The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

FREDERICK WILLIAM MAITLAND

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

C. F. CLAY, Manager

Edinburgh: 100, PRINCES STREET

Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO.

Leipzig: F. A. BROCKHAUS

New York: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

All rights reserved

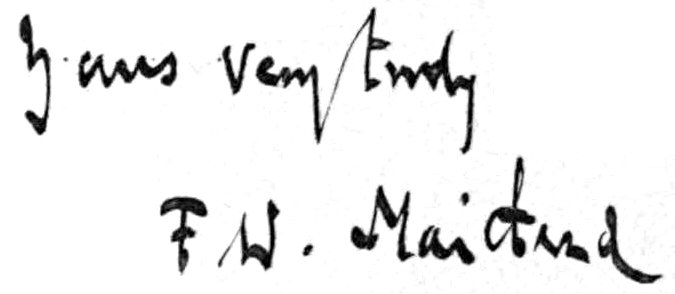

Photogravure by Annan & Sons Glasgow

Yours very truly

F.W. Maitland

BY

H. A. L. FISHER

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1910

Cambridge:

PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A.

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Whatever merit this Memoir may possess it owes to Maitland and to the circle of those who cherish his memory. My own disabilities will be made plain to the reader, but, lest he entertain false expectations, let me explain at the outset that I was educated neither at Eton, nor at Cambridge, nor at Lincoln's Inn, that I am no lawyer, and that I have never received a formal education in the law. Finally, I did not make Maitland's acquaintance till he was in his thirty-seventh year. These are grave shortcomings, and if I do not rehearse the long roll of benefactors who have helped me to repair them, let it not be imputed to a failure in gratitude. I cannot, however, forbear from mentioning five names. Before these sheets went to Press they were read by Mrs Maitland, by Mrs Reynell, by Dr Henry Jackson, by Dr A. W. Verrall and by Professor Vinogradoff. To their intimate knowledge and weighty counsels I owe a deliverance from many errors. Dr Jackson has generously laid upon himself the additional burden of helping me to see the volume through the Press.

H. A. L. FISHER.

May 1910.

The life of a great scholar may be filled with activity as intense and continuous as that demanded by any other calling, and yet is in the nature of things uneventful. Or rather it is a story which tells itself not in outward details of perils endured, places visited, appointments held, but in the revelation of the scholar's mind given in his work. Of such revelation there is no stint in the case of Frederic William Maitland. Within his brief span of life he crowded a mass of intellectual achievements which, if regard be had to its quality as well as to its volume, has hardly, if ever, been equalled in the history of English learning. And yet though a long array of volumes stands upon the Library shelves to give witness to Maitland's work, and not only to the work, but to the modest, brilliant and human spirit which shines through it all and makes it so different from the achievement of many learned men, some few words may be fitly said here as to his life and as to the place which he held and holds in our learning.

He was born on the 28th of May, 1850, at 53 Guilford Street, London, the only son of John Gorham Maitland and Emma Daniell. Father and mother both came of good intellectual lineage. John Gorham Maitland was the son of Samuel Roffey Maitland, the vigorous, learned and unconventional historian whose volume on the Dark Ages, published in 1844, dissipated a good deal of uncritical Protestant tradition. Emma Daniell was the daughter of John Frederic Daniell, a distinguished physicist, who became a Fellow of the Royal Society at the age of twenty-three, invented the hygrometer and published, as Professor of Chemistry at King's College, a well-known Introduction to Chemical Philosophy.

Such ancestry, at once historical and scientific, may explain some of Maitland's tastes and aptitudes. Indeed the words in which Dr Jessop has summarised the work of Samuel Maitland might be applied with equal propriety to the grandson. "Animated by a rare desire after simple truth, generously candid and free from all pretence or pedantry, he wrote in a style which was peculiarly sparkling, lucid and attractive." The secret of this stimulating and suggestive quality lay in the fact that Samuel Maitland was a man of independent mind who took nothing for granted and investigated things for himself. In 1891 his grandson wrote the following words to his eldest sister, who asked whether their grandfather's works would live. "Judging him merely as I should judge any other literary man I think him great. It seems to me that he did what was wanted just at the moment when it was wanted and so has a distinct place in the history[Pg 3] of history in England. The Facts and Documents (illustrative of the History, Documents and Rites of the Ancient Albigenses and Waldenses) is the book that I admire most. Of course it is a book for the few, but then those few will be just the next generation of historians. It is a book which 'renders impossible' a whole class of existing books. I don't mean physically impossible—men will go on writing books of that class—but henceforth they will not be mistaken for great historians. One has still to do for legal history something of the work which S. R. M. did for ecclesiastical history—to teach men e.g. that some statement about the thirteenth century does not become the truer because it has been constantly repeated, that 'a chain of testimony' is never stronger than its first link. It is the 'method' that I admire in S. R. M. more even than the style or the matter—the application to remote events of those canons of evidence which we should all use about affairs of the present day, e.g. of the rule which excludes hearsay."

Cambridge and the bar were familiar traditions. Samuel Maitland was a member of Trinity College, Cambridge, who, having been called to the bar, abandoned the professional pursuit of the law for historical research. He took orders, became Librarian at Lambeth, and ultimately retired to Gloucester to read and to write. John Gorham, seventh wrangler, third classic, Chancellor's medallist, crowned a brilliant undergraduate career by a Fellowship in his father's college and was then called to the bar, but finding little practice drifted away into the Civil Service, becoming first, examiner, and afterwards, in succession to his friend[Pg 4] James Spedding, secretary to the Civil Service Commission, which last office he held till his death in 1863, at the age of forty-five. That he could write with point and vigour is made clear by a pamphlet upon the Property and Income Tax, published in 1853, but the work of the Civil Service Commission must have left little leisure for writing, and early death cut short the career of a man whose high gifts were as remarkable to his friends as was the modesty with which he veiled them from the world[1]. Frederic William, too, passed from Cambridge to the law and then away to work more congenial to his rare and original powers.

Of direct parental influence Maitland can have known little. His mother died in 1851 when he was a baby, and twelve years afterwards, six months before a Brighton preparatory school was exchanged for Eton, he and his two sisters were left fatherless and the sole charge of the family devolved upon Miss Daniell the aunt, who stood in a mother's place. Dr Maitland, the historian, lived on till 1866 and his home in Gloucester, still called Maitland House, was from time to time enlivened by the visits of grandchildren. The fair landscape of Gloucestershire—the wooded slopes of the Cotswolds, the rich pastures of the Severn Valley with the silver thread of river widening into a broad band as it nears the Bristol Channel, the magical outline of the Malvern Hills, the blaze of the nocturnal forges in the Forest of Dean, were familiar to Maitland's boyhood. Gloucestershire was his county, well-known and well-loved. The[Pg 5] beautiful old manor-house of Brookthorpe, one of those small grey-stone manor-houses which are the special pride of Gloucestershire, stood upon the lands which had come into the possession of the family through the marriage of Alexander Maitland with Caroline Busby in 1785. Round it in the parishes of Brookthorpe and Harescombe lay "Squire Maitland's" lands—a thriving cheese-making district until Canada began to filch away the favour of its Welsh customers.

