The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ludwig van Beethoven, by Pitts Sanborn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Ludwig van Beethoven

The New York Philharmonic-Symphony Society Presents

Author: Pitts Sanborn

Editor: Herbert F. Peyser

Release Date: October 17, 2015 [EBook #50242]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan, Jude Eylander

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Beethoven on the bank of a stream.

By PITTS SANBORN

NEW YORK

Grosset & Dunlap

PUBLISHERS

Copyright 1939 and 1951 by

The Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York

The late Pitts Sanborn wrote this booklet under the title Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies and stated in a short preface that it made “no claim to originality and no secret of its indebtedness to the masterly treatises on the same subject.” I have left Mr. Sanborn’s pages on the symphonies virtually intact and have only expanded the work a little by incorporating here and there matter about other major works of Beethoven’s, especially some of the concertos, overtures, piano and vocal works, besides certain of the greater specimens of his chamber music. Even if this procedure probably lends the booklet a patchy character, I have followed it in order to supply a rather fuller picture of the composer’s creative achievements. No more than my predecessor do I make the slightest claim to originality of matter or treatment, or deny my indebtedness to Thayer and Paul Bekker.

Herbert F. Peyser

Printed in the United States of America

Ludwig van Beethoven was born on December 16, 1770, at Bonn, then one of the most important cities on the lower Rhine. Though Bonn was German and Beethoven’s mother and his father’s mother were both Germans, he was of Flemish descent through his father’s father, a native of the country that eventually became Belgium, whence the “van” in the name. Louis van Beethoven, a tenor singer, went to Bonn in his youth and promptly became a court musician to the resident archbishop-elector. His son Johann, Beethoven’s father, was also a singer in the Elector’s employ, but he was a worthless fellow, who was fortunate, however, in having as wife a woman of character. Realizing that his son Ludwig had been born with uncommon musical talent, he had the child begin to study violin and piano very early with the idea of putting him forward as a prodigy, as Mozart’s father had done. But 2 the young Ludwig was less precocious than Mozart and rebelled strenuously against the enforced training. However, he did appear at a concert on March 26, 1778.

So strong was the boy’s musical gift that it triumphed over every obstacle, including his own childish reluctance, and the Elector thought it worth while to send him to Vienna, then the musical capital of Europe. He had now been composing for several years, and Haydn accepted him as a pupil in counterpoint, an arrangement that did not turn out altogether to Beethoven’s satisfaction. He studied with other teachers in Vienna and in March 1795, made his first public appearance in that city, playing his own piano concerto in B flat major. This date marks the beginning of a kind of recognition that could only spur the young composer on to the activity that in a nature so vigorous and energetic meant enthusiastic creation. Of course he wanted to write a symphony. Mozart, dead in 1791, had left a legacy of forty-nine symphonies. Haydn, the author of many more, was in full career at 63. They were the world’s foremost symphonists.

Beethoven’s First Symphony was brought out at a concert which he gave in Vienna on April 2, 1800. It was immediately successful and within a few months carried its composer’s fame all over Germany. In the musical city of Leipzig it was described as “intellectual, powerful, original, and difficult.” That was in 1802. Today it is no longer difficult for our accomplished orchestras, but, as in the case of other works that have come to seem simple through the passage of time and changes 3 in fashions, it is no easy matter now for a conductor to catch and express the frank joyousness of its youthful speech.

The symphony is in the customary four sections or movements. The key is C major. Yet it does not begin in that key, but with a discord in F major which shocked some pedants at the time. The slow introduction of twelve measures leads to the first movement proper (“Allegro con brio”). Its pages have spirit, gaiety, elegance, for this symphony has well been termed a symphony of comedy, though here and there a cloud may for the moment obscure its sunny brightness. The eighteenth century was not over when Beethoven composed it, and he was still looking at music through the eyes of Haydn and Mozart, in spite of the fact that the student may readily discover Beethovenish characteristics that are not derived from either Haydn or Mozart and distinct intimations of the moods and manners of the nineteenth century to come. However, comedy itself is not all compact of sunshine and, as the German proverb has it, laughter and weeping dwell in the same bag.

This brisk Allegro is followed in the then-prevailing order by the slow movement (“Andante cantabile con moto,” in F major and consequently not too slow). It is mainly built up on a tricksy tune that no less an authority than Professor Tovey described as “kittenish.”

The attentive listener should observe in this movement the recurrent passage of dotted notes for drums on G and then 4 on C, the drums being tuned not in the tonic, but in the dominant. Yet bold though this device might have seemed, it was not wholly original. Mozart had anticipated Beethoven in his “Linz” Symphony.

The third movement in name is the minuet usual in symphonies of the eighteenth century (“Menuetto: Allegro molto e vivace,” in C major), but in reality Beethoven was already looking forward to the scherzo (Italian, joke) with which he was presently to replace the minuet. This movement, then, is much less the stately dance in triple rhythm than a scherzo of generous proportions, rich in modulations and glowing color. The scherzo, like the minuet, always includes a trio section. Listen in this trio to the delicious dialogue between wind instruments and strings and to the rousing crescendo that ends it just before the repetition of the minuet.

The Finale, in C major, opens with seven measures of Adagio devoted to the gradual release of a scale passage. So much accomplished, the music plunges into an “Allegro molto e vivace,” beginning with this sprightly theme which races along to the conclusion in a whirl of merriment and humorous sallies.

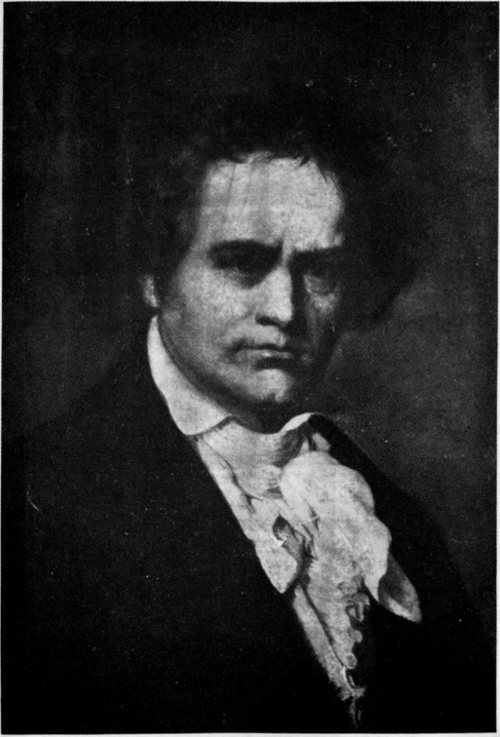

Beethoven as a young man.

From a painting by W. J. Mahler, 1808.

Beethoven’s birthplace in Bonn from the garden and from the street.

Beethoven had settled permanently in Vienna in the autumn of 1792 and the body of his work originated, of course, in the Austrian capital. We cannot, however, dismiss the compositions preceding the First Symphony as wholly negligible. The creations of this period are to a large extent relatively small in scale. There is a quantity of piano music largely in the form of variations, a number of songs and several arias, odds and ends of chamber music, dances, marches, and such. Some of the variations for piano and strings are based on melodies of Handel, Mozart, and a number of lesser lights. During his Bonn days Beethoven had composed a score for a “knightly ballet” (Ritterballet), performed by members of the Bonn aristocracy and ascribed at first to Count Waldstein. It was Beethoven’s first ballet score and preceded by some years his far more pretentious Creatures of Prometheus, written in Vienna to a scenario by the noted dancer, Salvatore Vigano.

The vocal compositions of this early period are not, perhaps, of conspicuous quality. Beethoven’s best-known song and, indeed, his most famous (though not the best) is the setting of Matthisson’s Adelaide—more a cantate than what we have come to classify as a genuine Lied. Considerably later he was to write the cycle An die ferne Geliebte, which together with some of his settings of Goethe poems and the stark but majestic Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur, may pass as Beethoven’s most memorable achievements in the province of the solo song. To his Bonn days, however, belongs a genuine cantata, the one composed in 1790 on the death of the Emperor Joseph II. This work survives chiefly because one of its finest pages was later utilized in the last scene of Fidelio, into which it fits admirably.

