FAMOUS DISCOVERERS

AND EXPLORERS OF AMERICA

FAMOUS LEADERS SERIES

Each, one volume, illustrated, $2.00

Except as otherwise noted

BY

CHARLES L. JOHNSTON

FAMOUS INDIAN CHIEFS

FAMOUS SCOUTS

FAMOUS CAVALRY LEADERS

FAMOUS PRIVATEERSMEN

FAMOUS FRONTIERSMEN

FAMOUS DISCOVERERS AND EXPLORERS OF AMERICA

FAMOUS GENERALS OF THE GREAT WAR

FAMOUS AMERICAN ATHLETES

| First Series | $2.50 |

FAMOUS AMERICAN ATHLETES

| Second Series | $2.50 |

BY

CHARLES LEE LEWIS

FAMOUS AMERICAN NAVAL OFFICERS

BY

EDWIN WILDMAN

FAMOUS LEADERS OF INDUSTRY—First Series

FAMOUS LEADERS OF INDUSTRY—Second Series

THE FOUNDERS OF AMERICA

or, Lives of Great Americans from the Revolution to the Monroe Doctrine.

THE BUILDERS OF AMERICA

or, Lives of Great Americans from the Monroe Doctrine to the Civil War.

FAMOUS LEADERS OF CHARACTER

(new revised edition)

or, Lives of Great Americans from the Civil War to To-day.

BY

TRENTWELL M. WHITE

FAMOUS LEADERS OF INDUSTRY

| Third Series | $2.50 |

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY, BOSTON

AMERIGO VESPUCCI (see page 45)

FAMOUS DISCOVERERS

and Explorers of America

Their voyages, battles, and hardships in traversing

and conquering the unknown territories

of a new world

By

CHARLES H. L. JOHNSTON

Author of “Famous Scouts,” “Famous Indian Chiefs,”

“Famous Cavalry Leaders,” “Famous Frontiersmen,”

“Famous Privateersmen,” etc.

Illustrated

THE PAGE COMPANY

BOSTON PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1917

By The Page Company

All rights reserved

Made in U. S. A.

Fourth Impression, September, 1928

Fifth Impression, March, 1932

THE COLONIAL PRESS INC.,

CLINTON, MASS.

Dedicated

To the Great Brotherhood of the Clergy

who, with self-sacrifice, devotion, and lack

of personal profit,

have consecrated their lives to

the education and development of the youths

of all English speaking countries.

PREFACE

My Dear Boys:

It has seemed fitting to include in the Famous Leaders Series this volume upon the discoverers and explorers, not only of North America, but also of Central and South America.

It has been impossible to include them all in a volume of this character; but I have selected the most important, and have omitted such men as Sebastian Cabot, Jacques Cartier, Sir Francis Drake, Baffin, Verendrye, Robert Gray, Lewis and Clark, Pike, Franklin, Frémont, and many others.

This is no new subject. The lives and histories of these discoverers have been written by many another; but I have endeavored to bring before you a series of pictures of some of the most noted of these men of daring and grim determination, and, if I have succeeded in painting the canvas with colors which are agreeable, then, my dear boys, I shall feel that the moments occupied in the preparation of these pages have been well spent.

Believe me,

Yours very affectionately,

Charles H. L. Johnston.

Chevy Chase, Maryland.

August, 1917.

THE VOICE

A voice came from the westward, it whispered a message clear,

And the dripping fog banks parted as the clarion tones drew near;

It spoke of shores untrodden, and it sang of mountains bold,

Of shimmering sands in distant lands which were covered with glittering gold.

It sang of hemlock forests, where the moose roamed, and the bear,

Where the eider bred near the cascade’s head, and the lucivee had his lair.

It praised the rushing water falls, it told of the salmon red,

Who swam in the spuming ripples by the rushing river’s head.

It chanted its praise of the languorous days which lay ’neath the shimmering sun,

Of the birch canoe and the Indian, too, who trapped in the forests dun.

Yea, it told of the bars of silver, and it whispered of emeralds green,

Of topaz, sapphire, and amethyst, which shone with a dazzling sheen.

Of warriors red with feathered head, of buffalo, puma, and deer,

Of the coral strand in a palm-tree land, and of dizzying mountains sheer.

And the voice grew louder and louder, and it fell upon listening ears,

Of the men who had heard strange music which was moistened with women’s tears.

Of the men who loved to wander, of the souls who cared to roam,

Whose bed was the hemlock’s branches, who rejoiced in the forest’s gloom.

Leif the Lucky, Magellan, deLeon and Cortés bold,

Cartier, Drake, and Franklin; Pizarro and Baffin, old;

Shackleton, Hudson, Roosevelt; brave Peary and gay Champlain,

Frémont, Lewis, Balboa; Verendrye, and the Cabots twain;

’Twas the voice that called them onward, ’twas the voice that is calling still,

And the voice will call ’till the end of it all, and the voice has a conquering will.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| Preface | vii |

| The Voice | ix |

| Leif Ericson | 1 |

| Christopher Columbus | 15 |

| Amerigo Vespucci | 43 |

| Juan Ponce de Leon | 61 |

| Vasco Nuñez de Balboa | 85 |

| Hernando Cortés | 107 |

| Ferdinand Magellan | 185 |

| Giovanni Verrazano | 203 |

| Francisco Pizarro | 217 |

| Hernando de Soto | 249 |

| Samuel de Champlain | 271 |

| Henry Hudson | 303 |

| Pierre Esprit Radisson | 337 |

| Father Marquette | 361 |

| Robert de La Salle | 383 |

| Robert Edwin Peary | 409 |

| Epilogue | 427 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Amerigo Vespucci (See page 45) | Frontispiece |

| Leif Ericson | 8 |

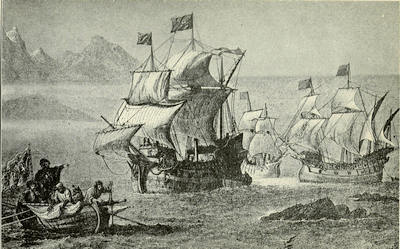

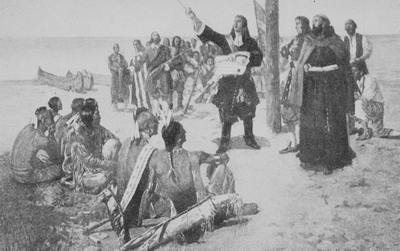

| The Landing of Columbus | 28 |

| Amerigo Vespucci off the coast of Venezuela | 48 |

| Juan Ponce de Leon at the Fountain of Youth | 80 |

| Balboa taking possession of the Pacific Ocean in the name of the King of Spain | 97 |

| Capture by Cortés of the City of Mexico | 178 |

| The Death of Magellan | 200 |

| Giovanni Verrazano | 208 |

| Execution of the Inca of Peru | 245 |

| De Soto in the Florida Wilderness | 256 |

| Champlain in the Indian Battle | 285 |

| Henry Hudson in New York Harbor | 317 |

| Marquette and Joliet discovering the Mississippi River | 369 |

| La Salle at the mouth of the Mississippi River | 397 |

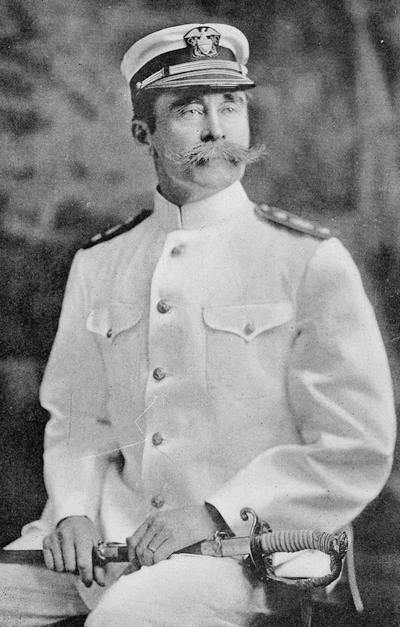

| Robert Edwin Peary | 413 |

LEIF ERICSON:

THE FIRST EUROPEAN TO EXPLORE, AND

SETTLE IN, AMERICA.

“From Greenland’s icy mountains; from Iceland’s rocky shore,

We sailed the ship which forged ahead and ruddy oarsmen bore;

We found the wild grape growing; we scoured the river’s bed,

And chased the moose whose horns were broad, whose blood was rich and red.

Our axes felled the wild-wood, our spears the Skraelings slew,

We sank their round skin-barges as the cutting North Winds blew,

Over the wild waves rolling, back to the fiords of home,

We safely came to anchor,—but we’ll never cease to roam.”

