The Mentor

“A Wise and Faithful Guide and Friend”

Vol. 1No. 36

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS WARD

FREDERICK WILLIAM MACMONNIES

GEORGE GREY BARNARD

DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH

AUGUSTUS SAINT GAUDENS

PAUL WAYLAND BARTLETT

By LORADO TAFT

Sculptor, and Author of “History of American Sculpture”

The story of American sculpture is a brief one compared with the chronicles of other lands. Our first professional sculptors, Horatio Greenough and Hiram Powers, were both born in 1805. In European countries the records of the last hundred years are but fragments, brief sequels to the story of ages of endeavor. It is difficult to realize that our actual achievement, from the very kindergarten stage of an unknown art to the proud eminence held by American sculpture in the Paris Exposition of 1900, was the work of but three score years and ten—was seen in its entirety by many living men.

BIRTHPLACE OF J. Q. A. WARD

Ward was born in 1830, on a farm in the neighborhood of Urbana, Ohio.

The beginnings of all arts in this country have been timid and imitative. Literature, music, and painting had something to found themselves upon in the national tradition; but sculpture was never abundant in England, and this art, usually one of the earliest, was the last to appear in America. Its first inspirations were Italian, and for half a century American sculpture was a crude parody on the art of Canova and Thorvaldsen. Many of our sculptors, like Powers, Greenough, Crawford, Story, Randolph Rogers, Rinehart, Ball, Mead, and Harriet Hosmer, made their homes in Florence and Rome, and welcomed the ever swelling tide of American travel with wistful greetings. Perhaps their influence was greater there upon the receptive travelers than it could have been at home; but one cannot help feeling a high regard for men like Palmer, John Rogers, and Ward, who “held the fort,” developing the native material of their own land.

About the time of the Centennial, France was suddenly discovered by our young sculptors. Her opportunities were appreciated, and soon the entire stream of students was diverted thither from Italy and Germany. Saint Gaudens was the first important product of the American-French school of sculpture, and his talent and training together offered an irresistible argument for the new methods.

PAUL WAYLAND BARTLETT AND JOHN QUINCY ADAMS WARD

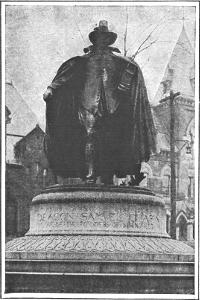

WASHINGTON, BY WARD

On Wall Street, New York City. The pedestal bears the inscription: “On this site, in Federal Hall, April 30, 1789, George Washington took the oath as the first President of the United States of America.”

Before speaking further of our greatest sculptor, a few words should be devoted to the last and most distinguished of the pioneers, John Quincy Adams Ward (1830-1910), who was privileged to see the triumphs of American sculpture at home and abroad, and to participate in them to the end. Always keenly alive and vibrantly responsive to the forces at work about him, he was ever a contemporary of the youngest men of his profession. Ward’s earliest success, “The Indian Hunter” in Central Park, New York City, was the result of a long journey among the red men. Its intensity is an unconscious revelation of the man who made it: no lackadaisical dreamer could have conceived the idea, much less have carried it to its happy realization. The emotion of war times found expression in “The Freedman,” and later in a notable series of memorials to heroes of the conflict, culminating in the great “Henry Ward Beecher” of Brooklyn, one of the most impressive portraits in this country. None but a big man could have grasped that character; none but a strong nature could convey to others that impression of exuberant vitality and of conscious power. The great preacher stands solidly upon his feet, enveloped in a heavy overcoat and cape, his hat in hand. The poise is superbly confident; the leonine head uplifted as if in command rather than in exhortation.

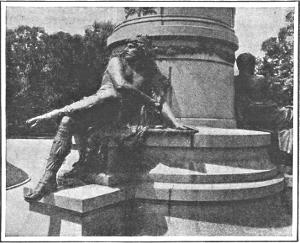

THE WARRIOR, BY WARD

One of the three figures that adorn the base of the Garfield statue at Washington. The other two are the “Statesman” and the “Student.”

New York City has many of Ward’s works. His “Pilgrim” and “Shakespeare” in Central Park are well known. His “Horace Greeley” is the last word in faithful characterization, as vivid as his Wall Street “Washington” is noble and detached. The admirable equestrian “General Thomas” and the “Garfield” monument in Washington are equally familiar. The uprightness and dignity of the whole life of the sculptor left their impress upon every portrait he modeled. Some are greater than others; but they are men, everyone of them. They stand firmly on their feet, and they make no gestures, no attempt to win us. There is no restlessness, no anxiety; you feel eternity in their attitudes, in their composure. Above all, the sculptor has known how to endow each with an individual intelligence.

