Front Cover

Front Cover

A LOCOMOTIVE AND TENDER.

A brief book for the boys. God gives you work to do in the world. He gives you honourable work. There is much done that is mean and dishonourable. Depend upon it, that is not His. In the beginning of your work, character grows out of it; as you go on, your character goes into it. Therefore the Bible declares that "God, without respect of persons, judgeth according to every man's work." We judge in the same way. This little book will show you how much the practice of the virtues, the humbler virtues, has to do with making good work.

But keep ever in mind that these virtues, however useful and important for your work in this world, have no saving power in them—they form no plea for the favour of God; the key which unlocks the door of Heaven is not found among them. Like the young man in the Gospel, you may have the loveliness of every natural virtue, and yet be lost.

As sinners in the sight of God, you need the atoning blood of the Redeemer; you need repentance and faith in that blood. Make Jesus Christ, therefore, the corner-stone of your character; on that foundation build your character. Cultivate the graces of the Gospel. Baptize the virtues with your Saviour's love. A noble Christian manhood can only be attained by the slow and steady endeavours of a heart fixed on God, and a hand diligent and delighting in the work He has given it to do.

| I. | LIFE AMONG THE COAL PITS, | 9 |

| II. | MENDING AND MAKING—LITTLE BOB, | 19 |

| III. | WHO BEGAN RAILROADS?—"PUFFING BILLY," | 30 |

| IV. | TWO CITIES THAT WANTED TO GET NEAR EACH OTHER—A NEW FRIEND, | 38 |

| V. | HUNTING UP HIS OWN WORK—AN ENTERPRISING QUAKER—WHAT WAS THE RESULT? | 46 |

| VI. | THE TWO CITIES TRYING AGAIN—BUGBEARS, | 58 |

| VII. | GRAPPLING WITH DIFFICULTIES—THE BOG—A PUZZLE—THE PRIZE OFFER, | 72 |

| VIII. | ROBERT'S RETURN—A CURIOUS ENCOUNTER—THE PRIZE ENGINE, | 86 |

| IX. | OPENING OF THE NEW ROAD—DIFFICULTIES VANISH—A NEW ERA, | 102 |

| X. | THE STEPHENSON CENTENARY—HONOUR TO WHOM HONOUR IS DUE, | 121 |

| LOCOMOTIVE AND TENDER, | Frontispiece |

| EARLY WORK, | 10 |

| A SAFETY LAMP, | 11 |

| BIRTHPLACE OF GEORGE STEPHENSON, | 12 |

| AT SCHOOL, | 17 |

| MENDING THE CLOCK, | 21 |

| THE SUN-DIAL, | 29 |

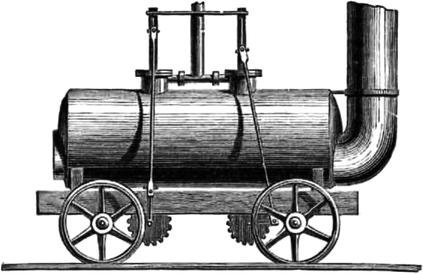

| GEORGE STEPHENSON'S FIRST ENGINE, | 35 |

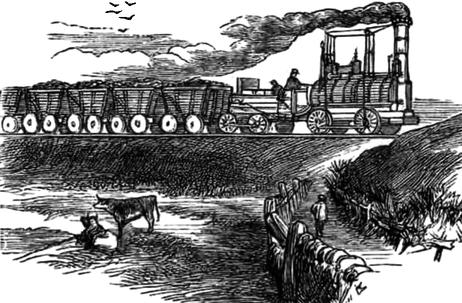

| "PUFFING BILLY," | 36 |

| THE VISIT TO "PUFFING BILLY," | 44 |

| THE TWO STRANGERS, | 50 |

| A TALK ABOUT RAILWAYS, | 54 |

| SURVEYING AT NIGHT, | 63 |

| CHAT MOSS, | 74 |

| GOOD SERVICE, | 81 |

| A CURIOUS ENCOUNTER, | 87 |

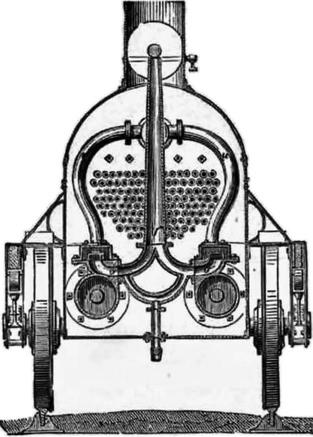

| SECTION OF THE FIRST BOILER IN USE, | 92 |

| SECTION OF A TUBULAR BOILER, | 93 |

| THE FAILURE, | 95 |

| TUBES OF A MODERN ENGINE, | 96 |

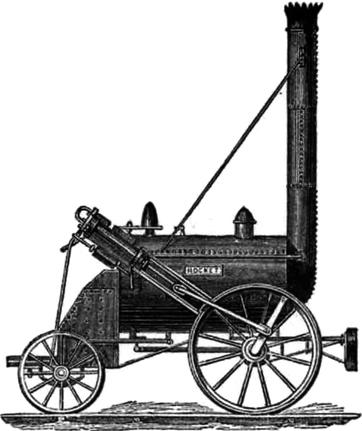

| THE "ROCKET," | 97 |

| OPENING THE LINE, | 104 |

| WHOLESOME REPROOF, | 115 |

| LATER DAYS OF GEORGE STEPHENSON, | 116 |

| VICTORIA BRIDGE, MONTREAL, | 118 |

What useful little fellow is this, carrying his father's dinner to him at the coal-pit? He takes care, also, of his little brothers and sisters, keeping them clear of the coal-waggons, which run to and fro before the cottage door. Then he is seen tending a neighbour's cows. Now, he is moulding mud engines, putting in hemlock sticks for blow-pipes; besides cutting many a good caper, and uttering all sorts of drolleries for the benefit of other little boys, who like himself swarm round, too poor to go to school, if school there were—but schools there were none.

The boys called him "Geordie Steve."

A lad is wanted to shut the coal-yard gates after work is over. Geordie offers his services and gets the post, earning by it twopence a day. A neighbour hires him to hoe turnips at fourpence. He is thankful to earn a bit, for his parents are poor, and every little helps. He sees work ahead, however, more to his taste. What? He longs to be big enough to go and work at the coal-pits with his father. For the home of this little fellow, as you already perceive, is in a coal region. It is in the coal district of Newcastle, in the north-eastern part of England.

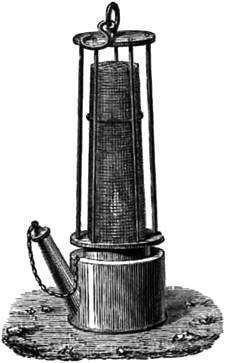

EARLY WORK.

I suppose you never visited a colliery? Coal is found in beds and veins under ground. Deep holes are made, down which the miners go and dig it out; it is hoisted out by means of steam-engines. These holes are called shafts. The pit-men have two enemies to encounter down in the coal-pits—water, and a kind of gas which explodes on touching the flame of a candle. The water has to be pumped out; and miners are now provided with a lamp, called a safety-lamp, which is covered with a fine wire gauze to keep the gas away from the flame.

SAFETY LAMP.

The coal is brought up from the pit in baskets, loaded on waggons running on tram-roads, and sent to the sheds. Tram-roads were a sort of wooden railway. A colliery is a busy and odd-looking spot.

Geordie's family lived in one room—father, mother, four boys, and two girls. Snug quarters, one would think; but the working-men of England at that time had smaller wages and poorer homes than they now have—for Geordie was born in 1781, in the little village of Wylam, seven miles from Newcastle, and his full name is George Stephenson.

BIRTHPLACE OF GEORGE STEPHENSON.

James, an elder brother, is "picker;" and by-and-by George is old enough to be a picker too, going with his father and brother to their daily tasks, like a man. To clear the coal of stones and dross is their business. There are a number of pits around, and each one has a name,—"Dolly Pit," "Water-run Pit," and so on.

I do not know how long he was picker, but we next find him driving a gin-horse, at a pit two miles off, across the fields. Away he goes in the early morning, gladdened all along by many bird songs. George and the birds are fast friends. He knows where their nests are in the hedgerows, and watches over them with fatherly affection. At home he has tame birds, whose pretty, knowing ways are the wonder of the neighbourhood. For many years a tame blackbird was as much one of the family as George himself, coming and going at pleasure, and roosting at night over his head. Sometimes it spent the summer in the woods, but was sure to come back with cold weather, to share his care and crumbs through the winter.

George, too, had a famous breed of rabbits; and as for his dog, it was one of the most accomplished and faithful creatures in the district. In fact, the boy had an insight into dumb-brute nature, as we shall find he had into other things, that gave him power over it—a power which he never abused, but used kindly and well.