Saga of the Vikings, 1000 a.d.

FAMOUS DISCOVERERS AND

EXPLORERS OF AMERICA.

LEIF ERICSON:

THE FIRST EUROPEAN TO EXPLORE, AND SETTLE IN, AMERICA.

ON the shore of a great fiord, or estuary of the sea, in the far northern country of Greenland, stood a little boy. He was sturdy-limbed, blue-eyed, flaxen-haired, and he was looking out across the water at a great high-prowed Viking ship which lay bobbing upon the waves.

He stood there thinking,—thinking, until, as he gazed enraptured upon the scene before him, a tall, bearded Norwegian came up behind him. He smiled upon the little boy, and, laying his hand upon his head, said:

“Little one, what are you dreaming about?”

The youthful Norwegian looked around and also smiled.

“Good Lothair,” he answered, “I am thinking of the time when I shall be able to sail far to the westward, with the older Vikings, and can have adventures of mine own.”

The other laughed.

“Ah, ha, that time will not be far distant,” said he, benignly. “You will wax tough and sinewy in this bracing air and by sailing in these blue fiords. And then, some day, one of the Vikings will want a stout fellow to man an oar. He will call upon Leif, little Leif. And I’ll warrant that little Leif will then be ready.”

“I will be.”

“And would you go far to the westward, to the land of the setting sun?”

“Even so.”

“And would you be willing to risk life and limb amidst ice and snow?”

“I’d be glad to do it.”

Lothair laughed loud and long.

“You are a true Viking, my boy. You are, indeed, one of those whom Thor has smiled upon and whom the Valkyrias would love to assist in battle. Keep up your spirit, and, some day, you may be famous,—who knows?”

So saying he walked away, still laughing softly to himself.

And the little boy still kept on thinking, thinking, and looking out upon the great, blue sea which seemed to beckon to him, to nod to him, and to sigh: “Come on! Come on! I have marvelous things to reveal to you, little boy.”

The youthful Viking turned around, went back to his home, and kept on working and sailing, and fishing, and playing, until a time came when he had waxed great in both strength and in stature, and, as he looked[5] at himself in the polished surface of his shield he said: “Ah! Now, indeed, I am a true Viking. I am ready for great things.”

This little boy was the son of Eric the Red, a strong man, and a bad man, also. Eric’s father lived in Iceland, whither he had been forced to fly from Norway, for he had killed a man there and he would himself have been killed, had he not jumped into a boat, rowed to a Viking ship, and sailed to the westward. And Eric the Red seems to have inherited the traits of his father, for he, too, killed another. He had lent some of his furniture to a neighbor who would not restore it. Eric, therefore, carried off his goods and the other pursued him. They met, and hot words passed; so they had a struggle and Eric killed the fellow. He was thus made an outlaw, so he went sailing away to find some place where he could live in peace, far from his brother Vikings. He found a land, where he settled,—and called it Greenland, for, said he, “other Vikings will come here and settle, also, if I give this place a good name.”

Eric the Red, had two children, of whom one was called Thorstein, and the other, Leif. The first developed into a thin youth with black hair and a sallow complexion, but the second was rosy-cheeked, fair-haired, blue-eyed, and sturdy-limbed. He was, in fact, the little boy to whom Lothair spoke as he stood upon the banks of the fiord, gazing far into the distance, determined, some day, to sail towards the West where he was certain that adventure and treasure, too, perhaps, were waiting for him.

One of the men who accompanied Eric, the murderer, to Greenland was named Herjulf. This bold and daring adventurer had a son named Bjarni, who roved the seas over, in search of adventure, for many, many years. Finally, in 986, he came home to Iceland in order to drink the Yuletide ale with his father. Finding that his parent had gone away, he weighed anchor and started after him to Greenland, but he encountered foggy weather, and thus sailed for many days by guess work, without seeing either the sun or the stars. When, at length, he sighted land, it was a shore without mountains. He saw, through the misty murk, only a small height covered with dense woods. So, without stopping in order to make explorations, he turned his prow to the north and kept on. He knew that this was not Greenland, and, so we may think it strange that he did not stop to examine the rugged coastline.

The sky was now fair and a brisk breeze was astern, so, after scudding along for nine or ten days, Bjarni saw the icy crags of Greenland looming up before him, and, after some further searching, found his way to his father’s house. He had more than once sighted a heavily timbered shore-line, to the west, while steering for home, and, when he told of it, great curiosity was excited amongst the Norsemen.

Little Leif had now grown to be a man of size and strength. He had made many a journey to Norway, and, when there, in the year 998, found that Roman missionary priests were preaching up and down the land, and had converted the King, Olaf Tryggbesson,[7] who had formerly worshiped the Gods Thor and Odin. Leif, himself, became a Christian and was baptized, so, when he returned to Greenland, he took several priests with him, who converted many of the people. Old Eric the Red, however, preferred to worship in the way of his fathers, and continued to believe in the mystical Valhalla, or hall of departed spirits, where the dead Vikings were supposed to drink huge cups of ale while feasting with their gods.

Upon a bright, warm day in the year 1000 a.d., a great Viking ship lay calmly upon the waters of the bay before the town of Bratthalid in Greenland, and on shore all was bustle and confusion. Leif Ericson, in fact, had determined to sail far to the westward, even as he had dreamed of doing when a little boy; and so, with thirty staunch adventurers, he was preparing to load his ship with sufficient provisions to last for the journey to that strange country of which Bjarni had brought news. It took several weeks to gather provisions and men, but at length everything was ready. The sail was hoisted, the great oaken oars were dipped into the water, and the sharp bow of the Viking ship was turned toward the open sea. “Huzzah! Huzzah!” shouted the Norsemen. “Huzzah!”

The Viking ship, which had a huge dragon’s head at the prow, was such a tiny affair, when compared with the massive ocean liners of to-day, that one can well imagine how she must have been tossed about by the great, surging waves; but she kept on and on, ever steering westward, until a land was discovered which seemed to be filled with flat stones, so they called it Helluland,[8] or flat-stone land. This was the Newfoundland of our maps, to-day.

Leaving this behind them, the Vikings kept on steering southward and westward, until they saw a low-lying and heavily wooded shore. This was Nova Scotia, and they coasted along it, for many days, occasionally coming to anchor in one of the deep bays, and heaving overboard their fishing lines, so as to catch some of the many fish which seemed to abound in these waters.

They sailed on towards the south, and at last reached a place where a beautiful river flowed through a sort of an inland lake into the sea. Many islands were near the mouth of this stream, and, as salmon seemed to abound in the waters of this blue and clear-flowing estuary of the Atlantic, Leif decided that this was a good place in which to spend the winter. So down went the anchor, the Viking ship was moored near the shore, and the men scrambled to the beach in order to erect huts in which to spend the cold season. Thus the dream of the little boy, as he had stood upon the shore of Greenland, years before, had come true, and Leif had reached a new world, to which he had been led by his daring and his love of adventure.

You see, that, although it was long supposed that Columbus was the first white man from Europe to ever set his foot upon the shore of America, such is not the case.

The real discoverer of America, of whom we have any definite record, was Bjarni, the son of Herjulf, who, in the midst of fog and murk, coasted along the shore of Nova Scotia in 986 a.d.

LEIF ERICSON

(From the statue at Boston, Mass.)

And the first European to make a settlement upon the shores of the new world was Leif Ericson, who sailed into that blue, salmon-filled river which flows “through a lake into the sea.” So, if you look along the coast of New England, and try to find a river which answers this description, you will, I think, find but one. This is the river Charles, which, emptying into the Charles River Basin—a huge lake, if you wish—flows into the blue Atlantic. And, if you search the shore upon the Cambridge side near the hospital, you will find, to-day, the cellars of four houses,—the houses, no doubt, which Leif and his men erected in the year 1000 a.d.

The Vikings built their huts, caught many salmon, and journeyed inland, where they found a profusion of wild grapes, so many, in fact, that they dried a great mass of them, loaded them into the hold, and called this land Vinland, the Good. They also found a race of people living in this country, who were ferocious in aspect, with ugly hair, big eyes, and broad cheeks. They were clad in the skins of the beaver, the lynx and the fox, and their weapons were bows and arrows, slings, and stone hatchets. As they screeched dismally when about to attack in battle, the Vikings called them Skraelings, or Screechers. It is apparent that the Skraelings were more like the Esquimaux, than like the Indians found by Columbus.

