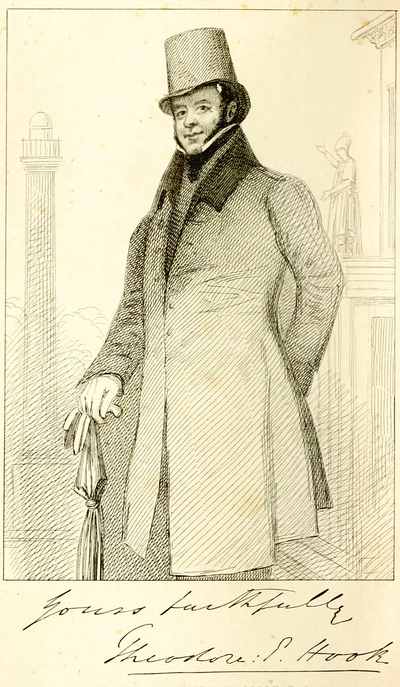

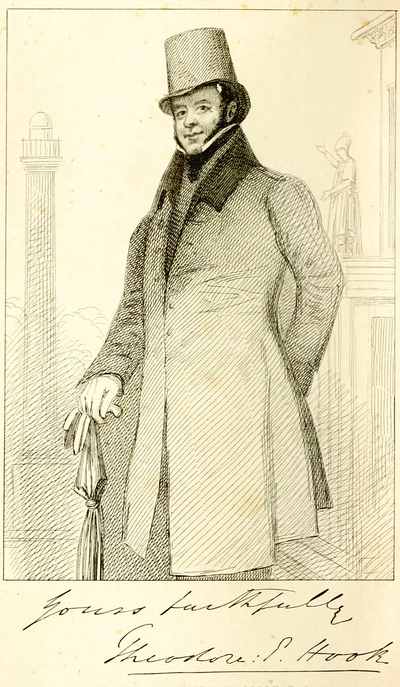

Theodore E. Hook

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources. Many passages have deliberate misspelling for humorous effect.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

A NEW EDITION

WITH

LIFE OF THE AUTHOR, PORTRAITS BY MACLISE AND D'ORSAY, CARICATURES, AND FACSIMILES

London

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1883

| PAGE | ||

| Memoir of Theodore Hook | 3 | |

| The Ramsbottom Papers:— | ||

| I. | Mrs. Ramsbottom's Party | 41 |

| II. | Miss Lavinia Ramsbottom | 43 |

| III. | Miss Lavinia's Letter from Paris, forwarding her Mother's Journal in England and France | 44 |

| IV. | Higginbottom and Ramsbottom | 52 |

| V. | Miss Lavinia Ramsbottom forwards the Continuation of her Mother's Diary | 53 |

| VI. | Adventures at Paris | 60 |

| VII. | Further Adventures at Paris | 62 |

| VIII. | Mrs. Ramsbottom back in London | 66 |

| IX. | Mrs. Ramsbottom at Rome | 69 |

| X. | Mrs. Ramsbottom objects to be Dramatised | 72 |

| XI. | Mrs. Ramsbottom writes from Dieppe | 73 |

| XII. | Hastings | 75 |

| XIII. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on the House of Commons | 78 |

| XIV. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on the Canning Administration | 81 |

| XV. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on Smoking | 84 |

| XVI. | Mrs. Ramsbottom's Conundrums | 85 |

| XVII. | A Letter from Cheltenham | 87 |

| XVIII. | Hastings again | 90 |

| XIX. | News from Hastings | 94 |

| XX. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on the relative merits of Margate and Brighton | 96 |

| XXI. | Mrs. Ramsbottom contemplates the Collection of her Letters into a volume | 102 |

| XXII. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on Popery | 105 |

| XXIII. | Mrs. Ramsbottom at the Royal Academy | 108 |

| [ii] XXIV. | Mrs. Ramsbottom at the "Chiswick Fête" | 111 |

| XXV. | A Letter from Walmer | 117 |

| XXVI. | A Peck of Troubles | 118 |

| XXVII. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on Public Events | 120 |

| XXVIII. | Mrs. Ramsbottom declares herself a Convert to "Reform" | 123 |

| XXIX. | Mrs. Ramsbottom on the House of Lords | 128 |

| Political Songs and Squibs:— | |

| Carmen Æstuale | 133 |

| Ass-ass-ination | 135 |

| Michael's Dinner | 138 |

| Mrs. Muggins's Visit to the Queen | 140 |

| Hunting the Hare | 147 |

| The City Concert | 152 |

| Invitations to Dinner | 156 |

| Vacation Reminiscences | 159 |

| Reminiscences Continued | 162 |

| Gaffer Grey | 166 |

| The Idle Apprentice turned Informer | 170 |

| The Queen's Subscription | 174 |

| Opposition | 178 |

| The Invitation | 184 |

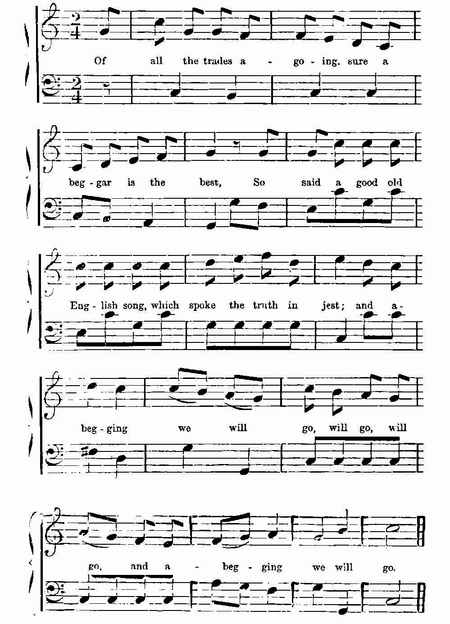

| The Beggars—A New Song | 188 |

| Bubbles of 1825 | 194 |

| The Grand Revolution | 197 |

| Imitation of Bunbury's "Little Grey Man" | 200 |

| Humpty-Dumpty | 203 |

| Parody—"While Johnny Gale Jones" | 204 |

| Parody—"The young May Moon" | 205 |

| Disappointment | 206 |

| Tentamen; or, an Essay towards the History of Whittington, some time Lord Mayor of London | 207 |

