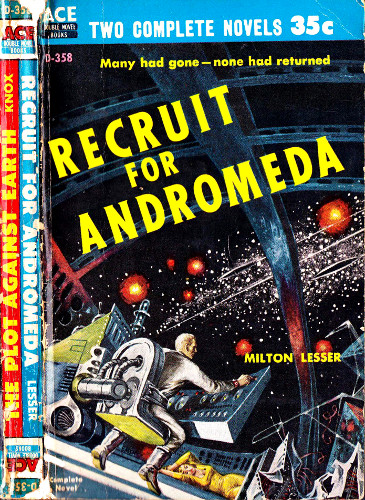

by MILTON LESSER

ACE BOOKS, INC.

23 West 47th Street, New York 36, N. Y.

RECRUIT FOR ANDROMEDA

Copyright 1959, by Ace Books, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in U.S.A.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any evidence

that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

TOURNAMENT UNDER NIGHTMARE SKIES

When Kit Temple was drafted for the Nowhere Journey, he figured that he'd left his home, his girl, and the Earth for good. For though those called were always promised "rotation," not a man had ever returned from that mysterious flight into the unknown.

Kit's fellow-draftee Arkalion, the young man with the strange, old-man eyes, seemed to know more than he should. So when Kit twisted the tail of fate and followed Arkalion to the ends of space and time, he found the secret behind "Nowhere" and a personal challenge upon which the entire future of Earth depended.

Contents

| CHAPTER I |

| CHAPTER II |

| CHAPTER III |

| CHAPTER IV |

| CHAPTER V |

| CHAPTER VI |

| CHAPTER VII |

| CHAPTER VIII |

| CHAPTER IX |

| CHAPTER X |

When the first strong sunlight of May covered the tree-arched avenues of Center City with green, the riots started.

The people gathered in angry knots outside the city hall, met in the park and littered its walks with newspapers and magazines as they gobbled up editorial comment at a furious rate, slipped with dark of night through back alleys and planned things with furious futility. Center City's finest knew when to make themselves scarce: their uniforms stood for everything objectionable at this time and they might be subjected to clubs, stones, taunts, threats, leers—and knives.

But Center City, like most communities in United North America, had survived the Riots before and would survive them again. On past performances, the damage could be estimated, too. Two-hundred fifty-seven plate glass windows would be broken, three-hundred twelve limbs fractured. Several thousand people would be treated for minor bruises and abrasions, Center City would receive half that many damage suits. The list had been drawn clearly and accurately; it hardly ever deviated.

And Center City would meet its quota. With a demonstration of reluctance, of course. The healthy approved way to get over social trauma once every seven-hundred eighty days.

"Shut it off, Kit. Kit, please."

The telio blared in a cheaply feminine voice, "Oh, it's a long way to nowhere, forever. And your honey's not coming back, never, never, never...." A wailing trumpet represented flight.

"They'll exploit anything, Kit."

"It's just a song."

"Turn it off, please."

Christopher Temple turned off the telio, smiling. "They'll announce the names in ten minutes," he said, and felt the corners of his mouth draw taut.

"Tell me again, Kit," Stephanie pleaded. "How old are you?"

"You know I'm twenty-six."

"Twenty-six. Yes, twenty-six, so if they don't call you this time, you'll be safe. Safe, I can hardly believe it."

"Nine minutes," said Temple in the darkness. Stephanie had drawn the blinds earlier, had dialed for sound-proofing. The screaming in the streets came to them as not the faintest whisper. But the song which became briefly, masochistically popular every two years and two months had spoiled their feeling of seclusion.

"Tell me again, Kit."

"What."

"You know what."

He let her come to him, let her hug him fiercely and whimper against his chest. He remained passive although it hurt, occasionally stroking her hair. He could not assert himself for another—he looked at his strap chrono—for another eight minutes. He might regret it, if he did, for a lifetime.

"Tell me, Kit."

"I'll marry you, Steffy. In eight minutes, less than eight minutes, I'll go down and get the license. We'll marry as soon as it's legal."

"This is the last time they have a chance for you. I mean, they won't change the law?"

Temple shook his head. "They don't have to. They meet their quota this way."

"I'm scared."

"You and everyone else in North America, Steffy."

She was trembling against him. "It's cold for June."

"It's warm in here." He kissed her moist eyes, her nose, her lips.

"Oh God, Kit. Five minutes."

"Five minutes to freedom," he said jauntily. He did not feel that way at all. Apprehension clutched at his chest with tight, painful fingers, almost making it difficult for him to breathe.

"Turn it on, Kit."

He dialed the telio in time to see the announcer's insincere smile. Smile seventeen, Kit thought wryly. Patriotic sacrifice.

"Every seven-hundred eighty days," said the announcer, "two-hundred of Center City's young men are selected to serve their country for an indeterminate period regulated rigidly by a rotation system."

"Liar!" Stephanie cried. "No one ever comes back. It's been thirty years since the first group and not one of them...."

"Shh," Temple raised a finger to his lips.

"This is the thirteenth call since the inception of what is popularly referred to as the Nowhere Journey," said the announcer. "Obviously, the two hundred young men from Center City and the thousands from all over this hemisphere do not in reality embark on a Journey to Nowhere. That is quite meaningless."

"Hooray for him," Temple laughed.

"I wish he'd get on with it."

"No, ladies and gentlemen, we use the word Nowhere merely because we are not aware of the ultimate destination. Security reasons make it impossible to...."

"Yes, yes," said Stephanie impatiently. "Go on."

"... therefore, the Nowhere Journey. With a maximum security lid on the whole project, we don't even know why our men are sent, or by what means. We know only that they go somewhere and not nowhere, bravely and not fearfully, for a purpose vital to the security of this nation and not to slake the thirst of a chessman of regiments and divisions.

"If Center City's contribution helps keep our country strong, Center City is naturally obligated...."

"No one ever said it isn't our duty," Stephanie argued, as if the announcer could indeed hear her. "We only wish we knew something about it—and we wish it weren't forever."

"It isn't forever," Temple reminded her. "Not officially."

"Officially, my foot. If they never return, they never return. If there's a rotation system on paper, but it's never used, that's not a rotation system at all. Kit, it's forever."

"... to thank the following sponsors for relinquishing their time...."

"No one would want to sponsor that," Temple whispered cheerfully.

"Kit," said Stephanie, "I—I suddenly have a hunch we have nothing to worry about. They missed you all along and they'll miss you this time, too. The last time, and then you'll be too old. That's funny, too old at twenty-six. But we'll be free, Kit. Free."

"He's starting," Temple told her.

A large drum filled the entire telio screen. It rotated slowly from bottom to top. In twenty seconds, the letter A appeared, followed by about a dozen names. Abercrombie, Harold. Abner, Eugene. Adams, Gerald. Sorrow in the Abercrombie household. Despair for the Abners. Black horror for Adams.

The drum rotated.

"They're up to F, Kit."

Fabian, Gregory G....

Names circled the drum slowly, live viscous alphabet soup. Meaningless, unless you happened to know them.

"Kit, I knew Thomas Mulvany."

N, O, P....

"It's hot in here."

"I thought you were cold."

"I'm suffocating now."

R, S....

"T!" Stephanie shrieked as the names began to float slowly up from the bottom of the drum.

Tabor, Tebbets, Teddley....

Temple's mouth felt dry as a ball of cotton. Stephanie laughed nervously. Now—or never. Never?

Now.

Stephanie whimpered despairingly.

TEMPLE, CHRISTOPHER.

"Sorry I'm late, Mr. Jones."

"Hardly, Mr. Smith. Hardly. Three minutes late."

"I've come in response to your ad."

"I know. You look old."

"I am over twenty-six. Do you mind?"

"Not if you don't, Mr. Smith. Let me look at you. Umm, you seem the right height, the right build."

"I meet the specifications exactly."

"Good, Mr. Smith. And your price."

"No haggling," said Smith. "I have a price which must be met."

"Your price, Mr. Smith?"

"Ten million dollars."

The man called Jones coughed nervously. "That's high."

"Very. Take it or leave it."

"In cash?"

"Definitely. Small unmarked bills."

"You'd need a moving van!"

"Then I'll get one."

"Ten million dollars," said Jones, "is quite a price. Admittedly, I haven't dealt in this sort of traffic before, but—"

"But nothing. Were your name Jones, really and truly Jones, I might ask less."

"Sir?"

"You are Jones exactly as much as I am Smith."

"Sir?" Jones gasped again.

Smith coughed discreetly. "But I have one advantage. I know you. You don't know me, Mr. Arkalion."

"Eh? Eh?"

"Arkalion. The North American Carpet King. Right?"

