Project Gutenberg's The Adventures of M. D'Haricot, by J. Storer Clouston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Adventures of M. D'Haricot Author: J. Storer Clouston Illustrator: Albert Levering Release Date: October 21, 2015 [EBook #50273] Last Updated: March 15, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ADVENTURES OF M. D'HARICOT *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

THE ADVENTURES OF M. D'HARICOT

“Adieu, the land of my birth!

Henceforth strange faces!”

—Boulevarde

N my window-sill lies a faded rose, a rose plucked from an English lane. As I write, my eyes fall upon the gardens, the forests, around my ancestral chateau, but the faint scent is an English perfume. To the land of that rose, the land that sheltered, befriended, amused me, I dedicate these memoirs of my sojourn there.

They are a record of incidents and impressions that sometimes have little connection one with another beyond the possession of one character in common-myself. I am that individual who with unsteady feet will tread the tight-rope, dance among the eggs, leap through the paper tambourine—in a word, play clown and hero to the melody of the castanets. I hold out my hat that you may drop in a sou should you chance to be amused. To the serious I herewith bid adieu, for instruction, I fear, will be conspicuously absent, unless, indeed, my follies serve as a warning.

And now without further prologue I raise the curtain.

The first scene is a railway carriage swiftly travelling farther and farther from the sea that washes the dear shores of France. Look out of the window and behold the green fields, the heavy hedge-rows enclosing them so tightly, the trees, not in woods, but scattered everywhere as by a restless forester, the brick farms, the hop-fields, the moist, vaporous atmosphere of England.

Cast your eyes within and you will see, wrapped in an ulster of a British pattern concealing all that is not British in his appearance, an exile from his native land. Not to make a mystery of this individual, you will see, indeed, myself. And I—why did I travel thus enshrouded, why did my eye look with melancholy upon this fertile landscape, why did I sit sad and sombre as I travelled through this strange land? There were many things fresh and novel to stir the mind of an adventurer. The name, the platform, the look of every station we sped past, was a little piece of England, curious in its way. Many memories of the people and the places I had known in fiction should surely have been aroused and lit my heart with some enthusiasm. What reason, then, for sadness?

I shall tell you, since the affair is now no secret, and as it hereafter touches my narrative. I was a Royalist, an adherent of the rightful king of France.

I am still; I boast it openly. But at that time a demonstration had been premature, a government was alarmed, and I had fled.

Hereafter I shall tell you more of the secret and formidable society of which I was then a young, enthusiastic member—the Une, Deux, Trois League, or U. D. T's, as we styled ourselves in brief, the forlorn hope of royalty in France. At present it is sufficient to say that we had failed.

Baffled hopes, doubt as to the future, fear for the present, were my companions; and they are not gay, these friends.

I felt—I confess it now mirthfully enough—suspicious of the porter of the train, of the guard, of the people who eyed me.

I was young, and “political offender” had a terrible sound. The Bastile, Siberia, St. Helena; were not these places built, created, discovered, for the sole purpose of returning white-haired, enfeebled unfortunates to their native land, only to find their homes dissolved, their families deceased, themselves forgotten? The truth is that I was already in mourning for myself. The prospect of entering history by the martyr's postern had seemed noble in the heat of action and the excitement of intrigue. Now I only desired my liberty and as little public attention as possible. I commend this personal experience to all conspirators.

Such a frame of mind begets suspicions fast, and when I found myself in the same compartment with a young man who had already glanced at me in the Gare du Nord, and taken a longer look on board the steamboat, I felt, I admit, decidedly uncomfortable. From beneath the shade of my travelling-cap I eyed him for the first half-hour with a deep distrust. Yet since he regarded me with that total lack of interest an Englishman bestows upon the unintroduced, and had, besides, an appearance of honesty written on his countenance, I began to feel somewhat ashamed of my suspicions, until at last I even came to consider him with interest as one type of that strange people among whom for a longer or a shorter time I was doomed to dwell, He differed, it is true, both from the busts of Shakespeare and the statues of Wellington, yet he was far from unpleasing. An athletic form, good features, a steady, blue eye, a complexion rosy as a girl's, fair hair brushed flat across his forehead, thirty years of truth-telling, cricket-playing, and the practice of three or four elementary ethical principles, not to mention an excellent tailor, all went to make this young man a refreshing and an encouraging spectacle.

“Bah!” I said to myself. “My friend may not be the poet-laureate or the philanthropic M. Carnegie, but at least he is no spy.”

By nature I am neither bashful nor immoderately timid, and it struck me that some talk with a native might be of service. My spirits, too, were rising fast. The train had not yet been stopped and searched; we were nearing the great London, where he who seeks concealment is as one pin in a trayful; the hour was early in the day, and the sun breaking out made the wet grass glisten.

Yes, it was hard to remain silent on that glorious September morning, even though dark thoughts sat upon the same cushion.

“Monsieur,” I said, “the sun is bright.”

With this remark he seemed to show his agreement by a slight smile and a murmured phrase. The smile was pleasant, and I felt encouraged to continue.

“Yet it does not always follow that the heart is gay. Indeed, monsieur, how often we see tears on a June morning, and hear laughter in March! It must have struck you often, this want of harmony in the world. Has it not?”

I had been so carried away my thoughts that I had failed to observe the lack of sympathy in my fellow-traveller's countenance.

“Possibly,” he remarked, dryly.

“Ah,” I said, with a smile, “you do not appreciate. You are English.”

“I am,” he replied. “And you are French, I suppose?”

At his words, suspicion woke in my heart. It was only as a Frenchman that I ran the risk of arrest.

“No; I am an American.”

This was my first attempt to disclaim my nationality, and each time I denied my country I, like St. Peter, suffered for it. Fair France, your lovers should be true! That is the lesson.

“Indeed,” was all he said; but I now began to enjoy my first experience of that disconcerting phenomenon, the English stare. Later on I discovered that this generally means nothing, and is, in fact, merely an inherited relic of the days when each Englishman carried his “knuckle-duster” (a weapon used in boxing), and struck the instant his neighbor's attention was diverted. It is thanks to this peculiarity that they now find themselves in possession of so large a portion of the globe, but the surviving stare is not a reassuring spectacle.

Yet I must not let him see that I was in the slightest inconvenienced by his attitude. The antidote to suspicion is candor. I was candid.

“Yes,” I said. “I am told that I do not resemble an American, but my name, at least, is good Anglo-Saxon.”

And I handed him a card prepared for such an emergency. On it I had written, “Nelson Bunyan, Esq.” If that sounded French, then I had studied philology in vain.

“I am a traveller in search of curios,” I added. “And you?”

“I am not,” he replied, with a trace of a smile and a humorous look in his blue eyes.

He was quite friendly, perfectly polite, but that was all the information about himself I could extract—“I am not,” followed by a commonplace concerning the weather. A singular type! Repressed, self-restrained, reticent, good-humoredly condescending—in a word, British.

We talked of various matters, and I did my best to pick him, like his native winkle, from the shell. Of my success here is a sample. We had (or I had) been talking of the things that were best worth a young man's study.

“And there is love,” I said. “What a field for inquiry, what variety of aspects, what practical lessons to be learned!”

He smiled at my ardor.

“Have you ever been in love?” I asked.

“Possibly,” he replied, carelessly.

“But devotedly, hopelessly, as a man who would sacrifice heaven for his mistress?”

“Haven't blown my brains out yet,” he answered.

“Ah, you have been successful; you have invariably brought your little affairs to a fortunate issue?”

“I don't know that I should call myself a great ladies' man.”

“Possibly you are engaged?” I suggested, remembering that I had heard that this operation has a singularly sedative effect upon the English.

“No,” he said, with an air of ending the discussion, “I am not.”

Again this “I am not,” followed by a compression of the lips and a cold glance into vacancy.

“Ah, he is a dolt; a lump of lead!” I said to myself, and I sighed to think of the people I was leaving, the people of spirit, the people of wit. Little did I think how my opinion of my fellow-traveller would one day alter, how my heart would expand.

But now I had something else to catch my attention. I looked out of the window, and, behold, there was nothing to be seen but houses. Below the level of the railway line was spread a sea of dingy brick dwellings, all, save here and there a church-tower, of one uniform height and of one uniform ugliness. Against the houses nearest to the railway were plastered or propped, by way of decoration, vast colored testimonials to the soaps and meat extracts of the country. In lines through this prosaic landscape rose telegraph posts and signals, and trains bustled in every direction.

“Pardon me,” I said to my companion, “but I am new to this country. What city is this?”

“London,” said he.

London, the far-famed! So this was London. Much need to “paint it red,” as the English say of a frolic.

“Is it all like this?” I asked.

