The Project Gutenberg EBook of Manual of Library Economy, by

James Duff Brown and W. C. Berwick Sayers

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Manual of Library Economy

Third and Memorial Edition

Author: James Duff Brown

W. C. Berwick Sayers

Release Date: September 6, 2015 [EBook #49895]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MANUAL OF LIBRARY ECONOMY ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Harry Lamé and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created

for this e-book and is placed in the public domain.

JAMES DUFF BROWN

MANUAL OF

LIBRARY ECONOMY

BY THE LATE

JAMES DUFF BROWN

CHIEF LIBRARIAN, ISLINGTON PUBLIC LIBRARIES

AUTHOR OF

‘SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION,’ ‘LIBRARY CLASSIFICATION AND CATALOGUING,’

‘A BIOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY OF MUSICIANS,’ ETC.

THIRD AND MEMORIAL EDITION

REVISED AND REWRITTEN BY

W. C. BERWICK SAYERS

CHIEF LIBRARIAN, CROYDON PUBLIC LIBRARIES

LECTURER IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF LIBRARIANSHIP

AUTHOR OF

‘CANONS OF CLASSIFICATION,’ ‘AN INTRODUCTION TO CLASSIFICATION,’

‘THE CHILDREN’S LIBRARY,’ ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS, FORMS, AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES

GRAFTON & CO.

COPTIC HOUSE, LONDON, W.C.1

1920

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY

OF

JAMES DUFF BROWN

1862-1914

This work was published by the late author in 1903, and a second, and largely remodelled, edition appeared in 1907. For some years past it has been out of print, to the loss of more recent students. The delay, however, has not been without its compensations, as librarianship has made several advances which have been generally accepted, and has made many experiments, the issue of which is not yet decided, in the twelve years since the publication of the second edition. The work has been regarded with much justice as the most comprehensive complete treatise on library economy, and is the standard to which most British libraries conform in general; indeed, it is not too much to say that the whole modern school of librarians here has been moulded by the work. When, therefore, I was asked to prepare a new edition I was faced with the question of how best to preserve its comprehensive character. I might have revised it conservatively, merely touching up the statistics, adding to the bibliographies, and correcting statements which have been modified by later experience; but that would have left the book partial and incomplete. Rightly or wrongly, I have rewritten almost every chapter, have added sections on questions touched upon only lightly or not at all in previous editions, and have omitted several statements in which strong personal views were expressed; in fact, I have tried to preserve everything that seemed to be of permanent value, to excise everything merely controversial, and to avoid obtruding any idiosyncrasies of my own. I cannot hope to have succeeded completely, and any suggestions for the improvement of future editions will be welcomed.

Both of the earlier editions retain their value for students,[vi] but the criticism which may fairly be levelled at them is that Brown rarely contemplated the needs of a library of more than 40,000 volumes, and, therefore, omitted much that is necessary in the administration of such libraries. I have tried to balance this. It is perhaps desirable to set out the particulars in which the third edition differs from the second. The following chapters have been rewritten in their entirety: IV., V., VI., XV., XVIII., XX. and XXVII. The following are new: all Divisions I., XIII. and XIV.; and Chapters VII., XXVII., XXVIII., XXIX. and XXX. Everything else has been retouched, except the chapter on museums and art galleries; that I have left, because although the librarian ought to have a knowledge of curatorship, that knowledge is not library economy; and, within its limits, the chapter is good common sense. I have dealt drastically with the bibliographies, which consisted in the main of lists of articles in library periodicals. Every library student knows that textbooks and treatises are supplemented by periodical literature, and a reference to the indexes of library journals should be an obvious thing for him to make on any subject; and seeing that we have Cannons’s Bibliography of Library Economy, 1876-1909, for the years covered by the title, and that the best articles are now indexed in the Library Association Index, it seemed sufficient to make a general reference to Cannons and otherwise restrict the lists with few exceptions to separate publications. Appendix II, “The Librarian’s Library,” has been revised by Mr Richard Wright, M.C., to whom my thanks are due. An important omission is the Appendix of “Factors and Percentages,” which gave figures for calculating the size, cost, output, etc., of libraries. This has been deliberate; the conditions created by the War are so fluid that factors which are likely to have a permanent value are impossible to compile. Brown’s Guide to Librarianship gives the pre-war factors, and it is unnecessary to reprint them here.

The Memoir is based upon the obituary notices and appreciations which were collected and edited by Mr L. Stanley Jast for The Library Association Record, the biographical facts in particular being drawn from the memoir by Brown’s nephew, Mr James Douglas Stewart, which is included in those notices. Others will share my regret that his preoccupation with his new work at Manchester prevented Mr Jast from revising this Manual. I cannot but perceive, now that my work is finished, how much better it would have been had he filled my place. A few notes, prepared by Mr Jast for Chapters I.-II., have been included.

Usually, when one has written a book, one has to acknowledge much help from other librarians, but, owing to the extraordinary circumstances in which this revision has been made, I felt that I ought not to call for help from others already overburdened. My own task has been completed under great pressure, most of the work being done between 6.30 and 8.30 a.m. My wife has saved me from many blunders, and her experience as a former member of Mr Brown’s staff has been most valuable to me.

W. C. BERWICK SAYERS

Postscript.—As the final proofs are leaving my hands I learn that the long-expected Government Bill to remove the penny rate limitation was introduced into the House of Commons by Mr Herbert Lewis and read a first time on the 28th of November. The second reading occurred on the 2nd of December, and the Bill became law on the 23rd of December 1919.

It is now practically certain that the powers in regard to Public Libraries which were held by the Local Government Board now accrue to the Ministry of Education, and, consequently, wherever the Local Government Board is mentioned in the Manual, the Ministry of Education should be understood.—W. C. B. S.

Croydon, 1919

The Publishers desire to thank those who have kindly allowed them the use of illustrations and have lent blocks, or have offered other facilities for reproduction; especially the following:

The Librarians of Bristol, Bromley, Cardiff, Chelsea, Coventry, Croydon, Fulham, Glasgow, Lambeth, Liverpool, Montrose, St Pancras, and Southend; The Library Association; Messrs Cedric Chivers Ltd., Messrs Fordham & Co., Messrs Kenrick & Jefferson, Mr Arthur W. Lambert of Croydon, Messrs Libraco Ltd., and Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons.

