By FRANK JEWETT MATHER, Jr.

Marquand Professor of Art and Archeology, Princeton University

THE MENTOR

SERIAL No. 48

DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS

MENTOR GRAVURES

| PORTRAIT OF HIMSELF | Dürer |

| PORTRAIT OF YOUNG WOMAN | Dürer |

| HIERONYMUS HOLZSCHUHER | Dürer |

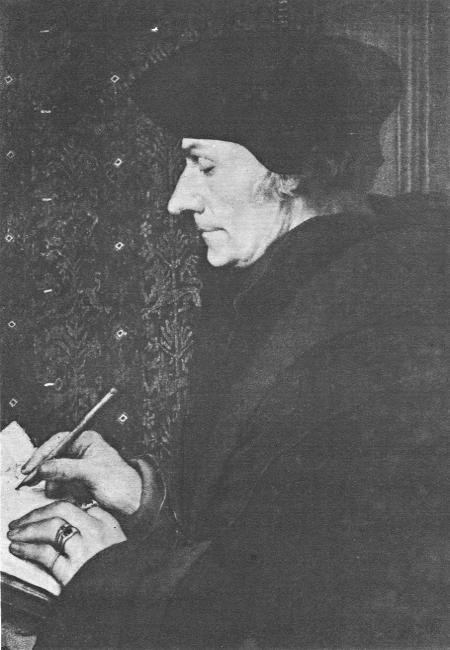

| ERASMUS | Holbein |

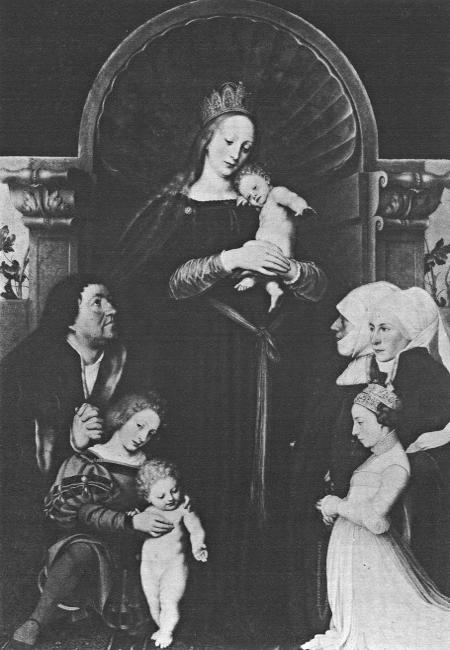

| MEIER MADONNA | Holbein |

| QUEEN JANE SEYMOUR | Holbein |

A great painter gives us much more than skilfully arranged lines and colors. These are only the symbols by which we may share his vision of the world. What we must try to find in any work of art is the soul of a great man. This is particularly true of so serious an artist as Albrecht Dürer (doo´-rer) of Nuremberg, who was born in 1471, a little before the outbreak of the Protestant Reformation. In that movement he shared heartily, but without bitterness for the Catholic Church, in which he had been bred. He was a broad-minded Christian, a thoughtful and thorough craftsman. In the little drawing he did of himself at thirteen we see the serious, worried lad already a competent draftsman. We may see him again in the Madrid portrait, the confident young painter of twenty-seven; at Munich, the mature and dignified artist of thirty-six; and finally, in the haggard woodcut profile, as a man grown old with unabated ardor of spirit.

The accent of study and concentration is present at every stage. He painted so carefully that such work did not pay him. The engravings, of which he did about 100 with his own hand, brought him in a comfortable fortune. They are marvels of faithful observation and of minute execution. When old age and illness made painting and engraving difficult, he wrote books on the proportions of the human body and the art of fortification. We must not expect a man of such stern and high ideals to be charming. He may, however, have many true things to tell about life and character that it behooves us to know.

