By

George O. Smith

CENTURY PUBLICATIONS

Chicago

Published by Century Publications, 139 N. Clark St., Chicago 2, Ill.

Printed in the United States of America

Characters and situations in this book are fictional and any

similarity to actual persons or places is purely coincidental.

Permission to use some of the refrains from the ballad:

THE CYCLOTRONIST'S NIGHTMARE

by Arthur Roberts

of

The State University of Iowa

was graciously granted, and is hereby acknowledged

with sincere appreciation.

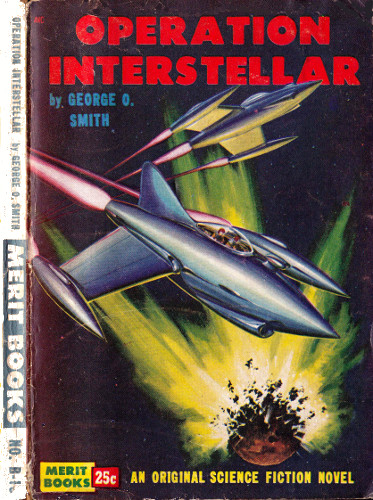

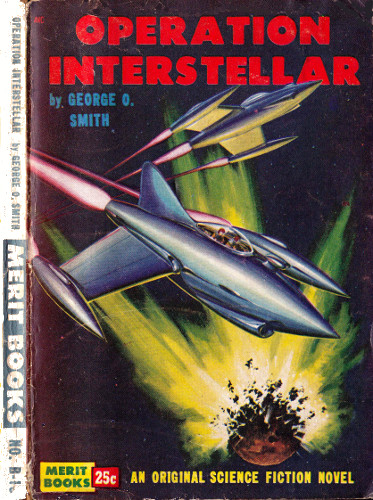

Cover by Malcolm Smith

Copyright 1950, Century Publications

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

| CHAPTER 1 |

| CHAPTER 2 |

| CHAPTER 3 |

| CHAPTER 4 |

| CHAPTER 5 |

| CHAPTER 6 |

| CHAPTER 7 |

| CHAPTER 8 |

| CHAPTER 9 |

| CHAPTER 10 |

| CHAPTER 11 |

| CHAPTER 12 |

| CHAPTER 13 |

| CHAPTER 14 |

| CHAPTER 15 |

| CHAPTER 16 |

| CHAPTER 17 |

Paul Grayson walked the city street slowly. He was sauntering towards the spaceport, but he was in no hurry. He had allowed himself plenty of time to breathe the fresh spring air, to listen to the myriad of sounds made by his fellow men, and to revel in the grand freedom that being out in the open gave him. Soon enough he would be breathing canned air, pungent with the odor of compressor oil and the tang of the greenery used to replenish the oxygen, unable to walk freely more than a few dozen steps, and unable to see what lies beyond his viewports.

Occasionally his eyes looked along the low southern sky towards Alpha Centauri. Proxima, of course, could not be resolved by the naked eye, much less the stinking little overheated mote that rotated about Proxima. Obviously unfit for human life and patently incapable of spawning life of its own, it was Paul Grayson's destination, and would be his home for a few days or a few weeks depending entirely upon whether things went good or bad.

Only during the last four out of two thousand millions of years of its life had this planet been useful. Man needed a place to stand; not to move the earth with Archimedes's lever but to survey the galaxy. Proxima Centauri I was the only planet in the trinary and as bad as it was, it was useful for a space station.

In an hour, Paul Grayson would be locked in a capsule of metal hurling himself through space towards Proxima I. He was looking forward to ten days cooped up in a spacecraft of the type furnished by the Bureau of Astrogation to its engineers which was a far cry from the sumptuous craft run by the Big Brass. His confines would be lined with functional scientific equipment; his air supply would be medically acceptable but aesthetically horrible; and his vision limited to the cabin, for beyond the viewports would be only the formless, endless, abysmal blackness of absolutely nothing while the ship mounted into multiples of the speed of light.

Then days in a building filled to the dome with power equipment and radio gear; timing mechanism and recorders; and a refrigerator set-up that struggled with the awesome heat poured into Proxima I by its close-by luminary but which succeeded only in lowering the temperature to the point where the potting compound in the transformers did not run out, where the calibrating resistors would not change their values, where the recording machines would still make a record.

And then again more days in the ship before it returned to earth. Call it thirty days and understand why Paul Grayson sauntered along killing time in the fresh air before taking off.

Paul grinned. Four years ago he had arrived a full hour early and wasted the hour in the smelly ship instead of filling his lungs with clean fresh air. Never again. He would arrive a full five minutes before check-in time.

He heard some radio music, its tone stripped of high frequencies from its passage through the slit of a partially-opened window. He sniffed the air and laughed because someone was cooking corned beef and cabbage. Then he was out of the range of the radio music. Paul liked music. He hummed a tune as he walked, and then as the fancy struck him, he started to sing. It was faint singing; it would not have carried more than a few feet, but it sufficed for Paul. It was a refrain from an early atomic-age ballad:

Paul stopped his song because the interesting click of high heels on the sidewalk pointed to the approach of someone who might view a cappella singing as an indication of inebriation.

She was coming towards him, walking on the same side of the sidewalk. Her step was quick and lithe, and the slight breeze outlined her frock against her body, revealing and at the same time concealing just enough to quicken the pulse and awaken the interest. Paul was thirty and unmarried, and experienced enough to catalogue her shrewdly.

No crude attempt at pick-up would work on this woman. She was sure of herself and obviously could not want for admirers. It would take careful strategy over a period of time to get to first base with a woman like her; an inept campaigner would be called out on strikes. And Paul Grayson had to be on the way to Centauri within the hour, which automatically eliminated the initial step in any plausible scheme to wrangle an introduction.

Paul Grayson grinned ruefully. It seemed to him that when he had hours to spend and nothing to do, the streets were barren of presentable women while the most interesting specimens of womanhood smiled and offered their charms when he was en route towards some schedule that could not be delayed.

This was woman enough to make a man forget his timetables—almost.

She came forward, her face lighted by the street lamp that Paul had just passed. Blue-eyed and fair-skinned, her hurried route was on collision course with his and with a minute shake of his head because he had neither the time nor the inclination to attempt anything as crude as striking up an acquaintance by barring her path, Paul angled his course aside.

She angled too.

"Hello," she said brightly. "I thought you'd be along sooner."

Paul Grayson gulped. Obviously she mistook him for someone else and a faint feeling of jealousy ran through him for the lucky man who owned her affections. The street lamp behind him must have cast heavy shadows across his face making identification difficult. He opened his mouth to explain away the mistake, but the girl came up to him, hardly slackening her pace until the last possible moment. Then instead of speaking, Paul found his parted mouth met by hers. Her lips were warm. Her arms came around him in a quick embrace, and his arms instinctively closed about her waist.

Paul kissed back, cheerfully accepting the pleasure of the error with a sort of devilish glee.

Then he stepped back.

"I'm sorry," he said, "that I am not the guy you thought I was."

She looked up at him with a blink. Her expression changed to surprise, and then her mouth opened in a scream as her eyes flicked away from him and centered over his left shoulder.

Paul started to whirl, but someone dropped the north pole on the back of his skull. It chilled him completely. Her scream rang in his ears as he fell forward. Vaguely he felt the silk of her dress against his outstretched hands, and then against his cheek just before the sidewalk rose up to grind against his face. Something pulled at his coat.

Then he felt nothing more. Only the frightened scream of the woman that rang in his ears, shrill, angry, fearful, and never ending——

----until Paul realized that the siren wail was not her scream but the ringing of his own ears, and that the girl was sitting a-sprawl on the sidewalk with his head between her thighs. She was rubbing the nape of his neck with her fingertips, quietly erasing the pain bit by bit.

The threshold of ringing in his ears diminished and his field of vision increased as the darting lights went away, and Paul Grayson then could hear the sound of running feet and the babble of voices.

"What happened?"

"This man was clipped by a thug."

"You saw it?" came the voices in a mad garble of scrambled speeches.

"Right in front of my eyes."

The babble broke into many and varied subjects. Curiosity, both morbid and Samaritan; anger both righteous and superficial, but both directed at the things that make such happenings possible; suggestions both sensible and absurd, and offers both welcome and ridiculous.

