Home Letters from an Officer at the Front

With Introductory Chapters by

Captain A. J. Dawson

Border Regiment (British Forces)

G. P. Putnam's Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1918

Copyright, 1918

BY

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

Permission has been given by the British War Office for the publication of this series of Letters written by a Temporary Officer of the New Army. No alteration has been made in the Letters to prepare them for the Press beyond the deleting or changing, for obvious reasons, of certain names used.

The writer has introduced this "Temporary Gentleman" to many good fellows in England, France, and Flanders, and is very anxious to introduce him on a really friendly footing to all his brothers-in-arms across the Atlantic; from New York to San Francisco, and from Quebec to Vancouver Island, also. But how best to do it? It really is no very easy matter, this, to present one simple, very human unit of the New Armies, to a hundred millions of people.

"Dear America: Herewith please find one slightly damaged but wholly decent 'Temporary Gentleman' who you will find repays consideration."

I think that is strictly true, and though, in a way, it covers the ground, it does not, somehow, seem wholly adequate; and I have an uncomfortable feeling that the critics might find in it ground for severe comments. But it is just what I mean; and I would be well content that all the kindly[Pg vi] men and women of America should just find out about this "Temporary Gentleman" for themselves, and form their own opinion, rather than that I should set down things about him in advance. If these letters of his do not commend him to America's heart and judgment, I am very sure no words of mine would stand any chance of doing so. Yes, for my part, warmly anxious as I am for America to know him, and to feel towards him as folk do in France and Flanders and Britain, I am perfectly prepared to let him stand or fall upon his own letters, which certainly discover the man to you, whatever you may think of him.

Withal, in case it may interest any among the millions of American families from which some member has gone out to train and to fight, to save the Allied democracies of the world from being over-ridden by the murderous aggression of its remaining autocracies, I take pleasure in testifying here to the fact that among the officers now serving in Britain's New Armies (as among those who, whilst serving, have passed to their long rest) are very many thousands who are just for all the world like the writer of these letters. I have watched and spoken with whole cadet-[Pg vii]training battalions of them, seen them march past in column of fours, chins well up, arms aswing, eyes front, and hearts beating high with glad determination and pride—just because their chance has nearly come for doing precisely what the writer of these letters did: for treading the exact track he blazed, away back there in 1915; for the right to offer the same sort of effort he made, for God and King and Country; to guard the Right, and avenge the Wrong, and to shield Christendom and its liberties from a menace more deadly than any that the world's admitted barbarians and heathens ever offered.

I know there are very many thousands of them who are just like this particular "Temporary Gentleman,"—even as there must be many thousands of his like in America,—because there have been so many among those with whom I have lived and worked and fought, in the trenches. And it does seem to me, after study of the letters, that this statement forms something of a tribute to the spirit, the efficiency, and the devotion to their duty, of the whole tribe of the Temporary Officers.

Their lost sense of humour (withered out of existence, I take it, by the poison gas of Prussian[Pg viii] Kultur) would seem to have made the German nation literally incapable of forming an approximately correct estimate of the capacities of any people outside the confines of their own machine-made, despotically ordered State, in which public sentiment and opinion is manufactured from "sealed pattern" recipes kept under lock and key in Potsdam and the Wilhelmstrasse. Their blunders in psychology since July, 1914, would have formed an unparalleled comedy of errors, if they had not, instead, produced a tragedy unequalled in history. With regard to America alone, the record of their mistakes and misreadings would fill a stout volume. In the earlier days of the War, I read many German statements which purported (very solemnly) to prove:

(a) That in the beginning of the War they killed off all the British officers.

(b) That the British officer material had long since been exhausted.

(c) That, since it was impossible for the British to produce more officers, they could not by any effort place a really big Army in the field.

And the queer thing is that German machine-made illusions are of cast-iron. They "stay put"; permanently. During 1917 I read again[Pg ix] precisely the same fatuous German statement regarding America and her inability to produce an army, that one read in 1914 and 1915 about Britain. The British New Armies (which Germany affirmed could never seriously count) have succeeded in capturing nearly three times as many prisoners as they have lost, and more than four times as many guns. From 1916 onward they steadily hammered back the greatest concentrations of German military might that Hindenburg could put up, and did not lose in the whole period as much ground as they have won in a single day from the Kaiser's legions. Yet still, in 1917, the same ostrich-like German scribes, who vowed that Britain could not put an army in the field because they could never officer it, were repeating precisely the same foolish talk about America and her New Armies.

Perhaps there is only one argument which Germany is now really able to appreciate. That argument has been pointedly, and very effectively, presented for some time past by the writer of these letters, and all his comrades. From this stage onward, it will further be pressed home upon the German by the armies of America, whose potentialities he has laboriously professed to ridicule.[Pg x] It is the argument of high explosive and cold steel; the only argument capable of bringing ultimate conviction to the Wilhelmstrasse that the English-speaking peoples, though they may know nothing of the goose-step, yet are not wont to cry "Kamerad," or to offer surrender to any other people on earth.

I know very well that the writer of these letters had no thought as he wrote—back there in 1916—of any kind of argument or reply to Potsdamed fantasies. But yet I would submit that, all unwittingly, he has furnished in these letters (on America's behalf, as well as Britain's) what should prove for unprejudiced readers outside Germany a singularly telling answer to the Boche's foolish boasts of the Anglo-Saxon inability to produce officers. As a correspondent in the Press recently wrote: "Why, for generations past the English-speaking peoples have been officering the world and all its waters—especially its waters!" And so they have, as all the world outside Germany knows, from the Yukon to Tierra del Fuego; from the Atlantic round through the Philippines to the golden gate and back.

It is a high sense of honour, horse sense, and sportsmanship, in our Anglo-Saxon sense, that lie[Pg xi] at the root of successful leadership. And one of Prussia's craziest illusions was that with us, these qualities were the sole monopoly of the men who kept polo ponies and automobiles!

Only the guns of the Allies and the steel of their dauntless infantrymen can enlighten a people so hopelessly deluded as the Germans of to-day. But for the rest of the world I believe there is much in this little collection of the frank, unstudied writings of an average New Army officer, who, prior to the War, was a clerk in a suburban office, to show that sportsmanship and leadership are qualities characteristic of every single division of the Anglo-Saxon social systems; and that, perhaps more readily than any other race, we can produce from every class and every country in the English-speaking half of the world, men who make the finest possible kind of active service officers; men who, though their commissions may be "Temporary" and their names innocent of a "von," or any other prefix, are not only fine officers, but, permanently, and by nature, gentlemen and sportsmen.

Withal, it may be that I should be falling short of complete fulfilment of a duty which I am glad and proud to discharge, if I omitted to furnish[Pg xii] any further information regarding the personality of the writer of these letters. And so, if the reader will excuse yet another page or two of wire entanglement between himself and the actual trenches—the letters, I mean—I will try to explain.

A. J. Dawson,

Captain.

London, 1918.

In the case of the Service Battalion officer of Britain's New Army who, with humorous modesty, signs himself "Your 'Temporary Gentleman,'" what is there behind that enigmatic signature that his letters do not tell us? The first of these homely epistles shows their writer arriving with his Battalion in France; and the visit is evidently his first to that fair land, since he writes: "I wonder if I should ever have seen it had there been no war!" That exclamation tells a good deal.

But of the man and his antecedents prior to that moment of landing with his unit in France, the letters tell us nothing; and if it be true that the war has meant being "born again" for very many Englishmen, that frequently quoted statement at all events points to the enjoyment of some definite status before the war.

Inquiry in this particular case speedily brings[Pg xiv] home to one the fact that one is investigating the antecedents of a well-recognised New Army type, a thoroughly representative type, as well as those of an individual. In his antecedents, as in the revolutionary development which the war has brought to him, this "Temporary Gentleman" is clearly one among very many thousands who have, so to say, passed through the same crucibles, been submitted to the same standard tests, and emerged in the trenches of France and Flanders, in Gallipoli and in Mesopotamia, in Africa, and in other places in which the common enemy has endeavoured to uphold his proposed substitution of Kultur for civilisation, as we understand it.

