A HISTORY OF SINAI

BY

LINA ECKENSTEIN

AUTHOR OF “WOMAN UNDER MONASTICISM”

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING

CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO.

1921

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

LONDON AND BECCLES.

FOREWORD

In the winter of 1905-6 Professor Flinders Petrie undertook the examination of the Egyptian remains in Sinai. After working at Wadi Maghara he removed into the Wadi Umm Agraf to copy the inscriptions and excavate the temple ruins at Serabit. His work is described in “Researches in Sinai, 1906,” and the inscriptions are in course of publication by the Egypt Exploration Fund. Among the workers at Serabit was myself. I had long been interested in the hermit life of the peninsula and in the growing belief that the Gebel Musa was not the Mountain of the Law. The excavations at Serabit and the non-Egyptian character of the ancient hill sanctuary supplied new material for reflection. In the hours spent in sorting fragments of temple offerings and copying temple inscriptions it occurred to me that we might be on the site which meant so much in the history of religion. Studies made after our return suggested further points of interest. The outcome is this little history which will, I trust, appeal to those who take an interest in the reconstruction of the past and in the successive stages of religious development.

LINA ECKENSTEIN

Easter, 1920.

APPROXIMATE DATING OF EGYPTIAN DYNASTIES

| DYNASTY | |||||||

| I. | b.c. | 5500. | Monument of | Semerkhet | in Sinai | ||

| IV. | ” | 4800. | ” | Khufu | ” | ||

| VI. | ” | 4300. | ” | the Pepys | ” | ||

| XII. | ” | 3600. | Amen-em-hats and Sen-userts | ||||

| XV. | ” | 2500. | Hyksos Conquest | ||||

| ” | ” | Time of Abraham and Joseph | |||||

| XVIII. | ” | 1580. | Amen hotep and Tahutmes | ||||

| ” | 1380. | Akhen-aten (Amen-hotep IV), (?) time of Moses | |||||

| XIX. | ” | 1328 | — | 1202. | Ramessides | ||

| ” | 1300 | — | 1234. | Ramessu II. | |||

RULERS OF PHARAN AND THE CONVENT OF SINAI

LIST TENTATIVELY ENLARGED FROM CHEIKHO

Bishops of Pharan—

Moses.

Natyr.

Macarius.

Photius.

Theodor.

Bishops of Sinai—

Constantine, 869.

Marcus I, 869.

Jorius, 1033.

John I, 1069.

Zacharias, 1103 or 1114.

George, 1133 or 1143.

Gabriel I, 1146.

John II, 1164.

Simeon (Archbishop), 1203-53.

Euthymius, 1223.

Macarius I, 1224.

Germanus I, 1228.

Theodosius, 1239.

Macarius II, 1248.

Simeon (? II), 1258.

John III, 1265.

Arsinius, 1290.

Simeon, 1306.

Dorotheus, 1324-33.

Germanus II, 1333.

Marcus II, 1358.

Job.

Athanasius.

Sabbas.

Abraham.

Gabriel II.

Michael.

Silvanus.

Cyrillus.

Solomon.

Macarius of Cyprus, 1547.

Eugenius, 1565-83.

Anastasius, 1583-92.

Laurentius, 1572-1617.

Joasaph, 1617-58.

(Nectarius)

Ananias (1667-77), 1658-68.

Joannicus I. (1677-1703), 1668-1703.

Cosmas, 1705.

Athanasius of Bari, 1706-18.

Joannicus II of Mytilene, 1718-29.

Nicephorus Mortales, 1729-49.

Constantius I, 1749-59.

Cyrillus II, 1759-90.

Dorotheus of Byzantium, 1794-96.

Constantius II, 1804-59.

Cyrillus III, 1859-67.

Callistratus, 1877-85.

Porphyrius, 1885.

CHIEF AUTHORITIES

For other works and writers see Alphabetical Index and page referred to.

Breasted, J. H., “Ancient Records of Egypt, 1906.”

“Perigraphe of Holy Mount Sinai, 1817.” (In Greek.)

Petrie, W. M. Flinders, “Researches in Sinai, 1906.”

Weill, Raymond, “La Presqu’île de Sinai, 1908.”

Wilson & Palmer, “Ordnance Survey, 1870-71.”

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword | iii | |

| Approximate Dating of Egyptian Dynasties | v | |

| Rulers of Pharan and the Convent of Sinai | vii | |

| Chief Authorities | ix | |

| List of Illustrations | xiii | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | Sinai a Centre of Moon-Cult | 8 |

| III. | The Sanctuary at Serabit | 17 |

| IV. | The Egyptians in Sinai. I. | 30 |

| V. | Early Peoples and Place Names | 41 |

| VI. | The Egyptians in Sinai. II. | 52 |

| VII. | The Israelites in Sinai. I. | 64 |

| VIII. | The Israelites in Sinai. II. | 74 |

| IX. | The Nabateans | 83 |

| X. | The Hermits in Sinai | 94 |

| XI. | The Writings of the Hermits | 106 |

| XII. | The Building of the Convent | 121 |

| XIII. | Mohammad and St. Katherine | 134 |

| XIV. | Sinai during the Crusades | 143 |

| XV. | The Pilgrims of the Middle Ages. I. | 155 |

| XVI. | The Pilgrims of the Middle Ages. II. | 165 |

| XVII. | The Convent between 1500 and 1800 | 173 |

| XVIII. | Sinai in the Nineteenth Century | 183 |

| Alphabetical Index | 195 | |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Fig. | page | |

| 1. | Situation of Sanctuaries | 9 |

| 2. | Figures of Baboons | 11 |

| 3. | Sneferu ravaging the Land | 13 |

| 4. | Khufu smiting the Anu before Thoth | 14 |

| 5. | Amen-em-hat III, Thoth and Hathor | 15 |

| 6. | Sanctuary Surroundings at Serabit | 19 |

| 7. | Figure with Semitic Script | 23 |

| 8. | Plan of Caves at Serabit | 27 |

| 9. | Upper Half of Stele of Amen-em-hat III | 37 |

| 10. | Temple Ruins at Serabit | 53 |

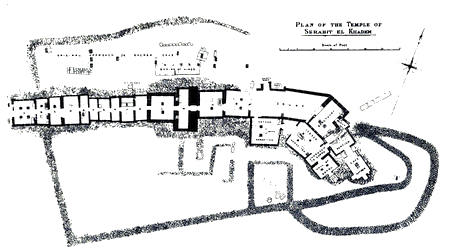

| 11. | Plan of Temple | 55 |

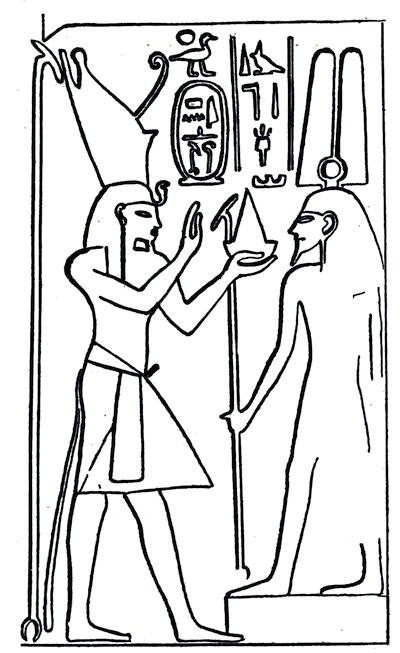

| 12. | Amen-hotep III offering to Sopd | 59 |

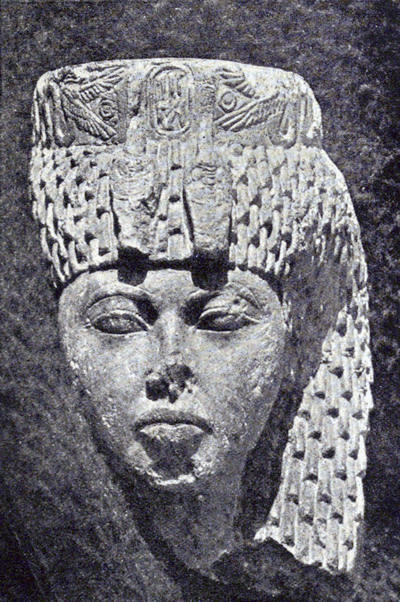

| 13. | Queen Thyi | 61 |

| 14. | Men in Burning Bush | 69 |

| 15. | Ayun Musa | 71 |

| 16. | View of the Convent | 123 |

| 17. | Chapel on Gebel Musa | 141 |

| 18. | El Arish | 145 |

| 19. | Zigiret el Faraun | 149 |

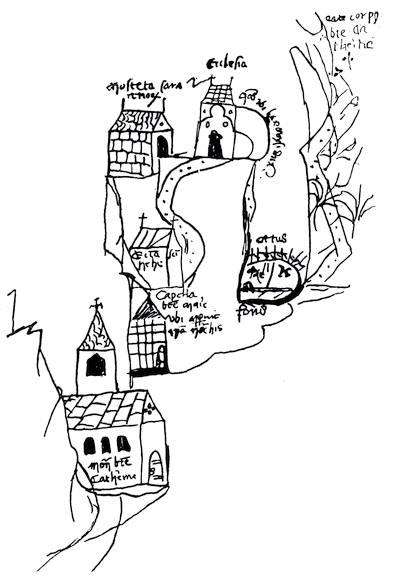

| 20. | Sketch of Convent Surroundings about 1335 | 159 |

| 21. | Ritter von Harff and St. Katherine | 169 |

| 22. | Sulyman abu Sīlm, a Bedawy | 187 |

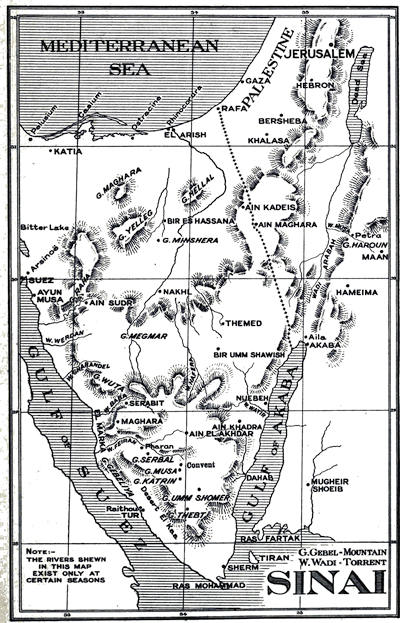

| 23. | Map of the Peninsula | 193 |

A HISTORY OF SINAI

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY[1]

SINAI is the peninsula, triangular in form, which projects into the Red Sea between Egypt and Arabia. The name used to be applied to the mountainous region of the south, now it is made to comprise the land as far north as the Mediterranean.