Paul groaned and tried to lift his hand to the raw spot on his chin where the sidewalk had removed some hide.

The woman looked down at him and smiled in a wan, apprehensive manner. "You're all right?"

Paul struggled to sit up and made it with her help. The wave of pain rose and localized in his head at about forty degrees right latitude. It made him want to carry his head at an angle with his neck ducked down below the level of the knot of pain. Hands helped him to his feet, led him across the sidewalk while he became stronger by the moment.

He shook his head to clear it and winced as the motion caused the knot of pain to vibrate nastily. "What happened?" he asked in a quavering voice. It sounded like someone else's voice to him, and surprised at the sound of it he repeated the question. It still sounded like someone else's voice and while he was wondering if his voice would sound like that for the rest of his life, the girl explained what had happened.

Paul missed most of it, but then asked another question: "Did you see him?"

"No," she said. Her voice was regretful, yet tinted with a dash of amusement. "He sort of rose out of the shadow behind you—you're a tall man, you know. All I saw was a ragged silhouette. He hit you. You fell. I screamed. He grabbed at your wallet——" Her voice trailed away unhappily.

Paul smiled. "Nothing in it but personal papers all replaceable. Not more than a few dollars. I'd have handed it over rather than get this clip on the skull. Too bad you couldn't see him."

The touch of amusement came again. "I had my eyes closed, sort of."

Paul smiled again. Inwardly he was welcoming the footpad to the contents of his wallet and accepting the bop on the bean as the price to pay for an introduction to the girl.

Someone in the crowd said: "You'd better come inside until you feel all right."

Paul shook his head and was happy to find that the knot inside had diminished to a faint pinpoint. His voice was sounding more like his own, too. "I've got to go," he said.

"But——"

The wail of sirens came and a police car dashed to the curb. It spilled policemen from all doors, who came warily. "What's going on here?" demanded the sergeant.

Paul explained.

"You'd better come to the station and lodge a complaint."

Paul shook his head. "I'm Paul Grayson of the Bureau of Astrogation," he said. "I could prove it but the crook has my identification papers. I'm due to take off for space within—" Paul looked at his watch—"within forty minutes," he finished.

"We'll require a complaint."

"Can't you take it?" pleaded Paul. "Good Lord, man, I can't identify a criminal that clipped me from behind. Hell, the only contact I had with him was hitting the back of my head against his blackjack."

The sergeant looked at the woman. "You can't help?"

"Not much more. He was just a blurred shadow to me, he looked like any other man wearing dark clothing—which can be changed all too easily."

The sergeant went to the police car and spoke to the main office over the radio. He returned in a moment. "The lieutenant says we're to run you over to the spaceport and take depositions en route. That'll save time for you, and it will get the dope for our records that we must have. You too, Miss—?"

"I'm Nora Phillips. I'll go along, of course. Will you have one of your men keep an eye out for a tall man who should have been passing here by now. He's overdue. He will be Tommy Morgan; we had a date but I came out to meet him on his way to my home. Tell him what happened and explain that I'll return home as soon as this matter is taken care of."

The sergeant smiled. "Toby, you take this stand and ask everybody that comes along if he's Mr. Morgan. Then explain."

"Right."

The ride, so far as official information went, was strictly a waste of time. Paul made a mental note of Nora Phillips' address and telephone number and decided that the incident called for good reason to renew the acquaintance. The sergeant made it easy by telling them: "When you return from your trip, Mr. Grayson, I'll ask you to come in to the station and make a formal complaint. You'll be there too, Miss Phillips."

"I'll be glad to help," she told them. Then she turned to Paul. "You're with Astrogation?"

He nodded.

"But why Proxima? I've heard it was a completely useless place."

Paul shook his head. "We want to measure the distance to better accuracy than heliocentric parallax will permit us," he said. "We know the speed of light to a fine decimal, and we can measure time to even a finer degree. So we started a radio beam towards Centauri four years ago, and it will be arriving in not-too-long a time. Then we'll have the distance to a nice detail of perfection."

Nora thought for a moment. "I suppose you're ultimately aiming at Neosol," she suggested.

"That's the idea."

"But Neosol is a hundred light years away—"

"One hundred and forty-three at the last count," Paul corrected.

"So it will take a hundred and forty—"

"No," he smiled. "Less than three years from now. You see, seven light years is the greatest distance that separates the stars between here and Neosol. We've got a nice network of radio beams criss-crossing the pathway between here and Neosol. Oh," he admitted with a smile, "the triangulation beams will be arriving from now until a hundred years from now, but they're mostly check-beams, and the final beam from Earth to Neoterra will take the full time. But in the meantime we can refine our space charts using the network of beams once they start to arrive. And each time one of the triangulation check-beams gets home, we'll be able to refine the charts even more. But there's no sense in waiting for a century and a half."

The sergeant looked at Paul. "You're certain you can fly with that bump on the head?"

"Sure."

"Why not let someone else take it."

Paul shook his head. "It's my job," he said quickly.

"But there must be someone else that can do it. What if you died?"

"Oh, there are others trained in this sort of job in that case."

"Why not let one of them take it, then?"

Paul shook his head again. "I'm all right," he said. He realized that his insistence was too vigorous and that his reasons were too lame. But he could not let them know why it was so important that Paul Grayson go in person. If Haedaecker got wind of what Paul carried in his spacecraft, there would be hell to pay. He thought of a plausible excuse. "Most of them aren't on earth right now."

"Couldn't you call one of them?"

Paul smiled ruefully. "They're outside of the solar system."

The sergeant nodded. "The Z-wave can't cross interstellar space," he said. It was a statement thrown in to display his knowledge to the technician from the Bureau of Astrogation, and also a leader for more conversation.

Paul did not bite.

"That's Haedaecker's Theory," added the sergeant. "Isn't it?" he added after another moment of silence.

"Haedaecker's Theory is that the Z-wave propagates only in a region under the influence of solar activity," explained Paul. He looked out of the police car and saw the spaceport only a few moments away. Then he talked volubly to fill in the time so that he could be off without further questioning. Haedaecker had plenty of evidence to support his theory, but they all were missing one point that was as plain as the nose on Haedaecker's face.

"We can talk with ease from the Zero Laboratory on Pluto to the Solar Lab on Mercury, to the boys who are working in the poisonous atmosphere of Jupiter, to the extra-terran paleontologists who are combing Venus," said Paul. "And the Radiation Laboratory sent a gang to try the five planets of Sirius. Again they got the Z-wave working after a bit of fiddling with the tuning. But we've not been able to get so much as a whisper from Sol to Proxima Centauri via Z-wave. What started Haedaecker thinking was the experiment they tried about ten years ago." Paul went on before anybody could interrupt.

"No one can measure the velocity of the Z-wave, you know. So they started a spacecraft running right away from Sol. So long as they were within a fair radius, the Z-wave went both ways easily. But once they went into superdrive and raced away from Sol and got out beyond the orbit of Pluto by quite a bit, they lost contact completely. They made some measurements but these were quite unsuccessful. All we know is that we can use the Z-wave for speech for a long distance beyond the orbit of Pluto, but beyond some distance that might lie between ten times that orbit and—I think they tried it at a light month—the Z-wave dies out abruptly. It falls off like a cliff, you know. There's no apparent attenuation of the Z-wave so long as it is strong enough to get there. Beyond that, there is not even the whisper of a signal. It's a peculiar thing, but we know very little about the Z-wave, and—"

The driver brought the police car to a screeching halt. "Here you are, folks," he chirped.

Paul got out of the car quickly. "I'll be back," he told the sergeant. "I'll call you." And then to Nora Phillips he added, "I'll call you, too."

"Do," she said pointedly. "I'd like to know more about the Z-wave."

Paul nodded amiably. He did not voice his inner thought: So would I, Baby!

The police car U-turned in the broad roadway and headed off to return Nora Phillips to her home and to pick up the officer set to sentry duty. Paul waved them off and then started to walk up the pavement towards the administration building.

He was feeling better. Everything pleased him vastly. The knot inside of his head was gone, he had made the acquaintance of a very delectable armful of femininity, and now he had been chauffeured to the spaceport by none other than the City Police Department, complete with siren.

