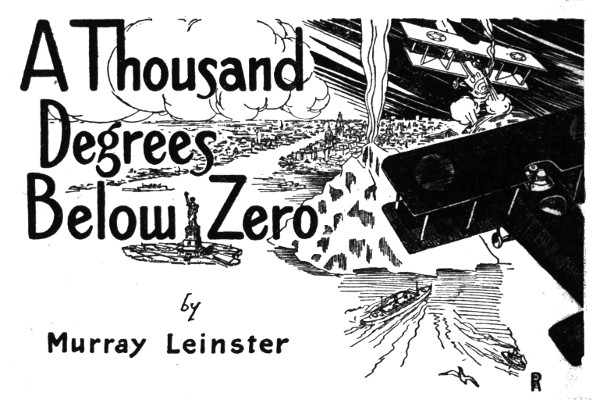

By Murray Leinster

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

The Thrill Book, July 15, 1919.]

Contents

| CHAPTER I. |

| CHAPTER II. |

| CHAPTER III. |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| CHAPTER V. |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| CHAPTER X. |

| CHAPTER XI. |

From some point far overhead a musical humming became audible. It was not the rasping roar of an aëroplane motor, but a deep, truly melodious note that seemed to grow rapidly in volume. The soft-voiced conversations on the upper deck were hushed. Every one listened to the strange sound from above. It grew and became clear and distinct. The source seemed to come nearer. At last the sound came from a spot directly overhead, then passed over and toward the Narrows.

A cold breeze beat down suddenly. It was not a cool sea breeze, but a current of air coming down from directly above the Coney Island steamer. It was actively, actually cold. A chorus of exclamations arose, full of the wit of the American a-holidaying.

"Br-r-r-r! I feel a draft!"

"Say, Min, are you givin' me the cold shoulder?"

"Sadie, d'you want to borrow all of my coat or only the sleeve?"

And one young man caused a ripple of laughter by remarking:

"Feels like my mother-in-law was around somewhere."

People hastened to put on such wraps as they had with them. On the lower decks there arose a sound of tired voices, saying with variations only in the names called:

"Johnnie, button up your coat. It's getting cold."

The cold wave lasted only for a few moments, however. As the steamer forged ahead the strata of cold air seemed to be left behind, and the humming sound grew fainter. If the passengers on the boat had listened, they might have heard a faint splash in the water behind them, but as it was the sound went unnoticed. The humming died away. The boat went on and docked, and the passengers dispersed to their homes. Every one of them woke the next morning to find himself or herself locally celebrated.

Half an hour after the Coney Island boat had docked a tramp steamer was nosing her way out of the Narrows. She was traveling at half speed, the air was clear, the channel was well buoyed, and there seemed no possibility of any harm or danger befalling her. The lookout leaned over the bow negligently, watching and listening to the indignant interchange of whistle signals between two small tugs in a dispute over the right of way. He dropped his eyes and stiffened, then turned toward the pilot house and shouted frantically, but too late. The shout had hardly left his lips before there was a shock and grinding sound, mingled with the raucous shriek of rent and tormented iron plates. The tramp steamer shuddered and stopped, and began to sink a trifle by the head. At the first intimation of danger the man on the bridge had ordered the water-tight doors, closed, and now he rang for full speed astern. The tramp swung free of the unknown obstruction, but the two bow compartments were flooded and the steamer's stern was lifted until the propeller thrashed helplessly in a useless mixture of air and water. Her whistle bellowed an appeal for help. "Want immediate assistance!"

Half a dozen tugs, including the two that had been quarreling by whistle, responded to the stricken steamer's call. Their small sirens sent cheery messages promising instant aid, and they began to tear across the water toward her. One tug reached the helpless vessel's side. A second rushed up and began to pull the unwieldy tramp away from the unknown obstacle. The lights of a third could be seen very near, when there was a crash and a frantic bellow from the tug. It also had struck the obstruction against which the tramp had run. The tramp bellowed anew.

A destroyer shot down the river with a searchlight unshipped, her crew standing by to rescue any persons who could be reached by lifeboats. She swung up and saw the tramp being hauled and pulled at by busy, puffing tugs. The long pencil of light danced over the surface of the water to find the derelict or wreck that had caused the trouble. Back and forth it swept, and then stopped with a jerk as if the operator could not believe his eyes.

Floating soggily in the water of New York harbor, in late August—the hottest time of the year—a wide cake of ice lay glistening under the searchlight rays! The harbor waves ran up to the edge of the ice cake and stopped. Beyond their stopping point the surface was still and glassy. The cake floated heavily in the water and showed no sign of cracks or fissures. It was evidently of considerable thickness.

A second searchlight reënforced the first. The two white beams moved back and forth, incredulously examining the expanse of ice. It was hundreds of yards across. At last one of the beams passed something at the center of the cake and hastily returned to the thing it had seen. Rising calmly and quietly from what seemed to be a small crater at the center of the ice cake, a plume of steam floated placidly into the air. It was a huge plume, precisely like the flowing of a white ostrich feather, rising from a small orifice in the center of the mass of frozen sea water.

A wail from the siren of the tug that had run against the ice cake caused the searchlights to turn in its direction. The engine had ceased to run and a cloud of escaping steam was pouring from the tug's funnel. Men on the deck gesticulated frantically. The destroyer ran as close as the commander dared, and he shouted through a mega-phone. It was impossible to distinguish words in the confused shouts that came back from half a dozen throats at once, but the searchlights soon showed the cause of the excitement. The men on the tug pointed over the side. The small harbor waves rolled unconcernedly up to a point some twenty feet from the stern of the tug, but there they stopped abruptly. The tug had become inclosed in the ice floe. As those on the destroyer watched, the twenty feet became thirty and the thirty forty. The ice cake was increasing in size with amazing rapidity.

A boat put off from the destroyer, and the commander shouted to the crew of the tug to take to the ice. There was a moment's hesitation, and then they jumped over the side and ran to the edge of the floe. The lifeboat touched the edge and was instantly frozen fast, but the sailors managed to break it free again by herculean efforts. It went back to the destroyer, whose wireless almost instantly began to crackle. Two other destroyers dashed down from the Brooklyn Navy Yard and turned their searchlights on the strange visitor in the harbor. The semaphore of the first destroyer on the scene began to flash, and the three lean naval craft began to circle around the huge ice cake, warning away all other craft and constantly measuring and re-measuring the size of the mass of ice. One of the destroyers at last slipped outside the Narrows and stayed there, patrolling back and forth to keep other vessels from running foul of the strange and as yet inexplicable phenomenon.

By daybreak the Battery was a black mass of people. They looked eagerly toward the Narrows, but could see nothing but a wall of mist, from which the gray shape of a destroyer now and then emerged. High in the air, however, the plume of steam was visible. It was now more than a thousand feet high and was dense and white. The first rays of the sun had gilded the top, while the ground below was still dim and dark, but now it rose in calm and quietness to an unprecedented height, mystifying the people who looked at it and causing a sudden silence to fall upon them all. A warm, moist sea breeze had blown in from the ocean during the night and had been changed to fog as it passed over the expanse of ice, so that the ice itself was hidden from view, but the tall plume of steam told of some mysterious menace to humanity that the crowd assembled at the Battery feared without understanding.

As the mass of people watched the supremely calm column of steam rising high in the air of that August morning, newsboys began to circulate among them, their strident cries sounding strangely among the silent multitude. The Narrows were frozen solidly from shore to shore, and all entrance to and egress from New York harbor was blocked. Small craft could go out behind Staten Island through the Kill van Kull, and some vessels could use the other channel which goes from the East River into the Sound, but the great Ambrose Channel—-one-third the size of the Panama Canal—and the broad opening that made New York the greatest port on the Atlantic coast was closed. The growth of the ice cake had greatly lessened, so that it could be predicted that it would not expand far beyond its present size, but its origin and the means by which it resisted the disintegrating effect of the August warmth were utterly unknown. The cause of the plume of steam from the center of the ice cake was an unfathomable mystery.

