TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

Italics were used in this book in an inconsistent way. Sometimes words, names and phrases in French were italicized, and sometimes not.

CONTENTS

THIS volume is written to show the life of the students in the Paris of to-day. It has an additional interest in opening to inspection certain phases of Bohemian life in Paris that are shared both by the students and the public, but that are generally unfamiliar to visitors to that wonderful city, and even to a very large part of the city's population itself. It depicts the under-side of such life as the students find,—the loose, unconventional life of the humbler strugglers in literature and art, with no attempt to spare its salient features, its poverty and picturesqueness, and its lack of adherence to generally accepted standards of morals and conduct.

As is told in the article describing that incomparably brilliant spectacle, the ball of the Four Arts, extreme care is taken to exclude the public and admit only artists and students, all of whom must be properly accredited and fully identified. It is well understood that such a spectacle would not be suitable for any but artists and students. It is given solely for their benefit, and with the high aim, fully justified by the experience of the masters who direct the students, that the event, with its marvellous brilliancy, its splendid artistic effects, and its freedom and abandon, has a stimulating and broadening effect of the greatest value to art. The artists and students see in these annual spectacles only grace, beauty, and majesty; their training in the studios, where they learn to regard models merely as tools of their craft, fits them, and them alone, for the wholesome enjoyment of the great ball.

It is a student that presents the insight which this volume gives into the life of the students and other Bohemians of Paris. It is set forth with the frankness of a student. Coming from such a source, and having such treatment, it will have a special charm and value for the wise.

The students are the pets of Paris. They lend to the city a picturesqueness that no other city enjoys. So long as they avoid riots aimed at a government that may now and then offend their sense of right, their ways of living, their escapades, their noisy and joyous manifestations of healthy young animal life, are good-naturedly overlooked. Underneath such a life there lies, concealed from casual view, another life that they lead,—one of hard work, of hope, of aspiration, and often of pinching poverty and cruel self-denial. The stress upon them, of many kinds, is great. The utter absence of an effort to reorganize their lives upon conventional lines is from a philosophical belief that if they fail to pass unscathed through it all, they lack the fine, strong metal from which worthy artists are made.

The stranger in Paris will here find opened to him places in which he may study for himself the Bohemian life of the city in all its careless disregard of conventions. The cafés, cabarets, and dance-halls herein described and illustrated have a charm that wholesome, well-balanced minds will enjoy. The drawings for the illustrations were all made from the actual scenes that they depict; they partake of the engaging frankness of the text and of its purpose to show Bohemian life in the Paris of to-day without any effort at concealment.

WE were in wonderful Paris at last—Bishop and I—after a memorable passage full of interest from New York to Havre. Years of hard work were ahead of us, for Bishop would be an artist and I a sculptor.

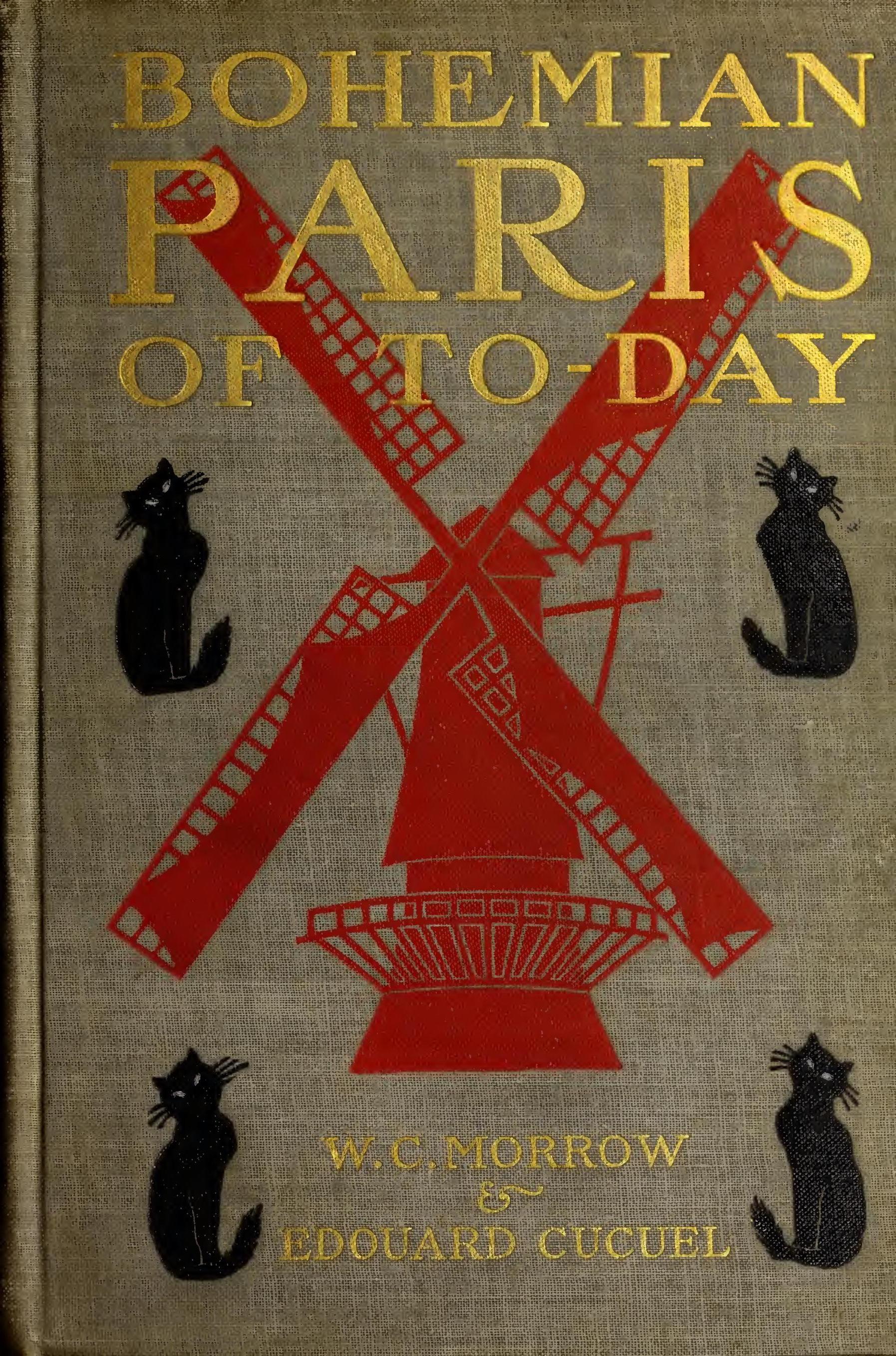

For two weeks we had been lodging temporarily in the top of a comfortable little hotel, called the Grand something (most of the Parisian hotels are Grand), the window of which commanded a superb view of the great city, the vaudeville playhouse of the world.

Pour la première fois the dazzle and glitter had burst upon us, confusing first, but now assuming form and coherence. If we and incomprehensible at could have had each a dozen eyes instead of two, or less greed to see and more patience to learn!

Day by day we had put off the inevitable evil of finding a studio. Every night found us in the cheapest seats of some theatre, and often we lolled on the terraces of the Café de la Paix, watching the pretty girls as they passed, their silken skirts saucily pulled up, revealing dainty laces and ankles. From the slippery floor of the Louvre galleries we had studied the masterpieces of David, Rubens, Rembrandt, and the rest; had visited the Panthéon, the Musée Cluny; had climbed the Eiffel Tower, and traversed the Bois de Boulogne and the Champs-Elysées. Then came the search for a studio and the settling to work. It would be famous to have a little home of our very own, where we could have little dinners of our very own cooking!

It is with a shudder that I recall those eleven days of ceaseless studio-hunting. We dragged ourselves through miles of Quartier Latin streets, and up hundreds of flights of polished waxed stairs, behind puffing concierges in carpet slippers, the puffing changing to grumbling, as, dissatisfied, the concierges followed us down the stairs. The Quartier abounds with placards reading, "Atelier d'Artiste à Louer!" The rentals ranged from two hundred to two thousand francs a year, and the sizes from cigar-boxes to barns. But there was always something lacking. On the eleventh day we found a suitable place on the sixth (top) floor of a quaint old house in a passage off the Rue St.- André-des-Arts. There were overhead and side lights, and from the window a noble view of Paris over the house-tops.