“Not quite,” he replied, in his good-humored tone.

“Thank God!” I exclaimed, devoutly. “I do not like to speak disrespectfully of any British institution, but this—my faith!”

We crossed the Thames, gray and gleaming in the sunshine, and now I am at Charing Cross. Just as the train was slowing down I turned to my fellow-traveller.

“Have you been vaccinated?” I asked.

“I have,” said he, in surprise.

You see even reticence has its limits.

“I thank you for the confidence,” I replied, gravely.

As he stood up to take his umbrella from the rack he handed me back my card.

“I say,” he abruptly remarked, in a tone, I thought, of mingled severity and innuendo, “I should have this legend altered, if I were you. Good-morning.”

And with that he was gone, and my doubts had returned. He suspected something! Well, there was nothing to be done but maintain a stout heart and trust to fortune. And it takes much to drive gayety from my spirits for long. I was a fugitive, a stranger, a foreigner, but I hummed a tune cheerfully as I waited my turn for the ordeal of the custom-house. And here came one good omen. My appearance was so deceptively respectable, and my air so easy, that not a question was asked me. One brief glance at my dress-shirts and I was free to drive into the streets and lose myself in the life of London.

Lose myself, do I say? Yes, indeed, and more than myself, too. My friends, my interests, my language, my home; all these were lost as utterly as though I had dropped them overboard In the Channel. I had not time to obtain even one single introduction before I left, or further counsel than I remembered from reading English books. And I assure you it is not so easy to benefit by the experiences of Mr. Pickwick and Miss Sharp as it may seem. Stories may be true to life, but, alas! life is not so true to stories.

Fortunately, I could talk and read English well—even, I may say, fluently; also I had the spirit of my race; and finally—and, perhaps, most fortunately—I was not too old to learn.

“In that city, sire, even the manner of breathing was different.”

—PIZARRO.

WAS in London, the vastest collection of people and of houses this world has ever seen; the ganglion, the museum, the axle of the English race; the cradle of much of their genius and most of their fogs; the home of Dr. Johnson, the bishops of Canterbury, the immortal Falstaff, the effigied Fawkes; also the headquarters of all the profitable virtues, all the principles of business. With an abandon and receptivity which I am pleased to think the Creator has reserved as a consolation for the non-English, I had hardly been half an hour in the city before I had become infected with something of its spirit.

“Goddam! What ho!” I said to myself, in the English idiom. “For months, for years, forever, perhaps, I am to live among this incomprehensible people. Well, I shall strive to learn something, and, by Great Scotland! to enjoy something.” So I turned up my trousers and sallied out of my hotel.

Ah, this was life, indeed, I had come into; not more so than Paris, but differently so. Stolidly, good-naturedly, and rapidly the citizens struggle along through the crowds on the pavement. They seem like helpless straws revolving in a whirlpool. Yet does one of them wish to cross the street? Instantly a constable raises a finger, the traffic of London is stopped, and Mr. Benjamin Bull, youngest and least important son of John, passes uninjured to the farther side.

“What is this street?” I ask one of these officers, as he stands in the midst of a crossing, signalling which cab or dray shall pass him.

“Strand,” says he, stopping five omnibuses to give me this information.

“Where does it lead me?”

“Which way do you wish to proceed?” he inquires, politely, still detaining the omnibuses.

“East,” I reply, at a venture.

“First to the right, second to the left, third to the right again, and take the blue bus as far as the Elephant and Angel,” he answers, without any hesitation.

“A thousand thanks,” I gasp. “I think, on the whole, I should be safer to go westward.”

He waves his hand, the omnibuses (which by this time have accumulated to the number of fourteen) proceed upon their journey, and I, had I the key to the cipher, should doubtless be in possession of valuable information. Such is one instance of the way in which the Londoner's substitute for Providence does its business.

I shall not attempt to give at this point an exhaustive description of London. The mandates of fortune sent me at different times to enjoy amusing and embarrassing experiences in various quarters of the city, and these I shall touch upon in their places. It is sufficient to observe at present that London is a name for many cities.

A great town, like a great man, is made up of various characters strung together. Just as the soldier becomes at night the lover and next morning the philosopher, so a city is on the east a factory, on the west a palace, on the north a lodging-house. So it is with Paris, with Berlin, with all. But London is so large, so devoid of system in its creation and in its improvements, so variously populated, that it probably exceeds any in its variety.

No emperor or council of city fathers mapped the streets or regulated the houses. What edifice each man wanted that he built, guided only by the length of his purse and the depth of his barbarism; while the streets on which this arose is either the same roadway as once served the Romans, or else the speculative builder's idea of best advancing the interests of his property. Then some day comes a great company who wish to occupy a hundred metres of frontage and direct attention to their business. So many houses are pulled down and replaced by an erection twice the height of anything else, and designed, as far as possible, to imitate the cries and costume of a bookmaker. And all this time there are surviving, in nooks and corners, picturesque and venerable buildings of a by-gone age, and also, of late, are arising on all sides worthy and dignified new piles.

So that the history of each house and each street, the mental condition of their architects and the financial condition of their occupants, are written upon them plainly with a smoky finger. For you see all this through an atmosphere whose millions of molecules of carbon and of aqueous vapor darken the bricks and the stones, and hang like a veil of fine gauze before them. London is huge, but the eternal mistiness makes it seem huger still, for however high a building you climb, you can see nothing but houses and yet more houses, melting at what looks a vast distance into the blue-and-yellow haze. Really, there may be green woods and the fair slopes of a country-side within a few miles, but since you cannot see them your heart sinks, and you believe that such good things must be many leagues below the brick horizon. More than once upon a Sunday morning, when the air was clear, I have been startled to see from the Strand itself a glimpse of the Surrey hills quite near and very beautiful, and I have said, “Thank God for this!”

It was in the morning that I arrived in London, and my first day I spent in losing my way through the labyrinth of streets, which are set never at a right angle to one another, and are of such different lengths that I could scarcely persuade myself it had not all been specially arranged to mislead me.

About one o'clock I entered a restaurant and ordered a genuine English steak—the porter-house, it was called. In quality, I admit this segment of an ox was admirable; but as for its quantity—my faith! I ate it till half-past two and scarcely had made an impression then. Half stupefied with this orgy, and the British beer I had taken to assist me in the protracted effort, I returned to my hotel, and there began the journal on which these memoirs are founded. As showing my sensations at the time, they are now of curious interest to me. I shall give the extract I wrote then:

“Amusing, absorbing, entertaining as a Chinese puzzle where all the pieces are alive; all these things is the city of London. Why, then, has it already begun to pall upon me? Ah, it is the loneliness of a crowd! In Paris I can walk by the hour and never see a face I know, and yet not feel this sense of desolation. Friends need not be before the eye, but they must be at hand when you wish to call them. For myself, I call them pretty frequently, yet often can remain for a time content to merely know that they are somewhere not too far away. But here—I may turn north, south, east, or west, and walk as far as I like in any direction, and not one should I find!

“Shall I ever make a friend among this old, phlegmatic, business-like people? Some day perhaps, an acquaintance may be struck with some such reticent and frigid monster as my fair-haired companion of the journey. Would such a one console or cheer or share a single sentiment? Impossible! Mon Dieu! I shall leave this town in three days; I swear it. And where then? The devil knows!”

At this point the writing of these notes was unexpectedly interrupted, only to be resumed, as it chanced, after some adventurous days.

A waiter entered, bearing a letter for me. I sprang up and seized it eagerly. It was addressed to Mr. Nelson Bunyan, Esq., and marked “Immediate and confidential.” These words were written in English and execrably misspelled.

It could come from but one source, for who else knew my nom de plume, who else would write “Immediate and confidential,” and, I grieve to say it, who else would take their precautions in such a way as instantly to raise suspicions? Had the secretary of the “Une, Deux, Trois” no English dictionary, that he need make the very waiter stare at this very extraordinary address? I did my best to pass it off lightly.

“From a lady,” I said to the man. “One not very well educated, perhaps; but is education all we seek in women?”

“No, sir,” said he, replying to my glance with insufferable familiarity, “not all by no means.”

Alas that the fugitive cannot afford to take offence!

I opened the letter, and, as I expected, it was headed by the letters U. D. T:

“Go at once to the house of Mr. Frederick Hankey, No. 114 or 115 George Road, Streatham. Knock thrice on the third window, and when he comes say distinctly 'For the King.' He will give directions for your safety.”

This missive was only signed F. II, but, of course, I knew the writer—our most indefatigable, our most enthusiastic, the secretary himself.

Well, here was something to be done; a friend, perhaps, to be made; a spice of interest suddenly thrown into this city of strangers. After my fashion, my spirits rose as quickly as they had fallen. I whistled an air, and began to think this somewhat dreary hotel not a bad place, after all. I should only wait till darkness fell and then set out to interview Mr. Frederick Hankey.

