The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Boys' Book of Rulers, by Lydia Hoyt Farmer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Boys' Book of Rulers Author: Lydia Hoyt Farmer Release Date: November 20, 2015 [EBook #50510] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOYS' BOOK OF RULERS *** Produced by Emmy, Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The aim of this book is to give in as concise manner as possible, consistent with graphic narration and biographical completeness, the most important and interesting events in the lives of these famous rulers; together with a brief history of the various epochs in which they lived, and a description of the manners and customs of the people comprising the several nations governed by these illustrious monarchs.

| PAGE | |

| Agamemnon | 1 |

| Cyrus the Great | 30 |

| Alexander the Great | 71 |

| Julius Cæsar | 110 |

| Charlemagne | 142 |

| Alfred the Great | 169 |

| Richard Cœur de Lion | 195 |

| Robert Bruce | 233 |

| Ferdinand V. of Spain | 266 |

| Philip II. of Spain | 291 |

| Gustavus Adolphus | 312 |

| Louis XIV. | 334 |

| Peter the Great | 367 |

| Frederick the Great | 398 |

| Napoleon I. | 433 |

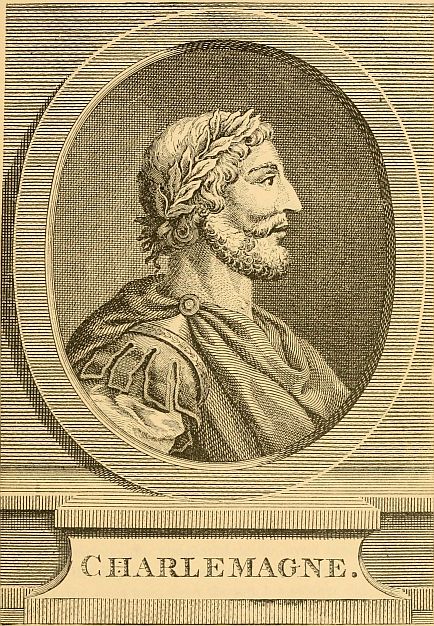

| Charlemagne | Frontispiece |

| Jupiter sending the Evil Dream to Agamemnon | Page 9 |

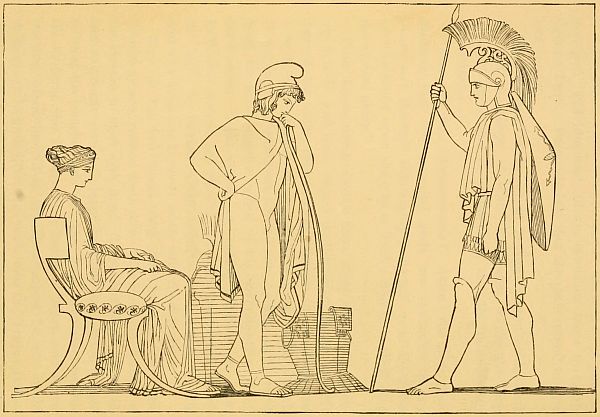

| Hector chiding Paris | 11 |

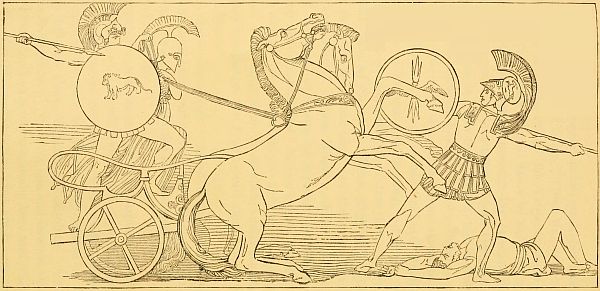

| Diomed casting his Spear against Mars | 17 |

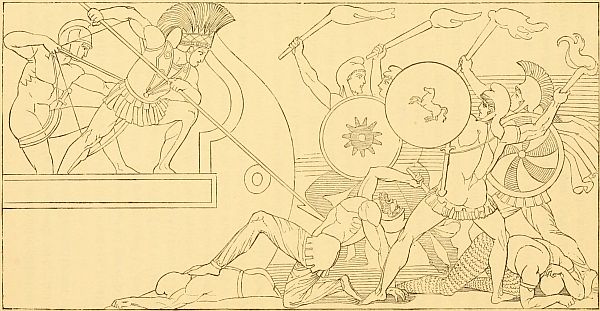

| Ajax defending the Greek Ships against the Trojans | 18 |

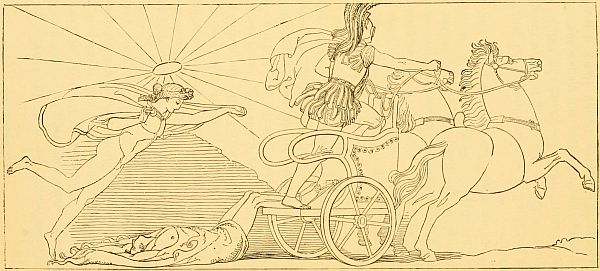

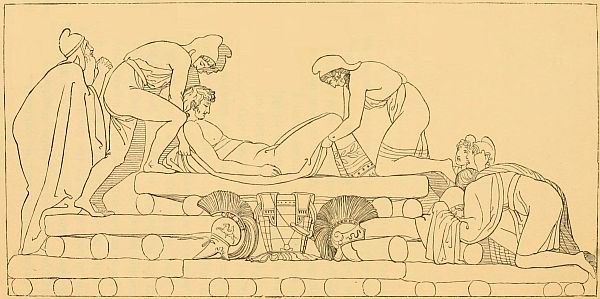

| Hector’s Body dragged at the Car of Achilles | 26 |

| The Funeral of Hector | 27 |

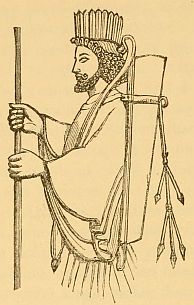

| Persian Guardsman carrying Bow and Quiver | 37 |

| Persian Soldier with Battle-Axe | 37 |

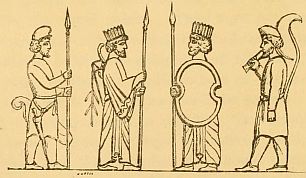

| Persian Foot Soldiers | 37 |

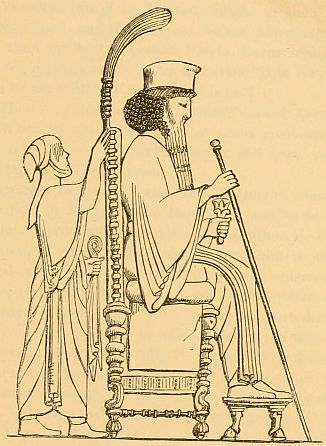

| Persian King seated on his Throne | 38 |

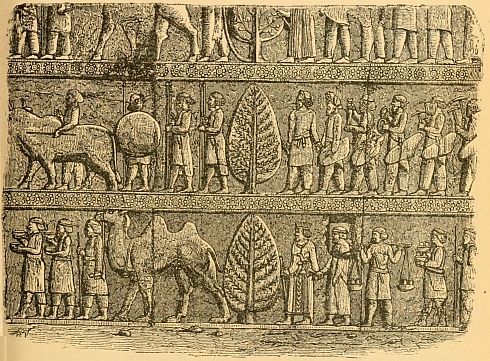

| Persian Subjects bringing Tribute | 58 |

| Chart of the Country around Babylon | 60 |

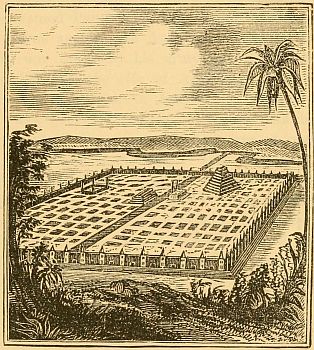

| Supposed Plan of Ancient Babylon | 62 |

| Babylonian King | 64 |

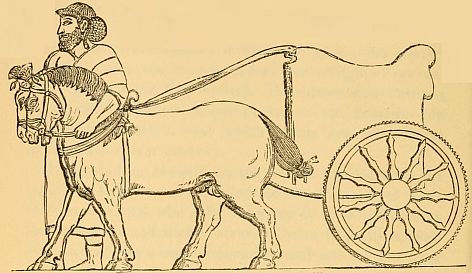

| Persian Chariot | 67 |

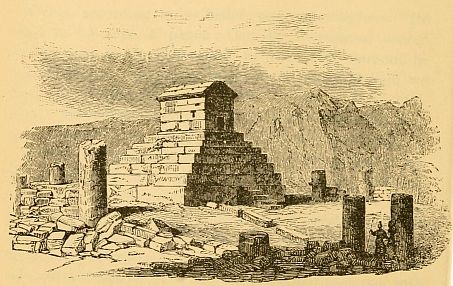

| Tomb of Cyrus | 67 |

| Ruins of Babylon | 70 |

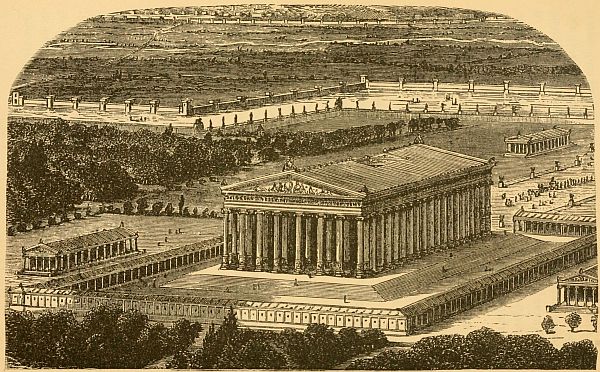

| Temple of Diana at Ephesus | 72 |

| Alexander the Great | 74 |

| Demosthenes | 80 |

| Darius | 92 |

| Julius Cæsar—from the Antique Bust | 110 |

| Julius Cæsar | 116 |

| Cæsar in Gaul | 122 |

| [x]The Landing of Julius Cæsar in Britain | 124 |

| Charlemagne—from Early Engraving | 142 |

| The Huns at Châlons | 144 |

| “Thrust him away or thou diest in his stead” | 147 |

| Charlemagne | 152 |

