PARIS

Grant Allen’s Historical Guides

Fcap. 8vo, Green Cloth, with rounded corners to

slip in the pocket. Price 3/6 net each.

PARIS

FLORENCE

CITIES OF BELGIUM

VENICE

ROME

DRESDEN with Nuremburg, etc.

LONDON: GRANT RICHARDS

9 HENRIETTA STREET COVENT GARDEN W.C.

GRANT ALLEN’S HISTORICAL

GUIDES

PARIS

LONDON: GRANT RICHARDS

1900

First Edition. Printed Jan. 1897

Second Edition. Printed Jan. 1900

THE object and plan of these Historical Handbooks is somewhat different from that of any other guides at present before the public. They do not compete or clash with such existing works; they are rather intended to supplement than to supplant them. My purpose is not to direct the stranger through the streets and squares of an unknown town towards the buildings or sights which he may desire to visit; still less is it my design to give him practical information about hotels, cab fares, omnibuses, tramways, and other every-day material conveniences. For such details, the traveller must still have recourse to the trusty pages of his Baedeker, his Joanne, or his Murray. I desire rather to supply the tourist who wishes to use his travel as a means of culture with such historical and antiquarian information as will enable him to understand, and therefore to enjoy, the architecture, sculpture, painting, and minor arts of the towns he visits. In one word, it is my object to give the reader in a very compendious form the result of all those inquiries which have naturally suggested themselves to my own mind during thirty-five years of foreign travel, the solution of which has cost myself a good deal of research, thought, and labour, beyond the facts which I could find in the ordinary handbooks.

For several years past I have devoted myself to collecting and arranging material for a set of books to embody the idea I had thus entertained. I earnestly hope they may meet a want on the part of tourists, especially Americans, who, so far as my experience goes, usually come to Europe with an honest and reverent desire to learn from the Old World whatever of value it has to teach them, and who are prepared to take an amount of pains in turning their trip to good account which is both rare and praiseworthy. For such readers I shall call attention at times to other sources of information.

These guide-books will deal more particularly with the Great Towns where objects of art and antiquity are numerous. In every one of them, the general plan pursued will be somewhat as follows. First will come the inquiry why a town ever gathered together at all at that particular spot—what induced the aggregation of human beings rather there than elsewhere. Next, we shall consider why that town grew to social or political importance and what were the stages by which it assumed its present shape. Thirdly, we shall ask why it gave rise to that higher form of handicraft which we know as Art, and towards what particular arts it especially gravitated. After that, we shall take in detail the various strata of its growth or development, examining the buildings and works of art which they contain in historical order, and, as far as possible, tracing the causes which led to their evolution. In particular, we shall lay stress upon the origin and meaning of each structure as an organic whole, and upon the allusions or symbols which its fabric embodies.

A single instance will show the method upon which I intend to proceed better than any amount of general description. A church, as a rule, is built over the body or relics of a particular saint, in whose special honour it was originally erected. That saint was usually one of great local importance at the moment of its erection, or was peculiarly implored against plague, foreign enemies, or some other pressing and dreaded misfortune. In dealing with such a church, then, I endeavour to show what were the circumstances which led to its erection, and what memorials of these circumstances it still retains. In other cases it may derive its origin from some special monastic body—Benedictine, Dominican, Franciscan—and may therefore be full of the peculiar symbolism and historical allusion of the order who founded it. Wherever I have to deal with such a church, I try as far as possible to exhibit the effect which its origin had upon its architecture and decoration; to trace the image of the patron saint in sculpture or stained glass throughout the fabric; and to set forth the connection of the whole design with time and place, with order and purpose. In short, instead of looking upon monuments of the sort mainly as the product of this or that architect, I look upon them rather as material embodiments of the spirit of the age—crystallizations, as it were, in stone and bronze, in form and colour, of great popular enthusiasms.

By thus concentrating attention on what is essential and important in a town, I hope to give in a comparatively short space, though with inevitable conciseness, a fuller account than is usually given of the chief architectural and monumental works of the principal art-cities. In dealing with Paris, for example, I shall have little to say about such modern constructions as the Champs Elysées or the Eiffel Tower; still less, of course, about the Morgue, the Catacombs, the waxworks of the Musée Grévin, and the celebrated Excursion in the Paris Sewers. The space thus saved from vulgar wonders I shall hope to devote to fuller explanation of Notre-Dame and the Sainte Chapelle, of the mediæval carvings or tapestries of Cluny, and of the pictures or sculptures in the galleries of the Louvre. Similarly in Florence, whatever I save from description of the Cascine and even of the beautiful Viale dei Colli (where explanation is needless and word-painting superfluous), I shall give up to the Bargello, the Uffizi, and the Pitti Palace. The passing life of the moment does not enter into my plan; I regard each town I endeavour to illustrate mainly as a museum of its own history.

For this reason, too, I shall devote most attention in every case to what is locally illustrative, and less to what is merely adventitious and foreign. In Paris, for instance, I shall have more to say about truly Parisian art and history, as embodied in St. Denis, the Île de la Cité, and the shrine of Ste. Geneviève, than about the Egyptian and Assyrian collections of the Louvre. In Florence, again, I shall deal rather with the Etruscan remains, with Giotto and Fra Angelico, with the Duomo and the Campanile, than with the admirable Memlincks and Rubenses of the Uffizi and the Pitti, or with the beautiful Van der Goes of the Hospital of Santa Maria. In Bruges and Brussels, once more, I shall be especially Flemish; in the Rhine towns, Rhenish; in Venice, Venetian. I shall assign a due amount of space, indeed, to the foreign collections, but I shall call attention chiefly to those monuments or objects which are of entirely local and typical value.

As regards the character of the information given, it will be mainly historical, antiquarian, and, above all, explanatory. I am not a connoisseur—an adept in the difficult modern science of distinguishing the handicraft of various masters, in painting or sculpture, by minute signs and delicate inferential processes. In such matters, I shall be well content to follow the lead of the most authoritative experts. Nor am I an art-critic—a student versed in the technique of the studios and the dialect of the modelling-room. In such matters, again, I shall attempt little more than to accept the general opinion of the most discriminative judges. What I aim at rather is to expound the history and meaning of each work—to put the intelligent reader in such a position that he may judge for himself of the æsthetic beauty and success of the object before him. To recognise the fact that this is a Perseus and Andromeda, that a St. Barbara enthroned, the other an obscure episode in the legend of St. Philip, is not art-criticism, but it is often an almost indispensable prelude to the formation of a right and sound judgment. We must know what the artist was trying to represent before we can feel sure what measure of success he has attained in his representation.

For the general study of Christian art, alike in architecture, sculpture, and painting, no treatises are more useful for the tourist to carry with him for constant reference than Mrs. Jameson’s Sacred and Legendary Art, and Legends of the Madonna (London, Longmans). For works of Italian art, both in Italy and elsewhere, Kugler's Italian Schools of Painting is an invaluable vade-mecum. These books should be carried about by everybody everywhere. Other works of special and local importance will occasionally be noticed under each particular city, church, or museum.

I cannot venture to hope that handbooks containing such a mass of facts as these will be wholly free from errors and misstatements, above all in early editions. I can only beg those who may detect any such to point them out, without unnecessary harshness, to the author, care of the publisher, and if possible to assign reasons for any dissentient opinion.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |||||

| Introduction | 3 | ||||

| How to Use these Guide-Books | 10 | ||||

| Origins of Paris | 11 | ||||

| I | The Île de la Cité | 16 | |||

| A. | The Palais de Justice and the Sainte Chapelle | 17 | |||

| B. | Notre-Dame | 22 | |||

| Map of Historic Paris | 33 | ||||

| II | The Left or South Bank | 34 | |||

| A. | The Roman Palace and the Musée de Cluny | 35 | |||

| B. | The Hill of Ste. Geneviève | 55 | |||

| III | Renaissance Paris (The Louvre) | 62 | |||

| A. | The Fabric | 64 | |||

| B. | The Collections | 71 | |||

| I. | Paintings | 72 | |||

| II. | Sculpture | 153 | |||

| 1. Antique Sculpture | 154 | ||||

| 2. Renaissance Sculpture | 168 | ||||

| 3. Modern Sculpture | 187 | ||||

| III. | The Smaller Collections | 189 | |||

| IV | The North Bank (Rive Droite) | 197 | |||

| A. | The Core of the Right Bank | 198 | |||

| B. | The Outer Ring of Louis XIV | 208 | |||

| V | The Faubourg St. Germain | 213 | |||

| VI | St. Denis | 230 | |||

| VII | The Outer Ring, Etc | 246 | |||

| Index | 253 | ||||

THE portions of this book intended to be read at leisure at home, before proceeding to explore each town or monument, are enclosed in brackets [thus]. The portion relating to each principal object should be quietly read and digested before a visit, and referred to again afterwards. The portion to be read on the spot is made as brief as possible, and is printed in large legible type, so as to be easily read in the dim light of churches, chapels, and galleries. The key-note words are printed in bold type, to catch the eye. Where objects are numbered, the numbers used are always those of the latest official catalogues.