“What door will fit this key?”

—Castillo Soprani.

S I ate my solitary dinner before starting upon my expedition to Mr. Hankey's house, I began to think less enthusiastically of the adventure. Here was I; comfortable in my hotel, though, I admit, rather lonely; safe, so far, and apparently suspected by none to be other than the blameless Bunyan. Besides, now that I could find a friend for the seeking, my loneliness suddenly diminished. Also I was buoyed by the thought that I was a real adventurer, a romantic exile, as much so, in fact, as Prince Charles of Scotland or my own beloved king. Now I was to knock upon the window of a house that might be either number 114 or 115, and give myself blindfold to strangers.

Yet on second thoughts I reflected that I knew nothing of English laws or English ways. Was I not in “perfidious Albion,” and might I not be handed over to the French government in defiance of all treaties, in order to promote the insidious policy of Chamberlain? Yes, I should go, after all, and I drank to the success of my adventure in a bottle of wine that sent me forth to the station in as gay a spirit as any gallant could wish.

I had made cautious inquiries, asking of different servants at the hotel, and I had little difficulty in making my way by train as far as the suburb in which Mr. Hankey lived. There I encountered the first disquieting circumstance. Inquiring of a policeman, I found there was no such place as George Road, but a St. George's Road was well known to him. If F. II had been so inaccurate in one statement, might he not be equally so in another?

I may mention here that the name of this road is my own invention. The mistake was a similar one to that I have narrated. In all cases I have altered the names of my friends and their houses, as these events happened so recently that annoyance might be caused, for the English are a reticent nation, and shrink from publicity as M. Zola did from oblivion.

Up an immensely long and very dark road I went, studying the numbers of the houses on either side, and here at once a fresh difficulty presented itself. In an English suburb it is the custom to conceal the number provided by the municipal authorities, and decorate the gates instead with a fanciful or high-sounding title. Thus I passed “Blenheim Lodge,” “Strathcory,” “Rhododendron Grove,” and many other such residences, but only here and there could I find a number to guide me. By counting from 84, I came at last upon two houses standing with their gates close together that must either be 114 and 115, or 115 and 116. I could not be sure which, nor in either case did I know whether the one or the other sheltered the conspiring Hankey. The gate on the left was labelled “Chickawungaree Villa,” that on the right “Mount Olympus House.” In the house I could see through the trees that all was darkness, and the gate was so shabby as to suggest that no one lived there. In the villa, on the contrary, I saw two or three lighted windows. I determined to try the villa.

The drive wound so as to encircle what appeared in the darkness to be a tennis-court and an arbor, and finally emerged through a clump of trees before a considerable mansion. And here I was confronted by another difficulty. My directions said, knock upon the third window. But there were three on either side of the front door, and then how did I know that Hankey might not prefer me to knock upon his back or his side windows? My friend F. II might be a martyr and a patriot; but business-like? No.

“Blind fortune is the goddess to-night,” I said to myself, and with that I tapped gently upon the third window from the door counting towards the right. I have often since consoled myself by thinking that I should have exhibited no greater intuition had I counted towards the left.

I tap three times. No answer. Again three times. Still no answer. It was diabolically dark, and the trees made rustling noises very disconcerting to the nerves of one unaccustomed to practise these preliminaries before calling upon a friend.

“The devil!” I say to myself. “This time I shall make Mr. Hankey hear me.”

And so I knocked very sharply and loudly, so sharply that I cracked the pane.

“Unfortunate,” I thought; “but why should I not convert Hankey's misfortune into my advantage?”

With the intention of perhaps obtaining a glimpse into the room, I pushed the pane till, with an alarming crash, a considerable portion fell upon the gravel.

With a start I turned, and there, approaching me from either side, were two men. Hankey had evidently heard me at last.

“Who are you?” said one of them, a stout gentleman, I could see, with a consequential voice. I came a step towards him. “For the King,” I replied.

He seemed to be staring at me.

“What the devil—?” he exclaimed, in surprise.

My heart began to sink.

“You are Mr. Hankey?” I inquired.

“I am not,” he replied, with emphasis.

Here was a delicate predicament!

But I was not yet at the end of my resources.

“May I inquire your name?” I asked, politely.

“My name is Fisher,” he said, with a greater air of consequence than ever, but no greater friendliness.

“What, Fisher himself!” I exclaimed, with pretended delight. “This is indeed a fortunate coincidence! How are you, Fisher?”

Still no answer.

I held out my hand, but this monster of British brutality paid no attention to my overture.

“Who are you?” he asked once more.

Not having yet made up my mind who I was, I thought it better to temporize.

“My explanations will take a few minutes, I am afraid,” I answered. “The hour also is late. May I call upon you in the morning?”

“I think you had better step in and explain now,” said Fisher, curtly.

They were two to one, and very close to me, while I was hampered with my British ulster. I must trust to my wits to get me safely out of this house again.

“I shall be charmed, if I am not disturbing you.”

“You are disturbing me,” said the inexorable Fisher. “In fact, you have been causing a considerable disturbance, and I should like to know the reason.”

Under these cheerful circumstances I entered Chickawungaree Villa, Fisher preceding me, and the other man, whom I now saw to be his butler, walking uncomfortably close behind.

“Step in here,” said Fisher. He showed me into what was evidently his dining-room, and then, after saying a few words in an undertone to his servant, he closed the door, drew forward a chair so as to cut off my possible line of flight, sat upon it, and breathed heavily towards me.

Figure to yourself my situation. A large, red-faced, gray-whiskered individual, in a black morning-coat and red slippers, staring stolidly at me from a meat-eating eye; name Fisher, but all other facts concerning him unknown.

A stiff, uninhabited-looking apartment of considerable size, lit with the electric light, upholstered in light wood and new red leather, and ornamented by a life-sized portrait of Fisher himself, this picture being as uncompromising and apoplectic as the original. Finally, standing in an artificially easy attitude before a fireplace containing a frilled arrangement of pink paper, picture an exceedingly uncomfortable Frenchman.

“You scarcely expected me?” I begin, with a smile.

“I did not,” says Fisher.

“I did not expect to see you,” I continue; but to this he makes no reply.

“I was looking for the house of Mr. Hankey.”

“Were you?” says Fisher.

“Do you know him?” I ask.

“No,” says Fisher.

A pause. The campaign has opened badly; no doubt of that. I must try another move.

“You will wonder how I knew him,” I say, pleasant.

Fisher only breathes more heavily.

“Our mutual friend, Smith,” I begin, watching closely to see if his mind responds to this name. I know that Smith is common in England, and think he will surely know some one so called. “Smith mentioned you.”

But no, there is no gleam of recognition.

“Indeed,” is all he remarks, very calmly.

There is no help for it, I must go on.

“I intended to call upon you some day this week. I have heard you highly spoken of—'The great Fisher,' 'The famous Fisher.' Indeed, sir, I assure you, your name is a household word in Scotland.”

I choose Scotland because I know its accent is different from English. My own also is different. Therefore I shall be Scotch. Unhappy selection!

“Do you mean to pretend you are Scotch?” says Fisher, frowning as well as breathing at me.

I must withdraw one foot.

“Half Scotch, half Italian,” I reply.

Ah, France, why did I deny you? I was afraid to own you, I blush to confess it. And I was righteously punished.

“Italian?” says he, with more interest. “Ah, indeed!”

He stares more intently, frowns more portentously, and respires more loudly than ever.

“A charming country,” I say.

“No doubt,” says Fisher.

At this moment the door opens behind him and a lady appears. She has a puffy cheek, a pale eye, a comfortable figure, a curled fringe of gray hair, and slightly projecting teeth; in a word, the mate of Fisher. There can be no mistake, and I am quick to seize the chance.

“My dear Mrs. Fisher!” I exclaim, advancing towards her.

With a movement like a hippopotamus wallowing, Fisher places himself between us. Does he think I have come to elope with her?

I assume the indignant rôle.

“Mr. Fisher!” I cry, much hurt at this want of confidence.

“Who is this gentleman?” asks Mrs. Fisher, looking at me, I think, with a not altogether disapproving glance.

“Ask him,” says Fisher.

“Madame,” I say, with a bow, “I am an unfortunate stranger, come to pay my respects to Mr. Fisher and his beautiful lady. I wish you could explain my reception.”

“What is your name?” says Mrs. Fisher, with comparative graciousness, considering that she is a bourgeois Englishwoman taken by surprise, and fearing both to be cold to a possible man of position and to be friendly with a possible nobody.

A name I must have, and I must also invent it at once, and it must be something both Scotch and Italian. I take the first two that come into my head.

