Minor errors in punctuation and formatting have been silently corrected. Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered during its preparation.

The frequent appearance of text in blackletter font is rendered here with this font.

Full-width images have been moved to paragraph breaks. The pagination used in the list of Plates is approximate, but are linked here directly to each plate.

Footnotes have been resequenced to be unique across the text, and were moved to the end of the text.

The cover image has been fabricated and is placed in the public domain.

LANGTON.Sc.MANcr

Portraits from Original Plates,—Bocchius by Bonasone, A.D. 1555; the others by Theodore de Bry, A.D. 1597.

Portrait of Shakespeare.

From the Oil Painting in the possession of Dr. Clay, of Manchester.

FEW only are the remarks absolutely needed by way of introduction to a work which within itself sufficiently explains and carries out a new method of illustration for the dramas of Shakespeare. As author, I commenced this volume because of various observations which, while reading several of the early Emblem writers, I had made on similarities of thought and expression between themselves and the great Poet; and I had sketched the whole outline, and had nearly filled it in, without knowing that the path pursued by me had in any instance been trodden by other amateurs and critics. From the writings of the profoundly learned Francis Douce, whose name ought never to be uttered without deep respect for his rare scholarship and generous regard to its interests, I first became aware that Shakespeare’s direct quotation of Emblem mottoes, and direct description of Emblem devices, had in some degree been already pointed out to the attention of the literary public.

And right glad am I to observe that I have had precursors in my labours, and companions in my researches; and that, in addition to Francis Douce, writers of such repute as Langlois of Rouen, Charles Knight, Noel Humphreys, and Dr. Alfred Woltmann, of Berlin, have, each by an example or two, shown how, with admirable skill and yet with evident appropriation, our great Dramatist has interwoven among his own the materials which he had gathered from Emblem writers as their source.

To myself the fact is an assurance that neither from aiming at singularity of conjecture, nor from pretending to a more penetrating insight into Shakespeare’s methods of composition, have I put before the world the following pages for judgment. Those pages are the results of genuine study,—a study I could not have so well pursued had not liberal-minded friends freely entrusted to my use the book-treasures which countervailed my own deficiencies. The results arrived at, though imperfect, are also, I believe, grounded on real similitudes between Shakespeare and his predecessors and contemporaries; and those similitudes, parallelisms, or adaptations of thought, by whichever name distinguished, often arose from the actual impression made on his mind and memory by the Emblematists whose works he had seen, read, and used.

As a suitable Frontispiece the portraits are presented of five celebrated authors of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: one a German—Sebastian Brandt; three Italian—Andrew Alciat, Paolo Giovio, and Achilles Bocchius; and one from Hungary—John Sambucus. They were all men of learning and renown, whom kings and emperors honoured, and whom the foremost of their age admired. The central portrait, that of Bocchius of Bologna, is from the famous artist Giulio Bonasone, and the original engraving was retouched by Augustino Caracci. The other portraits have been reduced from the “Icones,” or Figures of Fifty Illustrious Men, which Theodore de Bry executed and published during Shakespeare’s prime, in 1597. In their own day they were regarded as correct delineations and likenesses, and are said to be authentic copies.

The vignette of Shakespeare on the title-page is now engraved for the first time. The original is an oil-painting, a head of the life size, and possessing considerable animation and evidences of power. It is the property of Charles Clay, Esq., M.D., Manchester. Without vouching for its authenticity, we are justified in saying, when it is compared with some other portraits, that it offers equal, if not superior, claims to genuineness. To discuss the question does not belong to these pages, but simply and cordially to acknowledge the courtesy with which the oil-painting was offered for use and allowed to be copied, and to say that our woodcut is an accurate and well-executed representation of the original picture.

Of the ornamental capitals at the head of the chapters, and of the little embellishments at their end, it may be remarked that, with scarcely an exception, there are none later than our Poet’s day, and but few that do not belong to Emblem books: they are forty-eight in number. The illustrative woodcuts and photolith plates, of which there are one hundred and fifty-three of the former and nineteen of the latter, partake of the variety, and, it may be said, apologetically, of the defects of the works from which they have been taken. However fanciful in themselves, they are realities,—true exponents of the Emblem art of their day; so that, within the compass of our volume, containing above two hundred examples of emblematic devices and designs, is exhibited a very full representation of the various styles of the original works, and which, in the absence of the works themselves, may serve to show their chief characteristics. The Photoliths, I may add, have been executed by Mr. A. Brothers, of Manchester.

Doubtless both the woodcuts and the plates are very unequal in their execution; but to have aimed at a uniformity even of high excellence would have been to sacrifice truth to mere embellishment. It should be borne in mind what one of our objects has been,—namely, to place before the reader examples of the Emblem devices themselves, very nearly as they existed in their own day, and not to attempt the ideal perfection to which modern art rightly aspires.

The Edition of Shakespeare from which the extracts are taken is the very excellent one, in nine volumes, issued from Cambridge, 1863–1866. Its numbering of the lines for purposes of reference is most valuable.

Our work offers information, and consequently advantage, to three classes of the literary public:—

1st. To the Book Agent and Book Antiquarian, so far as relates to books of Emblems previous to the early part of the seventeenth century, A. D. 1616. In a collected and methodical form, aided not a little by the General Index, the first chapters and sections of our volume supply information that is widely scattered, and not to be obtained without considerable trouble and search. The authors, titles, and dates of the chief editions of Emblem books within the period treated of, are clearly though briefly given, arranged according to the languages in which the books were printed, and accompanied where requisite by notices and remarks. There is not to be found, I believe, in any other work so much information about the early Emblem books, gathered together in so compendious and orderly a manner.

2nd. To the Students and Scholars of Shakespeare,—a widely-extended and ever-increasing community. Another aspect of the Master’s reading and attainments is opened to them; and into the yet unquarried illustrations of which his marvellous writings are susceptible, another adit is driven. We may have followed him through Histories and Legends, through the Epic and the Ballad, through Popular Tales and Philosophic Treatises,—from the forest glade to the halls and gardens of palaces,—across the wild moor where the weird sisters muttered and prophesied, and to that moon-lighted bank where the sweet Jessica was sitting in all maiden loveliness;—but if only for variety’s sake it may interest us, even if it does not impart pleasure, to mark how much his mind was in accord with the once popular Emblem literature, which now perchance awakens scarcely a thought or a regret, though great scholars and men of genius devoted themselves to it; and how from that literature, imbued with its spirit and heightening its power, even he—the self-reliant one—borrowed help and imagery, and made his own creations more his own than otherwise they would have been.

And 3rd. To the great Brotherhood of nations among the Teutonic race, to whom Shakespeare is known as a chieftain among the Lares,—the heroes and guardians of their households. In him they recognise an impersonation of high poetic Art, and they desire to see unrolled from the treasures of the past whatever course his genius pursued to elevate and refine its powers;—persuaded that out of the elevation and refinement ever is springing something of his own inspiration to improve and ennoble mankind.

A word or two may be allowed respecting the translations into English which are offered of the Emblem writers’ verses occurring in the quotations. An accurate rendering of the original was desirable; and, therefore, in many instances, rhymes and strictly measured lines have been abjured, and cadence trusted rather than metre; the defect of the plan, perhaps, is that cadence varies with the peculiar pitch and intonation of each person’s voice. Nevertheless, among rhymes the Oarsman’s Cry (p. 61) might find a place on Cam, or Isis, and the Wolf and the Ass (p. 54) be entitled to abide in a book of fables.

In behalf of quotations from the original, it is to be urged that, to defamiliarise the minds of the public, so much as is now the custom, from the sight of other languages than their own, is injurious to the maintenance of scholarship; and were it not so, the works quoted from are many of them not in general use, and some are of highest rarity;—it is, therefore, only simple justice to the reader to place before him the original on the very page he is reading.

The value of the work will doubtless be increased by the Appendices and the very full Index which have been added. These will enable such as are inclined more thoroughly to compare together the different parts of the work, and better to judge of it, and to pursue its subjects elsewhere.