Baedeker’s Guides are so printed that each principal portion can be detached entire from the volume. The traveller who uses Baedeker is advised to carry in his pocket one such portion, referring to the place he is then visiting, together with the plan of the town, while carrying this book in his hand. These Guides do not profess to supply practical information.

Individual works of merit are distinguished by an asterisk (*); those of very exceptional interest and merit have two asterisks. Nothing is noticed in this book which does not seem to the writer worthy of attention.

See little at a time, and see it thoroughly. Never attempt to “do” any place or any monument. By following strictly the order in which objects are noticed in this book, you will gain a conception of the historical evolution of the town which you cannot obtain if you go about looking at churches and palaces hap-hazard. The order is arranged, not quite chronologically, but on a definite plan, which greatly facilitates comprehension of the subject.

PARIS is not, like Rome, London, Lyons, an inevitable city. It does not owe its distinctive place, like New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Melbourne, to natural position alone. Rather does it resemble Madrid or Berlin in being in great part of artificial administrative origin. It stands, no doubt, upon an important navigable river, the Seine; but its position upon that river, though near the head of navigation, when judged by the standard of early times, is not exactly necessary or commanding. Rouen in mediæval days, Havre at the present moment, are the real ports of the Seine. The site of Paris is in itself nothing more than one among the many little groups of willow-clad alluvial islets which are frequent along the upper reaches of the river. The modern city owes its special development as a town, first to its Roman conquerors, then to its bridges, next to its mediæval counts, last of all to the series of special accidents by which those counts developed at last into kings of the nascent kingdom of France, and inheritors of the traditions of the Frankish sovereigns. It is thus in large part a royal residential town, depending mainly for prosperity upon its kings, its nobles, its courts of justice, its parliaments, its university, its clergy, and its official classes; comparatively little, till quite recent times, upon the energy and industry of its individual citizens. We say, as a rule, that Paris is the capital of France; it would be truer to say that France is the country which has grouped itself under the rulers of Paris.

The name itself points back to the antiquity of some human aggregation upon this particular spot. It is the name of a tribe, not that of their capital. The Parisii were a Celtic people of comparatively small importance, who occupied the banks of the Seine at the period of the Roman conquest. Their town or stronghold, Lutetia, called distinctively Lutetia Parisiorum (Lutetia of the Parisii), was situated, says Cæsar, “in an island of the river Sequana”—the same which is now called the Île de la Cité. Two adjacent islands of the same alluvial type have long since coalesced to form the Île St. Louis; a fourth, the Île Louviers, is at present enclosed in the mainland of the northern bank by the modern quays.

This stockaded island village of the Parisii was conquered by the Romans in B.C. 53. Under Roman rule, it remained at first an unimportant place, the really large towns of Gaul at that time being Arles, Nîmes, Marseilles, Bordeaux, and Lyons. In the north, Treviri was the chief Roman settlement. Towards the end of the Roman period, however, Paris seems to have increased in importance, and overflowed a little from the island to the south bank. The town owed its rapid rise, no doubt, to the two Roman bridges which here crossed the two branches of the Seine, probably on the same sites as the modern Petit-Pont and Pont Notre-Dame. The river formed its highway. Constantius Chlorus, who lived in Gaul from A.D. 292 to 306, is supposed to have built in the faubourg on the south side the palace of the Thermes, which now forms a part of the Museum of Cluny. Julian certainly inhabited that palace in 360. The town was known as Lutetia almost as long as the Roman power lasted; but after the Frankish invasion (and even in late Roman times), the name of the tribe superseded that of the ancient fortress: Lutetia became known as Paris, the stronghold of the Parisii, just in the same way as the Turones gave their name to Tours, the Ambiani to Amiens, and the Senones to Sens.

After the occupation of Gaul by Clovis (Hlodwig), Paris sank for a time to the position of a mere provincial town. The Merwing (or Merovingian) kings, the successors of Clovis, resided as a rule at Orleans or Soissons. The Frankish emperors and kings of the line of Charlemagne, again (the Karlings or Carlovingians), held their court for the most part at Aix-la-Chapelle. The town by the Seine was so completely neglected under later sovereigns of the Karling line (who were practically Germans), that during the invasions of the Northmen from 841 to 885 it was left entirely to its own resources. But its count, Eudes, defended it so bravely from the northern pirates, that he became the real founder of the French State, the first inaugurator of France as a separate country, distinct from the Empire. His provincial city grew into the kernel of a mediæval monarchy. From his time on, Paris emerges as the capital of a struggling kingdom, small in extent at first, but gradually growing till it attained the size which it now possesses. The Teutonic King of the Franks was reduced for a time to the rocky fortress of Laon; the Count of Paris became Duke of the French, and then King of France in the modern acceptation.

As the kingdom grew (absorbing by degrees Flanders, Normandy, Aquitaine, Provence, Champagne, and Burgundy), the capital grew with it; its limits at various times will be more fully described in succeeding pages. From first to last, however, Paris preserved its character as rather the official and administrative centre than the commercial emporium. Nevertheless, even under the Romans, its symbol was a ship. Its double debt to the river and the monarchy is well symbolised by its mediæval coat of arms, which consists of a vessel under full sail, surmounted by the fleur de lis of the French kings, and crested above by a mural crown.

So few remnants of Roman Paris exist at our day, that we will begin our survey with the Île de la Cité, the nucleus of the mediæval town, leaving the scanty earlier relics to be noted later on in their proper places. But before we proceed to this detailed description, two other facts of prime importance in the history of old Paris must be briefly mentioned, because without them the character of the most ancient buildings in the city cannot be properly understood. These two facts—even if mythical, yet facts none the less—are the histories of the two great patron saints of the early burghers. It is not too much to say that to the mediæval Parisian, Paris appeared far less as the home of the kings or the capital of the kingdom than as the shrine of St. Denis and the city of Ste. Geneviève.

Universal tradition relates that St. Denis was the first preacher of Christianity in Paris. He is said to have suffered martyrdom there in the year 270. As the apostle and evangelist of the town, he was deeply venerated from the earliest times; but later legend immensely increased his vogue and his sanctity. On the one hand, he was identified with Dionysius the Areopagite; on the other hand, he was said to have walked after his decapitation, bearing his head in his hand, from his place of martyrdom on the hill of Montmartre (Mons Martyrum), near the site from which the brand-new church of the Sacré-Cœur now overlooks the vastly greater modern city, to a spot two miles away, where a pious lady buried him. On this spot, a chapel is said to have been erected as early as A.D. 275, within five years of his martyrdom; later, Ste. Geneviève, assisted by the people of Paris, raised a church over his remains on the same site. In the reign of King Dagobert, the sacred body was removed to the Abbey of St. Denis (see later), which became the last resting-place of the kings of France. It is probable that the legend of the saint having carried his head from Montmartre arose from a misunderstanding of images of the decapitated bishop, bearing his severed head in his hands as a symbol of the mode of his martyrdom; but the tale was universally accepted as true in mediæval days, and is still so accepted by devout Parisians. Images of St. Denis, in episcopal robes, carrying his mitred head in his hands, may be looked for on all the ancient buildings of the city. St. Denis thus represents the earliest patron saint of Paris—the saint of the primitive Church and of the period of persecution.

