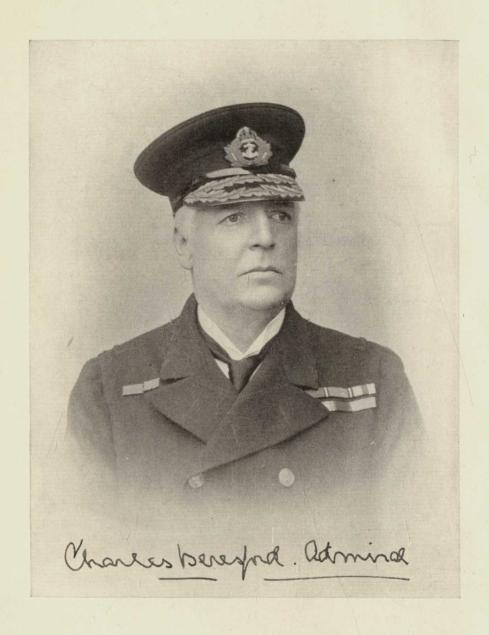

Charles Beresford, Admiral

WITH TWENTY-THREE ILLUSTRATIONS

FOURTH EDITION IN ONE VOLUME

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published (2 vols.) . . . . October 6th, 1914

Second Edition . . . . November, 1914

Third Edition . . . . December, 1914

Fourth Edition (1 vol.) . . . . September, 1916

TO

MY BROTHER OFFICERS

OF THE

ROYAL NAVY

PREFACE

This work is a record of my life from the year 1859, when I entered the Royal Navy, to the year 1909, when I hauled down my flag and came on shore.

For the Introduction and the Notes, which have been written in order to amplify the personal narrative and to connect it with the historical events of the period, Mr. L. Cope Cornford is responsible.

I have dedicated the book to my brother officers of the Royal Navy.

As luck would have it, my career has been of a singularly varied character. And my hope is that, in reading its story, boys and girls, as well as their elders, may find pleasure.

CHARLES BERESFORD

Admiral

1 GREAT CUMBERLAND PLACE, W.

June 1914

CONTENTS

CHAP.

III. THE SHIP OF HAPPIEST MEMORY

IV. THE SHIP OF UNHAPPY MEMORY

VI. STRICT SERVICE

VII. THE CRUISE OF H.M.S. GALATEA—

I. TO THE ANTIPODES

VIII. THE CRUISE OF H.M.S. GALATEA (continued)—

II. MY TWO FAITHFUL SERVANTS

IX. THE CRUISE OF H.M.S. GALATEA (continued)—

III. TAHITI AND THE SANDWICH ISLANDS

X. THE CRUISE OF H.M.S. GALATEA (continued)—

IV. OLD JAPAN. NOTE

XI. THE CRUISE OF H.M.S. GALATEA (continued)—

V. WITH THE DUKE IN JAPAN

XII. THE CRUISE OF H.M.S. GALATEA (continued)—

VI. THE HOMEWARD VOYAGE

XIII. FLAG-LIEUTENANT AT PLYMOUTH

XIV. POLITICAL EVENTS OF 1873-80 AND POSTSCRIPT. NOTE

XV. AN IRISH ELECTION AND IRISH POLITICS

XVI. MEMBER FOR WATERFORD, AND COMMANDER, ROYAL NAVY

XVII. WITH THE PRINCE IN INDIA

XVIII. THE EGYPTIAN WAR—

I. THE BEGINNING OF TROUBLE. NOTE

XIX. THE EGYPTIAN WAR (continued)—

II. THE BOMBARDMENT OF ALEXANDRIA

XX. THE EGYPTIAN WAR (continued)—

III. CHIEF OF POLICE

XXI. THE EGYPTIAN WAR (continued)—

IV. GARRISON WORK

XXII. PASSING THROUGH EGYPT

XXIII. THE SOUDAN WAR OF 1884-5—

I. SUMMARY OF EVENTS. NOTE

XXIV. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

II. HOW WE BROUGHT THE BOATS THROUGH THE GREAT GATE

XXV. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

III. UP THE CATARACTS AND ACROSS THE DESERT

XXVI. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

IV. THE FIRST MARCH OF THE DESERT COLUMN. NOTE

XXVII. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

V. THE DESERT MARCH OF THE FORLORN HOPE

XXVIII. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

VI. THE FIGHT AT ABU KLEA

XXIX. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

VII. THE FIGHT TO REACH THE RIVER

XXX. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

VIII. DISASTER

XXXI. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

IX. THE RESCUE

XXXII. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

X. THE EFFECT OF THE ACTION OF WAD HABESHI

XXXIII. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

XI. THE RETREAT

XXXIV. THE SOUDAN WAR (continued)—

XII. SEQUEL AND CONCLUSION

XXXV. ORGANISATION FOR WAR

XXXVI. THE TWENTY-ONE MILLION

XXXVII. H.M.S. UNDAUNTED—

I. WITH THE MEDITERRANEAN FLEET

XXXVIII. H.M.S. UNDAUNTED (continued)—

II. THE SALVING OF THE SEIGNELAY

XXXIX. THE SECOND SHIPBUILDING PROGRAMME

XL. STEAM RESERVE

XLI. VIEWS AND REVIEWS

XLII. COVETED CHINA. NOTE

XLIII. THE INTROMISSION OF THE ADMIRALS

XLIV. TRAFFICS AND DISCOVERIES—

I. CHINA

XLV. TRAFFICS AND DISCOVERIES (continued)—

II. JAPAN

XLVI. TRAFFICS AND DISCOVERIES (continued)—

III. THE UNITED STATES

XLVII. H.M.S. RAMILLIES

XLVIII. HER MAJESTY'S MIDSHIPMEN

XLIX. THE PARLIAMENTARY ANVIL

LI. BOAT RACING

LII. THE MEDITERRANEAN STATION

LIII. SPORTING MEMORIES—

I. RIDING AND DRIVING

LIV. SPORTING MEMORIES (continued)—

I. SHOOTING

LV. SPORTING MEMORIES (continued)—

III. FISHING

LVI. HOME WATERS: THE LAST COMMAND

POSTSCRIPT. THE MAKING OF AN ADMIRAL

(The "Notes" are by L. COPE CORNFORD)

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

THE AUTHOR … … … … … . . Frontispiece

From a photograph by Heath

CURRAGHMORE

From a photograph by G. D. Croker

SIR JOHN DE LA POER BERESFORD, 4TH MARQUESS OF WATERFORD

CHRISTINA, MARCHIONESS OF WATERFORD

From paintings at Curraghmore

THE AUTHOR AS NAVAL CADET

From a photograph

H.M.S. MARLBOROUGH, 1861

From a painting in the possession of the Author

THE OFFICERS OF H.M.S. SUTLEJ, 1865.

From a photograph

H.R.H. THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH

From a photograph by J. Russell & Sons

PIETER BOTH MOUNTAIN, MAURITIUS

From a photograph

THE AUTHOR AS LIEUTENANT

From a photograph

THE AUTHOR ÆT. 27

From a photograph

LADY CHARLES BERESFORD

From a photograph

THE BOMBARDMENT OF ALEXANDRIA, 11TH JULY 1882

From a chart drawn by the Author at the time

ON BOARD H.M.S. CONDOR, 11TH JULY 1882

From a drawing by Frederic Villiers

PROVOST-MARSHAL AND CHIEF OF POLICE, ALEXANDRIA, JULY 1882

From a drawing by Frederic Villiers

THE AUTHOR'S METHOD OF HAULING BOATS THROUGH THE BAB-EL-KEBIR

After a drawing made on the spot by the Author

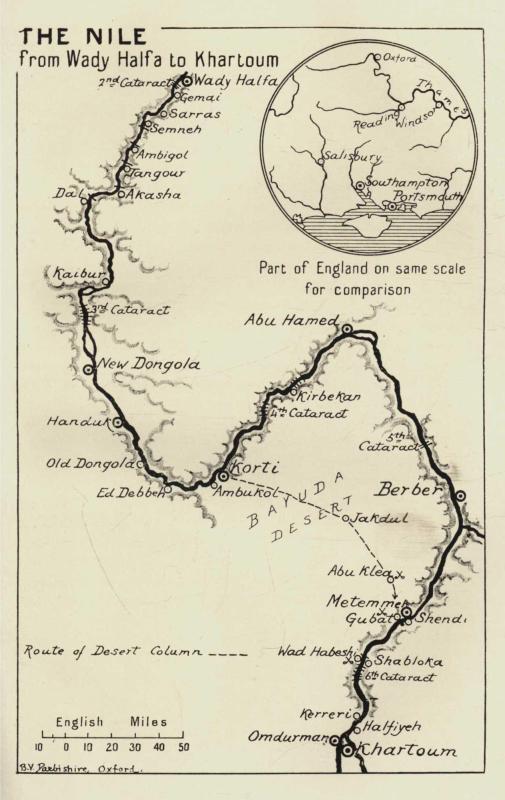

THE NILE FROM WADY HALFA TO KHARTOUM

THE AUTHOR

From a photograph by Hallen, New York

"RUNNING THE GAUNTLET"—THE ACTION OF THE SAFIEH

AT WAD HABESHI, 4TH FEBRUARY 1885

From a painting in the possession of the Author

FIELD-MARSHAL THE RIGHT HON. VISCOUNT WOLSELEY

From a photograph by Elliott & Fry

THE AUTHOR SPEAKING IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS ON

HIS TWENTY-ONE MILLION SHIPBUILDING PROGRAMME,

13TH DECEMBER 1888

From the drawing by J. Walter Wilson in the possession

of the Author

THE AUTHOR, 1898

From a drawing by Phil May in the possession of the Author

H.M.S. KING EDWARD VII ENGAGED IN BATTLE PRACTICE, 1907

From a photograph

(Design of Cover by HAROLD WYLLIE)