My offering I hang up where many brighter garlands have been placed,—and where, as generations pass away, many more will be brought; it is at his shrine whose genius consecrated the English tongue to some of the highest purposes of which speech is capable. For Humanity itself he rendered his Service of Song a guidance to that which is noble as well as beautiful,—a sympathy with our nature as well as a truth for our souls. God’s benison rest upon his memory!

| PAGE. | ||||||

| Frontispiece | ii | |||||

| Title-page | iii | |||||

| Preface | vii | |||||

| Contents | xiii | |||||

| CHAPTER I. | ||||||

| Emblems and their Varieties, with some Early Examples | 1–29 | |||||

| CHAPTER II. | ||||||

| Sketch of Emblem Book Literature previous to a.d. 1616 | 30–104 | |||||

| Sect. | 1. | General Extent of the Emblem Literature to which Shakespeare might have had Access | 30–37 | |||

| ” | 2. | Emblem Works and Editions down to the end of the Fifteenth Century | 38–59 | |||

| ” | 3. | Other Emblem Works and Editions previous to A.D. 1564 | 60–83 | |||

| i.e. | 1. | Before Alciat’s first Emblem Work, A.D. 1522 | 60–68 | |||

| 2. | Down to Holbein, La Perriere, and Corrozet, A.D. 1543 | 69–75 | ||||

| 3. | Down to Shakespeare’s birth, A.D. 1564 | 75–83 | ||||

| Sect. | 4. | Emblem Works and Editions from A.D. 1564 to 1616 | 84–104 | |||

| i.e. | 1. | Before Shakespeare had entered fully on his Work, A.D. 1590 | 84–92 | |||

| 2. | Until he had ended the Twelfth Night in 1615 | 92–104 | ||||

| CHAPTER III. | ||||||

| Shakespeare’s Attainments and Opportunities with respect to the Fine Arts | 105–118 | |||||

| CHAPTER IV. | ||||||

| The Knowledge of Emblem Books in Britain, and general Indications that Shakespeare was acquainted with them | 119–155 | |||||

| CHAPTER V. | ||||||

| Six direct References in the Pericles to Books of Emblems, some of their Devices described, and of their Mottoes quoted | 156–186 | |||||

| CHAPTER VI. | ||||||

| Classification of the Correspondencies and Parallelisms of Shakespeare with Emblem Writers | 187–462 | |||||

| Sect. | 1. | Historical Emblems | 188–211 | |||

| ” | 2. | Heraldic Emblems | 212–240 | |||

| ” | 3. | Emblems for Mythological Characters | 241–301 | |||

| ” | 4. | Emblems Illustrative of Fables | 302–317 | |||

| ” | 5. | Emblems in connection with Proverbs | 318–345 | |||

| ” | 6. | Emblems from Facts in Nature, and from the Properties of Animals | 346–376 | |||

| ” | 7. | Emblems for Poetic Ideas | 377–410 | |||

| ” | 8. | Moral and Æsthetic Emblems | 411–462 | |||

| CHAPTER VII. | ||||||

| Miscellaneous Emblems, Recapitulation, and Conclusion | 463–496 | |||||

| APPENDICES. | ||||||

| I. | ||||||

| Coincidences between Shakespeare and Whitney | 497–514 | |||||

| II. | ||||||

| Subjects, Mottoes, and Sources of the Emblem Imprese | 515–530 | |||||

| III. | ||||||

| References to Passages from Shakespeare, and to the corresponding Devices of the Emblems treated of | 531–542 | |||||

| GENERAL INDEX | 543–571 | |||||

| PLATE. | SUBJECT. | SOURCE. | PAGE. |

| I. | Dedication Plate | Alciat’s Emb. Ed. 1661 | 1 |

| Ia. | Tableau of Human Life,—Cebes, B.C. 330. | De Hooghe, 1670 | 13 |

| Ib. | Tableau of Human Life,—Cebes, B.C. 330. | Old Print | 68 |

| II. | Christ’s Adoption of the Human Soul | Otho Vænius, Divini Amoris Emb. 1615 | 32 |

| III. | Creation | Symeoni’s Ovid, Ed. 1559, p. 13 | 35 |

| IV. | Title-page,—Speculum Humanæ Salvationis. | A MS. of the 1st Edition, 1440 | 44 |

| V. | Leaf 31,—Speculum Humana Salvationis. | A MS. of the 1st Edition, 1440 | 44 |

| VI. | A page from the Biblia Pauperum. | Noel Humphreys, p. 40, Pl. 2 | 46 |

| VII. | Historia S. Joan. per Figuras,—Corser Collection. | Tracing from the Block-book | 49 |

| VIII. | Historia S. Joan. per Figuras,—Corser Collection. | Tracing from the Block-book | 49 |

| IX. | Title-page of Seb. Brandt’s Fool-freighted Ship | Locher’s Stultifera Navis, Ed. 1497 | 57 |

| X. | Title-page of Van der Veen’s Emblems. | Adams Appel, Ed. 1642 | 132 |

| XI. | Fall of Satan | Boissard’s Theat. Vit. Hum. 1596 Ed. | 133 |

| XII. | Occasion seized | David’s Occasio arr. &c. Ed. 1605 | 265 |

| XIII. | The Zodiac | Brucioli, Della Sphera, Ed. 1543 | 353 |

| XIV. | Life as a Theatre | Boissard’s Theat. Vit. Hum. Ed. 1596. | 405 |

| XV. | Seven Ages of Life,—an early Block-Print, British Museum. | Archæologia, vol. xxxv. 1853, p. 167. | 407 |

| XVI. | Providence making Rich and making Poor. | Coornhert, Ed. 1585 | 489 |

| XVII. | Time flying | Otho Vænius, Emblemata, Ed. 1612. | 491 |

Hesius, 1636.

Stans uno capit omnia puncto.

WHAT Emblems are, in the general acceptation of the word in modern times, is well set forth in Cotgrave’s Dictionary, Art. Emblema, where he defines an emblem to be, “a picture and short posie, expressing some particular conceit;” and very pithily by Francis Quarles, when he says,—“an Emblem is but a silent Parable.” Though less terse and clear than either of these, we may also take Bacon’s description, in his Advancement of Learning, bk. v. chap. 5;—“Embleme deduceth conceptions intellectuall to images sensible, and that which is sensible more forcibly strikes the memory, and is more easily imprinted than that which is intellectual.”

By many writers of Emblem books, perhaps by the majority in their practice if not in their theories, there is very little difference of meaning observed between Symbols and Emblems. We find, however, in other Authors a more exact usage of the word Symbol. The Greek poet Pindar[1] speaks of “a trustworthy symbol, or sign, concerning a future action,” or from which the future can be conjectured; Iago, recounting the power of Desdemona over Othello, act ii. scene 3, l. 326, declares it were easy

and Cudworth, in his True Intellectual System of the Universe, ed. 1678, p. 388, after giving Aristotle’s assertion “that Numbers were the Causes of the Essence of other things,” adds, “though we are not ignorant, how the Pythagoreans made also the Numbers within the Decad, to be Symbols of things.”

Claude Marginality, or Minōs, the famous commentator on the Emblems of Andreas Alciatus, in his Tract, Concerning Symbols, Coats of Arms, and Emblems,—eds. 1581, or 1608, or 1614,—maintains there is a clear distinction between emblems and symbols, which, as he affirms, “many persons rashly and ignorantly confound together.”[2] “We confess,” he adds, “that the force of the Emblem depends upon the Symbol: but they differ, I say, as Man and Animal; for people who have any judgment at all know, that here of a certainty the latter is taken more generally, the former more specially.” Mignault’s meaning may be carried out by saying, that all men are animals,—but all animals are not men; so all emblems are symbols, tokens, or signs, but all symbols are not emblems;—the two possess affinity but not identity,—they have no absolute convertibility of the one for the other.

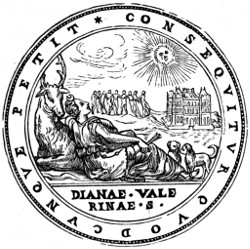

Symeoni, 1559.

An example of Emblem and Symbol united occurs in Symeoni’s Dedication[3] “To Madame Diana of Poitiers, Dutchess of Valentinois;” for Emblem, there are “picture and short posie” expressing the particular conceit, “Quodcunque petit, consequitur,”—She attains whatever she seeks; and for Symbols, or signs, the sun, the temple, the dogs, the arrow, and the stag; and for exposition, the stanza;

Thus metrically rendered,

The word emblem, ἐμβλημα, is one that has strayed very widely from its first meaning, and yet by a sort of natural process, as the apple grows out of the crab, its signification now is akin to what it was in distant ages. It then denoted the thing, whether implement or ornament, placed in, or thrown on, and so joined to, some other thing. Thus a word of cognate origin, Epiblēs, in the Iliad, bk. xxiv. l. 453,[4] denoted the bolt of fir that held fast the door;—it was something put against the door,—the peg or bar that kept it from opening. So in the Odyssey, bk. ii. l. 37,[5] the sceptre, the emblem of command, was the baton which the herald Peisēnor placed in the hand of the son of Ulysses; and again in the Iliad, bk. xiii. l. 319, 20,[6] the flaming torch was the implement which the son of Kronos might throw on the swift ships.