A room of fair size joined the studio, and from its vine-laced window we could look into the houses across the court, and down to the bottom of the court as well. The studio walls were delightfully dirty and low in tone, and were covered with sketches and cartoons in oil and charcoal. The price was eight hundred francs a year, and from the concierge's eloquent catalogue of its charms it seemed a great bargain. The walls settled our fate,—we took the studio.

It was one thing to agree on the price and another to settle the details. Our French was ailing, and the concierge's French was—concierges' French. Bishop found that his pet theory that French should be spoken with the hands, head, and shoulders carried weak spots which a concierge could discover; and then, being somewhat mercurial, he began floundering in a mixture of French and English words and French and American gestures, ending in despair with the observation that the concierge was a d——— fool. At the end of an hour we had learned that we must sign an iron-bound, government-stamped contract, agreeing to occupy the studio for not less than one year, to give six months' notice of our leaving, and to pay three months' rental in advance, besides the taxes for one year on all the doors and windows, and ten francs or more to the concierge. This was all finally settled.

As there was no running water in the rooms (such a luxury being unknown here), we had to supply our needs from a clumsy old iron pump in the court, and employ six flights of stairs in the process.

Then the studio had to be furnished, and there came endless battles with the furniture dealers in the neighborhood, who kept their stock replenished from the goods of bankrupt artists and suspended ménages.

These marchands de meubles are a wily race, but Bishop pursued a plan in dealing with them that worked admirably. He would enter a shop and price an article that we wanted, and then throw up his hands in horror and leave the place as though it were haunted with a plague. The dealer would always come tumbling after him and offer him the article for a half or a third of the former price. In this way Bishop bought chairs, tables, a large easel, beds, a studio stove, book-shelves, linen, drapings, water pitchers and buckets, dishes, cooking utensils, and many other things, the cost of the whole being less than one hundred and fifty francs,—and thus we were established. The studio became quite a snug and hospitable retreat, in spite of the alarming arrangement that Bishop adopted, "to help the composition of the room." His favorite cast, the Unknown Woman, occupied the place of honor over his couch, where he could see it the first thing in the morning, when the dawn, stealing through the skylight, brought out those strange and subtle features which he swore inspired him from day to day. My room was filled with brilliant posters by Chéret and Mucha and Steinlen,—they were too bold and showy for the low tone of Bishop's studio. It all made a pretty picture,—the dizzy posters, the solemn trunks, the books, the bed with its gaudy print coverings, and the little crooked-pane window hung with bright green vines that ran thither from a box in the window of an adjoining apartment. And it was all completed by the bright faces of three pretty seamstresses, who sat sewing every day at their window across the passage.

Under our housekeeping agreement Bishop was made cook, and I chambermaid and water-carrier. It was Bishop's duty to obey the alarm clock at six every morning and light the fire, while I went down for water at the pump, and for milk at the stand beside the court entrance, where fat Madame Gioté sold café-au-lait and lait froid ou chaud, from a sou's worth up. Then, after breakfast, I did the chamber work while Bishop washed the dishes. Bishop could make for breakfast the most delicious coffee and flapjacks and omelette in the whole of Paris. By eight o'clock all was in order; Bishop was smoking his pipe and singing "Down on the Farm" while working on his life study, and I was off to my modelling in clay.

Bishop soon had the hearts of all the shop-keepers in the neighborhood. The baker's dimple-cheeked daughter never worried if the scales hung a little in his favor, at the boucherie he was served with the choicest cuts of meat, and the fried-potato women called him "mon fils" and fried a fresh lot of potatoes for him. Even Madame Tonneau, the marchande de tabac, saw that he had the freshest packages in the shop. Often, when I was returning home at night, I encountered him making cheerily for the studio, bearing bread by the yard, his pockets bulging with other material for dinner. Ah, he was a wonderful cook, and we had marvellous appetites! So famous did he soon become that the models (the lady ones, of course) were eager to dine avec nous; and when they did they helped to set the table, they sewed buttons on our clothes, and they made themselves agreeable and perfectly at home with that charming grace which is so peculiarly French. Ah, those were jolly times!

The court, or, more properly, le passage, on which our window looked was a narrow little thoroughfare leading from the Rue St.-André-des-Arts to the Boulevard St.-Germain. It bore little traffic, but was a busy way withal. It had iron-workers' shops, where hot iron was beaten into artistic lamps, grills, and bed-frames; a tinsmith's shop; a blanchisserie, where our shirts were made white and smooth by the pretty blanchisseuses singing all day over their work; a wine-cellar, whose barrels were eternally blocking one end of the passage; an embossed picture-card factory, where twoscore women, with little hammers and steel dies, beat pictures into cards; a furniture shop, where everything old and artistic was sold, the Hôtel du Passage, and a bookbinder's shop.

Each of the eight buildings facing the passage was ruled by a formidable concierge, who had her dark little living apartments near the entrances. These are the despots of the court, and their function is to make life miserable for their lodgers. When they are not doing that they are eternally scrubbing and polishing. They are all married. M. Mayé, le mari de notre concierge, is a tailor. He sits at the window and mends and sews all day long, or acts as concierge when his wife is away. The husband of the concierge next door is a sergeant de ville at night, but in the early mornings as, in a soiled blouse, he empties ash-cans, he looks very unlike the personage dressed at night in a neat blue uniform and wearing a short sword Another concierge's husband fait des courses—runs errands—for sufficient pay.

Should you fail to clean your boots on the mat, and thus soil the glossy stairs, have a care!—a concierge's tongue has inherited the warlike characteristics of the Caesars. Rugs and carpets must not be shaken out of the windows after nine o'clock. Ashes and other refuse must be thrown into the big bin of the house not later than seven. Sharp at eleven in the evening the lights are extinguished and the doors locked for the night; and then all revelry must immediately cease. Should you arrive en retard,—that is, after eleven,—you must ring the bell violently until the despot, generally after listening for an hour to the bell, unlocks the catch from her couch. Then when you close the door and pass her lodge you must call out your name. If you are out often or till very late, be prepared for a lecture on the crime of breaking the rest of hard-working concierges. After the day's work the concierges draw their chairs out into the court and gossip about their tenants. The nearer the roof the lodger the less the respect he commands. Would he not live on a lower floor if he were able? And then, the top floor gives small tips!

It is noticeable that the entresol and premiers étages are clean and highly polished, and that the cleanliness and polish diminish steadily toward the top, where they almost disappear. Ah, les concierges! But what would Paris be without them?

Directly beneath us an elderly couple have apartments. Every morning at five the old gentleman starts French oaths rattling through the court by beating his rugs out of his window. At six he rouses the ire of a widow below him by watering his plants and incidentally drenching her bird- cages. Not long ago she rose in violent rebellion, and he hurled a flower pot at her protruding head. It smashed on her window-sill; she screamed "Murder!" and the whole court was in an uproar. The concierges and the old gentleman's pacific wife finally restored order—till the next morning.

Next, to my room are an elderly lady and her sweet, sad-faced daughter. They are very quiet and dignified, and rarely fraternize with their neighbors. It is their vine that creeps over to my window, and it is carefully tended by the daughter. And all the doves and sparrows of the court come regularly to eat out of her hand, and a lively chatter they have over it. The ladies are the widow and daughter of a once prosperous stock-broker on the Bourse, whom an unlucky turn of the wheel drove to poverty and suicide.

The three seamstresses over the way are the sunshine of the court. They are not so busy sewing and singing but that they find time to send arch glances toward our window, and their blushes and smiles when Bishop sends them sketches of them that he has made from memory are more than remunerative.

A young Scotch student from Glasgow, named Cameron, has a studio adjoining ours. He is a fine, jovial fellow, and we usually assist him to dispose of his excellent brew of tea at five o'clock. Every Thursday evening there was given a musical chez lui, in which Bishop and I assisted with mandolin and guitar, while Cameron played the flute. For these occasions Cameron donned his breeks and kilt, and danced the sword-dance round two table-knives crossed. The American songs strike him as being strange and incomprehensible. He cannot understand the negro dialect, and wonders if America is filled with negroes and cotton plantations; but he is always delighted with Bishop's "Down on the Farm."

Life begins at five o'clock in our court. The old gentleman beats his rugs, the milk-bottles rattle, the bread-carts rumble, Madame Gioté opens her milkstand, and the concierges drag the ash-cans out into the court, where a drove of rag-pickers fall upon them. These gleaners are a queer lot. Individuals and families pursue the quest, each with a distinct purpose. One will seek nothing but bones, glass, and crockery; another sifts the ashes for coal; another takes only paper and rags; another old shoes and hats; and so on, from can to can, none interfering with any of the others. The dogs are the first at the bins. They are regularly organized in working squads, travelling in fours and fives. They are quite adept at digging through the refuse for food, and they rarely quarrel; and they never leave one bin for another until they have searched it thoroughly.