"How did you know?" the man whose name was not Jones but Arkalion asked the man whose name was not Smith but might as well have been.

"When I saw your ad," said not-Smith, "I said to myself, 'now here must be a very rich, influential man.' It only remained for me to study a series of photographs readily obtainable—I have a fine memory for that, Mr. Arkalion—and here you are; here is Arkalion the Carpet King."

"What will you do with the ten million dollars?" demanded Arkalion, not minding the loss nearly so much as the ultimate disposition of his fortune.

"Why, what does anyone do with ten million dollars? Treasure it. Invest it. Spend it."

"I mean, what will you do with it if you are going in place of my—" Arkalion bit his tongue.

"Your son, were you saying, Mr. Arkalion? Alaric Arkalion the Third. Did you know that I was able to boil my list of men down to thirty when I studied their family ties?"

"Brilliant, Mr. Smith. Alaric is so young—"

"Aren't they all? Twenty-one to twenty-six. Who was it who once said something about the flower of our young manhood?"

"Shakespeare?" said Mr. Arkalion realizing that most quotes of lasting importance came from the bard.

"Sophocles," said Smith. "But no matter. I will take young Alaric's place for ten million dollars."

Motives always troubled Mr. Arkalion, and thus he pursued what might have been a dangerous conversation. "You'll never get a chance to spend it on the Nowhere Journey."

"Let me worry about that."

"No one ever returns."

"My worry, not yours."

"It is forever—as if you dropped out of existence. Alaric is so young."

"I have always gambled, Mr. Arkalion. If I do not return in five years, you are to put the money in a trust fund for certain designated individuals, said fund to be terminated the moment I return. If I come back within the five years, you are merely to give the money over to me. Is that clear?"

"Yes."

"I'll want it in writing, of course."

"Of course. A plastic surgeon is due here in about ten minutes, Mr. Smith, and we can get on with.... But if I don't know your name, how can I put it in writing?"

Smith smiled. "I changed my name to Smith for the occasion. Perfectly legal. My name is John X. Smith—now!"

"That's where you're wrong," said Mr. Arkalion as the plastic surgeon entered. "Your name is Alaric Arkalion III—now."

The plastic surgeon skittered around Smith, examining him minutely with the casual expertness that comes with experience.

"Have to shorten the cheek bones."

"For ten million dollars," said Smith, "you can take the damned things out altogether and hang them on your wall."

Sophia Androvna Petrovitch made her way downtown through the bustle of tired workers and the occasional sprinkling of Comrades. She crushed her ersatz cigarette underfoot at number 616 Stalin Avenue, paused for the space of five heartbeats at the door, went inside.

"What do you want?" The man at the desk was myopic but bull-necked.

Sophia showed her party card.

"Oh, Comrade. Still, you are a woman."

"You're terribly observant, Comrade," said Sophia coldly. "I am here to volunteer."

"But a woman."

"There is nothing in the law which says a woman cannot volunteer."

"We don't make women volunteer."

"I mean really volunteer, of her own free will."

"Her—own—free will?" The bull-necked man removed his spectacles, scratched his balding head with the ear-pieces. "You mean volunteer without—"

"Without coercion. I want to volunteer. I am here to volunteer. I want to sign on for the next Stalintrek."

"Stalintrek, a woman?"

"That is what I said."

"We don't force women to volunteer." The man scratched some more.

"Oh, really," said Sophia. "This is 1992, not mid-century, Comrade. Did not Stalin say, 'Woman was created to share the glorious destiny of Mother Russia with her mate?'" Sophia created the quote randomly.

"Yes, if Stalin said—"

"He did."

"Still, I do not recall—"

"What?" Sophia cried. "Stalin dead these thirty-nine years and you don't recall his speeches? What is your name, Comrade?"

"Please, Comrade. Now that you remind me, I remember."

"What is your name."

"Here, I will give you the volunteer papers to sign. If you pass the exams, you will embark on the next Stalintrek, though why a beautiful young woman like you—"

"Shut your mouth and hand me those papers."

There, sitting behind that desk, was precisely why. Why should she, Sophia Androvna Petrovitch, wish to volunteer for the Stalintrek? Better to ask why a bird flies south in the winter, one day ahead of the first icy gale. Or why a lemming plunges recklessly into the sea with his multitudes of fellows, if, indeed, the venture were to turn out grimly.

But there, behind that desk, was part of the reason. The Comrade. The bright sharp Comrade, with his depth of reasoning, his fountain of gushing emotions, his worldliness. Pfooey!

It was as if she had been in a cocoon all her life, stifled, starved, the cottony inner lining choking her whenever she opened her mouth, the leathery outer covering restricting her when she tried to move. No one had ever returned from the Stalintrek. She then had to assume no one would. Including Sophia Androvna Petrovitch. But then, there was nothing she would miss, nothing to which she particularly wanted to return. Not the stark, foul streets of Stalingrad, not the workers with their vapid faces or the Comrades with their cautious, sweating, trembling, fearful non-decisions, not the higher echelon of Comrades, more frightened but showing it less, who would love the beauty of her breasts and loins but not herself for you never love anything but the Stalinimage and Mother Russia herself, not those terrified martinet-marionettes who would love the parts of her if she permitted but not her or any other person for that matter.

Wrong with the Stalintrek was its name alone, a name one associated with everything else in Russia for an obvious, post-Stalin reason. But everything else about the Stalintrek shrieked mystery and adventure. Where did you go? How did you get there? What did you do? Why?

A million questions which had kept her awake at night and, if she thought about them hard enough, satisfied her deep longing for something different. And then one day when stolid Mrs. Ivanovna-Rasnikov had said, "It is a joke, a terrible, terrible joke they are taking my husband Fyodor on the Stalintrek when he lacks sufficient imagination to go from here to Leningrad or even Tula. Can you picture Fyodor on the Stalintrek? Better they should have taken me. Better they should have taken his wife." That day Sophia could hardly contain herself.

As a party member she had access to the law and she read it three times from start to finish (in her dingy flat by the light of a smoking, foul-smelling, soft-wax candle) but could find nothing barring women from the Stalintrek.

Had Fyodor Rasnikov volunteered? Naturally. Everyone volunteered, although when your name was called you had no choice. There had been no draft in Russia since the days of the Second War of the People's Liberation. Volunteer? What, precisely, did the word mean?

She, Sophia Androvna Petrovitch would volunteer, without being told. Thus it was she found herself at 616 Stalin Avenue, and thus the balding, myopic, bull-necked Comrade thrust the papers across his desk at her.

She signed her name with such vehemence and ferocity that she almost tore through the paper.

Three-score men sit in the crowded, smoke-filled room. Some drink beer, some squat in moody silence, some talk in an animated fashion about nothing very urgent. At the one small door, two guards pace back and forth slowly, creating a gentle swaying of smoke-patterns in the hazy room. The guards, in simple military uniform, carry small, deadly looking weapons.

FIRST MAN: Fight City Hall? Are you kidding? They took you, bud. Don't try to fight it, I know. I know.

SECOND MAN: I'm telling you, there was a mistake in the records. I'm over twenty-six. Two weeks and two days. Already I wrote to my Congressman. Hell, that's why I voted for him, he better go to bat for me.

THIRD MAN: You think that's something? I wouldn't be here only those doctors are crazy. I mean, crazy. Me, with a cyst big as a golf ball on the base of my spine.

FIRST MAN: You too. Don't try to fight it.

FOURTH MAN: (Newly named Alaric Arkalion III) I look forward to this as a stimulating adventure. Does the fact that they select men for the Nowhere Journey once every seven hundred and eighty days strike anyone as significant?

SECOND MAN: I got my own problems.

ALARIC ARKALION: This is not a thalamic problem, young man. Not thalamic at all.

THIRD MAN: Young man? Who are you kidding?

ALARIC ARKALION: (Who realizes, thanks to the plastic surgeon, he is the youngest looking of all, with red cheeks and peachfuzz whiskers) It is a problem of the intellect. Why seven hundred and eighty days?

FIRST MAN: I read the magazine, too, chief. You think we're all going to the planet Mars. How original.

ALARIC ARKALION: As a matter of fact, that is exactly what I think.

SECOND MAN: Mars?

FIRST MAN: (Laughing) It's a long way from Mars to City Hall, doc.

SECOND MAN: You mean, through space to Mars?

ALARIC ARKALION: Exactly, exactly. Quite a coincidence, otherwise.

FIRST MAN: You're telling me.

ALARIC ARKALION: (Coldly) Would you care to explain it?

FIRST MAN: Why, sure. You see, Mars is—uh, I don't want to steal your thunder, chief. Go ahead.