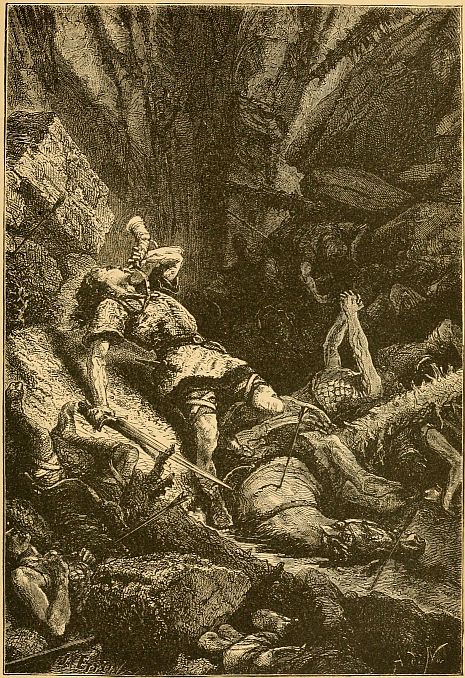

| Death of Roland | 160 |

| Alfred the Great | 170 |

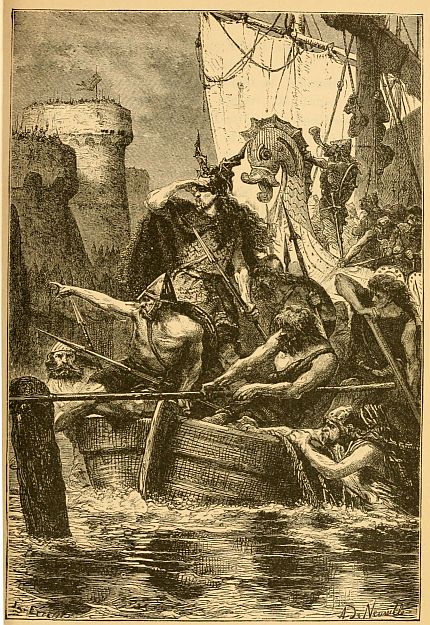

| The Northmen invading France | 174 |

| Alfred the Great | 182 |

| Alfred and the Cakes | 186 |

| Richard Cœur de Lion | 196 |

| Richard Cœur de Lion | 208 |

| Richard tearing down the Austrian Banner | 221 |

| “Most Holy Land, Farewell!” | 228 |

| King John | 230 |

| Warren, Earl of Surrey, Governor of Scotland under Edward I. | 235 |

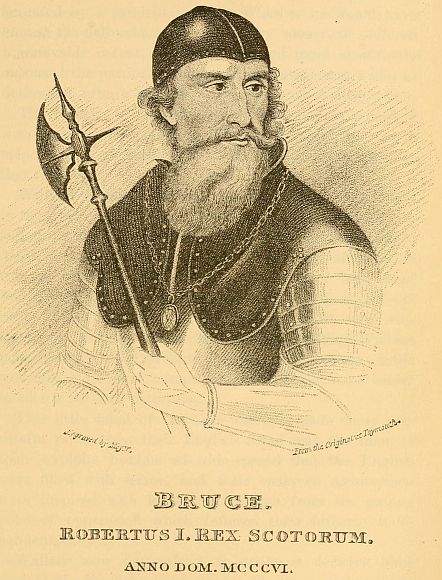

| Robert Bruce | 238 |

| “Bruce was not slow in taking the warning” | 243 |

| “See! I have spoiled my good battle-axe” | 260 |

| Ferdinand of Aragon | 266 |

| Isabella of Castile | 268 |

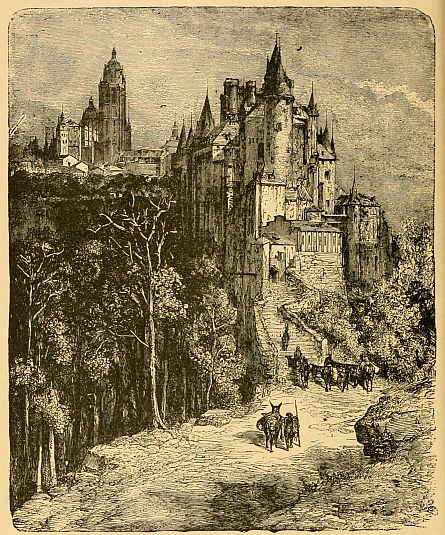

| Segovia: The Alcazar and Cathedral | 271 |

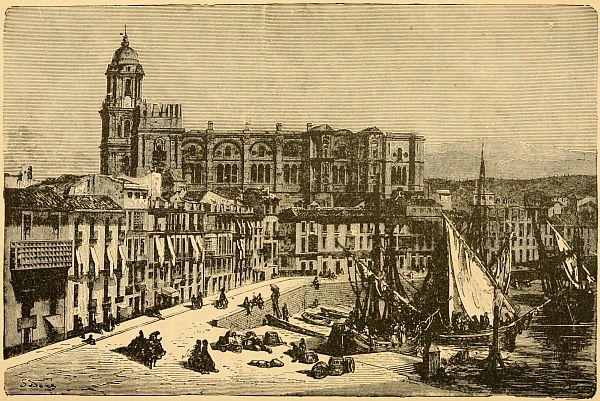

| The Cathedral and Port of Malaga | 274 |

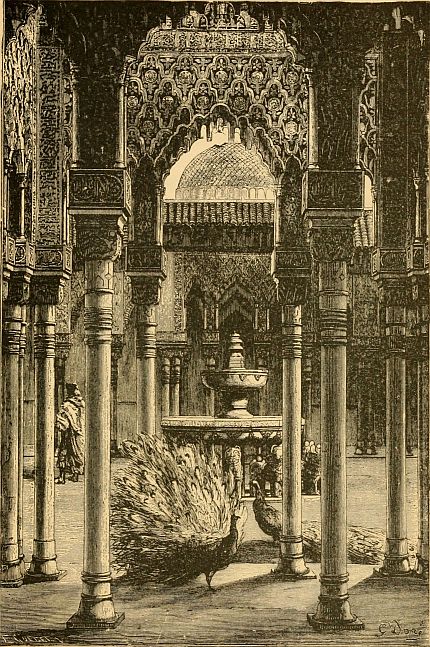

| Court of Lions, Alhambra | 280 |

| Columbus | 282 |

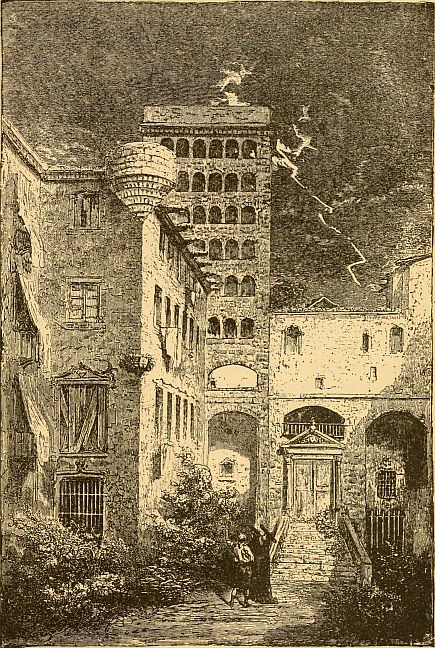

| Prison of the Inquisition at Barcelona | 286 |

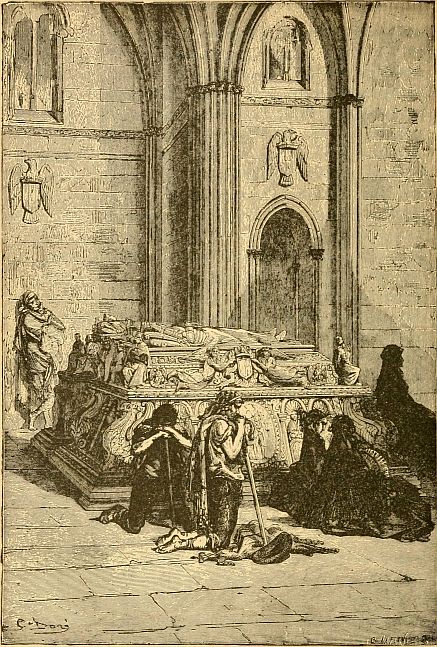

| Tomb of Ferdinand and Isabella in the Cathedral of Granada | 289 |

| Philip II. | 291 |

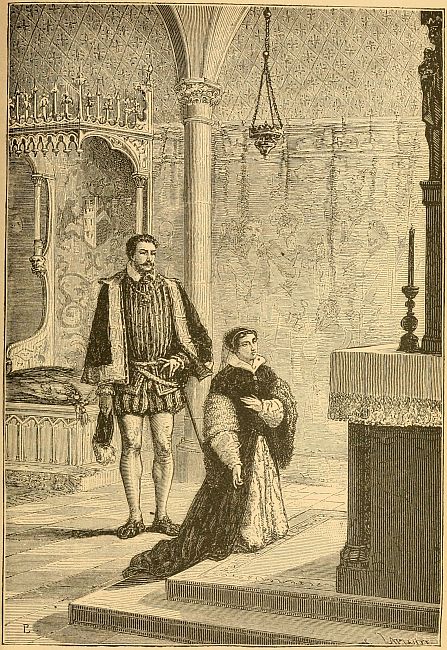

| Queen Mary plighting her Troth to Philip | 292 |

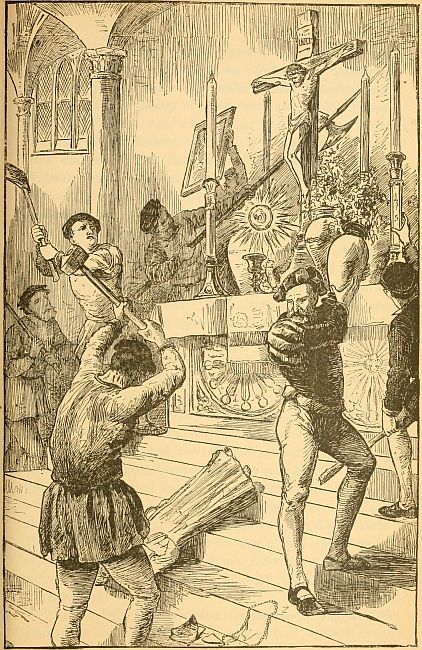

| Destroying Statues, etc., in the Cathedral at Antwerp | 304 |

| [xi]Philip II. | 308 |

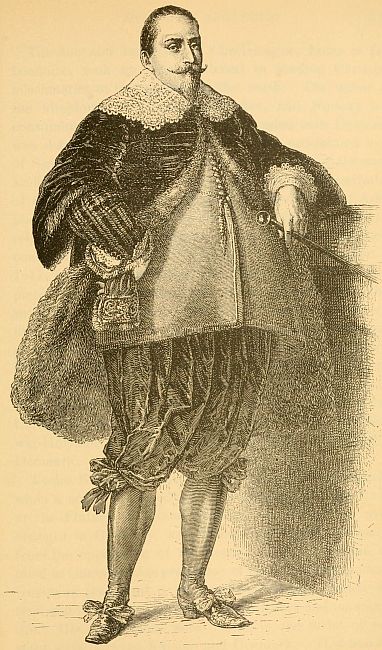

| Gustavus Adolphus | 312 |

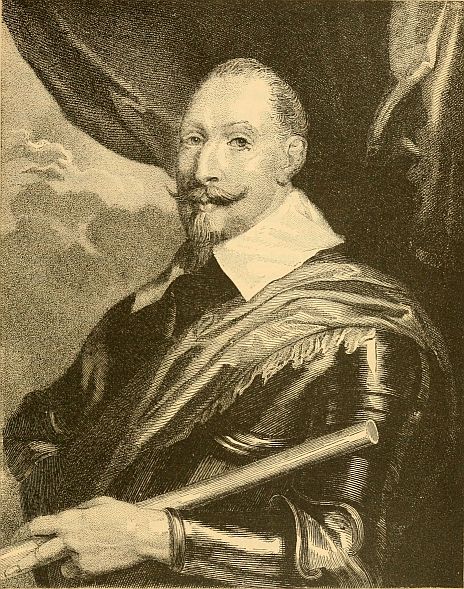

| Gustavus Adolphus—from a picture by Van Dyck | 318 |

| Death of Gustavus and his Page | 332 |

| Louis XIV. | 334 |

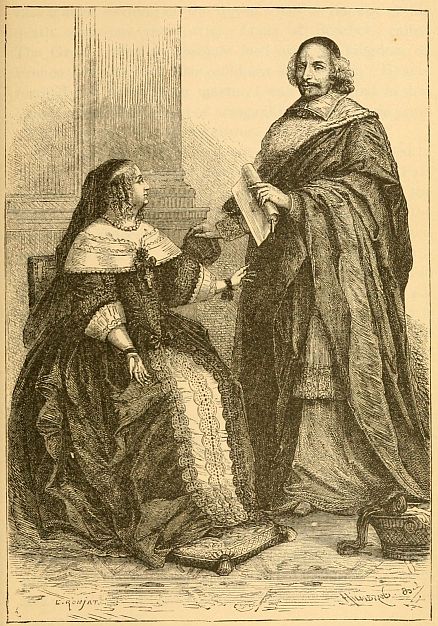

| Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin | 340 |

| Louis XIV. taking leave of Fouquet | 344 |

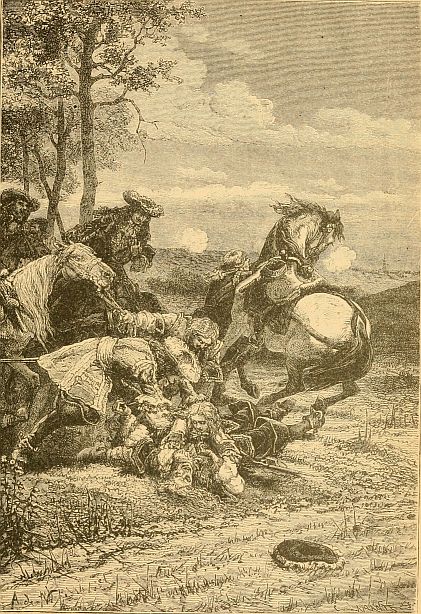

| Death of Turenne | 350 |

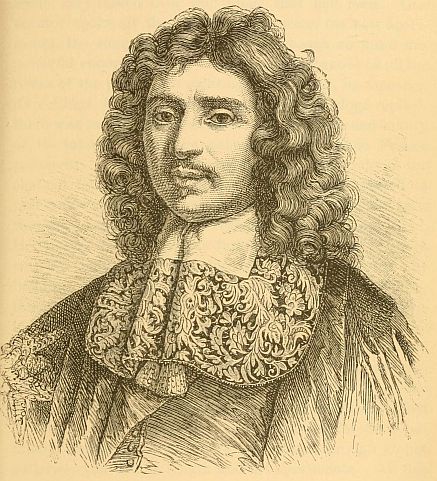

| Jean Baptiste Colbert | 352 |

| Revocation of the Edict of Nantes | 354 |

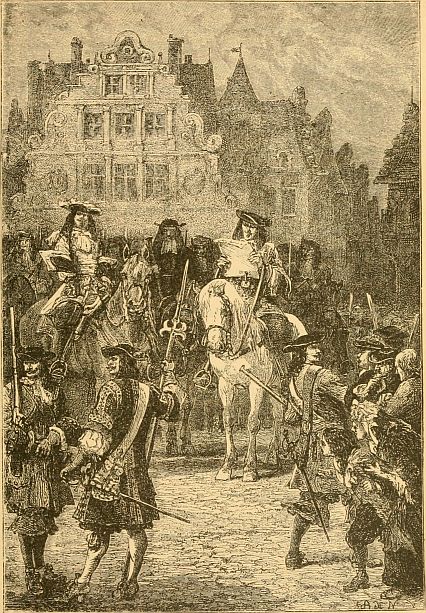

| Peter the Great | 368 |

| The Krémlin of Moscow | 373 |

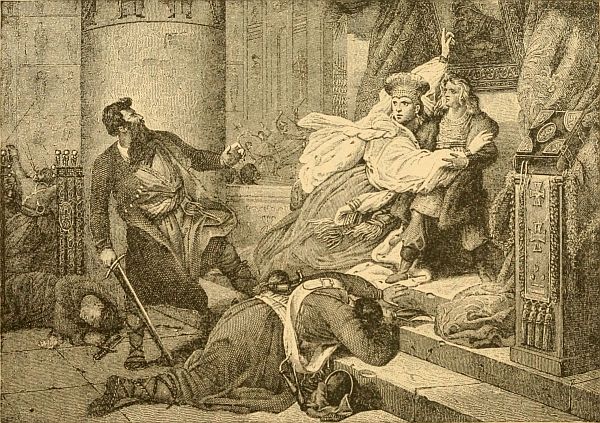

| Peter saved from Slaughter by his Mother | 374 |

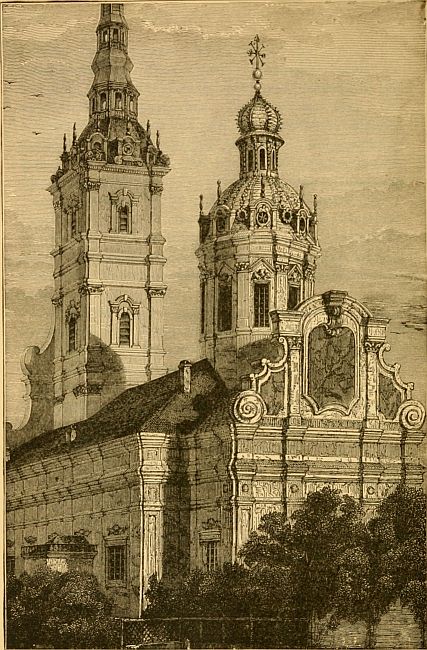

| Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul in the Fortress | 385 |

| Peter the Great in the Dutch Ship-yard | 389 |

| Peter the Great | 392 |

| Frederick II., King of Prussia, æt. 58 | 398 |

| Frederick the Great | 418 |

| Arrest of Voltaire by order of Frederick | 427 |

| Equestrian Statue of Frederick the Great, æt. 73 | 430 |

| Napoleon | 434 |

| Napoleon in the Prison of Nice, 1794 | 442 |

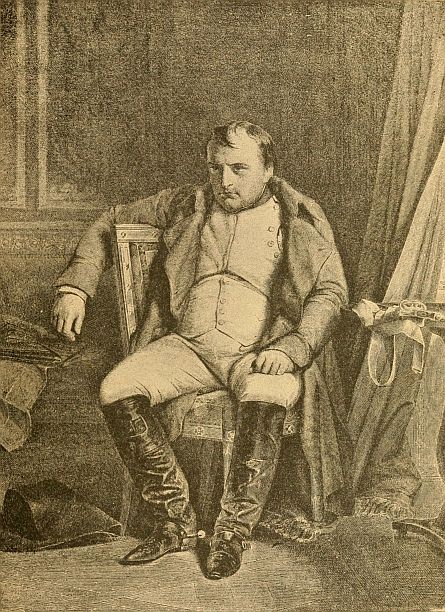

| Napoleon at Fontainebleau | 462 |

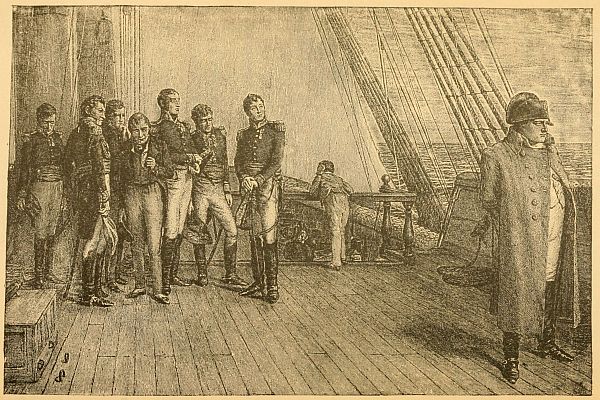

| Napoleon on Board the Bellerophon | 466 |

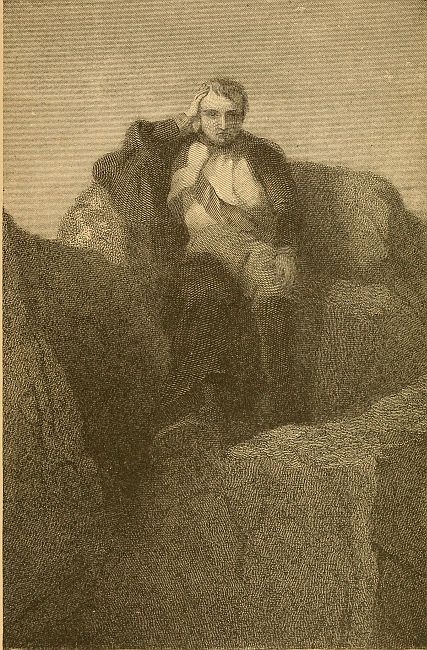

| The Rock at St. Helena | 474 |

