U.S. Department of Agriculture—Forest Service

State and Private Forestry—Southeastern Area

Forest Pest Management Group

This publication has been prepared to assist forest managers and homeowners in identifying pests of southern trees. The insects and diseases discussed are the more common ones attacking forest and ornamental trees. Prompt identification and treatment of these pests may mean the difference between losing or saving a valuable shade tree. Underlying all successful forest and ornamental pest control efforts, however, is the necessity to keep trees in a healthy, vigorous condition.

We have attempted to include pictures of the damage as well as pictures of the damage-causing organism or stage. Chemical suppression recommendations are not included in this publication. For pesticide information contact the local State or Federal extension specialist, forester, entomologist, or pathologist.

Credit for some of the pictures in this guide goes to the Southern and Southeastern Forest Experiment Stations and universities. We acknowledge the help of the Forest Pest Management field personnel who assisted in compiling this booklet.

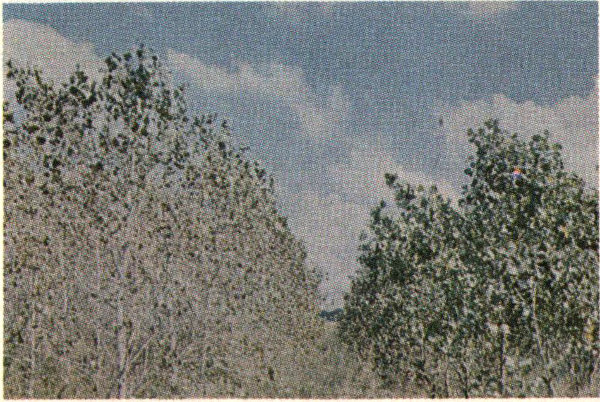

The elm spanworm is a native insect which is widely distributed over the eastern half of the United States and Canada from Nova Scotia south to Georgia and west to Colorado. The most widespread outbreak on record occurred during the period 1954-1963 when over one million acres of hardwood forests were defoliated in the mountains of western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee and northern Georgia. The elm spanworm feeds upon hickories and a variety of hardwoods; white oak, chestnut oak, and northern red oak are the species most heavily defoliated in the Appalachians. Repeated defoliation causes growth loss, reduces mast crops, and will eventually kill the tree.

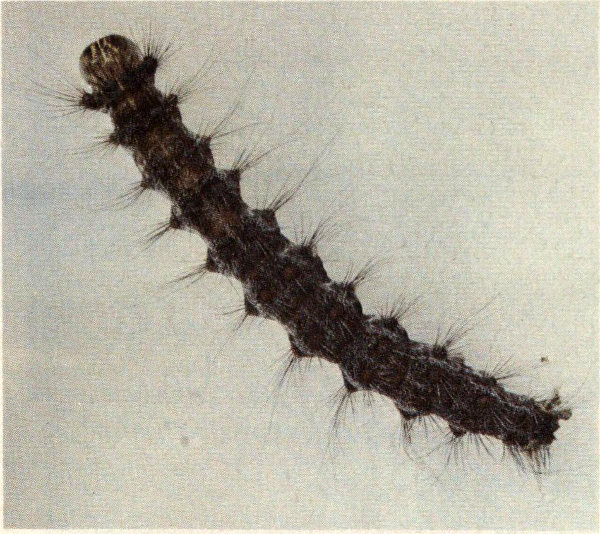

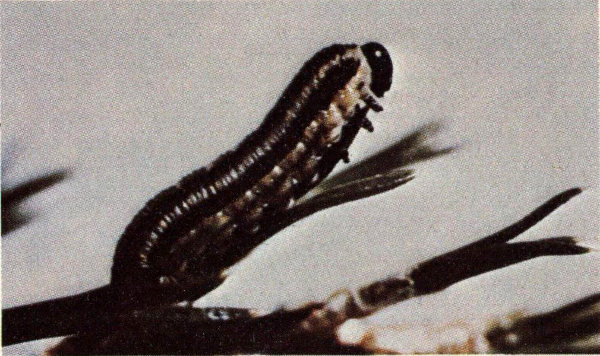

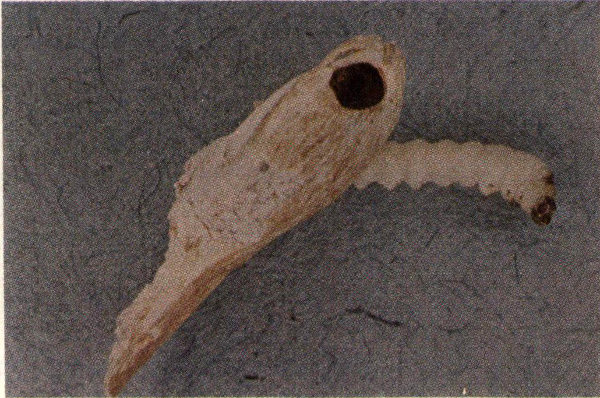

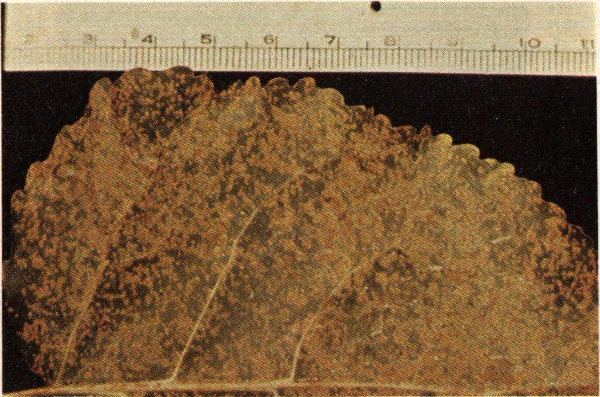

Sixth instar elm spanworm larva.

Eggs are laid in masses of 12 to 200 on the undersides of host tree branches in early July. Winter is spent in the egg stage. Larvae hatch in early spring when foliage opens. The larval stage is an “inchworm” or “looper”, approximately 1½ inches long when mature. Larval coloring varies from green or light brown to black, depending upon population density. The typical color of the larva in heavy populations is dark brown to black, with a dark-red head, legs, and anal shield. The larvae feed for about 1½ months, and then pupate in a loose cocoon for six to ten days. The adult, a snow-white moth, emerges in late June or early July. There is one generation per year.

Natural enemies help keep populations of the elm spanworm in check. One of the most important is Telenomus alsophilae, a tiny wasp which parasitizes eggs. Persistent outbreaks on high-value stands may require treatment with chemicals.

Elm span worms feeding on oak.

The fall cankerworm is widespread in the northern part of the United States, ranging south through the Appalachian Mountains to North Carolina. Larvae defoliate many species of hardwoods, but in the South seem to prefer oaks, hickories, and ash.

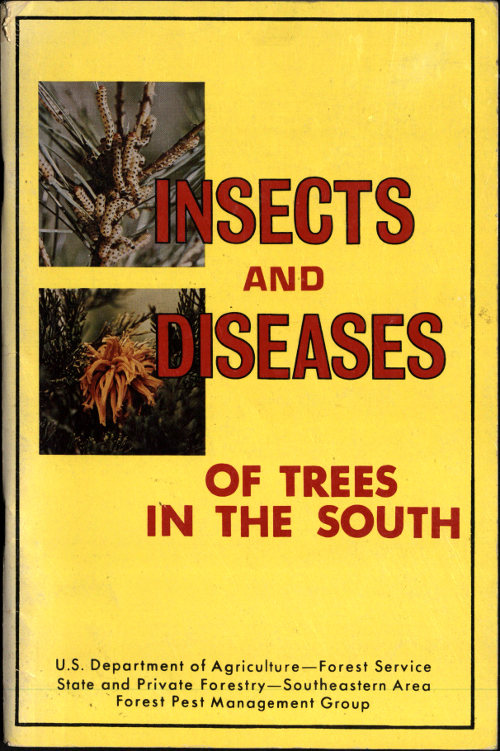

Mature fall cankerworm larva.

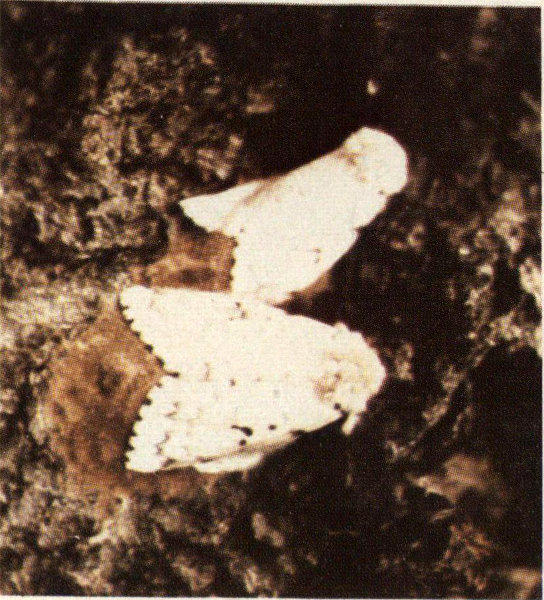

The winged male and wingless female adults emerge on mild days in November and December and mate. Females lay 6-300 eggs in neatly arranged masses encircling small branches and twigs. The pale green larvae hatch in late April or early May. As they mature they may remain light green, or change to a very dark brownish-green depending on the host. Newly hatched inch-worms (larvae) of the fall cankerworm chew small holes in expanding leaves of their hosts, or may completely skeletonize the leaves. Mature larvae consume all but the mid-rib and major veins of the leaf. Feeding is usually completed in four to five weeks, at which time larvae drop to the ground to pupate in the soil.

Cold, wet weather during the early larval period, and parasitization, are responsible for sudden declines in established populations. Chemical control has also been effective. A small wasp, Telenomus alsophilae Viereck, has caused a sharp decline in outbreaks of cankerworm populations. Usually, however, outbreak conditions must exist for several years before the parasite can attain the density needed to cause a decline.

Female cankerworm adult depositing eggs.

Larvae of this moth, one of the measuring worms, have periodically been responsible for scattered mortality of hardwoods throughout the eastern United States. Mortality is most likely to occur in stands on low-quality sites, particularly during periods of drought which favor this insect’s development and further weaken infested trees. This species is likely to be found in almost any hardwood area in the eastern United States. The insect feeds on a wide variety of trees and shrubs. Host trees in the Southeast include oaks, hickories, black tupelo, and black locust.

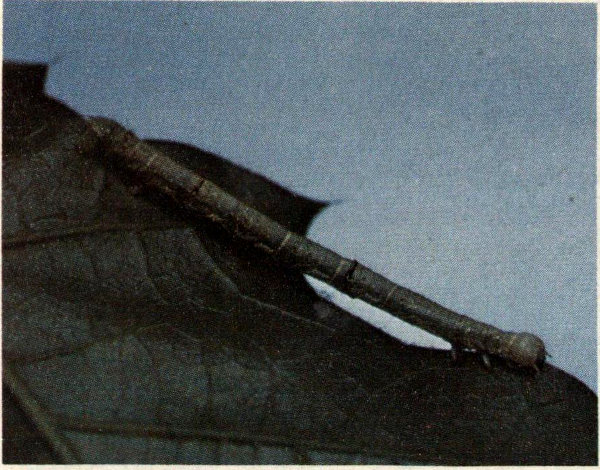

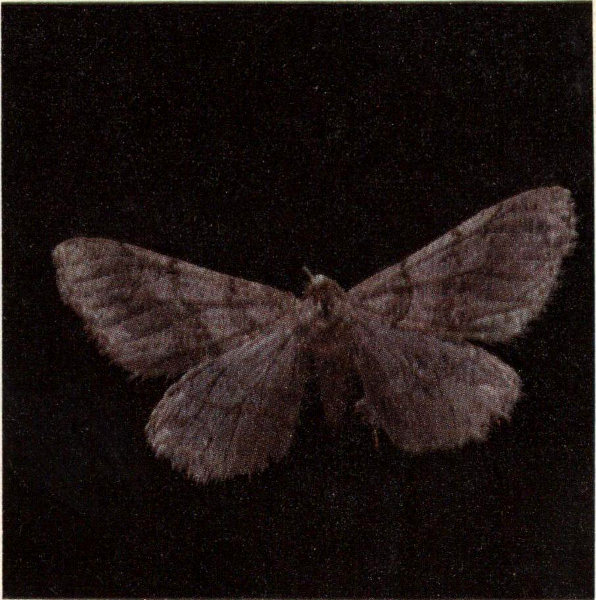

Phigalia adult male moth.

Phigalia titea overwinters as a pupa. Adults emerge in late March to mid-April, and mate. The female lays her eggs in protected sites on branches and trunks of hardwoods. Eggs are most often laid in crevices and beneath the bark of dead branches. Eggs hatch in April, and larvae feed until early June. Larvae often feed on unopened buds, causing irregular holes in the developing leaves. Larvae first eat just the surfaces of leaves, but later consume all leaf tissue between the major veins. When larvae are dislodged by wind or feeding predators they fall or descend on a silken thread and continue feeding in the lower crown or on understory vegetation. Pupation occurs on the soil surface or in the litter.

Phigalia larva.

Weather regulates populations of this insect. Soil-inhabiting insects and rodents are believed to destroy many pupae during the winter.

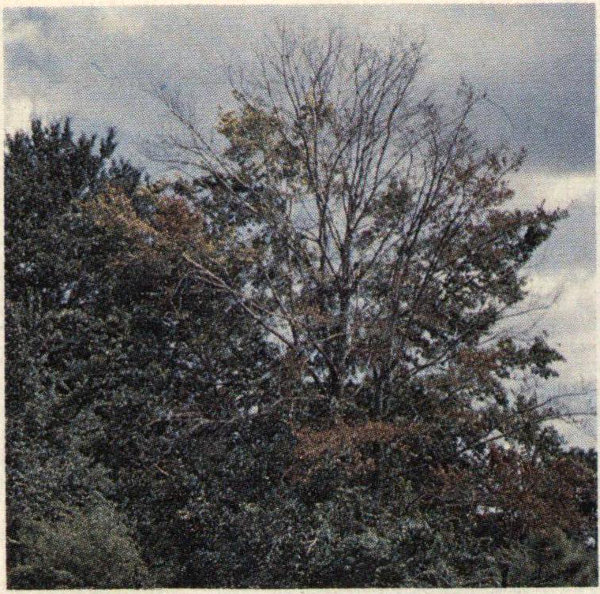

The presence of the eastern tent caterpillar is objectionable more from an aesthetic standpoint than from its effect on the host tree. The ugly tents constructed by the feeding larvae make this pest highly objectionable on shade trees. Black cherry and other species of the genus Prunus are preferred hosts, but other trees in the family Rosaceae are sometimes attacked. This insect is widely distributed wherever host trees are found east of the Rocky Mountains.

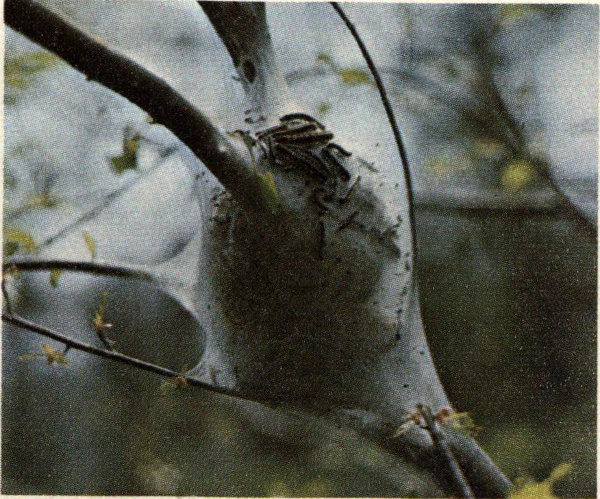

Larvae and tent of eastern tent caterpillar.

The caterpillars appear at about the same time the leaves of black cherry begin to unfold. The larvae construct a web or tent in the crotch of a small branch, and begin feeding. Usually they consume entire leaves, except for the large veins. As the larvae mature, they add to the tent, which may reach a foot in diameter and two feet in length. Reaching maturity in about six weeks, the larvae drop to the ground and pupate. The moths emerge in June and the females lay eggs. Eggs of the eastern tent caterpillar are shiny black masses which encircle the smaller twigs and are quite noticeable. The insect overwinters in the egg stage.

Control on ornamental, fruit, and shade trees is achieved by pruning off and burning the tents containing the caterpillars.

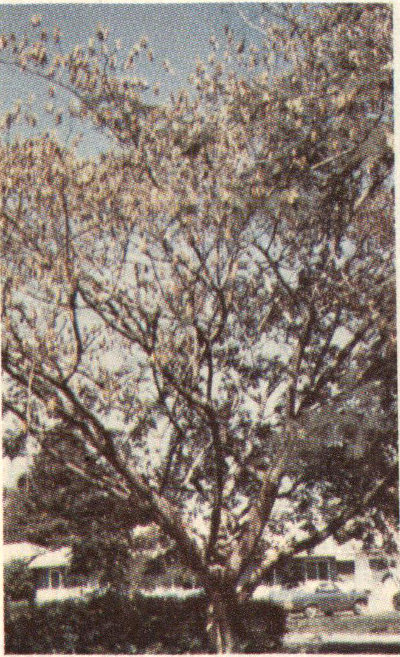

Tent caterpillar-infested black cherry.