On his way up the sidewalk, Paul planned the retort perfect. Anticipating some humorous sarcasm on the mode of his arrival, Paul hoped to crush any verbal volley with unanswerable repartee. Usually Paul's fount of boundless wit ran just a trifle slow, following the definition of a bon mot: something you think of on the way home. This time he was going to be prepared.

He swung the door airily and strode in, his tongue poised over a few words of terse wit.

The guard looked at him and swallowed a large lump. "How in hell did you get out?" he gasped.

This was not according to plan; unfortunately, the guard had not read Paul's script, and the prepared answer would not fit the question. "I was never in," said Paul lamely, again wishing he had a tongue full of ready wit instead of fumbling for a prepared speech.

"The hell you weren't."

Paul took it from there, ignoring the fact that the guard had not followed Paul's mental conversation. "That was a car reserved for very important personages," he said. "From now on you can call me Viper."

The guard by-passed this. "But how did you get out?" he asked. His voice was almost a plea. "You didn't pass me."

"Were you guarding the jail too?" chuckled Paul. "Fast man, no?"

"You came in a taxicab the first time."

"Ah yes. But that was years ago before people knew of my brilliance, importance, and high station. Now—"

"Years ago, my eye. Less than fifteen minutes ago—"

"I did not."

"You did."

"Not me." Paul's feeling of airy well-being came down a few thousand feet and mired in a cumulus cloud.

"Look, Grayson, you came in a taxicab and breezed in here about fifteen minutes ago as though you had only a minute to spare."

"You're thinking of someone else."

"Your picture said Paul Grayson, and so did your identification. How else would I be knowing you?"

"You've seen me often enough."

"Maybe. But don't forget that I see a few thousand people every day. And I know you only well enough to know that you do own bona fide credentials. You've got 'em?"

"I—" Paul blinked. A great searing light was starting to cut through the cobwebs of his brain. The airy feeling of well-being dropped below the cumulus cloud and made a one-point landing on strictly solid ground. "Look," he said soberly. "You claim a man came through here a few minutes ago, resembling me?"

"Unless you ain't who you are, he was you."

"He wasn't me. My papers were stolen less than an hour ago. He must have—"

The guard was no imbecile. He turned in a flash and hit a button on the desk beside him. An alarm bell rang in some inner room and four more guards came tumbling out of a doorway, alert and ready for trouble.

"Tommy," snapped the guard at the door, "Go check Paul Grayson's ship, that's number—"

"BurAst 33-P.G.1."

The guard looked at Paul carefully. "You're a dead ringer for the other guy that came through here," he said. "But you happen to know Paul Grayson's BurAst number. Anybody could memorize it."

Paul watched the other guards tumble out of the building and head off across the spaceport on a dead run, drawing pistols as they went. He started to follow them.

The guard barred his way.

"No you don't!"

"But that guy is stealing—"

"Maybe your name is Grayson and maybe the other guy is Grayson. You look alike and he had identification. I don't know Paul Grayson well enough to accept or deny you—or him. But until you show me credentials entitling you to roam this spaceport, you stay outside!"

"But—"

"The boys I sent out there are capable. Don't get in their way. They might shoot the wrong Paul Grayson."

"But—"

"Get your credentials. Get some sort of identification."

Paul looked at the big standard clock on the wall. "But I've got less than eight minutes until take-off time."

"There's always tomorrow. You'll get cleared first or no entry! And that's final."

"Hell's Eternal Bells!" exploded Paul. "The cops that brought me here did so because I was clipped on the bean and robbed."

"It's my job," explained the guard quietly. "I don't want to be any more of a bastard than I have to be. If you're Paul Grayson and the cops know you were robbed, there's the telephone."

Paul grabbed the phone and started to dial, fuming at the delay. First there was a few seconds until the dial tone came, then Paul dialed the outside line. Another few seconds of delay until he could dial the number of the municipal police department. Then a bored voice asked:

"Police headquarters, who's calling please."

"This is Paul Grayson at the Municipal Spaceport."

"What's the trouble out there?"

"A crook stole my identification."

"We'll send a man out to investigate."

"No!" yelled Paul to prevent the telephone operator from cutting off the line on the assumption that the call was closed. "You don't understand. I'm supposed to take off in—ah—seven minutes."

"We can't get a man there that quickly. You'll have to wait."

"Look," said Paul hurriedly, "there's a squad car that just dropped me here. I was clipped on Talman Avenue and they went there to investigate, they brought me here. Why not call them and ask them to come back and explain to the guards here what happened?"

"I'll check that and take action," promised the voice in a completely bored tone.

Paul fumed.

There was the sound of a shot outside, followed instantly by the shrill, whining song of a ricochet, probably a glance from the hard metal flank of a parked spacecraft.

The telephone went dead and a second later came the dial tone again. Paul hung it up reluctantly.

And that made it worse. Other hands were not as imbued with the importance of the project. To other hands it was a routine bit of trouble, not the matter of life and death that it was to Paul Grayson; yet he to whom this thing was vastly important must sit with folded hands while men handled the matter in ponderous routine.

The clock continued to turn inexorably. Paul's mathematically-inclined mind went to work; it was less than two minutes since the police car left. Give them a minute to check up, and a minute to make sure, then a minute to call the car. That was three of the precious seven minutes gone to hell. If it took them as long to return as it took them to get where they now were, throw another two minutes down the drain and that left two minutes in which to let the sergeant explain to the guard, clear Paul Grayson on a pro tem basis, get him across the spaceport to his ship, in, up, and away.

He groaned.

He wished frantically for some means of knowing what was going on; what measures were being made in his behalf. He wanted desperately to listen to the radio in the police car. He wanted to get on the radio himself and roar out explanations, to exhort them to greater effort—

The siren wail of the police car cut into his thoughts and Paul raced to the door to fling it open. The car slid to the curb and the siren whined down the scale as the driver turned it off. They got out of the car and came up the walk briskly.

"Hurry!" he called.

He cast a glance over his shoulder at the standard clock. He had three minutes.

"Tell 'em who I am!" he exploded breathlessly.

The sergeant blinked. "But I don't know who you are."

"But I've told you."

"Hell," grunted the guard. "You've told me, too." To the sergeant, the guard said: "Do you know anything about all this?"

"We got a call that this man had been clipped and robbed. He was." The sergeant looked at Nora Phillips. "Can you identify this man?"

Nora bit her lip. "He's Paul Grayson."

The guard speared Nora with a cold look. "Do you know that or is it just what he said?"

"Why I've—"

"She's never met him otherwise," put in the sergeant.

"That's true, but I think—"

"Thinking ain't good enough."

Nora looked at Paul. "Haven't you anything to show?"

Paul shook his head. "Nothing that would cut any ice. Belt buckle with initial G. A few laundry marks and cleaners' marks. A checkbook in my hip pocket but no name printed in it. I might check the balance against the bank, but that would be tomorrow morning. We might call Doctor Haedaecker, but by the time we arrived on some means of personal identification, take-off time would be gone and past."

Paul paused, breathless, his whole body poised tense and his head bent to listen. There came the patter of feet outside.

The standard clock was swinging towards the hour, two minutes remained, enough if all went quick and well.

One of the guards burst in. He took a quick look around and spotted the police sergeant. "Good," he said, breathing heavily. "We've just shot a man out there. You're needed."

"Was it the man who passed himself off as me?" shouted Paul Grayson.

"As we came up to BurAst 33-P.G.1, this guy jumped from the airlock and started to run. We gave chase and lost him in the dark beyond a group of parked spacecraft. We called for him to halt. We found him again on the far side of the ships and Joe fired a shot.

"It must of missed him because he kept running, and then we all started shooting, losing him behind another ship parked by the fence. You know old Mupol 3316? The way the guts are parked all over the spaceport and left to rust? A derelict if I ever saw one, and after this I'd say it was about time we cleaned up that old wreck—"

"—Please hurry," blurted Paul.

"—we got to the fence where he'd climbed out over some junk stacked behind Mupol 3316. We went after him, and then guess what?"

"What?"

"We found this character flat on his face in the road, as dead a corpse as ever died."

Paul exploded again. "That proves it," he said. "Now—"

The spaceport guard shook his head. This shake was echoed by the sergeant of police.

"But I've work to do—"

The sergeant smiled unhappily. "We've work to do too, son. I'll call you Grayson for the benefit of the doubt. There is not much doubt that something is highly rotten here, but we've got to be certain. There's been one slugging and robbery, the attempted theft of spacecraft, and now a man killed by armed guards in performance of their duty. This is going to require clearing up before we let you go."