Sinai is famous for the part which it has played in the religious history of mankind. It was at one time a centre of moon-cult, before it became the seat of the promulgation of the Law to the Jews at the time of Moses. In Christian times it was one of the chief homes of the hermits, and the possession of the relics of St. Katherine in the great convent of the south, caused Sinai to be included in the Long Pilgrimage throughout the Middle Ages.

A history of Sinai deals with the people who visited the peninsula at different times, rather than with its permanent inhabitants, who, in the course of centuries, seem to have undergone little change. They still live the life of the huntsman and the herdsman as in the days of Ishmael, sleeping in the open, and adding to their meagre resources by carrying dates and charcoal to the nearest centres of intercourse, in return for which they receive corn.

The country geographically belongs to Egypt, ethnologically to Arabia. It falls into three regions.

In the north, following the coast line of the Mediterranean, lies a zone of drift sand, narrowest near Rafa on the borders of Palestine, widening as it is prolonged in a westerly direction[2] towards Egypt, where it is conterminous with the present Suez Canal. This desert was known in Biblical days as Shur (the wall) of Egypt. “And Saul smote the Amalekites from Havilah (north Arabia), until thou comest to Shur that is over against Egypt” (1 Sam. xv. 7). The military highway from Egypt to Syria from ancient times followed the coast line of the Mediterranean, the settlements along which were modified on one side by the encroachment of the sea, on the other by the invasion of sand.

Adjoining this zone of drift sand, the land extends south with increased elevation to the centre of the peninsula, where it reaches a height of about 4000 ft., and abruptly breaks off in a series of lofty and inaccessible cliffs, the upper white limestone of which contrasts brilliantly in some places with the lower red sandstone. This region is, for the most part, waterless and bare. It is known in modern parlance as the Badiet Tîh (the plain of wandering). Its notable heights include the Gebel el Ejneh and the Gebel Emreikah. This plain is drained in the direction of the Mediterranean by the great Wadi el Arish and its numerous feeders, which, like most rivers of Sinai, are mountain torrents, dry during the greater part of the year, and on occasion like the fiumare of Italy, flowing in a spate. The Wadi el Arish is the River of Egypt of the Bible (Gen. xv. 18; Num. xxxiv. 5), the Nahal Muzur of the annals of King Esarhaddon.

The Badiet Tîh is crossed from east to west by the road from Akaba to Suez, along which the Holy Carpet, which is made at Cairo, was annually conveyed to Mecca. Halfway between Suez and Akaba, at Kalaat el Nakhl, the road is crossed by one coming from Gaza, which is prolonged south in several directions down precipitous passes. Kalaat en Nakhl is an important watering place, and was for a time a military station. It was known in the Middle Ages as a puteus Soldani (well of the Sultan).

The roads coming from Nakhl lead down the escarpment of Tîh to a belt of sand and gravel, varying in width, which, with the arid stretches adjoining it, covers an area of some thirty square miles. This is the Gebbeter Ramleh (belt of sand). Its western parts including the Wadi Jarf is the wilderness of Sin of the Bible (Exod. xvi. 1).

South of this great belt of sand, red sandstone reappears[3] in shelving masses leading up to the great mountainous district which forms Sinai proper, the third region of the peninsula. These mountains are traversed by many river-beds or wadies. Some of them, according to the ways of the country, do not bear the same name throughout their course, but the main stream frequently takes another name when it is joined by a tributary. Thus the Wadi Nasb after its junction with the Wadi Beda becomes the Wadi Baba, and so forth.

This sandstone district is cut into by deep gorges and canyons, that have sheer falls of several hundred feet in places. It comprises the mountains which yielded turquoise and copper, products that brought the neighbouring people into Sinai. Beads of turquoise were found in the pre-dynastic tombs of Egypt which probably came from Sinai, while there was an increasing demand for copper in the surrounding countries from the close of the Neolithic Age. If the name Milukhkha of the Babylonian records refers to Sinai, these people also came there several thousand years before our era.

Turquoise appears in a ferruginous layer in the sandstone at the height of about 2650 ft. at Serabit, and at the height of about 1170 ft. at Maghara above sea-level. The copper ore occurs in the Wadi Nasb, and in the Wadi Khalig, somewhat extensively in the latter, together with iron and manganese. Enormous slag heaps lie at the head of the Wadi Nasb and near the outlet of the Wadi Baba, which bear evidence to former smelting activity. Again, in the Wadi Sened, a dyke rich in copper traverses syenite for a distance of nearly two miles.

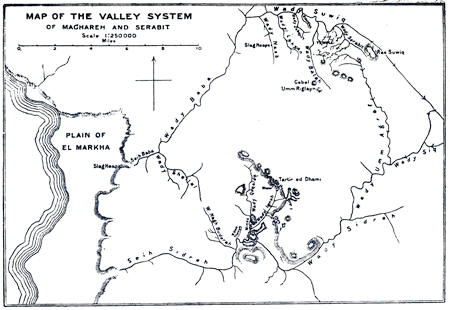

The district which was worked by the ancient Egyptians was comprised between the valley system of the Wadi Baba on the north, and that of the Wadi Sidreh on the south, both of which have their outlet in the direction of the coastal plain of El Markha. It was from this side that the ancient Egyptians approached Sinai. The chief height of the district is the Tartir ed Dhami (black cap), so called from the dark basalt that forms its summit, which rises to a height of 3531 ft. There is also the double-peaked Umm Riglên (mother of two feet) which rises to the south of the Wadi Umm Agraf and dominates the height of Serabit.

To the south of the ancient mining district the sandstone is connected in a manner highly interesting to the geologist with the plutonic rock which gives its imposing character to[4] the mountains of the south. Here lies the Wadi Feiran, one of the best watered and fruitful valleys of the peninsula, to the south of which Mount Serbal rises abruptly from a comparatively low elevation to the height of 6734 ft. This mountain has been described as one great lump of diorite, and its majestic appearance led some recent travellers, including Lepsius[2] and Bartlett,[3] to identify it as the Mountain of the Law. Further south lies the great group of mountains which include the Gebel Musa, 7359 ft. high, and the Gebel Katrîn with its three peaks, the highest of which rises to 8527 ft. The Gebel Musa from early Christian times was generally looked upon as the Mountain of the Law. At its foot lies the great convent of Sinai, at one time known as the Bush, which has carried on to the present day the traditions of the early Christian hermits, who settled in the peninsula. The Gebel Katrîn lying further south, was looked upon during the later Middle Ages, as the height on which the angels deposited the body of St. Katherine. Another imposing height of the group is the Ras Safsaf, 6540 ft. high, which has been put forward in recent times as a possible Mountain of the Law.

These mountains of the south contain many natural springs and fruitful valleys, which were formerly the home of Christian ascetics. They are divided from the Gulf of Suez on the west by the desert of El Kaa, which drains a large amphitheatre of hills, and becomes a coastal plain that extends as far as Ras Mohammad, the southernmost point of the peninsula. The desert of El Kaa has a harder subsoil which is so tilled that the accumulated moisture is thrown up at the coast near Tur, the chief harbour of the peninsula, and possibly an ancient Phœnician colony. Near it lay Raithou, a place of many oases and large date-palm plantations which were carefully tended by the monks during the Middle Ages.

The south-eastern parts of the peninsula are rarely visited by Europeans. There are some high mountains, including the Gebel Thebt (7883 ft.), the Gebel Umm Shomer (8449 ft.), and the Gebel Umm Iswed (8236 ft.), in districts that were recently explored by Dr. Hume.[4] The eastern coast-line[5] of the peninsula is relatively inaccessible. There are some creek ports at Sherm, some ten miles north of Ras Mohammad, and some palm trees with a good supply of water at Nakhb. From here it is less than eight miles across the sea to Ras Fartak, the nearest point of Arabia. Further north, opposite the coastland of what is now reckoned the land of Midian, lies Dahab and, beyond it, Ain en Nuêbeh, where the road that leads from the convent to Akaba at the head of the Gulf of Akaba, reaches the coast. From Akaba the mountains are prolonged in the direction of Palestine on both sides of the Wadi el Arabah, the great depression that extends northwards to the Dead Sea. This is “the land of Seir, the country of Edom” of the Bible (Gen. xxxii. 3). Edom signifies red in Hebrew, and the land may have been so called owing to the red sandstone of the district.

Sinai, generally speaking, is a country of stern desolation. Its mountains are bare, its plains are swept by the wind, its river beds are to all appearance waterless. But clusters of bushes that follow the valley floors or rise from the plains, show that moisture percolates the soil beneath the surface, and is procurable by digging down to the harder subsoil, (i.e. “striking the rock”) as was done at the time of the passage of the Israelites. Such digging is done by the Bedawyn at the present day, the holes for water being called hufrah in Arabic. In some places, however, the water along the valleys is thrown up and forms natural oases as in the Wadi Gharandel, the Wadi Feiran, and at Tur. In others, it is raised by means of the mechanical device of a water-wheel and by a shaduf.