The second patron saint of the city—the saint of the Frankish conquest—is locally and artistically even more important. Like Jeanne d’Arc, she touches the strong French sentiment of patriotism. Ste. Geneviève, a peasant girl of Nanterre (on the outskirts of Paris), was born in 421, during the stormy times of the barbarian irruptions. When she was seven years old, St. Germain, of Auxerre (of whom more will be said under the church of St. Germain l’Auxerrois), on his way to Britain, saw la pucellette Geneviève, and became aware, by divine premonition, of her predestined glory. When she had grown to woman’s estate, and was a shepherdess at Nanterre, a barbarian leader (identified in the legend with Attila, King of the Huns) threatened to lay siege to the little city. But Geneviève, warned of God, addressed the people, begging them not to leave their homes, and assuring them of the miraculous protection of heaven. And indeed, as it turned out, the barbarians, without any obvious reason, changed their line of march, and avoided Paris. Again, when Childeric, the father of Clovis, invested the city, the people suffered greatly from sickness and famine. Then Geneviève took command of the boats which were sent up stream to Troyes for succour, stilled by her prayers the frequent tempests, and brought the ships back laden with provisions. After the Franks had captured Paris, Ste. Geneviève carried on Roman traditions into the Frankish court; she was instrumental in converting Clovis and his wife Clotilde; and when she died, at eighty-nine, a natural death, she was buried by the side of her illustrious disciples. The history of her body will be given at length when we come to examine her church on the South Side, commonly called the Panthéon; but her image may frequently be recognised on early buildings by the figure of a devil at her side, endeavouring in vain (as was his wont) to extinguish her lighted taper—the taper, no doubt, of Roman Christianity, which she did not allow to be quenched by the Frankish invaders.

Round these two sacred personages the whole art and history of early Paris continually cluster. The beautiful figure of the simple peasant enthusiast, Ste. Geneviève, in particular, has largely coloured Parisian ideas and Parisian sympathies. Her shrine still attracts countless thousands of the faithful.

Having premised these facts, we are now in a position to commence our survey of the city. I strongly recommend the reader to visit the various objects of interest in the exact order here prescribed. Otherwise, he will not understand the various allusions to points already elucidated. But no necessary organic connection exists between the collections of the Louvre and the town in which they are housed. Therefore, they may be visited off and on at any time (see Introduction to the Collections in Part III). Utilize rainy days in the Galleries of the Louvre.

[THE Île de la Cité, the oldest Paris, consisted in the Middle Ages of a labyrinth of narrow and tortuous lanes, now entirely replaced by large and stately modern official buildings. In Roman and Frankish times, it comprised the whole of the town, save a small suburb extending as far as the present Museum of Cluny, on the South Side. Among its sunless alleys, however, in later mediæval days, numerous churches raised their heads, of which Notre-Dame and the Sainte Chapelle alone now remain; while others, dedicated to the oldest local saints, such as Ste. Geneviève-des-Ardents, St. Éloy, and St. Germain-le-Vieux, have been entirely destroyed. The west extremity of the island was formerly occupied by the old Royal Palace, parts of which still survive, included in the buildings of the modern Palais de Justice. On the east end stood the cathedral of Notre-Dame, with the episcopal palace in its rear; while, close by, rose the earliest hospital in Europe, the Hôtel-Dieu, said to have been originally founded by Clovis, and now represented by a vastly larger modern building on a different site. As the burgesses began to shift their homes to the quarters north of the Seine, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Cité was gradually given over to the clergy. The kings also removed from the Palace of the Capets to their new residences on the North Bank (Bastille, Hôtel Saint-Paul, old castle of the Louvre), and gave up their island mansion to the Parlement or Supreme Court, since which time it has been commonly known as the Palais de Justice, and extensively modernised. At the present day, the Cité has become the head-quarters of Law, Police, and Religion, and is almost entirely occupied by huge official structures, which cover enormous areas, and largely conceal its primitive character. It still contains, however, the most precious mediæval monuments of Paris.

At least two days should be devoted to the Île de la Cité; one to the Palace and the Sainte Chapelle, another to the Cathedral. Do not attempt to see them both together.]

Go along the Rue de Rivoli as far as the Square of the Tour St. Jacques. If driving, alight here. Turn down the Place du Châtelet to your right. In front is the pretty modern fountain of the Châtelet: right, the Théâtre du Châtelet; left, the Opéra Comique. The bridge which faces you is the Pont-au-Change, so-called from the money-changers’ and jewellers’ booths which once flanked its wooden predecessor (the oldest in Paris), as they still do the Rialto at Venice, and the Ponte Vecchio at Florence.

Stand by the right-hand corner of the bridge before crossing it. In front is the Île de la Cité. The square, dome-crowned building opposite you to the left is the modern Tribunal de Commerce; beyond it leftward lie the Marché-aux-Fleurs and the long line of the Hôtel-Dieu, above which rise the towers and spire of Notre-Dame. In front, to the right, the vast block of buildings broken by towers forms part of the Palais de Justice, the ancient Palace of the French kings, begun by Hugues Capet. The square tower to the left in this block is the Tour de l’Horloge. Next, to the right, come the two round towers of the Conciergerie, known respectively as the Tour de César and the Tour de Montgomery. The one beyond them, with battlements, is the Tour d’Argent. It was in the Conciergerie that Marie Antoinette, Robespierre, and many other victims of the Revolution were imprisoned.

These mediæval towers, much altered and modernized, are now almost all that remains of the old Palace, which, till after the reign of Louis IX (St. Louis), formed the residence of the Kings of France. Charles VII gave it in 1431 to the Parlement or Supreme Court. Ruined by fires and rebuilding, it now consists for the most part of masses of irregular recent edifices. The main modern façade fronts the Boulevard du Palais.

Cross the bridge. The Tour de l’Horloge on your right, at the corner of the Boulevard du Palais, contains the oldest public clock in France (1370). The figures of Justice and Piety by its side were originally designed by Germain Pilon, but are now replaced by copies. Walk round the Palais by the quay along the north branch of the Seine till you come to the Rue de Harlay. Turn there to your left, towards the handsome and imposing modern façade of this side of the Palais de Justice. The interior is unworthy a visit. The Rue de Harlay forms the westernmost end of the original Île de la Cité. The prow-shaped extremity of the modern island has been artificially produced by embanking the sites of two or three minor islets. The Place Dauphine, which occupies the greater part of this modern extension, was built in 1608; it still affords a characteristic example of the domestic Paris of the period before Baron Haussmann. Continue along the quay as far as the Pont-Neuf, so as to gain an idea of the extent of the Île de la Cité in this direction. The centre of the Pont-Neuf is occupied by an equestrian statue of Henri IV, first of the Bourbon kings. Its predecessor was erected in 1635, and was destroyed to make cannon during the great Revolution. Louis XVIII re-erected it. From this point you can gain a clear idea of the two branches of the Seine as they unite at the lower end of the Île de la Cité. To your right, looking westward, you also obtain a fine view of the Colonnade of the Old Louvre, with the southwestern gallery, and the more modern buildings of the Museum behind it. (See later.)

Now, walk along the southern quay of the island, round the remainder of the Palais de Justice, as far as the Boulevard du Palais. There turn to your left, and go in at the first door of the Palace on the left (undeterred by sentries) into the court of the Sainte Chapelle, the only important relic now remaining of the home of Saint Louis. You may safely neglect the remainder of the building.

[The thirteenth century (age of the Crusades) was a period of profound religious enthusiasm throughout Europe. Conspicuous among its devout soldiers was Louis IX, afterwards canonized as St. Louis. The saintly king purchased from Baldwin, Emperor of Constantinople, the veritable Crown of Thorns, and a fragment of the True Cross—paying for these relics an immense sum of money. Having become possessed of such invaluable and sacred objects, Louis desired to have them housed with suitable magnificence. He therefore entrusted one Pierre de Montereau with the task of building a splendid chapel (within the precincts of his palace), begun in 1245, and finished three years later, immediately after which the king set out on his Crusade. The monument thus breathes throughout the ecstatic piety of the mystic king; it was consecrated in 1248, in the name of the Holy Crown and the Holy Cross, by Eudes de Châteauroux, Bishop of Tusculum and papal legate.

Three things should be noted about the Sainte Chapelle. (1) It is a chapel, not a church; therefore it consists (practically) of a choir alone, without nave or transepts. (2) It is the domestic Chapel of the Royal Palace. (3) It is, above all things, the Shrine of the Crown of Thorns. These three points must be constantly borne in mind in examining the building.