“Dugald Cellarini,” I reply.

They look at one another dubiously. I must put them at their ease at any cost.

“A fine picture,” I say, indicating the portrait of my host, “and an excellent likeness. Do you not think so, Mrs. Fisher?”

She looks at me as if she had a new thought.

“Are you a friend of the artist?” she asks.

“An intimate,” I reply with alacrity.

“We have informed Mr. Benzine that we specially desired him not to bring any more of his Bohemian acquaintances to our house,” says the amiable lady.

I am plunging deeper into the morass! Still, I have at last accounted for my presence.

“Mr. Benzine did not warn me of this, madame,” I reply, coldly. “I apologize and I withdraw.”

I make a step towards the door, but the large form of Fisher still intervenes.

“Then Benzine sent you?” he says.

“He did, though evidently under a misapprehension.”

“And what about Smith?” asks Fisher, with an approach to intelligence in his bovine eye.

“Well, what about him?” I ask, defiantly.

“Did he send you, too?”

“My reception has been such that I decline to give any further explanations.”

“That is all very well,” says Fisher—“that is all very well—”

He is evidently cogitating what is all very well, when we hear heavy steps in the passage.

“They have come at last!” he exclaims, and opens the door.

“More visitors!” I say to myself, hoping now for a diversion. In another moment I get it. Enter the butler and two gigantic policemen.

“'Let me out,' said the mouse, 'I do not care for this cheese.'”

—Fables of Laetertius.

ICTURE now this comedy and its actors. Fisher of the porpoise habit, Mrs. Fisher of the puffy cheek, poor Dugald Cellarini, and these two vast, blue-coated, thief-catching “bobbies” (as with kindly humor the English term their police); all save Dugald looking terribly solemn and important. He, poor man, strove hard to give the affair a lighter turn, but what is one artist in a herd of Philistines? I was not appreciated; that is the truth. A man may defy an empire, a papal bull, an infectious disease, but a prejudice—never! “Constable,” says Fisher, “I have caught him.” Both bobbies look at me with much the same depressing glance as Fisher himself.

“Yes, sir,” says one, in what evidently was intended for a tone of congratulation. “So I see.”

The other bobby evidently agrees with this sentiment. Wonderful unanimity! I have noticed it in the Paris gendarmes also, the same quick and intelligent grasp of a situation.

The latter quality was so conspicuous in my two blue-coated friends that I named them instantly Lecoq and Holmes.

Holmes speaks next, after an impressive pause.

“What's he done?”

“That is the point,” says Fisher, in a tone of such damaging insinuation that I am spurred to my defence.

“Exactly—what have I done?”

“He has endeavored to effect an entry into my house by removing a pane of glass,” says Fisher.

“Pardon me; to call the attention of the servants by rapping upon a pane of glass.”

“Come now, none of that!” says Lecoq, with such severity that I see the situation at once. He is jealous. I have cast an imputation on some fair housemaid—the future Mrs. Lecoq, no doubt.

“An assignation, you think?” I ask, with a reassuring smile.

“Sir!” cries Mrs. Fisher, indignantly. “It was my daughter's window you broke!”

Shall I pose as the lover of Miss Fisher? I have heard that unmarried English girls take strange liberties.

“Your fair daughter—” I begin.

“Is a child of fifteen,” interrupts virtuous Mrs.

Fisher, “and I am certain knows nothing of this person.”

By the expression of their intelligent countenances, Holmes and Lecoq show their concurrence in this opinion.

“Confront her with me!” I demand, folding my arms defiantly.

It has since struck me that this was a happy inspiration, and in the right dramatic key. Unfortunately, it requires an imaginative audience, and I had two Fishers and two bobbies.

Rapidly I had calculated what would happen. The fair and innocent maiden should be aroused from her virgin slumbers; with dishevelled locks, and in a long, loose, and becoming drapery of some soft color (light blue to harmonize with her flaxen hair, for instance), she should be led into this chamber of the inquisition; then my eye should moisten, my voice be as the lute of Apollo, and it would be a thousand francs to a dishonored check that I should melt her into some soft confession. Not that I should ask her to compromise her reputation to save me. Never, on my honor, would I permit that. Indeed, if my plight tempted her to invent a story she might repent of afterwards, I should disavow it with so sincere and honest an air that my captors would exclaim together, “We have misjudged him!”

No, I should merely persuade her to confess that a not ill-looking foreigner had pursued her with glances of chivalrous admiration for some days past, and that from his air of hopeless passion it was not surprising to find him to-night tapping upon her window-pane.

Alas, that so promising a scheme should fail through the incurable poverty of the Fisher spirit! My demand is simply ignored.

“What acquaintance have you with my daughter?” asks Mrs. Fisher, icily.

“You will respect my confidence?” I ask, earnestly.

“We shall use our discretion,” replies the virtuous lady.

“Quite so; we shall use our discretion,” repeats her unspeakable husband.

“I am satisfied with your assurance,” I say. “The discretion of a Fisher is equivalent to the seal of the confessional. I thank you from my heart, and I bow to your judgment.”

“What do you know of my daughter?” Mrs. Fisher repeats, quite unmoved by my candor.

“Madame, I was about to tell you. You asked if I was acquainted with that charming, and, I can assure you on my honor, spotless young lady?”

“I did,” says Mrs. Fisher; “but I do not require any remarks on her character from you, sir.”

“Pardon me; they escaped me inadvertently What I feel deeply I am tempted to say. I do not know Miss Fisher personally. I have not yet ventured to address a word to her, not so much as a syllable, not even a whisper. My respect for her innocence, for her youth, for her parents, has been too great. But this I confess: I have for days, for weeks, for months, followed her loved figure with the eye of chaste devotion! On her walks abroad I have been her silent, frequently her unseen, attendant. Through every street in London I have followed the divine Miss Fisher, as a sailor the polar star! To-night, in a moment of madness, I approached her home; I touched her window that I might afterwards kiss the hand that had come so near her! In my passion I touched too hard, the pane broke, and here I stand before you!”

So completely had I been carried away on the wings of my own fancy that once or twice in the course of this outburst I had committed myself to more than I had any intention of avowing. Be emphatic but never definite, is my counsel to the liar. But I had, unluckily, tied myself to my inventions. The gestures, the intonation, the key of sentiment were beyond criticism; but then I was addressing Mr. and Mrs. Fisher, of Chickawungaree Villa.

They glance at one another, and Lecoq glances at them.

He, honest man, merely touches his head significantly and winks in my direction. The Fishers are not, however, content with this charitable criticism.

“My daughter only returned from her seminary in Switzerland four days ago,” says Mrs. Fisher.

“And she has never visited the streets of London except in Mrs. Fisher's company,” adds her spouse, with a look of what is either dull hatred or impending apoplexy.

Even at that crisis my wits did not desert me.

“My faith!” I cry, “I must be mistaken! It is not, then, Miss Fisher whom I worship! A thousand pardons, sir, and I beg of you to convey them to the lady whom I disturbed under a misapprehension!”

At this there is a pause, nobody volunteering to run with this message to the bedside of Miss Fisher, though I glance pointedly at Holmes, and even make the money in my pocket jingle. At last comes a sound of stifled air trying to force a passage through something dense. It proceeds, I notice, from my friend Fisher. Then it becomes a more articulate though scarcely less disagreeable noise.

“I do not believe a word you say, sir!” he booms.

“My friend, you are an agnostic,” I reply, with a smile.

Fisher only breathes with more apparent difficulty than ever. He is evidently going to deal a heavy blow this time. It falls.

“I charge this person with being concerned in the burglary at Mrs. Thompson's house last night, and with trying to burgle mine,” says he.

He pauses, and then delivers another:

“He has confessed to being an Italian.”

The constables prick up their ears.

“The organ-grinder!” exclaims Holmes, with more excitement than I had thought him capable of.

“The man as made the butler drunk and gagged the cook!” cries Lecoq.

Here is a fine situation for a political fugitive! I am indignant. I am pathetic. 'No use. I explain frankly that I came to see Mr. Hankey. That only deepens suspicion, for it seems that the excellent Hankey inhabited Mount Olympus House next door for only three weeks, and departed a month ago without either paying his rent or explaining the odor of dead bodies proceeding from his cellars. Doubtless my French friends had acted for the best in sending me to him, but would that he had taken the trouble to inform them of his change of address! And then, why had I ever thought of being an Italian? It appeared now that a gentleman of that nationality, having won the confidence of the Thompson children and the Thompson servants by his skill upon the hand-organ, had basely misused it in the fashion indicated by Lecoq. Certainly it was hard to see why such a skilled artist should have returned the very next night to a house three doors away, and then bungled his business so shamefully; but that argument is beyond the imagination of my bobbies. In fact, they seem only too pleased to find a thief so ready to meet them half-way.