Maitland was at Eton from 1863 to 1869, but failed to become prominent either in work or play. "He played football, was for a while a volunteer, rowed so much that he 'spoilt his style,' spent Sunday afternoons in running to St George's chapel to hear the anthem, and more than once began the holidays by walking home to Kensington[2]." Long afterwards when the question of compulsory Greek was being hotly debated in the Senate House at Cambridge he spoke with deep feeling of a "boy at school not more than forty years ago who was taught Greek for eight years and never learnt it ... who reserved the greater part of his gratitude for a certain German governess ... who if he never learnt Greek, did learn one thing, namely, to hate Greek and its alphabet and its accents and its accidence and its syntax and its prosody, and all its appurtenances; to long for the day when he would be allowed to learn something else; to vow that if ever he got rid of that accursed thing never, never again would he open a Greek book or write a Greek word[3]." We imagine a shy, awkward delicate boy bursting into jets [Pg 6]of wittiness at the least provocation, caring for things which other boys did not care for, misliking the classics, especially Greek, but "brought out by Chaucer" as his tutor Mr E. D. Stone reports, and discovering some taste for mathematics and a passionate interest in music. One contemporary remembers his "jolly, curiously-lined face"; another writes that he was regarded as "a thoroughly good fellow," but his striking originality of mind was perhaps only realised by one schoolfellow, Gerald Balfour, who was the sharer of many a Sunday walk and both at Eton and Cambridge bound to Maitland by close ties of friendship. To the masters Maitland presented none of the obvious points of interest. Even William Johnson, that learned and catholic scholar who made so many happy discoveries, failed to discover Maitland. The boy was not a Hellenist and his deficiencies in Greek and Latin prosody put him outside the intellectual pale. He was whimsical, full of eccentric interests, of puns and paradox and original humour. His closest school friend thought that he would possibly develop into "a kind of philosophic Charles Lamb[4]."

In the autumn of 1869 Maitland went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, as a Commoner. The learned Samuel Roffey had been a musician both in theory and practice, and the taste for music descended through the son to the grandson. The first year of Maitland's undergraduate life was given over to music, mathematics and athletics; but his earliest distinctions were[Pg 7] gained not in the most but in the least intellectual of these pursuits. Though he can never have looked otherwise than fragile, he had outgrown his early delicacy and become an active lad with considerable powers of endurance. He won the Freshman's mile in four minutes forty-seven seconds, excellent time as records went then, and obtained his "blue" as a three-miler in the Inter-University Sports. The two mile walking race, the quarter, and the mile, fell to him at various times in the Third Trinity Sports. Nor were his athletic activities confined to the running path. His friend Mr Cyprian Williams remembers his last appearance as a racing oarsman; how on the final day of the Lent races of 1872 the Third Trinity second boat after a successful week made a crowning bump, how in the moment of the victory the crew were tipped over into the cold and dirty waters of the Cam, and how in the evening the boat dined in Maitland's lodgings over Palmer's boot-shop and kept up its festivity well into the morning.

Long before this—at the beginning of his second year at Cambridge—Maitland found his way into Henry Sidgwick's lecture-room and made a discovery which shall be told in his own words. "It is now thirty years ago that some chance—I think it was the idle whim of an idle undergraduate—took me to Sidgwick's lecture-room, there to find teaching the like of which had never come in my way before. There is very much else to be said of Sidgwick; some part of it has been beautifully said this afternoon; but I should like to add this: I believe that he was a supremely great teacher. In the first place I[Pg 8] remember the admirable patience which could never be out-worn by stupidity, and which nothing but pretentiousness could disturb. Then there was the sympathetic and kindly endeavour to overcome our shyness, to make us talk, and to make us think. Then there was that marked dislike for any mere reproduction of his own opinions which made it impossible for Sidgwick to be in the bad sense the founder of a school. I sometimes think that the one and only prejudice that Sidgwick had was a prejudice against his own results. All this was far more impressive and far more inspiriting to us than any dogmatism could have been. Then the freest and boldest thinking was set forth in words which seemed to carry candour and sobriety and circumspection to their furthest limit. It has been said already this afternoon, but I will say it again: I believe that no more truthful man than Sidgwick ever lived. I am speaking of a rare intellectual virtue. However small the class might be, Sidgwick always gave us his very best; not what might be good enough for undergraduates, or what might serve for temporary purposes, but the complex truth just as he saw it, with all those reservations and qualifications, exceptions and distinctions which suggested themselves to a mind that was indeed marvellously subtle but was showing us its wonderful power simply because, even in a lecture room, it could be content with nothing less than the maximum of attainable and communicable truth. Then, as the terms went by, we came to think of lecture time as the best time we had in Cambridge; and some of us, looking back now, can say that it was[Pg 9] in a very true sense the best time that we have had in our lives. We turned away to other studies and pursuits, but the memories of Sidgwick's lectures lived on. The matter of the lectures, the theories and the arguments, might be forgotten; but the method remained, the spirit remained, as an ideal—an unattainable ideal, perhaps, but a model of perfect work. I know that in this matter I can speak for others; but just one word in my own case. For ten years and more I hardly saw Sidgwick. To meet him was a rare event, a rare delight. But there he always was: the critic and judge of any work that I might be doing: a master, who, however forbearing he might be towards others, always exacted from himself the utmost truthfulness of which word and thought are capable. Well, I think it no bad thing that young men should go away from Cambridge with such a master as that in their minds, even though in a given case little may come of the teaching ... I can say no more. Perhaps I have already tried to say too much. We who were, we who are, Sidgwick's pupils, need no memorial of him. We cannot forget. Only in some way or another we would bear some poor testimony of our gratitude and our admiration, our reverence and our love[5]."

Such teaching was precisely calculated to ripen Maitland's unsuspected powers. The pupil was as modest, as exact, as truth-loving as the master, and possessed a quick turn for witty casuistry which was quite individual though not dissimilar to Sidgwick's own gift in the same direction. Under Sidgwick's[Pg 10] influence Maitland's intellect deepened and widened. The piano was ejected from the college room; the University running path knew him no more; mathematics were abandoned for philosophy with such good result that a scholarship was gained at Trinity, and that in the Moral and Mental Science Tripos of 1872 Maitland came out at the head of the First Class, bracketed with his friend W. Cunningham, who has since won high distinction in the field of economic history. But the chief prize of undergraduate ambition, a Fellowship at Trinity, was denied him. Maitland competed, and was beaten in the competition by James Ward, now one of the most distinguished of living psychologists. Examiners make fewer mistakes than is commonly supposed, and on this occasion Henry Sidgwick and Thomas Fowler reached their decision not without hesitation. While admitting Maitland's literary brilliance and facility they discovered in his successful rival a deeper interest in the problems of philosophy and therefore a superior claim to a Fellowship in Moral and Mental Science[6].

Maitland's Fellowship dissertation entitled "A Historical Sketch of Liberty and Equality as Ideals of English Political Philosophy from the time of Hobbes to the time of Coleridge" is, despite some defects of proportion, a remarkable performance for so young a man. Not only does it cover a wide range[Pg 11] of reading, especially in the English moralists, but it is distinguished by two characteristic qualities—independence of judgment and a scrupulous estimate of the canons of proof. The scholar of Trinity says many good things[7], but says nothing at random. Even when it would have been tempting to sally forth with a flourish of affirmation, he prefers to stand within the zone of caution. "I am inclined to think," he writes, "(though there is great risk of such speculations being wrong) that Hobbes was led to exaggerate his account of man's naturally unsocial character by a desire to bring the state of nature into discredit." One cannot dogmatise about the motives of the dead; our dogmas are but plausible hypotheses, and so complex is human nature, so inexhaustible is life's casuistry that the likeliest conjecture may fail of the mark. "There is a great risk of such speculation being wrong." Touches like this reveal the fact that the disciple of Sidgwick had learnt his master's lesson.

The scholarship at Trinity, carrying with it a place at the scholar's table, brought Maitland into communion with the ablest men in the College. It often happens that a youth who has attracted little attention at school[Pg 12] by reason of his failure to satisfy the limited conventions of schoolboy excellence, springs into sudden prominence at the University. His conversation attracts notice; his friends discover that he has original opinions, or some peculiar charm of bearing, or that his gifts of mind or character are out of the common. So it was with Maitland. He soon achieved a reputation not only as a witty and brilliant talker, but as a charming companion and as the most original public speaker of his time. He was elected to be a member of the Apostles, a small society which for many university generations has been a bond between clever young Cambridge men and has brought them into friendly relations with their seniors: and by the suffrages of a larger and less select electorate he rose to be Secretary and then President of the Union Society.