Rain falls in the peninsula in sudden downpours, often in connection with a thunderstorm. When we camped in the Wadi Umm Agraf in January of 1906, it rained without ceasing for two days and a night, creating rivulets and a waterfall down the mountain slope. A week later the valley floor was carpeted with verdure and flowers, and the thorny bushes were masses of bloom. Rainstorms may result in a spate, the dreaded seil of the Bedawyn, which often appears several miles below where the rain has actually fallen. In the winter of 1914-15 the Wadi el Arish was twice in spate, and left extensive pools of water behind. The effect of a spate, seen on Dec. 3, 1867, in the Wadi Feiran by the Rev. F. W. Holland, was described by him. In little more[6] than an hour, the Wadi Feiran, at this point about 300 yards wide, was filled with a raging torrent from eight to ten feet deep. Men, animals, and trees were swept past upon the flood, and huge boulders ground along the wady bed with a noise of a hundred mills at work. In this spate perished thirty persons, scores of sheep and goats, camels, and donkeys, and it swept away an entire encampment that had been pitched at the mouth of a small valley on the north side of Mount Serbal.[5]

Disasters of this kind are in part attributable to the reckless deforestation of the country which has gone on unchecked for thousands of years, and continues at the present day. To this is attributable also the calamitous invasion of sand along the shores of the Mediterranean recorded by Arabic writers. In ancient times wood was extensively used for smelting purposes in different parts of the peninsula, as is shown by enormous slag-heaps in the Wadi Baba and in the Wadi Nasb. A great bed of wood ashes beneath the temple-floor at Serabit showed that wood was freely used in offering the holocaust in a district that is now entirely denuded of trees. According to the Mosaic Law, charcoal was used in early times at the Temple service as we gather from “a censer full of burning coals” (Lev. xv. 12).[6] For domestic use it was exported during the Middle Ages, and was regularly delivered by the Bedawyn as tribute to the Pasha in the nineteenth century. Its export continues to this day.

The heathen past tried to stem the ravages of deforestation by marking off certain valley floors, the use of which was reserved to the sanctuaries. Inside this holy ground, the hima, no animal might be hunted and no tree might be cut down. Many valleys of Sinai to this day contain one tree of great age and often of prodigious size, which is accounted holy and is therefore left untouched.[7] But the mass of the trees and with them the hope of a copious undergrowth, has gone. At the time of the passage of the Israelites, there must have been extensive tamarisk groves, since it is the tamarisk which yields manna, a product well-known in ancient Egypt.[7] Its abundance must have made an appreciable difference in their food-supply. Only a few tamarisk groves remain in the more southern mountains at the present day, chief among them the groves of Tarfat el Gidaran. Again neglect has destroyed the palm groves of which enormous plantations existed in the Middle Ages. We read of a plantation of over 10,000 date-palms at Tur, and the date since the earliest times was a staple article of diet. According to Arab tradition the land along the shores of the Mediterranean was of great fruitfulness before it was invaded by sand drifts. It was the same with the numerous fruit and vegetable gardens which were once cultivated by the monks and the hermits. With the exception of the garden belonging to the convent, they have passed away. Journeying across the wide stretches of the country which were formerly a wilderness and are now a desert, one wonders if a wise government could not impose restrictions which would stop the destruction of the undergrowth and regulate the water-supply. This would extend the cultivation of the date-palm, the tamarisk and of other food products, for the Bedawyn, the present inhabitants of the peninsula, live in a state of semi-starvation. Their various means of subsistence have steadily grown less with the centuries. Deforestation has influenced the fauna to the detriment of the huntsmen. The herds of gazelles which were numerous as late as the Middle Ages, are few and far between. Pasture lands which formerly fed sheep and goats were encroached upon by the introduction of the camel. The transport of goods and of pilgrims which gave occupation to the owners of camels during the Middle Ages has practically ceased. The convent formerly helped to tide over difficult times by means of its resources, but the advent in the east of the Turk reduced these resources to a minimum, and the convent is nowadays hardly able to satisfy its own needs. In the face of this state of things, it seems worth recalling the different periods in the past when Sinai held the attention of the outside world and helped in the making of history. For the recognition of her solitary ruins, and of her literary wealth still enshrined in the convent, taken with the needs of her people, may stimulate effort to inaugurate a new era to the profit of Christian and of Moslim alike.

CHAPTER II

SINAI A CENTRE OF MOON-CULT

THE name Sinai is first mentioned in the Song of Deborah (Judges v. 5), which is dated to about b.c. 1000, and in the story of Exodus. It perpetuates the early form of belief of the inhabitants of the peninsula. For the word Sinai together with Sin (Exod. xvi. 1) and Zin (Num. xiii. 21), all date back to Sin, a name of the moon-god in ancient Babylonia.

The word Sin appears as part of the name of Naram-Sin, king of Accad in Babylonia (c. b.c. 3700), whose great stele of victory, now in the Louvre, represents his conquest of Elam (Persia). The acts of Naram-Sin were considered in the light of lunar influence, for his Annals state that “the moon was favourable for Naram-Sin who at this season marched into Maganna.”[8] Maganna, otherwise Magan, was frequently named in early annals and inscriptions, notably on the great statues of King Gudea (b.c. 2500). It was the place where the diorite came from out of which the statues were made. The same inscriptions mention Milukhkha.[9] An ancient fragment of Assyrian geography which was engraved about the year b.c. 680, but the original of which is considered much older, names side by side: “The country of Milukhkha as the country of blue stone, and the country of Maganna as the country of copper.”[10] Of these names Maganna may refer to Sinai while the word Milukhkha recalls the Amalekites who dwelt in the peninsula. In any case the name Sin goes back to Babylonian influence, probably to the Semites who were powerful in the land of Arabia in the days of Khamurabbi.

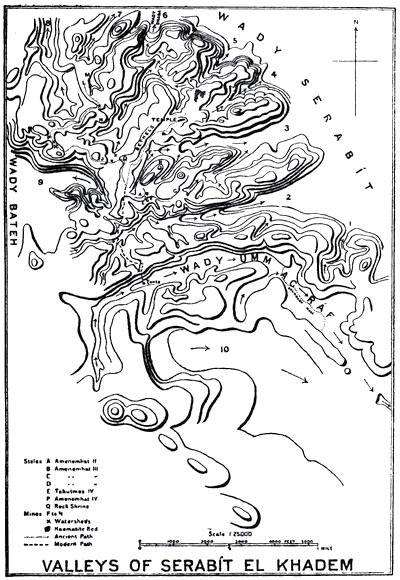

Fig. 1.—Situation of Sanctuaries. (Petrie: Researches in Sinai.)

The constant recurring changes of the moon caused this to be accepted as the ruler of times and seasons by the huntsman and the herdsman generally. The Hebrews came from a stock of moon-worshippers. It was from Ur of the Chaldees, a centre of moon-cult, that Terah and Abraham migrated to Haran on the way to Canaan about b.c. 2100.[11] The Arab writer Al Biruni (c. a.d. 1000) in his Chronology of the Ancient Nations, noted the connection of Haran with the moon-cult, and stated that near it was another place called Selem-sin, its ancient name being Saram-sîn, i.e. Imago lunæ, and another village called Tera-uz, i.e. Porta Veneris.[12]

The acceptance of moon-worship among the ancient Hebrews is confirmed by Artapanus, some of whose statements were preserved by Alexander Polyhistor (b.c. 140). Artapanus described the Syrians who came to Egypt with Abraham as “Hermiouthian” (i.e. worshippers of Hermes), and stated that Joseph’s brethren built Hermiouthian sanctuaries at Athos and Heliopolis.[13] Heliopolis, the city On of the Bible (Gen. xli. 45), was near the present Cairo; followers of Abraham were held to have settled there. Athos has been identified as Pithom. More probably it was Pa-kesem, the chief city of Goshen. The word Hermiouthian indicates moon-worshippers, as Hermes, the Greek god, was reckoned by the classic writers the equivalent of the Egyptian moon-god Thoth, as is shown by the place-name Hermopolis, (i.e. the city of Thoth), in Lower Egypt.

Another name for the moon-god was Ea or Yah, who was accounted the oldest Semitic god in Babylonia, to which his devotees were held to have brought the cultivation of the date-palm, an event that marked a notable step in civilisation.[14] The emblem of Sin was the crescent moon, the emblem of Ea was the full moon, who, in the Assyrian Creation story is described as “Ea the god of the illustrious (i.e. lustrous) face.”[15] On Babylonian seal cylinders Ea is shown standing up as a bull, seen front face, with his devotee Eabani (i.e. sprung from Ea), a man seen, front face also, who wears the horns and hide of a bull.[16] This representation perpetuates the conception of the horned beast as a sacrosanct animal that was periodically slain. We shall come across this conception later in the emblem worn by the Pharaoh, and in the story of the Israelites and the Golden Calf.

Sandstone Baboon from Serabit

| Glazed Baboon from Hierakonpolis | Glazed Baboon from Abydos |

Fig. 2.—Figures of Baboons. (Ancient Egypt, a periodical, 1914, Part i.)

The monuments found in Sinai contain information which points to the existence of moon-worship there at a remote period of history. These monuments consist in rock-tablets which were engraved by the Pharaohs from the First Dynasty onwards over the mines which they worked at Maghara, and of remains of various kinds discovered in the temple ruins of the neighbouring Sarbut-el-Khadem or Serabit. Maghara more especially was associated with the moon-god and was presumably the site of a shrine during the period of Babylonian or Arabic influence which preceded the invasion of the peninsula by the Egyptians (Fig. 1).

Among the Egyptians, Thoth, the moon-god, had shrines at Hierakonpolis and at Abydos in Upper Egypt, and in both these places he was worshipped under the semblance of a baboon. He was worshipped also at Hermopolis in Lower Egypt, but here he was represented as ibis-headed. In Sinai we find him represented sometimes as a baboon and sometimes as ibis-headed.