The Vikings spent a peaceful winter in Vinland and had no difficulty with the Skraelings, who left them[10] alone. The Norsemen felled a great many trees and loaded their ship with lumber, with dried fish and grapes. Spring at last came and the ice and snow melted in the deep forests, the gray geese began to fly northward, and the robins chanted a melodious welcome from the budding thickets. The followers of Leif deserted their huts, clambered aboard their low-lying vessel, and, singing a song of thanksgiving, turned her prow towards the blue Atlantic. They coasted past the islands at the harbor-mouth, and, driven by a stout breeze, were soon careening over the waves upon their journey to Greenland.

But adventures were not entirely over, for, upon the way home, a dark spot appeared upon the horizon, and, upon sailing up to it, Leif and his seamen discovered a boat-load of sailors. These poor fellows had been out in a large vessel, but she had foundered, and had gone to the bottom in a squall. The castaways were rescued, were taken aboard the home-going Viking ship, and were carried along to Bratthalid, where Leif and his followers received a royal welcome, and great interest was taken in the story of their adventures. Leif was christened Leif the Lucky, and by that name he was to be known forever afterwards.

The daring navigator never again sailed to the pine-clad coast of Vinland, but other Norsemen made the journey and some left their bones to bleach upon the shores of New England. Thus in 1002, when Eric the Red died, and Leif the Lucky succeeded to his Earldom, Thorstein (Leif’s brother) decided to explore the new-found country. So, with thirty or more men,[11] he sailed to the westward, found the huts which the first adventurers had erected, and had the pleasure of spending the winter there. These voyagers stayed here for several years, for, in the Spring of 1004, while some of the party were exploring, the ship was driven ashore in a storm, near a ness, or cape. They put a new keel into their damaged vessel and stuck the old one into the sand, calling the place Kjalarness, or Keel Cape. The cape was undoubtedly near the end of Cape Cod.

Thorstein was subsequently slain in a battle with the Skraelings, but his men returned to Greenland, bringing lumber, dried fish, and many tales of this wonderful country; so that other Vikings longed to go and explore. Thus, in the summer of 1011, two ships set sail for Vinland, one with Leif’s brother and sister, Thorwald and Freydis, and a crew of thirty men; the other with two brothers, Helgi and Finnibogi, and a crew of thirty-five. There were also a number of women.

Helgi and Finnibogi were the first to arrive at the huts which Leif had constructed, and had taken possession of them, when Freydis, arriving soon afterwards, ordered them to leave. Bad blood arose, and Freydis one day complained that Helgi had given her evil words and had struck her. She told Thorwald that he should avenge this insult, and taunted him so mercilessly, that, unable to bear her jeering words any longer, he was aroused to a deed of blood. Surrounded by his followers, he made a night attack upon the huts of Helgi and Finnibogi, seized and bound all the occupants, and killed them with cold steel. The peaceful[12] shores of the river Charles witnessed such a murder as has never occurred again.

In 1012 the survivors sailed for Greenland in the vessel of the murdered brothers, which was the larger of the two. The evil woman, Freydis, who had caused all this trouble, pretended that the other party had been left in Vinland, and that ships had merely been exchanged. She threatened her men, that, if any told on her, they would be murdered, but words were let fall which came to the ears of Leif the Lucky. Three of those who had just returned were put to the torture, until they told the whole story of murder and death in the peaceful country of Vinland.

Leif was greatly affected by the news, but said with great show of magnanimity: “I have no heart to punish my wicked sister Freydis as she deserves. But this I do say to Freydis and Thorwald,—that their posterity will never thrive.”

“And”—says an old Viking—“so it went that no one thought anything but evil of them from that time on.”

This is the last that we hear of Leif the Lucky. That little rosy-cheeked boy, who dreamed that one day he would be a great adventurer, had accomplished his purpose. He had found a new country, he had lived to see it explored by other Vikings, and he had opened the eyes of Europeans to the fact that, far away there was a land which was richer in furs and in timber than anything which they had about them.

The citizens of Boston, Massachusetts, have erected a bronze statue to this navigator, upon Commonwealth[13] Avenue; where, with hand shading his keen eyes, the staunch Norwegian is going out upon the Charles River;—that river, upon the banks of which in the year 1000 a.d., he and his followers spent a peaceful winter in the land of the Skraelings, the beaver, the bear, and the pink-fleshed salmon. Skoal, then, to Leif the Lucky! And remember that it was he, and not Columbus, who first trod upon the shores of America as an adventurer from the European world.

VINLAND

’Neath the scent of the green hemlock forests, near the sands of the storm-driven sea,

Lies a land which is good, filled with balsamy wood, and a voice there is calling to me;

There the grapes grow in reddening clusters, there the salmon jump clear of the falls,

And in crystalline splendor, the moon, in November, shines bright, as the lynx caterwauls.

From Moosehead the wild loon is screaming, from Rangely the trout jumps at play;

And from Kathadyn’s bold peak, comes the osprey’s fierce shriek, while the brown bear creeps near to its prey.

Oh! that is the land for the Vikings; yea, that is the kingdom of rest;

In the rude deer-skin boats, the warrior gloats, as the strangers press on to the West.

There is thunder for Thor and for Odin; there is silver for Tyr and Brogé,

In Jotunheim’s palace, there is envy and malice; but nothing but love far away:

Come, Vikings, hoist up your rude anchors! Come, seamen, row hard, as ye should!

And steer to the West, where there’s peace and there’s rest; steer straightway to Vinland the Good.

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS:

RE-DISCOVERER OF AMERICA, WHO GAVE

A NEW CONTINENT TO THE WORLD.

(1436-1506)

Great man, whose courage led you o’er

The ocean’s unknown length,

A thousand voices thankfully

Proclaim your power and strength.

The treasures of the tropic isles,

You found, but failed to gain.

The honor that was due, was lost,

You saw your subjects slain.

Your plans for empire sailed away,

Undone by other wills;

And left but glorious memories,

Which every seaman thrills.

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS:

RE-DISCOVERER OF AMERICA, WHO GAVE

A NEW CONTINENT TO THE WORLD.

(1436-1506)

THE good and genial friar Juan Perez was working, one day, in front of the convent of La Rabida, which had been dedicated to Santa Maria de Rabida, near the pleasant city of Palos, in Spain. It was a lonely place, built upon beetling cliffs which overhung the blue ocean. The friar, with his brown cassock tucked up around his fat legs, was busily engaged in hoeing some beans, when he saw a man standing at the little wicket gate which was between himself and the roadway. The man was thin, care-worn, and cadaverous-looking. His hair was quite gray and he held a small boy by the hand.

“Kind priest,” said he, “I am faint with hunger.”

The good friar dropped his hoe and stood there smiling; for he had a warm heart, and the little boy, whom the stranger held by the hand, was very wistful.

“In God’s name, my poor fellow,” said Juan Perez, “come into the convent with me, and I will give you all that you wish, for I see that you are faint with hunger. And the little boy is surely very ill.”

So the white-haired man and the little boy went into the convent of Santa Maria de Rabida, and there the priest fell into a long conversation with this traveler. He found out that the wanderer was named Christopher Columbus and that he had been born in Genoa, in Italy. The little boy was his son, Ferdinand.

The priest was a man of great learning and had been confessor to the Queen of Spain. He soon perceived that this Christopher Columbus was a man of considerable learning, also, and found out that he had been a sailor ever since he had been a boy of fourteen. Charmed and delighted with the conversation of this penniless mariner, he asked him to remain as a guest at the convent, for he saw that, within the lean body of this white-haired sailor, burned a spirit of adventure which was like a beacon light.

“Had I the money, the ships, and the men,” said Columbus, “I could discover a new country lying far to the west. But, you see, I am a pauper.”

“Yes,” replied the good priest. “But I have powerful friends who have both money and ships. These will doubtless help you in your contemplated voyage. Stay with me for a few days. I will call them hither, so that you can discuss this matter with them.”

Columbus was glad to have this prelate listen to his schemes for sailing far to the westward, for he had been endeavoring, for a long time, to get some one to give him the necessary financial assistance, so that he could fit out ships both with provisions and with men. In a day or two a physician arrived. He was a learned fellow, and his name was Garcia Fernandez. He was[19] accompanied by a wealthy navigator, called Martin Alonzo Pinzon, who listened to the schemes of Columbus with great enthusiasm.

“I, myself, will lend you money for this voyage westward,” said he. “And I will go in person upon this hazardous undertaking.”

The good priest, Juan Perez, had become most enthusiastic over the scheme.