Three years before the First Symphony Beethoven began the first orchestral score he decided to publish. This was the 6 B-flat Piano Concerto, which though we know it as No. 2, opus 19, actually preceded the one in C major, opus 15. It was performed for the first time by the composer March 29, 1795, on the occasion of his first appearance “as virtuoso and composer” before the Viennese public. It had been announced that he would play “an entirely new concerto” on this occasion of the first two annual concerts given for the benefit of the widows of the Tonkünstler Society. Thayer, following the lead of Nottebohm, felt certain that this “new” concerto was the one in B flat. Beethoven was tardy in completing it, and we are told that two days before the concert the Rondo was not yet on paper. In spite of illness he wrote it out at the eleventh hour, while four copyists sat in the next room and were handed the piece, sheet by sheet, as soon as the music was set down.

We know as good as nothing of the public reaction to the work. We do know, however, that the composer was far from satisfied with it and revised the score before playing it in Prague in 1798. At that, he confided to the publisher, Franz Hoffmeister, that he “did not consider it one of his best.” The first movement has a vigorous and arresting first theme, followed by a tranquil, songful one. Some of the cantabile phrases that follow have a rather Mozartean character. The Adagio begins with a devout, rather hymnlike melody, on which the piano subsequently embroiders. The Finale, a rondo with a playful recurrent theme suggestive of Haydn, contains a second lilting melody and another, partly syncopated, which, though in minor, does not lessen at all the high spirits of the movement.

Just as the composer considered the B-flat Concerto “not 7 one of his best works,” so he also questioned the value of the subsequent C major Concerto, written in 1797 and not published (like the First Symphony) until 1801. Yet this concerto is a great advance over its predecessor; it contains a beautifully expressive Largo and a deliciously brisk and zestful “Allegro scherzando” Rondo, marked by jocose sforzandi on weak beats and various striking rhythmic displacements. Taken as a whole, there is far more of what we recognize as a true Beethoven quality in this misnamed First Concerto than there is in the so-called Second.

The Third Piano Concerto (C minor, opus 37), composed in 1800 but not played publicly till about three years later, is a great advance on its two predecessors from every standpoint. The proximity of the more “heroic” Beethoven is immediately evident. Indeed, it probably possessed more of the unmistakably heroic quality than any other concerto written before its time. The solo part is different and more striking in originality than anything in the concertos in B-flat and C major; and a symphonic breadth pervades the work, notably the opening movement. The second movement—a Largo in E—begins in the piano and is then sung by muted strings. There is a passage that, strangely enough, sounds like a prophecy of the melody of the tenor air Salut demeure in Gounod’s opera Faust and may easily have suggested it to the French composer. Before the close of the Largo there is a cadenza “con gran espressione.” The Rondo brings back the key of C minor and is, in a variety of ways, a most remarkable movement. Curiously enough, the coda appears to have been inspired by the closing page of Mozart’s C minor Concerto which, some time earlier, had so struck Beethoven that 8 he remarked to another musician: “None of us will ever write anything like that!” And the composer was not to occupy himself further with piano concertos for several years till in 1806 he created his most deeply poetic (the Fourth, in G major, opus 56), and again till 1809, when he wrote his most spacious and lavish, the E-flat (“Emperor”), by which time he had behind him several of his monumental productions.

Beethoven composed the Second Symphony in very different circumstances from the first. The deafness that had first manifested itself several years previously and was in time to become complete had reached such a point that on the advice of his doctor he decided to spend the summer of 1802 in the village of Heiligenstadt, which, though near Vienna, was then deep in the country. It was a tragic summer for Beethoven, as he himself has testified in that infinitely pathetic document known as the “Heiligenstadt Will.” He would probably have taken his own life but for his determination to consecrate himself with new courage to his art. His life was further complicated by a love affair with the youthful Countess Giulietta Guicciardi. Whether or not this love affair was as serious as some have maintained, the Countess preferred Count Gallenberg to the turbulent composer and accordingly married him.

In such a setting Beethoven undertook his Second Symphony. This work, however, reflects his tragedy only here and there and in a richer romanticism than his music had previously expressed—a romanticism of the nineteenth century. As in the case of the First Symphony, the Second, in D major, 9 has a slow introduction (“Adagio molto”), but this introduction is much longer and, though based in style on Haydn’s symphonic introductions, is instilled with the new romantic freedom and contains a surprising prediction of the Ninth Symphony in a descending octave passage.

The “Allegro con brio” that follows starts off with a buoyant theme which sets the pace for an energetic and generally cheerful movement. It is in the ensuing Larghetto in A major that we hear in full proclamation the individual voice of Beethoven as we have not heard it before. This has been aptly called one of the most luxurious slow movements in the world, and its richness in melodies has been set down as “reckless.” Here are two of them:

The next movement, again in D major, is this time called frankly a “Scherzo,” not a “Menuetto.” This concise Allegro is particularly noteworthy for the prophecy in its Trio of the Trio of the Scherzo of the Ninth Symphony.

The Finale, “Allegro molto” in D, is a forthright, humorous rondo. In view of the tragedy of that summer, this symphony, at once romantic and exuberant, might perhaps best be looked upon as an escape. Brought out on April 5, 1803, at a concert of Beethoven’s works given by the composer at the Theater an der Wien, Vienna, it was coolly received, being regarded by many listeners as extravagant or enigmatic.

Beethoven’s next symphony, though begun in the summer of 1803, was not completed till the following year. As long before as 1802 Beethoven had declared his dissatisfaction with his works up to that time: “From today I mean to take a new road.” This symphony boldly takes that road. The Second Symphony still belongs largely to the eighteenth century. The Third embodies the developments with which Beethoven revolutionized the symphony. In amplitude and opulence no previous symphonic movement had ever equalled or even approached the initial “Allegro con brio,” and it may be doubted whether any has subsequently surpassed it. Sensitive listeners hearing it for the first time may well have cried out with Miranda: “O brave new world!”

There ensues a Funeral March that is one of the most tremendous lamentations conceived in any art. The Scherzo is not only the first but one of Beethoven’s symphonic scherzos, 11 it is also among the greatest. For the Finale Beethoven provides a theme and variations of astonishing diversity and splendor.

The first and dominating theme of the “Allegro con brio”

Beethoven very likely remembered from Mozart’s little Bastien und Bastienne overture, but he uses it here in the grand manner. The Funeral March begins with a striking phrase in C minor. A tender lyric passage in C major introduces an elegiac element into the sternness of the dirge. The Scherzo (“Allegro vivace” in E-flat major) is an enormously energetic movement and is interrupted by a Trio, prophetic in its turn of the Ninth Symphony and including a particularly brilliant and difficult passage for the horns.

The theme of the concluding variations (“Allegro molto” in E flat major) Beethoven had previously employed in his ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus. This theme, simple as it appears, contains the germ of one of the most remarkable sets of variations ever put down on paper.

The Third Symphony is universally known today less by its number and its key than by the title “Eroica” (“Heroic”). Everybody is familiar with the story of the relation of this symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte. Beethoven, sympathetic toward the republican ideals of the French Revolution, originally hailed General Bonaparte as the Great Liberator, but when in May 1804 he accepted the imperial crown of France, Beethoven saw him in an entirely different light. Such was his rage that he was on the point of destroying this symphony, which he had intended to dedicate to Bonaparte as a tribute to his services to mankind. Fortunately he desisted, tore Bonaparte’s name from the inscription, and entitled the work “Eroica.” It should not be forgotten, though, that when seventeen years later he heard of the death of Napoleon at St. Helena, he remarked, “I have already composed the proper music for that catastrophe,” which was an allusion to the Funeral March.

The meaning of the symphony as a heroic work is clear enough to anyone who hears the first movement and the Funeral March. Perhaps only Anton Rubinstein has ever questioned the heroic quality of the first movement and nobody has or could doubt the heroism of the mighty threnody that follows. But to fit the brilliant Scherzo and the dazzling set of variations into the picture has occasioned any amount of controversy. To go at length into the various theories is impossible here, but one might point out that the Scherzo has been interpreted as a scene in the hero’s camp, as an excited crowd waiting for the hero’s return and his triumphant address in the Trio, and as a picture of funeral games at the grave of the hero, such as one finds in the epic poems of 13 Homer and Virgil, this last theory being that of Berlioz. The variations of the Finale have been plausibly explained as the nations of the earth bringing each its tribute of flowers to deck the hero’s monument. The first performance of this transcendent symphony took place in Vienna on April 7, 1805.