The swish of water and a coarse brush broom announces the big, strong woman who sweeps the gutters of the Rue St.-André-des-Arts. With broad sweeps of the broom she spreads the water over half the street and back into the gutter, making the worn yellow stones shine. She is coarsely clad and wears black sabots; and God knows how she can swear when the gleaners scatter the refuse into the gutter!

The long wail of the fish-and-mussel woman, "J'ai des beaux maquereaux, des moules, poissons à frire, à frire!" as she pushes her cart, means seven o'clock.

The day now really begins. Water-pails are clanging and sabots are clicking on the stones. The wine people set up a rumble by cleaning their casks with chains and water. The anvils of the iron-workers are ringing, and there comes the tink-tink-tink of the little hammers in the embossed-picture factory. The lumbering garbage-cart arrives to bear away the ash-bins, the lead-horse shaking his head to ring the bell on his neck in announcement of the approach. Street-venders and hawkers of various comestibles, each with his or her quaint musical cry, come in numbers. "J'ai des beaux choux-fleurs! O, comme ils sont beaux!" The fruit- and potato-women come after, and then the chair-menders. These market-women are early risers. They are at the great Halles Centrales at four o'clock to bargain for their wares; and besides good lungs they have a marvellous shrewdness, born of long dealings with French housewives.

Always near eight may be heard, "Du mouron pour les petits oiseaux!" and all the birds in the court, familiar with the cry, pipe up for their chickweed. "Voilà le bon fromage à la crème pour trois sous!" cries a keen-faced little woman, her three-wheeled cart loaded with cream cheeses; and she gives a soup-plate full of them, with cream poured generously over, and as she pockets the money says, "Voilà! ce que c'est bon avec des confitures!" Cream cheeses and prayer! On Sunday mornings during the spring and summer the goat's-milk vender, blowing a reed-pipe, invades the passage with his living milk-cans,—a flock of eight hairy goats that know the route as well as he, and they are always willing to be milked when a customer offers a bowl. The tripe-man with his wares and bell is the last of the food-sellers of the day. The window-glass repairer, "Vitrier!" passes at nine, and then the beggars and strolling musicians and singers put in an appearance. In the afternoon the old-clo' man comes hobbling under his load of cast-off clothes, crying, "Marchand d'habits!" of which you can catch only "'Chand d'habits!" and the barrel-buyer, "Marchand de tonneaux!" The most musical of them all is the porcelain-mender, who cries, "Voici le raccommodeur de porcelaines, faïence, cristal, poseur de robinets!" and then plays a fragment of a hunting-song.

The beggars and musicians also have regular routes and fixed hours. Cold and stormy days are welcomed by them, for then pity lends activity to- sous. A piratical old beggar has his stand near the entrance to the court, where he kneels on the stones, his faithful mongrel dog beside him. He occasionally poses for the artists when times are dull, but he prefers begging,—it is easier and more remunerative. Three times a week we are treated to some really good singing by a blind old man, evidently an artist in his day. When the familiar sound of his guitar is heard all noises in the passage cease, and all windows are opened to hear. He sings arias from the operas. His little old wife gathers up the sous that ring on the flags. Sometimes a strolling troupe of two actors and three musicians makes its appearance, and invariably plays to a full house. There are droves of sham singers who do not sing at all, but give mournful howls and tell their woes to deaf windows. One of them, a tattered woman with two babies, refused to pose for Bishop, although he offered her five francs for the afternoon.

Her babies never grow older or bigger as the years pass.

We all know when anybody in the passage is going to take a bath. There are no bath-tubs in these old houses, but that difficulty is surmounted by a bathing establishment on the Boulevard St.-Michel. It sends around a cart bearing a tank of hot water and a zinc tub. The man who pulls the cart carries the tub to the room, and fills it by carrying up the water in buckets. Then he remains below until the bath is finished, to regain his tub and collect a franc.

Since we have been here the court entrance has been once draped in mourning. At the head of the casket of old Madame Courtoise, who lived across the way, stood a stately crucifix, and candles burned, and there were mourners and yellow bead wreaths. A quiet sadness sat upon the court, and the people spoke in whispers only.

And there have been two weddings,—one at the blanchisserie, where the master's daughter was married to a young mechanic from the iron shop. There were glorious times at the laundry that night, for the whole court was present. It was four in the morning when the party broke up, and then our shirts were two days late.

Thus ran the first months of the four years of our student life in Paris; in its domestic aspects it was typical of all that followed. We soon became members of the American Art Association, and gradually made friends in charming French homes. Then there was the strange Bohemian life lying outside as well as within the students' pale, and into the spirit of it all we found our way. It is to the Bohemian, not the social, life of Paris that these papers are devoted—a life both picturesque and pathetic, filled with the oddest contrasts and incongruities, with much suffering but more content, and spectacular and fascinating in all its phases. No one can have seen and known Paris without a study of this its living, struggling artistic side, so strange, so remote from the commonplace world surging and roaring unheeded about it.

On New Year's Day we had an overwhelming number of callers. First came the concierge, who cleaned our door-knob and wished us a prosperous and bonne année. She got ten francs,—we did not know what was coming. The chic little blanchisseuse called next with our linen. That meant two francs. Then came in succession two telegraph boys, the facteur, or postman, who presented us with a cheap calendar, and another postman, who delivers only second-class mail. They got a franc each. Then the marchand de charbon's boy called with a clean face and received fifty centimes, and everybody else with whom we had had dealings; and our offerings had a steadily diminishing value.

We could well bear all this, however, in view of the great day, but a week old, when we had celebrated Christmas. Bishop prepared a dinner fit for a king, giving the greater part of his time for a week to preparations for the great event. Besides a great many French dishes, we had turkey and goose, cooked for us at the rôtisserie near by, and soup, oysters, American pastries, and a big, blazing plum-pudding. We and our guests (there were eight in all) donned full dress for the occasion, and a bonne, hired for the evening, brought on the surprises one after another. But why should not it have been a glorious evening high up among the chimney-pots of old Paris? for did we not drink to the loved ones in a distant land, and were not our guests the prettiest among the pretty toilers of our court?

IT is about the fifteenth of October, after the long summer vacation, that the doors of the great École des Beaux-Arts are thrown open.

The first week, called "la semaine des nouveaux," is devoted to the initiation and hazing of the new students, who come mostly from foreign countries and the French provinces. These festivities can never be forgotten—by the nouveaux.

Bishop had condescendingly decided to become un élève de Gérôme—with some misgivings, for Bishop had developed ideas of a large and free American art, while Gérôme was hard and academic. One day he gathered up some of his best drawings and studies (which he regarded as masterpieces) and, climbing to the impériale of a Clichy 'bus, rode over to Montmartre, where Gérôme had his private studio. He was politely ushered in by a manservant, and conducted to the door of the master's studio through a hall and gallery filled with wonderful marble groups. Gérôme himself opened the door, and Bishop found himself in the great man's workshop. For a moment Bishop stood dazed in the middle of the splendid room, with its great sculptures and paintings, some still unfinished, and a famous collection of barbaric arms and costumes. A beautiful model was posing upon a rug. But most impressive of all was the white-haired master, regarding him with a thoughtful and searching, but kindly, glance. Bishop presently found a tongue with which to stammer out his mission,—he would be a pupil of the great Gérôme.

The old man smiled, and, bidding his model retire, inspected carefully the array of drawings that Bishop spread at his feet,—Gérôme must have evidence of some ability for the magic of his brain and touch to develop.

"Sont pas mal, mon ami," he said, after he had studied all the drawings; "non, pas mal." Bishop's heart bounded,—his work was not bad! "Vous êtes Américain?" continued the master. "C'est un pays que j'aimerais bien visiter si le temps ne me manquait pas."

Thus he chatted on, putting Bishop more and more at his ease. He talked of America and the promising future that she has for art; then he went into his little office, and, asking Bishop's name, filled out the blank that made him a happy pupil of Gérôme. He handed it to Bishop with this parting-advice, spoken with great earnestness:

"Il faut travailler, mon ami—travailler! Pour arriver, travailler toujours, sérieusement, bien entendu!"