GRIEF, BY SAINT GAUDENS

This mysterious figure is sometimes called “Death,” or “The Peace of God.” It is in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, and is a memorial to Mrs. Adams.

Augustus Saint Gaudens, like so many of our best citizens, was a product of another land; of two others, in fact. Born in Dublin in 1848 of a French father and an Irish mother, he represented an unusually fortunate combination of two artistic races. The humble family settled in 1850 in New York, where the boy was early apprenticed to a cameo cutter, supplementing his childish efforts with a rigorous training in the drawing classes of Cooper Union. In 1880, after some years abroad, he exhibited at the Salon his remarkable figure of Admiral Farragut, now in Madison Square, New York, which still remains one of his finest works. This statue—and its harmonious pedestal—met with instant success, and was followed by a series of triumphant works, so novel and original, so significant and admirably perfected, that the master’s position at the head of the profession in this country was constantly reaffirmed to the day of his death.

DEACON CHAPIN, BY SAINT GAUDENS

At Springfield, Massachusetts.

Indeed, in reviewing the life of this great artist, one asks what other sculptor of modern times has produced such a succession of notable achievements as the “Farragut”; the “Lincoln” of Chicago; the “Deacon Chapin” of Springfield, Massachusetts; the “Adams Memorial” in Washington; the “Shaw Memorial”; the “Logan”; the “Sherman”, and finally the seated “Lincoln.” Add to this the countless exquisite medallions, the delightfully decorative high relief portraits, and, perhaps most beautiful of all, that angelic brood of which the “Amor Caritas” is the type and culmination, and where shall we look for a more individual expression? Rodin himself, with all his contortions, has not produced so much beauty nor demonstrated himself more “original.”

Copyright, 1905, by De W. C. Ward.

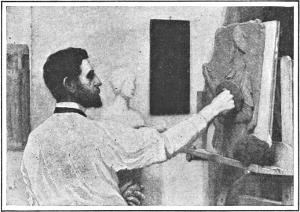

AUGUSTUS SAINT GAUDENS IN HIS STUDIO

From a painting by Kenyon Cox.

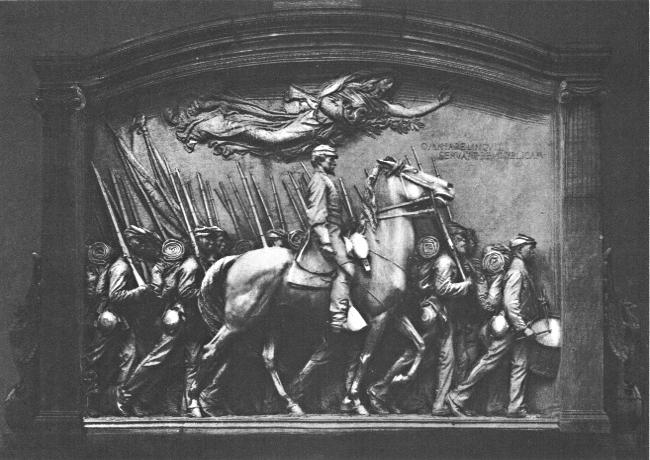

To different moods these great works make their differing appeals. The heroic “Lincoln,” with its strong, gaunt frame and its majestic head bowed in sympathetic tenderness; the sturdy “Chapin,” wrapped in a voluminous cloak and self sufficiency; the mysterious, inscrutable genius of the Adams tomb; the rhythmic momentum of the colored regiment with its fated leader riding serenely, square shouldered, and level eyed to his doom; the glorious “Victory” of the Sherman group, the most spiritual, most ethereal of all sculptured types,—what an array are these! What wealth to have brought to our national ideals!

BIRTHPLACE OF G. G. BARNARD

Barnard was born at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, where his parents were temporarily residing in 1863. The sculptor is really a Westerner.

Worthy successor to the great artist who put us all under such heavy obligations is Daniel Chester French, whose work is known throughout the land. French was born at Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1850, and grew up in Concord, Massachusetts, amid ideal surroundings. His first youthful effort in sculpture, “The Minute Man of Concord,” was a success, and his busy life has known no failures. No other American sculptor has produced so much, and we can name here but a few of his most important works.

MINUTE MAN, BY FRENCH

At Concord, Massachusetts.