Three years elapsed between the completion of the “Eroica” Symphony and the emergence of the Fourth Symphony. The latter was brought out in Vienna at a special subscription concert organized for Beethoven’s benefit in the middle of the latter part of March 1807. Little is known about the origin and composition of this work and its relation to the other circumstances of Beethoven’s life. Apparently he had been busy with his C minor Symphony (the Fifth) when in 1805 he laid that aside to write a symphony in B flat. This act of his is in line with his general procedure with regard to his symphonies, a lighter work following one of deep import. Robert Schumann, a distinguished critic as well as a great composer, likened the Fourth Symphony as related to the “Eroica” and the Fifth to “a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants.” This comparison, however, lays too much emphasis on youthful ingenuousness, for humor and the joy of living have their place here, and romance as well, with touches of passion and of mystery. One of its admirers has called it a “symphony of love.”

Mystery and romance are evoked in the elaborate introduction (Adagio), which this symphony like the Second possesses, 14 but the mood turns to merriment when the “Allegro vivace” enters with this skipping tune:

The second movement (Adagio in E-flat major) is related in its luxuriance and melodic richness to the Larghetto of the Second Symphony, establishing another bond between the two works. A hint of the beauty of this movement may be gathered from the first theme:

The fervor that breathes through its measures has been attributed to Beethoven’s contemporaneous engagement to the Countess Therese von Brunswick, to whom many believe he addressed the famous “Immortal Beloved” letter. Berlioz, like Schumann eminent not only as composer but as critic, accounts for this Adagio in a still loftier vein: “The being who wrote such a marvel of inspiration as this movement was not a man. Such must be the song of the Archangel Michael as he contemplates the world’s uprising to the threshold of the empyrean.”

For the third movement Beethoven returns to the name 15 “menuetto” (“Allegro vivace” in B-flat major; Trio, “un poco meno Allegro,” in B-flat major), though “scherzo” would do quite as well. This minuet is planned on a particularly large scale and is further remarkable for the fact that, as in the Scherzo of the Seventh Symphony, the Trio is played twice and the Minuet proper repeated each time. The attentive listener should also heed the striking change of key to B-flat minor at the fifth bar. The exuberant Finale (“Allegro ma non troppo” in B-flat major) is perpetual motion in music, flashing and glittering with tunefulness and fun.

“Beethoven’s work,” says Paul Bekker, “is based on the pianoforte; therein lie its roots and there it first bore perfect fruit.” Yet it is a curious paradox that he abandoned this phase of composition relatively early, producing the majority of his works for the keyboard before he was forty. A number of reasons might be cited for this—his growing deafness, the consequent impossibility of his public appearances as performing virtuoso, the circumstance that his intellect outgrew the expressive capacity of the piano, and the immense broadening and deepening of his creative faculties which demanded subtler and more ramified channels of expression. “The pianoforte is and always will be a disappointing instrument,” he said at one stage of his career. And he was distressed that his compositions for the piano exclusively always produced on him the most regrettable impression. “Oh! Beethoven, what an ass you were!” he exclaimed on one occasion when someone played him his own Variations in C minor.

Nevertheless, the tremendous series of thirty-two sonatas, which began, roughly speaking, in 1795 and continued more or less intermittently till 1822, are among his most moving, gracious, original, adventurous, and completely extraordinary achievements. They range all the way from the so-called “Pathétique,” “Pastoral,” and “Moonlight” to the “Waldstein,” the “Appassionata,” and the programmatic “Les Adieux, l’Absence et le Retour,” to the mighty series beginning in 1816 with the A major, opus 101, and culminating in the gigantic B flat, opus 106 (universally known as “for the Hammerklavier”), the extraordinarily imaginative ones in E major and A flat, opera 109 and 110, and the transcendent, Promethean C minor, opus 111. Within the cosmic limits of this stupendous succession there stretches a whole world of emotional experience and an incalculable diversity of invention. And we may as well mention here (though it was not composed till 1823) that prodigious set of Thirty-three Variations on a Waltz by the publisher Diabelli, which has not its like in the whole range of Beethoven’s output. Looking back over the immense panorama of the composer’s piano works (including variations, bagatelles, and solo sonatas) stretching, let us say, from the awesome summits of the “Hammerklavier,” the C minor, and the “Diabelli” Variations backward to the comparative simplicities of the sonatas Opera 2, 22, 26, and 27 leaves one with the dizzy impression of surveying a whole Alpine panorama.

As we have seen, Beethoven interrupted work on a symphony in C minor to write his Fourth Symphony. That done, he returned to the C minor Symphony, finishing it late in 1807 or early in 1808. Both this Fifth Symphony and its successor, the Sixth, were brought out in Vienna at the same concert on December 22, 1808. The Fifth Symphony has turned out to be the most unreservedly admired, the most generally beloved, and the most frequently performed of all Beethoven’s nine, in fact, of all symphonies. It is the drama in tone of man’s victorious struggle with destiny and it was largely composed at Heiligenstadt, Beethoven’s own spiritual battlefield. In 1801 Beethoven had made himself this promise: “I will take Fate by the throat; it shall not wholly overcome me.” The C minor Symphony opens with an intensely dramatic figure of four notes which Beethoven explains as “Fate knocking at the door”:

This rhythmic group not only dominates the concise first movement, but appears in every succeeding movement. The second movement (“Andante con moto” in A-flat major) consists of a graceful, flowing set of variations on a brave and lovely theme:

The uncanny Scherzo (Allegro in C minor), introduced merely by the common chord of C minor in arpeggio, is the musical embodiment of the terror that walketh by night. Berlioz said of the opening, “It is as fascinating as the gaze of a mesmerizer.” An extraordinary bridge passage, a supreme example of musical suspense, leads from the nightmare of the Scherzo finally in a breathtaking crescendo to the triumphant proclamation of the C major Finale. The effect produced by this symphony on a contemporary composer is indicated in the frenetic outburst of the veteran composer Lesueur to the youthful Berlioz: “Ouf! Let me get out; I must have air. It is unbelievable! Marvellous! It has so upset and bewildered me that when I wanted to put on my hat, I could not find my head!”

In the three symphonies that successively precede the Sixth, Beethoven, as we have seen, is concerned with man as lover or as hero, for the spiritual conflict of the Fifth Symphony is no less heroic than are the exploits and lamentations of the Third. The Sixth Symphony, however, though quite as personal, treats of man from a totally different angle. This 19 symphony, which the composer himself called “Pastoral,” is Beethoven’s monument to Nature. It expresses his personal devotion to the country and to what life in the country meant to him. He spent a great deal of time in the lovely Viennese countryside, especially at Heiligenstadt, but here the country is no battlefield as it had been in the summer of 1802, the summer of the “Heiligenstadt Will”; it is rather the cheerful, sunlit province of Nature’s healing power.

Copious and quaint is the verbal testimony to Beethoven’s pleasure in Nature. A lodging had once been bespoken for him at the coppersmith’s at Baden (near Vienna). When he saw there were no trees around the house, he exclaimed, “This house won’t do for me. I love a tree more than a man.” According to the Countess Therese von Brunswick, his one-time betrothed, “he loved to be alone with Nature, to make her his only confidante. When his brain was seething with confused ideas, Nature at all times comforted him. Often when his friends visited him in the country in summer, he would rush away from them.” Charles Neate, one of the founders of the London Philharmonic Society, who was on intimate terms with Beethoven in Vienna in 1815, assures us that he had “never met anyone who so delighted in Nature, or so thoroughly enjoyed flowers or clouds or other natural objects. Nature was almost meat and drink to him; he seemed positively to exist upon it.” Michael Krenn, Beethoven’s body-servant during the last summer of his life when he was staying at his brother’s house at Gneixendorf, relates that Beethoven spent most of his time in the open air from six in the morning till ten at night, ranging over the fields, often hatless, shouting (he had long been completely deaf), gesticulating, 20 and in general quite beside himself from the torrent of ideas in his mind.

The character of the Sixth Symphony Beethoven immediately makes plain on the dedicatory page. “Pastoral Symphony,” he calls it, “or a recollection of country life. More an expression of feeling than a painting.” The word “more” is important, for actually the symphony is in part a painting in tone, even if not for the greater part. Instead of keeping to the traditional four movements, this symphony rejoices in five, each carrying an identifying title. The first, “Allegro ma non troppo” in F major, explains itself thus: “The cheerful impressions excited on arriving in the country.” It begins immediately with this theme:

which really holds the germ of the entire movement and, as Beethoven develops it, becomes as the whole countryside in Maytime bloom.