FOR nine years the Greeks had besieged the city of Troy. This famous Trojan War, which is said to have occurred about 1184 B.C., has been embellished by romance and poetry; and although the real events have been much distorted by fabulous tales, it holds an important place in ancient Grecian history.

The marvellous Greek poet Homer has immortalized the wonderful story of this contest, in which, according to the old Grecian belief, gods and heroes fought for mastery; and it seems more fitting to the subject that we should view these events through the eyes of those ancient Greeks, whose weird yet fascinating fables peopled the mountains and seas with gods and goddesses; over whom proud Zeus or Jupiter ruled on the dread Mount of Olympus, from whence he hurled his awful thunderbolts, and shook the earth and heavens in his wrathful moods, when gods or mortals had dared to defy his imperial will. Agamemnon, king of Mycenæ, was the commander of all the Grecian hosts which for these[2] nine years had surrounded the walls of Troy. The cause of the quarrel may be thus briefly stated:—

Priam was the richest and most powerful of all the kings of Troy. His wife, Queen Hecuba, had dreamed that one of her children should become a firebrand which should consume the whole city. Whereupon, Priam was so alarmed, that he ordered that her next child should be exposed in a desert place among the mountains, and left to perish. Paris was this child, and when an infant, was hidden by his mother, that he might not be thus destroyed. Paris grew to be a youth of marvellous beauty, and was at length brought by his mother to the court of Priam. The king was so charmed by his beauty and accomplishments, that Paris ventured to make himself known, and was received by Priam, his father, with great kindness; for he was so pleased with the noble youth, that he ceased to remember the evil dream. This dream, however, was very strangely fulfilled years afterwards. Paris made an expedition into Greece, which country was at that time divided into many small kingdoms or states, each governed by its own king. Agamemnon was king of Mycenæ, and his brother Menelaüs was king of Sparta.

Agamemnon and Menelaüs were the sons of Plisthenes; but as their father died when they were very young, their mother Aërope was afterwards married to Atreus; and these two brothers were brought up by their step-father as his own children, to whom his name was given, as they were called Atridæ.

Atreus was afterwards murdered, and Agamemnon’s uncle Thyestes ascended the throne of Mycenæ. Agamemnon and his brother Menelaüs then fled to Sparta. The king of Sparta agreed to recover the kingdom for Agamemnon, if he would marry his daughter Clytemnestra,[3] and make her his queen. To this Agamemnon consented, and with the aid of Tyndarus, king of Sparta, he recovered his own kingdom, and married Clytemnestra. His brother Menelaüs afterwards became king of Sparta.