Reproduced from American Sculpture, by Lorado Taft. Copyright, 1903, by The MacMillan Co.

ALMA MATER, BY FRENCH

Adorning the approach to the Library of Columbia University, New York City.

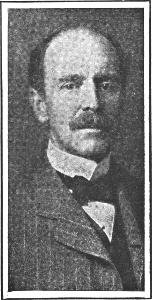

DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH

French is well known as a sculptor in both America and Europe.

Best beloved is the noble “Death and the Young Sculptor,” designed as a memorial to the sculptor, Martin Milmore. In this poetic group we have unquestionably one of the highest expressions of a purely American art. Other works of interest are the ascetic “John Harvard” of Cambridge; a vigorous “General Cass” and the touchingly sympathetic “Gallaudet” group, both in Washington, D. C.; the “O’Reilly” monument of Boston; the equestrian “Washington” in Paris and Chicago; “General Grant” in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia; and “General Hooker” in Boston. Among his most recent works are a “Lincoln” for Lincoln, Nebraska, and an “Emerson” for Concord.

The Columbian Exposition was crowned by French’s gigantic and truly monumental “Republic,” a superb figure which reappears, comfortably seated for all time, in the “Alma Mater” of Columbia. French does not disdain architectural sculpture, and has made beautiful groups for the Custom House of New York, the postoffice of Cleveland, and the pediment of the Brooklyn Institute. In the recent Parkman and Melvin memorials he has shown a treatment peculiarly adapted to the stone, a most valuable suggestion to our younger men. No one has greater influence upon the trend of American sculpture than has French, and many there are who owe to him their successful beginnings.

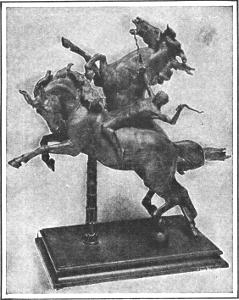

FREDERICK WILLIAM MacMONNIES

HORSE TAMERS, BY MacMONNIES

Two groups, one of which is shown, that adorn an entrance to Prospect Park, Brooklyn. They formed part of the sculptor’s remarkable exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900.

When in 1884 Frederick MacMonnies arrived in Paris he was equipped as no American had ever been before. He was twenty-one years old, and had already spent five years in the studio of Saint Gaudens, besides learning to draw like a skilled painter. His progress was proportionate, and it has been his joy ever since to meet his European competitors upon their own field and to rival them in whatever they undertake. If there is nothing distinctively American in his art, it is sculpture of the highest degree of workmanship, an international coin that passes current wherever good art is known.

BIRTHPLACE OF D. C. FRENCH

French was born in Exeter, New Hampshire, on April 20, 1850

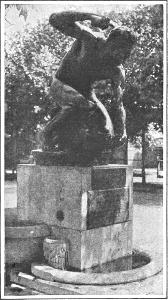

THE HEWER, BY BARNARD

The plate on the pedestal says, “Erected in memory of William Parker Halliday, and presented to the city of Cairo, Ill., A. D. 1906, in token of his unswerving faith in her destiny.”

No one has ever worked quite so feverishly as did MacMonnies during those wonderful first years of his career, and no one has ever done so much in the time. The list is too long even to chronicle here, much less to comment upon. Beginning with the “Nathan Hale” and “Stranahan” of the Salon of 1891, the sculptor came insistently into national view in 1893 with his great Columbian fountain, the jewel of the Chicago Exposition. It was the opportunity of a lifetime, and the young sculptor rose serenely and triumphantly to the occasion. The memory of that exquisite twilight vision remains a delight to all who saw it. Orders followed in rapid sequence, and brought more successes,—the archaistic “Shakespeare” of the Congressional Library; the irresistible “Bacchante”; “Sir Henry Vane” of Boston; and the sculptor’s various contributions to Prospect Park, Brooklyn,—the Memorial Arch, with its gigantic army and navy groups, and its glorious Quadriga above, and the “Horse Tamers.”

Upon the exhibition of these works at the Paris Exposition of 1900 MacMonnies decided that he wanted a rest, which in the case of one of his nervous temperament meant merely a change. He dropped his modeling tools absolutely, and for a number of years gave himself up to the joys of painting. All sculptors dream of this; but he could really do it. His work on canvas is no less masterly than his sculpture. Of late he has returned to his first love, and we look forward eagerly to the new products of his studio.

