PUBLISHED BY

HARMSWORTH BROS., Limited, London, E.C.

ARTICLES. |

|

|---|---|

| PAGE. | |

| ALBUM, A FAMOUS WIGMAKER'S FAMOUS. By Gavin Macdonald. Illustrated by Facsimiles | 356 |

| BALLOON JOURNEY, A GIRL'S, OVER LONDON. By Gertrude Bacon. Illustrated by Photographs | 400 |

| BEAUTIES, IRISH. By Ignota. Illustrated by Photographs | 484 |

| BLOODHOUNDS, A MAN HUNT WITH. By Alfred Arkas. Illustrated by Photographs | 383 |

| CHESHIRE TOWN, IN A DISAPPEARING. By Percy L. Parker. Illustrated by Photographs | 166 |

| "CHRYSANTHEMUMS CURLED HERE." A Chat with a Floral Barber. By Alfred Arkas. Illustrated by Photographs | 579 |

| CRACKERS, COSTLY CHRISTMAS. The Romance of Christmas Presents. Illustrated by Photographs | 439 |

| CRICKET AND CRICKETERS. Words by M. Randall Roberts. Pictures by Mr. "Rip" | 212 |

| CRICKET MATCH, A VERY QUEER. Mr. Dan Leno's Eleven v. Camberwell United C.C. By Gavin Macdonald. Illustrated by Photographs | 323 |

| CYCLIST, THE CLEVEREST AMATEUR, IN THE WORLD. Remarkable Trick Riding by a Military Officer | 493 |

| DANGER SIGNALS, NATURE'S. A Study of the Faces of Murderers. By J. Holt Schooling. Illustrated by special Photographs | 656 |

| DARLINGS, LITTLE. By Somers J. Summers. Photographic Illustrations by W. J. Byrne | 99 |

| DOCUMENTS, INCRIMINATING. With Facsimiles of Fatal Writings | 304 |

| DOOR-KNOCKERS, FAMOUS LONDON. Illustrated by Photos specially taken. | 216 |

| DOUBLES IN REAL LIFE, NOTABLE. With Photographic Evidence | 5 |

| ENGINE MATCH BETWEEN ENGLAND AND AMERICA, AN. By F. A. Talbot. Illustrated by Photographs | 651 |

| EXCUSE, OUR, FOR THE ISSUE OF A SIXPENNY MAGAZINE AT THREEPENCE | 3 |

| FIRE BRIGADE HEROES, TRAINING OUR. By Alfred Arkas. Illustrated by Photographs | 243 |

| FIRES, SOME SENSATIONAL. By Frederick A. A. Talbot. Illustrated by Photographs | 529 |

| FOOTBALL, MAKING A. An Essential Part of a Great Game. Illustrated. | 444 |

| FORTRESS, THE MOST REMARKABLE, IN THE WORLD. By Percy L. Parker. Illustrated by Photographs | 274 |

| MAN-OF-WAR, HOME LIFE ON BOARD A. Illustrated by Photographs | 86 |

| MAN IS MADE OF WHAT? By T. F. Manning. Illustrated by Photographs | 339 |

| MEDICAL DETECTIVE AND HIS WORK, THE. By T. F. Manning. Illustrated by A. Morrow and by Diagrams | 144 |

| MICE WORTH THEIR WEIGHT IN GOLD. By Gavin Macdonald. Illustrated by Photographs | 631 |

| MINIATURE CRAZE, THE MODERN. By H. M. Tindall. Illustrated by Charming Examples | 197 |

| MONEY, STRANGE KINDS OF. By Robert Machray. Illustrated by Photographs | 639 |

| MURDERS, LONDON'S UNDISCOVERED. By Lincoln Springfield. Illustrated by Photographs | 515 |

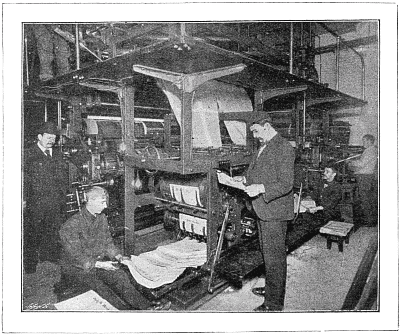

| NEWSPAPER, MAKING A MODERN. By Alfred C. Harmsworth | 38 |

| "PERPETUAL MOTION" SEEKERS. With Illustrations of Machines recently invented | 315 |

| PHOTOGRAPHIC LIES. With Remarkable Photos, proving the Uselessness of the Camera as a Witness | 259 |

| POISON DEVICES. Illustrated | 106 |

| POSTAGE STAMPS WORTH FORTUNES. Illustrated by Facsimiles of Valuable Stamps | 327 |

| RAILWAY SMASHES, FAMOUS. By Frederick A. Talbot. Illustrated by Photographs | 227 |

| [pg vi] ROYALTIES, LITTLE. Illustrated with Photographs by Speaight | 590 |

| ROYALTY, TATTOOED. By R. J. Stephen. Illustrated by Photographs | 472 |

| SANDOW, HOW, MADE ME STRONG. Illustrated with Photographs | 23 |

| SECRET CHAMBERS, REMARKABLE. Written and illustrated by Allan Fea | 416 |

| SERMONS WITHOUT WORDS. A Marvellous Performance in Dumb Show. By Alfred Arkas | 67 |

| SKELETONS, MODERN FAMILY. By Beatrice Knollys. Illustrated by A. S. Hartrick | 17 |

| SLEIGHS FOR CHRISTMAS. By J. E. Whitby. Illustrated by Photographs | 558 |

| SMOKER'S MUSEUM, FROM A. By T. C. Hepworth. With Illustrations | 370 |

| SPORT, THE MOST CRUEL, IN THE WORLD. By Sidney Gowing. Illustrated by Photographs | 182 |

| STATISTICS GONE MAD. By J. E. Grant. Illustrated by Diagrams | 609 |

| TEA, HOME OF FOUR O'CLOCK, THE. Illustrated by Photographs | 605 |

| TOY, A £10,000. Complete Working Railway in a Room. By Robert Machray. Illustrated by Photographs | 125 |

| WEATHER, HOW WE GET OUR. By Gavin Macdonald. Illustrated by Photographs | 55 |

| WHISTLER, THE WORLD'S CHAMPION. Illustrated by Photographs and Musical Examples | 546 |

| WHITE "ZOO," A. Lord Alington's Hobby. By Alfred Arkas. Illustrated by Photographs | 154 |

| WIVES, AMERICAN, OF ENGLISH HUSBANDS. Illustrated by Portraits | 289 |

| 1898. Your Everyday Life in the past Twelve Months. By Alfred Arkas | 455 |

| 3,000 MILES ON RAILWAY SLEEPERS. One Aspect of a Bicycle Tour Round the World. By Edward Lunn. Illustrated by Photographs | 619 |

STORIES. |

|

| BABY SANTA CLAUS, A. The Story of a Christmas Reconciliation. By Marion Elliston. Illustrated by Harold Copping | 521 |

| BEHAVIOUR OF WARRINGTON, V.C., THE. By Percy E. Reinganum. Illustrated by W. B. Wollen, R.I. | 236 |

| CHANCELLOR'S WARD, THE. By Richard Marsh. Illustrated by F. H. Townsend | 73 |

| CHOLERA SHIP, THE. By Cutcliffe Hyne. Illustrated by Richard Jack | 159 |

| CLEVER MRS. BLADON. By E. Burrowes. Illustrated by Sydney Cowell | 645 |

| COUNT AND I, THE. The Story of a Stolen Letter. By James Barratt. Illustrated by Robert Sauber | 447 |

| COURTSHIP BY PROXY. By H. A. Therrauld. Illustrated by Fred Pegram | 461 |

| CROWDED HOUR, A. By Clarence Rook. Illustrated by B. E. Minns | 634 |

| CURSE OF THE CATSEYE, THE. By Alfred Slade. Illustrated by E. Prater | 623 |

| DAPHNE. By Walter E. Grogan. Illustrated by Harold Copping | 361 |

| DESCENT OF REGINALD HAMPTON, THE. By Halliwell Sutcliffe. Illustrated by W. Rainey, R.I. | 189 |

| DESPATCHES FOR GIBRALTAR, THE. By Gilbert Heron. Illustrated by D. B. Waters | 389 |

| DESTINY, MY. A Wayside Romance. By C. K. Burrow. Illustrated by Fred Pegram | 347 |

| EDITOR'S ESCAPADE, THE. By Archibald Eyre. Illustrated by S. H. Vedder | 405 |

| FACE AT THE DOOR, THE. By Walter D. Dobell. Illustrated by S. H. Vedder | 373 |

| FAIR NEIGHBOUR'S PIANO, MY, AND WHAT CAME OF IT. By Henry Martley. Illustrated by F. H. Townsend | 281 |

| "FINDER WILL BE REWARDED, THE." A Bachelor's Romance. By Gerald Brenan. Illustrated by Sydney Cowell | 489 |

| FIVE HUNDRED POUND PRIZE, THAT. By Richard Marsh. Illustrated by John H. Bacon | 172 |