During the expedition into Greece, of Paris, the son of King Priam, he visited the court of Sparta, and was received most kindly by King Menelaüs. But the handsome and fascinating Paris ill-repaid this courteous reception, for he fell in love with Helen, the beautiful wife of Menelaüs, and carried her off with him on his return to Troy. Menelaüs, enraged at this wicked treachery, persuaded his brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenæ, to espouse his quarrel, and to join him in waging war with the Trojans, to revenge his indignity, and to recover, if possible, his wife, the fair Helen, who was so exquisitely beautiful, that all who saw her fell in love with her. Agamemnon was chosen commander-in-chief of all the powerful Grecian princes who now combined their forces to fight against Troy. Homer gives us the names of the most famous of these Grecian warriors. Agamemnon was sovereign lord of all the host, and Achilles was the bravest and most valiant man amongst them. But besides these, there was the yellow-haired Menelaüs, king of Sparta, and husband of the beautiful Helen; Ajax Oïleus, or, as men called him, the lesser Ajax, king of the Locri, swiftest of foot among the Greeks, after the great Achilles; Ajax Telamon, from Salamis; Diomed, son of Tydeus, king of Argos, and with him Sthenelus; Nestor, king of Pylos, oldest and wisest among the Greeks; Ulysses, king of Ithaca, most crafty in counsel; Idomeneus, grandson of the great judge Minos, king of Crete, and with him Meriones; Tlepolemus, son of Hercules, from Rhodes; Eumelus, from Pheræ, son of that[4] Alcestis, who died for her husband, and was brought back from death by Hercules, according to Grecian mythology; and many more heroes too numerous to mention: but the bravest and strongest of all was Ajax, son of Telamon, and the best horses were those of Eumelus; but there was none that could compare with Achilles and the horses of Achilles, bravest of men, and swiftest of steeds.

The heroes upon the Trojan side were also great and brave. The most famous of their chiefs were Hector, son of King Priam, most valiant of all the Trojan warriors; Æneas, whose father was Anchises, and whose mother was supposed to be the goddess Aphrodité; Pandarus, from Mount Ida, to whom Apollo had given a marvellous bow; Asius, the son of Hyrtacus, who came from the broad salt river, the Hellespont; Pylæmenes, king of Paphlagonia; and Sarpedon from Lycia, whom men affirmed to be the son of Zeus himself; and lastly, Glaucus his friend.

When the Grecian fleet had started upon this expedition against Troy, a wonderful incident had occurred. The fleet of the Greeks was detained by contrary winds at Aulis, owing to the wrath of the goddess Diana, whom King Agamemnon had offended by killing one of her favorite deer. In this emergency Calchas the soothsayer was consulted, and he declared that to appease the anger of the goddess. Iphigenia, the eldest daughter of King Agamemnon, must be sacrificed. She was accordingly led to the altar, and was about to be offered as a victim, when she is said to have suddenly disappeared, being caught up by Diana, who in pity substituted a stag in her place. Virgil, however, tells this story somewhat differently; for he relates that Iphigenia was actually sacrificed. The goddess having been appeased, the winds were favorable,[5] and the Grecian fleet sailed onward, and arrived safely at Troy; and for nine long years these famous warriors had been waging war around the walls of that city, within which, in the palace of Paris, son of King Priam, was concealed the matchlessly beautiful Helen, and much rich treasure, which that treacherous but fascinating prince had stolen from the Greeks.

But now within the Grecian camp a strife arises between King Agamemnon and Achilles, bravest of all his host. The Greeks, having been away from home so many years, were accustomed to make frequent raids upon the surrounding cities to supply their needs, and thus to enable them to continue still longer this weary siege. They had thus ruthlessly attacked a city called Chrysa, sacred to Apollo, where was a temple of that god.

The Greeks, in their plunderings, had not dared to molest the temple or its priest; but they had carried off, with other prisoners, the daughter of the priest of Apollo, named Chryseïs. The spoils obtained from these expeditions were divided between the various kings and heroes in the Grecian host; and the maiden Chryseïs had been apportioned as the share of King Agamemnon. The next day the priest Chryses came to the Grecian camp, bringing much gold, and wearing on his head the priest’s crown, that men might thereby reverence him the more. He demanded the return of his daughter, and offered his gold as her ransom. The Grecian chiefs were favorable to his suit, but King Agamemnon angrily repulsed him, exclaiming,—

The sorrowful priest turned away in silence, and as he walked along the seashore, he besought the aid of his god, Apollo, praying: “Hear me, God of the silver bow! If I have built thee a temple, and offered thee the fat of many bullocks and rams, hear me! and avenge me on these Greeks.”

And Apollo heard him and descended with awful wrath from dread Olympus, where dwelt the gods. The rattle of his arrows filled the air, as he twanged his deadly bow, and sent the fateful shafts of pestilence upon the Grecian fleet below; meanwhile, enwrapping his own form in shadows black as night, from which his baleful darts shot forth like lightning’s flash. And so for ten long days the pestilence raged, till heaps of dead men and beasts lined the shore, and the black smoke ascended from myriad funeral piles. Then Achilles called upon the seer, Calchas, to tell them why Apollo was so wroth with them. To whom the sage replied,—

“It is on behalf of his priest that Apollo is so wroth; for when he came to ransom his daughter, Agamemnon would not let the maiden go. Now then, ye must send her back to Chrysa without ransom, and with her a hundred beasts for sacrifice, so that the plague may be stayed.”

Then, with a threatening frown, King Agamemnon started from his gorgeous throne, with eyes which flashed with angry light, as he exclaimed in fury,—

“Prophet of plagues, forever boding ill! Still must that tongue some evil message bring. I will release the maid, that my people may be spared. But for this, my share of booty, shall the Greeks requite me.”

Then Achilles answered,—

“We have no treasures from which to make up thy loss. Let the maiden go! and when we capture Troy, we will repay thee fourfold.”

Then Agamemnon replied,—

“Shall I my prize resign while thou art possessed of thine? I will send back the maid to please Apollo; but know thou that I will seize thy share, even the girl Briseïs, that all may know that I am sovereign here.”

Whereupon, Achilles was so fierce with anger, that he fain would have slain the monarch, and had, forsooth, half drawn his sword from the scabbard, to thrust it into the haughty king. But lo! the goddess Athené stood behind him, and caught him by his long yellow locks of hair. None saw the goddess, save only Achilles, to whom he said,—

“Art thou come, fair Minerva, to witness these wrongs I bear from Atreus’ son? If thou dost see his crime, see also my proud vengeance.”

Whereupon, he raised his sword to strike; but the goddess said,—

“Forbear thy fury! Let great Achilles yield to reason. Put up thy sword; but if thou pleasest, use the dagger of thy tongue alone. With that, the gods permit thee to reproach him; but vengeance, leave thou to the care of heaven.”

So spake the goddess, and Achilles thrust his sword back into its sheath, and in proud scorn exclaimed, while turning to the king with blazing eyes,—

“Coward! thou rulest sure a puny race, else this had been thy last affront. Thou darest not to fight, but cowerest like a dog in safe retreat within the camp; but after we have fought and conquered, thou claimest the[8] richest booty! But know, for this my grievous wrong, the gods shall avenge it! And when the Greeks lie in heaps before the walls of Troy, slain by the dreadful Hector, then shalt thou miss the strong arm of Achilles from thy side, and thy proud heart shalt mourn the affront thy madness gave. For thou hast made the bravest Greek thy bitterest enemy.”

Then did Achilles dash his sacred sceptre on the ground, saying,—

“As surely as this sceptre, which was once a branch from off a tree, now starred with golden studs and bound with bronze, an ensign of Jove’s favor, shall never blossom more, so surely shalt thou miss the arm of brave Achilles, when the Trojans press thee sore. Thou canst play the master over others, but think not to master me! As to the maid, my prize, which the Greeks gave me, let them take it again if they will, but if thou darest to invade my tent and touch whate’er is mine, thy blood shall stream forth at the point of my revengeful blade.”

So saying, the great Achilles strode forth from the counsel-tent with wrathful looks, and the august brow of Agamemnon was overcast with threatening gloom. In vain had Nestor, eldest of the Grecian kings and wisest of counsellors, endeavored to quell this ominous quarrel. His words of reason moved not the two fierce warriors. And surely, in this strife, Achilles held the right, and Agamemnon showed himself a selfish, proud, and haughty monarch.

The priest’s daughter, Chryseïs, was sent back to her home with offerings to the god, and Ulysses was appointed to conduct her thither. But King Agamemnon would not be persuaded to renounce his purpose of seizing upon the war-prize which had been awarded to Achilles, namely,[9] the maiden Briseïs; and forthwith he sent heralds to the tent of Achilles to obtain her. The heralds approached the warrior with much dread, for they feared his awful wrath. But Achilles said to them,—

“Fear not, ye heralds! It is no fault of yours that you are sent on such an errand.”

Whereupon he commanded that the maiden should be brought from her tent and given to the heralds, who led her, much against her will, to the haughty Agamemnon. Then Achilles called upon his mother Thetis, who was a goddess of the sea, to avenge his wrongs. Thetis rose like a mist from the waves, and coming to Achilles, who sat upon the seashore, she comforted him and asked his trouble. Whereupon Achilles told her the cause of his anger, and besought her to go to the great Zeus, whom Thetis had once aided, when the other gods would have bound great Jove, by bringing Briareus of the hundred hands, who so fought for the mighty Jupiter, that the other gods dared no longer defy his power. And owing this kindness to the goddess Thetis, her son thought rightly that the great Jove would listen to her petitions on his behalf. So Achilles asked his mother to go to Olympus, and pray Zeus that he would help the sons of Troy and give them victory over the Greeks, whose sovereign king had thus dishonored the bravest of all his host.

This, Thetis did, going to the palace of Jupiter on the top of Olympus, and making her prayer in her son’s behalf. Zeus was loath to grant it, for he knew that it would anger his wife Heré, who loved the Greeks and hated the Trojans. Yet on account of the past favor of Thetis, he would not refuse, and in giving assent, nodded his awful head, thus causing Olympus to shake and tremble. So Zeus called one of his swift-winged messengers, called a Dream, and said,—

“Fly hence, swift Dream, and to the tent of Agamemnon go! Bid him lead all the Grecians forth to battle against Troy. Persuade him that the gods intend to give him victory.”

So this false Dream, flying to Agamemnon’s side, took to itself the shape of wise old Nestor, whom the king honored more than all beside, and thus the false Nestor counselled,—

“Sleepest thou, Agamemnon? Arise! for now Zeus declares that the immortal gods are favorable to thy plans, and through thy mighty hosts will send the doom of destruction upon the city of Troy; and thou shalt reap the eternal glory.”

Then Agamemnon awoke from sleep and, little thinking how he had been duped by this false Dream, quickly donned his tunic, fastened his sandals on his feet, and hung from his shoulders his mighty silver-studded sword. Wrapping his great cloak around him, he took in his right hand his royal sceptre, token of his sovereignty over all the Greeks. Thus attired, in martial grandeur, he went forth and roused his chiefs, and then the heralds called the hosts to battle. Only Achilles sat apart within his tent and went not forth to battle with the Greeks.

Now, as the two forces were about to fight, Paris, the Trojan prince, rushed forth and challenged the bravest of the Greeks to fight with him. Then Menelaüs, whom he had so greatly wronged, leapt from his chariot and rushed to meet his treacherous foe. But Paris was more beautiful in form and feature than brave in heart, and seeing the man whom he had so cruelly wronged, he was afraid to fight, and cowardlike ran back into the Trojan ranks. Then his brother, brave Hector, thus rebuked his cowardice.

“Fair art thou, Paris, beauteous indeed, but ill thy soul supplies a form so fair! Thou makest us the scorn of the proud Greeks, by thy unmanly fear. Little will it avail thee that thou art in form so stately, when thy soft curling locks and shapely limbs are lying in the dust. Thy silver lyre, nor all thy blandishments, will naught avert thy doom, for thou hast been the curse of Troy and ruin of thy race.”