“Thank you, sir,” says Holmes, at the conclusion of the painful scene. “We shouldn't mind a drop.”

This means that they are about to be rewarded for their share in the capture by a glass of Fisher's ale. And I? Well, I am not to have any ale, but I am to accompany them to the cells, and next morning make my appearance before the magistrate on one charge of burglary and another of attempted burglary.

I cannot resist one parting shot at my late host.

“Yes, Fisher,” I remark, critically, showing no hurry to leave the room, “I like that portrait of you. It has all your plain, well-fed, plum-pudding appearance, without your unpleasant manner of breathing and your ridiculous conversation—and it is not married to Mrs. Fisher.”

To this there is no reply. Indeed, I do not think they recovered their senses for at least ten minutes after I left the room.

“The comedy of the law is probably the chief diversion of the angels.”

—La Rabide.

VER the rest of that night I shall draw a veil. I was taken to Newgate, immured in the condemned cell, and left to my reflections. They were sombre enough, I assure you. Young, ambitious, ardent, I sat there in that foreign prison, without a friend, without a hope. If I state the truth about myself, this excuse will be seized for sending me back to France. And what then? Another prison! If I keep my identity concealed, how shall I prove that I am not the burgling musician?

As you can well imagine, I slept little and dreamed much. I was only thankful I had no parents to mourn my loss, for by this time I had quite made up my mind that the organ-grinder's antecedents would certainly hang me.

I cursed Fisher, I cursed the League, I cursed F. II, that indefatigable conspirator who had dragged me from a comfortable hotel and a safe alias to—what? The scaffold; ah, yes, the scaffold!

It may sound amusing now, when I am still unhanged; but it was far from amusing then, I assure you.

Well, the morning broke at last, and I was led, strongly escorted by the twins Lecoq and Holmes, towards the venerable law-court at Westminster. I recognized the judge, the jury, the witnesses, and the counsel, though my thoughts were too engrossed to take a careful note of these. In fact, in writing this account I am to some extent dependent on reports of other trials. They are all much the same, I understand, differing chiefly as one or more judges sit upon the bench.

In this case there was only one, a little gentleman with a shrewd eye and a dry voice—a typical hanging judge, I said to myself. I prepared for the worst.

First comes the formal accusation. I, giving the name of Dugald Cellarini am a blood-thirsty burglar. Such, in brief, is the charge, although its deadly significance is partly obscured by the discreet phraseology of the law.

Then my friend Holmes enters the box, stiff and evidently nervous, and in a halting voice and incoherent manner (which in France would inevitably have led to his being placed in the dock himself) he describes the clever way I was caught by himself and the astute Lecoq. So misleading is his account of my guilty demeanor and suspicious conduct, that I instantly resolve to cross-examine him. Politely but firmly I request the judge's permission. It is granted, and I can see there is a stir of excitement in the court.

“Did I struggle with you?” I ask.

Holmes, turning redder than ever, admits that I did not.

“Did I knock you down? Did I seek to escape?”

No, Holmes was not knocked down, nor had I tried to escape from the representatives of the law.

“And why, if I was a burglar, did I not do these things?”

“You wasn't big enough,” says Holmes.

Well, I admit he had the advantage of me there. The court, prejudiced against me as they were, laughed with Holmes, but at the next bout I returned his lunge with interest.

“What did Fisher give you to drink?” I ask.

The question is dismissed by my vindictive judge as irrelevant, but I have thrown Holmes into great confusion and made the court smile with me.

“That is all,” I say, in the tone of a conqueror, and thereupon Lecoq takes the place of Holmes, and in precisely the same manner, and with the same criminal look of abasement, repeats almost exactly the same words.

Against him I design a different line of counterattack. I remember his jealousy when I spoke of the servants, and, if possible, I shall discredit his testimony by an assault upon his character. Assuming an encouraging air, I ask:

“You know the servants at Fisher's house?”

He stammers, “Yes.”

“With one in particular you are well acquainted?”

He looks at the judge for protection, but so little is my line of attack suspected that the judge only gazes at us in rapt attention.

“I do,” says Lecoq, after a horribly incriminating pause.

“Now tell me this,” I demand, sternly. “Have you always behaved towards her as an honorable policeman?”

Would you believe it? This question also is disallowed! But I think I have damaged Lecoq all the same.

Next comes Fisher, red-faced, more pompous than ever, and inspired, I can see, with vindictive hatred towards myself. It appears that he is a London merchant; that his daughter heard a tapping on her window and called her father; that he and his servant caught me in the act of entering the chaste bedchamber through a broken window.

At this point I ask if I may put a question. The judge says yes.

“How much glass fell out?” I ask.

“Half a pane,” says he.

“And the rest stayed in?”

He has to admit that it did; very ungraciously, however.

“How many panes to the window?”

He cannot answer this; but the judge, much to my surprise, comes to the rescue and elicits the fact that there are six.

“How far had I gone through a twelfth of your window?” I ask.

His face gets redder, and there is a laugh through the court. I feel that I have “scored a try,” as they say, and my spirits begin to rise again.

But, alas! they are soon damped. Mrs. Thompson's butler steps into the witness-box, and a more shameless liar I have never heard. Yes, he remembers an organ-grinder coming to the house on various occasions during the past fortnight. Here I interpose.

“What did he play?” I ask.

“Not being interested in such kinds of music, I cannot say.”

“Possibly you have a poor ear?” I suggest.

“My ear is as right as some people's, but it has not been accustomed to the hand-organ,” says the butler, with a magnificence that seems to impress even the judge.

“You should have it boxed, my friend,” I cannot help retorting, though I fear this does not meet the unqualified approval of the judge.

Next he is asked for an account of his dealings with the musician when that gentleman visited the kitchen upon the night of the burglary, and it appears that, shortly after the grinder's departure, he lost consciousness with a completeness and rapidity that can only have been caused by some insidious drug surreptitiously introduced into the glass of beer he happened to be finishing at that moment. He scorns the insinuation (made by myself) that he and the musician were drinking together; he would not so far demean himself. That outcast did, however, on one occasion, approach suspiciously near his half-empty glass.

“Well,” I remark, with a smile, “the moral Is that next time you should provide your guests with glasses of their own.”

Again I score, but quickly he has his revenge. Does he recognize me as the organ-grinder? he is asked. He is not sure of the face, not taking particular notice of persons of that description, but—he is ready to swear to my voice!

It seems, then, that I have the same accent as an Italian organ-grinder! I bow ironically, but the sarcasm, I fear, is lost.

“What is so distinctive about this voice I share with your Italian boon companion?” I inquire, suavely.

He evidently dislikes the innuendo, but, in the presence of so many of his betters, decides to retaliate only by counter-sarcasm. “It's what I call an unedicated voice,” says he.

“Uneducated Italian or uneducated English?” I inquire.

“Italian,” he replies, with the most consummate assurance.

“You know Italian?”

“Having travelled in Italy, I am not altogether unfamiliar,” he answers.

I then put to him a simple Italian sentence.

“What does that mean, and is it educated or uneducated?” I ask.

“It means something that I should not care for his lordship to hear, and is the remark of a thoroughly uneducated person,” he retorts.

The court roars, and some even cheer the witness. For myself, I am compelled to join the laughter—the impudence is so colossal.

“My lord,” I say to the judge, “this distinguished scholar has so delicate a mind that I should only scandalize him by asking further questions.”

So the butler retires with such an air of self-satisfaction that I could have shot him, and the gagged cook takes his place.

This young woman is not ill-looking, and is very abashed at having to make this public appearance. It appears that her glimpse of the burglar was brief, as with commendable prudence he rapidly fastened her night-shift over her head, but in that glimpse she recognized my mustache!

“Could she tell how it felt?” I ask.

The point is appreciated by the court, though not, I fear, by the judge, who looks at me as though calculating the drop he should allow. Yes, it is all very well to jest about my mustache, but to be hanged by it, that is a different affair. And the case is very black against me.

“Has the prisoner any witnesses to call?” asks the judge.

“No,” I reply, “but I shall make you a speech.”

And thereupon I delight them with the following oration, an oration which should have gone on much longer than it did but for a most unforeseen interruption.

“My lord, the jury, and my peers,” I begin—remembering so much from my historical stories—“I am entirely guiltless of this extraordinary and infamous charge. No one but such a man as Fisher would have brought it!” [Here I point my finger at the unhappy tenant of Chickawungaree.]