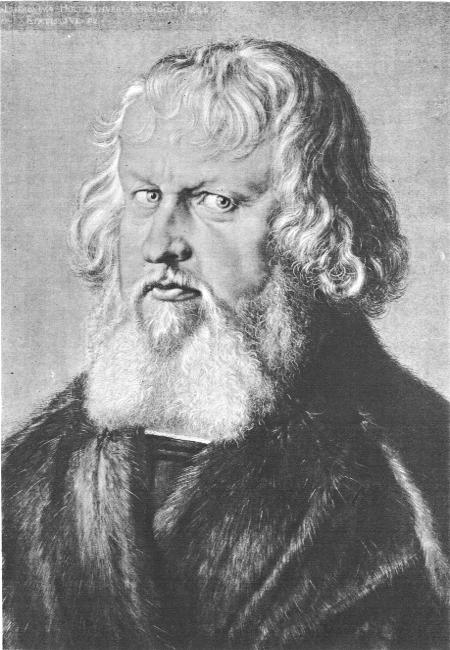

MICHAEL WOHLGEMUTH

By Dürer

At fifteen Dürer was apprenticed to the painter and woodcutter, Michael Wohlgemuth. The lad saw the advantages of the new process of woodcutting and copperplate engraving, by which a design might be multiplied. Then the good wife Agnes, whom he married by parental arrangement at twenty-three, came to be a thrifty saleswoman for the prints. The work was of the most taxing kind, being all done under a magnifying lens. When the firm lines had been graven in the copper they were filled with ink, which under heavy pressure from a roller press was transferred to paper. The lines of Dürer were so fine and closely spaced that the whole print got a charming pearly quality which is well represented in our reproductions. Bible stories, the life of Christ and the Virgin, popular customs, portraits of his learned friends, and a strange series of plates having a moral meaning may be specially noted. In 1513 and 1514 he engraved what are called the four master plates, two of which are reproduced.

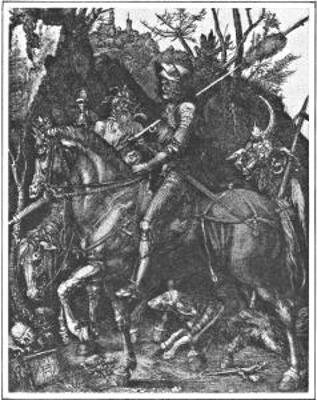

THE KNIGHT, DEATH, AND THE DEVIL, by Dürer

The Knight, Death, and the Devil. Upon a splendid steed an armored knight rides through a rocky defile, high above which is seen his goal, an imposing castle. Forms of horror beset the traveler. The horse sniffs impatiently at a skull in the road. King Death himself, mounted on a jaded nag, holds up an hourglass. The Knight’s hours are measured. Behind the horse stalks a swinelike form, which may represent the lower temptations that assail a warrior of the Lord. Regardless of these nightmare shapes, the Knight holds his restive horse in the road. Fortitude has overcome sin and fear of death. Such seems the large, informing idea of a picture which would be exquisite if regarded merely as minute delineations of forms of rocks and trees, and textures of hair and armor.

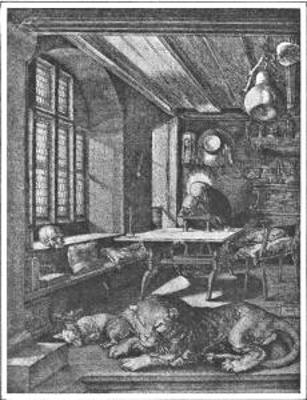

SAINT JEROME IN HIS STUDY, by Dürer

Saint Jerome in His Study. In depicting the Cardinal Saint, who in the late fourth century translated the Holy Scriptures into eloquent Latin, Dürer may well have wished to emphasize the enviable serenity of the scholar’s lot in contrast with the perilous course of the Knight. Everything in this study speaks of peace and steady, satisfactory endeavor. The light shimmers upon wall, floor, and ceiling like a blessing. It seems as if no sight or sound of troublous or unworthy sort could enter this scholar’s sanctuary. The skull and hourglass are no longer symbols of dread. The saint is oblivious of the passage of time, and looks forward to death as the opening of fuller knowledge. The elaborate and beautiful details of the room assure us that this is no mere dream of an idealist, but an actual place that a student of the divine mysteries might inhabit. A different kind of peacefulness pervades the small engraving of the Hermit Saint, Anthony of Egypt, behind whom rise the picturesque walls and roofs of Dürer’s own Nuremberg.

THE ARTIST’S FATHER

By Dürer

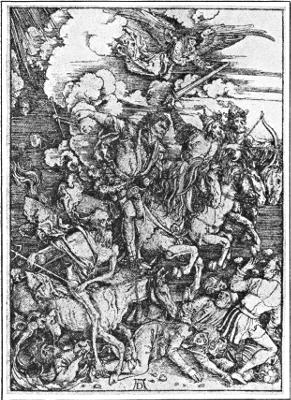

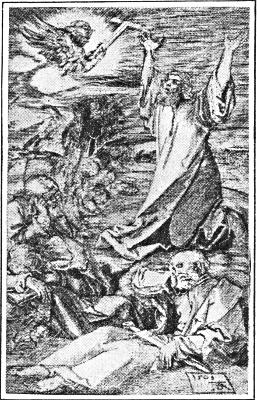

The engravings are by Dürer’s own hand; the woodcuts are copies of his designs by capable assistants. As early as 1499 he had published the impressive illustrations for the Revelation of Saint John. For terror and ferocity the print representing the four riders who begin the destruction of mankind before the last day has never been equaled. For twelve years he worked at the designs for the Life of the Virgin, and a large and a small series of the Passion of Christ. One woodcut from the Little Passion, Christ in Gethsemane with the sleeping apostles, is reproduced. He has used the small scale of the plate to indicate a peculiar heartlessness in the disciples calmly sleeping so near their agonized Lord. The postures of vehement prayer and of complete exhaustion are affectingly truthful. The basis of such designs is the artist’s own pen drawing, which is pasted or traced on a pear-wood plank. All the blank spaces are cut away with a knife, leaving the lines in relief. This wood block may be set up with type pages and printed on an ordinary press. It is thus better adapted to book illustration than engraving, which requires special printing.