| Miscellanies, in Verse and Prose:— | |

| [iii] Mr. Ward's Allegorical Picture of Waterloo | 249 |

| Letter from a Goose | 259 |

| The Hum-Fum Gamboogee Society | 262 |

| Moral Theatricals | 269 |

| Private Correspondence of Public Men | 275 |

| The Cockney's Letter | 280 |

| Byroniana | 284 |

| Lord Wenables | 288 |

| Lord Wenables Again | 304 |

| Modern Improvements (Two Letters) | 309 |

| Punning, with Cautionary Verses to Youth of both Sexes | 316 |

| Fashionable Parties | 322 |

| A Day's Proceedings of a Reformed Parliament | 325 |

| Clubs | 333 |

| Rachel Stubbs' Letter to Richard Turner | 336 |

| Mr. Minus the Poet | 338 |

| National Distress | 339 |

| Hints for the Levee | 347 |

| The Inconsistencies of Cant | 350 |

| Prince Puckler-Muskau's Tour | 355 |

| Prospectus for a General Burying Company | 388 |

| Letter from John Trot to John Bull | 392 |

| The March of Intellect | 395 |

| Sunday Bills | 400 |

| The Spinster's Progress | 405 |

| Errors of the Press | 409 |

| The Visit to Wrigglesworth | 413 |

| A Visit to the Old Bailey | 440 |

| The Toothpick-makers' Company | 453 |

| The Man-servant's Letter | 464 |

| The Bibliomaniac | 468 |

| Absence of Mind | 469 |

| A Distinguished Traveller | 470 |

| Daly's Practical Jokes | 471 |

| The Ballet | 492 |

| Toll-gates and their Keepers | 496 |

| Tom Sheridan's Adventure | 499 |

| Polly Higginbottom | 503 |

| Song—"Mary once had Lovers two" | 504 |

| Philip and Donna Louisa | 505 |

| [iv] The Blacksmith | 506 |

| "My Father did so before me" | 507 |

| "Throughout my Life the Girls I've pleased" | 508 |

| The Chambermaid | 509 |

| Song, "When I was a very little Fellow" | 509 |

| Sir Tilbury Tott | 511 |

| "Venice Preserved" | 513 |

| Daylight Dinners | 515 |

| Clubs! | 516 |

| Visitings | 518 |

| The Quill Manufacturer | 522 |

| Epigram on Twining's Tea | 522 |

| On the Latin Gerunds | 522 |

| The Splendid Annual | 523 |

| Anecdotes, Hoaxes, and Jests:— | |

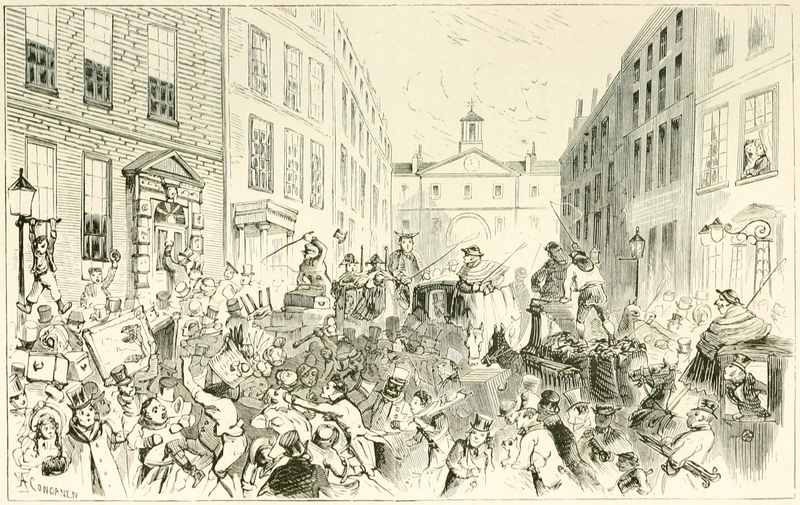

| The Berners-street Hoax | 539 |

| Romeo Coates | 541 |

| Hook, Mathews, and the Alderman | 542 |

| A Strange Dinner | 544 |

| Ludicrous Adventure at Sunbury | 547 |

| Charles Mathews and Hook | 552 |

| Hook's "First Appearance" | 553 |

| Hook and Dowton the Actor | 554 |

| Letter from Mauritius | 555 |

| Evading a Coach Fare | 557 |

| Unsuccessful Hunt for a Dinner | 559 |

| Hook at Lord Melville's Trial | 560 |

| The Thirty-nine Articles | 562 |

| "Chaffing" a Proctor | 562 |

| Summary Proceedings of Winter | 563 |

| "Something Wrong in the Chest" | 564 |

| Warren's Blacking | 564 |

| The Wine-cellar and the Book-seller | 565 |

| Sir Robert Peel's Anecdote of Theodore Hook | 565 |

| A Receipt against Night Air | 566 |

| Punting | 566 |

| "List" Shoes | 567 |

| [v] "The Abattoir" | 568 |

| Putney Bridge | 568 |

| "Mr. Thompson is Tired" | 568 |

| The Original "Paul Pry" | 569 |

| Hook and Tom Hill | 570 |

| Hook's Politeness | 570 |

| A Biscuit and a Glass of Sherry | 571 |

| Much Alike | 572 |

| Private Medical Practice | 572 |

| Hook's Street Fun | 572 |

| A Misnomer | 572 |

| "Contingencies" | 573 |

| "The Widow's Mite" | 573 |

| Hook's Extempore Verses | 573 |

| Hook Extemporises a Melodrama | 575 |

| "Ass-ass-ination" | 578 |

| "Weather or No" | 578 |

| Diamond Cut Diamond | 579 |

| Tom Moore—Losing a Hat | 579 |

| "Good Night" | 579 |

MEMOIR OF THEODORE HOOK.

The life of the distinguished humourist whose opera minora we now present to the world, was so chequered and diversified by remarkable incidents and adventures, and passed so much in the broad eye of the world and of society, as to be more than ordinarily interesting. The biography of a man of letters in modern times seldom affords so entertaining a narrative, or so instructive and pathetic a lesson, exhibiting how useless and futile are the most brilliant powers and talents, both original and transmitted, without a due admixture of that moral principle and wisdom in daily life necessary to temper and control them.

Theodore Edward Hook—one of the most brilliant wits, and one of the most successful novelists of this century—was born in London, at Charlotte Street, Bedford Square, on the 22nd of September, 1788, in the same year as Lord Byron, whose contemporary he afterwards was at Harrow. The first school that Theodore attended was an "academy," in the Vauxhall districts. The master, a Mr. Allen, had also other pupils in his charge who afterwards rose to eminence. Here he remained till his tenth year, when he was sent to a kind of seminary for young gentlemen, a green-doored, brass-plated establishment, in Soho Square. While at this school, he appears systematically to have played truant, to have employed his time in wandering about the streets, and to have invented ingenious excuses to explain his absence to the authorities. On the day of the illumination for the Peace[4] of Amiens, he preferred to spend the morning at home, and informed his parents that a whole holiday had been given on account of the general rejoicings. Unfortunately, his elder brother, James, happened to pass through the Square, and observing signs of business going on as usual at the academy, he went in, made inquiries, and found that the young scape-grace had not made his appearance there for three weeks. Theodore, instead of witnessing the fireworks, was duly punished, and locked up in the garret for the rest of the afternoon.

Theodore was the second son of Mr. James Hook, the popular musical composer, whose pleasing strains had delighted the preceding generation, when Vauxhall Garden was a fashionable resort. His mother (a Miss Madden) is described as a woman of singular beauty, talents,[1] accomplishments, and worth. To the fact that he lost her gentle guidance at the early age of fourteen, may be attributed many of the misfortunes and irregularities of his after-life.

There was but one other child of Mr. James Hook's first marriage, the late Dr. James Hook, Dean of Worcester; and he being Theodore's senior by eighteen years, had left the paternal roof long before the latter was sent to school.

The Dean, with a great deal of the wit and humour that made his brother famous,[2] and with perhaps much the same original cast of disposition and temper generally, had possessed one great advantage over him at the start of life. His excellent mother watched over him all through the years [5]of youth and early manhood. Theodore could only remember her, and fondly and tenderly he did so to the last, as the gentle parent of a happy child. He had just approached the first era of peril when this considerate and firm-minded woman was lost to her family. The composer soon afterwards married again; but Theodore found not, what, in spite of a thousand proverbs, many men have found under such circumstances—a second mother. But for that deprivation we can hardly doubt that he might, like his more fortunate brother, have learned to regulate his passions and control his spirits, and risen to fill with grace some high position in an honourable profession. The calamitous loss of his mother is shadowed very distinctly in one of his novels, and the unlucky hero (Gilbert Gurney) is represented as having a single prosperous brother, exactly eighteen years older than himself. But, indeed, that novel is very largely autobiographical: when his diary alludes to it as in progress, the usual phrase is, "Working at my Life."

Born in the same year with Lord Byron and Sir Robert Peel, he was their schoolfellow at Harrow, but not in the same memorable form, though he often alluded to the coincidence of dates with an obvious mixture of pride and regret—perhaps we ought to say, remorse.

We have met with no account of him whatever by any one who knew him familiarly at that period. That he was as careless and inattentive to the proper studies of the place, as he represents his Gurney to have been, will not be thought improbable by most of his readers. But his early performances, now forgotten, display many otiose quotations from the classics, and even from the modern Latin poets; and these specimens of juvenile pedantry must be allowed to indicate a vein of ambition which could hardly have failed, with a mind of such alacrity, to produce some not inconsiderable measure of attainment.

His entrance at Harrow was signalized by the perpetration of a practical joke, which might have been attended with[6] serious consequences. On the night of his arrival, he was instigated by young Byron, whose contemporary he was, to throw a stone at a window where an elderly lady, Mrs. Drury, was undressing. Hook instantly complied; but, though the window was broken, the lady happily escaped unhurt. Whatever degree of boyish intimacy he might at this time have contracted with his lordship, it was not sufficient to preserve him from an ill-natured and uncalled-for sneer in the "English Bards and Scotch Reviewers," an aggression amply repaid by the severe strictures which appeared in the John Bull on certain of the noble bard's effusions, and on the "Satanic school of poetry" in general. The acquaintance, such as it was, was broken off by Hook's premature withdrawal from Harrow, and does not appear to have been resumed.

In 1802, his excellent mother died, and with her perished the only hope of restraining the youthful Theodore within those bounds most essential to be preserved at his age, and of maintaining him in that course of study, which, if persevered in for a few years more, might have enabled him to reach a position not less honourable than that enjoyed by his more prosperous brother. Mrs. Hook appears, indeed, to have been one of those best of wives and women, who, by the unobtrusive and almost unconscious exercise of a superior judgment, effect much towards preserving the position and respectability of a family constantly imperilled by the indiscretion of its head—one who, like a sweet air wedded to indifferent words, serves to disguise and compensate for the inferiority of her helpmate.

Theodore's father, a clever but weak man, was easily persuaded not to send him back to Harrow. He was proud already of his boy, found his company at home a great solace at first, and even before the house received its new mistress, had begun to discover that one of his precocious talents might be turned to some account financially. Theodore had an exquisite ear, and was already, living from the cradle in[7] a musical atmosphere, an expert player on the pianoforte; his voice was rich, sweet, and powerful; he could sing a pathetic song well, a comic one charmingly. One evening he enchanted his father especially by his singing, to his own accompaniment, two new ballads, one grave and one gay. Whence the airs—whence the words? It turned out that verse and music were alike his own: in the music the composer perceived much that might be remedied, but the verses were to him faultless—meaning probably not much, but nothing more soft than the liquid flow of the vocables, nothing more easy than the balance of the lines. Here was a mine for the veteran artist; hitherto he had been forced to import his words; now the whole manufacture might go on at home. Snug, comfortable, amiable domestic arrangement! The boy was delighted with the prospect—and at sixteen his fate was fixed.