Bishop was so proud and happy that he ran all the way up the six flights of stairs to our floor, burst into the studio, and executed a war-dance that would have shamed an Apache, stepping into his paint-box and nearly destroying his sacred Unknown. That night we had a glorious supper, with des escargots to start with.

Early on the fifteenth of October, with his head erect and hope filling his soul, Bishop started for the Beaux-Arts, which was in the Rue Bonaparte, quite near. That night he returned wise and saddened.

He had bought a new easel and two rush-bottomed tabourets, which every new student must provide, and, loaded with these, he made for the Ecole. Gathered at the big gates was a great crowd of models of all sorts, men, women, and children, fat, lean, and of all possible sizes. In the court- yard, behind the gates, was a mob of long-haired students, who had a year or more ago passed the initiatory ordeal and become ancients. Their business now was to yell chaff at the arriving nouveaux. The concierge conducted Bishop up-stairs to the Administration, where he joined a long line of other nouveaux waiting for the opening of the office at ten o'clock.

Then he produced his papers and was enrolled as a student of the Ecole.

It is only in this government school of the four arts that the typical Bohemian students of Paris may be found, including the genuine type of French student, with his long hair, his whiskers, his Latin Quarter "plug" hat, his cape, blouse, wide corduroy trousers, sash, expansive necktie, and immense cane. The Ecole preserves this type more effectually than the other schools, such as Julian's and Colarossi's, where most of the students are foreigners in conventional dress.

Among the others who entered Gérôme's atelier at the same time that Bishop did was a Turk named Haidor (fresh from the Ottoman capital), a Hungarian, a Siamese, an American from the plains of Nebraska, and five Frenchmen from the provinces.

They all tried to speak French and be agreeable as they entered the atelier together. At the door stood a gardien, whose principal business is to mark absentees and suppress riots. Then they passed to the gentle mercies of the reception committee and the massier within.

The massier is a student who manages the studio, models, and masse money. This one, a large fellow with golden whiskers (size and strength are valuable elements of the massier's efficiency), demanded twenty-five francs from each of the new-comers,—this being the masse money, to pay for fixtures, turpentine, soap, and clean towels, et pour payer à boire. The Turk refused to pay, protesting that he had but thirty francs to last him the month; but menacing stools and sticks opened his purse; his punishment was to come later. After the money had been collected from all the nouveaux the entire atelier of over sixty students, dressed in working blouses and old coats, formed in line, and with deafening shouts of "A boire! à boire!" placed the nouveaux in front to carry the class banner, and thus marched out into the Rue Bonaparte to the Café des Deux Magots, singing songs fit only for the studio. Their singing, shouting, and ridiculous capers drew a great crowd. At the café they created consternation with their shouting and howling until the arrival of great bowls of "grog Américain," cigarettes, and gâteaux. Rousing cheers were given to a marriage-party across the Place St.-Germain. The Turk was forced to do a Turkish dance on a table and sing Turkish songs, and to submit to merciless ridicule. The timid little Siamese also had to do a turn, as did Bishop and W———, the American from Nebraska, who had been a cowboy at home. After yelling themselves hoarse and nearly wrecking the café, the students marched back in a disorderly mob to the Ecole. Then the real trouble began.

The gardien having conveniently disappeared, the students closed and barricaded the door. "A poil! à poil!" they yelled, dancing frantically about the frightened nouveaux; "à poil les sales nouveaux! à poil!" They seized the Turk and stripped him, despite his desperate resistance; then they tied his hands behind him and with paint and brushes decorated his body in the most fantastic designs that they could conceive. His oaths were frightful. He cursed them in the name of Allah, and swore to have the blood of all Frenchmen for desecrating the sacred person of a Moslem. He called them dogs of infidels and Christians. But all this was in Turkish, and the students enjoyed it immensely. "En broche!" they yelled, after they had made him a spectacle with the brushes; "en broche! Il faut le mettre en broche!" This was quickly done. They forced the Turk to his haunches, bound his wrists in front of his upraised knees, thrust a long pole between his elbows and knees, and thus bore him round the atelier at the head of a singing procession. Four times they went round; then they placed the helpless M. Haidor on the model-stand for future reference. The bad French that the victim occasionally mixed with his tirade indicated the fearful damnation that he was doubtless dealing out in Turkish.

A circle was then formed about him, and a solemn silence fell upon the crowd. A Frenchman named Joncierge, head of the reception committee, stepped forth, and in slow and impressive speech announced that it was one of the requirements of the Atelier Gérôme to brand all nouveaux over the heart with the name of the atelier, and that the branding of the Turk would now proceed. Upon hearing this, M. Haidor emitted a fearful howl. But he was turned to face the red-hot studio stove and watch the branding-iron slowly redden in the coals. During this interval the students sang the national song, and followed it with a funeral march. Behind the Turk's back a second poker was being painted to resemble a red-hot one.

The hot poker was taken from the fire, and its usefulness tested by burning a string with it. Haidor grew deathly pale. An intense silence sat upon the atelier as the iron was brought near the helpless young man. In a moment, with wonderful cleverness, the painted poker was substituted for the hot one and placed quickly against his breast. When the cold iron touched him he roared like a maddened bull, and rolled quivering and moaning upon the floor. The students were frantic with delight.

It was some time before Haidor could realize that he was not burned to a crisp. He was then taken across the atelier and hoisted to a narrow shelf fifteen feet from the floor, where he was left to compose himself and enjoy the tortures of the other nouveaux. He dared not move, however, lest he fall; and because he refused to take anything in good- nature, but glared hatred and vengeance down at them, they pelted him at intervals with water-soaked sponges.

The Hungarian and one of the French nouveaux were next seized and stripped. Then they were ordered to fight a duel, in this fashion: they were made to mount two stools about four feet apart. The Hungarian was handed a long paint-brush dripping with Prussian blue, and the Frenchman a similar brush soaked with crimson lake. Then the battle began. Each hesitated to splash the other at first, but as they warmed to their work under the shouting of the committee they went in with a will. When the Frenchman had received a broad splash on the mouth in return for a chest decoration of his adversary, his blood rose, and then the serious work began.

Both quickly lost their temper. When they were unwillingly made to desist the product of their labors was startling, though not beautiful. Then they were rubbed down vigorously with turpentine and soiled towels, and were given a franc each for a bath, because they had behaved so handsomely.

Bishop came next. He had made up his mind to stand the initiation philosophically, whatever it might be, but when he was ordered to strip he became apprehensive and then angry. Nothing so delights the students as for a nouveau to lose his temper. Bishop squared off to face the whole atelier, and looked ugly. The students silently deployed on three sides, and with a yell rushed in, but not before three of them had gone down under his fists did they pin him to the floor and strip him. While Bishop was thus being prepared, the Nebraskan was being dealt with. He had the wisdom not to lose his temper, and that made his resistance all the more formidable. Laughing all the time, he nevertheless dodged, tripped, wrestled, threw stools, and did so many other astonishing and baffling things that the students, though able to have conquered him in the end, were glad to make terms with him. In this arrangement he compelled them to include Bishop. As a result, those two mounted the model throne naked, and sang together and danced a jig, all so cleverly that the Frenchmen were frantic with delight, and welcomed them as des bons amis. The amazing readiness and capability of the American fist bring endless delight and perennial surprise to the French.

The rest of the nouveaux were variously treated. Some, after being stripped, were grotesquely decorated with designs and pictures not suitable for general inspection. Others were made to sing, to recite, or to act scenes from familiar plays, or, in default of that, to improvise scenes, some of which were exceedingly funny. Others, attached to a rope depending from the ceiling, were swung at a perilous rate across the atelier, dodging easels in their flight.

At half-past twelve the sport was over. The barricade was removed, the Turk's clothes hidden, the Turk left howling on his shelf, and the atelier abandoned. The next morning there was trouble. The director was furious, and threatened to close the atelier for a month, because the Turk had not been discovered until five o'clock, when his hoarse howls attracted the attention of the gardien of the fires. His trousers and one shoe could not be found. It was three months before Haidor appeared at the atelier again, and then everything had been forgotten.

Bishop was made miserable during the ensuing week. He would find himself roasting over paper fires kindled under his stool. Paint was smeared upon his easel to stain his hands. His painting was altered and entirely re-designed in his absence. Strong-smelling cheeses were placed in the lining of his "plug" hat. His stool-legs were so loosened that when he sat down he struck the floor with a crash. His painting-blouse was richly decorated inside and out with shocking coats of arms that would not wash out. One day he discovered that he had been painting for a whole hour with currant jelly from a tube that he thought contained laque.