THE HOUSE OF BERESFORD

Lord Charles William de la Poer Beresford, born in 1846, was the second of five brothers, sons of Sir John de la Poer Beresford, fourth Marquess of Waterford. Lord Charles's elder brother, Sir John Henry de la Poer Beresford (to give him his full title), Earl and Viscount of Tyrone, Baron de la Poer of Curraghmore in the county of Waterford, and Baron Beresford of Beresford in the county of Cavan, in the Peerage of Ireland, and Baron Tyrone of Haverfordwest in the county of Pembroke, in the Peerage of Great Britain, Knight of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, succeeded to these titles in 1866. Sir John joined the 1st Life Guards. He died in 1895, and was succeeded by his son (nephew to Lord Charles), as presently to be noted.

Of the other three brothers, Lord William de la Poer joined the 9th Lancers and became Military Secretary to five successive Viceroys of India, was a patron of the Turf, and died in 1900; Lord Marcus de la Poer joined the 7th Hussars, took charge of the King's racehorses, an office which he still fulfils, and was appointed Extra Equerry to King George; Lord Delaval James de la Poer (sixteen years younger than Lord Charles) ranched in North America and was killed in a railway accident in 1906.

The five brothers were keen sportsmen, hard riders, men of their hands, high-couraged, adventurous, talented in affairs, winning friendship and affection wherever they went. {xviii} Lord John-Henry, fifth Marquess, the eldest brother, inherited the family tradition of good landlordship. There was never any oppression of tenants on the Waterford estate. In the House of Lords and in the country, Lord Waterford took a strenuous part in the troubled and complex issues of Irish politics; although during the last years of his life he was crippled and helpless, the result of an accident which befell him in the hunting field. Lord William won the V.C. by an act of cool and audacious gallantry in the Zulu war of 1879; renowned for reckless hardihood, there was hardly a bone in his body which he had not broken; and it is probable that his injuries, diminishing his powers of resistance, caused him to succumb to his last illness. Lord Charles has broken his chest-bone,—a piece of which was cut out in his boyhood, leaving a cavity,—pelvis, right leg, right hand, foot, five ribs, one collar-bone three times, the other once, his nose three times; but owing to his extraordinary physique and strict regimen, he is younger and stronger at the time of writing than most men of half his age.

The family home of the five brothers was Curraghmore, a noble estate lying some twelve miles west of Waterford. The great house stands in a cup of the hills, whose slopes are clothed with woods of oak, the primæval forest of Ireland. The oak woods adjoining the house were planted with the design of supplying timber to the Royal Navy. Built foursquare, like most houses in Ireland, the mansion faces upon a vast gravelled quadrangle, closed in on left and right by the long ranges of stables. Beyond the lawns of the terraced garden, beyond the hanging woods, the bony shoulders of the mountains of Comeragh hunch upon the changing sky; nearer hand, darkens the lone hill of Croughaun; and day and night the noise of running waters, the voice of the Clodagh River, flowing through tawny shallow and sombre pool, breaking white-maned upon rock and fall, rises upon the quiet air. Looking westward from the bare summit of the hill above the deer-park, you shall {xix} view the rich valley parcelled into garden and farm and paddock, which are set among deep groves; in the midst, flanked by a gleam of water, the house darkens upon the westering sunlight; and beyond, the sparkling landscape fades into the profound and aerial blue of the mountain wall. Eastward, the rounded bosses of the forest clothe the hills; and in the valley's gentle opening, the river Suir, like a scimitar laid on cloth of tapestry, glimmers dark and bright upon the plain, which, studded with woods and dotted with white specks of villages, stretches to where the dim sea-line merges in the sky.

Over yonder, cloven through the heart of the ancient woods, a green drive rises to the skyline, bordered on either side by rhododendrons, like huge ropes of jewels, three miles long. In the forest there is silence. Few birds or none nest in that deep labyrinth of silver-barked and shaggy trees, rooted for centuries in the mould of their own perennial decay. The martin-cat is lord of that hoary solitude. As a boy, Lord Charles trapped the martin-cats, and presented his mother with a muff made from their skins.

High on the hill rising to the north of the house of Curraghmore, set in a grove of beeches and enclosed within a wall, the last resting-place of the Beresfords opens upon a great and shining prospect of wood and mountain. Here is a wide and broad stone platform, like an ancient altar, the hue of rusty iron, compact of the granite slabs whereon the names of the dead are graven. On three sides it is walled with the tall silver stems of beeches, whose branches high overhead interlace in a green canopy.

Hard by stands the private chapel, once the parish church of Clonegam, a bleak and an unfeatured edifice. Within, there reclines the bronze effigy of the third Marquess, he of the aquiline profile and the full beard, who broke his neck out hunting in 1859. Opposite to him lies the white marble figure, urbane and majestic, of Lord John, his successor, father of Lord Charles Beresford. In the south wall of the chancel, in an arched recess cut out of the {xx} thickness of the wall, the white light falls from an unseen opening above upon the sculptured figure of a lady, sleeping recumbent, and beside her nestles the tiny form of her child. She was the first wife of the fifth Marquess, and she died in childbirth. Near by the private chapel, high uplifted on the bare shoulder of the hill, stands a round tower, a mark for leagues, the monument set up to the memory of the little boy, Marcus, Lord le Poer, heir to Lord Tyrone, afterwards first Marquess. He died from the effects of a fall from his pony, the accident occurring when he was jumping hurdles just outside the great courtyard of the house. His portrait, painted by Gainsborough, hangs in the drawing-room. It is a noble head, done with Gainsborough's inimitable delicacy. The lad's blue eyes gaze frankly out of the picture; his fair hair curls upon his shoulders; his coat is scarlet, with the open falling collar of the time; the face is of a singular beauty.

Near by, in the centre of the wall, hangs Sir Joshua Reynolds's portrait of Sir Francis Delaval, K.B. A tremendous figure, Sir Francis, posed in a commanding attitude upon a hillside, right arm extended, grasping a musket with fixed bayonet, and clad in a rich suit of claret colour and cocked hat. He was the uncle of the wife of the second Marquess of Waterford. By reason of that alliance, many of the Delaval family pictures came to Curraghmore.

Here is Lord Delaval himself, who died in 1808, a nobleman of a somewhat rugged and domineering countenance. Here is the first Marquess of Waterford, with a long hooked nose; he is thin-lipped, narrow-eyed (it seems that he had a squint), wearing the ribbon and star of a Knight of St. Patrick. Henry, second Marquess, was painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence; a handsome head, crowned with a mass of fine light hair. In the hall hangs the portrait of the third Marquess; he whose bronze effigy lies in the chapel. He is reading. With his pale and finely cast features, his thick brown hair and beard, he might have been (but was not) an ascetic student. He married the Hon. Louisa {xxi} Stuart, second daughter and co-heiress of Charles, Lord Stuart dc Rothesay. The Marchioness was a lady of taste, and was considered the most talented amateur painter of her day. She laid out anew the gardens, where heretofore the horses used to graze close to the house, took great interest in the improvement of the mansion itself, designed the Cawnpore Memorial, designed Ford village, formerly the property of the Delavals in Northumberland, and achieved a series of cartoons representing religious subjects, which adorn the walls of the school at Ford.

These and many other ancestral portraits gaze from the walls of gallery and hall and chamber, in the great house of Curraghmore. Each generation as it grew up has traced in them its own lineaments fore-ordained, and has marked the miracle of heredity repeated again and again, from Sir Tristram Beresford, darkling in full armour, through the masterful Katherine le Poer and the beautiful Susanna Carpenter, whose mother was a Delaval, to the penultimate head of the house of De la Poer Beresford.