Erected later than Notre-Dame, it represents the pointed style of the middle of the thirteenth century, and is singularly pure and uniform throughout. Secularized at the Revolution, it fell somewhat into decay; but was judiciously restored by Viollet-le-Duc and others. The “Messe Rouge,” or “Messe du St. Esprit,” is still celebrated here once yearly, on the re-opening of the courts after the autumn vacation, but no other religious services take place in the building. The Crown of Thorns and the piece of the True Cross are now preserved in the Treasury at Notre-Dame.

Open daily, free, except Mondays, 11 to 4 or 5. Choose a very bright day to visit it.]

Examine the exterior in detail from the court on the south side. More even than most Gothic buildings, the Sainte Chapelle is supported entirely by its massive piers, the wall being merely used for enclosure, and consisting for the most part of lofty windows. As in most French Gothic buildings, the choir terminates in a round apse, whereas English cathedrals have usually a square end. The beautiful light flèche or spire in the centre has been restored. Observe the graceful leaden angel, holding a cross, on the summit of the chevet or round apse. To see the façade, stand well back opposite it, when you can observe that the chapel is built in four main stories,—those, namely, of the Lower Church or crypt, of the Upper Church, of the great rose window (with later flamboyant tracery), and of the gable-end, partially masked by an open parapet studded with the royal fleurs-de-lis of France. The Crown of Thorns surrounds the two pinnacles which flank the fourth story.

The chapel consists of a lower and an upper church. The Lower Church is a mere crypt, which was employed for the servants of the royal family. Its portal has in its tympanum (or triangular space in the summit of the arch) the Coronation of the Virgin, and on its centre pillar a good figure of the Madonna and Child. Enter the Lower Church. It is low, and has pillars supporting the floor above. In the polychromatic decoration of the walls and pillars, notice the frequent repetition of the royal lilies of France, combined with the three castles of Castille, in honour of Blanche of Castille, the mother of St. Louis.

Mount to **the Upper Chapel (or Sainte Chapelle proper) by the small spiral staircase in the corner. This soaring pile was the oratory where the royal family and court attended service; its gorgeousness bespeaks its origin and nature. It glows like a jewel. First go out of the door and examine the exterior and doorway of the chapel. Its platform was directly approached in early times from the Palace. The centre pillar bears a fine figure of Christ. In the tympanum (as over the principal doorway of almost every important church in Paris and the district) is a relief of the Last Judgment. Below stands St. Michael with his scales, weighing the souls; on either side is depicted the Resurrection, with the Angels of the Last Trump. Above, in the second tier, is Christ, holding up His hands with the marks of the nails, as a sign of mercy to the redeemed: to R and L of Him angels display the Crown of Thorns and the True Cross, to contain which sacred relics the chapel was built. Extreme L kneels the Blessed Virgin; extreme R, Sainte Geneviève. This scene of the Last Judgment was adapted with a few alterations from that above the central west door of Notre-Dame, the Crown of Thorns in particular being here significantly substituted for the three nails and spear. The small lozenge reliefs to R and L of the portal are also interesting. Those to the L represent in a very naïve manner God the Father creating the world, sun and moon, light, plants, animals, man, etc. Those to the R give the story of Genesis, Cain and Abel, the Flood, the Ark, Noah’s Sacrifice, Noah’s Vine, etc. the subjects of all which the visitor can easily recognise, and is strongly recommended to identify for himself.

The interior consists almost entirely of large and lofty windows, with magnificent stained glass, in large part ancient. The piers which divide the windows and alone support the graceful vault of the roof, are provided with statues of the twelve apostles, a few of them original. Each bears his well-known symbol. Spell them out if possible. Beneath the windows, in the quatrefoils of the arcade, are enamelled glass mosaics representing the martyrdoms of the saints—followers of Christ, each wearing his own crown of thorns: a pretty conceit wholly in accord with St. Louis’s ecstatic type of piety. Conspicuous among them are St. Denis carrying his head, St. Sebastian pierced with arrows, St. Stephen stoned, St. Lawrence on his gridiron, etc. Examine and identify each separately. The apse (formerly separated from the body of the building by a rood-screen, now destroyed) contains the vacant base of the high altar, behind which stands an arcaded tabernacle, now empty, in whose shrine were once preserved the Crown of Thorns, the fragment of the True Cross, and other relics. Amongst them in later times was included the skull of St. Louis himself in a golden reliquary. Two angels at the summit of the large centre arch of the arcade bear a representation of the Crown of Thorns in their hands. Above the tabernacle rises a canopy or baldacchino, approached by two spiral staircases; from its platform St. Louis and his successors, the kings of France, were in the habit of exhibiting with their own hands the actual relics themselves once a year to the faithful. The golden reliquary in which the sacred objects were contained was melted down in the Revolution. The small window with bars to your R, as you face the high altar, was placed there by the superstitious and timid Louis XI, in order that he might behold the elevation of the Host and the sacred relics without being exposed to the danger of assassination. The visitor should also notice the inlaid stone pavement, with its frequent repetition of the fleur-de-lis and the three castles. The whole breathes the mysticism of St. Louis: the lightness of the architecture, the height of the apparently unsupported roof, and the magnificence of the decoration, render this the most perfect ecclesiastical building in Paris.

In returning from the chapel, notice on the outside, from the court to the S., the apparently empty and useless porch, supporting a small room, which is the one through whose grated window Louis XI used to watch the elevation.

I would recommend the visitor on his way home from this excursion to walk round the remainder of the Île de la Cité in the direction of Notre-Dame, so as to gain a clear idea of the extent of the island, without, however, endeavouring to examine the cathedral in detail on this occasion.

Vary your artistic investigations by afternoons in the Bois de Boulogne, Champs Elysées, etc.

[In very early times, under the Frankish monarchs, the principal church of Paris was dedicated to St. Stephen the Protomartyr. It stood on part of the site now covered by Notre-Dame, and was always enumerated first among the churches of the city. A smaller edifice, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, also occupied a part of the site of the existing cathedral. About the middle of the twelfth century, however, it was resolved to erect a much larger cathedral on the Île de la Cité, suitable for the capital of so important a country as France had become under Louis VI and Louis VII; and since the cult of the Blessed Virgin had then long been increasing, it was also decided to dedicate the new building to Our Lady alone, to the exclusion of St. Stephen. The two early churches were therefore cleared away by degrees, and in 1163 the work of erecting the present church was begun under Bishop Maurice de Sully, the first stone being laid by Pope Alexander III, in person. The relics of St. Stephen were reverently conveyed to a new church erected in his honour on the hill of Ste. Geneviève, south of the river (now represented by St. Étienne-du-Mont, to be described hereafter), and Our Lady was left in sole possession of the episcopal edifice. Nevertheless, it would seem that the builders feared to excite the enmity of so powerful a saint as the Protomartyr; for many memorials of St. Stephen remain to this day in the existing cathedral, and will be pointed out during the course of our separate survey.

Notre-Dame de Paris is an edifice in the Early French Gothic style, the first great church in that style to be erected in France, and the model on which many others were afterwards based. Begun in 1163, it was consecrated in 1182, but the western front was not commenced till 1218, and the nave was only finished towards the middle of the 13th century. Much desecrated in the Revolution, the cathedral has been on the whole admirably restored. It stands at present lower than it once did, owing to the gradual rise of the surrounding ground; formerly, it was approached by thirteen steps (the regulation number, imitated from the Temple at Jerusalem). It has two western towers, instead of one in the centre where nave and transepts intersect, as is usual in England; so have all the cathedrals in France which imitate it. This peculiarity is due to the fact that French Gothic aims especially at height, and, the nave being raised so very high, a tower could not safely be added above it. Other differences between English and French Gothic will be pointed out in detail in the course of our survey.

Though Notre-Dame was the first great building in Paris proper, it must be borne in mind that the magnificent Basilica of St. Denis, four miles to the north, and also the Abbey Church of St. Germain-des-Prés, in the southern suburb, antedated it by several years.

Recollect three things about Notre-Dame. (1) It is a church of Our Lady: therefore, most of it bears reference to her cult and legends. (2) It is the cathedral church of Paris: therefore, it is full of memorials of local saints—St. Denis, Ste. Geneviève, St. Marcel, Bishop of Paris, etc., amongst whom must also be classed St. Stephen. (3) It is a royal church: therefore it contains many reminders of the close alliance of Church and State. Thus understood, Notre-Dame becomes an epic in stone.