Maitland's speeches at the Union printed themselves upon the minds of his audience as being very effective for their immediate purpose and yet quite unlike the speeches of ordinary vote-winners. His artifice was all his own. Others were more eloquent, more prompt in the cut and thrust of debate, but in the power of condensing an argument into a surprising phrase or epigram he stood alone. After his first successful appearance as the advocate of the opening of National Collections of Science and Art on Sunday afternoons he became the favourite undergraduate orator of his time. "You insist that we must keep the Mosaic Law," he argued in his maiden speech, "but under it a man who gathered sticks on the Sabbath was stoned to death. Now I have picked up sticks on Sundays. Will you in your consistency stone me?"[Pg 13] On another occasion he delighted the House by observing that at the Reformation the English State put an end to its Roman bride but married its deceased wife's sister. The shape of his opinions was frankly radical and fashioned by a vehement enthusiasm for free thinking and plain speaking. "There are two things," he remarked, "which we have learnt by costly experience that the Law cannot control—Religious Belief and the Rate of Interest." Compulsory attendance at College Chapel, Church Establishment, the closing of the Cambridge Union on Sunday mornings aroused his opposition and furnished the theme of well-remembered speeches. "O Sir," he once exclaimed to the President with outstretched hands, "I would I were a vested nuisance! Then I should be sure of being protected by the whole British Public."

There is a pleasant story contributed by Professor Kenny—to whom this portion of the narrative is greatly indebted—of a debate upon a motion that certain annotations upon the annual report of the Union's proceedings should be cancelled in the interests of "the literary credit of the Society." The notes were ungrammatical, ludicrous, unauthorised. They had been composed during the Long Vacation by the Society's senior servant in the name of the absent Secretary. There was nothing to be said for them save that it was hard that a good old man should be humiliated for an excess of official zeal. Maitland was Secretary at the time and chivalrously undertook the defence of his subordinate. It was the eve of the Fifth of November; the name of the mover was[Pg 14] James. Such an historical coincidence was not lost upon the ingenious mind of the Secretary. "Tomorrow," he observed, boldly carrying the war into the enemy's country, "is the Feast of the Blessed Saint Guy. Appropriately enough the House appears to be under search this evening for indications of a new plot. Enter King James the Third, surrounded by his minions, with a loud flourish of his own trumpet. He produces the dark lantern of his intellect and discovers—not a conspirator, but a mare's nest." And when, at last, by successive strokes of humour Maitland had won over the sympathies of the House, he proceeded to venture upon the merits of his defence. "We are attacked," he said, "for bad grammar. A great crime, no doubt, in some men's eyes. For at times I have met men to whom words were everything, and whose everything was words; men undistinguished by any other capacity, and unknown outside this House, but reigning here in self-satisfaction, lords of the realm of Tautology."

[1] "The Cambridge Apostles," by W. D. Christie. Macmillan's Magazine, Nov. 1864.

[2] A Biographical Notice by Mrs Reynell (privately printed).

[3] Cambridge University Reporter, Dec. 17, 1904.

[4] A punning squib, very spirited and amusing, entitled "A solemn Mystery," and contributed to The Adventurer, June 4, 1869, seems to have been Maitland's first appearance in print.

[5] Cambridge University Reporter, Dec. 7, 1900.

[6] There were four candidates for the Fellowship: W. Cunningham, Arthur Lyttelton, F. W. Maitland, and James Ward, every one of them distinguished in after life. With so strong a competition the College might have done well to elect more Fellows than one in Moral and Mental Science.

[7] Such for instance as:—

"The love of simplicity has done vast harm to English Political Philosophy."

"No history of the British Constitution would be complete which did not point out how much its growth has been affected by ideas derived from Aristotle."

"The idea of a social compact did not become really active till it was allied with the doctrine that all men are equal."

"In Hume we see the first beginnings of a scientific use of History."

The failure to obtain a fellowship broke off any design which may have been entertained of an academic career, and Maitland, following the family example, returned to London to try his fortune at the bar. Men of high academic achievement sometimes fail in the practical professions, by reason of a certain abstract habit of mind or from an engrained unsociability of temperament. Neither of these disad[Pg 15]vantages affected Maitland. A combined training in philosophy and law had given him just that capacity for deriving principles from the facts of experience, and of using the facts of experience as the touchstone of principles, which is essential to the adroit and intelligent use of legal science; and for all his learning and zeal there was nothing harsh and unsocial about him. On the other hand he was completely deficient in the moral alloy which appears to be an essential element in the fabric of most successful careers. He was entirely destitute of the arts of "push" or advertisement, and so disinterested and self-effacing that a world which is accustomed to take men at their own valuation was not likely to seize his measure.

Maitland entered at Lincoln's Inn in 1872 and was called to the bar in 1876, reading first with Mr Upton and afterwards with Mr B. B. Rogers, the brilliant translator and editor of Aristophanes. "I had only one vacancy," writes Mr Rogers, "in my pupil room and that was about to be filled by a very distinguished young Cambridge scholar. But he was anxious—stipulated I think—that I should also take his friend Maitland. I did not much like doing so, for I considered four pupils as many as I could properly take, and I knew nothing of Maitland and supposed that he would prove the crude and awkward person that a new pupil usually is, however capable he may be, and however distinguished he may become in later life. However, I agreed to take him as a fifth pupil, and he had not been with me a week before I found that I had in my chambers such a lawyer as I had never met before. I have forgotten, if I ever knew,[Pg 16] where and how he acquired his mastery of law; he certainly did not acquire it in my chambers: he was a consummate lawyer when he entered them. Every opinion that he gave was a complete legal essay, starting from first principles, showing how the question agreed with one, and disagreed with another, series of decisions and finally coming to a conclusion with the clearest grasp of legal points and the utmost lucidity of expression. I may add (and though this is a small point it is of importance in a barrister's chambers) that it was given in a handwriting which it was always a pleasure to read. He must have left me in 1877, and towards the end of 1879, my health being in a somewhat precarious state, and my medical advisers insisting on my lessening the strain of my work, I at once asked Maitland to come in and superintend my business. He gave up his own chambers and took a seat in mine (the chambers in 3 Stone Buildings where I then was are I think the largest in the Inn), superintended the whole of my business, managed my pupils, saw my clients and in case of necessity held my briefs in Court. I doubt if he would have succeeded as a barrister; all the time that I knew him he was the most retiring and diffident man I ever knew; not the least shy or awkward; his manners were always easy and self-possessed; but he was the last man to put himself forward in any way. But his opinions, had he suddenly been made a judge, would have been an honour to the Bench. One of them may still be read in Re Cope Law Rep. 16 Ch. D. 49. There a long and learned argument filling nearly two pages of the Report is put into the mouth of Chitty Q.C. and myself, [Pg 17]not one word of which was ever spoken by either of us. It was an opinion of Maitland's on the case laid before us which I gave to Chitty to assist him in his argument.... I cannot close this long though hastily written letter without expressing my personal esteem for the man. Wholly without conceit or affectation, simple, generous and courteous to everybody, he was the pleasantest companion that anybody could ever wish for: and I think that the three years he spent in my chambers were the most delightful three years I ever spent at the bar."

Working partly for Mr Rogers and partly for Mr Bradley Dyne, Maitland saw a good deal of conveyancing business and in after years was wont to lay stress upon the value of this part of his education. Conveyancing is a fine art, full of delicate technicalities, and Maitland used to say that there could be no better introduction to the study of ancient diplomata than a few years spent in the chambers of a busy conveyancer. Here every document was made to yield up its secret; every word and phrase was important, and the habit of balancing the precise practical consequences of seemingly indifferent and conventional formulæ became engrained in the mind. Paleography might teach men to read documents, diplomatics to date them and to test their authenticity; but the full significance of an ancient deed might easily escape the most exact paleographer and the most accomplished diplomatist, for the want of that finished sense for legal technicality which is the natural fruit of a conveyancing practice.[8]

Business of this type, however, does not provide opportunities for forensic oratory and Maitland's voice was rarely heard in Court[9]. But meanwhile he was rapidly exploring the vast province of legal science, mastering the Statute Books, reading Frenchmen, Germans and Americans, and occasionally contributing articles upon philosophical and legal topics to the Press.