The entrance hall of the mansion of Curraghmore is the ancient keep, which was built by the De la Poers in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, foursquare, the walls ten feet thick. The rest of the house is eighteenth century. The original edifice is briefly described in The Antient and Present State of the County and City of Waterford, by Charles Smith, published in Dublin in 1740, and in The History, Topography and Antiquities of the County and City of Waterford, by the Rev. R. H. Ryland, published by Murray in 1824. Sir Marcus, first Earl of Tyrone, and his son, afterwards first Marquess of Waterford, made considerable additions, which, according to the date inscribed upon the lead work, were completed in 1771. From the old keep, transformed into an eighteenth-century entrance hall, a flight of steps leads to the inner hall, whence a wide staircase rises, following the walls, and out of which open the reception rooms. These face upon lawn and fountain and terrace. Over the entrance door are carved the family coat; {xxii} and the crest of the De la Poers, a stag couchant bearing a cross upon his forehead, crowns the parapet. Upon the garden front are sculptured the Beresford shield and their crest, "a dragon's head erased, the neck pierced with a tilting spear, and holding the point broken off in the mouth." Motto, Nil nisi cruce.

Such was the home of the five brothers, when their father, Lord John dc la Poer Beresford, in holy orders, succeeded his brother in 1859. Lord Charles Beresford, who had been for some years at school in England, joined the Navy in that year. He came to Curraghmore in his brief and widely spaced intervals of leave, while his brothers came home more frequently during their vacations. In those days, the stables were filled with horses, the house was populous with guests; and the great courtyard in front of the house, now silent, resounded with the cheery bustle of a jovial company coming and going. All winter the house was thronged; there was hunting six days in the week; and more than a hundred horses were stabled at Curraghmore. Lord Charles Beresford has told how that many a time, when, as a midshipman, he was humping beef into the blood-boats for the Fleet, did he think not without envy upon his brothers, each with his two or three hunters, riding to hounds at Curraghmore.

The house of Beresford derives from the "very old and eminent English family of Beresford of Beresford, in the county of Stafford," and from the De la Poers, an ancient Breton family, and their quarterings include the noble houses of Hamilton, Monck, Carpenter, Plantagenet, Lastile and Leon, Mortimer, De Burgh, Holland, Wake, Wevill, Beauchamp, Delaval, Blake. The Beresfords represented the English plantation in the North of Ireland, until the marriage was made which united them with De la Poers, who were of the first English plantation in the South.

SIR JOHN DE LA POER BERESFORD, FOURTH MARQUESS OF

WATERFORD, FATHER OF LORD CHARLES BERESFORD.

CHRISTINA, WIFE OF THE FOURTH MARQUESS OF WATERFORD,

MOTHER OF LORD CHARLES BERESFORD

Tristram Beresford came into Ireland in the reign of James I., as manager of the corporation of Londoners, known as "The Society of the New Plantation in Ulster." {xxiii} The first Tristram settled at Coleraine, in county Londonderry. His son, Sir Tristram, first Baronet, in common with the first created Baronets of Ulster, bore on his shield the open red hand of Ulster, hitherto borne by the forfeited O'Neils. Sir Randal, second Baronet, sat in the first Parliament held after the Restoration.

Sir Tristram, his son, commanded a regiment of foot against King James II., and was attainted. He it was who married the Hon. Nicola Sophia Hamilton, concerning whom a legend of the supernatural is current. Briefly, it is that the friend of her early years, the Earl of Tyrone, visited her after his death, according to agreement, and, to prove the reality of his appearance, touched her wrist, shrivelling nerve and sinew, so that ever afterwards she wore a bracelet of black velvet. A picture, supposed to represent this lady, hangs in Curraghmore. It must be said that the evidence of it extant is so highly dubious, that the story is not worth telling in detail.

Sir Tristram was succeeded by his son, Sir Marcus, fourth Baronet, who married the Lady Katherine de la Poer, who was Baroness in her own right. Thus the two houses were conjoined. Lady Katherine was the only daughter and heiress of James, third and last Earl of Tyrone. She was allowed the Barony of La Poer in fee by resolution of the Irish House of Lords, on 16th November 1767. Sir Marcus her husband was created Earl of Tyrone in 1746. The son of Sir Marcus and Lady Katherine, George De la Poer, was created Marquess of Waterford in 1789, and Knight of St. Patrick at the Institution of the Order in 1783. First Marquess, he was the first De la Poer Beresford.

The De la Poer, Power, or Poher, family traces its descent from Comorre I., Count of le Poher, who married the widow of Jonas, King of Domnonée, and who died A.D. 554. Le Poher was one of the five independent states of Brittany, of which the others were La Domnonée, La Cornouailles, Le Vannes, and Le Leon. The genealogy of the Le Poers is {xxiv} interesting, if only by reason of its romantic names. From Comorre I., Count of le Poher, descended the Counts Comorre, Erispoë, Rivallon, Nominoë. Nominoë married one Argantal, defeated Charles the Bald, drove the Franks out of Brittany, and was proclaimed King of that country in 841. He was succeeded by his son Erispoë, who married Mormohec. From the aforesaid Rivallon descended Salomon, who (having achieved a little murderous intrigue) succeeded King Erispoë, and married Wembrit. From the brother of Salomon, Mathuedoi, descended Alain, Count of Vannes and Duke of Brittany, who fought against the Normans, and who was driven by them to take refuge in England. His son Alain (called Barbe-torte) returned to Brittany, drove out the Normans in his turn, and united Le Poer to the Duchy.

From the Pohers, in the female line, descended Arthur, Duke of Brittany, who was done to death by John, King of England, A.D. 1203. There is this other link between John of England and the De la Poers, that in the demesne of Curraghmore an ancient bridge of stone, over which the English King is said to have passed, spans the river and is called John's Bridge to this day. From the Duchess Constance, the mother of Arthur of Brittany, descended the Duchess Anne, who married King Louis XII. of France. Brittany was thus incorporated in France.

The Pohers seem to have come to England with Duke William of Normandy, called the Conqueror. In 1066 they are found in Devonshire; and later, in Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Herefordshire; a fructuous and an acquisitive clan. They came to Ireland in the reign of the second Henry: then came Sir Robert, Sir Roger, William and Simon. Sir Roger helped in the invasion of Ulster. But the founder of the De la Poers of Curraghmore was Sir Robert, who, in the year 1172, accompanied King Henry II. as Knight Marshal, and to whom was given by the King, the town of Waterford and a great parcel of county Waterford.

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, Sir Henry Sidney, in the course of his account of the province of Munster, communicated to the Lords of the Council, describes his visit to John, Lord le Poer, who was born in 1527. "27th Feb., 1575. The day I departed from Waterford I lodged that night at Curraghmore, the house that Lord Power is baron of, where I was so used, and with such plenty and good order entertained (as adding to it the quiet of all the country adjoining, by the people called Power country, for that surname has been since the beginning of the Englishman's planting inhabitants there), it may be well compared with the best ordered country in the English Pale. And the Lord of the country, though he be of scope of ground a far less territory than his neighbour is, yet he lives in show far more honourably and plentifully than he or any other, whatsoever he be, of his calling that lives in his province."

The "Peerage of Ireland" of 1768 urbanely observes: "It is very remarkable, that in so long a succession in this family, and in a country continually disturbed and torn by rebellion and civil wars, that not one of this family was ever engaged in any rebellion against the crown of England, nor was there ever a forfeiture in the family during the space of six hundred years that they have been planted in Ireland; and they at this day enjoy the family lands, and reside at the same place they were originally settled in, in the county of Waterford. In a grant of letters patent from King Charles II. to this Richard, Lord la Poer, bearing date the 9th May, the twenty-third year of his reign, there is this recital. That the ancestors of the said Richard, Lord la Poer, from their first planting in Ireland, for above four hundred years, had entirely preserved their faith and loyalty to the crown of England, in consideration therefore," etc.

Sir Tristram Beresford, up in the North, fought against King James Second; but the De la Poers harboured that monarch; who in the course of his retreat from Ireland, {xxvi} slept a night at Curraghmore, and departing thence took ship at Waterford, and was no more seen in Erin.

Sir Marcus, the son of Sir Tristram, as above recited, united the two houses by marrying the Lady Katherine le Poer; and their descendants, as in 1768, "at this day enjoy the family lands and reside at the same place they were originally settled in." The earldom of Tyrone, which was extinguished by the death of Lady Katherine's father, the third Earl, was revived in Sir Marcus Beresford. Tracing back the direct line of the De la Poers of Curraghmore, we find that Nicholas de la Poer was summoned to Parliament in 1375, in 1378, and in 1383, by the most ancient writs contained in the Rolls Office in Ireland. This Sir Nicholas of Curraghmore traced his descent from Brian Boru, King of Erin, who died in 1014. The line of Irish Kings (as recorded in Whitaker's Almanack) goes back to A.D. 4; and some say much further.

A collateral branch of the De Pohers, or Powers, was the Barons of Donoyle, or Dunhill, the ruins of whose castle remain to this day. It was stoutly defended against Cromwell by the Baroness; and, according to tradition, was betrayed into the hands of the enemy by the lieutenant of her garrison. These Powers were then transplanted to Connaught, and their estates were forfeited. Another collateral branch was the Powers of Knockbrit, county Tipperary. In the year 1789, to Edmund Power and his wife, who was a daughter of "Buck" Sheehy, was born Marguerite, who became Lady Blessington. It seems that her father, "Buck" Power, dissipated his fortune, as the mode was in those days; that he compelled his daughter to marry one Captain Farmer, who ill-treated her; that Mrs. Farmer left her husband, came to London with her brother, was painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, and, after Farmer's death, married Lord Blessington. Here is a link with my Lord Byron.