Then, being a nouveau, he could never get a good position in which to draw from the model. Every Monday morning a new model is posed for the week, and the students select places according to the length of time they have been attending. The nouveaux have to take what is left. And they must be servants to the ancients,—run out for tobacco, get soap and clean towels, clean paint-brushes, and keep the studio in order. With the sculptors and architects it is worse. The sculptors must sweep the dirty, clay-grimed floor regularly, fetch clean water, mix the clay and keep it fresh and moist, and on Saturdays, when the week's work is finished, must break up the forty or more clay figures, and restore them to clay for next week's operations. The architects must build heavy wooden frames, mount the projects and drawings, and cart them about Paris to the different exhibition rooms.

At the end of a year the nouveau drops his hated title and becomes a proud ancient, to bully to his heart's content, as those before him.

Mondays and Wednesdays are criticism days, for then M. Gérôme comes down and goes over the work of his pupils. He is very early and punctual, never arriving later than half-past eight, usually before half the students are awake. The moment he enters all noises cease, and all seem desperately hard at work, although a moment before the place may have been in an uproar. Gérôme plumps down upon the man nearest to him, and then visits each of his élèves, storming and scolding mercilessly when his pupils have failed to follow his instructions. As soon as a student's criticism is finished he rises and follows the master to hear the other criticisms, so that toward the close the procession is large.

Bishop's first criticism took him all aback. "Comment!" gasped the master, gazing at the canvas in horror. "Qu'est-ce que vous avez fait?" he sternly demanded, glaring at the luckless student, who, in order to cultivate a striking individuality, was painting the model in broad, thick dashes of color. Gérôme glanced at Bishop's palette, and saw a complete absence of black upon it. "Comment, vous n'avez pas de noir?" he roared. "C'est très important, la partie matérielle! Vous ne m'écoutez pas, mon ami,—-je parle dans le désert! Vous n'avez pas d'aspect général, mon ami," and much more, while Bishop sat cold to the marrow. The students, crowded about, enjoyed his discomfiture immensely, and, behind Gérôme's back, laughed in their sleeves and made faces at Bishop. But many others suffered, and Bishop had his inning with them.

All during Gérôme's tour of inspection the model must maintain his pose, however difficult and exhausting. Often he is kept on a fearful strain for two hours. After the criticism the boys show Gérôme sketches and studies that they have made outside the Ecole, and it is in discussing them that his geniality and kindliness appear. Gérôme imperiously demands two things,—that his pupils, before starting to paint, lay on a red or yellow tone, and that they keep their brushes scrupulously clean. Woe to him who disobeys!

After he leaves with a cheery "Bon jour, messieurs!" pandemonium breaks loose, if the day be Saturday. Easels, stools, and studies are mowed down as by a whirlwind, yells shake the building, the model is released, a tattoo is beaten on the sheet-iron stove-guard, everything else capable of making a noise is brought into service, and either the model is made to do the danse du ventre or a nouveau is hazed.

The models—what stories are there! Every Monday morning from ten to twenty present themselves, male and female, for inspection in puris naturalibus before the critical gaze of the students of the different ateliers. One after another they mount the throne and assume such academic poses of their own choosing as they imagine will display their points to the best advantage. The students then vote upon them, for and against, by raising the hand. The massier, standing beside the model, announces the result, and, if the vote is favorable, enrols the model for a certain week to come.

There is intense rivalry among the models. Strange to say, most of the male models in the schools of Paris are from Italy, the southern part especially. As a rule, they have very good figures. They begin posing at the age of five or six, and follow the business until old age retires them. Crowds of them are at the gates of the Beaux-Arts early on Monday mornings. In the voting, a child may be preferred to his seniors, and yet the rate of payment is the same,—thirty francs a week.

Many of the older models are quite proud of their profession, spending idle hours in studying the attitudes of figures in great paintings and in sculptures in the Louvre or the Luxembourg, and adopting these poses when exhibiting themselves to artists; but the trick is worthless.

Few of the women models remain long in the profession. Posing is hard and fatiguing work, and the students are merciless in their criticisms of any defects of figure that the models may have,—the French are born critics. During the many years that I have studied and worked in Paris I have seen scores of models begin their profession with a serious determination to make it their life-work.

They would appear regularly at the different ateliers for about two years, and would be gratified to observe endless reproductions of their graces in the prize rows on the studio walls. Then their appearance would be less and less regular, and they would finally disappear altogether—whither? Some become contented companions of students and artists, but the cafés along the Boul' Mich', the cabarets of Montmartre, and the dance-halls of the Moulin Rouge and the Bal Bullier have their own story to tell. Some are happily married; for instance, one, noted for her beauty of face and figure, is the wife of a New York millionaire. But she was clever as well as beautiful, and few models are that. Most of them are ordinaire, living the easy life of Bohemian Paris, and having little knowledge of le monde propre. But, oh, how they all love dress! and therein lies most of the story. When Marcelle or Hélène appears, all of a sudden, radiant in silks and creamy lace petticoats, and sweeps proudly into the crowded studios, flushed and happy, and hears the dear compliments that the students heap upon her, we know that thirty francs a week could not have changed the gray grub into a gorgeous butterfly.

"C'est mon amant qui m'a fait cadeau," Marcelle will explain, deeming some explanation necessary. There is none to dispute you, Marcelle. This vast whirlpool has seized many another like you, and will seize many another more. And to poor Marcelle it seems so small a price to pay to become one of the grand ladies of Paris, with their dazzling jewels and rich clothes!

An odd whim may overtake one here and there. One young demoiselle, beautiful as a girl and successful as a model a year ago, may now be seen nightly at the Cabaret du Soleil d'Or, frowsy and languishing, in keeping with the spirit of her confrères there, singing her famous "Le Petit Caporal" to thunderous applause, and happy with the love, squalor, dirt, and hunger that she finds with the luckless poet whose fortunes she shares. It was not a matter of clothes with her.

It is a short and easy step from the studio to the café. At the studio it is all little money, hard posing, dulness, and poor clothes; at the cafés are the brilliant lights, showy clothes, tinkling money, clinking glasses, popping corks, unrestrained abandon, and midnight suppers. And the studios and the cafés are but adjoining apartments, one may say, in the great house of Bohemia. The studio is the introduction to the café; the café is the burst of sunshine after the dreariness of the studio; and Marcelle determines that for once she will bask in the warmth and glow.... Ah, what a jolly night it was, and a louis d'or in her purse besides! Marcelle's face was pretty—and new. She is late at the studio next morning, and is sleepy and cross. The students grumble. The room is stifling, and its gray walls seem ready to crush her. It is so tiresome, so stupid—and only thirty francs a week! Bah!... Marcelle appears no more.

All the great painters have their exclusive model or models, paying them a permanent salary. These favored ones move in a special circle, into which the ordinaire may not enter, unless she becomes the favorite of some grand homme. They are never seen at the academies, and rarely or never pose in the schools, unless it was there they began their career.

Perhaps the most famous of the models of Paris was Sarah Brown, whose wild and exciting life has been the talk of the world. Her beautiful figure and glorious golden hair opened to her the whole field of modeldom. Offers for her services as model were more numerous than she could accept, and the prices that she received were very high. She was the mistress of one great painter after another, and she lived and reigned like a queen. Impulsive, headstrong, passionate, she would do the most reckless things. She would desert an artist in the middle of his masterpiece and come down to the studio to pose for the students at thirty francs a week. Gorgeously apparelled, she would glide into a studio, overturn all the easels that she could reach, and then shriek with laughter over the havoc and consternation that she had created. The students would greet her with shouts and form a circle about her, while she would banteringly call them her friends. Then she would jump upon the throne, dispossess the model there, and give a dance or make a speech, knocking off every hat that her parasol could reach. But no one could resist Sarah.

She came up to the Atelier Gérôme one morning and demanded une semaine de femme. The massier booked her for the following week. She arrived promptly on time and was posed. Wednesday a whim seized her to wear her plumed hat and silk stockings. "C'est beaucoup plus chic," she naively explained. When Gérôme entered the studio and saw her posing thus she smiled saucily at him, but he turned in a rage and left the studio without a word. Thursday she tired of the pose and took one to please herself, donning a skirt. Of course protests were useless, so the students had to recommence their work. The remainder of the week she sat upon the throne in full costume, refusing to pose. She amused herself with smoking cigarettes and keeping the nouveaux running errands for her.