“Wait until I write to our gracious Queen Isabella,” said he. “She, I know, will aid you in your contemplated journey. Be of good cheer, for she is the best of sovereigns, and cannot allow a Frenchman to have the honor of any discoveries in the West.”

Christopher Columbus was quite willing to have this done, for he was sure that, could he but gain access to the ear of the great Queen, she, herself would see the righteousness of his cause and aid and abet in that which filled him with zeal and enthusiasm. So he waited patiently at the convent while a letter was dispatched to the kind-hearted Isabella, carried to the court by one Sebastian Rodriguez, a pilot of Lepe, and a man of considerable prominence. The Queen was at the military camp of Santa Fé, where she was directing her troops against the city of Granada, which was held by the Moors.

Fourteen days went by, and, at last, Rodriquez returned to the heights of Palos.

“The Queen is much interested in your mariner friend, Columbus,” said he to Juan Perez. “She wishes greatly to add to the glory of Spain, and requests that you allow this sailor to travel to her military[20] camp. But first she wishes to talk with you, good priest.”

The friar was delighted. Quickly saddling his mule, he was soon upon his way to Santa Fé, where he was received with kindness and consideration. The Queen had a friend and companion called the Marchioness Moya who urged her to give aid to Columbus and thus bring much renown and glory both to herself and Spain. “This fellow has a great idea,” she said. “Surely you will allow him, in the name of Spain, to find out what lies far to the westward.”

Isabella was feeling particularly happy, just then, for her troops had nearly captured the city of Granada and the hated Moors were about to be driven from the soil of Spain. So she gave a great deal of money to the priest from Palos, in order that Christopher Columbus could buy a mule and sufficient clothing to appear at court. With smiles of satisfaction the good friar returned to the convent at La Rabida and the first link in the chain which led to the discovery of the West Indies by those of white complexion, had been forged.

The time had come when the schemes of western exploration, which for years had lain dormant in the breast of this penniless man from Genoa, were about to be put into execution. Columbus was now light-hearted, even merry, and, leaving his little son to the care of the good monks of Palos, he mounted a mule and journeyed to Santa Fé, accompanied by his friend Juan Perez.

It was a propitious moment. The Moorish leader had just handed over the keys of the city of Granada[21] to Queen Isabella, who, mounted upon her horse and surrounded by a retinue of ladies-in-waiting and courtiers, joyfully received the keys, as evidence that the Moors were at last driven from the soil of Spain. Columbus soon was admitted to her presence and there told of his desire to sail westward toward the setting sun.

“But,” said he, “if this voyage is a success, I must be made Admiral and Viceroy over the countries which I discover, and must also receive one-tenth of the revenues which come from these lands, either from trade or from agriculture.”

These terms did not suit the Queen’s counselors.

“It would be degrading to exalt an ordinary man to such high position,” said Talavera, the Queen’s foremost advisor. “The demands of this threadbare navigator are absurd.”

More moderate terms were offered to Columbus, but he declined them.

“Good-by, Your Majesty,” said he. “I will go to France, where the King will perhaps give me more advantageous offerings than you care to present.”

So the good man mounted his mule—the very one which the Queen had presented him with—but he did not seem to mind using it, and, turning his back on Santa Fé, and the convent of La Rabida, he started for the Pyrenees Mountains in order to journey to France.

As soon as he had gone the Queen began to feel sorry that she had allowed him to depart. Her friends gathered around her and had a good deal to say.

“What an opportunity you are losing to enhance the glory of Spain,” said several. “What a chance to make your own name forever great. If I were you, I would call this navigator back to court before he arrives upon the soil of France.”

Her husband, King Ferdinand, looked coldly upon the project, for his treasury had been exhausted by the fighting with the Moors and he did not wish to spend any more money, just then. But the Queen had many jewels which she could pledge in order to raise money for ships and for supplies.

“Ferdinand,” said she to her husband, “if you do not care to undertake this enterprise for the glory of the crown of Castile, I myself, will do so, and I will give all of my jewels as security for a loan to the navigator Columbus.”

A courier was sent post haste after the sailor from Genoa, who was then ambling along upon his mule and was crossing the bridge of Pinos, some six miles from Granada.

“The Queen has changed her mind towards you,” said the courier who had been sent to find the poor navigator. “Come back! You will now have funds with which to go upon your journey.”

Columbus hesitated a moment, for he feared that this was a lie, but, convinced of the truth of the statement, he turned about and whipped up his mule. They trotted along joyfully towards Santa Fé.

The Queen was now in a pleasant humor. Columbus was given all that he had asked for, but he was required to bear one-eighth of the expense of the journey.[23] Papers to this effect were drawn up and signed on April the seventeenth, 1492, and, a month later, the joyful navigator set out for Palos in order to get ready the ships and provisions for the long-hoped-for voyage of discovery.

By the terms of the agreement between himself and the King and Queen he was to be called Viceroy and Governor of the new provinces which he wished to conquer in the rich territories of Asia, the country which he thought to be in the far west. He was to receive one-tenth of the pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and merchandise of whatever kind, which might be taken by his followers in the kingdoms which he expected to take possession of. Good terms these! Let us see how he fared!

Three caravels were now equipped for the journey at the port of Palos. It was difficult to find sailors to man them with. All were frightened at the enterprise and shuddered when they thought of a long sail into the unknown West. But the King said that he would pardon all those who had criminal charges hanging over them, should they join the expedition. In this way a sufficient number of sailors were secured.

The three ships were called the Gallega, the Pinta, and the Nina. The first was to be the flagship of Columbus, so he changed her name to the Santa Maria, as he was of a religious turn of mind. The Pinta was commanded by Martin Pinzon, and the Nina by his two brothers, Francis and Vincent.

On Friday, August 30th, 1492, the caravels headed out to sea and started upon this voyage of discovery.[24] One hundred and twenty sailors had been secured, most of them with criminal records, so it was not to be expected that the Admiral, as Columbus was now called, would have an easy time with them. Some, in fact, were so anxious not to go that they purposely unshipped the rudder of the Pinta, when only a day from port, and the vessel had to be steered for the Canary Isles in order to repair the damage. Finally, after a three weeks’ delay, during which another rudder was made, the expedition again hoisted canvas and headed for the blue horizon of the west. The hearts of the Spanish sailors now failed them and many cried like little children, for they were fearful of what lay before them; some, indeed, even thinking that they would come to a great hole and fall in. As for Columbus, he tried to comfort them with the prospect of gold and precious stones in India and Cathay which he was sure that they would discover.

“On, on, my men,” said he. “On, and let us all be enriched by the treasures which we will soon come upon!”

But the ignorant sailors were constantly anxious and distrustful.

The bellying sails carried the three caravels ever to the westward. They sailed through vast masses of sea-weed on which small fish and crabs were hanging, and the sailors feared that they would be stranded upon this mass of vegetation. But when they threw lines into the water these did not touch the bottom, so they knew that they could go forward. The three vessels, in fact, were plowing through the Sargossa Sea, eight hundred[25] miles from the Canary Isles. This is a mass of tangled sea-weed over two miles in depth, so it is no wonder that the lines did not touch anything when they let them down.

Now birds began to fly around the caravels, such as gannets and sea-swallows.

“Land must surely be near,” cried many. “We have now been six weeks upon the water and Asia must certainly be before us.”

But, in spite of the birds and the floating sea-weed, the boats kept on and on and still no land came to view.

Columbus, himself, never lost his confidence in the ultimate success of the journey.

“My men,” said he, “land will eventually be sighted. You must bolster up your hearts and have great courage, for we will soon view the coast of Asia, where lives the mighty Khan.”

And, each evening, he made the sailors chant a hymn to the Virgin. Cheered by the words of this heroic man, the Spaniards gained renewed hope and eagerly scanned the horizon for some signs of palm trees or tropic vegetation.

Before the expedition had set out, King Ferdinand had promised a reward of 10,000 maravédis, or 400 pounds sterling ($2,000), to the sailor who first discovered land. So, do you wonder that the mariners eagerly scanned the blue distance for a dark line of earth!

As the ships drowsed along with a gentle easterly wind in their rear, numerous large birds, petrels, man-of-war birds and damiers, flying in couples, were a sign[26] that land must certainly be near, for otherwise how could these feathered sea-farers breed and lay their eggs? On, on, the mariners drifted, the sailors eager, depressed, even mutinous, but the courage of Columbus never wavered.