To the deepest and most serious minds the literature of knowledge is also the literature of power. Maitland's outlook and ideal were at the period of intellectual virility greatly affected by two books, Savigny's Geschichte des Römischen Rechts and Stubbs' Constitutional History. The English book he found in a London Club and "read it because it was interesting," falling perhaps, as he afterwards suggested, for that very reason "more completely under its domination than those who have passed through schools of history are likely to fall." Of the German he used to say that Savigny first opened his eyes as to the way in which law should be regarded.

Law was a product of human life, the expression of human needs, the declaration of the social will; and so a rational view of law would be won only from some height whence it would be possible to survey the great [Pg 19]historic prospect which stretches from the Twelve Tables and the Leges Barbarorum to the German Civil Code and the judgments reported in the morning newspaper. Readers of Bracton's Note Book will remember Maitland's description of Azo as "the Savigny of the thirteenth century," as a principal source from which our greatest medieval jurist obtained a rational conception of the domain of law. Savigny did not write the same kind of book as Azo. He worked in a different medium and on a larger canvas but with analogous effects. He made the principles of legal development intelligible by exhibiting them in the vast framework of medieval Latin and Teutonic civilization and as part of the organic growth of the Western nations. Maitland's early enthusiasm for the German master took a characteristic form: he began a translation of the history.

The translation of Savigny was neither completed nor published. Maitland's first contribution to legal literature was an anonymous article which appeared in the Westminster Review in 1879. This was not primarily an historical disquisition though it displayed a width of historical knowledge surprising in so young a man, but a bold, eloquent, and humorous plea for a sweeping change in the English law of Real Property. "Let all Property be personal property. Abolish the heir at law." This alteration in the law of inheritance would lead to great simplification and would remove much ambiguity, injustice and cost. Nothing short of this would do anything worth doing. A few little changes had been made in the past, "for accidents will happen in the best regulated museums," but it was no use[Pg 20] recommending timid subsidiary changes while the central anomaly, the source of all complexity and confusion, was permitted to continue. "It is not unlikely," remarked the author with grave irony, "that we are behind an age whose chief ambition is to be behind itself."

The article exhibits a quality of mind which is worth attention. Maitland never allowed his clear strong common sense to be influenced by that vague emotion which the conventional imagination of half-informed people readily draws from antiquity. He loved the past but never defended an institution because it was old. He saw antiquity too vividly for that. And so despite the ever increasing span of his knowledge he retained to the end the alert temper of a reformer, ready to consider every change upon its merits, and impelled by a natural proclivity of mind to desire a state of society in some important respects very different from that which he found existing. At the same time he is far too subtle a reasoner to acquiesce in the doctrinaire logic of Natural Rights or in some expositions of social philosophy which pretended to refinements superior to those provided by empirical utilitarianism. Two early articles contributed to the pages of Mind on Mr Herbert Spencer's Theory of Society contain a modest but very sufficient exposure of the shortcomings of that popular philosopher's a priori reasoning in politics.

With these serious pursuits there was mingled a great deal of pleasant recreation. Holidays were spent in adventurous walking and climbing in the Tyrol, in Switzerland, and among the rolling fir-clad hills of the[Pg 21] Black Forest, for Maitland as a young man was a swift and enduring walker, with the true mountaineer's contempt for high roads and level places. We hear of boating expeditions on the Thames, of visits to burlesques and pantomimes, of amusing legal squibs and parodies poured out to order without any appearance of effort. From childhood upwards music had played a large part in Maitland's life and now that the shadow of the Tripos was removed he was able to gratify his musical taste to the full. In 1873 he spent some time alone in Munich, listening to opera night after night and then travelled to Bonn that he might join his sisters at the Schumann Commemoration. Those were the days when the star of Richard Wagner was fast rising above the horizon and though he was not prepared to burn all his incense at one shrine, Maitland was a good Wagnerian. In London musical taste was experiencing a revival, the origin of which dated back, perhaps, to the starting of the Saturday Concerts at the Crystal Palace by August Manns in 1855. The musical world made pilgrimages to the Crystal Palace to listen to the orchestral compositions of Schubert and Schumann or to the St James' Hall popular concerts, founded in 1859, to enjoy the best chamber music of the greatest composers. New developments followed, the first series of the Richter Concerts in 1876 and the first performance of Wagner's Ring in 1882. Maitland with his friend Cyprian Williams regularly attended concert and opera. Without claiming to be an expert he had a good knowledge of music and a deep delight in it. One of his chief Cambridge friends, Edmund Gurney, best known per[Pg 22]haps as one of the principal founders of the Society for Psychical Research, wrote a valuable book on The Power of Sound and interested Maitland in the philosophy of their favourite art. "I walked once with E. Gurney in the Tyrol," Maitland wrote long afterwards, "What moods he had! On a good day it was a joy to hear him laugh!" Gurney died prematurely in 1888 and the increasing stress of work came more and more between Maitland and the concert room; but problems of sound continued to exercise a certain fascination over his mind and his last paper contributed to the Eranos Club at Cambridge on May 8, 1906, and entitled with characteristic directness "Do Birds Sing?" was a speculation as to the conditions under which articulate sound passes into music.

That by the natural workings of his enthusiastic genius Maitland would have been drawn to history whatever might have been the outward circumstances of his career, is as certain as anything can be in the realm of psychological conjecture. Men of the ordinary fibre are confronted by alternatives which are all the more real and painful by reason of their essential indifference. This career is open to them or that career, and they can adapt themselves with equal comfort to either. But the man of genius follows his star. His life acquires a unity of purpose which stands out in contrast to the confused and blurred strivings of lesser men. Other things he might do, other tastes he might gratify; but there is one thing that he can do supremely well, one taste which becomes a passion, which swallows up all other impulses, and for which he is prepared to sacrifice money and health and the[Pg 23] pleasures of society and many other things which are prized among men.

When Maitland stood for the Trinity Fellowship he was already aware that success at the bar would mean the surrender of the reading which had "become very dear" to him, and yet his ambition desired success of one kind or another. The varied humours of his profession pleased him; he loved the law and all its ways; yet it is difficult to believe that the routine of a prosperous equity business would ever have satisfied so comprehensive and enquiring a mind. The young barrister had a soul for something beyond drafts; he lectured on political economy and political philosophy in manufacturing towns and in London[11], wrote for the Pall Mall Gazette, then a liberal evening paper under the direction of Mr John Morley; but more and more he was drawn to feel the fascination and importance of legal history. Two friends helped to determine his course. Mr, now Sir Frederick, Pollock had preceded Maitland by six years at Eton and Trinity and was also a member of Lincoln's Inn. Coming of a famous legal family, and himself already rising to distinction as a scientific lawyer, Mr Pollock appreciated both the value of English legal history and the neglect into which it had been allowed to fall. He sought out Maitland and a friendship was formed between the two [Pg 24]men which lasted in unbroken intimacy and frequent intellectual communion to the end. An historical note on the classification of the Forms of Personal Action, contributed to his friend's book on the Law of Torts, was the first overt evidence of the alliance.

The other friend was a Russian. Professor Paul Vinogradoff, of Moscow, who had received his historical education in Mommsen's Seminar in Berlin, happened in 1884 to be paying a visit in England. The Russian scholar, his superb instinct for history fortified by the advantages of a system of training such as no British University could offer, had, in a brief visit to London, learnt something about the resources of our Public Record Office which was hidden from the Inns of Court and from the lecture rooms of Oxford and Cambridge. On January 20, Maitland and Vinogradoff chanced to meet upon one of Leslie Stephen's Sunday tramps, concerning which there will be some words hereafter, and at once discovered a communion of tastes. The two men found that they were working side by side and brushing one another in their researches. Correspondence followed of a learned kind; then on Sunday, May 11, there was a decisive meeting at Oxford. The day was fine and the two scholars strolled into the Parks, and lying full length on the grass took up the thread of their historical discourse. Maitland has spoken to me of that Sunday talk; how from the lips of a foreigner he first received a full consciousness of that matchless collection of documents for the legal and social history of the middle ages, which England had continuously preserved and consistently neglected, of an unbroken stream of[Pg 25] authentic testimony flowing for seven hundred years, of tons of plea-rolls from which it would be possible to restore an image of long-vanished life with a degree of fidelity which could never be won from chronicles and professed histories. His vivid mind was instantly made up: on the following day he returned to London, drove to the Record Office, and being a Gloucestershire man and the inheritor of some pleasant acres in that fruitful shire asked for the earliest plea-roll of the County of Gloucester. He was supplied with a roll for the year 1221, and without any formal training in paleography proceeded to puzzle it out and to transcribe it.