Open daily, all day long, free. Take your opera-glasses.]

Go along the Rue de Rivoli as far as the Square of the Tour St. Jacques. Walk through the little garden. Notice, in passing, *the tower—all that now remains of the church of St. Jacques-de-la-Boucherie—used at present as a meteorological observatory. Turn down the Rue St. Martin to the Pont Notre-Dame. In front, L, stands the Hôtel-Dieu; R, the Tribunal de Commerce; centre, the Marché-aux-Fleurs; at its back, the Prefecture de Police. Continue straight along the Rue de la Cité, passing, R, the main façade of the modern Palais de Justice (with a glimpse of the Ste. Chapelle) till you come to the broad and open Place Notre-Dame (generally known by its mediæval name of the Parvis). Take a seat under the horse-chestnuts on the north side of the Place, opposite the equestrian statue of Charlemagne, in order to examine the façade of the cathedral.

The **west front, dating from the beginning of the 13th century (later than the rest), consists of two stories, flanked by towers of four stories. The first story contains the three main portals: L, the door of Our Lady; centre, of her Son; R, of her Mother. On the buttresses between them stand four statues: extreme L, St. Stephen; extreme R, St. Marcel, Bishop of Paris (a canonized holder of this very see); centre L, the Church, triumphant; centre R, the Synagogue, dejected (representing between them the Law and the Gospel). This first story is crowned and terminated by the Galerie des Rois, containing figures of the kings of Israel and Judah, ancestors of the Blessed Virgin (others say, kings of France to the date of the building), destroyed in the great Revolution, but since restored. On the parapet above it stand, R and L, Adam and Eve; centre, Our Lady and Child with two adoring angels—the Fall and the Redemption. The second story contains the great rose window and two side-arches with double windows. The third story of the towers consists of a graceful open-work screen, continued in front of the nave, so as to hide its ugly gable (which is visible from further back in the Place), thus giving the main front a fallacious appearance of having three stories. The final or fourth story of the towers is pierced on each side by two gigantic windows, adding lightness to their otherwise massive block. The contemplated spires have never been added. This façade has been copied with modifications in many other French cathedrals.

Now approach the front, to examine in detail the **great portals, deeply recessed, as is usual in French cathedrals, owing to the massive masonry of the towers. The left or northern doorway—that of Our Lady (by which her church is usually entered) bears on its central pier a statue of the Virgin and Child; beneath her feet are scenes from the temptation of Eve, who brought into the world sin, and the first murderer Cain, as contrasted with her descendant, the Blessed Virgin, who brought into the world the Redeemer of mankind. Over Our Lady’s head, a tabernacle, representing the relics preserved within. In the tympanum, first tier, L, three patriarchs; R, three kings, typifying the ancestors of the Blessed Virgin. Above, second tier, the Entombment of the Virgin, placed in her sarcophagus by angels, and attended by the apostles with their familiar symbols. Higher still, third tier, the Coronation of the Virgin, in the presence of her Son, with adoring angels. The whole thus represents the Glory of Our Lady. At the sides below, life-size figures; extreme L, Constantine, first Christian Emperor; extreme R, Pope Silvester, to whom he is supposed to have given the patrimony of St. Peter—the two representing the union of Church and State. Next to these the great local saints: L, St. Denis, bearing his head, and guided by two angels; R, St. John Baptist, St. Stephen, and Ste. Geneviève, with the devil endeavouring to extinguish her taper, and a sympathizing angel. The figures on the arch represent spectators of the Coronation of the Virgin. Minor subjects—signs of the Zodiac, Months, etc.—I leave to the ingenuity and skill of the reader. The *centre doorway (commonly called the Porte du Jugement) is that of the Redeemer, Our Lady’s Son; on its central pier, fine modern figure of Christ blessing; above, in the tympanum, the usual Last Judgment. First tier (modern) the General Resurrection, with angels of the last trump, and kings, queens, bishops, knights, etc., rising from their tombs; conspicuous among them is naturally St. Stephen. Second tier, St. Michael the Archangel weighing souls, with devils and angels in waiting, the devils cheating; R, the wicked (on Christ’s left) hauled in chains to hell; L, the saints (on His right) ascending to glory. On the summit, third tier, the New Jerusalem, with Christ enthroned, showing His wounds in mercy, flanked by adoring angels holding the cross, spear, and nails; L, the Blessed Virgin, patroness of this church; and R, Ste. Geneviève, patroness of Paris, interceding for their votaries. (Last figure is usually, but I think incorrectly, identified as St. John the Evangelist, who has no function on a Parisian Cathedral.) This relief, closely copied at the Ste. Chapelle, is itself imitated from one at St. Denis. On the lintels the Wise (L) and Foolish (R) Virgins; L and R on jambs, life-size figures of the Twelve Apostles, with their usual symbols. Observe the beautiful ironwork of the hinges. The third or southern portal, that of St. Anne—the Mother of the Virgin—contains older work than the other two, replaced from the earlier church on the same site. The style of the figures is therefore Romanesque, not Gothic; so is the architecture represented in them. On the centre pier, St. Marcel, Bishop of Paris. Above, tympanum, history of St. Anne; first tier, centre, the meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate; L, Marriage of the Virgin; R, her Presentation by St. Anne in the Temple, etc. Second tier, the Nativity, and the visit of the Magi to Herod; at the summit, third tier, Madonna enthroned, with adoring angels, a king, and a bishop—Church and State once more identified. The work on this doorway much resembles that at St. Denis. Magnificent iron hinges, brought from old St. Stephen’s.

Walk round the quay on the South side to examine the body of the church. Notice the lofty Nave, and almost equally lofty Aisles, with (later) side-chapels built out as far as the level of the Transept; also, the flying buttresses. As in most French churches, the transepts are short, and project but little from the aisles. The South Transept has a good late façade with two rose-windows. Its portal—ill visible—is dedicated (in compensation) to the displaced St. Stephen, and contains on the pier a figure of the saint, robed, as usual, as a deacon; in the tympanum are reliefs of his preaching, martyrdom, death, and glorification. Note, to the R, a small relief of St. Martin of Tours dividing his cloak with the beggar.

Enter the little garden further east, which occupies the site of the former archevêché, in order to observe the characteristic French form of the choir—a lofty and narrow apse, with apsidal aisles and circular chapels added below, the whole forming what is called a chevet. The light flying buttresses which support the soaring and slender choir add greatly to the beauty and picturesqueness of the building. Pretty modern Gothic fountain. Quit the garden and continue round the Northern side of the Cathedral. The first (small) door at which we arrive—the Porte Rouge—admits the canons. It is a late addition, built in 1407 by Jean sans Peur, Duke of Burgundy, in expiation of his murder of the Duke of Orleans; the donor and his wife kneel on each side of the Coronation of the Virgin in the tympanum. Notice here the gargoyles and the graceful architecture of the supports to the buttresses. The second (larger) door—the Portail du Cloître, so called from the cloisters long demolished—in the North Transept contains a good statue of the Madonna on the pier; above, in the tympanum, confused figures tell obscurely the legend of the monk Theophilus, who sold his soul to the devil. Stand opposite this door, on the far pavement, to observe the architecture of the North Transept. The best point of view for the whole body of the cathedral, as distinct from the façade, can be obtained from the Quai de Montebello on the south side of the river.

To visit the interior, enter by the L, or northern door of the façade—that of Our Lady. The lofty nave is flanked by double aisles, all supported by powerful piers. Walk across the church and notice all five vistas. Observe the height and the delicate arches of the triforium, or pierced gallery of the second story, as well as the windows of the clerestory above it—the part of the nave which rises higher than the aisles, and opens freely to the exterior. Walk down the outer R aisle. The side-chapels, each dedicated to a separate saint, contain the altars and statues of their patrons. Notice the shortness of the Transepts, with their great rose windows; observe also the vaulting of the roof, especially at the intersection of the four main arms of the building. The entrance to the choir and ambulatory is in the R or S Transept. Close by, near the pillar, Notre-Dame de Paris, the wonder-working mediæval statue of Our Lady. The double aisles are continued round the choir, which is separated from them by a wall and gateways. Approach the brass grills, in order to inspect the interior of the choir, whose furniture was largely modernised and ruined by Louis XIV, in accordance with a misguided vow of his father. Chapels surround the ambulatory, many of them with good glass windows and tolerable frescoes. The chapel at the end is that of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows.