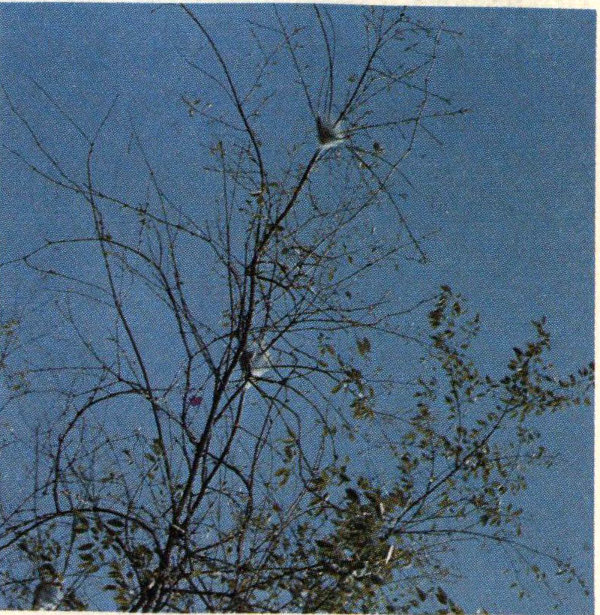

The forest tent caterpillar has caused repeated serious defoliation of hardwood forests throughout North America. Aspen, water tupelo, hard maple, gums, and oaks are preferred hosts but this insect will feed on a variety of other broadleaf trees.

Forest tent caterpillar larvae.

The shiny black egg masses encircling the twigs of host trees can be seen during winter months. Small black, hairy larvae hatch out just as the leaves are beginning to unfold. They do not construct a tent, but make a silken mat on the larger branches or trunk of the tree on which they rest between feeding periods. When full grown, the larvae are about two inches long, brownish-black with distinctive white, keyhole-shaped spots down the middle of the back, and blue lines along the sides. Just before pupating, the larvae spin a whitish silk cocoon on the bark or leaf of the host. In about ten days the light brown moths emerge, mate, and the females begin laying their eggs.

Parasitic flies are one of the more important agents which normally keep this insect under control. Outbreaks occur with some regularity, however, and chemicals may be required to prevent defoliation.

Colony of third instar larvae.

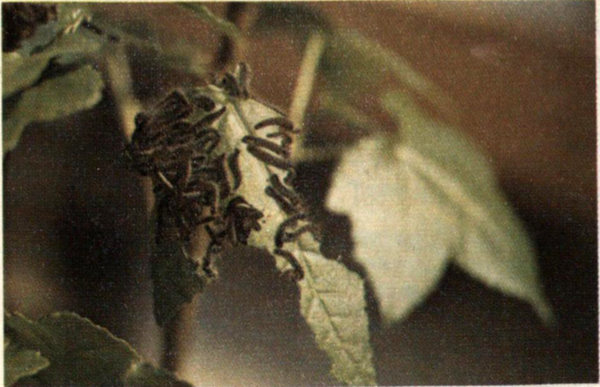

The fall webworm is not considered an important forest pest. However, ugly webs can seriously detract from aesthetic values. The preferred hosts in the South are persimmon, pecan, and sourwood, but it is also found on black walnut, hickory, cherry, sycamore, crab apple, and sweetgum. The insects range throughout North America.

Fall webworm larva.

The adult is a pure white moth about 1¼ inches long. The forewing is sometimes marked with blackish dots. The larva is about one inch long when full grown, generally pale yellow or greenish with a broad dark longitudinal stripe on the back and a yellowish stripe extending from black and orange warts. The insect has one generation per year in the northern part of its range, and two in the southern part. Moths of the first generation emerge from May to July and those of the second in July and August. Adult females lay 400-500 eggs in white cottony patches on the underside of the leaves of host plants. The eggs hatch in about a week, and the larvae form a web and begin to skeletonize the leaves by feeding in rows. As the larvae grow they expand the web to cover the colony. When the larvae are ready to pupate, they crawl or drop to the ground and form a brownish cocoon in the duff around the tree where they overwinter.

Fall webworm infestation.

Natural enemies usually keep this insect under control. Webs can be pruned from high-value trees in scenic or recreation areas.

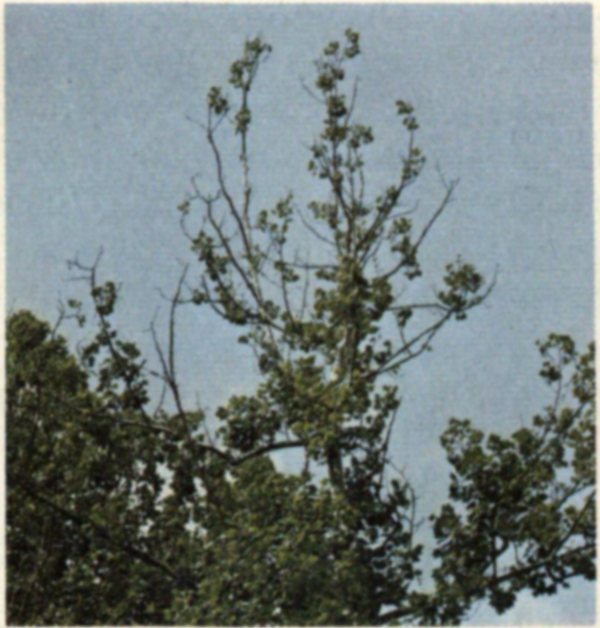

This oak leaf tier has been associated with the decline and mortality of several species of oak in the northeastern United States and southern Appalachians. An outbreak population in the mountains of West Virginia and Virginia in 1966-68 resulted in the loss of several thousand acres of scarlet oak. Usually such outbreaks coincide with periods of drought which increase the impact of defoliation on the host. Its hosts include northern red oak, black oak, scarlet oak, and pin oak. The latter two species seem to be hit hardest by this insect.

Leaf tier adult and pupa.

Croesia albicomana spends the winter in the egg stage. Eggs are glued to small twigs in the crown of the host tree. Hatch occurs from mid-April to early May. Young larvae, which emerge before bud-break, bore into and mine the expanding buds. When large numbers of this insect are present they can destroy most of the vegetative buds on a tree. Later the older larvae tie down a folded-over portion of a leaf and feed on it. Leaves fed on by the oak leaf tier appear to be full of shot holes. As the larvae near maturity they may tie the apical portion of two or more leaves together and feed on them. Mature larvae then drop to the ground to pupate in the litter. Adult moths emerge in June or early July, mate, and the female immediately begins laying eggs. The small, flat, oval eggs are deposited individually on small twigs, generally around nodes or leaf scars.

Scarlet oak killed by leaf tier.

Little is known of the natural factors which regulate population levels of this insect, but undoubtedly weather is important.

The variable oak leaf caterpillar periodically defoliates extensive areas of hardwood forest in the eastern United States. Its range covers all of the southern and eastern states as far west as east Texas. The larvae feed primarily on oaks but will also feed on beech, basswood, birch and elm. Other defoliating insects may be associated with outbreaks causing additional damage. Young larvae skeletonize the leaf while older larvae devour the entire leaf except the primary veins. Infestations are generally more severe in the South, where the insect has two generations per year causing two periods of defoliation in a single year. While infestations usually subside before many trees are killed, heavy defoliation reduces the tree’s growth and vigor.

Larva of the variable oak leaf caterpillar.

The variable oak leaf caterpillar overwinters as a non-feeding larva in a cocoon on the forest floor. It pupates and emerges as a moth the following spring. The female moth, gray in color and about 1¾ inches long, lays about 500 eggs singly on the leaves of host trees. The larvae feed on foliage for five or six weeks, drop to the ground to pupate, and emerge as adults in mid-summer. Larvae hatching from eggs laid by the second generation of moths defoliate the trees for a second time during late summer. By late October the mature larvae of the second generation have dropped to the forest floor to overwinter. The full grown larva is approximately 1½ inches long. Color varies among individuals. The head is generally amber brown with curved diagonal white and black bands. The body is usually yellow green with a narrow white stripe down the center of the back bordered by wider dark bands.

Outbreaks of the variable oak leaf caterpillar may be severe but generally subside before serious tree mortality occurs. Parasites and predators are not effective in controlling rising populations of the insect. Mice and predaceous beetles feed on the resting larvae and pupae in the litter and soil of the forest floor. While no chemical is currently registered for control of this insect, chemical spraying has been effective and safe in controlling closely related insects.

The locust leafminer is a destructive pest of black locust and honey locust in both the adult and larval stages. It is found throughout the range of these trees in the eastern half of North America. The adults also feed on other species of trees.

The adult beetles overwinter in crevices in the bark of trees and under litter on the forest floor. The beetles emerge and begin feeding in the spring, usually after mid-April. After feeding for a short time they deposit eggs on the undersides of leaves, piling them one upon another, somewhat shingle-like. Eggs are covered with brownish fecal matter. Larvae soon hatch and eat into the leaf tissue to form a mine. Newly emerged larvae feed gregariously in a single mine for a short time. They then construct new mines where the insects live singly. Several mines are constructed before the larvae reach maturity. The larvae pupate in the mines and emerge as adults in July to begin the second generation. The adult beetles are foliage feeders, eating irregular holes in leaves. When sufficient in number they may defoliate host trees.

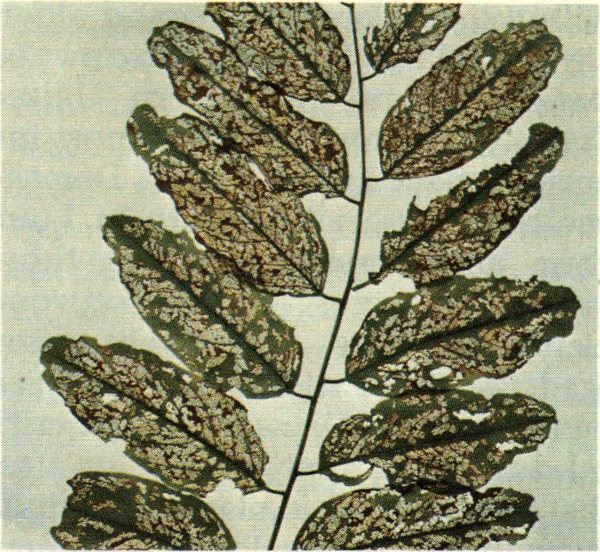

Damage to black locust caused by the locust leaf miner.

Under forested conditions no control is recommended. Rarely do trees die from attacks by this insect. Damage is objectionable mostly from an aesthetic viewpoint.

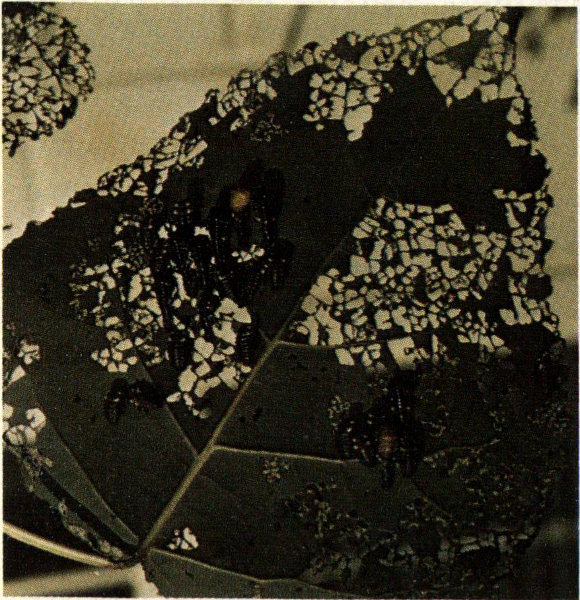

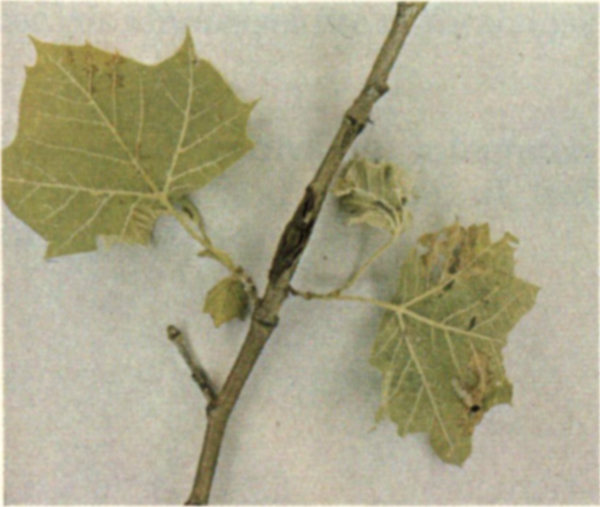

Willows, poplars, aspens and alders are attacked by the cottonwood leaf beetle in the eastern United States. Cottonwood is the most important host in the South. Damage has been especially severe in Louisiana and Mississippi where thousands of acres of cottonwood plantations are intensively managed. Adult beetles and larvae feed on the foliage. Damage is most critical during the first three years after the cottonwood is planted. Adults chew holes in the leaves and may attack the terminal shoots causing reduced growth or stem deformity. Young larvae skeletonize the foliage but older larvae consume all foliage except the leaf midribs. Damage may become severe enough to cause mortality.

Cottonwood leaf beetle adult.

The cottonwood leaf beetle overwinters in the adult stage. Eggs are laid in the spring. The female lays a cluster of about 75 yellowish eggs on the underside of a leaf. As the larvae mature they become yellow with black spots. After about nine days in the larval stage the beetle transforms into the non-feeding pupal stage which lasts five to ten days. The adult is about ¼-inch long and has a black head and thorax. The wing covers are yellow with longitudinal black stripes. The life cycle is completed in 25 to 30 days and several generations occur in a single year.

Larvae and pupae of the cottonwood leaf beetle.

Control may be needed in a plantation only during the first three years. Chemical sprays have been successful in the past but at the present time no insecticides are registered for cottonwood leaf beetle control.

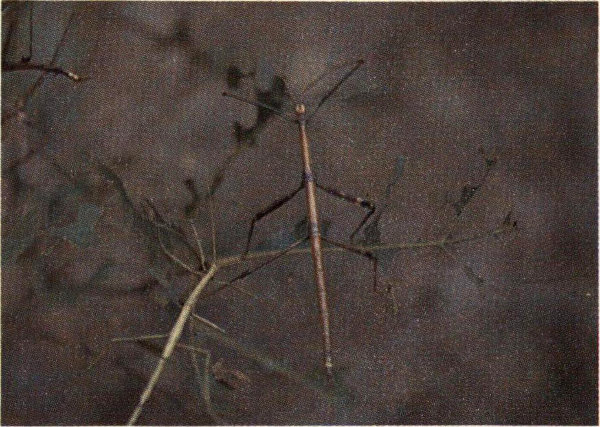

The walkingstick is a defoliator of broadleaved trees in North America. The black oaks, basswood, and wild cherry are the most common preferred hosts but numerous other hardwood species are attacked. This insect is widely distributed over the United States east of the Rocky Mountains as well as Manitoba and Ontario in Canada. At times, populations build in sufficient numbers to defoliate trees over large areas.

Male walkingsticks feeding on oak.

These slender, wingless, stick-like insects are pale green when young, but gradually change to a dark green, gray, or brown at maturity. The adult female measures up to three inches in length and is more stout-bodied than the male. Mating usually takes place in August and egg laying begins six to ten days later. The eggs are dropped to the ground where they overwinter in the leaf litter. In the northern part of the walkingstick’s range the eggs take two years to hatch. In the South, walkingstick eggs hatch the summer after they are laid, usually starting in mid-May. The newly hatched walkingstick looks like a miniature adult.

Parasitic wasps and flies are active against the immature walkingsticks but are not efficient enough to cause a substantial population reduction. Flocks of robins, blackbirds, and grackles have a much greater impact, however. The defoliation caused by walkingsticks generally occurs on upland sites in stands which are not of high value or intensively managed. For this reason there has been little interest in control.

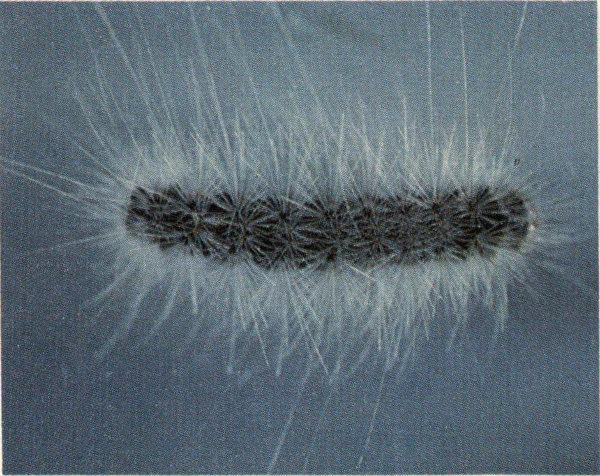

The gypsy moth is an introduced forest insect. It was brought into this country from Europe in 1869 and has been restricted to the Northeast. The gypsy moth feeds aggressively on oak, alder, apple, basswood, willow, and birch. As the caterpillars reach maturity they will also feed on hemlock, cedar, pine, and spruce.

Gypsy moth larvae.