About 1511 Dürer reprinted the Revelation, and published the three new books. They were justly popular, and from that time he painted only when he pleased. The woodcuts, which faithfully represent drawings made with a coarse quill pen, will look rude to eyes accustomed to the often meaningless finish of modern illustrations. It will require patience to see how direct, sincere, and vigorous is the expression. With so coarse a tool nothing can be left to chance or smoothed down. Every line must tell, and every line in the Dürer woodcut does tell its story of structure and feeling. Dürer’s woodcuts are as fine in their way as his more popular engravings.

THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

By Dürer

THE AGONY IN THE GARDEN

By Dürer

THE DESCENT FROM THE CROSS

By Dürer

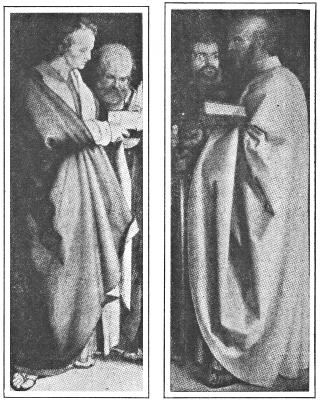

JOHN AND PETER

PAUL AND MARK

By Dürer.

From the first Dürer revealed in portraiture an inflexible curiosity as to form and insight as to character. The earlier portraits, those of his master Wohlgemuth, and of his own father, have a speaking lifelikeness. But the very endeavor to omit nothing and say everything with resolute truthfulness makes some of the early portraits stiff and forbidding. This defect is hardly noticeable in the three admirable portraits of his maturity, which are our special theme.

They were all painted after his Venetian visit of 1506. There he saw portraiture as faithful as his own, but softer and more agreeable. Open-minded student that he always was, he readily learned the lesson. The charming head of a young woman represents the fruits of this new experience. With a comeliness that is by no means merely pretty, one gets the sense also of character and of capacity. The tightly drawn hair, the head held alertly a little forward, tell of aggressiveness with self-control, of perfect physical and mental well-being. It was such strong mothers as this that bore the men who in finance, manufactures, commerce, and scholarship made the little city of Nuremberg famous. Initials on the bodice suggest that this may be the wife Agnes, who was an efficient business partner and a terror to certain easygoing friends. Firm yet minutely varied lines, modeling soft and lifelike but also decisive,—such are the technical merits of this masterpiece.

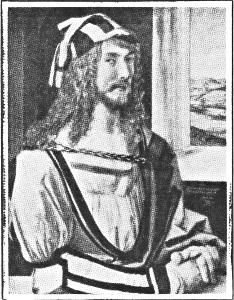

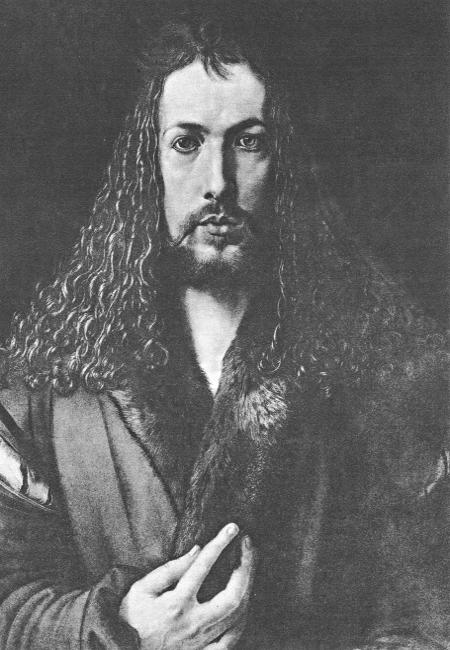

DÜRER, by himself

In the Prado, Madrid.

Among Dürer’s portraits of himself, the head in which the master gave himself the aspect of a Christ is the favorite of many people. The workmanship is of extraordinary carefulness and beauty. Every detail of the fur, of the flowing hair, of the powerful, slender hand, is there; but the effect remains large. There is in the face a sense of dignity, reserve, decision, and sympathy. Other portraits are probably much more like Dürer as Nuremberg saw him. This presents his own ideal of himself as creative artist, exemplifying a spiritual beauty that he ever strove to attain. Despite an old inscription reading 1500, we must date this portrait after that Venetian visit which brought to Dürer new power and self-confidence.