In the course of the following six years Theodore Hook produced at least a dozen vaudevilles, comic operas, and dramatic pieces for the stage, which all enjoyed a considerable run of popularity in their time, but are now entirely, and perhaps deservedly, forgotten. His coup-d'essai in this line appeared in 1805, under the title of "The Soldier's Return; or, What can Beauty do? a comic opera in two acts, as performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane."

It would be as absurd to criticise such a piece as last year's pantomime—like that, it answered its purpose and its author's, and no more is to be said. At the same time, amidst all its mad, impudent nonsense, there are here and there jokes which, if unborrowed, deserved the applause of the pit. A traveller coming up to an inn-door, says, "Pray, friend, are you the master of this house?" "Yes, sir," answers Boniface, "my wife has been dead these three weeks." We might quote one or two more apparently genuine Theodores. The dialogue, such as it is, dances along, and the songs read themselves into singing.

His modus operandi in producing this earliest piece, was[8] ingenious. He bought three or four French vaudevilles, filched an incident from each, and thus made up his drama.

The production of this little piece brought the young author into contact with Mathews and Liston. These distinguished comedians were both considerably his seniors. Both had their own peculiar style, and yet both seemed at their best when treading the boards together. With the view of providing an opportunity for their joint appearance, Theodore Hook planned his second afterpiece, "Catch Him who Can" (1806), in which abundant opportunity was contrived for exhibiting the grave irresistible drollery of Liston in contrast with the equally matchless vivacity and versatility of the prince of mimics and ventriloquists. In the course of the farce Mathews figured in, we think, seven different disguises. Such acting would have insured the triumph of even a worse thing than the "Soldier's Return,"—but this was better than that in every respect. One of Liston's songs was long in vogue, perhaps still survives—

"I sing the loves, the smiling loves,

Of Clutterbuck and Higginbottom."

There are three other readable songs, "Mary," "Donna Louisa Isabella," and the "Blacksmith," and not a few meritorious points in the dialogue. It is impossible, however, as we have already hinted, to be sure of the originality of anything either in the plot or the dialogue of these early pieces. Hook pilfers with as much audacity as any of his valets, and uses the plunder occasionally with a wonderful want of thought. Liston's sweetheart, for instance, a tricky chambermaid, knocks him down with Pope's famous saying, "Every man has just as much vanity as he wants understanding."

"The Invisible Girl" next followed (1806). The idea appears to have been taken from a newspaper account of a new French vaudeville;[3] but it was worked out by the adapter with very great cleverness.

The fun is, that with a crowd of dramatis personæ, a rapid succession of situations, and even considerable complication of intrigue, no character ever gets out more than yes, no, a but, a hem, or a still—except the indefatigable hero Captain Allclack—for whose part it is difficult to believe that any English powers but Jack Bannister's in his heyday could ever have been adequate. This affair had a great run; and no wonder. If anybody could play the Captain now, it would fill the house for a season. Under a somewhat altered form, and with the title of "Patter versus Clatter," it has indeed been reproduced by Mr. Charles Mathews, with great success.

In the following year (1807) a drama, by Hook, in three acts, entitled "The Fortress," and also taken from the French, was produced at the Haymarket. As a fair specimen of the easy jingle with which these pieces abounded, we select a song sung by Mathews, in the character of Vincent, a gardener, much in vogue in its day:—

"When I was a chicken I went to school,

My master would call me an obstinate fool,

For I ruled the roast, and I roasted all rule,

And he wondered however he bore me;

I fired his wig, and I laughed at the smoke,

And always replied, if he rowed at the joke,

Why—my father did so before me!

I met a young girl, and I prayed to the miss,

I fell on my knee, and I asked for a kiss,

She twice said no, but she once said yes,

And in marriage declared she'd restore me.

We loved and we quarrell'd, like April our strife,

I guzzled my stoup, and I buried my wife,

But the thing that consoled me at this time of life

Was—my father did so before me!

Then, now I'm resolved all sorrows to blink,

Since winkin's the tippy, I'll tip them the wink,

I'll never get drunk when I cannot get drink,

Nor ever let misery bore me.

[10]I sneer at the Fates, and I laugh at their spite,

I sit down contented to sit up all night,

And when the time comes, from the world take my flight,

For—my father did so before me!"

"Tekeli, or the Siege of Mongratz," produced about the same time, is now chiefly remembered as having occasioned some caustic lines in the "English Bards and Scotch Reviewers:"—

"Gods! o'er those boards shall Folly rear her head

Where Garrick trod, and Kemble lives to tread?

On those shall Farce display Buffoonery's mask,

And Hook conceal his heroes in a cask?"

"The Siege of St. Quentin," a drama of a similar description, quickly followed. The plot was founded on the famous battle of that name fought in 1557, when the French, endeavouring to raise the siege, were signally defeated. The object of the piece, which was to excite enthusiasm in favour of the Spanish nation, together with the magnificence of the mise en scène, won for it considerable success. It sleeps now with sundry others, such as "The Trial by Jury" (1811), "Darkness Visible" (1811), "Safe and Sound" (1809), "Music Mad" (1808). They all ran their course, and have perished—

"Unwept, unhonour'd, and unknown."

The last-named, however ("Music Mad"), perhaps deserves a word of notice, if only on account of its transcendent absurdity. The principal character, stolen bodily from Il Fanatico per la Musica (which had been considered the masterpiece of the celebrated Naldi), and rendered infinitely more ridiculous by being metamorphosed into a native of our most unmusical isle, is, as the title indicates, an amateur, and so passionately devoted to his favourite science as to insist upon his servant's wearing a waistcoat scored all over with crotchets and semiquavers.

In 1809, the destruction by fire of the two patent houses having compelled the rival companies to coalesce and repair to[11] the Lyceum, principally for the purpose of providing employment for the humbler members of the profession, Theodore Hook contributed the well-known after-piece of "Killing no Murder." Apart from the intrinsic merit of the piece itself, the admirable acting of Liston as Apollo Belvi, and of Mathews as Buskin, for whom it was especially written (though, by the way, it is but justice to add, on the authority of Mrs. Mathews, that the latter character was but "a sketch, which Mr. Mathews filled up ad libitum"),—there were circumstances attending its representation which invested it with peculiar interest, and enlisted all the sympathies of the audience in favour of the author. It appears that on the MS. being submitted to the deputy-licenser, Mr. Larpent, certain passages reflecting on the Methodist preachers induced that gentleman, in the first instance, to place a veto on the performance. A compromise, however, was effected, the objectionable scene remodelled, and the play allowed to proceed. Whether it would have been wiser, upon the whole, to have suffered it to go forth with its imperfections on its head, and to have trusted to the good taste of the public to demand the suppression of any incidental improprieties, may be a question, the more so, as the licenser's authority, extending only to the acted drama, could offer no hindrance to its publication. Some half-dozen editions, containing the passages omitted in the performance, were struck off and circulated like wildfire, together with a preface, from which, as the author has thus an opportunity of stating his own case, it may be as well to present our readers with a few extracts:—

"I should have suffered my gratitude to the public to have been felt, not told, had not some very singular circumstances compelled me to explain part of my conduct, which, if I remained silent, might be liable to misconstruction. On the evening previous to the performance of 'Killing no Murder,' I was much surprised to hear that it could not be produced, because Mr. Larpent, the reader of plays (as he is[12] termed), had refused to grant his license for it. The cause of the refusal was, I heard, political. I revolted at the idea; and, as a young man entering life, felt naturally anxious to clear my character from the imputation of disloyalty. Then I heard it rumoured that the ground of the refusal was its immorality. Here again I was wounded; for though I confess I have no pretension to sanctity, yet I hope I shall never prostitute my time in the production of that for which even wit itself is no excuse.

"Thus situated, I set off in search of the gentleman who had strangled my literary infant in its birth; and to find him I referred to the 'Red-book,' where I discovered that John Larpent, Esq., was clerk at the Privy Seal Office, that John Larpent, Esq., was deputy to John Larpent, Esq., and that the deputy's secretary was John Larpent, Esq. This proved to me that a man could be in three places at once; but on inquiry, I found he was even in a fourth and a fifth, for it was by virtue of none of these offices he licensed plays, and his place, i.e., his villa, was at Putney. Thither I proceeded in a post-chaise, in chase of this ubiquitarian deputy, and there I found him. After a seasonable delay to beget an awful attention on my part, he appeared, and told me with a chilling look, that the second act of my farce was a most 'indecent and shameful attack on a very religious and harmless set of people' (he meant the Methodists), 'and that my farce altogether was an infamous persecution of the sectaries.' Out came the murder. The character of a Methodist preacher, written for Liston's incomparable talents, with the hope of turning into ridicule the ignorance and impudence of the self-elected pastors, who infest every part of the kingdom, met with the reprehension of the licenser.