Suddenly, from the empty sky, there came a deep, musical humming. Instinctively people looked up. The humming grew louder and more distinct, while curious eyes swept the sky.

Then a black speck appeared below one of the fleecy white clouds and dropped toward the earth. A thousand feet, two thousand feet it fell, then checked and hung steadily in the air. Those who looked with the naked eye could only discern that it seemed like a wingless black splinter suspended above the earth, but those who had glasses saw the whir of dark disks above a black, stream-lined body. A small cabin was placed amidships, and a misshapen globe hung from chains below. It was still for several minutes. The passenger or passengers seemed to be inspecting the earth below, and particularly the ice cake, with deliberation and care. Then it began to rise with the same deliberation and certainty, swung around, and sped off with incredible speed toward the northeast. The humming sound grew fainter and died away, but the crowd standing on the Battery began to murmur with a nameless sense of fear.

New York was frightened, and the newspapers as they appeared did not allay that fear. The conservative Tribunal ran a scare head: HAS THE GLACIAL AGE COME AGAIN? and printed underneath a résumé of the phenomena up to the time of going to press—which did not include the appearance of the black flyer—with an interview from a prominent scientist. An enterprising reporter had routed the worthy gentleman out of bed and rushed him to the scene of the expanding ice cake in a fast motor boat, taking down in shorthand his comments on the matter. The scientist had been much puzzled, but spoke at length nevertheless. He said in part:

Has the glacial age come again? I do not know. I can only say that we have no certain knowledge of the original cause of the glacial period and we cannot say definitely that it did not begin in precisely this fashion. We have volcanos which radiate incredible quantities of heat to the country surrounding them. No phenomenon like this has occurred before, but it may be that some unknown cause may bring to the surface a condition the antithesis of a volcano, which, instead of radiating heat, will bring on local glacierlike conditions. One might go farther and suggest that the earth may alternate between periods of volcanic activity, during which it is warm and conditions are favorable for habitation and growth, and periods of this new antivolcanic activity during which frigidity is normal, and mankind may be forced to take refuge in the tropic zones. Still, I cannot say definitely.

The eminent scientist went on for two full columns, during which he refused to say anything definite, but suggested so many alarming possibilities that every one who read the Tribunal was thrown into a state of mind not far from panic. He offered no explanation of the plume of steam.

When the appearance of the black flyer became known in the newspaper offices, city editors threw up their hands. The less conservative printed the wildest explanations. They put forth a virulent-organism theory, which, it must be admitted, was no farther from the truth than most of the others. The story began with an interview with the boatswain in charge of the boat crew from the destroyer:

We were ordered to take the men off the ice and to take especial care not to be nipped ourselves. We rowed carefully toward the edge of the ice cake, with the light of the searchlights to guide us. We would see where the floe began, when the waves dropped back from it. I've been in Northern seas, but I never saw anything like that. The edge of the ice wasn't smooth and worn away by the waves. It was rough with frost crystals that reached out like fingers grabbing at the things near by. When we came close to the edge some of the men in my boat were scared, and I don't blame them. I'd dipped my hand overboard and the water was warm—and twenty feet away there was that mass of ice! We backed up to the ice cake and took off the men. I was looking over the side of the life boat, and saw those long crystals forming and growing while I watched. They were huge, from two feet long for the largest to three or four inches for the smallest. They reached out and reached out terribly. The stern of the boat was touching the ice, and I saw them reaching for the hull like the tentacles of an octopus. They fastened on and began to grow thicker. We took oars and smashed them, feeling frightened as one is frightened in a nightmare. As fast as we broke them they formed again, and the men on the ice seemed to be rotten slow getting into the boat, though I don't doubt but they were hurrying all they knew how. When they were all aboard we had to work like mad to get clear.

The paper went on to expound its own idea of what had happened:

The sinister growth of the ice crystals is significant There has always been notice of and comment upon the striking similarity between the growth of crystals and the growth of plants. Until now all scientific text-books have said that crystals could only grow in a supersaturate solution of their own substance, and claimed that they were not organic growths—in the sense of growths caused by an intelligence within the crystal. Is it not possible that the scientists have been wrong? Is it not possible that crystals are growths in the same way that plants are growths? Granting that, what is to keep a scientist from isolating and cultivating the crystal embryo? We have done that with germs, and with the life germs in eggs and plants. We can even use a process of parthenogenesis and create monsters from the unfertilized eggs of frogs and sea urchins. Why could not this scientist experiment until the life germ of the ice crystal could be developed and enlarged? Why could not this development continue until the germ could not only create its crystals under the most favorable conditions of temperature, but at the normal temperature of water? At the Harvard laboratories water has been, kept liquid far below its normal freezing-point, and under tremendous pressure has been found to remain ice at a temperature of one hundred degrees Fahrenheit! Can we doubt that this appearance of ice at this extraordinary season is due to the malicious activities of a foreign government, envious of our magnificent merchant marine and commerce?

The explanation was ingenious, but though the scientific facts quoted were quite correct the inference was hardly justifiable. Water can and does reach a temperature several degrees below 32° Fahrenheit without solidifying—as may be proved by putting a glass of water in a cold room in winter—but the slightest jar causes the instantaneous formation of ice crystals, and in a little while the whole mass is solid. The fact of "hot" ice must also be admitted, but it requires a pressure of rather more than fifty tons to the square inch, and is rarely attempted.

This paper also was forced to admit as inexplicable the plume of steam which rose from a thousand to fifteen hundred feet into the air. In any event, the claim that a certain unfriendly foreign government was trying to ruin the commerce of the United States was effectively squashed by cablegrams from Gibraltar, Folkestone, and Yokohama. Three great icebergs had formed in the Straits of Gibraltar and extended until they joined, when a solid mass of ice made a bridge that once more rejoined the continents of Africa and Europe, from Ceuta to the Rock. The plumes of steam were visible here, too. Three mighty columns of white mist rose at equal distances across the gap.

Folkestone harbor was a mass of ice. A great transatlantic liner had been caught in the expanding berg, and the huge hull had been crushed like so much cardboard. The passengers and crew had escaped across the ice. The great steam plume made a wonderful sight for miles around. Yokohama was similarly visited. Three battleships of the Japanese fleet were frozen in and their hulls cracked and broken. The plume of steam—nearly two thousand feet high—had aroused the latent superstition of the Japanese and was being exorcised in every Shinto temple in the kingdom.

The panic which was engendered by the mysteries of the icebergs and the unknown motives of the men so obviously responsible for their appearance grew in intensity. New York was in a blue funk. The police felt the tremor that means that at any moment the crowds thronging the streets might break and from sheer panic become uncontrollable. Every patrolman wore a worried frown and worked like mad to keep the crowds moving, moving always. The strain was becoming greater, however, and troops were being hastily moved into the city when an announcement was made by the British foreign office:

It has been decided to make public a communication received at the foreign office bearing on the blocking of Folkestone harbor, the Straits of Gibraltar, Yokohama, and New York. The communication is dated from "The Dictatorial Residence," and reads as follows:

"To the Premier of Great Britain: You are informed that the blocking of Folkestone harbor, as well as that of the Straits of Gibraltar, New York, and Yokohama, is evidence of my intention and power to assume control of the governments of the world as dictator. Present administrations and systems of government will continue in power under my direction and subject to my commands. The machinery of the League of Nations is to be used to enforce my decrees. You will readily understand that the same means I used to block the harbors and straits now frozen over can be extended indefinitely. Rivers can be made to cease to flow, lakes to irrigate, and all commerce and agriculture forced to suspend its activity. This will be done, if it is made necessary by the refusal of the governments of the world to accede to my demands. Given under my hand at the dictatorial residence,

"(Signed) Wladislaw Varrhus."

The foreign office offers this communication to allay the fears of the public that a new glacial period may be imminent, but at the same time it wishes to assure the British people that the demands of the writer are not taken seriously. It is evident that the maker of such absurd demands is insane, and though he may be able to cause perhaps serious inconvenience to commerce, a means of nullifying his invention will be forthcoming in a short while. British scientists are studying the Folkestone phenomena and are confident of a prompt solution of the problem.