| GASCOYNE'S TERRIBLE REVENGE. A Story of the Indian Mutiny. By J. F. Cornish. Illustrated by Vereker M. Hamilton. R.P.E. | 265 |

| [pg vii] GOLDEN CIRCLET, THE. By Charles Kennett Burrow. Illustrated by Ralph Peacock | 11 |

| HER LETTER! By J. Harwood Panting. Illustrated by W. B. Wollen, R.I. | 61 |

| HIS HIGHNESS THE RAJAH. The Quest of the Yellow Diamond. By Beatrice Heron-Maxwell. Illustrated by E. J. Sullivan | 549 |

| HIS SOVEREIGN REMEDY. By Clarence Rook. Illustrated by B. E. Minns | 94 |

| HOW THE BURGLAR HELPED AT CHRISTMAS. By Lucian Sorrel. Illustrated by H. M. Brock | 476 |

| HOW THE MINISTER'S NOTES WERE RECOVERED. By Beatrice Heron-Maxwell. Illustrated by Fred Pegram | 250 |

| IAN'S SACRIFICE. By Alick Munro. Illustrated by Ralph Peacock | 309 |

| "KLONDYKE, OFF TO." By George A. Best. Illustrated with Novel Life Photographs | 583 |

| LONDON'S LATEST LION. By Gilbert Dayle. Illustrated by Fred Pegram | 595 |

| "MAN OVERBOARD!" An Episode of the Red Sea. By Winston Spencer Churchill. Illustrated by Henry Austin | 662 |

| MISSING Q.C.'s, THE. By John Oxenham. Illustrated by Frank Craig and T. Robinson | 497 |

| MOTOR-CAR ELOPEMENT, AND HOW IT ENDED, THEIR. By Edgar Jepson. Illustrated by H. R. Millar | 49 |

| PRINCESS IN GREEN AND TAN, A. By Arthur Preston. Illustrated by A. Rackham | 611 |

| SHORT MEMORY OF MR. JOSEPH SCORER, THE VERY. By John Oxenham. Illustrated by H. M. Brock | 131 |

| STIR OUTSIDE THE CAFÉ ROYAL, THE. By Clarence Rook. Illustrated by Hal Hurst, R.B.A. | 319 |

| STONE RIDER, THE. By Nellie K. Blissett. Illustrated by Max Cowper | 30 |

| TELEGRAPH MYSTERY, A. By W. B. Northrop. Illustrated by H. H. Flère. | 539 |

| TRAGEDY OF A THIRD SMOKER, THE. By Cutcliffe Hyne. Illustrated by J. Finnemore. R.B.A. | 297 |

| TRAVELLING COMPANION, MY. By Catherine Childar. Illustrated by Fred Pegram | 115 |

FULL PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS. |

|

| "ANDRÉE, INDEED! I WAS THERE LONG AGO." From the Painting by T.C. Hepworth | 669 |

| BURDEN OF LOVE, A. From the Painting by N. Sichel | 224 |

| CHARLES I. ON HIS WAY TO EXECUTION. From the Painting by Ernest Crofts, R.A. | 331 |

| CHRISTMAS, THE FIRST. From the Painting of H. J. Sinkel | 434 |

| CUBAN BELLE, A. From the Painting by Gabriel Ferrier | 219 |

| DAUGHTER OF CANADA, A. Photographic Study | 565 |

| DECEMBER DAY IN THE OLDEN TIME, A. From the Painting by A. Perez | 568 |

| DRAGON AND GEORGE, THE. From the Painting by R. Holyoake | 333 |

| EMPTY CHAIR, THE. From the Painting by Briton Rivière, R.A. | 336 |

| EVERYBODY'S FAVOURITE. Photographic Study | 561 |

| FAVOURITE, THE. From the Painting by Arthur J. Elsley | 110 |

| FOR DEAR LIFE. From the Painting by Stanley Berkeley | 329 |

| GIRL OF THE PERIOD. From the Painting by Heywood Hardy | 668 |

| GOOD NIGHT! From the Painting by G. Hom | 112 |

| GORDONS AND GREYS TO THE FRONT. From the Painting by Stanley Berkeley | 430 |

| GREEK GIRLS PLAYING BALL. From the Painting by the late Lord Leighton | 577 |

| GREUZE'S MASTERPIECES, ONE OF. Now in the National Gallery | 425 |

| HAPPY AS A KING. Photographic Study | 671 |

| "HUSH!" From the Painting by Maud Goodman | 109 |

| IN RUSSIA—THE TERROR OF THE PLAIN. From the Painting by A. Von W. Kowalski | 672 |

| JOHN BULL FOR EVER—WHAT WE HAVE WE'LL HOLD. From the Painting by Maud Earl | 56 |

| [pg viii] JUDITH. From the Painting by N. Sichel | 334 |

| LAKE WINDERMERE IN THE WINTER OF 1885. From a Photograph | 564 |

| LAST ELEVEN AT MAIWAND, THE. From the Painting by Frank Feller | 566 |

| LAST MINUTE, THE. NOW OR NEVER. From the Painting by T. M. Hemy | 443 |

| LITTLE DEAR, A. Photographic Study | 667 |

| LIVE AND LET LIVE. From the Painting by A. W. Strutt | 332 |

| MAKING A MARRIAGE IN THE OLDEN TIME. From the Painting by A. T. Vernon | 221 |

| MANNERS AT TABLE. From the Painting by A. J. Elsley | 330 |

| MEDITATION. From the Painting by N. Sichel | 111 |

| MIRIAM THE PROPHETESS. From the Painting by N. Sichel | 574 |

| MOTHER'S DARLING. Photographic Study | 569 |

| NAPOLEON'S FLIGHT AFTER WATERLOO. From the Painting by A. C. Gow, R.A. | 666 |

| OPPORTUNITY FOR FLATTERY, AN. From the Painting by D. Hernandez | 575 |

| OVERTAKEN! From the Painting by John A. Lomax | 280 |

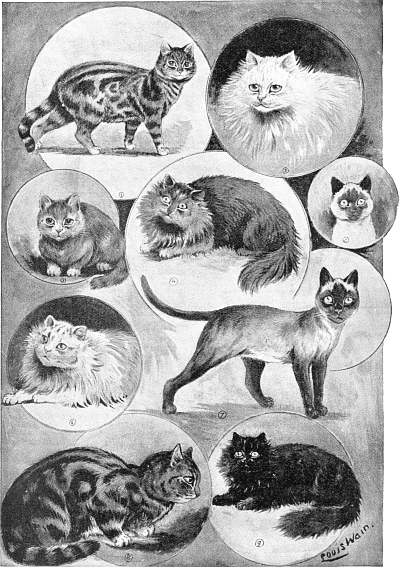

| PETS, SOME COSTLY. From Photographs | 85 |

| PRINCE, OUR. From the Painting by A. Stuart Wortley | 567 |

| PUSHING FAMILY, A. From the Painting by G. A. Holmes | 428 |

| RUSSIAN BELLE, A. Photographic Study | 571 |

| SALMON POACHER, THE. From the Painting by Douglas Adams | 335 |

| SON AND HEIR, THE. From the Painting by L. Schmutzler | 427 |

| SPAIN, A FLOWER OF. From the Painting by N. Sichel | 108 |

| SPAIN, A LITTLE MAID FROM. Photographic Study | 338 |

| SPANISH PEACE COMMISSIONER, A. From the Painting by Hal Hurst, R.B.A. | 665 |

| SUMMER. From the Painting by W. Reynolds Stephens | 220 |

| SWEET AND TWENTY. From the Painting by G. L. Seymour | 2 |

| TALLY HO! From the Painting by Heywood Hardy | 572 |

| TIME TO GET UP. From the Painting by A. J. Elsley | 426 |

| TURNER'S GREAT WORK—THE FIGHTING TEMERAIRE. Now in the National Gallery | 429 |

| VERY OLD, OLD STORY, A. From the Painting by L. Alma Tadema, R.A. | 670 |

| WAITS, THE. From the Painting by W. H. Trood | 570 |

| WATER CARRIER, THE. From the Painting by J. W. Godward | 222 |

| WHICH WINS? From the Painting by Arthur J. Elsley | 223 |

| WHY NO. I. WAS SO POPULAR. Head, from the Painting by A. Seifert | 563 |

| WHY THE ANTELOPES STAMPEDED. From the Painting by William Strutt | 226 |

| WILL HE COME? From the Painting by Marcus Stone, R.A. | 114 |

| YORKSHIRE LASS, A. Photographic Study | 573 |

POETRY. |

|

| BABY BELLE. By Bernard Malcolm Ramsay. Illustrated by Harold Copping | 482 |

| BABY, IN PRAISE OF. By Barrington McGregor. Illustrated by C. Robinson | 661 |

| GOLDEN HAIR AND CURLYHEAD. By Allan Upward. Illustrated by J. H. Bacon | 435 |

| LITTLE MAID. Illustrated by C. Robinson | 258 |

| ROGUEY MAN, THE. Illustrated by H. H. Flère | 346 |

| ROSE AT LAST, A. By Clifton Bingham. Illustrated by Harold Nelson | 22 |

| SAD FATE OF MISTRESS PRUE, THE. Illustrated by Robert Sauber | 399 |

| SHOE, A TINY. Illustrated by Archie Watkins | 308 |

| SUNSET, BEYOND THE. By Clifton Bingham. Illustrated by Charles Robinson | 235 |

| THREE SCORE AND TEN. Illustrated by T. Walter West | 388 |

| TO A BLANK SPACE. By the Rev. J. Hudson, M.A. Illustrated by Robert Wallace | 576 |

THE beginning of a new Magazine, once an event, is now so much a commonplace that the ancient excuse of the "long felt want" no longer serves.