Of the changes through which a word may pass, “the word Emblem presents one of the most remarkable instances.” They cannot be better given than in the “Sketch of that branch of Literature called Books of Emblems,” read in 1848 before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, by the late Joseph Brooks Yates, Esq. He says of the word Emblem, pp. 8, 9,—“its present signification, ‘Type or allusive representation,’ is of comparatively modern use, while its original meaning is become obsolete. Among the Greeks an Emblem (εμβλημα), derived from ενβαλλειν, meant something thrown in or inserted after the fashion of what we now call Marquetry and Mosaic work, or in the form of a detached ornament to be affixed to a pillar, a tablet, or a vase, and put off or on, as there might be occasion. Pliny, in his Natural History,” bk. xxxiii. c. 12, “mentions an artist called Pytheus, who executed works of this last description in silver, one of which, intended to be attached to a jar (in phialæ emblemate), represented Ulysses and Diomed carrying off the Palladium.[7] It weighed two ounces, and sold for 10,000 sesterces = 80l. 14s. 7d. of our money. According to one ancient manuscript of Pliny, it sold for double that amount. Marcus Curtius leaping into the gulph forms the subject of a beautiful silver Emblem, in the possession of the writer.[8] When the arts of Greece were transplanted into Italy and Sicily, the word Emblema became naturalised in the Latin tongue, though not without some resistance on the part of the reigning prince Tiberius. That emperor is reported by Suetonius,” Tiber. Cæsar Vita, c. 71, “to have found fault with the introduction of the word into a Decree of the Senate, as being of foreign growth. Cicero, however, had used it in his orations against Verres, where he accuses that rapacious governor (amongst other crimes) of having compelled the people of Haluntium to bring to him their vases, from which he carefully abstracted the valuable Emblems and inserted them upon his own golden vessels. Quintilian,” lib. 2, cap. 4, “soon after this period, in enumerating the arts of oratory used by the pleaders of his day, describes some of them as in the habit of preparing and committing to memory certain highly finished clauses, to be inserted (as occasion might arise) like Emblems in the body of their orations.”[9]

“Such was the meaning of the term in the classical ages of Greece and Rome; nor was its signification altered until some time after the revival of literature in the fifteenth century.”

Our own Geoffrey Whitney, deriving, as he does the other parts of his Choice of Emblemes from the writers on the subject that preceded him, gives very exactly the same explanation as Mr. Yates. In his address “To the Reader” (p. 2) he says;—“It resteth now to shewe breeflie what this worde Embleme signifieth, and whereof it commeth, which thoughe it be borrowed of others, & not proper in the Englishe tonge, yet that which it signifieth: Is, and hathe bin alwaies in vse amongst vs, which worde being in Greek ἐμβάλλεσθαι, vel ἐπεμβλῆσθαι is as muche to saye in Englishe as To set in, or to put in: properlie ment by suche figures, or workes; as are wroughte in plate, or in stones in the pauementes, or on the waules, or suche like, for the adorning of the place: hauinge some wittie deuise expressed with cunning woorkemanship, somethinge obscure to be perceiued at the first, whereby, when with further consideration it is vnderstood, it maie the greater delighte the behoulder. And althoughe the worde dothe comprehende manie thinges, and diuers matters maie be therein contained; yet all Emblemes for the most parte, maie be reduced into these three kindes, which is Historicall, Naturall, & Morall. Historicall, as representing the actes of some noble persons, being matter of historie. Naturall, as in expressing the natures of creatures, for example, the loue of the yonge Storkes, to the oulde, or of suche like. Morall, pertaining to vertue and instruction of life, which is the chiefe of the three, and the other two maye bee in some sorte drawen into this head. For, all doe tende vnto discipline, and morall preceptes of liuing. I mighte write more at large hereof, and of the difference of Emblema, Symbolum, & Ænigma, hauinge all (as it weare) some affinitie one with the other. But bicause my meaning is to write as briefely as I maie, for the auoiding of tediousnes, I referre them that would further inquire therof, to And. Alciatus, Guiliel. Perrerius, Achilles Bocchius & to diuers others that haue written thereof, wel knowne to the learned. For I purpose at this present, to write onelie of this worde Embleme: Bicause it chieflie doth pertaine vnto the matter I haue in hande, whereof I hope this muche, shall giue them some taste that weare ignoraunt of the same.”

Whitney’s namesake, to whom flattering friendship compared him, Geoffrey Chaucer, gives us more than the touch of an Emblem, when he describes, in the Canterbury Tales, l. 159–63, the dress of “a Nonne, a Prioresse,”—

So the “Cristofre,” which the Yeoman wore, l. 115,

was doubtless a true Emblem, to be put on, and taken off, as occasion served,—and was probably a cross with the image of Christ upon it: and if pictured forth according to the description in The Legend of Good Women, l. 1196–8, an emblematical device was exhibited, where

This form, the natural form of the Emblem, we may illustrate from a Greek coin, figured in Eschenburg’s Manual of Classical Literature, by Fisk, ed. 1844, pl. xl. p. 351.

The Flying Horse and other ornaments of this coin on the helmet of Minerva are Emblems,—and so are the owl, the olive wreath, and the amphora, or two-handled vase. Were these independent castings or mouldings, to be put on or taken off, they would be veritable emblems in the strict literal sense of the word.

Spenser’s ideas of devices and ornaments correspond to this meaning. Mercilla, the allegorical representation of the sovereign Elizabeth, is described as

In Cymbeline, Shakespeare represents Iachimo, act i. sc. 6, l. 188, 9, describing “a present for the emperor;”

So Spenser, Faerie Queene, iv. 4. 15, sets forth, “a precious rebeke in an arke of gold,” as

In the literal use of the word emblem Shakespeare is very exact. Parolles, All’s Well, act ii. sc. 1, l. 40, charges the young lords of the French court, as

“Noble heroes, my sword and yours are kin;” and adds, “Good sparks and lustrous, a word, good metals: you shall find in the regiment of the Spinii one Captain Spurio, with his cicatrice, an emblem of war, here on his sinister cheek; it was this very sword entrenched it.”

The Coronation Scene in Henry VIII., act iv. sc. 1. l. 81–92, describes the solemnities, when Anne Bullen, “the goodliest woman that ever lay by man,

Each sacred rite is then observed towards her;—

And down to Milton’s time the original meaning of the word Emblem was still retained, though widely departed from as used by some of the Emblem writers. Thus he pictures the “blissful bower” of Eden, bk. iv. l. 697–703, Paradise Lost,

Thus, in their origin, Emblems were the figures or ornaments fashioned by the tools of the artists, in metal or wood, independent of the vase, or the column, or the furniture, they were intended to adorn; they might be affixed or detached at the promptings of the owner’s fancy. Then they were formed, as in mosaic, by placing side by side little blocks of coloured stone, or tiles, or small sections of variegated wood. Raised or carved figures, however produced, came next to be considered as Emblems; and afterwards any kind of figured ornament, or device, whether carved or engraved, or simply traced, on the walls and floors of houses or on vessels of wood, clay, stone, or metal. These ornaments were sometimes like the raised work on the Warwick and other vases, and formed a crust which made a part of the vessel which they embellished; but at other times they were devices, drawings and carvings on a framework which might be detached from the cup or goblet on which the owner had placed them, and be applied to other uses.[11]

We may here remark, since embossed ornaments and sculptured figures on any plain surface are essentially Emblems, the sculptor, the engraver, the statuary and the architect, indeed all workers in wood, metal, or stone, who embellish with device or symbol the simplicity of nature’s materials, are especially entitled to take rank in the fraternity of the Emblematists. They and their patrons, the whole world of the civilized and the intellectual, are not content with the beam out of the forest, or with the marble from the quarry, or with even the gold from the mine. In themselves cedar, marble and gold are only forms of brute and unintelligent nature,—and therefore we impose upon them signs of deep-seated thoughts of the heart and devices of wondrous meaning, and out of the rocks call forth sermons, and lessons and parables, and highly spiritual suggestions. On the very shrines of God we place our images of corruptible things,—but then the soul that rightly reads the images lifts them out of their corruptibility and makes them the teachers of eternal truths.

The domains of the statuary and of the architect are however too vast to be entered upon by us, except with a passing glance; they are like Philosophy; it is all Natural,—and yet wisely men map it out into kingdoms and divisions, and pursue each his selected work.

So we remember it is not the Universe of Emblematism we must attempt, even though Shakespeare should lend us

should add the gift of “the poet’s pen,” so that we might

Our business is only with that comparatively small section of the Emblem-World, which, “like mummies in their cerements,” is wrapped up within the covers of the so called Emblem-books. Whether, when they are unrolled, they are worth the search and the labour, some may doubt;—but perchance a scarabæus, or an emerald, with an ancient harp upon it, may reward our patience.

By a very easy and natural step, figures and ornaments of many kinds, when placed on smooth surfaces, were named emblems; and as these figures and ornaments were very often symbolical, i. e., signs, or tokens of a thought, a sentiment, a saying, or an event, the term emblem was applied to any painting, drawing, or print that was representative of an action, of a quality of the mind, or of any peculiarity or attribute of character.[12] “Emblems in fact were, and are, a species of hieroglyphics, in which the figures or pictures, besides denoting the natural objects to which they bear resemblances, were employed to express properties of the mind, virtues and abstract ideas, and all the operations of the soul.”