The Pleas of the Crown for the County of Gloucester which appeared in 1884 with a dedication to Paul Vinogradoff is a slim and outwardly insignificant volume; but it marks an epoch in the history of history. "What is here transcribed," observes the editor, "is so much of the record of the Gloucestershire eyre of 1221 as relates to pleas of the Crown. Perhaps it may be welcome, not only to some students of English law, but also (if such a distinction be maintainable) to some students of English history. It is a picture, or rather, since little imaginative art went to its making, a photograph of English life as it was early in the thirteenth century, and a photograph taken from a point of view at which chroniclers too seldom place themselves. What is there visible in the foreground is crime, and crime of a vulgar kind—murder and rape and robbery. This would be worth seeing even were there no more to be seen, for crime is a fact of which history must take note; but the political[Pg 26] life of England is in a near background. We have here, as it were, a section of the body politic which shows just those most vital parts, of which, because they were deep-seated, the soul politic was hardly conscious, the system of local government and police, the organization of county, hundred, and township."

It was the publication of a new and fundamental type of authority accomplished with affectionate and exquisite diligence by a scholar who had a keen eye for the large issues as well as for the minutiæ of the text. And it came at a timely moment. Sir James Fitzjames Stephen's History of Criminal Law had recently appeared and Maitland has written of it in terms of genuine admiration; but remarkable as those volumes undoubtedly were, miraculous even, if regard be paid to the competing claims upon the author's powers, they did not pretend to extend the boundaries of medieval knowledge. The task of making discoveries in the field of English legal antiquity, of utilizing the material which had been brought to light by the Record Commission appeared to have devolved upon Germans and Americans. All the really important books were foreign—Brunner's Schwurgerichte, Bigelow's Placita Anglo-Normannica and History of Procedure in England, the Harvard Essays on Anglo-Saxon Law, Holmes' brilliant volume on the Common Law. Of one great name indeed England could boast. Sir Henry Maine's luminous and comprehensive genius had drawn from the evidence of early law a number of brilliant and fascinating conclusions respecting the life and development of primitive society, and had applied an intellectual impulse which[Pg 27] made itself felt in every branch of serious historical enquiry. But the very seductions of Maine's method, the breadth of treatment, the all-prevailing atmosphere of nimble speculation, the copious use of analogy and comparison, the finish and elasticity of the style were likely to lead to ambitious and ill-founded imitations. It is so pleasant to build theories; so painful to discover facts. Maitland was strong enough to resist the temptation to premature theorizing about the beginnings of human society. As an undergraduate he had seen that simplicity had been the great enemy of English Political Philosophy; and as a mature student he came to discover how confused and indistinct were the thoughts of our forefathers, and how complex their social arrangements. What those thoughts and arrangements were he determined to discover, by exploring the sources published and unpublished for English legal history. He knew exactly what required to be done, and gallantly faced long hours of unremunerative drudgery in the sure and exultant faith that the end was worth the labour. "Everything which he touched turned to gold." He took up task after task, never resting, never hasting, and each task was done in the right way and in the right order. The study of English legal history was revolutionised by his toil.

Before the fateful meeting with Vinogradoff at Oxford, Maitland had made friends with Leslie Stephen. In 1880 he joined "the goodly company, fellowship or brotherhood of the Sunday tramps," which had been founded in the previous year by Stephen, George Crome Robertson, the Editor of[Pg 28] Mind, and Frederick Pollock. "The original members of the Society about ten in number were for the most part addicted to philosophy, but there was no examination, test, oath or subscription, and in course of time most professions and most interests were represented." The rule of the Club was "to walk every other Sunday for about eight months in the year," and so long as Maitland lived in London he was a faithful member of that strenuous company. A certain wet Sunday lived in his memory and, though he did not know it, lived also in the memory of Leslie Stephen. "I was the only tramp who had obeyed the writ of summons, which took the form of a postcard. When the guide (we had no 'president,' certainly no chairman, only so to speak, a 'preambulator') and his one follower arrived at Harrow station, the weather was so bad that there was nothing for it but to walk back to London in drenching rain; but that day, faithful alone among the faithless found, I learnt something of Stephen, and now I bless the downpour which kept less virtuous men indoors." That wet Sunday made Maitland a welcome guest at the Stephen's house; and it brought other happiness in its train. In 1886 Maitland was married in the village church of Brockenhurst, Hants, to Florence Henrietta, eldest daughter of Mr Herbert Fisher, some time Vice Warden of the Stannaries, and niece of Mrs Leslie Stephen. Two daughters, the elder born in 1887, and the younger in 1889, were the offspring of the marriage.

[8] For a good instance of Maitland's trained insight see Domesday Book and Beyond, p. 232.

[9] Maitland once conducted an argument before Jessel, M. R. Re Morton v. Hallett (Feb. & May, 1880, Ch. 15, D. 143).

[10] Browning, Ring and the Book. See Maitland, Bracton's Note Book, vol. 1.

[11] An account of Maitland's "valuable" lectures "On the Cause of High and Low Wages," given to an average class of some twenty workmen in the Artizan's Institute, Upper St Martin's Lane, in 1874, and "followed by a very useful discussion in which the students asked and Mr Maitland answered many knotty questions" may be read in H. Solly, These Eighty Years, vol. II. p. 440.

Meanwhile Maitland had been recalled from London to his old University. The reading which had been "very dear to him" when he took the first plunge into London work, had become dearer in proportion as the opportunities for indulging in it became more restricted. He was earning an income at the bar which, though not large, was adequate to his needs, but a barrister's income is uncertain and Maitland may have felt that while he had no assured prospect of improving his position at the bar, the life of a successful barrister, if ever success were to come to him, would entail an intellectual sacrifice which he was not prepared to face. Accordingly in 1883 he offered himself for a Readership in English Law in the University of Oxford, but without success. A distinguished Oxford man happened to be in the field and the choice of the electors fell, not unnaturally, upon the home-bred scholar. But meanwhile a movement was on foot in the University of Cambridge to found a Readership in English Law. In a Report upon the needs of the University issued in June, 1883, the General Board of Studies had included in an appendix a statement from the Board of Legal Studies urging that two additional teachers in English Law should be established as assistants to the Downing Professor. Nothing however was done and the execution of the project might have been indefinitely postponed but for the generosity of Professor Henry Sidgwick, who offered to pay[Pg 30] £300 a year from his own stipend for four years if a Readership could be established. Sidgwick's action was clearly dictated by a general view of the educational needs of the University, but he had never lost sight of his old pupil and no doubt realised that Maitland was available and that he was not unlikely to be elected. The Senate accepted the generous offer, the Readership was established, and on November 24, 1884, Maitland was elected to be Reader of English Law in the University of Cambridge. In the Lent term of 1885 he gave his first course of lectures on the English Law of Contracts.

