LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

SEPTEMBER 15 1913

SERIAL NO. 31

THE

MENTOR

SPAIN AND

GIBRALTAR

By DWIGHT L. ELMENDORF

Lecturer and Traveler

DEPARTMENT OF

TRAVEL

VOLUME 1

NUMBER 31

TWENTY CENTS A COPY

ESTABLISHED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POPULAR INTEREST IN ART, LITERATURE, SCIENCE, HISTORY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL

CONTRIBUTORS—PROF. JOHN C. VAN DYKE, HAMILTON W. MABIE, PROF. ALBERT BUSHNELL HART, REAR ADMIRAL ROBERT E. PEARY, WILLIAM T. HORNADAY, DWIGHT L. ELMENDORF, HENRY T. FINCK, WILLIAM WINTER, ESTHER SINGLETON, PROF. G. W. BOTSFORD, IDA M. TARBELL, GUSTAV KOBBÉ, DEAN C. WORCESTER, JOHN K. MUMFORD, W. J. HOLLAND, LORADO TAFT, KENYON COX, E. H. FORBUSH, H. E. KREHBIEL, SAMUEL ISHAM, BURGES JOHNSON, STEPHEN BONSAL, JAMES HUNEKER, W. J. HENDERSON, AND OTHERS.

The purpose of The Mentor Association is to give its members, in an interesting and attractive way the information in various fields of knowledge which everybody wants and ought to have. The information is imparted by interesting reading matter, prepared under the direction of leading authorities, and by beautiful pictures, reproduced by the most highly perfected modern processes.

The object of The Mentor Association is to enable people to acquire useful knowledge without effort, so that they may come easily and agreeably to know the world’s great men and women, the great achievements and the permanently interesting things in art, literature, science, history, nature and travel.

The purpose of the Association is carried out by means of simple readable text and beautiful illustrations in The Mentor.

The annual subscription is Four Dollars, covering The Mentor Course, which comprises twenty-four numbers of The Mentor in one year.

SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, ROBERT M. DONALDSON; ASST. TREASURER AND ASST. SECRETARY, J. S. CAMPBELL

Copyright, 1913, by The Mentor Association, Inc. Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the post office at New York, N.Y.; under the Act of March 3, 1879.

“A Wise and Faithful Guide and Friend”