George next rose to be assistant fireman with his father, at a shilling a day. He was fourteen, but so small of his age that he used to hide when the inspector came round, lest he should be thought too small for his wages. If small in body, he was large in heart, intent in all things to do his best. And this made his work so well done, that it could not escape the notice of his employers. When he went to the office on Saturday night to receive his wages, double pay was given him—twelve instead of six shillings! George could scarcely believe in his good luck. When he found it was really no mistake, he took the money and rushed out of the office, exclaiming, "I am now a made man for life!"

George rapidly shot ahead of his father, a kind old man, who always stayed fireman, while his boy climbed one round after another up the ladder of promotion. At seventeen we find him plugman. What duty is that? A plugman has charge of a pumping-engine, and when the water in the pit is below the suction-holes, he goes down the shaft and plugs the tube, in order to make the pump more easily draw. The post required more skill and knowledge of machinery than any he had filled before, and he proved himself equal to it.

Indeed, he loves his engine as he loves his birds. It is a pet with him. He keeps it in prime order. He takes it to pieces, and cleans it, and studies it; pries into the whys and wherefores, and is never satisfied until he understands every spring and cog of the machinery, and gets the mastery of it. You never find him idling away his time. In leisure moments he is at his old kink, moulding clay engines, and putting new thoughts into them.

He wished to know the history of engines, and how they were thought out at first. Somebody told him about Watt, the father of steam-power, and that there were books which would satisfy his curiosity. Books! what good would books do poor George? He cannot read. Not read? No. He is eighteen, and hardly knows his letters. Few of the colliers did. They were generally an ignorant, hard-working, clannish set of men, whose pay-day was a holiday, when their hard-won earnings were squandered at cock-fights and in ale-houses.

If one was found who did read, what a centre of light was he! At night the men and boys gathered around him, when, by the light of his engine fire, he would give them the news from an old newspaper, or a scrap of knowledge from some stray magazine, or a wild story from an odd volume; and on these occasions no one listened with more profound attention than George.

Oh! it was so wonderful to read, he thought. It was to open the gates into great fields of knowledge. Read he must. The desire grew upon him stronger and stronger. In the neighbouring hamlet of Welbottle, old Robin Cowens taught an evening school.

"I'll go," cried George.

"And I too," echoed Tommy Musgrove, a fellow-workman, quite carried away by George's enthusiasm.

Now they went to Robin's school three evenings a week. I do not know how it was with Tommy, but old Robin never had a better scholar than George; indeed, he soon outlearned his master! His schooling cost him threepence a week, and, poor as it was, put into his hand the two keys of knowledge, reading and writing.

These mastered, he longs to use them. Andrew Robertson opens an evening school nearer than Welbottle, and Andrew proposes to teach arithmetic, a branch George is anxious to grapple with next. "And he took to figurin' wonderful," said Master Andrew, speaking of his new scholar, who soon left his classmates far behind. And no wonder. Every spare moment to George was more precious than gold dust, and was used accordingly. When not on duty, he sits by his engine and works out his sums. No beer-shop ever enticed him to its cups; no cock-fight ever tempted him to be its spectator. He hated everything low and vulgar.

AT SCHOOL.

Andrew was proud of his pupil, and when George removed to another pit, the old schoolmaster shifted his quarters and followed him. His books did not damage his interest in business. Was the plugman going to stay plugman? No. Bill Coe, a friend of his advanced to be a brakeman, offered to show George. The other workmen objected. And one in particular stopped the working of the engine when George took hold of it; "for," he cried angrily, "Stephenson can't brake, and is too clumsy ever to learn."

A brakeman has charge of an engine for raising coal from a pit. The speed of the ascending coal, brought up in large hazel-wood baskets, is regulated by a powerful wooden brake, acting on the rim of the fly-wheel, which must be stopped just when the baskets reach the settle-board, where they are to be emptied. Brakemen were generally chosen from experienced engine-men of steady habits; and in spite of the grumbling of older colliers, envious perhaps at his rise, it was not long before George learned, and was appointed brakeman at the Dolly Pit. This was in 1801.

George was now twenty—sober, faithful, and expert. Finding a little spare time on his hands, he took to cobbling to increase his gains, and from this source contrived to save his first guinea. To this greater diligence he was urged by his love for Fanny Henderson, a fine sweet-tempered girl, whom he shortly married, and began housekeeping in the upper room of a small cottage in Wellington, six miles from Newcastle. Happy were they in each other, and in their simple, industrious, and frugal habits; and when a little son was born to them, George, who loved birds, rabbits, and dogs so well, welcomed with all the tenderness of a father's heart the little Bobby.

Robert he was named, after the old fireman his grandfather.

Accidents, they say, will happen in the best-regulated families. Fanny's family was not an exception. One day the cottage chimney got on fire, and the neighbours, with friendly zeal, not only poured water enough down the chimney to put out a much bigger and more alarming fire, but enough to deluge the poor little home of the brakeman with soot and water, making a pitiful sight to the young husband when he reached it. His eight-day clock, the choicest bit of furniture the young couple had, was completely smothered by ashes. What was to be done? Sending it to a clock-maker for repairs was quite out of the question—it would cost too much.

"I'll try my own hand on it," said George. After righting everything else, he attacked the clock, took it to pieces, carefully cleaned it, put it together, set it, and it ticked—ticking on as faithfully and soberly as ever! The astonished neighbours sent him their clocks, and George became one of the most famous clock doctors thereabouts.

The young man's reputation for business soon won him a situation in Killingworth—the best and largest colliery in the region. But his brightened worldly prospects were soon clouded by a dark sorrow—the death of his young wife, after three happy years of married life. Poor George felt it deeply, which was perhaps one reason for accepting a situation in Scotland, hoping in a change of scene to change the mournful current of his thoughts.

MENDING THE CLOCK.

Leaving his little boy in kind hands, he set off to the north with his pack on his back, afoot and alone, for Montrose—a long journey in those days. Good wages he received, and good friends he no doubt made, for everybody loved his honest and generous character; yet by the end of the year he yearned to get back to the friends and scenes of his early days. It was not home in Scotland; for it is only home where the heart is. With his savings in his pocket—twenty-eight pounds—back he trudged to Killingworth; and not before his friendly presence was greatly needed to comfort his aged parents, plunged in debt and affliction. By a terrible accident his father had lost his eyesight. No longer able to work, and receiving little or no help from his other children, who were barely able to maintain themselves, the old couple had a hard battle with life. But George is back again; all will be righted. He paid off their debts, and removed them to comfortable lodgings beside his own. He has father, mother, and Bobby to look after, and is thankful and happy in doing it.

Those were dark days, however, for the working-men of England. War was draining the country of men and money. Taxes were high, wages low, bread scarce, and able-bodied men were liable at any time to be impressed for the army or naval service. George himself was drawn; and go he must, or find a substitute. He found one, but it cost all he had to hire him.

Poor George was in straits. His spirits were much damped by the prospect of things around and before him. All business was in a discouraging condition. Some of his friends were about to emigrate to America, and he at one time nearly concluded to join them. It was a sore trial to the young man. He loved his English home; and bitter tears did he in secret shed as he visited old haunts—the fields and lanes and scenes of his boyhood—feeling and fearing that all too soon the wide Atlantic might roll between him and them. But the necessary funds for such an enterprise were not forthcoming. George gave it up, therefore, and went to work for what wages the times would allow. Better times would come.

The thing nearest his heart was to afford his little son an education. Keenly alive to his own early deficiencies and disadvantages, he determined to make them up in Robert. Every spare moment was of two-fold value to him, and all the work he could pick up he cheerfully did. Besides tinkering old clocks and cobbling old shoes, he took to cutting out the pitmen's clothes. Never was there such a fit, for George acted fully up to the principle that everything which was worth doing was worth doing well.

Busy as were his hands, his mind was no less busy, catching up and using every scrap of knowledge which came in his way. And it was a perpetual surprise to his fellow-workmen to see what a knack he had at bettering things. Everything improved in his hands. There was always progress on his track.

A new pit was opened at one of the collieries. Streams of water rushed in, which the most vigorous strokes of the pump could not lower. On the engine went pumping, pumping, pumping for a year, and the water continued to flow in, until it was nearly concluded to give up the pit as a failure. George's curiosity and interest were much excited, and always, on seeing the men, he asked how matters were coming on.

"Drowned out, drowned out," was the one and the same answer.

Over he went to the poor pit, as often as he could, to see for himself; and over he turned in his mind again and again the whys and wherefores of the failure.

"Weel, George," said his friend Kit one day, "what do you mak' o' her? Do you think you could doctor her?"

"Man," answered George, "in a week's time I could send you to the bottom."