ALARIC ARKALION: Once every seven hundred and eighty days Mars and the Earth find themselves in the same orbital position with respect to the sun. In other words, Mars and Earth are closest then. Were there such a thing as space travel, new, costly, not thoroughly tested, they would want to make each journey as brief as possible. Hence the seven hundred and eighty days.

FIRST MAN: Not bad, chief. You got most of it.

THIRD MAN: No one ever said anything about space travel.

FIRST MAN: You think we'd broadcast it or something, stupid? It's part of a big, important scientific experiment, only we're the hamsters.

ALARIC ARKALION: Ridiculous. You're forgetting all about the Cold War.

FIRST MAN: He thinks we're fighting a war with the Martians. (Laughs) Orson Wells stuff, huh?

ALARIC ARKALION: With the Russians. The Russians. We developed A bombs. They developed A bombs. We came up with the H bomb. So did they. We placed a station up in space, a fifth of the way to the moon. So did they. Then—nothing more about scientific developments. For over twenty years. I ask you, doesn't it seem peculiar?

FIRST MAN: Peculiar, he says.

ALARIC ARKALION: Peculiar.

SECOND MAN: I wish my Congressman....

FIRST MAN: You and your Congressman. The way you talk, it was your vote got him in office.

SECOND MAN: If only I could get out and talk to him.

ALARIC ARKALION: No one is permitted to leave.

FIRST MAN: Punishable by a prison term, the law says.

SECOND MAN: Oh yeah? Prison, shmision. Or else go on the Nowhere Journey. Well, I don't see the difference.

FIRST MAN: So, go ahead. Try to escape.

SECOND MAN: (Looking at the guards) They got them all over. All over. I think our mail is censored.

ALARIC ARKALION: It is.

SECOND MAN: They better watch out. I'm losing my temper. I get violent when I lose my temper.

FIRST MAN: See? See how the guards are trembling.

SECOND MAN: Very funny. Maybe you didn't have a good job or something? Maybe you don't care. I care. I had a job with a future. Didn't pay much, but a real blue chip future. So they send me to Nowhere.

FIRST MAN: You're not there yet.

SECOND MAN: Yeah, but I'm going.

THIRD MAN: If only they let you know when. My back is killing me. I'm waiting to pull a sick act. Just waiting, that's all.

FIRST MAN: Go ahead and wait, a lot of good it will do you.

THIRD MAN: You mind your own business.

FIRST MAN: I am, doc. You brought the whole thing up.

SECOND MAN: He's looking for trouble.

THIRD MAN: He'll get it.

ALARIC ARKALION: We're going to be together a long time. A long time. Why don't you all relax?

SECOND MAN: You mind your own business.

FIRST MAN: Nuts, aren't they. They're nuts. A sick act, yet.

SECOND MAN: Look how it doesn't bother him. A failure, he was. I can just see it. What does he care if he goes away forever and doesn't come back? One bread line is as good as another.

FIRST MAN: Ha-ha.

SECOND MAN: Yeah, well I mean it. Forever. We're going away, someplace—forever. We're not coming back, ever. No one comes back. It's for good, for keeps.

FIRST MAN: Tell it to your congressman. Or maybe you want to pull a sick act, too?

THIRD MAN: (Hits First Man, who, surprised, crashes back against a table and falls down) It isn't an act, damn you!

GUARD: All right, break it up. Come on, break it up....

ALARIC ARKALION: (To himself) I wish I saw that ten million dollars already—if I ever get to see it.

They drove for hours through the fresh country air, feeling the wind against their faces, listening to the roar their ground-jet made, all alone on the rimrock highway.

"Where are we going, Kit?"

"Search me. Just driving."

"I'm glad they let you come out this once. I don't know what they would have done to me if they didn't. I had to see you this once. I—"

Temple smiled. He had absented himself without leave. It had been difficult enough and he might yet be in a lot of hot water, but it would be senseless to worry Stephanie. "It's just for a few hours," he said.

"Hours. When we want a whole lifetime. Kit. Oh, Kit—why don't we run away? Just the two of us, someplace where they'll never find you. I could be packed and ready and—"

"Don't talk like that. We can't."

"You want to go where they're sending you. You want to go."

"For God's sake, how can you talk like that? I don't want to go anyplace, except with you. But we can't run away, Steffy. I've got to face it, whatever it is."

"No you don't. It's noble to be patriotic, sure. It always was. But this is different, Kit. They don't ask for part of your life. Not for two years, or three, or a gamble because maybe you won't ever come back. They ask for all of you, for the rest of your life, forever, and they don't even tell you why. Kit, don't go! We'll hide someplace and get married and—"

"And nothing." Temple stopped the ground-jet, climbed out, opened the door for Stephanie. "Don't you see? There's no place to hide. Wherever you go, they'd look. You wouldn't want to spend the rest of your life running, Steffy. Not with me or anyone else."

"I would. I would!"

"Know what would happen after a few years? We'd hate each other. You'd look at me and say 'I wouldn't be hiding like this, except for you. I'm young and—'"

"Kit, that's cruel! I would not."

"Yes, you would. Steffy, I—" A lump rose in his throat. He'd tell her goodbye, permanently. He had to do it that way, did not want her to wait endlessly and hopelessly for a return that would not materialize. "I didn't get permission to leave, Steffy." He hadn't meant to tell her that, but suddenly it seemed an easy way to break into goodbye.

"What do you mean? No—you didn't...."

"I had to see you. What can they do, send me for longer than forever?"

"Then you do want to run away with me!"

"Steffy, no. When I leave you tonight, Steffy, it's for good. That's it. The last of Kit Temple. Stop thinking about me. I don't exist. I—never was." It sounded ridiculous, even to him.

"Kit, I love you. I love you. How can I forget you?"

"It's happened before. It will happen again." That hurt, too. He was talking about a couple of statistics, not about himself and Stephanie.

"We're different, Kit. I'll love you forever. And—Kit ... I know you'll come back to me. I'll wait, Kit. We're different. You'll come back."

"How many people do you think said that before?"

"You don't want to come back, even if you could. You're not thinking of us at all. You're thinking of your brother."

"You know that isn't true. Sometimes I wonder about Jase, sure. But if I thought there was a chance to return—I'm a selfish cuss, Steffy. If I thought there was a chance, you know I'd want you all for myself. I'd brand you, and that's the truth."

"You do love me!"

"I loved you, Steffy. Kit Temple loved you."

"Loved?"

"Loved. Past tense. When I leave tonight, it's as if I don't exist anymore. As if I never existed. It's got to be that way, Steffy. In thirty years, no one ever returned."

"Including your brother, Jase. So now you want to find him. What do I count for? What...."

"This going wasn't my idea. I wanted to stay with you. I wanted to marry you. I can't now. None of it. Forget me, Steffy. Forget you ever knew me. Jase said that to our folks before he was taken." Almost five years before Jason Temple had been selected for the Nowhere Journey. He'd been young, though older than his brother Kit. Young, unattached, almost cheerful he was. Naturally, they never saw him again.

"Hold me, Kit. I'm sorry ... carrying on like this."

They had walked some distance from the ground-jet, through scrub oak and bramble bushes. They found a clearing, fragrant-scented, soft-floored still from last autumn, melodic with the chirping of nameless birds. They sat, not talking. Stephanie wore a gay summer dress, full-skirted, cut deep beneath the throat. She swayed toward him from the waist, nestled her head on his shoulder. He could smell the soft, sweet fragrance of her hair, of the skin at the nape of her neck. "If you want to say goodbye ..." she said.

"Stop it," he told her.

"If you want to say goodbye...."

Her head rolled against his chest. She turned, cradled herself in his arms, smiled up at him, squirmed some more and had her head pillowed on his lap. She smiled tremulously, misty-eyed. Her lips parted.

He bent and kissed her, knowing it was all wrong. This was not goodbye, not the way he wanted it. Quickly, definitely, for once and all. With a tear, perhaps, a lot of tears. But permanent goodbye. This was all wrong. The whole idea was to be business-like, objective. It had to be done that way, or no way at all. Briefly, he regretted leaving the encampment.

This wasn't goodbye the way he wanted it. The way it had to be. This was auf weidersen.

And then he forgot everything but Stephanie....

"I am Alaric Arkalion III," said the extremely young-looking man with the old, wise eyes.

How incongruous, Temple thought. The eyes look almost middle-aged. The rest of him—a boy.

"Something tells me we'll be seeing a lot of each other," Arkalion went on. The voice was that of an older man, too, belying the youthful complexion, the almost childish features, the soft fuzz of a beard.