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | v | |

| List of Illustrations, Forms, etc. | xii | |

| DIVISION I.—INTRODUCTORY | ||

| Memoir | 1 | |

| Introduction | 11 | |

| DIVISION II.—FOUNDATION, COMMITTEES AND FINANCE | ||

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | Legislation | 19 |

| II. | Adoption of Acts, Foundation and Committees | 34 |

| III. | Finance, Loans and Accounts | 43 |

| IV. | Statistics and Reports | 60 |

| DIVISION III.—STAFF | ||

| V. | The Librarian | 71 |

| VI. | Assistants | 83 |

| VII. | Library Associations | 99 |

| DIVISION IV.—BUILDINGS | ||

| VIII. | Theory and General Remarks | 106 |

| IX. | Sites and Plans | 110 |

| DIVISION V.—FITTINGS AND FURNITURE[x] | ||

| X. | Miscellaneous Fixtures and Fittings | 132 |

| XI. | Shelving and Accessories | 141 |

| XII. | Furniture | 154 |

| DIVISION VI.—BOOK SELECTION AND ACCESSION | ||

| XIII. | Book Selection | 167 |

| XIV. | Accession Methods | 189 |

| DIVISION VII.—CLASSIFICATION AND SHELF ARRANGEMENT | ||

| XV. | General Principles. | 206 |

| XVI. | Systematic Classification Schemes | 209 |

| XVII. | Practical Application | 226 |

| DIVISION VIII.—CATALOGUING, FILING AND INDEXING | ||

| XVIII. | Cataloguing Methods, Rules and Codes | 241 |

| XIX. | Mechanical Methods of Displaying Catalogues | 259 |

| XX. | Filing and Indexing | 281 |

| DIVISION IX.—MAINTENANCE AND ROUTINE WORK | ||

| XXI. | Stationery and Records | 296 |

| XXII. | Bookbinding and Repairing | 303 |

| DIVISION X.—RULES AND REGULATIONS | ||

| XXIII. | Rules and Regulations | 322 |

| DIVISION XI.—THE LENDING, OR HOME READING, DEPARTMENT[xi] | ||

| XXIV. | Registration of Borrowers | 341 |

| XXV. | Issue Methods | 350 |

| XXVI. | Book Distribution | 366 |

| DIVISION XII.—THE REFERENCE DEPARTMENT | ||

| XXVII. | General Reference Library Method | 375 |

| XXVIII. | Local Collections | 399 |

| XXIX. | Libraries of Municipal Reference | 415 |

| XXX. | The Commercial Library; The Technical Library | 418 |

| XXXI. | Reading Room Methods | 424 |

| DIVISION XIII.—LIBRARY WORK WITH CHILDREN | ||

| XXXII. | The Children’s Department | 439 |

| XXXIII. | The Library and the School | 457 |

| DIVISION XIV.—LIBRARY DEVELOPMENT | ||

| XXXIV. | Lectures, Readings and Exhibitions | 467 |

| XXXV. | Rural Libraries | 477 |

| DIVISION XV.—MUSEUMS AND ART GALLERIES | ||

| XXXVI. | Museums and Art Galleries | 486 |

| APPENDICES | ||

| I. | The Nomenclature of Library Positions | 495 |

| II. | The Librarian’s Library | 498 |

| INDEX | 511 | |

| FIG. | PAGE | ||

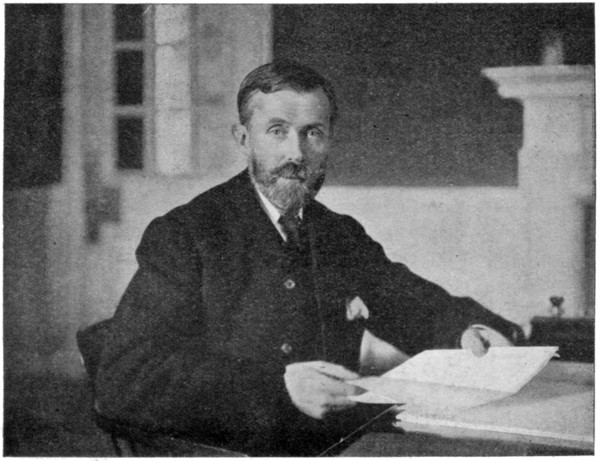

| James Duff Brown | Frontispiece | ||

| 1. | Form for Annual Estimates | 46 | |

| 2. | Returns of Library Expenditure | 47 | |

| 3. | Suggestion Slip | 56 | |

| 4. | Rulings for Issue Record Books | 62 | |

| 5. | Table of Librarians’ Salaries | 77 | |

| 6. | Staff Time Sheet | 89 | |

| 7. | Staff Work Book | 92 | |

| 8. | Salaries paid in 1911 | 93 | |

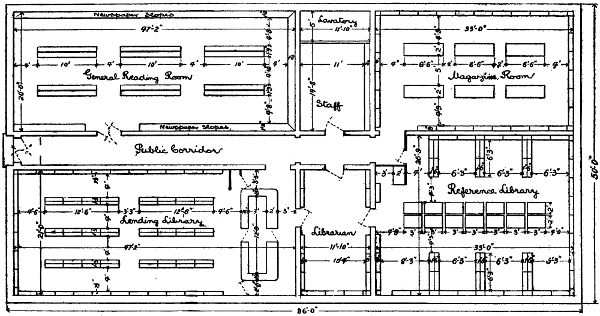

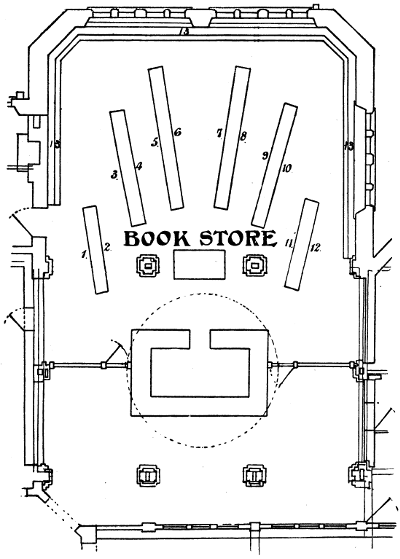

| 9. | Sketch Plan for Small Town Library | 116 | |

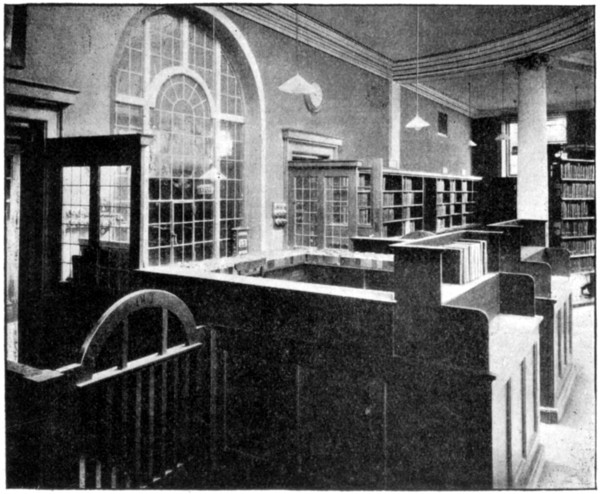

| 10. | North Islington Library—Reading Room | 117 | |

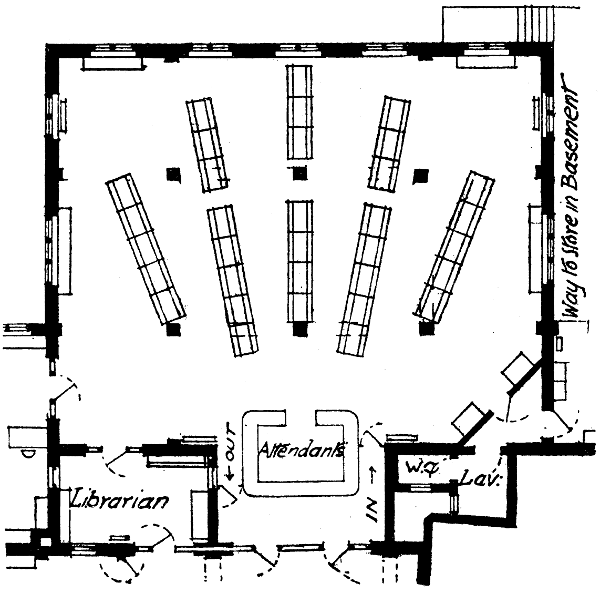

| 11. | North Islington Library—Lending Department | 118 | |

| 12. | Lambeth (Herne Hill) Open Access Lending Department | 119 | |

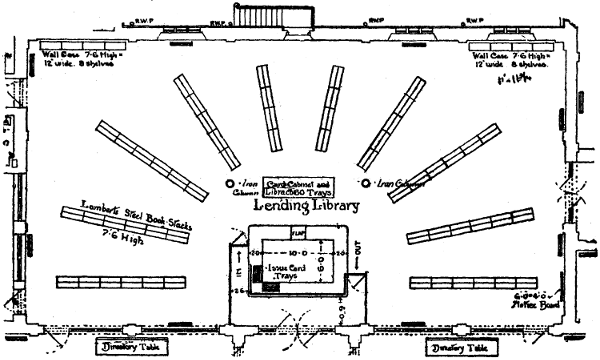

| 13. | Montrose Lending Library | 120 | |

| 14. | Bromley Lending Library | 121 | |

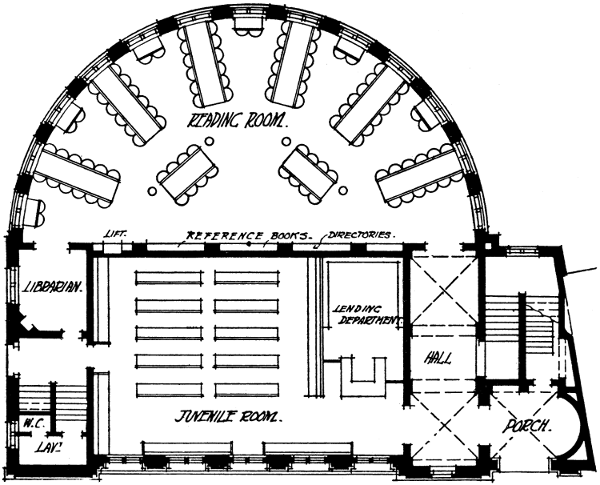

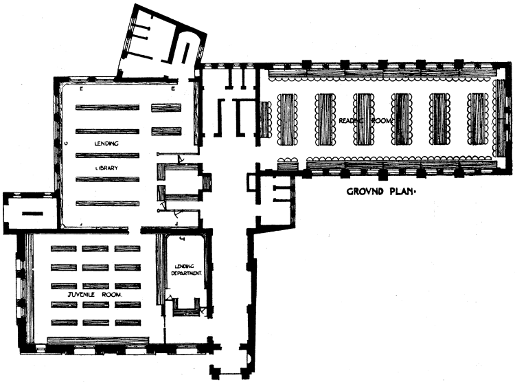

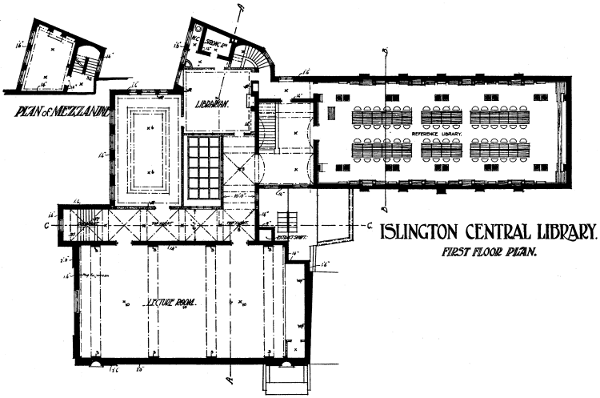

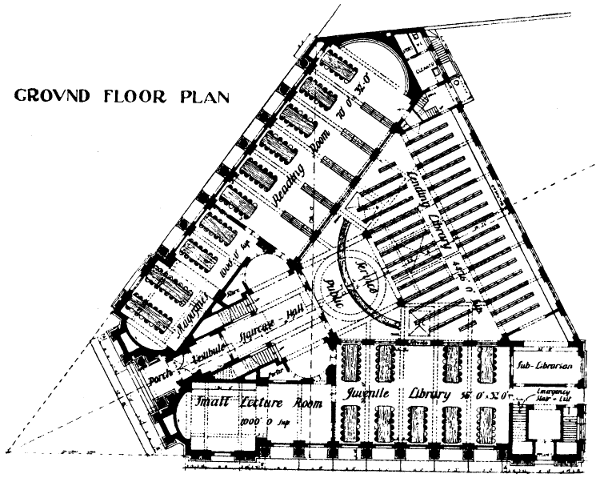

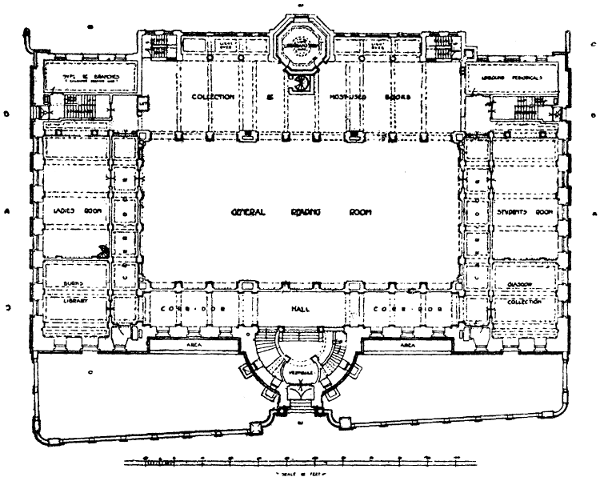

| 15. | Islington Central Library—Ground Floor | 122 | |

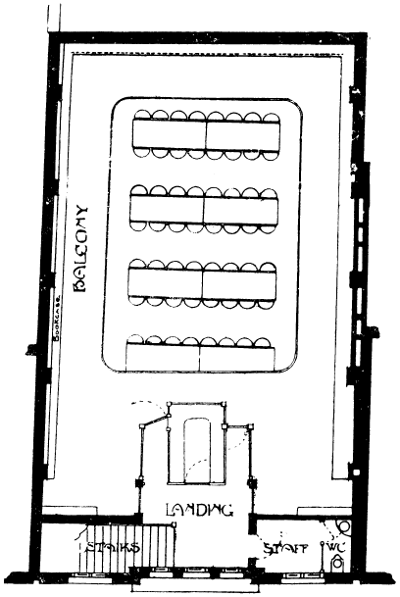

| 16. | Islington Central Library—First Floor | 123 | |

| 17. | North Fulham Library | 124 | |

| 18. | St Pancras Central Library | 125 | |

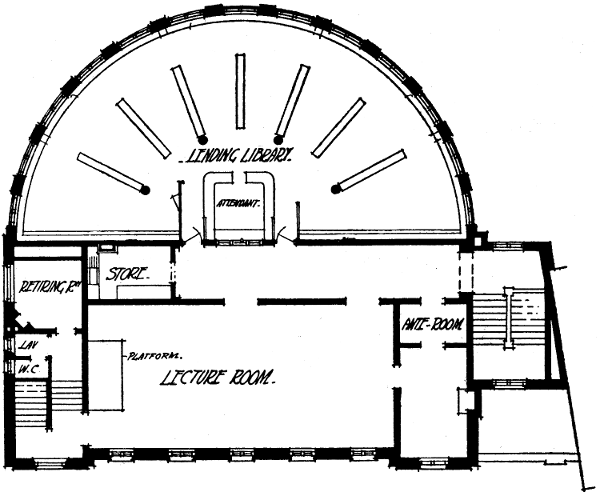

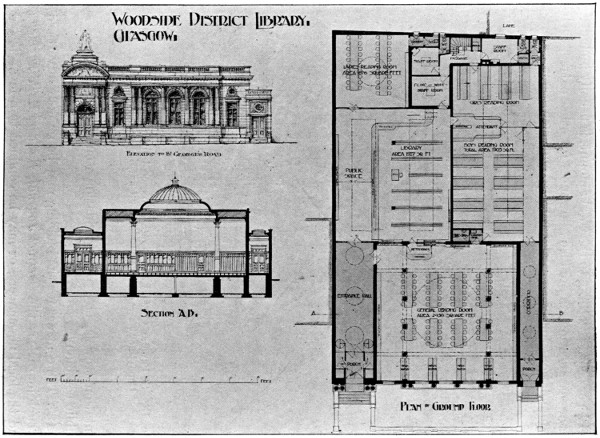

| 19. | Glasgow (Woodside) Library | 126 | |

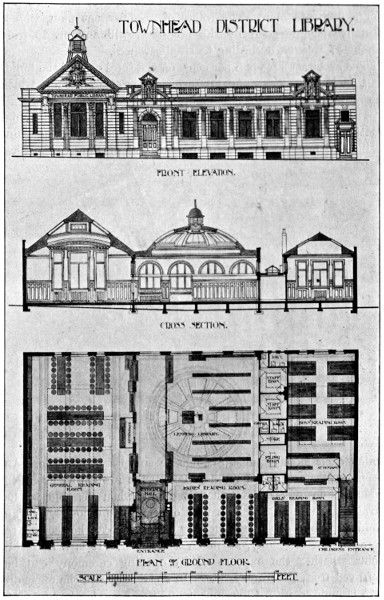

| 20. | Glasgow (Townhead) Library | 127 | |

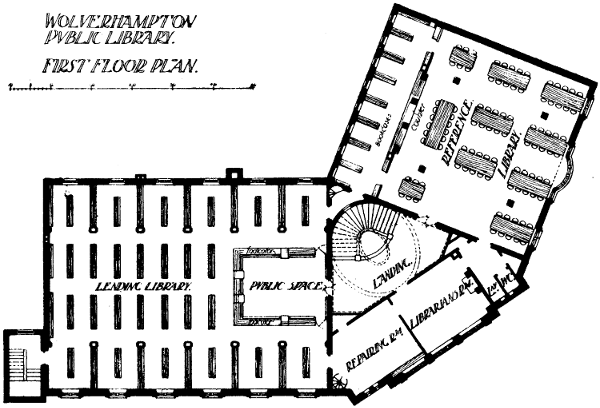

| 21. | Wolverhampton Library | 128 | |

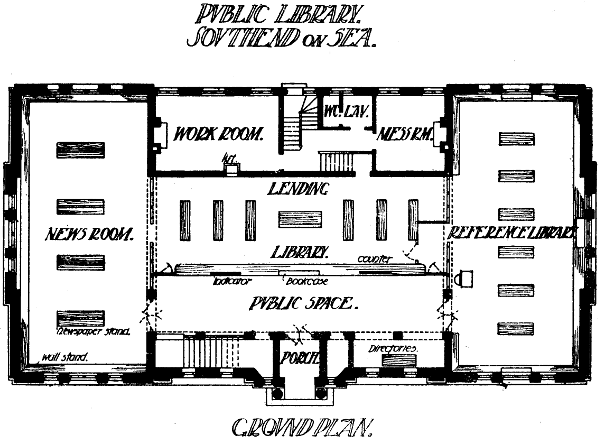

| 22. | Southend-on-Sea Library | 129 | |

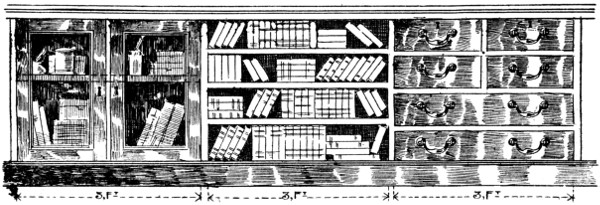

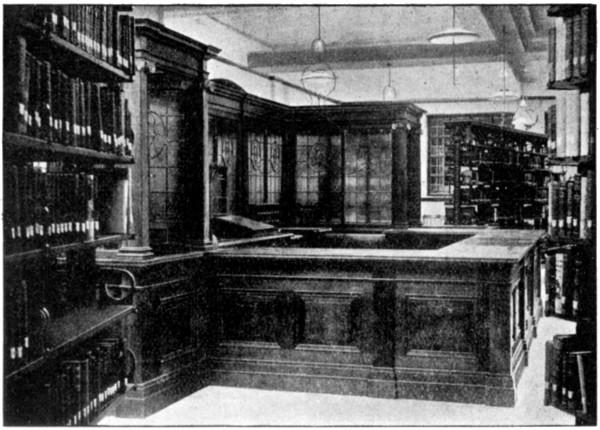

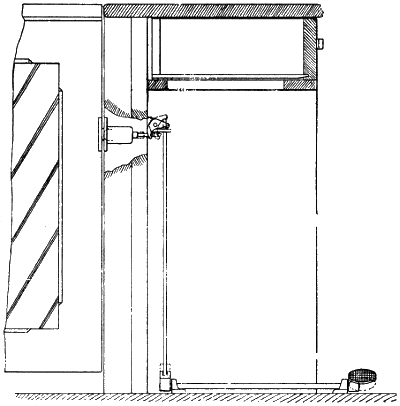

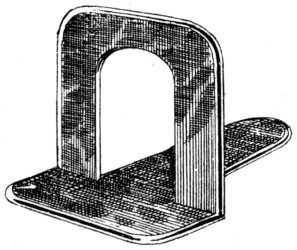

| 23. | Back of Library Counter | 133 | |

| 24. | West Islington Library | 133 | |

| 25. | North Islington Barrier | 134 | |

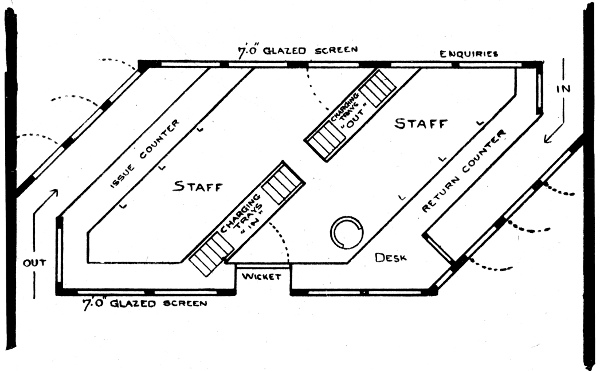

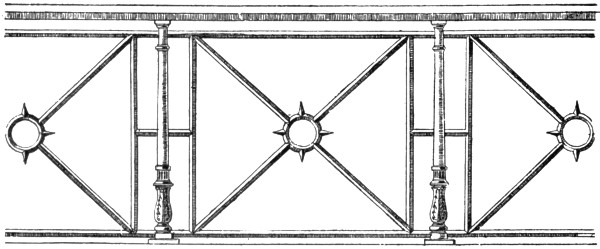

| 26. | Lambeth (Herne Hill) Barrier | 135 | |

| 27. | Croydon Central Library | 136 | |

| 28. | Triple Open Access Barrier | 137 | |

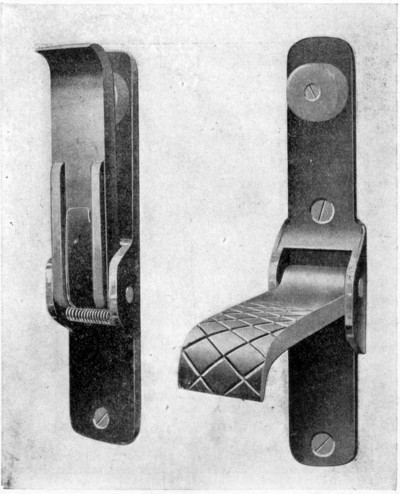

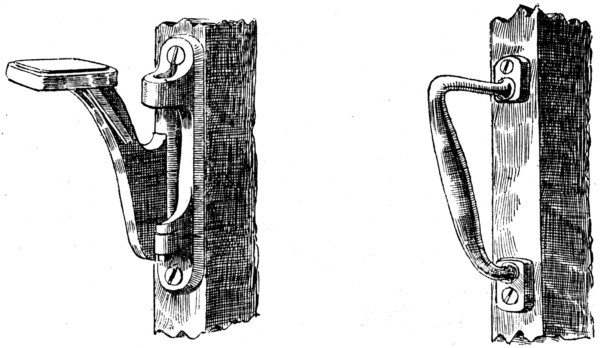

| 29. | Treadle Latch for Wicket | 138 | |

| 30. | Barrier for Dividing Rooms | 138 | |

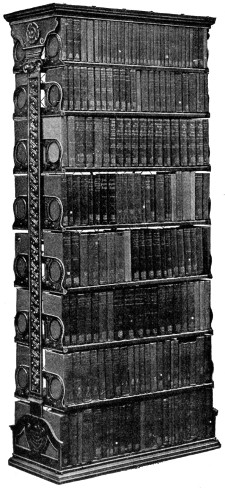

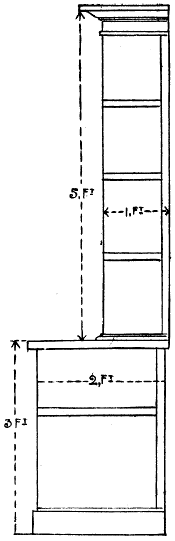

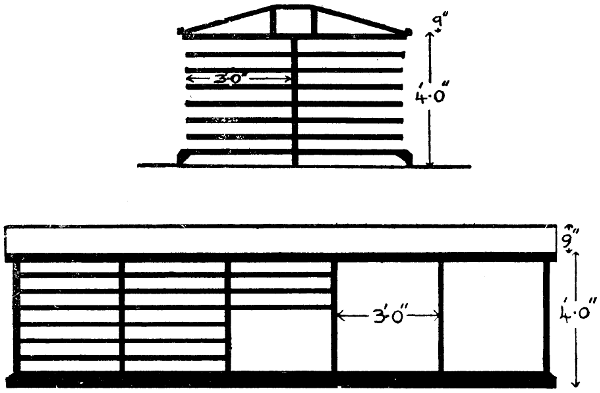

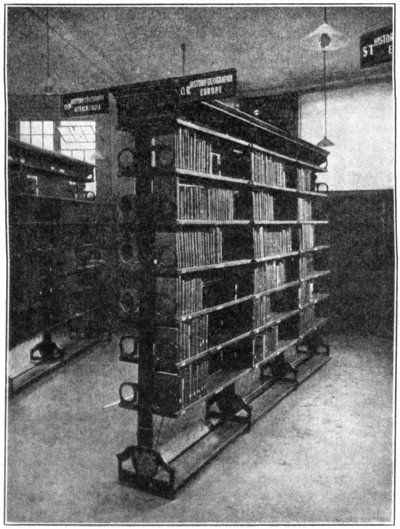

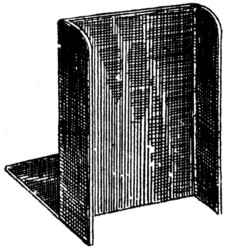

| 31. | Double Bay Standard Metal Book-Case | 143 | |

| 32. | Wood Wall-Case | 144 | |

| 33. | Tonks’ Fittings | 145 | |

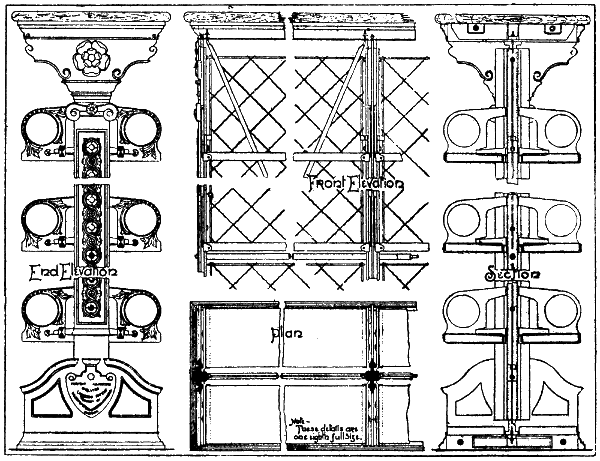

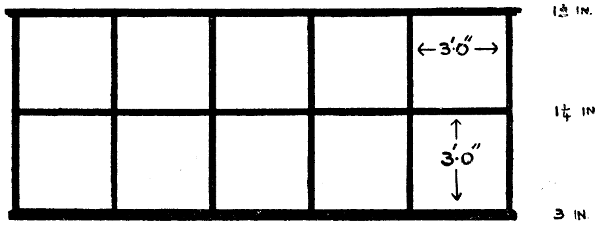

| 34. | Details of Adjustable Metal Shelving[xiii] | 146 | |

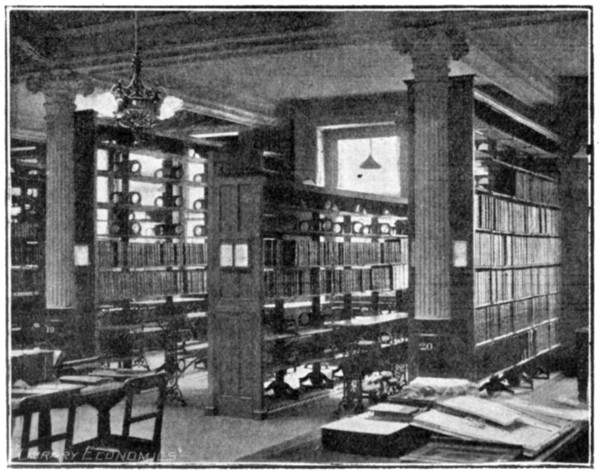

| 35. | Metal Shelving (Patent Office) | 147 | |

| 36. | Rack for Bound Newspapers | 148 | |

| 37. | Case for Large Folio Books | 149 | |

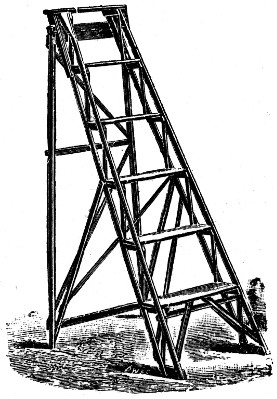

| 38. | Lattice-work Steps | 150 | |

| 39. | Short Steps | 150 | |

| 40. | Continuous Wooden Step and Handles | 151 | |