“No one else of the brave English would have stooped to injure an innocent and defenceless stranger! As to the butler and the cook, you have seen their untruthful faces, you have heard their incredible testimony. I say no more regarding them. The policemen have only shown that they found me an unwilling and insulted—though invited—guest of the perfidious Fisher. What harm, then? Have you never been the unwilling guests of a distasteful host?

“Who am I? Why did I visit such a person as Fisher? I shall tell you. I am a French subject, a traveller in England. Only yesterday I arrived in London. How can I, then, have burgled Madame Thompson? Impossible! Absurd! I had not set my foot upon the shores of England—”

At this point the judge, in his dry voice, interrupts me to ask if I can bring any witnesses to prove this assertion.

“Witnesses?” I exclaim, not knowing what the devil to add to this dramatic cry, when, behold! I see, sent by Providence, a young man rising from his seat in the court. It is my fair-haired fellow-passenger!

“May I give evidence?” says he.

“Though your name be Iscariot, yes!” I cry.

The judge frowns, for it seems the demand was addressed to him and not to me; but he permits my acquaintance to enter the box. And now a doubt assails me. What will he say? Add still more damaging testimony, or prove that I am the harmless Bunyan?

He does neither, but in a very composed and assured fashion, that carries conviction with it, he tells the judge that he travelled with me from Paris on the very night of the crime, adding that I had appeared to him a very harmless though somewhat eccentric person. Not the adjectives I should have chosen myself, perhaps; but, I assure you, I should have let him call me vulgar or dirty without a word of protest.

Of course it follows that I cannot be the musical burglar, while as for my friend Fisher, that worthy gentleman is so disconcerted at the turn things have taken that he seems as anxious to withdraw his share of the charge as he was to make it.

I am saved; the case breaks, down.

“How's that?” says the judge.

“Guiltless!” cries the jury.

And so I am a free man once more, and the cook must swear to another mustache.

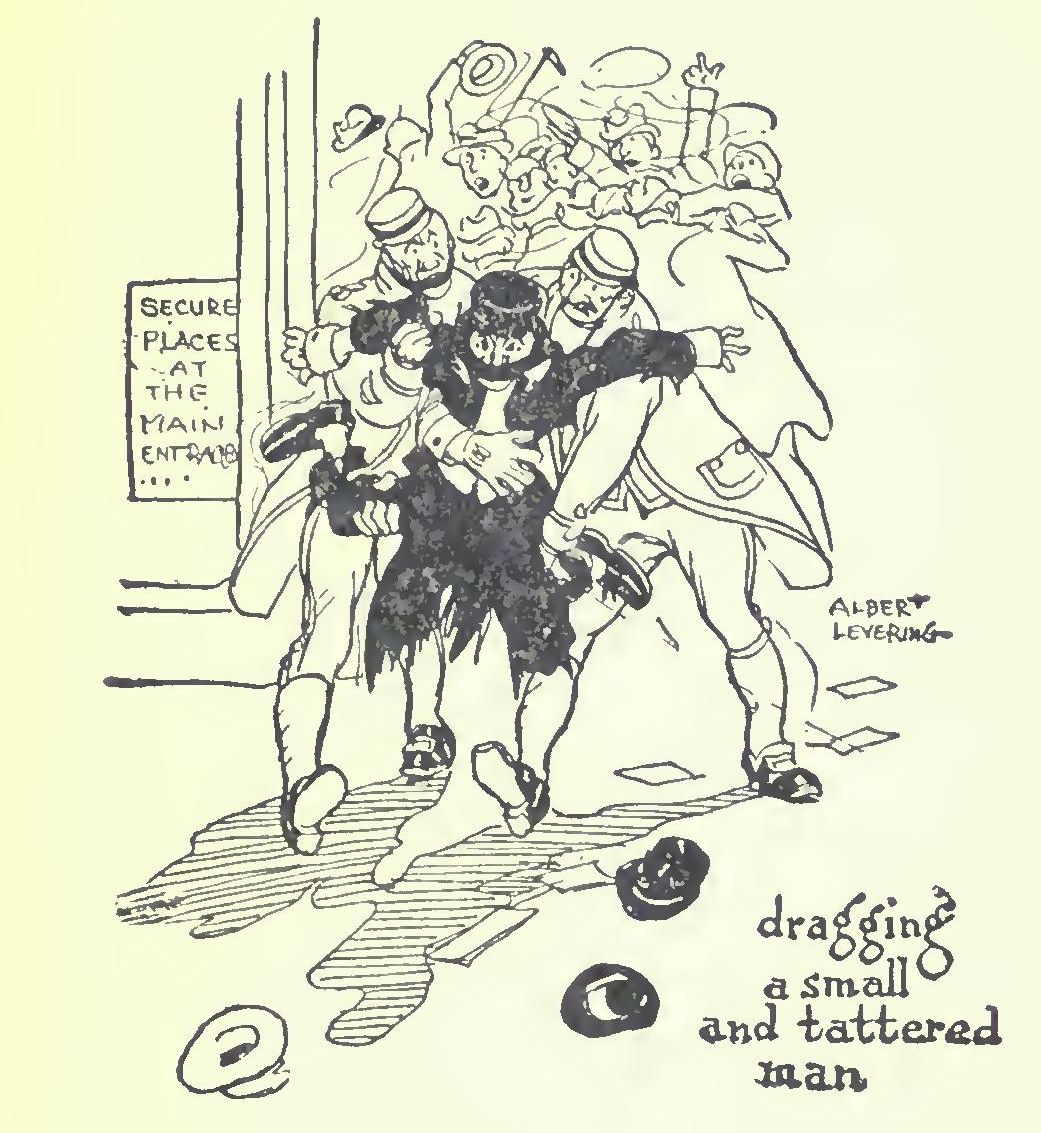

The first thing I do is to seize my witness and drag him from the court, repeating my thanks all the while.

“But how did you come to be in court?” I ask.

“Oh, I happen to be a barrister!” he explains. “I came in about another case, and, finding you'd been burgling, I thought I'd stay and see the fun.”

“Your case must take care of itself; come and lunch with me.”

Yes, he can escape. His case will not come on to-day, as mine has taken so long; and so we go forth together to begin a friendship that I trust may always endure.

And to this day I have never paid for Fisher's broken pane of glass.

“On earth men style him 'Richard,''

But the gods hail him 'Dick.'”

—An English Poet (adapted).

FRIEND in need.” say the English, “is a friend indeed. And who could be more in need of a friend than I at that moment? It was like the rolling up of London fog-banks and the smile of the sun peeping through at last. No longer was I quite alone in my exile. If you have ever wandered solitary through an unknown city, listened to a foreign tongue and to none other, eaten alien viands, fallen into strange misadventures, and all without a single friendly ear to confide your troubles to, you will sympathize with the joyous swelling of my heart as I faced my barrister at that luncheon.

And he, I assure you, was a very other person from the indifferent Englishman of the journey. The good heart was showing through, still obscured as it was by the self-contained manner and the remnants of that suspicion with which every Briton is taught to regard the insinuating European.

I have already given you a sketch of his exterior—the smooth, fair hair, the ruddy cheek, the clear eye, and, I should add, the compressed and resolute mouth; also, not least, the admirable fit of his garments. Now I can fill in the picture: Name, to begin with, Richard Shafthead; younger son of honest, conservative baronet; eldest brother provided with an income, I gather, Dick with injunctions to earn one. Hence attendance at courts of justice, a respectable gravity of apparel, and that compression of the lips. In speech, courteous upon a slight acquaintance, though without any excessive anxiety to please; on greater intimacy, very much to the point without regarding much the susceptibilities of his audience. Yet this bluntness was, tempered always by good-fellowship, and sometimes by a smile; and beneath it flowed, deep down, and scarcely ever bubbling into the light of day, a stream of sentiment that linked him with the poetry of his race. My friend Shafthead would have laughed outright had you told him this. Nevertheless this secret is the skeleton in the respectable English cupboard. Your John Bull is an edifice of sentiment jealously covered by a hoarding on which are displayed advertisements of pills and other practical commodities. It is his one fear lest any one should discover this preposterous and hideous erection is not the real building.

Dick's only comment on the above statement would probably be that I had mixed my metaphors or had exceeded at lunch. But he is shrewd enough to know in his heart that I have but spoken the truth, even though my metaphors were as heterogeneous as the ark of Noah. How else can you explain the astonishing contrast between those who write the songs of England and those whose industry enables them to recompense the singers?

No doubt there is a noticeable difference between the poet and the people in every land and every race, but in England it is so staggering. The hair of the English poet is so very long, his eye so very frenzied, his voice so steeped in emotion, so buoyed by melody. Even his prose appeals to the heart rather than to the head. Thackeray weeps as he writes of good women; Scott blushes as he writes of bad. No one is cynical but the villains. The heroines are all pure as the best cocoa.