"I'm Kit Temple," said Temple, extending his hand. "Arkalion, a strange name. I know it from somewhere.... Say! Aren't you—don't you have something to do with carpets or something?"

"Here and now, no. I am a number. A-92-6417. But my father is—perhaps I had better say was—my father is Alaric Arkalion II. Yes, that is right, the carpet king."

"I'll be darned," said Temple.

"Why?"

"Well," Temple laughed. "I never met a billionaire before."

"Here I am not a billionaire, nor will I ever be one again. A-92-6417, a number. On his way to Mars with a bunch of other numbers."

"Mars? You sound sure of yourself."

"Reasonably. Ah, it is a pleasure to talk with a gentleman. I am reasonably certain it will be Mars."

Temple nodded in agreement. "That's what the Sunday supplements say, all right."

"And doubtless you have observed no one denies it."

"But what on Earth do we want on Mars?"

"That in itself is a contradiction," laughed Arkalion. "We'll find out, though, Temple."

They had reached the head of the line, found themselves entering a huge, double-decker jet-transport. They found two seats together, followed the instructions printed at the head of the aisle by strapping themselves in and not smoking. Talking all around them was subdued.

"Contrariness has given way to fear," Arkalion observed. "You should have seen them the last few days, waiting around the induction center, a two-ton chip on each shoulder. Say, where were you?"

"I—what do you mean?"

"I didn't see you until last evening. Suddenly, you were here."

"Did anyone else miss me?"

"But I remember you the first day."

"Did anyone else miss me? Any of the officials?"

"No. Not that I know of."

"Then I was here," Temple said, very seriously.

Arkalion smiled. "By George, of course. Then you were here. Temple, we'll get along fine."

Temple said that was swell.

"Anyway, we'd better. Forever is a long time."

Three minutes later, the jet took off and soared on eager wings toward the setting sun.

"Men, since we are leaving here in a few hours and since there is no way to get out of the encampment and no place to go over the desert even if you could," the microphone in the great, empty hall boomed as the two files of men marched in, "there is no harm in telling you where you are. From this point, in a limited sense, you shall be kept abreast of your progress.

"We are in White Sands, New Mexico."

"The Garden Spot of the Universe!" someone shouted derisively, remembering the bleak hot desert and jagged mountain peaks as they came down.

"White Sands," muttered Arkalion. "It looks like space travel now, doesn't it, Kit."

Temple shrugged. "Why?"

"White Sands was the center of experiments in rocketry decades ago, when people still talked about those things. Then, for a long time, no one heard anything about White Sands. The rockets grew here, Kit."

"I can readily see why. You could look all your life without finding a barren spot like this."

"Precisely. Someone once called this place—or was it some other place like it?—someone once called it a good place to throw old razor blades. If people still used razor blades."

The microphone blared again, after the several hundred men had entered the great hall and milled about among the echoes. Temple could picture other halls like this, other briefings. "Men, whenever you are given instructions, in here or elsewhere, obey them instantly. Our job is a big one, complicated and exacting. Attention to detail will save us trouble."

Someone said, "My old man served a hitch in the army, back in the sixties. That's what he always said, attention to details. The army is crazy about things like that. Are we in the army or something?"

"This is not the army, but the function is similar," barked the microphone. "Do as you are told and you will get along."

Stirrings in the crowd. Mutterings. Temple gaped. Microphone, yes—but receivers also, placed strategically, all around the hall, to pick up sound. Telio receivers too, perhaps? It made him feel something like a goldfish.

Apparently someone liked the idea of the two-way microphones. "I got a question. When are we coming back?"

Laughter. Hooting. Catcalls.

Blared the microphone: "There is a rotation system in operation, men. When it is feasible, men will be rotated."

"Yeah, in thirty years it ain't been whatsiz—feasible—once!"

"That, unfortunately, is correct. When the situation permits, we will rotate you home."

"From where? Where are we going?"

"At least tell us that."

"Where?"

"How about that?"

There was a pause, then the microphone barked: "I don't know the answer to that question. You won't believe me, but it is the truth. No one knows where you are going. No one. Except the people who are already there."

More catcalls.

"That doesn't make sense," Arkalion whispered. "If it's space travel, the pilots would know, wouldn't they?"

"Automatic?" Temple suggested.

"I doubt it. Space travel must still be new, even if it has thirty years under its belt. If that man speaks the truth—if no one knows ... just where in the universe are we going?"

"Hey, looka me. I'm flying!"

"Will you get your big fat feet out of my face?"

"Sure. Show me how to swim away through air, I'll be glad to."

"Leggo that spoon!"

"I ain't got your spoon."

"Will you look at it float away. Hey spoon, hey!"

"Watch this, Charlie. This will get you. I mean, get you."

"What are you gonna do?"

"Relax, chum."

"Leggo my leg. Help! I'm up in the air. Stop that."

"I said relax. There. Ha-ha, lookit him spin, just like a top. All you got to do is get him started and he spins like a top with arms and legs. Top of the morning to you, Charlie. Ha-ha. I said, top of the...."

"Someone stop me, I'm getting dizzy."

They floated, tumbled, spun around the spaceship's lounge room in simple, childish glee. They cavorted in festive weightlessness.

"They're happy now," Arkalion observed. "The novelty of free fall, of weighing exactly nothing, strikes them as amusing."

"I think I'm getting the hang of it," said Temple. Clumsily, he made a few tentative swimming motions in the air, propelling himself forward a few yards before he lost his balance and tumbled head over heels against the wall.

Arkalion came to him quickly, in a combination of swimming and pushing with hands and feet against the wall. Arkalion righted him expertly, sat down gingerly beside him. "If you keep sudden motions to a minimum, you'll get along fine. More than anything else, that's the secret of it."

Temple nodded. "It's sort of like the first time you're on ice skates. Say, how come you're so good at it?"

"I used to read the old, theoretical books on space-travel." The words poured out effortlessly, smoothly. "I'm merely applying the theories put forward as early as the 1950's."

"Oh." But it left Temple with some food for thought. Alaric Arkalion was a queer duck, anyway, and of all the men gathered in the spaceship's lounge, he alone had mastered weightlessness with hardly any trouble.

"Take your ice skates," Arkalion went on. "Some people put them on and use them like natural extensions of their feet the first time. Others fall all over themselves. I suppose I am lucky."

"Sure," said Temple. Actually, the only thing odd about Arkalion was his old-young face and—perhaps—his propensity for coming up with the right answers at the right times. Arkalion had seemed so certain of space-travel. He'd hardly batted an eyelash when they boarded a long, tapering bullet-shaped ship at White Sands and thundered off into the sky. He took for granted the change-over to a huge round ship at the wheel-shaped station in space. Moments after leaving the space station—with a minimum of stress and strain, thanks to the almost-nil gravity—it was Arkalion who first swam through air to the viewport and pointed out the huge crescent earth, green and gray and brown, sparkling with patches of dazzling silver-white. "You will observe it is a crescent," Arkalion had said. "It is closer to the sun than we are, and off at an angle. As I suspected, our destination is Mars."

Then everyone was saying goodbye to earth. Fantastic, it seemed. There were tears, there was laughter, cursing, promises of return, awkward verbal comparisons with the crescent moon, vows of faithfulness to lovers and sweethearts. And there was Arkalion, with an avid expression in the old eyes, Arkalion with his boyish face, not saying goodbye so much as he was calling hello to something Temple could not fathom.

Now, as he struggled awkwardly with weightlessness, Temple called it his imagination. His thought-patterns shifted vaguely, without motivation, from the gleaming, polished interior of the ship with its smell of antiseptic and metal polish to the clear Spring air of Earth, blue of sky and bright of sun. The unique blue sky of Earth which he somehow knew could not be duplicated elsewhere. Elsewhere—the word itself bordered on the meaningless.

And Stephanie. The brief warm ecstasy of her—once, forever. He wondered with surprising objectivity if a hundred other names, a hundred other women were not in a hundred other minds while everyone stared at the crescent Earth hanging serenely in space—with each name and each woman as dear as Stephanie, with the same combination of fire and gentle femininity stirring the blood but saddening the heart. Would Stephanie really forget him? Did he want her to? That part of him burned by the fire of her said no—no, she must not forget him. She was his, his alone, roped and branded though a universe separated them. But someplace in his heart was the thought, the understanding, the realization that although Stephanie might keep a small place for him tucked someplace deep in her emotions, she must forget. He was gone—permanently. For Stephanie, he was dead. It was as he had told her that last stolen day. It was ... Stephanie, Stephanie, how much I love you....

Struggling with weightlessness, he made his way back to the small room he shared with Arkalion. Hardly more than a cubicle, it was, with sufficient room for two beds, a sink, a small chest. He lay down and slept, murmuring Stephanie's name in his sleep.