It was she who was the cause of the students' riot in 1893,—a riot that came near ending in a revolution. It was all because she appeared at le Bal des Quat'z' Arts in a costume altogether too simple and natural to suit the prefect of police, who punished her. She was always at the Salon on receiving-day, and shocked the occupants of the liveried carriages on the Champs-Elysées with her dancing. In fact, she was always at the head of everything extraordinary and sensational among the Bohemians of Paris. But she aged rapidly under her wild life. Her figure lost its grace, her lovers deserted her, and after her dethronement as Queen of Bohemia, broken-hearted and poor, she put an end to her wretched life,—and Paris laughed.

The breaking in of a new girl model is a joy that the students never permit themselves to miss. Among the many demoiselles who come every Monday morning are usually one or two that are new. The new one is accompanied by two or more of her girl friends, who give her encouragement at the terrible moment when she disrobes. As there are no dressing-rooms, there can be no privacy. The students gather about and watch the proceedings with great interest, and make whatever remarks their deviltry can suggest. This is the supreme test; all the efforts of the attendant girls are required to hold the new one to her purpose. When finally, after an inconceivable struggle with her shame, the girl plunges ahead in reckless haste to finish the job, the students applaud her roundly.

But more torture awaits her. Frightened, trembling, blushing furiously, she ascends the throne, and innocently assumes the most awkward and ridiculous poses, forgetting in that terrible moment the poses that she had learned so well under the tutelage of her friends. It is then that the fiendishness of the students rises to its greatest height. Dazed and numb, she hardly comprehends the ordeal through which she is now put. The students have adopted a grave and serious bearing, and solemnly ask her to assume the most outlandish and ungraceful poses. Then come long and mock-earnest arguments about her figure, these arguments having been carefully learned and rehearsed beforehand. One claims that her waist is too long and her legs too heavy; another hotly takes the opposite view. Then they put her through the most absurd evolutions to prove their points. At last she is made to don her hat and stockings; and the students form a ring about her and dance and shout until she is ready to faint.

Of course the studio has a ringleader in all this deviltry,—all studios have. Joncierge is head of all the mischief in our atelier. There is no end to his ingenuity in devising new means of torture and fun. His personations are marvellous. When he imitates Bernhardt, Réjane, or Calvé, no work can be done in the studio. Gérôme himself is one of his favorite victims. But Joncierge cannot remain long in one school; the authorities pass him on as soon as they find that he is really hindering the work of the students. One day, at Julian's, he took the class skeleton, and with a cord let the rattling, quivering thing down into the Rue du Dragon, and frightened the passers out of their wits. As his father is chef d'orchestre at the Grand Opéra, Joncierge junior learns all the operas and convulses us with imitations of the singers.

Another character in the studio is le jeune Siffert, only twenty-three, and one of the cleverest of the coming French painters. Recently he nearly won the Prix de Rome. His specialty is the imitation of the cries of domestic fowls and animals, and of street venders. Gérôme calls him "mon fils," and constantly implores him to be serious. I don't see why.

Then there is Fiola, a young giant from Brittany, with a wonderful facility at drawing. He will suddenly break into a roar, and for an hour sing one verse of a Brittany chant, driving the other students mad.

Fournier is a little curly-headed fellow from the south, near Valence, and wears corduroy trousers tucked into top-boots. His greatest delight is in plaguing the nouveaux. His favorite joke, if the day is dark, is to send a nouveau to the different ateliers of the Ecole in search of "le grand réflecteur." The nouveau, thinking that it is a device for increasing the light, starts out bravely, and presently returns with a large, heavy box, which, upon its being opened, is found to be filled with bricks. Then Fournier is happy.

Taton is the butt of the atelier. He is an ingénu, and falls into any trap set for him. Whenever anything is missing, all pounce upon Taton, and he is very unhappy.

Haidor, the Turk, suspicious and sullen, also is a butt. Caricatures of him abundantly adorn the walls, together with the Turkish crescent, and Turkish ladies executing the danse du ventre.

Caricatures of all kinds cover the walls of the atelier, and some are magnificent, being spared the vandalism that spares nothing else. One, especially good, represents Kenyon Cox, who studied here.

W———, the student from Nebraska, created a sensation by appearing one day in the full regalia of a cowboy, including two immense revolvers, a knife, and a lariat depending from his belt. With the lariat he astonished and dismayed the dodging Frenchmen by lassoing them at will, though they exercised their greatest running and dodging agility to escape. They wanted to know if all Americans went about thus heeled in America.

There is something uncanny about the little Siamese. He is exceedingly quiet and works unceasingly. One day, when the common spirit of mischief was unusually strong among the boys, the bolder ones began to hint at fun in the direction of the Siamese. He quietly shifted a pair of brass knuckles from some pocket to a more convenient one, and although it was done so unostentatiously, the act was observed. He was not disturbed, and has been left strictly alone ever since.

One day the Italian students took the whole atelier down to a little restaurant on the Quai des Grands-Augustins and cooked them an excellent Italian dinner, with Chianti to wash it down. Two Italian street-singers furnished the music, and Mademoiselle la Modèle danced as only a model can.

EVER since New Year's, when Bishop began his great composition for the Salon, our life at the studio had been sadly disarranged; for Bishop had so completely buried himself in his work that I was compelled to combine the functions of cook with those of chambermaid.

This double work, with increasing pressure from my modelling, required longer hours at night and shorter hours in the morning. But I was satisfied, for this was to be Bishop's masterpiece, and I knew from the marvellous labor and spirit that he put into the work that something good would result.

The name of his great effort was "The Suicide." It was like him to choose so grisly a subject, for he had a lawless nature and rebelled against the commonplace. Ghastly subjects had always fascinated him. From the very beginning of our domestic partnership he had shown a taste for grim and forbidding things. Often, upon returning home, I had found him making sketches of armless beggars, twisted cripples, and hunchbacks, and, worse than all, disease-marked vagabonds. A skull-faced mortal in the last stages of consumption was a joy to him. It was useless for me to protest that he was failing to find the best in him by developing his unwholesome tastes. "Wait," he would answer patiently; "the thing that has suffering and character, that is out of the ordinary, it is the thing that will strike and live."

The suicide was a young woman gowned in black; she was poised in the act of plunging into the Seine; a babe was tightly clutched to her breast; and behind the unspeakable anguish in her eyes was a hungry hope, a veiled assurance of the peace to come. It fascinated and haunted me beyond all expression. It was infinitely sad, tragic, and terrible, for it reached with a sure touch to the very lowest depth of human agony. The scene was the dead of night, and only the dark towers of Notre-Dame broke the even blackness of the sky, save for a faint glow that touched the lower stretches from the distant lamps of the city. In the darkness only the face of the suicide was illuminated, and that but dimly, though sufficiently to disclose the wonderfully complex emotions that crowded upon her soul. This illumination came from three ghastly green lights on the water below. The whole tone of the picture was a black, sombre green.

That was all after the painting had been finished. The making of it is a story by itself. From the first week in January to the first week in March the studio was a junk-shop of the most uncanny sort. In order to pose his model in the act of plunging into the river, Bishop had rigged up a tackle, which, depending from the ceiling, caught the model at the waist, after the manner of a fire-escape belt, and thus half suspended her. He secured his green tone and night effect by covering nearly all the skylight and the window with green tissue-paper, besides covering the floor and walls with green rugs and draperies.

The model behaved very well in her unusual pose, but the babe—that was the rub. The model did not happen to possess one, and Bishop had not yet learned the difficulties attending the procuring and posing of infants. In the first place, he found scores of babes, but not a mother, however poor, willing to permit her babe to be used as a model, and a model for so gruesome a situation. But after he had almost begun to despair, and had well advanced with his woman model, an Italian woman came one day and informed him that she could get an infant from a friend of her sister's, if he would pay her one franc a day for the use of it. Bishop eagerly made the bargain. Then a new series of troubles began.