Vol. 1 No. 31

TOLEDO CATHEDRAL

ROYAL PALACE, MADRID

ALCÁZAR AT SEVILLE

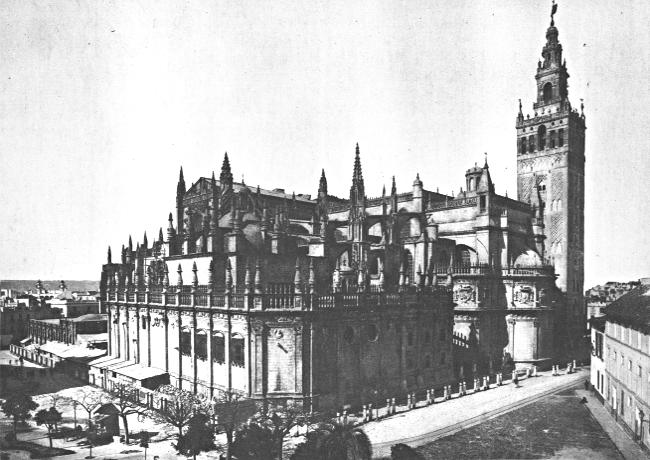

SEVILLE CATHEDRAL

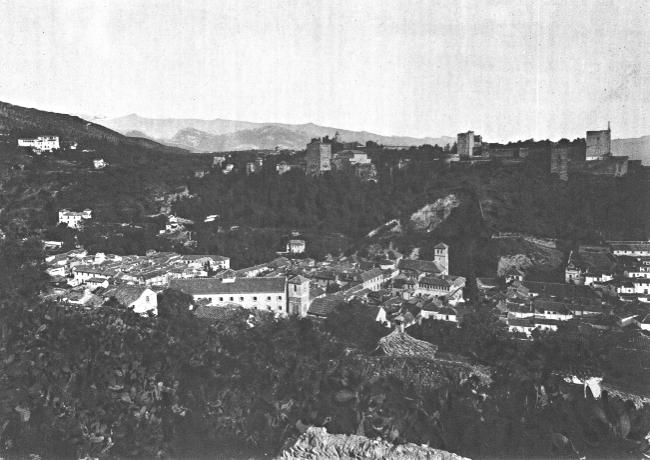

THE ALHAMBRA, GRANADA

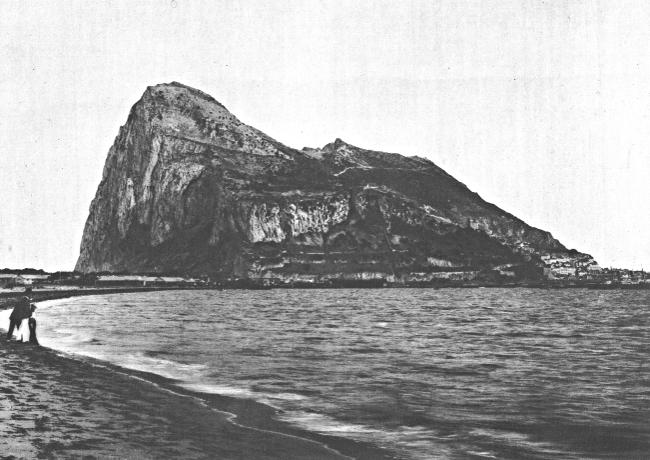

GIBRALTAR

A Trip Around the World with

DWIGHT L. ELMENDORF, Lecturer and Traveler

Gone is the ancient glory of Spain. To the visitor it appeals chiefly as a country of a splendid past. This is not true, of course, of some of the more populous localities. Barcelona is full of life and commercially enterprising, and Madrid is full of activity and is a natural center of interest as the capital of the nation. But many of the cities and towns of Spain attract chiefly as interesting and picturesque survivals. They breathe the atmosphere of a former age. We feel the influence of it wherever we turn. Spain is not much traveled by tourists. More would go perhaps if they realized what splendid scenery was there, and how rich in historic and romantic associations the country was.

Since the days of the first inhabitants, the Iberians, and beginning with the Celts who crossed the Pyrenees some five hundred years B. C., Spain has been invaded by Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals and Visigoths, Arabs and Moors, and each of these races has left evidences of its dominion, in monuments of one kind or another, in architectural forms, in roads and buildings, and in the language and customs of communities. The interesting Basque people of the northern provinces of Spain are declared by students of history to be almost unmixed descendants of the original Iberians.

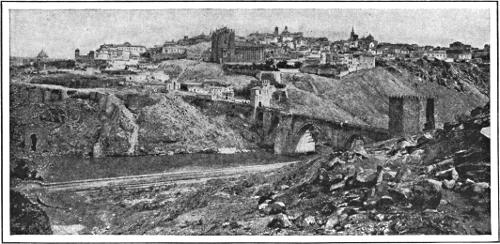

GENERAL VIEW OF TOLEDO

Toledo is one of the most ancient cities in Spain. It was at its zenith under the Moors. Later it became the residence of the kings of Castile.

And in these many years what glory has been Spain’s! She has been aptly called an “eddy of tribes and races.” Under Moorish rule she commanded the Mediterranean. Then as a Christian kingdom, beginning with Rodrigo the Cid and Alfonso VI in the eleventh century, and extending through several hundred years under such famous rulers as Ferdinand and Isabella and later Charles V and Philip II, Spain acquired the whole peninsula and rose to be a great world power. In war she was a dreaded foe of France, England, and the Netherlands. Her armada for years swept the seas. In search of treasure and to extend Spain’s power and possessions, Vasco da Gama discovered India and Columbus opened up the new continents of the western world.

All the achievements of Spain in the brilliant past are brought home to the visitor who spends even a few weeks in that country. So many things in Spain are interesting for what they were! The visitor soon comes to know the mood of Washington Irving, who dwelt for a time in the Alhambra. His impressions are like those of a beautiful dream. Irving withdrew from the world of his day and immersed himself in the romance of the past. That is the mood in which the traveler will enjoy himself most when visiting many places in Spain.

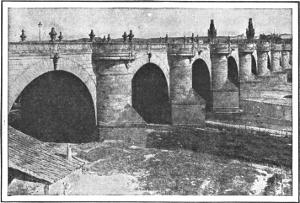

Puente de Toledo, Madrid

The bridge of Toledo at Madrid was completed in 1872. The banks of the stream are continually rising, and the piers are therefore partly buried in the ground.

The very entrance to Spain is a fit preparation for the strange, interesting and beautiful things to be seen there. No one can forget the day that he crosses the impressive boundary between France and Spain, winding about and tunneling through the majestic Pyrenees. Once this superb mountain range is passed, the traveler feels as if he had come upon a different world from any that he has seen before. His attention turns first, most naturally, to the great cities, which differ essentially from one another. Perhaps no two more contrasting cities could be selected than Toledo and Madrid. Toledo was from the earliest times a capital city. The Romans, Goths, Moors, and finally the Christians, made it the headquarters of authority. It was the scene of the triumph of that world-admired hero of the eleventh century, Rodrigo the Cid. Toledo is in all respects an impressive relic of bygone splendor. Madrid, on the other hand, is a modern city. In the days when Toledo was most magnificent and had a population of over 200,000, Madrid was a little town. Today Madrid numbers over 500,000 inhabitants, while Toledo’s population has dwindled to less than 30,000. In Toledo we find many things as they have been for hundreds of years. The city is still famous for its swords. The Toledo blade is known the world over today as it was in Roman times.

The traveler does well to visit Toledo first. Its very situation is extraordinary. The river Tagus flows about it and almost binds it in like a rope. The banks of the river are rocky and steep, and spanned by several interesting old stone bridges.