GEORGE GREY BARNARD

George Grey Barnard is a Westerner, although he chanced to be born in Pennsylvania, where his parents were temporarily residing in 1863. The sculptor’s father is a clergyman, and the fortunes of the ministry afterward led him to Chicago, and thence to Muscatine, Iowa, where the son passed his boyhood. One cannot doubt that these circumstances had their profound influence upon the character of the young artist. In it is something of the largeness of the western prairies, something of the audacity of a life without tradition or precedent, a burning intensity of enthusiasm; above all, a strong element of mysticism which permeates all that Barnard does or thinks.

Reproduced from American Sculpture, by Lorado Taft. Copyright, 1903, by The MacMillan Co.

MICHELANGELO, BY BARTLETT

A vivid representation of the mighty Florentine, is one of the bronze effigies that decorate the rotunda of the Congressional Library.

The stories of his student struggles in Chicago and Paris are familiar. The first result of all this self sacrifice became tangible in that early group, a tombstone for Norway, in which the youth portrayed “Brotherly Love,” a work of “weird and indescribable charm.”

In 1894 Barnard completed his celebrated group, “Two Natures,” upon which he had toiled, in clay and marble, for several years. This masterful achievement gave him at once high standing in Europe, and his work has never since ceased to interest the cultivated public of the world’s capitals. Then followed an extraordinary “Norwegian Stove,” a monumental affair illustrative of Scandinavian mythology; and “Maidenhood” and the “Hewer,” two of the finest nudes thus far produced in America.

The great work of Barnard’s recent years has been the decoration of the Pennsylvania capitol. It has been said of him that he was “the only one connected with that building who was not smirched”; but his part is a story of heroism and triumph. The writer has not yet seen the enormous groups in place, but is familiar with fragments that have won the enthusiastic praise of the best sculptors of Paris. They are inspiring conceptions which point the way to still mightier achievements in American sculpture.

LAFAYETTE, BY BARTLETT

In the square before the Louvre, Paris

Paul Wayland Bartlett was born in 1865 of artistic ancestry, his father being Truman Bartlett, teacher and critic. The boy grew up in Paris, entering the Beaux-Arts at the age of fifteen, and working also at the Jardin des Plantes under the helpful guidance of Frémiet, the great animalist. His art has always offered an interesting blend of the two influences, animal forms appearing in nearly all his compositions.

Bartlett’s first important exhibit was the “Bohemian Bear Trainer”; the second, the Indian “Ghost Dancer,” shown at the Chicago Exposition. Soon followed those striking works for the Congressional Library, his “Columbus” and “Michelangelo.” The former shows the discoverer in a new light,—no longer the gentle dreamer, the eloquent pleader, the enthusiast, nor yet the silent victim in chains, but a hero of might and confidence, hurling proud defiance at his calumniators. The “Michelangelo” is, if possible, an even more vivid though less vehement presentation of its theme. The short, gnomelike figure with stumpy legs; the big, powerful hands; the stern face, rough hewn, with its frown and tight lips,—all these combine to make this at first sight a not very winning presentation of the great master; but it has the quality that will outlive all others. It was left to an American sculptor to grasp his character profoundly, and to create an adequate representation of the mighty Florentine.

Bartlett’s young “Lafayette” stands in one of the most coveted sites in all Paris, in the square before the Louvre. It is well worthy of the honor, and is a monument to the artist’s capacity for “taking pains,” representing as it does many years of study and experiment.

Bartlett collaborated with Ward upon the pedimental group of the New York Stock Exchange, and a logical result of the good work done there was the commission to design the long awaited pediment for the House of Representatives in Washington, a gigantic undertaking of great significance, which is now in progress.

To select these six names out of a hundred seems invidious. One wants to talk of Herbert Adams and his beautiful busts, of Karl Bitter and all the fine things he has done, of MacNeil and Grafly and Aitken and the Piccirillis and the Borglums and all the rest, of the Boston men, of the women sculptors, even of the little western group; but space fails. They are all working enthusiastically for the love of their art and for the fair fame of America.

BLACK HAWK, BY LORADO TAFT

A concrete work of gigantic proportions, overlooking Rock River, Illinois.

SUPPLEMENTARY READING—“History of American Sculpture,” Lorado Taft; “American Masters of Sculpture,” Charles H. Caffin.

MAGAZINE ARTICLES—“George Grey Barnard, Sculptor,” G. B. Thaw World’s Work, December, 1902; “Daniel Chester French, Sculptor,” Lorado Taft Brush and Pencil, Vol. 5; “Bartlett” (“Some American Artists in Paris,”) Francis Keyser, Studio, Vol. 13; “Frederick MacMonnies, Sculptor,” H. H. Grier, Brush and Pencil, Vol. 10; “Augustus Saint Gaudens,” Kenyon Cox, Century, Vol. 13; “The Work of J. Q. A. Ward,” Russell Sturgis, Scribner’s, Vol. 32.