In the days of the Nabobs, the gentle shaking of the Pagoda tree sufficed to bring great stores of wealth, but these be the times of the fallen rupee. Your modern Anglo-Indian toils out his existence for a bare pittance. And it is so in the making of Magazines. One hundred and fifty years ago the mere issue of the "Gentleman's" stirred to their depths the Coffee Houses and the Clubs, not only here in the Old Country, but in our North American Colonies as well.

Times are changed, alas! "The Harmsworth Magazine," though, indeed, it appeals to an English-speaking audience of over one hundred millions, will at best provoke a little favourable comment in the train and the library, for the Magazine field has been vastly exploited, and especially of late. A modern buyer of periodical publications rises as warily to a new lure as a twice-shot-over partridge to the gun.

The reader of Magazines has of late years been harried by a direct, by an enfilading, and a ricochetting fire of new adventures, some honestly and avowedly frivolous, others portentously literary, a few loftily artistic. Every imaginable plan has been adopted whereby his capture might be effected. Projectiles calculated to vanquish by size and weight of paper have been hurled at him; there have even been surreptitious and spy-like attempts to enter his domestic circle by seeking the favour of his wife and daughters by means of "Women's Departments," all frocks, furbelows, and complexion cures; and worse, his very children have been attacked by page on page of "Nursery Chat" and "Tiny Tales for Little Listeners."

Last straw of all, he has been patronised by the vast army of "Great Authors" of the period. And if the chit-chat of the press is to be believed there never were in Rome, in Athens, or in the days of Elizabeth herself, so many distinguished litterateurs as at present. The unfortunate victim has trembled at the solemn pomp of

"The editor of the 'Monster Magazine' has pleasure in announcing he has been so fortunate as to secure the masterpiece of Mr. ——."

or,

"It is rumoured that Mr. —— has been induced to enter into an agreement to contribute an important series of short stories to the "Monster Magazine" during the Spring of 1905. Mr. —— is entirely occupied in the fulfilment of various contracts until that time."

It is "right here," as our American kinsmen have it, that "The Harmsworth Magazine" comes in.

Together with a great many other people, we came to the conclusion long since that a good deal of the literary wares that are foisted on the public by means of the ordinary advertising methods of personal paragraphs and "interviews" is mainly rubbish. Frankly and openly do we, therefore, declare that mere "names" will never command an entrance to the pages of this Magazine. As with our "Daily Mail" and our other journals, we shall rely on new writers. The public is weary of the reiteration of the same contributors to each of the monthly publications. He (and she) wants something new. It is our desire, for the sake of the public, for the benefit of young artists and others, and for our own profit, to avoid the productions of the professional "ring" of much advertised mediocrity which most assuredly dominates many of our Magazines to-day, though the work of really representative men and women will always be secured, without regard to its cost.

In selecting the price at which "The Harmsworth Magazine" should be issued to the British, Canadian, Australasian, South African, and Anglo-Indian public, we choose that of the two most distinguished journals in our language, "The Times" and "Punch."

Can such a publication as this be sold for 3d.? Provided we reach a gigantic circulation, we can do it. We are enabled to issue a threepenny Magazine containing more expensive literary matter, more numerous pictures, and more pages than the sixpenny Magazines of a few months back, at so ridiculous a price, because this Magazine is only a small incident in an organization controlling four daily journals and nearly thirty weekly periodicals; because we already possess and are now building printing machinery of an entirely novel and labour-saving nature.

The Magazine will be cheap as to price only. In every respect, save, perhaps, mere bulk, "The Harmsworth Magazine" will compete frankly, and without reserve, with older friends in the same field.

The experiment, largely due to a devoted band of workers, headed by my brother Cecil, is at least an interesting one. Will it succeed? Much depends upon the good word of those who read it. If it meets with your approval, if you consider that the enterprise is worthy of commendation, will you make our effort known to your circle?

With Photographic Evidence.

I T is pretty generally believed that the Czars of Russia are in the habit of employing understudies to personate them when some more than usually hazardous public appearance has to be made. Whether or not this is true we cannot take upon ourselves to say, but it is very clear that if Nicholas II. were in need of a "double," he would not require to go outside the circle of his own relatives to find an almost exact replica of himself in our Duke of York. The two Princes are first cousins, but the facial resemblance existing between them is far more remarkable than is ordinarily the case between near relations. It is true, of course, that the Duke of York is a better-looking man than his cousin, but any make-up artist, by the employment of a few pencilled lines round the eyes, and by re-arranging the hair, could transform H.R.H. into an exact likeness of the Czar.

More noteworthy still, because of the absence of relationship between them, is the likeness of the present Postmaster-General, the Duke of Norfolk, and the veteran novelist, Mr. George Manville Fenn. Looking upon the two portraits, it is not easy to believe that Mr. Fenn is sixteen years the senior of the head of the great house of Howard. Another curious feature in connection with the two cases before us is the fact that, although the Duke of Norfolk is almost as much like Mr. George Manville Fenn as one pea resembles another, his resemblance to certain portraits of the great Charles Dickens is rather remote, whereas Mr. Fenn's is very close.

It should here be mentioned that in the case of most of our doubles the likeness is even more pronounced in actual life than it appears from the photographs. In many instances the gestures, the walk, and the little mannerisms of the personages here portrayed are practically identical. The writer recalls to mind the example of a gentleman well-known in the West end of London who resembles the present Duke of Devonshire as closely as the Duke of York resembles the Czar. The Duke of Devonshire's imitator—if he be such—not only wears his hat pressed down over his eyes in the well-known fashion of the Duke, but assumes almost as inimitably that intensely [pg 6] bored look that has deceived so many people as to the true character of the head of the Liberal Unionist party. Mere photographs would inevitably fail to do justice to a case of this kind.

In regard to the adjoining portraits of Mr. Austen Chamberlain and that of his scarcely less distinguished father, it is noticeable that in addition to the striking facial resemblance, there is the same defect in the sight of the right eye occasioning the use of the monocle. Even if we take it for granted that Mr. Joseph Chamberlain has indulged in the harmless foible of dressing his hair and arranging the cast of his countenance to accentuate his likeness to the member for East Worcestershire, it cannot be gainsaid that the similarity between the son and the father is real enough to merit illustration in this gallery of "doubles."

Jesting apart, those who have studied Mr. Austen Chamberlain in the House and on the platform, prophesy for him a very remarkable career. He has much of the readiness and all the imperturbability that have made his father the ablest "parliamentary hand" since the retirement of Mr. Gladstone. It is interesting to note that the disbelief of Mr. Chamberlain père in exercise, as a means of recruiting the health, is not shared by Mr. C. fils, who is an enthusiastic cyclist.

London Stereoscopic Co., photo.Elliott & Fry, photo.

MR. L. ALMA-TADEMA, R.A. THE LATE MR. GEO. DU MAURIER.

The late Mr. Du Maurier was of French extraction, while Mr. Alma-Tadema was born at Dronryp, in Holland, yet they might have been twin brothers, so strangely alike were they. If Mr. Du Maurier had worn his hair a little longer and parted it in the middle, the most intimate mutual friends of the two distinguished artists must have found it difficult to tell which was which. An amusing story is told illustrating this point. Mr. Du Maurier, dining at a friend's house one evening, was placed next to a lady whom he did not recollect to have met before. A brief dialogue, something to this purpose, ensued:

Lady: "You know, Mr. Alma-Tadema, that you are supposed to resemble Mr. du Maurier very closely. For my part, I do not see how the most superficial observer could be deceived in the matter!"

Mr. Du Maurier: "Pardon me, but I am Mr. Du Maurier!"

Some people tell the story the other way round—with Mr. Alma-Tadema as the second party in the dialogue—with equal effect.

These are portraits of Professor Stuart, M.P. for Hackney, and Mr. Stanley J. Weyman, the novelist. If Mr. Weyman ever becomes a member of Parliament it is to be hoped that he will not relinquish his eyeglass. Were he to do so he would run a great risk of merging his identity in that of the Professor. He might not object to this, however, nor would Professor Stuart protest very indignantly we may be sure, were he to find himself suddenly credited with the authorship of Mr. Weyman's fascinating romances. Let us hope that Mr. Weyman will not enter the political arena, bestowing on Westminster the gifts that were meant for mankind.