The effect of Toledo viewed from the south and looking across the gorge through which the river flows is remarkable. The city is inclosed within ancient Moorish and Gothic fortifications, and presents an aspect of a jumble of housetops dominated by two great structures, the cathedral and the Alcázar.

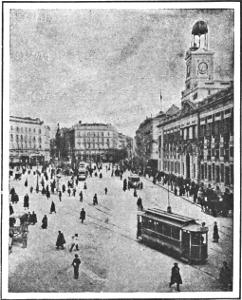

PUERTA DEL SOL, MADRID

The “Gate of the Sun,” the big square in the center of Madrid and the busiest spot in the city, has long been the real political arena of Spanish history.

Enter Toledo, and you find novelty and picturesqueness on every side. The streets are narrow and crooked. The houses are blind and forbidding on the outside, reserving their attractions for their inner courts. Everything about you is strange and curious, and full of historic significance. If you wish to get the history of Spain in condensed form, you will find it in Toledo.

The cathedral is the most important feature of the city, and one of the finest and most interesting in Europe. The religious life of Spain centered there for centuries. On that site a Christian temple stood in the sixth century. When the Moors came they made a mosque of it. Then Alfonso VI took possession in 1085, and the Moors were driven out. In the thirteenth century the old building was torn down and the present edifice was begun. During 265 years it was in course of construction—a lifework for many architects and artisans. And there the great archbishops of Toledo controlled the government and civilization of Spain for years. Everything of importance that made Spanish history was then in their hands. You are made to realize this when you visit the cathedral. It contains many valuable relics of history and art treasures. When you have seen these go to the tower. The view will repay you. The most prominent object to be seen from there is the Alcázar, standing on the highest ground of the city. This building is the phoenix that has risen over conflagrations of former structures on that site. The original building was a Roman citadel. When the Cid reigned supreme, in the eleventh century, he resided there. Afterward fires consumed the building, and it was rebuilt several times. It has been in turn a castle, a palace, a cadet academy, and now it stands there a stately and imposing monument to the past.

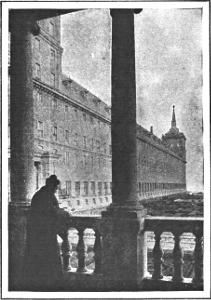

THE ESCORIAL

This immense building was constructed at the great cost of over $3,000,000, by Philip II of Spain. It was the result of a vow made by the king to build a monastery to Saint Lawrence.

Madrid was made the capital by Philip II in 1560. It was not by nature attractive. The winter winds are cruel, and the summer heat is intense. The country roundabout is bleak, and for years after it became the capital it remained a city of small buildings and unimposing appearance. But the court being there, it was the center of all political and religious activities. Arts and letters received their greatest stimulus under the patronage of church and court. Cervantes lived there, and it was in Madrid that he finished his immortal “Don Quixote.” The Bourbons came into power in the eighteenth century, and then the great royal palace was built. After that Madrid increased rapidly in population and improved in appearance. Today it is a city of great activity, full of life, gaiety, and fashion; in short, the Spanish Paris.

The two things that command most interest in Madrid are the palace and the museum. The palace, which stands on high land on the site of the old Moorish Alcázar, was erected between 1738 and 1764, and is a most imposing structure, no matter from what side it is viewed. Some idea of its immensity may be gathered from the statement that it covers 26,900 square yards of ground and its sides are 500 feet long. Like many great structures in Spain, it is built of native granite. It is not easy to gain access to the interior of the palace. Sometimes in the absence of the royal family permission may be obtained, and those who have the privilege of being admitted find there many relics of historic value, a priceless collection of tapestry, a number of most interesting old works of art, and a library containing many volumes of unique worth.

THE ESCORIAL

One of the monks of the monastery on the balcony, overlooking the formal gardens.

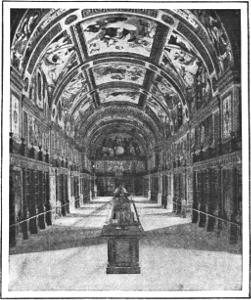

LIBRARY OF THE ESCORIAL

This splendid room contains many rare and valuable works. The older books stand with their fronts toward the spectator and have their titles stamped on the gilt edges.

The collection of paintings in the art museum is one of the finest in all Europe. There is a magnificent representation of the Spanish school, and especially of the great painter Velasquez. There are sixty pictures of his, including some of his most brilliant works. There are also many splendid examples of the art of Murillo, and many paintings by Rubens and Van Dyck.

Situated twenty-seven miles from Madrid is the village and palace of Escorial. The Escorial is a most extraordinary building. Many of the Spanish people regard it as the eighth wonder of the world. It is a fitting memorial of the cold, cruel monarch who built it. It is related that Philip II constructed the Escorial in fulfilment of a vow, made during the battle of St. Quentin, which took place on Saint Lawrence’s day, August 10, 1557. King Philip declared that he would, in case of victory, erect a memorial building to Saint Lawrence that would transcend any structure of its kind that had ever been built before.