Thus the excavations of the temple-ruins at Serabit in 1906 led to the discovery of several figures of baboons. One was the rude figure some three inches high which is here represented; it was found in the cave that was the treasure-house of the sanctuary. This little figure is similar in appearance and in workmanship to figures found at Hierakonpolis and at Abydos, the centres of moon-worship in Upper Egypt. Several of these figures were found at Hierakonpolis.[17] At Abydos more than sixty were discovered in the winter of 1902 in a chamber at the lowest temple level, where they were apparently placed when the later cult of Osiris superseded the earlier cult of Thoth. This took place in pre-dynastic times.[18] The figure of the baboon who stood for the lunar divinity in Egypt, was doubtless deemed a suitable offering[13] to the sacred shrine at Serabit in Sinai, because of the nearness of this shrine to the centre of moon-worship of the country. If the figure was carried to Sinai at the time when similar figures were offered in Egypt, the establishment of the moon-cult in the peninsula dates back to the pre-dynastic days of Egypt.[19]

Fig. 3.—Sneferu ravaging the land. (Ancient Egypt, a periodical, 1914, Part i.)

Another baboon, carved life-size in limestone with an inscription around its base, came out of one of the chambers of the adytum to the sacred cave at Serabit, the work and inscription of which dated it to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. The presence of this figure suggests that the Egyptians[14] associated their moon-god with the moon-worship of the peninsula.

Fig. 4.—Khufu smiting the Anu before Thoth.

The chief shrine or sanctuary of the moon god in the peninsula probably lay in Wadi Maghara where mining on the part of the Arabs preceded that of the Egyptians, for the Egyptians here fought for the possession of the mines. This is shown by the tablets carved in the living rock, which commemorate the Pharaohs from King Semerkhet (I 7) of the First Dynasty onwards. They are represented as smiters of the enemy above the mines which they worked. One of these tablets represents Sneferu, the ninth king of the Third[15] Dynasty, who wears a head-dress that consists of a double plume which rises from a pair of horns as is seen in the illustration. The double plume is well known, but the horns are foreign to Egypt, and recall the lunar horns that are worn by Eabani, the devotee of the moon-god Ea or ancient Babylonian seal cylinders. The adoption of horns by the Pharaoh of Egypt seems to indicate that he has usurped the authority of the earlier ruler of the place (Fig. 3).

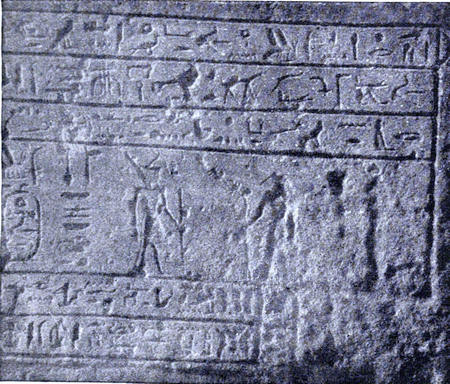

Fig. 5.—Amen-em-hat III, Thoth and Hathor. Maghara. (Petrie: Researches in Sinai.)

Other monuments found at Maghara point to the same conclusion. Thus one rock-tablet represents King Khufu (IV 2), the great pyramid builder, smiting the Anu in front of the ibis-headed figure of Thoth who stands holding out his sceptre facing him (Fig. 4). Other Pharaohs are represented as smiters. But after the Fifth Dynasty the opposition[16] which the Pharaohs encountered in Sinai must have come to an end, for later Pharaohs were no longer represented as smiters, but are seen in the double capacity of lord of Upper and of Lower Egypt standing and facing the ibis-headed figure of the moon-god Thoth, who now holds out to them his sceptre supporting an ankh and a dad, the Egyptian emblems of life and stability. Among the Pharaohs so represented was Amen-em-hat III, sixth king of the Twelfth Dynasty, who is shown facing the god Thoth behind whom the goddess Hathor is seen (Fig. 5). The interpretation is that the Pharaoh is now acting in complete agreement with the divinities of the place. Of these Thoth stands for the moon-god who originally had his shrine at Maghara, and Hathor stands for the presiding goddess who had her shrine at Serabit. This shrine or sanctuary at Serabit is of special importance in the religious associations of the peninsula.

CHAPTER III

THE SANCTUARY OF SERABIT

THE existence of the sanctuary at Serabit in Sinai was unknown to Europeans till the year 1762, when it was chanced upon by Carsten Niebuhr, who did not, however, record its name. Seetzen who visited it between 1809 and 1810 noted this as Serrabit-el-Chadem.[20] Sarbat is Arabic for height, khadem signifies slave. But Prof. Sayce claims for the name a different derivation. In ancient Egyptian ba, plur. bit, signifies hole or mine, khetem signifies fortress. Serabit el Khadem thus signifies mine fortress, with the prefix sar, which probably stands for exalted.

Other place names in the district probably date from the ancient Egyptians also. Thus the valley leading up from the coastal plain of El Markha to the mine district is called Wadi Baba, i.e. mine valley. Again, a tributary of the Baba, with its valley head close to Serabit, is the Wadi Bateh, a name which probably includes the word for mine also.

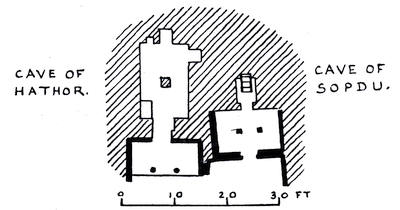

The sanctuary of Serabit[21] at the outset consisted of a cave, or rather of two caves adjacent to one another, of which the larger, which has been squared, measures 20 by 10 feet, the smaller one measures 6 by 4 feet with three steps leading up to a round-headed apse or recess (Fig. 9).

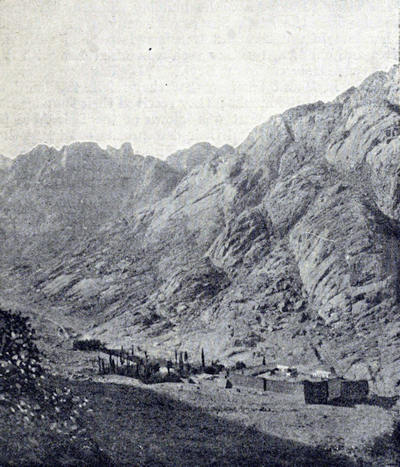

These caves have separate entrances and lie in a knoll facing a plateau in the midst of wild, upland scenery. The plateau lies some 2680 feet above sea level, and is difficult of access on all sides (Fig. 6).

To the north it communicates with the Wadi Suweig along the steep and tortuous Wadi Dhaba, which is marked number 6 on the map. The word dhaba signifies panther, probably in[18] allusion to the feline animal which was at one time associated with the presiding female divinity at Serabit. Another valley, marked number 7 on the map, leads up to the temple ruins, with a path passing the mines which contain inscriptions in an early Semitic script. But it was not along these gorges, but along a path leading up from the plain El Markha along the Wadi Baba and the Wadi Nasb that the ancient Egyptians approached the sanctuary. This path has been included in the Ordnance Survey of 1871. A rock tablet marked P on the map, which commemorates the Pharaoh Amen-em-hat IV (XII 7), lies near the watershed, and this shows that the Egyptians passed here. A small Egyptian shrine (Q) was also discovered at the western end of the plateau.

To the south of the plateau, and separated from it by several ravines and valley heads, extends the Wadi Umm Agraf which is comparatively remote from the valleys communicating with the Wadi Suweig and the Wadi Baba, and relatively close to the sanctuary. The approach to the temple from this side was unknown to Europeans till the winter of 1905-6, when Prof. Flinders Petrie and his party, who worked at excavating the temple ruins, pitched their tents here. A path was constructed from the camp up the mountain side to the temple by clearing away the stones. In parts an old path was re-used, the existence of which showed that there was at one time frequent intercourse between the sanctuary and the Wadi Umm Agraf. Some way down the Wadi Umm Agraf the valley floor is crossed by a wall made of rough stones piled together, the purpose of which was to mark off the upper reaches of the Wadi as is seen by a glance at the map. These upper reaches evidently constituted a tract of land the use of which was reserved to the sanctuary. A copious supply of good water is obtainable at a well some miles down the valley. The separation wall across the valley is undoubtedly old. A similar wall crosses the Wadi Maghara, which was dated by Prof. Petrie to at least the Fourth Dynasty. Its purpose, like that near Serabit, was to mark off the upper reaches of the valley, which in this case may have represented the hima or tract of land that was originally appropriated to the sanctuary of the moon-god.

Fig. 6—Sanctuary surroundings at Serabit. (Petrie: Researches in Sinai.)