Though it might have been expected that such an announcement as that of the intention of an unknown and probably insane man to make himself ruler of the world would have caused even greater panic, the reverse was actually the case. The motive behind the creation of the icebergs was made so clear that the world settled back with a sort of sporting interest to see what would happen. It had not long to wait.

A hint came by some underground channel that Professor Hawkins had offered a suggestion to the American government that had been accepted as a basis for experiment. A reporter went post-haste to the professor's home. He was admitted, but the professor would not see him at the moment. The reporter sat down patiently to wait. A motor car drove up to the house and a man in soldier's uniform stepped out. The reporter gave a whistle. A second car discharged a quietly dressed man in civilian clothes attended by two other army officers. The reporter stared. He recognized the men. Most people on two continents would have recognized them. They passed through the house to the professor's laboratory at the rear. A long time passed. The reporter fidgeted nervously. Some conference of colossal importance was taking place back there in the laboratory.

It was an hour later that the visitors left. With them went a young man the reporter had not seen before. The professor came slowly into the room and smiled apologetically.

"I am very sorry to have kept you waiting, but it was necessary. I think that in about two hours I will have some news for you. In the meantime there is nothing more to say."

"Can you tell me what really happened? How did this Varrhus make the berg?"

"It's the simplest thing in the world," said the professor with a smile. "I've managed to duplicate it on a small scale back in my laboratory. Suppose you come back there and I'll show you."

A girl appeared in the doorway with a worried frown on her face.

"Father, has Teddy gone?"

"Yes. We'll hear in about two hours." The professor turned to the reporter with instinctive courtesy. "This is my daughter, Evelyn."

The girl shook hands.

"You want to know about the iceberg, too? Teddy has gone to break it up now."

"To try to break it up," corrected the professor with a smile. "'Teddy' is my assistant."

"But how?" insisted the reporter. "You seem to be so confident, and every one else does nothing but guess."

"I'll show you quite clearly," the professor said gently, "if you'll come back to the laboratory."

They moved toward the rear of the house. A hullabaloo of whistles broke out in the harbor. The girl turned toward the professor.

"Teddy already?"

The professor frowned.

"He hasn't had time." He went to a window and looked out, inspecting the sky keenly. A slender black splinter hung suspended in the air. The professor flung open the window, and a musical humming filled the room. As they watched a smoking object detached itself from the black flyer and fell downward.

"That must be Varrhus," said the professor.

A winged flyer with the insignia of the American aviation corps painted on the under surface of its wings darted into their field of vision. Black smoke trailed behind it as it shot toward the sinister black craft. There was an instant's pause, and then little puffs of white mist appeared before the propeller of the aëroplane.

"He's firing his machine gun!" said the reporter excitedly.

As he spoke the black flyer dropped like a stone, and the American plane shot above it. Almost instantly the black flyer checked in mid-air and rose vertically with amazing speed. The American plane drove on for a second, and then wavered. It began to climb, stalled, and dropped toward the earth in a series of side slips and maple-leaf turns. It came down erratically, crazily.

"Killed!" said the professor with compressed lips.

His daughter uttered a cry:

"And Varrhus is getting away!"

The black flyer had become but the merest speck. It had attained an almost unbelievable height. Now it deliberately swung around and headed off toward the northeast with its same incredible speed.

Teddy Gerrod was stuffing his feet into heavy, fur-lined arctic boots. Ten or twelve soldiers were loading clumsy, awkward-looking engines on improvised sledges resting on the ice at the foot of the fort embankments. Others were putting equally ungainly iron globes with winged metal rods attached to them on other sledges. A dozen befurred and swathed figures came down the slope of the embankment and examined the preparations. A naval launch ran smartly alongside the edge of the ice, and a messenger came over at the double to the commandant of the fort, who stood by Teddy Gerrod. The messenger saluted.

"Sir, the object dropped from the black flyer was a tin float having a message attached. The smoke was from a smoke fuse, lighted to attract attention."

He handed over the letter, saluted again, and retired. The commandant tore open the letter and read it through, then swore frankly.

"A threat to freeze the Croton reservoir and cut off New York City's water supply if an answer to his previous demands is not given within forty-eight hours! And he can do it! Mr. Gerrod, you've simply got to settle this business. New York would go crazy if the people knew this. There'd be no way to supply the water the city has to have. And seven million people without water——"

Teddy smiled grimly.

"I'm going to try. Professor Hawkins is usually right, and we ought to be able to do something about this berg."

A second messenger came up and saluted.

"Sir, Lieutenant Davis reports that the plane has been recovered and Lieutenant Curtiss' body examined. There are no bullet marks, and the body seemed to be frozen solidly. He cannot say, as yet, what caused Lieutenant Curtiss' death."

"Frozen," said Teddy laconically.

"In mid-air?" asked the commandant sharply. "And in a fraction of a second, wearing heavy aviator's clothing?"

Teddy nodded, and buttoned up the huge fur coat in which he was enveloped.

"I'm ready to start off now, if the sledges are."

The little party moved away from the shore. The heavy mist still hung over the expanse of ice, but near the shore the ice was thinner. The sledges were roped together, and Teddy walked at the head. The party tugged at the ropes on the sledges, puffing out clouds of frosty breath at every exhalation. Teddy had taken the compass bearings of the steam plume, and after he had gone a hundred yards from the shore the wisdom of his course became apparent. They were completely surrounded by a thick fog in which objects five yards off were lost to view. Teddy, leading the small column, could not be seen except as a dim and shadowy figure by the men hardly more than two paces in his rear. He referred constantly to his compass, and once or twice glanced at the thermometer he had strapped on the sleeve of his great coat.

"Forty degrees," he murmured to himself. "And in New York it's eighty-four in the shade. The ice must be colder still because it's dry and hard."

The party toiled on. Presently small snow crystals crunched underfoot.

"Frozen mist," said Teddy, and glanced at his thermometer. "H'm! Twenty-two degrees. Ten below freezing."

The party stopped for a breathing spell.

"I hope you men smoke," said Teddy, "because it's going to be cold a few hundred yards farther on. We'll come clear of this mist presently. If you smoke, and inhale, it'll probably warm up your lungs a little. You don't need it yet, though. Any of you who haven't pulled down the flaps of your helmets had better do so now."

A moment or so later they took up their march again. The sledges, with their heavy loads, were cumbersome things to drag over the uneven surface of the ice. The men panted and gasped as they threw their weight on the ropes. Teddy felt the air growing colder still, and presently noticed that the mist no longer seemed to be as thick as before. He glanced down at the front of his heavy fur coat. It was covered with tiny white crystals. He held up his hand with the thick mitten on it to form a dark background, and saw numberless infinitesimal snowflakes drifting slowly toward the ice under his feet. His thermometer showed two degrees above zero—and New York, six miles away, was sweltering in August heat!

"Not much farther," he called cheerfully. "We're almost there."

They panted and tugged on, a hundred and fifty yards more. Then they stopped and stared.

Three hundred yards away the great column of steam was issuing from the ice. A hollow hillock of snow and ice rose to a height of twenty feet, like the miniature crater of a volcano. From it, in an unbroken stream, the mass of steam emerged with a roaring, rushing sound. It rose five hundred feet before it broke into the plumelike formation that was so characteristic. There was a space, perhaps six hundred paces across, in which there was no mist. The cold was too intense to allow of the formation of fog. Water vapor condensed instantly in that frigid atmosphere. But around the clearing the mist rose from the surface of the ice. It became noticeable when it was merely waist-high, then rose to the height of a man, and climbed to a height of fifty feet in a circular wall all about the strange white open space. Teddy, looking at the top of the wall of vapor, saw that it undulated gently, as if waves were flowing back and forth around the tall column of steam.