The regular engineers were in high dudgeon with the forth-putting brakeman. What right had he to know how to cure an evil that had baffled them? His words, however, were reported at head-quarters; and the contractor was not long in hastening over to see if he could make his words good.

"Well, George," he said, "they tell me you think you can put that engine to rights."

"Yes, sir," replied the young man modestly; "I think I can."

As matters could be no worse, Mr. Dodds was ready to let him try; and George agreed, on condition that he should choose his own men to help him. The old hands were highly indignant, but there was no help for it. So they were ordered off, and George with his gang went on.

The engine was taken to pieces, examined, righted, and put together again. It was set to work. Did it go? Many a looker-on shook his head doubtfully, and prophesied in his inmost heart, "No go." It pumped and pumped. The obstinate water found it had an antagonist that could master it. In less than two days it disappeared from the pit, and workmen were sent to the bottom. Who could gainsay George's skill?

Mr. Dodds, of course, was delighted. Over and above his wages he put a ten-pound note into the young man's hand, and engaged him to superintend his works for the future.

A profitable job was this.

The fame of this engineering exploit spread far and wide. As an engine doctor he took the lead, and many a wheezy old thing was brought him to cure. Envious engineers tried to put him down. But real merit cannot be put down. It is stern stuff.

George's cottage showed the bent of his tastes. It was like an old curiosity shop, full of models of engines, complete or in parts, hanging and standing round; for busy as he had need to be—eking out his means by engineering, by clocks, and by coats—the construction and improvement of machinery for the collieries was his hobby.

Likeness of taste drew a young farmer often to the cottage—John Wigham—who spent most of his evenings in George's society. John had a smattering of chemistry and philosophy, and a superior knowledge of mathematics, which made him a desirable companion. George put himself under his tuition, and again took to "figuring." Tasks set him in the evening were worked out among the rough toils of the day. And so much honest purpose did not fail to secure progress. Drawing was another new line of effort. Sheets of plans and sections gave his rude desk the air of mind-work somewhere. Thus their winter evenings passed away.

Bobby was growing up in a little thought-world by himself; for he could not fail to be interested in all that interested his father—that father always making his son the companion of his studies, and early introducing him into the curious and cunning power of machinery.

Ah, that was a proud day when little Bob was old enough, and knew enough, to be sent to the academy at Newcastle. He was thirteen. His father's means had happily been increased. The old engine-wright of the colliery having died, George Stephenson was promoted to the post, on the salary of a hundred pounds a year. This was in 1812.

The new office relieving him from incessant hard work, and the necessity of earning a shilling by extra labours, he had more time for study and for verifying his plans of practical improvement; and the consequence was very considerable improvement in the machinery of the colliery to which he was attached.

Meanwhile Robert's education went on apace. The boy was hungry for knowledge, not only for himself, but to satisfy the voracious appetite of his father, and the no less keen one of John Wigham.

Robert joined a literary and philosophical society at Newcastle, whose fine library opened a rich storehouse of material. Here the boy spent most of his time out of school, storing his mind with principles, facts, and illustrations, to carry home on Saturday afternoon. Books also. The "Edinburgh Encyclopædia" was at his command. A volume of that at the cottage unfolded a world of wonders. But the library had some books too choice to be trusted away. How was Robert to get the gist of these home? His father had often said that a "good drawing and a well-executed plan would always explain itself;" and many a time he had placed a rough sketch of machinery before his son, and told him to describe it. Robert, therefore, when he could do no better, put his drilling to the test, and copied diagrams and drew pictures, thus taking many an important and perhaps rare specimen of machinery and science to Killingworth, for his father's benefit.

We can well imagine Saturday afternoon was as much a holiday to father as to son. Robert's coming was hailed with delight. John did not lag far behind. Some of the neighbours dropped in to listen to discussions which made the little room a spot of lively interest and earnest toil. A wide-awake mind allows nothing stagnant around it.

THE SUN-DIAL.

Among the borrowed books of the day was Ferguson's "Astronomy," which put father and son to calculating and constructing a sun-dial for the latitude of Killingworth. It was wrought in stone, and fixed over the cottage door; and there it is still, with its date, August 11, 1816—a year or two before Robert left school—a fair specimen of the drift of his boyish tastes.

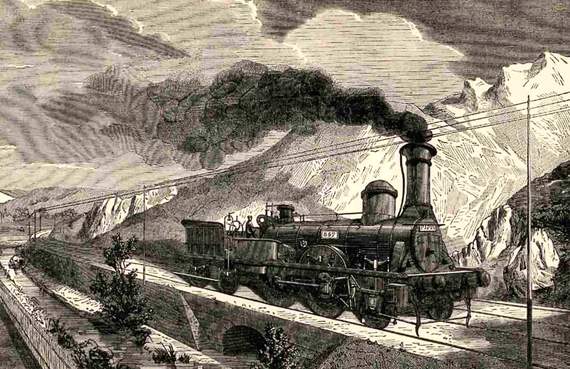

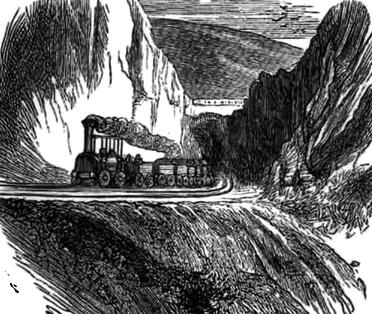

Familiar as it has become to us, who does not stop to look with interest at the puffing, snorting, screaming steam-horse? And who does not rejoice in the iron-rail, which binds together, with its slender threads, the north and the south, and makes neighbours of the east and the west?

"Who began railroads?" ask the boys again and again.

The first idea of the modern railroad had its birth at a colliery nearly two hundred years ago. In order to lighten the labour of the horses, the colliers laid straight pieces of wood into the road leading from the pit to the river, where the coal was discharged; and the waggons were found to run so much easier, that one horse could draw four or five chaldrons. As wood quickly wore out, and moreover was liable to rot, the next step was nailing plates of iron on the wooden rails; which gave them for a time the name of "plate-way roads." A Mr. Outram making still further improvements, they were called "Outram roads," or, for shortness' sake, "tram-roads;" and tram-roads came into general use at the English collieries.

"There's mischief in those tram-roads," said a large canal owner, foreseeing they would one day drive canal stock quite out of the market.

Improvements thus far had centred on the roads. To convoy heavy loads easier and faster was the point aimed at. Nobody had yet thought of self-going trains. Watt, the father of steam-engines, said steam-carriages might be built. He, however, never tried one, but rather left the idea to sprout in the brain of an old pupil of his, William Murdock, who did construct a very small one, running on thin wheels, and heated by a lamp. It was a curious success in its way, and set other minds thinking.

One of these was a tin-miner of Cornwall, Captain Trovethick, a friend of Murdock, who joined a cousin of his in getting a patent for building a steam-carriage. It was built, and an odd piece of machinery it was. It ran on four wheels over a common road, looked like a stage-coach, and delighted both the inventor and his friends.

They determined to exhibit it at London. While on its journey, driving it one day at the top of its speed, they saw a toll-gate in the distance. Not being able to check it in time, bump it went against the gate, which flew open in a trice, leaving the affrighted toll-man, in answer to their inquiry, "How much to pay?" only able to gasp out, "No—nothing to pay! Drive off as fast as you can! Nothing to pay!"

It reached London in safety, and was some time on exhibition. Multitudes flocked to see it, and some called it a fiery dragon.

"Ah," said Sir Humphrey Davy, very much interested in the invention, "I hope to see the captain's dragons on all the roads of England yet."

But the captain exhibited it only as a curiosity, the unevenness of the roads rendering it for all practical purposes a failure; and he had neither pluck nor genius enough to lay or clear a track for it himself. This was in 1803.

The idea, however, was in England, lodging itself here and there in busy brains; until, at last, a colliery owner in Newcastle, seeing the great advantage of having a locomotive on his tram-roads, determined to try what he could do. Accordingly, he had one built after the Cornish captain's model. It burst up at starting. Noways baffled, he tried again. The engine proved a clumsy affair, moved at a snail's pace, often got off the rails, and at length, voted by the workmen a "perfect plague," it was taken off. The unsuccessful inventor was called a fool by his neighbours, and his efforts an apt illustration that "the fool and his money are soon parted." In spite of failure, Mr. Blackett had faith that the thing could be done. He built a third, and ran it on the tram-road that passed by old Bob Stephenson's cottage door. And George at his colliery, seven miles off, as you may suppose, listened to every account of it with profound interest. Over he went, as often as he could, to see "Black Billy," as the locomotive was called—a rough specimen of machinery at best, doing very little service beyond what a good horse could do.

George carried "Black Billy" back in his mind to Killingworth, studying its defects, and laying plans to improve it. I do not know how long he was in coming to it, but he at length gave it as his opinion that he could make a better "travelling engine" than that.