Then Paris, stricken with just shame, replied,—

“Thou speakest well, Hector, and thy rebuke is just. Thy heart is like iron; yet are beauty and love also the gift of the gods, and not to be despised. Now let Menelaüs and me fight for the fair Helen and all her possessions, and if he prevail, let him take her, and them, and depart to Greece. But if I prevail, then shall the Greeks depart in peace without her.”

This saying, which at last betokened some spirit, pleased Hector well; and going before the Trojan ranks, holding his spear by the middle, he kept them back. The Greeks would have hurled spears upon him, but Agamemnon cried out,—

“Hold! Hector has somewhat to say to us.”

Then Hector announced that Paris would fight with Menelaüs for the fair Helen and all her wealth. To which Menelaüs readily agreed, but demanded that King Priam should himself come and, with King Agamemnon, make a covenant with sacrifice, that the fair Helen and all her wealth should go to the one who should prevail.

When the heralds went to bring the old King Priam, he was found on the wall with the beautiful Helen near him, to whom he was talking and asking the names of brave Grecian heroes whom he beheld among the hostile host. And in this wise he spake to fair Helen,—

“Come near, my daughter, tell me about these old friends of thine. Who is that warrior, that I see, so fair and strong? There are others taller than he, but none of such majesty.”

And Helen answered,—

“Ah, my father, would that I had died before I left the fair land of Greece! That one is King Agamemnon, a good and brave soldier, and my brother-in-law, in the old days. And that one is Ulysses of Ithaca, who is better in craft and counsel than all other men.”

Then Priam said,—

“Who is that stalwart hero overtopping all others?”

“That,” said Helen, “is mighty Ajax, the bulwark of the Greeks; and as for the other chiefs, I could name them all. But I see not my two brothers, Castor and Pollux;” for she wot not that they were already dead.

Thereupon came the heralds and told King Priam that the armies had called for him. After the covenant between the Trojan and Grecian kings, Priam and Agamemnon, Hector and Ulysses marked out a space for the fight, and Hector shook two pebbles in a helmet, to decide which one should be the first to throw the spear, Paris or Menelaüs.

The lot fell upon Paris, and the two warriors having armed themselves, came forth into the space and brandished their spears with wrathful eyes. Then Paris threw his spear. It struck the shield of Menelaüs, but pierced it not; and thereupon Menelaüs, with a prayer to Jupiter, cast his long-shafted spear. It struck the shield of Paris, pierced it through, and passing through both corselet and tunic, would have bruised the side of Paris, but he shrank aside, and so was wounded not. Then Menelaüs drew his sword and struck a mighty blow[13] upon the top of Paris’ helmet; but the sword brake in four pieces in his hand. Then he rushed forward and seized Paris by the helmet, and fain would have dragged him to the Grecian host, but the goddess Aphrodité loosed the strap that was beneath the chin, and the helmet came off in the hand of Menelaüs, and the goddess snatched Paris away, covering him with a mist, and put him safely in his own palace in Troy.

Then King Agamemnon said,—

“Now, ye sons of Troy, give back the fair Helen and her wealth!”

But just at this time the goddess Athené took upon herself the shape of Laodocus, and going to Pandarus, the false Laodocus, said,—

“Darest thou aim an arrow at Menelaüs?”

Now Pandarus had a marvellous bow made from the horns of a wild goat and tipped with beaten gold, and Pandarus strung his bow, his comrades, meanwhile, hiding him behind their shields. Then took he a sharp-pointed arrow from his quiver and laid it on the bow-string and let it fly. Right well the aim was made; but the gods decreed that the dart should not be fatal. For though it passed through belt and corselet and strong girdle, and pierced the skin so that the red blood rushed out, which sight filled Menelaüs and King Agamemnon with sore dismay, Menelaüs soon perceived the barb of the arrow, and so knew that the wound was not fatal; and when it was drawn forth by the physician Machaon, and the blood was staunched with healing drugs, King Agamemnon rejoiced that he should not thus lose his brave brother Menelaüs.

Then the mighty hosts of Greeks and Trojans went forward to the battle, and on either side the gods urged[14] them on, Athené aiding the Greeks, and Ares—called also Mars—strengthening the Trojan warriors. Many were the valiant exploits that day performed; but we can mention but a few of them. So close pressed host on host, that the armies dashed together, shield on shield and spear on spear. Ajax Telamon slew Simoisius, and Antiphon, son of King Priam, aimed at Ajax, but missing him, slew Leucus, the friend of the valiant Ulysses.

Whereupon, Ulysses, in great anger, to avenge his death, strode boldly midst the Trojan ranks and hurled his spear at Democoön, a son of Priam, whom he slew. At length the Trojan hosts were borne backward by the mighty onslaught of the Greeks, till Apollo cried from the heights of Pergamos,—

“On, Trojans! The flesh of these Greeks is not stone or iron, that ye cannot pierce it; and remember that the great Achilles fights not with them to-day!”

Athené also urged the Greeks to valiant deeds. This goddess aroused Diomed to battle, making a wondrous fire shine forth from his helmet, which made him seem a god, and he raged through the battle so furiously, that he was now seen amongst the Grecian ranks, now boldly invading the Trojan forces, and striking down his foes with mighty arm. Then Pandarus aimed an arrow at him and smote him on the shoulder. But the brave Diomed cared not for the arrow, and leaping from his chariot he called to Sthenelus, his charioteer, to draw the arrow from the wound; and praying to Athené for aid, he rushed madly into the Trojan ranks, slaying a man at every blow.

Meanwhile, Æneas, driving his swift chariot, said to Pandarus,—

“Climb up into my chariot, and thou shalt fight, and I will drive.”

So Pandarus mounted the chariot, and the two drove towards Diomed, and as they came near, Pandarus cast his spear, which passed through the shield of Diomed and reached his corselet; whereupon Pandarus cried,—

“Ha, now he bleeds! Low will this haughty Grecian lie!”

But Diomed replied,—

“Thy dart has erred! Now I will try my spear.”

And straightway he hurled his keen lance toward his boasting foe. Through nose and jaw it crashed, and cleft the tongue in two; and the bright point came forth beneath the chin.

Pandarus fell from the chariot mortally wounded, and Æneas leapt to the ground with drawn spear to defend the dead body of his friend. But Diomed raised a huge stone and hurled it at Æneas, and crushed his hip-bone, felling him to the earth.

Then had brave Æneas perished, but his goddess mother, Aphrodité, caught him in her white arms and threw her veil about him. But so great was the rage of Diomed, that he spared not even the goddess, but rushing upon her, he wounded her in the wrist, and with a shriek of pain she dropped her son; but Apollo caught him up and covered him with a thick mist. Thrice Diomed pursued, and thrice Apollo drove him back. But as the rash Diomed advanced a fourth time, the god exclaimed,—

“O son of Tydeus, beware! Nor think to match the immortal gods!”

So Apollo carried Æneas out of the battle and placed him in safety in Troy. Meanwhile, fair Venus, pale from the wound which mortal man had dared inflict, was conducted by swift-winged Iris to the stern god Mars, her brother; and Venus begged his car to mount the distant[16] skies, where in the fair realms of the gods her wounded hand was healed by sacred balm. Then Mars went down upon the field of battle to aid the Trojans, and Hector rushed to the front with the god Mars by his side; and he dealt death and destruction through the Grecian ranks. Juno and Minerva saw him from Mount Olympus, and they prayed Jupiter to allow them to stop him in his fury. The mighty Zeus consented, and the two goddesses yoked horses to the chariot of Juno and passed down to earth with flying strides. Having reached the battle-field, Juno took the shape of Stentor with the lungs of brass, whose voice was as the voices of fifty men, and thus she cried,—

“Shame, men of Greece! When Achilles fought, the Trojans dare not leave the city; but now they fight even by the very ships.” Then Minerva chided Diomed for want of bravery, to whom he replied: “I know thee, great goddess, daughter of Jupiter! and ’tis thy commands I obey. Thou didst bid me fight with none of the immortals save only with Aphrodité; and therefore I gave place to Hector, for I perceived that he was aided by great Mars.”

But Athené answered: “Heed not Ares! drive thy chariot at him and hurl thy spear. This morning did stern Mars promise to aid the Greeks, and now he joins with our Trojan foes.”

So saying, the goddess pushed the charioteer of Diomed from his place, and herself mounted and seized the reins and lashed the horses furiously. With swift speed they drove together till they found the god Mars, or Ares, where he had just slain Periphas the Ætolian. Minerva was even invisible to the god, for she had donned the helmet of Hades; and so Ares, not seeing her, cast his spear at Diomed; but the goddess caught the spear and turned[17] it aside. Then Diomed thrust forth his spear, and Minerva leaned upon it, so that it even pierced the side of the god Mars, who shouted so loudly with the pain that the Greeks and Trojans trembled with fear; while the god of war, wounded by the fair goddess Athené, covered himself with a thunder-cloud, and in much rage ascended to Olympus.

When Ares had departed, the Greeks prevailed again; but the seer Helenus said to Hector and Æneas: “Draw back the Trojan army and encourage them; and you, Hector, go within the city and bid thy mother queen, with the daughters of Troy, take the costliest robe she hath, and go to the temple of Athené and offer it to the goddess with prayers and sacrifice, that perchance she may relent and have pity on us and keep this terrible Diomed from our walls.”

This counsel prevailed, and Hector departed to the city, whence he dispatched his queen mother to Athené’s temple, and exhorted his brother Paris to arm himself and come forth to battle. Hector then took a fond farewell of his much-loved wife Andromaché and his only child, called beautiful-headed as a star, and departed with Paris, who came forth clad in shining armor; and they fell upon the hosts of the Greeks and slew many chiefs of fame.

Again came Athené to help the Greeks; and meeting the god Apollo, they agreed to stay the battle for that day; and to this end inspired Hector and King Agamemnon to agree that Hector should fight alone with the bravest of the Greeks, while both armies should rest from battle.

Then Menelaüs desired to meet brave Hector in single combat. But King Agamemnon would not consent to this, fearing his brother would perish. Whereupon it was[18] resolved to decide the matter by lot, which fell upon Ajax the Greater, who, having armed himself, stepped forth to battle with the mighty Hector. First Hector hurled his spear, which passed through six folds of Ajax’s shield. Then Ajax threw his lance, striking proud Hector’s shield. Through shield, corselet, and tunic it passed, but Hector shrank from the sharp point, and the flesh was not pierced. Then again they rushed together with wild fury. And Ajax drove his spear at Hector’s shield and grazed his neck, so that the blood leaped forth. Then Hector hurled a mighty stone at Ajax; but his shield broke not. Whereupon Ajax raised a mightier stone and threw it with such aim that it broke the shield of Hector and felled him backwards to the ground. But Apollo raised him up, and as they drew their swords for deadlier conflict, the heralds held their sceptres between them and bid them cease. So Hector and Ajax, both mighty warriors and brave of heart, agreed to part as friends; in token whereof, Hector gave to Ajax a silver-studded sword, and Ajax to Hector a buckler splendid with purple. So they parted, and the conflict was stayed that night. In the morning came Trojan heralds to King Agamemnon’s host, saying: “This is the word of Priam and the sons of Troy. Paris will give back all the treasures of the fair Helen and much more besides, but the fair Helen herself will he not give up. But grant a truce that we may bury our dead.”

So the truce was given, and the dead of both armies were burnt. Then the Greeks and Trojans both feasted through the night. But all through the hours of darkness the terrible thunder rolled on Mount Olympus; for mighty Zeus was counselling evil against the hapless Trojans.