The men began to unload their sledges. The awkward little trench mortars were set in place and careful measurements made of the distance to the steam plume. While the men labored, Teddy moved forward toward the central cone. Five degrees below zero, fifteen degrees below zero, thirty degrees below zero——His breath cut sharply when it went into his lungs. Teddy put his mittened hand over his nose and face to partially warm the air before he breathed it in. Now, even through the heavy, arctic clothing he wore, he felt the bitter cold. He detached the thermometer from his sleeve and clumsily tied it to a cord. He had hoped to be able to lower it down the rim of the crater, but that was impossible. He flung it toward the hillock of snow and ice, let it remain there an instant, then hastily drew it back to read it. The ether in the thermometer had frozen into a solid mass in the bulb of the instrument.

Teddy went back to where the men had made ready. Four of the wicked little guns would fling their three-hundred-pound bombs into the center of the column of steam. If all went well, at least one charge of T.N.T. would explode far down the orifice.

The propelling charges had been inserted, and now the slender rods were put into the muzzles of the short, squat weapons. The winged bombs were balanced on the muzzles like top-heavy oranges on as many sticks. At half-second intervals, the four guns went off one after the other.

Before the last had exploded, or just as the flame leaped from its muzzle, the hillock of ice rose as in an eruption. Four cracking detonations blended into one colossal roar that half stunned the little fur-clad party. The rush of air threw them from their feet. When they rose again a huge hole showed in the center of the clearing, a gaping chasm that went down deep into the heart of the ice. A cloud of yellowish smoke floated above them. And the column of steam had ceased! Only a few stray wisps of white vapor floated up from the opening.

"It's done!"

Teddy gave orders for a quick return to the fort. The mortars could be returned for. At the moment the important thing was to send the news to England and Japan.

The return trip was made quickly, and Teddy made hurried explanations to the commandant of the forts of what should be done. Men should bore deep holes twenty feet apart, the holes to be along the edges of clearly defined sections of the ice. Simultaneous blasts should be set off, and the sections would float free. The iceberg would not grow again. It was done for.

Cablegrams were prepared and rushed through to Folkestone, Yokohama, and Gibraltar. If men took trench mortars and fired shells that would fall down the holes from which the steam issued, the cause of the ice cakes would be destroyed and the ice itself could be blasted off and towed out to sea to melt.

Teddy rushed back to the professor's home to report to him the full verification of his theories, and it was there and then that the first authentic explanation of the ice floe was given to the world. Word of his effort and of the disappearance of the steam plume had preceded him, and as he sped uptown in the taxicab newsboys were already on the streets with their extras. Only the front pages—showing signs of having hastily been hacked to pieces to make room for the story—had anything about the latest development, and those extras are singularly perfect reflections of the public attitude at that time.

Teddy threw himself out of the machine and rushed up the steps. Evelyn opened the door before he could ring, and his beaming face told her the news he had to give even without his enthusiastic, "It worked!"

"The steam plume has stopped?" asked the professor anxiously.

"Absolutely," said Teddy cheerfully. "Not a sign of steam except from two or three puddles of hot water that were cooling off when we left to get back to the fort. The commandant was setting his men to work with the navy-yard men when I started here."

"Tell me about this, won't you?" said the reporter briskly. "I'll catch the devil from the city editor for missing out on that part of it, but if you'll give me the full story——"

"What's your paper?"

The reporter told him.

"That's all right," said Teddy easily. "They were calling extras of that paper as I came uptown. The professor has told you the theory of the thing?"

"No," said Evelyn. "He was starting to, but the black flyer appeared and shot down the other aëroplane, and father was so much upset that he couldn't go into details. Was the pilot of the aëroplane killed?"

Teddy nodded.

"Frozen, poor chap. He never knew what struck him."

"What did happen?" asked the reporter again. "You people seem to take this so much as a matter of course, and no one else can do anything but guess."

"The professor knows more about low temperatures than any other man in the world," explained Teddy. "It's only natural that he should be fairly certain of his facts."

He smiled at the professor as the old man made a deprecating gesture.

"Father is much upset," said Evelyn. "I think it would be best if Teddy explained. Will that be all right?"

"Only, in your account of the matter," said Teddy decidedly, "the professor must be given credit for the whole thing. It's his work, and he's entitled to it."

"No, no," protested the professor. "Teddy did a great deal."

Evelyn pressed his arm, and he obediently was quiet. The two young people smiled at him.

"You see how I am ruled," said the professor in mock tragedy. "My daughter——"

"Is going to see that you rest a while," said Evelyn, with a twinkle in her eyes. "Teddy, you go and explain the whole thing while I take father out and discipline him."

With a laugh, she led the old man away. Teddy smiled.

"We aren't accustomed to reporters," he said, "or I suspect we'd act differently. Miss Hawkins is a most capable physicist, and helps her father immensely. The three of us work together so much that——Well, come along to the laboratory."

The two went to the rear of the house. On the way they passed through a long room full of glass cabinets in which odd bits of metal work glittered brightly.

"The professor's hobby," said Teddy, with a nod toward the cases. "Antique jewelry and ancient metal work. He's probably better informed on low temperatures than any one else I know of, but I really believe he's as much of an authority on that, too. This is Phœnician, and that's early Greek. These are Egyptian in this case. This way."

He opened a small door and they were in the laboratory.

"I'm afraid I'll have to lecture a bit," said Teddy. "Here's how the professor used to work out what was taking place out in the harbor."

He showed an intricate combination of silvered globes, tubes, and half a dozen thermometers.

"You see," Teddy began, "the water in the harbor was at a certain temperature. At this time of the year it would be around 52° Fahrenheit. The professor knew that fact, and then the fact that a huge mass of it was turned into ice. When you turn water into ice you have to take a lot of heat out of it, and that heat has to go somewhere. When water freezes normally in winter that heat goes into the air, which is cold. In this case the air was considerably warmer than the ice, and was as a matter of fact, undoubtedly radiating heat into the ice, instead of taking it away. The heat that would have to be taken from say ten pounds of water at 52° to make it freeze, if put into another smaller quantity of water would turn the smaller quantity of water into steam. You see?"

"The steam plume!" exclaimed the reporter.

"Of course," said Teddy. "We measure heat by calories usually. That's the amount of heat required to raise a pound of water one degree Fahrenheit. Suppose you have a mass of water. To make it freeze you have to take twenty thousand calories of heat out of it. Suppose you take that heat out. You've got to do something with it. Suppose you put it into another smaller mass of water. It will make that second mass of water hot, so hot that it will turn into steam at a high temperature."

"Then Varrhus," said the reporter thoughtfully, "was taking the heat from a big bunch of water and putting it into a small bunch, and the small bunch went up in steam. Is that right?"

"Precisely." Teddy turned to a file on which hung a number of sheets of paper covered with figures. "Here are the professor's calculations. We could only figure approximately, but we knew the size and depth of the ice cake, very nearly the temperature of the water that had been frozen, and naturally it was not hard to estimate the number of calories that had had to be taken out of the harbor water to make the ice cake. To check up, we figured out how much water that number of calories would turn into steam. The professor appealed to the government scientists who had watched the cake from the first. He found that from the size of the plume and the other means of checking its volume, he had come within ten per cent of calculating the amount of water that had actually poured out in the shape of steam."

"But—but that's amazing!" said the reporter.

"It was good work," Teddy said in some satisfaction. "Then we knew what Varrhus had done, and it remained to find out how he'd done it. Nothing like that had ever happened before. He couldn't very well have an engine working there in the water. The professor took to his mathematics again. Assume that I have a stove here that will make it just so warm at a distance of five feet. I'm leaving warm air out of consideration now and only thinking of radiated heat. If I put my thermometer ten feet away how much heat will I get?"

"Half as much?" asked the reporter.

"One-quarter as much," said Teddy. "Or three times away I'll get one-ninth as much, or four times away I'll get one-sixteenth as much. You see? If I want to make the ends of an iron bar hot, and I can only heat the middle, the middle has to be red-hot or white-hot to make the ends even warm. If I have to make the middle of a bar red-hot to have the ends warm, you see in order to make the ends cold the middle would have to be very cold indeed."

"Y-yes, I understand."