The relation of the De la Poer Beresfords with the Delavals of Seaton-Delaval in Northumberland, consists in the marriage of Sir Henry de la Poer, second Marquess {xxvii} (1772-1826), with Lady Susanna Carpenter, who was the granddaughter of Lord Delaval. Her mother, daughter of Lord Delaval, married George, second Earl of Tyrconnel. The Lady Tyrconnel was famed for her beauty. The portrait of her daughter, Lady Susanna, now at Curraghmore, represents a singularly beautiful, fair-haired creature, delicately featured, blue-eyed. The Delavals would seem to have been a high-spirited, reckless, and spendthrift race. Extravagant entertainments were devised at their house of Seaton-Delaval, which was built by Sir John Vanbrugh, playwright and architect. The actor Foote was a friend of the family; they were devoted to amateur theatricals; and Garrick once lent Drury Lane Theatre to them. The Delavals were singularly addicted to practical jokes; a tendency to the same diversion has reappeared in later generations. Lord Delaval's only son died young, and the title expired. There is a picture of the sturdy, brown-haired lad at Curraghmore. It is worth noting that an ancestor of Lady Susanna, and, therefore, of Lord Charles Beresford, was a naval officer of some distinction. George Delaval, vice-admiral of the Red, was present at the action fought off Cape Barfleur in May 1692.

The generation of the second Marquess, he who married the Lady Susanna, produced an Archbishop: even the Right Honourable and Most Reverend Lord John George de la Poer Beresford, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of all Ireland. He was born in 1773, and died in 1862. Possessing great wealth, he was known for his immense benefactions. He gave largely to Dublin University, and to the College of Saint Columba; restored the Cathedral at Armagh at a cost of £30,000; and augmented the salaries of his clergy. The bust of this magnificent prelate stands in the private chapel at Curraghmore. His body is interred in Armagh Cathedral. The Archbishop bequeathed his Property in county Cavan to Lord Charles Beresford; the townlands on the estate bearing such euphonious names as Ballyheady, Corraleehan Beg, Crockawaddy, {xxviii} Kiltynaskeelan, Derrynacrieve, Gubnagree, Scrabby, Tullynamoultra.

The third Marquess, Sir Henry de la Poer, having met his death in the hunting-field, was succeeded in 1859 by his brother, Sir John, who was Dean and Prebendary of Mullaghbrack, in the Arch-diocese of Armagh. He married, in 1843, Christina Leslie, daughter of Charles Powell-Leslie. She was born in 1820, and lived until 1905. The Marchioness learned to ride when she was between forty and fifty years of age, and speedily became a noted rider to hounds. Their sons, as before recited, were Sir John-Henry de la Poer, fifth Marquess of Waterford; Lord Charles, Lord William, Lord Marcus, and Lord Delaval; of whom Lord Charles and Lord Marcus survive at the time of writing. Lord Charles was born on 10th February 1846 at Philipstown Glebe, Louth. It was the year of the great famine; and at Curraghmore, half a regiment was then quartered in the house.

The fifth Marquess, elder brother of Lord Charles, was succeeded in 1895 by his son, nephew to Lord Charles. The sixth Marquess lost his life by a sad accident in 1911. The present heir is a minor.

In this chronicle, brief as it is, three notable figures cannot be omitted: Mr. Commissioner John Beresford, Admiral Sir John Poo Beresford, and the Marshal. (For information concerning these worthies, I have drawn upon the Dictionary of National Biography.)

John Beresford, whose name is even yet occasionally reproached by the descendants of his political opponents, was born in 1738, and died in 1805. He was the second son of Marcus, Earl of Tyrone (brother of the first Marquess) and Lady Katherine, Baroness de la Poer. Appointed First Commissioner of Revenue in 1780, John Beresford became in fact ruler of Ireland. He was entrusted by Pitt with the management of all Irish affairs. Viceroys came and viceroys went, but Beresford continued to hold a position "greater than that of the Lord Lieutenant {xxix} himself"; much to the indignation of Lord Fitzwilliam, who, when he was appointed Lord Lieutenant, permitted himself to address the First Commissioner in terms so indigestible that Beresford promptly challenged him. The duel, however, was prevented. John Beresford took a great part in the preparation and passing of the Act of Union; was M.P. for Waterford and a Privy Councillor; and did much to improve the city of Dublin, the fine Custom-house being built under his auspices. He married Barbara Montgomery, who was one of the "Three Graces" in the painting done by Sir Joshua Reynolds, now in the National Gallery. The other two Graces were her sister, Lady Mountjoy, and the Marchioness of Townshend.

Admiral Sir John Poo Beresford (1768 (?)-1884) was a natural son of the first Marquess of Waterford. He entered the Royal Navy in 1782; fought a smart action in the capture of the French store-ships in Hampton Roads on 17th May 1795; and performed distinguished service in the West Indies. He took part in the famous eight months' blockade off Ferrol in 1808, and in the blockade of Lorient, commanding one of those "weather-beaten ships upon which the Grand Army never looked." In 1810 he was co-operating off Lisbon with Wellington's army, with which his younger brother the Marshal, in command of the Portuguese Army, was also co-operating. He represented in Parliament, in succession, Coleraine, Berwick, Northallerton, and Chatham. In 1835 he was Junior Lord of the Admiralty. His career, a combination of fighting seaman, member of Parliament, and Junior Lord, presents a singular resemblance to the career of his relative, Lord Charles Beresford.

Marshal Beresford, or, more precisely, General Viscount William Carr Beresford, was born in 1768 and died, full of years and honours, in 1854. Son of the first Marquess, he also, like the Admiral, bore the bar sinister on his escutcheon. As captain of the 69th Regiment, he was with Lord Hood at Toulon in 1793, and commanded the storming party at the tower of Martello. He was present at the {xxx} captures of Bastia, Calvi, and San Fiorenzo. After service in India, Beresford's brigade led the march across the desert in the Egyptian campaign of 1801. Eighty-four years later, his relative, Captain Lord Charles Beresford, took his Naval Brigade across the desert with Sir Herbert Stewart's forlorn hope.

Beresford was present at the capture of Cape Colony under Baird in 1805. Then he went up to Buenos Ayres, and with 1200 men took that place from the Spanish. After three days' hard fighting, Beresford was driven out of Buenos Ayres by an overwhelming force. Then he went with Sir Arthur Wellesley to Portugal; where he commanded two brigades under Sir John Moore. In the terrible winter retreat to Corunna, Beresford's brigade, told off to assist the rescue, was constantly engaged with the French vanguard. At Corunna, Beresford fought on the English left, achieving the greatest distinction.

In 1809, at the request of the Portuguese Government, Beresford was appointed to reorganise the Portuguese Army. Gifted with that marvellous capacity for handling men and for organisation, which Irishmen of English descent sometimes combine with a reckless gallantry, Beresford speedily transformed an ill-found, insubordinate mob into an efficient, well-fed, fighting force. He knew how to establish obedience to discipline, together with the confidence that good conduct would be rewarded; or, in Lord Charles Beresford's phrase, he coupled "commendation with condemnation." The Portuguese Government made him marshal in the Portuguese Army while he was lieutenant-general in the British Army; nor did the annoyance discovered by British officers at the double rank, which gave Wellington trouble, perturb the Marshal in the least. His Portuguese fought well alongside the English at Busaco, an action which earned Beresford the K.C.B. and other decorations.

He won the battle of Albuera, defeating Soult, though not without heavy losses. The victory was said to be due {xxxi} to the action of one of his Staff, rather than to Beresford's tactics; a good deal of controversy was waged on the subject, in which the Marshal, after his retirement, took a vigorous part; but the fact remains that Albuera was won.

Beresford was present at the tremendous siege of Badajoz and at the battle of Salamanca, at which he was severely wounded. He speedily recovered, and fought at Vittoria in 1813, in the battles of the Pyrenees, and in the battles of Nivelle, Nive, and Arthez. He then returned to Portugal to command the Portuguese Army; so that he was not present at Waterloo. At the conclusion of the war he was created Baron. He left Portugal in 1822, and took his seat in the House of Lords, where he was a sturdy supporter of the policy of the Duke of Wellington. In 1828 he was appointed Master-General of Ordnance. In 1830 he retired.

Wellington wrote of the Marshal in 1812: "All that I can tell you is that the ablest man I have yet seen with the army, and that one having the largest views, is Beresford ... he is the only person capable of conducting a large concern." And upon another occasion, Wellington affirmed that if he were removed by death or illness, he would recommend Beresford to succeed him, not because he was a great general, but because he alone could "feed an army."

General Lord Beresford married the Hon. Louisa Hope, his first cousin, daughter of the Most Rev. William Beresford, Archbishop of Tuam and Lord Decies, and widow of Thomas Hope, author of Anastatius. His stepson was A. T. Beresford-Hope, sometime member for Cambridge University.