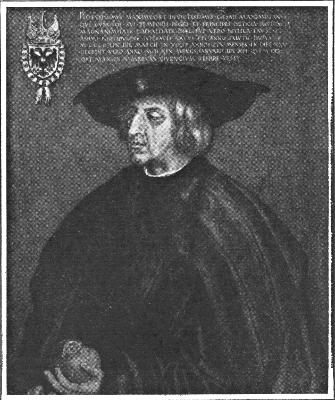

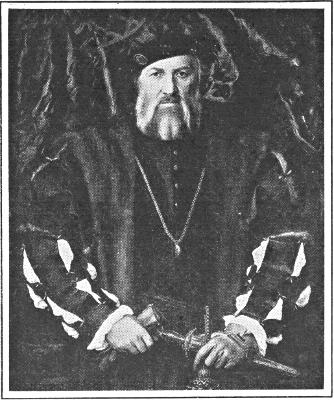

EMPEROR MAXIMILIAN I

By Dürer. In the Imperial Gallery, Vienna.

Efficiency was the trait Dürer most admired. His merchant friend Hieronymus Holzschuher possessed this quality in a high degree, as his portrait shows. He still directs toward an admiring world the bluest, brightest, steadiest eyes ever painted. The silvery hair and beard glisten like a halo before a blue sky. The firm, thin lips under the scant, well kept mustache still tell of the sagacity and persistence that won for Hieronymus a fortune and the mayoralty of a proud city. Nor is this power and rectitude without kindness. One feels the living presence of a man absolutely just, but also quick to see another man’s side, and withal humorous. Of an old age not too frosty and wholly vigorous, this picture is a most remarkable embodiment. That Dürer’s genius is as marked in a slight sketch as in elaborately executed works, witness the charcoal study which he did of his old mother just before her death. Have a few lines ever told more piteously of resigned decrepitude?

In his last years Dürer painted as a legacy to his native town the stately figures of the apostles Paul, Mark, Peter, and John. Already the Protestant movement which he held so dear was breaking up into wrangling sects. Dürer wished to recall men to the founts of Christian wisdom and unity. The apostles wear their grand robes with Roman dignity. The heads are sharply distinguished by temperament. The burning determination of Saint Paul is very unlike the excitability of Saint Mark; the inward serenity of Saint John most unlike the careworn pensiveness of Saint Peter. These are men to move a world.

On the 6th of April, 1528, he passed away, only fifty-seven years old, but exhausted by constant effort. The great bankers, merchants, scholars, and craftsmen of Nuremberg knew that a notable citizen had gone. He had known familiarly Melanchthon and Luther. Raphael had been glad to exchange drawings with him. His engravings and woodcuts were admired throughout Europe. After four centuries he remains the finest exemplar in art of the peculiar steadfastness and thoroughness of the German race. Goethe, the greatest of German poets, has written the finest tribute to Germany’s greatest artist:

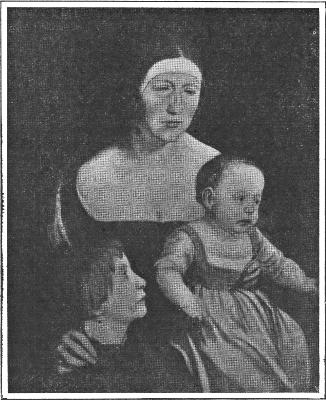

HOLBEIN’S WIFE AND CHILDREN

In Basel Museum.

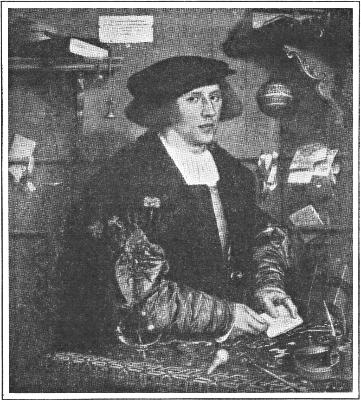

PORTRAIT OF GEORG GYZE. By Holbein. In the Berlin Gallery.

HOLBEIN, by himself

At 25 years of age.

Whoever understands the art of Dürer needs little introduction to that of Holbein (hole´-bine). Hans Holbein was born in 1497, when Dürer was just beginning to be famous, at the imperial city of Augsburg, which was merely a larger Nuremberg. Holbein’s father was a painter, and the lad was early perfected in the craft. By his seventeenth year he was working at Basel, where for some ten years he practised book illustration, designing for metal and glass, religious subjects, wall painting. Such versatility he renounced later for the better paying branch of portraiture. In 1526 some German merchants called him over to London. There he soon became court painter to Henry VIII, and there he remained for the most part until his death by the plague in 1543. He was one of the first of those cosmopolitan portrait painters who follow their market, a homeless man, separated from wife and children, a completely detached person. That he was fitted for the part, the sturdy, confident portrait of himself shows.