"It was in vain I adduced Mother Cole in the 'Minor,' Mawworm in the 'Hypocrite,' Barebones in the 'London Hermit,' and half-a-dozen other parts. The great licenser[13] shook his head 'as if there was something in it,' and told me that Lord Dartmouth had the piece; if he did not object, it might yet be played; but if his lordship concurred with him, not a line should be performed. I took my leave, fully convinced how proper a person Mr. Larpent was to receive, in addition to his other salaries, four hundred pounds per annum, besides perquisites, for reading plays, the pure and simple performance of which, by his creed, is the acme of sin and unrighteousness. His even looking at them is contamination—but four hundred a-year—a sop for Cerberus—what will it not make a man do?

"Now, in defence of the part of 'Apollo Belvi,' as originally written, I consider it necessary to speak. It is a notorious fact that the Methodists are not contented with following their own fashions in religion, but they endeavor hourly to overturn the Established Church by all means, open and covert; and I know, as a positive fact, that it is considered the first duty of Methodist parents to irritate their children against the regular clergy, before the poor wretches are able to think or consider for themselves. Nay, they are so ingenious in their efforts for this purpose, that they inculcate the aversion by nick-naming whatever object the children hate most after some characteristic of the Episcopal religion; and I have known a whole swarm of sucking Methodists frightened to bed by being told that the bishop was coming—the impression resulting from this alarm grows into an antipathy, and from having been, as children, accustomed to consider a bishop as a bugbear, it became no part of their study to discover why—the very mention of lawn sleeves throws them into agonies ever after. Seeing, then, with what zeal these sectaries attack us, and with what ardour they endeavour to widen the breach between us by persecution and falsehood, I did conceive that the lash of ridicule might be well applied to their backs, particularly as I prefer this open mode of attack to the assassin-like stab of[14] the dagger, to which the cowardly Methodist would, for our destruction, have no objection to resort.

"But my ridicule went to one point only. Mr. L. Hunt, in his admirable Essays on Methodism, justly observes, that a strong feature in the Methodists' character is a love of preaching. If it be possible that these self-elected guardians and ministers have an ascendency over the minds of their flocks, and have the power to guide and direct them, it becomes surely the duty of every thinking being to consider their qualifications for such a task.

"The wilful misleadings of the clever Methodists, from the small proportion of talent that exists among them, are more harmless in their tendency than the blasphemous doctrines of ignorance. The more illiterate the preacher, the more infatuated the flock; and there is less danger in the specious insinuation of a refined mind than the open and violent expressions of inspired tailors and illuminated cobblers. It was to ridicule such monstrous incongruities, that, without any claim to originality, I sketched the part of 'Belvi,' in the following farce. I conceived, by blending the most flippant and ridiculous of all callings, except a man-milliner's (I mean a dancing-master's), with the grave and important character of a preacher, I should, without touching indelicately on the subject, have raised a laugh against the absurd union of spiritual and secular avocations, which so decidedly marks the character of the Methodist. Of the hypocrisy introduced into the character, I am only sorry that the lightness of the farce prevented my displaying a greater depth of deception. All I can say is, that, whatever was written in 'Killing no Murder,' against the Methodists, was written from a conviction of their fallacy, their deception, their meanness, and their profaneness."

Another farce, "Exchange no Robbery," produced at a somewhat later period, under the pseudonym of "Richard Jones," deserves honourable mention. Terry, another intimate associate from that time forth, had in Cranberry a[15] character excellently adapted to his saturnine aspect and dry humour; and Liston was not less happily provided for in Lamotte.

Almost all these pieces were written before Hook was twenty years of age. Had he gone on in this successful dramatic career, and devoted to such productions the experience of manhood and that marvellous improvisatore power which was to make him the facile princeps of the satirists and humourists of his time, there can be no doubt he must have rivalled any farce-writer that ever wrote in any language.

It was in his twentieth year that Theodore Hook made his first appearance as a novelist, under the pseudonym of Alfred Allendale.[4] Lockhart characterizes the work as "a mere farce, though in a narrative shape and as flimsy as any he had given to the stage. As if the set object," he says, "had been to satirize the Minerva Press School, everything, every individual turn in the fortunes of his 'Musgrave' is brought about purely and entirely by accident." The sentimental hero elopes with his mistress. A hundred miles down the North road they stop for a quarter of an hour—order dinner, and stroll into the garden. Behold, the dreaded rival happens to be lodging here—he is lounging in the garden at this moment. The whole plan is baulked. Some time afterwards they elope again—and reach Gretna Green in safety.

"Cruel mothers, chattering friends, and flattering rivals all were distanced—the game was run down, he was in at the death, and the brush was his own. False delicacy at Gretna is exploded; a woman when she goes into Lanchester's is known to want millinery (people say something more), when she lounges at Gray's she is understood to stand in need of trinkets, when she stops at Gattie's she wants complexion, and when she goes to Gretna she wants a husband.

"That being the case, not to talk of marriage is as absurdly outré as not to call for supper, and therefore Musgrave with a sly look at his blushing bride, ordered a couple of roasted fowls and a parson to be ready immediately; the waiter, perfect in his part, stepped over to the chandler's shop, hired the divine, and at half-past ten the hymeneal rites were to be solemnized."—Vol. i., p. 84.

The fowls are put to the fire—the blacksmith appears—the ceremony has just reached the essential point, when a chaise dashes up to the door—out spring the heroine's mother and the rival again. Farther on, the hero comes late at night to an inn, and is put into a double-bedded room, in which the rival happens to be deposited, fast asleep. The rival gets up in the morning before the hero awakes, cuts his thumb in shaving, walks out, sees a creditor, jumps on the top of a passing stage-coach, and vanishes. The hero is supposed to have murdered him—the towel is bloody—he must have contrived to bury the body; he is tried, convicted, condemned;—he escapes—an accident brings a constable to the cottage where he is sheltered—he is recaptured—pinioned—mounts the drop; he is in the act of speaking his last speech, when up dashes another post-chaise containing the rival, who had happened to see the trial just the morning before in an old newspaper. And so on through three volumes.

It abounds, as a matter of course, in play upon words: for example, a rejected suitor's taking to drinking, is accounted for on the plea that "it is natural an unsuccessful lover should be given to whine,"—a pun, by the way, better conveyed in the name "Negus," which he is said to have bestowed upon a favourite, but offending, dog. There are also introduced a couple of tolerably well-sketched portraits, Mr. Minns, the poet (T. Moore), and Sir Joseph Jonquil (Banks). An epigram, referring to the celebrated duel of the former with Jeffrey, in consequence of an article in No. 16 of the Edinburgh Review, is worth repeating,—the[17] more so, as its paternity has been subject of dispute, the majority attributing it to one of the authors of "Rejected Addresses!"—

"When Anacreon would fight, as the poets have said,

A reverse he displayed in his vapour,

For while all his poems were loaded with lead,

His pistols were loaded with paper;

For excuses Anacreon old custom may thank,

Such a salvo he should not abuse,

For the cartridge, by rule, is always made blank,

Which is fired away at Reviews."

But the oddest part of the whole is that Hook himself, sixteen years afterwards, thought it worth while to re-cast precisely the same absurd fable, even using a great deal of the language, in his "Sayings and Doings." (Series first, vol. iii. Merton.) Of course the general execution of that tale is vastly superior to the original edition; but some of, all things considered, its most remarkable passages are transcribed almost literatim.

Mr. Allendale's novel excited little or no attention, and remained unacknowledged. It is worthless, except that in the early filling up occasionally we have glimpses of the author's early habits and associations, such as he was in no danger of recalling from oblivion in the days of "Sayings and Doings." When the hero fell in love, for example, "Bond-street lounges became a bore to him—he sickened at the notion of a jollification under the Piazza—the charms of the pretty pastry-cooks at Spring Gardens had lost their piquancy." A Viscountess's fête at Wimbledon has all the appearance of having been sketched after a lark at Vauxhall with a bevy of singing women. In the re-cast, it is right to say, he omitted various gross indecencies, some rude personalities, and a very irreverent motto.[5]

Of such an ephemeral character were the earlier writings of a man whose later works have charmed and delighted [18]thousands wherever the English language is spoken. But his brilliancy in the social circle and the fame of his marvellous hoaxes had already spread far and wide, when an unexpected event occurred which changed the whole tenor of his life, and removed him from English society and from English literature for nearly seven years.

Up to 1812, Theodore Hook had been almost, if not entirely, dependent upon his pen for pecuniary supplies; his father was in no condition to assist him; and at the rate of two or three farces a year, which seems to have been about the average of his productions, an income could scarcely have been realized by any means commensurate with the expenses of a fashionable young gentleman "upon town;" debts began to accumulate, and he had already resorted to the pernicious expedient of raising money upon his "promise to write," (a draught upon the brain, honoured, on at least one occasion, by Mr. Harris, the manager of Covent Garden,) when he was presented with an appointment which promised to place him in easy circumstances for the remainder of his life—that of Accountant-General and Treasurer at the Mauritius, worth about £2,000 per annum. It was not, however, till October, 1813, that after a long but agreeable voyage he entered upon his duties at the Mauritius.