By far the most interesting object in the interior, however, is the series of **high reliefs in stone, gilt and painted (on the wall between choir and ambulatory), executed early in the 14th century by Jehan Ravy and his nephew, Jehan de Bouteillier, which, though inferior in merit to those in the same position in Amiens cathedral, are admirable examples of animated and vigorous French sculpture of their period. The series begins on the N side of the choir, at the point most remote from the grill which leads to the Transept. The remaining subjects (for some, like the Annunciation, are destroyed) comprise the Visitation; Adoration of the Shepherds; Nativity; Adoration of the Magi (note the Three Kings, representing the three ages of man; the oldest, as usual, has removed his crown, and is offering his gift); the Massacre of the Innocents; the Flight into Egypt (where a grotesque little temple, containing two odd small gods, quaintly represents the prevalence of idolatry); the Presentation in the Temple; Christ among the Doctors; the Baptism in Jordan (with attendant angel holding a towel); the Miracle at Cana; the Entry into Jerusalem (with Zacchæus in the tree, and the gate of the city); the Last Supper; the Washing of the Apostles’ feet; and the Agony in the Garden. The tourist should carefully examine all these subjects, the treatment of which strikes a keynote. Similar scenes, almost identical in their figures, will be found in abundance at Cluny and elsewhere. Note, for example, the symbolical Jordan in the Baptism, with St. John pouring water from a cup, and the attendant angel, all of which we shall often recognise hereafter.

The series is continued on the other (S) side of the choir (a little later in date, with names in Latin underneath; better modelled, but neither so quaint nor so vigorous). The subjects begin by the grill of the South Transept, with the “Noli me tangere” or Apparition to Mary Magdalen (Christ as a gardener); the Apparition to the Marys; to Simon Peter; to the Disciples at Emmaus (dressed as mediæval pilgrims); to the Eleven Apostles; to the Ten and Thomas; to the Eleven by the sea of Tiberias; to the Disciples in Galilee; and on the Mount of Olives. The intervening and remaining subjects—Scourging, Crucifixion, Ascension, etc.—were ruthlessly destroyed by Louis XIV, in order to carry out his supposed improvements in accordance with the vow of his father, Louis XIII. The woodwork of the choir-stalls, executed by his order, is celebrated, and uninteresting. You may omit it. The Treasury contains little of artistic value. The Crown of Thorns still figures in its inventory.

Leave the Choir by the door by which you entered it, and seat yourself for a while at the intersection of the Nave and Transepts, in order to gain a good idea of the Apse, the Choir, and the general arrangement of the shortly cruciform building. Observe the beautiful vaulting of the roof, and the extent to which the church is born on its piers alone, the intervening walls (pierced by windows and triforium-arches) being intended merely for purposes of enclosure. Note also the fine ancient glass of the rose windows. Quit the church by the North or Left Aisle, and come back to it often.

Those who are not afraid of a spiral staircase, mostly well lighted, should ascend the Left or North Tower (tickets fifty cents. each, at the base of the tower). Stop near the top to inspect the gallery, with the famous birds and demons. The view hence embraces from the front the Tower of St. Jacques; behind it, the hill of Montmartre, with the white turrets and cupolas of the church of the Sacré-Cœur; a little to the L, St. Eustache; then the Tribunal de Commerce; St. Augustin; the Louvre; the roof of the Ste. Chapelle; the Arc de Triomphe; the twin towers of the Trocadéro; the Eiffel Tower; the gilded dome of the Invalides; St. Sulpice, etc. The Île de la Cité is well seen hence as an island. Note also the gigantic size of the open screen, which looked so small from below. Ascend to the top. Good general panorama of the town and valley. This is the best total view of Paris, far superior to that from the Eiffel Tower, being so much more central.

Return by the Pont d’Arcole (whence you get a capital notion of the bifurcation of the Seine around the Île St. Louis), and then pass the modern Hôtel-de-Ville, with St. Gervais behind it, on your way home to the Rue de Rivoli.

[Map of] HISTORIC PARIS

This Map represents approximately the growth of Paris, outside the island, at different epochs. Earlier buildings are printed in black; later streets and edifices are shown by means of dotted lines. But the Map does not represent the aspect of Paris at any one time; it merely illustrates this Guide: thus, the original Château of the Louvre is marked in black; the later Palace is dotted; whereas the Madeleine, a much more modern building than the Louvre of François I, is again inserted in black, because it does not interfere with the site of any more ancient building. In very early times the town spread south as far only as Cluny, and north (just opposite the island) as far as the Rue de Rivoli. The subsequent walls are marked approximately on the Map, with the chief edifices enclosed by them. The fortifications of Louis XIII were demolished by Louis XIV, who substituted for them the broad streets still known as the Boulevards. This Map shows, roughly speaking, the extent of Paris under Louis XIV; by comparing it with Baedeker’s Map of Modern Paris, the small relative size of the 17th-century town will be at once appreciated. Nevertheless, the inner nucleus here mapped out contains almost everything worthy of note in the existing city.

[THE earliest overflow of Paris was from the Île de la Cité to the Left or South Bank (Rive Gauche).

The reason for this overflow is clear. The city was situated on a small island, near the head of navigation; it guarded the passage of the Seine by the double bridge. Naturally, however, at a time when all civilization lay to the south, as the town began to grow, it spread southward, towards Rome, Lyons, Marseilles, Bordeaux, Toulouse, Arles, Nîmes, and the Roman culture. To the north at that time lay nothing but comparative barbarism—the Britons and the Germans; or later, the English, the Normans, and the Teutonic hordes. Hence, from a very early date, Paris first ran southward along the road to Rome. Already in Roman times, here stood the palace of Constantius Chlorus and Julian, now the Thermes—the fortress which formed the tête du pont for the city. Later, the southern suburb became the seat of learning and law; it was known by the name which it still in part retains of the Université, but is oftener now called the Quartier Latin. At first, however, only a small portion of the Left Bank was built over. But gradually the area of the new town spread from the immediate neighbourhood of the old Hôtel-Dieu, with its church or chapel of St. Julien-le-Pauvre, to the modern limit of the Boulevard St. Germain; and thence again, by the time of Louis Quatorze, to the further Boulevards just south of the Luxembourg. It is interesting to note, too, that all this southern side, long known as the Université, still retains its position as the learned district. Not only does it include the students’ region—the Quartier Latin—with many of the chief artistic studios, but it embraces in particular the Sorbonne, or University, the Institute of France, with its various branches (Académie Française, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Académie des Sciences, des Beaux-Arts, etc.), the École des Beaux-Arts, the École de Médicine, the Collège de France, the Lycées St. Louis, Louis-le-Grand, and Henri IV, the École Polytechnique, the École des Mines, the Bibliothèque Ste. Geneviève, the Jardin des Plantes, and the Luxembourg Museum of Modern Paintings. In short, the Left Bank represents literary, scientific, artistic, and educational Paris—the students in law, arts, and medicine, with their own subventioned theatre, the Odéon, and their libraries, schools, laboratories, and cafés. It is further noticeable that these institutions cluster thickest round the older part of the southern suburb, just opposite the Cité, while almost all of them lie within the limits of the outer boulevards of Louis XIV.

The Quartier Latin surrounds the Sorbonne, and is traversed by the modern Boulevard St. Michel. The Faubourg St. Germain, immediately to the west of it (surrounding the old Abbey of St. Germain-des-Prés) is of rather later date; it owes its origin in large part to the Renaissance spirit, and especially to Marie de Médicis’ palace of the Luxembourg. It is still the residence of many of the old nobility, and is regarded as the distinctively aristocratic quarter of Paris, in the restricted sense, while the district lying around the Champs Élysées is rather plutocratic and modern than noble in the older signification of the word.

The visitor will therefore bear in mind distinctly that the South Side is the Paris of the Students.]