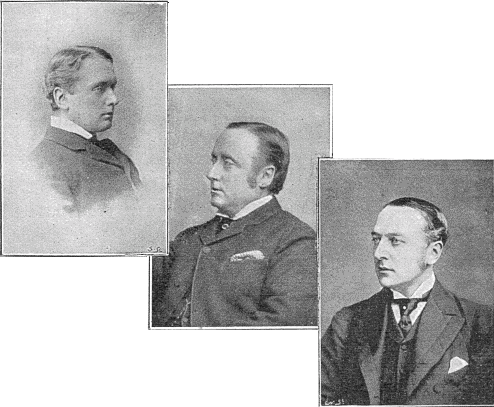

Most of us have forgotten that Mr. Anthony Hope contested a seat in Parliament in 1892, but few of us are sorry that the gifted author failed to get in. Mr. Anthony Hope Hawkins, to give him his full name, is an excellent speaker, but even that gift is not so useful in Parliament as consistent and unquestioning voting-power, and until members are allowed to read their speeches the gift of authorship will remain at a discount there. A good many of us, perhaps, could cut tolerable figures at Westminster, but our Anthony Hopes and Stanley Weymans are few and far between, and we would wish to keep them to their proper work of literature. Mr. Edward German, Mr. Anthony Hope's double, is a young composer who has done very well already, and may be expected to do better in the future.

A close examination of the portraits of the Rt. Hon. Cecil John Rhodes and of Sir John Stainer, the Professor of Music at Oxford, should well repay the expert physiognomist. At first blush it seems hardly probable that the man of action, the empire builder, should have much in common with the scholarly musician—though indeed Mr. Rhodes has "faced the music" right manfully more than once in the course of his splendid career. Examine carefully the mouths of our two celebrities, and take note of the well-defined lines leading downwards from the corner of the nose. The eyes, too, and the contours of the two faces are strangely similar. There [pg 8] is a dimple in Mr. Rhodes' cheeks that proves conclusively, if we had no other evidence, that Mr. Rhodes is a man of humour, nor are similar indications wanting in the adjoined portrait of Sir John Stainer. If Sir John had taken himself off to South Africa in early youth it might have been his fate to add another empire to the Queen's dominions; if Mr. Rhodes had stayed on at Oriel College, Oxford, and devoted his vast abilities to the study of music, he might now be occupying the professional chair in that art at his Alma Mater.

There is a distinct style of theatrical face that we all recognise directly we see it. For instance, the heavy tragedian with the blue chin and luxuriant hair, à la Sir Henry Irving, is known wherever he is seen, and quite a number of pages of our Magazine might be filled with his doubles. But Mr. John Hare and Mr. Arthur Roberts whose portraits we give side by side are comedians (of widely different styles), and are not particularly theatrical in appearance. Off the stage Mr. Hare might be taken for an eminent Q.C., while "Arthur" might be supposed to move exclusively in turf circles. Mr. Hare, whose real name is Fairs, is, of course, the best "old man" actor we have. In connection with this fact he himself tells a rather good story. He was in a carriage on the Underground Railway when he met an old school-fellow. Gradually the conversation turned to theatres. "Are you fond of the stage?" Mr. Hare was asked by his friend. When the reply was "Yes," he presumed that Mr. Hare had seen a certain play at the Prince of Wales's.

"No," said Mr. Hare, "I can't say I have seen it!"

"Then you should go at once," said his friend. "It's a capital play, and a devilish clever old man acts in it—a fellow named Hare!"

A. Sachs, photo, Bradford.London Stereoscopic Co., photo.

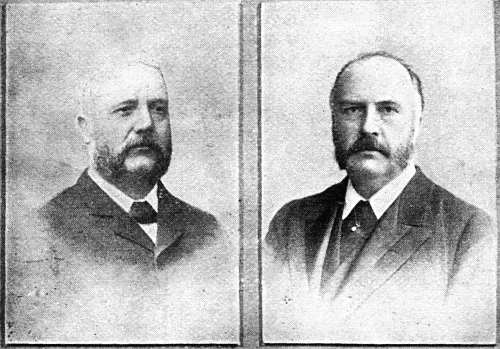

MR. MARK OLDROYD, M.P.LORD BALFOUR OF BURLEIGH.

Lord Balfour of Burleigh, the Secretary for Scotland, and Mr. Mark Oldroyd, M.P. for Dewsbury, are an interesting pair of political doubles. Lord Balfour (whose title by the way was attainted in 1716 and only restored to the present peer in 1869) is one of the hard workers in the House of Lords, and knows more about [pg 9] education, water supplies, and Sunday closing, than an omnibus-full of average members of the Lower House. When not actively engaged, in his Secretarial capacity, in looking after the interests of the Northern Kingdom, Lord Balfour is wont to put in a little light work as chairman of a factory or rating committee. Mr. Mark Oldroyd divides his time between his political duties and his business, as a woollen manufacturer, in Dewsbury. He has been mayor of the famous Yorkshire town, and is as proud of his native place as his townsfolk are proud of him.

Two youthful baronets and Members of Parliament now claim our attention. Sir Edward Grey is almost as distinguished in Parliament as he is in the world of athletics—he is once more tennis (not lawn-tennis) champion for England. As Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the last Government, he was a pronounced success—his manner being voted only less superior than that of the extremely superior person, the Hon. George Curzon, who ornaments the same office at the present time. Sir Thomas Esmonde, born in the same year (1862) as Sir Edward Grey, should have a splendid parliamentary future before him, for he is a descendant of no less a celebrity than the great Henry Grattan.

Lord Rosebery has at least two doubles among public men. This is not to be wondered at when one considers how popular a man is the last Liberal Prime Minister.

When the Duke of Wellington was living, it was the pride of many a private citizen to be thought like the great Duke; and Disraeli had many doubles, the late Sir James Stansfeld being one of them. In Germany, at the present moment, we may meet passable duplicates of Bismarck in every town. Who does not recollect the perfect army of Randolph Churchills that invaded society when that brilliant young statesman's fame was at its greatest? It is surely a harmless conceit that causes an inoffensive private person, if he in any way resembles a great man of whom everybody is talking, to accentuate the likeness by every means in his power.

But in the case of Lord Rosebery's doubles it is somewhat different. Both Mr. Arnold Morley and Mr. Philip Stanhope are distinguished men themselves, and we may be quite sure that they do not spend much of their time dressing up to the likeness of their political leader. Mr. Philip Stanhope is a near relative of Lord Rosebery's, and is of exactly the same age. Mr. Arnold Morley is two years younger than Lord Rosebery (having been born in 1849), was Postmaster-General in the last Liberal Administration, and may some day be Prime Minister.

Valentine & Sons, photo.Westfield, photo, Walmer.

THE LATE RT. HON. W. E. GLADSTONE.MR. H. PAGE, J.P.

With doubles of Mr. Gladstone we might easily fill several pages of this magazine. Mr. Henry Page, J.P., of Deal, is an almost exact replica of the venerable statesman, and has been the recipient of attentions really meant for Mr. Gladstone on more than one occasion. It is a singular fact that Mr. Page's father bore a remarkable likeness to the Duke of Wellington.

The reader will have noticed already that the greater number of our doubles is to be found in the ranks of the politicians. It is really quite astonishing to contemplate how many doubles are to be found in the House of Commons itself.

Mr. H. O. Arnold Forster and Mr. E. F. G. Hatch, M.P. for the Gorton Division of South-West Lancs, for instance, it is said grow more like one another every day.

The difficulty experienced by the Speaker in attaching the right name to these gentlemen when they rise to "catch his eye" must be very considerable.

Lord George Hamilton, who, with Mr. J. Roche, M.P., makes up the last pair of our doubles, is an excellent example of the immense disadvantage attaching to a public man whose features do not lend themselves to caricature. Had Lord George overcome his natural deficiencies in this respect by the adoption of an eyeglass, an orchid, or an eccentric brand of waistcoat, he might ere now have been ranked among our Prime Ministers, for it is an undoubted fact that these details are better remembered by the public at large than years of devoted hard work.

Disraeli's cork-screw curl on the forehead is less likely to be forgotten than his splendid services to the Empire, while it may be asserted with confidence that Mr. Chamberlain's eyeglass and orchid will linger in the public mind long after his personal sacrifices for the principle of Unionism are familiar to none but the student of history.

When at the General Election of 1868 Lord George captured the seat for the County of Middlesex—then regarded as an impregnable Liberal stronghold—a dazzling future was prophesied for him. If these prophecies have not been realised to the full extent it is not, as we believe, because Lord George has not lived up to his earlier reputation, but simply because Nature has not gifted him with a remarkable personal appearance, nor art with a satisfactory substitute. However, a Statesman even of the first rank who has occupied with distinction such important offices as First Lord of the Admiralty and Secretary of State for India, has no reason to be dissatisfied with himself. No doubt each reader of this article will be able to add considerably to our gallery of "doubles," but we have done enough if we have opened up an amusing and interesting train of ideas.

Illustrated by Ralph Peacock.

ANNESLEY walked past the main entrance to the Century Theatre in the curious condition of one who is able partly to regard himself from the outside. The boards were placarded with the announcement of a new play, to be produced that day week, "The Golden Circlet," by Conrad Howe. Now Annesley and Conrad Howe were the same person; but it was difficult to convince the former, who had worked so deadly hard and failed so often, that the latter was now within sight of what might prove a great success. Annesley saw people stop to look at the announcement and read his other name, with a feeling that he was almost guilty of a serious misdemeanour; he was taking them, as it were, at a disadvantage; he was almost inclined to tap one elderly gentleman on the shoulder and assure him that no harm was intended to him or any one else.