The month of October had now arrived and the Admiral announced to his crews that the ships had traveled 1,272 miles to the westward. In reality, they had sailed 2,100 miles; but Columbus hid the truth from his followers, for he knew them to be on the point of mutiny, and, should they learn how far they were from home, they would wish to return. On October the seventh the crews were much excited by hearing several musketry discharges from the Nina, the commander of which thought that he had discovered land. But this was an illusion; what he took to be land was but a patch of sea-weed, bobbing on the glassy waves.

A number of parroquets went flying by in a southwesterly direction, and, thinking that they were doubtless winging their way towards their homes, the Admiral was requested to steer more towards the south. This he did, and it is well that he so traveled, for, had the vessels kept due westward, they would doubtless have run aground upon the great Bahama Bank and would have been destroyed.

But why did not land appear?

Each evening the sun dipped down behind an interminable horizon of water. Sea-weed floated past, birds flew around upon every side, and still no land came to view. The Spaniards began to murmur loudly against Columbus.

“He is a Genoese, a foreigner,” said some. “What does he care for Spaniards! He has enticed us from our own country only to drown us all. One thrust of a poniard and he will be out of the way forever!”

The Admiral heard of these remarks and knew that his sailors plotted his destruction, but his spirit never faltered, and, as the men still worked the ships, he kept courageously onward.

The eleventh of October had now come, and, as the bold navigator was looking over the side of the Santa Maria, he noticed a reed, still green, floating upon the top of a wave. His heart beat faster, for he realized that land must certainly be in the offing. Almost at the same time the men on board the Nina perceived the branch of a thorny tree, covered with blossoms, which bobbed upon the sprawling waves. All rejoiced exceedingly, for they knew that the coast of some strange country must be near. Night fell over the sea, and Columbus took up his position on the foremost part of his vessel, where he could watch until morning. About ten o’clock he thought that he saw a light in the distance and called to a sailor, Pedro Guitierrez, a chamberlain in the King’s service, who confirmed it. Once or twice, after this, the Admiral again saw the light, which looked as if some person were carrying a flambeau on shore, or in a boat, tossed by the waves.

Columbus spent a restless night. When morning broke, a sailor called Rodrigo de Triana, saw land from the deck of the Pinta, and a thrill of joy and thanksgiving ran through every heart. It was only two miles away, and the vessels quickly headed towards the low-lying[28] shore. Every one eagerly crowded forward, with shouts and cries of joy, as the three caravels drew nearer and nearer to the sandy beach. The vessels anchored, and, crowding into the boats, Columbus, with his followers, rowed towards the breaking combers. All were eager to set foot upon the new-found territory.

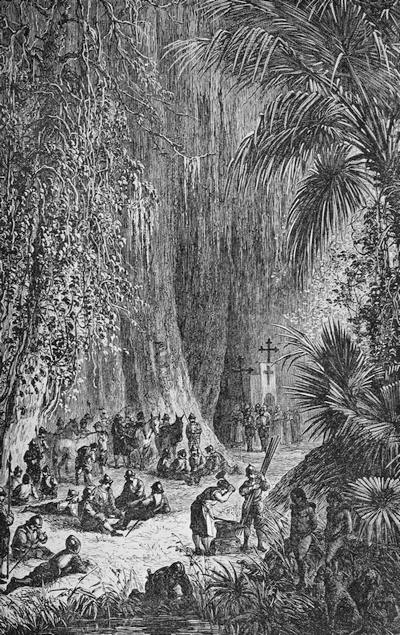

Columbus had on a scarlet coat; and in one hand he held a cross, in the other a sword. When he reached the beach he knelt upon one knee and kissed the soil, while one of his followers held over his head the royal banner of gold, embroidered with crowns and with an F and I, the initials of Kind Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. He gave thanks to God; while all his crew of malcontents joined him in singing the Te Deum. His sailors gathered about him, embracing him with fervor, and begging his forgiveness for their mutinous spirit.

At this moment some naked savages appeared from behind the tropic foliage and came timidly towards the Spaniards. None of the men appeared to be over thirty years of age, and the women, too, were young. They were well made, their figures handsome, and their faces agreeable. Their hair, as coarse as the tail of a horse, hung down in front as far as their eyebrows, while behind it formed a long mass which was apparently never cut.

As they approached, the Spaniards greeted them kindly, and, when the voyageurs showed them their swords, the poor natives seized them in their hands so that they cut their fingers.

THE LANDING OF COLUMBUS

The Spaniards roamed about for some time, glad indeed to stretch their legs, and then jumped into their long boats, in order to go back to the ships. Several of the natives plunged into the water and swam after them, crying out with apparent pleasure. Next day they came in crowds around the vessels, paddling themselves in enormous canoes shaped from the trunks of trees and guided by means of broad paddles, like a snow shovel. Several of the islanders wore little plates of gold hanging from their nostrils, which interested the Spaniards more than anything else. “Where did you get this?” they signaled to the chattering Indians. The natives pointed towards the south, when they understood what the mariners wished to know, and this made the voyageurs eager to get away, for gold was ever that which has lured the Spaniard onward.

Columbus named the island San Salvador, and believed that he had arrived upon the coast of Asia. The place was beautiful. Gray and yellow parroquets chattered and screamed from the trees, and brilliant tropic birds fluttered before them, as the Spaniards explored the interior. A small lake was in the center of the island, but there was no sign of gold or of gold mines. So the voyageurs turned away, disgusted, and determined to sail southward where the natives told them was a mighty monarch who possessed great vessels of gold, and immense riches.

The next morning, at day-break, Columbus gave orders to have the ships prepared for sea and all set sail towards the south, coasting along the western side of the island, while the natives, running down to the shore, offered the Spaniards water and cassava bread,[30] made from the root of a plant called the “yucca.” The Admiral landed upon the coast at different points and carried off some of the natives, so that he might exhibit them in Spain. Poor, ignorant islanders! Little did they guess that soon the white-skinned strangers would tear them from their country in order to sell them as slaves.

The Spaniards were really among the West Indies; but Columbus still had the idea that he was near China, the home of the mighty Khan, stories of whose wealth and possessions had already been brought to Spain. So, after the three caravels had left the island of Cuba, two emissaries were dispatched into the interior in order to take presents to the Khan. They soon returned, telling of the peaceful natives, beautiful groves of palm trees, but of no signs of the Asiatic potentate. They reported that both the native men and women smoked tobacco by means of a forked pipe, and that they had cotton houses made in the form of tents.

The crews now began to grow restless. They had come to find Asia or India, where were great hoards of gold. Instead of this they had found merely some tropic islands, populated by a race of naked savages who had no great treasures and knew nothing of gold mines. The Admiral sailed onward and kept discovering other islands, in all of which he found many articles of gold, but no particularly great city or town with riches and treasure. And there were no signs of the mighty Khan of Asia.

While exploring the coast of an island called Hayti,[31] a young chief visited the caravels, attended by two hundred subjects. He spoke little, but gave the Admiral a curious belt and two pieces of gold, for which Columbus, in return, presented him with a piece of cloth, several amber beads, colored shoes, and a flask of orange water. In the evening the native was sent on shore with great ceremony and a salute was fired in his honor, which both surprised and interested him.

A short time after this a still greater chief, named Guacanagari, sent a messenger to the Admiral requesting him to come to his part of the island. The ships were therefore turned in the direction of this chief’s home, and had sailed within a mile of his residence, when the Santa Maria ran upon a sand bank and quickly went to pieces. When news of this was brought to the native ruler, he sent his followers to unload the vessel and guard the contents, and his family to cheer the Spanish navigator and to assure him that everything which he possessed was at his disposal. All of the Spaniards went on board the Nina and were later entertained by the prince. So well, indeed, did Columbus like this island that he determined to erect a fort upon the coast, and to leave there a certain number of men with a year’s provisions of bread, wine, and seed, also the long boat of the Santa Maria.

As a matter of fact the Spaniards were now eager to return to Spain, for, although they had discovered a new territory, they had not found the great quantities of gold. As for the mighty Khan, he was certainly not in the vicinity of these tropic isles, with their green paroquets screaming from the waving branches of the[32] palm trees, and their naked savages with soft voices and hollowed canoes. The majority of the seamen thought that they had done quite sufficient exploring and were certainly ready to return to the bullfights and the crooked streets of old Seville.

“Back to Spain,” they said to Columbus. “Back to Spain and let other adventurers come here if they wish. We have found the way for them. Let them explore and develop this territory.”