THE MENTOR

ISSUED SEMI-MONTHLY BY

The Mentor Association, Inc.

381 Fourth Ave., New York, N. Y.

Vol. 1 No. 36

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. FOREIGN POSTAGE, SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE, FIFTY CENTS EXTRA. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE AT NEW YORK, N. Y., AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER.

“Seek knowledge wherever it can be found throughout the world.” So spoke Mutsuhito, late Emperor of Japan. It was a favorite maxim of his, and one frequently repeated by his subjects. It might well be a legend of The Mentor, for the wise thought beneath that injunction of the emperor’s is just what inspired The Mentor plan.

The method pursued in The Mentor finds, too, a striking parallel in Japanese life. In seeking knowledge and in the enjoyment of beautiful things, the Japanese set their minds on “one thing at a time.” Their habit of thought and their method of study are such as might be expressed in The Mentor principle, “Learn one thing every day.”

The thoroughness of the Japanese is well known. Their intelligence, enterprise, and up-to-dateness have been illustrated many times in the arts of peace and in the science of war. In this one particular principle of concentration in study, and single mindedness in the enjoyment of beautiful things, the Japanese may well be taken as a model for the rest of mankind.

My friend Takashima showed me lately a beautiful vase. It stood on a pedestal in a room that seemed to me empty. Simple matting covered the floor; simply decorated screens covered the walls; a few pieces of furniture, equally simple, were all that the room contained—beside that vase. “Is it not beautiful?” he said, and then he gave me its history, telling me who, among the early masters of Chinese pottery, had designed and shaped this exquisite work of art. I remarked on the reverence that he showed for a single work of art in devoting a room to it alone. “Enjoy one thing of beauty at a time,” he said. “I could not enjoy this vase in a room filled with miscellaneous things. As well go to a shop. The mind would be in chaos—knowing nothing well and appreciating nothing to the full.”

Such had always been Takashima’s habit. He said it was a habit of his people. “Why,” he asked, “should you have more than one thing of beauty in your room at a time? Enjoy it to the full. Then place something else there, but, before removing it, get out of it all that there is in it of beauty and of knowledge. You cannot do this in the confusion of a room filled with many varied things.” The incident was so strikingly in accord with The Mentor idea that it seemed as if Takashima might the next moment have added the phrase, “Learn one thing every day.”

And so the principle underlying the plan of The Mentor Association is one approved and exercised by a nation of intelligent people. How many other people follow this direct and simple path to knowledge we cannot say, but that it is not only the direct and simple way, but the one satisfying and effective way of acquiring knowledge, is plain. On that principle The Mentor Association is founded, and by following that principle, the members of the Association can add day by day to their store of knowledge, and can fully and intelligently enjoy the beautiful things in art.

COPYRIGHT 1903 THE MACMILLAN CO

HENRY WARD BEECHER—JOHN QUINCY ADAMS WARD

REPRODUCED FROM “AMERICAN SCULPTURE” BY LORADO TAFT

Monograph Number One in The Mentor Reading Course

The life of John Quincy Adams Ward was a long record of dignified success. Born in the beginning of the last century, at the time when American sculpture was in a very elementary stage, he lived to see this art mature into something of which our country may well be proud. Quiet simplicity and impressiveness of mass characterize Ward’s work. Everything he did was big and effective.

John Quincy Adams Ward was born on June 29, 1830, near Urbana, Ohio. He was a boy that enjoyed play; but he did not neglect his work. He loved the open air. Riding, hunting or fishing—he liked them all. He received his education in the village schools.

One day the young boy found some clay on his father’s farm. He took a handful of it and modeled the face of an old negro who lived nearby. Everyone who saw this early attempt said that it was “wonderful.” It may have been. At any rate, Ward did not immediately begin to dream of becoming a great sculptor. In this he differed from most beginners whose first work is called great by their friends.

Not until he was nineteen years old did he really find out his destiny. In 1849 he paid a visit to a sister in Brooklyn. One day he happened to pass the studio of the sculptor H. K. Browne. The door of the studio was open, and Ward glanced inside. The scene fascinated him. He returned to the place again and again. Finally he found his way into this world of mystery, and at length by some miracle became one of the sculptor’s pupils.