[The primitive nucleus of the suburb on the South Side consists of the Roman fortress palace, the tête du pont of the Left Bank, now known as the Thermes, owing to the fact that its principal existing remains include only the ruins of the baths or thermæ. This colossal building, probably erected by Constantius Chlorus, the father of Constantine, covered an enormous area south of the river. After the Frankish conquest, it still remained the residence of the Merwing and Karling kings on the rare occasions when they visited Paris; and it does not seem to have fallen into utter decay till a comparatively late date in the Middle Ages. With the Norman irruptions, however, and the rise of the real French monarchs under Eudes and the Capets, the new sovereigns found it safest to transfer their seat to the Palace on the Island (now the Palais de Justice), and the Roman fortress was gradually dismantled. In 1340 the gigantic ruins came into the hands of the powerful Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, near Mâcon, in Burgundy; and about 1480, the abbots began to erect on the spot a town mansion for themselves, which still bears the name of the Hôtel de Cluny. The letter K, the mark of Charles VIII (1483–1498), occurs on many parts of the existing building, and fixes its epoch. The house was mostly built by Jacques d’Amboise, abbot, in 1490. The style is late Gothic, with Renaissance features. The abbots, however, seldom visited Paris, and they frequently placed their town house accordingly at the disposition of the kings of France. Mary of England, sister of Henry VIII, and widow of Louis XII, occupied it thus in 1515, soon after its completion. It was usual for the queens of France to wear white as mourning; hence her apartment is still known as the Chambre de la reine blanche.

At the Revolution, when the property of the monasteries was confiscated, the Hôtel de Cluny was sold, and passed at last, in 1833, into the hands of M. du Sommerard, a zealous antiquary, who began the priceless collection of works of art which it contains. He died in 1842, and the Government then bought the house and museum, and united it with the Roman ruin at its back under the title of Musée des Thermes et de l’Hôtel de Cluny. Since that time many further objects have been added to the collection.

At Cluny the actual building forms one of the most interesting parts of the sight, and is in itself a museum. It is a charming specimen of a late mediæval French mansion; and the works of art it contains are of the highest artistic value. I am able briefly to describe only what seem to me the most important out of its many thousands of beautiful exhibits. At least two whole days should be devoted to Cluny—one to the lower and one to the upper floor. Much more, if possible.]

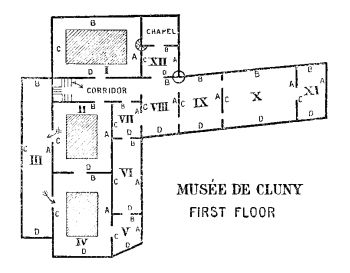

MUSÉE DE CLUNY GROUND FLOOR

Go to the Place du Châtelet; cross the bridge, and the Île de la Cité; also, the Pont St. Michel to the South Side. Good view of Notre-Dame to L. In front lies the modern Boulevard St. Michel, with the Fontaine St. Michel in the foreground (statue by Duret). Continue along the Boulevard till you reach the Boulevard St. Germain, another great modern thoroughfare which cuts right through the streets of the old Faubourg and the narrow alleys of the Latin Quarter. The Garden at the corner contains all that remains of the Roman Palace. Notice its solid masonry as you pass. Then, take the first turn to the L, the Rue du Sommerard, which leads you at once to the door of the Museum.

Notice the late semi-Gothic Gateway, resembling that of an Oxford college. Pass through the flat-arched gate into the handsome courtyard. To the L is a late Gothic loggia, containing a few antiques. In front stands the main building, with square windows and high dormers, bearing the staff and pilgrim’s scallop, the symbol of St. James, with the cardinal’s hat and scutcheons and devices of the family d’Amboise, thus indicating the name of Jacques d’Amboise, the abbot who built it. Entrance to the R. Open free, daily, 11 to 4 or 5, except Mondays.

The first suite of rooms which we enter form some of the apartments of the original building. Observe the fine timbered ceilings.

Room I.—Panels, etc., in wood-carving.

Room II.—*Fine French chimney-piece, by Hugues Lallement, dated 1562, representing Christ and the Woman of Samaria at the well, brought from a house at Châlons-sur-Marne. R and L of entrance (wall A on plan), wooden seats, with canopy, holding good Gothic wood-carvings. Notice L of door, a Deposition in the Tomb; (801) Madonna and Child; then, Birth of the Virgin, with St. Anne in a bed; and below, head of a Saint, hollow, intended to contain her skull or relics. Near it (762), decapitation of St. John Baptist, German, 16th century; and (789) Death of the Virgin. R of doorway, three reliquary heads, and (783 and 784) two groups of the Education of the Virgin. Above, several representations of the Circumcision. Wall B, between the windows, (745) quaint reliquary head of St. Mabile, one of St. Ursula’s 11,000 virgins, the hair gilt, Italian, 15th century; near it, Angel of the Annunciation; Madonna and Child; and Flight into Egypt. Fine wooden chests. In the cases, collections of shoes, uninteresting.

Room III.—Wood-carvings, more or less Gothic. Wall A, (788) Madonna supporting the dead Christ, under a canopy, 16th century; (816) Holy Women, with small figure of the donor, kneeling. (709) large carved altar-piece, end of 15th century; in the centre, Crucifixion, with quaintly brutal Roman soldiers, fainting Madonna, and Holy Women in fantastic head-dresses of the period; below, Nativity, and Adoration of the Magi; L side, above, Flagellation, with grotesquely cruel soldiers; beneath it, angels displaying the napkin of St. Veronica; R side, above, Deposition in the Tomb; beneath it, angels supporting the instruments of the Passion—a splendid piece of Flemish carving. Above, two statues of St. George. Further on (712), votive triptych against the plague, Flemish, carved, with painted flaps on the doors; L, St. Sebastian, with arrows of the pestilence; R, St. Roch exhibiting his plague-spot, with angel who consoled him and dog who fed him (see the legend in Mrs. Jameson); centre, Adoration of the Magi; the Three Kings represent (as usual) the three ages of man, and also the three old continents, Europe, Asia, Africa; hence the youngest king is represented as a Moor. Other episodes (Flight into Egypt, Return of Magi, etc.), in the background—late 15th century. Wall B, first window, stained glass, German panes, 15th century, Annunciation, in two panels (1960 and 1957). Beyond it (830), in woodwork, 16th century, Coronation of the Virgin by Christ and God the Father—a somewhat unusual treatment. Above (758), Stem of Jesse, representing the descent of Christ; notice David with his harp and other kings of Israel; late 15th century. Second window (1958 and 1959), St. Hubert and St. Lambert, companions to the Annunciation; (721) dainty little Crucifixion (16th century), in coloured German wood-carving; (1686) Flemish painting, school of Van Eyck, Crucifixion. Wall D, windows (1961 and 1962), St. Peter and St. George; (1963 and 1964) St. Hubert, and St. Antony Abbot (with his pig, staff, and bell). Wall C, altar-piece, unnumbered; subjects much as opposite; centre, Crucifixion; beneath it, Nativity, Adoration of Magi. L, Way to Calvary (with grotesquely brutal soldiers); beneath it, Annunciation (notice the prie-dieu, book, and bed in the background), and Visitation; R, Descent from the Cross, with St. John and the Marys; beneath it, Circumcision, and Presentation in the Temple. (710) Deposition from the Cross, very good, with painted wings from the Passion. All the wood-carvings in this room deserve careful attention. Inspect them all, and, as far as possible, discover their subjects.

Room IV.—Fine Renaissance chimney-piece, by Hugues Lallement, 16th century, representing Actæon transformed into a stag by Diana, whom he has surprised in the act of bathing. (Subjects from the myth of Diana are favourites with the French Renaissance artists, owing to the influence of Diane de Poitiers.) From Châlons-sur-Marne, same house as that in Room II. Wall A (1779 and 1778), Renaissance classical paintings, part of a large series continued elsewhere; (1428) fine Renaissance carved cabinet (Diana and Chimæras); contrast this and neighbouring Renaissance work with the mediæval carvings in adjacent rooms. Wall B (6329), quaint old Flemish tapestry, representing the Angels appearing to the Shepherds; the Nativity; the Adoration of the Magi; and the Agony in the Garden. Study the arrangement of all these figures, which are conventional, and will reappear in many other examples of various arts. Wall C, R and L of fireplace, good Renaissance wood-carving. Wall D, fine cabinets. In the cases, medals.