The secret of the authorship of "The Golden Circlet" had been well kept. Only three people were in the know, and not one of these was a woman. Annesley therefore felt safe. He had assumed the other name because his own had brought him no luck; he imagined people shrugging shoulders and wagging wise heads; he could hear the murmur,—"What! Annesley still writing plays? If he hadn't wasted his time over that, he might have had some money left. What a fool the man is!" Annesley had therefore put down the pen and Conrad Howe had taken it up. Moreover, Conrad Howe had actually written a play which seemed to have in it the elements of popularity; hence newspaper paragraphs, discussions as to identity, and finally the fixing of the first night and the appearance of the posters.

"The Golden Circlet" represented six months' grinding work. He had practically shut himself away from the world. He had declined invitations, paid no calls, risked everything on a last throw. When the thing was finished it seemed like coming into fresh air again; he remembered people whose names he had almost forgotten, and above all a girl whom he had told himself it might be wiser to forget; and, while his passionate working fit was on, he had almost succeeded, seeing her only as a possibility at the beginning of success. It is wonderful what hard work may do for a man, for a time. But when the pause comes human nature must always have its backward glance, its old heart searchings, its reviving pains.

Annesley, then, stood watching the entrance to the Century Theatre, and, as he stood there, suddenly his heart commenced a wild stampede. He slipped into the doorway of a shop just in time to escape the eyes of a girl who was walking quickly up the Strand. He waited for a moment; she did not pass. After a time he ventured to glance out; she had left the theatre, and was disappearing in the crowd.

His first impulse was to overtake her and make a clean breast of everything, but a moment's reflection convinced him that, having restrained himself so far, it would be folly to make a doubtful step then. Connie Bolitho had probably no idea that Conrad Howe was a cloak for Herbert Annesley, and he saw an opportunity for a little comedy not to be neglected. Since his position had grown stronger he felt free to indulge his humours; a year before life had seemed all tragedy, with a diminishing banking account, and a [pg 12] sheaf of unpaid bills. He walked carelessly up to the box-office.

"Did a lady take seats a moment ago; a lady with a red hat and fur-trimmed cloak?"

"Pretty?" asked the clerk.

"Very pretty," said Annesley.

"Yes,—two stalls."

"Two!" said Annesley, with an inner question in the word. "Are the next seats engaged—the ones, I mean, on either side of those two?"

The man looked at the plan.

"No," he said.

"Book them to me, please."

The clerk smiled benignly as he handed the tickets to Annesley; the life in a box-office is dull during business hours.

Annesley walked away with his tickets, feeling that he had done a good morning's work. He had at any rate made sure of a seat near Miss Bolitho; if her companion were a man he must brace himself to eclipse that fortunate individual; if a woman, it did not matter. He would prefer the woman, for in six months a great deal might have happened. Miss Bolitho was not bound to him in any way; they had seemed to understand each other, but a struggling writer with only debts to his credit, had not dared to lay those debts and a doubtful future at his lady's feet.

During the next week Annesley's time was fully occupied, but when the great day came and the final rehearsal was over he had a few hours in which to feel that almost unendurable excitement which precedes an ordeal the result of which is not in our own hands. His part of the work was over, but would the actors rise to theirs? He believed they would, but belief is a poor support when so much depends upon it. His excitement was also doubled by the prospect of watching the effect of his work on Miss Bolitho.

Annesley reached the theatre five minutes before the curtain rose. The house was full; the gallery seethed like a hive, people were already standing at the back of the pit. A glance showed him that Miss Bolitho was there, with a man whom he had never seen before at her side. He made his way quickly to his seat and was there before she had observed him.

"You are as interested in plays as ever?" he asked.

"Mr. Annesley!" she cried. He was sure that the hand she gave him trembled a little.

"May I ask you to forgive me for the past six months? I've been working terribly hard, almost night and day."

"At a play?"

"Yes,—at a play."

"You are forgiven," she said sweetly, "because you are brave and stick to your ideals."

"I am rewarded," he murmured. A glance at her face assured him that her beauty was not less; that, at any rate, had remained unchanged.

"Do you know who this Mr. Conrad Howe is?"

"No one seems to know; his identity has been kept secret most successfully."

"Do you suppose it is not his real name?"

"I have an idea it isn't; it sounds assumed, doesn't it?"

"I'm not sure. What do you think, [pg 13] Tom? Let me introduce you to Mr. Annesley,—my cousin, Captain Bolitho, who is just home from India." They bowed severely to each other.

"We were discussing," said Connie, cheerfully, "whether Conrad Howe was a real or a pen name. What do you think?"

"I don't know anything about these writing Johnnies. I don't see why they shouldn't use their own names unless they're ashamed of them."

"Perhaps you don't quite understand, Tom," Miss Bolitho suggested.

"Perhaps I don't!" said Tom.

"The climate of India is so trying," Miss Bolitho whispered to Annesley.

"It must be," he said, smiling.

The orchestra glided into a slow movement and the curtain rose. I need not tell you the story of the play; it was simple, but intensely human, having in it the philosophy learnt in years of struggle, but always with hope and faith in the ultimate good beyond. It presented no problem of the gutter raised to drawing-room standard by meretricious gilding; it had the singular distinction of being perfectly clean and also entirely dramatic. As Annesley saw his work develop before his eyes, and felt how it was taking hold of a breathless audience, he did not grudge the experience that had gone to its making or regret that he had kept his ideals unsoiled. When the curtain fell upon the first act the clamour of applause was the true expression of genuine emotion aroused by legitimate means. Annesley felt weak and almost sick. He realised vividly what it all meant to him; he realised, above all, of what little value it would be if he failed in the greater matter of his love. Connie leaned towards him; she had tears in her eyes.

"This is the kind of thing we've been waiting for," she said. "This is quite true and human. Conrad Howe should be a happy man to-night."

"If he is in the house."

"I hope he is; there's sure to be a call." Annesley's heart thumped.

"That must be awfully trying to a man," he said.

"Why don't you write plays of this kind?"

"It's rather the sort of thing I've been aiming at."

"Go on aiming at it, then, and you'll succeed."

"With your encouragement I feel I could do anything."

"This isn't a bad play, is it?" asked Captain Bolitho.

"It's splendid," said Connie.

"The fellow knows something, too. There's not all that confounded footle that leads you nowhere. The girl's ripping."

"She is," said Annesley. As a matter of fact she was a careful study of Miss Bolitho; for that reason Miss Bolitho appeared entirely unconscious of it.

"There are only three acts, too," said the Captain; "that's sensible. Five acts, with long waits between, are killing. I call it taking your money on false pretences. You don't come to a theatre to hear the band play."

When the curtain rose again the house instantly settled into silence, a sure [pg 14] sign that things were going well. Connie leaned forward with something of the eagerness of a child; even Captain Bolitho unhinged himself, as it were, and indicated interest by a slightly curved back. Annesley began to feel master of himself again; part of the future, at least, was now safe; how much that means to a man who steps from poverty to the security of a decent income can only be realised by those who have been in a like case; the mere fact of being able to pay a debt with promptitude is capable of affording a very exquisite joy. But, now that so much was within his grasp, he longed for all; the horizon of desire, like the horizon of the actual world, always recedes as we advance; since a few months before he had travelled innumerable miles towards success; that being reached, there was still an infinite distance beyond.

In the second act there was a simple love-scene that appeared to take the audience by surprise; it was direct, touching, convincing. Annesley noticed that no one laughed, a thing almost unprecedented in a London theatre when sentiment attitudinises upon the boards. This gave him a glow of well-earned triumph; he had mentally decided beforehand that that was the crucial point of the play; when it was passed he dropped back and closed his eyes.

"You didn't see all that act," Connie said to him in the interval; "are you tired,—were you asleep?"

"I'm neither tired nor sleepy, I heard everything."

"Didn't you think the love-scene beautiful?"

"Yes," he said, blushing at his own candour.

"I didn't think much of that," said Captain Bolitho, "I suppose because I can't see myself saying pretty things to a girl. It's not in my line, you know. I feel 'em, but can't express 'em. My notion is that the girl should make love to me."

"But you must begin, surely," Connie said.

"That's just the deuce of it," said the Captain, "I can't."

Annesley rose. "I must go now," he said, "to another part of the house. When it's over will you remain here till I come? I've an idea that I can find out who this Conrad Howe is. May I bring him to see you if I'm right?"

"Do, I'll wait for you." He went out into the Strand and lit a cigarette. The aspect of the world had changed for him; he even saw cabs and buses with different eyes. Every passenger upon the pavement seemed a friend, the roar of traffic had new music in it,—the stars above the housetops looked down with kindly eyes. The cool air put fresh courage into him, soothed his pulse, made his hope seem real. Inside the theatre it had been altogether difficult to understand substantial facts; but out there in the hurry of the street it was easy enough. There was no doubt about "The Golden Circlet," or Connie Bolitho, or about himself; they all existed, they all were of the world. The name of Conrad Howe stared at him from the placards; he even touched the letters with his fingers to make quite sure. Ten minutes later he re-entered the theatre by the stage door.