It would have been hard for Ward to have found a better master in all America. He studied under Browne from 1850 to 1857. He learned everything, from kneading clay to marble carving. By 1861, when he opened a studio of his own in New York City, he had executed busts of Joshua R. Giddings, Alexander H. Stephens, and Hannibal Hamlin, prepared the first sketch for “The Indian Hunter,” his great work now in Central Park, New York City, and made studies among the Indians themselves for this work.

From that time on success was his. He worked hard and conscientiously. His statues of Washington, Beecher, and Horace Greeley are all recognized as great pieces of portrait sculpture. Unlike many of the early sculptors of America, he acquired his training, his inspirations, and his themes from his own country.

When the National Sculpture Society was organized in New York in 1896, Ward was elected to be the first president. He died in New York City on May 1, 1910.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1. No. 36 SERIAL No. 36

COPYRIGHT 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE SHAW MEMORIAL—AUGUSTUS SAINT-GAUDENS

Monograph Number Two in The Mentor Reading Course

St. Gaudens is the name of a little town in the south of France and close to the foot of the Pyrenees. A humble shoemaker named Bernard Paul Ernest dwelt there, and in 1848, after he had moved to Dublin, Ireland, he had a son, to whom he gave the name Augustus. The mother of the boy was a native of Dublin; her maiden name was Mary McGuinness. Such was the origin of a master in sculpture, Augustus Saint Gaudens. His parents came to America when he was an infant, and after a short stay in Boston took up their residence in New York City. Augustus Saint Gaudens attended school until he was thirteen. Then he was apprenticed to a cameo cutter named Avet. After three years’ service he left his master and found employment with a shell cameo cutter named Le Breton, with whom he worked for several years. During this time young Saint Gaudens was studying drawing at night; first at Cooper Union, and then for two years at the National Academy of Design.

Augustus Saint Gaudens was always a thoughtful, quiet youth, with extraordinary power of concentration. He pursued the art of modeling with great enthusiasm. It was said of him that his sense of form and of objects in relief was so vivid that with his eyes closed he could fairly “see with his fingers.” His cameo cutting naturally assisted him in the perfection of art in high and low relief.

When twenty years old Saint Gaudens was already a well trained artist. He went to Paris and worked in the School of Fine Arts in the studio of M. Jouffroy. There he studied the human figure in all phases, and quickly mastered it. A residence of several years in Italy followed, with constant art activity and steady artistic growth. He came back to the United States in 1874, and his first work was a bust in marble of William M. Evarts. Then came a commission for a large decorative relief for St. Thomas’ Church, New York City, and in 1878 he began work on the statue of Admiral Farragut that now stands in Madison Square, New York City, which is one of the most widely known and admired of all his works.

The years that followed were full of distinguished achievements. His “Lincoln,” which was unveiled in Lincoln Park, Chicago, in 1887, has been hailed as the greatest portrait statue in the United States.

Saint Gaudens was not only the most skilful of American sculptors, but also the most versatile. This will be appreciated by anyone who looks first at the Farragut statue, then at the severe, imposing character of Deacon Chapin, a statue that is often called “The Puritan.” Let him then contrast the stirring Shaw Memorial, on Boston Common, with the strange, mysteriously beautiful figure in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D. C., that has been called variously “Grief,” “Death,” and “The Peace of God.”

Saint Gaudens enjoyed the distinction of being America’s leading sculptor for many years before he died. His life was crowned with honors, sweetened by many fine friendships, and enriched and mellowed by broad, liberal, mature art intelligence. He was a great master of art in thought and in expression. He died in New York City in 1907.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1. No. 36 SERIAL No. 36

COPYRIGHT 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

DEATH AND THE YOUNG SCULPTOR. by Daniel Chester French

Monograph Number Three in The Mentor Reading Course

Nature smiled on Daniel Chester French. All the circumstances of his birth and breeding conspired to help his development. He was born at Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1850. Among many well known relatives he numbered Daniel Webster and John Greenleaf Whittier. His ancestors were men who stood high in the communities in which they lived. His father was a lawyer, a judge, and assistant secretary of the United States treasury. He was always interested in public welfare, and was known for his good taste and good works. His descendants said that he “beautified every place in which he lived.”