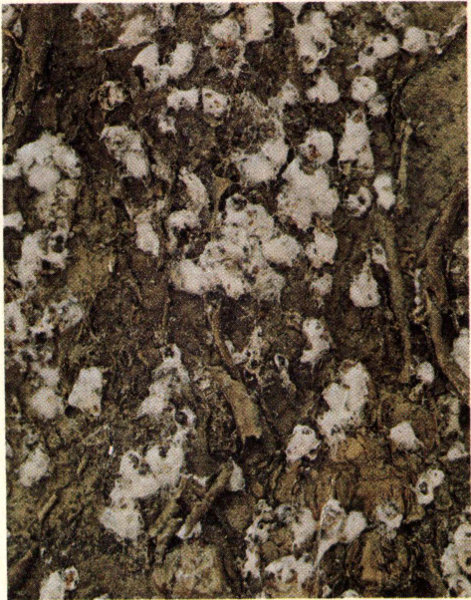

In the Northeast, the gypsy moth has a single generation per year, overwintering in the egg stage. Eggs hatch in late April and May and larvae are present for approximately two months. Full-grown caterpillars measure more than two inches long and are easily identified by the five pairs of blue spots and six pairs of red spots arranged in a double row along the back. The adult moths are active from late June to early September. Female moths, their bodies heavy with eggs, are unable to fly and must rely on a powerful sex attractant to lure male moths. This sex attractant has been chemically synthesized and is used as a trap bait in surveys designed to determine the presence of gypsy moths in areas suspected to be infested. Each female deposits from 200 to 800 eggs in a buff-colored mass which she attaches to any convenient surface including cars, trailers, and other vehicles.

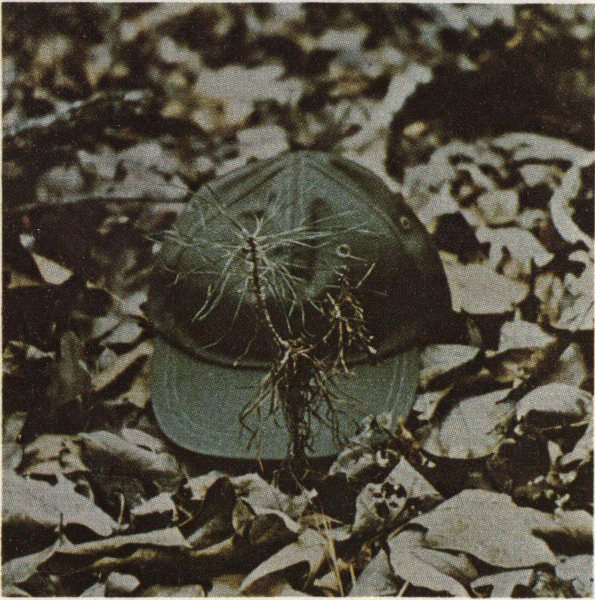

Female gypsy moths depositing egg masses.

During the past 75 years the gypsy moth has been the target of many large-scale control programs, and much money has been spent trying to reduce the impact of gypsy moth infestations. Current control efforts are handicapped by the unavailability of a safe and effective persistent chemical. In the North two predators and nine parasites have been successfully established to help control the gypsy moth. The greatest problem in controlling gypsy moth spread, however, lies in the fact that recreational vehicles transport egg masses and larvae from infested sites into uninfested areas.

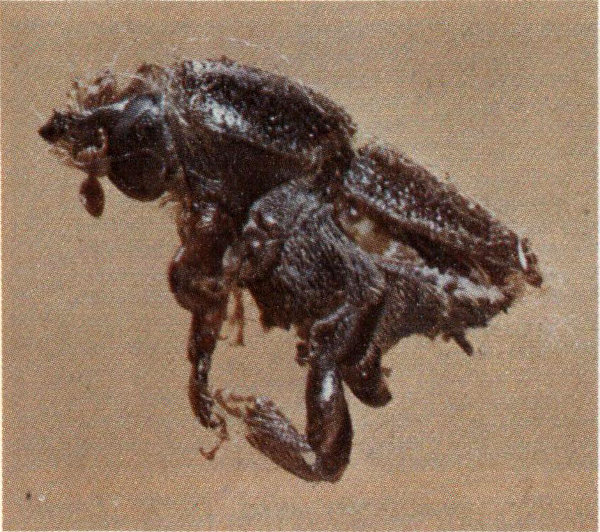

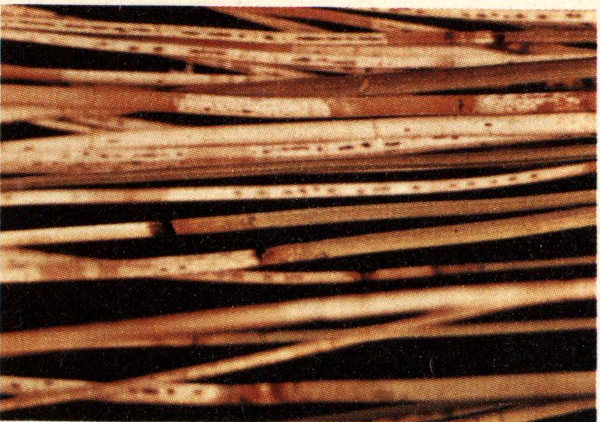

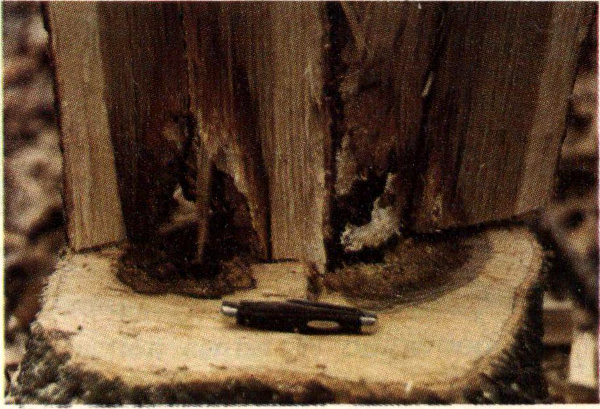

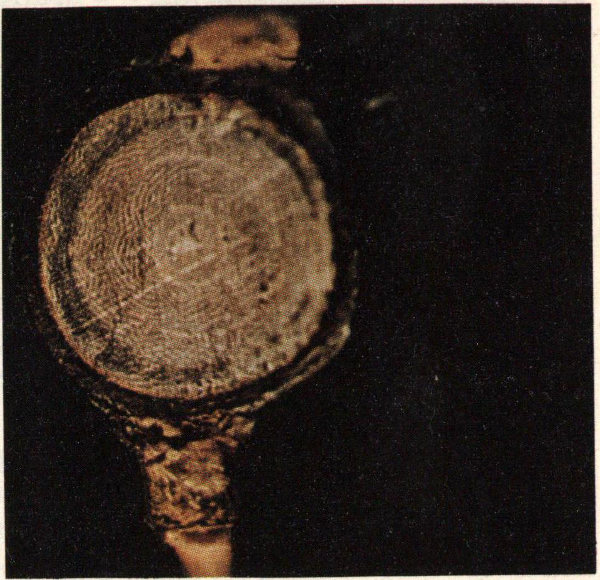

The hickory bark beetle is reported to be the most serious insect pest of hickory in the United States. Population explosions where thousands of trees were killed have been reported from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and recently from Georgia. Hickory bark beetles are distributed throughout the range of their host in eastern United States. All species of hickory are subject to attack, as well as pecan and possibly butternut. Adult beetles emerge in May and June in the southern portion of their range. They feed for a short time by boring into the petioles of leaves and into small twigs of the host. Dying leaves and twigs are the first evidence of attack. After feeding, the beetles fly to the trunk and larger branches of the host and bore into the inner bark to lay their eggs. Short, longitudinal egg galleries are etched into the sapwood and from 20 to 60 eggs deposited in small niches cut on either side of the gallery. As the larvae develop, their galleries radiate out from the egg gallery. Two generations per year have been reported from northern Mississippi. The beetle overwinters in the larval stage. With the coming of warm weather in the early spring, it changes into the pupal stage, and finally, in May, to an adult.

Hickory bark beetle adult.

Outbreaks of this insect begin in periods of hot, dry weather and subside when rains commence.

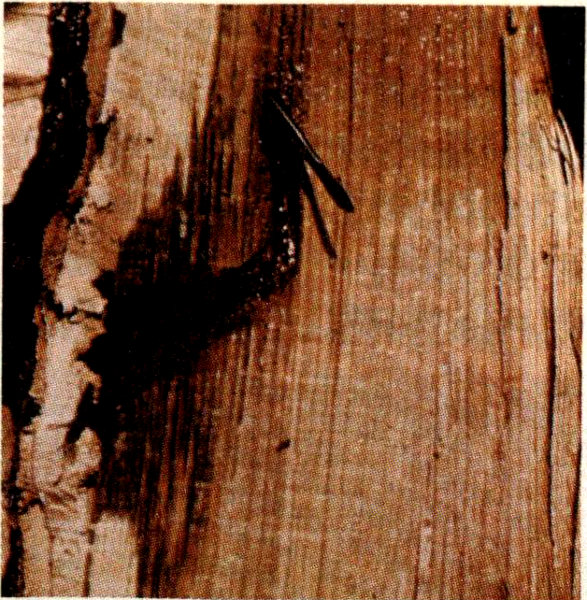

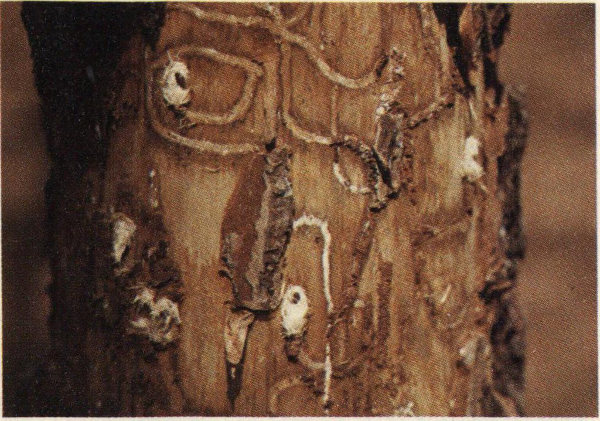

Larval galleries of the hickory bark beetle.

The smaller European elm bark beetle was first reported in the United States in 1909. Its presence in this country was given significance with the introduction of the Dutch elm disease in 1930. The beetle attacks all native and introduced species of elms and now occurs wherever the hosts are present. The feeding of the adult beetles in the spring is responsible for transmitting the Dutch elm disease from diseased to healthy trees. The Dutch elm disease is now our most important shade tree disease.

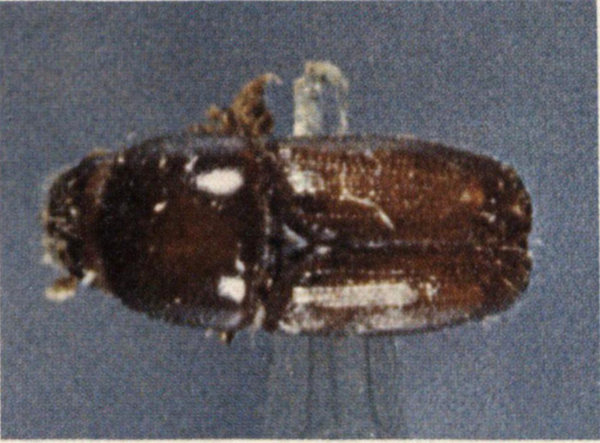

Smaller European elm bark beetle adult.

Adult bark beetles emerge in the spring from dead or dying elms and begin feeding on the twigs of healthy elms. The female then excavates an egg gallery in the bark of dead or weakened elms. Eggs are deposited along the walls of the gallery. The larvae, upon hatching, burrow into the bark at right angles to the egg gallery. Pupation occurs at the end of the larval tunnel. New adults tunnel to the bark surface and leave the tree through circular emergence holes. There are usually two generations a year. The beetles overwinter in the larval stage.

Chemical control and good tree maintenance are the two methods used to reduce bark beetle populations. Insecticides are used to prevent feeding by the adults in the spring. Tree sanitation involves removal and disposal of dead elms and elm limbs which eliminate breeding and larval development sites.

All hardwood trees in the eastern half of the United States are subject to attack by the Columbian timber beetle, but oaks, maples, birch, basswood, yellow-poplar, and elm are the preferred hosts in the South. The beetle causes two major types of damage: 1) physical damage caused by the 1/32″ to 1/16″ hole excavated by the adult into the sapwood, and 2) degrade caused by stain which may extend for a considerable distance above and below the gallery. Large diameter trees are preferred as hosts, but trees as small as one and one-fourth inches in diameter may be attacked.

Callow adult and pupae of the Columbian timber beetle.

There are two and sometimes three generations of this insect each year. Adults from the first generation emerge from late May through June and those from the second in October. The first evidence of attack is the white dust which collects at the entrance hole. Later, depending on the tree’s physiological condition, a sap-soaked area may develop around the entrance hole. The adult bores a horizontal hole into the sapwood of a healthy tree for a few inches and later constructs two or three shorter lateral branches. “Cradles” (or egg chambers) are then constructed for a short distance perpendicular to these galleries. The female deposits a single egg in each chamber. The offspring spend their entire developmental period within the cradles feeding on fungi which grow on the sapwood. It is this fungus which causes the extensive staining characteristic of Columbian timber beetle attack. Winter is spent in both the pupal and adult stages in the brood galleries.

Columbian timber beetle entrance holes in yellow-poplar.

Chemical control is not practical for forest trees.

The cottonwood twig borer is widely distributed throughout the entire range of eastern cottonwood, from Canada to the Gulf States and west to Missouri. The larvae of the cottonwood twig borer feed in the terminals of the host. This feeding results in reduction of terminal growth and forked and crooked trunks. Damage is especially severe on young trees.

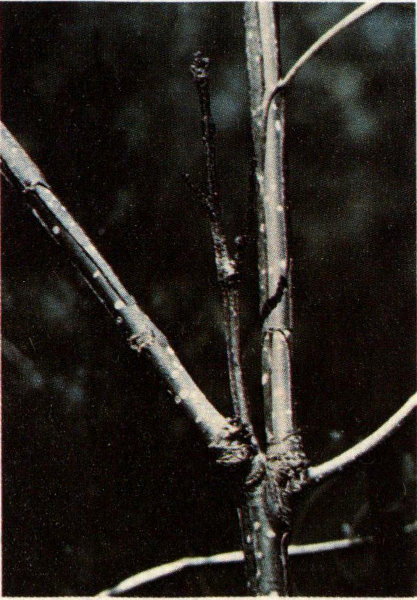

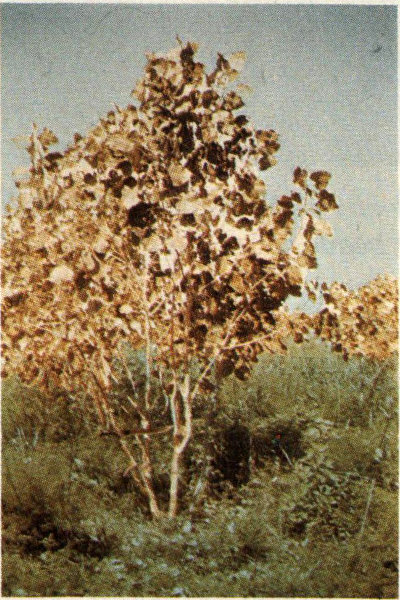

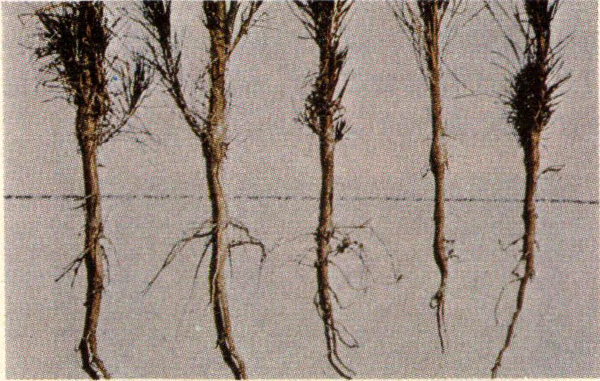

Cottonwood twig borer damage to cottonwood sapling.

Three-year-old cottonwood stunted by twig borers.

The female moth lays eggs on the upper surface of leaves along the mid-rib, singly or in groups of two to eight. Hatching occurs in about five days and the young larvae cover themselves with silk mixed with trash, and then tunnel into the mid-rib. After the first molt, larvae leave the tunnels and bore into tender shoots. Larvae reach maturity in about 21-23 days and begin moving down the trunk of the tree where they spin cocoons in sheltered bark crevices, in litter, or between leaf folds. The adult moths emerge in eight or nine days. It takes from 40-45 days to complete the life cycle in mid-summer.

The most effective natural control is a potter wasp, Eumenes sp. which tears open tender cottonwood shoots and removes twig borer larvae from their galleries. Other wasps parasitizing the twig borer include Bracon mellitor (Say), Apanteles clavatus (Provancher) and Agathis sp.

The cottonwood borer is limited in range to the southern half of the United States. Hosts include cottonwood, poplars and willows. The adults feed on the tender shoots of young trees causing them to shrivel and break off. The larval stage of this insect tunnels in the inner bark and wood at the base of the tree and may kill or severely weaken it.