Columbus was quite ready to set sail across the Atlantic, for he had found a new country for the Spanish Crown, and had added many square miles of territory to the possessions of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. It was now the month of January; the skies were blue and the weather was balmy; so all seemed propitious for a safe and speedy passage. Leaving thirty-nine men to garrison a fortress which he ordered to be constructed, and to search for gold until he could come back again from Spain, and naming one Rodrigo de Escovedo as their commander, the Admiral boarded the Nina, and, after fighting a mimic sham battle with his men, in order to amuse the Indians, he turned the prow of the little vessel toward the rising sun. The Pinta, under the command of Martin Pinzon, had been cruising to the south for some days; but she now returned, with the news that, although the natives had told of a great island to the south where there was much gold, none existed. The sailors were much distressed in mind, for they had certainly expected to find a quantity of gold and treasure in this tropic country.

It was now the seventh day of January and the boats[33] lay to, in order to stop a leak which had sprung in the hold of the Nina. Columbus profited by the delay and explored a wide river which flowed from the base of a high mountain, called Monti Christi by some of the crew. The Admiral found the banks of this stream were full of gold-dust—so much, in fact, that he named it the Golden River. In spite of this discovery the Spanish sailors were still anxious to return and began to murmur against the authority of Columbus. Thus, on the ninth day of January, the two caravels set sail, and, steering towards the southeast, skirted the coast, en route for Spain.

As they swung lazily along, the natives sometimes followed them in their canoes. One day they began to shoot at the sailors with their arrows, so that discharge of musketry had to be resorted to, in order to drive them away. Two or three of the islanders were killed in this little affair, and thus, for the first time, the blood of an Indian flowed beneath the hand of a European.

Four of the natives were captured and taken on board so that they might be exhibited in Spain. They went unwillingly, but, when they endeavored to escape, were bound to the masts and were forced to join the Spanish adventurers. So, cruel even in this first expedition to the new world, just as they were ever afterwards, the Spanish navigators plowed eastward towards the land of Ferdinand and Isabella. The passage proved to be a quick one until the twelfth day of February, when the vessels encountered a fearful storm lasting three days.

The little caravels with their three-cornered sails were slapped around on the surging billows until all thought that they were lost, and the sailors swore on bended knee that they would go and pray in their shirts, and with naked feet, at the monastery of our Lady of Loretto, if a Kindly Heaven would only put an end to this fearful raging of the waters. Columbus seems to have given up all hope of ever reaching land, for he wrote out a description of his voyages, placed it inside a cask, and hurled it into the sea. This included a request that whoever should find this document would forward it to the King of Spain.

Luck, however, was with him, and the storm at length abated to such a degree that the two caravels cast anchor at the island of St. Mary, one of the Azores. The crew went ashore, and were immediately thrown into prison; but, after a period of five days, were allowed to leave by their Portuguese jailors. Again the two caravels headed for Spain, but again the winds blew vigorously, so that the Pinta was driven into the Bay of Biscay and the Nina had to take refuge at the mouth of the Tagus, in Portugal.

Here the Portuguese welcomed the Admiral in a kindly fashion, but he was anxious to return to Spain, and, as soon as the weather would permit, the Nina again set sail. Finally, on the fifteenth day of March, after seven months of navigation, she cast anchor at the port of Palos, that little harbor from which the man with a great idea had sailed with a half-hearted and distrusting crew.

Columbus had guessed correctly. A new land did[35] lie far to the westward across the blue Atlantic, and it was a land where was gold, that which every Spaniard prized the most. The Genoese mariner had discovered the islands of San Salvador, Conception, Great Exuma, Long Island, the Mucaras, Cuba, and San Domingo.

The first man to give him a welcoming pat on the back was the good old friar Juan Perez.

“You have done well, my good Columbus,” said he. “How glad I am that I introduced you to the gracious Queen Isabella. You have indeed fulfilled the dreams that you dreamed in the convent of La Rabida.”

Ferdinand and Isabella were then at Barcelona, and, hearing of the safe return of Columbus, a message was immediately dispatched to ask him to come at once to court. The Admiral landed, offered thanks to God for preserving him in all his trials, and, taking with him the Indian captives, started on his journey to the residence of his King. From all parts of the country the Spanish people ran to look at him as he passed. They threw their hats in their air, shouting: “Long live Columbus! Long live the discoverer of new countries! All honor to the Admiral!” He was preceded by a troop of cavalry and a band of music when he entered Barcelona, and flowers were strewn in his pathway.

Ferdinand and Isabella received him with great pomp at the Deputation. After hearing his story, told by him with graphic words, all knelt and chanted the Te Deum. Christopher Columbus was then ennobled by letters patent, and the King granted him a coat of arms[36] bearing the device: “To Castile and Leon, Columbus gives a New World.”

The fame of the poor navigator rang throughout all the then civilized world; the Indians were baptized in the presence of the whole court; and all tongues gave praise to this poor and unknown sailor who had dreamed a dream of conquest which had come true.

Strength of purpose and strength of will had won the day. Had the Genoese mariner given in to discouragement when his half-criminal sailors grew mutinous and wished to return to Spain after they had passed the Sargossa Sea, to some one else would have belonged the honor of the discovery of the West Indies. Had he not used a firm hand in dealing with them, they would have marooned him on one of the islands which he discovered and would have left him there to die. Had he not been sure that he would find what he was after, Queen Isabella would not have aided him to glory and renown. Great and valiant Sailor, you should indeed be remembered with reverence, for you knew how to triumph over doubt and discouragement and your faith was sublime! All honor then to Christopher Columbus!

The remaining adventures of this gallant soul can be briefly narrated. Upon a second voyage to the West Indies he found the men whom he had left behind him had all been murdered by the Indians. After Columbus had sailed to Spain the Spaniards had stolen some of the Indian women and had consequently stirred up the wrath of the great chief who lived in the interior of[37] the island of Hayti, where they had been instructed to build a fort and live until the return of their companions. A row of graves under the swaying palm trees showed where once had been thirty-nine adventurous souls from Palos in Spain.

The Spaniards came over in numbers after this expedition, but, although they founded a city and attempted to settle in the new world, there were continual dissensions with the natives; fights; ambuscades; massacres. The men from Castile were lazy; greedy for gold; cruel to the natives; and treated them brutally when the poor Indians could not furnish them with the glittering metal which they so keenly desired. Then the more rapacious ones turned on Columbus himself, threw him in irons on one occasion, and continually derided him to the King of Spain, who, because the Indies did not produce the revenues which he had expected them to, turned coldly upon the mariner from Palos, and rather took the part of these malcontents against him. Like all persons who reach a certain pinnacle of greatness, Columbus could not remain a popular idol, for all men are human and he had the ambitions of others to contend with. There were fights with the natives; fights among the Colonists themselves; fights with the malaria, the yellow fever, and with other diseases.

Columbus himself fared badly. After the death of good Queen Isabella, Ferdinand would not aid him in the least. He had saved no money, after all these adventures, and, as his life drew to a close, had to live by borrowing. He did not even own a home in Spain, and had to reside at Inns and at boarding houses.[38] Alone, neglected, miserable, poor, he finally passed to another and better world, on May the twentieth 1500. He was seventy years of age.

Buried in the convent of St. Francisco, at Valladolid, Spain, his body was removed to the monastery of Las Cuevas at Seville, and, still later, to the cathedral of San Domingo at Hispaniola. But again it was taken up, and transported by vessel to Havana, Cuba, that rich tropic isle which the great navigator himself had discovered. Here to-day it is lying, and the sad spirit of this strange man of destiny hovers over the richest of all the possessions which Spain held in the West Indies, until wrested from her feeble grasp by the people of the United States in the year 1898, and magnanimously presented to the Cuban people themselves, to govern as they wished.

Could the poor old mariner, as he lay dying at Valladolid, have but looked forward into the centuries and seen the New World which he had discovered, he would have indeed been well satisfied. Had he known that a great Exposition would have been held to his memory and fame, and could he have guessed that the children of the civilized world would ever afterwards be taught the history of his life, of his perseverance, his courage, and his faith, he would indeed have been cheered in those last cheerless and poverty-stricken days.

In the career of this poor Italian dreamer, studying in every moment of leisure, asking assistance year after year from crowned heads until he was fifty-six years of age, in order that he might make his immortal discoveries, is a lesson to all who feel that their lives have[39] not been perhaps worth while as they near middle age. The lesson is:—keep on trying to win, and, even though you may not be appreciated during your lifetime, history will always give you a proper niche in the temple of fame. And do not believe that youth is the only time for adventurous discoveries. Columbus did not sail upon his epoch-making journey towards the West until after he had reached his fifty-sixth year. Middle age and perseverance, then, are good aids to place one within the halls of the immortals.