The second movement, “Andante molto moto” in B-flat major, is more definite in its treatment of Nature. Beethoven calls it “Scene by the brookside,” and from the very first note you hear the purling of the water in the lower strings.

Against this murmurous background lovely melodies bud and flower and the whole orchestra seems filled with the tiny, numberless noises of summer. Near the end occurs a specific imitation of the call of birds, nightingale, cuckoo, and quail. Beethoven himself said that he meant these measures as a joke, and others have termed them parody or caricature. But, joke or parody, the unconquerable artist in Beethoven has made them of one substance with the heavenly summer light and shade that pervade this interlude of leisure by the brook.

Though not entitled Scherzo, the third movement, Allegro in F major, is one in fact. Here the human beings that people this countryside possess the picture. Beethoven labels the movement “Jolly gathering of country folk.” Its downright gayety brings in its train an amusing takeoff on a village band, especially the befuddled bassoon. The middle part of the movement, “In tempo d’allegro,” corresponding to the usual trio, has been construed by some as a quarrel among the dancers, by others as just a rude episode in the dance. The jolly character of the movement is evident in these consecutive tunes, in the contrasting keys of F and D, that start it off:

The last three movements of the symphony are continuous. A dominant seventh of F ends the “Jolly Gathering,” but, instead of its resolving, an ominous drum roll on D flat immediately ushers in the fourth movement, “Thunderstorm; Tempest” (Allegro in D minor), the storm without which no country scene is perfect. In spite of the formidable title, this is by no means a devastating outburst, though quite sufficient to postpone festivities. Memorable is the feeling of tension in the opening measures, the distant grumbling of the thunder, the first staccato raindrops. The disappearing tempest is followed directly by the last movement: “Shepherd’s Song; joyous and thankful feelings after the storm.” Happiness settles on the landscape once more, as this light-hearted tune abundantly proves:

Some of the melodies in this symphony are said to be derived from Carinthian or Styrian folk songs. As we have observed, the work was originally brought out at the same concert in Vienna (December 22, 1808) with the Fifth Symphony. Since it had an earlier place on the program, it was known for a while as the Fifth and the Fifth as the Sixth, but the mistake was soon rectified.

The period of Beethoven’s Second, Third, and Fourth Symphonies covers, roughly speaking, a number of other compositions, some of them relatively trifling, others of greater moment, still others of altogether sovereign importance. Among the first type we can mention the Romances in G and F for violin and orchestra, composed in 1802; the oratorio “Christ on the Mount of Olives,” from the same year; and the Triple Concerto for piano, violin, and cello, which dates from 1805. The two Romances are fluent, lyrical movements, but without special depth or originality. The “Mount of Olives,” a sort of dramatic cantata which at first enjoyed an almost incredible popularity, for which it has paid with speedy and wholesale neglect, is a score of extremely uneven value, which handles a religious subject in a superficial, operatic fashion scarcely in keeping. Here and there it is possible to find in it interesting details but the chances for a revival of this work (which Beethoven’s intelligent contemporary, Rochlitz, criticized in spots as “comic”) are remote. The Triple Concerto, though not a masterwork of the first order, has been somewhat too harshly dismissed by many and therefore seldom visits our concert halls.

Otherwise the principal productions of these years include a quantity of the brightest jewels in Beethoven’s crown. Leaving aside the chamber music, which we prefer to consider by itself, they comprise the opera Fidelio and the three “Leonore” Overtures written in connection with it; the Violin Concerto (which the composer also arranged as a sort of piano concerto); and the “Coriolanus” Overture.

Fidelio, which Beethoven originally called Leonore, was begun in 1804. A child of sorrow to its composer, it was not to achieve the form in which we now know it till 1814. In the odd century and a half of its existence it has been attacked for countless reasons in spite of which it lives on with an incredible tenacity and obstinately refuses to die. It has been reproached for being poor theater, undramatic, unvocal, patchy, and countless other things. The book, originally adapted from Leonore, ou l’amour conjugale, by the Frenchman, Bouilly, and translated into German by Joseph Sonnleithner, was cast into its definitive form by Friedrich Treitschke. For a variety of reasons the work failed when it was first performed at the Theater an der Wien in November 1805. A bold attempt at revision the following season did not manage to keep it afloat and it was not till eight years later that the composer, with the clever dramatic surgery of Treitschke, made a final attempt to salvage it. Just how drastic were the alterations that the composer and librettist made in the piece can best be appreciated by those who have had the opportunity to examine the reconstruction of the original version which Erich Prieger published in 1905 on the occasion of the centenary of the work. From this it can be seen that not only have entirely new musical numbers supplanted the old but the opera (or rather Singspiel) has been reduced from its original three acts to two and that the dramaturgy betrays a vastly more experienced hand. The musical changes and condensations of Beethoven have, in their way, been no less thorough.

Far from being bad theater or unoperatic as sometimes charged, Fidelio is basically one of the most dramatic and 25 profoundly moving masterpieces the lyric theater can show. The 1805 version lacked a number of its most striking musical features. The original, for example, shows no trace of the great outburst, Abscheulicher, which introduces Leonore’s tremendous scena in the first act; and in the second, Florestan’s dungeon air lacks its present “Und spür ich nicht holde, sanft säuselnde Duft,” which took the place of the long-winded bravura phrases the composer originally gave the presumably starving prisoner to sing. Even the present touching close of the dungeon episode was originally quite different.

It has often been claimed that the previous “failure” of the work so discouraged the composer that his operatic achievements ended then and there. As a matter of fact, Beethoven to the end of his days never gave up his search for another libretto. That he never found it was due to the very special slant of his requirements. As for the “unvocal” character of his writing for voices, it is necessary to remember that, for all the opera’s undeniable exactions, generations of great dramatic singers have repeatedly triumphed in the chief roles of Fidelio.

Beethoven composed four overtures to his opera—the three so-called “Leonore” Overtures in C and the one in E major, known as the “Fidelio” Overture. The last-named was written in 1814 for Treitschke’s new version of the piece. It is the slightest of them all and is the one that invariably prefaces performances of the opera. For years controversies have raged as to the order in which the “Leonore” Overtures were written and for what reason one supplanted the other. The Second Leonore was the first used to preface the drama at its 1805 hearing; the Third introduced the 1806 revision. 26 Theories have been bandied about for generations to account for the First Overture, which was issued as Opus 138 only some years after the composer’s death. The researches of Dr. Joseph Braunstein in his exhaustive study Beethovens Leonore-Ouvertüren, eine historischstilkritische Untersuchung have settled the problem for us. The overtures were composed in the order of their numbering. “Leonore” No. 1 was found too light for its purpose and, after a private try-out, was discarded before being publicly performed. “Leonore” No. 2, less polished and formally perfect than the more structural and popular No. 3, ranks if anything as more dramatic, modern, and powerful, even if it does lack the brilliantly jubilant coda that is the particular glory of No. 3. Neither of these two, however, is a wholly well-conceived introduction to Fidelio, for the reason that both overpower the opera as a whole and might almost be said to render the drama superfluous. Actually, a Fidelio representation profits by the omission of all the “Leonore” Overtures, though practically every audience these days expects the “Leonore” No. 3 quite as a matter of course and ordinarily gets it as a sort of interlude between the dungeon and the concluding scenes.

A word as to the “Fidelio” Overture of 1814, which has none of the features of the “Leonore” tone poems, either thematically or otherwise. It is more in the character of a Singspiel overture and has as good as no dramatic connection with the opera itself—no reference to Florestan’s dungeon song nor to the off-stage fanfare of the rescue scene; yet it leads quite properly into the light moods of the opening episodes of the chattering Marzelline and Jacquino in the first scene and does not, like the Second and Third “Leonore,” 27 completely overweight the remainder of the score. At that, it is structurally and otherwise fully worthy of its composer and is a more logical adjunct to Fidelio than any one of the “Leonore” Overtures. Actually, it is a good deal more interesting in its own right than the average person imagines and merits far closer study than it ordinarily receives.