Cambridge offered opportunities for study such as Maitland had not yet enjoyed. A little volume on Justice and Police, contributed to the English Citizen series and designed to interest the general reading public, came out in 1885, and affords good evidence of Maitland's firm grasp of the Statute book and of his easy command of historical perspective. But this book, excellent as it is, did not represent the deeper and more original side of Maitland's activity any more than an admirable series of lectures upon Constitutional History which were greatly appreciated by undergraduate audiences but never published in his lifetime. The Reader in English Law was by no means satisfied with providing excellent lectures covering the whole field of English Constitutional history, though he had much that was fresh and true to say about the Statutes of the eighteenth century and about the degree to which the theories of Blackstone were applicable to modern conditions, and though he drew a picture for his undergraduate audience which in some important[Pg 31] respects was closer to fact than Walter Bagehot's famous sketch of the English Constitution published while Maitland was an Eton boy. Text book and Lectures were but interludes in the main operations of the campaign against the unconquered fastnesses of medieval law. First came a remarkable series of articles contributed to the Law Quarterly Review upon the medieval doctrine of seisin which Maitland's sure insight had discerned to be the central feature in the land law of the Norman and Angevin period: and then in 1887 Bracton's Note Book.

"Twice in the history of England has an Englishman had the motive, the courage, the power to write a great readable reasonable book about English Law as a whole." The task which William Blackstone achieved in the middle of the eighteenth century, Henry de Bratton, a judge of the King's Court, accomplished in the reign of Henry III. His elaborate but uncompleted treatise De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliæ, composed in the period which lies between the legal reforms of Henry II. and the great outburst of Edwardian legislation, while the Common law of England was still plastic and baronage and people were claiming from the King a stricter observance of the great Charter, is naturally the most important single authority for our medieval legal history. Though influenced by the categories and scientific spirit of Roman Law, Henry de Bratton was essentially English, essentially practical. His book was based upon the case law of his own age—[Pg 32]Et sciendum est quod materia est facta et casus qui quotidie emergunt et eveniunt in regno Angliæ—and especially upon the plea-rolls of two contemporary judges, Walter Raleigh and William Pateshull. An edition in six volumes executed for the Rolls Series by Sir Travers Twiss had been completed in 1883, the year before Maitland paid his first visit to the Record Office and discovered the plea-rolls of the County of Gloucester; but the text was faulty and far from creditable to English scholarship.

On July 19, 1884, Professor Vinogradoff, "who in a few weeks" wrote Maitland, "learned, as it seems to me, more about Bracton's text than any Englishman has known since Selden died," published a letter in the Athenæum drawing attention to a manuscript in the British Museum, which contained "a careful and copious collection of cases" for the first twenty-four years of Henry III., a collection valuable in any case, since many of the rolls from which it was copied have long since been lost, but deriving an additional and peculiar importance from the probability that it was compiled for Bracton's use, annotated by his own hand and employed as the groundwork of his treatise. Yet, even if the connection with Bracton could not be established, a manuscript containing no fewer than two thousand cases from the period between 1217 and 1240 was too precious a discovery to be neglected. Here was a mass of first-hand material, valuable alike for the genealogist, the lawyer, the student of social history:—glimpses of archaic usage, of local custom, evidence of the spread of primogeniture, important decisions affecting the status of the free man who held villein lands, records of villein service, vivid little[Pg 33] fragments of family story, some of it tragic, some of it squalid, as well as passages of general historical interest, entries concerning "the partition and therefore the destruction of the Palatinate of Chester" or the reversal of the outlawing of Hubert de Burgh the great justiciar who at one time "held the kingdom of England in his hand."

The Note Book was edited by Maitland in three substantial volumes and with the lavish care of an enthusiast. An elaborate argument, all the more cogent because it is not overstrained, raised Vinogradoff's hypothesis to the level of practical certainty. "The treatise is absolutely unique; the Note Book so far as we know is unique; these two unique books seem to have been put together within a very few years of each other, while yet the Statute of Merton was nova gracia; Bracton's choice of authorities is peculiar, distinctive; the compiler of the Note Book made a very similar choice; he had, for instance, just six consecutive rolls of pleas coram rege; Bracton had just the same six; two-fifths of Bracton's five hundred cases are in this book; every tenth case in this book is cited by Bracton; some of Bracton's most out of the way arguments are found in the margin of this book ... the same phrases appear in the same contexts.... Corbyn's case, Ralph Arundell's case are 'noted up' in the Note Book; they are 'noted up' also in the Digby MS of the treatise; with hardly an exception all the cases thus 'noted up' seem plainly to belong to Bracton's county.... Lastly we find a strangely intimate agreement in error; the history of the ordinance about special bastardy and the 'Nolumus' of[Pg 34] Merton is confused and perverted in the two books. Must we not say then that, until evidence be produced on the other side, Bracton is entitled to a judgment, a possessory judgment?" The penultimate argument in the pleading was characteristic of Maitland's ingenuity and also of a favourite pastime. He describes an imaginary walking tour through Devon and Cornwall and points out that ten cases noted up in the margin of the Note Book refer to persons and places which must have been well known to Bracton. "Many questions are solved by walking. Beati omnes qui ambulant."

The appearance of the Note Book showed that Cambridge possessed a scholar who could edit a big medieval text with as sure a touch as Stubbs, and the book received a warm welcome from those who were entitled to judge of its merits. It had been a costly book to prepare and it was brought out at Maitland's own charges. In the introduction he took occasion to point out that in other countries important national records were apt to be published by national enterprise; and that in England the wealth of unpublished records was exceptional. "We have been embarrassed by our riches, our untold riches. The nation put its hand to the work and turned back faint-hearted. Foreigners print their records; we, it must be supposed, have too many records to be worth printing; so there they lie, these invaluable materials for the history of the English people, unread, unknown, almost untouched save by the makers of pedigrees." As an advertisement of these unknown treasures no more fortunate selection could have been made than this[Pg 35] manuscript note book which could with so high a degree of probability be associated with the famous name of Bracton. But Maitland was not content with urging that the publication of our unknown legal records should not be left to depend upon the chance enthusiasm of isolated scholars; he demanded, as things necessary to the progress of his subject, a sound text of Bracton's treatise and a history of English Law from the thirteenth century.

In 1888 there was by reason of the death of Dr Birkbeck a vacancy in the Downing Chair of the Laws of England. Maitland stood and was elected. His Inaugural Lecture delivered in the Arts School on 13th October, 1888, was entitled, "Why the History of Law is not written." The reason was not a lack of material; on the contrary England possessed a series of records which "for continuity, catholicity, minute detail and authoritative value has—I believe that we may safely say it—no equal, no rival in the world," nor yet the difficulty of treating the material, for owing to the early centralization of justice, English history possessed a wonderful unity. Rather it was "the traditional isolation of English Law from every other study" and the fact that practising lawyers are required to know a little medieval law not as it was in the middle ages, but as interpreted by modern courts to suit modern facts. "A mixture of legal dogma and legal history is in general an unsatisfactory compound. I do not say that there are not judgments and text books which have achieved the difficult task of combining the results of deep historical research with luminous and accurate exposition of existing law—[Pg 36]neither confounding the dogma nor perverting the history; but the task is difficult. The lawyer must be orthodox otherwise he is no lawyer; an orthodox history seems to me a contradiction in terms. If this truth is hidden from us by current phrases about 'historical methods of legal study,' that is another reason why the history of our law is unwritten. If we try to make history the handmaid of dogma she will soon cease to be history."

Maitland concluded with an appeal for workers in an untilled field, but with characteristic veracity held out no illusory hopes. "Perhaps," he wrote, "our imaginary student is not he that should come, not the great man for the great book. To be frank with him this is probable; great historians are at least as rare as great lawyers. But short of the very greatest work, there is good work to be done of many sorts and kinds, large provinces to be reclaimed from the waste, to be settled and cultivated for the use of man. Let him at least know that within a quarter of a mile of the chambers in which he sits lies the most glorious store of material for legal history that has ever been collected in one place and it is free to all like the air and the sunlight. At least he can copy, at least he can arrange, digest, make serviceable. Not a very splendid occupation and we cannot promise him much money or much fame.... He may find his reward in the work itself: one cannot promise him even that; but the work ought to be done and the great man when he comes may fling a footnote of gratitude to those who have smoothed his way, who have saved his eyes and his time."

stock or marketable securities which undoubtedly are not the same things as the land and trade marks.'