Then look at the check suits and the stony eyes of Mr. Cook's protégées. Do they understand what Tennyson has written for them? If not, why do they pay for it?

John Bull and John Milton; William Bull and William Shakespeare; Lord Bull and Lord Byron; Charles Bull and Charles Dickens; how are these couples related? By this religious, moral, sentimental stream; welling in one, hidden in another under ten tons of shyness and roast beef; a torrent here, a trickle there, sometimes almost dry in a dusty season. That is how.

Does Dick again recommend teetotalism as a cure for these speculations? Come with me to your rooms, my friend, and let us glance through your library.

I take up a volume of Shakespeare and find it contains the sonnets.

“Ah, Shakespeare's sonnets,” I say, with an air of patronage towards that eminent poet. “You know them?”

“Used to know 'em a little.” He is giving me another taste of that characteristic British stare. Evidently he is offended by my tone, and will fall an easy victim to my next move.

“They are much overrated,” I say, putting the book away.

“You should write to the Times about it,” he replies, sarcastically, and then adds, with conviction, “They are about the finest things in English.”

“Yet no Englishman reads them,” I remark, lightly.

“I used to know half a dozen of 'em by heart,” he retorts.

Half a dozen of those miracles of sensuous diction off by heart! Prosaic Briton! I do not say this aloud, but take next the songs of Kipling, and profess not to understand one of them. To convince me it is not mere nonsense, he reads and expounds.

He has been round the world, and shot wild beasts on the veldt and in the jungle, and can explain allusions and share exotic sentiments.

Is this man mere plum-pudding and international perfidy, who feels thus the glamour of the song?

“Ah, here is a novel of Zola!” I exclaim. “You enjoy him, of course?”

“A filthy brute,” says Dick. “I read half of that, and I am keeping it now for shaving-papers.”

There is perhaps more strength of conviction than critical judgment in this comment. I might retort that all the water in the world neither has been passed through a filter nor foams over a fall, and that the pond and the gutter have their purpose in the world. I do not make this reply, however; I merely note that a strong sentiment must underlie a strong prejudice.

As you will perhaps have gathered, my good Dick had his limitations. He could be sympathetic; if, for instance, he were to see me insulted, beaten, robbed of my purse and my mistress, and blinded in one eye, he would, I am sure, feel for me deeply, and show himself most tactful in his consolation. But it would require some such well-marked instance to open the gates of his heart; and in minor matters I should not dream of applying to him, unless, indeed, it was a practical service he could perform.

He himself had held his peace and confided in no one when his fair cousin married the wealthy manufacturer of soda-water, and his heart had long since healed. In the days of his wild oats, when duns were knocking at his door, he had retired from St. James Street to a modest apartment in the Temple, sold such of his effects as were marketable, and philosophically sought a cheap restaurant and a coarser tobacco. His debts were now paid and all was well again. When he did not get the degree he was expected to at Oxford, he may have said “damn,” but I doubt if he enlarged on this observation. What did that disappointment matter to-day? Then why should other people make a fuss if they were hurt?

Yet his heart was as a child's if you could extract it from its wrappings of tin-foil and brown paper, and I am happy I knew him long enough to see him “play the fool,” as he would term it.

On that first afternoon of our acquaintance I found him courteous before lunch, genial after (I took care to “make him proud.” as the English say). I was perfectly frank; told him my true name, the plot that had miscarried, my flight to England—everything.

“I am not Bunyan, I am not even Cellarini, but merely Augustine d'Haricot, eternally at your service,” I said. “You have saved me from prison, perhaps from the scaffold.”

He laughed.

“It wouldn't have been as bad as that, but I'm glad to have been of any use.”

And then changing the subject, as an Englishman does when complimented (for they hold that either you lie and are a knave, or tell the truth and are a fool), he asked:

“What are you going to do now?”

“That depends upon your advice,” I replied. “What is my danger? How wise is it to move freely in this country?”

“There is no danger at all if it is only a political offence,” he answered. “Unless you've been picking pockets, or anything else as well.”

I answered him I had not, and he promised to inquire into the case and give me a full assurance on the next morning.

“And now,” I said, “tell me, my friend, how to live as an Englishman. I do not mean to adopt the English mind, the English sentiment, but only to move in your world, so long as I must live in it. I want to see, I want to hear, I want to record my impressions and my adventures. As the time is not ripe to wield the sword, I shall wield the eyes and the pen. Also, I shall doubtless fall in love, and I should like to hunt a fox and shoot a pheasant.”

We laughed together at this programme; in brief, we made a good beginning.

That afternoon we set out together to look for suitable apartments for myself, and by a happy chance we had hardly gone a hundred paces before we spied a gentleman approaching us whom Shafthead declared to be a veritable authority on London life; also a cousin of his own.

“But will he not be busy?” I inquired.

“Young devil,” answered Shafthead, “it will serve to keep him out of mischief for an hour or two.”

Thereupon I was presented to Mr. Teddy Lumme, a young gentleman of small stature, with a small, cheerful, clean-shaven, dark face, and a large hat that sloped backward and sideways towards a large collar. His elbows moved as though he were driving a cab; his boots shone brightly enough to serve for mirrors; his morning-coat was cut in imitation of the “pink” of a huntsman; a large mass of variegated silk was fastened beneath his collar by a neat pearl pin; in a word, he belonged to a type that is universal, yet this specimen was unmistakably English. In age I learned afterwards that he was just twenty-five, emancipated for little more than a year from the University of Oxford, and still enjoying the relief from the rigorous rules of that institution. No accusation of reticence to be made against Mr. Lumme! He talked all the time, cheerfully and artlessly.

“You want rooms?” he said. “Quelle chose? I mean, don't you know, what kind? I don't know much French, I'm afraid. Oh, you talk English? Devilish glad to hear it. I say, Dick, you remember that girl I told you of? Well, it's just as I said. I knew, damn it all. What do you want to give?” (This to me.) “You don't care much? That simplifies matters.”

In this strain Mr. Lumme entertained us on our way, Shafthead regarding him with a half-amused, half-sardonic grin, of which his relative seemed entirely oblivious, while I enjoyed myself amazingly. I felt like Captain Cook on the gallant Marchand palavering with the chiefs of some equatorial state.

“I demand a cold bath and an English servant,” I said. “Anything else characteristic you can add, but those are essential.”

I do not know whether Lumme quite understood this to be a jest. He took me to three sets of apartments, and at each asked first to be shown the bathroom, and then the servant, after which he inquired the price, and whether a tenant was at liberty to introduce any guest at any hour.

Finally, to end the story of that day, which began in jail and ended so merrily, I found myself the tenant of a highly comfortable set of apartments, with everything but the valet supplied at an astonishingly high price.

“However,” I said to myself, “it may be expensive, but it is better than ten years' transportation for burgling Fisher!”

“Little, cheerful, and honest—do you not know the species?”

—Kovaleffski.

HAD left my hotel and settled in my apartments; the labels with “Nelson Bunyan” were removed from my luggage; I had been assured that so long as I remained on English soil I was safe. Next thing I must find a servant; one who should “know the ropes” of an English life. Lumme had promised to make inquiries for me, and I had impressed upon him that the following things were essential—in fact, I declared that without them I should never entertain an application for one instant. First, he must be of such an appearance as would do me credit, whether equipped in the livery I had already designed for him, in the cast-off suits I should provide him with, or in the guise of an attendant at the chase or upon the moors. Then, that he must be honest enough to trust in the room with a handful of mixed change, sober enough to leave alone with a decanter, discerning enough to arrange an odd lot of sixteen boots into eight pairs, cleanly enough to pack collars without soiling them. Finally, he must be polite, obliging, industrious, discreet, and, if possible, a little religious—not sufficiently so to criticise my conduct, but enough to regulate his own.

I wrote this list down and handed it to the obliging Teddy.

“You will procure him by this afternoon?” I said.

“I know a man who keeps a Methodist footman in his separate establishment,” answered Lumme, after a moment's reflection. “That's the kind of article you require, I suppose. If you get 'em too moral there's apt to be a screw loose somewhere, and if you get 'em the other way the spoons go. Well, I can't promise, but I'll do my best.”

So this amiable young man departed, and I, to pass the time, walked into Piccadilly, and there took my seat once more upon the top of an omnibus to enjoy the sunshine, and be for a time a spectator of the life in the streets. To obtain a better view I sat down on the front bench close to the driver's elbow, and we had not gone very far before this individual turned to me and remarked with a cordiality that pleased me infinitely, and a perspicacity that astonished me:

“Been long in London, sir?”

“You perceive that I am a stranger, then?” I asked.