"But you know where to find me. I'm due on Proxima Centauri I to check the arrival of the Bureau of Astrogation survey beam. I'm to take off—"

"IF you are Paul Grayson."

"If the other guy was Paul Grayson, would he have run from cops?"

The sergeant laughed bitterly. "This may come as a shock to you, son. But you have no idea of how many of our Nicest People, Pillars of Society, and Solid Citizens have secrets in their daily lives that make them shun Law and Order when Law and Order comes toward them with a drawn pistol, a subpoena, or a warrant for arrest."

The loudspeaker came to life at that moment. "BurAst 33-P.G.1 taking off for Proxima Centauri I. Timing signal for synchronization first check ..." the voice died to be replaced by a series of clicks, one second apart.

"That's my notice—"

The guard snapped a switch. "Master Control," he said quietly. "This is Edwards, guard at the main gate, hold the flight."

"Hold the flight?" answered the speaker.

"Hold the flight. We've had trouble here."

"Is that what the shooting was all about?" The timing clicks died in the background. "What's the trouble?"

"We've got two Paul Graysons wanting to take off."

"Tell 'em to draw straws. This is costing money."

"One of them—"

"Goddammmit!" yelled Paul, "I'm Paul Grayson and I've—"

"That you'll have to prove, son," said the sergeant.

"—is dead," finished the guard.

"Dead?" gasped the speaker. "Which one?"

"It ain't funny," said the guard seriously. "Just hold the flight."

"Okay, sport. But—"

Paul spoke up, "Can you get the Elecalc free for a course for tomorrow night?"

"Who's that speaking?"

"I'm Paul Grayson."

"The live one, huh?" chuckled the unimpressed voice from the speaker. His bantering tone made Paul want to rip out his larynx with a crooked thumb and shove it down his throat. "Okay. We'll have the electronic calculator figure out a course for Proxima I for tomorrow night. Doubtless someone will take the flight."

"Oh damn!" groaned Paul. "Why does this have to happen to me?"

The sergeant smiled. "If this were the first attempt to steal a spacecraft, I'd be surprised."

The guard shook his head. "It's more than that," he added sagely. "If the other guy was a thief bent on swiping a BurAst ship, he could have gone off in it ten minutes before the second Paul Grayson arrived. He didn't. He was waiting for the take-off signal; and if he were a crook, he hoped to fill in the real Paul Grayson's place. If he was the real Grayson, we've killed a frightened Bureau man, and this bird here—"

Paul looked at the standard clock. It was now moving past the precise second marked for take-off. He sighed resignedly and relaxed. "For the moment we'll assume that I am Paul Grayson," he said quietly. "So soon as we can find someone to corroborate me, the second part of your supposition will have no grounds."

The sergeant shook his head. "I think we'd all best head for the station and wait this thing out."

Paul gulped. "You're going to jug me?"

"Both of you."

"But you can't arrest me—"

"Five will get you eight," chuckled the sergeant.

Nora Phillips came forward until she stood between Paul and the sergeant. "Why am I being arrested?" she demanded.

The sergeant smiled affably. "No one is being arrested."

"Why am I being detained, held, or otherwise prevented from enjoying my rights of freedom?" she snapped.

Paul shrugged. "I've missed my take-off," he said. "I'll have to wait until tomorrow anyway. And I can get identification in an hour or so without any trouble. In fact, I'll gladly go along with you if you'll permit me the telephone. They can bring my stuff down there and we can settle this quickly. But there is no reason to hold Miss Phillips."

The sergeant turned to the woman and bowed deferentially. "Forgive a harried policeman his habits," he said quietly. "As a shoe salesman will mentally catalog the shoes of the people sitting opposite to him on the street car, and a physician will mentally diagnose the ills of his fellow-spectators at a baseball game, a policeman habitually views the acts of his contemporaries with one eye toward their motives."

"Meaning what?" demanded Paul Grayson.

The policeman faced Paul and said with a level voice: "So far as every bit of evidence goes, you are Paul Grayson. You behave as a man might behave when placed in the position you appear to be in. On the other hand, if you were a smart man, you would behave as you are now behaving even though you had reasons most dire to execute as soon as you leave the watchful eye of law and order. This is a bit too trite. A stolen wallet containing only a few bucks and a whale of a lot of identification, complete with a witness to the crime, makes fine story material to use in establishing a false identity. Motive can come later—if any. If you are Paul Grayson, I will make abject apology. If your tale is not true, there will be some tall explaining to make."

"How about Miss Phillips' boy friend?"

"Now that's a nice thought, but not necessarily conclusive proof. He might easily and sensibly be included to give any story an air of veracity. However, we can check with Toby Reed as soon as we get back to the patrol car."

Paul Grayson awoke the following morning to the tune of the telephone beside his bed. "This is Sergeant Hollowell," said the other man, "I've just called to apologize once more and to tell you that everything is OK. We'll even give you a guard if you want it."

Paul stretched and said, sleepily: "Thanks, Sergeant. I guess everything will come out all right without a guard."

"Okay. I'm glad for all concerned. For your information and not to be repeated, the character we got last night is—was—a petty crook with a record as long as your arm. A plain case of theft. Interrupted luckily. We call it closed."

"Thanks again. And the ship?"

"It's there as it was last night. So far as we and the BurAst guards know, no one but the crook was near it, and no one will be permitted to go near it until you come to take it up."

Paul breathed easier. "Okay, see you later."

"Your wallet, intact, will be delivered to your apartment within the hour. That closes that case, too." The policeman's voice sounded well pleased with himself and the night's work. Paul hung up and sprawled back in bed, thinking.

There was no point in arousing the policeman's suspicions again. A howl of 'Why?' might delay Paul Grayson; might cause another technician to be sent to Proxima I to check the arrival of the radio beam. Paul had all the reason in the galaxy for wanting to be there himself, and an equally large quantity of reasons for not wanting someone else running his ship.

But there was more to this than met the eye.

Paul reached for a cigarette and laid back in bed blowing smoke at the ceiling. A smile touched his lips. Aside from the annoyance at being delayed for twenty four hours, it had been one large evening.

Then his grin died and he reached out one quick arm and picked up the telephone again. He dialed a number and waited until the ringing was answered.

"Stacey?"

"This is Stacey's office."

"Is he there?"

"Who's calling, please?"

"Tell him Paul Grayson—if he's up yet."

"He's up," came the cheerfully amused voice at the other end. "But he's still grumpy."

"I'll cheer him up," promised Paul. There was the click of a connection made and one quick burr from the ringing of the distant telephone.

"Stacey," came the reply.

"Paul Grayson."

"Hell's Eternal—I thought you were on your way to Proxima."

"Got delayed a day."

Stacey was silent for a moment; Paul imagined that he could hear the clicking of the other man's mind as it started to analyze the situation. Then Stacey said: "What's on the technical mind, Paul? You didn't call me at this outrageous hour just to pass the time of day."

"John, how much will it cost me to have a matter looked into?"

"Normal charge is twenty-five a day and expenses. I think I owe you a few favors. Make it expenses if it isn't too involved."

"It might be."

"Then we'll make some arrangement as soon as we know how involved it is. But Migawd, Paul, what brings you to the employment of a detective?"

"Someone tried to steal my spacecraft last night."

"Nuts. Call the coppers."

"Nope. There's more to this than meets the eye."

"What, for instance?"

"I'll be over to tell you about it."

"Big?"

"I don't know. Bothersome, anyway."

"I'll wait. Make it quick."

Paul hung up, and then went into a whirlwind of action. He dressed and shaved and gulped a glass of orange juice. He eschewed breakfast, promising his stomach that food would come in due time. He took his car from the garage where he had parked it for a month the evening before, and within a few minutes after hanging up the telephone, Paul Grayson was heading towards Stacey's office.

It was a small office. Stacey's secretary knew Paul by sight if not by telephone voice, and she nodded him in to the inner office. Stacey's inner office was as small as the outer office because file cabinets lined the room. The detective sat with his chin in his hand, poring over some pages of writing. He looked up at once and greeted Paul with a smile.

"So someone tried to swipe your ship?" he blurted. "And why isn't that a case for the cops?"

"John, how would you go about stealing a ship?"