Now it may occur to you that in their anxiety to avoid a confusion of the persons our courts fall into the opposite of error and divide the substance. But that is not so. The old things still exist and are owned, though new things 'transferable in the books of the company' have come into being. Also it seems possible that we may easily over-estimate the creative powers of lawyers and courts and legislators. Let us remember that these new things will be things for the man of business, things for the Stock Exchange. And in passing let us ask ourselves whether if these 'things' are not unreal, the personality of the company must needs be fictitious?

Fragment of a Lecture

As yet Maitland had not conceived himself as the author of that "History of English Law from the thirteenth century," the need for which he proclaimed to his Cambridge audience. A less extensive scheme had framed itself in his mind "some thoughts about a plan of campaign for the History of the Manor." The thoughts were communicated to Frederick Pollock and were not unfruitful, for they grew up seven years later into that massive History of English Law which is perhaps Maitland's most enduring title to fame; but of his learned projects in this seed-time and of some other concerns, grave and gay, a few scraps of correspondence may here most fittingly be adduced in evidence.

6, New Square,

Lincoln's Inn.

28 April, 1884.

I am indeed glad that you are working at Bracton and settling the relation between the MSS. I wish that you would stay here and teach us something about our old books. Pollock is looking forward to your paper and I am diligently reading Bracton in order that I may understand it. I have written for Pollock a paper about seisin and had occasion to deal with a bit of Bracton which, as printed, is utter rubbish. I therefore looked at some of the MSS and found that the blunder was an old one. I shall not have occasion to say any more than that there are manuscripts which[Pg 38] make good sense of the passage—but I have made a note[12] about the matter which I send to you thinking it just possible that you may care to see it, as it goes some little way (a very little way) to show that certain MSS are closely related.

I have to dine in Oxford on Saturday, 10th May, and shall be there on Sunday the 11th. I hope that you will be in Oxford on that day and that we shall meet.

To Frederick Pollock.

(On a postcard.)

Jan. 1881.

Et Fredericus de Cantebrigia essoniavit se de malo lecti, et essoniator dixit quod habuit languorem. Set quia essonium non jacet in breui de trampagio consideratum est quod summoneatur et quod sit in misericordia pro falso essonio suo. Postea uenit et defendit omnem defaltam et sursisam et dicit quod non debet ad hoc breve respondere quia non tenetur ire in trampagio nisi tantum quando dominus capitalis suus eat in persona sua propria nec vult nec debet ire cum ballivo vel preposito, et ipse et omnes antecessores sui semper a conquestu Anglie usque nunc habuerunt et habent talem libertatem, et de hoc ponit se super patriam, etc.

Revera predictus F. seisitus fuit de uno frigore valde damnando. Judicium—Recuperet se ipsum.

15, Brookside,

Cambridge.

12 Nov. 1887.

Very many thanks to you for a copy of your book on "Torts"—I am already deep in it and am reading it with delight. You will believe that coming from me this is not an empty phrase, for you will do me the justice of believing that I can find a good book of law very delightful. I hope that it may be as great a success as "Contracts"—I can hardly wish you better. I now see some prospect of getting the Law of Torts pretty well studied by the best of the undergraduates. For weeks I have been in horrible bondage to my lectures—Stephen's chapters about the Royal Prerogatives and so forth—I speak of the Stephen of the Commentaries—are a terrible struggle: when one is set to lecture on them three days a week one practically has to write a book on constitutional law against time.

I cannot, alas, be at the Selden meeting on Monday, for I have undertaken to audit some accounts.

F. W. Maitland.

15, Brookside,

Cambridge.

12 June, 1887.

"Cuius linguam ignorabant"—I feel now the full force of these words—I am in tenebris exterioribus, and there is stridor dencium; but I heartily congratulate you upon having finished your book[13], and thank you warmly for the copy of it that you sent me and for the kind words that you wrote upon the outside. Also I can just make out my name in the Preface and am very proud to see it there. Also I have read the footnotes and they are enough to show me that this is a great book, destined in course of time to turn the current of English and German learning.

My book also is finished, but the printers are slow. I hope to send you a copy in the autumn. I have been able to add a few links to the chain of argument that you forged. My happiest discovery was about a note that you may remember, "Ermeiard et herede de Hokesham." I found (1) that the heir of Huxham was in ward to William of Punchardon, (2) that William's wife was Ermengard, (3) that Ermengard brought an action for her dower against Henry of Bratton. I have also had some success with Whitchurch, Gorges, Corner and Winscot.

Jubilee Teapot Tor,

Horrabridge.

26 July, 1887.

Horrabridge seems to be as much our post town as any other place; but I have not fully fathomed our postal relations. The legend is that the old gentleman who squatted here—and if ever I saw an untitled squatment I see one now—held that the post was "a new found holiday" and charged the postman never to come near him—and the postman, holding this to be an acquittance for all time, refused and still refuses to visit Pu Tor, but leaves our letters somewhere, I know not where, whence they are fetched by Samuel the son of the house—which Samuel learned the first half of the alphabet in the school "to" Sumpford Spiney Church-town when as yet there was a school, but the school scattered and beyond N Samuel does not go—howbeit, there will be a school again some day if ever Mr Collier can catch A. J. Butler at the Education Office, which is hardly to be expected. But if I begin to tell the acts of the Putorians, I shall never cease, for they are a race with a history and a language and (it may be) a religion of their own. Villani de Tawystock fecerunt cariagium—but the ignorant beggars did not know Pu Tor cottage and it seemed that we should wander about all night. This is a right good spot and we are grateful to you for discovering it. We have a sitting-room and two bedrooms and we could find place for a visitor if his[Pg 42] stomach were not high. Have you seen the new ordnance map of the moor? Mr Collier showed it me. Pew Tor is the spelling that it adopts.

15, Brookside,

Cambridge.

7 April, 1888.

I have returned from a brief incursion of Devonshire. Verrall and I made a descent upon Lynton which is still beautiful and at this time of the year un-betouristed. Bank Holiday was tolerable. I suppose that you spent it upon your freehold and are now returning to the law. You have got an excellent number of the L. Q. R.[14] this quarter; really it ought to sell and if it doesn't the constitution of the universe wants reforming....

If P objects to "ville" as a termination for names in America what does he say to "wick" as a termination for names in England? I have been puzzling over the use of "villa" in Kemble's Codex. It seems to be used now for a village or township and now for a single messuage, and thus seems similarly elastic. One never can be quite certain what is meant when a villa is conveyed.

I have had some thoughts about a plan of campaign for the history of the manor. The graver question is whether the story should be told forwards or backwards. I am not at all certain whether it would not[Pg 43] be well to begin by describing the situation as it was at the end of cent. XIII. and then to go back to earlier times. But we can talk of this when "possession" is off your mind. Remember that you have to stay here as an examiner. Meanwhile I hope to form a provisional scheme for your consideration.

I have got hold of a German, one Inama Sternegg, who seems to be the modern authority as to the growth of the manorial system on the continent.

To Frederick Pollock. (On a postcard.)

9 May, 1888.

Predicti sokemanni habebunt remedium per tale breve de Monstraverunt.

R tali duci salutem. Monstraverunt nobis N N homines de trampagio vestro quod exigis ab eis alia servicia et alias consuetudines quam facere debent et solent videlicet in operibus et ambulationibus, et ideo vobis precipimus quod predictis hominibus plenum rectum teneas in curia tua ne amplius inde clamorem audiamus, quod nisi feceris vicecomes noster faciat. Teste Meipso apud Cantebrigiam die Ascen. Dn̄i.

3, Albany Terrace,

St Ives,

Cornwall.