The plateau of Serabit falls away abruptly on its southern and western edge, and the stratum here appears which anciently yielded turquoise. The wish to control access to this turquoise no doubt originally led to the permanent occupation of the caves, and we shall probably not be far wrong if we imagine this in the possession of a clan or hereditary priesthood, who, in return for offerings brought to their cave, gave turquoise or the permission to work it inside the appropriated area. The offerings brought to the cave naturally led to a sacrifice and feast which, in the course of time, would hallow the precincts of the place. Prof. Robertson Smith remarked that almost every sacred site in Palestine had its cavern or grotto which served to store the vessels and utensils that were used at the sacrifice that took place near it. No religious significance originally attached to the cave. But the holiness of the sacrifice reflected on it, and in the course of time it was identified as the abode of the divinity.[22]

The plateau in front of the caves at Serabit served as a High Place of Burning. Such high places were in use in Canaan before and after the Exodus. Prof. Robertson Smith showed how the barren and unfrequented hill top would be one of the most natural places chosen for the holocaust, and in this connection recalled the proposed sacrifice of Isaac on the mountain.[23] We read in the history of Samuel how he was called upon to sanctify the sacrifice on the height, of which the people would not partake until it had received his blessing (1 Sam. ix. 12); also that Solomon visited Gibeon, where he burnt sacrificial flesh and offered a thousand burnt offerings upon the altar (1 Kings iii. 4). In consequence of the building of the Temple at Jerusalem efforts were made to draw to it all the offerings, but the High Places seem to have continued till the Captivity. They finally came under the ban of the ceremonial law.[24]

The use made of the plateau of Serabit as a High Place of Burning was shown by the excavations. In front of the caves, beneath the stone floor of the Temple buildings that were erected by the Egyptians after their appropriation of the site, there was found a continuous bed of wood-ashes which extended all across the temple area and out as far as the buildings and stone walls on the south, in all fifty feet in breadth.[21] Outside the area covered by the stone floor the ashes would be carried away by wind and rain. In the words of Prof. Petrie: “We must therefore suppose a bed of wood ashes at least 100 by 50 feet very probably much wider, and varying from 3 to 18 inches thick, in spite of all denudation that took place before the XVIII dynasty. There must he on the ground about 50 tons of ashes, and these are probably the residue of some hundreds of tons of ashes. The ashes are certainly before the XVIII dynasty.” In further explanation of the way in which the sacrifice was treated, Prof. Petrie tells us that “the fires were not large, as the ash is all white, and no charcoal of smothered fire remains. No whole burnt sacrifice was offered, as no calcined bones were found; and some kind of feeding at the place is suggested by the finding of a few pieces of pottery jars and of thin drinking cups. These belonged to the age of the XII dynasty.”[25]

The space in front of the caves was fenced in by a wall built of rough stones loosely piled together, similar in construction to the walls that cross the Wadi Umm Agraf and the Wadi Maghara. The temple area which the wall enclosed varied at different periods. It was finally 200 feet in its greatest length and 140 feet at its greatest breadth. Behind the caves across the knoll its course was doubled. It thus enclosed a vast temenos of oblong form which included large open spaces that were again partitioned off, besides the ground that was covered by the Egyptian temple buildings (Fig. 11).

Outside the temenos wall and well in view of the knoll, rough circular enclosures lie scattered here and there on the plateau, which were made by clearing the ground of stones and piling these together in the same way as the walls were built up. These stone enclosures are for the most part four to six feet inside measurement, a few are larger, and many of them contain one stone of larger size that was set up at one side of the enclosure and propped up by other stones. There were also some uprights without enclosures.

Similar uprights and enclosures are found in Syria; their devotional and commemorative origin is apparent from incidents related in the Bible.

Thus in the story of Jacob we read how, coming from Beersheba, he lighted on a certain place that was holy ground,[22] and tarried all night because the sun was set. “And he took of the stones of that place and put them for his pillows” (Gen. xxviii. 11; LXX at his head). In the night he had his wonderful dream and on the following morning he set up the stone and poured oil on it and called it Bethel (i.e. house of El), saying, “And this stone which I have set for a pillar (mazzebh) shall be God’s house” (Gen. xxviii. 22). On another occasion he made a covenant with Laban in ratification of which he took a stone and set it up for a pillar (mazzebh), and called his brethren to take stones and make an heap (perhaps an enclosure), “and they did eat there upon the heap” (Gen. xxxi. 45, 46). Again when the Israelites camped in Sinai, Moses erected an altar, and set up twelve pillars (mazzeboth), and when they crossed the Jordan, Joshua took twelve stones from the river which he set up at the place which was known as Gilgal (Joshua iv. 1-9, 19-20). The name Gilgal in this case was associated with “rolling” away the reproach of Egypt (Joshua v. 9). But the word Gilgal signifies “circle of stone.”[26] In the Septuagint the word generally stands in the plural Galgala (Joshua iv. 19, 20, etc). If the single stones (mazzeboth) were set up inside circular stone enclosures, this would correspond with the way the uprights were set up at Serabit.

In the course of the Twelfth Dynasty, the Egyptians secured a foothold in Serabit where they erected inscriptions and steles, and commemorated the female divinity of the place under the name of Hathor. A statuette of Hathor was the usual gift to the shrine of the Pharaohs of this dynasty. Her cult was at first coupled with that of the moon-god Thoth as the representative of the neighbouring Maghara, later she appears alone or associated with the local divinity Sopd.

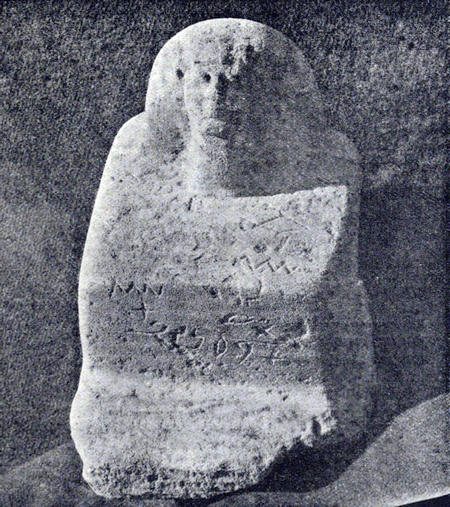

At Wadi Maghara, Hathor appears on one tablet following the ibis-headed Thoth, who faces the Pharaoh Amen-em-hat III (XII 6), as already mentioned (Fig. 5). On a corresponding tablet found at Serabit she is seen holding out to the same king a sceptre which supports the ankh and the dad. There were many Hathors in Egypt, for Hathor here took the place of earlier mother-divinities in much the same way as the Virgin Mary took the place of local mother-divinities in Europe. The goddess Hathor in Sinai was generally represented wearing[23] a head-dress that consists of a pair of horns which support the orb of the full moon, and she is described as mistress of the turquoise land, and later simply as mistress of turquoise (mafkat). Hathor stands for the unwedded mother-goddess who appears as Ishtar in Babylonia, as Ashtoreth in Canaan, and as the Queen of Heaven generally. At Serabit her name appears in script which may be Semitic. One of these inscriptions is on a figure of the usual squatting type that came out of the sanctuary (Fig. 7). Another is on a peculiar[24] sphinx that is now in the British Museum. Others are on much-battered steles that were carved on the rock in the mine along the valley marked number 7 (Fig. 6). The name consists of a sequence of four signs, which Dr. Alan Gardiner reads as Ba-alat: “Almost every Egyptian inscription from Serabit names the goddess Hathor, and there could not possibly be a better equivalent for the name of this goddess than Ba-alat.”[27]

Fig. 7.—Figure with Semitic Script. (Petrie: Researches in Sinai.)

The name Ba-alat recalls Alilat whom Herodotus (c. b.c. 450) named as the chief divinity of Arabia (iii. 8), and who reappears as Al-Lat in the Koran (c. a.d. 630). Al-Lat had her sanctuary at Taïf, about forty miles north-north-east of Mecca, which consisted of a cave in an upland plain in which clothes, jewels, incense, silver and gold, were stored. The goddess was held to be incarnate in a white rock that was afterwards seen lying under the mosque, and which was described by Hamilton and by Doughty as a mass of white granite now shattered with gunpowder and shapeless.[28] Appropriated to the sanctuary at Taïf was a guarded and reserved tract of land, the hima, where no idah-tree might be cut and no animal hunted, and the reluctance of Mohammad to dislodge the goddess was shared by the Taïfites, to whom the gatherings near the shrine were a source of wealth.

Another cave sanctuary at El Nakhl, not far from Mecca, which was associated with El Uzza, likewise consisted of a cave with accumulated wealth and owned a reserved tract of land or hima.[29] The arrangement at Serabit was apparently the same, and proves the Arabian or Semitic origin of the place.

The excavations at Serabit, moreover, led to the discovery of temple furniture such as served the “Queen of Heaven” elsewhere.

Thus several short stone altars were found, of which one, broken in half, was 22 inches high with a cup hollow on the top, 3½ inches wide and one inch deep. Another was described as “well finished, and on the top the surface was burnt for about a quarter of an inch inwards, black outside and discoloured below. This proves that such altars were used for[25] burning, and from the small size, 5 to 7 inches across, the only substance burnt on them must have been highly inflammable, such as incense,”[30]

Two rectangular altars cut in stone were also found, each with two saucer-like depressions, ten inches wide all over, and seven inches across inside, which “might well be for meat offerings, or cakes of flour and oil, a kind of pastry.”[31] According to a passage in Jeremiah, the Israelite women, who repudiated visiting the sanctuary of the Queen of Heaven without their husbands, which was forbidden to them, said, “And when we burned incense to the queen of heaven, and poured out drink-offerings unto her, did we make her cakes to worship her, and pour out drink-offerings unto her, without our men?” (Jer. xliv. 19). The utterance shows that offerings in food and drink as well as incense burning was customary in the cult of the Semitic goddess.

Offerings that consisted of cakes continued in Arabia into Christian times. For Epiphanius of Cyprus († 403), in his book, Against all Heresies, denounced certain Christians as Collyridians, from the cakes which they placed under an awning and offered in the name of the Virgin.[32]

Hathor, however, was not the only divinity whose cult was located at Serabit. While the larger of the two caves was appropriated to her, the smaller adjacent cave was associated with Sopd, who was repeatedly named here from the reign of Amen-em-hat III (XII 6) onwards. One inscription of the sixth year of this king named him together with Hathor. Another of the forty-second year mentioned Sebek-didi who set up an inscription and described himself as “beloved of Hathor; mistress of the mafkat-country; beloved of Sopd, lord of the east; beloved of Sneferu and the gods and goddesses of this land.”[33]

The special association of Sopd with the Pharaoh Amen-em-hat III is shown by an open hall that was erected outside the temple at Serabit in the course of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the decoration of which caused Prof. Petrie to call it the hall of the kings. On the inner wall of this building are the[26] figures of the divinities and the kings who were especially associated with Serabit. Among them is Sopd who is seen holding in one hand an ankh, in the other a staff of justice, and who follows the Pharaoh Amen-em-hat III.[34] Sopd during the Eighteenth Dynasty was reckoned the equal of Hathor. For the entrance to a mine that was opened conjointly by Queen Hatshepsut and her nephew Tahutmes shows Tahutmes offering incense to Hathor and Hatshepsut in a corresponding scene offering incense to Sopd.