THE LEANING TOWER OF SARAGOSSA

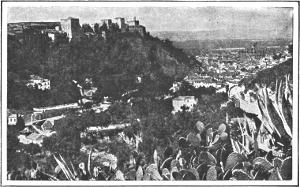

GRANADA AND THE ALHAMBRA

The Alhambra occupies the plateau of the Monte de la Assabria. This wonderful building was begun by Mohammed I, who was the originator of the motto “Walâ ghâliba ill’ Allâhta âlà” (there is no conqueror but the Most High God), which is so conspicuous among the inscriptions of the Alhambra.

Saint Lawrence, it will be remembered, was burned to death on a gridiron, and it is said that, in memorial of this, the structure of the Escorial was planned to resemble a gridiron in form. There is nothing authoritative to substantiate this tradition, however. It is simply the story that goes with the place. This monstrous building was begun in 1563 and was completed in 1584. It is a monastery and a palace at the same time. Its vastness overwhelms the mind. At first sight you are awed by the solemn, stern, and forbidding aspect of the building, and this first impression is deepened after going through the immense courts, corridors, and chambers. It has but little ornament to relieve its severity. It is the work of a morbid and superstitious man. As one visitor has put it, “Philip was the proudest among kings and the most bigoted among devotees. What wonder that he should build a convent and palace and make its costliest room his sepulcher!”

The Escorial staggers description. Perhaps an adequate idea of it may be had from a brief statement of facts. It cost three and one-quarter million dollars, and covers 500,000 square feet. It is 700 feet long, 580 feet wide, and is divided into sixteen courts. The great towers at the corners rise 200 feet. The main cupola or tower above the church, in the center, is 320 feet in height. When we add that there are 86 staircases, 89 fountains, 15 cloisters, 1,200 doors, 2,600 windows, and miles of corridors, we sum up in a measure the astounding dimensions of this wonderful structure.

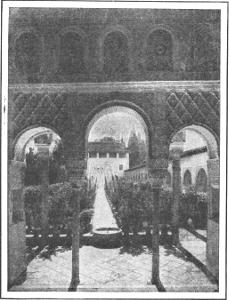

PALACIO DE GENERALIFE, GRANADA

The Palace of the Generalife was the summer residence of the Moorish kings. This interior view shows the Patio de la Acequia.

The Escorial is well kept by the Augustinian brothers who are in charge. The surrounding terrace and gardens are carefully cultivated, and these outer adornments help a little to soften the austerity of the stupendous pile of granite buildings.

BELL TOWER, CORDOVA CATHEDRAL

This tower is three hundred feet high, and was built on the foundations of the Moorish minaret. At the top is a figure of Saint Raphael with a weather vane.

In this country of contrasts there is no more striking contrast than that between the cruel Escorial and the romantic Alhambra. It is pleasant to turn south to Granada; for the greatest treat of all for a visitor in Spain awaits him there. Granada is picturesquely situated in a valley, on ground that rises toward the hill of the Alhambra. The view from the highest points is beautiful.

NOTE.—Further information concerning the Alhambra will be printed in a future number of The Mentor, devoted to “Beautiful Buildings of the World.”

A SEVILLE INTERIOR

The private life of Seville is focused in the inner courts of the houses. This picture shows the beauty of one of these courts.

Granada is not especially attractive in itself. It is chiefly a city of the past. It is the Alhambra that draws the visitor there. This celebrated building is a dream of Moorish magnificence made real. It is impossible to do justice to its wondrous beauties in brief space. An extensive literature has been written in description and in appreciation of its architectural splendors and of its romantic interest. Washington Irving has done most for the subject in his “Tales of the Alhambra.” He lived there for a time, and wrote there during his stay. You will find his name registered in the visitors’ book under date of 1829. The Alhambra, like many Moorish buildings, is severely simple on the outside; but when you enter your senses are captivated by the exquisite beauty of design and decoration that stretches out before you as you go through the courts and halls of this wonder palace. While in the whole it presents an effect of uniformity, there is infinite variety in detail, and there are countless forms of beauty about you that captivate the mind and fill the soul with delight.

THE GARDENS OF THE ALCÁZAR, SEVILLE

The plants and flowers of these gardens are very beautiful.

Aside from the Alhambra there are two buildings in Granada that command special attention,—the Palace of Charles V, which adjoins the Alhambra, and the Palace of the Generalife. Both of them have features of great architectural beauty. The former building was never completed. The palace of the Generalife is situated to the east of the Alhambra and 165 feet higher. It was the summer residence of the Moorish kings. From there the finest view about Granada can be had, covering the Alhambra below and stretching far across the vega (plain) to the distant mountains. The interior of the Generalife in its time must have been as beautiful as that of the Alhambra. The most beautiful spot is the garden of the Generalife, with its terraces, pools, grottoes, hedges, and overhanging trees.