Tidings came to Killingworth about this time that the trial of a new engine was to take place on a certain day at Leeds, and George did not lose the chance of being present. Though the engine moved no faster than three miles an hour, its constructer counted it a success. It proved, however, unsteady and unreliable, and at last blew up, which was the end of it.

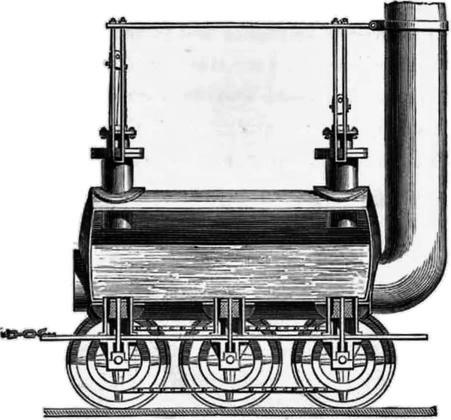

What did George think then? He more than ever wanted to try his hand at the business. Lord Ravensworth, knowing enough of Stephenson to have faith in him, hearing of this, advanced means for the enterprise. Good tools and good workmen were alike wanting; but after much labour, alteration, and anxiety, in ten months' time the engine was completed and put on the railway, July 25, 1814.

Although the best yet made, it was awkward and slow. It carried eight loaded waggons of thirty tons weight at a speed not above four miles an hour. The want of springs occasioned a vast deal of jolting, which damaged the machinery, and at the close of a year's trial it was found about as costly as horse-power.

How to increase the power of his engine? that was the puzzling question which George studied to answer. He wrestled with it day and night, and at length determined to try again. In due time another was built, "Puffing Billy," which most persons looked upon as a marvel; but, shaking their heads, they prophesied it would make a terrible blow-up some day. "Puffing Billy," however, went to work, and worked steadily on—a vast advance on all preceding attempts. It attracted little or no attention outside the narrow circle of the collieries. The great men of England did not know that, in a far-off nook of the realm, there was slowly generating a power, under the persistent thought of an humble working-man, which before many years would revolutionize the trade of the kingdom, and create a new source of wealth.

GEORGE STEPHENSON'S FIRST ENGINE.

"Puffing Billy," in fact, humble as its pretensions were, has proved to have been the type of all locomotives since.

"PUFFING BILLY."

Had George Stephenson satisfied himself? No. His evenings were chiefly spent at home with his son Robert, now under him in the colliery, studying and discussing together how to evoke the hidden power yet pent up in "Puffing Billy." The son was even more sanguine than his father, and many an amendment had "Billy" to undergo to satisfy the quick intellect and practical judgment of the youth.

Mr. Stephenson, delighted with Robert's scientific tastes and skill, and ever alive to the deficiencies of his own education, was anxious to give him still further advantages. For this purpose he took him from a promising post at the colliery, and sent him to the University of Edinburgh.

Here he enjoyed a six months' course of study; and so well prepared was he for it by his well-formed habits of application and thinking, that he gained in six months as much as many a student did in three years. Certain it was his father felt amply repaid for the draft it made on his purse, when Robert reappeared at the cottage, in the spring, with a prize for successful scholarship in mathematics. He was eighteen then.

Manchester, thirty miles north-east of Liverpool, is the great centre of the cotton trade in England. Its cloths are found in every market of the world. Cotton coming to Liverpool is sent to the Manchester mills; and the goods which the mills turn out are returned to Liverpool to be shipped. The two cities, therefore, are intimately connected by constant intercourse and mutual interest.

Two water communications existed between them; one by the rivers Mersey and Irwell, the other by the famous Bridgewater Canal, which did an immense business at an enormous profit. But the Manchester mills were fast outgrowing these slow and cumbersome modes of travel. Liverpool warehouses were piled with bales of cotton waiting to go, and the mills at Manchester had often to stop because it did not come. Goods also found as much difficulty in getting back. Merchants and manufacturers both grumbled. Business was in straits. What was to be done? Carting was quite out of the question. Canal owners were besought to enlarge their water-power. No, they would do nothing. They were satisfied with things as they were. Their dividends were sure.

But want demands supply; need creates resources. Something must be done to facilitate the transit of goods between the two cities. What? Build a tram-road, or rail-road. Nobody, however, but a very fast man would risk his good sense by seriously advising a rail-road. Solid men would certainly shun him. A tram-road was a better understood thing. The collieries had used small pieces of them for years. A tram-road then. Business men put their heads together and began earnestly to talk of a tram-road.

William James, a rich and enterprising man, entered heartily into the project, and undertook to make surveys for a suitable route. And not long after a party of surveyors was seen in the fields near Liverpool. Their instruments and movements excited attention. People eyed them with anxiety; suspicions were roused; the inhabitants became alarmed. Who were they, making such mysterious measurements and calculations on other people's land? A mob gradually gathered, whose angry tones and threatening gestures warned the surveyors of a storm brewing over their heads. Wisely considering that flight was better than fight, they took themselves off, and by-and-by turned up farther on.

The landowners, who might be supposed to have known better, told the farmers to drive them off; and the farmers, with their "hands," were only too ready to obey. They stationed themselves at the field gates and bars with pitch-forks, rakes, shovels, and sticks, and dared the surveyors to come on. A poor chain-man, not quite so nimble as his pursuers, made his leap over a fence quickened by a pitch-fork from behind! Even women and children joined the hue and cry, pelting the strangers with stones and dirt whenever they had a chance. The colliers were not behind the farmers in their foolish hostility. A stray surveyor was caught and thrown into a pit.

At a sight of the theodolite their fury knew no bounds. That unoffending instrument they seemed to regard as the very Sebastopol of the enemy, to seize and destroy which was to win the day. Tho surveyors, therefore, were obliged to hire a noted boxer to carry it, who could make good his threats on the enemy. A famous fighter among the colliers, determined not to be outdone, marched up to the theodolite to capture it. A fist-and-fist fight took place; the collier was sorely beaten, but the rabble, taking his part against the poor instrument, pelted it with stones and smashed it to pieces.

You may well suppose that surveying under such circumstances was no light matter. What was the gist of the hostility? It is hard to tell. The canal owners might have had a hand in scattering these wild fears; fears of what, however, it is not so easy to find out. There was nothing in a simple horse rail-road, or tram-road, as it is called, to provoke an opposition so bitter from the people. It was a new thing; and new things, great improvements though they may be on old ones, often stir up a thousand doubts and fears among the ignorant and unthinking.

Nor did the project generally take among those who would be most benefited by it. Mr. James and his friends held public meetings in all the towns and villages along the way; enterprising men in Liverpool and Manchester talked it up, and tried to create a public interest; but there was a holding back, which, while it checked all actual progress in the enterprise, did not cause it to be altogether given up. The time had not come; that was all.

Mr. James had a secret leaning towards the use of steam on the new road. He would have immediately and unhesitatingly advocated a rail-road run by locomotives. But that was out of the question. The public were far behind that point, and to have openly advocated it would have risked his judgment and good sense in the opinion of the best men. Therefore Mr. James wisely held his tongue. But hearing of the Killingworth locomotives, and of a collier who had astonished the natives by his genius, he determined to make a journey to Newcastle, and see the "lions" for himself.

Stephenson was not at home. "Puffing Billy" was; and "Billy" puffed in a way that took Mr. James's heart at once. He seemed to see at a glance "Billy's" remarkable power, and was struck with admiration and delight. "Here is an engine," he exclaimed, "that is destined before long to work a complete revolution in society."

The image of "Puffing Billy" followed him home.

"Why," he wrote to Stephenson's partner in the patent, "it is the greatest wonder of the age, and the forerunner, I believe, of most important changes in the modes of travel in the kingdom."

A few weeks later he made another visit to Killingworth, taking his two sons with him. "Puffing Billy" was at work, as usual.

The boys were frightened at the sight of the snorting monster; but Stephenson encouraged them to mount, with their father, and see how harmless and manageable the monster was.

The second visit was even more gratifying than the first.

"Mr. Stephenson," said James, "is the greatest practical genius of the age. His fame will rank with that of Watt."

Mr. James lost all hesitation now about speaking his mind. "Puffing Billy" had driven the backwardness out of him, and he was willing, at all hazards, boldly to advocate rail-roads and the steam-horse. No more tram-roads; steam or nothing. This was in 1821.

Mr. James entered heart and soul into the new idea of the age. On his return to Liverpool, it was everywhere his theme; and wherever he had influence, he tried to stir up men's minds to the benefits and blessings puffing out in "Puffing Billy."

THE VISIT TO "PUFFING BILLY."