| 41. | Spring Step | 152 | |

| 42. | Swinging Step, with Improved Handle | 153 | |

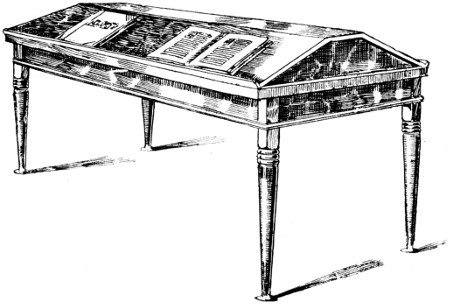

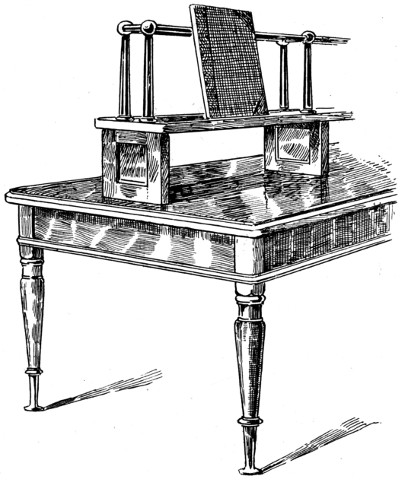

| 43. | Desk-Topped Table | 154 | |

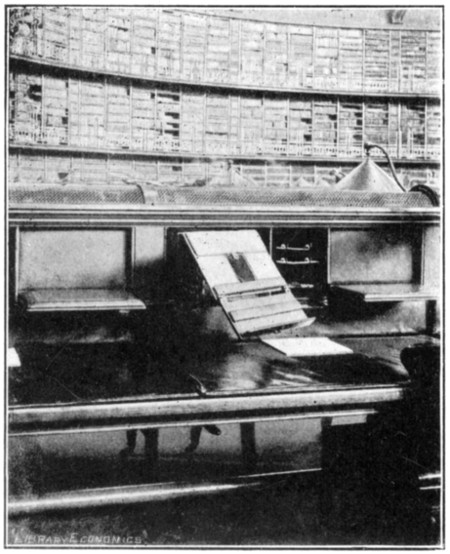

| 44. | British Museum Reading Table | 155 | |

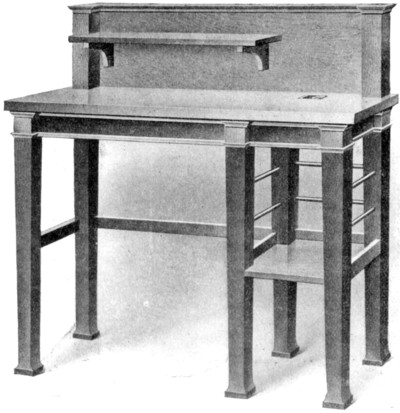

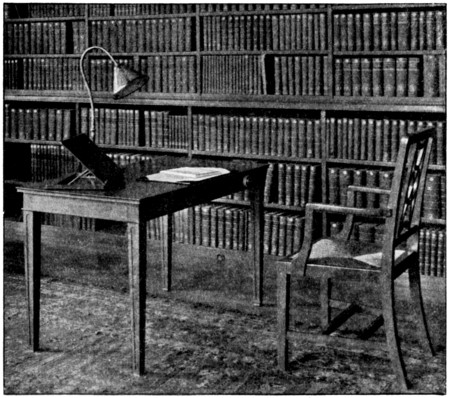

| 45. | Reference Room Table | 156 | |

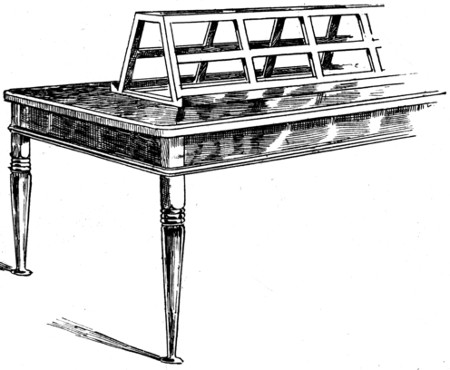

| 46. | Table with Elevated Periodical Rack | 157 | |

| 47. | Periodical Rack on Table | 158 | |

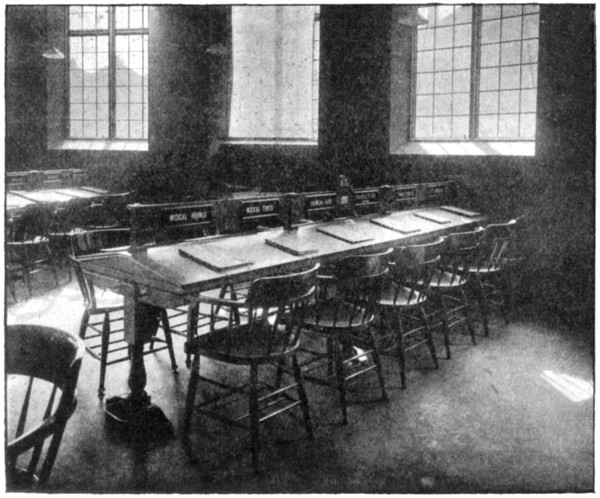

| 48. | Reading Table with Partition for Titles | 159 | |

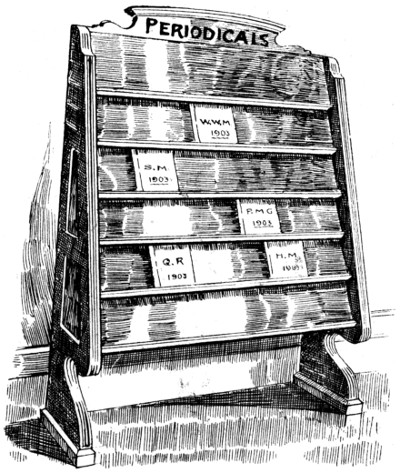

| 49. | Periodical Rack | 160 | |

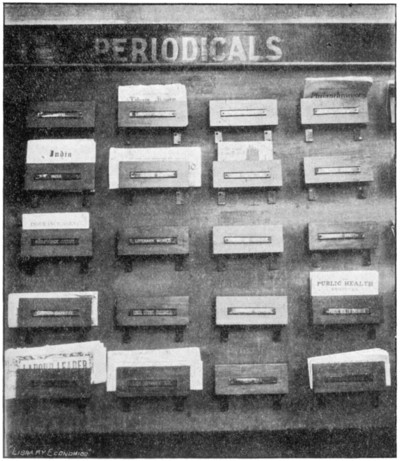

| 50. | Rack for Odd Periodicals | 161 | |

| 51. | Railway Time-Table Rack | 162 | |

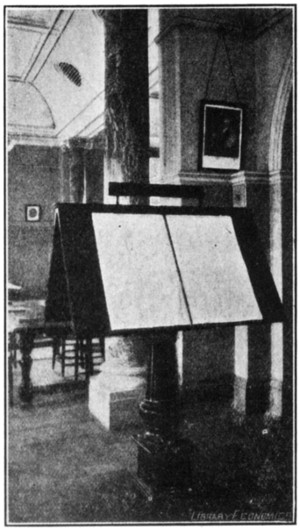

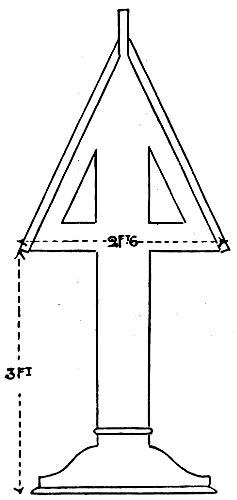

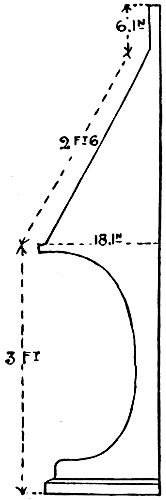

| 52. | Metal Reading Easel | 163 | |

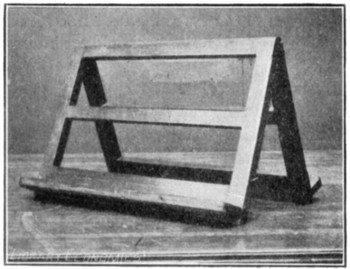

| 53. | Wooden Reading Easel | 163 | |

| 54. | Chair with Anchorage | 164 | |

| 55. | Arm Chair with Hat Rail | 165 | |

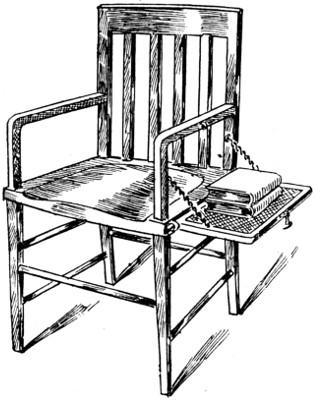

| 56. | Chair with Folding Tray | 165 | |

| 57. | Donation Acknowledgment | 190 | |

| 58. | Donation Book Ruling | 191 | |

| 59. | Proposition Book Ruling | 191 | |

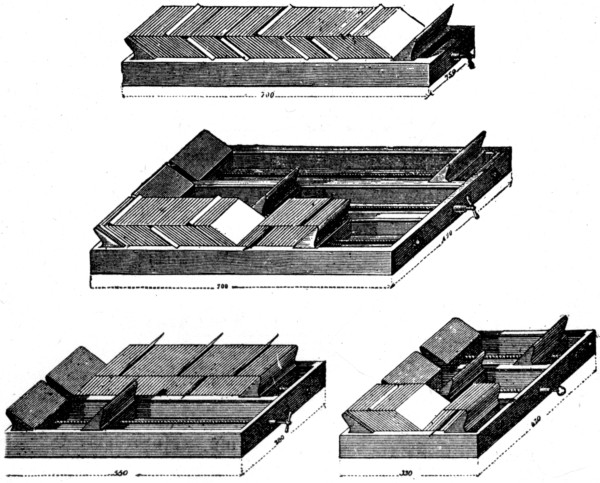

| 60. | Book-Order Sheet | 193 | |

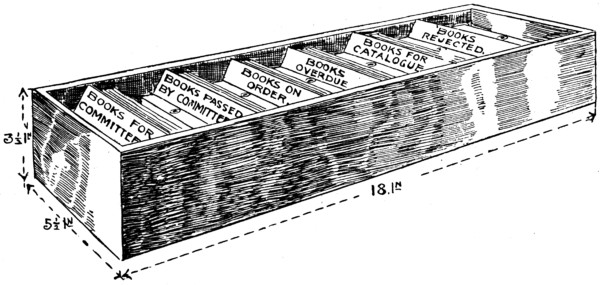

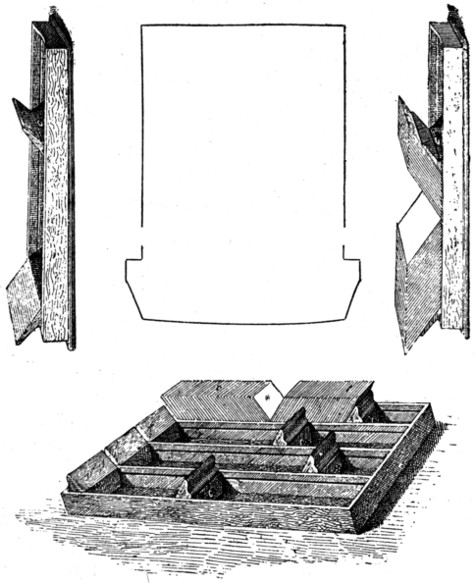

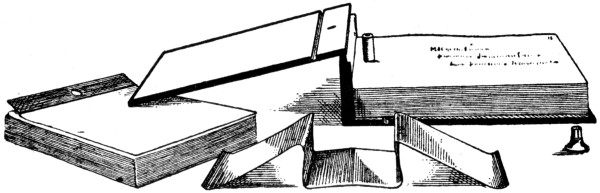

| 61. | Book-Order Tray | 194 | |

| 62. | Accessions Number Book | 195 | |

| 62A. | Accessions Routine Book | 196 | |

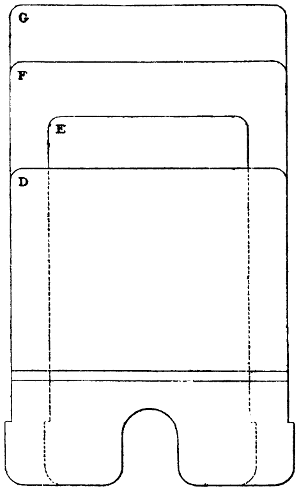

| 63. | Manila Book Card | 197 | |

| 64. | Board Label | 198 | |

| 65. | Date Label | 199 | |

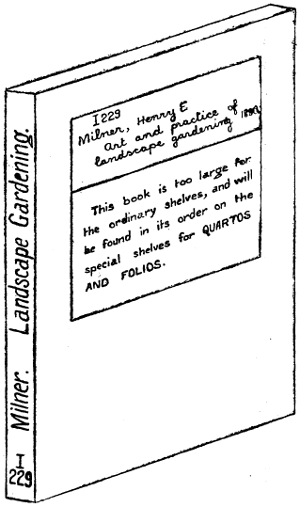

| 66. | Warning Label | 200 | |

| 67. | Map and Plate Label | 200 | |

| 68. | Process Stamp | 201 | |

| 69. | Stock Book—Left folio | 202 | |

| 70. | Stock Book—Right folio | 202 | |

| 71. | Abstract Sheet for Stock | 203 | |

| 72. | Withdrawals Book | 204 | |

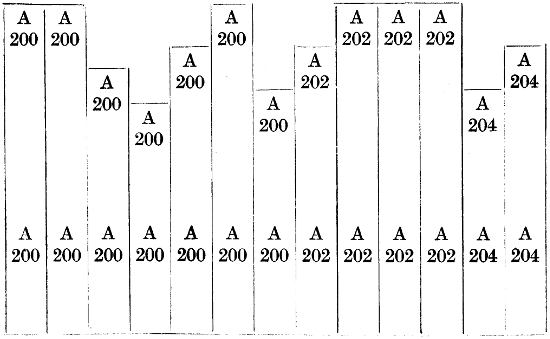

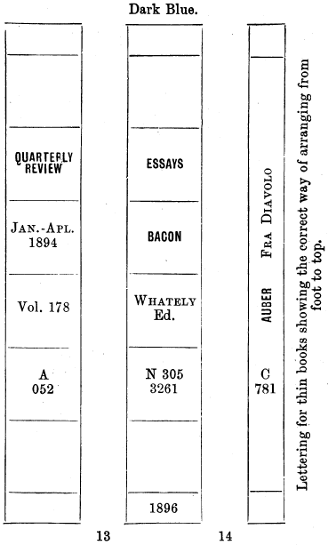

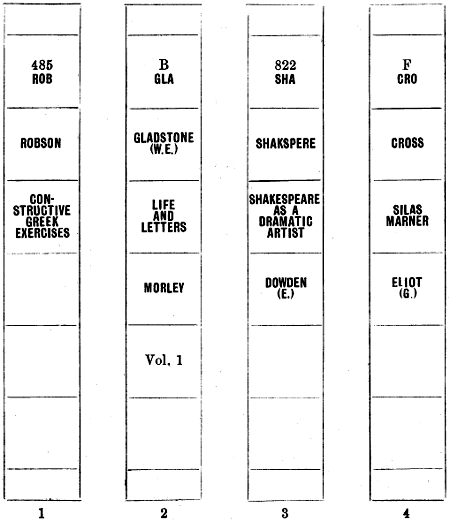

| 73. | Lettering of Class Numbers[xiv] | 226 | |

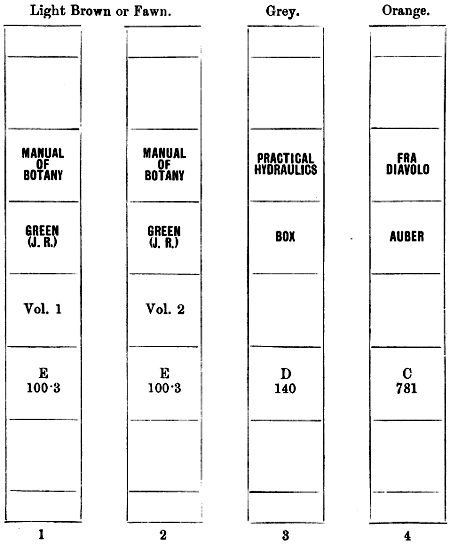

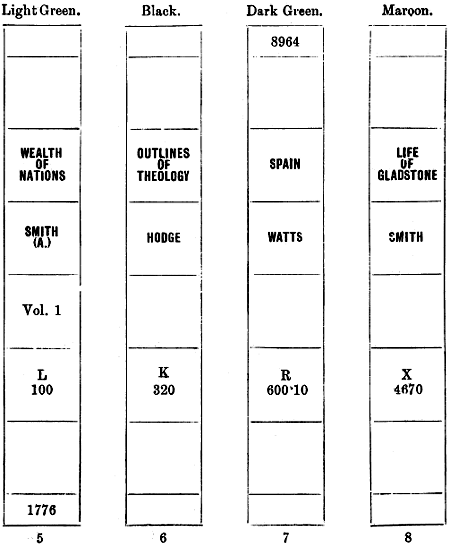

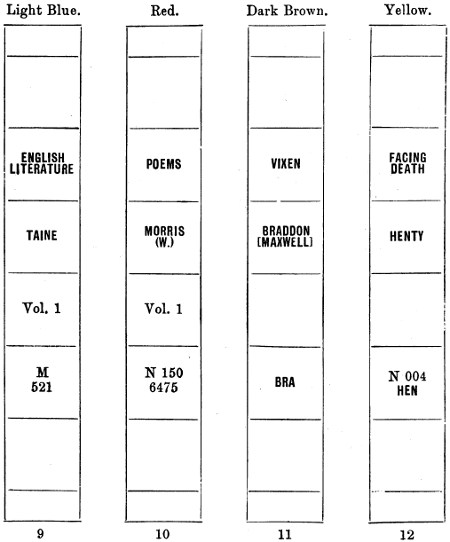

| 74. | Colour Marking of Books | 228 | |

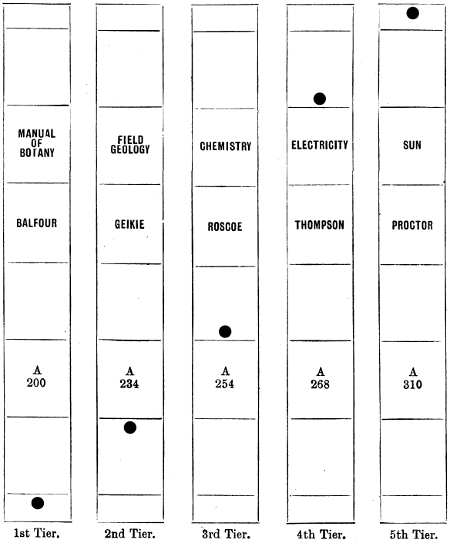

| 75. | Tier Marking of Books | 229 | |

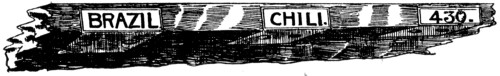

| 76. | Shelf Front, with labels | 230 | |

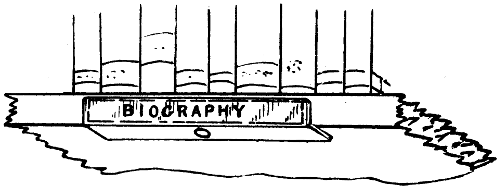

| 77. | Tier Guide | 230 | |

| 78. | Tier Guide Lettering | 231 | |

| 79. | Class Guide | 232 | |

| 80. | Bookcase with Classification Guides | 233 | |

| 81. | Shelf-Check Register | 234 | |

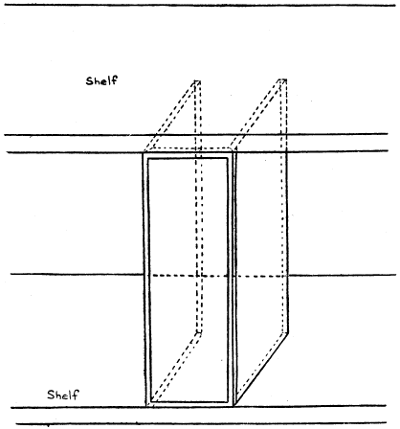

| 82. | Shelf Dummy | 235 | |

| 83. | Millboard Dummy | 236 | |

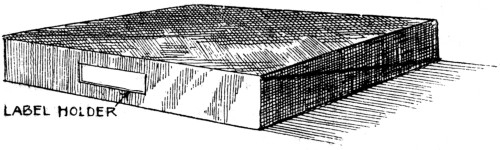

| 84. | Xylonite Label-holder | 237 | |

| 85. | Tongued Metal Book-rest | 237 | |

| 86. | Flanged Metal Book-rest | 237 | |

| 87. | Combined Book-rest and Shelf Guide | 238 | |

| 88. | Yale Book-rest | 238 | |

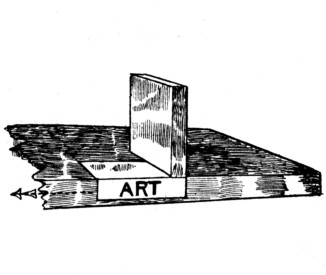

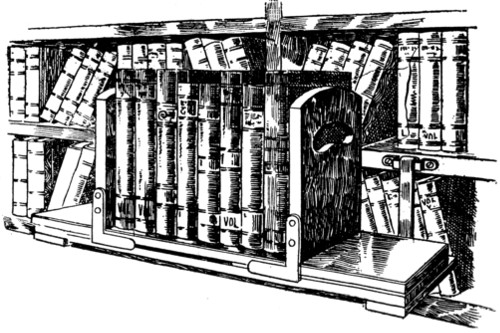

| 89. | Book-carrier in front of Book-case | 239 | |

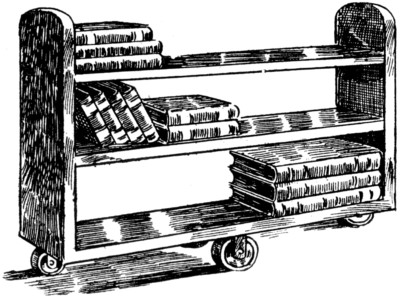

| 90. | Book-truck | 239 | |

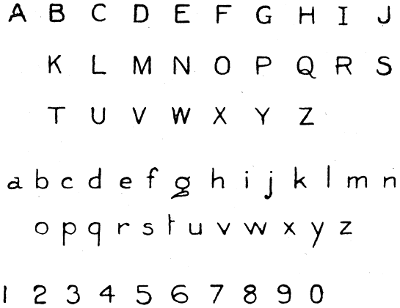

| 91. | Hand-printing Models | 256 | |

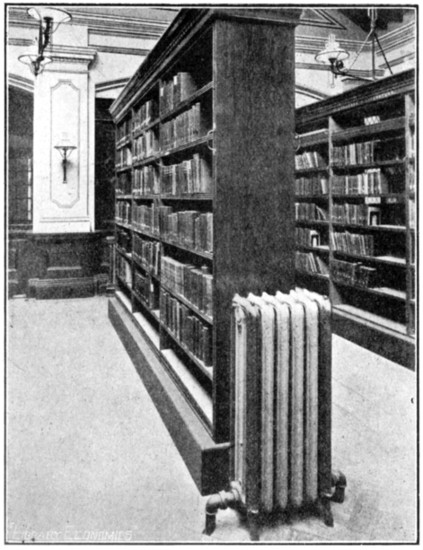

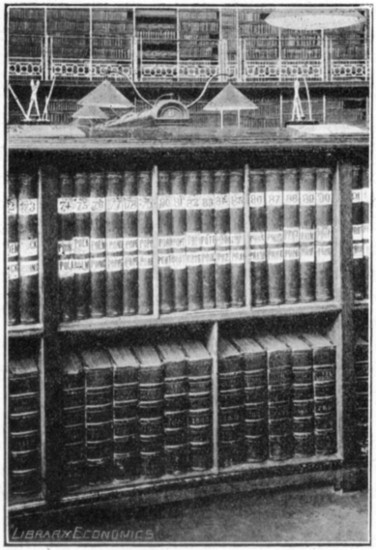

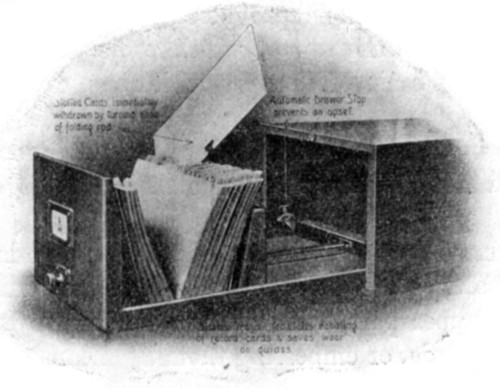

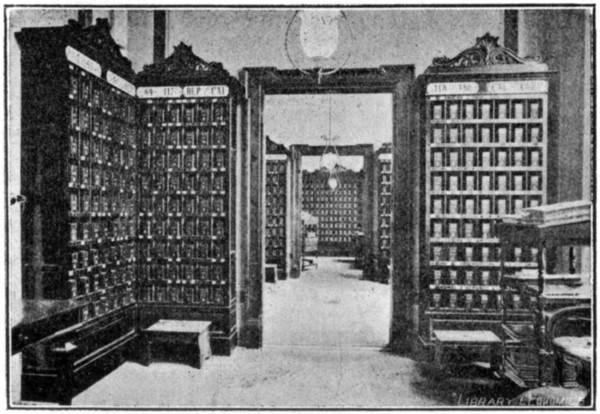

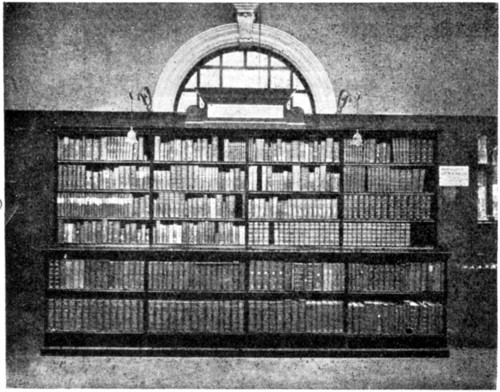

| 92. | Catalogue Shelves, British Museum | 260 | |

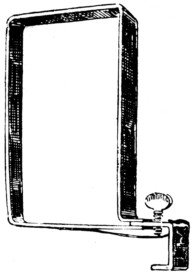

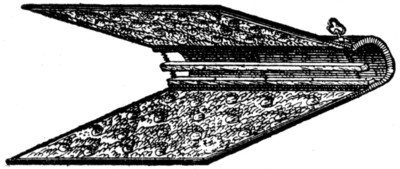

| 93. | Adjustable Screw Binder | 261 | |

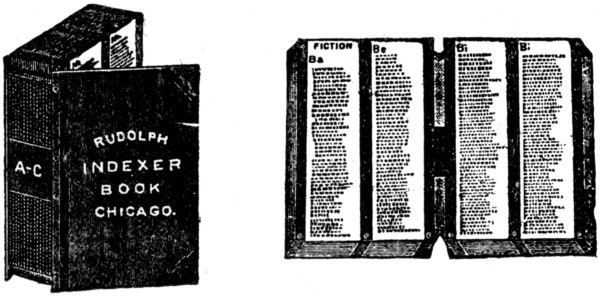

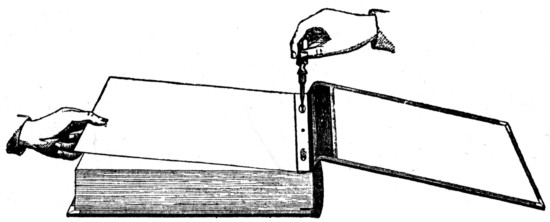

| 94. | Rudolph Indexer Book | 262 | |

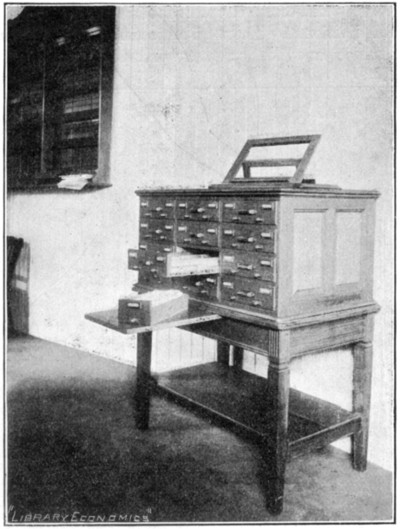

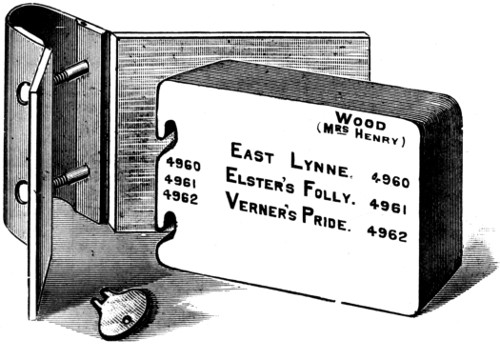

| 95. | Card Catalogue Cabinet, with extension runners | 263 | |

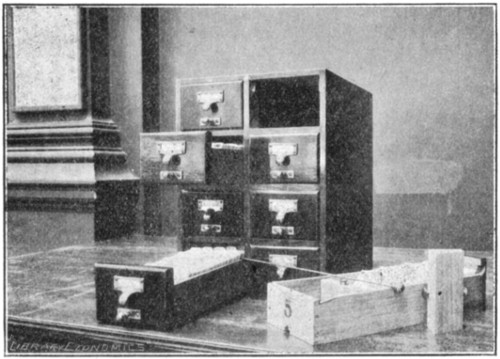

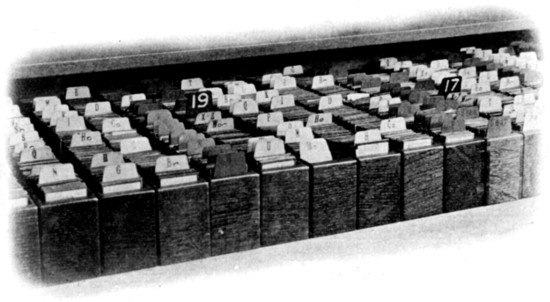

| 96. | Cabinet of Card Trays | 264 | |

| 97. | Sideless Card Catalogue Tray | 265 | |

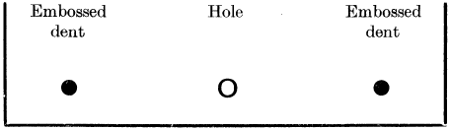

| 98. | Cards for Bonnange Catalogue Trays | 267 | |

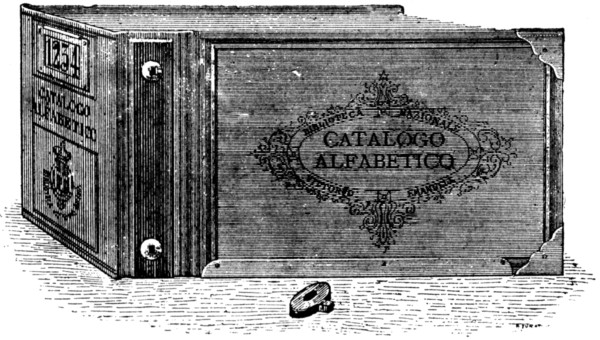

| 99. | Bonnange Card Catalogue Trays | 268 | |

| 100. | Staderini Card Trays and Cards | 269 | |

| 101. | Duplex Card Catalogue | 270 | |

| 102. | Leyden Slip Holder | 271 | |

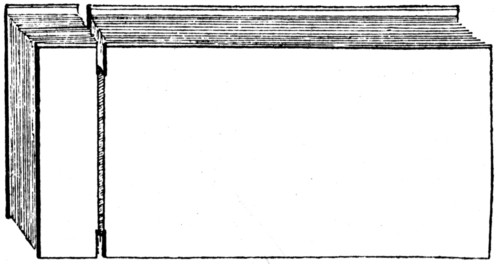

| 103. | Volume of Staderini Sheaf Catalogue | 271 | |

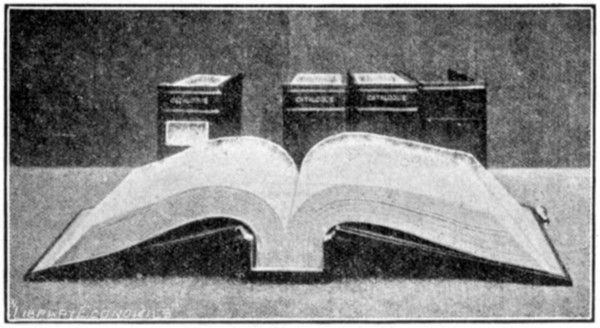

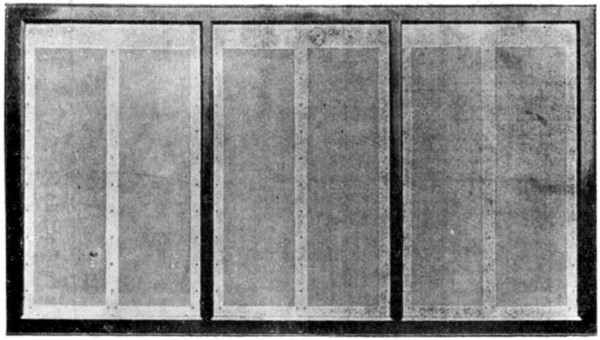

| 104. | Staderini Sheaf Catalogue | 272 | |

| 105. | Sacconi Sheaf Catalogue | 273 | |

| 106. | Adjustable Sheaf Catalogue | 273 | |

| 107. | Adjustable Sheaf Catalogue | 274 | |

| 108. | Adjustable Sheaf Catalogue, with Cradle and Key | 274 | |

| 109. | Front of Sheaf Catalogue Author Slip | 275 | |

| 110. | Reverse of Sheaf Author Slip | 276 | |

| 111. | Sheaf Title Slip | 276 | |

| 112. | Sheaf Subject Slip | 277 | |

| 113. | Adjustable Placard Catalogue[xv] | 278 | |

| 114. | Folder for Vertical File | 282 | |

| 115. | A Drawer of a Correspondence Filing Cabinet | 283 | |

| 115A. | Specimen of Jast Classification of Library Economy | 284 | |

| 116. | Address, and Correspondence, Index Card | 286 | |

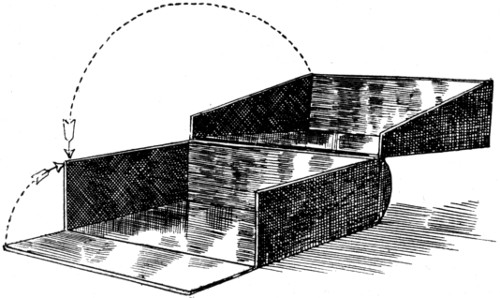

| 117. | Pamphlet Box | 287 | |

| 118. | Prints Box | 289 | |

| 119. | Lantern-slide Index Card | 290 | |

| 120. | Supplies Location Card | 292 | |

| 121. | Withdrawals Card | 293 | |

| 122. | Missing Books Index Card—front | 294 | |