He awoke to the faint hum of the air-pumps, got up feeling rested, forgot his weightlessness and floated to the ceiling where only an outthrust arm prevented a nasty bump on his head. He used hand grips on the wall to let himself down. He washed, aware of no way to prevent the water he splashed on his face from forming fine droplets and spraying the entire room. When he crossed back to the foot of his bed to get his towel he thrust one foot out too rapidly, lost his balance, half-rose, stumbled and fell against the other bed which, like all other items of furniture, was fastened to the floor. But his elbow struck sleeping Arkalion's jaw sharply, hard enough to jar the man's teeth.

"I'm sorry," said Temple. "Didn't mean to do that," he apologized again, feeling embarrassed.

Arkalion merely lay there.

"I said I'm sorry."

Arkalion still slept. It seemed inconceivable, for Temple's elbow pained him considerably. He bent down, examined his inert companion.

Arkalion stirred not a muscle.

Vaguely alarmed, Temple thrust a hand to Arkalion's chest, felt nothing. He crouched, rested the side of his head over Arkalion's heart. He listened, heard—nothing.

What was going on here?

"Hey, Arkalion!" Temple shook him, gently at first, then with savage force. Weightless, Arkalion's body floated up off the bed, taking the covers with it. His own heart pounding furiously, Temple got it down again, fingered the left wrist and swallowed nervously.

Temple had never seen a dead man before. Arkalion's heart did not beat. Arkalion had no pulse.

Arkalion was dead.

Yelling hoarsely, Temple plunged from the room, soaring off the floor in his haste and striking his head against the ceiling hard enough to make him see stars. "This guy is dead!" he cried. "Arkalion is dead."

Men stirred in the companionway. Someone called for one of the armed guards who were constantly on patrol.

"If he's dead, you're yelling loud enough to get him out of his grave." The voice was quiet, amused.

Arkalion.

"What?" Temple blurted, whirling around and striking his head again. A little wild-eyed, he re-entered the room.

"Now, who is dead, Kit?" demanded Arkalion, sitting up and stretching comfortably.

"Who—is dead? Who—?" Open-mouthed, Temple stared.

A guard, completely at home with weightlessness, entered the cubicle briskly. "What's the trouble in here? Something about a dead man, they said."

"A dead man?" demanded Arkalion. "Indeed."

"Dead?" muttered Temple, lamely and foolishly. "Dead...."

Arkalion smiled deprecatingly. "My friend must have been talking in his sleep. The only thing dead in here is my appetite. Weightlessness doesn't let you become very hungry."

"You'll grow used to it," the guard promised. He patted his paunch happily. "I am. Well, don't raise the alarm unless there's some trouble. Remember about the boy who cried wolf."

"Of course," said Temple. "Sure. Sorry."

He watched the guard depart.

"Bad dream?" Arkalion wanted to know.

"Bad dream, my foot. I accidentally hit you. Hard enough to hurt. You didn't move."

"I'm a sound sleeper."

"I felt for your heart. It wasn't beating. It wasn't!"

"Oh, come, come."

"Your heart was not beating, I said."

"And I suppose I was cold as a slab of ice?"

"Umm, no. I don't remember. Maybe you were. You had no pulse, either."

Arkalion laughed easily. "And am I still dead?"

"Well—"

"Clearly a case of overwrought nerves and a highly keyed imagination. What you need is some more sleep."

"I'm not sleepy, thanks."

"Well, I think I'll get up and go down for breakfast." Arkalion climbed out of bed gingerly, made his way to the sink and was soon gargling with a bottle of prepared mouthwash, occasionally spraying weightless droplets of the pink liquid up at the ceiling.

Temple lit a cigarette with shaking fingers, made his way to Arkalion's bed while the man hummed tunelessly at the sink. Temple let his hands fall on the sheet. It was not cold, but comfortably cool. Hardly as warm as it should have been, with a man sleeping on it all night.

Was he still imagining things?

"I'm glad you didn't call for a burial detail and have me expelled into space with yesterday's garbage," Arkalion called over his shoulder jauntily as he went outside for some breakfast.

Temple cursed softly and lit another cigarette, dropping the first one into a disposal chute on the wall.

Every night thereafter, Temple made it a point to remain awake after Arkalion apparently had fallen asleep. But if he were seeking repetition of the peculiar occurrence, he was disappointed. Not only did Arkalion sleep soundly and through the night, but he snored. Loudly and clearly, a wheezing snore.

Arkalion's strange feat—or his own overwrought imagination, Temple thought wryly—was good for one thing: it took his mind off Stephanie. The days wore on in endless, monotonous routine. He took some books from the ship's library and browsed through them, even managing to find one concerned with traumatic catalepsy, which stated that a severe emotional shock might render one into a deep enough trance to have a layman mistakenly pronounce him dead. But what had been the severe emotional disturbance for Arkalion? Could the effects of weightlessness manifest themselves in that way in rare instances? Temple naturally did not know, but he resolved to find out if he could after reaching their destination.

One day—it was three weeks after they left the space station, Temple realized—they were all called to assembly in the ship's large main lounge. As the men drifted in, Temple was amazed to see the progress they had made with weightlessness. He himself had advanced to handy facility in locomotion, but it struck him all the more pointedly when he saw two hundred men swim and float through air, pushing themselves along by means of the hand-holds strategically placed along the walls.

The ever-present microphone greeted them all. "Good afternoon, men."

"Good afternoon, mac!"

"Hey, is this the way to Ebbetts' Field?"

"Get on with it!"

"Sounds like the same man who addressed us in White Sands," Temple told Arkalion. "He sure does get around."

"A recording, probably. Listen."

"Our destination, as you've probably read in newspapers and magazines, is the planet Mars."

Mutterings in the assembly, not many of surprise.

"Their suppositions, based both on the seven hundred eighty day lapse between Nowhere Journeys and the romantic position in which the planet Mars has always been held, are correct. We are going to Mars.

"For most of you, Mars will be a permanent home for many years to come—"

"Most of us?" Temple wondered out loud.

Arkalion raised a finger to his lips for silence.

"—until such time as you are rotated according to the policy of rotation set up by the government."

Temple had grown accustomed to the familiar hoots and catcalls. He almost had an urge to join in himself.

"Interesting," Arkalion pointed out. "Back at White Sands they claimed not to know our destination. They knew it all right—up to a point. The planet Mars. But now they say that all of us will not remain on Mars. Most interesting."

"—further indoctrination in our mission soon after our arrival on the red planet. Landing will be performed under somewhat less strain than the initial takeoff in the Earth-to-station ferry, since Mars exerts less of a gravity pull than Earth. On the other hand, you have been weightless for three weeks and the change-over is liable to make some of you sick. It will pass harmlessly enough.

"We realize it is difficult, being taken from your homes without knowing the nature of your urgent mission. All I can tell you now—and, as a matter of fact, all I know—"

"Here we go again," said Temple. "More riddles."

"—is that everything is of the utmost urgency. Our entire way of life is at stake. Our job will be to safeguard it. In the months which follow, few of you will have any big, significant role to play, but all of you, working together, will provide the strength we need. When the cadre—"

"So they call their guards teachers," Arkalion commented dryly.

"—come around, they will see that each man is strapped properly into his bunk for deceleration. Deceleration begins in twenty-seven minutes."

Mars, thought Temple, back in his room with Arkalion. Mars. He did not think of Stephanie, except as a man who knows he must spend the rest of his life in prison might think of a lush green field, or the cool swish of skis over fresh, powdery snow, or the sound of yardarms creaking against the wind on a small sailing schooner, or the tang of wieners roasting over an open fire with the crisp air of fall against your back, or the scent of good French brandy, or a woman.

Deceleration began promptly. Before his face was distorted and his eyes forced shut by a pressure of four gravities, Temple had time to see the look of complete unconcern on Arkalion's face. Arkalion, in fact, was sleeping.

He seemed as completely relaxed as he did that morning Temple thought he was dead.

"Petrovitch, S. A.!" called the Comrade standing abreast of the head of the line, a thin, nervous man half a head shorter than the girl herself. Sophia Androvna Petrovitch strode forward, took a pair of trim white shorts from the neat stack at his left.

"Is that all?" she said, looking at him.

"Yes, Comrade. Well, a woman. Well."

Without embarrassment, Sophia had seen the men ahead of her in line strip and climb into the white shorts before they disappeared through a portal ahead of the line, depositing their clothing in a growing pile on the floor. But now it was Sophia's turn, after almost a two hour wait. Not that it was chilly, but....

"Is that all?" she repeated.