"Well, the professor worked on that principle. He knew the temperature of the edges, and he knew the size of the ice cake. It was easy to figure what the temperature must be in the middle. It worked out to within two degrees of absolute zero!"

"What's that?"

"There isn't any limit to high temperatures. You can go up two thousand degrees, three thousand, four, or five. Some things almost certainly produce a temperature of as much as eight thousand degrees. But high temperatures are produced by putting more heat in—by stuffing the thing with calories. I make an iron bar red-hot by putting calories in. I make it cold by taking calories out."

"Well?"

"If you keep that up you reach the point where there aren't any more calories left to take out. When you get to that point you have a temperature of 425° Centigrade, or one thousand and seventy-eight degrees Fahrenheit below zero. That's absolute zero."

Teddy spoke quite casually, but the reporter blinked.

"Rather chilly, then."

"Rather," Teddy agreed. "But our calculations told us that Varrhus had reached and was using a temperature within two degrees of that in the center of his ice cake. And right next to that temperature he had a very high one, as evidenced by the plume of steam."

"I can't see how you got anywhere," said the reporter hopelessly. "I'm all mixed up."

"It's very simple," said Teddy cheerfully. "On one side of a wall the man had what amounted to a thousand and some odd degrees below zero. On the other he had probably as much above zero. Evelyn—Miss Hawkins, you know—made the suggestion that solved the problem. She showed us this."

Teddy picked up what seemed to be a square bit of opaque glass.

"Smoked glass?"

"Yes, and no." Teddy smiled. "You can't see through it, can you?"

"No."

"Come around to this side and look."

The reporter made an exclamation of astonishment.

"It's clear glass!"

"It's a piece of glass on which a thin film of platinum has been deposited. It lets light through in one direction, but not in the other. Evelyn suggested that Varrhus had something which did the same thing with heat. It would let heat through in one direction, but not in the other. Of course if it would take all the heat from the air on one side and wouldn't let any come back from the other——"

"It would be cold?"

"On one side. The glass looks black because it lets the light go through and lets none come back. The surface, we have assumed, would be almost infinitely cold because it would let heat go through and would let none come back. We decided that Varrhus had made a hollow bomb of some shape or other, composed of this hypothetical material. Heat from the outside would be radiated into the interior because the surface absorbed heat like this glass absorbs light. It would act as a surface at more than a thousand below zero. Because something had to be done with the heat that would come in, Varrhus made the bomb hollow and left two openings in it. The inside of the bomb is intensely hot from the heat that has been taken out of the surrounding water. The hole at the bottom radiates a beam of heat straight downward which melts a very small quantity of ice and lets the water flow into the bomb, where it is turned into steam. Naturally, it flows out of the other hole at the top. There you have the whole thing."

"And you stopped it——"

"By dropping a T. N. T. bomb down the steam shaft. It went off and blew the cold bomb to bits. The iceberg will break up and melt now."

The reporter stood up.

"I'd like to thank you for this, but it's too big," he said feverishly. "Man, just wait till I wave this before the city editor's eyes!" He rushed out of the house.

The newspapers that afternoon had frantic headlines announcing the destruction of the steam plume and the fact that noticeable signs of melting had begun to show themselves on the ice cake. Smaller captions told of the dynamiting that had begun and of the destruction of the Yokohama and Folkestone bergs by soldiers acting on cabled instructions. The Straits of Gibraltar were cleared by salvos fired from the heavy guns on the Rock at the three great plumes of steam. The world congratulated itself on the speedy nullification of the menace to its democratic governments. It did not neglect, however, to rush detachments of men with trench mortars and hand bombs to its reservoirs, prepared to destroy any possible cold bombs on their first appearance. The aviation forces, too, made themselves ready to fight the black flyer on its next appearance, despite the mysterious means by which it had killed the American pilot.

This state of affairs lasted for possibly a week, when, within three hours of each other, the papers found two occasions to issue extras. The first extra announced the death by heart failure of Professor Hawkins, who had been found by his daughter, dead in his laboratory, holding in his hands an antique silver bracelet he had just opened at the clasp. The second, three hours later, announced the formation of an ice cake in the Narrows which grew in size even more rapidly than the original one, and was entirely unattended by the steam plume which gave Teddy Gerrod an opportunity to destroy the first. Within three hours the Narrows were closed, and the ice floe was creeping up toward New York.

In rapid succession came the news that Norfolk harbor was frozen over and Hampton Roads closed, that Charleston was blocked, then Jacksonville. The next morning delayed cablegrams declared that the Panama Canal was a mass of ice, and almost simultaneously the Straits of Gibraltar were again admitted to be firmly locked.

Teddy put his hand comfortingly on Evelyn's shoulder.

"There isn't anything I can say, Evelyn," he said awkwardly, "except that I couldn't have loved him more if he'd been my own father, and it hurts me terribly to have him go like this."

Evelyn looked up.

"Teddy," she said bravely, trying to hold back her sobs, "I've been fearing this for a long time, but—I can't believe it wasn't caused by that fearful Varrhus."

"The professor did work very hard over that problem," admitted Teddy.

"I don't mean that the work he did caused his heart to fail. I mean I think Varrhus killed father." Evelyn's eyes were dark and troubled as she looked at Teddy Gerrod.

"But, Evelyn, why do you think such a thing? You knew his heart was weak."

Tears came again into Evelyn's eyes, but she forced them back determinedly.

"Will you go upstairs and look at his fingers—inside? I was—crossing his hands—on his breast. Please look."

Teddy went soberly up the stairs to where the professor lay quietly on the bed he was occupying for the last time. Teddy turned back the sheet that covered the figure and looked at the gentle old face. A lump came in his throat, and he hastily turned his eyes away. He lifted the sheet until the professor's thin hands came into view. He looked, at the fingers, then lifted one of the white hands and examined the inside. Small but deep burns disfigured the finger tips. When Teddy went down-stairs his face was white and set, and a great anger burned in him.

"You are right, Evelyn," he said grimly. "Where is the bracelet he was holding when he was found?"

"On the acids table. He was lying beside it when—when I saw him." Evelyn was grief-stricken, but she forced herself to be calm. "Do you think you know what happened?"

"I'm not sure."

Teddy went quietly into the laboratory and found the massive silver bracelet lying where Evelyn had said. He looked at it carefully before he touched it, and when he lifted it it was in a pair of wooden tongs.

"That thermo-couple, Evelyn, please. And start the small generator, won't you?"

The two worked on the bracelet for half an hour, then stopped and stared at each other, their suspicions confirmed.

"Varrhus," said Teddy slowly. "Varrhus caused your father's death. This earth has gotten too small for both Varrhus and me to live on."

"He knew father could wreck his plans," Evelyn said in a hard voice, "and he wished to rule the world. So he killed my father."

Teddy's lips were compressed.

"Before God," he burst out, "before God, I'm going to kill Varrhus!"

The bell rang, and in a moment the commandant of the forts was ushered in.

"Mr. Gerrod, Miss Hawkins," he nodded to them, and then said: "They tell me Professor Hawkins is dead. The Narrows are frozen over again. Hampton Roads is frozen over. Charleston is frozen over. The Panama Canal is frozen over! There's no steam plume to blow up. Washington is worried. They're calling me to clear out the channel. The navy department is going crazy. If it were a case of fighting men I'd know something, but I can't fight a chemical combination. What's to be done, since the professor is dead? Who on earth can fill his place?"

He looked from one to the other, already beginning to show the strain under which he was laboring.

"Professor Hawkins," said Teddy quietly, "was murdered by Varrhus some four hours ago."

"Murdered! Varrhus has been here!"

"No, Varrhus has not been here, but we may be able to trace him. I'll get the police. Then we'll talk about ice floes. We know Varrhus' method now. We'll soon be able to anticipate him."

"But in the meantime," the commandant snapped angrily, "he'll play the devil with the world."

"We'll play the devil with him when he is caught," said Teddy evenly. "I've no intention of letting Varrhus get away. Just now there's a possibility of catching him in the ordinary way. He mailed a present to the professor, an antique bracelet. Ancient jewelry was the professor's hobby. He examined the bracelet and died.