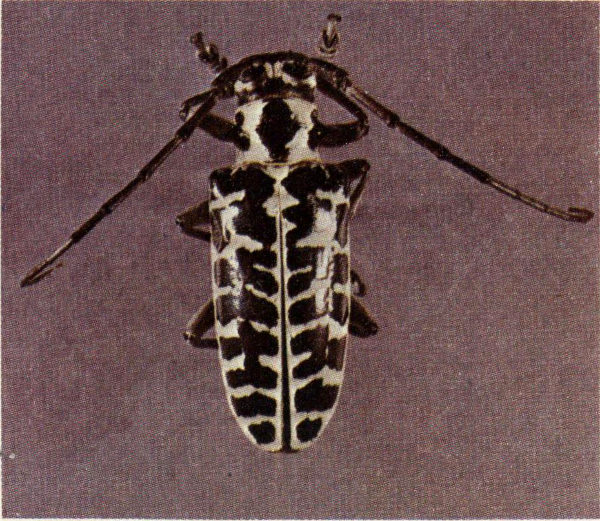

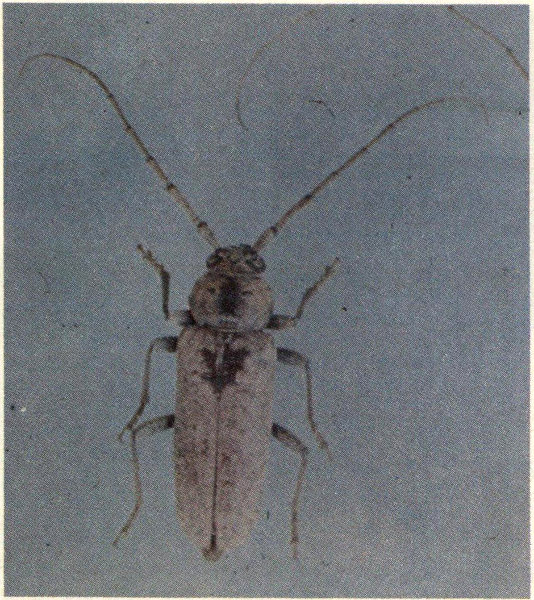

Adult cottonwood borer.

The adult beetles appear in midsummer. After feeding briefly on the tender bark of the terminals the adults descend to the bases of host trees where the female deposits her eggs in small pits gnawed in the bark. Eggs hatch in about three weeks. The larvae bore downward in the inner bark, entering a large root by fall. Larval feeding continues into the second year as the larvae bore into the inner bark and wood. The larvae transform into the non-feeding pupal stage and finally into an adult in the summer of the second year thus completing a two year life cycle. Adult beetles are 1¼ to 1½ inches long. They are black with lines of cream-colored scales forming irregular black patches.

The best control for the cottonwood borer is to maintain a vigorous, healthy stand. Slow growing, off-site plantings of host trees are the most severely damaged. While some systemic insecticides have shown promise, there is currently no registered chemical control method.

A recent survey of damage caused by various wood borers to three species in the white oak group revealed an estimated annual loss in the South exceeding 20 million dollars. One of the more important borers responsible for this damage is the white oak borer.

Adult white oak borer.

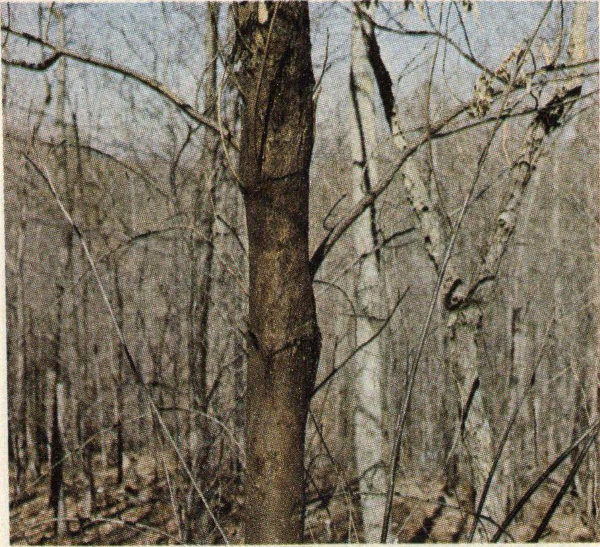

Usually the white oak borer attacks oaks one to eight inches in diameter. The damage, like that of other hardwood borers, is the result of larval feeding in the wood. Galleries up to one-half inch in diameter extend upward through the sapwood into the heartwood. The white oak borer takes three to four years to complete one generation. The mated adult female beetle lays her eggs singly in the inner bark through a small oval niche chewed through the outer bark. After about three weeks the eggs hatch and the larvae immediately bore into the sapwood. Later they bore upward into the heartwood. The boring frass ejected out of the entrance is evidence of an active infestation. Pupation occurs behind a plug of excelsior-like frass at the upper end of the gallery in the heartwood. In about three weeks, adults emerge by boring separate and perfectly round holes through the wood and bark. In the South, adults generally emerge in May and June and feed for a short time on oak leaves and the tender bark of twigs before the females lay their eggs.

Woodpeckers may destroy up to 25 percent of the larvae during the winter months, but this and the small toll taken by insect predators and parasites are not sufficient to keep the white oak borer population low enough to avoid serious economic loss.

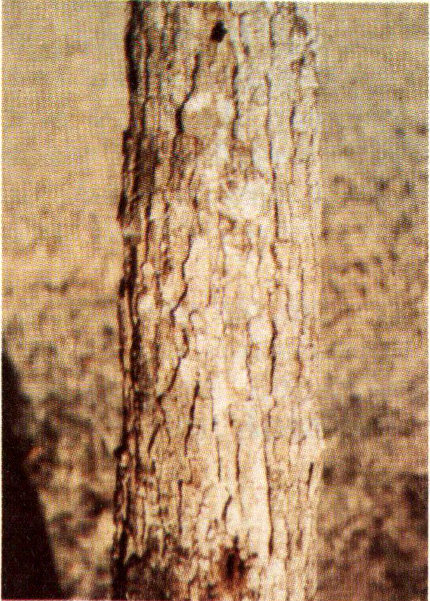

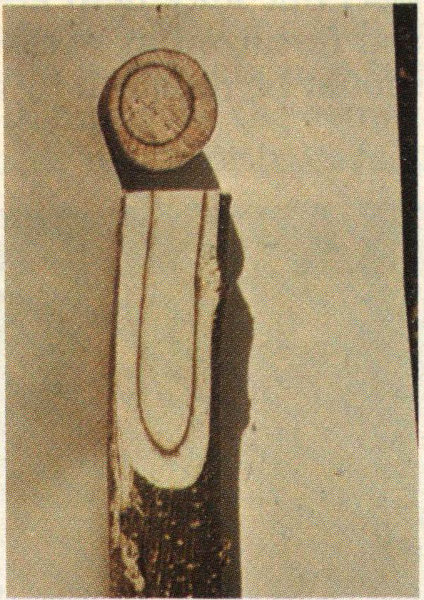

Entrance and emergence holes in white oak.

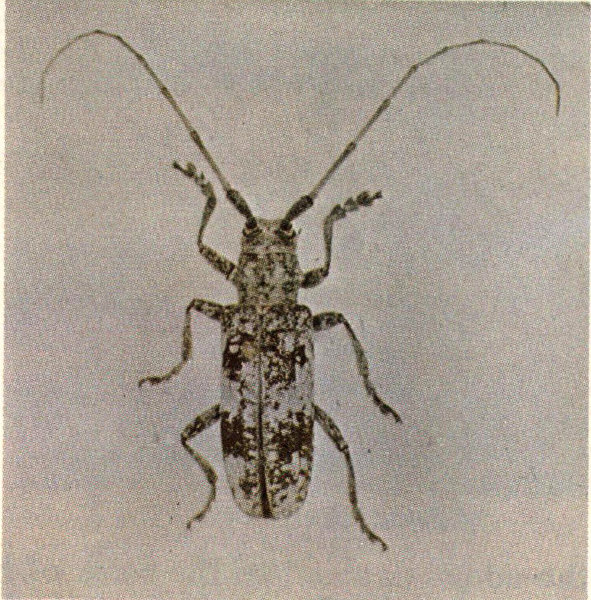

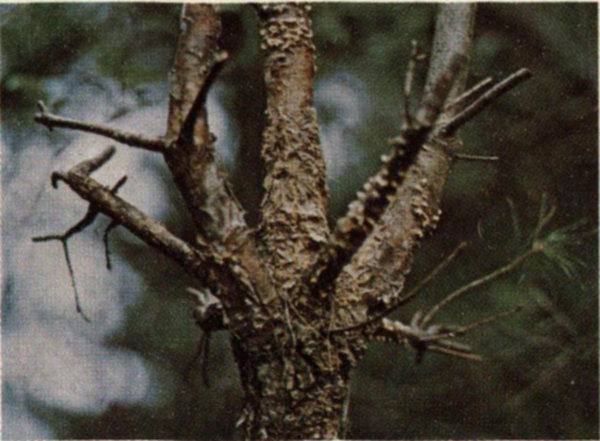

The red oak borer is a serious pest of trees in the red oak group. It ranges throughout eastern North America wherever host species grow. It is estimated that defects caused by larval tunnels in the sapwood and heartwood of host trees costs the hardwood timber industry millions of dollars each year.

Adult red oak borer.

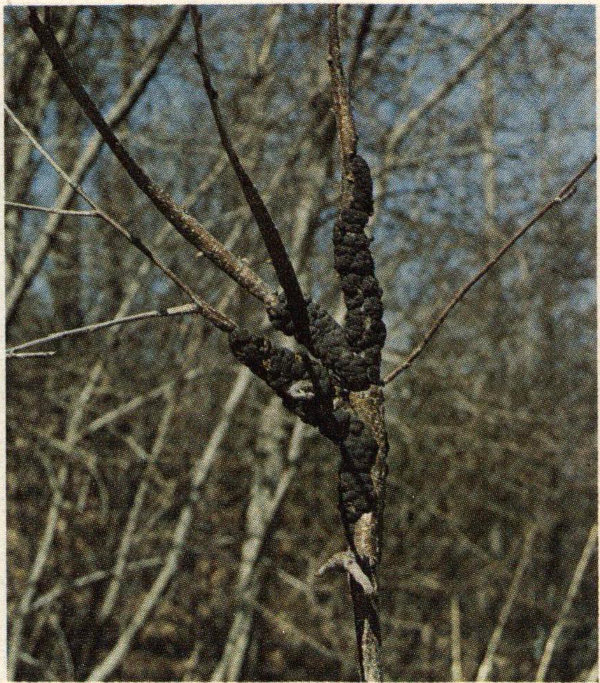

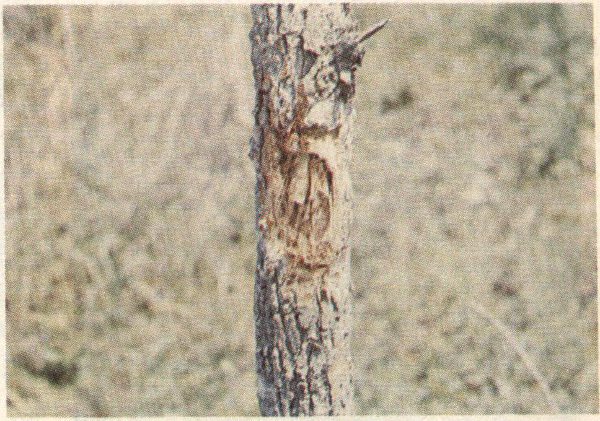

Eggs of the red oak borer are laid during early and mid-summer in bark crevices or under patches of lichen on host trees. After hatching, larvae bore into the inner bark region where they feed until mid-summer of the next year. This feeding in the inner bark causes characteristic catfaces or bark pockets. Once larvae enter the wood they bore upward through the sapwood and into the heartwood and pupate behind a plug of excelsior-like frass. The larval galleries are from one-fourth to one-half inch in diameter, and six to ten inches long. Usually the galleries are within six inches of the center of the tree. The adult emerges at the lower end of the tunnel, using a hole cut through the bark by the larva just prior to pupating. Adults emerge in June and July. The timing of the two-year life cycle of the red oak borer is such that the adult population is greatest in odd-numbered years.

Generally, borers such as the red oak borer infest trees of poor vigor. It is possible, therefore, to reduce borer populations by maintaining vigorous stands and by removing cull trees.

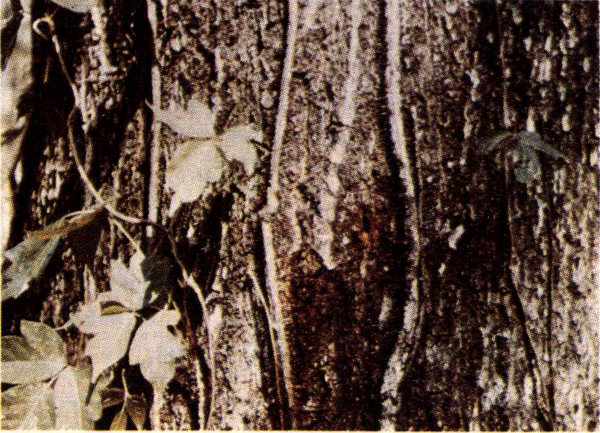

Red oak borer attack on Nuttall oak.

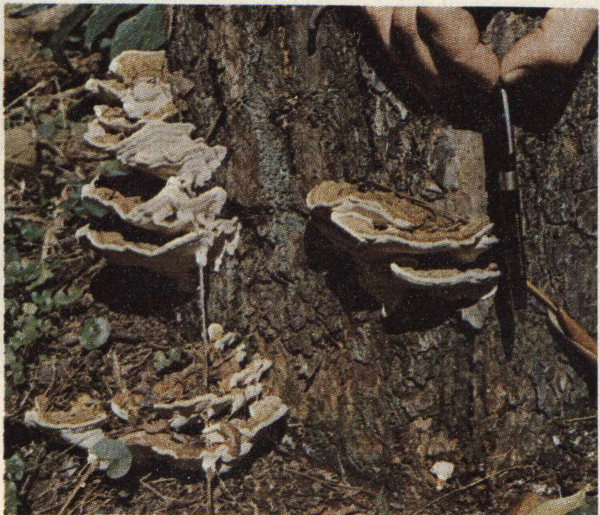

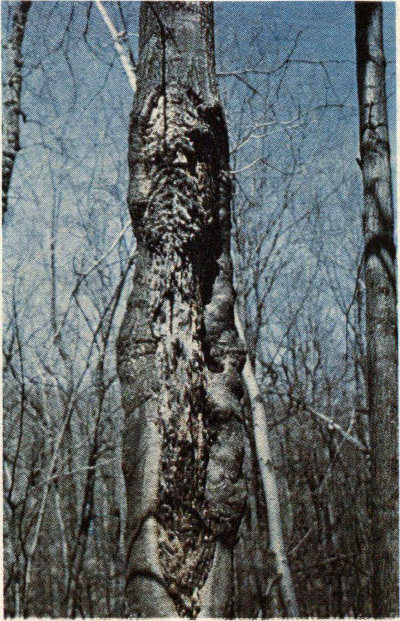

The carpenterworm bores in the wood of living hardwood trees, causing costly damage to commercial timber species. In the South, oak species are preferred hosts but black locust, maples, willows, and fruit trees are also attacked. The carpenterworm is distributed throughout the United States.

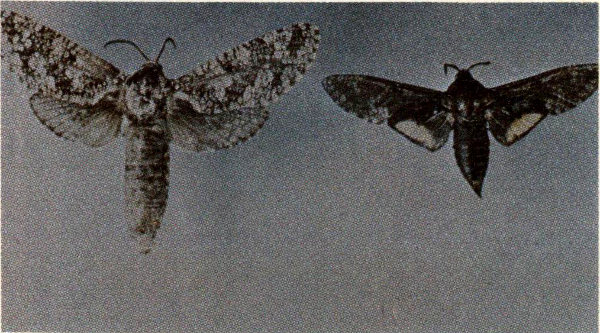

Carpenterworm adults.

Adult moths emerge in late April to early June, mate, and the females lay groups of eggs in bark crevices or wounds. Each female lays 200 to 500 eggs during her one-week life span. After hatching, the larvae wander over the bark for a short time before boring into the inner bark where they feed until half-grown. The larvae then bore into the sapwood and heartwood, returning occasionally to feed in the inner bark. The larval period lasts from two to four years. Pupation usually occurs deep within the heartwood. Just prior to emergence, the pupa wiggles to the entrance hole where it remains slightly protruding until the adult moth emerges. The large winding tunnels constructed by the larvae in the sapwood and heartwood of living hardwoods serve as an entrance for wood-rotting fungi and insects such as the carpenter ant. In extreme cases, the tree may be structurally weakened and subject to wind breakage.

Carpenterworm galleries in nuttall oak.

Some chemicals which have a fumigating action have proved effective in controlling this insect in shade trees, but no practical control has yet been found for forest trees.

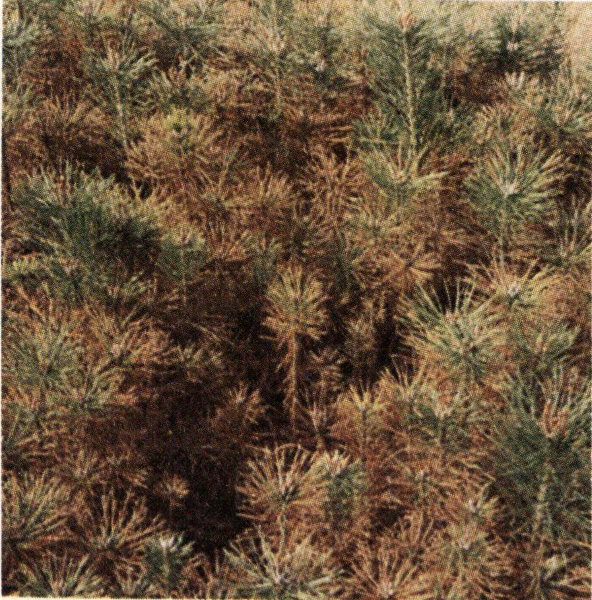

Ugly, compact masses of brown excrement or frass pellets around the stem of pine seedlings mark infestations of the pine webworm. Rarely is the defoliation severe enough to kill the seedlings, but it undoubtedly has an impact on growth. Found throughout the eastern United States, the webworm commonly attacks red, white, jack, loblolly, shortleaf, and slash pines.