In 1824 the Marshal purchased the ancestral estate of the Beresfords in Staffordshire. His portrait, which bears a singular resemblance to Lord Charles, hangs in Curraghmore. It depicts a burly, martial figure, gorgeous in full uniform, with a broad, jovial, open countenance, and a bold blue eye, head thrown back, and a vast spread of chest and {xxxii} shoulder. Endowed with extraordinary physical strength, he was a born fighter, a great administrator, a big, warm-hearted, quick-tempered, irrepressible Beresford.

The formal list of his titles is: Viscount and Baron in the peerage of England, Duke of Elvas in the peerage of Spain, Conde de Trancoso in the peerage of Portugal, K.C.B., etc., colonel-in-chief 60th Rifles, colonel 16th Regiment, general in the English Army, marshal in the Portuguese Army.

The generations pass: the House remains. The House of de la Poer Beresford derives, from among other sources innumerable, from the Counts of Brittany, in the sixth century; from Brian Boru, King of Ireland, in the eleventh; from the Beresfords, that "very old and eminent English family," Norman in origin; from the Delavals of Northumberland, whose forefathers fought in the Crusades. This is the virtue of ancient lineage: that from generation to generation, an honourable tradition of service, of peculiar obligation, gathers reinforcement. Every scion of the House is judged by the stern company of his forefathers; who, together with his dower of body and of mind and heritage of land or wealth, bequeath him warning or example. No traffic in titles can purchase that unique inheritance, nor can any forfeiture of material possessions diminish its essential value.

L.C.C.

I saw the Navy for the first time in the year 1858, when I was twelve years old. The Channel Squadron came into the Downs; the admiral, who was a friend of my father, invited me to visit his flagship. The admiral put off from Deal in a six-oared galley, and I was taken into a second boat. Both crews began to pull with all their might. I remember being intensely excited, beating with my hand on the gunwale and urging the men to row faster. We were overhauling the admiral, when the boat in which I was slackened her pace.

"Row!" I shouted. "Why don't you go on rowing?"

"We can't pass the admiral, sir," said the coxswain. And that was my first lesson in naval etiquette.

As we drew near to the ships, there arose a great tumult of shouting, and I could see the men running to and fro and racing aloft, and presently they stood in rows along the yards, manning yards in honour of the arrival of the admiral.

The neatness and order of the stately ships, the taut rigging, the snowy sails, the ropes coiled down neatly on deck: these things left an abiding impression upon my youthful mind.

It was in the winter of the same year, 1858-9, that a certain young soldier, who had fought throughout the Indian Mutiny with great gallantry and conspicuous ability, came to his home in County Waterford on his first furlough. He was Lieutenant Roberts, V.C.; now Field-Marshal Earl Roberts of Kandahar.

"During the winter months," he writes, "I hunted with the Curraghmore hounds, and was out with them the day before Lord Waterford was killed. We had no run, and at the end of the day, when wishing us good-bye, he said 'I hope, gentlemen, we shall have better luck next time.' 'Next time' there was 'better luck' as regarded the hunting, but the worst of all possible luck for Lord Waterford's numerous friends; in returning home after a good run, and having killed two foxes, his horse stumbled over quite a small ditch, throwing his rider on his head; the spinal cord was snapped, and the fine sportsman breathed his last in a few moments." (Forty-one years in India. By Field-Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar. Bentley. 2 vols. London, 1897, p. 451, vol. 1.)

My father, the Rev. Lord John Beresford, succeeded to the marquisate. In the same year, 1859, I joined the Naval Service. I remember, some years afterwards, thinking with some degree of envy of my two younger brothers, each of whom had three hunters, while I was only the "blood-boat" (the jolly-boat bringing beef to the ship) midshipman of a man-of-war.

At that time the Navy consisted of both sailing ships and steamships. Steam was used as seldom as possible in those ships which were fitted with masts and yards. The flagships of the Cape of Good Hope, East Indies and China, South-east Coast of America, Pacific and North America and West Indies stations were all sailing ships. The Navy List of 1859 gives the names of no less than 548 "effective" ships, together with a list of 185 "steam gunboats" and a list of 121 vessels employed in Harbour Service.

That there was so large a number of "steam gunboats" {3} was the result of the Crimean war, during which very many were built for service in the Baltic. There is a story that an admiral returning from foreign service noticed eight gunboats aground on the Spit. Upon his inquiry, he was informed by one of his crew that they were "commanded by these old Baltic War mates and second masters, the sort what knows nothing and fears nothing." But of the sailing master there will be more to say.

The line-of-battle sailing ships which were flagships on naval stations abroad were:—the Boscawen, 70 guns, Rear-Admiral Hon. Sir Frederick W. Grey, Cape of Good Hope; Calcutta, 84, Rear-Admiral Sir Michael Seymour, East Indies and China; Cumberland, 70, Rear-Admiral Sir Stephen Lushington, S.E. Coast of America; Ganges, 84, Rear-Admiral R. L. Baynes, Pacific; Hibernia, 104, Rear-Admiral H. J. Codrington, Malta; Indus, 78, Vice-Admiral Sir Houston Stewart, North America and West Indies.

The number of ships distributed among the various stations in 1859 was no less than 130. "Trade follows the flag."

East Indies and China . . . . . . . 36

Pacific . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

W. Coast of Africa . . . . . . . . 17

N. America and W. Indies . . . . . 14

S.E. Coast of America . . . . . . . 13

Mediterranean . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Cape of Good Hope . . . . . . . . . 5

Australia . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

River Gambia . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Channel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

---

Total 130

===

The presence of so large a force in Chinese waters was due to the affair of "the lorcha Arrow," which occurred on 8th October, 1856, in the Canton River. The Arrow, a small vessel flying the British flag, was captured by the Chinese authorities and the crew were arrested on a charge of piracy. In the result, Admiral Sir Michael Seymour bombarded {4} Canton. Operations were suspended during the Indian Mutiny, to be resumed in 1858, with the assistance of France. Canton was captured, and the treaty of Tien-Tsin was concluded with China. It was not, however, ratified, and in June, 1859—six months before I entered the Navy—hostilities were resumed, to terminate in the burning of the Summer Palace at Pekin, and the subsequent signing of a convention.

I was sent to sea for the somewhat vague reasons which so often determine a boy's future. There was a belief that I was of a delicate constitution, and an impression—perhaps justified—that I needed discipline. I was sent to Bayford School in England when I was very young, together with two of my three brothers. We were known as the three "wild Irish." Among my schoolfellows were the present Lord Rosebery, James Lowther, Lord Newport, Lord Claud Hamilton and Lord George Hamilton, Lord Worcester, and Lord Methuen. From Bayford I went to the educational establishment of the Rev. David Bruce Payne (afterwards Canon) at Deal, where I first saw the ships of the Royal Navy, as already related. Canon Payne was a splendid type of the best British clergyman, and I had a great respect and affection for him. I was afterwards a pupil of the Rev. Mr. Foster, of Stubbington, Fareham.

I received my nomination from Captain Charles Eden, C.B., and qualified as a naval cadet on 12th December, 1859. The qualifying certificate must be signed by the candidate; a regulation which, simple as it seems, was nearly my undoing.

"Do you always sign your Christian name William with one 'l'?" asked the examiner.

It was a critical moment. Irish resource supplied the answer.

I said, "Only sometimes, sir."

The examiner smiled grimly. But he passed me. It was my first narrow escape in the Navy.

I have the faded blue paper before me as I write. The signature, laboriously written in a round hand, is "Charles Wiliam Delapoer Beresford."

The qualifying examination was not very formidable in those easy days. The knowledge required consisted of a little "English," less French or Latin (with the "aid of a dictionary"), a "satisfactory knowledge of the leading facts of Scripture and English History," a certain amount of geography, and an elementary knowledge of arithmetic, algebra and Euclid. The preliminary course of education afforded to "Volunteers," as the naval cadets used to be called, at the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, had been abolished in 1837, and for the next twenty years cadets were sent straight to sea. In 1857, cadets were entered for training in the Illustrious, Captain Robert Harris. The number of cadets exceeding the accommodation in the ship, the Britannia was commissioned on 1st January, 1859, by Captain Harris. But not for many years did the entrance examination become the competitive ordeal for which cramming is the only preparation, known to the present generation. But I remember Admiral William Bowles, commander-in-chief of Portsmouth, taking me kindly by the shoulder and saying, "Well, my little man, you are very small for your age. Why are you being sent to sea?"

I said that I wanted to go to sea.

"Are you good at your books?" asked the admiral. "Bless me, I know many an admiral who could not pass the examination you have passed. Good Heavens, what they expect boys to do nowadays!"

The Britannia was then moored at the entrance to Haslar Creek in Portsmouth Harbour, where the depot ships of the submarines are moored to-day. Alongside her, in the following year, lay the training frigate Eurydice, which was afterwards capsized off the Isle of Wight on 24th March, 1878, when 318 lives were lost out of a complement of 320. I learned to heave the lead from the chains of the Eurydice.