The divinity Sopd has no place in the older Egyptian pantheon, and is to all appearance an Egyptianised divinity of Semitic origin. He is named among the gods who are favourable to the Pharaoh Sen-usert I (XII 2) in the so-called Tale of Sanehat, which describes an incident of the time and is looked upon as a genuine historical account.[35] The cult of the god seems to have gained a firm foothold in connection with the forced retreat of the Mentu people. For it says in a nome text of Edfu, “Shur is here Sopd, the conqueror of the Mentu, lord of the east country, and in Edfu golden Horns, son of Isis, powerful god Sopd.”[36]

One mention of Sopd in Egypt is on a tablet of Sen-usert II (XII 4) that was found in the temple of Wadi Qasus in the desert of Kossayr on the borders of the Red Sea. On it Sopd is described as “lord of the eastern foreigners (sut), and of the east (Neb-Apti).”[37]

The description “lord of the east,” refers to the cult of Sopd in the land of Goshen, the twentieth nome of Lower Egypt, the capital of which, Pa-kesem, was known also as Per-Sopd, i.e. the House of Sopd. The amulet of Sopd at Per-Sopd was of turquoise, which bore out his connection with Sinai. An Egyptian text, moreover, described Sopd as “noblest of the spirits of Heliopolis.”

Now the Syrians or Hebrews, as already stated, had a foothold at Heliopolis since the days of Abraham, while the land of Goshen, as we know, was allotted to the Israelites. The inference is that Sopd who had a sanctuary in Sinai, had sanctuaries in Heliopolis and in the land of Goshen also.[27] The study of these sanctuaries shows that they had features in common with some of the early sanctuaries in Palestine.

The ancient city Per-Sopd in Egypt, known as Phakusa in Greek, and as Kesem in the Septuagint, is now called Saft-el-Henneh. The change from Sopd to Saft suggests a possible origin of certain place names in Palestine, including Tell-es-Safi, which is situated between Jerusalem and Gaza, and Safed, which is situated north of the Sea of Galilee. Both of these were hallowed by ancient religious associations.

Fig. 8.—Caves at Serabit. (Ancient Egypt, a periodical, 1917, Part iii.)

Modern Safed occupies a conspicuous position on the summit of a mountain. Together with Jerusalem, Hebron and Tiberias, it ranked as a holy city of Palestine.[38] It is named Tsidphoth in the Travels of an Egyptian Mohar,[39] and is Tsapheth in the Talmud, and Sephet in the Vulgate of Tobit.

On the other hand Tell-es-Safi, situated between Jerusalem and Gaza, was identified as a High Place of Burning by recent excavations. Possibly it was Gath of the Bible, one of the five holy cities of Palestine. The excavations at Tell-es-Safi led to the discovery of features which recall the arrangements at Serabit in Sinai. At a depth of 11 to 21 ft. the pre-Israelite ground was reached, on which stood several pillars (mazzeboth), some of which were enclosed in the largest of several chambers[28] that were built on slightly higher level. The long wall of the chamber which included the uprights, had a break, roughly in the form of an apse that was 4 feet 5 inches wide and 2 feet 4½ inches deep. A rude semicircle built of stone stood 20 inches high from the ground a distance of a few feet, facing it.[40] This apse corresponds with the recess at the back of the cave of Sopd in Sinai.

The likeness between the place names Per-Sopd, modern Safet in Egypt, and the place names Sephet, modern Safed, and Safi in Palestine, suggests that the cities in Palestine also were the site of a shrine of the Semitic divinity who figures in Egypt and in Sinai under the name Sopd. It is possible that Sopd is the verbal equivalent of the Hebrew word shophet, Phœnician sufet, which signifies judge. Among the early Semites the sanctuary was the seat of justice, and the priests were its administrators, who, in this capacity, gave out the pronouncements. As such they were sacred and, with reference to the joint divinities (El) of the tribes, they were at first called Elohim, later Kohanim. The word shophet itself indicates the Supreme Judge, as in the passage, “Shall not the Judge (shophet) of all the earth do right?” (Gen. xviii. 25), while the relation between the Judge and His administrators is indicated by the words, “And the heavens shall declare his righteousness, for Elohim is Shophet himself” (Psa. l. 6).

The shrine of Sopd in Sinai and the one at Per-Sopd in Egypt, perhaps the one at Heliopolis also, served the same purpose as the shrine at Tell-es-Safi. The priest would stand in the recess with his face towards the suppliant, who, at Safi, stood in the low semicircle.

In Sinai the cave of Sopd was adjacent to that of the moon-goddess (Fig. 8). According to information already cited, a shrine at Heliopolis where Sopd was “noblest of spirits” dated from the “Hermiouthians,” who came there with Abraham, while Hermiouthian sanctuaries were erected in Goshen by the brethren of Joseph. We are left to infer that a shrine of Sopd, presumably a centre for the administration of justice, was connected here also with the localised cult of the moon.

Other features at Serabit confirm the non-Egyptian[29] character of the cult of Sopd. Thus, on the northern approach to the temple stood a stone tank measuring 54 by 32 inches, with a hollow of 37 by 17 inches. Inside the temple area, in one of the courts which were built in the Eighteenth Dynasty, stood a circular tank, 31 inches across with a hollow of 25 inches, and another rectangular tank, 44 by 30 inches stood in the same court, and a further rectangular tank in the hall on the approach to the lower cave. The disposition of these tanks was such that the worshipper who approached the temple from the north, passed the tank outside and the various other tanks on his way to the lesser cave. The use of tanks outside and inside the temple, is foreign to Egypt. They are in keeping with the apsu or stone tank of the Babylonian temple; and with the regulations of Moses regarding the laver that stood between the entrance to the temple and the altar (Exod. xxx. 18). In Jerusalem in the temple of Solomon was a “molten sea” that was round about, and there were ten lavers of brass, five on the right and five on the left side of the house. (1 Kings vii. 23, 38, 39). A similar arrangement prevails to this day in the Arab mosque. Outside stands the well or place for legal washings ghusl, and inside is the circular tank for ablution wazur.[41] The tanks at Serabit were therefore connected with the cult of Sopd, and their presence confirms the Semitic character of the place.

CHAPTER IV

THE EGYPTIANS IN SINAI I.

THE monuments which the Egyptians erected in Sinai are evidence of their continued connection with the place. These were examined and studied in the winter of 1906.[42] They comprised many monuments which were carved in the living rock, and were found in the Wadi Maghara, the Wadi Nasb and at Serabit. At Serabit, moreover, there were found numerous offerings consisting of statuettes, vases, pottery, and other objects which were brought from Egypt to the sanctuary. Outside this sanctuary the Egyptians set up steles near the holy caves and on the neighbouring hillside, and they built chambers and porticoes inside the temenos, and covered these with scenes and inscriptions. Thus the buildings outside the caves went on increasing till the place assumed the appearance of a vast temple.

The baboon figure which was discovered in the temple of Serabit, and the turquoise that was found in early graves in Egypt, show that the Egyptians came to the peninsula in pre-dynastic days. The beginning of dynastic history in Egypt was dated by Prof. Breasted (1909) to about b.c. 3400,[43] and by Prof. Petrie (1914) to about b.c. 5500. Scholars are more and more inclining to accept the earlier date.

At the beginning of the First Dynasty the Egyptians had secured a firm foothold in the peninsula, as is shown by the inscriptions on the living rock of the Pharaohs of this dynasty. These rock-inscriptions are close to the mine holes in the hillside about 170 feet above the valley floor. Besides these[31] there were many inscriptions of kings of the Third, Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. They were known to Europeans in the eighteenth century, and some were drawn and described. But their importance was not fully recognised and many perished in the blasting, when the search for turquoise was renewed in the nineteenth century. Among those which were ruthlessly destroyed was the great tablet of King Khufu (IV 2), here reproduced. A full record was therefore made of those which remained in 1906, and, in order to save the tablets, they were removed to the Museum in Cairo. One only was left in situ. It was the oldest of all, dating from King Semerkhet (I 7), seventh king of the First Dynasty, which is engraved on the rock 394 feet above the valley floor in a position which seems to guarantee its safety.

The earliest tablets in the Wadi Maghara represented the Pharaoh under three aspects: as king of Upper Egypt, as king of Lower Egypt, and as smiter of the enemy who crouches before him. There is, at first, little wording beside the names and the titles of the king. As a smiter the king holds a mace in one hand and a staff in the other, and the enemy has a bold cast of countenance, abundant hair, a peaked beard, and wears a loin-cloth. The Pharaoh holds him by the top-knot, together with a carved object which he seems to have taken from him. This may be a feather; possibly it is a boomerang or throwstick.

The rock inscription of Semerkhet was worked by cutting away the face, and leaving the figures and the hieroglyphs standing in relief. A little in front of the scenes, and worked on the same scale, was the general of the expedition, who wears no distinctive dress, but the word Mer-meshau (leader of troops), written in hieroglyphs, is before him. He is without head-dress and carries arrows and a bow of the double-curved Libyan type.

Semerkhet was probably not the first Pharaoh who worked in Sinai. For a small plaque found at Abydos represents Den-Setui, an earlier king of the First Dynasty, who is seen in the same attitude as the Pharaohs on the Sinai rock tablets, and the cast of countenance of the enemy is also the same.[44]

Little is known of King Semerkhet outside Sinai. It is[32] supposed that the First Dynasty at his time was weakening. No records in Sinai mention kings of the Second Dynasty, who were indigenous to the Nile valley, and whose energies were devoted to reconstructing the older elements of government at home.