"Get into the spaceport on some pretext, get into the ship by some means, and then take off like I had to make Messier 31 by mid-afternoon—or whatever place happened to be aligned at the time."

"That's what I've been thinking."

"So—?"

"You wouldn't worry about the dispersion factor. You wouldn't worry about course. Your main interest would lie in getting the hell out of there before someone came along and decided that you were intent upon theft."

"Naturally."

Paul nodded. Then he explained as well as he knew, and as well as he could remember, everything that had taken place on the previous evening. He finished up with: "So I've met a gorgeous gal, kissed her by accident and found it fun; was clipped by a footpad and sort of nursed back to the conscious level by the same luscious dame; had two rides in a police patrol car; one trip to the hoosegow; cleared of all suspicion by an official courier arriving with officially sealed pouch of identification; was escorted home in style."

"Go on. There's more to this than that."

"Remember what Sergeant Hollowell said: That a stolen wallet and a witness were fine dovetails towards the establishment of a false identity?"

"Yeah."

"What better way to louse Paul Grayson up than to decoy him with a flagrantly beautiful woman; a dame possessed of self-assurance and poise, yet incredibly feminine enough to betray a warm, human passionate hunger for some one man. Natural male concupiscence would draw any man into the game of trying to divert her affection towards himself."

"Speak for yourself, wolf."

Paul grinned at Stacey. He stood up. "Maybe I'd better look into this thing myself. Set Stacey on the trail of a glam-amorous female and—"

"Siddown. I'm a married man."

"I was thinking of your poor, deluded wife and daughter."

"Gloria knows all about your natural male concupiscence; and 'Ginny will know you as a doddering old man by the time she discovers that you can tell a man from a woman without looking at their clothing."

Paul sat down again. He had not intended to leave anyway. "So," he said, "what better way to divert Paul Grayson than to bait him with a gorgeous dame?"

Stacey grunted. "To divert you long enough to clip you, to steal your papers, to enter your ship—for what purpose?"

"That's where the mystery comes in. The guy had plenty of time to fire up the drivers and grab an armful of sky. The galaxy makes a fine hiding place, John. They scoured the stellar systems of a hundred and more suns before they found that Neosol had a planet that was capable of harboring Terran life without difficulty. God knows, no man hunting for a place to live would wait and head for Proxima I. Yet that seems to be what the crook had tried to do."

Stacey shook his head. "You are supposing that Nora Phillips was mingled in some sort of plot to steal a spacecraft. Granting that, Paul, explain me one thing. Just why would a person intent upon delaying you go so far towards helping you?"

"Huh?"

"She did sort of rub your skull, didn't she?"

"And a fine job she did of it, too."

"Professional?"

"Seemed as if. If not professional, at least experienced."

"So she brought you out of the unconscious, painful dark in time to intercept the criminal at his business?"

"Uh—"

"And Nora Phillips strode up and kissed you with warm, mad passion on the street, thus immobilizing your skull long enough for the enterprising sharpshooter to take a stance and perfect his backswing."

"So you don't think so?"

Stacey thought for a moment. "This does not smack of simple theft," he said at length.

"Hell," growled Grayson, "That's what I've been trying to tell you."

"Um. I see—"

"So someone looks like me. He tried to swipe my ship, it would appear. But they didn't need a dame to distract me; I could have been pushed off by a gunman. Frankly, I am of the type that will gladly hand over my wallet, my shoes, and/or my worldly goods rather than to have a hole drilled through my dinner. So, John, here is Nora Phillips' address. You can get the name of the defunct crook from the police, I'm sure. See what connection they might have had."

Stacey looked at Paul with a smile. "You're not making uranium out of broken pop bottles are you?"

"Nope. I'm just a guy working for the Bureau of Astrogation."

"Uh-huh. But with a secret under his hat large enough to keep him from yelping too loud."

"You know the reason for that."

"And how many others?"

"Damned few. Less than six, I'd guess."

Stacey shook his head again. "They don't clip screwballs for having a half-baked idea crammed in their simple skulls. So far as I can see it, you've got nothing to conceal, nothing to steal, and nothing much worth hiding."

"If Haedaecker knew what I had—"

Stacey grunted. "If Haedaecker wanted to stop you he would not have to hire a bunch of phony actors to do it," he said succinctly.

"But what else?"

"My life of crime," chuckled Stacey, "tells me that there are as many motives for crime as there are men with ambition, avarice, and ability. The trouble is that there are more motives for crime than there are varieties of crime. If there is a motive for this cockeyed affair—and I've yet to see a crime without a motive, however involved or simple—you must know it."

"Aside from spacecraft stealing—"

"That's ruled out."

"Then I'll be eternally relegated to the nether regions if I know what it is."

Stacey nodded. "Maybe you know it and don't recognize it."

"Maybe I should visit my family psychiatrist?"

"He might be able to ferret out the hidden secret. But I'd waste no time on it. Just proceed and see what happens."

"Like another busted head?"

"As I recall, it's hard enough."

Paul laughed. One could hardly be sour in Stacey's presence. Nothing appeared serious to the detective; he managed to make everything sound quite cheerful and amusing, even the threat of further depredations. It was a trait disliked by many people, which was probably the main reason why Stacey was a small time operator instead of being the mainspring of a world-wide agency.

It took a long acquaintanceship with Stacey before people realized that the light banter was only a false front used to keep Stacey's own spirits from bogging down in the world of trouble. A sympathetic sort himself, Stacey forced himself to treat every case as impersonally as he could because only a man uninvolved emotionally can make clear decisions based on fact and not feelings. Newcomers meeting Stacey resented the fact that the detective obviously treated their troubles as less than the most important thing in the world.

But Paul Grayson knew Stacey well and he was willing to let the detective handle the case completely from this point, knowing that Stacey would do it honestly and quickly, friend or not. Paul waved good-bye at the door and drove towards home. He went in and sat down, ticking things off on the fingers of his hand.

One, identification cleared

Two, wallet returned

Three, puzzle-solution started

Four—

Grayson went to the telephone and called the spaceport, was connected with the calculations department.

"Grayson," he said. "How's for my course this evening?"

"Sure you want to go?" came the dry retort.

"Absolutely."

"Want to bet?"

"Look," grunted Grayson, no longer angry at the voice, "you've got a fine calculating gadget there. Why not have it figure out the betting possibilities and make book on me?"

"We tried to make it pick horses for us once but the answer came back as 'Data incomplete, factors uncertain.' The elecalc does not like horses."

"But I'm not a horse."

"I hear there's a woman tied up in this thing. That's the predictably unpredictable factor, that men, the imbeciles, will get involved with women—even as you and I. Anyway, Grayson, we'll have you a course. It won't be as cold turkey as last night's, but it will serve in a way."

"In what way?" asked Paul.

"We can't set the spotter ship. Not enough time. You'll have to aim the ship visually. It'll make the dispersion-factor somewhat large."

"I don't mind."

"Good thing you don't," came the glum reply.

Both of them knew that the job of aiming a stellar ship was accepted by the public as one of the things that had to be done; few of them knew what went into the job. All stars are but pinpoints in the sky, there is no quick way to tell a close-by star from a distant star by visual inspection. To the untrained, even the solar planets blend with the interstellar reaches. Only the trained eye can tell planets from the stars by the lack of twinkle.

The true distances between the stars is too vast to be comprehended. Men speak of light years. Yet even the learned must indulge in quite a bit of cerebration to understand the length of a year, the velocity of light presents figures too extreme for comprehension. Light travels at 328 yards per millionth of a second, 328 yards can be grasped, as a distance of three-football fields, but a millionth of a second cannot be grasped readily; 186,000 miles per second offers only one factor capable of being understood. One can count "Ten-Hundred-One" and realize that a second has passed. But the mind is incapable of grasping the fact that during that time of counting, a beam of light traverses 186,000 miles.

Proxima Centauri is four light years away. Using the longest base that the solar system provided, the beginning and the end of the aimed course was like trying to hit a match head at ten thousand yards with a snub-barrelled pistol. A misalignment too minute for the eye to see meant a probable target dispersion as broad as the outer orbits of the solar system.

Aim a ship at a target four light years away across aiming points a couple of light hours apart. At a velocity within a couple of percent of precise, multiplied by a number of seconds mounting into five or six figures, you can establish the volume which will contain the spacecraft on its arrival. A volume of probabilities; far, far from the layman's idea of a precise science.