In the year 1896 there died, in a south-western suburb of London, a builder and contractor in a small, suburban way of business. An industrious, striving, kindly, and honourable man, he had had a number of different irons in the fire, as the saying goes, and some of them, it may be, would have provided a good reward for his industry if he had lived. As the event proved, however, the winding-up of his affairs produced for his widow a sum representing no more than maintenance upon a very modest scale of a period of perhaps three years. The widow was not alone in the world.[Pg xv] She had a little daughter, aged five, and a sturdy son, aged eight years. Nineteen years later that boy, into whose youth and early training not even the mention of anything military ever crept, was writing letters home from fire trenches in France, and signing them "Your 'Temporary Gentleman.'"

For seven years after his father's death the boy attended a day school in Brixton. The tuition he there received was probably inferior in many ways to that which would have fallen to his lot in one of the big establishments presided over by the County Council. But his mother's severely straitened circumstances had rather strengthened than lowered her natural pride; and she preferred to enlarge the sphere of her necessary sacrifices, and by the practice of the extremest thrift and industry to provide for the teaching of her two children at private schools. The life of the fatherless little family was necessarily a narrow one; its horizon was severely restricted, but its respectability was unimpeachable; and within the close-set walls of the little Brixton home there never was seen any trace of baseness, of coarseness, or of what is called vulgarity. The boy grew up in an atmosphere of reticence and modesty, in which the[Pg xvi] dominant factors were thrift, duty, conscientiousness, and deep-rooted family affection.

The first epoch of his fatherless life closed when our "Temporary Gentleman" left school, at the age of fifteen, and mounted a stool in the office of a local auctioneer and estate agent, who, in the previous decade, had had satisfactory business dealings with the youth's father. This notable event introduced some change into the quiet little mother-ruled ménage; for, in a sense, it had to be recognised that, with the bringing home of his first week's pay, the boy threatened to become a man. The patient mother was at once proud and a little disconcerted. But, upon the whole, pride ruled. The boy's mannishness, brought up as he had been, did not take on any very disconcerting shapes, though the first cigarette he produced in the house, not very long after the conclusion of the South African War, did prove something of a disturbing element just at first.

The South African War affected this little household, perhaps, as much as it would have been affected by a disastrous famine in China. It came before the period at which the son of the house started bringing home an evening newspaper, and while the only periodicals to enter the home[Pg xvii] were still The Boy's Own Paper and a weekly journal concerned with dressmaking and patterns. As a topic of conversation it was not mentioned half a dozen times in that household from first to last.

The next really great event in the life of the auctioneer's clerk was his purchase of a bicycle, which, whilst catastrophic in its effect upon his Post Office Savings Bank account, was in other respects a source of great happiness to him. And if it meant something of a wrench to his mother, as a thing calculated to remove her boy a little farther beyond the narrow confines of the sphere of her exclusive domination, she never allowed a hint of this to appear. Her son's admirable physique had long been a source of considerable pride to her; and she had wisely encouraged his assiduity in the Polytechnic gymnasium of which he was a valued supporter.

For the youth himself, his bicycle gave him the key of a new world, whilst robbing the cricket and football clubs to which he belonged of a distinctly useful member. He became an amateur of rural topography, learned in all the highways and by-ways of the southern Home Counties. His radius may not have exceeded fifty miles, but yet his[Pg xviii] bicycle interpreted England to him in a new light, as something infinitely greater and more beautiful than Brixton.

Quietly, evenly, the years slid by. The boy became a youth and the youth a man; and, in a modest way, the man prospered, becoming the most important person, next to its proprietor, in the estate agent's business. The mother's life became easier, and the sister (who had become a school-teacher) owed many little comforts and pleasures to the consistent kindliness of one who now was admittedly the head of the little household and its chief provider. He never gave a thought to the State or felt the smallest kind of interest in politics; yet his life was in no way self-centred or selfish, but, on the contrary, one in which the chief motive was the service of those nearest and dearest to him. Whilst rarely looking inward, his outward vision was bounded by the horizon of his well-ordered little home, of the Home Counties he had learned to love, and of the south-coast seaside village in which the family spent a happy fortnight every summer.

They were in that little seaside village when the Huns decreed war and desolation for Europe in August, 1914, and the three were a good deal upset[Pg xix] about the whole business, for it interfered with the railway service, and broke in very unpleasantly upon the holiday atmosphere, which, coming as it did for but one fortnight in each year, was exceedingly precious to the little family. However, with the Englishman's instinct for clinging to the established order, with all the national hatred of disturbance, they clung as far as possible to the measured pleasantness of their holiday routine, and, after a week, returned to the workaday round of life in Brixton.

Then began a time of peculiar stress and anxiety for the little household, the dominating factor in which was the growing strangeness, as it seemed to them, of its actual head and ruler; of the man in the house. At first he talked a great deal of the war, the overpowering news of the day, and he passed many scathing criticisms upon the conduct of the authorities in their handling of the first stages of the monstrous work of preparation. He had much to say of their blunders and oversights; and somewhat, too, of what he called their criminal unpreparedness. He stopped talking rather abruptly at breakfast one morning; and one of the headlines which subsequently caught the eyes of his sister, in the newspaper her brother had[Pg xx] propped against the coffee-pot, put this inquiry, in bold black type:

"WHOSE FAULT IS IT, MR. CITIZEN, THAT THE COUNTRY IS UTTERLY UNPREPARED FOR WAR?"

Those nightmarish early days of the great war slowly succeeded one another, and the mother and daughter grew perturbed over the change they saw creeping over their man. He talked hardly at all now. All the old cheery, kindly good humour which had provided half the sunshine of their lives seemed to be disappearing and giving place to a queer, nervous, morose sort of depression. It was as if their man lived a double life. Clearly he was much affected, even absorbed, by some mental process which he never so much as mentioned to them. Morning and evening they saw him, and yet it was as though he was not there, as though he lived and had his being in some other world, aloof from the old cosy, familiar, shared world in which they had always been together. The house-wifely eye of his mother noted with something like alarm that his bedroom candlestick required a fresh candle every day. One had been wont to serve him for a fortnight. Always, she thought[Pg xxi] he would unburden himself when he kissed her good-night. But he said never a word; and the nerve strain in the little household, which had been so quietly happy and bright, became almost unendurable.

Then the end came, with the beginning of the third week in September. The evening was extraordinarily peaceful and fine. The sister and a girl friend were at the little cottage piano. The visitor had a rather rich contralto voice, and sang with considerable feeling. In the middle of her third song the master of the house rose abruptly and walked out of the room, closing the door sharply behind him. The song was one of those called a "recruiting song." Late that night, when the visitor had departed, the brother apologised to his mother and sister for leaving them so abruptly, and spoke of a sudden headache. And the next evening he brought home the devastating news that he had enlisted, and would be leaving them next day for a military depot.

The news was received in dead silence. In some mysterious way neither of the women had contemplated this as possible. For others, yes. For their man—the thing was too wildly, remotely strange to be possible. There was his business;[Pg xxii] and, besides—It was merely impossible. And now he was an enlisted soldier, he told them. But, though they hardly suspected it, not being given to the practice of introspection, their man was not the only member of the little household in whom a fundamental and revolutionary change had been wrought by the world-shaking news of the past six weeks. In the end the women kissed their man, and the central fact of his astounding intelligence was not discussed at all. They proceeded direct to practical, material arrangements. But when the time came for her good-night kiss, the mother said, very quietly, "God bless you, dear!"; and the sister smiled and showed a new pride through the wet gleam of her eyes.

And then the auctioneer's clerk disappeared from the peaceful purlieus of Brixton and went out alone into an entirely new world, the like of which had never presented itself to his fancy, even in dreams. He became one of fifteen men whose home was a bell tent designed to give easy shelter to perhaps half that number. He began to spend his days in a routine of drill which, even to him with his gymnasium training, seemed most singularly tiresome and meaningless—at first.