A new spirit arose with the kings of the Third Dynasty, of whom Sanekht (III 1) was represented at Wadi Maghara in the usual scenes with the addition of the jackal-nome standard, one of the earliest represented in Egypt, which may refer to the troops that accompanied his expedition. The face of Sanekht is strongly Ethiopian in character, not unlike the present Sudanys. The jackal-nome standard appears also on the tablet of Zeser (III 2), the next Pharaoh recorded, who was seen in the regular group of smiting with the addition of the familiar titles, “giver of purity, stability, life, gladness for ever.”[45]

The intercourse between Egypt and Sinai found a new development under Sneferu (III 9), who was represented wearing the horned head-dress mentioned above, and the wording of his tablet described him as “Great god ravaging the lands,” here reproduced. Sneferu worked not only at Maghara, but was in contact also with the sanctuary at Serabit. To this he presented the figure of a hawk, his favourite emblem, worked in grey limestone, which was discovered in the winter of 1906 in the sacred cave itself. Its work and inscription mark it as a contemporary monument. It is now in the British Museum. Later ages looked upon Sneferu as especially connected with Sinai, reckoning him as one of the protecting divinities of the place, and his haul in turquoise was referred to in the Twelfth Dynasty as exceptional. “I obtained more turquoise than any man since Sneferu.”[46] The value which was set on turquoise in Egypt during his reign is shown by one of the so-called Tales of the Magicians, which relates how the damsels of the harim of Sneferu went rowing on the lake. One dropped her jewel of “new turquoise” into the water, which was recovered by magical means.[47]

The next Pharaoh who was commemorated at Maghara[33] was Khufu (IV 2), the great pyramid builder, who, as already mentioned, was figured smiting the enemy before the ibis-headed figure of the god Thoth. At Maghara several tablets recorded him, which were of large size and of excellent workmanship. The chief one had fortunately been drawn and photographed before it was entirely smashed during the recent blasting. On this tablet, the Pharaoh, here named Khnumu-Khufu, was described as a smiter of the Anu, a word written with three pillar signs, with a man as a determinative (Fig. 4).

Next in date at Maghara was the tablet of Sahura (V 2), which was framed by a colossal Uas-sceptre on either side and a row of stars along the top. Sahura was described in the wording as “smiter of the Mentu.” The same words were used to describe Ra-en-user (V 6), whose tablet at Maghara measured 63 by 102 inches, and was the largest of all. This tablet has the additional feature of an enormous vase supported by two ankhs with the words: “The lord of foreign lands (neb Setui) gave coolness,” which suggests that a water supply was made accessible by some local sheykh.

The Pharaohs at Maghara, between the First and the Fourth Dynasties, were always represented as smiters. The tablets of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties are for the most part broken or destroyed, but what is left of them points to more peaceful relations, and records the mining expeditions with additional detail.

Thus the tablet of Dadkara (V 8) states that the expedition (upt) was sent in the year after the fourth cattle census, which dates it to the eighth or ninth year of the reign of this king. Again, a tablet of Pepy I (VI 3) was dated by “the year after the eighteenth cattle census”. These tablets, moreover, mention some of the dignitaries who took part in the expedition. That of Dadkara named the ship-captain Nenekt-Khentikhet; that of Pepy I the ship-captain Ibdu; a further one of Pepy II (VI 5) the ship-captain Benkeneph.[48] This shows that the Egyptians approached the mine-land by water. There is mention on these tablets also of princes, of scribes, of a commander of recruits (hez-uz-neferu), of inspectors (uba), of interpreters of princes (sehez-saru), of the[34] seal-bearer to the god (neter sahu), of a chief of the land (mer ta), of a chief of the storehouse (mer ab), of a chief of the elders (mer uru), and of others, which shows how carefully the expeditions were organised. The tablet of Dadkara, moreover, mentions for the first time the Fkat country, fkat being short for mafkat, the ancient Egyptian word for turquoise. There is always a difficulty in reading aright the names of precious stones. Mafkat was often rendered as malachite, and it needed the turning over of the rubbish heaps at Serabit and the discovery of turquoise, in order fully to establish the nature of the stone that was the product of the area appropriated to “Hathor of Mafkat.”

The close of the Sixth Dynasty brought a break in the relations between Egypt and Sinai, which is attributable, no doubt, to changes in Egypt itself, of which we know little at this period. Perhaps there were movements among the people of the east. Among those who threatened Egypt from this side were the Mentu, who were Asiatics, and whose successful defeat was achieved, as mentioned above, with the help of the devotees to Sopd.

The Egyptians probably resumed work in Sinai during the Eleventh Dynasty, since workmen’s pots, found in the Wadi Maghara, are dated to this dynasty by their style.[49] The reign may have been that of Mentu-hotep III (XI 7), for a group of four kings seated at a table carved in stone was discovered at Serabit, with the names of the kings along the edge of the table on which their hands were placed. They were Sneferu (probably), Mentu-hotep III (XI 7), Amen-em-hat I (XII 1), and his son Sen-usert (XII 2), who was probably the donor of the group.[50]

When work was resumed in Sinai in the Eleventh Dynasty, the attitude of the Egyptians towards Serabit had undergone a marked change. In early days they had approached the sanctuary as quasi-worshippers, presenting offerings such as the baboon and the hawk. Now the sanctuary itself was drawn within the sphere of their influence, and they erected uprights or mazzeboth on the approach to the cave on which they recorded their mining expeditions.

Uprights of this kind are entirely unknown in Egypt.[35] The mazzeboth erected by the Egyptians in Sinai were therefore set up in deference to the custom of the place. They were worked in red sandstone which was quarried on the north side of the temple height judging by a great square cutting that remains there, and the work of inscribing them was done in situ by Egyptian stone-cutters who were attached to the expeditions. These steles are for the most part 6 to 12 feet high, 2 to 4 feet broad, and 6 to 8 inches thick. Their tops are rounded, which gives them the appearance of gravestones, and this led some of the earlier travellers to describe the height of Serabit as a place of burial.

The oldest of the mazzeboth were erected on a prominent spot outside the temenos within sight of the sanctuary; later these steles were placed along the approach to the cave, more and more crowding the adytum. These Egyptian inscribed mazzeboth all have a flat stone at the base which suggests a place of offering, and their purpose seems to have been to recommend the members of the expedition who set up the stone to the good graces of Hathor of Mafkat.

In keeping with this, a statuette of Hathor was presented to the shrine by the Pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty, every one of whom organised one, if not several, expeditions to Sinai, in order to secure turquoise. Several of these statuettes, varying in size and in workmanship, were discovered inside the temple area during the winter of 1906; most of them were sadly mutilated.

One statuette was the gift of Amen-em-hat I (XII 1), the founder of the dynasty, who erected a portal outside the lesser cave as was shown by a stone lintel bearing his name, which was found here. His successor, Sen-usert I (XII 2), added to this portal as was shown by a piece of limestone bearing his name. The larger cave about this time was squared, its walls were smoothed and a slab was fixed inside, on which were placed the more important Egyptian offerings, including the hawk presented by Sneferu, and the statuettes of Hathor. It served also to hold a hawk worked in sandstone that was presented by Sen-usert himself, which named him, his queen Khent, their daughter Sebat, and Ankhab, chief or overseer of the north land.

The same Ankhab also set up a tablet of his own, inside the cave on which he was represented offering loaves to Amen.

Of the next king, Amen-em-hat II (XII 3), there was found the usual statuette of Hathor, which was presented by the ship-captain Sneferu. Inscriptions on a hill at some distance from the caves showed that the Egyptians now worked turquoise mines at Serabit on their own account on land which they had acquired. One inscription was of the seventeenth year of Amen-em-hat II, another of his twenty-fourth year. The latter mentioned the “mine chamber which Men, born of Mut, triumphant and revered, excavated.” Two steles erected in the approach to the sanctuary likewise recorded the seventeenth and the twenty-fourth year of the reign of the same king.

The next kings, Sen-usert II (XII 4) and Sen-usert III (XII 5), made the usual gift of a statuette of Hathor. The latter was presented by five officials, including Merru, two inspectors, a scribe of the cattle, and an Amu or Syrian named Lua or Luy, “a name which corresponds to the Semitic Lévy.”[51] This shows a Semite in actual contact with the place. A stele of the same Pharaoh stood in a knoll of hæmatite on the plateau, the exposed position of which caused it to fall and crumble long ago; its remains strew the ground.

The reign of the next Pharaoh, Amen-em-hat III (XII 6), marked a climax in the intercourse of Egypt and Sinai. Of the forty-four years of his reign, at least fourteen witnessed expeditions to Sinai, which were commemorated by inscriptions set up in Wadi Maghara, in Wadi Nasb, and at Serabit.

A great inscription of the second year, mentioned above, stands on a boulder at the entrance to Wadi Maghara, which shows the king facing the ibis-headed Thoth and Hathor, and the accompanying wording mentions Khenti-hotep Khenemsu, who was commissioned to fetch turquoise and copper, and who had with him 734 men. Another inscription was set up by Harnakt, who “crossed the sea and secured stones of great excellence.”[52]

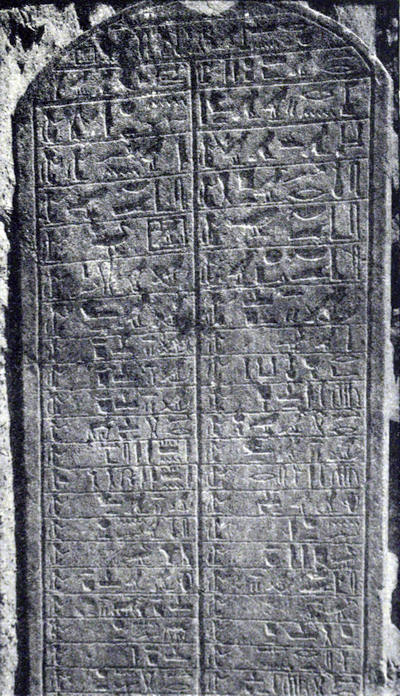

At Serabit also Amen-em-hat III was commemorated by many inscriptions. Large stone steles, set up on the plateau, recorded the 4th, 8th, 13th, 23rd, 30th, 44th, and 45th year of this reign. Several of these steles mention by name the Retennu people, of whom we now hear for the first time in Sinai.