As a painter Holbein was Dürer’s superior, though inferior to him as a man. Where Dürer set his bright colors in rather harsh combinations, Holbein worked out arrangements of mosaiclike depth and brilliance. Usually the background is pale blue, green, or other solid tone, against which the pale flesh tints, with crimson, green, or black of the rich costumes, glow like some precious enamel. He is as accurate in his drawing as Dürer, with less sense of effort.

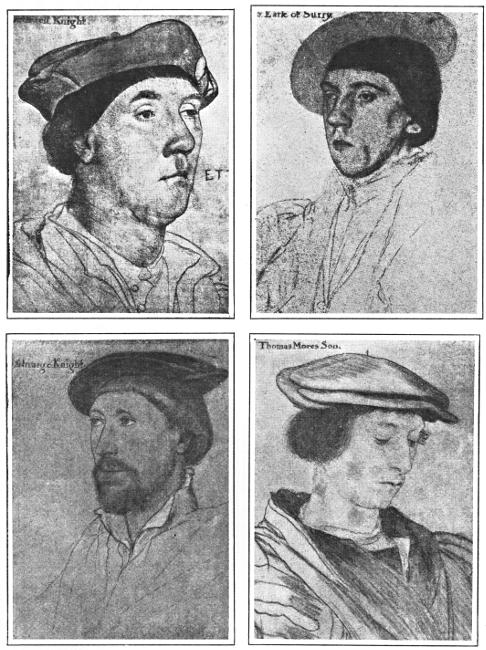

STUDIES FROM LIFE, IN THE WINDSOR COLLECTION

By Holbein.

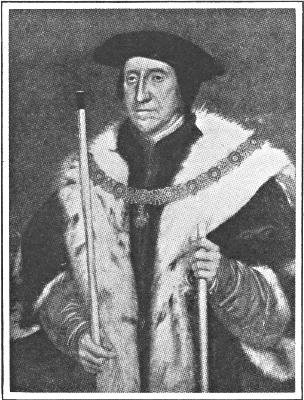

SIEUR de MORETTE, by Holbein

Holbein painted the profile portrait of the scholar Erasmus about 1523. Erasmus was not merely very learned but also a wit, and Holbein has combined with the self-control and concentration of the face a sense of astuteness. The set lips would readily break into a smile. The gentle and careful pose of the hands is noteworthy. It is as if the great stylist caressed the paper to invite a happy phrase. Very effective too is the setting of the figure in the frame. Everything forms a beautiful pattern. Cut off the margin ever so little, and the figure will seem out of balance.

DUKE OF NORFOLK, by Holbein

Finely composed again is the famous Madonna of the Meier family. The kneeling figures make the base of a pyramid, the lines of which are carried up by the Madonna’s cloak and the Christ Child’s outstretched hand. Perhaps the formal arrangement and the stately niche are a little out of keeping with the evident simplicity of all the people. In fact, the greatness of the picture lies mainly in its vitality, in the sense of strength and devotion it conveys. Holbein, like Dürer, conceives the Virgin simply as a German mother, none too intelligent, and rather ungraceful, but wholly wrapped up in the Divine Child, who is after all much like an ordinary German baby. The gentleness of Mary’s clasped hands is one of the many beautifully studied details.

A consummate example of his work is the Jane Seymour of 1536. In the third wife of Henry VIII Holbein had only a moderately good subject. She seems a stolid person. Yet a certain shrewdness is also in the face. The setting in the frame is perfect, and the gold-embroidered robes and jewelry are done with a quiet dexterity that simply takes one’s breath away. The sketch for the portrait is preserved. Holbein always made a careful crayon drawing for every portrait, introducing slight tints, or even writing down the color of hair, eyes, etc. From such a study, which was made in a few hours, the picture was painted. We have then the most lifelike portraits known to art painted with the model absent. Today artists plague themselves and the sitter to poorer purpose. By utmost concentration upon the original drawing, Holbein seems to have omitted all unimportant or merely general traits of his subject, fixing upon the few that were really characteristic. Moreover, he stood upon his first reading of the character.

At any rate, these splendid sketches are the finest flower of Holbein’s genius. Scores of them are preserved at Windsor Castle. I reproduce only the rather vain and weak face of the poet, warrior, and dandy, the Earl of Surrey. I must repeat that Holbein was less of a man but in some ways more of an artist than Dürer, unqualifiedly superior as a mere painter. Dürer was full of profound ideas about religion and life. His work is truly a criticism of the life of his age. Holbein had virtually no ideas, and genially accepted his world as very good to live and paint in. He brought not a great mind to his art, but a tolerant temper, a most discerning eye, and a magnificently sure hand.