In addition to the ordinary school curriculum on board the Britannia, the cadets were taught seamanship, gunnery and navigation. Book-work did not interest me, but I took great pains to become proficient in seamanship, in which I always secured a high place.

A cadet entering the Britannia under 14 years of age, would be rejected from the Service if he failed to pass the fourth quarterly examination after his entrance. Having entered the Britannia in December, 1859, I was sent to sea in March, 1861. I was very happy during my time in the Britannia. Out of school time, we did a great deal of boat-pulling. My boat was called the Gazelle. I remember that one day, when I borrowed a private boat to put off to the Gazelle, my comrades pushed me out into the stream, and I drifted out to Spithead, without oars. There was nothing in the boat but a painter, which I considered it to be my duty neatly to coil down. Then I sat still and waited until a boat came to fetch me.

Seamanship was taught by the use of models, and sail-drill was taught upon the mizen-mast. I remember being haunted by a doubt lest the handling of small models, and going aloft in a stationary ship, might not enable me to practise the knowledge thus acquired when I came to deal with the real full-size objects and to go aloft in a ship at sea. My prevision was largely justified; and when I came to command a ship, I made the youngsters learn their business by handling real things and not the models of them. For if anything goes wrong while teaching a youngster, for instance, to lay out a 6-ton anchor upon a model, he puts it right with his finger and thumb and thinks he can do the same with the real anchor.

The captain of the Britannia was Robert Harris, to whom the Service owes the inestimable benefit of cadet training ships. The first lieutenant was George S. Nares (now Vice-Admiral Sir George S. Nares, K.C.B.). He commanded the Challenger in her voyage of scientific discovery of 1872, during which he was recalled to proceed {8} upon his celebrated voyage of Arctic exploration. Another lieutenant was William H. Heaton, whose long whiskers afforded the cadets much innocent amusement. On a windy day his whiskers used to stream backwards over his shoulders. Lieutenant Heaton chose to wear his stripes running longitudinally up his arm, a peculiarity which exemplifies the prevailing latitude with regard to uniform. There was no rule prescribing the pattern of cap or great-coat worn in the Service. Officers might wear the mohair band and badge on any kind of cap that took their fancy. Some of them used to transfer plain clothes buttons to a uniform coat or greatcoat, if they were going ashore, for the sake of economy; for we were nearly all poor in those days. The chaplain and naval instructor was the Rev. Robert M. Inskip.

My chest on board the Britannia stood between the chests of poor "Andy" Wauchope and Henry John Thoroton Hildyard. Both subsequently left the Navy for the Army. The late Major-General Andrew Gilbert Wauchope, D.S.O., was fatally wounded at Magersfontein during the South African war. General Sir Henry J. T. Hildyard, G.C.B., K.C.B., retired in 1911, after long and distinguished service. I was strongly inclined to follow the example of my comrades and to join the Army; and I have since occasionally regretted that I remained in the Navy, in which Service there is less opportunity for attaining the highest rank.

I was raised to the rank of "captain" in the Britannia; but I regret to say that my enjoyment of that dignity was singularly brief, for I was disrated upon the same day, even before I had time to put on the stripe. For my delight at my promotion so exhilarated me, that I forgot to resist the temptation to empty a bread-barge upon the head of the old master-at-arms as he was coming up the hatchway, and the spectacle was so amusing that I stayed to laugh at it.

When I entered the Service, the system of training {9} young seamen, as well as cadets, was in operation. To Sir James Graham, First Lord of the Admiralty, is due the credit of introducing the training of seamen. In 1854, he caused the Illustrious, two-decker, to be commissioned for that purpose, under the command of Captain Robert Harris. The fact was that as sails gave place to steam and as the science of gunnery progressed, it became necessary to enter seamen as boys and to train them for continuous service. For some time the short service and long service systems were concurrent. When I went to sea, captains still entered men direct from the merchant service, and very good seamen they were. They were engaged for a commission, at the end of which they could re-engage or not as they pleased. But in the meantime, under the admirable administration of Captain Harris, "Jimmy Graham's novices," as they were called, earned an excellent reputation in the Fleet; and continuous service gradually replaced intermittent service. In the continuous service system resided our chief superiority over foreign Navies. The objection to it on the part of the Government was (and is) the increasing permanent charge of pensions. But in the interests of the Service and of the country, it cannot be too clearly understood that the system is well worth the cost, and that the revival of the short service system is profoundly to be regretted.

NOTE

H.M.S. Britannia.—She was the seventh ship of her name. She was launched at Plymouth in 1820, was pierced for 120 guns, and her complement was 900 men. Her length, beam and draught were 205 feet, 53 feet and 18 feet respectively. In the Crimean war, she landed 200 men as part of the naval brigade which assisted the Army at the siege of Sevastopol, and took part in the bombardment of that town. She was commissioned on 1st January, 1859, by Captain Robert Harris, as a training ship for cadets. {10} The Britannia was stationed first in Portsmouth Harbour, then at Dartmouth. She was broken up in 1869. The memory of Captain Robert Harris deserves to be held in high honour. Vice-Admiral Sir William Fanshawe Martin, who himself achieved great reforms in the discipline of the Fleet, while in command of the Mediterranean Fleet, wrote to Captain Harris under date 18th January, 1861, "There is no man in England whose opportunity of doing good to our country for ages to come is greater than yours; and assuredly the Navy is greatly your debtor." (The Story of the Britannia, by Commander E. P. Statham, R.N. Cassell.)

The successor of the Britannia in which Lord Charles Beresford received his training, the eighth of her name, known and remembered with affection by all naval officers save the new generation, lay at Dartmouth for more than forty years, when her functions were transferred to the colleges on shore. (The King's Ships, by H. S. Lecky, Lieut. R. N. Muirhead. Vol. 1.)

On the 25th of March, 1861, I was appointed naval cadet in the Marlborough. As I climbed up her side by the hand-rungs, while my chest was being hoisted in over all, I perceived two huge men looking down upon me, and I heard one say to the other:—

"That white-faced little beggar ain't long for this world, Dick."

The speaker was John Glanville (called Clamfy Glanville), boatswain's mate (of whom more anon), and he addressed this lugubrious remark to Dicky Horne, the quartermaster, a very fat man. It was a far from encouraging welcome to the sea; but the fact was that I had been ill, and was feeling very cold as I climbed up the side of the ship. At first, I was much disappointed at having been sent to a large ship, for we youngsters had a notion that there were more freedom and independence in a small ship; and besides, I wanted to go to China. But I went to China all in good time.

The Marlborough was the flagship of the Mediterranean station. She was a wooden line of battleship, three-decker, launched in 1835, 4000 tons burthen old measure, 6390 displacement new measure, fitted with single screw horizontal Maudslay engines. The length of her gundeck was 245 feet 6 inches, her extreme beam was 61 feet, her maximum draught was 26 feet. Her complement was 950, and she always carried 100 or more supernumeraries. She was pierced for 131 guns and she carried 121 guns. She was {12} one of the first ships to be fitted with wire lower rigging. In the Marlborough the old 24-inch hemp cable was used for laying out anchor at drill. It was the same class of cable as that which was used in Nelson's time; it was superseded by the chain cable.

The vice-admiral in command of the Mediterranean station was Sir William Fanshawe Martin (called "Fly" Martin); the captain, William H. Stewart; the commander, Thomas Brandreth: three of the finest officers that ever lived. The captain of the Fleet was Rear-Admiral Sydney C. Dacres, C.B. His duties were those of what we should now call a chief of staff. The office was subsequently abolished; and it was always my desire to see it restored.

Ships in those days were manned according to the number of guns they carried. The theory was that if the boats' crews were absent from the ship, there should always be sufficient men on board to work the sails and the guns. The watch-bills were made out upon this principle, the men being distributed among what were called the "parts of the ship." In the case of a newly commissioned ship, the making out of the watch-bills and assigning his place to each man, was the first thing to be done. It was no small task, especially as no printed forms were supplied for the purpose. The watch-bills were ruled and entered by the officers on paper supplied by themselves, and were arranged upon the tradition handed down for centuries. Even the signalmen supplied their own pencils and paper. Each ship made its own arrangement. It was not until 1860 that uniform watch-bills, quarter-bills and station-bills were instituted.

The men were classed in the following categories, each "part of the ship" being divided into port watch and starboard watch.

The Forecastlemen

The Foretopmen

The Maintopmen

The Mizentopmen

The Gunners

{13}

The Afterguard

The Royal Marines

The Idlers

The Forecastlemen were most experienced seamen. They wore their caps a little differently from the others. They manned the foreyard, and worked the foresail, staysail, jib, flying jib, jibboom, flying jibboom and lower studdingsails.

The Foretopmen worked the foretopsail, foretopgallant and foreroyal yards, foretopgallantmast, foretopmast and topgallant studding-sails.