At the end of four weeks he returned home for a[Pg xxiii] Saturday night and Sunday in the Brixton house; and he wore one stripe on the sleeve of his service jacket. To his intelligence there now was nothing in the whole intricate round of section, platoon, and company drill which was meaningless, however wearing it might sometimes seem. There was a tan on his cheeks, a clear brightness in his eyes, an alert swing in his carriage, and a surprisingly crisp ring in his voice which at once bewildered and delighted his womenfolk. He seemed not so much a new man as the man whom they had always loved and respected, in some subtle way magnified, developed, tuned up, brought to concert pitch.

In November he was advised by his Company Commander to apply for a Commission. The officer badly wanted him for a Sergeant, but this officer had long since learned to place duty first and inclination a long way behind; and it was apparent to him that in this tall, alert Lance-Corporal of his, as in so many hundreds of other men in the ranks, there was the making of a good officer.

Shortly before Christmas, 1914, he was gazetted a Second Lieutenant, and on New Year's Day he found himself walking across a parade ground to[Pg xxiv] take his place in front of the platoon he subsequently led in France, after long months of arduous training in several different English camps.

Three-quarters of a year passed between the day of this "Temporary Gentleman's" enlistment and his writing of the first of the letters now published over his pseudonym; and it may well be that all the previous years of his life put together produced no greater modification and development in the man than came to him in those nine months of training for the New Army. The training had its bookish side, for he was very thorough; but it was in the open air from dawn till dark, and ninety per cent. of it came to him in the process of training others.

The keynotes of the training were noblesse oblige, sportsmanship and responsibility, that form of "playing the game" which is at the root of the discipline of the British Army. While he taught the men of his platoon they taught him, in every hour of the day and many hours of the night. They learned to call him "A pretty good sort," which is very high praise indeed. And he learned to be as jealous of his men as any mother can be of her children. He learned to know them, in fair weather and in foul, for the splendid fellows they[Pg xxv] are; and in the intensely proud depths of his own inner consciousness to regard them as the finest platoon in the New Army.

And then came the longed-for day of the departure for France, for the land he was to learn to love, despite all the horrors of its long fighting line, just as he learned most affectionately to admire the men and reverence the women of brave, beautiful France. In the letters that he wrote from France he had, of course, no faintest thought of the ultimate test of publication. That is one reason why his name is not now attached to documents so intimate, even apart from the sufficiently obvious military reasons.

A. J. D.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The First Letter | 1 |

| The First March | 9 |

| The Tale of a Tub | 18 |

| The Trenches at Last | 28 |

| A Dissertation on Mud | 37 |

| Taking over on a Quiet Night | 46 |

| "What It's Like" | 56 |

| The Dug-out | 67 |

| A Bombing Show | 79 |

| Over the Parapet | 89 |

| The Night Patrol | 99 |

| In Billets | 111 |

| Bombardment | 121 |

| The Day's Work | 132 |

| Tommy Dodd and Trench Routine | 142 |

| Stalking Snipers | 152 |

| An Artful Stunt | 160 |

| The Spirit of the Men | 169 |

| An Unhealthy Bit of Line | 179 |

| They Say—— | 188 |

| The New Front Line | 197 |

| A Great Night's Work | 210 |

| The Coming Push | 220 |

| Front Line to Hospital | 229 |

| The Push and After | 239 |

| Blighty | 250 |

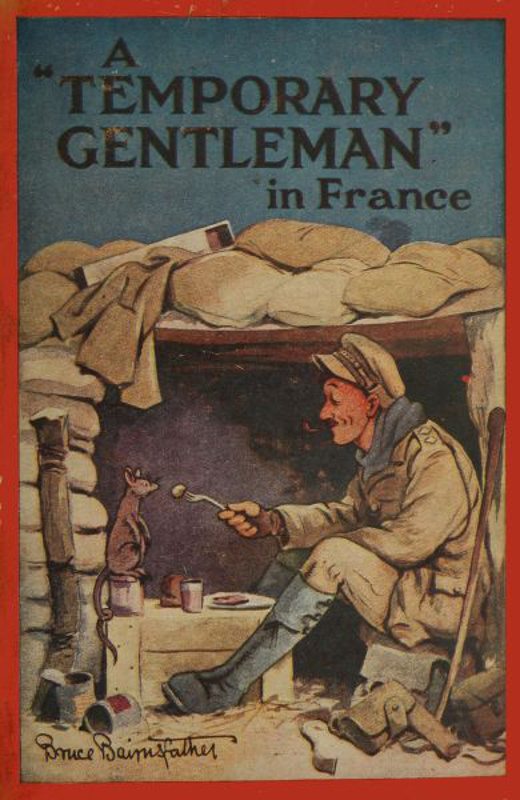

A "Temporary Gentleman" in France

Here we are at last, "Somewhere in France," and I suppose this will be the first letter you have ever had from your "Temporary Gentleman" which hasn't a stamp on it. It is rather nice to be able to post without stamps, and I hope the Censor will find nothing to object to in what I write. It's hard to know where to begin.

Here we are "at last," I say—we were nearly a year training at home, you know—and I shall not easily forget our coming. It really was a wonderful journey from Salisbury Plain, with never a hitch of any sort or kind, or so much as a buttonstick gone astray. Someone with a pretty good head-piece must arrange these things. At ten minutes to three this morning we were on the[Pg 2] parade ground at —— over a thousand strong. At twenty minutes to eleven we marched down the wharf here at ——, well, somewhere in France; and soon after twelve the cook-house bugle went in this camp, high up on a hill outside the town, and we had our first meal in France—less than eight hours from our huts on the Plain; not quite the Front yet, but La Belle France, all the same. I wonder if I should ever have seen it had there been no war?

Our transport, horses, mules, and limbers had gone on ahead by another route. But, you know, the carrying of over a thousand men is no small matter, when you accomplish it silently, without delay, and with all the compact precision of a battalion parade, as this move of ours was managed. Three minutes after our train drew up at the harbour station, over there in England, the four companies, led by Headquarters Staff, and the band (with our regimental hound pacing in front) were marching down the wharf in column of route, with a good swing. There were four gangways, and we filed on board the steamer as if it had been the barrack square. Then off packs and into lifebelts every man; and in ten minutes the Battalion was eating its haversack breakfast ration,[Pg 3] and the steamer was nosing out to the open sea, heading for France, the Front, and Glory.

The trip across was a stirring experience in its way too. The wide sea, after all, is just as open to the Boche as to us, and he is pretty well off for killing craft and mines. Yet, although through these long months we have been carrying troops to and fro every day, not once has he been able to check us in the Channel. The way the Navy's done its job is—it's just a miracle of British discipline and efficiency. All across the yellow foam-flecked sea our path was marked out for us like a racecourse, and outside the track we could see the busy little mine-sweepers hustling to and fro at their police work, guarding the highway for the British Army. Not far from us, grim and low, like a greyhound extended, a destroyer slid along: our escort.

The thing thrilled you, like a scene in a play; the quiet Masters of the Sea guarding us on our way to fight the blustering, boastful, would-be stealers of the earth. And from first to last I never heard a single order shouted. There was not a single hint of flurry.

It is about seven hours now since we landed, and I feel as though we had been weeks away[Pg 4] already—I suppose because there is so much to see. And yet it doesn't seem very foreign, really; and if only I could remember some of the French we were supposed to learn at school, so as to be able to understand what the people in the street are talking about, it would be just like a fresh bit of England. Although, just a few hours away, with no sea between us, there's the Hun, with his poison gas and his Black Marias and all the rest of the German outfit. Well, we've brought a good chunk of England here since the war began; solid acres of bully beef and barbed wire, condensed milk and galvanised iron, Maconochie rations, small-arm ammunition, biscuits, hand grenades, jam, picks and shovels, cheese, rifles, butter, boots, and pretty well everything else you can think of; all neatly stacked in miles of sheds, and ready for the different units on our Front.