HOLBEIN, by himself

LIFE OF ALBRECHT DÜRER (Translated from the German.)—By Moritz Thausing. The standard biography.

ALBRECHT DÜRER—(“Classics of Art”). Complete collection of reproductions of Dürer’s works in half tone.

ALBRECHT DÜRER—By Lina Eckstein. (Popular Library of Art.) A concise but readable epitome of the main facts.

ALBRECHT DÜRER—By T. Sturge Moore. (Scribner’s.) Somewhat fuller and of excellent literary quality.

ALBRECHT DÜRER—By Frederick Nüchter. (Macmillan.) Especially recommended as a biography and for excellent cuts of good scale at a moderate price.

HANS HOLBEIN AND HIS TIMES. (Translated from the German)—By A. Woltmann. The standard biography.

HANS HOLBEIN—By G. S. Davies. A recent and thorough work, in folio, with many illustrations.

HANS HOLBEIN—(“Classics of Art”). Useful collection of half tone cuts of all his work at a moderate price.

THE MENTOR

ISSUED SEMI-MONTHLY BY

The Mentor Association, Inc.

381 Fourth Ave., New York, N. Y.

Volume 1 Number 48

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. FOREIGN POSTAGE, SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE, FIFTY CENTS EXTRA. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE AT NEW YORK, N. Y., AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER.

In the letters that we have received from members of The Mentor Association we have had appreciation in full measure from readers of mature minds. The young people were yet to be heard from.

It meant a great deal to us, therefore, to receive a letter from a teacher concerning the work that she was doing with The Mentor. She had under her charge a class in High School, the pupils varying in age from 14 to 18 years. The teacher has been using The Mentor regularly. She distributes the pictures and the pupils read Monday’s Daily Reading on Monday, and so following, day by day throughout the week. On Friday afternoon she gives an hour to The Mentor. The article in The Mentor is read aloud to the class and also the Saturday Daily Reading. The teacher then reviews the subject with the pupils and asks them questions. In this way, she tells us, her class thoroughly absorbs each weekly subject in turn. Since receiving this letter we have made inquiry, and we find that a number of teachers are doing the same thing. We call the attention of teachers generally to this. It is a plan worth trying.

So much for the reading matter and the profit to be obtained for children therefrom. We have said nothing about the pictures, and surely it is not necessary to lay stress on the appeal made to children by beautiful pictures. And it is not merely a dull, crude interest that it arouses. It is in many cases an intelligent taste, that readily responds to cultivation. A writer in one of our daily papers called attention recently to an impressive scene that may be observed every Saturday morning at the Metropolitan Museum. It is a gathering of school children, who are assembled with open eyes and ears and eager and hungry minds to see and hear and know the things of beauty and of curious interest in the museum. These pupils are invited by the Metropolitan Museum itself, and under the sponsorship of The School Art League of New York.

When this was started the Museum people, it is said, doubted whether it would work. They were afraid perhaps that the school children would feel that they were being “done good to” and wouldn’t come. As a matter of fact, however, those who came first told the others that the visit was simply wonderful, and more and more came, until now you may see 600 children at the Metropolitan on Saturday morning, hanging on the lips of the people who are telling them about the art of the pictures and the stories that go with them. It is a most inspiring sight for those who are interested in education.

Most children are born with a certain understanding of the beautiful and a longing for it. They “want to know,” and they listen eagerly as long as anyone can tell them something that is interesting as well as informing. That is the attitude of mind that The Mentor addresses itself to, whether it is the mind of a child or of a grown-up. We have had plenty of assurances that The Mentor has interested and helped older readers. It is most gratifying to learn of the benefit that The Mentor is bringing to young readers—to have word from our readers that the children in the school or in the home are enjoying The Mentor. One reader tells us that he is taking The Mentor particularly for his children. “I want them to grow up with it,” he says. That interests us deeply. We want The Mentor to be a real factor in the life of the home, and a real part of the education of the young generation.

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG WOMAN—Dürer

ONE

Albrecht Dürer was born on May 21, 1471, at Nuremberg, Germany. His father was named Albrecht Dürer also. He was a goldsmith, who at the age of forty married his master’s daughter, who was only fifteen years old. In spite of the difference in their ages, the marriage was a happy one, and was blessed with eighteen children, of whom Albrecht was second.

As a boy he showed himself more worthy of an education than any of his many brothers, and was apprenticed to a goldsmith. But he wanted to become an artist, and, being his father’s favorite son, his wish was granted. So at the age of fifteen he was apprenticed to the principal painter of Nuremberg, Michael Wohlgemuth. Here, as one of the artist’s assistants, he turned out little sketches of religious subjects, and some woodcuts for book illustrations. He had a hard time, as his companion apprentices were a rough crowd, and took great delight in making young Dürer suffer.