Heading as he was for Proxima Centauri, that tiny star would be the focus of his aim. But Proxima is a tiny star, one of a trinary, and the other two magnificent stars overwhelmed the feeble light of Proxima. So the system of Alpha Centauri would lie on the cross-hairs of Paul's telescope.

And the cross-hairs of the telescope would be displaced from the axis of drive by a small angle. It was this angle that required the use of the electronic calculator.

Not only because Proxima lies a smidgin of space apart from the more brilliant pair, but because Alpha Centauri drifts along in the galactic swing, and Sol moves as well. The eye sees Alpha Centauri where it was four years ago. Any trip across space, lasting ten days, must bring the traveller down out of supervelocity and into the realm of visibility at the position where Alpha will be ten days after take-off—not where Alpha was four years ago.

This was a problem not yet licked. Like the 'sighting-in' of a brand new pistol, each shot fired added to the knowledge of the correction factor that must be applied.

For the same reasons of inward anxiety that makes a man who has missed a train on Monday turn up two hours early on Tuesday, Paul turned up at the spaceport early. The guard greeted him with a cynical smile but checked the identification carefully before waving him through the gate.

Paul went to the Elecalc office to get his folder of course-data. The usual procedure was to have the course calculated as early as possible before the date of take-off, so that the busy department could sandwich course-data in between the longer range jobs. This was different, undoubtedly some long-range job had been stopped in mid-calc so that Paul's course could be run off. He was not too surprised to have the man at the desk smile and point a finger at the Superintendent's Office and say:

"It's in there. Go on in, he's expecting you."

Paul went to the door, opened it, and then swallowed a lump as large as his fist.

The man sitting quietly behind the desk, huge hands folded in his lap, was Chadwick Haedaecker.

Chadwick Haedaecker was the kind of man who collected college degrees, both earned and honorary, and had them lettered on his office door like a collection of trophies. He had enough ability and ambition to get to the top of his particular heap, and once he got there he had garnered enough additional power to stay there. He was a tall man with piercing eyes and an indomitable nature and he used both to quell any objectors to his plans, projects, ideas, and theories. Twenty years of authority in a position where no man was permitted to doubt his word or argue with his self-assured proclamations had completely erased any trace of humility he ever had.

But whether Haedaecker was a prince among men or a jackal among jackals depended entirely upon the beholder. When Haedaecker believed in your idea, he was a staunch supporter, throwing all he had—and he had plenty—behind your idea. His whip cracked just as hard in your behalf as it lashed against your back when Haedaecker was not convinced of the soundness of your idea.

Since Haedaecker was head of the Bureau, his presence here made Paul blink.

While Paul tried to think of something clever to say, Haedaecker smiled and nodded, finally speaking after he knew the state of discomfiture of his employee.

"You've had quite a time, haven't you?" asked Haedaecker.

Paul nodded ruefully.

"Just what happened?"

Paul explained, carefully, completely. He would have preferred to answer Haedaecker with nods or grunts or shakes of the head on the theory that opening the mouth is the first step towards spilling the whole tale, or at least enough of it to give a man as cagey as Haedaecker to think that there was more equipment in the BurAst spacecraft than radio beacon checking gear. Haedaecker was not the kind of man to come forth to console a man; especially one that apparently came out of the deal with nothing lost. Haedaecker's principle was to get 'em off balance and keep 'em off balance, because when they're off balance they cannot get set to swing. Paul knew that he would have to play this interview with the same finesse that a mouse should use to escape the cat's corner.

"Have any ideas about this?" asked Haedaecker.

Paul's ideas were all confused ones but he did not say so. "The police accept it as a plain case of attempted theft," he said.

"And you?"

Paul spread his hands in a universal gesture. "I can't make more out of it than the police," he said.

Haedaecker speared Paul Grayson with those piercing eyes. "You're not mixed up in anything, are you?"

"Lord no!"

Haedaecker's glare lessened. "I don't mean anything lawless or underhanded."

Paul looked at Haedaecker coldly. "Then what else?"

Haedaecker smiled blandly. "You are an ambitious young man. You are idealistic. You are enthusiastic and energetic. You are also determined."

"Are those unfavorable traits?" asked Paul with a slight edge to his voice. He hated this baiting; knew that he should take the sting of Haedaecker's acid tongue without flaring back. Haedaecker had Paul over the proverbial barrel, from which position there is little chance for counter-attack.

"Listen to me," snapped Haedaecker. "You were twenty four when you came to this department. Two years later you came to me with an idea. You hoped to link the stars by voice. An ideal. A magnificent hope and plan for mankind on earth and upon Neosol. For years everybody who has had a touch of space has been trying, testing, and experimenting towards that end. Men of learning, both abstract and concrete; men who have spent years studying that very idea."

"What has that idea got to do with my getting a lump on the head?" queried Paul.

"Only this. As a member of this department, you were given a job to do. You have proceeded well and executed this job proficiently. Four years ago, Grayson, I told you that the experiments you suggested had been tried. I was patient. I explained that there was a certain appropriation set aside for communications research; that the appropriation intended for this galactic survey was under no circumstances to be used for communications."

"I remember that. I also claim that my experiments have never been tried."

"Nonsense. I accepted your theory and have had other scientists check your reasoning. They state that there is no relation such as you claim. Now, to get back to the correlation between that crack you got on the head and my presence here, it goes as follows:

"Until last evening I let you alone. I knew that you continued to hold that mad theory despite arguments against it. But a man can have his dreams, and so I permitted you to dream. I assumed you to be honest. I believed that you would not defy orders and employ funds for Z-wave research. But when a man who has no great wealth, no vengeful enemies, no polygonal love affairs, and no power to dispute or usurp gets involved in a tangle as well-contrived as this, there is but one thing left: I am convinced that you are planning to test the Z-wave!"

Paul laughed, bitterly. "Just why do you assume that this is some sort of plot? Why not accept it as attempted theft as the police do?"

"If I were a thief," said Haedaecker softly, "And managed to break into the spaceport, I would not wait until the guards came after me, then to drop from my stolen spacecraft and run! A thief does not need the spotter craft to lay his course. He takes off for anywhere so long as it is off and away. A man contrived to resemble you closely enough to pass superficial inspection follows you before the take-off, clips you on the skull, and steals your wallet. You are the traditional technician, Grayson. You do not dress like Beau Brummel, nor do you show evidence of affluence. Any footpad would look for a more wealthy client. He knew you, Grayson. He clipped you for your credentials!"

"So?"

"Why?"

"I don't know."

"I can suggest a theory. Because he knew that you were going to try the Z-wave."

"Nonsense!"

Haedaecker smiled with a wolfish serenity. "Can you think of any reason why any man would want to put a monkey wrench into our plans to survey the galaxy?"

"No—"

"Then it must be your wild schemes."

"But just the same question, Doctor Haedaecker; if I were going against orders and attempting to test the Z-wave, why would a man attempt to stop me?"

"You are an idealistic simpleton," snapped Haedaecker. "You have a manner of convincing people of the worth of whatever idea you happen to hold dear. Despite the reams of evidence to the contrary, you have the enthusiasm necessary to convince people who have not the truth at their fingertips of the validity of your ideas."

"Piling supposition upon supposition," smiled Paul, cynically, "if that has been done, I fail to see any reason why any man would not want to be linked to Neosol by voice."

"You have a lot to learn about human nature, Grayson. You'll find as you grow older that whenever someone proposes a plan for the benefit of mankind, there are violent factions that will work hard to circumvent it. How many leagues of united nations have failed throughout history because of jealousy, aggrandization, megalomania. Both personal and national. In one instance after the Bomb convinced all men that uniting as one was the smart, safe, sensible thing to do, people hailed with joy the creation of a new sovereign state apart from its neighbors. Another nation blocked amity because of an ideology. A third nation presented a territorial possession with its freedom and at the same time contemplated the addition of two new states to its union. Grayson, once a man rises above his daily job and tries to set up something beneficial to mankind, he will find other men who see that plan as a threat to their own ambitions."

Paul leaned forward over the desk. "Why not let me try?" he asked eagerly.

Haedaecker leaned back wearily. "We've been all through that."

"But why?"