"I heard he was dead," said the commandant restlessly. "The paper said heart failure."

"So did the doctor." Teddy took down the receiver of the telephone. "Give me police emergency, please."

In a few moments he hung up again. The statement that Professor Hawkins had been murdered and that there was a chance of catching Varrhus was all he needed to say. Hardly five minutes had passed before the commissioner of police himself was in the room with two of his keenest men.

"You'll have to explain what happened," he said at once to Teddy. "When news of the professor's death came I phoned at once to the doctor mentioned in the paper and asked if there were any possibility of foul play. To tell the truth, I'd been rather afraid something like this might happen. What was it?"

"Varrhus electrocuted the professor by an antique bracelet."

He handed over the ornament. The commissioner examined it gingerly.

"Nothing funny about this except the workmanship."

"And the surface," said Teddy. His set calm was surprising himself. "It looks as if it had been lacquered. That's Varrhus' secret."

"What is it? A powerful battery?"

Teddy turned to the materials with which he and Evelyn had been working.

"I'll show you. Here's an instrument that measures the resistance of a given coil. This is one of the professor's evaporation machines for producing low temperatures quickly. He evaporates ether in this sheath that surrounds this oven and objects in the oven are cooled far below freezing point. Look at this coil of silver wire. We measure the resistance at room temperature. One hundred and twenty ohms. It is very fine wire. We put it in the cooling oven and set the engines going——" For some minutes there was silence while the small electric pump thumped and rattled. "Now we'll take the coil out. The thermometer inside the oven says twelve below zero." Teddy handled the small coil of silver wire with thick gloves. "We'll measure the resistance again. Fourteen and a half ohms resistance, approximately. Low temperatures decrease resistance and increase the conductivity of metals. You see?"

"Yes, but why——"

"The inside of that bracelet is nine hundred degrees below zero. The whole thing is coated with Varrhus' lacquer, which, in this case, radiates all the heat from the inside out, leaving it incredibly cold within. That cold makes the silver conduct electricity better."

"Well?"

"At eight hundred degrees below zero Fahrenheit silver has no measurable resistance to the passage of an electric current. Now watch."

Teddy laid the bracelet on top of a frame wound with many turns of glistening copper wire. He threw on a switch, and a small generator at one side of the laboratory began to run with a humming purr.

"Eddy currents are whirling all around that bracelet. A strong current is running in an endless circle in that closed circuit of silver, nine hundred degrees below zero. Silver at that temperature offers no resistance to an electric current. Closed circuits have been left at that degree of cold for over four hours, and at the end of that time the electric current was still flowing round and round like a squirrel in a cage."

Teddy picked up the bracelet with a pair of wooden tongs. He took a second pair in his other hand. Rubber handles insulated the tongs from their handles.

"There's a current flowing around the inside of this bracelet. There was one flowing around it when the professor received it in the mail. He opened it with his bare hands, suspecting nothing. I open it with these insulated tongs. Watch."

He jerked on the two tongs. The bracelet parted at the catch, and a dazzling, blinding flash of light appeared with a sharp crackle at the parting.

"I made the current jump the gap. The professor took it through his body and it killed him. Are you satisfied?"

"God!" said the commissioner of police, aghast.

"The box and wrapper," said one of the men who had come with the commissioner. "Let us have the box and wrapper the bracelet came in and we'll get the man that mailed it. But we'll handle him with tongs, too, when we close in on him."

They took what they wanted and left. Teddy turned to the commandant.

"Now, sir, we'll see what can be done about the new berg. You say there's no plume of steam. Have you had an aëroplane fly above it to make sure?"

"Yes. The pilot says the whole ice cake is covered with mist, except for a round spot in the middle, but there's no sign of a steam plume."

Teddy nodded at Evelyn.

"No holes in this cold bomb. I wonder what happens to all the heat that comes in?"

"Father mentioned that he expected something of the sort, but didn't say what he thought could be done about it."

"The same as we did with the other, I suppose," said Teddy reflectively. "Only this time we'll have to blast down to the bomb and then break it up."

"I'll set men to work if you'll find the bomb," said the commandant.

"Almost any one could find it," Teddy remarked, "but there are going to be some queer difficulties when you get near the cold bomb. If you'll allow me, I'd like to be at hand when it is broken up. I may really be of use there."

He began to pick out instruments he thought he might need. Among other things he took what seemed to be two silvered globes with small necks. They were Dewey bulbs. Several low-temperature thermometers and a thermocouple connected with a delicate galvanometer completed his preparations.

The two men left the house and started for the launch that would take them to the forts. On the way Teddy was asking crisp questions about the explosives he could have placed at his disposal, quite ignorant of what was happening at that moment in Jacksonville.

The river there was a mass of ice from one shore to the other. All the little reedy islands and the swampy shores were frozen solidly. To see the slender palm trees rising from icy shores, their reflections visible on the narrow strip of mist-free ice that ran along the shores of the river was an anomaly. To see fur-clad tourists stepping out of the tropical foliage to step gingerly out on the ice "just to say they'd done it" was even more strange. At the moment, however, interest centered on a little group of soldiers out in the central clearing in the cloud of mist. They were bundled in furs and swathed in numberless garments until they looked like fat penguins or some strange arctic animals. A major of engineers was waving them to the right and left, forward and back until they stood at equal distance around the clearing. Each man moved backward until the mist that rose gradually from the ice reached his waist. Then, at a whistle signal from the major, they began to move forward toward a common center. The major had reasoned that the cold bomb must be precisely underneath the exact center of the clearing, and this was a rough-and-ready means of finding that center. They advanced toward each other, and as they went nearer the center of the clearing the cold grew more intense. Infinitesimal ice crystals glittered in little clouds where the moisture of their breath froze instantly in the terrific cold. At a second whistle from the major they halted. They formed a fairly even circle about forty yards across. Each man began to stamp and fling his arms about to keep from freezing in that more than frigid atmosphere. No man could have stood that cold, no matter how hardy he might be, for more than a very few moments. The major trotted around the circle, marking the place where each man stood. Four small sledge loads of explosives stood out in the clearing. The major intended to blast down toward the cold bomb with them.

The major was marking the position of the last man, completing his circle under which the cold bomb must lie, when a peculiar tremor was felt by every man there. It was not like the shiver of an earthquake or the reverberation of an explosion. It was an infinitely shrill vibration that a moment later was followed by a creaking sound that seemed to come from the center of the ice cake. The men on the ice stopped their stamping and swinging of arms to listen in instinctive apprehension.

The center of the circle around which they stood seemed to rise in the air. The ice on which they stood was shivered into tiny fragments. A colossal and implacable roar filled the air, and a great sheet of flame of the unearthly tint of a vaporized metal rose to the heavens. The swathed and bundled soldiers were annihilated by the blast. A great hole five hundred feet across gaped in the center of the ice cake. Jacksonville shook from the concussion, and the plate-glass windows of its stores and office buildings splintered into a myriad tiny bits that sprinkled all its streets with sharp-edged, jagged pieces.

Teddy Gerrod, all unconscious of the fate of those who had attempted to meddle with the Jacksonville ice cake, went on out to bare and blast open the cold bomb that blocked New York harbor.

Teddy Gerrod straightened up and beat his hands together.

"Forty-seven below," he said to the soldier behind him. "Put a marker here."

He moved off to the right. Already a dozen little flags showed where the temperature reached that degree. Teddy was drawing what he would have termed an isothermal line—a line where the temperature was the same. He was making a circle about a large part of the open clearing on the ice floe. Other flags led back into the mist, marking a path, and from time to time a party of four or five fur-clad soldiers arrived from the fort, dragging a loaded sledge behind them. They emptied the load from the sled, turned, and vanished into the mist again. A small pile of drills, explosives, and two of the squat trench mortars had already been made.