I think the French are glad to see us. They have a kind of a welcoming way with them, in the streets and everywhere, that makes you feel as though, if you're not actually at home, you are on a visit to your nearest relations. A jolly, cheery, kindly good-natured lot they are, in spite of all the fighting in their own country and all[Pg 5] the savage destruction the Huns have brought. The people in the town are quite keen on our drums and bugles; marching past them is like a review. It makes you "throw a chest" no matter what your pack weighs; and we are all carrying truck enough to stock a canteen with. The kiddies run along and catch you by the hand. The girls—there are some wonderfully pretty girls here, who have a kind of a way with them, a sort of style that is French, I suppose; it's pretty taking, anyhow—they wave their handkerchiefs and smile. "Bon chance!" they tell you. And you feel they really mean "Good luck!" I like these people, and they seem to like us pretty well. As for men, you don't see many of them about. They are in the fighting line, except the quite old ones. And the way the women carry on their work is something fine. All with such a jolly swing and a laugh; something brave and taking and fine about them all.

If this writing seems a bit ragged you must excuse it. The point of my indelible pencil seems to wear down uncommonly fast; I suppose because of the rough biscuit box that is my table. We are in a tent, with a rather muddy boarded floor, and though the wind blows mighty cold[Pg 6] and keen outside, we are warm as toast in here. I fancy we shall be here till to-morrow night. Probably do a route march round the town and show ourselves off to-morrow. The C. O. rather fancies himself in the matter of our band and the Battalion's form in marching. We're not bad, you know; and "A" Company, of course, is pretty nearly the last word. "Won't be much sleep for the Kaiser after 'A' Company gets to the Front," says "the Peacemaker." We call our noble company commander "the Peacemaker," or sometimes "Ramsay Angell," as I think I must have told you before, because he's so deadly keen on knuckle-duster daggers and things of that sort. "Three inches over the right kidney, and when you hear his quiet cough you can pass on to the next Boche," says "the Peacemaker," when he is showing off a new trench dagger. Sort of, "And the next article, please," manner he has, you know; and we all like him for it. It's his spirit that's made "A" Company what it is. I don't mean that we call him "the Peacemaker" to his face, you know.

We can't be altogether war-worn veterans or old campaigners yet, I suppose, though it does seem much more than seven hours since we landed.[Pg 7] But everyone agrees there's something about us that we did not have last year—I mean yesterday. From the Colonel down to the last man in from the depot we've all got it; and though I don't know what it is, it makes a lot of difference. I think it is partly that there isn't any more "Out there" with us now. It's "Out here." And everything that came before to-day is "Over in England," you know; ever so far away. I don't know why a man should feel more free here than in England. But there it is. The real thing, the thing we've all been longing for, the thing we joined for, seems very close at hand now, and, naturally, you know, everyone wants to do his bit. It's funny to hear our fellows talking, as though the Huns were round the corner. If there's anything a man doesn't like—a sore heel, or a split canteen of stew, or a button torn off—"We'll smarten the Boche for that," they say, or, "Righto! That's another one in for the Kaiser!"

You would have thought we should have had time during the past six months or so to have put together most of the little things a campaigner wants, wouldn't you? especially seeing that a man has to carry all his belongings about with him and yet I would make a sporting bet that[Pg 8] there are not half a dozen men in the Battalion who have bought nothing to carry with them to-day. There is a Y. M. C. A. hut and a good canteen in this camp, and there has been a great business done in electric torches, tooth-powder, chocolate, knives, pipe-lighters, and all manner of notions. We are all very glad to be here, very glad; and nine out of ten will dream to-night of trenches in France and the Push we all mean to win V.C.'s in. But that's not to say we shall forget England and the—the little things we care about at home. Now I'm going to turn in for my first sleep in France. So give what you have to spare of my love to all whom it may concern, and accept the rest yourself from your

"Temporary Gentleman."

We reached this long, straggling village in pale starlight a little after six this morning; and with it the welcome end of the first stage of our journey from the port of disembarking to our section of the French Front.

In all the months of our training in England I never remember to have seen "A" Company anything like so tired; and we had some pretty gruelling times, too, during those four-day divisional stunts and in the chalk trenches on the Plain; and again in the night ops. on the heather of those North Yorkshire moors. But "A" Company was never so tired as when we found our billets here this morning. Yet we were in better form than any other company in the Battalion; and I'm quite sure no other Battalion in the Brigade could march against our fellows.

The whole thing is a question of what one has to carry. Just now, of course, we are carrying every blessed thing we possess, including great-[Pg 10]coats and blankets, not to mention stocks of 'baccy, torches, maps, stationery, biscuits, and goodness knows what besides; far fuller kits, no doubt, than tried campaigners ever have. (I found little M——, of No. 3 Platoon, surreptitiously stuffing through a hedge a case of patent medicines, including cough-mixture and Mother Somebody's Syrup!) If you ever visit France you probably won't travel on your own ten toes; but if you should, be advised by me and cut your kit down to the barest minimum; and when you've done that, throw away a good half of what's left.

Boots and socks. Some people will tell you that stocks and shares and international politics are matters of importance. I used to think the pattern of my neckties made a difference to our auctions. I know now that the really big things, the things that are really important, are socks and boots, and hot coffee and sleep, and bread—"Pang—Compree?" says Tommy to the French women, with a finger at his mouth—and then socks and boots again. You thought we paid a good deal in the shop for those swanky trench boots, W—— and myself. That was nothing to what we've paid since for wearing 'em. Excellent trench boots, I dare say; but one has to walk[Pg 11] across a good bit of France before getting to the trenches, you know. Those boots are much too heavy to carry and no good for marching. They look jolly and workmanlike, you know, but they eat up too much of one's heels. Tell all the officers you know to come out in ordinary marching boots, good ones, but ordinary ankle boots. Plenty time to get trench boots when they get to the trenches. Good old Q.M. Dept. will see to that. Our respected O.C. Company had no horse, you know (we haven't yet made connection with our transport), and his heels to-day look like something in the steak line about half-grilled.

We left camp at the port I mustn't name about eight o'clock last night, and marched down the hill to the station in sort of thoughtful good spirits, the packs settling down into their grooves. To save adding its immensity to my pack, I wore my imposing trench coat, with its sheep-skin lining; waist measurement over all, say a hundred and twenty-five. Two of us had some difficulty about ramming "the Peacemaker," through his carriage door into the train, he also being splendid in a multi-lined trench coat. Then we mostly mopped up perspiration and went to sleep.

Between twelve and one o'clock in the morning[Pg 12] we left the train (not without emotion; it was a friendly, comfortable train), and started to march across France. The authorities, in their godlike way, omitted to give us any information as to how far we were to march. But the weather was fine, and "A" Company moved off with a good swing, to the tune of their beloved "Keep the Camp Fires Burning." The biggest of packs seems a trifle, you know, immediately after four hours' rest in a train. But after the first hour it's astonishing how its importance in your scheme of things grows upon you; and at the end of the third or fourth hour you are very glad to stuff anything like bottles of Mother Somebody's Syrup through a gap in the nearest hedge.

It was at about that stage that word reached us of one or two men falling out from the rear companies. At this "the Peacemaker" began jogging up and down the left of our Company—we march on the right of the road in France—and, for all his sore heels and tremendous coat, showing the skittishness of a two-year-old. And he's even good years older than any of the rest of us, or than anyone else in the Company. I chipped my fellows into starting up another song, and my Platoon Sergeant cheerfully passed the word[Pg 13] round that if anybody in No. 1 dared to fall out he'd disembowel him with a tin-opener.

As an actual fact not a single "A" Company man did fall out, though in the last lap I was a bit nervy about old Tommy Dodd in 3 Section, whose rifle I carried, and one or two others. At the end "the Peacemaker" was carrying the rifles of two men, and everybody was thankful for walls to lean against when we stood easy in this village. My chaps were splendid.

"Stick it, Tommy Dodd!" I said to the old boy once, near the end. His good old face was all twisted with the pain of his feet and the mass of extra kit which no doubt his wife had made him carry.

"Stick it!" says he, with his twisted grin. "Why, I'm just beginning to enjoy it, sir. Just getting into me stride, I am. I wouldn't 've missed this for all the beer in England, sir. But you wait till we get alongside them blighted Boches, sir, an' see if I don't smarten some of 'em for this. I'll give 'em sore 'eels!"

It was only by lying to the extent of at least ten years that the old thing was able to enlist, and you couldn't get him to "go sick" if you drove him with a whip. The only way old Tommy[Pg 14] Dodd's spirit could be broken would be if you sent him to the depot and refused him his chance of "smartening them blighted Boches."