Daniel Chester French showed ability at an early age, but no particular leaning toward sculpture. He was simply a bright, good-looking boy, with a liking for outdoor life and exercise. One day, when about nineteen years old, during a period of work on his father’s farm, he showed his parents a queer figure of a frog that he had cut out of a turnip; “Daniel, there is your career!” were the words that expressed the feelings of both father and mother. The farm was near Concord. There dwelt Miss May Alcott, the “Amy” of “Little Women,” and an artist of some ability. She encouraged young French in his study of drawing and modeling, and he plunged into his art career with an enthusiasm that bordered on boyish frenzy. His nature was ardent and poetic, and it carried him into forms of expression that were doomed to disappointment. The best thing for him was a visit that he made to the veteran sculptor J. Q. A. Ward. This took place when he was staying with relatives in Brooklyn, New York, and it opened the boy’s eyes to the fuller meaning of sculpture. Months of earnest work followed, during which Daniel French’s talents rapidly ripened.

When he was only twenty-three years old he received a commission of real national importance, that of modeling the statue of “The Minute Man.” This interesting piece of sculpture, now well known, was unveiled at Concord in 1875. In celebration of it Ralph Waldo Emerson and George William Curtis made speeches, and James Russell Lowell read a poem. At this time Daniel French had sailed for Italy, where he remained for a period in study. In 1879 he modeled a bust of Emerson from life—a work so vivid and lifelike that the poet-philosopher said, “The more it resembles me, the worse it looks,” and then added, with a nod of approval, “That is the face that I shave.”

French’s art took rapid strides. He is known today equally well by his fine portrait busts and his great allegorical compositions. One of the most imposing of his compositions is the great heroic female figure entitled “Alma Mater,” seated at the approach to the library of Columbia University, New York. No American sculptor is better known than Mr. French in his home land or abroad. He bears high honors on both continents.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1. No. 36 SERIAL No. 36

COPYRIGHT 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

COPYRIGHT 1903 THE MACMILLAN CO.

NATHAN HALE—FREDERICK MACMONNIES

REPRODUCED FROM “AMERICAN SCULPTURE” BY LORADO TAFT

Monograph Number Four in The Mentor Reading Course

To many Americans the name of Frederick MacMonnies became known by the imposing Columbian Fountain at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The composition was a majestic barge, on which Columbia sat enthroned on high. At the prow was a fine figure of Fame with trumpet upraised. On the stern Father Time watched the progress of the barge, which was urged on by the oars of eight women of great beauty representing the Arts and Industries. The work had style, and it was also imposing in its massed effect. MacMonnies was only twenty-seven years old when this commission was given to him in 1891. He got it largely through the influence of his instructor, Augustus Saint Gaudens. All the summer of 1893 people were asking about the young sculptor. They found that he was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1863, of Scottish parentage. He came by an art inheritance from one of his parents at least,—his mother, Juliana Eudora West, a niece of the famous early American painter, Benjamin West.

Frederick MacMonnies had to leave school when a mere boy and earn his living as clerk in a jewelry store. He found time to study there, and when he was sixteen years old he attracted the notice of Saint Gaudens, who took him into his studio as an apprentice. That was the beginning of MacMonnies’ fame. He could scarcely realize at that age what a few years’ training under Saint Gaudens would mean. He worked hard in the studio and in the classes of the Academy of Design and Art Students’ League; so that when in 1884 he was able to go abroad he had a ground knowledge of modeling that fitted him to make the most of his study in foreign schools. He had been in the fullest sense “put in right” by Saint Gaudens. Through all the years of his study he had the advantage of close, familiar association with the greatest artists of this country and some of those abroad. MacMonnies went at once to Paris and joined the School of Fine Arts, where he made friends, and his progress was rapid. Back and forth he went during the next few years, from Paris to New York, according as his means and his plans of work required.

He got his first commission in 1889,—an order for three life-sized angel figures in bronze for Saint Paul’s Church, New York City. This brought him commendation, and, with the help of the great Saint Gaudens, other commissions were placed in his hands, notably the Nathan Hale statue, which stands in City Hall Park, New York City, and the portrait statue of James S. T. Stranahan of Brooklyn. These works preceded the Columbian Fountain, and since MacMonnies’ name has come to be known they are counted among his most admired creations.

In 1894 the famous Bacchante appeared,—the dancing, laughing girl that attracted so much public comment for a time.

Mr. MacMonnies is known by many figures and compositions in public places, notably the groups in bronze of the Army and the Navy on the Brooklyn Memorial Arch at the entrance to Prospect Park.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1. No. 36 SERIAL No. 36

COPYRIGHT 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE TWO NATURES, by George Grey Barnard

Monograph Number Five in The Mentor Reading Course

Success is deserved by hard work, although it does not always follow. But in the case of George Grey Barnard hard work combined with genius made him one of the great sculptors of America, and one of whom this country may well be proud.