Stephenson rejoiced in such a friend. It was just what he and "Billy" most needed—somebody to introduce them into the great world. And Stephenson and his partner offered him a share in the profits of whatever business he could secure to them.

But what can one man, or a few men, do in an enterprise like this, depending upon the verdict of that important power, Public Opinion? And Public Opinion had not yet made up its mind to it.

A thousand difficulties bristled in the way. There were both the indifference of friends and the opposition of enemies at home. In addition to this, a violent opposition was foreseen in Parliament, which it needed all the strength and courage of a united constituency to meet.

Under these discouraging circumstances, there were not enough men of pluck to push the matter through.

So everything about the new road went by the board. It was laid on the shelf, at least for the present, and Liverpool and Manchester trade jogged on as before.

It appears strange to us that so simple a thing as the laying of a rail seems to be should have taken years of thought and experiment to do it. Nothing looks easier to prepare than the straight, smooth track of a railway, such as we now see in use; and yet it was only arrived at by slow steps through two hundred years.

In pondering upon the powers of "Puffing Billy," George Stephenson saw that the efficiency of locomotives must, in a great measure, depend on what kind of roads they had to run upon. Many were sanguine that steam-carriages would some day come into use on common roads. After a long series of experiments, George Stephenson said, "No; the thing wouldn't pay." For a rough surface seriously impairs the powers of a locomotive; even sand scattered upon the rails is sufficient to slacken, and even stop an engine. The least possible friction is desirable, and this is found on the smooth rail.

Could they ever be laid uphill, or on "ascending gradients", as the scientific term is? No; as nearly level as possible, Stephenson's experiments showed, was the best economy of power. Then how to get rid of the jolts and jars and breakages of the rails as they were then laid. He studied and experimented upon both chairs and sleepers, and finally embodied all his improvements in the colliery railway.

"Puffing Billy" was in every respect a most remarkable piece of machinery, and its constructer one of the most sagacious and persistent of men. But how was the public, ever slow in discovering true merit or accepting real benefits, to discover and appreciate them? Neither influence, education, nor patronage had Stephenson to command mind and means, or to drive his engine through prejudice, indifference, and opposition, to profit and success.

But what he could not do, other men could do, and did do. Find a hook, and there is an eye to fit it somewhere. Yes; there were already men of property and standing alive with the new idea. While he worked, they talked—as yet unknown to one another, but each by himself clearing the track for a grand junction.

One of these men was Edward Pease, a rich Quaker of Darlington, who, his friends said, "could look a hundred miles ahead." He needed a quicker and easier transit for his coals from the collieries north of Darlington to Stockton, where they were shipped; and Mr. Pease began to agitate, in his mind, a railroad. A company for this purpose was formed, chiefly of his own friends, whom he fairly talked into it. Scarcely twenty shares were taken by the merchants and shipowners of Stockton, whose eyes were not open to the advantage it would by-and-by be to them. A survey of the proposed road was made, when to the indifference of the many was added the opposition of the few. A duke was afraid for his foxes! Shareholders in the turnpikes declared it would ruin their stock. Timid men said it was a new thing, and that it was best to let new things alone. The world would never improve much under such counsel. Edward Pease was hampered on all sides. Nobody convinced him that his first plan was not the right one by all odds; but what can a man do in any public enterprise without supporters? So he reluctantly was obliged to give up his rail-road, and ask Parliament for liberty to build a tram-road—horse-power instead of steam-power: he could seem to do no better, and even this was gotten only after long delay and at considerable cost.

Among the thousands who carelessly read in the newspapers the passage through Parliament of the Stockton and Darlington Act, there was one humble man whose eye kindled as he read it. In his bosom it awakened a profound interest. He went to bed and got up brooding over it. He was hungry to have a hand in it; until at last, yearning with an irrepressible desire to do his own work in the world, he felt he must go forth to seek it.

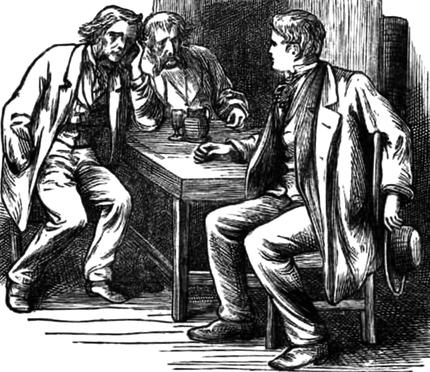

One night a couple of strangers knocked at the door of Edward Pease's house in Darlington, and introduced themselves as two Killingworth colliers. One of them handed the master of the mansion a letter of introduction from a gentleman of Newcastle, recommending him as a man who might prove useful in carrying out his contemplated road.

To support the application, a friend accompanied him.

The man was George Stephenson, and his friend was Nicholas Wood. It did not take long for Edward Pease to see that Stephenson was precisely the man he wanted.

THE TWO STRANGERS.

"A railway, and not a tram-road," said Stephenson, when the subject was fairly and fully opened.

"A horse railway?" asked Pease.

"A locomotive engine is worth fifty horses," exclaimed Stephenson; and once on the track, he launched out boldly in its behalf.

"Come over to Killingworth and see my 'Puffing Billy,'" said George; "seeing is believing." And Mr. Pease, as you may suppose, was quite anxious to see a machine that would outride the fleetest horse. Yet he did not need "Puffing Billy" to convince him that its constructer knew what he was advocating, and could make good his pledges. The good Quaker's courage rapidly rose. He took a new start, and the consequence was that all other plans and men were thrown aside, and Stephenson was engaged to put the road through much in his own way.

The first thing to be done was to make an accurate survey of the proposed route. Taking Robert with him, who had just come from college, and who entered as heartily into the enterprise as his father, with two other tried men, they began work in good earnest. From daylight till night the surveyors were on duty. One of the men going to Darlington to sleep one night, four miles off, "Now, you must not start from Darlington at daybreak," said Stephenson, "but be here, ready to begin work, at daybreak." He and Robert used to make their home at the farm-houses along the way, where his good-humour and friendliness made him a great favourite. The children loved him dearly. The dogs wagged their approving tails at his approach. The birds had a delighted listener to their morning songs, and every dumb creature had a kind glance from his friendly eye.

But George was not quite satisfied. He wished Mr. Pease to go to Killingworth to see "Puffing Billy," and become convinced of its economical habits by an examination of the colliery accounts. He promised, therefore, to follow George thither, along with a large stockholder; and over they went in the summer of 1822.

Inquiring for Stephenson, they were directed to the cottage with a sun-dial over the door. George drove his locomotive up, hoisted in the gentlemen, harnessed on a heavy load, and away they went. George no doubt showed "Billy" off to the best advantage. "Billy" performed admirably; and the two wondering stockholders went home enthusiastic believers in locomotive power.

A good many things had to be settled by the Darlington project. One was the width of the gauge; that is, the distance between the rails. How wide apart should they be? Stephenson said the space between the cart and waggon wheels of a common road was a good criterion. The tram-roads had been laid down by this gauge—four feet and eight inches—and he thought it about right for the railway; so this gauge was adopted.

One thing which hampered Stephenson not a little was the want of the right sort of workmen—quick-minded, skilful mechanics, who could put his ideas into the right shape. The labour of originating so much we can never know. He had nothing to copy from, and nobody's experience to go by. Happily he proved equal to his task. We can readily imagine his anxiety as the work progressed. Hope and fear must have in turn raised and depressed him. Not that he had any doubts in regard to the final issue of the grand experiment of railroads. They must go!

Dining one day at a small inn with Robert, and John Dixon, after walking over the route, then nearly completed—"Lads," he said, "I think you will live to see the day when railroads will be the great highway for the king and all his subjects. The time is coming when it will be cheaper for a working-man to travel on a railway than to walk on foot. There are big difficulties in the way, I know; but it will surely come to pass. I can hardly hope to live to see that day, much as I should like to do so; for I know how slow all human progress is, and how hard it is to make men believe in the locomotive, even after our ten years' success in Killingworth."

While the father roughed it through, Robert's health failed. His close application to business made sad inroads upon a frame naturally more delicate than his father's; and an offer to go out and superintend some mining operations in South America was thankfully accepted, in the hope that a sea-voyage and less exciting labours might restore him.

A TALK ABOUT RAILWAYS.

Robert shortly sailed; and his father pushed on alone, with that brave spirit which carried him through many a darker hour.

On the 27th of September the Stockton and Darlington Railway was finished and opened. A great many came to see the new mode of travelling, which had proved a fruitful subject of talk, far and near, for many months;—some to rejoice; some to see the bubble burst; some with wonder, not knowing what to think; some with determined hostility. The opposition was strong: old England against young England; the counter currents of old and new ideas.

The road ran from Stockton to Darlington, a distance of twelve miles, and thence to the Etherly collieries—in all, thirty-two miles.