It so happened that the island, which had been captured from the French in 1811, had been since that time under the control of Mr. (afterwards Sir R. J.) Farquhar, who, as Governor, united in his own person all the executive and legislative powers. Nothing could have been more favourable to the young official than this circumstance, Mr. Farquhar being not only esteemed throughout the colony, on account of his judgment, moderation, and affability, but being also connected with Dr. James Hook, by the latter's marriage with his sister. The reception which met Theodore on his arrival was as encouraging as could have been wished, and his own convivial qualities and agreeable manners soon[19] made him as popular among the élite of Port Louis as he had been in the fashionable and literary circles of London. In a letter addressed to his old friend, Mathews, about a couple of years after his establishment in what he terms "this paradise, and not without angels," he gives a most spirited and joyous account of his general mode of life, and of the social resources of the island:—

"We have," says he, "operas in the winter, which sets in about July; and the races, too, begin in July. We have an excellent beef-steak club, and the best Freemasons' lodge in the world. We have subscription concerts and balls, and the parties in private houses here are seldom less than from two to three hundred. At the last ball given at the Government House, upwards of seven hundred and fifty ladies were present, which, considering that the greater proportion of the female population are not admissible, proves the number of inhabitants, and the extent of the society."

It may be supposed, that if he was delighted with the Mauritius, its society was enchanted with him. He was but twenty-five when he arrived; and the sudden advancement of his position and enlargement of his resources, must have had rather an exciting than a sobering influence on such a temperament as his at that buoyant age. He was of course the life and soul of the hospitalities of the place and all its amusements and diversions—the phœnix of his Thule. He became, among other things, a leading man on the turf, and repeatedly mentions himself as having been extremely successful in the pecuniary results of that dangerous pursuit. His own hospitality was most liberal; many an Indian veteran yet delights to recall the cordial welcome he found at La Reduite during a brief sojourn at the Mauritius; and not a few such persons were unconsciously sitting for their pictures in crayon then, and in pen and ink afterwards, while they displayed their Oriental airs before the juvenile Treasurer, their profuse Amphitryon. His journal would make it easy enough to identify not a few of the Quihis in his "Sayings and Doings,"[20] and other novels of later life—but perhaps their spectres still haunt the long walk at Cheltenham—requiescant!

Towards the end of 1817, General Farquhar found it necessary, from the state of his health, to repair for a time to England, and Major-General Gage John Hall was sworn in as deputy-governor during his absence. On this occasion the Governor appointed a commission consisting of five of the principal men in the colony, to examine the accounts and contents of the Treasury, in order that the finance department might be handed over to his successor in a condition of ascertained correctness. The commissioners signed a report that they had examined the whole accordingly, and that books and chest were all in the proper state. Their report was dated November 19th, and Sir R. Farquhar sailed.

On the 15th of January, 1818, Lieutenant-Governor Hall received a letter from William Allan, a clerk in the Treasury-office, announcing to him, that, notwithstanding the above report, a grave error existed, and had been passed over in the Treasurer's accounts. No credit had been given for a sum of 37,000 dollars, which sum he, Allan, knew to have been paid in at the Treasury some fifteen months before.

General Hall instantly communicated this information to Mr. Hook, and appointed another commission to re-examine the condition of the public chest and accounts. The commission began their work on the 11th of February: Allan was examined vivâ-voce before them on that and on several successive days. He addressed, while his examination was in progress, letters upon letters to the deputy-governor and also to the commissioners, in which he reiterated his assertions that a large deficiency existed, that its existence had been known to himself during many succeeding quarters, and that he had so long concealed it from reluctance to bring himself into collision with his superior, the Treasurer. His letters, from the first very strangely written, became wilder at every step; and on the morning of the 27th, before the commissioners met, he shot himself. His last letter alleged[21] that he had been tampered with by Hook, who offered to pay him thenceforth an allowance of twenty-five dollars per month if he would instantly make his escape from the Mauritius, and never re-appear there; but the person whom he named as having brought Hook's message instantly contradicted the statement in toto on oath before the commissioners. There were many other witnesses; and the result was the detection of not a few irregularities, omissions, and discrepancies in the books of the Treasury.

The inquiry proceeded till the 9th of March; at eleven that night Hook was arrested at a friend's house, where he was supping, and dragged, by torchlight, through crowded streets to the common prison. The town having shortly before been the scene of a terrible conflagration, the prison had been almost entirely destroyed. There was only one cell in which the Treasurer could be placed, and that was in so wretched a condition that at three in the morning he was admitted to bail, escorted to the house of his bail-man, and left there under his surveillance by the police. After a few days he was handed over to the care of a millitary detachment, and embarked with them for England as a culprit, to be tried for crimes. Before he sailed, his property in the island was disposed of, and the whole amount placed to the public credit in the Treasury. Even the minutest articles belonging to him were seized. After he was on board ship, a negro slave came alongside to beg his acceptance of his writing-desk, which the poor fellow had bought at the auction for ten shillings.

He had a protracted and most unhappy voyage of nine months. For one whole month they were tossed in a hurricane off the Cape of Good Hope, and for six weeks reduced to the allowance of half a pound of mouldy buiscuit and half a pint of water by the day. While refitting at the Cape, however, Hook, who had by that time conciliated the regard of his keepers by his unshaken fortitude and good-humoured submission, was made their companion on shore,[22] on parole; and how completely he could, under such calamitous circumstances, exert his faculties of observation, we may judge from the most picturesque sketches of the Cape, the capital, and its inhabitants, which occur in one of his subsequent stories—Maxwell. The ship also stopped for a day or two at St. Helena; and by the kindness of the officers, Hook accompanied them when they went to Longwood to be presented to Napoleon.

The ship reached Portsmouth in January, 1819, and the warrant of arrest and other documents were transmitted to London, and referred to the law officers. The Attorney-General reported, that however irregular Mr. Hook's official conduct might have been, and however justly he might be prosecuted for a civil debt, there was no apparent ground for a criminal procedure. He was therefore liberated; and reaching London with two gold mohurs in his pocket, was immediately subjected to the scrutiny of the Audit Board—a scrutiny which did not terminate until after the lapse of nearly five years.

During this long suspense, eternal commissions and cross-examinations before the auditors of public accounts, and a very voluminous series of correspondence with them and others on the subject of the defalcation, had not occupied the whole of Hook's attention. If they had, he must have starved; for though his successor was not appointed till late in the inquiry, he never received a farthing in his official capacity, from the time of his original arrest.

By the end of 1819, Hook had established himself in a very humble cottage at Somers Town, where his household consisted of a single maid-servant; and formed connections with newspapers or magazines, which supplied the small necessities of the passing day. He seems at first to have felt his position far too painfully to think of reclaiming any but a few of his older and, comparatively speaking, humble allies—such as Mathews, Terry, and good little Hill; the last of whom had encountered sad reverses during his[23] absence, and was now, perhaps, except himself, the poorest of the set. On their kindness he might rely implicitly—as well as upon the cordial friendship and sound professional advice of Messrs. Powell and Broderip.

It was shortly after his location at Somers Town that Hook renewed his acquaintance with Mr. Wilson Croker, in whose society no small portion of his time was spent, both at the Admiralty and at the latter's villa at Molesey. He was also occasionally a visitor at General Phipps's (a relation of his mother's), in Harley-street, where he met and speedily became intimate with the late Speaker, Lord Canterbury. They were afterwards seen a great deal together, and the pair strolling arm-in-arm down St. James's-street, forms the subject of one—not the most happy—of the HB sketches.[6] With these exceptions, for a long period his position as a public defaulter, together with the res angustæ domi, confined him to the narrow and comparatively inexpensive circle of his old literary and theatrical associates.

During the summer of 1820, Theodore Hook opened his campaign against the Queen by a thin octavo, which at the time made considerable noise. It was entitled "Tentamen; or an Essay towards the History of Whittington and his Cat," by Dr. Vicesimus Blenkinsop. The Whittington, of course, was no other than Alderman Wood, and Caroline was the cat. "Throughout the whole libellus," says Lockhart, "there was a prodigious rattle of puns and conundrums—but the strong points of the case against Whittington and Co. were skilfully brought out, nevertheless. Hook being as yet quite in obscuro, nobody suspected him. It was pretty generally ascribed to the manufacturers of the 'New Whig Guide.'"

"Tentamen" was followed by several similar pamphlets, chiefly in verse, all directed against Alderman Wood and [24]the other supporters of the Queen, and all published in the same year (1820) by Wright, of Fleet-street. They are also to be distinguished by a caricature likeness of the celebrated Alderman, the same portrait appearing on the title-page both of "Tentamen" and the others. One of these we recollect is entitled Solomon Logwood.[7]

In the spring of this year (1820), Hook, with the assistance of his old friend, Daniel Terry, started a small periodical. It was published, and we believe suggested, by Mr. Miller, who had recently engaged extensive premises in—what was then expected to prove a great mart for the lighter description of literature—a sort of occidental "Row,"—the Burlington Arcade. Hence the name of the first-born, "The Arcadian," but which, to say the truth, had little of the pastoral in its composition, if we except a certain long ballad of melodious rhythm and provoking pungency, addressed to Lady Holland, and commencing,—

"Listen, lady, to my measures,

While they softly, gently flow,

While I sing the harmless pleasures

Of the classic, silver Po," etc.