He met the manager in the wings. That gentleman was simmering with joy, his congratulations were overwhelming. Annesley bore them with resignation.

"There's sure to be a call for 'Author,'" said the manager; "you'll go to the front, won't you? It's always better; pleases them, you know. Do you feel nervous? Come to my room and have some champagne. This is a howling success, Mr. Howe—nothing like it for years. Just [pg 15] listen to that applause? You've fetched 'em, no doubt about it. Come along and have that champagne." Annesley went readily enough; the atmosphere of the theatre was getting on his nerves again.

When the last curtain fell the pit and gallery got upon their feet and cheered; the rest of the house was equally decisive if more discreet; "The Golden Circlet" was a success. And in the midst of the hubbub Annesley found himself before the curtain, bowing, dazzled by the footlights and straining his eyes to see one face. And, as though in obedience to his call, it rose before him, flushed, glowing, with eyes from which the delight and astonishment had hardly died, and with lips whose smile seemed tremulous with coming tears. That was the true moment of his triumph.

As soon as he could escape he found his way into the empty stalls; one figure remained. As he approached Connie raised her head. The colour had died out of her face; she was as pale as Annesley was himself. He held out his hand.

"I have brought Conrad Howe to see you," he said.

"Why didn't you tell me before? It was cruel of you."

"Perhaps it was because I thought that if I failed I could not bear that you should know it."

"That was not true friendship."

"Did I ever profess friendship for you?"

She hesitated, and played with her fan. A little wave of colour flowed back into her cheeks.

"You see," he went on, "I was pretty much alone in the world, and had to make my mark in my own way. A few months ago things were very black with me. I shut myself up and worked."

"It must have been hard for you," she said, "to cut yourself off from everything like that."

"It was hard, I'm not going to pretend it wasn't. But I had hope—not very bright, perhaps, but still it was enough to keep me from going under."

"You had faith in yourself and in your own work."

"I had more than that. Can you guess what it was?" Their voices sounded curiously hollow in the empty theatre,—the attendants were already putting up and covering the seats.

"You hoped to get fame and money?"

"Yes, but more than either I wished to win your love. Don't kill my illusion, don't ring down the curtain on my romance, Connie, and leave me in the dark. Everything I did was for you. You inspired whatever was good in 'The Golden Circlet.' The thought of you kept my head above water. I can come to you now without feeling ashamed."

"You might have come before. You need never have been ashamed. I could have helped you, oh, so much!"

"But now that the dark days are over, you won't turn your back on me and say I don't need your help? I need it more [pg 16] than ever. My love, the golden circlet is yours if you will take it from me."

She, gave him both her hands and lifted her face to his.

"I am your's always," she said, "but I think, perhaps, I loved you better when you were quite poor, but you never asked me then to love you. Think of what you've lost!"

Annesley took her in his arms in spite of a watchful attendant. "Never mind," he said, "everything's in the future for both of us, never mind the past. They may even damn my play now if they like."

At this point Captain Bolitho's voice was heard in loud protest.

"I tell you," he was saying, "I left a lady in your confounded theatre, and she hasn't come out. I've had a cab waiting ten minutes."

"It's Tom," Connie whispered, "I forgot all about him. Poor Tom!"

"Miss Bolitho's quite safe," said Annesley, "we've just been settling a little matter of great importance to both of us."

Captain Bolitho peered into the face of each in the uncertain light and seemed to understand.

"The devil you have!" he murmured under his breath. Then he said aloud, "Anyhow, Connie, I can't keep the cab waiting any longer. I congratulate you, Mr. Annesley Howe, on your 'Golden Circlet.' That was a deuced neat little surprise you'd hatched for us. I like your play, and I daresay I shall like you when I know more of you. Dine with me next Thursday, will you? Good-night."

A FAMILY ghost is a possession almost as respectable as a patent of nobility, and happy is the house reputed, on satisfactory evidence, to be haunted by one. There are still a few hereditary ghosts left, and a few leasehold and freehold ghosts; but these last are often the property of retired manufacturers and American millionaires who have bought house and lands, pedigrees, portraits, and family ghosts all together as they stood.

In this article it is my intention to be the biographer of a few ancient and well-born ghosts only, as space will not permit me to condescend to mere one-generation ghosts, pedigreeless spirits.

A. was an Airlie who killed a poor drummer, whose spirit plays a drum at Cortachy Castle, Kirriemuir, Scotland, whenever any member of the Ogilvy family is going to die. The origin of this tradition is that the drummer, for some reason or other, in his lifetime so enraged a former Lord Airlie that he had him thrust into his own drum and flung from the window of a tower of Cortachy Castle, though the drummer threatened to haunt the family ever after if his life were taken.

He has seemingly kept his word, for in 1849, before the decease of a Lord Airlie, and again in 1884, before the death of a Lady Airlie, the beat of the drum was on each occasion distinctly heard by different guests of the family. One of these guests was a lady staying in the castle, who was so ignorant of the tradition that, having heard the beating of a drum while dressing for dinner, she innocently asked her host—Lord Airlie—at the table who his drummer was. The question made the peer turn quite white, for the sound had preceded the loss of his first wife, and it was only a few months after this ominous dinner party that the second wife died.

The Combermere family have two ghosts in their record. In Combermere Abbey there is an old room, once a nursery, and here has been seen the spirit-figure of a little girl fourteen years old, dressed in a very quaint frock with an odd little ruff round its neck. It appeared to a niece of the late Lord Cotton as she was dressing for a very late dinner one evening in this former nursery, now used as a bedroom. She had just risen from her toilet-glass to get some article of dress when she saw the child standing near her bed—a little iron one which stood out in the room away from the wall—and presently the figure began running round the bed in a wild, distressed way, with a look of suffering in its little face, which the lady could see quite plainly as the full light of her candles fell upon it.

On mentioning this apparition, her widowed aunt, Lady Cotton, called to remembrance that the late Lord Cotton had told her of the sudden death years ago of a favourite little sister of his, with whom he had been playing, he being also a child then, by running round and round the bed with her, just the night before—indeed, only a few hours before, her decease.

A stranger story still, and one that has not yet, I believe, appeared in print, is that where quite recently a lady took an amateur photograph of the drawing-room of a house once inhabited by the late Lord Combermere—at Brighton I think it was. The lady in question saw, to her horror and astonishment, visible on the plate, the ghost of the old peer—a tall man with rather stout face and a moustache—reproduced sitting in one of the easy chairs of this drawing-room, though not apparent to the naked eye.

The Drake ghost—the spirit of Sir Francis Drake—might be termed a sporting spirit, as it has been frequently seen in different parts of Devonshire and Cornwall—notably Plymouth—driving a hearse drawn by headless horses and followed by a pack of headless hounds.

Two Gordon ghosts live at Fyvie Castle in Scotland. One is a lady dressed in a magnificent costume of green brocade, who is seen, candle in hand, passing through a tapestried room of the old castle when any important event is going to happen to the family.

The other spirit is by profession a trumpeter, who tradition affirms haunts the castle in revenge for having during his lifetime been seized by the press-gang at the instigation of the then Gordon of Fyvie Castle, who wished to get rid of a rival in the affections of a pretty daughter of his factor or bailiff.

The girl, however, remained faithful to the trumpeter, the separation from him making her die of a broken heart; and now, like the drum of Cortachy Castle, a trumpet is heard whenever misfortune is in store for the unlucky Gordons. Ill-fated they certainly are, as beside being the hereditary owners of unlucky ghosts, they are also under a hereditary curse—the curse of a "Thomas the Rhymester"—who, when the gates of the castle long years ago were churlishly closed against him in the days of wandering minstrelsy, declared that the property should never descend in a direct line till three "weeping" stones were found; but up to twenty years ago, when a relative of the writer was staying at the castle, only one weeping stone had been discovered.

In Fyvie Castle there is also a sealed room, which is always kept religiously closed; for the saying is, should the door be ever opened, the master would die and his wife go blind. Faith and fear have prevented the saying being proved, as the room has never been opened; but as regards the curse of "Thomas the Rhymester," it is certainly a fact that the [pg 19] Gordons have never inherited in a direct line.