Four steam-engines were employed, and two stationary engines to hoist the train over two hills on the route. The locomotives were of six-horse power, and went at the rate of five or six miles an hour. Slow as this was, it was regarded with wonder. A "travelling engine" seemed almost a miracle. One day a race came off between a locomotive and a coach running on the common highway; and it was regarded as a great triumph that the former reached Stockton first, leaving the coach one hundred yards behind.

The road was built for a freight road, to convey lime, coal, and bricks from the mines and kilns in the interior to the sea-board for shipment abroad. Carrying passengers was not thought of. Enterprise, however, in this direction took a new start. A company was soon formed to run two coaches on the rails between Darlington and Stockton by horse-power. Each coach accommodated six inside passengers, and from fifteen to twenty outside; was drawn by one horse; and went at the rate of nine miles an hour.

"We seated ourselves," said a traveller of those days, "on the top of the 'Defence' coach, and started from Stockton highly interested with the novelty of the scene and of this new and extraordinary conveyance. Nothing could be more surprising than the rapidity and smoothness of the motion." Yet the coach was without springs, and jerked and jolted over the joints of the rails with a noise like the clinking of a mill-hopper.

"Such is the first great attempt to establish the use of railways," writes a delighted editor, "for the general purposes of travelling; and such is its success, that the traffic is already great, and, considering that there was formerly no coach at all on either of the roads along which the railroad runs, quite wonderful. A trade and intercourse have arisen out of nothing, and nobody knows how."

Such was their small and imperfect beginning, we should say, now that railroads, improved and perfected, have fulfilled Stephenson's prediction uttered in the little inn, and have become the great highways of the civilized world.

One, two, three years passed by, and the Liverpool and Manchester project started up again. It was not dead, it had only slept; and the three years had almost worn out the patience of both merchants and manufacturers. Trade between the two cities must have speedier and easier transit. Trade is one of the great progressive elements in the world. It goes ahead; it will have the right of way; it will have the right way—the best, safest, cheapest way of doing its business. Yet it is not selfish; its object is the comfort and well-being of men. To do this, it breaks down many a wall which selfishness has built up, it cuts through prejudices, it rides over a thousand "can't be's" of timid and learned men; for learned men are not always practical. They sometimes say things cannot be done, when it only needs a little stout trying to overcome difficulties and do them.

A learned man once said that crossing the Atlantic by steam was impossible.

"For the good of the race, we must have something truer than wind and tougher than sails," said Trade. And it was not many years before ships steamed into every port.

"Carriages travelling at twelve, sixteen, eighteen, twenty miles an hour! Such gross exaggerations of the power of a locomotive we scout. It can never be!" cries a sober Quarterly.

"You may scout it as much as you please," rejoins Trade; "but just as soon as people need a cheaper, pleasanter, swifter mode of travel, it will be done." And now the railway carriages thread the land in their arrowy flight.

"The magnetic telegraph! a miserable chimera," cries a knowing statesman. "Nobody who does not read outlandish jargon can understand what a telegraph means."

"You will soon find out," answers Trade. And now it buys pork by the hundred barrels, and sells grain by the thousand bushels; while armies march and fleets sail at its bidding. Treaties are signed at its word; and the telegraph girdles the world.

You see Trade is a civilizer; and Christian civilization makes all the difference in the world between Arabs and Englishmen.

Liverpool merchants were now fairly awake. "What is to be done?" was the question. Something. Could there be a third water-line between the two cities? No; there was not water enough for that.

Would the Bridgewater Canal increase its power and reduce its charges? No.

A tram-road or a rail-road, then. There was no other alternative.

Mr. James, who was so much interested before, had failed and left the country. When he left, he said to his friends, "When you build a road, build a railroad, and get George Stephenson to do it."

The Darlington and Stockton enterprise could not fail to be known at Liverpool; and a drift of opinion gradually began to set in strongly in favour of the railway. People talked about it in good earnest.

"A railway!" cried the canal owners. "It is absurd; it is only got up to frighten us; it will slump through, as it did before." They were easy.

"Let us go to Darlington and Killingworth and see for ourselves," said the merchants; and four gentlemen were sent on a visit of inquiry. They went first to Darlington, where the works were in vigorous progress, though not done. It was in 1824, the year before they were finished. Here they met Stephenson. He took them to Killingworth to see "Puffing Billy."

Seeing was believing. "Billy's" astonishing feats won them completely over; and they went back to Liverpool warm for a railroad. Their clear and candid report convinced merchants, bankers, and manufacturers, who gave a verdict in its favour. Public opinion was now coming over.

Books were opened for funds. There was no lack of subscribers. Money was ready. To be sure of the safety of locomotive power, a second deputation was sent to Killingworth, taking with them a practical mechanic, better able to judge about it than themselves. The man had sense enough to see and to own that while he could not insure safety over nine or ten miles an hour, there was nothing to be afraid of slower than that. Then a third body went. The enterprise required caution, they thought.

Yes, it did.

Having decided upon steam-power, the next thing was to secure the right sort of man to carry on the work. Stephenson was that man. His energy and ability were indispensable. Before trying to get a charter from Parliament, the route needed to be surveyed again, and a careful estimate of expenses made.

The Stockton road done, Stephenson was free to engage in this new enterprise; his success in that proving his principles true on a larger scale.

The canal owners now took alarm. They saw there was a dangerous rival, and they came forward in the most civil and conciliatory manner, professing a wish to oblige, and offering to put steam-power on their canals. It was too late. Their day had gone by.

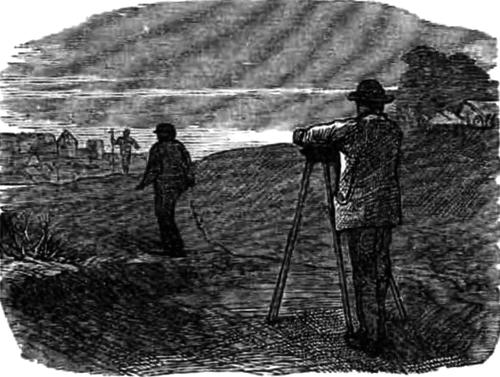

You know the violent opposition made to a former survey. How would it be again? Did three years scatter the ignorance out of which it grew? Ah, no. There was little if any improvement. The surveyors were watched and dogged by night and by day. Boys hooted at them, and gangs of turbulent men threatened them with violence. Mr. Stephenson barely escaped duckings, and his unfortunate instruments capture and destruction. Indeed, he had to take with him a body-guard to defend them. Much of the surveying had to be done by stealth, when people were at dinner, or with a dark lantern at night.

When dukes and lords headed the hostility, you cannot wonder that their dependants carried it on. One gentleman declared that he would rather meet a highwayman or see a burglar on his premises than an engineer; and of the two he thought the former the more respectable! Widows complained of damaged corn-fields, and gardeners of their violated strawberry-beds; and though Stephenson well knew that in many cases not a whit of damage had been done, he paid them for fancied injuries in the hope of stopping their tongues.

SURVEYING AT NIGHT.

A survey made under such circumstances must needs have been imperfect; but it was as good as could be made. And no time was lost in taking measures to get a Bill before Parliament.

A storm of opposition against railways suddenly arose, and spread over every corner of the kingdom. Newspapers and pamphlets swarmed with articles crying them down. Canal and turnpike owners spared no pains to crush them. The most extraordinary stories were set afloat concerning their dangers. Boilers would burst, and passengers be blown to atoms; houses along the way would be burned; the air would become black with smoke and poisoned by cinders; and property on the road would be stripped of its value.

The Liverpool and Manchester Bill, however, got into Parliament, and went before a Committee of the House of Commons to decide upon it, in March 1825.

First, its friends had to show the necessity of some new mode of travel between the two cities; and that it was not difficult to do.

But when it came to asking for liberty to build a railway and run a locomotive, the matter was more difficult to manage. And to face the tremendous opposition rallied against it, the pluck of its friends was severely tried.

The battle had to be fought inch by inch.

Stephenson, of course, was the chief witness for locomotives. But what headway could he, an uneducated Northumbrian mechanic, make against members of Parliament, backed by all the chief engineers of the kingdom? For very few had faith in him; but those few had strong faith. He was examined and cross-examined. They tried to bully him, to puzzle him, to frighten him. On the subject of locomotives his answers were clear. He declared he could drive an engine, and drive it safely, at the rate of twelve miles an hour!

"Who can believe what is so notoriously in the teeth of all experience?" cried the opposition; "the witness is a madman!"

Famous engineers were called on the stand. What had they to say? One declared the scheme a most wild one. He had no confidence in locomotives. They were affected by wind and weather; with difficulty were kept on the track, and were liable to constant accidents; indeed, a gale of wind would render it impossible to start a locomotive, either by poking the fire or keeping up the steam till the boiler should burst: they could never be relied on.