It is a great relief to turn from the squalor in Granada to the comforts and delights of Seville. There is no town or city in Spain that can compare in charm with Seville. By its snow-white cleanliness, its fragrant fruit and flowers, its luxurious foliage, its gay and harmonious life, it invites the traveler to stay—and few can resist the invitation. Once introduced to the home life of the inhabitants, the visitor is apt to renounce gladly for a time all thought of departure. Everywhere about him is competence, comfort, and content. It seems as if families vie with one another in making their homes attractive. The family life is in the inner court or patio. That is the summer parlor, and there in the midst of flowers, plants, and beautiful birds friendly parties gather in happy companionship. It is in Seville, it seems to me, that the life of the native Spaniard may be seen in its most attractive light.

THE HARBOR AT BARCELONA

Through Barcelona passes almost one-fourth of the entire foreign commerce of Spain. This city is the most important commercial and industrial town in Spain, and has a population of 530,000.

The two most notable sights in Seville are the Alcázar, which was the palace of the Moorish kings and afterward the home of Spanish rulers, and the cathedral, which is one of the finest, largest, and most beautiful Gothic churches to be found anywhere.

The Alcázar has much of the beauty that is to be found in the Alhambra. Many of the interior decorations are not of the original building, but were the result of a restoration, and in this work many of the designs were frankly borrowed from the Alhambra.

The cathedral is one of the largest and most beautiful in Europe. Within this great building there are so many interesting and valuable works of historic and art interest that it might fairly be called a museum. One feature of the exterior of the cathedral arrests the eye of a New Yorker at once,—the tower. He is apt to exclaim on sight of it, “The Madison Square Tower!” The similarity is close. When the plans of the Madison Square building were made the tower of Seville was copied.

We have gone now far to the south. A few miles brings us to Cádiz, on the ocean coast, or Malaga on the Mediterranean. The distance from either of these two attractive cities to Gibraltar is short.

FORTIFICATIONS AT GIBRALTAR

This, the key to the Mediterranean, is one of the most important coast fortresses in the world. It has been in possession of Great Britain since 1704.

And when we reach Gibraltar the change of scene and life is abrupt and almost startling. If we go to Gibraltar by the road from Spain, we cross a narrow strip called Neutral Ground. It is arbitrarily fixed territory between Spanish and British ground. It is so low that it can hardly be seen from a distance. The effect is to make Gibraltar seem like an island. In case of emergency it would not be difficult to blow up this neutral strip and make an actual separation.

The rock of Gibraltar has been for years the symbol of stability and of strength. It is in a military sense the “key to the Mediterranean.” It was taken by the British in 1704, during the war of the Spanish Succession, by Admiral George Rooke, who commanded the British fleet. It has been fortified by the English government in a manner that is most discouraging to anyone contemplating a hostile advance through the straits.

VIEW ACROSS THE NEUTRAL GROUND BETWEEN GIBRALTAR AND SPAIN

In the distance is seen the misty outline of the Rock

The shape of Gibraltar is that of an enormous lion. As Thackeray says, “It crouches there, to guard the passage for its British mistress.” At the base of the rock are batteries; up on the summit are guns of heavy caliber, and over its face are holes through which cannon muzzles look out across the water like sullen and malignant eyes.

Gibraltar is over 1,400 feet high and is composed of limestone. Under its present conditions of fortification it is declared to be impregnable. It looks it. At the foot of the great rock is a town of 30,000 inhabitants, of whom 6,500 are soldiers, composing the British garrison. In this town is to be found a cosmopolitan mixture of men, and the character of it shifts from time to time according to conditions of traffic through the straits. There is enough to entertain a visitor for a day. Life there for a long time must grow monotonous. The impressions, however, of a single day at Gibraltar are not forgotten. You carry away the conviction that, whatever might happen to anything else in this world, Gibraltar is likely to stay.

| Spanish Cities | C. A. Stoddard |

| Spain and Morocco | Henry T. Finck |

| Castilian Days | John Hay |

| Tales of the Alhambra | Washington Irving |

| Spain | Edmondo De Amicis |

| The Story of Spain | E. E. and Susan Hale |

| Spain: Its Greatness and Decay (1479-1788) | Martin Hume |

| Modern Spain (1788-1898) | Martin Hume |

| A Record of Spanish Painting | C. G. Hartley |

| Gibraltar and Its Sieges | J. H. Mann |

| Gibraltar | H. M. Field |

CATHEDRAL OF TOLEDO, SPAIN

ONE

Rodrigo, last of the Gothic Kings of Spain, heard in his palace at Toledo that the Moors had crossed from Africa to Gibraltar. A little army led by Tarik landed in 711 and marched northward, conquering as it went. King Rodrigo, with a great force of Spaniards, met them in Andalusia. He commanded the center. The wings were led by King Witiza’s sons, who, hoping to recover the country that Rodrigo had taken from their father, joined the Moors, and pressed with them into battle. Rodrigo was surrounded and cut down. The Moors marched northward, taking city after city in the name of Mohammed, till all Spain was theirs. The last of the Gothic kings had fallen.