When the morning came, the two hosts again went[19] forth to battle with each other. Till midday neither side prevailed; but then great Jupiter sent fear and panic amidst the Grecian forces, and they fled to their ships in terror.

As the Greeks were flying in wild confusion, brave Hector driving in his chariot pursued them; and called to his horses, “Now Xanthus, Æthon, Lampus, and Podargus, speed ye well! Ye Flame of Fire, White Foot, and Brilliant, named! carry me fast, and well repay the tender care of my sweet wife Andromaché, who often from her fair white hands has fed thee! For I would win old Nestor’s marvellous shield of purest gold, and strip from off proud Diomed his boasted breastplate, wrought by the mighty Vulcan.”

But Jupiter willed not that this should be; for King Agamemnon prayed aloud to Zeus for succor, and Jupiter heard his prayer, in token whereof he sent a sign, namely: an eagle flew above the Grecian hosts and dropped a kid out of his claws. Then did the Greeks take courage and renewed the fight with vigor. But the darkness came, and each host rested on their arms.

Meanwhile, King Agamemnon called a council of war, and fain would have returned to Greece and leave this invincible city of Troy. But brave King Diomed would not receive such craven counsel, and angrily exclaimed,—

“Even though all the men of Greece depart, yet will I and Sthenelus abide the doom of Troy, for surely the gods have brought us hither.”

To these brave words the Grecian chiefs agreed; and wise Nestor counselled that King Agamemnon should send to brave Achilles and seek to make peace with him that they might have the strong help of his mighty arm. To which King Agamemnon consented, and sent messengers[20] to the tent of Achilles to seek his favor, promising him seven kettles of brass, ten talents of gold, twenty caldrons, twelve fleet horses, seven women slaves skilled in the work of the loom, and, more than all, the return of the maid Briseïs, the cause of all their quarrel; and when Troy should be taken, much spoil besides. And even more; for when they should return to Greece, King Agamemnon promised him one of his own daughters for his wife, and seven cities by the sea. But all this moved not the wrathful soul of stern Achilles, and he would not be appeased; nor would he come to help the Greeks against the Trojans, but still sat silent in his tent. Then it was decided that Diomed and Ulysses should go that night disguised into the Trojan camp, to spy out, if possible, their strength and plans. This same strategy had Hector also planned, and had already sent one Dolon, swift of foot, towards the Grecian host. But as he ran he met Diomed and Ulysses, who seized him, and under threatenings forced him to reveal the Trojan secrets. Then did they slay Dolon, and forthwith proceeded to where some men of Thrace, allies of the Trojans, lay sleeping. These Thracians possessed most matchless steeds—horses so fair and tall, whiter than snow and fleeter than the winds. Diomed and Ulysses would fain secure these as a rich prize, and so they slew the sleeping Thracians and led the captured horses back to the Grecian hosts, and arrived in safety at the ships. The next day the battle waged hot again. Ulysses was wounded, and Paris shot an arrow and pierced the brave physician Machaon. Meanwhile, Achilles was standing on his ship and looking upon the conflict. When he beheld Nestor bearing the wounded Machaon to the ships, he called to his friend Patroclus and bid him see if Machaon’s wound was fatal.

Most fierce the battle raged. On the left, the Grecians prevailed, but on the right brave Hector and his host fought even to the very ships, dealing most deadly blows. So great were the shouts of battle that old Nestor, who was tending the wounded Machaon, was roused; and going forth he met King Agamemnon, and with him Diomed and Ulysses, who had been wounded that day. Then they counselled together. Again Agamemnon advised flight; but the others thought it not good to flee thus, and they counselled King Agamemnon that he should go to the Grecian ranks, bidding them bear themselves bravely and put courage into their hearts. This did he do, and roused their waning strength to fresh exploits. Then Ajax smote brave Hector with a mighty stone, which felled him to the ground; and the Greeks, with a great cry, rushed forth to bear him to their ranks; but the Trojans held their shields before him, and his friends lifted him up and carried him to a place of safety. But he was sorely bruised. Then Apollo, at Jupiter’s bidding, poured courage into his heart and healed him of his wound, so that he rushed once more upon the field of battle, strong and well and valiant as ever. Then were the Greeks struck with dire dismay. Then did Patroclus lament to Achilles on account of the ill fortune of the Greeks, and besought the mighty warrior, if he would not fight himself in their behalf, to let him go accompanied by the valiant Myrmidons, whom Achilles always led to battle. At which the heart of Achilles was moved; and he said,—

“I will not go to battle until it reaches my own ships, but thou mayest put my armor upon thee and lead my Myrmidons to the fight.”

So this was done; and when the Trojans beheld these[22] famous Myrmidons led by one who wore the armor of the mighty Achilles, their hearts were faint with fear, for they supposed great Achilles himself had come against them. Thrice did Patroclus rush against the men of Troy, and each time slew nine chiefs of fame; but the fourth time Apollo stood behind him and struck him, and his eyes were darkened, and the helmet fell off his head, so that the waving plumes were soiled with dust. Never before had this proud helmet of Achilles touched the ground. Then Apollo broke his spear, and struck the shield from his arms, and loosed his corselet. Then all-amazed, poor Patroclus stood defenceless; so Hector struck him dead, and seized the matchless armor of the mighty Achilles.

Fierce was the fight about the body of Patroclus, and many chiefs fell dead striving to obtain the prize. Then fled Antilochus to bear the ill tidings to the great Achilles, who, upon hearing of this dire defeat, poured dust upon his head, and called upon his goddess-mother to come to his aid.

“Why weepest thou, my son?” said the sea-goddess Thetis, rising from the waves.

“My friend Patroclus is dead, and Hector has my arms I gave him to wear, and, as for me, I care not to live unless I can avenge myself.”

Thus Thetis said,—

“Be comforted, my son; to-morrow I will go to mighty Vulcan; he shall forge new arms for thee.”

Even as they spoke together, so sore the Trojans pressed the Greeks, that Jupiter sent Iris to Achilles, and bade him show himself to the Greeks that they might be filled with courage.

“How can I go without arms?” replied Achilles.

But the gods gave him courage, and he went, and Athené put her matchless shield upon his shoulders, and wrapped a golden halo round his head, so that he seemed clothed in godlike armor; and he shouted to the Trojans with a mighty voice, which so filled them with fear that they fell back, and the horses of the Trojan chariots were so terrified at the flaming fire above his head that they thrice fell back, and trampled on the Trojans, as thrice the awful voice of Achilles was heard and his shining form revealed. Thus was the body of Patroclus then secured, and carried on a bier, Achilles walking, weeping by his side.

That night the conflict rested. Meanwhile, Thetis the goddess went to the dread Vulcan, and prayed him make new armor for her son Achilles. To this did stern Hephæstus consent, saying, “Be of good cheer! I will obey thy wish; for kind thou wast to me when my mother thrust me forth from heaven because she saw I was deformed and lame. I will make such arms for Achilles as the gods themselves might proudly wear.”

So great Vulcan wrought at his mighty forge. First he made a ponderous shield, and wrought upon it the earth, and sky, and sea, and sun, and moon, and stars. He pictured upon it, also, two cities; one at peace, and one in dire confusion where war raged. In the peaceful city, they led a bride to her home with music and dancing, and women stood to see the show, and in the market-place judges sat, and men bartered. But around the other city, an army was besieging, and soldiers stood upon the walls, defending. Also, he wrought fields where men ploughed, and others reaped, and vineyards where youths and maidens gathered baskets of grapes while minstrels played on harps of gold. Also, he wrought herds of[24] oxen going to the pasture, and sheepfolds, and a dance of youths and maidens who wore coronets of gold and belts of silver. Then, too, he pictured a fierce fight between lions and angry bulls. Around the shield he wrought the mighty ocean. He made also a corselet, brighter than fire, and a helmet of gold. At dawn the goddess Thetis brought to her son this marvellous armor, which when Achilles saw, his eyes flashed wild with joy; and seizing them, he put them on most eagerly, and rushed forth to rouse the Greeks to battle. Then an assembly was called, and Achilles stood up in the midst, saying, he had put away his wrath, and King Agamemnon, who had been wounded in the battle, declared that he had been wrong, and straightway commanded to be sent to the tent of Achilles all that he had promised him, including the maid Briseïs, which was done. The Greeks gathered again to battle. Then did the fight wage sore against the Trojans, who fled within the city gates; only brave Hector remained outside to meet the mighty Achilles, who rushed towards him to engage in single combat. Then did King Priam and Queen Hecuba beseech their much-loved son that he would come within the city walls, and not risk his life by thus meeting this dread foe; but Hector answered,—

“Woe is me if I go within the walls!”

But as Achilles came near, brandishing his great Pelian spear, while the flash of his arms was as a flame of fire, Hector trembled, and dared not abide to meet him, but fled around the walls, Achilles pursuing. Thrice they ran round the city, while the immortal gods looked down upon them from dread Olympus, and Jupiter said: “My heart is grieved for Hector. Come, ye gods! shall we save him?”

But Minerva—she who was called the goddess of wisdom, for she sprang forth from the mighty head of Jove completely armed—thus counselled,—

“Great Sire, is it well to rescue a man already doomed to die? If it be thy august will, then do it; but the other gods approve not.”

To whom Zeus answered,—

“My heart is loath, but be it as thou wilt.”

Then did the goddess descend down from high Olympus in hot haste, and Athené lighted from the air at Achilles’ side, and whispered: “This is our day of glory, great Achilles! Hector shall be slain; but tarry a moment, that I may give him heart to meet thee in battle; so shalt thou slay him.”

Then Minerva took the form of Deïphobus, and came near to Hector, saying, “Achilles presseth thee hard, my brother; let us stay and fight him.”

Then was brave Hector glad to find one of his brothers faithful to him, and answered,—

“I always loved thee best of all my brothers, good Deïphobus, and much more now to know thou darest to stand by my side in this hour of deadly peril.”

Thus was Hector encouraged to meet Achilles, and Hector said to him: “Thrice, great Achilles, hast thou pursued me round the walls of Troy, and I dared not withstand thee; but now I will meet thee like a warrior. If Jupiter gives me the victory, I will do no dishonor to thy body; only thine armor will I take. Do thou the same to me.”

But Achilles frowned, and answered,—

“I make no covenants with thee. There is no agreement between wolves and sheep. Show thyself a warrior if thou canst. Athené shall kill thee by my spear.”

Then did they meet in deadliest conflict. Achilles threw his mighty spear; but Hector, crouching, avoided it, and the great spear fixed itself in the ground beyond. But, unseen by Hector, Athené brought it back to proud Achilles. Whereupon, Hector cried, “Thou hast missed thy aim, great Achilles. Look out for my spear!”

And as he spake, he threw his long-shafted spear with so good an aim, that it struck the very middle of Achilles’ shield; but it pierced it not, and it bounded far away. And when Hector turned to his supposed brother, Deïphobus, to get from him another spear, lo! he was gone; and Hector knew then that his doom had come. Then thought he to himself: “Though Athené has cheated me, and Jupiter and Apollo are against me, if I must die, I will die in such manner as shall do honor to my name.” Then he drew his mighty sword, and rushed upon Achilles. But at that same instant Achilles charged to meet him, and holding his shining shield before him, with his helmet plumes waving in the air, he raised his long-pointed spear, which gleamed like a star, and drove it through the neck of the brave Hector, so that the point stood out behind; and Hector fell dying in the dust. Then with his last breath, he besought Achilles to spare his body from the Greeks; for King Priam would ransom it with much gold and treasure, to give it burial rites. But Achilles, moved with fierce wrath, cried,—

“Dog, seek not to entreat me! No gold could ransom thee.”