Thus, the Tablet of Cebes, a work by one of the disciples of Socrates, about B.C. 390, is an explanation, in the form of a Dialogue, of a picture, said to have been set up in the temple of Kronos at Athens or at Thebes, and which was declared to be emblematical of Human Life.

One of the older Latin versions, printed in 1507, presents the foregoing illustrative frontispiece.

As the book has come down to modern times it is, generally, what has sometimes been named, nudum Emblema, a naked Emblem, because it has neither device nor artistic drawing, but, like Shakespeare’s comparison of all the world to a stage in which man plays many parts, the course of Life, with its discipline, false hopes and false pleasures, is in the Tablet so described,—in fact so delineated,[13] as to have enabled the Dutch designer and engraver, Romyn de Hooghe, in 1670, to have pictured “the whole story of Human Life as narrated to the Grecian sage.”

The Moral of the Allegory may not be set forth with entire clearness in the picture, but it can be given in the words of one of the Golden Sentences of Democritus,—see Gale’s Opus. Mythol.:—

“That human happiness does not result from bodily excellencies nor from riches, but is founded on uprightness of mind and on righteousness of conduct.”

Coins and medals furnish most valuable examples of emblematical figures; indeed some of the Emblem writers, as Sambucus in 1564, were among the earliest to publish impressions or engravings of ancient Roman money, on which are frequently given very interesting representations of customs and symbolical acts. On Grecian coins, which Priestley, in his Lectures on History, vol. i. p. 126,—highly praises for “a design, an attitude, a force, and a delicacy, in the expression even of the muscles and veins of human figures,”—we find, to use heraldic language, that the owl is the crest of Athens,—a wolf’s head, that of Argos,—and a tortoise the badge of the Peloponnesus. The whole history of Louis XIV. and that of his great adversary, William III., are represented in volumes containing the medals that were struck to commemorate the leading events of their reigns, and though outrageously untrue to nature and reality by the adoption of Roman costumes and classic symbols, they serve as records of remarkable occurrences.

Heraldry throughout employs the language of Emblems;—it is the picture-history of families, of tribes and of nations, of princes and emperors. Many a legend and many a strange fancy may be mixed up with it and demand almost the credulity of simplest childhood in order to obtain our credence; yet in the literature of Chivalry and Honours there are enshrined abundant records of the glory that belonged to mighty names. I recall now but one instance. In the fine folio lately emblazoned with the well-known motto “GANG FORWARD,” “I AM READY,” what volumes, to those who can interpret each mark and sign and tutored symbol, are wrapped up in the Examples of the ornamental Heraldry of the sixteenth Century: London, 1867, 1868.

The custom of taking a device or badge, if not a motto, is traced by Paolo Giovio, in his Dialogo dell’ Imprese militari et amorose, ed. 1574, p. 9,[14] to the earliest times of history. He writes,

“To bear these emblems was an ancient usage.” Gio. “It is a point not to be doubted, that the ancients used to bear crests and ornaments on the helmets and on the shields: for we see this clearly in Virgil, when he made the catalogue of the nations which came in favour of Turnus against the Trojans, in the eighth book of the Æneid; Amphiaraus then (as Pindar says) at the war of Thebes bore a dragon on his shield. Similarly Statius writes of Capaneus and of Polinices, that the one bore the Hydra, and the other the Sphynx,” &c.

But these were simple emblems, without motto inscribed. The same Paolo Giovio, and other writers after him,[15] assign both “picture and short posie,” to two of the early Emperors of Rome.

“Augustus, wishing to show how self-governed and moderate he was in all his affairs, never rash and hasty to believe the first reports and informations of his servants, caused to be struck, among several others, on a gold medal of his own, a Butterfly and a Crab, signifying quickness by the Butterfly, and by the Crab slowness, the two things which constitute a temperament necessary for a Prince.”

The motto, as figured below,—“Make haste leisurely.”

The Device is thus applied in Whitney’s Emblems, p. 121, and dedicated to two eminent judges of Elizabeth’s reign;

Symeoni.

The other is the device which the Aldi, celebrated printers of Venice, from A.D. 1490 to 1563, assumed, of the dolphin and anchor, but which Titus, son of Vespasian, had long before adopted, with the motto “Propera tarde,”[16] Hasten slowly: “facendo,” says Symeoni, “vna figura moderata della velocità di questo, e della grauezza di quell’ altra, nel modo che noi veggiamo dinanzi à i libri d’ Aldo.”

But the heraldry of mankind is a boundless theme, and we might by simple beat of drum heraldic collect almost a countless host of crests, badges, and quarterings truly emblematical, and adopted and intended to point out peculiarities or remarkable events and fancies in the histories of the coat-armour families of the world.

The emblematism of bodily sign or action constitutes the language of the dumb. An amusing instance occurs in the Abbé Blanchet’s “Apologues Orientaux,” in his description of “The Silent Academy, or the Emblems:”—

“There was at Hamadan, a city of Persia, a celebrated academy, of which the first statute was conceived in these terms; The academicians shall think much, write little, and speak the very least that is possible. It was named the silent Academy; and there was not in Persia any truly learned man who had not the ambition of being admitted to it. Dr. Zeb, an imaginary person, author of an excellent little work, The Gag, learned, in the retirement of the province where he was born, there was one place vacant in the silent Academy. He sets out immediately; he arrives at Hamadan, and presenting himself at the door of the hall where the academicians are assembled, he prays the servant to give this billet to the president: Dr. Zeb asks humbly the vacant place. The servant immediately executed the commission, but the Doctor and his billet arrived too late,—the place was already filled.

“The Academy was deeply grieved at this disappointment; it had admitted, a little against its wish, a wit from the court, whose lively light eloquence formed the admiration of all ruelles.[17] The Academy saw itself reduced to refuse Doctor Zeb, the scourge of praters, with a head so well formed and so well furnished! The president, charged to announce to the Doctor the disagreeable news, could scarcely bring himself to it, and knew not how to do it. After having thought a little, he filled a large cup with water, but so well filled it, that one drop more would have made the liquid overflow; then he made sign that the candidate should be introduced. He appeared with that simple and modest air which almost always announces true merit. The president arose and, without offering a single word, showed, with an appearance of deep sorrow, the emblematic cup, this cup so exactly filled. The Doctor understood that there was no more room in the Academy; but without losing courage, he thought how to make it understood that one supernumerary academician would disarrange nothing. He sees at his feet a roseleaf, he picks it up, he places it gently on the surface of the water, and did it so well that not a single drop escaped.

“At this ingenious answer everybody clapped hands; the rules were allowed to sleep for this day, and Doctor Zeb was received by acclamation. The register of the Academy was immediately presented to him, where the new members must inscribe themselves. He then inscribed himself in it; and there remained for him no more than to pronounce, according to custom, a phrase of thanks. But as a truly silent academician, Doctor Zeb returned thanks without saying a word. He wrote in the margin the number 100,—it was that of his new brethren; then, by putting a 0 before the figures, 0100, he wrote below, they are worth neither less nor more. The president answered the modest Doctor with as much politeness as presence of mind. He placed the figure 1 before the number 100, i.e. 1100; and he wrote, they will be worth eleven times more.”

The varieties in the Emblems which exist might be pursued from “the bird, the mouse, the frog, and the four arrows,” which, the Father of history tells us,[18] the Scythians sent to Darius, the invader of their country,—through all the ingenious devices by which the initiated in secret societies, whether political, social, or religious, seek to guard their mysteries from general knowledge and observation,—until we come to the flower-language of the affections, and learn to read, as Hindoo and Persian maidens can, the telegrams of buds and blossoms,[19] and to interpret the flashing of colours, either simple or combined. We should have to name the Picture writing of the Mexicans, and to declare what meanings lie concealed in the signs and imagery which adorn tomb and monument,—or peradventure to set forth the art by which, on so simple a material as the bark of a birch-tree, some Indians, on their journey, emblematized a troop with attendants that had lost their way. “In the party there was a military officer, a person whom the Indians understood to be an attorney, and a mineralogist; eight were armed: when they halted they made three encampments.” With their knives the Indians traced these particulars on the bark by means of certain signs, or, rather, hieroglyphical marks;—“a man with a sword,” they fashioned “for the officer; another with a book for the lawyer, and a third with a hammer for the mineralogist; three ascending columns of smoke denoted the three encampments, and eight muskets the number of armed men.” So, without paper or print, a not unintelligible memorial was left of the company that were travelling together.