Pine webworm damage to loblolly pine.

The adult moth has a wingspread of about one inch. The forewing usually is gray in the middle portion and darker at the base and tip. The hind wings and body are smokey gray. The full-grown larva is a caterpillar approximately ⅘ of an inch long. The head is tan with darker markings and the body light brown with dark longitudinal stripes running down each side.

Eggs are usually laid on seedlings, occasionally on larger trees, between May and September. After eggs hatch, the caterpillars live in silken webs surrounded by masses of frass, and feed on the needles. Generally each web contains one or two larvae but occasionally 25 or more may be found. After feeding is completed, the caterpillars drop to the ground and pupate below the soil surface. In the South, there are usually two generations each year.

In plantations, hand picking is an effective method of control. When high value nursery stock becomes infested, chemical control may become necessary.

The bagworm is distributed throughout the eastern half of the United States. It is generally recognized as a defoliator of conifers, particularly juniper, cedars, and arborvitae, but it is also found on many hardwood trees including maple, wild cherry, poplars, oaks, and apple.

Bagworm cases on pine.

The wingless, maggot-like adult female bagworms are present in September and October and spend their entire lives within the protective cover of the tough, silken bag which they construct as larvae. Males are quite agile fliers and can often be seen in the fall flying around infested shrubs in search of a mate. Mating takes place through the open end of the bag. Shortly thereafter the female deposits her egg mass containing 500 to 1,000 eggs in her pupal case. The eggs remain in the bag throughout the winter. In the deep South, hatching can occur as early as April, but occurs in May or June further north. During the early stage of development, the larvae, housed in their tiny bags, are quite inconspicuous. As they mature, the bags become quite noticeable, and the amount of foliage consumed increases rapidly.

Outbreak populations of bagworm are in most cases quickly reduced by low winter temperatures and a complex of several parasites. On shrubs and shade trees around a home, it is often practical to control bagworms by picking and destroying the bags.

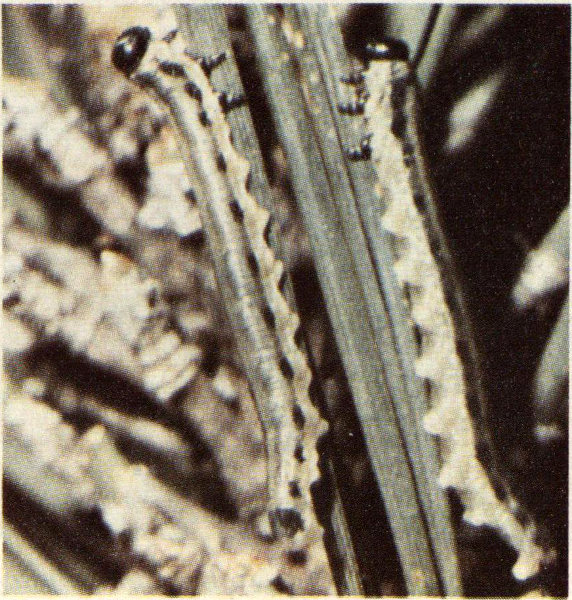

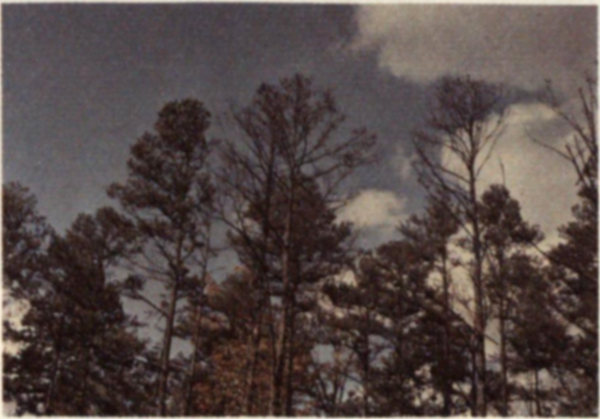

Colaspis beetles are found throughout the Southeast, but are more common in the Gulf states. They seem to prefer slash pine but have been found on many of the southern pines. The pine colaspis beetle is not a serious forest pest but feeding damage caused by large populations occasionally produces a spectacular browning effect of the needles similar to that caused by fire.

Adult pine colaspis beetle feeding damage on pine.

The adult beetles chew the edges of needles to produce an irregular, saw-like edge which turns brown. Occasionally only the tips of the needles show signs of the infestation. Later, however, the entire needle may die, causing the whole tree to become brown as though scorched by fire. Trees that have been attacked do not die, and little or no growth loss results. Attacks usually occur in early summer; by late summer the trees appear green and healthy again. This pest is sporadic in its occurrence and may not develop again in the same area for several years. The adult female lays her eggs in the soil during the summer. Larvae hatch and feed on roots of grasses and other vegetation, and overwinter in this stage. The larvae pupate in the spring; adults emerge in early summer to feed. There is only one generation a year.

Under forest conditions, no control measures are recommended for the pine colaspis beetle. On ornamentals and shade trees, insecticides can be used to prevent unsightly damage.

This pine sawfly is found throughout the southeast from Virginia to Texas. Loblolly and shortleaf pine are preferred hosts, but pond, slash, longleaf, and Sonderegger pine are also attacked. The larvae do not do well on the latter two species. As with most sawflies, the larvae feed in groups on the host needles. Generally the old needles are preferred, but all of the needles are eaten when large numbers of larvae are present. Three or four young larvae usually encircle a needle and, starting from the tip, consume all but a central core. When nearing maturity they eat the entire needle.

Pine sawfly larvae.

Four or five generations of this sawfly may occur each year. Adult females begin to lay their eggs in slits cut in the needles during late March. The eggs hatch in 10-21 days, and the larvae feed for about five weeks. When mature the larvae usually crawl to the ground and spin a cocoon in the loose litter at the base of the tree. Although all stages of the life history can be found at any time during the growing season, the peak adult emergence occurs in late summer. Larvae from this late summer generation are responsible for most of the damage which, although never directly responsible for mortality, may predispose the trees to attack by other insects (particularly bark beetles) and diseases.

Natural control factors generally bring outbreak populations under control after one season. Hogs, armadillos, mice, and shrews are reported as being of significant value in regulating the sawfly population. Insect parasites, predators, and disease are also effective control agents.

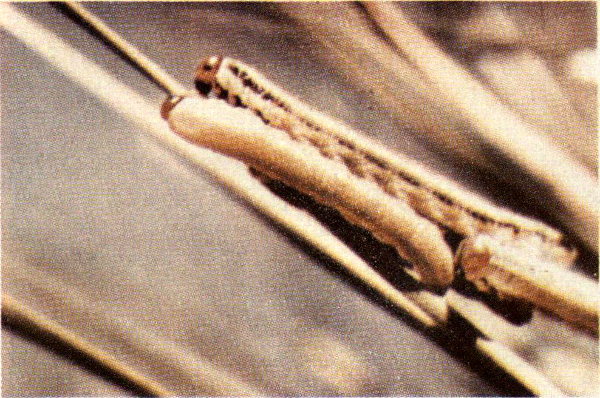

Loblolly and shortleaf pines are the only trees attacked by the Arkansas pine sawfly. Periodic outbreaks of this insect over large areas in the south-central states cause substantial growth losses, but the insects seldom kill trees.

Arkansas pine sawfly larvae.

This insect has a single generation each year. In the spring, eggs which have overwintered hatch into tiny caterpillar-like larvae. The larvae feed in groups for 30-40 days (primarily on the older foliage) before crawling to the ground and pupating in the topsoil or litter. Adults emerge during warm days in October and November, mate, and the females begin laying eggs. Sawflies get their name from the manner in which the eggs are laid. The female is equipped with a saw-like “ovipositor” with which she cuts a slit in the needle into which the egg is inserted. From two to ten eggs are laid in a single needle. Each female deposits from 90 to 120 eggs.

An important natural control agent of this sawfly is a polyhedral virus disease that sometimes destroys large numbers of the larvae. Rodents destroy many cocoons. Several species of larval parasites are also known to exist. Of these, a parasitic fly, Anthrax sinuosa (Wied.) and an ichneumon wasp, Exenterus canadensis (Prov.) appear to be the most important.

The Virginia pine sawfly is found from Maryland to North Carolina, and west to Illinois. The insect prefers Virginia and shortleaf pine, but it will also oviposit and feed on pitch and loblolly pine.

Virginia pine sawfly larva.

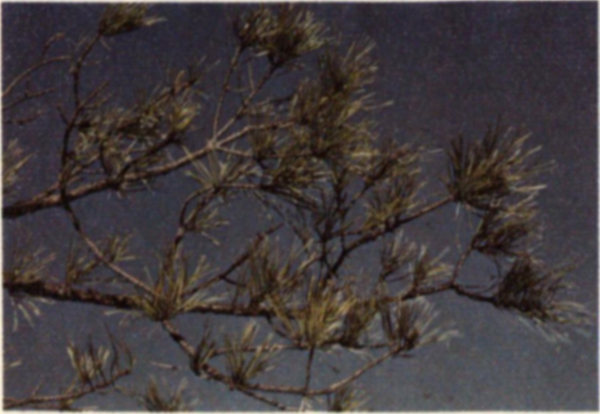

On warm sunny days in late October and early November, the adult sawflies emerge from their cocoons in the litter, mate, and the females lay eggs. The female is equipped with a saw-like ovipositor with which she cuts a slit at the edge of a needle and inserts a small, white, oval egg. Several eggs are usually laid at evenly spaced intervals in each needle, but in only one needle per fascicle. From 30 to 100 eggs are deposited in this manner by each female. The eggs hatch the following April and the young larvae feed gregariously on the old needles. Larval development is usually completed by the time the new needles come out, giving heavily defoliated trees a tufted appearance. Mature larvae crawl to the ground and spin cocoons in the litter or surface soil. They remain as prepupae until late September when pupation occurs.

Pine defoliated by the Virginia pine sawfly.

Heavy defoliation for two or more years can weaken trees and make them more susceptible to other insects and diseases, particularly when associated with drought. In commercial stands the growth loss caused by several years of 50% defoliation by this insect can amount to ⅓ of the expected growth.

Several parasites, predators, and a virus attack the Virginia pine sawfly, but weather conditions seem to be primarily responsible for the drastic fluctuations in sawfly populations. Several chemicals have proven effective in preventing damage to ornamentals.

The redheaded pine sawfly did not become an important pest until extensive planting of pine in pure plantations began in the 1920’s. Since then, outbreaks in young natural pine stands and plantations have been common in the South, the north-central states, and eastern states. Feeding is primarily restricted to the two- and three-needled pines under fifteen feet in height. Shortleaf, loblolly, longleaf, and slash are the species most commonly attacked in the southern states.

Redheaded pine sawfly larva.

In the fall, sawfly larvae drop to the ground, spin cocoons in the duff or topsoil, and overwinter as prepupae in a small, brown cocoon. With the coming of spring, pupation occurs and adult emergence follows in about two weeks. Some prepupae may remain in a resting stage for more than one season before emerging. Each female lays about 120 eggs. She cuts a small slit in the edge of a needle and deposits a single egg inside each slit. Eggs laid by a single female are generally clustered on the needles of a single twig. Eggs hatch in three to five weeks, depending on temperature and locality. Larvae feed gregariously on the host for 25 to 30 days. When fully grown, larvae drop to the ground and spin their cocoons. In the South there are at least two generations per year with a maximum of five being recorded. Colonies of different ages may co-exist in the late fall or early winter.

Outbreaks occur periodically and tend to subside after a few years of heavy defoliation. Numerous parasitic and predatory insects play an important role in causing the decline of infestations, as do adverse weather conditions during the larval stage. When deemed necessary, chemical treatment is an effective control.

Damage caused by the Texas leaf-cutting ant, or town ant, is confined in the United States to southeast Texas and west-central Louisiana. The ant causes damage to a variety of green plants throughout the year and causes serious damage to pine seedlings during the winter when other green plants are scarce. During this period, stands of young seedlings may be completely defoliated and the stems girdled. The ant carries bits of needles, buds, and bark back to its nest to serve as the medium on which it cultivates a fungus. The fungus is the ant’s only known food.

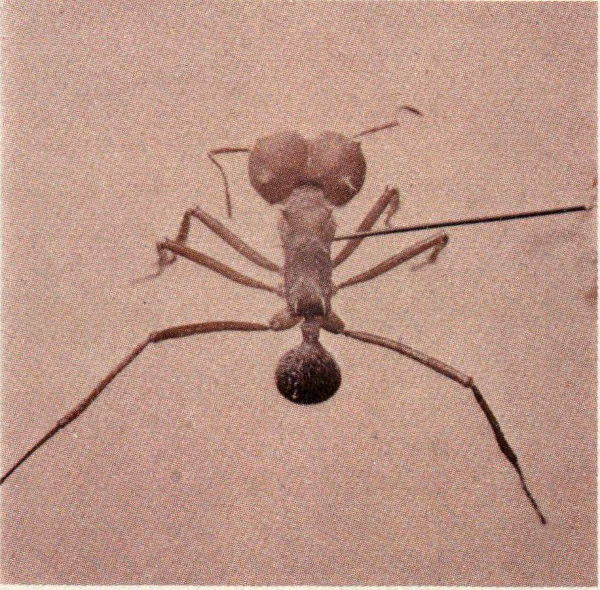

Texas leaf cutting ant.

Ant colonies are characterized by numerous crescent-shaped mounds five to fourteen inches high, and by a series of well defined foraging trails cleared of vegetation. The mounds may be confined to a relatively small area or extend over an acre or more. Each mound serves as the entrance to a football-sized, hemispherical-shaped nest which the ants construct at depths up to 20 feet below the surface. The nests are interconnected by a series of narrow tunnels, and connected to lateral foraging tunnels which may surface a hundred yards or more from the colony. Leaf-cutting ants, like many other social insects, are segregated into castes. The queen dominates the colony and is responsible for its reproduction. Large worker ants, or soldiers, provide protection from intrusion by other insects, while the smaller workers collect the leaves and tend the fungus gardens.

Various chemicals such as fumigants, contact poisons, and baits have been used to control the leaf-cutting ants with varying success. No natural control has yet been found.

Probably no other insect is of more concern to managers of southern pine forests than the southern pine beetle. Loblolly and shortleaf pine seem to be preferred hosts, but all of the southern pines may be attacked wherever they occur in North and Central America.

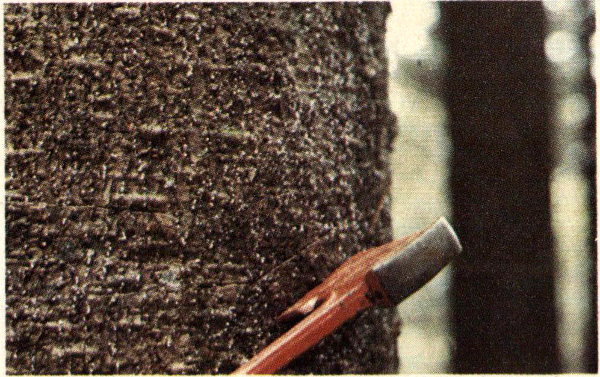

Adult beetles are about the size of a grain of rice, stout and reddish-brown in color. While they commonly attack lightning-struck or weakened trees, they can also quickly build up to high populations capable of successfully attacking healthy trees during periods favorable to their development. Adult beetles bore directly through the bark, mate, and the females begin to excavate S-shaped egg galleries in the inner bark. Eggs are deposited in niches on either side of these galleries and hatch into small legless grubs within four to nine days. The grubs mine for a short distance before boring into the outer bark where they pupate. There are from three to seven generations per year depending on locality and weather. Drought seems to be associated with major outbreaks of this insect.

Adults of the black turpentine beetle, the southern pine beetle and three species of Ips engraver beetles.

Control includes rapid salvage and utilization of infested trees and piling and burning of infested material. Outbreaks usually subside with the advent of unfavorable weather and improved host vigor.

Southern pine beetle larval galleries.

Southern pine beetle pitch tubes.