"I will not have one of my own men involved in an experiment as ridiculous as yours!"

Paul eyed Haedaecker quietly. "But—"

Haedaecker shook his head. "You are not to attempt this." He eyed Paul angrily.

"Who says I am?" demanded Paul.

"Reason and logic. And," said Haedaecker coldly, "excepting for one thing, I'd go out and inspect that ship of yours for Z-wave gear. But Paul Grayson is smart enough to smuggle the Z-wave gear on earlier trips, not leaving his evidence for the last attempt, so I would find nothing at this time."

Paul felt his heart pound thrice and then settle down again. The one thing that he was trying to avoid was not going to come off.

But Haedaecker glared at Paul once again. "I absolutely forbid you to do this."

Paul glared back. "What have we to lose?"

"I'll not have the ridicule attendant to such an abortive experiment pinned onto my department."

Paul laughed sarcastically. "It seems to me that a man in your position might like to have the name of being willing to have himself proven wrong."

"What do you mean?" demanded Haedaecker.

"Can your own personal ambition be great enough to block and forestall the linking of Sol and Neosol by Z-wave?"

"You young puppy—"

"Your position is due to the proposal of Haedaecker's Theory," said Paul. "I am not attempting to insult you, Doctor Haedaecker. I want you to view this in another light. According to all of the evidence at hand, Haedaecker's Theory is correct and we cannot communicate with the Z-wave across interstellar space. The proposition of that theory and its math have made you a famous man. Perhaps you fear that if Haedaecker's Theory is shown to be incorrect, you will lose your position. This is not so. Men have always been on the side of a great man who was humble enough to doubt his own theories occasionally, who was willing to see them attacked. It means a lot to mankind; show mankind that your personal ambition is not so great as to prevent them from having the benefits of—"

"You're talking as though you knew that your plan would be successful," sneered Haedaecker.

"I believe it will be if I am given the opportunity to try."

"I tell you that it will not, and I forbid you to try." Haedaecker speared Paul with a glance from the icy eyes. "You understand, whether or not the experiment might be successful, if I hear of your trying it, you will be subjected to every bit of punitive action that the law permits."

Paul leaned back easily. "Now," he said with cool candor, "you're assuming that I have all intention of attempting it without official permission."

"I would not put it past you. In fact I believe you are."

"All predicated upon the fact that a footpad belted me and swiped my wallet?"

"Yes. For what other reason?"

"Theft is usually done for—"

Haedaecker stood up angrily. "I've heard enough," he snapped.

Haedaecker strode to the door and hurled it open with one swing of a powerful arm.

What happened next was not too remote a coincidence. It has happened to everybody, several times. Someone with the intention of entering a room will brace themselves, turn the doorknob, and thrust, only to have the door opened from the other side. The net result is that the muscular effort, tensed to strive against the mass and inertia of the door, will find its force expended against no resistance. Doors are pulled from one side and pushed from the other. If the shover pushes first, the would-be puller gets slapped in the hand with the doorknob, sometimes resulting in a broken finger or thumb. But if the puller pulls first, the shover finds himself catapulted forward by his own muscular effort. The results of this latter can be both comic or tragic.

In this case the result was a flurry of splash-printed silk, a bare white arm, a fine length of well-filled nylon, and the frightened cry of a woman.

Paul gulped.

Haedaecker's reflexes worked fast. He caught Nora Phillips before the girl went headlong to the floor and he stood her up, retaining a light grip on her waist until she got her bearings and her breath.

"Young woman," stormed Haedaecker angrily, "Are you used to bustling into closed conferences?"

Nora looked at Haedaecker with eyes large, luminous, and fetching. "I didn't know it was a closed conference," she said in her cool contralto. "I'm most sorry."

"Miss Phillips, Doctor Haedaecker. She is the woman I met last night, Doctor Haedaecker."

"What are you doing here?" demanded Haedaecker.

"I did not know this was any kind of conference," she explained. "I came to see Mister Grayson, and the guard said he was in this room, talking."

"Why didn't you wait?" stormed Haedaecker.

Nora smiled, wanly. "I was excited," she said. "It may have occurred to you, too, that the man who tried to steal Mister Grayson's spacecraft last night was not playing a game. Everything seemed wrong. He was not smart. I got to wondering why he just didn't get into the ship and take off.

"Well, less than fifteen minutes ago a flash came over the air. Among the news was the statement that the criminal killed last night in attempted spacecraft theft was Joel Walsh. He was an escapee from penitentiary in Antarctica. That explained it."

"How?" demanded Haedaecker, "does that explain anything?"

"Of course it does," said Nora. "He was in jail for ten years. He must have been sent away when he was about twenty. How many men are competent space pilots at that age?"

"Not many," agreed Paul.

"And being in jail for the last ten years, it's natural that he did not know how to run the ship."

"Um," grumbled Haedaecker.

"He probably wanted to stow away," said Nora. "Once he did that, he could hold a gun at the pilot's head and make the pilot do his bidding until he learned how to run the ship."

There was one very fine flaw in Nora's reasoning, but Paul did not want to belabor this point at this moment. He had not intended to push Haedaecker to the point of firing him for impertinence, insubordination, or rank carelessness. For on the "BurAst 33.P.G.1" was the Z-wave gear that Haedaecker's vindictive nature accused him of stowing away.

Paul laughed. "So much for your intrigue," he said.

Haedaecker glared at Paul angrily. "Your intrigue," he said with heavy emphasis on the first word. "Just let me find you trying it!"

Paul smiled crookedly and looked Haedaecker in the eye coldly. "Doctor Haedaecker," he said in a level, voice, "if I ever try it and fail, no one will know of my failure. If I try and succeed, I assure you that you will be able to do nothing to me."

Haedaecker nodded, his manner as cold as Paul's voice had been. The gage had been hurled, the swords measured and weighed. So far it was stalemate. But only until Paul Grayson really did something against the rules, large enough to let Haedaecker really clip him deep, lasting, and legally justifiable.

Haedaecker left and Paul turned to Nora Phillips. She smiled at him and asked: "What is this intrigue business, or is it a top secret?"

Paul shook his head. "I'd prefer to tell you after I return."

"Do that," she said. "I'd like to hear about it."

Paul pondered briefly. The obvious thing was to offer her a chance to look over his ship. He could do that, now that he had all of his credentials and papers back. But the Z-wave gear was evidence against him, and even though it was parked in a convenient locker, certain hunks of cable-endings and associated bits of equipment were a dead giveaway; the same sort of evidence in the shape of capped pipes will tell the observer that plumbing once existed in a certain room. Paul had no intention of trusting anybody at this moment.

Mayhap Nora's timely information about the deceased thief were true. Still, there was a hole in her tale. If the thief wanted only to stow away until take-off time, he would pick another spacecraft than the BurAst P.G.33-1. The registry number glowed in luminescent paint a yard high, and matched the numbers on his identification card. Certainly no half-idiot would try to stow away in an official ship that was almost certain to be investigated as soon as the hue-and-cry was heard.

He suspected Haedaecker's hand in this; anything to keep Haedaecker's Theory in high gear, to keep Haedaecker top man in his field. He might as well suspect Nora, too. At least until motive or innocence could be shown.

He decided to lie glibly. "Normally I could take you aboard and show you the crate," he said. "But this is an experimental run and subject to security, though I'll not be able to explain why they think it so."

Nora laughed and shook her head. "Space ships are cold, powerful, and dangerous things to me," she said. "I'd feel uncomfortable on one of them."

"Then let me show you the elecalc."

"What?"

"Elecalc. Short word for electronic calculator. I'm here to get an aiming point for my trip tonight."

"Now that I would like to see," said Nora, hooking an arm in Paul's.

"I'm pointing for Alpha Centauri," said Paul. "And so that's what we calculate for."

Nora looked at the bays of neat equipment and shook her head. "Why not aim at it and run?" she asked. "Surely you do not need this billion dollars' worth of stuff to point out your destination."

"We do," objected Paul. "You see, if I took off with my telescope pointed along the axis of drive with the cross-hairs pointing at Alpha Centauri, I'd be heading for the star where it was four years ago. I intend to be on the way for nine days. So I'll want to point the nose of the ship at the spot where Alpha will be nine days in the future instead of four years in the past. Since Sol and Alpha drift in space, the motion and velocities of both systems must be taken into account, a correction-angle found, and then used to aim my ship. My telescope will angle away from the ship's axis by that correction-angle. Add to that the fact that I am taking off from earth, which will give me some angular velocity and some rotational velocity differing from an hypothetical take-off from Sol itself. Furthermore, I want Proxima Centauri instead of Alpha, and that must be taken into consideration too.