And so we come to the very Early Examples—if not the earliest—of Emblematical Representation, as exhibited in fictile remains, in the workmanship of the silversmith, and of those by whom the various metals and precious stones have been wrought and moulded; and especially in the numerous specimens of the skill or of the fancy which the glyptic and other artizans of ancient Egypt have left for modern times.

For the nature of Fictile ornamentation it were sufficient to refer to the recently published Life of Josiah Wedgwood;[20] but in the antefixæ, or terra cotta ornaments, derived from the old Etruscan civilisation, we possess true and literal Emblems. As the name implies, these ornaments “were fixed before the buildings,” often on the friezes “which they adorned,” and were fastened to them by leaden nails. For examples, easy of access, we refer to the sketches supplied by James Yates, Esq., of Highgate; to the Dictionary of Gk. and Rom. Antiquities, p. 51; and especially to that antefixa which represents Minerva superintending the construction of the ship Argo. The man with the hammer and chisel is Argus, who built the vessel under her direction. The pilot Tiphys is assisted by her in attaching the sail to the yard. The borders at the top and bottom are in the Greek style, and are extremely elegant.”

And the pressing of clay into a matrix or mould, from which the form is taken, appears to be of very ancient date. The book of Job xxxviii. 14, alludes to the practice in the words, “it is turned as clay to the seal.” Of similar or of higher antiquity is “the work of an engraver in stone, like the engravings of a signet,” Exodus xxviii. 11. And “the breastplate of judgment, the Urim and the Thummim,” v. 30, worn “upon Aaron’s heart,” was probably a similar emblematical ornament to that which Diodorus Siculus, in his History, bk. i. chap. 75, tells us was put on by the president of the Egyptian courts of justice: “He bore about his neck a golden chain, at which hung an image, set about, or composed of precious stones, which was called Truth.”[21]

Among instances of emblematical workmanship by the silversmith and his confabricators of similar crafts, we may name that shield of Achilles which Homer so graphically describes,[22] “solid and large,” “decorated with numerous figures of most skilful art;”—or the shields of Hercules and of Æneas, with which Hesiod, Eoeæ, iv. 141–317, and Virgil, Æneid, viii. 615–73, might make us familiar. Or to come to modern times,—to days our very own,—there is the still more precious, the matchless shield by Vehm, whereon, in most expressive imagery, are hammered out the discoveries of Newton, Milton’s noble epics, and Shakespeare’s dramatic wonders. We may, too, in passing, allude to the richly-embossed and ornamented cups for which our swift racers and grey-hounds, and those “dogs of war,” our volunteers, contend; and the almost imperial pieces of plate, such as the Cæsars never beheld, in which genius and the highest art combine, by their “cunning work,” to carve the deeds and enhance the renown of some of our great Indian administrators and illustrious generals; these all, truly “choice emblemes,” intimate the extent to which our subject might lead. But I forbear to pursue it, though scarcely any path offers greater temptations for wandering abroad amid the marvels of human skill, and for considering reverently and gladly how men have been “filled with the spirit of God, in wisdom, and in understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship.” Exodus xxxi. 3.

Of glyptic art the most ancient, as well as the most ample, remains are found in the temples and the other monuments of Egypt. Various modern explorers and writers have given very elaborate accounts of those remains, and still are carrying on their researches; but of old writers only Clemens, of Alexandria, who flourished “towards the end of the second century after Christ,” “has left us a full and correct account of the principle of the Egyptian writing,”[23] and has declared what the subjects were which were included in the word hieroglyphics;[24] and as far as is known, no other early author, except Horapollo of the Nile, has written expressly on the Hieroglyphics of Egypt, and declared that his work—which was probably translated into Greek in the reign of the emperor Zeno, or even later—was derived from Egyptian sources; indeed, was a book in the language of Egypt.

Probably the best account we have of the author and of the translator, is given by Alexander Turner Cory, in the Preface to his edition of Horapollo. He says, pp. viii. and ix.,—

“At the beginning of the fifth century, Horapollo, a scribe of the Egyptian race, and a native of Phœnebythis, attempted to collect and perpetuate in the volume before us, the then remaining, but fast fading knowledge of the symbols inscribed upon the monuments, which attested the ancient grandeur of his country. This compilation was originally made in the Egyptian language; but a translation of it into Greek by Philip has alone come down to us, and in a condition very far from satisfactory. From the internal evidence of the work, we should judge Philip to have lived a century or two later than Horapollo; and at a time when every remnant of actual knowledge of the subject must have vanished.”

However this may be, it is certainly a book of Emblems, and just previous to Shakespeare’s age, and during its continuance was regarded as a high authority. Within that time there were at least five editions of the work,—and it was certainly the mine in which the writers of Emblem books generally sought for what were to them valuable suggestions. The edition we have used is the small octavo of 1551,[25] with many woodcuts, imaginative indeed, but designed in accordance with the original text. J. Mercier, a distinguished scholar, who died in 1562, was the editor. In 1547 he was professor of Hebrew at the Royal College of Paris, and in 1548 edited the quarto edition of Horapollo’s Hieroglyphics.

Horapollo, 1551.

From the edition of 1551, p. 52, we take a very popular illustration; it is the Phœnix, and may serve to show the nature of Horapollo’s work.

“How,” he asks, “do the Egyptians represent a soul passing a long time here?” “They paint a bird—the Phœnix; for of all creatures in the world this bird has by far the longest life.”

Again, bk. i. 37, or p. 53, “How do they denote the man who after long absence will return to his friends from abroad?” By the Phœnix; “for this bird, after five hundred years, when the death hour is about to seize it, returns to Egypt, and in Egypt, paying the debt of nature, is burned with great solemnity. And whatever sacred rites the Egyptians observe towards their other sacred animals, these they observe towards the Phœnix.”

And bk. ii. 57,—“The lasting restoration which shall take place after long ages, when they wish to signify it, they paint the bird Phœnix. For when it is born this bird obtains the restoration of its properties. And its birth is in this manner: the Phœnix being about to die, dashes itself upon the ground, and receiving a wound, ichor flows from it, and through the opening another Phœnix is born. And when its wings are fledged, this other sets out with its father to the city of the Sun in Egypt, and on arriving there, at the rising of the Sun, the parent dies; and after the death of the father, the young one sets out again for its own country. And the dead Phœnix do the priests of Egypt bury.”

But the drawings, which in the old editions of Horapollo were fancy-made, have, through the researches of a succession of Egyptian antiquaries, assumed reality, and may be appealed to for proof that Horapollo described the very things which he had seen, though occasionally he, or his translator Philip, attributes to them an imaginative or highly mythical meaning. The results of those researches we witness in the editions of Horapollo, first by the celebrated Dr. Conrad Leemans, of Leyden, in 1835,[26] and second, by Alexander Turner Cory, Fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 1840;[27] both of which editions, by their illustrative plates, taken from correct drawings of the originals, present Horapollo with an accuracy that could not have been approached in the sixteenth century. We have indeed of that age the great work of Pierius Valerian (ed. folio, Bâle, 1556, leaves 449), the Hieroglyphica, dedicated to Cosmo de’ Medici, with almost innumerable emblems, in fifty-eight books, and with about 365 devices. But it cannot be regarded as an exposition of the Egyptian art, and labours under the same defect as the early editions of Horapollo,—the illustrations are not taken from existing monuments.

An example or two from Leemans and Cory will supply sufficient information to enable the reader to understand something of the nature of Horapollo’s work, and of the actual Hieroglyphics from which that work has in great part been verified.

Leemans’ Horapollo, 1835.

The following is the 31st figure in the plates which Leemans gives; it is the pictorial representation to explain “What the Egyptians mean when they engrave or paint a star.”[28] “Would they signify the God who sets in order the world, or destiny, or the number five, they paint a star; God, indeed, because the providence of God, to which the motion of the stars and of all the world is subject, determines the victory; for it seems to them that, apart from God, nothing whatever could endure; and destiny they signify, since this also is regulated by stellar management,—and the number five, because out of the multitude which is in heaven, five only, by motion originating from themselves, make perfect the management of the world.”

Of the three figures which are delineated above, the one to the left hand symbolizes God, that in the middle destiny, and the third, the number 5, from five rays being used to indicate a star.

The same subjects are thus represented in Cory’s Horapollo.

Cory’s Horapollo, 1840.

Cory’s Horapollo, bk. i. c. 8, p. 15, also illustrates the question, “How do they indicate the soul?” by the accompanying symbols; of which I. represents the mummy and the departing soul, II. the hawk found sitting on the mummy, and III. the external mummy case. The answer to the question is:—

“Moreover, the Hawk is put for the soul, from the signification of its name; for among the Egyptians the hawk is called Baieth: and this name in decomposition signifies soul and heart; for the word Bai is the soul, and ETH the heart: and the heart according to the Egyptians is the shrine of the soul; so that in its composition the name signifies ‘soul enshrined in heart.’ Whence also the hawk, from its correspondence with the soul, never drinks water, but blood, by which, also, the soul is sustained.”