The Maintopmen worked the maintopsail, maintopgallant and main-royal yards and maintopgallantmast, maintopmast and topgallant studding-sails.

The Mizentopmen worked the mizentopsail, mizentopgallant and mizen-royal yards, and mizentopgallantmast, mizentopmast and mizencourse (if there was one), also the driver.

The upper-yard men were the smartest in the ship, whose character largely depended upon them.

The Gunners, assisted by the Afterguard, worked the mainsail and mainyard. These were generally old and steady men, who were not very quick aloft. The gunners were also responsible for the care and maintenance of the gun gear, side tackles, train tackles and the ammunition. The senior warrant officer was the gunner.

There were only three warrant officers:—gunner, boatswain and carpenter.

The Royal Marines were divided between fore and aft, working on forecastle and quarterdeck. I remember seeing a detachment of Marines, upon coming aboard, fallen in while the blacksmith, lifting up each man's foot behind him, wrenched off and dropped into a bucket the metal on the heel of his boot, lest it should mark the deck.

The Afterguard worked on the quarterdeck and helped with the mainyard. They were the less efficient men and were therefore employed under the eye of the commander.

The Idlers were not idlers. They were so called because (theoretically) they had their nights in, although actually they turned out at four o'clock a.m. They were artificers, such as carpenters, caulkers, plumbers, blacksmiths, etc. They worked all day at their several trades until their supper-time. They were nearly all old petty officers, steady and respectable. It was part of their duty to man the pumps every morning for washing decks. I made up my mind that, if ever I was in a position to do so, I would relieve them of an irksome and an inappropriate duty.

In action, the carpenters worked below decks, stopping holes with shot-plugs, while many of the other Idlers worked in the magazines. Among the Idlers was the ship's musician—unless the ship carried a band—who was a fiddler. He used to play to the men on the forecastle after working hours and when they manned the capstan. Personally I always considered the name of Idlers to be anomalous. They are now called Daymen.

Among the ship's company were several negroes. At that time, it was often the case that the captain of the hold and the cooper were coloured men.

An instance of the rapidity and efficiency of the organisation of the Marlborough occurred upon the night before she sailed for the Mediterranean. She was newly commissioned, and she carried a large number of supernumeraries on passage. We took out 1500 all told. A fire broke out on the orlop deck; the drum beat to quarters; every man instantly went to his station, to which he had previously been told off; and the fire was speedily extinguished. The event was my first experience of discipline in a big ship.

The nature of the discipline which was then in force, I learned on the way out to the Mediterranean. In the modern sense of the word, discipline was exemplified by the Royal Marines alone. I cannot better convey an idea of the old system than by means of an illustration. Supposing that a Marine and a bluejacket had each committed an offence. The Marine was brought up on the quarter-deck before the {15} commander, and the charge was read to him. The commander asked him what he had to say. The prisoner, standing rigidly to attention, embarked upon a long rambling explanation. If his defence were invalid, the commander cut him short, and the sergeant gave his order. "Right turn. Quick march." The Marine, although continuing to protest, obeyed automatically, and away he went. He continued to talk until he was out of hearing, but he went. Not so the bluejacket. He did not stand to attention, not he. He shifted from one foot to the other, he hitched his breeches, fiddled with his cap, scratched his head.

"Well, sir," said he, "it was like this here, sir," ... and he began to spin an interminable yarn.

"That'll do, my man," quoth the commander. But, not at all. "No, sir, look here, sir, what I wants to say is this"—and so on, until the commander had to order a file of Marines to march him below.

But both Marine and bluejacket had this in common: each would ask the commander to settle the matter rather than let it go before the captain; and the captain, to sentence him rather than hold a court-martial.

The explanation of the difference between the old system of discipline and the new is that in the sailing days it was of the first importance that the seaman should be capable of instant independent action. The soldier's uniformity and military precision were wholly unsuited to the sailor, who, at any moment, might have to tackle an emergency on his own initiative. If a seaman of the old days noticed anything wrong aloft, up he would run to put it right, without waiting for orders. Life and death often hung upon his promptitude of resource.

In the old days, we would often overhear such a conversation as the following:—

Officer: "Why the blank dash didn't you blank well do so-and-so when I told you?"

Man: "Why didn't I? Because if I had I should have been blank well killed and so would you."

Officer: "Damn you, sir, don't you answer me! I shall put you in the report."

Man: "Put me in the ruddy report, then."

And the next day the commander, having heard both sides, would say to the officer,

"Why, the man was quite right." And to the man, "You had no right to argue with the officer. Don't do it again. Now get away with you to hell."

And everyone would part the best of friends.

The change came with the improvement and progress in gunnery, which involved, first, the better drilling of the small-arm companies. In my early days, the small-arm companies used to drill with bare feet. Indeed, boots were never worn on board. It was of course impossible to wear boots going aloft for a sailor going aloft in boots would injure the heads and hands of his topmates. Occasionally the midshipmen went aloft barefooted like the men. So indurated did the feet of the sailors become, that they were unable to wear boots without discomfort, and often carried them when they were ashore.

A sailor's offences were hardly ever crimes against honour. They rather arose from the character induced by his calling. Its conditions were hard, dangerous and often intensely exciting. The sailor's view was devil-may-care. He was free with his language, handy with his fists and afraid of nothing. A smart man might receive four dozen for some violence, and be rated petty officer six months afterwards. Condemnation was then the rule. Personally, I endeavoured to substitute for it, commendation. For if there are two men, one of whom takes a pride in (say) keeping his rifle clean, and the other neglects it, to ignore the efficiency of the one is both to discourage him and to encourage the other.

Before the system of silence was introduced by the Marlborough the tumult on deck during an evolution or exercise was tremendous. The shouting in the ships in Malta Harbour could be heard all over Valetta. The Marlborough introduced the "Still" bugle-call. At the {17} bugle-call "Still" every man stood motionless and looked at the officer. For in order to have an order understood, the men must be looking at the officer who gives it. During the Soudan war, I used the "Still" at several critical moments. Silence and attention are the first necessities for discipline. About this time the bugle superseded the drum in many ships for routine orders.

There were few punishments, the chief punishment being the cat. The first time I saw the cat applied, I fainted. But men were constantly being flogged. I have seen six men flogged in one morning. Even upon these painful occasions, the crew were not fallen in. They were merely summoned aft "for punishment"—"clear lower deck lay aft for punishment" was piped—and grouped themselves as they would, sitting in the boats and standing about, nor did they even keep silence while the flogging was being inflicted. The officers stood within three sides of a square formed by the Marines. Another punishment was "putting the admiral in his barge and the general in his helmet," when one man was stood in a bucket and the other had a bucket on his head.

Very great credit is due to Admiral Sir William Martin, who reformed the discipline of the Fleet. The Naval Discipline Act was passed in 1861; the New Naval Discipline Act in 1866. In 1871 a circular was issued restricting the infliction of corporal punishment in peace time. Flogging was virtually abolished in 1879. (Laird Clowes' The Royal Navy, vol. 7.) Now we have proper discipline and no cat. In former days, we had the cat but no proper discipline.

The men were granted very little leave. They were often on board for months together. When they went ashore, there they remained until they had spent their last penny; and when they came on board they were either drunk or shamming drunk. For drunkenness was the fashion then, just as sobriety is, happily, the fashion now. In order to be in the mode, a man would actually feign drunkenness on coming aboard. In many a night-watch after leave had been {18} given have I superintended the hoisting in of drunken men, who were handed over to the care of their messmates. To-day, an intoxicated man is not welcomed by his mess, his comrades preferring that he should be put out of the way in cells. It was impossible to keep liquor out of the ship. Men would bring it aboard in little bladders concealed in their neckties. Excess was the rule in many ships. On Christmas Day, for instance, it was not advisable for an officer to go on the lower deck, which was given up to license. I remember one man who ate and drank himself to death on Christmas Day. There he lay, beside a gun, dead. Other cases of the same kind occurred in other ships.

The rations were so meagre that hunger induced the men constantly to chew tobacco. For the same reason I chewed tobacco myself as a boy. Nor have I ever been able to understand how on such insufficient and plain diet the men were so extraordinarily hardy. They used to go aloft and remain aloft for hours, reefing sails, when a gale was blowing with snow and sleet, clad only in flannel (vest) serge frock and cloth or serge trousers, their heads, arms and lower part of their legs bare. Then they would go below to find the decks awash in a foot of water, the galley fire extinguished, nothing to eat until next meal time but a biscuit, and nothing to drink but water.

Seamen often curse and swear when they are aloft furling or reefing sails in a gale of wind; but I have never heard a sailor blaspheme on these occasions. Their language aloft is merely a mode of speaking. Although in the old days I have heard men blaspheme on deck, blasphemy was never heard aloft in a gale. To be aloft in a whole gale or in a hurricane impresses the mind with a sense of the almighty power of the Deity, and the insignificance of man, that puny atom, compared with the vast forces of the elements.