Everyone in the village was asleep when we got there, but on the door we found chalked up (as it might be "Lot So-and-so" at a sale) "1 Officer, 25 men, 'A' Coy.," and so on. We officers shed our packs and coats in the road—the joy of that shedding!—and went round with our platoons picking out their quarters, and shepherding them in before they could fall asleep. We knocked up the inhabitants, who came clattering out in clogs, with candle-ends in big lanterns. Most remarkably cheery and good-natured they all seemed, for that time of day; mostly women, you know, you don't find many home-staying men in France to-day. The most of the men's billets are barns and granaries, and there is a good supply of straw. I can tell you there was no need to sound any "Lights Out" or "Last Post." No. 1 Platoon just got down into their straw like one man, and no buck at all about it.

Then when we had seen them all fixed up, we foraged round for our own billets. Mine proved a little brick-floored apartment, in which you might just swing a very small cat if you felt like that[Pg 15] kind of jugglery, opening out of the main room, or bar, of an estaminet—the French village version of our inn, you know. Here, when they had had their sleep, the men began to flock this afternoon for refreshment. The drinking is quite innocent, mostly café au lait, and occasionally cider. The sale of spirits is (very wisely) entirely prohibited. It's most amusing to hear our chaps "slinging the bat." They are still at the stage of thinking that if they shout loudly enough they must be understood, and it is rather as a sort of good-humoured concession to the eccentricities of our French hosts, than with any idea of tackling another language, that they throw in their "Bon jor's" and the like.

"Got any pang, Mum?" they ask cheerfully. Another repeats it, in a regular open-air auction shout, with a grin and an interrogative "Compree?" at the end of each remark. Some, still at the top of their voices, are even bold enough to try instructing the French. "Françaisee, 'pang'—see? In Engletairy, 'bread'—see? Compree? B-R-E-A-D, bread." And the kindly French women, with their smiling lips and anxious, war-worn eyes, they nod and acquiesce, and bustle in and out with yard-long loaves and bowls of coffee of[Pg 16] precisely the same size as the diminutive wash-hand basin in my room. I tell you one's heart warms to these French women, in their workmanlike short frocks (nearly all black), thick, home-knitted stockings, and wooden clogs. How they keep the heels of their stockings so dry and clean, I can't think. The subject, you notice, is one of peculiar interest to all of us just now—sock heels, I mean.

There have been a good many jobs for officers all day, so far, and only an hour or so for rest. But we have arranged for a sumptuous repast—roast duck and sausages and treacle pudding—at six o'clock, and the C.O. and Providence permitting, we shall all turn in before eight. We don't expect to move on from here till early the day after to-morrow, and shall have our transport with us by then. I gather we shall march all the way from here to the trenches; and really, you know, it's an excellent education for all of us in the conditions of the country. People at home don't realise what a big thing the domestic side of soldiering is. Our C.O. knew, of course, because he is an old campaigner. That's why, back there in England, he harried his officers as he did. We have to know all there is to know[Pg 17] about the feet, boots, socks, food, cleanliness, and health of each one of our men, and it has been made part of our religion that an officer must never, never, never eat, sleep, or rest until he has personally seen to it that each man in his command is provided for in these respects. He has made it second nature to us, and since we reached France one has learned the wisdom of his teaching. I must clear out now—a pow-wow at Battalion Orderly Room: the village Ecole des Filles. The weather has completely changed. There's a thin, crisp coating of snow over everything, and it's clear and dry and cold. We're all rather tired, but fit as fleas, and awfully thankful to be getting so near the firing line. So make your mind quite easy about your

"Temporary Gentleman."

If inclined to revile me for apparent neglect of you these last few days, be charitable and revile lightly.

It's astonishing how full one's days are. And then when late evening arrives and arrangements for next morning are complete, and one's been the round of one's platoon billets and seen all in order for the night—then, instead of being free to write one's own letters, one must needs wade through scores written by the men of one's platoon, who—lucky beggars!—have three times the leisure we can ever get. Their letters must all be censored and initialed, you see. Rightly enough, I suppose, the military principle seems to be never to allow the private soldier to be burdened by any responsibility which an officer can possibly take. The giving away of military information in a letter, whether inadvertently or knowingly, is, of course, a serious offence. (German spies are everywhere.) When I have endorsed all my[Pg 19] platoon's letters, the responsibility for their contents rests on my shoulders and the men run no risks.

If I were an imitative bird now, you would find my letter reading something after this style:

"Just a few lines to let you know how we are getting on, hoping this finds you in the pink as it leaves me at present. We are getting very near the Germans now, and you can take it from me they'll get what for when we come up with 'em. The grub here is champion, but we are always ready for more, and I shan't be sorry to get that parcel you told me of. Please put in a few fags next time. The French people have a queer way of talking so you can't always understand all they say, but they're all right, I can tell you, when you get to know 'em, and I can sling their bat like one o'clock now. It's quite easy once you get the hang of it, this bong jor and pang parley voo. Milk is lay, and not too easy to get. The boys are all in the pink, and hoping you're the same, so no more at present," etc.

One sometimes gets mad with them for trifles, but for all the things that really matter—God bless 'em all! By Jove! they are Britons. They're always "in the pink" and most things are "cham[Pg 20]pion," and when the ration-wagon's late and a man drops half his whack in the mud, he grins and says, "The Army of to-day's all right"; and that, wait till he gets into the trenches, he'll smarten the Boches up for that! Oh, but they are splendid; and though one gets into the way of thinking and saying one's own men are the best in the Army, yet, when one means business one knows very well the whole of the New Army's made of the same fine stuff. Why, in my platoon, and in our Company for that matter, they are every mother's son of them what people at home call rough, ignorant fellows. And I admit it. Rough they certainly are; and ignorant, too, by school standards. But, by Jingo! their hearts are in the right place, and I'd back any one of them against any two goose-stepping Boches in the Kaiser's Prussian Guard.

And, with it all, mind you, they're so English. I mean they are kind, right through to their bones; good fellows, you know; sportsmen, every one of 'em; fellows you'd trust to look after your mother. They're as keen as mustard to get to the strafing of Boches; but that's because the Boche is the enemy, war is war, and duty is duty. You couldn't make haters of 'em, not if you paid[Pg 21] 'em all ambassadorial salaries to cultivate a scowl and sing hymns of hate. Not them. Not all the powers of Germany and Austria could make baby-killers, women-slayers, and church-destroyers of these chaps of ours. If I know anything about it, they are fine soldiers, but the Kaiser himself—"Kayser," they call him—couldn't make brutes and bullies of 'em. Warm their blood—and, mind you, you can do it easily enough, even with a football in a muddy field, when they've been on carrying fatigues all day—and, by Jove! there's plenty of devil in 'em. God help the men in front of 'em when they've bayonets fixed! But withal they're English sportsmen all the time, and a French child can empty their pockets and their haversacks by the shedding of a few tears.

But I run on (and my candle runs down) and I give you no news. This is our last night here, and I ought to be asleep in my flea-bag, for we make an early start to-morrow for our first go in the trenches. But it's jolly yarning here to you, while the whole village is asleep, and no chits are coming in, and the Battalion Orderly Room over the way is black and silent as the grave, except for the sentry's footsteps in the mud.[Pg 22] I'm in rather good quarters here, in the Mayor's house. When we left that first village—I'm afraid I haven't written since—we had three days of marching, sleeping in different billets each night. Here in this place, twelve miles from the firing line, we've had five days; practising with live bombs, getting issues of trench kit, and generally making last preparations. To-morrow night we sleep in tents close to the line and begin going into trenches for instruction.

But, look here, before I turn in, I must just tell you about this household and my hot bath last night. The town is a queer little place; farming centre, you know. The farm-houses are all inside the village, and mine—M. le Maire's—is one of the best. From the street you see huge great double doors, that a laden wagon can drive through, in a white wall. That is the granary wall. You enter by the big archway into a big open yard, the centre part of which is a wide-spreading dung-hill and reservoir. All round the yard are sheds and stables enclosing it, and facing you at the back the low, long white house, with steps leading up to the front door, which opens into the kitchen. This is also the living-room of M. le Maire and his aged mother. Their family lived here before[Pg 23] the Revolution, and the three sturdy young women and one old, old man employed on the farm, all live in the house.