The war-cry of "The Arcadian" was of course "King and Constitution," for its editor was Conservative, or rather Tory (the former euphuism was not then in vogue) to the heart's core. Much, too, of that personality was introduced in its pages, which rendered its more fortunate successor, the John Bull, so formidable. The same contemptuous tone, in treating of theatricals, is observable both in the John Bull [25]and its tiny predecessor. "The Arcadian" contains a most exquisite critique, a perfect masterpiece of irony, upon the "first appearance" of a certain young lady, and some caustic remarks on the stage and its attractions, curious as coming from a popular dramatist, writing in the thirty-second year of his age.

Full of fun and spirit as the little magazine was, it nevertheless came to an untimely end: only two numbers ever made their appearance. Such was the difficulty which the publisher experienced in making up the second, owing to Hook's listlessness, or more probably preoccupation, that he declined venturing on a third.

This was the prelude of John Bull. The most important event with which the name of Theodore Hook stands connected, is unquestionably the establishment of the John Bull newspaper, at the close of 1820. The universal, instantaneous, and appreciable effect produced on the great political movements of the day by its appearance, is perhaps unparalleled in the history of periodical literature.

The Queen's affair had gone on all the summer and autumn; the madness of popular exacerbation gaining new intenseness with every week that passed. None who remember the feelings and aspects of the time will think it possible to exaggerate either in description: but we shall make no such attempt. The explosion scattered brilliant terror far and wide. No first appearance of any periodical work of any class whatever has, in our time at least, produced such a startling sensation—it told at once from the convulsed centre to every extremity of the kingdom. There was talent of every sort, apparently, that could have been desired or devised for such a purpose. It seemed as if a legion of sarcastic devils had brooded in synod over the elements of withering derision. But, as far as Hook's MSS. allowed his biographers to judge, he was really and truly alone; and, at all events, they exonerate most completely certain other persons who were at first saddled with a large share of the[26] merit and the obloquy of the Bull. Of the famous songs during the winter of 1820-21, only one, he used to say, was an extraneous contribution.

The paper set out with one specific object: the extinction of the Brandenburgh House party; and, to accomplish this, Hook's varied talents—his wit and humour, his sarcasm and bitterness, his keenness of argument, fiery zeal, and unscrupulous daring—were all brought to bear with concentrated energy upon the ranks of the Opposition. Any man reckless of legal consequences, or beyond their reach, familiar with the current scandal of the day, and having so powerful an engine as a public paper at his disposal, may inflict a vast amount of injury upon his adversaries; but to these conditions, in the present case, may be added powers, if not of the very highest order, doubtless the best adapted to the purpose, sources of information peculiar and inexplicable, a singleness of purpose, and firm conviction of its justice, that combined to render Bull the most formidable antagonist that had as yet entered the lists against the Queen.

Many of Bull's songs, in construction, and even in execution, were very little different from those which Hook used to improvise in the course of a festive evening. It has been said by one who knew him, that a person who never witnessed that marvellous performance could not take a better notion of what it was than from such a piece as the "Visit of Mrs. Muggins," in thirty-one stanzas.

Here also Hook commenced and continued from time to time, for ten years, that famous series of Ramsbottom Papers, which were the precursors of all the Mrs. Malaprops, Mrs. Partingtons, and Mrs. Browns of a later generation, and which, like nearly all originals, greatly surpassed in genuine humour and excellence the cleverest imitations that have since appeared.

By his flagellations of the Whigs, meantime, Hook had shut against himself the gates of forbearance at Whitehall. He might have thought himself well off, if he had not[27] tempted harshness into play against him. He thought he had: he always persisted that the auditor's final report on him was an unjust deliverance; and he maintained equally the opinion that the measures of the Government consequent on that report were unusually severe. The award was at last given in the autumn of 1823, and it pronounced him a debtor to the Crown of over £12,000.

On his arrest under the Exchequer writ (August, 1823), he was taken to the dwelling and spunging-house of the sheriff's officer, his captor, by name Mr. Hemp, and still hoping that a protracted imprisonment was not seriously intended, he chose to remain there week after week, and month after month, until Easter. The expense of board and lodging at a house of that class is always heavy; his accommodations were mean, and the situation about the worst in London—Shire Lane, so named as separating part of the City from Middlesex—a vile, squalid place, noisy and noxious, apparently almost inaccessible either to air or light, swarming with a population of thief-catchers, gin-sellers, and worse. But his spirit was not yet to be broken. He endured the unwholesome confinement with patience—no sooner was hope knocked down in one quarter than it sprung up again in another—he kept himself steadily at work in the mornings, and his few intimates commonly gathered round him in the evening.

In April, 1824, Hook at last took his leave of Shire Lane. He had, as usual, made himself a great favourite with Hemp and his family, and such a guest could not be allowed to depart without a farewell banquet. The company exhibited in harmonious contrast Mr. Hook's theatrical and literary confidants of the time, and sundry distinguished ornaments of his hospitable landlord's own order. The sederunt did not close without a specimen of the improvisatore; and his ballad "showed up" Mr. Hemp and his brethren, as intrusted with the final offices of the law in the case of the grand culprit before them:—

Chorus—

"Let him hang with a curse,—this atrocious, pernicious

Scoundrel that emptied the till at Mauritius!"[8]

The close confinement in the bad air of Shire Lane had affected his health, and indeed his personal appearance was permanently damaged in consequence of the total disuse of exercise for so many months, and the worry of mind which even he must have been enduring. He came out pale and flabby in the face, and with a figure fast tending to corpulence. He was transferred to the Rules of the King's[29] Bench, within which he hired a small separate lodging, in an airy enough situation—Temple Place.

In 1824 Theodore Hook published the first series of that collection of tales which, under the title of "Sayings and Doings,"[9] placed him at once in the highest rank of the novelists of his generation; above all his contemporaries, with the one exception, of course, of the Author of "Waverley." The first idea and plan of the work was struck out during the sitting of a sort of John Bull conclave held at Fulham, and had origin in the suggestion of a friend, who, delighted with the anecdotes of Colonial life which Hook was pouring forth, conceived that they might be turned to better account than the mere entertainment of a dinner-party, and hit upon a title, at which Hook caught with eagerness. So convinced was the latter that his first tale, "The Man of Sorrow," had not been fairly appreciated, that he actually embodied in his new essay the rejected attempt of Mr. Alfred Allendale, condensed, indeed, and purged from its impurities, but not materially altered from the original. Much better in every respect is the story of "Danvers, the Parvenu."

The more prominent characters in Hook's novels are, in spite of his disclaimer, unquestionably portraits. To many of the Anglo-Indian sketches, the journal kept during the author's sojourn at the Mauritius would doubtless supply a key.

Hook, indeed, always denied the possession of inventive faculties. There was doubtless truth as well as modesty in his assertion: "Give me a story to tell, and I can tell it, but I cannot create."

The popularity of the first series of "Sayings and Doings" (three vols.) may be estimated from his diary, which records the profit to the author as £2,000. There were, we believe,[30] three considerable impressions before the Second Series, also in three vols., was ready in the spring of 1825. And shortly after that publication he was at length released from custody—with an intimation, however, that the Crown abandoned nothing of its claim for the Mauritius debt.

The first series of "Sayings and Doings" were soon followed (1825-1829) by a second and third, which are generally considered in every way superior to the former ones. The author was of this opinion himself, and the public as certainly ratified his verdict.

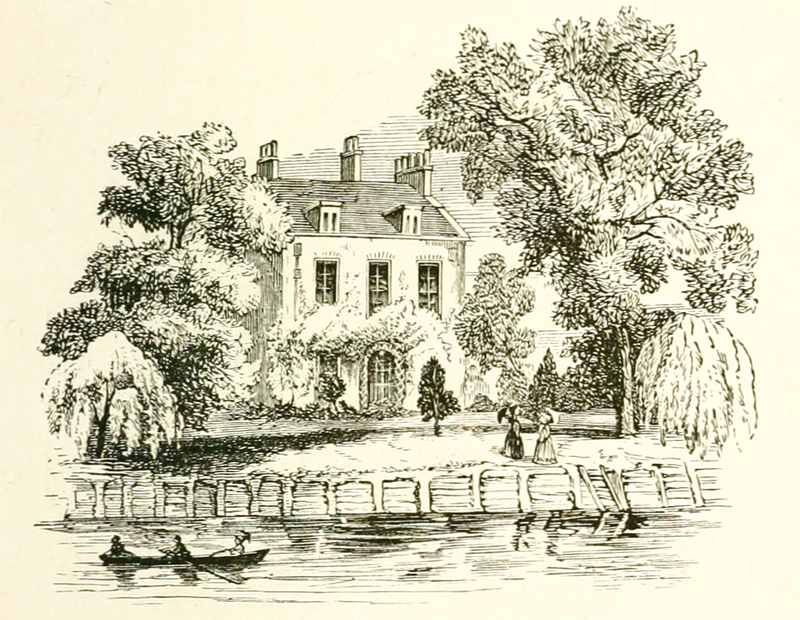

In the meantime Theodore Hook, released from his temporary confinement, had taken a cottage at Putney, of which neighbourhood he had always been fond, and may be said to have re-entered society, though his circle of acquaintance continued limited for a couple of years more.