And in a similar way many of the sacred engravings or drawings are interpreted. A serpent with its tail covered by the rest of its body, “depicts Eternity;”[29] “to denote an only begotten, or generation, or a father, or the world, or a man, they delineate a SCARABÆUS;”[30] a Lion symbolises intrepidity,—its FOREPARTS, strength, and its HEAD, watchfulness;[31] the Stork denotes filial affection, the Crane on the watch, a man on guard against his enemies, and the FEATHER of an Ostrich, impartial justice,—for, adds the author, “this animal, beyond other animals, has the wing feathers equal on every side.”[32]

Christian Art, like the Religious Art of the world in general,—from the thou and thee of simplest Quakerism, outward and audible sounds of an inward and silent spirit, up to the profoundest mystic ritualism of the Buddhist,—Christian Art abounds in Emblems; gems and colours, genuflexions and other bodily postures supply them; they are gathered from the mineral, animal, and vegetable kingdoms, and besides are enriched from the whole domain of imaginary devices and creatures. Does the emerald flash in its mild lustre?—it is of “victory and hope, of immortality, of faith, and of reciprocal love,” that it gives forth light. Is blue, the colour of heaven, worn in some religious ceremony?—it betokens “piety, sincerity, godliness, contemplation, expectation, love of heavenly things.” Do Christian men bare the head in worship?—it is out of reverence for the living God, whose earthly temples they have entered. The badge of St. John the Baptist, is a lamb on a book,—that of St. John the Evangelist is a cup of gold with a serpent issuing from it. The Pomegranate, “showing its fulness of seed and now bursting,” typifies the hope of immortality;—and a Fleur-de-lys, or the Rose of Sharon, embroidered or painted on a robe,—it marks the Blessed Virgin. With more intricate symbolism the Greek Church represents the Saviour’s name ΙHϹΟΥϹ ΧΡΙϹΤΟϹ.—IesuS CHristuS. The first finger of the hand extended is for I, the second bent for C or s, the thumb crossed upon the third finger for Χ or Ch, and the fourth finger curved for Ϲ or s. Thus are given the initial and final letters of that Holy Name, the Saviour, the Christ.[33]

Of early Emblems examples enough have now been given to indicate their nature. Whether in closing this part of the subject we should name a work of more ancient date even than the Greek version of Horapollo would admit of doubt, were it not that every work partakes of an emblematical character, when the descriptions given or the instances taken pertain, as

Whitney says, “to vertue and instruction of life,” or “doe tende vnto discipline, and morall preceptes of living.”

Under this rule we hesitate not to admit into the wide category of Emblem writers, Epiphanius, who was chosen bishop of Constantia in Cyprus, A.D. 367, and who died in 402. His Physiologist, published with his sermon on the Feast of Palms, is, like many writings of the Fathers, remarkable for highly allegorical interpretations. An edition, by Ponce de Leon, a Spaniard of Seville, was printed at Rome in 1587, and repeated at Antwerp[34] in 1588. It relates to the real and imaginary qualities of animals, and to certain precepts and doctrines of which those qualities are supposed to be symbolical. As an example we give here an extract from chapter XXV. p. 106, “Concerning the Stork.”

Epiphanius, 1588.

The Stork is described as a bird of extreme purity; and as nourishing, with wonderful affection, father and mother in their old age. The “interpretation” or application of the fact is;—“So also it behoves us to observe these two divine commands, that is to turn aside from evil and to do good, as the kingly prophet wrote; and likewise in the decalogue the Lord commands, thus saying;—Honour thy father and thy mother.”

In a similar way the properties and habits of various animals,—of the lion, the elephant, the stag, the eagle, the pelican, the partridge, the peacock, &c., are adduced to enforce or symbolize virtues of the heart and life, and to set forth the doctrines of the writer’s creed.

To illustrate the Emblem side of Christian Art a great variety of information exists in Sketches of the History of Christian Art, by Lord Lindsay (3 vols. 8vo: Murray, London, 1847); and Northcote and Brownlow’s Roma Sotterranea, compiled from De Rossi (8vo: Longmans, London, 1869) promises to supply many a symbol and type of a remote age fully to set forth the same subject.

Giovio, 1556.

IN the use of the word Emblem there is seldom a strict adherence observed to an exact definition,—so, when Emblem Literature is spoken of, considerable latitude is taken and allowed as to the kind of works which the terms shall embrace. In one sense every book which has a picture set in it, or on it, is an emblem-book,—the diagrams in a mathematical treatise or in an exposition of science, inasmuch as they may be, and often are, detached from the text, are emblems; and when to Tennyson’s exquisite poem of “Elaine,” Gustave Doré conjoins those wonderful drawings which are themselves poetic, he gives us a book of emblems;—Tennyson is the one artist that out of the gold of his own soul fashioned a vase incorruptible,—and Doré is that second artist who placed about it ornaments of beauty, fashioned also out of the riches of his mind.

Yet by universal consent, these and countless other works, scientific, historical, poetic, and religious, which artistic skill has embellished, are never regarded as emblematical in their character. The “picture and short posie, expressing some particular conceit,” seem almost essential for bringing any work within the province of the Emblem Literature;—but the practical application of the test is conceived in a very liberal spirit, so that while the small fish sail through, the shark and the sea-dog rend the meshes to tatters.

A proverb or witty saying, as, in Don Sebastian Orozco’s “Emblemas Morales” (Madrid 1610), “Divesqve miserqve,” both rich and wretched, may be pictured by king Midas at the table where everything is turned to gold, and may be set forth in an eight-lined stanza, to declare how the master of millions was famishing though surrounded by abundance;—and these things constitute the Emblem. Some scene from Bible History shall be taken, as, in “Les figures du vieil Testament, & du nouuel” (at Paris, about 1503), Moses at the burning bush; where are printed, as if an Emblem text, the passage from Exodus iii. 2–4, and by its side the portraits of David and Esaias; across the page is a triplet woodcut, representing Moses at the bush, and Mary in the stable at Bethlehem with Christ in the manger-cradle; various scrolls with sentences from the Scriptures adorn the page:—such representations claim a place in the Emblem Literature. Boissard’s Theatrum Vitæ Humanæ (Metz, 1596) shall mingle, in curious continuity, the Creation and Fall of Man, Ninus king of the Assyrians, Pandora and Prometheus, the Gods of Egypt, the Death of Seneca, Naboth and Jezabel, the Advent of Christ and the Last Judgment;—yet they are all Emblems,—because each has a “picture and a short posie” setting forth its “conceit.” To be sure there are some pages of Latin prose serving to explain or confuse, as the case may be, each particular imagination; but the text constitutes the emblem, and however long and tedious the comment, it is from the text the composition derives its name.

“Stam und Wapenbuch hochs und niders Standts,”—A stem and armorial Bearings-book of high and of low Station,—printed at Frankfort-on-Mayne, 1579, presents above 270 woodcuts of the badges, shields and helmets, with appropriate symbols and rhymes, belonging as well to the humblest who can claim to be “vom gutem Geschlecht,” of good race, as to the Electoral Princes and to the Cæsarean Majesty of the Holy Roman Empire. Most of the figures are illustrated by Latin and German verses, and again “picture and short posie” vindicate the title,—book of Emblems.

And of the same character is a most artistic work by Theodore de Bry, lately added to the treasure-house at Keir; it is also a Stam und Wapenbuch, issued at Frankfort in 1593, with ninety-four plates all within most beautiful and elaborate borders. Its Latin title, Emblema Nobilitate et Vulgo scitu digna, &c., declares that these Emblems are “worthy to be known both by nobles and commons.”

And so when an Emperor is married, or the funeral rites of a Sovereign Prince celebrated, or a new saint canonized, or perchance some proud cardinal or noble to be glorified, whatever Art can accomplish by symbol and song is devoted to the emblem-book pageantry,—and the graving tool and the printing press accomplish as enduring and wide-spread a splendour as even Titian’s Triumphs of Faith and Fame.

Devotion that seeks wisdom from the skies, and Satire that laughs at follies upon the earth, both have claimed and used emblems as the exponents of their aims and purposes.