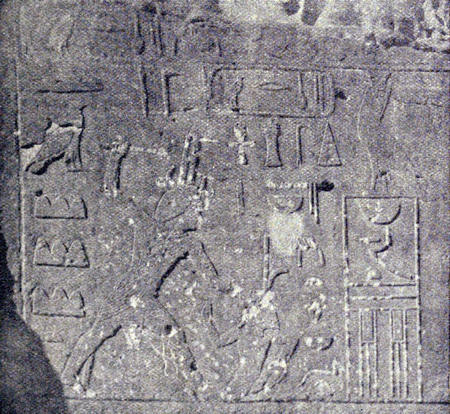

Fig. 9.—Upper half of Stele of Amen-em-hat III. (Petrie: Researches in Sinai.)

The stele of the fourth year contained in two columns the names and titles of over a hundred persons who took part in[38] the expedition. The names start in fairly large hieroglyphs at the top, and diminish in size lower down. A few additional names were roughly inscribed along the edge of the stele as the result of an afterthought. This splendid stele stood about ten feet high in the approach to the temple, but, worn through at the base by the continued action of wind and rain, it fell, and snapped in two in the falling (Fig. 9).

Not far from this stele stood one that was set up by Horoura, describing an expedition which reached the mines in hot weather. “The desert burnt like summer; the mountains burnt like fire; the vein seemed exhausted; the overseer questioned the miners; the skilled workers who knew the mine replied, There is turquoise to all eternity in the mountain, and at that moment it appeared.”[53]

The reference is to the turquoise mines opened by Amen-em-hat II, which were now further developed. The neck of rock which contained the turquoise had hitherto been worked from the north. This neck of rock was now attacked from the south, and, as the work became complex, a shaft of about ten feet square was sunk from above, which brought light and air into the passages. This shaft was wrongly described by some travellers as a reservoir. The passages eventually extended about 220 feet into the rock. A great inscription on the rock, near the chief opening, gives an idea of the offerings which the Egyptians made at the sanctuary at this time; evidently in return for the permission to work here. It mentions “a thousand loaves, jars of beer, cattle, fowls, incense, ointment, and everything on which the gods live.” The offerings in this case were presented by Sebek-her-heb, chief chamberlain, who declared, “I excavated a mine-chamber for my lord, the workmen came in full quota, never was there any neglect.”[54]

The same Sebek-her-heb erected the stele of the 44th year of Amen-em-hat III on the plateau. It is inscribed on one side only and stands in a rough stone enclosure with a flat stone at the base. The inscription runs “a royal offering to Hathor, mistress of turquoise (mafkat), for the family spirit (ka) of the chief chamberlain Sebek-her-heb, and the[39] ka of the seal-bearer, deputy of the overseer of seal-bearers, Kemnaa, born of Ka-hotep.”[55]

Another inscription of the 45th year of Amen-em-hat III, named Ptahwer, triumphant, who described himself as “delivering the Anu Sut (eastern foreigners) to the Pharaoh, and bringing the Mentu to the halls of the king.”[56]

During the reign of Amen-em-hat III the caves at Serabit were re-modelled to their present shape. The larger cave, without the recesses, now measures 20 by 10 feet. A square pillar of rock was left standing in its centre as a support to the roof. On one side of this pillar the Pharaoh was represented facing the goddess Hathor, wearing a high head-dress, who held out to him a sceptre. Beneath this scene Khenum-su, Ameny-seneb, seal-bearer, and other officials were seen.[57] The walls of the cave at the same time were smoothed and inscribed with mortuary prayers. But their surface for the most part has crumbled away, perhaps owing to intentional desecration, and the inscriptions are lost.

Ameny-seneb who was represented on the squared pillar, also set up in the cave an altar in the name of his king. This altar measured 40 by 26 inches, and probably stood at the back of the cave in a recess of corresponding dimensions. It was found in another part of the cave. This altar had the ordinary appearance of an Egyptian altar and was worked in the red sandstone of the place. It apparently took the place of an earlier stone or altar of different appearance, fragments of which were also found inside the cave. The smashing of this altar also points to an intentional desecration of the place.

The smaller cave which was appropriated to Sopd, was probably re-arranged at the same time. There was here no sign of inscription or tablet. It was simply a rounded apse with three steps leading up to it.

The other work which was done during the reign of Amen-em-hat III included mining in the Wadi Nasb, where an inscription at the head of the valley recorded his 20th year.[58]

The head of the valley floor of the Wadi Nasb is covered[40] with an enormous mass of slag, which points to extensive copper smelting. The mass of slag is 6 to 8 feet deep, 300 feet wide, and extends about 500 feet down the valley. It “may amount to 100,000 tons.” The provenance of the copper that was smelted here is insufficiently known. It can hardly have been brought up from the mines in the Wadi Khalig. But even at Serabit, now entirely denuded of trees, a crucible was found.

After the long reign of Amen-em-hat III came the short reign of Amen-em-hat IV (XII 7), the last king of his dynasty. An inscription in the Wadi Maghara recorded work done there in his sixth year, and, at Serabit, the small rock tablet mentioned above, was set up on the western side of the plateau. A portico-court about 10 feet square was also built by him outside the larger cave. This court was roofed over with slabs of stone, the roof being supported by two fluted columns which, like the rest of the building, were worked in the red sandstone of the place. The walls of this portico were inscribed, the subject being Hathor seated with the Pharaoh offering to her, and a long row of officials behind him. The same scene reversed was represented on the other side of the entrance. But the surface of the wall has crumbled so that the general character only of the scenes is visible and the names of the officials have gone.

CHAPTER V

EARLY PEOPLE AND PLACE NAMES

THE ancient peoples and place names of Sinai claim separate attention.

The earliest Egyptian rock inscription at Maghara represents the Pharaoh as a smiter, and describes him as such with the signs of a hand, an eagle, and the determinative of hills. The term is held to apply to no people in particular, and is therefore rendered as “barbarians.”

King Khufu (IV 2), in addition, is described as a smiter of the Anu; the word is written with the pillar sign. The word Anu was applied in Egypt to cave-dwellers generally, more especially to those of Nubia. The Anu are first mentioned on the Palermo Stone in connection with a king of the First Dynasty whose name is broken away, but who was probably King Den-Setui.

In the estimation of the historian Josephus (c. a.d. 60), the inhabitants of Sinai at the time of Moses were cave-dwellers, for he stated that Moses, in going to Sinai, went among the “troglodytes” (Antiq., ii. 11).

Among the early inhabitants of the peninsula were the Horites. The Babylonian kings who fought against the four kings of southern Syria who revolted in the time of Abraham, “smote the Rephaims in Ashteroth Karnaim, and the Zuzims in Ham, and the Emims in Shaveh-Kiriathaim, and the Horites in their mount Seir unto El Paran, which is by the wilderness” (Gen. xiv. 5-6). This associates the Horites with Mount Seir, which extended along the depression between the head of the Gulf of Akaba and the Dead Sea.

In the estimation of Prof. Robertson Smith the Horites of the Bible were troglodytes, which would bring them into line with the Anu of the Egyptian inscriptions. These[42] Horites were accounted of low stock by the Hebrews, and were probably in the stage through which the Israelites had passed before they formed a confederacy. Prof. Robertson Smith pointed out that the list of their so-called dukes (Gen. xxxvi. 20) is not a literal genealogy, but an account of their tribal and local division, since five of the names are animal or totem names.[59] The view that the Horites were cave-dwellers was based on the likeness between the name Horite and the Hebrew word hor, which signifies mountain. The connection between the names is now denied, and the Horites of the Bible are identified with the Kharu or Khalu of the Egyptian texts. The Kharu appear in the Annals of Tahutmes III (XVIII 6) and of Amen-hotep IV (XVIII 10), among the people against whom the Egyptians fought on the way to Naharain i.e. Mesopotamia.[60] But the word Kharu on the Egyptian side has been interpreted as “mixed multitude.”

The next people who are mentioned on the Egyptian monuments in Sinai are the Mentu. King Ra-en-user (V 6) was described as “great god of the smiting countries and raider of the Mentu.” Again, the tablet of Men-kau-hor, mentioned a royal expedition to the Mentu; and Ptahwer in Sinai of the Twelfth Dynasty was described as “bringing the Mentu to the king’s heels.”

The Mentu took part in the great Hyksos invasion of Egypt between the Twelfth and the Eighteenth Dynasties. For when the tide of foreign nations was rolled back, they were among the conquered. King Aahmes I (XVIII 1), after seizing the foreign stronghold Avaris, “made a slaughter of the Mentu of Setiu, and going south to Khent-hen-nefer, he destroyed the Anu-Khenti.”[61] Among the conquered people who were represented around the throne of Amen-hotep II (XVIII 7) are the Mentu, who have the appearance of true Asiatics. An Edfu inscription, as mentioned above, stated that the Mentu were thrown back with the help of the devotees of the god Sopd.

The people who figured most prominently in the Egyptian annals of Sinai were the Retennu, who were mentioned again and again on the steles which were set up at Serabit in the course[43] of the Twelfth Dynasty. On three separate steles it says that the Egyptian expedition was sped across the desert by the brother of the sheykh (sen-heq-en) of the Retennu country, whose name was Khebdet or Khebtata, and who is represented riding on an ass which is led by a man in front, with a servant carrying his water flask behind him. On one stele six Retennu are named.[62]