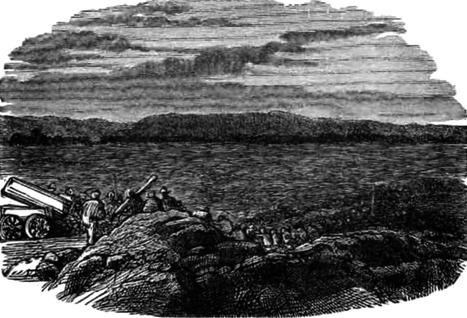

The proposed route had to cross an ugly quagmire, several miles in extent, called Chat Moss, a very shaky piece of land, no doubt; and here the opposition took a strong stand. "No engineer in his senses," cried one, "would think of going through Chat Moss. No carriage could stand on the Moss short of the bottom."

"It is absurd to hold out the notion that locomotives can travel twice as fast as stage-coaches," said another; "one might as soon trust himself to a rocket as to the mercy of a machine going at that rate."

"Carriages cannot go at anything like that speed," added another; "if driven to it, the wheels would only spin on their axles like a top, and the carriages would stand stock-still!"

So much for learned arguments against it.

Then came the dangers of it. "The dumb animals would never recover from the sight of a locomotive; cows would not give their milk; cattle could not graze, nor horses be driven along the track," cried the opposition.

"As to that," said Stephenson, "come to Killingworth and see. More quiet and sensible beasts cannot be found in the kingdom. The farmers there never complain."

"Well," asked one, "suppose, now, one of those engines to be going along a railroad at the rate of nine or ten miles an hour, and that a cow were to stray upon the line and get in the way of the engine; would not that, think you, be a very awkward circumstance?"

"Yes," answered Stephenson, with a droll twinkle in his eye; "very awkward indeed—for the coo!"

The fellow, as you may suppose, backed off.

The danger in other respects was thus dwelt on: "In addition to the smoke and the noise, the hiss and the whirl which locomotive engines make, going at the rate of ten or twelve miles an hour, and filling the cattle with dismay, what," asked an honourable member, "is to be done with all those who have advanced money in making and mending turnpikes? What with those who may still wish to travel in their own or hired carriages, after the fashion of their forefathers? What is to become of coach-makers and harness-makers, coach-masters and workmen, inn-keepers, horse-breeders, and horse-dealers? Iron would be raised one hundred per cent., or more probably exhausted altogether! The price of coal would be ruinous. Why, a railroad would be the greatest nuisance, the biggest disturbance of quiet and comfort, in all parts of the kingdom, that the ingenuity of man could invent."

Not content with belittling his engine, they could not stop short of abusing Stephenson himself. "He is more fit for Bedlam than anywhere else," they cried; "he never had a plan—he is not capable of making one. Whenever a difficulty is pressed, as in the case of a tunnel, he gets out of it at one end; and when you try to catch him at that, he gets out at the other."

"We protest," they said, "against a measure supported by such evidence and founded upon such calculations. We protest against the Exchange of Liverpool striding across the land of this country. It is despotism itself."

What had the friends of locomotive power to say?

"We beseech you," they pleaded to the Committee, "not to crush it in its infancy. Let not this country have the disgrace of putting a stop to that which, if cherished, may in the end prove of the greatest advantage to our trade and commerce. We appeal to you in the name of the two largest towns in England; we appeal to you in the name of the country at large; and we implore you not to blast the hopes that this powerful agent, Steam, may be called in for the purpose of aiding land communication: only let it have a fair trial, and these little objections and private prejudices will be done away."

Flaws were picked in the surveys, and the estimate of costs based on them. The surveys, quite likely, were imperfect; indeed, how could they be otherwise, when every mile of the line had to be done at the risk of life?

The battle lasted two months, and a very exciting one it was. It was skilfully and powerfully carried on. Who beat?

The opposition. The Bill was lost.

Matters looked dark enough. Judging from appearances, the enterprise was laid on the shelf, and the day of railways long put off. As for poor Stephenson, his short day of favour seemed about gone. His being called a madman, and regarded as a fool, as he had been by the opposition, was not without its effect upon his newly-made friends. Their faith in him sensibly cooled. But he did not lose faith in himself, not he. He had waited long for the triumph of his engine, and he could wait longer. A great blessing to the nation was locked up in it he well knew; and the nation would have it some time, in spite of everything.

Was the enterprise a second time to be abandoned?

No, no. Taking breath, its friends again started to their feet. "Never give up," was their motto, for they were in earnest. They rallied, and met in London to consult what to do next.

Mr. Huskisson, a member of Parliament for Liverpool, came into the meeting and urged them to try again—to try at the next session of Parliament.

"Parliament must, in the end, grant you an Act," he said, "if you are determined to have it." And try they determined to, for a horse railroad at least.

For this purpose another and more careful survey had to be made.

Stephenson was left out. A known man must be had. They meant to get surveyors and engineers with well-established reputation to back them up. Stephenson was too little known. He had no fame beyond a little circle in one corner of the kingdom. How did he feel to be thus thrown in the back-ground? George was not a man to grumble; he was too noble to complain. In fact, you see, he was ahead of the times; too far ahead to be understood and appreciated. He could afford to wait.

Two brothers of the name of Rennie were appointed in his stead. In time the new survey was finished; the plans drawn, and the expenses reckoned up. Changes were made in the route. Ill-tempered landowners were left on one side, and every ground of complaint avoided that could be.

The new Bill was then carried to Parliament, and went before the Committee in March the next year. The opposition was strong, indeed, but less furious. Much of its bitterness was gone. It made a great show of fears, which the advocates of the Bill felt it was not worth while to waste words in answering. They left it to the road to answer them. Build it, and see.

Mr. Huskisson and others supported it in a strong and manly tone; and after a third reading, the Bill passed in the House of Commons. So far, so good. It then had to go to the House of Lords. What would befall it there? The same array of evidence on both sides was put forward. The poor locomotive engine, which had proved such a bugbear in the House of Commons, was regarded as quite a harmless affair by most of the lords; and the opposition made such poor work in showing off its dangers, that no plea in its behalf was called for. They were satisfied, they said; and the Bill passed almost unanimously. Victory! victory!

The victory cost more than twenty thousand pounds! For a first cost it looked large. But nothing worth doing can be done without effort, and effort made in faith. Nothing done, nothing have.

The real work was now to be done. Hopes and fears had yet to be verified.

At the first meeting of the directors, a man to put the enterprise through was to be chosen. Who? The Rennies were anxious to get the appointment. They naturally expected it. They had made the survey, and their name had had weight in getting the Act of Parliament. But they could not superintend the details of the work. They had other enterprises on foot.

Stephenson, no doubt, was the man. The directors felt him to be so. No one could long be with him without feeling his power. Besides, what he had done had been ably done. At the risk of offending the Rennies and their friends, they chose him, and the result proved the wisdom of their choice.

On receiving the appointment, he immediately moved to Liverpool, and the work began in good earnest. It was a stupendous undertaking for those days. Chat Moss had to be filled in, sixty-three bridges built, excavations made, tunnels cut, and all the practical details carried out, with very little past experience to profit by. Neither was the kind of labour well understood, nor was there that division of labour between contractors and engineers which relieves one man of too heavy a responsibility. In fact, tools and men had to be made; and Stephenson had to make both!

The great quagmire was first grappled with. "No man in his senses would undertake to make a road over Chat Moss," opposers said in Parliament; "that were to undertake the impossible." Stephenson, however, meant to try. Formidable it certainly was. Cattle ploughing on farms bordering the bog, where it ran underneath the tilled land, had to wear flat-soled boots in order to keep their hoofs from sinking down into the soft soil.

The proposed route ran four miles across it, and the way had to be drained and filled in with sand and gravel. The drainage tasked their ingenuity to the utmost, and almost baffled the workmen. After that was in some degree accomplished, waggon-load after waggon-load of earth was thrown on for weeks and weeks: but it only sank into the mire and disappeared—not an inch of solid footing seemed gained; and on they went, filling and filling, without apparently having made the least impression on the Moss,—the greedy bog only cried out for more.

CHAT MOSS.

Stephenson's men began to have their doubts. The opposition might have judged more correctly after all. They asked him what he thought. "Go ahead!" was his answer. By-and-by the directors began to have their fears. It looked to them like a very unpromising job. So it was. After waiting and waiting in vain for signs of progress, they called a meeting on the edge of the Moss, to see if it were not best to give up. The bog, they were afraid, might swallow up all their funds, as it had done everything else. Stephenson lost not a whit of his courage. "Go ahead!" was his counsel. He never for a moment doubted of final success. And considering the great outlay already made, they wisely gave in to him.