| 123. | Missing Books Index Card—back | 294 | |

| 124. | Inventory Book | 299 | |

| 125. | Inventory Slip—front | 300 | |

| 126. | Inventory Slip—back | 300 | |

| 127. | Class Lettering and Numbering | 310-313 | |

| 128. | Class Lettering and Numbering | 314 | |

| 129. | Binding Sheet | 317 | |

| 130. | Binding Order Book | 318 | |

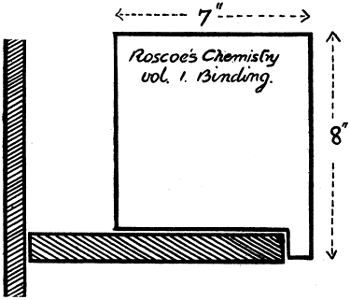

| 131. | Binding Slip | 319 | |

| 132. | Renewal Slip | 337 | |

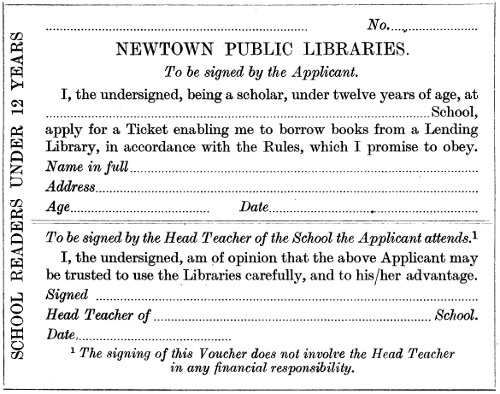

| 133. | Ratepayer’s Voucher | 343 | |

| 134. | Non-Ratepayer’s Voucher—front | 344 | |

| 135. | Non-Ratepayer’s Voucher—back | 345 | |

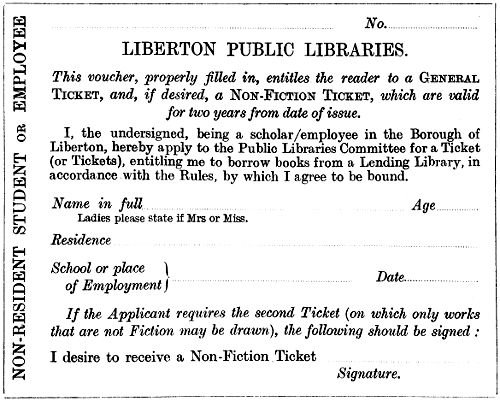

| 136. | Non-Resident’s Voucher | 345 | |

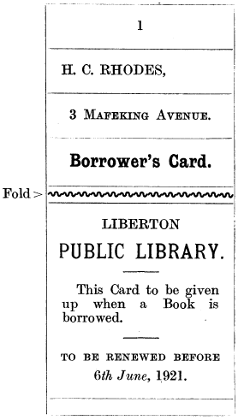

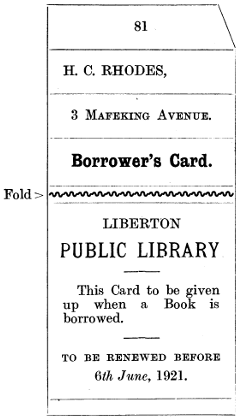

| 137. | Borrower’s Card | 347 | |

| 138. | Borrowers’ Number Register | 348 | |

| 139. | Book Issue Card | 351 | |

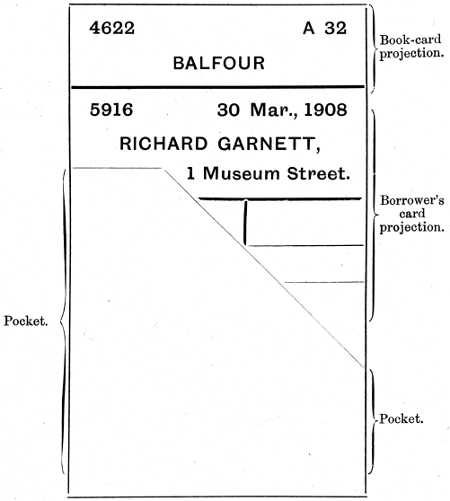

| 140. | Book and Borrower’s Cards in Pocket | 353 | |

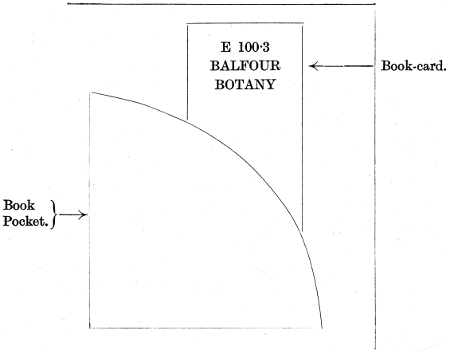

| 141. | Book Pocket and Card | 354 | |

| 142. | Borrower’s Card with Pocket | 355 | |

| 143. | Borrower’s Card and Book Card conjoined | 355 | |

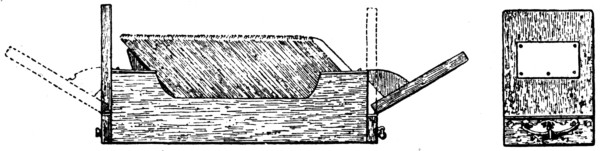

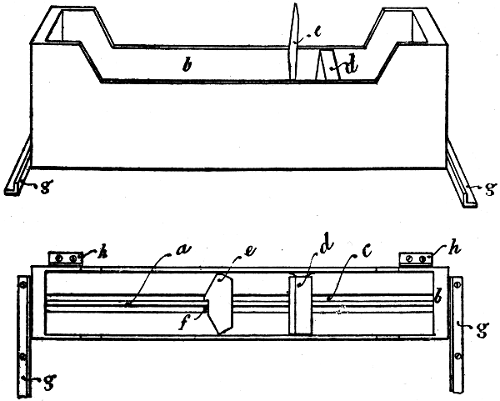

| 144. | Elevation Plan of Card Charging Tray | 356 | |

| 145. | Card-charging Trays in Position | 357 | |

| 146. | Diagram of Elliot Indicator | 359 | |

| 147. | A Library Indicator | 360 | |

| 148. | Diagram of Periodicals Indicator | 363 | |

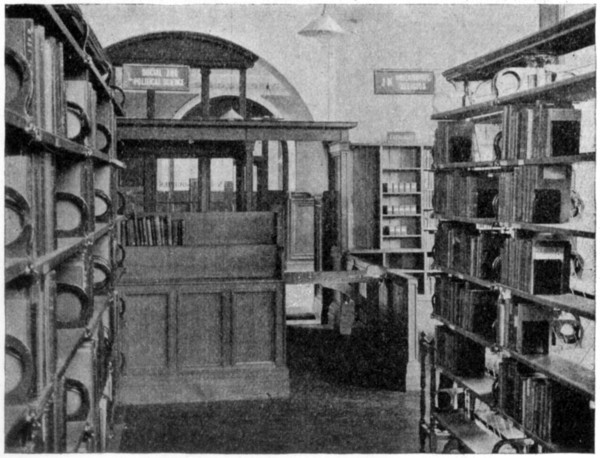

| 149. | Quick Reference Collection, Glasgow | 367 | |

| 150. | Branch Library Return | 369 | |

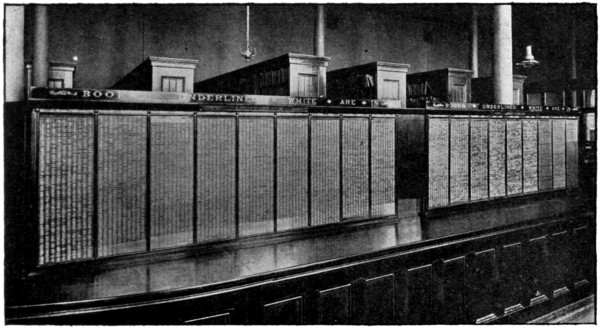

| 151. | Mitchell Library, Glasgow | 376 | |

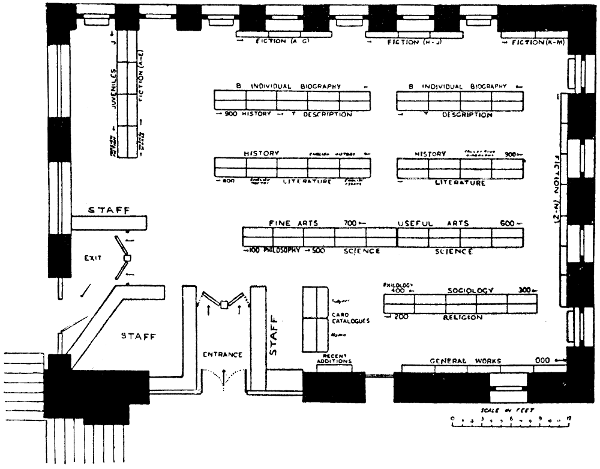

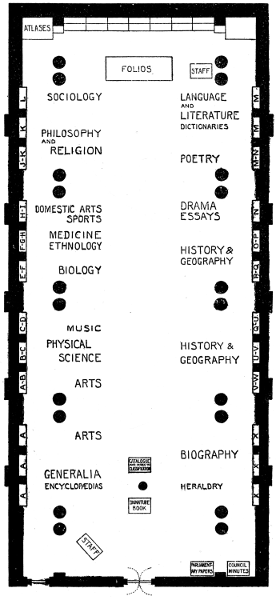

| 152. | Plan of Islington Reference Library[xvi] | 377 | |

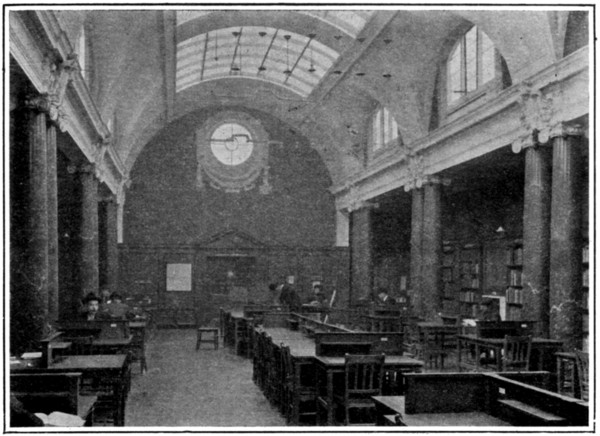

| 153. | Islington Reference Library | 379 | |

| 154. | Reference Library Application Form | 381 | |

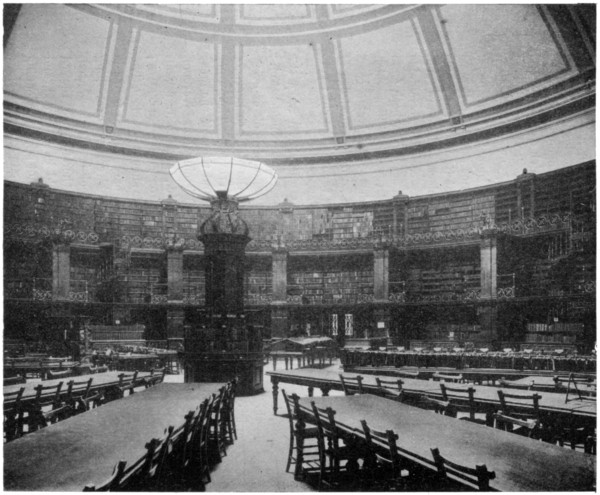

| 155. | Picton Reading Room, Liverpool | 384 | |

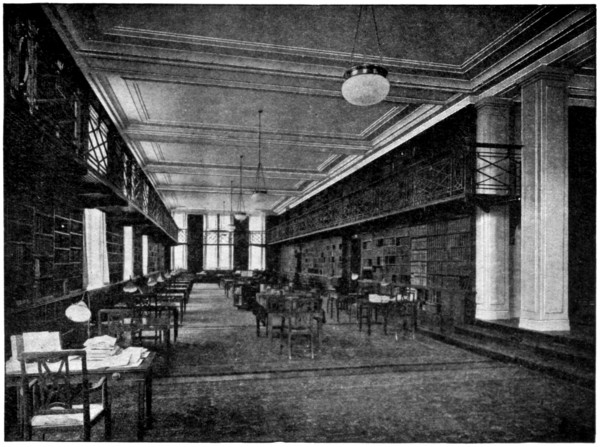

| 156. | Reading Room, Royal Society of Medicine | 387 | |

| 157. | Reading Room, Reading Table, Chair, etc. | 389 | |

| 158. | Clippings Index Slip | 391 | |

| 159. | Application for Loan of Reference Book | 393 | |

| 160. | Application for Loan of Reference Book—back | 393 | |

| 161. | Application for Loan of Reference Book—Refusal Form | 394 | |

| 162. | Application for Loan of Reference Book—Refusal Form, with reasons | 394 | |

| 163. | Label of Photographic Survey | 411 | |

| 164. | Print Index Slips | 412 | |

| 165. | Double Newspaper Stand, Chelsea | 427 | |

| 166. | Double Newspaper Stand | 428 | |

| 167. | Wall Newspaper Stand | 428 | |

| 168. | Simplex Newspaper Holder | 430 | |

| 169. | Revolving Newspaper Holder, with Clips | 430 | |

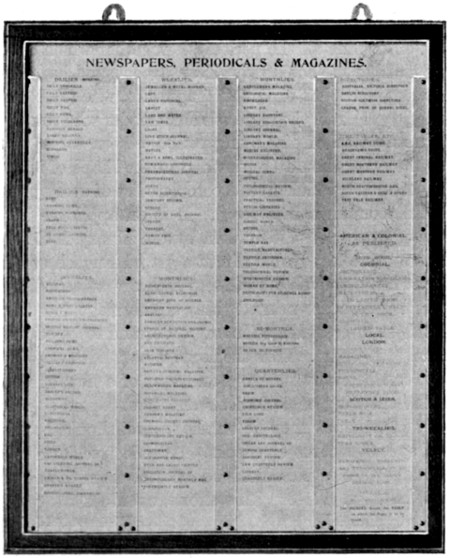

| 170. | Adjustable Periodicals List | 433 | |

| 171. | Periodicals Check Card, Monthlies | 435 | |

| 172. | Periodicals Check Card, Weeklies | 435 | |

| 173. | Periodicals Check Card, Dailies | 436 | |

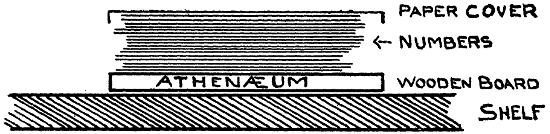

| 174. | Periodicals File | 437 | |

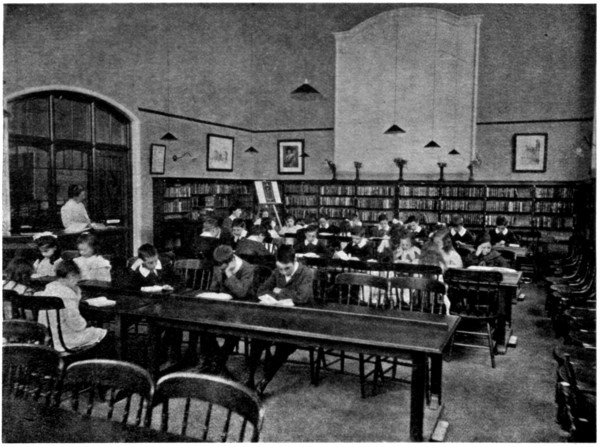

| 175. | Cathays Children’s Hall, Cardiff | 442 | |

| 176. | Voucher for Children | 444 | |

| 177A. | School Libraries Return Card—front | 462 | |

| 177B. | School Libraries Return Card—back | 463 | |

| 178. | Lecturer’s Memorandum | 470 | |

| 179. | Privilege Issue Notice | 471 | |

| 180. | Privilege Issue Notice, Information Slip | 472 | |

| 181. | Rural Library Board Label | 480 | |

| 182. | Rural Library Board Label, Charging Card | 482 | |

| 183. | Rural Library Board Label, Charging Card—back | 482 | |

On Christmas Day 1878 a Scottish lad of seventeen, having realized a cherished desire and obtained an appointment as junior library assistant at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, presented himself before the then unimposing portals of that institution at the north corner of Ingram Street, and found them closed. He concluded characteristically that this was because the librarian was an Englishman. The lad who endeavoured to begin what was his real life-work on this unusual day was James Duff Brown, who was to become in many ways the greatest practical influence of his time in the British public library movement, who lived through its most expansive period, codified and published its methods and results, experimented boldly, faced and overcame a remarkable force of opposition, and left behind him a memory which present librarians revere, and works which will not easily be forgotten.

We have no record of his earliest years, other than that he was born at Edinburgh on 6th November 1862, and during boyhood showed tenacity and mental acquisitiveness. At thirteen he became an apprentice in the publishing house of Edmonstone & Douglas in his native city, and in the same year, when Mr Douglas left that firm at the establishment of that of Douglas & Foulis, he remained with Mr Douglas. A year later found him at Glasgow with the firm of W. R. McPhun & Sons. The work done for these firms gave him an initiation of a kind into literature, but the earlier Glasgow period was never a happy memory of his, and his true career began at the Mitchell Library. Here he spent ten years, enlarging his knowledge, specializing thoroughly in librarianship, devoting much of his leisure to musical lore, and by ability and purposefulness working his way[2] to responsible positions on the library staff. When he was twenty-one he began to collect material for his Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, which appeared four years later in 1886; at twenty-three was Glasgow correspondent to The Musical Standard; and he was the editor and reviser of the six large quarto volumes of Chalmers’s Caledonia which appeared 1887-90. The industry thus shown was inherent in his character. He told Mr T. A. Aldred that he acquired the early-rising habit in youth, and that most of his work was done in the mornings before he began his official day’s work at 9 a.m.; and the Mitchell was at some distance from his home. This habit, which few of us ever acquire, he retained through life. It is interesting to know that he served from 1886 to about 1888 in the Third Lanark Volunteers; a little booklet from his pen, A Volunteer Reconnaissance, records his experiences.