From that day to this Toledo has never regained her position as the capital of Spain. In the royal palace Tarik found twenty-five crowns of the old Gothic kings, golden and richly jeweled; the Psalms of David written on goldleaf with dissolved rubies, and the emerald table of Solomon. Those crowns may still be seen; but no one has ever seen the other treasures.

The Moorish kings, though they ruled Toledo mildly, had no end of trouble from the haughty nobility, who, robbed of their high position, were always in revolt against the conquerors. At last Sultan Hakim decided to punish his unruly subjects. He gave them a governor of their own race, who pretended to hate the foreigners, but was secretly in league with Hakim.

Amron soon won the hearts of his people and built a great castle in the middle of the city. There he held a reception for Prince Abd-er-Rahman, to which all the nobles and rich citizens of Toledo were invited. Feeling the honor of royal presence, which their city had not enjoyed for many years, the Toledans went by thousands to the castle. Told to enter one by one, noble and grandee went in—but not to feast. Five thousand lost their heads in the trap. Amron thought, no doubt, that it was a good joke; but he had not much time to enjoy it. When the people realized what he had done a mob gathered and burned his castle, with Amron in it.

Toledo was early freed from Moorish rule, and the greatest of those who helped to maintain her independence was Rodrigo Diaz the Cid, who, next to Napoleon, is held by many to be the foremost heroic figure in European history. He held important court offices under Alfonso, living in the Alcázar at Toledo. Many poems and stories have been written about the Cid. He belonged to a noble family, married the granddaughter of Alfonso V, and later made himself a king. The fate of a battle was never in doubt if the Cid was fighting; for his side was sure of victory. Toward the end of his life, after hundreds of battles and duels, he made his most famous conquest, the taking of Valencia from the Moors, in 1094. He ruled well and justly for the next five years over Valencia and Murcia, and in 1099 died of anger over the defeat of his favorite lieutenant. The Cid is Spain’s hero and saint, familiar to all in legend and in song.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 31

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

ROYAL PALACE, MADRID, SPAIN

TWO

Standing on the grand stairway of the Royal Palace, his hand upon the balustrade, and looking at the splendor about him, Napoleon Bonaparte said to his brother Joseph, to whom he had given the throne of Spain, “You are better housed than I am.” That was the emperor’s opinion of the royal residence in Madrid. To Napoleon the conquest of this ancient and famous land of Spain was one of his greatest victories.

Many people, when they first see the country around Madrid, are surprised at the lack of trees there. It is known that the mountains of that region were once covered with a heavy growth of forest which has since been cut away. The trees were felled to put money into the royal treasury. One reason they were never replanted is that many of the Castilians have a strong dislike for trees. They think only of the birds that nest among the branches and feed in grain fields; they forget that trees are both useful and beautiful in themselves, giving shade and moisture and beautifying the scenery.

In later years a wise government has come to see that the slight loss of farmland is not nearly so important as the effect woodlands have on climate. Groves now dot the landscape with patches of refreshing green, and the climate about Madrid is already improving. It is hoped that the bleak country, which now grows only a spare crop of corn, will become fertile and fruitful again when new forests have influenced a more regular rainfall and a steadier temperature. Scientific forestry can probably redeem the error that was committed centuries ago.

Madrid, though a modern city, has been from the beginning a center of art and literature. Velasquez went there from Seville to spend the greater part of his life. It was there that Cervantes, author of “Don Quixote,” lived and died. More important, perhaps, than any other figure in the Spanish drama was Lope de Vega, a native of the city. He led an eventful life while writing poems and plays with wonderful readiness. According to his own statement, more than a hundred of his plays were written so quickly that it took only twenty-four hours from the time he started to compose each one of them until it had been produced on the stage. He wrote 1,800 plays. He is said to have printed 21,300,000 lines, which, if we can believe his own account, was only a part of all that he wrote. To do this he must have written nearly nine hundred lines a day all through his life.

Many other artists and writers have worked in Madrid, and the Spanish capital is still a well known center of culture.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 31

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

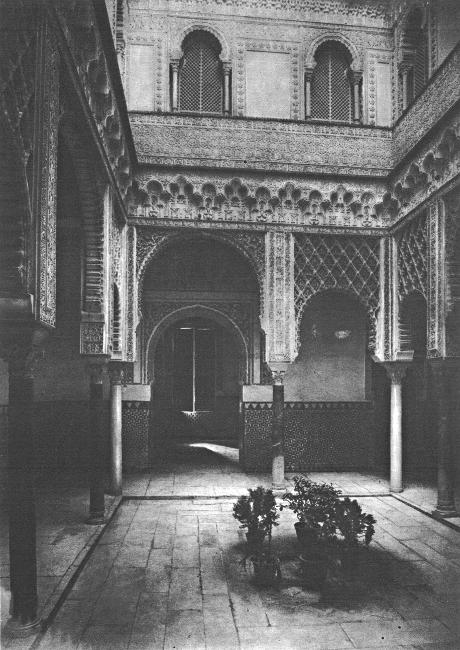

ALCÁZAR AT SEVILLE, SPAIN

THREE

Tranquilly amid its gardens that glow with roses and orange blossoms, the Alcázar of Seville, palace of the old Castilian kings, stands now as it stood in the days of the Moors. Here and there a ceiling, a stairway, or a colonnade, damaged by fire or earthquake, has been repaired according to architectural ideas of more modern times; but in the main those Moorish kings who built it could sleep, if they were there today, in their own rooms undisturbed by any feeling of strangeness.