The babe objected most emphatically to the arrangement. It refused to nestle in the arms of a strange woman about to plunge into eternity, and the strange woman had no knack at all in soothing the infant's outraged feelings. Besides, the model was unable to meet the youngster's frequent demands for what it was accustomed to have, and the mother, who was engaged elsewhere, had to be drummed up at exasperatingly frequent intervals. All this told upon both Bishop and Francinette, the model, and they took turns in swearing at the unruly brat, Bishop in English and Francinette in French. Neither knew how to swear in Italian, or things might have been different. I happened in upon these scenes once in a while, and my enjoyment so exasperated Bishop that he threw paint- tubes, bottles, and everything else at me that he could reach, and once or twice locked me out of the studio, compelling me to kick my shins in the cold street for hours at a time. On such occasions I would stand in the court looking up at our window, expecting momentarily that the babe would come flying down from that direction.

When Bishop was not sketching and painting he was working up his inspiration; and that was worst of all. His great effort was to get himself into a suicidal mood. He would sit for hours on the floor, his face between his knees, imagining all sorts of wrongs and slights that the heartless world had put upon him. His husband had beaten him and gone off with another woman; he had tried with all his woman-heart to bear the cross; hunger came to pinch and torture him; he sought work, failed to find it; sought charity, failed to find that; his babe clutched at his empty breasts and cried piteously for food; his heart broken, all hope gone, even God forgetting him, he thought of the dark, silent river, the great cold river, that has brought everlasting peace to countless thousands of suffering young mothers like him; he went to the river; he looked back upon the faint glow of the city's lights in the distance; he cast his glance up to the grim towers of Notre-Dame, standing cold and pitiless against the blacker sky; he looked down upon the black Seine, the great writhing python, so willing to swallow him up; he clutched his babe to his breast, gasped a prayer....

At other times he would haunt the Morgue and study the faces of those who had died by felo-de-se; he would visit the hospitals and study the dying; he would watch the actions and read the disordered thoughts of lunatics; he would steal along the banks; of the river on dark nights and study the silent mystery and tragedy of it, and the lights that gave shape to its terrors. In the end I grew afraid of him.

But all things have an end. Bishop's great work was finished in the first days of March. Slowly, but surely, his native exuberance of spirits returned. He would eat and sleep like a rational being. His eyes lost their haunted look, and his cheeks filled out and again took on their healthy hue. And then he invited his friends and some critics to inspect his composition, and gave a great supper in celebration of the completion of his task. Very generous praise was given him. Among the critics and masters came Gérôme and Laurens at his earnest supplication, and it was good to see their delight and surprise, and to note that they had no fault to find,—was not the picture finished, and would not criticism from them at this juncture have hurt the boy without accomplishing any good? Well, the painting secured honorable mention in the exhibition, and five years later the French government completed the artist's happiness by buying one of his pictures for the Luxembourg Gallery.

But about the picture: the canvas was eight by ten feet, and a frame had to be procured for it. Now, frames are expensive, and Bishop had impoverished himself for material and model hire. So he employed a carpenter in the court to make a frame of thick pine boards, which we painted a deep black, with a gold cornice. The whole cost was twenty- five francs.

Next day we hired a good-sized voiture-à-bras at eight sous an hour, and proceeded to get the tableau down to the court. It was a devilish job, for the ceilings were low and the stairs narrow and crooked. The old gentleman below us was nearly decapitated by poking his head out of his door at an inopportune moment, and the lady below him almost wiped the still wet babe from the canvas with her gown as she tried to squeeze past. The entire court turned out to wish Bishop good success.

The last day on which pictures are admitted to the Salon, there to await the merciless decision of the judges, is a memorable one. In sumptuous studios, in wretched garrets; amid affluence, amid scenes of squalor and hunger, artists of all kinds and degrees have been squeezing thousands of tubes and daubing thousands of canvases in preparation for the great day. From every corner of Paris, from every quarter of France and Europe, the canvases come pouring into the Salon. Every conceivable idea, fad, and folly is represented in the collection, and most of them are poor; but in each and every one a fond hope centres, an ambition is staked.

Strange as it may seem, most of these pictures are worked upon until the very last day; indeed, many of them are snatched unfinished from their easels, to receive the finishing touches in the dust and confusion and deafening noise of the great hall where they are all dumped like so much merchandise. We saw one artist who, not having finished his picture, was putting on the final touches as it was borne ahead of him along the street on the back of a commissionnaire.

And all this accounts for the endless smearing everywhere noticeable, and for the frantic endeavors of the artists to repair the damage at the last moment.

One great obstacle to poor artists is the rigid rule requiring that all tableaux shall be framed. These frames are costly. As a result, some artists paint pictures of the same size year after year, so that the same frame may be used for all, and others resort to such makeshifts as Bishop was compelled to employ. But these makeshifts must be artistically done, or the canvases are ignored by the judges. These efforts give rise to many startling effects.

It was not very long, after an easy pull over the Boulevard St.-Germain, before we crossed the Seine at the Pont de la Concorde, traversed the Place de la Concorde, and turned into the Champs-Elysées, where, not far away, loomed the Palais des Beaux-Arts, in which the Salon is annually held in March. The Avenue des Champs-Elysées, crowded as it usually is in the afternoons, was now jammed with cabs, omnibuses, hand-carts, and all sorts of moving vans, mingling with the fashionable carriages on their way to the Bois. The proletarian vehicles contained art,—art by the ton. The upper decks of the omnibuses were crowded with artists carrying their pictures because they could not afford more than the three-sous fare. And such an assortment of artists!

There were some in affluent circumstances, who rolled along voluptuously in cabs on an expenditure of thirty-five francs, holding their precious tableaux and luxuriantly smoking cigarettes.

The commissionnaires had a great day of it. They are the ones usually seen asleep on the street corners, where, when awake, they varnish boots or bear loads by means of a contrivance on their backs. On this day every one of them in Paris was loaded down with pictures.

Many were the hard-up students, like Bishop, tugging hand-carts, or pairing to carry by hand pictures too large to be borne by a single person. And great fun they got out of it all.

Opposite the Palais de Glace was a perfect sea of vehicles, artists, porters, and policemen, all inextricably tangled up, all shouting or groaning, and wet pictures suffering. One artist nearly had a fit when he saw a full moon wiped off his beautiful landscape, and he would have killed the guilty porter had not the students interfered. Portraits of handsome ladies with smudged noses and smeared eyes were common. Expensive gold frames lost large sections of their corners. But still they were pouring in.

With infinite patience and skill Bishop gradually worked his voiture-à- bras through the maze, and soon his masterpiece was in the crushing mass at the wide entrance to the Salon. There it was seized and rushed along, and Bishop received in return a slip of paper bearing a number.

While within the building we reconnoitred. Amid the confusion of howling inspectors, straining porters bearing heavy pictures, carpenters erecting partitions, and a dust-laden atmosphere, numerous artists were working with furious haste upon their unfinished productions. Some were perched upon ladders, others squatted upon the floor, and one had his model posing nude to the waist; she was indifferent to the attention that she received. Thoughtful mistresses stood affectionately beside their artist amants, furnishing them with delicate edibles and lighting cigarettes for them.

Some of the pictures were so large that they were brought in rolled up. One artist had made himself into a carpenter to mount his mammoth picture. Frightful and impossible paintings were numerous, but the painter of each expected a première médaille d'honneur.

It was nearing six o'clock, the closing hour. Chic demoiselle artistes came dashing up in cabs, bringing with them, to insure safe delivery, their everlasting still-life subjects.

Shortly before six the work in the building was suspended by a commotion outside. It was a contingent of students from the Beaux-Arts marching up the Champs-Elysées, yelling and dancing like maniacs and shaking their heavy sticks, the irresistible Sarah Brown leading as drum-maior. She was gorgeously arrayed in the most costly silks and laces, and looked a dashing Amazon. Then, as always, she was perfectly happy with her beloved étudiants, who worshipped her as a goddess. She halted them in front of the building, where they formed a circle round her, and there, as director of ceremonies, she required them to sing chansons, dance, make comic speeches, and "blaguer" the arriving artists.

The last van was unloaded; the great doors closed with a bang, and the stirring day was ended. All the students, even the porters, then joined hands and went singing, howling, and skipping down the Champs-Elysées, and wishing one another success at the coming exhibition. At the Place de la Concorde we met a wild-eyed artist running frantically toward the Salon with his belated picture. The howls of encouragement that greeted him lent swifter wings to his legs.

The pictures finally installed, a jury composed of France's greatest masters pass upon them. The endless procession of paintings is passed before them; the raising of their hands means approval, silence means condemnation; and upon those simple acts depends the happiness or despair of thousands. But depression does not long persist, and the judgment is generally accepted in the end as just and valuable. For the students, in great part, flock to the country on sketching tours, for which arrangements had been already made; and there the most deeply depressed spirits must revive and the habit of work and hope come into play. Year after year the same artists strive for recognition at the Salon; and finally, when they fail at that, they reflect that there is a great world outside of the Salon, where conscientious effort is acceptable. And, after all, a medal at the Salon is not the only reward that life has to offer.