A large library, however liberally administered, does not often offer opportunities for a man’s larger initiative unless he occupies one of the chief positions; and the exercise of his gifts did not come fully until his appointment in 1888 to the newly-established Clerkenwell Public Library in London. The building is a comparatively small edifice occupying a triangular site, and hardly one in which experiments little short of epoch-making might be expected; but Brown was a man of ideas and courage who could make the most of such a building. Moreover, London offered him openings which he did not hesitate to take. Retiring in person as a rule, nervous in speech, and in appearance of no special significance, he yet threw himself with quiet energy into the work of the Library Association. It must be remembered that from about 1888 to 1898 the public library movement in England received its greatest impetus, probably because in those years the full effects of the Education Act of 1870 came into play. Few of the libraries founded in that period are entirely without marks of his influence. In 1891 he conceived the idea—very old in itself, but quite new in its application to municipal libraries in this country—of throwing open the shelves to the choice of readers; and he formulated a scheme, which he called by the somewhat tautological name of “safe-guarded open access,” and published it anonymously in The Library in a paper entitled “A Plea for Liberty to Readers to Help Themselves.” A visit[3] to America in 1893, where he attended the Chicago Conference of the American Library Association as a delegate of the Library Association, confirmed him in his opinion of the practical desirability of the system, although he says, “There was no such thing as proper safe-guarded open access as now understood anywhere in America when I was there”; but free access there was, without the locking wickets and other safeguards which he introduced at Clerkenwell. In brief, his method was to admit readers to the shelves, but by way of a wicket at which their credentials were checked unobtrusively, and to allow them to pass out at another wicket at which the books chosen were charged. Thus the reader was locked in the library while making his choice. The results of his experiment were presented to the Belfast Conference in a paper he wrote in collaboration with one of his Committee, Mr Henry W. Fincham, entitled “The Clerkenwell Open Lending Library,” which was modest and restrained in tone; but although the discussion that ensued was generous and appreciative to an extent, it was the fiercest yet known amongst librarians, and the question became the most contested one in our work. So sharp were the divisions the simple suggestion created that the municipal library profession went into two armed camps, and friendships and good-feeling were frequently destroyed by it. It is difficult for younger librarians to realize the courage and confidence that were needed to champion open access twenty-five years ago against the active antagonism of 90 per cent. of the profession. There were not wanting men, however, who were drawn to the champion, amongst them Mr L. Stanley Jast, then librarian of Peterborough, Mr T. Johnston, librarian of Croydon, and Mr Brown’s own assistants, Mr Charles Riddle in particular, who opened the first library outside London on this system at Bournemouth in 1895. In 1896 Croydon adopted it, Hornsey followed in 1898, and although progress was slow at first, to-day it has so far won the battle that the opening of a new library on any other system is a matter for surprise, and many of the more conservative libraries, even in the largest cities, have adopted it at least in some part of their system; moreover, the question itself has become impersonal, and no librarian to-day would criticize another for any views he might hold in connexion with it. It was, as Sir J. Y. W. MacAlister[4] declared in 1894, “the dawn of a new epoch; a hundred years hence the authorities of the greater municipal London, which will then be carrying on the work now only attempted by the present congeries of village communities, will pass a resolution ordering a tablet to be fixed to the wall of a quaint three-cornered building in Clerkenwell, to commemorate the fact that here, in 1894, the revolution had begun which in a few years had changed the entire system of public libraries throughout the land.”

Although safe-guarded open access was the principal practical contribution of Brown to library practice, he introduced other things of great importance. His Quarterly Guide was the first annotated library bulletin published in England. He invented an indicator, more compact and perhaps as effective as most others, as a challenge to another similar inventor. He improved the sheaf catalogue, and indeed many of the commonest appliances now in use were of his contriving. A description of these, and others, he gave in his Handbook of Library Appliances, 1892, published by the Library Association. As open access abolished the need for alphabetical indicator-keys, he was at liberty to consider the question of catalogues radically; and he advocated the classified catalogue and class-lists as fulfilling the needs of students and readers better than other forms. In this advocacy he secured the vigorous co-operation of Mr Jast; and in this matter also a great controversy ran for some years, dignified amongst librarians as “the battle of the catalogues.” The issue is still in doubt as to the entire desirability of the classified catalogue for all purposes and places, but to-day the classified catalogue is certainly as common as any other form.