The “Coriolanus” Overture virtually coincides, in point of time, with the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Symphonies. One of its creator’s most striking, yet economically fashioned works, it is in no way related to Shakespeare’s Coriolanus as has frequently been imagined, but was derived from a Coriolanus tragedy by Heinrich von Collin. Yet many (including Richard Wagner) have interpreted it in terms of Shakespeare’s drama, the basic emotional pattern of which it can suggest.

After the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, Beethoven let several years pass without giving the world another, though he continued to compose diligently in spite of uncertain health and ever-increasing deafness. At length, in 1812, he finished two symphonies, which were probably played in private for the first time at the house of the Archduke Rudolph in Vienna on April 20, 1813. He was unable, however, to obtain a public performance for either of them till the Seventh Symphony was given in the great hall of the University of Vienna on December 8 of the same year.

Beethoven himself spoke of this work as his “most excellent” symphony, an opinion that not a few have echoed. He composed it in all the exuberance of his creative maturity, 28 and each of its four movements brims over with the fiery essence of his inspiration. The listener is overpowered by the very lavishness of its beauty. In this symphony you feel Beethoven’s genius as something inexhaustible, glorying in its own titanic power, as of a high god ignoring lesser breeds, proud in the knowledge of invincible strength, unfettered, carefree, save where the Allegretto acknowledges a divine melancholy.

Coming after the “Pastoral” with its avowed meaning, does this symphony “mean” anything in the sense in which that work and the “Eroica” do? Beethoven has not helped us with the clue of a title. However, there are students of the Seventh to whom it has yielded a quite definite meaning. Two of the most eminent are Richard Wagner and the French composer Vincent d’Indy. To Wagner the Seventh Symphony is the “apotheosis of the dance.” To d’Indy it is a second “Pastoral” Symphony, full of bird-calls and other country sounds. Of course Wagner’s definition recognizes the great part played in it by rhythm.

The Seventh Symphony begins in its title key of A major with a long introduction (“Poco sostenuto”), which almost has the importance of a separate movement. The second theme of this introduction—a capricious, tripping melody, first given out by a solo oboe—is not only one of the most captivating that Beethoven ever invented, but might very well be taken for an invitation to the dance or, perhaps equally well, for the caroling of a bird:

The principal theme of the main body of the movement (Vivace in A major), first announced by the flute, dominates the whole movement with its dotted dactylic rhythm. This theme, in its turn, might be a further invitation to the dance or again the piping of a bird.

The second movement, an Allegretto opening in A minor on a long-held, mysterious 6-4 chord of the tonic, is one of the most remarkable pages in all Beethoven. Here, if the dance simile is to be preserved, it must be a solemn, ritual dance. Thus the movement has been likened to a procession in the catacombs. But it has been likened as well to the love dream of an odalisque!

The third movement is a brilliant Scherzo, though marked only “Presto” (in F major). Twice it is interrupted by the fascinating strains of the somewhat less rapid Trio (“Assai meno presto” in D major), enshrining a melody that is said to be taken from a pilgrims’ hymn of Lower Austria:

The Finale is an Allegro of enormous energy and rhythmic incisiveness, whose tumultuous measures have been specifically compared to widely diverse dances. Some have heard here the rough jollity of dancing peasants, a “Bauertanz” or “Dance of Peasants,” while to others it is nothing less than the ceremonial dance of those priests of Cybele, the Corybantes, around the cradle of the infant Zeus.

In 1809-10—or only two or three years before the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies—Beethoven was commissioned to write incidental music for Goethe’s tragedy of the Netherlands under Spanish oppression, Egmont. The F minor Overture ranks indisputably as one of his finest, if it is less spare and less dour than the one to Coriolanus. It is a dramatic tone poem, but not a theatrical compendium in the manner of the “Leonore” Overtures. Yet it has an exultant coda not wholly dissimilar to the tremendous close of “Leonore” No. 3. This coda is identical with the so-called “Triumph” Symphony which concludes the play and was actually composed before the overture proper.

The greater Beethoven overtures might be termed off-shoots or by-products of the symphonies. Let us consider 31 them briefly at this stage irrespective of their precise dates of composition. Not all the rest, to be sure, rise to the heights of the “Leonore” Overtures, the “Egmont,” or the “Coriolanus.” But it is only proper to allude to such symphonic prefaces as the early overture to the Creatures of Prometheus ballet (from the period of the First Symphony), the tenuous ones for the Kotzebue plays The Ruins of Athens and King Stephen, the “Namensfeier” Overture (an “occasional” piece, written in 1814), and the magnificent, if slightly known and largely undervalued, “Consecration of the House,” composed as late as 1822 for the opening of the Josefstädter Theater in Vienna. The influence of Handel is powerfully manifest in this late creation, which is strongly contrapuntal in its texture but at the same time strangely suggestive from a dramatic, even a pictorial, standpoint.

Having paid something of a compliment to Handel in the “Consecration of the House” Beethoven was on the point of composing an overture on the letters of Bach’s name a couple of years later. The formula B-A-C-H represents in German notation B flat, A, C, and B as employed contrapuntally not only by Bach himself but by countless other masters since Bach’s epoch. Unfortunately, though he worked on studies for such an overture till 1825, Beethoven was too occupied with other schemes and never lived to complete it.

Although played privately in Vienna at the Archduke Rudolph’s on April 20, 1813, the Eighth Symphony had no public performance till it was brought out at the Redoutensaal 32 (Vienna) on February 27, 1814. The Seventh Symphony was on the same program and its Allegretto was encored, as it had been at its world première of the previous December. But the new work was received with less favor. A reviewer generously remarked that it was a mistake to place it after the manifold beauties of the Seventh. He had no doubt that it would be well received in future if given alone. Nevertheless this symphony was long neglected, in spite of attempts to make it succeed with the public by interpolating the popular Allegretto of the Seventh!

Beethoven himself called the Eighth his “little symphony in F” in contrast to the “great” symphony in A (Seventh). Yet the indifference of the audience at the Redoutensaal annoyed him and he testily remarked that the Eighth was “much better” than the Seventh, perhaps saying more than he really meant. There have been attempts to interpret this symphony, to provide it with a specific program. One such would make of it a “military trilogy” and d’Indy, still under the spell of the “Pastoral,” detects in it the impression made by Nature on Beethoven’s soul. He also hears a peasant band burlesqued in the Trio of the Menuetto, and the Hungarian theme employed in the Finale suggests to him the presence of gypsy musicians amid the festivities.

Be all that as it may, this is the symphony of laughter—not the laughter of childlike glee or of a reckless or despairing levity. Rather it is the “vast and inextinguishable laughter” that Shelley speaks of in Prometheus Unbound. It is the laughter of a man who has lived and suffered and, scaling the heights, has achieved the summit. So he has fashioned his own humor and dares survey the very stars in their appointed 33 courses as integrals of a cosmic comedy. Only here and there does a note of rebellion momentarily obtrude itself, and here and there, in brief lyrical repose, we have, remembering Sir Thomas Browne, an intimation of Divinity more than the ear discovers.

The first movement (“Allegro vivace e con brio” in F major) begins at once with a sprightly tune which tells right away the nature of the work. The second subject of the rollicking movement is one of Beethoven’s most delicious inspirations:

The second movement (“Allegretto scherzando” in B-flat major) is unique in symphonic literature. The persistent staccato ticking that runs through it has lent credibility to the story that the movement is based on a canon or round, “Ta, ta, ta, lieber Maelzel,” sung as a tribute to Maelzel—the inventor of that invaluable mechanical timebeater, the metronome—at a dinner given for Beethoven before he left Vienna for the country in July 1812. Thayer, who investigated the story carefully, says: “That Maelzel’s ‘ta, ta, ta’ suggested the Allegretto to Beethoven, and that at a parting meal the canon on this theme was sung, are doubtless true; but it is by no means sure that the canon preceded the symphony.” There is a story that Beethoven himself set the date of the dinner 34 late in December 1817. In any event, the irrepressible sixteenth notes tick away metronomically, and here is the airy theme that leads them on:

Berlioz says of this movement: “It is one of those productions for which neither model nor pendant can be found. This sort of thing falls entire from heaven into the composer’s brain. He writes it at a single sitting, and we are amazed at hearing it.” This would be all very well but for the fact that Beethoven’s sketches show how mightily he labored over the wholly spontaneous-seeming movement. When that eminent pessimist, the philosopher Schopenhauer, heard it, he declared it could make one forget that the world is filled with nothing but misery!