With what surpassing beauty and nobleness both of expression and of sentiment does Otho Vænius in his “Amoris Divini Emblemata,” Antwerp, 1615, represent to the mind as well as to the eye the blessed Saviour’s adoption of a human soul, and the effulgence of love with which it is filled! (See Plate II.) They are indeed divine Images portrayed for us, and the great word is added from the beloved disciple,—“Behold, what manner of love the Father hath bestowed upon us, that we should be called the sons of God.” And the simple Refrain follows,—

And that clever imitation of the “Stultifera Nauis,” the Fool-freighted Ship, of the fifteenth century, namely, the “Centifolium Stultorum,” edition 1707, or Hundred-leaved Book of Fools of the eighteenth, proves how the Satirical may symbolize and fraternize with the Emblematical. The title of the book alone is sufficient to show what a vehicle for lashing men’s faults the device with its stanzas and comment may be made; it is, “A hundred-leaved book of Fools, in Quarto; or an hundred exquisite Fools newly warmed up, in Folio,—in an Alapatrit-Pasty for the show-dish; with a hundred fine copper engravings, for honest pleasure and useful pastime, intended as well for frolicsome as for melancholy minds; enriched moreover with a delicate sauce of many Natural Histories, gay Fables, short Discourses, and edifying Moral Lessons.”

Among the one hundred distinguished characters, we might select, were it only in self-condemnation, the Glass and Porcelain dupe, the Antiquity and Coin-hunting dupe, and especially the Book-collecting dupe. These are among the best of the devices, and the stanzas, and the expositions. Dupes of every kind, however, may find their reproof in the six simple German lines,—p. 171,

meaning pretty nearly in our vernacular English,

But Politics also have the bright, if not the dark, side of their nature presented to the world in Emblems. Giulio Capaccio, Venetia, 1620, derives “Il Principe,” The Prince, from the Emblems of Alciatus, “with two hundred and more Political and Moral Admonitions,” “useful,” he declares, “to every gentleman, by reason of its excellent knowledge of the customs, economy, and government of States.” Jacobus à Bruck, of Angermunt, in his “Emblemata Politica,” A.D. 1618, briefly demonstrates those things which concern government; but Don Diego Saavedra Faxardo, who died in 1648, in a work of considerable repute,—“Idea de vn Principe Politico-Christiano, representada en cien Empresas,”—Idea of a Politic-Christian Prince, represented in one hundred Emblems (edition, Valencia, 1655), so accompanies his Model Ruler from the cradle to maturity as almost to make us think, that could we find the bee-bread on which Kings should be nourished, it would be no more difficult a task for a nation to fashion a perfect Emperor than it is for a hive to educate their divine-right ruling Queen.

But, so great is the variety of subjects to which the illustrations from Emblems are applied, that we shall content ourselves with mentioning one more, taking out the arguments, as they are named, from celebrated classic poets, and converting them into occasions for pictures and short posies. Thus, like the dust of Alexander, the remains of the mighty dead, of Homer and Virgil, of Ovid and Horace, have served the base uses of Emblem-effervescence, and in nearly all the languages of Europe have been forced to misrepresent the noble utterances of Greece and Rome. Many of the pictures, however, are very beautiful, finely conceived, and skilfully executed;—we blame not the artists, but the false taste which must make little bits of verses where the originals existed as mighty poems.

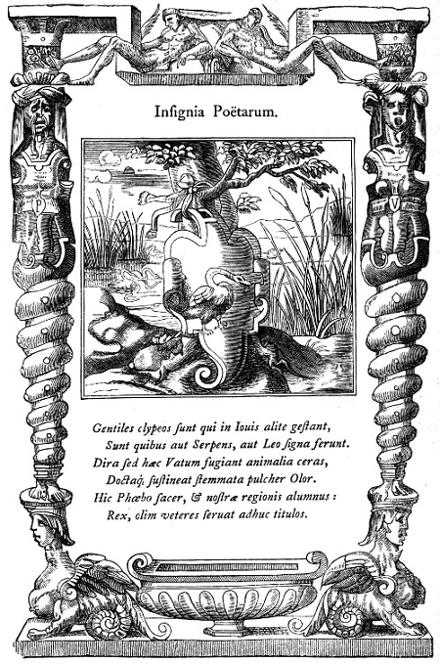

Generally it is considered that the Ovids of the fifteenth century were without pictorial illustrations, and could not, therefore, be classed among books of Emblems; but the Blandford Catalogue, p. 21, records an edition, “Venetia, 1497,” “cum figuris depictis,”—with figures portrayed. Without discussing the point, we will refer to an undoubted emblematized edition of the Metamorphoses of Ovid, “Figurato & abbreviato in forma d’Epigrammi da M. Gabriello Symeoni,”—figured and abbreviated in form of Epigrams by M. Gabriel Symeoni. The volume is a small 4to of 245 pages, of which 187 have each a title and device and Italian stanza, the whole surrounded by a richly figured border. The volume, dedicated to the celebrated “Diana di Poitiers, Dvchessa di Valentinois,” was published “A Lione per Giouanni di Tornes nella via Resina, 1559.” An Example, p. 13, (see Plate III.,) will show the character of the work, of which another edition was issued in 1584. The Italian stanzas are all of eight lines each, and the passages of the original Latin on which they are founded are collected at the end of the volume. Thus, for “La Creatione & confusione del Mondo,” the Latin lines are,

Of the devices several are very closely imitated in the woodcuts of Reusner’s Emblems, published at Frankfort, in 1581. The engravings in Symeoni’s Ovid are the work of Solomon Bernard, “the little Bernard,” a celebrated artist born at Lyons in 1512; who also produced a set of vignettes for a French translation of Virgil, L’Eneide de Virgile, Prince des Poetes latins, printed at Lyons in 1560.

“Qvinti Horatii Flacci Emblemata,” as Otho Vænius names one of his choicest works, first published in 1607, is a similar adaptation of a classic author to the prevailing taste of the age for emblematical representation. The volume is a very fine 4to of 214 pages, of which 103 are plates; and a corresponding 103 contain extracts from Horace and other Latin authors, followed, in the edition of 1612, by stanzas in Spanish, Italian, French and Flemish. An example of the execution of the work will be found as a Photolith, Plate XVII., near the end of our volume; it is the “Volat irrevocabile tempus,”—Irrevocable time is flying,—so full of emblematical meaning.

From the office of the no less celebrated Crispin de Passe, at Utrecht, in 1613, issued, in Latin and French verse, “Specvlvm Heroicvm Principis omnium temporum Poëtarum Homeri,”—The Heroic Mirror of Homer, the Prince of the Poets of all times. The various arguments of the twenty-four books of the Iliad have been taken and made the groundwork of twenty-four Emblems, with their devices most admirably executed. The Latin and French verses beneath each device unmistakeably impress a true emblem-character on the work. The author, “le Sieur J. Hillaire,” appends to the Emblems, pp. 69–75, “Epitaphs on the Heroes who perished in the Trojan War,” and also “La course d’Vlisses, son tragitte retour, & deffaicte des amans qui poursuivoient la chaste & vertueuse Penelope.”

What might not in this way be included within the wide-encompassing grasp of the determined Emblematist it is almost impossible to say; and therefore it ought to be no matter of surprise to find there is practically a greater extent given to the Literature of Emblems than of absolute right belongs to it. We shall not go much astray if we take Custom for our guide, and keep to its decisions as recorded in the chief catalogues of Emblem works.

Horapollo, 1551.

LEAVING for the most part out of view the discussions which have taken place as to the exact time and the veritable originators of the arts of printing by fixed or moveable types, and of the embellishing of books by engravings on blocks of wood or plates of copper, we are yet—for the full development of the condition and extent of the Emblem Literature in the age of Shakespeare—required to notice the growth of that species of ornamental device in books which depends upon Emblems for its force and meaning. We say advisedly “ornamental device in books,” for infinite almost are the applications of Symbol and Emblem to Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, as is testified by the Remains of Antiquity in all parts of the world, by the Pagan tombs and Christian catacombs of ancient Rome, by nearly every temple and church and stately building in the empires of the earth, and especially in those wonderful creations of human skill in which form and colour bring forth to sight nearly every thought and fancy of our souls.

Long before either block-printing or type-printing was practised, it is well known how extensively the limner’s art was employed “to illuminate,” as it is called, the Manuscripts that were to be found in the rich abbeys or convents, and in the mansions of the great and noble. For instance, the devices in the Dance of Macaber, undoubtedly an Emblem Manuscript of the fourteenth century, were of painter’s workmanship, and afterwards employed by the wood-engravers to embellish type-printed volumes of a devotional character. To this Brunet, in his Manuel du Libraire, vol. v. c. 1557–1560, bears witness, when speaking of the printer Philip Pigouchet, and of the bookseller Simon Vostre, who “furent les premiers à Paris qui surent allier avec succès la gravure à la typographie;” and adds in a note, “La plus ancienne édition de la Danse macabre que citent les bibliographes est celle de Paris, 1484; mais, plus d’un siècle avant cette date, des miniaturistes français avaient déjà figuré, sur les marges de plusieurs Heures manuscrites, des Danses de morts, représentées et disposées à peu près comme elles l’ont été depuis dans les livres de Simon Vostre; c’est ce que nous avons pu remarquer dans un magnifique manuscrit de la seconde moitié du quatorzième siècle, enrichi de nombreuses et admirables miniatures qui, après avoir été conservé en Angleterre dans le cabinet du docteur Mead, à qui le roi Louis XV. en avait fait présent, est venu prendre place parmi les curiosités de premier ordre réunies dans celui de M. Ambr. Firmin Didot.”