His brain and pen were active throughout life. In 1897 he published, in conjunction with Stephen Stratton, a British Musical Biography, another valuable biographical dictionary. In 1898 he founded, and for many years was to edit, The Library World, an independent and radical journal of library methodology and politics, which has held its own to this day. Opinions of all kinds were expressed in its pages; Brown wrote innumerable articles for it; and many librarians of present distinction first saw themselves in print in its pages. Especially did Brown encourage through its pages the struggles of young and unknown[5] men at a time when encouragement was of priceless value to them. A list of his works is given at the end of this chapter, and will be sufficient to show his energy; but the appearance of his Manual of Library Classification and Shelf Arrangement, 1898, which contained his Adjustable Classification, was a real event, because it was the first comprehensive treatment of a till then little understood and much abused subject; as was that of his greatest work, the Manual of Library Economy, which first appeared in 1903, and has influenced all library methodology.

Quiet as he was in many ways, he was of a social disposition, a trait which found an outlet to some extent at the Library Association, of which he was a councillor from 1890 to 1911; but for closer purposes of camaraderie he founded, with Mr Jast, the well-known Pseudonyms, a dining-club of librarians and their friends, which had its origin in the ‘nineties, and flourished for many years. The meetings were held in various Bohemian restaurants in Soho, professional and literary topics were debated, and Brown reported them in The Library World. The reports had little relation to the actual proceedings, and few people were more entertained, and, incidentally, astonished at their own wittiness (as reported) than the Pseudonyms themselves. This is but one instance of his humorous way of regarding all things. In conversation, and in writing of even the most dryasdust subjects, it seemed impossible for him to talk or write without humour.

Brown’s sixteen years at Clerkenwell made the library perhaps the most reputed in the country. Mr Jast may be quoted upon this: “Mr Brown’s influence and reputation extended far beyond his own country. Foreign librarians visiting London almost invariably made for two places; one was the large and handsome room overlooking a stately west-end square, which Mr J. Y. W. MacAlister occupied for so many years; and the other was a small room, high up in a rather dingy-looking triangular building, overlooking a dingier street in Clerkenwell, which was so hidden away that one rather stumbled upon it than found it, where Mr J. D. Brown worked in his official capacity as Librarian, before he was called to a sphere more worthy of his labours, in Islington. How many librarians, how many members of library committees, how many workers in the Library movement have been charmed,[6] interested, and instructed in these two rooms?” Not only was he required to give advice in his own country; at different times he was called upon to lecture on “free public libraries” in the United States, in Holland and in Belgium. “A Bruxelles,” writes M. Paul Otlet, “il parla devant l’auditore du Musée du Livre et son succès fut très grand.” I cannot help thinking that his success depended more upon his subject and his clear writing than upon his speaking; he was on the whole an indifferent speaker, his nervousness was painful to himself and others, and his ineradicable Glasgow accent was a real obstacle. He told my wife that the only place in which he enjoyed speaking was the meetings of the Islington Staff Club; he confessed to a horror and nervousness in public speech.

In 1904 he was appointed the first Borough Librarian of Islington. Here the public libraries scheme had its very beginnings under his care, and he was responsible for the interior design of the fine central library and the north and west branches; probably also for the south-east branch, but of that I am not sure. These libraries, I dare affirm, represented the highest achievement in library-planning in this country, with their handsome, adequate and practical rooms, economy in working, and general suitableness for their purpose. Here he brought into practice two of his principal innovations. The first was the Subject Classification, a huge, minute scheme, which we describe in more detail in the later pages of this book, which challenged comparison with the great and more popular American schemes in its completeness, logical arrangement, and admirable notation. Its focus upon British requirements made it specially attractive to British librarians, and although it may never supersede the more universal Decimal System of Melvil Dewey, it is nevertheless a work of the greatest value to all librarians. The second and more revolutionary innovation was the exclusion of the newsroom as usually understood from the libraries. In his account of his visit to America, he mentioned with something approaching disapproval the absence of this department from American libraries and the sense of desertion which resulted there; but at Islington he adopted the American plan. I am told that the Islington public did not approve the omission quite as much as did its author, but the arguments he used for it were[7] common-sense ones, although he has had few, if any, British imitators.