Instead of a scherzo Beethoven proceeds with a stately Minuet (“Tempo di Menuetto” in F major), which is not the symphonic minuet of the First and the Fourth symphonies, but a minuet in the noble manner of the eighteenth-century dance and perhaps not untinged with irony. Here is its courtly opening melody:

In the Finale (“Allegro vivace” in F major) the joy is truly unconfined and the music roars and billows with the impact of Olympian laughter.

Aside from the above-mentioned oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, Beethoven’s major religious compositions consist of the Mass in C major, written in 1807, and the stupendous one in D—the overpowering Missa Solemnis—begun in 1817 but not completed till 1825. The C major Mass must not be thought of as an early creation or a thing in the manner of the Mount of Olives. Actually, it is a work of the composer’s maturity, virtually contemporaneous with the great “Leonore” Overture and the Fifth Symphony. It was written at the instance of one of the Esterhazy princes who, when he heard the mass, infuriated Beethoven by asking: “Well, my dear Beethoven, what is it you have gone and done now?” Strangely enough, the C major Mass for all its unquestionable beauties is treated in rather stepchildly fashion. No greater mistake could be made than to compare it with the Missa Solemnis of a much later date and of basically different premises. “It expresses in the region of sacred music the joyful and victorious mood of the overture and the Symphony,” says Paul Bekker. “An atmosphere of simple piety pervades the Mass; no inner disunion, no brooding doubt, no unsatisfied thirst for knowledge finds expression here. The Mass in C is a confession of the composer’s faith and is at the same time liturgically practicable; it expresses a great artist’s confident belief, at a time when he was one in thought and feeling with the ‘spiritual powers that be’ of his period.”

The great Mass in D is a totally different proposition. It was the slow and gradual outgrowth of one of the periods 36 of Beethoven’s life where soul-shaking problems crowded ceaselessly upon him. He began to work upon it with the idea of producing it at the enthronement of his friend and pupil, the Archduke Rudolph, as Archbishop of Olmütz. But as it slowly expanded the composer forgot more and more why he had originally conceived it. It became in the grandest and deepest sense an expression of its creator’s profoundest philosophies. Barring three movements of the work, none of the Missa Solemnis was ever performed during the composer’s lifetime. And, singularly enough, those three movements were presented at the concert on May 7, 1824, at which the Ninth Symphony was heard for the first time. They had one other performance before Beethoven died—in St. Petersburg at the instigation of the Prince Galitzin.

The Mass in D, stupendous creation that it is, is far from a practical church work. It lacks all pretense of ritualistic use. For one thing, its vast proportions, the length of the individual sections, and the duration of the score as a whole would completely unfit it for ecclesiastical ceremony. The Mass is “unchurchly” in the highest degree. According to Bekker, Beethoven “breaks through the walls which divide the church from the world; his church extends to the limits of his vision; his altar is the heart of the universe, and he will suffer no dogmatic limitations.” Above the Kyrie the composer inscribed the words: “From the heart—may it go to the heart.” He intended the work “for the democratic concert hall rather than for polite social circles.”

The peak of the Missa Solemnis is undoubtedly the great fugue “Et vitam venturi” of the Credo. And here, incidentally, the demands on the singing voices are perhaps more 37 cruel than anywhere in the last movement of the Ninth Symphony or in the most arduous pages of Fidelio. Only now and then is there a wholly satisfying performance of the Mass in D. Be this as it may, there are two pages so extraordinary that no listener can ever fail to be stirred to the depths by them. One is the “Benedictus,” with its transfigured violin solo and a prefatory orchestral movement so spiritualized that it takes rank by the side of the loftiest slow movements the composer ever wrote; the other is the “Agnus Dei” and its “Prayer for inner and outer peace,” in which Beethoven causes the drums and trumpet calls of war to alternate with agonized supplications for peace.

All the same, despite the sublimities of the work and the vaunted “morality” of the composer, Beethoven did not hesitate to offer the score to at least three different publishing houses at practically the same time! Small wonder that, before long, a London concert agent was writing: “For heavens’ sake, don’t have any dealings with Beethoven!” If the master was not above attempting a little business skulduggery now and then he did not go about it cleverly!

More than ten years passed after the initial performance of the Eighth Symphony before Beethoven brought out its successor, his ninth and last, on May 7, 1824. The earlier part of this period was comparatively unproductive. Beethoven was profoundly disturbed by quarrels over his guardianship of his nephew Karl, which eventually were taken to court. His 38 health and spirits suffered and, meantime, his deafness became complete. Nevertheless his creative impulse found expression in two works of the grandest dimensions, the Mass in D and the Ninth Symphony. Sketches for the symphony were made as early as 1815—perhaps even earlier—and he went to work on it in earnest in 1817.

The première took place at the Kaerthnerthor Theater, Vienna, on May 7, 1824. The problems of performance were complicated by the composer’s using in the final movement a chorus and a quartet of soloists. Michael Umlauf conducted and the solo singers were Henriette Sontag (one of the most famous sopranos of her day), Karolina Unger, Anton Haitzinger, and J. Seipelt. The difficulty of Beethoven’s voice parts gave trouble at rehearsals. Mmes. Sontag and Unger begged him to alter their music, but in vain. Mme. Unger declared in his presence that he was a “tyrant over all the vocal organs.” Still, at the first performance it was she who led the composer from where he had been sitting in the midst of the orchestra to the edge of the stage to see the excited waving of the audience and to bow.

Beethoven in Vienna, 1820-25.

Pen and ink sketch by J. P. Lyser.

These solo parts have lost none of their difficulty for singers, and from the sopranos of the chorus Beethoven well-nigh demands the superhuman. With a view to helping matters some conductors have transposed the Finale down a whole tone, thus dimming its brilliance and upsetting Beethoven’s scheme of keys. Wagner believed that Beethoven by having words and singers in the Finale had closed the cycle of purely orchestral music. Others, however, regard the singers as a mistake and maintain that Beethoven recognized his error. So devout and searching a student of Beethoven as Professor Tovey, while dismissing as absurd the theory of Beethoven’s discontent with instrumental music, holds that every part of the Ninth Symphony becomes clearer when we assume that the choral Finale is right, and that hardly a point in the work but becomes difficult and obscure when we assume that the choral Finale is wrong. Though he admits that Beethoven, long after the production of the symphony, told some friends that the choral inclusion was a mistake and that perhaps some day he might write an instrumental Finale, he sets this down to a fit of depression. At any rate, the Finale stands as written 40 and there is no choice but to grapple with its problems.

For three movements the symphony is of course, purely instrumental. Of the first movement (“Allegro, ma non troppo, un poco maestoso,” in D minor) Ricciotto Canudo has written: “In the beginning was space; and all possibilities were in space; and life was space.” It begins pianissimo in empty fifths. A descending figure of two notes, from the heights to the depths, is reiterated while a tremendous crescendo leads to the theme that dominates the movement, given out fortissimo in unison and octaves:

The entire movement, which is well stocked with other themes, has the majesty and impetus of a titanic tragedy, and its propulsive drama ends with a defiant proclamation of the chief theme.

Now Beethoven reverses his usual procedure by postponing the slow movement and introducing a “Molto vivace” (in F minor), which has been called at once the greatest and the longest of his scherzos. A phrase of three notes, repeated on each interval of the chord of D minor, begins it, followed immediately by this fugal subject:

The enormous vitality and rhythmic drive of the Scherzo have deafened some hearers to the bitter strain in the jest. Joy unalloyed has not yet burst upon the scene.

And meanwhile Beethoven gives us the slow movement, a combination of an “Adagio molto e cantabile” (in B-flat major) and an “Andante moderato” (in D major), which as a whole has been described conveniently and with reasonable accuracy as a set of variations on two alternating themes:

Language has been ransacked for words to express the beauty and elevation of this Adagio-Andante. Its seraphic 42 song is dying away when the initial D minor of the Finale, presto and fortissimo, roughly smites our ears.