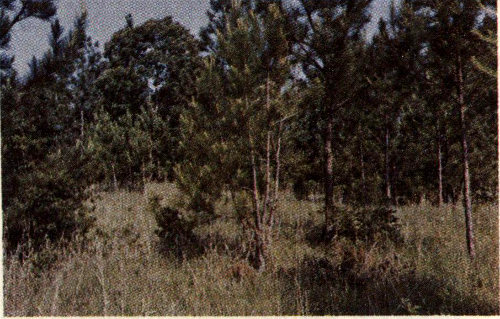

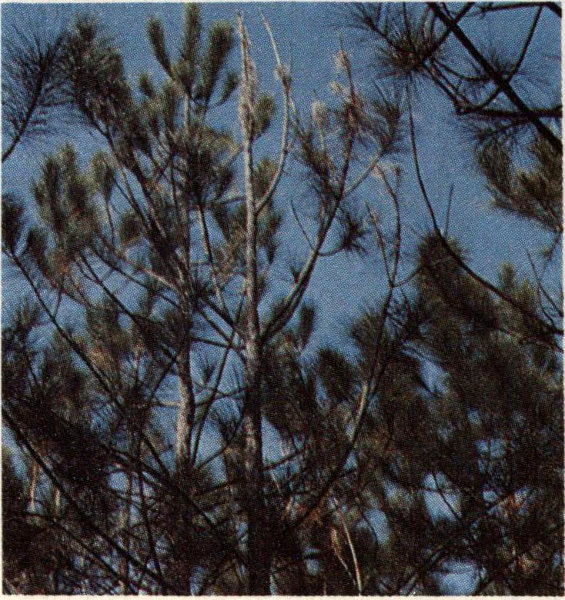

With the possible exception of the southern pine beetle, no other insects cause as much mortality to southern pine forests as do the three species of Ips engravers. Usually they attack severely weakened trees, lightning-struck trees, or fresh slash left by logging operations. During drought periods they can successfully attack otherwise healthy pines.

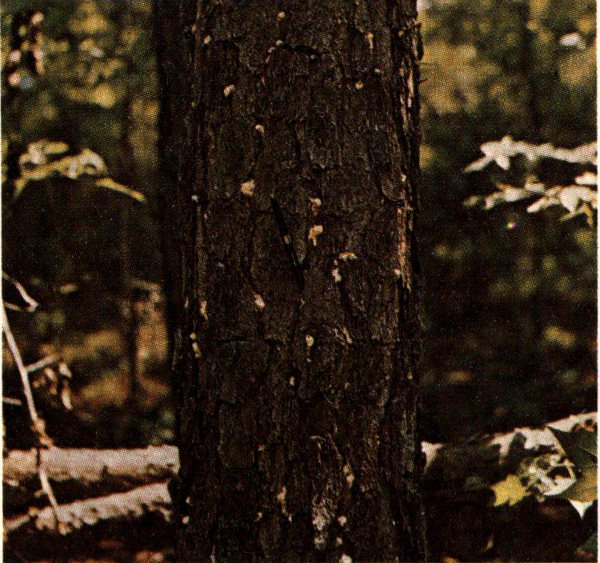

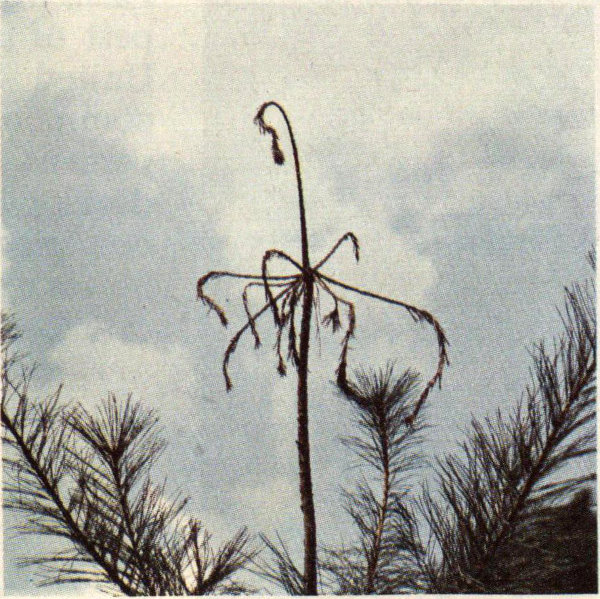

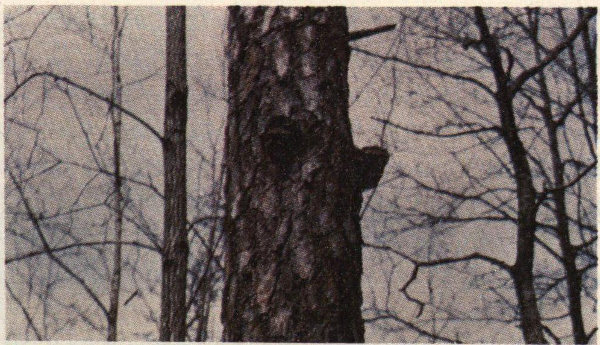

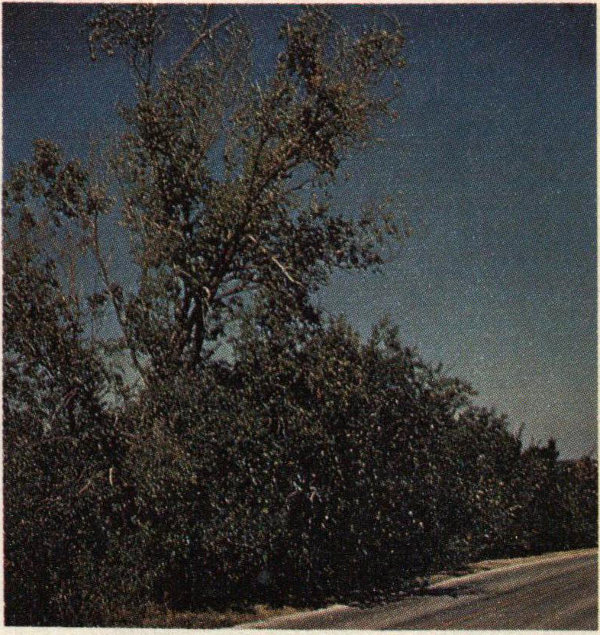

Pine showing typical symptoms of Ips attack.

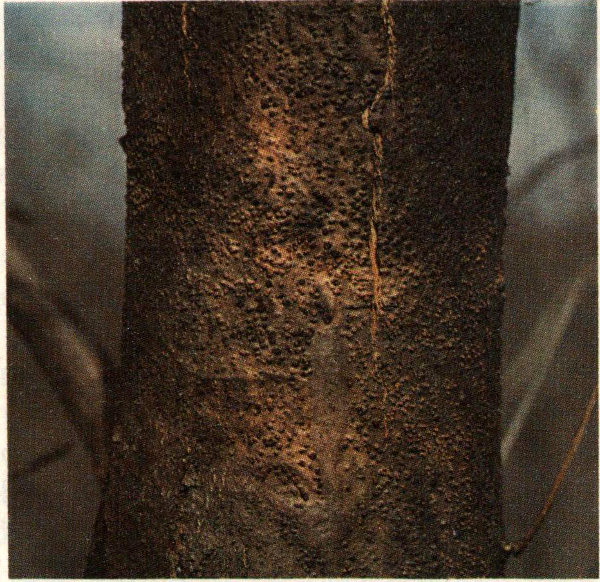

Attacked trees are quickly girdled by the adults as they construct their egg galleries in the inner bark. Death is usually hastened by the introduction of blue-stain fungi which blocks the flow of sap. Small reddish pitch tubes are frequently the first sign of attack, but they are usually absent in trees suffering from drought. Peeling back the bark of an infested tree will reveal typical Y- or H-shaped egg galleries with short larval galleries extending perpendicular to them on either side. Ips beetles are easily recognized by their “scooped out” posteriors which are surrounded by varying numbers of tooth-like projections. It takes only 18-25 days to complete one generation, allowing populations of these beetles to increase very rapidly during favorable conditions.

At present the best control is the speedy removal and utilization of actively infested trees, making sure that the bark and slabs are destroyed.

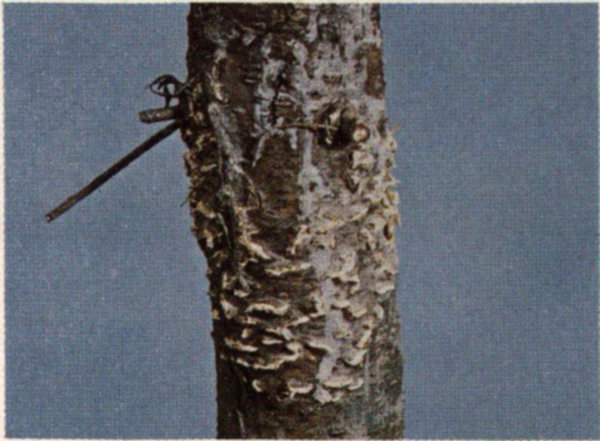

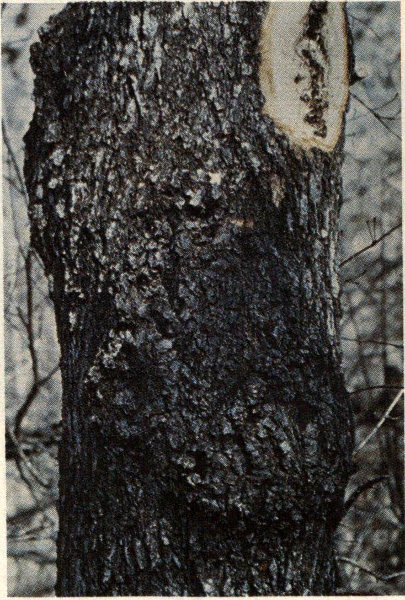

The black turpentine beetle is found from New Hampshire south to Florida, and from West Virginia to east Texas. It is a particularly serious pest in the Gulf States where recent outbreaks have killed large acreages of timber. Attacks have been observed on all pines native to the Southeast, and also on red spruce.

Life stages of the black turpentine beetle: adult, callow adult, pupa, larva and eggs.

This is the largest of the southern bark beetles, varying in length from ⅕ to ⅓ of an inch, or about the size of a raisin. They are reddish-brown to black in color. The beetle attacks fresh stumps and living trees by boring through the bark and constructing galleries on the face of the sapwood where eggs are laid. Fifty to 200 eggs are laid in a group. They hatch into white larvae which feed on the inner bark. The beetle may girdle trees when several broods occur at approximately the same height, killing the trees. From 70 to 90 percent of the trees attacked by the beetle die.

After the larvae complete their development, they pupate. Adult beetles emerge and infest more pine trees. The entire life cycle takes from 2½ to 4 months, depending on temperature. In the insect’s southern range there usually are two generations and part of a third each year. In its northern range, the third generation does not develop; consequently the beetle is not a serious pest there.

Weather is probably the most influential factor in regulating the numbers of this insect. During outbreaks the removal or chemical treatment of infested trees helps to keep losses to a minimum.

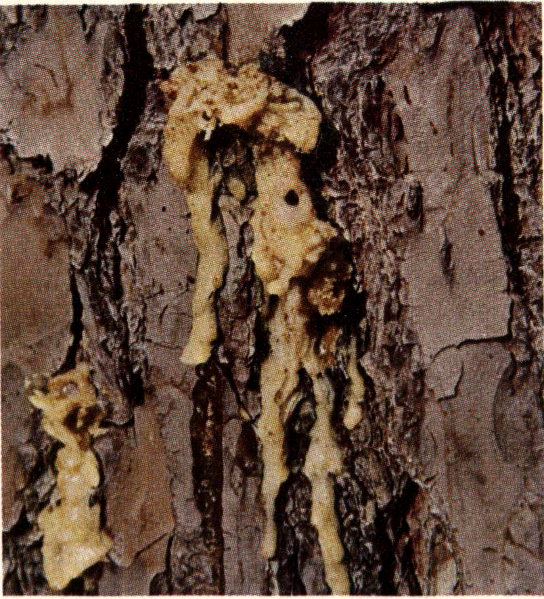

Close-up of black turpentine beetle pitch tubes.

Ambrosia beetles are represented in the South by several species of the genus Platypus of which only P. flavicornis (F.) is known to attack dead or dying southern pines. P. flavicornis (F.) will secondarily invade other conifers and on some occasions may be found in hardwood trees. It is so abundant in the South that few dying pines, stumps, or logs escape attack. The beetle is found from Texas east to Florida and north to New Jersey.

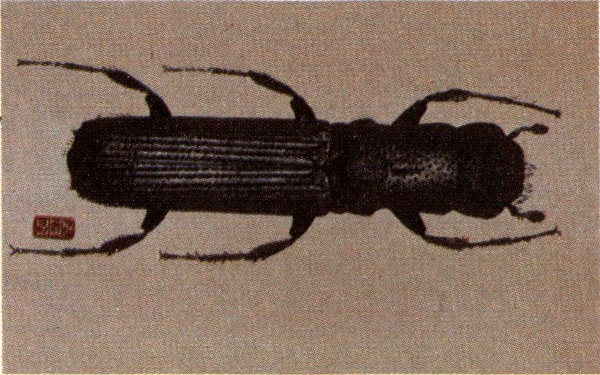

Adult of the Platypus ambrosia beetle.

The adult is a reddish-brown elongate beetle approximately one-fourth inch in length. The male of the species has a pair of blunt tooth-like structures on the third abdominal segment. Several males are usually found in the presence of a single female. This species requires moist wood which is favorable to the growth of fungi upon which they feed. The adults bore into sapwood or heartwood of logs and lumber, making pin-sized holes which are stained by the ambrosia fungus. The female lays eggs in small clusters in the tunnel and the developing larvae excavate tiny cells extending from the tunnel parallel to the grain of wood. There may be several generations a year.

Ambrosia beetle damage to green sawlogs and lumber may result in considerable degrade and strength reduction. The best control is rapid utilization of dead or dying trees. Lumber should be seasoned as soon as possible to reduce or eliminate losses.

In the South, dying pines and fresh logs are quickly attacked by the pine sawyers. In sufficient numbers they may cause a significant loss of wood fiber and degrade sawlogs. These species are commonly found in the South infesting southern pine, fir, and spruce wherever the hosts grow.

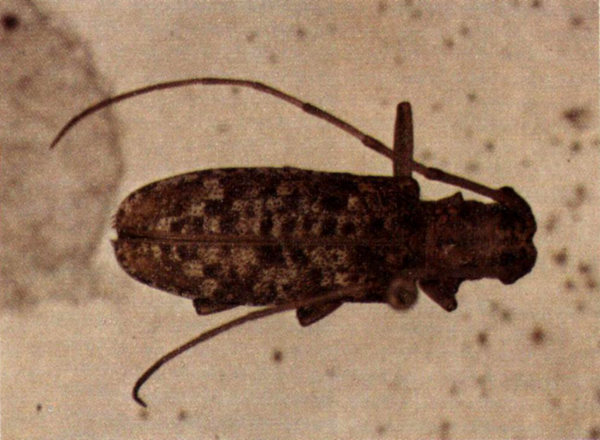

Adult southern pine sawyer beetle.

The adults emerge in the spring or summer and begin to feed on the bark of twigs. After mating, the female gnaws pits through the bark of freshly felled or dying pine. The female beetle lays one to several eggs in each pit. After eggs hatch the larvae bore beneath the bark for 40-60 days, converting the inner bark into coarse, shredded frass. The larvae then enter the wood and make deep U-shaped cells through the heartwood and sapwood. The entrance is plugged with frass and the far end is excavated into a pupal chamber. The larvae pupate the following spring or early summer, transform into adults, and emerge that same season. The insect has two or three generations per year in the South.

Pine sawyers render storm- or fire-damaged pines unfit for salvage and are also a problem in wood-holding yards. Rapid salvage and utilization of dead or dying trees or green logs will reduce losses significantly.

The impact of the Nantucket pine tip moth on pine plantations varies widely with tree species, host vigor, and environmental factors. Heavily infested trees may be severely stunted or deformed but mortality is rare. Generally, the tree grows out of the susceptible stage within a few years. In seed orchards, the tip moth is receiving increasing attention because of its impact on height growth and, more importantly, because of its effect on flower and cone production. All species of pine within the range of the tip moth except white pine and longleaf pine, are attacked. It has been reported from all states in the eastern hard-pine region extending across east Texas, Oklahoma, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and southern New York State.

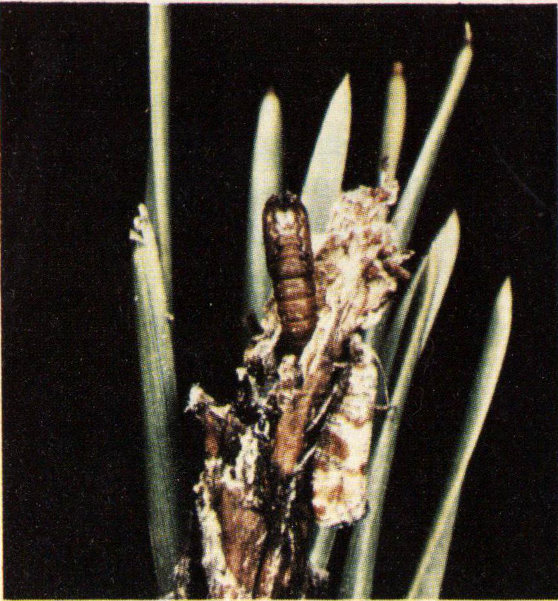

Nantucket pine tip moth larva on pine bud.

The tip moths overwinter as pupae in the tips of infested trees. In the South the adults emerge on warm days during the late winter months, mate, and the females lay eggs in the axils between needles and stem near the terminal bud of host trees. On hatching, larvae bore first into the base of developing needles, and later into the new terminal growth or buds. There are two to four generations per year in the southern part of the tip moth’s range.

Chemical control is generally not considered practical in forest plantations, but several pesticides have proved effective in reducing insect damage in seed orchards.

Newly emerged adult tip moth on a damaged shortleaf pine tip.

Pales weevil is perhaps the most serious insect pest of pine reproduction in the southeastern United States. Losses in susceptible areas commonly run 20-25 percent, but exceed 90 percent under circumstances favoring weevil development. Pales weevil is found throughout pine-growing regions of eastern United States and Canada. Feeding has been reported on most coniferous species, and all species of southern pines appear to be susceptible in varying degrees.