When the circle of little red flags had been completed, two signal-corps men set up their instruments and accurately located the center. Directly under that spot, if Teddy's reasoning was correct, the new cold bomb was resting. The sledge from the fort arrived again, bearing a curious trench catapult for flinging bombs. Four long strips of black cloth were unrolled, under direction of the signal-corps men, pointing accurately to the center of the circle. No one had been able to approach nearer, thus far, than thirty yards from the center. At that distance Teddy's thermocouple indicated a temperature of more than seventy-two degrees below zero, and flesh exposed to the air was frostbitten on the instant. What the temperature of the air might be directly above the cold bomb could only be conjectured.

One of the infantry men from the fort, the best grenade man in the garrison, now picked up a Mills grenade, and after carefully picking out the target with his eye, aided by the strips of black cloth, flung the small missile. A hole perhaps four feet deep and twice as much across was blasted in the brittle ice. A second, third, and fourth grenade followed. At the end of that time the size and depth of the hole had been doubled.

The trench catapult was set up. Half a dozen grenades were bundled together and flung into the now much enlarged opening in the surface of the ice. There was no explosion. One automatically braced oneself for the report, and the utter silence that succeeded the disappearance of the grenades came as a peculiar shock.

"Too cold," remarked Teddy to the young lieutenant in charge.

The lieutenant nodded stiffly.

"We'll try again."

A second batch of grenades was flung into the hole, and the same quiet resulted.

"I would suggest——" Teddy begin.

"We'll fire a trench-mortar bomb," said the young lieutenant.

The heavy winged projectile flew up into the air, and then descended squarely into the opening in the ice. Those standing fifty yards away could hear the crash as it struck, and then a sound as of musical splintering. The young lieutenant swore.

"The fuses are no good. Try once more."

"You can shoot all day and they won't go off," said Teddy mildly. "It's too cold down there."

The officer said nothing, but supervised the firing of a second mortar bomb with precisely the same result. He swore again.

"It's probably quite as cold as liquid air down there," said Teddy. "In fact, there's quite possibly a pool of liquified air at the bottom of the hole. Your bombs fall into that air and are frozen so solidly before they strike that the metal gets brittle and simply falls to powder from the shock. You can't do anything going on this way."

The young lieutenant hesitated, then turned to Teddy somewhat sulkily.

"What do you suggest, then?"

"We'd better enlarge the hole first. Blast down the walls of the present cavity, then use wrapped dynamite until we have a shallow crater. Then we'll place our explosives by long poles, keeping them warm by running resistance wires around them and heating them electrically."

The young lieutenant considered and agreed. Teddy went back to the fort to arrange for the heated bombs and the long poles. When he returned there was only a saucerlike depression in the ice clearing. It was quite fifty yards across, but no more than twenty deep. Standing near the edge, one could see the ice near the bottom glistening liquidly. Air, liquified by the intense cold at the bottom of the crater, wet the surface of the ice there.

"And that means the temperature down there is three hundred and twenty-five degrees or more below zero Fahrenheit," explained Teddy casually. "Here's where we use our heated explosives."

For an hour the party worked busily. Storage batteries brought out on sledges furnished the current that kept the explosives from becoming inert through cold. Charge after charge was fired, and the bottom of the crater grew steadily deeper. At the lowest point a little puddle of liquified air collected.

"We must be pretty nearly at the cold bomb now," said Teddy thoughtfully. "There's a mass of liquid air at the bottom of our crater, and something tells me there's solidified air at the bottom of that puddle. That means seven hundred-odd degrees below zero."

He was clad in the warmest garments that could be found, and every one of the others working in the clearing was quite as warmly clothed, but the cold was intense. One of the soldiers by the small pile of explosives was chewing a cud of tobacco. He spat. The brownish liquid froze in mid-air and bounced merrily away across the ice. The soldier looked at it with his mouth open, then shut it quickly. A thin film of ice had formed from the moisture on his teeth. The breast of every member of the party was covered with sparkling snow crystals from the congealed moisture of their breath.

"I begin to doubt if we can keep our stuff from freezing much deeper," Teddy commented. "We want to go down as deep as we can before we use our Dewey bulbs, though. I've only two of them."

The young lieutenant bustled away, and presently returned.

"The men say that the last bomb won't go off," he said aggrievedly. "Your heating plan doesn't work."

"I didn't expect it to work indefinitely," said Teddy mildly. "We want to clear out that liquid air and shoot our two Dewey globes before it's had time to reform. Will you please have a charge made ready to be fired just above the surface of that puddle? That should clear it away. Immediately after that charge has gone off we'll drop our two T. N. T. charges in the Dewey bulbs. They ought to show us the cold bomb."

The dynamite charge was suspended about a foot above the surface of the watery, bubbling pool. Air was in that pool, air turned to transparent liquid by the intense cold. At -325° Fahrenheit air becomes a liquid. Here, exposed to the sunlight and the blue sky, a pool of liquified gas had collected from the incredible cold of the cold bomb below. The charge of explosive burst with a shattering roar. The echoes of the explosion had not died away when the two Dewey bulbs filled with T. N. T. fell into the bared ice cavity. A Dewey bulb is a combination of six vacuum bottles placed one outside the other. They are used for the keeping of liquid gases at a low temperature, but are obviously just as effective in protecting their contents from exterior cold. They fell some five yards apart and rolled, then were still. Their fuses sputtered. They went off together. A huge mass of shattered ice was thrown aside, and a dark, globular mass was exposed to view. Almost as soon as it was exposed to the air a crust of frozen air coated it, and liquified air began to trickle down its misshapen sides. There could be no doubt but that it was the cold bomb, invented by an insane genius to make him master of the world.

Those about the rim of the crater looked at it and turned away. Just as the intense heat of a blast furnace sears unprotected flesh even yards from its flame, so the incredible cold of the dark object pinched and wrung with its freezing rays. Not one man who looked upon the cold bomb but suffered from a deep frostbite.

"We can't approach that thing," said Teddy, with his hand over his eyes. "I'd just as soon, or sooner, try to tinker with burning thermite. We'll have to shoot armor-piercing shells at it. They'll freeze when they get near it, but the impact ought to crack the thing."

He motioned to the fur-clad soldiers to move back from the crater, and after a hasty consultation with the lieutenant went off toward the fort to ask for a small-caliber field gun.

The lieutenant paced back and forth restlessly. He was an ambitious young man. He did not relish taking orders from a civilian like Teddy. His eye fell on the heap of equipment that had been brought out from the fort. Two trench mortars, a trench catapult, a liquid-flame apparatus—one of the American inventions that had far outdone the original German flamenwerfers! There had been some thought of trying to reach a point just above the cold bomb and melting the ice down to it with liquid flame. That had been quickly proven impracticable, but the liquid-fire apparatus had not been sent back. The young lieutenant was not stupid. On the contrary, he was a singularly intelligent man. In a flash he saw how the liquid flame could have been used much more efficiently than Teddy's resistance coils about his explosive charges. The idea simply had not occurred to Teddy, or the young lieutenant, either. Now, however, he became all eagerness. If he succeeded in breaking up the cold bomb during Teddy's absence it would be a feather in his cap. If, in addition, he pointed out a method of dealing with the cold bombs superior to Teddy's plodding system, it would certainly mean his promotion and a very desirable reputation for himself in his profession.

He gave his orders briskly. The liquid-flame tank was set up, and began to spray out its stream of fire. The young lieutenant had it trained so that it passed just above the top of the ungainly cold bomb and grazed the upper edge. Then the two trench mortars were made ready for firing. The young lieutenant set them at their proper elevation himself. He was tremendously excited. He pointed the two mortars with the most meticulous precision. To aim them properly he had to expose his face again and again to the direct rays from the cold bomb, but he paid no attention to the searing, freezing rays.

The stream of liquid fire shot upward in a perfect parabola, and fell evenly, exactly, where it was aimed. The young lieutenant knew that a mortar bomb would be frozen by the intense cold if it were fired at the cold bomb direct, but his plan got around that difficulty. With the liquid fire playing just above and grazing the cold bomb, when the shell from the mortar struck the incredibly cold surface, both the shell and the cold bomb would be bathed in flame.