In 1490 he finished his apprenticeship, and began his “years of travel.” These lasted until 1494. He visited Colmar, Basel, Strasburg, and other German cities. Shortly after his return in July, 1494, he married Agnes Frey, who was a good wife for him. She was an excellent housekeeper and a shrewd business woman. They had no children.

But Dürer had not been married more than a few months when he decided to make a journey to northern Italy to complete his artistic education. He was very poor, and the great expense of such a trip made it necessary for him to leave his wife behind. He did not stay away long. Sometime in 1495 he returned to Nuremberg, where he lived without change for the next ten years.

Like many another artist, Dürer had his early struggles against poverty and indifference. Painting did not pay; so he turned to wood and copper engraving, and in this way made a fair living.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 48, SERIAL No. 48

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

PORTRAIT OF HIMSELF—Dürer

TWO

Dürer visited Venice in the fall of 1505, and stayed there until the spring of 1507. The main reason for this journey was the commission to paint a picture for the Germans living at Venice. His fame had spread greatly, and as his countrymen wanted to dedicate a picture in the Church of Saint Bartholomew they chose him to paint it. The picture that Dürer did for them was the “Adoration of the Virgin,” better known as the “Feast of the Rose Garlands.” Emperor Rudolf II later got hold of it. It was carried to Vienna upon men’s shoulders, as a thing of great value. It is now, greatly injured, in the monastery of Strahov at Prague.

At Venice, Dürer was treated with great respect and admiration. He held a high position there; although most of the Italian artists were jealous of him. But in spite of his desire to remain in Italy for the rest of his life, he returned to Nuremberg in 1507.

All over Europe, Dürer was now recognized as a great painter. All the living master artists of the age were his friends or acquaintances. The great Raphael felt honored to exchange drawings with him.

But his intimate life was not so happy. It has been said that his wife plagued him to death with her meanness. It is undoubtedly true that, although Agnes was a good housewife and manager, she made the artist overwork himself for money. For years her name was held up among the Germans as an example of an unworthy wife. In none of his letters does Dürer speak of her with tenderness or affection.

Beyond this the artist’s life was uneventful. The years from 1507 to 1511 he spent in painting. The three following he devoted mostly to engraving on both wood and copper. Copper engraving especially took up much of his time. At the same time he resumed etching. He was also interested in mathematical and anatomical studies on the proportions and structure of the human frame.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 48, SERIAL No. 48

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

HIERONYMUS HOLZSCHUHER—Dürer

THREE

The last period of Dürer’s life began in 1520. Emperor Maximilian was his friend and patron; but his death in 1519 stopped all the things that Dürer was doing for him. So in July, 1520, the artist, with his wife and her maid, set out for the Netherlands to secure a continuance of the patronage and privileges granted during the lifetime of Maximilian. Everywhere he was handsomely received. Throughout all his travels, which lasted a year, he was entertained by the best and most intellectual society of his time.

On July 12, 1521, Dürer reached home again. His mind was now filled with schemes for religious pictures; but he produced comparatively little. One reason for this was the bad state of his health. Another was that he gave more and more of his time to mathematical study, which he considered important. His most famous picture of this time is the portrait of Hieronymus Holzschuher at Berlin.

At Nuremberg, in 1525, was published his book on geometry, and in 1527 appeared a work on fortification. But his health was failing. He had caught a fever in the Low Countries, from which he never fully recovered. On the night of April 6, 1528, he died, so suddenly that there was not even time to call his dearest friends to his side.

He was buried in a vault belonging to his wife’s family, in the cemetery of Saint John, at Nuremberg. Luther, the great reformer, said of the famous artist in a letter, “As for Dürer, assuredly affection bids us mourn for one who was the best of men; yet you may well hold him happy that he has made so good an end, and that Christ has taken him from the midst of this time of trouble, and from greater troubles in store, lest he, that deserved nothing but the best, should be compelled to behold the worst. Therefore may he rest in peace with his fathers. Amen!”

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 48, SERIAL No. 48

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

ERASMUS—Holbein

FOUR

Hans Holbein came of an artistic family. Indeed, he is usually known as Holbein the Younger; for his father, Hans Holbein the Elder, was a painter of great ability himself. His uncle also, his mother’s father, and most of his family were painters and decorators in the city of Augsburg, Germany, where Holbein the Younger was born sometime toward the end of the fifteenth century.

No one knows exactly the year in which Holbein first opened his eyes. In those times they did not keep such an accurate record of births and deaths as they do nowadays. So, unless a man was the son of a king or some other important person, it did not matter much when he was born. Still, we are probably right when we say that Hans Holbein was born in 1497.