There is a perfect spirit vault of ghosts at Glamis Castle, the ancestral residence of another old and celebrated Scotch family, the Lyons, the head being the Earl of Strathmore. They also possess a secret chamber, which is supposed to be connected with some terrible mystery known only to each owner, the next heir, and the house-bailiff, of the time being. Even the exact locality of the room is never revealed to others than those three, and though more than one heir-apparent has promised to tell the secret to his bosom friends as soon as the attainment of his twenty-first year entitled him to learn it; yet after he has known it, a solemn silence on the subject has been maintained, and beyond the fact that a stonemason is supposed to be secretly employed to close the approach to this chamber after each visit, nothing more definite is known. The strangest part of it all is the evident necessity that each successive house steward should be made acquainted with this mystery, which looks as if to him was intrusted the duty of providing food for some person or thing imprisoned in those walls of fifteen feet thickness. Whether the mystery is in any way connected with the apparition of a bearded man, who flits about the castle at night, and hovers over the couches of children, is not known; perhaps it has something to do with a figure which appeared at a window to a guest staying at Glamis Castle, and sitting up late one moonlight night. The owner of the pale face, lit up with great sorrowful eyes, seemed to wish to attract attention, but it was suddenly pulled away as if by some superior power. Presently, horrible shrieks rent the night air, and an hour or so later, the guest, gazing horror-stricken from the window of the room, saw a dark huddled figure, like that of an old decrepit woman, carrying a bundle, pass across the waning moonlight outside, and vanish.

Perhaps the most interesting legend attached to this magnificent old castle is the historical tradition that in one of its rooms Duncan was murdered by Macbeth, "Thane [pg 20] of Glamis," and this Duncan is perchance the tall bearded ghost in armour who haunts the old square tower, and on one occasion nearly frightened to death a child who, with its mother, was on a visit to the castle. The child was asleep in a dressing-room off its mother's bedroom. She herself was lying awake, when a cold blast extinguished her light suddenly, but not the night-light in the dressing-room, from whence, immediately after, proceeded a shriek. The mother rushed in and found her child awake, and in an agony of fear, because the tall mailed figure she herself had seen pass into the dressing-room had come to the side of the cot and leant over the face of the child. As a matter of fact, tradition and truth are so mixed up with all the stories connected with this very ancient fortress-palace, that it is difficult, in fact impossible, to know what to believe and what to disbelieve.

A more peaceable spirit is the Townshend ghost of Rainham, in Norfolk, commonly known as the "Brown Lady." She is described as tall and stately, dressed in a rich brown brocade, with a sort of coif on her head. The features are clearly defined, but where the eyes should be are nothing but hollows. She is seen walking about the old mansion every now and then, though no reason can be discovered to account for her restlessness. Lord Charles Townshend, on being asked by a lady if he also believed in the apparition, replied, "I cannot but believe, for she ushered me into my room last night."

The Lonsdale spirit seems to have been as rowdy in death as it was during life when it inhabited the body of Jemmy Lowther, well known as the "bad Lord Lonsdale." For years after his decease the inhabitants of Lowther Hall and the neighbourhood were kept in a constant state of excitement by continual disturbances in the house, noises in the stables, and the galloping across country of Lord Lonsdale's phantom "coach and six."

The Powys Castle ghost was a much more amiable spirit, and of quite a superior character to the devil-may-care spirit of Jemmy Lowther. His object was benevolent, and his manners were well-bred and gracious when he appeared. His last visit was to a poor pious workwoman, who, in the absence of the Herberts from Powys Castle, was purposely put by the servants in the haunted bedroom, a handsomely furnished apartment with a boarded floor, a big bedstead in one corner, and two sash windows. A good fire was made up in the room, and a chair and a table with a large lighted candle on it was placed in front of the fire. She had just sat down in the chair to read her Bible, when to her astonishment in walked a gentleman. He wore a gold-laced hat and waistcoat, with coat and the rest of his attire to correspond. He went over to one of the sash windows, and putting an elbow on the sill, rested his [pg 21] face on the palm of his hand. She supposed afterwards that he stood quietly thus to encourage her to speak, but she was too frightened. Then he walked out of the room, and the poor woman, rising from her chair, fell on her knees and began to pray. Whilst praying, the spirit appeared again, walked round the room, and came close behind her. He again departed, and again appeared behind her as she still knelt. She said, "Pray, sir, who are you, and what do you want?"

It lifted its finger and said—

"Take up the candle and follow me, and I will tell you."

She did as she was bid, and followed him into a very small room, where, tearing up a board, he pointed to an iron box underneath, and then to a crevice in the wall where lay hidden a key. These he commanded were to be sent to the Earl of Powys, then in London. This was done, though history does not relate what the box contained; but it was known that this poor Welsh spinning woman was provided for liberally by the Powys family till she died about the beginning of this century.

Though one does not associate ghosts with such a city of excitement, life, and renovation as London, yet it does possess several haunted houses. One belonging to a present-day peer, and situated in Park Lane, is said to be haunted by fashionable spirits having a dance. Some people can only hear the buzz of their voices and the swish of dresses and the tap of feet, while others can see the figures themselves talking and dancing.

Yes, there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy.

I T was only a rosetree slender

On a dingy window sill,

In the heart of the busy City,

With its mingled good and ill.

And the Angels must have seen it,

Unwilling to let it die,

For it thrived and bore a rose-bud

Under that darksome sky!

AWHITE face watched it daily

With joy in its childish eyes,

As she played alone in the garret

Under the city skies:

It brightened the dingy windows,

Each night as she crept to bed,

Though hungry and loveless and lonely,

"It will soon be a rose," she said.

T HERE at the window one morning,

The bud was a rose so fair,

But the garret was still and silent,

There was no little white face there!

It was smiling in happy slumber,

Its pain and loneliness past,

For the Angels who loved her were saying,

That the bud was a rose at last!

IT was a question of going to South Africa or running the risk of a short life in England; health dictated the question, and the answer depended on many things. Someone suggested Sandow's School of Physical Culture as a compromise; and finally England, backed up by financial and other reasoning, carried the day.

I was a puny youth, weak of spirit and frail of frame, when I first visited Sandow's muscle factory in St. James's Street, London, and said that I had come to be made into a strong and healthy Englishman—to obtain a fresh lease of life if possible.

Sandow fingered my arms and chest as he might a prize ox, and remarked that I should make an admirable subject for his purpose; he liked pulling folks out of their graves. Whereupon I imagined I should be passed into the gymnasium to swing a dumb-bell for an hour or so, and be invited to drop in again when I was next that way. But I was mistaken. Had my object been to enlist in Her Majesty's forces, the examinations and tests I was subjected to could not have been more extensive or peculiar. I was sounded, measured, weighed, pounded and questioned, the results being solemnly entered into a big ledger, as though it might all be used as evidence against me should the need ever arise. Weight 120 lbs., chest measurement 32 in., height 5 ft. 6½ in., though the latter is immaterial, as Sandow does not bargain to make one grow in that direction when nature considers her duty done.

Though I felt ashamed of the figures myself, they did not seem to affect my burly interrogators in any way, and the examination proceeded. Had I indigestion, and did I smoke? I confessed to a little of either weakness of the flesh. Was there any particular ailment in the family, and would I take a full breath and blow down this tube? As I did so, a little clock-like machine ticked merrily away, till it registered that my pair of lungs—or "one and a decimal," as a blunt old doctor had once informed me—could contain at full pressure 185 cubic inches of air—a poor record, be it said.

Next came dumb-bell and weight tests, careful note being made of the exact number of pounds I could lift with one hand, two hands, hold at arm's length, and support above my head. The record ran thus:—One hand lift, 65 lbs.; at arm's length, 18 lbs.; raised from shoulders (1) 40 lbs., (2) 35 lbs. each. Bar-bell raised above head, 85 lbs. So the examination ended, and when my photograph had been taken as a sort of example "before trying," I was free to join the little army of health-and-muscle seekers whenever I chose.

A very mixed army it was. Stern-visaged men were there going through the exercises as seriously as if life itself depended on them; sprightly veterans taking again to regular exercise, so much missed since they joined the half-pays; middle-aged men making up for the negligences of earlier days; clerks and students of all kinds going into strict training in order to be in form for the cricket and running [pg 24] season; and finally a goodly sprinkling of puny youths working hard to attain the weight and chest measurement necessary to give them another chance at Sandhurst or Woolwich, where they had just been declined "for physical reasons."

The display was not without its humour. A plump stockbroker is a common and natural enough sight in the city, but he forms a different spectacle as, minus the glossy hat and black coat of his calling, he energetically whirls a pair of dumb-bells in the frantic endeavour to exchange his superfluous avoirdupois for sinew and muscle, especially when his immediate neighbour, a very lean littérateur, is performing the same evolutions with the secret hope of putting on flesh.

It would require a keen eye, supported by a good imagination, to discover any outward visible sign of the "strong man" about the various instructors of Sandow's school, dressed as they are in ordinary attire, to say nothing of fashionable collars and the latest thing in neckties. Any one of them might have strolled in from Bond Street, mistaking the place for the club, yet any one of them would think nothing of snatching up a 100 lb. dumb-bell and raising it aloft with the ease with which most people might perform a similar feat with an umbrella.

When I presented myself at the gymnasium for my first course of instruction I was handed a pair of dumb-bells weighing not more than 3 lbs. each. I protested that I had been in the habit of using bells three times as heavy. It did not matter, I was informed,—lead pencils would be almost as serviceable, providing I concentrated my whole attention on each exercise in turn.

It must not be supposed, however, that dumb-bells do not play an important part in Sandow's system. On the contrary, as will be seen from the photographs herewith, they figure in numerous exercises, but their weight is practically immaterial. They usually vary according to the physical condition of those using them.