25 July, 1888.

I ought before now to have sent you my address to meet the case of your having any MS to send me.[Pg 44] I have been going over and over again in my mind many parts of the pleasant talk that we had at Cambridge during two of the most delightful days of my life. I hope that you were not weary of instructing me. Let me say that the more I think of your theory of folk land the better I like it. Of course it is a theory that must be tested and I know that you will test it thoroughly: but it seems to me a true inspiration, capable of explaining so very much, and I think that it will be for English readers one of the most striking things in your book. Should you care for notes on any of the following matters I can send them to you out of my Selden materials—(1) persons with surname of "le Freman" paying merchet, (2) free men refuse to serve on manorial jury, (3) the lord makes an exchange with the Communa Villanorum, (4) persons who pay merchet on an ancient demesne manor use the little writ of right.

3, Albany Terrace,

St Ives,

Cornwall.

5 Aug. 1888.

Many thanks for your telegram: it was kind of you to send so prompt a message[15]. I feel it a little absurd that I should be thanking you for the telegram and no more—but I must be decorous. However, let us put the case that in a public capacity you regret the [Pg 45]result, still it is allowed me to think that in the capacity of friend you rejoice with me and of course I am very happy. I wonder whether you dined in Downing. I hope that my essoin was taken in good part; but really I thought that there would be an insolent confidence apparent in my journeying from St Ives to Cambridge in order to be present at a dinner. It might, I think, have been reasonably said that I did not come all that way to grace the triumph of another man.... Well, I am glad that I have ceased to regard you as my judge and can resume unrestrained conversation.

3, Albany Terrace,

St Ives,

Cornwall.

6 Aug. 1888.

Your letter from Downing tells me what I expected, namely, that the struggle was severe. I can very well understand that there was much to be said against me—some part of it at all events I have said to myself day by day for the last month. My own belief to the last moment was that some Q.C. who was losing health or practice would ask for the place and get it. As it is, I am reflecting that in spite of all complaints the bar at large must still be doing a pretty profitable trade, otherwise this post would not have gone begging.

22, Hyde Park Gate, S.W.

September, 1888.

Has this occurred to you?—how extremely different the whole fate of English land law would have been if the King's court had not opened its doors to the under-vassals, to the lowest freeholders. But this was a startling interference with feudal justice and only compassed by degrees, in particular by remedies which in theory were but possessory etc. Now if the lower freehold tenants had not had the assizes, the line between them and the villein tenants would have been far less sharp. You hint at all this in chap. IV but might it not be worth a few more words—for there will be a tendency among your readers to say of course freeholders had remedies in the King's courts while really there is no of course in the matter. The point that I should like emphasized—but perhaps you are coming to this—is that not having remedies in the King's own court is not equivalent to not having rights.

Downing.

14 Oct. 1888.

I have been picking up my strength and am doing a little work. Yesterday I got through my inaugural lecture; possibly I may print it and in that case I will ask you to accept a copy; but it was meant to be heard and not read and so I allowed myself some exaggerations.

... I am now quite ready to see proofs of your book.... My Introduction for the manorial rolls is taking shape; it will deal only with the courts, their powers and procedure. You can I think trust me not to take an unfair advantage of our correspondence and your kindness—but if you had rather that I did not see the sheets of your book which deal with the courts, please say so. I hope to have got this Introduction written in a month or six weeks.

The West Lodge,

Downing College,

Cambridge.

11 Dec. 1888.

I have been reading your proof sheets[16] with great interest, and really as regards the parts which most concern me I have little to suggest. I think the chapter on law and morality particularly good. Were I writing the book I should in my present state of ignorance "hedge" a little about continental notions of law. Since I had some talk with you I have been reading several German law books, and my view of the duties of a German judge is all the more hazy. I find that a jurist, even when he is writing about elementary legal ideas, e.g. possession, will cite "Entscheidungen der oberste Gerichte von Celle, Darmstadt, Rostock etc.," if he thinks them sound—but how far he would think himself bound as judge by [Pg 48]decisions which made against his theory I cannot tell. All seems rendered so vague by the notion of a heutige römische Recht. But I think that you have just hit off the English idea of a good judge—he does justice when he sees an opportunity of doing it. I do not think that a man could be a judge of quite the highest order without a strong feeling for political morality. On p. 92, chap. XII. you might add if you could do so that our highest courts of appeal, House of Lords and Judicial Committee, hold themselves bound by their own decisions in earlier cases.

As regards the existence of different laws in different parts of a country you might reckon among the advantages the gain in experience. I have no doubt that Scotch experience has improved English law and English experience Scotch law. Thus some use of an experimental method is made possible; e.g. take "Sunday closing" we can experiment on Wales and Cornwall. On the whole I have been surprised to find how little harm is done by the difference between Scotch and English law. I have read but very few cases that were caused by such differences.

I admire the chapter on International Law and Morality; it is the best thing that I have read about the subject. In my view the great difficulty in obtaining a body of international rules deserving the name of law lies in the extreme fewness of the "persons" subject to that law and the infrequency and restricted range of the arguable questions which arise between them. The "code" of actually observed rules is thus all shreds and patches. In short, international law is so incoherent.

20 Feb. 1889.

You ask me about the Preface[17]—well I think it grand work, and on the whole I think it will attract readers because of its very strangeness; but you will let me say that it will seem strange to English readers, this attempt to connect the development of historical study with the course of politics; and it leads you into what will be thought paradoxes; e.g. it so happens that our leading "village communists" Stubbs and Maine are men of the most conservative type while Seebohm who is to mark conservative reaction is a thorough liberal. I am not speaking of votes at the polling booth but of radical and essential habits of mind. I think that you hardly allow enough for a queer twist of the English mind which would make me guess that the English believer in "free village communities" would very probably be a conservative—I don't mean a Tory or an aristocrat, but a conservative. On the other hand with us the man who has the most splendid hopes for the masses is very likely to see in the past nothing but the domination of the classes—of course this is no universal truth—but it comes in as a disturbing element.

The West Lodge.

12 March, 1889.

Your long letter was very welcome. When I wrote I must have been in a bad temper and after I had written I wished to recall my letter. But now I no longer regret what has brought from you so pleasant an answer. Really I have no fear at all about the success of your book, if I had I would expatriate myself. But it stands thus:—Introductions are of "critical importance," by which I mean that they are of importance to critics, being often the only parts of a book which casual reviewers care to read. As a matter of prudence therefore I put into an Introduction a passage about the book which I mean critics to copy, and they catch the bait—it saves them trouble and mistakes. But your "philosophy of history," I mean philosophy of historiography, will not lend itself to such ready treatment and may give occasion to remarks as obvious and as foolish as mine were. But I hope for better things. All that you say about Stubbs and Seebohm and Maine is, I dare say, very true if you regard them as European, not merely English, phenomena and attribute to them a widespread significance—and doubtless it is very well that Englishmen should see this—still looking at England only and our insular ways of thinking I see Stubbs and Maine as two pillars of conservatism, while as to Seebohm I think that his book is as utterly devoid of political importance,[Pg 51] as, shall I say Madox's History of the Exchequer? But you are cosmopolitan and I doubt not that you are right. You are putting things in a new light—that is all—if "the darkness comprehendeth it not," that is the darkness's fault.

And now as to Essay I. I have nothing to withdraw or to qualify. I think it superb, by far the greatest thing done for English legal history. I am looking forward with the utmost anxiety to Essay II.

Downing.

15 Nov. 1891.

Even the title page has been passed for the press and I am now awaiting your book. I shall be proud when I paste into you the piece of paper that you sent me. I have felt it a great honour to correct your proof sheet and am almost as curious about what the critics will say as if the book were my own. I often think what an extraordinary piece of luck for me it was that you and I met upon a "Sunday tramp." That day determined the rest of my life. And now the Council of the University has offered me the honour of doctor "honoris causa." I was stunned by the offer for it is an unusual one and of course I must accept it. But for that Sunday tramp this would not have been. As to the reception of your book my own impression is that it will be very well received. Good criticism you can hardly expect, for very few people here will be able to judge of your work. But I think that you will[Pg 52] be loudly praised. Perhaps you will become an idol like Maine—who can tell? I hardly wish you this fate, though you might like it for a fortnight. I was ill in September, but am better now and have been doing a good many things—preparing myself for some paragraphs about Canon law.