M. le Maire is a warm man, reputed to have a thorough mastery of the English tongue, among other things, as a result of "college" education. So I gather from the really delightful old mother, who, though bent nearly double, appears to run the whole show, including the Town Hall opposite our Battalion Headquarters. I have never succeeded in inducing the Mayor to speak a word of English, but he has a little dictionary like a prayer-book, with perfectly blinding print, and somehow carries on long and apparently enjoyable conversations with my batman (who certainly has no French), though, as I say, one never heard a word of English on his lips.

I know what the newspapers are. They pretend to give you the war news. But I'll bet they'll tell you nothing of yesterday's really great event, when the Commander of No. 1 Platoon took a hot bath, as it were under municipal auspices, attended by two Company Headquarters orderlies, his own batman, and the cordially expressed felicitations of his brother officers, not to mention the mayoral household, and the whole of No. 1[Pg 24] Platoon, which is billeted in the Mayor's barns and outbuildings. Early in the day the best wash-tub had been commandeered for this interesting ceremony, and I fancy it has an even longer history behind it than the Mayor's pre-Revolution home. It is not definitely known that Marie Antoinette used this tub, bathing being an infrequent luxury in her day; but if she had been cursed with our modern craze for washing, and chanced to spend more than a year or so in this mud-set village of M——, she certainly would have used this venerable vessel, which, I gather, began life as the half of a cider barrel, and still does duty of that sort on occasion, and as a receptacle for the storing of potatoes and other nutritious roots, when not required for the more intimate service of M. le Maire's mother, for the washing of M. le Maire's corduroys and underwear, or by M. le Maire himself, at the season of Michaelmas, I believe, in connection with the solemn rite of his own annual bath, which festival was omitted this year out of deference to popular opinion, because of the war.

The household of the Mayor, headed by this respected functionary himself, received me at the portals of his ancestral home and ushered me most[Pg 25] kindly and graciously, if with a dash of grave, half-pitying commiseration, to what I thought at first was the family vault, though, as I presently discovered, it was in reality the mayoral salon or best parlour—as seen in war time—draped in sacking and year-old cobwebs. Here, after some rather embarrassing conversation, chiefly gesticulatory on my side—my conversational long suit is "Pas du tout! Merci beaucoup," and "Mais oui, Madame," with an occasional "Parfaitement," stirred in now and again, not with any meaning, but as a kind of guarantee of good faith, because I think it sounds amiable, if not indeed like my lambs in their billets, "Bien gentil," and "Très convenable, Monsieur." It is thus they are invariably described to me when I go inspecting. As I was saying, here I was presently left alone with the household cat, two sick rabbits in a sort of cage which must once have housed a cockatoo or parrot, my own little towel (a torn half, you know, designed to reduce valise weight), my sponge (but, alack! not my dear old worn-out nail-brush, now lying in trenches on Salisbury Plain), and the prehistoric wash-tub, now one quarter filled by what the Mayor regarded, I gathered, as perhaps the largest quantity of hot water ever accum[Pg 26]ulated in one place—two kettles and one oil-can full, carried by the orderlies.

The cat and the rabbits watched my subsequent proceedings with the absorbed interest of an intelligent mid-Victorian infant at its first pantomime. The cat, I blush to say, was female, and old enough to know better, but I trust the rabbits were of my own sex. Anyhow, they were sick, so perhaps it doesn't matter. The entire mayoral household, with my batman and others, were assembled in the big kitchen, separated from the chamber of my ablutions only by a door having no kind of fastening and but one hinge. Their silence was broken only by an occasional profound sigh from the Mayor's aged mother, and three sounds of reflective expectoration at considerable intervals from the Mayor himself. So I judged my bathing to be an episode of rare and anxious interest to the mayoral family.

My feet I anointed copiously with a disgusting unguent of great virtue—it's invaluable for lighting braziers when one's only fuel is muddy coke and damp chits—called anti-frostbite grease, that is said to guard us from the disease known as "Trench Feet," rumoured prevalent in our sector by reason of the mellow quality and depth of[Pg 27] its mud, which, whilst apparently almost liquid, yet possesses enough body and bouquet—remember how you used to laugh at our auction catalogue superlatives in cellar lots?—to rob a man of his boots at times. For my hands—chipped about a bit now—I used carbolated vaseline. (Do you remember the preternaturally slow and wall-eyed salesman, with the wart, in the Salisbury shop where we bought it?) And then, clothed most sumptuously in virginal underwear, I crawled into my flea-bag, there to revel from 10.40 P.M. to 6 A.M., as I am about to do now, less one hour in the morning. How I wish one could consciously enjoy the luxury of sleep while sleeping! Good night and God bless you! God bless all the sweet, brave waiting women of England, and France, and Russia; and I wish I could send a bit of my clean comfort to-night to as many as may be of our good chaps, and France's bon camarades, out here.

When next I write we shall have seen a bit of the trenches, I hope, and so then you should have something more like real news from your

"Temporary Gentleman."

You must forgive my not having sent anything but those two Field Service post cards for a whole week, but, as our Canadian subaltern, Fosset, says, it really has been "some" week. My notion was to write you fully my very first impression of the trenches, but the chance didn't offer, and perhaps it's as well. It couldn't be fresher in my mind than it is now, and yet I understand it more, and see the thing more intelligently than on the first night.

We are now back in the village of B——, three miles from our trenches. We are here for three days' alleged rest, and then, as a Battalion, take over our own Battalion sub-sector of trenches. So far, we have only had forty-eight hours in, as a Battalion; though, as individuals, we have had more. When we go in again it will be as a Battalion, under our own Brigade and Divisional arrangements, to hold our own Brigade front, and be relieved later by the other two Battalions of our Brigade.

"A" Company is, I am sorry to say, in tents for these three days out; tents painted to look like mud and grass (for the benefit of the Boche airmen) and not noticeably more comfortable than mud and grass. An old fellow having the extraordinary name of Bonaparte Pinchgare, has been kind enough to lend us his kitchen and scullery for officers' mess and quarters; and we, like the men, are contriving to have a pretty good time, in despite of chill rain and all-pervading mud. We are all more or less caked in mud, but we have seen Huns, fired at 'em, been fired at by them, spent hours in glaring through rag and tin-decked barbed wire at their trenches, and generally feel that we have been blooded to trench warfare. We have only lost two men, and they will prove to be only slightly wounded, I think; one, before he had ever set foot in a trench—little Hinkson of my No. 2 section—and the other, Martin, of No. 3 Platoon, only a few hours before we came out.

Hinkson was pipped by a chance bullet in the calf of the leg, as we passed through a wood, behind the support trench. Very likely a Boche loosed that bullet off in mere idleness, a couple of thousand yards away; and I doubt if it will mean[Pg 30] even a Blighty for Hinkson. He may be put right in the Field Ambulance or Clearing Station near here, or, at farthest, down at the Base. Or he may chance to go across to Blighty—the first casualty in the Battalion. The little chap was furiously angry over getting knocked out before he could spot a Hun through the foresight of his rifle, but his mate, Kennedy, has sworn to lay out a couple of Boches for Hinkson, before he gets back to us, and Kennedy will do it.

First impressions! Do you know, I think my first impression was of the difficulty of finding one's way about in a maze of muddy ditches which all looked exactly alike, despite a few occasional muddy notice-boards perched in odd corners: "Princes Street," "Sauchiehall Street," "Manchester Avenue," "Stinking Sap," "Carlisle Road," and the like. I had a trench map of the sector, but it seemed to me one never could possibly identify the different ways, all mud being alike, and no trench offering anything but mud to remember it by. In the front or fire-trench itself, the firing line, one can hop up on the fire-step, look round quickly between bullets, and get a bearing. But in all these interminable communication and branch trenches where one goes to[Pg 31] and fro, at a depth varying from six to ten or twelve feet, seeing only clay and sky, how the dickens could one find the way?