THE SONG OF THE ISLANDER

O brother, good brother, look out on the bay,

What’s that that is nearing, so long and so gray?

’Tis a palm tree, I’ll warrant, so large and so lean,

That it o’ershadows all palm trees that e’er I have seen.

O brother, good brother, it stops and is still;

White clouds are above it, they beckon and fill;

Two sticks running upward are covered with vines,

And a humming resounds like the wind when it whines.

O brother, good brother, a puff of white smoke

Rolls upward and onward—a voice surely spoke,

’Tis the speech of God Tezcal, he’s calling aloud,

For the rest of the Gods to gather and crowd.

O brother, good brother, what’s that to the rear?

A canoe is approaching, it fills me with fear,

For the white gods are paddling; they dress all in red,

And the skin of their hands looks like that of the dead.

O brother, good brother, bend low and keep still.

See the God in the bow, he is white-haired and ill.

Let us hide in the palms, ere they step on the shore,

Let us watch in the grass ’til this danger is o’er.

They jump to the beach, raise a cross-stick on high,

They speak a strange tongue and utter a cry.

O brother, good brother, what’s that shines and gleams?

On their breasts, on their backs,—it glitters and beams.

Let us talk with these strangers, let us speak with these men,

There are hundreds of brothers behind in the glen,

They surely can’t harm us, they come from the sky,

And they smile as they see us. Then let us draw nigh.

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

O brother, good brother, had I never been near,

These pale-visaged Gods who from Spain traveled here,

I’d be in the forest, not bound to the mast,

As the Nina rolls on and the shore flyeth past.

Good-bye, tropic islands! Good-bye, Salvador!

My spirit is crushed; my free life is o’er.

Farewell, beloved palm trees! Farewell and adieu!

My home is behind me and fades from my view.

AMERIGO VESPUCCI:

FLORENTINE NAVIGATOR FROM WHOM

AMERICA HAS DERIVED ITS NAME.

(1452-1512)

AMERIGO VESPUCCI:

FLORENTINE NAVIGATOR FROM WHOM

AMERICA HAS DERIVED ITS NAME.

(1452-1512)

ABOUT the beginning of the thirteenth century a family called Vespucci established themselves in the City of Florence, Italy. Anastatio Vespucci was the head of the family in 1451 and lived in a stately mansion, now occupied as a hospital for the poor, near the gate of the city known as Porta del Prato. He was Secretary of the Senate, and, although he lived in a palatial dwelling, had little besides the salary attached to his high office. Upon March the ninth, 1451, the third son of this official was born, and, when three days of age, was duly christened Amerigo. He has since been called Americus.

Almost from his cradle the boy was destined to become a merchant. Yet he had a good schooling, too, and was educated at a private institution presided over by his father’s brother, a monk of the Order of San Marco, who, before the birth of Americus, had become famous as a teacher of the noble youths of the city. Here the boy was taught mathematics, astronomy, geography, and the classics. He became especially interested[46] in geography and was ambitious to excel as a geographer.

Amerigo, or Americus, seems to have remained a student under the direction of his uncle for a number of years, yet we have no record of when it was that he followed the wishes of his father and entered upon mercantile pursuits. At any rate, he never lost his early interest in geography. In spite of his days in a counting house, he eagerly studied maps and charts. He made a collection of them, and, for one map alone, paid a sum equivalent to five hundred and fifty-five dollars.

Americus had an elder brother, Geralamo, who had left home to seek his fortune in foreign climes and had established himself in business in Asia Minor. He became immensely wealthy, and all went well with him, until one day, while he was at church, thieves broke into his house and robbed him of all that he possessed. This greatly impoverished the family, so that Americus determined to leave Florence and journey to some other country where he could retrieve his brother’s losses. He selected Spain as the scene of his future labors.

Just as Magellan deserted Portugal for Spain, so, also, Americus felt that here were fame and fortune awaiting him. Ferdinand and Isabella were then waging war upon the Moors who held the southern part of the peninsula, and, as this was regarded as a holy war, many of the young nobles from surrounding countries were in Spain fighting for the crown of Castile. The war created a demand for many articles of commerce, so Americus went to Spain as the agent for one of the[47] Medici, a ruling family in Florence. At the beginning of the year 1492, when Columbus made his first journey of exploration to the West Indies, we find the young Italian associated with one Berardi, who, after the return of Columbus from his first voyage, was commissioned to furnish and equip four vessels to be sent to the New World at different intervals. Vespucci met Columbus, had lengthy conversations with him regarding the New World, and, from his letters, we can see that he had a very clear idea that Cuba was not the main land, as Columbus supposed it to be, but was an island.

Berardi died in December, 1495, and the management of all his affairs devolved upon the shoulders of Vespucci, who soon wearied of seeking the favors of fortune and determined to abandon mercantile life for something, “laudable and stable.” He formed, in fact, a determination to visit the various parts of the world, a determination which he soon put into execution.

A navigator, called Ojeda, was about to set sail for the West Indies with four vessels and we find that Americus became one of his crew. According to some, he was to be one of the principal pilots; according to others he was to be an agent of the King and Queen, having a voice in the direction of the ships. On May 10th., 1497, the fleet left Cadiz, and, after reaching the Canary Islands, sailed so rapidly that, at the end of twenty-seven days, it came in sight of land. This was the coast of South America.

The Spaniards anchored and attempted to hold some[48] intercourse with the natives, but the Indians were very shy and refused to come out to visit them. So, coasting along the shore, they came upon a village, which, much to their surprise, was built after the fashion of the city of Venice, Italy. The houses were placed upon piers in the water, and had entrances by means of drawbridges, so that the inhabitants, by leaving the bridges down, could traverse the whole town without difficulty. The explorers therefore called it Venezuela, a name which has endured to the present day.

The inhabitants, at first, shut themselves up in their houses and raised the drawbridges, and, as the ships came nearer, the savages embarked in their canoes and rowed out to sea. The Spaniards made every mark of friendship and invited the Indians to come to their ships, but the brown-skinned natives hastened away, making signs for the Spaniards to wait where they were, as they would return. They came back, bringing with them sixteen young girls, who beckoned to them and made signals of peace. The Castilians were much impressed by this; so much so, in fact, that their suspicions were not aroused by the sight of numerous natives who came swimming towards the ships. Suddenly they noticed that some of the women at the doors of the huts were wailing and tearing their hair, as if in great distress.

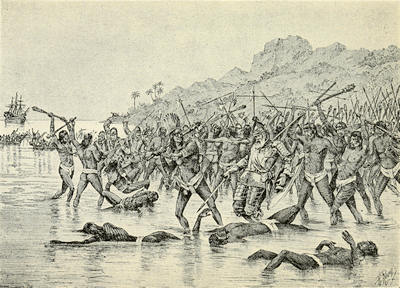

While wondering what this meant, suddenly all the girls sprang from their canoes, and the Spaniards saw that many men—who had been heretofore hidden by them—were armed with a bow and arrows. Each native in the water had a lance in his or her hand. Hardly had the white men perceived this before they were furiously attacked.

AMERIGO VESPUCCI OFF THE COAST OF VENEZUELA

The Spaniards vigorously defended themselves with their muskets and then made a dash for the canoes in their long boats. They overturned several, killed about twenty of the South Americans, and took two of the girls and three men prisoners. Many of the natives were wounded. The Spaniards did not burn the town, but returned to their ships, where they placed the three men, whom they had captured, in irons. Then they sailed southward, but, when morning dawned, discovered that the natives had managed to wiggle out of their irons and had jumped overboard.

Keeping their course continually along the coast, the explorers came to anchor about eighty miles from this new-world Venice, where they saw about four thousand persons gathered upon the shore. These set up a wild yelping, when the Spaniards let down their boats, and fled into the forest. The white men followed and found a camp where two natives were engaged in cooking iguanas, an animal which the early discoverers describe as a serpent. The two cooks fled, of course, but the whites disturbed nothing in the camp, in order to reassure the natives, and then leisurely returned to their boats.

Upon the following day these Indians paddled to the ships, and when they saw the two girl prisoners whom the Spaniards had taken, they became suddenly very friendly, for these girls belonged to a tribe with which they were then at war.

“We have only come here for the fishing,” said one[50] of them, a chief. “We live far back in the country and wish you to journey to see us as our friends.”

The invitation was received with great satisfaction by the whites.

“They importuned us so much,” says Vespucci in his narrative of these events, published some years afterwards, “that, having taken counsel, twenty-three of us Christians concluded to go with them, well prepared, and with firm resolution to die manfully, if such was to be our fate.”