George Grey Barnard was born at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, on May 24, 1863. His father was a clergyman at Muscatine, Iowa, where the sculptor passed his boyhood. He delighted in stuffing the skins of birds and animals, and became quite an expert taxidermist. He also liked to model animals; and a bust of his little sister convinced his family that he should turn his talents to some trade in which he could make a good living.

So he became apprentice to an engraver. Later he moved to Chicago. Here it was that the first desire to become a sculptor entered his mind. For a long time he debated the question. If he remained at his trade, he could rest assured of a good income all his life; while if he decided to study sculpture, he would practically have to starve for a few years.

At last he entered the Art Institute of Chicago. He had been there about a year and a half, when a bust of a little girl brought him three hundred and fifty dollars. He decided to go to Paris on this small sum. He set off in 1883, and began study in the Atelier Cavelier of the Beaux Arts.

Barnard worked hard, and denied himself all the luxuries, and even many of the necessities of life. His first year in Paris cost him just eighty-nine dollars, so it can be imagined what self-denial the young man must have practised for the sake of his art. Barnard took life seriously; but he never complained.

His first noteworthy production was “The Boy,” which he finished in marble in 1885. The following year he made a heroic-sized statue of Cain, which he afterward destroyed. “Brotherly Love,” a tombstone executed at the order of a Norwegian, he modeled in 1887. This was the best thing he had done up to that time.

Other works followed in rapid succession,—“The Two Natures,” in the Metropolitan Museum of New York City; “The Norwegian Stove,” an allegorical fireplace; “The God Pan,” in Central Park, New York City; “The Hewer,” at Cairo, Illinois; “The Rose Maiden,” and the simple and graceful “Maidenhood.”

All of these were successful, and in 1902 Barnard received the reward for all his hardships and struggles. He was selected to execute all the sculptured decorations for the new capitol for the state of Pennsylvania at Harrisburg. And the work he did there promises even greater from this sculptor in the future.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1. No. 36 SERIAL No. 36

COPYRIGHT 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

COPYRIGHT, 1902. DETROIT PHOTO CO.

PRIMITIVE MAN. by Paul Wayland Bartlett

Monograph Number Six in The Mentor Reading Course

Everyone knows the saying, “Genius is the capacity for taking infinite pains.” If this adage is true, then Paul Wayland Bartlett is a great genius; for in everything this sculptor does he pays the closest attention to details. He attends personally to every part of his work. And this “capacity for taking pains” accounts largely for his success.

Paul Wayland Bartlett was born amid scholarly surroundings at New Haven, Connecticut, in 1865. He was the son of Truman H. Bartlett of Boston, an art critic and sculptor. Many years ago Bartlett and his mother went to live in Paris. Here the young man found his vocation. When he was only fifteen years old he entered the École des Beaux Arts. He quickly became an excellent modeler. He worked hard, and in addition took up a course on animal sculpture. As he could thus help other sculptors as an animal specialist, he was able to earn money to carry on his studies.

Bartlett tells about the time when he and a friend, M. Gardet, used to go around “doing animals” wherever they got the opportunity. Among the modernized decorations of the Porte St. Denis is a lion, “fierce and terrible,” which is the work of his hands. An “Orpheus” in the Luxembourg has attached to it a three-headed dog that he modeled. And he created on one occasion for the Exposition of Amsterdam an elephant of gigantic proportions.

Bartlett lived during this time in a quaint little street off the Rue de Vaugirard, where he had a little vine-covered studio. It was there that he began “The Bear Tamer,” which is now in bronze in the Metropolitan Museum of New York City. He spent a year upon it, and then became dissatisfied with it and spent another year in changing the composition.

Many works followed this successful effort. First appeared the “Ghost Dancer,” a vicious looking savage. Then came the equestrian statue of Lafayette, presented to the French republic by the school children of America; the powerful and virile Columbus, and the Michelangelo, both of which are in the Congressional Library at Washington; the lifelike “Dying Lion,” and many others.

Besides these works Bartlett has modeled beetles, fishes, reptiles, and crustaceans. Here his skill with patinas (the coloring of bronzes) is shown. A wealth of color is seen in his small figures of beetles and snakes.

Bartlett’s work is not finished. More and greater is still to come. No man is better equipped for his work than he.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 1. No. 36 SERIAL No. 36

COPYRIGHT 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.