The site on which the Alcázar was built is probably the oldest in Seville. The palace replaces an old Gothic castle, which had been erected on the foundations of a Roman villa. Uncertain traditions and the imagination of historical writers have pictured the houses of shepherds on the same spot before history began.

There are many stories about the Alcázar, both true and fabulous. The Court of Maidens took its name from one of these. It was said that a tribute of a hundred maidens paid to the Mohammedan ruler had been lodged in that part of the Alcázar. History does not show that the calif ever asked for such a tribute, and it is probable that the Court of Maidens had not been built at the time when this incident is supposed to have taken place. Nevertheless, such a story has grown up, and has given the court a name that it will doubtless bear for all time.

After Castile had thrown off Moorish rule Seville was made the capital of Spain. For several centuries Christian kings lived in the Alcázar, adding somewhat to the original structure as the Moors had left it. The name of Pedro is more closely connected than any other Spanish ruler with the history and fiction of the building. He was called Pedro the Cruel. A grim sense of humor and a habit of going through the streets of Seville in disguise have made him the subject of many odd tales and rumors. Some of these stories are merely whimsical. He is said to have met four candidates for a judge’s position beside a pool in the gardens where they had gone to find him. Pedro, turning to the first, asked him what was floating in the pool.

“An orange,” replied the candidate without hesitation.

The second and third gave him the same answer.

The fourth fished out the piece of fruit with his staff, examined it, and replied more accurately, “Half an orange.”

Pedro immediately gave him the appointment.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 31

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

CATHEDRAL OF SEVILLE, SPAIN

FOUR

There is a Spanish proverb that says, “Whom God favors he gives a house in Seville.” The privilege of living in that bright, gay city is considered by a Spaniard to be the height of happiness. Other cities are larger, wealthier, or more important politically than Seville; but none holds a higher place in the hearts of the Spanish people. When in the beginning of the fifteenth century the old cathedral was damaged by an earthquake, a meeting was held to discuss what should be done to restore it. Then one proposed that, instead of repairing the old church, they should build a new edifice, larger and more magnificent than had ever been imagined. They planned a cathedral that should make all who saw it wonder at the daring of those who began it. What the public funds would not supply they agreed to furnish out of their own purses.

Only 117 years were consumed in the erection of this wondrous structure, which is a short time as old cathedrals go. After St. Peter’s at Rome and the Mezquita at Cordova, it is the largest church in the world. It is 414 feet long, 271 feet wide, and 100 feet high to the top of the nave. The immense pillars, as you look down the church between them, seem to diminish in the distance to the thickness of reeds. Many another cathedral could stand inside the nave of this one.

There are numerous churches in the city; most of the older ones are built on the foundations of mosques. The church of La Caridad has a strange legend connected with it. Don Miguel de Manara, the founder, had been a profligate in his youth, a sort of Don Juan, and was known far and wide for his excesses. One night when he was returning home alone he lost his way, and wandered about in a daze, unable to find his home. In imagination he met a funeral procession, and stopping one of the bearers inquired who it was that they were taking to eternal rest at such an hour.

“Don Miguel de Manara,” he replied.

Greatly surprised at hearing his own name, Don Miguel uncovered the face and saw there his own features. The procession immediately vanished; but left him so deeply impressed that he was converted and built a church and a hospital.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 31

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

VIEW OF ALHAMBRA. GRANADA, SPAIN

FIVE

The city of Granada was the last Moorish stronghold in Spain. The usurpers had been driven from province after province, while the power of Castile increased in all the country round. Only the province of Granada held firm. Even there, losses in war had so weakened the Moors that their kings paid tribute to the Christian rulers, down to the time of Muley Hassan. He was a proud and cruel monarch, so fond of the dignity his fathers had held that he not only withheld the tribute, but even made inroads into Spanish territory.

A ten years’ war followed. Spain determined to drive her enemy out of Europe once and for all. In battle after battle the Christians narrowed Hassan’s kingdom, till the people of Granada rose in revolt against the ruler whose bad luck and tyranny made him so unpopular. He was dethroned, and the kingdom given to Boabdil, his son. Boabdil was if anything more unfortunate than his father; for Ferdinand and Isabella pushed their conquest little by little up to the very walls of Granada.

A long siege followed. The Moors, as they lost the power they had held so long over the rich and delightful lands of Spain, tried every trick of warfare without effect. Ferdinand had given orders not to attack the city. He intended to win by starving his enemies rather than by fighting, while the Moors did all they could to provoke a battle. One daring knight named Yarfe rode out of the gates; unexpectedly he made his way to the Christian camp, and threw a spear into the ground close by the royal pavilion as an insult to Queen Isabella. In return Hernando del Pulgar, disregarding the order of Ferdinand, broke through the gates of Granada with a few followers and pinned a tablet on the door of a mosque with his dagger. Upon the tablet were the words, “Ave Maria.” Thus the knights of both sides showed their recklessness under the long siege.