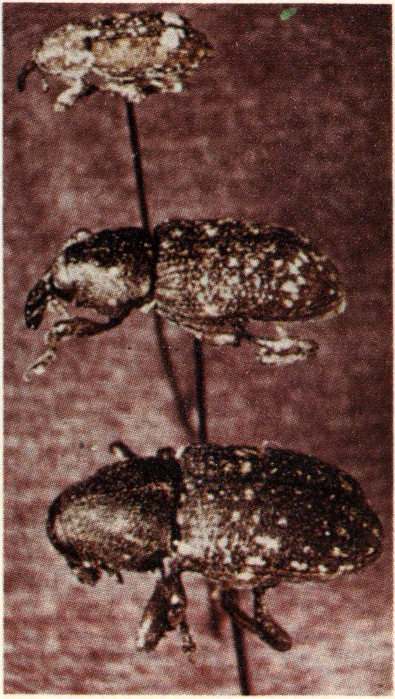

Pitch-eating weevils in the genera Pachylobius, Hylobius, and Pissodes.

Adult weevils are attracted by the odor of fresh pine resin, and quickly invade logging areas. Eggs are laid in lateral roots of fresh pine stumps, where they hatch in approximately five to ten days. Larvae feed on the inner-bark tissues of roots. At maturity, larvae usually construct a chip cocoon in a chamber cut into the wood, and pupate in the cocoon. On emerging, adults feed on the tender bark of seedlings, or twigs of trees. The small irregular feeding patches in the bark are characteristic of weevil damage. Heavy feeding girdles the stem or twig, causing wilting and eventual death. Newly emerged adult females feed for approximately one month before laying eggs. Females may lay eggs sporadically through two growing seasons. The average female lays about 50 eggs in her lifetime. In the South there are two peaks in adult weevil population each year; the first occurs in the early spring (March-May) followed by a second somewhat lower peak in July and August.

This insect can be controlled by delaying planting in cut-over areas for at least nine months, or by treating seedlings with a suitable insecticide.

Adult pales weevil feeding on seedling.

The white pine weevil is generally regarded as the most serious insect pest of white pine. Although it usually does not cause mortality, trees suffering repeated attacks become stunted and deformed to the point of being commercially unusable. The weevil has become such a problem in some areas that it prohibits the growing of white pine. In addition to eastern white pine, the white pine weevils also attack Norway spruce and jack pine. Other pines and spruces are attacked to a lesser degree. The weevil is found throughout the range of eastern white pine.

Pine leader damaged by the white pine weevil.

During the latter half of April, the adults may be found on the terminal shoots of host trees where the female lays her eggs. Up to 200 eggs are deposited over a six-week period. The eggs are laid in feeding punctures in the bark, and hatch about two weeks later. Characteristically, the young larvae position themselves around the shoot and begin feeding as a group down the terminal through the inner bark. Small holes scattered over the bark are characteristic of white pine weevil attacks. After five or six weeks the larvae construct pupal chambers in the pith or wood of the terminal shoot and transform into adults. The young adults remain in the dead terminal until late October and November when they move to favorable overwintering sites on the ground, usually at the base of the host tree.

Control of the white pine weevil is difficult. It is possible, however, to reduce the damage by making conditions in a young stand unfavorable for egg laying. This is possible because the female weevil will only lay eggs within a rather narrow range of temperature and relative humidity. Various techniques involving the use of shade from “nurse trees” have been developed but require intensive management. Under certain circumstances, chemical control can be used.

In the Gulf Coast States the pitch-eating weevil is probably the most troublesome insect pest of pine seedlings. No accurate figures are available on the damage directly attributable to this pest, but mortality losses are estimated to average about 30 percent in susceptible areas. All of the southern hard pines and other conifers are probably suitable breeding and host material for the pitch-eating weevil. Its range overlaps that of the pales weevil, being reported from Labrador, Canada, south to Florida and west to Texas. It occurs in damage-causing numbers only in the Gulf Coast States.

Pitch-eating weevils breed in the roots of freshly cut stumps. The adults burrow down through the soil, sometimes a considerable distance from the stump, and lay their eggs in niches chewed in the root bark. On hatching, larvae mine the inner bark, packing their galleries with frass. Pupal cells are excavated in the sapwood, and a chip cocoon is constructed from the excelsior-like material removed during the cells’ construction. Development time varies from six to ten months depending on when the stumps are initially infested. Emerging adult pitch-eating weevils feed by night on the tender bark of seedlings. Small irregular patches of bark are removed, eventually girdling the seedling and causing its death. The pitch-eating weevil exhibits a population trend similar to that of the pales weevil, and is a threat mostly in early spring and in the fall.

The most effective control for pine reproduction weevils is to wait nine months before replanting or until the stumps in an area are no longer attractive to the weevil. Chemical control can be used when such a delay is considered impractical.

This snout beetle is very similar to the white pine weevil both in appearance and habits. It is found throughout the south- and mid-Atlantic states from southern New Jersey west to Missouri. Although deodar cedar is the preferred host, Atlas cedar, Lebanon cedar, and several species of southern pines are also attacked.

Galleries and chip cocoons of the deodar weevil.

Adults emerge from April to May and feed briefly on the inner bark of leaders and lateral branches of host trees. Heavy feeding frequently girdles the stem and can kill small trees. The adults are dormant during the summer, but resume activity in the fall to lay their eggs. From one to four eggs are deposited in feeding punctures. The newly hatched larvae bore into the inner bark where they construct winding galleries which girdle the stem. Evidence of such infestations is often delayed until January when the branches begin to turn brown. Winter is spent in the larval stage. The larvae pupate in March or April and the cycle is complete.

Keeping shade trees in a vigorous condition by proper watering and fertilization helps reduce their susceptibility to weevil attack.

Coneworms are perhaps the most destructive insect pests of pine cones in the South. They are particularly serious in superior-tree seed orchards where they frequently cause substantial economic loss. There are five important species of coneworms in the South, one or more of which attack all of the native and exotic pines.

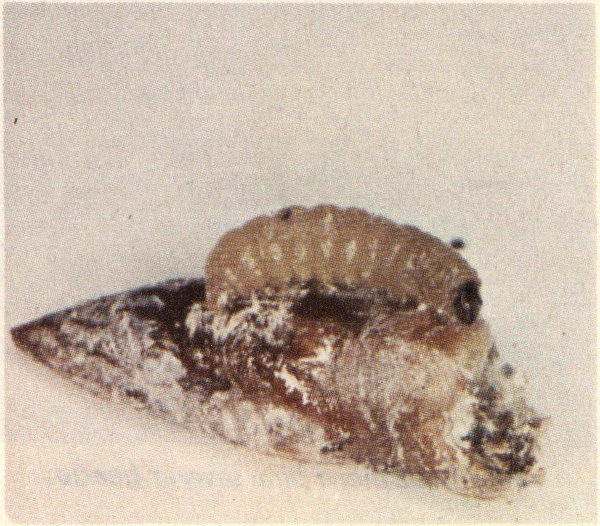

Coneworm larva feeding on a pine shoot.

Although the number of generations per year varies with the species, their general life history is similar. Female moths lay their eggs around wounds, cankers, galls, etc., but also deposit particularly on terminal growth. Eggs generally hatch in about a week. Larvae may stay at a single feeding site, or move to several different sites before completing their development. This latter behavior often results in a single larva destroying several cones or shoots. Pupation takes place in a chamber constructed by the larva at the feeding site. Depending on the species and time of year, the adult may emerge in two to three weeks or overwinter in the pupal stage. Coneworms cause several kinds of damage. They may mine through the inner bark, bore up the center of a shoot, or completely hollow out a cone. Their attacks are sometimes marked by fecal pellets and large pitch masses.

Slash pine cone damaged by coneworm larva.

Several parasites attack coneworms but are seldom effective enough to prevent population build-ups. Chemical control is often necessary on seed orchards to ensure adequate protection of the cone crop.

Until recent years little has been known about pine seedworms. These insects are found throughout the South but seldom have population explosions. An exception to this is on slash pine in Florida where over 70 percent of one year’s cones were reported infested. Longleaf pine cones in Texas and Louisiana have also had over 60 percent cone infestation on occasion. Loblolly and shortleaf pine cones are seldom over 20 percent infested. Seedworms have been found infesting longleaf, loblolly, shortleaf, slash, and Virginia pine cones. Laspeyresia anaranjada Miller attacks primarily slash pine, occasionally longleaf pine, and rarely loblolly pine. L. ingens Heinrick attacks primarily longleaf and slash pine. L. toreuta Grote attacks Virginia, shortleaf, and loblolly pine in the South.

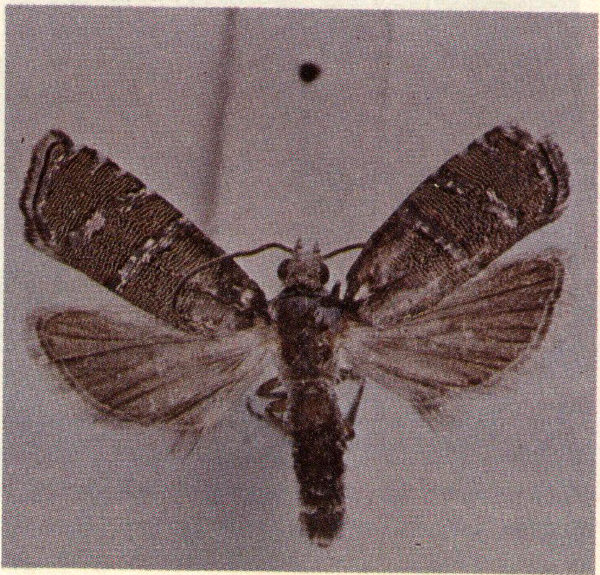

Adult pine seedworm.

The female moth lays eggs from April through May on second-year cones. There is one generation per year. Larvae feed within developing seeds until the cone matures. In late fall, larvae either bore into the cone axis or remain in a hollowed-out seed, and overwinter. Pupation occurs within the cone and moths emerge through the hollow seeds. External evidence of seedworm attack is not visible in immature cones. As cones mature, damaged seeds are retained in the cone. Heavily damaged cones do not open properly. In high-value seed orchards and seed production areas some protection from seedworm attack may be obtained through the use of pesticides applied in a carefully timed program.

Pine seedworm larva in longleaf pine seed.

Eggs and wool-covered adult balsam woolly aphids.

The balsam woolly aphid was introduced into northeastern North America from Europe around the turn of the century. Since then it has become a pest of major importance to true firs on the east and west coasts of the continent, and threatens some 60,000 acres of Fraser fir in the southern Appalachians. Usually the balsam woolly aphid has two generations per year in the southern Appalachians. Eggs of the first generation hatch in late June and July followed by the second generation in September and October. The immature stage of the aphid known as a “crawler” is the only motile stage in the aphid’s life cycle. Once the crawler begins feeding, it transforms into an adult and never again moves. Reproduction is parthenogenic with each female laying approximately 100 eggs during her lifetime.

In the feeding process the aphid injects a salivary substance into the host tree, which causes growth abnormalities. Initial symptoms of aphid attack may include “gouting” of buds or twig nodes and some twig and branch die-back. Heavy stem attacks reduce the tree’s ability to translocate food and water. Usually a heavily infested tree dies within two to seven years.

Chemical control is effective but extremely costly and thus limited to very high-value areas along scenic road-ways. Other control measures include removal and destruction of infested material.

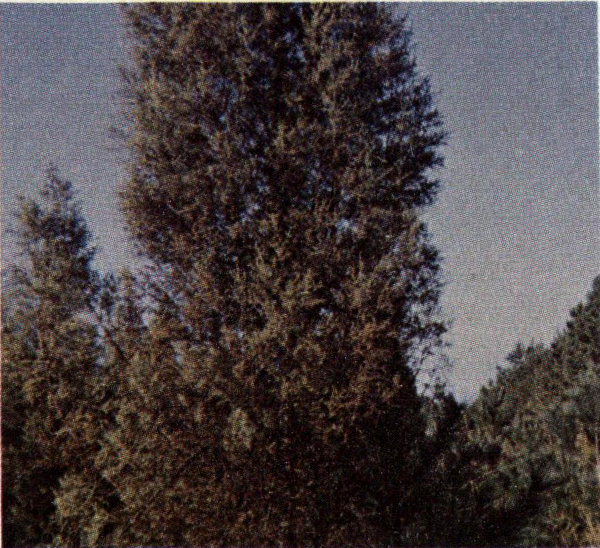

Fraser fir infested by balsam woolly aphid.

Needle cast is a very common disease of conifers throughout eastern and southern United States. Eastern white, loblolly, longleaf, pitch, pond, shortleaf, table mountain, and Virginia pines are all susceptible. Hypoderma lethale is probably the most common cause of needle cast on the above hosts, with the exception of longleaf pine. Lophodermium pinastri is also associated with needle cast.

Hypoderma needle cast on loblolly pine.

Current pine needles are infected in the early summer, and by winter or early spring begin to turn brown at the tips. At this time the tree usually has a scorched appearance. Later, the browning progresses down the needle and the fungal fruiting bodies are produced. These are small, black, elongated structures known as hysterothecia, which open along a slit during moist weather to release their spores. The infected needles are often “cast,” leaving only the new growth, and causing the tree to have a tufted appearance.

Controls are seldom needed for this disease in forest stands. Infected trees usually recover and put out new foliage the year following heavy attacks. Nurseries or plantations should not be established in areas where needle cast is prevalent.

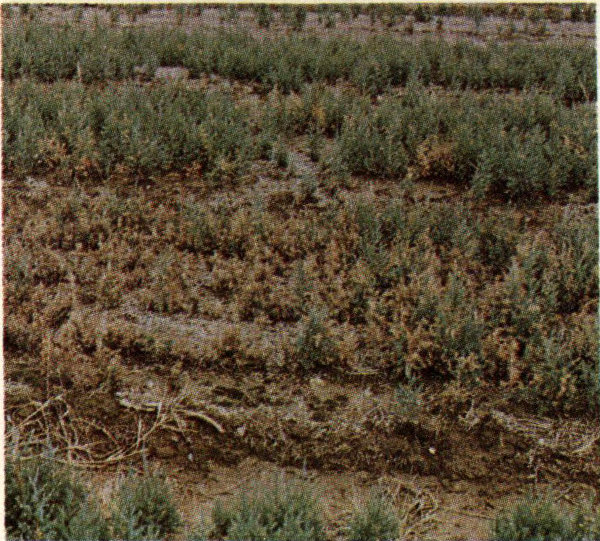

Lophodermium needle cast on 2-0 nursery stock and 5 year old scotch pine, Spanish variety.

Brown spot or brown spot needle blight is caused by the fungus Scirrhia acicola. Brown spot occurs in all the coastal states from Virginia to Texas, and inland to Arkansas and Tennessee. All southern pines are attacked by the fungus, but only longleaf pine seedlings are seriously damaged.

Brown spot needle blight on longleaf pine reproduction.

Initial infection of pine needles results in the development of small, circular spots of grey green color, which later turn brown. As the fungus continues to grow, a necrotic area encircles the needle, appearing as a brown band. The infected area will then increase in size, eventually resulting in the death of the needle. Fruiting bodies, called acervuli, develop in the dead areas of the needle. Spores are extruded from the acervuli in a water soluble gelatinuous matrix throughout the entire year. The spores are washed apart and splashed short distances by rain drops. These spores spread the disease from seedling to seedling. During the winter and early spring, the sexual stage of the fungus is produced on dead needles. Ascospores, produced in a fruiting body called a perithecium, are light and wind-disseminated. These spores are responsible for disease spread. During the grass stage, seedlings often become heavily infected by the brown spot fungus, resulting in partial to complete defoliation. Seedlings which are nearly defoliated every year remain in the grass stage and eventually die. Three successive years of complete defoliation will result in death. The disease is very damaging during wet years, especially in areas where the fungus has become well established in the absence of controls.

The disease can be reduced by control burning during the winter months. On seedlings, fire burns the diseased needles and reduces the amount of available inoculum for reinfection, leaving the large terminal bud unharmed. Often a single prescribed burn reduces the disease intensity to such low levels that vigorous seedling height growth begins the following year. Fungicide sprays will also reduce brown spot on high valued trees.

Fruiting bodies of pine needle rust on loblolly pine.

Nearly all the native pines in southern United States are attacked by various needle rust fungi of the genus Coleosporium. This disease is very common, but causes little harm to the trees. Many species of this rust also attack broadleaved weeds in addition to the pines, needing both host types to complete their life cycle.

Needle rusts are most prevalent on young trees in the seedling to sapling stage. In the spring or early summer small, delicate white fungus “cups” filled with yellow to orange spores are produced on the needles. From a distance entire seedlings may appear to have a whitish or yellowish cast. Individual needles which are heavily infected may die, turn brown, and drop from the tree. However, the entire tree is rarely defoliated. Small red “rust pustules” form on the undersurface of the weed leaves. These are replaced by dark structures later in the summer.

The needle rusts are not important enough to warrant control in natural forests or plantations. If the weed (alternate) host is known, it can be eradicated around nurseries of susceptible pine species. However, it would be better to establish nurseries in rust free areas.