And then, it is not always good for a student to be successful from the start. Just as his social environment in Paris tries his strength and determines the presence or absence of qualities that are as useful to a successful career as special artistic qualifications, so the trial by fire in the Salon exhibitions hardens and toughens him for the serious work of his life ahead. Too early success has ruined more artists than it has helped. It is interesting also to observe that, as a rule, the students who eventually secure the highest places in art are those whose difficulties have been greatest. The lad with the pluck to live on a crust in a garret, and work and study under conditions of poverty and self-denial that would break any but the stoutest heart, is the one from whom to expect renown in the years to come. Ah, old Paris is the harshest but wisest of mothers!

"H! ah! vive les Quat'z' Arts! Au Molin Rouge—en route!" the lamplit streets of Paris as cab after cab and bus after 'bus went thundering across town toward Montmartre, heavily freighted with brilliantly costumed revellers of les Quat'z' Arts. Parisians ran from their dinner- tables to the windows and balconies, blasé boulevardiers paused in their evening stroll or looked up from their papers at the café-tables, waiters and swearing cabbies and yelling newsboys stopped in the midst of their various duties, and all knowingly shook their heads, "Ah, ce sont les Quat'z' Arts!"?

For to-night was the great annual ball of the artists, when all artistic Paris crawls from its mysterious depths to revel in a splendid carnival possible only to the arts. Every spring, after the pictures have been sent to the Salon, and before the students have scattered for the summer vacation, the artists of Paris and the members of all the ateliers of the four arts—painting, sculpture, architecture, and engraving—combine their forces in producing a spectacle of regal splendor, seen nowhere else in the world; and long are the weeks and hard the work and vast the ingenuity devoted to preparations,—the designing of costumes and the building of gorgeous floats.

During the last three weeks the élèves of the Atelier Gérôme abandoned their studies, forgot all about the concours and the Prix de Rome, and devoted all their energies to the construction of a colossal figure of Gérôme's great war goddess, "Bel-lona." It was a huge task, but the students worked it out with a will. Yards of sackcloth, rags, old coats, paint rags, besides pine timbers, broken easels and stools, endless wire and rope, went into the making of the goddess's frame, and this was covered with plaster of Paris dexterously moulded into shape. Then it was properly tinted and painted and mounted on a chariot of gold. A Grecian frieze of galloping horses, mounted, the clever work of Siffert, was emblazoned on the sides of the chariot. And what a wreck the atelier was after all was finished! Sacré nom d'un chien! How the gardiens must have sworn when cleaning-day came round!

The ateliers in the Ecole are all rivals, and each had been secretly preparing its coup with which to capture the grand prix at the bal.

The great day came at last. The students of our atelier were perfectly satisfied with their handiwork, and the massier made all happy by ordering a retreat to the Café des Deux Magots, where success to the goddess was drunk in steaming "grog Américain." Then Bellona began her perilous journey across Paris to Montmartre and the Moulin Rouge.

This was not an easy task, as she was fifteen feet high; signs and lamp- posts suffered, and sleepy cab-horses danced as their terrified gaze beheld the giant goddess with her uplifted sword. Crowds watched the progress of Bellona on the Avenue de l'Opéra, drawn by half a hundred students yelling the national hymn. The pull up the steep slope of Montmartre was heavy, but in less than two hours from the start at the Ecole the goddess was safely housed in the depths of the Moulin Rouge, there to await her triumphs of the night.

Bishop, besides doing his share in the preparation of the figure, had the equally serious task of devising a costume for his own use at the ball. It was not until the very last day that he made his final decision,—to go as a Roman orator. Our supply of linen was meagre, but our only two clean bed-sheets and a few towels were sufficient, and two kind American ladies who were studying music and who lived near the old church of St. Sulpice did the fitting of a toga. The soles of a pair of slippers from which Bishop cut the tops served as sandals, and some studio properties in the way of Oriental bracelets completed his costume. I was transformed into an Apache Indian by a generous rubbing into my skin of burnt sienna and cadmium, which I was weeks in getting rid of; a blanket and some chicken-feathers finished my array. Our friend Cameron, next door, went in his Scotch kilts. After supper we entered the Boul' Mich' and proceeded to the Café de la Source, where the students of the Atelier Gérôme were to rendezvous.

The Boul' was a spectacle that night. Time had rolled back the curtain of centuries; ancient cemeteries had yielded up their dead; and living ghosts of the ages packed all the gay cafés. History from the time of Adam had sent forth its traditions, and Eves rubbed elbows with ballet- girls. There was never a jollier night in the history of the Quartier Latin.

We found the Café de la Source already crowded by the Gérôme contingent and their models and mistresses, all en costume and bubbling with merriment and mischief. It was ten o'clock before all the students had arrived. Then we formed in procession, and yelled and danced past all the cafés on the Boul' Mich' to the Luxembourg Palace and the Théâtre de l'Odéon, to take the 'buses of the Montmartre line. These we quickly seized and overloaded in violation of the law, and then, dashing down the quiet streets of the Rive Gauche, headed for Montmartre, making a noise to rouse the dead. As we neared the Place Blanche we found the little streets merging from different quarters crowded with people in costume, some walking and others crowding almost innumerable vehicles, and the balconies and portes-cochères packed with spectators. The Place Blanche fronts the Moulin Rouge, and it was crowded and brilliantly lighted. The façade of the Moulin Rouge was a blaze of electric lights and colored lanterns, and the revolving wings of the mill flamed across the sky. It was a perfect night. The stars shone, the air was warm and pleasant, and the trees were tipped with the glistening clean foliage of early spring. The bright cafés fronting the Place were crowded with gay revellers. The poets of Bohemia were there, and gayly attired cocottes assisted them in their fun at the café tables, extending far out into the boulevard under the trees. At one corner was Gérôme's private studio, high up in the top of the house, and standing on the balcony was Gérôme himself, enjoying the brilliant scene below.

As the Bal des Quat'z' Arts is not open to the public, and as none but accredited members of the four arts are admitted, the greatest precautions are taken to prevent the intrusion of outsiders; and wonderful is the ingenuity exercised to outwit the authorities. Inside the vestibule of the Moulin was erected a tribune (a long bar), behind which sat the massiers of the different studios of Paris, all in striking costumes. It was their task not only to identify the holders of tickets, but also to pass on the suitability of the costumes of such as were otherwise eligible to admittance. The costumes must all have conspicuous merit and be thoroughly artistic. Nothing black, no dominos, none in civilian dress, may pass. Many and loud were the protestations that rang through the vestibule as one after another was turned back and firmly conducted to the door.

Once past the implacable tribunes, we entered a dazzling fairy-land, a dream of rich color and reckless abandon. From gorgeous kings and queens to wild savages, all were there; courtiers in silk, naked gladiators, nymphs with paint for clothing,—all were there; and the air was heavy with the perfume of roses. Shouts, laughter, the silvery clinking of glasses, a whirling mass of life and color, a bewildering kaleidoscope, a maze of tangled visions in the soft yellow haze that filled the vast hall. There was no thought of the hardness and sordidness of life, no dream of the morrow. It was a wonderful witchery that sat upon every soul there.

This splendid picture was framed by a wall of lodges, each sumptuously decorated and hung with banners, tableaux, and greens, each representing a particular atelier and adorned in harmony with the dominant ideals of their masters. The lodge of the Atelier Gérôme was arranged to represent a Grecian temple; all the decorations and accessories were pure Grecian, cleverly imitated by the master's devoted pupils. That of the Atelier Cormon repre sented a huge caravan of the prehistoric big- muscled men that appeal so strongly to Cormon; large skeletons of extinct animals, giant ferns, skins, and stone implements were scattered about, while the students of Cormon's atelier, almost naked, with bushy hair and clothed in skins, completed the picture. And so it was with all the lodges, each typifying a special subject, and carrying it out with perfect fidelity to the minutest detail.

The event of the evening was the grand cortège; this, scheduled for one o'clock, was awaited with eager expectancy, for with it would come the test of supremacy,—the awarding of the prize for the best. For this was the great art centre of the world, and this night was the one in which its rivalries would strain the farthest reach of skill.