"Certainly. Strip and move along, Comrade." The nervous little man appraised her lecherously, she thought.

"Then I must keep some of my own clothing," she told him.

"Impossible. I have my orders."

"I am a woman."

"You are a volunteer for the Stalintrek. You will take no personal property—no clothing—with you. Strip and advance, please."

Sophia flushed slightly, while the men behind her began to call and taunt.

"I like this Stalintrek."

"Oh, yes."

"We are waiting, Comrade."

Quickly and with an objective detachment which surprised her, Sophia unbuttoned her shirt, removed it. Her one wish—and an odd one, she thought, smiling—was for wax for her ears. She loosened the three snaps of her skirt, watched it fall to the floor. She stood there briefly, lithe-limbed, a tall, slim girl, then had the white shorts over her nakedness in one quick motion. She still wore a coarse halter.

"All personal effects, Comrade," said the nervous little man.

"No," Sophia told him.

"But yes. Definitely, yes. You hold up the line, and we have a schedule to maintain. The Stalintrek demands quick, prompt obedience."

"Then you will give me one additional item of clothing."

The man looked at Sophia's halter, at the fine way she filled it. He shrugged. "We don't have it," he said, clearly enjoying himself.

In volunteering for the Stalintrek, Sophia had invaded man's domain. She had watched not with embarrassment but with scorn while the men in front of her got out of their clothing. She had invaded man's domain, and as she watched them, the short flabby ones, the bony ones with protruding ribs and collar-bones, those of milky white skin and soft hands, she knew most of them would bite off more than they could chew if ever they tried what was the most natural thing for men to try with a lone woman in an isolated environment. But she was in a man's world now, and if that was the way they wanted it, she would ask no quarter.

She reached up quickly with one hand and unfastened the halter, catching it with her free hand and holding it in front of her breasts while the nervous little man licked his lips and gaped. Sophia grabbed another pair of the white shorts, tore it quickly with her strong fingers, fashioning a crude covering for herself. This she pulled around her, fastening it securely with a knot in back.

"You'll have to give that back to me," declared the nervous little Comrade.

"I'll bet you a samovar on that," Sophia said quietly, so only the man heard her.

He reached out, as if to rip the crude halter from her body, but Sophia met him halfway with her strong, slim fingers, wrapping them around his biceps and squeezing. The man's face turned quickly to white as he tried unsuccessfully to free his arm.

"Please, that hurts."

"I keep what I am wearing." She tightened her grip, but gazed serenely into space as the man stifled a whimper.

"Well—" the man whispered indecisively as he gritted his teeth.

"Fool!" said Sophia. "Your arm will be black and blue for a week. While you men grow soft and lazy, many of the women take their gymnastics seriously, especially if they want to keep their figures with the work they must do and the food they must eat. I am stronger than you and I will hurt you unless—" And her hand tightened around his scrawny arm until her knuckles showed white.

"Wear what you have and go," the man pleaded, and moaned softly when Sophia released his numb arm and strode through the portal, still drawing whistles and leers from the other men, who missed the by-play completely.

"So we're on Mars!"

"It ain't Nowhere after all, it's Mars."

"Wait and see, buster. Wait and see."

"Kind of cold, isn't it? Well, if this was Venus and some of them beautiful one-armed dames was waiting for us—"

"That's just a statue, stupid."

"Lookit all them people down there, will you?"

"You think they're Martians?"

"Stupid! We ain't the first ones went on the Nowhere Journey."

"What are we waiting for? It sure will feel good to stretch your legs."

"Let's go!"

"Look out, Mars, here I come!"

It would have been just right for a Hollywood epic, Temple thought. The rusty ochre emptiness spreading out toward the horizon in all directions, spotted occasionally with pale green and frosty white, the sky gray with but a shade of blue in it, distant gusts of Martian wind swirling ochre clouds across the desert, the spaceship poised on its ungainly bottom, a great silver bowling ball with rocket tubes for finger holes, and the Martians from Earth who had been here on this alien world for seven-hundred-eighty days or twice seven-eighty or three times, and who fought in frenzied eagerness, like savages, to reach the descending gangplank first.

Earth chorus: Hey, Martians, any of you guys speak English? Hah-ha, I said, any of you guys....

Where are all them canals I heard so much about?

You think maybe they're dangerous? (Laughter)

No dames. Hey, no dames....

Who were you expecting, Donna Daunley?

What kind of place is Mars with no women?

What do they do here, anyway, just sit around and wait for the next rocket?

I'm cold.

Get used to it, brother, get used to it.

Look out, Mars, here I come!

Martian chorus: Who won the Series last year, Detroit?

Hey, bud, tell me, are dames still wearing those one piece things, all colors, so you see their legs up to about here and their chests down to about here? (Gestures lewdly)

Which one of you guys can tell me what it's like to take a bath? I mean a real bath in a real bath tub.

Hey, we licked Russia yet?

We heard they were gonna send some dames!

Dames—ha-ha, you're breaking my heart.

Tell me what a steak tastes like. So thick.

Me? Gimme a bowl of steamed oysters. And a dame.

Dames. Girls. Women. Females. Chicks. Tomatoes. Frails. Dames. Dames. Dames....

They did not seem to mind the cold, these Earth-Martians. Temple guessed they never spent much time out of doors (above ground, for there were no buildings?) because all seemed pale and white. While the sun was weaker, so was the protection offered by a thinner atmosphere. The sun's actinic rays could burn, and so could the sand-driving wind. But pale skins could not be the result of staying indoors, for Temple noted the lack of man-made structures at once. Underground, then. The Earth-Martians lived underground like moles. Doing what? And for what reason? With what ultimate goal, if any? And where did those men who did not remain on Mars go? Temple's head whirled with countless questions—and no answers.

Shoulder to shoulder with Arkalion, he made his way down the gangplank, turning up the collar of his jumper against the stinging wind.

"You got any newspapers, pal?"

"Magazines?"

"Phonograph records?"

"Gossip?"

"Newsfilm?"

"Who's the heavyweight champ?"

"We lick those Commies in Burma yet?"

"Step back! Watch that man. Maybe he's your replacement."

"Replacement. Ha-ha. That's good."

All types of men. All ages. In torn, tattered clothing, mostly. In rags. Even if a man seemed more well-groomed than the rest, on closer examination Temple could see the careful stitching, the patches, the fades and stains. No one seemed to mind.

"Hey, bud. What do you hear about rotation? They passed any laws yet?"

"I been here ten years. When do I get rotated?"

"Ain't that something? Dad Jenks came here with the first ship. Don't you talk about rotation. Ask Dad."

"Better not mention that word to Dad Jenks. He sees red."

"This whole damn planet is red."

"Want a guided tour of Nowhere, men? Step right up."

Arkalion grinned. "They seem so well-adjusted," he said, then shuddered against the cold and followed Temple, with the others, through the crowd.

They were inoculated against nameless diseases. (Watch for the needle with the hook)

They were told again they had arrived on the planet Mars. (No kidding?)

Led to a drab underground city, dimly lit, dank, noisome with mold and mildew. (Quick, the chlorophyll)

Assigned bunks in a dormitory, with four men to a room. (Be it ever so humble—bah!)

Told to keep things clean and assigned temporarily to a garbage pickup detail. (For this I left Sheboygan?)

Read to from the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and Public Law 1182 (concerned with the Nowhere Journey, it told them nothing they did not already know).

Given as complete a battery of tests, mental, emotional and physical, as Temple ever knew existed. (Cripes, man! How the hell should I know what the cube root of -5 is? I never finished high school!)

Subjected to an exhaustive, overlong, and at times meaningless personal interview. (No doc, honest. I never knew I had a—uh—anxiety neurosis. Is it dangerous?)

"How do you do, Temple? Sit down."

"Thank you."

"Thought you'd like to know that while your overall test score is not uncanny, it's decidedly high."

"So what?"

"So nothing—not necessarily. Except that with it you have a very well balanced personality. We can use you, Temple."

"That's why I'm here."

"I mean—elsewhere. Mars is only a way station, a training center for a select few. It takes an awful lot of administrative work to keep this place going, which explains the need for all the station personnel."

"Listen. The last few weeks I had everything thrown at me. Everything, the works. Mind answering one question?"

"Shoot."

"What's this all about?"

"Temple, I don't know!"

"You what?"

"I know you find it hard to believe, but I don't. There isn't a man here on Mars who knows the whole story, either—and certainly not on Earth. We know enough to keep everything in operation. And we know it's important, all of it, everything we do."

"You mentioned a need for some men elsewhere. Where?"

The psychiatrist shrugged. "I don't know. Somewhere. Anywhere." He spread his hands out eloquently. "That's where the Nowhere Journey comes in."