Having grasped his "three-pounders," the student is made to stand in an attitude of ease, the inner side of his arms fronting outwards. His very first step on the road to muscular development is to alternately bend each arm at the elbow, bringing the dumb-bell close to the shoulder. This has to be repeated some twenty or thirty times, to the measured "One, two, three," of the instructor.

The same thing is then gone through with the arms turned the other way, so that the knuckles instead of the finger-tips are brought up to the shoulders. Next the [pg 25] arms are extended outwards in a straight line, each being bent in turn at the elbow, and the dumb-bell brought immediately above the shoulder. And here comes the student's first difficulty; for in extending the arms each time it is necessary to keep them straight and rigid in order that the muscles may be benefited by the strain. It is amusing to watch various pairs of arms gradually drooping as this exercise proceeds.

Altogether the dumb-bells are used in about twenty different positions, each affecting a different set of muscles. There is the lunge, for instance, exercising both arms and legs. First standing at ease, the pupil takes a stride forward and strikes out alternately with his left and right, as though an adversary awaited the blow. Some twenty-five or thirty such lunges, however, are calculated to transform the most bellicose among Sandow's disciples into members of the Peace Society.

The wrists are strengthened in this fashion: once more extending the arms in a line with the shoulders the pupil now holds the dumb-bells by the ends, instead of in the usual way, and with a circular motion of the wrists revolves the bells first from right to left, then from left to right.

Next comes what the flippant call the "see-saw" motion. With the inevitable dumb-bell in each hand the student stands erect; the see-saw consists of nothing more remarkable than bending the upper portion of the body from side to side, without moving the lower limbs. These are cared for in the next exercise. Lying at full length on the ground, the pupil actually proceeds to kick his legs in the air! Not particularly graceful, perhaps, but highly beneficial, it is claimed, to the "hinges" at the knees and hips. What this motion does for the lower limbs, the next does for the upper part of the body. Lying at full length on the ground as before, and keeping the legs perfectly stiff, the student raises his head and shoulders from the ground, and with a quick movement swings forward until his body is bent almost double, then returning slowly to the former position. The dumb-bells are now forsaken for a time. The lesson to be learned is to support the body on the hands and toes, and to alternately lower and raise it by respectively bending the elbows and straightening the arms, taking care not to touch the ground with any part of the body. It looks and sounds easy enough; so it is, to do it once, but quite another thing to keep it up in quick succession until the instructor sees fit to cry "halt!" which is timed, it seems to the student, specially to remind him of the penultimate straw and the camel's back.

Dumb-bells are now resumed, this [pg 26] time attached to stout elastic strands, these in turn being fixed to the wall. Exercises of much the same kind as before are gone through, except that the strain on the muscles is now greater, seeing that almost every movement involves stretching the rubber bands to their fullest extent, and allowing them to return to their natural state slowly, not with a snap. The same principle is applied to the development of the legs and neck, ingenious devices in the shape of "harness"—forming an interesting branch of the system—being requisitioned for the purpose. In each case the elastics have to be stretched as much as possible, the strain being in turn centred on sets of muscles that could be reached by no other method.

If after having gone through all these exercises the pupil should pine to develop his knowledge of Physiology as well as his frame, he may learn that this little action affects the latissimus dorsi, that that tiny movement seeks out the neglected deltoid, that another bend of the body, insignificant though it may seem, means much to the pectoralis major, and so forth. But the gentle student usually prefers not to burden his brain with these things, and in this respect he is perhaps not unlike the gentle reader. So no more shall be inflicted.

Every pupil has to attend Sandow's School at least twice a week, and when there to repeat each of the exercises named some twenty times, though this number is a kind of moveable feast, advancing or decreasing with his condition, reaching as high as sixty and as low as ten. Beyond that he is supposed to practise every day at home, and regularity in this greatly facilitates the development, just as home-lessons assist a schoolboy's education. There, probably, the simile ends; certainly the majority of Sandow's followers do conscientiously work out of school hours.

When students have been got into trim generally—this takes about a month—they are allowed to add weight-lifting, with and without "harness," to their regular exercises. To do so before the body was in a supple condition might result in serious strains occasionally. A still further stage is practice on the Roman pillar. This consists of hanging backwards suspended from the knees, and from that rising to an upright position, lifting with the body a bar-bell weighing anything between 30 lbs. and 120 lbs.

Every few months examinations are held, the same tests and measurements as on entering being gone through, and the results put down side by side in the ledger, so that one's weak points can be seen at a glance and receive particular attention forthwith.

Personally, I had not been in the school a few weeks before I began to feel its benefits. The first signs were the arrival of [pg 27] an appetite and the disappearance of indigestion and insomnia. Gradually I exchanged loose flesh for firm muscle; my weight increased; my chest measurement advanced. My weight-lifting crept up by "fives" and "tens," till at the end of three months I could raise 70 lbs. with one hand, 350 lbs. with two, and 500 lbs. in "harness," all with comparative ease.

Every time I blew into the little lung-testing machine I felt apprehensive of its breaking or getting out of order under the strain. My course of instruction commenced ten months ago; at the last examination, held recently, my record ran:—One hand lift 130 lbs. (an increase of 65 lbs.). Held at arm's length 35 lbs. (increase 17 lbs.). Raised from shoulders, one hand, 90 lbs. (increase 50 lbs.), both hands, 160 lbs. (increase 90 lbs.). Raised above head 175 lbs. (increase 90 lbs.). Weight, 10 st. 0 lb. (increase 1 st. 6 lb.); chest measurement, 36 inches (increase 4 inches). Lift with "harness" 800 lbs.; without 550 lbs. Perhaps it should be added that this result was not achieved by irregular attendance at the school or occasional practice at home. I worked diligently every day on rising in the morning, and before retiring at night, and I fancy I have no need to go to South Africa now.

A little about the St. James's School itself. Incredible though it may seem, it is not a limited company. Every one connected with the place, from the manager downwards, has to go through the system. That is why the door is opened to you by a young Hercules whose clothes are bursting over him, and who, rumour says, is afraid to take them off o' nights lest he should never be able to get into them again; that is why, if you call early or late enough, you will see a muscular charwoman scrubbing the front steps to the quick time of "Sandow's March," for even she is not exempt. There is, by the way, a special course of training for lady pupils.

Every one connected with the place participates in the profits, which must be large, from the head-manager down to the two humbler individuals just mentioned. That, doubtless, is why the door is always opened to you with commendable alacrity, and may account for the fact that the front steps are the whitest in St. James's Street, and that the brasswork about the establishment positively dazzles the eyes with its gleam.

Of course Sandow has his "secret." It [pg 28] is that he does not believe in developing one part of the body at the expense of another. His aim is not to turn out pupils with runners' legs or rowers' arms, but of good physique generally. If a runner enters the school his legs are naturally better developed than the average. They will, therefore, require less attention than usual, and more will be given to other parts of his body. And so forth.

The exercises are so devised that no set of muscles in the body is overlooked. In the ordinary course they are all developed together, at much the same rate; but this, of course, cannot always be adhered to. It frequently happens that a pupil desires chest expansion above all else, in which case he will devote himself primarily to the exercises specially framed to bring about that result. In several cases a couple of inches in the way of chest measurement has stood between pupils at Sandow's and commissions in Her Majesty's army.

Much depends, Sandow avers, on mind concentration.

"It is of little use," he says, "going through the exercises mechanically. As each one is performed, it should occupy the whole attention. Merely swinging a dumb-bell the regulation number of times will do no good. It should be regarded as serious work, and one's heart should be in it. It has not been my aim to produce what are known as strong men; it is a comparatively easy task to pick out a few men exceptionally endowed by nature, and train them until they attain great proficiency in particular feats of strength and activity. It may be considered somewhat ambitious, but my honest desire is nothing less than to permanently raise the standard of physique in the whole race, and to restore, as far as possible, the old types of physical strength and beauty, for the loss of which civilization is so largely responsible."

One naturally asks: What is the age limit at which physical development necessarily ceases? Perhaps Sandow's school-register best answers the question. His pupils range from fourteen to seventy-three. The gentleman of the latter age felt so rejuvenated after one week's attendance that he promptly put himself down for a whole year's course, and has since declared his intention of "never leaving school" until old age compels him.

It is interesting to recall how Sandow first came before the public as an exponent of strength. Some nine years ago it was [pg 29] the practice of a "strong man" then performing at a London theatre of varieties to issue nightly from the stage a challenge to the world generally to accomplish any of his feats, which included the lifting of great weights, the snapping of steel chains, and the bending of iron bars. One night, to everyone's surprise, the challenge was accepted by a member of the audience, and a young man stepped upon the stage in immaculate evening dress. When this was removed the customary attire of the stage "strong man" was revealed. It was Sandow, then unknown.

Amid the wildest excitement he performed every one of the wonderful feats. The next day a new "strong man" had dawned.

It is Sandow's ambition to start schools of muscular development in all the principal cities and towns in the kingdom, and if they become as popular as those in London, there is hope for the country, physically, yet. The tendency of the Englishman, since he acquired the habit of living in towns, has been to take too little exercise. Roast beef and Sandow may do more for the race than the former ever accomplished alone.