A series of orchestral sections, in contrast and conflict, occupy the battleground of the earlier pages before the baritone soloist, first using words by Beethoven himself, introduces the human voices and Schiller’s “Ode to Joy.” Two of the themes brought in here the listener should keep carefully in mind: the first is employed later by the baritone in demanding sounds of gladness, and the second is the so-called theme of joy:

Now chorus and soloists join valiantly in the good fight for “mirth and rapture blended” till the symphony ends in the victorious D major paeans, vocal and at the very last instrumental, of universal rejoicing. The burden of Schiller’s praise of Joy is held in these two lines:

“All mankind are brothers plighted

Where thy gentle wings abide.”

And universal brotherhood is thus voiced by the tenors and the basses in unison.

If Beethoven’s best-known and most widely performed works are the nine symphonies, his chamber music represents the most far-reaching, diversified, profound, original, spiritualized, and at the same time the most problematic manifestations of his genius. It is through his quartets, when all’s said, that his influence has been most felt. In these dwell the germs of more or less everything out of which subsequent music has, in one way or another, developed. If Beethoven may be called a “musician of the future” it is by reason of his sixteen string quartets more than by anything else. More than all else he composed they continue, in great measure, to be in advance not only of the master’s own time but even of our own.

It may be said that his chamber music spanned his life. The earliest specimens of it date from his Bonn days, from around his fifteenth year. From then on they continued (intermittently, it is true) almost up to the time of his death—indeed, the last composition he completed was a new finale 44 for the B-flat Quartet, opus 130, to replace the original one, the Great Fugue, now opus 133, which early audiences could not grasp and which, to this very day, is a stumbling block for most hearers although one of the most extraordinary and transcendent pages Beethoven ever produced. And though at his demise he left a quantity of sketches (including studies for a tenth symphony) there is every reason to assume that an even more copious quantity of chamber music might have come from his pen had he lived five or ten years longer.

The mass of such chamber music as he did bequeath us includes sonatas for piano and violin as well as for piano and cello; a Quintet in C major, opus 29, for two violins, two violas, and cello, dating from 1801; a quintet fugue in D, written in 1817 but published as opus 137; a number of trios for a variety of instrumental combinations, several duets and serenades, and other miscellany for more or less intimate performance. Lastly, the famous Septet in E flat, for clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello, and double-bass, opus 20. This septet was composed about 1800 and was at one time so immeasurably popular that Beethoven himself wearied of it. Despite the vogue it long enjoyed, it is far from one of its creator’s most inspired flights.

The series of trios for piano and strings constitute something of a counterpart to the great string quartets. Opus 1 consists of three such trios, and the composer’s friend Ries wrote that “when the three were first heard by the musical world at one of Prince Lichnowsky’s soirées nearly all the foremost artists and amateurs of Vienna were invited, among them Haydn, whose opinion was awaited with intense interest.” The trios caused a sensation. Haydn, who was enthusiastic 45 about them on the whole, had reservations to make about the third, in C minor, and advised the composer not to publish it. Beethoven took this advice in bad part, the more so because he regarded this trio as the best, and imagined that his famous contemporary was actuated by envy. The truth of the matter was that Haydn, struck by the bold originality of the score, was honestly afraid that the public might not understand it. But it is precisely this quality that has lifted the C minor Trio far above the other two of opus 1.

The other trios for piano and strings are the pair in D major and E-flat, opus 70, and the supremely great one in B flat, opus 97, called the “Archduke” Trio because it was dedicated to the composer’s friend and pupil, the Archduke Rudolph. The Opus 70 creations are remarkable for the somewhat restless, indeed forbidding, quality that fills some of their pages. The first has been named the “Ghost” Trio on account of an eerie figure that pervades the slow movement and lends it a strangely weird and hollow sound. The “Archduke” Trio has a spaciousness and elevation, particularly in its Largo, which is a series of five variations on a theme in the character of a hymn. Wisely enough, Beethoven placed the Scherzo before the profound slow movement, as he was again to do in the “Hammerklavier” Sonata and the Ninth Symphony. But this scherzo utilizes in its middle part a curious, winding chromatic figure which ranks with the master’s most striking ideas at this stage of his progress.

Between 1799 and 1802 Beethoven wrote eight of his ten sonatas for violin and piano. The most famous of these eight are the fifth—the so-called “Spring” Sonata in F, opus 24, which opens with a theme of lovely grace and has an adorable 46 serenity throughout its four movements—and the set in A major, C minor, and G major, opus 30, which was published with a dedication to Czar Alexander I of Russia. The C minor Sonata reveals a heroic quality which lends it something of the spirit of the “Eroica” Symphony, and the closing Presto of the finale has about it an element of dramatic grandeur. However, none of these sonatas quite reaches the level of the “Kreutzer” or the much later Sonata in G major, opus 96. The A major, opus 47, derived its name from the fact that it was dedicated to Rudolph Kreutzer. It was first played by a mulatto violinist named Bridgetower, while the composer performed the piano part. Despite the haste with which the work was composed (Czerny spoke of “four days”), the sonata, “written in a very concertante style,” has remained probably the best-known and most widely popular of all Beethoven’s sonatas for violin and piano. The music has an expansiveness and plenitude that surpass any other work Beethoven designed for this instrumental combination. The finale, a whirlwind Presto originally conceived for the first sonata of the opus 30 set, influenced Schubert when he composed the last movement of his D minor Quartet. Undoubtedly it is the most original, not to say the most exciting, part of the work—more so, indeed, than the Andante, with its series of variations so arranged that each artist is given his adroitly balanced share.

The G major Sonata, composed in 1812 and first performed by the French violinist Pierre Rode and the Archduke Rudolph, is unquestionably the most intellectual and the subtlest of Beethoven’s violin sonatas. In any case it has 47 some of the unmistakable traits of the master’s later style about it.

The sonatas for cello and piano, in F major and G minor, were composed as early as 1796 and performed in Berlin before the King of Prussia by Beethoven and the Court cellist, Duport. But the memorable cello sonatas of Beethoven’s are the one in A major, opus 69, one of his most lavish and magnificent works; and the C major and D major, opus 102. The first named, like the “Kreutzer” Sonata or the “Appassionata” of the piano series, is a creation that needs no defense and no far-fetched explanations. On the other hand, the opus 102 pair, despite their indisputable profundities, are among Beethoven’s more unapproachable and recondite works. Indeed, they have about them a certain hard-shelled quality which scarcely lends them an especially intimate or endearing effect.

The great series of string quartets begins with the six of opus 18, published in 1801, and concludes, officially speaking, with the masterpiece in F major, opus 135, completed only in 1826, but not printed till something like half a year after his death. The half-dozen works constituting the earlier opus had been ripening in the form of sketches and experiments of one sort or another for several years. They were finally issued in two numbers, each consisting of three scores. It is not possible to determine precisely the order in which they were written, but that fact is unimportant because the lot do not exhibit any definite line of development. It seems that one version of the first quartet, in F, was completed in 1799. 48 Beethoven gave it to his friend, the young ecclesiastical student Carl Amenda, but asked him to show it to nobody because “I have altered it considerably, having just learned to compose quartets aright.” Bekker finds that the revision “tends to a freer, more soloistic treatment of the accompanying parts, a clearer individualization of the cello part and a greater tonal delicacy in the ensemble effects.... The main idea of the composition, however, remained unchanged. This is no disadvantage, for the fresh naiveté of the content and the unassuming clarity of structure are great charms, and more would have been lost than gained by overmeticulous revision. As the work stands it is gratifying to the performer and offers pleasant, not over difficult problems to the listener.”

The finest part of the work is undoubtedly the second movement, an “Adagio affetuoso ed appassionato.” It is the richest in texture and certainly the most poetic and emotional of the four. When the composer played it to Amenda he is said to have inquired what the music suggested to him. “It suggests a lover’s parting,” replied Amenda; whereupon Beethoven replied, “Well, the tomb scene from Romeo and Juliet was in my mind.” And Bekker insists that this Adagio is “a most moving song of sorrow such as only Beethoven could accomplish when he turned to the grave D minor key.”

The second quartet, in G major, has been christened in some German countries the “Compliment Quartet.” It is graceful and rather courtly but it reaches none of the depths of the more moving pages of the preceding work, The Finale, however, is an instance of that “unbuttoned humor” that Beethoven was to exhibit on later occasions and of which he gave us supreme instances in the last movement of the 49 Seventh Symphony, the Eighth Symphony, and moments in the last quartets, the “Diabelli Variations,” and several of the final piano sonatas. Opus 18, No. 3, in D, is likewise marked by a quality of gaiety, though hardly of the “unbuttoned” kind.