To give in detail all his work for Islington would be to occupy a disproportionate space in a memoir of this compass. Suffice it to say that he provided this not entirely grateful Borough with a system which is the admiration of our profession. He gathered round him an accomplished staff, published a model select catalogue, encouraged the formation of an excellent staff guild for his assistants, and did many other invaluable things. He had long been a teacher of young librarians. When the Library Association courses were inaugurated at the London School of Economics he became the lecturer in library organization and routine, and served in that capacity for many years. As one of his students, I can vouch for his conscientious, painstaking teaching, his care in clearing up difficulties, the encouraging and friendly way in which he answered our questions, marked our exercises, and generally made our work of interest and value. No librarian who turned to him for advice ever went unhelped, whatever his age or school of thought. He wrote hundreds of letters to such purpose in his beautiful minute handwriting, and a collection of these would form, I believe, an excellent journal of contemporary librarianship. He seemed, in particular, to have a minute knowledge of all librarians and library assistants, their capacities and work accomplished. His obvious sympathy with young assistants first drew many of us to him. From the day I met him in 1896 at Bournemouth to his death he showed me by constant signs his regard for younger men and women who had a real interest in the work that he himself loved. He treated us with equal consideration in his correspondence, and the youngest correspondent received the same courtesy as his elders. He drafted the constitution of the Library Assistants’ Association, which with slight modifications has proved most wise and successful; and he frequently, especially in his last years, attended the meetings of this Association, taking part in the discussions when invited to do so, but seldom intruding his opinions unasked upon his young listeners, who, be it remarked, were always eager to hear him.

It is a difficult task to sketch “the man in his habit as he lived,” but a few words may be written. The portrait which forms our[8] frontispiece is almost life-like, with its thoughtful, quiet, and, if one looks carefully enough, intent and humorous face. In person he was small, but not too obviously so; fragile-looking, but yet compact and vital in appearance and movement; he had brown hair and beard, delicate features, deft and supple hands; he thought calmly, was a rapid, consistent, and persevering worker; what he began he finished. His writings have been pronounced by Dr E. A. Baker to possess unmistakable quality, although “he scoffed at the word ‘style’ as denoting some futile kind of verbal legerdemain” (I think he must have done so jokingly, as his own personal library showed that he was by no means blind to the qualities of literary expression). “Shrewd, practical common sense, rough on cranks and sentimentalists, unmerciful to muddlers, impervious to a good many ideas, but a steady assertor of those he had tried and approved—this was the stuff of Brown’s writing,” is Dr Baker’s estimate, and in the main it coincides with my own. His personal tastes may be inferred from his work. “He once told me,” writes Mr Aldred, “he knew three subjects only, viz., library economy, music, and Scotland. I forget the order in which he placed them. Being a Scotsman, probably Scotland came first. In many respects, however, J. D. B.’s knowledge was of the encyclopædic order—he appeared to know a little of any subject named.”

In early life he was pronounced to be consumptive, but he told me, “I have lived to see the doctors who condemned me in their graves,” by careful living, and probably by sheer will power. But in his later years he had to meet many difficulties at Islington, where the libraries became the sport of a political party and he had a committee which was unable to assess his powers. It is useless to revive this now, but it probably helped to bring about his early death. He first became seriously ill in 1911, and with a few intervals, when we believed him to be practically himself again, he gradually weakened. In the last few months of his life a stay at Bournemouth was tried as a final resource, and here he read musical biography assiduously and maintained the keenest outlook upon all things; but no improvement ensued in his health, and he returned to London a dying man. The end came at his house, 15, Canonbury Park South, Islington, on 26th February 1914; and he was buried, amid every sign of[9] regret and affection, at New Southgate Cemetery. His only memorial to the present are his works; I believe they will be an enduring one.

To sum up: Brown entered upon his library career at a time when the library movement received its greatest impetus, and brought the whole force of a fertile and inventive mind and a ready pen into its service. He wrote the first text-books actually intended for English public librarians, collected and systematized all available methodology, and, thoroughly believing in his mission, this man more than any other in his generation fashioned in this country a living, interesting profession out of the despised materials of the popular library. An impression written by Alderman H. Keatley Moore, B.A., B.Mus., J.P., a veteran worker for public libraries, who made his acquaintance early, may serve to conclude this necessarily brief account of our author:

“What was it especially that made one feel so clearly that one was in the presence of a true man, of an absolute master of his subject, of one, in fact, whom it was an honour to know?

“I think it was that curious quietness, the repose of a man who has thought out everything fully for himself, and is content to leave the facts as he has arranged them to tell their own story. He was still, because he was so strong; he was undisturbed by clamour because he had been through it all, and now stood in the open with the conquered fortress behind him, its strength his strength made visible; one gradually grew rather timid of this shy talker because he always had the facts on his side.... He was the most unaffected and modest man of real mark that I have ever met in my long public life. I shall always be glad to have known him. I shall always remember the great services he rendered to me, to my town, to our country. Across my sincere regret at his loss flickers the whimsical thought of how he would wonder at the fuss we are making over him.”

The following is a list of Brown’s separate publications. His articles were legion, and will be found by reference to the indexes of all library periodicals and transactions. Nearly all the[10] anonymously-written articles and editorials in The Library World from 1898 to about 1906 are his:

1886. Biographical Dictionary of Musicians: with a bibliography of English writings on Music. Paisley: A. Gardner.

1888. A Volunteer Reconnaissance.

1892. Handbook of Library Appliances: fittings, furniture, charging systems, etc. L.A. Series, 1.

1893. Guide to the Formation of a Music Library. L.A. Series, 4.

1897. Greenwood’s Library Year-Book. Scott, Greenwood.

(The second edition, 1900-01, was entitled British Library Year-Book.)

1898. Manual of Library Classification and Shelf Arrangement. Libraco Series. Library Supply Co.

(Chapter vi., which contains “The Adjustable Classification,” was published separately under that title.)

1903. Manual of Library Economy. Scott, Greenwood. Second edition, 1907. Library Supply Co.

1904. Annotated Syllabus for the Systematic Study of Librarianship. Libraco.

Classified List of Current Periodicals: a guide to the selection of magazine literature. L.A. Series, 8.

1906. Manual of Practical Bibliography. Routledge. Subject Classification. 1906, Libraco. Second edition, 1914, Grafton.

1907. The Small Library: a guide to the collection and care of books. Routledge.

1909. Guide to Librarianship: reading lists, methods of study, etc. Grafton.

(Supersedes the “Annotated Syllabus.”)

1912. Library Classification and Cataloguing. Grafton.

(Incorporates much of the matter in the “Manual of Library Classification” in revised form.)

1913. A British Library Itinerary. Grafton.

1897. With Stratton, S. S. British Musical Biography: a dictionary of musical artists, authors and composers born in Britain and its Colonies. Birmingham: Stratton.

1901. With Moffat, Alfred. Characteristic Songs and Dances of all Nations.

1915. Stewart, J. D., and Others. Open Access Libraries: their planning, equipment and organization. With Introduction by J. D. Brown. Grafton.

(This work was planned by Brown.)

I. Library economy is a term covering every branch of work concerned with libraries; and libraries may be defined in a phrase as institutions devoted to the collecting, conserving and exploiting of literature. Originally the prevalent character of libraries was that of conserving rather than exploiting institutions, and much of the technical equipment of the modern librarian has come into being as a result of their progress from their original “museum” to their present “workshop” character. Our subject, then, covers the founding, organizing, administration and routine of libraries. It is one of much wider compass than is commonly supposed. Whatever may have been the original intention, for example, of the pioneers of the municipal public library movement, and there are still many who seem to regard that movement as a counter-attraction to the seductions of the saloon bar and similar places of recreation, the present public library is a many-sided, active civic institution, making its appeal to all classes of the community as a centre of education, culture and recreation, with a trained service to direct it. Nearly every other type of library also is most concerned with the best means of attracting people to make use of literature, and is an active force in the community rather than a passive one.

II. Libraries have been recognized as important in all ages, and a brief study of the early civilizations of the East and of the Mediterranean countries, as well as all later periods, shows the existence of state, public, ecclesiastical and monastic libraries for which there was some sort of librarianship, with even such seemingly modern appliances as classification and cataloguing of a kind. But the library as we know it to-day, and librarianship in particular, may almost be said to be the creation of the last half of the nineteenth century. Earlier town libraries[12] indeed existed, the first, it is believed, being that at Norwich, which was opened to the public in 1608; but although there were individual instances, the municipal public library (commonly but erroneously called the “free library,” because no charge is made for its use) was a result of the Libraries Act of 1850 promoted by William Ewart, M.P., who had at his back the real pioneer of public libraries, Edward Edwards, whose Memoir of Libraries is the most monumental of treatises on library history and administration. The Act of 1850 had in view the needs of the poor, sanctioned the levying of a halfpenny rate, and, with curious want of vision, left the provision of books to the generosity of private donors. The debates upon the bill before it became law are curious and entertaining reading; and it appears that the special purpose of libraries was the prevention of crime! Progress was slow at first, but in 1853 it was stated that thirteen towns had adopted the Act. In 1855 its provisions were extended to Ireland, and in this amending bill the amount that might be levied for libraries throughout the kingdom was increased to a limit of one penny in the pound.

III. We need not follow the history of the movement, as an excellent monograph by J. J. Ogle, The Free Library, is available on the question; nor need we go into the parallel and in some respects more wonderful development of the movement in America. So far as this country is concerned libraries have grown up in every considerable town, with very few exceptions; but the whole movement has been retarded, even crippled, by the retention of the limit of one penny in the pound as the amount a local authority may spend on library provision. The advance in general education—it must be remembered that in 1850 not more than one-seventeenth of the children of the people were receiving an education which could be called satisfactory even when judged by the low standards of that time—has created a new reading public more vast than was contemplated by the promoters of the Act; but the only legal help towards meeting its demands has come from the increased product of rate assessments; the limit remains sixty-five years after its imposition. But the increase we have mentioned has not been negligible, even if it is entirely insufficient, and it has been assisted in a remarkable way by private generosity. Amongst many who[13] have provided towns with public library buildings, Passmore Edwards, Lord Brassey, Henry Tate, Colonel Gamble and Professor Sandeman may be mentioned; but the greatest impetus to the movement was given by the systematic and almost universal munificence of Andrew Carnegie, which began in 1886 and has been continued by him and by the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, which he has endowed, to the present. His system has been to provide a suitable building on the condition that the authority accepting it adopted the Libraries Act and provided a site from other charges than the library rate. By this means scores of towns which were without or had only inferior library buildings now possess one in some way worthy of the name.

IV. The expansion of libraries gave rise to the modern profession of librarianship. The older libraries were usually in the charge of scholars, whose main work was that of “keeper” of the books, a title which the librarian in charge of the British Museum still bears, although it does not now comprehend his work. The municipal library required a man who was not primarily a scholar, although scholarship was an invaluable basis for his work; he was rather required to be an administrator, a purveyor of books, and, because of the very limited moneys at his disposal, something of a business man. For some years, however, there was no definite science or art of librarianship in this sense. Edward Edwards, in the second volume of his Memoirs of Libraries, laid firmly the foundations of present library economy in a résumé and exposition of the multifarious methods of cataloguing, classification, library planning and administration used in the various libraries of the world. Little followed in England until the growing needs of the work caused a few far-seeing librarians to find some means of bringing librarians together. This they succeeded in doing in the successive conferences of librarians, British and international, the first of which was held in London in 1877. Out of these sprang the Library Association in 1878, with Mr Henry R. Tedder and the late E. B. Nicholson as its first honorary secretaries, and the late Robert Harrison as honorary treasurer. In the first year the late E. C. Thomas succeeded Nicholson, and somewhat later he was associated in his office with Mr (now Sir) J. Y. W. MacAlister,[14] one of the most significant and creative personalities in our work; while Mr Tedder assumed the office of treasurer, which he holds to this day, an office in which his wisdom and counsel as well as his unsparing industry have done much to create the present stability of the Association. By means of frequent gatherings, especially by its annual meetings, the Library Association gradually brought together the whole body of librarians in this country, who read and discussed professional papers, published proceedings, initiated scheme after scheme for the promotion and improvement of libraries, and generally became the controlling factor in library polity. It was incorporated by Royal Charter in 1898. For many years it was recognized that training in technical methods was necessary for librarians, and the Association has devoted much attention to this work. At first it held summer schools and, from 1898, other brief courses for library students, and examined the students upon them. Later it established, in connexion with the Governors of the London School of Economics, regular courses of lectures at that institution. A carefully-designed and remarkably helpful syllabus of instruction was drawn up, and on this examinations were held and certificates leading up to a diploma in librarianship were issued. The latest phase of the educational work of the Association has been the securing of a grant from the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust for the establishment of a School of Librarianship at University College, London, which it is expected will commence on 1st October 1919. This will primarily be a day school with courses of study founded on the syllabus of the Association, which has been carefully revised and extended to meet the new circumstances. It is ridiculous to prophesy, but if this School is a success it is probable that it will revolutionize the whole character of library service in this country.

V. There have been various definitions of the purpose of libraries and librarians, few of them entirely adequate. We shall not attempt another dogmatically, but we may suggest that that purpose is to provide a representative and systematically arranged collection of literature from the daily newspaper to the elaborate treatise and encyclopædic work of reference. The methods of doing this, and of exploiting in the public interest the collection when made, are the subject-matter of this manual.[15] Until this primary purpose of a library is fulfilled any attempts at those added activities which are advocated by some librarians to-day are likely to be mistaken, or at least ill-advised. The Library Association has not issued a comprehensive manifesto covering this matter, and might very well do so, if care were taken, as no doubt it would be, to give considerable elasticity to the definitions. At the Annual Meeting in 1917, however, it did adopt a series of resolutions of great importance, which, as the almost unanimous pronouncement of the profession, must find a place here. In the light of the rough definition given, their inadequacy as a comprehensive statement of library work is obvious enough, but they have great value as showing the trend of that work in the effort to meet the remarkable intellectual, industrial and other conditions created by the European War; and this seems to us a justification for treating each of the resolutions at greater length in the following pages:

1. “That the aim of the library as an educational institution is best expressed in the formula ‘Self-development in an atmosphere of freedom,’ as contrasted with the aim of the school, which is ‘Training in an atmosphere of restraint or discipline’; in the school the teacher is dominant, because it is possible to pass on a form, to teach an art; but in the library the pupil strikes out his own line, and becomes his own teacher; the library supplies the material upon which the powers awakened and trained in the school can be exercised; the library and the school depend upon different ideas, deal with different material in different ways, and there is no administrative relation between the two; furthermore, the contacts of the library with organized education necessarily cease at the point where the educational machinery itself terminates, but the library continues as an educational force of national importance in its contacts with the whole social, political and intellectual life of the community; that the recognition of the true place of the library in education must carry with it the provision of adequate financial resources, which is impossible under the present limitation on the library rate; such limitation therefore should be removed at the earliest possible moment.”

2. “That the creation in the child of intellectual interests, which is furthered by a love of books, is an urgent national need;[16] that while it is the business of the school to foster the desire to know, it is the business of the library to give adequate opportunity for the satisfaction of this desire; that library work with children ought to be the basis of all other library work; that reading-rooms should be provided in all public libraries, where children may read books in attractive surroundings, under the sympathetic and tactful guidance of trained children’s librarians; but that such provision will be largely futile except under the conditions which experience, especially in America where the importance of this work has long been recognized and where it is highly developed, has shown to be essential to success.”

3. “That in view of meeting trade conditions after the war, commercial libraries should be established in all the great trade centres of the kingdom, as a part of the municipal library system, where business men may obtain reliable commercial information, by means of the collection and arrangement for rapid consultation of all Government and other publications relating to commerce; that such libraries should act as outliers or branches of the Commercial Intelligence Department of the Board of Trade; and that such Department should further the work of these libraries in every possible way; that in the smaller towns commercial collections should be formed.”

4. “That technical libraries are as essential, both to technical education and to manufacture, as the laboratory or the workshop; that discovery and invention are stimulated by books; that the technical library, therefore, should be established as a special department of the public library in all important manufacturing towns, with a special organization, including a librarian trained not only in library method and in the bibliography of technology, but possessing also a sufficient technical knowledge to enable him to act as a source of information to inquirers.”

5. “That collections of books and other printed and manuscript matter bearing upon questions of local government should be established in connexion with municipalities; that such collections to be effective must be in charge of a trained librarian; that the management of such collections should be placed under the library committee; that the cost of such libraries will be small in proportion to the valuable part they will play in serving the needs, not only of officials entrusted with the carrying out[17] of public work, but also of members of the municipality responsible for local government finance and policy.”