Then Hector died, and Achilles drew out the spear from the corpse, and stripped off the arms. Then great Achilles did a shocking deed; for he bound the body of the dead Hector to his chariot, letting the brave and noble head lie in the dust; and so he dragged the corpse of the[27] valiant Trojan round the walls of Troy, even to the Grecian ships. And sorrowing Priam saw him from the walls; and fair Andromaché, the wife of Hector, also beheld this dreadful spectacle, and thereupon fell in a deadly swoon; and from her beautiful head dropped the golden wreath and diadem, which Aphrodité gave her on her bridal day.

Then did old King Priam gather rich gifts, and aided by the gods, mount his swift chariot and go to the tent of great Achilles, to beg the body of his much loved son, brave Hector, praying to Jupiter that Achilles might have pity on him. This did Jove grant; for Achilles received him kindly, and gave up the body of dead Hector, which King Priam carried back into the city of Troy. For nine days the people wailed and mourned, and gathered much wood for a funeral pile, upon which they laid brave Hector; and when his body was burnt to ashes, they gathered up the white bones and put them in a chest of gold, and covered it with purple. This chest they placed in a coffin and laid upon it many stones, even until they had raised a mighty mound above it. Thus did they bury the valiant Hector, bravest of Trojan princes.

Such is a brief outline of the story of the famous Trojan War, as told by the illustrious Homer in his matchless poem of the “Iliad.” Now we return to the few further facts regarding King Agamemnon which can be culled from history.

There are two different accounts of the final overthrow and capture of Troy. According to one of these, Antenor and Æneas treacherously betrayed the Palladium to the Greeks, and at the same time threw open the gates of the city at night. The other account relates that the capture was effected by the stratagem of the wooden horse, which[28] was planned by the cunning of Ulysses. A huge, hollow structure resembling a horse, was filled with armed men, and left standing in the plain, while the Greeks went on board their ships and sailed to the island of Tenedos, which lay not far distant. By an artful manœuvre, the Trojans were made to believe that this horse was an offering to Minerva, and that they would achieve a great triumph by carrying it into the city. Accordingly they made a breach in the wall, and transported the horse within. In the dead of night the Greeks broke out of their concealment, and set the city on fire. The fleet, on a signal given, sailed back from Tenedos; the army landed. Troy was taken and destroyed.

This event is usually placed about 1184 B.C. In the division of the spoils, after the taking of Troy, Cassandra, one of the daughters of King Priam, fell to the lot of Agamemnon. She was endued with the gift of prophecy, and warned Agamemnon not to return to Mycenæ. This warning, however, was disregarded by the king, who, upon his return from Troy, was carried by a storm to that part of the coast of Argolis where Ægisthus, the son of Thyestes, resided. This king, Ægisthus, had entered into a wicked agreement with Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, to put that monarch to death upon his return from Troy, so that Ægisthus could seize the throne of Mycenæ, and marry Queen Clytemnestra. There are two accounts of the death of Agamemnon. One states that Ægisthus had set a watchman, with a promise of a large reward, to give him the earliest tidings of the return of the king. As soon as he learned that Agamemnon’s fleet was on the coast, he went out to welcome him, and invited him to his mansion. At the banquet in the evening, with the consent of Clytemnestra, he[29] placed twenty armed men in concealment, who fell on King Agamemnon and killed him, together with Cassandra and all their attendants. Another account makes Agamemnon to have fallen by the hands of his wife Clytemnestra, after he had just come forth from a bath, and while he was endeavoring to put on a garment, the sleeves of which she had previously sewed together, as well as the opening for his head; thus giving her time to commit the bloody deed before any succor could reach him. His death, however, was avenged by his son Orestes.

With regard to the extent of Agamemnon’s sway, Homer states that he ruled over many islands, and over all Argos; meaning not the city Argos, over which Diomed ruled, but a large portion of the Peloponnesus, including particularly the cities of Mycenæ and Tiryns. Homer also says that Agamemnon possessed the most powerful fleet; and as he was chosen the sovereign of all the Grecian kings, and commander-in-chief of all the Grecian hosts during the Trojan War, he may doubtless be called the greatest and most famous of all the more ancient Grecian rulers.

IN a lonely and desolate country, in the depths of a dark forest, at the edge of a yawning precipice, there once lay an infant, robed in costly garments, which betokened noble or royal birth. The baby lay in a small basket cradle, made of golden wires and lined with richly embroidered cushions. It seemed to be slumbering, for it moved not, even when the afternoon shadows gathered more densely around it; and a rapacious bird of prey might have been seen hovering above its dangerous retreat, and the noise of wild beasts was heard in the dark forests around. Was there no one near to protect and care for this lovely child? Ah, see! as that vulture swoops down towards its helpless victim, a lonely watcher rushes forth from the forest, and drawing his bow, an arrow flies into the heart of the bird, which falls dead into the awful chasm below. But why does not the babe awake? and why is it left in this desolate spot? Just then a lion steals out of the brushwood, and after a stealthy glance at the tempting prey so near his reach, he prepares to spring. But again the watcher leaps forth from the shadow, and hurls a sharp javelin with so true an aim that the lordly beast is mortally wounded, and retreats to the forest, roaring with pain. And still the infant sleeps on.

Just outside of the dreary forest is a poor herdsman’s hut. Here, too, might have been found an infant; but it is crowing and smiling as it raises its chubby fists to its mouth and tries to catch the sunshine, which streams in through the open door, and falls upon the wall over its head. This baby is clothed in the coarse garments of a peasant’s child. And yet the infant in the costly robes, in the wild forest, is really the dead child of a poor herdsman; and this crowing, laughing baby, dressed in peasant clothes, and lying in the lowly hut, is none other than the future Cyrus the Great, upon whom hang the destinies of a vast empire. The remarkable story regarding the birth and early boyhood of Cyrus the Great is recounted by Herodotus, one of the greatest and earliest of Grecian historians. Herodotus and Xenophon—a noted Grecian general, as well as historian—are the chief sources of information regarding most of the important historical events of that period of the world. Some parts of their accounts are thought to be historical romances, founded on facts; but as they have become a part of the history of those times, I shall gather the story of Cyrus from the events related by both these writers.

About 599 B.C. there were three kingdoms in the centre of Asia: Assyria, Media, and Persia. Astyages was king of Media. One night Astyages awoke from a terrible dream: he had dreamed that a fearful inundation had overwhelmed his kingdom. As the deluge seemed in some mysterious manner to be connected in his mind with his only daughter, Mandane, he imagined that it portended that evil should come to his throne through her children. And so he arranged that she should marry Cambyses, ruling prince of Persia. In this manner he hoped to remove her so far distant, and place her in so weak a kingdom, that he need have no fears.

A year after his daughter’s marriage to the king of Persia, Astyages had another dream,—of a great vine which overspread his kingdom. This vine also appeared to be associated in his mind with his daughter. So he called the soothsayers, who declared that it portended the future power of his daughter’s son, who should become a king.

Astyages was now so alarmed that he determined to destroy the child. So, with seeming kindness, he invited his daughter Mandane to make him a visit. He placed her in a palace and surrounded her with his own spies and servants. As soon as the infant son was born, Astyages sent for an officer of his court, named Harpagus, whom he thought was unscrupulous enough to obey his evil commands. Astyages ordered Harpagus to go and request the attendants of Mandane to allow him to see the infant; and then, under pretence that his grandfather Astyages desired that the infant should be brought to him, Harpagus should take the child away, and in some manner cause it to be put to death.

Harpagus did not dare to refuse, and accordingly went to the palace in which Mandane was residing. Her attendants, not suspecting his evil designs, arrayed the infant in its most beautiful robes, and delivered it into his care. Harpagus took the child home and consulted with his wife what he should do. He did not dare to disobey the king, and also, as Mandane was the daughter of the king, he feared to carry out the terrible deed himself.

In his perplexity he sent for one of his herdsmen, named Mitridates, living near wild and desolate forests. When Mitridates arrived, Harpagus gave the infant to him, commanding him to expose it in the forests for three days, and when the child was dead, to send him word.

The herdsman dared not refuse this wicked mission, and took the child home to his hut. His wife Spaco had at that time just lost an infant of the same age, and its dead body was still unburied. When she saw the beautiful babe of Mandane, she implored her husband to let her keep it in place of her dead child, who was accordingly arrayed in the costly robes of the young prince, while the royal baby was dressed in the coarse garments of the little dead peasant. The body of the dead infant was then placed in the royal cradle, or basket, in which the little prince had been carried from the palace; and after being exposed in the forest for three days, attended by watchers to keep away the wild beasts, the herdsman sent word to Harpagus that the infant was dead. Harpagus sent trusty messengers to see if the report was true; and when they saw the dead infant in the royal robes, they returned with the assurance that his orders had been complied with, and that they had seen the dead child. Harpagus gave orders to have the body buried, and sent word to King Astyages that the infant was dead.

The truth about the young Cyrus was not discovered until ten years after, and came about in a very strange way. Cyrus had now grown to be a strong, bright boy of ten years of age, and was supposed to be the son of the peasant herdsman. Several of the sons of the Median nobles were accustomed to meet in the neighborhood where he lived, for their sports, and Cyrus was always their leader in all pursuits. The story goes that he was once chosen as their king in a boyish game; and one of the nobles’ sons, being one of his subjects, and having disobeyed his commands, the boy king Cyrus punished him very severely. The father of the young noble complained to King Astyages of this ill treatment which his son had[34] suffered at the hands of a peasant boy. Whereupon, the herdsman Mitridates and his supposed son were summoned to appear at court.

When the young Cyrus entered the presence of the king, Astyages was astonished at his manly bearing and his unusual beauty, and with an unaccountable feeling of interest in the supposed peasant boy, he inquired if the complaint of the noble was true. The little disguised prince looked up into the face of the dread monarch, in whose presence all his subjects trembled, and with perfect self-possession, replied,—

“My lord, what I have done I am able to justify. I did punish this boy, and I had a right to do so. I was king, and he was my subject, and he would not obey me. If you think that for this I deserve punishment myself, here I am; I am ready to suffer for it.”

Astyages was so surprised at this unlooked-for answer that he hastily commanded that Mitridates should be brought before him; and under threats of severe punishment, he demanded that he should tell him the truth about the lad; for he had grave doubts about his being the peasant’s son. Mitridates, frightened by the stern manner of the king, confessed the truth, and related all the circumstances regarding the infant who had been committed to him by Harpagus.

Astyages had deeply regretted his evil intentions towards his grandson, which, as he supposed, had ended in his death, and gladly claimed Cyrus as his own. But with strange inconsistency, he was equally incensed against Harpagus, who had dared to disobey his commands, by not causing the infant to be put to death; and he determined to celebrate in a strange and most shocking manner his joy at the recovery of his grandson, and his anger[35] at the disobedience of Harpagus. So with wicked craftiness he sent word to Harpagus that his grandson had been discovered, and commanded that Harpagus should send his son, a boy about thirteen years of age, up to the palace to be a companion for young Cyrus. Furthermore, he announced that he was about to celebrate his joy at the recovery of his grandson, by a grand festival, at which he invited Harpagus to be present.