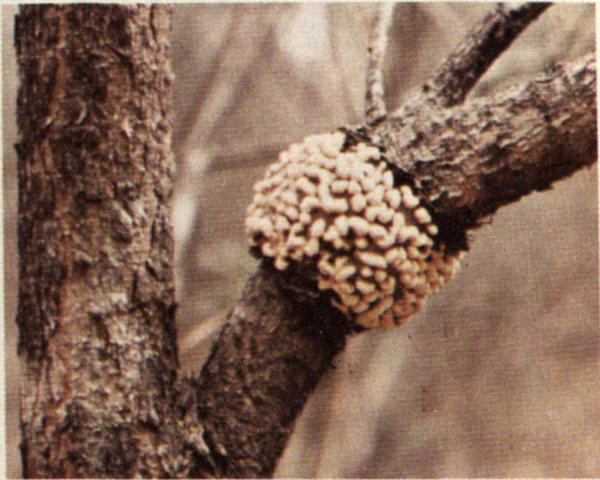

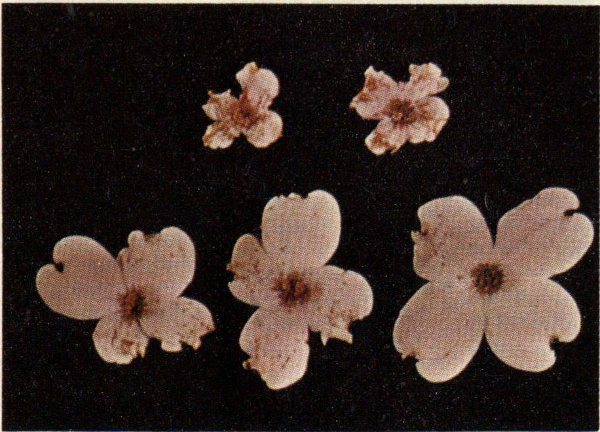

Cedar apple rust, caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae, is important commercially in the apple-growing regions of the Virginias, Carolinas, and the Mississippi Valley. The alternate hosts of this rust are eastern red cedar and several species of junipers.

Fruiting galls containing spores on cedar tree.

Fruiting on apple leaf the alternate host.

Cedar “apples” or galls are the characteristic signs of the fungus on cedars. Cedar needles are infected in the summer by wind-borne spores from apple leaves. By the next spring or early summer galls begin to appear as small greenish brown swellings on the upper needle surfaces. By fall, the infected needle turns into a chocolate brown gall covered with small circular depressions. The following spring, orange jelly-like tendrils protrude from the galls producing an attractive ornament for the cedar tree. Spores produced from these orange spore masses are then capable of reinfecting apple leaves, thus completing the fungus life cycle.

No practical control of the rust on cedars is available because of the low value of cedar. However, considerable effort is expended to protect apple trees. Where apple is to be protected, cedars should be eliminated in the vicinity or, rust galls should be picked or cut off cedars before the galls mature.

Cedar blight, caused by Phomopsis juniperovora, is most severe on eastern red and Rocky Mountain cedars. Other hosts include arborvitae, cypress, and Atlantic white cedar. The disease ranges from the mid-West to the Atlantic coast and south to Alabama where it is most common in nurseries.

Needle symptoms on 1-0 eastern red cedar nursery stock and 5 year old Arizona cypress.

Symptoms on red cedar resemble that of drought. The tips of branches are killed back and sometimes entire trees will turn brown. The fungus forms black fruiting bodies on needles and stem lesions. Fungus spores are distributed by rainwater; nursery overhead sprinkling systems also facilitate blight spread.

Control of cedar blight is initiated by removing and burning infected nursery stock early in the season before infection becomes heavy. Seedbeds should be well drained. Avoid introducing cedar stock to an infected nursery. The location of cedars in the nursery should be changed frequently and, where possible, cedar beds should be kept well away from older cedar or cedar hedges. Seedlings growing in low-density seed beds are more vulnerable to the blight; thus beds should be fully stocked. Cedar mulch should never be used on cedar beds. Avoid wounding nursery transplants. No economically feasible control is available for forest stands.

Galls on 1-0 pine nursery stock.

Damage caused by fusiform rust infection.

Fusiform rust, caused by Cronartium fusiforme, is one of the most important diseases on southern pines. This rust is found from Maryland to Florida and west to Texas and southern Arkansas. The rust’s most important impact is in nurseries, seed orchards, and young plantations. Loblolly and slash pines are very susceptible to this rust. Pitch and pond pines are moderately susceptible, longleaf pine is fairly resistant, and shortleaf pine is highly resistant.

The most easily recognized symptom is the spindle-shaped canker on the pine branches or main stem. In early spring these swellings appear yellow to orange as the fungus produces powdery spores. As host tissue is killed, older stem cankers may become flat or sunken. Cankers often girdle trees and wind breakage at the canker is common. Fungus spores from the pine infect oak leaves. Brown hair-like structures, produced on the underside of the leaves in late spring, are the most conspicuous signs. These projections produce spores which in turn reinfect the pine trees, completing a “typical” rust cycle.

Fruiting fusiform-shaped canker on main stem of southern pine.

Silvicultural practices may lessen the incidence of infection in plantations. Avoid planting highly susceptible species such as slash and loblolly pines in areas of known high rust incidence. In these areas more resistant species such as longleaf or shortleaf pine should be planted. Pruning infected branches will prevent stem infection in young plantations. Rust-resistant pines should be readily available from the nurseries in the near future. Culling out seedlings with obvious galls before outplanting will reduce the disease incidence in new plantations.

White pine blister rust, caused by Cronartium ribicola, was introduced to North America on nursery stock about 1900. It is the most important disease on white pine in the United States. In the South, the disease is found on eastern white pine in the Appalachian mountains.

Fruiting cankers showing yellow-colored spores of blister rust on eastern white pine.

The disease is caused by a fungus that attacks both white pine and wild and cultivated currant and gooseberry bushes, called Ribes. Both hosts must be present if the fungus is to complete its life cycle. Attack by the disease is followed by the development of cankers on the main stem or branches. Infected pines die when a canker completely girdles the main stem or when many of the branches are killed by girdling. The most conspicuous symptoms of the disease are the dying branches or crowns (“flags”) above the girdling cankers, and the cankers themselves.

Initially, a narrow band of yellow-orange bark marks the edges of the canker. Inside this band are small irregular dark brown scars. As the canker grows, the margin and bank of dark scars expand and the portion formerly occupied by the dark scars is now the area where the spores that infect Ribes are produced. During the months of April through June white sacs or blisters containing orange-yellow spores (called aeciospores) push through the diseased bark. The blisters soon rupture and the orange-yellow spores are wind-dispersed for great distances. Generally, there is some tissue swelling associated with the canker, which results in a spindle-shaped swelling around the infected portion of the stem.

Loss of white pines from blister rust can be prevented by destroying the wild and cultivated Ribes bushes. Bushes may be removed by uprooting by hand, grubbing with a hand tool, or with herbicides. Pruning infected branches on young trees will prevent stem infections and probably tree mortality.

Fruit gall showing orange colored spores on loblolly pine.

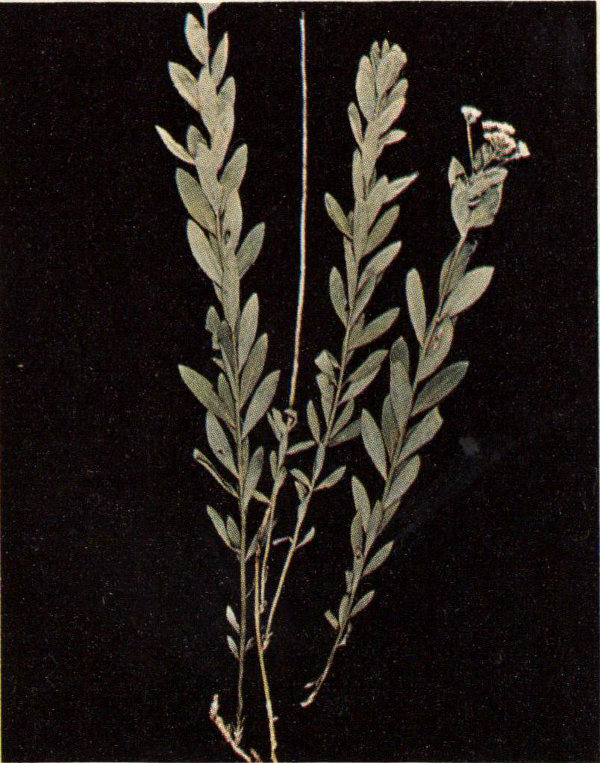

Alternate host—false toadflax.

Comandra blister rust, caused by the fungus Cronartium comandrae, is a canker disease of hard pines. The disease presently occurs in widely scattered areas throughout the western, central, and southern United States. In the South, the primary hosts are loblolly, shortleaf, pond, and Virginia pine. Herbaceous plants of the genus Comandra, commonly known as false toadflax or comandra, are also attacked.

The fungus infects pines through the needles and grows from the needle into the branch or main stem where it forms a gall or canker. Dark orange-colored spores which are produced on the surface of the gall in the spring are wind-blown and infect the leaves or stems of the comandra plants. Two to three weeks after infection, urediospores are produced on the underside of the comandra leaf. These are wind-blown and can only infect other comandra plants. Eventually hair-like structures known as telia are produced on the comandra leaves and stems. The telia produce spores which are wind-blown and infect the pine host through the needle. The necessary combination of a susceptible pine host, the alternate host, and the pathogen is presently known to occur only in northern Arkansas, eastern Tennessee, and northern Alabama.

No effective method of controlling the disease in forest stands is presently known. Silvicultural or forest management practices which reduce the abundance of the alternate host offer promise of long term control. Maintenance of dense stands and heavy ground cover as a means of shading out the intermediate host plants, may be helpful in reducing rust damage in many areas.

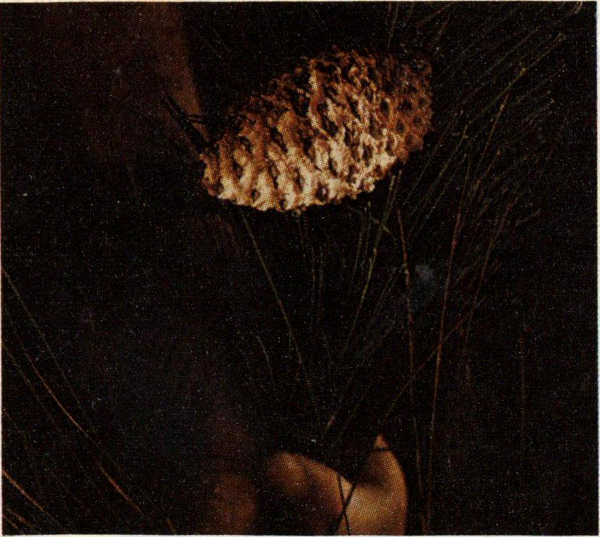

Eastern gall rust, caused by the fungus Cronartium cerebrum, attacks many species of eastern hard pines. The disease ranges eastward from the Great Plains and is most severe in the South on Virginia and shortleaf pines. Like most rusts this fungus requires an alternate host in addition to its pine host. In this case oaks, especially the red oak group (black, red, scarlet and pin) are the alternate hosts. Damage to the oaks is generally not of economic importance as only the leaves are affected.

Fruiting gall showing red-orange spores on Virginia pine.

On pines the fungus causes the formation of globose to sub-globose galls. Canker formation occurs occasionally but mortality generally results from wind breakage at the gall rather than by canker formation as literally hundreds of galls may appear on a single tree. They are not lethal to the tree, but may ruin tree form and on a large stem they can lead to an open decayed wound, as decay fungi are often secondary invaders of rust infections. The shape of galls and the arrangement of the spore sacs filled with red-orange spores present a cerebroid (brain-like) appearance. During the spring the bright orange galls are very striking.

This disease is sometimes a problem in nurseries where seedlings are attacked and killed. This is where control efforts are concentrated. Fungicide protectants are applied to the seedling foliage to prevent infection from spores produced on oaks. Contact your local forestry extension agent or the nearest Division of Forest Pest Management for the latest recommendations. Under forest conditions, control is not economically feasible. Trees of poor form should be removed during thinning operations.

Southern cone rust is caused by the fungus Cronartium strobilinum. It has been reported to completely destroy slash and longleaf pine cone crops in Georgia and along the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas.

Cone rust symptoms on slash pine.

Like most other rusts, the fungus requires oaks and pines to complete its life cycle. Although infection of oak leaves occurs annually, no significant economic damage is done to the oaks. Fungus spores produced on oak leaves infect the mature female pine flowers about the time of pollination (January-February). The fungus grows through the developing conelet causing it to swell abnormally. By early April or late May the infected cones are three to four times larger than the normal first-year cones and even exceed the maturing second-year cones in size. The swollen cone scales are reddish in color. Cavities in the cone filled with orange-yellow spores burst and the cones become orange-yellow. The swollen orange-yellow cones in the tree crowns can be easily distinguished from normal cones by an observer on the ground. By late summer most of the diseased cones have died and fallen.

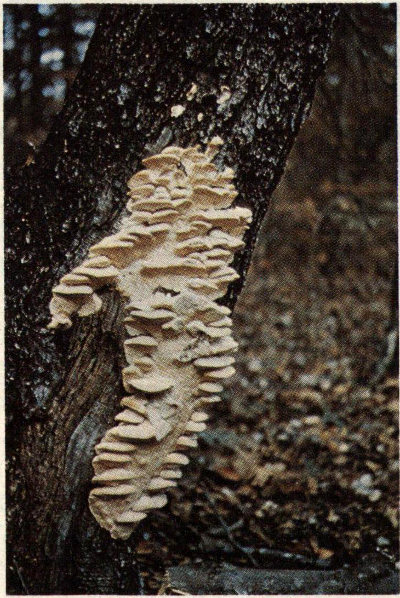

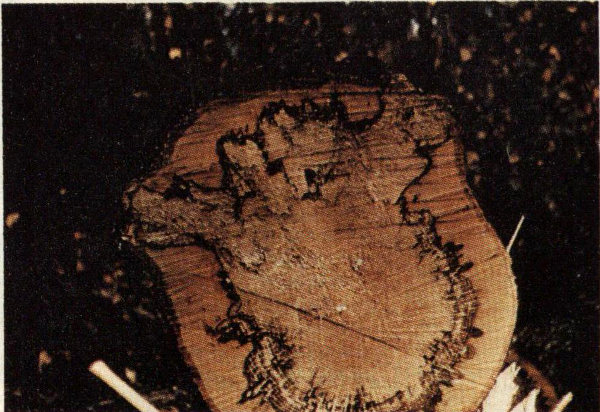

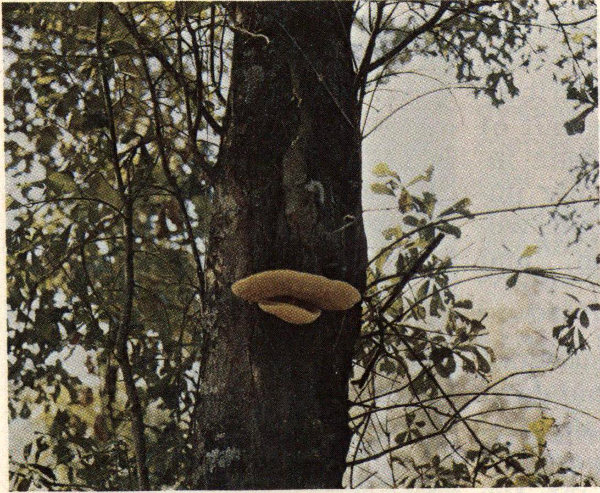

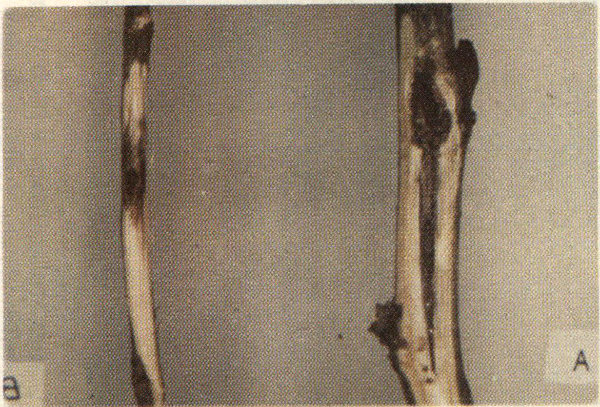

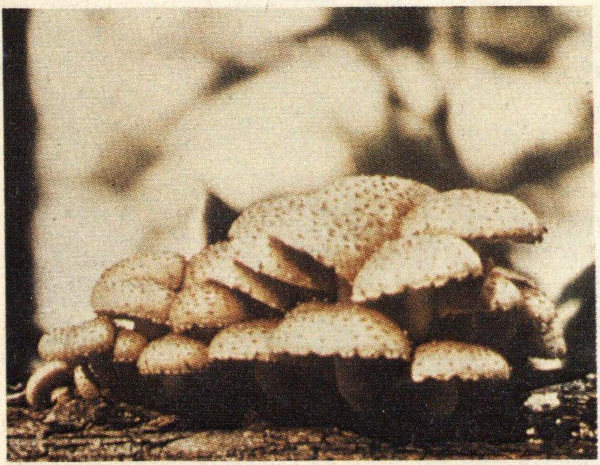

Control at present is confined to seed orchards. Hydraulic spraying of the flowers with fungicides gives a significant reduction in infections. Consult your local forester, county extension agent or the nearest Forest Pest Management Office for current control recommendations.