"Surely you can tell me something more than—"

"Absolutely not. It isn't that I don't want to. I can't. I don't know."

"Well, one more question I'd like you to answer."

The psychiatrist lit a cigarette, grinned. "Say, who is interviewing whom?"

"This one I think you can tackle. I have a brother, Jason Temple. Embarked on the Nowhere Journey five years ago. I wonder—"

"So that's the one factor in your psychograph we couldn't figure out—anxiety over your brother."

"I doubt it," shrugged Temple. "More likely my fiancee."

"Umm, common enough. You were to be married?"

"Yes." Stephanie, what are you doing now? Right now?

"That's what hurts the most.... Well, yes, I can find out about your brother." The psychiatrist flicked a toggle on his desk. "Jamison, find what you can on Temple, Jason, year of—"

"1987," Temple supplied.

"1987. We'll wait."

After a moment or two, the voice came through, faintly metallic: "Temple, Jason. Arrival: 1987. Psychograph, 115-bl2. Mental aggregate, 98. Physcom, good to excellent. Training: two years, space perception concentrate, others. Shipped out: 1989."

So Jase had shipped out for—Nowhere.

"Someday you'll follow in your brother's footsteps, Temple. Now, though, I have a few hundred questions I'd like you to answer."

The psychiatrist hadn't exaggerated. Several hours of questioning followed. Once reminded of her, Temple found it hard to keep his thought off Stephanie.

He left the psychiatrist's office more confused than ever.

"Good morning, child. You are Stephanie Andrews?" Stephanie hadn't felt up to working that first morning after Kit's final goodbye. She answered the door in her bathrobe, saw a small, middle-aged woman with graying hair and a kind face. "That's right. Won't you come in?"

"Thank you. I represent the Complete Emancipation League, Miss Andrews."

"Complete Emancipation League? Oh, something to do with politics. Really, I'm not much interested in—"

"That's entirely the trouble," declared the older woman. "Too many of us are not interested in politics. I'd like to discuss the C.E.L. with you, my dear, if you will bear with me a few minutes."

"All right," said Stephanie. "Would you like a glass of sherry?"

"In the morning?" the older woman smiled.

"I'm sorry. Don't mind me. My fiance left yesterday, took his final goodbye. He—he embarked on the Nowhere Journey."

"I realize that. It is precisely why I am here. My dear, the C.E.L. does not want to fight the government. If the government decides that the Nowhere Journey is vital for the welfare of the country—even if the government won't or can't explain what the Nowhere Journey is—that's all right with us. But if the government says there is a rotation system but does absolutely nothing about it, we're interested in that. Do you follow me?"

"Yes!" cried Stephanie. "Oh, yes. Go on."

"The C.E.L. has sixty-eight people in Congress for the current term. We hope to raise that number to seventy-five for next election. It's a long fight, a slow uphill fight, and frankly, my dear, we need all the help we can get. People—young women like yourself, my dear—are entirely too lethargic, if you'll forgive me."

"You ought to forgive me," said Stephanie, "if you will. You know, it's funny. I had vague ideas about helping Kit, about finding some way to get him back. Only to tackle something like that alone.... I'm only twenty-one, just a girl, and I don't know anyone important. No one ever comes back, that's what you hear. But there's a rotation system, you also hear that. If I can be of any help...."

"You certainly can, my dear. We'd be delighted to have you."

"Then, eventually, maybe, just maybe, we'll start getting them rotated home?"

"We can't promise a thing. We can only try. And I never did say we'd try to get the boys rotated, my dear. There is a rotation system in the law, right there in Public Law 1182. But if no men have ever been rotated, there must be a reason for it."

"Yes, but—"

"But we'll see. If for some reason rotation simply is not practicable, we'll find another way. Which is why we call ourselves the C.E.L.—Complete Emancipation League—for women. If men must embark on the Nowhere Journey—the least they can do is let their women volunteer to go along with them if they want to—since it may be forever. Let a bunch of women get to this Nowhere place and you'll never know what might happen, that's what I say."

Something about the gray haired woman's earthly confidence imbued Stephanie with an optimism she never expected. "Well," she said, smiling, "if we can't bring ourselves to Mohammed.... No, that's all wrong!... to the mountain...?"

"Yes, there's an old saying. But it isn't important. You get the idea. My dear, how would you like to go to Nowhere?"

"I—to Kit, anywhere, anywhere!" I'll never forget yesterday, Kit darling. Never!

"I make no promises, Stephanie, but it may be sooner than you think. Morning be hanged, perhaps I will have some sherry after all. Umm, you wouldn't by any chance have some Canadian instead?"

Humming, Stephanie dashed into the kitchen for some glasses.

There were times when the real Alaric Arkalion III wished his father would mind his own business. Like that thing about the Nowhere Journey, for instance. Maybe Alaric Sr. didn't realize it, but being the spoiled son of a billionaire wasn't all fun. "I'm a dilettante," Alaric would tell himself often, gazing in the mirror, "a bored dilettante at the age of twenty-one."

Which in itself, he had to admit, wasn't too bad. But having reneged on the Nowhere Journey in favor of a stranger twice his age who now carried his, Alaric's face, had engendered some annoying complications. "You'll either have to hide or change your own appearance and identity, Alaric."

"Hide? For how long, father?"

"I can't be sure. Years, probably."

"That's crazy. I'm not going to hide for years."

"Then change your appearance. Your way of life. Your occupation."

"I have no occupation."

"Get one. Change your face, too. Your fingerprints. It can be done. Become a new man, live a new life."

In hiding there was boredom, impossible boredom. In the other alternative there was adventure, intrigue—but uncertainty. One part of young Alaric craved that uncertainty, the rest of him shunned it. In a way it was like the Nowhere Journey all over again.

"Maybe Nowhere wouldn't have been so bad," said Alaric to his father, choosing as a temporary alternative and retreat what he knew couldn't possibly happen.

Couldn't it?

"If I choose another identity, I'd be eligible again for the Nowhere Journey."

"By George, I hadn't considered that. No, wait. You could be older than twenty-six."

"I like it the way I am," Alaric said, pouting.

"Then you'll have to hide. I spent ten million dollars to secure your future, Alaric. I don't want you to throw it away."

Alaric pouted some more. "Let me think about it."

"Fair enough, but I'll want your answer tomorrow. Meanwhile, you are not to leave the house."

Alaric agreed verbally, but took the first opportunity which presented itself—that very night—to sneak out the servants' door, go downtown, and get stewed to the gills.

At two in the morning he was picked up by the police for disorderly conduct (it had happened before) after losing a fistfight to a much poorer, much meaner drunk in a downtown bar. They questioned Alaric at the police station, examined his belongings, went through his wallet, notified his home.

Fuming, Alaric Sr. rushed to the police station to get his son. He was met by the desk sergeant, a fat, balding man who wore his uniform in a slovenly fashion.

"Mr. Arkalion?" demanded the sergeant, picking at his teeth with a toothpick.

"Yes. I have come for Alaric, my son."

"Sure. Sure. But your son's in trouble, Mr. Arkalion. Serious trouble."

"What are you talking about? If there are any damages, I'll pay. He didn't—hurt, anyone, did he?"

The sergeant broke the toothpick between his teeth, laughed. "Him? Naw. He got the hell beat out of him by a drunk half his size. It ain't that kind of trouble, Mr. Arkalion. You know what an 1182 card is, mister?"

Arkalion's face drained white. "Why—yes."

"Alaric's got one."

"Naturally."

"According to the card, he should have shipped out on the Nowhere Journey, mister. He didn't. He's in serious trouble."

"I'll see the district attorney."

"More'n likely, you'll see the attorney general. Serious trouble."

The trouble with the Stalintrek, Sophia thought, was that it took months to get absolutely nowhere. There had been the painful pressure, the loss of consciousness, the confinement in this tight little world of dormitories and gleaming metal walls, the uncanny feeling of no weight, the ability—boring after a while, but interesting at first—to float about in air almost at will.

Then, how many months of sameness? Sophia had lost all track of time through ennui. But for the first brief period of adjustment on the part of her fellows to the fact that although she was a woman and shared their man's life she was still to be inviolate, the routine had been anything but exciting. The period of adjustment had had its adventures, its uncertainties, its challenge, and to Sophia it had been stimulating. Why was it, she wondered, that the men who carried their sex with strength and dignity, the hard-muscled men who could have their way with her if they resorted to force were the men who did not violate her privacy, while the weaklings, the softer, smaller men, or the average men whom Sophia considered her physical equals were the ones who gave her trouble?