So, the Spaniards journeyed inland, remained three days at the fishing camp, and then set out for the interior, where they visited so many villages that they were nine days on the journey, and their comrades on board the vessels grew very uneasy about them. The Indians, in fact, showed them great attention, and when they were about to return to the ships, insisted upon carrying them along in hammocks, slung upon the shoulders of strong and willing porters. When the explorers arrived at the shore, their boats were almost swamped by the numbers of savages who wished to accompany them, while swarms of natives who could not get into the boats, swam alongside to the ships. So many came aboard, that the mariners were quite troubled, fearing that they might make a sudden and unexpected attack. A cannon was fired off to impress the natives with the power of the explorers. At the explosion of the piece, many leaped into the sea, like frogs plunging into a marsh. Those who remained seemed to be unafraid and took leave of the mariners with many demonstrations of affection.

The Spaniards had now been thirteen months at sea, so their thoughts turned towards home. It was therefore decided to careen their vessels on the beach, in order to calk and pitch them anew, as they leaked badly, and then they would return to Spain. The Castilians made a breastwork of their boats and their casks, and placed their artillery so that it would play upon any enemies who might advance; then, having unloaded and lightened their ships, they hauled them on land to make much needed repairs.

No attack was made by the natives. Instead of this the South Americans brought them food, begging them to assist them in punishing a very cruel tribe of people who came to their country, every year, from the sea, and killed many of their warriors. They afterwards would eat them. Against these enemies they said that they were unable to defend themselves. When the Spaniards promised to march against the cannibals, no words could express their gratitude. Many wished to go with them, but the whites wisely rejected such offers, permitting only seven to accompany them.

The Spaniards sailed in a northeasterly direction for seven days, and then came upon some islands, many of which were peopled. They cast anchor before one of them and lowered the boats; but, as they did so, they saw about four hundred men and women gather on the beach; the men armed with bows, arrows, and lances, their naked bodies painted with various colors. As the Castilians approached to within bowshot of the shore, the savages sent a flight of arrows at them in an effort to prevent them from landing.

The cannon were therefore loaded and fired. As some of the Indians fell dead, the rest retreated. The Castilians, with a cheer, hastily landed and fell upon the savages, who put up a stiff fight. The battle raged for about two hours without a decisive victory upon either side; some of the Indians were killed and some of the whites were injured. At last, tired out, the explorers were glad enough to return to their vessels.

Next day the Spaniards landed again, and, under the leadership of Vespucci, had a bloody battle with the cannibals. The natives were at length badly worsted, were driven to their village, and this was burned to the ground. Only one of the explorers was killed, while twenty-two were wounded. Many of the Indians were burned in the ruins of their thatched huts.

Well satisfied with the outcome of this affair, the mariners now set sail for Spain, with the plaudits of the savages, whom they had assisted, ringing in their ears. They arrived in October, 1498, after an absence of about nineteen months, and were well received by the King and Queen, for they brought considerable gold, jewels, and skins of strange beasts and birds. Vespucci was highly pleased; he had been the first to visit the shore of South America and had really done something great in exploration,—his dream for many years.

Shortly after his return, a second expedition was prepared for a journey to this new-found country, headed by one Ojeda, a Spaniard of some wealth and influence. A fleet of four vessels was equipped, and the latter part of the Spring of 1499 saw them ready[53] for sea. The reputation of Vespucci as a geographer was such as to make him the very man needed for this particular voyage, and, although at first disinclined to leave home at so early a date, he finally yielded to the entreaties of Ojeda, and joined the party.

They set sail from Cadiz in May, 1499, and twenty-four days later saw land. The shore was low and so densely covered with small aromatic trees that the explorers concluded to return to their ships and try some other spot. After coasting along in a southerly direction they came to the mouth of a great river, and, having manned their boats with twenty well-armed adventurers, entered the stream and ascended it for more than fifty miles. But the land was as low, up-stream, as it was at the mouth, so the reconnoitering party floated down-stream to the fleet again. Anchors were raised, the ships stood out to sea, and, sailing in a southerly direction, encountered the great equatorial current which sweeps along the coast of Brazil.

“We could scarcely make any headway against it,” says Amerigo, in his description of this journey published some years later. “Seeing that we made no progress, or but very little, and also seeing the danger to which we were exposed, we determined to turn our prows to the northwest.”

Ten degrees north of the equator, the explorers again saw land, and, drawing nearer, found that this was an island. Many of the inhabitants were gathered upon the shore; but, when the pale-faced strangers landed, they took fright and ran into the woods. Fortunately two were captured and acted as envoys, so, after a time,[54] the rest allowed the Spaniards to approach and speak with them. They were cannibals, eating the bodies of all those whom they killed or captured in war, and had the heads and bones of those who had been eaten piled up in a big heap. Much disgusted at what they had seen, the Spaniards sailed away.

Drowsing along the coast of this island they came to another village of the same tribe, where they were hospitably received and were fed by the brown-skinned inhabitants. But they moved onward, sailed westward, and soon anchored near one of the mouths of the Orinoco River, where was a large village close to the sea, the inhabitants of which regaled the mariners with three different kinds of wine, and presented them with eleven large pearls, more than a hundred smaller ones, and a small quantity of gold. Here the navigators remained seventeen days, feasting upon fruits and the savory acorns with which the place abounded. Then they continued along the coast, stopping occasionally to hold intercourse with the natives.

These, for the most part, were unfriendly, and the Spaniards had many a battle with the South Americans.

Vespucci says: “Many times not more than sixteen of us fought with two thousand of them, and, in the end defeated them, killing many and robbing their houses. We were obliged to fight with a great many people, but we always had the victory.”

Thus they progressed upon their way, fighting, trading, exploring, until their stock of provisions became so nearly exhausted that it was impossible for them to[55] proceed further. Their ships, too, were sea-worn and leaky, so that the pumps could scarcely keep them free from water.

Other Spanish adventurers had founded a city called Hispaniola, not long before this, situated upon the eastern coast of Panama. The Ojeda expedition was now about three hundred and sixty miles from the point, but it was decided to sail thither in order to repair the ships and secure food, such as Europeans were accustomed to. After a voyage of several weeks, the Spanish caravels anchored in the harbor of the city founded by their countrymen, where they remained for two months.

Refreshed by their stay at Hispaniola, the Spaniards now cruised for some time among the numberless small islands north of Hayti, but the provisions which they had secured soon began to give out; they were reduced to six ounces of bread and three small measures of water a day for each man; and the ships began to leak again, in spite of all the caulking which had been done at Hispaniola. The leaders of the expedition, therefore, decided to capture some slaves for the purpose of selling to wealthy grandees in Spain, and to return home.

This harsh resolution was well carried out. Two hundred and thirty-two unfortunate natives were torn from their island home and their pleasant, indolent life, and were taken on board the ships. It was a dastardly thing to do, but men in these times were like the German invaders of Belgium in ours,—they were brutes. The prows of the four caravels were now turned towards[56] Spain, and, after an uneventful voyage, they arrived at their place of departure, June 8th., 1500, after an absence of about thirteen months. Of the fifty-seven men who had set out upon the expedition, two had been killed by the Indians, the rest returned home. Thirty-two of the slaves died upon the journey across the Atlantic, the rest were sold to the Spanish grandees.

Amerigo wrote freely of the journey to South America and his letters had a wide circulation, for he was the first newspaper correspondent: the forerunner of the modern Richard Harding Davis-es and Frank G. Carpenters. By means of these epistles he gained a wide celebrity and his name became more closely connected with the New World than that of Columbus. Such being the case, it is no wonder that people began to call these new possessions after the man who wrote so graphically of what he had seen there. Amerigo Vespucci told of a land which came to be known as the land of Americus, or America. It should really have been called Columbia, after Christopher Columbus, but Columbus did not happen to have the facility for writing interesting letters.

Amerigo, greatly pleased with what he had accomplished, was resting quietly at Seville, when an invitation came from the King of Portugal to have him visit him, and, when he arrived at Lisbon, the King had much to say to him.

“Would he undertake another expedition to the new world under the Portuguese banner?” Yes, he would.

No sooner said than done. On May 13th, 1501, Vespucci left on another journey with three armed caravels.[57] They ran south, touched at the Canary Islands, and then, through fierce and violent tempests, plowed towards the coast of South America. This they reached at length, and, coasting southward, frequently landed on the shore, where they had intercourse with the natives, most of whom were cannibals.