Room V, to the side. Debased Italian and Spanish work of the 17th and 18th centuries. Centre, Adoration of the Magi, a meretricious Neapolitan group of the 17th century, intended to place in a church as a Christmas berceau. The costumes of the Three Kings, representing the three continents, the ruined temple in which the action takes place, and the antique statue in the background of the Madonna and St. Joseph, should all be noticed. Contemptible as a work of art, this florid composition of dolls is interesting and valuable for its spirited arrangement, and for the light it casts on the conception of the subject. The room also contains other similar church furniture of the 17th and 18th centuries. Observe their theatrical tinsel style and their affected pietism, as contrasted with the simplicity, naïveté, and truth of earlier periods. Take, as an extreme example of this tendency, the relief of the Annunciation on Wall D, to the R of the entrance door, and compare it with examples of the same subject in other rooms of the collection. Wall B, facing the entrance, good case of miscellaneous woodwork containing excellent Spanish art of this bad period—a Last Supper, a St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, a Massacre of the Innocents, the Faint of St. Catherine, St. Antony the Abbot, St. Antony of Padua carrying the infant Christ, and other figures. A large gilt tabernacle, on Wall C, also contains a debased figure of St. Anthony of Padua, from an altar dedicated to the Saint. Identify as many of these saints as possible, and remember their symbols.

We now quit the older suite of apartments, and enter a large central glass-covered court—Room VI, entirely modern. The Corridor is occupied by early altar paintings, for the most part of little value. Notice on the L, by the staircase (1701), a Giottesque Madonna and Child—Florentine, 15th century. Near it (1666), two oval panels, representing the Annunciation, divided (as frequently happens with this subject) into two distinct portions, and probably flanking a doorway in their original position—Italian, 14th century. All the paintings on this wall, mostly unsatisfactory as works of art, are valuable for their symbolism and the light they throw on the evolution of their subjects. For example: (1676), between the Annunciation pictures, represents the distribution of holy wine which has touched the relics (I think) of St. Hubert. Further on, we have a group of six Apostles; beginning from the R, St. Peter with the keys, St. John Evangelist with the cup and serpent, St. Andrew with his cross, St. Bartholomew with his knife, St. James the Greater with the pilgrim’s staff and scallop, and St. James the Less with a crosier and book. R of the staircase is a stone figure of St. Denis bearing his head, French, 15th century; also, a good statue of the Madonna, a little later. Above the doorway, R, are portions of a large Spanish altar-piece; in the centre, the Crucifixion; extreme R, Assumption of the Virgin, etc. Beyond it comes the continuation of the tabernacle already noticed, containing the six remaining Apostles, with the symbols of their martyrdom. Next, a fine Spanish altar-piece of the 15th century, from a church of St. Martin; in the centre, St. Martin dividing his cloak with the beggar; round it various other subjects, among them St. Antony with his pig, St. Stephen, in deacon’s robes, with the stones of his martyrdom, St. Jerome in the desert beating his bosom with a flint before the crucifix, St. Francis displaying the stigmata or five wounds of Christ, St. Paul the hermit with his lion, etc. R, towards the courtyard, a fine figure of Adam from St. Denis, a splendid example of the best French nude sculpture of the 14th century.

We now enter the covered courtyard or Room VI proper, filled with fine examples of French mediæval sculpture. Several of the objects bear labels sufficiently descriptive. I will therefore only call attention to a few among them. Wall D, two wooden Flemish statues (Our Lady and St. John at Calvary), R and L of the doorway; (417) carved marble monument of the 10th or 11th century; very fine workmanship, with distinct reminiscences of the antique. Wall A, *Magnificent stone frieze or reredos, originally gilt and coloured, representing the History of St. Benedict, from St. Denis; in the centre, Baptism in Jordan (compare the relief of the same subject in Notre-Dame); R and L, preaching and miracles of St. Benedict (overthrow of idols, cure of a dying woman). Middle of wall (6328), fine Italian tapestry, 16th century, representing the Adoration of the Magi; observe the attitude of the kings, together with the ox and ass in the background, invariable concomitants of the Nativity in art. Beneath (728), early wooden Madonna (13th century, Auvergne), with Byzantine aspect. Beautiful Romanesque capitals—Creation of Eve, etc. Wall B*(237), exquisite stone frieze or reredos from the church of St. Germer, about 1259, much-mutilated, but originally one of the most perfect specimens of French 13th century carving; it still betrays traces of colour. In the centre, Crucifixion, with Virgin and St. John: on either side (as at Notre-Dame), the Church, with cross and chalice, and the Synagogue, with eyes blinded: then, R and L of cross, St. Peter and St. Paul: beyond them, Annunciation and Visitation: finally, L, St. Ouen, uncle of St. Germer, cures a wounded warrior; R, St. Germer asks leave of King Dagobert to found the Abbey from which this came. Above it (509), exquisitely grotesque relief of the Resurrection with sleeping Roman soldiers, one of a set in alabaster, French 14th century (500 to 512), all of which deserve to be inspected; meanings of all are obvious except (501) St. Ursula. Still higher, fragment of the original Last Judgment on the central west door of Notre-Dame, Paris, before the restoration—interesting as showing the grounds on which Viollet-le-Duc proceeded; (6322), tapestry, Arras, 15th century, various scriptural subjects, confused, but decipherable. Beneath it, L, *beautiful stone relief (reredos) of the legend of St. Eustace, from the church of St. Denis—a fine French work of the 14th century. In the centre, Crucifixion; extreme L, St. Eustace, hunting, is converted by the apparition of the Christ between the horns of the stag he is pursuing; further R, his baptism, nude, in a font, as in all early representations; still further R, his trials and history; while he crosses a river with one of his children, a wolf seizes one, while a lion devours the other; last of all, reunited miraculously with his family, he and they are burned alive as martyrs by the Emperor Trajan, in a brazen bull. Observe naïf boy with bellows. The whole most delicately and gracefully sculptured. Next, coloured stone relief of the Passion—French 14th century; subjects, from R to L: the kiss of Judas (observe Peter drawing the sword); Flagellation; Bearing of the Cross, with Simon of Cyrene; Deposition in the Tomb; Resurrection; and Christ in Hades, delivering Adam and Eve from the jaws of death, realistically represented here and elsewhere as the mouth of a monster; notice in this work the colour and the Gothic architecture and decoration of the background, which help one to understand features that are missing in many other of these reredoses. Then, stone relief of the Annunciation, Visitation, and Nativity, very simply treated: notice the usual ox and ass in the manger. Above it, *(4763), good mosaic of the Madonna and Child with adoring angels, by Davide Ghirlandajo, of Florence, placed by the President Jean de Ganay (as the inscription attests) in the church of St. Merri at Paris. Wall C (513–518), interesting alabaster reliefs of the Passion, French, 14th century. Between them, Coronation of the Virgin, French, 15th century. (725) Good wooden figure of St. Louis, covered with fleur-de-lis in gold, from the Sainte Chapelle. [Here is the door which leads to the Musée des Thermes. Pass it by for the present.] Beyond it, continuation of the alabaster reliefs (514 and 517), etc.: examine them closely. Between them (435), Circumcision, in marble, early 15th century, French, full of character. Beneath it (429, etc.), admirable figures of mourners, from the tomb of Philippe le Hardi, at Dijon, 14th century. Wall D, again (1291), terra-cotta, coloured: Madonna and St. Joseph, with angels, adoring the Child (child missing), ox and ass in background; R, Adoration of Magi; notice once more the conventional arrangement: L, Marriage of the Virgin, a high priest joining her hand to Joseph’s, all under Gothic canopies, 15th century, from the chapel of St. Éloy, near Bernay, Eure. I omit many works of high merit.

The centre of this room is occupied by several good statues. Examine each; the descriptive labels are usually sufficient. (A noble *St. Catherine; St. Barbara with her tower; St. Sebastian, pierced with the holes where the arrows have been; a beautiful long-haired wooden Madonna; a fine [Pisan] Angel of the Annunciation, in wood, etc.) Also, several excellent figures of Our Lady. The large part played by the Madonna in this Room, indeed, is typical of her importance in France, and especially in Paris, from the 13th century onward. The church of Notre-Dame is partly a result, partly a cause, of this special cult of the Blessed Virgin.