She had always accepted her beauty, the obvious attraction men found in her, with an objective unconcern. She had been endowed with sex appeal; there was not much room in her life to exploit it, even had she wanted to. Now, now when she wanted anything but that, it gave her trouble.

Her room was shared, of necessity, with three men. Tall, gangling Boris gave her no trouble, turned his back when she undressed for the evening, even though she was careful to slip under the covers first. Ivan, the second man, was short, thin, stooped. Often she found him looking at her with what might have been more than a healthy interest, but aside from that he kept his peace. Besides, Ivan had spent two years in secondary school (as much as Sophia) and she enjoyed conversing with him.

The third man, Georgi, was the troublemaker. Georgi was one of those plump young men with red cheeks, big, eager eyes, a voice somewhat too high. He was an avid talker, a boaster and a bore. In the beginning he showered attentions on Sophia. He insisted on drawing her wash-basin at night, escorted her to breakfast every morning, told her in confidence of the conquests he had made over beautiful women (but not as beautiful as you, Sophia). He soon began to take liberties. He would sit—timorously at first, but with growing boldness—on the corner of her bed, talking with her at night after the others had retired, Ivan with his snores, Boris with his strong, deep breathing. And night after night, plump Georgi grew bolder.

He would reach out and touch Sophia, he would insist on tucking her in at night (let me be your big brother), he would awaken her in the morning with his hand heavy on her shoulder. Finally, one night at bedtime, she heard him conversing in low whispers with Ivan and Boris. She could not hear the words, but Boris looked at her with what she thought was surprise, Ivan nodded in an understanding way, and both of them left the room.

Sophia frowned. "What did you tell them, Georgi?"

"That we wanted to be alone one evening, of course."

"I never gave you any indication—"

"I could see it in your eyes, in the way you looked at me."

"Well, you had better call them back inside and go to bed."

Georgi shook his head, approached her.

"Georgi! Call them back or I will."

"No, you won't." Georgi followed her as she retreated into a corner of the room. When she reached the wall and could retreat no further, he placed his thick hands on her shoulders, drew her to him slowly. "You will call no one," he rasped.

She ducked under his arms, eluded him, was on the point of running to the door, throwing it open and shouting, when she considered. If she did, she would be asking for quarter, gaining a temporary reprieve, inviting the same sort of thing all over again.

She crossed to the bed and sat down. "Come here, Georgi."

"Ah." He came to her.

She watched him warily, a soft flabby man not quite so tall as she was, but who nevertheless outweighed her by thirty or forty pounds. In his eagerness, he walked too fast, lost his footing and floated gently to the ceiling. Smiling as demurely as she could, Sophia reached up, circled his ankle with her hand.

"I never could get used to this weightlessness," Georgi admitted. "Be nice and pull me down."

"I will be nice. I will teach you a lesson."

He weighed exactly nothing. It was as simple as stretching. Sophia merely extended her arm upwards and Georgi's head hit the ceiling with a loud thunk. Georgi groaned. Sophia repeated the procedure, lowering her arm a foot—and Georgi with it—then raising it and bouncing his head off the ceiling.

"I don't understand," Georgi whined, trying to break free but only succeeding in thrashing his chubby arms foolishly.

"You haven't mastered weightlessness," Sophia smiled up at him. "I have. I said I would teach you a lesson. First make sure you have the strength of a man if you would play a man's game."

Still smiling, Sophia commenced spinning the hand which held Georgi's ankle. Arms and free leg flailing air helplessly, Georgi began to spin.

"Put me down!" he whined, a boy now, not even pretending to be a man. When Sophia shoved out gently and let his ankle go he did a neat flip in air and hung suspended, upside down, his feet near the ceiling, his head on a level with Sophia's shoulders. He cried.

She slapped his upside down face, carefully and without excitement, reddening the cheeks. "I was—only joking," he slobbered. "Call back our friends."

Sophia found one of the hard, air-tight metal flasks they used for drinking in weightlessness. With one hand she opened the lid, with the other she grasped Georgi's shoulder and spun him in air, still upside down. She squirted the water in his face, and because he was upside down and yelling it made him choke and cough. When the container was empty she lowered Georgi gently to the floor.

Minutes later, she opened the door, summoned Boris and Ivan, who came into the room self-consciously. What they found was a thoroughly beaten Georgi sobbing on the floor. After that, Sophia had no trouble. Week after week of boredom followed and she almost wished Georgi or someone else would look for trouble ... even if it were something she could not handle, for although she was stronger than average and more beautiful, she was still a woman first, and she knew if the right man....

"Did you know that radio communication is maintained between Earth and Mars?" the Alaric Arkalion on Mars asked Temple.

"Why, no. I never thought about it."

"It is, and I am in some difficulty."

"What's the matter?" Temple had grown to like Arkalion, despite the man's peculiarities. He had given up trying to figure him out, feeling that the only way he'd get anywhere was with Arkalion's cooperation.

"It's a long story which I'm afraid you would not altogether understand. The authorities on Earth don't think I belong here on the Nowhere Journey."

"Is that so? A mistake, huh? I sure am glad for you, Alaric."

"That's not the difficulty. It seems that there is the matter of impersonation, of violating some of the clauses in Public Law 1182. You're glad for me. I'm likely to go to prison."

"If it's that serious, how come they told you?"

"They didn't. But I—managed to find out. I won't go into details, Kit, but obviously, if I managed to embark for Nowhere when I didn't have to, then I wanted to go. Right?"

"I—uh, guess so. But why—?"

"That isn't the point. I still want to go. Not to Mars, but to Nowhere. I still can, despite what has happened, but I need help."

Temple said, "Anything I can do, I'll be glad to," and meant it. For one thing, he liked Arkalion. For another, Arkalion seemed to know more, much more than he would ever say—unless Temple could win his confidence. For a third, Temple was growing sick and tired of Mars with its drab ochre sameness (when he got to the surface, which was rarely), with its dank underground city, with its meaningless attention to meaningless detail. Either way, he figured there was no returning to Earth. If Nowhere meant adventure, as he suspected it might, it would be preferable. Mars might have been the other end of the galaxy for all its nearness to Earth, anyway.

"There is a great deal you can do. But you'll have to come with me."

"Where?" Temple demanded.

"Where you will go eventually. To Nowhere."

"Fine." And Temple smiled. "Why not now as well as later?"

"I'll be frank with you. If you go now, you go untrained. You may need your training. Undoubtedly, you will."

"You know a lot more than you want to talk about, don't you?"

"Frankly, yes.... I am sorry, Kit."

"That's all right. You have your reasons. I guess if I go with you I'll find out soon enough, anyway."

Arkalion grinned. "You have guessed correctly. I am going to Nowhere, before they return me to Earth for prosecution under Public Law 1182. I cannot go alone, for it takes at least two to operate ... well, you'll see."

"Count me in," said Temple.

"Remember, you may one day wish you had remained on Mars for your training."

"I'll take my chances. Mars is driving me crazy. All I do is think of Earth and Stephanie."

"Then come."

"Where are we going?"

"A long, long way off. It is unthinkably remote, this place called Nowhere."

Temple felt suddenly like a kid playing hookey from school. "Lead on," he said, almost jauntily. He knew he was leaving Stephanie still further behind, but had he been in prison on the next street to hers, he might as well have been a million miles away.

As for Arkalion—the thought suddenly struck Temple—Arkalion wasn't necessarily leaving his world further behind. Perhaps Arkalion was going home....

Stephanie picked up the phone eagerly. In the weeks since her first meeting with Mrs. Draper of the C.E.L., the older woman had been a fountain of information and of hope for her. Stephanie for her part had taken over Mrs. Draper's job in her own section of Center City: she was busy contacting the two hundred mothers and fifty sweethearts of the Nowhere Journey which had taken Kit from her. And now Mrs. Draper had called with information.

"We've successfully combined forces with some of the less militant elements in both houses of Congress," Mrs. Draper told her over the phone. "Do you realize, my dear, this marks the first time the C.E.L. has managed to put something constructive through Congress? Until now we've been content merely to block legislation, such as an increase in the Nowhere contingent from...."

"Yes, Mrs. Draper. I know all that. But what about this constructive thing you've done."

"Well, my dear, don't count your chickens. But we have passed the bill, and we expect the President won't veto it. You see, the President has two nephews who...."

"I know. I know. What bill did you pass?"

"Unfortunately, it's somewhat vague. Ultimately, the Nowhere Commission must do the deciding, but it does pave the way."

"For what, Mrs. Draper?"

"Hold onto your hat, my dear. The bill authorizes the Nowhere Commission to make as much of a study as it can of conditions—wherever our boys are sent."

"Oh." Stephanie was disappointed. "That won't get them back to us."