the greatest of all difficulties, because you have shifted the responsibility. To this person you can even turn for advice and decision.

The first question to decide is always the character of the tableaux; whether they are to be of mixed variety, with no special subject in view but of pretty or amusing entertainment, or whether they are to teach or illustrate a special theme. The latter is generally preferable, and always so at the time of a great festival, such as Christmas. This point settled, the next would naturally be whether the entertainment should be entirely, or in part, of a religious character. If in part religious, it would be delightful to show Christmas Carillons, Twelve Chimes, Christmas to Twelfth Night.

The First Tableau would be entitled the Annunciation, when

"The angel greets the Virgin mild;

Hail, Mary, full of grace! thy child

The Son of God shall be."

This tableau represents an interior: the room has a deep frieze drapery over the mantel, before which Mary kneels on a low cushion; to her left, and considerably before her, is a large jardinière filled with ascension lilies; and directly before her is a table, on which is a roll of parchment partly unfastened. By the table stands the angel with hand outstretched towards her.

Tableau Second.—The shepherds see the angels bright.

Scene out of doors, with shepherds in their usual costume, each shepherd holding a crook, while back of them, huddled close together, stand the herds of sheep. Before the shepherds, and a trifle to their right, is the angel, with outstretched hand, indicating the way.

Tableau Third.—Ye lads and lassies, go fetch ivy, holly, and mistletoe.

An out-of-door winter scene, showing overturned trees, dried and leafless branches, frozen streams, and a light snow, while playfully rushing down the hillside come the gay young people with armfuls of green branches.

Tableau Fourth.—Bringing in the boar's head.

"Was-haile!

Bring in, upon his silver tray,

With minstrelsie

The boar's head, armed with garlands gay

And rosemarie."

The jolliest and tallest boy should take this character, and hold the tray above his head.

If the readers will find the Harper's Monthly for December, 1880, they can copy the tableaux with greatest ease.

While these tableaux are shown the poem should be recited in entirety, and, if thought advisable, more tableaux might be readily added.

Other examples of the religious would be to show an out-of-door winter scene, with snow-covered hills and leafless tree branches, on which a little snow has fallen. Towards the front of the stage half a dozen girls and boys, in gay attire with picturesque wraps and hats, should stand. They should be naturally grouped; some of the boys should have their hands in their pockets, others, again, have them drawn under their short cloaks. It is a cold night, and the young people should indicate it. While they thus stand an invisible chorus should sing a hymn of the Nativity. Or, with a similar background, show five girls standing in a straight line, a tall one in the centre; the two shortest should stand on each end. The girls should be attired differently, but all in warm apparel, with fur-edged cloaks or fur garments of any sort; each girl should have her hands in a muff. Show a quantity of warm color, which can readily be done by silk mufflers, frocks, ribbons, and feathers. Back of these girls an invisible chorus must sing a Christmas carol.

A catchy tableau series would be Mother Goose and her children celebrating Christmas.

Tableau First.—Mother Goose in her tall cone-shaped[Pg 137] hat, riding on an enormous goose. Copy hers and all the other costumes from Mother Goose's book.

Tableau Second.—Her children faithfully charactered. Little Jack Horner should be sitting in a corner, eating his Christmas pie. The King in his parlor should be dressed to represent a king. Simple Simon should meet pie-man going to the fair, etc.

Tableau Third.—A sleeping apartment, Mother Goose and her family in bed. Great prominence must be shown to Mother Goose, whose bed is in front, and near hers some of her more notable children. This scene may be readily arranged by putting small cots on the stage; the children can lie down dressed, the coverlets hiding their clothing. Near each bed put that which would indicate their character, as example, the big pie for the pie-man.

Tableau Fourth.—Santa Claus at home about time to start. Interior of a room, simply packed with all sorts of hobby-horses, dolls—big and little, dressed and undressed—musical birds, woolly sheep, sleighs, drums, tenpins, everything in the toy line that could be imagined or described, while in a large easy-chair before the lighted grate-fire sits old Santa himself, as gray-bearded, fat, and jolly as ever.

Tableau Fifth.—Little Bo-Peep fell fast asleep and dreamt—

Show Santa Claus again, this time out-of-doors, on his sled drawn by swift reindeers; but the reindeers have stopped, for Bo-Peep stands before them, her shepherd's crook leaning over her shoulder, her sheep all around, and they, as also Po-Beep, gazing at the presents—sled, Santa Claus's pack, hat, beard, miniature tree, full stockings, and all. Bo-Peep wears the regular shepherdess costume, the sheep are toy sheep on wheels. The bells should jingle loudly until Bo-Peep appears.

Tableau Sixth.—The Christmas tree.

A large tree filled with toys; leaning against it is a ladder, which Mother Goose climbs, and then unfastens the various gifts. Her children are all grouped around the bottom, and impatiently await the arrival of their presents.

Tableau Seventh.—The Christmas dance.

Mother Goose and her children dance around the Christmas tree. Waltz music is played; they dance once around, when the curtain is drawn.

Tableau Eighth.—Mother Goose's children eating their Christmas supper. A long table covered with a white cloth, and decorated with lighted candelabra, flowers, bonbons, fancy cakes, china, silver, and cut glass. All the children are seated around, Mother Goose at the head, and to her right her son Jack, then Jack's wife, then a boy, then a girl, and so on around. Each child is in the act of eating, drinking, lifting a cup, a candy, or indicating some natural movement at a supper table; their heads should be turned as though they were in conversation.

Tableau Ninth.—Mother Goose and her family in a well-arranged group now stand and sing a jolly good-night song. This song may be acted by those on the stage, but the singing is done by an unseen chorus.

Follow this with two tableaux, opposite in meaning.

Tableau One.—The empty stocking. A poverty-stricken-looking room—bare floor, a hard wood chair and table (on the table stand a few pieces of cheap china), a window with a broken pane, in which a bunch of paper or canton matting is stuffed to keep out the snow; a small kerosene lamp, the light from which comes dimly. A poorly clad and as poorly fed appearing little girl; one of her thin hands rests on the table, while the other holds an empty stocking, on which the child sadly gazes.

Tableau Two.—Bless you honey-bugs! Yo' feels gay.

This also is a plainly furnished room, but it is trimmed with Christmas greens, a large star and tree being particularly conspicuous. There are several colored children running around, some dancing, with toys in one hand and a full stocking in the other, others taking things off a little tree, others again eating sugar plums, or striding across the bare door in eager pursuit of a dropped cornucopia or cinnamon cake. Their dusky-faced mammies, meanwhile, laugh at them through the half-open doorway.

And thus tableau might be described after tableau, but a few hints may be helpful.

Carefully study scenic effect. "How beautiful!" is so often the exclamation regarding a well-dressed stage, even before any person appears or one word is spoken. Remember to use harmonizing colors, and to throw on different-colored lights. The latter may cost a little money, but it will repay a hundredfold. A white light, changing to pink, again to yellow, rose, or green, as the scenery may require. In every way catch the eye.

Remember, the tableau is but for a minute; let that minute be perfection.

Sometimes, for example, let a fountain play in the large grounds or garden. This can be easily arranged by the proper management of a hose. You can surely place a piece of oil-cloth under the moss over which the water flows, and have sponges conveniently near.

Be careful to select pretty and noticeable toilettes. If you are taking the character of a queen at a drawing-room, dress as the queen, not as her maid; but should you be a maid, wear jaunty, gay attire, and not costume yourself in a severely cut brown-cloth tailor suit.