In later life, I once said to a young man whom I heard using blasphemous language in a club:

"If you were up with me on the weather yard-arm of a topsail yard reefing topsails in a whole gale, you would be {19} afraid to say what you are saying now. You would see what a little puny devil a man is, and although you might swear, you would be too great a coward to blaspheme."

And I went on to ram the lesson home with some forcible expressions, a method of reproof which amused the audience, but which effectually silenced the blasphemer.

The fact is, there is a deep sense of religion in those who go down to the sea in ships and do their business in the great waters. Every minister of God, irrespective of the denomination to which he belongs, is treated with respect. And a good chaplain, exercising tact and knowing how to give advice, does invaluable service in a ship, and is a great help in maintaining sound discipline, inasmuch as by virtue of his position he can discover and remove little misunderstandings which cause discontent and irritation.

The discomforts of the Old Navy are unknown to the new. The sanitary appliances, for instance, were placed right forward in the bows, in the open air. If the sea were rough they could not be used. On these occasions, the state of the lower deck may with more discretion be imagined than described. As the ship rolled, the water leaked in through the rebated joints of the gun-ports, and as long as a gale lasted the mess-decks were no better than cesspools. It is a curious fact that in spite of all these things, the spirits of both officers and men rose whenever it came on to blow; and the harder it blew, the more cheery everyone became. The men sang most under stress of weather; just as they will to-day under the same conditions or while coaling ship. After a gale of wind, the whole ship's company turned-to to clean the ship.

In those days the men used to dress in cloth trousers and tunic with buttons. The men used to embroider their collars and their fronts with most elaborate and beautiful designs. They had two hats, a black hat and a white hat, which they made themselves. The black hats were made of straw covered with duck and painted. Many a man has lost his life aloft in trying to save his heavy black hat from being blown away.

The fashion of wearing hair on the face was to cultivate luxuriant whiskers, and to "leave a gangway," which meant shaving upper lip, chin and neck. Later, Mr. Childers introduced a new order: a man might shave clean, or cultivate all growth, or leave a gangway as before, but he might not wear a moustache only. The order, which applied to officers and men (except the Royal Marines) is still in force.

Steam was never used except under dire necessity, or when entering harbour, or when exercising steam tactics as a Fleet. The order to raise steam cast a gloom over the entire ship. The chief engineer laboured under considerable difficulties. He was constantly summoned on deck to be forcibly condemned for "making too much smoke."

We were very particular about our gunnery in the Marlborough; although at the same time gunnery was regarded as quite a secondary art. It was considered that anyone could fire a gun, and that the whole credit of successful gunnery depended upon the seamanship of the sailors who brought the ship into the requisite position. The greater number of the guns in the Marlborough were the same as those used in the time of Nelson, with their wooden trucks, handspikes, sponges, rammers, worms and all gear complete. The Marlborough was fitted with a cupola for heating round-shot, which were carried red-hot to the gun in an iron bucket. I know of no other ship which was thus equipped.

The gunnery lieutenant of the Marlborough, Charles Inglis, was gifted with so great and splendid a voice, that, when he gave his orders from the middle deck, they were heard at every gun in the ship. We used to practise firing at a cliff in Malta Harbour, at a range of a hundred yards or so. I used to be sent on shore to collect the round-shot and bring them on board for future use. I remember that when, in the course of a lecture delivered to my men on board the Bulwark more than forty years afterwards, I related the incident, I could see by their faces that my audience did not believe me; though I showed to them the shot-holes in the face of the cliff, which remain to this day. {21} On gunnery days, all fires were extinguished, in case a spark should ignite the loose powder spilt by the boys who brought the cartridges to the guns, making a trail to the magazines. At "night quarters," we were turned out of our hammocks, which were lashed up. The mess-tables were triced up overhead. The lower-deck ports being closed, there was no room to wield the wooden rammer; so that the charges for the muzzle-loading guns were rammed home with rope rammers. Before the order to fire was given, the ports were triced up. Upon one occasion, so anxious was a bluejacket to be first in loading and firing, that he cherished a charge hidden in his hammock since the last night quarters, a period of nearly three months, and, firing before the port was triced up, blew it into the next ship.

In those days, the master was responsible for the navigation of the ship. He was an old, wily, experienced seaman, who had entered the Service as master's mate. (When I was midshipman in the Defence, the master's assistant was Richard W. Middleton, afterwards Captain Middleton, chief organiser of the Conservative Central Office.) The master laid the course and kept the reckoning. As steam replaced sails, the office of master was transferred to the navigating officer, a lieutenant who specialised in navigation. The transformation was effected by the Order in Council of 26th June, 1867.

The sail-drill in the Marlborough was a miracle of smartness and speed. The spirit of emulation in the Fleet was furious. The fact that a certain number of men used to be killed, seemed to quicken the rivalry. Poor Inman, a midshipman in the Marlborough, a great friend of mine, his foot slipping as he was running down from aloft, lost his life. His death was a great shock to me.

The men would run aloft so quickly that their bare feet were nearly indistinguishable. Topmasts and lower yard were sent down and sent up at a pace which to-day is inconceivable.

I once saw the captain of the maintop hurl himself bodily down from the cap upon a hand in the top who was slow in {22} obeying orders. That reckless topman was Martin Schultz, a magnificent seaman, who was entered by the captain direct from the Norwegian merchant service, in which he had been a mate.

Mr. George Lewis, an old topmate of mine, who was one of the smartest seamen on board H.M.S. Marlborough, has kindly sent to me the following interesting details with regard to the times of sail-drill and the risks incidental to the evolutions.

Time allowed Time in

by Admiral. _Marlborough_.

Min. Sec. Min. Sec.

Cross topgallant and royal yards 1 0 0 30

Down topgallant yards with royal

yards across 2 0 1 13

Up topgallant mast, cross upper

yards and loose sails 2 30 1 27

Shift topgallant masts from royal

yards across 7 0 5 40

Up topgallant mast and make all

plain sail 4 0 2 40

Up topgallant mast and make all

possible sail 6 0 3 0

Shift topsails from plainsail 6 0 4 50

In all boom boats from away aloft 7 0 6 0

Out all boom boats 7 0 5 40

Away lifeboat's crew 0 30 0 20

What Mr. Lewis means by "admiral's time," let him explain in his own words. "When our admiral" (Sir William Martin) "was captain of the Prince Regent, which was considered the smartest ship in the Navy, he brought all her times of all her drills to the grand old Marlborough along with him; and you know, my lord, that he allowed us six months to get our good old ship in trim before we drilled along with the Fleet; but we started to drill along with the Fleet after three months, and were able to beat them all."

"Now, my lord," continues Mr. Lewis, "I come to one of the smartest bits of our drill. When we were sailing in the Bay of Naples under all possible sail, our captain wanted to let the world see what a smart ship he had and what a smart lot of men was under him. From the order 'Shift topsails and courses make all possible sail again'"—which really means that the masts were stripped of sails and again {23} all sails were hoisted—"Admiral's time 13 minutes, our time 9 minutes 30 seconds. All went without a hitch, within 400 yards of our anchorage."

Mr. Lewis proceeds to recount a very daring act of his own. "We were sending down upper yards and topgallant mast one evening, and it was my duty to make fast the lizard. But I could only make fast one hitch, so I slid down the mast rope and it turned me right over, but I managed to catch the lizard and hold on to it, and so saved the mast from falling on the hundred men that were in the gangway. No doubt if it had fallen on them it would have killed a good many...."

What happened was that Lewis, in the tearing speed of the evolution, not having time properly to secure the head of the mast as it was coming down, held the fastening in place while clinging to the mast rope and so came hurtling down with the mast. He adds that he "felt very proud"—and well he might—when the captain "told the admiral on Sunday that I was the smartest man aloft that he had ever seen during his time in the Service." He had an even narrower escape. "I was at the yard-arm when we had just crossed" (hoisted into place). "I was pulling down the royal sheet and someone had let it go on deck, and I fell backwards off the yard head-foremost. I had my arm through the strop of the jewel block, and it held me, and dropped me in the topmast rigging, and some of my topmates caught me."

Mr. Lewis himself was one of the smartest and quickest men aloft I have ever seen during the whole of my career. The men of other ships used to watch him going aloft. "My best time," he writes—and I can confirm his statement "from ''way aloft' to the topgallant yard-arm was 13 seconds, which was never beaten." It was equalled, however, by Ninepin Jones on the foretopgallant yard. The topgallant and royal yard men started from the maintop, inside of the topmast rigging, at the order '"way aloft." The height to be run from the top, inside of the topmast rigging, {24} to the topgallant yard-arm was 64 feet. From the deck to the maintop was 67 feet. At one time, the upper-yard men used to start from the deck at the word "away aloft"; but the strain of going aloft so high and at so great a speed injured their hearts and lungs, so that they ascended first to the top, and there awaited the order "away aloft."

The orders were therefore altered. They were: first, "midshipmen aloft," when the midshipmen went aloft to the tops; second, "upper-yard men aloft," when the upper-yard men went aloft to the tops, and one midshipman went from the top to the masthead.