All was ready. The lieutenant fixed his eyes on the cold bomb and gave the signal. The two small trench mortars spouted flame. Two ungainly bombs rose high in the air and fell hurtling down toward the strange, frosted object at the bottom of the crater. One of the bombs would fall a little to the left. The other—squarely on top!

The cracking explosion of the bomb from the trench mortar was lost in the greater roar that followed it. Before the young lieutenant or any of his men could lift a finger they were enveloped by a colossal sheet of vaporized metal that seemed to fill the earth, the air, and all the sky. Of a weird and unearthly tint, the white-hot flame leaped into the air. It sprang up three thousand feet in hardly more than two seconds. The blast had the velocity of many rifle balls, and the withering heat of molten metal. The young lieutenant and his men were swept into nothingness in the fraction of a second. The crater they had worked for hours to blast out was as a puny ant hole beside the vast chasm that opened in the ice down to the red clay far beneath the bed of the Narrows. And New York shook and trembled from the shock of the terrific explosion.

Teddy was thrown down by the concussion, and fell in a heap against the commandant. He leaped to his feet and rushed to the window, from which the glass had disappeared. He saw the remnants of the sheet of flame dying away and saw that the low-lying cloud of mist had been blown from the surface of the ice. A gaping orifice, five hundred feet across, showed itself where Teddy and the lieutenant had been working. Of the lieutenant and his men no trace could be seen. Two or three of the little red flags that had marked the path through the mist still remained, however, and a small sledge was lying, overturned, beside the sledge route. Four tiny black figures lay in twisted attitudes beside the sledge. As Teddy looked one of them began to struggle feebly.

Teddy stared, speechless. For a moment he was dazed by the suddenness and the overwhelming nature of the calamity that had befallen the young lieutenant and his detachment. Only accident had saved him from a similar fate. Then his professional instinct re-asserted itself, and he began to piece together what he knew of the bomb. In a moment the solution came to him.

"Varrhus planned this," he said unsteadily. "He filled up his hollow cold bombs with solid iron. The heat that would come in would first melt and then vaporize the interior until the pressure inside was more than the still-solid crust could stand. And all that vaporized iron would burst out. What a fiend that man must be!"

An hour later, baffled and discouraged, he was sitting in the laboratory with his head in his hands, trying desperately to grapple with this new problem. The new cold bombs apparently could not be assailed without destruction of those who attacked them. It was impossible to imagine that volunteers could be found to sacrifice their lives to destroy each new bomb as it was placed. The horror of being annihilated by a blast of metallic vapor would deter men who would not hesitate to face death in a less terrible form. And Varrhus was evidently able to place them again nearly as fast as they were blown up. Telegrams announcing the explosion of the Jacksonville and Charleston ice floes lay before Teddy, supplemented by a cablegram from Panama saying that the Miraflores Locks had been destroyed by the blast when the Panama cold bomb had burst. Teddy was nearly certain that the next morning would find the exploded bombs replaced. Varrhus' black flyer was evidently capable of carrying a great weight at an immense speed. It also seemed able to reach an almost incredible height, from the fact that the second cold bomb had been dropped in the Narrows in broad daylight without the flyer having been sighted.

Evelyn turned from the instruments with which she had been working. She had scraped off a small bit of the lacquerlike surface of the silver bracelet, and had been analyzing it in the hope of finding what element or combination had been used to produce the mystifying heat-inductive effect.

"Teddy," she said depressedly, "I can't find a thing. The lacquer effect seems to be simply the appearance of some way he has treated the metal. The surface gives just the same analysis as the filings from the inside of the metal. I took a spectro photo and it gives silver lines with a trace of lead. Analysis by arsenic reduction gives the same result."

"Perhaps those detectives will be able to trace Varrhus by the mailing box they took," said Teddy, without much hope. "It's not very likely, though. We've got to think of something!"

Silence fell in the laboratory again, broken only by the faint whistling sound of the flame Evelyn had used in her analytical work.

"The trouble is," said Teddy grimly, "that we've been trailing Varrhus, instead of anticipating him. If we could know where he was going to be——"

"He'll have to show up sooner or later," Evelyn commented. "We know, for instance, that he'll have to replace that bomb in the Narrows or let the harbor stay open. The use of these new explosive bombs means that he has to expose himself more than he'd have to with the old ones."

"There ought to be an aërial patrol above the city——"

Teddy stood up sluggishly, discouragement in every line of his figure. A servant tapped on the door of the laboratory.

"Lieutenant Davis, of the military flying corps, sir."

"Show him in," said Teddy listlessly.

A slim young officer came in. His friendly, boyish face was full of a whimsical humor.

"This is rather an intrusion, I'm afraid," he said half apologetically, "but I thought you might be able to help me out."

"I've done nothing so far," said Teddy in a rather discouraged tone. "Miss Hawkins and I were just canvassing the situation. You're talking about the iceberg and Varrhus, aren't you?"

"Of course. No one talks about anything else nowadays. My taxi had a tough time getting through the crowds on the streets. They don't understand about the explosion in the Narrows yet."

Teddy introduced him to Evelyn.

"Pleasure, I'm sure," said Davis with a smile. Then his face sobered. "That was rotten hard luck about your father, Miss Hawkins. I'm not good at making speeches, but I hope you realize that every one is sympathizing with you and in a measure sharing your sorrow."

Evelyn shook hands.

"I will allow myself to grieve when Varrhus has been disposed of," she said quietly. "Until then I dare not let myself think."

Davis released her hand and turned to Teddy.

"Varrhus—or the chap in the black flyer, anyway—killed my best friend, Curtiss. He was driving the little Nieuport that attacked Varrhus the day you blew up the first bomb. I was the first man to reach the spot where Curtiss had crashed, and I swore I'd get Varrhus for that."

"I remember," said Teddy. "Frozen."

Davis nodded, his face grave.

"I have what is probably the fastest little machine in the United States, at the fort. A two-seater, with twin Liberty Motors that shoot her up to a hundred and fifty miles an hour without any trouble at all. I think I can get Varrhus with it. I came to you to learn what you think about Varrhus' weapons. It's only the part of wisdom to learn all you can about your opponent, you know."

Teddy found the young man impressing him very favorably.

"I haven't given the matter much thought," he confessed, "but you remember Varrhus' tactics?"

"He dropped like a tumbler pigeon," said Davis, "and Curtiss overshot him. There wasn't a sign of firing except from Curtiss. He simply overran the place where Varrhus had been three or four seconds before and then dropped. He was frozen stiff when I found him."

"I think," said Teddy carefully, "that Varrhus had shot up a jet of some liquified gas, probably hydrogen. It hung suspended in the air for a moment, and in that moment the biplane ran into it. A drop of liquid hydrogen placed in the palm of your hand would freeze your arm solidly up well past the elbow. It's something over five hundred degrees below zero. Your friend ran into what amounted to a shower of it."

Davis considered:

"Cheerful thing to fight against, isn't it?" he asked, with a smile. "Tactics, mustn't run above the black flyer and mustn't run below it. He can probably shoot it straight down, too."

"And almost certainly from the sides," said Teddy. "The man must have been working on this thing for years, and even if he's insane he'd be a fool not to make his weapon as efficient as possible."

Davis' expression became rueful.

"And so I'm supposed to keep my distance," he remarked, "and take pot shots at him while dancing merrily around in mid-air. Can't we do anything about that stuff to nullify it?"

"Burn it," suggested Evelyn. "Liquid hydrogen burns just as readily as the same gas at normal temperatures."

The three of them were silent for a moment.

"Would rockets set it afire?" asked Davis presently. "I could keep a stream of fire balls shooting out before my machine."

"They ought to." Teddy was losing his discouragement in this new prospect of coming to grips with Varrhus. "I say, will your machine burn readily?"

"Only the gas tank. The wings and struts are fireproof. New process."

Davis stood up suddenly.

"Would it bother you to come over and look at my machine? We could probably figure out the thing better then."

Teddy rose almost enthusiastically.

"We'll go over now if you say so."