And yet, do you know, so quickly are things borne in upon you in this crude, savage life of raw realities, so narrow is your world, so vital your need of knowing it; so unavoidable is your continuous alertness, and so circumscribed the field of your occupation, that I feel now I know nothing else in the world quite so well and intimately as I know that warren of stinking mud: the two sub-sectors in which I spent last week. Manchester Avenue, Carlisle Road, Princes Street, with all their side alleys and boggy by-ways! Why, they are so photographed on the lining of my brain that, if I were an artist (instead of a very muddy subaltern ex-clerk) I could paint the whole thing for you—I wish I could. Not only do I know them, but I've merely to shut my eyes to see any and every yard of them; I can smell them now; I can feel the precise texture of their mud. I know their hidden holes and traps, where the water lies deep. I know to an inch where the bad breaks are in the duck-boards that you can't see because the yellow water covers them. Find one's way! I know them far better than I know the Thames[Pg 32] Embankment, the Strand, or Brixton Hill! That's not an exaggeration.

Duck-boards, by the way, or duck-walks, are a kindly invention (of the R.E., I suspect) to save soldiers from the bottomless pit, and to enable officers on duty to cover rather more than a hundred yards an hour in getting along their line of trench. Take two six-or eight-feet lengths of two inches by four inches' scantling; nail two or three inch bits of batten across these with two or three inch gaps between, the width of the frame being, say, eighteen inches. Thus you have a grating six or eight feet long and narrow enough to lie easily in the bottom of a trench. If these gratings rest on trestles driven deep down into the mud, and your trenches are covered by them throughout—well, then you may thank God for all His mercies and proceed to the more interesting consideration of strafing Boches, and avoiding being strafed by them. If you haven't got these beneficent inventions of the R.E., and you are in trenches like ours, then you will devote most of your energies to strafing the R.E., or some other unseen power for good, through your own headquarters, for a supply of duck-walks, and you will (if you are wise) work night and day without check,[Pg 33] in well and truly laying every single length you can acquire.

("Acquire" is a good, sound word. I would never blame a man for stealing duck-walks from any source whatsoever—providing, of course, he is not so far lost to all sense of decency as to steal 'em from "A" Company; and even then, if he could manage it, his cleverness would almost deserve forgiveness; and, equally, of course, that he's going to use 'em for their legitimate purpose, and not just to squat on in a dug-out; least of all for the absolutely criminal purpose of using as fuel.)

"What a fuss you make about mere things to walk on!" perhaps you'll say. "I thought the one thing really important was getting to grips with the enemy." Mmmf! Yes. Quite so. It is. But, madam, how to do it? "There be ways and means to consider, look you, whateffer," as Billy Morgan says. (Billy was the commander of No. 2 Platoon, you remember, and now, as reserve Machine-Gun officer, swanks insufferably about "the M.G. Section," shoves most of his Platoon work upon me, and will have a dug-out of his own. We rot him by pretending to attribute these things to the influence of his exalted[Pg 34] compatriot, the Minister of Munitions. As a fact, they are due to his own jolly hard work, and really first-rate abilities.)

This trench warfare isn't by any means the simple business you might suppose, and neither, of course, is any other kind of warfare. There can be no question of just going for the enemy bald-headed. He wishes you would, of course; just as we wish to goodness he would. You have to understand that up there about the front line, the surrounding air and country can at any moment be converted into a zone of living fire—gas, projectiles, H.E. (High Explosive, you know) flame, bullets, bursting shrapnel. If you raise a finger out of trenches by daylight, you present Fritz with a target, which he will very promptly and gratefully take, and blow to smithereens. That's understood, isn't it? Right. To be able to fight, in any sort of old way at all, you must continue to live—you and your men. To continue to live you must have cover. Hence, nothing is more important than to make your trenches habitable, and feasible; admitting, that is, of fairly easy and quick communication.

To live, you see, you must eat and drink. The trenches contain no A B C's. Every crumb of[Pg 35] bread, every drop of tea or water, like every cartridge you fire, must be carried up from the rear on men's shoulders, along many hundreds of yards of communicating trenches. Also, in case you are suddenly attacked, or have to attack, quick movement is vital. Nature apparently abhors a trench, which is a kind of a vacuum, and not precisely lovable, anyhow; and, in this part of the world, she proceeds wherever possible to fill it with water. Pumps? Why, certainly. But clay and slush sides cave in. Whizz-bangs and H.E. descend from on high displacing much porridge-like soil. Men hurrying to and fro day and night, disturb and mash up much earth in these ditches. And, no matter how or why, there is mud; mud unspeakable and past all computation. Consider it quietly for a moment, and you will feel as we do about duck-walks—I trust the inventor has been given a dukedom—and realise the pressing importance of various material details leading up to that all-important strafing of Boches.

But there, the notion of trying to tell you about trenches in one letter is, I find, hopelessly beyond me, and would only exhaust you, even if I could bring it off. I can only hope gradually to get[Pg 36] some sort of a picture into your mind, so that you will have a background of sorts for such news of our doings as I'm able to send you as we go on. Just now, I am going to tackle an alarming stack of uncensored letters from Nos. 1 and 2 Platoons—some of the beggars appear to be extraordinarily polygamous in the number of girls they write to; bless 'em!—and then to turn in and sleep. My goodness, it's a fine thing, sleep, out of trenches! But I'll write again, probably to-morrow.

The men are all remarkably fit and jolly. One or two old hands here have told me the line we are taking over is really pretty bad. Certainly it was a revelation to our fellows, after the beautiful, clean tuppenny-tubes of trenches we constructed on Salisbury Plain. But one hears no grousing at all, except of the definitely humorous and rather pleased kind—rather bucked about it, you know—the men are simply hungry for a chance to "get" at the Hun, and they work like tigers at trench betterment. We are all well and jolly, and even if sometimes you don't hear often, there's not the slightest need to worry in any way about your

"Temporary Gentleman."

The second of our rest days is over, and to-morrow night we shall go into the firing line and relieve the ——s. We shall march back the way we came out, down the sad-looking green valley round the lips of which some of our batteries are hidden; through the deserted streets of ——, with its boarded-up shops and houses; on over the weed-grown railway track, through a little village whose church is still unbroken; though few of its cottage windows have any glass left in them; across the busy little river to Ambulance Corner—a favourite target for Boche shells, that bit of road—and so through the wooded hollow where the German gas lies deadly thick when it comes, into the foot of Manchester Avenue, the long communication trench leading up to the Battalion's trench headquarters in the support line, where "A" Company will branch off to the right, "B" to the left, and "C" to the extreme left of our sub-sector.

That town I mentioned—not the little village close to Ambulance Corner, where most roofs and walls show shell-torn rents and a few are smashed to dust—is rather like a city of the dead. It has a cathedral which the gentle Hun has ranged on with thoughtful frightfulness. But though, under the guidance of his aerial observers, the Boche has smashed up that cathedral pretty thoroughly, and its tower has great gaping chunks riven out of its sides by shells, yet, as folk say miraculously, its crowning attraction, a monstrous gilt figure of the Madonna and Child, thirty to fifty feet high, remains intact. But this remarkable gilt statue has been undermined at its base by H.E. shell, and now hangs over at right angles to the street far below it—a most extraordinary sight. The devout naturally claim that no German projectile will prove powerful enough to lower the sacred emblem any farther. Boche savagery in France has not weakened anyone's faith, I think; possibly the reverse.

A foundry or factory near by is now a tangled mass of scrap iron, and as one marches through the town one has queer intimate glimpses of deserted bedroom interiors, with homely furnishings exposed to all the weather, where a shell has sliced[Pg 39] one wall clean down from a first or second storey and left the ground floor intact.

But I was going to tell you about trenches. When I first began to walk up Manchester Avenue, my thought was, "There's nothing much to grumble at here. I call this pretty good. A little sloppy under foot perhaps, but really nothing to write home about." I've often laughed at that since. For several hundred yards it cuts through a ridge of chalk. It is wide enough to enable one to pass a man in it anywhere with comfort. Its parapet and parados tower white, clean, and unbroken a foot or so over your head. Its sides are like the sides of a house or a tunnel; good, dry, solid chalk, like our Salisbury trenches, with never a sign of caving in about them. And on the hard bottom under foot-perhaps two or three inches of nice clean chalky slime and water. It has a gentle gradient which makes it self-draining.