Monstrous stories were afloat of the terrible accidents taking place there. Every now and then the stage drivers brought into Manchester the astonishing news of men, horses, carts, and Stephenson himself submerged and sunk for ever in the insatiable quagmire! Time corrected one only to publish another. Newsmongers were kept in a state of delightful excitement, and tea-table gossip was spiced to suit the most credulous and marvel-loving taste, until the Moss was conquered, as conquered it was acknowledged to be, when, six months after the directors had met to vote to leave it to its original unproductiveness, they were driven over it on a smooth and secure rail to Manchester!

Another tough job was tunnelling Liverpool—excavating a mile and a third of road through solid rock. Night and day the boring, blasting, and hewing were kept in vigorous execution. Sometimes the miners were deluged with water, sometimes they were in danger of being overwhelmed by heavy falls of wet sand from overhead. Once, when Stephenson was gone from town, a mass of loose earth came tumbling on the heads of the workmen, frightening them, if nothing more. On his return they were in a most refractory state, complaining of the dangers, and stoutly refusing to go back to work. Wasting no time on words, Stephenson shouldered a pick-axe, and called for recruits to follow. Into the tunnel he marched, and the whole gang after him. Nothing more was heard of fears, and the work went bravely and steadily on.

Besides laying out all the work, Stephenson had to make the tools. All the waggons, trucks, carriages, switches, crosses, signals, were planned and manufactured under his superintendence, besides meeting and providing for a thousand exigencies constantly occurring in a new enterprise like this, giving full scope to all the sagacity, invention, and good-humour which naturally belonged to him.

The expenses of the road were heavy, and money was not always forthcoming. If the works lagged in consequence of it, the hopes of the directors fell; so that Stephenson's energies were taxed to the utmost during the four years of the work; and he showed, what observation and history both teach us, that efficient men are men of detail as well as men of great plans.

Remember this, boys—for we sometimes despise little particulars and the day of small things—that the secret of effective doing lies not only in making wise plans, but in filling up the minutest parts with promptness and fidelity. There must be detail, to achieve any great and good work. If you would possess the fruits of learning, you must get them by the toil of daily drudgery. If you undertake to become rich, you must not despise the small gains and little economies by which a fortune is made. If you would obtain a noble Christian manhood, you must not neglect hourly self-restraint, watchfulness, and prayer, or the daily exercise of those humbler virtues and godly industries which make the woof of character.

Stephenson strikingly illustrated the practical force of this principle. The minutest detail of every plan in this new enterprise was thought out and carried on by himself, or under his direct supervision. Both in summer and winter he rose early. Before breakfast you might find him on a morning round, visiting the extensive workshops where the machines and tools were made; or perhaps Bobby is brought to the door, and mounted on this his favourite horse, he is off fifteen miles to inspect the progress of a viaduct—a ride long enough to whet the appetite for a tempting breakfast, one would think. But nothing tempts him from his frugal habits: he eats "crowdie"—and that made by himself—which is nothing more or less than oatmeal hasty-pudding and milk. Again he is off, inspecting the labours of his men all along the line from point to point, pushing the works here, advising there, and inspiring everywhere. Bobby is a living witness that one beast, at least, is not to be scared by a locomotive. He can face the snorting monster without so much as a shy step, or a prick of the ears. He afraid! not Bobby.

Returning home, pay-rolls are to be examined, perhaps, when every item of expense must be accounted for; or drawings are to be made, or directions given, or letters written.

Several young men were received into his family to be trained for engineers. A second wife—frugal, gentle, and friendly—superintended his household. Their evenings were passed in study and conversation, brightened by the genial humour of the remarkable man whose genius drew them together, and whose good-tempered pleasantries relieved the heavier tasks of mind and body. The compendium of all his instruction was,—Learn for yourselves, think for yourselves, master principles, persevere, be industrious, and there is no fear for you. It is an indication of the value of these instructions, that every young man trained under him rose to eminent usefulness. "Ah," he sometimes said, on relating a bit of his own early history, "you don't know what work is in these days." And yet work is work all the world over.

In spite of the best Stephenson could do, the directors, looking at their unproductive capital, and not fully comprehending all the difficulties to be overcome, sometimes urged greater despatch.

"Now, George," said Friend Cropper one day, "thou must get on with the railway; thou must really have it opened by the first of January next."

"Consider the heavy nature of the works, sir," rejoined George, "and how much we have been delayed by want of money, to say nothing of the bad weather. The thing is impossible."

"Impossible!" cried Cropper. "I wish I could get Napoleon to thee; he would tell thee there is no such word as 'impossible.'"

"Tush!" exclaimed George, "don't tell me about Napoleon. Give me men, money, and material, and I'll do what Napoleon couldn't do—drive a railroad over Chat Moss."

He might have retorted more significantly by asking the directors what they meant to do; for Liverpool was tunnelled and Chat Moss railed before they could agree what kind of power to put on it. There were some who insisted upon using horse-power; but the majority thought that was out of the question. Meeting after meeting was held, debate followed debate, and the whole body became more and more puzzled as the road itself neared completion.

Some kind of machine; but what?—ah, that was the question. You would naturally have thought, "A locomotive, of course." But no; since Parliament opposition raged against it, steam had lost ground in the public estimation, and it was very slow in getting back to favour. Locomotives, or "travelling engines," as they were called, were hid in a cloud of doubts,—and more than ever since the Parliament debates. "They were dangerous, they were frightful, they could never go fast enough,—their utmost speed would not be ten miles an hour." Some of the most distinguished engineers would give no opinion of them at all. They had none. It was certainly hard to patronize them in spite of their indifference, and possibly their sneers. Certainly, if the poor locomotive depended on their verdict, its fate was sealed.

GOOD SERVICE.

One stanch friend remained. Stephenson stood faithfully by "Puffing Billy," puffing away in his far-off Northumberland home. He never flinched advocating its principles, and urged the directors to try one on the road. They at last ordered one to be built,—one that would be of service to the company, and no great nuisance to the public. It was built, and excellent service it did, drawing marl from the cuttings and excavations to fill up the bogs and hollows. Nevertheless, it settled nothing, and convinced nobody not already convinced.

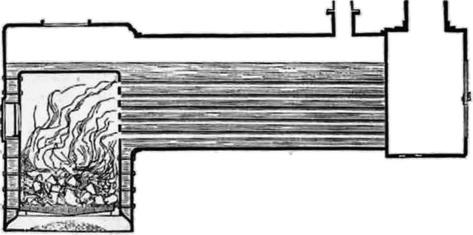

Meanwhile the directors were deluged with projects, plans, and advice for running their road. Scheme upon scheme was let loose upon them;—some engines to go by water-power, some by gas, some by cog-wheels. All the engineering science in the kingdom was ready to engineer for them in its own way; but who among all could pronounce the best way, and upon the whole decide which was the right motive power?

A deputation was despatched to Darlington and Stockton to inspect the fixed and locomotive engines employed on that road; but the deputation came back differing so among themselves, that the directors were more puzzled than ever. Two professional engineers of high reputation were then sent, who, on their return, reported in favour of fixed engines—for safety, speed, economy, and convenience, fixed engines by all odds; reiterating again and again all the frightful stories of danger and annoyance charged upon steam. They proposed dividing the road into nineteen stages, of a mile and a half in length, and having twenty-one stationary engines at different points to push and draw the trains along. The plan was carefully matured.

Poor Stephenson! how did he feel? "Well," he said, with the calm earnestness of a man of faith, "one thing I know, that before many years railroads will become the great highways of the world."

Could the directors accept the project without consulting him? Again they met. What had he to say concerning it? Fight it he did. He dwelt upon its complicated nature, the liability of the ropes and tackling to get out of order, the failure of one engine retarding and damaging and stopping the whole line; a phase of the matter which did not fail to make an impression. The directors were moved. The rich Quaker, Cropper, however, headed the stationary-engine party, and insisted upon adopting it. "But," answered the others, "ought we to make such an outlay of money without first giving the locomotive a fair trial?" And Stephenson pleaded powerfully, as you may suppose, in its behalf. "Try it, try it," he urged; "for speed and safety there is nothing like it." And the words of a man with strong faith are strong words. "Besides," he said, "the locomotive is capable of great improvements. It is young yet; its capacities have never been thoroughly tested. When proper inducements are held out, a superior article will be offered to the public."

Never were directors in a greater strait. There was no withstanding Stephenson, for he knew what he was talking about. All the rest were schemers. At last one of the directors said, "Wait; let us offer a prize for a new locomotive, built to answer certain conditions, and see what sort of engine we can get."

That was fair. It was right his engine should be properly tested. All agreed; and in a few days proposals were issued for the building of one. There were eight conditions, two of which were that if the engine were of six tons weight, it should be able to draw twenty tons, at a speed as high as ten miles an hour. The prize was five hundred pounds.