While at Putney, in 1826, he from motives of pure kindness re-wrote, that is to say, composed from rough illiterate materials, the very entertaining "Reminiscences" of an old theatrical and musical friend of his—Michael Kelly. The book was received with astonishment, for he generously kept his own secret.

In 1827 he took a higher flight, and became the tenant of a house in Cleveland Row—on the edge of what, in one of his novels, he describes as "the real London—the space between Pall Mall on the south, and Piccadilly on the north, St. James's-street on the west, and the Opera House to the east." The residence was handsome, and indeed appeared extravagantly too large for his purpose. He was admitted a member of several clubs; became the first attraction of their house-dinners; and in those where play was allowed, might usually be seen in the course of his protracted evening. Soon he began to receive invitations to great houses in the country, and from week after week, often travelled from one to another, to all outward appearance, in the style of an idler of high condition. He had soon entangled himself with habits and connections which implied considerable[31] curtailment of his labour at the desk, and entailed a course of expenditure more than sufficient to swallow all the profits of what remained.

His next novel, "Maxwell," published in 1830, is, in point of plot, by far the most perfect of his productions; the interest which is at once excited, never for an instant flags, and the mystery, so far from being of the flimsy transparent texture, common to romances, is such as to baffle the most practised and quick-witted discoverer of dénoûments, and to defy all attempts at elucidation.

New debts began to accumulate on him so rapidly, that about 1831, he found it necessary to get rid of the house at St. James's, and to remove to one of more modest dimensions close to Fulham Bridge, with a small garden looking towards the river. Here in the locality which had long been a favourite one with him, he remained till his death; but though he took advantage of the change to drop the custom of giving regular dinners, and probably to strike off some other sources of expense, he not only continued his habits of visiting, but extended them as new temptations offered.

Probably few of his admirers ever knew exactly where Hook lived. His letters and cards were left for him at one or other of his clubs, but it is doubtful if the interior of his Fulham cottage was ever seen by half a dozen people besides his old intimate friends and familiars. To the upper world he was visible only as the jocund convivialist of the club—the brilliant wit of the lordly banquet, the lion of the crowded assembly, the star of a Christmas or Easter party in a rural palace, the unfailing stage-manager, prompter, author, and occasionally excellent comic actor of private theatricals.

But, notwithstanding the round of gaiety and pleasure in which the greater number of his evenings were spent, the time so employed cannot be said to have been altogether wasted; for, to a writer who has to draw from life, whose[32] books are men and women, and to whom the gossip and on dits of the day are the rough material of his manufacture, a constant mixing in society of every accessible rank is absolutely necessary—to one of his taste and discrimination, the higher the grade the better. Whithersoever he went he carried with him not only an unfailing fund of entertainment, but also unslumbering powers of observation, that served to redeem what otherwise would have appeared mere weakness and self-indulgence. And that he was not slow to avail himself of the advantages that fell to his share, no one will deny, who casts a glance over the list of productions he gave to the world, during a period when the intellectual exertion of his convivial hours alone would have exhausted the energies, physical and mental, of well-nigh any other man.

In 1832 he published the "Life of Sir David Baird," a standard biographical work, and one spoken of in the highest terms by the best reviews of the day. So satisfied were the family with the manner in which he executed his task, that they presented him with a magnificent gold snuff-box set with brilliants, the gift of the Pasha of Egypt to the subject of the memoir. Hook seems to have tossed the trinket aside as an unconsidered trifle into a drawer, from which it was happily rescued on the accidental discovery of its value and importance.

In 1833 he sent forth no fewer than six volumes, full of originality and wit; a novel called the "Parson's Daughter," and a couple of stories under the title of "Love and Pride." In one of the latter, the supposed resemblance of Liston to a certain noble lord is happily turned to account; the being mistaken for Mr. Buggins, principal low comedian of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, forming a light and pointed climax to the congeries of ridiculous miseries heaped on the unfortunate Marquis.

In 1836, Theodore Hook undertook the editorship of the New Monthly Magazine, at a salary of four hundred[33] pounds a year, irrespective of the sums to be paid for original contributions. Here he commenced his "Gilbert Gurney," accommodating himself to the exceedingly uncomfortable practice, now all but universal among popular and prolific novelists, of delivering his tale by monthly instalments. To this plan, though obliged to succumb to it, he always took exception, as not only wearisome to the reader, but fatal to fair development of plot.

Of all his works, "Gilbert Gurney" is by far the most mirth-provoking and remarkable. His own adventures form the groundwork of the comedy; himself and his friends figure as the dramatis personæ, and throughout the whole there appear an unrestrained expression of private feelings, and a frequency of personal allusion, that give it the semblance and almost the interest of true history.

In his next novel, "Jack Brag," Hook again hit upon a character with which he could go to work con amore. Vulgar, vain, and impudent, a cross between a tallow-chandler, and what, in the cant phrase of the day, is termed a sporting gent, a hanger-on upon the loose branches of the aristocracy, and occasionally thrown into society more respectable, Mr. Brag's gaucheries convulse the reader; while those who scorn not to read a warning, even on the page of a novel, may be led to devote more than a passing thought to the folly (to say the least of it) of indulging in the very silly and very common habit of perpetual though petty misrepresentation, as regards their means and position in life, and the nature and degree of their acquaintance with individuals of a rank higher than their own. There is no lower depth of drawing-room degradation than is involved in the exposure of one of these pretenders; unrecognised, perhaps, by his "most intimate friend" Lord A——, cut by his "old crony" Sir John B——, or never "heard of" by his "college chum," the Bishop of C——.

"Jack Brag" was followed, in 1839, by "Births, Marriages, and Deaths," which, notwithstanding its infelicitous[34] title,—as far as fitness goes, it might as well have been called "Law Notices," or "Fashionable Intelligence," or by any other newspaper "heading,"—was a novel of a higher class than any he had before attempted: the humour is scantier and more subdued than heretofore, and though the magnificent Colonel Magnus, and his rascally attorney Brassey, here and there afford admirable sport, the latter, with his economical wardrobe, to wit:—"one tooth-brush twisted up in a piece of whitey-brown paper; a razor by itself tied with a piece of red tape to a round pewter shaving-box (enclosing a bit of soap), with the tip of its handle peeping from the bottom of a leathern case, like the feet of a long-legged Lilliputian sticking out of his coffin; a remarkably dirty flannel under-waistcoat, edged with light blue silk and silver; one pair of black silk socks, brown in the bottoms," &c.—yet the general effect is heavy,—heavier, that is, than the public were inclined to accept from the pen of Theodore Hook.

This, in point of fact, may be considered his last finished work. "Precepts and Practice" appeared in 1840,—the name an obvious plagiarism, and from himself, being merely a collection of short papers and tales, published during the preceding year or two, in the New Monthly, of which he was the editor. As for "Fathers and Sons," portions of which appeared in the same magazine, and "Peregrine Bunce," we believe neither of them to have been completed by his own hand; of the latter, about one hundred pages of the last of the three volumes were certainly supplied by another writer.

The production of thirty-eight volumes, within sixteen years, Hook being all the while editor, and almost sole writer, of a newspaper, affords sufficient proof that he never sank into idleness; but in other respects there had been great changes within that period. Two unhappy errors into which he had fallen marred the happiness of the remainder[35] of his life. Before his arrest in 1823, he had formed a liaison, which, though perhaps excusable in his position at Somers Town, was persisted in afterwards under less adverse circumstances, until the righteous consequences of guilt could not be averted. This connection soon became such as, in his position, and with the kind and manly feelings which adhered to him, made it impossible for him to marry in his proper condition; and though he often thought of atoning to his partner, and in some sort to the children she had borne him, by making her his wife, he never took courage to satisfy his conscience by carrying that purpose into effect. The second error regarded his debt to the Crown, which, though during the last twenty years of life he was in receipt of an affluent income from his writings, he made no real or adequate effort to repay by instalments. Hook never denied that he was in justice responsible for a deficit of £9,000; and those who had the sole authority to judge of the matter, pronounced the rightful claim to be £12,000. When he was released from the King's Bench, he was told distinctly that the debt must hang over him until every farthing was paid. We know that he had, in his great and various talents, left from that hour at his free command, means of earning far more than enough for his own decent maintenance, and that of his unfortunate family; and most clearly every shilling that he could make beyond that ought to have been, from time to time, paid into the Exchequer towards the liquidation of his debt. In neglecting this, he threw away the only chance before him of effectually vindicating his character, together with all reasonable chance of ever again profiting by the open patronage of either the Crown or its Ministers. In every page of his works we trace the disastrous influence of both these grand original errors, perpetually crossing and blackening the picture of superficial gaiety—indications, not to be mistaken, of a conscience ill at ease; of painful recollections and dark antici[36]pations rising irrepressibly, and not to be stifled; of good, gentle, and generous feelings converted by the stings of remorse into elements of torture.