“Well,” said the man, as he cracked his whip and drove his lumbering coach straight at an orifice between two cabs just wide enough, it seemed to me, for a wheelbarrow, “I'm a observer, I am. When I sees that speckled tie droopin' from a collar of unknown horigin, and them rum kind of boots, I says to myself a Rooshian, for 'alf a sovereign. Come from Rooshia, sir?”

The man's naïveté delighted me.

“I belong to an allied power,” I replied, wondering if his powers of observation would enable him to decide my nationality now.

He seemed to debate the question as, with an apropos greeting to each cabman, his 'bus bumped them to the side and sailed down the middle of the street.

“Native o' Manchuria, perhaps?” he hazarded.

“Not quite; try again.”

“Siberia?” he suggested next.

Seeing that either his imagination or my appearance confined his speculations to Asia, I told him forthwith that I was French.

“French?” he said. “Well, now I'm surprised to 'ear it, sir. If you'll excuse me saying so, you don't look like no Frenchman.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“I always thought they was little chaps, no bigger than a monkey. Why, you're quite as tall as most Englishmen.”

Considering that my friend could not possibly have measured more than five feet, two inches, and that I am five feet, nine inches, in my socks, I was highly diverted by this.

“Have you seen many Frenchmen?” I asked him. “I knew one once,” he replied, after a minute or two's thought, and a brief interruption to invite some ladies on the pavement to enter his 'bus. “'E was a waiter at the Bull's 'Ead, 'Ighbury. I drove a 'bus that way then, and there was a young lady served in the bar 'im and me was both sweet on. Nasty, greasy little man 'e was—meaning no reflection on you, sir. They couldn't make out where the fresh butter went, and when 'e left—which 'e 'ad to for kissing the missis when she wasn't 'erself, 'aving 'ad a drop more than 'er usual—do you know what they found, sir?”

I confessed my inability to guess this secret. “Why, 'e'd put it all on 'is beastly 'air, two pounds a week, sir, of the very best fresh butter in 'Ighbury. Perhaps, sir, I've been prejudiced against Frenchmen in consequence.”

I admitted that he had every excuse, and asked him whether my buttered compatriot had won the maiden's affections in addition to his other offences.

“No, sir,” said he, “I'm 'appy to say she 'ad more sense. More sense than to take either of us,” he added, with a deep sigh, and then, as if to quench melancholy reflections, hailed another driver who was passing us in the most hilarious fashion.

“'Old your 'at on, ole man!” he shouted. “Them opera-'ats is getting scarce, you know!”

The other driver, a bottle-nosed man, redeemed only from unusual shabbiness by the head-gear in question, winked, leered, and made some reply about “not 'aving such a fat head underneath it as some people.”

My friend turned to me with a confidential air. “You saw that gentleman as I addressed?” he said, in an impressive voice. “Well, that man was driving 'is own kerridge not five years ago. On the Stock Exchange 'e was, and worth ten thousand a year if 'e was worth a penny; 'ouse in Park Lane, and married to the daughter of a baronite. 'E's told me all that 'isself, so it's true and no 'umbug.

“'Ow did 'e lose 'is money? Hunfortunit speculations and consols goin' down; but you, being a furriner, won't likely understand.”

Looking as unsophisticated as possible, I pressed my friend for an explanation of these mysteries.

“Well,” said he, “it's something like this: If you goes on the Stock Exchange you buys what they calls consols—that's stocks and shares of various sorts and kinds, but principally mines in Australia, and inventions for to make things different from what they is at present. That's what's called makin' a corner, which ain't a corner exactly in the usual sense—not as used in England, that's to say, but a kind o' American variety.

“What, O Bill! Bloomin', thank you. 'Ow's yourself?” (This to another driver passed upon the road.)

“As I was savin', sir, this 'ere pore friend o' mine speculated in consols, and prices being what they calls up, and then shiftin', he loses and the bank wins. Inside o' twenty-four hours that there gentleman was changed from one of the richest men in the city into a pore cove a-looking out for a job like you and me.”

“And he chose driving an omnibus?” I asked. “'Adn't got no choice. He was too much of a gentleman to sink to a ordinary perfession, and drivin' a pair o' 'orses seems to 'im more in keepin' with 'is position than drivin' one 'orse in a cab, which was the only thing left.”

He paused, and then shaking his head with an air of sentiment, continued:

“Wunderful 'ow sensitive he is, sir. He wouldn't part with that there hopera-'at, not if you give him five 'undred pounds; yet he can't a-bear to 'ear it chipped, not except in a kind o' delicate way, same as I did just now. You 'eard me, sir? 'Hop-era-'ats is scarce,' says I; but I dursn't sail closer to the wind nor that. 'E'd say, “Old your jaw, Halfred,' or words to that effec', quick enough. Comes o' being bred too fine for the job, I tells 'im often; I says it to 'im straight, sir.' Comes o' being bred too fine for the job,' says I.”

At this point my friend's attention was called from the romantic history of his fellow-driver to the exigencies of their common profession, and I had an opportunity of studying more attentively this entertaining specimen of the cockney.

He was, as I have said, a very short man, from thirty to thirty-five years of age, I judged, redcheeked and snub-nosed, with a bright, cheerful eye, and the most friendly and patronizing manner. Yet he was perfectly respectful and civil, despite his knowledge of my unfortunate nationality. In fact, it seemed his object to place me as far as possible at my ease, and enable me to forget for a space the blot upon my origin.

“There's some quite clever Frenchmen, I' ve 'eard tell,” he said, presently. “That there 'idro-phobia man—and Napoleon Bonyparty, in his way, too, I suppose, though we don't think so much of 'im over 'ere.”

“I am sorry to hear that, I said.

“Well, sir,” he explained, “we believes in a man 'aving his fair share of what's goin'. Like as if me and a friend goes inter a public 'ouse, and another gentleman he comes in and he says, 'What's it going to be this time?' or, 'Name your gargle, gents,' or words to some such effec'; and we says, 'Right you are, old man,' and 'as a drink at his expense. Now it wouldn't be fair if I says to the young lady, 'I'll 'ave a 'ole bottle of Scotch whiskey, miss, and what I can't drink I'll take 'ome in a noospaper,' and I leaves 'im to pay for all that; would it, sir? Well, that's what Bonyparty done; 'e tried to get more nor his share o' what was goin' in Europe. Not that it affec's us much, we being able to take care of ourselves, but we don't like to see it, sir. That's 'ow it is.”

All this time we had been going eastward into the city of London, and now we were arrived at the most extraordinary scene of confusion you can possibly imagine. I should be afraid to say how many 'buses and cabs were struggling and surging in a small open space at the junction of several streets. Foot-passengers in hundreds bustled along the pavements or dodged between the horses, and, immobile in the midst of it, the inevitable policeman appeared actually to be sifting this mob according to some mysterious scheme.

“Cheer-O,” cried my friend upon the box. “'Ow's the price o' lime-juice this morning?

“That there's wot we calls the Bank, sir, where the Queen keeps 'er money, and the Rothschilds and the like o' them; guarded by seven 'undred of the flower o' the British army, it is, the hofficer bein' hinvariably a millionaire hisself, in case he's tempted to steal. Garn yerself and git yer face syringed with a fire-'ose. You can't clean it no 'ow else. The 'andsome hedifice to your right, sir, is the Mansion 'Ouse; not the station of that name, but the 'ome of the Lord Mayor; kind o' governor of the city, 'e is; 'as a hextraordinary show of 'is own on taking the hoath of hofflce; people comes all the way from Halgiers and San Francisco to see it; camels and 'orses got up like chargers of the holden time, and men disguised so as their own girls wouldn't know 'em. Representing harts, hindustries, and hempire, that's their game. Pleeceman, them there bloomin' whiskers of yours will get mowed off by a four-wheel cab some day, and then 'ow'll you look? Too bloomin' funny, am I? More'n them whiskers is, hinterfering with the traffic like that.”

“Yes, sir, we 'as a rest 'ere for a few minutes; we ain't near at the end yet, though.”

I shall leave it to your judgment to guess which of these remarks were addressed to me and which to various of his countrymen in this vortex of wheels and human beings. For a few minutes he now sat at ease in a quieter street (though, my faith! no street in this city of London but would seem busy in most towns), apparently deliberating what topic to enter upon next. I say apparently deliberating, but on further acquaintance with my good “Halfred,” as he called himself (the aspirated form of “Alfred” used by the cockney Alfred being the name of England's famous monarch), I came to the conclusion that his mind never was known to go through any such process. What came first into his head flew straight to his tongue, till by constant use that organ had got into a state of unstable equilibrium, like the tongue of a toy mandarin, that oscillates for five minutes if you move him ever so gently.

In a word, Halfred was an inveterate chatterbox.