VI. Since the succeeding chapters of this manual were revised the Ministry of Reconstruction has issued a report on libraries and museums which has been made by its Adult Education Committee. This traverses in a general way the ground covered by the Library Association resolutions and makes recommendations of much moment and gravity. The aim of the report is to explain the extent of libraries and to secure their co-ordination. It criticizes Resolution 1 on the ground that it represents the aims of education inadequately, and it deduces from several very cogent arguments the policy of placing libraries under the local education committees in order that they may be merged into and worked as an extension of the national education system. For London this would mean taking libraries from the boroughs and placing them in the care of the county. The matter is too unsettled to admit of argument here, but such a policy, if carried out, might alter radically the whole character of library provision and administration. The linking up of libraries is recommended by means of a central lending library in London, the municipal libraries, special libraries, and rural libraries; the central lending library would supply the more expensive, little-used books to students direct or through the municipal or rural libraries, and special libraries should be drawn upon in their specialities for books to be used throughout the country. To the end that the service should be developed to the greatest extent, the present income of libraries should be increased, either by an increase in the separate library rate or by abolishing that rate altogether and allowing the estimates of the library to be included in general education estimates.

It seems quite probable that the near future will see a removal of the main financial difficulties.

VII. This manual is based upon the syllabus of the Library Association, but excludes sections 1 and, in part, 2 (Literary History and Bibliography), and includes the subject-matter of the resolutions of 1917. Primarily it is a manual of municipal library practice, but is by no means exclusively so. Special libraries have their individual methods, and a general conspectus of librarianship cannot include them; and state, university,[18] institutional, club and private libraries are equally matters for specific treatment such as would be impossible here. But all libraries are faced with very similar problems of selection, accession, classification, cataloguing, etc., or at any rate they differ in these matters in degree rather than in kind; and it is hoped that for them much that follows will be at least interesting and suggestive. To this end the method aimed at is expository rather than argumentative; and when two or more methods are in vogue they have been placed side by side in order that the student may review them and form his own judgment of their relative merits. Where we are dogmatic we are so unconsciously, and we hope that aberrations of this kind will be passed over with forbearance.

1. Municipal Libraries: Acts of Parliament.—The principal Acts of Parliament under which British public municipal libraries are now constituted consist of the following:—

1855. “18 & 19 Vict., c. 40. An Act for further promoting the establishment of Free Public Libraries and Museums in Ireland.” (The principal Act.)

1877. “40 & 41 Vict., c. 15. An Act to amend the Public Libraries Act (Ireland), 1855.”

1894. “57 & 58 Vict., c. 38. An Act to amend the Public Libraries (Ireland) Acts.”

1902. “The Public Libraries (Ireland) Amendment Act.” Gives power to District Councils to adopt the Acts, and empowers County Councils to make grants in aid of libraries.

1887. “50 & 51 Vict., c. 42. An Act to amend and consolidate the Public Libraries (Scotland) Acts.” (The principal Act.)

1894. “57 & 58 Vict., c. 20. An Act to amend the Public Libraries Consolidation (Scotland) Act, 1887.”

1899. “62 & 63 Vict., c. 5. An Act to amend the Public Libraries (Scotland) Acts.”

1892. “55 & 66 Vict., c. 53. An Act to consolidate and amend the law relating to Public Libraries.” (The principal Act.)

1893. “56 Vict., c. 11. An Act to amend the Public Libraries Act, 1892.”

1898. “61 & 62 Vict., c. 53. An Act to provide for the Punishment of Offences in Libraries.”

1901. “1 Edw. 7. An Act to amend the Acts relating to Public Libraries, Museums and Gymnasiums, and to regulate the liability of managers of libraries to proceedings for libel.”

[Note.—This Act does not deal with actions for libel. It was originally intended to do so, but the clauses were struck out of the bill, and the title escaped emendation.]

2. The whole of these are in force, and they repeal all the former Acts dating from 1850, while incorporating some of their provisions. In addition to these general Acts, a considerable number of local Acts have been passed on behalf of various towns, which include provisions for the modification of the general Acts, chiefly in regard to removing the limitation of the rate, and for other purposes. Such powers are usually contained in improvement or tramway Acts, and the principal towns which have obtained them include Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Halifax, Darwen, Sheffield, Cardiff, etc. Several towns, like Brighton, Huddersfield, Kingston-on-Thames, have also special Acts which confer the power of establishing libraries, independently of the general Acts, so that the public libraries of Britain are not constituted under one general law.

3. The Public Library Law is further modified or extended by various other statutes which were passed for different purposes, and the principal Acts of this kind are as follows:

“24 & 25 Vict., c. 97. An Act to consolidate and amend the Statute Law of England and Ireland relating to malicious injuries to property,” 1861.

This gives power to prosecute for misdemeanour any person who unlawfully and maliciously destroys or damages any book, manuscript, etc., in any public museum, gallery, cabinet or library.

“56 & 57 Vict., c. 73. An Act to make further provision for local government in England and Wales,” 1894.

Enables rural parishes to adopt the Public Libraries Act, 1892, by means of a parish meeting or poll of the voters in the parish.

“62 & 63 Vict., c. 14. An Act to make better provision for local government in London,” 1899.

Confers the power of adopting the Public Libraries Act, 1892, on the Metropolitan Borough Councils, by extending to them the provisions of the Public Libraries Act, 1893.

The remaining statutes which in any way deal with public or private libraries will be noticed in connexion with the departments of library administration, to which they specially refer, such as loans, rating, etc.

The only other Acts of Parliament which may in the future influence public libraries are the Education Acts passed since 1902. Under these Acts local Education Boards are empowered to “promote the general co-ordination of all forms of education,” and in many districts the education and library authorities are amalgamated for common purposes. It remains to be seen what further extensions will take place.

4. Main Provisions of the Municipal Libraries Acts.—A brief summary of the leading practical points of the various Acts will serve to give an idea of the powers which are conferred upon municipal authorities in regard to libraries:

(a) Adoption of Acts in Towns.—The Acts may be adopted in any city, county borough, burgh or urban district by a resolution passed by the council, at a special meeting of which a month’s notice shall have been given, and the resolution must be advertised publicly in the usual way, and a copy sent to the Local Government Board, if the adoption is in England or Ireland; while a notice of the fact of adoption must also be sent.

(b) Adoption of Acts in Parishes.—In parishes in England and Scotland the Acts can only be adopted by a majority vote of the householders or voters.

(c) Library Rate.—A rate of one penny in the £ on the rateable value of an administrative area is the limit fixed by the Act, but power is given parishes to fix a smaller sum by a popular vote, and urban districts of all kinds to remove or fix any rate within the limit of one penny by resolution of the council.

(d) Powers.—The Library Authority may provide public libraries, museums, schools for science, art galleries and schools for art, and for that purpose may purchase and hire land, and erect, take down, rebuild, alter, repair and extend buildings, and fit up, furnish and supply the same with all requisite furniture, fittings and conveniences. The Library Authority shall exercise the general management, regulation and control of every department established under the provisions of the Acts, and may provide books, newspapers, maps and specimens of art and science, and cause the same to be bound and repaired when necessary. Also appoint salaried officers and servants, and dismiss them, and make regulations for the safety and use of every library, museum, gallery and school under its control, and for admission of the public thereto. Power is also given to make agreements with other library authorities for the joint use of library or other buildings; and to borrow money, with the sanction of[22] the central authorities, for the purpose of buying sites, erecting buildings and furnishing them. The Irish Act of 1877 also gives power to establish schools of music as part of a library scheme.

5. Non-Municipal Libraries: Acts of Parliament.—The legislation affecting the large number of British libraries which are not supported out of the rates is neither extensive nor satisfactory. The chief feature of most of the Acts of Parliament which have been passed seems to be the benevolent one of granting certain facilities to various kinds of landowners to divest themselves of their property in order to provide sites for literary and scientific institutions. There are similar clauses in the Public Libraries Acts, and, of course, most of the Acts named apply to municipal libraries; but in reality this kind of legislation is not particularly valuable. To make the transfer of land for public purposes more easy is quite laudable, but it has not yet had the effect of inducing landowners to part with free plots of land as building sites, either to public library authorities or literary institutions.

6. The principal Act bearing on literary and scientific institutions is entitled “An Act to afford greater facilities for the establishment of Institutions for the promotion of Literature and Science and the Fine Arts, and to provide for their better regulation,” 17 & 18 Vict., c. 112, 1854. This is nearly all taken up with provisions for transfers of lands and other property, and with a few regulations concerning members, rules, altering, extending or dissolving the institution, etc. This Act was afterwards to some extent modified by “An Act to facilitate the transfer of Schools for Science and Art to Local Authorities,” 54 & 55 Vict., c. 61, 1891. These, and the other Acts referred to, which deal with transfers of property, have had very little to do with the development of voluntary literary and scientific institutions or libraries; the principal statute under which most of them are now governed being an Act passed primarily for quite a different purpose. This is the “Act to amend the ‘Companies Act, 1862,’” 30 & 31 Vict., c. 131, 1867, under Section 23 of which power is given the Board of Trade to grant licences to literary and similar associations, providing for registration with limited liability, and conferring all the privileges attaching to limited companies. In connexion with this Act, and those of 1862 and 1877, the Board of Trade have issued[23] a series of circulars and forms, which include draft rules, articles of association, etc. Under these licences a considerable number of British literary institutions have been established and organized.

7. British Colonial Library Legislation has proceeded very much on the lines adopted in the mother country, and in every case the permissive character of the Acts has been preserved, and, in most cases, the rate limitation. On the other hand, some effort has been made to keep in touch with schools and universities.

In South Africa a Government proclamation established the South African Public Library at Cape Town in 1818. This was further regulated by an ordinance passed in 1836, which gave the library the right to receive a free copy of every publication issued in Cape Colony. Other libraries in the large towns now receive grants from the Government, and a large number of smaller libraries also receive grants equal to the annual average amount raised by subscriptions and donations during the three preceding years; but in no case shall the amount of the Parliamentary grant exceed £150 for any one library in one year. No grants are made if less than £25 is raised by subscription. In return for the grant, reading-rooms and reference libraries are to be open free to the public, and an annual report has to be presented to the Government. In Natal the same arrangement is made, though on a much smaller scale. In both colonies books are only lent for home reading to subscribers. In 1874 an Act was passed by the Legislature of Natal for regulating literary and other societies not legally incorporated.

In Canada, under a General Libraries Act of 1854, County Councils were authorized to establish four classes of libraries: (1) Ordinary common school libraries in each school-house for the use of children and ratepayers; (2) a general public library available to all ratepayers in the municipality; (3) professional libraries of books on teaching, etc., for teachers only; and (4) a library in any public institution under the control of a municipality. Arrangements were made whereby the Education Office sold books at low rates to the school libraries; and afterwards the Education Department of the Legislature gave annual grants, equal to the amounts contributed by members for book purchase,[24] to mechanics’ institutes, etc., and subsequently increased such grants for books to $400 (£80) annually. The province of Ontario, in 1882, passed “An Act to provide for the Establishment of Free Libraries,” on lines very similar to the English Acts. Power is given any city, town or incorporated village to provide libraries, newsrooms, museums and branches, on the petition and with the consent of the qualified electors. The management is vested in a board chosen from the Town Council, citizens other than councillors, and the Public School Boards. The library rate is limited to an “annual rate not exceeding one half of a mill in the dollar upon the assessed value of all rateable, real and personal property.” This form of limitation is borrowed from the practice of the United States. About ninety places have adopted this Free Libraries Act in Ontario. In 1895 an Act was passed in Ontario to enable mechanics’ institutes to change their names and transfer their property to municipalities on condition that the libraries were made free to the public.

The Australian colonies have all passed separate laws, somewhat similar to those in force in other parts of the Empire, in regard to their adoption being left to local option, and rates being more or less limited. In 1870 Victoria passed an Act establishing the Library, Museum and National Art Gallery at Melbourne, and in 1885 “The Free Libraries Act” was passed. But, in 1890, these Acts were repealed by “An Act to consolidate the Laws relating to Libraries.” The Melbourne Public Library, which was established in 1853, is now wholly supported by Government, and it lends books to any municipality in the colony. In addition, the Government make grants from public funds to most of the mechanics’ institutions, athenæums and other literary societies in Victoria.

South Australia has quite a body of library laws, dating from 1863, when the South Australian Institution was incorporated, but most of them have been repealed or incorporated in the two principal Acts regulating institutes and free libraries. By the various Acts passed in connexion with institutes or literary societies, grants in aid are made by Parliament on lines similar to those in force in the other colonies, while rules and regulations are made and power given to transfer such institutes to the municipalities. Public libraries are regulated by “An[25] Act to establish Free Libraries in Corporate Towns and District Councils,” 1898, subsequently amended by an Act of 1902. This Act gives local authorities power, on the request and with the consent of the ratepayers, to adopt the Act, subject to the rate not exceeding 3d. in the £. Municipal libraries are also entitled to receive the same grants as are made to institutes.

In New South Wales public libraries may be established under the “Municipalities Act,” 1867. The Government makes grants for the purchase of books on a scale according to population, and other funds must be provided by the subscriptions of members. Schools of art are entitled to receive a Government grant in proportion to the amount of monetary support accorded by the public. In addition, the Sydney Public Library (established in 1869) is entirely supported by the Government, and it sends out carefully selected boxes of books to 128 institutes throughout New South Wales, the entire cost being defrayed by Parliament.

In Western Australia grants are made to institutes as in the other colonies, but there is no general Library Act in existence yet. In 1887 the Government established a Public Library at Perth, and contributes £3000 per annum for its maintenance. The only legislative enactment concerning libraries in Western Australia is an Act for establishing a Law and Parliamentary Library for the Legislature, which was passed in 1873 and amended in 1889.

Queensland passed an “Act to consolidate and amend the Laws relating to Municipal Institutions, and to provide more effectually for local government,” 1878. This was extended by the “Divisional Boards Act” of 1887, and now Municipal Councils or Divisional Boards may make bye-laws for the establishment, maintenance and management of public libraries. Brisbane Free Public Library, the only library of importance opened under this Act, has an annual grant from the municipal funds varying from £800 to £1000. One hundred and forty schools of art throughout the colony also receive Government grants for library and other purposes to the extent of about 8s. 2d. for every pound subscribed by members.

Tasmania has a model library law, which is worthy of adoption in every civilized country. It is contained in “An Act to[26] amend the Law relating to Public Libraries,” passed in 1867. It is so short, and so much to the point, that the whole of it may be quoted. After a two-line preamble it declares that: “The Municipal Council of every municipality may, from time to time, apply such sum as it sees fit, out of the rates of such municipality, in and towards the formation and maintenance of Public Libraries within such municipality.” That is the whole Act, and it gives no indication of the grudging limitations which other countries inflict. The only blemish on this admirable statute is the fact that it is not compulsory. Most of the Tasmanian towns being small, only Hobart has put the library law into force, by appropriating a penny rate to the support of the Tasmanian Public Library (1849), which is also maintained by Government grants. The small libraries throughout Tasmania receive grants, on the usual conditions, from the Government.

The library law of New Zealand is based on a series of Acts, similar to those passed in this country for the regulation of municipal libraries and literary institutions. The principal Acts are: (1) “An Act to promote the establishment of Public Libraries,” 1869, giving power for the governing body of a city, village or district to adopt the Act with the consent of the ratepayers, and to levy a rate not exceeding 1d. in the £; (2) “An Act to confer powers on Public Libraries and Mechanics’ Institutes,” 1875—a series of rules for incorporation and management; (3) “An Act to promote the establishment and support of Public Libraries,” 1877. In this Act it is laid down that the grant for public libraries is to be apportioned among provincial districts, in proportion to the population of such districts, and that a subsidy equal to the amount of the library rate is to be paid to municipal libraries established under the Act of 1869. Free admission to reading-rooms is permitted, but no person to be allowed to borrow unless he contributes not less than 5s. per annum.

None of the West Indian dependencies have legislation relating to libraries, although grants are paid from Government funds towards the maintenance of libraries in different British possessions.

In India the Government subsidizes only libraries connected[27] with the leading departments of State, such as law and parliamentary libraries for the use of legislators and the Councils forming the Indian Government. It cannot be said to redound to the credit of the Government that the only public library systems in India have been established in native States. The Gaekwar of Baroda has instituted such a system, which extends from the capital city to the smallest village, and his example has been followed by the native State of Indore.