The fourth work of the opus 18 set, in C minor, is more or less a work distinct from its companions. “A mood of deep seriousness is common to it and the C major Quintet, opus 29,” believes Bekker, “but the Quartet is full of passionate excitement,” and he alludes to its “mournful earnestness ... and restless dissatisfaction, the very opposite of the cheerful sense of concord with the world and mankind expressed in the other five.” The Quartet in A major has been termed Mozartean by some, operatic by others. Certainly it is fluent and lilting music, of which the Minuet is in some respects the most winning portion even if the final Allegro excels it in expressiveness.

The B-flat Quartet, sixth of the series, is particularly significant for the sombre adagio beginning of its otherwise jubilant allegretto Finale. Beethoven has headed this introduction (which is recalled dramatically during the movement) “La Malinconia: Questo pezzo si deve trattare colla più gran delicatezza” (“Melancholy: this piece must be played with the greatest delicacy”). This eerie and wholly romantic movement is a true glimpse of the Beethoven into whose newer world we shall presently penetrate.

With the three monumental quartets of opus 59 we have entered this new sphere. They belong to the year 1806, which means that they are of the epoch of the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, the third “Leonore” Overture, and the Violin 50 Concerto and the G major Concerto for piano. Beethoven dedicated them to the Russian Count Rasoumovsky, whose name is thus imperishably linked with these masterpieces; and it was perhaps as a compliment to this nobleman that he introduced into the first and second of these works authentic Russian themes. Indeed, the Scherzo of the E minor Quartet utilizes that great melody around which, more than half a century later, Moussorgsky was to build the coronation scene in his opera Boris Godounov.

The “Rasoumovsky” trilogy exhibits Beethoven’s inventive and technical faculties at the ideal symmetry they had achieved at the flood tide of his so-called “Second” period. The F major, C major, and E minor Quartets are in some ways the most ideally “balanced” ones he ever wrote; and, with all their splendor of form and substance, they are still replete with the most astonishing originalities and departures. Indeed, the amazing “Allegretto, scherzando” movement of the F major Quartet so astounded the players who first undertook to perform it that they imagined Beethoven’s rhythmic motto theme was intended as a joke at their expense and almost refused to go through with it. The Adagio, on the other hand, develops, with the utmost richness of sonority and color possible to four stringed instruments, two gorgeously songlike themes till it seems as if they had become expanded to orchestral dimensions. The E minor Quartet, less a display piece than its companion works, is in a totally different and quite as unprecedented manner, while its slow movement (“Molto Adagio”) sounds a deep, spiritual note which seems to have been inspired in the composer by a nocturnal contemplation of a starry sky in the country around 51 Baden, near Vienna. As for the C major Quartet, the third of the “Rasoumovsky” set, it closes in a jubilant, sweeping fugue, which is like a paean of triumph.

There are two E-flat quartets in Beethoven’s output: the first, opus 74, is known as the “Harp” Quartet by reason of the numerous passages of plucked strings in the first movement; the second is the tremendous opus 127. The former is the dreamier, less challenging of the two; it is rich not only in a sort of romanticism that looks forward to the age of Schumann, but also in unexpected effects bearing the unmistakable stamp of the Beethoven of the “Emperor” Concerto period, though in its way it is rather less venturesome than the “Rasoumovsky” trilogy. But the quartet that was written down in 1810—the F minor, opus 95—is in another category. It is the product of a new period of emotional ferment and a disquiet pervades the score with the irascible pertinacity of a gadfly. There is, indeed, a new quality of storm and stress in this Quartetto Serioso, as the composer himself designated it. Here he is in no mood for trifling. “At the moment when Beethoven had fought out his battle, when he could look back on all stages of the contest and taste the fruits of victory, he became most intensely aware of what it had cost him,” writes Paul Bekker, adding that “the autographed title shows that the composer sought no happy solution of his problem”—in spite of which the F minor Quartet does, surprisingly enough, end on a note of laughter.

Beethoven did not busy himself with the composition of string quartets for another fourteen years. This stretch of time is longer than any other interval in the various series of his compositions. It must be recalled, however, that in 52 this space he wrote the last three symphonies, the last half-dozen piano sonatas, the Missa Solemnis, the definitive revision of Fidelio together with its new E major overture, the Ferne Geliebte song cycle, the “Consecration of the House” Overture, and a quantity of other works only less significant. Spiritually, of course, he had traversed cycles of experience and had become, in an intellectual and artistic sense, another being.

It is almost inevitable, therefore, that the next great masterpiece of chamber music, should lift the curtain on a new creative realm. The E-flat Quartet, opus 127, has been properly likened to a majestic portal opening on the grand landscape of the last four quartets—the B-flat, opus 130; C-sharp minor, opus 131; A minor, opus 132; and the relatively short F major, opus 135, which may be described as a short of epilogue to the series.

There is nothing quite like these “last quartets” in Beethoven’s myriad-faceted output. In its way the series may be said to transcend even the Ninth Symphony, the “Hammerklavier” Sonata, and the “Diabelli” Variations. The novelty, the explosive qualities, the far-darting influence of these works (which span the nineteenth century and might even be said to help leaven the musical art of our own time) cannot be fully evaluated, let alone described, in this book.

It must suffice here to point out that the E-flat Quartet places the listener at once in a world of unimagined wonders. The very opening measures of the first movement with their powerful chords sound like a heraldic annunciation. The second movement, (“Adagio ma non troppo e molto cantabile”) is a series of variations of deepest earnestness. It is as if the composer endeavored to bring to his hearers revelations newly unfolded to his searching vision. The “Scherzando vivace” that follows is wildly and even uncannily humorous—and, incidentally, the longest of Beethoven’s scherzos. The Finale is a sort of triumphal march in which “some adventurer from the heavens seems to visit the earth ... with tidings of gladness, to return to his home in the heavens once more.”

Portrait of Beethoven in later life.

Etching of Beethoven’s study.

The B-flat Quartet is, if anything, more unusual and amazing, and it is in reality bound by a kind of mystical thematic kinship with the A minor and the C-sharp minor Quartets which come next. This kinship can be traced through the Great Fugue and is carried through the following quartets with a variety of profound philosophical modifications. The seven relatively brief movements of the B-flat masterpiece culminate in the hyper-emotional Cavatina (of which Beethoven said that remembrance of the feelings that inspired him to compose it always stirred him to tears); and to this sentimental outburst the harsh if stupendous fugue provided a truly beneficent purgation. The later-written closing Allegro, if lively and effervescent, is much less truly “in the picture.”

While it is risky, if not really impossible, to speak of the “greatest” of the last quartets, more than one musician would vote for the fourteenth—the tremendous one in C-sharp minor. The composition has seven movements, extraordinarily diversified. Beethoven tried out one of his little pleasantries on Schott, the publisher, and declared at first the quartet was “pieced together out of sundry stolen odds and ends.” A little later he reassured the frightened, unimaginative man of business that it was really “brand new.” And subsequently 54 he said impulsively that he considered the C-sharp minor “my best.” The introductory “Adagio non troppo” was called by Wagner “the most sorrowful thing ever said in music.” All the same, the mighty creation, after passing through unbelievable emotional transformations, closes in a triumphal frenzy which Wagner likened to “the dance of the whole world.”

The A minor Quartet, opus 132, doubtless begun somewhat earlier than the two preceding, is scarcely less amazing. Its heart is the “Molto Adagio” movement which Beethoven called “Song of Thanksgiving in the Lydian mode offered to the Deity by a convalescent.” It is filled with a mystical quality, a religious mood explained by the circumstance that the composer wrote the movement (one of his longest) when recovering from an illness. But the still more amazing fact about this quartet is that some pages of it were conceived for other works. It is a strange phenomenon that Beethoven on several occasions designed a quantity of pages not wholly sure where they would best fit, though in the end his artistic intuitions invariably led him to discover the right place. Just as he once intended the last movement of the “Kreutzer” Sonata for one of the sonatas of the opus 30 set, so he at one time intended the “Alla Marcia” that begins the finale of the A minor Quartet for the Ninth Symphony. And the last quartets furnish other instances of the same kind of thing.