The Spanish army lay so long encamped on the vega (plain) within view of the city walls and the magnificent buildings of the Alhambra that at last, after the tents had been accidentally burned, Ferdinand ordered a city to be built for the soldiers. Each of the towns of Spain sent its share of materials and in a remarkably short time Santa Fé, as it was called, stood side by side with Granada.

When all the vega was laid waste, when the Moors were starving and discontented, and a hostile walled city frowned in sight of the Alhambra, Boabdil at length made terms of peace. He said farewell to the palace of Moorish kings and all the luxuries he had enjoyed as its ruler, surrendered the keys of the city to Ferdinand, and went away greatly humbled. Never afterward did the Moors hold power in Spain.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 31

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

ROCK OF GIBRALTAR

SIX

One night over two centuries ago a band of Spaniards, led by a goatherd, crept up the rock of Gibraltar to St. Michael’s cave, where dawn overtook them, and where they remained all through the next day. As soon as darkness had fallen again they scaled the wall, surrounded the signal house, and in a few moments overpowered the guard. The British in the fortress never dreamed of danger so close at hand. Ropes and ladders were lowered stealthily over the precipice, and the Spaniards, feeling sure of victory, brought up several hundred men for the attack. If all had gone well, Gibraltar might have been in the hands of Spain again before sunrise; but some part of the work was clumsily done, for British sentries caught the alarm, and a body of grenadiers, hastily called together, rushed out upon their midnight assailants. Gibraltar was saved for the British. Some of the Spaniards they hurled over the cliff; the rest surrendered and were taken prisoners.

The history of Gibraltar was for many centuries one of sieges and captures. The rock was first known to the Greeks and Romans as one of the pillars of Hercules; the other, Mt. Abyla, stands on the African shore. But at that period, when ships rarely sailed out of the Mediterranean, the “pillar” was unimportant to any great nation in war. It fell into the hands of Phoenicians, Romans, Carthaginians and Visigoths at different periods in history. Tarik, landing there when he crossed from Africa into Spain, built a castle on the rock, which was therefore called Gebel-al-Tarik (Hill of Tarik), the original form of the name Gibraltar. It fell into the hands of England after the Spaniards and Moors had fought over it for centuries.

Once again, in the great siege that began in 1779 and lasted more than three years, England came dangerously near losing the fortress. Spain and France took advantage of British losses in America to open fire on the Mediterranean stronghold. After the garrison of over 5,000 men had been reduced to starvation, and only the bravery of General Eliott could keep them together, Gibraltar was bombarded from the mainland. Just when his command seemed lost under the strain of attack and of hardships endured so long, the Scotsman led his troops to the attack, and, taking the much larger Spanish army by surprise, drove them back and burned their fortifications. Again Spain and France attacked from the sea; but Eliott burned their ships with redhot cannonballs. The struggle was renewed from time to time all during the siege, until at last peace was proclaimed. General Eliott, returning home, was received with the highest military honors for his courage.

England has been offered all of Spain’s possessions in Africa in exchange for the one great sterile rock; yet nothing will induce her to give up that hold on the gate of the Mediterranean.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 31

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

The Course for One Year Provides:

1—A growing library of the world’s knowledge—twenty-four numbers a year.

2—A beautiful art collection for the home—one hundred and forty-four art prints in sepia gravure and color.

3—One hundred and forty-four crisp monographs—one to accompany each Mentor Gravure.

4—A reading course throughout the year.

5—An education for all the family, under the direction of the foremost educators in this country—in art, literature, science, history, nature, and travel.

Send the names of three friends whom you wish to nominate for membership, and to whom you would like to have us send presentation copies of The Mentor.

THE MENTOR

This service covers the needs of those who want to gain knowledge by an easy and agreeable method.

Send for our booklet descriptive of The Mentor Club Service. It presents many varied Mentor courses specially planned for the use of reading clubs.

The Mentor Association will supply to its members supplementary reading courses dealing with any or all of the subjects in The Mentor Courses. These courses of reading are prepared under the direction of the Advisory Board of The Mentor—all of them prominent educators.

The Mentor Association will also secure books for members, supplying them postpaid at special prices.

The Mentor Inquiry Department gives to its members a full and intelligent service in answering inquiries concerning books, reading, and all matters of general information having a bearing on The Mentor Courses.

MANY READERS HAVE COME TO KNOW THE VALUE OF THE MENTOR SERVICE. IN THE FULLEST SENSE IT SUPPLEMENTS AND ROUNDS OUT THE PLAN OF THE MENTOR. ALL MEMBERS OF THE ASSOCIATION ARE INVITED TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THIS SERVICE

MAKE THE SPARE

MOMENT COUNT