"Then there is the question of velocity and time. We cannot see when we are exceeding the velocity of light. We must run at so many light-velocities for so many seconds. A minor error in timing or velocity will create a rather gross error in position at the end of the run."

"Oh," said Nora, but her tone indicated a lack of comprehension.

Paul smiled. "One second of error at one light-velocity equals a hundred and eighty-six thousand miles of error. One second of error at a hundred times the velocity of light equals eighteen millions of miles error. Not much as cosmic distance goes, but a long way to walk."

Nora understood that, and said so.

Grayson's data had been handed to him by Haedaecker. But apparently the long-range calculations that had been temporarily halted were still halted, for the operator was taking this opportunity of feeding some future flight-constant information to the big machine.

It was not a complex calculation as some computations may go, but there were a myriad of factors. Terran latitude and longitude, the instant of take-off as applied to the day and the year, an averaging of previous dispersion-factors noted from previous trips, velocities, vector angles, momentum, and others, all obtained from tables and entered in the machine before the start lever was pulled. The machine mulled the information over, tossed electrons back and forth, chewed and digested a ream of binary digits, and handed forth a strip of paper printed with an entire set of coordinates in decimal angles.

Paul showed Nora his folder of data. "The rest," he said, "is up to me."

He led Nora from the computation room, intending to hit the dining room for coffee. Half-way across the lobby of the administration building he was hailed by the autocall. He went to the telephone.

It was Stacey.

"I've a couple of things to let you think over," said Stacey.

"So?"

"I've been on the job. I haven't much, but there are a few items you might mull over."

"Shoot."

"One. Your deceased thief was an ex-convict, escaped from the penal colony on Antarctica."

"This I've heard."

"Then I suppose you know that the guy was cashiered from the Neoterra run for smuggling."

"Huh?" blurted Paul.

"An ex-pilot, tossed out on his right ear for conduct hardly becoming a safecracker and a thief, let alone an officer and a gentleman."

"That I didn't know. How long ago?"

"Five years, almost."

It was not quite the ten that Nora had claimed.

"Well, that makes it—"

"That ain't all," came Stacey's voice. "The weapons carried by the Spaceport guards are regulation Police Positives. Our erstwhile felon was shot once, right between the eyes, with a forty-five, which according to all of the expert opinion, came from an automatic at a distance of three feet, plus or minus six inches. Know what that means?"

"I'm just digesting the information now. You tell me."

"It means that the ex-crook was killed by a party or parties unknown, someone other than one of the guards. Furthermore, he was facing his executioner, not taking it on the lam. How do you make that?"

"It doesn't make good sense."

"Sure it does. It keystones nicely. Men of that calibre are often chilled because they fumble a job and the mainspring doesn't enjoy the prospect of having a fumbler running around with information that might lead to the capture, arrest, conviction, and/or demise of aforementioned mainspring. They made one error. They should have used a thirty-eight revolver instead of a forty-five automatic. The forty-five is a gangster's weapon. And they should have drilled their ex-companion from behind between the scapulae to make it look as though the guards were better shots than they really are."

"That's food for thought," said Paul.

"That isn't all," said Stacey. "Here's one more bit of information that may be either juicy or full of sawdust depending upon how you taste it. Your girl friend, Nora Phillips was born and raised on Neoterra."

"You're certain of that?"

"So the Bureau of Vital Statistics claims."

"But how—?"

"Negative evidence, my fine scientist. Negative evidence. I offer you two alternatives. Either she was born on Neoterra, or she is employing an alias, pseudonym, or nom de jour." Stacey's French lacked a certain vocabulary, but it was none the less to the point. "She is certainly not born Nora Phillips of Terra. I'll let you pick your choice. But enough of that. A couple of hours ago she received a telephone call. Nice position she must have. She chinned for about three minutes and then leaped to her feet and took off like jet propelled. Didn't bother to say anything to the management of the joint at all. Then—"

"Where does she work?" asked Paul.

"Timothy, McBride, and Webster, Attorneys-at-Law. We couldn't tap their telephone, but we had a lip-reader peering at her through a telescope from a room in the building opposite hers."

"What did he catch?"

"Nothing, she just listened, and then took off. And can that dame drive! If we didn't have an idea of where she was going after the first few minutes, my man would have lost her for certain. She with you now?"

"Uh-huh."

Paul thought fast. Just what unearthly reason why people would try to stop his plans for creating voice-fast communications with Neosol, Paul could not fathom. Obviously there was one faction working against him. But how had they—

Paul paled.

Had the criminal hoped to lay Paul low enough to keep him quiet until the criminal could take off in Paul's place? True identification would be impossible once the crook were in space. But what could he accomplish? Certainly—

Suppose the thief that clipped him intended to place Paul in a position where he could be captured easily. To take Paul's place to perform certain acts in Paul's name, while Paul was held captive. Then, once these acts were consummated Paul could be found in the wreck of a spacecraft or the ruin of a radio beacon on Proxima Centauri I.

But why? Columbus had been kicked around for having screwy ideas, and the Brothers Wright had been thoroughly laughed-at. But people did not try to murder characters who had cockeyed ideas. Of course, there was Galileo, but Galileo had publicized his screwy ideas, whereas Paul Grayson's theories were known to very few.

But Nora Phillips could not be held as part of that particular mob. It seemed to Paul that the woman had done a fine job towards keeping Paul hale, hearty, healthy, and imbued with ideas available only to a man in the finest of health of mind and body. If Nora belonged to some group intent on stopping Paul Grayson, she was working against them, too. For she had done a fine job of smoothing the headache out of his skull with fingers that acted with experience and practise.

On the other hand, Nora Phillips had behaved as though she wanted Paul to succeed, and she acted—if this were an act—as though she enjoyed her work.

So what had really happened last night when Paul Grayson was clipped unconscious?

Had Nora forestalled them—them?

Nora was quite a woman. Her loveliness was not of the untouchable, fragile, bandbox variety; perfection that must not be marred by a misplaced hair or a wrinkle in the frock—or a clue of rouge, printed offset from her own ripe lips to her own smooth cheek by Paul. Nora was all-desirable woman, and neither complete dishabille nor minor imperfection would mar her appeal. Paul recalled the lithe slenderness of her body. Her sculptured arms were molded with the smooth, well balanced muscle of fine tonus. Her waist was slender but not too soft—

"Hey! Are you there?"

"Yeah, Stacey. I was thinking."

"Don't think so hard."

"Look, Stacey. Can you tell me whether the man who clipped me turned up with scratches on his face?"

"I don't know. Why?"

"Just a loose end."

"I might be able to find out."

"Take a swing at it; but it's not too important."

"Okay, Paul. Have I given you something to think about?"

"More than," said Paul soberly. He hung up, turned, and saw the guard of the previous evening standing near by, about to go on duty. Paul went over and asked: "Hi!"

"Hello. Say, I'm sorry about last night—"

"Forget it, you were doing your duty. But can you tell me: Did the guy who used my identification last night have any scratches on his face?"

The guard frowned in thought. "All he had was some well-applied make-up, and a fine job it was, too. He looked me right in the eye."

"No marks?"

"Not a trace."

Paul smiled and went back to Nora, thinking furiously. Something must have interfered with their little plan. He looked at Nora, lissome, lovely, as lithe as a tiger. All desirable—

But maybe it might be a good idea for him to learn her desires, to ascertain her limit before he took any liberties with her beautiful white body. Intelligent women did not scream or faint these days, nor did they rake their attacker with fingernails. They employed Judo.

Now, if Nora Phillips knew Judo, it was plausible that the erstwhile footpad instead of finding an inert victim and an hysterical woman, discovered that the woman was capable of defending her outraged dignity, revenging their cowardly attack, and thwarting any further plans the criminal held for them both. It would explain in part why the criminal's little idea did not culminate as expected.

If Nora Phillips knew Judo.

Paul smiled faintly. He had not changed his mind about Nora Phillips; she was still the type of woman that would react unfavorably to any crude attempt at approach.