His pecuniary embarrassments became deeper and darker every year. Even in the midst of his abundant dissipation he worked hard in the mornings—certainly he covered with his MS. more paper than would have proved, in almost any other man's case, the energetic exertion of every hour in every day that passed over his head; and little did his fine friends understand or reflect at what an expense of tear and wear he was devoting his evenings to their amusement.

About a month before his decease he wrote to Mr. Barham, whom he requested to run down to Fulham and see him, as he was too ill to leave home himself; and of the interview which ensued we are enabled to give a somewhat full account, committed to paper shortly afterwards, and evidently with the view of fixing the impression, yet fresh, in the writer's mind:—

"It was on the 29th of July, 1841, that I last saw poor Hook. I had received a note from him requesting me to come down and see him, as he wished much to talk over some matters of importance, and could not, from the state of his health, drive into town. I went accordingly, and after a long conversation, which related principally to * * * and to his novel, 'Peregrine Bunce,' then going through the press, but which he never lived to complete, a roast fowl was put on the table for luncheon. He helped me and took a piece himself, but laid down his knife and fork after the first mouthful, which, indeed, he made an unsuccessful attempt to swallow. On my observing his unusual want of appetite—for his luncheon was in general his dinner—he said: 'It is of no use, old fellow; the fact is I have not tasted a morsel of solid food these five days!' 'Then what on earth have you lived upon?' to which he replied, 'Effervescing draughts;' adding afterwards, that he was allowed to take occasionally a [37]tumbler of rum and milk, or a pint of Guinness's bottled porter.

"On hearing this, I strongly pressed on him the necessity of having further advice, which he at length promised he would do, if he were not better in a day or two. I told him that my wife and myself were going down to the Isle of Thanet, and pressed him very much to throw work overboard for a while, and accompany us and be nursed. He said, however, 'he was completely tied to his desk till he had concluded what he was then writing for Colburn and Bentley; but that he should get quite clear of his trammels in about a month, and then, if we were still there, he would make an effort to pay us a visit.'"

In truth, he was soon past writing; death was advancing upon him with rapid strides, while earthly prospects were growing, daily, darker and more threatening. It is painful to reflect that his last hours, ere the struggling mind had sunk into insensibility, were disturbed by the apprehension of inability to meet a couple of bills of comparatively trifling amount, on the point, as he believed, of becoming due. On Friday, the 13th of August, he took finally to his bed, the stream hurried on with increasing velocity as it approached the fall—a brief agitated interval, happily not neglected, was left for the first, last work of erring man, and on the evening of the 24th he expired.

The disorder under which he had been labouring for years, arose from a diseased state of the liver and stomach, brought on partly by mental anxiety, but principally, it is to be feared, by that habit of over-indulgence at table, the curse of Colonial life, which he had early acquired, and to which he held with fatal perseverance to the end. It needed no ordinary powers to enable him to sustain the contest so long; but his frame was robust and his constitution vigorous; and he seems to have possessed in a remarkable degree that power of maintaining the supremacy of mind over matter,[38] which rendered him indifferent to, or unconscious of, the first slow approaches of decay. He was buried with extreme privacy at Fulham; a simple stone bearing his name and age marks the spot, which is immediately opposite the chancel window, and within a few paces of his former home.

1822-1831.

NOW FIRST COLLECTED.

[The Letters of Mrs. Ramsbottom, complete and unabridged, are here published in a collected form for the first time. They originally appeared in the pages of the John Bull newspaper, where their publication extended over a period of ten years. A complete set of the John Bull is now very rare, and, in proof of this, we may state that when a London publisher recently issued a cheap edition of the "Ramsbottom Letters," thirteen were all that he could give, whereas the whole of the twenty-nine are here given, and genuine—just as they left the pen of the witty author.]

THE RAMSBOTTOM PAPERS.

April, 1822.

On Thursday last, Mrs. Ramsbottom, of Pudding-lane, opened her house to a numerous party of her friends. The drawing-room over the compting-house, and the small closet upon the stairs, were illuminated in a most tasteful manner, and Mr. Ramsbottom's own room was appropriated to card-tables, where all-fours and cribbage were the order of the night. Several pounds were won and lost.

The shop was handsomely fitted up for quadrilles, which began as soon as it was dark; the rooms being lighted with an abundance of patent lamps, and decorated with artificial flowers. The first quadrille was danced by—

| Mr. Simpson, Jun. | and | Miss Ramsbottom |

| Mr. Botibol | Miss E. A. Ramsbottom | |

| Mr. Green | Miss Rosalie Ramsbottom | |

| Mr. Mugliston | Miss Charlotte Ramsbottom | |

| Mr. Higginbotham | Miss Lilla Ramsbottom | |

| Mr. Arthur Stubbs | Miss Lavinia Ramsbottom | |

| Mr. O'Reilly | Miss Frances Hogsflesh | |

| A French Count (name unknown) | Miss Rachel Solomons. | |

At half-past ten the supper-room was thrown open, and presented to the admiring eyes of the company a most[42] elegant and substantial hot repast. The mackerel and fennel-sauce were particularly noticed, as were the boiled legs of lamb and spinach; and we cannot sufficiently praise the celerity with which the ham and sausages were removed, as the respectable families of the Jewish persuasion entered the room. The port and sherry were of the first quality. Supper lasted till about a quarter past two, when dancing was resumed, and continued till Sol warned the festive party to disperse.

The dresses of the company were remarkably elegant. Mrs. Ramsbottom was simply attired in a pea-green satin dress, looped up with crimson cord and tassels, with a bright yellow silk turban and hair to match; a magnificent French watch, chain, and seals were suspended from her left side, and her neck was adorned with a very elegant row of full-sized sky-blue beads, pendant to which was a handsome miniature of Mr. Ramsbottom, in the costume of a corporal in the Limehouse Volunteers, of which corps he was justly considered the brightest ornament.

The Misses Ramsbottom were dressed alike, in sky-blue dresses, trimmed with white bugles, blue bead necklaces, and ear-rings en suite. We never saw a more pleasing exhibition of female beauty, the sylph-like forms of the three youngest, contrasted with the high-conditioned elegance of the two eldest, formed a pleasing variety; while the uniform appearance of the family red hair, set off by the cerulean glow of the drapery, gave a sympathetic sameness to the group, which could not fail to be interesting to the admirers of domestic happiness.

The Misses Solomons attracted particular notice, as did the fascinating Miss Louisa Doddell, and the lovely Miss Hogsflesh, delighted the company after supper with the plaintive air of "Nobody coming to marry me;" Mr. Stubbs and Mr. J. Stubbs sang "All's well" with great effect, and Mr. Doddell and his accomplished sister were rapturously encored in the duet of "Oh Nanny, wilt thou gang wi' me?"

Among the company we noticed—

The French Count (name unknown, but introduced by Mr. J. Stubbs).

Mistresses Dawes, Bumstead, Gordon, Green, five Smiths, Jones, Hall, Ball, Small, Wall, Groves, Taylor, Dixon, Figgins, Stubbs, Lightfoot, Hogsflesh, Muggins, Higginbottom, Cruikshanks, Barnet, Levi, Solomons, Ricardo, Hume, Hone, Parker, Wilde, Cummins, Farthing, Thompson, Anderson, Tod, Smallpiece, Flint, Doddell, Peppercorn, Adcock and Pyman.

Misses Stubbs, 2 Grubbs, 11 Smiths, Lightfoot, Simmons, 3 Halfpennys, Hall, Ball, Small, Wall, Barton, 3 Jones's, Hogsflesh, Eglantine Hogsflesh, 2 Greens, 4 Hones, Ricardo, Williams, 2 Doddells, Peppercorn, Holman, Figgins, Garbett, Burton, Morgan, Ellis, Levi, Flint, 3 Farthings, Eversfield and Parkinson.

Doctor Dixon, Lieut. Cox, R.N., Ensign Ellmore, H.P.

Messrs. Green, Halfpenny, Butterfield, Dabbs, Harmer, Griffiths, Grubb, Hogsflesh, Hall, Ball, Small, Wall, Taylor, Tod, Adcock, Flint, Doddell, J. Doddle, A. Doddell, T. Doddell, Farrell, O'Reilly, Yardley, Muscatt, Dabbs, Giblett, Barber, Sniggs, Cocker, Hume, Bernelle, Moses, Levi, Hone, Ellice, Higginbottom, White, Brown, Stubbs, J. Stubbs, S. Rogers, Hicks, Moore, Morgan, Luttrell, etc.

His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex, Lady Morgan, Mr. Ex-Sheriff Parkins, Sir Robert Wilson, and General Pepe were expected, but did not come.

April 27, 1823.

The following is from no less a personage than our fair favourite, Miss Lavinia Ramsbottom:—