A strictly emblematical work in English is the following, “from a finely written and illuminated parchment roll, in perfect preservation, about two yards and three quarters in length,” “The Five Wounds of Christ.” “By William Billyng;” “Manchester: Printed by R. and W. Dean, 4to, 1814.” The date is fixed by the editor, William Bateman, “between the years 1400 and 1430;” and the poem contains about 120 lines, with six illuminated devices. We give here, on page 40, in outline, the Device of “The Heart of Jesus the Well of everlasting Lyfe.”

Five wounds of Christ, 1400–1430.

There follows, as to each of the Emblems, a Prayer, or Invocation; the Device in question has these lines,—

An Astronomical Manuscript in the Chetham Library, Manchester, the eclipses in which are calculated from A.D. 1330 to A.D. 1462, contains emblematical devices for the months of the year, and the signs of the zodiac; these are painted medallions at the beginning of each month; and to each of the months is attached a metrical line explanatory of the device.

| Januarius. | Ouer yis feer I warme myn handes. |

| Februarius. | Wyth yis spade I delve my londes. |

| Martius. | Here knitte I my vynes in springe. |

| Aprilis. | So merie I here yese foules singe. |

| Mayus. | I am as Joly as brid on bouz. |

| Junius. | Here wede I my corn, clene I houz. |

| Julius. | Wyth yis sythe my medis I mowe. |

| Augustus. | Here repe I my corn so lowe. |

| September. | Wyth ys flayll I yresche my bred. |

| October. | Here sowe I my Whete so reed. |

| November. | Wyth ys knyf I steke my swyn. |

| December. | Welcome cristemasse Wyth ale and Wyn. |

This manuscript contains, as J. O. Halliwell says of it, “an astrological volvelle—an instrument mentioned by Chaucer: it is the only specimen, I believe, now remaining in which the steel stylus or index has been preserved in its original state.”

Doubtless it is a copy of the Kalendrier des Bergers, which with the Compost des Bergers, has in various forms been circulated in France from the fourteenth century almost, if not quite, to the present day. An edition in 4to, of 144 pages, printed at Troyes, in 1705, bears the title, Le Grand Calendrier et Compost des Bergers; composé par le Berger de la grand Montagne.

Kindred works issued from the presses of Venice, of Nuremberg, and of Augsburg, between 1475 and 1478, in Latin, Italian, and German, and are ascribed to John Muller, more known under the name of Regiomontanus, a celebrated astronomer, born in 1436, at Koningshaven, in Franconia, and who died at Rome in 1476. One of these editions, in folio, was printed at Augsburg in 1476 by Erhard Ratdolt, being the first work he sent forth after his establishment in that city. (See Biog. Univ., vol. xxx. p. 381, and vol. xxxvii. p. 25.) But the most thoroughly emblematical work from Ratdolt’s press was an “Astrolabium planũ in tabulis,” “wrought out anew by John Angeli, master of liberal arts, MCCCCLXXXVIII.” There are 414 woodcuts, and all of them emblematical. The library at Keir contains a perfect copy, 4to, in most admirable condition. Brunet, i. c. 290, names a Venice edition in 1494, and refers to other astronomical works by the same author.

In its manuscript form, too, the celebrated “Speculum Humanæ Salvationis,” Mirror of Human Salvation, exhibits throughout the emblem characteristics. Of this work, both as it exists in manuscript and in the earliest printed form by Koster of Haarlem, about 1430, specimens are given in “A History of the Art of Printing from its invention to its wide spread developement in the middle of the sixteenth century;” “by H. Noel Humphreys,” “with one hundred illustrations produced in Photo-lithography;” folio: Quaritch, London, 1867. Pl. 8 of Humphreys’ learned and magnificent volume exhibits “a page from a manuscript copy of the Speculum Humanæ Salvationis, executed previous to the printed edition attributed to Koster;” and pl. 10, “A page from the Speculum Humanæ Salvationis attributed to Koster of Haarlem, in which the text is printed from moveable types.”

The inspection of these plates, and the assurance by Humphreys, p. 60, that “the illustrations, though inferior to Koster’s woodcuts, are of similar arrangement,” may satisfy us that the Speculum Humanæ Salvationis, and all its kindred works, in German, Dutch, and French, amounting to many editions previous to the year 1500,[35] are truly books that belong to the Emblem literature. Thus pl. 8, “though without the decorative Gothic framework which separates, and, at the same time, binds together the double illustrations of the xylographic artist,” exhibits to us the exact character of “the double pictures of the Speculum.” “These double pictures,” p. 60 of Humphreys, “illustrate first a passage in the New Testament, and secondly the corresponding subject of the Old, of which it is the antitype. In the present page we have Christ bearing His cross (Christus bajulat crucem) typified by Isaac carrying the wood for his own sacrifice (Isaac portat ligna sua).” “The engravings,” p. 58, “i.e., of Koster’s first great effort, occur at the top of each leaf, and the rest of the page is filled with two columns of text, which, in the supposed first edition, is composed of Latin verse

(or, rather, Latin prose with rhymed terminations to the lines, as the lines do not scan); and in later editions, in Dutch prose.” “This specimen,” pl. 8, p. 60, “will enable the student to understand precisely the kind of manuscript book which Koster reproduced in a cheaper form by xylography, to which he eventually allied the still more important invention of moveable types.”

From a very fine MS. copy of the Speculum Humanæ Salvationis, belonging to Mr. Henry Yates Thompson, our fac-simile Plates IV. and V., though on a smaller scale, present the Title and the first Pair of devices with their text. The work is in twenty-nine chapters, and to each there are four devices in four columns, with appropriate explanations in Latin verse, and at the foot of the columns are the references to the Old or the New Testament.

The manuscript entitled “De Volueribus, sive de tribus Columbis,”—Concerning Birds, or the Three Doves, in the library “du Grand Seminaire,” at Bruges, is also an emblem-book. It is excellently illuminated, and the workmanship is probably of the thirteenth century. (See the Whitney Reprint, p. xxxii.)

The illuminated Missal,[36] executed in 1425 for John, Duke of Bedford and regent of France, according to the account published of it by Richard Gough, 4to, London, 1794, and by others, abounds in emblem devices. It contains “fifty-nine large miniatures, which nearly occupy the page, and above a thousand small ones in circles of about an inch and half diameter, displayed in brilliant borders of golden foliage, with variegated flowers, &c. At the bottom of every page are two lines in blue and gold letters, which explain the subject of each miniature.” “The Missal,” says Dibdin, “frequently displays the arms of these noble personages,” (John, Duke of Bedford, and of his wife Jane, daughter of the Duke of Burgundy,) “and also affords a pleasing testimony of the affectionate gallantry of the pair: the motto of the former being ‘A VOUS ENTIER;’ that of the latter, ‘J’EN SUIS CONTENTE.’” Among its ornaments are emblems or symbols of the twelve months, and a large variety of paintings derived from the Sacred Scriptures, many of which possess an emblematical meaning.

Not aiming at any exhaustive method in the information we gather and impart respecting Emblem works and editions previous to the year A.D. 1500, we pass by the very numerous other instances in support of our theme which a search into manuscripts would supply. The “Block-Books,”[37] which, in the main, are especially emblematical, we next consider. We select two instances as representative of the whole set;—namely, the “Biblia Pauperum,” Bibles of the Poor, and the “Ars Memorandi,” The Art of Remembering.

In his “Bibliographical Decameron,” vol. i. p. 160, Dibdin tells us, “The earliest printed book, containing text and engravings illustrative of scriptural subjects, is called the Histories of Joseph, Daniel, Judith, and Esther. This was executed in the German language, and was printed by Pfister at Bamberg in 1462. It is among the rarest of typographical curiosities in existence.” Dibdin’s dictum is considerably modified, if not set aside, by Noel Humphreys; who, though affirming, p. 41, that “a late German edition of the Biblia Pauperum has the date 1475, but that before that period editions had been printed at the regular press with moveable types, as, for instance, that of Pfister, printed at Bamberg in 1462,”—yet had previously declared, p. 39, “many suppose that Laurens Koster, of Haarlem, who afterwards invented moveable types, was one of the earliest engravers of Block-books, and that in fact the Biblia Pauperum was actually his work.” “The period of its execution may probably be estimated as lying between 1410 and 1420: probably earlier, but certainly not later.”

The earliest editions of these Biblia Pauperum contain forty leaves, the later editions fifty, printed only on one side. Opposite to p. 40, Noel Humphreys gives, pl. 2, “A Page from the Biblia Pauperum generally supposed to be one of the earliest block-books.”