Those were the days of Augsburg’s prosperity. All its magnificence is gone now; but then it boasted of many merchant princes, men of distinction, and patrons of the fine arts. It was a favorite city of Emperor Maximilian himself. There was less travel at that time than now, and consequently the citizens of each town were much more closely bound together. Civic pride ran high. It was the period of the Renaissance, that great period of awakening to the appreciation of fine things in art and literature. So of course Augsburg had its Guild of Painters, and Holbein the Elder was a member of it.

Hans was the favorite son, and both he and his brother Ambrose were educated to be artists in their father’s studio. There they worked until 1515, when Hans and Ambrose journeyed to Basel, at that time a center of learning and art.

There Holbein’s chief occupation was the drawing of title pages for books. Erasmus, the great scholar, is said to have been his patron, and helped him in many ways. Another powerful patron was Jacob Meier, the first commoner who ever held the office of burgomaster of Basel, and under whose rule the reformation of the city laws was peaceably carried out. He was the original of Holbein’s first portrait painted in Basel, and for him, eight or nine years later, was painted the famous Meier Madonna.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 48, SERIAL No. 48

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE MEIER MADONNA—Holbein

FIVE

In 1517 Holbein left Basel on a journey of two years. No one knows exactly where he traveled. It is said that he did not go to Italy; but others maintain that he must have spent some time there. Anyway, in 1519 he returned to Basel, and in the same year his brother Ambrose died. The next year, 1520, was an important one in the artist’s life. Erasmus returned to Basel, and Holbein became a citizen of the town, and was admitted to the Guild of Painters. Also at this time he married. His wife was a widow with two children. She was some years older than the artist, and seems to have been somewhat of a shrew. It is said that it was her tongue that drove Holbein to England in the summer of 1526. More probably it was the usual desire,—to make more money than he was earning at Basel.

At that time art was having a hard time in Germany. The Reformation—when Luther and his followers broke away from the Roman Church—forced painters to do almost anything for a living. Stained glass designing, furniture decoration, and book illustration made up most of Holbein’s commissions.

It was at this time also that he drew his famous Dance of Death series. These drawings are not dated; but they must have been made sometime before 1527, for in that year the engraver, Hans Lützelberger, who was doing that part of the work, died, leaving his work unfinished. Another wood engraver able to render the action and expression of the little faces could not be found. So for ten years their publication was delayed.

The Dance of Death is a highly moral set of pictures, depicting the work of the great Reaper in all fields of life. In the various pictures Death is shown taking grim satisfaction in the consternation of his victims. Pope, emperor, preacher, nun, rich and poor, young and old, all are unready for his coming. All vainly resist. The artist must have worked hard and carefully over these engravings.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 48, SERIAL No. 48

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

QUEEN JANE SEYMOUR—Holbein

SIX

Holbein arrived in London toward the end of 1526. It is said that the English called him, colloquially, “Master Haunce.” He went immediately to Chelsea, where Sir Thomas More lived. Erasmus had given him a letter of introduction to this famous statesman and author, and the artist was made welcome, and given many commissions for portraits. Holbein remained at Chelsea throughout his first visit to England. Sir Thomas More introduced him to many of the greatest men of the day.

At this time England was just beginning to feel the first influence of the Renaissance. London was still a dirty, noisy town of the Middle Ages. The houses were made of wood and mud, and built with the earth as a flooring. The streets were narrow and crowded, with the houses and little shops set close together. From the highest to the lowest, London was far from being the center of fashion it was to become not many years later.

Consequently, when the dreaded plague broke out in 1528, London was just the kind of city in which it would spread most rapidly. So Holbein gave up his work in England and returned to Basel. There he finished the decorations for the town hall, which had been begun in 1521. But he was not happy there. All his friends were either dead or had left the city. So about 1531 he returned to London.

This time he needed no introduction. His reputation was established in England. The merchants of the Steelyard, the great German trading company established on the banks of the Thames, gave him plenty of work to do, and he did it well. These portraits contain some of Holbein’s most careful work.

In 1537 he painted the great portrait of Henry VII with Elizabeth of York, and Henry VIII with Jane Seymour, for the privy chamber of the Palace of Westminster. This picture was destroyed in the fire that burned the palace in 1698. In 1543 the plague broke out again in England.

A will, presumably made in October, 1543, by Holbein, was found in London some years ago. And not long after making this, in November, the great artist died, probably of the plague. His death was surrounded by mystery. Not even the place of his burial is known for certain. It was either in the church of Saint Andrew Undershaft or Saint Catharine Cree. His death, in the prime of his active life, was a great loss to the world; but his work survives, and will live forever.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 48, SERIAL No. 48

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.