Harpagus suspecting no evil, and rejoicing at the happy sequel of that deed which had occasioned him much disquiet, having sent his son to the palace, according to the command of the king, related to his wife the strange events which had taken place. Neither of them were suspicious of any evil design in this seeming kindliness of Astyages, and thought it a fitting honor for their son, that he should be chosen as the companion of Prince Cyrus. Harpagus went to the festival, and was given a seat of honor at the table. Various dishes were set before the guests, and the attendants were especially attentive to see that Harpagus was most bountifully served. At the end of the feast, Astyages asked Harpagus how he had liked his fare. Harpagus expressed himself as being well pleased. The king then ordered the servants to bring in a basket, which they uncovered before Harpagus, and he beheld with horror the head, hands, and feet of his own son.

The story relates that Harpagus did not display his terrible despair by word or look; and when the wicked king asked him if he knew what he had been eating, he replied that he did, and whatever was the will of the king was pleasing to him. Such shocking cruelties reveal the wickedness of those despotic times.

Harpagus satisfied his revenge against the cruel Astyages,[36] many years afterwards, in a manner which will be disclosed as this story continues. A king whose greed of power could condemn an own grandson to death would not scruple at other crimes. Astyages now again consulted the soothsayers as to his safety in recognizing Cyrus as his grandson and giving him his royal place at court. The Magi now replied, that as Cyrus had already been a king, even though it was only in a childish game, still, as he had been called a king, the oracles had been fulfilled, and Astyages need fear no further danger to his kingdom. Astyages therefore sent Cyrus to his parents in Persia, who received their long-lost son with overwhelming delight; and the youthful Cyrus was no doubt astonished and rejoiced to find himself the son and grandson of powerful kings, rather than a simple peasant boy, the son of a poor herdsman.

Cyrus is described by the historians as being tall and handsome, and excelling in all youthful exploits.

Xenophon describes the life of young Cyrus in the court of his father Cambyses, king of Persia. The sons of all the nobles and officers of the court were educated together in the royal palace. They were not taught to read, as there were no books, but they had certain teachers who explained to them the principles of right and wrong, and described to them the various laws of the land, and the rules by which controversies should be settled. These were put to practical use in deciding the various cases which occurred among the boys themselves; and judges were chosen from their number who should discuss and decide these questions. Right decisions were rewarded, and wrong ones punished. Cyrus himself was once punished for a wrong decision. The case was this:—

A larger boy took away the coat of a smaller boy,[37] whose coat was bigger than his own, and gave him his own smaller coat. The smaller boy appealed to Cyrus, who decided that each boy should keep the coat that fitted him. The teacher condemned his decision in these words,—

“When you are called upon to consider a question of what fits best, then you should determine as you have done in this case; but when you are appointed to decide whose each coat is, and to adjudge it to the proper owner, then you are to consider what constitutes right possession, and whether he who takes a thing by force from one who is weaker than himself, should have it, or whether he who made it or purchased it, should be protected in his property. You have decided against law and in favor of violence and wrong.”

PERSIAN GUARDSMAN CARRYING

BOW AND QUIVER.

|

PERSIAN SOLDIER WITH

BATTLE-AXE

|

PERSIAN FOOT SOLDIERS.

| |

The boys at this Persian court were taught many kinds of manly exercises. They were trained to wrestle and run, and were instructed in the use of all kinds of arms then known. Each one was furnished with a bow and arrows, a shield, a sword, or dagger, which was worn at the side in a scabbard, and two javelins, one of which they were to throw, and the other to keep in the hand for use in close combat with the wild beasts which they might encounter in their hunting expeditions. These excursions were often long and fatiguing, which they took by turns with the king in the neighboring forests.

They were subjected to long marches, to cold and hunger and storms, and sometimes dangerous conflicts. These experiences were considered necessary to fit them to become good soldiers in the future.

When Cyrus was about twelve years of age, he was invited by his grandfather Astyages to make him a visit in Media. When Cyrus arrived in Media with his mother[38] Mandane, he was surprised at the magnificence and pomp of the royal court; as the manners and habits of the Persians were very simple, and as he had been sent to Persia as soon as his royal rank had been discovered, he had not before had an opportunity of seeing the splendor of his grandfather’s court.

In his first interview with Astyages, Cyrus displayed his great tact and natural courtesy. When he came into the presence of his grandfather, who wore a purple robe richly embroidered with gold and covered with precious stones, and bracelets upon his arms, and a long, flowing wig, while his face was painted and powdered, Cyrus exclaimed,—

“Why, mother, what a handsome man my grandfather is!”

Cyrus was dazzled by the great display around him, for in the Persian court, Cambyses his father, and all his nobles, were clothed with great simplicity. Mandane then said to Cyrus,—

“Which one do you think the handsomer man, your father or your grandfather?”

It was a very unwise question to ask a child, but Cyrus was equal to the emergency, and replied with great tact and politeness,—

“My father is the handsomest man in Persia, but my grandfather is the handsomest of all the Medes.”

Astyages was much pleased with the aptness of this reply, and Cyrus became a great favorite with his grandfather, who lavished upon him costly garments, rich feasts, rare jewels, and the attentions of a retinue of servants. But after the first novelty had passed away, Cyrus preferred his more simple raiment and plainer food.

At one time, Astyages invited Cyrus and his mother[39] to one of his grand feasts in his palace, and ordered the rarest viands to be served for Cyrus in the most elegant and costly dishes. Instead of being flattered, Cyrus showed no particular pleasure or surprise, and when Astyages asked him if he did not delight in such rich and delicate food, and if the feast before him was not much finer than any he had seen in Persia, Cyrus replied,—

“We manage much better in Persia; it is very troublesome to eat a little of so many things.”

“How do you manage in Persia?” asked Astyages.

“When we are hungry, we eat plain meat and bread, and so we get health and strength and have very little trouble,” answered Cyrus.

Astyages then told Cyrus that he might continue his plain fare in Media, if he thought it was better for his health. Cyrus then asked his grandfather if he would give him all the costly dishes before him to do as he wished with them. To this Astyages consented, and Cyrus, calling up one of the attendants after another, presented to them as gifts the various elegant dishes with their contents. To one he said, “I give you this because you serve the king faithfully”; to another, “I make you this present because you are faithful to my mother”; and to another, “Because you have taught me to throw the javelin.” Thus he went on until all the gifts had been disposed of. Now the king had one servant, whom he honored above all others, who held the office of cup-bearer.

In those days this was an important trust, for those despotic monarchs possessed so many enemies that they were in constant danger of assassination or of being poisoned. The king’s cup-bearer must superintend the food of his master, and taste all wines himself before offering them to the king.

Great dexterity and grace were necessary to perform the latter service acceptably, as the king’s cup must not be placed to the lips of his cup-bearer, but a small portion must be poured into the palm of his hand, and lifted gracefully to his mouth.

Astyages’ cup-bearer was a Sacian; he was an officer of high rank, tall and handsome, and magnificently dressed. In distributing his gifts, Cyrus had neglected this officer, and when Astyages asked him his reason, Cyrus replied that he did not like the Sacian. Astyages inquired the cause of this dislike, and remarked, “Have you not observed how gracefully and elegantly he pours out the wine for me, and then hands me the cup?”

Cyrus replied that he could pour out the wine and offer the cup as well as the Sacian, and requested his grandfather to allow him to try. To this the amused king consented, and Cyrus, taking a goblet of wine in his hand, retired from the room. He soon re-entered with the pompous and dignified bearing of the Sacian, and so mimicked his manner of gravity and self-importance as to occasion much mirth amongst the assembled guests.

Cyrus, having advanced to the king, presented him with the cup, neglecting not even one single motion of the usual ceremony, except tasting the wine himself. Mandane and the king laughed heartily, and the would-be cup-bearer, becoming the child again, jumped into his grandfather’s arms, exclaiming, “Now, Sacian, you are ruined; I shall get my grandfather to appoint me in your place. I can hand the wine as well as you, and without tasting it myself at all.”

“But why did you not taste it?” asked his grandfather.

“Because the wine was poisoned,” replied Cyrus.

“What makes you think it is poisoned?” inquired Astyages.

“Because,” said Cyrus, “it was poisoned the other day when you made a feast for your friends on your birthday. It made you all crazy. The things that you do not allow us boys to do you did yourselves, for you were very rude and noisy; you all bawled together so that nobody could hear or understand what any other person said. Presently you went to singing in a very ridiculous manner, and when a singer ended his song, you applauded him, and declared that he had sung admirably, though nobody had paid attention. You went to telling stories too, each one of his own accord, without succeeding in making anybody listen to him. Finally, you got up and began to dance, but it was out of all rule and measure; you could not even stand erect and steadily. Then you all seemed to forget who and what you were; the guests paid no regard to you as their king, but treated you in a very familiar and disrespectful manner, and you treated them in the same way; so I thought that the wine that produced these effects must be poisoned.”

“But have not you ever seen such things before?” asked Astyages. “Does not your father ever drink wine until it makes him merry?”

“No,” replied Cyrus, “indeed, he does not; he drinks only when he is thirsty, and then only enough for his thirst, and so he is not harmed.” He then added in a contemptuous tone, “He has no Sacian cup-bearer, you may depend, about him.”

“But why do you dislike this Sacian so much, my son?” asked Mandane.

“Why, every time that I want to come and see my grandfather,” replied Cyrus, “he always stops me, and will not let me come in. I wish, grandfather, you would let me have the rule of him for just three days.”

“What would you do?” asked Astyages.

“I would treat him as he treats me now,” answered Cyrus. “I would stand at the door, as he does when I want to come in, and when he was coming for his dinner, I would stop him and say, ‘You cannot come in now; he is busy.’” Cyrus repeated these words in the tones and with the grave manner of the Sacian.

“Then,” continued Cyrus, “when he was coming to get his supper, I would say, ‘You must not come in now; he is bathing, or he is going to sleep; you must come some other time, for he cannot be disturbed.’ Thus I would torment him all the time, as he now torments me in keeping me from you when I want to see you.”

When the time arrived for Mandane to return to Persia, Astyages was very desirous to have Cyrus remain with him; Mandane gave her consent if Cyrus should wish to do so. Astyages told Cyrus that if he would stay, the Sacian should torment him no more, but that he should be allowed to come into his presence whenever he wished to do so, and, moreover, he should have the use of all his grandfather’s horses. He should also have boys of his own age for companions, and they would be allowed to hunt the animals in the park. They could pursue them on horseback and shoot them with bows and arrows, or throw the javelins at their prey. This pleasure of riding and hunting was a rare one to Cyrus, for the Persians had few horses, and there were no bodies of cavalry in their armies. Cyrus represented to his mother the great advantage it would be to him to be a skilful horseman, as that would give him a superiority over all the Persian youths. Mandane was somewhat anxious lest the luxurious habits and haughty manners of his grandfather should prove a bad example for Cyrus, but he assured[43] her that she need have no fears, as his grandfather required all to be submissive to himself, and allowed imperiousness in no one but the king. So it was decided that Cyrus should remain in Media, and Mandane departed for Persia.

Cyrus now applied himself with great diligence to acquire all the various accomplishments and arts then most highly prized, such as leaping, vaulting, racing, riding, throwing the javelin, and drawing the bow. In the friendly contests among the boys, Cyrus would courteously challenge those superior to himself in these exercises, thus giving them the pleasure of winning the prize, and benefiting himself by thus having the greater stimulus of contesting with attainments higher than his own. He accordingly made rapid progress, and speedily learned to equal and then surpass his companions without occasioning any envy or jealousy.