You could easily go right up it to Battalion Headquarters in the support trench in ordinary marching boots, and be none the worse. And since then I've known what it means to get a bootful of muddy water, when wearing trench boots; rubber thigh-boots, you know, with straps buckling to your belt. The change begins a little[Pg 40] way above the Battalion Headquarters dug-out, in support line. You leave the chalk behind you and get into clay, and then you leave the clay behind you and get into yellow porridge and treacle. And then you come to a nice restful stretch of a couple of hundred yards or so, in which you pray for more porridge; and it seems you're never coming to any more. This is a vein of glue in the section which "A" will go to-morrow night.

"Very old and curious!" "Remarkably fine, full body!" Oh! that glue vein is from the end bin, genuine old-vatted, I can assure you. It must have eaten up some hundreds of pairs of boots by now, and a regular Noah's Ark full of trench stores, ammunition, and other useful material.

The glue vein probably had a bottom in bygone days, but now I fancy the Hun has knocked the bottom out of it. In any case, we never met anyone who had found bottom in that bit of line, and as the tallest man in the company is only six foot two, I hope we never shall. At first you think you will skip along quick, like skating fast on very thin ice, and with feet planted far apart, so as to get the support of the trench sides. That bit of trench is possessed of devils, and they laugh[Pg 41] when you stretch your legs, meaning to get through with it as quick as you can. The glue's so thick and strong, after the soupy stuff you've been wading through, that you welcome the solid look of it. (That's where the devils begin their chuckling.)

Perhaps at the first few steps you only sink about a foot, leaving your knees easily clear. "Oh! come!" you say (and that's where the devils of the glue patch laugh out loud). At the next step you go in a little deeper, and in your innocence give quite a sharp tug to lift your foot. You lift it all right, perhaps half-way up the leg of your boot, possibly ripping off a brace button in the process, if you've been unwise enough to fasten up the top straps of your boots that way. (The devils go on laughing.) Then you pause, reflectively, while shoving your foot down in your boot again, and take a good look round you, wondering what sort of a place you've struck. (This is where the devils have to hold their sides in almost painful hilarity.)

While you reflect you sink, so slowly and softly that you don't notice it till you try the next step. And then, with the devils of that section roaring their ugly Hunnish heads off all round you, if[Pg 42] you have no better luck than Tommy Dodd had, his first night in, you may continue reflecting for quite a long while, till somebody comes along who knows that particular health resort. Then two or three Samaritans with picks and shovels and a post or two will be brought, and, very laboriously, you'll be dug and levered out; possibly with your boots, possibly without either them or your socks.

But what reduces the devils to helpless, tearful contortions of merriment, is a coincidental decision on the part of a Boche gunner to start peppering that bit of trench with shrap., or a machine-gun, during your reflective period. Then it's great; a really first-class opportunity for reviewing the errors of your past life.

After this substantial pièce de résistance (yes, thanks, I'm progressing very nicely with my French this term), you come to a delicately refreshing dessert in Sauchiehall Street, where the water lies very deep in most parts, but so sweetly liquid as to wash the glue well off up to our coat pockets. This innocent stuff can be pumped out quite easily, and is pumped out every day, into a gully, which we devoutly hope leads well into a Boche sap. But pump as you will, it fills up very[Pg 43] rapidly. And so, with new washed boots (and coat pockets) to Whizz-bang Corner, where Sauchiehall Street enters the fire trench, and the Hun loves to direct his morning and evening hymns of hate in the hope of catching tired ration-carriers, and, no doubt, of spilling their rations. It was there that Martin of No. 3 Platoon got his quietener on the morning we came out. But with luck and no septic trouble, hell be back in a month or so. The surroundings are a bit toxic, as you may imagine. That's why, after even the slightest wound, they inoculate with anti-tetanus—marvellously successful stuff.

The fire trench in this particular bit is rather a mockery, as "the Peacemaker" said, when he tried to climb out of it, our first night in, to have a look at the barbed wire and No Man's Land. He had a revolver in one hand and a bomb in the other, but I am pleased to say the safety-pin of that bomb was efficient; and, in any case, I relieved him of it after he fell back the second time. The sides of that trench have been so unmercifully pounded by the Boche, and the rain has been so persistent of late that the porridge here is more like gruel than the breakfast dish, and the average sand-bag in the parapet, when not submerged,[Pg 44] is as unfriendly to get a grip on, as one of those crustaceous pink bombs they sometimes swindle you with at restaurants. You know, the kind you chase round your plate and find splinter-proof.

Thirty or forty yards north from Whizz-bang Corner, in the fire trench, you come to a loop turn to the rear called Whitehall, not because there's a War Office there, but because there's a queer little vein of chalk which disappointingly peters out again in less than a dozen paces. That leads to the Company Headquarters dug-out; an extraordinary hole, I thought, when I first saw it; a jolly nice, homely dug-out I think it now, and with a roof—well, not shell-proof, you know, but water-tight, and quite capable of standing a whizz or a grenade, or anything short of serious H.E. You stride over a good little dam and then down two steps to get into it, and it has a real door, carried up, I suppose, from the village in the rear. It also has a gilt-edged looking-glass, a good packing-case table, the remains of two wooden chairs, two shelves made of rum-jar cases, and two good solid wire-strung bunks, one over the other. There's no doubt it is some dug-out.

And, madam, don't you go for to think that there's anything contemptible about our trenches,[Pg 45] anyhow. Perhaps I pitched it a bit strong about that glue patch. In any case, I promise you two things: (1) They'll be very different trenches before long if "A" Company has two or three turns of duty in them. (2) They're every bit as good as, and a bit better than, the trenches opposite, where the Hun is; and I know it because I've been there. I meant to have told you of that to-night, but I've left it too late, and must wait for my next letter. But it's quite right. I've had a look at their front line and found it distinctly worse than ours, and got back without a scratch, to sign myself still your

"Temporary Gentleman."

Last evening brought an end to our rest cure, as I told you it would, and saw us taking over out section of the firing line. Now I have just turned into the Company dug-out for a rest, having been pretty much on the hop all night except for a short spell between two and four this morning. As I think I told you, this is not at all a bad dug-out, and quite weather-proof. It has two decent bunks one over the other. We all use it as a mess, and "the Peacemaker," Taffy Morgan, and myself use it for sleeping in; Tony and "the Infant" kipping down (when they get the chance) in a little tiny dug-out that we made ourselves when we were in here for instruction, just the other side of Whizz-bang Corner, in the fire trench.

You remember "the Infant," don't you? No. 4 Platoon. His father's doctoring now in the R.A.M.C. He's a nice boy, and has come on a lot since we got out here. He was to have been[Pg 47] a land surveyor, or something of that sort, and has a first-rate notion of trench work and anything like building.

In writing to you I'd like to avoid, if I could, what seems to be a pretty common error among men at the front, and one that leads to some absurd misapprehensions among people at home. I remember listening once in a tram-car at home to two Tommies, one of whom had returned from the front. The other was asking him how they managed in the matter of shifting wounded men back to some place where they could be attended to.

"Oh! that's simple enough," said the chap who'd been out. "They've a regular routine for that. You see, there are always barges waiting, and when you're wounded they just dump you on board a barge and take you down the canal to where the dressing station is."

"I see; so that's the way it's done," said the other man.

And I could see that the impression left on his mind was that barges were in waiting on a canal right along the five hundred miles of Franco-British line.

You see what I mean. A fellow out here knows[Pg 48] only his own tiny bit of front, and he's very apt to speak of it as if it were the Front, and folk at home are apt to think that whatever is applicable to their man's particular mile or so is applicable to the whole Front. Which, of course, is wildly wrong and misleading. When in trenches one battalion may find itself in a wood, another on a naked hillside, one in the midst of a ruined village, with the cellars of smashed cottages for dug-outs, and another with its trenches running alongside a river or canal. So don't make the mistake of thinking that what I tell you applies to the Front generally, although in a great many matters it may be typical enough.